1 I’M ISSUE #005 September 2020 Florida ITALIANS DO IT BETTER! When was the last time you felt good doing nothing? mobsters The Tampa Family Socials and teenegers... Handel with care The Most Charming Italian Restaurant in Florida 7 things you donʻt know about Italian cuisine How America became Italian Daytona Beach ISSN 2688-0601 (PRINT) ISSN 2688-061X (ONLINE) $14.50 PADRE PIO: SCANDALS OF A SAINT

HILTON DAYTONA BEACH OCEANFRONT RESORT

100 NORTH ATLANTIC AVENUE, DAYTONA BEACH, FLORIDA, 32118, USA

TEL: +1-386-254-8200 FAX: +1-386-253-0275

Vibrant dining and fun at beach resort in Daytona Set in the heart of the Ocean Walk Village on the ‘World’s Most Famous Beach,’ Hilton Daytona Beach Oceanfront Resort offers stunning views of the Atlantic Ocean and easy access to the thriving seaside attractions and the business district in Daytona Beach. Step out onto the beach for a day in the sun, or relax by the outside pool with a refreshing cocktail in hand. Enjoy diverse dining options and fun daily activities – no need to leave the hotel!

www3.hilton.com

I’M Issue #005 September 2020 The Most Charming Italian Restaurant in Florida 56 DINING OUT IMMIGRATION 38 How America became Italian 66 Padre Pio: Scandals of a Saint Actuality I’M Italian is a hoffmann & Hoffmann LLC magazine, printed and published in the USA and distributed all over the world. Subscriptions available via Amazon or www. imitalian.press. hoffmannpublish@gmail.com - For advertising: fabrizio@hoffmannpublisher.com Hoffmann & Hoffmann LLC, 1139 Magnolia Avenue, 32114 Daytona Beach, Florida, US.

6 IN MEMORY Anna Magnani Totò Gianni Versace FASHION DONATELLA VERSACE SOCIALS AND MEDIA Socials and teenegers... PSYCHOLOGY Italians do it better! 12 16 22 26 MOBSTERS The Tampa Family 7 things you donʻt know about Italian cuisine 30 ITALIAN THINGS

AnnaLaMagnani diva 6

La

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

INMEMORY

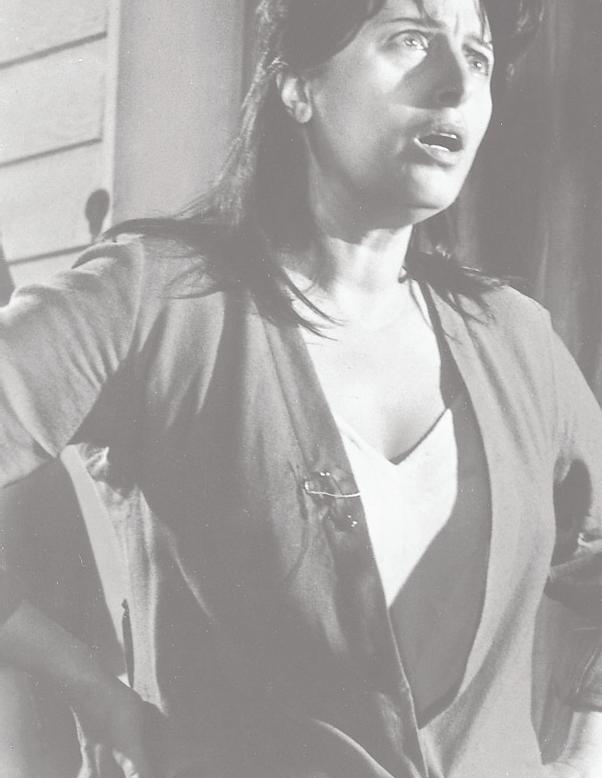

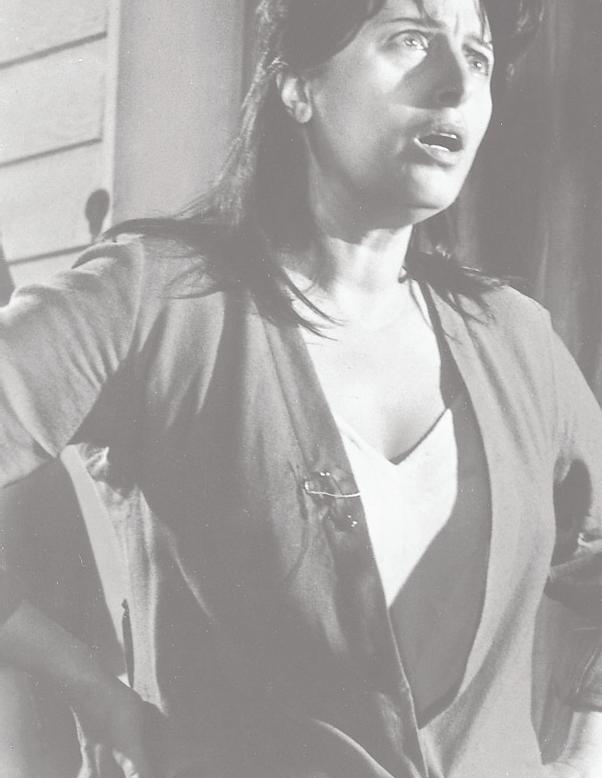

Anna Magnani and Burt Lancaster in The Rose Tattoo (1955).

Anna Magnani, (born March 7, 1908, Rome, Italy—died September 26, 1973, Rome), Italian actress, best known for her forceful portrayals of earthy, working-class women.

Born out of wedlock, Magnani never knew her father and was deserted by her mother. She was reared by her maternal grandparents in a Roman slum. She briefly attended the Academy of Dramatic Art in Rome before joining a touring repertory company. As an entertainer in Roman nightclubs, she specialized in bawdy street songs and in vaudeville. She made her film debut in La cieca di Sorrento (1934; The Blind Woman of Sorrento). When she appeared in Roberto Rossellini’s classic Neorealist film Roma

città aperta (1945; Open City), she achieved international renown. Representative of her many roles, in which she often portrayed emotions that ranged from mental torment and deep grief to exuberant comedy, were the dynamic housewife in L’onorevole Angelina (1947), who led a fight against black-marketeering in postwar Italy; a shepherdess in Il miracolo (1948; The Miracle), who was seduced by a stranger she imagined to be a saint; an aggressive stage mother in Bellissima (1951); the robust widow of a truck driver in The Rose Tattoo (1955), her first Hollywood film, for which she won the Academy Award for best actress; and the wife of an Italian mayor in The Secret of Santa Vittoria (1969).

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Totò The Prince

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Totò, by name of Antonio de Curtis Gagliardi Griffo Focas, (born Nov. 7, 1898, Naples, Italy—died April 15, 1967, Rome), Italian comic, most popular for his film characterization of an unsmiling but sympathetic bourgeois figure, likened by international film critics to the American film comic Buster Keaton. Totò was born to a family of impoverished Italian nobility. He served in the military during World War I and then began his stage career by working in music halls. He appeared extensively on the legitimate stage prior to his 1936 film debut in Fermo con le mani (“Keep Your Hand Still”). From that time on, the screen was his medium, and, as Totò, he became one of Italy’s favourite comics.

Most of his 100 films were made in Italy and include 29 in the “Totò” series, such as Totòtarzan (1950) and Totò e Cleopatra (1963). Other films include Guardie e ladri (1951; Cops and Robbers), L’oro di Napoli (1954; Gold of Naples, a four-part comedy drama directed by Vittorio De Sica), La Loi c’est la loi (1958; The Law is the Law, with the French comic Fernandel), La Mandragola (1965; The Love Root and the Mandragola), and the allegorical Uccellacci e uccellini (1966; “Big Birds and Small Birds”; Eng. trans. The Hawks and the Sparrows), a film written and directed by Pier Paolo Pasolini.

