football medicine & performance

In this issue

Injuries In Professional Football - Shouldering the Burden

Bringing well-being into the performance picture

Ultrasound Assessment of Hamstring Muscle Architecture – The link to injury

Tactical periodisation in football

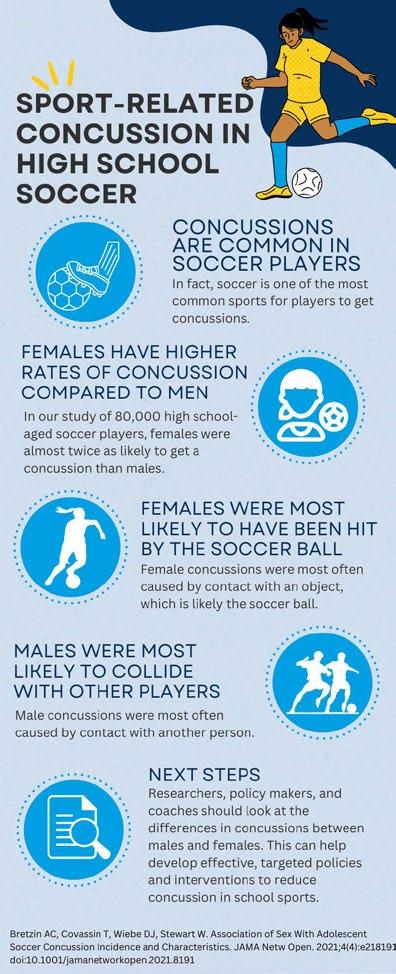

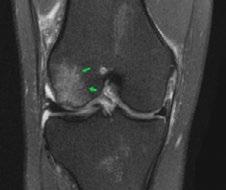

Sport-Related Concussion in High School Soccer

Legal • Education • Recruitment • Wellbeing www.fmpa.co.uk

Issue 42 Spring 2023

The official magazine of the Football Medicine & Performance Association

Enigma Legal provides legal services and advice to managers, coaches and professionals working within the sports industry, its unique structure utilising a panel of expert barristers all with extensive experience of the sports industry, most notably their work with the League Managers Association.

Enigma Legal lawyers are tried and trusted to work in a flexible, agile and responsive way, demonstrating their understanding of the unique demands of the sports industry. A creative and pragmatic approach will ensure that Enigma Legal offers real value to the FMPA Membership.

www.enigmalegal.com

admin@fmpa.co.uk

CEO MESSAGE

“Phones are for calling people and cameras are for taking photographs”, lamented one member;

“We should all work together and be able to do much the same work as each other”, suggested another.

The underlying question these comments ask is ‘should we have strict parameters and guidelines around each discipline so that everyone knows precisely what their role is OR should we all have an understanding of each other’s work sufficient that the best person for the job is the one who will get the most out of a player regardless of discipline?’

It’s an interesting question.

The comments were of course a reference to the plethora of different specialist practitioners within our industry and the way in which they integrate - or not - on a day-to-day basis in managing players.

Recently, a member called to complain that they had not been involved in a players rehab. It turned out that the player had been passed around between a sports therapist, a sports scientist then on to a physiotherapist and finally a Strength and Conditioning Coach. Given the players career was ultimately on the line and the overall rehab process had not been successful, this had led to finger pointing and blame being bandied about amongst those involved. Some of our members jobs were also therefore on the line.

Like it or not this scenario is not uncommon and staff integration is a topic that arises more frequently than any other in general conversations.

The answer to such a scenario might just be found at our Annual Conference, which explores the roles and contribution that each discipline can make to the overall rehabilitation process. With a raft of case studies and superb line-up of speakers I am sure there will ensue a lively debate and maybe a workable solution to an ongoing issue.

Salmon Eamonn Chief Executive Officer Football Medicine & Performance Association

3 www.fmpa.co.uk

FROM THE EDITORS

As we come to the end of another exciting football season, we reflect on the many triumphs and challenges that we have encountered over the course of the season. In this edition, we bring you a range of articles covering a diverse set of topics, starting with an overview of common injuries experienced by professional footballers as well as avenues of management.

We also explore the use of ultrasound assessment of hamstring muscle structure, offering a valuable tool for monitoring and managing injuries in this important muscle group. As well as hamstring muscle assessment, this edition delves into the assessment of another important structure and a common site of injury in footballers, the hip and groin. We take a closer look at the latest research and practical strategies in managing and preventing these common injuries. We feel the two areas above are important to cover, especially at times of fixture congestion or towards the end of the season. This leads us to the topic of tactical periodisation and how it aims to optimise the athlete’s preparation to football matches. This is particularly key towards the end of the season and this article is the first of a two part series on this topic.

As well as injuries, this edition explores the role of sports nutrition and psychology in the process of returning players to the pitch, highlighting key strategies and considerations for effective rehabilitation. Hence, we feel this edition offers a multidisciplinary approach to the care of footballers by covering multiple domains.

We hope you enjoy the 42 nd edition of Football Medicine & Performance and as usual, we always welcome your feedback.

Dr Sean Carmody Editor, FMPA Magazine

Dr Fadi Hassan Editor, FMPA Magazine

Dr. Andrew Shafik Editor, FMPA Magazine

5 www.fmpa.co.uk

Sean Carmody Fadi Hassan Andrew Shafik

ABOUT

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

REVIEWERS

Football Medicine & Performance Association 43a Moor Lane, Clitheroe, Lancs, BB7 1BE

T: 0333 456 7897 E: info@fmpa.co.uk W: www.fmpa.co.uk

FMPA_Official Officialfmpa fmpa_official LinkedIn: Football Medicine & Performance Association

FMPA_Register FMPARegister fmpa_register

Chief Executive Officer Eamonn Salmon eamonn.salmon@fmpa.co.uk

Commercial Manager Angela Walton angela.walton@fmpa.co.uk

Design Oporto Sports www.oportosports.com

Photography Alamy, FMPA, Unsplash

Cover Image Rangers’ Kemar Roofe receives medical treatment. Kemar Roofe could be set for another lengthy spell on the sidelines as the Rangers striker waits on the prognosis of a shoulder injury. 15th Janauary 2023

Football Medicine & Performance Association. All rights reserved. The views and opinions of contributors expressed in Football Medicine & Performance are their own and not necessarily of the FMPA Members, FMPA employees or of the association. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a retrieval system without prior permission except as permitted under the Copyright Designs Patents Act 1988. Application for permission for use of copyright material shall be made to FMPA. For permissions contact admin@fmpa.co.uk

Photo: Alamy

Ian Horsley Lead Physiotherapist

Dr Jon Power Director of Sport & Exercise Medicine

Dr Dáire Rooney Doctor

Dr Andrew Butterworth Senior Lecturer Frankie Hunter Lead Sports Scientist

Dr Manroy Sahni Medical Doctor

Eleanor Trezise Medical Student

Matthew Brown Academy Sports Scientist

Callum Innes Medical Doctor

Kevin Paxton Strength & Conditioning Coach

Dr Avinash Chandran Director

Mike Brown Head of Physical Performance Jake Heath Elite Sports Specialist Podiatrist

Lisa Edwards Sports Therapist

Dr Jose Padilla MD Sports Medicine Specialist

Dr Daniela Mifsud Doctor & Physiotherapist

Dr Danyaal Khan Academy Doctor

Photo: Alamy

Ian Horsley Lead Physiotherapist

Dr Jon Power Director of Sport & Exercise Medicine

Dr Dáire Rooney Doctor

Dr Andrew Butterworth Senior Lecturer Frankie Hunter Lead Sports Scientist

Dr Manroy Sahni Medical Doctor

Eleanor Trezise Medical Student

Matthew Brown Academy Sports Scientist

Callum Innes Medical Doctor

Kevin Paxton Strength & Conditioning Coach

Dr Avinash Chandran Director

Mike Brown Head of Physical Performance Jake Heath Elite Sports Specialist Podiatrist

Lisa Edwards Sports Therapist

Dr Jose Padilla MD Sports Medicine Specialist

Dr Daniela Mifsud Doctor & Physiotherapist

Dr Danyaal Khan Academy Doctor

37 The Rise of

Imaging in Elite

42 Sport-Related Concussion in High School Soccer: Females have Higher Injury Rates and Longer Return-to-Sport than Males

