The Contemporary Doors of Return

Minutes from AFROINNOVA IV (Tumaco – Cali 2022) Paula Moreno (President of Manos Visibles) Giuliana Brayan (Empowerment Manager of Manos Visibles) with support from the AFROINNOVA team Uma Ramiah, Luis Cassiani, Valeria Brayan, Diana Restrepo, Carlos Ortíz, Maria Inés Requenet, Maité Rosales, Ana Isabel Vargas Jeison Riascos “El Murcy” (Photographer in Cali) Written by:

“Those who dedicate themselves to creation know the power of screens, images and writing to temporarily reverse so many absences and limitations. So many impulses of transformation of worlds are born when we finally see ourselves also as fictions and in them, we build ourselves in other ways. So much political power that we squander for the self”

Remedios Zafra, El Entusiasmo

2

3 About Manos Visibles The AFROINNOVA Pathway, 2015-2023

Africas: The Continent and Its Descendants

The Two

comes next? A Second Key: The Images We Need… A Third Key: Technological Todays and Tomorrows The Fourth Key: The Movement That We Need A Fifth Key: How do we distribute our content? The Sixth and Seventh Keys: The Capital and the Strategy Our Conclusions INDEX 4 5 9 10 11 19 22 26 33 36 40 50

What doors are closed, and which ones are just now swinging open? Key One: The Words We Need What

ABOUT MANOS VISIBLES 13 YEARS

of Building Leadership for Racial Equality in Colombia and Beyond

After Brazil and the U.S., Colombia is home to the third largest African diaspora population outside the Continent. As an NGO based in Colombia, our power rests in uplifting Afro-Colombians and in our ability to inspire the country, the continent, and the entire diaspora. Africa is critical to rewriting our own history and creating brighter horizons. Manos Visibles currently has a network of 25,000 members and 500 organizations. AFROINNOVA is our international strategy whose objective is to nurture and build leadership

and strategic connections around the world, and to change power relations in Colombia and beyond. In Latin America, AFROINNOVA is a permanent platform for conversations about the global reach of Africa and its descendants, given that when you take Brazil and Colombia together, you are now talking about more than 110 million people, the largest regional African diaspora on the globe.

4

THE AFROINNOVA PATHWAY

AFROINNOVA harnesses the power of community innovation by connecting leaders, initiatives, and experiences from across the African diaspora. In 2017, we defined the African diaspora as an intentional gathering of people and communities with a collective awareness as sons and daughters of the African exodus, with the ability to challenge and change power relations in the world. Created by Manos Visibles in 2015, the group recognizes the critical need for Africa and its descendants to rise as a new global power: Africa the people, Africa the place. AFROINNOVA’s first meeting, called “The Power of the Diaspora”, took place in the cities of Cartagena and San Basilio de Palenque. The objective for this group of experts was to create a discussion around the current state of affairs and to ponder more strategic ways to conceptualize power. The second meeting was called “The Technology of the Diaspora: Inspiration and Aspiration” and it was held in the cities of Buenaventura and Cali. The main theme was “From Inspiration to Aspiration,” an exercise that required us to take a look at ourselves, recognize each other, and come together. The meeting provided a space in which we defined the diaspora using four strategic themes: culture, technology, communications and capital. “Afro-prospective: Mirrors and Reflections of Africa and Its Diaspora” was the name of our third meeting that got underway in Quibdó and Medellín. This gathering emphasized what the Afrodiasporic future could look like, working within the framework of power.

With the closing of the 2022 cohort, more than fifty leaders from fourteen countries have become members of this platform.

5

After the COVID pandemic, we opened our eyes and looked upon the future with a sense of uncertainty, with a special focus on culture. This led to our fourth gathering and work group, which took place on the Colombian Pacific coast in the municipalities of Tumaco and Cali. Tumaco is known as a powerhouse of Marimba music. As expressed by Kiluanji from Angola, Tumaco is “a cultural miracle where ancient music practices are even more alive today in this major Afro descendant town on the Colombian border with Ecuador than on the [African] continent.” After Tumaco, Cali is the second city in Latin America after Salvador de Bahia with a substantially large Afro descendant population. During our visit, Cali hummed as an epicenter of Black culture as it hosted the Petronio Alvarez Festival, the world’s largest Afro-Latino festival that attracts more than 100,000 visitors and features traditional music at the center of an explosion of gastronomy, visual arts and fashion, among other cultural expressions. In this festival, Brazil was the guest of honor as well as multiple representatives of the African diaspora such as the extraordinary Susana Baca from Perú. There could have been no better stage for our reflection on “Diasporic Futures: The New Doors of Return - The Contemporary Black “I” in the World,’’ which was centered on building:

A Network

of capabilities, strategies, conceptualizations, negotiation of ideas and transnational collective learning.

A Space A Pathway

for cultivating leadership, renewing approaches, and generating a collective understanding of the African Diaspora and its context.

to construct new narratives, so that our people may see and define their own individual struggles.

An Allowance

to construct new narratives, so that our people may see and define their own individual struggles.

6

THE 2022 AFROINNOVA COHORT

7

Gilbert Shang-Ndi (Cameroon)

Biola Alabi (Nigeria)

Moky Makura (Nigeria)

Edna Liliana Valencia (Colombia)

Kiluanji Kia Henda (Angola) Rafael Palacios (Colombia)

Rafael Murta Reis (Brazil)

Salym Fayad (Colombia)

Bruno Duarte (Brazil)

Eddy Bermúdez (Colombia)

Baff Akoto (Ghana - England)

Graciela Selaimen (Brazil)

Uma Ramiah (United States)

Lucía Mbomio (Spain - Equatorial Guinea)

IN MEMORIAM

In 2020, we lost one of our members, Janisha Gabriel from Black Lives Matters. Rest in Power.

“Telling these stories that humanize.

Telling those stories allows us to not just talk about numbers, but to make connections to the context, to the families, which is to humanize the causes and show the differences”

Janisha Gabriel, Black Lives Matter RIP In Memoriam

THE TWO AFRICAS: THE CONTINENT AND ITS DESCENDANTS

The global landscape of racial equality is quickly shifting. The devastating effects of COVID-19 are unfolding over time with a greater power of content and technology that has increased the global response to systemic racial inequalities. The growing presence of Afro-descendants in government (e.g., the first Black female vice presidents in both Colombia and the U.S. as well as six Black ministers in Brazil) is evidence of a growing level of representation. The question as to whether that representation translates into tangible results is still up in the air. (When is a win an actual win and not just a symbolic victory that results in more vocal and aggressive push back from the oppressors?) Taking the title from one of the exhibitions of Kiluanji, the lingering question is now that we have power, what do we do with it? Before the pandemic, we mapped one thousand organizations of the African diaspora through our AFROINNOVA directory. We observed a growing trend of organizations that are already connecting and becoming more visible through social networks, resulting in an impulse in transnational power. In this context, AFROINNOVA IV brought a group of creatives from the diaspora together physically in a post pandemic world because –as one of our members Zakiya Carr Johnson put is—“Our greatest asset is us.”

The main topic of the fourth gathering was “Contemporary Doors of Return” that designated cultural expressions as the key to opening more doors in the creation and dissemination of shared memories and collective renewed visions. But this wasn’t only about focusing on the past but also mapping out the future. For example, some audiovisual expressions through digital platforms grew during the pandemic and this phenomenon changed the film landscape forever. For this reason, our fourteen cultural leaders from across the worlds of dance, literature, media, visual arts, film, business, and philanthropy met to discuss how to expand the poetic, economic, social and political potential of the future from diasporic arts and cultures around the world. What are the doors we are opening? What are the keys and where can we find them? What is the art and platforms we need?

9

The world is coming to an end. And it ends for you and for me, many times over.

