RIDING IN SILENCE & THE CRYING DERVISH

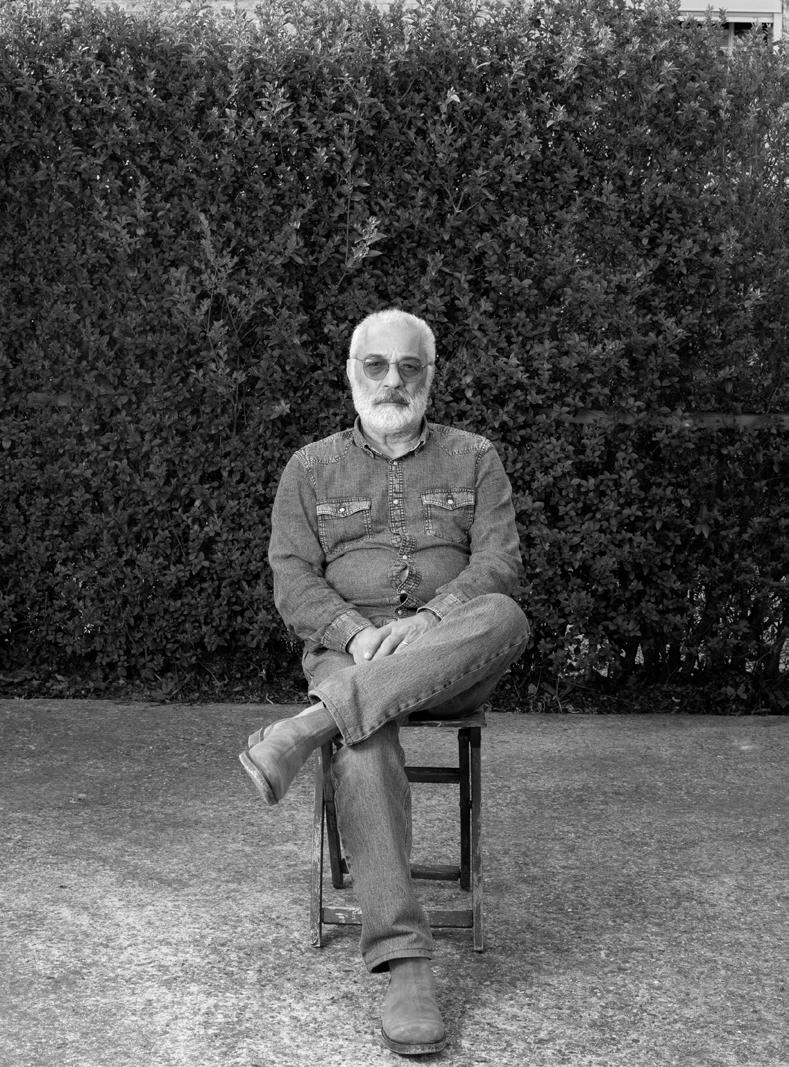

MASHID MOHADJERIN

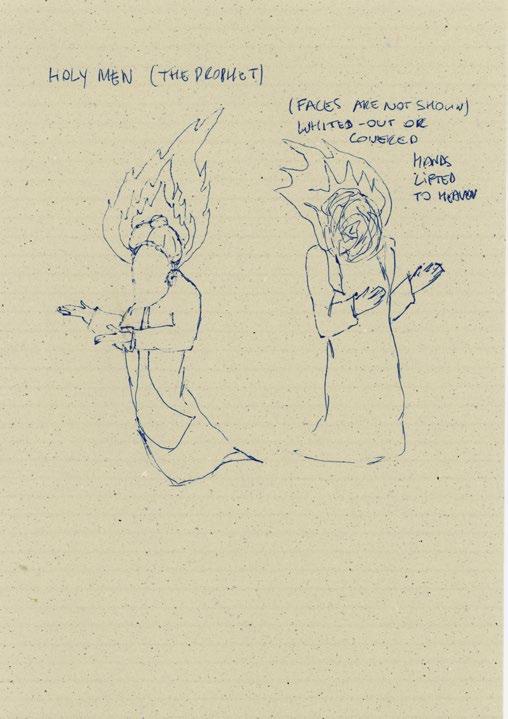

What if the dervish had not entered the mosque in the small town of Dowlatabad? And what if he had attended the commemoration in silence instead of passionately crying his heart out?

