Pensar y pintar. El tránsito entre estos dos actos, y su vinculación, articula gran parte del trabajo de Manolo Quejido: ¿piensa el artista a través de la pintura, es la pintura el resultado, o el inicio del pensamiento? Desde que iniciara su trayectoria a mediados de la década de 1960, transitando por estilos como el pop, el expresionismo o la experimentación geométrica, hasta sus producciones recientes, centradas en la reflexión sobre la propia pintura, Manolo Quejido (Sevilla, 1946) se ha convertido en una de las figuras más destacadas del arte español de las últimas décadas.

Distancia sin medida, la exposición antológica que le dedica el Museo Reina Sofía en el Palacio de Velázquez, en el madrileño Parque del Retiro, nos permite adentrarnos en su fascinante universo creativo. A través de una selección de más de un centenar de piezas, la muestra pone de relieve las constantes que han marcado la evolución de su trabajo sin dejar de atender a las problemáticas sociales y políticas, Quejido ha dialogado con grandes artistas de la historia del arte, especialmente con Diego de Velázquez, al que alude de manera explícita en muchos de sus cuadros.

Esta exposición nos brinda la oportunidad de conocer las diferentes etapas y vertientes de la obra de este artista, dejando constancia no solo del carácter profundamente experiencial que tienen sus investigaciones plásticas en torno a la idea de la pintura como pensamiento —“como cosa de pensantes, como cosa de pintantes”, en palabras de la comisaria de la muestra Beatriz Velázquez—, sino también de la lucidez y rigor de sus investigaciones, y de su profundo inconformismo crítico.

Enhorabuena al Museo Reina Sofía por brindar al público la oportunidad de (re)descubrir el apasionado y apasionante trabajo de Quejido, un autor que nos invita, nos fuerza, a mirar de forma diferente, y nos obliga a discutir la forma en que pensamos y miramos la pintura.

Thinking and painting. The passage between these two acts and their connection articulate much of the work of Manolo Quejido. Does the artist think through painting, and is painting the result or the beginning of thought? Since he began his career in the mid-1960s, passing through styles like Pop Art, Expressionism, or geometric experimentation, up to his most recent productions, centered on reflection on painting itself, Manolo Quejido (b. 1946, Seville) has become one of the most prominent figures in the Spanish art of recent decades.

Immeasurable Distance , the anthological exhibition that the Museo Reina Sofía is dedicating to him at the Palacio de Velázquez in Madrid’s Retiro Park, allows us entry to his fascinating creative universe. Through a selection of over one hundred pieces, the show highlights the constants in the development of his oeuvre. Without failing to attend to social and political problems, Quejido has engaged in dialogue with great artists of history, especially Diego de Velázquez, to whom he alludes explicitly in many of his pictures.

This exhibition offers us an opportunity to discover the different phases and facets of the work of this artist, evidencing not only the profoundly experiential character of his artistic investigations of the idea of painting as thought—“as a thing of thinkers, as a thing of painters,” writes the curator of the exhibition, Beatriz Velázquez— but also the lucidity and rigor of his research and his profound critical nonconformity.

Our congratulations to the Museo Reina Sofía for giving the public the chance to (re)discover the passionate and impassioning work of Quejido, an artist who invites and forces us to look differently, and who obliges us to question the way we think and view painting.

A lo largo de sus más de cinco décadas de trayectoria, Manolo Quejido (Sevilla, 1946) ha reflexionado con infatigable constancia acerca de las intersecciones entre el pintar y el pensar. En este sentido, el trabajo con y sobre la pintura, entendida en toda su amplitud polisémica, ha constituido el principal eje articulador de su obra. Tal vez, como nos indica Isidro Herrera, en un primer momento “él quería solamente pintar”, pero al hacerlo se encontró pintando pensamientos —figurada y literalmente—y de ahí pasó a “pensar en pintura”, utilizando la expresión acuñada por Paul Cézanne. Algo que, por otra parte, no deja de ser una (pre)ocupación que ha compartido con otros muchos artistas, entre ellos, su paisano Diego de Velázquez, referente ineludible a la hora de abordar la obra de Quejido.

La “conexión Velázquez” queda patente de muchas formas en Distancia sin medida, la muestra retrospectiva que le dedica el Museo Reina Sofía. En ella, y en el presente catálogo que la acompaña, se repasa la carrera de Manolo Quejido a través del análisis de aspectos clave y de su producción —sus tempranas reflexiones sobre el problema de la correspondencia en la representación, su indagación sobre los parámetros que acotan una escena de interior, su crítica a lo que él describe como la “maraña de la mediación”, sus ejercicios pictóricos metalingüísticos en torno a la polisemia del propio vocablo “pintura”—, a la vez que se pone de relieve la unidad que hay tras su “deliberado pluri-estilismo en permanente metamorfosis”.

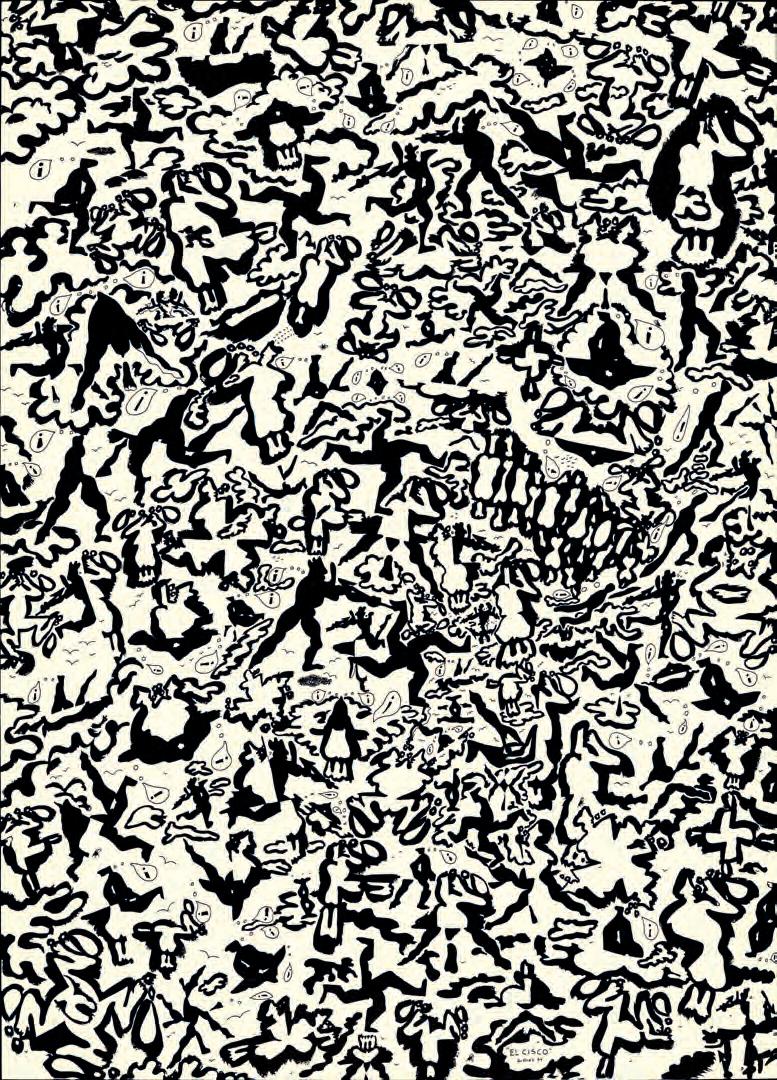

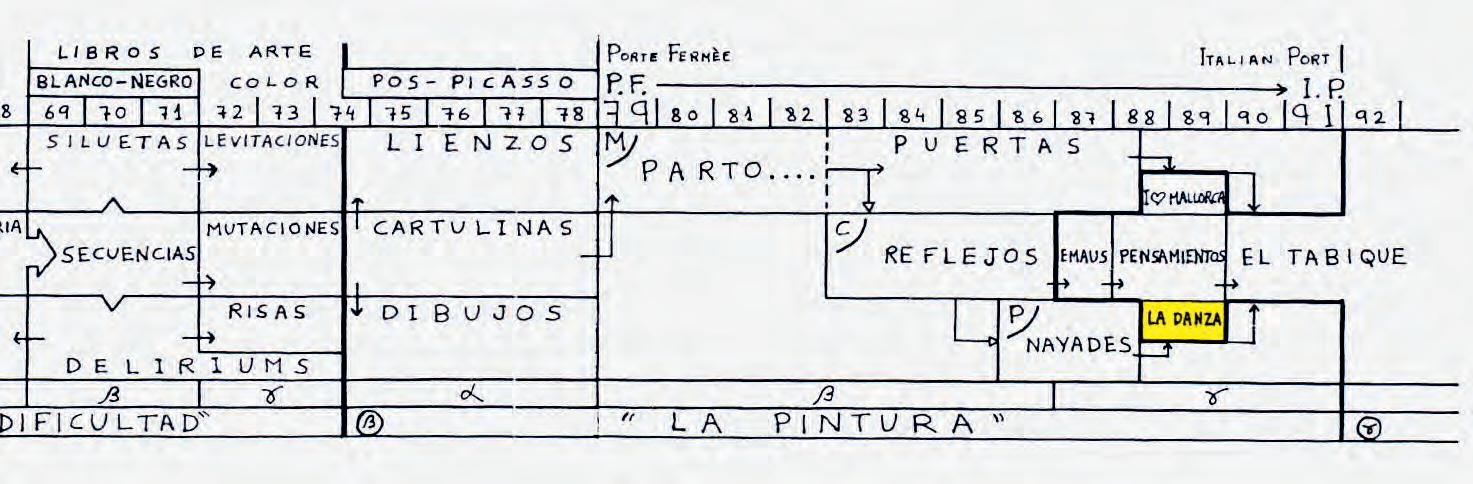

Ese pluri-estilismo está ya presente en sus obras de la década de 1970 cuando, experimentando con diversos medios expresivos como el pop, el expresionismo y la abstracción geométrica, crea las series Siluetas, Secuencias o Deliriums, que ya nos muestran su concepción del quehacer artístico como un proceso de constante búsqueda de (auto)conocimiento, no exento de un cierto componente místico.

Tras esta primera etapa de tanteo, en 1974, coincidiendo con el inicio de sus Cartulinas, Manolo Quejido comienza a contemplar la posibilidad de una vuelta a la pintura, asumiendo su condición expandida pero manteniéndola siempre dentro de parámetros reconocibles. Como nos señala Beatriz Velázquez, comisaria de la exposición, en estas cartulinas, cuyos motivos (objetos, figuras humanas, animales, ideas, lugares) son representados con diversos grados de abstracción y

