SALUTE TO SERVICE

Special Section | November 2023

Stories of Midlanders who answered the call

Special Section | November 2023

Stories of Midlanders who answered the call

Ross Wimer’s revered platoon leader, Lt. Robert Kelly, died when he stepped on a mine

STEVE LIEWER

World-Herald Staff Writer

Ross Wimer’s family already stood on edge when that first letter from Afghanistan arrived on a bitter cold day.

It was January 2011, and the Marine corporal from West Point, Nebraska, had already been deployed for two months to the Sangin district of Helmand province — the bloodiest corner of Afghanistan, in the bloodiest year of a 20-year war to save the country from the terror of Taliban rule. A war that, in the end, failed at that goal.

“This deployment time was the darkest time for our family,” said Jayne Wimer, Ross’ mother. “We prayed, worried and prayed some more, hoping that he would be able to come home safely.”

Defying the cold, Rick Wimer — Ross’ dad, himself a Marine veteran — tore open the letter with shaking hands, right there at the mailbox.

Some deployed soldiers and Marines fill their letters home with pleasantries and platitudes, avoiding talk of pain and killings.

Ross Wimer did not.

“It is a sad day (for 1st Platoon) as we have lost a good friend once again,” he wrote in the letter’s first paragraph. “Cpl. Derek Wyatt. He was shot in the head by a sniper.”

Already Wimer’s 33-man platoon had lost 12 Marines — three dead, nine wounded, he wrote.

A corporal who stepped on an IED — “lost his left leg and is fighting to keep his right.”

A sergeant, the very next day, “KIA — stepped on an IED.”

His revered platoon leader, Lt. Robert Kelly, also was killed when he stepped on a mine. Kelly was the son of Marine Corps Lt. Gen. John Kelly, who years later would serve as President Donald Trump’s chief of staff.

“On days like these 2, many marines feel as if they are waiting in line for their turn,” Wimer wrote. “Fear is undoubtedly the son of war, and it’s every marine’s unwanted brother.”

a retired marine

y sergeant from West Point, Neb., hold’s his son ross’ first letter home, dated Dec. 6, 2010, during a bloody combat tour in Afghanistan. Cpl. ross Wimer served with the 3rd battalion, 5th marine regiment.

But he also accepted his role, and his fate.

“I have no choice but to brush it off and stay positive,” Wimer wrote. “Negative emotions can be a poison in the platoon.”

The letter brought tears to his father’s eyes.

“I believe he was at the point that he had to accept that at any given time he could be killed,” Rick

Wimer said last month.

The Wimer family’s story ended happily. Though his unit was bloodied badly, Ross finished his tour without serious injury. He left the Marine Corps a month after returning from Afghanistan in 2011 and enrolled that fall at the University of Nebraska at Omaha to study business.

It was a relief, he said, but disorienting, too. College life was so different from combat. It took a long while to feel completely comfortable on campus.

“It’s tough to adapt,” said Wimer, who now lives in Omaha. “(My) attention span in the classroom was a little short.”

From his early boyhood, there was little doubt that Wimer would follow his father into the Marines. Rick served from 1975 to 1989, on active duty and in the Reserves. (So did his younger brother, Brandt, 32, a Cobra helicopter pilot, and his sister, Jena, 25, who serves with a Reserve engineer maintenance unit.)

“There was never an ‘aha!’ moment,” Wimer said. “Even at the age of a kid, I always thought I would be a Marine.”

The wish had cemented into a plan by the time he was in eighth

grade. The 9/11 terror attacks only increased his motivation. The escalating wars in Iraq and Afghanistan by the time he finished high school in 2007 didn’t discourage him. He enlisted a month after graduating.

His parents supported his decision, even though they had no illusions about the danger.

“I was very proud that Ross joined the service so that he could be a part of making a difference in the world,” Jayne Wimer said.

After boot camp in San Diego, he was assigned to the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment at Camp Pendleton, California.

Wimer loved Marine Corps life but grew impatient during his first two deployments as part of a Marine Expeditionary Unit, traveling by Navy ship to Asia. He enjoyed jungle training in the Philippines and went ashore in Jordan but never saw combat.

