This time of year, when the days are short and dark, and the weather is usually miserable and cold, gathering on the boat to watch a movie or play a board game with friends and family is o en the only “boating” we can do and that’s OK. A recent experience drove this home for me.

is fall, long-time Paci c Yachting contributor, Peter Vassilopoulos asked me if I’d be interested in giving boating lessons to a friend of his. We’ll call him Bob. Bob is brand new to boating and now that he’s retired, he has the time and the means to pursue his late-adopted hobby. It’s been fun going through the learning experience with him and watching his comfort level gradually increase.

On our most recent lesson, just before we were about to leave the dock, we discovered the kicker wasn’t spitting water (we’ve all been there). With the wind up a bit and not wanting to be without a backup in case the stern drive packed it in, we decided to stay put and hang out on the boat, have a beer and look up videos on potential xes for the outboard. is wasn’t the rst mishap of our brief boating friendship and a er sitting there a short while watching the rain run down the windows, Bob looked at me with a wry smile and asked, “Am I having fun? Is this boating?”

I couldn’t help but laugh. Bob was learning fast. “Well, I don’t know

whether you’re having fun,” I said. “But you know what, this is de nitely boating.” And it’s the truth, at least the partial truth. Sometimes you don’t leave the dock. Maybe the weather isn’t cooperating, maybe the outboard isn’t spitting water or maybe you just don’t feel like leaving the dock that day. It was fun to hangout in the heated cockpit, shooting the breeze and wearing our mechanics hats for a couple hours even if it wasn’t what we had planned for the day.

is time of year, when the days are short and dark, and the weather is usually miserable and cold, sitting in the boat at the dock is de nitely boating and hey, it’s fun! At least, hopefully it’s fun because it might be the only option until spring.

On a somber note, Paci c Yachting’s longest-tenured employee, Gordon Fidler, passed away this fall. Known around the o ce as Gandalf, because of his long white beard and his love for fantasy and science ction novels, Gord was a kind-hearted and hardworking fellow with a quiet but infectious laugh and a penchant for beef and Guinness stew. Gordon had been working from home since the start of the pandemic, but was still an important part of the team, putting together the classi eds section of the magazine each month. Gordon “Fiddles” Fidler will be truly missed.

–Sam BurkhartEDITOR

Sam Burkhart editor@pacificyachting.com

ART DIRECTOR Arran Yates

ASSISTANT EDITOR Blaine Willick blainew@pacificyachting.com

AD COORDINATOR Summer Konechny

DIRECTOR OF SALES

Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031 tyrones@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416 kathy@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052 meena@pacificyachting.com

PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller GROUP CONTROLLER Anthea Williams ACCOUNTING Angie Danis, Elizabeth Williams CONSUMER MARKETING Craig Sweetman

CLASSIFIED AD COORDINATOR Gordon Fidler

CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE

Roxanne Davies, Lauren McCabe, Marissa Miller

SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE 1-800-663-7611

SUBSCRIBER ENQUIRIES: subscriptions@opmediagroup.ca

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

One year Canadian and United States: $48.00 (Prices vary by province). International: $58.00 per year.

Contents

ISSN 0030-8986 802-1166 Alberni Street Vancouver, BC, Canada V6E 3Z3

Tel: (604) 428-0259 Fax: (604) 620-0245

FOR AL LUBKOWSKI

e cartoon above this article reminded me of the passing of a dear sailing friend. He was part of what we loosely called “boyz cruises.” A er he died, about 40 or so of us gathered before a day’s race and shot his ashes out over Cowichan Bay from a potato gun. e sun’s rays caught the ashes in a spectacular cloud as be tted the occasion.

—Martin Golder

doing boat maintenance, I’ve o en had to reproduce an eccentric curve, and have tried numerous (mostly ine ective) ways to do so, such as cutting and sticking card to the curve in pieces and then peeling it o . Inevitably, the nal shape has not matched the original. e joggle stick, simple and e ective, solves that problem. Let’s have more ‘Hands On Boater’ tips.

—Rick HudsonWe couldn’t agree more. If you’re interested in more hands on tips check out part one of Martyn’s new series on “Marlinspike Seamanship,” also known as ropework, on page 44 of this issue —Eds.

1. Verify that all seacocks are closed, except for the cockpit. Also check that leaves don’t clog the cockpit scuppers, which could ll the cockpit and force drains underwater, backooding the boat.

2. Check your dock lines for security and chafe. Winter storms can put a lot of strain on dock lines so make sure you use a good chafe guard, and make sure the boat is tied so it can’t get caught under the dock during tide changes.

3. Make sure the boat is well-ventilated. Air circulation prevents mold and mildew from forming down below and keeps the boat smelling fresh. Treat any mold that you nd now, before it gets worse.

4. Check the operation of the automatic bilge pump. It should work even if the battery switch is o . Manually turn on the switch to verify the pump comes on.

5. Inspect the shore power cord for damage and make sure the battery charger is operating. Verify the battery electrolyte hasn’t evaporated and add some if needed. If you spot corrosion on battery terminals, clean it o immediately.

6. Look for fuel, oil or coolant leaks. You don’t want your bilge pump to spew oil into the water. In addition to polluting the environment, you could be in for a big ne.

7. If you haven’t already removed expensive electronics, now’s the time. Marinas are like ghost towns in the winter and can be easy pickings for thieves.

8. If your boat is stored ashore, check that the jack stands haven’t shi ed or sunk into the ground, and are chained together under the boat. Tell the boatyard if something doesn’t look right.

9. Make sure that water isn’t pooling on deck or in the cockpit. Nothing good ever comes from standing water inside or outside a boat; water can damage the gelcoat and cause stains.

10. If your boat is in the water, take a walk around it at the dock. Are there any changes in the waterline? If so, check the bilge for water, a good practice at any time. If you nd any, locate the source. It might be a leaky thru-hull or stu ng box, or be coming from the deck through a hatch or portlight.

VANCOUVER BOAT SHOW RETURNS!

e Vancouver International Boat Show is back for 2023, running from February 1 to 5. Check out vancouverboatshow.ca for more details as they are announced. We can’t wait to see you there!

arks Canada has announced that they are removing the mooring balls in Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve. According to a release, the mooring buoys in Gwaii Haanas are no longer safe and must be replaced prior to next operating season. In the interim, all buoys will be removed for safety purposes. Current safe moorages are the Shuttle dock and Ellen Island dock in the event of an emergency and need for safe harbour.

It’s your last chance to enter Pacific Yachting’s annual photo contest! It’s not too late to submit your best boating photos from 2022 for a chance to be featured in the February issue of Pacific Yachting and win some awesome prizes, including a Yeti V Series Stainless Steel Cooler valued at $1,100. For contest rules and to enter, visit pacificyachting.com/photo-contest.

Deadline: December 15

SEATTLE BOAT SHOW DATES ANNOUNCED

e 2023 Seattle Boat Show is returning to Lumen Field Event Center and Bell Harbor Marina, February 3 to 11. Learn more at seattleboatshow.com.

THE SEATTLE CHRISTMAS BOAT PARADEA TIME HONOURED TRADITION

December 17, South Lake Union is year’s parade begins in front of Fremont Tugboat Co. on Lake Union, just east of the Aurora Bridge and ends at Morrison’s Fuel Dock. e parade will be led by the bright yellow and blue Western Towboat tug which will be followed by dozens of brightly lit and holiday decorated boats of all types. ere will be ve categories that judges will decide on, including Best in Show, Best Santa and Reindeer theme, Best and Biggest Christmas Tree, Best Christmas Snowman and Most Overall Christmas Lights. e associated Toy Drive will support the Seattle Children’s Hospital. For more information and to get involved go to seattlechristmasboatparade.com.

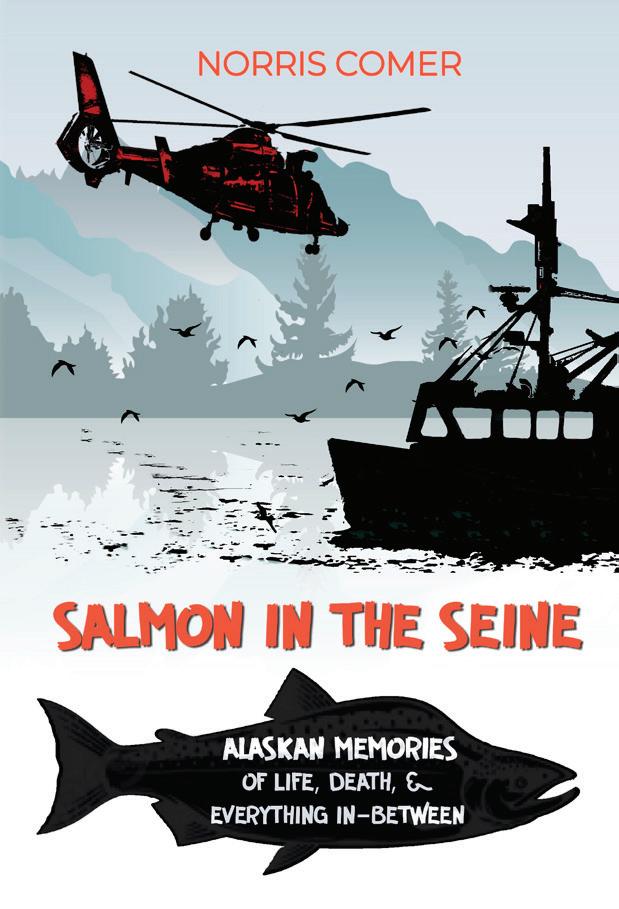

By Norris Comer, Milspeak Books, 2022. 228 pages, $18.95.