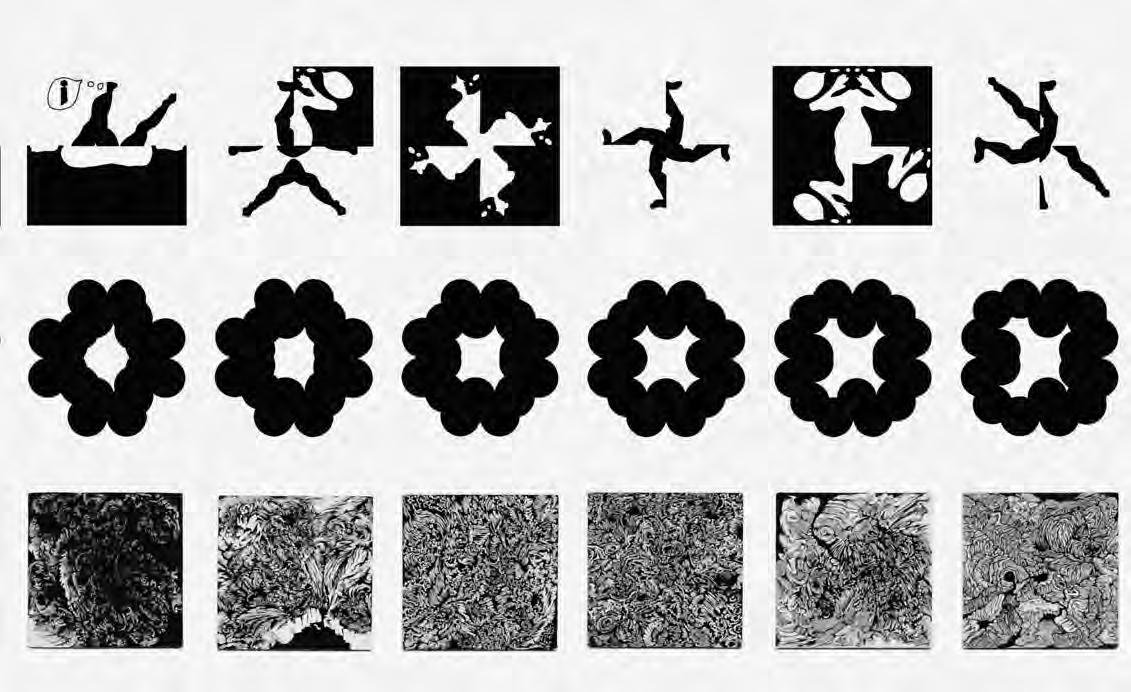

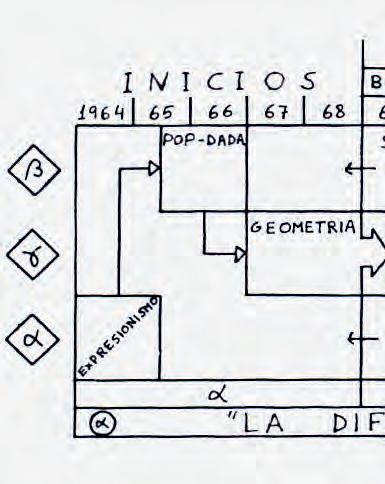

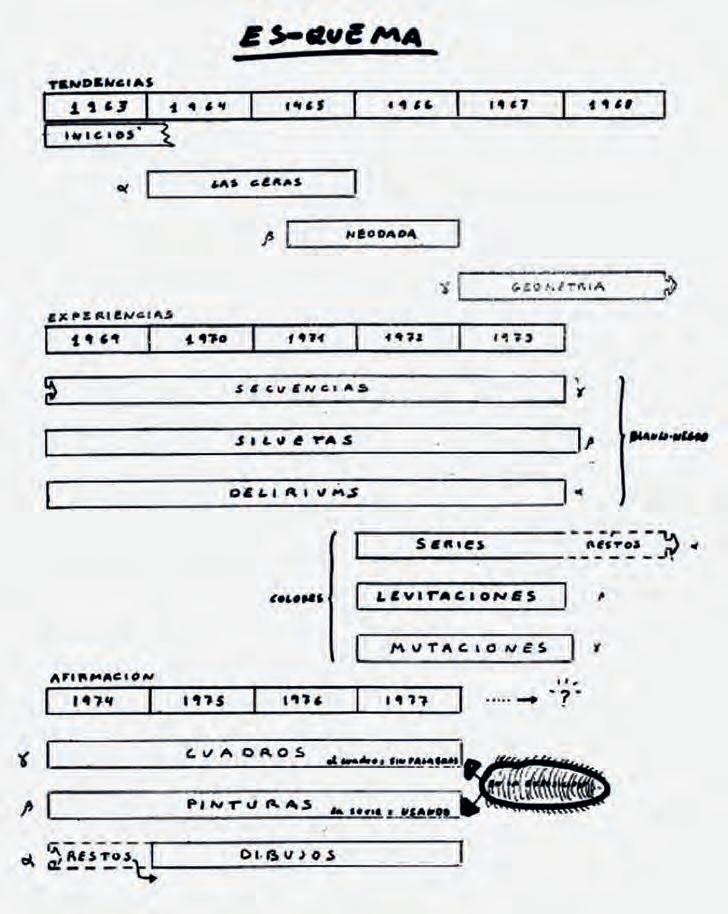

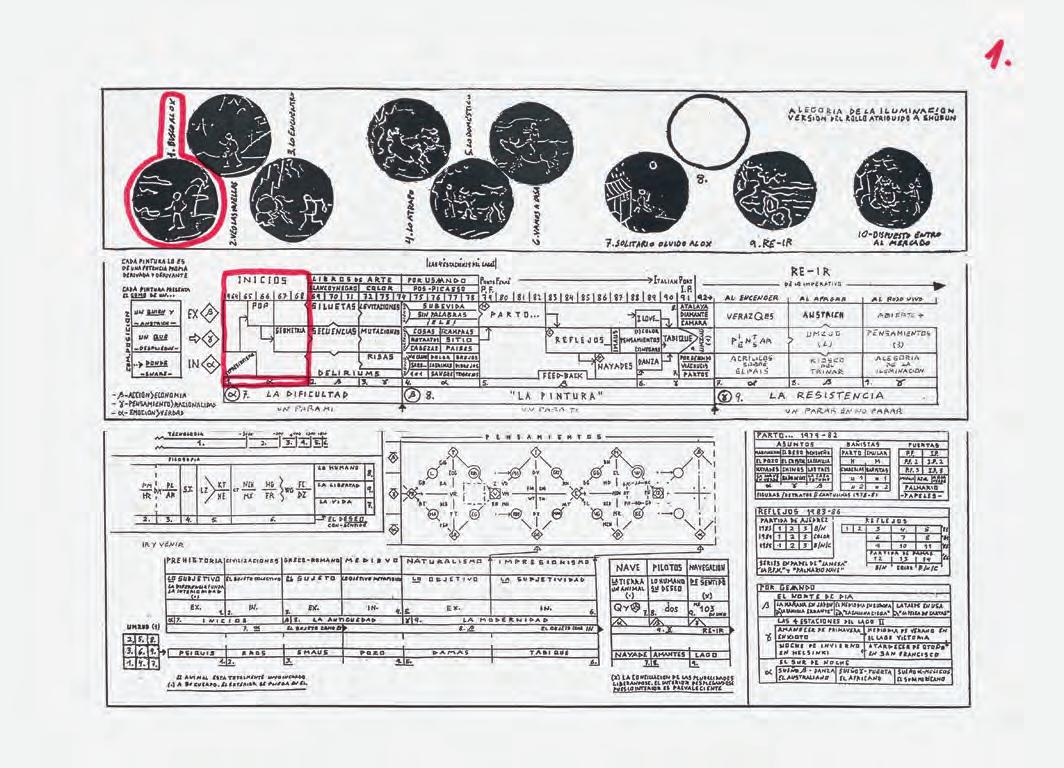

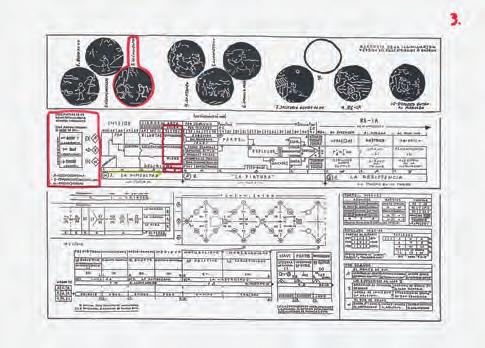

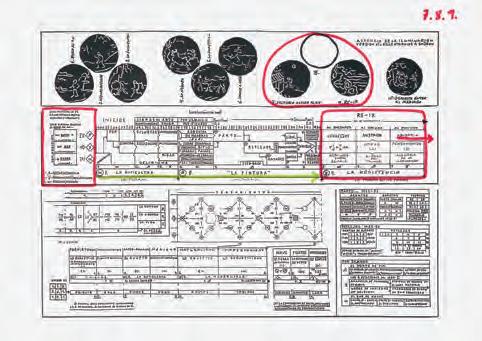

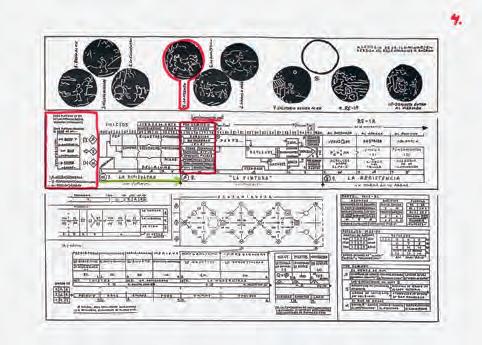

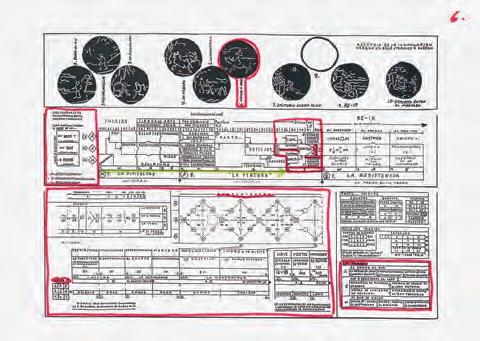

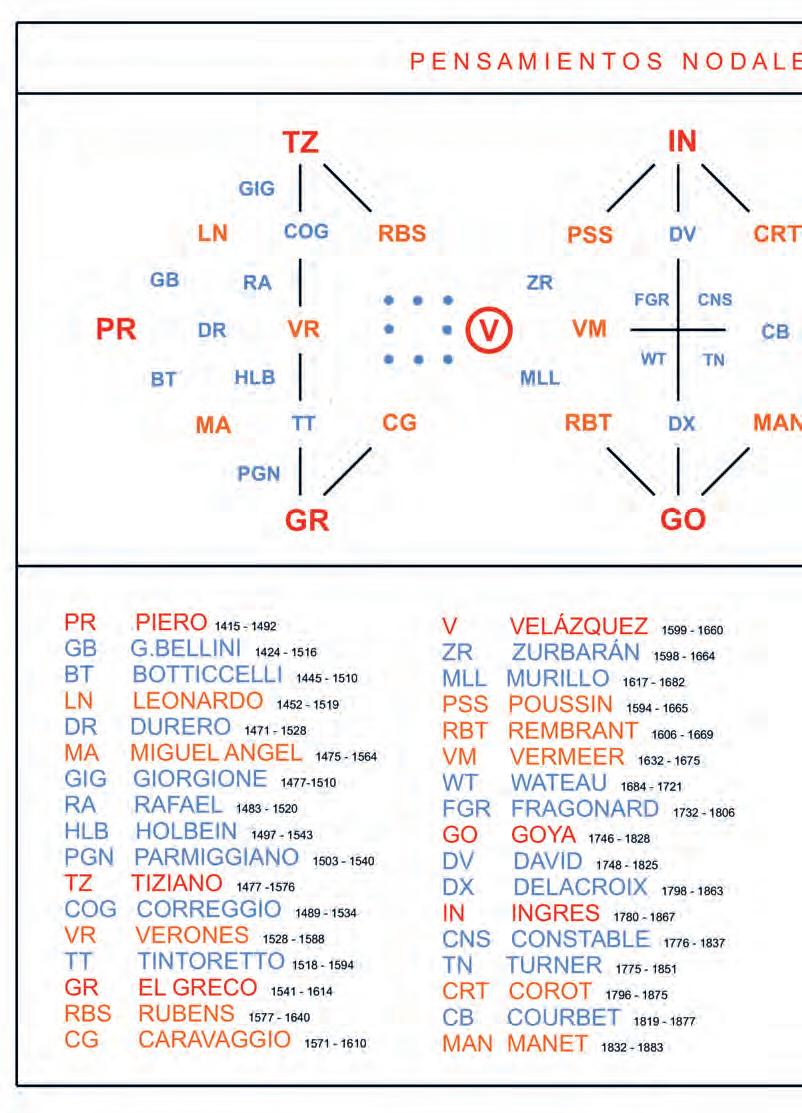

naturalismo, ya empieza a enfatizar la cualidad pensante/lingüística de lo pictórico. La imagen en la que el artista vuelca esta dualidad es la de la flor del pensamiento. En su serie de Pensamientos, iniciada en 1988, Quejido incide en la idea del pintor como herramienta que la pintura usa para materializarse a través de la creación de cuadros que a menudo adoptan una estructura diagramática. En ellos representa a diferentes pintores como flores de pensamiento, incorporando en cada una ellas elementos que aluden a las particularidades estilísticas del autor referenciado, y asignándoles un lugar determinado en relación con las demás, como si la historia de la pintura pudiera quedar estructurada en un sistema de “pensamientos”. Su interés por la estructura diagramática se pone de manifiesto en los numerosos esquemas que elabora sobre su propia obra. Esquemas donde, como nos cuenta Pablo Allepuz, “revisa, relaciona y sistematiza las transformaciones de su producción plástica, otorgándole y otorgándose un lugar concreto en la tradición de la pintura occidental”.

Con los años, en series como La pintura (2002), Nacer pintor (2006) y Los pintores (2015) y su sostenida reflexión sobre el pensamiento y la pintura le lleva a dar una gran centralidad en su trabajo a la indagación en torno a los diferentes pero contiguos sentidos que tienen las nociones de “pintura”/“pintar” y “pintor”.

Manolo Quejido nos confronta así con la indisolubilidad entre el sujeto que pinta, la acción que realiza y el objeto al que dicha acción da lugar, siendo quizás esta “concurrencia inextricable” lo que el artista llama “distancia sin medida”, expresión que da título a esta muestra y que aludiría a la ínfima y, a la vez, inconmensurable separación del pintar respecto a lo pintado, de lo aún no creado respecto de la obra que tomó ya ser y forma.

La motivación de Manolo Quejido para decantarse definitivamente por la pintura a finales de la década de 1970 y principios de la de 1980 fue su exploración, de inequívoca ascendencia velazqueña, en torno a la sustancia y espacialidad de la pintura, a cómo abordar y desbordar la irrupción (o la ilusión) de lo real en la superficie plana del lienzo.

Quejido revisita el cuadro de Las meninas tanto en su serie de los Reflejos/Espejos, de mediados de los ochenta, como en los Tabiques, que pinta ya en los inicios de los noventa, ejercicios de gran complejidad

formal y conceptual sobre la representación de un espacio de interior. Los cuadros de la serie Tabiques son obstinadamente planos, en lo que podemos interpretar como una impugnación de la posibilidad de profundidad que el lienzo de Velázquez postula. Quejido parece querer suspender sus cuadros en la superficialidad de la pintura, explicitar su bidimensionalidad, borrando cualquier efecto de espesor y de ilusión volumétrica. Su reciente interés por la cinta de Moebius —superficie continua que, plegándose sobre sí misma, no tiene más que una cara—, constituye una continuidad de esta investigación sobre la posibilidad de una pintura que, en palabras de Herrera, sea toda “superficie sin profundidad o con un mínimo volumen menguante”.

