An

Voluspa Jarpa (b. 1971 Rancagua, Chile). Judd Shaft, Serie lo que ves es lo que es, 2016, stainless steel and transparent acrylic and film. Dimensions variable, box: 120 x 83 x 53 cm. Courtesy of Voluspa Jarpa.

Necroarchivos de las Americas: An Unrelenting Search for Justice

Through the lens of contemporary art, Necroarchivos de las Americas: An Unrelenting Search for Justice, investigates diverse responses to the “disappeared” and a long history of state-condoned terror. From the 1960s to the 1990s, intellectuals, artists, and activists in countries such as México, Colombia, Chile, Guatemala, and Uruguay were kidnapped, tortured, exiled, and, in numerous instances, murdered for demanding human rights and opposing authoritarian regimes and censorship. More recently, from the late 1990s to today, many have been victims of ongoing failed policies such as the War on Drugs, the continued presence of dictators, and a brutal state and border apparatus.

Coined by the curator of the exhibition, the term Necroarchivos defines the contemporary artworks that denounce necropolitics. Conceptualized as a “politics of death,” by Cameroonian historian Achille Mbembe, “necropolitics” is the process of subjugating life to the power of death. Under necropolitics, the sovereign dictates who lives and who must die, “who matters and who does not, who is disposable and who is not.”

In this exhibit, the Necroarchivos examine state violence through video art, installation, sculptures, and artists’ books. Necroarchivos document and archive these conditions to not only create awareness of the past, but to reflect on the present where bodies, and communities at large, continue to be rendered superfluous and expendable. Representing multiple regions throughout the Americas, the artists in this exhibition highlight voices and stories from a variety of countries participating in a transnational and intergenerational exchange. While addressing “los desaparecidos” (the disappeared) of the Americas, they also condemn violence engendered by CIA-backed regimes, neo-imperialism, colonization, and ongoing authoritarian rule. The exhibit seeks to contest this milieu and incite change, inviting viewers to join the artists’ call for justice, reparations, and collective memory.

This exhibition is curated by Adriana Miramontes Olivas, PhD, Curator of Academic Programs and Latin American and Caribbean Art.

Teresa Margolles

(b. 1963 Sinaloa, México)

Teresa Margolles (b. 1963 Sinaloa, México), A través, 2007-2022. 24 cement blocks. Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York; L2023:143.1

Teresa Margolles (b. 1963 Sinaloa, México) Dos bancos, 2020. Cement; water infused with material traces collected from the ground where a person was assassinated. Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York; L2023:143.2

Teresa Margolles (b. 1963 Sinaloa, México) Ajuste de cuentas/El enjollado, 2008. Gold; glass shards collected from the site where a murder occurred and 24K gold chain. Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York; L2023:143.3

Since the early 1990s Teresa Margolles has actively denounced corruption, impunity, and the expendability of bodies—first by working with corpses at the morgue, and more recently, by visiting crime scenes. Leaving the morgue for the streets, Margolles has been able to document aggressions against others, and as a byproduct, against the self.

In A través, Margolles traces bodily fluids from immigrants living in New York. She invited survivors of the current diaspora to donate their worn garments. The t-shirts of the undocumented participants were then rubbed against windows to extract their sweat, marking the gallery space with their memory and lived experiences. Finally, the t-shirts were buried in cement, in a characteristic approach by Margolles, to not only render them useless, but paradoxically, to protect and preserve them.

In her artistic inquiries, Margolles also collects material remnants from crime scenes such as glass, soil, water, and blood. The artist and her team “clean” crime scenes in México and other countries in an archival gesture to document offenses against bodies. In Dos bancos, remnants from a murder scene were collected and mixed with cement to create two benches (dos bancos). Here, the water, natural soil, and debris from the street all come into contact to display the vulnerability of some members in our communities and a violent regime that does not guarantee the right to live.

