PLA (y) ZA

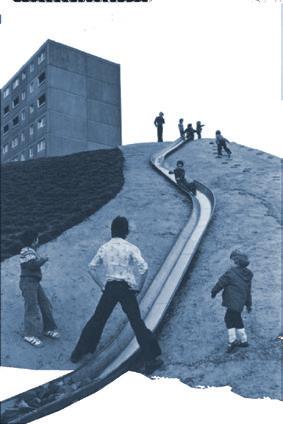

An urban infrastructure for physical play, daydreaming, and reverie

Daniel Moonsoo Kim

Advised by Aki Ishida AIA

Undergraduate Thesis Documentation

Part 2

Virginia Tech School of Architecture + Design

An urban infrastructure for physical play, daydreaming, and reverie

Daniel Moonsoo Kim

Advised by Aki Ishida AIA

Undergraduate Thesis Documentation

Part 2

Virginia Tech School of Architecture + Design

An urban infrastructure for physical play, daydreaming, and reverie

Undergraduate Thesis Documentation • Virginia Tech School of Architecture + Design By Daniel

• Advised by Aki

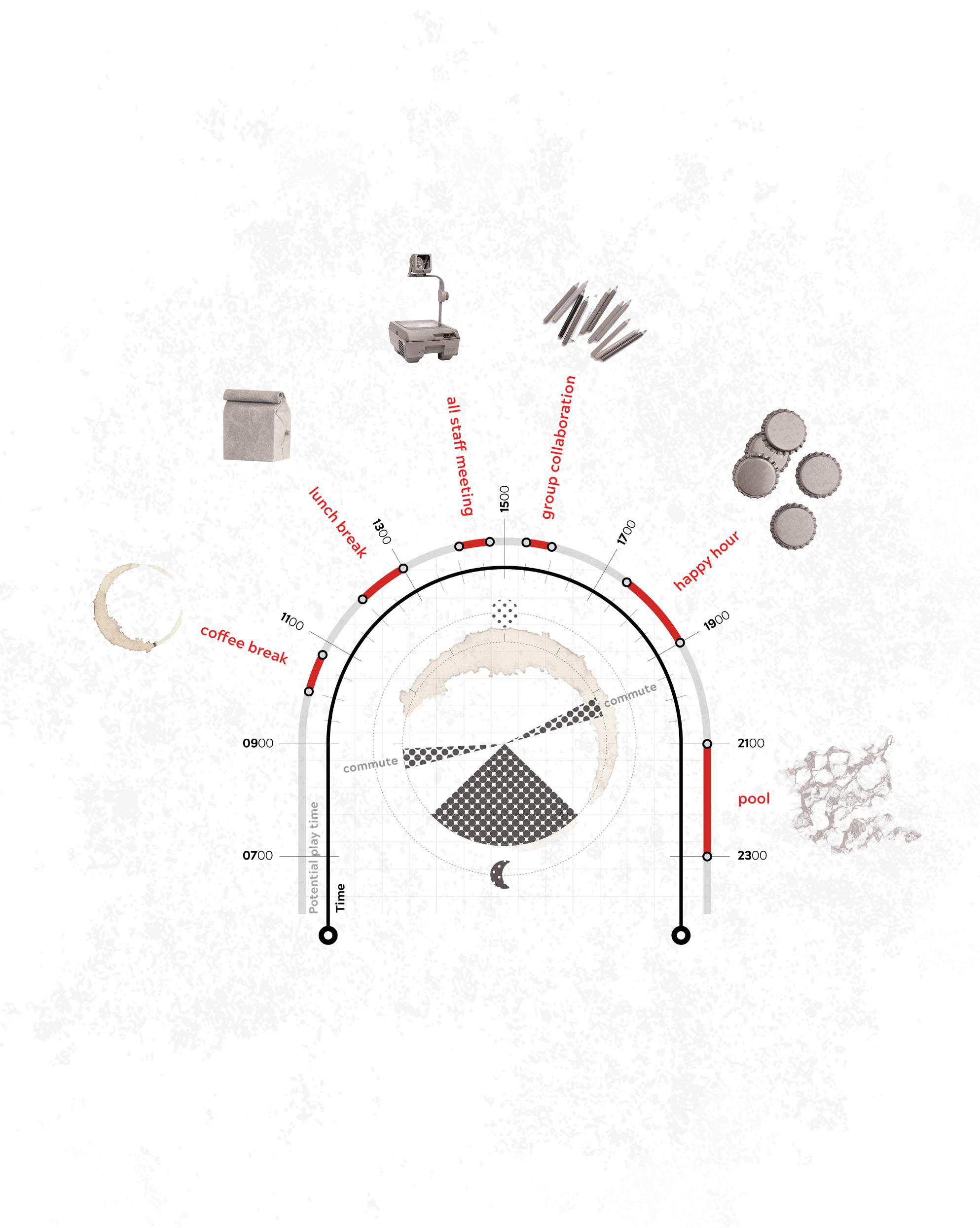

Monday through Friday, nine to five. The unavoidable weekly schedule exhausts us to surrentder to only checking off our lists of tasks and obligatory chores. Play and leisure time is the counter balance to these moments of obligation, rigidness, and productivity. The imporatance of engageing in activities that make us forget time and what we think truly fulfills us should always be present not in the times of adolessence, but also at all times throughout one’s life. Although play is largely associated with childhood, Erik Erikson states that maintaining a sense of playfulness is critical for interesting and fulfilling adult lives. 5

As work culture is shifting from fixed office spaces to flexible work schedules such as allowing half the week to work remotely, the necessity of public temporary workspaces will have high demands. The less rigid schedule and work environment allows space for breaks, and times of gathering that involves playful settings.

Play not only relieves stress and improves brain function, but also improves relationships and builds connections as well as stimulates the mind and boosts creativity. 6 It

also assures us that we are capable of causing effects and exerting influence on the world, rather than merely be affected.

Playgrounds, which are the sacred spaces for such an unrestricted range of activities for children, create a safe space for risk taking and diving into their fantasy world. In his book The Experience of Architecture, the author Henry Plumer writes that during play, “each manipulation, no matter how modest, confirms to the child that he or she can act, can have a creative impact and is the source of these self-guided powers.” 7 Just like children, adults are re-assured with the power of knowing that one has the ability to cause effects, rather than be affected.

The definition of play for adults may fall into two main categories: entertainment and recreational activities. A brief observation of the hub for adult entertainment, Las Vegas shows a lavish fantasy world in reality and a study into an un-realized project by Cedric Price and Joan Littlewood’s called Fun Palace (page 51) demonstrates an iteration of a flexible and temporary space purely for fun and enjoyment with numerous recreational activities.

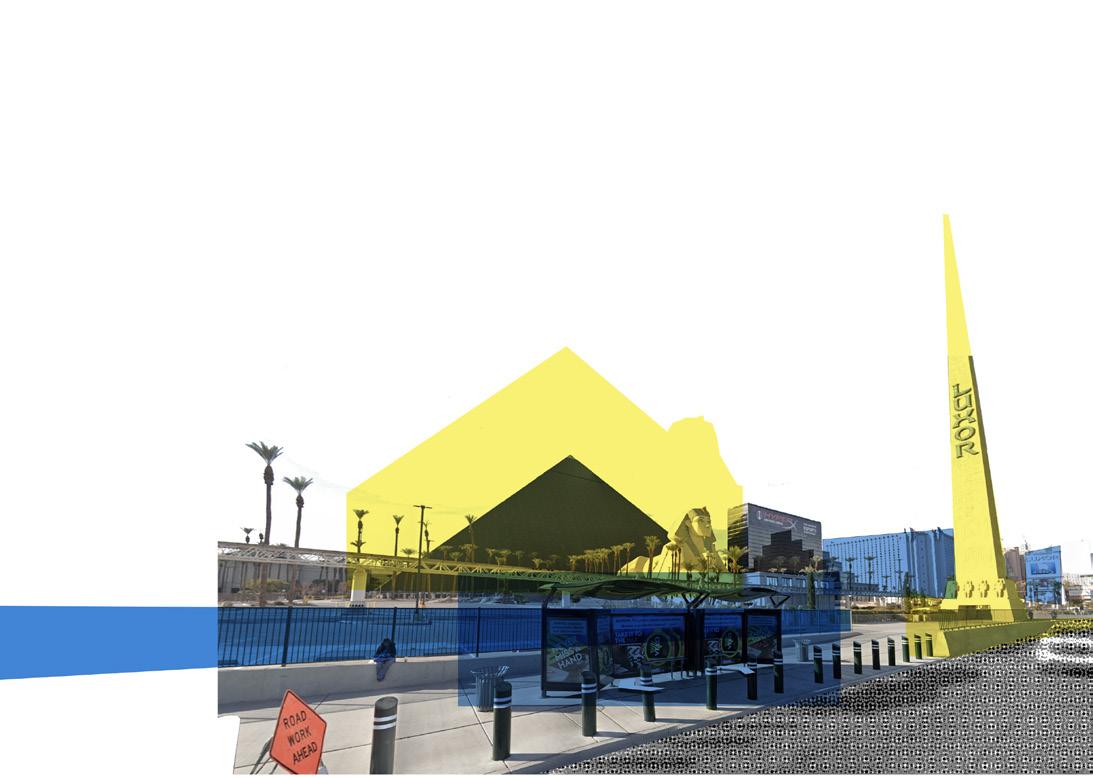

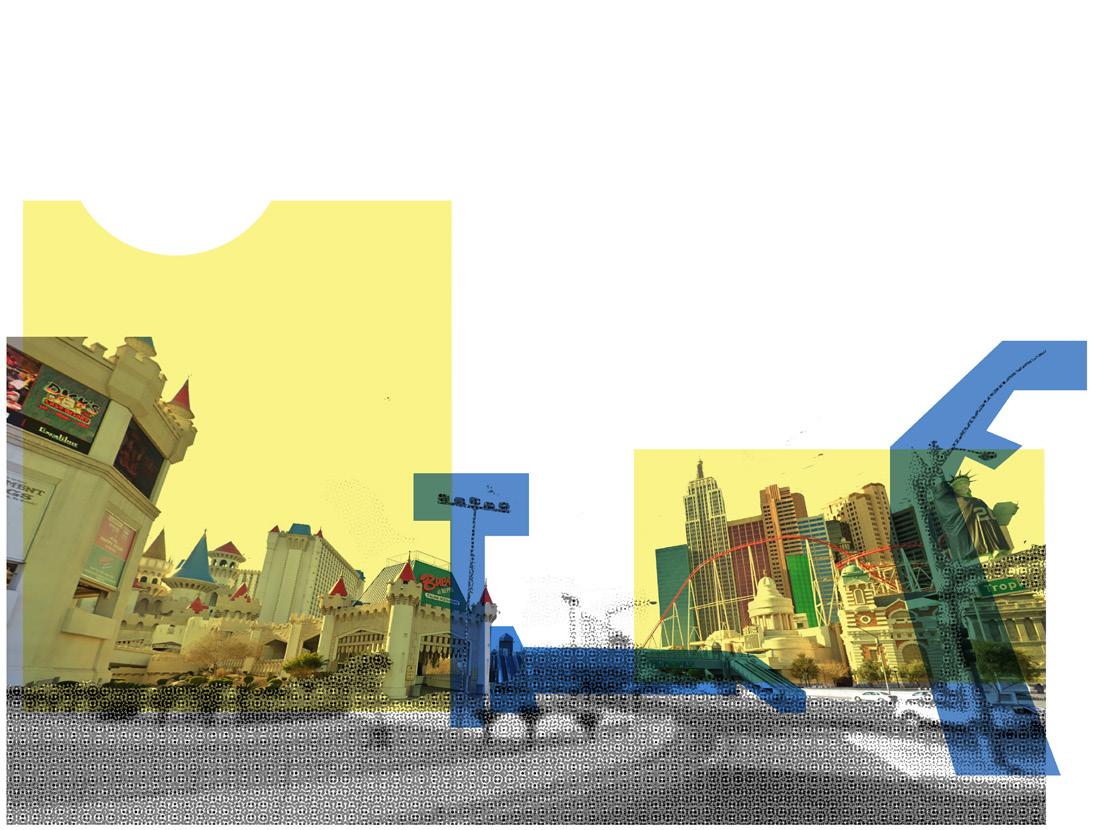

A balance of the real and of the fantasy

Las Vegas is a destination of magical lure and of omnipotence for visitors. Through gambling and lavish consummerism, as shown in Paul Fallon’s studies at M.I.T, the idea of play is expressed in a form that could be considered anti-intellectual or even primal. 8 The city distances itself from reality and sits in the midst of an expansive desert in Nevada. As a place that appears to be clearly isolated from everyday life and with the mix of typical urban infrastructure or architecural elements and oddly scaled elements of fantasy, Las Vegas is a city of fantasy with fragments of reality in between.

Elements of fantasy are sprinkled throughout the city from the scale of automobile transportation and trickles down to detailed, human scale elements. Fallon writes, “The architectural form of Las Vegas, like its spatial quality, its furnishings, and even its use of chips as currency, is designed to enhance and reinforce and altered reality in [Las Vegas]”. This overly heightened sense of belonging in a abstract ‘world of pretending’ is counterbalanced with bits of reality and familiarity. Courtyards that are in front of variously scaled motels and hotels contain typical landscaping elements such as greenery

and water. Balconies and terraces arrayed on building facades confirm the point that the city consists hints of human scale within the extra-ordinary shapes, colors, and decoration. If Las Vegas were to only incorporate overscaled monuments and eye-catching artificial lights, the visitor will feel overwhelmed and may withdraw from the place. Fragments of reality help guide the path of each fantasmical chapter within one’s journey and exploration in the city. A visitor may identify as a centurian at Ceasar’s Palace and a playboy at the Riviera. The physical attributes of Las Vegas creates a place to escape from reality, a quality that seems adoptable to other, perhaps less excessive conditions of a place of fun, enjoyment, and un-prescribed play. Other projects and ideas shed light on other aspects of play and entertainment for adults, such as the Fun Palace, designed by Cedric Price in the 1960s.

