THE AFTERGUARD

Some friends and I are currently in the process of organizing an overseas charter for a milestone birthday. The idea is to get a small group of friends together, charter a boat for a week somewhere warm and have an amazing time on the water. It sounds perfect. The only question is: Where should we go?

I’m lucky to work in the boating industry. It means that I have a few contacts who know a thing or two about chartering a boat overseas. Within this very magazine we’ve covered many, if not most, of the popular cruising destinations around the world—from the Sea of Cortez (January 2022) to the Greek Saronic Islands (November 2021). They all sound like bucket list locations that I would love to visit.

So, I am familiar with the main charter destinations around the world and we’ve narrowed our choice down to somewhere in the Caribbean. Hoping to gain some more intel, I reached out to long-time Pacific Yachting contributor Zuzana Prochazka, who knows every rock and reef from the Mediterranean to the South Pacific and here is her recommendation for a Caribbean charter:

“If you’ve never been, I’d say start with the British Virgin Islands (BVIs) because there are many pluses:

1. Lots of boats and companies to choose from so the availability and prices are better.

2. Islands are line of sight so you always have the next destination close by which is good for guests.

3. There is good snorkeling and diving spots within an easy sail.

4. Lots of bars, restaurants and shopping so people have something to do.

5. If the weather gets rough, there are lots of places to hide.

6. It’s easy to get to if you fly to St. Thomas and take the ferry to Road Town.

7. Lots of hotels to stay before and after.

8. Go with a brand name like Moorings, Sunsail, Dream Yacht or Navigare. There are others, but bargain boats may be rough.

9. Anegada is a nice sail from Virgin Gorda and easy to get to now that they’ve marked the channel.

10. Go to the Baths early in the morning or you’ll not get a mooring.

11. The best times are early December (nobody around comparatively speaking), July (it’s risky but still good) and May-June. Christmas to Easter is packed.

12. Get the BoatyBall app. Almost all the anchorages have been taken up by reserve-only moorings. Monohulls are still available and cheaper but I’d opt for a catamaran and see if you can get another couple to join you. Most boats down there are cats.”

It helps to have the local knowledge of someone who’s experienced a place firsthand. Zuzana’s second choice for a Caribbean charter is the Grenadines, but I think our decision is easy: The BVIs. Now the question becomes: When can we go?

–Sam BurkhartEDITOR Sam Burkhart editor@pacificyachting.com

ART DIRECTOR Arran Yates

COPY EDITOR Dale Miller

AD COORDINATOR Rob Benac

DIRECTOR OF SALES

Tyrone Stelzenmuller 604-620-0031 tyrones@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER (VAN. ISLE) Kathy Moore 250-748-6416 kathy@pacificyachting.com

ACCOUNT MANAGER Meena Mann 604-559-9052 meena@pacificyachting.com

PUBLISHER / PRESIDENT Mark Yelic

MARKETING MANAGER Desiree Miller

GROUP CONTROLLER Anthea Williams

ACCOUNTING Elizabeth Williams

CONSUMER MARKETING Craig Sweetman CIRCULATION & CUSTOMER SERVICE

Roxanne Davies, Lauren McCabe, Marissa Miller

DIGITAL CONTENT COORDINATOR Mark Lapiy

SUBSCRIPTION HOTLINE

1-800-663-7611

SUBSCRIBER

50%

After reading Gordon Currie’s article in your July 2023 issue regarding the Lund Hotel and Pub we felt compelled to reply. We tied up at the Lund Breakwater, planning to stay two days and looking forward to a good meal at the Lund Pub. We discovered the pub is only open three or four single shifts per week and not on the days we were going to be there. We walked around the town, bought two of Nancy’s cinnamon buns, cooked on board and left the following morning, rather concerned at the decline we see happening at the Lund Hotel.

The hotel itself, in the article, was only mentioned in passing. We learned from a knowledgeable local businessperson that the hotel may never re-open. It was closed in 2020, the heat was turned off

and all the renovations that had been done were for naught. Mold has started to take over the building and furnishings. The present owners have allowed this historic building to be ruined. Quite possibly, us taxpayers will be on the hook to repair it all. Very sad to see.

[I am] a semi-retired journalist (I left the Parliamentary Press Gallery in Ottawa last year to move to Nanaimo) who specializes in defence and aviation. I am currently a boatless sailor. That said, after dealing with the aftermath of a lead-acid battery fire some years ago on my C&C 27, which I left behind

in Ottawa, I have done considerable research on extinguishers which leave no residue, i.e. the Halon option. That, however, is obviously not without issues, namely its displacement of oxygen and its cost. A couple of years ago, I came across a product which is mainly used in the automotive sector but offers a solution in the marine environment. These are Element extinguishers which were developed in Italy and which leave absolutely no residue while not displacing oxygen. Feel free to check out YouTube demonstrations. They are effectively the same size as a roadside flare and are activated much the same way, i.e. striker ignition. They have not yet been tested by Underwriters Laboratories (rebadged as UL Solutions) and it seems Transport Canada as well as the Canadian and US coast guards won’t authorize them until UL tests and approves them. They do seem expensive at first blush but the $100 version suppresses flames for 50 seconds and are a single-use device. However, add in the fact that most of the conventional extinguishers are out of product in less than half the time and leave a considerable mess to clean up while also potentially damaging electrical or electronic components and I think there’s a strong case for them.

