SPIRITS

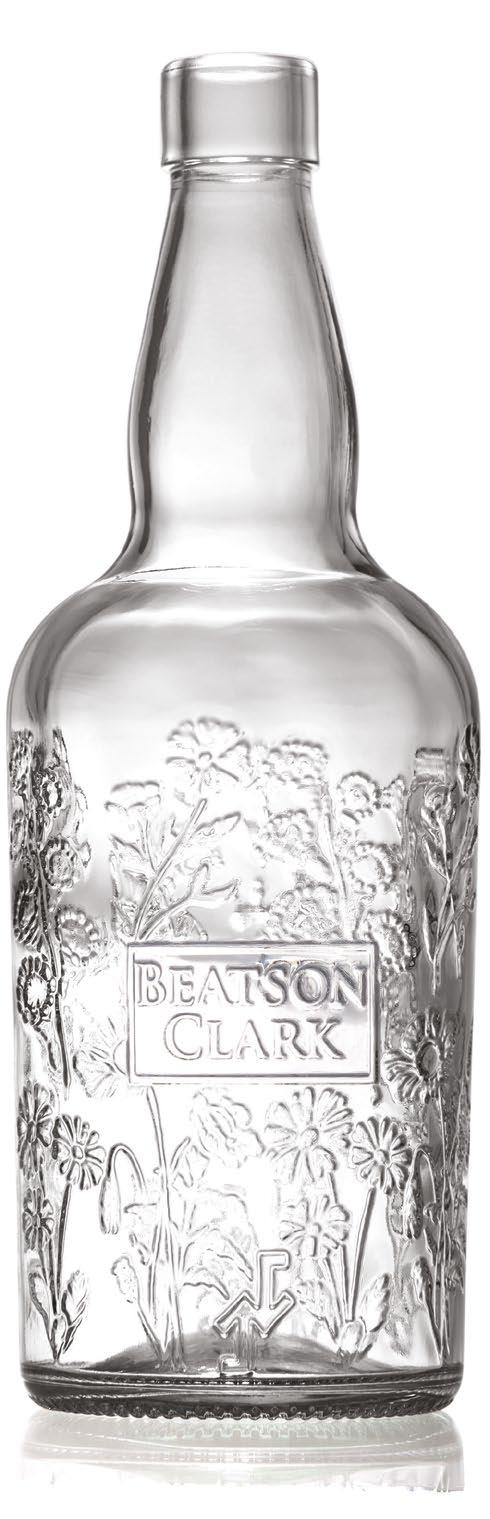

distinctive bottles

Our in-house designers specialise in

creating definition in even the most intricate designs so you can stand out from the competition.

spirit bottles are designed and manufactured in

UK glass works, giving you the confidence of reliable supply, hands on quality support and design expertise

can trust.

At first glance this issue’s main features might seem very much like an eclec tic collection. They range from sake being brewed in Arizona, to Kenyan gin made with fresh juniper berries, to London absinthe, to Brighton’s leading distillery.

Little in common, you think.

No, there is very much a common thread with all, for what do you do in a crowded or unforgiving market? You stand out with innovation and quality, so nobody mistakes you for another.

I had read a short article in National Geographic Traveller which mentioned a Japanese master sake brewer creating award winning sake in the middle of no where-Arizona. I thought there had to be much more a story than NGT reported so while on a trip to this stunningly beautiful western state, I decided to meet Atsuo Sakurai and bring back his story to you.

The day started off bad. I was about two-hours away from Holbrook where Arizona Sake is located and thanks to picking up a nail in a rear tyre, hitting the road at 8am turned into a 10.30 leaving time. This being mid-February and being in the red rock mountains of Sedona, not only had an ice storm come through the night before, now there was a forecast for heavy snow later that day. Leaving at 8am would have meant dodging the snow; leaving at 1030 meant hitting it on the way back, just as night was falling.

Atsuo was welcoming but puzzled; unbelievably modest, he couldn’t figure out why I drove that far to see him and in such bad weather conditions.

I’ll be honest, as I looked at the sky

GIVING YOU THE WORLD

turning gun barrel grey, I was beginning to wonder the same. Although in Japan he had married an American Navajo woman who taught English, Atsuo would never be confused with one of her ace students. But bit by bit, he started telling me his story.

If you’re ever in Seattle and down by the marina next to the Ballard Bridge, you’ll see some black, wooden fishing boats, dating back to the 1920s. They’re not museum pieces but active fishing boats which steam north to Alaskan waters for halibut, perhaps the most regulated fishery in the world. While the catch is valuable, what is extremely valuable is the fishing licence. There hasn’t been a new one granted for a serious number of years. If you want to catch halibut, that piece of paper will cost you a lot more than your boat.

In Japan, Atsuo faced something similar. The Japanese government controls the number of sake distilleries and if you want to break into the market, be pre pared to spend at least $1 million to buy out an existing sake brewer and get their licence. Atsuo is a certified master sake brewer and he’s worked for some famous sake houses. But he wanted to start his own craft sake brewery. He wanted it to be innovated and creative, something he couldn’t explore where he worked.

When his wife suggested they move to America, he was all for it. What he was not expecting was how isolated Holbrook is, which they went to first since it’s next to the Navajo reservation where his wife’s family lives. I won’t go further into his journey; you can read the story. But I’ll leave you this: A lesson he had to learn was, it’s not the water or the ingredients or the salt air that makes a beverage, it’s the brewer/distiller.

Procera Gin set high standards for themselves. The botanicals are to be all African, the bottles – hand blown at a plant that can only average about 100 a day – and the juniper berries have to be fresh. Wine isn’t made with dried raisins; why should gin, they reasoned. And speaking of high standards, the price tag for a bottle of their least expensive to £80 pounds. You want to stand out? Procera brings this notion to new heights. But it’s actually working. How? Read the story.

A young couple’s Devil Botany Distillery is creating London-based absinthe for the first time ever. Allison Crawbuck and Rhys Everett are taking one of Europe’s most misunderstood spirits and putting an East London spin to it.

And Kathy Caton of the Brighton Distillery is proving you can be ethical, transpar ent, inclusive in hiring, one of the nicest people in the industry – and still be successful.

Not trying to toot my own horn – okay, I am – you’re going to love these stories and what else is in this issue. Enjoy the read.

Velo Mitrovich Editor Distillers Journal

And more than just as PS...

The joint Brewers/Distillers Congress will be held on 9 December, 2022, at Lon don’s Business Design Centre. This joint show will consist of lectures, exhibitions and a huge assortment of free beer and spirit samples. Running from 10am to 18.30, the BDC is just a few minutes walk from Angel Tube Station. For ticket information, please contact Josh Henderson at: josh@reby.media I will see you there!

EVOLUTION

GREEN GLASS Want to craft an eco-concious bottle? Speak to our team.

The future of glass manufacturing is now, and we are committed to reducing our environmental impact, striving towards a net-zero future.

We are redefining what’s possible in glass manufacturing through innovative technologies, pioneering alternative materials, and establishing a circular economy.

Partnering with leading and emerging spirits brands we have elevated their brand with sustainable packaging and are constantly innovating to develop less resource-intensive glass packaging.

CONTENTS

Gin growth in new areas

As the gin market cools in the UK and Spain, it is beginning to heat up in Canada, Japan, Brazil, South Africa and India

Tonic war heats up

Nobody seems to have told New Zealand tonic brand East Imperial that the UK market is sewn up tight. This fast growing tonic will be here soon

A guide to sourcing those special casks

Casks made from exotic woods can add a special finish to your spirit. However, finding and buying these barrels can be a real challenge

Breaking into the hospitality trade

For craft producers, it feels like you need to be a robber to get your bottle into a bar. Understanding what you’re up against is the first step

Legally giving it away

If you think nothing is easier than giving away free samples of your spirit, think again. How you do could be like walking in a mine field.

Ask a bartender – colour

Nothing brings more expectation to a drink than its colour. Not enough looks bland; too much looks artifical. This is even more important with low/no

Cover story – Brighton Distillery

Can good guys finish first in the spirit industry?

Kathy Caton and her hard bike peddling team are out to prove they can

Gin by the numbers

No one disputes the human nose in producing spirits; no one disputes how easy it is to throw it off. Time to take a scientific view of gin quality

Absinthe gets new life Allison Crawbuck and Rhys Everett of Devil’s Botany are distilling absinthe for the first time ever in London. Green Muse or Guillotine of the Soul, you decide.