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

10 I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

GianniVersace

Jul 11, 2020

Italian fashion designer

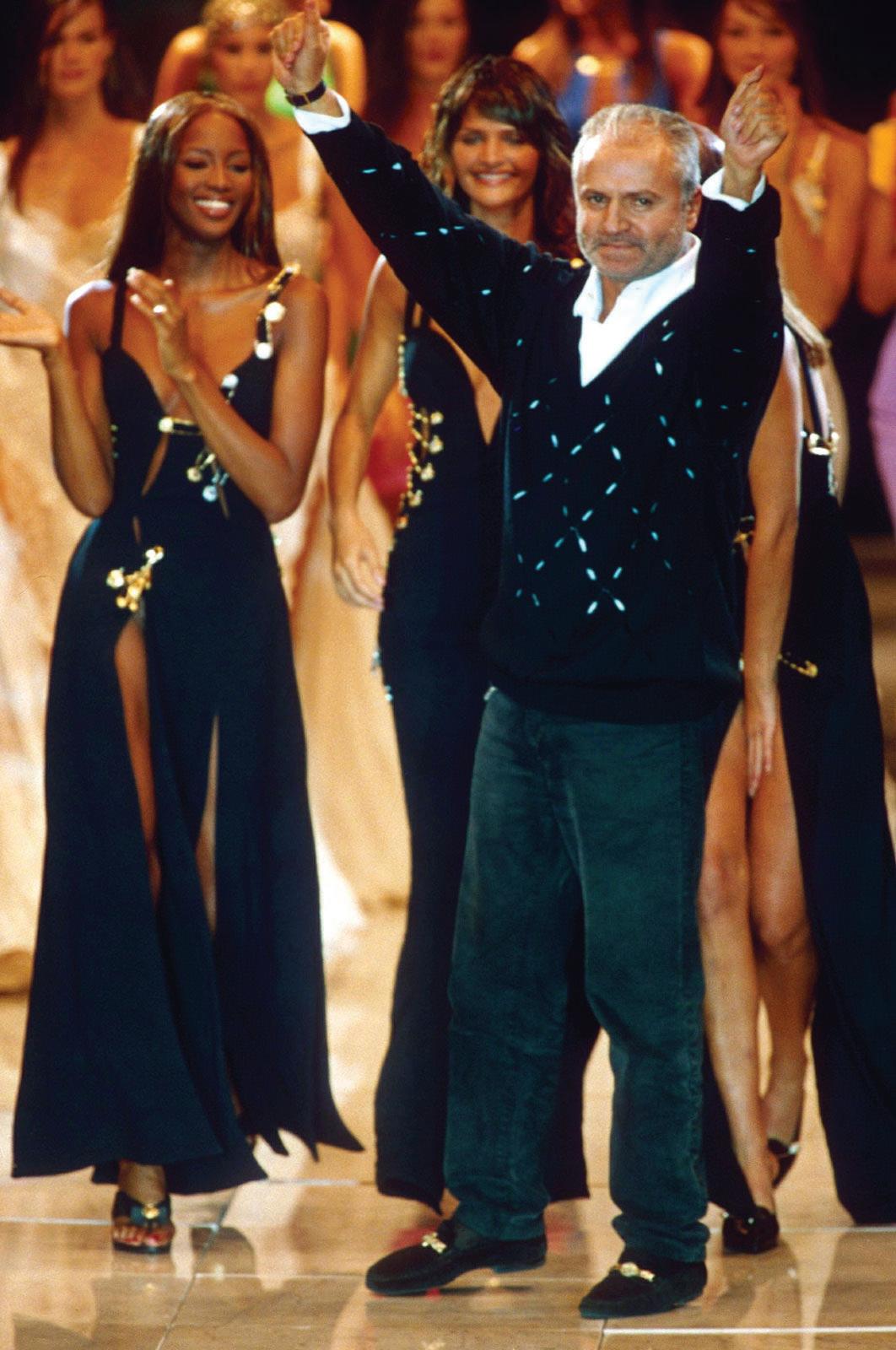

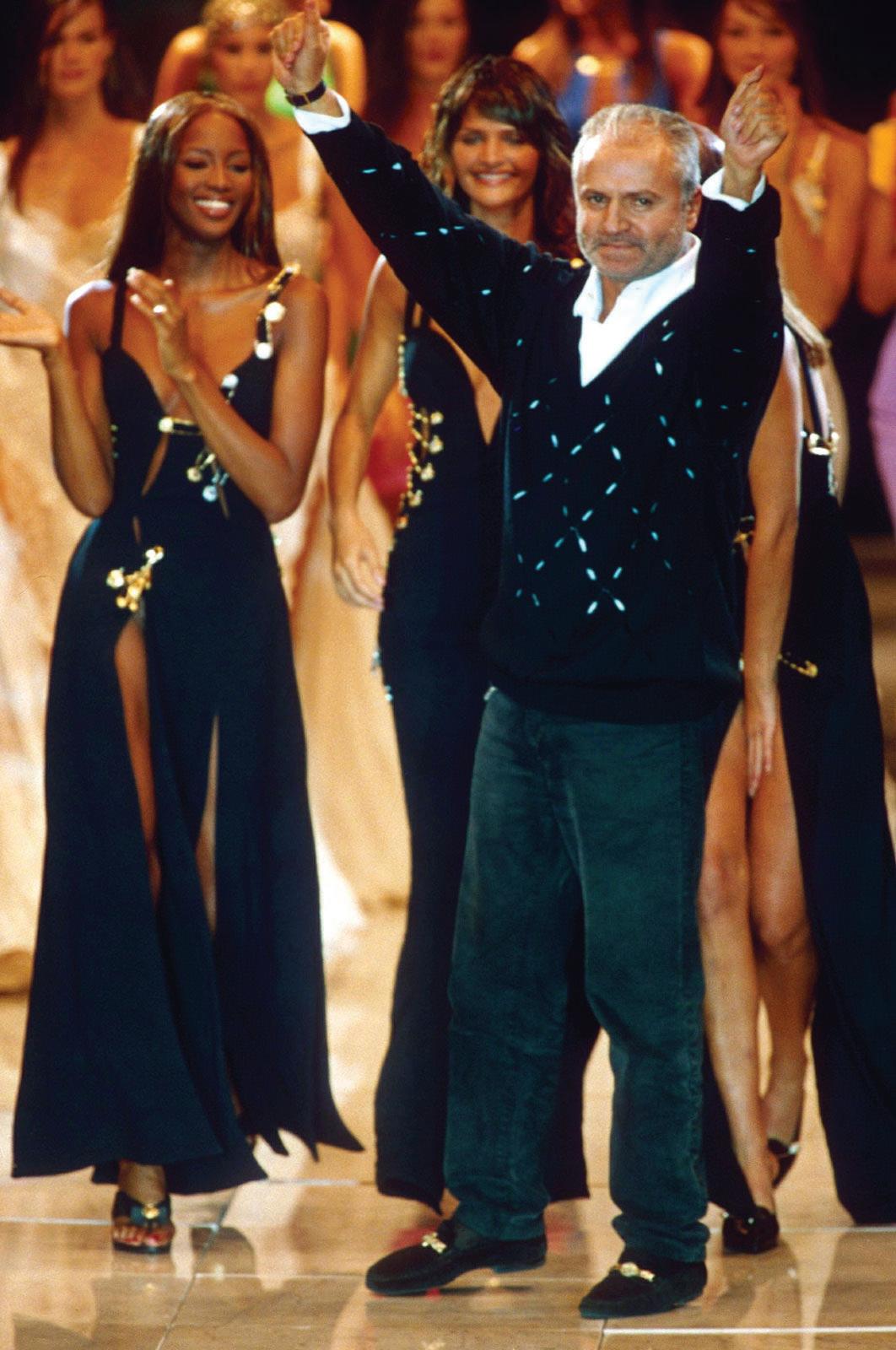

Gianni Versace, (born December 2, 1946, Reggio Calabria, Italy—died July 15, 1997, Miami Beach, Florida, U.S.), Italian fashion designer known for his daring fashions and glamorous lifestyle.

His mother was a dressmaker, and Gianni was raised watching her work on designs in her boutique. After graduating from high school, Versace worked for a short time at his mother’s shop before moving in 1972 to Milan, where he worked for several Italian ateliers, including Genny, Complice, Mario Valentino, and Callaghan. Backed by the Girombellis, an Italian fashion family, Versace established his own company, Gianni Versace SpA, in 1978 and staged his first ready-to-wear show under his own name that same year. His brother, Santo, served as CEO, and his sister, Donatella, was a designer and vice president.

Versace designed throughout the 1980s and ’90s and built a fashion empire by producing ensembles that oozed sensuality and sexuality. His most famous designs included sophisticated bondage gear, polyvinyl chloride baby-doll dresses, and silver-mesh togas. Versace’s detractors considered his flashy designs vulgar. Unfazed by such criticism, Versace staged his seasonal fashion shows like rock concerts at his lavish design headquarters in Milan, with groupies and paparazzi awaiting the arrival of both his celebrity friends, such as Elton John and Madonna, and his loyal models, such as Cindy Crawford, Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington, and Naomi Campbell, who were paid such high salaries that the press dubbed them “supermodels.” Versace was credited with turning the fashion world into the high-powered, celebrity-besotted industry it remains to the present day.

11

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

FASHION

Donatella Versace

Italian fashion designer

12company’s

Donatella Versace, in full Donatella Francesca Versace, (born May 2, 1955, Reggio Calabria, Italy), Italian fashion designer whose roles at Gianni Versace SpA included vice president and artistic director and whose contributions—business and artistic—furthered the company’s sophisticated high-end image.

Meet extraordinary women who dared to bring gender equality and other issues to the forefront. From overcoming oppression, to breaking rules, to reimagining the world or waging a rebellion, these women of history have a story to tell.

Versace was born the youngest of four children. Her older sister, Tina, died of a tetanus infection at the age of 12, leaving Donatella, Santo, and Giovanni (later Gianni) to carry on the Versace name. Gianni, the second oldest, began his fashion career by moving to Milan in 1972. The next year, Donatella began studying foreign languages in Florence. Though she was studying to become a teacher, she made frequent visits to Milan to assist her brother, who valued her insights and critiques as he made his start in the fashion industry.

When Gianni Versace SpA was founded in Milan in 1978, Donatella assumed the role of vice president. From 1978 to 1997, Donatella acted largely as a creative hand and critic for her brother, Gianni, though she did maintain control of her own lines, specifically Young Versace and Versus, the latter of which was dropped in 2005 but revived in 2010. After its relaunch, Versus, alongside Young Versace, became a staple for the company. A Versace perfume, Blonde, was released by Gianni in honor of Donatella in 1995.

