H.M.

Alessandro Mazzola

7:46 am I wake for the first conscious time

8:07 am I am totally perfectly awake (1st time)

8:31 am Now I am really completely awake (1st time)

8:35 am time to see relaxing TV

9:06 am now I am perfectly, superlatively awake (1st time)

My name is A.M., but I might be H.M, K.C., P.B., F.C. I know Paris is the capital of France but I cannot recall when I learned it.

I was wandering for a long time, I am still wandering but I do not move.

I know how to make a great coffee. Or maybe I don’t. I fought during the World War I, I run a stationery shop and I love her.

Neighborhood sounds familiar to me even though I cannot project myself into the future.

11:45 am first cup of coffee arrives

12:31 pm after lunch I am really perfectly awake

12:54 pm time for a walk

1:50 pm I am really, superlatively, completely awake (1st time)

D.W. “I called his name. There was no reply. I went into the bedroom the bed was empty and I knew something terrible had happened”

Narrator “Over the next few hours Debora rang hospital and police stations across London. No one had seen Clive”.

D.W. “and we sat and we sat and we sat, and then a man’s voice, the phone rang, and the man’s voice said “are you Mrs. Wearing?” “Yes” “We’ve got your husband” “Thank God” “Clive had gone out fully dressed with his overcoat and a copy of “The Times” under his arm, hailed a cab, but couldn’t remember where he lived. He wanted to go home and he couldn’t remember where he lived” [ ] “So we go there and we took him home and Clive went to walk past the gate and I stopped him and I said, “No, it’s here” and he said “Oh, is this where we live?” [ ] “We go to the hospital and I just remember going through these clear plastic rubber doors, they were like a valve and as those doors flapped shout behind us, it was just like our life as we knew it was over”

two minutes later

D.W. “Where would you like to go?”

C.W. “Best pub in the country”

D.W. “If you could go anywhere where would you like to go?”

C.W. “I have no idea. No idea”

D.W. “Well, I’m gonna take you home”

C.W. “Oh, I see. That’s marvellous, yes”

D.W. “Do you know where home is?”

C.W. “No”

D.W. “Guess”

C.W. “Yesterday”

D.W. “Home is yesterday [ ] that’s not a bad answer, actually”

S.C. “How do you feel answering so many questions and doing all the tests that we give you?”

H.M. “I don’t mind, what I found out about me help you to help others”

S.C. “That’s right, that’s very true”

H.M. “and I figure that it’s more important in a way”

Narrator “His mood swung from euphoria to sadness within weeks and confusion and despair set in”.

A.W. “he was in severe shock so he was just crying all the time. You’d come in and you’d say, “Oh hi, I’m your son” “you’re my son, I don’t recognize you!” “and then he’d be crying again and you are just stuck in that loop for months”

D.W. “Clive, can you tell me why you are crying? and he said “No” “and I handed him a little notepad and a pen and I said “can you write it?” I said “just write quickly why are you crying” and he wrote “I am completely incapable of thinking”

S.C. “What do you do during a typical day?”

H.M. “What...I don’t remember things”

S.C. “Do you know what you did yesterday?”

H.M. “No, I don’t”

S.C. “What about this morning?”

H.M. “I don’t even remember that”

S.C. “Could you tell me what you had for lunch today?”

H.M. “I don’t know, to tell you the truth”

S.C. “What do you think you’ll do tomorrow?”

H.M. “Whatever is beneficial”

“Oh please come,

please come at the speed of light”

“Oh please come, please come at the speed of light”

D.W. “I remember last time we were here, you were conducting the Lassus Requiem”

C.W. “Was I? oh”

D.W. “and it was for the International Lassus Festival that you put on and you came in here and none of the pews were here and you used the whole building”

C.W. “For the acoustics”

D.W. “it was far from a concert, it was actually a celebration of the mass as if Lassus has just died. It was extraordinary. And it was so moving that were people here who were crying and it was broadcast live to five countries and you were directing it. And it was so moving that everyone was in tears”

SR What does it mean to regret something?

KC Something you don’t like doing or wish that you hadn’t done.

SR Can you name some things a person might regret?

KC: If someone lost a large sum of money.

SR: Do you have any regrets?

KC: I don’t think so.

SR: What do you regret most about your life?

KC: Nothing – I can’t think of anything.

SR: What are some things a person might do if they feel regretful about something?

KC: Try to make it right.

Narrator “Clive condition was difficult for Deborah to bear”

D.W. “You asked me when did I decide to divorce him and when did I decide to leave? It wasn’t really a decision, it was an imperative. There was no way any human being could continue in that way” “We had the same dialogue in a loop tape, repeated verbatim with the same inflection, the same tone of voice, the same expression on the face for, well, the whole 9 years until I left and we were still having that conversation as I was backing out of the room”

C.W. “Can you imagine what it’s like to have one night 20 years long with no dream? That’s what it’s been like. Just like death. No difference between day and night, no thoughts at all. In that sense it has been totally painless which is not something which is very desirable really, is it? ‘Cause it’s precisely like death.”

C.W. “I know what’s like to be dead now. Day and night, the same thing. No difference between dreams or anything like that. No sense at all. The brain has been totally inactive. No dreams, no thoughts of any kind of whatever.”

Interviewer “What do you say to Clive when he gets confused and disorientated? How do you deal with that?”

D.W. “Well, he’s disorientated all the time, but it doesn’t matter, because we don’t need to be in time. We don’t need to be in any particular place. We’re on another plane, Clive and I. We’re in a world where there is no time”

Interviewer Could he configure an image of the future?

S.C. No, he couldn’t construct an agenda. One of his constant little things were these little monologues. One of them was about how he wanted to be a brain surgeon.

Interviewer Aw.

S.C. But he believed he couldn’t, because he wore glasses. He thought they’d be dirty so he couldn’t see properly, or the nurse would wipe his brow and dislodge his glasses, or blood would spurt up in his glasses. If this happened, and his vision was impaired, he might make a mistake and harm someone. He would talk about the kind of things he might do to them, he had a real conscience and he didn’t want to do anything like that to someone else. The interesting thing was that he didn’t have a plan B. He actually had no plans. When I asked him what he’d do tomorrow, he said whatever’s beneficial, full stop. He couldn’t create a future and he was never able to chase his dreams because he didn’t have any.

Interviewer What was Henry’s relationship like with the other sex?

S.C. Well, he was certainly always very polite, to the point of being chivalrous. I have several pictures of him with a woman named Maude, from I think it’s 1946. One is of the two of them standing together on the beach and they have their arms around each other. The other picture was of Maude in a pin-up like pose and on the back it reads, “To Henry, Love Maude.”

