38 minute read

02 Enlightenment (not received) 03 Identity Tectonics

The Expansion of Iron Technology

The Crystal Palace was designed and constructed by Joseph Paxton in 1851. It serves as a substantial example of iron being used in Architecture during the nineteenth century due to its composition of mainly iron and glass, but rarely of masonry. Due to this, the Crystal palace served a firm purpose in the spirit of modern industry. “It embodied the utilitarian spirit of modern industry, built without masonry, almost exclusively of standardized components of iron and glass”5. Moving onto the Halle au Ble that was rebuilt by Francois - Joseph Belanger in 1813, it contains quite a bit of iron and glass in the way it was constructed. This building was reconstructed due to it being destroyed by a fire. During the renovations, quite a few durable and resilient materials were used to replace the wood and glass cupola, such glass and iron. “In Paris in 1813 Frangois - Joseph Belanger (1744-1818) replaced the spectacular wood and glass cupola of the Halle au Ble, which had been destroyed by fire, with a glass dome on an iron frame, covering a diameter as large as that of the Pantheon in Rome”6. Even though the building still consists of masonry, iron and glass are what saved this beautiful structure. Due to the substantial example provided on the use of iron and glass to construct a building, the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II that was designed and built by Guiseppe Mengoni in 1863 is a excellent example of the expansion of iron and glass technologies throughout the nineteenth century. It serves as a newly unified Arcade that consists of a four block area and connects Italy’s two major public spaces. In addition, the architect designed plans that would allow the structure to include a central glass cupola over it. Pictured below is an analysis of the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II. “The architect, Giuseppe Mengoni (1829-1877), designed the cruciform plan with ferro-vitreous vaults culminating in a central glass cupola over the crossing”7. Due to the iron and glass used to construct this Galleria, it is always thought of as an amazing masonry structure with a glass roof.

Advertisement

GLASS PALACE: AN AREA OF TRANSITION [CESAR DASILVA] The crystal palace was built in an era of innovative technology where steel and glass became more prominent in construction and the work moved away from artisanship to assembly line style. Workers no longer had to be well-trained with a few instructions, they could do their job. This style of construction with the change in materiality as well as modern technology like insulation and elevators. The building was a symbolism of modernity at the time and can even be said “It embodied the utilitarian spirit of modern industry, built without masonry, almost exclusively of standardized components of iron and glass”4. While the glass palace did not resemble its predecessor the masonry steel structured building or newer skyscrapers, it is an important part of architectural history because it shows the ingenuity and creativity that went into a building style that one day be used to create skyscrapers. The glass palace was an exhibition space that inspired glass and steel structure around the globe by utilizing the steel framing we had seen in brick buildings and lots of steel columns to create an open space that really had a presence because it almost felt as though there should be more structure. These developments started the race to what would eventually become skyscrapers that held a similar presence of being bigger than life and almost impossible.

The Transformation of the Boston John Hancock [Alex Markarian]

The John Hancock Tower was constructed in Boston, Massachusetts in 1969. The overall structure is made from steel and glass. However, the skyscraper was built at a certain angle where it goes against the wind, there-fore, this caused many structural issues. Due to these high winds it started to shatter windows and began to sway the whole building causing tremendous danger to the people inside and below. Although the main skeleton of the tower is steel, it still had problems sustaining against the outside forces. In conclusion, to fix these problems, John Hancock went through a severe structural makeover. Steel trusses and diagonal beams were installed in the interior glass facade, allowing a more stable and stronger resistance against the wind. Also, two 30-ton steel structures which were called tuned mass dampers. The Tuned mass damper was placed on the 58th floor, one on each end. The set on a lubricant oil so the building can sway and move underneath this block, but the block does not move.

During the mid-19th centurypost Industrial Revolution - emerging technologies were being utilized across the globe in a way that paved a path for structurally-sound, light forms of architecture. Using iron, steel, and glass, the new age of building encompassed a range of structures - both old and new alike. Europe became the precedent for techniques using these technologies, seen in places such as the Crystal Palace, which influenced America to follow in their footsteps. However, the idea of iron structural skeletons was not as appealing to America, so the frame was often hidden behind more substantial materials and ornamental expression became typical on the exterior of these buildings. Expansion in technology allowed for an evolution in construction, but also in function and form. With the advent and use of new materiality came new systems of infrastructure, such as the iron railways. Dubbed the agent of “creative destruction” by philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm, railway infrastructure became a powerful force that stood out in the rural landscapes it traversed. Railways brutally eliminated both urban and rural settings to accomplish the goal of revolutionary transportation. This technological advancement allowed for the easy shipment of goods and services, effectively expanding society and connecting people to one another more easily, while also progressing the standard of architecture.