Change came on July 15, 1997, when Gianni was shot and killed outside his Miami Beach home by American serial killer Andrew Cunanan. After a lengthy leave from Gianni Versace SpA, Donatella reemerged to assume the roles of chief designer and vice president of the board. She also obtained a 20 percent stake in the company, while Allegra Versace Beck—her daughter with Paul Beck—received 50 percent. Donatella’s brother, Santo, received the remaining 30 percent, and her son, Daniel Paul Beck, was willed no portion of the company upon Gianni’s death.

As artistic director and vice president, Versace advanced the company’s image through her public relations skills and confident design direction. After her brother’s death, she significantly increased the company’s exposure in markets across the globe and enhanced its reputation. Advertising efforts grew in Europe and the U.S. as Versace attached the faces of Madonna, Jennifer Lopez, Lady Gaga, Beyoncé, and other stars to the Versace line. Versace also collaborated with celebrities to produce designs. Such connections put her in high social esteem, with people such as Sir Elton John, Kate Moss, and Prince Charles

12

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Versace also led the company through a design reinvention after her brother’s death in 1997. This task required her to remove herself from Gianni’s inspirations and stylings—one of her biggest challenges as artistic director, by her own account. She sought to make the Versace look her own and, in doing so, gained the fashion house critical acclaim and a reputation for sophistication, especially in women’s fashion. Her direction turned out such creations as a green dress worn by Lopez at the Grammy Awards ceremony in 2000. The piece was deemed an instant classic in fashion history.

Versace also participated in several of the company’s high-profile business collaborations and partnerships that were intended to pursue new markets and consumers, including one with the automaker Lamborghini beginning in 2006 and another with the retail clothing chain H&M in 2011. She was at the helm when the Versace company entered real estate in 2000, opening the luxury hotel Palazzo Versace in Australia. She also made final design decisions in the construction of Versace’s second hotel, in Dubai, completed in 2015.

Over the years, changes in ownership and management of the company loosened the Versace family’s control—the multinational financial services firm Blackstone purchased 20 percent of the company in 2014, for example, and in 2016 Jonathan Akeroyd was appointed CEO—but Donatella maintained her leadership roles. In 2018 it was announced that Michael Kors Holdings Ltd. was acquiring the business for some $2 billion, though Donatella was expected to “continue to lead the company’s creative vision.”

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Carla Bruni-Sarkozy, Claudia Schiffer, Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford and Helena Christensen in last year’s Versace Tribute show, an homage to Gianni Versace’s 1991

finaleVENTURELLI/WIREIMAGE I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

SOCIALSAND MEDIA

Social and teenagers ....

How kids use social media and how many risks they can run without being aware of it.

16

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

handle with care ...

by Rosanna Mazzitelli

by Rosanna Mazzitelli

It is often abused in the use of such systems that are considered harmless only because they are used by everyone, and in reality there are dark sides not to be underestimated either by the children, much less by the reference adults who are responsible for their children. . Among the most used social networks we find Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, but the one that is really depopulating among children, even very young and under the age that the regulation provides for the subscription to the app which is 13 years old , is Tik Tok. In fact, it is the new frontier of social media and is putting everyone else in crisis. Born from Musically, Tik Tok is the company most loved by teenagers, but on it linger doubts about its safety.

One of the biggest criticisms leveled to TikTok is that the many minors on the platform expose their image without any protection. We have already seen in a previous article, how much children can run the risk of becoming addicted to the use of the INTERNET. To encourage the onset of this excessive use of the network, there are systems linked to the use of social networks, likes necessary to feel cool and visible, challenges proposed in the various platforms that put children in a position to always keep up with new trends social media to be part of the huge INTERNET group.

Just as acceptance is sought in peer groups, a typical need for adolescents, today acceptance is sought more widely. They are the social networks with their likes and comments that make a guy / a feel like others The more we conform and follow the various trends, the more adolescents feel that they are part of a system that can make them feel wanted and considered and consequently their self-esteem is also gratified by the positive responses that the web sends back. The big risk, however, is the inclemency of the virtual world, the harsh criticisms and offenses that often result from exposure to social media.

In fact, one of the widespread phenomena on social networks is Cyberbullying. Many very young people do not put any brake on what they express by losing the filters and solemnly affirming things that they would not normally dream of saying in person, even going to the extreme. Anonymity allows you to wear a mask through the creation of virtual profiles that are difficult to trace and the victims of such attacks can experience various difficulties, including anxiety, depression, addiction and loneliness. In extreme cases, to suicide.

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Thisexposure to the unconditional judgment of the other, therefore, can become very dangerous for a boy who is not yet structured from a personality point of view: for him / her a criticism made by a stranger who feels free to express himself behind the keyboard. offensive comments, it can represent a fact considered real and not questioned because it comes from the web, a source of knowledge and omniscence for the generations born with the cell phone in the cradle. It is clear how much this can affect a teenager’s self-esteem and how risky it can be, also because there is no direct confrontation with those who take the liberty of hurting through a social network. To these risks are added other even more dangerous, namely those of running into pedophiles who use these social networks to know and lure minors.

There are more and more frequent cases of children, even very young ones, who have trusted unknown people who, through a process of rapprochement, lead minors to trust up to, for example, sending pornographic material, if not even a live meeting.

To make young people think about the conscious use of technology, Safer Internet Day, the world day for network security, was established and promoted by the European Commission, which is celebrated on the second Tuesday of February. Safer Internet Day 2020 was celebrated simultaneously in over 150 countries including Italy. A recent investigation conducted by “Telefono Azzurro” together with Doxa, Kids, shows the controversial relationship between teenagers and social networks.

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

The study predicted that the boys indicated a maximum of three negative aspects of social media: about a third of them indicated that they were distracted from studying; 29% referred to lack of personal contact and relationships with others; in 21% of cases, however, a negative aspect was the illusory dimension networks of contacts that, in fact, would give the impression of having many friends, often simply strangers.

The children also referred to the way in which social networks negatively affect the perception of themselves and others; 28% of the sample analyzed then indicated the problem of addiction to social networks.

Therefore it seems that Italian teenagers know the risks deriving from presence on social networks, but at the same time it seems that they find it very difficult to abandon them.

The adult's task is to monitor their children through the various control systems that the network allows. Not leaving minors at the mercy of the network and its dangers is the necessary prerequisite to avoiding major risks. In addition to this, it is important to empower children by discussing with them what are both the positive aspects of the use of social networks but also the risky ones that a teenager, due to age characteristics, does not really take into consideration, even though he knows them well.

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Italians do it better! “When was the last time you felt good doing nothing?”

By susanna Casubolo

By susanna Casubolo

Our culture always puts productivity in the foreground and does not value “empty time” to the point that we fail to consider it without noise, without activity, without technology or other people. Time is not wasted, time is money, but time is precious even when it is empty, even when it is used for the recovery of our body and mind, to be able to continue practicing our other activities effectively for the rest of the time. This is why our holidays are so important.

A study, conducted in the United States by the Travel Association and Project, found that while 95% of Americans take their vacation time off, more than half do not fully use all of their contracted vacation days. This is because many are “martyrs” of overwork, that is, they think that by working more and more they will have more success, more career, more money, more happiness. But the data show instead that people who go on vacation for less than 10 days a year have a 34.6% chance of getting a promotion or a bonus within a 3-year period. For people who go on vacation for more than 10 days a year, the possibility increases to 65.4%.

PSYCHOLOGY 22 I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

This year, planning the holidays has been very difficult, especially due to the anxiety of contagion and the limitations given by the rules to avoid it. But there are those who have not given up doing it and the Italian summer 2020 will be remembered not only for the Covid 19 emergency but also for the rediscovery of "made in Italy" holidays and local tourism, in fact the Italian regions have been chosen as a destination for 93% of Italians, compared to 86% last year. The beach remained the most popular preference, but there was no lack of tourism in the mountains and that in small villages and smaller centers.

According to AvantGrade, the places that recorded a leap in Italian searches on Google for holidays were Gallipoli (+ 300%), the Conero Riviera, the island of Elba, the island of Giglio, the Cinque Terre (+ 200%), Vieste (+ 180%), Finale Ligure (+ 150%), Porto Cesareo, Palinuro and Sperlonga (+ 140%).

Instead of giving up their holidays, in August, 3 out of 4 Italians reviewed their programs and looked for alternative solutions to recharge their body and mind. According to Coldiretti, the holidays were shorter and dedicated to family relaxation. The alternative solutions have seen cuts in the available budget or reduction of the holiday period. One in four Italians preferred a destination close to home, within their region of residence. Many have chosen to re-open second homes owned, or stay at those of friends and family or rent, someone chose camping or camper. Among the favorite leisure activities alongside art, tradition, relaxation and pure fun, the search for local food and wine has become the real added value of “made in Italy” holidays in 2020 with about 1/3 of the budget allocated to food for consumption in the restaurant or for the purchase of souvenirs.

As Coldiretti points out, Italy is a world leader in food and wine tourism, relying on the greenest agriculture in Europe with 305 specialties with a geographical indication recognized at community level and 524 PDO / PGI wines, 5155 traditional regional products surveyed along the Peninsula, leadership in the organic sector with over 60 thousand organic farms and the largest world network of farmers’ markets and farms in Campagna Amica, in addition to the numerous enhancement initiatives such as the wine or oil roads .