With about a year left in his tour, Wimer transferred to the 3-5 Marines, which were bound for Afghanistan. He was assigned to the first platoon of Lima Company — commanded by Kelly, a 29-yearold former enlisted combat veteran who had recently been commissioned as a second lieutenant.

A day before deployment, Kelly

warned his Marines of what was ahead.

“He said, ‘This is going to be the real (expletive) deal. I want you to be prepared,’” Wimer recalled.

Wimer described Kelly as a “lead-from-the-front commander” who joined his Marines on patrol.

“He understood the enlisted side, what a corporal job was,” Wimer said.

Kelly died in the first weeks of the deployment, a blow to a company that was already taking heavy casualties. The unit got through with a savvy platoon sergeant who got the Marines through with a focus on their work, and a replacement lieutenant who earned their respect.

“You eventually just say, ‘This is the job,’” Wimer said. “You still crack jokes. Anything to keep it positive.”

His letter home reflected that humor. He ended with a joke about woodchucks and Chuck Norris and signed off by saying “That’s it! Semper fi, love y’all.”

Rick Wimer’s response to his son’s letter was to send care packages to his son and Tim Wagner, another West Point Marine who was also serving with Darkhorse battalion. All together, he sent 146

packages and 27 padded mailers filled with 2,200 pounds of candy, pizza, fajitas and ramen as well as odd goodies, like toy tractors and tool sets.

“That’s how I kept my sanity when he was over there,” Rick Wimer said.

He also reached out to Lt. Gen. Kelly to offer condolences for his son’s death.

The general replied that his thoughts remained with the Marines of his son’s unit.

“I continue to go through the motions,” he wrote to Rick in an email. “Wish I could get back in the fight as all else seems irrelevant.”

Ross Wimer said he had mixed emotions over the end of his tour, and his Marine career.

“You had this eagerness to get home,” he said. “But it’s weird to think about leaving it behind — the crazy adrenaline rush. You know this is what your job is, and you go.”

It took awhile, but he adapted to civilian life.

“The Marine Corps taught me perseverance,” Wimer said.

After graduating from UNO, he got a job recruiting service members separating from the military for tech service jobs. Recently he started a job with an Omaha company that places health care workers in temporary jobs. He is devoted to his dog, a rescue lab named Ma-

dyson.

Like many veterans, he doesn’t like to talk about the combat he saw, or post-traumatic stress. But he acknowledges there have been suicides among the Marines he served with. “Buddy checks” are now part of his life.

In 2019, he traveled with Madyson to Washington, D.C., on Patriotic Productions’ Purple Heart and Gold Star honor flight. At Arlington National Cemetery, he visited the graves of Wyatt and Kelly, who are buried near each other.

He enjoyed sitting with older Vietnam War veterans and hearing stories of combat not so different from his own, but from a different era.

Last spring, Wimer attended a reunion of 3-5 Marines for the first time. Once the beers started to flow, so did the stories.

“What binds us is Sangin,” he said.

When Wimer reflects on his service, he can remember the words that brought tears to his father’s eyes that winter day years ago.

“(T)he pride earned out here is eternal,” he wrote from the battlefield. “If you can become part of the history books in a good way, then that’s a life well-lived.”

sliewer@owh.com; twitter.com/Steve Liewer

Contactsalesprofessionalfordetails. Notresponsibleforerrorsoromissions.Adcorrectionsmaybeviewedatwww.nfm.com.Somequantitiesmaybelimitedand/orwillnotarriveonschedule.Wereservethe righttolimitquantitiesandtorefuseanyorder(nodealersales).Wereservetherighttoreclaimanypremiumitemorreducerefundamountbytheoriginalvalueofthe premiumiforiginalitemisreturned.Marksusedarethetrademarksoftheirrespectiveowners.Printedorbroadcastoffersmaynotbeavailableonline.Notallofferscanbe combined.

Anthony

Weathers, who spent 24 years in the Air Force, says ‘a lot of things you keep within’

MARJIE DUCEY World-Herald Staff Writer

Anthony Weathers knows how important it is for fellow veterans to have someone to listen to their stories.

He has a few of his own. The sounds of dropping bombs. Dealing with the health effects from Agent Orange.

“Some have headaches and heartaches, and even today they don’t want to talk about it,” Weathers said. “A lot of things you keep within.”

