Strands Across Time:

Historic Southwestern Textiles

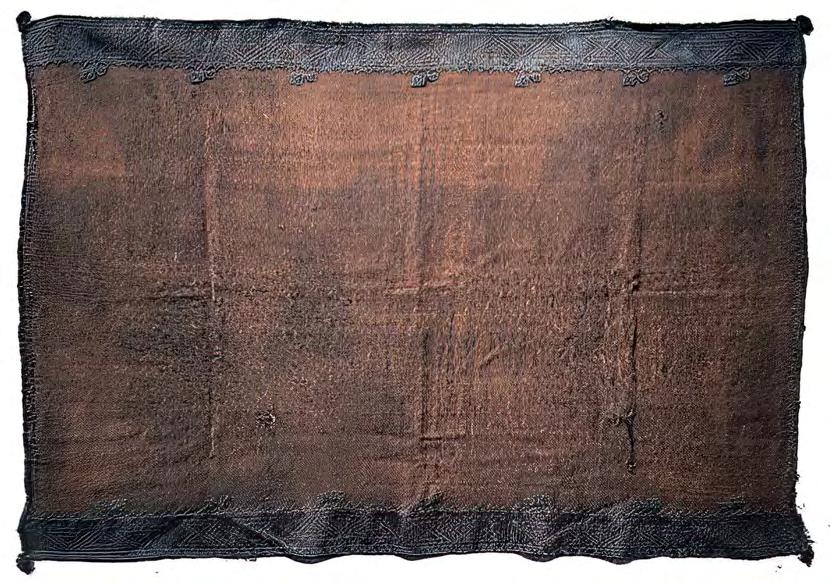

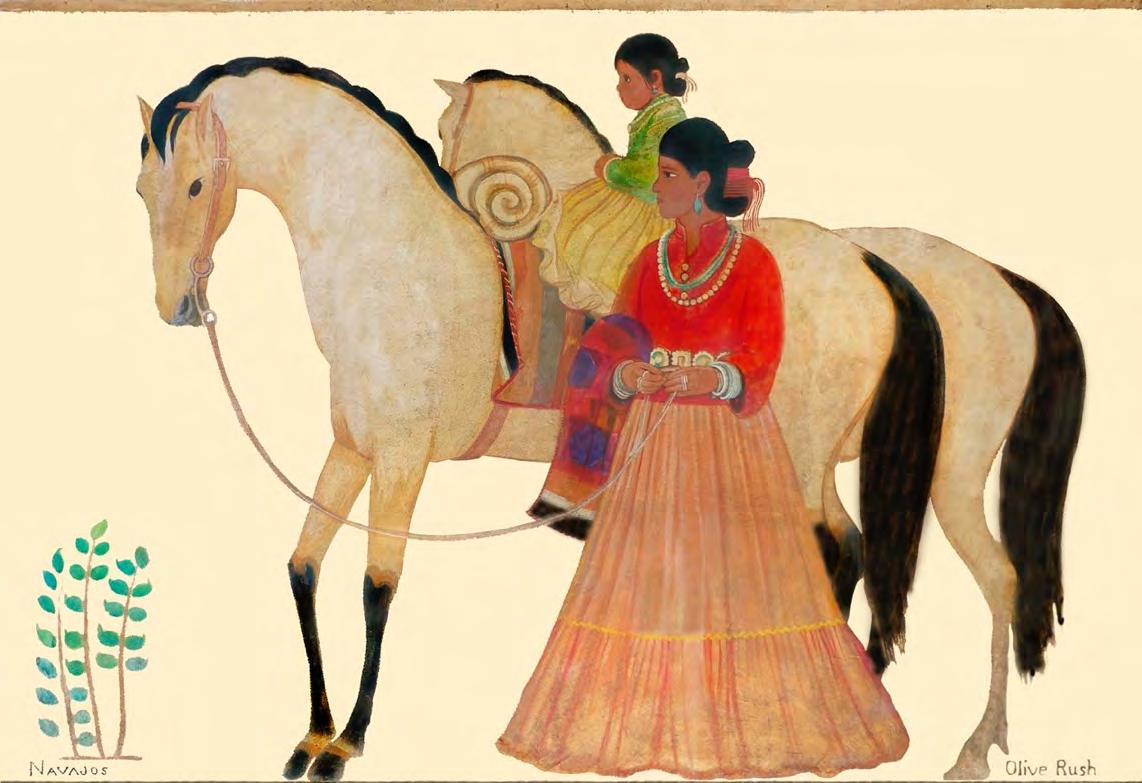

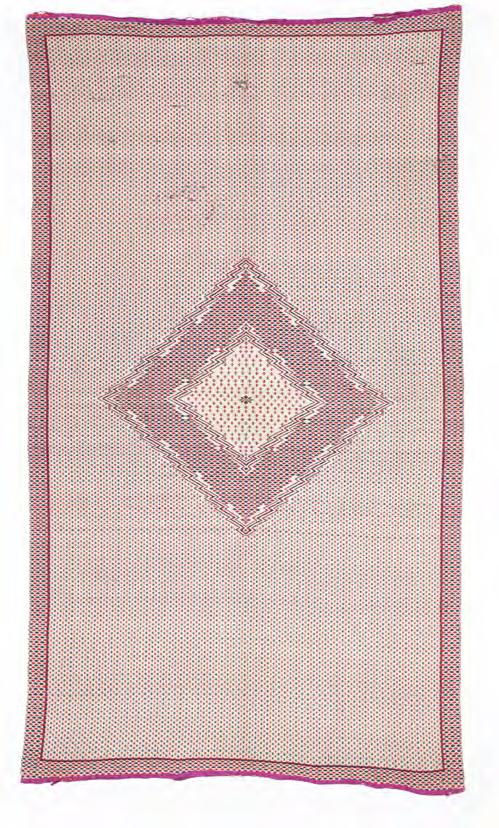

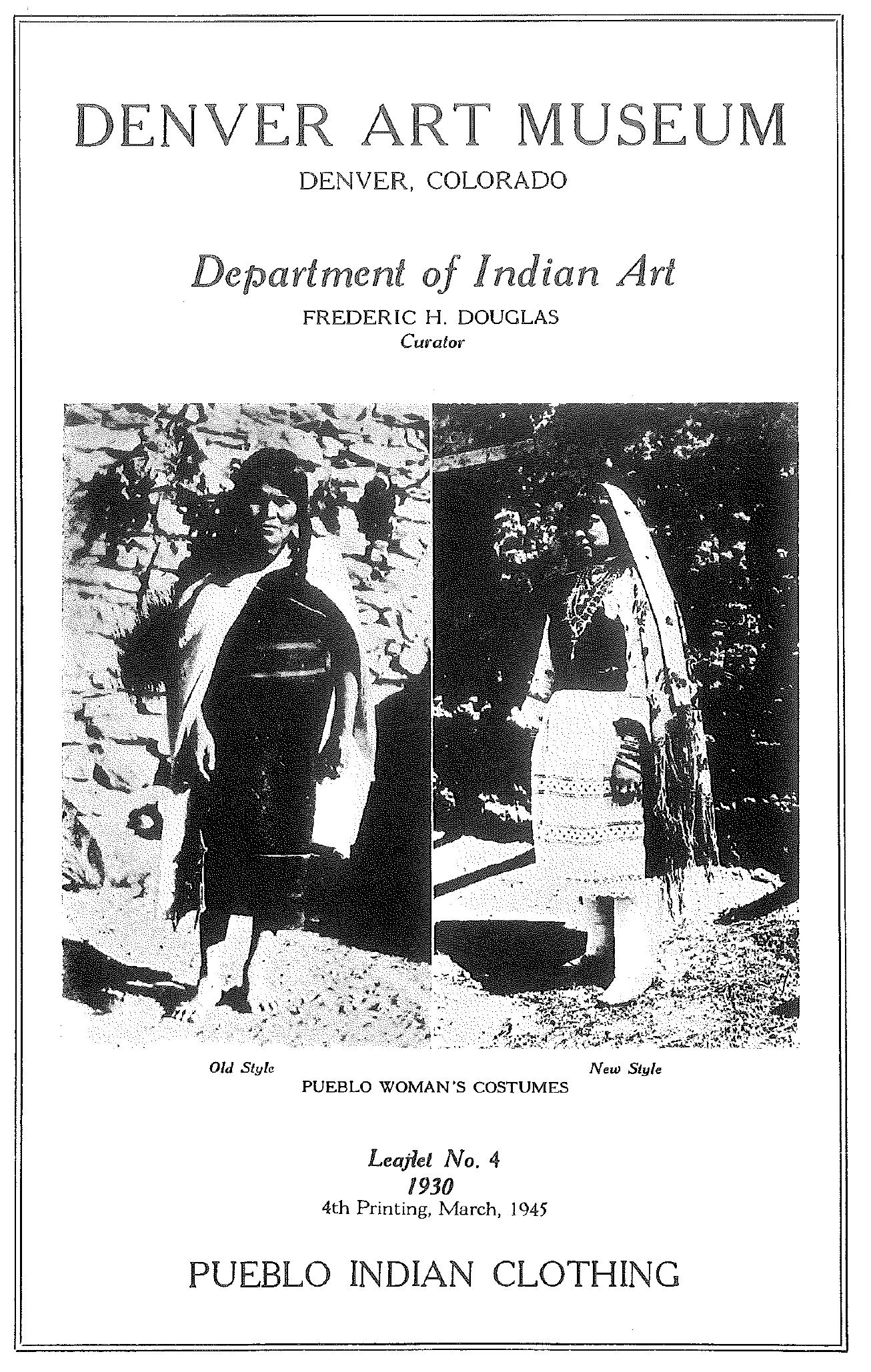

Exhibit 36: Dinè (Navajo) dress, 43.5" X 21" 1972, maker unknown, with a Pueblo style belt as well as solid colors and stripes reminiscent of Pueblo blanket designs. The "cloud lift" designs are a common of Pueblo motif. The black background has the superficial look of a Pueblo manta, although a manta worn as a dress would have one side off the shoulder, rather than a central head opening. The overall presentation is in keeping with the ability of the Dinè to borrow from other cultures, leading to an expression which is transformed into something that is uniquely Dinè. Source: Anonymous.

Strands Across Time

Historic Southwestern Weaving

by Paul R. Secord

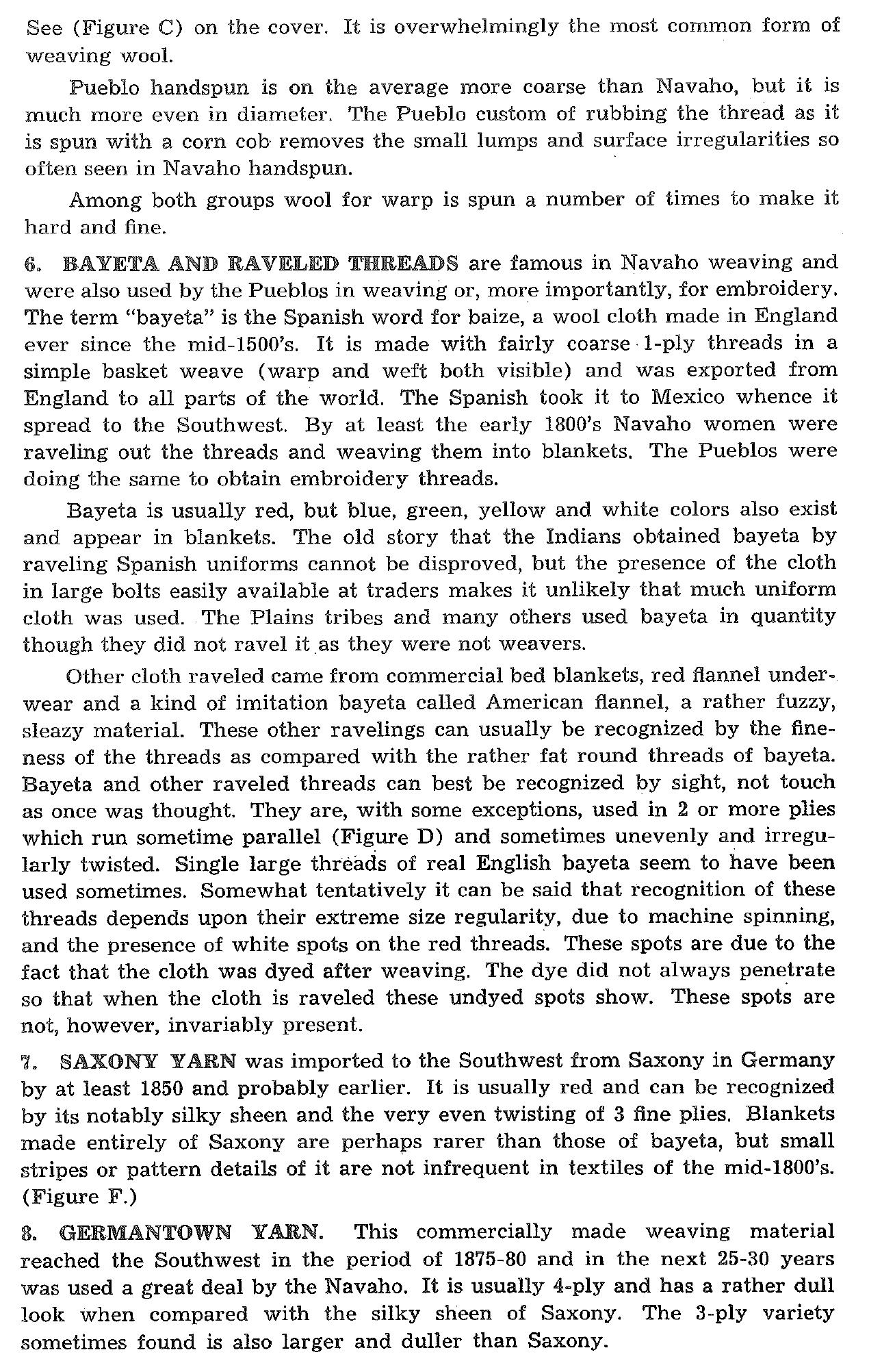

by Paul R. Secord

with contributions by L.

Bruce Weekley

Marjorie A. Chan

Published in conjunction with the exhibition: Kim Martindale Objects of Arts Show, Aug. 10-20, 2023, El Museo, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Copyright © April 2023 by Paul R. Secord

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems without the permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

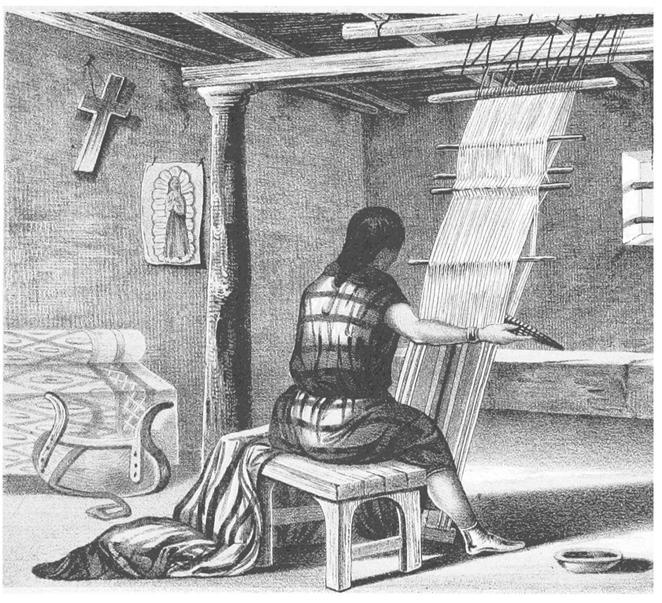

Cover: Colored photolithograph derived from a photograph taken during the summer of 1879 at Hopi by government photographer John Karl Hillers (1843-1925), Bureau of American Ethnology, Second Annual Report, 1880-81, Figure 710, following p. 454, US Government Printing Office, Washington DC 1883.

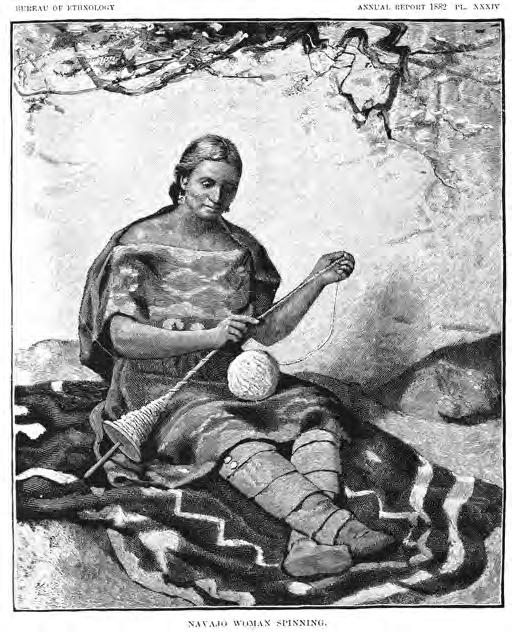

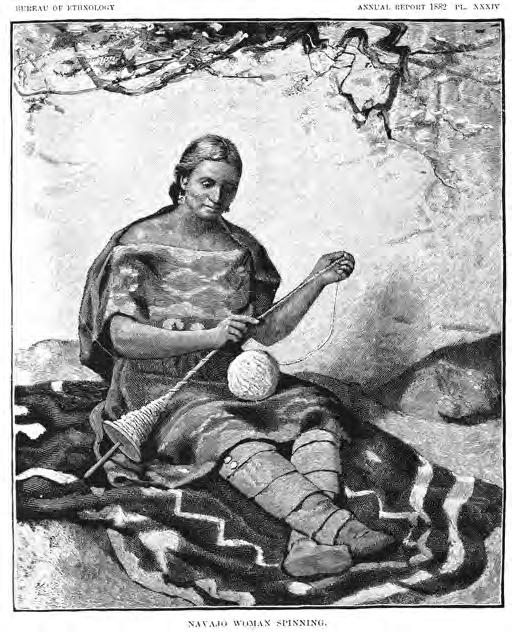

Backpiece: Dinè woman hand spinning wool, Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report 1882, Plate XXXIV

ISBN: 9798393799755

LCCN: 2023910813

Secord Books

Albuquerque, New Mexico

DEDICATION

To the memory of Charles "Gil" Mull (1935-2021)

"Lover of RagsCollector of BlanketsMentor to us All"

i TABLE of CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................. v PREFACE ........................................................................................................................ vi CHAPTERS Chapter 1: An Historical Overview of Native American Textiles 1 Chapter 2: An Historical Overview of Spanish American Textiles 3 Chapter 3: What Does the Future Hold? 5 Chapter 4 Materials and their Processing . 6 Chapter 5: Manufacturing Techniques 10 Vertical Loom ................................................................................................................................ 10 Twill Weave 11 Horizontal Loom ............................................................................................................................ 12 Backstrap and Belt Loom 13 Braiding and Sashes 13 Knitting and Crocheting 14 Chapter 6: The Textiles in the Exhibit .................................................................................................... 15 Pueblo Textiles ................................................................................................................................. 15 Mantas - 16 Black Mantas 16 Tewa Weavers and others 20 Other Pueblo Textiles 21 Pueblo Embroidered Mantas and Designs .......................................................... 21 White Wedding Mantas 22 Pueblo Wearing Blankets .................................................................................... 23 Hopi Maiden Shawls 24 Pueblo Shirts ....................................................................................................... 26 Dinè (Navajo) Textiles 27 Double Faced/Twill Weaves ................................................................................................. 29 Saddle Blankets 32 Spanish American Textiles .............................................................................................................. 36

LIST of FIGURES (illustrations specific to this catalogue)

HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE BRUCE WEEKLEY COLLECTION

ii

Figure 1: The Pueblo backstitch ............................................................................................................. 1 Figure 2: Native American groups addressed in this book 2 Figure 3: Hopi Cotton Plan Gossypium hopi 7 Figure 4: Dinè woman hand spinning wool ........................................................................................... 8 Figure 5: Hopi man c.1880 spinning and twisting a cotton thread 8 Figure 6: Dinè wool processing tools ..................................................................................................... 9 Figure 7: Illustration of a vertical Native American loom. 10 Figure 8: Dinè woman weaving a blanket/rug ..................................................................................... 11 Figure 9: Diagram and photograph showing twill weave patterns 11 Figure 10: Horizontal loom of the type used by the Spanish ................................................................. 12 Figure 11: Backstrap and belt looms 13 Figure 12: Methods of braiding.............................................................................................................. 13 Figure 13: Knitting vs Crocheting 14 Figure 14: Zuni weaving from an 1821 illustration ............................................................................... 15 Figure 15: Tewa Weaving, Old Town Albuquerque, ca. 1940 20

Photograph 1: Isleta Pueblo Woman 41 Photograph 2: Isleta Pueblo Woman 41 Photograph 3: Tesuque Pueblo Governor's wife 42 Photograph 4: Zia Pueblo Woman ....................................................................................................... 42 Photograph 5: Isleta mother and child 43 Photograph 6: Hopi woman in two mantas .......................................................................................... 43 Photograph 7: Isleta Pueblo woman 44 Photograph 8: Hopi man knitting ......................................................................................................... 44 Photograph 9: Hopi men in black mantas 45 Photograph 10: Hopi women in black mantas ....................................................................................... 45 Photograph 11: Zuni Pueblo woman wearing black twilled mantas 46 Photograph 12: Zuni Pueblo men and women 46

LIST of EXHIBITS (textiles found in the subject exhibition)

iii

Exhibit 1: Zuni Blue Bordered Manta 50” x 40” c.1860 or earlier 17 Exhibit 2: Zuni Black Manta 51" x 41" c. 1890 ................................................................................ 17 Exhibit 3: Zuni Black Manta 61" x 37.5" c. 1895 18 Exhibit 4: Pueblo Black with Indigo Manta 51" x 39" c.1890 18 Exhibit 5: Pueblo Manta 56” x 41” c.1870 or earlier 19 Exhibit 6: Navajo or Zuni Manta 50 x 39" c.1860 - 1865 ................................................................ 19 Exhibit 7: Hopi Woman's Cape, 41 1/2" x 39" c.1885. .................................................................... 21 Exhibit 8: Acoma Pueblo Manta 58" x 37" c.1860 21 Exhibit 9: Hopi cotton Wedding Blanket, 70" x 51" c.1890 ............................................................. 22 Exhibit 10: Blue Moki (Hopi) Striped Blanket 50" X 80" c.1870.. .................................................... 23 Exhibit 11: Child's Hopi Style Plaid Blanket 23" X 34" 2018. ........................................................... 23 Exhibit 12: Dinè Woven Hopi Maiden Shawl 44" x 36"c1920 ........................................................... 24 Exhibit 13: Hopi Maiden Shawl 42” x 43” c.1850-1860. ............................................................... 25 Exhibit 14: Hopi Maiden Shawl 46” x 37” c.1860 or earlier 25 Exhibit 15: Pueblo shirt 60” x 25” c.1800-1850. ............................................................................ 26 Exhibit 16: Pueblo shirt 56" sleeves, 20"chest, 29" length c.1870 -1890. 26 Exhibit 17: Third phase Chief's Blanket72" X 48" c.1865 - 1870" .................................................... 27 Exhibit 18: Dinè Late Classic man's Moki (Hopi) Style Blanket, 53" X 67", c.1875 - 1880 ............ 27 Exhibit 19: Dinè Germantown "Eyedazzler" Wearing Blanket, 43" X 72" c.1880 - 1890 28 Exhibit 20: Dinè Germantown Woman's Wearing Blanket, 61" X 48" 1875 - 1880. 28 Exhibit 21: Dinè Diamond, Birdseye and Polygon Twill Child's Blanket 53" x 31" c.1890 ................. 29 Exhibit 22: Dinè Childs Blanket 36” x 51”, c.1870-1875 30 Exhibit 23: Dinè Twill Banded Blanket, 51"x 36.5" c.1750 - 1840. 31 Exhibit 24: Dinè Woven Double Saddle Blanket 52" x 38" c.1880 32 Exhibit 25: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 42" x 39" c.1890 32 Exhibit 26: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 50" x 32" c.1895 32 Exhibit 27: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 45" x 29" c.1895. 33 Exhibit 28: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 59" x 32" c.1895 33 Exhibit 29: Dinè Single Saddle Blanket 26" x 28" c.1920 33 Exhibit 30: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 44" x 27" c.1895. 34 Exhibit 31: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 45" x 29" c.1920 34 Exhibit 32: Dinè Single Saddle Cover 18" x 12" c.1920 34 Exhibit 33: Dinè Single Saddle Cover 20" x 14" c.1890 35 Exhibit 34: Dinè Saddle Cover 27" x 26" c.1896 35 Exhibit 35: Dinè Diagonal Twill Weavers Pad 33" x 18" c.1900 ....................................................... 35 Exhibit 36: Dinè (Navajo) dress 43.5" X 21" 1972 ................................................................. frontispiece Exhibit 37: New Mexican Double Panel Jerga 120” x 42” c. 1870-1875 36 Exhibit 38: New Mexican Triple Panel Jerga Cover 72” x 48” c.1875............................................... 36 Exhibit 39 New Mexican Single Panel Jerga 90” x 24”, c.1825-1830. 37 Exhibit 40: New Mexican Single Panel Banded Jerga 120” x 24” c.1875-1880 37 Exhibit 41: Rio Grande New Mexican One-piece Blanket 96” x 51”, c. 1875-1880. 38 Exhibit 42: Rio Grande Sarape 49” x 90” c.1850-1860. 38 Exhibit 43: Late Classic Diamond Center Saltillo Sarape 51” x 89” c.1850-1875 39 Exhibit 44: Saltillo Sarape 47” x 78” c.1875-1885 .................................................................... 39 Exhibit 45: Chimayo Hispanic Weaving, 39" X 23 c.1920. 40

APPENDICES

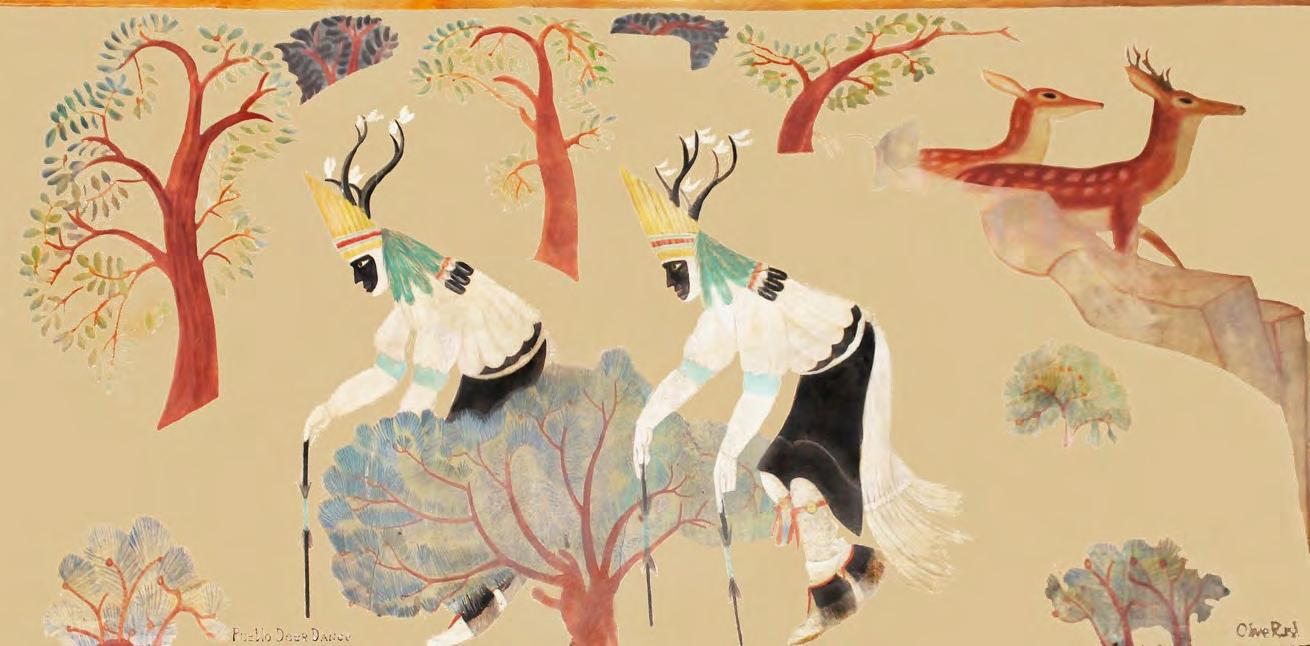

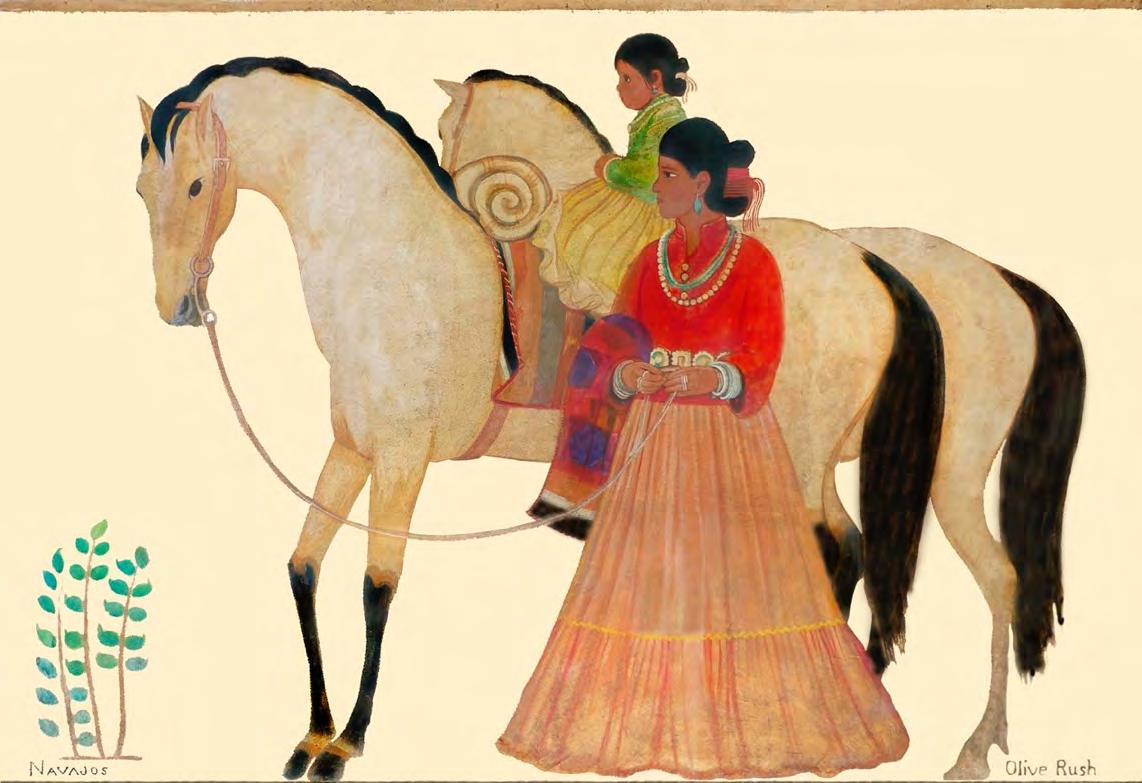

Appendix A: Textiles Depicted on the 1939 Murals at Maisel's Store, Albuquerque, NM ................ A-1

Appendix B: Pueblo Indian Clothing B-1

Appendix C: Southwestern Weaving Materials ................................................................................... C-1

Appendix D: Historic Publications Pertaining to Pueblo Cotton ........................................................ D-1

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

iv REFERENCES................................................................................................................47

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to many supporters including Kim Martindale, Jamie Compton –James Compton Gallery, Michael Higgins – Michael D. Higgins Antique Indian Art, Mark & Linda Winter – Toadlena Trading Post, Scott Gutting and Leslie Jones, Nancy Briggs, and Gerald Tomlinson.

v

PREFACE

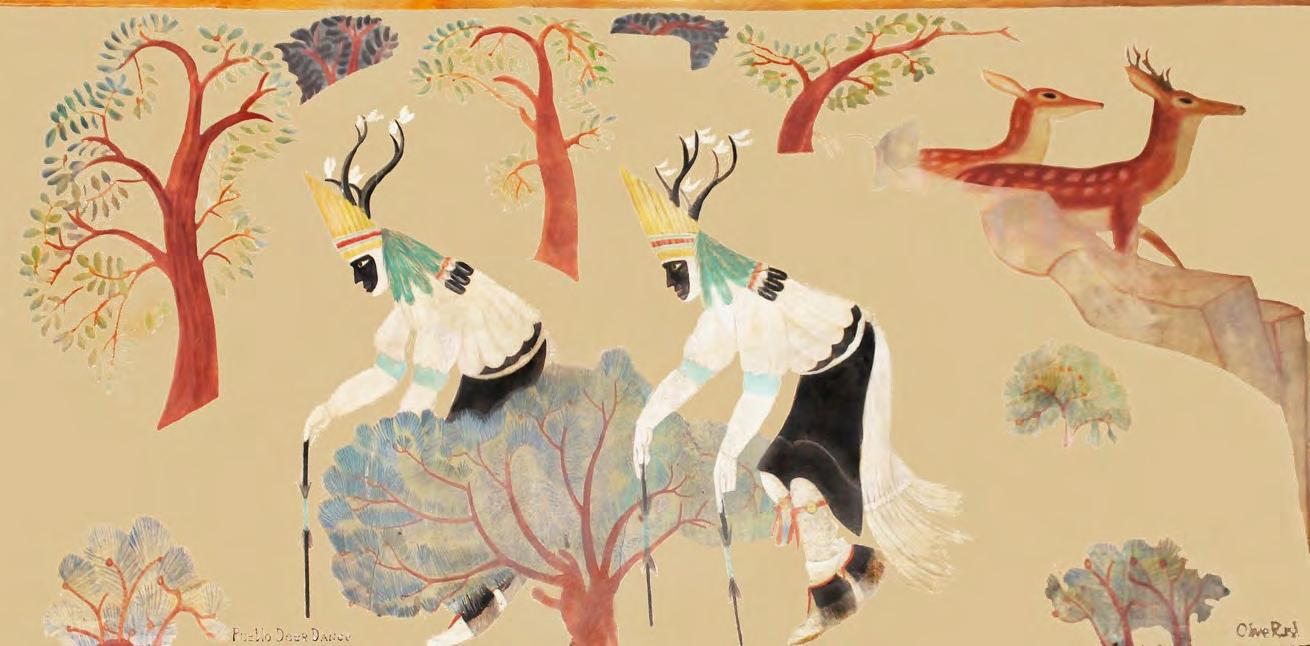

The exhibit described in this catalogue examines aspects of the manufacture and use of historic textiles in the American Southwest. The subject is approached from the perspective of technology, i.e. how textiles are made, rather than from the of iconography of textiles A number of "traditional" garments are only seen today as components of ceremonial regalia, especially textiles using embroidered and brocaded designs applied to a plain-woven fabric While manufacturing techniques lead to a multiplicity of design variations, textiles with representational designs, specifically those produced for ceremonial purposes are not included here.

Pueblo iconography is highly complex, many layered, and with deep cultural significance. A discussion of these topic is thus outside of the purview of this book

The range of historic Southwestern textiles as defined here are those dating from the 17th through the 20th centuries. It is intended as an overview of the subject, highlighting key aspects of the subject, and is by no means comprehensive. While Native American have been producing textiles since time immemorial, this look into textiles focuses on three primary historic cultural traditions; two of which are Native American, the Dinè (Navajo) and Pueblo world of what is now Arizona and New Mexico, with the third being Hispanic textiles from New Mexico that derive from Spanish and Mexican precursors. In a number of cases cultural cross-over from one of these traditions to the other(s) will be highlighted.

This book is oriented toward the general reader and, to the extent possible avoids jargon, technical terms, and footnotes. We have identified key weaving terms in the body of the text, as well as included a number of illustrations. In addition, a comprehensive bibliography contains a detailed listing of background and source material relevant to the topics in this book. Items and photographs included as part of the exhibition are identified as "Photo x" and "Exhibit x", while images seen only in this catalogue are identified as figures.

vi

CHAPTER 1

AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW of NATIVE AMERICAN TEXTILES

Traditions of textile manufacture and design have shown remarkable continuity and resilience throughout the Southwest They are expressions of locally developed weaving traditions that have been shared and borrowed from outside contacts, often through trade or domination, and subsequently adapted to become a unique cultural expressions. This richness is strikingly seen in prehistoric textiles that exhibit a broad range of styles, techniques and materials. This book does not explore prehistoric textiles; that subject has been well covered in works by Lynn S. Teague, PhD and Laurie Webster, PhD, cited in the Bibliography.

Textiles were/are manufactured using several techniques, the earliest being finger weaving and belt looms, simple methods using the fingers or a simple loom attached to a strap around the weavers back. Small horizontal looms are also known prehistorically; however their use did not continue amongst the Pueblos into historic times.

Most importantly, techniques of manufacture demonstrate an inventiveness unique to the region. This is seen most dramatically in the invention of the vertical loom in the Four Corners region where the States of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona and Utah meet) sometime before 1000 BC. This loom was adopted some hundreds of years later by the Dinè for their iconic blankets and rugs.

