texts by

spring / summer 2011

spring / summer 2011

jutta brückner ute frevert assaf gavron friedrich w. graf margot käßmann noémi kiss thomas lehr sibylle lewitscharoff dorota masłowska jürgen mlynek volker mosbrugger herfried münkler armin nassehi aleks scholz raoul schrott michel serres andrzej stasiuk andreas weber harald welzer

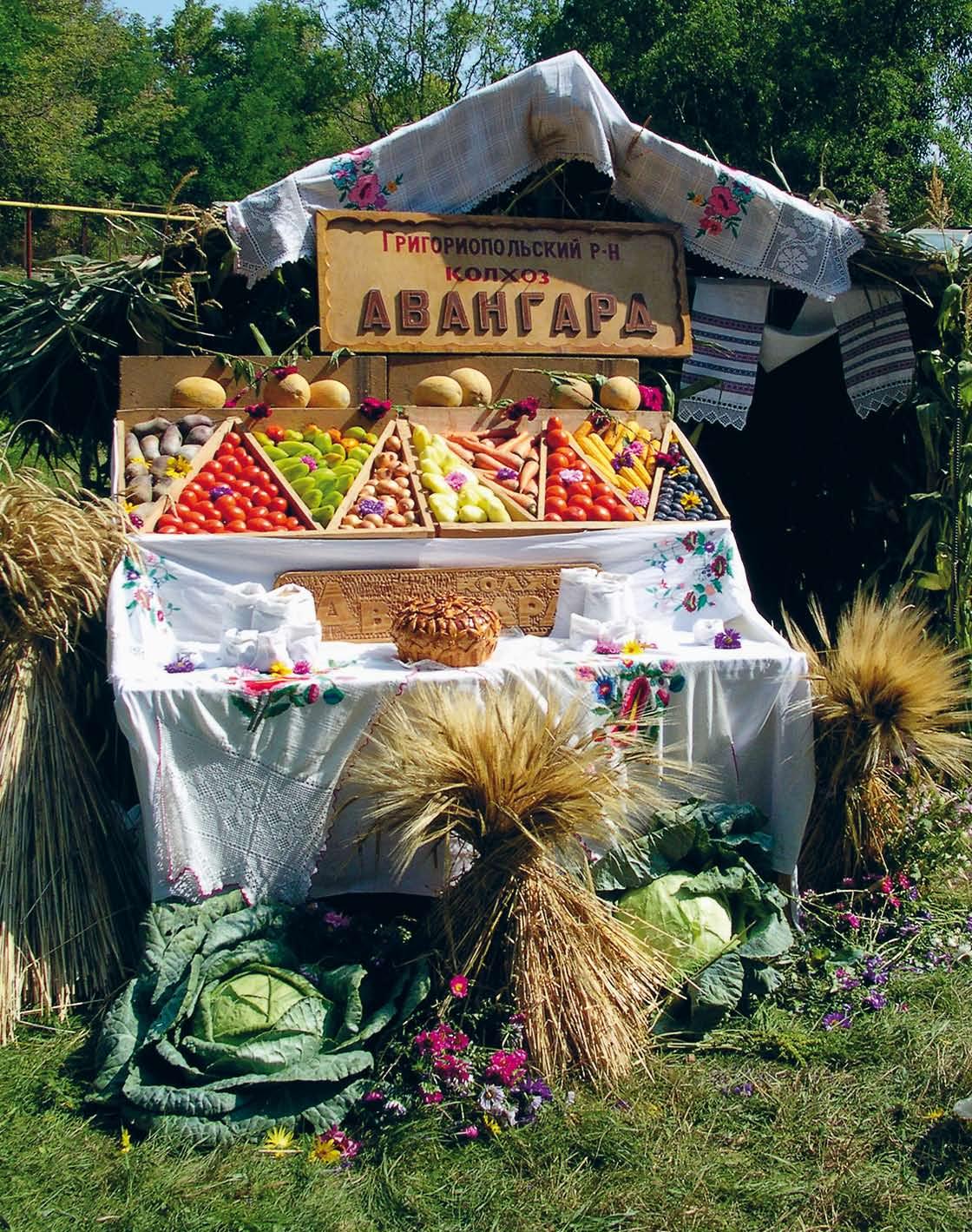

Harvest 2010 Seed 95 ¤ / ha

Fertilizer 76 ¤ / ha

Pest control 45 ¤ / ha Total expenses: 586 ¤

Cost of labour 250 ¤ / ha

Property expenses 120 ¤ / ha

Yield : 13 56 dt / ha × 34 ¤ / dt = 459 ¤ / ha

No matter whether we’re talking climate change, demographic trends, cultural education, integration, religious tolerance or so cial equity a change in awareness and more sustainability in thinking and action are needed now more than ever before. What do we need for the future? What do we want? What can we live without? What can we do to sustain survival on our planet and how can we ensure that it remains a place worth living in?

The Federal Cultural Foundation is addressing these questions in a multifaceted programme titled Über Lebenskunst [www.ueber-lebenskunst.org]. For those familiar with the sub tleties of the German language, the title is a play on words that can either mean »About the Art of Living« or »The Art of Survival«. And this ambiguity is intended. In view of the crises unfolding around the world, the individual’s art of living, based on the ancient concept of ars vivendi, is quickly transforming into a globally-minded art of surviv al which recognizes the necessity of making vitally important provisions for coming generations.

From 17 to 21 August 2011, Über Lebenskunst will hold a theme-based festival in cooperation with the Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin, at which thousands of visitors are expected. Our preparations for the festival began last year. It aims to exam

ine the art of living from every angle, down to the smallest detail, starting with the most elementary aspects such as eating and sleeping. For example, myvillages.org, a group of female artists, has set up a real food pantry, with which they hope to feed the many visitors at the festival over several days.

Pantries have become somewhat antiquated in this age of frozen foods and discount supermarkets that offer industrially proc essed foodstuffs imported from around the world. We believe there’s an alternative. This is not only about feeding people and attempting to produce and process grain for bread, linseed for cooking oil and milk for cheese in an energy-efficient manner on location. The pantry project is also about the procedures and history of collecting, conserving and producing food, as well as forms of trade and exchange. The concept of food storage in this consumption-based, throwaway society has a cultural dimen sion. To actually implement it, though, planning foresight and economical logistics are required .

This real-world food pantry inspired our wish to create an in tellectual pantry. What do we need for tomorrow? What kind of knowledge do we want to refer back to in the future? We decided to dedicate this issue of our magazine to the art of living/ survival. We asked a number of well-known cultural and scien

tific figures to tell us what ideas they would store inside their in tellectual pantry. We received numerous responses back — some of which were quite personal — and were impressed at their di versity. We’ve presented these stories, essays and reflections in such a way that they resemble various items in a pantry where the ham hangs among the sausages, the dried pepperoncini lies next to the onions and the fruit preserves are placed on the shelf next to the jars of pickles. Our intellectual pantry does differ from normal pantries in an important way its products have no expiration date.

The three longer articles focus not so much on the art of living but rather on the adversity and happy coincidence of survival. The Austrian writer Raoul Schrott ventures forth in the dramatic search for the first geological records pertaining to the birth of our planet. The French philosopher Michel Serres asks how our planet can continue to sustain life and builds conceptual life boats. The filmmaker Jutta Brückner has written a touching arti cle about her mother, whose dementia has allowed her to escape to a world of her own.

pantry harald welzer moral inventory 6 ute frevert shared happiness 6 andreas weber people have, plants are 7 sibylle lewitscharoff hoarding 8 margot käßmann teaching them to read 8 assaf gavron time capsule 9 armin nassehi stop predicting! 9 andrzej stasiuk what if… 10 herfried münkler an [almost] impossible art 10 thomas lehr the dream of the golden nut 11 friedrich wilhelm graf getting wise 12 jürgen mlynek diagnosis and therapy 12 aleks scholz the inner idiot 13 volker mosbrugger neither god, nor devil 14 noémi kiss mother in the pantry 14 dorota masłowska slow thinking 15 michel serres everyone into the lifeboats! 17 raoul schrott the first earth 23 jutta brückner in the realm of spirits 29 news 32 new projects 34 committees + imprint 38

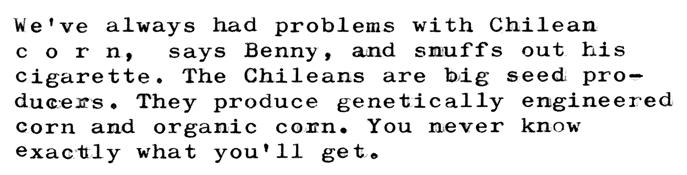

The drawings, photos, aquarelles and text collages in this issue were made by the artist Antje Schiffers . Born in Heiligen dorf in Lower Saxony in 1967, she co-founded the artists’ group myvillages.org in 2003 together with Kathrin Böhm und Wapke Feen stra. The project focuses on villages as places of cultural production. Antje Schiffers, who now lives in Berlin, was a flower illustrator in Mexico, a traveling painter in Italy, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, a commercial artist for the tyre industry, and ambassador and correspondent for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Leipzig. From 2007 to 2009 she collaborated with Thomas Sprenger on the project I like being a farmer and want to stay one , which the Federal Cultural Foundation funded through the »Future of Labour« programme. The idea of an Über Lebenskunst pantry was inspired by myvillages.org and its involvement in agriculture, local production and the International Village Store . Several il lustrations printed here were made on a trip Schiffers took to Chile for several weeks last autumn.