36

Kenya’s Procera Gin

Wine is made with fresh grapes, not raisins, so why isn’t gin made with fresh juniper berries?

56

High desert sake maker

The hardest lesson Atsuo Sakurai had to learn was:

It’s not the equipment, ingredients, water, or fresh salt air that makes a drink, it’s all down to the distiller/brewer.

One hundred bottles of gin

There is a reason why Sean Murphey is grinning, he’s written The Scottish Gin Bible.

CONTACTS

Velo Mitrovich Editor

velo@rebymedia.com

+44 (0)1442 780 591

Tim Sheahan Managing Editor

tim@rebymedia.com

+44 (0)1442 780 592

Josh Henderson Head of sales

josh@rebymedia.com

+44 (0)1442 780 594

Jon Young Publisher

jon@rebymedia.com

Reby Media Portlet House 6 Grove Road, Hemel Hempstead, Herts, HP1 1NG, UK

SUBSCRIPTIONS

The Distillers Journal is a published four times a year and mailed every January, April, July and October. Subscriptions can be purchased for four issues. Prices for single issue subscriptions or back issues can be obtained by emailing: subscribe@ rebymedia.com

UK & IRELAND £29 INTERNATIONAL £49

The content of The Distillers Journal is subject to copyright. However, if you would like to obtain cop ies of an article for marketing purposes high-qual ity reprints can be supplied to your specification. Please contact the advertising team for full details of this service. The Distillers Journal is printed at Manson Group, St Albans, UK.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the express prior written consent of the publisher. The Distillers Journal ISSN 2754-0006 is published quarterly by Reby Media, Portlet House 6 Grove Road, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, HP1 1NG. Subscription records are maintained at Reby Media, Portlet House 6 Grove Road, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, HP1 1NG. The Distillers Journal accepts no responsibility for the accuracy of statements or opinion given within the Journal that is not the expressly designated opinion of the Journal or its publishers. Those opinions expressed in areas other than editorial comment may not be taken as being the opinion of the Journal or its staff, and the aforementioned accept no responsibility or liability for actions that arise therefrom.

UK DUTY FREEZE SUPPORTS SCOTCH WHISKY SECTOR

The Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) has said that the new UK gov ernment is delivering on promises to help the industry.

Mark Kent, chief executive of the SWA, commented on the freeze on spirits duty announced by the Chancellor. “Prime Minister Liz Truss said that it was important to back the Scotch whisky industry to boost growth, and today the government has delivered.

“The Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng has frozen duty on Scotch whisky and other spir its, meaning the planned double-digit inflationary increase will now not go ahead. This will save consumers £1.35 on the average priced bottle of Scotch whisky and help the industry as it deals with the dual challenge of rising energy costs and supply chain pressures.

“On behalf of the SWA’s members, I want to thank the government for listening to the concerns of the industry and taking action to Support Scotch. The duty freeze will not only support our sector, but the hospitality industry and the wider econo my.

“Further action will be needed to bring down the 70 percent tax burden on Scotch whisky in the UK, which remains the highest in the G7 and one of the highest in the world. We look forward to working with the new HM Treasury team to ensure Scotch Whisky can deliver investment, employment, and growth in Scotland and across our supply chain.”

This is highly important to the industry as the tax burden on the average priced bottle of Scotch whisky it at 70 percent due to high rates of spirits duty. A recent survey revealed over half of Scotch whisky distillers have seen their costs double in the last 12 months and expect further increases in the next year. In the survey conducted by the SWA, it found that 57 percent of distillers have seen energy costs increase by more than ten percent in the last year, with nearly a third (29 percent) seeing their energy costs double. Nearly 40 percent of business es, which produce the UK’s number one food and drink export, reported shipping costs doubling in the last 12 months, with 43 percent also reporting supply chain cost rises of more than 50 percent.

The survey also found most distillers see costs rising further over the next year, with 57 percent of businesses expecting energy costs to go up by a further 50 percent and nearly three quarters (73 percent) anticipating another 50 percent increase in shipping costs. However, despite rising costs, the industry expects to continue to invest in opera tions and supply chain. 57 percent of distillers reported an increase in their number of staff in the past 12 months, with all respondents expecting to need to add to their workforces in the coming year.

GIN GROWTH TO COME FROM NONTRADITIONAL MARKETS

As the gin boom cools in established markets such as the UK and Spain, growth opportunities emerge in a num ber of non-traditional markets, including Brazil and India.

The quest for new markets will be ever more important, according to spirit data collection agency IWSR, with the total UK gin market forecasted to decline at a CAGR of -4 percent between 2021 and 2026,

Data from IWSR shows that the UK and Spain have now reached ‘peak gin’, with volume consumption plateauing – but both markets are set to remain important sources of innovation and value for the category in the future. Meanwhile, flavour diversification is a major trend driving gin for established brands in particular, but a new wave of locally produced premium gins is also exploiting growth opportuni ties in non-traditional gin markets, such as India and Brazil.

According to IWSR forecasts, global volumes of standard-and-above priced gins are poised to grow at a CAGR of +5 percent between 2021 and 2026. While volume growth in the three largest gin markets of the US, UK and Spain will be subdued, strong gains are expected in other top 20 markets: IWSR expects dou ble-digit CAGR volume growth in markets including Canada, Japan, South Africa, and India from 2021 to 2026, alongside CAGR volume growth of just under 10 percent in markets such as Italy, Brazil, and Australia.

“While established gin markets have seen category growth starting to peak, there are a number of other non-tradi tional markets that are seeing gains. The ongoing recovery of the key on-trade channel post-Covid has reinforced previously emerging tailwinds for gin in these markets,” said Jose Luis Hermoso, research director at IWSR.

In India, locally produced IMFL gins dominated the market for many years,

but – as in South Africa – the emergence of a local craft scene has transformed the category. Meanwhile, imported gins are growing strongly, but from a small base. Total gin volumes increased by 50% in 2021, remaining below pre-pandemic lev els. However, volumes for the standardand-above price bands have more than doubled since 2019, and are expected to almost treble by 2026, according to IWSR figures.

“The Indian craft category is expected to go from strength to strength, with the strong likelihood of more brands and more investment, from large and small players alike,” said Jason Holway, market analyst at IWSR. “Leading international players are also able to offer a well-re garded gin brand, which should help to maintain momentum at the premi um-plus end of the category, moving the centre of gravity gradually upwards.”

CASAMIGOS FASTEST GROWING BRAND

George Clooney’s Casamigos Tequila is the fastest-growing spirits brand, almost tripling in value since last year and is now valued at $450 million, up 177 percent. After its sale to the UK-based multina tional alcohol company Diageo in 2017 for around $1 billion, Clooney’s brand contin ues to perform strongly with tequila sales skyrocketing globally. Not only has the brand followed sector-wide trends, but it has also pushed further than others by doubling sales this year.

The brand has also announced its plans to invest over $500m to expanding pro duction capabilities in Mexico, with the increased investment expected to assist in securing further growth for the brand in coming years.

Every year, leading brand valuation con sultancy Brand Finance puts 5,000 of the world’s biggest brands to the test, and publishes around 100 reports, ranking brands across all sectors and countries. The world’s top 50 most valuable and strongest spirits brands are included in the annual Brand Finance Spirits 50

George Clooney’s Casamigos

Tequila is the fastest growing spirit brand and the envy of all other celebrity spirits

ranking.

In addition to brand value, Brand Finance determines the relative strength of brands through a balanced scorecard of metrics evaluating marketing invest ment, stakeholder equity, and business performance.

NEW GM FOR RAMSBURY

Ramsbury Brewing & Distilling Compa ny has announced the appointment of, Nikolas Fordham, as general manager. Fordham will oversee the operations of the Ramsbury Brewing & Distilling Com pany, which produces Ramsbury single estate gin and vodka. He has joined Ramsbury with over a decade’s worth of industry experience, following his first position as distillery manager at Chivas Brothers Limited back in 2008. Before joining Ramsbury, he was head of operations of Tarquin’s Gin since 2017, where he was instrumental to its growth and success as a business, from NPD to site wide operations. Prior to that, he was master distiller and head of oper ations at The Bombay Spirits Company. Fordham said: “I’m thrilled to be appoint ed to general manager of Ramsbury Brewing & Distilling Company. Operating

a true grain to glass approach, every ele ment is harvested from the Ramsbury Es tate, from planting and growing the trees that fuel our biomass boiler to harvesting the Horatio and Spotlight wheat, all on a single field.”