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

The search for "empty time" should become a push to find the best vacation to recharge, going on vacation does not just mean moving to another place, it means shifting attention to what is happening, to loved ones, to what is there. it's around, immerse yourself in what's happening. Being entirely inside what is happening means avoiding distractions, staying in contact with yourself and others without being obsessed with the mobile phone, getting out of the multitasking mode as important for productivity as it is useless for rest, enjoying the present moment and the lived experience . And the Italians seem to have understood the importance of holidays very well, preferring to change their travel habits in order not to give up the fundamental period of "empty time" to recharge their batteries. But we know "Italians do it better".

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

MOBSTERS The Tampa Family

Tampa's underworld

by FC

Tampa crime started with Charlie Wall who, in the 1920s, controlled a number of gambling rackets and corrupt government officials. Wall controlled Tampa from the neighborhood known as Ybor City, he employed Italians, Cubans and men of other ethnicities into his organization. Charlie Wall's only competition was Tampa's earliest Mafia boss Ignacio Antinori.

Antinori gang

The first Italian gang in the Tampa Bay area was created by Ignazio Antinori in 1925. a Sicilianborn immigrant, became a well-known drug kingpin and the Italian crime boss of Tampa in the late 1920s. A smaller Italian gang in the area was controlled by Santo Trafficante Sr., who had lived in Tampa since the age of 18. Trafficante had already set up Bolita games throughout the city and was a very powerful man. Antinori took notice of Santo Trafficante and invited him into his organization and together they expanded the Bolita games across the state. By the 1930s Ignazio Antinori and Charlie Wall were in a bloody war for ten years, which would later be known as "Era of Blood". Wall's closest associate, Evaristo "Tito" Rubio, was shot on his porch on March 8, 1938. The war ended in the 1940s with Ignacio Antinori being shot and killed with a sawn-off shotgun. Both Wall's and Antinori's organizations were weakened leaving Santo Trafficante as one of the last and most powerful bosses in Tampa.

Trafficante Sr. era

Santo Trafficante Sr. had now taken over a majority of the city and started to teach his son Santo Trafficante Jr. how to run the city. In Trafficante Sr.'s adult life he only portrayed himself as a successful Tampa cigar factory owner.Santo was being watched closely by police and made Salvatore "Red" Italiano the acting boss. With the untimely Kefauver hearings and Charlie Wall testifying in 1950, both Trafficantes fled to Cuba. He always wanted to make it big in Cuban casinos and dispatched his son, Santo, Jr., to Havana in 1946 to help operate a mob owned casino. The Tampa mob made a lot of money in Cuba, but never achieved its ambition of making the island part of its own territory. After the hearings ended the Trafficantes returned to Tampa to find out that Italiano had just fled to Mexico leaving Jimmy Lumia the biggest mobster in the city. Santo had Lumia killed after finding out he was bad mouthing him while he was in Cuba and he took over again. In 1953 Santo Jr. survived a shooting. The family suspected it was Charlie Wall and they had him killed in 1955. Trafficante remained the boss of Tampa until he died of natural causes in 1954.

26

26

ofmoneyin butnever Afterthe afterfinding

Santo Trafficante at San Souci’s bar. Havana, Cuba.

cigarfactoryowner.Santo

outhe overagain. theyhad

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Trafficante Jr. era

Santo Trafficante, Jr. succeeded his father as the boss of Tampa and ruled his family with an iron fist.[3] Despite numerous stunted ambitions, he was regarded as one of the most powerful mob bosses of the American Mafia. Santo Jr. was born in the United States on Nov. 15, 1914 and was one of five sons of Mafia boss Santo Trafficante. He maintained close working ties with the Lucchese and Bonanno crime families from New York City. Santo Jr. worked closely with Lucchese family boss Tommy Lucchese, who was a friend of his father, and a man who helped train him in the 1940s.

Santo Jr. was known to have been deeply involved in the CIA efforts to involve the underworld in assassination attempts on Fidel Castro. Under pressure of a court order granting him immunity from prosecution, but threatening him with contempt if he refused to talk, Trafficante admitted to a Congressional committee in 1975 that he had in the early 1960s recruited other mobsters to assassinate Castro."It was like World War II" he told the committee. "They told me to go to the draft board and sign up." In 1978, Trafficante was called to testify before members of the United States House Select Committee on Assassinations investigating possible links between Lee Harvey Oswald and anti-Castro Cubans, including the theory that Castro had President John F. Kennedy killed in retaliation for the CIA's attempts to assassinate Castro.

Santo, Jr. never spent a day in jail, and he died of natural causes in 1987.

LoScalzo era

In 1987 Vincent LoScalzo became boss of the Trafficante family and Florida became open territory. The Five Families of New York City could work in any city in the state. LoScalzo's new family was smaller because many of the older mobsters were dead or retired.He has interests in gambling, prostitution, narcotics, union racketeering, hijacking and fencing stolen goods. He controls a few bars, lounges, restaurants, night clubs and liquor stores all over the state of Florida. Loscalzo has ties to California, New Jersey, and New York as well as being connected to the Sicilian Mafia. On July 1, 1989, LoScalzo was indicted on racketeering charges that included grand theft. The charges were later dropped and then reinstated. LoScalzo plead no contest on October 7, 1997 and received three months of probation. In 1992, LoScalzo was arrested at the Tampa International Airport for carrying a loaded .38-caliber pistol in his brief case. The weapon showed up on the x-ray scanner. He was convicted for the charge in 1999 and was sentenced to 60 days in jail.

27

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

South Florida operations

Santo Jr. started the family’s south Florida crew in the early 1980s, putting Steven Bruno Raffa in charge. Bruno ran the crew with associates and freelancers after the death of Santo Jr. Raffa maintained a good relationship with LoScalzo, the new boss of the family and Genovese mobster John Mamone. In 2000 nineteen members of the crew were arrested and Raffa committed suicide.

North Florida Operations

The Trafficante Family expanded their reach into North Florida cities like Daytona and Jacksonville during the late 1980s. The North Florida operations were run by the Maglianos & Granados. The activities of this crew included money laundering, racketeering, narcotics distribution, and illegal gambling. In May 2015, 13 people in Jacksonville were indicted by the Federal government on money laundering charges.

Current Status

As of November 25, 2007, Vincent LoScalzo is a 70+ year old semi-retired mobster and a "regular Joe" according to Scott Deitche, author of Cigar City Mafia. The old family membership has died and the Tampa Mob has fallen into the shadows of the NYC mobs.

Gambinos in Tampa

Recently statements have spread across Florida that John A. “Junior” Gotti, son of the late Gambino crime family boss John Gotti, has been running organized crime in Tampa since his release from prison in 2005. Gotti is allegedly a captain in the Gambino family. On August 5, 2008 Gotti was indicted on charges of racketeering, kidnapping, conspiracy to commit murder and drug trafficking. He and five others were indicted by a Florida grand jury.

John A. “Junior” Gotti

John A. “Junior” Gotti

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

ItalianThings

By Carmine Rodi

By Carmine Rodi

7 things you donʻt know about Italian cuisine

30

1.If you canʻt write it right, you probably canʻt make it right

2.Recipes presented as Italian, except they arenʻt

3.Stop putting chicken everywhere!

4.Pizza is not your take-all garbage bin

5. There are only so many ways to i nsult pasta

6.You guys use a lot of garlic – NO WE DONʻT

7.For coffee, Italy really is a world apart

Ireally have to start from this. In times of ubiquitous wi-fi Internet and search engine precision, it really baffles me how the hell is it still possible to make spelling mistakes on a printed menu.

I go to a high-rating restaurant to open the menu, and find horrors such as “arabiatta” (arrabbiata) and “rissoto” (risotto). Would I buy a car advertised as “Merzedec” or a phone branded “Samsnug”? Same goes with food.

I don’t trust a place with a messed up menu, because I think the manager – and anybody else who had an eye on the paperwork, really – was just plain lazy, or didn’t care enough to dedicate those extra 5 minutes to spell check the dish names.

Plus, I can understand if mistakes happen in Bangkok or somewhere else in the far side of the world (not sure how many Chinese restaurants get the names right in the west, after all), but in the heart of Europe, really? Surely in Berlin, Zurich or Prague there must be some Italian tour guide, language teacher, food enthusiast or just any person literate enough to give a half an hour look at the material and correct all the double “p” and “s”. The fact that a high-standard restaurant doesn’t even bother to check if the language is right before printing, completely defies my understanding. Really, guys, it’s simple: don’t assume you are writing it right just because some people told you, or you heard it somewhere, or even because it sounds right in your language. Ask an expert, or missing that, double check everything on the Internet first. Little details make a lot of difference.

Not to mention that some mistakes are honestly hilarious.

“Pene” in Italian means “penis”. If a restaurant lists “pene arrabbiata” (or something similar) on the menu, chances are it is trying to sell you some angry male genitals. You should probably avoid those (you should probably just avoid eating genitals all together, but one step at the time).

“Cane” means “dog”. “Chili con cane” (instead of carne, which in Spanish AND Italian means “meat”) means you are going to eat a spicy dog.

Really, it is sad. Stop doing it. We take it personal.

Ok – you are not supposed to learn the grammar of a country, just because you want to open a restaurant. That’s why I will be a bit more merciful here, hoping to help.