—Ken Pole, Nanaimo

—Ken Pole, Nanaimo

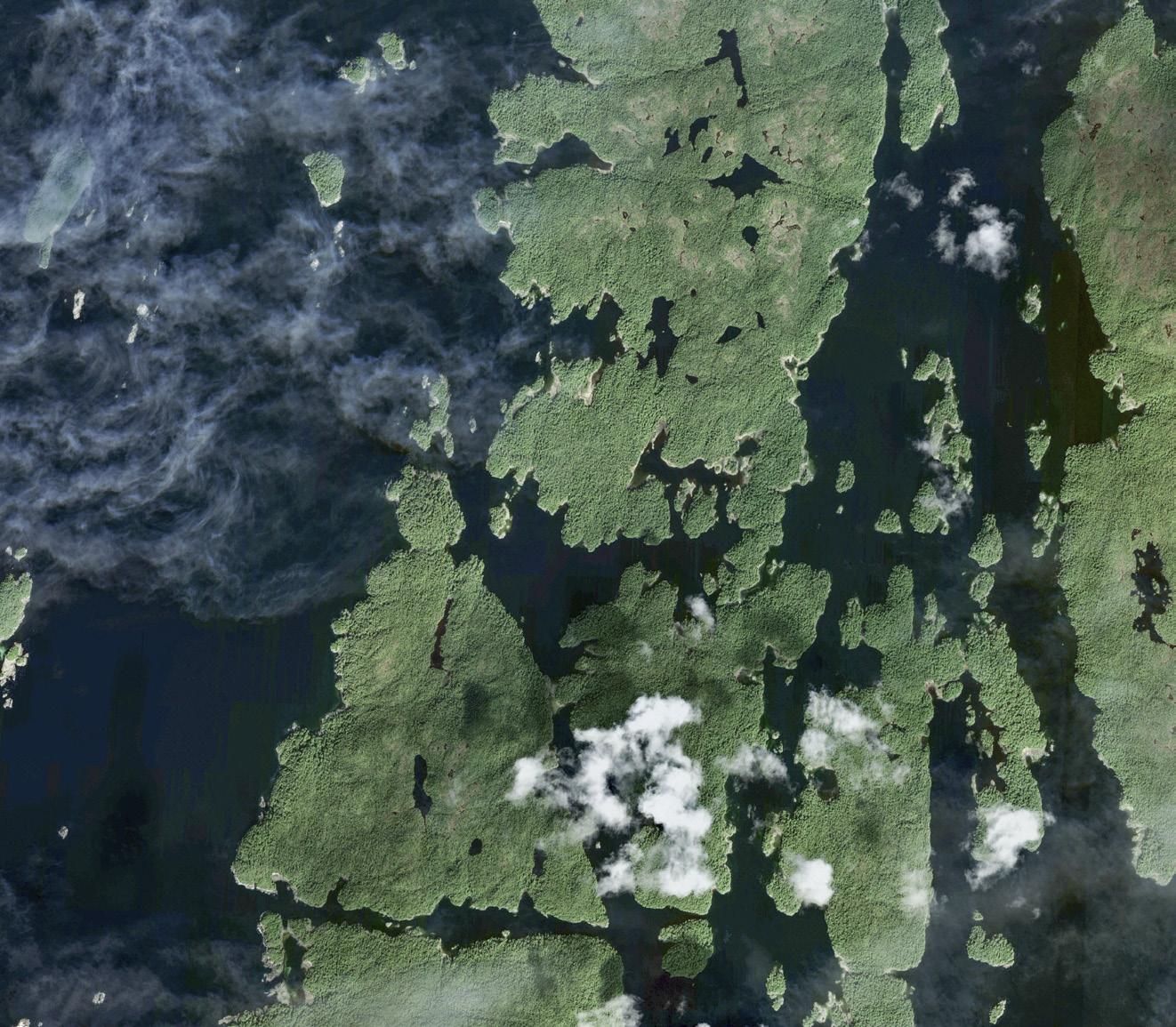

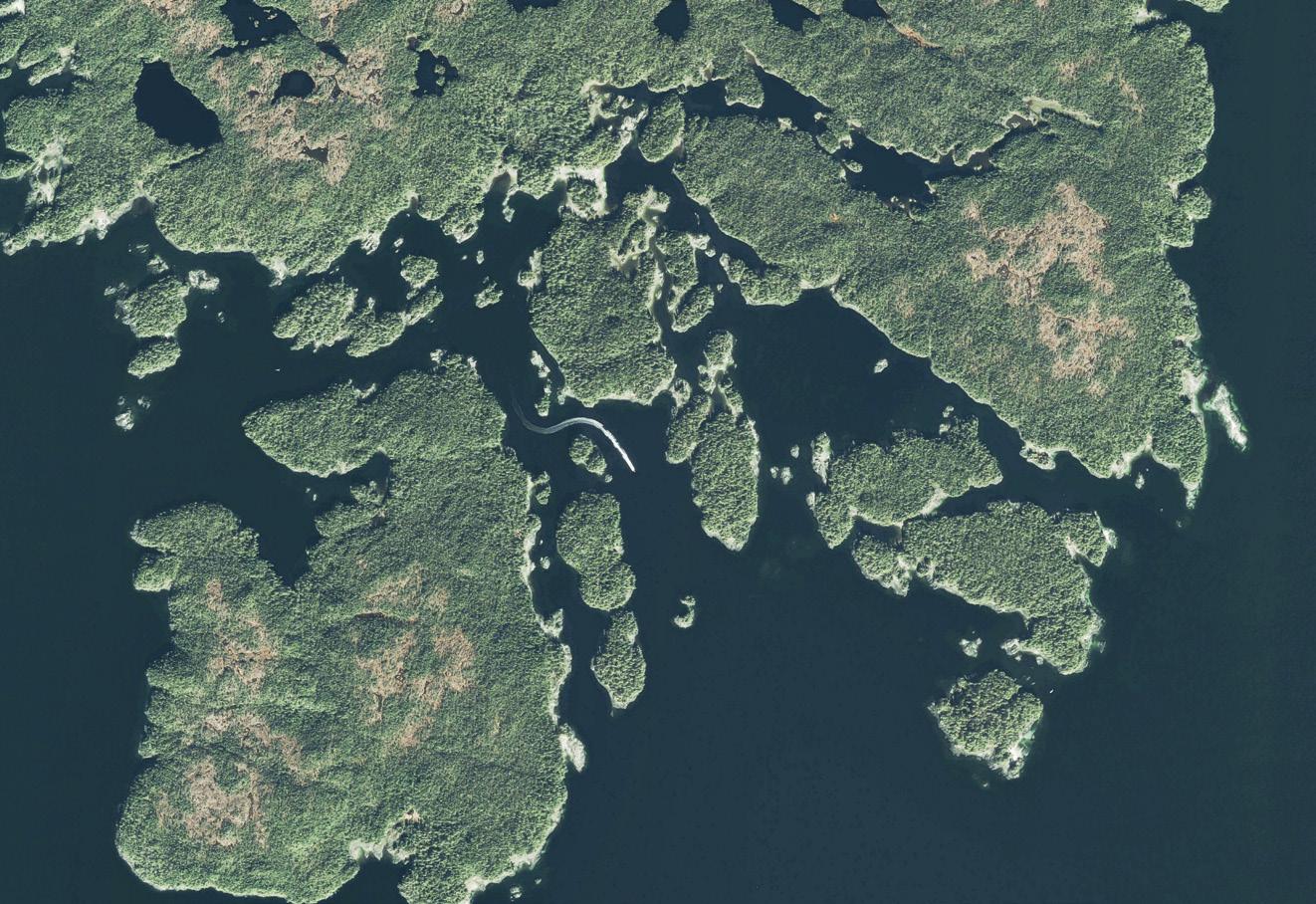

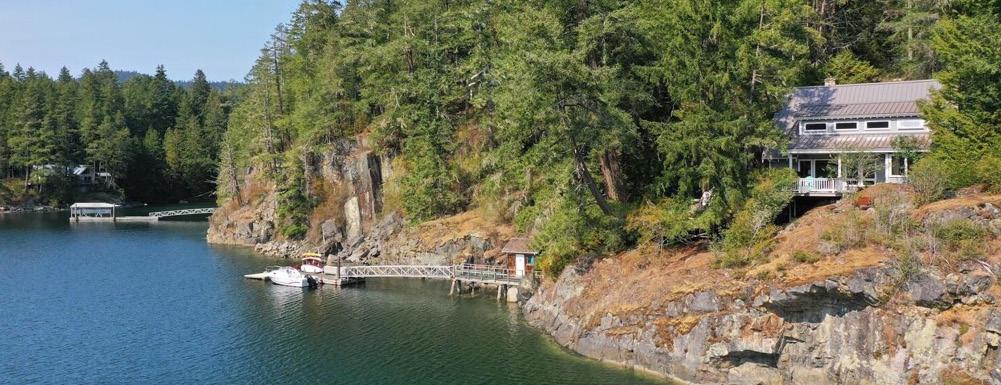

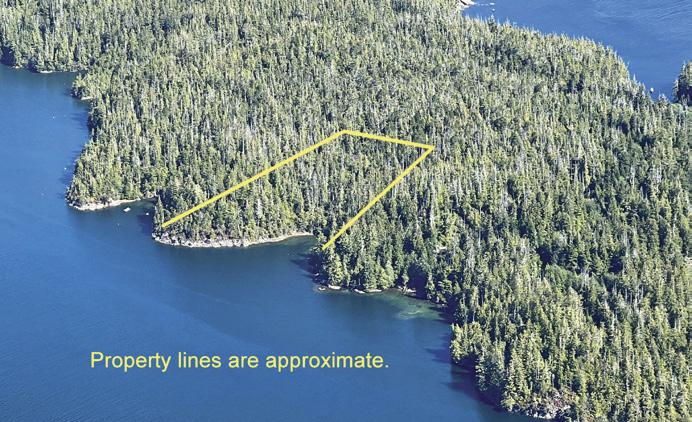

While our first Geo Guesser may have been too easy, last month’s may have been too hard. At the time of publication, the location had not been guessed correctly. We’ll include a hint here and give people another month to guess.

Hint: The October location is within Desolation Sound Marine Park. We’ve chosen a more well-known spot for this month’s photo. Good luck!

Deadline: October 27. Send your guesses along with your name and address to editor@pacificyachting.com for a chance to win a PY hat!

If you’re heading to the Gulf Islands this fall, be sure to check out this new Mayne Island eatery which opened this year. Located in Fernhill Centre in what used to the home of Wild Fennel Restaurant, which sadly closed over 10 years ago, Stephanie McBurney and Jeff McPherson are cooking up a storm and ensuring the visitors have as much fun at the Montrose

as they and their family are having. This couple really know their island and what makes for a good community—in addition to what the fixings of a great meal and fun evening need to be. Along with their two chefs, Mike Smith and Jan Gumbmann, and their

family of three, Rowyn and Ryder Magee, both 15, and six-year-old daughter, Abby McPherson, they really whip up some creative cuisine and lively evenings.

The couple have worked toward this dream for five years and both have ex-

perience in the culinary field as well as a long history with the island and its community. They were still awaiting their liquor license when we visited in early August, but this hasn’t been a problem for them. “The delay has allowed us to get a clear idea of who we want to be,” McBurney says, and her partner agrees: “We don’t want to be a pub. We want to focus more on having a community space for visitors and for locals, a place to come in for a coffee and a game of foosball, meet with friends, work on the puzzle or come for a fun evening.”

McPherson tells me he loves creating different ethnic foods with his two other chefs, ensuring that the dishes are constantly changing. They all have fun in the kitchen, experimenting and challenging one another. “We feature freshness and quality—everything comes in

fresh except for the prawns and everything is made from scratch. And the culinary theme nights, where our chefs collaborate, is very popular. We had a Szechuan meal the other night and it was booked out. We had to hold it a second night as well. It was Indian food in September.” Who knows what winter will bring?

The venue itself is as colourful and as zesty as the dishes: local art festoons the walls, puzzles and games invite visitors to take their time and relax. There’s no doubt that this is always going to be a place for families and locals to hang out, and this couple thinks it’s a good thing. There’s even a community table. Have a look at their active Facebook page, then jump on the boat and cruise over. This is a true ‘Gulf Island style’ experience you’ll never get in the city.

—Cherie ThiessenThe Vancouver International Boat Show will run from January 31 to February 4 at BC Place and on the water at Granville Island. Go to vancouverboatshow.ca for more information.

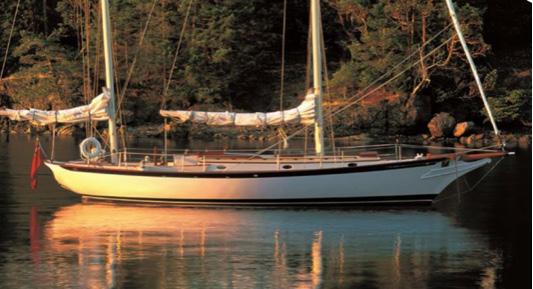

Arecently launched venture is setting out to help revitalize the BC yacht building sector—by building zero-emission luxury yachts. The concept is to eliminate hydrocarbon use from propulsion, cooking, heating, and other systems. The hulls will be built from recyclable aluminum and use replaceable marine modular batteries for electric power. Charging will be through arrays of solar panels and regenerative charging from the propellor while under sail.