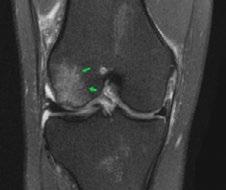

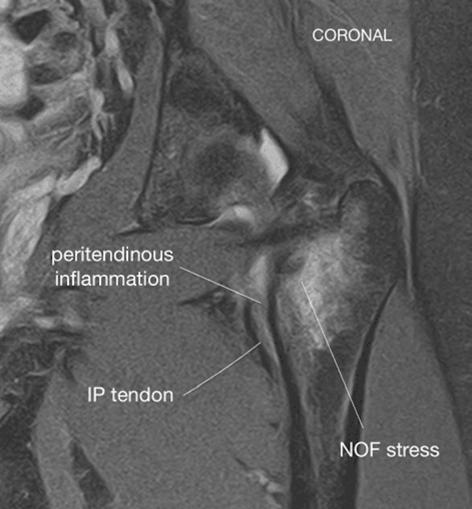

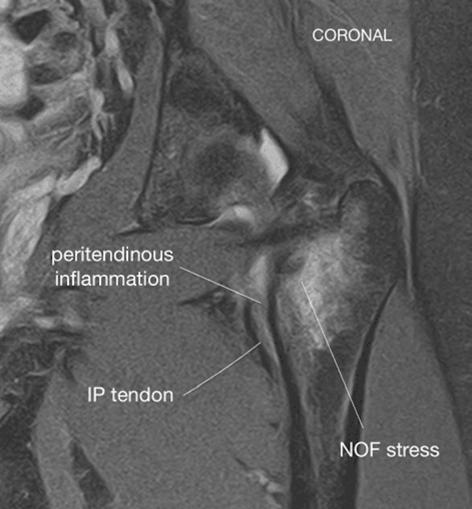

46 Unravelling Hip & Groin Pain

Noake

09 22 42 26 CONTENTS FEATURES 7 www.fmpa.co.uk 12 30 46 18 37 09 Injuries In Professional Football - Shouldering the Burden Dr Ian Horsley 12 Bringing Well-being into the Performance Picture Sarah Murray interview by Dr Andrew Shafik 18 Ultrasound Assessment of Hamstring Muscle Architecture Kevin Cronin 22 Tactictal Periodisation in Football - Part 1 Rainer van gaal appelhof 26 Interdisciplinary Practice Integrating Sports Nutrition & Sports Psychology into the Return to Play Pathway Dr Ian Rollo

30 FMPA Conference Programme

Musculoskeletal

Women’s Football Eddie Craghill

Abigail C. Bretzin

James

INJURIES IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL - SHOULDERING THE BURDEN

FEATURE

/ DR IAN HORSLEY PHD, MCSP, MMACP, CSCS

Football is the most popular team sport worldwide. In the last global census undertaken by FIFA, it was estimated that there are over 300,000 clubs and 265 million people who participate in the sport along with more than 5 million referees. This equates to 4% of the world’s population. In this country, The Football Association represents about 37,000 clubs and millions of players . A recent FIFA study reported that in the last decade more than 13 million women have been recorded playing football at both amateur and elite levels across the globe (FIFA, Women’s Football MA’s Survey Report, 2019).

There is a saying in sport that “injury is just part of the game”. In other words, injury is seen as an inevitable consequence of participation in sport (Chalmers, 2002). Within a professional football team with a squad of 25 players, the team will endure about 50-time loss injuries each season. This equates to two injuries per player per season (Ekstrand et al., 2011).

A recent systematic review and meta- analysis of 44 studies that reported the epidemiology of injuries in male professional football concluded that the overall incidence of injuries

in professional male football players was 8.1 injuries/1000 hours of exposure, with match injury incidence being approximately 10 times higher than training injury incidence rate (Lopez-Valenciano et al., 2020). This tallies to 50-55 time loss injuries per team/season (2 injuries per player/season) which equates to approximately 14% of squad unavailable at any time.

A similar systematic review and metaanalysis carried out in Women’s football reported that the overall incidence of injuries in female football players was 6.1 injuries/1000 hr of exposure, and that match injury incidence is almost six times higher than the training injury incidence rate (Lopez-Valenciano et al., 2021).

Both papers reported that lower limb injuries were most prevalent with muscle/tendon injuries being the most common injury type. This was also confirmed in a study carried out by Kirkendall and Dvorakould (2010) who reported that the most common injured site was the lower limb (67.7%). Furthermore, they also reported that the next most injured area was upper limb (13.4%) .

Recent FIFA data shows the prevalence of upper limb injuries by playing position (Table 1) and anatomical location of upper limb injuries (Table 2).

Player Position Upper Limb Recorded Injury Defender 3% Midfield 2% Forward 2% Goalkeeper 19%

Upper Limb Injury Area Goalkeeper Outfield Player Shoulder 9% 1.5% Arm 3% 0.2% Wrist/Hand 7% 0.4%

9 feature www.fmpa.co.uk medicine & performance football

Table 1: Percentage of upper limb recorded injuries by field position

Table 2: Location of upper all injuries

Injuries have considerable negative physical, psychological and financial short and long-term outcomes for an individual player and their respective clubs (LopezValenciano et al., 2021). So, it is necessary to construct efficient preventive risk mitigation strategies (Roe et al., 2017) and improve our understanding of causality, effective management and rehabilitation of injuries.

In recent years, shoulder injuries have represented an increasing health problem in football players (Lungo et al., 2012). There have been a few studies which have analysed the incidence of shoulder injuries within professional (male) football. Walden et al.,( 2007) reported an 8.8% prevalence during Euro 2004, Junge et al., (2006) reported a 6.4% prevalence during the Athens Olympic Games, and Junge et al., (2004) reported a prevalence ranging from 2-13% over a four-year review of FIFA tournaments and Olympic Games.

Within the Women’s game similar figures have been returned for shoulder injuries; 5.3% (Faude et al., 2005), 2% ( Jacobsen et al., 2007), 4.7% (Tegnander et al., 2008) and 5.5% (Walden et al., 2007).

Just over a quarter of shoulder injuries (28%) sustained by professional football players are classed as severe as this results in the said players to be unavailable to train or play matches for around 28 days (Ekstrand et al., 2011). In a study carried out during the 20062008 UEFA European Championships, a total of 34 severe injuries were documented, of which two were dislocations of the shoulder (Hagglund et al., 2009). One review assessed the serious shoulder injuries sustained in professional football over a period of four competitive seasons for all English Premiership Football teams. Based on health insurance claims, this review noted that 3.3% of all claims were shoulder injuries (1335). This equates to an average of 445 serious shoulder injuries per year. The vast majority of surgical procedures were arthroscopic stabilisations (26%) and labral repairs (23%) (Pritchard et al., 2011).

With the gradual increase in shoulder injuries within football, there has been a drive to prevent shoulder injuries. Following the successful implementation of the FIFA 11+ programme which was developed to prevent lower limb injuries (Bizzini & Dvorak, 2015), FIFA developed the FIFA 11+ shoulder (FIFA 11+S) (Ejnisman et al., 2016) which targets the prevention of shoulder injuries in goalkeepers but can be applicable to outfield players also.

The program consists of three parts which takes 20-25 minutes to complete and should be carried out as part of the goalkeeper warm up as explamfied.

• Exercises to develop strength and balance of the shoulder, elbow, wrist, and finger muscles (part II)

A randomised controlled trial of the programme to assess the effectiveness of the FIFA 11+S program in reducing the incidence of upper extremity injuries among amateur soccer goalkeepers (Attar et al., 2021), reported 50% fewer upper extremity injuries among soccer goalkeepers, compared with a regular warm-up.

Return to play after shoulder injury should be founded on objective measurements (Gumina et al., 2008) and includes evaluation of the player’s health status, participation risk and extrinsic factors (Lephart, 1994).

Since the whole kinetic chain has a role in optimal function of the shoulder girdle, the distal elements and their influence on local function should be taken into consideration. It is vital, therefore, that an attempt is made to identify sub-optimal movement strategies along the length of the whole kinetic chain and focus on these in the rehabilitation process. In summarising the primary functional requirements of the kinetic chain, Boyle (2016) enquired whether the primary requirement for the shoulder girdle to function optimally is mobility or stability. It was concluded that the shoulder girdle requires alternating both stability and mobility.

• General warming-up exercises (part I)

• General warming-up exercises (part I)

feature 10 info@fmpa.co.uk

Kinetic chain shoulder rehabilitation incorporates the dynamic link of biomechanics to produce proximal-to-distal motor-activation pattern with proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation and closed kinetic chain exercise techniques. This method centres on movement patterns rather than isolated muscle exercises. Patterns consecutively uses the leg, trunk, and scapular muscle system to facilitate less active shoulder musculature, to gain an increase in active range of motion, and increase in force output.

Examining the kinetic chain from the ground up, we can consider the optimal requirements of the joint; namely whether the primary requirement of the joint is that of stability or mobility (See Table 3). The results are an alternating prerequisite of stability and mobility along the whole kinetic chain.

In addition to this, it is necessary to consider the “strength” requirements of the shoulder girdle such as muscle force production characteristics and whether there is a requirement for a high rate of force production, high endurance capacity or high-speed movement. Moreover, the type of muscle action (concentric, eccentric, isometric) in what part of the available joint range (inner range, middle range, outer range) is required.

Furthermore, it is necessary to understand the functional requirements of the shoulder of the player. It goes without saying that the functional requirements of the shoulders of a goalkeeper is much more complex than that of an outfield player, but one needs to consider the role of the arms (and thus shoulders) in outfield players in activities such as jumping, fending off an opponent or taking throw ins. This can be broadly broken down into what percentage of time is the arm used below the level of the shoulder, in line with the shoulder or above the shoulder. The consensus for this distribution is shown in Figure 1.