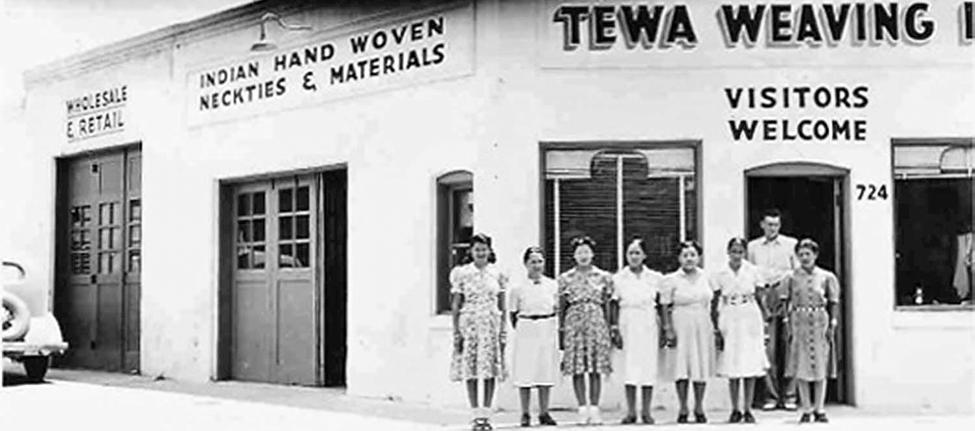

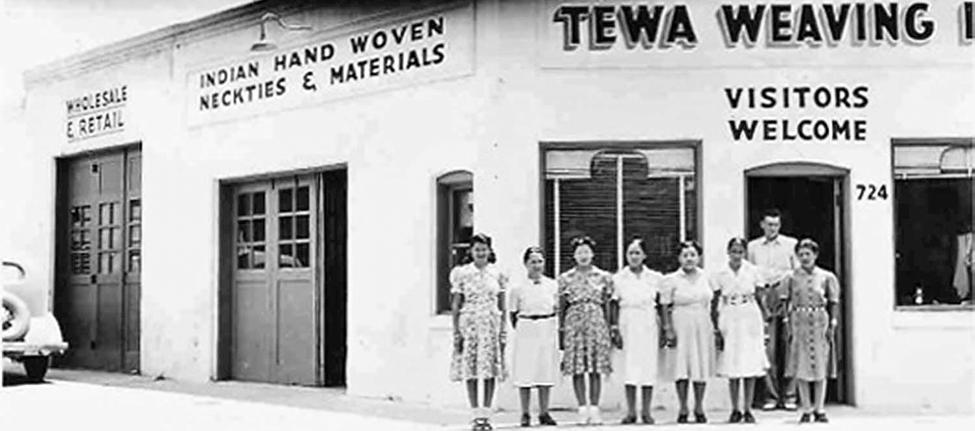

Large horizonal frame looms are a European invention brought into the Southwest by the Spanish. These allow the creation of fabrics of considerable length to be made quickly and in quantity. There use by the Pueblo peoples has generally been limited to commercial operations first established by the Spanish, and later by Anglos, e.g. the Tewa Weavers shop in Albuquerque, during the latter half of the 20th Century.

An important development for producing designs was the “Pueblo stitch” or “Pueblo backstitch”. Because this is solely related to imagery and symbolism, it is not pursued in this book. However as a textile technique unique to the region, we would be remiss in not mentioning it. The Pueblo stitch is an embroidery technique applied to a finished fabric, rather than a brocade technique in which the design is woven into the fabric. The two techniques can be very difficult to distinguish, unless a fairly large example survives. In any case, both the Pueblo stitch and brocades are currently being produced and used. When the Pueblo stitch comes to prominence in Pueblo textile decoration is not clear. But what is clear is that the Pueblo stitch and brocade techniques are both uniquely Pueblo and more than likely were invented in prehistoric times. There is nothing like either of these techniques in other parts of the Americas or in Europe.

1

Figure 1: The Pueblo backstitch. Source: We Dance With Them - Pueblo Indian Embroidery, School of Advanced Research, Santa Fe, < https://sarweb.org/embroidery/default.htm>.

The first Spaniards to enter the Southwest were impressed by the beauty and quality of Pueblo garments. The following is a translation Hernan Gallegos's description of his visit to a southern Tiwa town (probably in the vicinity of modern Socorro, New Mexico) in the 1580s:

Some (men) adorn themselves with pieces of colored cotton cloth three-fourths of a vara (a vara is about a yard) in length and two-thirds in width, with which they cover their privy parts Over this they wear, fastened at the shoulders, a blanket of the same material, decorated with many figures and colors, which reaches to their knees, like the clothes of the Mexicans. Some, in fact, most, wear cotton shirts, hand-painted and embroidered, that are very pleasing . . . Below the waist the women wear cotton skirts, colored and embroidered; and above, a blanket of the same material, figured and adored like those used by the men. They adjust it after the fashion of Jewish women and gird it with embroidered cotton sashes adorned with tassels. (Hammond and Rey 1966:70).

The Hopi villages and the Pueblo towns along the Rio Grande were major centers of cotton production. Men were the principal weavers. According to the initial Spanish accounts, most spinning and weaving took place in the kivas (i.e. ceremonial chambers, that also functioned as a sort of men’s club houses) during the winter months when men were free from agricultural responsibilities. This pattern was undoubtedly true in prehistoric times, as evidence of loom weaving has been found in excavated kivas.

Tribute textiles produced at the missions and workshops in New Mexico were often made by men, in keeping with traditional practices. However, women also wove fabric in textile shops, as well as engaged in spinning and knitting. This contrasts with the missions of Texas and California where women worked on treadle-looms.

Because of their remoteness the Hopi villages remained on the perimeter of Spanish incursion and were not dominated by the Spaniards following the reconquest in 1692 after the Pueblo Revolt, nor were they subject to the imposition of taxation/tithes/tribute by the Spanish Crown which included vast quantities of plain weave wool fabric to which the Pueblos of the Rio Grande region were subject. In addition, refugees from several Rio Grande Pueblos remained at Hopi, most notably by the Tewa people living at the First Mesa Village of Hano, resulting in the maintenance of strong connections between the Rio Grande Pueblos and Hopi.

2

Figure 2: Native American groups addressed in this book. The Navajo now refer to themselves as the Dinè

CHAPTER

2

AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW of SPANISH AMERICAN TEXTILES

The following is abstracted directly from the Introduction by Kate Peck Kent to H.P. Mera's: Spanish-American Blanketry, SAR Press 1987 (2001 ed).

Dr. H.P. Mera commenced his research on Spanish-American weaving at the beginning of the 20th century, a time of little information and many-misconceptions about the art. He had completed a manuscript on the subject by the late 1940s, only a few years before his death in 1951. The School of American Research (SAR) prepared the book for publication in 1965, setting type and making color transparencies for twenty-four plates, but a shortage of funds kept the book from being printed, and it was consigned to the SAR archives. It has since been consulted by a few students of Spanish-American weaving as a starting point for their research. E. Boyd referred to the manuscript in Popular Arts of Spanish New Mexico, as did several authors in Spanish Textile Tradition of New Mexico and Colorado, edited by Nora Fisher. It is now published for the first time in the relevant portion of this text

The history of the early Spaniards in the Rio Grande Valley had not been completed when Mera wrote, explaining a few errors and lacunae in his book His most serious mistake is dating the introduction of the treadle loom or flat horizontal harness loom, as he calls it to about A.D. 1750, or somewhat more than a hundred years later than we now believe it to have occurred. We know that Juan de Onate and his colonists, arriving in 1598, brought no loom parts or weaving tools with them and depended on the Pueblos' annual tribute of mantas to supplement their clothing needs, as Mera describes. However, less than forty years after Onate's arriva l, woven goods were being produced on treadle looms for trade to Chihuahua. Mera records a 1638 trade invoice listing nineteen pieces of sayal, each about one hundred meters long, which could only have been woven as yard goods on treadle looms with cloth and yarn beams capable of holding such lengths. It is a matter of record that by that time, Governor Luis de Rosa had established an obraje, or workshop, in Santa Fe, employing captive Apaches and Utes and perhaps some Pueblos as weavers. He was accused of seizing "looms owned by private citizens in order to give to his own workshop a greater monopoly over local textile production."

As Mera points out, "Pueblo weaving would seem to have no direct relationship with the development of the Rio Grande blanket," but not, as he assumes, because Rio Grande Pueblos had ceased to weave in the 1700s and so could not affect Spanish arti- sans. The weaving of clothing for domestic use continued in some of the Pueblo villages through the 19th century, although many people turned to the western Pueblos to supply their needs.

That the weaving of the Pueblos had little influence on Spanish textiles is interesting and explained by a number of factors. The Pueblos principally wove articles of traditional clothing in a style quite different from that of the Spaniards. After the Spaniards brought their own looms, they could weave blankets to their own tastes rather than using Pueblo-style mantas. In addition , the looms of the two groups were geared to produce different kinds of textiles: to weave a Spanish-style blanket on a Pueblo loom is feasible enough, but it is not possible to produce a Pueblo manta with decorative end borders on a narrow treadle loom. Finally, the traditional Pueblo weaver was a man working in a kiva (ceremonial chamber), removed from public view, which would have discouraged exchange of ideas between Pueblos and Spaniards.

None of the research on dyestuffs reported in Fisher's 1979 publication was available to Dr. Mera, so he

3

speaks of dyes in the terms generally current in his time and indeed until the late 1970s. He assumes yellow to have been extracted from chamiso (chamisa, or rabbit brush). This is one common source of yellow used by handloom weavers in New Mexico for generations, but it was not identified as the dye in any of the twelve samples of yellow tested by Max Saltzman and reported in Spanish Textile Tradition of New Mexico and Colorado.

Mera and other writers speak of logwood (Campeche wood) and brazilwood as one dye, the source of the reddish-brown color distinctive in one type of Spanish-American striped blanket . In fact, logwood yields black , blue, purple, and silver-gray, but not red- dish tones, and is quite distinct from brazilwood. Saltzman found no brazilwood in theRio Grande blankets he tested, one of which is that illustrated here in Plate 2. He does state that the reddish browns may be from a closely related red dye wood. Red in the three-ply imported yarn referred to by Mera in the caption to Plate 4 proved to be cochineal, as did three-ply red yarns in the cotton blanket illustrated in Plate 13.

Mera uses the term "tapestry" for what is currently spoken of as "weft-faced" weave, which simply means that the wefts are battened tightly together to obscure the warps of a fabric. Weft-faced plain weave was the standard technique for Rio Grande banded-pattern blankets. Plain weave tapestry, a technique in which discontinuous wefts of different colors build a pattern of geometric or floral' motifs, is the technique used in Mera's "hybrid style" blankets and other figured pieces. Also, when he states that "the colonial blanket weaver seems never to have attempted any sort of twilling," he is speaking solely of blankets, knowing perfectly well that the coarse yard-age used for clothing, sacks, and floor coverings-was usually woven in twill on the treadle loom.

Finally, Mera's description of double-woven blankets is confusing and incorrect. Trish Spillman, in Spanish Textile Tradition of New Mexico and Colorado, explains the process acc urately. d ouble -woven blankets are almost all weft-faced plain weave patterned by simple weft stripes, Mera's "early striped style." It is the blankets woven in two pieces and then sewn together that are more elaborately designed

Dr. Mera concluded his study in the 1940s, when he saw the weavers producing for the tourist trade blankets and other articles that bore little resemblance in design or quality to the fine old 19thcentury Rio Grande textiles. He wrote that "attempts to duplicate anything like the achievements of the past are apparently destined to prove unavailing.... All the efforts to accomplish this have thus far come to naught." Instead, since about 1970, there has been a revival of interest in 19th -century tex tile traditions, and a number of Spanish artisans are weaving blankets of great beauty, the designs inspired by the work of their ancestors. For a good account of Hispanic tex tile production in 20thcentury New Mexico, see the chapter by Charlene Cerny and Christine Mather in Spanish Textile Tradition of New Mexico and Colorado.

Despite these minor shortcomings, Mera's work offers an excellent picture of the blankets woven by Spanish -Americans in the Rio Grande Valley in the 19th cen tury. He is the first scholar to have recognized their beauty and historic importance, and the first to show definitively that they are who lly Spanish, owing nothing in technique or design to the Pueblo weaving that preceded the Spaniards and their looms in the Southwest. His remarks on the influence of Navajo design on Spanish weavings of the 1870s and 1880s are particularly insightful. He describes clearly the ''class of loomwork" popularly called Chimayo weaving that developed after about 1900 in and near the village of Chimayo, and he distinguishes it from 19th -century Rio Grande weaving Spanish - American Blanketry is indeed a valuable contribution on a little-known subject, remarkably complete for its time and still useful to scholars and others interested in Spanish colonial arts .

4

CHAPTER 3

WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD?

The survival of traditions of Native American textile use and production is due in large part to the continuation of Dinè and Pueblo cultural identity. In addition, weaving on horizontal and belt looms has persisted in Hispanic villages, primarily in Northern New Mexico At the village of Chimayo, about 30 miles north of Santa Fe, weaving has, since the 19th century, been a commercial enterprise. While markedly reduced, the Dinè and Pueblos did not completely lose their homelands and did not suffer the extent of the fate of relocation, unlike many other Indigenous cultures. They have also managed to retain their unique world view, with Christianity serving as just another layer on top of an already complex, sophisticated moral guidance systems. Although the Christians made a concentrated effort to impose their views to the exclusion of traditional beliefs, they failed. Significant aspects of Dinè and Pueblo ritual went underground. The result of this today is a lineage of production and styles which clearly extends directly back into the prehistoric past.

Many weaving and decoration techniques, as well as tools, have been lost over time or supplanted by others. This appears to have been true, to some extent, in prehistoric times, and most dramatically as a result of European incursion into the Southwest. New techniques can bring forth complex issues. Indeed, there is controversy today over the use of applied machine sewn designs, rather than hand embroidery. What is “traditional?” Is it the design applied to a fabric, no matter how the fabric is produced, or is the method of creation that is a critical factor in its value and meaning, however value and meaning is defined? Such questions are far beyond the content of this book.

Designs applied to fabrics, as previously mentioned, are not addressed in the book. These include embroidery and brocading in which a design is stitched into a woven fabric. Such techniques are typically found on historic Pueblo ceremonial garments.

5

CHAPTER 4 MATERIALS and PROCESSING

The Hopi and middle Rio Grande Pueblo villages appear to have been the main centers for the growing of cotton. For the Hopi the climate limited the places where cotton could be grown, and a significant trade arose by late prehistory based on the exchange of cotton, corn, and other agricultural products for bison robes, deer hides, meat and salt from the Rio Grande Pueblos and more easterly (no longer occupied) Pueblos in the Salinas and Galisteo Basin regions of central New Mexico.