Technology’s Modernity [Rachel Carfagno]

When it comes to technology modernity’s and emerging technology, not a lot of thought is put into it and the struggle many Architects have had with it during the nineteenth century when it came to the structures and buildings they designed. A lot of ideas and thinking is put into technology when it comes to designing it, but not as much as when it is put into Architecture. The entire process is not as difficult on Architects today as it was in the nineteenth century, but it is still such a crucial topic to learn about and focus on. Even though it was a struggle for architects to process and try to understand the spread of technology in architecture, there were also many wide – eyed opportunities that came along with it, and we see that a lot in technology today. Whenever a certain individual looks around outside or inside, all they see is modern technology everywhere. No matter where they go, there is technology and electronics. During the twenty-first century today, it is easier to handle and understand by everyone, especially architects. But back in the nineteenth century, there were many struggles’ Architects had with it all. In conclusion, the world of Architecture would not be what it is today if it were not for technology’s modernity and the spread of technology.

AGE OF STEEL [SHANE STONE] In the early 19th and 20th century, new materials started coming to fruition, opening a new gateway of possibilities with construction and design. One of the new prime building materials that rose above was Steel. “Wrought iron and steel are both strong in tension. Systems of open web struts, organized into triangular, folded, or crisscross patterns, can be made from either material into skeletal trusses that have the depth of beams without the mass.”13 Steel was a more lightweight, fire-resistant and stronger material than the past traditional methods of stone. Where this superior method of building shined was the Old Penn Station (1910) by McKim, Mead and White. The interior structure consisted of multiple steel trusses and arches within its construction. The glass accompanied the building, making this enclosed space its own separate environment. Steel revolutionized the way buildings were constructed, internally and externally, paving the way for the age of steel.

Architecture From Engineering

Engineers like George Stephenson (1781-1848) set the stage for ferro-vitreous techniques and influenced architects to use iron, steel, and glass to allow structure to dictate form. Crown Street Station in Liverpool was the first of its type in terms of railway stations, possessing the basic elements of the new railway station form. Including a platform for boarding trains, a drop-off court, a large hall where the ticket office was, a place to wait, and a covered train shed, Crown Street Station featured many aspects that would be common in future stations, such as the Euston Station which opened in 1837. Classically trained architect, Philip Hardwick (1792-1870) was hired alongside engineer Charles Douglas Fox (1840-1921) to construct Euston Station in a way that bridged the gap between classical forms and the new industrial forms. “Hardwick’s colossal Doric Propylaia at the Euston Arch marked the entry to the drop-off court, becoming the first monument to railway travel.”11. The nod to ancient Greek structure was an important aspect of the station, as it was the feature which seemed to centralize the building in the city, rather than regarding it as a point on the outskirts of the city. This connection to ancient iconography allowed modern travel

to be enhanced and regarded as a thing of affluence and grandeur. As the station type itself involved decoration and ornament over time, the train shed type was maintaining a functionalist form. That is, until Kings Cross Station (1851) was designed by Lewis Cubitt (1799-1883) and featured a facade merged with the shed design in a natural balance. This, along with large interior spaces, exudes an organic relationship between old and new. “...a wrought iron truss in the shape of a half circle creates an open interior 105 feet across, and 72 feet tall. The roof is covered in glass, which adds to the effect of an open space by bringing in an abundance of natural light.”12. Cubitt approached this and other station designs by regarding the shed as an integral part of the station and designing in a way that reacts to its shape. Large thermal windows and a lunette trace the aspects of the shed in an effort to connect the new technologies to classical forms.

Industrial Materials in New Forms

In contrast, St. Pancras Station in London had a very obvious disconnect between its various components. Separated by time, the wrought-iron and glass vault shed is very different in appearance from the Midland Grand Hotel, which sits in front of the shed and was constructed several decades later. The combination of the two major structures transformed the area from a poor neighborhood to a national symbol. Shortly after the birth of iron railways and architecture was the colossal advancement of iron-truss and steel-cable bridges. George Stephenson was not only an integral part of the Crown Street Station, but also a pioneer in engineering when it came to bridges. Structures such as the Britannia Bridge of 1850 over the Menai Strait were prime examples of Stephenson’s invention of longspan bridges. “To guarantee the stability of the bridge and absorb the lateral forces of moving trains ; he created a long, wroughtiron tube with a rectangular section that pierced through three masonry pylons.”14. Even more groundbreaking for its time, Isambard Kingdom Brunei (1806-1859) constructed the Thames Tunnel, which was the first tunnel to be successfully built to travel underwater. This utilized new technology invented by Brunel’s father called the tunneling shield, which allowed workers to dig the tunnel without being compromised by the surrounding water. Other adventurous technological endeavors of the time include the Royal Albert Bridge in Saltash by Brunel with its wrought-iron tubes and suspension cables, and Stephenson’s Britannia Bridge, which utilized the same techniques but accomplished it with half the material and cost of the Royal Albert Bridge. Like Brunel, a man named Gustave Eiffel began as an entrepreneur in the post-war era designing many bridges with iron truss systems, and later culminated his experience to construct the world’s tallest structure at the time - the Eiffel Tower. The Eiffel Tower utilizes the web-truss system common in bridges to allow the tower to eliminate wind-pressure as a potential risk. Supported by a masonry foundation, the tower continues to demonstrate the connection between emerging technologies and previously utilized forms. Another prominent engineer during this time, John Augustus Roebling (1806-1869) from Germany, designed woven steel cables to support his bridges, which were ultimately more structurally sound. This bridge and other structures in architecture and engineering during this time, represented major cultural breakthroughs as they were defining features of America’s modernity.