Joint Primary Requirement

1st MTP Mobility

Mid Tarsal Stability

Ankle Mobility

Knee Stability

Hip Mobility

Lumbo-Pelvic Spine Stability

Thoracic Spine Mobility

Scapula Stability

Glenohumeral Mobility

Table

Although not part of the functional requirements of players during match play, ever increasing elaborate goal celebrations may place shoulders in vulnerable positions- such as when completing a cartwheel!

Once all these characteristics have been considered, an assessment process can be carried out to identify whether these attributes are available to the player.

Further information regarding management of shoulder injuries in football can be found at TheGoalieshoulder.co.uk along with specific prevention and rehabilitation interventions.

Attar WSA, Faude O, Bizzini M, Alarifi S, Alzahrani H, Almalki RS, Banjar RG, Sanders RH. The FIFA 11+ Shoulder Injury Prevention Program Was Effective in Reducing Upper Extremity Injuries Among Soccer Goalkeepers: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Sports Med. 2021 Jul;49(9):2293-2300.

Bizzini M, Dvorak J. FIFA 11+: an effective programme to prevent football injuries in various player groups worldwide-a narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(9):577–579.

Boyle M. Functional Training for Sports (2nd edn). Human Kinetics 2016.

Chalmers DJ. Injury prevention in sport: not yet part of the game? Inj Prev. 2002 Dec;8 Suppl 4(Suppl 4):IV22-5. Ekstrand J, Hägglund M, Waldén M. Injury incidence and injury patterns in professional football: the UEFA injury study. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:553–8.

Ejnisman B, Barbosa G, Andreoli CV, de Castro Pochini A, Lobo T, Zogaib R, Cohen M, Bizzini M, Dvorak J. Shoulder injuries in soccer goalkeepers: review and development of a FIFA 11+ shoulder injury prevention program. Open Access J Sports Med. 2016 Aug 8;7:75-80.

Faude O, Junge A, Kindermann W, et al. Injuries in female soccer players: a prospective study in the German national league. Am J Sports Med 2005;33(11):1694-700.

Gumina S, Giorgio GD, Postacchini F, Postacchini R. Subacromial space in adult patients with thoracic hyperkyphosis and in healthy volunteers. La Chirurgia degli Organi di Movimento 2008;91(2):93-96

Hagglund M, Walden M, Ekstrand J. UEFA injury study: an injury audit of European championships 2006–2008. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(7):483–484.

Jacobson I, Tegner Y. Injuries among Swedish female elite football players: a prospective population study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2007;17(1):84-9.

Junge A, Langevoort G, Pipe A, et al. Injuries in team sport tournaments during the 2004 Olympic Games. Am J Sports Med 2006;34(4):565-76.

Junge A, Dvorak J, Graf-Baumann T, et al. Football injuries during FIFA tournaments and the Olympic Games, 1998-2001: development and implementation of an injury-reporting system. Am J Sports Med 2004;32(1 Suppl):80S-9S.

Kirkendall DT, Dvorak J. Effective injury prevention in soccer. Phys Sports Med. 2010;38(1):147–157.

Lephart SM. Re-establishing proprioception, kinesthesia, joint position sense and neuromuscular control in rehab. In: Rehabilitation Techniques in Sports Medicine, St. Louis, MO, Mosby 1994;118–37

Longo UG, Loppini M, Berton A, Martinelli N, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Shoulder injuries in soccer players. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2012;9(3):138–141.

López-Valenciano A, Raya-González J, Garcia-Gómez JA, Aparicio-Sarmiento A, Sainz de Baranda P, De Ste Croix M, Ayala F. Injury Profile in Women’s Football: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2021 Mar;51(3):423-442.

López-Valenciano A, Ruiz-Pérez I, Garcia-Gómez A, Vera-Garcia FJ, De Ste Croix M, Myer GD, Ayala F. Epidemiology of injuries in professional football: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Jun;54(12):711-718.

(Pritchard C, Mills S, Funk L, et al Incidence and management of shoulder injuries in premier league professional football players British Journal of Sports Medicine 2011;45:A15.)

Roe M, Malone S, Blake C, et al. A six-stage operational framework for individualising injury risk management in sport. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4(1):26.

Tegnnder A, Olsen OE, Moholdt TT, et al. Injuries in Norwegian female elite soccer: a prospective one-season cohort study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2008;16(2):194-8.

Walden M, Hagglund M, Ekstrand J. Football injuries during European Championships 2004-2005. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15(9):1155-62.

Below The Shoulder In Line with The Shoulder Above the shoulder 1% * (25% Goalkeepers) 50% (Goalkeepers) 99%* (25% Goalkeepers)

Figure 1: Estimation of Functional Shoulder Position in Football

3: Primary Requirements of the Kinetic Chain (Boyle, 2016)

11 www.fmpa.co.uk medicine & performance football

BRINGING WELL-BEING INTO THE PERFORMANCE PICTURE

FEATURE / SARAH MURRAY INTERVIEW BY DR ANDREW SHAFIK

This is a transcript of the FMPA Podcast episode of the same name that was released in March 2021. It has been edited for clarity and to improve readability. It was transcribed by Elle Trezise.

If you’d prefer to listen, episodes can be found on the FMPA website, Apple Podcasts, SoundCloud and Spotify.

In this podcast episode host Dr Andrew Shafik, a medical doctor working in professional football and a Senior Editor in the FMPA Education Team, speaks to Sarah Murray, a self-employed Sports Psychologist who at the time of recording was a Senior Psychologist at a Women’s Super League (WSL) club.

Andrew

I am delighted to be joined by Sarah Murray. Sarah is currently the Women’s Senior Psychologist for a WSL team (top tier).

Sarah graduated with a degree in Sports Science and then completed a PGCE in PE Teaching. After eight years as a physical education teacher, she decided to pursue her passion for the mental side of performance and completed a MSc in Sports Psychology at Brunel University, going on to gain BASES accreditation. Before going full-time in football, she ran her own consultancy working with both individual athletes and teams including England Cricket, professional golfers, England Athletics, AASE programmes, England Lacrosse, Football Referees Association and Sports Coach UK. Sarah has many years coaching and playing experience in sport, including having played national league hockey and played at regional level in cricket, tennis and football.

Thank you for joining us today, Sarah.

Sarah

Thanks very much. Nice to be here.

Andrew

Today we’re going to discuss a little bit more about your experiences today as well as sports psychology which I know will be of great interest to our listeners. So, following on from the intro, do you mind telling us a little bit about your journey to date?

Sarah

Yeah, sure. So, I guess you came up to the point where I found myself, unplanned, in full time professional football. So as a performance psychologist - we’re going back to 2013 - I was fortunate enough to have

been offered a full-time role with my current club. Which at the time was incredibly rare. There were only a couple of other full-time performance psychologists in football anywhere in the country.

It was the first time that the club had a performance psychologist on that sort of level. I think they’d had some workshops here and there, but they were really keen that if they were going to look into the mental side of the game and support players with that, they were going to do it properly with somebody full-time and a full programme. So, I think, to be honest, it probably took the first four or five years to really work out where does this sit within the club? Where will it add the most value? Who will I be working most closely alongside? Between myself and my colleagues in the sports science and medical department, and my colleagues in the coaching and Academy departments, we sort of figured out where it adds value and where the role is best suited. Then I was fortunate enough to be able to build the department and employ other performance psychologists within the club to support the work that we did. As time passed, it was genuinely the most privileged experience that I’ve had to be able to build that department. Particularly within the Academy. So, under-23s and down is where the focus of the performance psychology was. Alongside a little bit of lecturing, just to keep my hand in with the latest applied research, it’s been a great journey so far.

Andrew

That’s great. Really, really interesting to hear about your background there, Sarah. Delving a little bit more into the performance psychology side of things, what is it about the narrative of well-being and elite performance that is important? What is it? What isn’t it?

What’s your take on it?

Sarah

This is something that I’ve spoken passionately about and sort of worked really hard with over the last few years, particularly since being in football. There’s a historic narrative of well-being or performance that we’re shifting away from, and we’re shifting away from very quickly both within football but culturally within performance sport and actually within society more broadly, I’d say.

After years of almost battling for acknowledgement of how well-being supports performance, I was really keen to shift the narrative and actually have well-being as a key part of performance. Certainly, if we have well-being without performance, then we’re not a high performing elite football environment because we have to have the performance piece. But equally if we have performance and we are focused heavily on performance without a well-being underpinning, then we end up in the historical cases of burnout and - worst case scenariosome of the historical mental health problems that athletes have had when well-being hasn’t been a part of the conversation, or hasn’t been a narrative. So, I think this idea of bringing well-being into the performance environment deliberately as a key part of supporting athletes to perform is absolutely invaluable.

Andrew

That’s interesting. Obviously, there’s been lots of media attention. We’ve seen the recent article from Sky Sports about psychology in sport and if it’s a missed opportunity in the English game. Why do you think now is really the time for performance psychology in sport as well as football?