“With informality goes flexibility”

Although ultimately un-realized, the Fun Palace was a platform or house for constant interaction and discovery. The architectural and social experiment began as the brainchild of theatre producer Joan Littlewood. The sense of theatre and play are deeply rooted in the project; as Stanley Mathews writes, “Her enduring dream had been to create a new kind of theatre-not of stages, performers, and audiences, but a theatre of pure performativity and interaction,” 9 and as a result realized a building that acts as a stage for multiple activities to occur simultaneously in one space. The range of events and programs is then introduced to the visitors all at once, allowing him or her to search for their personally desired activity and even to be exposed with novel recreations within the vicinity. Section drawings and diagrams of the proposed building by Cedric Price illustrates pivoting escalators and moveable wall panels for the structure to embody endless variations.

Price’s vision of designing an active and dynamic building would permit multiple uses and events, and of a range of program typologies. He thought of the Fun Palace as a constant process, as events in time rather than objects

in space, embracing indeterminancy as a core design principle. 10

A major turning point for the Fun Palace during the project development phase was the incorporation of cybernetics and computer technology. The flexible structure itself would learn behavioral patterns and plan for future activities according to principles in cybernetics and game theory strategies. Essentially a physical algorithm that tracks popularity in activities, the building morphs into only states of mainstream culture. Mathews writes that the Fun Palace was therefore, “not the conventional sort of diagram of architectural spaces, but much closer to what we understand as the computer program: an array of algorithmic functions and logical gateways that control temporal processes in a virtual device.” If the building only adapts on a basis of popularity, where will the diverse activities ready for discovery exist?

With neglected activities and programs based on the “algorithm”, odds of finding desired activities inevitably decrease, failing to heighten the sense of internal locus of control. This concludes to one point: The building should not be dictated by an algorithm, but rather focus on heightening a sense of selfhood.

The Fun Palace: Cedric Price’s experiment in architecture and technology

It was not a museum, nor a school, theatre, or funfair, and yet it could be all of these things simultaneously or at different times. The Fun Palace was an environment continually interacting and responding to people.

Stanley Mathews, 2005

An acting area will afford the therapy of theatre for everyone: men and women from factories, shops and offices, bored with their daily routine, will be able to re-enact incidents from their own experience, wake to a critical awareness of reality ... But the essence of the place will be informality - nothing obligatory - anything goes. There will be no permanent structures. Nothing is to last more than ten years, some things not even ten days: no concrete stadia stained and cracking, no legacy of noble contemporary architecture, quickly dating ... With informality goes flexibility. The ‘areas’ that have been listed are not segregated enclosures. The whole plan is open, but on many levels. So the greatest pleasure of traditional parks is preserved the pleasure of strolling casually, looking at one or other of these areas or (if this is preferred) settling down to several hours of work- play.

Automation is coming. More and more, machines do our work for us. There is going to be yet more time left over, yet more human energy unconsumed.

Price thought of the Fun Palace in terms of process, as events in time rather than objects in space, and embraced indeterminacy as a core design principle.

Price, Littlewood, and Pask considered that the day-today configuration and activities of the Fun Palace could be controlled by cybernetic analysis of usage patterns. They proposed seven administrative sec- tions to oversee and maintain the Fun Palace. 37 Yet, again, the intent was that administration would be passive and supportive, and that the cybernetic controls could directly monitor the patterns of use and desire, thus allowing the building to control and reprogramme and control itself.

August 1964, Ideas Group chair, psychologist John Clark submitted his own ‘List of 70 Projects for a Fun-Palace’, which describes various virtual realities.. The inhabited universe Why not try a trip around the moon in our realistic space-capsule Simulator? Captain Nemo’s cabin: An underwater restaurant The grotto of kaleidoscopes The Camera Lucida The maze of silence

Activities that are considered to be within the domain of play, leisure, and entertainment broadly have two categories: Conscious play and unconscious play. 11 Conscious play refers to all th organized recreational activities and sport, in which play is framed in a certain set of rules and often incorporates a sense of goal to win over the opponent. Activities that are of the “conscious play” realm could be poker, chess, tennis etc. Conscious play is the result of an intentional decision by a person to engage in the activity. Unconscious play which this thesis focuses on, is more associated with the engagement in imagination, fantasy, daydreaming and reverie, where play has no set of rules and there is an absence of competition. It suspends the world around us by creating another imaginative world. There’s a delight to choose our course of events with free will.

Children effortlessly bounce back and forth between their imagination and their physical surroundings. They could be exploring a thick jungle with friends in search for treasure in their back yard jungle gym or build a fortress in the sand box with imaginary figures occupying the world that they have created. Children are great at world play and it strengthens their character, who they are, and where their minds wander to during their free time. As

adults, it’s hard to even identify a glimpse of a moment in diving into the imaginative state. Most of leisure time is filled up with endless media consumption or watching a comedy show. This passive state of consuming entertainment rather than actively participating in whatever entertaining ultimately loses an opportunity of growth in one’s character and ownership of his or her leisure time.

Although this realm of play does not require a specific loaction, it can be prompted by the surroundings, personal memories, or often in between the two. 12 Memory overlapped with reality is what creates unconscious play. When the environment offers one or two clues which recall our past or some well known entity, our mind is prone to make new combinations of these discrete elements, thereby creating a reality from a few bits. 13

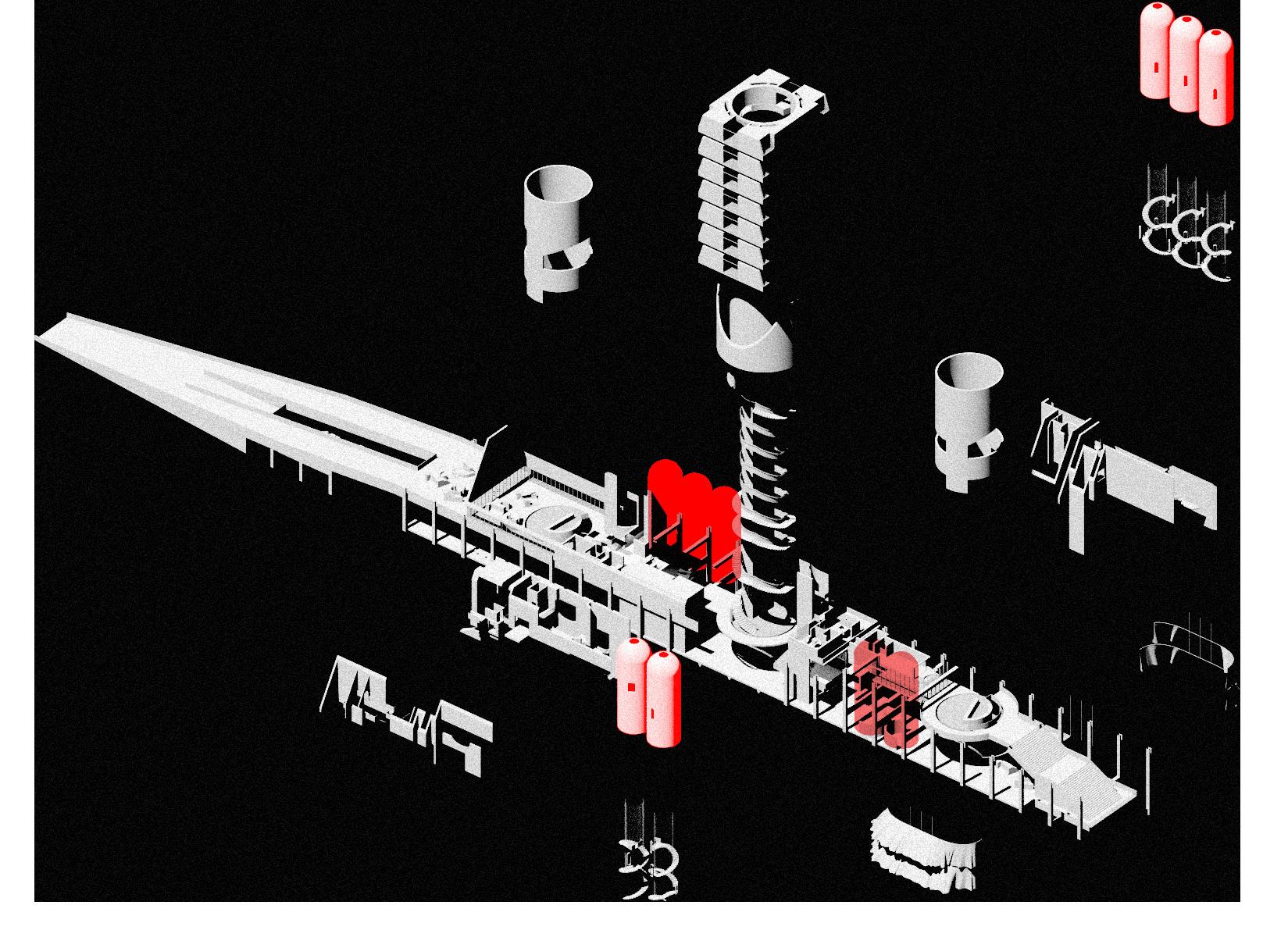

The next chapter lists some studies and explorations of designing play elements that deviate away from precise function or outcome of activities, but rather more abstract in hopes to achieve unconscious play. Sculptural furniture pieces and climbable columns are a few examples.

