THE ROMAN SHELTER

MANIFESTO FOR THE CONTEMPORARY HUT

Fabio Balducci

Paolo Marcoaldi

director

Alessandra Capuano

studio leaders

Orazio Carpenzano

Alfonso Giancotti

tutors

Fabio Balducci

Paolo Marcoaldi

students

Veronica Caprino

Domenico Faraco

Daniele Frediani

Andrea Parisella

Claudia Ricciardi under the auspices of

2021 SEOUL BIENNALE OF ARCHITECTURE

CROSSROADS, Building the resilient city

DATES

16.09.2021

31.10.2021

PLACES

Dongdaemun Design Plaza(DDP)

Seoul Hall of Urbanism & Archtecture

Sewoon Plaza

DIRECTOR

Dominique Perrault

GLOBAL STUDIOS CURATORS

Archiworkshop

Seong Kang (Assistant Curator)

Marc Brossa (Ex-Curator 09.20>03.21)

WEBSITE

2021.seoulbiennale.org

Bureau du Directeur Général - SBAU 2021

6 rue Bouvier 75011 PARIS / FRANCE

T + 33 (0)1.44.06.00.00 seoulbiennale@perraultarchitecture.com

Seoul Metropolitan Government

110 Sejong-daero, Jung-gu, Seoul Republic of Korea

Tel : (Korea) +82-2-2133-7623

seoulbiennale@seoul.go.kr

Text notes

01. Shelter - Claudia Ricciardi, pp. 72-75

02. Elements - Andrea Parisella, pp. 76-79

03. Caterva - Daniele Frediani, pp. 80-83

04. Material - Domenico Faraco, pp. 84-87

05. Crossroads - Veronica Caprino, pp. 88-91

CONTENTS

Invitation

Dominique Perrault

Foreword

Orazio Carpenzano

Global Studios call for proposals

The Roman Shelter. Themes and toolkits for a contemporary hut Fabio Balducci, Paolo Marcoaldi

The first house and the last one Fabio Balducci

The multiple dwelling of the refuge, between cave and hut Paolo Marcoaldi

Manifesto. What can you live without?

Orazio Carpenzano, Alfonso Giancotti, Fabio Balducci, Paolo Marcoaldi, Veronica Caprino, Domenico Faraco, Daniele Frediani, Andrea Parisella, Claudia Ricciardi

Afterword

Giancotti Apparatus - Multimedia - Exhibition in Rome - Bibliography 8 12 16 22 36 46 56 92 96 98 106

Alfonso

DOMINIQUE PERRAULT

Dear Participant,

I am delighted to welcome you as one of the participants who will be presented in the exhibitions of the Seoul Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2021 (SBAU 2021 ). Supported by the City of Seoul, the Biennale is becoming increasingly important on the world architectural scene, with more than 450,000 visitors in 2017, and more than 710,000 visitors in 2019. We strongly hope that this new edition will further strengthen its international visibility.

Through this third edition, entitled Crossroads, Building the Resilient City, I am asserting the importance of dialogue, of cross-fertilization of expertise and approaches, as a nourishing ground tor architectural design and urban planning, and a space tor the fertilization of new territories. I wish tor a Biennale that does not separate but brings together the fields of reflection, and manifests the creative torce of interactions, creating a new type of physical network expanding the limits of architecture.

We are now a few months away from the SBAU2021 opening. The Biennale's organizing committee and curators have now finalized the selection of

all the participants, who will have the opportunity to present their work in its various sections and exhibitions. More than a hundred cities will be represented, through a wide variety of high-quality projects, and about two hundred participants, including severa! hundred students and teams.

In this particular year, impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic, that has gone through many uncertainties, we are very happy to have been able to maintain all the physical exhibitions of the Biennale.

The six exhibitions will take piace in three locations in the city of Seoul. The Global Studios section, curated by Korean architectural studio Archiworkshop, will be associated with the Thematic & Cities sections within the Dongdaemun Design Plaza, iconic Zaha Hadid building of the South Korean metropolis. I am delighted that the exhibitions can feature well established creators specifically selected for the relevance of their projects, as well as also promote newness thanks to young talented teams, of all ages and backgrounds. Until then, I trust that your commitment will make this edition a success. lndeed, the richness of the exhibitions will rely on the quality of each contribution exhibited.

