PLA (y) ZA

An urban infrastructure for physical play, daydreaming, and reverie

Daniel Moonsoo Kim

Advised by Aki Ishida AIA

Undergraduate Thesis Documentation

Part 1

Virginia Tech School of Architecture + Design

An urban infrastructure for physical play, daydreaming, and reverie

Daniel Moonsoo Kim

Advised by Aki Ishida AIA

Undergraduate Thesis Documentation

Part 1

Virginia Tech School of Architecture + Design

An urban infrastructure for physical play, daydreaming, and reverie

Undergraduate Thesis Documentation • Virginia Tech School of Architecture + Design By Daniel

• Advised by Aki

Acknowledgements

Aki Ishida, AIA, LEED AP

A professor, Architect, and the school’s Interim Associate director and now a director of the College of Architecture and Graduate School of Architecture & Urban Design in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis. Thank you for the constant feedback during the year and always encouraging me to push further, you steered my studies to the right direction.

Kevin Jones, AIA

A professor and architect. Thank you for the numerous conversations during pinups along the year and giving me constructive advice on my work.

Jason Kim

A colleage, and a friend. I will forever cherish the endless discussions about architecture and design. Our dialogues constantly fueled a string of questions and established numerous discoveries.

Jae Yoo

A colleague, and a friend. Thank you for listening to my work and always giving me constructive feedback. Your comments pushed me to assess decisions once more and helped the projects to be more focused on the right ideas.

John Tan

A colleague, and a friend. Thank you for encouraging me with my work and being there as we bot developed our thesis throughout the year.

Kyoung-Suk Moon

A professor, mentor, and mother. Thank you for sending me sources and writings related to my inquiry. Your personal studies on developmental psychology and personal identity was the foundation of my thesis.