Dr Andrew Shafik

Sarah Murray

feature 12 info@fmpa.co.uk

Sarah

I think everything comes around in cycles. Performance psychology has been around for decades but there’s no question that potentially last to the table in terms of really utilising it as a sport, you could argue has been football. But what I love about the game and about football is that once they do get hold of something they genuinely will go all in and run with it and many football clubs are now running some fantastic performance side programmes and getting some really great professionals in to work into this space. But I think the fluffy stuff, as I’ve heard it called, the fluffy stuff – “do you wear a white coat and then players come in and cry on your sofa?” And a lot of the cultural assumptions around the word “psychologist” even… it takes a long time to break these down and then for a performance psychologist to work into a sports space and particularly football which is where I’ve spent the last eight years, as being normal, as being something whereby an athlete will have access to great physios, doctors, sport scientists, nutritionists, and actually to have a performance psychologist as part of that MDT, is just the norm. At my current club certainly. I think now more broadly in football we’re seeing less and less news articles - which is really pleasing to see - whereby it becomes an article on BBC Sport or perhaps Sky Sports that X footballer, who’s a professional footballer, seeks a psychologist. Whereas if that footballer is struggling with his change of pace, his speed, whatever, it wouldn’t be a story that he went to see a sport scientist. Because actually, there’s no difference. So, I think it’s coming.

As we record this today, we’re still in a lockdown and we have been for the best part of a year, and there’s no question that it’s accelerated the conversation of mental health and wellbeing just more broadly in society and self-care, and a realisation of how this can then support performance. So, mental recovery and physical recovery for the players that I work with are equally valued in my environment and measured as something that will then support the performance on the Sunday.

Andrew

That’s interesting and I think it’s definitely an integral part of the whole performance picture. I recently listened myself to the High Performance Podcast and in an episode with Tyrone Mings, he was explaining some of the barriers before COVID to seeking psychology and how he now finds it is an integral piece to his overall performance picture. So, it’s partly due to that breaking down of barriers which is great to hear. What are some of the challenges that you found when tackling down some of those barriers, especially now? You mentioned COVID but are other things associated as well?

Sarah

Yeah, certainly. I mean, if I take myself back to

when I when I first came into a full-time role as a performance psychologist, what I expected and my reality were quite different. So, what I expected to walk into was an environment that was high performance, professional football, male dominated. So as a female, as a psychologist, you know, when we have the -ologist on the end of our job title, it can be quite unhelpful, I have found. So I actually expected that there might be a lot of blocks and barriers to the work that I was doing and to the way I wanted to support athletes and staff alike. The reality was that there wasn’t. I’m very fortunate that actually I work in an environment that is incredibly open to supporting not just the players within the club, but the staff as well. So those blocks and barriers I thought I might face, I haven’t. That said, I can only speak for my reality, and that’s been my reality. I have colleagues that have not been so fortunate and have had far greater struggles with integrating performance psychology into a performance environment, and really breaking down that idea of it being for the weak and breaking down that idea of it being for simply issues-based problems.

I think, on a personal level, coming from a performance background and playing to a fairly good level myself in hockey, and always being performance focused has helped me in terms of my understanding of the performance culture, and actually working with somebody whether they are in a fantastic space, so they’re mentally in a great space and there’s always work to be done to make that better. Equally, if somebody is struggling and they’re not in a great space, is there work to be done to actually bring them

into a better space to be able to perform on a Saturday or on a Sunday? So, I guess, coming in from the angle that I have done, the blocks and barriers weren’t necessarily there but culturally to seek help, culturally to go and see a psychologist or a psychiatrist in the UK, is still not something that has happened or been talked about for decades. Whereas if we look at America and other countries where it’s the norm, everybody has a psychiatrist, everyone has a psychologist. I appreciate that is a sweeping generalisation. However, it’s certainly part of their culture. For us, it’s the open conversation around mental health that’s happening at the moment and actually the way in which, from an athletic point of view, athletes can be supported by looking after [their mental health] is helping us to break down those barriers, and to make it part of something that can support the human - the man behind the shirt or the girl behind the shirt - which ultimately, then when they step onto a pitch, or a court, is going to support them to perform.

Andrew

That’s brilliant. You’ve mentioned your wealth of experience across a variety of sports there which kind of leads onto the next question: how does psychology look when it’s integrated into a high performance environment?

Sarah

Oh my goodness. I think that’s something else that as a profession we’ve probably struggled with because it can look so different, because it is very much dependent on the person, on the psychologist, on their philosophy, their way of working, as to how it looks in the environment. So how it can look is… traditionally it was based in sport science and medicine. Certainly when I joined my current club, I was put into the sports science and medicine department but over the years, just found myself immersing myself in the world of the coaches and spending my time in an amongst the coaching staff to then become actually a member of that department, although working across. So, when sports psychology is integrated into any kind of sport, I think it’s dependent on, you know, what are the needs of that organisation, or that particular team, or

13 medicine & performance football www.fmpa.co.uk

Bringing well-being into the performance environment deliberately as a key part of supporting athletes to perform is absolutely invaluable

that individual? What is it that they’re wanting to get from it? I think it’s a case of making sure that the needs of the organisation are met by the sport psychologist because certainly if there’s a disconnect or there’s not a fit between the philosophies and the values of the sports psychologist coming in and what they see as their role, if it doesn’t connect with what the organisation wants, then same with any profession, it’s not going to be as effective. So, broadly speaking, it’s looking at working across the MDT, supporting staff, supporting coaches.

Certainly for me, one of the other shifts over the last eight years is that I’m far more staff-facing now than I probably would have been ten years ago when I was a little more traditional in terms of working with the athlete, working with the young footballer one-to-one and supporting him and that was it. Working at a systems and organisational level now as a performance psychologist is far more common. If we think about the long-term impact of having performance psychology, mental health and well-being embedded into elite environments, then that’s the way forward, to do it from a systems level, to work with the coaches, to support the sport scientists. You’ve had some great guys on this podcast already that I’ve worked closely with within my role at my current club even and yeah, so, definitely holistic.

Andrew

That’s great. You’ve kind of mentioned towards the end there that it’s been more staff facing. So, looking at an athlete or a coach and trying to get buy in, how’ve you found that element? Any skills or tips in regard to getting buy in? What do you define as the performance benefits to them?

Sarah

I mean, if I were to anecdotally think about the amount of conversations that I would overhear and many of your listeners would overhear in their sport environment that are coach to coach, player to coach, player to player. So many of the conversations are based in the mentality, the mindset of the player. So many of them. So actually, there’s massive value placed on the mindset and the mental side of the game.

However, because it’s psychology, because there’s an -ologist… it’s not as data driven as sport science, so it’s harder to say, “this psychologist can come in and this data here will be improved in six months’ time” and it’s really easy for us all to see and understand. So, there’s been this fear of “we really value it but we’re not quite sure how it works or what to do with it. So, we’re not too sure if we want to bring it in.” Although, as I said, all the conversations are driven towards the mentality side of the game. So, to get buy in, it’s no more or less than supporting coaches to get the best from themselves and to get the best from the players that are around them.

The more we know and understand about our athletes, and understand their context, their journey, and why they do what they do, why do they behave as they do on a match day? Why does that member of staff perform so well in this environment and do this but then maybe struggle here? The more we understand about people, ultimately the people behind the badge, the more we are going to find those connections and actually be able to support them to get the best out of themselves and understand themselves when they’re asked to step up on a Sunday or a Saturday on a match day, in a highpressure situation and perform and do their role.

So really, I guess it’s just about formulating. Formulating on players, formulating on staff. How do we get the best out of them? What are their protective factors in life? What’s their context? What’s their journey? How do they feel and act and sound in our environment when they’re at their best and how do we help them to do that?

Andrew

That’s really interesting. I think it’s a really strong message. A lot of conversations, even a lot of the podcasts around sport are associated with the mindset of performance. It is a nonnegotiable having that psychology element when you’re a professional who’s experienced in that environment.

Just to finish off, you’ve worked across age groups, across individual and team sports, the

men’s and women’s game as well as across plenty of sports generally. What are the things that you’ve found most useful to transfer across to football? What are the similarities and some of the differences? I know that’s quite a difficult question!

Sarah

I’ll do my best! I think ultimately, whilst there are contextual differences in terms of what happens for an athlete and their experience, whether they are a real tennis player or they’re a lacrosse player or a golfer, their environment might be slightly different. But ultimately, many of the skills needed to be able to be at your best and understand yourself in a performance environment actually remain quite similar across many of the sports and some of the transferable things I’ve taken from other sports into football would be understanding the culture and actually understanding what’s going on for the people in that world. So, for me to come in and think that I know everything about football as a professional… absolutely not, you know. I’ve learned along the way I don’t need to have played elite level football to be able to walk into football and make some impact. So, it’s a two-way learning process. I think one of the most influential experiences I had early on would have been as a young practitioner, working across lots and lots of sports. So, whilst I was really lucky, and I worked with the England Women’s Cricket pathway and GB Real Tennis and then some elite golfers, I also worked with a lot of grassroots athletes.

