CAMPUS IN INDIA BEFORE TIME

-KETKI JAYBHAVE

Indian organized educational systems have a long history. Even though the Gurukul educational system is among the oldest in the world, it was behind the Guru Shishya system, which was in use at the time. The guru shishya system was one in which the guru imparted knowledge verbally to disciples, who then passed it on orally to future generations. On campus in India before In India, planning for campuses began in the seventeenth century BC. The first universities were Buddhist centers of study that could hold more than 5000 students at once and drew intellectuals from all around Asia. A hub of Islamic scholarship existed during the medieval era. Consider Taxila, where a number of learning institutes were spread out around the city. The learning atmosphere resembled a medieval monastery; professors and pupils coexisted around a central assembly hall.

The fact that the oldest institution, the Nalanda institution, is located in India demonstrates the solid foundation of Indian education. Later, the Western educational system merged with the Indian learning culture as a result of colonial domination in the nation. In India, formalized educational systems have a long history. Due to the fact that the majority of institutions are located in cities, this idea is still relevant today. Urban infilling is the perfect campus, according to educators and planners. On the Nalanda University campus, there were around 3000 monks; many students reside in a collection of monasteries. This campus’s growth as a collection of monasteries and an area with a stupa gave it quality, scale, and character. Campus design, on the other hand, has always focused on a specific entity rather than the larger context of the urban fabric, which is why campuses have fallen to become an essential component of the city fabric. Special emphasis was paid to the subject of education during the Mughal invasion in the 11th century, Shah Fathullah Shirazi worked to reform the educational curriculum during Akbar’s rule, and Islamic schools were linked to mosques, Sufi khangas, and cemeteries. Additionally, special educational facilities were built, with the costs covered by endowments. Lahore, Delhi, and Ajmer were the major seats of learning during the time of the Mughal emperors. Dacca, Allahabad, Ahmadabad, and Lucknow. From Persia and central Asia, where eminent academics earned set stipends from the royal treasury, many intellectuals were drawn to these institutes. Additionally, these institutes provided free education to their students.

The larger cultural background, customs, and values of the neighborhood or region where an institution of learning is located are referred to as the campus’s cultural context. In order to create an atmosphere that is responsive to the requirements and preferences of the community, it is crucial to comprehend and respect the local culture.

The campus has a unique visual character because of its architecture. It aids in creating an overall and identifiable look that represents the institution’s beliefs, customs, and objectives. The institution’s general vision and aims should be reflected in the style, which should also take context and cultural relevance into account. Material

The campus’s architectural design and aesthetic appeal can be determined by the materials used. Modern elements like glass, steel, or concrete may provide a contemporary and inventive aesthetic, while more traditional materials like brick, stone, or wood can evoke a feeling of history and sturdiness. The overall visual effect is affected by the texture, pattern, and material quality.

Open areas with thoughtful design may operate as outdoor classrooms, offering chances for hands-on learning, group discussions, and artistic endeavors. outdoor seating that promotes social contact and physical exercise. An inviting and visually beautiful atmosphere is greatly influenced by the campus’s landscape design and open areas. The placement of the campus’s trees, gardens, paths, and outdoor meeting areas might influence its cultural environment.

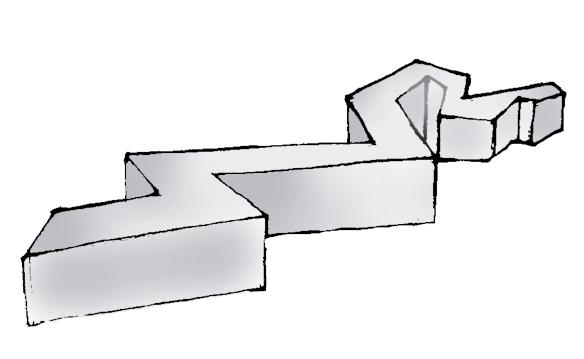

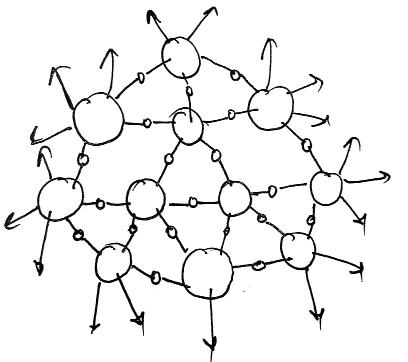

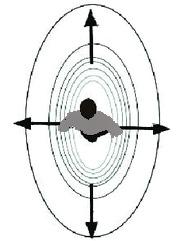

In this pattern, the central core of campus can expand at either end as the university grows.