Klein Steimke, Lower Saxony,

Klein Steimke, Lower Saxony,

At the beginning of the 18th century, Daniel Defoe was traveling through the region of Newcastle, the most important coal pro ducing area of England at the time. He was awestruck by the »prodigious heaps, I might say Mountains of Coal, which are dug up at every Pit, and how many such Pits there are! It astonishes us and we wonder where the People might live, who consume it.«1

In the meantime, we know quite well who consumed those pro digious amounts of fossil fuels which were extracted from the earth in Newcastle first the inhabitants of England, then Ger many, North America, and after a considerable delay, all of Eu rope and many other parts of the world. Unfortunately, the coal is not yet exhausted. The fact that there’s plenty left is rather trag ic, as many countries and companies continue investing in coal power in the medium term, despite its well-documented, devas tating impact on the global climate.

But I do not mean to make this the primary focus of my ›moral‹ pantry. Rather, I wish to return to Defoe’s amazement. At that moment, this extremely imaginative man who wrote Robin son Crusoe , who through his novels and later film adapta tions demonstrated the blessings of a rationally organized civilization to generations of Western children, found himself una ble to believe his eyes. He couldn’t fathom what was taking shape before him namely the build-up to the Industrial Revolution which would radically and permanently change the face of Eng land, Europe and eventually the entire planet. And how could he have? No one could have imagined at that time that the indus trial use of coal as a fossil fuel would revolutionize the energy demands of society and give rise to all those visions of progress, growth and endlessness which economists, politicians and man agers continue to pay homage to even today.

It is even less likely that anyone could have predicted that this vision of endlessness would result in such plundering and pollu tion of our planet and to such an extent that two hundred years later, it would find itself on the brink of collapse. No, I cor rect myself it’s not the planet on the brink of collapse, but the

human societies that populate it. Many of them are not even aware that they are sorting themselves up into the winners and losers of climate change. Neither Germany nor the current environmental »bad-guy«, China, for example, will resemble what they think they will look like in 2030. In fact, they find themsel ves in the exact situation as Daniel Defoe did two centuries ago. They lack what Günter Anders coined moral imagination the ability to visualize what one is capable of producing. But this moral imagination absolutely belongs in every pantry. Such pantries are stocked in anticipation of a future situation. For example, storing the summer’s harvest so that one can eat in the winter, or saving up in years of plenty to survive through bad times. Obviously the inhabitants of the fossilistic world have lost touch with the concept of seasonal planting and consumption, or that of »bad times«. Most people think they only happen in soap operas, and besides, you can get anything anytime at Lidl, and occasionally at denn’s.

In any case, it appears that neither the average consumer nor LO HAS realizes that their world of consumption is based on three conditions first, that energy prices remain as low (and skewed) as they are now; second, that resources remain constant; and third, that nothing dramatic happens, e.g. the oceans don’t reach the »tipping point« or a huge metropolitan city isn’t wiped out by an extreme weather phenomenon. If just one of these conditions is not met, the times when you can get anything anytime will be over. And when the Lifestyle of Health and Sustainability ( LOHAS 1.0 ) becomes the Lifestyle of Health and Survival ( LOHAS 2.0 ), let’s see who is better off the farmer from Africa or the banker from Frankfurt.

It turns out that those who are accustomed to living with the bare minimum are much better at managing a pantry than those who haven’t yet encountered the possibility of scarcity. In a way, they are better at visualizing the future than those who are more afflu ent, because they have always had to calculate whether they’d have enough to survive into the next week or month. This is the existential aspect of moral imagination; it will take much more effort to incorporate moral imagination into the highly-cultivat ed, abstract circumstances of life and economy in which we live. According to Günter Anders, »the determining task of today consists in developing moral imagination, that is in the attempt to bridge this ›gap‹, to adjust the capacity and elasticity of our im agination and our feeling to the dimensions of our products and to the unpredictable excess of that which we may perpetrate; bringing, to the same level of us producers, our faculties of imagination and feeling.«2

If we do not go to the trouble of bridging this Promethean gap that exists between the destructive potential of our lifestyle and our lack of imaginative ability, we will not be able to fathom what is happening before our eyes and our failure would certainly be more harmful and less innocent than in Defoe’s case. We do know, but we are so firmly situated in our comfort zone that any movement not only seems bothersome to us, but absolutely im possible. Setting up a pantry would certainly represent a shift away from the comfort zone. We would only regard such a pantry as vital if we recognized that reality is actually a mechanism of illu sion, manufactured with enormous amounts of resources. Indeed, this pantry both symbolic and real is the counter-concept to the practices of a consumer society which is blind to the pend ing apocalypse, in which approximately 40 percent of all food is not consumed, but rather discarded, and many things are pur chased, but never used. It’s the exact opposite of stocking up it’s preemptive disposal, the transformation of resources into trash. When things get this far, society loses its sense for survival and with it, all its pre-consumerist capacity for responsibility, fairness and mindfulness. Yet without these skills, it becomes difficult to cope outside the comfort zone. So we had better start getting used to another way of life. Günter Anders recommends doing »moral stretching exercises«, »going beyond one’s limits of imagination and feeling«. In this way, we could prepare ourselves for the era after peak oil, peak soil, peak everything. Or better yet altogether avoid the end of the anything anytime era, and start making provi sions for a life with a future.

Harald Welzer teaches Social Psychology at the University of St. Gal len and is the director of the Center for Interdisciplinary Memory Research at the Institute for Advanced Study in the Humanities in Essen. Together with Christian Gudehus and Ariane Eichenberg, he edited the book Erinnerung und Gedächtnis. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch [Re membering and Memory. An Interdisciplinary Handbook], published by the J. B. Metzler Verlag (Stuttgart) in 2010. In 2008, he wrote Klimakriege. Wofür im 21. Jahrhundert getötet wird [Climate Wars. What People Will Kill for in the 21st Century], Fischer Verlag (Frankfurt). Welzer and Sönke Neitzel recently collaborated as editors on Soldaten. Protokolle vom Kämpfen, Töten und Sterben [Soldiers. Reports on Fighting, Killing and Dying], published by the S. Fischer Verlag (Frankfurt) in April 2011

1 As quoted by Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Geschich te der Eisenbahnreise. Zur Industri alisierung von Raum und Zeit im 19. Jahrhundert . Frankfurt/M.: Fischer 2004, p. 9 2 Günter Anders, Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen. vol. 1. Munich: Beck 1979, p. 273

Emotional economy, as I call it, plays an integral role in the art of living and survival. By this, I’m not thinking of markets, limited re sources, supply or demand. Rather, I have the ancient Greek word oikos in mind a complex socio-ethical construct with tasks that far ex ceed the scope of production and distribution of goods. Francis Hutcheson referred to this concept in 1728 when he reflected on the disor derly nature of passions caused by custom, edu cation and company. In his treatise, he argues that it is essential that »just Ballance and Oecono my« exercise control over the passions, as this would »constitute the most happy State of each Person, and promote the greatest Good in the whole«.

We could learn much from Hutcheson and his successors. Of course, there have always been those who gladly give their two-cents worth re garding how best to deal with human affections and passions. There have been times when the fear of fiery emotions was fanned, when voices lavished praise on the happy medium, on a sound balance between hot and cold, passion and tem perance. Although the moral philosophers of the 18th century joined this bandwagon, they al so attempted to relate Ballance and Oeconomy to the fundamental forms of social communica tion. What emotional economy did a modern society need, like that which was developing on the British Isles at the time? What passions were good or bad for a capitalistic economic system, the theory of which Adam Smith outlined in 1776? Egotism and selfishness were obviously insufficient (although they were important and deserved to be defended against religious or po litically motivated attacks).