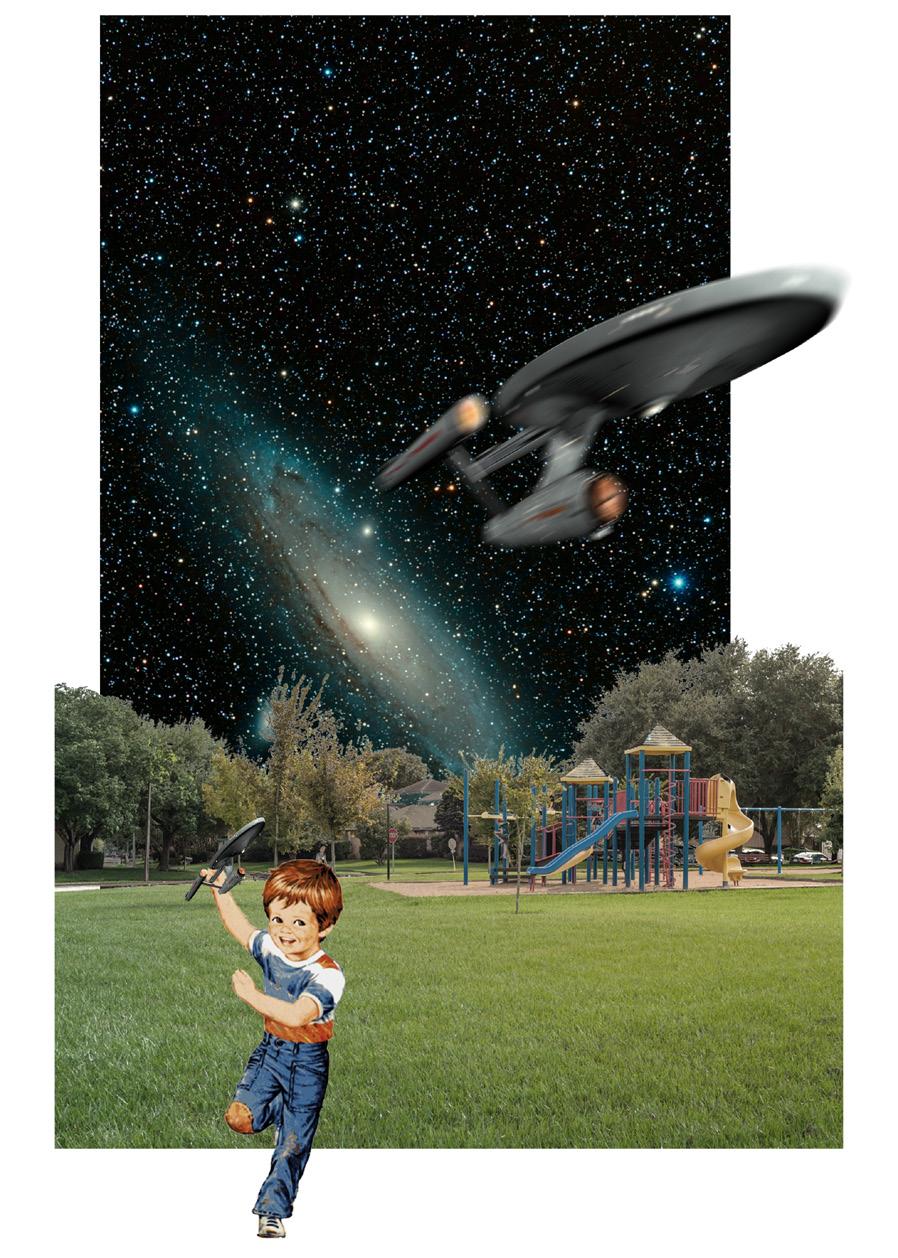

Fantasy and reality often overlap.

During play, children encounter new discoveries and form new imaginations. As a result, they naturally gain a stronger sense of selfawareness and a sense of one’s own will, or identity. If the act of free play is the key to self development, where are the play spaces for adults and of all ages?