HOW IRON CHANGED 19TH CENTURY INTERIORS [MILO OLIVA] The innovations in iron technology during the 19th century allowed for the construction of long spans, which were not previously possible with wood or masonry. The use of large, open spaces creates dramatic interiors that are easy to navigate. This is why the technology was adopted for the architecture of several railway stations in London. At King’s Cross Station, a wrought iron truss in the shape of a half circle creates an open interior 105 feet across, and 72 feet tall. The roof is covered in glass, which adds to the effect of an open space by bringing in an abundance of natural light. Unlike the Sainte-Geneviève Library in France, The facade of King’s Cross Station reflects the openness of the inside.⊃1; It has a large semicircular window which covers most of the wall, and 3 bays with glass doors for entering the building. The SainteGeneviève Library also uses iron to create an open interior, however the exterior expression is heavy and solid in appearance due to its minimal amount of glazing.

Modernism in Post-Imperial Societies

At the same time that America and other similarly developing countries were experiencing the major sociological changes associated with Western industrialism, places like Asia and Africa were experiencing the colonization of European countries and how militarily forced colonies slowly replaced imperialism. This was especially true in areas such as India which was directly controlled by British rule ever since the Indian War of Independence in 1857, beginning the forced conversion into an architectural Gothic revival. Simultaneous to the Arts and Crafts movement, colonial architects in India were designing more gothic and orientalist-style structures than anything as a way to divert from neoclassicism. Many places driving these styles were also merging the designs with local culture and iconography, yet maintaining an undertone of authority in all societal growth. British and other European authorities made clear their intentions to remain in the places they conquered, whether it be through imitating Beaux Art models or implementing strong urban visions, yet ultimately relinquished control of some populations like India. Regardless, the relentless goal of industrial nations during the nineteenth century to conquer and colonize all under-developed countries was a clear indication that “white men” would continue to impose their ideals by offering new technology to indigenous cultures in hopes of gaining profit.

THE DEFEAT OF BRITISH RAJ [RAJAN RAUT] The Gateway of India was created to symbolize the power of British rule over India, but it ended up doing the opposite. George Wittet was the architect behind the gate, who used the IndoSaracenic style. The monument celebrated the arrival of the king as the author writes,“ First built in ephemeral materials at a dockside position for the arrival of King George V and Queen Mary in 1911”17. The structure was a Roman triumphal arch combined with Indian iconography. The gateway has a vertical axis of symmetry in the middle. Also, in the middle, there’s a portal-like opening that connects the seaport to the city of Mumbai. The gate was used as a connector that symbolized how the British entered the country and conquered it. However, as India became free, it was a symbol of defeat for Britain as the author says, “Ironically, it is also the site of the symbolic exit of the British from India”18. In the end, this great symbol the British created to display their conquest became a sign of defeat.

05 Housing and the Metropolis

Technology and Infrastructure in the 19th Century

During the 1850s-1890s, the art of architecture expanded to be taller. William Le Baron Jenny designed the first skyscraper in Chicago, Illinois. This became a very big change in the living aspect. As Chicago started to create more skyscrapers to conduct more business and living spaces for others, New York took that advantage as well. As skyscrapers became more convenient, there were some obstacles that occurred. Having skyscrapers all over the city, it started to become overpopulated and the conditions living in these “apartments” became unsatisfactory.

New York, Mills House, a bachelor hotel, Ernest Flagg, 1898. Although, there were different materials that were introduced for these skyscrapers. The purpose to show different qualities was to visualize different working classes. There were developments made to the sewer systems and water systems to counteract the unsanitary conditions and to continue with this architectural movement. While trying to make the city cleaner and richer, the working class was made an afterthought, with the architecture reflecting social hierarchy and the importance of space. By pushing these people aside, room for the wealthy grew. These infrastructure issues were pushed onto the working class as a social hindrance. Mass housing, an idea that cropped up around factory workers, held the same primitive living ideas as these cramped skyscrapers. With the rise of social ranking and the expectations that came with being wealthy, it became increasingly harder to avoid such harsh living conditions.