Such questions and considerations sound surprisingly contemporary. Even today we continue to put much thought into how the egotism of an individual can be reconciled with the common weal. The excessive greed of many investment

bankers and the unrestrained ambition of some scientists stand accused. Praise is heaped, on the other hand, on the beneficence and selflessness of philanthropic activists; along with Mother Theresa, Doctors Without Borders have become iconic for modern empathy. The wide variety of humanitarian interventions, beginning with the campaign against slavery in the late 18th century, maintain some of the highest operational budg ets in the world. Each year, such organizations turn over several billion euros, and the amount is increasing.

And so it seems that sympathy, to which both David Hume and Adam Smith refer, has be come a globally active force. Both philosophers contrast self-love with the equally natural and necessary emotion of sympathy. According to their line of argumentation, modern societies strongly rely on their citizens acting not only in self-interest, but also with sympathy toward oth ers. Smith describes this as fellow-feeling, by which he means the ability to put oneself in another’s shoes and feel what they feel. He asserts that all human beings are born with the ability to sym pathize, and recent neuroscientific experiments and studies support this claim.

Yet just because the expression of sympathy is natural and possible does not mean that it actually happens. For almost three hundred years, scien tists and philosophers have debated which conditions are necessary for evoking Smith’s fellow-feel ing (which we call ›empathy‹ nowadays). It most always involves feeling someone else’s suffering. Whether it’s possible to feel sympathy with our neighbour or someone living halfway around the world, whether it results from the innocence of the sufferer, and whether it helps the sufferer or lends power to the sympathizer are all questions discussed and debated in myriads of books, talk shows and TV documentaries. But few people have reflected on the ability to sympathize with another’s joy. Smith also em phasized the ability and necessity to sympathize with the happiness of others. This normally happens anyway in personal relationships among friends and family. We feel happiness at seeing our children and parents happy. We experience the joy of our friends as if the joy were ours. But what about the joy of those who we don’t care about so deeply? Do we feel happy for a col league who has won a prestigious award? Or do we believe in secret that we were more deserving

Let‘s fill our pantry! I would put flower bulbs into our storeroom. Kept at a suitably cool temperature, they would hold for a long time. Each bulb is tiny, shrivelled, brown and drab. But each contains tremendous energy. In each bulb slumbers a birth as fresh as creation and an ever-present promise of death. In a way, these inconspicuous dormant organs are like Leibniz’s mon ads self-contained flames, yet luminous the world over. I would choose snowdrop bulbs. Granted, they are a little poi sonous. But snowdrops with their bells hanging in the gray air at the end of winter are truly a new beginning. The embodiment of a fresh start. Two years ago I discovered snowdrops growing wild in an abandoned garden plot. I found them amidst the wilted leaves of a scraggy apple tree where garden clippings had been dumped the previous summer. About a dozen blossoming is lands had pushed their way through the leaves. It seems the ex ceptionally hard winter that had ravaged above their heads hadn’t bothered them in the least. With perseverance that only the truth is capable of, they had, in the frigid darkness, developed into what they were destined to become. I made my way through the brush of the abandoned plot to the apple tree without much hope of finding anything. And at first, I didn’t. But then, after closer inspection, I discerned the fine blades among the crystals of ice, white buds and finally the first

blossoms drooping heavily from thin stalks. The bells hung like tender muscles from their stems, guided by flexible necks, as if they were connected to the earth by an elastic band. Flower chains. The petals, rolled up like interlocked fingers, the cup and stem pushing through a fine skin which would remain behind like the skin of an onion when the flower finally bloomed. Layer by layer, the inevitable spring arrived, peeling away the winter from the light. To defy the frost, cold and dreariness, it seems the highest degree of fragility and tenderness is required. I remained kneeling in the grace of these snowdrops for quite some time. It was this that saved me, at least for the short time these flowers would be allowed to grow here. The garden plots were all being ploughed flat. A new park was planned. I knelt by the flowers and didn’t notice the numbness in my legs. Fine crys talline drops rolled off the petals, reflecting the edges, casting rays of light upon the brightly bending necks of the stems, shim mering in the almost non-existent breeze. The dew drops made each blossom into a crystal chandelier, imperceptibly swinging above the bottomless canyon of a white sky.

Springtime is a period of convalescence, the final stages of an ill ness which carries with it new life, like the scab of a wound con cealing the new, soft skin beneath. If one looked very closely, one would see a spidery web of cracks spanning and crisscrossing the entire landscape, the signs of a new beginning readying itself to burst through the colourless surface. The longer I looked, the more it seemed that the flowers had freed themselves. Perhaps it was happening imperceptibly before my eyes. Like thorns, the tips of the snowdrops penetrated the wet leaves, enshrouded by their decay. Dying is a process of birth in reverse; at the end comes the inconceivable moment of a new beginning arising from nothing.

Every day, sometimes more than once, I returned to the lumi nous bed of snowdrops. I wanted to make sure that they were still

there. I had the intense feeling that everything was contained in these flowers’ tiny gesture. It was the feeling that the thin stems, the green blades of their leaves, the whitest white of their blos soms, their sudden existence one day in March, their inevitable disappearance in the impending maelstrom of spring (buried be neath the budding life) couldn’t be made any more perfect and complete. What a celebration life is, what a long, roaring party, as powerful as space and as fragile as gossamer in the wind.

It’s this effortless waste of energy that we humans don’t under stand this muscle tautened to the point of shredding, com prised of nothing but a wisp of light, yet holding this conver gence in its hand. The flowers had arrived. With the patience of all of creation, they had waited a whole year for this moment when they could finally surrender themselves to the light. In Danish, snowdrops are called spring’s fools. We should embrace their slim necks and let them hold us above an abyss of grace. One morning almost all the flowers were gone. Someone had dug them out, bulbs and all. When I got there, when I saw what remained from afar, a thought crossed my mind up close, these islands of light outshine everything, but from far away, they look rather unremarkable. And then I saw the holes. Wild boars, I thought, the wild boars must have eaten the bulbs. But then I realized that someone had dug them out. Carefully I ap proached and tried to take comfort in the last remaining blos soms, as if I were warming myself with a match whose flame could extinguish at any moment.

Andreas Weber, born in Hamburg in 1967, studied Biology and re ceived a doctorate in Philosophy. Now a journalist, he has written several books, including Biokapital. Die Versöhnung von Ökonomie, Natur und Menschlichkeit [Biocapital. The Reconciliation of Economy, Na ture and Humanity], published by the Berlin Verlag in 2008. His latest book, Mehr Matsch. Kinder brauchen Natur [More Mud. Children Need Nature], will be published by the Ullstein Verlag, Berlin in 2011

of the award? Do we feel joy when we hear of the success and fortune of others? Or do we take se cret pleasure in hearing of someone’s misfor tune or blunder? It’s no coincidence that we’ve got a word for this schadenfreude along with its company of scorn, mockery and ridicule. And interestingly enough, this German word not only exists in English, but also French, Ital ian, Spanish, Portuguese and Polish. By no means does this imply that schadenfreude is a German invention. The German term was likely introduced into other languages through cultural and scientific transfer (in particular, in the field of psychoanalysis). Whatever the rea son, it’s obvious that people everywhere not only in Germany, Austria and eastern Switzer land occasionally feel pleasure at hearing of others’ misfortunes. Psychologists and neuro scientists from Japan, Israel, the United States and the Netherlands have had no difficulty finding enough test subjects for studies on the causes and effects of schadenfreude However, far less energy has been expended for researching its positive counterpart not schadenfreude, but rather mit-freude, or »shared happi ness«. There are numerous reasons for this. Like

the old adage in journalism »bad news sells«, se rious public discourse primarily focuses on that which is problematic, dangerous or perplexing. »Feel-good« topics, on the other hand, are the do main of bad novels, self-help books and health magazines. I don’t mean to pick bones with this division of labour. I also have no intention of promoting happiness as an auto-suggestive elix ir to increase one’s vitality and performance or join Erich Kästner’s readers in asking »What about the positive aspects?«

What I have in mind is more along the lines of Friedrich Schiller’s joyous ode along with its mu sical echo, which, by no coincidence, eventually became the European anthem. Schiller describes joy not only as the powerful mainspring of individual action, but also the ferment of human socialization. Happiness creates a bond between friends, lovers, and even between »brothers«, by which he means potentially »all men« (whether women are included remains unclear). His words, »Those who dwell in the great circle, pay hom age to sympathy!« resemble those of Smith’s but with a new twist and touch of more ancient cos mology. Sympathy and shared happiness are the great assets of social order which Schiller

attributes to the European-cosmopolitan ideal that of openness, meritocracy and solidarity values which are certainly worth drinking to.