You might recognize the name Norris Comer from the pages of Paci c Yachting, where he’s published numerous articles in recent years, from dinghy buyers’ guides to a feature on transiting Seattle’s Ballard Locks. Having read these articles, I knew he was a good writer, but I was still delightfully surprised reading Salmon in the Seine. More than just a sherman’s tale of a season in Alaska, the book provides a unique outsider’s perspective on joining the tight-knit shing community in Cordova, Alaska. Norris goes from a naive greenhorn to an experienced deckhand with blood on his hands and he takes the reader along for the ride. e bravado, the racism, the brutal reality of life on a seiner is all on display. is lifestyle is not for the faint of heart, but Norris tackles it

head on and with a Jack London-like philosophy. e prologue concludes: “Man is sh. Fish is man… We know heaven like salmon know the crooning apes who kill them for pro t. For all I know, God is a sherman with bills to pay.” So, you know Norris went through some stu while he was up there. I recommend reading the book to nd out what.

By Joe Martin and Alan Hoover, Royal BC Museum, 86 pages, $24.95.

By Joe Martin and Alan Hoover, Royal BC Museum, 86 pages, $24.95.

In his dedication, Joe Martin writes of his late brother, Bill Martin, who was happiest when they were both together carving canoes in the forest. e canoe intersects nature and tradition and those connections runs through the book, embodying it with much more signi cance than other how to manuals.

But what is a chaputs exactly? It’s not an easy word to describe. e Royal BC Museum’s site explains the roughly translated meaning of that intriguing word: “ e chaputs carries Indigenous cultural knowledge passed down through generations, not only of the

practical forestry and woodworking that shape every canoe, but also of the role and responsibilities of the canoe maker.” Described as both an artform and a technological marvel, the journey of a dugout canoe, from forest to sea, is described both in pictures and text. So not surprisingly, what I took away from this book is the signi cance in the building of these cra and how deeply this practice weaves together the honouring of the forest with the people. e dugout canoe is one of the most iconic symbols of the Northwest Coast. roughout the canoe’s life it was treated with great care and it was very important for the males of the tribes to know how to make a one. Who better to tell this story than a renowned carver with a history of expertly cra ing over 60 high-quality canoes? Tia-o-quiaht master canoe maker, Joe Martin, has teamed with the former museum curator, Alan Hoover, to create this beautifully illustrated book which accomplishes a whole lot more than just describing the process of creating a dugout canoe (although it does this beautifully as well).

Martin, who lived in Opitsaht village on Vancouver Island’s west coast, has been involved in canoe making since learning at his father’s side as a child. As I read along I could hear Martin’s voice speaking to me, telling me the importance of selecting the right tree, of splitting the core with wooden wedges and driving them in alternatively for even splitting, of levelling the canoe before nishing the hull by using a rock and a string, pegging and sealing the stern piece with spruce gum and spruce root and of the importance of steaming and placing rocks in the canoe to avoid later cracks. Step by step—in photos and text—he leads us through the whole process as well as giving us the stories and history of

many of the canoes he created and the people he worked with.

It’s a journey well worth taking, an ode to a canoe with a gentle reminiscence and reminder of nature and history.

By Rick M. Harbo, Harbour Publishing,

By Rick M. Harbo, Harbour Publishing,

352 pages, $28.95.

When the rst edition of this eld guide came out in 1999 it was immediately hailed as the de nitive guide on West Coast marine life. It soon became di cult to obtain, so not surprisingly 12 years later the book was reprinted with some changes and updating. I recall reviewing this second edition for Paci c Yachting readers and then adding it to our limited space bookshelf on our boat Aquila, where it has received copious attention over the years.

So, I was very happy to read that

Whelks to Whales was once again hitting the bookshelves in its third revised and updated edition. Additional colour photos and newly altered names have been added to this eld guide and it covers marine life all down the West Coast from Alaska to northern California. What further recommendation does it need?

More than 500 species are shown and examined in the book. Almost every local sea creature and plant can be quickly identi ed, even by novices, due to the colour coded sections, the photos, and the brief but accurate info that accompanies each species.

I’ll be glad to replace my wellthumbed and salt encrusted second edition with this new one. I really like that the additional information contains a section on non-native species as well as instructions on how to identify what molluscs has just squirted at me by looking at its siphon rather than by digging down to uncover the culprit. Most of the book’s photos are taken by the author, and must represent years and years of diving, uncovering and discovering the ocean’s inhabitants.

Blissfully unaware of its impending dismissal from my marine bookshelf, my second edition will not be wasted— my niece has asked for it. She grew up with her aunt consulting the compendium every summer to answer her numerous “whys, wheres, whats and how comes?” Many of the muddy thumbprints on the photos are hers.

Author Rick M. Harbo lives in Nanaimo and is a diver and retired senior marine biologist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada. He also volunteers as a research associate with the Royal BC Museum. He has authored three other books on marine life as well as several pocket guides, so readers are in good and well-informed hands.

—Cherie iessen

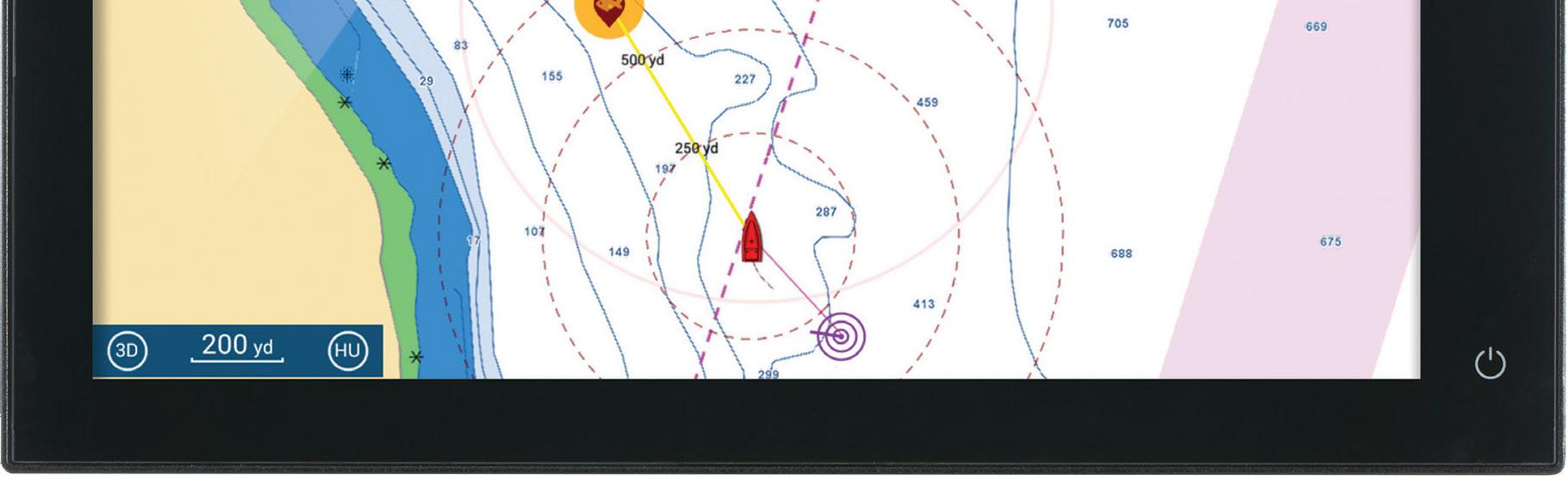

THE US COAST Guard has put out a notice to inform the boating public of shoaling in Swinomish Channel: “Signi cant shoaling exists in Swinomish Channel, especially the south entrance between South Entrance Buoy 5 (LLNR 18802) and South Entrance Daybeacon 12 (LLNR 18812). e project depth of Swinomish Channel is 12 feet, however, the controlling depth of Swinomish Channel is 4.1 feet based upon the latest available hydrographic data. is controlling depth of 4.1 feet is re ected on NOAA ENC products. Raster products do not re ect this sounding information, as they are no longer being updated with most routine corrections. Mariners should consult ENC cells for the most up-to-date information. Mariners should transit the Swinomish Channel waterway with caution, especially at low tidal conditions.”

Furuno recently received ve “Product Of Excellence” accolades at the 2022 National Marine Electronics Association (NMEA) Awards ceremony, bringing their total up to a 247 NMEA award victories since 1971. Each year, NMEA members vote for the products they feel are most deserving of these prestigious awards. Membership in the NMEA is reserved for dealers, distributors, industry experts, and NMEA-approved technicians.

I would love to be that woman. The one out on the foredeck with the wind screaming through her hair, poised to raise the first spinnaker, daring the waves to wash her overboard; willing her boat over the finish line ahead of

Iall the others. The sun would be shin ing, the sky and water gloriously blue. My spinnaker would blossom—full of wind—and I’d take a minute to look back. I’d revel in the gorgeous colours; reds, whites, greens, and yellows, the puffs of white clouds in the endless sky. I’d gaze for a moment at majes tic Mount Baker, gleaming white and bright in the distance.

The truth is, I’m scared to death of foredecks, and reefing sails and hik ing out over the side—all of the things that would make my boat go faster are not for me. Except maybe in races

like the Duck Dodge on Seattle’s Lake Union in the summer, when it’s hot and sunny, when the worst thing that could happen is a refreshing plunge into the water—or the wind dies.

But during frostbite season, every one knows that if it were up to me, the minute a decent wind came up, I’d drop the sails to the deck and motor as quickly as possible to the nearest dock, hang onto it for dear life and wait for spring. So, I watch from shore, happily. I count the brave boaters as they go by, some alone, others in packs, and think what a wonderful way—for other

Every day on the water is a blank canvas. A chance to seek new horizons and ride endless waves. So drop the hammer. Or the anchor. And let adventure be your guide.

MERCURY ENGINES ARE MADE FOR EXPLORING.

SO ARE YOU. GO BOLDLY.

Every day on the water is a blank canvas. A chance to seek new horizons and ride endless waves. So drop the hammer. Or the anchor. And let adventure be your guide.