New York City tenements - Alex Rithiphong

Housing conditions in New York tenements were some of the worst units to occupy and live in. The rooms within these tenements were small but needed to shelter a number of people, which led to overcrowding of the room. The tenements posed unsafe living conditions to the people who lived there. Residents of these tenements were usually the working class. Flagg had designed the Mills House specifically to house the poor and working class. New York tenements share a similarity with tenements from other cities around the world. Cities within the United States, such as Chicago, followed a block design for the apartments, leading to them being called apartment blocks. Within them was a repetitive collection of square or rectangular rooms. Typically, an apartment block would have at least 2-3 floors. Some apartment blocks had 6-8 floors with the same room layout on each floor. Tenements in Chicago were cramped and landlords used them to create as much revenue as they could. Tenements from both New York and Chicago had differences in appearance but served the same purpose, which was to house as many people in a single building as possible. This would ultimately lead to changes in the regulation of building codes for the future.

Berlin mietskaserne - Luc Thorington

If you were to tell someone today that you were currently living in a Berlin Mietskaserne you would likely feel comfortable doing so and expect pleasant reactions. However, these street-facing apartment buildings in Germany weren’t

“A time-lapsed view of a Mietskaserne being constructed, divided into three phases. Phase 1 is the street-facing buildings, Phase 2 is the construction of buildings in the courtyard, with Phase 3 filling in the last bits of extra space.” ¹ always so desirable. The mietskaserne has a dark and complicated history. They were first built prior to the first World War when Berlin became the capital, immigrants were flooding in, and urban development was on the rise. The layout of the city had already been planned, but finding a way to house so many people needed a quick solution. Buildings with street access were prioritized first, so every street was lined with tenements, leaving large courtyards in between. These remaining green spaces were then gradually and randomly filled until dozens of small courtyards remained. The apartments nearest to the street were the most sought after, with the bottom floors generally housing the mid to upper class. However, as you moved farther up and farther back away from the street, the lower class was crammed into the small apartments and provided with little light and poor sanitary conditions. In some cases, single bathrooms were shared amongst entire floors. These apartments did have proximity to the courtyards, but due to the planning of the Mietskaserne, these were not the courtyards that we’re used to today. They were small and completely shadowed by the surrounding multi-story tenements, and usually featured nothing more than a few trash cans. So, how did these dirty and overcrowded buildings become associated with Berlin’s upper class? After the Second World War, many of Berlin’s buildings were destroyed and the population had drastically decreased. This meant that the Mieskaserne was rebuilt very differently. The streethugging building typology remained, but many of the previous “phase 1” and “phase 2” tenements were not rebuilt. This meant larger and more beautiful courtyards.

“Kottubsser Tor/Kottbusser Damm in 1928 (left). An image of the same block from 2020 on the right.” ¹

Additionally, the breakdown of class within the Mietskaserne changed. Thanks to elevators, upper-level apartments became much more valued. The lower levels transformed into shops and restaurants, and people started to seek out these once disgraced buildings. As of now, these new and improved living conditions have worked out well for Berlin. They’re able to support the current population and provide people with access to amenities and green space. One concern, though, is what will start to happen as Berlin’s population inevitably continues to rise? Will the greenspaces again become the sites for additional tenements? Will the Mietskaserne become overcrowded? These are all issues that Berlin could face in the future, but with their given attention now, maybe these apartments can maintain their new reputation.

Back-to-back housing - Jonathan Yiu

While mass housing is generally a good idea, it presents challenges as well. One example is the back to back housing in Birmingham, England. These were built in the 1830s-40s in the booming industrial parts of England. Conceived for the purpose of general housing for the working class, these houses were known for their cost and extremely proximity to each other. Even though they were beneficial to the people paying for them, they were in no way helpful to those who had to inhabit them.

Public Health Infrastructure in Paris Rajan Raut, Shane Stone, Cris Vasquez

The industrial revolution brought many changes to the world, countries' economies were boosted, technology was advancing, and the population was growing exponentially. However, all of this did not come without risk, the urban cities were becoming overcrowded, people's lifestyles and health were poor, and there were poor water/sewerage systems to support the population. At the time, Paris was one of three cities to advance the most and became a center for new workers and immigrants, which quickly turned the city into a crowded and unsafe place to live and work. Emperor Napoleon III wanted to modernize Paris and make it a better city, so he appointed Georges-Eugène Haussmann to carry out this urban project. In doing so, Haussmann renovated and transformed the city of Paris into a clean, safe, and urban city. While all of these new technologies and changes were being developed all

Housing Density “Hicks, D. (2015). (Cesar DaSilva CC BY) Birmingham's back-toback houses. Birmingham Live. Retrieved February 16, 2022, from https://www. birminghammail.co.uk/ news/nostalgia/gallery/ birminghams-back-to-backhouses-9135861.