We can witness how powerful these assets can be, when, in rare circumstances, shared happi ness is produced and communicated on a mas sive scale for example, the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989, the inauguration of Barack Obama on 20 January 2009, and the suc cessful rescue of the Chilean miners on 13 Octo ber 2010. It is just as important to study the con ditions and requirements of such collectively shared moments of happiness and investigate their repercussions as it is to understand the mechanisms of schadenfreude. We could even go so far as to weigh the benefits of teaching the ability to feel happiness with others. Shared happiness can be an educational goal, as schools in the English-speaking world have already dem onstrated with programmes to promote empa thy. This need not only apply to schools, but al so within one’s family, at one’s workplace, in sports, etc.

Of course, there is something artificial and forced about such utopian visions. But we also

know that not all feelings develop naturally. Many feelings require fostering, cultivation and incentives. We also know that every utopia can be discredited by pointing to the extremes and unintended consequences, for example, a land of frozen smiles. This is not about implement ing a totalitarian master plan, but rather creat ing more opportunity for humans to expand on their ability to share in each other’s happiness in our modern emotional economy. We have good reason to hope that this would benefit the art of living and surviving immensely.

Ute Frevert, born in 1954, is a historian with exper tise in the areas of social and cultural history of modernity, emotional history, gender history and modern political history. In 2007 she became the director of the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin. In 1998 Fre vert received the Leibniz Prize . In 2009 she edited the special issue Geschichte der Gefühle. Ges chichte und Gesellschaft [History of Feelings. History and Society], published by Vandenhoeck & Ru precht, Göttingen.

My greatest concern is that men will disappear. It is quite possible that the only men left in our latitudes will be those infantile specimens who refuse to develop rugged features or those, who at 40 or 50, can barely keep the last few strands of hair on their heads. That’s why our symbolic pantry should be stocked with books with men in them. Men of broken, sophisticated hero ism upon whom my mind’s eye gazes with a touch of yearning, not to say cute flirtation. We cannot forget Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye . Oh, oh, oh, like a girl smitten, I see the drunken Terry Lennox stumble out of his little sports coupe what a character! A polite drunkard with scars in his very pale face and as we learn little by little a man with a dra matic war history. Speaking of sports cars, let’s put Jack Bickerson Bolling, the Moviegoer , by Walker Percy on the shelf in our pantry. Also a gentlemanly hero, yanked right out of the war in the Pacific and thrown into the novel, an ex cellent sports car driver a low-set MG , whose chassis scrapes every bump in the road a real guy, melancholy but not lame, sensitive but not a sissy caught up in himself.

Some people might say I’m too old for such erotic swimming sensations and sports cars, for sure. They’re probably right. A real junkie doesn’t abandon her favourite drug on sound advice. That’s why I’m smuggling a third hero into my pantry another who’s been around for while F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby . Here’s another improbable fellow, very rich, very hon ourable despite a dishonourable past, strongly attached to his first love, albeit foolishly so, a character and I’d eat a broom, the handle and all if I’m wrong who never existed in reality. That’s enough of the Eros-lisping hero-hoard ing. Now to more serious things, to Kafka. Kaf ka, of course, is essential, every literature crack would agree. His diary, in particular, is essential; the mother of all diaries, so surprising, enthusi astically jumping from topic to topic, and yet laced with more penetrating introspection than any other in the world. His unfinished Amerika , don’t forget the Process , and if pos sible, let’s throw in his complete works; it’s not like they take up countless metres of shelf space. Now we come to Herman Melville. We need to have his Bartleby , this slender, extraordinary eccentric, who in some intricate and elegant way says No to everything people ask of him, by which he brings the world to the brink. An American messiah of determination, who con vinces you with his gentle voice that nothing need be or remain the way it is. And that brings me to Mrs. Dalloway , this wonderful, floating phenomenon of post-war London in the

early twenties, as fresh, tender and clear today as she appeared back then. Everything simultane ous, everything in silent uproar, the phenomena touch one another with an energy that Virginia Woolf’s highly sensitive fingertips inspired even beyond the grave. What a work of magic! I also want to have fun. The Three Right eous Combmakers by Gottfried Keller is just the thing. Everything Züs Bünzli does to keep her three suitors interested is so mind-numbingly humorous, I have to laugh when her first name is mentioned Züs, nicknamed Züssi, you bone-dry spinster, mean as a wasp, ingenious as a small-town Machiavelli, I bid you welcome! Speaking of wasps, I do not wish to go without Francis Ponge’s fine portrait of the wasp in La Rage de l’Expression , without his oyster, the fig, the pine-wood, the bumblebee, the peb ble, the frog, the moss, his cigarette or the clam organic, inorganic, and though not human, displaying something humanlike, to blink one’s eyes, to smile at us and hold a tiny speech with tiny gesticulating arms. If the world were to col lapse around us, the speeches, like the one the cigarette delivers to us in the dark, would mean a lot.

But now the Federal Cultural Foundation is urg ing me to pack faster; everything that must go into storage should go without longwinded ex planations. Wunschloses Unglück by Peter Handke, Versuch über die Juke box , in you go, Westend by Martin Mose bach and Was davor geschah , then the

feather-light Pigafetta by Felicitas Hoppe, Porzellan and Vom Schnee by Durs

Grünbein, let’s not forget the irritating timber cutting by Thomas Bernhard, and how could I forget my beloved Lost Ones by Samuel Beckett. My explanation would be very drawn out indeed, if I had to tell you why I’d include the Bible, naturally Martin Luther’s original translation in its not so easily digestible, greaseladen German, and definitely Homer’s Odys see and definitely Dante’s Divine Come dy (perhaps in two translations, one of which should be the eccentric one by Rudolf Bor chardt); and if, after having hastily thrown to gether such company of high calibre, I accident ly include a pulpy Ellroy crime story fine by me!

Sibylle Lewitscharoff, born in Stuttgart in 1954, was awarded the Ingeborg Bachmann Prize in 1998 Since then she has received numerous literature prizes, the most recent of which was the Leipzig Book Fair Award 2009 for her latest novel Apostoloff , which was published the same year by Suhrkamp. Lewitscharoff is currently working on her next novel about the philosopher Hans Blumenberg.

When I was a child, money was tight. We were four kids, one of my brothers died in infancy, and the three of us were expected to go to school, graduate with an Abitur, get an education. Our fam ily never had a scholarly library like the ones I saw in the homes of children whose parents were theologians, lawyers or philoso phers. But our mother never skimped on books. We were allowed to read. Karl May, Enid Blyton, you name it. It wasn’t about pro viding us with »high-quality literature«, but simply having fun reading.

And how wonderful it is to plunge into a book, to let it take you to another place, to let your imagination run free, to try to under stand other worlds! Reading’s allure is impressively strong. I re member when I was a kid, reading underneath the bedcovers with a flashlight, unable to put my book down long after my par ents had announced »lights out!«

When I began studying at university and especially while I was working on my doctoral thesis, reading became a profession. The more I read, the less well-read I felt! I encountered an academic world of philosophy, ecclesiastical history, practical theology and systematology which I often had difficulty understanding. But when I finally slogged my way through and comprehended, I was rewarded with a feeling of elation I understand. We can understand together and think further.

There were times when I wasn’t able to read as much. As a work ing mother with four children, I sometimes had no energy left to

open up a book in the evening, no leisure to dive into another world, no concentration to follow the narrative arc. The sum mers we spent together with many families were absolutely won derful. All of us mothers agreed to read a different book together every year. I recall our vacation in France when all eight of us read Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time We nibbled on the obligatory Madeleines as we read our books.