ADVANCED MARINE POWER

MercuryMarine.com

Campbell River, BC | 250-287-9130

SO ARE YOU. GO BOLDLY.

ALBERNI POWER & MARINE

Port Alberni, BC | 250-724-5722

BILL HOWICH MARINE

Campbell River, BC | 250-287-9514

BRIDGEVIEW NORTH Prince Rupert, BC | 250-624-5809

BRIDGEVIEW MARINE LTD. Delta, BC | 604-946-8566

BRIDGEVIEW SANDSPIT

MERCURY ENGINES ARE MADE FOR EXPLORING.

Sandspit, BC | 250-637-5432

CASCADE MARINE & SUPPLY Chilliwack, BC | 604-792-1381

CV MARINE Courtenay, BC | 250-334-3536

DEAN’S MARINE Duncan, BC | 250-748-0829

DELTA MARINE SERVICES Sidney, BC | 250-656-2639

INA MARINE

Victoria, BC | 250-474-2448

INLET MARINE

Port Moody, BC | 604-936-4602

LA MARINE

Port Alberni, BC | 250-723-2522

MercuryMarine.com

M&P MERCURY SALES Burnaby, BC | 604-524-0311

MONTI’S MARINE & MOTOR SPORTS Duncan, BC | 250-748-4451

ROD’S POWER & MARINE LTD. Tofino, BC | 250-725-3735

LUND AUTO & OUTBOARD LTD. Lund, BC | 604-483-4612

MADEIRA MARINE 1980 LTD. Madeira Park, BC | 604-883-2266

SEA POWER MARINE CENTRE LTD. Sidney, BC | 250-656-4341

VECTOR YACHT SERVICES LTD. Sidney, BC | 250-655-3222

people—to spend the day. I don’t care which boat crosses the finish line first, or if they finish. To me, everyone deserves a blue ribbon. I cheer them on, then retire to the galley, where, surrounded by cookbooks, I watch cooking shows and pray for my soufflé to rise to a puff y, golden treasure of eggy, cheesy goodness. I ponder ways to perfect my next favourite recipe.

Lately, I’ve been working on pâté. I want a recipe that doesn’t require multiple steps, exotic ingredients, or dozens of bowls. My friends wrinkle their noses and ask why. Why go to all that work? Because I can’t go to Paris every time I need a slice of pâté for lunch, for a gift, or to fill up a charcuterie board. Actually, it’s not difficult, and because it has to chill for a couple of days before serving, it’s a fabulous make-ahead dish for celebrations year-round. You can create it and forget about it while you focus on other menu items.

When it’s time to serve, just slice it, garnish with some cornichons and a few greens, and voilà! You have a tasty, savory appetizer, or add a baguette and green salad, and you have an elegant luncheon. It’s perfect with a slightly fruity red wine, or in the summer, with a dry rosé.

A few words about ingredients. This recipe calls for three ingredients you may not have on hand, but I’ve included substitutes. Armagnac is a brandy, so cognac or brandy make good substitutes, or in a pinch, a sturdy white wine. Green and white peppercorns can be replaced by freshly ground black pepper. Juniper berries may be a little expensive and difficult to find, and they are too hard for a mortar and pestle, so require a spice grinder or coffee grinder, but fear not. They have a piney, slightly fruity flavour, so you can substitute rosemary, or if you like, gin.

Finally, don’t be put off by the chicken livers. Personally, I have a love-hate relationship with them. I love the way they team up with the spices and wrap around the other meats in terrines and

pâtés, but I hate the way they look when I put them in the food processor. I steel myself for the pulpy mess and give it a whirl. Because it’s worth it.

And now, whether or not you venture into making pâté, I wish you a joyous holiday season and that only good things come your way in 2023.

Special Equipment: food processor, terrine or small loaf pan, and if using juniper berries, a spice or coffee grinder

For two nine by 13-centimetre (3.5 by five-inch) terrines (can freeze half to cook later)

•675 grams (1.5 lbs) chicken livers

•675 grams (1.5 lbs) pork butt, cubed (approx. four centimetres / 1.5 inches)

•112 grams (1/4 lb) fatback or fat from bacon, or fatty bacon, chopped very finely

•1/4 cup Armagnac (substitute cognac, brandy, sturdy white wine)

•6 cloves garlic, minced

•3/4 cup finely chopped shallots

•2 tablespoons butter

•2 teaspoons salt

•1 tablespoon freshly ground black pepper

•1/2 tablespoon each green and white peppercorns, crushed in mortar (substitute ground black pepper)

•2 tablespoons juniper berries, ground (substitute 1 teaspoon dried rosemary needles or 1 tablespoon gin)

•1/4 cup heavy cream

1. In a small saucepan, over medium heat, simmer Armagnac for 30 seconds. Cool.

2. Sweat shallot and garlic in butter. Cool.

3. Add seasonings to shallot/garlic. Mix well.

4. Pulse pork in food processor until coarsely ground. Remove to mixing bowl.

5. Remove connective tissue from livers and pulse briefly in food processor.

6. Mix everything thoroughly.

7. Chill several hours or overnight.

8. Preheat oven to 165◦ C (325◦ F).

9. Fry a nugget of the pâté. Taste. Correct seasonings.

10. Place parchment paper crosswise in terrine or loaf pan with ends hanging out.

11. Press meat mixture into pan.

12. Cover tightly.

13. Place terrine in a larger pan. Add hot water half-way up the side.

14. Bake one hour or until temperature reaches 54° C (130° F).

15. Remove cover and bake approximately 30 minutes or to 66 C° (150° F).

16. Cool. Pour off excess fat.

17. Press down firmly with weight; refrigerate two days. Important: If it’s not compressed, it will fall apart when you slice it.

STORY & PHOTOS BY KAYLEEN VANDERREE

STORY & PHOTOS BY KAYLEEN VANDERREE

AAt least 30 stark white vessels with glimmering chrome trim circled us. Their burgees flew proudly above their flybridges and their bow thrusters pushed them perfectly into their slips. The differences be tween the types of boating in British Columbia was obviously ap parent in False Creek Harbour, downtown Vancouver. Boats rafted together, caked in green moss, sat at anchor sprinkled from Jericho Beach to Science World. The shiny yachts that circled by us earlier, found their homes in yacht clubs and marinas along the edges of the harbour. And then there was our boat, somewhere in between the two extremes. We classify ourselves as the cruiser type and our towels and underwear—hung to dry on the lifelines, flapping in the breeze—make that quite obvious. Despite the differences in lifestyle that come with each vessel, we all share the commonality of being drawn to the ocean.

We typically seek out anchorages surrounded by wilderness. With the sound of sirens nearby and the constant hum of activity it was obvious that we were far from our regular waters, although we were definitely in the midst of a jungle, albeit a concrete one. A series of medical appointments brought us to Vancouver in the first place and the thought of staying for free on the hook instead of paying for a few nights worth of hotels fit our cruisers budget perfectly.

Vancouver Harbour Authority offers two weeks free moorage, which is en forced by an intimidating Police boat that makes its rounds, visiting those who ignore the rules. We displayed our temporary permit in an effort to avoid a visit from the police and then made our way to one of the many dinghy docks that are free for use. Upon arrival we were kindly greeted by one of the locals who was bailing out his tender after the heavy rains. In a thoughtful gesture he glanced at our brand-new outboard en gine and warned us that theft was com mon here and to take all of our tender’s accessories with us. We decided that perhaps carrying our fuel line around the city was a bit excessive, but we did take his warning seriously and locked both our outboard and dinghy to the thick wood railing that surrounded the dock. A few hours later we saw the same fellow in his yellow foul weather gear lugging around his single paddle wherever he went, it was obvious he had learned the hard way. Thankfully, we had no issues while we were there.

We’ve been to Vancouver many times before by vehicle. The intensity of city life doesn’t really appeal to us when stuck in traffic half the time. However, despite the heavy rains, the need to lock everything and the occasional neigh bour anchoring too close, visiting Van couver by boat brought a whole new joy to the city. The hustle and bustle was more endearing when swinging on the hook and tackling each day at our own speed. We found ourselves commuting from our anchorage to Granville Island and Yaletown by our tender, not having to be reliant on an Uber or water taxi. Getting to appointments was easy and left lots of time for finding a local pool for showers, picking up fresh prawns at Fisherman’s Wharf, and adventuring along the Seawall.

When not exploring False Creek by tender, we pulled out our newly pur chased folding e-bike and hit the pave ment. The warm rays of the off-season sun were extra welcoming after a few days of monsoon style rain that left

everything on board a little bit soggy. We warmed up on the Seawall, cruising as far as our battery would take us. Half of Vancouver had the same idea, but we

Boaters need to get a permit to anchor in False Creek when they are:

•Anchoring more than eight hours during the day (09:00 to 23:00), or

•Anchoring anytime between 23:00 and 09:00 the following day.

The permit will allow boaters to anchor a maximum of 14 full or partial days of 30 days during high season (April 1 to September 30) and 21 days of 40 days in low season (October 1 to March 31).

wove our way between the other joggers, cyclists, and Canadian Geese that wandered in a type of contentment that only comes after surviving a long winter.

We circled back to our tender, stopping only for gelato, because we may as well take advantage of city living while we are here, right?

No anchoring is allowed within the navigable channel in False Creek. In addition, anchored boats must not impede access or egress from any of the ferry docks or marinas in False Creek.

If your boat does not comply with the rules, it will be removed at your expense.

For more visit: vancouver.ca/streets-transportation/ anchoring.aspx

The lure of Vancouver’s conveniences taunted our wallets just enough, so when our appointments were finished we felt it was time to leave and return to the wilderness again—the type of wilderness where the only sushi we can get is the kind we catch and make ourselves.