The 71-year-old Papillion man spent 24 years in the Air Force, retiring in 1995 with the rank of master sergeant.

Just as promised when he “took a leap of faith” and enlisted in 1971, he traveled the world. He was stationed in Thailand, Germany, Korea, Europe and throughout the United States. You saw places and things you never knew existed, Weathers said.

Weathers first became a security police specialist, which he calls “the ground troops of the Air Force.” They were the call-up forces when he enlisted out of high school, next in line to help in the Vietnam War effort, which ended in 1975.

During training, he learned the different sounds of weaponry and dropping bombs.

He experienced those sounds firsthand when he was stationed in Thailand, not far from the Vietnam border. The Ubon air base was fired upon one night when he was on duty. Thirty-seven mortars were used in the attack but no U.S. personnel were injured.

It was the only time he saw conflict. He was in shock until his training kicked in.

“Believe it or not, once is enough,” he said. “I’m a 19-yearold kid at the time.”

He went on to work at nuclear

silos for the rest of his career, on bases that were located in places such as Maine, Wyoming, North Dakota and Missouri and far from big cities.

“They were there for a reason,”

Weathers said. “You learn a lot, you learn a lot of skills dealing with snow up to your waist. This was my calling, this was my job. You got told to do something without questions. If you didn’t do it, you got court-martialed.”

He didn’t have access to the weapons themselves but monitored the alarms, had units respond if there were incidents and was involved when the missiles were transported. Missile code changes meant long work days.

When Weathers decided to retire at last in 1995 while in his 40s, downsizing was a key word. Finding a job wasn’t easy.

He worked for the U.S. Post Office and in retail to support his

Weathers said he still works diligently at his church, St. John’s AME in Omaha, where he is a trustee. He speaks with veterans, sharing with them how to navigate the sometimes frustrating system to get their benefits.

Often he just listens.

“You don’t have to be a certified counselor to talk to someone,” he said. “I can relate to some things. If you can’t relate, you try to find someone who can help them.”

He’s shared his own battle with cancer recently at his Vietnam Veterans of America Chapter 279 here in Omaha.

No one had talked about it before, and he said he was stunned by the conversations he had afterward with other veterans.

“Nobody is going to say anything about it until one person gets up. No one wants people to know about it,” he said. “You can’t keep everything in. You can see in their faces them taking a load off themselves letting it out.”

wife, Julia, and three children.

“By the grace of God, I made it through. Everything worked out well,” he said.

It was at that same time that Weathers began to have health issues that he says were caused by Agent Orange, an herbicide used in the Vietnam War.

An asthmatic from birth, he began having problems with his lungs and a weak immune system. He’s had five heart attacks, three blood clots, open heart surgery and pneumonia several times. He was recently diagnosed with prostate cancer.

He said the many health issues associated with the herbicide are receiving much more attention from the military. He praised the care he’s received at the Weathers has a collection of challenge coins. and has kept a positive attitude throughout.

“I’ve lived my life according to the good book. He’s not ready yet. There’s times I’m surprised I’m still here,” he said. “You just smile every day you wake up. There’s someone worse than you.”

In 2021, he met Lynn DeShon at a conference. She told him about the quilts of honor and quilts of valor project. Like many others, he knew nothing about the program that donates patriotic quilts to veterans. They deserve one, he said. Weathers worked with DeShon to provide five quilts for veterans who served in Vietnam, were a minority and were honorably discharged.

“This is her thing. She loves doing it,” Weathers said. “She will do it as much and as long as she can. She charges no fee.”

Another five will be going out to veterans in a ceremony Dec. 9 at St John’s AME Church, 2402 N. 22nd St. The program starts at 11 a.m. With his health issues, Weathers said it would be easy to sit back and take it easy. But that’s not him. One of seven kids, he’s worked since he was a teen.

“Sitting at home is not my cup of tea,” he said. “If you are healthy enough to do something, do something and be positive. You can help others and make your day. I’m very happy and satisfied.”

marjie.ducey@owh.com, 402-4441034, twitter.com/mduceyowh

Heath Hoppes’ interest in aviation was piqued when he worked at an airport in high school

DAVID GOLBITZ

Council Bluffs Nonpareil

For retired Navy pilot Heath Hoppes, Veterans Day is a day for honoring the men and women of the armed forces whose bravery and determination to support and defend the Constitution is the bed-

rock upon which the United States was built.