Based in Port Alberni, the company is owned by Chris Baker, an accomplished sailor with local government management and leadership experience. Baker has partnered with renowned Vancouverbased yacht designer Ron Holland and ground-breaking Naval Architect Laura Fuge.

Their first offering is a “go anywhere” 64-foot expedition sailboat that can be configured for cruising or as a dedicated research vessel. It is being designed to be independent of marinas for extended periods of time and to make long ocean passages fast and comfort-

able. This is to be a truly local project as there are many skilled welders, carpenters and marine tech companies on the BC coast and Port Alberni has the workforce, the room for an expanding shipyard and a desire to develop more of a blue economy.

The prototype is still in the development stage with the structural design in place while the electrical design is in progress with help from the University of BC. The venture has benefitted from a network of business supports, including an entrepreneurship program at UBC—where all three principals have ties—and an ocean-based business accelerator program in Victoria called Coast. Alberni Yachts is seeking government support for the prototype and is looking forward to announcing project partners.

Once the prototype design and engineering is complete, and a client, investor or government funding is in place, Alberni Yachts expects the first vessel could be built in 18 months.

The team at Alberni Yachts aims to highlight the maturity of BC’s marine sector for the world and help shape the future of Canada’s ocean brand.

—Peter A. Robson|

MERCURY 5.7L V10 350 AND 400HP

V10 Verado outboards shift your expectations performance feels like. They come to power, propelling you forward to sensational smooth, quiet and refined, they deliver only Verado outboards can provide.

VECTOR YACHT SERVICES LTD. Sidney, BC | 250-655-3222

Mercury engines are made for exploring.

What if every journey began with the push of a button? Where would you go? With the Mercury Avator 7.5e electric outboard, all you need is a destination. Its portable design and quick-connect battery will have you ready for the water, no matter where adventure takes you. Avator is intelligent, all-electric propulsion, designed to make exploring effortless.

expectations of what high-horsepower to life with impressively responsive sensational top speeds. Exceptionally deliver an unrivaled driving experience exploring. So are you. Go Boldly.

Let your journey begin with Mercury Avator.

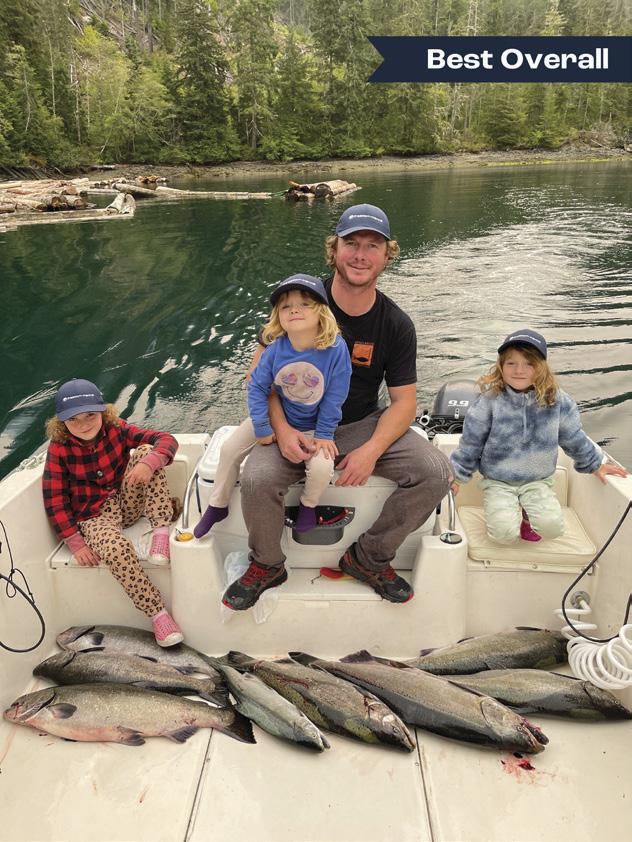

Pacific Yachting’s annual photo contest is back! Send us your best boating photos from 2023 for a chance to be featured in Pacific Yachting. Prizes include a Yeti GoBox, a Salus Abacus PFD and a Mustang MIT 100. For contest rules and to enter, visit pacificyachting.com/photo-contest.

Deadline: December 15

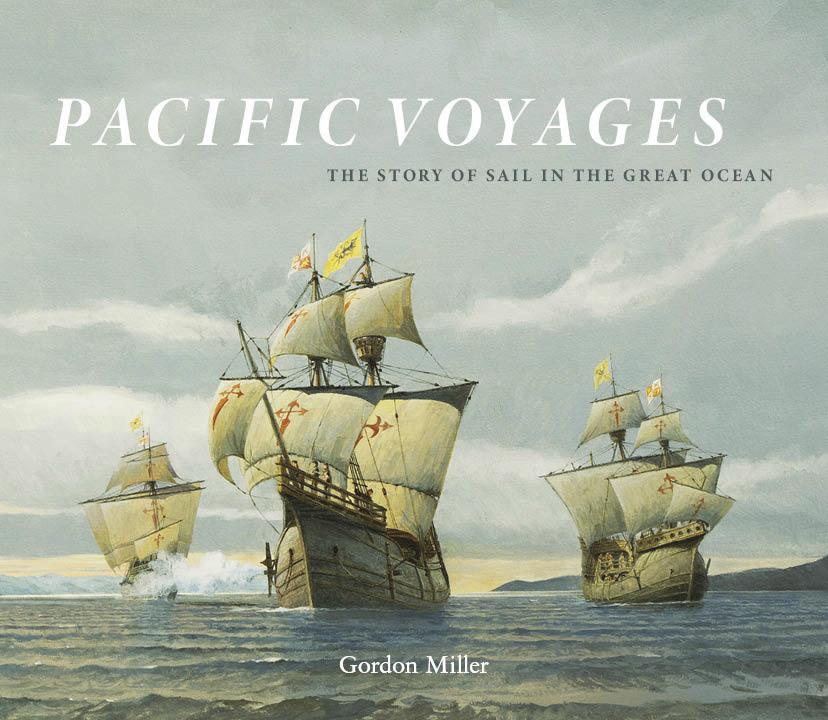

Gordon Miller, historian, artist, illustrator and designer has published a new book on the countless seafarers who sailed the Pacific. Like his earlier book, Voyages to the New World and Beyond, Miller brings the same historic accuracy and meticulous research to this volume and has again displayed his artistry in the accompanying watercolours, oil paintings and drawings. I was smitten both by his elegant prose and by his depictions of vessels of all sizes in all kinds of conditions that illuminate the descriptions of the royalty and aristocrats who sent out their sailing ships to find such luxury items as gold, silver, silks, spices, furs and porcelains. And, of course, to seize as much land—and subjugate as many people—as they could for their respec-

tive crowns and trading companies.

No single book can cover the entire history of all the explorations in the Pacific, but reading Miller’s book and studying the text, paintings and ship plans can provide an excellent overview of the main players ranging from canoe paddlers to clipper sailors.

Miller begins his book with drawings of early vessels like kayaks, baidarkas, different canoe styles, Chinese and Japanese junks, reed boats and catamarans/outriggers. He describes how early seafarers crossed oceans using their knowledge of stars, wind and currents to navigate vast distances—colonizing the spread-out south Pacific Islands and eventually New Zealand and Australia. Maps frequently accompany the text and through this combination we learn about Marco Polo’s land travels describing the riches of China, which may have inspired westerners to explore further by sea. Enter Henry the Navigator and his dapper Portuguese explorers, with the Dutch and Eng -

lish all vying to control the trade in spices—nutmeg and cloves were literally worth their weight in gold—and Spanish seafarers finding real gold and silver in South America. The Russians tried to find the Northwest Passage from the west and fought the Tlingit for control of Alaskan territories. Britain committed piracy against Spain and also established its first colony in Australia by exporting its brigands, and as usual, paying no attention to the people already there.

Miller’s research on ocean mammal hunting describes the slaughter of whales for their valuable oil, as well as their relentless pursuit of Steller’s seacows (who became extinct), sea otters and fur seals for their prized furs, and trading with Indigenous people who hunted these fur-bearing animals. He does not neglect scientific seafaring, outlining the land excursions and research conducted by Darwin aboard the Beagle.

He also describes and depicts many generic ship models like the 17th century Manila Galleon; junks and dhows; and Dutch and Russian ships; Pacific Voyages is a valuable and beautiful book which I plan to consult and enjoy often.

—Marianne Scott

By Richard R. Moreno. Self-pub-

By Richard R. Moreno. Self-pub-

lished, 2022

Author Richard Moreno and his pal Rocky Wesley were friends since childhood in Argentina. They reconnected again in their mid-20s in Canada where they hatched a plan. They would travel to Argentina, first crossing the Pacific Ocean, making pit stops in California, Hawaii, Fiji and Australia. The two friends bought a boat Moreno’s dad had recommended—the Nootka 28 plywood cutter. It was in their budget, but in need of some serious attention.