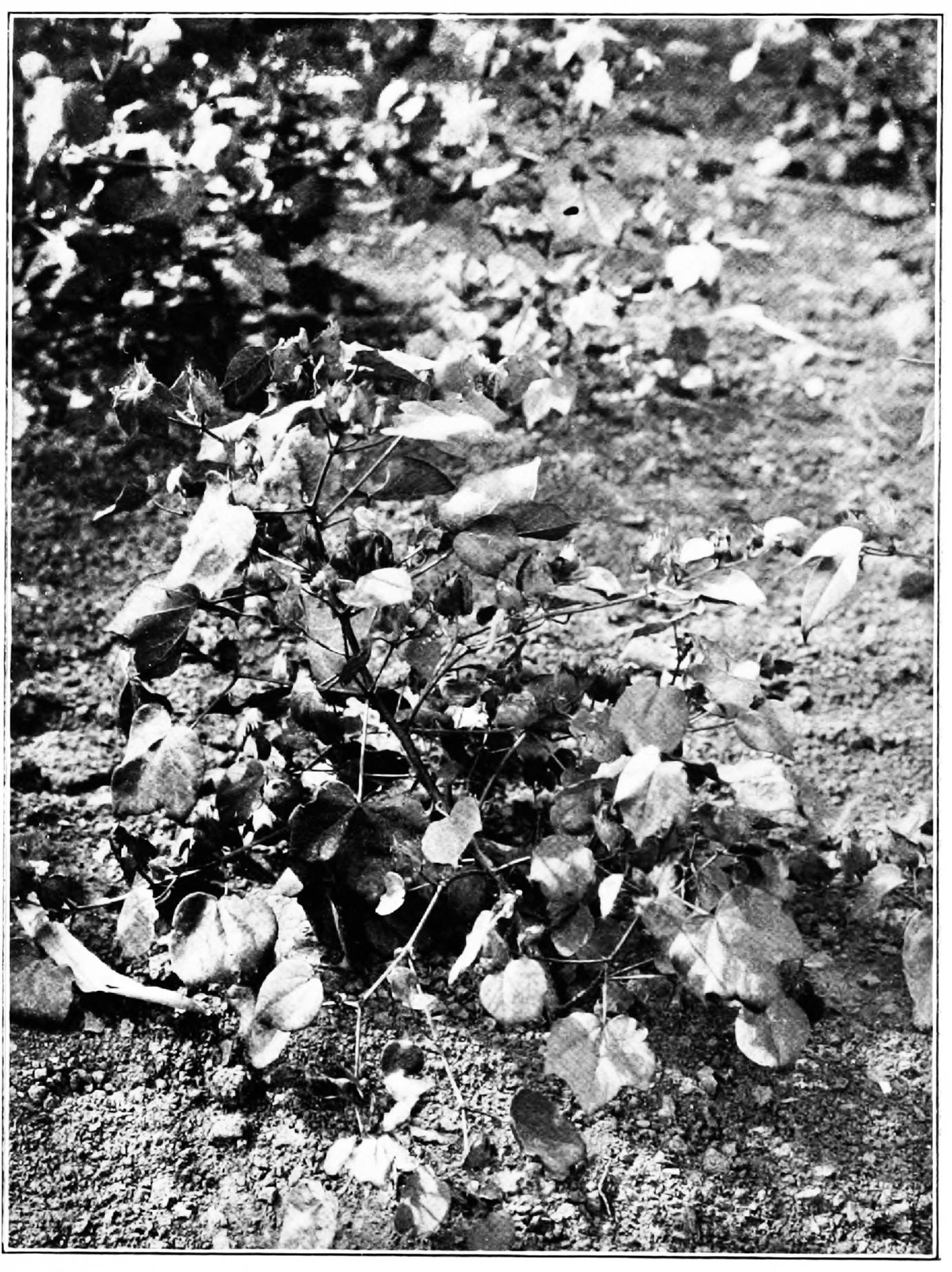

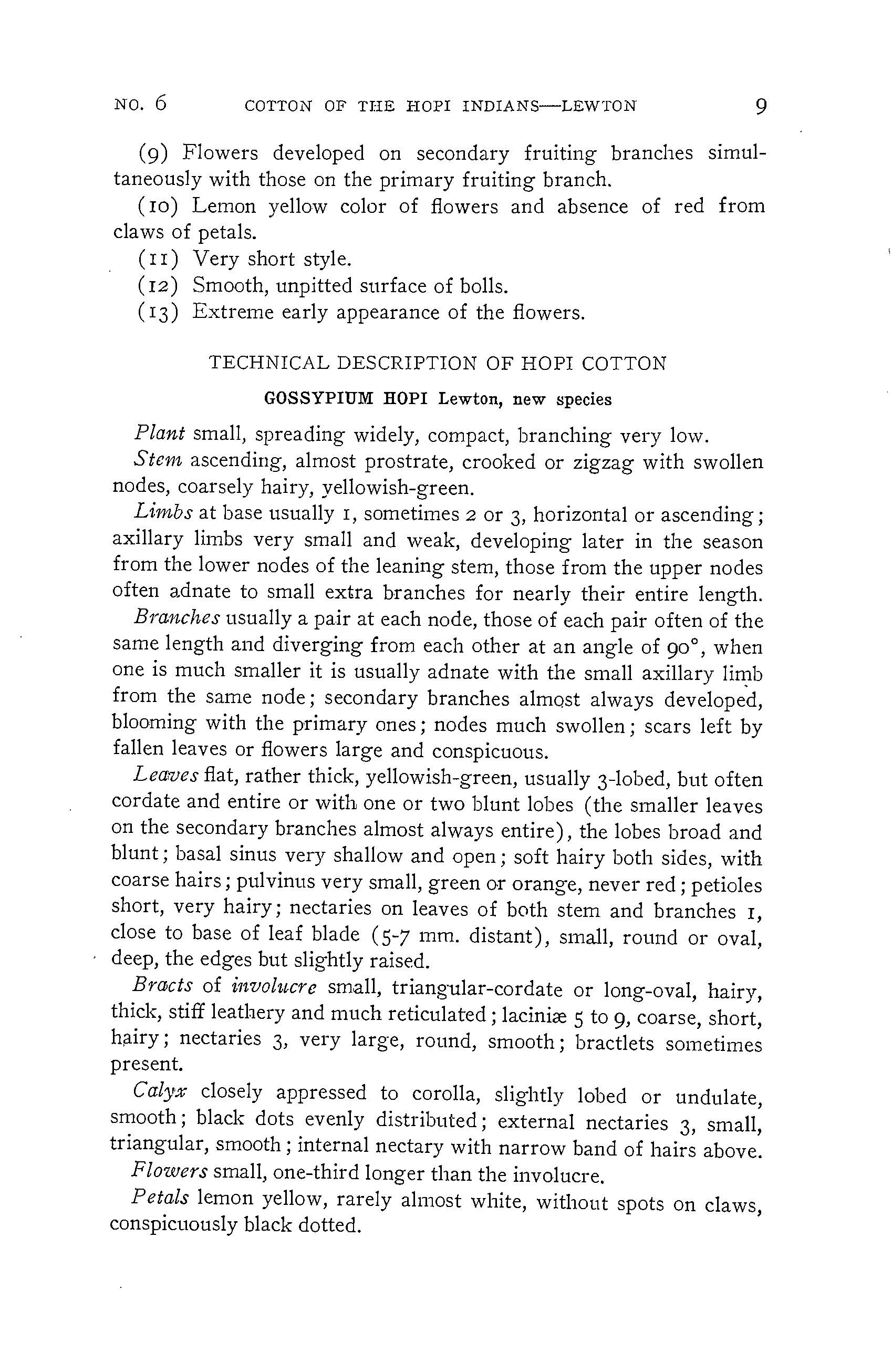

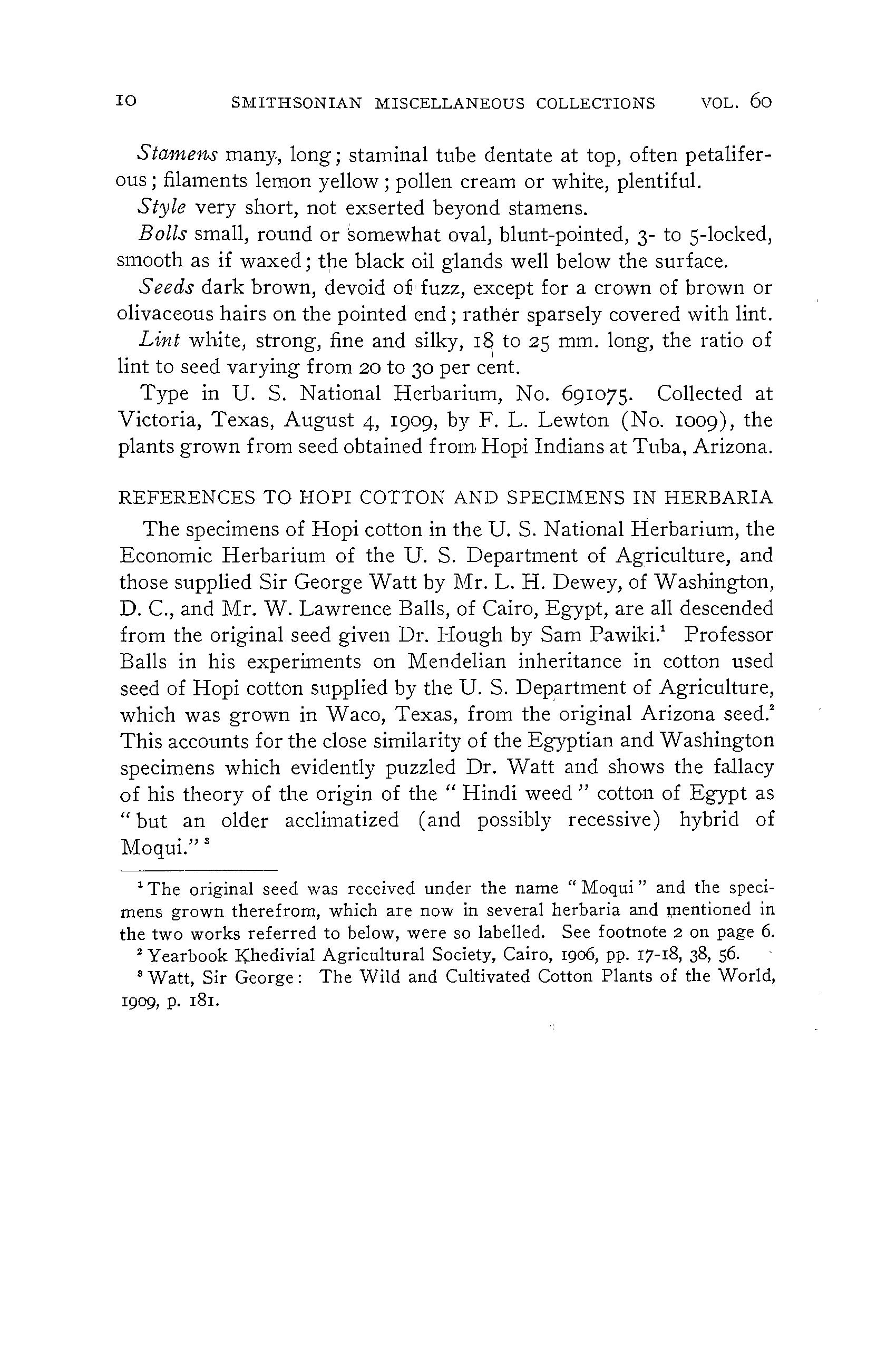

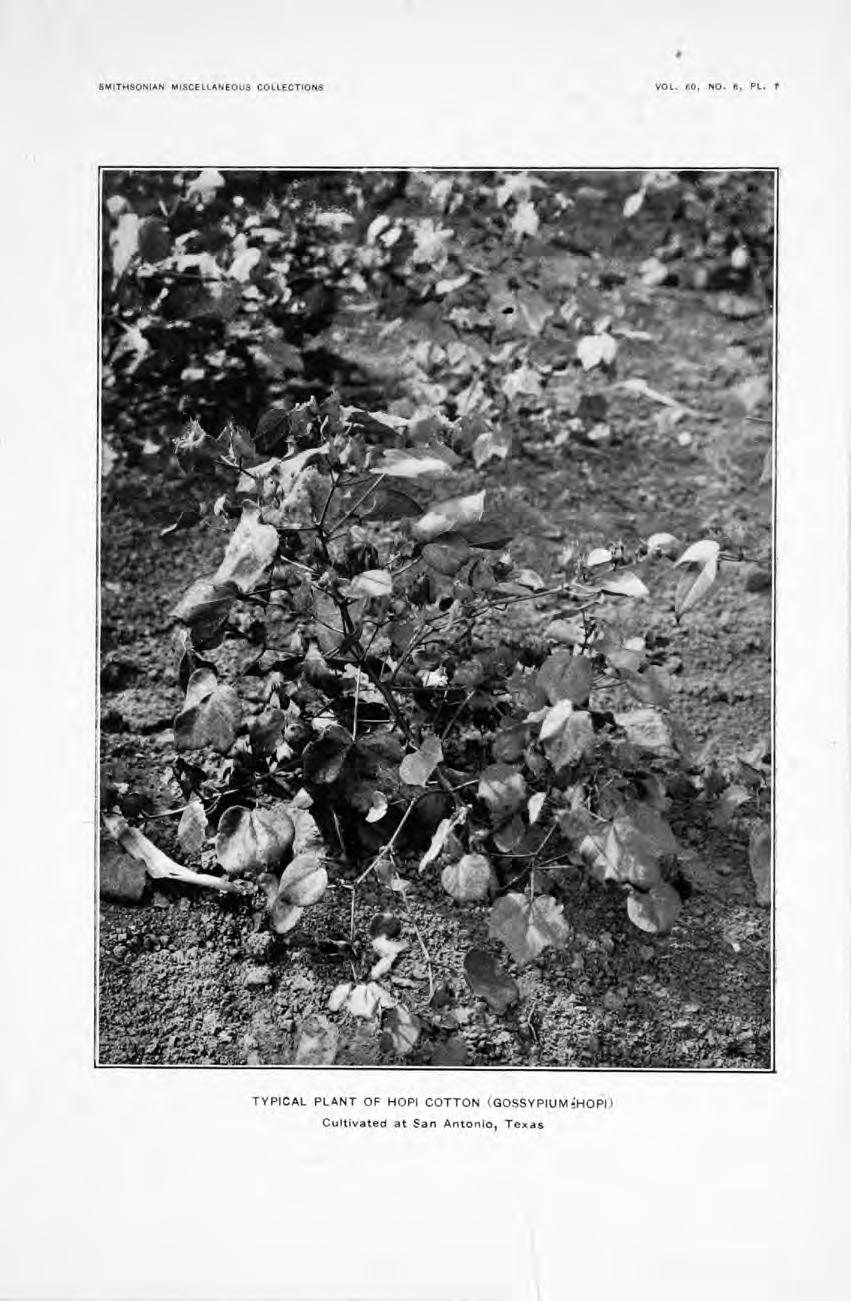

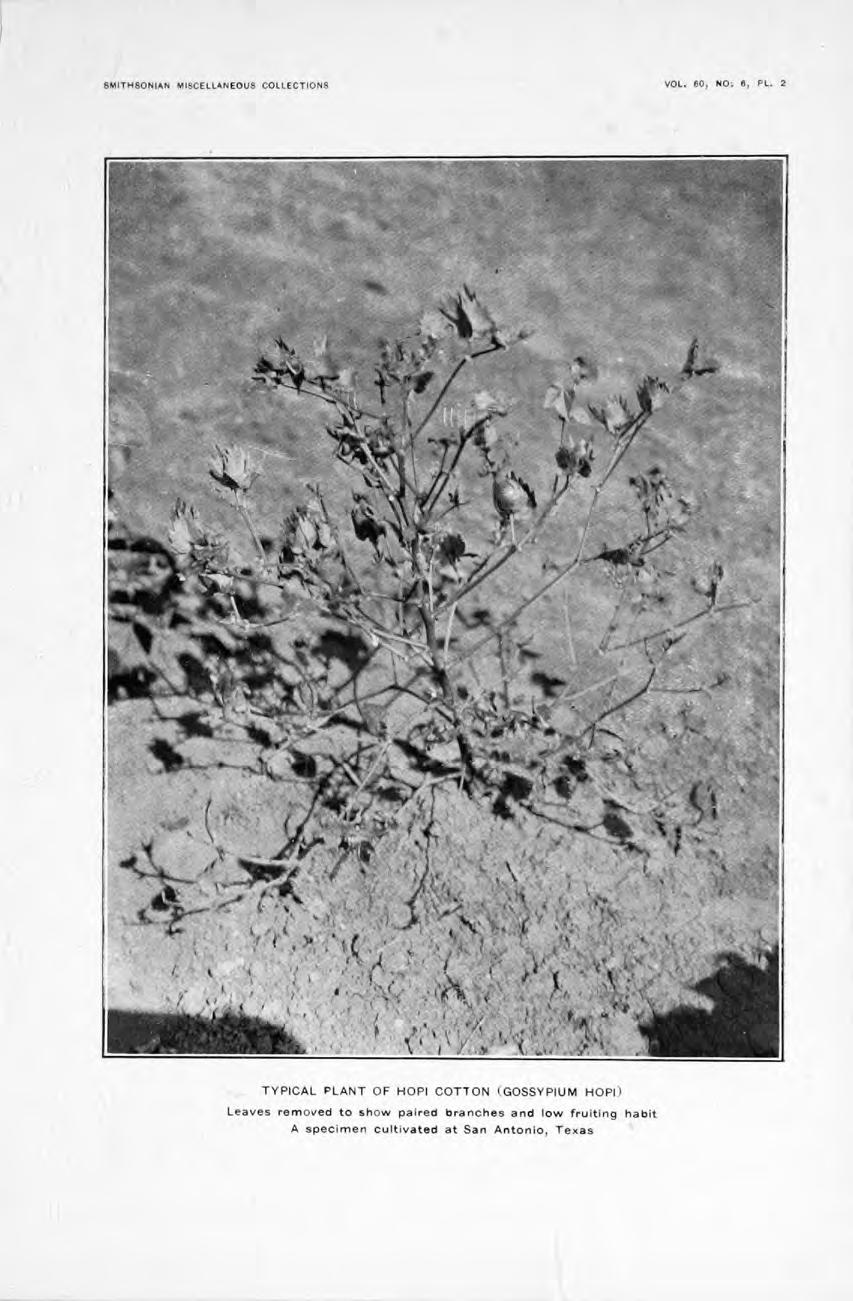

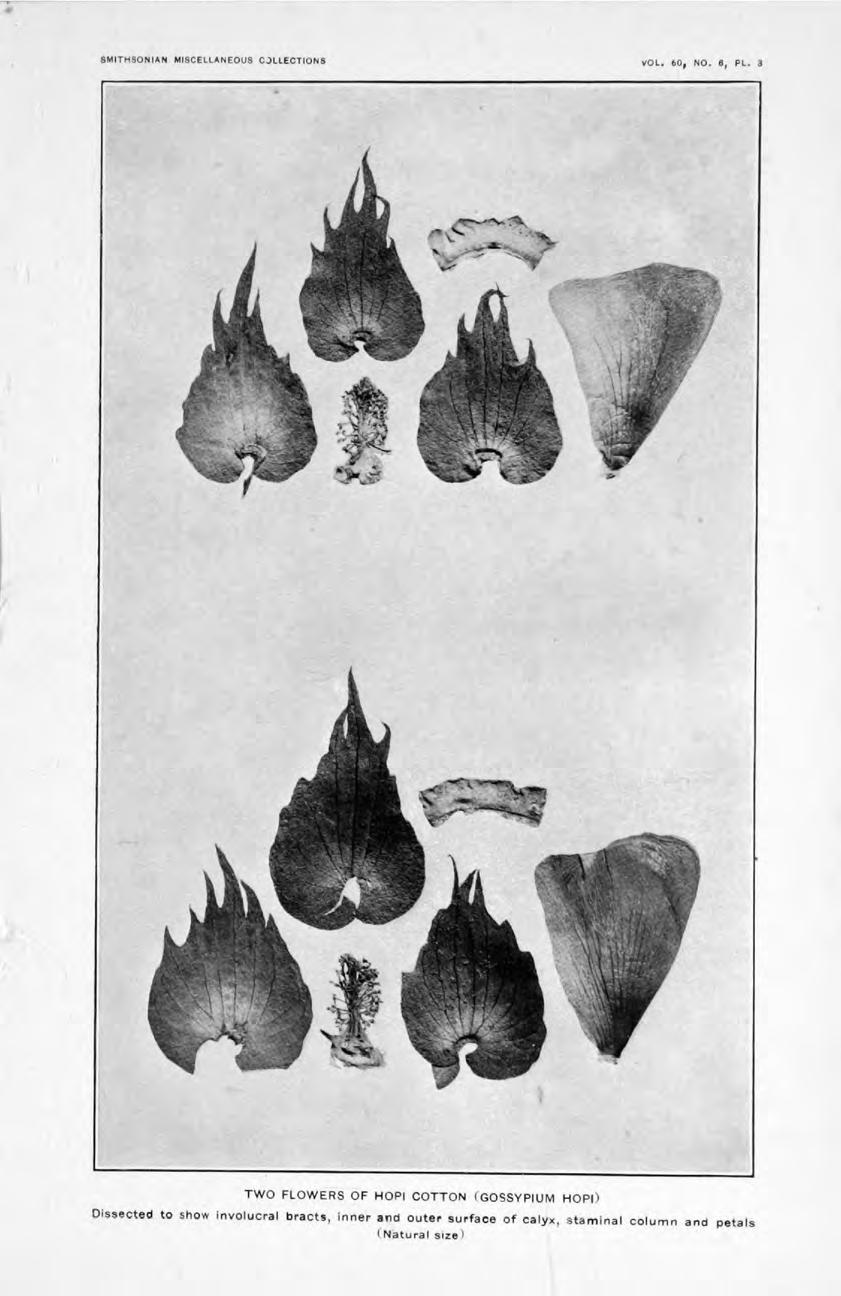

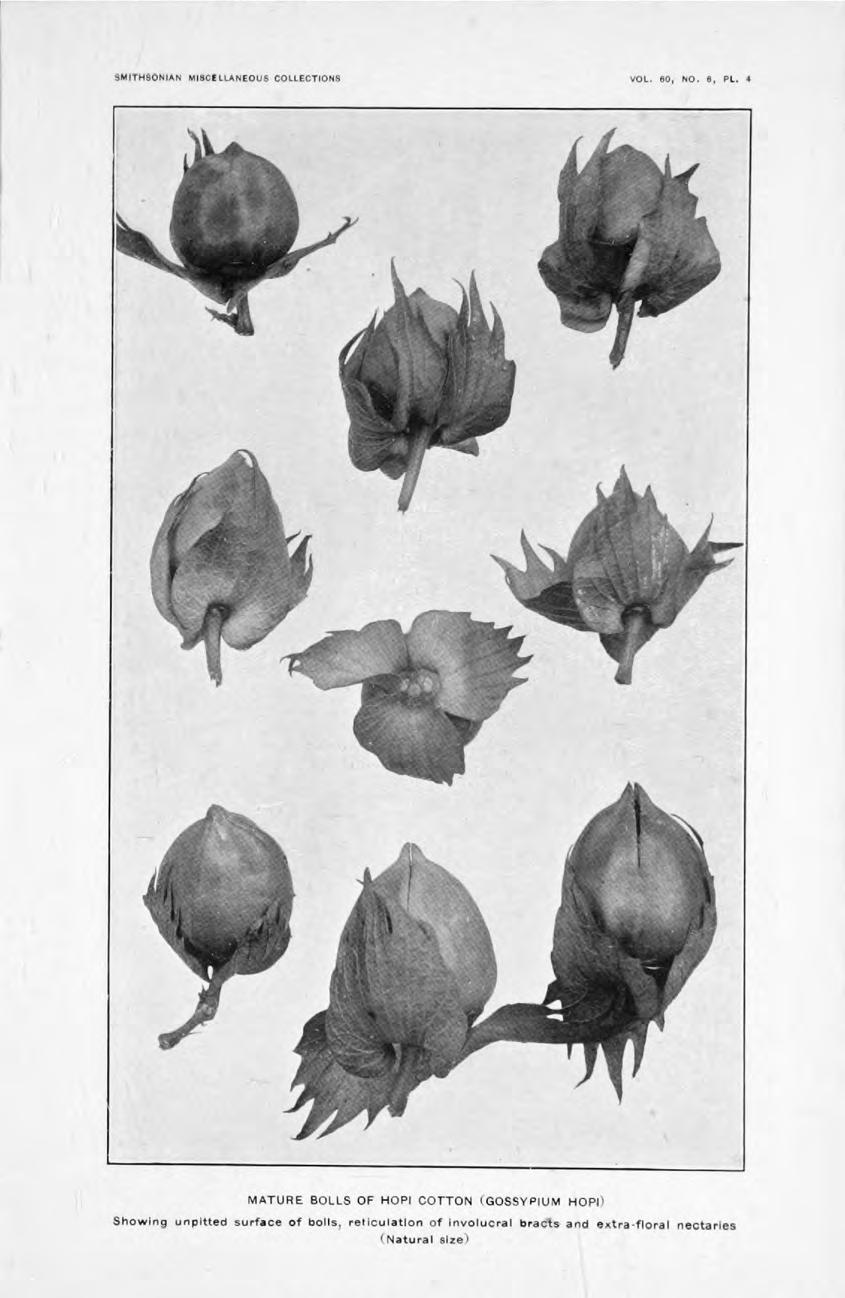

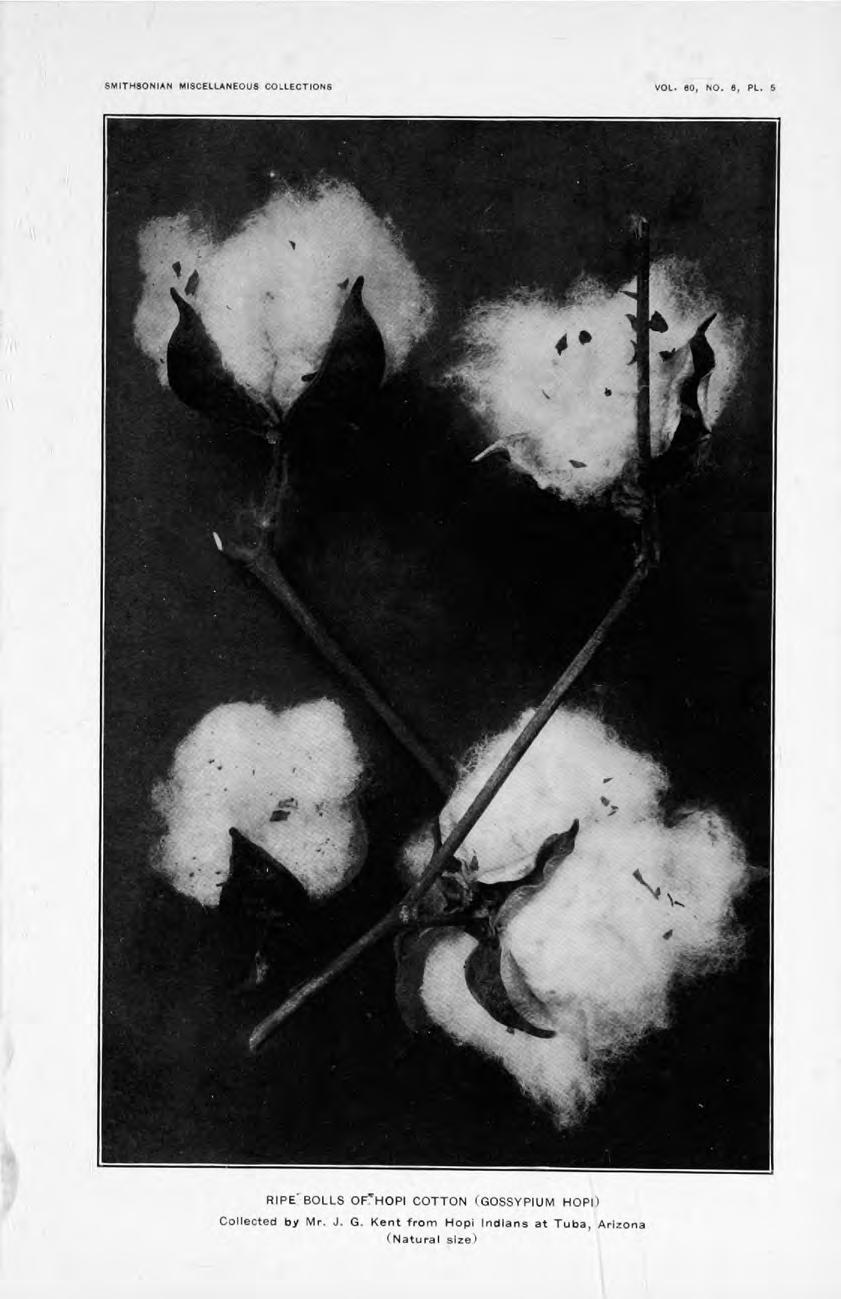

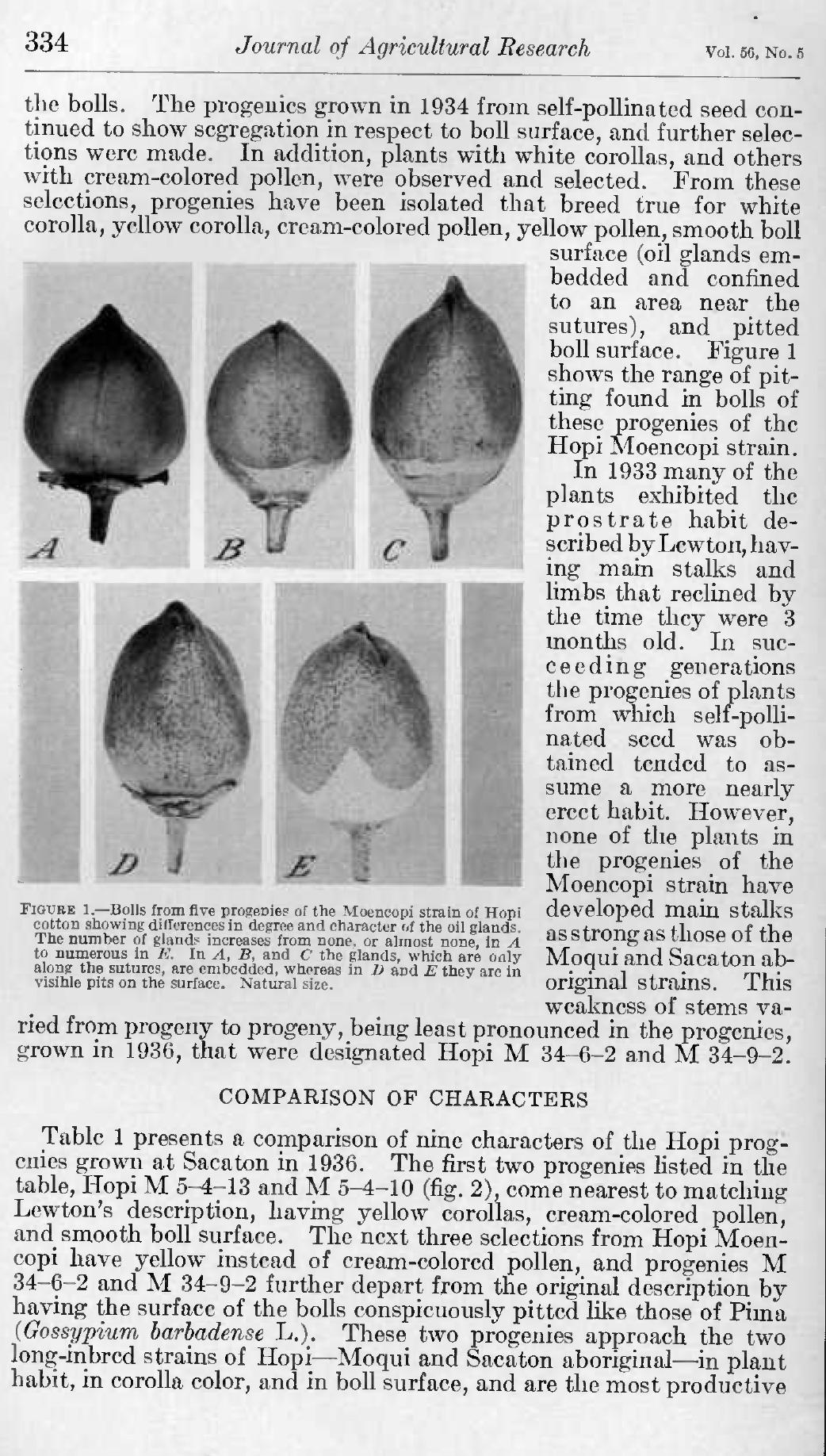

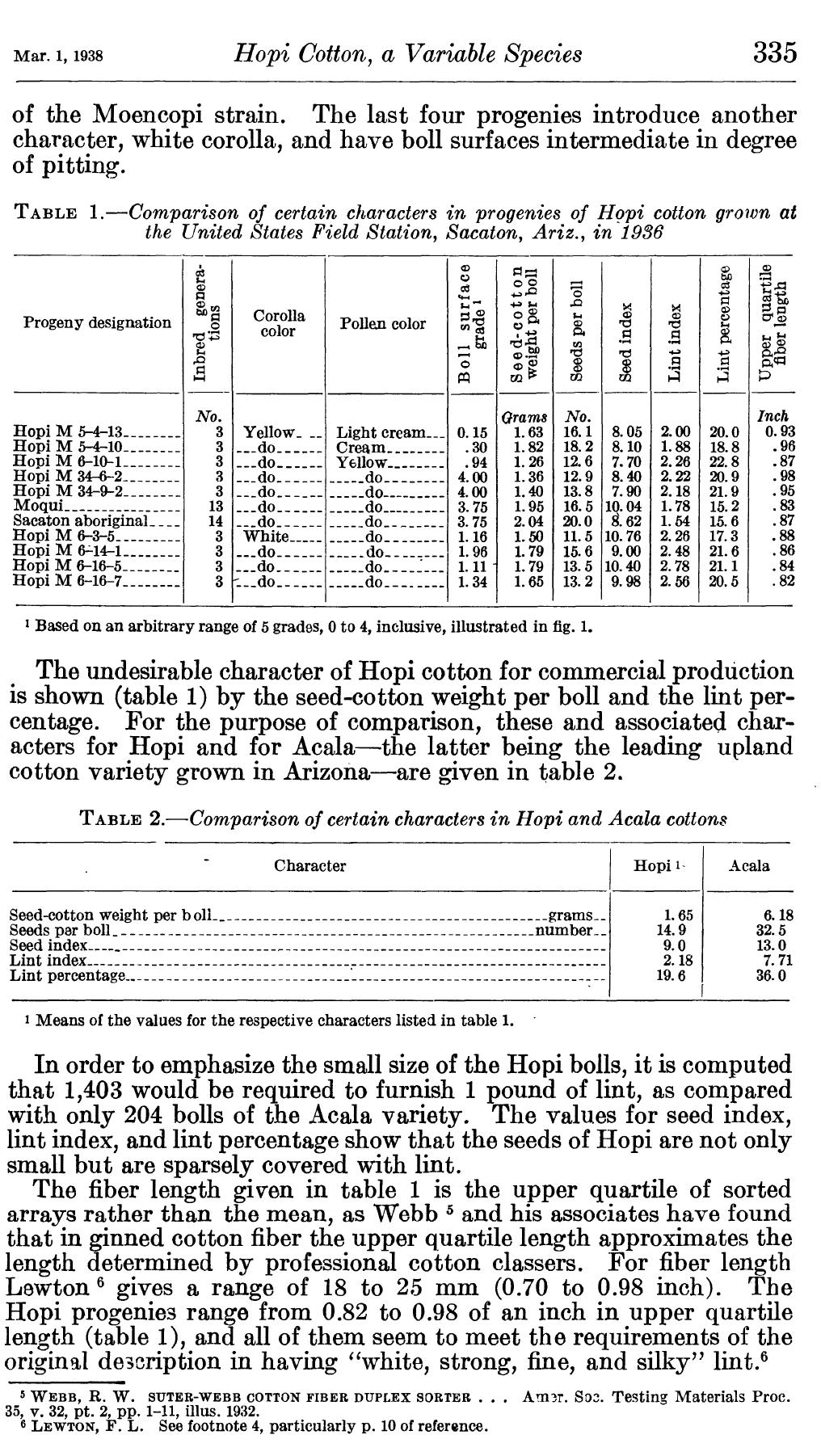

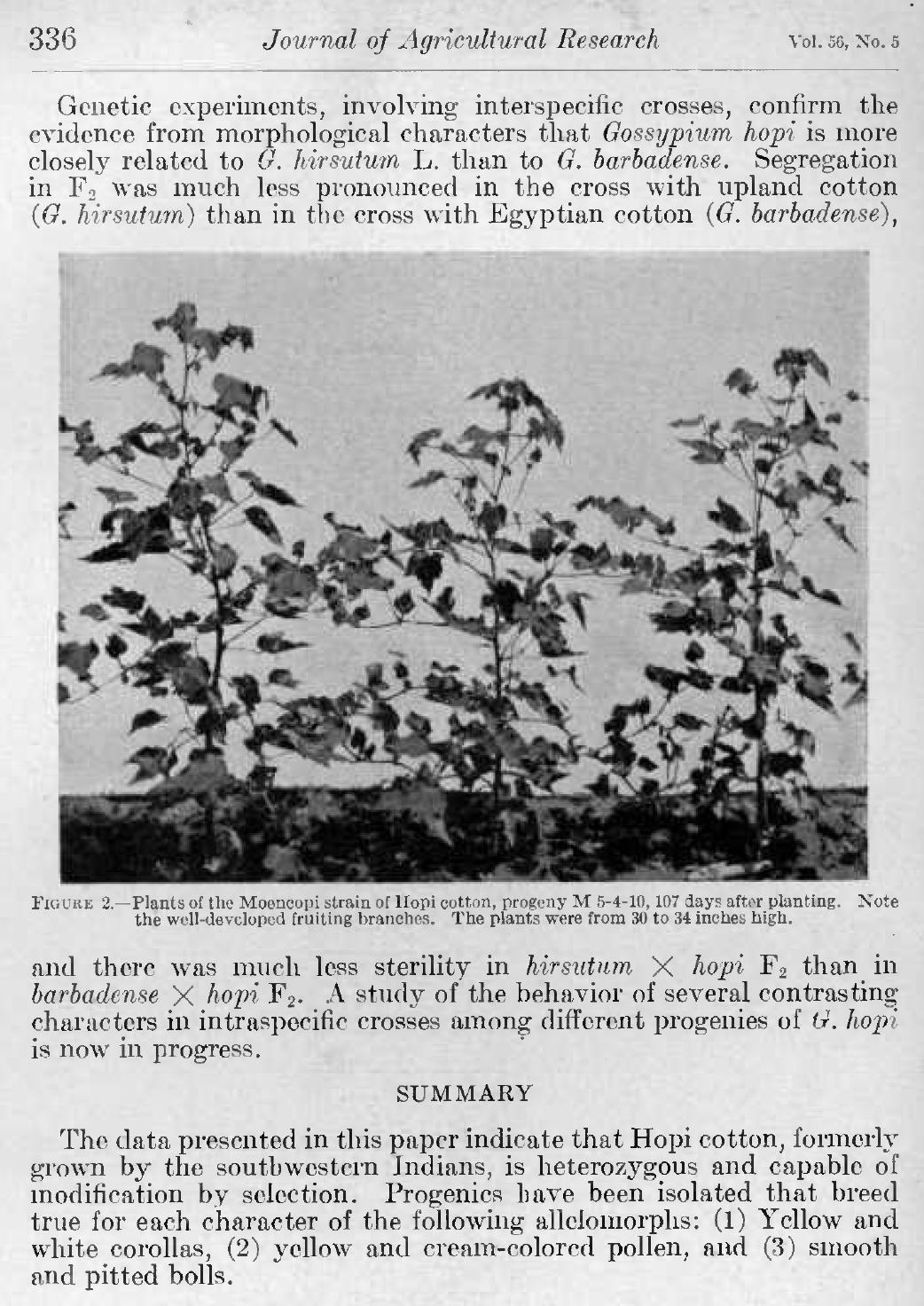

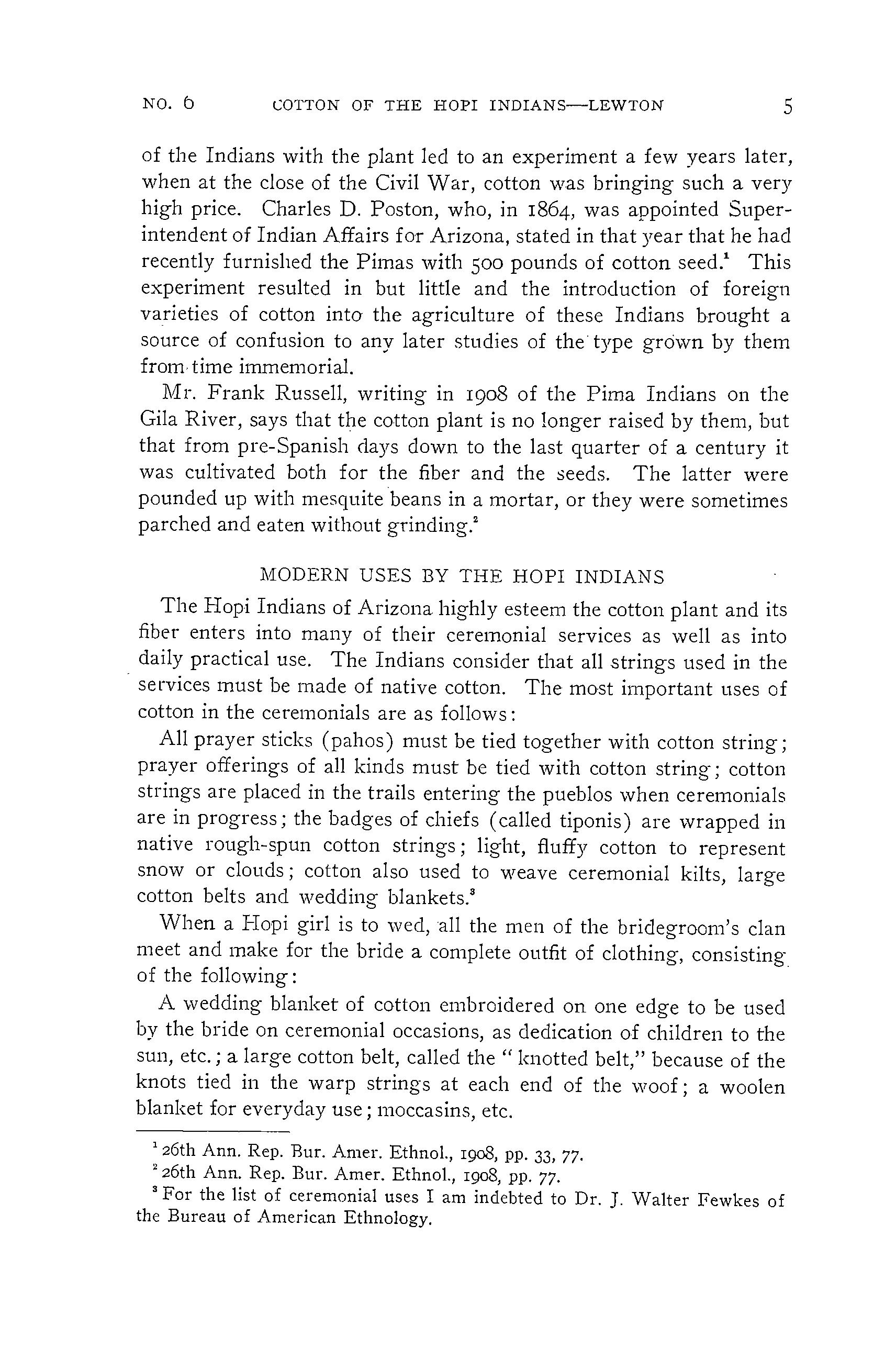

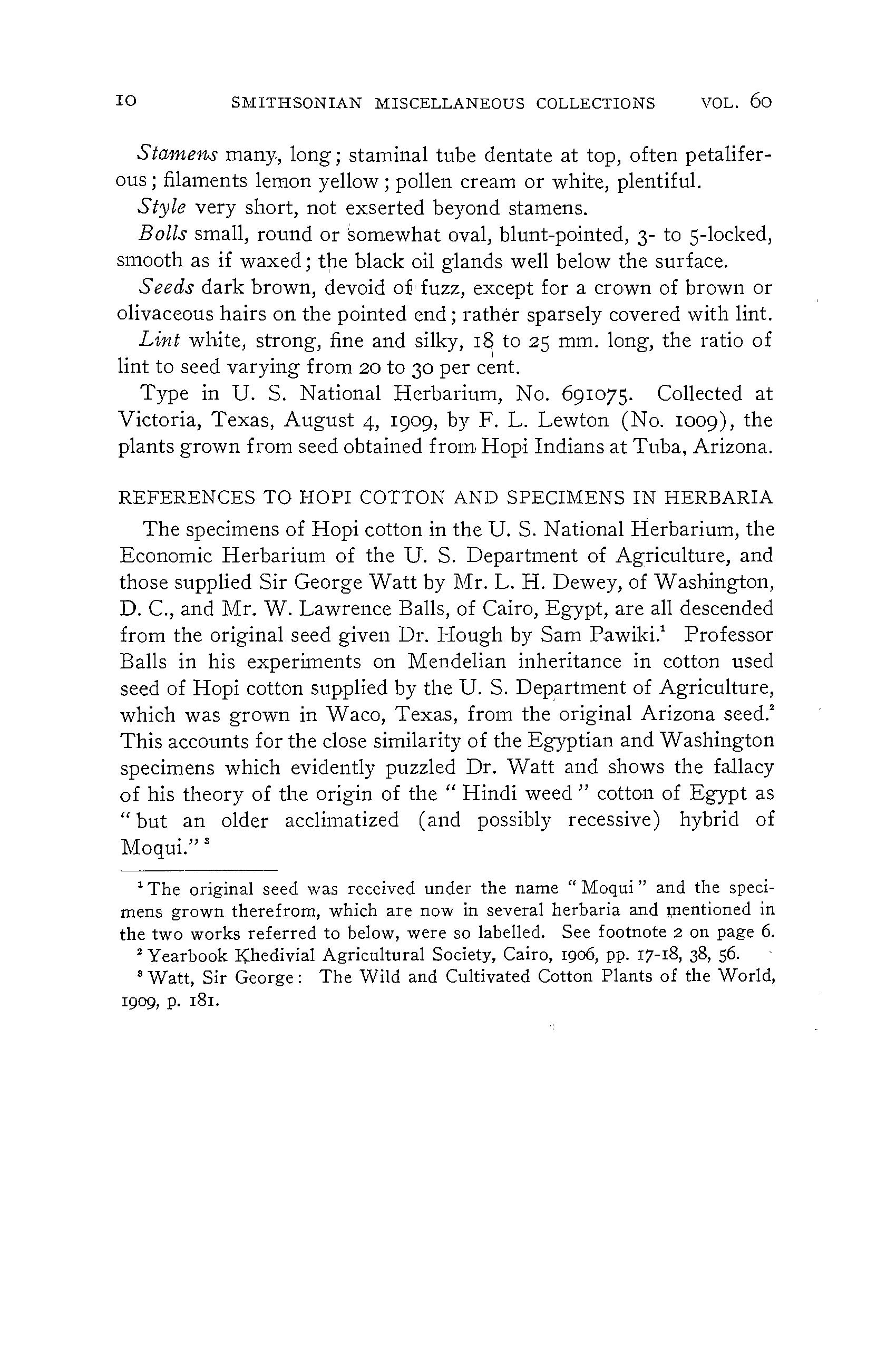

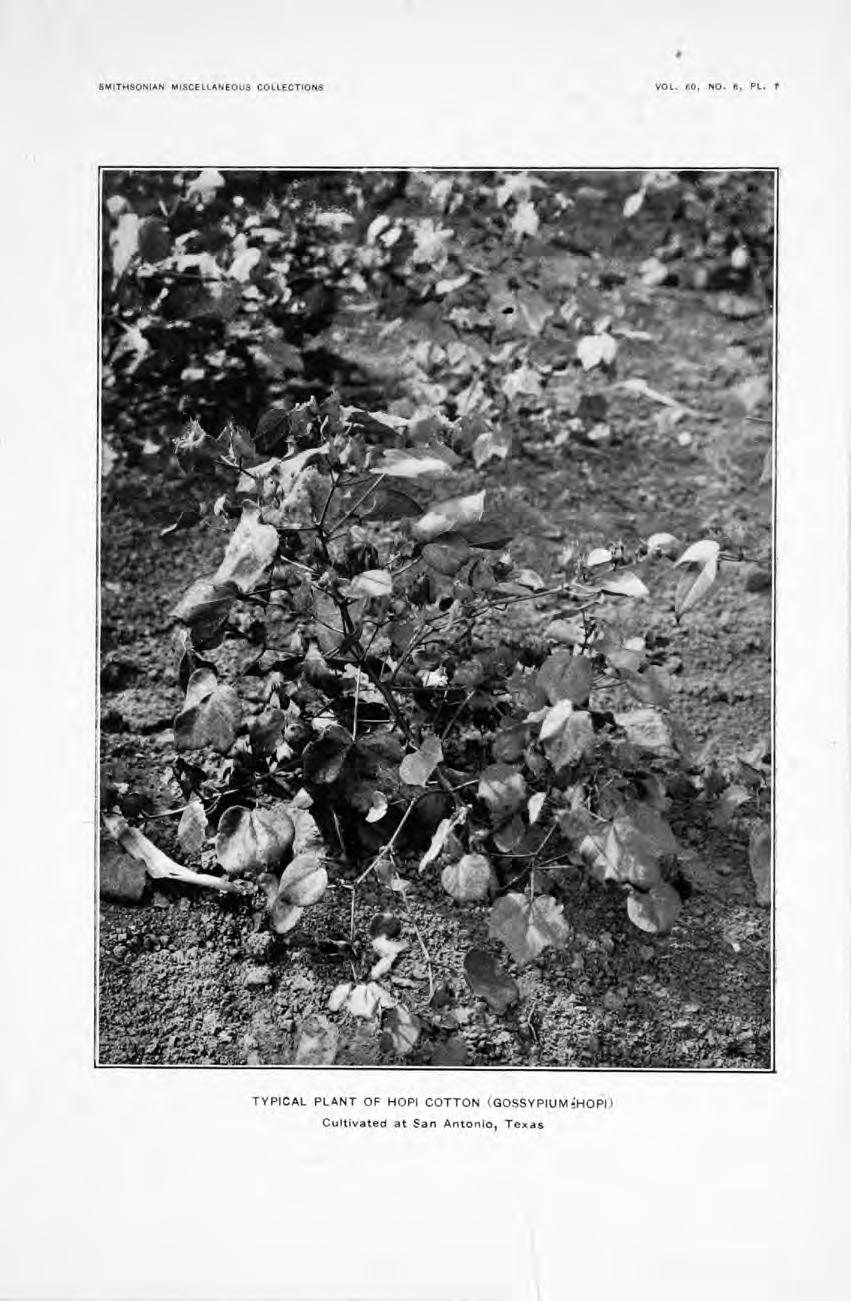

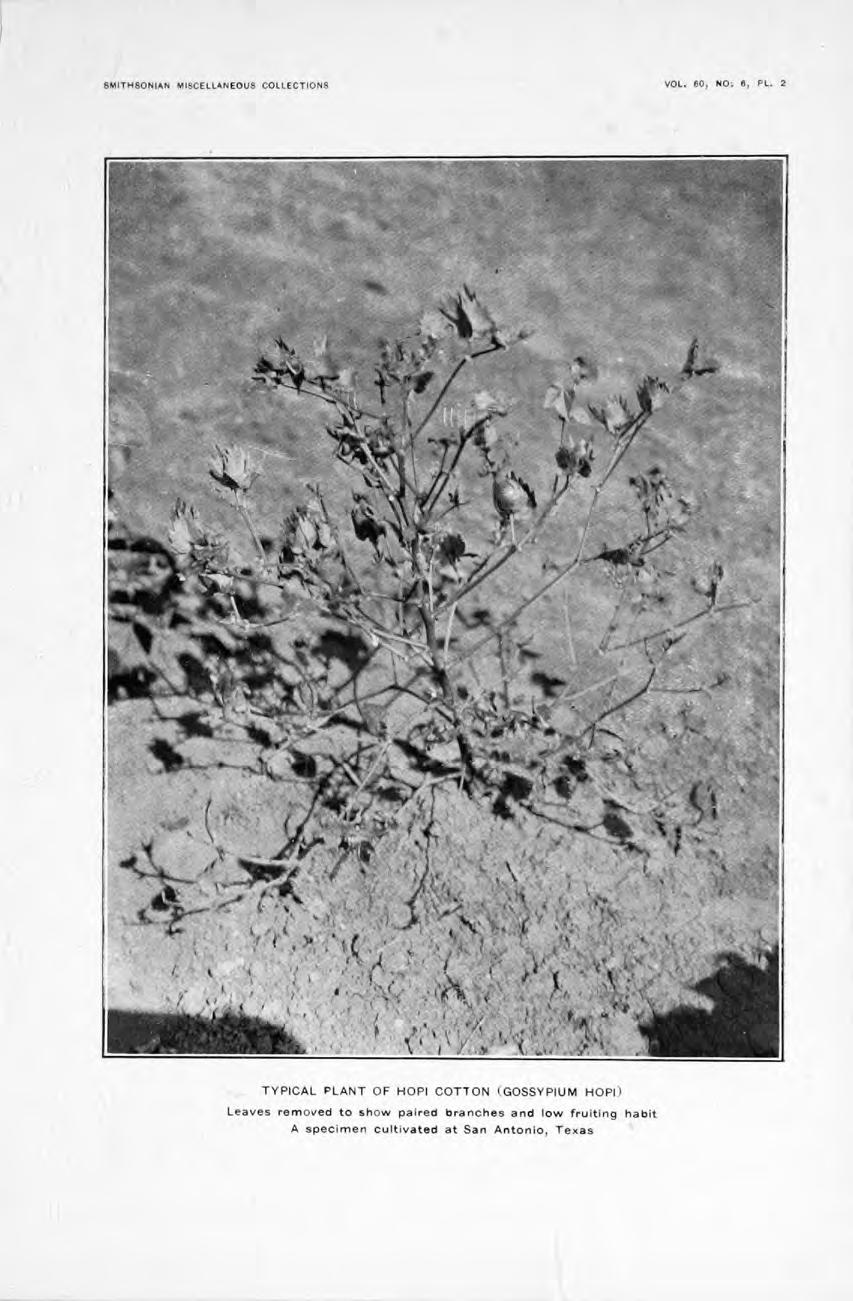

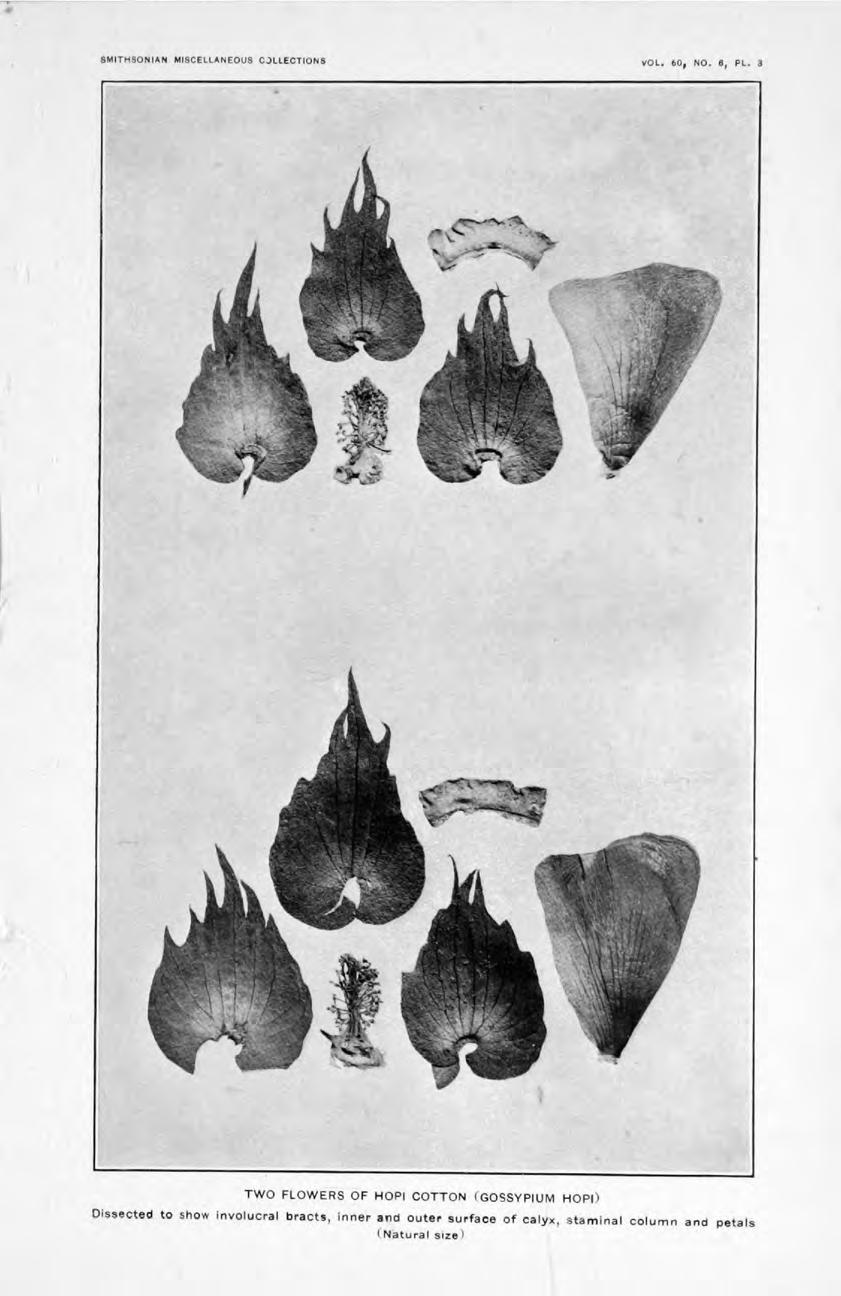

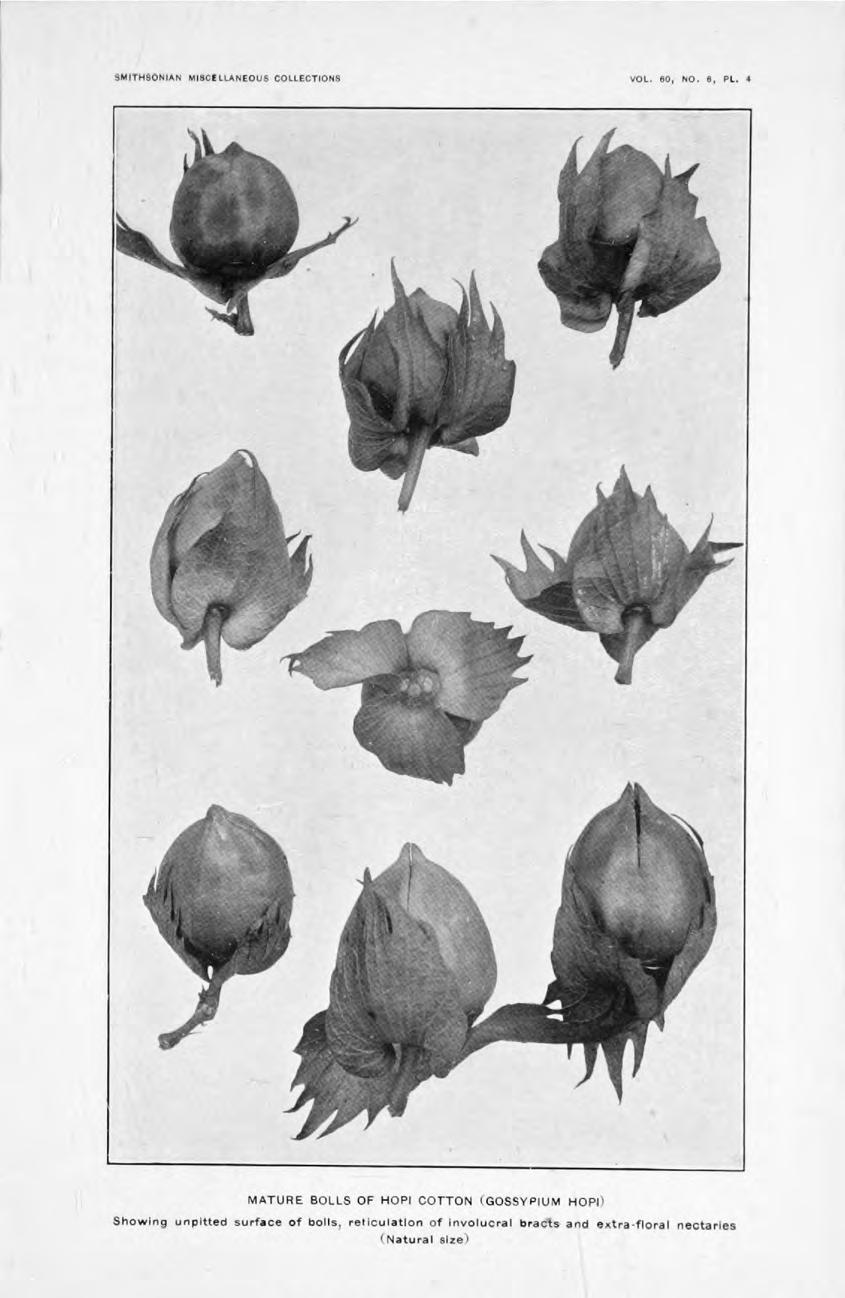

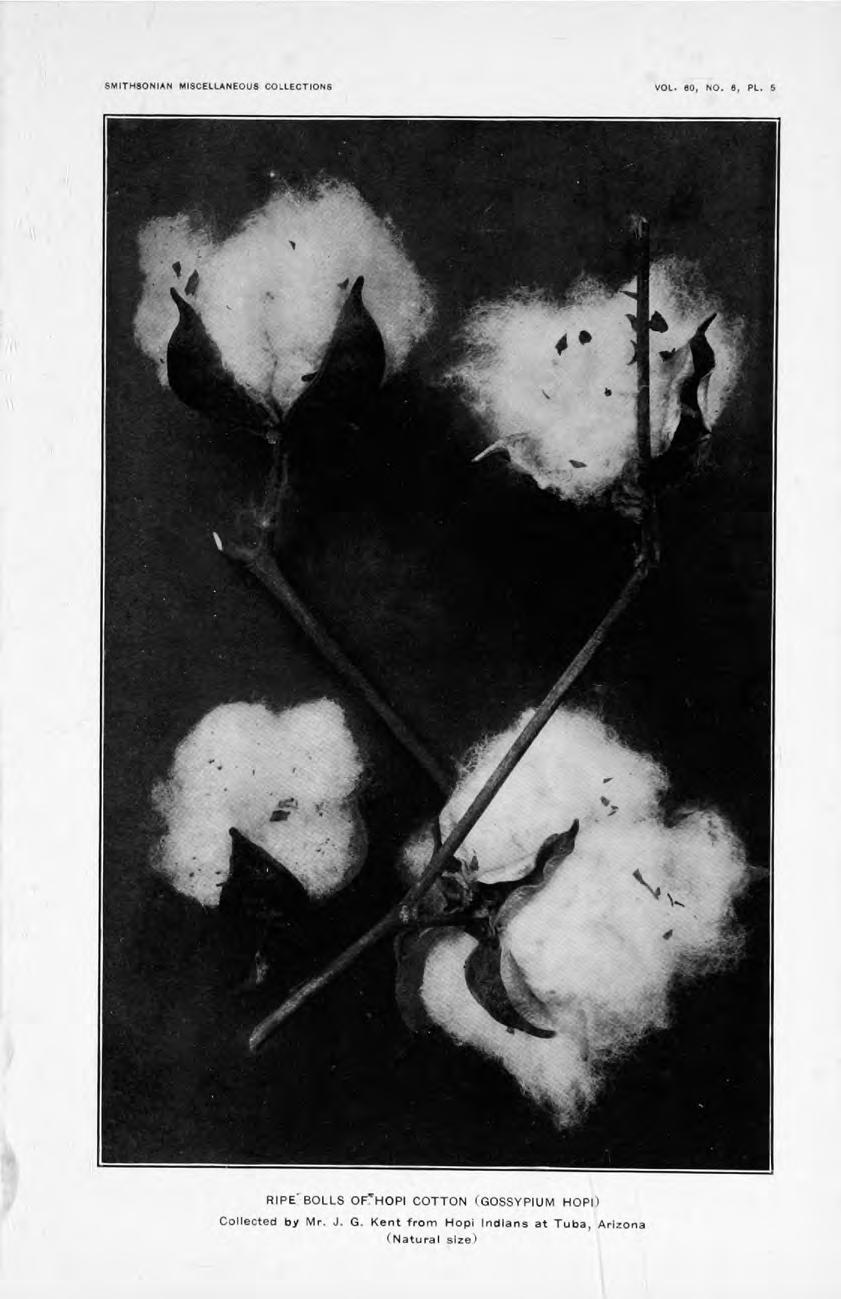

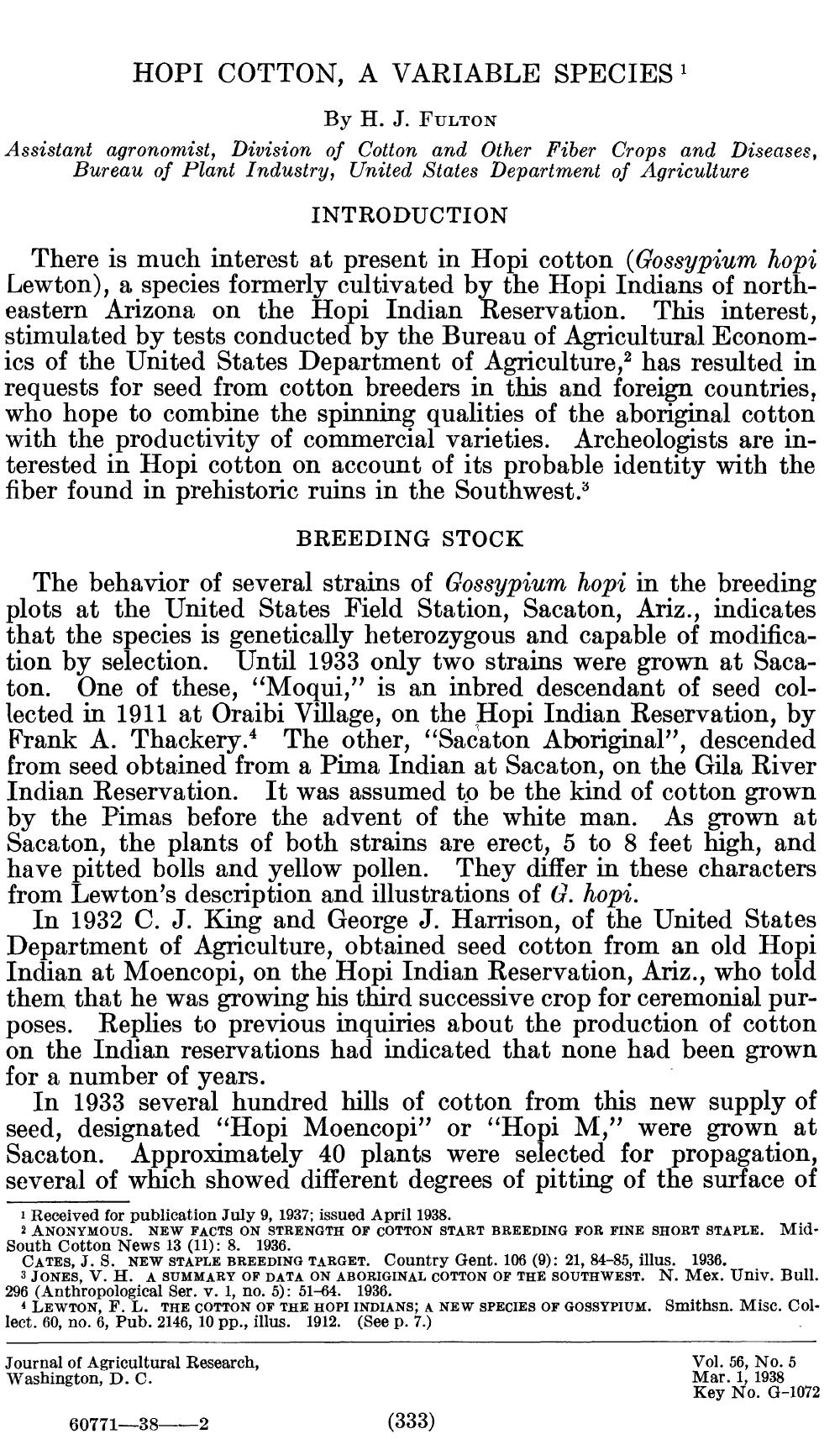

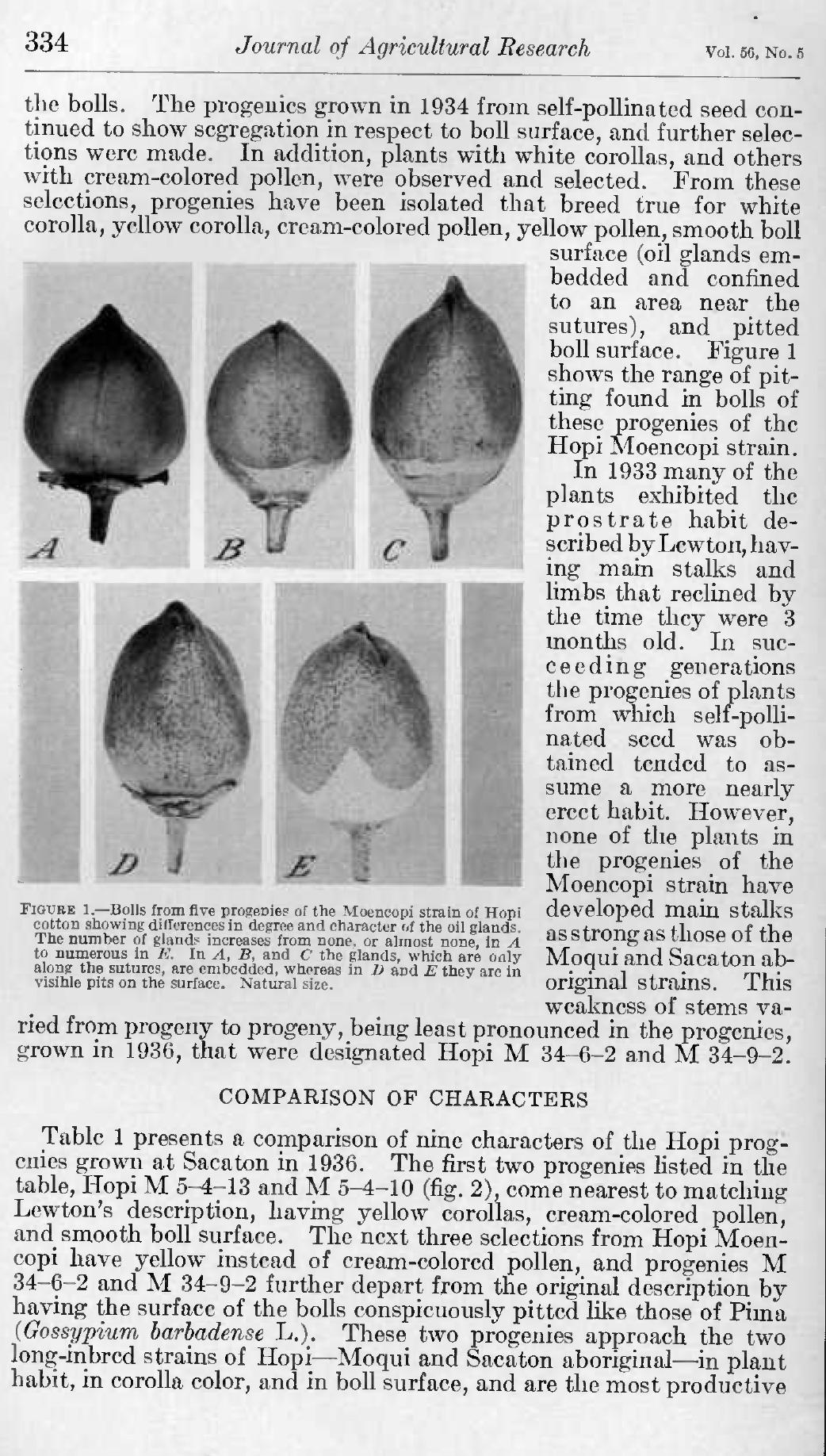

Cotton first appears in the Southwest, apparently from Mesoamerica, sometime before 500 B.C.E., although the way(s) by which it came into the region are not known. The species generally though to have been used from prehistoric times into the historic period is Gossypium hopi, so named and described in 1912 by Frederick L. Lewton, from plants found in Hopi gardens at Moenkopi and Oraibi. It has a short growing period, with bolls ripening in 84 to 100 days, and are adapted to growth at high altitudes, as well as arid conditions. Samples gathered in the 1920s and 1930s from Native American gardens in New Mexico at Zuni, Santa Ana Pueblo and Española, as well as from Arizona at Havasupai, Pima and Sacaton proved to be the same species.

The Hopi have carried on the weaving of their prehistoric ancestors, who wove fabrics from cotton, yucca fibre, fur strips and feathers. The earliest mention of Hopi weaving is by Espejo in 1581. He describes white cotton dresses evidently like "Wedding Mantas" still made today.

Wool and wool yarn, along with the Pueblo Stitch, came into prominence following the Spanish introduction of sheep during their colonization beginning in 1600. From the start of the Spanish occupation in the Southwest, vast quantities of plain weave fabrics were produced, initially a tribute and made on vertical looms within the Pueblo villages and by the early 1600s, in production shops. One such shop was excavated adjacent to the plaza in Santa Fe. These fabrics were one of the most important exports to Mexico from the resource poor northern Spanish Colony of Nuevo México.

By the mid-17th Century wool had mostly supplanted cotton and the production of local fabrics was breaking down. Traditional men’s clothing was the first casualty of the newly imposed economy. This occurred because men were more subject than women to Spanish work requirements and had more direct contact with Europeans. Women’s traditional dress survived for everyday wear, although in a somewhat simplified form, until well into the 20th century.

However, while the cultivation and weaving of cotton greatly declined in the Pueblo world during the historic period and all but disappeared from the Rio Grande Pueblos, it managed to persist at Hopi.

By the 19th century the types of garments described by Gallegos had become almost exclusively used for ritual/ceremonial functions.

6

7

Figure 3: Hopi Cotton Plat Gossypium hopi. Source The Cotton of the Hopi Indeians. A New Species of Gossypium, by Frederick L. Lewton, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vol. 6 No. 6, Plate 1.

Source: https://chestofbooks.com/crafts/general/Pueblo/Cotton-Part-2.html

8

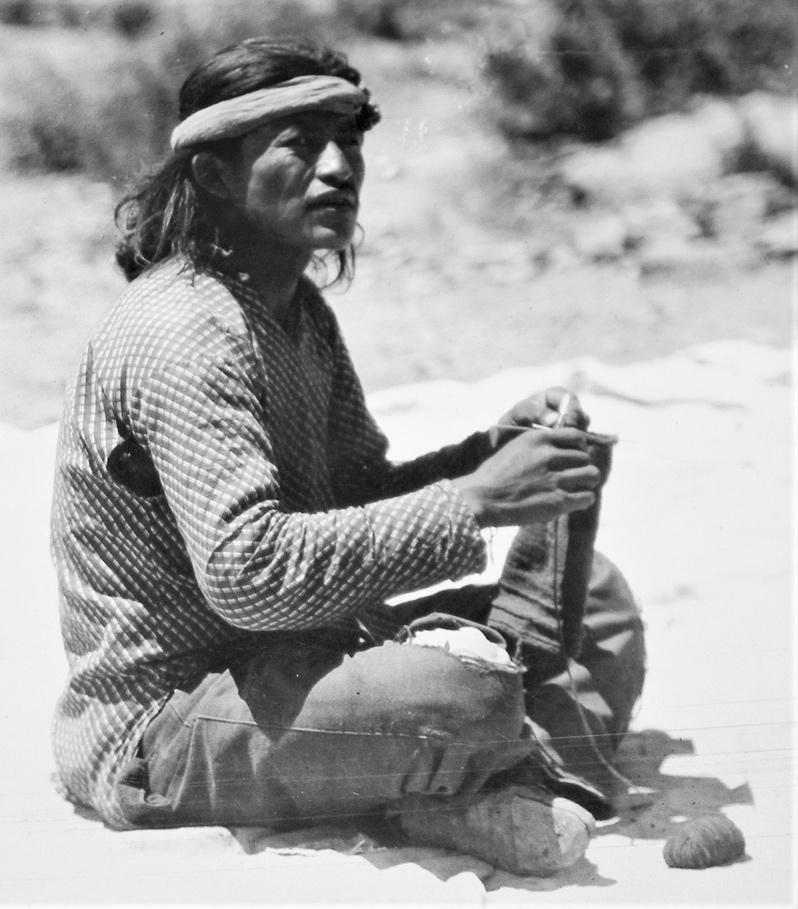

Figure 4: Dinè woman hand spinning wool, note design on her dress and the Dinè blanket she is sitting on Source: Bureau of American Ethnology Annual Report 1882, Plate XXXIV.

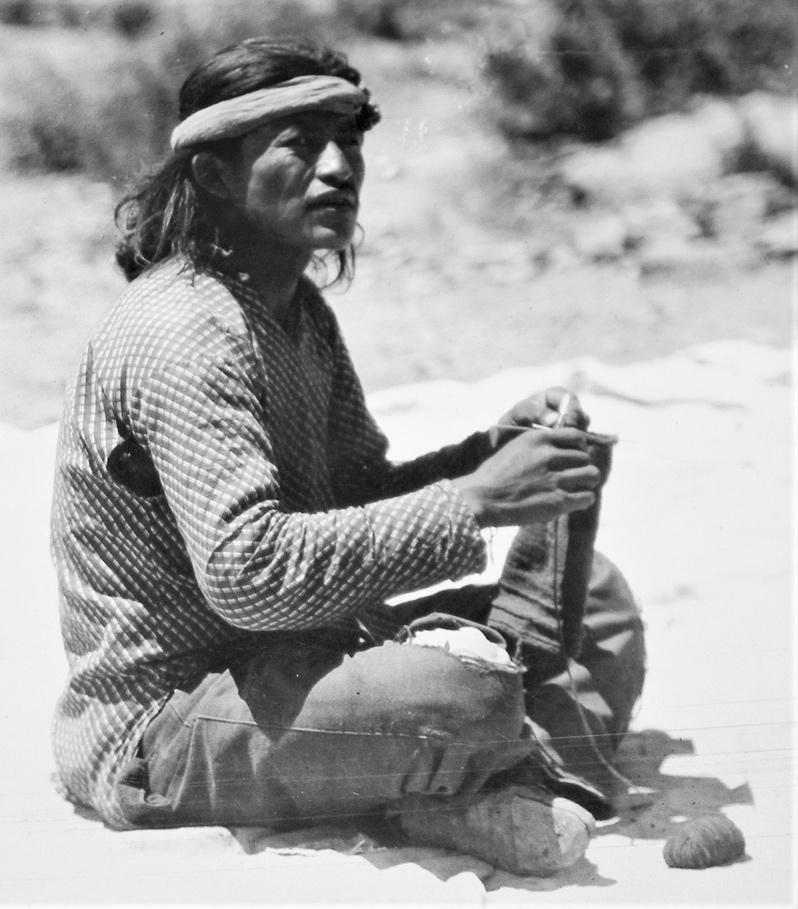

Figure 5: Hopi man c.1880 spinning and twisting a cotton thread, note the banded design on the Hopi blanket he is sitting on, as well as his woven garters. His foot is holding down the spindle to keep tension on the yarn.