11. Paul Fallon, “Architecture that affords play,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1981), p.30

12. Fallon, Paul, “Architecture that affords play,” p. 32

13. Karl Groos, The Play of Man, (New ork: D. Appleton and Company, 1901), p. 135

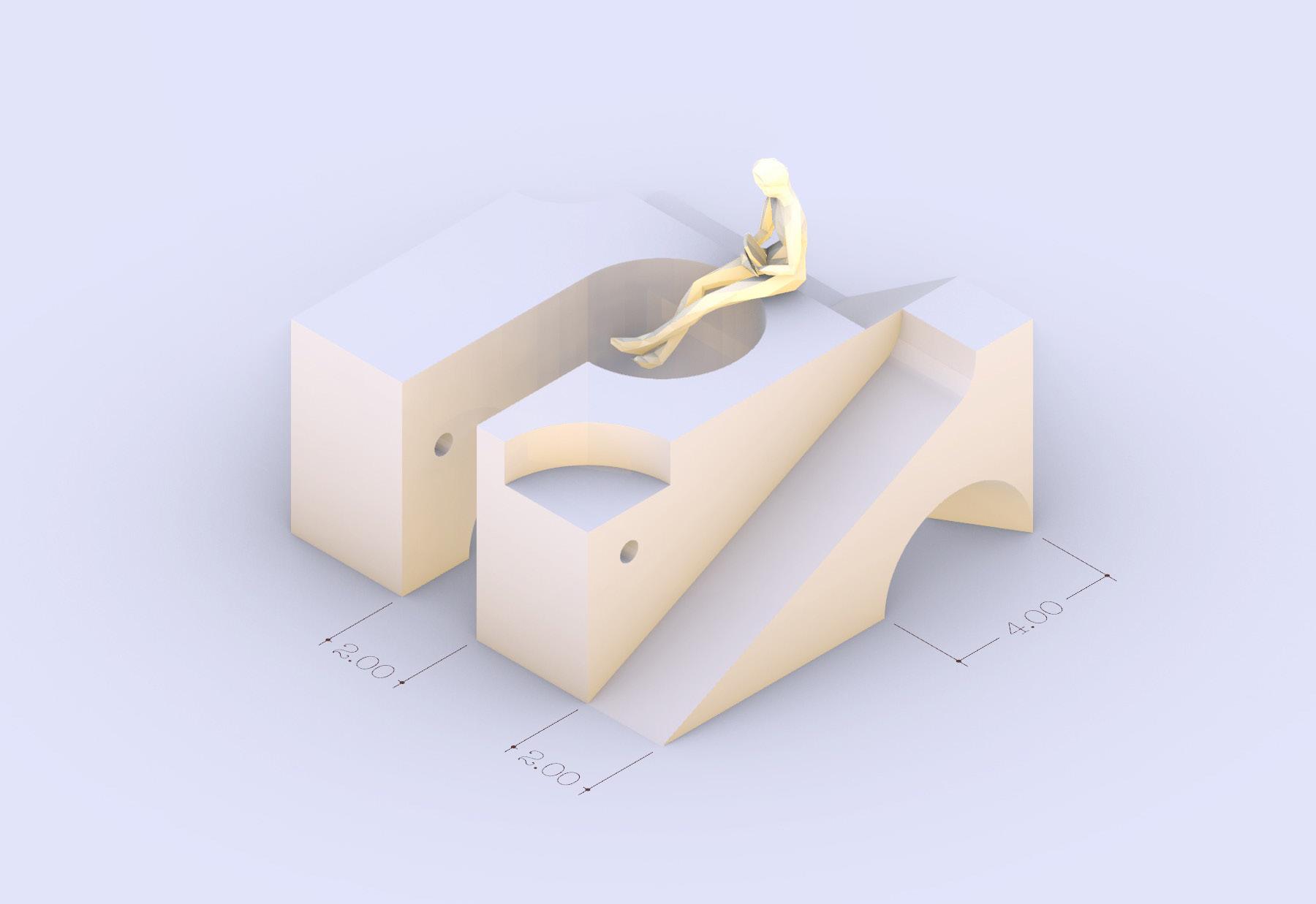

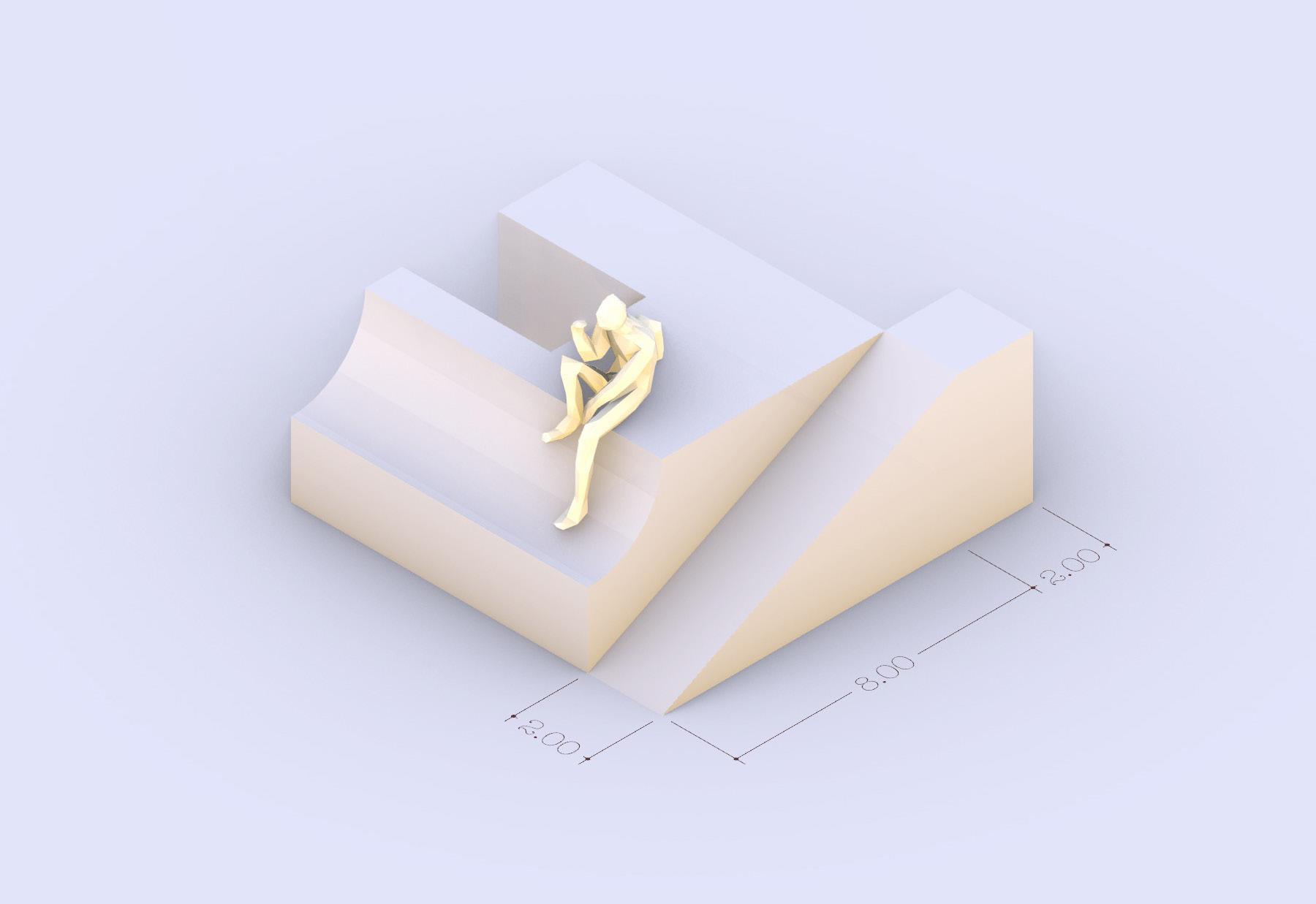

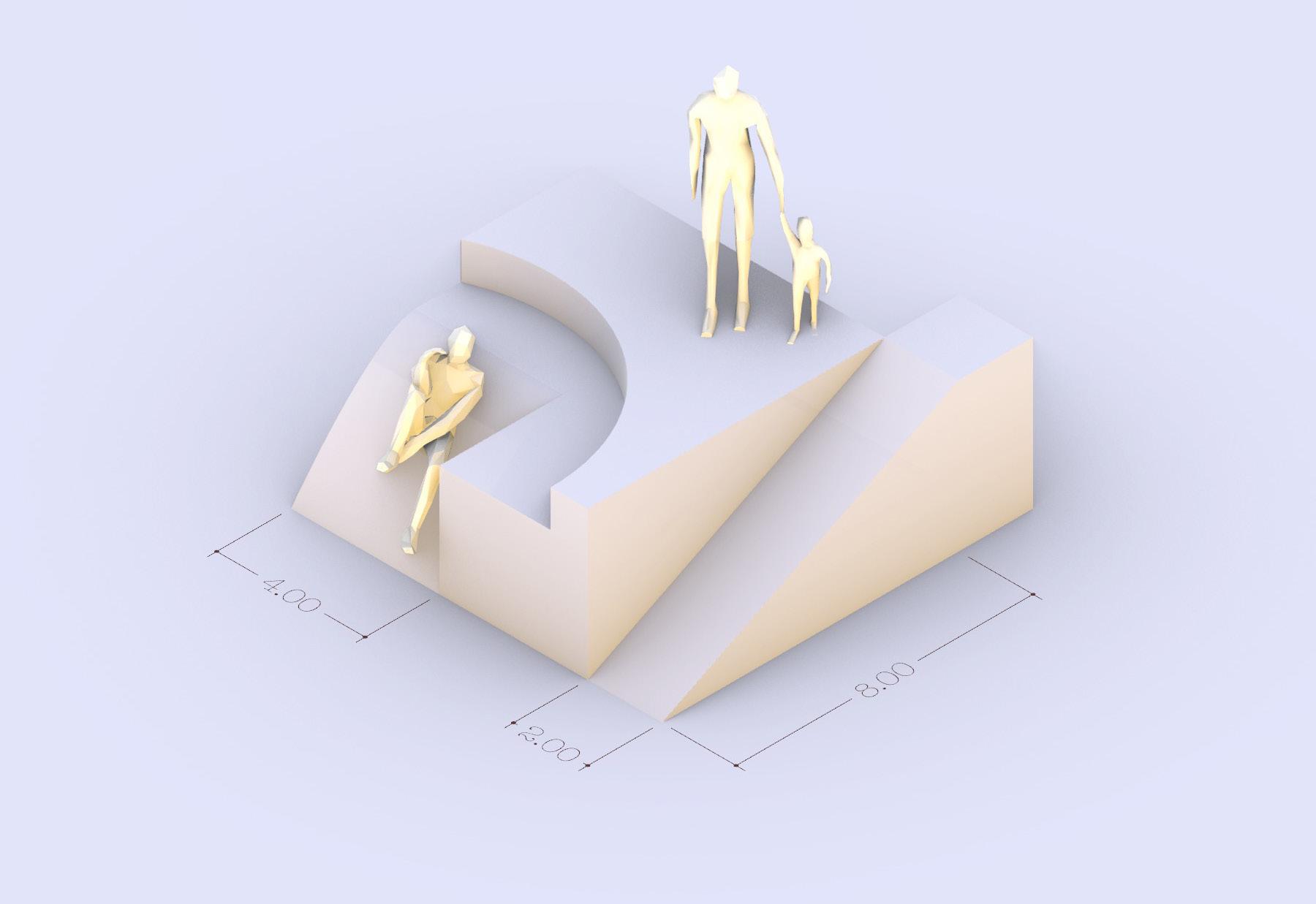

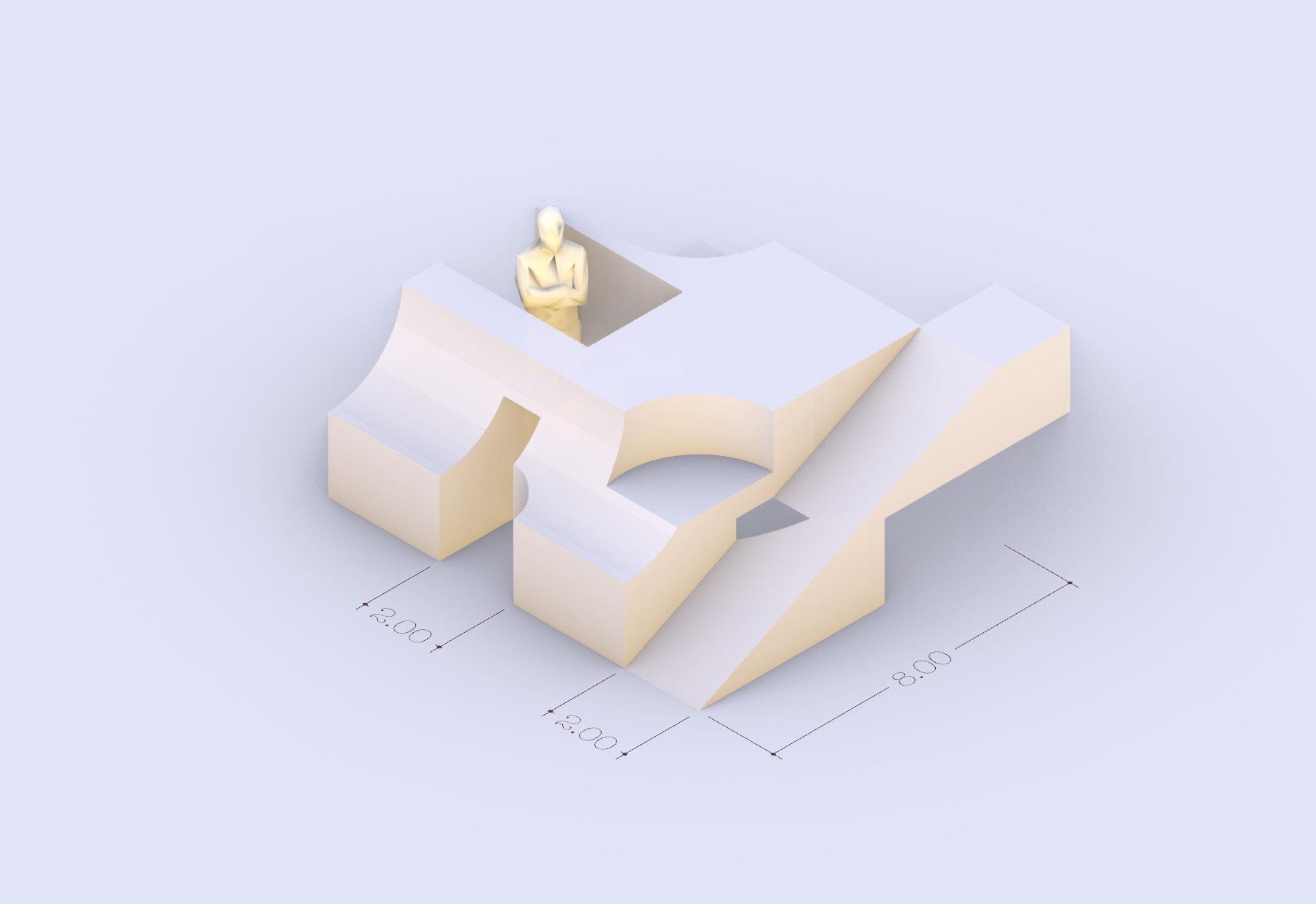

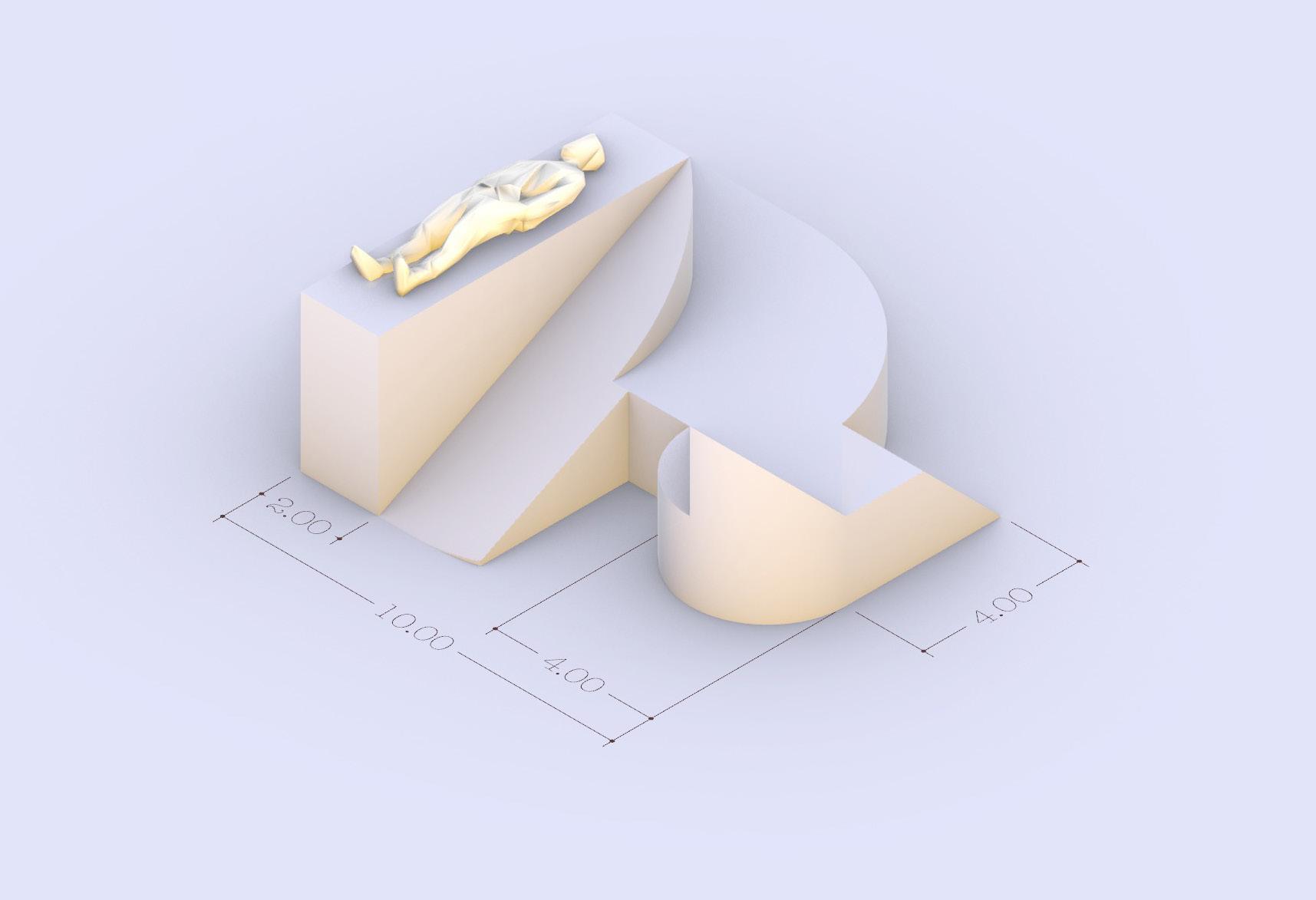

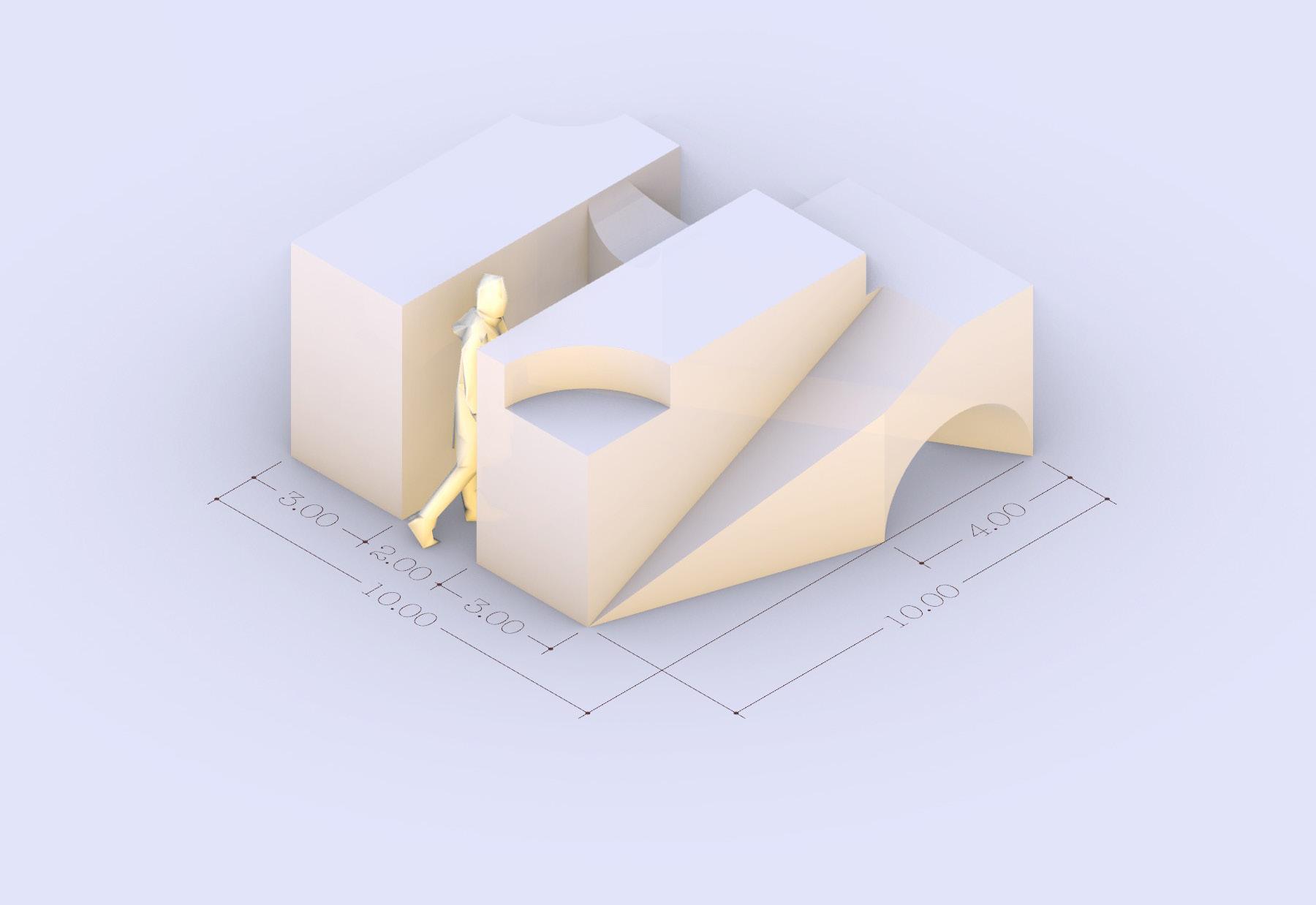

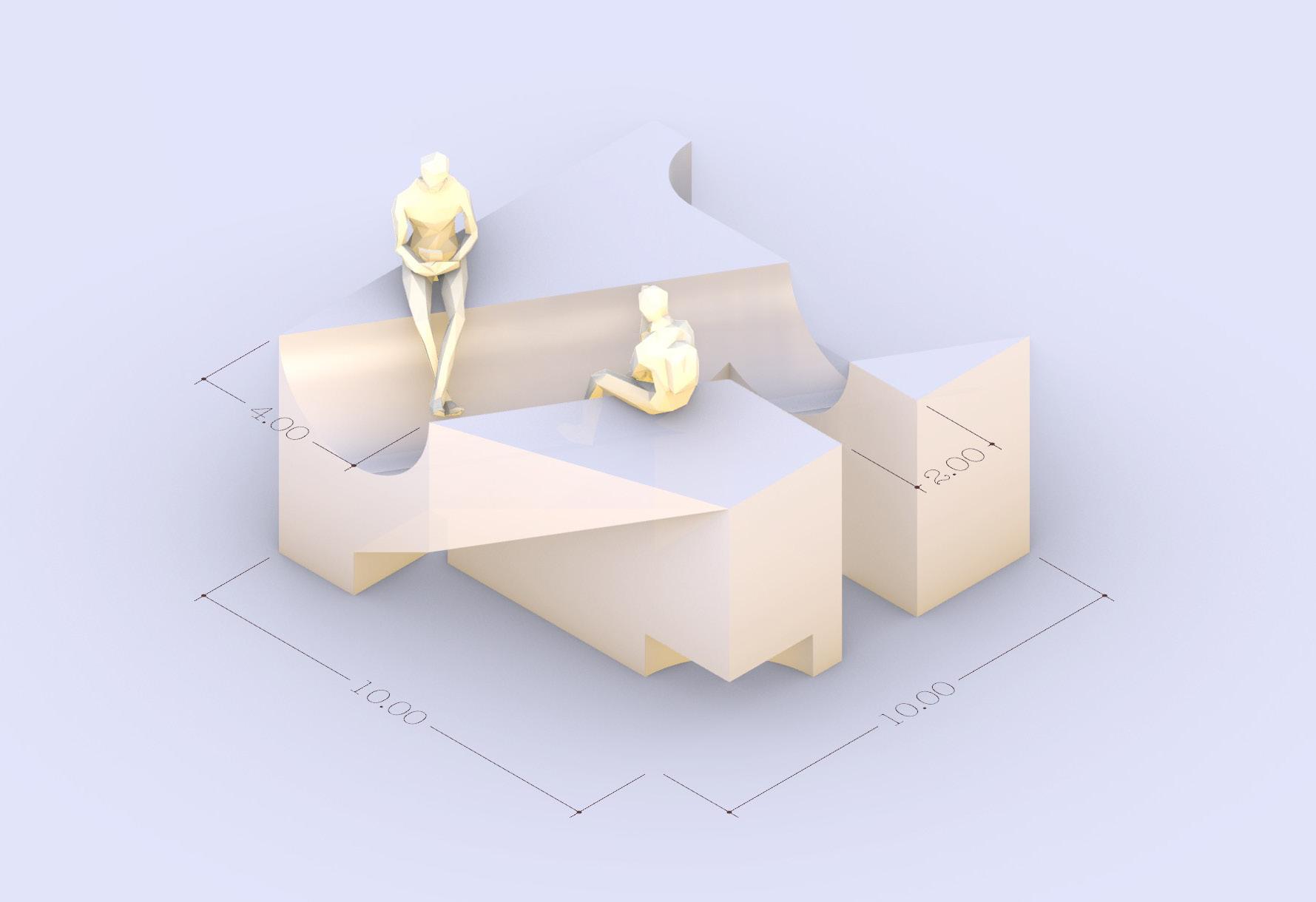

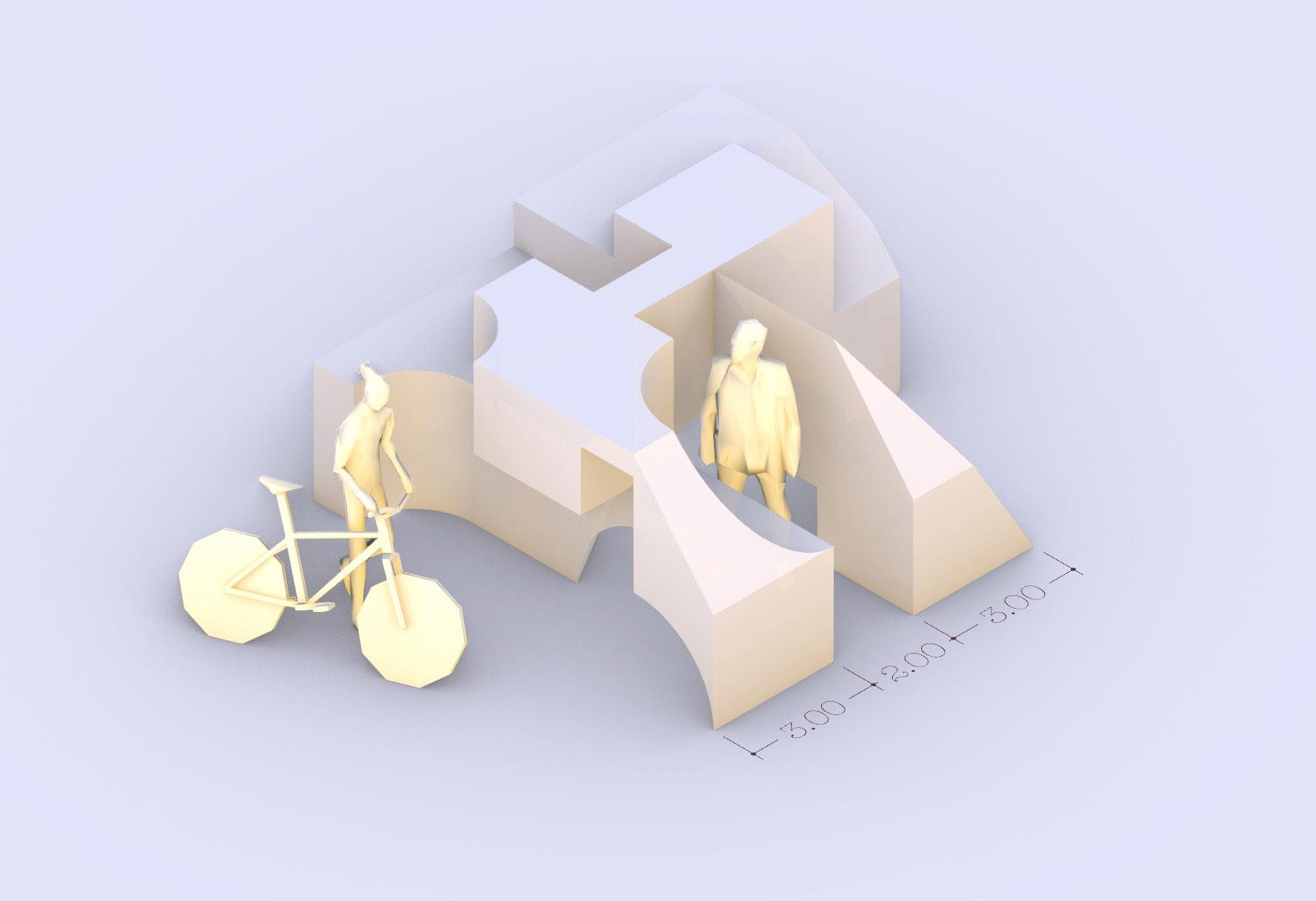

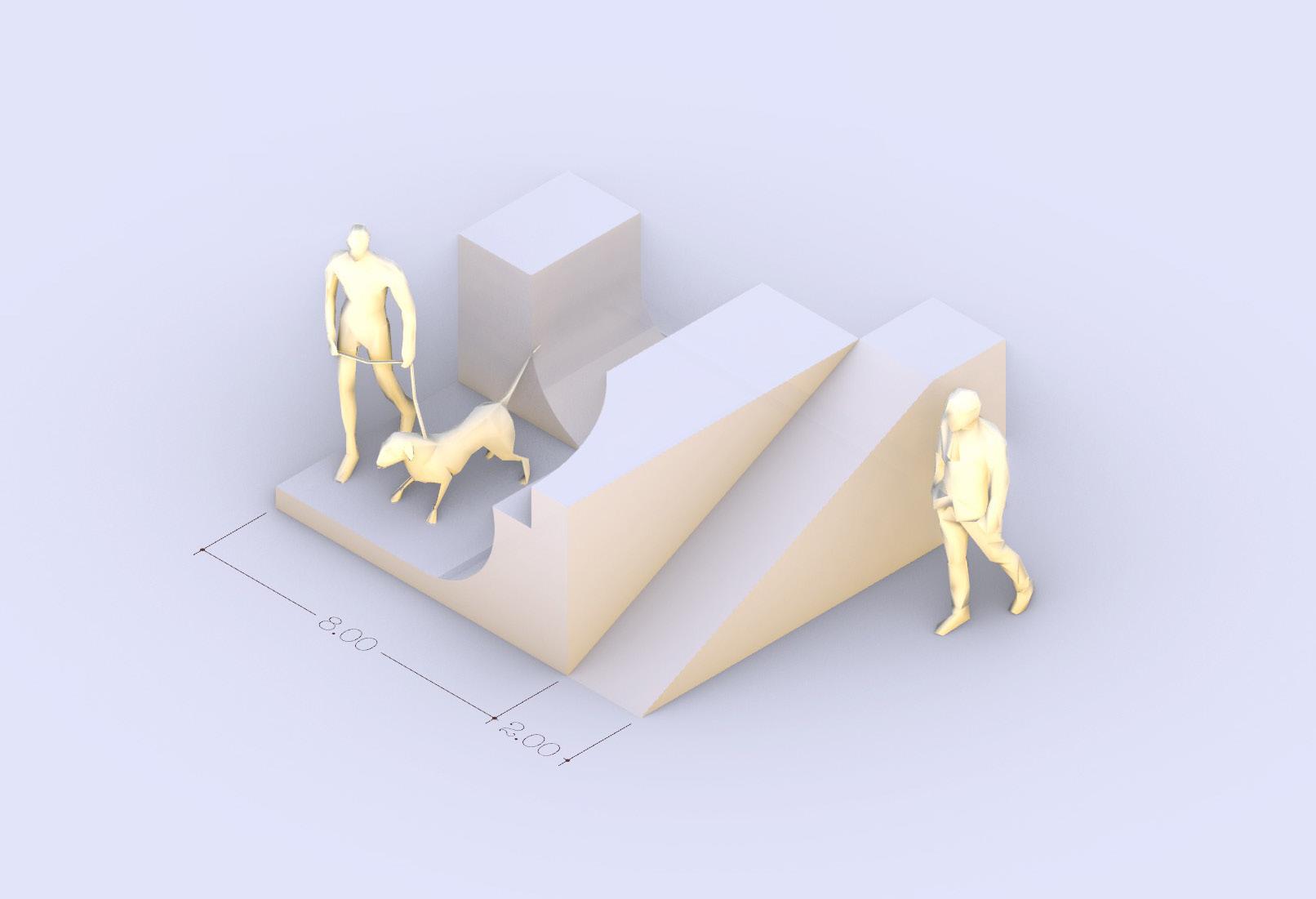

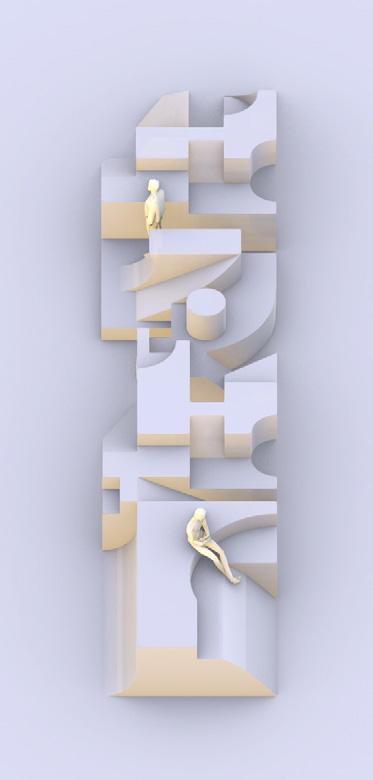

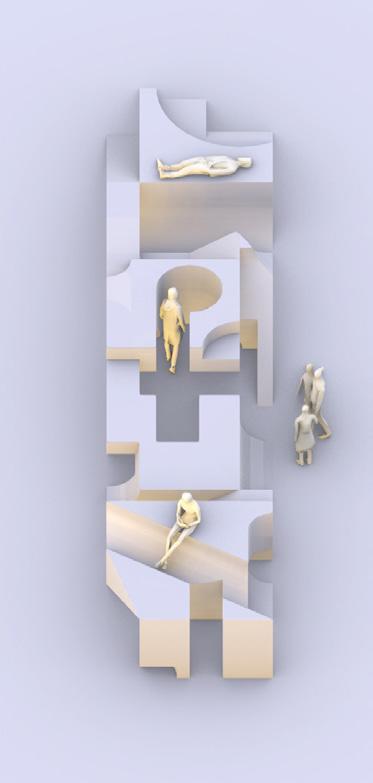

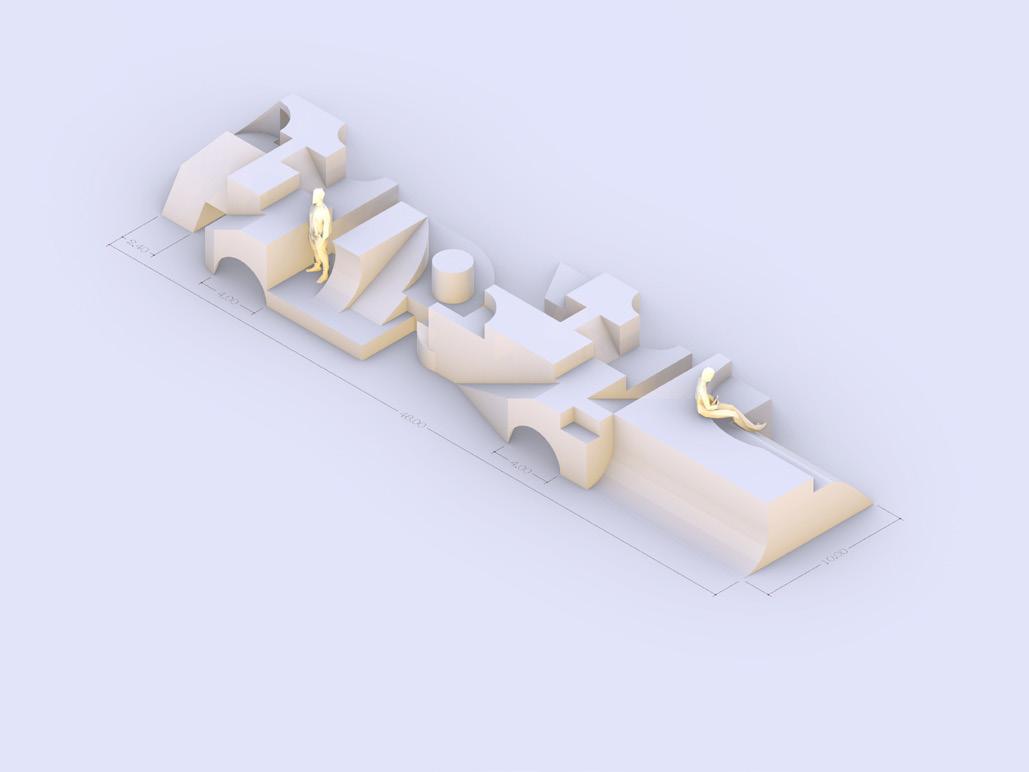

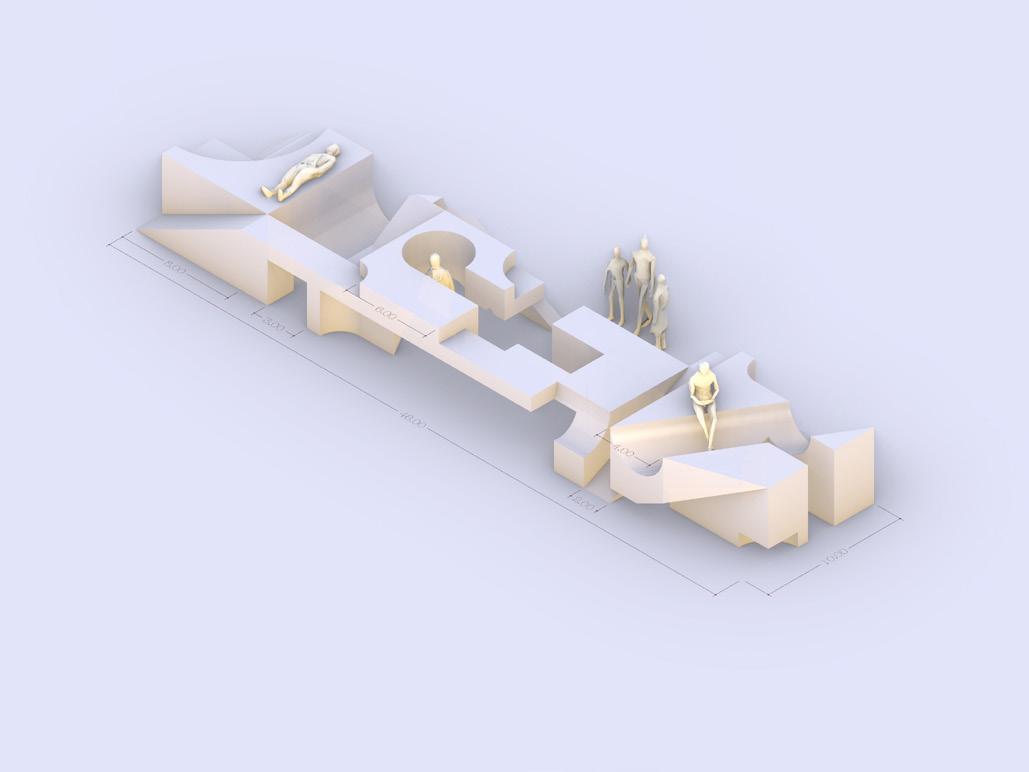

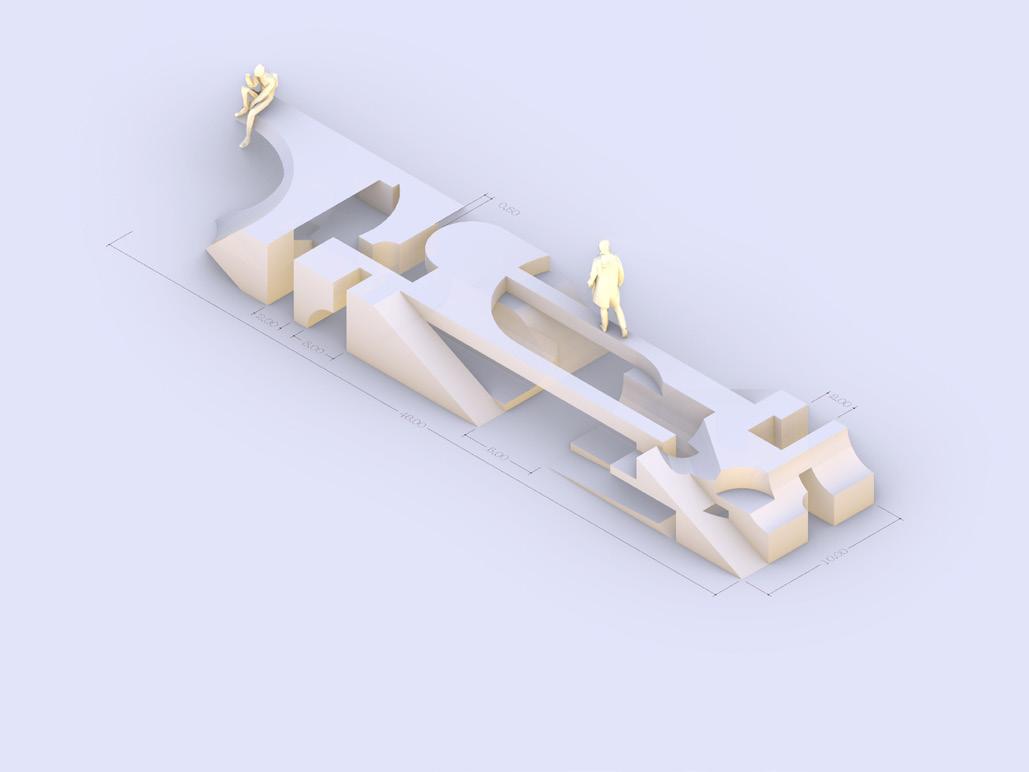

From Aldo van Eyck’s “open function” method of design in playground spaces and play elements, to observing how playgrounds do need to include moments of risk taking, all studies are distilled to nine iterations of 10’x10’ carved blocks that act essentially as furniture throughout the building.

Eliminating generic tables and seating areas opens up creative methods of forming public hang out spaces. The nine ambiguous, sculptural objects resemble mini play structures and can be used in different settings, whether it be active, reserved, social, private. Geometries of no particular order or symmetry are carved and create dead ends, openings, and ledges for that are open for interpretation in use. Object no.2 has a circular void in the middle for intimate socializing