6 minute read

Leveling Up

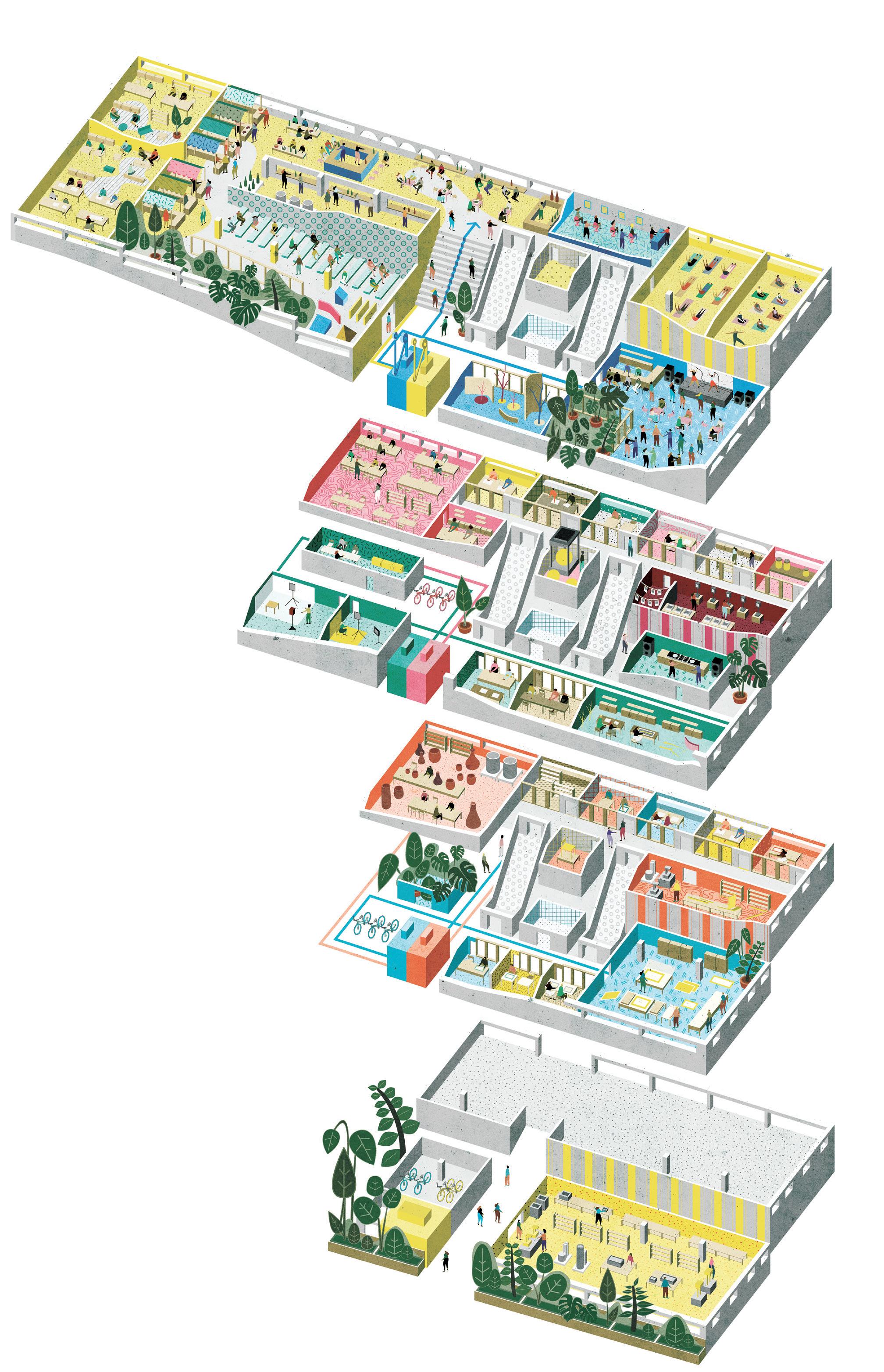

Peckham Levels transforms the interior floors of an underused London, UK parking garage

By Cheryl Mahaffy

Peckham Levels is a temporary solution to the question of what will become of an 80s parking garage in London.

Tim Crocker

What can you do with a 353-space 1980s parking garage that has outlived its original purpose? Southwark Council in southeast London posed that challenge after its plan to demolish a largely vacant 1980s carpark (built to serve a supermarket that soon closed) met with grassroots resistance. Adding to the challenge, the borough wanted a “meanwhile” project—a temporary use for the site while its long-term future is sorted out. Peckham Levels is the result. From the outside, the structure remains true to its origin. Inside, however, the stalls that once held cars (and later drug deals, sex for hire and people sleeping rough) provide affordable space for more than 100 independent businesses, accelerating the revitalization of the once-struggling Peckham neighbourhood.

Listening Local

The spaces that once held cars are now filled with small businesses and cultural spaces that benefit the community of Peckham.

Carl Turner Architects

Carl Turner Architects and a social enterprise now called Make Shift won the competition to reimagine the empty levels within the carpark, in part by promising to involve and serve the surrounding community. True to that promise, they met early on with Bold Tendencies Community Interest Company, which for a decade has used the structure’s rooftop (an area excluded from the meanwhile project) for sculpture exhibits, music events and a popular summertime bar. Those discussions confirmed a desire to leave the spiral ramp intact for easy transport of large sculptures and other hefty objects. The partners also consulted with Peckhamplex, an independent cinema located in the former grocery store, to ensure that intended uses would complement rather than compete. “It was really important to us that we didn’t displace anyone,” says Carl Turner Architects’ Paul O’Brien, who was intimately involved.

Different levels attract different sorts of tenants, ranging from eateries to yoga studios, woodworkers to breweries, and architects to therapists.