I learned a lesson, namely that we are less likely to forget a book we’ve read together with someone else than one we’ve read by ourselves. Discussing books make them profoundly deeper. My oldest daughter read a lot, always, constantly. My two middle daughters, twins, were not big readers, they were busy with sports and music. But surprisingly when they studied at university, they practically devoured the books they were assigned to read. As for my youngest daughter, I feared she’d never read, a child grow ing up in the age of computers and Internet. But then she got her hands on The Lord of the Rings . I didn’t see her for days. Then came Harry Potter . She and the leading ac tress in the film versions were the same age, and you could say they grew up together. She read the third book in the series in English with no problem though her English wasn’t especially good. There it was again, that feeling, the fascination of reading, the discovery of new worlds, the enthusiasm, the inability to put the book the down. Wonderful, amazing! It doesn’t have to be Goethe or Descartes. Reading itself is a cultural asset! And reading is a matter of justice and moral responsibility. Mar tin Luther translated the Bible into German so that normal peo ple could read it. Prior to that time, church services were held in Latin. Parishioners only had images, but no words for the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The translation represented an enormous cultur al achievement. In Luther’s times, Bavarians and East Frisians could barely understand one another and to some extent, it’s still that way today. But language educated and integrated! Furthermore, the translation of the Bible was a remarkable aca demic achievement. In his letter to the »Christian nobility of the

German Nation«, Luther called on the German rulers to estab lish schools for both boys and girls so that they might learn to read and write. A measure, he argued, that would allow them to personally temper their conscience according to the Bible’s teach ings. That was a revolutionary cultural achievement! Yes, for me, reading is integral for the art of living. Losing oneself in a book. Not being able to stop, even when it’s time to go to sleep. Rooting for the characters! Reevaluating the world, under standing it differently, seeing it from a different viewpoint. There happens to be a fitting reference to this in the Bible. In the Acts of Apostles according to Luke, chapter 8, Philip meets a »eunuch« reading the scripture of the prophet Isaiah. »Philip ran up and heard him reading Isaiah the prophet and said, ›Do you under stand what you are reading?‹« Philip explains the scriptures to him. The eunuch comes to believe and has Philip baptize him. In my view, Philip was the first reading patron. If only we had more of them! People who would make time to teach children to read. There are a number of wonderful projects out there already just think of all the worlds that children are discovering! Read ing is also a central aspect of integration. Sharing texts and litera ture is a bonding experience. Debating and discussing the writ ten word that contributes to peace. Being acquainted with common texts that creates common identity. And that’s why, for me, reading is an important aspect of the art of living.

»Yes, who are you?«

Two people sit behind a metallic desk. Men, as far as I can tell. Serious, as far as I can detect. The room is huge, maybe as big as an aircraft hangar. But inside it looks like a room. White walls. A metallic desk. Two people. I approach them. »Excuse me?«

»Who are you?«

»Gavron.«

»Yes, Gavron. When are you from?« Now I remember. They woke me up in the middle of the night. Told me to quickly pack my time traits, the attributes of my era, for an urgent dispatch into the future. As usual, they didn’t give me enough time. I shoved a few things into three capsules and then I can’t remember what happened. Next thing I knew, I was in this room. The metallic table. The people.

»I’m from around the turn of the millennium.«

»Which millennium?«

»End of the second, beginning of the third. A few decades on ei ther side. What year are we in?«

One of them glares at me sternly. »We’re in the future,« he says and looks down. »Yes, I see here. Gavron. You must be talking about the Christian calendar, and you are probably referring to A.D. All right. What have you got for us?«

»I have three capsules. In the first one I threw some cultural artefacts.«

They look at each other and then back to me. »Cultural arte facts?«

»Cultural artefacts: records that hold music in their grooves. Rolls of film containing movies and pictures. Books made of pages, which are made of paper. Artefacts. Stuff. Things you can feel. Touch.«

»What is the use of that?«

»People like liked to touch things. They found it pleasing to know that art is tangible. That it exists in space, that it occupies

volume. That it’s not just air. Air you can amass and listen to and watch in all sorts of beautiful and elegant computerized versions, but still just air, sounds and images and words you cannot grasp with your hand and say ›I own this.‹« They make no response, so I continue: »They like to give and receive, to caress things, smell things. They also like to gather together to watch movies and plays, or listen to music.«

»Together?«

»Lots of people in the same room. A shared, social experience. Communal consumption of culture. Is that something you have here, now, in the future?«

»Mr. Gavron, this exercise is not about us in the future, but about your present. What’s in your second capsule?«

»Liquids.«

»What kind of liquids?«

»I have two bottles, each containing a different liquid. One is fu el, the other is water. Are you familiar with water?« They keep looking at me without saying anything, so I go on. »You need fuel to drive cars and fly planes. And you need water to live. They are both growing scarce in my time, so people are fighting over them. Because of these liquids there are wars.« I vaguely detect a wrin kle appear over one of the men’s foreheads. »There have already been a few wars over oil, so it’s probably all finished now in the world.« I look at the white wall to my right, as if searching for a window through which I might be able to see which year I’m in and what the status of oil is. »Water is a more recent story, but it’s also starting to disappear because the world is getting warmer. So people are beginning to fight over that, too.«

»Are you proposing that we hold onto these two liquids?«

»No. I just hope you’ve found a more available and cleaner energy source than oil. And that you’ve somehow been able to pre serve your water. Water is definitely something from my era that I think should be preserved for future generations.«

They say nothing. One of them drums on the metallic table with something that looks like a pen. I wonder if I’ve disappointed them.

»In the third capsule is an illegal settlement outpost,« I say to break the silence.

»Excuse me?«

»An illegal outpost. It’s something that’s going on where I live. It’ll take too long to explain the whole story, so I’ll keep it simple: different people claim ownership of the same piece of land. Vari

ous forces, at various times, tried to divide the land and establish borders, but they were unsuccessful. The borders are unclear, the leaders are weak, the civilians and subjects are angry, and some of them take the law into their own hands and do whatever they want. For example, they set up settlements without legal permits, with murky support from some authorities and opposition from oth ers. They create confusion, resistance, sometimes violence. They and their opponents are often motivated by an aggressive and uncompromising ideology that stems from religion and nation alism, from laws and dogmas which, they say, reflect an eternal truth that is inarguable and must be obeyed.«

The man who was drumming with the pen, who has been silent up to now, looks at me curiously. This time he speaks: »And what will your illegal outpost bequeath to future generations? What about it are you seeking to preserve for us?«

»Maybe just a warning: about the dangers of religion. The dan gers of borders. I don’t know what sort of world you live in, but if enough time has gone by and you’ve learned how to live without borders, I’m happy for you. If people have continued to wander around the world and races have mingled and procreated in such a way that has significantly diluted the number of ›pure‹ people, turning ›mixed‹ people into the majority, so much so that nation alism and racism have become meaningless because there is no one left to support them or direct them at then so much the better for you. And if the power of religion has diminished, or at least the use of religion to justify immoral, inconsiderate acts, acts that lack any logic more complex than a reliance on ancient texts then I envy you.«

They look at one another. I think I see the pen-holder smirk at his colleague. The other man puts both hands on the table and shouts: »Next!«

Talking about the future is easy. And talking about the future is risky. It’s easy, because we don’t know the future. And for the same reason, it’s also risky. The future is the ultimate projec tion surface. In the truest sense of the word, it is the pre-tense of a future that will never be and only the starting point for new future designs. It is no accident that utopias have always been fu turistic visions, because at the moment they are envisioned, their validity never had to stand the test of time. So why talk about something that will never come to pass, at least not as it has been envisioned?

At first glance it may seem that this position re jects the topic at hand. And that’s what it does.

But at a second glance, this position is not borne of intellectual indulgence, the validity of which need not be ascertained, but is the response of a detached observer at a time when it is en vogue to be suspicious of futuristic scenarios, especial ly in view of their inadequate predecessors. But perhaps this position is more than an attempt to wriggle free of responsibility, because, after all, the future is a matter that »matters« to our fu ture.

It’s worth examining earlier futuristic concepts for the future. The history of futuristic concepts is in fact a history of past presents, and by this, I mean the illusions or wishes or fears of the fu ture which each present harbours. We only have to look back at the cultural, Eurocentric eupho ria of the 19th century or the 1960s technologi cal fantasies of metropolitan futures which were mainly spawned by the world’s technical capa bilities and the optimism of Western middleclass realities. Such futuristic visions were ulti mately extrapolations, as they offered an image of the future based on their present time and what other basis was there? Alright, they might have known better, but they didn’t.

The kinds of future concepts we make today are all characterized by consensus and expectation. They generally relate to matters of democracy, de mographics and demotoxification i.e. the forms of state and legitimate decision-making routines of the future, various population trends in global society and poisoning people with too much in formation, with environmental toxins and the impact of energy production. I have no wish to go into these future scenarios here.

