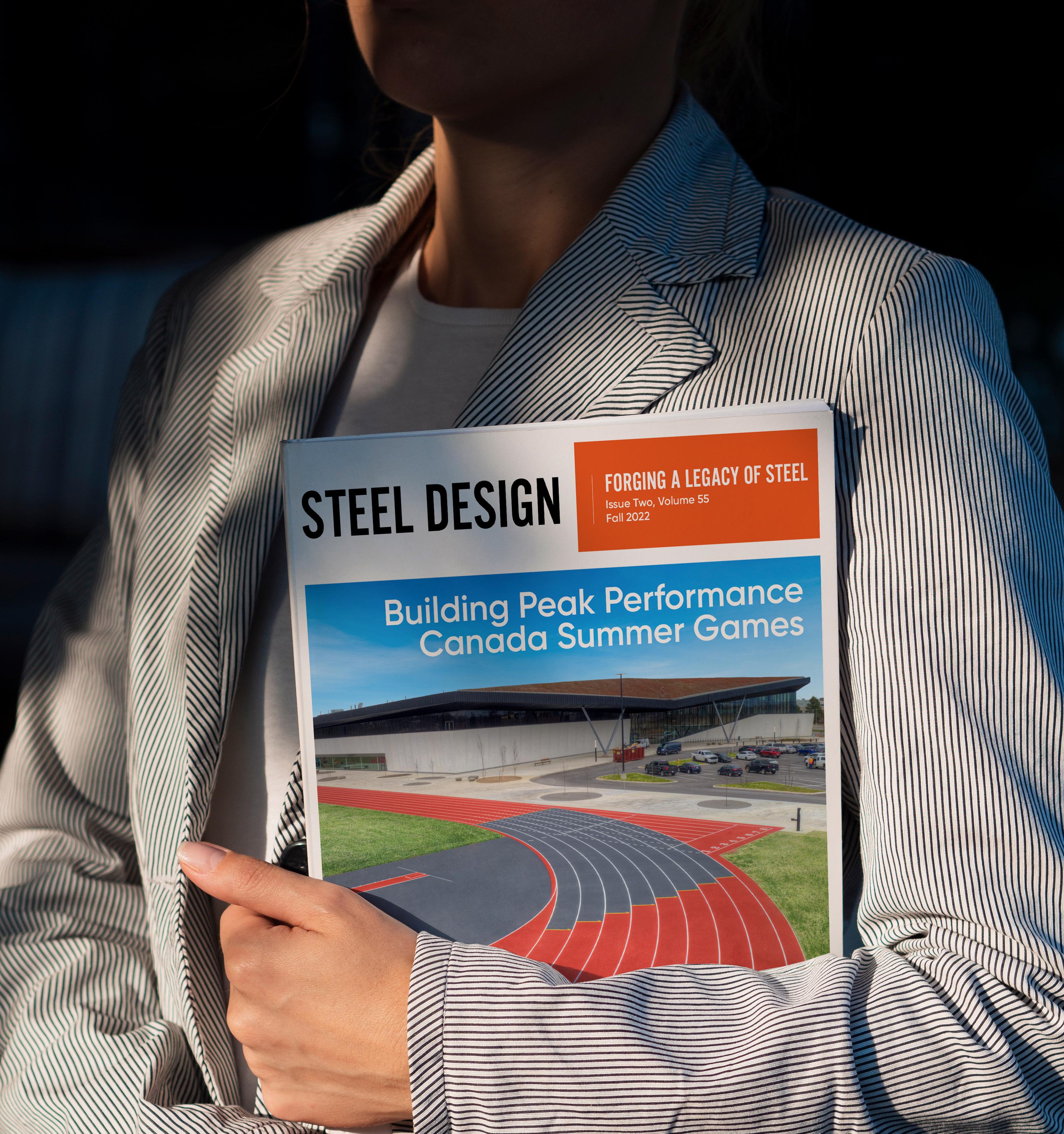

Rethinking architecture through a sustainability lens.

An exclusive interview with AIA Gold Medal winners Angela Brooks and Lawrence Scarpa.

Lisa Landrum and Darryl Condon report on the progress towards a National Architecture Policy.

Best practices for implementing carbon budgets in new and exist ing buildings in Canadian cities.

Bringing prefab panellized deepenergy retrofits to Canada.

Advanced MEP systems help reduce the operational energy of buildings but is the high embodied energy cost worth it?

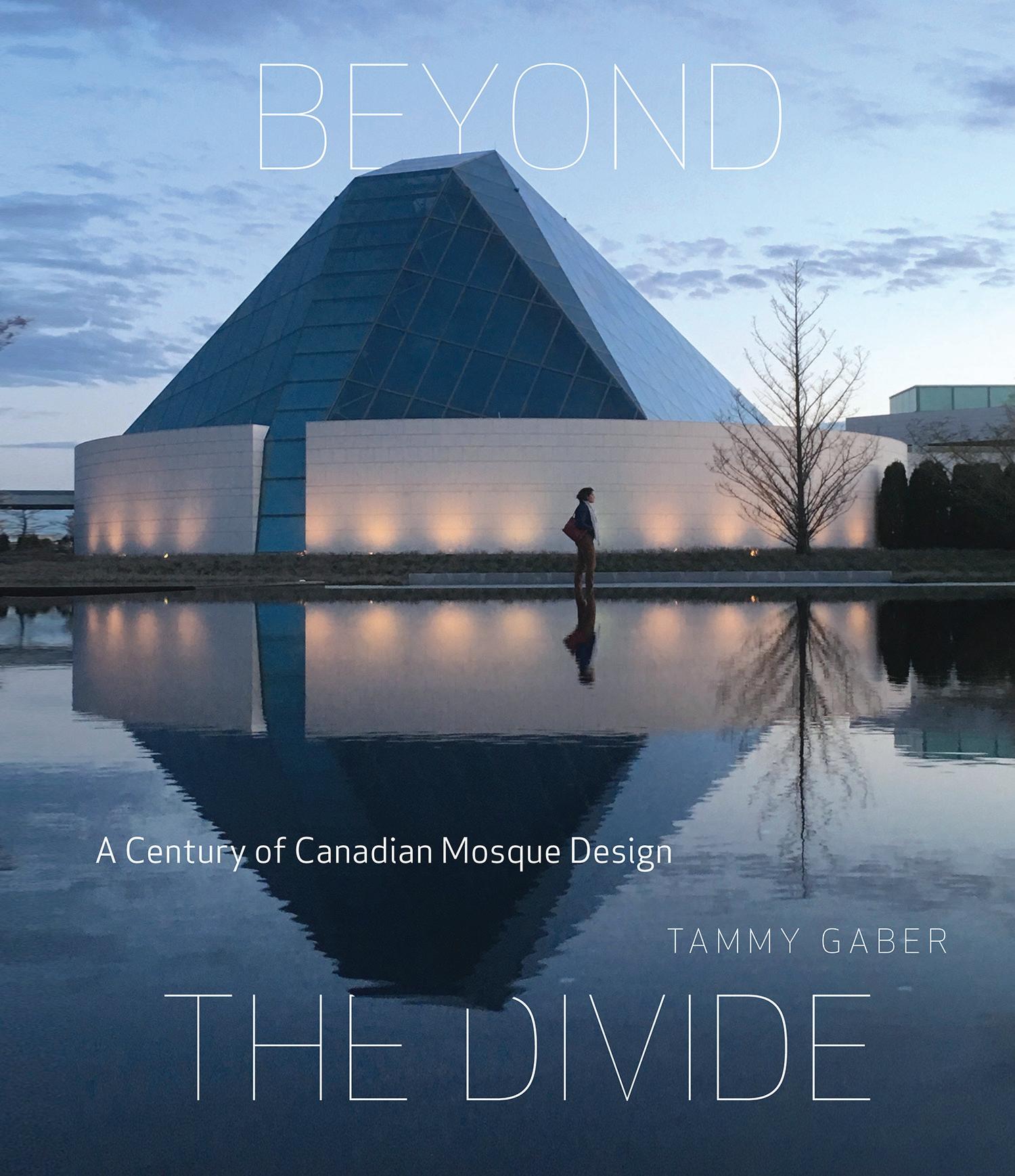

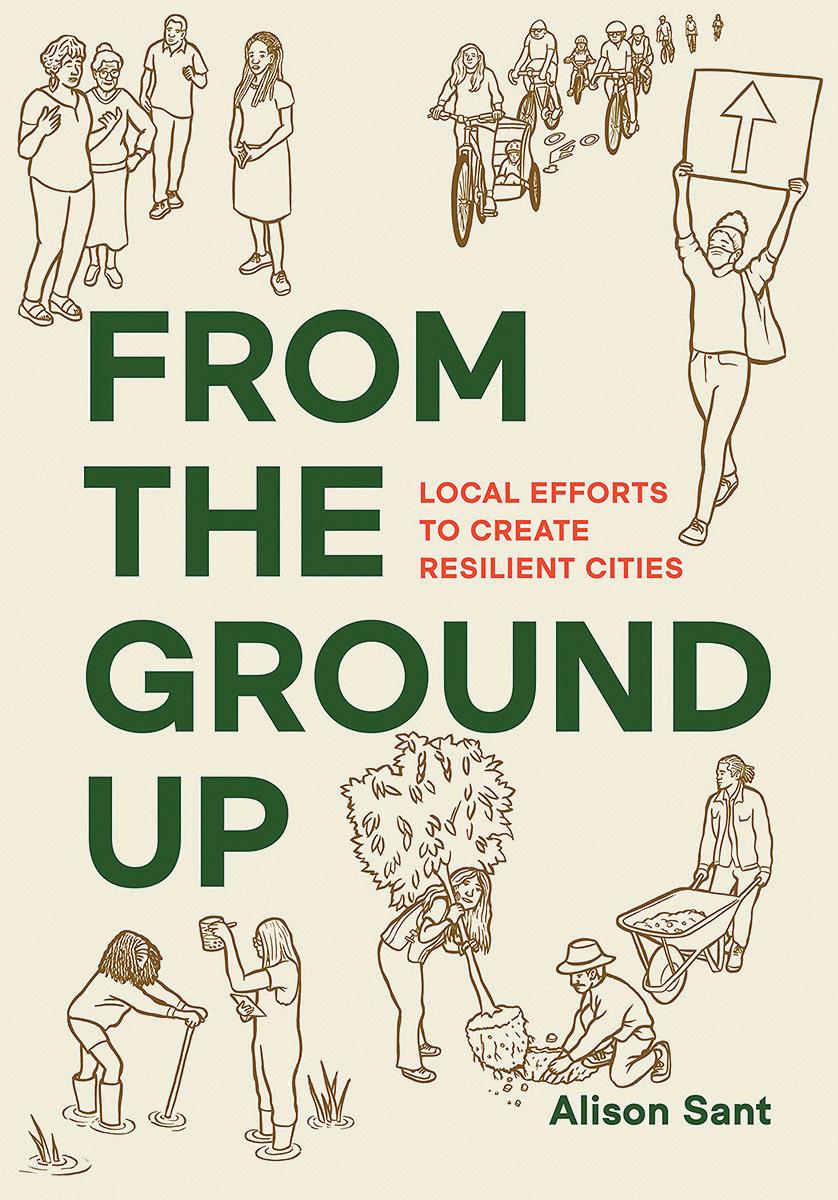

A memoir by Jack Diamond, new research on Canada’s mosques, and local resiliency efforts.