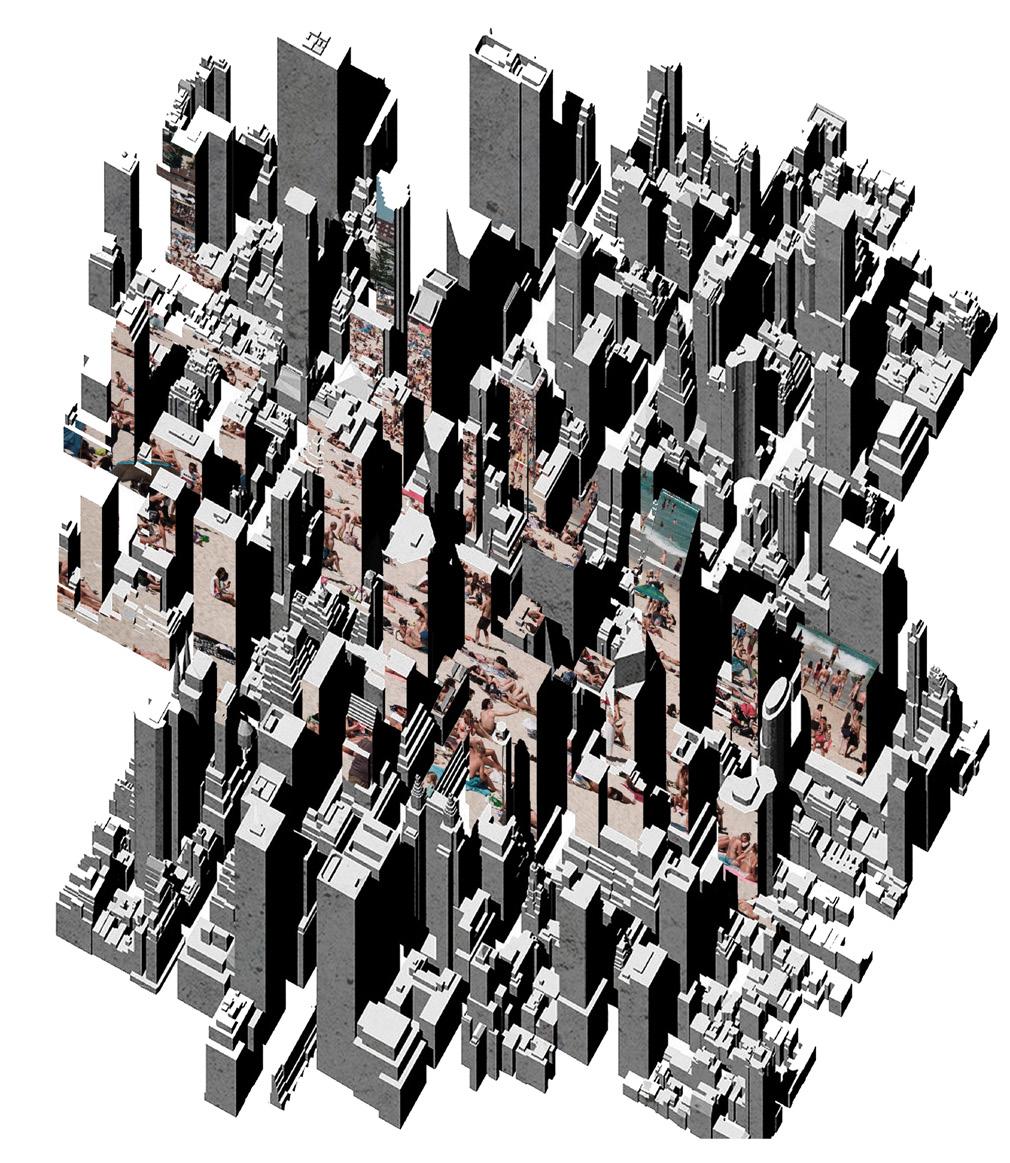

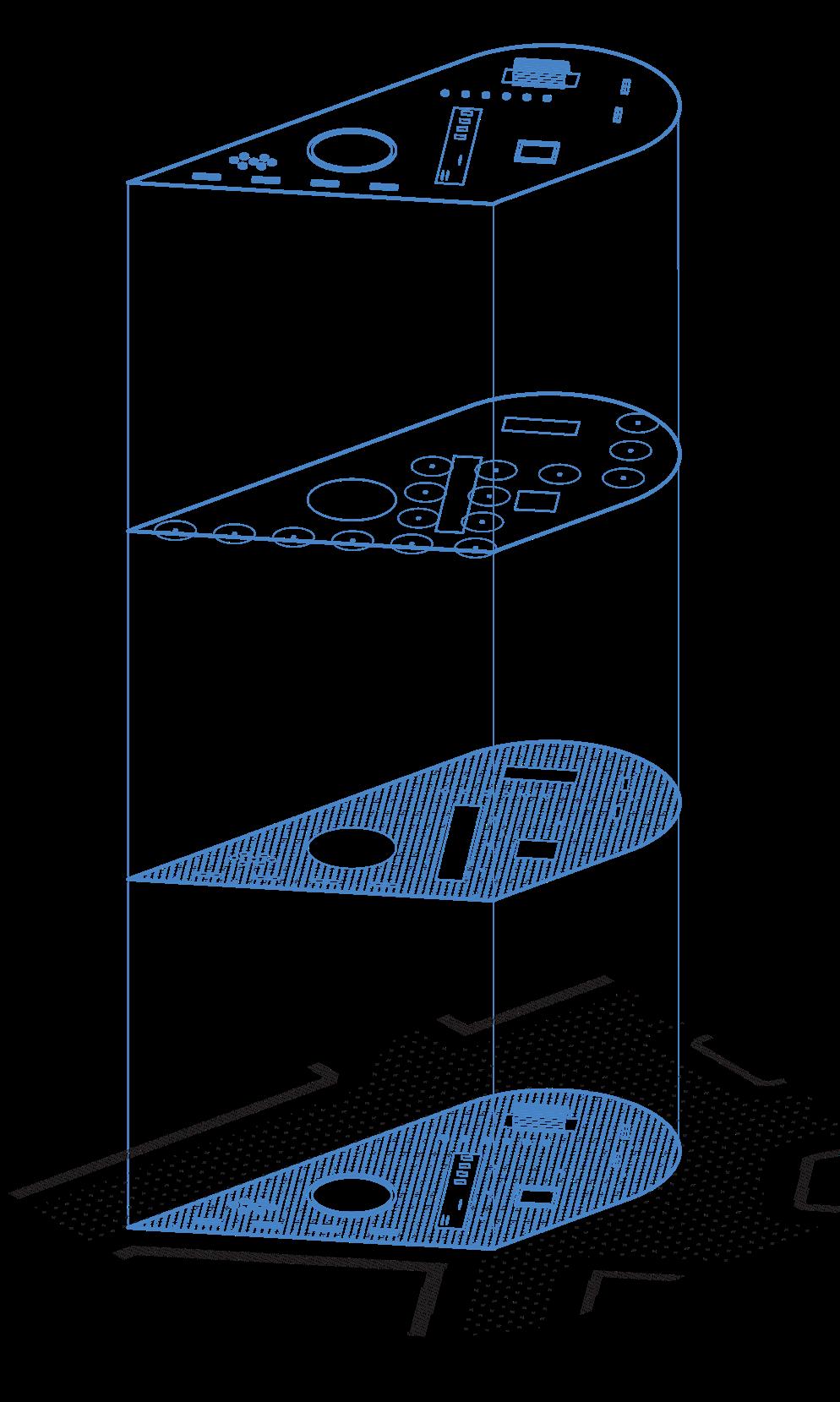

Playza is an urban infrastructure on a portions of Park Avenue’s median spaces in Manhattan for the everyday urbanite to momentarily pause, daydream, fantasize, and connect; It is a plaza woven in to the everyday world, offering an oasis where everyone is given the chance to re-new their selfhood.