“Salami” is plural in Italian (singular, “Salame“). Same for “Panini” (singular, “panino“). “Fettuccini” doesn’t even exist: the correct plural form is “Fettuccine“. And “Pepperoni” is twice wrong: first, it means “bell peppers” and second, it’s spelled with single “p” (singular, peperone. Plural, peperoni).

32

The way Italian food is misrepresented, or sometimes just done horribly wrong

1. If you canʻt write it right, you probably canʻt make it right.

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

The most interesting story I found is “Baloney“. It probably comes from the American transliteration of “Bologna”. It became synonym of “cold meat”, probably because of the delicious mortadella produced in Emilia. And also (for reasons that escape me completely) it is now used as a generic term for “nonsense”. So, to recap: mortadella is this:

A lot of people seem to be under the assumption that every Italian word ends with “i” or “ini”. Short tip: stop embarrassing yourself. It’s a bit more complicated than that. So at least try to imagine that there must be some structure in the language, hidden somewhere, and that you cannot just get it right by throwing random words around and improvising it all. Gesticulating wildly will not help, either.

Recipes presented as Italian, except they arenʻt.

Fettuccine Alfredo don’t even exist in Italy. The story goes that an Italian guy started selling in New York a variation of “pasta with butter and cheese”, a simple dish that every Italian mom cooks when their children are sick. Instead of butter, he found cream. Nowadays, some Italian restaurants include it in the menu to please the American taste (which is a disgrace, really), but don’t expect to come to Italy looking for the real thing because… there is no such thing.

“Pasta with meatballs“, yeah, thanks a lot, Disney. So this is what happened: a lot of people watched two dogs eating in a movie, and desperately wanted to have the same thing. It makes perfectly sense. Strange it didn’t happen with Planet of the Apes, too.

The “Caesar Salad” was apparently invented in the U.S. by an Italian (named Caesar) emigrated there after World War I. The story is not clear, and its first original name may have been “Aviator’s Salad”, because it was a favorite of the US Air Force who went on license during the prohibition. One thing is for sure, the recipe was certainly not inspired by Julius Caesar, mainly because Caesar had no way of communicating with the Americas. Plus, he couldn’t speak English (mainly because English – and England – hadn’t been invented yet). You can find it in many touristic places in Italy, but that means you will be eating Italian food trying to imitate American food trying to imitate Italian. I think it’s enough.

“Pasta bolognese” has an even more obscure origin. “Ragu alla Bolognese” is a thing, but “Spaghetti bolognese” or simply “pasta bolognese” are not existing concepts in Italian food.

33

2

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

. Stop putting chicken everywhere!

Tothe Italian taste, chicken is either too dry, or not noble enough, to be a proper pasta or pizza complement. With a few less known regional exceptions, you wouldn’t find any variation of “Pasta with chicken” in a self respecting restaurant in Italy. I was recently in Prague in a place where (I counted them) 7 out of 10 main pasta dishes included chicken, in a way or another. Simply put: you are doing it wrong.

And the “but people really like it!” argument is invalid, sorry. We have already cleared that in the disclaimer section. In the restaurant business, your task is to educate the masses, not to please them passively. They want chicken, they can go to KFC.

. Pizza is not your take-all garbage bin.

One would say that the old DON’T PUT PINEAPPLE ON PIZZA was well understood by now, but no. It’s still one of the most popular recipes found in pizzerias all over the world. Oh well.

Time for a bit of history. Its inventor was a Greek Canadian (who died recently) who tried putting canned pineapple on pizza “for the fun of it”. The fact that so many people loved it is a celebration of how a mistake can have glorious consequences, but the fact remains: it was a mistake.

The “meat fest” pizza with meat, spicy sausages and… chicken wings. Because of course.

The secret of Italian cuisine is its simplicity. Traditional favorite pizza recipes are simple and classic matches like “prosciutto e funghi” (ham and mushrooms) or “salame e olive” (salame with olives). Potatoes and even fries can be found (I know, this comes as a shock to many of my friends), but again, only in simple combination with a few other, selected ingredients. So, try to resist the urge to add this ingredient that you like, and then this other ingredient, and this other one… the result may surprise you. Less is more in this case.

. There are only so many ways to insult pasta.

specially in summer, Italians love a “Pasta salad”. The idea there would be to cook pasta (and cook it well), then serve it cold with a mix of vegetables, cold cuts, herbs and dressing. Overcooked pasta used as a side dish would make a food lover cringe anywhere in the peninsula. That’s just such a waste of potential!

So let’s see a quick summary of what NOT TO DO when dealing with pasta: don’t overcook it! Seriously, DON’T! but seriously, the things you need to remember are few. In short, you can’t just turn the fire on, and leave to attend other business. A well made pasta dish wants you to be there.

34

3

4

5

E

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

. You guys use a lot of garlic – NO WE DONʻT.

Simply put, it’s a false stereotype that the Italian cuisine is rich with garlic flavour.

In fact, my first encounter with a “garlic soup” happened in Central Europe. And I still remember it.

True, garlic is used heavily to flavour Bruschette (roasted bread flavoured with fresh tomato, and more)

It’s spelled BRU-SCHET-TA (plural, BRUSCHETTE), it’s pronounced “Brruskaetta”. Certainly not “brusheta“, or whatever I heard over time. Ah, and “Buscetta” was a mafia boss, so you certainly don’t want to order a bit of THAT as a starter. or in some fish sauces, but that’s about it. In the traditional Italian cuisine some garlic (chopped or whole) is used to flavor the olive oil as a base for the sauce, but that’s all.

It is often separated from the rest before the finishing touches, because its strong taste is considered too dominant.

So, if your dish has a way too strong garlic flavor in it – don’t blame it on Italian food.

Iwasn’t even sure whether to include a section on coffee, or not. Because it’s such a big topic, and one of the most stereotyped.

The story is complicated. Italians have very particular tastes when it comes to coffee, with so many variations as one can possibly imagine. Even I find some of them frankly too much. I found a good and exhaustive collection here.

“Coffee etiquette in Italy has more strictures than a Catholic wedding” it states in the opening lines. How true.

So for this one, rather than criticising other countries’ coffee cultures – which is not my intention at all – I will just describe the basic elements of the Italian one.

At least, this is my objective: readers should be able to go to Italian bar and cafeterias and self confidently place their orders, attracting knowing nods and admired looks by bartenders and customers.

The basic elements are:

if you order a “latte”, you will get a glass of milk. It actually happened to an Irish friend of mine, who was visiting for the first time. Because “latte” in Italian means just that: “milk”.

In Italy there are several ways of getting “milk and coffee”.

A “caffè macchiato” will bring you a drink that is mainly coffee, with a shot of milk. A “latte macchiato” is the other way around. “Macchiato” means “stained”. Then you can have a “macchiato caldo” or “macchiato freddo“, depending if you want the spot of milk warm, or cold. People have sophisticated coffee tastes, I told you.

“Cappuccino“ (please notice double “p” and “c”) has nothing to do with anything you can find in a Starbucks is the frothy delicious beverage that brings pleasure to so many of us. It comes with a warning: people don’t drink it right after meals, because they consider it too heavy.

35 6

7

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

. For coffee, Italy really is a world apart.

That’s right, eating 2 or 3 fresh cannoli or 200 grams of chocolate cake after a big lunch is seen as a perfectly fine way to end a meal, but a cappuccino is not. If you think it doesn’t make any sense – you are not alone. But still, that’s the way culture works. So be advised, unless you want to appear as the occasional, naive tourist. You have been warned. With all of the above, soy milk is now considered a perfectly fine alternative, and you should be fine ordering it as a substitute for animal milk in your coffee anywhere but in the most remote, rural places.

A “Freddo” is served ice cold, usually for a small extra price (for reasons that I will never be able to understand. Some people say it’s because of the refrigeration (?), some other argue that it actually contains more coffee than the standard cup). And finally, you don’t need to say “espresso“. Just order a regular coffee (caffè) and that’s what you will get, because any sensible bartender knows what is the natural choice. If you want a larger, much more watered down “mug coffee”, order an “Americano“. The reaction to this order may vary from cold indifference, to amusement, to open mistrust.

Also, and that’s strange in a culture not famous for strict time management, Italians drink their coffee in one shot, while standing at the bar. It’s usually a very quick business. “Let’s meet for a coffee” has very different implications than in the rest of Europe, as sometimes it literally just means “let’s quickly catch up”. In many coffee places, there is an extra price to pay if customers want to sit at the table for their order (because it means extra time and service). You have been warned, again! So, that’s it!

I hope you enjoyed reading this as much as I loved writing it. It’s only a way to make fun of the “expat nostalgia”, and it’s a semi serious topic. Nowadays there is not so much to boast about Italy – certainly not the political or economical power, and even football prowess is in decline –so people stick fiercely to what they have. Food really is one of the most serious topics all over the country, and its rich and diverse historical tradition – combined with a wide variety of fresh ingredients easily available – probably made Italian food the deep and respected discipline that it is nowadays. We certainly love it! And I hope that, maybe after reading this post, some of you will know a little bit more about it.

Special thanks to all my group of expat friends, who supported me a lot with inspiration and suggestions: Andrea, Fabrizio, Matteo, Emilio, Tony (I hope I am not forgetting anybody). We sure love to eat!