Sputnik Architecture’s passion project to revive local ice har vesting and sculpting practices.

COVER Centennial College Downsview Campus Bombardier Centre for Aerospace and Aviation, Downsview Park, Toronto, Ontario, by MJMA Architecture & Design + Stantec — Architects in Association. Photo by doublespace photography.

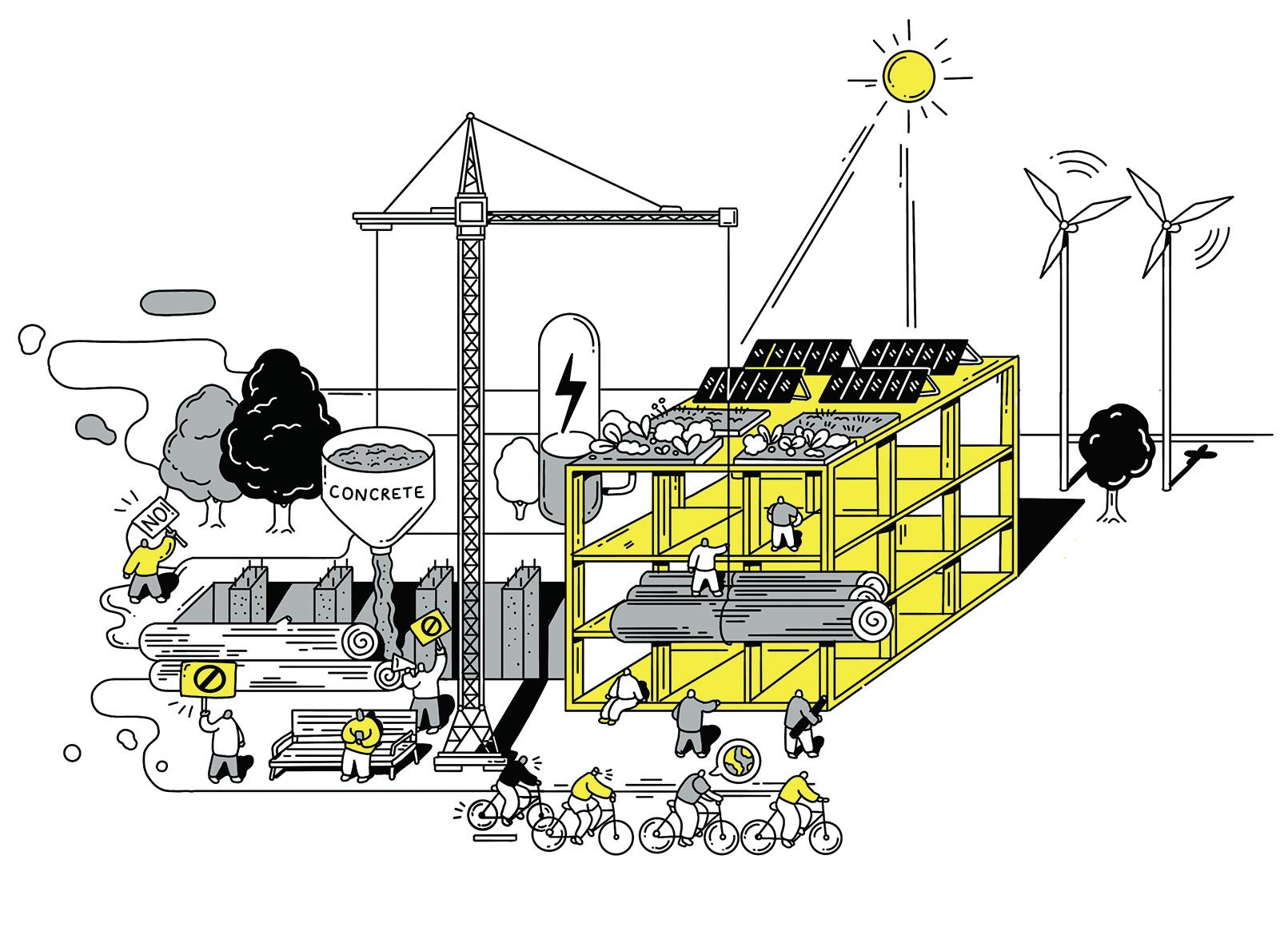

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2022 report focuses on the impacts of climate change, and the capacities of natural and human systems to adapt. Among its find ings, it notes how the implementation of lowcarbon practices within specific sectors— including buildings—is key to mitigation.

The report highlights strategies such as using more wood in buildings to lower emissions, the wide deployment of green roofs in urban areas to reduce extreme heat, and using passive design strategies for heating, cooling, and ventilation.

But there are also implicit trade-offs: for in stance, enhancing space conditioning in build ings can tame the health risks of extreme heat, but comes with a carbon cost. Tightly sealed buildings reduce energy consumption, but may also lead to moisture build-up in envelopes. Increased insulation without shading and ventilation can come with a lowered ability to benefit from nighttime cooling. And while policy changes can be effective, they can ex acerbate inequities. “Changes to design stan dards can scale quickly and widely, but retrofit of existing buildings is expensive, so care must be taken to avoid potential negative impacts on social equity,” write the report’s authors.

Altogether, “building today for resilience and lower emissions is far easier than retrofit ting tomorrow,” notes the report. Some $90 trillion USD is expected to be invested in new urban development by 2030. It’s “a global op portunity to place adaption and mitigation dir ectly into urban infrastructure and planning,” write the report’s authors. “If this opportunity is missed, if business-as-usual urbanisation persists, then social and physical vulnerability will be not so easily confronted.”

These issues were top of mind for speakers at the Facades+ conference, which convened in Toronto this summer. While many individual architects and researchers are developing exper tise in highly sustainable construction, how do we instigate a change in construction culture, so that higher performance buildings are the norm, rather than the exception? Can we create build ings that radically reduce their reliance on— or entirely eliminate—mechanical heating and cooling? And how do we balance operational energy efficiency with sharp reductions in the embodied energy needed to create buildings?

“We cannot continue with a myopic focus on operational energy, full stop,” said Kelly Alv arez Doran, Senior Director of Performance &

Provenance at MASS Design Group. As director of the Ha/f Research Studio at the University of Toronto’s Daniels Faculty, Alvarez Doran has led research on how to halve the embodied car bon emissions of new buildings in Toronto, using currently available materials and technology.

With his students, he has identified key drivers of high embodied carbon in Toronto’s mid-rise residential buildings—including underground parking areas (made with high embodied-carbon concrete) and aluminum extrusion-based glazing systems (the highest embodied global warming potential by volume of all materials in their study). They’ve also done a deep dive into mass timber buildings, revealing substantial upfront and operational emission reductions achieved by reducing window-to-wall ratios and incorporating mass timber into façades.

Considering façade construction, panellist Cathy McMahon, of Moriyama & Teshima Architects, asked: “How can we be growing the things that clad our buildings rather than extracting them from halfway around the world?” Her firm is collaborating with Acton Ostry Architects on Limberlost Place, under construction for George Brown College in Toronto. They’re aiming to achieve both low operational and embodied carbon: the 10-stor ey building boasts a mass timber structure and was originally designed with terracotta tile cladding (later revised to metal panels due to weight), and has a projected thermal energy demand of 54 kwh/m2/year.

The project team is also geared towards sharing knowledge around the project’s de velopment and design: a three-hour workshop on the afternoon of the conference detailed the technical decisions, construction coordination, and technologies used to design and manufac ture Limberlost’s high-performance prefabri cated façade system. Its structure, too—a beamless system that achieves nine-metre column-free spans, an optimal depth for daylit classrooms— is a non-proprietary system developed by Fast+Epp. “Anyone in Canada can use this,” said Phil Silverstein of Moriyama & Teshima.

We’ve packed this issue of Canadian Architect with recent research and practices in low-carbon construction that we hope will be useful to your work. To move with the speed needed to ad dress the accelerating climate crisis, we will need to learn from each other—and work together.

Summon your ultimate shower with a touch. With the intuitive design of digital controls, supreme power over water is now at your fingertips. Even Poseidon is impressed.

Montreal-based Les architectes fabg has been selected to design the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec’s Espace Riopelle. The new pavilion will house the world’s largest public collection of works by Jean Paul Riopelle.

The firm was selected through an international competition launched in March. Their design echoes Riopelle’s creative journey by taking shape as a dynamic, climbing path through a signature building. The circuit will culminate in a circular space devoted to Riopelle’s master piece, L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg (1992), where visitors will also enjoy views onto the Plains of Abraham and the St. Lawrence River. Wooden ceilings evoke the artist’s studio, while the pavilion's green terraces will reflect the Isle-Aux-Grues landscape.

The Chair of the Board of Directors of the Riopelle Foundation, Michael Audain, together with a group of Canadian philanthropists, has donated $120 million in works and funding for the project.

The new building is slated for opening in early 2026. www.mnbaq.org

Designed by Moriyama & Teshima Architects and Bélanger Salach Architecture, Northern Ontario’s first multidisciplinary Francophone arts centre, Place des Arts, has opened in Sudbury.

The building includes a 300-seat theatre, a multi-use studio per

ABOVE Les architectes fabg’s winning design for Espace Riopelle, a new pavilion for the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec.

formance space, a contemporary art gallery, library and national pub lishing house, boutique, bistro, daycare, and offices.