As shown in the illustration above, these houses were placed with their ‘backs’ to each other, packed close together with little to no breathing room. Bedrooms were often overcrowded and thus the hygienic conditions were very poor. On top of that, housing costs varied, such as whether or not they faced the street, even though the conditions were still deplorable either way. Eventually, because of their quality of life (or lack thereof), these buildings were deemed uninhabitable. Clearly, while mass housing is a good idea, it certainly brings its own challenges. While the cost of building is decreased, quality of life may also decrease as well, as can be seen in the back-to-back houses of Birmingham. This leads to the question whether or not profit should be put before people’s living conditions when designing housing for many people.

throughout Paris, a microscopic evil was lurking in the shadows and water. Cholera. In 1849, this waterborne disease had taken the lives of 20,000 people in Paris, becoming a call to action for stronger health infrastructure. The technocrat George-Eugene Haussman had deemed Paris a “sick” city. Being accustomed to technical dimensions of infrastructure, he began massive planning to rip apart the area and begin digging deep into the heart of the city's many needs. “During his two decades of power in Paris, he proudly referred to his design method as eventrement, or "disemboweling." He proposed "surgical" interventions involving costly expropriations and massive demolitions to obtain a healthy ensemble of level and paved tree-lined streets, perfectly aligned apartment buildings, asphalt sidewalks, underground water mains, sewers, and gaslights.”

Hausmann’s interventions in Paris. The gray represents the new blocks built over the old clustered layout. White represents new streets and boulevards. Adapted by Richard Ingersoll, WORLD ARCHITECTURE: A Cross-Cultural History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

Some of the most substantial interventions were aqueducts and a major sewer network that ran beneath the boulevards. The aqueducts had changed the way Paris obtained its water by no longer relying on the river as its primary source. Other major improvements were sewer trunk lines and future buildings planned to link with drains and water mains.

Before (Left) and After (Right) the substantial growth of Haussman’s sewer lines in Paris between the years of 1837 and 1878. Adapted by Megan Mahon, The Underground City - The Modernization of Subterranean Paris, Historical Geography of the Formation of Cities, October 7, 2014, https://historicalgeographyoftheformationofcities.wordpress.com/2014/10/17/theunderground-city-modernization-of-subterranean-paris/

“He further improved the city's hygiene with the installation of eleven sewer trunk lines that dumped effluents farther downstream at Asnieres. Newly constructed buildings had to conform in plan and elevation to these lines in order to plug into the complex network of drains and water mains.” The effects of Haussman’s intervention in Paris cured the “sick” city, lowered Cholera transmissions, and improved overall hygiene in the rising metropolis. Overall, Haussmann's work and plans transformed Paris into a clean and safe city. He helped create better water and sewerage systems, which helped bring clean water to the public. Clean water cures and reduce many transmissions of waterborne diseases such as Cholera. To reduce the overcrowded slums and dense housing which lead to many health problems, he proposed wider streets, which also brought more light into the city block and created spaces for trees and parks. Some people did lose their homes during the renovation, but the question that came up is did they really lose? If they were given new homes nearby, then they did not lose as much as they gained. Before, they lived in dense areas with poor water and lifestyle compared to where they had clean water, open parks, and better lifestyles. During the late nineteenth century, New York and Chicago reached sizes and levels of complexity, like those of Paris and London. New York pulled ahead of Philadelphia as the largest American city after the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825. New York becomes America's first and largest metropolis. By 1900 it had more than 3 million people and handled the majority of the country’s imports and exports. Chicago grew at the same time as New York as the pivot of inland shipping and train transport. The two cities fed on each other’s success while developing a strong architectural rivalry. In the mid-1800, Chicago consisted of mostly wooden buildings. After a fire destroyed about a third of them, the city’s architecture shifted typologies. “New tall buildings that replaced [wooden structures] were designed as solid, fireproof volumes with scant reference to European styles of decoration” ¹. These buildings allowed for a different architectural expression due to the freedom that steel framing provided. Many of Chicago’s skyscrapers can be characterized by their boxy appearance and use of Chicago windows, which are made up of a large fixed window and two smaller operable windows on either side. The Reliance Building designed by Burnham & Root took advantage of these windows and also used white terracotta spandrel panels. The result was a thin, non-bearing facade with a strong sense of repetition and horizontal lines. Department stores adopted steel-framed structures to maximize space at a minimal cost and risk of fire. It also allowed for the lower level to consist mostly of glass, which was desirable to allow people to see inside. The Scott Department Store designed by Louis Sullivan is an example of this and demonstrates a lightness that was not previously possible with masonry construction.