Voluspa Jarpa

(b. 1971 Rancagua, Chile)

Voluspa Jarpa (b. 1971 Rancagua, Chile) Judd Shaft, Serie lo que ves es lo que es, 2016. Stainless steel and acrylic Courtesy of the artist; L2023:69.1

Voluspa Jarpa investigates notions of imperialism, neocolonialism, and decolonization as an artist, researcher, and archivist. Leaving behind painting to investigate sculpture and installation, her work focuses on language, the written word, and censured narratives. In 2002-2003, she began to examine declassified files from the CIA in her work to question and reveal USA interventions throughout Latin America.

From the early 1950s to the 1990s, the United States backed dictatorial regimes to contest communism. Within this context, intellectuals, activists, students, journalists, and others who opposed political, economic, and ideological repression in Chile, Brazil, Argentina, and elsewhere, were disappeared, tortured, murdered, and disposed of at sea, in mass graves, and in yet to be determined locations.

In Judd Shaft, Serie lo que ves es lo que es, Jarpa alludes to minimalist artists Donald Judd and Frank Stella (the latter famously stated “what you see is what you see”) to counter their formalist questions with politically charged installations. In Judd Shaft, Jarpa shows the declassified files from the CIA to highlight histories of intervention and to bring awareness of the multiple factors, and local and transnational political agents, that cause violence. In her installation, Jarpa renders these files both accessible and inaccessible to display the irony of their legibility and illegibility and their clandestine nature.

Oscar Muñoz

(b. 1951 Popayán, Colombia)

Oscar Muñoz (b. 1951 Popayán, Colombia) Breath, 1995. Photo serigraph impression with grease on twelve discs. Courtesy of the artist and Sicardi Ayers Bacino; L2023:70.1

Oscar Muñoz explores the fragility of life and the unreliability of memory in paintings, video work, photography, and sculptures. Throughout his artistic career, spanning more than five decades, he has been committed to aesthetic questions but also resisting ongoing violence in his native country. As Muñoz explains, “In Colombia and Latin America as a whole, one commonality is there is a broad spectrum of approaches to the implications of systemic violence, a problem that has affected all of us.”

Collecting images from the obituary section in newspapers, Muñoz shares an interest in preservation—that of the image and of memories. In Aliento, he adopts mirrors and demands an intimate encounter between viewers and the artworks. He also urges viewers’ participation for the completion of the artwork. Each viewer is asked to breathe upon each mirror, temporarily creating an image of a deceased person. This tension, and engagement between visibility/invisibility and presence/absence evokes the complexity of mourning. Similar to the newspapers that once displayed the obituary portraits, personal and collective memories are in flux, asking viewers to consider not only what but who is remembered.

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer

(b. 1967 Mexico City, México)

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (b. 1967 Mexico City, México) Level of Confidence, 2015. A face-recognition camera that has been trained with the faces of the 43 disappeared students from Ayotzinapa school in Iguala, México; computer, screen, webcam. Courtesy of the artist; L2023:71.1

Rafael Lozano-Hemmer’s artistic practice is inextricably connected to technology. Since the late 1980s, he has employed a variety of high-tech machines to create artworks. He first championed radio art and later embraced satellite communications and computer software to examine systems of surveillance, the global border apparatus, and human-tohuman interactions. His artworks have traced humans’ heart rates, breathing patterns, and bodily movements to establish communications across countries via light, sound transmissions, or textual referents.

In Level of Confidence, Lozano-Hemmer uses face-recognition technology to search for the forty-three students who were disappeared from Ayotzinapa in the Mexican state of Guerrero on September 26, 2014. “The 43” were on a bus on their way to Mexico City, only six hours away from their homes, to participate in a protest for fellow students, the disappeared and murdered students of México’s infamous Tlatelolco massacre on October 2, 1968. Yet, they never arrived to the capital. Instead, they were stopped, detained, and arrested by the local police. The whereabouts of “the 43 of Ayotzinapa” remains unknown.