8 THE ROMAN SHELTER

SBAU 2021 General Curator

INVITATION

9 INVITATION NATURAL ARTIFICIAL HERITAGE MODERN CRAFT AI ABOVE / BELOW

ORAZIO CARPENZANO

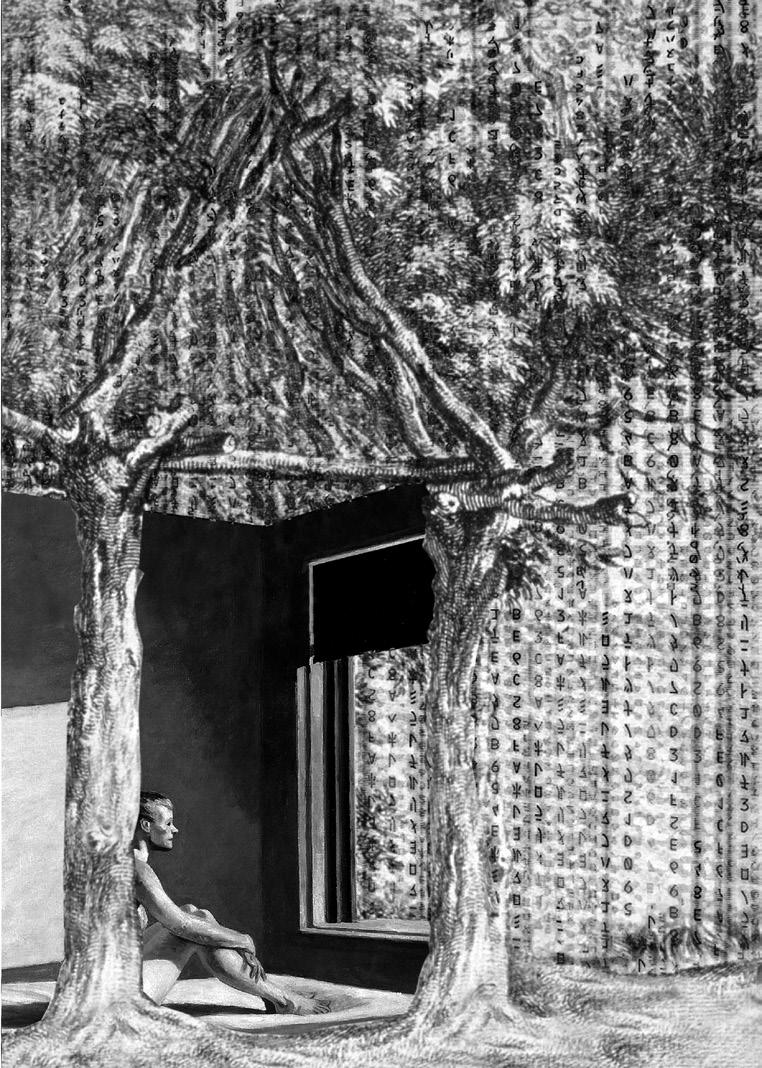

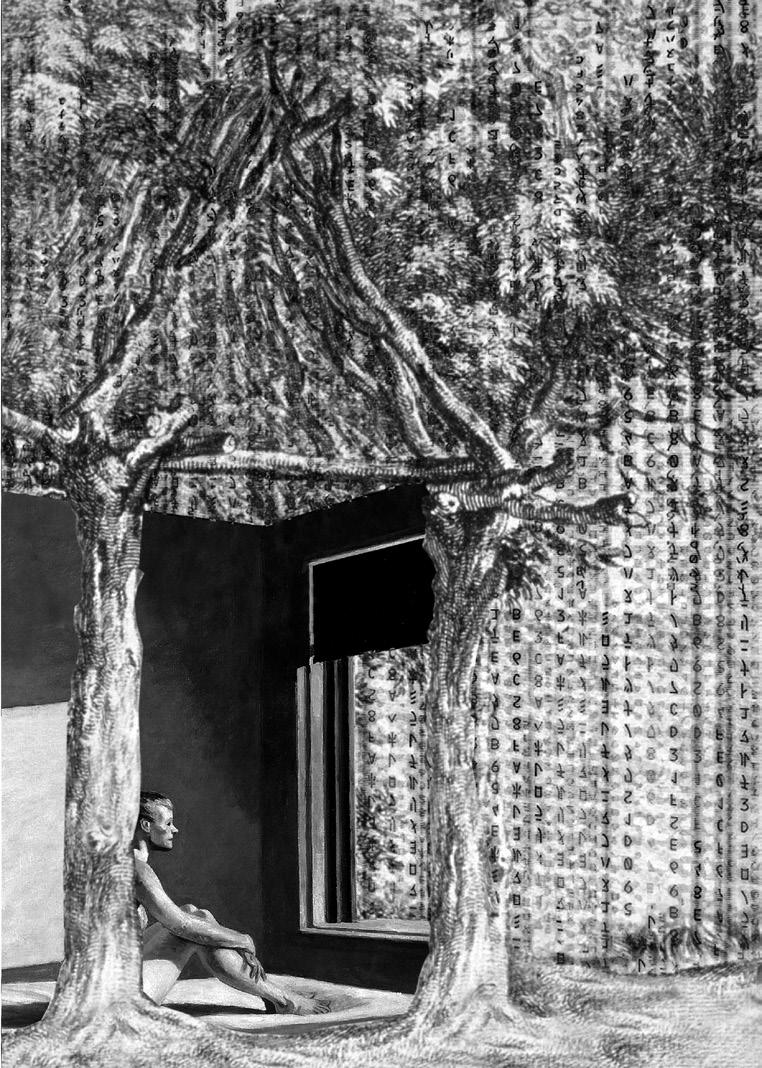

Shelter as a theme continues to manifest its ambivalent nature in the contemporary condition. For those who have to face the consequences of war or natural disasters, the shelter is a safe dwelling, a stronghold far from the dangers that rage in the spaces we have abandoned to reach it: an armoured, robust, impregnable place. But for those who are fortunate enough not to have to face the fears of the world, the refuge is a place where they can experience feelings of remembrance and intimacy. Refuge is also nest, alcove, home. It is a place of hermitage, comfort and welcome, and as such it has traversed the history of religions and societies. In this sense, refuge is also Eden, a Hebrew noun meaning pleasure, delight, translated in the Vulgate by the biblical scholar Jerome as paradisus voluptatis. According to recent studies, Eden may instead derive from the Sumerian word edenu, which corresponds to the steppe, the desert. A refuge in the desert: an oasis where, according to Sumerian myths, the plant of immortality grows. In any case, including Catholic civilisation in this excursus, we can speak of Eden as the cosmic soul of matter. A myth of the origin of the world, suspended in the magical balancing act between the identical and the different, where God

is in the material reality it contains and to which it gives order and life, not for any other purpose than human. The animating force of the world has only human purposes. In architecture, the figure of the shelter is associated with theoreticalcritical speculations on the principles by which the human kind builds his dwelling. These are derived from nature, where we can find the toolbox of actions and techniques that are useful for interweaving and interlacing the different habitats of living species: they contemplate the act of digging, assembling, juxtaposing, lifting, kneading.

The project of the Sapienza University of Rome working group for the Seoul Architecture Biennale 2021 aims to place itself in an intermediate space between these two poles, seeking to preserve from both the principles that define them. The hut is a carapace detached from the earth and the sky, suspended between them, not to defy the laws of nature, but to mark a distance from a contaminated and corrupted territory where it becomes difficult to live.