I also have letters from two friends of his who were in the service during WWII. They talked a lot about dames, babes and going out and getting married and all these kinds of things. So it was part of his conversation, but I don’t honestly know the extent to which these are true.

Interviewer Did he ever mention girls after the operation?

S.C. No. We asked him about girlfriends, and he never mentioned Maude, which is very interesting.

Interviewer “And what does love mean Mr. Wearing?”

C.W. “Zero intentness and everything in life”

D.W. “Good answer....good answer”

C.W. “That what it’s about love, isn’t it? Everything”

“Henry Molaison was much more than a collection of test scores and brain images.

He was a pleasant, engaging, docile man with a keen sense of humor, who knew that he had a poor memory and accepted his fate.

There was a man behind the initials, and a life behind the data.

Henry often told me that he hoped that research into his condition would help others live better lives.

He would have been proud to know how much his tragedy has benefited science and medicine.”

TEXTS

ANSEL BOURNE

Ansel Bourne (1826 – 1910) was a famous 19th-century psychology case due to his experience of a probable dissociative fugue. The case, among the first ever documented, remains of interest as an example of multiple personality and amnesia. Bourne was an evangelical preacher living in

Rhode Island. On January 17, 1887, he went to Providence, Rhode Island, then continued on until he reached Norristown, Pennsylvania where he set up shop as a stationer and confectioner using the name A. J. Brown. On Monday, March 14, he awakened in the morning not knowing where he was and with no memory of the preceding two months, still believing it was January. After he was returned home with the assistance of his nephew, psychologist William James of Harvard University and Richard Hodgson of the Society for Psychical Research traveled to study him. Under hypnosis, they found, he could be induced to assume the personality of either Bourne or Brown, and neither personality had any knowledge of the other. The story of Ansel Bourne was “most

likely” an inspiration for the name ‘Bourne’ in the movie and novel series The Bourne Identity.

LOCI TECHNIQUE

The method of loci is a technique for memorizing information by placing a mnemonic image for each item to be remembered at a point along an imaginary journey. The information can then be recalled in a specific order by mentally walking the same route through the imaginary journey and converting the mnemonic images back into the facts that they represent. Loci is the plural for of the Latin word, locus, meaning place or location.

The method of loci has many other names, including the memory palace technique, the Roman room system, and the journey method. The resulting mental spaces can be referred to by various terms like memory journeys, memory spaces, and Sherlock’s mind palace. The technique was featured in the book Moonwalking with Einstein. The method of loci originated in prehistoric times and is found in many cultures. The earliest surviving historical mentions of the method of loci in European culture appear in the Rhetorica ad Herennium, Cicero’s De Oratore, and Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria.

Roman legend attributed the method to a Greek poet, Simonides of Ceos, who discovered the technique while identifying bodies in the wreckage of

a collapsed building that he had been sitting in just moments before.

Historical records of the technique only go back to Simonides in the 6th Century BCE, but the method of loci goes far back into prehistory.

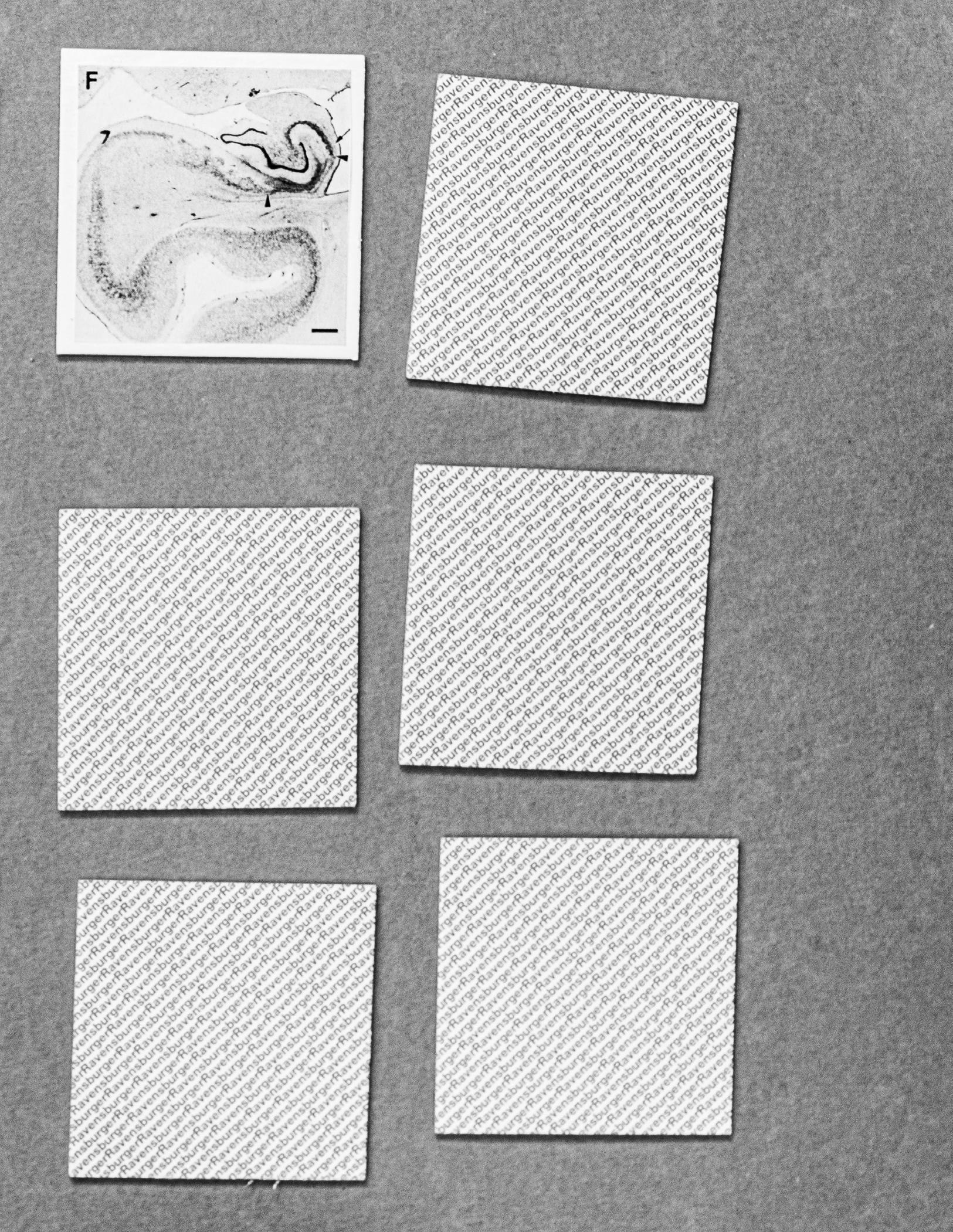

BRAIN’S MEMORY CAPACITY

The Salk team, while building a 3D reconstruction of rat hippocampus tissue [ ] noticed something unusual. In some cases, a single axon from one neuron formed two synapses reaching out to a single dendrite of a second neuron, signifying that the first neuron seemed to be sending a duplicate message to the receiving neuron. At first, the researchers didn’t think much of this duplicity, which occurs about 10 percent of the time in the hippocampus. [ ] if they could measure the difference between two very similar synapses such as these, they might glean insight into synaptic sizes, which so far had only been classified in the field as small, medium and large.