In Lozano-Hemmer’s artwork, we search for the disappeared. As viewers approach the artwork, it is activated by each viewer’s presence and image, only to fail to identify any of “the 43” with every interaction. The artwork asks participants to become witnesses of corruption, impunity, and the fragility of democracy when institutional and political power goes unchecked.

Regina José Galindo

(b. 1974 Guatemala City, Guatemala)

Regina José Galindo (b. 1974 Guatemala City, Guatemala) Tierra, 2013. Single-channel digital color video with sound, 33:30 minutes.

Photo: Bertrand Huet; Commissioned and produced by Studio Orta, Les Moulins, Paris, France; L2023:72.1

Best known today as a performance artist, Regina José Galindo moved beyond her earlier work as a poet to disrupt public spaces and denounce gender violence in Guatemala, Mexico City, and Costa Rica. Since 1999 she has been an advocate for Indigenous communities and women of color, using her own body to render visible the crimes committed against these bodies.

In Tierra, Galindo condemns aggressions against people due to their race, gender, or class. Here Galindo centers her body against the excavator, acknowledging the helicopters, airplanes, and automobiles that have been used to kidnap, discard, and bury bodies across the Americas during civil wars, dictatorial regimes, and the narco-wars.

Adopting a confrontational stance, she remains immobile in the plot of land, in defiance of the enormous machine representing the state apparatus. Tierra recognizes the methods of “disposal” and technologies used by former dictators in Guatemala to commit genocide and demonstrates that, oblivious to her presence, the excavator continues to remove land from the site to prepare it for a/her [mass] burial. Her performance and video call attention to ongoing violence in the country, despite Guatemala’s transition to democracy, and informs viewers of a tragic history of crimes against humanity.

Valaria Tatera

(b. 1967 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA)

Valaria Tatera (b. 1967 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA) Justice: Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and 2 spirits, 2020. Ribbon and text. On loan from the artist; L2023:73.1

For more than one hundred years, Indigenous children in the United States were forcibly removed from their homes and displaced to Native American boarding schools. Many never returned home and were never reunited with their parents. Today, Indigenous women continue to disappear and there is an alarming trend of unsolved crimes against Native people in Canada and the USA. In 2018, May 5th was declared National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Native Women and Girls in the USA, but the disappearance and homicide of these women remains largely unreported, understudied, and underrepresented. In her work, Valaria Tatera investigates this shortfall in the scholarship, the arts, and the art historical discourse.

A Milwaukee-based artist, Tatera is an enrolled member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. Adopting birch, cotton, oil, water, wire, and found objects, she focuses on neglected and forbidden stories. In Justice, she employs more than four hundred ribbons to reflect on the large quantity of Indigenous women who go missing. The word “justice” is inscribed upon each ribbon as an urgent call for change.

Luis Camnitzer

(b. 1937 Lübeck, Germany)

Luis Camnitzer (b. 1937 Lübeck, Germany) Leftovers, 1970. Eighty cardboard boxes, gauze and polyvinyl acetate. Collection of Yeshiva University Museum, Gift of the artist; L2023:86.1

From 1968 to 1972, Uruguay experienced a state of emergency followed by a coup d’état and a dictatorial regime (1973-1985). Leftovers evokes the social and political turmoil of the time, when protesters were detained, kidnapped, tortured, murdered, or forced into exile. The boxes, wrapped in surgical bandages and stained with fake blood, are inscribed with Roman numerals and the word “LEFTOVER.” As two puddles of red pigmented resin extend from these boxes into the gallery space, the installation prompts viewers to consider the contents of these containers in an unsettling encounter.

Luis Camnitzer, an advocate of 1960s Conceptual Art, invites viewers to engage with language and to consider the loss of life under authoritarian regimes, political instability, and war. He believes in the power of art to create consciousness, to defy normative behavior and complacency. As Camnitzer declares, “El arte no es un campo de producción de objetos. El arte es una metodología para adquirir e impartir conocimiento y para desafiar ordenes establecidos, para buscar ordenes nuevos. Y esta parte es la que no se explota totalmente, ni por el artista, ni por el sistema educativo.” (Art cannot be defined by the production of objects. Art is a methodology to acquire and share knowledge and to defy established orders, to search for new ways of being. This is not fully exerted by artists or by the educational system.)