“Our country’s based on the willingness of its citizens to stand up and protect what we believe as a moral people, to protect our citizens,” Hoppes said. “Veterans Day is to honor the sacrifices of those people that have served in the United States.”

Hoppes credits working at the Fremont (Nebraska) Municipal Airport during high school with sparking his love of aviation. But it was his father’s and grandfather’s military service that instilled in him

a sense of duty to his country.

“My dad was drafted in Vietnam as an infantryman and my grandpa was in World War II as an infantryman, so I had a lot of family history of military service,” Hoppes said. “And combine that with my love of aviation, I thought ‘I’ll try to fly for the military.’”

One day, one of the flight instructors offered to take a young Hoppes up for a ride.

“I loved it. Fell in love right away,” he said. “I liked the freedom. I like the idea of, I can take off from here and go up in the air and, you know,

‘slip the surly bonds.’”

Hoppes earned his private pilot’s license while attending Fremont High School, and he received a Naval ROTC scholarship from the University of South Carolina. Upon graduation in 2002, he was shipped off to Pensacola, Florida, for flight training.

“Of course, I wanted to be a fighter pilot because that’s the coolest thing in the world,” Hoppes said.

Hoppes trained with a Beechcraft T-34 Turbo-Mentor, which has since been retired.

Hoppes’ Navy career took him around the country and around the world, including stops in Meridian, Mississippi, where he trained in airto-air and air-to-ground tactics; Naval Air Station Miramar, California, where parts of the movie “Top Gun” were filmed; and Afghanistan, where he helped provide overwatch in support of ground units.

“We spent about four or five months flying combat missions out of the north Arabian Sea,” Hoppes said. “Typically, missions were eight hours long. We would launch off the carrier, fly up through Paki-

stan, refuel in-country, and then go basically provide armed overwatch and close air support to the guys on the ground.”

In between overwatch missions, Hoppes was assigned other missions, the purposes of which he never did find out.

“I did all kinds of weird (stuff),” Hoppes said. “We tracked a motorcycle for, like, 250 miles one time, whatever they thought he was doing.”

Hoppes would also use his jet’s ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) technology to search for improvised explosive devices, or IEDs, ahead of ground convoys he was escorting.

“The IR (infrared) capabilities can kind of see temperature differences,” Hoppes said. “You kind of could look out ahead of the convoy or you can try to identify potential threats to the ground guys before they before they walked into an ambush.”

Flying overwatch for the ground troops in Afghanistan gave Hoppes another close tie to his father.

“I heard my dad’s stories about Vietnam and all the times that they were happy to have air support, so I felt a kind of connection with doing that,” he said.

Following his tour in the Middle East, Hoppes volunteered for what would become one of his favorite assignments: train with Great Britain’s Royal Air Force as part of an exchange program.

Hoppes trained with its Eurofighter Typhoon fighter jet, at RAF Coningsby, about 150 miles north of London, and became an instructor.

“It was a great experience,” he said. “I was a combat-experienced F-18 pilot, but you still got to go learn a new program and a new airplane and a new military and how they do things.”

One of the things that Hoppes quickly learned is the difference between American English and the original.

“They speak English and not American — I learned that,” Hoppes said. “I came to find out that, yeah, there were some subtle differences.”

Hoppes spent three and a half years stationed at RAF Coningsby, which, after moving every six months or so, was a welcome respite.

“I was enjoying living in the little village in England and traveling, do-

ing a ton of traveling, and flying the Typhoon all over England,” Hoppes said. “We were doing low flying all over the country, through their mountains and all these places in Scotland. It was an absolute blast.”

While home on leave during Thanksgiving, Hoppes met Katie, the woman he would ask to marry him after only three months. They got married while he was still stationed overseas.

“Once we were married, the decision was basically made that I was going to live in Omaha,” Hoppes said. Katie attended the University of Nebraska Medical Center and works as a physician at Methodist Hospital.

In 2013, when he was no longer on active duty, Hoppes got a parttime job with the Navy Reserve out of Key West, Florida.