AMERICAN

‘SINGLE MALT’

CLASSIFICATION

The Alcohol and Tobacco Tax Trade Bureau has started to create an official

“American Single Malt” designation, reports The Denver Gazette.

The rules to qualify as an American Sin gle Malt whiskey are as follows:

u Made from 100% malted barley

u Distilled entirely at one distillery u Mashed, distilled and matured in the USA

u Matured in oak casks of a capacity not exceeding 700 litres

u Distilled to no more than 80% ABV u Bottled at 40% ABV

The Bureau is currently in the public comment phase of the process to “set forth the standards to identify distilled spirits,” according to its website. TBB offi cials said the proposal came after years of industry lobbying, mostly by the Amer

ican Single Malt Whiskey Commission. US distillers of single malt whiskey feel that by having the designation, it will put them on the same par as bourbon, Irish whiskey, and Scottish whisky.

ABV DIVERSITY WITH RTD

Data sows shows that ready to drink (RTD) product launches are increasing ly leaning into super-premium pricing, packaging with less plastic, fewer direct health claims, and greater diversity of alcohol content, with half of all new RTD products having an ABV of 5% or higher. New RTD brand owners, as well as established producers, are increas ingly introducing products with higher ABV rather than focusing on the more traditional 3-5% ABV range. Around half of all new RTDs launched in the second half of 2021 had an alcohol content of five percent or higher. This trend has been led by China, the US, and Australia, but is not universal. Other countries such as Ger many and Japan are seeing a decrease in new innovations with higher ABVs.

The RTD markets continues to fly. This is true across the key RTD markets –Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Germany, Japan, Mexico, South Africa, the UK, and the US – which represent 85 percent of global consumption of RTDs.

“The ability to respond to consumer needs goes some way to explaining the rapid rise of RTDs,” says Brandy Rand, COO Americas at IWSR which conducted the research.

The number of RTD products using plastic-only packaging is reducing. Data shows that just one percent of new RTD products used plastic-only packaging in the second half of 2021, down from five percent in the first half of the year. In the UK, a strong majority of RTD beverages are sold in metal cans.

HUGE WHISKY WAREHOUSE FOR DALMENY

Scottish Construction News reports that a pre-planning application for the

RTD consumers are willing to pay more for premium brands which are eco-friendly with packaging and have a higher ABV

redevelopment of an industrial site has been submitted to the City of Edinburgh Council with plans to invest £150 million into building a whisky warehouse. The £150m investment in redeveloping the industrial estate will go towards 40 new bonded warehouse buildings which will accommodate 80,000 square metres of regulatory compliant maturation space together with associated disgorging and ancillary accommodation.

US CANNABIS LOUNGES CHALLENGING BARS

While like in here in the UK the number of alcohol drinkers drop each year as the latest generations seemed turned-off by spirits and beer, US cannabis laws are allowing pot lounges and here is where growth is happening, according to Sev enFiftyDaily.

A Gallup poll found that 49 percent of US adults have used cannabis compared to 45 percent two years earlier. It appears in early studies that younger generations, the first to have widespread legal access

to recreational cannabis as soon as they turned of age, have an even stronger preference for cannabis. A survey by the cannabis research firm New Frontier Data found that 69 percent of people aged 18 to 24 preferred cannabis over alcohol. However, while this might be the trend of the moment, no one is sure if it’s got legs. Brandon Dorsky, CEO of cannabis edible brand Fruit Slabs, says he excepts the draw of cannabis lounges could be short-lived.

“While consumption lounges are a great option for tourists, people with children who cannot consume at home, and those wanting a novelty experience, they are still expensive relative to consum ing outside of the lounge,” Dorskey told SevenFiftyDaily.

An issue, too, is that many users of cannabis in the States prefer the use of edibles as opposed to inhaling cannabis. If users are partaking edibles in a lounge, what will they do for the one to two hours before the effects start kicking in?

In the UK, cannabis lounges for the time are not an issue. However, many people believe that the laws pertaining to can nabis will change if and when the Tories leave office. Already the UK is Europe’s largest legal grower of cannabis, and most UK police forces are not enforcing

drug laws when it comes to personal use. For the past 300+ years, almost every UK law regarding spirts has revolved around taxation, not public health. Distillers Journal believes that this will spur the government into legalising cannabis.

TONIC WAR HEATS UP

According to data collection agency Shepper (see elsewhere in issue), the UK’s tonic water market is sewn up be tween Fever-Tree, Schwepps, and a few in-house brands. The problem for anyone trying to crack this market is bar/pub space availability – a bar’s refrigerator can only hold so much product. Nobody, however, seems to have told New Zealand’s tonic brand East Imperial this, which will be hitting the UK soon, according to its website. So far, East Imperial has been a mere fly to Fever-Tree’s elephant. Despite a huge downturn in business last year, for the first half of 2022 Fever-Tree made a pretax profit of £17.6 million (this is opposed

to £25.3m for the same period last year). East Imperial made around £3 million during the same period last year. However, a problem East Imperial has in selling in the all-important US market will soon be solved when a bottling deal

New Zealand’s East Imperial brand tonic water is entering the tough world of international brands led by Fever-Tree and Schwepps

is signed in the States. This will eliminate costly shipping across the Pacific. Will this be enough to start taking a significant share of Fever-Tree’s market? Only time will tell.

DISTILLERS CHRISTMAS PARTY

A GUIDE TO SOURCING SPECIALIST CASKS

DISTILLERS ARE WORKING IN AN EXCITING TIME, WRITES NICOLAS LAFITTE OF ALTER OAK, AS MORE EXOTIC WOOD CASKS ENTER THE SCENE WHICH CAN MAKE YOUR SPIRIT REALLY STAND OUT. HOWEVER, FINDING THESE CASKS CAN BE A CHALLENGE.

We live in exciting times as more and more spirits are arriving on the market with

increasingly exotic ageing and finishes: Marsala, Saké, Vin Santo, Amaro, Mizunara oak, Colombian oak, etc. But sourcing the casks to obtain these glamourous spirit finishes can prove to be an adventure in itself. Indeed, it would be easy to assume that new and used casks are readily available and easily purchased. However, from the point of view of the cooper or cask supplier, it can be an involved process, especially when it comes to exotic casks.

Let’s examine the case of new oak supply such as Japanese Mizunara casks, made from one of the most qualitative and expensive oaks in the world, or Quercus Humboldtii (Andean oak/Columbian oak), another innovative option from Latin America. The demand for this type of oak has increased in recent years and rightly so. However, not only is it expensive and qualitative, but it is also extremely rare and protected. What are the hidden challenges behind sourcing this type of cask that one needs to consider?

Time to test the barrels: At a cost of several thousand euros, Mizunara oak casks are typically purchased in small quantities at first. The testing time frame for liquid development can be several months and by the time this testing is complete, the availability of supply to reorder these barrels may have changed significantly. For a larger order, both production and shipping times must be added, thus the landscape and lead-time of purchasing might have changed.

Logistical challenges: When acquiring exotic barrels, we have to be prepared for exotic situations. This also applies

to logistics. We are facing certain extreme situations in some parts of the globe, with typhoons and heavy rains, damaged roads, criminal activity, etc. If the cooperage is located in a remote area, as is often the case, this can cause challenges and delays to transport goods to the port of departure.

Lead-time: This depends on the buying process. The local supplier must find a reliable and legal wood source, often including a license to fell trees. In the case of Mizunara oak, high level government officials have to sign the extraction permits. Time is needed to then dry the staves sufficiently. The cooper then works the wood and makes the casks. Often, the more exotic the wood, the harder it is to work. All of these stages, which are equally important, result in quite an important lead time which should be considered when buying casks.

Volume supply: There is a worldwide pressure for wood but not always because it is scarce. The demand from multiple sectors such as construction, whisky industry, etc. has dramatically increased, therefore leading to competition in the supply of wood. It is clear that forest protection is one of the vital issues facing our industry and therefore puts some additional pressure on the volume available of timber. It is worth noting that wood suppliers often favour their long-standing customers with whom they already have established a relationship of trust: this can result in longer lead-times for new buyers.

Knowledge of these different elements is useful when defining purchasing and supply strategies in order to avoid any unexpected delays. Good suppliers should be able to give context on this

Knowledge of these different elements is useful when defining purchasing and supply strategies” Nicolas Lafitte

because they are used to dealing with these challenges across the globe. The points discussed above also often apply to select second-hand casks.

