Political discourse in our country and in our state has deteriorated. Confidence in our government is at an all-time low. Polarization often prevents legislative compromise. Legislation often results from the actions of the party in power; rarely is it bipartisan.

Many media outlets capitalize on the polariza tion, focusing less on the day’s news and more on the resulting conflicts. The media recogniz es that conflicts draw the attention of readers and viewers. Rarely, do we see “good news” reported. Just problems and conflict. Conflict and problems.

Our courts are not immune to this polariza tion. The reporting that surrounds significant court decisions is often prefaced by identifying the political affiliation of the judges and, in the case of federal judges, the political party of the president who appointed the judges. Citizens from the same political party view themselves as constituents of judges from their party. They naturally conclude that judg es’ party affiliations are one explanation for their decisions.

Judges are unable to advocate for themselves. The most they can do is to write complete and thorough opinions each time they issue a decision. Unlike members of the legislative and executive branches, judges are ethically prohibited from walking up to a media outlet’s microphone to answer questions about their actions.

In such a landscape, where judges are elected like other members of government and where their decisions are often viewed as political, how can we best advocate for an independent judiciary and teach Pennsylvania citizens about the importance of judicial independence?

Let’s start with high school students. Let’s be sure they understand how our three branches

of government work and why there are checks and balances. Let’s teach them how our courts operate and why. Let’s provide resourc es that explain the process of seeking justice in our judicial system. Let’s take PBA-member lawyers/judges into high school classrooms across the state, show the students an inspir ing documentary film about a federal lawsuit and then explain how that lawsuit wound its way from the district court to the court of appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court and back down to the district court.

How do we do that? Teen Screen.

Teen Screen is a unique program offered to Pennsylvania high schools by Film Pittsburgh, a nonprofit that seeks to advance the art of independent film and uses film as an edu cational tool. Film Pittsburgh’s Teen Screen program curates independent films from around the world that deal with issues of interest to today’s youth. Many of those issues are part of the regular high school curriculum. Teen Screen works with teachers to select a film from its extensive film library, provides teaching resources to complement the film, arranges to screen the film either in the class room or at a movie theater and provides out side experts to discuss the themes presented by the film.

Recently, Teen Screen obtained the rights to screen a documentary about a federal lawsuit. Youth v. Gov is a documentary film that chron icles the case of Juliana v. United States, a lawsuit commenced in the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon by a group of youth who claim that the actions of our federal gov ernment have contributed to climate change, depriving the plaintiffs of their constitutional right to a clean environment. The claims are novel and the procedural posturing of the case as depicted in the film provide PBA lawyers/

“

”

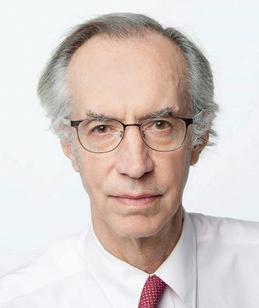

Let’s start with high school students. Let’s be sure they understand how our three branches of government work and why there are checks and balances.Jay N. Silberblatt

Appointed to committees of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania: Judge Joffie C. Pittman III, Philadelphia, and Judge Karen E. Zucker, Montgomery County, Minor Court Rules Committee; and Judge Wendy G. Rothstein, Montgomery County, and Luke T. Weber, Lancaster County, Committee on Rules of Evidence.

Jillian F. Zacks of the Pittsburgh office of McAndrews Mehalick Connolly Hulse and Ryan PC, named board vice chair of Achieva, a nonprofit that advocates for, em powers and supports people with disabili ties and their families.

PBA President-elect Michael J. McDonald, McDonald & MacGregor LLC, Scranton, re cipient of a Lackawanna Pro Bono Attorney Robert W. Munley Distinguished Service Award.

Amy L. Rosenberger of Philadelphiabased Willig, Williams & Davidson, named Alumna of the Year by Eastern Mennonite University.

John M. Quain Jr. of the Lancaster office of Barley Snyder, named the 2022 Pennsylvania Immigration Resource Center Light of Liberty Pro Bono Attorney, recog nizing his exceptional service and support to the organization.

Widener Law Commonwealth students Keri L. Nace and Koury A. Trout , awarded the Patrick J. Murphy Law and Government Fellowship, which entails research on government law issues; representing the Law and Government Institute to the stu dent body; interacting with policymakers, alumni and other members of the Widener Law community; and planning institute activities.

Catherine N. Reeves of Harrisburg-based Metzger Wickersham PC, selected for the 2022-23 National Asian Pacific American Bar Association Leadership Advancement Program.

Kila B. Baldwin, formerly of Kline & Specter PC, Philadelphia, and Jason E. Matzus , for merly of Matzus Law LLC, Pittsburgh, have formed Baldwin Matzus LLC, with offices in both cities.

Lucas J. Csovelak , elected partner at the Harrisburg office of Weber Gallagher Simpson Stapleton Fires & Newby LLP.

Gabrielle M. Gesek has joined as an asso ciate in the litigation practice group at the Philadelphia office of Armstrong Teasdale LLP.

With the merger of Marcello & Kivisto LLC with Saxton & Stump, Douglas B. Marcello, partner, and Alyssa A. Adams and Tiffany M. Peters , associates, have joined Saxton & Stump’s trucking and commercial trans portation practice group in the Harrisburg office.

Joining as associates at Blue Bell-based Wisler Pearlstine LLP: Mark J. Burgmann and Bethany O’Neill Byrne, education prac tice group; and Joseph M. Gagliardo, busi ness, corporate and tax practice group.

Bryce R. Beard has joined as associate in the energy, utilities and telecommuni cations practice group at the Harrisburg office of Eckert Seamans Cherin & Mellott LLC.

Alexandria Bondy has joined as an associ ate at Philadelphia-based Hofstein Weiner & Meyer PC. ⚖