If I was to say the absolute top transferable skill, it would be that ultimately, I work with human beings. So, whether it’s our conversation today, whether it’s an under-9 tennis player playing for their local club, or whether it’s a 32-year-old professional male footballer that’s in the premiership, the value of working with the human in front of you - as a human first, an athlete second - doesn’t change for me. So, that’s transferable across all contexts across any performance environment, be it sport, business, cricket or football.

Andrew

That’s brilliant, Sarah. Thank you very much for joining us today. I think that’s been a really good insight into performance psychology within the men’s game as well as across sports. I think it will be applicable to those working in academy football, men’s football, women’s football as well as other sports as well. Listeners, I’ll put up the links to the papers mentioned and if you enjoyed today, please subscribe to the FMPA on our Spotify and SoundCloud accounts where you can reach all of our podcasts. Alternatively, our podcasts are also available for free in the podcast section of the FMPA website. Thanks again, Sarah.

15 medicine & performance football www.fmpa.co.uk

The skills needed to be able to be at your best and understand yourself in a performance environment actually remain quite similar across many of the sports

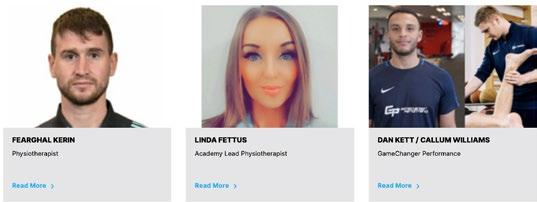

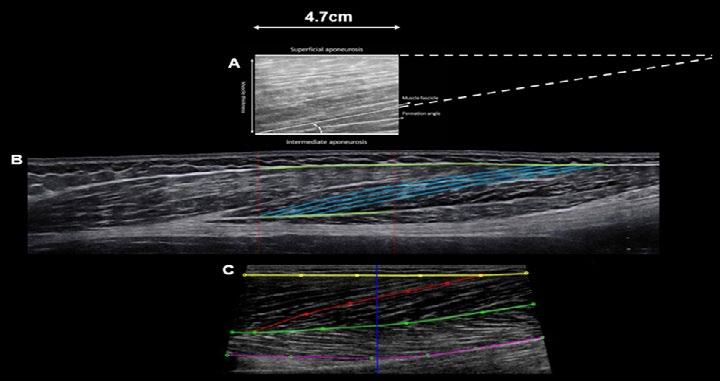

ULTRASOUND ASSESSMENT OF HAMSTRING MUSCLE ARCHITECTURE – THE LINK TO INJURY

Introduction

In field-based sports, if a player sustains an injury, medical staff are often asked by the team management “when can he/ she play again?” (Ekstrand et al., 2016). Hamstring Strain Injuries (HSI) are one of the most common injury in sports (Ekstrand et al., 2016), with the majority of injuries occurring in the Bicep Femoris long head muscle (Green et al., 2020). They have a high injury burden for fieldbased sports athletes, particularly soccer, accounting for 37% off all muscular injuries in that sport, which is the world’s most popular sport (Askling et al., 2013; van der Horst et al., 2015). Despite considerable research to identify athletes vulnerable to HSI, a mean increase in the rate of HSI (4%) is observed (Ekstrand et al., 2016; Ekstrand et al., 2022). Indeed the prevalence of hamstring strain re-injury ranges from 14% - 34% within the same

competitive season (Green et al., 2020). Researchers, medical staff, and the athletes themselves have little control over intrinsic factors often linked to developing an HSI such as increasing age, ethnicity, and previous HSI. However, researchers and medical staff are aware of some modifiable risk factors, such as understanding the link and importance of the architectural characteristics of skeletal muscle and how it impacts HSI.

Muscle Architecture

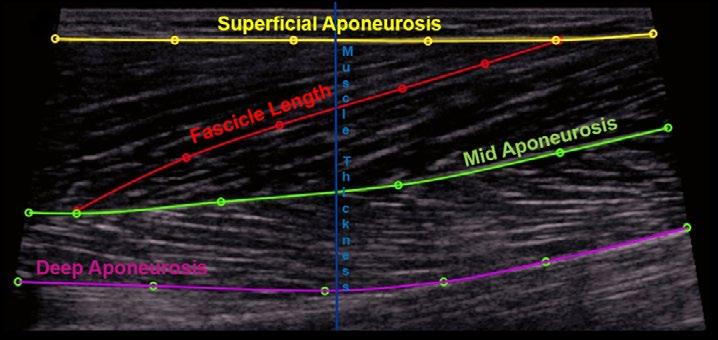

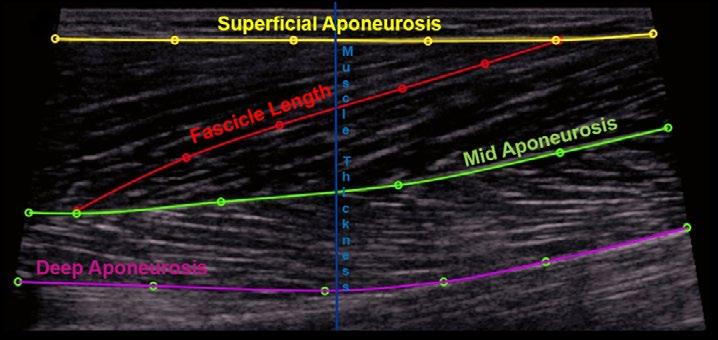

Muscle architecture refers to the geometric distribution of fascicles within a muscle. Muscle architecture governs the mechanical function of a muscle, influencing its maximal force output and its contraction velocity (Lieber and Ward, 2011). The angle of trajectory of a muscle fascicle between the

superficial aponeurosis and its insertion into the mid aponeurosis is referred to as its pennation angle (Figure 1). Large pennation angles associate with shorter muscle fascicles, which reduces the contractile velocity and excursion range of the muscle. In contrast, small pennation angles associate with longer muscle fascicles, which decreases the physiological cross-sectional area and maximal force output of the muscle. Muscle excursion range is proportional to muscle fascicle length (Lieber and Ward, 2011) (Figure 1). Indeed, when compared to short muscle fascicles, long muscle fascicles contain more sarcomeres in series (Timmins et al., 2016b). During fast eccentric activity (i.e., the typical mechanism associated with hamstring strain injuries), the muscle tendon unit undergoes active lengthening (Blazevich and Sharp, 2006). During this type

FEATURE

KEVIN CRONIN

/

feature 18 info@fmpa.co.uk

Lecturer, School of Medicine, University College Dublin, Ireland

of contraction, long muscle fascicles, compared to short muscle fascicles, will exhibit less strain per sarcomere in series (Timmins et al., 2016a).

Muscle Architecture and Hamstring Injury

While limited evidence exists to characterise the effect of hamstring muscle architectural characteristics on strain injury, a single prospective study of 152 elite-level Australian soccer players has demonstrated that those athletes who possessed shorter Bicep Femoris long head fascicle lengths (<10.56cm) were four times more likely to sustain a future HSI than those with longer fascicles (Timmins et al., 2016a). Shorter muscle fascicles contain less sarcomeres in series, which will result in a reduced maximal shortening velocity, which could increase the risk of re-injury (Timmins et al., 2016a). Indeed, previous research identified that the level of probability of Bicep Femoris long head muscle injury was reduced by 21% for every 1cm increase in fascicle length (Timmins et al., 2016a). Therefore, the ability to accurately quantify the architectural characteristics of the hamstring muscles may assist clinicians in the management of athletes with acute or recurrent hamstring strain injuries.