There are many things to think about when buying select, quality, used barrels. First is seasonality. I need to replenish my stock of casks of a specific wine. Are these casks available at the moment? If not, when is the harvest period for this wine? Given that harvest time can vary by several months and therefore delay the availability of barrels.

Is the wine from the barrel I am using for finishing in a growing or declining consumer market as we have already seen in the sherry industry?

Will I scale this product? If so, discuss possible volumes in good time with the cask supplier.

Can I be less specific on my labelling to ensure a wider sourcing to meet my volumes in the future.

We hope the elements in this article may help you in supplier conversations to allow simple changes in foresight and planning of cask inventory. In the current context all of us are looking for sensible and sustainable solutions for future sourcing while maintaining excellent impact of wood on spirit maturation.

The cask specialist team at Alter Oak in France

YOU CAN BREAK INTO THE ON-TRADE MARKET

BIG GIN MIGHT HAVE A GRIP ON THE UK HOSPITALITY TRADE, BUT THIS DOESN’T MEAN YOU CAN’T GET IN. GETTING THE RIGHT DATA WILL HELP YOU UNDERSTAND YOUR MARKET AND COMPETITORS.

REPORTS

On the surface it doesn’t

look great for craft gin distillers who want to get into the hospitality trade.

Despite the massive

boom in local and small batch craft gin brands, big gin is favoured in the UK’s ontrade and hospitality industry, according to Toby Darbyshire of data collection agency Shepper. Darbyshire tells Distillers Journal that around 50 percent of the UK marketplace is dominated by Beefeater at 22 percent, Tanqueray at 18 percent, and Bombay Sapphire and Gordons combined at 10 percent. But, he adds, this isn’t a closed market and you can get in with the right information.

This research was conducted by Shepper’s community of data-collectors – called ‘Shepherds’ – and was based on a sample of 1,000 independent freetrade sites, alongside some regionally

and nationally managed pub and bar groups, showcasing the gin and tonic buying experience. How accurate is this data?

“I view this as very much real people collecting real data in real places. We don’t use any sort of data, web scraping for information, we’re not building our insight out that way. We collect the state of the nation information as it’s happening on the shelf, giving you an instant view of reality,” says Darbyshire. While most of the time Shepherds are gleaming information for specific clients, in this case Shepper itself was the client. How it would normally work would be for a company to approach Shepper, let’s says Brown’s Whisky. Brown’s wants to find out if its whisky is being place on supermarket shelves as its distributor is claiming. It wouldn’t be practical for Brown’s to send out its own employees

to visit 500 supermarkets, so it hires Shepper, which in turns sends out its Shepherds.

Besides checking Brown’s product placement, its Shepherds can also look at Brown’s competition in these markets. With this real data, Shepper can advise Brown’s about its distributor/distribution, any apparent missed opportunities, trends, or even if the market is saturated.

With gin, Shepper was curious about the whole market – not a specific brand –and saw this as an opportunity to create a report distilleries would be interested in buying.

“I think for everyone, gin is a leading category. Within spirits, there’s huge choice and I was interested to see how that differs and alters amongst the trade landscape,” says Darbyshire. “My professional history sits in in alcohol sales and predominantly spirits. So, this was something quite close to my heart and I was interested to see the results, having witnessed this market over the years.”

According to Darbyshire, the Shepherds were giving the instruction of going into a pub, bar, restaurant, or hotel and order a gin and tonic.

“They didn’t ask for a specific gin; they showed no preference. The base point was getting a really organic serve and organic operational behaviour,” he says. “Most customers don’t ask for a specific gin; they just ask for a gin and tonic and we wanted to duplicate this.”

The lower priced G&Ts were around £5.60 with the most expensive over £20, which begs the question: Why? “Location, it is all about location. We looked at the entire landscape, with the most expensive G&T served at the American Bar in The Savoy, which when you think about it, it’s probably not that surprising,” he says. “We wanted to keep some of those real prestige, exclusive venues in there just to understand the game, to have a real sort of broad spectrum of segmentation in there. “In the Midlands and East Midlands, the average price was coming out at about £5-6, with the absolute cheapest found in Nottingham at £3.20. But certainly, London had a disproportionate number

of expensive gins. I think the next one after that was somewhere in Mayfair, Kensington, for about £16.50. So yeah, location is king!”

BRIGHTON GIN

“When the report came in, we could see that Brighton has got huge local support for its local Brighton Gin, it’s ubiquitous in the town. It’s also got support of a couple of established pub groups as well, which gives it more of a reach than maybe your regular independent gin,” says Darbyshire. “There’s also a similar thing in Scotland, where we ran our survey in Edinburgh and where Edinburgh Gin was seen in maybe 50 to 100 places.

(53 per cent) serving the mixer. It was followed by Schweppes at 16 per cent. Only one in four outlets served a tonic other than one of these two brands. Franklin & Sons was over-indexed in the East Midlands, which is close to the home of the brand.

“This would be a very hard market for someone to break into,” says Darbyshire, with one of the main problems being the lack of space in a bar/pub’s refrigerator.

SMALL BREAKING IN

When looking at Edinburgh Gin or Brighton Distillery, one thing that both of them got right was to become masters of their own territory, says Darbyshire. [See Brighton Gin in this issue.] In addition to this, you need to get on a bar’s menu so consumers will ask for your gin.

I know my first port of call would be trying to get featured on that menu” Toby Darbyshire, Shepper

“Historically the menu is the biggest key driver of a purchasing decision. Whether it’s giving the consumers a real call to action, or perhaps providing additional liquid credentials, or price point, or even a flavour profile,” says Darbyshire. “All these things aid their decision in asking for your gin.

“If I was a gin brand and going into an ontrade environment, I know my first port of call would be trying to get featured on that menu to really try and change consumers buying decisions. We see this everywhere. Menus are ubiquitous, they’re use to try to get people to make a more informed decision based on what their preferences are.”

What is interesting that we didn’t see this duplicated in Leeds, Manchester, or Liverpool as much.”

One thing Shepper hadn’t expected was that the shape of the glass could influence what the price of a G&T was. “It appeared that the higher the price point, the more a balloon glass – or those typical – were used. Less than £6-7 pounds and they weren’t used, so that seems to be the price point when consumers are expecting a nicer glass,” he says.

Another thing the report discovered was how wrapped up the tonic market is. Fever-Tree was by far the most customary tonic on offer with over half

For more on this report with Toby Darbyshire, be sure to listen to Distillers Journal’s podcasts.

THE ART OF LEGALLY GIVING AWAY ALCOHOL

This article tries to distil

(sorry!) the complex rules of what is a bona fide giveaway of alcohol compared to sales of alcohol requiring a licence. We are looking at England and Wales; Scotland has different rules.

Given the rise in popularity of low alcohol and zero alcohol spirits, it is worth noting that any drink below 0.5% ABV at the time of sale falls outside of the definition of an alcoholic drink and therefore is exempt. Let’s start with the basics. Licensing legislation in the context of alcohol is concerned with sales from regulated premises. For these purposes, the world is neatly divided into premises where alcohol can be legally sold and the rest of England and Wales where it can’t. But matters are not quite that simple. Sales of alcohol are defined in S1 (a) Licensing Act 2003 as relating solely to ‘sales by retail’ of alcohol or, for completeness, supply of alcohol in the context of private member’s clubs.

So, firstly, wholesale of alcohol is not regulated. This is explicitly set out in the Licensing Act (s.192(2) – for those who are interested – as an exemption from the definition of sale. Therefore a ‘sale’ to a trader, a personal licence

holder, a premises licence holder, or a premises user in relation to a temporary event notice permitting sales of alcohol – where that person is then selling the alcohol on – is not a ‘sale’ in the eyes of licensing law.

The reason is this: only the person selling the alcohol to the consumer needs to hold a licence. In practical terms, a distillery does not need a premises licence to sell alcohol, so long as the sales are wholesale. This is well understood, of course.

So, a sale will only ever be a sale if it is to a consumer. But we still have not clarified what a ‘sale’ in this context is. For instance, if you buy a ticket to an event which includes a ‘free’ drink, would this be a sale? What if you give alcohol away to customers, but ask for a voluntary donation, or perhaps, make it necessary for the person receiving the free drink to buy a place mat, for, say the price of a gin and tonic? All of these have been tried in the past. Most have fallen foul of the law. This is because the first offence set out in the legislation relating to sales of alcohol makes it illegal to ‘carry on to attempt to carry on’ a sale of alcohol from any premises not licensed to do so, or at times not licensed to do so. This is why the old fashioned ‘lock-in’ is illegal.