WHAT DOORS ARE CLOSED, AND WHICH ONES ARE JUST NOW SWINGING OPEN? LET US FIND THE KEYS.

10

KEY ONE: THE WORDS WE NEED

by Gilbert Ndi Shang Ph, Cameroonian Writer and Professor

WHO WE ARE AND WHY

In a people’s rise from oppression to grace, a turning point comes when thinkers determined to stop the downward slide get together to study the causes of common problems, hammer out solutions and organize ways to apply them.

For centuries now, our history in Africa has been an avalanche of problems. We’ve staggered from disaster to catastrophe, enduring the destruction of Kemt, the scattered millions wandering the continent in search of refuge, the waste of humanity in the slave trade organized by Arabs, Europeans and myopic, crumb-hungry Africans ready to destroy a land now carved up into fifty idiotic neocolonial states in this age when large nations seek survival in larger federal unions. Even fools know that fission is death.

It may look as if all we ever did was endure this history of ruin, taking no steps to end the negative slide and turn things around. But that impression is false. Over these disastrous millennia, there have been Africans dedicated to working out solutions to our problems and acting on them. The traces these markers left are faint because the illustrious ones were murdered and the land poisoned. Now whenever a future seed seeks to take root, it must push through an arid earth. Still, even in defeat, the creative ones left vital signs. They left traces of a moral mind path visible to this day; provided we relearn how to read the signs to lost paths. Then, connected with times past and future spaces through recovered knowledge, Africans with illuminated minds will seek out each other in this common cause and will bring together the best of humanity for the world ahead, putting an end to the rule of slaver drivers.

11

“SOMETIMES SHE’D FEARED THE ENERGY SHE NEEDED, FOR MOTION MIGHT NEVER COME”

Ayi Kwei Armah

WE DEMAND INTELLIGENT ACTION TO CHANGE THESE REALITIES. FOR WE INTEND, AS AFRICANS, TO BRING BACK THE HEART, MIND AND AURA THAT OUR ANCESTORS USED TO SOAR TO HIGHER HEIGHTS. THAT IS THE ESSENCE OF WHO WE ARE.

12

GILBERT’S REFLECTIONS ON OUR STORYTELLING

African literature is a new door to our renaissance. A new wave of creativity has emerged now that African writers have not only published books for the local diaspora but have also gained worldwide readership. But a major task still lies before us: When will more AfroLatinos authors be read on the Continent? Literature opens doors, and it is one of the keys. Creative storytelling is and has always been indispensable for individual and collective self-representation, and it leads to progressive re-appropriation of power over our memories and history. It allows us to rename and redefine ourselves in contexts where we have always been defined from external, stereotypical and colonizing perspectives. This dialogue with African literature constitutes a highly symbolic gesture that marks a form of transatlantic reconnection at the level of our histories and our imaginings, bringing together cultures that have been separated for centuries but have never lost their common roots. These are cultures that were transformed once they hit American soil but remain strongly connected to African epistemologies.

Success stories are important, but we should also share how some of these transatlantic connections have fallen short. Here is where I think we have failed: The diasporas all have different experiences and histories, and we often find that our expectations are not aligned even when we try to connect them in a collaborative fashion. We need to be aware of

13

other eventualities that are not as successful as the ones we are experiencing here at AFROINNOVA. Why have previous attempts at connection misfired? Let’s think about diasporic connection through fiction and the issue of origins and ask ourselves for whom do we write our stories? For whom do we produce choreographic performances? What are the images we project through our work?

Audience is important. For the writer in the post-modern context, for example, the ability to subvert without pandering is paramount. We must make readers rethink and subvert their assumptions without being concerned about what the audience might expect from us. We should not be complicit to the audience. If you want to focus on your art, avoid being beholden to outside perceptions and expectations. Bruno, Kiluanji and all these artists in this realm are disruptors. There is an issue of temporality because the Motherland and her diasporas are all different. A Martinican author developed a differentiation between globalization and globalism in which globalism is defined as a much more subtle exchange on a deeper level. How do we examine how Black culture spreads in the Americas, back to Africa and throughout the Caribbean?

Toni Morrison says when someone tells you that you are not human, you try to prove them wrong instead of spending that energy on solving issues that affect you. We don’t need to explain our humanity. We don’t need to explain we’re human to anyone. Our writings are judged by Euro or American standards, standards that dictate the trends, and what is considered sellable. How does this reality condition our practices? Our task is to continuously subvert that media of validation. But you do that when you are very sure of the capacity of finding alternative financing, etc. If you’re not established enough, where do you find the power to speak truths to those who fund you? You must possess symbolic capital to gain a certain sense of independence. We need to tell stories about life on the Continent and its diasporas. But as an artist, what you produce does not always need to be comprehensible to everybody. Art rewards its opacity. But [in our society], the Black body must be legible and readable. But in Black history there was always the capacity for Black

bodies to be intentionally unreadable. To be pan-optical in order to subvert the line of vision of the all-seeing eye that seeks to look at your body with the intention to objectify, discipline, control, or orient it towards a certain aim that is always in the interest of the slave driver. Now there’s an intention in Black art and choreography not to be comprehensible to the spectator. One of the greatest advantages is that now the discourse is not created about us, but rather it is constructed with us and for us.

“And how do we transcend? With transcending—that is, what we see as the future—the focus should be on knowing the present situation and reality of the African diaspora. We should also know the situation in the Motherland, but not necessarily zero in on ancestry while focusing on current dynamism. We should also defy expectations.

In the midst of his experiences while living among different cultures of the African diaspora, Gilbert pointed out the importance of understanding that as global leaders of the diaspora, there is a responsibility to connect from what each individual knows how to do best. In his case, the aim is to also accompany those written narratives from a literary perspective and the work with the academics in the precise search to recognize the work that has already been done. Gilbert states that “written narratives have the power to connect in such a unique way, that we can go from Salvador de Bahia to the Colombian Pacific, then go to Peru and end up in any African country...in the end, it’s the landscapes, the faces and spirituality that guide us.”

The next level that Gilbert defines for the narratives is to appropriate the narratives as part of a single whole housed in one single homebase because there is an ancestral union that will never be erased. The academics must continue to be involved because it is an important space for research. But the challenge is to attract more people from the diaspora into academics from a systemic perspective towards the need to investigate what unites the diaspora.

14

MOKY CONNECTS THE STORIES AND THE LEADERSHIP THAT WE NEED

Moky spoke of the need to change narratives on the African continent and explore truly African stories, and for the diaspora to learn of the real context of a region that is also their home. “Why must narratives change? Because if narratives don’t change, there are no futures to imagine, no hopes to achieve and no desire to dream of something better,” she articulates. The trends and stories that are shown on the African continent are framed in poverty, corruption, disease and armed conflicts. The key is in the recognition of that other Africa that is a framework of innovation, creativity, joy and talent. The stories define the way the world views us, that is why it is so critical to analyze our global representation as a diaspora in critical and innovative ways so we can face our challenges of representation in the media and other forms of mass communication.

But once we have more stories to tell the world, we need to have a systemic approach to open the spaces and infrastructures so that these stories can transcend on a global level. This requires leadership. With that in mind, what can Afro descendants do

differently? When we procure positions of leadership, we don’t always bring our people with us. We need to be intentional about this: When you open a door and walk through it, reach back and bring others with you. We assume this happens quite often, but this is not always the case. We need to guarantee that Afro leaders are giving back. For every opportunity that comes your way, you must give back by supporting someone else. And how do you increase the representation of Afro descendants globally so that we can actually create a more influential community? We need to focus on the things we already have in common, such as music and food. And ways of doing things that we enjoy. Why not take a group of Colombians to Nigeria and vice versa? Where does that money come from? Maybe we can build a metaverse of African tourist experiences where all we have to do is put on some virtual glasses and we’re in Lagos, bypassing any passport or visa issues. Has a Colombian president ever been on an official trip to several countries in Africa? Can it be done digitally, even if it’s just a pilot experience? How do you make this happen?