This contemporary hut is a machine for tuning into the energies of the biosphere, drawing from it and

12 THE ROMAN SHELTER

Sapienza University of Rome - Studio Leader Dean of the Faculty of Architecture

FOREWORD

Il rifugio come tema manifesta ancora nella condizione contemporanea la sua natura ambivalente. Per chi affronta le conseguenze della guerra o dei disastri naturali, il rifugio è dimora sicura, roccaforte lontana dai pericoli che imperversano negli spazi che abbiamo abbandonato per raggiungerlo: luogo blindato, robusto, inespugnabile. Ma chi ha la fortuna di non dover affrontare le paure del mondo vede il rifugio come luogo dove esperire sentimenti di raccoglimento e intimità. Rifugio è anche nido, alcova, casa. Luogo di eremitaggio, del conforto e dell’accoglienza, e come tale ha attraversato la storia delle religioni e delle società. In tal senso, rifugio è anche Eden, sostantivo ebraico che corrisponde a piacere, a delizia, tradotto nella Vulgata del biblista Girolamo come paradisus voluptatis. Da studi più recenti, Eden potrebbe derivare invece dal termine sumerico edenu che, al contrario, corrisponde alla steppa, al deserto. Quindi, un rifugio nel deserto: un’oasi dove cresce, secondo i miti sumeri, la pianta dell’immortalità. In ogni caso, comprendendo in questo excursus la civiltà cattolica, possiamo parlare di Eden come anima cosmica della materia. Mito dell’origine del mondo, sospeso nel magico equilibrismo tra l’identico e il diverso, dove Dio è nella

realtà materiale che contiene e a cui dà ordine e vita, non per altri scopi oltre quelli umani. La forza animatrice del mondo ha solo scopi umani.

In architettura, alla figura del rifugio si associano le speculazioni teoricocritiche sui principi attraverso i quali il genere umano costruisce la propria dimora. Essi sono ricavati dalla natura, dove è rinvenibile lo strumentario di azioni e tecniche utili ad intrecciare e tessere i diversi habitat delle specie viventi: queste contemplano l’atto dello scavare, dell’assemblare, del giustapporre, del sollevare, dell’impastare.

Il progetto del gruppo di lavoro di Sapienza Università di Roma per la Seoul Biennale of Architecture 2021 intende collocarsi in uno spazio intermedio tra questi due poli, sforzandosi di conservare da entrambi i principi che li determinano. Il rifugio è un carapace sottratto alla terra ed al cielo, tra essi sospeso non per sfidare le leggi della natura, ma per marcare una distanza da un territorio contaminato e corrotto, sul quale diventa difficile vivere.

Questa capanna contemporanea è una macchina per entrare in sintonia con le energie della biosfera, per trarre da essa e continuamente