Measuring Muscle Architecture

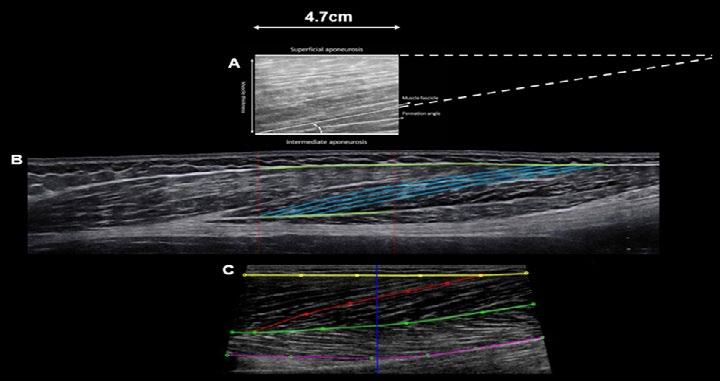

Hamstring Architecture Acquisition Brightness mode (B-mode) ultrasound

is the most commonly used medical imaging modality to assess the architectural characteristics of skeletal muscle. It is non-invasive and well tolerated by the athletes. However, the acquisition of accurate high quality ultrasound images of the architectural characteristics of the hamstring muscles is challenging and operator dependent (Balius et al., 2019). The majority of published research using B-mode ultrasound to measure the architectural characteristics of the hamstring muscles has utilised a field of view that is typically shorter that the fascicle being measured (Timmins et al., 2016a; Duhig et al., 2019). . In these cases, fascicle length is estimated with various linear approximations (trigonometric linear method) using the measured muscle thickness and pennation angled values. However, these methods fail to consider the variability associated with fascicular curvature and as such are prone to error, often estimating at least 50% of the entire fascicle (Figure 2A). Indeed, extended field of view ultrasound technique has been used to permit full fascicle visibility in the past. Extended field of view ultrasound is a dynamic technique that requires the operator to shift the ultrasound probe along the muscle to generate a composite ultrasound image from a series of images. However, the Bicep Femoris long head muscle exhibits a heterogenous muscle architecture with fascicles orientating themselves in a nonlinear path and thus, any misalignment of

the ultrasound beam from the plan of the fascicles will lead to fascicle length errors (Klimstra et al., 2007; Bolsterlee et al., 2016) (Figure 2B). Extended field of view is a technically challenging ultrasound technique, often leading to fascicle crossover (meaning the fascicle cannot be measured accurately) and is not supported on some ultrasound imaging systems. Recently, wide field of view ultrasound was utilized to quantity the hamstring muscles architectural characteristics, illustrating excellent repeatability for measuring fascicle length (Cronin et al., 2022). Wide field of view is a reliable ultrasound technique to acquire hamstring muscle architecture permitting full fascicle visibility. Wide field of view ultrasound utilizes a field of view (>92mm) that is typically longer than the fascicles within the bicep femoris long head muscle (Figure 2C).

Hamstring Architecture Analysis

Once ultrasound images of the hamstring muscles are acquired, it is necessary to measure the architectural characteristics (e.g. fascicle length). Acquired static sonograms of the hamstring muscle architecture are often manually digitised which requires the operator to manually select points along a fascicle to determine fascicle length. These manual skeletal muscle image tracking algorithms quantify fascicle length in a linear fashion, and fail to account for fascicle curvature and as such are prone to error (Pimenta et al., 2018). More recently, automated

Figure 1: A schematic ultrasound image of the Bicep Femoris long head muscle.

Figure 1: A schematic ultrasound image of the Bicep Femoris long head muscle.

19 medicine & performance football www.fmpa.co.uk

tracking algorithms have been developed primarily to quantify skeletal muscle for studies using a large number of ultrasound images (Zhao and Zhang, 2011; Farris and Lichtwark, 2016; Drazan et al., 2019). These tracking algorithms are developed to account for fascicle curvature which improves fascicle length measurement accuracy however they still estimate fascicle length as the acquired sonograms are captured with ultrasound field of views typically smaller that the fascicle length. Furthermore, one key limitation of these automated tracking algorithms is, frequently the same fascicle is not tracked overtime (Zhao and Zhang, 2011). This is often due to the variation in the “intensity of the fascicle” from the resultant sonogram (Zhao and Zhang, 2011), in other words the inability of the automated tracking device to analyse the same fascicle in a different sonogram due to software difficulties in identifying the fascicle. This further emphasises the need for high quality sonograms to ensure that these automated tracking algorithms work efficiently by capturing the same fascicle overtime, and effectively reducing fascicle length measurement error. Recently, a group of researchers in University College Dublin have developed a semi-automated tracing software tool that exhibited excellent precision when measuring the architectural characteristics of the hamstring muscles (Cronin et al.,

2021). The semi - automated tracing tool has been demonstrated for static ultrasound images which permits full fascicle visibility within the ultrasound image. The semi – automated tracing software tool could be of substantial interest to clinicians interested in hamstring strain injuries who may want to precisely measure fascicle lengths following injury and in response to exercise – based interventions.

Ultrasound screening to reduce hamstring strains?

A limitation of many prospective studies is that associations with injury risk are made from measurements taken at a single time point (e.g., pre – season) (Opar et al., 2022), whereas hamstring strain injuries can occur at any time period when the athlete is training or in competitive action (Green et al., 2020). However, more regular assessment at multiple time points throughout the course of an athletes competitive season of the hamstring muscle architecture provides a better reflection of the association of fascicle length with hamstring injury, because Bicep Femoris fascicle lengths change over the course of a season (Timmins et al., 2017). Further, as previously mentioned, the ability to trend hamstring architectural characteristics is dependent on the accuracy and

precision of the ultrasound measurement technique (ultrasound image acquisition and image analysis software). A potential approach for overcoming the aforementioned ultrasound imaging limitations is through employing a transducer with a wide field of view that captures the entire fascicle (Cronin et al., 2022), avoiding the need to estimate fascicle length and precisely measuring fascicle length on a software that accounts for fascicle curvature (Cronin et al., 2021).

Conclusion:

• Hamstring muscle architecture is an extrinsic risk factor for injury.

• To trend hamstring architecture accurately in athletes is dependent on the ultrasound technique and measuring software tool used.

• Wide field of view ultrasound is a reliable ultrasound technique to acquire high quality ultrasound images of the hamstring muscle architecture.

• The aforementioned semi – automated tracing tool precisely measures the hamstring muscle architecture.

Acknowledgements:

Professor Eamonn Delahunt, Dr Shane Foley, Dr Sean Cournane, Fearghal Kerin.

Figure 2: Longitudinal ultrasound images of the Bicep Femoris long head muscle, A: Limited field of view (Timmins et al., 2016a), B: Extended Field Of View (Franchi et al., 2020), C: Wide field of view (Cronin et al., 2022).

feature 20 info@fmpa.co.uk

Askling, C.M., Koulouris, G., Saartok, T., Werner, S., and Best, T.M. (2013). Total proximal hamstring ruptures: clinical and MRI aspects including guidelines for postoperative rehabilitation. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA 21(3), 515.

Balius, R., Pedret, C., Iriarte, I., Sáiz, R., and Cerezal, L. (2019). Sonographic landmarks in hamstring muscles. Skeletal Radiology, 1-9. doi: 10.1007/s00256-019-03208-x.

Blazevich, A.J., and Sharp, N.C.C. (2006). Understanding Muscle Architectural Adaptation: Macro- and Micro-Level Research. Cells Tissues Organs 181(1), 1-10. doi: 10.1159/000089964.

Bolsterlee, B., Gandevia, S.C., and Herbert, R.D. (2016). Effect of Transducer Orientation on Errors in Ultrasound Image-Based Measurements of Human Medial Gastrocnemius Muscle Fascicle Length and Pennation. PLoS ONE 11(6), e0157273-e0157273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157273.

Cronin, K., Delahunt, E., Foley, S., De Vito, G., McCarthy, C., and Cournane, S. (2021). Semi-automated Tracing of Hamstring Muscle Architecture for B-mode Ultrasound Images. International Journal of Sports Medicine.

Cronin, K., Foley, S., Cournane, S., De Vito, G., and Delahunt, E. (2022). Hamstring muscle architecture assessed sonographically using wide field of view: A reliability study. PloS one 17(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0277400.

Drazan, J.F., Hullfish, T.J., and Baxter, J.R. (2019). An automatic fascicle tracking algorithm quantifying gastrocnemius architecture during maximal effort contractions. PeerJ 7, e7120-e7120. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7120.

Duhig, S.J., Bourne, M.N., Buhmann, R.L., Williams, M.D., Minett, G.M., Roberts, L.A., et al. (2019). “Effect of concentric and eccentric hamstring training on sprint recovery, strength and muscle architecture in inexperienced athletes”. (OXFORD: Elsevier Ltd).

Ekstrand, J., Waldén, M., Hägglund, M., Medicinska, f., Institutionen för medicin och, h., Linköpings, u., et al. (2016). Hamstring injuries have increased by 4% annually in men’s professional football, since 2001: A 13-year longitudinal analysis of the UEFA Elite Club injury study. British Journal of Sports Medicine 50(12), 731-737. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095359.

Ekstrand, J., Bengtsson, H., Waldén, M., Davison, M., Khan, M.K and Hagglund, M. Hamstring injury rates have increased during recent seasons and now constitute 24% of all injuries in men’s professional football: the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021/22 British Journal of Sports Medicine Published Online First: 06 December 2022. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2021-105407

Farris, D.J., and Lichtwark, G.A. (2016). UltraTrack: Software for semi-automated tracking of muscle fascicles in sequences of B-mode ultrasound images. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 128, 111-118. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2016.02.016.

Franchi, M.V., Fitze, D.P., Raiteri, B.J., Hahn, D., and SpÖRri, J. (2020). Ultrasound-derived Biceps Femoris Long Head Fascicle Length: Extrapolation Pitfalls. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 52(1), 233-243. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002123.

Green, B., Bourne, M.N., van Dyk, N., and Pizzari, T. (2020). Recalibrating the risk of hamstring strain injury (HSI) - A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for index and recurrent HSI in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, bjsports-2019-100983. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100983.