15

WHERE IT ALL STARTED. IS THIS TUMACO (COLOMBIA) OR A TOWN IN ANGOLA?

TUMACO: A LITTLE ANGOLA ON THE PACIFIC COAST

Tumaco is a great African village in Colombia. It is a Colombian space where the majority of its population is of African descent, and its cultural history is based on the essence of its African ancestors. Do Africans know that Tumaco exists? When did this journey of Little Africa begin? Tumaco is known as “The Pearl of the Pacific.” It is referred to as a pearl for its memory, a pearl for its history, a pearl for its people. It is an African village full of contrasts and contradictions, but it’s also a place that stands out for its cultural power. The cultural miracle of the African diaspora is deeply compelling in towns like Tumaco or Palenque, despite all the attempts to extinguish their history and heritage. This town borders Colombia and Ecuador and it hosted the assembly of not only

some members of the AFROINNOVA consortium, but also for more than 100 Afro-Colombian leaders. Through the lens of their organizations, leadership networks and enterprises, these cultural leaders shared and interacted with AFROINNOVA members from Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana and South Africa. This meeting was also an opportunity for the Afro-Colombians in Tumaco to see and meet their mirror images from the African continent and to reflect upon the dynamics of the global diaspora.

16

ALL THAT WE SHARE: MEMORIES, MUSIC, FOOD, DANCE…

First, we visited the Casa de Memoria de Tumaco, a unique space in the Colombian Pacific that connects a past and present of violence with the importance of youth leadership that safeguards memories and transforms them into tools for interaction and life projects for the new future of Tumaco. In this space, the forum “Works of Memory: A View from Visual Arts and Music” was held. It was moderated by Paula Moreno and with the participation of AFROINNOVA members Salym Fayad (Colombia) and Kiluanji Kia Menda (Angola).

The conversation revolved around the concept of the power of images. Paula Moreno highlighted that “image takes on the role of registering and validating our existence as a diaspora. The absence of current images compels us to rebuild and deconstruct our society, because for municipalities like Tumaco, as well as in African countries, violence is the most visible manifestation of Black existence. We have always walked so close to death but as a collective, we continually strive for life despite the losses. We have so much in common with

17

African countries, from recent independence and governments, armed conflicts and a vibrant cultural community. What is the role of art in this context? How do you see art, violence and healing? How can we give a different meaning to so much trauma and grief while simultaneously calling for new futures?

Kiluanji reflected that “there are some particularities on the African continent that intersect with the Pacific coast in Colombia. Examples of this are issues like illegal mining, palm crops, illegal drug trafficking and violence against women. Just as conflicts intersect, so do confrontational gazes, one of which is undoubtedly the confrontation from art towards the different types of violence.” Salym Fayad, on the other hand, provided a view from the experience of being Colombian and developing his art and actions from within an African country, South Africa. The conflict in a single African country permeates the rest of the neighboring countries. Salym reaffirmed the importance of understanding that although we are not in a period of colonization in discursive terms, the actions of the 20th century were very invasive. This is why we see conflict as something regional when in fact the ills that cause it are global.

Being in the Casa de la Memoria de Tumaco for these AFROINNOVA members and having this conversation from the perspective of conflict, image and memory was undoubtedly understanding that culture has a narrative and construction that also arises from civil society. Art then fulfills a primary responsibility to rename, represent and embody the spaces that today are not only part of the present and the past, but also need to be reconstructed and developed to imagine new futures. These new futures do not deny the continuity of pain and trauma, but rather challenge the possibilities of a revamped reality. What are the transnational images that we need? What name can we bestow upon this uplifting future? Salym added that “my lens always gives a disruptive view because my mirrors not only accompany the political justification of why I do things, but also because they allow me to see potentialities, networks, talents and people who believe in the image as a social transformer.”

18

WHAT COMES NEXT?

Kiluanji and Salym shared three main points bringing together the reflections with cultural leaders in Tumaco. On one hand, the need to have an integrative approach to the arts, not to see the artistic practice in silos. One of the best examples is the growing audiovisual power of the African and Afro-descendant arts that incorporate music, dance, moving image and storytelling. This is a major call to understand this multi-pronged approach and the dialogues that nurture the arts. On the other hand, a call for identifying and managing the mobility of artistic products in those other Africas, the other communities with which we feel and have a connection. The distribution and circulation of what already exists must be a priority. Finally, how we generate more interactions and artistic creations together. The key question is how do we unite costs, communities and leadership? In a moment where systemic and global responses are critically required—and in which the arts could not only provide a representation of reality past and present, but also shape the future—our main challenge remains in effectively connecting the artistic powers of Africa and its diaspora, even if we see each other more through social media. This could be all we need to effectively translate our efforts into a transformative power.

After this enriching conversation, we visited the Tumac Foundation, the oldest cultural house of music in Tumaco and a hotbed for children’s and youth groups. Tumac has provided the space for a generation of disruptive ideas to transcend violence and the context of impoverishment of Tumaco. The four floors of the foundation have born witness to the African legacy. It has seen the construction of drums, marimbas and all the music instruments take place on the first floor. On the second floor, the school of traditional and modern marimba music is housed along with a recording studio. On that floor, we have the performance of Plu con Pla band, a top Afro-Colombian music combo that performed an updated version of the Colombian national anthem. In the words of the Tumac Foundation, the cultural sector in Tumaco has signified an act of new independence. There is a potential for artistic expression that can generate economic independence for cultural leaders, a task that is yet to be fully realized. The challenge is how to make music produc-

tion profitable and educating the audiences on the need for consumption and investment. Climbing to the third floor, we encounter the dance studio where marimbas were played while others danced currulao. A group of children so proud of their traditions prance around us and across the room, moving in time with the music and doing a dance that lives and breathes through a diasporic expression.

20

The second day in Tumaco for the AFROINNOVA members focused on this cultural exploration with an initial visit to the Changó Foundation, which also represents one of the musical groups in Tumaco and provides a safe haven for young people and children caught in the crossfire of violence. This allowed AFROINNOVA members to continue their reflections on the power of artistic production, challenging conflict and dignifying history. Then, the visit to the Escuela Taller de Tumaco and its gastronomic exploration connected this experience with a necessary and unfettered reflection of how tourism works in the African diaspora. The members also inquired about how we generate new touristic, commu-

nity, authentic and sustainable narratives. They were interested in knowing what the contribution of AFROINNOVA members was to these processes, including the call to unite agendas and better promote tourism in the area. A particular example of economic democracy was made with viche, the traditional beverage that has become an official part of Colombian patrimony, based on the traditional knowledge of communities in the Pacific coast.

21

A SECOND KEY: THE IMAGES WE NEED…

22

Kiluanji’s Reflections on Our Storytelling and Moving Images

What kind of stories do we want to share as Africans? As a writer, you can never hide the reality of your society because you are true to yourself and your environment. I want to bottle that power. My country is a semi-dictatorship. How do we subvert and transcend these phenomena?

Kiluanji started pointing to the theme of a contaminated past by implementing audiovisual collectives as the anchor of new innovations and narratives. Kiluanji mentioned that “the art we need to develop is the one that helps people understand their history and their present. That art should help eliminate those narrow ideas about Africa.” Grounding his reflection in this diasporic connection, he added that the only way to extend that vision, the vision of Afro-diasporic arts, is the acceptance of what already exists with dignity and love. He states that “not everything in the past is lost because it can be transformed. This is why it is important that art has a concept.” Kiluanji highlighted the need to practice self-nurturing by not limiting ourselves to only words and verbal discourses because both the still and moving ima-

ges that come from our bodies serve as knowledge and a global solution.