They set off from Victoria on this epic voyage to much fanfare on July 20, 1980. Did I mention that neither of them could sail?

They also didn’t know whether they would enjoy sailing or if they had the sea legs to succeed. During the voyage they read classic sailing books like Sea Sense, Heavy Weather Sailing, and other how-to-sail books.

A previous owner called the Nootka, “a damn fine boat,” and this wooden ship lived up to her reputation. While sailing, conditions never remain the same for long. Some waves hit their little boat with such force they thought it would split the hull wide open. On some days, the boat would sail herself, which she did very well.

Since the best action stories need a crisis and a resolution, I kept thinking these two sailors seemed to be one wave away from a shipwreck. Since there were only the two of them to take turns on deck to keep watch in three-hour increments, Moreno knew it would drain them both physically and emotionally. Sure enough, they

wanted to give up after 12 days at sea. But they didn’t.

They experienced a multitude of problems and near calamities too numerous to mention but lived to write about them. Their greatest challenges were major storms off the coast of Oregon and another one near Australia with winds above 60 knots.

After being lost and directionless for two days, Moreno said, “One of the best times of the day while sailing the open ocean was during the early morning watch. Seeing the sun rise over the horizon was always a comforting moment, for it would always remove the tension of sailing blind.”

The author mused, “I often wondered, if we had known about a sailor’s life would we have ventured this far. I’m glad and thankful that we didn’t know and we left on this voyage. How we did it still boggles our minds especially when we think how little experience we had.”

This book will appeal to those neophyte sailors who have dreams of sailing but have never sailed before. Seasoned mariners will just shake their heads in wonder that these two young men survived.

American author Ernest Hemingway, who knew his way around the sea, wrote you must live life and deal with its problems to the best of your ability. Man is not made for defeat. Neither it seems were these two landlubbers from Patagonia.

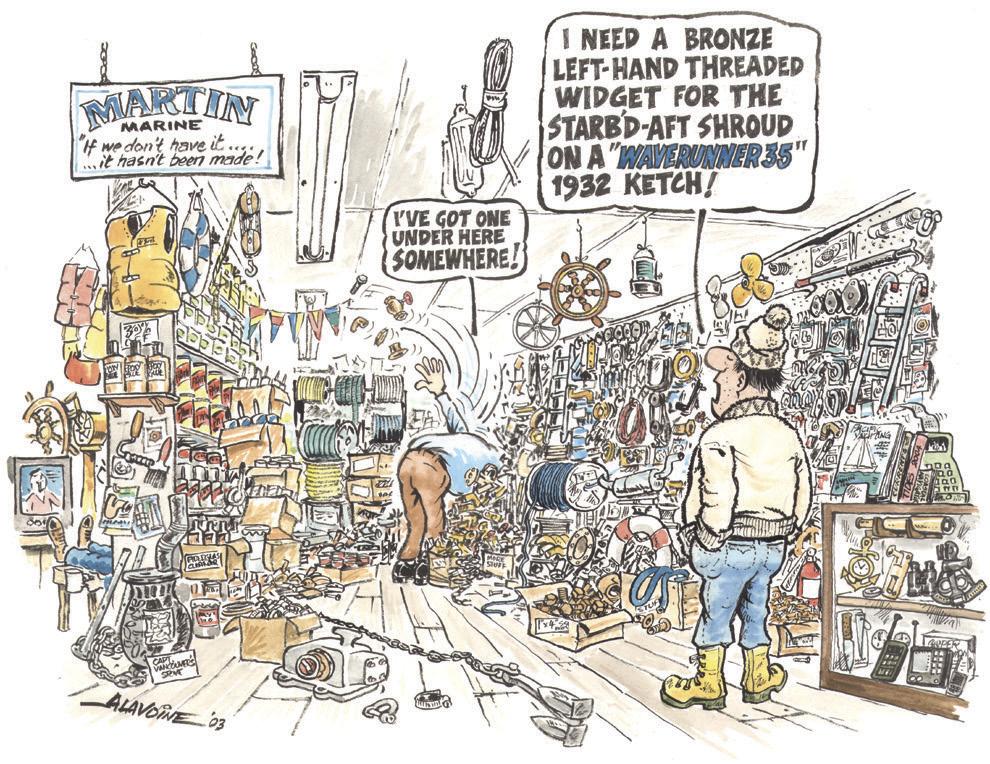

—R.M. DaviesANCHOR MARINE

Victoria, BC 250-386-8375

COMAR ELECTRIC SERVICES LTD

Port Coquitlam, BC 604-941-7646

ELMAR MARINE ELECTRONICS

North Vancouver, BC 604-986-5582

GLOBAL MARINE EQUIPMENT

Richmond, BC 604-718-2722

MACKAY MARINE

Burnaby, BC 604-435-1455

OCEAN PACIFIC MARINE SUPPLY

Campbell River, BC 250-286-1011

PRIME YACHT SYSTEMS INC

Victoria, BC 250-896-2971

RADIO HOLLAND

Vancouver, BC 604-293-2900

REEDEL MARINE SERVICES

Parksville, BC 250-248-2555

ROTON INDUSTRIES

Vancouver, BC 604-688-2325

SEACOAST MARINE ELECTRONICS LTD

Vancouver, BC 604-323-0623

STRYKER ELECTRONICS

Port Hardy, BC 250-949-8022

WESTERN MARINE CO

Vancouver, BC 604-253-3322

ZULU ELECTRIC Richmond, BC 604-285-5466

journey.

Never miss another target, from close-in to the horizon and beyond, with NXT technology.

Tour reservoirs and nourish our crops, but it awakens the wetlands—prepares them to welcome trumpeter swans.

This year, instead of whining about the wet, blustery weather, I’m embracing it. I’m glad the heavens have opened up. Not only does the rain fill

Although they will forage in fields, eating terrestrial plants, trumpeters prefer roots, shoots, and leaves of aquatic plants. They feed by upending and probing the bottom with their bills. So, quiet, shallow water suits them best, and as ponds, lakes, and streams begin to freeze over in the north, they migrate south.

Come spring, it’s important to get back to their breeding grounds in Alaska, Yukon, and northern British Columbia as early as possible. Cygnets are not capable of flight until they are three or four months old, and they need time to develop their flight muscles for the next migration.

Until recently, I had no idea that some of these majestic birds winter on the Gulf and San Juan islands. I may find them on ponds just minutes away from my house. If you live

anywhere near the British Columbia or Washington coast, for the next few months they may be your neighbours, too. Now that I know, I plan to make up for lost time. My binoculars are standing by.

Trumpeters are the largest North American waterfowl and one of the heaviest of all our birds who fly. The adult male’s wingspan is a little over two metres and they may weigh more

than 11 kilograms. In the air, they fly in a low V formation and stretch out to approximately 1.8 metres.

Adult plumage is entirely white, but so is the plumage of the mute and tundra swans, and mute swans are almost as large. So, how will I know which ones I’m looking at?

Trumpeters have strong black bills and when swimming, hold their necks up straight. Tundra swans also have

•2 2/3 cups flour

•1 teaspoon yeast

•1 teaspoon sugar

•1 1/2 cups water at room temperature (warm but not hot)

•2 tablespoons olive oil, plus more as needed

•1 teaspoon salt

•1 1/2 cups finely grated pecorino, parmesan, or similar tangy, salty cheese

Optional

•Balsamic vinegar and a good fruity olive oil for dipping

1. In a mixing bowl, dissolve yeast in one cup water and one teaspoon sugar. Wait five to 10 minutes. It should foam and look creamy.

2. Add one cup of the flour. Mix, cover, and let stand 30 minutes.

3. Add remaining flour and water and two tablespoons olive oil. Stir with a wooden spoon until no dry flour remains. It will look lumpy and wet.

4. Cover and let rest 10 minutes. Then sprinkle salt over dough and mix thoroughly and cover and rest 20 minutes.

5. Wet hands and starting on one edge, gently lift and fold dough into the middle. Turn the bowl and repeat, until it is all folded over (about six folds.) Cover and rest 20 minutes.

6. Repeat lifting and folding over. Then cover and rest 10 minutes.

7. Coat a baking sheet generously with olive oil and turn the dough out onto it. Spread the dough into an oval about half the size of the baking sheet.

8. Coat the top of the dough liberally with oil and cover tightly with plastic wrap. Then refrigerate approximately 20 hours.

9. 1.5 to two hours before baking, remove from refrigerator and gently press the dough toward the edges of the baking pan. Sprinkle with one cup of the cheese. Press it into the dough slightly.

10. When it doubles in bulk, make characteristic focaccia dimples with a fingertip.

11. Bake in 230° C degree (450◦ F) oven 18 to 25 minutes, rotating pan halfway, just until top is lightly browned and dough is cooked through. Do not overbake!

12. Remove from oven; immediately sprinkle with remaining cheese.

black beaks and hold their necks up straight, but are about half the size and their necks are proportionally shorter. Mute swans’ bills are orange and they generally hold their neck curved.

Jumbo jets of the local bird kingdom, trumpeters require a long runway and a lot of flapping to get airborne. As their metre-long wings unfurl and begin to push the air down, they run across the surface, their large webbed feet slapping down on the water. Some have described the sound as similar to galloping horses. Trumpeting as they go, they run and flap until they reach the speed of 21 kilometres per hour. Only then can they lift off.