Life aboard really allows us to see places in a new perspective and Vancouver is no different. Although the sights, sounds and smells were slightly overwhelming at times, I can see why the anchorage is always full. Vancouver by boat is charming and full of life for any type of boater; those with shiny chrome bits, those with their laundry on the line, or even those with leaky dinghies.

saw Telegraph Cove, it was a typical, old, West Coast town, with sewage on the beach, dilapidated houses, a generally low-rent place,” said Gordon. “We liked fishing and thought a fishing re sort would be popular here.”

The Grahams, who’d married in 1970, were then living in Port Alice, a village on Neroutsos Inlet, one of the many bays and arms that form Quatsino Sound. Gordon, usually called Gordie, was a tree faller. “I loved the profes sion,” he said. “We felled and bucked timber for Sitka Falling Ltd.” But Mari lyn, a public-health nurse, knew that logging was Canada’s most dangerous industry and did not want to raise the couple’s two daughters on her own. “I was born in Saskatchewan,” she said. “But Gordie grew up on a dairy farm in the Fraser Valley.”

Gordie had become acquainted with Telegraph Cove’s sawmill that was still operating in the 1970s. “I sometimes bought lumber there,” he said. He ob served that the eclectic group of mill worker homes surrounding the board walk village posed a huge fire risk. “These wooden buildings had mostly knob-and-tube wiring installed in the first half of 20th century,” said Gordie. “Very dangerous.”

Gordon Graham invites me to board his golf cart and we mosey down to Telegraph Cove’s Forest RV Campground, with its more than 100 camp sites. Most of the campers are in recreational vehicles of all sizes—some quite glamorous—but tenters are welcome too.

Beginning in 1979, it was the first place Gordon (77) and Marilyn (76) cre ated at Telegraph Cove, a small harbour off Johnstone Strait. “When we first

GTELEGRAPH COVE AS a village started in 1912, when the Superintendent of Telegraphs sought to expand the tele graph network north of Campbell River. He picked this small harbour, naming the site after the transmission device of the day—then as important to communications as the internet is today. Bobby Cullerne maintained the telegraph line that was strung on tree branches and became the cove’s first inhabitant. The expanded version of his one-room shed still stands on the side of the boardwalk.

In 1922, Alfred Marmaduke “Duke” Wastell, bought land around the har bour and eventually opened three busi nesses, the Broughton Lumber and Trading Company, the Telegraph Cove

One couple’s journey to turn a coastal outpost into a boating haven

Mill and a salmon saltery. Buildings accommodating these enterprises were erected and houses and cottages for the workers sprung up—many on stilts. His son, Fred, took over the industries, but when he died in 1985 and the enterprises shut down, the Grahams bought all of Telegraph Cove’s buildings and began to update and repurpose them, creating a new industry—tourism. “It was a huge thing for us that Telegraph Cove’s history be preserved,” said Gordie. “But we didn’t want to make the houses and cottages too pretty, not transform them into five-star destinations, but make them distinct, cosy and comfortable while retaining their historical character. We left the moss on the roofs.”

WITHOUT THE COMPLETION of Highway 19 in the 1970s, Telegraph Cove would not have flourished. Before then, only boats could reach the isolated coastal settlements—using the marine highway just like the Indigenous ’Namgis and the Kwakwaka’wakw who fished and traded there for millennia. “Without the road, our village wouldn’t have found success,” said Gordie, adding that during many summers more than 100,000 people visited the cove (in the winter, only 10 to 15 people reside here).

Over the years, the Grahams rebuilt and maintained the marina and the boardwalk that surrounds the harbour, doing much of the work themselves. “You cannot afford to hire contractors to do the work,” said Marilyn. “You simply have to do it yourself.”

The renovated houses are rented to visitors—many from Europe. “We’ve hosted people from Africa and even Mongolia,” Marilyn added. “And celebrities like Oprah, former UK prime minister John Major, Jimmy Pattison and George Bush senior have visited. They came to view the wildlife and because no one bothered them here.”

Industrial-age artifacts are positioned around the village, including old fire-

fighting equipment and a rusty Dodge truck. Every few metres a green metal plaque explains a piece of the village’s century of enterprise, as well as intro ducing the people who first inhabited certain houses. Some of the signs hon our the saltery and mill workers of Japa nese descent who were interned during the Second World War. “A grandson brought his grand mother in her 80s back for a family re union,” said Marilyn.

“She’d lived here be fore the war. We’ve also met other de scendants of people who once lived here.”

“We’ve maintained a little sawmill to make planks for the boardwalk and cut timber for new and revamped buildings,” Gordie added. The Grahams are especially proud of the recent reconstruction of the old lumber warehouse building, which houses the Whale Interpretive Cen tre. “We built it in the same style,” said Gordie. “Just raised the ceiling to better display the whale skeletons.”

Managed by the Johnstone Strait Killer Whale Interpretive Centre So ciety, it lays claim to being the larg est marine mammal museum in BC. Besides displaying the skeletons of marine mammals (it’s remarkable how much their appendages resemble human hands), the museum offers programs for school kids that teach biodiversity, conservation and animal adaptations in the Salish Sea.

In 1994, Bell Canada shot a com mercial in Telegraph Cove. “They rented houses, brought in extras from

No visit to Telegraph Cove is complete without a walk along the boardwalk and a stop at the Whale Interpretive Centre.

Port McNeill and we had to join the Actors Guild,” Gordie said. “We had a coffeeshop but no restaurant to feed all these folks. That persuaded us to add a West Coast style restaurant, the Old Saltery Pub.”

The commercial played across Can ada and gave Telegraph Cove a terrific boost.

Summer activities abound. The ma rina is home to a fleet of fishing boats with some spaces available for visiting yachts. Stubbs Island, founded in 1980, was the first whale watching company in BC (now operated by Prince of Whales). A fleet of rental kayaks, along with knowledgeable guides, are avail able. A bear watching company whisks

visitors out into Knight Inlet to view grizzly and black bears. On the board walk outside the pub, Gordie still grills slabs of marinated salmon. A new 24room modern lodge, built to resemble the style of the Whale Interpretive Centre, opened recently.

AFTER MANAGING TELEGRAPH Cove for more than 40 years, the couple are thinking about its future. “We’re working on a retirement plan,” said Marilyn. “Our daughters worked here many summers and know how much work it is to run the place. We’d like to eventually find people who’ll want to maintain the houses, museum and boardwalk, and

keep their history alive.”

After all the years of hard work, the Grahams have no regrets about their long tenure, although Gordie grumbles a bit about government regulations that don’t always fit a seasonal business, and the tough times caused by the pandem ic. “I’ve loved living here though, and reinventing Telegraph Cove with Mari lyn and some family members,” he said.

“We’ve won many prizes and awards.”

“Our biggest joy has been to see how much people enjoy it here. Most have never viewed an orca or bear, or anything like it,” continued Marilyn.

“We’ve made so many friends and 99 percent of our guests are wonderful. We will miss them.”