Defining ‘Play’ calls for both studies in the realm of the physical which refers to active play in social settings, and of the mind, which refers to reverie and fantasy in a reserved, personal state. Through studies on children playgrounds, novel architectural ideas on leisure and entertainment, memory’s impact on daydreaming, and on juxtaposing different play spaces, a concept of spatial collaging is formed and deployed directly above the avenue to realize a place for reintroducing play into our lives.

The journey of this project begins with asking the question of how we spend our excess time and perhaps a realization that as adults, we have lost the notion of play. With this question, follows a deep dive into the crossroad between play and architecture; What makes a space engaging and invites a sense of curiosity as well as being present with the mitigation of, or even pure absence of productivity and practicality - in a positive sense?

Form typically follows function, but there are cases such as play spaces that should be more loose in function and objective. Artist Isamu Noguchi’s sculptural pieces like the Ziggurat (1968), and and stage sets like Frontier (1935) for Martha Graham embody this design ehos and go further to even being titled with the phrase, U seless Architecture in The Noguchi Museum. From this seperation from form following a common sense of rationale, spaces open up for interpretation, meaning, and use. His playground and landscape projects evoke not only the visual sense but invites all the senses. With the ambiguous spatial qualities, calls for a participitory, subjective exploration of the physical universe. The phrase “useless architecture or useful sculpture” describes the purposefully ambiguous target Noguchi explored in his work. This thesis similarly poses this notion of an impracti -

cal, unresolved, sculpture-like space as a key philosophy while exploring play spaces for not only children, but for everyone, of all ages.

Throughout the investigation there were multiple checkpoints of revisiting the abstract, as different questions surfaced. The following checkpoints show how the abstract has evolved along with new questions and discoveries.

During Play, one gains a heightened sense of “internal locus of control” or the belief that fate is in his hands. Through sequences of voluntary actions and thoughts, one obtains a deeper understanding of his identity and discovers what he is innately attracted to, how he understands his surroundings, and who he is as a being. Play should always be a part of one’s life but where are the play spaces for not only children but for those of all ages?

With the recent pandemic accelerating the inclusion of remote work and workplaces promoting a hybrid system, office spaces will decentralize, and people will have the

freedom to work anywhere. Could there be a place that simultaneously encourages physical/bodily play and also that serves as a place of productivity that caters to remote workers?

Checkpoint 2

In a culture of speed, productivity and constant data consumption, how are times of non-productivity spent? What do we do with our excess energy and time? As important as our professional career and work, how we spend our free time defines who we are and what we are innately gravitated to. Children physically engage with their curiosity and imagination in playgrounds, but where are the sacred play spaces for adults? How can architecture cherish the moments of pause, of no objective?