“The architecture of Place des Arts expresses the long history of the Francophone arts community in the Sudbury Region,” says Brian Rudy, Partner at Moriyama & Teshima Architects. “With its sculptural form, the building calls out an invitation to the community, while the use of natural materials such as weathered steel and wood, along with the art istic reuse of historic artifacts on the interiors, provides a welcoming patina and speaks to the deep-rooted presence and hospitality of the community.” www.maplacedesarts.ca

The winners of the Prairie Design Awards, originally scheduled to take place in 2020 but postponed due to the pandemic, have been announced. The awards recognize the top architecture, interior design, landscape, small projects and student projects across the prov inces of Alberta, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan.

Awards of Excellence were given to: Qaumajuq / Inuit Art Gallery in Winnipeg by Michael Maltzan Architecture (Design Architect) with Cibinel Architecture (Associate Architect); Capilano Library in Ed monton by Patkau Architects and Group 2; and the National Music Centre in Calgary by Allied Works in association with Kasian Archi tecture, Interior Design and Planning.

Awards of Merit in the category of Recent Work went to 62M in Winnipeg by 5468796 Architecture; Grow in Calgary by Modern Of fice for Design and Architecture; Kathleen Andrews Transit Garage in Edmonton by gh3* (design architect) with Morrison Hershfield (prime consultant); Parkade of the Future in Calgary by 5468796 Architecture in collaboration with Kasian Architecture, Interior Design and Planning; Manitou a bi Bii Daziigae at RRC Polytech in Winnipeg by Diamond Schmitt Architects in joint venture with Number TEN Architectural Group; Windsor Park Library in Winni peg by david penner architect + h5 architecture.

In the category of Interior Design, Awards of Merit went to Attabot ics Headquarters in Calgary by Modern Office of Design and Archi tecture and Snider Orthotic Design in Winnipeg by 1 x 1 architecture.

Landscape Architecture Awards of Merit were given to 5th Street Underpass Enhancement in Calgary by the marc boutin architectural collaborative, Manitoboggan in Winnipeg by Public City Architec ture, and Paul Kane Park Redevelopment in Edmonton by GEC Architecture.

Two Small Projects Forest Pavilion in Winnipeg by Public City Architecture and Rainbow Butterfly in Winnipeg by a group of In digenous designers at Brook McIlroy also received Awards of Merit.

The jury included James Brittain, D’Arcy Jones, Bruce Kuwabara, Elsa Lam, Lola Sheppard, and Mark van der Zalm, and the program received 166 submissions. www.prairiedesignawards.com

The Northwest Territories Association of Architects has announced the winners of its 2020 Architectural Awards and Architectural Photog raphy competition.

The program’s top distinction, the Awards of Honour, went to three projects by Taylor Architecture Group: Łutsel K’e Dene School Addi tion/Renovation, Kugaaruk Hamlet Office Community Hall, and Liard Highway Welcome Pavilion. The firm also received Awards of Merit for Łutsel K’e Dene School Landscape Design and Gjoa Haven Hamlet Office. Stantec Architecture’s Iqaluit Aquatic Centre was also recognized with an Award of Merit.

Citations were awarded to the MacBride Museum Addition & Reno vation in Whitehorse by Kobayashi + Zedda Architects, the Iqaluit International Airport Improvement Project by Stantec Architecture, and the Haines Junction Lift Station by Stantec Architecture.

All our architectural products serve a distinct, functional purpose. From louvers to wall coverings to every detail we perfect. But, at the same time, we never lose sight of the a ect a building has on people. The inspiration it provides. The satisfaction it brings to all who enter. For 70 years, we’ve based our success on the idea that putting people rst is the foundation for building better buildings. And, for 70 years, our partners have depended on us for architectural product solutions. Are you ready to think beyond the building with us? Visit c-sgroup.com.

The second edition of the NWTAA’s architectural photography com petition recognized photographs by Patrick Fung and Wayne Guy. www.nwtaa.ca

Landscape designer, scholar, activist and educator Jane Wolff has received the 2022 Margolese Prize. The $50,000 award recognizes a Canadian designer in early to mid-career whose work and advocacy in the built environment address the pressing human and environmental challenges of our time and improve peoples’ lives and communities.

Wolff, a professor at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto, works to build collective understanding around landscape design’s role beyond its physical presence. She designs playful tools that encourage people to understand and participate in the future of landscapes that surround them capabilities urgently needed in a rapidly changing world.

“Jane Wolff’s work on landscape literacy has had a significant im pact on our collective understanding of critical environmental issues,” writes the jury. “Her human-centric tools of writing, hand drawing and public engagement reach a wide audience without compromis ing the complexity of the subject matter.”

Wolff’s work includes the Gutter to Gulf website, an open-access tool that explains the history, engineering, and possibilities of New Orleans’s water systems; Bay Lexicon , a visual dictionary about San Francisco’s shoreline that reveals the implications of sea level rise; Delta Primer, a book and deck of playing cards that describe the fiercely contested ecosystem of the California Delta in terms that transcend the usual boundaries of interest groups; and the co-curation of the Toronto Land scape Observatory, an interactive exhibition that invited Indigenous and settler knowledge keepers, scholars, and artists to create instruments for observing the environment.

www.margoleseprize.com

Moshe Safdie has donated his professional archive to his alma mater, McGill University, and pledged his personal apartment at Habitat 67 to ensure that it remains a resource for the university, and the public at large.

“I have always valued the great education I received at McGill that has guided me through my professional life. Moreover, Canada has em braced and supported me, making possible the realization of several seminal projects. It is therefore fitting that McGill, Quebec, and Can ada will be the home of my life’s work,” says Safdie.

The archive features over 100,000 pieces, including loose sketches, sketchbooks, models, drawings, and correspondence related to unbuilt and built projects across the globe.

The original model and master copy of Safdie’s McGill undergradu ate thesis, ‘A Case for City Living’, which inspired his design for the Habitat 67 residence, is also included.

Safdie’s personal apartment at the Habitat 67 housing complex will be the centrepiece of the archive. The four-module duplex unit will serve as a resource for scholarly research, artist-in-residence programs, exhib itions, and symposia, thereby expanding the impact of the collection.

Fondation Habitat 67, a non-profit foundation, will collaborate with McGill on the preservation and maintenance of the apartment as part of its mandate to promote the property for public educational activities.

“On behalf of the McGill community, I would like to express our

gratitude to Moshe Safdie for his remarkable gift,” said McGill Principal Suzanne Fortier. “This is a historic moment for McGill. One of the most influential and important architectural archives in the world, from one of our most celebrated graduates, will forever be a part of our University.” www.mcgill.ca

Carleton University’s Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism has appointed architect, historian and educator Anne Bordeleau as its new Director for a five-year term commencing on January 1, 2023. Bordeleau spent 15 years with the University of Waterloo’s School of Architecture, where she served as O’Donovan Director since 2016. Her teaching, research and practice have covered many fields, from nineteenth-century architectural history and theory, to modern cultural history, to accessibility and the broadening of the discipline. She is one of four principals who worked on The Evidence Room , an exhibition in the central pavilion of the 15th Venice Architectural Biennale in 2016.

In her roles within the university as well as across multiple organiza tions in Canada and beyond, Bordeleau has been been looking at the ways in which architectural education and organizations frame our idea of the architect as well as architecture’s role in society. architecture.carleton.ca

According to a recently released Statistics Canada report, “Forging Ahead During the Pandemic: How Selected Service Industries Bounced Back in 2021,” revenue from architectural services made a strong comeback

last year. The report shows that revenue for architectural services rose 15.4 per cent, surpassing pre-pandemic levels by more than 1/10. Much of this growth can be accounted for by residential construction which hit an all-time high in 2021 as well as business and public investment in non-residential buildings.

In 2021, residential construction made its largest contribution to gross domestic product since comparable data became available in 1962. “Low interest rates and the need to accommodate teleworking boosted housing starts by 24.5 per cent to 271,198 units in 2021, with both single and multiple dwellings in high demand,” says the report. “In addition, busi ness and public investment in non-residential buildings posted strong growth, further strengthening the demand for architectural services.”

The report also noted how specialized design services benefit from retrofitting of physical spaces and improving economic conditions.

“The pandemic disrupted many facets of how businesses and the popu lation in general interact in physical spaces. Specialized design services, mainly interior design services, helped people connect and improve vir tual and physical interactions and experiences, in terms of both lifestyle and business,” it notes.

The website of the Ontario Association of Architects (OAA) includes a 2018 report by Altus Economic Consulting that confirms economic activity from the architecture industry’s entire footprint in Ontario to talled $128.4 billion, or 14 per cent of the province’s GDP www.statcan.gc.ca / www.oaa.ca

For the latest news, visit www.canadianarchitect.com/news and sign up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.canadianarchitect.com/subscribe

We’ve welcomed four on trend colours to our Architectural Series family, starting with Creekside, Shadow Ridge, and Spring Hill, each in matt and velour finishes. These sophisticated, neutral tones lend modern elegance to commercial and residential projects. Our new White Ash brick, featuring an iron spot finish, delivers a light brick with a hint of old-world character.

Savings by Design

Youdale,

Development

Success Story

OttawaPassive House

Housing

ne of the common threads woven throughout the AIA National Confer ence held in Chicago this June was that of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion. DEI considerations have become more and more prevalent in how we structure our teams to better mirror the clients that we serve. But this is only the initial mechanism for steps we must take to truly make a difference in our built environment.

I was in attendance for Angela Brooks and Lawrence Scarpa’s acceptance of this year’s AIA Gold Medal. They were celebrated in part for their deep portfolio that models the possibilities for centering social purpose with in complex and beautiful design responses. In recognizing them, we have the opportunity to find inspiration and to realize what is indeed possible when we blend policy commitment with great design. Brooks and Scarpa work to shift the conversation with neighbours, chang ing the perception that all affordable housing and its occupants are undesirable. Instead, they demonstrate that thoughtful design brings value to both the neighbourhood and the residents.

My greatest takeaway was a reminder of architecture’s power to either help or harm people. There is no turning back the tidal wave of awareness that came upon us with the #MeToo movement, Black Lives Matter, and inaction on the Truth and Recon ciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, among many other issues. The time is now to make an immediate plan of action on how archi

tects can get involved in the larger commu nity, along with non-profits and change agents, to leverage the best outcomes for socially minded work.

AIA Canada Society’s Director of Diversi ty, Equity and Inclusion, Pauline Thimm, sat down with Angela Brooks and Lawrence Scarpa to discuss their path to bringing poet ry to problem-solving in the built environ ment. We have also included a profile of the AIA’s Housing and Community Development Knowledge Community for some readily available resources to support our members’ journeys along one branch—affordable hous ing—of design inclusivity and equity.