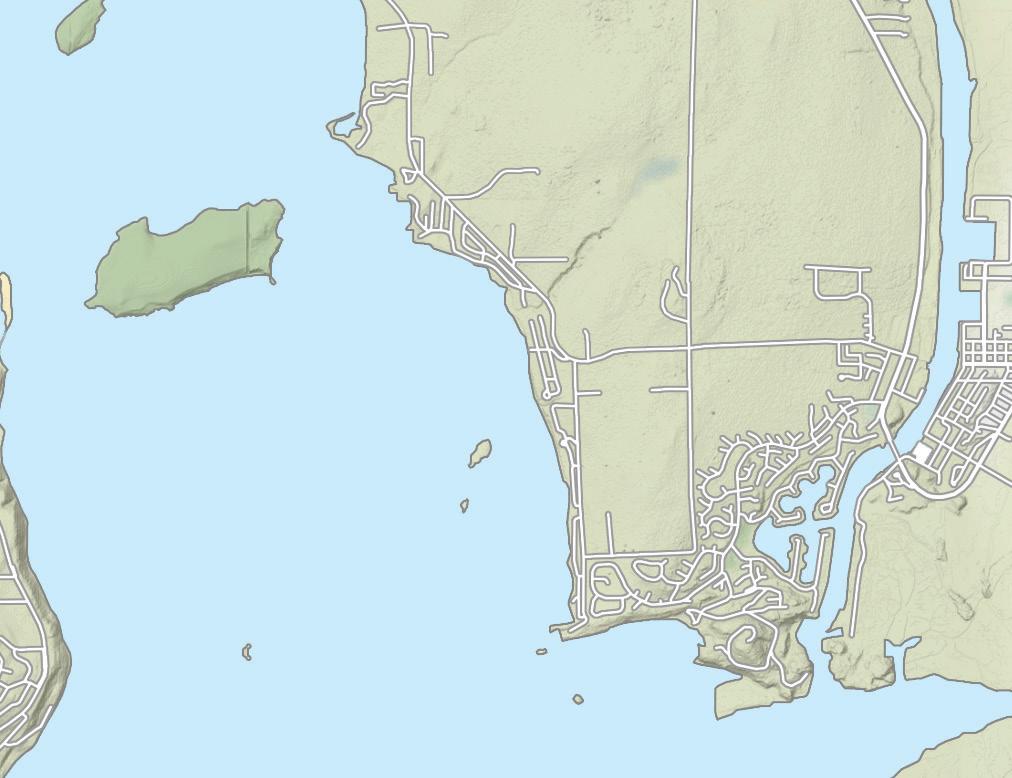

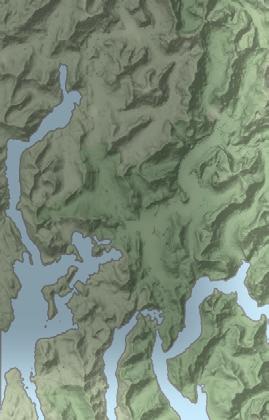

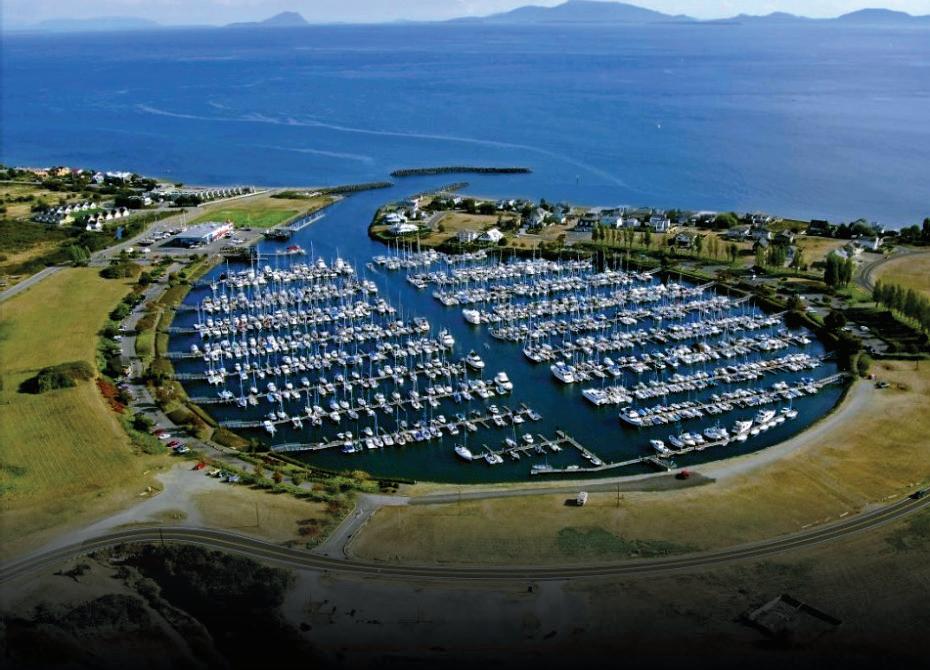

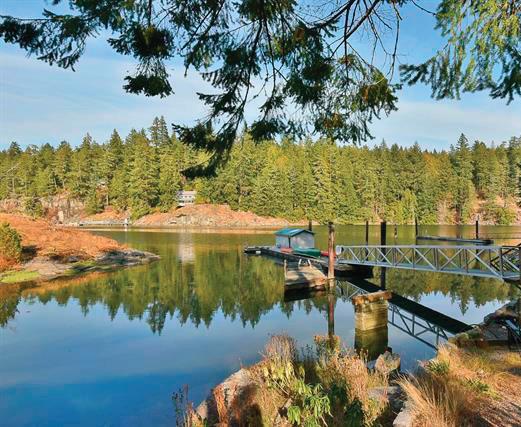

From left to right: The marina, The Ways, the downtown area and ferry dock, the bridge to the old mill site which is now a fish nursery, and behind it all, the Link Lake Dam.

Getting to know this memorable town on BC’s Central Coast Story

Come in out of the rain. Sure, it’s a gentle rain that drifts down from the low clouds overhead—you can turn your face up to it without being pummeled. In the bay the mirror calm of the inlet’s surface is broken by a million stipples. It’s beauti ful and mesmerizing.

But come in out of the rain anyway. It rains a lot here in Ocean Falls, with its back against the Coast Range. Pacific clouds, full of moisture from their slow transit across the world’s largest ocean, arrive at these steep slopes, rise, and dump staggering amounts of precipita tion on the inlet and the occupants below. The annual rainfall is 169 inches or 4.3 metres. Do the math—that’s almost half an inch per day. More than four times what North Vancouver gets. And yet, for all that amount, it falls gently in the summer. The locals like to joke that you can tell it’s summer—the clouds are still there, but the rain is warm.

It’s early August and it’s been raining on the mid-coast, without a break, for almost a week. We’re tired of watching it run down windowpanes and we’re tired of watching the pipes on the up per deck jet it overboard. What to do?

We head to Ocean Falls, a place we’ve frequently heard about but have never visited. It’s out of the way, and far enough removed that it’s not easy to combine with anything else. But those who have visited say it’s well worth the detour, and so here we are, tied to the dock in the little marina. There are ben efits to being off the main routes.

Inlet is a treat. If the clouds aren’t blocking the view, the soaring peaks above the town are dramatic. At the head of the bay is the wall of the Link Lake dam—almost 700 feet across and 70 feet high. The recent rain has meant the spillway is in full flood. You can see white water plunging down the wall and churning along the raceway. It’s worth the effort to walk up to the

1

1. Initially built to provide power for the growing pulp mill, the Link Lake Dam is a short walk out of town, and was spilling hard after a week of steady rain. 2. “The Shack” at the public dock has free wifi, tables, chairs and a book exchange.

overlook. It’s about a 20-minute amble through town, where the roads are cracked and grass pokes through, up the hill to where the paving turns to gravel, the bush encroaches from ei ther side, and then you’re there.

The lake behind the dam is almost 30 kilometres long and is the result of the first dam, built in 1910. The dam was raised during the First World War

to provide more power to run an everexpanding pulp mill. Today, there are two intake floodgates that drive the turbines. Unlike most places in the world, Ocean Falls has a surplus of power that can’t find a market. As you motor up Cousins Inlet, you’ll have noticed the power poles on the west side. They supply the communities of Shearwater and Bella Bella.

3 4

3. Despite having a small resident population, BC Ferries services the town bi-weekly from Port Hardy and Bella Coola. 4. The Ways are over a century old. Now owned by local Les LeMarston, who also runs the Old Bank Inn and the ice cream shop, it’s worth a visit, if Les is available. Ask at the inn.

PERHAPS WE SHOULD start at the beginning. First there was a sawmill in 1909, and it wasn’t long before they built a dam to power it. A pulp mill quickly followed. In 1921 the dam was raised for the second time. More power. More pulp. Ocean Falls was on a roll, as the mill expanded so too did the town with people streaming in looking for work.

Pacific Mills Ltd., owners of the pulp mill, knew they had to be special to attract people to a place that was ef fectively the end of the line. Sure, there was ferry service, and even air service at times, but to compensate for the re moteness, they paid above average wag es and sponsored anything that helped to build a community—churches, soci eties and sports teams.

In 1954 ownership shifted to Crown Zellerbach Ltd. The town was still on the move. A few years earlier, the Martin Inn had been built with 265 rooms. Five years after that they added another 105 rooms to the inn. Imagine that— it was the biggest hotel on the coast, including Vancouver! A ski resort was built. The baseball fields were ex panded. It’s estimated there were about 3,500 people living in Ocean Falls at the time.

SADLY, LIKE MANY isolated one-in dustry towns, when conditions change the effects can be devastating. In the early ‘70s, Crown Zellerbach closed the mill. Under pressure, the BC Govern ment took it over, but by 1980 they too had to call it quits. Workers and their families left. The plant and equipment were sold off. The hydro station was privatized to Boralex, a Quebec compa ny. Homes with waterfront views sold for as little as $2,000.

Later, the government sent in ma chines to flatten much of the place. The remaining residents resisted vigorously. After a standoff, much of the town’s centre was spared; but it was a false hope. Slowly, inevitably, the forests encroached, despite the best efforts of those who stayed.

As the permanent population shrank to about 50 souls it became strikingly obvious that Ocean Falls needed a new economy. For a while it looked like the conversion of the old mill site, by Nor wegian fish food giant Mowi, into an Atlantic salmon hatchery, raising fry for fish farms might be the answer. But the staff lived in their own accommoda tions and came and went on company transport, with minimal benefit to the town.

WHAT DID OCEAN Falls offer? It was a small, hardy community. And it had 13 megawatts of mostly surplus elec tricity. That last feature attracted an unlikely customer. In 2010, cryptocur rency was just gaining traction. To

“mine” Bitcoin, you need a lot of com puting power. And computers guzzle a lot of electricity.

After numerous false starts, Vancouver-based entrepreneur Kevin Day convinced Boralex that his company was solid and, after a bit of back and forth, it agreed to sell Day up to 6 MW of power (at an undisclosed rate). Day set up his data centre in one of the least crumbly buildings in the old pulp mill. In 2017 Ocean Falls Blockchain began operations. Day’s timing was good— the cryptocurrency went from $200 to almost $20,000 that year. But that was followed by some serious price hiccups in 2018 and 2019.

Unfortunately, none of this has really benefitted the town. Computers don’t need a lot of attention or employees.

TONI ZIGANASH AND Les LeMar ston own the Old Bank Inn and Little Licker Ice Cream Store—pretty much the only businesses in town. They aren’t sure about cryptocurrency, but they like that there’s someone else looking to Ocean Falls’ future. The average age in town is 70-plus, so there’s little energy for anything new.

Sure, there’s a town hall, a post office, a first aid clinic and an RCMP post, but all of it is part-time (the RCMP keep a vehicle on charge outside their build ing, but they rarely come to town). Which is a problem. LeMarston wor ries that every time someone does a ‘ghost town’ story on Ocean Falls, it attracts odd people who arrive to squat in the deserted buildings. “People don’t realize that these properties are owned. They may be neglected, but they aren’t up for grabs.”

All the abandonment doesn’t help those left behind. Your house might be well cared for, but when the ones on either side are being swallowed by BC bush, it doesn’t look good. The other problem is that much of the downtown is owned by a small group of business men on Vancouver Island who have shown little interest in renovating or repairing.

AND LEMARSTON would like to see more young people. With the imminent arrival of fibreoptic, this might happen. If Covid has taught us anything, it’s that a lot of people can telecommute. In the inter im, they are busy. Their inn provides accommodation to visitors who arrive by ferry from Bella Coola or Port Har dy. You can also fly in from Port Hardy on Wilderness Seaplanes.

