Indice

Introduction

Cherubino Gambarella

Confiscated assets in Villa Literno and the role of Agrorinasce

Giovanni Allucci

Wonderful creature

Concetta Tavoletta

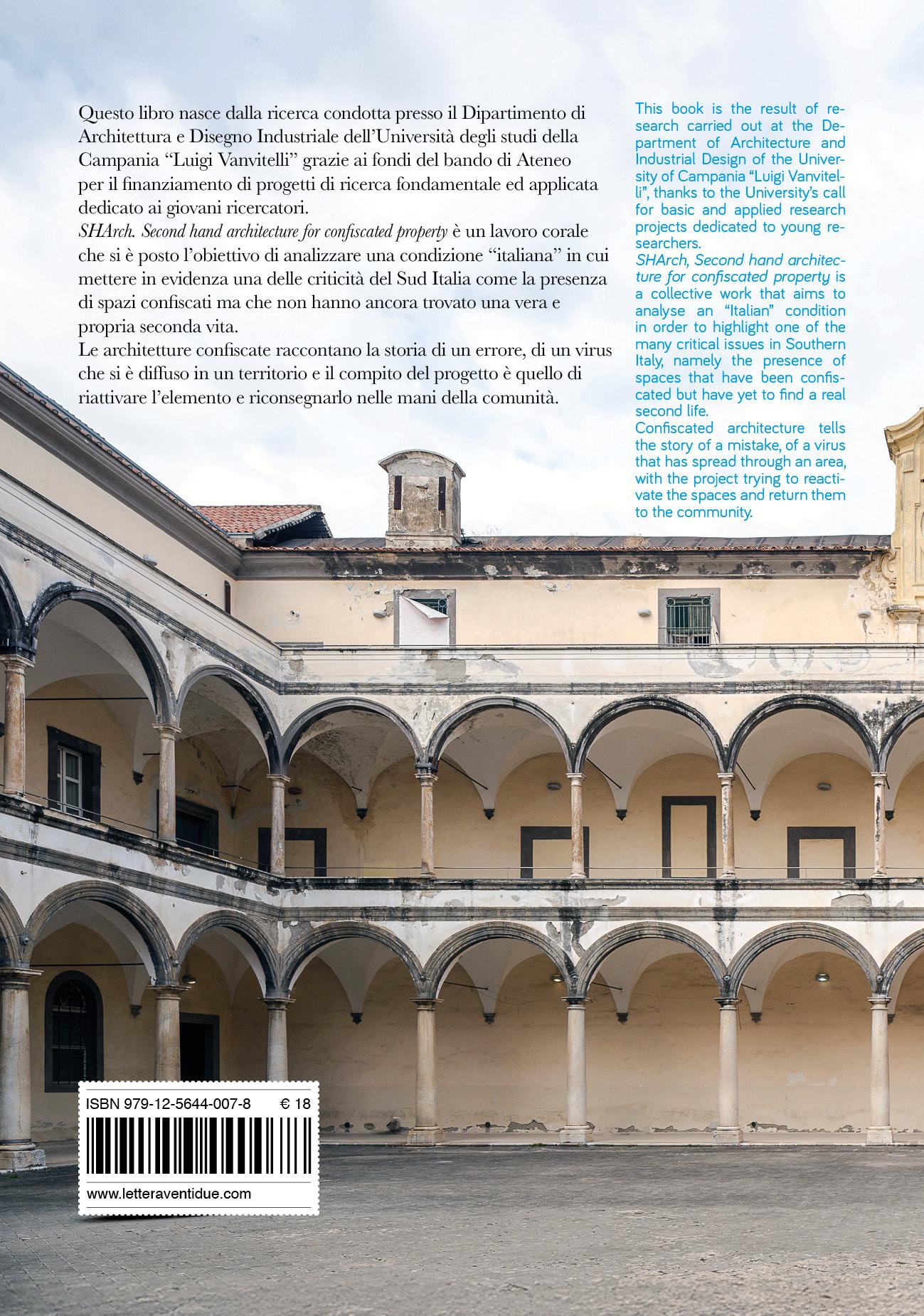

Recovery and Re-functionalisation: a second life for abandoned artefacts

Efisio Pitzalis

Necessary regeneration

Luca Molinari

Architecture. Stones and things already done

Corrado Di Domenico

The Structural Perspective: The Material Question

Claudia Cennamo

Architecture without form. An operative palimpsest of an informal alphabet

Maria Gelvi

Movable magnets

Simona Ottieri

Simona Ottieri 9 14 19 26 29

Introduzione

Cherubino Gambarella

I beni confiscati a Villa Literno e il ruolo di Agrorinasce

Giovanni Allucci

Meravigliosa creatura

Concetta Tavoletta

Recupero e Rifunzionalizzazione: una seconda vita per i manufatti abbandonati

Efisio Pitzalis

Rigenerazione necessaria

Luca Molinari

Architettura. Pietre e cose già fatte

Corrado Di Domenico

Il punto di vista strutturale: la questione materica

Claudia Cennamo

Architettura sine forma. Palinsesto operativo di un alfabeto informale

Maria Gelvi

Calamite Mobili

Strategie per Architetture di “Seconda Mano” decarbonizzate e circolari

Monica Cannaviello

Il riuso dei materiali da costruzione. Risorsa e opportunità

Marco Russo

Ipotesi ritmiche per l’intervento sull’esistente

Luigi Arcopinto

Archeologia del perturbante

Marco Pignetti

Lo avete costruito voi, ora lo usiamo NOI. Un censimento critico dei beni sottratti alla criminalità organizzata