“We were amazed to find that the difference in the sizes of the pairs of synapses were very small, on average, only about eight percent different in size. No one thought it would be such

a small difference. This was a curveball from nature,” [ ] Because the memory capacity of neurons is dependent upon synapse size, this eight percent difference turned out to be a key number the team could then plug into their algorithmic models of the brain to measure how much information could potentially be stored in synaptic connections. [ ] Our new measurements of the brain’s memory capacity increase conservative estimates by a factor of 10 to at least a petabyte, in the same ballpark as the World Wide Web.”

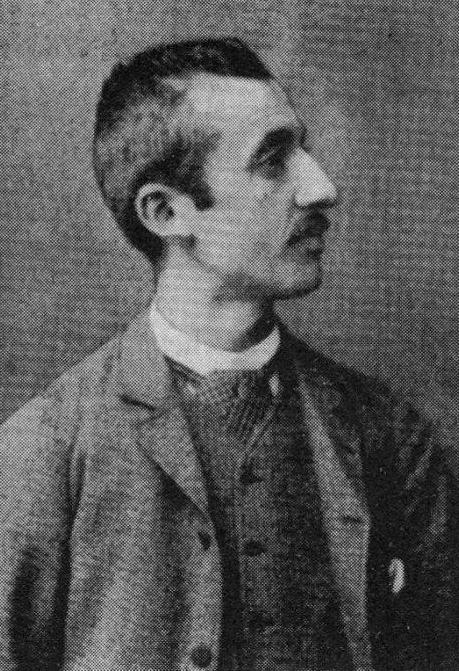

ANTHELME MANGIN

Anthelme Mangin (1891 – 1942), real name Octave Félicien Monjoin, was an amnesiac French veteran of the First World War who was the subject of a long judicial process involving dozens of families who claimed him as their missing relative. In 1938 he was determined to be the son of Pierre Monjoin and Joséphine Virly.

On 1 February 1918, a French soldier was repatriated from Germany and arrived at the Gare des Brotteaux in Lyon, suffering from amnesia and

lacking military or civil identification documents. When questioned, he gave a name that sounded something like Anthelme Mangin, and this became the name by which he is known to history. He was diagnosed with dementia praecox and placed in an asylum in Clermont-Ferrand.

In January 1920 Le Petit Parisien published a front-page feature with photos of several asylum patients, including Mangin, in the hope that their families would recognize them. The Mazenc family of Rodez claimed that he was their son and brother Albert, who disappeared in Tahure in 1915. He was therefore transferred to the asylum in Rodez and confronted with various pre-war friends and acquaintances, none of whom recognized him. Anthropological records revealed several differences between Albert Mazenc and Mangin, including a difference of 10 cm in height.

In 1922 the Ministry of Pensions published Mangin’s photo in the hope of identifying him. Several dozen families responded to the photo. After a lengthy investigation by the psychiatrists at the Rodez asylum, only two claimants seemed plausible: Lucie Lemay, who claimed the man as her missing husband, and Pierre Monjoin, who claimed him as his son. In 1934 Anthelme was taken on a visit to Saint-Maur, Indre, the home of Pierre Monjoin, and permitted to walk around the village. Starting at the railway station, Mangin walked unaccompanied to the Monjoin family home, though he did not acknowledge

the old man. He noted the changed appearance of the village church, whose steeple had been struck by lightning during his absence. The authorities determined that he was Monjoin’s son, but an appeal lodged by the Lemay family prolonged the case for some time.

The asylum tribunal ruled on the man’s identity in 1938, and remanded him to the custody of his father and brother. However, by this time both had died. He therefore spent the rest of his life in the Sainte-Anne psychiatric hospital in Paris, where he died on 19 September 1942, apparently of malnutrition. He was buried in a common grave. In 1948 his remains were transferred to the cemetery of SaintMaur-en-Indre and buried under the name Octave Monjoin.

JEAN-ALBERT DADAS

Jean-Albert Dadas (1860 – 1907) was the latest in a long line of men who worked for a gas company. His mother died when he was 17 and his father was a syphilitic hypochondriac who spent money as soon as he’d earned it. At age eight, Dadas had fallen out of a tree and suffered a concussion, with fits of vomiting and a migraine—a head injury that modern-day psychologists suggest may have instigated his distinctive penchant for travel.

Apprenticed to a manufacturer at the gas company at age 12, Dadas disappeared one day, only to resurface in a nearby town. When his brother

discovered and confronted him, the pre-teen, who had been assisting a traveling umbrella salesman, blinked as if awakening from a deep sleep. He had no idea where he was, or why he happened to be carting umbrellas for a stranger.

The umbrella incident marked just

the the first episode in a lifetime of the unexplainable. For much of his young adult life, Dadas blacked out and spontaneously traveled. He woke up on Parisian benches, in policy custody, and on trains headed to cities he’d never been to before. Often he would have wandered so far away that he had to work odd jobs to earn the money to get home. Dadas took a ship to Algeria, scrubbed pots in the galley of a ship bound back for France, and was eventually arrested in the city of Aix, where he was working as an undocumented agricultural laborer. Between these states of fugue, Dadas would return home and moonlight at the gas company. “How he kept this job was a mystery to me because he was always wandering off,” says Maud Casey, the author of a fictionalized version of Dadas’s life called The Man

Who Walked Away. Over these many years, marked by short stints in prisons or asylums, Dadas began to make a name for himself as an accidental, entranced tourist.