and object no.3 poses multiple slopes for casual engagements while slouching on these slopes. Object no.7’s half pipe could be a gathering space for a group of 6 to 8 family friends, or the rectilinear void in the middle could be intimitely occupied by a couple seeking for more privacy.

The terrain of the objects are assymetrical and therefore require a certain level of dexterity while engaging with the abstract furniture. This is where risk taking is

involved. One may briefly ponder in thought if he or she could make the leap to a surface across from a gap or could slide down a steep slope. For example, objects no.1 through no.4 have landings that are not connected to the rest of the top surfaces which acknowledges the visitor to be present in the moment and to position footsteps accordingly.

The odd slopes and curves of the objects also invite the visitors to not only sit and spend time together but have the accessibility to dynamically engage with one’s surroundings. This physical dynamism will further fuel a more active engagement within the visitors of the buildings at all times. The objects work together with their surrounding spaces and together create a space of mystery, blured boundaries, and of open interpretation.

contrast to Aldo van Eyck’s dispersed play elements, the engagement with the nine sculptures is continuous.

Target quadrant for the play objects: ambiguous in use, close proximity to other play elements

The nine ‘objects’ are cubic forms for a range of physical engagement in a personal and social setting. This formal study resulted in creating nine abstract furniture pieces, or mini playgrounds that have the potential to be scattered around a platform or landscape. The closer these individual objects are in relation to eachother, there is a higher chance of different goups of individuals mingling together to create new spontaneous relationships. The individual objects come together to form a landscape of mini playgrounds, enhancing a playful terrain open for possibilities.

There were more studies done in larger scale, which are shown on the next page. More possibilities rise along with the larger footprint of the objects. Although the footprint increased while studying the three models, the key idea stayed the same: Create alcoves, bridges, voids, and slopes in adult scale to provoke curiosity and a sense of ownership in determining how to occupy a specific part of the ambiguous objects.

“When we are drawn into a muscular and dexterous interplay with architectural mechanisms, and when their motions are playful and the efects magical, rather than predictable and dull, the operation reveals something beyond its practical merits - evidence that we are human beings able to exert real influence on the world, who are capable of the unexpected and have the power to cause effects, rather than merely be affected.”

- Henry Plumer 1

The interaction with one’s surroundings, whether it be from physically manipulating an element or space, to simply observing the impact or response from an action one exerts, will always be present from our curious minds. The more responsive the surroundings, the more likely one is willing to engage with the given environment.