9

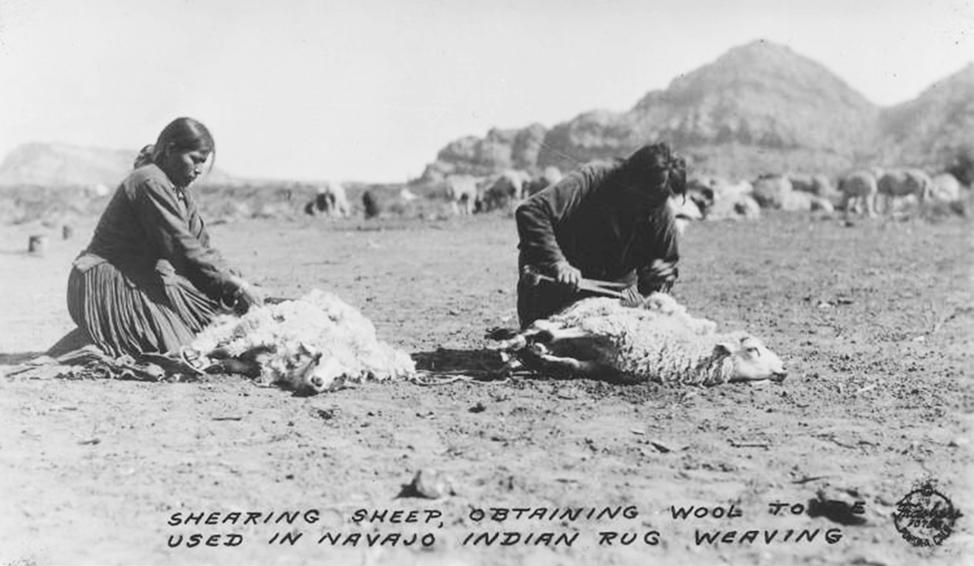

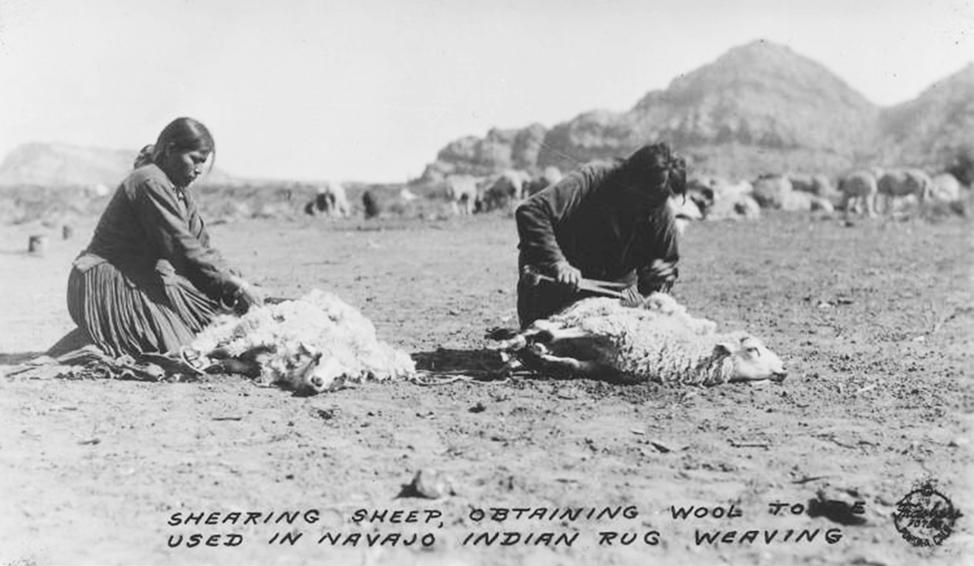

Figure 6: Dinè wool processing tools; Upper, various tools for processing and spinning raw wool. Source: https://www.pinterest.com/pin/262264378282426309. Lower, shearing sheep, note large sheering being used on the sheep at the right, 1930s photo postcard.

CHAPTER 5 MANUFACTURING TECHNIQUES:

Only weaving techniques used to produce textiles displayed in the subject exhibition are presented here. There are a number of others, of which several were common during the prehistoric period but for which examples from the historic period have not been found.

Vertical Loom:

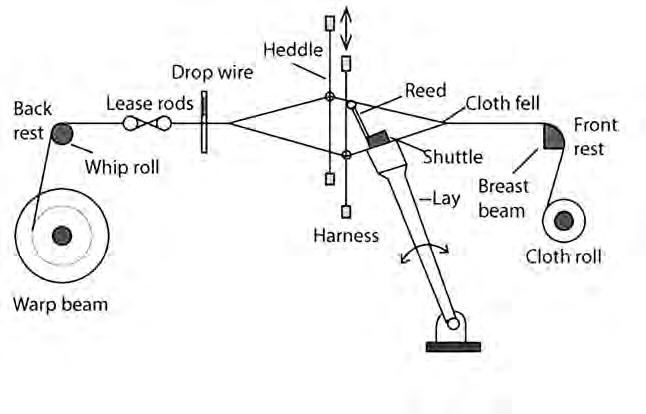

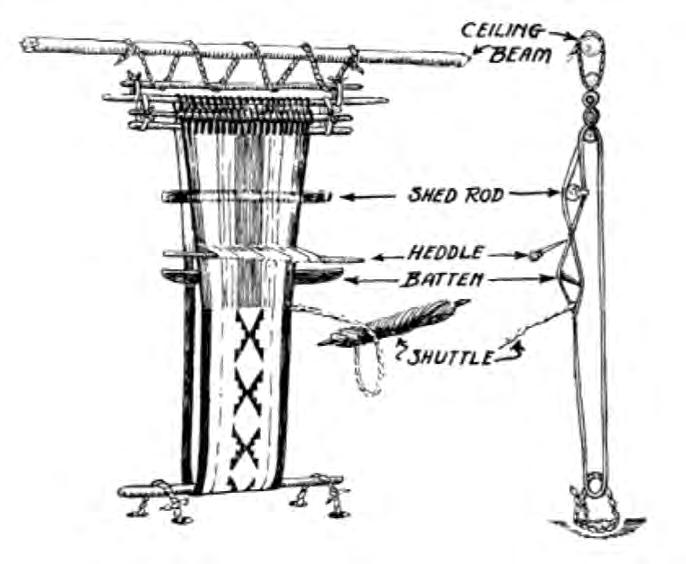

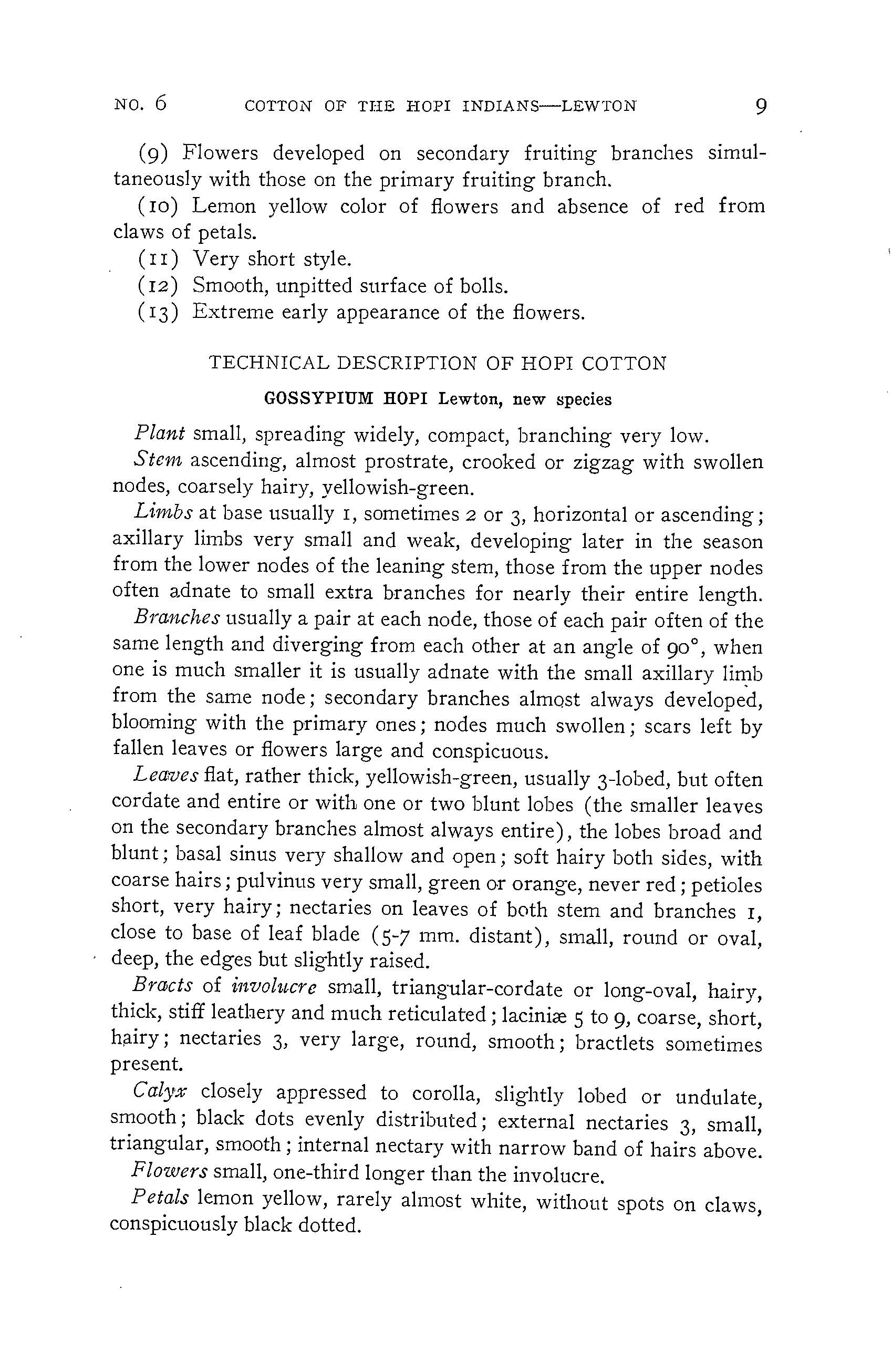

As mentioned previously, the vertical loom appears to be a Southwestern Pueblo innovation that originated about 650 BC by peoples living in the Four Corners region. This loom allows for the production of relatively large plain weave blankets known as mantas that serve a number of purposes. Within plain weave fabrics the warp and the weft are aligned so that they form a simple crisscross pattern, with each being equally visible. A burlap bag shows a coarse version of this weave.

The color/pattern of a Dinè and Pueblo blanket and rug weaving is produced by a tapestry weave that is carried by the weft threads. In contrast, with the float warp weave, the color/pattern is controlled by warp threads. The weft which holds the weaving together is almost invisible being since it’s formed of fine black or white thread. Narrow fabrics, including belts, garters and headbands are produced in this way on a belt loom. Some weavers work solely with their fingers, while others use a slender stick and/or supplementary heddles. As work proceeds the finished work is pulled around rollers so that there is always an unworked section facing the weaver. With a tapestry weave the result is weft-faced in that the warp threads are hidden in the completed work and all design and color is carried by the weft.

10

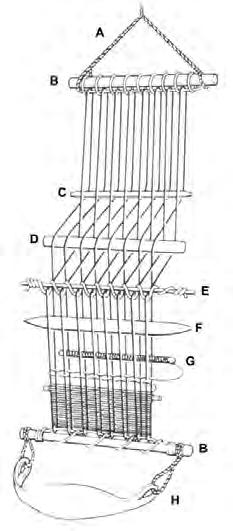

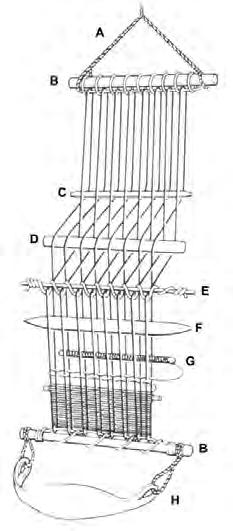

Figure 7: Illustration of a vertical Native American loom. Source: We Dance With Them - Pueblo Indian Embroidery, School of Advanced Research, Santa Fe, < https://sarweb.org/embroidery/default.htm>.

Twill Weave:

This weave is produced by various over/under combinations of warps across combinations of weft in that the weft does not pass over every other warp, but rather over every two or more wefts. Twill weaving can produce diamond shapes, diagonal patterns and herringbone or V-shapes. A number of the fabrics highlighted in the book use the distinctive technique.

11

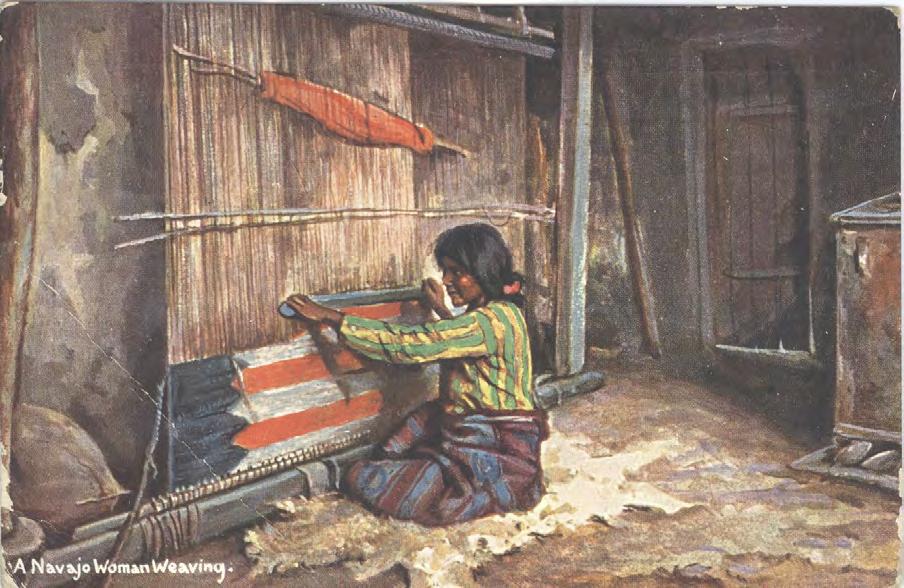

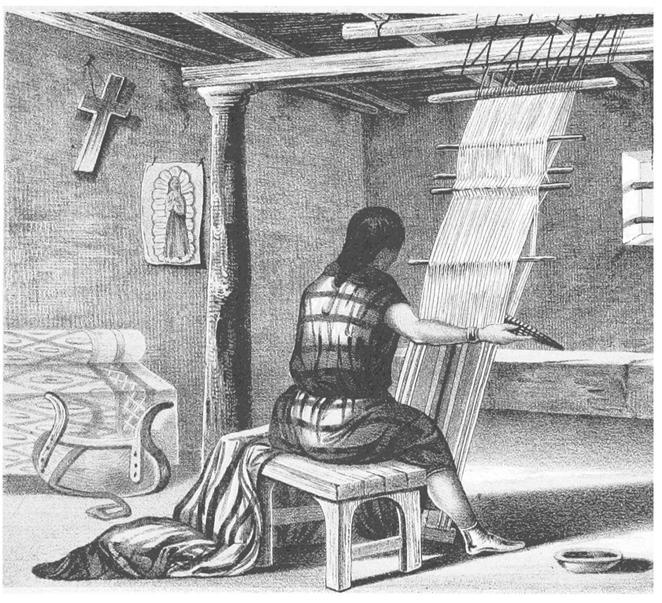

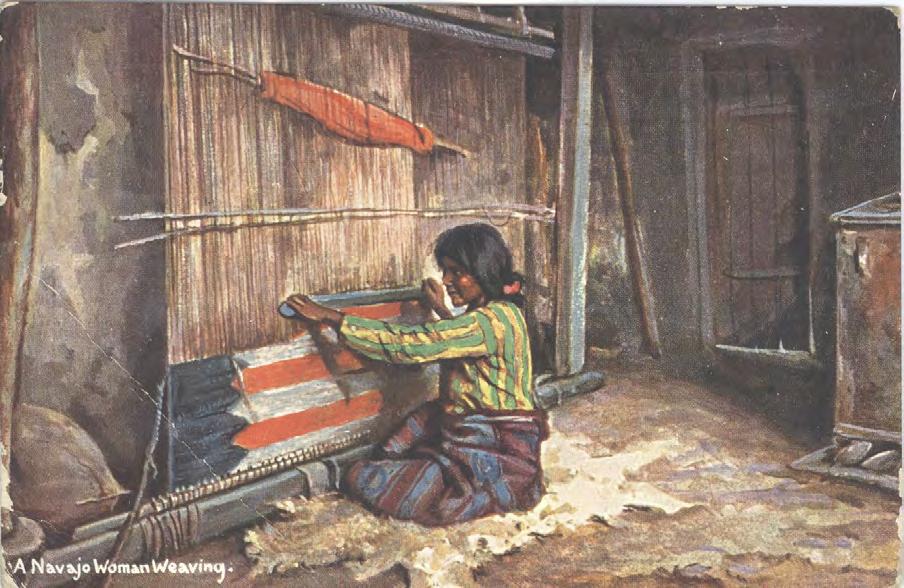

Figure 8: Dinè woman weaving a rug and weaving a blanket, 19th century color postcard. Source: Author's collection.

Figure 9: Diagram and photograph showing twill weave patterns Source: Third Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1881-'82, Government Printing Office, Washington, 1884, pages 371-392.

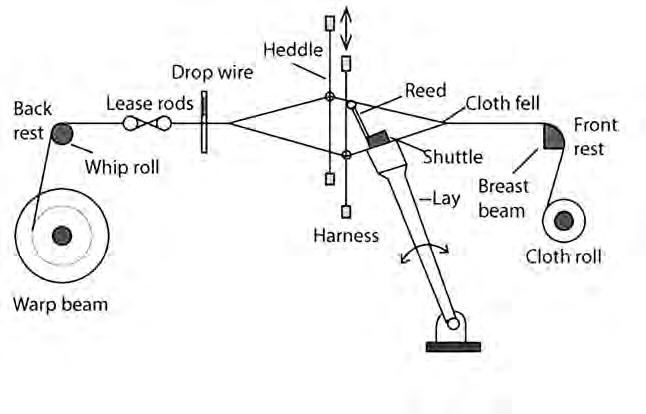

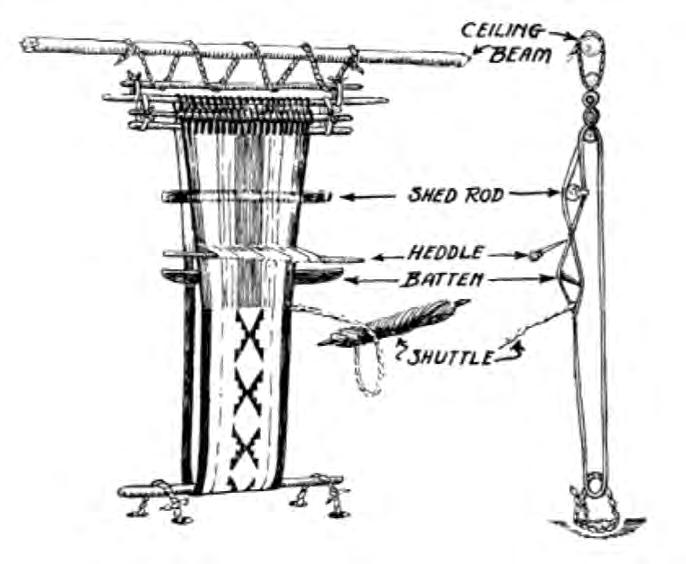

Horizontal Loom:

The Pueblos may also have used a wood frame horizontal loom, similar to the type introduced by the Spanish, essentially a vertical loom laid flat with side supports. Such looms are found in Mexico and were used as early as the 11th Century in the Mogollon region of southern New Mexico where a depiction of one is seen on a Mimbres pottery vessel. Their use by the Rio Grande and Hopi Pueblos is not well understood and such looms, may have been eclipsed by the vertical loom in pre-contact times.

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Schematic-diagram-of-a-weaving-loom

12

Figure 10: Horizontal loom of the type used by the Spanish.