Allegheny County

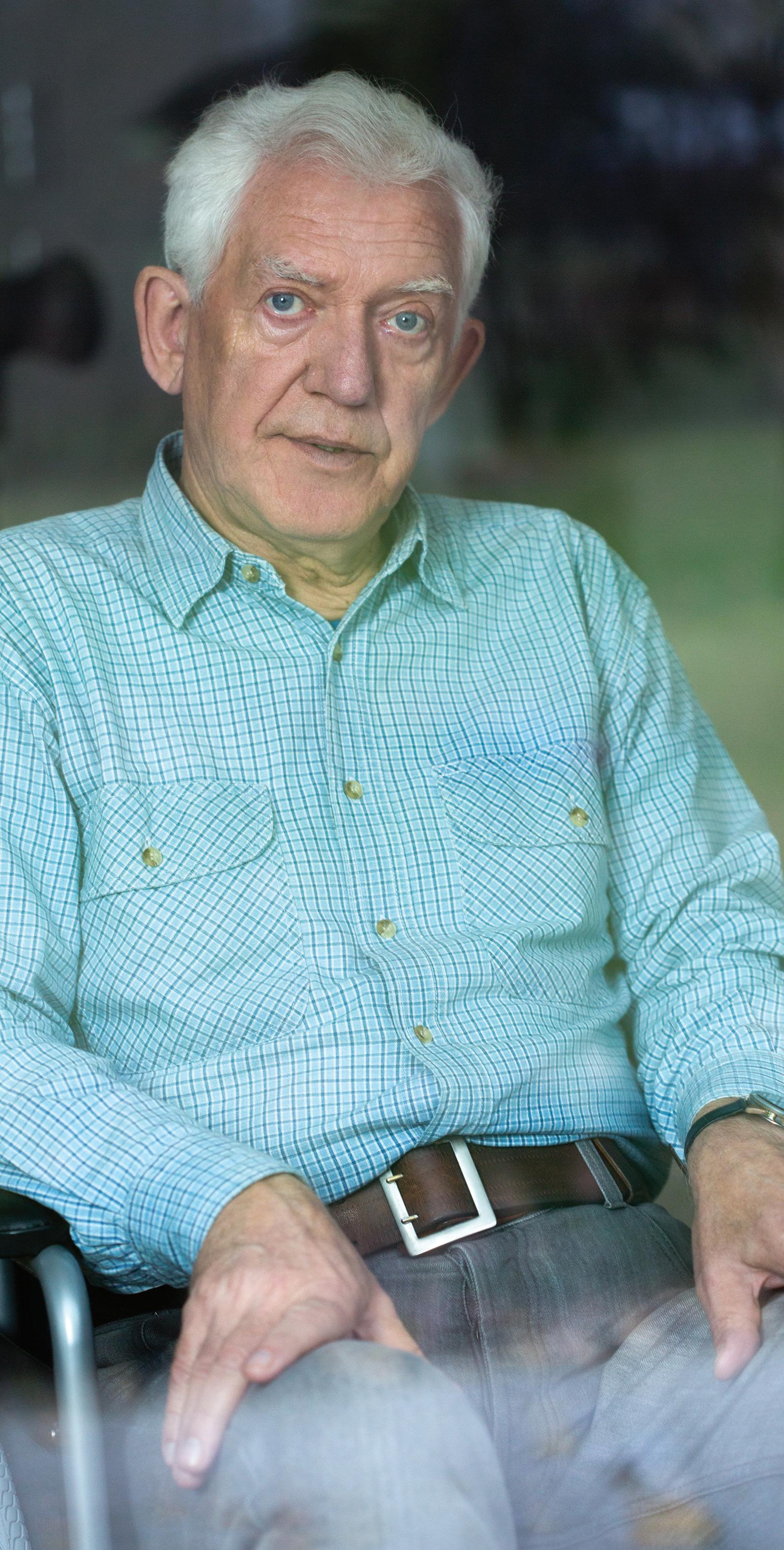

Chief Justice Max Baer, 74, Pittsburgh

Baer was elected to the Supreme Court in 2003 and was sworn in as chief justice in 2021. He was to retire at the end of this year, after reaching the mandatory retirement age of 75. Baer was elected to the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas in 1989. He spent the majority of his time in the court’s family division. Among the many programs he initiated were the Statewide Adoption Network (SWAN), a one judge/one family policy in juvenile court, the CYF family mediation project to facilitate adoptions at the point of termination of parental rights, a Permanency Planning List to pinpoint delays in adoption cases and the Hearing Officer Project to assist judges in the hearing of dependency cases. Baer received multiple accolades for his work. He was named Pennsylvania Adoption Advocate of the Year and PBA Child Advocate of the Year, and President Bill Clinton presented him with the federal Department of Health and Human

Services Adoption Excellence Award for Judicial Innovation. PBA President Jay Silberblatt noted Baer “was known across the country for his dedication to and innovative ideas in juvenile justice. His history, background and commitment to the bar were remarkable.”

Sanford P. Gross,* 86 Pittsburgh

Lackawanna County Irwin Schneider,* 91 Fleetville

Montgomery County Joseph J. McGrory Jr., 64 Limerick

Roseann B. Termini, 69 Wynnewood, a frequent contributor to The Pennsylvania Lawyer

Wyoming County Gerald C. Grimaud, 80 Tunkhannock, a past president of the Wyoming/Sullivan County Bar Association

York County Edward A. Stankoski Jr., 69 York

• Judge, Court of Judicial Discipline

• Former Chairman, Judicial Conduct Board of Pennsylvania

• Former Chairman, Disciplinary Board of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

• Former Chairman, Continuing Legal Education Board of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

• Former Chairman, Supreme Court of PA Interest on Lawyers Trust Account Board

• Former Federal Prosecutor

• Selected by his peers as one of the top 100 Super Lawyers in Pennsylvania and the top 100 Super Lawyers in Philadelphia

• Named by his peers as Best Lawyers in America 2022 and 2015 Philadelphia

“Lawyer of the Year” Ethics and Professional Responsibility Law and Legal Malpractice Law

Editor’s note: The following were emailed to author [and PBA Quarterly editor] Robert E. Rains regarding his article titled “Disinheriting Pennsylvania’s Children” in the September/October 2022 issue. They appear here with the writers’ permission.

I finished reading your intriguing article on disinheriting children. Thank you very much for an interesting article. I have drafted a number of wills in which my clients have disinherited children who have abandoned them or refused to communicate in some fashion. There’s every reason to protect mi nors who are disinherited, but I [also] see a good reason for a capable testator to be allowed to disinherit a child who has broken the relationship with her or his parent — sometimes. There are other times when the disinheriting seems to be flowing from a religious disagreement or lifestyle choice. That, it seems to me, is a gray area. But the whole topic is certainly worthy of discussion, especially as it affects minors who cannot support themselves. Thanks again.

Andrew D. Cotlar Doylestown

Andrew D. Cotlar Doylestown

Just finished your article in the current Pennsylvania Lawyer. Well done. You lay out a persuasive case for reexamining our law.

It is interesting that a policy of allowing the disinheritance of children, which presumes the parent prefers that result by not having provided otherwise in the will, sits side by side with the probate code provision giving a “forced” share to “after born” children. So, the testator who gives nothing in his will to his existing children is thereby

presumed to want the child born after he signs his will to have a share! Huh?

Richard Grossman Norristown

Thank you, Professor Rains, for an excellent article on this subject. The information about the present law of the U.K. was par ticularly interesting.

And along these same lines, there’s the Pennsylvania law of adoption of adults. It can be done without notice to anyone: not to the biological parents of the adult in question (who will be disinherited if the adopted adult dies without issue, and/ or who, conversely, may be relying on the intestate laws to ensure that their now legally unrelated issue inherits) nor to the adopter’s biological issue whose share of the adopter’s estate will be reduced.

Both this and the issue you so interesting ly explored, in my opinion, require more legislative scrutiny of the parent-child relationship.

Emeline L.K. Diener Pocono LakeHats off to Tom Wilkinson on an outstand ing and timely article [“Abraham Lincoln: Lessons in Civility, Professionalism and Equality” in the September/October issue]. We live in a time when civility, profession alism and equality are lost on some in our profession. Lincoln taught us and Tom has reminded us of the importance of these at tributes. His article couldn’t be more timely. This excellent article should be mandatory reading for all law students and highly rec ommended for everyone in our profession. Thank you, Tom, for reminding us of what it means to be an attorney and the extremely important role we play in our society.

James T. Davis UniontownEnjoying the recent article on Abraham Lincoln in the September/October edition of The Pennsylvania Lawyer. I particularly liked the author’s emphasis on Lincoln’s reputation for hard work, honesty, civility and professionalism. The article, however, is titled (in part) “Lessons in ... Equality.” American historians have spent consider able time over the past 150+ years trying to determine Lincoln’s views on racial equality. They have realized Lincoln was a man of his time — early and mid-19th century America — a time when most but not all Americans viewed Black people as inferior to white people.

As a person, Lincoln was absolutely op posed to slavery, particularly after visiting the slave markets in New Orleans in 1828. After that visit, he believed that economic equality “rewarding each person, slave or non slave, for his labor” was a laudable and defensible goal. As a politician, howev er, Lincoln in the 1858 senatorial election in Illinois against Stephen Douglas twice repeated the position that “the physical difference between the white and Black races [would] forever forbid the two races living together in terms of social and politi cal equality.”

As stated by David Potter in his 1976 Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Impending Crisis: America before the Civil War — 1848-1861: “Certainly, Lincoln understood that most of his fellow citizens, both in Illinois and in the North generally, might support the abstract idea of emancipation, but not the idea of racial equality.” David Donald in his one-volume Lincoln (consid ered the best single volume on Lincoln) in 1995 wrote, “Lincoln fortunately escaped the most virulent strains of racism [and] when he agreed the Blacks did not have

If you’re a PBA member and you want the legal community to know about your appointment, promotion, recent speaking event or other law-related news, why not submit your announcement to run as a “People” item?

The most frequent types of “People” announcements we run are for appointments/ elections, awards/honors, being published, firm moves and speaking engagements. We run items on recipients of county bar awards, but we do not list county bar commit tee and section appointments. We do not run prospective notices, particularly for speaking or meeting events, as these are subject to change, and we do not include lawyer and law-firm “best of” announcements. Given the PBA’s large member base, we also monitor for how frequently individuals are listed in the column. Photos are welcome. If provided elec tronically, photos should be high resolution. Most electronic photos we receive are as JPEG files.

The editors reserve the right to reject “People” submissions and to edit for style and length of announcement. Accepted announcements will appear in either the PBA’s Pennsylvania Lawyer magazine or Pennsylvania Bar News tabloid, depending on when notices are received in the editorial cycle.

Email “People” column notices to editor@pabar.org or mail to the Pennsylvania Bar Association, Attn. People Column, 100 South St., P.O. Box 186, Harrisburg, Pa. 17108-0186.

the same civil rights as whites, he nearly always added in the next breath that they were the equal of whites in the enjoy ment of the natural rights pledged in the Declaration of Independence.”

It would take another century for a Black man, a son of the South, Martin Luther King Jr., to emerge and to challenge the American people, civilly and professionally, to accept the concept of racial equality — economic, political and social equality. Therein lies one of American history’s great themes and America’s greatest tragedy.

Daniel R. Schuckers Camp Hill

Daniel R. Schuckers Camp Hill

Editor’s note: The following were emailed to author (and PBA Past President) Thomas G. Wilkinson Jr. regarding his article titled “Abraham Lincoln: Lessons in Civility, Professionalism and Equality” in the September/October 2022 issue. They appear here with the writers’ permission.

Rather than begin my Saturday morning by reading a brief, I opted instead for your ex cellent article on Lincoln. As a fan of most “Lincolnalia,” I greatly appreciated your insights into both the man and what he so often had to say about civility and the need to come together. Lincoln’s memory endures. Let’s hope his message does as well.

A very timely piece, for which I thank you.

Senior Judge D. Brooks Smith U.S. Court of Appeals for the 3rd Circuit of Pennsylvania Duncansville

Just finished reading your very delightful, insightful and comprehensive article on Mr. Lincoln in the [September/October] Pennsylvania Lawyer magazine. I reckon

this work took some time and research. [PBA Past President] Forest Myers and I share lunch together every three weeks or so, and with some sad regularity, we talk about the lack of professionalism and civility that we observe with our colleagues. Civility seems to be on life support; hoping it’s not DOA.