The AIA Housing and Community Development Knowledge Communi ty (HCD) is a network of approxi mately 12,000 architects and allied stakeholders that promotes equity in hous ing, excellence in residential design, and sustainable, vibrant communities for all, through education, research, awards, and advocacy. Their mission is to track housing issues and develop relationships with indus try stakeholders to encourage and promote safe, attractive, accessible, and affordable housing for all.

Each year, the HDC sponsors an awards program that emphasizes the importance of good housing as a necessity of life, a sanctuary for the human spirit, and a valuable national resource. The jury evaluates entries relative to the AIA Framework for Design Excellence, with considerations including equity, resilience, innovation and delight.

Following this year’s announcement of award winners, a moderated panel discussed the winners’ approaches to addressing various challenges through design. Panellists discussed the design criteria used as the basis of selec tion, including the role of housing as an oppor tunity to rethink diverse forms of living, inno vating to combat shortages, and how to pro mote sustainable, responsible designs.

The Housing and Community Development Knowledge Community’s seminars are avail able for AIA and AIA Canada Society members to view at no cost. aia.org/hcd

AIA Canada Chapter Board of Directors has openings for both the Treasurer and Secretary positions commencing January 2023. If interested, please reach out to Rommy Rodriguez at rommy@aiacanada society.org for a nomination form. Nomi nations are due October 31, 2022.

The submission deadline for this year’s AIA Canada Design Awards is October 28, 2022. Winners will be published in the AIA Canada Society’s Journal, within the pages of Canadian Architect. Two winners will be selected to participate in the 2023 awards program with the AIAI at no addi

tional cost. Submission categories include: Architecture, Interior Architec ture, Special Projects, Urban Design, Community Engaged Design (new catego ry—entry fee waived) and Student. The winning student will receive a $1,000 scholarship.

the artistic endeavour. They don’t need to be mutually exclusive. We consider ourselves artists—plying our trade to the highest stan dards—and we also do it with purpose.

ideas. I was a frustrated urban planner—I just didn’t know it then!

In those early years, we worked together on ‘fun’ things—like competitions—on the weekends. We eventually started working together, first with another partner until 2010, and then with just the two of us as partners for the last 12 years.

AB: We work with non-profit developers [such as Livable Places] who tell us that good design makes people heal. It doesn’t necessarily cost more to design well, in fact, it often costs less because you are design ing in a way that is reflective of a symbiotic relationship to how people really live.

The winners of the 2022 AIA Gold Medal, the organization’s top award, are Angela Brooks, FAIA and Lawrence Scarpa, FAIA, co-founders of the Hawthorne, California–based firm Brooks + Scarpa. Those famil iar with their work will not be surprised to learn that this well-deserved honour has been over 30 years in the making—with much more in store.

AIA Canada Society’s Pauline Thimm caught up with Angela Brooks and Lawrence Scarpa this July to find out more about what they stand for, how they have evolved, and where they are going.

Pauline Thimm: On behalf of AIA Canada, I am thrilled to congratulate you on your Gold medal win. At this moment of intense interest, how would you like people to know you?

Lawrence Scarpa: We want to be known as ‘artists who are citizen-architects’. We really believe that good design is for everyone. Art and craft are important, and that has always been part of the artistic mission, but purpose is equally important. We work with purpose.

Angela Brooks: Not everyone knows that we did not start out working together. We first met in architectural school in Florida, and moved to California after school. Larry started a small practice with another part ner. I started out working for a non-profit development company, to get a more prag matic understanding of how communities are developed. I was never really interested in only designing a singular building—I’ve al ways been interested in exploring the bigger

LS: I also worked with Paul Rudolph early on. I used to dig out archived drawings when we worked with historic structures. They were incredible to see—sometimes just four sheets, with simple notes like “contractor to build best quality possible.” We can’t even do general notes like this anymore, let alone an entire drawing set. It is really a different world, and it requires a team effort. It takes a lot of expertise; it takes a combination of strengths in many, many areas. As a firm, we think of ourselves as a small soccer team that comes together around projects—every body does everything at Brooks + Scarpa. Angie and I complement each other with real and equal strengths and interests. Now we work alongside each other every day. Thinking how to work through a project, Angie starts off with the big-picture context, I take it through the design stages, and Angie closes it—she is so detail-oriented.

AB: I believe that in another life, Larry would have been a sculptor. He is a true artist— and he is always designing.

In our current era, there is an emerging recognition of social purpose in architec tural awards—with this AIA Gold Medal, as well as with recent Pritzker Prize winners. How do you see this evolution, and how do we keep moving forward from here as a profession?

AB: There was also this year’s AIA Firm Award for MASS Design, as part of this increased recognition of social equity and climate justice.

LS: We are just doing what we think is right. We are lucky that people think that what we have done—and continue to do—has mean ing. The aspect of doing work that matters for other people is equally as important as

AB: Our profession has so much to give back to our communities, but often by the time architects get involved, all the big decisions have been made. We have always felt that we could make a bigger impact designing for under-resourced people and communities. And now we know that’s true.

LS: It’s not just for—or about—us, it’s for the greater good. We’re lucky that the stars align now, and that others think this approach is important too. It’s a great trend.

You’ve noted that you don’t want Brooks + Scarpa to be viewed as a brand, and you eschew labels. Why is this important? How does this impact the work you are able to do?

LS: Everyone wants to pigeonhole design ers today—as school designers, affordable housing designers, etc. We’ve always been interested in doing a lot of different things— there is a lot to learn and contribute. Our goal is: “Don’t plagiarize yourself!” This can hap pen when you get branded and end up doing the same thing repeatedly. It can sometimes lead to having less and less impact.

AB: Sometimes, when working on a project type you’ve never worked on before—you can bring a fresh perspective.

LS: It’s not rocket science to do different ty pologies, but we aim to do it well. We tend to pick the things that are not seen as glamour ous and where the existing work is often re ally bad. In affordable housing, for example, we initially thought it wouldn’t take much to be a hero; we found out it wasn’t easy. We like those kinds of challenges—when it is not just about the design potential, but the chance to provide good design to those who don’t ordinarily get it.

AB: I’ve asked Larry, “Can’t we just do the same project type twice? Do we have to

Top: The SIX is a 52-unit affordable housing project in L.A. that provides a home, support services, and rehabilitation for disabled veterans. It includes generous public areas, including a large raised court yard, that encourage community-oriented living. Above: Located in Santa Monica, Colorado Court Housing is a five-storey affordable housing project that is designed to be 100-percent energy indepen dent, providing a model for sustainable living.

do something completely different every time?” I realize now how our approach has made Brooks + Scarpa stronger, though. Because we have such a diverse range of project types, and as a team we represent a lot of different interests, our diversity has helped us weather adversity. We survived the 2006 recession because we had so many different things happening—it’s what kept us going.

The rigour and discipline brought to your work is really apparent, as well as a deep sense of curiosity. The inherent beauty of

the resulting design response is so often complex and layered. What feeds your curiosity?

LS: I’m always interested in finding a better way. And I teach. I tell my students, “I am here to learn as much as to teach.” I’m inspired by how students take the most mundane things and turn them into a design prob lem. It’s always interesting and usually not something I would have necessarily thought about. I am always learning something.

It’s also important to always be aware of what is right in front of you—to try to tell

the story of what is already there. There is so much to learn right in front of your face!

AB: And we bring our strength as big-idea thinkers. It’s so hard to take an idea from concept through to construction. Everyone who works with us is a good designer who sees and knows what good design is—they all understand. This is how we are able to consistently deliver on our big ideas, even if there has been an evolution of the details.

Can you build on that notion of delivering the big idea and talk a little bit about your design process, including how you give voice to the user? Do you engage in post-occupancy evaluation as part of your process?

AB: Brooks + Scarpa is really good at carry ing the key design thread through a project. We would never give the construction phase to someone else—we are involved all the way through. Even after construction is complete, we’ll go back to the client and see how things worked out. We really like surveys—and not just those that are sustainability-focused for the energy side of the analysis, but also sur veys for the users. We ask: How is it working? What do you like? What don’t you like?

We translate this thinking and this feedback beyond the building to its context— constantly thinking about the larger view, the bigger ideas around the projects and in the neighbourhoods where we are putting people. When we create multi-family hous ing, dense housing, and affordable housing projects, we really want it to be near transit, or in commercial areas or zones. We are constantly telling the story of how neigh bourhoods are for everyone.

Our profession could do a better job of telling the story about how communities can look in the future and how they can be better. Then those deciding where transit goes, how wide streets will be, and how dense projects can be around transit will actually see that this is where we could go.

Our commitment to the follow-up has created a lot of repeat clients for us. The message is that beyond good design, we are shepherding the process all the way through, and we are going to make this work for you in the best way possible, so you will end up with a great, well-designed project. We really care about that. And we know this means a lot to our clients as well.

You have spoken about how you’ll often come to a project and rework the design problem, as a way to address the big

good design. We believe that if you do these common sense things that make a place good to live in, the building will have longev ity. If it’s just an exercise in form-making, it’s not as likely to have a long life.

I like to quote James Wines [architect and founder of SITE Environmental Design] who in essence says that a building that is an energy hog that everyone loves is ultimately more sustainable than a net-zero building that no one likes or wants to live in. In other words, if anything is to have longevity or sustainability, it has to be loved. It comes down to fact that good design matters. If you can inspire people with what you do, they will love it and care for it. If you don’t treat it that way, it will not last.

Is there a design problem out there you are dying to get your hands on?

The Unplanning Miami research project investigates a new framework for urban design and architec ture that uses amphibious strategies to adjust to rapid sea-level rise—a necessity for adapting to cli mate impacts in South Florida.

picture. How do you tackle that, so that the design problem is understood to be more holistic and community-based? How do you bring clients along on that journey?

AB: It really depends. Effecting change is sometimes hard to do on a single project, so we’ve created projects for ourselves. We get involved in really knowing the policy context, the zoning code. We take our lumps, and always ask how we can do better next time. It usually comes down to the ability to change the code in some way, or finding additional money. For our Colorado Court housing proj ect, Larry found half a million dollars of un used grant money with the utility companies that could pay for the project’s solar panels.

LS: Brooks + Scarpa wrote the Small Lots Ordinance for the City of Los Angeles [passed in 2005 to regulate the construc tion of single-family infill housing and restore small lot development] and we have affected state-level policy change on the energy code. It took threatening to sue the state, and enlisting state representatives to agree it was a good idea. We believe the effort is worth it—getting a policy change in place changes it for everyone. We also real ize that, for better or worse, policy is not permanent—in fact, it is less permanent than the buildings themselves.