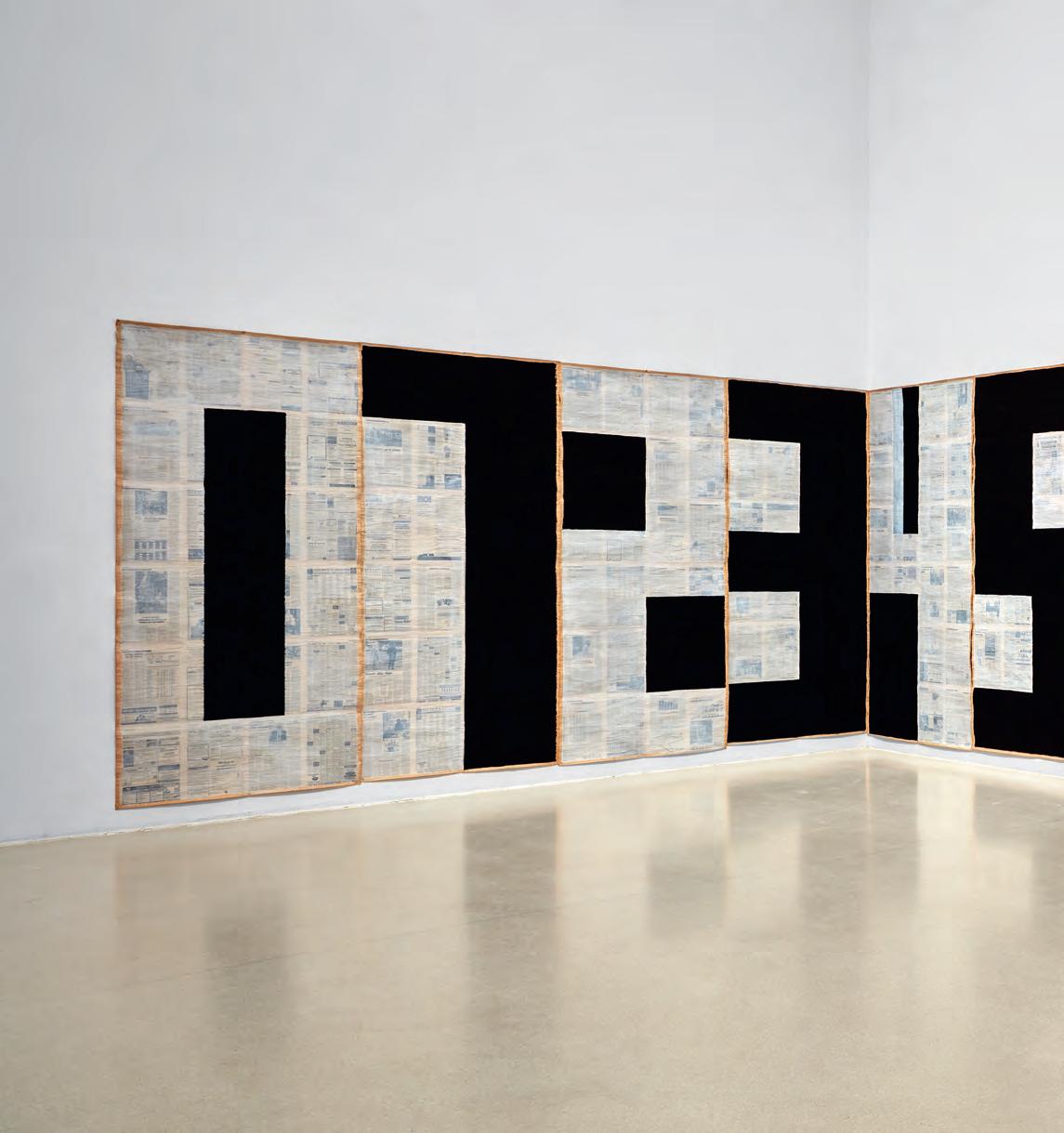

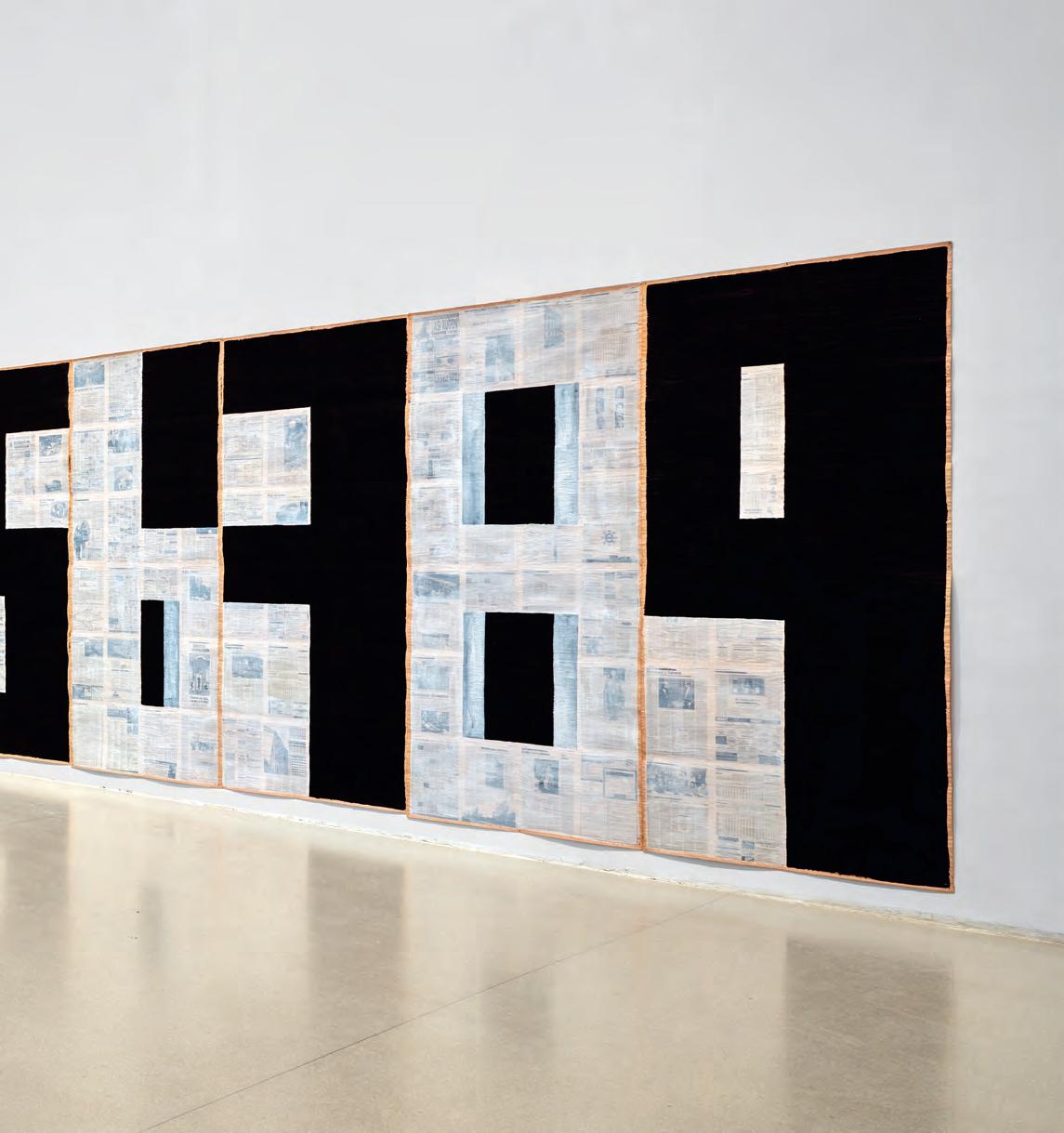

A mediados de la década de 1990, Manolo Quejido trabaja además en torno a lo que él describe como una crítica a la “mediación generalizada” que rige la vida de los ciudadanos en las sociedades contemporáneas. Son obras en las que, sin abandonar la voluntad de explicitación de la superficialidad de la pintura a la que acabamos de aludir, el artista sevillano se vale de un cierto registro o cualidad de veracidad. Esta crítica a los “encantamientos de la mediación” se articula de formas muy diversas en obras como Sin consumar (19971999), la serie Sin nombre (1997-1998) o los Leaves left [Hojas restantes, 2010-2011], en los que utiliza como soporte papel de periódico, denuncia la función anestesiante y disciplinadora de los medios de comunicación, tratando de convertir su pintura en artilugio que atrape y nos confronte con la esencia insoportable, en tanto que nos habla del fracaso del proyecto civilizatorio, de imágenes y noticias con las que ellos mercadean como si fuera un objeto de consumo más.

Distancia sin medida nos brinda la oportunidad de introducirnos en el poliédrico corpus de maquinaciones que Manolo Quejido ha ido generando a lo largo de su extensa trayectoria. Al examinar retrospectivamente la obra de este artista, la muestra no solo nos permite tomar conciencia de la lucidez y rigor de sus investigaciones plásticas, sino también de su carácter radicalmente crítico, pues nos invita a redefinir los parámetros desde los que pensamos y miramos la pintura y lo que a través de ella se puede (y no se puede) contar y mostrar. Quizás, la clave de su vigencia reside justamente ahí, en su capacidad de hacernos pensar mientras miramos y mirar mientras pensamos.

Over a career spanning more than five decades, Manolo Quejido (b. 1946, Seville) has reflected with indefatigable constancy on the intersections between painting and thinking. In this respect, work with and on painting, understood in all its polysemous broadness, has constituted the main articulating thread of his oeuvre. Perhaps, as Isidro Herrera says, he initially “just wanted to paint,” but in doing so, he found himself painting thoughts, figuratively and literally, and from there he went on to “thinking in paint,” to borrow an expression coined by Paul Cézanne. This (pre)occupation is moreover one he has shared with many other artists, among them his fellow Sevillian Diego de Velázquez, a key referent for any study of Quejido’s work.

The “Velázquez connection” is evident in many respects in Immeasurable Distance, the retrospective exhibition that is now being dedicated to him by the Museo Reina Sofía. In it, and in this accompanying catalogue, the career of Manolo Quejido is surveyed through the analysis of key aspects of his production, such as his early reflections on the problem of correspondence in representation, his investigation of the parameters that set limits for an interior scene, his criticism of what he describes as the “tangle of mediation,” and his metalinguistic pictorial exercises centered on the polysemy of the word “painting” itself. At the same time, it highlights the unity lying behind his “deliberate stylistic plurality in constant metamorphosis.”

This stylistic plurality is already present in his works of the 1970s, when his experimentation with various expressive media like Pop Art, Expressionism, and geometric abstraction led to the creation of series like Siluetas (Silhouettes), Secuencias (Sequences), and Deliriums, which already show us his concept of artistic activity as a constant quest for (self-)knowledge with a certain component of mysticism.

After this initial experimental phase, Manolo Quejido began his Cartulinas (Cardboards) in 1974, and it was then that he started to weigh up the possibility of a return to painting, assuming its expanded condition but always keeping it within recognizable parameters. Beatriz Velázquez, the curator of this exhibition, points out that in these cardboards, whose motifs (objects, human figures, animals, ideas, places) are represented with different degrees of abstraction and naturalism, the thinking/linguistic quality of the pictorial already

starts to be emphasized. The image into which the artist pours this duality is that of the pansy, a flower whose Spanish name, pensamiento, also means “thought.” In his Pensamientos series, begun in 1988, Quejido explores the idea of the painter as a tool used by painting to materialize itself through the creation of pictures that often adopt a diagrammatic structure. In them, he represents different painters as pansies, incorporating elements into each of them that allude to the stylistic peculiarities of the referenced artist, and assigning them a particular place in relation to the others, as if the history of painting could be structured as a system of “thoughts.” His interest in diagrammatic structure is made evident by the numerous schemes he concocts on his own oeuvre. In these schemes, as Pablo Allepuz tells us, “he revises, relates, and systematizes the transformations of his plastic production, assigning it and assigning himself a particular place in the tradition of Western painting.”

Over the years, in series like La pintura (Painting, 2002), Nacer pintor (Being Born a Painter, 2006), and Los pintores (The Painters, 2015) and their sustained reflection on thought and painting, he came to substantially center his work on an investigation of the different but contiguous senses of the notions of “painting” / “paint” and “painter.” Manolo Quejido thus confronts us with the indissolubility between the subject that paints, the action carried out, and the object this action gives rise to. This “inextricable concurrence” is perhaps what the artist calls “immeasurable distance,” an expression that gives this exhibition its title, and which alludes to the minute yet vast separation of painting from what is painted, of what is not yet created from the work that has already come into being and taken shape.

Manolo Quejido’s motivation for opting definitively for painting in the late 1970s and early 1980s was his exploration—unequivocally inspired by Velázquez—of the substance and spatiality of painting, and of how to approach and outflank the incursion (or the illusion) of the real on the flat surface of the canvas.

Quejido revisits the picture of Las Meninas both in his series of Reflejos/Espejos (Reflections/Mirrors), of the mid-1980s, and in the Tabiques (Partition Walls), which he painted in the early 1990s. Both are exercises of great formal and conceptual complexity on the representation of an interior space. The pictures of the

Tabiques series are obstinately flat in what we might interpret as a refutation of the possibility of depth that is postulated by Velázquez’s painting. Quejido seems to want to suspend his pictures in the superficiality of the painting, making its two-dimensionality explicit and erasing any effect of thickness and volumetric illusion. His recent interest in the Moebius strip—a continuous surface twisted over itself that has only one side—is a continuation of this research into the possibility of a painting that, in Isidro Herrera’s words, will be “all surface without depth or with a minimum diminishing volume.”