He would not have drawn so much attention to himself then. My great-great-grandfather would not have noticed nor invited him to his house, he would not have stayed there for weeks and would not have told him about the execution of the holy man.

I lie awake in my bed early morning, or is it the middle of the night, miles away from where I was born, and in my half-asleep state I mull over their stories. What would our lives have been like without this crying dervish? Would I then still be in this bed, in my pink pajamas, on a different continent from theirs?

My father deeply hates the old religion of his greatgrandfathers. Perhaps it was because his neighbours pasted his front door with dog shit, or because it’s the religion that rejected him and eventually forcefully pushed him out to an unknown place, one with narrow houses and grey skies. At least in this new place he could be comfortable in his silence.

In this new place, he would not be bothered. He took his girls, mom, me and my sister.

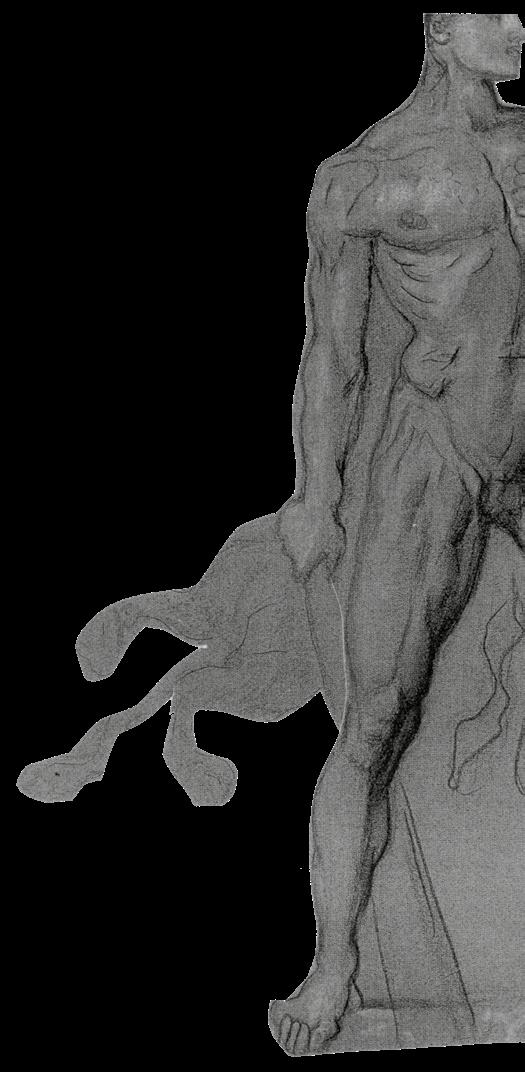

We could have started the story with a shooting squad waiting for the smoke of their guns to settle. It’s 1850 and the holy man and his companion have disappeared behind that smoke. They find him in his cell, finishing the last chapter of his book. The firing squad refuses to shoot a second time.