36

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Ciao! I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Thatʻs it for now.

IMMIGRATION

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005 38

How America became Italian

By Vincent J. Cannato

By Vincent J. Cannato

When baseball legend Yogi Berra passed away last month, MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred called the late Yankees catcher “a beacon of Americana.” Sportswriter Frank Deford had employed the same theme a decade earlier, calling Berra “the ultimate in athletic Americana.”

That is quite a testament to a man born Lorenzo Pietro Berra to Italian immigrant parents and raised in the Italian enclave of St. Louis known as the Hill. There, he developed the outsize personality that would color the American experience with Italian wit.

Traditionally, when we think of Americana, we recall Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” or Betsy Ross sewing the Stars and Stripes. Now we can also invoke Berra and his famous quote, “It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Berra, an anchor of the dynastic New York Yankees of the mid-20th century, exemplifies the broad influence that Italian Americans have had on American culture since arriving as impoverished and denigrated immigrants isolated in urban ghettos. From sports and food to movies and music, they haven’t just contributed to the culture, they have helped redefine it.

That would have surprised many native-born Americans in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe was on the rise. Most Italians came from the poverty-stricken southern regions of Sicily, Calabria, Campania and Abruzzo (although Berra’s parents were part of the minority that hailed from the North). These immigrants worked mainly as semi-skilled and unskilled laborers, providing much-needed muscle for the United States’ booming industrial economy. They toiled in steel mills and coal mines as “pick and shovel” day laborers or as brick- and stone-laying masons, as my grandfather and great-grandfather were.

vincent.cannato@umb.edu I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

How America became Italian

Americans of that era saw Italians as a poor fit for democratic citizenship. Since many Italian immigrants were illiterate, immigration restrictionists sought to impose a literacy test for admission to the country that would have excluded Italians in large numbers. There was also a common belief that Italians were prone to violence. In 1893, the New York Times called Italy “the land of the vendetta, the mafia, and the bandit.” Southern Italians were “bravos and cutthroats” who sought “to carry on their feuds and bloody quarrels in the United States.” Three years later, the Boston Globe published a symposium titled “Are Italians a Menace? Are They Desirable or Dangerous Additions to Our Population?”

Nearly half of Italian immigrants were “birds of passage” who eventually returned to Italy. Those who stayed in America often settled together, forming poor ethnic neighborhoods. But these barrios were not simply replicas of their residents’ native country. Regional cultures — which distinguished Sicilians from Neapolitans — blended along with American customs that children brought home from public schools.

Two events in particular helped develop the Italian American identity. Congress passed immigration quotas in the 1920s that primarily targeted people from Southern and Eastern Europe. The Immigration Act of 1924 slashed the annual quota for Italian immigrants from more than 42,000 to less than 4,000. Stemming the flow of newcomers into ethnic neighborhoods caused Little Italys to gradually shrink, and Italian Americans moved to the suburbs and diverse neighborhoods where they were more influenced by purely American music, movies and culture.

Then came World War II, which forged a strong feeling of national unity — one that was more inclusive than the nativist campaign for “100 percent Americanism” during World War I. At the beginning of the war, Italian immigrants who had not become U.S. citizens were deemed “enemy aliens.” But President Franklin D. Roosevelt determined that the designation was counterproductive as he sought Italian American support for the war and lifted it on Columbus Day 1942 , so Italians largely escaped the fate of interned Japanese Americans. A halfmillion Italian Americans (including Berra, who earned a Purple Heart) served in the U.S. military during World War II, with some of them fighting in the Italian countryside that had been their parents’ home.

As they joined the military and integrated into suburbs, Italian Americans shed the popular stereotypes surrounding them. Gradually, the customs developed in Little Italys found acceptance in the mainstream and were absorbed into broader American culture.

Food is a good example of this phenomenon. In the early 20th century, Italian immigrant dishes were scorned and became the root of slurs like “spaghetti bender” and “garlic eater.” Garlic’s pungency seemed un-American and uncivilized, and the strong smell was seen as evidence of Italians’ inferiority. Its popularity in American markets and recipes today shows how drastically this perception has changed and how enmeshed Italian American culture has become in broader American life.

become in broader American life.

That’s also apparent in red-sauce dishes that are staples in U.S. homes and restaurants. Big plates of spaghetti and meatballs, baked ziti, and chicken parmigiana are not common in Italy, but they reflect the unique Italian American culture immigrants created. Red sauce became prevalent in immigrants’ kitchens because canned tomatoes were readily available in U.S. markets. Meat was a rarity in southern Italy but abundant in America, and the growing incomes of even working-class Italian households allowed for larger portions of meatballs and other dishes.

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Pizza, believed to have originated in Naples, epitomizes Italian Americans’ outsize influence on our culture, where pizza took on an entirely new meaning. Generally, Americans don’t like the original Neapolitan pizza, whose crust tends to be a bit soggy in the middle — unlike the crispier Italian American version. An Italian restaurant owner who opened a pizzeria in New York featuring Neapolitan pies told me his customers complain that his pizzas are undercooked.

Italian Americans have continued to put new spins on the Neapolitan creation. In Chicago, they created the deep-dish pizza. New Haven’s legendary Frank Pepe Pizzeria Napoletana is famous for its white clam pizza, as well as its regular red-sauce and cheese version. In the classic American way, corporations also got into the act, from Domino’s to California Pizza Kitchen. Few foods are more ubiquitous in the American diet, and few are more synonymous with American cuisine.

While Italian Americans’ kitchens were changing the nation’s palate, their creativity was winning over the popular culture. Before the dawn of rock-and-roll, many of the singers who defined American music were Italian Americans: Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Vic Damone, Tony Bennett, Perry Como and Louis Prima among them.

Sinatra, specifically, transcended his time and has influenced American music beyond his death. His songs have become the cornerstone of what critics call the Great American Songbook. The music itself is a cultural mash-up, borrowing from African American jazz with lyrics often written by Jewish songwriters. But with his cocked hat, Sinatra possessed an air of confidence that popularized Italian American swagger and sartorial style. He sang without an accent, but between songs listeners heard a voice from the streets of Hoboken, N.J., with Italian-dialect slang thrown in.

Italian Americans have also made a mark on film. Two of the four greatest American movies, as judged by the American Film Institute, were not only directed by Italian Americans but narrate stories about the Italian American experience. Martin Scorsese’s “Raging Bull” is a gritty, hyper-realistic tale of the rise and fall of middleweight boxing champ Jake La Motta. And Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather,” based on the novel by Mario Puzo, is a tale about the tensions of assimilation, as Michael Corleone abandons his American ambitions to take over from his father as crime boss.

Coppola and Puzo were walking a fine line with “The Godfather.” The movie reinforced the connection that many Americans made between Italians and organized crime, a stereotype that bothered Italian Americans. But Coppola and Puzo turned the Corleones into classic American characters, embodying the broadly relatable conflict between fathers and sons, tradition and modernity.

Italian immigration, at least on a large scale, is now a thing of the past. But the influence of Italian American culture remains. These immigrants and their children did not simply melt into a homogenous stew of Americanism; they created a lively ethnic community that helped shape mainstream culture.

Today, Americans are once again concerned about the number of new immigrants and their ability to assimilate. It might not quite be “deja vu all over again” (to borrow from Yogi Berra), but the Italian American experience reminds us that immigration is a process of transformation for the individuals and for American society. That bilateral cultural evolution will continue to mold who we are as a nation.

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Hilton Bentley Miami-South Beach 101 Ocean Drive, Miami Beach, FL 33139 +1 305 938 4600 www.hilton.com

By Frank Sturino

Italian Canadians

Italian Canadians are among the earliest Europeans to have visited and settled the country. The steadiest waves of immigration, however, occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries. Italian Canadians have featured prominently in union organization and business associations. In the 2016 census, just under 1.6 million Canadians reported having Italian origins.

As a group, they were singled out as enemy aliens due to Canada's allegiances in the Second World War, and have been stereotyped as mafiosi due to widespread portrayals of organized crime as an Italian phenomenon. However, the community as a whole has thrived in Canada, and Italians have played a major role in developing and promoting multiculturalism. The earliest Italian contact with Canada dates from 1497, when Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot), an Italian navigator from Venice, explored and claimed the coasts of Newfoundland for England. In 1524, another Italian, Giovanni Verrazzano, explored part of Atlantic Canada for France. Under the French regime in the 1640s, Francesco Giuseppe Bressani was part of the Jesuit missionary advance into Huron country and later published a sympathetic account of life in Iroquoian-speaking bands as part of the Jesuit Relations (or reports). Enrico di Tonti (Henri de Tonty) acted as RenéRobert Cavelier de La Salle’s lieutenant in the first expedition to reach the mouth of the Mississippi River in 1682. Italians served in the military of New France (e.g., in the Carignan-Salières Regiment),

in which several distinguished themselves as officers. Several hundred Italians also served with the de Meurons and de Watteville Swiss mercenary regiments in the British army during the War of 1812. Following the example of Italian ex-soldiers in New France who settled on the land in the late 17th century, some 200 of the mercenaries took up lots granted by Britain in the eastern townships of Québec and in southern Ontario.