“I flew the F-5, which is, it’s that plane from ‘Top Gun’ with the black and the red star on it,” Hoppes said.

“Basically, our job was to play bad guy for the F-18s. We would go up and do dog fighting and air-to-air training.””

He held that job for about four years, and also became a pilot for Delta Air Lines in 2015. He and Katie also had started having kids and bought farmland in Pottawattamie County. Hoppes realized that something had to give.

“Trying to balance all those things, I decided it was unsustainable,” he said.

In 2018, Hoppes joined the Ne-

braska Air National Guard out of Lincoln, where he would fly a Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker.

After four years of flying parttime for the Air National Guard, Hoppes retired as a lieutenant colonel.

“A little over 20 years in the military, and I never had a non-flying job my entire time,” Hoppes said. “I got to fly four different airplanes over 20 years and never had a desk job. From a pilot standpoint, that’s what you call a victory, I think.”

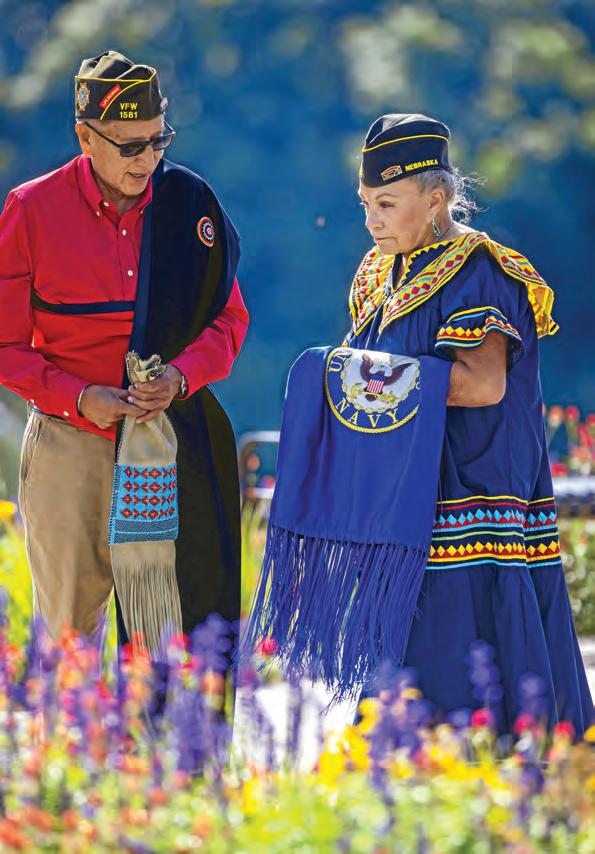

Patricia Whitebear, 79, a U.S. Navy veteran and member of the Yankton Sioux Tribe, at the Nebraska Urban Indian Health Coalition at 2226 N. St. in omaha. She came from humble beginnings and ended up traveling the world.

712-328-5797•Fax712-328-5726

www.pottcounty-ia.gov/departments/veteran_affairs/ OfficeHours:Monday-Friday8:00am-4:30pm

PottawattamieCountyVeterans Service Office is “Your GatewaytoVeteranServices”.Our Nationally AccreditedCaseworkers can assist Veteransin filingforbenefitsthey maybe entitledtoreceive.

STAFF

PeggyBecker–Administrator

PaulRosenberg–CaseworkerII

SamPettit–CaseworkerII

KaraBehrens,AdministrativeAssistant

RebekahAdair,AdministrativeAssistant

COMMISSIONERS

HollyCollins–Chairwoman

DavidHazlewood–Secretary

MickGuttau–Member

Dr.DanKinney–Member

JamesMurray–Member

AndrewDewey–Ex-Officio

LynnGrobe–Ex-Officio

A member of the Yankton Sioux Tribe, Patricia WhiteBear knew little about the military when she enlisted

EMILY NITCHER World-Herald Staff Writer

It wasn’t love for her country or a sense of patriotic duty that prompted Patricia WhiteBear to enlist in the U.S. Navy.

It was 1981, and she was 35. College hadn’t been the answer. And WhiteBear needed a fresh start, but she didn’t know where to go or what to do with her life.