I can’t wait to watch this. I’m waiting for a relatively calm day to put on my rain gear and wellies and see if I can find them.

When I get home again, I’ll want to make a big pot of soup. And if I plan ahead, I’ll have a crisp, hot, cheesetopped focaccia to go with it.

I’ll mix the dough the night before and put it in the refrigerator. A couple of hours before I want to bake it, I’ll shape it into a loaf. While I chop and cook onions and vegetables, it will double in bulk, and by the time the soup is done, it will be ready to tuck into the oven.

I use the following super simple recipe. If you’re not familiar with yeast doughs, you don’t have to be afraid of it. There’s no kneading involved, the dough is forgiving, and the result is fantastic. Crisp and warm from the oven, it will fill your mouth with moist, tender goodness and delectable flavour. Enjoy!

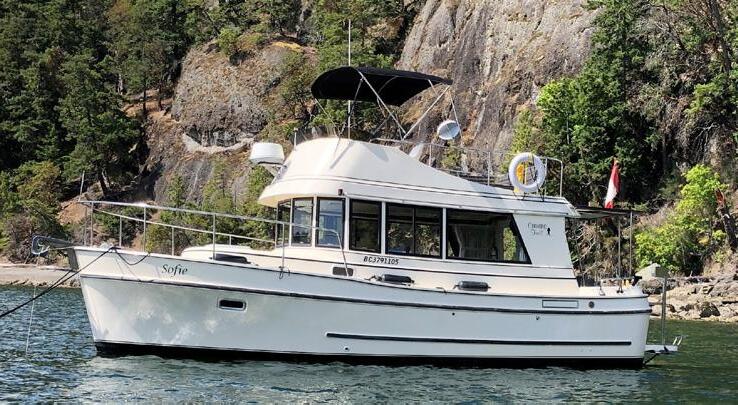

Aover the sticky sand and shell bottom of Westcott Bay, located on the west side of San Juan Island. We took shelter for the next couple of days from the approaching weather front and its predicted 25-knot southerlies, in the lee of Bell Point.

rents must be considered most of the time.

Arriving at low slack, under a clear cobalt sky and zero wind it was a glorious fall afternoon. We set Easy Goin’s hook with 16 feet of water beneath the hull

The approach to Westcott Bay is via Mosquito Pass, which connects Roche Harbor and Haro Strait. It’s narrow and meandering enough to make things interesting and tidal cur-

The narrow navigation channel winds through what appears to be a wide, safe passage between Henry and San Juan islands. Passage is not difficult if you’re vigilant—follow the navigational aids marking the curving channel. There is a five-knot wake speed limit when transiting the pass. It’s basic straightforward navigation, but you would be surprised how many

boats cut the corner and tap the sand bottom. Mid-way through the pass a channel leads east into Westcott Bay.

The bay is outlined with homes, summer cottages, forest lands and the family operated Westcott Bay Shellfish Company. If you enjoy fresh oysters and clams as we do, the shellfish farm offers a fine selection of tasty oysters, clams and mussels. Check westcottbayshellfish.com for hours.

In the late ‘70s, the bay’s tidelands were home to Westcott Bay Seafarms, a thriving shellfish company. Over the years the farm went into steady decline and was put up for sale as a home site Henry Island residents Erik and Andrea Anderson bought the farm in 2013 with the vision of restoring it to its former glory. Over the next three years they worked to replant the depleted shellfish crops, rebuild and replace farm infrastructure and make improvements to the property.

ONCE SETTLED AND after enjoying some lunch we launched the tender, set two crab traps and ventured off to explore our cosy little gunkhole and the surrounding area. In the southern corner of the bay is a rock and sand beach to land the dinghy and up the

low bank is a picnic table and the 1.6-kilometre Bell Point Loop Trail. The trail will not only lead you out to the point, providing a wonderful view of the anchorage, but also lead us to Garrison Bay English Camp and the trail up Young Hill.

English Camp was the site of the British encampment during the San Juan Pig War. Today, English Camp along with American Camp at the other end of the island, is part of the San Juan Island History Park.

From English Camp we made our way along a 1.3-kilometre trail to the top of 650-foot Young Hill for an expansive view of Westcott Bay, Garrison Bay, Mosquito Pass, Haro Strait, Vancouver Island, and across the Juan de Fuca Strait to the Olympic Mountains. During our hike we were lucky enough to see a number of black-tail deer and bald eagles.

On the way back to Easy Goin’ we checked the crab traps and were rewarded with one legal size Dungeness. It made two large crab cocktails for dinner.

THAT EVENING THE wind began to blow as predicted but there was hardly a ripple in our hide-out, while it

reached 20 knots in Haro Strait. The wind blew most of the night and by morning it was a light breeze but was predicted to pick-up as we progressed through the day.

Mid-day we were joined in our hidey-hole by two other boats. One set his hook to the north and the other to the east. That afternoon when the second boat went to depart, he discovered a cable, attached to the bottom, was hanging over the flukes of the anchor and he could rise the anchor just above the surface. After a 30-minute wrestling match with the tangled mess, the anchor was free and the cable was returned to the bottom. I marked the location of the cable on the chart plotter for future reference.

The following morning the weather had passed and we awoke to a windless morning. Before moving on to our next destination we enjoyed the beauty of Westcott Bay and its mirror like surface while sipping on our morning cups of coffee.

A destination with a rich history and a promising future

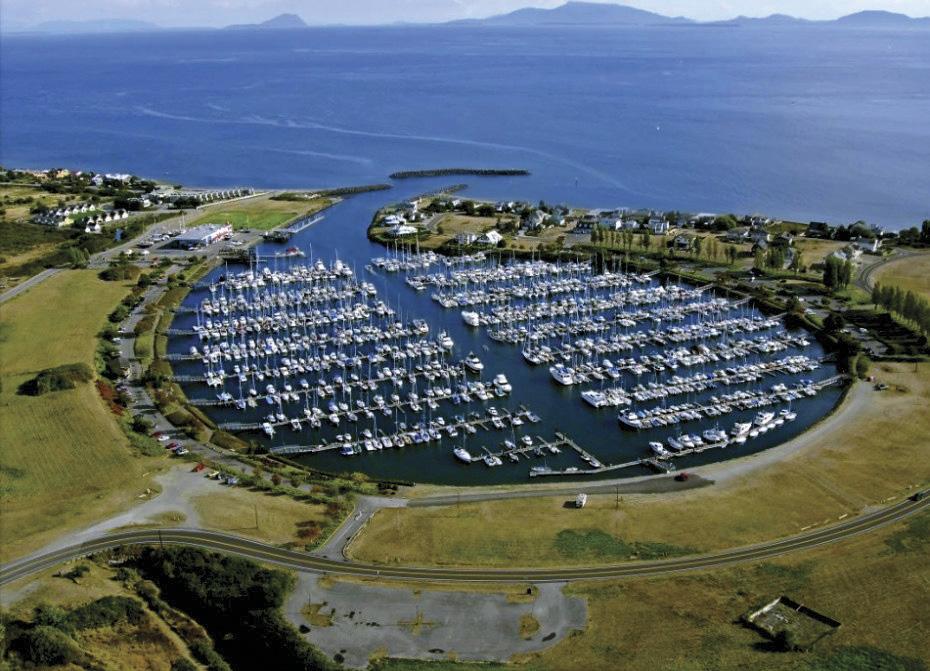

NNanoose Bay is one of those places I’ve always bypassed. Getting to the little nub of a peninsula located just north of Nanaimo, on Vancouver Island, meant transiting the controversial Canadian Forces’ torpedo-testing range of Whiskey Golf and winding through the 19 islands that make up the Ballenas-Winchelsea Archipelago. So I always sailed past, thinking it seemed like a good someday destination. But then, in 2020, the BC Parks Foundation (the same group that in 2019 crowd-funded over $3 million to protect 800 hectares of Princess Louisa Inlet) worked their magic again and bought West Ballenas Island. And in June of this year, I learned that veteran restaurant partners Eli Brennan, Alan Tse, and Chef Todd Bright had taken over the restaurant at Fairwinds Marina, turning it into the Nanoose Bay Café. At the same time, I also discovered that the marina itself was going through a major upgrade. So, someday turned into now.

NANOOSE BAY IS the traditional home of the Snaw-nawas People, often called the Nanoose First Nation. Drawn by the region’s abundance, which includes herring roe, clams and salmon as well as game, plants and berries such as salal, the Hul’q’umi’num’ speaking people lived on the peninsula in villages not far from Notch Hill from time immemorial. In the 1890s, as more settlers started farming and logging on the peninsula, the federal government forced the Snawnaw-as off their traditional lands and onto their reserve on the bay’s southern shore. In 1905, the Canadian Pacific Railway line was extended through Nanoose (cutting through

the reserve land and reducing its size). With the rail line, even more settlers began to arrive, along with several businesses including a brick-making plant at Brickyard Bay and the Great Powder Company, which produced explosives for mining and land clearance. The next arrival was Straits Lumber Mill which supplied lumber to ships from around the world.