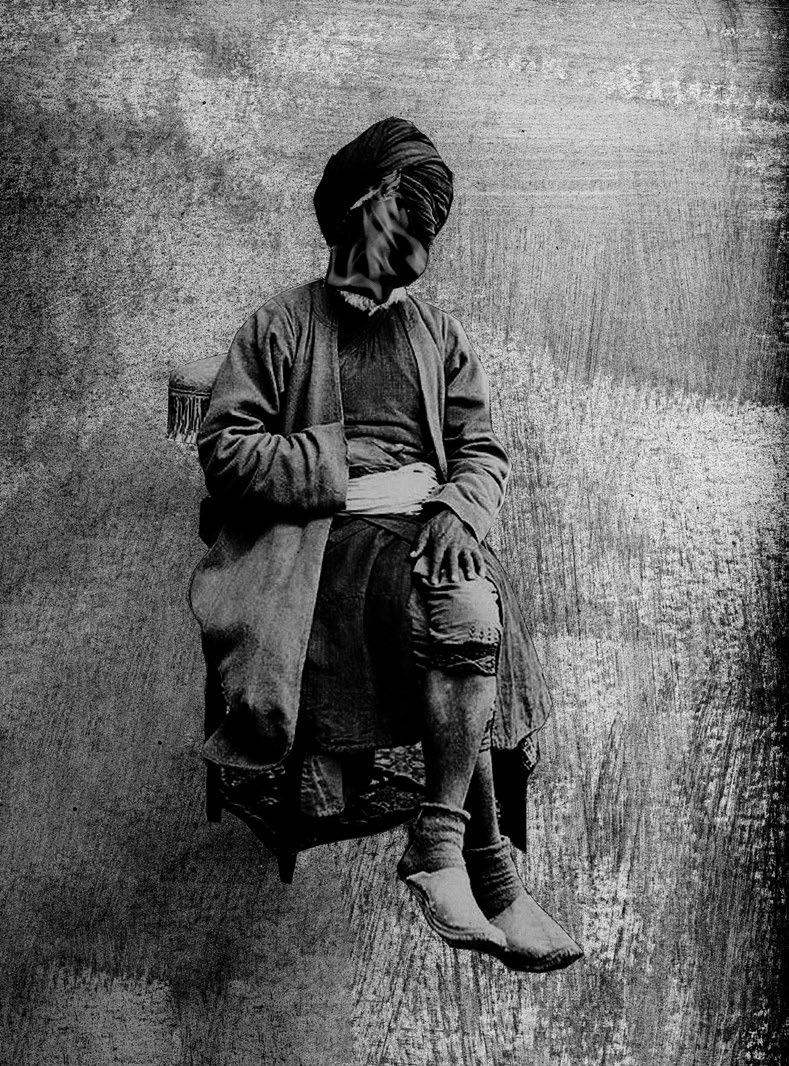

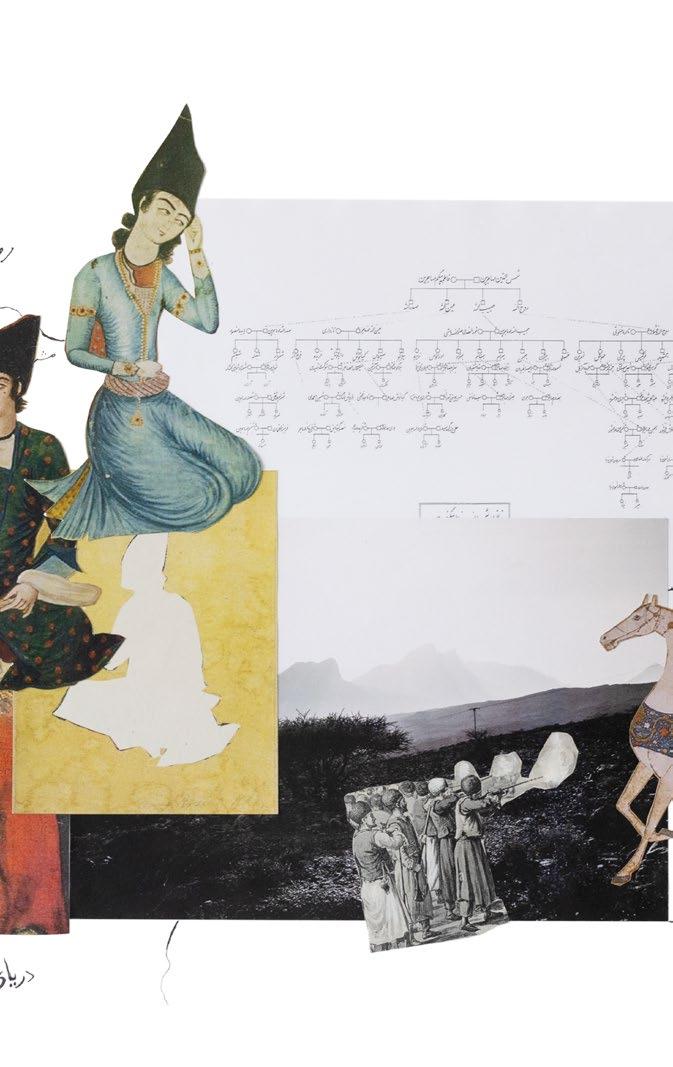

When Ali Akbar noticed the crying dervish on that particular day of ashura, he became curious about the origins of the man’s pain. The dervish told him about Bab, a man whose prophetic revelations would release creative energies and capabilities that lead to global unity and beauty. Tragically, he had recently been executed. This was the reason for his agony.

This new ideology would change everything for Ali Akbar and the generations that followed.