Maybe the Marines? But that wasn’t the answer either —she was too close to the cutoff age. The recruiter suggested the Navy instead.

“So I went to the Navy, and they said, ‘Sure, we’ll take you,’” WhiteBear said with a laugh while recalling her journey in the military.

A member of the Yankton Sioux Tribe, WhiteBear, now 79, grew up in South Dakota and Omaha. She knew very little about the military or its possible benefits when she enlisted.

Coming from humble beginnings, WhiteBear never would have believed she’d end up sitting on a beach in Waikiki, traveling the world or spending months on a ship in the middle of the ocean.

“My goals were set as I reached them,” WhiteBear said. “I had dreams, but I never thought they’d ever come true.”

Within a week of signing up for the Navy, WhiteBear was sent to basic training in Orlando, Florida,

beginning her 14-year Navy career. The initial introduction to military life was rough.

“It was terrible,” WhiteBear said of basic training. “It was hot and fruit flies were all over your nose, and you couldn’t scratch them or shoo them away. You just had to suffer.”

The last one in her group to complete all the physical requirements, WhiteBear said she couldn’t believe she made it.

“But I did,” WhiteBear said. After training, WhiteBear was assigned to Pearl Harbor. She started as a seaman recruit and worked in the technical library. It was WhiteBear’s job to find manuals and blueprints for things on ships that needed to be repaired or replaced.

“It’s like a scavenger hunt almost every day,” WhiteBear said. WhiteBear then spent six years in the calibration lab on the USS Jason, a repair ship.

Nothing prepared WhiteBear for what it’s like to be out at sea. She remembers on her very first day feeling sleepy and groggy from the combination of floating and the ship swaying back and forth like a giant rocking chair.

For months at a time, WhiteBear said sailors had almost no contact with the outside world. They all had hobbies, but WhiteBear enjoyed walking around the ship and talk-

ing to people about their stories and backgrounds.

And WhiteBear watched the sunsets. She remembers one evening in the Persian Gulf when the sky turned pink and the clouds looked like big puffs of cotton candy.

“It looked like we were sailing into a magic kingdom,” WhiteBear said. “Everyone was outside.”

Life on the ship also was very challenging. Women had only just begun serving aboard ships, and some male sailors were resentful of their new co-workers.

Most people on the ship were young White men. WhiteBear was an older Native American woman. Their differences created some tension.

“You had to earn everything you did,” WhiteBear said. “You had to earn it sometimes twice as hard as the guys did.”

WhiteBear also served in the Persian Gulf during the first Gulf War. She remembers going to sleep in her uniform, with her shoes, gas mask and helmet nearby so she’d be ready to jump out of bed at the sound of an alert.

“We were scared, but you had a lot of people to be scared with,” WhiteBear said.

During her time on the ship, WhiteBear was also able to travel the world, including visits to Hong Kong, the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Korea, Japan, China and Bahrain.

“I rode camels in Saudi Arabia, I rode elephants in Thailand, and I made sure I took every opportunity that presented itself to me,” WhiteBear said.

By the time WhiteBear, a petty officer second class, was medically discharged from the Navy in 1993, she had come to see her service as her patriotic duty and felt proud to wear her uniform.

“To me, that was a symbol of strength and courage, and when you wore it, you were not seen as a woman,” WhiteBear said of the uniform. “You were seen as a serviceperson, as a person in the Navy. Not really a woman but an equal.”

After leaving the Navy, WhiteBear spent 20 years with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service before moving back to Omaha to be closer to family at age 70.

WhiteBear said she tries to encourage high school students to consider joining the military especially if they don’t know where their life is headed.

“Where that journey comes to is up to them,” she said.

emily.nitcher@owh.com, 402-4441192, twitter.com/emily_nitcher

Matt Calbreath says seeking a military career was one of the smartest things he did as a young man

TIM JOHNSON

Council Bluffs Nonpareil

Master Sgt. Matt Calbreath of Council Bluffs served in the Air Force for 24 years, including time spent guarding critical equipment.

Calbreath, 63, joined the U.S. Air Force in 1980 after talking to recruiters for the Marine Corps and Air Force.

“Probably one of the smartest things I did in my young life,” he said. “I had no plans or aspirations.”

