6 minute read

One For The Books

Reimagining Historic Libraries

By Graeme Matichuk

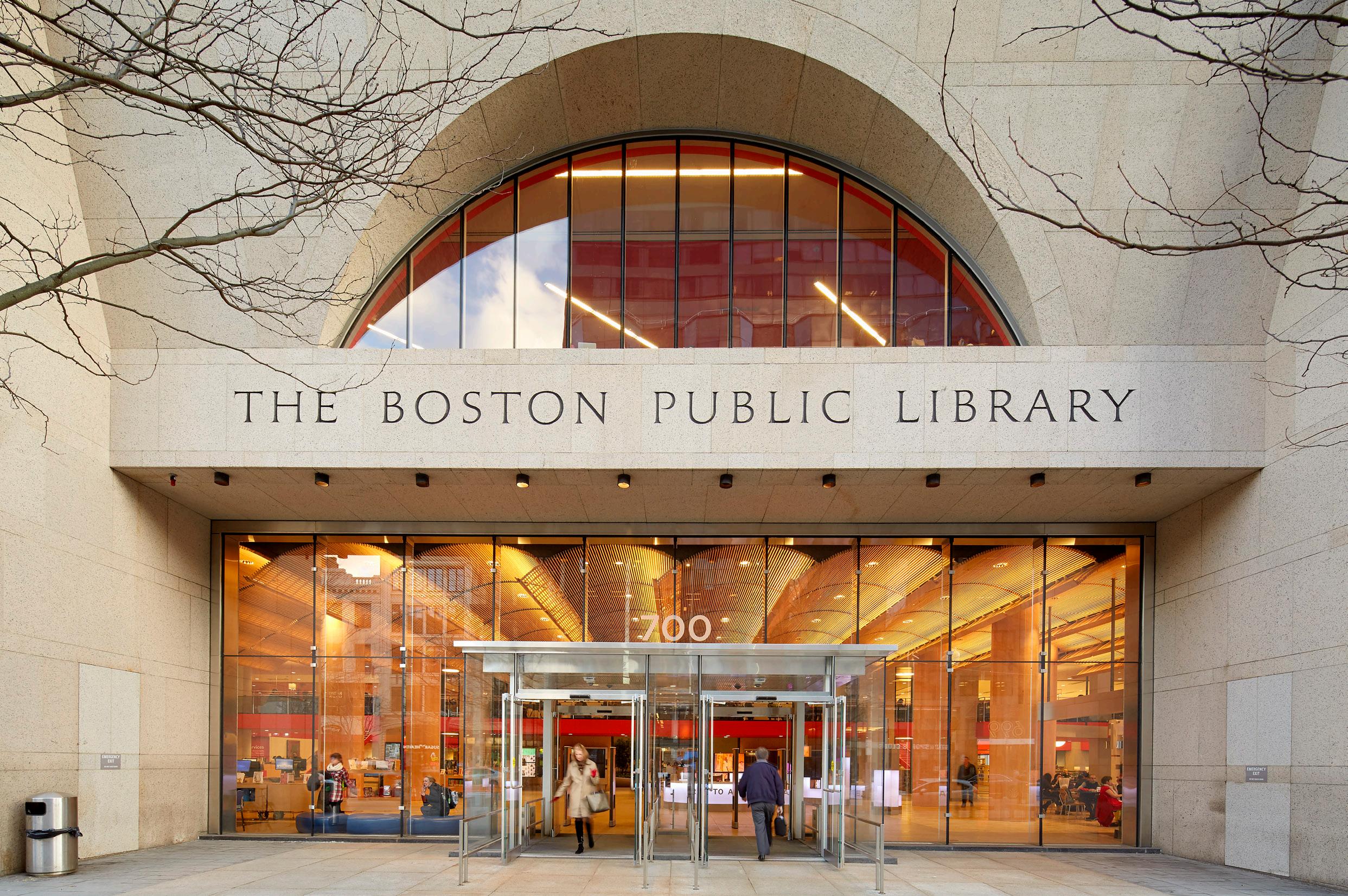

The refreshed Boston Public LIbrary's Johnson Building

Michael Muraz

Side by side, Boston Public Library’s 1895 McKim building and 1972 Johnson Building stand as monuments to their vastly different eras. “There is a space, not readily discernible, two-and-a-half inches between the old McKim palace and the new Johnson Building,” project engineer John Doherty remarked in 1986. “That way, either building can move a little without bothering the other.”

While Doherty’s observation was technical, it suggests a broader story of challenges in reimagining historic libraries designed by monumental architects. Elements defining a building’s historic significance might create challenges for using a space forty years after it was built. But propelling a building too deeply into another era might erase its history. Often we need a metaphorical two-and-a-halfinch gap between the old and the new to let each era breathe.