“As an African artist who is part of the diaspora, we should feel free to create, respect our traditions and ancestry, and also feel free to explore ideas from a future perspective. Fantasy. I see a lack of freedom because the western world controls the narratives and how they want to see artists. Artists want to be political artists, but if they do surrealism, they can find a space in anthropology. The works of Lucia’s [Equatorial Guinean] artist uncle in Spain are not displayed in the Spanish art museums. They are in the museum of anthropology. Why? Fiction allows us to break this endless loop because it’s not just about the market, but also about the audience. The audience has an expectation of what they want to see from Africa. As an artist I can’t allow myself to become a mirror to this reality. We can crack the mirror or contort its reflections. There are a series of concepts and the narrative of replication and counternarratives give us the possibility to defy it. We’re not this, we’re that.”

23

“Despite having a good script for a [nonfiction] story, fiction still gives me freedom. When you write, you have the privilege to lie without being called a liar. You can fictionalize. I compare artists with journalists as we both have a massive way to distribute, like a golden Kalashnikov. Artists must recognize their ability to disseminate ideas. I admire how ancestral knowledge has been conserved, but we can’t get stuck in ancestry. The African diaspora has a close relationship with sci-fi through topics like alien abduction, for example. When someone is abducted from their reality and then reinserted in a place that’s foreign to them, that turns them into an alien. Many of us understand this.”

DO WE REALLY SEE EACH OTHER? IF SO, HOW AND WHAT DO WE SEE AND NOT SEE?

24

“Marlon Riggs is someone who took documentary parameters to inflect the way he wanted to talk about himself. I want to put myself in front of the camera in the same way. He talked about stereotypes and about Black gay men living in the US during the AIDS pandemic. He envisioned a possible future.

“And what about Negropolitics by Chinua Achebe? People don’t fully understand the book well. We are still creating culture in the face of struggle, but we are also doing some amazing things, things that obscure our suffering. We suffer. We die because of politics. But we are still producing and creating life in the face of all this. Afro-fabulation. We’re working hard to push the narratives in Brazil.

“I think we need to explore the economics of storytelling. We are creating, yes, but to create, we need our infrastructure. Our organizations. Our property rights. Where are they? Where are the websites and blogs with the critics, the authors, and people like that? There is a physical aspect of storytelling that we need to establish, too. With these resources at hand, we challenge the traditional means of the production in the audiovisual world,” Bruno attested. He underscored the power of investments in artistic products that are generated and developed in those so-called peripheral areas and with the young population. Triggering creativity and innovation requires a fresh lens that

understands the diverse realities that Afro-descendant populations experience. This ranges from the issue of incidence and the generation of products that spring from their own narratives followed by the wide distribution of those products.

In this conversation, the main reflection is understanding the power of image as a key dimension of representation, an intentional composition of visibility and a key that can open the possibility for action. What is the new composition and the new context we aim to create and reframe? What does the future hold? Are there aspects we don’t want the future to bring into the light of day?

25

Bruno Duarte, Brazilian Filmmaker

“FIRST, I FEEL SO COMFORTABLE HERE IN THIS SPACE. IT’S SOMETIMES SO ISOLATING TO DO THIS WORK, BUT NOW HERE [WITH AFROINNOVA], I KNOW SO MANY OTHER PEOPLE [ACROSS THE DIASPORA] ARE TALKING ABOUT THESE THINGS”

A THIRD KEY:

TECHNOLOGICAL TODAYS AND TOMORROWS

26

Salym Fayad’s reflections on the visual arts and technology

“Netflix, understood as profit and access, seems to be where everyone hopes to get. But is that what we really want? The content that Netflix is providing is curated through a certain model. When Netflix launched their initiative to purchase and broadcast African content, this was celebrated in the continent, for sure. Then it was clear that they were considering the profit to be made. They started broadcasting content that is produced with an American standard, through a Western lens. The kind of drama that includes lots of action and car chases or melodrama, but not necessarily reflecting African narratives or perspectives. I understand and I share the desire of exposure that these platforms may provide to storytellers, but we should insist on not falling into a certain model. The Netflix and UNESCO Scholarship for Content Creators and Filmmakers and other grants provide positive opportunities, and they open the way to a whole new generation of producers. But it should be understood that these stories going into the mainstream are often filtered in a way that do not criticise the status quo or that touch on certain social or political issues.

We can also use our own spaces of action and spaces of work to influence other spaces or to create new ones. If we approach an editor of a mainstream media organization with the intention of broadcasting, let’s say, an African documentary, it’s not going to be an easy sell. We’re going to have to create new narratives from within, using the influence that we have, like our networks, like this group.

The formats of storytelling are also tools to influence and enrich perspectives. If I tell a producer that I have material about the Congo, they will automatically assume that the content and format are intense or heavy or that it follows a specific model often attached to stereotypes. What if I say it’s a comedy? They might be surprised or interested.

“Akasha”, directed by Hajooj Kuka, is a movie about a rebel in Sudan who falls in love with his gun. His girlfriend gets jealous. It’s an absurd comedy about this love triangle. However, it can still approach topics about the absurdity or cruelty of war, about displacement and human rights. You can talk about these topics without being victimizing or patronizing, and that’s a very useful vehicle to get to audiences, but also to editors who wouldn’t otherwise take on African content.

Salym Fayad mentions the importance of collective resource management as one of the challenges and tasks within the AFROINNOVA agenda. “In terms of work networks, there is an increasing group of agents interested in investing in audiovisual content from the continent. We should be able to identify them and promote this content. Just as there is a who’s who among filmmakers, a who’s who of investment agents must also be generated and identified. We must also broaden the profile of the filmmakers and know what resources they can contribute”.

27

Baff Akoto’s reflections on technology and a multi-prong artistic approach

From this initial identity perspective, Baff Akoto delved into the question in which Black artists are encapsulated in a single artform. “There are times that they demand that we only be in the cinema, or music or dance and it even generates questions that in the end take away the validity of our talent and forces us to speak from a single platform.” He also left the question on the table about where the discussion between art and technology in the diaspora lies, and he expressed that this priority could be a new point of separation between the black arts and the rest. He mentioned that “if we want to talk about innovation and taking art to another level, we cannot go back and ignore the role of technology as a generator of new views, new audiences and new forms of distribution and circulation of

products that are created from the diaspora itself”.

Akoto goes on to add, “Yes, and how do we do that with technology? We cannot ignore technology. There is an opportunity in the art world where the creative and the exploratory come together through technology. I’m interested in emerging tech, especially as it compares to legacy media like traditional newscasts, films, TV, dance and fine arts. Those are well defined ecosystems and value chains. We need to understand how a dollar invested returns capital to the stakeholders. The R&D activity needed to come up with new solutions is risky money because there’s no established ecosystem as it’s still being cultivated. We are an under-capitalized community as a diaspora, from the national

level on down to the individual. Those resources and capital need to be mobilized. We need our own research and development launchpad so that applications can be converted into products.

“Let’s think about what Bruno started talking about, looking at the means of production. In Marxist tradition, it’s about who owns the means and the capacity. How can the different types of capital at the table come together to create a platform here? We want to own our intellectual property. Those of us fostered by the current ecosystems must be weaned off them and transition into a place where we are able to speak to private capital that makes sense for how we can own our own IP. Can we set an agenda for that? For Black creatives talking about the Continent and the diaspora, “Black Panther” filmmaker Ryan Coogler came through the entry level filmmaking ecosystems in America. Now, Disney is funding his company. You look at that pipeline and ask, “How do you transition from one ecosystem to another?” Both areas need to speak to each other and feed off each other. We as practitioners need to understand where we sit in the market. That’s the thing to figure out, like what Africa No Filter [Moky Makura’s organization] does. At some point we’re going to have to figure out how to navigate and negotiate with Netflix, for example, and think about how we can start to negotiate for our own rights. We need to swim in the waters of the commercial world.”