Calbreath completed basic training at Lackland Air Force Base in Texas and then trained for security work. Over the years, his duties included guarding Minuteman II missile sites during repairs and maintenance, guarding President George H.W. Bush’s aircraft during a visit to Springfield, Missouri, and investigating on- and off-duty injuries and fatalities.

Less glamorous duties included controlling access to restricted areas, watching surveillance video and performing inspections.

Calbreath spent one year at a NATO base in Greece, then was assigned to Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri, where he spent 18 of his 24 years in the Air Force. The timing of his return from Greece may have prevented him being deployed for Desert Storm, he said. Though he was never deployed, he was subject to being called up on short notice for deployment.

“My bags were packed and ready to go a few times,” he said.

And Calbreath was sent to help when there were natural disasters — after a tornado in Wichita, Kansas, and when rivers in Missouri were flooding.

Calbreath was put in charge of crowd control once when anti-nuke protesters assembled outside Whiteman’s gate. However, participants were peaceful, and no one had to be restrained or arrested.

Calbreath received special clearance for missile security and was assigned to provide security during missile transportation, repairs and maintenance. Sometimes it was so the missile’s guidance system could be replaced.

“You provided security at the top while the guys were down with the missile,” he said.

When Minuteman II missiles were deactivated in 1993, Calbreath moved into bomber

when people were off duty — but he had to investigate those incidents and write a report on them, too. He soon realized his writing needed improvement.

“Report writing was a huge part of that job,” he said. “It was a career-rounding experience.”

With his seniority, Calbreath was able to rent a house off base. It happened to be just a few houses down from where the woman lived who would become his wife. At the time, Michelle was a single mother and could use some help with her three kids.

“I was the single guy with a dog down the street,” he said. “I hope I was a father figure in a couple of their lives.”

When he returned to Whiteman, they kept in touch, and he visited frequently.

Calbreath also did a stint at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio. He retired in 2004 with the 509th Bomb Wing at Whiteman. Since then, he has worked security at an Omaha Public Power District power plant and was enterprise safety manager at First National Bank of Omaha for seven states.

security, guarding such elite aircraft as the B-2 Spirit stealth bomber.

In 1997, Calbreath retrained at Offutt Air Force Base for a career in safety.

“Safety was totally different,” he said. “We worked with the whole base and not just other security people.”

Calbreath advised everyone from new recruits up to commanders on preventing injuries, and investigated incidents that resulted in injuries or fatalities. He taught them about safety hazards in their environment, not just their jobs.

Calbreath discovered he wasn’t the most popular person on base.

“No one wants to see a security guy or a safety guy,” he said. “You had to kind of feel

proud about what you did and see the worth in it.”

Safety tasks also could be unpredictable, Calbreath said.

“Something could happen to change your work routine for a month,” he said.

Perhaps the hardest thing Calbreath had to do emotionally was to investigate the death of a pilot candidate during a training exercise that involved parachuting into a lake and dragging the parachute to shore. He had to interview people who had just watched their friend die, then write a report on the incident.

For on-duty accidents, Calbreath had to bring in neutral parties, such as civilian law enforcement officers.

Most injuries and fatalities happened

“I don’t have any regrets with joining or the careers I chose,” he said.

He earned degrees in safety and security in the Air Force, a bachelor’s degree in occupational health and safety and several associate degrees. He is a certified CPR instructor.

Calbreath grew up mostly in northern Iowa and graduated from high school in LeRoy, Illinois. The son of a preacher, he and his family moved often.

“I moved six or seven times before I graduated from high school, which was a social challenge,” he said.

Calbreath is a member of Veterans of Foreign Wars, supports Disabled American Veterans, and volunteers at his church.

Michelle has seven grandchildren, which she shares with Calbreath.

Ron Hernandez’s nonprofit helps with housing and other basic needs

Sarpy County Times

After serving 25 years in the U.S. Army, Ron Hernandez is still at service. For the past 13 years, Ron and his wife, Kimberly, have dedicated their lives to helping veterans attain their basic home needs and regain their independence.

Their nonprofit — Moving Veterans Forward — not only helps homeless veterans find housing, it also goes one step further. The group fills each home with donated furniture, toiletries, food, appliances and other household essentials, all moved into the house for free with the help of volunteers.