Origins

Over 75 per cent of Italian immigrants to Canada have come from Italy’s rural south, especially from the regions of Calabria, Abruzzi, Molise and Sicily, each with over 10 per cent of the total. About three-quarters of these immigrants were small-scale farmers or peasants. Unlike northern Italy, which dominated the newly formed (1861–70) Italian state and continued to industrialize, southern Italy remained rural and traditional. Overpopulation, the fragmentation of peasant farms, poverty, poor health and educational conditions, heavy taxation and political dissatisfaction acted as a “push” towards emigration. Factors that “pulled” Italians to Canada included rising expectations,

army the regions Canada

the low cost of ocean travel, the example of successful relatives and friends in the New World, and the significantly higher wages there. The devastation of the Second World War, which resulted in shortages of food, fuel, clothing and other necessities, exacerbated pre-existing poor conditions. After the war, the northeastern part of Italy contributed a larger refugee component (because of the loss of Istria to Communist Yugoslavia). Friuli, which already had a long tradition of emigration to Canada, joined the southern regions as a major source of immigrants.

Early Migration and Settlement

Italian immigration to Canada occurred in two main waves, from 1900 to the First World War and from 1950 to 1970. During the first phase, 119,770 Italians entered Canada (primarily from the US), the greatest number in 1913, a year before the war interrupted immigration. About 80 per cent of these people were young males, most of whom went to work at seasonal, heavy labour in railroad construction and maintenance, mines, lumber-camps and building projects. Many labourers eventually decided to settle permanently in Canada, and by the First World War Italians were to be found not only in major urban centres but also in Sydney, NS, Welland, Sault Ste. Marie and Copper Cliff, ON, and Trail, BC. The 1911 census recorded over 7,000 people of Italian origin in Montréal and over 4,600 in Toronto.

In the early 19th century, a sizable number of Italians, many in the hotel trade, resided in Montréal. Throughout the century, Italian craftsmen, artists, musicians and teachers, primarily from northern Italy, immigrated to Canada. Italian street musicians (hurdy-gurdy men, street singers) were particularly noted by Canadians, and by 1881 almost 2,000 people of Italian origin lived in Canada, particularly in Montréal and Toronto.

In 1897, Mackenzie King, then working as a journalist, described the first street entertainer who lived in Toronto in the 1880s. This early Italian immigrant, King wrote, had worn out five street pianos and earned an average of $15 daily in his first years in the city. Some of the wandering street musicians eventually settled down to teach music or to organize bands and orchestras.

Late 19th Century

In the late 19th century, millions of Italian peasants emigrated to South America, the US and Canada, as well as western Europe. Professional recruiters and the example of successful migrants who returned to Italy encouraged Italians to set out for North America, where work was available on the railways, in mining and in industry. By 1901, almost 11,000 people of Italian origin lived in Canada, particularly Montréal and Toronto. Those who settled in Canada's growing cities worked as construction and factory workers and building tradesmen, as food and fruit merchants, or as artisans such as barbers and cobblers. Out of modest beginnings, a few — e.g., Onorato Catelli of Montréal in the foodprocessing industry and Vincent Franceschini of Toronto in road construction — were highly successful. While the great majority of immigrants settled in urban centres, agricultural colonies were established at Lorette, MB, and Hylo, AB. In the Niagara Peninsula and Okanagan Valley, Italian proprietors of orchards, vineyards and vegetable farms prospered. Many Italian truck farmers on the cities' outskirts grew small crops for local consumption.

Despite tighter immigration restrictions following the First World War, over 29,000 Italians had entered Canada by 1930. Many of them were farm labourers or wives and children sponsored by breadwinners in Canada. This movement, however, virtually ended with the Great Depression.

The Depression Era

Throughout the 1930s strong family networks and thrift helped Italian Canadians absorb some of the economic shock of unemployment and deprivation. Their problems were compounded after 1935, when Canadian hostility towards fascism was directed against Italian Canadians, many of whom were sympathetic towards Mussolini. As a consequence of Italy’s alliance with Germany in the Second World War, Italian Canadians were designated “enemy aliens” and were the victims of widespread prejudice and discrimination. Men lost their jobs, shops were vandalized, civil liberties were suspended under the War Measures Act, and hundreds were interned at Camp Petawawa in northern Ontario. While a few of these men had been active fascists, most were not; and they, as well as their families, who were denied relief, bore the brunt of hostilities. As a result, many Italians later anglicized their names and denied their Italian background.

45

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

After the Second World War, the widespread shortage of labour caused by a booming economy, as well as Canada's new obligations within NATO, once again made the country receptive to Italian immigration. Postwar immigrants, who numbered over half a million, came to comprise almost 70 per cent of the Italian Canadian population. Many Italians initially immigrated under the auspices of the Canadian government and private firms. The Welch Construction Company, for example, which was founded at the turn of the century by two former labourers, Vincenzo and Giovanni Veltri, specialized in railway maintenance. Men often arrived under oneyear contracts to do hard physical labour similar to that of their earlier compatriots, though now the great majority came as permanent settlers, later sponsoring wives, children and other relatives. Family "chain migration" from Italy was so extensive that in 1958, Italy surpassed Britain as a source for immigrants. Starting in 1967, new regulations based admissibility on universal criteria such as education; this "points system" spelled out conditions for family sponsorship that would apply to a limited range of relatives. As a result, Italian immigration dropped significantly in the ensuing years.

Settlement and Economic Life

In 2016, 59 per cent of Italian Canadians lived in Ontario, 21 per cent in Quebec and 10 percent in British Columbia. The majority of Italian Canadians lived in towns and cities. The most significant concentrations being in Toronto, where Italian Canadians numbered 484, 360, in Montreal where they numbered 279, 795 and in Vancouver where they numbered 87,875. In the 2016 census, 695,415 Canadians listed Italian as their single ethnic origin and 892,545 listed Italian as part of their ethnic origin (multiple response) for a total of 1,587,960 million Italian Canadians.

In cities where Italians have settled in sufficient numbers, they have tended to create ethnic neighbourhoods. These "Little Italys," with their distinctive shops, restaurants, clubs and churches, are easily recognizable, but they have rarely been ghettos segregated from the rest of society. Over the years, these immigrant areas have decreased significantly in size, though they have generally survived as viable socio-economic centres. While the movement out of immigrant neighbourhoods to more prosperous residential areas has been significant, even in the suburbs it is still common to find concentrations of Italian Canadians who have chosen to live near one another because of kinship or village ties. Seventy-five per cent of immigrants coming in after the Second World War were employed in low-income occupations, but this changed dramatically with the second and subsequent generations. By the mid-1980s, the children of immigrants had achieved a level of higher education at par with the national average, a fact reflected in their increasingly important positions in professional and semi-professional occupations. Italian Canadians have the highest rate of home-ownership in Canada, reflecting the centrality of the family. By the 1980s, 86 per cent owned their own home compared to 70 per cent of the population generally.

Much like their American counterparts, Italian Canadians have often been indelibly associated with the mafia. The November 2011 Charbonneau commission inquiry into the corruption of public officials in exchange for construction contracts may have added to the public perception of crime as a mostly Italian activity. Fueled by the dozens of murders which took place following the arrest, extradition and incarceration of Montréal mafia boss Vito Rizzuto in 2004. However, as the 2010 report from Criminal Intelligence Service Canada states, "There is not a single dominant organized crime group across Canada."

46

the after par for perception I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Mutual-aid societies, many of which grew out of village organizations, were among the earliest institutions established by Italian immigrants. The Order of the Sons of Italy (the first Canadian branch was established in Sault Ste. Marie in 1915) was open to all people of Italian heritage. In 1927, some Québec lodges, opposed to the order's pro-fascist leanings, broke away to form a parallel structure, which a decade later was renamed the Order of Italo-Canadians. Wartime hostilities inhibited the work of the mutual-aid societies, but their decline was really made inevitable by the growing influence of the welfare state and insurance companies.

After the Second World War, numerous new clubs and societies were established around regional, religious, social or sporting functions. Building on the work of the Italian Immigrant Aid Society, in the early 1960s the Centre for Organizing Technical Courses for Italians (COSTI) was founded in Toronto to provide technical education and upgrading, as well as English courses and counselling. In the mid-1970s, COSTI also established a special program to meet the needs of immigrant women and during the next decade expanded to assist many newer immigrant groups (e.g., Chinese, Portuguese, Latin American, etc.).

In 1971, the Italian Canadian Benevolent Corporation (ICBC) was founded in Toronto. Undertaking what was the largest project of its kind in North America, the ICBC built a multifaceted complex with senior citizens' housing and a community centre offering recreational, cultural and social services. Similar projects followed in quick succession in Italian communities across Canada including those in Thunder Bay, Winnipeg and Vancouver.

The founding in Ottawa in 1974 of the National Congress of Italian Canadians was an attempt to bring national cohesion to the greater Italian Canadian community and increase its political influence. The congress coordinated the raising of millions of dollars from across Canada to provide relief for the victims of earthquakes that devastated Friuli in 1976 and Campania and Basilicata a few years later. In the late 1980s, the congress took up the issue of the wrongful internment of Italian Canadians during the Second World War, for which it received an apology from the prime minister. Given the large size of the group, it is not surprising that internal divisions would occur along regional, political, generational and class lines. The Canadian Italian Business and Professional Association and the Italian Chamber of Commerce represent the interests of employers and professionals, while working-class Italian Canadians have sought to protect their interests through various organized labour movements. Comprising a conspicuously large proportion of the labour force in both the construction and textile industries, Italian Canadians have been especially prominent, for example, in the International Labourers Union and the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America.