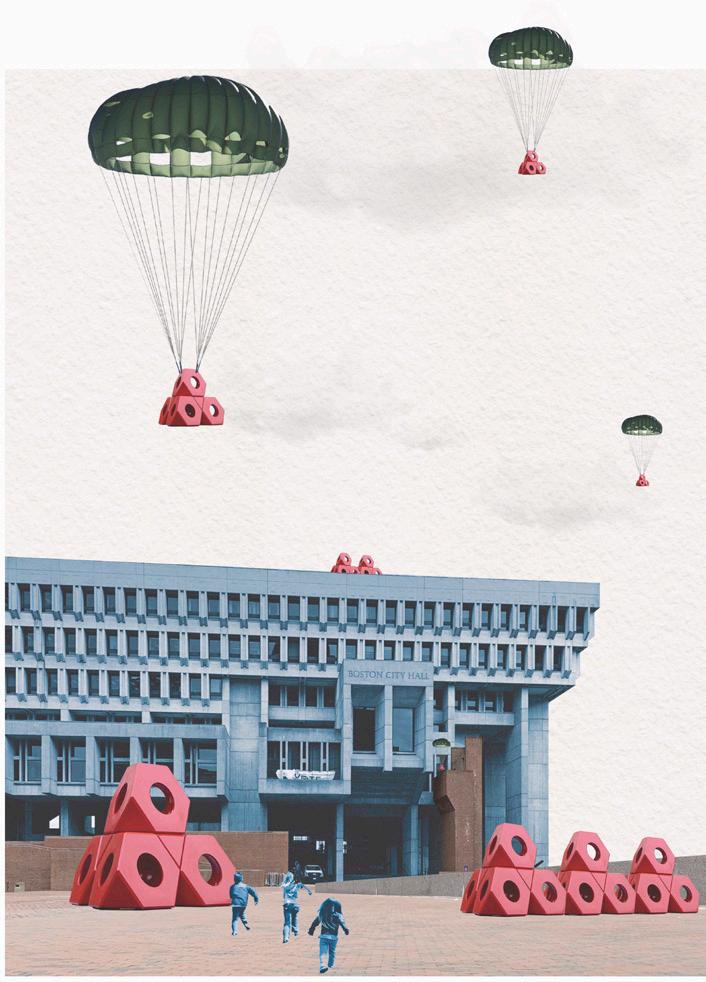

An assembly of follies will be interspeersed within the dense fabric of New York City. Playgrounds that encourage visitors to move and explore their surroundings evoke a casual atmosphere, sense of curiosity, and range of social interactions. The set of follies provides a space of play for adults and enables the residents to meaningfully enjoy their leisure time.

Checkpoint 3

Play- or fun, imaginative, and voluntarily-directed activities- is a key part in life for not only children, but also for adults. The act of engaging in play helps us to build social constructs, understand the nature of the world, and create new ideas and thoughts. Play additionally increases the sense of one’s internal locus of control, or the sense of being in control in one’s internal locus of control, or the sense of being in control in one’s life Due to the lack of a product or result at the end of “playing” or engaging in a recreational activity, we often neglect the importance of spending our excess time in a meaningful manner. We have surrendered to the state of a lethargic and passive state of receiving an infinite stream of media and data through multiple social networking apps and other digital feeds. How then, in a culture of speed, effieciency, and data consumption, can times of non-productivity be spent in a state of physical and mental presence? Children physically engage engage with their curiosity and imagination in playgrounds, but where are the sacred play spaces for adults?

Before diving in, here is a list of words and phrases that are commonly visited and that will be used throughout the book frequently.

Play (verb)

1 a : to engage in sport or recreation

b : to have sexual relations

c : (1) : to move aimlessly about (2) : to toy or fiddle around with something

2 a : to engage or take part in a game

b : to perform an action during one’s turn in a game

Daydream (noun)

: a pleasant visionary usually wish ful creation of the imagination

Reverie (noun)

: the condition of being lost in thought

A psychological concept that refers to how strongly people believe they have control over the situations and experiences that affect their lives.

Internal locus of control refers to the belief that their life is a result of the effort and work that has been personally invested in to a set of activities.

External locus of control refers to the belief that their successes and failures result from external factors such as luck, fate, injustice, and bias.

(The concept was developed by Julian B. Rotter in 1954, and has since become an aspect of personality psychology.)

“We are never more fully alive, more completely ourselves or more deeply engrossed in anything than we are playing.”

- Charles Schaefer¹

Playgrounds are safe spaces for children to emerge in the built reality and their imaginative universe. The abstract nature of playgrounds helps children stitch the range of play objects to their world and therefore encourages a state of mind that limbos between reality and fantasy. Could we re-introduce such a space that could stir up one’s imagination, for not only children but also for adults? This called for analyzing multiple play spaces in order to understand the different architectural elements that form to promote creative, self-driven activities. From Aldo van Eyck’s post war playgrounds to Isamu Noguchi’s sculpted landscapes, and even junkyards of the 60’s in Manchester, each investigation added insight in what consists of a successful playground (here, the level of successfulness refers to the level of engagement and the openness for interpretation of a particular play space). Aldo van Eyck’s play elements were constructed in abstract, simple geometries due to the lack of accessible materials after World War II. As a result, the odd forms resemble a ruin of scattered play elements that could be

interpreted in multiple manners. Noguchi’s play sculptures such as the Octetra also adopted simple, geometric forms that were open for interpretation by the user. His carved landscapes such as the Play Mountain suggest a free and continuous movement with generous curves and slopes. Through the research of other playgrounds and even ruin-like junk yards, a good playground contains various ranges of risks for children to encounter. There could be pockets of pits or slippery curved surfaces. However with the presence of risk, invites creative responses to reacting with the space. Children’s rights activist Lady Marjory Allen advocated that children should be given space to take risks and once said “Better a broken bone than a broken spirit.” 2