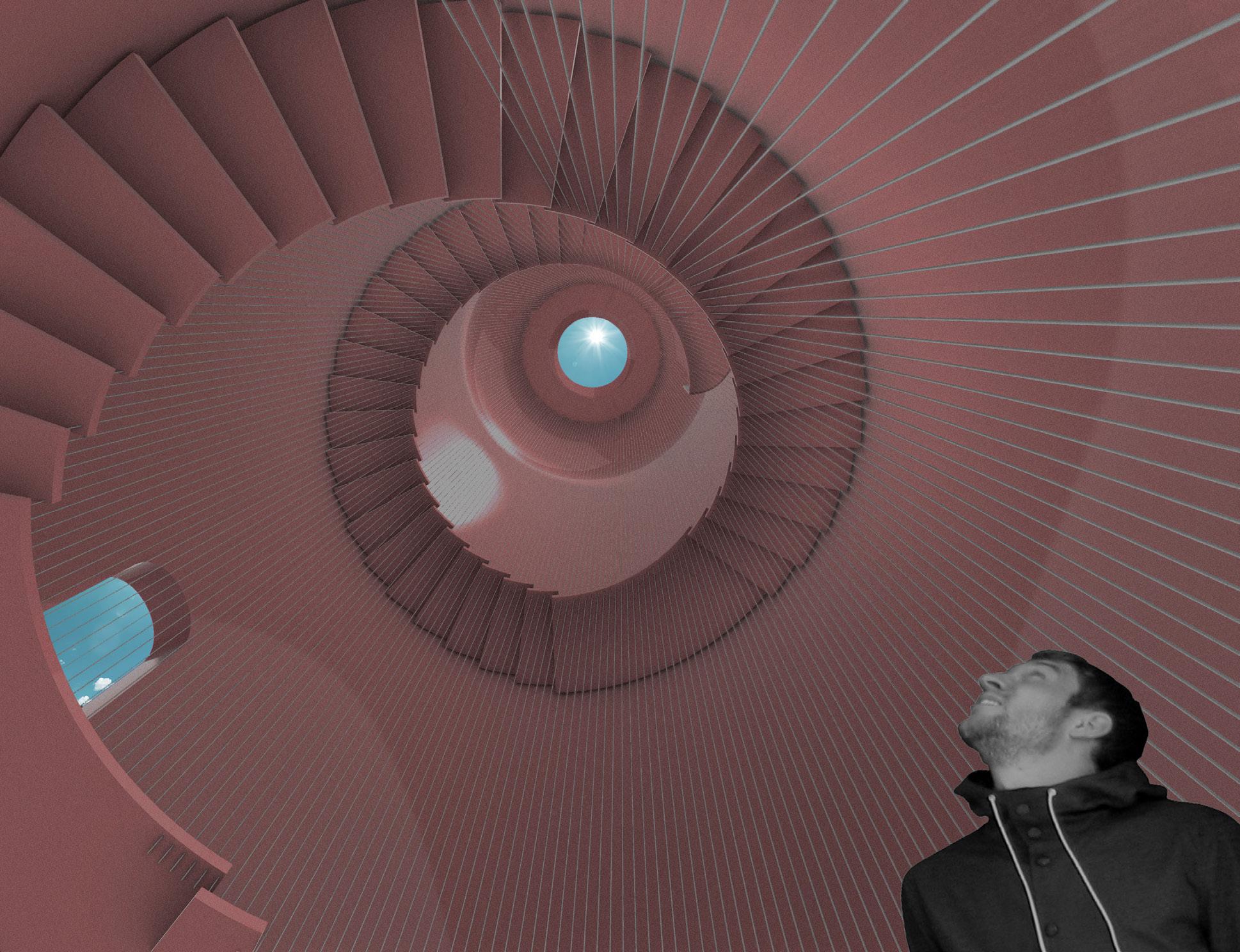

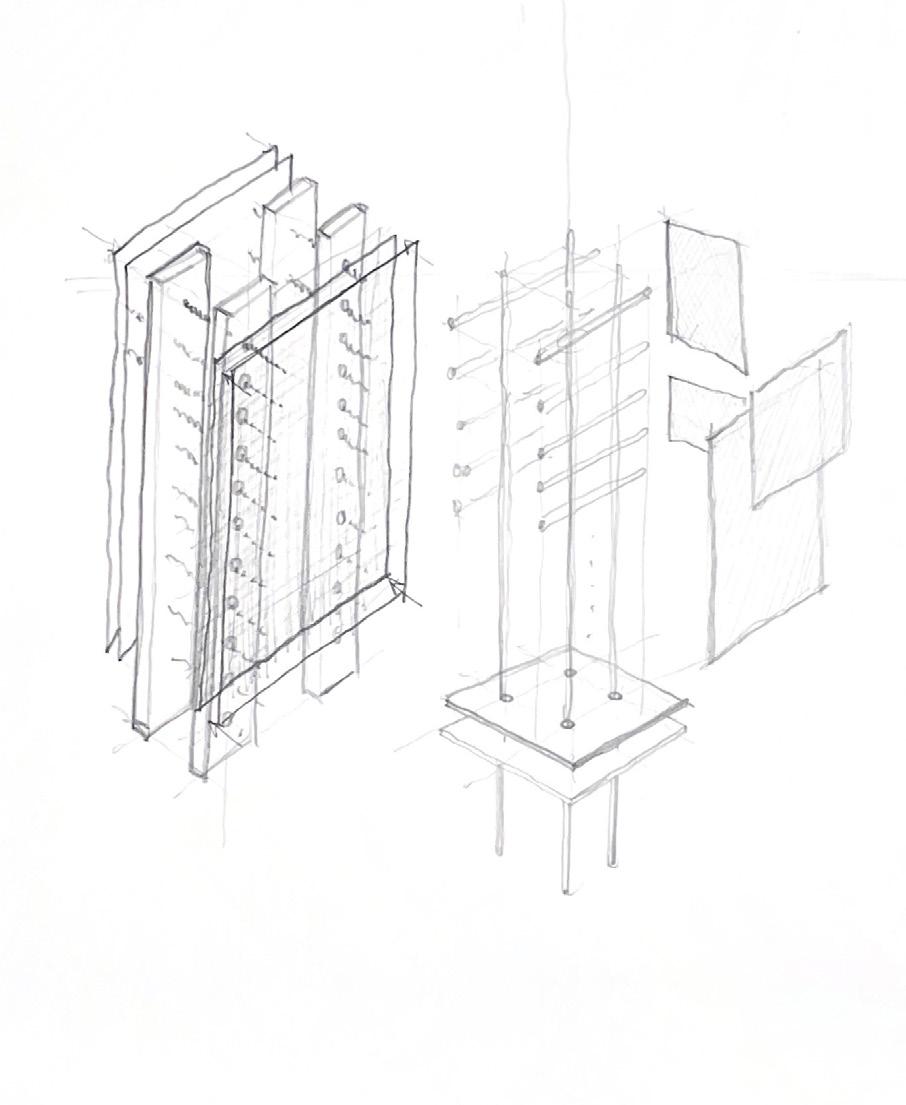

A number of interactive elements and spaces are scattered throughout the building and invites visitors to interact with the space. Visitors encounter giant floating cyliners that resemble silos in rural landscapes, and can react with the vertical space with sound. The silo’s responsive quality to sound unlocks a level of “open

function” and invites the visitor to play with the space while also being fully present at the moment. With a nostalgic form to some, the acoustic silos are placed throughout the proposed design and positioned to look out to different directions on the site. A stream of light from the top lights up at the bottom of the silos, guiding the visitors’ footsteps to the flight of stairs. The view ing decks above can act as points to look out and wander freely in thought, or be space for a couple wanting a more intimate space.

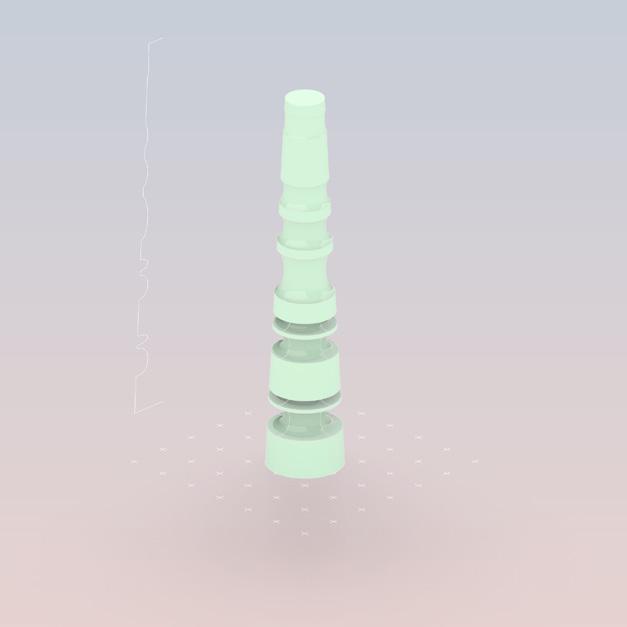

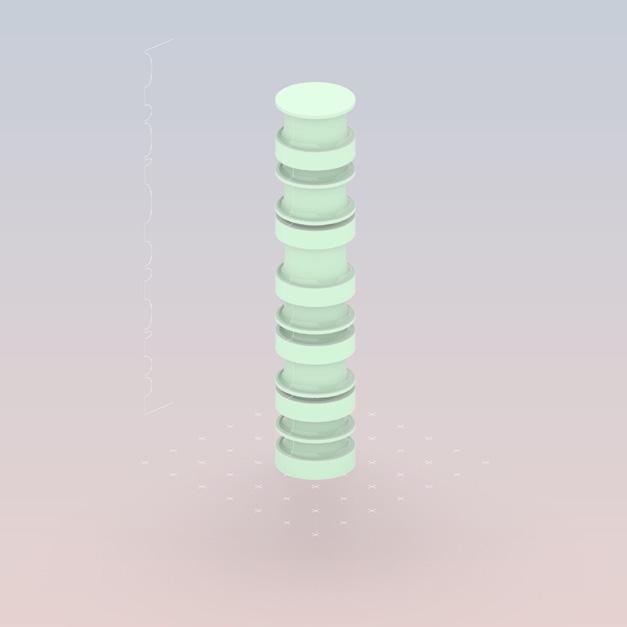

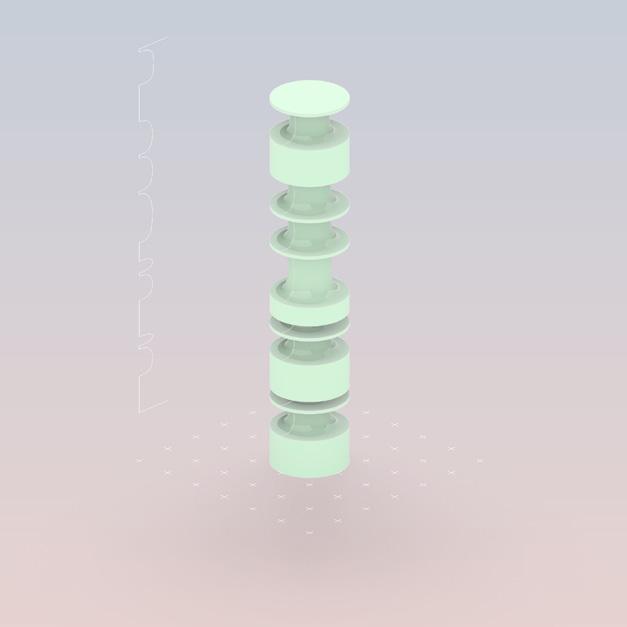

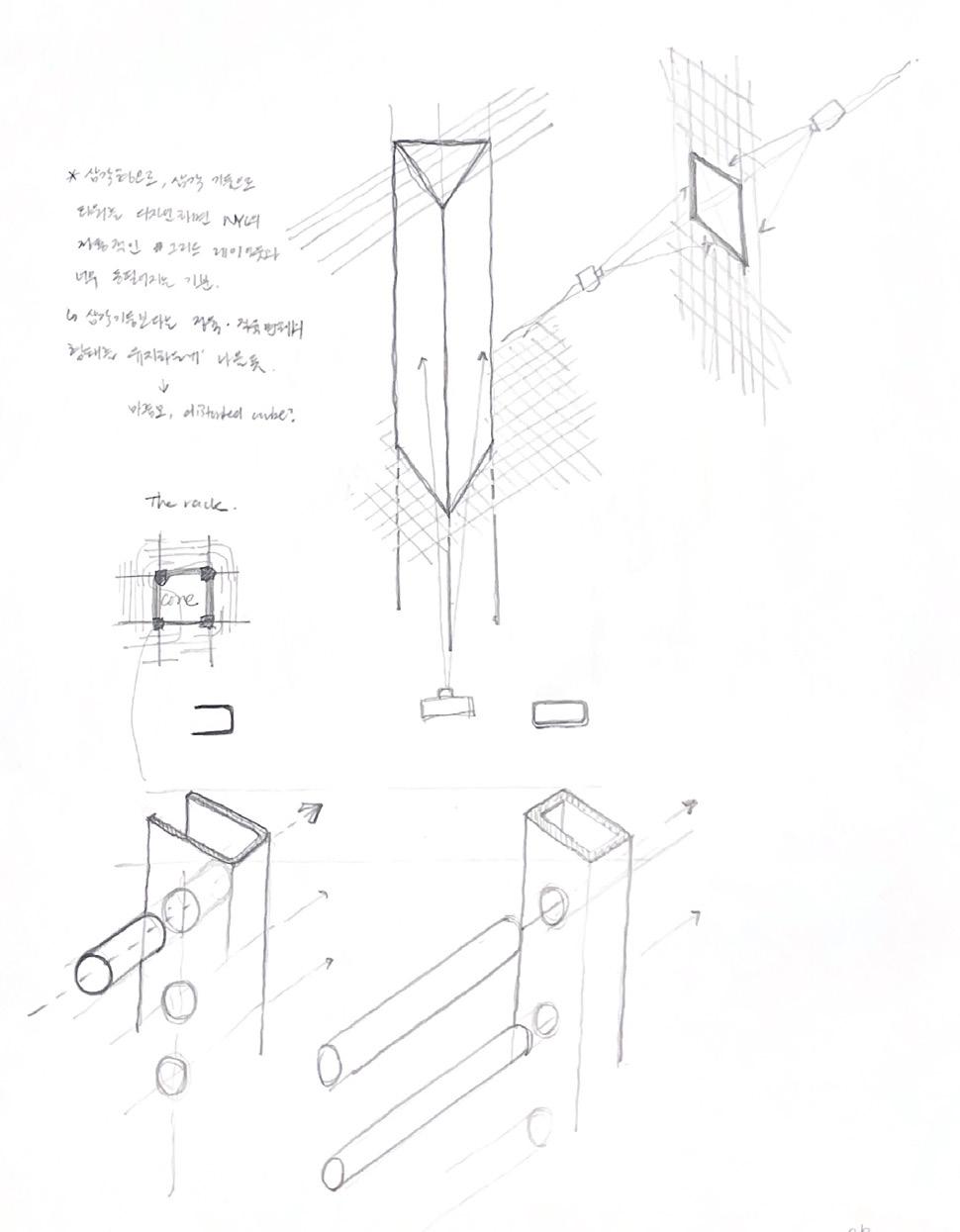

Structural columns have the potential to become more interactive objects while maintaining their structural integrity. The verticality of columns permit them to become climbing elements and also objects to temporarily sit, or lean on.

Structural columns for climbing, sitting, and leaning.