Abel Barroso

(b. 1971 Pinar del Rio, Cuba)

Abel Barroso (b. 1971 Pinar del Rio, Cuba) Border Patrol, 2007. Woodcut, engraving on plexiglass, wooden mechanism. General Acquisition Fund Purchase; 2010:31.1

Trained as a printmaker, Abel Barroso continues to reference his early passion for woodblock prints through sculptural works that rely on this technique and its materials. Interested in engaging viewers, he creates interactive artworks that resemble foosball tables, pinball machines, and labyrinth board games. In his oeuvre, his playful approach defies the seriousness of the topics that he investigates, which include migration and different forms of power associated with nationality, class, or race. Portraying passports, embassies, maps, and borders, Barroso questions the legitimacy of these constructs and institutions and their effectiveness in serving all humans equally.

In Border Patrol, the themes of surveillance and the massive security apparatus are exposed. His artwork asks: who resists borders and who profits from them? Who, or what, is able to cross them and who is prevented and why? Sealife, cellphones, and skeletons at the bottom of the container provide some clues to the challenges and possibilities of the actual border regime.

Carlos Castro Arias

(b. 1976 Bogotá, Colombia)

Carlos Castro Arias (b. 1976 Bogotá, Colombia) Risus Sativus, 2013. Multimedia, wood, knives. Museum purchase with funds from the Ramsing Estate; 2013:40.1

A multimedia artist, Carlos Castro Arias is known for his large-scale woven tapestries, intervened fish tanks, and beaded sculptures. Interested in the role of monuments in public spaces and Op-art, his works merge together seemingly disparate aesthetic languages and societal spheres. Tourism and narco-tourism, colonization and decolonization, as well as law enforcement agencies and criminal organizations are topics and institutions that occupy his mind. Responding to these antagonistic relationships, Castro Arias’s artworks reveal the complexity of our interactions and institutions and the difficulties encountered in separating them when they already work in tandem and parallel ways.

Part of a larger series presented in both Tijuana, México and in Bogotá, Colombia, called Legions (2011-2015), Risus Sativus features knives confiscated from the streets. In tune with their functionality, the violent weapons serve as a call to arms through their melodies. Yet paradoxically, they become instruments of artistic creation and sound.

Ars Shamánica Performática

Guillermo Gómez Peña (b. 1955 Mexico City, México); Felicia Rice (b. 1954 San Francisco, USA); Gustavo Vázquez (b. 1973 Carolina, Puerto Rico); Zachary James Watkins (b. n.d. USA), Jennifer González (b. 1976, San Juan, Puerto Rico). DOC/UNDOC Documentado/Undocumented Ars Shamánica Performática, 2014. Mixed media, prints, accordion book, painted box with ephemera and electronic audio components, video dvd, audio cd. Museum purchase with funds from the Patricia Noyes Harris Bequest; 2015:8.1

Created collaboratively, DOC/UNDOC reflects the diverse backgrounds and interests of its creators in performance, artists’ books, sound, and video art. First conceived as a video series by Guillermo Gómez-Peña and Gustavo Vázquez, the duo invited Felicia Rice to respond to the film series. After seven years of joint effort, the work included not only a traveling case with its intriguing objects, but also a thirty-one-foot, six-inch book that is highly illustrated and both readable and unreadable.

Refusing easy categorization, DOC/UNDOC can be variously defined as engaging with conceptual art and portable art as well as with art of the border. Similarly defying a simplistic designation, the artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña asks, “What is this, exactly? An immersive experience? A ritual exploration of the senses? A personalized installation? A participatory gameplay? The box will be handmade out of metal, with velvet lining. It will open up into three panels. The central one will have a mirror. To play, or not to play? Active, inactive? Interactive, participatory?”