After World War II, the Dutch architect Aldo van Eyck developed hundreds of playgrounds in the city of Amsterdam. These public playgrounds were located in parks, squares, and derelict sites, and consisted of minimalistic aesthetic play equipment that was supposed to stimulate the creativity of children. Whereas a slide or a swing dictates what a child is supposed to do, van Eyck’s play

Through play, children discover who they are and what feels natural to them. What could the equivalent playscape look like for people of all ages?

equipments invite the child to actively explore the numerous affordances (action possibilities) it provided. Such play elements with numerous affordances include rectangular or circular sandpits and climbing domes. Matter such as sand is endlessly sculptable and may be transformed freely within the sandpit. Climbing domes also generate a range of motions, acting as a stage for choreographies of physical movements along the curved surface of the dome.

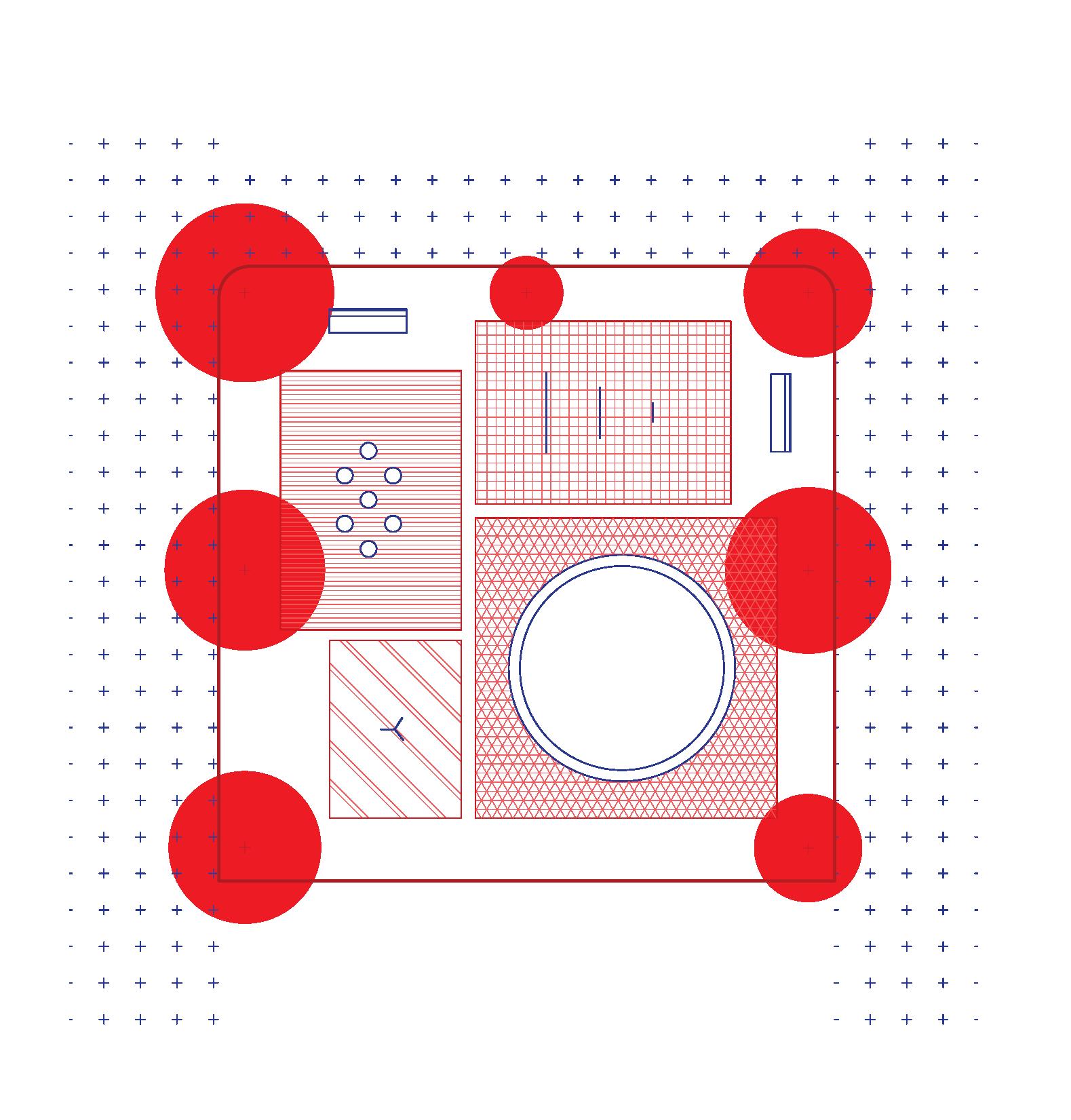

A basic design method is identified in studying eight playgrounds designed by Aldo Van Eyck. These playgrounds which were for Amsterdam children in the mid 20th century share common design intentions such as the use of vegitation as loose boundaries for the playground and the simplicity of the play elements in terms of form and function. Elements were also scaled properly for child use. The incrememnts of bars, width of two parallel bars, and the height of climbable pillars are all propotional to the limbs of a young child or adult.

Although the play elements adopted simple geometric forms which led to open-interpretation for the children engaging with the objects, VAn Eyck’s playgrounds do have one drawback, Play elements are too ordered and

spaced out. Too much symmetry, order and regularity toward play element designs partially weaken a playspace as a whole, ultimately limiting the creative potential of the user. 3

Most, if not all of Aldo van Eyck’s post WWII playgrounds consumed un-desirable and odd lots around the city of Amsterdam. Each lot had its unique shape and context; however the play elements were standardized and were deployed accordingly to each playground site. Some lots were narrow, most were fully surrounded by busy streets. Aldo Van Eyck sysematically deployed trees along the edge of these playgrounds to create a subtle boundary between the vehicular traffic and the occupiable play spaces. The loose boundaries of some playgrounds suggest a subtle presence of risk, pushing children to consider external factors that may cause risk (moving vehicles on the surrounding streets) during imaginative and physical play.

The web of playgrounds that filled up the empty cracks and gaps of the city became a net of social interaction and provided places for children to obtain their own recognizable domain within the city. The main components of each playground consist of the use of vegetation,