The idea for the nonprofit sparked in 2010 when Ron befriended fellow veteran Mike Flowers, who opened his eyes to the issue.

“He was in a homeless program and excited to get his new apartment,” Hernandez said, “and then he realized it’s going to be an empty apartment.”

After researching the problem, Hernandez, who lives in Papillion, came to realize that while the Department of Veterans Affairs will find veterans housing and pay for rent, utilities and the deposit, the veterans are still greeted with an unfurnished, bare home.

“We’re setting somebody up for failure, especially when they have nothing to start with in the first place,” Hernandez said. “So that was the spark that began my mission.”

With the help of Hernandez, Flowers became the first of thousands of veterans helped by Moving Veterans Forward. Today, Flowers pays it forward and volunteers with MVF whenever he can.

The nonprofit’s motto, “No Veteran Left Behind,” has driven the Hernandez couple and area volunteers to accomplish 2,112 moves in

13 years, impacting more than 3,400 lives.

“You see a homeless vet and you assume it’s due to drugs and alcohol, but it’s not, and if it is, it’s a coping mechanism as a result of homelessness,” Hernandez said.

“The military is a life-changing event; transitioning into normal life is difficult, and coping with the combat you saw is difficult.”

Hernandez’s decision to join the military in 1985 was an easy one. His family has made serving the country a tradition that dates back to the Revolutionary War.

“I guess I just had it ingrained in me growing up. I knew I was going to serve in the military,” Hernandez said. “I just had to choose what branch it was, and I chose the Army.”

Ron Hernandez retired as a master sergeant with experience as an Airborne and Cavalry Scout, along with a distinguished military history. He was involved in combat

operations during the 1988 Operation Just Cause in Panama, subsequently completing two tours in Bosnia, two tours in Kosovo and three deployments in Iraq.

Sadly, his military career came to an end in 2010 after severe injuries, including a broken back, leg and head injury.

“The only thing I miss overall is the camaraderie of the brotherhood, of the bonds that you make in the military,” Hernandez said. “I mean, there are hundreds of stories, but it’s just that bond that you build with other soldiers.”

Today, Hernandez finds that same camaraderie with the same people, going above and beyond to ensure a smooth transition into civilian life, just as he did 13 years ago.

In addition to making empty homes into livable spaces, MVF also offers safe spaces for veterans who may have fractured family relationships. Some families fracture

during overseas deployments or, in some cases, due to homelessness.

The Hernandez couple saw the need and tasked themselves with creating a space where they could have the opportunity to spend time with their children.

“Sometimes you have to live in your car,” Hernandez said. “Nebraska doesn’t like when you have a whole family live in a car, they’ll come in and move the children. We have the rec room up front and a big park and pond out back. They can be a family for a few hours until they get their family put back together.”

MVF’s next mission is the nonprofit’s biggest feat to date because healing takes a village — literally.

In the next year, Moving Veterans Forward plans to erect a village in Sarpy County of 20 to 25 tiny homes, a veterans center and a rehabilitation center to function as a transition home for veterans to get on their feet after returning

from deployment. The new center will focus on teaching life skills and preparing veterans to enter new trades.

“There’s a huge concentration of vets in Sarpy County, Bellevue and Papillion,” Hernandez said. “With that, you have a lot of retirees in this area that want to pay it forward and continue to help their brothers and sisters in the military, so it just makes sense to go where the help is.”

With a legion of veteran friends and supporters, Hernandez was invited to a multitude of Veterans Day events, but he’d rather spend it with the people that matter the most: his family.

“Veterans Day is every day. But I know we only get one day a year,” Hernandez said. “It’s a day of freedom, but it’s also a day of remembrance for those who went before us.”

Learn more or donate to Moving Veterans Forward at mvfne.org.

VeteransDayis a nationalholiday observedforhonoringallwhohave servedinthearmedforcesforour country.We encourageeveryone totake a momentto reflect,honor andthankthemenandwomenwho

protectedorcontinuetosecure the freedomsweenjoy.

Today, RoederMortuarieswouldlike tocelebrateandcommemorateall militaryveteransfortheirservice. Threelocationsinthe