In the mid-1990s, Manolo Quejido also worked on what he describes as a critique of the “generalized mediation” that governs the lives of citizens in contemporary societies. Without abandoning the desire we have just mentioned to make the superficiality of painting explicit, the Sevillian artist makes use in these works of a certain register or quality of veracity. This critique of the “enchantments of mediation” is articulated in very diverse forms in works like Sin consumar (Unconsummated, 1997–99), the series Sin nombre (Without Name, 1997–98), and Leaves left (2010–11), where he uses newsprint as a support. Denouncing the anesthetizing and disciplining function of the media, he tries to turn his painting into a device that speaks to us of the failure of the civilizing project while trapping and confronting us with the unbearable essence of news and images that are traded as if they were merely another consumer item.

Immeasurable Distance offers us an opportunity to enter the multifaceted corpus of schemes that Manolo Quejido has generated in the course of his extensive career. In its retrospective examination of this artist’s work, the show allows us to gain awareness not only of the lucidity and rigor of his artistic investigations but also of their radically critical nature, as it invites us to redefine the parameters from which we think and look at painting and what can (and cannot) be shown and told through it. Perhaps the key to his relevance lies precisely in that capacity to make us think as we look and look as we think.

143 AUTOBIOGRAFÍA

175

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF PAINTING: THE SCHEMES OF MANOLO QUEJIDO, OR HISTORY (ITSELF) AS PERPETUAL SCHEMING Pablo Allepuz García

Hubo un momento en que Manolo Quejido añadió el “sentir” al par “pintar/pensar” con que describía su trabajo. Seguramente fue por cuanto sus pinturas tienen de alumbramiento, de solución (o, al menos, de enunciado) de cuestiones que nos interpelan desde la desmesura de lo inefable. Pero, teniendo en frente las obras con las que esta exposición trata de repasar la trayectoria del artista —iniciada en 1964, y sin interrupción—, lo que la obra de Quejido me devuelve es pensamiento, pensamiento y más pensamiento. Pensura, quisiera llamarlo, para denotar la espesura por la que transita quien acomete el estudio de su pintura.

Razón tenía Manolo Quejido al decir, en alguna ocasión, que cree que su pintura trata de dar que pensar. Pues bien, he aquí un muestrario de lo que me ha dado que pensar a mí. He aquí el resultado de varias figuraciones, urdidas por la observación de cuatro aspectos de su producción: el problema de la correspondencia en la representación en su pintura más temprana; sus reflexiones sobre la sustancia y espacialidad de lo pintado, intensas en la década de 1980; el hacer de su pintura cuerpo y soporte de lo que se quiere destinar a ser pasado por alto; y el largo recorrido de sus disquisiciones sobre la pintura como arte más grande que uno mismo, como cosa de pensantes, como cosa de pintantes.

Encarnar carne

Tras unos primeros años en los que Manolo Quejido investigaba acerca de las posibilidades plásticas geométricas o figuraciones delirantes, en 1974 el artista entra por fin a pintar. Lo hace a través de sus Cartulinas, que se llegan a contar por centenas, en las que plasma asuntos de lo más misceláneo: objetos, personajes, personas concretas,

animales, ideas, lugares. Lo hace con distintos recursos de escala, de factura, y de grados de abstracción o naturalismo; pero siempre dentro de la uniformidad del formato dado por el tamaño, 100 × 70 cm, de una cartulina.

En las cartulinas, y en las primeras pinturas a las que estas dieron paso, Quejido se topa con el pantano de la representación, con las resistencias que el mundo ofrece a ser expresado con imágenes o con palabras, así como con la inexacta correspondencia entre estos tres órdenes. Para la primavera de 1978, cuando Quejido expone en la Galería Buades de Madrid, el “taco” de sus cartulinas comprendía varias decenas. En la invitación a la exposición, el artista escribe una frase para tratar de clasificarlas: TRIANA ENCARNA CARNE. De manera que las cartulinas caerán en alguna de las tres categorías: serán “Triana”, serán “encarna”, o serán “carne”.

La atribución de cartulinas a cada categoría suscita reflexiones sobre lo particular y lo genérico, sobre lo sustantivo, sobre lo representable. “Triana” es un nombre propio y, como tal, sirve para designar algo que es singular de forma absoluta, algo que no puede quedar determinado dentro del coto de palabras de una definición. De forma similar, las cartulinas del tipo Triana expresan el singular evocado, pero sin llegar a definirlo. Es el caso, por ejemplo, de lo que Quejido llama “países” (como Rojo, 1975, p. 1).

En cambio “carne” es un nombre común, hace referencia a la generalidad de una especie. Así, entre las cartulinas que Quejido sitúa bajo esta rúbrica están las que llama “cosas”, que sí funcionan en buena medida como definiciones. Obras como Termómetro o Cerillo (ambas de 1976, pp. 7, 3) muestran ostensiblemente el aspecto del objeto en cuestión, a la vez que sugieren su propósito. El fondo bermellón y de pincelada agitada que rodea al termómetro remite al calor; mientras que en el cerillo el contorno amarillo lo recorta luminosamente del negro que lo enmarca. Y una luz acusada incide sobre él: todo insinúa su potencial estado útil como iluminador.

Con todo, las cartulinas que se encuadran en la sustantividad de la carne no dejan de ofrecer contratiempos en su empresa definitoria. La escala desmesurada respecto de la realidad a la que se refieren, en Termómetro, Cerillo o Galleta (1976, p. 5). O los límites de lo que puede considerarse como perteneciente a una especie en casos como Jamón (1978), donde a la vista aparece tan solo el resto ya consumido, el garrón, inscrita su figura en la sombra del jamón que fue.

En otra de las cartulinas que quedan bajo la categoría de carne, Regla (1976, p. 14), se encabalgan los comentarios sobre el problema de la definición. Por una parte, está escrito que lo que vemos es “La regla”, indicándonos el artículo determinado, “la”, que lo que se presenta es la regla por antonomasia, compendio de todo lo que —y únicamente lo que— una regla es. Pero la representación traiciona nuestra expectativa porque, escandalosamente, se trata de una regla que no es recta y que no puede, por tanto, desempeñar su función de medir distancias. Es más, desconfiaremos de las medidas que exhibe como referencia. Estas dicen llegar solo hasta los 100 centímetros, que son justamente la medida de la altura de la cartulina en que la regla se inscribe: así que, dado su pronunciado desarrollo curvo, la pretendida regla tiene necesariamente una longitud mayor. La regla no es, pues, en casi nada regla. En un sentido figurado, parecería más bien ser una excepción. Todo apunta a que el patrón se muestra esquivo a ser fijado y descrito, que la regla no puede sujetarse en una representación ideal, que la reducción del mundo a sus representaciones (las del arte, y las de la lengua) es costosa tarea.

Detengámonos en el título “encarna”. Encarnar es personificar ideas o cualidades. Así, serán de tipo encarna las cartulinas que recurran a esta estratagema. Entre ellas, las llamadas “trampas”, que sirven a conceptos complejos y distantes de la sustantividad. Un ejemplo sería Planamente (1976, p. 16): encarnación de un adverbio, de la idea de transcurrir o suceder “planamente”, que toma forma mediante alusiones, como juego de imágenes y palabras, como trampa al fin.

“Triana encarna carne”, la frase con que Manolo Quejido clasificó sus cartulinas, era el eco de una obra anterior, Matilde disimula un pensamiento, de 1974, obra que se instala en el atolladero de la representación de enunciados. En su estructura directa, Matilde disimula un pensamiento recuerda a las frases de la cartilla escolar, que se apoyan en ilustraciones con las que entablan una sencilla correspondencia: la oración “Susi me puso sopa” admite su equivalente en el dibujo de una niña con el gesto de servirse de una sopera. Sin embargo, ¿cómo puede figurarse un enunciado complejo como “Matilde disimula un pensamiento”, en que ni la acción ni el objeto se refieren a estados del mundo físico? Manolo Quejido lo hace a través de una suma de imágenes que, una a una, remitan a las partículas del enunciado. Quejido representa a Matilde, a la que yuxtapone una encarnación del “disimula”, le añade una imagen de pensamiento. Pasando por alto las disparidades de

escala, los elementos de cada parte de la obra se adecúan al tamaño de una cartulina, lo que acentúa que estamos ante un traslado biunívoco entre sintagmas e imágenes. No obstante, el enunciado así recompuesto no consigue traducir la frase de origen a imagen con completa limpieza, porque no se acallan ni las peculiaridades de las distintas representaciones ni sus fricciones con las palabras. Por una parte, “Matilde”, nombre propio, sujeto del enunciado, puede tomar forma de retrato. La desnudez puede responder a la pretensión de que la Matilde representada nos indique que quiere decir simplemente “Matilde”, pero la imagen no prescinde de los accidentes de que sonríe, de que fuma, de que calza chanclas. En cuanto a la acción “disimula”, que se resiste a la representación en tanto que acción de alto grado de abstracción, se encarna como juego de palabras. Y “un pensamiento” toma cuerpo mediante el equívoco, pues lo figurado no representa un pensamiento de la mente, sino que, recurriendo a la literalidad, se sirve de un segundo significado del término “pensamiento”, el de la flor. Aunque es precisamente así, vistiendo el pensamiento de otra cosa, como la obra abunda en el sentido de disimulo que su título declara. Para cuando da el salto a la pintura sobre lienzo de gran formato, Quejido ha cosechado ya muchas cartulinas en las que hay inadecuación entre el mundo, las palabras y las imágenes. No es extraño, entonces, que decida titular como Sin palabras su obra de mayores dimensiones de 1977 (pp. 34-35). En ella Quejido quiere significar el umbral entre la noche y el día. Un punto de por sí indeterminado, pues tiene la propiedad infinitesimal de lo que es instantáneo. Se trata, además, de un concepto para el que nuestra lengua no dispone de palabra: hay cruce de día y noche tanto en el amanecer como en el anochecer, pero el hecho mismo de cada uno de esos tránsitos no queda designado con una palabra propia. Así que Sin palabras no caería bajo el dominio de lo que Quejido llamaba “carne” y de sus representaciones de especies, sino bajo el de “encarna”. Quejido figura noche y día como personajes andantes, y su concurrencia se insinúa en la anticipación de que, en el momento siguiente al plasmado en la obra, sus trayectorias van a confluir. El cuadro es un díptico, con una pieza dedicada al espacio del día y la otra al de la noche. Los paramentos de sus respectivos fondos arquitectónicos —fuertemente iluminado uno, en casi completa oscuridad el otro— comparten la arista que les sirve de esquina. Pues bien, el artista sitúa tal arista precisamente en el lugar de los bordes verticales conjuntos de las dos piezas del díptico: así, la arista es única en tanto

parte de la imagen pero, a la vez, materialmente queda replicada en la fisicidad de cada pieza. Se apunta así a lo indiscernible que tiene un momento como tránsito entre día y noche: en analogía con la arista y con su presencia en las dos piezas del díptico, el momento de tránsito puede adscribirse tanto al día como a la noche pero, a la vez, es un instante distinto de ambos, y único. Por lo demás, la imagen aparece paradójicamente saturada de cosas que sí son nombrables: pelota, helado, guitarra, cigarro. Pero no importa cuántas palabras añadamos durante nuestra lectura del cuadro: ese límite instantáneo del cruce quedará necesariamente, por necesidad de su naturaleza, sin nombrar.

El espesor de la pintura

Gran parte de la pintura que Manolo Quejido produce en los años ochenta —desde la serie de los Reflejos/Espejos, que comienza en 1983, hasta la de los Tabiques de 1990-1991, pasando por las Náyades de 1986— no visita ya tanto las adversidades de la representación sino, por un lado, la condición de la pintura en lo que concierne a su participación en la realidad; y, por otro, el espacio que la pintura atrapa, por la dificultad de casarlo con la cualidad plana del soporte.

Las Náyades toman como pretexto una reunión campestre cuya cotidianeidad queda interrumpida por la aparición extraordinaria de la náyade, divinidad del lugar. Pero como en Náyade futura, o en Náyade azul (pp. 60, 61), la ninfa no se erige como plena corporeidad sino que es esquemática, esbozada, plana. Es más, sendos fondos enmarcados tras las náyades opacan la visión posterior de la escena. Quizás sean puertas que comunican con el espacio normalmente inaccesible de lo divino, o quizás lienzos empotrados en el suelo del paraje; pero en todo caso no puede concluirse ni que la náyade vaya a terminar de precipitarse en lo sólido, ni que vaya a permanecer siempre suspensa en la planeidad de un no estar ni aquí ni allá. Así también la pintura parecen decir estas obras— se entromete en el orden de lo real sugiriendo sustancia, pero sin alcanzar la densidad indiscutible del bulto redondo.