AB: We’ve found that when clients see that you are all-in, that you will do what you need

to do to get it done, people tend to get onboard and help you. They see you are work ing towards a vision that it is bigger than just a project. A recent example, in our era of mass shootings and hardened schools, is the need to deliver projects that are fullysecure—with bullet-proof glass, gates, etc. It’s about showing the client how there can be multiple solutions—that through design, you can make a project feel really open and look really open, yet be completely secure.

LS: It’s not always easy, sometimes you have to wear them out. You need a bag of tricks. And sometimes you still lose.

AB: We are persistent. We show our clients that we will figure out a way to make it work.

Thinking about the life of a project, and how inhabitants and the building will function in the future, how do you approach design solutions tuned for the next 100 years?

AB: The way we approach and talk about projects really depends on who the owner is, and their stake. Long-term owners are often easier to talk with—they want a build ing that will last into the future.

LS: We focus on things my grandmother would say are just good Jewish common sense: natural light, cross-ventilation. We know these elements are the foundation of

LS: Climate change—sea level rise and coastal areas, specifically. Our Founding Peoples have always lived near water. We need water to survive. We are at a time now where all major places to live that are near water are on track to a catastrophic future. Brooks + Scarpa has spent the last five years writing an elaborate manual for coastal adaptation for the east coast of Florida, where sea level rise issues have been occurring for over a decade.

AB: The City of Fort Lauderdale hired us because they wanted creative minds who would think outside of the box—they wanted experts to apply design thinking to the complex problem. They enlisted designers to lead multidisciplinary teams of coastal biologists, engineers, and others to really think about what the future will look like.

This is the type of complex problem that architects can lead. We have the design pro cess and vision to bring everyone else along. We have the capacity and skill to be not just problem solvers—but to be problem-setters. We are the ones who can identify the true nature and scope of the problem into the future, and then start to think about how we can go about solving it now.

It would be great if more of us could get involved in the design of infrastructure. As architects, we are ideally suited and should be involved in this bigger picture context, and in visionary future-thinking. This is where the profession can start to evolve and grow.

Architect Pauline Thimm is an Associate at DIA LOG, and AIA Canada Society’s Director of Diversi ty, Equity, and Inclusion.

Since 2016, a task force of Canadian architects and educators has been mobilizing conversations on the future of architecture and developing a framework for an architecture policy for Canada. The group shared their preliminary work in a 2019 Canadian Architect interview. Editor Elsa Lam reconnected with this group now called Rise for Architec ture to check in on their progress and plans.

Elsa Lam: When we last spoke in 2019, your group was planning an ambitious series of consultations with architectural professionals as well as student groups, aimed at informing a national policy that would highlight the value of architecture, helping to feed public debate and influence legislation. How did those consultations go?

Darryl Condon: Just before the pandemic, we talked to over 2,000 architects from across Canada roughly 20% of the profession. These

face-to-face workshops took place at the 2019 RAIC conference in Toronto and at regional meetings from St. John’s to Victoria to Yellow knife. When COVID cancelled our planned coast-to-coast consulta tions with Canadian communities, we reinvented our public outreach strategy with an online platform. Rise for Architecture launched in 2021, and results from an Angus Reid poll were published in April 2022. Overall, we’ve heard from nearly 5,000 Canadians, most of whom are keen to help shape better built environments and support an architecture policy for Canada.

Lisa Landrum: The Canadian Architecture Forums on Education (CAFÉ) began in September 2019. The series brought together all 12 Canadian schools of architecture in conversations about the profession’s future. Five forums were held at five campuses in Halifax, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg and Calgary involving nearly 1,000 students,

More than 30 countries have or are developing architecture policies.

academics and community members. The last CAFÉ took place in March 2020. Online forums, a survey, and a manifesto competition continued through the summer, and a Summary Report was published in September 2020. This year, we created “CAFÉ Capital: Towards Equity in Architecture,” with three online workshops and an in-person forum in Ottawa, from September 29 to October 2.

DC: Again and again, we heard about the desire for change. Architects believe in architecture’s potential to make positive social and environ mental impacts. But they also feel constrained by inflexible procurement and regulatory processes that put profits and risk aversion over long-term value. From the public, we heard general dissatisfaction, but also encour aging evidence that they value good design. Results of the 2022 Angus Reid Poll show that most Canadians do not see themselves, their culture, and their values reflected in the places they live. People further feel dis connected from decision-making processes shaping their communities. Our survey results confirmed these findings, with 76% of respondents supporting better design and planning policies.

LL: The voice of the next generation of architects resounds with crea tivity, conviction and hope. The CAFÉ series had five key takeaways: 1) Engage architecture as a tool for climate action; 2) Engage archi tecture as a tool for social justice; 3) Enable radical diversity in the profession and radical accessibility in the built environment; 4) Pur sue architectures of healing and enjoyment at multiple scales and sensibilities; and 5) Support holistic design excellence, communityengaged processes, and Indigenous empowerment. We also learned that architecture’s future is a trans-generational project. New stu dents and seasoned practitioners have much to contribute and to learn from one another.

How did the pandemic affect your group’s methods? Has the mission of your group been adjusted to take account of lessons-learned from the past two-and-a-half years, when Canadians have been interacting with architecture especially public architecture in different ways?

DC: Challenges in the last couple of years have underscored the need for the architectural profession to renew its social contract with the public it serves. Access to safe and healthy environments, affordable homes, and inclusive and inspiring public spaces has never been more important. Moreover, the climate catastrophe is accelerating. Living in Vancouver, I have seen the unprecedented floods and fires of the last two years. Resilient infrastructure and sustainable buildings are top priorities. The socio-political and environmental contexts in which architects work are rapidly changing. Yet, many of our professional frameworks are static. It’s time for change!

LL: Remote learning magnified problems of accessibility in architectur al education. The pandemic was a wake-up call for well-being and work-life balance. There are also renewed calls for anti-racism and social justice. The Black Lives Matter movement and the painful con firmation of unmarked graves at former residential school sites have impacted academic institutions and architecture programs in sobering ways. Most schools have formed Equity, Diversity and Inclusion com mittees and committed to decolonizing curriculums. Yet, biases of gender, race and class are entrenched. Addressing systemic racism in Canada’s architecture schools , as school director Anne Bordeleau has explained, is a slow process (see CA, Feb 2021). This fall’s CAFÉ ,

Equity in Architecture,” encouraged open discussion

these

Installer: Keith Panel Systems

Installer: Keith Panel Systems

TOP Ini Adedapo, a University of Calgary M.Arch student, reports on architecture and potential at the CAFÉ West event in March 2020.

Kind Hart Women Singers contribute a song ceremony to the CAFÉ Prairie event in February 2020.

Jonathan Kabumbe and Noémie Lavigne lead a presentation in November 2019 at CAFÉ Québec.

DC: This month, we will publish our key findings and recommended ac tions. We’ll present these at the CACB Conference in Ottawa at the end of October 2022. The goal is to communicate the need for change and potential for the profession to rise to the challenge of self-transformation. We aim to garner further support for change within the architectural community, so this can be leveraged through advocacy for better policies at federal and regional levels. We will also publish a study of architecture policies in Europe, which can guide Canadian policy makers. Ultimately, governments write policy. Our group’s role has been to sketch policy pri orities, encourage architectural advocacy, and model the change we want to see at government levels. Our next steps will include building a collab orative platform for industry partners to work toward the changes we can make without government intervention.

LL: Following CAFÉ Capital, we further plan to publish a white paper towards equity in architectural education, to share best practices among academic and professional sectors, and to advocate for these priorities in institutional processes and policy.

What are the key recommended actions?

DC & LL: We call on the entire architectural profession to more boldly commit to addressing the climate crisis; to improving diversity, equity and inclusion in the profession, as well as accessibility in built environ ments; to meaningfully involving communities in the design process affecting them; to working in partnership with Indigenous peoples to advance the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commis sion of Canada; to expanding the definition of public interest; and to renewing governance and accountability among architectural regulators and advocates, professionals and educators. The challenges we face and the change we need require everyone working together architects, regulators, educators, students, advocacy bodies and allied professions.

How might the architecture community support these efforts?

DC & LL: Read our report. If you support its recommendations, write to your association and to the RAIC, and urge action toward influencing legislation. Write to your Members of Parliament, and encourage them to read the report and move an architecture policy forward. Above all, act within current mandates to effect positive change. We will be calling on all within the profession to move towards a renewed social contract.

DC: We would like to thank all the members of task force, the Advisory Group, all the professionals who shared feedback, as well the RAIC, the Regulatory Organizations of Architecture in Canada (ROAC), and the Canadian Council of University Schools of Architecture (CCUSA) for their support.

LL: Thanks also to everyone participating in CAFÉ , especially the stu dents who have assisted in the research and reporting, and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

Darryl Condon is managing principal of hcma architecture + design in Vancouver and Chair of the Rise for Architecture / ROAC future of architecture working group.

Lisa Landrum is a professor of architecture and associate dean at the University of Manitoba, CAFÉ project lead, and Rise for Architecture steering group member.

MIDDLE

TEXT Jonathan Tinney

TEXT Jonathan Tinney

THIS SUMMER, ARCHITECTURE AND PLANNING FIRM SVN CONVENED A SERIES OF CONVERSATIONS WITH INDUSTRY THOUGHT-LEADERS ON DECARBONIZING OUR CITIES AMIDST THE CLIMATE CRISIS. HERE’S A REPORT ON ONE OF THOSE TALKS.

Over the last two decades, the building industry has been developing new ways of decreasing energy use and related carbon emissions in new build ings be it through the use of a range of rating systems or improved build ing codes such as BC’s Step Code but programs and policies to drive reductions in the existing building stock have proved more challenging.

In early 2022, the City of Montreal rolled out a new requirement for large, existing buildings to measure and disclose their fossil fuel usage on an annual basis. Tracking and disclosing energy usage will be followed by mandatory reduction targets. This comes on the heels of legislation implemented by the Province of Quebec that will prohibit new oil-based heating systems and limit new natural gas systems, beginning in 2024. These are bold moves, and so watching how these policies roll out in Montreal will be helpful for informing similar policies across the country.

I recently spoke with Philippe Dunsky, President of Dunsky Energy + Climate Advisors as part of SvN Architects & Planners’ LinkedIn Live Series – SvN Speaks. Based in Montreal, Dunsky brings over 30 years of experience supporting governments, utility companies, businesses, and non-profits across North America to accelerate the transition to clean energy through policies, strategies and investment decisions.