By failing to offer concrete positions regarding the future and only reflecting on the strange perspectivity of future concepts, it might appear as if I were trying to avoid the unavoidable. However, my reference to perspectivity, in other words, the imprisonment of every concept with in the perspective of the individual, might be exactly what signifies the social present-day.

Perhaps we would be better off with fewer future concepts, fewer survival strategies, and simply be less enthralled with what the future holds. Perhaps we should be more interested in learn ing how things develop.

This could well be the basic experience of mod ern times that our view of the world engen

ders the world we see and not vice versa. Post structuralist, cybernetic and system-theoretical theories and neurophysiological research find ings are trying to tell us something that every body can now experience on their own. One cannot perceive things beyond one’s senses see beyond what the eye can see, hear beyond what the ear can hear, taste beyond what the tongue can taste, smell beyond what the nose can smell, feel beyond what the skin can feel, and think beyond what our minds are capable of thinking of. We are bound by what our eyes, our ears, our tongue, our nose, our skin and our minds communicate to us.

We are also entangled in our perspectives of the world which differ economically, politically, scientifically, religiously and legally versus the logic of the mass media. This entanglement is evident in our daily conflicts and misunder standings, because these perspectives are the only vehicles we have for communication. If com munication doesn’t seem to work, it’s because communication is not an amalgamation, but rather the tool for processing differences in per spective. Maybe the only reason communica

Assaf Gavron, born in 1968, grew up in Jerusalem, studied in London and Vancouver, and now lives in Tel Aviv. He has written five books and is one of Israel’s best-selling authors today. He has also translated Jonathan Safran Fo er, Philip Roth and J.D . Salinger into Hebrew and is a singer and songwriter of the Israeli cult band »The Mouth and Foot«. In 2010 Gavron was awarded a fel lowship by the DAAD Artists-in-Berlin Programme. His novel Alles Pal etti [Moving], translated into German by Barbara Linner, was published last year by the Luchterhand Verlag, Munich. Translated from the Hebrew by Jessica Cohen.tion exists is because we as people are inaccessi ble and opaque to one another. Yet at the same time, communication promises to remove this mutual opacity. There is no escaping this para dox we must simply learn to live with it. And now I will talk about the future. What we need in the future (in other words, right now ) is a better understanding of how we are entangled within our own perspectives. We have to learn that the problems and solutions of this world all have different implications and significance in terms of their functional perspective their economic, political, religious, scientific, legal and even cultural perspectives. We need solu tions which take this perspectivity into account. Is this too abstract? Possibly, but it’s equally pos sible that our solutions to date have been too concrete, because they always wanted to see what they’d look like when they were put into practice. In terms of Lebenskunst, the art of liv ing, one might think of composure, of enduring one’s present times, on the simultaneous con tingency and inescapability of one’s own perspective. Perhaps Über Leben(s) Kunst , or ›the art of surviving‹ has more to do with art, be cause if anything, there are two lessons that art can teach us learning to understand the ines capability of forms and perspectives and negotiating between total contingency and necessity. Art is capable of seeing more, because it can see seeing and that, by the way, is the oldest modern utopia. We have no need of a new one if we can find a way to stop fighting our own per spectivity and start utilizing it operatively.

… or maybe, instead of preparing ourselves to live on in some illdefined way, we could consider a Plan B ?

Consider simply leaving, disappearing. It seems we have no other task beyond the biological survival of the species. Certain repre sentatives of that species are going to be richer and richer and will live longer and longer. Others, quite the opposite. Neither the first perspective nor the second seems worth the effort. We’re go ing to live longer and longer, and get more and more bored. To keep from being bored we’ll have to buy more and more. More and more stuff, more and more health, more and more life, more and more organ transplants. It’ll be a tedious longevity, and an even more tedious eternity, which some may attain. It doesn’t bear thinking about. And it’s even harder to think about those who are never going to attain anything. Who’ll be born, die in short order, and no one will ever hear of their existence. They’ll die of hunger, sickness, of fear and of sadness. They’ll die in the awareness that somewhere well-fed, healthy, immortal people are going on living. Perhaps it’s the case that we’ve already accomplished what we were supposed to and it’s time to go away time for Plan B . Nothing is left of the great religious, metaphysical plan. We were una ble to carry it out. We couldn’t bear the weight of the knowledge that we’re not alone in this world, nor keep our faith in the idea that it’s not the last of worlds. That didn’t succeed. Plan A was a failure. Our life turned out to be as random and egotistical as the life of monkeys, or of shrimp. More so even, because mon keys are at least useful for experiments, and shrimp are food for whales. Our life, on the other hand, is perfectly selfish and serves only for its own survival and self-duplication. Well, maybe we’re of some use to illnesses, to bacteria and viruses. It’s a somewhat ironic turn of events: once we served God, now we serve mi crobes. It would be hard to find beings whose existence carries less meaning. And that’s the end of it. The last historical, hysteri cal attempt to preserve what was left of humanity probably took place in 1917. At that time some of us at least tried to cobble to gether something along the lines of Genesis or the Big Bang. And in fact the world came close to going up in smoke. All the same, it was a bold idea: to create a new sort of human being, since the old kind seemed inadequate.

One way or the other, things don’t look good: as a mass, as a crowd, as globalized manure we’re going to be serving the few on their path to immortality. It’s going to happen eventually: bio technology will be the victorious successor to religion and revo lution. The chosen few will be able to live so long that they’ll be overcome with boredom, they’ll have had enough. At the same time they’ll see to it that the rest should live short enough that they won’t constitute any competition. Because can you imagine one generation after another arriving in the world and not dy ing? Living and living and living, using up what’s left of the ener gy and food and air and light on this cramped planet? It’s a vision from a cosmic horror story. The richest ones, the immortals, will ensure that we croak like ants or termites the moment we stop being useful. You don’t need futurology to understand this, it’s enough to look at the present. It’s enough to imagine to yourself that the whole of Africa, for example, could be removed from the map of the world and no one (aside from the Africans them selves) would notice a thing. Yes indeed, you could simply snip off that part of the map with your scissors and watch it disappear into the blue waters of the ocean, and then into the depths of space. Naturally, beforehand it would be necessary to extract everything of value from the earth: oil, minerals and so on. But do the people who live there constitute anything of value for the rest of the world? Surely only as cheap labor. At least until they lose what’s left of their strength. Strength? Yet human strength is less and less necessary. We fight like dogs over the scraps that the richest fling down to us. We wag our tails so someone will notice how useful we are. In the mean time we become less needed with every day. Like the Africans, just a little more slowly and in a slightly healthier climate. What was supposed to make our lives easier ended up making them su perfluous. And that’s why Plan B seems a way out that, though perhaps somewhat desperate, is at least honorable. If the dino saurs vanished, why should we remain? I see no purpose in it, and furthermore I see no chance that we will ever create such a purpose. We can live a little longer in the knowledge that we’re needed by bacteria and viruses. But ultimately that purpose too will disappear.

kulturstiftung des bundes magazin 17

Over the course of time, our attitude toward »middle ground« and »moderation« has changed. Whenever advocated by an old er generation, they are scorned as the pinnacle of narrow-mind edness, the expression of fear of the future and a sign of conservative stubbornness. Then there are times when more people voice their belief that society can only have a future if it takes the middle path and exercises moderation. In the first case, call ing for a return to the middle ground and moderation is scorned

as an expression of mediocrity, as the ideology of the unexcep tional. In the second case, the middle ground and moderation are praised as the prerequisites of human survival. In other words, embracing the moderation of the middle is the only way we can control the self-destructive forces of unleashed selfishness and our fatal penchant for exaggeration and excess. In this case, shift ing our focus to the middle and moderation is like erecting a barricade across the collective path into the abyss.

In Germany, the criticism of moderation and middle ground peaked around 1968 when the maxim of mediocrity was coun tered by the burgeoning desire for self-fulfilment and the de mand for radicality. Being radical meant tackling problems at their root and no longer accepting »lame compromises«. Friedrich von Logau’s aphorism, »In situations of great danger and need / the middle road leads to death», dating back to the Thirty Years’ War, became the recipe of inevitable doom for the levelled playing field of middle-class society, as Helmut Schelsky once described the young Federal Republic of Germany. To counter the social stasis of the middle ground and moderation, the New Left focused on the dynamics of future orientation with ideals and visions which were intended to shake up the calcified cir cumstances.