PREMESSA

ORAZIO CARPENZANO

Sapienza Università di Roma - Studio Leader

Preside della Facoltà di Architettura

13 PREFACE

Sapienza Università di Roma

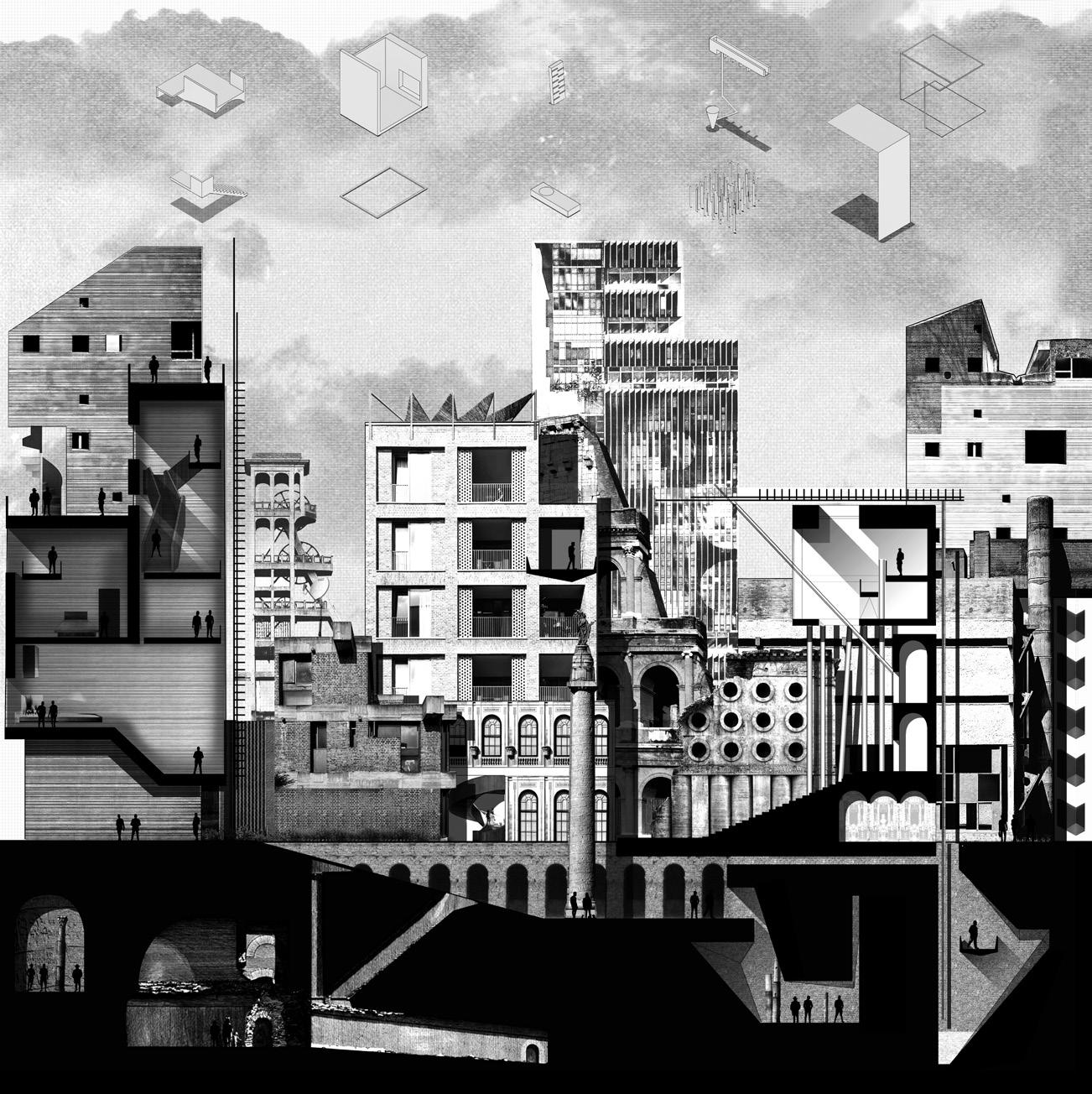

ELEMENTS AND THE CITY

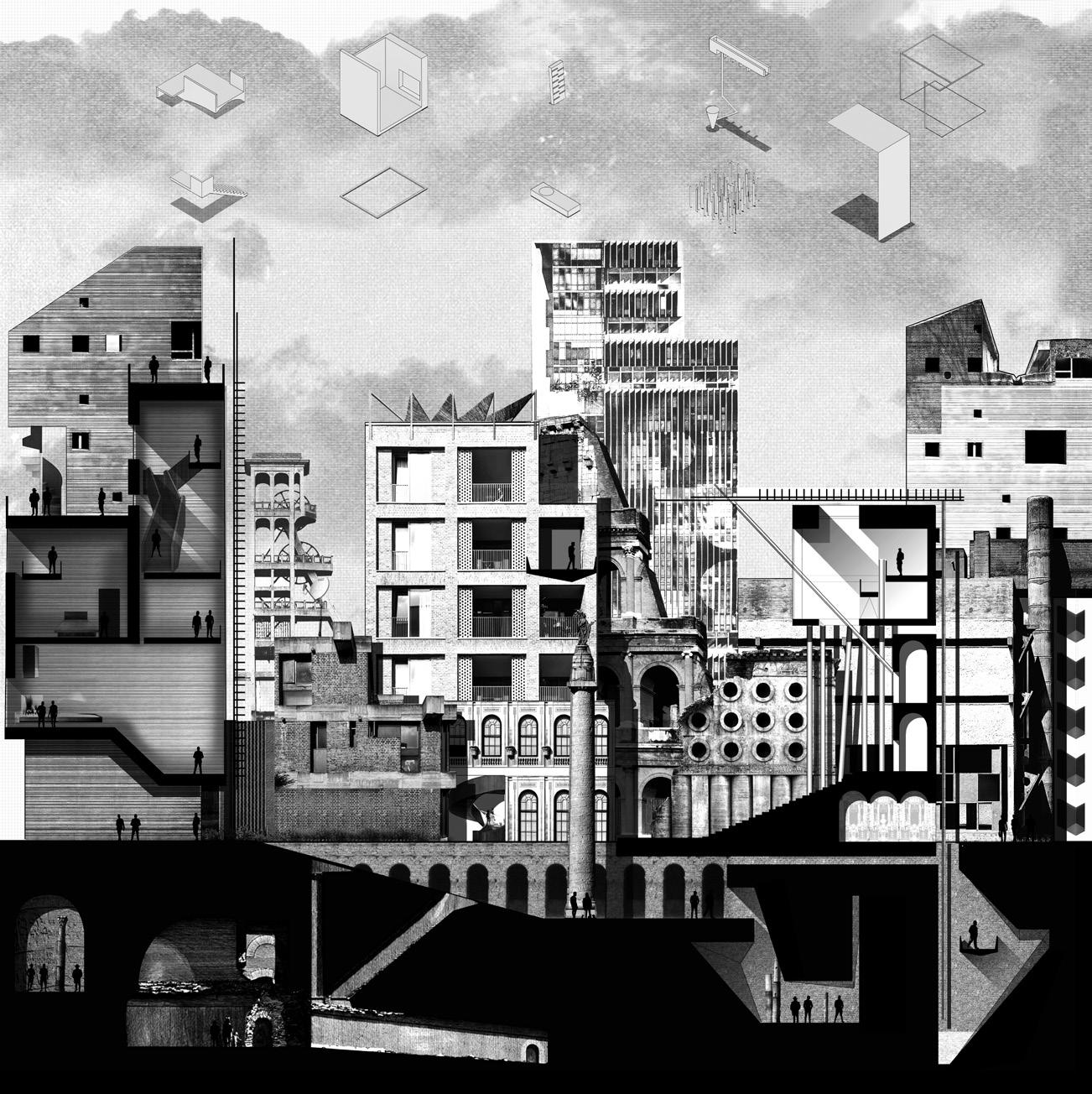

The urban context in Rome has become a paradigmatic reference for our investigation into shelter as a space for protection within the contemporary society.