Dunsky’s firm played a key role in Montreal’s climate bylaws, first by mapping Montreal’s Greenhouse Gas (GHG) footprint, and then assessing reduction opportunities and costs. This initial work found that the Greater Montreal Area has the potential to realistically achieve 55-60% GHG reductions by 2030 and 100% or “net zero” emissions by 2050. The City of Montreal adopted those targets, and proceeded to develop a plan, with Dunsky’s support, to achieve them.

The plan’s focus on emissions from buildings is noteworthy. At a high level, owners must measure and disclose their buildings’ emissions to the

City by 2024, a reasonably simple requirement because measuring the fos sil fuels required to heat buildings doesn’t include measuring embodied carbon. The disclosure process begins with buildings over 15,000 square metres, followed by buildings above 5,000 square metres and 2,000 square metres in 2025 and 2026, respectively. After this initial “informa tion” period, mandatory GHG performance requirements take effect, starting in 2028, when the largest buildings have to satisfy the first level of mandatory emissions reductions.

As Dunsky noted, “What’s critical is that the emissions caps are going to be laid out in advance so that everyone knows where they need to be at each milestone leading up to 2040, when every building will have to be at net zero.”

What anticipated effects will Montreal’s energy performance and dis closure have on the building industry? Will the insurance or finance sec tors help or hinder market uptake? Dunsky explained that disclosure and performance criteria are both necessary for a workable plan, adding, “If the banks have a clear understanding of how standards evolve, they will require building owners to make sure their investments are not just nearterm or simply aesthetic but can achieve net zero to avoid future liability.”

Change is inevitable, but not all building owners will embrace it. Still, Dunsky believes the clarity of the message is essential: by setting a hard target of net zero emissions by 2040, building owners and the real estate community at-large know the end-game, and can plan ac cordingly. Furthermore, in leading by example the City of Montreal

ABOVE Phillippe Dunsky, president of Dunsky Energy + Climate Advis ors, was interviewed by SvN Architects + Planners partner Jonathan Tinney as part of a series of climate policy talks organized by SvN.

is requiring that its own buildings achieve net zero a full 10 years earli er, by 2030 “the city will make it a lot harder to say, ‘this is impossible or crazy.’” He also acknowledged a growing consensus on the need to act on climate change, with building owners and lenders increasingly stepping up, and many supporting strong regulations so that everyone can be on a level playing field.

While the City of Montreal took the lead within the Greater Mont real Area to set net-zero targets, surrounding municipalities have yet to adopt similar measures. Could Montreal’s ambitious policies harm its economy? Dunsky believed that most stakeholders understand the inevitability of climate change, citing the gas utilities, who generally supported Montreal’s policies because they want to be part of the solu tion. Gas utilities are currently looking at renewable natural gas as a source of net-zero energy. He added, “Ultimately, the way to address the competitiveness issue between Montreal and the surrounding sub urbs is not to sit back and do nothing out of fear of a race to the bot tom. To the contrary, Montreal is saying ‘We need a race to the top.’ Already, their approach has been applauded by the Province, and will likely inspire similarly ambitious moves throughout the province.”

Outside Quebec, the City of Toronto announced a similar intent to Montreal’s net-zero policies. In May 2022, the City of Vancouver an nounced a similar policy to Montreal’s, setting 2040 net-zero targets for large commercial and institutional buildings. With Toronto, Mont real and Vancouver going in the right direction, setting stricter carbon budgets begins to feel normal. Another important precedent is the BC Energy Step Code, an optional compliance path in the BC Building Code that local governments can use to incentivize or require a level of energy efficiency in new construction that exceeds the requirements of the BC Building Code. Builders may voluntarily use the BC Energy Step Code as a new compliance path for meeting the energy-efficiency requirements of the BC Building Code. The Step Code continues to influence other provinces like Nova Scotia or the federal government as it works to revise its National Building Code.

As we move to decarbonize our buildings, the proliferation of glassy, gas-heated condominium developments appears increasingly out of step with our cities’ desire to achieve net zero. But as Dunsky pointed out, the City of Montreal has the authority to regulate GHG emissions, not energy efficiency. A condo building that uses natural gas as a central ized system will have to have it replaced, while upgrades to building

GHG EMISSIONS

inventory of Montreal's building stock—and its contributions

greenhouse gas emissions—was a first step in setting netzero

city.

envelopes are outside the purview of the current regulation. Interesting ly, Vancouver plans to move beyond GHG emissions and include energy efficiencies as part of its thermal intensity requirements by 2040.

Will setting net-zero targets create disincentives to improve existing buildings, possibly resulting in the unintended consequences of replacing rather than retrofitting a building? Because Montreal focuses on energy systems rather than building envelopes, changing a natural gas system to either a renewable natural gas system or heat pumps is not cost-pro hibitive. As for creating incentives, Dunsky noted examples of policies encouraging compliance with decarbonizing regulations. He cited the Canada Infrastructure Bank’s Building Retrofits Initiative, which Dun sky designed. Part of its Green Infrastructure support programs made $2 billion available to provide low-cost financing to help de-risk major building retrofits focused on decreasing emissions. Under its terms building owners won’t see a cheque from the government: instead, their banks would offer a lower-interest loan for green developments commit ted to lowering a building’s carbon footprint than for standard projects.

Our current policies need to include embodied carbon in our build ings, not just energy use. Dunsky acknowledged that we could get there, but we first need to address the issue of direct GHG emissions. Once a set of commonly accepted rules for measuring carbon is achieved, we can then standardize voluntary incentive programs, fol lowed by effective regulatory approaches. There is room for evolution and growth when defining standards for carbon budgets of new and existing buildings. “I’m a big believer of the 80-20 rule. Get the big stuff done now, and leave the rest as a next step,” Dunsky added.

As we continue to evolve net-zero strategies, the need to implement practical and implementable policies to decarbonize our buildings has never been more urgent.

Jonathan Tinney is an urban planner and partner of SvN Architects + Planners.

on each of the five talks in the SvN Speaks series can be found at canadianarchitect.com, and the talks can be viewed

entirety

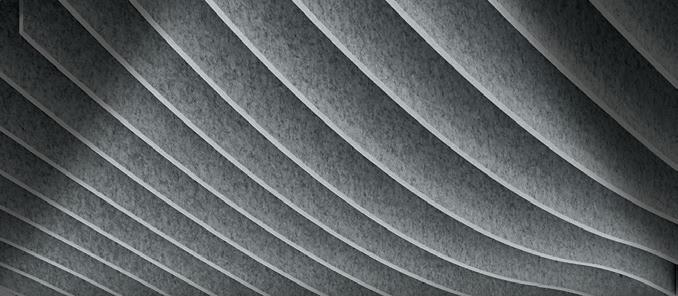

FeltWorks® Blades can help you create understated interiors with soothing movement and subtle color – or dramatic pops of color, shape, and direction. Transform mundane to modern and absorb sound with a soft visual texture. Both standard and custom panels are part of the Sustain® portfolio – meeting the most stringent industry sustainability compliance standards today. Learn more about tranquil sophistication at armstrongceilings.com/feltworks

FELTWORKS ® BLADES EBBS & FLOWS KITS / THE SHEWARD PARTNERSHIP OFFICE, PHILADELPHIA, PA

FELTWORKS ® BLADES EBBS & FLOWS KITS / THE SHEWARD PARTNERSHIP OFFICE, PHILADELPHIA, PA

When Place Ville Marie opened in downtown Montreal in 1962, the design, by Henry Cobb working with I.M. Pei, included an elevated grand plaza, bookended by equally grand staircases. One of those stairs facing McGill Avenue and leading to the gates of McGill Uni versity was displaced, for over 50 years, by an entrance to the com plex’s underground parking.

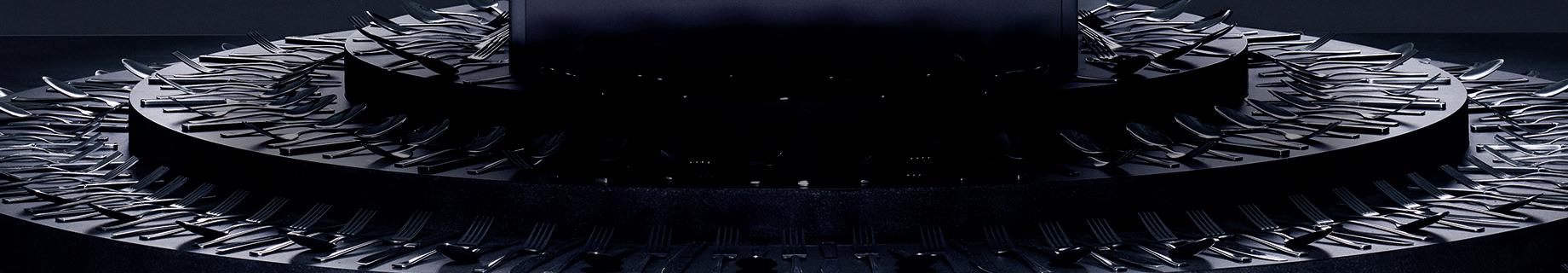

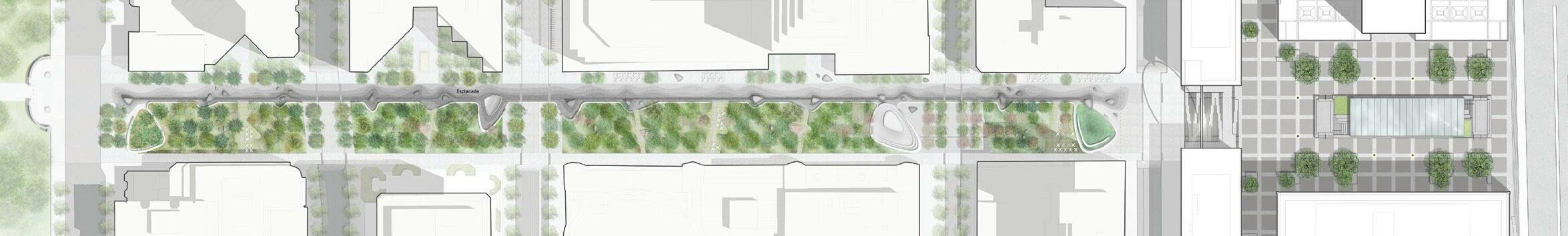

In 2018, the current owner, Ivanhoe Cambridge, set out to revitalize the raised esplanade, working with Sid Lee Architecture to add massive skylights connecting the plaza to the restaurant spaces below, and restor ing the north staircase as it had been originally designed. To cap off the $200-million project, the owner asked local landscape architecture firm Claude Cormier et associés to create an installation that would com plete the space above the new grand stair.