Barbara Bonanno

Progetti per l’Ex Zuccherificio IPAM a Villa Literno (Caserta)

Cherubino Gambardella

Selezione dei progetti presentati dagli studenti

Concetta Tavoletta

SHArch. L’allestimento

Cherubino Gambardella, Maria Gelvi, Concetta Tavoletta

Strategies for decarbonized and circular “Second Hand” Architectures

Monica Cannaviello

The reuse of construction materials. Resource and opportunities

Marco Russo

Rhythmic Hypotheses for the intervention on existing buildings

Luigi Arcopinto

Disturbing archaeology

Marco Pignetti

You built it, now WE are using it. A critical census of properties confiscated from organized crime

Barbara Bonanno

Projects for the former IPAM sugar refinery in Villa Literno (Caserta)

Cherubino Gambardella

A selection of the projects presented Concetta Tavoletta

SHArch. Setting up Cherubino Gambardella, Maria Gelvi, Concetta Tavoletta

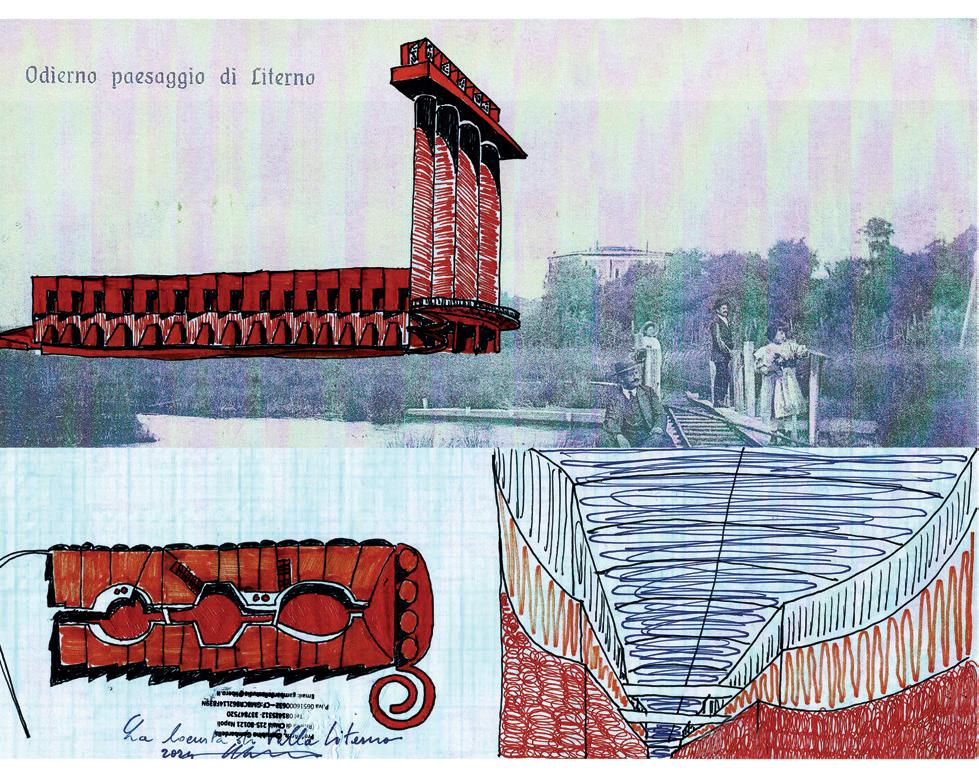

Cherubino Gambardella, Odierno paesaggio di Liternum, mixed media, 2023.

Netx pages: Cherubino Gambardella, sketches.

Cherubino Gambardella, Odierno paesaggio di Liternum, tecnica mista, 2023. A seguire Cherubino Gambardella, schizzi.

Cherubino Gambardella

Introduzione

Il tema dei beni confiscati è molto sentito in questi ultimi tempi perché questa formula di lotta alla criminalità sta trovando una sua ulteriore forma di successo non solo mediante lo strumento della detenzione quanto, piuttosto, nella privazione di beni economici affinché vengano ridistribuiti alla collettività.