“Even though everybody loves Black culture, our communities are perceived as riskier than others. From an agenda standpoint, there needs to be more thought and purpose behind how you see and fund those ecosystems, and how you encourage private enterprise to come up with capital, donated or otherwise. There’s no track record of this yet so it becomes a big gamble for those enterprises.”

29

“WE MUST GENERATE PHILOSOPHICAL VIEWS THAT CREATE DIALOGUE FROM THE AFRICA THAT WE HAVE IN OUR PERSONAL HISTORY, AND THE COLLECTIVE VIEWS THAT UNITE US TO AFRICA REGARDLESS OF WHERE WE COME FROM”

Graciela’s reflections on technology and the african diaspora

Graciela delved deeper into the topic of technology in the diaspora. The notation in the technology agenda must contemplate new ways in which technological tools are developed. “For me, writing a code is writing the future,” says Graciela. What are the futures that we want these codes to transcribe? If we talk about more justice and equity, we need the codes to speak from that standpoint. Another provocation generated by the panel for Graciela is how technology is used to bring artistic discussions to the peripheries of society, precisely because technology must connect and be at the service of exploration.

“The artists and the technologists, many interesting things can be born from this collaboration. But this multiplicity of visions and layers is a very interesting agenda to push forward for developing, especially this marriage between art and tech that already exists, but not with the desired intentions. Having Black creatives, tech developers and industry people who can spark this dialogue can be the source of a very interesting interaction.”

“The technology that we need to appropriate is not one that is already up and running. What we have to appropriate is the deve-

lopment of our own technologies because they are our future and the way in which we are competitive depends on them. With regards to the existing platforms, we need to remember the invisible rules: the algorithms. We must explore the business side of it all and discover how these algorithms behave. We can inquire as to if white people are watching the same content as Black people, who is receiving the data? How is that algorithm behaving and what are the messages that are being delivered? What messages should be delivered?

Technology must be a bridge and a tool to generate connections between regions to expand knowledge of solutions. In Biola’s words, “There is so much knowledge, capital and talent that it would be a mistake to continue working in a closed manner and not generate a network. We must believe that we ourselves have the power to reach that other level of change.”

THE JOURNEY CONTINUES. THE SECOND STOP:

CALI AND THE PETRONIO ALVAREZ PACIFIC MUSIC FESTIVAL

Cali is the city in Colombia with the highest concentration of Afro-descendant population, and it’s the second Afro-descendant capital of Latin America after Salvador de Bahía (Brazil). Cali is the most important cosmopolitan urban epicenter of Afro-descendants in Colombia, and it is also known as the Capital of Salsa music. The Petronio Alvarez Festival is named after one of the most renowned musicians and composers of marimba and various music expressions of the Pacific Coast. The festival is the largest and most spectacular event that celebrates Black culture in Colombia with more than a thousand artists and 50 musical groups who take the stage. Most of them are from Colombia, but this year was a special case because Afrobrazil was the guest of honor with Ike Aye and more that 100 Brazilian entrepreneurs in an exchange with Feira Preta. Likewise, a special tribute was paid to Susana Baca, the top Afro Peruvian and music figure before the more than 325,000 attendees. It is a full-on celebration of crafts, food, traditional beverages like viche and more than 1,300 exhibitors. Kiluanji…it is a cultural miracle that marimba music is more alive on Colombia’s Pacific coast than in Angola...500 young people playing Marimba in Tumaco.

The festival is an economic democracy cultural exercise since the only beverages allowed and consumed by the 100 thousand plus attendees are viche-based drinks…the fashion, the food, the hot clothes…pure Afro commerce.

WHERE WERE YOU?

WHY DIDN’T I SEE YOU THERE??

32

THE FOURTH KEY: THE MOVEMENT THAT WE NEED

33

Rafael’s reflections on the movement of movements

Rafael Palacios from the area of dance mentioned the volatility of the sector and the dilemma between what Afro dance companies really want to develop and how that conflicts with the themes and visions in which the sponsors want to invest. “The next level question is how to make this trajectory in dance transcend and not be volatile,” Rafael intimates, “and how to make this conversation include more people, not just the dancers. This will allow us to see a real evolution.”

Rafael took a moment to focus on academics and posed the question, Where are Black artists getting their training? He highlighted the need to have control over the curriculum and our legacy for the future generations. We also need to create more spaces of diasporic exchanges to highlight our own techniques, philosophies and ways of dancing, thinking and undertaking cultural practice. “And we should focus on a life of training. Where do the Black artists get their training? Under which approaches? After that, we have the liberty to narrate without limits or Black art being put in a box. We’re not interested in being labeled as ‘ethnic’. I do believe it’s important not to set conditions for ourselves. I want everything to

be anti-colonial and anti-racist, but I can’t expect that all my students will make art from my perspective. Still, I would like artists to be able to train based on parameters that are disruptive against a world that’s against us. “Everything that’s important in our lives as a diaspora has not yet been told, story-wise. But we need to avoid African romanticism, that the ‘solution’ lies in Africa. We need to balance Eurocentric education because we have been denied our African education. We must use different tools for how we see ourselves, but we don’t have to look for a specific line of creation or fiction. What we’re experiencing right now is what we have to tell stories about. Like the unfairness of life for us and how our happy lives have been broken. But how do we tell those stories?

ACCOMMODATING LIES

We joined to celebrate the 25th Anniversary of Sankofa

Accommodating Lies challenges the stereotypes surrounding Afro-descendant traditions. Through costumes that emphasize stereotypical bodily features of Black men and women, dancers reveal sexualization and exoticism as exaggerated categories that the Western gaze has imposed on their bodies, whether symbolically or literally.

As a result, what is presented on stage is a caricatured body that contradicts the essence of Afro-descendant culture. In an effort to uphold the right to protect the meaning of our artistic and spiritual expressions, we insist on not being represented, but rather self-represented in the memory and wisdom of our community.

A FIFTH KEY: HOW DO WE DISTRIBUTE OUR CONTENT?

36

Lucia’s reflections on communications

Lucia pointed out in her speech that the next level of those communications that speak of the experiences and situations of the diaspora is the recognition of their diversity. She related that “the problem before was that we did not exist in communications. Now the challenge is to recognize that there are diversities and themes that make us part of societies. They pigeonhole us in everything from our geography to our tastes and dreams and do not let us project ourselves and tell our stories in unique ways.” Issues such as mental health, and representation of the LGBTQ+ community is not only a general issue, but also a reality of the African diaspora. We must transcend the differential approach given to the agenda that communicates these contexts.

What kind of stories do we want to share as Africans? I want to bottle that power. “My [upcoming] Netflix series needed Black writers but there were no Black screenwriters in Spain because it’s just too expensive to study in

that area. But as I open doors for other writers, producers, makeup artists, etc., they can do the same for even more people.” So, we also must make an impact in training for scholarships for minorities, but not only in the university setting but also in other [technical and community] educational institutions. Training is important to empower people.

It is key to renew the language, to transform the local and community media outlets, and to promote journalist ethics with regards to Afro communities. Not only is it crucial to change and shape the way of speaking about “minorities” with all their intersectionalities, but also how they are portrayed in the news and media. The African Diaspora needs and deserves a better portrayal and an effective representation in order to promote positive change. It’s so powerful how one speaks about someone, because it can dignify them or degrade them.