The email address for letters to the editor of The Pennsylvania Lawyer magazine is editor@pabar.org. Letters by mail should be sent to the Pennsylvania Bar Association, Attn. Editor, 100 South Street, P.O. Box 186, Harrisburg, Pa. 17108-0186.

Civil Litigation Section Regional Dinner Nov. 1, Harrisburg

Pennsylvania Civil Procedure: A Primer Nov. 1, various locations and via webcast

Commission on Women in the Profession Fall Retreat Nov. 4-5, Hershey

Business Law Institute Nov. 15-16, Philadelphia and webcast

Board of Governors Meeting Nov. 16, Harrisburg

Committee/Section Chair Board of Governors Reception Nov. 16, Harrisburg

Committee/Section Day Nov. 17, Harrisburg

Pennsylvania Bar Foundation Night Out Nov. 17, Harrisburg

House of Delegates Meeting Nov. 18, Harrisburg

Collaborative Law Lunchtime Q&A Nov. 29, via Zoom

Family Law Section Winter Meeting Jan. 13-15, 2023, Hershey

Board of Governors Meeting Jan. 25, 2023, Lake Buena Vista, Fla.

Midyear Meeting Jan. 25-29, 2023, Lake Buena Vista, Fla.

Please check the PBA calendar at www.pabar.org/site/Calendar for the most current meetings and events information.

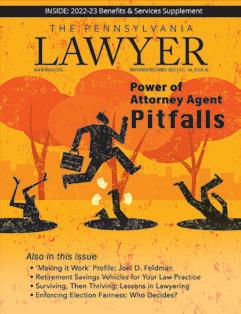

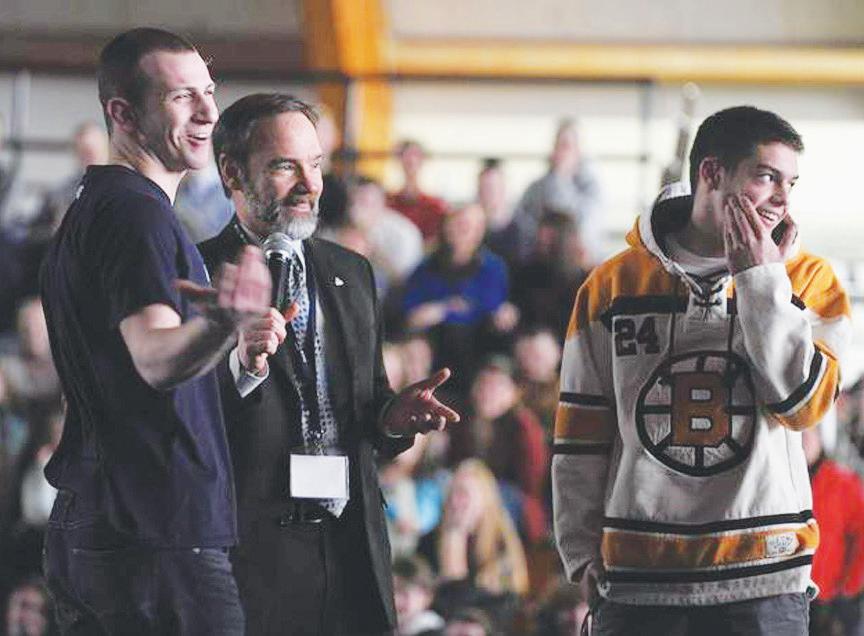

Michael J. Lyon (bottom) of the PBA Law-Related Education Committee and PBA President Jay Silberblatt lead a discussion on Youth v. Gov with students from the Pittsburgh Environmental Charter School.

The Pennsylvania Lawyer is your PBA membership magazine. Our mission is to inform, educate, analyze and provide a forum for comment and discussion.

We’re always looking for informative articles of 2,000 to 3,000 words that help lawyers understand and deal with trends in the profession, offer ways to practice more efficiently and shed light on issues of importance. If you’re interested in writing for us, we’d like to hear from you. To submit an article proposal or request our writer guidelines, email editor@pabar.org or write to Pennsylvania Bar Association, Attn. Editor, The Pennsylvania Lawyer, P.O. Box 186, Harrisburg, Pa. 17108-0186.

> from page 2

judges with the ideal opportunity to teach a civics lesson to high school students.

The PBA Law-Related Education Committee, chaired by Judge Mark Kearney of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, has partnered with Teen Screen. Teen Screen’s first display of Youth v. Gov took place in April at the Pittsburgh Environmental Charter School. Following the screening, yours truly and Michael Lyon from the Law-Related Education Committee “Zoomed” into the classroom to discuss the themes of the film and answer questions from the students that touched on subjects ranging from standing to redressability to remedies to appellate review.

The students were inquisitive and inspired by the film. The teachers were appreciative that a couple of real lawyers took time to explain the way our federal civil justice system operates.

The goal of the partnership between Teen Screen and the PBA is to display Youth v. Gov in as many high schools throughout Pennsylvania as possible. Each time the film is screened, PBA-member lawyers/ judges will have an opportunity to meet with the students and talk about our civil justice system, the rule of law and the importance of an independent judiciary. This is a winwin program. The task at hand is to be sure

our Pennsylvania high schools are aware of the opportunity and invite Teen Screen and the PBA into their classrooms. The program is free; it is generously supported by Film Pittsburgh and its many grants.

If you’re interested in this program for your local high school, arrange for the school to contact Teen Screen Director Lori Sisson at lsisson@filmpittsburgh.org to obtain the curriculum materials and schedule a screening date. Once Teen Screen is contacted by the school, it will in turn contact Susan Etter, PBA director of County Bar Services and Special Projects and staff liaison to the Law-Related Education Committee, who will arrange for PBA-member lawyers/judges to visit the classroom in conjunction with the screening of the film.

Helping our high school students better understand how our courts operate and ad vocating for our independent judiciary are core missions for the PBA. Be part of the solution; get your local high school involved in Teen Screen. ⚖

Jay N. Silberblatt PBA PresidentWe’re

a

Bankruptcy Institute 2022

Nov. 11 | 5 sub/1 ethics

Outstanding topics, speakers & updates on recent developments in bankruptcy law in the Eastern & Middle Districts of Pennsylvania— plus quick hits on the top commercial and consumer cases of the year!

Business Law Institute 2022

Nov. 15-16 | 10 sub/2 ethics

Join PBI for our 2022 Business Law Institute, bringing transactional attorneys and in-house counsel throughout Pennsylvania under one roof to learn, share and challenge emerging developments, trends, and practices in the corporate industry.

Nov. 29-30 | 10 sub/2 ethics

Join us for The 29th Annual Estate Law Institute as we continue our tradition of bringing you cuttingedge concepts, current trends, legal updates, first class reference manuals, and top-notch faculty.

Dec. 12 | 4 ethics

All newly admitted Pennsylvania attorneys are required to complete the Bridge the Gap program at an accredited CLE provider prior to their first PA CLE compliance deadline. This course is also a refresher for lawyers, regardless of years in practice. The program is designed to provide basic, yet important, information and insight relative to ethics and professionalism.

Access to over 600 programs from the comfort of your home or office.

Executive Editor: Jeffrey A. Gingerich

Editor: Patricia M. Graybill

People Editor: Andy M. Andrews

Contributing Writers: Fredrick Cabell Jr., Robert A. Creo, David J. Millstein, Barry M. Simpson, Victoria White, Jay N. Silberblatt, Thomas G. Wilkinson Jr.

Design: Kelly Cassidy-Vanek, Cassidy Communications Inc. www.cassidycomm.com; Bethlehem, Pa.

Display Advertising: PBA Communications Department; Phone: 800-932-0311, ext. 2226.

Classified Advertising: PBA Communications Department; Phone: 800-932-0311, ext. 2226.

Views expressed in The Pennsylvania Lawyer do not neces sarily reflect the official views or policies of the Pennsylvania Bar Association. The appearance of a product or service advertisement herein does not constitute an endorsement of the product or service by the Pennsylvania Bar Association. The Pennsylvania Lawyer welcomes editorial submissions from members of the bar. Letters to the editor from readers on all topics concerning the legal profession are welcome. The publisher reserved the right to select letters to be published. Letters may be edited for length and style.

Editorial items and correspondence should be mailed to the Pennsylvania Bar Association, Attn. Lawyer Magazine Editor, 100 South Street, P.O. Box 186, Harrisburg, Pa. 17108-0186. Telephone: 800-932-0311. Email address: editor@pabar.org. Unsolicited manuscripts will not be returned unless accompa nied by a self-addressed, stamped envelope.

The Pennsylvania Lawyer is distributed to all PBA members as a membership benefit. Subscription is $30 per year. To join the PBA, call 800-932-0311. The Pennsylvania Lawyer is underwritten in part by the Pennsylvania Bar Insurance Fund. Soy-based inks used in printing.