Reliance Building Analysis by Camilla Maruca. Figure A, Scott Department Store Analysis by Santiago Diaz. Figure B

New York`s middle-magnificence commuters unfold throughout the East River to Brooklyn. Before the development of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883, they reached the downtown workplace district via means of a twelve-minute journey on the ferry between Brooklyn and Manhattan. In 1869 Vanderbilt created Grand Central Terminal, New York`s important transportation hub. The layout of the construction changed into a right away end result of the iron and glass shape of the education sheds. The company of Warren and Wetmore rebuilt the station in 1904 2 as a multilevel complex ruled by means of an incredible vaulted corridor worthy of a Roman bath. The Empire State Building has a symmetrical massing, or shape, due to its massive lot and comparatively brief base. The five-tailed base occupies the complete lot, whilst the 81-tale tower above its far, set again sharply from the base. There are smaller setbacks at the higher stories, permitting daylight to light up the interiors of the pinnacle flooring, and positioning those flooring far from the noisy streets below. The construction has been named one of the Seven Wonders of the Modern World via means of the American Society of Civil Engineers. The construction and its road ground indoors are particular landmarks of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission and are shown via means of the New York City Board of Estimate. It changed in particular as a National Historic Landmark in 1986. In 2007, it changed to first on the AIA`s List of America's Favorite Architecture.

Empire State Building Construction. Figure A, New York, Grand Central Terminal. Figure B (interior).

THE DYSTOPIAN UTOPIA The ideal city environment, despite how it was envisioned in the 19th and 20th centuries, is in fact not an infinitely vast plane of a single repeated building. Contrary to that belief was the work of King Camp Gillette, whose idea of a metropolis consisted of a building designed by his hand, repeated on and on until the end of the horizon. Ingersoll has this to say about his work, as outlined in the book World Architecture: “Published in 1894, his work The Human Drift outlined a grandiose, authori-tarian scheme run by a benevolent state corporation that coerced the entire nation to live in a single rigidly planned metropolis.” This however is in stark contrast to the modern-day ideals of utopia. In fact, Gillette’s idea for a utopian society would be viewed as dystopian by today’s standards. One of the biggest benefits of using architecture to define cityscapes and societies is that it allows for expressions of beauty and freedom, which come from having buildings that are patently different. If a city had only the same building copy and pasted over and over, it would be boring, and oppressive. It’s easy to understand where Gillette was coming from, though. In theory, having differences in architecture and residential spaces would enforce the differences between social classes, since only the richest or highest class would be able to afford quality living spaces. Gillette identified the problem, he just was unable to identify the solution. The only way that can be surpassed while still embracing the expressive nature of architecture would be to ensure that all interior spaces are beautiful and successful in terms of comfort. As for exterior spaces, there’s no need to enforce the same standard, since everyone has an intrinsically different preferred style of architecture. While all buildings should have a beautiful and wellthought-out exterior, the style can be vastly different while still engaging in that beauty. There’s no way to classify gothic or modern styles as being better or worse because it's up to preference. Therefore, the mixing of styles actually removes class differences from architecture, even more so than the utopian scheme suggested by Gillette.

Perspective, Carson, Pirie, Scott Department Store (now the Schlesingerand Mayer Building), Chicago, Illinois, 1899 by Louis Sullivan (Santiago Diaz CC BY) Adapted from Ginger Juliano. “Schlesinger & Mayer Building II.” chicagology, November 16, 2021. https://chicagology. com/goldenage/goldenage035/. Accessed 17 February 2022.

THE BALANCE OF MATERIALITY: IRON AND CONCRETE Over the span of a decade, Chicago managed to change the ways materials were used in the construction of buildings. The Scott Department Store is the pioneer of buildings with a complete steel structure. This type of structure can be easily noticed when the distance in between the windows is thin and starts two create a sectional grid. Also, it is important to note that Louis Sullivan changed the design of a typical skyscraper being the foundation made of very light materials like steel and glass. The first floors of the building have very large and inviting glass windows which made the building an icon in the city. “Chicago began using steel-frame structures, reducing their reliance on masonry for support. The great department stores became the most eager clients of this technology, seeking to maximize space while minimizing costs and reducing fire hazards”. Furthermore, the design of the building starts to create a hierarchy between the materials used for the façade, the first floor is made of very light materials, and the rest of the façade is covered with more solid materials like concrete. This design is comparably more efficient than earlier skyscraper designs like “the Home Insurance Building” because it is mostly made from steel rather than a big amount of concrete that was typically used to support the structure of the earlier high-rise towers.