The Johnson Building was built as an addition onto its connected neighbour, the McKim building. Vocal opponents have criticized the Johnson Building as “a graceless granite tomb,” “an old, grotesque armory,” and, more recently, “a fortress.” Philip Johnson considered his addition onto the McKim building as “the most difficult design problem in the United States.” It was no small feat to design an addition that was complementary and not overwhelming, not too similar but not drastically different, from an iconic, historic building.

Johnson’s addition carried many of the McKim building’s characteristics: a ninesquare grid with a central atrium to convey “the monumentality of a central space,” in his words, exterior granite from the same quarry, and a copycat roof line. Respecting the McKim building’s heritage, he purposefully crafted an understated façade. These elements are just some of the many pieces defining the Johnson Building’s historic character.

In 2016, William Rawn Architects completed a massive reimagine of the Johnson Building. The Library saw this as an opportunity to elevate its central branch to 21st Century library grandeur. As the oldest library system and second-largest public library collection in the United States, Boston Public Library has some responsibility to lead innovation, and its reimagine would do just that.

The most transformative exterior change actually ran in opposition to Johnson’s vision for the building. Where 2,000-pound granite slabs once barricaded ground-level windows from Boylston Street to protect the library from the sidewalk bustle, windows facing the street now blur interior and exterior spaces into a continuous environment. Reed Hilderbrand, the landscape architecture firm that reimagined the Johnson Building, wrote that the Library “now extends beyond the building itself to shape the city’s public realm.” Boston Public Library’s head of major projects considers this transformation essential to the Library’s new era: “This was an inward-facing fortress, and now it’s going to be the total opposite.”

Drawing the public into the Library from Boylston Street meant more than just knocking down the granite slabs. The interior spaces were long overdue for a fresh coat of paint and a bright burst of colour. With the recent renaissance in library innovation, it was also a priority to bring the Johnson Building up to 21st Century library standards.

The exterior granite of the Johnson Building at Boston Public Library was taken from the same quarry as its connected neighbour, the 1895 McKim building.The Boston Public Library

Bruce T. Martin Photography

Within the first three levels, the design team cleared away the original grey-andbrown palette and applied a striking, saturated colour scheme, injecting energy to the dated building. The reimagined design included new children’s and teens’ areas, a street-level cafe, a community learning centre equipped with modern technologies, a new lecture hall, and more.

Daniel Coolige, the architect of the McKim Building’s 1980’s restoration, said during a Boston Globe interview in 1986 that the Johnson Building is “a very handsome and expensive warehouse.” In fact, any mention of the Johnson Building in this article focuses on its extensive collections and reading rooms.

Part of the Johnson Building’s 2016 reimagine included strengthening the connection between the McKim and Johnson Buildings. LeMessurier structural engineers carved a 36-foot opening in the McKim-Johnson dividing wall, an original masonry wall of the McKim building supported by a granite foundation and timber piles. The temporary framing to support this endeavour balanced over one million pounds, a feat perhaps only possible with today’s innovations in engineering. This connection, similar to the removal of the exterior granite slabs, would further open the Johnson Building to its surrounding environment.

The Johnson Building’s reimagine draws people from the streets into a vibrant space for collaboration. The shelves of books and multimedia and newspapers are still vital, but they are not the sole occupants. The Johnson Building is a plaza for the people, not a fortress for books.