LeMarston has taken over The Ways, a magnificent old marine structure built at the end of the First World War. A century later, there’s a slight list to landward, but the pilings are sound

and Les is jacking the base beams back to level. He has the original engineer ing drawings of the place. In the short term, there’s no plan to provide com mercial haul-outs, but the building is worth a visit. He is often found there and if not busy he will give you a tour of the place. Massive timbers, clear first-growth beams without a knot in them, make for an impressive sight. Older visitors will remember Herb and Lena Carpenter, who previously owned The Ways. They have retired to Keremeos where Herb said he had, “one final house” to build.

Others may remember bearded

‘Nearly Normal’ Norm Brown, a local character who had a museum of memorabilia, salvaged from the town’s slow demise. An inveterate collector, his accumulation was housed in the co-op building until 2008, and then moved to the upper floor of The Ways. It too is worth a visit—green toy frog collections, notice boards from the sides of buildings, ladies’ face cream jars, Walt Disney LP records, dreamcatchers and Christmas diorama cutouts crowd other unrelated objects in the large loft, which in past times was the paper testing lab for the mill. Norm Brown died of cancer in early 2022.

The collection is now lightly managed by LeMarston.

EVA BRINE IS the wharfinger of Ocean Falls Harbour. Her husband was born there, and she’s lived in Martin Valley for more than two decades. There’s 1,500 feet of dock space, 20 and 30amp electricity and potable water. There’s also “The Shack” where you can hang out and use the free wifi; there are tables and chairs, lights and a book exchange.

There are no longer any restaurants in Ocean Falls. Until Covid, Eva, a European-trained chef, ran one that delivered elegant cuisine quite out of the normal fare. No longer. There’s also no fuel and no garbage collection.

For exercise, there’s the dam overlook or you can hike the two kilometres to Martin Valley, named for Archie Martin, the mill’s first manager. The road follows the shoreline and brings you into a residential community which is better cared for than the downtown area. Using the Merlin Bird ID app on our phones, we identified 11 bird species on that walk, although we saw only one—a violet-green swallow. A short distance along the road is the Fairy Rock, a remarkable place known for sightings of little mystical people, with a variety of fairies about, and even coins lying

around to be collected (please advise the wharfinger if you have found treasure, so she can ensure it is replaced later).

THE BAROMETER WAS rising, the gale warning on the outer coast had been downgraded and the rain had eased. So, we let go the lines with a feeling of genuine sadness, leaving Ocean Falls in our wake. Our stay had been unexpectedly upbeat despite the grey days, and we were sorry to be going. It was a great place to get out of the rain.

When You Go Ocean Falls Harbour 250-289-3374.

Rain People: The Story of Ocean Falls, BC. Bruce Ramsey, Wells Gray Tours Ltd, 1997.

Whistle up the Inlet: The Union Steamship Story, G.A. Rushton, published by J.J.Douglas Ltd, 1974.

Raincoast Chronicles series, Harbour Publishing, 1972.

Four young women take inspiration from

By Erin Beaudoin

By Erin Beaudoin

The crew sighed with relief as we floated our way into Green Bay after a windy afternoon on choppy waters. With an eightfoot beam and a 2.5-foot draft, By All Means—our 28-foot North Pacific—is an economical boat in a headwind, but bobs around uncomfortably in bigger waves advancing from any other direc tion. The other members of the crew and I were keen to be done bobbing for the day as we were still finding our sea-legs on week two of an eight-week expedition to retrace the famed adventures of captain-author Muriel Wylie Blanchet. Annie Means, our captain, first picked up Blanchet’s memoir, The Curve of Time, when she was 14 and had planned on recreating the trip ever since. She mentioned the voyage to me when our college group took a weekend trip to Lo pez Island for Annie’s 20th birthday. As the future crew read The Curve of Time, we became equally enchanted with the idea of recreating Blanchet’s voyages. (Fittingly, we would begin and end our voyage at Lopez Island over a year later.) Things started coming together. We got permission to borrow Annie’s father’s vessel, By All Means, took boating cours es, and marked many destinations from The Curve of Time on a map, including Green Bay.

WATER TRICKLED OFF the cliff in Green Bay, sending ripples across the linn. It was day 15 of our voyage and we were fortunate to have the anchorage to ourselves except for a few dinghies tied to private docks. We fixed ourselves windward, triangulated a good distance from a dock, a reef and the waterfall and then dropped the hook. The boat didn’t catch the first time we lowered the an chor, so we pulled it up and tried again. Annie hit the button to reel in the chain,

but, alarmingly, the anchor winch made a clunky noise as it appeared to tie the chain into knots.

Annie immediately took her hand off the button while Uhane rushed to the bow to investigate. I held my breath, hoping it was a quick fix. The space where we floated suddenly seemed much smaller than it had before. The stress level in the boat rose as the reef, the shore and the dock closed in around us. Emery and I kept lookout, while An nie used the thrusters to make sure we stayed in place. Uhane re-entered the wheelhouse, wiping her hand across her forehead under the brim of her beanie and reported that a part of our windlass that directs the chain toward the anchor locker was completely snapped. We all groaned, resistant to leave the relief we experienced moments before.

WE BEGAN OUR expedition as novice boaters and after having read about the many unexpected trials and tribula tions in Blanchet’s memoir, we expected the learning curve to be as steep as the fjords we set out to explore. That never lessened my desire to do the trip; I was inspired by Blanchet’s self-sufficiency and adventurous spirit.

We were focused on visiting the same places as Blanchet—and in a similar boat—but it was harder to imagine how we would embody her way of life 100 years later. But in a series of unex pected ways, we managed to come close by navigating the challenges we faced— like our anchor winch troubles—and learning as we went.

We attempted our first anchorage of the expedition on day three, June 13, in a windy bay around Ganges. We pulled into a space between two white sail boats and began to lower the anchor.

Unfortunately, before the anchor could catch we were pushed too close to our

neighbours. Wind whipped our faces and threw the crew’s voices to the sea as we tried to shout to each other, so we de cided to move to a more protected, less crowded bay.

Our second anchoring attempt was even less successful, ending before the anchor even reached the seafloor when the button that lowered the anchor stopped working. As we stood dumbly on the deck, the wind slapped my hair against my face as if to say “stupid, stu pid.” And the wind was right. It dawned on us after paying for a slip for the night that the issue was the circuit breaker: we just needed to turn it off and on again.

I had always heard that superstitions grow on the sea and I felt the full force of fate after a subsequent anchoring at tempt failed in a bay marked on the chart as a good anchorage. When we pulled our anchor up, it was slathered in a layer of mud. Why hadn’t it held?

One thing was clear: we needed better luck. Annie took her mother’s St. Chris topher necklace from a drawer and hung it over the dashboard—the patron saint of travellers would help us with our next anchorage.

Perhaps St. Christopher preferred the drawer, because there in Green Bay we were forced to haul in 150 feet of line, inch by inch. Uhane and Emery hauled it up and fed it through the windlass with two-point redundancy, while I tugged at the chain from below to make sure it didn’t wrap on itself again.

IN ONE CHAPTER of The Curve of Time, Blanchet’s engine stops just be fore dark. She gets into her dinghy and rows five miles to the nearest shore with her trawler and children in tow. Hours later, she lands in a remote bay on Cor tes Island. Thinking about this on our way back left us with no room to com plain. Instead, we focused on solving our problem. We found out that the broken piece is called a fleming and marveled that something so essential is made from flimsy plastic. The local boat shops did

Annie leaning out of the vessel one early morning on log watch.

not carry the part, so we had to order from its mother company in the United States. Annie sat on multiple, painful customer-service phone calls repeating “speak to representative!”

The soonest the new fleming could arrive was two weeks later, so we made the painful decision to skip Princess Louisa until we had a working windlass. Instead, we headed north toward Deso lation Sound because a teacher from Uhane’s hometown of Lopez Island, Brian, was in Prideaux Haven with his partner and their dog. They were gener ous enough to let us raft up to their sail boat for a couple of nights.

During the warmest days of the sum mer, Brian helped us create a more ef ficient manual anchor system: with a crate strapped to our bow, we pulled out 200 feet of chain and line, then reeled it into the crate—no windlass needed. To thank him, we threw a big afternoon barbecue between our rafted boats. It turned into a warm, wonderful night. We discussed our unfinished novels, photography and the bioluminescence in the water under the dull light of a waning crescent moon.

THE MANUAL ANCHOR system allevi ated the stress weighing on us from the missing fleming. The following days

in Prideaux Haven were spent swimming in hypnotizing seas full of moon jellyfish and hiking around the dense green woods in search of Phil’s cabin from The Curve of Time. We found the cherry trees and ivy that supposedly surrounded the cabin, but there was no sign of the building itself.

THE FIRST TIME we took up anchor with the new method, Emery received a shower of muck that splattered off the chain as she pulled hand-over-hand. When she turned around with her pajamas covered in mud, we all gaped in surprise that erupted into laughter when she immediately dove into the chilly morning ocean to wash her clothes. The following mornings, I stood next to Emery with a telescoping boat hook and whacked the mud off before it could reach her.

More than just working however, the manual anchoring system endowed us with an education in anchoring we never would have received simply using the windlass. We learned to clearly judge a good anchorage from a bad one by listening closely while the anchor set and watching the vibrations on the chain. When the seafloor is muddy, the chain takes tension, then slowly and silently releases. On a flat rock floor, you can feel the chain vibrating and sometimes hear a deep scrape; and on a diverse, rocky floor you can see the splashing-rattle of the chain as it makes its way around rocks until settling in a crevice for the night. During our days

of manual anchoring, Emery took the brunt of the weight when hauling the chain back into the crate and earned her new nickname, the “anchor wench.”