La serie de los Reflejos/Espejos, iniciada en 1983, surca una senda de investigación diferente, la de la pintura como mera ilusión. Es significativo que el artista vacile al nombrar las obras: a veces las ha llamado “reflejos” y a veces “espejos” porque, al fin y al cabo, sería difícil

pintar un espejo dejando aparte el reflejo que siempre devuelve. Ya El cristal, de 1980 (p. 38), se adelantaba a estas preocupaciones. Al disponernos a pintar un cristal podemos optar por que lo figurado sea lo que se ve a través de él, en atención a la completa transparencia que se le supone a un cristal ideal. Nos moveríamos entonces dentro del paradigma de la pintura como ventana. O, como hace Quejido, la pintura del cristal puede mostrar lo que en este se refleja: se intoxica entonces de la falta de nitidez de los contornos y de la equivocidad de lo observado; y se inviste con ello, solamente, del estatus minorado de realidad de lo que es reflejo o ilusión.

En el desarrollo de la serie de los Reflejos/Espejos, y hasta Partida de damas (1985, p. 69), el artista va resolviendo el enigma de la ambigüedad de las imágenes puesto que, obra a obra, desvela que era mera superficie pintada lo que por inverosímil o por indefinido nos extrañaba en la anterior. Así, entre lo que vemos en Espejo 8 (1984, p. 67) está una figura que contempla un cuadro. Pero la factura de ambos, cuadro y figura, es igualmente imprecisa, lo que nos dificulta identificar a la figura como distinta del cuadro. Además, es una situación poco probable, porque quien mira la pintura, en esta escena de interior, parece ser un bañista. En Espejo 11 (1985, p. 68), todo lo figurado en Espejo 8 queda como fragmento de la nueva escena y aparece como una pintura contemplada por otro personaje. Las explicaciones que demanda el espectador quedan temporalmente satisfechas, aunque Espejo 11 contiene otras dificultades que provocan desconcierto, sobre todo la gravedad silente de las figuras, su nula interacción, el estar encerradas en esa trampa plana que es el dominio de la pintura.

Será en Partida de damas donde Manolo Quejido atienda de nuevo nuestra necesidad de coherencia. El Espejo 11 se revela de nuevo como pintura que queda situada al fondo del cuarto. Esta obra ya no alberga más juegos, y de hecho no recibe título ni de espejo , ni de reflejo . Resuelve la serie, y pretende una cota mayor de participación en lo real. La figura del niño y lo que adivinamos como su mirada imbrican la obra con el espacio del espectador. Hay ecos de la figura del aposentador de Las meninas de Diego de Velázquez, pues ambos se representan de perfil en un espacio de umbral entre el cuarto y lo que está más allá. Pero mientras que Velázquez sugiere que el aposentador está entrando o saliendo del cuarto, el niño de Quejido forma parte de la escena en el instante anterior y posterior. Resulta clave su posición particular, con los pies en la misma línea de tierra de la obra, P. 41

Densueño 1979 Acrílico sobre lienzo 190 × 180 cm

Maquinando 1980 Acrílico sobre lienzo 190 × 180 cm

y con su cuerpo como los de las damas— prácticamente en el plano del cuadro: las leyes de la perspectiva implican, entonces, que sus figuras se proyectan en verdadera magnitud. El plano de introducción a la pintura está a nuestra escala, y nos permite entender Partida de damas no ya como reflejo o ilusión, sino como partícipe de nuestro orden de cosas. Solo la paleta limitada de colores, blancos, azules y negros, sigue desmintiendo la veracidad de la obra.

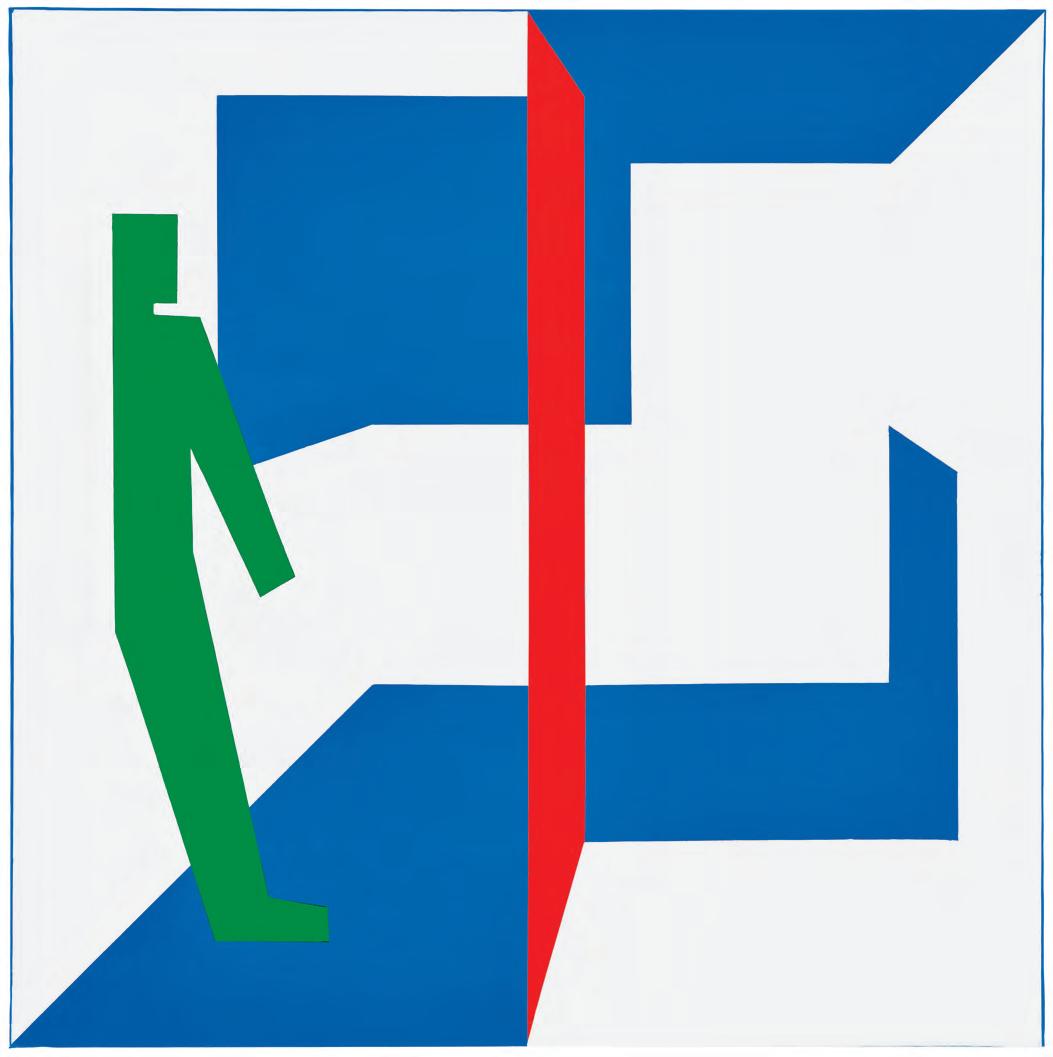

También en la serie de los Tabiques Quejido se aventura a evocar Las meninas. Sin embargo, deja de lado la especulación sobre si la pintura es verdad o reflejo. Meninas y tabiques presentan el espacio interior de un cuarto, el del estudio del pintor, pero los Tabiques parecen contestar a Las meninas impugnando la posibilidad de profundidad. En Tabique VI (1991), por ejemplo, solo la luz que entra por el ventanal asume cierta cualidad volumétrica, mientras que los componentes arquitectónicos se conforman con ser un caleidoscopio de planos de color. Si el haz de luz consigue escapar de esta sobredeterminación plana es gracias a un artificio: Quejido nos presenta la incidencia sobre el suelo del chorro de luz en perspectiva caballera, en contradicción flagrante con la perspectiva cónica de la pared lateral y del techo. Sus extremos no fugan, como sí lo hacen el resto de líneas paralelas de la mitad izquierda del cuadro.

La planicidad de los Tabiques, el reducido espacio que permiten albergar, ya pertenecía al lenguaje habitual del artista. Por ejemplo, La familia (1980, p. 39), Densueño (1979, p. 36), Maquinando (1980, p. 37) contenían a sus figuras en un pequeño interior. Algo similar ocurría en escenas de exterior como Bañistas de 1981 (p. 57) o el propio El cristal, que apilaban varios personajes en una grada de escaso recorrido. Por lo demás, en muchos trabajos (desde PF a IP, de 1979-1980 y 1980 respectivamente, pp. 58, 59, pasando por Palmario, de 1981) Quejido había parapetado el plano del cuadro con una acumulación de planos paralelos. Pero en los Tabiques, en un momento en que Quejido está lejos del pictoricismo, este procedimiento es más acusado.

En esta serie, el tabique esconde totalmente su materialidad de pared a pesar de tener un vano que daría cuenta de su espesor. Del tabique solo vemos uno de sus paramentos: queda restringido a constar solamente de una cara. Quejido relaciona esta insólita apariencia con el tratarse todo de una pintura, porque fuerza la relación entre el tabique y el lienzo y caballete que están a sus pies. El caballete gobierna la configuración visual del Tabique, porque hace suponer la presencia de

un pintor que se dispone a trabajar en lo que ve. Como además queda representado frontalmente, el punto de vista del supuesto pintor y el punto de fuga quedan determinados como necesariamente contenidos en el plano vertical medio del caballete que es perpendicular a este y a la propia obra. Pero es justo ahí, en ese mismo plano vertical de punto de fuga y de vista, donde se encontraría el espesor del tabique; por eso tal espesor nos queda negado porque proyecta frontalmente solo como recta vertical. El tabique y su espesor obedecen, pues, a la ley plana que el artista ha impuesto a estas obras.

La presencia de caballete y lienzo contribuye de una segunda manera a refutar la profundidad. En Las meninas, tanto el escorzo del bastidor del lienzo que ocupa a Velázquez como el hecho de que se muestra solamente su envés —con la consiguiente expectativa sobre lo que se ocultará en su anverso—, apoyan una fuga hacia el interior del cuadro. Sin embargo, en sus Tabiques Manolo Quejido exhibe directamente el anverso de ese bastidor y su lienzo, que contrasta con el resto de la obra porque hace ostentación de estar en blanco, de ser somero. Y, aunque la perspectiva cónica debería proyectarlo sobre el cuadro como un trapecio, Quejido lo presenta como un perfecto rectángulo: es como si se hubiera abatido sobre el plano vertical, vaciando toda la cabida de su pintura fuera de sí. Es más, las patas también abatidas del caballete determinan justamente la línea de tierra, y así el blanco del lienzo se superpone al plano real del cuadro, que el artista califica como lugar de puro vacío, que expulsará todo lo que se pretenda alojar dentro de él. En la escasa profundidad, en la recurrencia de la idea de umbral, Quejido suspendió sus obras en la superficialidad de la pintura. Las sujetó a la condición de su bidimensionalidad, subrayando así lo improbable de que puedan albergar enunciados volumétricos en el nimio espesor que queda entre su transparente anverso y su reverso opacado. Quizás de ahí le venga al artista el interés por la cinta de Moebius, superficie continua que, plegándose sobre sí misma, no tiene más que una sola cara. Hacia 2005 Manolo Quejido comenzó a ensayar la inscripción de la cinta en la superficie de un cubo, como queriendo afrontar el misterio de la cámara que se hace cavidad cuando se proyecta en un cuadro, de su tridimensionalidad arrojada a la superficie de la obra. Los Moebius Q-vista (pp. 186-189) constituyen otra forma de ser la pintura a la vez volumétrica y superficial. Por otro lado, en la cinta de Moebius no pueden distinguirse un interior ni un exterior. Por eso las figuras que, en los Moebius de Quejido, atraviesan la cinta, no

pasarán de estar dentro a estar fuera de ella, ni viceversa. Extendiendo el planteamiento, tampoco las figuras pertenecen o no a la pintura: por eso dónde están y si —por contraste con la pintura— son del orden de lo real, es algo que queda irresuelto como pregunta.

En la obra de Quejido existe otro registro, muy distinto, en que el artista se sirve de la superficialidad de la pintura, a la que reclama una cuota de realidad o, más bien, de veracidad. El artista enuncia una repulsa ante el estado del mundo, que llama de “mediación generalizada”: “la insoportable imagen que produce la timocracia a través del estado, la guerra, el consumismo y los medios de comunicación”1, frente a la que Quejido responde desde 1993.

Frente a este estado del mundo, Quejido reacciona de formas muy diversas. Así, por ejemplo, vuelve su mirada una vez más hacia Diego de Velázquez y el elaborado ilusionismo de sus obras. Si Antonio Palomino escribía sobre Las meninas que “es verdad, no pintura”, Quejido desplazará la cuestión de la veracidad en Velázquez hacia la de la verdad sentida, esa que grita a la conciencia desde el disgusto por cómo funcionan las cosas. En sus trípticos VerazQues, realizados a partir de La fragua de Vulcano, Las hilanderas y Las meninas, Quejido aloja sendas alegorías del ejército, la corona y la banca (pp. 70-72, de 2005, si bien existen versiones desde mediados de los noventa). VerazQues; veraz qué es, qué es lo veraz, entonces veraz es que banca, corona y ejército nos gobiernan, por más que su imperio quede enmascarado en la maraña de la mediación.