Questo è un vero e proprio strumento innovativo per trasformare in potenza territoriale e architettura quello che prima si annidava nei meandri poco chiari di una finanza generata da uno sfruttamento immobiliare assolutamente contro la legge.

In questo senso, è particolarmente significativo scoprire come la tecnica di dare spazio a questo tipo di azione sociale si disponga in una vera e propria linea di continuità con quanto fatto, in altri versi, nella mia attività di docente, ricercatore e progettista riguardo al tema dello sviluppo di una architettura autoriale basata più che sulla demolizione e ricostruzione sulla rigenerazione architettonica centrata sulla nuova modellazione e sull’aggiunta di nuove potenzialità ai manufatti urbani oggetto di confisca.

Aggiungere e trasformare, quindi, diviene una vera e propria strategia.

Questo modo si sviluppa anche attraverso azioni che possono sembrare minimali o trascurabili ed è sempre un atto meritorio perché permette all’architettura di rivolgersi al territorio con occhi diversi, meno privatistici, più collettivistici e pertanto più legati a un mondo contemporaneo che ha quanto mai necessità e bisogno della condivisione

The subject of confiscated property has been very much in the news recently as this formula for fighting crime continues to be successful not only through the instrument of imprisonment but also through the seizure of economic assets so that they can be redistributed to the community.

This is a truly innovative tool for transforming into territorial power and architecture what previously lurked in the obscure meanders of a finance generated by the illegal exploitation of property. In this sense, it is particularly significant to discover how the technique of giving space to this type of social action is arranged in continuity with what I have been doing, in other ways, in my work as a teacher, researcher and designer on the theme of developing an authorial architecture based more on architectural regeneration centred on new modelling and giving new potential to urban artefacts subject to confiscation than on demolition and reconstruction. Adding and transforming thus becomes a real strategy. This path is developed even through actions that may seem minimal or negligible. It is always a meritorious act, since it allows architecture to look at the territory with different eyes, less privatistic, more collectivistic, and therefore more connected to a contemporary world that needs sharing more than ever to overcome the absolute incommunicability that often invades our lives. The compositional technique we wanted to apply was to preserve as much as

possible the traces and volumes of the assets to recall their origins, but also to intervene with very precise signs that try to reverse the sense and meaning of these architectures, transforming the artefacts into assets accessible to the community.

One of the most striking features of the properties confiscated from the Camorra is generally the presence of large concrete walls that prevent access and visibility to the properties, making them look like impregnable castles.

The strategy is therefore precisely to open up these bulwarks and walls in order to bring them back into play, symbolically and concretely.

They are buildings that, despite the terrible linguistic and stylistic features that characterise them, can represent the potential for redemption in a territory that unfortunately also suffers from a backwardness that it does not deserve.

It is an agricultural area of ancient memory, a place marked by the millenary presence of the Ager Campanus and the Roman settlement routes.

In the post-war period, these places have been completely enclosed in an increasingly petty, marginal and crime-ridden economy.

This book seeks to address the issue of the recovery of assets seized from the Camorra through a process of rehabilitation, starting from the design of a series of concrete elements to be applied in the area of Villa Literno, in the province of Caserta, and the former IPAM sugar refinery, which is currently considered, in its physical testimony, a great visual element in the rural plain of the Ager Campanus.

In this sense, the multidisciplinary approach, starting from the design of the architectural composition for a series of spaces linked to the recovery of this relevant plastic evidence, succeeds in touching other disciplines, so that it is possible to assess more concretely its feasibility, its usefulness for the scientific community, the need to think of something that can be transformed not only into a concrete study, but also into an arrangement with a strong iconic power linked to the various occasions and opportunities that can symbolically relate to this space.

As Dean of Architectural Design at the Department of Architecture and Industrial Design of the University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, I hope that the discipline of Design will be able to lead a synthesis with the other subjects of Architecture and Design, in order to trigger this virtuous process of recovery in an area whose demand for quality living spaces has been forgotten or “put in brackets” for too long.

per superare l’assoluta incomunicabilità che spesso invade le vite di ognuno di noi.

La tecnica compositiva che abbiamo voluto mettere in essere è stata quella di conservare quanto più è possibile tracce e volumetria dei beni per ricordarne la loro origine e intervenire, invece, con segni ben precisi che provino a invertire il senso e il significato di queste architetture, affinché i manufatti si trasformino in veri e proprio beni accessibili alla comunità.

Una delle caratteristiche più evidenti del bene confiscato alla Camorra è, in genere, la presenza del grosso recinto di cemento che impedisce l’accesso e la vista delle proprietà, le rende come dei castelli inespugnabili.