AFTER WE FINALLY RECEIVED the new fleming only to find it rendered useless by bent screws, we continued to use our manual method, this time, however just as much out of love as necessity. Before our journey to Princess Louisa, however, we finally took the time to replace it. If Blanchet could fix an engine alone on Cortes Island, we figured we could fix a windlass at a public dock with cell service. We couldn’t find the right kind of screws in any of the small towns we passed, so Uhane, handy by nature, took two screws out of the plastic casing for the windlass and used them instead. She threaded the new fleming around the gypsy, clicked the notches into place, and secured it with the screws from the casing, while the rest of us sat on the dock examining the windlass manual and handing Uhane tools.

IT TOOK US until Princess Louisa, the tail end of our journey, to use our anchor winch confidently. After so many early mornings of yanking up countless feet of heavy chain, it felt strange to take up or let out chain with a button. We would mill about the wheelhouse, unsure of what to do with ourselves. But after the anchor was set, we sat back to enjoy the mountainous views dotted with spindly waterfalls knowing we had earned the technology. Our anchorage was as sure as our newfound independence.

The crew of By All Means is making a documentary about their adventures from this summer, which will come out next year. Follow their instagram for more details on the expedition and updates on post-production @Capimovie.

It’s not a term used much anymore— “marlinspike seamanship”—but, no matter if you are a sailor or a powerboater, it is an essential part of the boating experience. Unfortunately, knotting and splicing can seem complicated to many boaters but these skills, which form the basis of marlinspike seamanship, can be tackled in a fairly straightforward manner. It is hoped that this introduction will simplify the useful business of turning rope into an indispensable tool aboard your boat. And for the more experienced mariners, we have a knot-tying trick or two in there for you as well.

Like most topics that are designed to improve our lives a oat, a little dedication and a lot of practice are called for to insure that we are engaging in a practical, and not an academic, exercise. In the world of ropework, using and tying the correct knot could make the di erence

between a boat staying properly secured to a wharf or dri ing away, or a crew member safely riding a bosun’s chair alo or making a rapid and possibly crippling descent to the deck.

Every language has its idiosyncrasies and this is no more evident than in the language of the sea. For example, “rope” becomes “line” when it leaves the yacht chandlers and is put to use aboard a boat. Just to keep you on your toes, however, working with line, as in tying knots, bends, or hitches, or putting in a splice or a whipping is called “ropework” not “linework!”

On top of this, each line, with a speci c designation, has a speci c job to do:

Sheets: You could forgive a landlubber for thinking that the sails are called ‘sheets’, because they look like bed sheets somewhat, but sheets are, of course,

used for trimming the sails; hence main sheet for the mainsail, jibs sheets for the jibs and spinnaker sheets for the… you get the picture.

Halyards: Derived from “haul yards”, these are lines that haul sails up, each with a speci c name referring to the sail they raise such as main halyard, jib halyard, staysail halyard, etc. When sails were lashed to a yard in a square-rigged vessel the name made a little more sense as it was the yard that was hauled alo .

Down Haul: A line that pulls a sail down to lower it or improve the tautness of its lu (leading edge).

Out Haul: A line that pulls a sail out (usually on the end of a boom or yard) to tighten it.

Rode: Less well known, a rode is the line that attaches an anchor to a boat,

more commonly called an anchor line. Beware! In sailing terminology ‘rode’ can mean something entirely di erent such as ‘wind rode’ or ‘tide rode’ whereby the direction of a boat’s bow at anchor is a ected by the force of the wind or the tide.

Dock Lines: ere are a lot of these in use when tied to a dock and, unfortunately, they o en get misnamed. A ‘bow’ line and ‘stern’ line make sense as they lead from the bow forward and from the stern a respectively. ‘Spring’ lines are a little more tricky as the ‘forward spring’ leads a to the dock from a forward position on the boat and the ‘a spring’ leads forward from a . ese are valuable lines as they keep the boat from surging at the dock. And then there’s the ‘breast’ line which is short and leads at 90° to the vessel and keeps it snug to the wharf. Great for loading groceries but don’t leave it on for long. Being short, it allows for very little play, which you may need if a surge gets up. Many a torn out cleat or bent stanchion bare mute witness to a neglected breast line!

Here’s a trick question to try on your fellow boaters: How many ropes are on a boat? e standard answer is none (they are all ‘lines’) or one (a bell rope) but, in fact, there are a few. Here’s what I’ve found, in addition to a bell rope: a ‘bolt rope’ (used to reinforce the edge of a sail); a ‘foot rope’ (slung under a yard to support a crew member); a ‘tiller rope’ (for lashing or controlling a large tiller); a ‘tow rope’ (for towing a disabled vessel); a ‘man rope’ (dropped on either side of a rope ladder to assist in boarding or disembarking a vessel).

Loosely speaking, a knot is anything you do with line—turns, tucks, passes. However, the knot is broken down into four groups: knots, hitches, bends and splices. No one is going to make you walk the plank if you call a hitch a knot (on one level it is a knot) but there may be some curmudgeon at the yacht club bar who is a devotee of the Ashley Book of Knots and is unlikely to contribute to a second round of drinks unless you

acknowledge the distinction between the two!

e plot thickens: there are actually two kinds of knots. e rst kind are used to form a

loop, such as the bowline and are called loop knots. At this point I will stick my neck out and say categorically and undeniably: “If you are only going to know how to make one knot in your life, let it be the bowline.” (But more on this in Part II.)

Let’s now take a quick look at some terminology connected to cordage so that we may better understand knotting, hitching and bending down the road.

Wrapping

The part of the rope being manipulated.

Usually the opposite to the working end, which should be made fast when referring to the bitter ends of anchor rodes (literally, connected to the “bitts” or Sampson post).

The inactive part, or in the case of block and tackle the part of the rope attached to the eye of the block that doesn’t move.

A curve or loop in a piece of rope, or any central part of a rope coiled between its ends. When the anchor line is running out never stand in a bight (remember ‘bights’ bite)!

e second kind of knot is one in which a knob or bunch is formed to prevent fraying or unreeving or perhaps for a handhold. is second family of knots are known as knob knots and include the popular gure of eight knot or stopper knot. As we all know (or should) a stopper knot will prevent a line inadvertently snaking out through a block or fairlead especially jib sheets and the mainsheet aboard a sailing vessel.

A hitch is a method of making a rope fast to another object. Possibly the most common hitch is the clove hitch in which a line is made fast to a post or stanchion. is is a great way of securing fenders to a stanchion because the weight of the fender aids the clove hitch in staying put. Unfortunately, this particular hitch doesn’t like anything but a constant load and can

work itself loose otherwise. We will look at how to prevent this when we examine it more closely.

A bend secures two ropes together, unlike the hitch which secures a rope to an object. e sheet bend is most commonly used in this connection and has the advantage of doing a good job of securing two lines of di erent diameters together.

Incidentally, both the bowline and the sheet bend can appear to be tied correctly when, in fact, their strength and knotability are severely compromised. Again, more on this later.

Splicing can be viewed as a permanent knot. Most common is the eye splice which sometimes calls for a marlinspike in a three-strand rope or a hollow d in braided line. e end

of docklines, sheets, halyards, anchor rodes—you name it—all cry out for eye splices. For some reason, newcomers to boating view the eye splice as a tricky piece of work. In fact, the opposite is the case, especially in threestrand line that’s not laid up too tightly. Braided line is a di erent story and takes practice. Braided line that’s been in service for a while is almost impossible to splice e ectively so we will restrict our instructions to “twisted” or “stranded” rope.

Less commonly used, but useful, are the short and long splices for joining two lengths of line together and the grommet which is really a form of the long splice.

Next time we will examine in more detail some particular and useful knots and how to tie them correctly.

$530

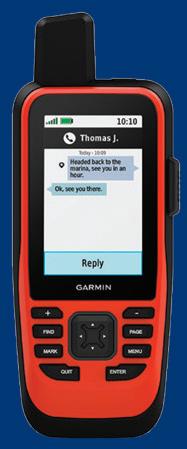

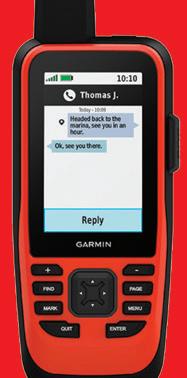

Regardless of your boating skills, it is not unusual for loved ones to worry if a trip takes longer than it should. Get the adventurous boater in your family the inReach Mini 2 and stay in touch. It does not rely on cellphone coverage. Instead, the Mini uses a global satellite network to relay information. The Mini can send and receive texts, share locations, be a digital compass, access weather forecasts and has an interactive SOS alert system for emergencies. garmin.com/en-CA

$329

We all know a boater who is a bit too disorganized. Well, for the cluttered cruiser there is the durable RUX 70 L. A collapsible outdoor bag/ bin that fits whatever the adventure requires. Being fully weatherproof and with multiple configurations, this storage unit is at home on the foredeck, tucked away in a cabin or even strapped on your back. RUX is great for storing valuable gear in rough conditions and collapses down when not in use.

rux.life

BY BLAINE WILLICK

Every cruiser can appreciate a good tune, whether relaxing in the cockpit or working in the depths of the engine room. The JBL Flip 6 is the perfect fit for both occasions. Waterproof and dustproof, this little speaker can take anything you throw at it. With 12 hours of battery life and two-way sound, it will keep rocking long after the sun is down and you’re still working on the engine. jbl.com

$180 to $256

Not every boat has all the room in the world, so if the family fisher or the cockpit cook needs some extra workspace there’s the SeaSucker Cutting Tables. These tables suction onto the inside of the transom and are great for cutting bait, filleting fish or even as a serving table. The tray hangs over the edge, so it is easy to clean. With several sizes on offer there is an option for every type of boat. seasucker.com

$580

GoPro is synonymous with adventure and the outdoors. So, it is no surprise that their latest model made the list. If you or a loved one hasn’t upgraded their GoPro in a few years this might be the time to do so. The Hero 11 got a big boost in photo quality, has award-winning hypersmooth stabilization, and the front and rear LCD screens help frame the perfect shot. Who doesn’t love showing off their time on the water. gopro.com

6.