Dadas’s most spectacular flight began in 1881, when he joined and deserted the French army near the city of Mons and headed east. He passed through Prague, Berlin, Posen, and Moscow— on foot. At one point in Prussia, a vicious dog bite landed him in the hospital, where he was recognized as the inveterate traveler. His timing, however, was dreadful, as the czar had just been assassinated and Dadas, known to have been a nihilist, was thrown in prison. Three months later, he and the remaining prisoners were marched by sword-toting guards to Constantinople, where the French consul gave him enough money for a fourth-class train ticket. Like clockwork, Dadas returned to the gas factory.

Finally in 1886, Dadas found himself in the Saint-André hospital in Bordeaux, France, where he fell into the care of young neuropsychiatrist Phillipe Auguste Tissié. Tissié grew obsessed with this strange patient, whom he diagnosed with dromomania, or the uncontrollable urge to wander or travel. The psychiatrist soon learned Dadas could only recall his mad travel under hypnosis, and used that to compile a massive tome of his experiences, though it is best not to take them too seriously. But Dadas was patient zero, just the beginning.

[ ] Physicians characterized dromo-

mania as an impulse control disorder, similar to kleptomania (the need to steal things), pyromania (the need to burn things), or dipsomania (the need to drink alcoholic things), according to a 1902 article in The British Medical Journal. In the United States, physician and noted racist Samuel A. Cartwright invented a related mental disorder called drapetomania, the urge that led slaves to run away. He claimed the only treatment was extreme whipping.

According to Benjamin Kahan, a professor of English and women’s and gender studies at Louisiana State University, and author of The Book of Minor Perverts, the dromomaniac was one of a “numberless family of perverts” that were highly specific and yet interconnected. “Dromomania really established stability as a key kind of condition for normalcy, or heterosexuality,” Kahan says.

[ ] Dromomania vanished almost as soon as it appeared. In 1909, at a conference in Nantes, leading psychiatrists entirely redefined the concept of a fugue state, writes Peter G. Toohey in Melancholy, Love, and Time: Boundaries of the Self in Ancient Literature. Instead of an independent disorder, it was now understood as a symptom of a deeper mental illness, such as schizophrenia. Furthermore, the encroaching tensions of World War I led European countries to seal their borders, prohibiting the easy train trips Dadas once relied on. Within 23 years, diagnoses trickled to a halt and dromomania had more or

less disappeared.

Today, occasionally dromomania is mentioned in the context of homelessness, or to refer to the disorientation associated with dementia.

MIRROR TRACING

When we discuss memories, we often mean memories of facts and events: What you did last Sunday, the capital of Austria, your best friend’s cell phone number. There is another kind of memory that is largely unconscious, but very important. We learn and remember essential skills, such as walking, using chopsticks, or riding a bicycle. The mirror-tracing activity is a visual and motor test that involves learning a new motor skill. The task requires you to move a pencil to trace the diagram of a star while looking at your hand only as a reflection in a mirror. The act of drawing is a learned skill that requires visual and proprioceptive feedback to control muscle movement. Proprioception is a special sense that tells your brain the position of various parts of your body [ ]. What happens when the visual feedback that our brain recei-

ves is not what is expected? By concentrated effort, can we overcome a reversed visual field and follow new rules? Can we learn these new rules and improve with practice?

LOBOTOMY

In 1936, the American neuropsychiatrist Walter Freeman performed the first lobotomy in the United States—a procedure which he adopted and adapted from the Portuguese neurologist Antonio Egas Moniz. A few years later, he began looking for a more efficient way to perform the operation without drilling directly into the skull.

As a result, he created the transorbital lobotomy in which a pick-like instrument was forced through the back of the eye socket to pierce the thin bone that separates it from the frontal lobes. This procedure—which later became known as the “ice-pick” lobotomy—could be performed in under ten minutes without anesthetic. Shortly after that, Freeman took to the roads with his ice-pick and hammer, touring hospitals and mental

institutions around the country. He performed ice-pick lobotomies for all kinds of conditions, including headaches. Eventually, he began performing the operation in his van—which later became known as “the lobotomobile.” At one point, he undertook 25 lobotomies in a single day. Many of his patients never recovered, including Rosemary Kennedy, sister to JFK.

CLIVE WEARING

Clive Wearing (b. 1938) was born in the United Kingdom and,over the course of his early life, he became an accomplished musician, singer, and composer who specialized in choral and classical music. In 1985, at the height of his career, Wearing contracted a form of viral encephalitis caused by the herpes simplex virus. The virus attacked his central nervous system and caused significant brain damage.

Both his left and right temporal lobes

were damaged, as well as his frontal lobes. Wearing’s hippocampus was also severely damaged by the illness. The brain is complex and its various

lobes’ functions are not fully understood, but both the temporal lobes and the hippocampus are thought to be essential to the creation and storage of memories. The frontal lobes are responsible for many functions, including social behavior. In Wearing’s case, the damage caused by the viral infection severely impacted his memory. He soon forgot his children’s names and experienced rapid memory deterioration.

Clive Wearing’s is one of the most severe cases of amnesia ever recorded. Wearing experiences complete retrograde amnesia, which means that he has lost all memories of his past. In addition, he also experiences anterograde amnesia, meaning that he is unable to form and store new memories. Doctors and phycologists who have worked with Wearing estimate that he can only retain new information for an average of around thirty seconds (and sometimes as little as seven seconds) before he forgets it. He therefore lives in a perpetual present without anchors to the past or the ability to learn anything new. Historically, most patients diagnosed with amnesia experience only one form of the disorder at a time; either retrograde or anterograde. Clive Wearing’s case is highly unusual in this respect, as he experiences both forms of amnesia simultaneously. This has made life for Wearing particularly difficult. Due to his profound confusion and inability to retain new information, Wearing now lives in an assisted living facility so that he can receive the help he needs. Although

he does not remember his life prior to the onset of his amnesia, Wearing has retained some amazing skills and a level of understanding that is localized to certain concepts.

Deborah Wearing (b. 1957) is Clive Wearing’s second wife. The two married only a year prior to the onset of Wearing’s battle with viral encephalitis, and she is the only person whom Wearing still recognizes. Although he cannot remember anything specific about their life together, he consistently greets Deborah with great love and enthusiasm. She visits him often, and though he cannot recall her visits afterward, he is always delighted to see her. His love for Deborah is one of the only things that he is able to recall even in her absence, sometimes talking or writing about her even when she isn’t present. This is notable in that it may be an indication that his memory has improved slightly in the decades since his illness began. He is also aware, when prompted, that he has children, although he cannot remember anything about them and cannot recognize them.