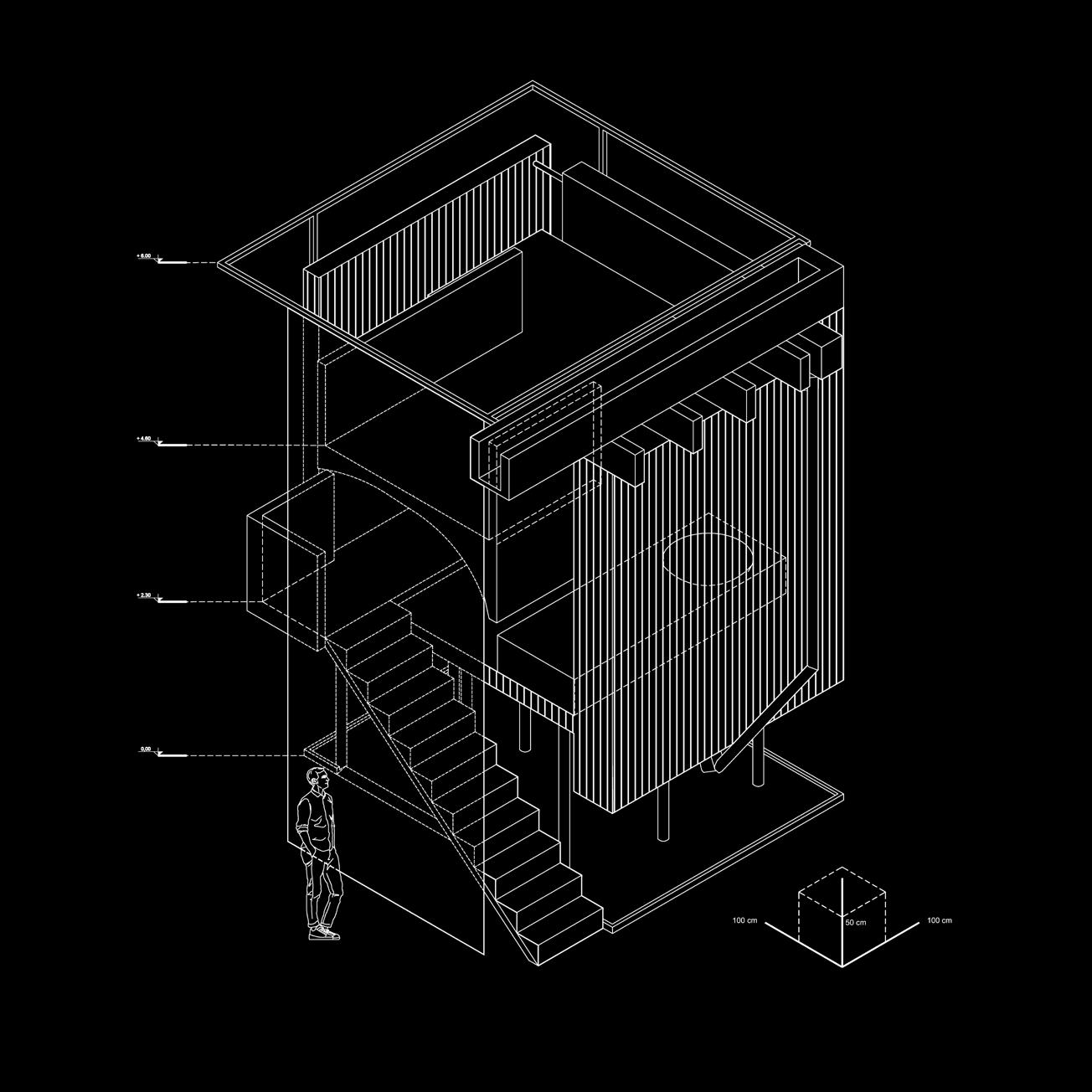

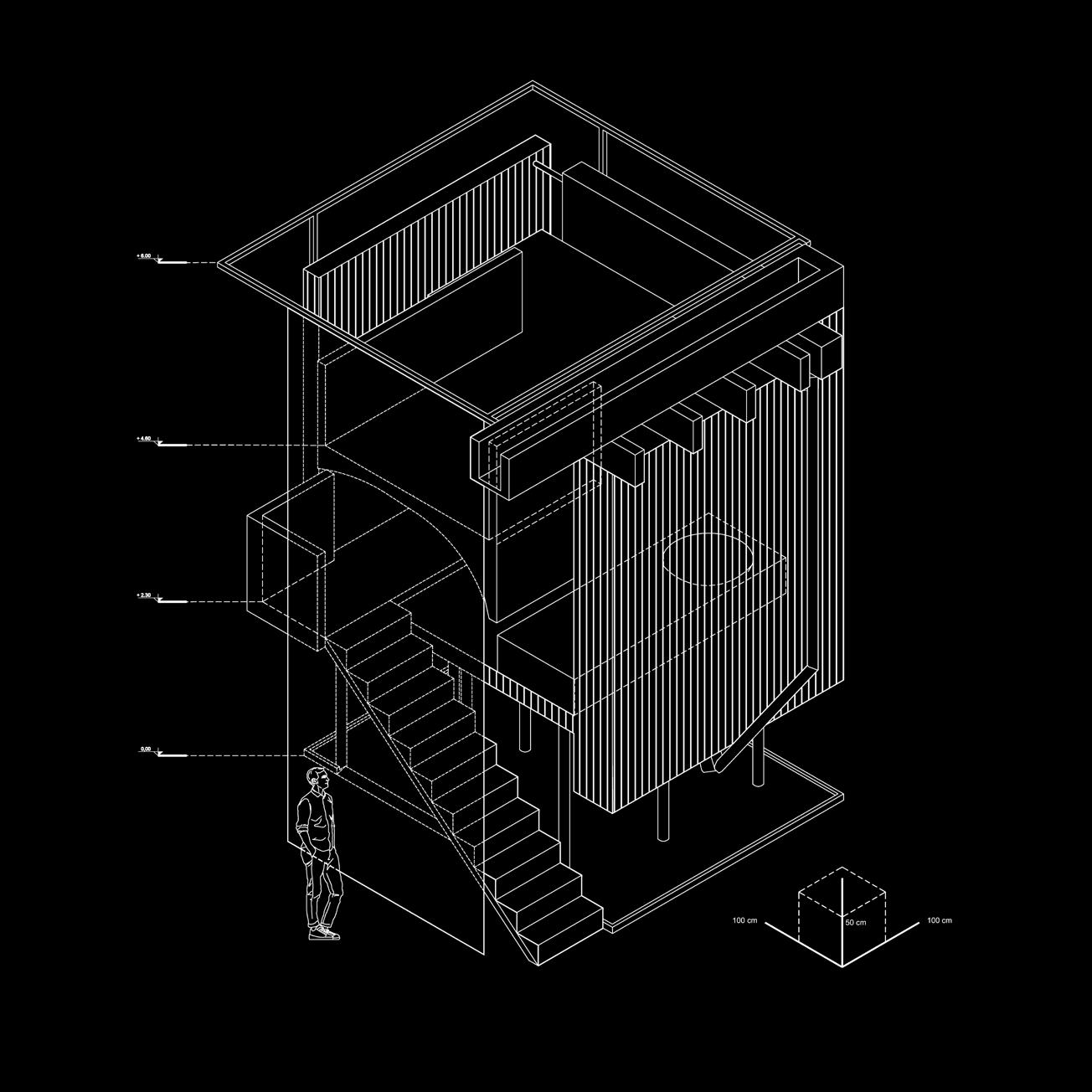

The city’s dense fabric is formed through overlapping traces and fragments, creating a palimpsest that preserves the recognizability of its constituent parts. By reducing this complex system to its essential elements, we can identify universal components that can provide an answer to basic human needs. These components, designed around human body shapes, gestures, and domestic rituals, form an operative toolkit for building a basic shelter. This approach promotes a return to a primitive condition, where we strip away the superfluous to identify what is truly essential.

ELEMENTI E CITTÀ

Il contesto urbano di Roma è diventato un riferimento paradigmatico per la nostra indagine sul rifugio come spazio di protezione all'interno della società contemporanea.

Il fitto tessuto della città si forma attraverso la sovrapposizione di tracce e frammenti, creando un palinsesto che conserva la riconoscibilità delle sue parti costitutive. Riducendo questo sistema complesso ai suoi elementi essenziali, possiamo identificare componenti universali che possono fornire una risposta ai bisogni umani fondamentali. Queste componenti, progettate intorno alle forme del corpo umano, ai gesti e ai rituali domestici, formano un kit di strumenti operativi per la costruzione di un riparo elementare. Tale approccio favorisce il ritorno a una condizione primordiale, in cui ci si spoglia del superfluo per individuare ciò che è veramente essenziale.

1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. roof bearing structure ladder drainpipe roof terrace staircase water basin bedroom/fireplace columns curtain Toolkit

1. 2. 3.

5.

4.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

THE MULTIPLE DWELLING OF THE REFUGE, BETWEEN CAVE AND HUT

Anyone accustomed to visiting libraries and bookshops will not have failed to notice how the subject of primitive living has recently flared up under the relentless blows of the pandemic crisis1.

Among the topics that have been debated in recent years, we should mention Roberto Secchi’s interesting book Primitivismo e architettura, in which the author describes, through projects and theoretical arguments, the particular phenomenon of the search for the original, the authentic and the essential, in an attempt to transcend the relativity imposed by time and history.

“[...] the recourse to an imagery of forms evoking the human figure suspended in time, outside the trajectories of linear progress hoped for and theorised by modernity, seems to be a refuge from the aleatoric nature of things, from fashions, from the desire to make differences a sign of division and particular interests”2.

And what more than primordial forms, than archetypes, can transcend the limits of time and space and turn to a universal elsewhere, where images once again become εἶδος, morphogenetic principles?

As is well known, in Platonic