Backstrap and Belt Loom:

From prehistoric times to the present, the Pueblo people have woven belts. Backstrap looms were used for belts and sashes in the 19th and early 20th Centuries. Today they are made on a simple belt loom, by which the warp is attached at the top to a wooden roller instead of a rod, as with a vertical loom. Up until the early 20th Century its other end is held in place by a band passing around the back of the weaver, while today it is most often fixed in a small rectangular wooden frame. Belt warps, heddle manipulation and designs are quite complicated. They are also made on a small fixed small version of a vertical loom.

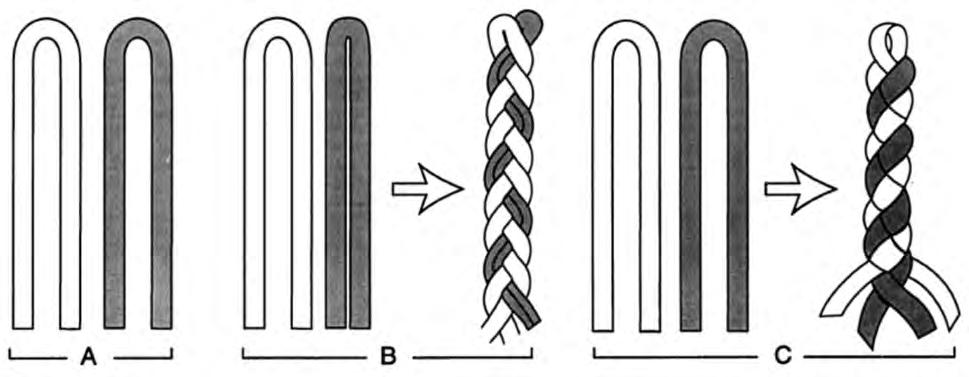

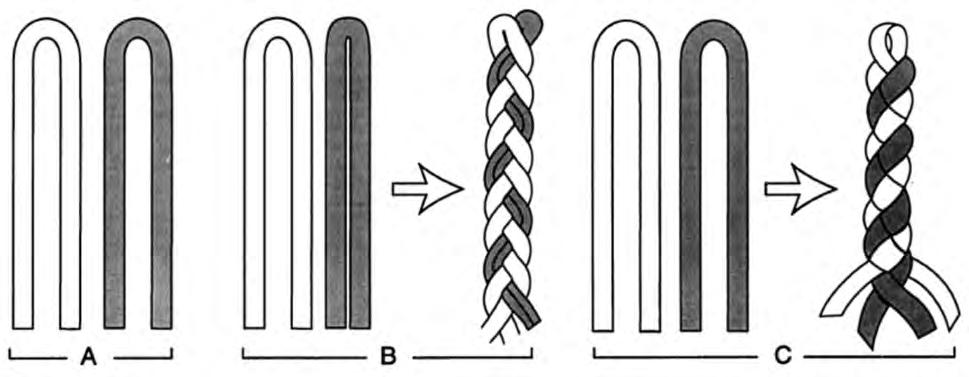

Braiding and Sashes:

Three and four strand braiding goes back thousands of years; primarily used for rope and cordage for belts, socks, sandals, nets and bags. Today these techniques are usually used to make plain white sashes commonly referred to as Rain Sashes or Wedding Sashes described in the following section.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Schematic-representation-

13

Figure 11: Backstrap and belt looms Source: We Dance With Them - Pueblo Indian Embroidery, School of Advanced Research, Santa Fe, < https://sarweb.org/embroidery/default.htm>.

Figure 12: Methods of braiding. Source:

of-the-two-braiding-techniques-illustrating-the-three-groups

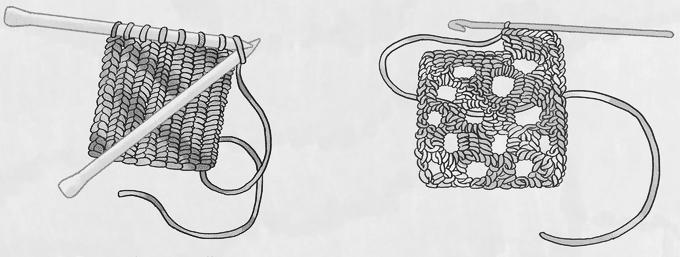

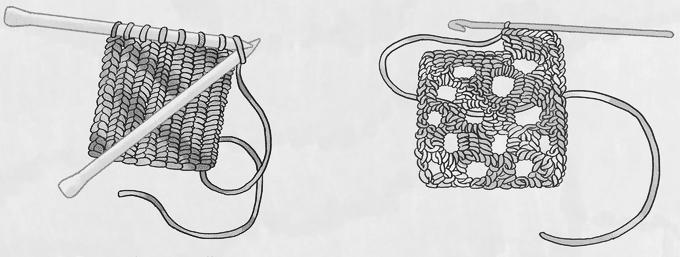

Knitting and Crocheting:

These techniques are used primarily for leggings and appear to have been introduced by the Spaniards. They are the only European methods of manufacture to have replaced pre-contact techniques in early historic times. Fabrics recovered from Hopi that date from the Seventeenth Century include both cotton looping, as well as wool knitting. This suggests that an introduced technique was associated with an introduced fiber, i.e. knitting for work with wool and looping reserved for native cotton.

Figure 13: Knitting vs Crocheting

Source: https://www.thesprucecrafts.com/differences-between-knitting-and-crochet-4077447.

14

knitting crocheting

CHAPTER 6 THE TEXTILES in the EXHIBIT

The textile traditions presented in this exhibition each include many features that are distinctive their individual cultural expression, while at the same time overlapping in style and technique. This is a result of the commonality of weaving techniques, all of which lend themselves more to straight and angular designs, rather than curvilineal designs, as well as to a shared geography and close association through trade, family ties, and exploitation, e.g. the use of European style horizontal looms by Pueblo weavers for the production of tribute textiles the Spanish sent to Mexico.

The three primary traditions described presented here have a general chronological hierarchy. First and oldest is that of the Pueblos. This is by far the most complex with many prehistoric antecedents. Many techniques used today have been used since time immemorial, with others lost in time. Secondly are Dinè weavings. Archaeology shows that the Dinè, who speak a language that is distinct from Puebloan languages, (as different as English is from Japanese) first appear in the Southwest sometime in the early sixteenth century, not all that long before the arrival of Europeans. While they undoubtedly had their own textile traditions, once in contact with the Pueblos they adopted many of their neighbors weaving methods and with the establishment of Anglo run trading posts, each looking for a unique outside market niche, developed a series of regionally specific designs conventions, that are instantly recognizable as Dinè. The third tradition present here is that of Spanish American weaving as described in Chapter 3.

PUEBLO TEXTILES

15

Figure 14: Zuni weaving illustration from a Report of an Expedition Down the Zuni and Colorado Rivers in 1851, by Captain L Sitgraves, published by Richard Armstrong, Washington D.C., 1853.

Mantas - Plain, Twill Weave and White Wedding Mantas:

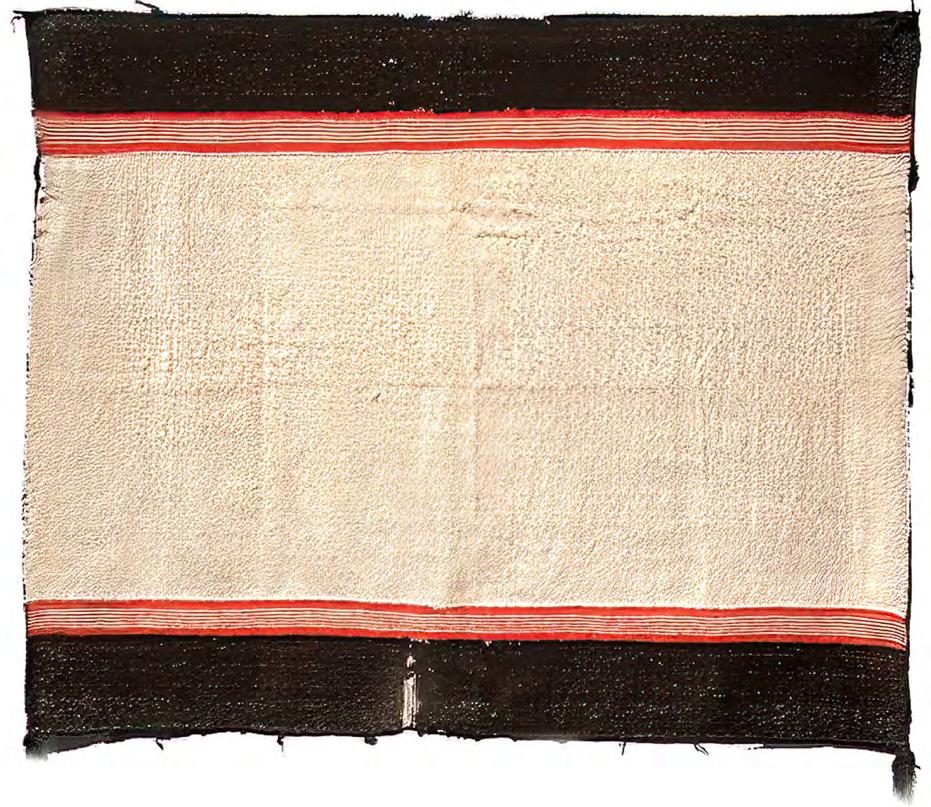

Although Navajo blankets of similar age (Late Classic Period 1850-1868 and Transition Period 1868-1890) are well documented, Pueblo mantas have received little attention by comparison, despite the high quality of manta weavings in incredibly detailed patterns; timeless, elegant and understated in black. Traditionally, woman would wear a Spanish style simple white blouse underneath the manta, and often with their prized jewelry.

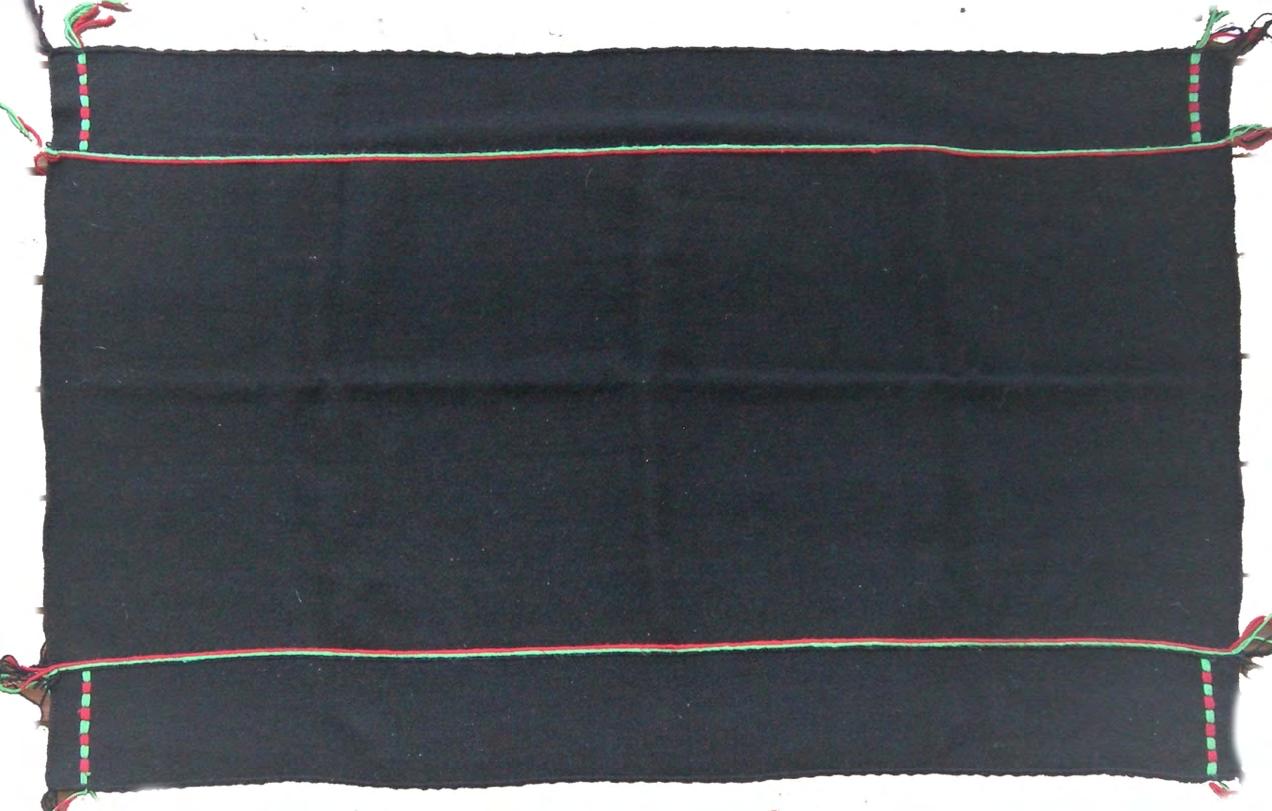

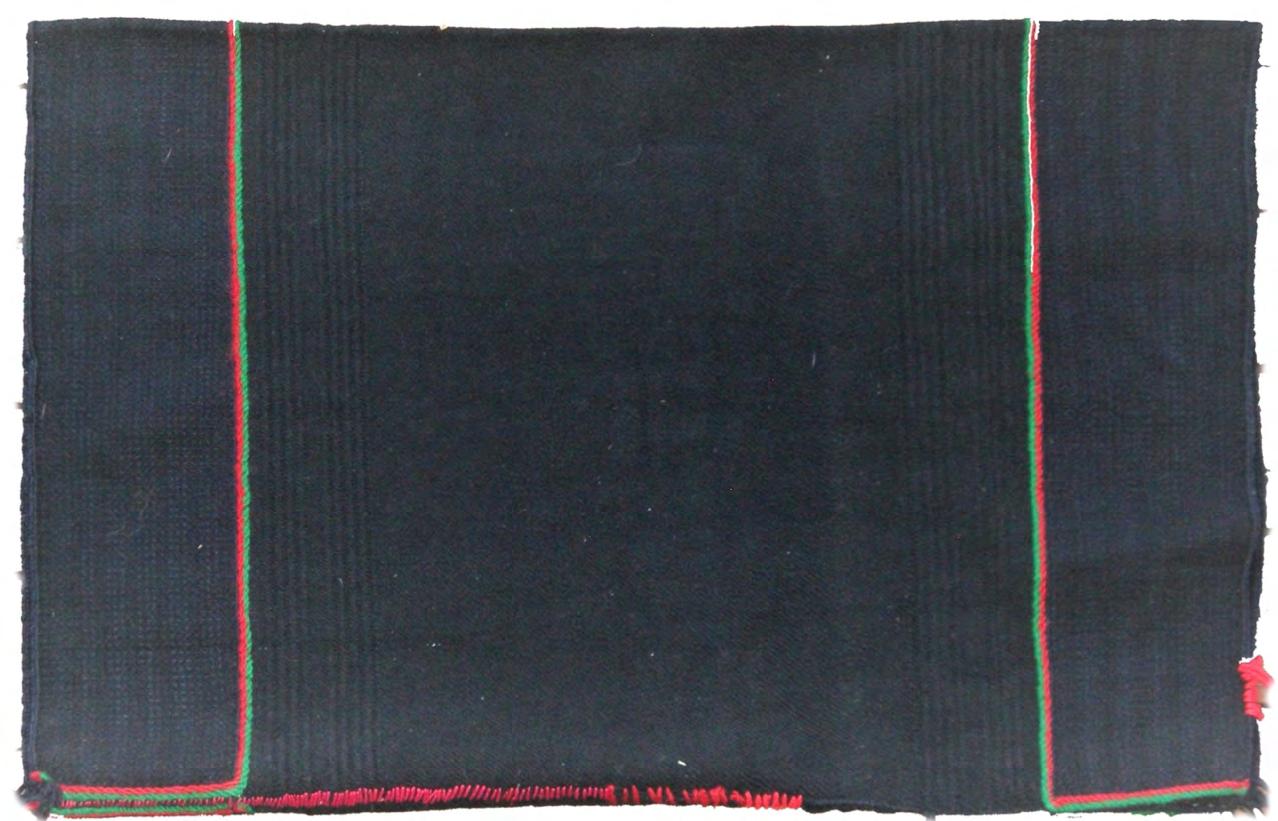

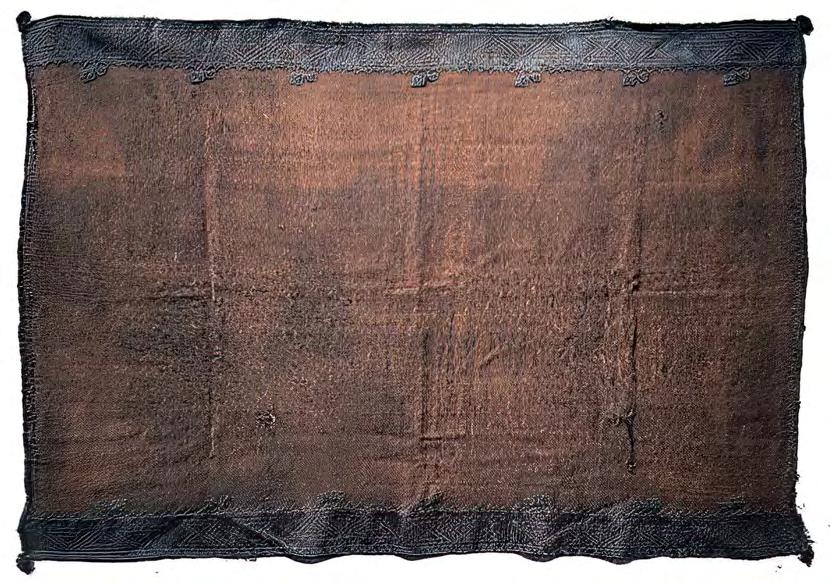

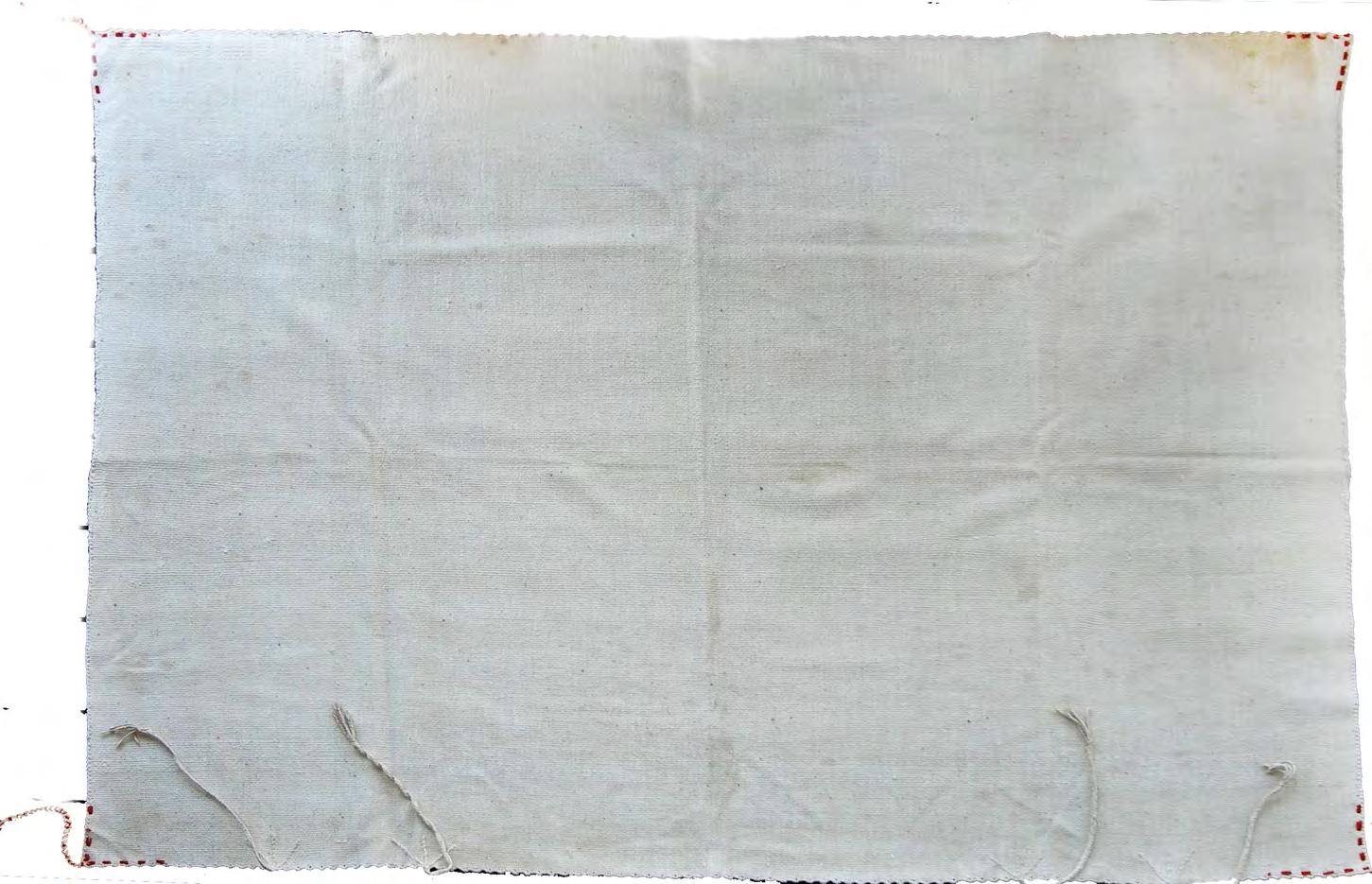

Manta is the Spanish words for blanket and cape. They are rectangular fabrics, either decorated or undecorated, with the larger about six by five feet and the smaller about five by four feet, as well as made in a variety of other sizes and proportions. Today, mantas are typically made from commercial fabrics, in prehistoric and into the historic period the fabric would have been of native cotton woven on a vertical loom. In the historic period the warp is often commercial cotton string. Plain white undecorated mantas rubbed with a fine white clay were, and still are, used as wedding robes. The only decoration these mantas have are elaborate tassels. After their use for a wedding such mantas may be embroidered for use as ceremonial regalia. The customs and designs, from one Pueblo group to the another are not standardized and can be quite complicated. In the seventeenth century the plain-weave Pueblo-woven manta was a universal medium of exchange.

The traditional clothing for women during the early historic period and well into the 20th century was a black dress/manta with an indigo blue diamond twill bottom and top panel. These were worn as a wraparound dress held at the waist with the traditional, primarily red, woven belt. The fabric would be connected over the wearers right shoulder, with the left shoulder left bare. The dyed diamond twill portions of the fabric resulted in a subtle contrast between the black center of the textile and the indigo blue ends. After around 1900, commercial blue dye began to replace indigo dye. Such dresses clearly have prehistoric antecedents. Examples are seen on kiva murals of black fabric, which were undoubtedly dyed cotton; however all historic examples are of wool. Solid color black cloth fabrics, with some measure of embroidered and/or applied decoration are often seen worn by female dancers on Pueblo Feast days.

Black Mantas:

These mantas are mostly woven from handspun churro wool yarn in hues of brown and black and often with indigo (blue plant) dyed end panels. The twill weave was one of the most technically difficult techniques in weaving that required true virtuosity of the weavers. There are a variety of "twill" weaves with end panels of various diamond twill, diagonal, herringbone, and birds-eye patterns. The simpler central panels of "diagonal twill" seem to be predominant.

Four by nine inch manta end panels are often indigo but have had overdying of pinon through the years Black pinon dye was created by crushing roasted pine nut shells that may than be mixed with charcoal. In many garments you can see the brown or indigo blue remnants or the color radiating through the black overdye. After 1900, aniline black dye was utilized to refresh black color of these manta garments.

16

17

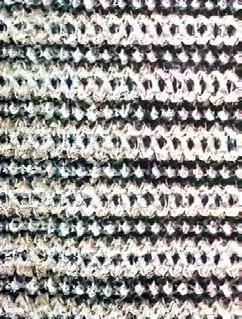

Exhibit 1: Zuni Blue Bordered Manta, 50” x 40” c.1860 or earlier. The body is natural brown handspun wool in a diagonal twill. The top and bottom bands are woven with natural white dyed with indigo in a diamond twill. Affixed with a paper tag inscribed: Zuni Squaw Dress - Hopi Type with Quail's eye top and bottom / Purchased by RHR from Zuni prob around 1922. Source: James Compton Gallery.

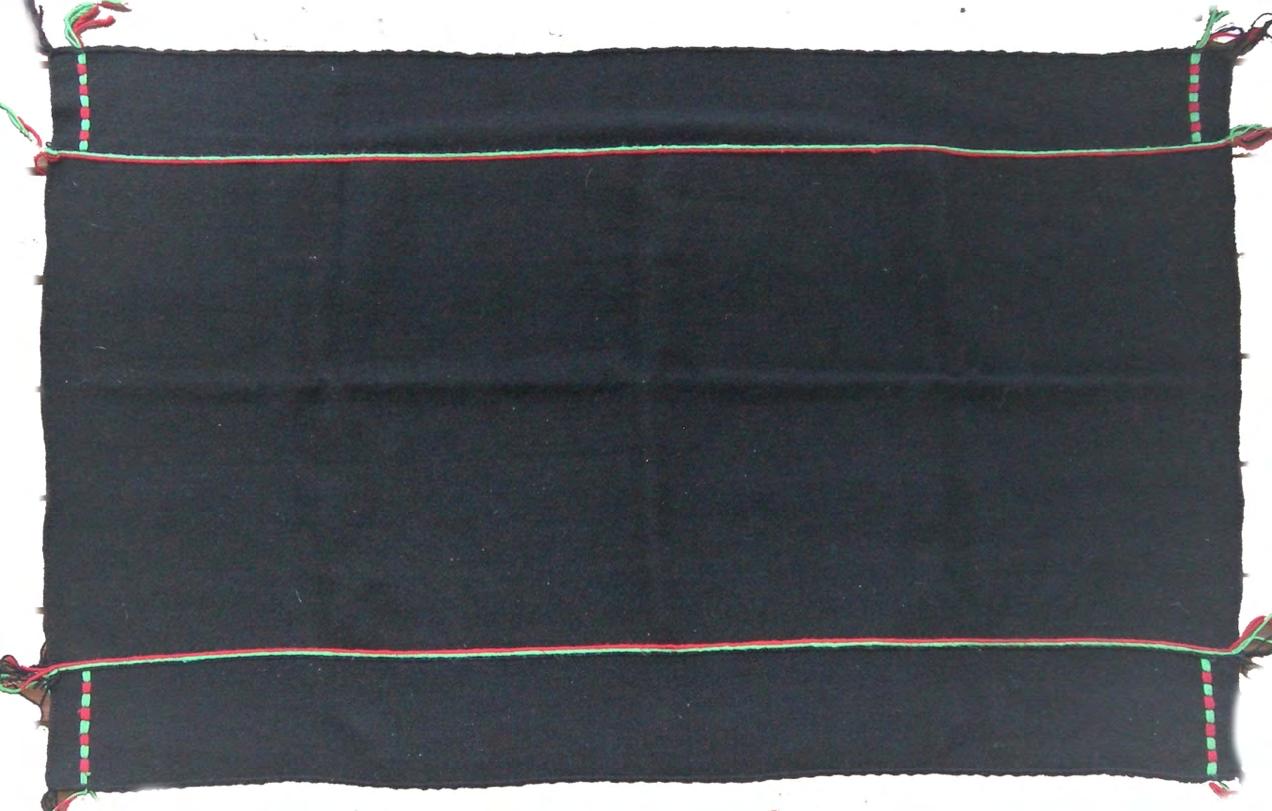

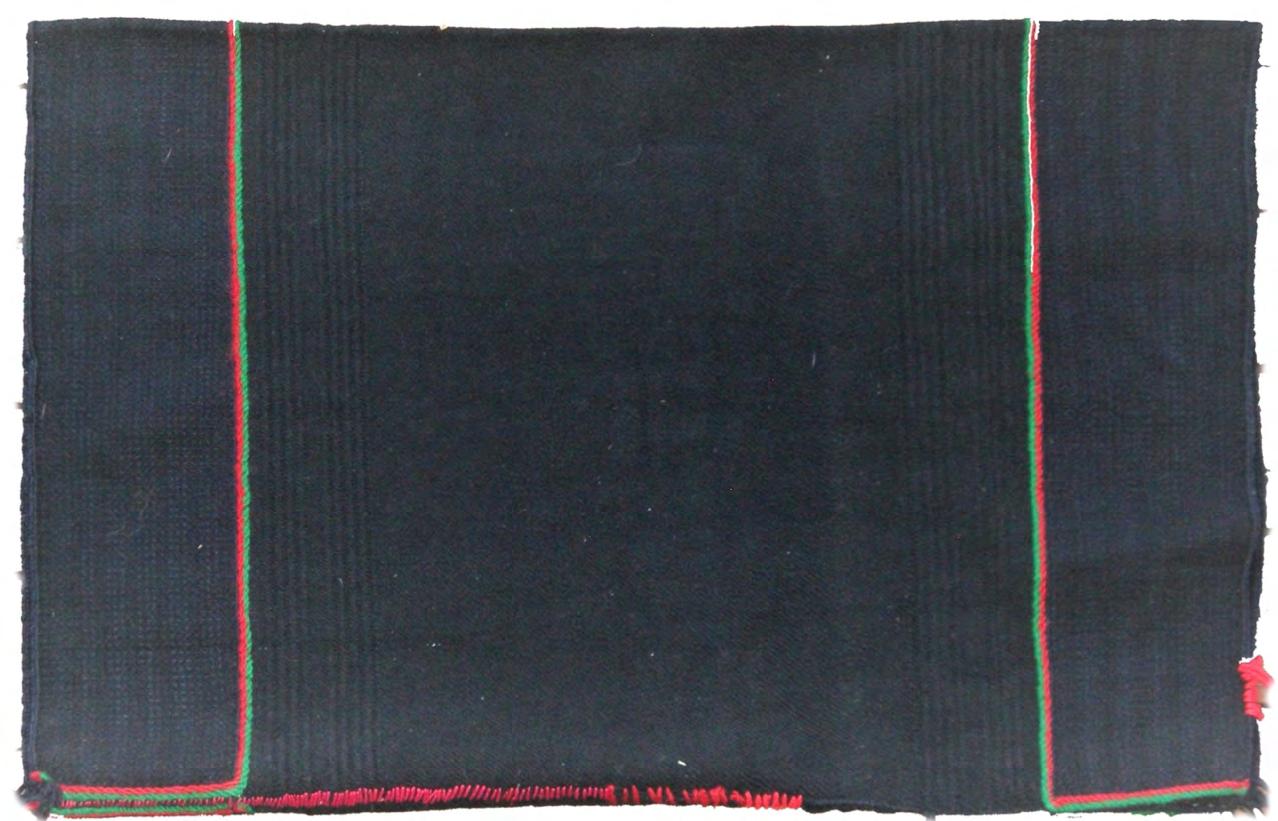

Exhibit 2: Zuni Black Manta 51" x 41" c. 1890. Diamond twill Indigo End Panels / Diagonal Twill Center With 3 Rows of 4 Raised Hills and Valley Center Panel Elements and 4 Ply Green Embroidery Trim, Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW2.

18

Exhibit 3: Zuni Black Manta 61" x 37.5" c. 1895. Diagonal twill end panels / diagonal twill center with checkerboard 4-ply green and red embroidery Ttrim Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW4.

Exhibit 4: Pueblo Black with Indigo Manta 51" x 39" c.1890. Diagonal twill pnd Panels / diagonal twill center with elaborate 4-ply green and red embroidery trim. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW6.

19

Exhibit 5: Zuni Embroidered Manta 56” x 41” c.1870 or earlier. The body is natural brown handspun wool in a diagonal twill. The top and bottom bands are natural white handspun dyed with indigo embroidered on after the blanket was woven. Affixed to the manta is the collection history: Zuni Emilia Pinto 7/8/25. Source: James Compton Gallery.

Exhibit 6: Navajo or Zuni Manta 50 x 39" c.1860 - 1865. Indigo Diamond Twill End Panels with yellow supplemental weft and brown diagonal twill center panel with lazy lines Source: James Compton Gallery JC36.

Tewa Weavers and others: Tewa Weavers was a commercial operation which employed only Native Americans, providing work for the unemployed/underemployed primarily from Isleta Pueblo from just before WWII up through the 1970s (with a short break because of the war). Tewa Weavers it was a notably altruistic measure by the founders, who also ran the Post Office at Isleta Pueblo and had resided at the Pueblo since about 1906. They primarily supplied tourist “trading-posts” along Route 66 with hand loomed goods such as shawls and neckties. However, they also supplied mantas for the Pueblo ceremonial market. Mantas, and other textiles, were woven on large horizontal treadle-looms and supplied to Pueblos across the Southwest. These fabrics can still be seen at Pueblo Feast Day dances. Such mantas could be produced much more inexpensively, quickly and in greater quantity than those made on vertical looms. But an unintended consequence of these mantas may well have been a drastic reduction in the production of locally made fabrics. It should be noted that small shops in the Rio Grande region also produced fabric for the Pueblo market. In some cases, such as the treadle loom(s) operated at the Okay Owingeh Crafts Cooperative, they were established by, and used by, Native Americans. This Co-op was an outgrowth of the San Juan Pueblo Day School and opened in 1969.

20

Figure 15: Tewa Weaving, Old Town Albuquerque, ca.1940. Source: Anonymous

OTHER PUEBLO TEXTILES

The Pueblos of the Southwest have, since time immemorial, made a multiplicity of textiles. Many of these traditional textiles are today limited to being worn on special occasions and as ritual regalia. At many Pueblos wearing such items is restricted to a ritual context, they are not included in this book. Such textiles include sashes of several types, elaborately decorated kilts, breech cloths, banners, leggings, belts, mantas with special designs, and ritual shirts. While today many such textiles are made much as they were made in prehistoric times, new techniques and materials are also being used. The best place to see such regalia is at public Feist Days; check with specific Pueblos for dates of such events.

Pueblo Mantas with Designs

21

Exhibit 7: Hopi Woman's Cape, 41 1/2" x 39" c.1885. Dark and light green and black embroidery elements joined at the center Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW14.

Exhibit 8: Acoma Pueblo Manta 58" x 37" c.1860. Cochineal-dyed Saxony wool yarn embroidery on indigo and brown twill end panels. Source: Michael D. Higgins

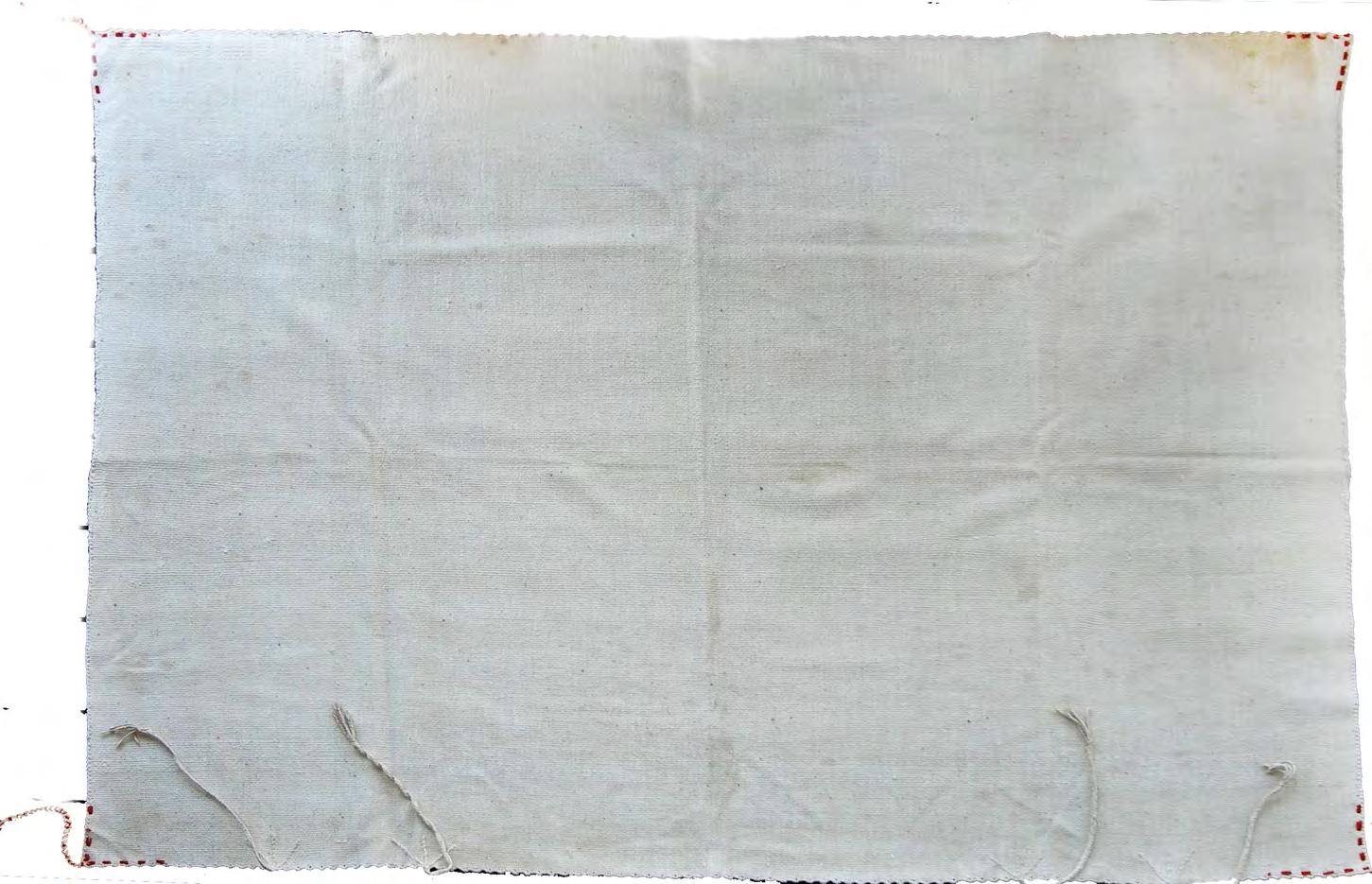

White Wedding Mantas

Large white mantas for brides are the largest articles made of cotton. While once ubiquitous throughout the Pueblo world, by the 20th Century they were restricted to the Hopi in both manufacture and use. As is the case with many modern cotton pieces of all types the warp is often commercial string. These wedding robes are in two sizes. The larger is about 5 x 6 feet and the smaller about 5 x 4 feet The proportions and sizes vary considerably. Both are plain white without pattern. They are rubbed with fine white clay and have elaborate tassels in the lower corners

Sometime after the wedding either of these plain robes may be embroidered. Some Hopi villages decorate the larger size and some the smaller. Customs are not standardized and the whole subject is complicated. After they have been embroidered the robes are used as ceremonial regalia

22

Exhibit 9: Hopi cotton wedding blanket, 70" x 51" c.1890. Diagonal twill edge and handspun red yarn embroidery, as well as with unusual three 2-ply cotton cord embroidery and braided ties and an elaborate scalloped border. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW13.