A mullah is someone who had a religious education, a scholar of Islamic learning, my father explains. This was before Western style schools became the norm. After this education, you could become “an influencer”. Now you just need Instagram.

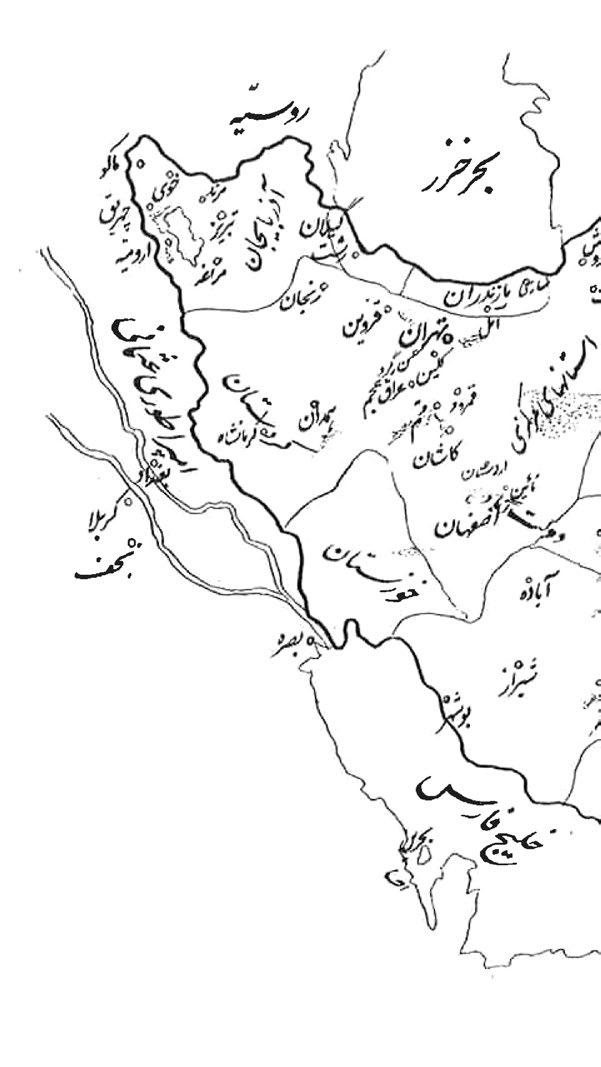

I only recently found out that my great-great grandfather was a mullah. He had been assigned to move to a small town near Isfahan called Dowlatabad, he had come from Tehran.

We could have started the story with the eventful arrest and death-sentence of my great-great grandfather five (or six?) generations earlier. A series of unexpected invents led him and his brothers to escape their unfortunate faith.