The offence, if a sale is made, can occur anywhere.

So why would it be a sale, for instance, to give away free drinks as part of an event where customers buy tickets to attend? Sales, in this context are broadly defined. Where there is a requirement to purchase a ticket before receiving any ‘free drinks’, this would be considered a sale as there is a clear value assigned to the gift of the alcohol, whether your guests take you up on the offer or not.

Other enlightening examples of how this works in practice would be where a hairdresser or bridal boutique offers an alcoholic drink to their customers. Where you are incentivised to purchase something, or you are offered a drink once you are in the barber’s chair or trying on dresses, you have value for the drink. This would therefore constitute a sale. To be a genuine give-away, and therefore not a sale, you would technically have to offer the same drinks to anyone passing by who

asked, irrespective of whether they then committed to a bit off the top or to tie the knot, or not.

Some people have attempted to get around having to hold a premises licence by offering drinks to anyone who asks, but then suggesting a ‘voluntary’ donation is made to keep the premises going, or a ‘voluntary’ purchase of a beer mat at a suggested price more akin to a cost of a pint than a circle of printed card.

If the ‘voluntary’ element is in fact more like a ‘wink wink voluntary’ donation, again, there is value for the alcohol and this would be illegal. By the way, it is irrelevant whether you make a profit or not.

It is worth noting that the offence of selling alcohol without a licence, can lead to unlimited fines and potentially up to six months in prison for those found guilty of offences, so there can be serious consequences for trying to grift the system.

On the positive side, let’s look at what

you can do without a licence. Giving away samples, for instance, would not be classified as a sale, as there has been nothing of value received at the time of the give-away. This is, of course, so long as there is no requirement for the sampler to buy anything.

However, some caution is needed to ensure that, if you are providing samples in public spaces, you have the relevant permissions from the council to do so. It is also worth bearing in mind that samples should be exactly that. Also, putting in place measures to ensure you are not giving away alcohol to children and that samplers are not relying on your largess to get merry makes good practical and legal sense.

What is the key take-away here? Well, it can be summed up nicely by reference to the ‘sniff test’. If it smells like a scam, it is likely to be a scam. If you start with the premise that giving something away should come with no strings attached, you are unlikely to go wrong – but if in doubt, seek advice.

BARTENDER

ASK A BARTENDER ABOUT: COLOURS, SPIRITS & COCKTAILS

IN TRYING TO FIGURE OUT THE NEXT BIG THING, YOU CAN TALK TO DISTILLERS, OR YOU CAN TALK TO THOSE POURING FOR CUSTOMERS, BARTENDERS. PICK A QUIET NIGHT, PULL UP A STOOL, AND FIND OUT WHAT PEOPLE ARE DRINKING.

We’ve all done this. You’re at a pub, bar, or even a restaurant. You know what you’re going to have when suddenly a drink or a plate of food catches your eye. “I’ll have one of those instead,” you say. Why? Most probably it was the colour. This plays an important part in what we choose to drink and if you’re not thinking about colour, you could be missing out on sales.

According to research by Charles Spence on the psychological impact of food colour – published by BioMed Central – colour is the single most important product-intrinsic sensory cue when it comes to setting people’s expectations regarding the likely taste and flavour of food and drink.

the younger group’s judgment of the overall flavour intensity of the chicken bouillon was influenced by the amount of colouring that had been added to the sample. More colour, more flavour. Some researchers have conducted a number of psychophysical studies showing that the addition of food colouring can deliver as much as 10 percent perceived sweetness. In other research, it has been shown that people will consume more candy if it comes in a variety of colours than if presented in just a single colour even if that colour happens to be the consumer’s favourite one. Increasing the colour variety – as in Smarties, M&Ms and Jellybeans – increases the amount consumers eat.

ASK

A huge amount of laboratory research has demonstrated that changing the hue or intensity/saturation of the colour of food and beverage items can exert sometimes a dramatic impact on expectations. You see something with a brilliant fruity red, you’ll expect the drink to have just as intense flavour as its hue. One study examined the effect of food colouring on perceived flavour intensity and acceptability ratings in samples of chicken bouillon and chocolate pudding. These foods were presented with no colour added, with the normal (commercial) level of food colouring, or with twice the normal level of colour added.

The participants tasted and evaluated the three samples of either food, using visual analogue scales. Younger adults (20 to 35 years of age) were found to be more affected by the presence of food colouring than were the older adults (60 to 90 years of age). Interestingly,

While for years in the States, cereal manufacturers were telling children that multicoloured cereals such as Trix, Fruit Loops, and others were flavoured according to the colour. For example, red was cherry, yellow was lemon, and orange pieces were orange flavoured. Manufacturers have since come clean and admitted Trix and Fruit Loop pieces all have the same flavour, despite for years kids arguing that they could taste the different between each colour. However, should the colour not match the expected taste, then the result may well be a negative.

Given the ambiguity in the meaning of colour in foods and beverages, it can sometimes be important that the name and description of a food or beverage set the right sensory or expectations or else help to disambiguate between the different possible meanings that may be associated with a given colour.

Researchers demonstrated that when the meaning of food colouring is misinterpreted – it sets the wrong

sensory expectations – then this can have an adverse effect on people’s subsequent taste ratings.

In a study, participants were given a bright pink ice cream to taste. One group of participants was given no information about the dish, another group was informed that the food was called ‘Food 386’, and a third group was told that what they were about to eat was a frozen savoury smoked salmon mousse – which is what it was.

Those participants who had not been given any information about the dish, were led by their eyes into expecting that they would taste a strawberry-flavoured ice cream.

Expecting this and getting smoked salmon turned them off to the mousse, with most rating it as being too salty. By contrast, those participants in the other two groups rated the seasoning of the dish as being just right, and what is more, liked the savoury ice far more as well. In one famous study, dinner party guests were invited to dine on a meal of steak, chips, and peas. The only thing that may have struck any of the diners as odd was how dim the lighting was. However, this aspect of the atmosphere was actually designed to help hide the food’s true colour.

Part-way through the meal, the lighting was returned to normal, revealing that the steak had been artificially coloured blue, the chips looked green, and the peas had been coloured red. A number of the guests suddenly felt ill when the lighting was turned to normal levels, with several of them apparently heading straight for the bathroom.

Different cultures perceive a colour as tasting different. This can be extremely valuable to know if you’re thinking of marketing a product to a foreign country. For example, in the UK a bluish drink is assumed to be raspberry flavoured. In Taiwan, it’s mint. Red in the UK is seen as cherry or strawberry flavoured. Again, in Taiwan, it’s seen as being cranberry flavoured.

A few years back Burger King, and then followed by McDonalds, used squid ink to create a black bun for sales in Japan and the Philippines. While this was a

massive hit in Asia due to people having more exposure to different seafoods, it was a flop in the States when Burger King tried to market it as a Halloween burger. There appeared to be two major factors. The first was that in the West, people perceive food which is black as being rotten. The second was that the colouring used in the bun would turn your stool green.

And then there’s no colour.

In the USA, commercial slots during the Super Bowls are more expensive than any other time of the year and the most anticipated. Hit it right, you’ll make a fortune like when Apple introduced Macintosh Computer in 1984. Hit it wrong and you’ll be remembered for that. Halfway through Super Bowl 1993, a commercial broke with ‘Right Now’ by the rock band Van Halen, and featured an astronaut, a rhino, and a woman drinking an oddly clear drink. “Right now, we’re all thirsty for something different, introducing Crystal Pepsi!”

It was a drink giving you all the great flavour of Pepsi, but clear. Millions of Americans were excited to try it and millions did – once. There were few second takers, and it was a massive flop, later called one of the biggest product failures of all time by Time Magazine David Novak, the former Pepsi marketing executive who created the soft drink said in reflection, long after Crystal Pepsi had been pulled from the shelves: “It could have been more than a novelty,” he said. “It was probably the best idea I’ve ever had – and the most poorly executed.”

While there are a number of theories out there in marketing literature about what went wrong, one suggestion is that when such drinks are tasted away from their packaging, then it’s likely the drinker gets an experience that they are not expecting. People saw a clear liquid in a glass and were expecting it to taste like lemonade or soda water. When the flavour they tasted, however, was cola, the non-expectation of this led to a negative experience.