philosophy the word archetype is the idea, the ideal form, which seeks its possible and plausible declination in reality.

Platonic ideas, in their most primitive state, reside in a metaphysical place beyond the vault of the heavens, the Hyperuranium, where concepts are found in all their perfect purity and abstraction. They are unchanging universal principles, not subject to becoming and change like empirical objects. The latter, as far as ideas are concerned, stand in a relationship of imitation or resemblance.

The archetype is therefore a form of innate imitation, in that it stands as the figurative means by which man seeks to unite, through reason, the spiritual dimension, which is by nature timeless and a-contextual, with the material dimension, which is instead subject to spatial and temporal variations.

In his Treatise on the History of Religions, the anthropologist Mircea Eliade dwells at length on the concept of the archetype and its possible applications in reality.

“The repetition of archetypes highlights the paradoxical desire to achieve an ideal form (= the archetype) within the conditions of human existence, to stand in duration without bearing its weight, that is,

46 THE ROMAN SHELTER

MARCOALDI

PAOLO

Chi è abituato a frequentare biblioteche e librerie non può non aver notato come il tema dell’abitare primitivo sia recentemente deflagrato sotto i colpi incessanti della crisi pandemica1.

All’interno di questo argomento così dibattuto negli ultimi anni, vale la pena ricordare l’interessante libro Primitivismo e architettura di Roberto Secchi, in cui l’autore descrive, attraverso progetti e argomentazioni teoriche, quel particolare fenomeno che riguarda la ricerca dell’originario, dell’autentico e dell’essenziale nell’aspirazione ad oltrepassare la relatività indotta dal tempo e dalla storia.

“[…] il ricorso a un immaginario di forme che evochi la figura umana sospesa nel tempo, fuori dalle traiettorie del progresso lineare auspicato e teorizzato dal Moderno, appare un rifugio al riparo dalla aleatorietà delle cose, dalle mode, dalla volontà di fare delle differenze il marchio della divisione e degli interessi particolari”2.

E cosa più delle forme primordiali, degli archetipi, può travalicare i confini del tempo e dello spazio, rivolgendosi ad un altrove universale, in cui le immagini tornino ad essere

, principi morfogenetici?

Come è noto, infatti, nella filosofia

platonica la parola archetipo è l’idea, la forma ideale, che cerca una sua possibile e plausibile declinazione nella realtà.

Le idee platoniche, nella loro condizione più primitiva, risiedono in un luogo metafisico oltre la volta celeste, l’Iperuranio, in cui i concetti si trovano in tutta la loro perfetta purezza e astrazione. Si tratta di principi universali immutabili, non soggetti quindi al divenire e al mutamento come gli oggetti empirici. Questi ultimi, rispetto alle idee, si pongono in un rapporto di imitazione o somiglianza.