OFFICERS

President: Jay N. Silberblatt

President-elect: Michael J. McDonald

Vice President: Nancy Conrad

Immediate Past President: Kathleen D. Wilkinson

Chair, House of Delegates: Jonathan D. Koltash Secretary: Jacqueline B. Martinez Treasurer: James R. Antoniono

YOUNG LAWYERS DIVISION REPRESENTATIVES

Chair: Patrice M. Turenne

Chair-elect: Jennifer A. Galloway

Immediate Past Chair: Paul D. Edger

GOVERNORS

Minority Governor: Rodney R. Akers

Minority Governor: Judge Cheryl L. Austin

Unit County Governor: Matthew M. Haar

Woman Governor: Amy J. Coco

Zone 1: Jennifer S. Coatsworth

Zone 2: Eric M. Prock

Zone 3: Lisa M. Benzie

Zone 4: John P. Pietrovito

Zone 5: Sean P. McDonough

Zone 6: Judge Damon J. Faldowski

Zone 7: John F. Alcorn

Zone 8: Christopher G. Gvozdich

Zone 9: Carolyn R. Mirabile

Zone 10: Melissa Merchant-Calvert

Zone 11: Adrianne Peters Sipes

Zone 12: Lawrence R. Chaban

Chair: Bernadette M. Hohenadel; Vice Chair: Judge William I. Arbuckle III; Members: Emeline L.K. Diener, Mary Wagner

Fox, Richard J. Frumer, Judge Thomas King Kistler, Peter W. Klein, Alyson Tait Landis, Stephanie F. Latimore, Michael J. Molder, Catherine R. O’Donnell, Riley H. Ross III, Cheri A. Sparacino, Jill M. Spott, Ryan W. Sypniewski, Andrij V.R. Szul, Zanita Zacks-Gabriel; Board of Governors Liaison: Jonathan D. Koltash

PBA Staff — Executive Director: Barry M. Simpson; Deputy Executive Director: Francis J. O’Rourke; Director of Communications: Jeffrey A. Gingerich; Director of CLE Content Delivery: Erika Bloom; Director of CLE Content Development: Clair A. Papieredin; Director of County Bar

Services & Special Projects: Susan E. Etter; Director of Finance: Lisa L. Hogan; Director of Information Technology: Terry Rodgers; Director of Legislative Affairs: Fredrick

Cabell Jr.; Director of Meetings: Wendy A. Loranzo; Director of Member Services: Karla Andrews; Director of Western Pennsylvania Services: Bridget M. Gillespie

June 25 through August 19, 2022

Following review and approval of the joint petition in support of discipline by a three-member panel of the Disciplinary Board, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on Aug. 4 ordered Timothy Nicholas Tomasic subject to a public reprimand on consent and probation for two years, sub ject to conditions including his abstinence from drugs and alcohol, attendance at weekly meetings of Narcotics Anonymous and the appointment of a sobriety mon itor. According to the disciplinary report, Tomasic was charged with violations of the Rules of Professional Conduct including failure to provide competent representa tion, failure to act with reasonable diligence and promptness, and that a lawyer shall not represent a client or shall withdraw from the representation if the lawyer’s phys ical or mental condition materially impairs the lawyer’s ability to represent the client. According to the report, in reaching the recommendation for discipline, the panel considered as an aggravating factor that Tomasic failed to comply with the Office of Disciplinary Counsel’s (ODC’s) multiple requests for documentation regarding his pursuit of sobriety and, as mitigating

factors, his lack of prior discipline and that he accepted responsibility for his miscon duct by virtue of his consent to the imposi tion of a public reprimand with probation. The report also indicated that if the matter were to proceed to a disciplinary hearing, Tomasic would seek to establish that his substance use disorder was a causal factor in his misconduct per Office of Disciplinary Counsel v. Seymour H. Braun; that “the facts of this case would also support a finding of Braun mitigation” and, if the matter were to proceed to a disciplinary hearing, that he and others would testify to his sobriety since December 2021 and his regular attendance at Narcotics Anonymous meetings. The panel concluded that that the recommended sanction “satisfies the primary purpose of the disciplinary system in that it would notify the public that [his] drug use adversely impacted his represen tation of a client while also protecting future clients from the possibility of such adverse impacts through monitoring to detect future drug use.”

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on July 5 ordered Anthony Hugh Rodriques subject to a public reprimand with conditions including that he submit proof that he has made payment to his client in the relevant matter to the Disciplinary Board prothono tary and ODC and that he return all of the client’s documents.

Following review and approval of the joint petition in support of discipline by a three-member panel of the Disciplinary Board, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania on Aug. 5 ordered Steven Ronald Savoia subject to a public reprimand. According to the disciplinary report, Savoia’s mis conduct involved violations of the Rules of Professional Conduct and Rules of Disciplinary Enforcement including failure

to act with diligence and promptness, failure to consult with the client and to keep the client informed, and failure to respond to the ODC’s request for a statement of po sition. In reaching the recommendation for discipline, the panel considered Savoia’s disciplinary history, which included two in formal admonitions for misconduct similar to the instant case, as well as his remorse and consent to discipline, and concluded that “prior disciplinary intervention has not been sufficient to abate [his] misconduct, suggesting more serious discipline is nec essary. Precedent supports the imposition of public discipline, without suspension, for attorneys who engage in neglect and failure to communicate and have a record of private discipline.”

EMERGENCY TEMPORARY SUSPENSION — Rule 208(f)

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ordered the following attorneys placed on emergency temporary suspension: Manrico A. Troncelliti Jr., Montgomery County, on July 1; Brian M. Puricelli, Bucks County, on July 11.

TEMPORARY SUSPENSION — Rule 214

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ordered the following attorney placed on temporary suspension under a rule of disci plinary enforcement pertaining to attorneys convicted of a crime: Brad J. Koplinski, Cumberland County, on Aug. 10. Justice Kevin M. Dougherty did not participate in the consideration or decision of the matter.

215

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ordered the following attorneys disbarred on consent under a rule of disciplinary enforcement pertaining to resignations by attorneys who are being investigated for allegations of misconduct: Nicholas Urick, Beaver County, on Aug. 10; Royce W. Smith, Philadelphia,

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

More than 900,000 lawyers nationwide turn to Fastcase to smartly complete their legal research needs. Fastcase proudly partners with over 50 national, state, and county bar associations to provide a comprehensive books, treatises, and journals available to meet their practice needs, along with partner service integrations such as Docket Alarm, HeinOnline, LexBlog, Clio, Courtroom Insight, and TransUnion. See today why Fastcase is a smarter way to legal research. We provide our users with unlimited usage, unlimited service support – all at no additional cost.

Fastcase puts the whole national law library on any internet connected device with cloud-based access to cases, statutes, regulations, and can be viewed at Fastcase.com/coverage.

on Aug. 16, following his temporary suspen sion on April 8.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania imposed reciprocal discipline on the following attorneys: Michael Nielson Behunin, Sandy, Utah, disbarred, on July 28, for like discipline imposed by the Utah Supreme Court; Charles Kevin Blackmon, Greensboro, N.C., disbarred, on July 28, for like discipline imposed by the Council of the North Carolina State Bar; Alfred DiGirolomo Jr., Garden City, N.Y., disbarred, on July 28, for like discipline imposed by the Supreme Court of New York, Appellate Division, Second Judicial Department; Arthur P. Fisch, Brooklyn, N.Y., disbarred, on July 28, for like discipline imposed by the Supreme Court of New York, Appellate Division, Second Judicial Department; Thomas A. Fadner II, Sioux City, Iowa, disbarred, on Aug. 5, for like discipline im posed by the Supreme Court of Wisconsin; Freddie Jay Berg , New York, N.Y., disbarred, on Aug. 16, for like discipline imposed by the Supreme Court of New York, Appellate Division, Second Judicial Department; James Thomas Hytner, St. James, N.Y., disbarred, on Aug. 16, for like discipline imposed by the Supreme Court of New York, Appellate Division, Second Judicial Department; Vincent J. Mitchell, Coventry, R.I., disbarred, on Aug. 16, for like disci pline imposed by the Supreme Court of Rhode Island; Daniel Warren Morse Jr., Milwaukee, Wis., suspended for one year and one day, on Aug. 16, for like disci pline imposed by the Supreme Court of Wisconsin.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania granted reinstatement to Herbert Karl Sudfeld Jr., Bucks County, on Aug. 11, from a four-year suspension on consent, as recommended by the Disciplinary Board. Chief Justice Max Baer and Justice P. Kevin Brobson dissented from the court’s order. According to the reinstatement report, Sudfeld was ordered suspended on June 22, 2020, retroactive to April 8, 2016, the date of his temporary suspension relat ed his conviction for insider trading and making false statements to authorities. As indicated in the report, at the reinstatement hearing Sudfeld “accepted full responsi bility for his misconduct and expressed genuine remorse for his criminal conduct and the embarrassment he caused to the profession, his law partners, his family and friends,” “expressed a sincere desire to earn back the respect of the legal com munity, which he ably served for nearly 40 years prior to his suspension” and present ed seven character witnesses who provided credible testimony as to his moral qualifica tions and fitness to resume the practice of law. The board determined that “although [Sudfeld’s] misconduct represented a seri ous breach of his professional ethics, … we conclude that he has met his reinstatement burden … [He] presented clear and convinc ing evidence that he spent his suspension period engaged in genuine rehabilitation and he is fit to be reinstated to the practice of law through demonstration of his moral qualifications, competence, and knowledge in the law.”⚖

The recent disciplinary actions of the court are posted at https://www.padisciplinary board.org/cases/recent-cases

It pays to advertise in the ‘Marketplace,’

As my career as Pennsylvania Bar Association executive director enters its last few months, I want to make sure I prioritize comments about my appreciation of the unparalleled PBA staff. Over the years, I have observed that at times like this, an outgoing thanks to staff is frequently relegated to just a few closing remarks. That cannot and will not be the case here. That is because all the great work and accomplishments of the individual PBA volunteers, sections, committees, YLD and other PBA entities run through the highly professional efforts of the PBA staff — many times through one staff person, but far more frequently through their team efforts. Indeed, at most times the team effort is such that only nominal direction is required by senior staff.