installation of interactive, yet simple play objects, and splitting zones with different floor finishes. dividing up play zones help break down the scale and suggest the ground to appear to be broken up, rather being a large singular slab. This not only brings the scale of the space down to human-scale, but even further to children-scale, hence catering to the majority of the users, children and young teenagers.

Three main characteristics are distilled after the study of Van Eyck’s mid 20th century playgrounds in Amsterdam:

1. Splitting zones/breaking up the space

2. Playing with a hint of risk

3. Open Function

Playgrounds are divided into separate areas of play and each zone is occupied with a particular interactive unit, or a group of such elements. Different floor finishes create subtle boundaries and break down the scale of the site. The notion of splitting the playground to different zones suggest a space that is assembled with multiple sub-spaces of different forms of play. Dividing up the uniformity of the ground breaks down the overall scale of the ground plane, which makes the space more approachable to children and allows them to understand spatial boundaries within each play zone. However, the idea of dividing the ground could have been pushed further thanmerely changin the floor finishing to distinguish certain play spaces. There is an absence of elevation change, which could potentially help the space to be more dynamic and

willing to explore and physically experience the playgrounds.

Some lots which were transformed to the playgrounds were as odd as being fully surrounded with vehicular traffic. Such conditions naturally form a dangerous boundary around the playground but does not necessarily mean that the increased amount of risk limited the act of play. In some of the parks such as in the Buskenblaserstraat, because there is enough space for tossing and kicking balls around, children engage in activities that generally require safe boundaries and so they have had to come up with unique game rules that permit play without anyone being hit by passing traffic. Climbing domes and a group of climbable concrete pillars also adopt a sense of danger and risk during every part of the child’s maneuvers. The playgrounds invite young users to develop the skill of anticipating danger and managing it in physically challenging and creative choreographies.

The trees that act as subtle boundaries at the edges of a playground lend a porous nature of the boundaries

and promotes ease of access to the public spaces while also providing a hint of excitement from a sense of risk surrounded by moving vehicles. Tree shadows also drape over the playgrounds, creating constantly changing light conditions for the dynamic, public space.

From sandboxes to parallel bars, abstract play elements fill the playgrounds. The simplicity of the abstract elements and the attention to scale offers a range of uses, suggesting multimple interpretations of use and interactions with the play objects.