Existing elements extend outwards and grow independently of one another, new ones are added to extensions of the core which never becomes shut in as in the concentric pattern.

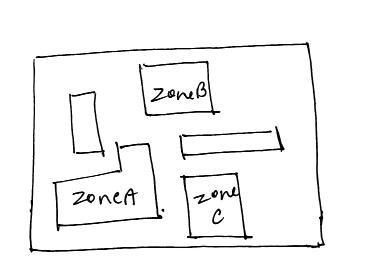

This is typical American style of planning. Zones are specifically allotted to academic, residential or recreational, handicapping integration of campus activities.

The central area or core of the campus becomes tightly enclosed and successive rings of development shut in and prevent selective expansion.

Growth accomplished through addition of self-contain units or molecules, each a microcosm of the whole. The campus is complete at each stage of growth, but the system is perhaps limited to a many cantered campuses rather than a ‘centralized ‘type.

Depending on the form and type of instructions given, campuses can be broadly categorised. It is simpler to characterise campuses by analysing their respective physical attributes or shapes and their planned system of growth than by attempting to classify differences in campus design philosophy or “style.” Since time, geography, conditions, attitudes, and intents vary in each situation, no two campuses are alike. In truth, campuses have unique characteristics like members of the human race. Even though, as Repower noted, there are two major groups.

Homogeneous-style campuses are an institutional style that uses the same materials and forms continuously throughout the project to create an empty space in any type of geometric arrangement. The campus is harmonic, well-balanced, and proportionate in every way because to the use of basic geometric shapes like squares and rectangles in its planning.

Using uniform materials, colours, and textures throughout the campus, connecting buildings with the help of corridors, and creating a homogeneous campus are all approaches to do this. This pattern is based on a closed system. In other words, it was planned and constructed as a whole, with only minimal future growth predicted or accepted. However, given that many new campuses are homogeneous and plan for significant future expansion, this may not always be the case. Campuses of this style promote a Kind of self-image or an identity as a whole. Eg: Tougalou college Mississippi.

Heterogeneous campuses are made up of individually designed structures that are separate entities and are not necessarily in harmony with one another. They also lacking an impactful enough context to unite them into a cohesive whole. The bulk of campuses that have suffered throughout the years at the hands of successive administrators and designers share these traits. For instance, take Roorkee University in Roorkee, India. Such a style is undoubtedly flexible, and significant development takes place. But for the most part, future development receives very little guidance. Institutions that have grown up are not particularly horrible, but they often are when individual structures are really well-built. By rebuilding the campus, a heterogeneous campus can be created as a homogenous campus.

1. In addition to the designer’s attitude and background, additional variables that may affect design approach and shape include the educational policy of the organisation, the site’s characteristics, the climate, the materials that may be used, and local technology.

2. The educational philosophy or the characteristics of the location are typically the biggest influences on the design of new campuses.

3. For the institution to be at all successful, the nature of the specific sort of specialised educational programme to be accommodated, or the functional needs determiningform, must be satisfied.

4. The characteristics of the site and its surroundings can either significantly enhance or significantly detract from the final shape that evolves.

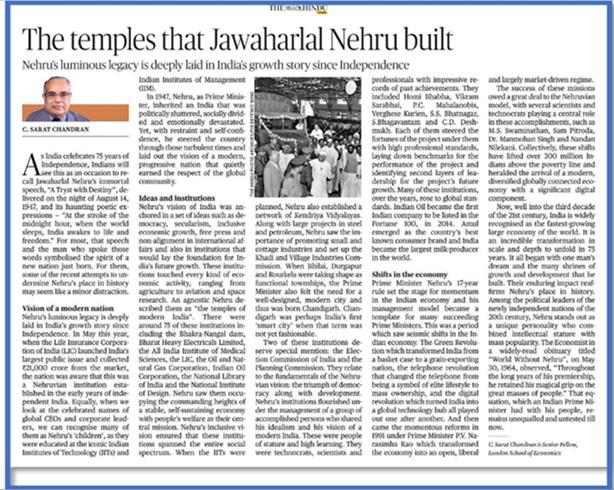

Source: The post is based on the article “The temples that Jawaharlal Nehru built” published in The Hindu on 16th August 2022.