URBAN EXPANSION CAN CHANGE ARCHITECTURAL STYLES As Urban expansion began in London during the mid-1800s, the architecture began to change from the urban area to the rural areas. As London’s expansion began Edwin Lutyens and Gertrude Jekyll constructed many homes 25 miles south of London in 1896. One of these houses was called the Munstead Wood. The Munstead Woodhouse was a completely different style of architecture than the buildings in central London. The Munstead Woodhouse's main style is Gothic Victorian while Londons’s architecture is a mix of colonialism, Romanticism, and gothic styles. Victorian style features contain decorative gables and rooftop finials adorned the exteriors. Has many chimneys, decorated windows, and steep rooftops. The gothic characteristics come from the bland concrete stone walls. “Together they forged a synthesis of the arts, combining architecture with furniture, textiles, and stained glass.” The steep roof of the house is possible by gables lining up to create more space in the attic. In conclusion, due to urban expansion, many architecture styles become drawn out and faded into new designs because of new infrastructure issues and changes in the environment.

This perspective drawing of the Munstead Woodhouse shows the two main staples it contains within the building design. Both share Victorian and Gothic style architecture and how different architecture can change during urban expansion.

THE ROLE MODEL FOR SKYSCRAPERS Being the fastest constructed building in its day and age the Woolworth Building set expectations on how future skyscrapers would be designed. Construction was completed in 1913, which foreshadowed future highspeed skyscrapers buildings, such as the Empire State Building. The building was revolutionary for its lit exterior, strong steel frame structure, stunning white terracotta facade, and even high-speed elevators. The interior, specifically the lobby, was luxurious with its high ceilings, mosatics, and large windows resembling a cathedral. The ceiling being gold plated also had carved designs as well. Inside the building were shops, restaurants, health clubs, and arcades that served as entertainment for daytime visitors and guests. This building was so iconic that it’s still highlighted in the city’s skyline, even though much taller buildings have been constructed since.

Perspective view of the Woolworth Building of 1913 by Cass Gilbert, adapted from Wayne Andrews/ Esto, accessed 2/17/22, https://www.britannica. com/place/WoolworthBuilding. Perspective view adapted from Jason Cochran, accessed 2/17/22, https://www.frommers. com/slideshows/847993the-whimsical-wonders-ofthe-woolworth-buildingforbidden-for-years

The Paris Opera House was designed in 1861 by Charles Garnier. Front perspective view of the interior of Grand Staircase. Paris, France August 26th, 2011 Paris Opera House

PARIS OPERA HOUSE The Paris Opera House was built over a century ago in 1874 and was based on the Bordeaux Staircase. The interior was built mostly of marble-like onyx in certain instances.

Front Elevation view of Mietskaserne. Designed by Adolf Erich Witting and was built between 1860 and 1914. Accessed 17 February 2022

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE RENTAL BARRACKS The Mietskaserne, also known as the “rental barracks,” is considered one of the largest tenements in the world. This structure was quite popular during World War I. “The tenements were thrown up with incredible speed mainly in the period between German unification (1871) and the First World War”. It is in Berlin Germany and was designed by Adolf Erich Witting between 1860 and 1914. This structure has had so much put into it to make it the significant array of buildings that it is present - day. It consists of five buildings that are used as rental dwellings and are in synchronization with each other with a large courtyard in the center of it all. Even though this has had an impact on the culture and counterculture of Germany positively, as well as being seen as a beautiful building, the rentals in this structure are not in the greatest condition. They are slumpy, packed, and quite overcrowded. But overall, it really stands out in the city of Berlin, Germany, and is seen as one of the most satisfying pieces of Architecture this country has seen.

WILLIAM G. LOW HOUSE

THE TRIUMPHAL TERMINAL The Grand Central Terminal in New York City was built in 1913 to replace an existing iron and glass train shed that burned down due to a steam locomotive crash. After this track fire in 1902, the decision to electrify the train brought new possibilities in terms of architecture. When Reed & Stem, a firm that mostly focused on engineering, won the competition brief, they decided to break away from the iron and glass which became so popular with the Industrial Revolution and decided to lean more towards Beaux-Arts and Roman Bath forms. “Vanderbilt's architects opted for an exterior reminiscent of Napoleon Ill’s additions to the Louvre in Paris, with tall, billowy mansards”[1]. It was important for the architects to consider the terminal as being a huge point of circulation between the streets, railways, and houses of the growing city. In the construction, the architects used a vaulted plaster ceiling which is held up by a steel substructure- a nod to the new engineering feats of the era. Along with resembling the Roman Bath forums, the building also drew from the Roman form by using many triumphal arches, decorating the facade with elaborate sculptures, and a large, raised terrace that became a city street itself. Inside, windows help natural light illuminate the large hallways which link the offices to the main space and facade. Outside, the facade is created to exude an emotion of triumph to represent the pride in the new railroad system which makes this structure so important and labeled as the gateway to the city. “For a century, New Yorkers have used Grand Central as their town commons, a beloved gathering place for shared experiences, distinctive displays, and important events—a home for broadcast studios, rallies, art exhibits, and tightrope walkers.”[2]