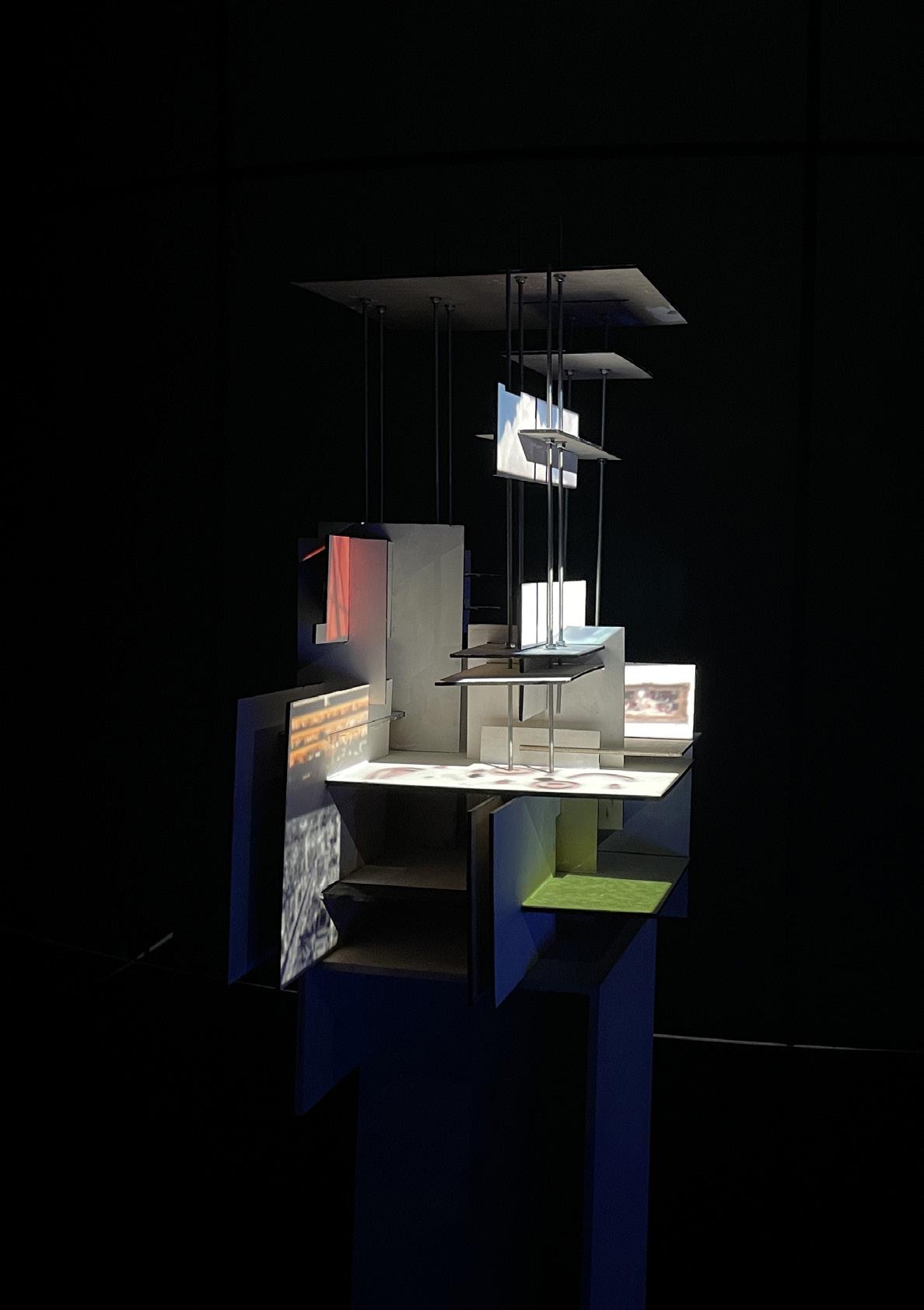

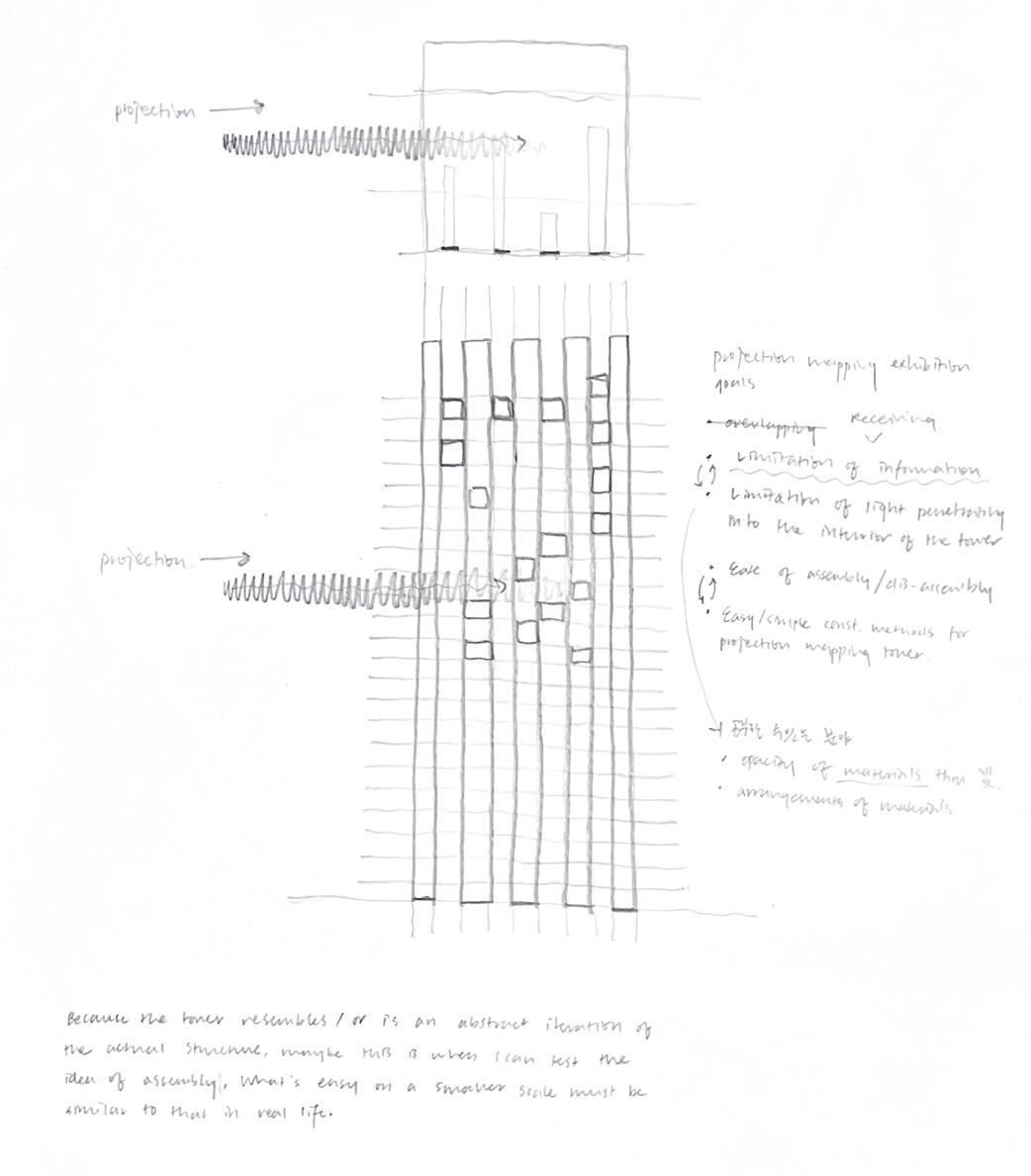

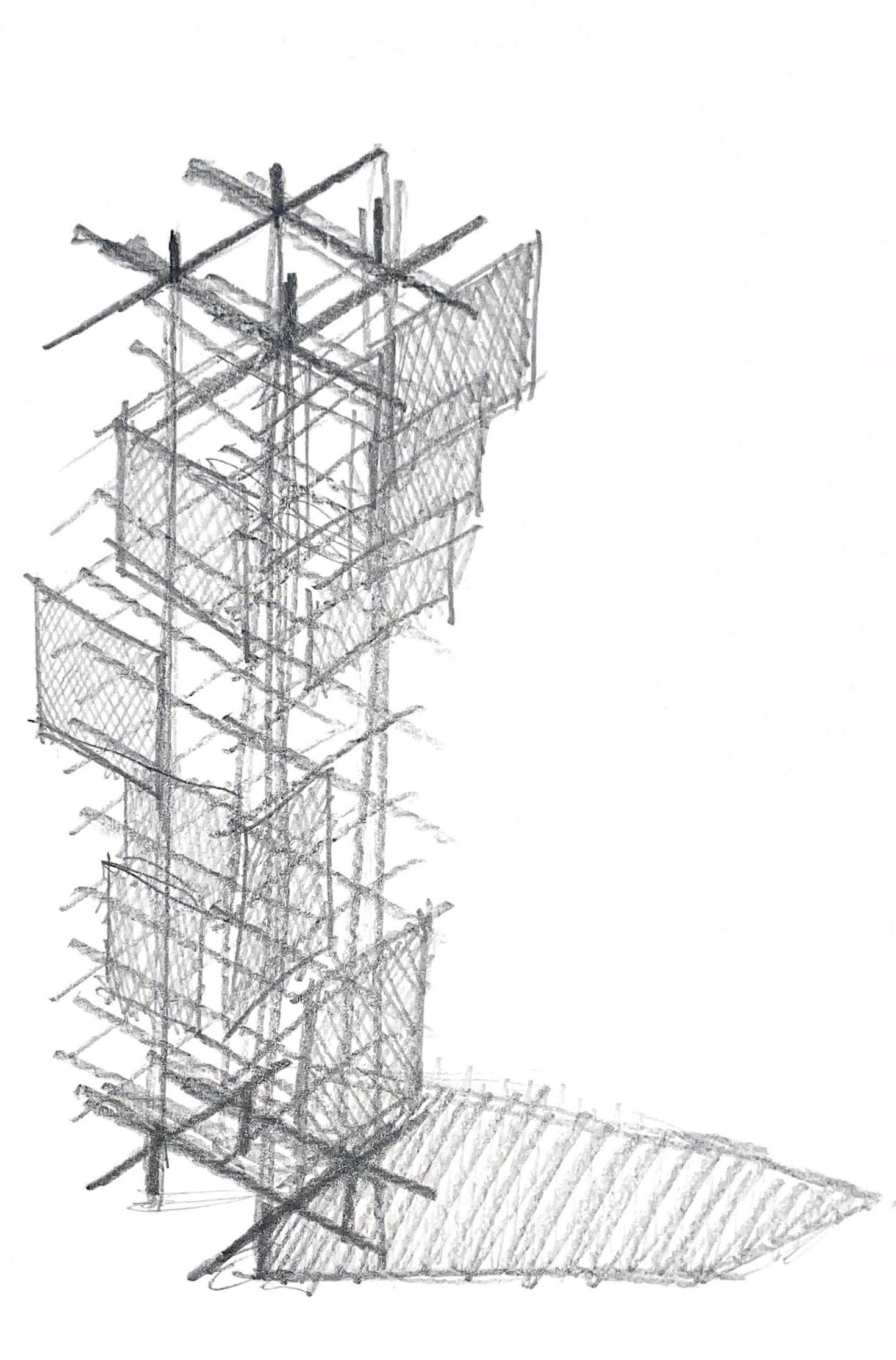

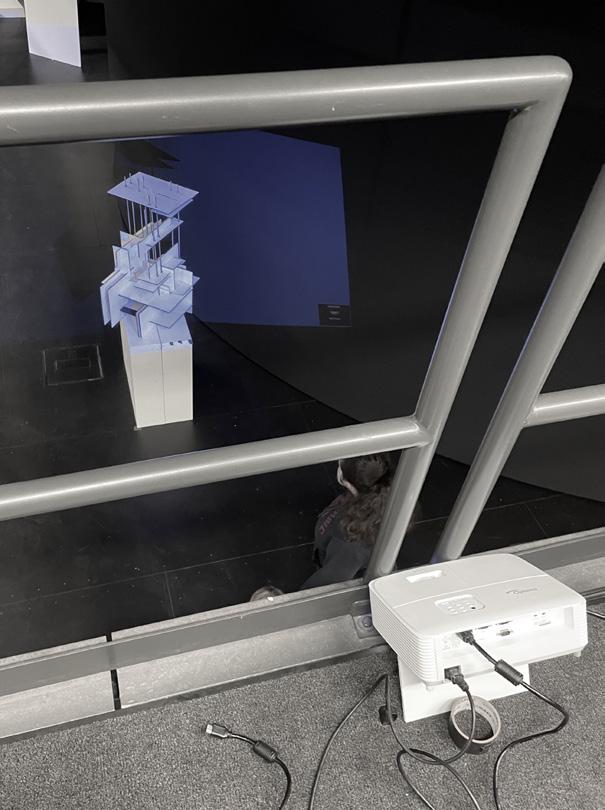

Projection mapping is a video projection technique on a three-dimensional surface using light and colors to project virtual images and video files. As a medium of art and visual graphics, the largest advantage of projection mapping is in the ease of giving character to blank surfaces or structures.