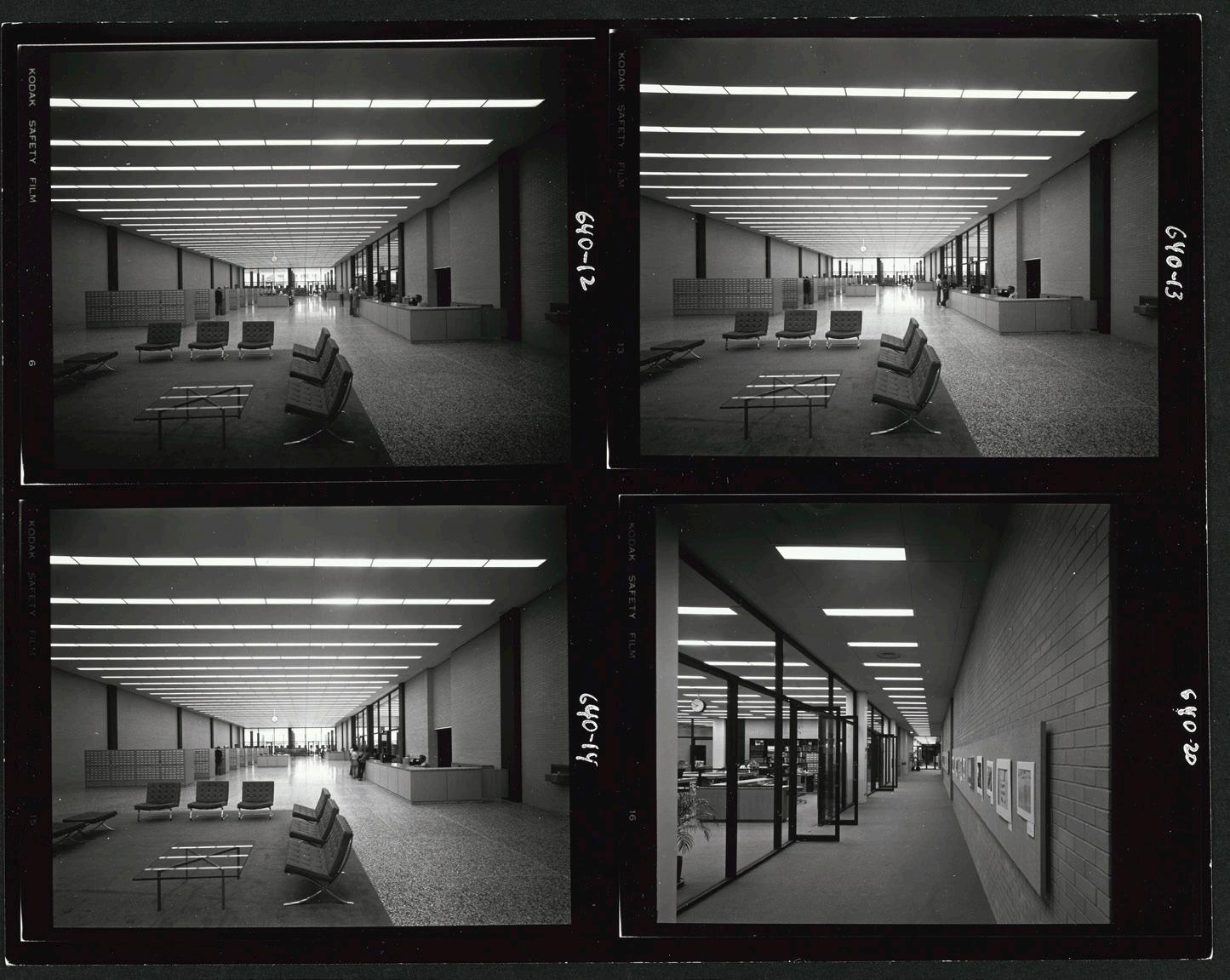

The Johnson Building's original design was controversial, termed by opponents a "graceless granite tomb."

Boston Pictorial Archive

Washington’s central library was incomplete when it opened in 1972. At least, that’s what architecture critic Wolf Von Eckhardt wrote about Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s library design. “Mies would not want it to be. He carefully designed his buildings as simple enclosures of space, envelopes, if you will, for the life and change within them.”

As the first public building named after civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr., the only realized library design by Mies, and the only Mies building in DC, the Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK Jr.) Memorial Library holds a special place in American architectural history.

During its design, however, so much of Mies’ vision was lost due to budget constraints. His colleague, Jack Bowman, who completed the design after Mies’ early death, remarked that they never solved the confusing wayfinding, such as the hidden stairwells. The tan brick was supposed to be veined green marble. But these concessions, preservationists argue, are part of the historic designation because they capture society at the time when the building was constructed.

In contrast to the Boston Public Library’s Johnson Building, renovations to the MLK Jr. Memorial Library were modest due to restrictions from its historic designation. Extensive research into Mies’s design philosophies, including those he applied to his library design, shows that he rarely centred his design on the functional, forward-thinking elements that characterize libraries today. His philosophies largely focused on materials and form.

Far from a transformative reimagine, the changes mostly added new spaces, like a theatre and a rooftop garden, and cleared sightlines for improved navigation through the Library. Interior spaces were reconfigured to seat people at the windows, rather than lining the perimeter with stacks of books.

Mies van der Rohe’s philosophy, which informed the design of the MLK Jr. Memorial Library, largely focused on materials and form.

Courtesy of DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division

Each of these changes was grounded in the idea of the library as an urban centre. Architects at Mecanoo called the Great Hall “the beating heart of the library.” With an energized Great Hall and a new cafe, the ground level would become a public plaza for events and conversation. Meanwhile, stairwells with translucent entries and spacious pathways—no longer narrow brick towers—would draw visitors to exciting venues on the upper levels. The fifth-floor addition of a rooftop garden and performance theatre would become the lookout point with views of the cityscape.

Like the Johnson Building, the reimagine design team for the MLK Jr. Memorial Library aimed for a people-focused library. But they had to balance grand expectations with the limitations of their historic status. Design teams for both of these reimagine projects embarked on extensive research into Philip Johnson and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and the histories of their respective libraries. The reimagined designs of the Johnson Building and the MLK Jr. Memorial Library succeeded by balancing the important historic elements with the need to make these libraries functional 50 years after they were first designed, recognizing that a library is a functional building for the people, not just a work of art for history books.

New spaces were added to MLK Jr. Memorial Library, designed to serve as an urban plaza, or “the beating heart of the library.”

Mecanoo

Today’s public buildings are open, weaving their interior sightlines into the streets and up to the sky, drawing the public indoors and welcoming sunlight. Libraries in the 21st Century have shunned the idea of a fortress. Instead, they are a public plaza of learning and gathering.