37

Edna Liliana Valencia On Distribution Platforms

Edna Liliana defines that the next level of communication technologies is to generate their own transmedia platforms. She expresses that “the pending task is that the content we produce also has our communities as the first consumer, so the balance of audiences is necessary in the planning of transmedia content.” Additionally, she considers the importance of the black aesthetic that the image represents, all in the understanding that this is a fundamental part of the conceptual construction of how we want to see ourselves.

I have Identified three possible scenarios for our entry: (i) platforms that already exist such as streaming, television, digital, print etc.; (ii) the new ones that we create; (iii) journalism and the news. “But to start, we need to have more diversity. We need Afro people with awareness working in these places, people that are fair to our diaspora and not just echoing traditional messages provided by the system. For traditional media, we need to see changes from within. And it’s important that we have individuals from the African diaspora talking about all topics, not just ones related to Afro agendas. We must relate to the leaders of the media, including directors of festivals, Netflix, and other outlets. We need to meet with directors and give them convincing reasons for diversifying, including how it can be profitable for them. This isn’t just about philanthropic approach.

We can put together a board made up of brilliant individuals from the Afro diaspora, led by someone who possesses in-

ternational goodwill. Together with members from our different profiles and achievements, we can go out and address the executives of media outlets and platforms. Alone, we will continue to be isolated within the system. But if we go there together as AFROINNOVA Communications, for example, we can better express why they should produce these stories and how they can generate revenue for them. We can present them with our own content creators and act as project consultants while together we locate sponsors who can make things happen.

“Within the board we could have specialties: Salym for festivals, Lucia and Edna for the media and so on. We can go to Netflix and Disney Plus as a consortium because as a group, we can bring a condensed approach to making content, meeting, telling them why these stories are good. We can get their attention on it collectively so that proposals can be heard. And about us being a communication platform, we could be a little like a consultancy with its own platform where we can advertise our contents and provide guidance. The book about AFROINNOVA – Look, this is the most important group of the Afro diaspora. We can do this together. More AFROINNOVA cohorts will spring up.

39

“HOW DO WE INSPIRE CHILDREN IF THEY CANNOT BE SEEN? AFRO AESTHETICS IN AUDIOVISUAL REPRESENTATION IS PART OF THE BACKBONE OF THE CONCEPT BY WHICH WE MOVE AND MAKE AFRO PRODUCTS. WITHOUT DETAILS, THE PRODUCT DOES NOT INSPIRE AND SUPPRESSES NEW BLACK IDENTITIES”

THE SIXTH AND SEVENTH KEYS: THE CAPITAL AND THE STRATEGY

40

Biola reflects on how to make it all possible

“There is a place for all these things to coexist. No one’s experience can be discounted. How do we create more places for these things to coexist, and for our stories to be monetized? We know that the capital flowing to platforms that tell our story is insufficient. Platforms want to know how big your potential viewership is on a local and global level. When looking at Africa from a streaming provider’s perspective, when they don’t feel like they would get enough viewers, they will refocus their attention on a country like India, a place with a population of one billion people under one currency. Netflix is little interested in 54 countries with 54 different currencies. So how do we work together to approach these platforms?

“That’s what initiatives like AFROINNOVA can do. “Black Panther’’ was global from the beginning, so I know where that audience is. From a capital perspective, we need to tell them where the audience is and what their spending power is. People like Moky can start to see returns on the stories they invest in. This is economic empowerment.

“We need to work on distribution platforms, capital, ownership, and [Black creatives] owning the work they’re creating. Those are skills we need to equip people with, like how to get a seat at the table to participate in those conversations, like for them to inform us of the kinds of roles we need training for. Are there ways we can create a platform like this to tell Google and Netflix that these are the kinds of stories we want to tell?”

The concept note of the company I was telling you about, Afropolitan, has raised $2.1 million for the “creating a new nation” that can transcend barriers. They’ll come back out to market, but it won’t be from a traditional lens of creative personnel. Rather, it will be through the lens of a tech platform created for everyone. Creatives will have a space here, too, but the underpinning is technology. Sometimes it’s about which market entry you use. We might reconsider the entry is through technology first, leading the way for creatives. The bottom line is about how we engage capital.

41

Graciela adds some final reflections

Graciela highlighted in her presentation that the next level of strategic collaboration must be defined from a systemic concept, where the importance of changing narratives within a system is recognized. But it is also important to analyze the existing structure, better understand how it works and see what each of the actors contributes so as not to repeat the mistakes of the past while moving towards change. One of Graciela’s central reflections was based on the role of collective spaces to listen, contemplate, feel, imagine and interconnect these visions of the African diaspora, because the solution lies there within.

The existing system has some gaps that collective power can correct. “That is why fiction and imagination are important in a reality in which creativity is the key to change. Uniting creativities and visions is the way to building shared futures with collective resources and powers,” Graciela states.

Responding to what the African and diaspora leadership needs on a higher level, Biola mentioned the need to find a sweet spot between media and the use of technology. First of all, it is important to understand what images you want to make visible and through what lens. It is necessary to make visible real stories of the Black population, to understand that there are complex contexts but also contexts of development, success and talent in the population. Secondly, there is the importance of investing in people with vision. Investing in women and youth is vital because many agendas affect both populations as well as the putting forth a critical and futuristic vision that local solutions provide for the communities.

Finally, we talked about these big platforms, streaming services, Google, Netflix and others. It’s important to have this training for people to understand their role in our lives. It’s critical to make space to do this collectively because they are doors that need to open for everyone. And it’s always important to understand relations to power and the associative work needed to create those relationships. We need to talk to the markets because they are deregulated but with minimal regulation, there lies the possibility for intervention. Looking at Brazil, we see that they are living a historical struggle of civil society. This is a situation that is happening all over the world where access to public funds is restricted as they continue to be funneled to the same players of the elite classes. We need to change these rules and redistribute funding from a legislative standpoint. This way, we are not just assigning resources but doing so under the parameters of the corresponding legislation in order to guarantee a fair distribution. This will help guarantee content creation and full participation by Black and native peoples.”

42

“THAT IS WHY FICTION AND IMAGINATION ARE IMPORTANT IN A REALITY IN WHICH CREATIVITY IS THE KEY TO CHANGE. UNITING CREATIVITIES AND VISIONS IS THE WAY TO BUILDING SHARED FUTURES WITH COLLECTIVE RESOURCES AND POWERS”

Rafael Murta and His Systemic Approach

Rafael pointed out the importance of understanding art as a deeper way of understanding Black narratives and contributing to the racial literacy that the Black population needs. Rafael mentions the importance of continuing to work on racial literacy, which involves both the black population and the system as a whole. “If we are clear that the change of narratives is the bridge to new situations, then the action we have in the arts, the media, literature and others must have a pedagogical intention,” Rafael insists. “This is because we need openness not only within ourselves but also in the other logics that are part of the system. Both the private sector and governmental entities must adopt these new narratives.”