L’archetipo è, dunque, una forma di imitazione innata, in quanto si pone come il tramite figurato con cui l’uomo cerca di unire, attraverso la ragione, la dimensione spirituale, intrinsecamente atemporale e acontestuale, alla dimensione materiale, che invece è subordinata alle variazioni spaziali e temporali.

Nel Trattato di storia delle religioni l’antropologo Mircea Eliade si sofferma a lungo sul concetto di archetipo e sulle sue possibili applicazioni nella realtà.

“La ripetizione degli archetipi evidenzia il desiderio paradossale di conseguire una forma ideale (= l’archetipo) entro le condizioni stesse dell’esistenza umana, di stare nella

L’ABITARE MOLTEPLICE DEL RIFUGIO, TRA CAVERNA E CAPANNA

47 THE

MULTIPLE

DWELLING OF THE REFUGE, BETWEEN CAVE AND HUT

εἶδος

PAOLO MARCOALDI

underworld in search of her daughter was called the world” 7 .

Every form of archetype uses a transversal architectural lexicon, which is therefore not the exclusive domain of a particular culture or context, but is perfectly recognisable by everyone and in every age. Once again, Eliade comes to our aid: “At the root of the various religions are always the same archetypes, that is, the same fundamental images and symbols in which the human condition as such is expressed, beyond all epochs and civilisations”8.

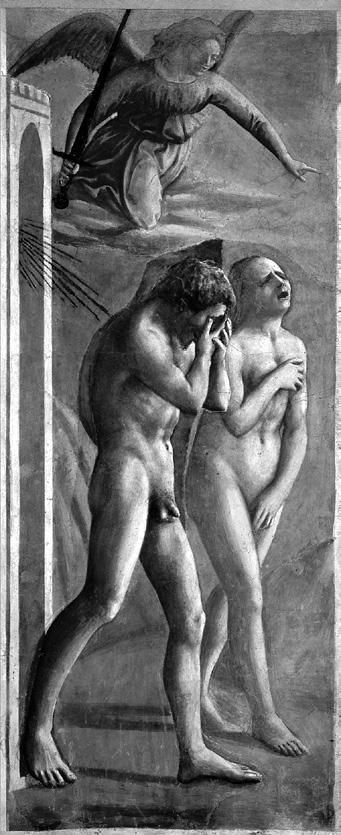

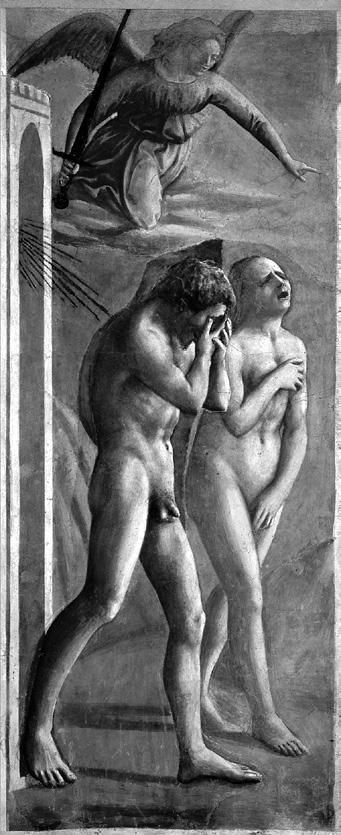

And indeed, as in ancient Greece, the cave myth plays a central role in Christian iconography. Although the canonical gospels do not describe the place of Jesus’ birth in detail9, two apocryphal Gospels give more information about the episode. In chapter XVIII of the Proto-Gospel of James, Jesus is said to have been born in a cave, while in chapter XIII of the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew there is mention of a divine light: “[...] illuminated the cave in such a way that there was no lack of light, neither by day nor by night, as long as the Blessed Mary remained there”.

But in the Christian religion, the cave is also the place of passage from earth to heaven; the resurrection is therefore the passage from darkness to light, the new life after returning to the womb of earthly matter. This is why the cave, as a womb, is also a symbol of fertility, but also an image of the centre and the heart.

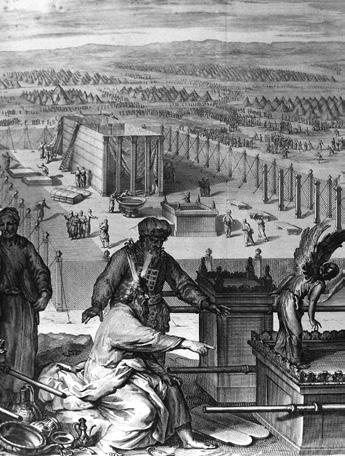

The hut, and in particular its most transient form, the tent, represents a model of settlement that is

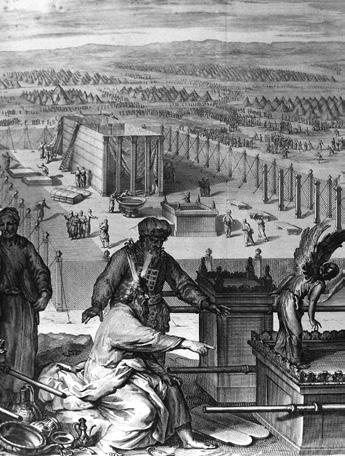

fundamentally different from that of the cave. The inhabitant of the tent is a nomad, and as such lives by moving his body and, with it, the space that surrounds him. Precisely because it is not tied to a specific place, the tent was described in ancient times as a divine refuge.

In Judaism, the tabernacle was the portable dwelling place of the divine presence, built according to the dictates revealed by God to Moses on Mount Sinai. And Solomon also mentions the tent as the archetype of the divine home: “Thou hast commanded me to build the temple of thy most holy name, and also an altar in the city where thou dwellest, after the pattern of the most holy tent which thou hast prepared from the beginning!”10

The shelters erected over the earth, like the dominion of fire, are the emblems that establish the definitive primacy of man over other animals. According to Lucretius, by moving into huts, humans lose their original cave fertility: “(homines) vulgivago vitam tractabant more ferarum”11 .