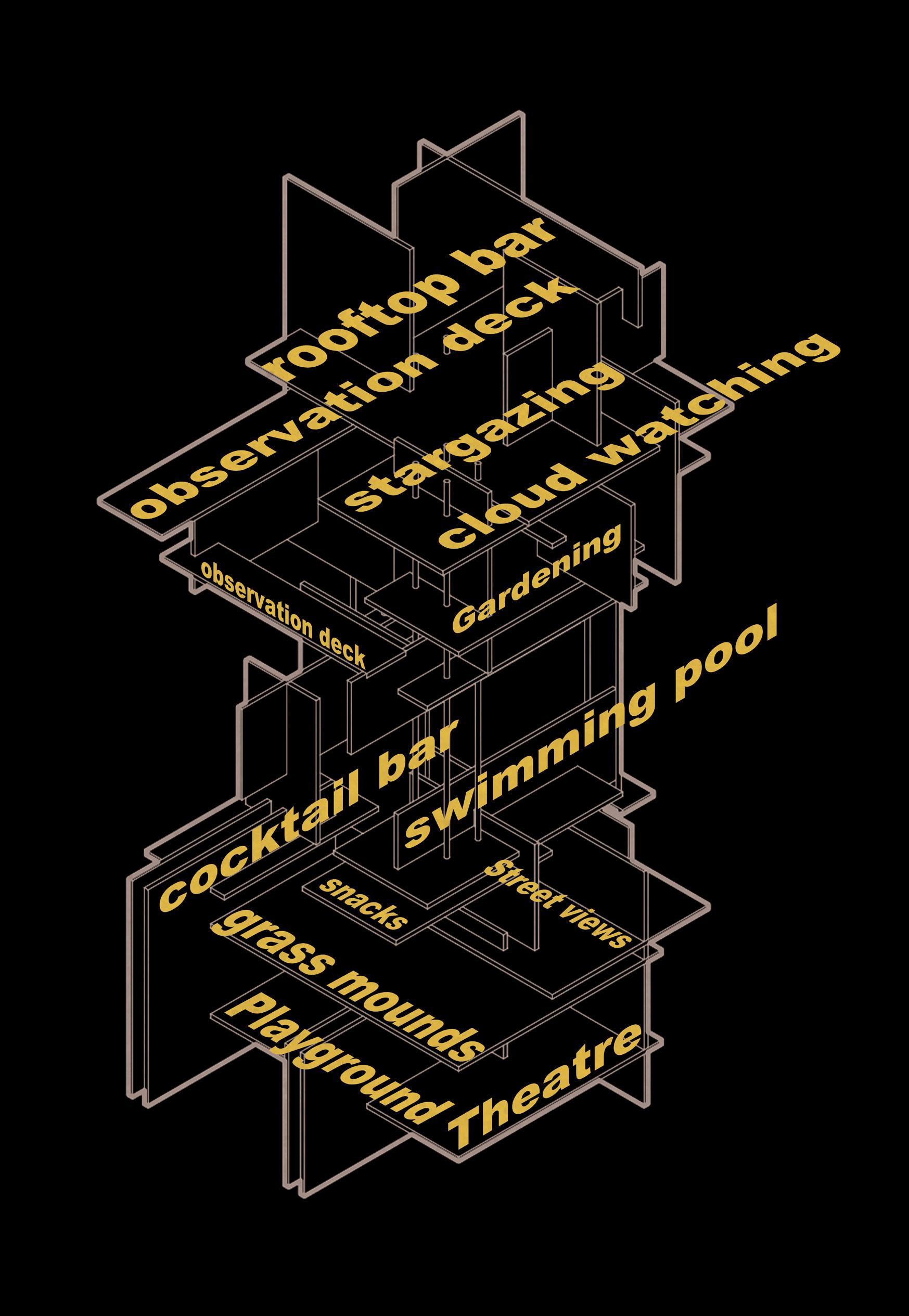

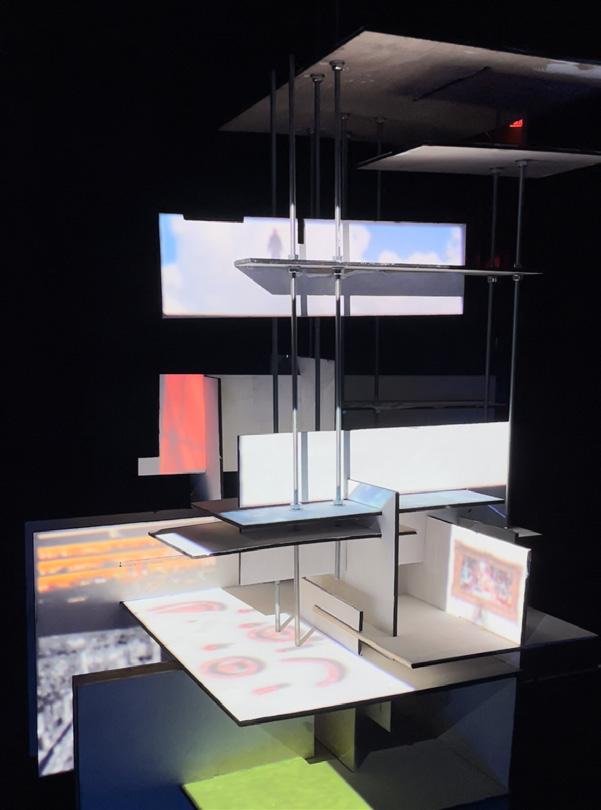

With the oppurtunity to experiment with projectors and projeection mapping, the technique is used to visualize a space with various programs juxtaposed with eachother, much like what Cedric Price’s Fun Palace wanted to achieve. Public spaces such as swimming pools and cocktail bars are adjacent to more reserved spaces such as places viewing the busy avenues of Manhattan or observation decks for cloud watching.

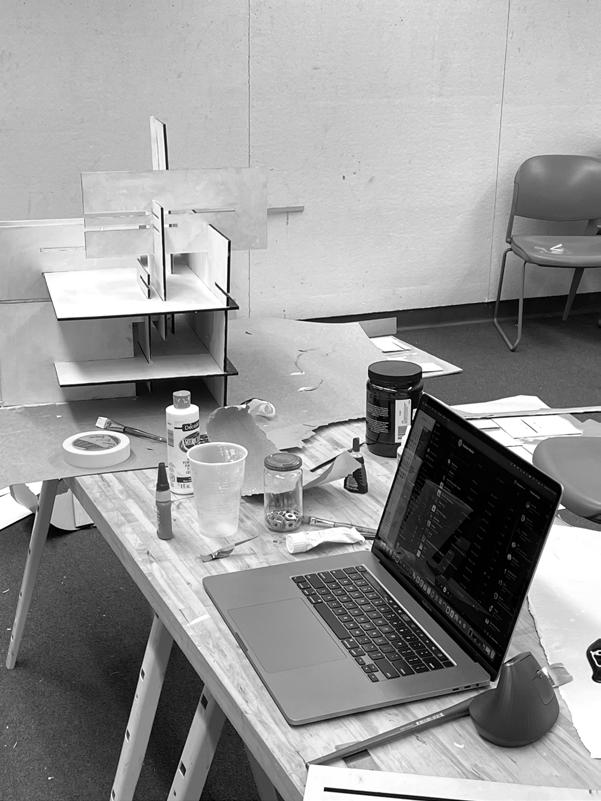

The juxtaposition of different programs helps visualize the potential of blurring the boundaries of different activities. This woven natrure of different spaces enhance a place to read as playful and motivates users to explore what’s around them. Having the benefit of the technology, moving images in the form of .gif files were projected onto selected surfaces of the physical model instead of

still images. This helped visualize the dynamic nature of the thesis: Just like immersive playgrounds with interconnected play elements, the different programs related to leisure, play, and entertainment create a place of pleasant surprises and a place to provide a place of choice. The visitors are introduced with various activities and the inner locus of control is heightened as they choreograph their exploration throughout the space.

The potential idea of creating a space of various activities and making the place a social hub was experimented in the projection mapping as well. The moving image files were timed so that a story was narrated within the various frames of projections. Two people enjoy the abstract model with their preffered activities and eventually socialize on a grass field juxtaposed with a cocktail bar adjacent to the public space.

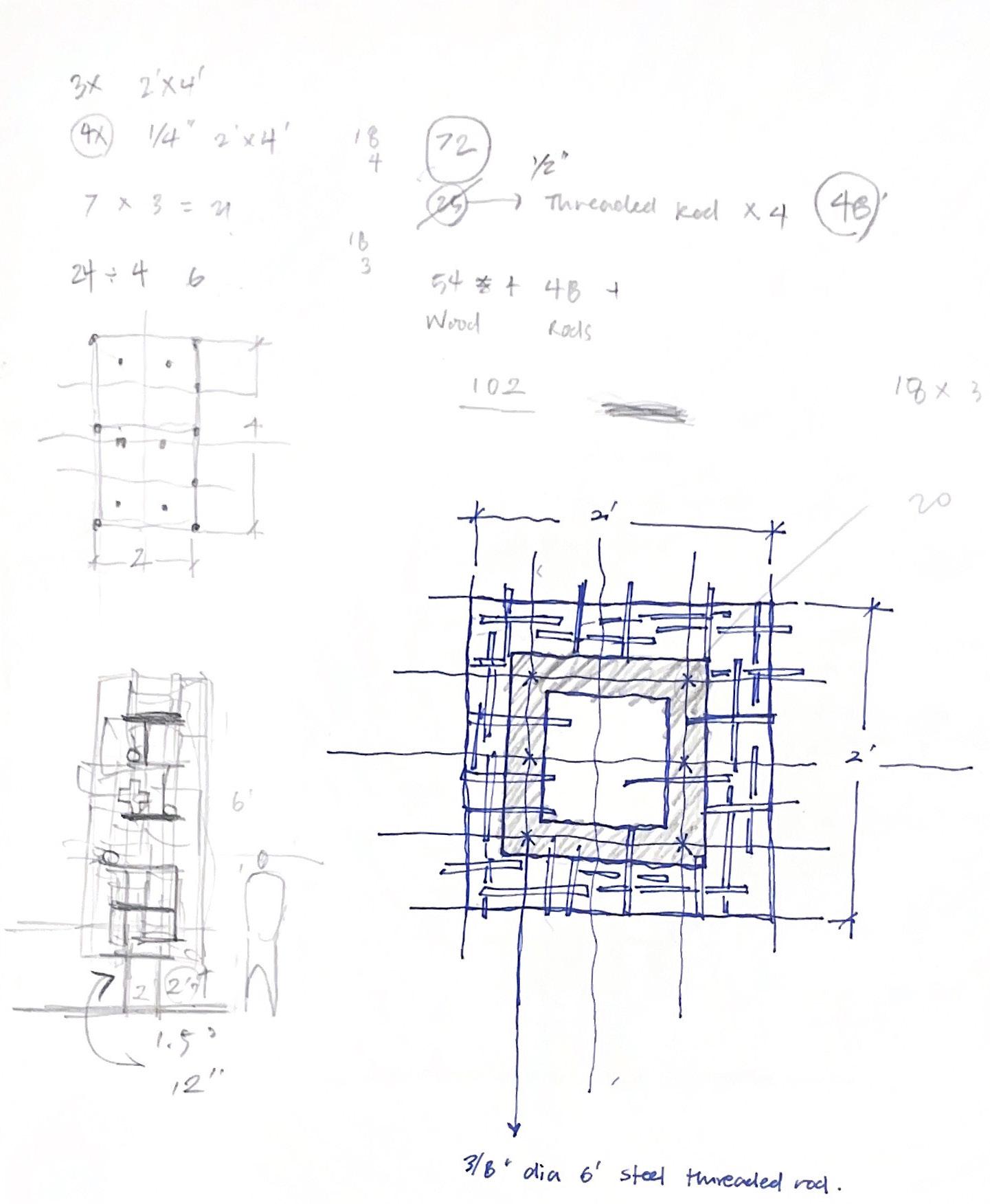

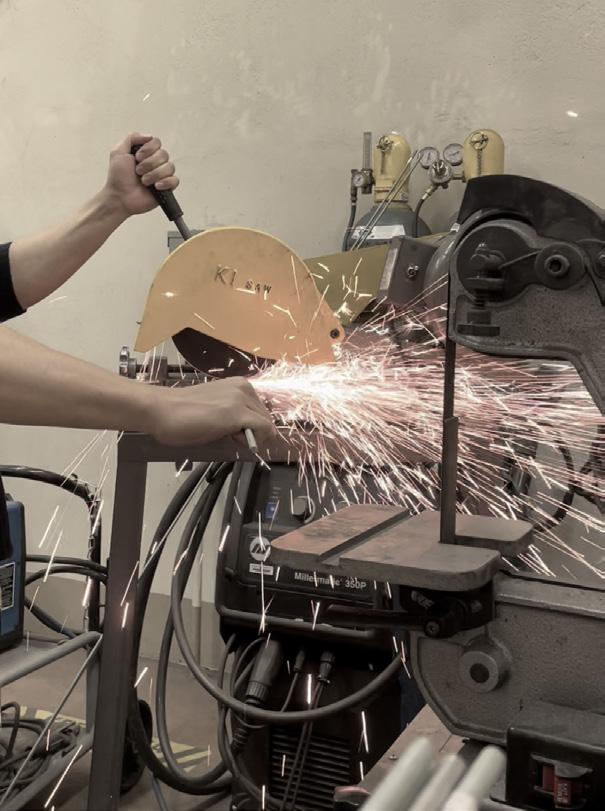

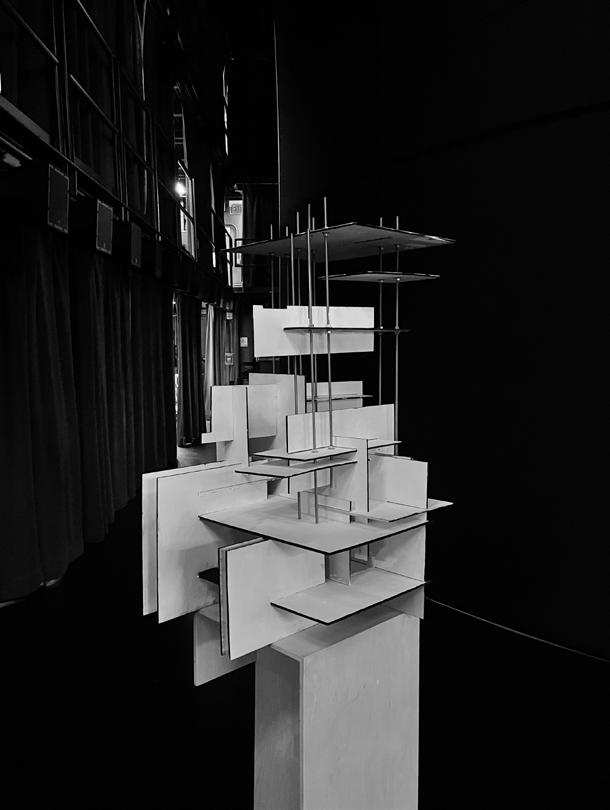

• With a laser cutter, quarter-inch birch plywood panels are cut to produce the various sizes of panels

• Ten threaded steel rods are cut to identical lengths.

• Individual panels have slits so that they interlock with eachother. Ten steel rods act as a structural core for the model.

• The model is positioned at 45 degrees from the source of the projection light.

• Fragments of projections are mapped on to the various surfaces with a single projector.

• Time sensitive .gif files are syncronized to tell a story of two visitors wandering about and eventually crossing paths in the end in the abstract model.