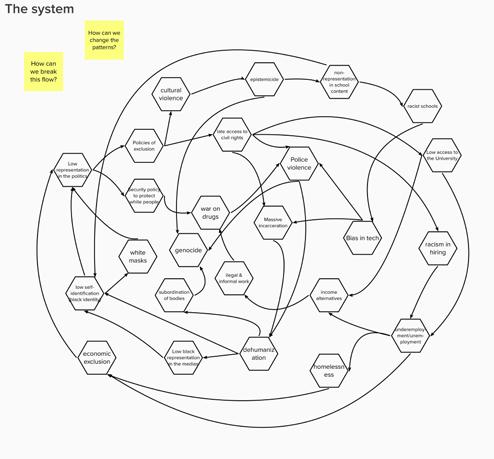

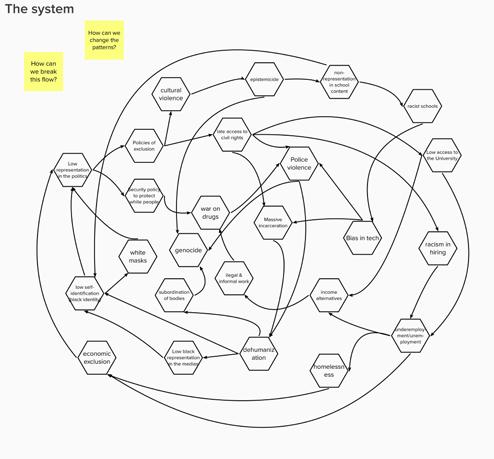

He emphasized the creation of a course of action that can track and verify true future change. From an advocacy perspective, there are two main points on which we must continue working and creating critical mass. These points are fiscal (i.e., investment policy and public spending) and justice. Additionally, it is necessary to invest in the generation of a network with more diverse leaderships within black communities to achieve sectorized action agendas for women, youth, public health, entrepreneurship and cultural, among others. For this purpose, Rafael designed a conceptual map of structural racism in Brazil describing the system and how the flow that perpetuates discrimination and alienation for Black communities could be broken.

43

With a map of aspects that demand change, Rafael described how they designed a production chain for new artists. We have two points in a debate about narrative. Two points of representation: How Africa/the diaspora is represented by others, and how the world understands this Africa. Beyond a space to an idea. As values. As a story. This is key. It’s something we all need to bring back to work with. We need to be able to create a whole new outlook/narrative. How do we achieve representation between the diaspora and the Continent? With these group values and the stories we share? And this access we share in this space? He adds, “There’s also the possibility to co-produce, to build things collectively and bring them to all of us in Africa and the diaspora. And not just looking at the US or Europe [for guidance.] But the possibility and critical thinking about the context of one’s self.

“We have issues with distance and language across the diaspora, but we have other ways of communication. For example, think of how festivals bring together individuals from all spectrums of the African diaspora and they find ways to communicate and explore ideas beyond words. They use music, sports, food and dancing as ways to connect, allowing them to cross boundaries regardless of the differences in language. In these physical spaces, we are able to know Africa from a Brazilian standpoint, and they can all learn about each other’s lives. We can see that tourism is another way for interchanges among people from across the diaspora, allowing those from outside of Africa to interact with them and vice versa.

44

“And what about digital possibilities to learn more? Think of virtual reality to put kids on Africa soil. To go to Cameroon with Gilbert from here. Learning about it. Learning why this place or that is important, especially to the diaspora. How about a virtual tour guide for youngsters? And other possibilities of Afro-diasporic linguistic connections with the world. Of course, we need to produce constant narratives and content. We need producers. How can we create production spaces? How do we get a script for those people to produce content to represent ourselves to the world? We need to learn about ourselves and others. To think about a new narrative of production, to produce knowledge, research, data. And we need data production so when we tell the stories, the characters are actually coming from a place of truth.

“It’s also so important to think about how we get money to produce these things. And how we get more Black people on the production chain. It’s very important to understand the audience. We are producing young leadership. It’s not only about creating spaces for them to keep producing. It’s also about turning them into future leaders. We need short-, medium- and long-term actions. How can we stimulate more production in young people? We need new public policies.” Rafael summarized in this second map how to create a framework of change and encourage the members of AFROINNOVA to think about a new system and to build new structures. This reflection left us with the following questions: What do the new structures look like? How do we set up a new system? How do we connect our efforts? How can we strengthen ourselves as leaders?

During the final moment of this session, Graciela reflects on the islands of sanity that we need and the containers of our personal and professional balance. To end the session, a group dynamic takes place in which we take each other’s hand, look into each other’s eyes and express the following sentiment: I need you.

45

A GLOBAL LEADER THAT OPENS DOORS:

AN IN-DEPTH DIALOGUE WITH DARREN WALKER

Darren Walker is the President of the Ford Foundation and has been a leading figure for the areas of the arts and philanthropy. The following dialogue was based on narratives, structures and strategies for a global leading role of Afro descendants through the arts. Darren Walker is a great strategist with a global outlook, and deep awareness of how art provides an important landing pad based on the next level of management of actions of African and Afro-descendant populations, and how the evolution of philanthropy brings all of these initiatives together. The leaders of AFROINNOVA shared the essence of their work with him: they talked about the challenges, but also the achievements of the diaspora in the world and in Colombia, a place where it is possible to create a network and manage effective connections. Based on some reflections by Mr. Walker on the importance of the arts and culture, the AFROINNOVA members outlined their visions and their commitment to continue working towards an all-inclusive future for historically excluded communities. The following narrative was based on Mr. Walker´s pontifications on the following query: Some doors are closing while others are opening. The locks are being changed on others.

What

keys do we need to gain access?

Darren Walker’s reflections that guided the conversation with AFROINNOVA members:

“The arts and humanities address a kind of poverty that goes beyond money: a poverty of imagination. I hear the words that leaders use to describe other human beings. I look at those leaders and I say that this is a person who has clearly never read poetry or has an underdeveloped empathy muscle. [That muscle] is only developed through the experience of the arts and humanities. They fail to recognize that the arts are not a privilege. The arts represent the beating heart of our humanity, and the soul of our civilization, a miracle to which we all deserve to be witness. The thing that we need today is compassion, love and grace. This is what will get us through these times. Can we imagine a better world? That is what I hope for all of us. And that is what the arts can help

47

us to do. Many of our countries (the U.S., Colombia or Brazil) unfortunately have engaged in the exclusion of the arts, cultures and stories of people of African descent”.

“The arts changed my life. They imbued me with the power to imagine, the power of dream, and the power to know I could express myself with dignity, beauty and grace. The arts have the power to open our hearts and our minds, to help us imagine new possibilities for ourselves and the world. I look for hope in the arts because I believe that artists see what others do not see or refuse to see. You see possibility there. That is why the arts and the artists like many of you, are so important. And why a life in the arts, and informed by the arts, is not a frivolous luxury or a selfish pursuit but a necessity. Because the arts allow us to dream of, and empower us to create, futures that do not yet exist. And they cultivate within us the empathy, the understanding of the human experience, our shared dignity and potential. That is the seed of hope. What we can learn from those experiences (with the arts) is empathy. We develop the empathy muscle that allows us to see humanity in other people. To put ourselves in their shoes, to imagine what it must be like to be marginalized, dispossessed, disrespected and disregarded.”

During the engagement, Darren also shared the experience of Simone Leigh and the U.S. pavilion in the Venice Biennale and the critical role that philanthropy played in recognizing that this was a historic moment for Black women artists, taking their place on the vanguard in the top spaces for visual arts globally. At the same time, he shared the Ford Foundation’s role in diversifying the landscape of curators and managers in museums, just to give an example of a systemic approach to open doors. He shared the experience of the Art for Justice Fund that supports the critical situation of mass incarceration in the U.S. by creating a financial fund through the donation of artwork.

48

Recognizing ourselves in the history of the other.

After the working lunch in which the AFROINNOVA had the opportunity to learn the story of Darren Walker, it was time to work in pairs and talk about those moments in his life that brought him to this current moment. The time had come to recognize each other. Graciela intimated that “all of us present have moments, stories in our lives where interactions with specific people and specific situations lead us to this present moment. As a result, these stories build and complete all of us”.

The first moments of the second day of work in Cali gave attendees the opportunity to meet and recognize each other’s experiences. One of the main lessons learned after this exercise for Gilbert was to join compatibilities with peers not only from the goals that they all share towards racial equity, but also from gaps or moments that have made them leave their comfort zone in order to move forward and create new ideas.