Play elements that embody an “Open Function” approach to design strenghthens the state of internal locus of control because the participant engaged in play choreographs and communicates with the objects subjectively, crafting their own narrative with the play spaces and objects.

Adjacent Street

boundary Trees

Adjacent buildings

play elements

Zoning Areas

* Splitting of zones with different floor patterns are absent here. The planted trees instead loosly create different play zones.

Splitting zones:

Over the years as playgrounds became increasingly controlled and conservative in terms of risk taking due to an attempt to eliminate all possible accidents, playgrounds have become safer places but now lack the sense of exhilarating exploration and of essential learning opportunities. Moments of uncertainty and an opportunity of growing self-confidence has been traded off with safety. Although designing playgrounds with concerns of children running into accidents and injuries are necessary, children should engage in play that involves taking risks and as a result will experience positive emotions including fun, thrill, pride, and self-confidence. 4 Exploring different modes to take safe and calculated risks develop a habit and resilience to determine and push through obstacles in life as adults and take upon greater opportunities.

If risk taking is an important factor in the idea of child play, which playgrounds have more instances of risk taking? Although Aldo Van Eyck’s playgrounds were mostly situated in urban contexts always close to ve-hicular traffic, the level of risk taking is perhaps less than junkyards, in which

play obstacles are unknown if they are even structurally sound for exploration.

Immersive playgrounds also incorporate a sense interconnectedness amongst the various play components. A web of play structures creates an atmosphere where the children can stitch their own sequence of experiences within a range of obstacles and objects. In contrast to the symmetrical forms of Aldo van Eyck’s play structures, junkyards and jungle gyms are a sum of individual play elements that have merged to create a dynamic and immersive environment for imaginative play. The complexity and asymmetry of the playgrounds are also benefited with the individual play elements that embody the idea of open function. Providing the freedom for interpretation allows children to gain a sense of internal locus of control, or the confidence that one’s life is in his or her hands, based on their subjective decision making.

The graph on the right laysout various playground elements such as a slide, seesaw , and swings according to

the level of risk as well as the range of affordances a play element can offer to the user.

Playground elements take upon various forms and sizes. Some elements contain clear methods of engaging with the object and other elements are rather ambiguous. A slide presents itself to a child only one way to interact with the object unlike a rope climbing wall where it presents itself with different routes to explore while the child engages with the structure. Play elements with a range of interpretations promotes self-guided kinetic movements, physically manifesting a state of exploration and self-awareness. With a hint of risk and ambiguous usages, play elements are more exciting and joyful to interact with alone, or in a social and public setting as well.

The following two graphs distill playgrounds to their levels of ambiguity, risk, and the closeness of individual play elements.

Essentially having no function or practicality, playgrounds take upon various forms and scales. Some play spaces are spread out, while ohers have overlapping elements close together. Some playgrounds are isolated from the real world, creating a safe space for children to be im -

mersed in their imaginative world and other playgrounds have a sense of risk, in which the subtle notion of danger is always present on the site or from the form and construction of the play structures. As an abstract space for pure play and imagination, playgrounds are most effective and exciting when individual play elements or obstacles are placed closer together to create multiple threads of exploration, weaving new narrative stories every play session. Play spaces should also present children to a controlled amount of risk. Through trial and error, they gain self-confidence and feel truly alive during play.

Without risk, there is no stimuli. Wishout stimuli, there is no spark for creativity and curiosity, the key elements for play. Public spaces created from the idea of excitement and risk with open ended explorations and spatial experiences invite playful interpretations of a space.

Most of the playgrounds placed along the graphs have one other interesting similarity, but architecturally a strange one. Responding to the surrounding context is limited. Other than the trees creating a separation between the street and playground, Aldo Van Eyck’s play elements are irrelitive to the site. Sandpits and climbing domes propell children to dive into their imagination. Noguchi’s playful sculptures and slides aren’t sensitive to responding what’s around the objects, but speak for themselves and are foreign forms to wherever they are placed.

Although responding to the surrounding environment and cultural context is standard practice in place making, a playgrounds is foreign, strange, and in some ways, could be an oasis in a cityscape. The priority of playful spaces aren’t in blending into its surroundings, but are in for provoking a sense of curiosity, and an open interpretation of space. Playgrounds don’t have to be site specific, but rather oddly misfitting to its surroundings, and that’s good.

Questioning play and site specificity: Do playgrounds need to respond to their surrounding context?