Klimstra, M., Dowling, J., Durkin, J.L., and MacDonald, M. (2007). The effect of ultrasound probe orientation on muscle architecture measurement. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology 17(4), 504-514.

Lieber, R.L., and Ward, S.R. (2011). Skeletal muscle design to meet functional demands. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences 366(1570), 1466-1476. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0316.

Opar, D.A., Ruddy, J.D., Williams, M.D., Maniar, N., Hickey, J.T., Bourne, M.N., et al. (2022). Screening Hamstring Injury Risk Factors Multiple Times in a Season Does Not Improve the Identification of Future Injury Risk. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 54(2), 321-329. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002782.

Pimenta, R., Blazevich, A.J., and Freitas, S.R. (2018). Biceps Femoris Long-Head Architecture Assessed Using Different Sonographic Techniques. Med Sci Sports Exerc 50(12), 2584-2594. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001731.

Timmins, R.G., Bourne, M.N., Hickey, J.T., Maniar, N., Tofari, P.J., Williams, M.D., et al. (2017). Effect of Prior Injury on Changes to Biceps Femoris Architecture across an Australian Football League Season. Medicine and science in sports and exercise 49(10), 2102-2109. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001333.

Timmins, R.G., Bourne, M.N., Shield, A.J., Williams, M.D., Lorenzen, C., and Opar, D.A. (2016a). Short biceps femoris fascicles and eccentric knee flexor weakness increase the risk of hamstring injury in elite football (soccer): a prospective cohort study. British Journal of Sports Medicine 50(24), 1524-1535. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095362.

Timmins, R.G., Shield, A.J., Williams, M.D., Lorenzen, C., and Opar, D.A. (2016b). Architectural adaptations of muscle to training and injury: a narrative review outlining the contributions by fascicle length, pennation angle and muscle thickness. British Journal of Sports Medicine 50(23), 1467-1472. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094881.

van der Horst, N., Smits, D.-W., Petersen, J., Goedhart, E.A., and Backx, F.J.G. (2015). The Preventive Effect of the Nordic Hamstring Exercise on Hamstring Injuries in Amateur Soccer Players : A Randomized Controlled Trial. American Journal of Sports Medicine 43(6), 1316-1323. doi: 10.1177/0363546515574057.

Zhao, H., and Zhang, L.-Q. (2011). Automatic tracking of muscle fascicles in ultrasound images using localized radon transform. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 58(7), 2094-2101. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2011.2144593.

21 medicine & performance football www.fmpa.co.uk

TACTICAL PERIODISATION IN FOOTBALL PART 1

Introduction

Football is characterised by the chaotic nature of the game. It is up to the trainer and his or her staff to prepare players physically, technically, tactically, and mentally. While traditional periodisation models often focus almost exclusively on the physical aspect, the concept is applied in a well-considered way in so-called tactical periodisation.

The game model of the team determines the content of training, and one does not train the components separately, rather they are integrated, like they occur during a match. In short, it is a different view of the same thing! The purpose of this article is to explore the role tactical periodisation in developing professional footballers.

From tactics to physical

In recent years we have seen a shift in the approach to football training and periodisation. (1) In an attempt to simplify the complexity of the sport, many traditional periodisation models emphasised physical attributes. However, to do justice to the identity of football, as well as to make an optimal transfer to the game, it is impossible

to train the different dimensions separately. Maximising performance is the result of multiple physical, technical, tactical, and mental skills. Tactical periodisation challenges the simplified thinking about football, which tends to limit itself to training one aspect at a time. (2,3) The concept of block periodisation, based on the idea that a large part of the training process is aimed at a minimum number of skills, has given way to this alternative approach to training and periodisation.

As the name suggests, the team’s style of play is at the heart of the entire training process. This game model is a collective term for everything that has been agreed in a team about the way they want to play, i.e., how it pressures the opponent, how the team builds up in-possession, what formation they play and so on. As a result, it gives more order and predictability to the unpredictable nature of football so the team can ultimately try to influence the result of the game. The concept of periodisation is applied in a well-considered way and refers to the tactical principles that are trained throughout the season. Driven by tactical

principles, as much training as possible should be completed in the holistic core where all dimensions overlap (see Figure 1). The game model (or style of play) acts as the overlapping dimension in which the other dimensions exist. This perspective contradicts with the common view in which the four dimensions are considered separately and with equal priority.

Method and principles

The main principle of the model is known as specificity. This relates to the extent that what you train corresponds to the match situation. The different dimensions (tactical, technical, physical, and mental) are not trained separately through isolated exercises, but together. Ideally, each exercise relates to at least one (but usually all four) moments of the game (see below), the appropriate space, game-like intensity, and decision making:

1) offensive organisation;

2) defensive organisation;

3) transition from defence to attack;

4) transition from attack to defence. (1)

Players are repeatedly exposed to football

FEATURE / RAINER VAN GAAL APPELHOF

Head of Sport Science and Strength & Conditioning FC Utrecht

feature 22 info@fmpa.co.uk

Photos: FC Utrecht

situations where the physical dimension is related to one (or multiple) tactical principles of the team. Guided by these principles, they are challenged to execute technical skills while making the right choices. For example, defending zonally, where players are responsible for a specific part of the field instead of an opponent, forces them to think about their position in relation to fellow players and opponents. Another example would be compulsory folding back (or recovery runs) and closing in from behind over a specific line of restraint during games. This will not only lead to retaining compactness or holding defensive shape. Players are implicitly forced to do more high-intensity running (all distance covered above a speed of 20 km/h). Thus, rather than training individual attributes, they are trained in an integrated way, as in the game. This does not necessarily mean that only 11-a-side is played. There are times when the game is deliberately simplified, so that players better understand how to handle various game situations. Examples of such adjustments might include changing the number of players, the size and/or shape of the field of play, the work/rest ratio, the rules of the game, etc. However, it is important that this is done without losing the chaotic nature and complexity of the game. Otherwise, we would train in a way that has no connection to the reality of the game.

Besides the principle of specificity, the model has 3 sub-principles that are used to make this possible: (2,3)

1) Making the game model trainable

This is done by creating situations that make specific principles appear more often. These principles are tactical guidelines that apply in almost all situations. For example, a principle of play in offense could be that, for a striker to be available, a coach might instruct him to move to the side where the ball is. In this way, players can experience situations several times, find solutions and learn by repetition. This can be done, for example, by devising an exercise in which the attacking team is confronted with a situation in which there is a good chance of them losing the ball and they are forced into a defensive changeover. After a short period of playing on, the organisation of the exercise is restored, and the same situation occurs again. By changing the shape of the playing field, players are implicitly forced into certain actions.

2) Systematically repeating game principles

This follows a wave-like motion. The nonlinear progression can take place during the season both in the short term, from match to match, and in the long term. At the start of the season, the priority is on the fundamentals that are an integral part

of the game model. Later in the season, usually after preparation, this shifts to more complex and positional principles that can vary from match to match. There are weekly or even daily variations while the basic principles return systematically in the training programme. For example, a basic principle in defending is that players are not (wo)man-oriented. No man marking is played, but players coach their teammates to “take over” opponents when they enter their zone.

3)

Stable and recurring weekly schedule

The same distribution of physical load is maintained in relation to match days (MD: match day). The tactical objectives of each training session may vary according to the specific needs of the team, but the physical component trained on a particular day in relation to the match day (e.g. MD+1, MD-4, etc.) remains the same.

From macro to micro

Football consists of a succession of complex situations. It is characterised by highintensity actions of which the duration and intervals are unpredictable. Players need to possess a wide range of physical, tactical, and technical skills, combined with fast information processing to make the right choices under pressure. Because a football season has a long competitive period stretching over several months, with one or more matches scheduled each week, there is no such thing as peak performance. To achieve success, you need to be able to perform at a consistent level. It is therefore very important to ensure that players receive the right physical load and tactical knowledge every week, while ensuring adequate recovery and regeneration. According to the founding fathers of tactical periodisation, adaptation only occurs when training is carried out at a constant volume and high intensity every week. (1) Maximum concentration and intensity are also required

during recovery training. Players must still perform each exercise similar to how they would do it in the game. However, the complexity and duration of each exercise will be shorter and maximum recovery between repetitions is generally aimed for. Nonetheless, to stimulate players both physically and mentally, it can sometimes happen that they are not given the time to fully recover. For example, during the preseason, training is regularly carried out after a match under fatigued conditions.

The weekly dynamics of the training content remain stable in terms of the type of load, volume, intensity, and complexity. (1,2,3) Due to this cyclical nature, each training week shows only subtle tactical differences, while the physical objectives are stabilised. Table 1 shows an overview of a typical training week with one game. To avoid overtraining, recovery during the week takes place by varying the dominant pattern of muscle contraction (strength, endurance, or speed). As a result, no consecutive days have the same objective to ensure the cumulative effect of fatigue is limited. (1,3) Therefore, the complex game is broken down into daily objectives to maintain an optimal performance level. The distribution of the different variables that determine the training content, also known as Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), is always organised in relation to both the previous and upcoming match. When planning the week, the complexity of the training is therefore also considered. Especially the mental load plays an important role here. Not only the body, but the brain needs space and time to recover too. Processing information quickly and making choices under time pressure results in cognitive overload. For example, football is generally experienced as more intensive than isolated running, because high-intensity actions such as dribbling, duelling, shooting and tackling follow each other in quick succession. During

Figure 1: The traditional way of periodisation versus tactical periodisation.