Clive Wearing lacks declarative memory, which involves memory of specific people, places, and events. Declarative memories are formed when people encode and retain new memories. Although Wearing has no such ability, he has maintained his procedural memory, or muscle memory. This is the kind of memory that allows people to complete tasks that they have done before. Wearing

knows how to read and write, and while his social skills were slightly impacted by his illness, he still understands and accurately displays appropriate social behaviors.

By far the most extraordinary example of Wearing’s retained procedural memory is his ability to play the piano. He is able to skillfully play complex piano pieces, and playing the piano is one of the only ways that Wearing can experience any kind of continuity in his current life: even if he cannot remember starting to play the piece, he can complete it without getting lost or confused. After he finishes playing, Wearing quickly forgets ever having done so, although he has expressed an awareness that he used to be a musician.

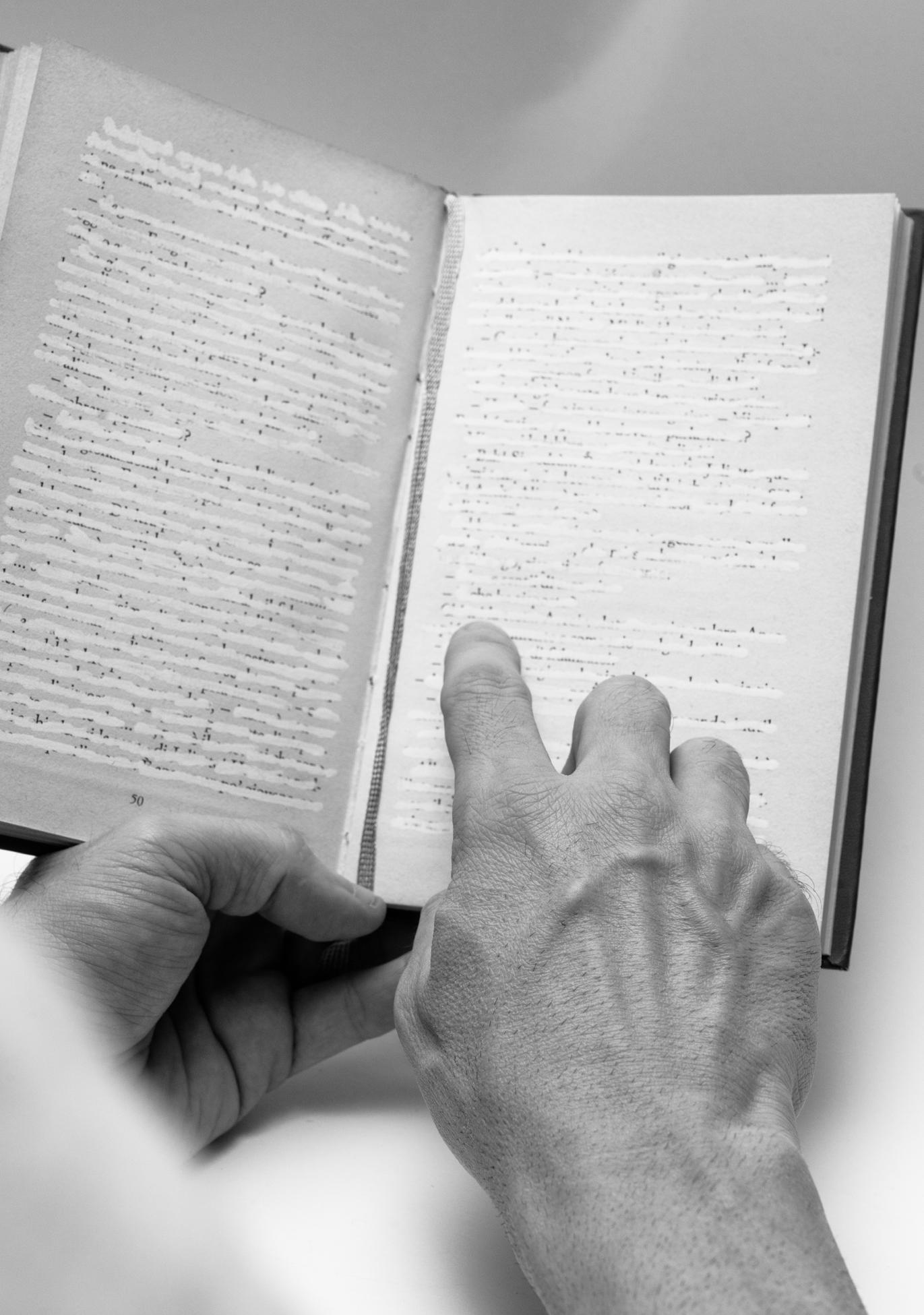

One of the most compelling elements of Wearing’s story is his journal, a diary provided by his carers. Wearing was encouraged to record his thoughts on the journal. Page after page was filled with entries similar to the following:

8:31 AM: Now I am really, completely awake.

9:06 AM: Now I am perfectly, overwhelmingly awake.

9:34 AM: Now I am superlatively, actually awake.

Earlier entries were usually crossed out, since he forgot having made an entry within minutes and dismissed the writings. He did not know how the entries were made or by whom, although he did recognise his own han-

dwriting. Wishing to record ‘waking up for the first time’, he still wrote diary entries in 2007, more than 20 years after he started them.

KENT COCHRANE

Kent Cochrane (1951 – 2014) also known as Patient K.C., was a widely studied Canadian memory disorder patient who has been used as a case study in over 20 neuropsychology papers over the span of 25 years.

In October 1981, Cochrane was invol-

ved in a single-vehicle accident on his way home from his job at a manufacturing plant when the motorcycle he was riding veered off of an exit ramp. He suffered a traumatic brain injury. Upon arrival at a hospital, Cochrane was experiencing clonic epileptic seizures and was unconscious. Surgery to remove a left-side subdural hematoma was successful. After a few days in the hospital, Cochrane was able to respond to simple commands. After one week he was able to recognize his mother. A follow up CT scan revealed a chronic bilateral frontal subdural hematoma, enlarged ventricles and sulci,

and left occipital lobe infarction.

Upon arrival at a rehabilitation facility, Cochrane was able to recognize friends and family, but still exhibited slower thinking ability, as well as partial right side paralysis and vision problems with his right eye. Upon his discharge from the rehabilitation facility in July 1982, the full extent of Cochrane’s neurological injuries was determined. He had severe injury to his medial temporal lobes, along with almost complete bilateral hippocampal loss. Ultimately, his neurological profile stabilized, as seen in CT scans he received once each decade following the accident.