Nehru’s vision of India was founded on concepts such as democracy, secularism, inclusive economic growth, freedom of the press, and non-alignment in foreign affairs, as well as institutions that would lay the groundwork for India’s future progress.

These institutes had an impact on every economic sector, from agriculture to aviation and space research. He even referred to them as “modern India’s temples.”

The Bhakra-Nangal dam, Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, the LIC, the Oil and Natural Gas Corporation, the Indian Oil Corporation, the National Library of India, and the National Institute of Design were among the 75 institutions. These institutions covered the full socioeconomic range thanks to Nehru’s inclusive worldview.

In planning the IITs, Nehru also developed a network of Kendriya Vidyalaya’s, for example. The accomplishments of IITs and IIMs the renowned Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and Indian Institutes of Management have produced some of the mostwell-known CEOs and business executives in the world (IIM). Nehru’s plan has two components. First, to establish in India top-tier institutions. He spent his time in the United States of America learning about how the colleges there were providing the nation with a technological and scientific advantage. His historic visit to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1949 resulted in the establishment of the five iconic Indian Institutes of Technology at Kharagpur (1950), Bombay (1958), Madras (1959), Kanpur (1959), and Delhi (1959). (1961). All of these institutes were publicly supported to ensure that a lack of money would never prevent Indians from receiving the highest education possible.

Title – The Geometry of Feelings

Author – Juhani PallasmaaPublisher- White Falcon Publishing

It is directly related to what the author is attempting to convey, which is that architects should focus on the spaces formed inside the structure and attempt to introduce and put poetic thoughts into the spaces. The author also claims that architects cannot design buildings just as physical things, but must also consider the images and sentiments of the people who will utilize the rooms. He proposed that architecture may activate or bring back memories for consumers, indicating

The Geometry of Feeling’ by Juhani Pallasmaa addresses the link between architecture and form, the sensation that people get while entering places, and the phenomenology of architecture. The author highlights in the study how architects currently put a greater focus on the shape of the structure than on the spaces. Furthermore, buildings are constructed nowadays as though function follows form rather than form follows function, which stresses the spaces first before introducing the form. The author also claims that architecture may be used as a kind of art, with the work of art existing solely in the awareness of the person experiencing it, implying that it is more than simply a form. The author is attempting to emphasize how significant spaces are in comparison to shapes, although initial glances or first impressions always manage to capture everyone’s attention. What is underneath and within, however, is more significant and interesting, as these are the areas that will have a greater influence on the users when they occupy the space. Furthermore, what is the sense of having a lovely architectural shape if the spaces are meaningless? Thus, spaces and forms are equally vital and work in tandem to create amazing architecture.

Author

– Achyut Kanvinde and James Miller

– Achyut Kanvinde and James Miller

Publisher- Printed by Jostens/American Yearbook Co, Topeka, Kan., [1969]

Kanvinde and Miller's book, Campus Design in India - Experience of a Developing Nation, sheds light on the difficulty of designing a well-functioning university campus capable of efficiently adapting to growth and development. It was the authors' pleasant notion, both notable architects, to cooperate on producing such a collection to assist university authorities: its release is both timely and welcome. The book claimed to be a helpful guide for developing appropriate campus settings in postcolonial India, and it was written in response to the Indian government's extraordinary boost to tertiary education in the 1960s as part of its post-independence nation-building goal.

"We have begun to understand that designing our physical environment does not mean to apply a fixed set of esthetics, but embodies rather a continuous inner growth, a conviction which recreates truth continually in the service can kind.”