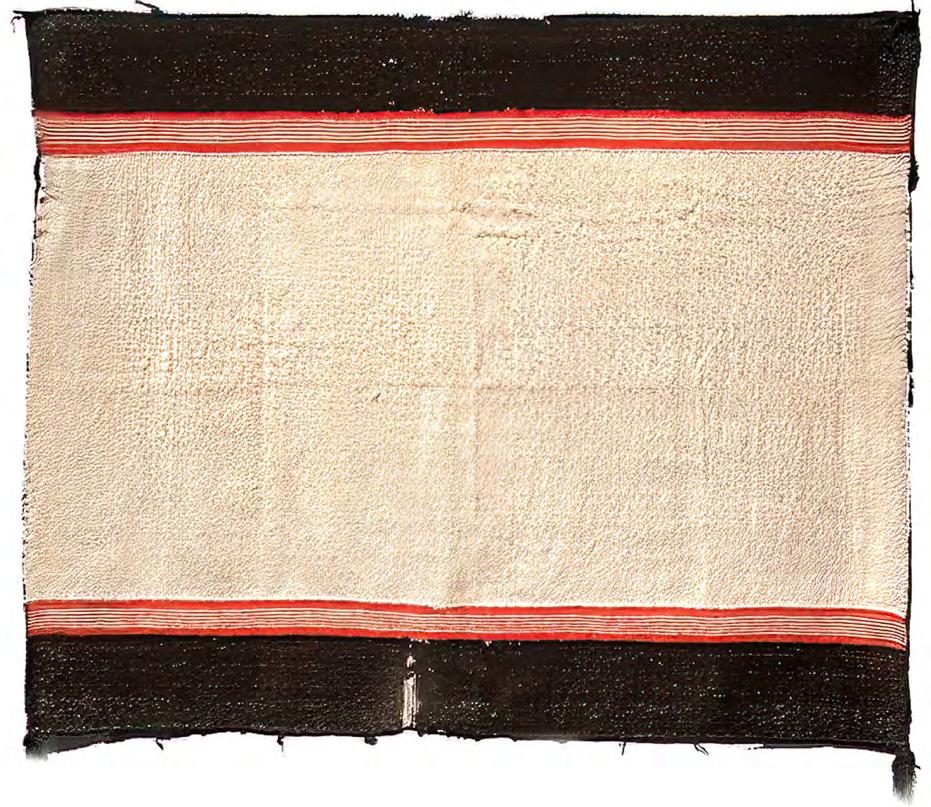

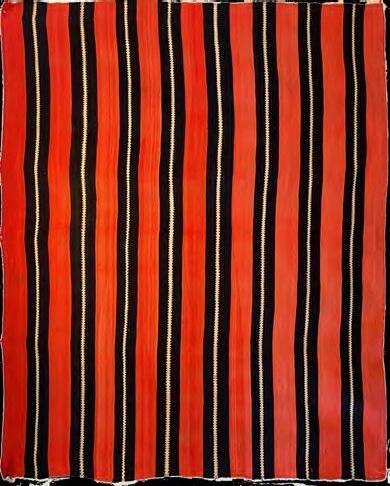

Pueblo Wearing Blankets

23

Exhibit 10: Blue Moki (Hopi) striped blanket 50" X 80" c.1870. Handspun cochineal and indigo dyed yarn with alternating rows of narrow bands. Source: Scott Gutting.

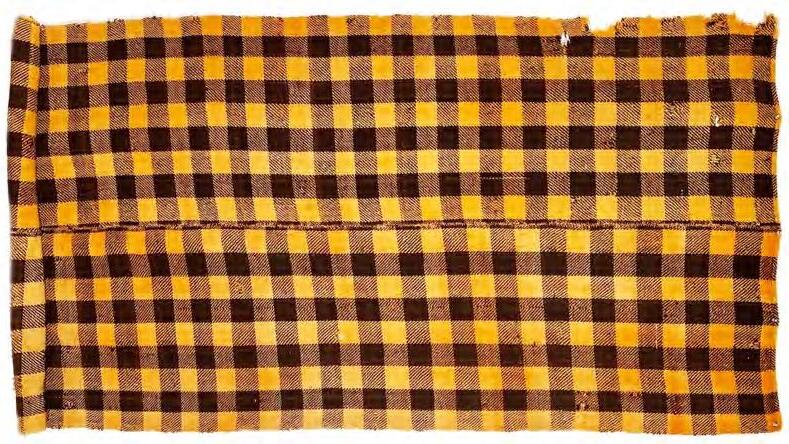

Exhibit 11: Child's Hopi plaid blanket 23" X 34" 2018. It was made by Louie Garcia of single ply commercial wool fabric. Source: Anonymous.

Hopi Maiden Shawl

The term "maiden shawl "is applied to white shawls with red and blue, solid blue or solid black wool edge stripes. The white center section often have a diagonal weave. While generally worn by young unmarried women their use is not restricted to such. There is considerable variation in size, the average of being 36 x 43 inches. The lengths range from 37 to 48 and the widths from 30 to 37. The most common type has two stripes several inches wide along each edge, the outer being blue and the inner red. The blue edged type is very much less common; and that with a black edge is only known from a few examples. These colored stripes are created by substituting colored wool wefts for the white cotton ones used in the rest of the shawl. The blue edges are often made in a diamond weave and the red stripes in a diagonal weave. Both are woven so that most of the colored yarn appears on one face. Hence there are definite right and wrong sides to these shawls. These are worn draped over the shoulders or over one shoulder and under the opposite arm, the colored stripes being horizontal.

24

Exhibit 12: Dinè Woven Hopi Maiden Shawl 44" x 36"c1920. Handspun wool in natural white, brown and aniline red bands Source: L. Bruce Weekley

or earlier. The body of the manta is cotton hand spun warp and

a diagonal

The top and bottom bands are brocaded with wool handspun natural brown in a diamond, uneven twill. The fine red bands are raveled bayeta dyed with a mixture of lac and cochineal and woven into the blanket as an uneven diagonal twill. Affixed with two paper labels inscribed: Old Hopi cotton. Very rare / Rec. 1/6/27 and: A.D. 138 75.00. Source: James Compton Gallery.

25

Exhibit 13: Hopi maiden shawl 42” x 43” c.1850-1860. Black diamond twill borders on a natural white cotton body, alternating bayeta red diagonal twill in the broad bands with narrow cotton lines. Source: Mark and Linda Winter.

Exhibit 14: Rio Grande Pueblo Manta 46” x 37” c.1860

weft undyed in

twill.

Pueblo Shirts

These shirts follow a common pattern with a long oblong section with a central hole for the neck, the ends hanging over the back and chest; and two sleeve sections made separately and sewn to the shoulders of the body section. The edges of the body and sleeve pieces are not sewn, being held together with ties placed at intervals. The shoulders, ends of the body section and cuffs of the sleeves of some are covered with heavy embroidery, and small embroidered units are placed regularly over the back and chest. Because of their ceremonial use such decorated examples are not presented here.

Exhibit 15: Pueblo Man’s Shirt 60” x 25” c.1800-1850. Finely woven with handspun white yarn dyed with indigo in a diagonal twill. The body of the shirt is woven like a tunic and opens up as a single piece (51” x 21”). There are hills and valleys at each end. The tunic has an opening for the head in the center (8.5” x 3”) with a rolled edge. The sleeves are woven as a single, trapezoidal piece (19” x 16”) and are folded over to form the sleeve and match the tunic in the fineness of the diagonal twill. Each sleeve has hills and valleys at each end to match the tunic. The shoulder end of the sleeve has 5 hills, and the cuff end has 3 hills. Source:

26

James Compton Gallery.

Exhibit 16: Pueblo shirt 56" sleeves, 20"chest, 29" length c.1870 -1890. Indigo diagonal and diamond twill weave aniline red design element from the “Fred Harvey Collection.” There is a letter documenting this piece from the Hopi House at the Grand Canyon by Fred Timeche (Hopi) who was a salesman at the Hopi House. Source: Michael D. Higgins

HISTORIC DINÈ (NAVAJO) BLANKETS

The earliest known Dinè weavings were found in Massacre Cave, Canyon del Muerto, Canyon de Chelly, Arizona, where a group 115 Dinè, mostly women and children, were killed by the Spanish in 1825. The first half of the 19th century was an especially important period for Dinè weavings, that soon became highly prized by Native Americans across the Great Plains. The Dinè spun their own wool from their own variety of Spanish Churro sheep and the quality was soft, warm and light, making them ideal for wearing blankets.

Only a few early, rare example are included here. There are numerous books on Dinè rugs made since the late 19th century for the tourist trade.

27

Exhibit 17: Third Phase Chief's Blanket, 72" X 48" c.1865 - 1870. Handspun narrow rose Bayeta yarn, with indigo stripes. This blanket is illustrated as a color plate in the book The Navajo and His Blanket by U.S. Hollister, 1903. This is the first color plate of a Third Phase Chief blanket to be published in a book. Source: Scott Gutting.

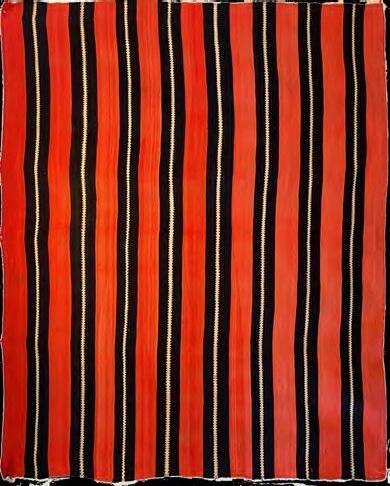

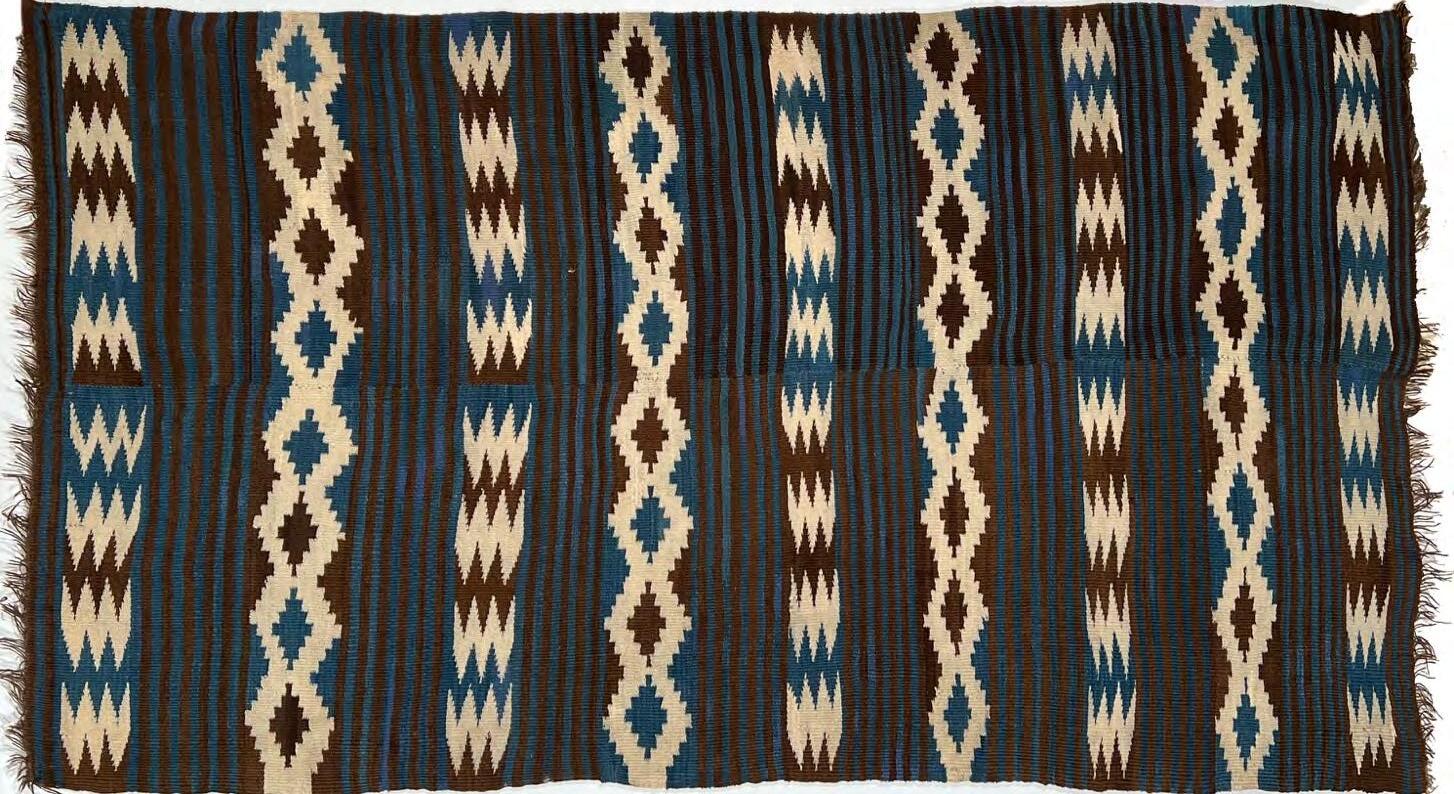

Exhibit 18: Dinè Late Classic man's Moki (Hopi) Style Blanket, 53" X 67", c.1875 - 1880. Source: Scott Gutting.

28

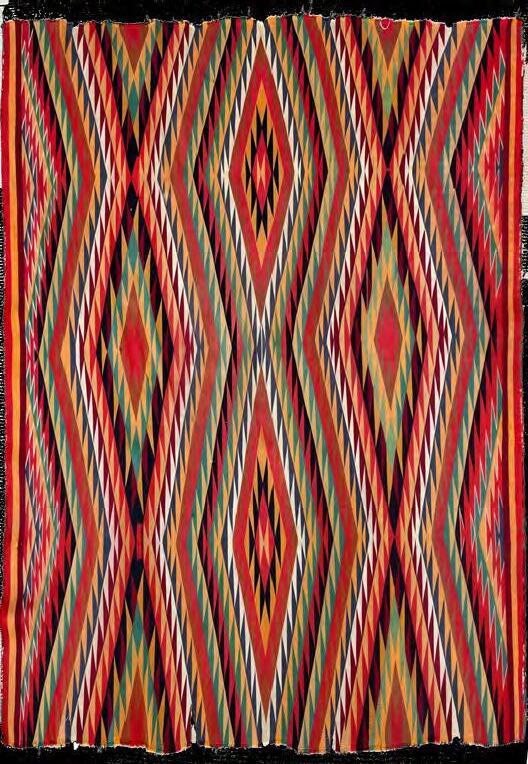

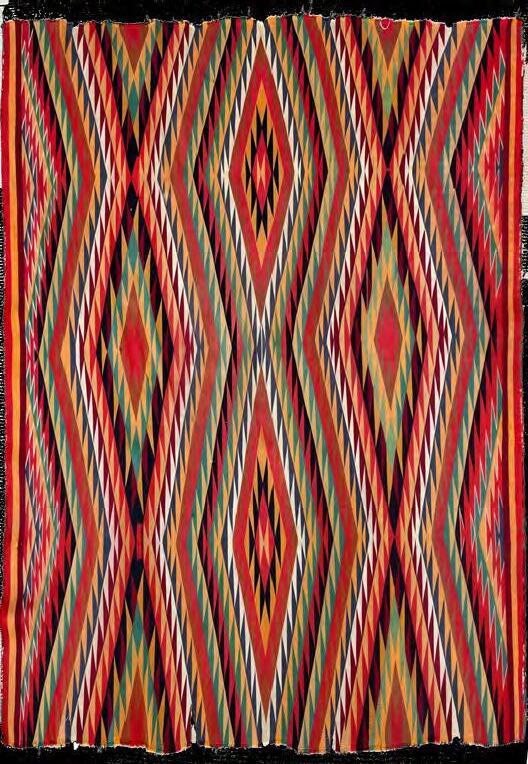

Exhibit 19: Dinè Germantown "Eyedazzler" Wearing Blanket, 43" X 72" c.1880 - 1890. Red, maroon, green, white, black and yellow 3-ply commercial wool. Source: Scott Gutting.

Exhibit 20: Dinè Germantown Woman's Wearing Blanket, 61" X 48" 1875 - 1880 A small slit in the center of this blanket's design field is called the "Spider Woman's Hole" in reference to Spider Woman who taught the Dinè to weave. It allows the design energy that went into the piece to go back into the world. All commercial Germantown yarn in red, black, white and dark blue. Source: Scott Gutting

DINÈ Double Faced / Twill Weave

29

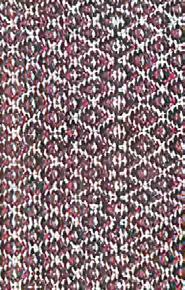

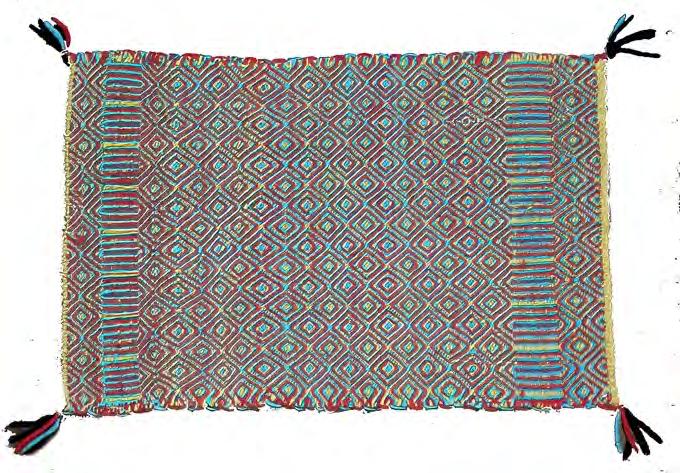

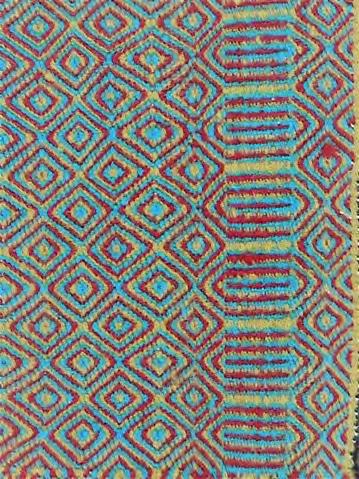

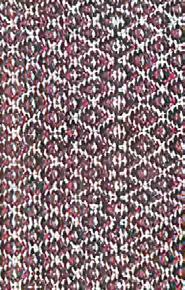

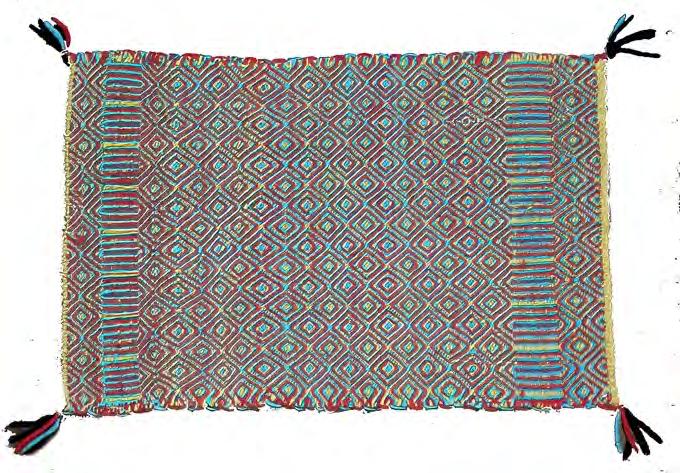

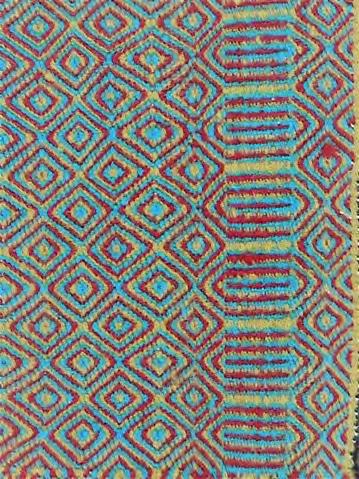

Exhibit 21: Dinè Diamond, Birdseye and Polygon Twill Child's Blanket 53" x 31" c.1890. Red, white, light green, blue, orange and black Germantown yarn. Complexly woven in varying sizes of diamond twills to create an eye dazzler riot of color and movement. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW27.

30

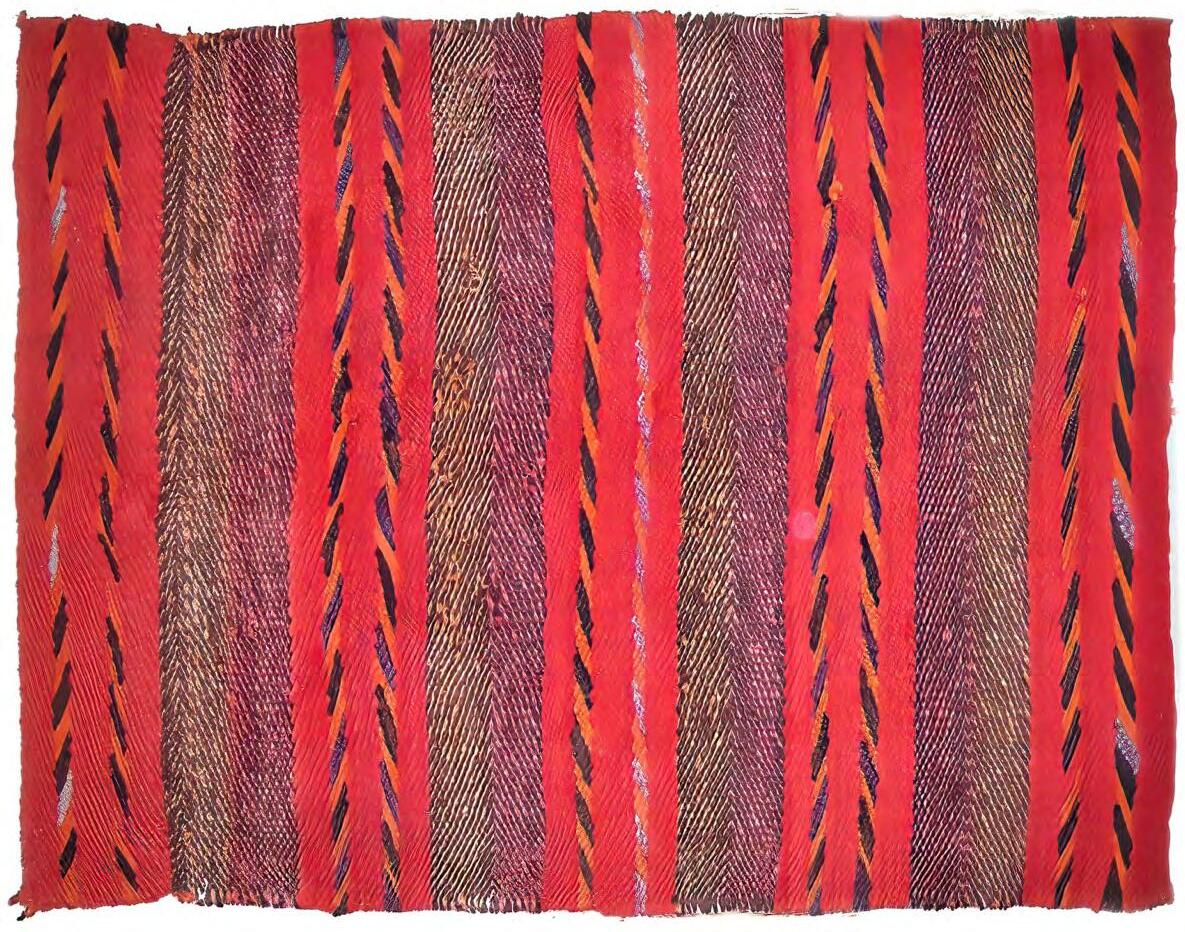

Exhibit 22: Dine Child’s Blanket 36” x 51”, c.1870-1875. Handspun aniline red, orange, and purple wool, with hand-carded pink and natural white and brown yarns. This blanket is executed in alternating bands of diagonal twill to achieve vibrating visual patterns of color and direction. Source: James Compton Gallery.

is one of the earliest known Dinè blankets. The red is a coarse bayeta dyed with cochineal, light indigo dominates the body with dark indigo, yellow and green in the finer bands. The

goes from diamond in the body to herringbone in the bands. Source:

31

ß

Exhibit 23: Dinè Twill Banded Blanket, 51"x 36.5" ca.1750 - 1840 (Joe Ben Wheat dates it to c.1805). This

twill

James Compton Gallery JC35

Dinè Saddle Blankets

Some saddle blankets were made to sit atop a saddle to show their fancy weave and colors, while others were utilitarian saddle padding. They were made for domestic use, rather than for sale to tourist, with many examples being quite inexpensive.

32

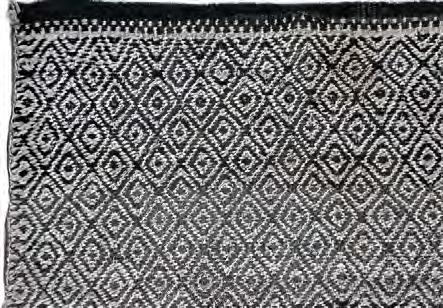

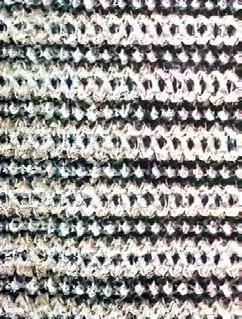

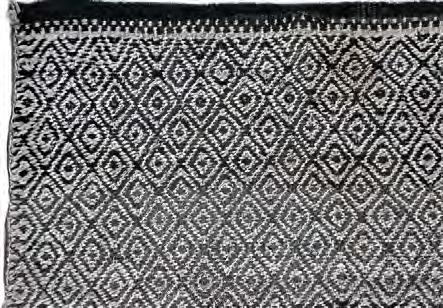

Exhibit 24: Dinè Woven Double Saddle Blanket 52" x 38" c.1880 Large birdseye twill woven squares and rail road track elements Black and white handspun wool with 3-ply red selvage. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW16.

Exhibit 25: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 42" x 39" c.1890. Diamond twill red, black and white wool. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW17.

Exhibit 26: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 50" x 32" c.1895. Diagonal twill red, black and white wool. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW18.

33

Exhibit 27: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 45" x 29" c.1895. Birdseye and diamond twill carded gray, black and white wool. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW19.

Exhibit 28: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 59" x 32" c.1895. Small and large alternating diamond twill brown, black and white wool bands. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW20.

Exhibit 29: Dinè Single Saddle Blanket 26" x 28" c.1920. Large birdseye twill black and white wool bands Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW21.

34

Exhibit 30: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 44" x 27" c.1895. Diagonal diamond and elongated hexagon twill red, black and gray wool. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW22.

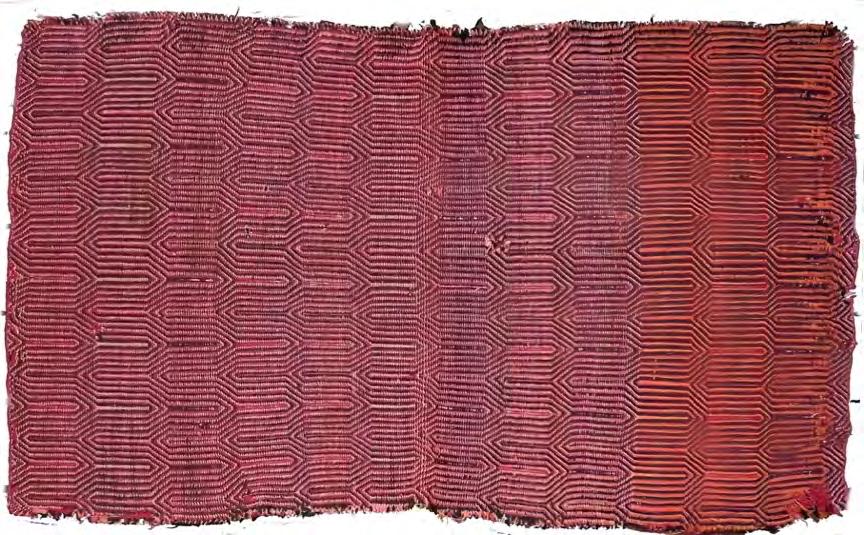

Exhibit 31: Dinè Double Saddle Blanket 45" x 29" c.1920. Elongated "arrow head" twill in red, white and black wool. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW23.

Exhibit 32: Dinè Single Saddle Cover 18" x 12" c.1920. Double diamond and square block in red, black, yellow and blue wool. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW24

35

Exhibit 33: Dinè Single Saddle Cover 20" x 14" c.1890. Diamond twill block rows in red, green, yellow and white Germantown yarn and end fringe with bundled tassels. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW25.

Exhibit 34: Dinè Saddle Cover 27" x 26" c.1896. Green, black, yellow and red handspun wool yarn in alternating rows of diagonal twill, with an old Mike Kirk tag in. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW26.

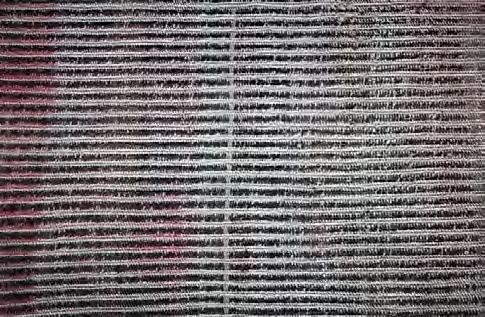

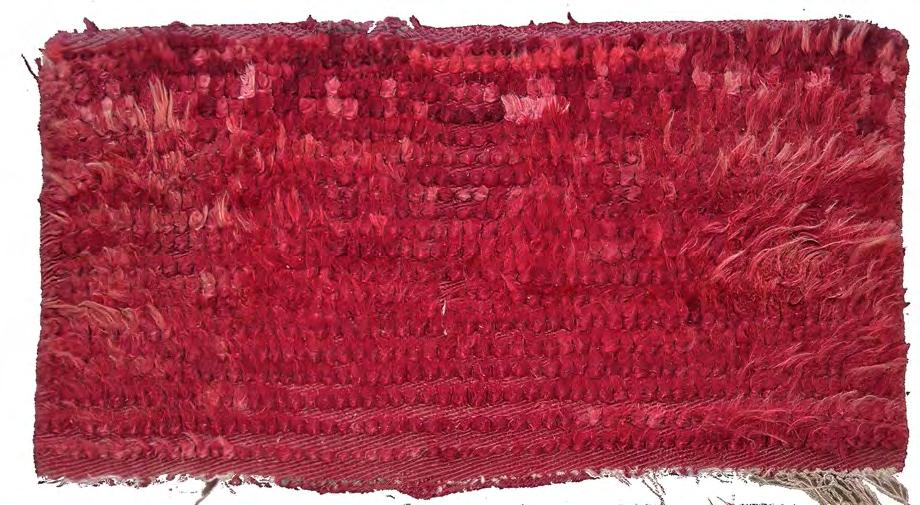

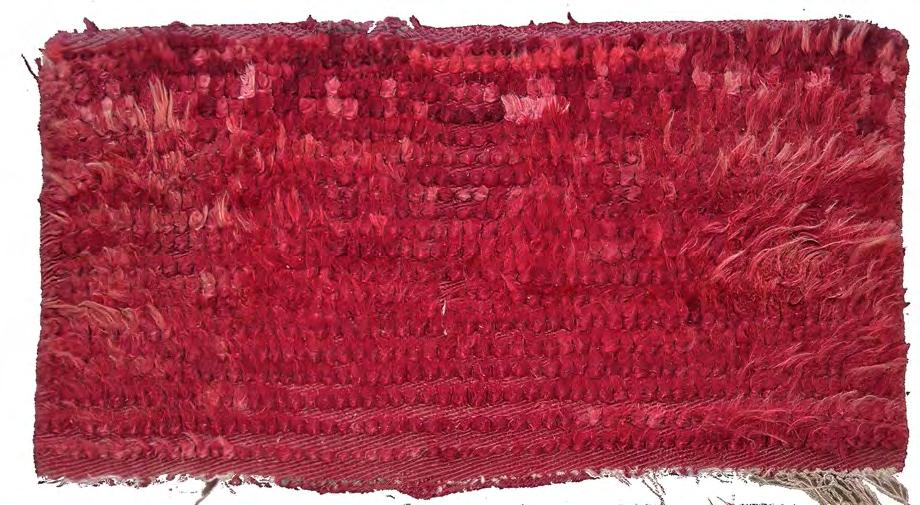

Exhibit 35: Dinè Diagonal Twill Weavers Pad 33" x 18" c.1900. Alternating bands of diagonal twill rows and dyed looped mohair sheep wool on the surface in aniline red. Source: L. Bruce Weekley BW28.

SPANISH AMERICAN TEXTILES

The word Jerga is a Spanish term for a length of wool fabric. They were often used as runners and carpets or tied up in bundles to transport goods. It was exported in large amounts to New Mexico. Because of their utilitarian use19th century examples are rare.