As a result of his neurological damage, Cochrane suffered severe cognitive deficits that hindered his ability to form new episodic memories. However, both his semantic memory and noetic consciousness remained unimpaired. To illustrate this, research conducted on Cochrane has shown that he was able to recall factual information that he learned prior to his accident, such as his ability to know the difference between stalactites and stalagmites. However, Cochrane was unable to remember emotional details of events from his past such as his brother’s death and a dangerous fall he had at his home.

Cochrane also suffered from severe impairment of his autonoetic consciousness. This meant that he was unable to envision himself in the future. When asked what he would be doing later in a given day, mon-

th, or even a year, he was unable to respond with an answer. Just as he could not remember being physically involved with events from his past, he was unable to imagine future events. Ultimately, he lost any memory of his current actions once his thoughts were directed elsewhere.

Neuropathologically, Cochrane suffered from both anterograde amnesia and temporally graded retrograde amnesia. Both forms of amnesia are characterized by damage to the medial temporal lobes, specifically within the hippocampal region. The trauma caused by Cochrane’s accident left him with severe anterograde amnesia that has made it impossible for him to remember both new personal experiences and semantic information. As far as his temporally graded retrograde amnesia is concerned, he was considered an anomaly; in other words, his ability to recall events prior to the accident was dependent on when those events occurred. Although he could not remember personally experienced events, his semantic knowledge prior to his accident remained intact. For example, his recollection of factual information in math, history, and science, was unaffected.

Studies on K.C., along with others of similar patients, provided strong evidence that our episodic and semantic memories rely on different brain circuits. The hippocampus helps record both types of memories initially, and it helps retain them for the medium term. The hippocampus also helps us access old personal memories

in long-term storage in other parts of the brain. But to access old semantic memories, the brain seems to use the parahippocampus, an extension of the hippocampus on the brain’s southernmost surface. K.C., whose parahippocampuses survived, could therefore remember to sink the eight ball last in pool (semantic knowledge), even though every last memory of playing pool with his buddies had disappeared (personal knowledge).

What’s more, while a healthy hippocampus usually records new semantic, factual memories, the parahippocampus can—albeit excruciatingly slowly—absorb new facts if it has to. For instance, after years of shelving books as a volunteer at a local library, K.C.’s parahippocampus learned the Dewey decimal system, even though he had no idea why he knew it.

K.C. helped neuroscience come to grips with another important distinction in memory research, between recollection and familiarity. Colloquially, recollection means I specifically remember this, while familiarity means this sounds familiar, even if the details are fuzzy. And sure enough, the brain makes the same distinction. In one test, K.C.’s doctors compiled a list of words (El Niño, posse) that entered the common parlance after his accident in 1981. They then sprinkled those recent words into a list of pseudowords—strings of letters that looked like plausible words but that meant nothing. Time and again K.C. picked out the real word and did so with confidence. But when asked to

define the word, he shrugged. From a list of common names he could pick out the names of famous people, even those who had become famous after 1981 (Bill Clinton). But he had no inkling what Clinton had done. In other words, K.C. found these terms familiar, even though specific recollection eluded him. This indicates that recollection once again requires the hippocampus, while a feeling of familiarity requires only certain patches of cortex.

H.M.

Henry Molaison (1926 – 2008), known widely as H.M., is probably the best known single patient in the history of neuroscience. His severe memory impairment, which resulted from experimental neurosurgery to control seizures, was the subject of study for five decades until his death. Work with H.M. established fundamental principles about how memory functions are organized in the brain.

In 1952, Brenda Milner was completing her doctoral research at McGill University under the direction of Donald Hebb. At about this time, she encountered two patients (P.B. and F.C.) who had become severely amnesic following unilateral removal of the medial structures of the left temporal lobe for the treatment of epileptic seizures (Penfield and Milner, 1958). This unfortunate outcome was entirely unexpected, and it was proposed that in each case there had been a preexistent, but unsuspected, atrophic

lesion in the medial temporal lobe of the opposite hemisphere. In that way, the unilateral surgery would have resulted in a bilateral lesion, an idea that was confirmed at autopsy some years later for patient P.B. After the two cases were presented at the 1955 meeting of the American Neurological Association, Wilder Penfield (the neurosurgeon in both cases) received a call from William Scoville, a neurosurgeon in Hartford, Connecticut. Scoville told Penfield that he had seen a similar memory impairment in one of his own patients (H.M.) in whom he had carried out a bilateral medial temporal lobe resection in an attempt to control epileptic seizures. As a result of this conversation, Brenda Milner was invited to travel to Hartford to study H.M.

H.M. had been knocked down by a bicycle at the age of 7, began to have minor seizures at age 10, and had major seizures after age 16. (The age of the bicycle accident is given as 9 in some reports; for clarification see Corkin, 1984.) He worked for a time on an assembly line but, finally, in 1953 at the age of 27 he had become so incapacitated by his seizures, despite high doses of anticonvulsant medication, that he could not work or lead a normal life. Scoville offered H.M. an experimental procedure that he had carried out previously in psychotic patients, and the surgery was then performed with the approval of the patient and his family.

When Milner first visited H.M., she saw that the epilepsy was now controlled but that his memory impairment was even more severe than in Penfield’s two patients, P.B. and F.C. What she observed was someone who forgot daily events nearly as fast as they occurred, apparently in the absence of any general intellectual loss or perceptual disorder. He underestimated his own age, apologized for forgetting the names of persons to whom he had just been introduced, and described his state as “like waking from a dream ... every day is alone in itself...” (Milner et al., 1968, p. 217).

The first observations of H.M., and the results of formal testing, were reported a few years later (Scoville and Milner, 1957). This publication became one of the most cited papers in neuroscience (nearly 2500 citations) and is still cited with high frequency. H.M. continued to be studied for five decades, principally by Brenda Milner, her former student Suzanne Corkin, and their colleagues (Corkin, 1984, 2002; Milner et al., 1968). He died on December 2, 2008, at the age of 82. It can be said that

the early descriptions of H.M. inaugurated the modern era of memory research. Before H.M., due particularly to the influence of Karl Lashley, memory functions were thought to be widely distributed in the cortex and to be integrated with intellectual and perceptual functions. The findings from H.M. established the fundamental principle that memory is a distinct cerebral function, separable from other perceptual and cognitive abilities, and identified the medial aspect of the temporal lobe as important for memory. The implication was that the brain has to some extent separated its perceptual and intellectual functions from its capacity to lay down in memory the records that ordinarily result from engaging in perceptual and intellectual work.