As stated by Jennifer González, DOC/UNDOC also asks who is documented or undocumented? And what does it mean to be documented or undocumented? Throughout the artwork the artists examine these questions to reference the socio-political environment of our times and highlight their commentary on erased histories in their lifelong decolonial agendas.

Alfredo Manzo Cedeño

(b. n.d. Cuba)

Alfredo Manzo Cedeño (b. n.d. Cuba) The Cuba’s Soup: Homage Warhol (Revolution, History, Ideology, Religion, Censored), 2003. Collage, silkscreen, gouache, ink, and pencil on paper, A/P Museum purchase through the Hartz FUNd for Contemporary Art; 2017:47.1-5

Andy Warhol’s Pop Art aesthetic is evident in Alfredo Manzo Cedeño’s series, where he uses mixed media to include iconic photographs of Fidel Castro (b. 1926 Biran, Cuba–2016 Havana, Cuba) and Che Guevara (b. 1928 Rosario, Argentina–1967 La Higuera, Bolivia). A commentary on the social character of photography in Cuba’s politics and cultural life, the images portray propagandistic views of the revolutionaries addressing the masses with portraits that would serve to idealize and memorialize them. These images, the “Cuba’s Condensed Soups,” were not only massproduced and distributed widely, but readily accessible and meant to be consumed daily.

Manzo Cedeño’s criticism goes beyond the idea of consumption to investigate concepts such as national sovereignty, foreign intervention, and the leadership that guides communities. Pop Art’s language allows Manzo Cedeño to undertake a strong evaluation of the regime in a nonthreatening approach that is both dynamic and straightforward.

Rigoberto Díaz Julián

(b. 1992 Oaxaca, México)

(b. 1992

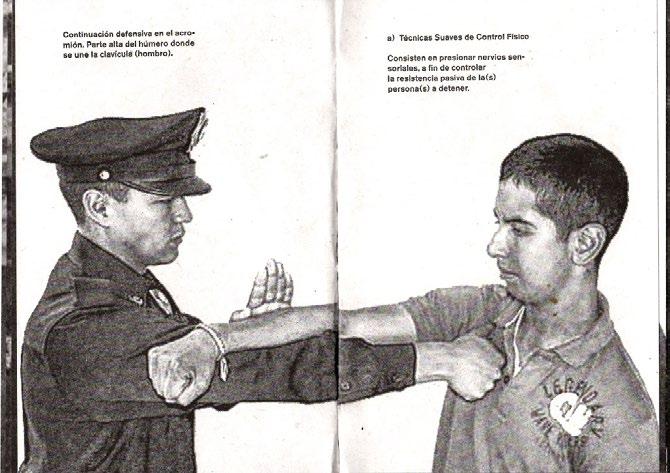

Nochixtlán: Manual de técnicas para el uso de la fuerza, 2018. Artist book, risograph, black and white, 32 pp. University of Oregon, Design Library, Artists’ Books, N7433.4.D529 N63 2018; L2024:30.1

Rigoberto Díaz Julián

Oaxaca, México)

A photographer and educator, Rigoberto Díaz Julián is interested in time, language, and the environment. In his artist books and photography, he investigates origin myths by examining caves, green spaces, and urban parks as well as the life produced within their confines. He has stated, “Buscar el origen es como cavar en la arena/Searching for the origin is like digging in the sand.” Departing from the ubiquitous imagery of rocks, tree trunks, and mountains that viewers often encounter in his oeuvre, in Nochixtlán Díaz Julián adopts an activist and political tone.

“Nochixtlán no se olvida/Nochixtlán is not forgotten” is a popular phrase that refers to the tragic incidents that occurred on June 19, 2016, in the town of Nochixtlán, Oaxaca, México, where teachers and community members protested against the Government’s education reform. The political demonstration that halted traffic on the highway and in the vicinity of Oaxaca was met with the use of excessive force and violence from the police. The tragic responses by law enforcement officers resulted in the death of six people and more than one hundred wounded. Díaz Julián’s Nochixtlán examines the training manuals used by the Mexican police to question the procedures and guidance the agency receives.