I generally view my role as the executive director is to make sure we continue to have great and talented staff members, provide them with the resources we can afford to ac complish the tasks at hand and then stay out of the way. I can do this because I have the utmost confidence in the skills and initiative of the PBA staff. American Bar Association bar executive programs routinely featured a presenter who said a great association staff member is one who always anticipates what needs to be done, takes the initiative and is so far out in front that the volunteers occasionally have to reel him/her back in as opposed to the volunteers having to look over their shoulders and urge the staff member to hurry to catch up. By that measure, our PBA staff seldom fail to perform. And if they do, it is almost always because they have so many balls in the air that some serious juggling is required. As managers, it is our job to keep that juggling to a minimum and, when need be, to help catch any balls that appear to be getting lost in the air. I assure you that has not happened often!

The “PBA staff” is often mentioned as if it is one never-changing unit. Of course, it is anything but that. Nevertheless, we have been fortunate that stability and longevity are hallmarks of our staff. For example, five current staff members were here when I ar rived in 1999 — some have been with the PBA 15 or 20 years more than I have. Of course, as the times change, along with the way law is practiced, the staff evolves. Existing staff members learn new skills; new hires add even more skills. It has always been my pleasure to see staff members working together, almost like a family.

The last nearly three “pandemic” years have, of necessity, brought a number of changes to the PBA staff. Many of you experienced some thing similar at your offices. The pandemic hit at the same time that we were midway through absorbing the Pennsylvania Bar Institute back into the PBA to make it more efficient and cost effective as the continuing legal education department of the PBA. Both that merger and the pandemic resulted in the shrinking of the number of staff. What did not shrink were the services and programs the PBA provided to our members, to other lawyers and judges and the general public. Technology, Zoom and fewer live meetings and CLE programs permitted a reduction in staff. But so did the willingness of individual staff members to take on more responsibilities. For that we all should be thankful and appreciative. I certainly am.

I will miss working with the talented and dedi cated staff listed on the next page. I hope they permit me to come by and say hello from time to time. I will remain a member even after my retirement from the PBA and will continue to appreciate all that they do for the attorneys and citizens of Pennsylvania.

“

”

I am frequently asked what made working at the PBA enjoyable, and my response has been that at the end of the day, when we put our head on the pillow, we know that in both big and small ways, we all made the commonwealth a better place.

I am frequently asked what made working at the PBA enjoyable, and my response has been that at the end of the day, when we put our head on the pillow, we know that in both big and small ways, we all made the commonwealth a better place. So, I will tell my fellow staff members to continue to enjoy their days at the PBA, as I have, and at the end of each day, rest well. They all deserve it.⚖

Barry M. Simpson Executive Director

Barry M. Simpson Executive Director

Jason Adams

Tameka Altadonna

Andy Andrews

Karla Andrews

Joel Bailey

Diane Banks

Megan Barrick

Erika Bloom

Taylor Burton

Randall Byler

Fredrick Cabell Jr.

Adriane Davis

Lauren Derrick

Maria Engles

Susan Etter

Becky Frank

Bridget Gillespie

Jeffrey Gingerich

Sandra Graver

Patricia Graybill

Ashley Heffernan

Garrett Helf

Lisa Hogan

Karen Hoover

Christian Ierley

Andrew Jamouneau

Anita Jones

Coleen Jones

Elijah Jones

Lisa Jones

Pamela Kance

Anna King

Karen Kreis

Carrie Larock

Kyle Leach

Wendy Loranzo

Jennifer McCreary

Kevin McVeigh

Lucas Mace

Ursula Marks

Ross Miller

Gabriele Miller Wagner

Nathan Morneau

April Murphy

Jillian O’Connell

Francis O’Rourke

Clair Papieredin

Susan Pesavento

Katey Rhone

Melissa Roane

Terry Rodgers

Tina Schreiber

Joanne Schumacher

Kate Sherman

Rebecca Silvia

Barry Simpson

Julie Sipe

Paul Skolka

Melisa Spinelli

Logan Stover

Sabine Tate

Stacey Thomas

David Trevaskis

Amanda Tucci

Adam Tulibacki

Vincent Wallace Jr.

Cassandra Ward

Julia Weaver

Holly Wertz

Victoria White

Susan Wolf

Philip Yerger

Jennifer Zeigler

The duties of an agent are set forth in 20 Pa.C.S. Section 5601. Among the agent duties set forth in that section are the agent’s obligations to: 1) keep a record of all receipts, disbursements and transac tions made on behalf of the principal; 2) act so as not to create a conflict of inter est that impairs the agent’s ability to act impartially in the principal’s best interest and 3) attempt to preserve the principal’s estate plan to the extent actually known by the agent, if preserving the plan is consistent with the principal’s best interest based on all relevant factors.

This article discusses a few significant cases, including a 2021 case, that show how courts have applied these statutory principles in specific circumstances. The cases illustrate the traps that await unwary agents and provide lessons for agents and their attorneys to consider in their efforts to reduce agent exposure to liability.

Under 20 Pa.C.S. Section 5610, courts have discretion to order agents subject to the provisions of 20 Pa.C.S. Chapter 56 to file accounts of their administration: An agent shall file an account of his administration whenever directed to do so by the court and may file an account at any other time. All accounts shall be filed in the office of the clerk in the county where the principal resides. The court may assess the costs of the accounting proceeding as it deems appropri ate, including the costs of preparing and filing the account. (emphasis added). 20 Pa.C.S. § 5610 (2022).

Case law makes clear that a court may order an agent under a power of attorney to file an accounting even if a petitioner lacks standing to do so. In re Dardarian, 2013 Pa. Dist. & Cnty. Dec. LEXIS 292, *4, 29 Pa. D. & C. 5th 316, 320 (2013).

In Dardarian, an 82-year-old mother residing in a nursing home made a friend her power of attorney. According to the court, before executing the power of attorney, Dardarian executed a will in which she excluded her daughter and a later will in which she left her estate equally to her agent under the power of attorney (POA) and three other friends.

Almost two years after Dardarian named her friend as an agent under her power of at torney, her daughter petitioned the Chester County Orphans’ Court to order the agent to file an account of her administration of Dardarian’s finances. The court noted that the daughter did not disclose to the court when she filed her petition that she had fallen out of favor with her mother.

According to the court, Dardarian had executed a will in which she specified that her daughter was excluded. In a later will, Dardarian specifically excluded her daughter and grandsons from her estate.

Dardarian’s daughter filed a petition in the Chester County Orphans’ Court seeking an order requiring the agent under the power of attorney to file an accounting. The court noted that the parties had agreed that the agent would file an accounting and ordered that the agent file the accounting in compli ance with local county rules.

The court said that there was no allega tion in this case that Dardarian was not in

possession of her faculties or that her mind had been imprisoned by the machinations of another. To the contrary, Dardarian made no accusations against her agent, filed a sworn affidavit affirming that she gave the daughter a significant gift, acknowledged an awareness that her agent was being paid $800 per week for services rendered to her under the power of attorney and expressed her overall satisfaction with the agent’s services, according to the court.

Discussing the issue of standing, the court concluded that any inquiry into the alleged misuse of a power of attorney is properly made by the principal, who granted the power, or by the personal representative of his or her estate after the principal’s death. The court further noted that for persons who have been adjudicated as incapacitated, their guardians succeed to the necessary standing to compel accountings.

Discussing precedents, the court stated that a beneficiary whose interest was al legedly damaged by the exercise of a power

A court may order an agent under a power of attorney to file an accounting even if a petitioner lacks standing to do so.

of attorney has no standing to demand an accounting. Moreover, the court cited Rosewater Estate, 25 Fid. Rep. 2d. 83 (O.C. Mont. Co. 2005), which involved a chal lenge to an agent’s withdrawal of funds from a decedent’s trust, for the proposition that a close blood relative or an intestate heir of the principal does not necessarily have standing to demand an accounting from the principal’s agent.