H.M.’s intact intellectual and perceptual functions, and similar findings in other patients with large medial temporal lesions, have been well documented. A key additional finding was that H.M. had a remarkable capacity for sustained attention,

including the ability to retain information for a period of time after it was presented. Thus, he could carry on a conversation, and he exhibited an intact digit span (i.e., the ability to repeat back a string of six or seven digits). Indeed, information remained available so long as it could be actively maintained by rehearsal. For example, H.M. could retain a three-digit number for as long as 15 min by continuous rehearsal, organizing the digits according to an elaborate mnemonic scheme. Yet when his attention was diverted to a new topic, he forgot the whole event. In contrast, when the material was not easy to rehearse (in the case of nonverbal stimuli like faces or designs), information slipped away in less than a minute. These findings supported a fundamental distinction between immediate memory and long-term memory (what William James termed primary memory and secondary memory). Primary memory [immediate memory]

...comes to us as belonging to the rearward portion of the present space of time, and not to the genuine past (James, 1890, p. 647).

Secondary memory [long-term memory] is quite different.

An object which has been recollected. is one which has been absent from consciousness altogether, and now revives anew. It is brought back, recalled, fished up, so to speak, from a reservoir in which, with countless other

objects, it lay buried and lost from view. (James, 1890, p. 648).

Notably, time is not the key factor that determines how long patients like H.M. can retain information in memory. The relevant factors are the capacity of immediate memory and attention, i.e., the amount of material that can be held in mind and how successfully it can be rehearsed. The work with H.M. demonstrated that the psychological distinction between immediate memory and long-term memory is a prominent feature of how the brain has organized its memory functions.

Perhaps the most unexpected discovery about H.M., given his profound and global memory impairment, came when Brenda Milner tested his ability to acquire a visuomotor skill (Milner, 1962). H.M. was shown a five-pointed star, with a double contour, and asked to trace its outline with a pencil, but in a condition when he could only see his hand and the star as reflected in a mirror. H.M. acquired this mirror-drawing skill during ten trials and exhibited excellent retention across 3 days. Yet at the end of testing, he had no recollection of having done the task before. This demonstration provided the first hint that there was more than one kind of memory in the brain and suggested that some kinds of memory (motor skills) must lie outside the province of the medial temporal lobe.

For a time, it was rather thought that

motor skills were a special case and that all the rest of memory is impaired in patients like H.M. Later it became appreciated that motor skills are but a subset of a larger domain of skill-like abilities, all of which are preserved in amnesia. The demonstration of a fully preserved ability to learn the perceptual skill of mirror reading suggested a distinction between two broad classes of knowledge: declarative and procedural (Cohen and Squire, 1980). Declarative memory is what is meant when the term “memory” is used in everyday language, i.e., conscious knowledge of facts and events. Procedural memory refers to skill-based knowledge that develops gradually but with little ability to report what is being learned.

In the years that followed, other preserved learning abilities began to be reported for amnesic patients, and the perspective shifted to a framework that accommodated multiple (i.e., more than two) memory systems. As Endel Tulving wrote:

But even if we accept the broad division of memory into procedural and propositional forms ... there are phenomena that do not seem to fit readily into such a taxonomy (Tulving et al., 1982, p.336).

Subsequently, the terms declarative and nondeclarative were introduced with the idea that declarative memory refers to the kind of memory that is impaired in H.M. and is dependent on the medial temporal lobe. Non-

declarative memory is an umbrella term referring to additional memory systems. These include systems that support skill learning, habit learning, simple conditioning, emotional learning, as well as priming and perceptual learning. The structures with special importance for these kinds of memory include the basal ganglia, the cerebellum, the amygdala, and the neocortex. The starting point for these developments was the early discovery that motor skill learning was preserved in H.M. This finding revealed that memory is not a single faculty of the mind and led ultimately to the identification of the multiple memory systems of the mammalian brain.

H.M.’s memory impairment has generally been taken as reflecting a failure to convert transient, immediate memory into stable long-term memory. A key insight about the organization of memory, and medial temporal lobe function, came with a consideration of his capacity to remember information that he had acquired before his surgery. The first exploration of

this issue with formal tests asked H.M. to recognize faces of persons who had become famous in different decades, 1920-1970 (Marslen-Wilson and Teuber, 1975). As expected, H.M. was severely impaired at recognizing faces from his postmorbid period (the 1950s and 1960s), but he performed as well as or better than age-matched controls at recognizing faces of persons who were in the news before his surgery. This important finding implied that the medial temporal lobe is not the ultimate storage site for previously acquired knowledge. The early descriptions of H.M. conform to this view. Thus, H.M. was described as having a partial loss of memory (retrograde amnesia) for the 3 years leading up to his surgery, with early memories “seemingly normal” (Scoville and Milner, 1957, p. 17). Similarly, about 10 years later it was remarked that there did not appear to have been any change in H.M.’s capacity to recall remote events antedating his operation, such as incidents from his early school years, a high-school attachment, or jobs he had held in his late teens and early twenties (Milner et al.), developed to assess the specificity and the detail with which such recollections could be reproduced. In the earliest efforts along these lines, as summarized by Suzanne Corkin (Corkin, 1984), H.M. produced well-formed autobiographical memories, from age 16 years or younger. It was concluded that H.M’s remote memory impairment now extended back to 11 years before his surgery. The situation seemed to change further as H.M. aged. In an update prepared nearly

20 years later (Corkin, 2002), H.M. was described as having memories of childhood, but his memories appeared more like remembered facts than like memories of specific episodes. It was also said that he could not narrate a single event that occurred at a specific time and place. Essentially the same conclusion was reached a few years later when new methods, intended to be particularly sensitive, were used to assess H.M.’s remote memory for autobiographical events (Steinvorth et al., 2005). These later findings led to the proposal that, whatever might be the case for fact memory, autobiographical memories, i.e., memories that are specific to time and place, depend on the medial temporal lobe so long as the memories persist.

There are reasons to be cautious about this idea. In 2002-2003, new MRI scans of H.M. were obtained (Salat et al., 2006). These scans documented a number of changes since his first MRI scans from 1992-1993 (Corkin et al., 1997), including cortical thinning, subcortical atrophy, large amounts of abnormal white matter, and subcortical infarcts. These findings were thought to have appeared during the past decade, and they complicate the interpretation of neuropsychological data collected during the same time period. Another consideration is that remote memories could have been intact in the early years after surgery but then have faded with time because they could not be strengthened through rehearsal and relearning. In any case, the optimal time to assess the

status of past memory is soon after the onset of memory impairment.