En los VerazQues las imágenes de Velázquez han perdido su volumen, pues Quejido las ha reducido a masas indistintas de figuras en arquitecturas aplanadas. Es una estrategia contra los encantamientos de la mediación, en favor de un mensaje directo que permite a Quejido alzar la voz. Y si en Velázquez el juego de las figuras, su conversación, coreografiaba las escenas dándoles una narratividad —el gesto anunciador de Apolo, la ofrenda del búcaro a la infanta, la atención de la hilandera a quien descorre la cortina—, Quejido hace actuar a sus figuras

1 Manolo Quejido, “Notas al condensador”, en Manolo Quejido: Pintura en acción, Sevilla, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, 2006, p. 158 [cat. exp.].

solidariamente. Sus cuerpos no interactúan, simplemente se confunden: cada masa de personajes es una sola corporación que actúa de manera monolítica.

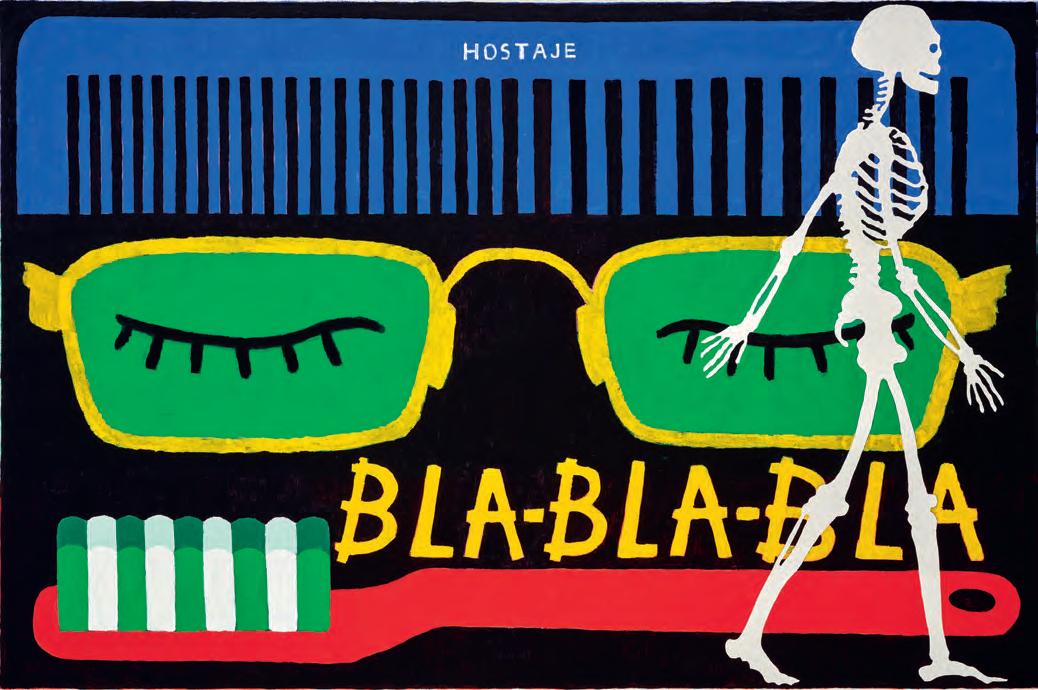

Sin consumar (1997-1999, pp. 126-127) constituye otra réplica al estado de mediación, en particular al consumismo. La monumentalidad de la obra, friso pseudopublicitario engalanado con todo tipo de productos, evoca la desmesura consumista y reproduce la promesa hipertrofiada que nos hace el mercado de lo disponible. Promesa de abundancia —en la escala amplificada de los productos, en la distorsión del tamaño entre pequeños y grandes como anunciando la misma satisfacción relativa—; de higiene y asepsia, dada la sobrerrepresentación de productos de limpieza, y de ganga, con toda una marea de precios flotando alrededor de los bienes prometidos.

Quejido explica el fracaso del consumismo en términos de no consumación de su promesa: presenta Sin consumar como mosaico completamente fragmentado que no consigue componer una unicidad; incide y reincide en la presentación de envases, sin aclarar si tienen verdaderamente un contenido. Y, de nuevo, recurre a una planicidad completa: no existe indicación de espacio sino simple yuxtaposición de imágenes y, en consecuencia, se niega la consistencia de los productos que la obra ofrece al consumidor.

En otra serie de obras, Sin nombre, Quejido opera en sentido contrario. En ellas, donde se reproducen imágenes de prensa, trata más bien de dar cuerpo y hondura a lo que, limitado al blanco y negro del periódico, y empleado apenas como ilustración para entretener la noticia, sirve a la mediación como membrana entre el espectador y el dolor del mundo.

Así, en el número 84 de esta serie, Psiquiátrico (1998, pp. 118-119), Quejido somete la imagen de prensa al color. El amarillo invade techo, paredes y suelo para hacerlos indistintos, revelando lo angustioso de esa sala de estar donde, sin calidez, se suceden marcialmente las sillas para las personas internas. Por su parte, el blanco, empastado, destaca su textura sobre la uniformidad límpida del amarillo, de manera que convierte en algo inteligible lo que en la fotografía de origen son reflejos en el suelo encerado. Algo que ofrece resistencia a la comprensión y que alimenta así un desasosiego. Por lo demás, Quejido deja de dibujar las patas de muchas de las sillas; deja ver cómo esta estancia puede ser un lugar sin suelo, sin reposo posible.

En Sin nombre nº 31 (1997, p. 114) Quejido da cuenta de la violencia del imperio de las cotizaciones. Para ello, descarna a la persona que

escribe precios de oferta y demanda sobre un encerado. Afanado en este escribir de apariencia inocua, en este jeroglífico de máximas abstracciones, su humanidad quedará transmutada en un contorno de líneas blancas sobre fondo negro, exactamente como las propias cifras que escribe. Quedará alienado en lo absurdo de lo que reclama su atención y su trabajo.

Una a una, y según la estrategia que más convenga a cada caso, Quejido va trasponiendo cada fotografía en un Sin nombre. Se trata de componer un catálogo de hechos consumados, deteniendo la velocidad frívola con la que la lógica de la mediación los despacha. Manolo Quejido los arresta, confrontando así lo insoportable que supone el constatar en ellos el fracaso del proyecto humano. Si bien opta por mantenerlos en el dominio de lo sin nombre o, mejor dicho, de lo innombrable: se asegura entonces de que el título que reciben atestigüe su obscenidad, por más que la mediación generalizada trate de dulcificarla.

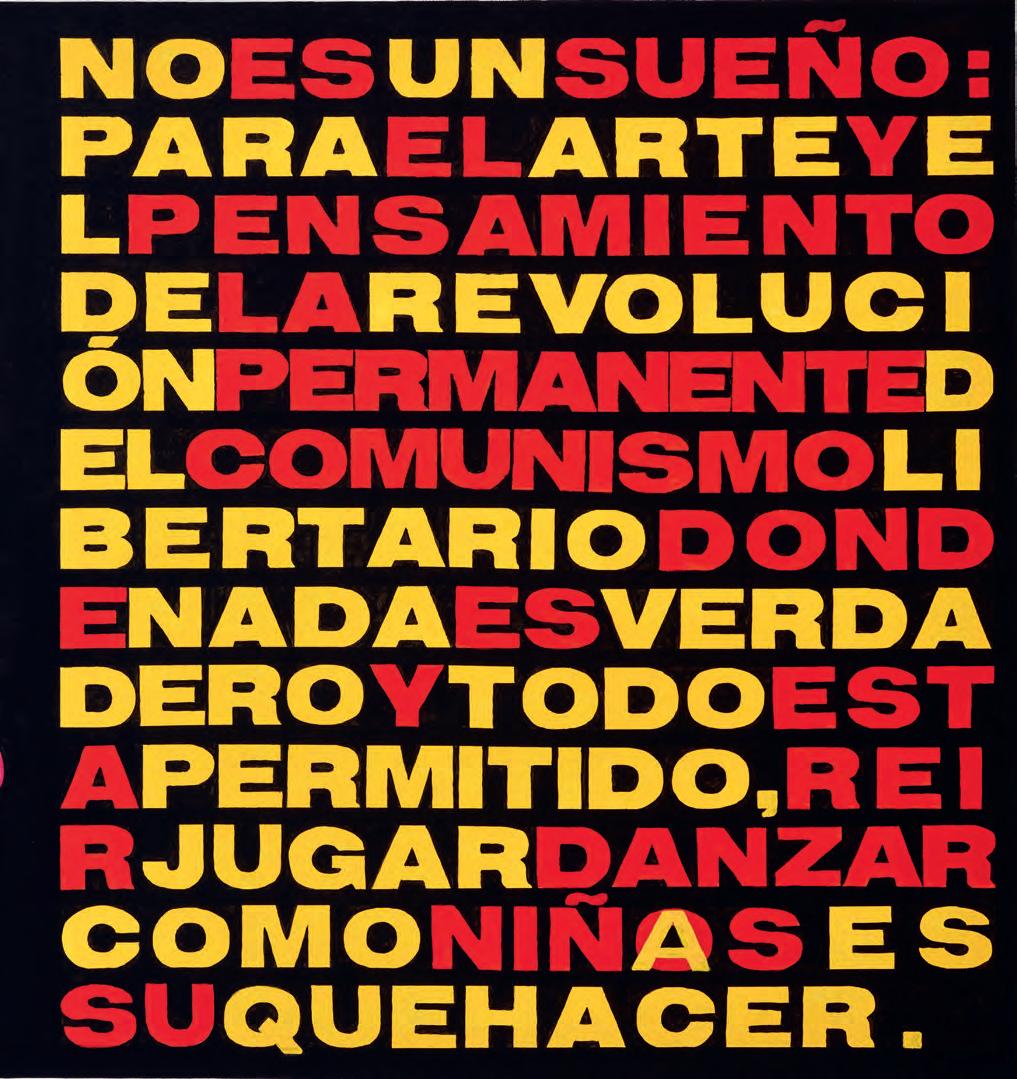

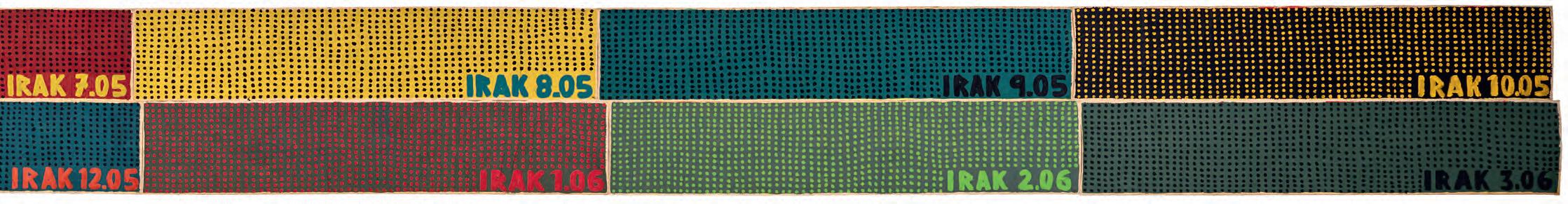

El papel lo aguanta todo. Más aún, en el régimen de la mediación, donde el papel de periódico y su texto infinito neutralizan, catástrofe tras catástrofe, el interés de lo que queda contado como noticia. Desde mediados de los noventa, a menudo Quejido protestará contra esa función del periódico, esa digestión de lo insoportable: aglutinará con engrudo las hojas de El País, cancelando así la retórica de su texto, y utilizando el resultado como soporte de otra cosa, de su pintura. Irak mes a mes (2005-2006, pp. 154-155), por ejemplo, apunta a la saturación de información que desactivaba la apreciación de la gravedad de la situación de la guerra de Irak. La obra niega todo lo escrito pero, además, subraya su esterilidad, pues la traducción que hace Quejido de toda la pila de reportajes sobre Irak se reduce a campos de puntos sobre superficies monocromas: mensaje indescifrable, contenido indiscernible, lejanía total con respecto de la verdad.

Años después, el soporte empastado de El País acogerá protestas más explícitas, quizás ante un sentido de premura por la situación de mediación agravada. De hecho, algunas obras de 2010-2011, llamadas

Leaves left [Hojas restantes, pp. 151-153], recurren al mensaje que se desvela cuando se nos va a acabar un librillo de papel de fumar: “Only

5 leaves left”, “solo quedan 5 hojas”, nos dice el librillo mientras nos apremia a acudir al estanco a por su repuesto. Probablemente, para el Manolo Quejido de entonces parecían quedar pocas oportunidades para que las denuncias fueran fructuosas. Y le parecería también que el arma de que se dispone sea tan frágil y efímera como el papel de fumar,

y que cada oportunidad pudiera consumirse y olvidarse con la rapidez con la que se extingue un cigarro.

Los Leaves left de Quejido no se limitan a cancelar la habladuría de la prensa —como hacía Irak mes a mes al sumir el periódico bajo la uniformidad del monocromo—, sino que sobre el engrudo del periódico incluyen palabras y signos a modo de poemas, que no por enigmáticos ocultan su carácter amargo. Pintura, pintante, pensado

Hacia 2000, Manolo Quejido repite con variaciones el planteamiento de La pintura (2002, p. 89), donde vemos a un personaje que está pintando un cuadro. Pero, ¿qué es, de todo ello, lo que da título a la obra? Lo que da pie a llamar la obra como “La pintura” pudiera ser el cuadro, en tanto que pintura, o también la acción presentada, en tanto acto de pintar.