Ratio, a concept already discussed in detail by Aristotle, is what distinguishes man from other living beings, since, according to Aristotelian doctrine, man is the only one who also possesses the third function of the soul, the rational function, i.e. the intellect.

And it is this ratio that, according to Vitruvius, allows man to progress from the cave to the house, to the domus in stone and to more sophisticated achievements.

50 THE ROMAN SHELTER

Gerard Hoet, The erection of the Tabernacle and the Sacred vessels, 1728 illustration published by P. de Hondt

uomo e natura è di tipo mutevole, metamorfico.

Nelle tradizioni iniziatiche greche, l’antro rappresenta il mondo. Questo riferimento è esplicito nel Commento alle Bucoliche di Servio: “La caverna attraverso la quale Cerere era discesa agli Inferi per cercare la figlia, era chiamata il mondo” 7 .

Qualunque forma di archetipo utilizza un lessico architettonico trasversale, che quindi non è di esclusivo dominio di una cultura o di un contesto in particolare, ma è perfettamente riconoscibile da chiunque ed in ogni epoca. Ancora una volta ci viene in aiuto Eliade: “Al fondo delle varie religioni operano sempre gli stessi archetipi, cioè le stesse immagini e gli stessi simboli fondamentali, nei quali si esprime la condizione umana come tale, al di là di tutte le epoche e di tutte le civiltà”8 .

Ed infatti come nell’antica Grecia, anche nell’iconografia cristiana il mito della caverna ha un ruolo centrale. Sebbene i vangeli canonici non descrivano dettagliatamente il luogo della nascita di Gesù9, due Vangeli apocrifi danno maggiori informazioni sull’episodio. Nel cap.

XVIII del Protovangelo di Giacomo si racconta che Gesù nacque in una grotta, mentre al cap. XIII del Vangelo dello pseudo Matteo si parla di una luce divina che: “[…] illuminò la grotta in modo tale che né di giorno né di notte, fino a quando vi rimase la beata Maria, la luce non mancò”.

Ma la caverna nella religione cristiana è anche il luogo di passaggio dalla terra al cielo, la resurrezione è dunque la transizione dal buio alla luce,

la nuova vita dopo essere tornati nel grembo della terra mater. Per questo la caverna, in quanto utero, è anche simbolo di fertilità, ma anche immagine del centro e del cuore.

La capanna, ed in particolare la sua forma più transitoria, la tenda, rappresentano un modello insediativo profondamente diverso da quello della caverna. L’abitante della tenda è un nomade, ed in quanto tale abita muovendo il corpo e con esso lo spazio che lo circonda. La tenda, proprio in quanto non legata ad un luogo particolare, veniva designata nell’antichità come il rifugio divino.

Nell’ebraismo il tabernacolo era la dimora trasportabile della presenza divina, costruita secondo i dettami rivelati da Dio a Mosè sul Monte Sinai. Ed anche Salomone menziona la tenda come l’archetipo della casa divina: “Tu mi hai ordinato di costruire il tempio nel tuo santissimo Nome, e anche un altare nella città in cui tu abiti, secondo il modello della tenda santissima, che tu avevi preparato fin dall’inizio!”10

I rifugi eretti sopra la terra, al pari del dominio del fuoco, sono gli emblemi che stabiliscono la definitiva primazia dell’uomo sugli altri animali. Secondo Lucrezio gli uomini, spostandosi nelle capanne, perdono l’originaria ferinità cavernicola: “(homines) vulgivago vitam tractabant more ferarum”11.

La ratio, concetto già ampiamente trattato da Aristotele, è ciò che contraddistingue l’essere umano dagli altri esseri viventi, in quanto, secondo la dottrina aristotelica, l’uomo è l’unico a possedere anche la terza funzione dell’anima, la funzione

51

THE

MULTIPLE DWELLING OF THE REFUGE, BETWEEN CAVE AND HUT

Masaccio, Cacciata dei progenitori dall'Eden, 1424-25, Cappella Brancacci, Firenze

ORAZIO CARPENZANO ALFONSO GIANCOTTI FABIO BALDUCCI

MANIFESTO

What can you live without?

The contemporary society essentially stands between the two antithetical conditions of ISOLATION and HYPERCONNECTION. They define the field of analysis in which to investigate the idea of refuge as a home, or the home as a refuge, highlighting the dichotomous relationship between the domestic space, that intimately embodies the ego, and the house intended as a shelter, that provides protection

PAOLO MARCOALDI VERONICA CAPRINO DOMENICO FARACO

DANIELE FREDIANI ANDREA PARISELLA CLAUDIA RICCIARDI

MANIFESTO

from an unexpected emergency. The idea of time, of permanence within the domestic space, is precisely referred to the latter meaning. If the refuge is such for the traveler during the recovery period of a sudden emergency, it changes when it becomes a permanent space that syncs and overlaps the place where return and the place where to stay, a spatial extension of our own body.

To live refers to the visceral action

Di cosa non puoi fare a meno?

La società contemporanea si trova essenzialmente tra le due condizioni antitetiche di ISOLAMENTO e IPERCONNESSIONE. Esse definiscono il campo di analisi in cui indagare l'idea di rifugio come casa, o di casa come rifugio, evidenziando la relazione dicotomica tra lo spazio domestico, che incarna intimamente l'Io, e la casa intesa come rifugio, che offre protezione da un'emergenza imprevista.

L'idea di tempo, di permanenza all'interno dello spazio domestico, è proprio riferita a quest'ultima accezione. Se il rifugio è tale per il viaggiatore durante il periodo di recupero di un'emergenza improvvisa, cambia quando diventa uno spazio permanente che sincronizza e sovrappone il luogo del ritorno e quello del soggiorno, un'estensione spaziale del nostro stesso corpo. Abitare si riferisce all'azione viscerale

58 THE ROMAN SHELTER

The contemporary hut: Charles Eisen, Edward Hopper and The Matrix

MANIFESTO

59

axonometry

axonometry

plan section

axonometry

axonometry