“We came up with the idea quite easily,” recalls Claude Cormier. His team wanted to reference the modernist grid of Cobb’s design, but offer a fresh take on it. A circular ring was the perfect fit for the space, fitting snugly in the 30-metre-wide opening, while providing enough clearance below for pedestrians to walk under it easily.

The Ring frames some 200 years of history, says Cormier. “At the end of the axis, we have McGill University, founded in 1821; in the back, we have Olmsted’s Mount Royal Park, from 1874, with the white cross, put up in 1950 to commemorate Maisonneuve, the founder of Montreal.”

The preservation of the visual axis along Avenue McGill College also encompasses a more recent history, says Cormier. In 1984, Phyllis

LEFT The 30-metre-diameter stainless steel ring fits snugly between Place Ville Marie's north buildings and is suspended above a new grand staircase to the elevated plaza.

Lambert blocked a large mixed-use complex from being constructed in front of Place Ville Marie, he says. “She fought her own brother [the developer] to create this iconic moment in downtown Montreal.”

“For me, that’s what building a city is about one thing after another, they all work together in resonance. Phyllis Lambert had a vision in her mind of something that was bigger,” says Cormier. “The Ring is trying to showcase that all together.”

The artistic installation also looks towards the future. The city’s cen tral train station is nearby, and the Ring sits atop the location where a new set of underground municipal rail tracks will enter the station. Following the construction, Avenue McGill College will be recon structed as a forest-like linear park designed by civiliti + Mandaworks and SNC-Lavalin.

To create the Ring, the design needed to respond to many constraints, including minimizing impact to the newly renovated heritage towers. To achieve this, the team engaged NCK’s Franz Knoll the structural engineer that had worked on the original Place Ville Marie, as well as landmarks including the Louvre Pyramid. Knoll devised a solution that touches the towers in just four places, pinching the building’s structure at its strongest points to support the 23,000-kilogram Ring.

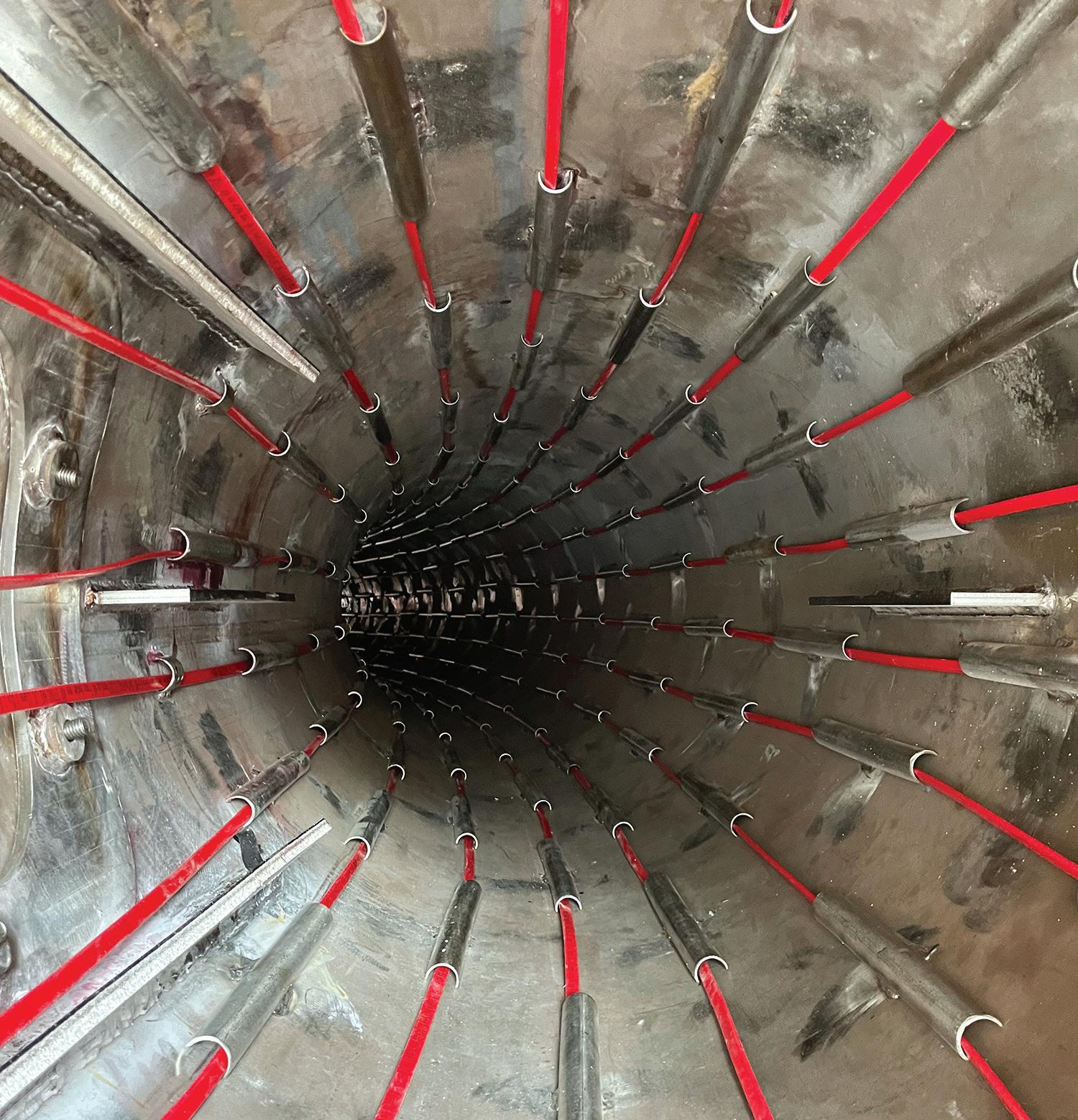

Knoll also advised on the structure of the Ring itself, which takes shape as a self-supporting stainless steel cylinder, with 9.5 mm-thick walls on top and bottom, and 16 mm-thick walls at the sides. It was created in six segments, with connecting flanges hidden behind ac cess doors. Inside the cylinder, 1,800 linear metres of heating cables

The patented TcLip™ is a key component of the holistic SYSTEM2 approach. Used alone, or together with our SYSTEM2 approach, the TcLip™ helps achieve the thermal performance required by various building codes in North America.

ABOVE The Ring frames a vista through Montreal's past history, and also considers the future transformation of the site through the competi tion-winning concept design for “McGill College: Reinventing the Avenue,” developed by civiliti + Mandaworks with SNC-Lavalin for the Ville de Montréal. RIGHT The 23,000-kilogram ring is suspended from four points on the recently restored buildings.

assure that the installation will resist ice and snow accumulation. The 1-millimetre joints of the structure are virtually invisible, giving the resulting design the appearance of a pure, single form.

The project “has created a love interest in the media since it was un veiled,” says Cormier. But not all of that attention has been positive its $5-million price tag has also been the subject of hot debate.

“Some people were really offended by this, doing something with no purpose,” says Cormier. But he says that while the Ring may not be strict ly functional, it does indeed have purpose: “It creates identity, a notion of place, taking care of our city, investing in our city,” he says. “We were busy enough in making it work, but we had the feeling it was right.”

Turning off Keele Street, just minutes north from the commotion of Toronto’s busy Highway 401, the city retreats. It is quiet, calm. The expansive grass fields and unobstructed sky views of the former Downsview Airport are a fitting landscape for a new aviation hub.

Centennial College’s facility for Aviation and Engineering Tech nology & Applied Science, designed by MJMA and Stantec with ERA as Heritage Architects, is an adaptive reuse project situated within the geographic heart of Canadian aviation history. The school proudly occupies one of the most significant of several sprawling air craft buildings that flank the lengthy Downsview runway. The his toric de Havilland of Canada building is the oldest surviving aircraft factory in Canada; it’s where nearly 3,000 Tiger Moth aircraft and some 1,134 Mosquito bombers were built; where the company developed the Twin Otter and Dash-8; and where the first Canadian satellite, Alouette I, was assembled. After the plant’s closure, the hangar was used by CFB Toronto, and later served as an air and space museum before being mothballed in 2011.

By the time Centennial College acquired the facility, the 1929 build ing had preserved its additions from 1937, 1939, 1940, and 1944, but was

LEFT A glass-box hangar was added to the adaptively reused de Havil land building, allowing modern aircraft with larger wingspans to be used as teaching aids for aviation technicians-in-training.

slowly falling into disrepair. Through selective demolition and addition, the designers undertook the challenge of uniting the complex, while respecting its original fabric and rich history. Today, it welcomes a new generation of aviation technicians-in-training.

A glass overhang stretches along the property’s entrance off Carl Hall Road. This element frames the restored masonry of the 1939 and 1940 façades and builds on a tradition of bold civic entrances. Canti levered at either end, the canopy refers to an acrobatic aeroplane wing. A wall adorned with historic images creates an exterior public gallery, and the backdrop to an appealing barrier-free ramp. This welcoming gesture one of just a few bold architectural moves within the project sets the tone of the design as a strategic refurbishment, which takes its cues from the history of the building.

“The site had a clear story to tell,” says MJMA principal Robert Allen, explaining that the ambition of the team was to reveal that story as clearly as possible. Stephen Philips, senior vice president at Stantec, adds that “patience, patience, patience” was key to achieving this goal. The two firms worked closely together to develop an architectural strategy that preserved and made highest use of the building’s existing fabric, including its large open spaces.

Today’s LEDs may last up to 50,000 hours, but then again, Kalwall will be harvesting sunlight into museum-quality daylighting™ without using any energy for a lot longer than that. The fact that it also filters out most UV and IR wavelengths, while insulating more like a wall than a window, is just a nice bonus.

photo: Scott Norsworthy

photo: Scott Norsworthy

One such space is a former double-height warehouse area, which has become the Student Commons, just inside the main entrance. Here, varied aspects of student life converge with informal gathering areas, food vendors, and study rooms. Tall ceilings and clerestory windows contribute to a sense of openness, despite a compact layout. Imprinted into the terrazzo floor of the Commons is an oversized windrose a reminder of how the site’s unique wind patterns shaped the airport’s runway configuration, along with the de Havilland building’s placement and orientation.