- Walter GropiusAuthor Achyut Kanvinde on page no 14 and 15 says that “Having recognized the key role of education and having assigned the highest priority to education in her five-year plans, India nevertheless is still falling short of meeting the actual needs of higher education. Her needs can be analyzed as to their nature and Scope. The nature of the need is primarily to improve the quality of education. There are four elements that constitute any education al institution: students, faculty, and physical facilities, as well as academic programs. The quality of the education imparted by a particular institution directly depends on the quality of each of these four elements and their interactions.

A major objective of this book is to delineate the interdependent relationships among the quality of campus. environment (physical facilities), the quality of the educational experience, and ultimately the quality of the graduate. It is granted that quality of academic content is most important, but it depends on the quality of the social-living-work-study environment of a college or university campus. On page no 20 it is said that “Experience with institution-building the world over has proved the wisdom of careful pre-planning by qualified professionals according to accepted procedures and mini mum standards of quality. True, it may take more time and may cost more initially, but ultimately it is more economical and a far wider policy. Such planning would permit India to utilize her scarce resources in the best possible manner to provide campus environments suitable for the nation's educational needs and the fulfillment of her aspirations.”

In this article, Nivedita discusses how the spaces we design might contain a mix of them, but it is your duty as an architect to select in what proportion based on your fundamental study of the User-Function-Space that you plan to create. She cited the Jewish Museum in Berlin, where architect Daniel Libeskind was able to influence the conception, realization, and experience of the user and their experience. He was able to make a strong connection between physical, spiritual, and historical significance in consciousness because he had a greater understanding of design context. These emotions aided in the formation of a bond between the User-Function-Space to make the Architecture experience more memorable and meaningful for the user. In simple terms, a user is an individual or group of individuals who obtain a certain form of advantage from interacting with and experiencing an activity carried out in a single or multiple places. It is not only the creation of the architectural structure's outside surface.

However, sensory interaction with a distinct experience produces an emotional reaction to encourage user engagement. User-Function-Space-Experience should be considered when designing. On the one hand, visual and sensory perception of space may work as instruments in shaping the future of architectural design as experiences through form and spatial sequences with user engagement as key elements to design. Nivedhitha believes that it is time to realize, recognize, and work on “Form Follows Experience” to consider architecture as a human experience.

– Humane Architecture

It is directly related to what the author is attempting to convey, which is that architects should focus on the spaces formed inside the structure and attempt to introduce and put poetic thoughts into the spaces. The author also claims that architects cannot design buildings just as physical things, but must also consider the images and sentiments of the people who will utilize the rooms. He proposed that architecture may activate or bring back memories for consumers, indicating that the places developed may catch their attention and create a personal and deep relationship with them.The Geometry of Feeling’ by Juhani Pallasmaa addresses the link between architecture and form, the sensation that people get while entering places, and the phenomenology of architecture. The author highlights in the study how architects currently put a greater focus on the shape of the structure than on the spaces. Furthermore, buildings are constructed nowadays as though function follows form rather than form follows function, which stresses the spaces first before introducing the form. The author also claims that architecture may be used as a kind of art, with the work of art existing solely in the awareness of the person experiencing it, implying that it is more than simply a form.The author is attempting to emphasize how significant spaces are in comparison to shapes, although initial glances or first impressions always manage to capture everyone’s attention. What is underneath and within, however, is more significant and interesting, as these are the areas that will have a greater influence on the users when they occupy the space. Furthermore, what is the sense of having a lovely architectural shape if the spaces are meaningless? Thus, spaces and forms are equally vital and work in tandem to create amazing architecture.

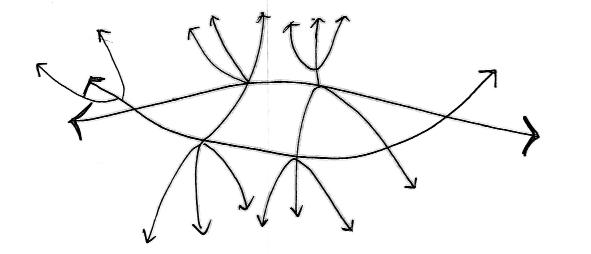

Fig.4.4.2 Relation of form-function-meaning