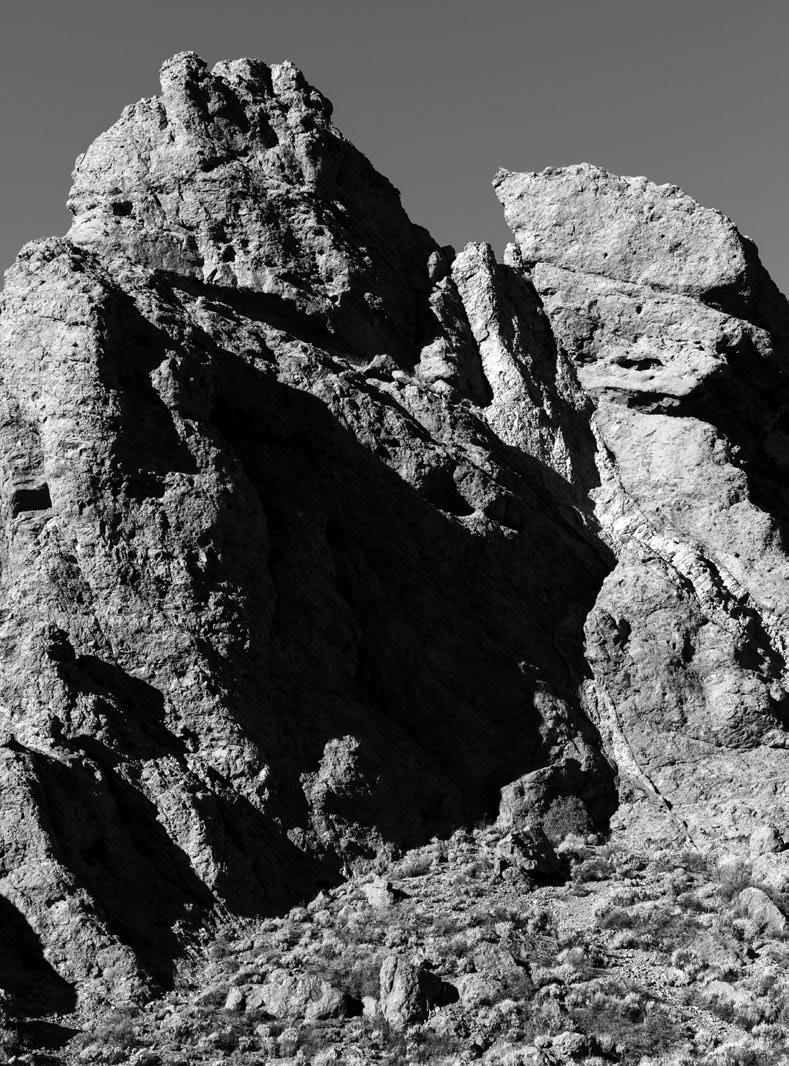

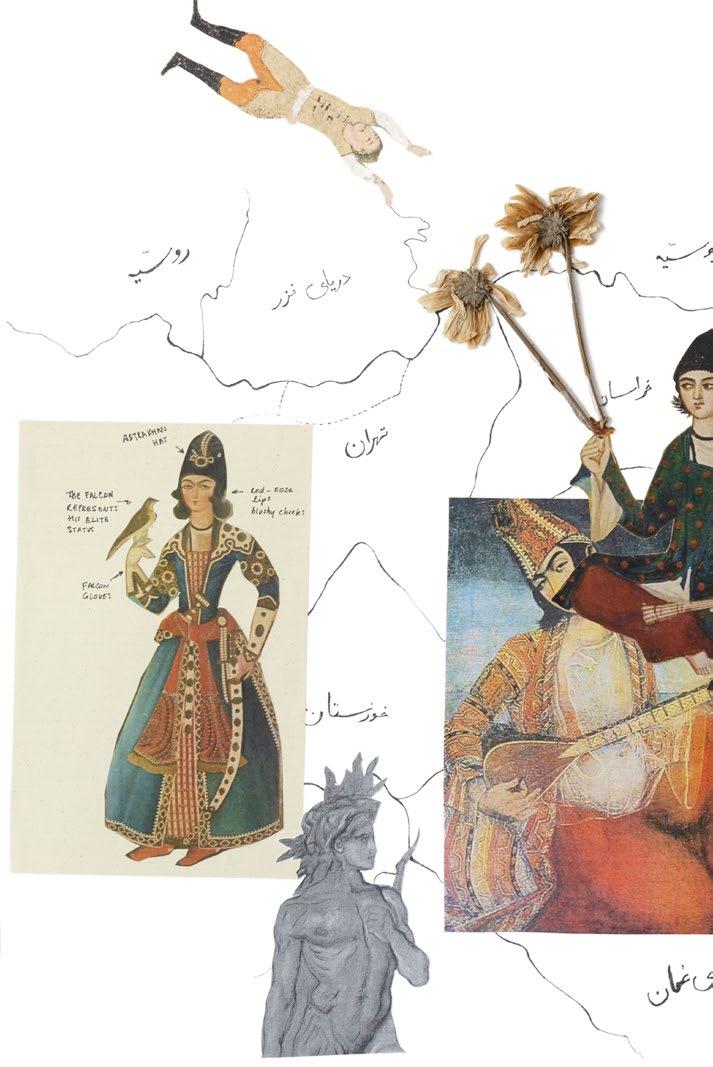

They had made a long and dangerous journey by horse to what was then Palestine to meet the exiled holy man called Baha’ullah. They had met road pirates, had done their share of trading to make it through the mountains and hills leading to the prison of Acre.

In contrast with my mother’s family, my father’s is dominated by men, and at the top of the family tree, we are still missing the name of a great-great grandmother.

There is a harem, yes, but we know next to nothing about these wives of Mister Ali Akbar, who started a mosque, a religious school, and then married several women. Only one is named: Seyeddeh Khanoom. This was five generations before my father’s birth –six before mine

We could have started the story with the eventful arrest and death-sentence of my great-great grandfather five generations earlier. A series of unexpected events led him and his brothers to escape their unfortunate fate.

They had made a long and dangerous journey by horse to what was then Palestine to meet the exiled holy man called Baha’ullah. They had met road pirates, had done their share of trading to make it through the mountains and hills leading to the prison of Acre.

You don’t get any choices. You just give them the money. You get yourself to Zahedan, the border with Pakistan. From there, it’s out of your hands.

Everyone knows that no-one goes to Zahedan for holidays. So if the Police stop you, they too, know.

When we arrived, we handed over our car and stepped into their jeep and took off into the mountains. Now, we no longer have control over our lives.

At some point we got to a clay house in the middle of the desert, my father says. What was this house doing there? He had wondered. I remember it looking like a tiny village.

The next day we travelled on camelbacks, riding through the desert for nine hours! I fell off once in the dark and ran behind.

It was almost noon when we were dropped off, in a tent this time. We were numb, didn’t care anymore. We couldn’t imagine going anywhere worse than where we were coming from.

At the border, they left us by ourselves in an open space, with the order to hide. They left.

We were there for what felt like hours. Dad says the ground was black, perhaps some kind of volcano dust. We all fell asleep.

At dusk a rusty van arrived and we were taken to an immigration point over the border. We travelled to Quetta for paperwork, then to Rawalpindi and eventually to Peshawar. We were neighbors with the Taliban. They were still organizing themselves then. They were nice to us.

“When I think of it now I realize we took such a big risk”, dad says. But at the time we didn’t realize it. All we wanted was to get away from our situation, from the hell we were in.

When we came to Peshawar, we couldn’t believe life could be like this.