For those wondering just how important colour is in a drink, award-winning bartender, mixologist, TV drinks’ expert,

and creator of Crossip – a non-alcoholic adult drink – Carl Anthony Brown tells Distillers: “Ultimately, flavour is the most important aspect of any finished drink. But when it comes to the full experience of drinking a cocktail, the presentation of that drink is incredibly important, hence why cocktails have been developed with specific glassware, garnishes and even the flamboyant manner with which that drink is made. The colour of the finished drink is a key element of this presentation that should not be overlooked,” he says.

When behind a bar, do people choose drinks by colour?

“I personally would not say that colour is the driving factor for people choosing specific drinks, otherwise cocktail menus across the globe would feature images rather than a list of ingredients. But there’s no doubt that oftentimes, people will come to the bar and ask for ‘what he/ she’s having’ because of the allure of the colour and presentation of a drink they’ve spotted.”

With a cocktail, you want to give people something new and exciting, but would you say you also have to give them something they’re expecting, especially when it comes to colour?

“Subconsciously, I believe that people look for a drink whose colour is authentic. Yes, a bright colour may be attractive, but it must be created using the true colours of the ingredients themselves. Creating a flavourful drink and then, say, using food colouring to match the expectation of the person ordering it, just doesn’t sit well with me.”

With Pepsi Clear, do you think it could have worked or are we too entrenched that cola drinks are dark caramel coloured?

“It absolutely could have worked! Times are changing, as are perceptions. In my world of non-alcoholic drinks, 15 years ago, the notion of a No & Low beverage that was full of flavour was unthinkable. The perception was that non-alcoholic drinks were poor substitutes of the real thing and required compromise. That perception has now changed, but it needs to be developed over time with the right messaging, which is where I believe Pepsi Clear went wrong. The

narrative around the product was a bit confused, as they tried to market a product that was full of sugar as being ‘pure’!”

During the five years it took to produce the first Crossip beverages, you’ve mentioned how you were after certain mouth sensations and flavours. Did colours also rate pretty high?

“Colour was always rated highly, but not at the detriment of the flavour experience. I refused to compromise on this for the sake of presentation. I always had the confidence that the hues of the raw natural ingredients would produce a final colour that was fitting of our brand with an air of authenticity and quality.”

Did you make any trial Crossips which while tasted good, but looked horrible? “’Horrible’ might be a strong way of terming it, but we absolutely had to play around with the filtration process until we had a final liquid that was fitting of the look and feel we were looking for. Ultimately, we didn’t want to lose the flavour quality of the liquid but recognised we couldn’t offer a liquid whose colour was a touch ‘bartender brown’!”

Do you use any artificial colours or is it all natural?

“There are absolutely no artificial colours used in any Crossip flavour. We’re extremely proud of this.”

With something like your Pure Hibiscus, it being red is no surprise. But with Dandy Smoke, were you after a specific colour? “Dandy Smoke was borne out of the flavour profiles of rum, whiskey and mezcal based cocktails, so there’s no doubt we were happy that the final colour was akin to these traditional alcoholic spirits. But that was not the goal from the outset, it was more a happy coincidence that we had an inkling was likely due to the colours of the lapsang tea leaves which are the core ingredient in Dandy Smoke.”

With your newest flavour, Blazing Pineapple, what are your thoughts regarding its colour?

“Blazing Pineapple is bright and powerful,

that’s for sure!! It really does emulate the flavour profiles of the tiki tropical ingredients with the fiery nature of the scotch bonnet peppers. When I created the first batch of Blazing Pineapple, I saw the colours as the raw ingredients were being macerated and I knew we were onto a winner.”

You’re at numerous trade and consumer shows with Crossip, if people for some reason don’t notice the bottle’s name of Pure Hibiscus, do they immediately twig on that being the flavour or do they guess something else?

“Pure Hibiscus can sometimes be the most difficult flavour to articulate. Ultimately, it’s a bitter, floral and herbal taste experience, which perhaps does not tie into the pink hue which many perceive as being sweet. When we speak with the trade and consumers at the events you mentioned, it’s often Pure Hibiscus that has the biggest impact because of the sensory disruption; we love seeing their eyes light up at the first sip,” says Brown.

Carl Anthony Brown, is an award-winning bartender, mixologist and TV drink’s expert. Some of Carl’s accolades include winner

CROSSIP PURE SOUR

Light floral on the nose with rose peeking through backed up with crisp lemon and herbal bitterness on the palate.

35ml Crossip Pure Hibiscus

20ml Lemon Juice

10ml Rose Syrup

10ml Aquafaba

Add all ingredients to a shaker with no ice and shake. Fill shaker with Ice, shake again and strain into a chilled fancy glass. Garnish with rose petals.

of ‘The Young British Foodies’, IMBIBE

‘Drinks List of the Year and many more.

He’s worked for 18 years in the bar and drinks industry, including creating the drinks concept across the Dishoom group.

His latest venture has been launching the alcohol-free spirit, Crossip in 2020.

He is best described as a man who is seldom without an opinion.

GREETINGS FROM THE REPUBLIC OF BRIGHTON

A SPIRIT BY NATURE CAN HAVE A SMELL AND TASTE WHICH REFLECTS THE NATURAL AREA WHERE IT WAS DISTILLED AND AGED. BUT A SPIRIT CAN ALSO REFLECT THE VIBE AND FEEL OF THE CITY WHERE IT WAS MADE. DON’T BELIEVE THIS? JUST ASK KATHY CATON. VELO MITROVICH REPORTS

Rome might be the eternal city, New York the city that never sleeps, and San Franciscans say their city is actually European

– a claim made by people who have obviously never been to Europe. But Brighton is…well…it’s Brighton. While on one hand it would be easy to take the micky out of the City of Brighton & Hove – there has to be more nose ring piercings here per capita than any other part of the UK – survey after survey lists Brighton as being one of the happiest places to live and work. It’s also considered among the friendliest cities in the UK.

ABBA won the Eurovision song contest here; the first Body Shop opened in 1976; it’s the LGBTQ capital of Britain; and it’s a place where locals support independent shops and cafes.

During a recent data survey conducted by Shepper [see elsewhere in magazine] that looked at which gins were being poured in pubs, bars, restaurants, and hotels. Except for only two areas in all of the country, it was the three leading gin producers that ruled. The exceptions were Edinburg and Brighton, where local gins from Brighton Distillery prevailed. Could Brighton Distillery, ut existat, been founded anyplace else? That is extremely doubtful.

Kathy Caton, founder and managing director of Brighton Distillery – and one of the nicest people you can ever hope to meet – is asked whether her distillery just happens to be located in Brighton or is it a Brighton distillery?

“So, for full disclosure, I’m not Brighton born and bred, but I’ve been here now for 23 years. The identity of Brighton runs through me like a stick of rock,” says Caton. “For me, it was so important that something be locally identified, and I always wanted my Brighton gin to be called Brighton Gin. It’s made and

produced in the glorious City of Brighton & Hove.”

However, since we’re talking about full disclosures, Caton is the first to admit that not all is wonderful in setting up a distillery in Brighton. Londoners, wanting to escape from one of the UK’s least friendly cities, have sold high, allowing them to buy in Brighton and at the same time, drive up prices.

“It comes with lots of complications, with that this is an incredibly expensive place to live and work – any suitable space that would have been great for a distillery has all been turned into luxury flats a long, long time ago.”

There is, too, considerable bureaucracy and hoops to jump through in setting up a distillery in the area and just as many in even moving an existing distillery just a nudge into a new location.

“But for me, it’s just really, really important that something that has the has the name on the tin, is made and done and created in the place that it’s identified with,” she says.

“I think Brighton Gin is about the people who make it, that’s a really core thing. At the distillery, we’re a small team of friends and family, incredibly diverse by almost every measure. People who really actively engage in the community, people who go out a lot – everyone goes to the theatre, to the cinema, to see gigs and to love all the things that Brighton has to offer.”

To be fair to you readers, if you haven’t guessed already, with Caton all answers lead back to Brighton. But to be fair to Caton, it’s easy to understand why. If there was ever a meeting of the Lesbian Gin Distillers of Britain, Caton would only have to book a room with one chair. As progressive as many of us believe the industry is, Distillers Journal has been told otherwise by gay and ethnic minority distillers.

Kathy Caton (middle) surrounded by most of the Brighton Distillery team. The eCargo delivery bicycle is how most local deliveries are made.

Kathy Caton (middle) surrounded by most of the Brighton Distillery team. The eCargo delivery bicycle is how most local deliveries are made.