Atelier Hu and Carl Turner Architects

The partners also involved community leaders in a steering group, rented a nearby storefront to solicit ideas and sketches and reached out to local entrepreneurs who might be looking for space to grow. “Development companies often do what they call community engagement—drop-ins and meetings—but then build what they already planned to do,” says Make Shift’s Michael Pryke. “We really listen. We believe if we’re going to stop the adverse effects of gentrification, we need to build things that are useful and suitable to local people.”

The former parking garage has been recognized as “one of London’s most fashionable places to hang out” and one of the capital’s “most successful regeneration stories.”

Tim Crocker

Some intriguing ideas, such as building a swimming pool and importing earth for gardens, proved unworkable due to load limits and cost. But other input profoundly influenced the design. "Artists talked about how important natural light is," Pryke says. “So all the units are located around the exterior, with large windows.” Lack of affordable space also surfaced as a concern. “Some spaces sound affordable per square metre, but what they don’t put on the glossy brochures is that you have to rent a lot of space,” Pryke says. To address that barrier, Peckham Levels offers low-cost co-working space, studios as small as a parking stall and 10 discounted units for local artists in residence.

Listening paid off. Peckham Levels boasts an occupancy average of 96 per cent and a waiting list of 1,000 for its 80 available studios. What’s more, 65 per cent of occupants are local. “If you invest in what the community wants and can afford,” Pryke says, “you don’t have to ship people in.”

The original wayfinding and footprints of the parking spaces were kept, a clever reminder of what the building used to be.

Tim Crocker

The ‘Meanwhile’ Challenge

Turning an elongated, open-air parking garage into a creative hub takes its own brand of creativity, O’Brien notes. “Whoever designed the carpark would never have thought it would be used this way.” Ramps take up significant space, and the six interior floors are not only offset as in a split-level house but sloped to the edges for drainage.

“All those features are still there,” says Pryke, who joined the team post-renovation. “So if your chair has wheels you do roll slightly down toward the windows.” The original wayfinding signs remain, he adds. “To me, that’s one of the triumphs of the design. You can forget you’re in a carpark and then see this massive arrow on the floor and suddenly remember.”

The fact that it’s a meanwhile project—originally slated to last five years although extended to 15 just before opening— demanded “a lot of value engineering,” O’Brien says. “We used very robust, very simple, easily adaptable materials like OSB (oriented strand board) and chipboard. And nothing that isn’t necessary, which is our ethos anyway. The aesthetic is very much ‘carpark,’ although we might have done some of it differently with a longer lease.”

The carpark’s low-hanging support beams (just 2.2 metres above slab) proved a major challenge. To make the ceilings seem higher, dividing walls extend directly below the beams, providing a headspace of 2.8 metres throughout much of each studio. That approach results in footprints of one or more parking spaces, another nice nod to the original use of building.

Turning the carpark’s dearth of water, sanitation and power into an opportunity, architects clustered toilets, darkrooms and other uses that rely less on light in the interior, served by a new vertical riser. Exposed ductwork runs beside and between beams, with air exchange intakes built around the window system. “It was a very simple and clear servicing strategy, working with the layout of the floorplates,” O’Brien says.

Design loads impacted plans more than anticipated, O’Brien observes. “Yes, it’s a big concrete carpark, but cars are mostly full of air, as a structural engineer pointed out, and they generally park over the beams. If you take that same 12 square metres and put 50 people dancing on it, that’s as much as twice the design load. We had to move our event space and strengthen the beams with carbon fibre strips.”

Peckham Levels boasts a vibrant synergy owed to its varied startups and small businesses working side by side.

Tim Crocker

In all, it took £3 million GBP ($5.26 million CAD) to fit up 8,730 square metres of space, or £250 GBP ($613 CAD) per square metre, not including fit-out of tenant spaces. Major costs included weatherproofing, filling in the space between levels (largely with windows) and compartmentalizing high-risk areas such as kitchens and kiln rooms. The brick façade was left largely intact, significantly reducing material costs. It also helps that Southwark Council leased the interior levels rent-free in return for 25 per cent of profit once the project breaks even plus continued commitment to local training, employment and community involvement.

“It’s affordable. That’s the good thing,” O’Brien says. “There’s always a lot of anxiety about development in general in London; as soon as an area is popular, there’s fear the people living there will be displaced. That’s happening to a certain extent in Peckham, but this project is looking to address that. It’s providing for people who are there already.”

Pride of Place

Opened in December 2017, Peckham Levels won the New London Awards Meanwhile Category in 2018. A recent issue of Southwark magazine salutes it as “one of London’s most fashionable places to hang out” and among the capital’s “most successful regeneration stories.”

Being in a carpark gives the project a distinct identity, O’Brien observes. “The name Peckham Levels comes from wondering what could happen on the empty carpark levels. It was able to capture people’s imagination.” Levels 5 and 6 attract public foot traffic with eateries, event space, a children’s play area and a yoga studio. The lower levels contain studios for woodworkers, a brewery/distillery, painters, architects, therapists, jewelry makers, musicians and more; a co-working space (The Ramp) that appeals to start-ups; and collaborative spaces for 3D printing, music, ceramics, screen printing, art and design.

“It’s designed as pipeline space, to build your business and then move on,” O’Brien says. “It’s exciting to think about who might go through this space. Will one of them win the Turner prize, or write the Pulitzer winning novel, or record a Grammy-winning album?”

Equally exciting, he adds, is the synergy that occurs as creative types work side by side with the aim of building up the surrounding community, as well as their own enterprises. “Members really want the project to fulfill its potential to the local community—they feel fiercely protective of that,” he says. “It’s about being really aware of how powerful those communities can be when people feel ownership of their space.”