THESE DAYS, THE peninsula is known more for the lush, manicured fairways of Fairwinds Golf Course and the 350-berth marina, than heavy industry. In recent years, Nanoose Bay gained a wealth of parks and hiking trails, and a handful of small agritourism businesses including Springford Farm, where you can pick up island grown foods and the Rusted Rake, a brewery where they grow their own barley for the beer they serve. Add in a well-managed marina, some interesting offshore islands and a world-class restaurant, and I was pretty sure Nanoose had all the makings for a great getaway destination—complete with sublime views.

WHEN APPROACHING NANOOSE Bay, the first step is checking to see if Whiskey Golf is active. You can do this by calling 1-888-221-1011 or listening to Winchelsea Control on VHF 10. Once that’s taken care of you can start exploring your way through the gorgeous, and underrated, archipelago. The Ballenas-Winchelsea Archipelago is a rugged collection of islands located within the Snaw-naw-as traditional territory. Providing habitat for nesting and resting birds, California and Steller sea lions and exceptional Garry oak and coastal Douglas-fir ecosystems, the islands and islets have

been identified as an ideal location for a marine park—a long standing conservation goal of the Mount Arrowsmith Biosphere Reserve. Among the islands is 10.4-hectare South Winchelsea, which was acquired in 1998 and is now owned by the Nature Trust of BC. This island along with 12-hectare Gerald Island Provincial Park, which was established in 2013, features a rocky coastal bluff ecosystem and is open to visitors. North Winchelsea Island is a bit different. With its abundance of communication arrays it serves as the operations centre for Canadian Forces Maritime Experimental and Test Ranges—reports say if you get too close you’re

asked to move away. Farther up the chain, South Ballenas Island remains Crown land held by the Government of Canada and is off limits to visitors. The island I was most excited about seeing was West Ballenas Island, an undeveloped 40-hectare island that most boaters know for its small lighthouse. Coming around the north end of Ballenas, Mike Bellis, our skipper from Haida Gold Adventures pointed out some of the prime fishing spots off the islands—where you can catch salmon, lingcod and rockfish or drop crab and prawn traps. He also told us to keep an eye out for whales (ballena means whale in Spanish). Now that the humpbacks have returned to the

Salish Sea they’ve also come back to the archipelago. On the east side of the island we headed into the small bay created between the two islands and anchored close to the shore of South Ballenas—here we watched seals go after the small herring that were hiding under rafts of seaweed.

It’s this near-pristine richness that compelled the BC Parks Foundation to start a crowd sourcing campaign to buy the island when it came on the market in 2020. Slated to be divided into individual development parcels, the foundation secured an agreement

to buy West Ballenas for a reduced price of $1.7 million. Once this opportunity was presented, people from all over the region kicked in and helped with its successful purchase. With ownership now in the hands of the Snaw-naw-as People and BC Parks—the goal is to develop the island for cultural purposes and low impact recreation. But for now it’s pretty tricky to get ashore and explore—so we admired it from the water and then headed the short distance back to Fairwinds Marina, checking out the other islands along the way.

PREVIOUSLY KNOWN AS Schooner Cove, Fairwinds Marina has just announced a three-year, three-phase update. First up will include relocating the fuel dock to ensure it’s more accessible and updating the wobbly docks to a more stable cement style. With 550 feet of transient space, the marina offers the usual pump-out, showers, laundry and wifi as well as unique perks including a shuttle to the golf course and easy access to Fairwinds Landing, home to the Nanoose Bay Café and the Fairwinds Residences, a collection of 11 oceanfront vacation

rental suites for those who prefer to sleep on land.

As a fan of Nanoose Bay Café’s renowned sister restaurants; Qualicum Beach Café and Water Street Café in Vancouver’s Gastown neighbourhood, I was excited to try the newest establishment in the group. A step up from typical marina eateries—the menu of the gorgeous family-run restaurant centres on local ingredients, products and suppliers (the sockeye on roasted butternut squash gnocchi was my favourite). It also has a great wine list and a killer view—making it perfect for a lingering afternoon. If you need a few supplies, the market carries local eggs, meats and other foods as well as arts and crafts from 50 local vendors.

MY STAY IN Nanoose Bay was too short—but I did find time to wander the hilly roads and check out a local park—which offered views of West Ballenas and a humpback spouting

in the distance. It was a view that was both timeless and current. The hope is in the years to come the entire Ballenas-Winchelsea Archipelago and several of the parks that line the peninsula’s shore will be designated as a marine park under the joint management of the Snaw-naw-as People and BC Parks. In the meantime I’ve learned Nanoose Bay has more to offer than I ever expected and my next someday visit will happen much sooner.

While it’s possible to anchor in Nanoose Bay—doing so is a bit different than anchoring in most places in BC. Before arriving you’re required to call in to Winchelsea Control (VHF Channel 10 or 16), to inform them of your plan to visit Nanoose Harbour. You’ll then be asked to register your arrival, intended duration of stay and departure from the harbour by contacting the King’s Harbour Master (Nanoose Harbour) at 250-327-4142, or a harbour official at 250-3637584/250-363-2160.

Once in the harbour you’ll be directed to an anchorage south of a line drawn west of Datum Rock and near Fleet Point. You may be required to moor with two anchors and will need to follow all directions given by the harbour officials.

Most cruisers who visit the midcoast are bent on getting north, to Prince Rupert, Haida Gwaii or Alaska. Time is of the essence and a departure in early May helps to make each daily transit less onerous and give the cruiser a few foul weather days of grace. But for others, hammering up Fitz Hugh Sound and across Seaforth Channel is missing the point. There are archipelagoes aplenty on the outer coast, many somewhat sheltered by the Goose Group which lies seven miles offshore, and there’s much to see and do in the Hakai and Outer Central Coast Islands Conservancies.

The challenge is often choosing where to anchor. On the charts, there appear to be a multitude of likely places, but the reality is rather different. Many apparently protected locations have seabeds deeper than 20 metres, and most of us are reluctant to drop 60 to 70 metres of chain into the blue. Then there are the prevailing winds— mostly light summer northwesters, but even in summer they can change quickly, and what seemed like a snug anchorage can quickly morph into an exposed hell-hole with a freshening breeze or a shift in wind direction. Finally, a lot of ocean water pumps in and out of the many fjords running far into the mainland, meaning the outer coast experiences strong

currents. Since most high tides are at night, what seemed like a well protected spot in the afternoon can change to a main thoroughfare after dark when rocks and sandbars are covered.

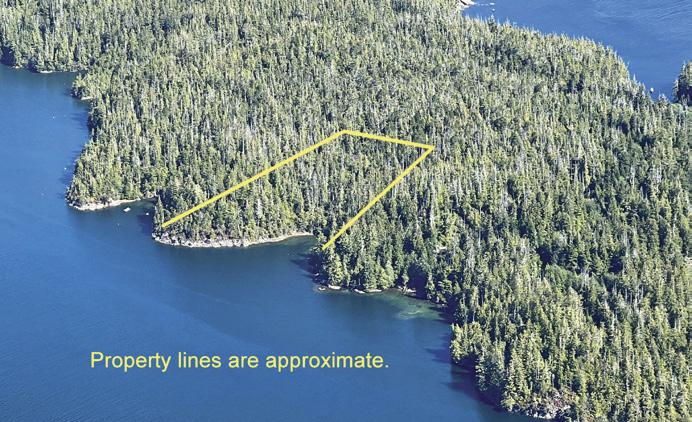

With that in mind, here are another five hidden gems that provide safe harbour. From them you can explore this fascinating, complicated coastline.

popular fishing spot reached from the communities of Bella Bella and Shearwater via protected channels. Only after leaving the mouth of Cultus Sound do you experience the outer swells that roll up from the southwest. The Canadian Sailing Directions notes: “Superstition Ledge, 0.2 miles SSW of Superstition Point, consists of a group of drying and below-water rocks. The sea breaks heavily at times on the ledge and there are strong tiderips in the vicinity.”

Just in from the point is Superstition

Above: Kayak Cove, just in from Queens Sound, is a well positioned anchorage (2), close to good fishing to the west and protected cruising to the north. There is also a white sand beach that provides family entertainment.

Bay, close to the fishing action, sheltered from a southeaster, and backed by a pale sand beach. The bay offers shelter from the rollers of Queens Sound. Anchor over sand and mud in

10 metres, surrounded by cedar forest. It’s not recommended after prolonged summer northwesters, as swells can leak into the bay, despite it being 0.4 miles deep; but in a southeaster it’s excellent. A path leads from the back of the bay north across the peninsula to Kayak Cove beach.

On numerous occasions when we’ve walked that path to visit the beach, we’ve encountered a variety of waders and peeps—semipalmated sandpipers, greater yellowlegs, and even a pair of sandhill cranes.

The southern entrance to Cultus Sound and Sans Peur (‘without fear’) Passage is just to the north of Superstition Point, buttressed by the McNaughton Group to the north and Hunter Island to the south and east. The big swells that roll up Queens Sound quickly calm and shortly thereafter one of our favourite anchorages appears on the starboard bow. Kayak Cove, with its outer protective islets and its sandy beach, is a great place to drop the hook after the excitement of transiting Queens Sound. There’s good protection in most directions, apart from a rare northeaster. Anchor inside the islets over sand and shell in 10 metres.