Other work has tended to support the earlier estimates that H.M.’s remote memories were intact. First, Pen-

field’s two patients described above, P.B. and F.C., were reported after their surgeries to have memory loss extending back a few months and 4 years, respectively, and intact memory from before that time (Penfield and Milner, 1958). Second, methods like those used recently to assess H.M. have also been used to evaluate autobiographical memory in other patients, including patients like E.P. and G.P. who have very severe memory impairment (Kirwan et al., 2008). In these cases, autobiographical recollection was impaired when memories were drawn from the recent past but fully intact when memories were drawn from the remote past.

Memory loss can sometimes extend back for decades in the case of large medial temporal lobe lesions (though

additional damage to anterolateral temporal cortex may be important in this circumstance). In any case, memories from early life appear to be intact unless the damage extends well into the lateral temporal lobe or the frontal lobe. These findings are typically interpreted to mean that the structures damaged in H.M. are important for the formation of longterm memory and its maintenance for a period of time after learning. During this period gradual changes are thought to occur in neocortex (memory consolidation) that increase the complexity, distribution, and connectivity among multiple cortical regions. Eventually, memory can be supported by the neocortex and becomes independent of the medial temporal lobe. The surprising observation that H.M. had access to old memories, in the face of an inability to establish new ones, motivated an enormous body of work, both in humans and experimental animals, on the topic of remote memory and continues to stimulate discussion about the nature and significance of retrograde amnesia.

H.M. was likely the most studied individual in the history of neuroscience. Interest in the case can be attributed to a number of factors, including the unusual purity and severity of the memory impairment, its stability, its well-described anatomical basis, and H.M.’s willingness to be studied. He was a quiet and courteous man with a sense of humor and insight into his condition. Speaking of his neurosurgeon, he once said, “What he learned

about me helped others, and I’m glad about that.” (Corkin, 2002, p. 159).

An additional aspect of H.M.’s circumstance, which assured his eventual place in the history of neuroscience, was the fact that Brenda Milner was the young scientist who first studied him. She is a superb experimentalist with a strong conceptual orientation that allowed her to draw from her data deep insights about the organization of memory. Because he was the first well-studied patient with amnesia, H.M. became the yardstick against which other patients with memory impairment would be compared. It is now clear that his memory impairment was not absolute and that he was able to acquire significant new knowledge (Corkin, 2002). Thus, memory impairment can be either more severe or less severe than in H.M. But the study of H.M. established key principles about how memory is organized that continue to guide the discipline.

REFERENCES AND CREDITS

Baines J., The Man with the 30-Second Memory, VICE, June 6, 2013;

Branswell H., Toronto amnesiac whose case helped rewrite chapters of the book on memory dies, The Canadian Press, April 1, 2014. Credit Galit Rodan, photography page 167;

Corkin S., Prigioniero del presente, Adelphi, 2009, photography page 15;

Demand T., “Grotto”, 2006 on stage at “Process Grottesco”, Fondazione Prada, 2021, pages 20-21;

Dworschak M., The man without a memory, Spiegel International, May 2, 2005;

Elhassan, K., 10 Strange Pastimes which People from Previous Generations Enjoyed, History Collection, March 13, 2018;

Freeman W. and J. W. Watts, Psychosurgery: Intelligence, Emotion and Social behavior following prefrontal lobotomy for mental disorders, Springfield, Ill.: Thomas, 1942, photography pages 7, 30-31, 121;

Hayes S. M., Fortier C. B., Levine A., Mcglinchey R. E., Implicit Memory in Korsakoff’s Syndrome: A Review of Procedural Learning and Priming Studies, Neuropsychology Review 22(2):132-53, May 2012;

Intini E., La memoria umana? 10 volte più capiente del previsto, Focus Psicologia, April 2016;

Le Naour J.Y., Le soldat inconnu vivant, Fayard, August 22, 2018;

Magnifico T., Sindrome di Korsakov e “il marinaio perduto”, Missione Scienza, December 24, 2020;

Parkin A.J., Human memory: The hippocampus is the key, Science Direct, Volume 6, Issue 12, December 1996, Pages 1583-1585

Rempel Clower N.L. et al., memory impairment after hippocampal formation lesions, Journal Neurosceince, August 15, 1996, 16(16): 5233-5255;

Rorschach H., author re-interpretation, pages 39-43;

Squire L. R., The legacy of Patient H.M. for Neuroscience, Neuron. 2009 Jan 15; 61(1): 6–9;

Tamagnini F., i segreti della memoria: come salviamo le informazioni, ImpactScool Magazine, March 21, 2019;

The Man With The Seven Second Memory (Amnesia Documentary) | Real Stories;

Carte établie par le Dr. Niko Sharer, Les Fous voyageurs de Ian Hacking, éd. Les empêcheurs de tourner en rond, 2002, photography page 40;

Neural implant and electrode array, https://neuralink.com/, photography pages 52-53;

https://www.lacagnadedouard. fr/450293276, photography pages 159;

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clive_Wearing

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sindrome_di_Wernicke-Korsakoff

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benzodiazepine

https://revistagalileu.globo.com/ Ciencia/noticia/2017/10/8-casos-bizarros-de-amnesia-que-renderiam-bons-filmes.html

https://revistagalileu.globo.com/ Ciencia/noticia/2017/10/8-casos-bizarros-de-amnesia-que-renderiam-bons-filmes.html

http://smallstatebighistory.com/ two-selves-one-skull-ansel-bournes-strange-interlude/

https://www.copyrightbookshop.be/ en/shop/philippe-herbet-dadas-edition-of-400-copies/

https://www.domusweb.it/it/notizie/2015/04/29/lara_favaretto_ good_luck.html

https://philarchive.org/archive/ GENSAT-4

cover and back-cover: Rey Osterrieth

Figure, pictures from Rempel Clower et al., memory impairment after hippocampal formation lesions, Journal Neurosceince, August 15, 1996, 16(16): 5233-5255

COLOPHON

Images

Alessandro Mazzola

Texts

Dialogues included in the book are extracted from:

“The Man with 7 Seconds Memory”, documentary film, directed by Jane Treays, 2005; “Prigioniero del presente”, Suzanne Corkin, Adelphi, 2009; “Neuropsychologia”, issue 57, May 2014, Pages 191 - 195, Professor R. Shayna Rosenbaum interviewing Kent Cochrane.

Design

Door publishing

Editing

Massimo Mastrorillo & Alessandro Mazzola

Printed by XXXXXXXX

Thanks to DOOR Academy, Massimo Mastrorillo and David Mozzetta for their inspiration and critical support along the entire project, thanks to NAMA and in particular to Massimo Atzeni and Margherita Nardi for their availability for shooting and Tommaso Tanini for his review and advices.