36

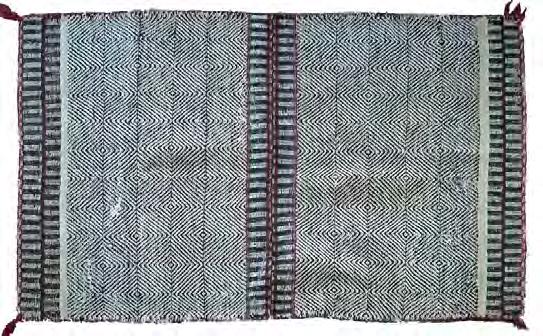

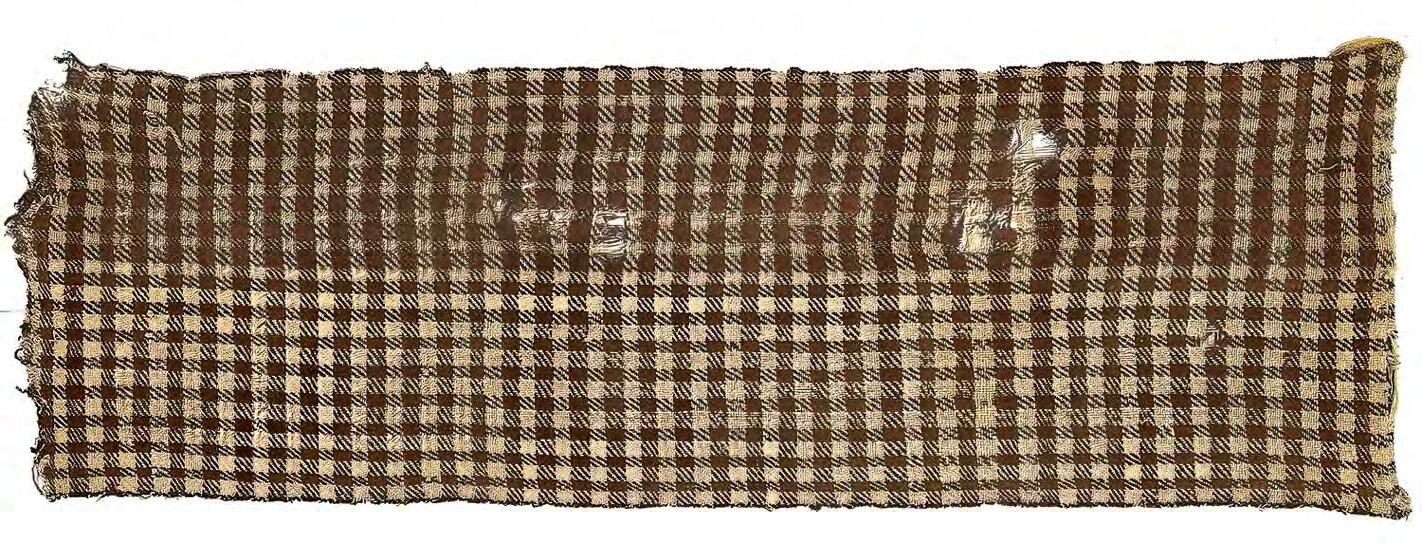

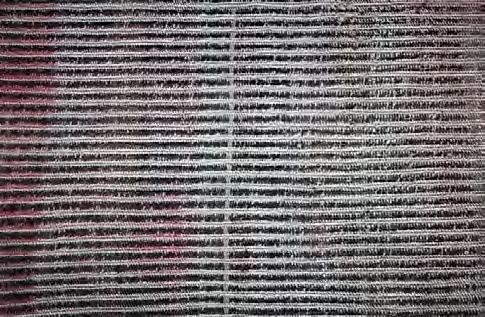

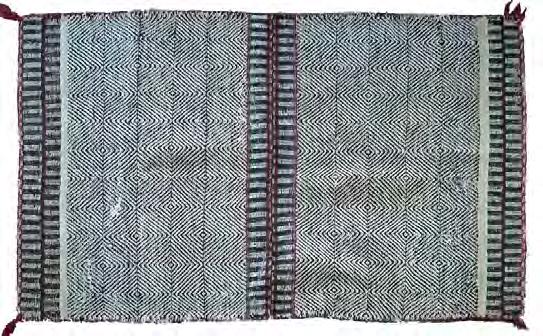

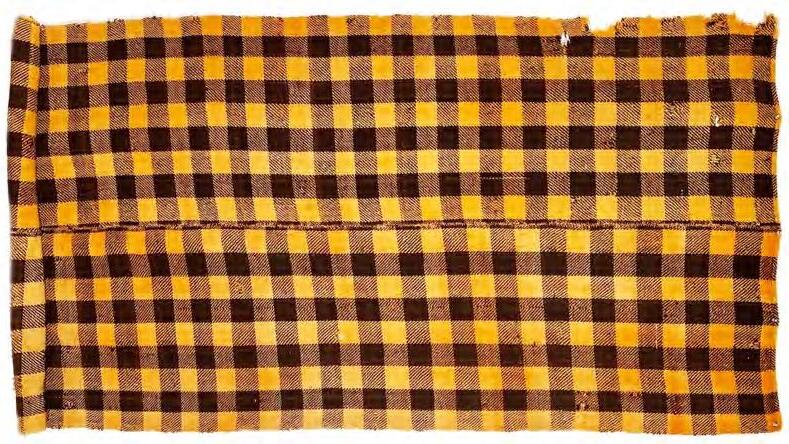

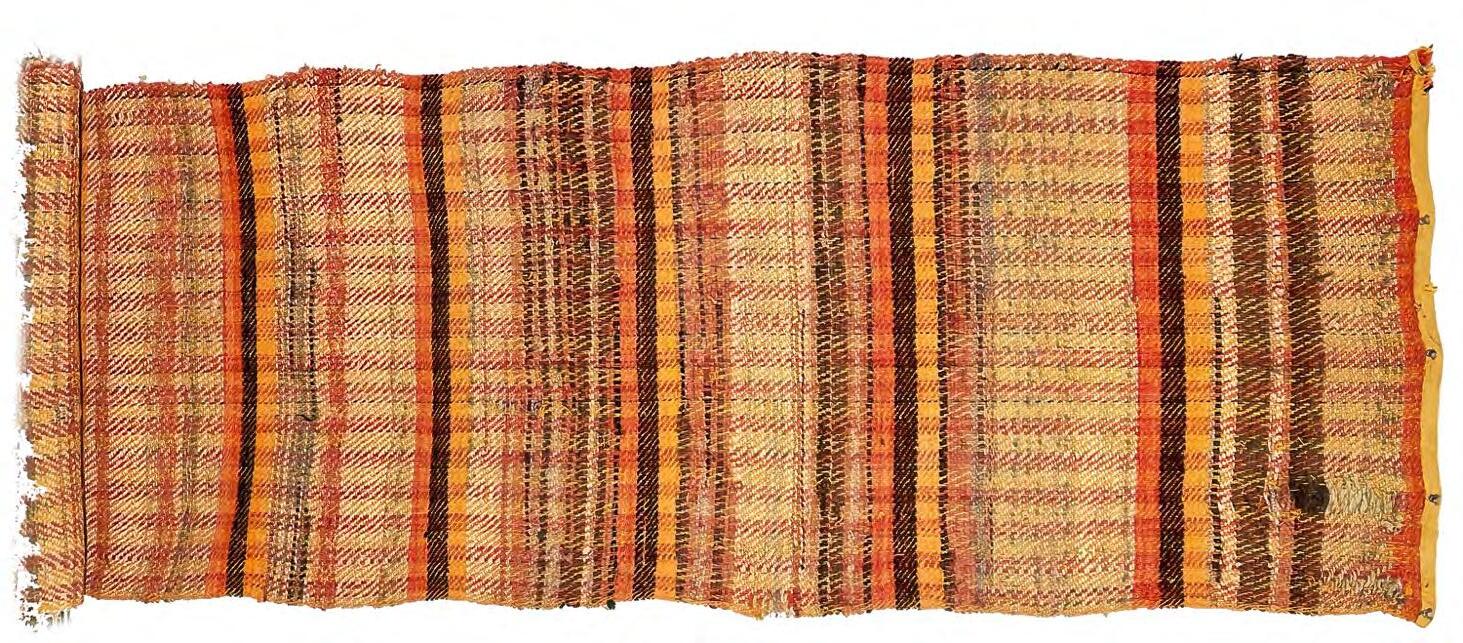

Exhibit 37: New Mexican Double Panel Jerga 120” x 42” (partly folded in image) c. 1870-1875. Handspun light and dark brown twill woven wool yarns. Mark and Linda Winter.

Exhibit 38: New Mexican Triple Panel Jerga Cover 72” x 48” c.1875. Banded elements of twill woven hand-spun tan, dark brown, and off-white wool. Mark and Linda Winter.

37

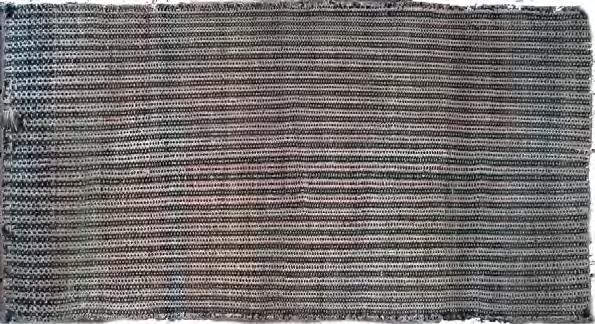

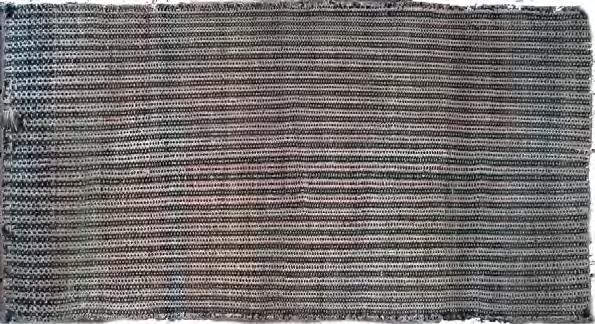

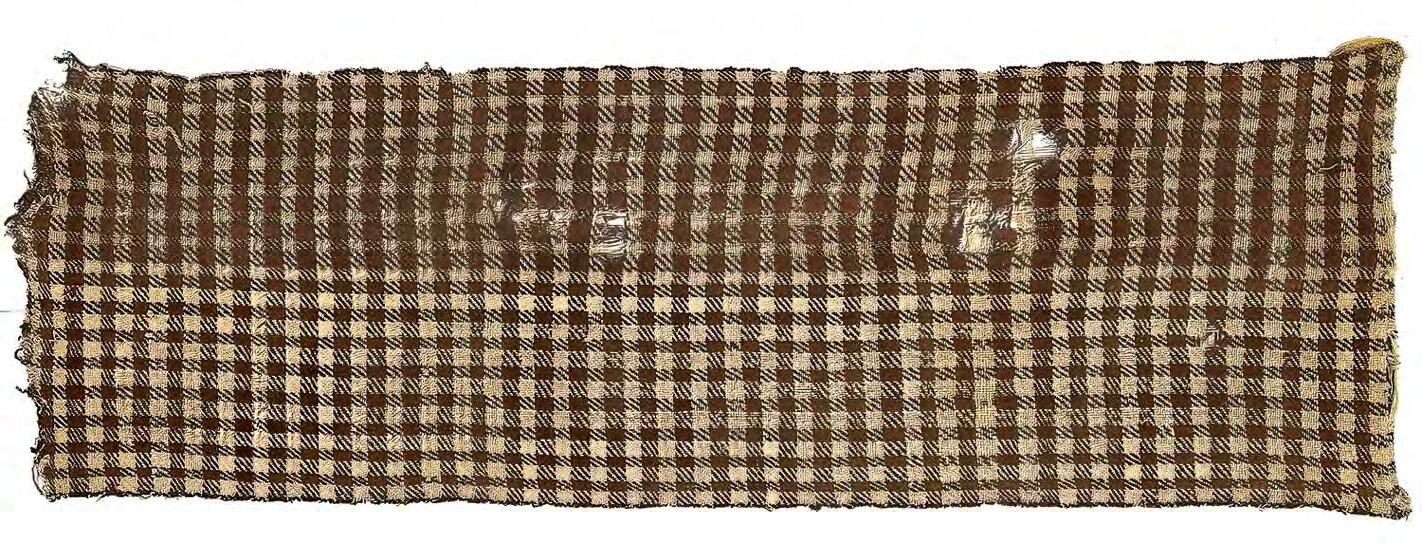

Exhibit 39: New Mexican Single Panel Jerga 90” x 24”, c.1825-1830. Twill woven hand-spun natural brown and white wools. Mark and Linda Winter.

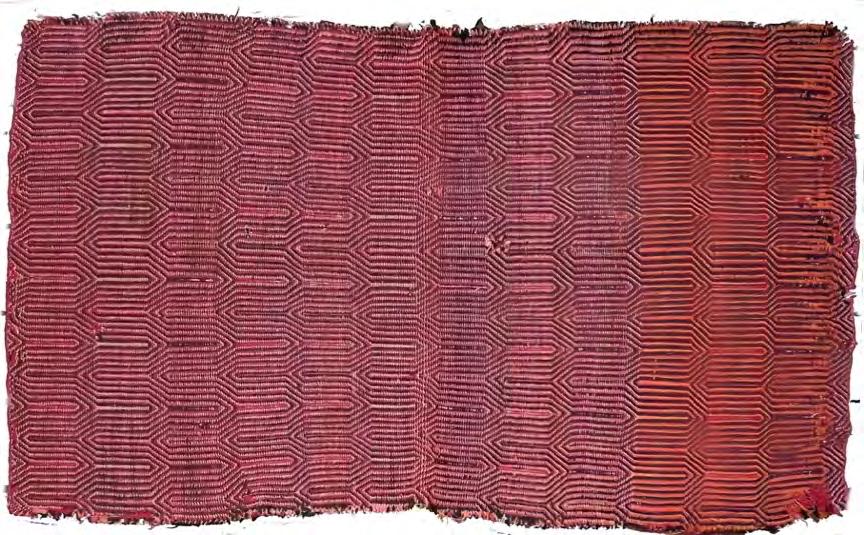

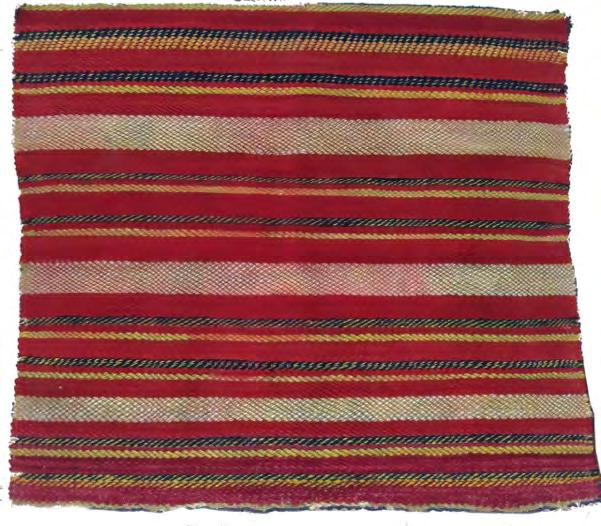

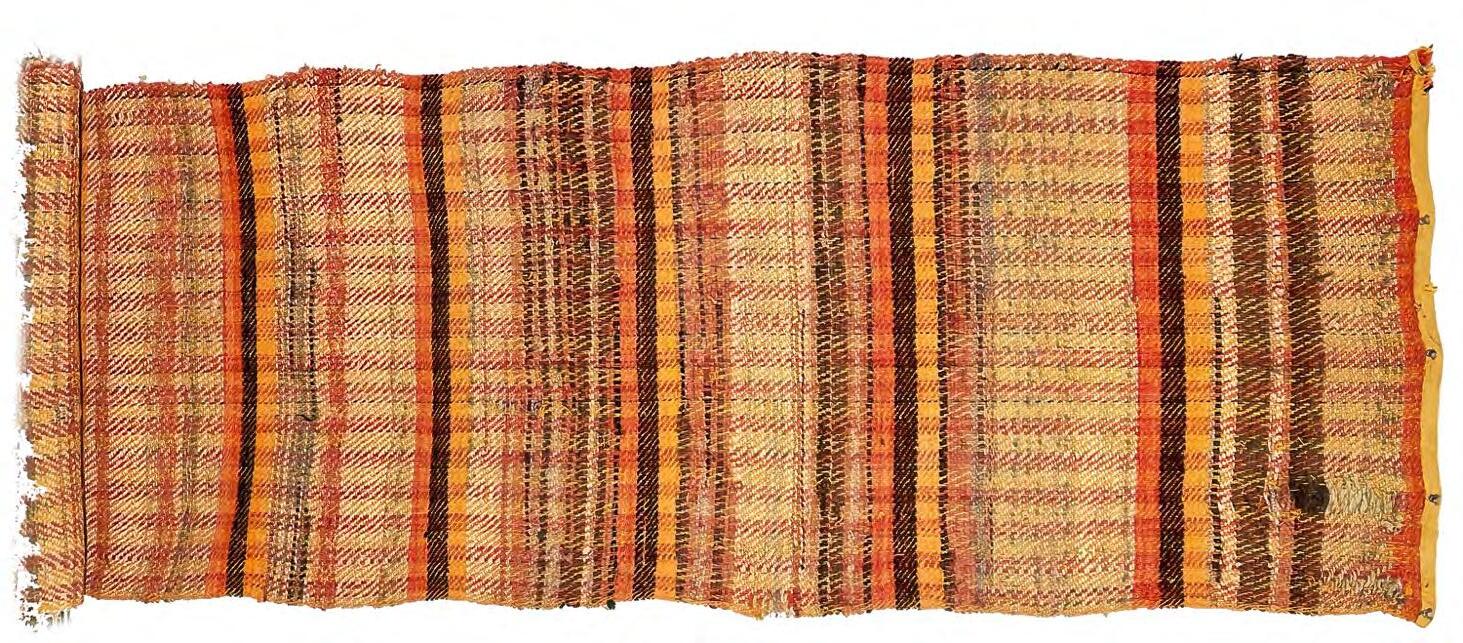

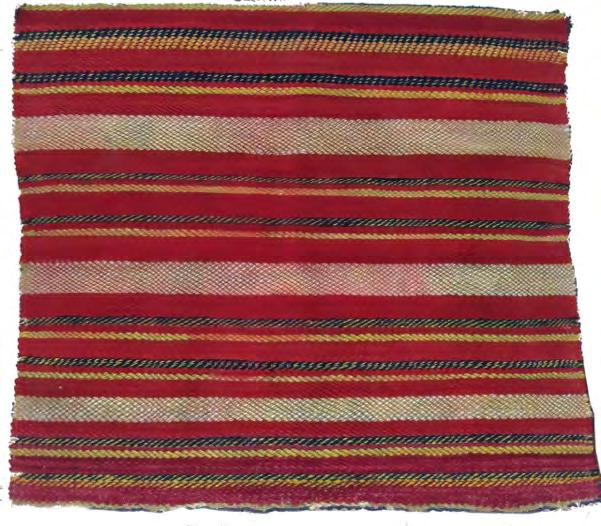

Exhibit 40: New Mexican Single Panel Jerga 120” x 24” (partly folded in image), c.1875-1880. Twill woven red, black, yellow, and blended wool yarns, with some rows of cloth strips. Mark and Linda Winter.

38

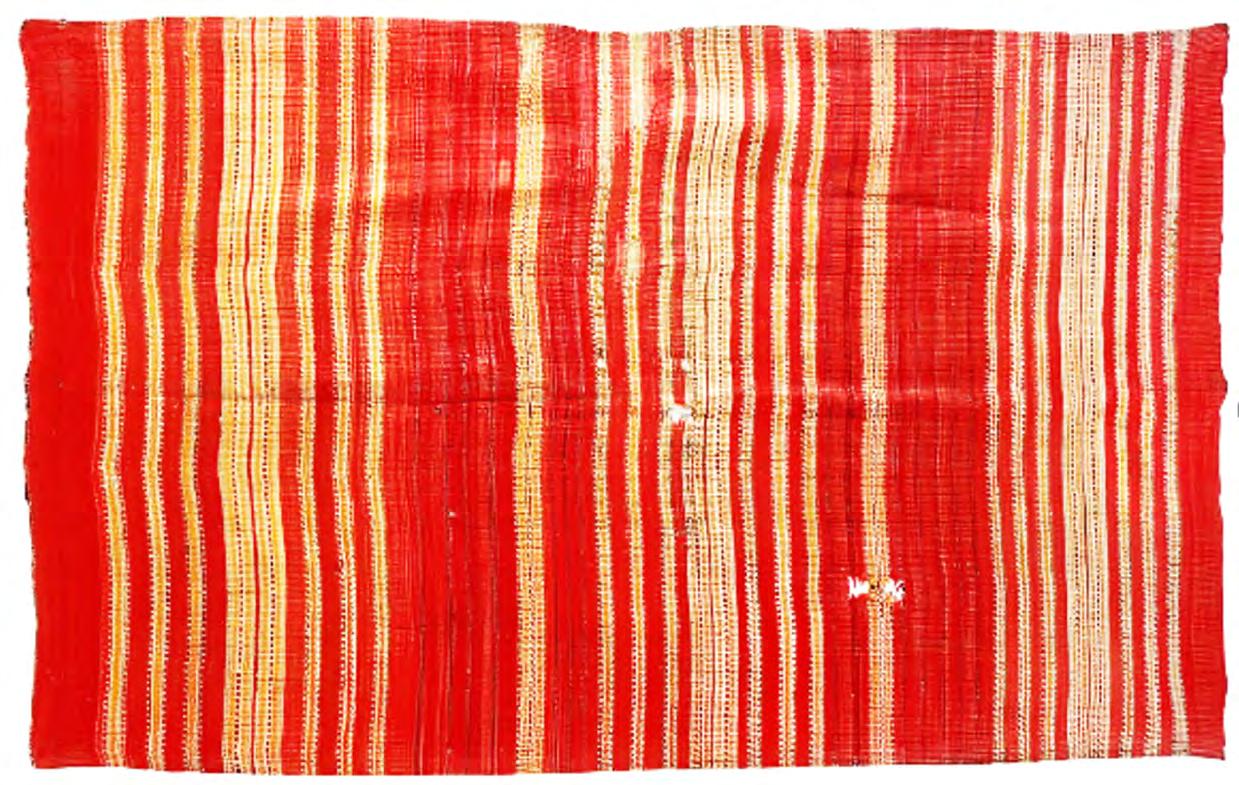

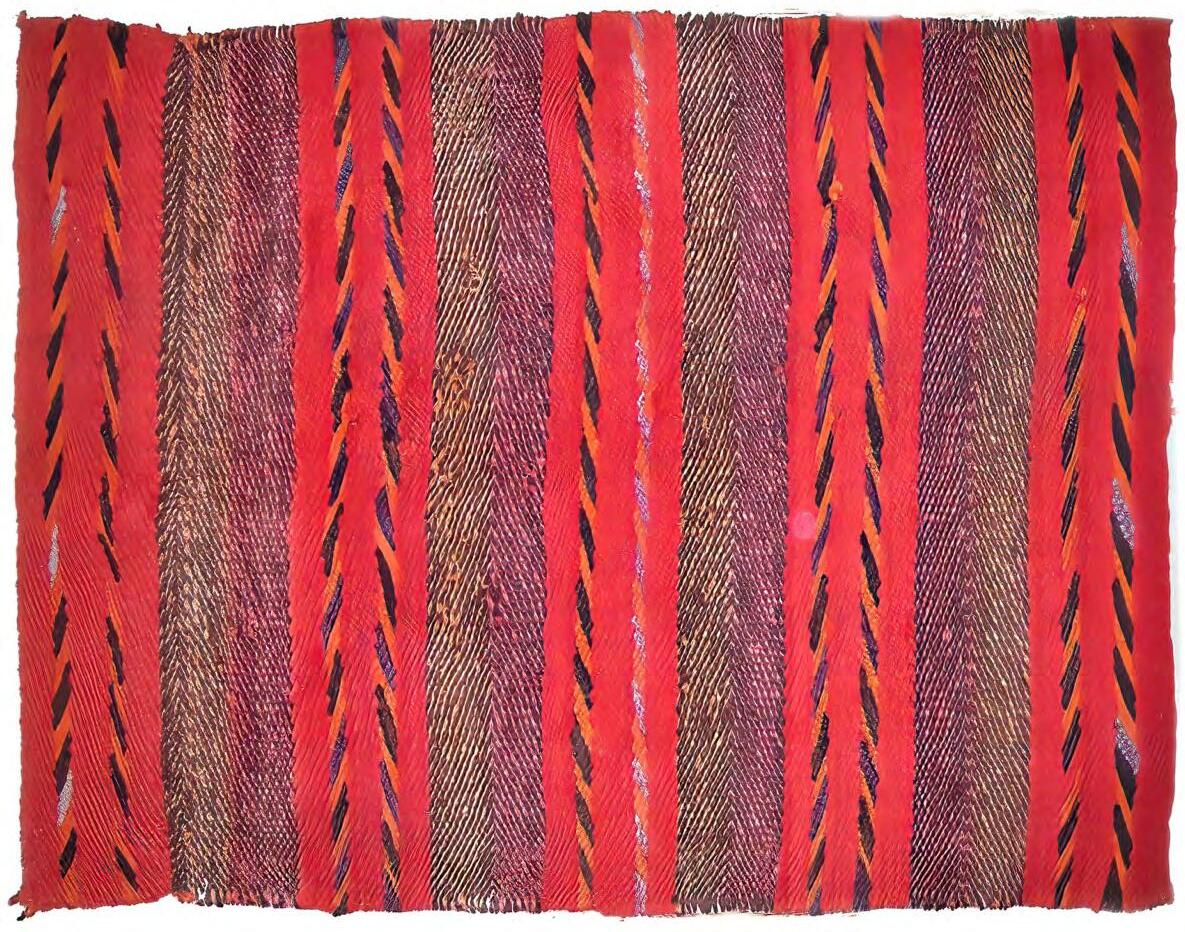

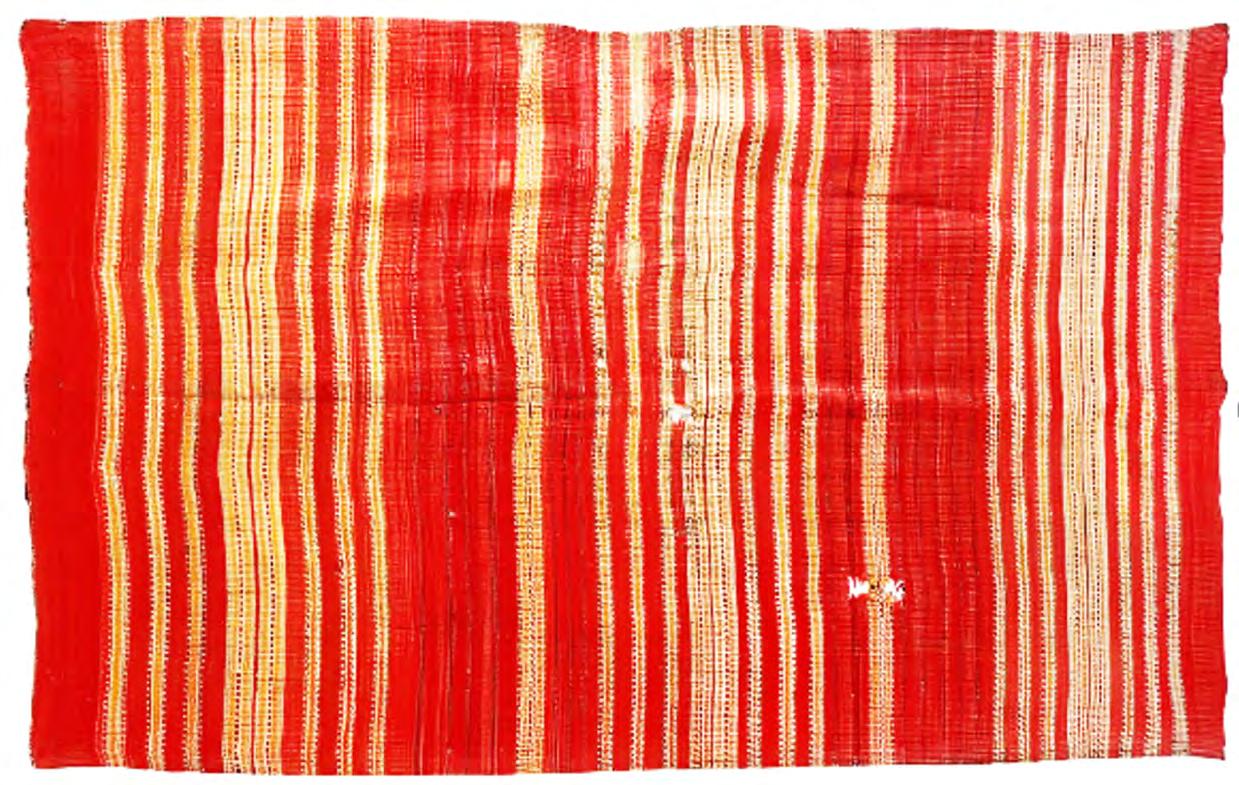

Exhibit 41: Rio Grande New Mexican One-piece Blanket, 96” x 51”, c. 1875-1880. Handspun aniline dyed red, pink, orange, purple wool, and natural white wool. Bruce Weekley.

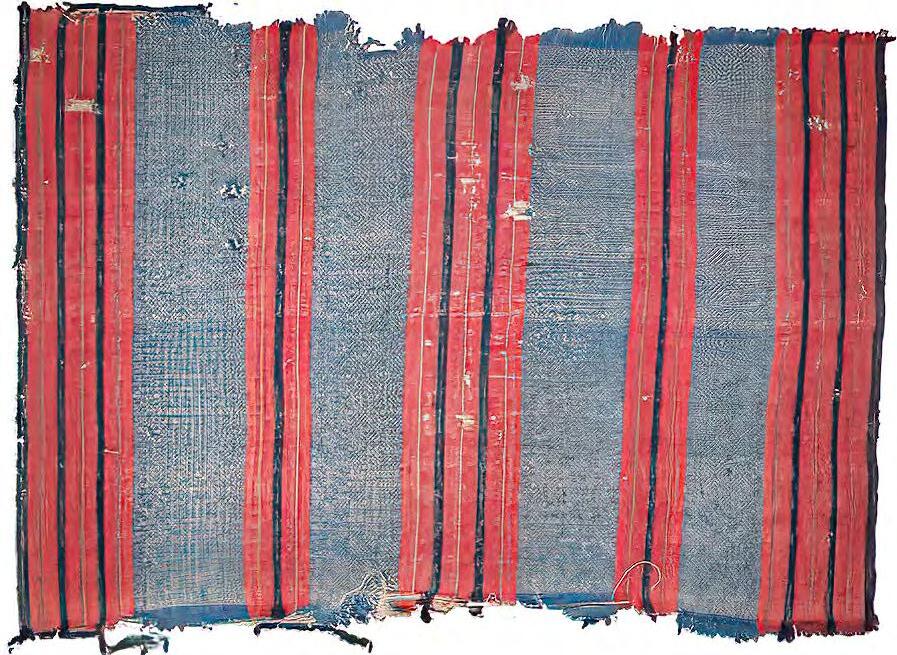

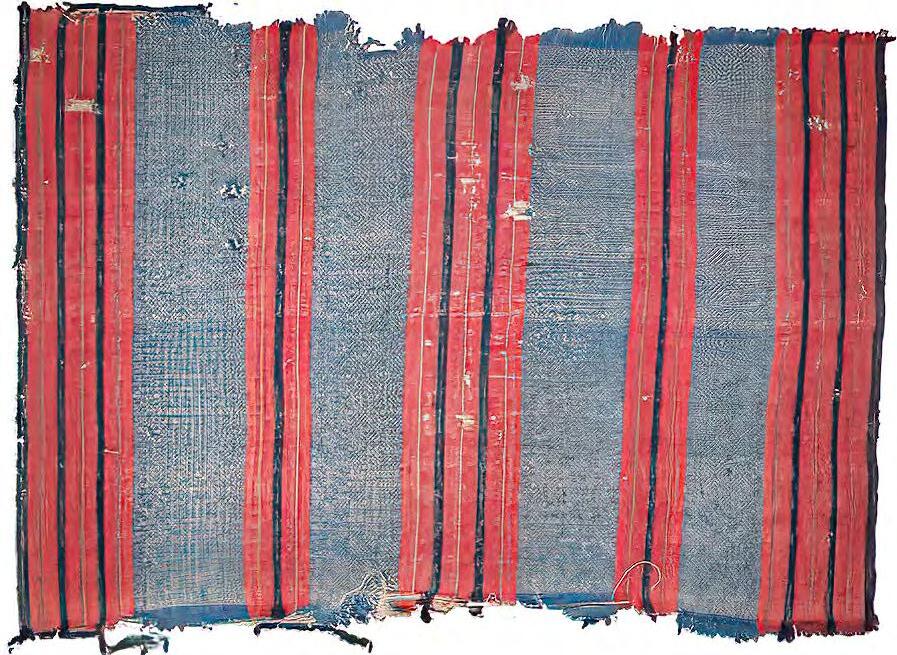

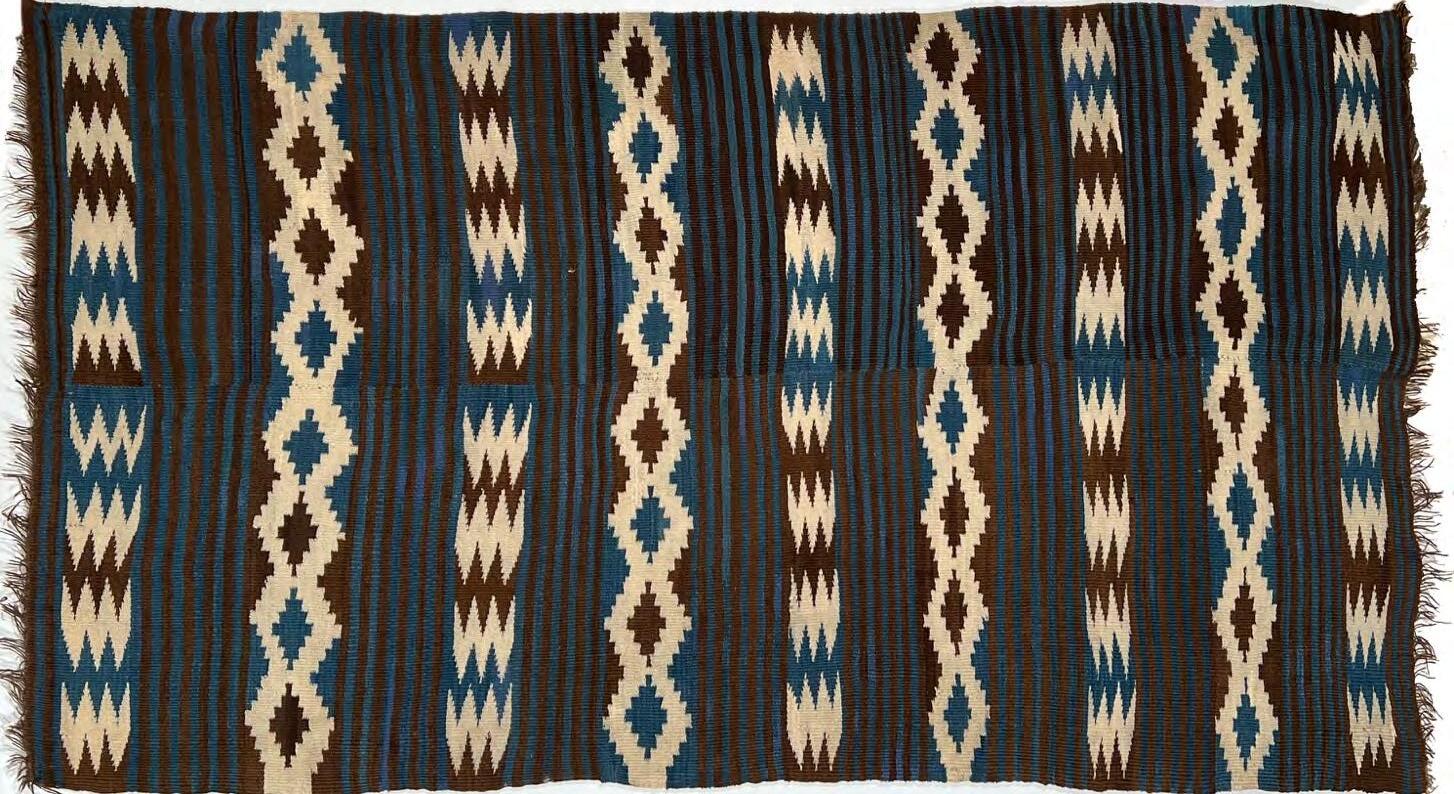

Exhibit 42: Rio Grande Sarape 49" by 90" c. 1850 - 1860, Two-piece indigo dyed blue and natural brown wool striped blanket seamed up the center, of chevrons and diamonds.on hand plied wool warp. Mark and Linda Winter.

39

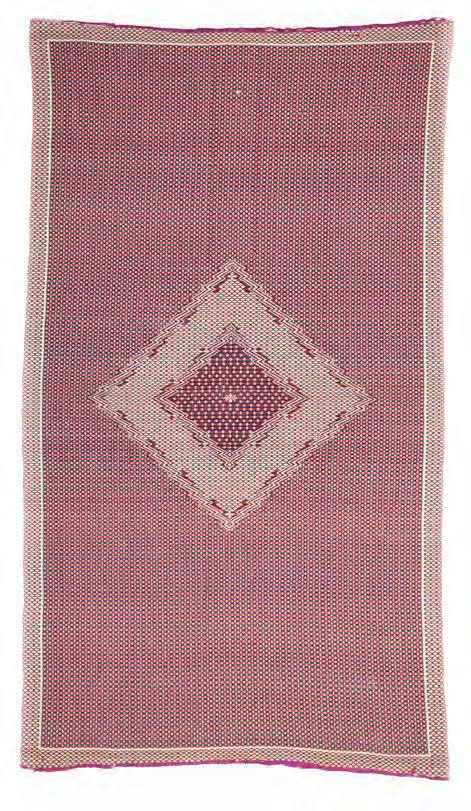

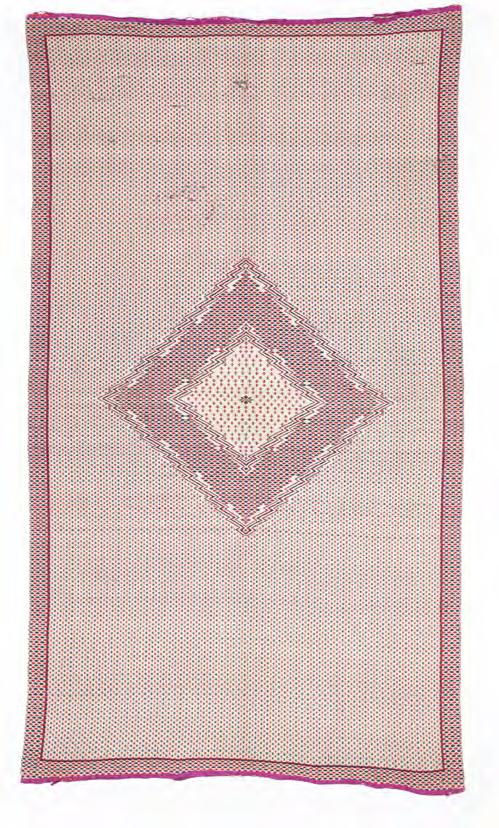

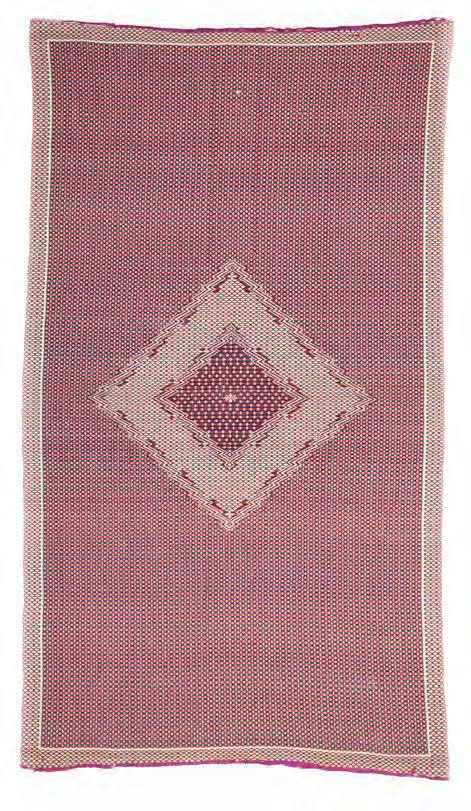

Exhibit 43: Late Classic Diamond Center Saltillo Sarape 51” x 89” c.1850-1875. A rare double sided natural dyed wool piece with hand plied cotton warp. Mark and Linda Winter.

Exhibit 44: Saltillo Sarape 47” x 78” c.1875-1885. Natural and aniline dyed handspun and commercial wool yarns on plied cotton warp. Mark and Linda Winter.

40

Exhibit 45: Chimayo Hispanic weaving from Chimayo New Mexico, 39" X 23" c.1920. This weaving was used by the author's grandfather as a trunk cover. Various types of textiles in similar designs continue to be made at Chimayo to this day

HISTORIC PHOTOGRAPHS from the L. BRUCE WEEKLEY COLLECTION

41

Photograph 1: Isleta Pueblo Woman c.1890. She is wearing a black twill woven manta decorated with silver coin manta pins down the seam. William Henry Cobb photographer.