In Rosewater Estate, stepsons of the decedent, Mrs. Rosewater, were remaind ermen of a marital trust created in her will. The marital trust gave Mr. Rosewater “the unlimited right, fully exercisable at any time following my death, whenever and as often has he may wish, to withdraw as much of the principal as he may request in writing.”

Pursuant to a power of attorney, Mr. Rosewater’s agents, who were two of his children, withdrew all of the assets in the trust, which were valued at over $5 million, leaving nothing for his stepsons to inherit upon his death. The court said that had the

withdrawal not been made, the stepsons would have received two-thirds of the assets.

Rejecting the stepsons’ petition on the ba sis of their lack of standing, the Rosewater court noted that any court-imposed sur charge would benefit the decedent’s estate, not the decedent’s late wife’s marital trust nor his stepsons. The Orphans’ Court held that the stepsons had no substantial, direct and immediate interest in any dispute over whether the decedent’s power of attorney agents acted appropriately by directing the withdrawal of funds from the marital trust.

Citing precedents, the court stated that the stepsons’ lack of a substantial, direct and immediate interest required that their petition be rejected on standing grounds. Accordingly, the Rosewater court held that the stepsons lacked standing to raise a breach of fiduciary duty claim and sustained the estate’s preliminary objections.

Relying on Rosewater, the Dardarian court rejected Dardarian’s daughter’s petition.

But although the court rejected the daugh ter’s petition for an accounting, the court nevertheless ordered Dardarian’s friend and agent to file an accounting in the proper format for the court’s review.

Key Point: The court ordered the agent to file an accounting with the court despite the daughter’s lack of standing. This case illustrates that the Orphans’ Court has wide discretion to order an accounting even when a petitioner lacks standing.

In Estate of Newcomer, 121 A.3d 1127, Pa. Super. Unpub. LEXIS 881 (Pa. Super. Ct. Apr. 10, 2015) (unpublished), the Pennsylvania Superior Court affirmed an Orphans’ Court finding that the agent under a power of attorney attempted to deprive his father’s paramour of 28 years of an annuity specifically set aside for her through a purported beneficiary change.

Less than one year after Newcomer named his girlfriend as the sole beneficiary of an annuity, he executed a power of attorney that named his son his attorney in fact and agent. Soon thereafter, his son/agent executed a beneficiary change request form that removed the girlfriend as beneficiary of annuity proceeds and named himself and his brother as the beneficiaries of the annuity.

About five months later, Newcomer died testate. Later that year, his last will and testament was filed in the Fayette County Orphans’ Court.

That same year, Newcomer’s girlfriend petitioned the Orphans’ Court to issue a rule to show cause in an effort to recover approximately $40,000 in annuity proceeds that were payable on his death. According to the court, the annuity had originally named the girlfriend as the sole beneficiary.

The Orphans’ Court issued a rule directing the sons to show cause why the $40,000 annuity should not be paid to the girl friend. According to the Superior Court, the Orphans’ Court had concluded that, despite the authority granted to the agent/son, pursuant to the power of attorney to make beneficiary changes, the son had engaged in deception and attempted to commit a fraud by improperly signing his father’s name on a beneficiary change request form.

The court noted that the decedent’s son had not signed his own name as attorney in

fact pursuant to a power of attorney when he signed the form, but instead signed his father’s name with no indication that he had done so. The Orphans’ Court concluded that the son’s failure to sign the form properly made the beneficiary change request form a nullity.

Citing this agent misconduct, the Orphans’ Court ordered the annuity be paid to the girlfriend. The sons then appealed to the Superior Court, alleging, in part, that the beneficiary change form signed by the agent of the deceased was valid to change the beneficiary of the annuity.

Rejecting the son’s appeal, the court af firmed the Fayette County Orphans’ Court’s decision that the son/agent had engaged in deception. The Superior Court upheld the Orphans’ Court’s finding that, by signing his father’s name on the beneficiary change form without acknowledging he was signing pursuant to a power of attorney that had named the son as his father’s agent, the son had attempted fraud.

The Superior Court acknowledged that the power of attorney explicitly authorized the son/agent to change beneficiary designa tions. The court noted, however, that the son did not sign his name as an agent pursuant to the power of attorney, but instead simply signed his father’s name.

The court found that by signing his name, without designating himself as “Jr.” — as set forth in the power of attorney that gave him

the authority to act for his father — and by failing to refer to the power of attorney — the son/agent disavowed the power of attorney as a source of authority.

Finding that the son tried to pass off his signature as his father’s, the Superior Court held that the son/agent had attempted to convert the annuity to an asset of his and his brother’s and failed to keep accurate records as to who actually signed the benefi ciary change request concerning that asset. Based on that holding, the court concluded that the beneficiary change form signed by the agent of the deceased was invalid to change the annuity beneficiary. The court also concluded that the son/agent violated his fiduciary duty as an agent to carry out the wishes of his father.

Key Point: The Superior Court focused on whether the agent of the power of attorney signed his name as POA. The Superior Court’s opinion suggests that if the agent had inserted those three letters — POA — after his signature on the beneficiary change form, the agent’s actions would perhaps have been insulated from legal challenge.

The Pennsylvania Superior Court recently surcharged an agent for taking actions that were inconsistent with the principal’s estate

plan. The court found that the principal had not authorized the agent’s actions with full knowledge of the relevant facts. In re Estate of Waite, 260 A.3d 143 (Pa. Super. Ct. 2021).

The Superior Court concluded that the record supported the trial court’s finding that the agent’s actions created a conflict of interest under 20 Pa.C.S. § 5601.3(b)(2). The Superior Court upheld the trial court’s decision to surcharge the agent for her conflict of interest.

Summarizing the case record, the court not ed that the decedent, Eric Waite, had lived on a working farm with his wife. He and his wife, who had died earlier, had one daugh ter and two sons. One of the sons, James, married and later divorced the appellant in this case, who was Eric’s agent.

The court record indicated that Eric’s daugh ter-in-law called him to ask for help after she and James had a domestic dispute. After Eric picked her up, she lived with him and his wife at his farm for an undisclosed period.

According to the court, a few weeks after executing a will, Eric was admitted to the hospital. He was suffering from acute deliri um resulting from severe dehydration.

A hospital social worker advised Eric that he could no longer live by himself, although the court said that he had apparently regained

Prudent agents should take care to disclose all relevant facts that might reasonably affect decisions of the principal.

his mental faculties after the hospitalization. Eric moved in with his daughter-in-law and James while they searched for a long-term care facility, according to the court.

While living with his daughter-in-law, Eric signed a power of attorney naming her as his agent. According to the court, the drafter of the power of attorney was an experienced estate attorney who had prepared hundreds of powers of attorney, had spoken with Eric at some length before preparing the power of attorney naming his daughter-in-law as his agent and had determined that Eric had the capacity to execute the document.

The court noted that after drafting the power of attorney, at Eric’s direction, his daughterin-law took him to his credit union, where he asked the teller to remove his daughter and add his daughter-in-law as the power of attorney and designated beneficiary of his checking and savings accounts. The court said that the daughter-in-law did not join the discussion until after the account change card was completed.

After becoming a resident at a care facility, Eric sold his farm and equipment. At his direction, his daughter-in-law deposited the proceeds of that sale into his savings

account, the court said. Soon thereafter, Eric executed a codicil to the will naming his daughter-in-law the executor of his will, with her husband James’ agreement.

The Superior Court noted that Eric’s daugh ter-in-law later divorced James, but never informed her father-in-law of the divorce, ac cording to the trial court. The Superior Court focused on one key finding: Eric apparently never had the opportunity after that divorce to make a fully informed decision regarding whether he wanted to remove his former daughter-in-law as his power of attorney or as a one-third beneficiary of his estate.

After his father’s death, James learned that his former wife was the sole beneficiary of his father’s credit union accounts. During the Orphans’ Court litigation that ensued after Eric’s death, his daughter-in-law claimed that, pursuant to the Multiple-Party Accounts Act (MPAA), 20 Pa.C.S. §§ 63016306, she was legally entitled to all of the proceeds of her father-in-law’s credit union accounts.

The court noted that even though the daugh ter-in-law was a one-third beneficiary of the estate, the credit union accounts contained a significant amount of the estate. The court

said that James had apparently testified credibly that had he known sooner that his former wife was his father’s designated beneficiary, he would have challenged the power of attorney and made sure that his father’s credit union accounts became part of his father’s estate.

Challenging the daughter-in-law’s actions as agent, the other two beneficiaries of the will, Eric’s daughter and James, filed a petition in the Orphans’ Court seeking, among other things, rescission of agent actions taken under the power of attorney. They claimed that the daughter-in-law, in designating herself as the beneficiary of the credit union accounts, engaged in unfair dealing, exerted undue influence over her father-in-law and violated her duties under the power of attorney.

The Superior Court noted that at the trial court hearing on the petition, counsel for the other beneficiaries examined the daughterin-law regarding the deposit of her father-inlaw’s funds into the credit union accounts and her failure to create a separate account. Rejecting the daughter-in-law’s procedural arguments, the Superior Court concluded that even if the other beneficiaries failed

Traps await unwary agents.

to plead that the daughter-in-law breached the power of attorney based on a conflict of interest or commingling assets, the trial court was entitled to consider that evidence.