La strategia, pertanto, è proprio quella di aprire questi baluardi e queste murazioni per riuscire, simbolicamente e concretamente, a riportare in gioco queste sostanze.

Sono corpi edilizi che, indipendentemente dall’orribile corredo linguistico e stilistico che le caratterizza, possono costituire delle potenzialità di riscatto in una terra purtroppo anche afflitta da un’arretratezza che non merita.

Si tratta, infatti di un sito in una terra agricola di antichissima memoria, un luogo segnato dalla presenza millenaria dell’Ager Campanus e dalle direttrici romane dell’insediamento.

Questi luoghi si sono chiusi completamente, nel dopoguerra, in un’economia sempre più gretta, marginale e dedita alla criminalità.

Questo libro vuole affrontare a tuttotondo la problematica del recupero dei beni sequestrati alla camorra attraverso un processo di riqualificazione che parta dal disegno di una serie di elementi concreti che si applicheranno nell’area di Villa Literno in provincia di Caserta e dell’Ex Zuccherificio

Concetta Tavoletta

Meravigliosa creatura

Prediligere una poetica, una modalità di approccio al tema del progetto è un atto politico, lo è da sempre e le differenti scelte applicative hanno avuto il ruolo di determinare una visione del mondo. Architettura e società non possono essere due entità separate proprio perché chi traccia i segni dello spazio dell’abitare deve emergere come un facilitatore, una figura che attraverso un umanesimo tecnologico1 si configura come strumento che aziona i fenomeni sociali e urbani. Il progettista ha assunto nel tempo anche un ruolo differente, una sorta di ‘disinnescatore’ di bad practies che hanno mutato l’aspetto dei luoghi attraverso dinamiche che sono sfuggite all’azione anche dei più attenti studiosi delle pratiche sociali e urbane2.

Nell’osservazione di ciò che resta, di elementi che si manifestano come i nuovi reperti della contemporaneità, l’immagine delle opere di Auguste Rodin con la loro voluta incompiutezza, che riprende Michelangelo e prima di lui Donatello ma anche Leonardo da Vinci, racchiude il segreto della bellezza dell’opportunità di ciò che si è cristallizzato nel tempo nella sua incompiutezza.

L’architettura nel contemporaneo vive questa strana condizione di osservazione di un fenomeno corrosivo – il resto di ciò che non è – ma allo stesso tempo di fascinazione poiché consente all’osservatore di interpretare con i suoi occhi le possibili vite di ciò che appare un elemento da allontanare dallo sguardo.

È emersa, quindi, la necessità di chiedersi come cambiare rotta rispetto alla moltitudine di spazi anonimi,

Favouring a poetic approach to the subject of design is a political act, it has always been so, and the different choices of application have had the role of defining a world view. Architecture and society cannot be two separate entities, precisely because whoever traces the signs of living space must appear as a mediator, a figure configured by a technological humanism1 as an instrument that drives social and urban phenomena. Over time, the designer has also taken on another role, a sort of ‘defuser’ of bad practices that have changed the appearance of places through dynamics that have escaped the notice of even the most attentive scholars of social and urban practices2

In the observation of what remains, of the elements that manifest themselves as the new relics of contemporaneity, the image of Auguste Rodin’s works with their deliberate incompleteness, echoing Michelangelo and before him Donatello but also Leonardo da Vinci, holds the secret of the beauty of the possibility of what has crystallised in time in its incompleteness.

Contemporary architecture lives in this strange state of observation of a corrosive phenomenon – the rest of what is not – but at the same time of fascination as it allows the observer to interpret with their eyes the possible lives of what seems to be an element to be removed from the gaze. The need has therefore arisen to ask how to change course in relation to the multitude of anonymous, abandoned

Progetto di Simone Aiezza,Vincenzo Roncone e Salvatore di Gennaro, realizzato nell’ambito del Laboratorio di Progettazione Architettonica IV del Prof. Cherubino Gambardella presso il Dipartimento di Architettura e Disegno Industriale, Università degli studi della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” di Aversa.

Project by Simone Aiezza, Vincenzo Roncone and Salvatore di Gennaro, drawn up as part of the of Architectural Design IV Laboratory held by Prof. Cherubino Gambardella at the Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” in Aversa.

Progetto di Roberto Nugnes e Dominique Silvestre, realizzato nell’ambito del Laboratorio di Progettazione Architettonica IV del Prof. Cherubino Gambardella presso il Dipartimento di Architettura e Disegno Industriale, Università degli studi della Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” di Aversa.

Project by Roberto Nugnes and Dominique Silvestre, drawn up as part of the of Architectural Design IV Laboratory held by Prof. Cherubino Gambardella at the Department of Architecture and Industrial Design, University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli” in Aversa.