COMMUNITY LOYALTY

Why do people in Brighton buy Brighton Gin? You could start by saying it’s because the numerous award-winning gin is excellent. Its botanical list includes Macedonian juniper, milk thistle, fresh orange and lime zest from unwaxed fruit, angelica root, locally grown coriander seed which gives a spicy, lemony flavour, and it is distilled with an organic wheat alcohol base. A course, being made in Brighton, it’s certified vegan – including the packaging. And a course, the used botanicals are put into a compost heap.

Caton is a huge gin & tonic fan, drinking G&Ts back when they weren’t cool for her age group. Although she’s now become a bit of a straight-gin sipper, from day one she wanted to produce a gin that worked well in a G&T, as well as tasting wonderful in a martini or negroni.

But with the UK’s gin drinkers having more choices of gin available than anywhere else in the world – Distillers estimates this number could be as high as 2,700 to 3,000 – there is an overabundance of good to excellent gins in the £30 to £40 range.

So there has to be something else that makes people in Brighton buy Brighton Gin. Maybe it’s because you just look at the bottle and think Brighton.

The concept of Brighton Gin’s bottle is to reflect the city’s famous pier. Bespoke made by Allied Glass, its squarish shape reflects Brighton’s pier – or at least its pre-fire shape. The colour used in the label and wax is a take-off of the pier’s colour and the sea, and indeed, this colour is used in all of Brighton Distillery’s marketing. This includes the colour of the distillery’s bicycles.

“One of the very few perks that you get when you join Brighton Gin – apart from lots of gin – is that everyone gets offered a bicycle. We have lots of reconditioned former post office bikes that have been spray painted Brighton Gin-green,” says Caton, adding, however, that a drawback with this is if you ride like an idiot, everyone can recgonise that you’re from Brighton Distillery.

Local deliveries to pubs, bars and restaurants are made with a Brighton

Distillery painted eCargo bike, which Caton says “basically looks like a nicely decorated coffin on wheels” which can hold a considerable amount of gin bottles.

“It’s battery boosted so it’s possible to actually ride it around town even with all the hills. It’s been one of those wins, where it not only is much quicker and so much cheaper to do deliveries, but also works with our eco credentials.

“Being as ethical and sustainable as we can be in every way is a key thing for us and it also looks great. Rachel Blake seems to be the one making deliveries and she’s had a few times small children shouting, ‘Ice cream, stop, stop’ and her

shut down 85 percent of our business overnight. We were in the fortunate position in that we were able to get our licences in place to be able to sell direct through our website. We went absolutely hell bent for leather on that front,” she says.

But Caton being Caton, she sees the silver lining of this time.

“There are always positives from any crisis. One is that we’ve really got to connect with our customers again. We were all out on our bicycles, masked up, doing safe, safe deliveries to people’s doorsteps, and talking to people.

“It was quite a humbling thing. We donated around Brighton & Hove 10s of 1000s of bottles of hand sanitizers that we made. I was delivering gin and hand sanitizer to a woman in Hove on my push bike, rang the doorbell and stepped back by several metres. As she came and collected her bag off the doorstep, she said: ‘I’ve already got three bottles of your gin inside, I just want to see you guys survive.’ I have to say I had a proper cry into my face mask at the side of the road.

going ‘I can’t sell you what’s in this bike till you grow-up’,” says Caton.

In total, the distillery team has completed over 3,600 miles worth of deliveries in town, with the majority of staff commuting by bike as well.

For the on-trade, the distillery is offering them refillable five-litre vats. “As one of the bike delivery bods, I can say it’s great fun delivering gin by the five-litre vat!” says Rachel Blake who champions Brighton Gin’s green and sustainable efforts.

If home delivery was just a fun idea, it turned into a serious one when the Covid pandemic struck and on 23 March 2020, the majority of Brighton Distillery’s business customers shut their doors.

“It was a terrifying moment because that

“People were cute, really cute. They sent packages of gin to friends and family around the country for lots of missed occasions, which we could see through our handwriting the cards. You know, ‘Sorry, we won’t be together for your 30th, your 40th’. In one case it was a woman’s 100th birthday and in another, it was a young man being ordained to the priesthood. All these people celebrating milestones in their lives, during this time, and doing it with our gin. It was really humbling.”

Also, during this time Brighton Distillery started a ‘Buy for a Friend’ campaign, in which people were asked, when ordering a bottle, to consider buying another one which would be donated to essential workers.

NEW LOCATION

In what has taken up a considerable amount of time for Caton has been the very recent move of the distillery into a larger, but nearby location.

You would think that because you’re making the same product, in the same area, with the same number of staff, etc,

Sometimes you have to take that nervous swallow, take your risk, take your chance, and hope for the best” Kathy Caton

Above: The team following Caton into the English Channel last November.

Right: Rachel Blake making a delivery.

Above: The team following Caton into the English Channel last November.

Right: Rachel Blake making a delivery.

that it would be just a case of changing the address line on the licence and Bob’s your uncle. Nothing could have been further from the truth and Caton explains that it was like she was setting up a distillery for the first time.

While elsewhere part of the problem would have been neighbourhood opposition – the distillery is located very much in a residential area – with the building licenced for commercial use and with the previous tenants being rumoured cannabis growers, neighbours were actually thrilled with Brighton Distillery moving in. And indeed, while Distillers was at Brighton Gin, a local woman walked in to have her bottle filled at the refilling station, saving £5.

“For the move, I think the whole process took two years and then of course, ironically, now that we’ve actually been able to make this happen and take

on the new space, we’re lurching into this tremendously challenging time in terms of costs, whether its energy or spiralling costs of raw materials,” says Caton. “Sometimes you have to take that nervous swallow, take your risk, take your chance, and hope for the best.

“But now in terms of mental and physical well-being, it’s incredible to have more space and to be able to actually move safely without clogging your head on a pallet rack or stuff. We had totally plateaued; we couldn’t do any more in our previous space. We’re now just hoping that the world doesn’t totally, totally collapse.”

You want your distillery to be a thing of beauty, to have your still be eye candy to attract customers, but Caton says that there are advantages in staying with smaller stills.

If money was no issue, a course she’d go

big and copper. But with money always an issue, she has found that she can keep up production by running three small stills (the third is a recently bought used i-Still) in parallel and to run them more frequently.

“I should be honest, we have what we can afford. But we figured this is what we got, so let’s work out how to make it work,” she says. “But also, if something goes wrong with one – we had an issue with a heating element the other day, and a power surge, and all sorts of things – it means that there’s a backup and that we can keep our production going.

“This depends slightly on whether there’s a pandemic going on or not, but I’m guessing we do around 28,000 bottles a year,” she says. “We’re still at the stage where I talk about things in terms of bottles. Somewhere we’ve got a spreadsheet with nine litre cases on it but yeah, we’re still in the bottles territory. It

Far left: Head distiller Paul Revell

Right and centre: 79-year-old Judith White, Caton’s mother and working member of staff.

Lower centre: Refilling station

still seems like a bloody lot, considering they’re all done by hand, and I’ve got my poor mum lugging things around.” [Her mother, Judith White, is the distilleries oldest employee at 79. She is often referred to as St Jude.]

FUTURE PLANS

As it stands today, Brighton Distillery has two core products – Brighton Gin Pavilion Strength (40% ABV) and Brighton Gin Seaside/Navy Strength (57% ABV), which are hand bottled at the distillery. The distillery also has three RTD cocktails which are canned off-site. Originally when it was decided to go with RTD drinks, Caton used small glass bottles but quickly realised that Brighton’s pebbly beach and a glass bottle was not a good combination. This was probably a good move considering that the team at Brighton Distillery

volunteers for the Brighton Beach Cleans.

“Our RTD cocktails are all natural, they’re made with beautiful quality ingredients, and they’re delicious. They have given us the chance to let more people try Brighton gin who might not want to invest in a £38 bottle from the off licence – but I’m at a gig and I really fancy this lemon verbena garden Collins. So, they’ve given us an interesting new route.”

When looking at any distillery’s future plans, it is always interesting to note what they call themselves. Does their name limit them to only one product?

Caton’s distillery is called Brighton Distillery – not Brighton Gin – although everyone, including Caton, usually refers to it by that name.

So, what else is in store?

“We have two core products and that’s

been a deliberate choice. It’s also been quite a hard one to stick to. I love making new things. I get very excited. And we could do this and that. For me, the idea is the easy bit, it’s the execution that is the difficult part,” she says. “We need to have blinders on and stay in our lane. I would rather do a couple of things brilliantly than a lot of things not.