The Superior Court upheld the Orphans’ Court’s findings that the daughter-in-law understood that her being her fatherin-law’s sole beneficiary for a significant portion of his assets, namely the proceeds of the credit union accounts, was inconsis tent with the three-part distribution plan of his will. According to the Orphans’ Court, the daughter-in-law knew that Eric planned to leave her a third of the assets and wanted to divide the other two-thirds of his estate between his son James and James’ sister.

The Superior Court also upheld the Orphans’ Court’s findings that the daughterin-law 1) failed to keep her assets separate from her father-in-law’s; 2) kept her status as the sole credit union beneficiary designa tion a secret from her then-husband James and his sister; 3) knew that, contrary to her father-in-law’s estate plan, her divorce from James would ensure that James would have no right to the proceeds of the credit union accounts and 4) favored her own interest

in the credit union proceeds ahead of her father-in-law’s interests as expressed in his will.

Concluding that the record supported the Orphans’ Court’s finding that the daughterin-law had a conflict of interest, the court said there was no abuse of discretion or legal error in the trial court’s determina tion that she placed her own self-interest ahead of the interests of her father-in-law. The Superior Court therefore affirmed the Orphans’ Court’s decision to direct the daughter-in-law to restore the credit union accounts to her father-in-law’s estate for distribution as a surcharge for her conflict of interest.

Key Point: Agents may be subject to sur charge if they take actions: 1) without the full and informed consent and authorization of the principal, 2) that are inconsistent with the principal’s estate plan and 3) wherein the agent appears to have a conflict of inter est with respect to those actions. Prudent agents should also take care to disclose all relevant facts that might reasonably affect decisions of the principal and explain and document any actions of the principal or agent that are inconsistent with the princi pal’s stated wishes and estate plan.

The case law concerning agent obligations illustrates at least three important points: 1) the Orphans’ Court has wide discretion to order an accounting even if no petitioner with standing requests an accounting; 2) power of attorney agents must determine the extent of their authority and comply with the statutory formalities when acting as agents; and 3) agents who are found to have received a financial benefit by having placed their interests above those of their principals may be surcharged. ⚖

John B. Spitzer, a Pennsylvania attorney based in Merion Station, works for Scribe Inc., which offers editorial and production services to a wide range of legal, religious and association publishers. The views expressed in the article are personal.

If you would like to comment on this article for publication in our next issue, please send an email to editor@pabar.org.

Joel D. Feldman is 20 minutes into a presentation on distracted driving to a group of parents and their teenage children when he gets to the heart of his talk.

He asks the young people how they react when, while on the road, they see a driver in a nearby car texting, oblivious to the very real possibility that their inattention might at any moment cause a crash that could kill or hideously disfigure themselves or others.

They use words like “disrespectful,” “rude” and “selfish.”

When he turns to the parents, though, he gets a different reaction. Theirs, likely reflecting life experience, is more analytical, not so much from the heart. “Risky,” said one. “Dangerous,” said another. “Reckless,” answered a third.

Feldman has given hundreds of such talks, and it is very rare for adults to respond in the more intuitive way of their children. And that, he believes, with plenty of research to

By Chris Mondics

By Chris Mondics

back him up, is a key to changing driver habits of texting, talking on a cellphone or other distracted driving practices that cause on average some 3,000 traffic fatalities a year.

“We don’t think it is dangerous when we do it,” Feldman says. But, touching on the peculiar cognitive dissonance that defines distracted driving practices that run the gamut from texting to eating lunch while at the wheel, Feldman adds, “We are angry when we see other people do it.”

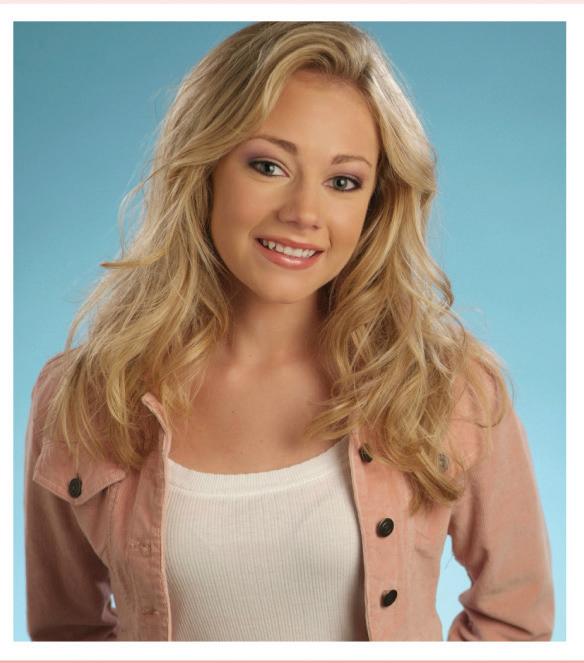

Feldman, a personal injury lawyer at Center City Philadelphia’s Anapol Weiss, has come to the subject painfully. His 21-year-old daughter Casey, a beautiful, vivacious communications major at Fordham University, was run over in a crosswalk in Ocean City, New Jersey, by a van on July 17, 2009. She died in the hospital a few hours later.

The driver of the van, a snack deliveryman, who accord ing to the only eyewitness, had rolled through the stop sign, had taken his eyes off the road for a moment as he

apparently reached for his GPS and struck Casey when she was two-thirds of the way through the crosswalk. There was no evidence of drug or alcohol use by the driver, and the call log showed that he was not on the phone at the time.

He was charged with careless driving and failing to yield to a pedestrian.

Casey’s loss was a devastating blow for Feldman, his wife Dianne and their son Brett. It spurred Feldman to take on the subject of distracted driving and, since that time, he’s become a leading national voice on the subject. His efforts, which have been recognized by the federal Department of Transportation, helped spur further research on the subject and galvanized many employers to stress the importance of attentive driving. He and Dianne established the Casey Feldman Foundation and set up the website EndDD.org to deepen public understanding of the harm of distracted driving and to promote ways of persuading the public to put down their phones and pay more attention to the road.

In all, Feldman has given talks to more than 200,000 people since he started the campaign. Other public speakers affiliat ed with EndDD.org, including hundreds of lawyers, have reached 300,000 more. In Pennsylvania alone, the program has reached more than 68,000 people.

“There are so many more opportunities in Pennsylvania for lawyers to do this kind of work,” Feldman said.

Feldman brings a certain authority and verve to his presentations, and his audience typically is receptive.

He runs the 50-minute sessions as a kind of Socratic dialogue whereby through his pos ing pointed, thought-provoking questions, the audience members arrive at insights on their own, rather than being force-fed prepackaged information.

He also plays the role of father/confessor. In each of his talks, Feldman asks the audi ence whether they’ve ever driven distracted. Typically, several sheepishly raise their hands. He then goes on to explain that he, too, once was a repeat offender. As a personal injury lawyer, he’d spent years taking depositions from drivers who had caused crashes that killed or other wise harmed clients, and he had tried cases to verdict. But, after leaving the courtroom or the deposition, he often would find him self driving while on his cellphone.

He now makes a pledge every time he drives to stay off his cellphone and give his full attention to the road. He recommends that drivers use the Do Not Disturb setting

“We are angry when we see other people do it.”

on their phones or simply place them in Airplane Mode.

Before Casey’s death, Feldman had gone back to graduate school to earn a degree in counseling, the better to understand the trauma and grief his clients had to deal with. “As a parent, I saw their overwhelming grief, but I felt helpless,” he said. “I felt that I needed to do more for my client.”

Casey’s passing only deepened his empathy for clients — and his passion for understand ing human behavior.

The paradoxes and contradictions at the heart of human behavior define distracted driving. Ask people whether texting while driving is an acceptable behavior, and most will say no, of course not. Multiple studies have confirmed this. Yet substantial num bers of people do it anyway.

One study by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety found that 96% of drivers say talking, reading or typing on a cellphone while driving is extremely dangerous, yet 43% of respondents admitted speaking on a handheld phone while driving, 38% said they had read texts and 29% said they had

typed out a text in the 30 days before they were queried.

The question then becomes, if so many think it is a bad idea, why do so many do it?

Game theory might provide some answers.

While most drivers will say that talking on the phone or texting while driving is a dan gerous practice, many conclude that their chances of getting in an accident are small. Most drivers know that when they are texting or otherwise engaging in some activity — fiddling with the GPS, entertainment apps or the radio — that takes their attention from the road, that there is a potential risk.

But they calculate that the risk is small, so the momentary diversion is acceptable.

This thinking is flawed because, if for no other reason, the potential harm is so great. In the five or six seconds that a driver takes his or her attention away from the road, a car traveling at 55 mph can cover the length of a football field.

And a lot of bad things can happen in that short time. And the risks are considerable.

But also, as Feldman points out in his talks, statistically the odds worsen with each act of distracted driving. On any given occasion, one might not have an accident, but, each time a driver does it, the chances of an accident increase. A University of Utah study concluded that speaking on a cellphone posed the same level of risk as driving while intoxicated.