The Commons is surrounded by program on all sides, including a two-storey glass partition that looks into the building’s most dra matic space a cathedral-like, 2,600-square-metre hangar, complete with a 28-meter-wide bridge crane capable of lifting 3,000 kg. In this case, new construction was necessary, as the historic hangars were too small to accommodate the wingspans of the commercial aircraft that students are learning to service. Like the grace of a heavy aircraft taking off, the hangar appears to hover effortlessly above its concrete

floor. An ambitious structural design leaves its glass enclosure appearing weightless. Despite the hangar’s program as a functional classroom, it has been conceived with thought and care replace the Cessna Cita tion II commuter jet and Bell 206 helicopter with Richard Serra sculptures, and it could easily be the showstopping atrium of a con temporary art gallery.

An equal thoughtfulness is evident through the project. The team from MJMA, Stantec, and ERA was careful to balance between nar rating the building’s historic significance while creating architecture for daily use: after all, the building is now a teaching facility, not an aviation museum. Throughout the facility, glazed interior partitions connect common areas and circulation zones with meeting rooms, classrooms, and labs. This allows the structural bones of the heritage architecture to enjoy a continuous presence throughout, while also putting the contemporary teaching artifacts on display, including im pressively ornate, elephant-sized engines. Existing walls were stripped to reveal restored masonry, while new walls were embellished with

aeronautics-themed infographics. Fittingly, the building’s high-performing mechanical systems are exposed throughout.

Following an old aviation tradition, the building’s green roof bears the name of the College today visible by pilots and passengers, as well as Google map viewers. Classrooms at the building’s centre are given sky views through clerestory windows. While several of the lab spaces are double-height, the 1939 portion of the building is topped by a second level, housing additional classrooms and computer labs. In the upper storey space, an informal study zone overlooks the Stu dent Commons below, while a glass-enclosed boardroom also enjoys views over the two teaching hangars its sightlines similar to those of an air traffic control tower.

MJMA , Stantec, and ERA have brilliantly brought themes out of the existing elements, while skillfully adding their own mark. The result is thoughtfully executed architecture that reads lightly. Centen nial College's Centre for Aerospace and Aviation at Downsview inspires a new generation of aviation experts while demonstrating that, for architects embarking on adaptive reuse projects, the sky is the limit.

Aidan Mitchelmore is a Toronto-based Intern Architect who has a passion for architec ture and public buildings.

ABOVE The secondary hangar, now used as a teaching area, is a repur posed hangar from the 1940 portion of the building. The original bridge crane is still used to move helicopters and small aircraft within the space. OPPOSITE In a nod to an old aviation tradition, the building's green roof bears the name of the College.

Something big is happening east of downtown Toronto. The Don River runs through one of Toronto’s major ravine systems, and is one of the most urbanized watersheds in North America. In the largest design and construction project of its kind currently underway in North America, crews are restoring the natural systems of the mouth of the Don River, where it empties out into Lake Ontario. The river, in its current con figuration, is being moved.

It’s a monumental effort to carve a new river channel out of the exist ing industrial lands. This entails dismantling buildings, remediating soils, layering new habitat on top, and setting the stage for future develop

ment. This de-engineers over a century of development, and will ultim ately recover the site’s deep ecological history as a dynamic estuary: the mouth of the Don River was once the largest freshwater wetland on the Great Lakes. But people are also a big part of the picture: the result will include large-scale urban parks, as well as an urban neigh bourhood embedded in nature.

A landscape architecture firm as opposed to an engineering firm is leading the overall master planning and design efforts for this pro ject. This meant that the design process for Villiers Island, as the landform defined by the re-directed river will be known, began with

ABOVE To imitate natural ecosystems, where trees are sometimes stranded in rivers and streams, a series of large, dead trees are anchored in the riverbed. Snags provide critical shelter and spawning sites for fish, as well as a set of surfaces where biofilms can form, supporting other aquatic invertebrates. OPPOSITE Designed to provide green infrastructure for migrating birds, the landscape includes an island at the south end of the site that is inaccessible to people. Although yet incomplete, these areas are already starting to attract swallows and waterfowl. But nesting birds can engender a stop to construction activity, so the crew includes a falconer, whose bird and dog are trained to drive away wildlife without harming it.

a close examination of the area’s ecology. Michael Van Valkenburgh and Associates (MVVA), the winner of a design competition for the masterplan in 2008, asked: How could the infrastructure of the river bed become the foundation for place-making in this part of Toronto?

By considering the larger hydrological network and reconnecting to the Don River Ravine system, the scheme also designs for resiliency in the context of climate change.

The design strategy takes its form from the morphology of the Don River, rather than from colonial urban grid laid down by John Graves Simcoe in the late 1700s, or the Keating Channel that redirected the Don through a sharp 90-degree turn in 1893. A single, complex parkland is used to naturalize the mouth of the Don River, provide a floodway for storm events, and allow for recreational uses. Rather than attempting to restore back the site to a pre-settler “pastoral” condition, MVVA’s design for Villiers Island takes a more layered approach which reveals the site’s previous uses, including its industrial regimes, creating references between the restored ecologies, the river, and the City of Toronto itself.

Dating back to prehistoric times, Toronto was a meeting place for First Nations, and Ashbridges Bay was a fertile fishing and hunting ground. The site’s history as an Indigenous cultural landscape added another layer to the design. MVVA has integrated Indigenous profes sionals into the design team, and Waterfront Toronto has established a Memorandum of Understanding with the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation, which holds Treaty 13 with Toronto, moving their role towards partnership rather than simply consultation. This input has helped to inform the project, which for Indigenous stakeholders rep resents an important healing of the land and re-engagement with the river, providing renewed access to the water. The design of the area’s interconnected green spaces also support Indigenous-led program ming: an event lawn includes a lookout and spaces for pow wows along the river, fire pits allow for ceremony, and gathering areas invite sunrise gatherings. The planting palette is also informed by Indigenous knowledge, with species chosen for their cultural and ecological import ance to the pre-settler landscape.

The design is also attuned to the needs of local animal species. In the future Promontory Park, a restored wetland is already attracting local wildlife. Colourful flags have been strung up to protect the growing fish population from predatory birds until it is fully established. In other parts of the site, new sandy riverbanks are attractive to swallows: the ecological restoration team includes a trained falconer, who is charged with keeping the birds away until the landscape is completed if they become estab lished, nesting birds could mean a stop to construction.

Much of the design is geared towards protecting new development, as well as adjacent neighbourhoods, from flooding but in a way that works with nature, rather than against it. In 1954, Hurricane Hazel brought 110-kilometre-per-hour winds and dropped 285 millimetres of rain on Toronto in 48 hours, resulting in widespread flooding that was exacerbated by the artificial mouth of the Don River. The new river valley in the Port Lands is designed to mitigate similar events: the river is set in a 30-metre-wide floodplain, with wetlands lining the river to act like a sponge, and a new channel helping to draw floodwaters out, conveying them to Lake Ontario. Nature trails allow the wetlands to be enjoyed during drier times; these trails would not be accessible during a flood event. More permanent programming is located at the top of the bank, including parks, picnic areas, and play structures.

OPPOSITE In River Valley Park, an existing historic firehall has been relocated outside the floodplain and set back, to be repurposed as an amenity space for the neighbourhood. ABOVE Four new bridges for the site include a paired set that will house a roadway and future streetcar line for the realigned Cherry Street. The bridges were fabricated in Halifax and floated up the St. Lawrence Seaway, then set into place over the future waterways.

Toronto-based Urban Strategies led the development of the Villiers Island masterplan, which is currently being updated by O2 Planning & Design. Over the next several years, RFPs will be going out to develop ers, who will in turn be hiring architects to design the individual parcels.

All new development in the Portlands will follow design guidelines crafted by the City of Toronto in partnership with Waterfront Toronto. These guidelines will includes requirement for green infrastructure in all new developments, such as green roofs that will assist in Villiers Island’s role as an important flyway for North American bird migrations.

The urban plan also integrates innovation in its urban massing: the planned mid-rises maintain view corridors and gradually increase in height from south to north, giving the buildings greater access to sun light. MVVA’s initial design proposal included the managing and con veying of stormwater flows from buildings through the streets into the parks, but this was not permitted under current city guidelines. A dis trict energy plant is in the works for the Island as part of a 30-year plan.

The area will be home to some 10,000 residents, living in 5,000 resi dential units; schools and some 3,000 employment opportunities are also envisaged for the Island. Alternative mobilities are also part of the

plans: the area is close to the East Harbour GO Train station and the new Ontario Rapid Transit Line, currently being built. The Toronto Waterfront Business Improvement Area is actively campaigning for funding to implement a light rail transit line that will traverse the area.

Villiers' streets will include integrated pedestrian and bike systems; its waterways will invite boating a shared kayak system is in the works. Four new bridges were added to the site, designed by Entuitive, Grimshaw Architects, and SBP one of these, the Cherry Street North Bridge, is designated for a future transit line into the Port Lands. In several cases, the bridges currently span dry land, making the con struction of supports easier. As a final step when the landscape is com pleted, plugs at the ends of the new waterway will be removed, allowing the river to be filled.

Introducing a naturalized river mouth, the plan for Villiers Island stands in contrast to the willful engineering of the Keating Channel, which forced the Don River into a right-angle turn towards Lake Ontario. The island also resists the existing Simcoe street grid to instead develop topography-sensitive diagonal elements and through-block pedestrian

OPPOSITE Plantings for the future string of parks and wetlands include some 5,000 trees, 77,000 shrubs, and over two million herbaceous plants. During construction, a worker discovered local wetland plants growing in the construction area: further investigation revealed that they were from seeds bur ied over a century ago, when the original estuary was infilled for industrial development. The seedlings were recovered, and are currently being propa gated in a University Toronto facility. Researchers are also scouring the soil for more seeds to help restore the plants that were originally found at the site. ABOVE Because of the layered natural and industrial histories of the area, the project has entailed carefully tracking and moving over 1.4 million cubic metres of earth—an amount equivalent to the volume of the Rogers Centre. The project is anticipated to be completed in 2024.

connections. It is itself an act of engineering, even more intense than the original redirection of the Don: a $1.25-billion effort, funded equally by all three levels of government, that has involved moving 1.4 million cubic metres of soil, roughly the volume of the Rogers Centre. The new river bed and wetlands are set into place, rather than being open to changes over time, and fully lined to prevent groundwater contamination.

But rather than confronting nature, the landscape and urban design takes its cues from and even strives to enhance its ecological and en vironmental setting. It suggests how Canadian cities can be more sensi tive to the topography of places and landscapes that were long stew arded by First Nations.