Verónica Dondero

(b. 1957 Talca, Chile)

Verónica Dondero (b. 1957 Talca, Chile) República de Chile: pasaporte, 1993. Artist book, 16 pp. University of Oregon, Design Library, Artists’ Books, N7433.4.D677 R47 1993; L2024:30.2

A graduate of the University of Oregon (Fine and Studio Arts Management FBA and Master of Fine Arts MFA 1993), Verónica Dondero experienced firsthand the violent overthrow of Salvador Allende’s democratically elected government when a military junta, aided by the CIA and Chilean elite, forced Allende and his followers from the presidency, resulting in Allende’s suicide and the subsequent dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (r. 1973-1990). Dondero was only twelve years old at the time and living in the country amidst the political turmoil.

In República de Chile: pasaporte the user’s identification remains unknown, yet exit stamps and employment authorization marks visibly trace the owner’s journey. Eventually, one of its pages names María Verónica Álvarez as the passport’s holder, providing some hints of its user’s identity, but no definitive answers. Unambiguously, however, are the testimonies and warnings provided, including the alarming statement: “All rights of the people were suspended…violations of civil liberty, should not be allowed to fade from memory lest they be repeated again and again….” Finally, an homage to the assassinated educator, singer-songwriter, and activist Victor Jara (1932-1973) is provided at the end of the book through one of his poems. Jara, along with numerous other intellectuals and activists, was murdered in the Santiago soccer stadium during Pinochet’s authoritarian regime.

Doris Salcedo

(b. 1958 Bogotá, Colombia)

Doris Salcedo (b. 1958 Bogotá, Colombia) Plegaria Muda, 2008-2010, wood, mineral compound, metal, and grass. Each 64 5/8 x 84 ½ x 24 inches. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Purchase, by exchange, through a fractional gift of Shirley Ross Davis.

Doris Salcedo (b. 1958 Bogotá) has shown her work internationally for over three decades. Her installation Plegaria Muda—which can be roughly translated as “silent prayer”—honors victims of violence. Conceived from 2008 to 2010, the artwork consists of sixteen pairs of tables carefully aligned by the artist in the gallery space, as groups and individually. Together they create a pathway, and therefore a journey, which visitors must complete to fully experience the artwork.

Plegaria Muda was created after Salcedo interviewed mothers in Los Angeles, California, whose children had been victims of gun violence. It is also a response to victims of violence in her native country, Colombia, and reflects the conditions that render life expendable in both the Global South and the Global North. Salcedo states, “I wanted a piece that if you turn it around is exactly the same, it is the fate of poor people, because if you are poor, you inhabit a gray zone, that has been described as social death.” She adds, “I wanted to make this mass grave and I wanted to isolate each body as though a precarious funeral took place. It is very important to create a poetics of death in my work so all these lives are recognized as life.”

Plegaria Muda invites viewers to reflect on power structures of “necropolitics” that grant some people the right to live and deny others such a possibility. Her necroarchivo—or archive of the dead—highlights the loss of life to encourage collective memory and mourning, and ultimately calls for a politics of care, life, and social change.

Plegaria Muda is presented with the generous support of Allison and Larry Berg, and the support of JSMA members. Other funding is provided by the Latinx Studies Faculty Seed Grant from the Center for Latino/a and Latin American Studies (CLLAS) and the Division of Equity and Inclusion at the University of Oregon.

The only academic art museum in Oregon accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, the University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (JSMA) features engaging exhibitions, significant collections of historic and contemporary art, and exciting educational programs that support the university’s academic mission and the diverse interests of its off-campus communities. The JSMA’s collections galleries present selections from its extensive holdings of Chinese, Japanese, Korean and American art. Special exhibitions galleries display works from the collection and on loan, representing many cultures of the world, past and present. The JSMA continues a long tradition of bridging international cultures and offers a welcoming destination for discovery and education centered on artistic expression that deepens the appreciation and understanding of the human condition.

About the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art