There’s not much left of that spirit of optimism. Many of the leading 68ers who embarked on a radical path have, in the meantime, →

Armin Nassehi, born in Tübingen in 1960, is a professor of Sociology at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Univer sität in Munich. His most recent book, Mit dem Taxi durch die Gesellschaft. Soziologische Storys [Taxi Ride Through Society. Sociological Sto ries], was published by Murmann, Hamburg in 2010 Andrzej Stasiuk , born in Warsaw in 1960, writes critiques and essays for major Polish and German daily newspapers. In the early 1980s, Stasiuk was actively involved in the Polish pacifist opposition movement, and in the mid1990s, he started his own publishing company. In 2005 he was awarded the Nike Award for Best Polish Book of the Year. His recent novel Winter. Fünf Geschichten [Winter. Five Stories], translated into German by Renate Schmidgall and Olaf Kühl, was published in 2009 by the Insel Verlag, Frank furt/Main. Translated from the Polish by Bill JohnstonIf I were a fine artist and were given the permuta tion above, I would find plenty of ways to ex press the significance of that little gap between the words Über and Lebenskunst .* But I am a writer, and for purely egotistical and prac tical reasons, I’d be satisfied to ask my own exis tential questions using the four phrases above. Should I put art above life or vice versa ? Does art come after survival? Is it worth surviving with out art? Should we know more about art life in order to survive, leaving it open to debate, whether we mean to save our artificial or artistic life?

As I see it, the answer is simpler than these many questions suggest. I create art in order to survive, and I believe that survival without art wouldn’t be worth experiencing. However, thinking about artificial survival gets more interesting when we reveal the hidden or suppressed connector OF as in the »art (of) survival«. We could, or perhaps should, attach the social aspect to it. This would allow us to view the tense interplay between the personal art of survival and the survival of art as such, which are bound in a complex, antagonistic, but also symbiotic relationship. The max ims for one’s personal will could find a place be tween the extremes of James Bond’s To Live and Let Die and Kant’s categorical impera tive.

If this were only about my personal art of sur vival, then I could exploit the rest of the world in the most deceptive and unscrupulous manner and do it so intelligently (here comes the art) that no one would catch or persecute me. I could also be less criminally minded and live as well as I could to the best of my ability without giving a care for the others as far as they let me. My only offense would be indifference, but then I’d have to take my chances that the Furies might come to haunt me. But, I want nothing more than to do the greater whole a great favour, even if it costs me everything but my credibility. The idea of a pantry may well be the solution for the apparently inherent antagonism between individual and collective benefit. Materially speaking, it cannot eliminate the conflict, for as we know, we only have one real pantry at our disposal the planet Earth. We argue every day and will continue arguing about how we use, exploit and preserve our planet. Society must always pay for whatever the individual takes for him self, and vice versa. What we’d need is some

thing like a golden nut (pantries always evoke the image of squirrels), something that we could store away and take out without inciting dissent and with no need to compete for resources. It’s obvious that this golden nut can be nothing more than a dream, or by extension, an object of the mind. Humanity still has enormous re serves at its disposal. Whether they truly help us is the real question. We have unlimited resourc es of great ethical maxims and general places, but they are not all very believable. Religions, which have been making headlines lately, don’t make me overly optimistic either, especially be cause I am reluctant to see social behaviour tied to the world hereafter (which rarely generates any pleasant forms of the art of living). And who would be so brazen as to carry the bloodencrusted fetish of revolution where, for what, from whom into the pantry? It seems to me that it would be best to look for a concrete, down-to-earth answer, as if my best friend, or better yet, my own child asked me the question. Just now, my ten-year-old daughter came in and asked me what I was writing. After I explained it to her, she naturally wanted to know the answer. And so I said: knowledge and love the content of the golden nut, two halves, which, by no accident, resemble the brain. When I was a young man reading Bertrand Russell, who took the idea from Baruch de Spinoza, I learned to regard knowledge and love as the foundation and basic maxims of human behaviour. With English pragmatism Russell argued that with out love there is no good reason to do some thing for oneself or for others. Without knowl edge, this love would remain helpless and inef ficient, and would be forced to capitulate in most cases of emergency. In Spinoza’s Ethics , one also finds a magnificent, beautifully crystalline

system of thought, which, although no longer believable, is an intellectually rewarding read. Anyway, back to my ten-year-old daughter who didn’t appear completely satisfied with my an swer. I turned the tables and asked her to tell me what she would put into the pantry. She replied, »Peace, agreement, environmental protection, trust, not only work but also fun, and modesty«. That’s not much worse than Russell and Spino za, in my opinion. She also thought my answer was very good and elegant, but a bit short. So I’ll throw in courage as the nutshell, perhaps in the variation offered by Francis of Assisi the courage to change the things I can. You forgot the joy of living, my daughter says and to that I have nothing to add.

*Translator’s note: Depending on the arrangement of the three root words »über« [above, about, through], »Leben« [life] and »Kunst« [art], one can create entirely different meanings. The project title, Über Lebenskunst , can thus be interpreted to mean »About the Art of Life« or »The Art of Survival« an ambiguity that was clearly intended.

Thomas Lehr, born in Speyer in 1957, studied Biochemistry before becoming a writer. He has re ceived numerous awards for his novels, e.g. the Wolf gang Koeppen Literature Prize by the City of Greifswald ( 2000 ). His most recent novel September. Fata Morgana (Munich: Hanser Verlag, 2010 ) was shortlisted for the German Book Prize 2010. In 2011 Lehr was awarded the Berlin Literature Prize by the Foundation of Prussian Maritime Commerce. Thomas Lehr lives in Berlin.

shifted to the middle and not only socially, but also politically. And in view of the rampant capitalistic forces unleashed by the neoliberals, the call for an appropriate level of moderation no longer seems as old-school conservative as it did in the late 1960s.

The debate on greed, as exemplified by the bonuses paid to bank ers and stockbrokers in the wake of the financial and economic crises, brought the ideals of moderation and restraint back into fashion, uniting the political left with the middle-class. The con cept of the middle ground and moderation gained an anti-capi talistic thrust. In light of the dynamic socio-economic develop ment which has resulted in new fractures and formed new bub bles capable of bringing entire national economies to their knees, the calls for a shift to the middle and more moderation have re sembled an attempt to find the brake pedal in a car careening to ward the edge of a cliff. If middle ground and moderation em bodied social stasis and cultural boredom in the late 1960s, they have now become the epitome of deceleration in a dynamic de velopment which no longer contains the promise of progress. The political semantics of the middle ground and moderation are variable and clearly depend on how the social situation on a whole is perceived. Such semantics might reflect resigned ac ceptance of the circumstances, about which »nothing can be done«, or express determined resistance against developments which could ultimately lead to devastating consequences. The

painter-poet Wilhelm Busch, a Schopenhauerian par excellence, illustratively and poetically summed up the former and became the aphorist of conservative-minded comfort. In his view, the selfindulgent, the greedy and the malicious are bound to fail and be ground to a pulp in the gear-wheels of society like Max and Moritz. The pleasure of watching others fail is the moral reward, reaped by those who exercise moderation. Busch’s characters overestimate themselves and have to admit that sometimes one is better off not to hold one’s head too high and be satisfied with a moderate »now and then«. Resignation evolves into a quicken ing insight into the inevitable fate of the mediocre. The counter-concept was expressed by the ancient philosopher Aristotle who connected the ability to hit the middle, that small point in a system of concentric circles, with the remarkable skill of the archer, who can compensate for the gravitational pull on the arrow, the influence of the wind and his own disposition to deviate when aiming. In this sense, hitting the middle is the com plete opposite of mediocrity. It actually represents an extraordi nary and outstanding achievement, of which only few are capa ble. Average people, on the other hand, whose will rarely corre sponds to their skill, do not hit the middle. They are unable to precisely calculate the external influences and their internal dis position, and as a result, their arrows end up hitting the edges and they involuntarily find themselves on the fringe, at the ex

treme. Perhaps they want to keep to the middle, but they are un able to. Nowadays the Aristotelian notion of the archer is an ap propriate image of the great art of hitting the middle. But that’s not to say that Wilhelm Busch will be back in fashion someday when the resistance to the middle ground and moderation be comes resigned comfort.