At low tide the beach is a treat, wide and curved, though shaded because it faces north. Black sands create whimsical patterns in the intertidal zone. And if you’re lucky, you may run into what Iain Lawrence (Far-Away Places,

Orca Books, 1995) calls ‘the little people’—sea kayakers who favour sheltered beaches for their overnight camping spots. Step into the tall cedar forest just behind the white sand and you’ll find paths to tent clearings and whimsical furniture constructed from driftwood. Like leprechauns, the little people are seldom seen. When on the water they may give you a wave as you pass slowly, to avoid rocking them in your wake, but a land sighting is as rare as spotting a sandhill crane.

Sometimes, if you’re lucky, there will be two or four colourful hulls pulled up above the high tide line at Kayak Cove. Approach slowly—they can be flighty, and they value their solitude.

Usually, they’re paddling some long route such as Ketchikan to Seattle, or Prince Rupert to Vancouver. If you probe gently, you’ll discover a deep underlying yearning for true wilderness, something that’s noticeably lacking in the 21st century. They seem to find it here. Wish them well. If you have a loaf of bread to spare, it will always be greatly appreciated, as there’s only so much Swedish knäckebröd a person can pack into a kayak. Or eat on a daily basis.

There’s a trail leading south from Kayak Beach to Superstition Bay Beach, leaving about mid-point along the sand. It’s roughly 250 metres through tall cedars and dense salal, and is a good way to stretch your sea legs. On the way you may hear (but seldom see) Townsend and Wilson’s warblers.

The islands forming the McNaughton Group don’t appear to be named individually. The group forms the west side of Sans Peur Passage, which is a popular and sheltered route to transit north or south, rather than out in roly-poly Queens Sound.

The islands collectively offer two natural harbours, both approached from the northwest. Upon entering the 0.5-mile-long channel, there’s a drying reef mid-channel that is ob -

vious. Apart from that, the route is straightforward. The outer anchorage is large with depths of 15 metres over sticky mud. Caution should be taken in the event of a northwester blowing, as many of the islets forming the northwest side have reefs and islets that submerge at high tide, allowing swells to leak into the basin.

A more secure anchorage is the inner harbour directly east of the first one. Beware of a lone rock off the starboard bow when transiting the narrow-ish entrance (80 metres wide). Once inside this inner sanctum, you are well enclosed from any outside weather. Anchor over sticky mud in five to eight metres surrounded by western red cedar, sitka spruce and shore pine.

There’s much to explore in the McNaughton Group. For kayakers (no propeller to worry about) there are two fine circuits that make for interesting paddling. Immediately east of the inner anchorage, a narrow slot

floods east at high tide and allows the paddler to pop out into a channel parallel to Sans Peur Passage. Time it right so you get a push from the rising tide. Once out of the squeeze, there are many nooks and crannies to explore, and the surface is generally calm.

There’s also an excellent exit south from the outer anchorage. It too dries at low tide, but once flooded, makes a very pleasant way to explore the large island that lies to the west. Drifting south over the recently covered shallows shows a diverse variety of marine life. Continue south into deeper water, where at the island’s southern end a long, narrow, sheltered channel leads west to Queens Sound, with views across the water to the Simonds Group offshore. On calm days, paddling the cliffs on the west side of McNaughton Island allows you to circumnavigate it, returning via the entrance to the anchorages. On wild and windy days, return to the sheltered

waters of the channel behind you, and the calm of the inner islands.

Another interesting exploratory trip is to the deep bay at the northern tip of the group. It dries at low water, so approach it on a rising tide. At the back of the bay lies a large midden and a stream fed from an inland lake. This was the site of a Heiltsuk village in pre-contact times.

At the southern tip of Campbell Island, and protected from the south by Dodwell Island, is one of our all-time favourite gunkholes. Approach from the west-southwest off Queens Sound, or with caution from the southeast, finding a well sheltered inner basin north of Dodwell. There are rocks and reefs from both directions, but with caution and a

bow watch, passage is straightforward. Anchor in five to 10 metres over sticky mud and shell. Just northeast of the anchorage is a massive clam garden that dries at low water, and a midden with huge cedars growing in it (the trees appear to like the alkaline soil).

I have written about this anchorage in more detail before (August, 2015) because the main attraction is the archipelago that surrounds you. It’s fun to explore its sheltered waters and there’s good crabbing and excellent fishing out in Queens Sound. But the real treat is the five-lagoon passage, located to the northeast of the anchorage. Time it to enter about 30 minutes before high water and get carried in on the last of the flood’s current. Four narrows separate five lagoons. The first two narrows are filled with Pacific kelp, making it tricky for propeller craft, but easy for paddleboards or kayaks. Notice how the marine life changes as you get deeper into the chain of basins, as the ocean energy drops. At the very back are muddy flats where wading birds are often seen. If you’ve timed it right, you should reach the final basin as the tide turns to ebb, and you can then be carried back out again with a mini-

mum of effort. To find out more go to pacificyachting.com/two-lagoons.

This anchorage (again unnamed) is close to the previous one (4), but approached from Hunter Channel on the east side of Campbell Island. Turn in at Soulsby Point, passing a derelict cabin on an islet to starboard. Motor carefully up the channel northwest to a large inner basin. The channel is quite thick with kelp, but there’s adequate depth.

The middle of the anchorage is deep (30 metres) but the western side shallows to five to 10 metres. Pay attention to the high points in the seabed— there’s plenty of room between them. We have always favoured the zone close to the trees to the west. Looking south, there appears to be a wide entrance into the anchorage from that direction. We’ve not tried it, as the charted rocks and reefs make the passage appear foul.

From the basin you are close to the five-basin lagoon (described above), plus a suite of islets that are worth exploring at any time. The anchorage is just outside the Hakai Conservancy boundary, which ends at the north shore of Dodwell Island.

Visiting remote anchorages means you will be dropping the hook in different depths and different surroundings with different seabeds. Some find this intimidating. It shouldn’t be. Practice makes perfect. Here are a few suggestions:

1. Have a decent anchor that’s large enough to do the job properly. Everyone has their own opinion of what a good anchor is. If you don’t have an opinion, ask at the boaters’ pub, and prepare to have your ear bent. Or walk around the marina and check out the well-used anchors. Avoid the polished, stainlesssteel ones that have clearly never hit the saltchuck.

Be consistent with your units. Our charts are in metres, so our depth sounders and chain are set to metres. Converting in your head between fathoms on the depth sounder, feet on the chain, and metres on the charts just leads to confusion. It can happen to the most experienced pilots. Keep it simple and consistent.

2. Have plenty of chain. We carry 90 metres/300 feet of chain, with another 45 metres/150 feet of rode, but to be honest, we have never put out more than 70 metres, and that was in a major storm. Normally we anchor with a 3:1 ratio in deeper water (>10 metres), about 4:1 in shallow (five to 10 metres).

3. Much of the mid-coast is well charted, but we still have a ritual we follow every time we drop the hook. We approach our planned drop point, and pass over it, continuously watching the depth sounder(s). We call the depths to each other while one person is on bow watch. About 50 metres beyond the proposed drop point we turn hard and motor a slow circumference, with our planned drop point in the centre, all the while calling the depths back and forth. There’s nearly always a

shallow side and a deeper one. Once we’ve completed the circle, we continue on the circumference until directly downwind of the centre point, and then turn upwind. By now, we should have a good idea of what the bottom looks like. If it doesn’t resemble the chart, reconsider the anchorage! Otherwise, drop at the centre, drift downwind, test the set with a couple of judicious reverse pulls on the chain, which should stretch tight and then slacken off as its weight pulls the vessel forward. Watch the left and right horizon to see that the boat is moving forward. Watch the chartplotter too, to confirm the boat is moving up. If you come forward, the anchor has set properly.

4. Know your tides! Check the next high tide and let out at least three times that amount of chain/rode. If you’re expecting high winds or strong currents, put out more. In shallow water, add the height of the roller above the water to the water depth. Remember that in depths less than five metres there’s a likelihood of weed on the bottom that can fool you into thinking you have a good set, when in fact you just have a ball of kelp holding you there.

5. This is such a simple process, if done properly. In 15 years of anchoring we’ve only dragged a few times. Anchor often, and hone your technique until it becomes second nature. If you have a failure, don’t get mad at someone. Analyze what went wrong and change your routine to avoid that error in the future.

By Ellen Massey Leonard

By Ellen Massey Leonard

Ever since we first sailed to the Tuamotu archipelago 15 years ago, Seth and I wanted to dive the famous South Pass of Fakarava Atoll. At that time, we were still new to ocean sailing and certainly to scuba diving. We were partway along our first blue-water journey, our voyage around the world, and we were both in our early 20s. Seth and I had sailed Heretic, our primitive 38-foot copy of the Sparkman & Stephens yawl, Finisterre, from Maine through the Panama Canal and across the Pacific to French Polynesia. Before the voyage, we had both been small-boat sailors and racers, but those 10,000 miles were our first offshore ones. As for scuba diving, we were complete novices. We had only breathed underwater for the first time in the British West Indies while en route to Panama. In the Galapagos, we had earned our advanced dive certifications. In the Marquesas, we had made our first dives from Heretic without a guide. We were keen on our new sport, but little did we know that when we reached the Tuamotu atolls, we would be hooked for life.