Distinguishing the façade of Grand Central Terminal as a structure more reminiscent of Roman form rather than the industrialized iron and glass structures of the era. Elevation view of the Grand Central Terminal, 1913, by architects Reed & Stem. adapted from “Grand Central Terminal New York.” Simon Fieldhouse, May 4, 2017. http://simonfieldhouse.com/new-york-icons/grand-central-terminal-new-york/. During the 19th century, following the Industrial Revolution, architects saw an expansion in types of structural and design materials. The use of steel and glass together led to many large-scale buildings, which began to move architecture into a more modern era. As building designs modernized, the large-scale buildings grew and took the perimeters of the cities with them. The designing of skyscrapers in Chicago inspired architects in New York, where new architectural ideas formed, forwarding this movement into modern-day cities. The growth these big cities first experienced rose at an alarming rate, with housing quickly overflowing, causing an age of sanitary and spatial adjustments. The engineering of these buildings failed to account for disease spread and overcrowding6. There were developments made to the sewer systems and water systems to counteract the unsanitary conditions and to continue with this architectural movement. While trying to make the city cleaner and richer, the working class was made an afterthought, with the architecture reflecting social hierarchy and the importance of space. By pushing these people aside, room for the wealthy grew. These infrastructure issues were pushed onto the working class as a social hindrance. Mass housing, an idea that cropped up around factory workers, held the same primitive living ideas as these cramped skyscrapers. With the rise of social ranking and the expectations that came with being wealthy, it became increasingly harder to avoid such harsh living conditions.

06 Counter-Industrial Movements

[Introduction: Architecture in the craft and the industrial age ] Cesar D.

While the industrial revolution changed how we design and build structures throughout the world in this age of industrialization, growth in size and volume did not come without its opposition. The Beaux-Arts style and Arts and Crafts movement was a response to the changing architectural and building styles. This arts style stemming from French neoclassicism and mixing artisan detailed work that is far from the industrialized architecture with new materials like large pane glass and steel.As we dive deeper into Art and Crafts we also see the push back to industrialization from art nouveau followers. This type of architecture and building uses nature as its inspiration for form and building, creating structures with organic shapes and using materials that are less processed like wood and clay-brick as opposed to steel.Going hand in hand with this more natural form of construction is the movement of japaneseism where buildings used large wooden beams for their primary structures and have a strong connection with nature.This influence from japanese architecture are paintings was very prominent during the rize of the industrial revolution. This connection with nature was a big part of the push back against the industrialization of entire cities and can be seen in many different movements at the time. Throughout this writing piece we will explore the connection between art, nature and architecture and how this connection developed throughout the industrial revolution regardless of push back.

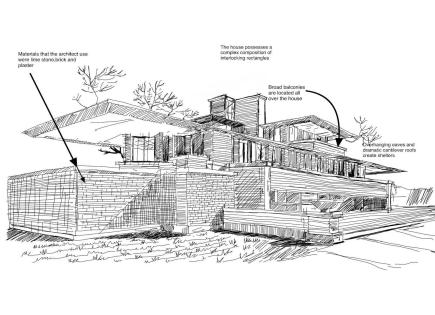

[THE ROBIE HOUSE ,RODRIGOMORENO]

Revival of Art Nouveau Architecture

The ornamental style of Art Nouveau that used sinuous organic lines first began to flourish in between 1890 and 1910. “Louis Sullivan's skyscrapers like the Wainwright Building and Chicago Stock Exchange are often counted among the best examples of Art Nouveau's wide architectural scope.” (The Art Story). Art Nouveau had become very popular in the United States as well as Europe at the time. Surprisingly, during the 1960s a popular revival for Art Nouveau began and it soon became thought of as an important predecessor or an integral part of modernism. During 1966 psychedelic posters began to appear in San Francisco and quickly became associated with Art Nouveau and soon after in 1968 art Nouveau would make an appearance in Vogue because Pierre Koralnik used Gaudi’s architecture in Barcelona as a backdrop for his show at the time. (Ericson Bonilla).