TACTICAL

TACTICAL TECHNICAL PHYSICAL MENTAL 23 medicine & performance football www.fmpa.co.uk

TECHNICAL PHYSICAL MENTAL

the week, a training session (or match) with a lot of variation and information to process will rarely be followed by another training session with complex exercises. After a match or day off, main principles are trained that are an integral part of the game model (= low complexity). Towards the next match more focus is placed on tactical and positional details, taking into account the strategy of the upcoming opponent. The complexity will therefore increase. This does not mean that isolated forms of training are not used at all. For example, players with less physical load during the week are compensated two days before the match (MD-2) by means of isolated running drills. Furthermore, these are also used for substitutes immediately after a match (MD) if no group training or (practice) match is scheduled the following day (MD+1). Although these are tailored to the conditioning status of each player, they have a lower specificity due to the predictable nature of the exercise. While this approach may differ from what’s been described above, this shows that, on occasion we might need to be flexible in our approach depending on the context. Thinking in terms of opportunities and possibilities to offer each player an optimal training week might deserve more attention in the future. Think for example of a training immediately after the game or a different weekly schedule for substitutes.

The art and science of coaching

There is no one-size-fits-all solution for an optimal training week. Every player has his or her own way of playing at a similar position, which results in a different load. In addition, no two players react in the same way to a certain imposed load because each individual has a different load capacity. For example, a player in his thirties may need more time to recover while the same may

be true for a youth player who has only recently been added to the squad and may be exposed to cognitive and physical overload.

Finding the right balance within a group of players with different backgrounds and histories (e.g., injury history, number of years first team experience, etc.) requires an individual approach within the team periodisation. Each player is assigned to one of three load capacity groups (low, medium and high) based on both objective (e.g., scores on test programs and/or particulars from sports medical examinations) and subjective criteria (e.g., mental overload for a player who comes from youth training or abroad).

Furthermore, the match schedule in modern football is such that players often have to play multiple matches in a short period of time, with minimal recovery¬ periods in between. Due to mechanical, metabolic, and cognitive demands the resulting fatigue persists into the following days. The cause is usually

attributed to both central and peripheral factors. (4) After heavy exercise, the ability of the central nervous system to activate or control muscles is reduced. Also, muscle fibre recruitment will be reduced due to disturbances in the contractile function of muscles. Recent research has shown that these reduced functions persist up to 72 hours post-match. The same applies to subjective indicators of fatigue. Both the feeling of fatigue and the psychological lack of motivation to train persist until 72 hours afterwards (see Table 1). The divergent recovery between the perception of fatigue and objective measurements of neuromuscular function highlights the multifactorial nature of fatigue.

To design individualised training programmes, total distance (see box) is probably the most widely used load indicator in professional football. However, it does not appear to be sensitive enough and, to date, has not been associated with fatigue-related markers (4). Hader and colleagues concluded in a systematic review that the distance ran at high speed (> 19.8 km/h) is the only variable that correlates with markers of muscle damage and peak power output from muscle fibres. This Very-High Intensity Distance (VHID) could explain up to 50% of the creatine kinase (CK) concentration and neuromuscular (peak power output) responses. In practical terms, for every 100 metres of VHID, the intracellular CK concentration in muscle fibres increases by 30%, whereas the peak power output during a counter movement jump (CMJ) decreases by 0.5% up to 24 hours postmatch. Other significant relationships between external load and fatigue-related variables remain to be determined (5). Empirical evidence shows that an increase in the number of accelerations and

feature 24 info@fmpa.co.uk

Figure 2: Perceptual responses measured before, after, and 24, 48, and 72 hours post-match (4).

Table 1: Weekly structure of the micro cycle decelerations causes an increased score on muscle soreness and consequently a decreased sense of recovery. It is possible that structural damage at the muscle level also plays a role in this.

Conclusion

There are many different models, but they all have the same goal, which is to optimally prepare players for playing matches. Tactical periodisation is increasingly recognised as an alternative approach to traditional periodisation models. The holistic interplay of all the key training factors (i.e., tactical, technical, physical and mental) means that exercises are chosen that fit the coach’s game model, while also incorporating the other aspects (technical, physical and mental) in order to train as match-specific as possible.

1. Delgado-Bordonau JL & MendezVillanueva JA (2018). Tactical periodization: a proven successful training model. London: SoccerTutor.com.

2. Afonso J et al. (2020). A systematic review of research on tactical periodization: absence of empirical data, burden of proof, and benefit of doubt. Human Movement, 21 (4), 37-43.

3. Delgado-Bordonau JL & Mendez-Villanueva A (2012). Tactical periodization: Mourinho’s bestkept secret? Soccer Journal (May/June), 29-34.

4. Brownstein CG et al. (2017). Etiology and recovery of neuromuscular fatigue following competitive soccer match-play. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 831-844.

5. Hader K et al. (2019). Monitoring the athlete match response: can external load variables predict post-match acute and residual fatigue in soccer? A systematic review with metaanalysis. Sports Medicine - Open, 5 (1), 48.

Currently the

head of sport science and strength & conditioning, Rainer has held various roles within the performance department of the club. He holds a MSc. in human movement sciences from the Catholic University of Leuven and is certified with the Australian Strength and Conditioning Association (ASCA), as well as the National Strength and Conditioning Association (CSCS). Furthermore, he holds a UEFA A Elite Youth Coaching badge. Questions or comments? Email to r.vangaalappelhof@fcutrecht.nl

Recovery Loading Tapering MD+1 (starters) MD+1 (subs) MD+2 MD-4 MD-3 MD-2 MD-1 MD Dimensions 1/3 pitch 2/3 pitch Full pitch 2/3 pitch 1/2 pitch Full pitch 2/3 pitch Full pitch 1/2 pitch Relative field size N/A Medium Sized Games (5v57v7+GK) 125 - 200m2/field player Medium Sized Games (5v5-7v7+GK) 125 - 200m2/field player Large Sized Games (8v8-10v10+GK) ≥ 200m2/field player Large Sized Games (tactical) Small Sized Games (1v14v4+GK) ≤ 125m2/field player Medium Sized Games (maximal 5v5+GK) or Small Sized Games (1v14v4+K) ≤ 125m2 /field player Strength - density Duration - volume Speed - intensity -/+ - -- -(Z4 // -20 km/h) +++ ++ ++ (Z5 // 20-25 km/h) +++ + + (Z5 // 20-25 km/h) ++ +++ ++ (Z5-Z6 // 20-25+ km/h) +(++) ++ +++ (Z6 // 25+ km/h) +/-+/(high intensity/ low volume) +++ +++ +++ Physical goal Recovery Compensate Off Strength Duration Speed Activate Max effort Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s) High Intensity Distance (HID) (14,4 – 19,7 km/h) Very High Intensity Distance (> 19,8 km/h) Accelerations Decelerations Accelerations Decelerations Explosive distance Total distance Very High Intensity Distance (> 19,8 km/h) Maximal speed Sprint entries (> 25,1 km/h) Compensate Taper Post Activation Potentiation (PAP) % KPI 30% 60% 60% 75% 60% 30% 100% Estimated recovery (% KPI * 72h) 21,6 h 43,2 h 43,2 h 54 h 43,2 h 21,6 h 72 h Complexity (cognitive)(minimal) Main principles Predictable drills (i.e., passing & kicking) + + (average) Main principles Sub-principles (tactical/ positional details, some flexibility can be allowed to adapt to an opponent) + (low) Main principles (normally don’t change from game-to-game, maintaining the team’s identity) +++ (high) Sub(-sub) -principles (tactical/ positional details, even more flexible to a specific opponent) ++ (average) Sub(-sub) -principles (tactical/ positional details, even more flexible to a specific opponent) +/(high/low) Main principles Strategic principles (low volume) +++ (maximal) Pre-activation / Warming-up Mobility Injury prevention (eccentric) (Postural) stability Injury prevention (eccentric) Multidirectional Anterior chain Absolute speed Posterior chain Coordination Plyometrics Speed Own preferences Strength training Upper body + prevention Upper & lower body + prevention Lower body Max strength Optional Individual focus Full Body Strength-speed & power Rainer van Gaal Appelhof has spent nearly six years at FC Utrecht,

is an ambitious club in

top-flight of

Dutch Eredivisie.

which

the

the

club’s

25 medicine & performance football www.fmpa.co.uk

INTERDISCIPLINARY PRACTICE INTEGRATING SPORTS NUTRITION & SPORTS PSYCHOLOGY INTO THE RETURN TO PLAY PATHWAY

1. Introduction