7.

$115

In the past few years a few portable solar panels have popped onto the market, but we like the BigBlue 3. BigBlue is a bit heavier than the competition, but it continually outperforms them in cloudy weather. Its heft means you might not be taking it on a hike, but it’s perfect for keeping those small electronics charged up. It’s collapsible so when it’s time to use it you simply spread it out on deck and point it toward the sun. Folded, it is 11.6 inches by 6.3 inches. amazon.ca

$1,200

Boaters who battle the waters outside of the summer months need increased protection. The EP Jacket is up to the task no matter what the wild West Coast has to throw at it. Manufactured in Burnaby and made from high-quality Goretex, this updated version features a streamlined cut to reduce bulk. Specifically designed nylon reinforcements ensure this jacket is built for repetitive use. Articulated elbows and a slit sleeve cuff provide superior range of motion. The high-visibility hood, face shield, cinch collar, and adjustable Exoskin wrist cuffs block out the wind, and the fleece-lined neck provides warmth while reducing irritation and chafing. mustangsurvival.com

$1,000

the

When paired with the EP Jacket, this salopette creates a head-to-toe waterproof solution that can withstand our winter weather. The reinforced seat and knees provide highly durable performance. A two-way waterproof zipper allows convenient relief and flexible venting while ensuring you stay dry underneath. The streamlined fit doesn’t compromise mobility, a double waist cinch gathers in the front when working in a bent-over or crouched position, and shoulder straps adjust to fit an extended range of torso sizes. A windowed cargo pocket and knife attachment keep gear accessible, and reflective trim on chest and cargo pockets increases visibility. mustangsurvival.com

$200

while the UV treatment

cessory which attaches to and the large chest pockets that can

In the June, 2021 issue of PY we reviewed the MoonShade, a sturdy polyester awning which can be put up next to your boat, on the dock or on the beach. The ripstop polyester provides shelter from the wind and rain while the UV treatment protects against the sun’s harmful rays. The latest release is the MoonWall accessory which attaches to the MoonShade providing additional protection or privacy. Of course, it can also be used on its own as a tarp or wind break. It’s made from durable, lightweight poly so it’s ideal for boat life. moonfab.com

Any early morning boater knows fair conditions can still mean chilly temperatures. This wind shell provides an exceptionally light protective layer for when the wind picks up or when travelling at high speeds. Useful for peak season early morning launches or late returns when a fully-lined jacket is overkill. We liked how the hood could be stowed away to keep it from flapping in the breeze when not needed and the large chest pockets that can hold all your essentials. The Ventus windbreaker is perfect for boaters who are out on the water all day long. mustangsurvival.com

The annual August Rendezvous of the Bluewater Cruising Association was held at Port Browning Marina on Pender Island. In total, there were 36 boats and 67 sailors in attendance.

The weekend was filled with fun ac tivities, including dinghy boat races, boat visits and a fabulous happy hour and potluck dinner—the best dinner since the “pre-Covid days!”

One of the highlights of the week end was the presentation of “Leavers Kits” to captains and crews of three boats, all of whom were leaving to go offshore in August.

Feedback included, “This year’s ren

dezvous was an absolute blast! It’s al ways wonderful to see everyone who shows up!”

This year, the Catalina Rendezvous was a great success after a long Covid hiatus for the last two years. We had over 20 boats ranging in size from 27 to 45 feet at Telegraph Harbour Marina on Thetis Island. The Friday evening was a fun meet and greet with a social potluck of appies, BC wines and craft beer. Saturday was busy with a potluck breakfast, Tele graph Harbour pub crawl, a hilari ous blindfolded dinghy race, and a potluck barbecue dinner. Next year’s

rendezvous will be held from July 7 to 9. Anyone interested in joining us can contact Rob Johnson at sailor guyrob@gmail.com.

The 2022 Classic Yacht Association Fleet Rendezvous was held in Ganges at the Salt Spring Marina August 29 and 30.

With 20 classic powerboats from 1910 to 1963, the event was truly a “Cruise Back in Time.”

The Classic Yacht Association began in 1970 when a small group of vin tage wooden powerboats enthusiasts decided to form an organization to perpetuate their interests. Thus the

the 2022 cruising season

Classic Yacht Association was organized with a dedication to promote and encourage the preservation, restoration, and maintenance of fine old power-driven pleasure craft.

Anyone interested in joining the Canadian Fleet can contact Gord Wintrup at gord@bayfield.ca.

The 2022 Commander Rendezvous was held at Ladysmith Community Marina on July 8 to 10 with 14 boats and 32 people in attendance. It was so nice to get together, compare notes and share stories with the group. We were especially pleased to see our US members again.

We were also delighted to be able to return to our regular activities including happy hour, the potluck dinner, informative guest speakers and the sharing of boat improvement projects and maintenance tips. New this year, and certain to become a regular event, was the Ladies Champagne Chat in lieu of our regular Book Club discussion.

We are looking forward to next year when our rendezvous is planned for Cap Sante Marina in Anacortes, on July 7 to 9.

There was a great turnout by the Canadian Chris Craft Rendezvous

group. It was fantastic to see some new faces and to welcome back our American friends after a few years. We had a beautiful weekend at Ladysmith Community Marina, with 12 boats registered and over 26 people attending! Friday featured a pizza night on the dock, while Saturday was highlighted by the Chris Craft “Show and Shine” and our famous potluck with live music on the dock late into the night. Sunday welcomed new plans for our beloved Chris Crafts to venture home or travel to destinations anew, with many of us bumping into each other en route. Thanks to everyone for making the Canadian Chris Craft Rendezvous such a success!

The Freedom Marine rendezvous was once again held at Dent Island Lodge with a wonderful turnout of Princess, Galeon and BRABUS boats. We are already looking forward to next year!

12 Boats and four members without boats attended the MacRendezvous at the Union Steamship Marina on Bow en Island June 3 to 5. Saynomore, Zeph yr, Cassiopeia, Windchime, Mover, Tickety Boo, Nauti Nuff Time, Heaven Sent, DeeSeas, Gemini, 2Wish’N and Blackjack arrived by boat while the crews of Summerzcool, Rapture, Auro ra and Impulse made the trip by ferry. The workshop “Seven things Not To Do with Your MacGregor” hosted by

6 7

Todd of Blue Water Yachts offered many ideas for members to consider. There was a flurry of activity following the presentation as members inspect ed their steering and rudder systems. Sunday morning saw the Burrard Inlet flotilla depart to catch slack and the Sunset Marina flotilla departed soon after. Three boats crossing or heading down the strait decided to avoid the nasty weather and stay another night at the marina to catch the better winds and ebb currents on Monday.

On July 23 and 24, Monaro pow erboats gathered to mark the 42nd anniversary of the rendezvous. As in many meets in the past, it was held at Port Browning Marina on North

Pender Island.

This year the number of boats at tending was down slightly due to a few factors. With Covid still on the minds of people, a gathering of owners could possibly pose a health risk. The high cost of fuel was also a deterrent to travel for some. Despite these fac tors Peter and Lisa, long time Monaro owners in Seattle still came up for the meet. Also attending were Bob and Gail, long time multi-Monaro owners arriving in their 298.

Dinner was in the marina pub with breakfast at the famous local favourite of Joe’s Place, a short walk away.

The largest Nordhavn Owners Ren dezvous (NOR) ever got underway

May 10 at Victoria International Marina on Vancouver Island. A re cord setting number of Nordhavns and owners gathered for five days of education, camaraderie, food and fun; for many, the rendezvous served as a kick-off to cruising up to Alaska and beyond.

With 48 Nordhavns packed into the marina, it marked the most Nordhavn yachts ever gathered in the same place, although not all who attended came by boat. In total, owners of 67 Nord havns representing 16 different mod els, mingled at dock parties, cocktail events, boat hopped and attended two days of seminars.

This year’s Sea Sport Rendezvous was

held in mid-September in pictur esque Friday Harbor. It was attended by people from all over including California, Alaska and Wyoming. The event gives us the chance to re connect with our boat owners and their families in a casual atmosphere. People and boats of all ages were wel come and we couldn’t ask for a more enjoyable group of people than we have in our Sea Sport community. If you own one of our boats and you haven’t joined us in the past, you need to change that. If you don’t own a Sea Sport and you’re curious about our boats, our owners are all willing to share their experiences as well as a peek into their homes on the water. Email julie@nmiboats.com to sign up for our 2023 rendezvous!

Held September 16 to 18, on Salt Spring Island’s Kanaka Dock in Ganges, WWBA’s Fall Rendezvous was a huge success with 23 boats and nine members without boats attending. It was an especially hap py rendezvous since we were able to welcome some of our US members for the first time in three years and the weather was warm and sunny. The boats were open for the always popular public viewing on Saturday afternoon, followed by the AGM and a potluck in the evening. We are looking forward already to the Spring Rendezvous in May 2023. For information about WWBA, go to wwbaca.com

I’ve gone on the record as a fan of both one-design and handicap racing. Onedesign is wonderful, I’ll admit. Equal boats, tight, tactical racing, it’s a no excuses kind of gunfight. When the smoke clears, those who manage the course and the competition best, will come out on top. I also love the challenge of sailing against a variety of boats under handicap systems like ORC and PHRF. I fully appreciate and accept that not everyone wants to race a Martin 242, Melges 24,

Moore 24, Etchells and the like. Individuality is important, and handicap racing can still provide close, thrilling racing, albeit with a few extra twists. Here are a few thoughts and observations from a couple of recent, though very different, regattas I had the pleasure to compete in: The Puget Sound Sailing Championship (One-design) and the Thermopylae Regatta (PHRF).