47 Community Life

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Cultural Life

Like many major community organizations, the Italian-Canadian press and media have promoted cohesion and have mediated between their constituency and the wider society. The first Italian newspaper in Canada was published in Montréal in the late 19th century; by 1914, several others had been founded from Toronto to Vancouver. After 1950, dozens of Italian newspapers and magazines, many aimed at particular regional, religious or political markets, proliferated across Canada. By the mid-1960s, Italian-language publications had a readership of 120,000. The most influential of these are Il Corriere Italiano of Montréal, and, prior to its demise in May 2013, Il Corriere Canadese of Toronto, which carried an English-language supplement to reach younger Italian Canadians. In 1978, the owner of Il Corriere Canadese had launched a multilingual television station in Ontario, CFMT (rebranded as OMNI TV in 1986 after being purchased by Rogers), which transmits in Italian andother languages daily. A few years later, the Telelatino Network commenced operations as a national cable system for Italian and Spanish programming. Currently, Italian and Chinese are the most widespread non-official languages in Canadian television and radio broadcasting.

Italian Canadians have altered society's tastes in food, fashion, architecture and recreation, thus helping to bring a new cosmopolitanism to Canadian life. They have also made important contributions to the arts. Mario Bernardi of Kirkland Lake, Ontario, for example, was appointed the first conductor of Ottawa's National Arts Centre Orchestra in 1968 and helped guide it to international stature. The avant-garde paintings of Guido Molinari of Montréal now hang in leading galleries. At the more popular level, Bruno Gerussi, a former Shakespearean actor, became a well-known radio and TV personality. Among the many writers of Italian background are J.R. Colombo, a best-selling author of reference works and literature, and the Governor General’s Award-winning author Nino Ricci (see also Italian Canadian Writing; Ethnic Literature).

Education

Dante Alighieri societies throughout Canada offer films, lectures, Italian-language courses and other programs to foster knowledge of Italy. In 1976, the Canadian Centre for Italian Culture and Education was founded in Toronto to design and institute Italian-language programs in schools. Also important are the cultural institutes run by the Italian government, the Italianlanguage holdings of public libraries and the many Italian clubs in universities and high schools. The 1970s ushered in major changes in Canadian education as a result of the adoption of multiculturalism in public policy. By the mid-1980s, all provinces, except for those of Atlantic Canada, had developed heritage language programs, which included the teaching of Italian where sufficient demand existed. In Ontario, over 40,000 elementary school students were enrolled in Italian courses, comprising almost half the total enrolment in non-official languages. Great strides were made by Italian Canadians in educational achievement, as reflected in post-secondary statistics. By the mid-1980s, the percentage of Canadian-educated Italians (Canadian-born and those emigrating before age 15) with a university degree was above the 10 per cent mark, which represented the total population. Over one-quarter had a community college education, 3 per cent more than overall. Over 7 per cent of male Italian Canadian students were enrolled in the professional fields of law, dentistry and medicine (which was at par with the average for all groups) and had one of the highest proportions undertaking graduate studies.

48

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Religious Life

Italian ethnicity in Canada is closely connected to Roman Catholicism, the faith of 95 per cent of Italian Canadians. Historically, the Catholic Church has sought to minister to Italians through religious orders, especially the Servites in Montréal, the Franciscans in Toronto and the Oblates in the West Coast. Scalabrinian priests specializing in work with immigrants became active in major cities after the Second World War, and great expansion occurred in the 1960s when many national parishes and Italian-language services were established across the country. By 1970, Montréal's Italians were being served by eight churches, while in Toronto (where they accounted for one-third of the city's Catholics) they were served by three times this number, and by 65 Italian-speaking priests.

As well as addressing the spiritual needs of its members, the church has been involved in immigrant aid, education and recreation, and contributed toward the preservation of the Italian Canadian community’s language and culture. A distinctive Italian-Canadian Catholicism has been preserved by two major practices — the honouring of the saints' days throughout feste and the celebration of the sacraments (especially marriage) through banquets. These practices are both religious and social and often bring together several hundred relatives and paesani.

In daily life, the influence of Catholicism can be seen in the strong family values of Italian Canadians, which give the group higher rates of marriage and fertility, and lower rates of divorce and separation, compared to the overall Canadian average. The majority are opposed to divorce, abortion and even artificial contraception. Most Italian Canadians believe they have a responsibility to care for aged parents, a conviction reflected in living arrangements showing almost half in multi-family households.

Politics

The first successes of Italians in politics occurred in northern Ontario and the West Coast rather than major cities. Through the 1930s, Italian Canadians were elected to local councils and mayoral offices in Fort William (now Thunder Bay), ON, Mayerthorpe and Coleman, AB, and Trail and Revelstoke, BC. One of these, Mayor Hubert Badanai of Fort William, in the 1950s was elected as one of the first Italian federal members of Parliament for the Liberal Party. In 1952, Philip Gaglardi of Mission City, BC, was elected to the provincial legislature for Social Credit and became the first cabinet minister of Italian origin in postwar Canadian politics. However, it was not until 1981 that Charles Caccia — initially elected as a Toronto MP in 1968 — was appointed the first federal Italian-Canadian cabinet minister by Prime Minister Trudeau. Moreover, a former St. Catharines councillor, Laura Sabia, became chairperson of the Ontario Council on the Status of Women in 1973 and a leading activist in the women’s movement.

Federally, the Italian vote has generally supported the Liberals, partly because they were perceived as being more open toward immigration and more committed to multiculturalism. Like other Canadians, Italians have tended to vote differently at the provincial level. In both Ontario and British Columbia, for example, many have supported the New Democratic Party. In the 1984 federal election, however, the Progressive Conservative Party made gains among the group, especially in Québec where two Montréal candidates of Italian background were elected. By the mid-1980s, Italian Canadians had attained a level of political representation commensurate with their numbers. In 1993, 15 Italian Canadians were elected to Ottawa. This comprised five per cent of House of Commons seats, which compares favourably with their standing at about four per cent (multiple origins) of the Canadian population. As of 2012, 14 members of Parliament had been born in Italy.

49

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

Cultural Conservation

While group cohesion among Italian Canadians has been provided by a sense of shared history, community institutions, and distinctive cultural and religious traits, cultural conservation rests upon the bedrock of the family. The most significant social institution among Italian Canadians has been the family, both nuclear and extended. Commonly, in the traditional family in Italy the roles were clearly defined, mirroring similar patterns around the world. The husband was considered family head and provider; the wife was expected to be a good homemaker and mother. Children were to show obedience and respect towards their parents. Each member was to act for the betterment of the whole family rather than for his or her individual interest. Many Italian immigrants have attempted to maintain such family patterns, but change was inevitable.

Because traditional ways differed markedly from what was expected in the wider Canadian society, the resulting conflict was often at the root of many social problems. At times the children of immigrants have found that their aspirations for upward mobility and individual expression conflicted with the family's insistence on solidarity and the fulfilment of traditional roles. The second-generation ItalianCanadian family, however, has changed considerably. While usually maintaining an emphasis on family cohesion, respect and loyalty, it has increasingly moved toward a greater equalization of roles between husband and wife. The family still provides its members with important support, and the extended family (relatives to third cousin) is frequently reunited at weddings, baptisms and similar events. Often friends are drawn from the extended family and economic favours are exchanged among family members. Related to this, local loyalties among Italian Canadians from the same village often link extended families into a much larger group (paesani) connected by personal bonds.

This is not to suggest, however, that Italians have wished to live as an ethnic enclave. Prewar Italian-Canadians, by 1941, had a higher rate of intermarriage (45 per cent) than most other major ethnic groups and in the postwar period a similar rate was again reached by the mid-1980s. In Québec, Italian Canadians integrated more easily into the francophone society than do many other cultural communities. The 2006 census recorded 476,905 Canadians who reported Italian as their mother tongue (first language learned). This number fell to 437,725 in the 2011 census, and then again to 407,455 in the 2016 census.

The expansion and consolidation of the Italian-Canadian community since the Second World War has been due to a strong degree of commitment on the part of immigrants and their children. The resulting high level of institutional completeness provides Italian Canadians with the possibility of expressing their ethno-cultural identity through a wide spectrum of activities, ranging from Italian-language television to sports leagues.

50

I’M ITALIAN ISSUE #005

www.autism20.com Autistic people rock

ITALIANS IN FLORIDA

“The people who had lived for centuries in Sicilian villages perched on hilltops for protection from marauding bands and spent endless hours each day walking to and from the fields, now faced a new and strange life on the flats of Ybor City.” –Tony Pizzo, The Italians in Tampa.

The Italians of Ybor arrived almost exclusively from Sicily. Life in that island off Italy’s southern coast was unimaginably hard in the mid- to late 1800s. Most of the immigrants whose eventual destination was Ybor City came from Sicily’s southwestern region, a hilly area containing the towns of Santo Stefano Quisquina, Alessandria della Rocca, Cianciana and Bivona. Dependent on agriculture (including the cultivation of almonds, pistachios, flax, olives, wheat and wool), mining and limited trade contacts, the residents of the area struggled with poor soil, malaria, bandits, low birth rates, high land rents and absentee landlords.