Water ran out. Electricity shut down. There was dirt everywhere. We stayed there for over 15 months before getting the papers to move to Belgium. Why Belgium? I ask.

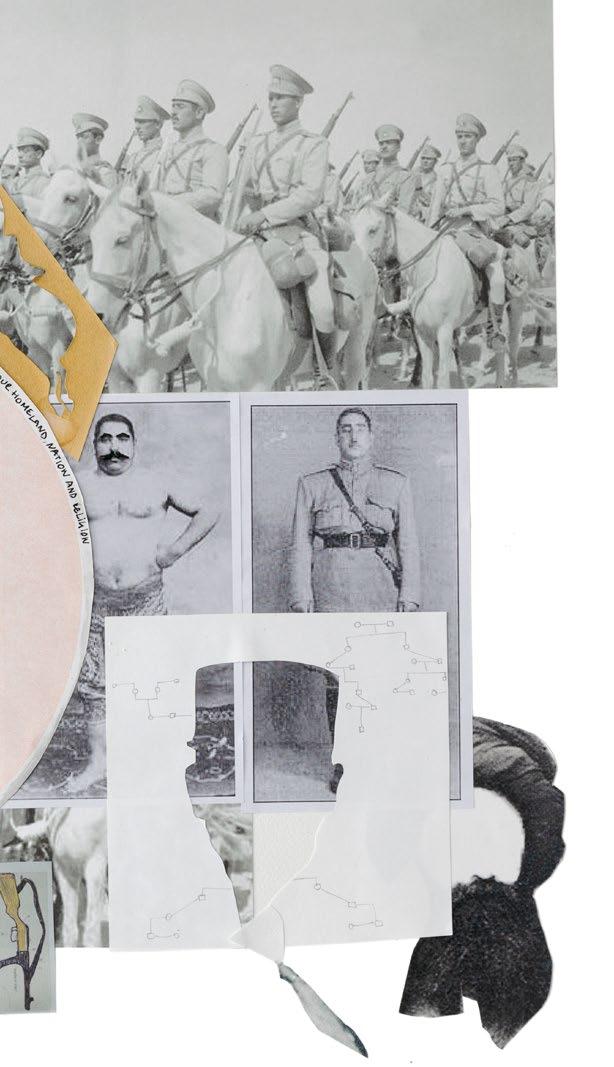

My father had to return his salary starting in 1979 because of his so-called “illegal” employment –Baha’ is no longer had permission to work. He had initially missed the notice to turn himself in.

When he told his boss, the man got so upset, he needed to go out for a walk.

The next week a man with a briefcase was waiting for him at work.

My father was taken to military court.

“There was a long hallway with interrogation rooms on each side”, he remembers.

The man in the room was talking to someone else. Suddenly he turned towards him in the middle of the conversation and said: “Where were you? We already told you, you are guilty of espionage.”

We finished at noon, they let me call your mom. She brought your grandma. Grandma got me out.

After this, they came regularly by the house. I remember the man with the briefcase. Mom made him cold syrup water with ice cubes. Dad went regularly to court.

At some point they asked, Dad tried not to offend them. He said he likes his ideology, he won’t change his mind.

That was it.

The man with the briefcase said we now have to wait for the verdict.

We sold everything. We contacted the people who take people. We bought a car in their name.

We told your grandmother: we are moving to Isfahan.

We told you and your sister: we are going on a vacation.

“How did grandmother not know?” I asked. Perhaps she didn’t want to know.

The vast majority of students were male, and the importance of the new knowledge was formulated in the gendered language of honor. New schools’ influence on the masculinity of male students extended well beyond the appropriation of new facts and forms of knowledge. It included new practices of discipline and inculcated new forms of bodily comportment and dress and new uses of time that were important to the formation of a new educated manhood in Iran.

This

is a preview of the first 55 pages of Mashid Mohadjerin’s book, ‘Riding

in Silence & the Crying Dervish.’