Parece que Quejido suscribe esas entradas de diccionario en que un sustantivo, en este caso “pintura”, se describe como acción y efecto del verbo que lo origina. Si estas definiciones suelen ser problemáticas —pues cómo puede algo ser una acción y un efecto dentro de la misma acepción—, el artista alega aquí la naturalidad con la que no pueden separarse pintura pintante de pintura pintada. Es quizás esta concurrencia inextricable del trabajo y su objeto lo que Quejido da en llamar una distancia sin medida, la no separación entre el sujeto que pinta, el pintar, y el objeto del pintar.

En La pintura, además, se sugiere que la figura negra pintante es una personificación de la acción de pintar. De nuevo, qué pequeña distancia la que hay entre ella y su pintura pintada. Hay apenas una indicación, a la altura de sus pies, de que se encuentra en un suelo diferente del suelo del cuadro que está pintando; aunque, a la vez, la parte superior de su cuerpo parece recortarse del plano de lo pintado. La pintura pintante habita a la vez fuera y dentro de lo que se afana en producir. De hecho, el pigmento negro que aplica para convertirlo en pintura pintada parece consustancial con su mismo cuerpo negro.

La pintura sirve también a Quejido para exponer algo que a menudo ha dejado escrito: que la pintura es despreocuparse en lo que la ocupa. Entendamos aquí que la pintura pintada es, particularmente, la imagen de la modelo que figurará en el cuadro. Esta imagen aún no ocupa la pintura pintada, ni la propia obra, pues la parcela de lienzo que ocupará su

figura está aún sin pintar. Solamente pre-ocupa pues, por lo demás, su figura ya se adivina por contraste con lo ya pintado. Diría Quejido que está en un estado de pre-ocupación (como, por otro lado, su gesto pensativo sugiere), y adquirir imagen sería, entonces, una forma de des-preocuparse. Esa despreocupación, ese ocupar lo que estaba solamente pre-ocupado, es precisamente lo que mantiene a la pintura pintante tan ocupada.

Quejido aborda también la cuestión del acto de pintar en series como Los pintores, iniciada a mediados de los noventa. En esta serie (por ejemplo, en la p. 99, de 2015) se atiende a los dos usos del término “pintar”: uno intransitivo, el del pintar como cubrir de color, y otro el del pintar de la pintura; es decir, el del pintar que tiene un objeto (una pintura, un cuadro).

Los pintores nos muestra los dos tipos del pintar, pues se representan un pintor de pinturas, pincel en mano, y a una pareja de pintores de brocha gorda que pintan sendos tabiques. Ahora bien, el pintor de brocha gorda del plano del fondo pronto llama la atención por una dificultad en la representación: tiene que estar pintando un soporte transparente, o nos resultaría imposible verlo. Será el pintor de pincel quien resuelva la situación, pues queda superpuesto al pintor de brocha gorda, como pintándolo. Se dan tanto una sugerencia de la ventaja del pintar pintura sobre el mero cubrir de pintura, como un comentario acerca de la imposibilidad de transparencia de la pintura.

A la vez, el paisaje de Los pintores define el ser pintor dinámicamente. Como si el ser pintor solo ocurriese mientras se está pintando: en ese tiempo imperfectivo del participio presente, en el ser/estar pintante.

Manolo Quejido añade consideraciones de otra índole sobre qué es ser pintor en las distintas versiones de Nacer pintor (como la de las pp. 90-95, 2006). En ellas rescata los motivos de las obras con las que, en los primeros años ochenta, se decantó definitivamente por la pintura. A lo que fueron representaciones disjuntas confiere ahora un orden de secuencia narrativa, contando la historia de un niño que crece hasta convertirse en pintor. Es como si, en la contemplación retrospectiva de lo que ha sido su trabajo, Quejido advirtiese cómo su propia condición de pintor ha emergido paulatinamente, y casi sin su concurso. Como en ese nacer inacusativo en el que el sujeto que nace es casi simplemente objeto del propio nacer.

Los pintores y Nacer pintor remiten, entonces, a distintos aspectos del ser pintor: uno agente, el del pintor pintante que está ejerciendo la

acción de la pintura; y otro paciente, en el que el pintor es casi producto de la pintura misma. A menudo, el pensamiento de Quejido se ha detenido en esta cuestión, la de la relación entre los pintores y la pintura. Escribe en 1991 acerca de la agencia de la pintura: “Pienso a la pintura, como si ella la pintura fuera la creadora de toda pintura pintada o por pintar. Y pienso a los pintores y pintoras como sus manos”2.

Pero para Quejido, cada pintor define también un punto particular en el espacio de variables que conforman toda la pintura pensable: unas coordenadas de factura, de color, de forma. Desde 1988 va perfeccionando esta idea, representando a los pintores como flores de pensamiento: todas comparten el que son pintores, son pensamiento, pero cada una reproduce la manera de un pintor para así señalar su diferencia específica.

Si en las primeras series de Pensamientos (1988-1989) Quejido observa un cierto naturalismo al imitar, en la flor del pintor correspondiente, su manera característica de pintar, pronto abstraerá todas las particularidades cualitativas para traducirlas en un código de componentes mínimos: solo seis colores, que se combinan para definir un pintor en el fondo, en pétalos, marcas de los pétalos y pistilo. A la vez, Quejido decide situar este ramillete de pintores en un diagrama espacial (pp. 100-101) orientado según la historia de la pintura, pero que, a la vez, determina el espacio de las formas posibles de pintura, pues todas quedan como combinación de las formas de los nodos-pintor del diagrama.

Quejido hace de su sistema de pintores una representación de la pintura y, en obras como Diamante (1992, p. 104), emplea el recurso de la literalidad para defender esta idea. En Diamante el sistema de pintores, que podríamos pensar como plano o mapa de la pintura, adquiere verticalidad y se muestra efectivamente como una pintura. El título de la obra, “diamante”, remite a que en ella solo se recogen diez de los más escogidos pintores-pensamiento, pero también alude a la idea del diamante como resultado de una de cristalización cúbica, porque de nuevo Quejido reflexiona sobre la planeidad y cavidad de la pintura representando su diamante de pintores el interior de una cámara cúbica. Y se adivina también una fuga: violentando la proyección de la perspectiva, una barandilla marca tanto un afuera de la cámara como un afuera del plano de la pintura. Las investigaciones sobre la pintura como suma de pintores, como pintura pintada, como superficie plana y cúbica, se entreveran en esta obra.

Que Manolo Quejido encarne carne, con sus Cartulinas, que tantee el espesor de ese tabique que es la pintura o que entrelace en su obra de pintor sus pensamientos acerca de la pintura y su espanto ante el escándalo de la mediación, son solo algunas materias de entre las pensuras en las que Manolo Quejido se ha adentrado. La presente exposición es también la de las Secuencias (1969-1971) o la interrogación sobre si la obra de arte puede responder completamente a una determinación previa; la de las Siluetas (1970) y su juego de elección entre permutaciones, o la del sinfín del pintar en la constante acreción de lo que la pintura es: el corpus de las maquinaciones de Quejido, materia prima que nos ha entregado y que queda disponible para el pensar de otros figuradores.

There was a moment when Manolo Quejido added “feeling” to the pairing of “painting/thinking” with which he described his work. It was probably because of what there is in his paintings of an illuminating solution—or, at least, an enunciation—for questions that cry out to us from the enormity of the ineffable. However, as I confront the works with which this exhibition tries to review the artist’s career, uninterrupted since 1964, what Quejido’s art gives back to me is thought, thought, and more thought. Pensura (“To Paint/Think”), I should like to call it, to denote the density through which those who tackle the study of his painting have to pass.

Manolo Quejido was right when he said on some occasion that he believes his painting tries to provide food for thought. Well, I have here some examples of the food for thought it has given me. Here is the result of several figurations obtained from the observation of four aspects of his production: the problem of correspondence in representation in his earliest painting; his reflections on the substance and spatiality of the painted work, intense in the 1980s; the making of his painting into body and support for what is intended to evade notice; and his long sequence of disquisitions on painting as an art that is greater than oneself—as something for thinkers, and as something for painting painters.

After his early years, when Manolo Quejido investigated geometric possibilities or delirious figurations, the artist finally dedicated himself fully to painting in 1974. He did so with his Cartulinas (Cardboards), numbering in their hundreds, where he represented the most miscellaneous subjects: objects, figures, specific people, animals, ideas, places. He used various scales, techniques, and degrees of abstraction or naturalism, but

always within the uniform format given by the size of a sheet of cardboard, 100 × 70 cm.

In the cardboards, and in the first paintings they led to, Quejido encountered the quagmire of representation, with the resistance the world offers up to being expressed in images or words, and the lack of an exact correspondence between the three orders.

By the spring of 1978, when Quejido exhibited at the Galería Buades in Madrid, he had built up a “bloc” of several dozen cardboards. On the invitation to the exhibition, the artist wrote a phrase in an attempt to classify them: TRIANA ENCARNA CARNE (TRIANA INCARNATES FLESH). The cardboards would thus fall into one of these three categories: “Triana,” “Incarnate,” or “Flesh.”

The attribution of cardboards to each category gives rise to reflections on the particular and the generic, on the substantive and on the representable. “Triana” is a proper noun and, as such, it serves to designate something that is absolutely singular, and which cannot be determined within the words allotted to a definition. Similarly, the cardboards of the Triana type express an evoked singularity without coming to define it. This is the case, for example, of what Quejido calls “países” (landscapes), such as Rojo (Red, 1975) (p. 1).

On the other hand, “flesh” is a common noun that refers to a general species. Thus, among the cardboards that Quejido places under the heading of flesh are those he calls “cosas” (things), which do function largely as definitions. Works like Termómetro (Thermometer, 1976) and Cerillo (Matchstick, 1976) (pp. 7, 3) ostensibly present the appearance of the object in question while at the same time suggesting their purpose. With its agitated brushwork, the vermilion background that surrounds the thermometer refers to heat, while the yellow outline of the match luminously sets it off from the black that frames it. A strong light also falls on it, all insinuating its potential utility as an illuminator.

Even so, the cardboards that fit into the substantivity of flesh pose certain problems in their enterprise of definition. One is the outsized scale with respect to the reality referred to in Termómetro, Cerillo, or Galleta (Cookie, 1976) (p. 5). Another has to do with the limits that can be considered as belonging to a species, a case in point being Jamón (Ham, 1978), where all that appears is the consumed remnant, the shank whose figure is inscribed in the ham it once was.

In another of the cardboards that fall into the flesh category, Regla (Ruler, 1976) (p. 14), our comments on the problem of definition start to

heap up. On the one hand, it is written that what we see is “La regla.” The definite article la indicates that what is presented is the epitome of the ruler, a compendium of all that a ruler is, and only that. However, the depiction betrays our expectations because, scandalously, this ruler is not straight, and so cannot perform its function of measuring distances. Furthermore, we come to mistrust the measurements it exhibits as a reference. These say they come to no more than 100 centimeters, which is exactly the height of the cardboard in which the ruler is inscribed. Given its pronounced curves, the supposed ruler must necessarily be longer. The ruler, then, is hardly a ruler in any way. In a figurative sense, it would rather appear to be an exception. Everything points to a pattern that eludes being fixed and described, to a ruler that cannot be tied down to an ideal representation, and to a task, the reduction of the world to its representations (those of art, and those of language) that proves far from simple.

Let us dwell for a moment on the title “incarnate.” To incarnate is to personify ideas or qualities. The cardboards belonging to the incarnate type will, then, be those that resort to this stratagem. Among them are the so-called trampas (traps), which serve distant and complex concepts of substantivity. An example is Planamente (Flatly, 1976) (p. 16), the incarnation of an adverb, the idea of occurring or happening “flatly,” which takes form through allusion as a game of words and images— in short, as a trap.

“Triana incarnates flesh,” the phrase Manolo Quejido used to classify his cardboards, was the echo of an earlier work, Matilde disimula un pensamiento (Matilde Conceals a Thought, 1974), a work that plunges into the morass of the representation of utterances. In its direct structure, Matilde disimula un pensamiento recalls the sentences in school textbooks, which are supported by illustrations that establish a simple correspondence with them. The sentence “Susi served me some soup” admits an equivalent drawing of a little girl performing the gesture of serving soup from a tureen. However, how is one to represent a complex utterance like “Matilde conceals a thought,” where neither the action nor the object refers to a state in the physical world? Manolo Quejido does so through a summation of images that refer one by one to the particles of the utterance. Quejido shows Matilde, whom he juxtaposes with an incarnation of “conceals,” adding an image of thought. Ignoring disparities of scale, the elements of each part of the work are adapted to the size of a sheet of cardboard, which accentuates the

sense that we are faced with a one-to-one transfer between phrases and images. Nevertheless, the utterance thus recomposed does not manage to translate the original sentence absolutely cleanly into an image because the peculiarities of the different representations are not silenced, nor are their frictions with the words. On the one hand, “Matilde,” a proper noun and the subject of the utterance, can take the form of a portrait. The nudity may result from an intended indication that the Matilde represented means simply “Matilde,” but the image does not relinquish the accidents that she is smiling, that she is smoking, and that she is wearing sandals. As for the action “conceals,” which resists representation as an action with a high degree of abstraction, it is incarnated as a play on words. And “a thought,” “un pensamiento,” is embodied in an equivocation, as what is shown does not represent a thought of the mind but resorts to a second literal meaning of the word pensamiento, the flower “pansy.” However, it is precisely in this way, dressing thought up in something else, that the work elaborates on the sense of concealment announced in its title.