»Teach us to remember that we must die, that we may become wise.« This is how Martin Luther translated Psalm 90, verse 12 . In the Zurich Bible based on Ulrich Zwingli’s reformation in Zu rich, the verse goes like this: »Teach us to count our days aright that we may gain wisdom of heart.« It is clear from both transla tions that those who recited this ancient psalm had a definite idea of what the art of living meant. The verse implies that the most important task of each individual is to be aware of his fi niteness and mortality. This is not a matter of some ars moriendi, the art described in many ancient moral teachings and religious treatises to honorably bid the world farewell in humility before God and be conscious of one’s sinfulness and need for salvation. One could argue that dying is a decisive moment in our lives and therefore, the art of living must also include the art of dying. But those who recite Psalm 90 in prayer have little interest in the final phase of life before death or the end of life as a specific point in time. Rather, much more fundamentally, they wish to gain a new view of life as a whole, a radical shift in perspective. They regard the real art of living as a specific, religiously represented attitude of reflection, that of constantly being aware of their own finite ness. Emphasizing such sensitivity toward death is certainly not intended to cast a somber shadow over life. Rather it is meant to in crease and strengthen the intensity of life. Reflecting on the inev itability of our death serves to make our lives stronger and more intense. »Lord, teach us to remember that we must die, that we may learn to live«.

Learning to live means taking full advantage of the lifetime we are given, aware of the unavoidable finitude of our life. Unfortu nately, there are many people who are unwilling or unable to live in the here and now. Instead they look forward to a better, more fulfilling life in the relatively near future when they finally retire, or at a stage of life when they earn more money, and hope that once they’ve achieved this or that, their life will be happier. These people postpone living for an imaginary future, a tomorrow, or even a day-after-tomorrow, when everything will be much better. Such ›postponers‹ of happiness are notoriously incapable of liv ing in the present. They do have their own ideas of a good life. They also like being masters of the art of living but only a little later in life under subjectively more appropriate conditions. How ever, they suffer from a basic lack of artistic sense and artistry

which are beneficial to life. To be successful at the art of living, one must be willing and able to educate oneself to become a life artist. A religiously conveyed, completely non-fanatic, relaxed sen sitivity toward death is the most decisive lesson in learning the art of living. It allows us to differentiate between what is impor tant and less important, and it helps us to take the here and now seriously, to live in the present moment. Those who can regard each moment of life as meaningful, who can shape and fully take advantage of any given moment in the precious time that we are allotted, are able to increase the intensity of their life, and in turn, the pleasure of living. It is wise to seize the moment and live in the here and now for we are inno position to decide the future. That is the essence of the future despite all of our socio-tech nological efforts to predict, forecast and assess risks, we can never know for sure what will happen.

The presentism of life, as I’ve recommended here, seems to be at odds with the doctrines of moral institutions, which often warn of the destructive, dangerous characteristics of contemporary lifestyles that threaten the chances of life for coming generations. Yet intensified perception of the present moment certainly does not preclude examining the conditions of survival for those who come after us. Wisdom a regrettably underrated virtue in the current ethical discourse commands us to live in the here and now in such a way that others may live out their given time as cheerfully, happily and comfortably as possible tomorrow and beyond. But as a free individual, one must defend oneself from the moral arrogance of others who claim that he or she alone is responsible for the survival of future generations or the fate of the entire planet. Here, too, we can refer to the storehouse of symbol ism contained in religious writings. The holy scriptures of many religions, not only the Bible, all remind us of our limited time and the finiteness of our life’s resources. That’s why I am putting a Bible (or if I were Muslim, the Koran) into my intellectual pan try. Because once in a while I need something to remind me that I must live my life in the present if I, for the sake of others, want to have a future.

Friedrich Wilhelm Graf, born in 1948, is a Protestant theologian and professor of Systematic Theology and Ethics at the University of Munich ( LMU ). In 1999 he was awarded the Leibniz Prize by the German Research Foundation ( DFG ). Two of his books have just been published this year, Kirchendämmerung [Twilight of the Church] (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2011) and Der heilige Zeitgeist [The Holy Spirit of the Times] (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011).

In his Theory of Evolution of 1859, Charles Dar win described the principles that determined the survival of all living things only the ›fit test‹ survive and propagate, in other words, those species which are best adapted to their environ ment and can use it to their advantage. This was Darwin’s conclusion after meticulously analys ing decades of countless observations. As a scientist, he cast aside the old lines of argument and suggested another which remains valid today and has allowed further advances in biology and medicine. Recognizing the laws of nature is

one of the most significant fruits of scientific study, but it is not the only one. Our under standing of the laws of nature has also given us a certain degree of formative power we create new technology on the basis of research. By em ploying its intellect and inventive spirit, the hu man species has been able to spread to the most inhospitable environments on earth. In a sense, science itself is an art of survival for humans. In fact, I would even claim it’s the most important. But can science continue to meet such expecta tions in the future? Because we’ve been so suc cessful as a species, we now face global challeng es of an entirely new quality. It is now disturb ingly evident that our lifestyle has begun to cause far-reaching changes to the earth and to deplete our natural means of existence a develop ment substantiated by scientific evidence. Now science must go further than providing a diagnosis it must offer a therapy. This is what sci ence can contribute to our survival on this everchanging earth. But what solutions can we ex

»We are all scientists and very poor ones at that.« This could be a quote by Feynman or Chandrasekhar, for example, but it’s actually my own. Granted, the first part was the title of an essay by Thomas Henry Huxley, a contemporary, colleague and sup porter of Charles Darwin, and great-grandfather of the perhaps better known brothers Aldous and Julian. In his essay, Huxley convincingly argues that the essential mental operations which scientists use to induce natural laws are quite like those that de termine the daily operations of absolutely ordinary people. He uses apples in his introductory example. When a scientifically untrained person takes a bite of a hard, green apple and finds it to be sour, takes a bite of another apple and comes to the same con clusion, he or she will induce a general natural law in the same exact manner as a scientist and deem it unnecessary to bite into a third hard, green apple.

Huxley’s example with the apple also illustrates why we are such poor scientists; we are much too impatient. Obsessed with the desire for conclusiveness, our mind this inner idiot presents us with a finished natural law (hard and green, therefore sour), even when the sample is miniscule. At least in the case of the ap ples, the number of measured values is n=2 , but in many cases, our inner idiot is satisfied with n=1. A typical example of this is something I’ve heard quite frequently this winter: »Cold today all this talk about global warming can’t be right.« When I said ›frequently‹, of course, I meant ›once or twice‹.

The inner idiot is not only guilty of forming anecdotal »n=1« conclusions. It also has difficulties in neatly selecting and evalu ating samples, because it feels its own experience is of more con

sequence than that of its neighbour, or because it has forgotten experiences that happened long ago. The inner idiot is suscepti ble to several hundred of such faulty mechanisms, and these are only the ones we know about. Our n=1 problem is better known by the name Fallacy of the Lonely Fact, but there are far more exotic creatures in this zoo of false conclusions, such as the No True Scotsman Fallacy. This is a daring assertion based on a sample size n= 0, i.e. with no empirical verification at all. When someone claims »No Scotsman is gay«, but is proven wrong (by someone who happens to find a gay Scotsman), they adhere to their former assertion by expertly disqualifying the exception, saying »No true Scotsman is gay«. It’s an amazing accomplishment that even crocodiles couldn’t achieve.

Why does the inner idiot insist on anecdotal conclusions? Be cause these anecdotes sustain it. Life is not a mass of objective data, collected under controlled circumstances, but a series of subjective anecdotes, singular experiences and emotions which can not be exactly reproduced. Who in their right mind would burn their hand on a stove a thousand times before making an asser tion about the charring characteristics of human flesh? Without this current of unique, subjective episodes, our inner idiot would dissipate and change into something entirely different, for exam ple, into a garden gnome that has no idea what makes him differ ent from an identical gnome next door.

Astronomy is a science which has some similarity to the inner id iot in that its objects of study cannot be examined in a laboratory environment. We just can’t purchase 100,000 hard, green stars and bite into them, but have to accept what the universe gives us. Up until now, for instance, the universe has given us only one planet that looks like Earth, and as a result, all the conclusions we make about how the Earth was created are rather shaky a trag ic predicament. But generally the natural sciences want nothing to do with anecdotes. They remove the inner idiots and clear the way for testing massive, objective samples.

But something interesting has happened as a result. In order to work empirically, scientists have been forced to remove them

selves from their own conclusions. The master builders of this scientific world view don’t even include themselves. This is a problem, because we usually like to explain everything not everything less one essential component. How does the inner idiot deal with this problem? Well, it reverts to the petitio principii, another beloved fallacy. After excluding itself, the observing subject, it claims that the subject doesn’t really exist, or at least, can explain it away scientifically, like it can with stars or stones.