Sooner or later, it could catch up with you. Yet, Feldman says, scare stories typically don’t work. A lot of drivers don’t believe them. He points to one study of drivers passing a highway billboard reporting the number of drivers killed in traffic accidents on that stretch of highway. The finding? Accident rates spiked in the one or two miles following the billboard.

Some states have made it illegal to use a handheld cellphone while driving, and there is some research showing the practice declines markedly when law enforcement mounts a high-profile ticketing campaign.

Feldman, though, is not an advocate of the punitive approach and tends more toward consensus building.

Feldman has put the issue on the national radar and given the issue far more prominence than ever.Feldman teaches students about the dangers of distracted driving and effective ways to speak up when their driver is distracted.

The takeaway from his presentations is that a more effective approach is appealing to a person’s better nature and our innate sense of responsibility for others. Hundreds of years ago, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant observed that fundamental to human nature was a recognition of right and wrong, one of his so called categorial imperatives.

We instinctively know whether an action is morally defensible, our gut instinct tells us that; it’s not something we need to be taught.

And this plays out all the time in everyday life. Feldman notes in one presentation that people who put themselves and others at risk by driving distracted would, in an entire ly different situation, show great concern for other people.

He uses the example of a person approach ing a door carrying a pile of packages. Typically, people nearby would go out of their way to open the door for that person. It is an everyday act of common courte sy, concern and empathy. A basic human instinct, it appears, is to put ourselves in the place of others. True, the harsh demands of living in a competitive society often force that impulse into remission. So, many of

those same people, amid the press of daily deadlines and responsibilities, will take a chance and text while driving or fiddle with a music app.

In the face of those pressures, Feldman says, the idea is to reinforce better instincts.

Another powerful motivator is regret, or the potential for it. Feldman has worked with 20 or so drivers who caused fatal or crippling accidents because they were using their cellphones. Courts refer them to Feldman as part of their community service. Some have served jail time. The thing they most regret is having taken another human life. It’s very hard to live with, and Feldman often asks his audiences to imagine that possibility.

“I ask them, what is the worst thing about this,” he said, of the drivers who are sent to him. “They never say the jail sentence. They say it’s ‘knowing what I did to another person, another family.’ As awful as it is to lose a child, I can’t imagine what it is like to be the cause of an accident that killed someone else.”

Feldman knows about risk and how to man age it. He was a competitive skier in high school and still enjoys time on the slopes. Feldman once skied without a helmet, but it was his daughter Casey who urged him to

His efforts have helped spur further research on the sub ject and galvanized many employers to stress the impor tance of attentive driving.

Talking about the need to treat others with decency and concern is an emotional pitch that resonates with many people.

wear one, observing that if safety was an is sue for the children, it should be for adults.

Children might be the key to widespread acceptance of safer, more attentive driving without the distractions of cellphones.

When, during his presentations, Feldman queries parents and children on their reactions to distracted drivers, he is making a point. The more personal response of the children forms the core of a persuasive argument in favor of safer driving practices.

Talking about danger is a statistical abstrac tion. Talking about the need to treat others with decency and concern is an emotional pitch that resonates with many people. When children describe distracted driving as disrespectful or rude, they are making a point people can relate to.

In this way, Feldman believes that children and young adults hold the potential to becoming a vanguard for the campaign to change driving habits. He encourages stu dents to gently remind parents who yield to the temptation to pick up a cellphone in the car that it makes them feel unsafe.

In keeping with his belief that young drivers will help initiate change, Feldman is part nering with Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and Harvard Medical School researchers to survey high school students nationally.

The idea is to come up with concepts for persuading students to put down the phone while driving. Once the surveys are complete, the plan is to engage a handful of talented student filmmakers across the country to produce public service announce ments urging all drivers to keep their focus on the road.

By one measure, Feldman’s campaign still has a long way to go. The annual number of highway fatalities attributable to distracted driving has remained stubbornly within the 3,000 range. The most recent research

shows that large numbers of drivers engage in dangerous distracted driving practices, even though they know it raises the risk of an accident.

But there is no doubt that Feldman has put the issue on the national radar and given the issue far more prominence than ever. More people are thinking about the harms of distracted driving and how to change driver habits. Surveys of people who attend his presentations show the presentations caused them to change their attitudes on distracted driving.

He tells the story of a young woman who approached him recently as they were both boarding a plane. She said she had attended one of his presentations at a Philadelphia area high school and thanked him for his work on the subject, and then gave him a hug.

“I feel I have a purpose,” he said. “I am doing something in Casey’s memory, and I think there is some force, whether it is God or something else that pushed me in this direction. At times I think I am the most fortunate person in the world to be able to do this for my daughter.” ⚖

Chris Mondics is a freelance journalist and author based in Philadelphia. In earlier assignments, he was the legal affairs writer for The Philadelphia Inquirer from 2007 through 2017 and had been a Washington correspondent for the newspaper for a decade before that. He focuses much of his work on legal and national security issues, as well as politics and the economy.

Photos of Joel and Casey Feldman courtesy of Joel Feldman.

If you would like to comment on this article for publication in our next issue, please send an email to editor@pabar.org.

PBA

By Michael D. Alder and Matthew Kelly

By Michael D. Alder and Matthew Kelly

Afew months ago, we were presenting a continuing education session on employee benefit programs. One of the attendees remarked that he had a hard time getting clear answers regarding what kinds of retirement savings plans were available for small and mid-size law practices from his advisors. He suggested that we write an article explaining the differences in plans, limits in contribution amounts and other differences. This article is the outcome of that conversation.

Managing a successful legal practice, whether you are a solo practitioner, part of a multiple-attorney firm or part of a larger (even a regional or multinational) law firm, can be complicat ed on a number of levels. It can be easy to focus too much on your day-to-day practice rather than plan and act strate gically on your business. This risk is even bigger when you’re juggling the needs of the firm as well as those of your staff. What follows are a few insights about some of the retirement savings tools at your disposal and how they can fit into your practice. Whether you are a one-person firm or tasked with designing a benefits program for a large enterprise to help attract and retain talented staff, there are excellent choices available to you.

Saving for retirement is a challenge across all ages and income levels. Finding the right balance between funding your current lifestyle and future needs can be difficult. Surveys indicate that, as a whole, Americans are well behind (trillions of dollars behind as a whole) their retirement savings targets. While everyone’s plans for retirement are different, here are some solid general sav ings goals to consider:

Age Band Savings Goal (Household Balance)

30–39 1–2 times annual household income

40–49 3–4 times annual household income

50–59 6–7 times annual household income

60–69 8–10 times+ annual household income

Another way to look at savings is how much you save on a regular, monthly or annual basis. Using that metric, we recommend our clients save 15-20% of their income each and every year in order to have sufficient funds set aside for retirement and other purposes. It is important to note that some of these savings should be set aside in nonretirement accounts, so that the funds are accessible should you need them prior to age 59.5 (prior to this age, there is a 10% excise tax assessed for accessing retirement funds early). The focus of this article is retirement account options, but we thought it also would be helpful to at least mention that a balance between retire ment savings and other savings should be considered.

Takeaway: Start as soon as you can, and save as much as you comfortably can, in a variety of places.

Choosing the right retirement plan for your practice can go a long way toward helping you and your staff reach retirement savings goals. Various plan types provide assort ed options for investments, contribution amounts and tax advantages. The following information provides summary-level infor mation about different types of retirement plans that you can use in concert with a discussion with a financial advisor to help determine the best fit for you, your firm and your needs.

Solo practitioners have options mostly not available to larger ones, starting with a traditional or Roth individual retirement ac count (IRA) (assuming the solo practitioner does not exceed the income limitations).

A Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) plan allows higher contribution amounts and removes the income limitations that apply to IRAs, while still not requiring any third-par ty administration of the plan. Finally, a one-participant or Solo 401(k) plan allows a single-employee firm to benefit from the

Choosing the right retirement plan for your practice can go a long way toward helping you and your staff reach retirement savings goals.

401(k) rules, allowing for greater contri butions and diversity in how you can save (Roth vs. pre-tax). Moving from a traditional or Roth IRA to a SEP to a 401(k) plan adds complexity, flexibility and cost.

Table 1 summarizes some key features of these three plans. Note that dollar limits are 2022 limits, which may in crease in 2023 (limits typically increase at an inflationary rate, but sometimes

change considerably due to legislation). Features and rules are summarized and may not provide all details.

If you’re making decisions for a firm with two or more employees, there are added complexities that must be considered when making the choice of retirement plans. You’re now balancing what’s best for recruiting and retaining staff, staff needs and what’s best for the owner(s) of the practice. Some key features of com mon organization-focused retirement plan choices follow.

Tax Treatment Options

Deferred tax (tradi tional) or no tax on distribution (Roth)

Deferred tax only (No Roth option)***

Deferred tax (tradi tional) or no tax on distribution (Roth)

Investment Choices Many (per brokerage) Many (per brokerage) Many (per brokerage)

Deferral Limits (Individual)