Bruno Duarte, based on his personal experience, reflected on the importance of telling us why there is a culture of silence of experiences. “It is as if, because we are part of a community, we have to talk about these issues. But in reality, there are specific situations that lead us to this point of work for racial equity.” Bruno’s reflection made the AFROINNOVA attendees realize in the context that as black communities, a feeling of loneliness is created in our stories that damages our self-esteem. But it is from this place of pain where each person is able to express him- or herself.

WORDS THAT DEFINED THIS MOMENT: CONNECTION, DIASPORA, AFFECTION, COMMUNITY, BROTHERHOOD, RESILIENCE, COMPANY, HISTORY, BALANCE

49

OUR CONCLUSIONS

THE AFROINNOVA AGENDA 10 YEARS (2024-2034)

AFROINNOVA expert Rafael Murta diagrammed this cohort’s interests, work and abilities based on our final group sessions.

50

THE STRATEGY. WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

AFROINNOVA plays a role, like an octopus with its many tentacles. After discussing which are the priority issues for the connection, the AFROINNOVA group defined the 4 lines of its strategic agenda.

In the words of Paula Moreno

“IT IS AN AGENDA THAT IS FUNCTIONAL AS A TEAM THAT LOOKS TO GENERATE TRANSFORMATIONS, BUT IT IS ALSO USEFUL FOR OUR PERSONAL AGENDAS AND INDIVIDUAL COMMITMENTS”.

51

ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY

Understanding that the AFROINNOVA group during all the conversations conceptualized the next level of the arts in Africa and the diaspora with technology to close gaps and create new production models.

Members:

Baff + Graciela + Biola + Bruno

CONCLUSIONS OF THIS GROUP:

The main challenge in this union of arts and technology is how we enter into the algorithms of the channels that transmit artistic and cultural production. The agenda of this intersection must contemplate who the key actors are that allow the Continent and the diaspora to use technology as a disruptive ally when it comes to creating and also disseminating information.

52

FICTION

This point is created from the question What are the stories, images and movements that connect us? AFROINNOVA members are clear that there are some key contents that unite the African continent and the diaspora, but the challenge is to find an attractive point that generates their connection in a more natural way. They must also take into account the reflection of the audiences who are interested in seeing them get involved in cultural productions.

Members:

Gilbert + Kiluanji + Rafael Palacios

CONCLUSIONS OF THIS GROUP:

It is necessary to join efforts for connections between the Continent and the diaspora not only from the ancestral standpoint as there is also a present and a future that can unite them. That present and future is what allows us to understand why we read today and why we support artistic and audiovisual works. As artists and cultural creators, we must strike a balance between strategic audiences and those that we as creators want to reach. In this sense, it is important to enter into a dialogue with these strategic actors without losing the essence and intention of the products. Interdisciplinarity must be one of the pluses that identifies the work of artists and cultural creators from the Continent and from the diaspora. Pigeonholing the art of a person in a single technique restricts the imagination and the ability to generate new ways of creating and resolving issues. Fiction gives us freedom to create and we must continue exploring it because it provides us with evidence of the new ways in which we see links between the Continent and the diaspora. The global agenda and investment interest are embedded in those innovative ideas and trends. That’s why fiction should be on the production agenda of Black communities. Too much reality is bogging us down because the present is too present.

53

REPRESENTATION AND SYSTEMIC LEADERSHIP

This point of the agenda arises from the following questions: What are the advocacy ecosystems? What is the type of change that we need? What kinds of leaderships are ideal for this moment and the future that we strive for?

Members:

Moky Makura + Rafael Murta

CONCLUSIONS OF THIS GROUP:

Representation matters and is most effective when the person who occupies a new position of power is accompanied by their own. It is important to understand and delve deeper into the support networks that leaderships can bring from not only the community but also from strategic sources of support. Systemically, it is crucial to understand the role of everyone as political components. We must develop a critical route of actions that can generate incidence and movements from the artistic and cultural environment. There are some paths that have already been well-traveled, but disruptive action is something that requires constant reflection so that it always draws the attention, and its impact is relevant. Generating a mechanism that allows each strategic actor to identify its spheres of influence is also a necessity. Systemic leadership goes through the recognition of its own means of influence and accompaniment in a specific agenda both on the Continent and in the diaspora. However, it is still essential to generate a critical mass that understands the logic of the market and public policy management. Public and private funds still carry a great weakness in the deeper understanding of the conditions of access and benefit of inclusion of Black artists and cultural creators.

54

CONCLUSIONS OF THIS GROUP: DISTRIBUTION, CIRCULATION AND PLATFORMS

REPRESENTATION AND SYSTEMIC LEADERSHIP:

This line arises from the reflection of the AFROINNOVA members in the midst of the effects left by the pandemic at the level of spaces for the distribution of artistic and cultural products. The questions that arise are: How do characteristics become new forms? How are we being strategic in the midst of this post-pandemic scenario for circular content? How do we move in from the margins with a mentality of greater exposure?

Members:

Edna Liliana + Lucia + Salym

Three scenarios were identified in this group. The first focuses on the platforms that already exist and are successful, with diverse audiences expecting continuous content. Secondly, there are the people who create new content. Although this information is new, these creators can count on a support network that allows them to disseminate their content effectively. And lastly is journalistic communication. It is important to always call on people from the Continent and from the diaspora to fill positions related to diversity advisory and inclusion. This is crucial because a critical mass of African and Afro-descendant people is needed in front of and behind the cameras, writing scripts, setting the scenes, creating concepts, and verifying sources. This question remains: In what areas should this critical mass be trained and what are the real academic opportunities to be developed?

55

CAPITAL AS A CROSS-SECTIONAL THEME OF ALL THE PREVIOUS LINES:

AFROINNOVA members agree on the importance of understanding capital from the management and strategic use of resources. In that order, it must be considered that each strategic line must contemplate a look at the capital and those other resources. Each member must have a disposition of the new calls to action that arose from the AFROINNOVA meeting.

CONCLUSIONS OF THIS GROUP IN GENERAL:

The strategy of the capital that is managed and that the Continent and the diaspora must already be focused on respecting the intellectual property of productions. The challenge is how we generate narrative agendas that convince the private sector of our terms of creation and use. The new question is how we learn to negotiate and be relevant in our points to financial gain.

The economy of the narrative is key. An important part of the management and investment of resources must be concentrated on the creation of infrastructure, of a physical space that allows the production that is being presented to have support for its effective distribution, circulation and quality.

56

CLOSING: I NEED YOU, WE NEED EACH OTHER

As a symbolic act of closure, an activity was carried out that consisted of the delivery of the AFROINNOVA pin and key with words that symbolized the commitment that we were assuming. Additionally, it was an opportune moment for gratitude and recognition of the powers and talents that became more visible as the AFROINNOVA agenda developed.

57

WE SEND OUR DEEPEST GRATITUDE TO THE FOLLOWING LOCAL PARTNER

ORGANIZATIONS:

Fundación Tumac (Tumaco)

Agrupación musical Plu con Pla (Tumaco)

ACOP - Agencia de Comunicaciones del Pacífico (Tumaco)

Escuela Taller (Tumaco)

Fundación Changó (Tumaco)

Casa de la Memoria (Tumaco)

Colectivo del Mar a la Olla (Tumaco)

Festival Petronio Alvarez (Cali)

Sankofa Danzafro (Cali)

Fundación Catanga

@afroinnova @afroinnovaglobal

This meeting was made possible thanks to the support of The Warner Music Group / Blavatnik Family Foundation Social Justice Fund and the Ford Foundation.

58

WHAT COMES NEXT? AFROINNOVA V

Towards ten years of this diasporic network and platform

2024-2034

59