By the time he made the leap to large-format painting on canvas, Quejido had already produced many cardboards in which a lack of adaptation is shown between the world, words, and images. No wonder, then, that he should have decided to call his largest work of 1977 Sin palabras (Without Words) (pp. 34–35). Here, Quejido tried to signify the threshold between night and day. In itself, this is an indeterminate point as it has the infinitesimal property of being instantaneous. Moreover, it is a concept for which our language has no word. There is a crossover between day and night at both dawn and dusk, but the actual fact of each of these transitions is not designated with a word of its own. Sin palabras would not, then, fall into the domain of what Quejido called “flesh” and its representations of species, but into that of “incarnate.” Quejido shows night and day as walking figures, and their concurrence is insinuated in the anticipation that their paths are going to converge in the next moment after that represented in the work. The picture is a diptych, with one piece dedicated to the space of day and the other to that of night. The faces of the walls of their respective architectural backgrounds, one strongly lit and the other in almost complete darkness, share the edge that forms their corner. This edge is located by the artist precisely on the joint vertical sides of the two pieces of the diptych, and so it is unique as a part of the image but at the same time materially replicated in the physical nature of each

piece. This points to the indiscernibility of a moment like the transition between night and day. By analogy with the edge and its presence in both pieces of the diptych, the moment of transition can be ascribed either to day or to night, but at the same time it is a different and unique moment of each. Otherwise, the image is paradoxically saturated with things that are nameable: ball, ice cream, guitar, cigarette. Nevertheless, it does not matter how many words we add during our reading of the picture, for that instantaneous limit of the crossing point must necessarily remain nameless owing to the requirement of its nature.

Much of the painting produced by Manolo Quejido in the 1980s—from the series of the Reflejos/Espejos (Reflections/Mirrors), begun in 1983, to the Náyades (Naiads) of around 1986 and the Tabiques (Partition Walls) of 1990–91—is less concerned with the adversities of representation than, on the one hand, with the condition of painting as regards its participation in reality and, on the other, with the space that is trapped by painting, owing to the difficulty of matching it with the flatness of the support.

The pretext of the Náyades is a gathering in the country whose ordinariness is interrupted by the extraordinary appearance of the naiad, the divinity of the place. As in Náyade futura (Future Naiad, 1986) or Náyade azul (Blue Naiad, 1986) (pp. 60, 61), however, the nymph does not rise up in full corporality, but is schematic, sketchy, and flat. Moreover, the two backgrounds framed behind the naiads render the subsequent view of the scene more opaque. Perhaps they are doors communicating with the normally inaccessible space of the divine, or perhaps canvases embedded in the ground, but it cannot in any case be concluded either that the naiad is going to end up precipitated in the solid, or that she is going to remain forever suspended in the flatness of a neither here nor there. Painting too, these works appear to say, bursts into the order of the real with a suggestion of substance, but without achieving the indisputable density of the rounded object.

The series of Reflejos/Espejos, which Quejido began in 1983, plows a different line of investigation, that of painting as mere illusion. It is significant that the artist hesitates in naming the works. Sometimes he has called them “reflejos” and sometimes “espejos,” for it would after all be

difficult to paint a mirror without the reflection it always returns. El cristal (Glass, 1980) (p. 38) already anticipated these concerns. In preparing to paint a sheet of glass, we can opt to make what is seen through it into the figurative content by virtue of the complete transparency supposed as an ideal property of glass. We would then be moving within the paradigm of painting as a window. Alternatively, as Quejido does in El cristal, the painting of the glass can show what is reflected in it. It then becomes intoxicated with the lack of clarity of the outlines and the equivocation of what is observed, and it thus invests itself only with the reduced status of reality pertaining to a reflection or an illusion.

In the development of the Reflejos/Espejos series, and up to Partida de damas (Game of Checkers, 1985) (p. 69), the artist gradually resolves the enigma of the ambiguity of the images, since he reveals work by work that what surprised us as improbable or indefinite in the previous one was merely painted surface. Thus, among what we see in Espejo 8 (1984) (p. 67) is a figure contemplating a picture. However, the rendition of both picture and figure is equally imprecise, making it hard for us to identify the figure as separate from the picture. Moreover, the situation is an improbable one, since the person looking at the picture in this interior scene appears to be a bather. In Espejo 11 (1985) (p. 68), everything shown in Espejo 8 is left as a fragment of the new scene, and appears here as a painting contemplated by another figure. The explanations demanded by the viewer are temporarily provided, but Espejo 11 contains other difficulties that prove disconcerting, particularly the silent gravity of the figures, their complete lack of interaction, and the fact that they are enclosed in that flat trap which is the domain of painting.

It is in Partida de damas that Manolo Quejido once more attends to our need for coherence. Espejo 11 is once more revealed as a painting located at the back of the room. This work no longer contains any games, and indeed it is not given the title of either a “mirror” or a “reflection.” It resolves the series, and aims at a higher level of participation in the real. The figure of the child and what we intuit as his gaze imbricate the work with the viewer’s space. There are echoes of the figure of the chamberlain in Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, as both are shown in profile in a threshold space between the room and what lies beyond it. However, while Velázquez suggests that the chamberlain is entering or leaving the room, Quejido’s child forms part of the scene at the preceding and succeeding instant. An

essential factor is his peculiar position, with his feet on the groundline of the work, and with his body—like those of the ladies—practically on the picture plane. The laws of perspective thus imply that their figures are projected in their true magnitude. The picture plane is on our scale, and allows us to understand Partida de damas no longer as a reflection or illusion but as a participant in our order of things. Only the limited palette of colors—whites, blues, and blacks—continues to militate against the veracity of the work.

In the series of the Tabiques, Quejido also ventures to evoke Las Meninas. However, he here evades speculation on whether painting is truth or reflection. Meninas and partition walls present the interior space of a room, that of the painter’s studio, but the Tabiques appear to contest Las Meninas by impugning the possibility of depth. In Tabique VI (1991), for instance, only the light entering the window assumes a certain volumetric quality, while the architectural components are content to remain a kaleidoscope of color planes. If the beam of light manages to escape from this flat overdetermination, it is thanks to an artifice: Quejido presents the incidence of the beam on the floor in cavalier perspective, in flagrant contradiction with the conical perspective of the side wall and the ceiling. Its extremes do not recede, as the rest of the parallel lines on the left side of the picture do.

The flatness of the Tabiques and the reduced space they are able to house were already part of the artist’s common language. For example, La familia (The Family, 1980) (p. 39), Densueño (Dreamlike, 1979) (p. 36), and Maquinando (Scheming, 1980) (p. 37) contained their figures in a small interior. Something similar occurred in exterior scenes like Bañistas (Bathers, 1981) (p. 57) and in El cristal itself, where several figures were heaped together on a narrow step. Otherwise, in many works—from PF (1979–80) to IP (1980) (pp. 58, 59) and Palmario (Obvious, 1981)—Quejido had bolstered the picture plane with an accumulation of parallel planes. In the Tabiques, however, at a moment when Quejido was a long way from pictoricism, this procedure is more in evidence.

In this series, the partition wall completely hides its materiality despite having an opening that ought to indicate its thickness. All we see of the wall is one of its sides, and it is therefore restricted to one face only. Quejido relates this unusual appearance to the fact that the whole thing is a painting, since it forces a connection between the wall and the canvas and easel that stand at its foot. The easel governs the visual configuration of the Tabique because it conjures up the presence of

a painter getting ready to work on what he sees. As it is moreover shown frontally, the viewpoint of the supposed painter and the vanishing point are determined as necessarily contained on the vertical plane by means of the easel, which is perpendicular to it and to the work itself. However, it is precisely there, on that same vertical plane of the vanishing point and viewpoint, that the thickness of the wall ought to be discerned. That thickness is therefore denied us, as it is projected frontally as a straight vertical only. The wall and its thickness thus obey the law of flatness that Quejido has imposed on these works.

The presence of the easel and canvas makes a second contribution to the refutation of depth. In Las Meninas, both the foreshortening of the stretcher of the canvas Velázquez is painting and the fact that only its back is shown—with the consequent expectation of what might be hidden on the front—support a receding perspective toward the interior of the picture. In his Tabiques, however, Manolo directly exhibits the front of the easel and its canvas, which contrasts with the rest of the work in that it is ostentatiously blank and summary. And although the conical perspective ought to project it onto the picture as a trapezoid, Quejido presents it as a perfect rectangle. It is as though it had fallen flat onto the vertical plane, emptying itself of all its content of paint. Furthermore, the legs of the easel, also flattened, exactly determine the groundline, and the white of the canvas is thus superimposed on the real picture plane, which is rendered by the artist as a place of pure emptiness that will expel anything that tries to lodge in it.

In their scarce depth and the recurrence of the idea of the threshold, Quejido suspended his works in the superficiality of painting. He subjected them to their two-dimensional condition, and so emphasized the improbability of their containing volumetric enunciations in the negligible thickness between their transparent obverse and their opaque reverse. Perhaps this is the origin of the artist’s interest in the Moebius strip, a continuous surface twisted over on itself that has only one face. Around 2005, Manolo Quejido started to experiment with the inscription of the strip on the surface of a cube, as though trying to confront the mystery of the chamber that becomes a cavity when projected in a picture, and of its three-dimensionality flung onto the surface of the work. The Moebius Q-vista works (pp. 186–189) constitute another way in which painting is both volumetric and superficial at the same time. In the meantime, it is not possible to distinguish an inside and an outside on a Moebius strip. For this reason, the figures that

cross the strip in Quejido’s Moebius paintings will not pass from the inside to the outside or vice versa. To extend this reasoning, neither do the figures belong or not belong to the painting. Where they are, and whether—by contrast with the painting—they belong to the order of the real, is therefore a question that remains unresolved.

There is another register in Quejido’s oeuvre, a very different one, in which the artist makes use of the superficiality of painting, for which he claims a quota of reality, or rather of veracity. The artist voices his repulsion at the state of the world, which he calls one of “generalized mediation”—“the unbearable image produced by the timocracy through the state, war, consumerism, and the media” 1 —to which Quejido has been responding since 1993.

Quejido reacts in very different ways to this state of things. For example, he looks once more toward Diego Velázquez and the elaborate illusionism of his works. While Antonio Palomino wrote of Las Meninas that it “is truth, not painting,” Quejido displaces the question of veracity in Velázquez toward that of felt truth, the kind that cries out to the conscience out of displeasure at how things work. In his VerazQues triptychs, created on the basis of Vulcan’s Forge, The Spinners, and Las Meninas , Quejido inserts corresponding allegories of the army, the crown, and the banks (pp. 70–72) (these date from 2005, although there have been versions since the mid-1990s). VerazQues decontracts to veraz qué es, or “what is true?” The truth, then, is that the banks, the crown, and the army govern us, no matter how much their rule is masked by the tangle of mediation.

In the VerazQues works, Velázquez’s images have lost their volume, as Quejido has reduced them to indistinct masses of figures in flattened architectures. It is a strategy against the charms of mediation and in favor of a direct message that allows Quejido to raise his voice. And while the interplay of the figures in Velázquez—their conversation—choreographed the scenes by endowing them with narrativity (Apollo’s gesture of

1 Manolo Quejido, “Notas al condensador,” in Manolo Quejido. Pintura en acción, exh. cat. Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo (Seville: Junta de Andalucía, 2006), 158.

annunciation, the vase offered to the Infanta, the spinner’s attention to the person drawing the curtain), Quejido makes his figures act as one. Their bodies do not interact, they merely blend together. Each mass of characters is a single corporation that functions monolithically.

Sin consumar (Unconsummated, 1997–99) (pp. 126–127) is another response to the state of mediation, and particularly consumerism. The monumentality of the work, a mock advertising frieze decked with all kinds of products, evokes excessive consumption and reproduces the overblown promises made to us by the market of what is available. There is promise of abundance in the amplified scale of the products, and in the distortion of size between large and small as though announcing the same relative satisfaction; of hygiene and sterilization in the over-representation of cleaning products; and of a bargain, with a whole mass of prices floating around the tendered goods.

Quejido explains the failure of consumerism in terms of the non-consummation of its promise. He presents Sin consumar as a completely fragmented mosaic that does not manage to compose a unity. He insists again and again on the presentation of packaging without clarifying if it really has a content. And he resorts once again to complete flatness: there is no indication of space but only a simple juxtaposition of images, and the consistency of the products that the work offers the consumer is consequently denied.

In another series of works, Sin nombre (Nameless), Quejido moves in the opposite direction. In these reproductions of images from the press, which are limited to the black and white of the newspaper and barely used as more than an illustration to enliven the article, he tries to give body and depth to what serves as a mediating membrane between the spectator and the world’s sorrows.

In number 84 of this series, Psiquiátrico (Psychiatric Hospital, 1998) (pp. 118–119), Quejido thus subjects the press photo to color. Yellow invades the ceiling, walls, and floor to make them indistinct, revealing the anguish of this sitting room where the chairs are coldly lined up in martial succession for the inmates. In the meantime, the impastoed texture of the white stands out from the limpid uniformity of the yellow, so that what in the original photograph are reflections on the polished floor, are transformed into something unintelligible, resisting understanding and thereby causing an uneasiness. Besides this, Quejido leaves the legs of many of the chairs undrawn, showing how this room can be a place without a floor, with no possibility of repose.