Photograph 2: Isleta Pueblo Woman c.1885. She is wearing a black manta with a heavy coin silver bead necklace with naja Russell and Wittick photographer

42

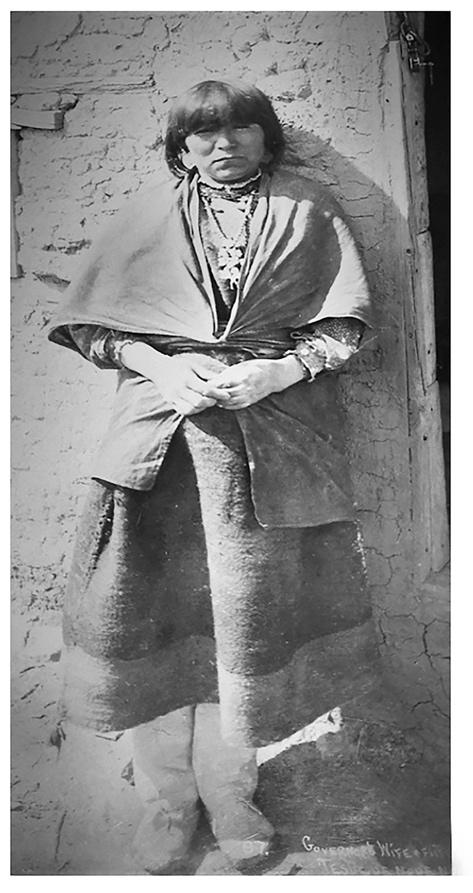

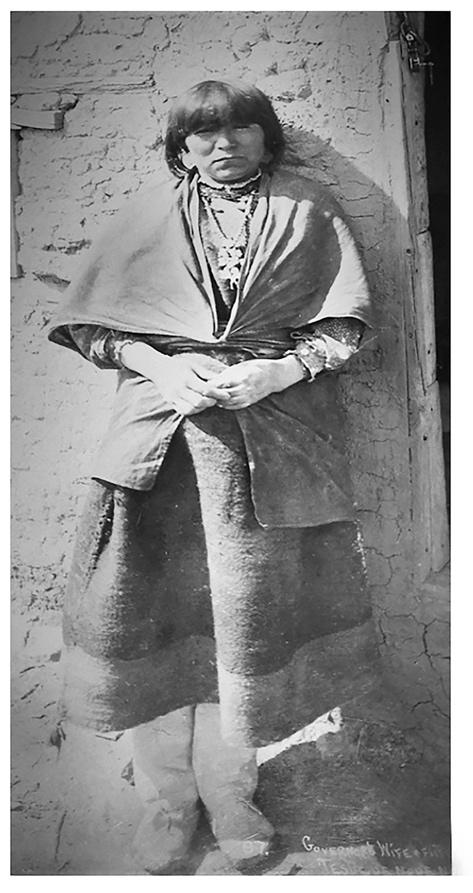

Photograph 3: Tesuque Pueblo Governor's wife c.1890. She is wearing a black manta with indigo blue end panels and a ceremonial necklace. Unknown photographer

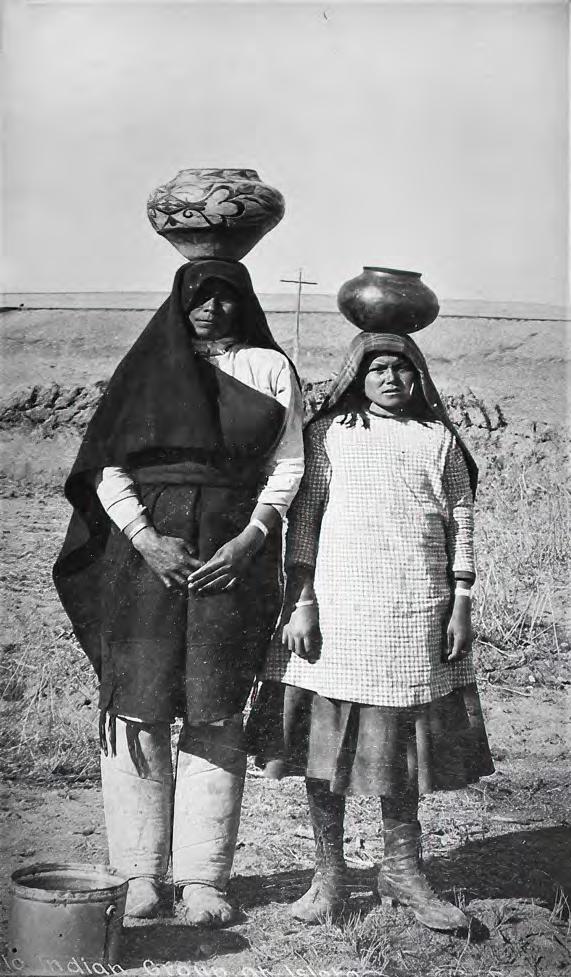

Photograph 4: Zia Pueblo Woman 1883. She is wearing a black manta with indigo end panels in a portrait from the Tertio Millenial Fair. Ben Wittick photographer.

43

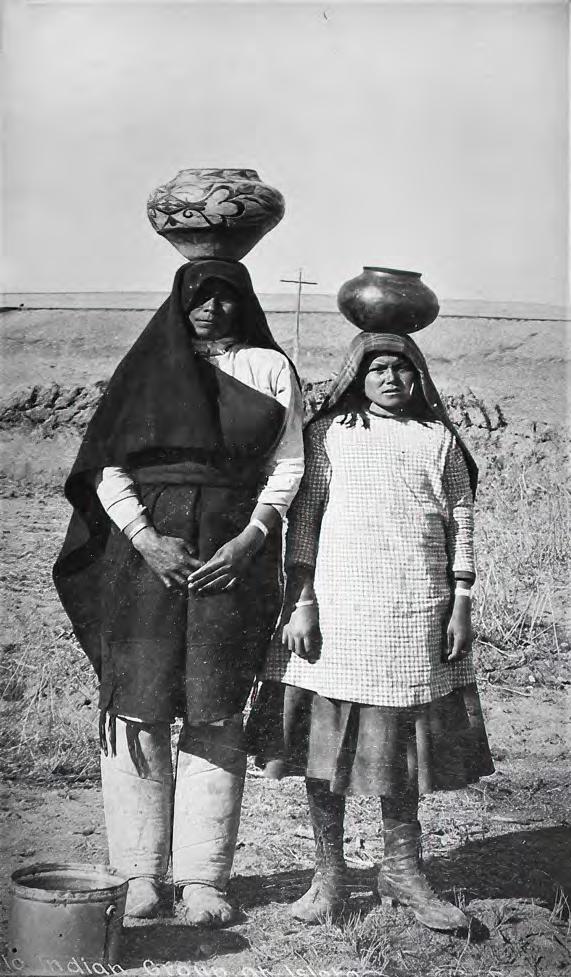

Photograph 5: Isleta Mother and Child c.1890. She wears a twill woven black manta with an Isleta Olla on her head at the Isleta Trading Post railroad station. Unknown photographer.

Photograph 6: Woman at Hopi mesa c.1880. She is wearing two mantas, the outer one as a shawl clearing showing the "hills and valleys" design. Unknown photographer.

44

Photograph 7: Isleta Pueblo woman c.1890. She is wearing a twill weave manta with indigo end panels and an Isleta cross "dragonfly" silver necklace. William Henry Cobb photographer.

Photograph 8: Hopi man knitting leggings. Hopi 1st Mesa. Unknown photographer.

45

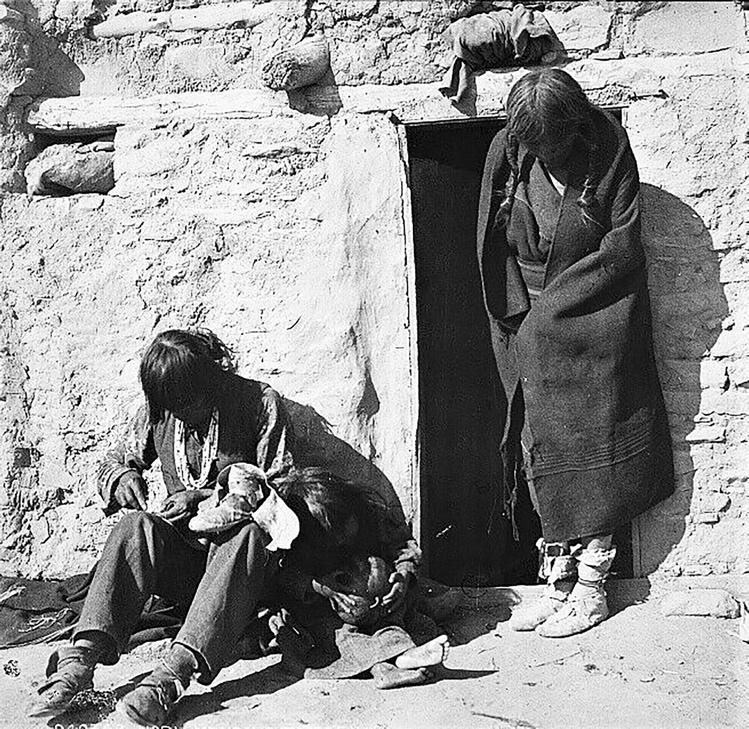

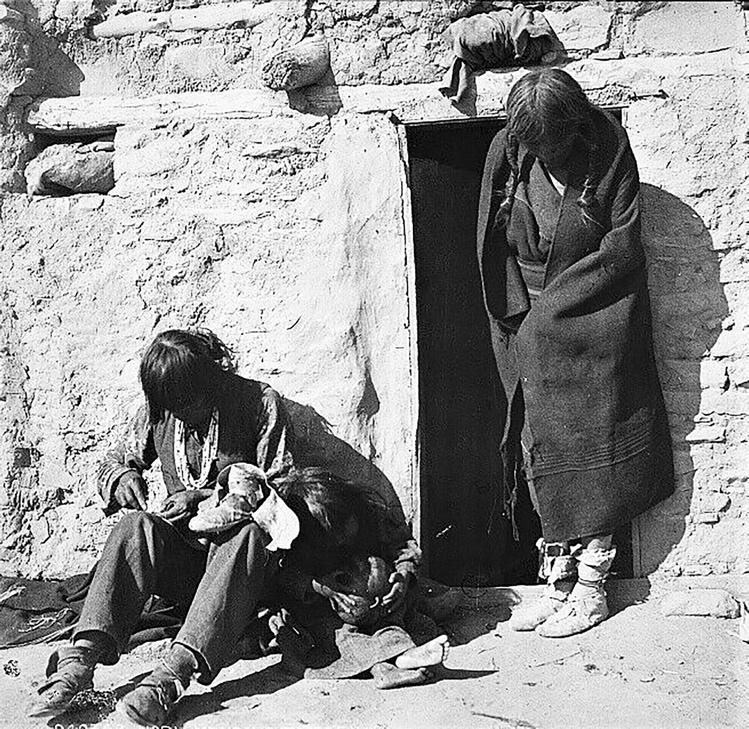

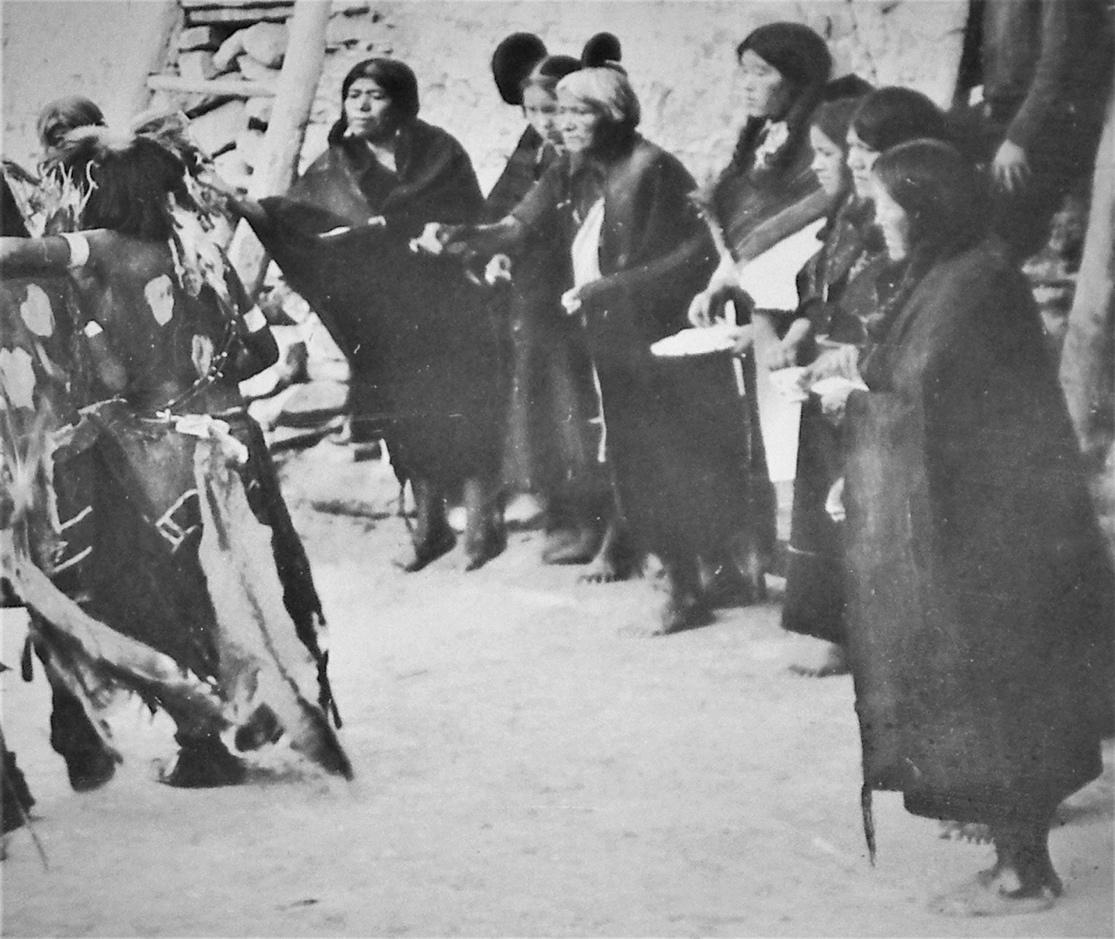

Photograph 9: Hopi men in black mantas c.1890. The men are blessing the Snake Dancers with corn meal at Walpi. Unknown photographer

Photograph 10: Hopi women in black mantas c.1890. The women are blessing the Snake Dancers with corn meal at Walpi. Unknown photographer

46

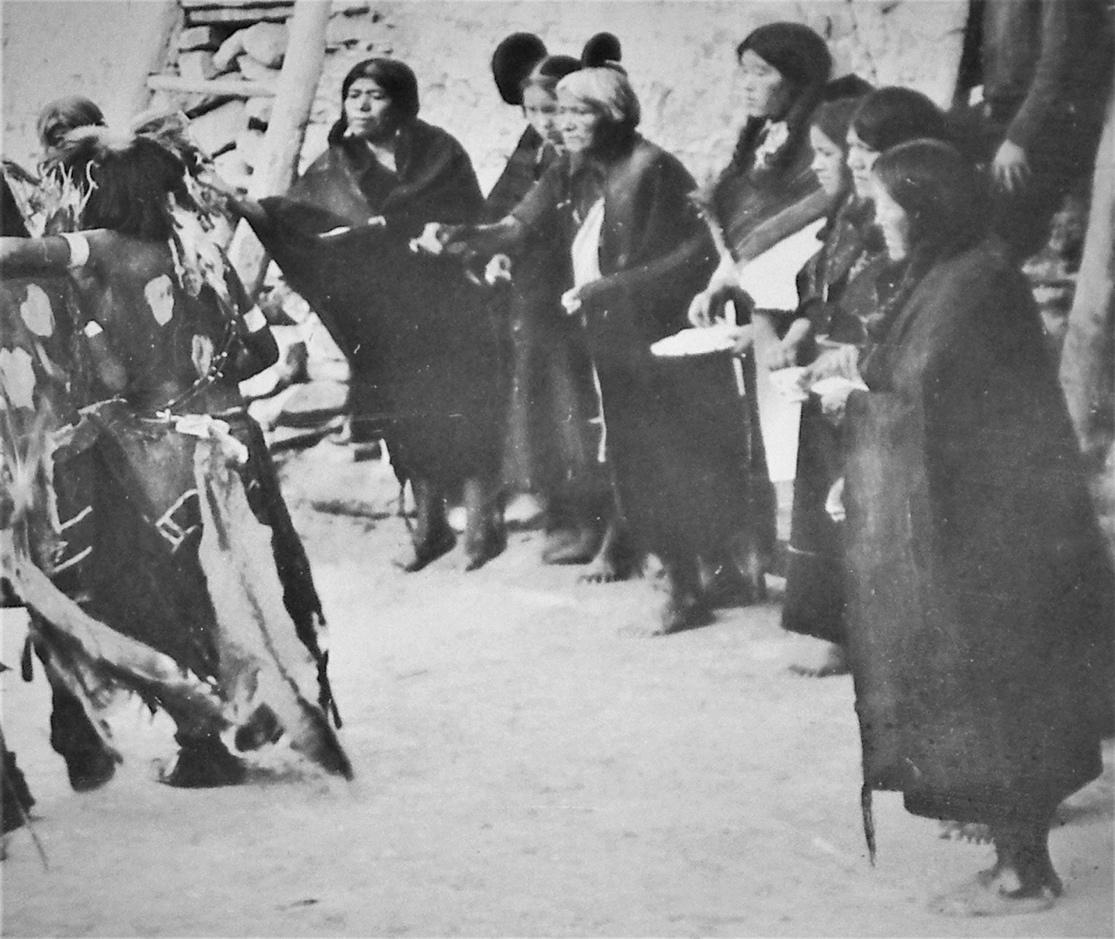

Photograph 11: Zuni Pueblo Woman c.1895. They are wearing black twilled mantas with white blankets wrapped at the waist for a ceremonial dance. Unknown photographer.

Photograph 12: Zuni Pueblo men and women c.1880. They are wrapped in black mantas as it is winter. The mother with baby appears to wear one with an indigo or brown center. Unknown photographer.

Adovasio, James M.

REFERENCES

1970 “The Origin, Development and Distribution of Western Archaic Textiles” Doctoral Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Aitken, Barbara

1949 “A Note on Pueblo Belt Weaving” in Man – A Monthly Record of Anthropological Science, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. XLIX, Article 46. London, England.

Anawalt, Patricia Rieff

1990 Indian Clothing Before Cortes: Mesoamerican Costumes from the Codices. The Civilization of the American Indian Series Book 156, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

Baldwin, G. C.

1939 "Prehistoric Textiles in the Southwest" Kiva, Vol 4, No. 4, pgs. 15–18.

Bloom, Lansing B. Bloom,

1927 “Early Weaving in New Mexico” in The New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. 2. No. 3. Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Brenneman, Dale S.

1994 Ethnohistoric Evidence for the Economic Role of Cotton in the Protohistoric Southwest. Unpublished Master's thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson.

Campbell, Tyrone D.

2003 Timeless Textiles – Traditional Pueblo Arts 1840-1940. Catalogue from the Exhibit: Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Colton, Mary-Russell Ferrell

1930 The Hopi Craftsman. Museum Notes 3(1). Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff.

1931 Techniques of the Major Hopi Crafts. Museum Notes 3(12). Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff.

1932 Wool for our Weavers: What shall it be? Museum Notes 4(12):1-15. Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff.

1933 Hopi Courtship and Marriage. Museum Notes 5(8): Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff.

1938 The Arts and Crafts of the Hopi Indians, Museum Notes 11(1). Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff.

1965 Hopi Dyes. Museum of Northern Arizona Bulletin, no 41. Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff.

Crotty, Helen Koefoed

1995 Anasazi Mural Art of the Pueblo IV Period, A.D. 1300 – 1600: Influences, Selective Adaptation, and Cultural Diversity in the Prehistoric Southwest. Doctoral Dissertation in Art History, University of California, Los Angeles, California.

Dockstader, Frederick J.

1978 Weaving Arts of the North American Indians, Crowell Publishing, New York, New York.

Douglas, Frederic H. and d’Harnoncourt, Rene

1941 Indian Art of the United States. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York.

47

Douglas, Frederic H.

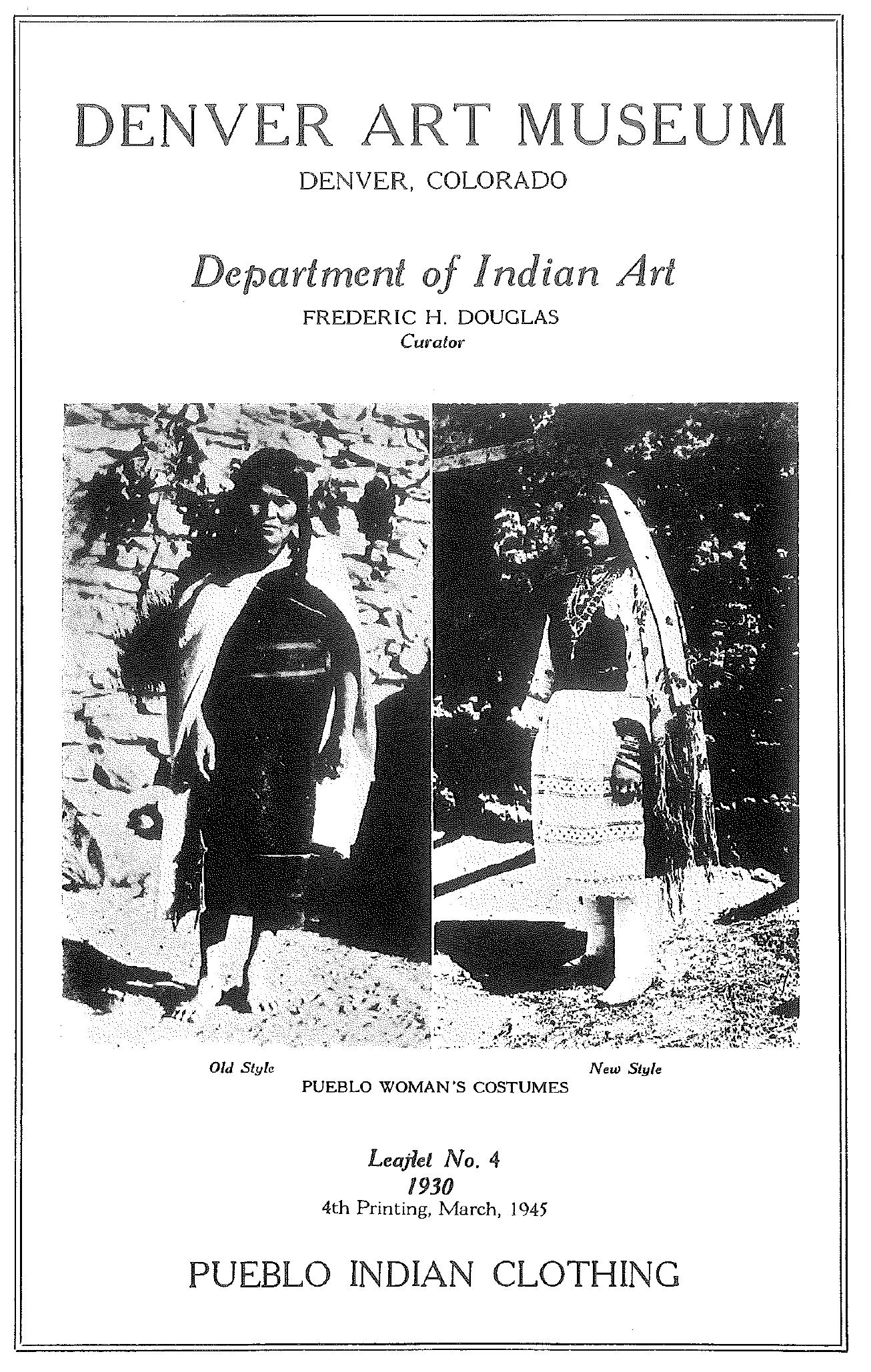

1930 Pueblo Indian Clothing. Denver Art Museum, Denver, Leaflet 4

1931 Hopi Indian Weaving. Denver Art Museum, Denver, Leaflet 18

1939a Acoma Weaving and Embroidery. Denver Art Museum Leaflet 89.

1939b Weaving in the Tewa Pueblos. Denver Art Museum Leaflet 90.

1939c Weaving of the Keres Pueblos, Tiwa Pueblos and Jemez. Denver Art Museum Leaflet 91.

1940a Main Types of Pueblo Cotton Textiles. Denver Art Museum Leaflet 92-93

1940b Main Types of Pueblo Woolen Textiles. Denver Art Museum Leaflet 94-95

1940c Weaving at Zuni Pueblo. Denver Art Museum Leaflets 96-97.

1953 Southwestern Weaving Materials. Denver Art Museum Leaflets 116.

Dutton, Bertha P.

1963 Sun Father's Way: the Kiva Murals of Kuaua. University of New Mexico Press. Albuquerque, New Mexico.

d'Harcourt, Raoul

1934 Textiles of Ancient Peru and Their Techniques, first published in Paris in 1934, 1962 translation by Sadie Brown, edited by Grace G. Denny and Carolyn M. Osborne, reprinted in 1974, University of Washington Press, Seattle, Washington.

Feder, Norman

1958a “Hopi Yarn Anklets, Embroidered Kilts, Cochiti Parrot Dance.” The American Indian Hobbyist, Vol. IV, No. 7 and 8, Mar. Apr. 1958.

1958b “Hopi Men and Women's Butterfly Dance Costume, Hopi Butterfly Dance,” The American Indian Hobbyist, Vol. IV, No. 9 and 10, May June 1958.

Fewkes, Jesse Walter

1899-1900 “Hopi Katchinas Drawn by Native Artists,” Bureau of America Ethnology, Twenty-First Annual Report, Government Printing Office 1903, Washington, D.C.

Fisher, Nora and Joe Ben Wheat

1979 “The Materials of Southwestern Weaving” in Spanish Textile Tradition of New Mexico and Colorado, Museum of International Folk Art. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe.

Folb, Lisa

1996 Cotton Fabrics and Wupatki Pueblo. Unpublished Master's thesis, Department of Anthropology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff.

Fox, Nancy L.

1978 Pueblo Weaving and Textile Arts. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe.

Franke, Paul R. and Watson, Don

1936 “An Experimental Cornfield in Mesa Verde National Park” in Symposium on Prehistoric Agriculture, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Garcia, Louis

2016 “Cotton Spinning and Sprang in the Pueblo Southwest” PLY Magazine. Issue 12, Spring 2016, pg 64

Geib, Phil R.

67

2000 Sandal Types and Archaic Prehistory on the Colorado Plateau, Anthropology Faculty Publications. 139. University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Hammond, George P. and Rey, Agapito,

1966 The Rediscovery of New Mexico, 1580-1594. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

48

–

Hays-Gilpin, Kelly A.; Webster, Laurie D.; Schaafsma, Polly

2004 “The Iconography of Tie-dye Textiles in the Ancient Americas” in Cosmos 20 (2004), pp. 33-56, Journal of the Cosmology Society, Airdrie, Canada, (see also Kiva Journal of the Arizona Archaeological Society, 2006.)

Hedlund, Ann L.

1990 Beyond the Loom: Keys to Understanding Early Southwestern Weaving. Johnson Publishing Co., Boulder.

Hibben, Frank C.

1975 Kiva Art of the Anasazi at Pottery Mound. KC Publications, Las Vegas, Nevada.

Holmes, William Henry

1881-1882 “Prehistoric Textile Fabrics of the United States Derived from Impressions on Pottery” Bureau of America Ethnology, Third Annual Report, Government Printing Office 1884 [1885], Washington, D.C.

1884-1885 “Textile Art in its Relation to the Development of Form and Ornament” Bureau of America Ethnology, Sixth Annual Report, Government Printing Office 1888 [1889], Washington, D.C.

Irving, David

1986 Living Traditions: Kate Peck Kent and the Study of Historic Pueblo Textiles. Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, Santa Fe.

James, Carol

2017 The Arizona Openwork (Tonto) Shirt Project” in PreColumbian Textile Conference VII / Jornadas de Textiles PreColombianos VII, ed. Lena Bjerregaard and Ann Peters (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. 415–425.

Jones, Volney H.

1936 “A Summary of Data on Aboriginal Cotton of the Southwest” in Symposium on Prehistoric Agriculture. University of New Mexico Bulletin #296, Anthropological Series Vol. 1, No. 5. Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Kent, Kate Peck

1940 “Braiding of a Hopi Wedding Sash” in Plateau 12:46-52. Flagstaff: Museum of Northern Arizona.

1957 The Cultivation and Weaving of Cotton in the Prehistoric Southwestern United States. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 47, No. 3. Philadelphia.

1983a Pueblo Indian Textiles – A Living Tradition – With a Catalogue of the School of American Research Collection. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe.

1983b Prehistoric Textiles of the Southwest. School of American Research Press, Santa Fe.

1983c “Temporal Shifts in the Structure of Traditional Southwestern Textile Design” in Structure and Cognition in Art, edited by Dorothy K. Washburn, pp. 113-137. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

King, Mary Elizabeth

1974 “Textiles and Basketry” in Chapter 6, Medio Period Perishables, in Casas Grandes: A Fallen Trading Center of the Gran Chichimeca: Volume 8 by Charles C. Di Peso, John Rinaldo, and Gloria J. Fenner, Pp. 76-113. Amerind Foundation, Inc., Northland Press, Flagstaff.

Kolb, Emery Clifford

18xx Collection of Prehistoric Fiber (ten photographs of Riker mounts), Northern Arizona University, Cline Library Special Collections and Archives, Flagstaff, Az.

Leach, Melinda

2017 “Ancient Twined Garments of Fur, Feather, and Fiber: Context and Variation Across the American Desert West” in Quaternary International #468 (2018) 211-227, Journal of the Union for Quaternary Research, Elsevier Science, Tarrytown, New York.

49

Lewton, Frederick L.

1912 The Cotton of the Hopi Indians: A New Species of Gossypium, Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, Vo. 60, No. 6, Washington, D.C.

Magers, Pamela C.

1983 “Weaving at Antelope House”, in Archaeological Investigations at Antelope House by Bob P. Morris, pp. 224-276. National Park Service, Washington, D.C.

Mera, H. P. (Harry P.)

1975 Pueblo Indian Embroidery. William Gannon, Santa Fe reprint of the 1943 edition. Originally published as Memoirs of the Laboratory of Anthropology, No. 4., Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Mera, H. P. with introduction by Peck, Kate Peck

1987 Spanish-American Blanketry, Its Relationship to Aboriginal Weaving in the Southwest, School of Advanced Research, Santa Fe, new Mexico.

Minar, Jill

2000 “Spinning and Plying: Anthropological Directions” in Beyond Cloth and Cordage: Archaeological Textile Research in the Americas, edited by Penelope Drooker and Laurie Webster. Pp. 85-100. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Neff, Linda Stephen

1996 Ancient Pueblo Spinning Traditions in the Northern Southwest. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona.

O'Neal, Lila M.

1948 Textiles of Pre-Columbian Chihuahua. Contributions to American Anthropology and History, Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication, Vol. 9, No. 45, Washington, DC.

Phillips, David A.

2009 “Adoption and Intensification of Agriculture in the North American Southwest: Notes Toward a Quantitative Approach” in American Antiquity 74(4), Society for American Archaeology. Washington D. C.

Pojoaque Poeh Museum

1996 Honoring the Weavers. Catalog to the Pueblo Textile Exhibition at the Poeh Museum, Kiva Publishing, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Raney, Anne

2005 Weaving Identity: Social Boundaries and Cultural Interaction in the Prehistoric Southwest. Unpublished Master's thesis, Department of Anthropology, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff.

Roediger, Virginia More

1941 Ceremonial Costumes of the Pueblo Indians: Their Evolution, Fabrication, and Significance in the Prayer Drama. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

Sayers, Robert

1980 “Recycled Hopi Manta” in The Kiva 45:301-315.

1981 “Symbol and Meaning in Hopi Ritual Textile Design” in American Indian Art Magazine 6:70-77.

1989 “Hopi Weaving: Context and Continuity” in Seasons of the Kachina: Proceedings of the California State University, Hayward, Conferences on the western pueblos, 1987-1988, edited by Lowell John Bean, pp. 73-83. Anthropological papers, no. 34. Ballena Press, Menlo Park, California, and California State University, Hayward.

50

Secord, Paul R.

2020 The Maisel's Mural Restored - A Viewer Guide. Secord Books, Albuquerque, New Mexico,

Smith, Watson

1952 Kiva Mural Decorations at Awatovi and Kawaika-a with a Survey of Other Wall Paintings in the Pueblo Southwest. Reports of the Awatovi Expedition Report No. 5, Papers of the Peabody Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Saltzman, Max

1979 Spanish Textile Tradition of New Mexico and Colorado. Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe.

Spier, Leslie

1924 “Zuni Weaving Technique” in American Anthropologist 26:64-85.

Stevenson, Matilda Coxe

1987 “Dress and Adornment of the Pueblo Indians” in The Kiva 52(4) :275-312. 1911 manuscript edited by Richard Ahlstrom and Nancy Parezo.

Tafoya, Shawn

2005 “Thoughts from a Santa Clara Pueblo Traditional Embroiderer” in Native American Voices on Identity, Art and Culture: Objects of Everlasting Esteem, Williams, Wierzbowski and Preucel editors, p. 55. University of Pennsylvania Museum Press, Philadelphia.

Tanner, Clara Lee

1968 Southwestern Indian Craft Arts. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona.

1976 Prehistoric Southwestern Craft Arts. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona.

Teague, Lynn S. and Teiwes, Helga

1992a “Textiles in Late Prehistory” in Proceedings of the Second Salado Conference, Globe, Arizona, edited by R. Lange and S. Germick, Arizona Archaeological Society, Mesa, Arizona.

1992b Textiles and Identity in Prehistoric Southwestern North America. Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings, No. 587; Textile Society of America, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska.

1998 Textiles in Southwestern Prehistory. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Teague, Lynn S.

1992 Textile and Identity in Prehistoric Southwestern North American. Textile Society of American Symposium Proceedings, 587. Arizona State Museum, Tucson, Arizona.

1999 “Textiles and Prehistory” in Archaeology Southwest, Fall 1999. Center for Desert Archaeology, Tucson, Arizona.

2000 “Revealing Clothes: Textiles of the Upper Ruin, Tonto National Monument” in Beyond Cloth and Cordage: Textile Research in the Americas, Penelope Drucker and Laurie Webster editors, pp. 161-178. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Underhill, Ruth

1944 Pueblo Crafts. U.S. Department of the Interior. Bureau of Indian Affairs. Washington, D.C.

Van Pool, Christine s.; Van Pool, Todd L.; and Downs, Lauren W.

2017 “Dressing the Person: Clothing and Identity in the Casas Grandes World” in American Antiquity 82(2), Society for American Archaeology. Washington D. C.

51

Wade, Edwin and Evans, David

1973 “The Kachina Sash: A Native Model of the Hopi World” in Western Folklore, Vol. 32, No. 1. Western Folklore Society, Long Beach, California.

Webster, Laurie D.

1997 Effects of European Contact on Textile Production and Exchange in the North American Southwest: A Pueblo Case Study. Doctoral dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson. University, Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

1999a “Evidence of Affiliation: Relationships of Historic Hopi and Prehistoric Salado Textiles and Basketry” in Hoopoq'yaqam Niqw Wukoskyavi (Those Who Went to the Northeast and Tonto Basin), by T. J. Ferguson and Micah Lomaomvaya, pp. 261-300. Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, Kiqotsmovi.

1999b “The Anthropology of Clothing: An Example from the Historic Pueblos” in Archaeology Southwest, Fall 1999. Center for Desert Archaeology, Tucson, Arizona.

2000a “Perpetuating Ritual Textile Traditions: A Pueblo Example” in Proceedings of the Seventh Biennial Symposium of the Textile Society of America, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

2000b “The Economics of Pueblo Textile Production and Exchange in Colonial New Mexico” in Beyond Cloth and Cordage: Archaeological Textile Research in the Americas, edited by Penelope Ballard Drooker and Laurie D. Webster, pp. 179-204. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City, Utah.

2001 “An Unbroken Thread: The Persistence of Pueblo Textile Traditions in the Postcolonial Era” in The Road to Aztlan: Art from a Mythic Homeland. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles.

2003 “Relationships of Hopi and Hohokam Textiles and Basketry” in Yep Hisat Hoopoq'yaqam Yeesiwa (Hopi Ancestors Were Once Here): Hopi-Hohokam Cultural Affiliation Study, edited by T. J. Ferguson, pp. 165209. Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, Kiqotsmovi.

2004a Textiles and Basketry from the Zuni Middle Village. Manuscript submitted to the Zuni Cultural Resource Enterprise. Pueblo of Zuni, New Mexico.

2005 “Ritual Costuming at Pottery Mound: The Pottery Mound Textiles in Regional Perspective” in New Perspectives on Pottery Mound, Chapter Nine, edited by Polly Schaafsma. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

2009 “Technological Styles and Social Boundaries of Perishable Artifacts of the Early Agricultural/Basketmaker II Period” in The Latest Research on the Earliest Farmers, ed. Sarah A. Herr, Archaeology Southwest, Vol 23-1,Tucson, Arizona.

2017 “Hopi Weaving and the Colonial Encounter: A Study of Persistence through Change” in New Mexico and the Pimeria Alta – The Colonial Period in the American Southwest, Part I, Chapter 4, edited by John G. Douglas and William M. Graves. University Press of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado.

Webster, Laurie and Loma'omvaya, Micah

2002 “Textiles, Baskets, and Hopi Cultural Identity” in Identity, Feasting, and the Archaeology of the Greater Southwest. Proceedings of the 2002 Southwest Symposium. Edited by Barbara J. Mills. University Press of Colorado.

Wheat Joe Ben

1978 “Rio Grande, Pueblo, and Navajo Weavers: Cross Cultural Influence” in Spanish Textile Tradition of New Mexico and Colorado, compiled and edited by Nora Fisher, pp. 29-36. Museum of International Folk Art, Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe.

2003 Blanket Weaving in the Southwest, University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

Whitaker, Kathleen

2002 Southwest Textiles: Weavings of the Navajo and Pueblos, University of Washington Press in association with the Los Angeles Southwest Museum, Seattle, Washington.

Whiting, Alfred F. and Coin, William