“When we release something to the world not only do I want to know that it’s the best we can do, but also that it’s repeatable. This is one of the issues with very small production, does each bottle taste the same?”

There are new products which have been developed, but as of yet, they haven’t passed approval of Caton or head distiller, Paul Revell.

“There’s a definite hope and aspiration that we’ll have more spirits in our spirits list. Gin is always going to be my absolute

first love. Bartenders used to laugh in my face when, as a young person, I’d ordered a gin and tonic I absolutely love it. I think it’s magic booze. But I’m also really interested in exploring experimenting with other things within the team.

“I know that there’s lots of interest in brandies and I would love to make absinthe. We’re a seaside town so I’d say yes to rum. Whiskey will be an amazing thing. But that’s a whole different setup. We always have this tension between all of the things we’d love to do and in the meantime being practical and keeping on the lights.”

BRIGHTON OVER TO YOU

The lesson for all distillers to take from Kathy Caton and Brighton Distillery is the importance of tapping into your local community, becoming part of it, and perhaps the most important, having the right team.

Caton knocks completely on the head the belief that becoming a success hinges on having the right equipment, the right software, the right building, and the right location. For six years her distillery’s location was nicknamed ‘The Cave’, due to the basement room having zero windows and natural light. The only plant she had was a plastic cactus and even that didn’t look too lively!

But she and her team have succeeded.

If her three stills were placed out on the street, it’s doubtful a rag-and-bone man would stop for a millisecond and eye them over.

But she and her team have succeeded with over 20 regional, national, and international awards coming from liquid made with those stills.

Just like everyone else, Caton has her list. She would love to have a beautiful copper Muller still, a distillery in Brighton central or even better, right next to the

sea. She should have much, much more international sales. Although Brighton Gin sells well in Germany – thanks in great part to having two members of staff who speak German – the City of Brighton is well known in the LGBTQ communities around the world. Why the world’s Pink Dollars aren’t beating a path to Brighton Distillery shows that on her wish list needs to be added a marketing wizard. Still, in many ways, it is easy to see that Brighton Distillery could become a major player with craft gin and in some ways they already are. Is the child’s book The Little Engine that Could be required reading for new hires?

But, as you leave Brighton Distillery, getting handshakes and hugs from Kathy and the team, you have to think: Things actually are pretty perfect the way they are.

CORRECTING 300 YEARS OF MISTAKES

USING FRESH JUNIPER BERRIES? CHECK. LIMITED PRODUCTION HAND-BLOWN BOTTLES? CHECK. NO LABELS? CHECK. ULTRAPREMIUM PRICE TAG? CHECK. AND, LAST BUT NOT LEAST, DEMAND? CHECK. VELO MITROVICH REPORTS

Before we even begin a story about a Kenyan gin, there is a jumbo of an elephant in this savanna of a room that needs to

be addressed. Only you will be able to ultimately answer the question this pachyderm brings up.

In the UK currently there around 820 gin distilleries, ranging in all sizes, and at least 80 contract gin distillers. If you take a very low-ball number of three gins from each distillery, at any given time the British consumer has access to 2,700 different gins. Add to this mix are gins from Finland, Sweden, Iceland, the USA, Vietnam, India, Indonesia, Panama, South Africa, and other locations, leaving at least 3,000 different gins available here.

So, do UK consumers really need another gin, do they need a gin which will set them back anywhere from £80 to £110 per 700ml bottle, and do they need a gin from Kenya?

If you spend any time talking with the team at Procera, your answer will be a resounding ‘yes’.

BERRY FRESH

Roger Jorgensen was minding his own business in South Africa when Guy Brennan contacted the master distiller and wine maker. He had heard of Jorgensen and his expertise and sent him some fresh African juniper berries from the mountains of Kenya.

Brennan, born in Australia, originally worked as a banker and his job was to provide micro-credits for Africans, which

took him to almost all the countries of sub-Sahara Africa. He finally landed in Kenya where he met his American wife.

One evening he was sitting on the terrace with friends, all enjoying G&Ts, when it struck him that most of the botanicals in the gin were grown in Africa.

Brennan asked: “Why are we sending all these botanicals to London for some guy to distil, to put it in a bottle, and then send it back here for us to drink. Why don’t we just make gin here?”

And then this question followed. “And why don’t we make this gin using fresh African juniper berries?”

Juniperus procera, commonly known as African juniper, the African pencil-cedar, or about a half-dozen other names, is native to the mountainous regions of the Arabian Peninsula and eastern Africa, from Ethiopia down to Zimbabwe. A fairly close relative of the familiar gin berry producer, Juniper communis, it has the distinction of being the only juniper found naturally south of the equator.

It grows naturally – and is farmed – as a tree, not a bush. The wood of the African juniper is used in building houses, poles, furniture, and fuel; the bark is used to make beehives. But with the berries (cones), there is no real usage – or at least until recently.

Brennan and a few Kenyan partners thought the berries could be used to make gin, but were not having much luck, thus they turned to Jorgensen. He thought why not, basically scribbled some instructions on the back of a cigarette pack and sent it to Brennan.

The Australian understood many things, but not how to make gin based on some scribbled instructions. He invited Jorgensen to Kenya who was immediately taken with the whole idea of making gin from fresh juniper berries.

After all, with his wine making he never used dried raisins, always fresh. With something such as juniper, which has such a huge impact on the flavour of gin, Jorgensen started questioning why gin distillers for the last 300 years have been content to use dried instead fresh?

Having now a master distiller at the helm, the potential of using fresh African juniper berries became clear, even when sampled immediately off the still. However, as important as use of the berries was, Brennan wanted everything to be African, from all the botanicals to the glass bottles, which would end up having to be hand-blown. And then there are the hand-carved stoppers….

If you’re suddenly hearing the sound of a cash register going off in the background as all these costs are added up, you’re not far off the mark.

“If you look at the history of the spirits category, every single category has premium distillations with the exception of gin,” says Brennan. “It’s happening now in agave spirits, it’s happened in vodka, bourbon, whisky – every spirit except for gin. It’s a good question as to why it hasn’t happened.

“At Procera we feel is that there’s never really been before a justification for an expensive gin product, which is why there has never been a gin

Procera Gin team on a Kenyan juniper tree. Guy Brennan (centre in tree) , Roger Jorgensen (bottom right)

Procera Gin team on a Kenyan juniper tree. Guy Brennan (centre in tree) , Roger Jorgensen (bottom right)

premiumisation category.

“When you look at the business model we’ve undertaken and the incredible cost structure of using handblown bottles, hand-carved stoppers, collecting the juniper berries ourselves from trees –not bushes – and producing less than 100 bottles a day, there’s a reason why Procera has to be more expensive.

“We don’t want to sound immodest, but there’s a lot of gins out there and we believe gin has been made the wrong way for the last 300 years. Sometimes it takes a place with no history of distilling – like here in Kenya – to look at things a little bit differently, to be a little bit irreverent. And to ask: ‘Why do you use dried juniper in gin?’ If you make an apricot brandy, you don’t use dried apricots, you will use freshest apricots you can find,” he says.

Does using fresh juniper, however, make any difference or is it just clever marketing?

Not surprising, Brennan and Jorgensen say it makes a HUGE difference and it is actually very, very, very difficult to get them off the subject. But, in looking at reviews from the UK, USA, Hong Kong, and elsewhere, everyone seems to agree with them.

Some of Master of Malt reviews state: “The smooth taste of this gin is something to behold. Even non gin drinkers have tried this and loved it. As advertised, [it is] much smoother than most other gins with a deep unique flavour. Everything about it including the bottle and stopper just smacks of being a one off.” “Super Smoooooth. Being a member of a gin club and having accumulated over 60 gins, I can honestly say this one is head and shoulders above the rest. Outstanding delicious and worth the money.”

Other gin sites describe Procera as being “a full-on experience” and “worth the money”. In Paul Jackson’s The Gin Guide Review, he says: “With Procera Gin’s enviable and unique bottles, and such importance given to the species of juniper used, it is a gin with a lot to live up to, but it delivers on the promise triumphantly. The abundant juniper is ever-present and beautifully balanced,

An aerial view of Kijabe

and the mouthfeel is full and oily.” And in 2020, the IWSC awarded Procera a gold award, giving the distillery 96 out of 100 points in blind tastings across the range.

OTHER BOTANICALS