TUAMOTU MEANS “MANY motu” in the local language, a motu being a coral islet It’s a perfect name for this great arc of coral atolls stretching more than 1,000 miles across the South Pacific. Diving in the Tuamotu is all about sharks and fast currents. Most of the diving takes place in the passes that lead into the atolls and on an outgoing tide these passes are dangerous for sailors and divers alike. The ebb pours out of some of the lagoons at speeds exceeding eight knots, generating steep standing waves as it sets against the wind. Beneath the waves, the outflow creates a ferocious down-current, potentially lethal to any diver caught in it. All drift dives are consequently done on flood tides, going into the lagoon. Sailors navigate these passes at slack water or at the beginning of the flood, when the surface is calm and the current negligible.

The largest atoll of the archipelago, Rangiroa, has one of the strongest currents. When Seth and I sailed there 15 years ago, we managed to time our arrival for slack tide. Given that we were arriving at the end of a six-day passage (from the Marquesas, the archipelago about 600 miles to the northeast), our

Marquesas Is.

favourable timing was mostly luck, but we took it and wafted through the placid pass under only our genoa. Then we rounded the corner into the anchorage, tacked up into shallower water, luffed into the wind, and dropped the hook. We were true sailing purists—and also impoverished 20-year-olds—and we never used our engine if we could help

it. A few hours later, while taking a walk ashore, we saw what Tiputa Pass becomes on the ebb: With dolphins leaping from the steep white water, it was quite a sight, and not something we would want to be caught in.

THE FOLLOWING DAY, on the flood tide, we slipped underwater to experi-

ence Rangiroa’s phenomenal diving. We began by backrolling into the open ocean, right into a school of barracuda and then descending to a school of gray reef sharks. I remember marveling at the otherworldly sensation of floating weightless in a water column that felt as clear as air and being sur-

rounded by the predators who live there. Then we let the current take us into the pass, and we flew along faster and faster. It was exhilarating to the point where I ran out of air and had to breathe from the dive guide’s extra regulator. Toward the end, a huge manta ray was turning somersaults right in our path.

When Rangiroa’s fringe of palms dipped below the horizon in Heretic’s wake about 10 days later, we vowed we’d come back someday. Through a series of very lucky circumstances, we managed to do so nearly 12 years later. We had sold Heretic by then and had bought another old classic to replace her, Celeste, a 40-foot, cold-molded wooden sloop designed by Francis Kinney, editor of Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design.

In 2018 we again made the long passage across the Pacific to French Polynesia, this time from Mexico. After a week or so in the Marquesas, we set off for the southern end of the Tuamotu chain, to an atoll called Hao. The first time we’d sailed from the Marquesas to the Tuamotu, we’d enjoyed a pleasant and even-keeled, if slow, six-day amble downwind. This time would be different. Our angle on the trade wind was a close reach and the breeze was strong. Instead of swaying before the wind wing on wing, we punched into head seas for 4.5 days under triple-reefed main, jib, and staysail.

NOW IN OUR 30s, we were too conscientious to rely solely on luck for either our weather forecasting or timing our tides. And so, of course, we got worse weather—strong headwinds — and we got the tides all wrong. (In fact, our tide tables were wrong.)

Once inside Hao’s lagoon, it was quick and pleasant work to skim across the water to the anchorage.

The anchorage was in fact a crumbling wharf, convenient and very sheltered. Hao is a sleepy place without any tourist infrastructure. The atoll is the site of the former French military base from which nuclear tests were launched between 1966 and 1996. Until fairly recently, no one was allowed to visit the

place. Seth and I were curious to see it. Underwater, we were saddened to see the state of the lagoon: murky, much of the coral dead and with significant debris, seemingly thrown there at random. The lagoon was fortunately not what Jacques Cousteau called the “universal sewer,” but it did seem to have been the trash heap. There were a surprising number of reef fish and eels despite the debris and algae-covered coral.

In a place like this there are no scuba operators. So, Seth and I were thrilled to be invited to join the Fafapiti Diving Club, a group of French teachers at the local school on Hao who had come together to buy a boat and an air compressor. These French divers were all very skilled and rather risk-loving and so preferred to make deep dives on the coral walls outside the lagoon entrance. Indeed, that is where most of the big critters were: reef sharks cruising above seemingly infinite schools of red bigeyes; manta rays turning lazy circles just below us at 140 feet and occasionally above us; schools of rainbow runners and sometimes a big tuna or amberjack; once or twice a five-metre-long tiger shark.

AFTER TWO MONTHS between Hao and an even more remote neighbouring atoll, it was time to sail back to the Marquesas, where we planned to leave Celeste for the cyclone season after our visas ran out. We rode the back of a low-pressure system east for two days beneath overcast skies—easy reaching under genoa and single-reefed main— but we were slower than the system, and soon we were back to clear skies

and trade winds well forward of the beam. We had a splendid reward for our upwind sailing, however, when we dropped anchor in the moonlight all alone among the spires of the famous Baie des Vierges on Fatu Hiva. We spent the following year in the Marquesas, but in 2020 we returned once again to the Tuamotu. This time, our main destination was the place we had long dreamed of diving: Fakarava Atoll.

FAKARAVA LIES IN the middle of the Tuamotu arc and is one of the largest of the group, its coral motu encompass-

ing a lagoon with a surface area of over 1,000 square kilometres. Two passes lead into the lagoon from the ocean— the mile-wide Garuae Pass in the north and the narrow, coral-lined alleyway of Tumakohua Pass in the south. It is this pass that has made the atoll renowned among divers and has led to Fakarava’s status as a UNESCO biosphere reserve. The coral reefs are brilliantly alive, hosting thousands of reef fish, from little dartfish hiding in the coral to behemoth Napoleon wrasse that can tip the scales at 400 pounds.

While we had expected our passages

to and from Hao to be more or less upwind, we hoped to repeat the easy downwind passage we had made 14 years earlier. Instead, Celeste took us for a fast gallop to windward. With the wind well in the south—and thus forward of the beam—and the combined wind and swell height reaching 12 feet, it was a wet and bouncy ride. With only jib and staysail up, we had the lee rail buried nearly the entire time and were shipping so much water over the bow that we couldn’t open the centre hatch for air. As we plotted our noon position each day, however, we found we were

consistently making our fastest runs ever: 180 miles each day and that in a boat with only a 28-foot waterline. We covered the 550 miles and raised the atoll in only three days.

Upon arrival, we decided first to dive Garuae Pass, and this turned out to be one of the most adrenaline-pumping dives I’ve ever done. We would backroll into the open ocean just outside the pass during the height of the flooding current and then we’d make a rapid descent to the coral shelf at 120 feet in order to keep from being swept into the lagoon before we’d seen anything. Down at

depths close to decompression limits, we would hook onto outcroppings of dead coral and stare out into the blue at the parade of reef sharks. The current flowing over us was occasionally so strong that it threatened to tear my regulator out of my mouth. I’d made decompression dives before, and wreck dives well inside submerged ships, but this was thrilling, exactly the sort of challenge I’d hoped for.

TUMAKOHUA—SOUTH PASS—was beckoning, however. To get there, Seth and I sailed Celeste the full length of Fakarava’s lagoon, nearly 40 miles along the coral motu lining the windward side. The protected waters once again made for superb sailing. Instead of pitching against head-seas and shipping green waves over the bow, Celeste heeled cleanly and flew along through

the flat water. When we’re offshore, Celeste’s tiller is usually hooked up to her wind vane, but inside these lagoons we instead attached the tiller extension and stood out on the windward deck, steering her like she was a dinghy.

The anchorage off the South Pass is not protected, however—it’s open to quite a lot of fetch across the wide lagoon—and so is only comfortable when there is little wind. Therefore, we were unable to dive the South Pass as much as we would have liked. Every time the wind got up, we’d retreat seven miles upwind to a perfectly protected bay tucked into the southeast corner of the lagoon. But when we could anchor near the dive site, it was spectacular.

I have never seen such pristine coral than where we began the dive at the drop-off at 90 feet down. Plate after plate of it staircased into the abyss. The

first time we went, we were visited by five of the most enormous eagle rays I’ve ever seen, but the sharks were the stars of the show. In the mix were a species one doesn’t often see: blacktips— not blacktip reef sharks but the openwater species that are faster and more energetic. Just as in the North Pass, we drifted into the lagoon with the current, skimming over beautiful coral and colourful fish until we ascended beside a ball of snapper, scales shimmering in the sunlight.

BUT SAILORS LIKE to sail, so after as many dives as we could do, we set off for the less-visited atoll of Toau. We made the trip in just a couple of daysails. First, we had a perfect downwind trip back north over Fakarava’s smooth lagoon, and then after a night’s sleep, we exited the lagoon at slack tide and

swayed downwind over the swell. We anchored in several different spots on Toau over the next week or so, doing a few dives from our dinghy, snorkeling, walking the beaches, and getting to know the few residents. Then we returned to Rangiroa.

The overnight sail to this largest atoll, the site of so many of our best memories, was the sort to make any ocean sailor forget all the gales and upwind slogs he’s ever made. I had one of those night watches you don’t want to end, ghosting downwind with 12 knots on the quarter, a clear sky glittering with stars overhead, and phosphorescence shining in the wake. Perfect.

A ball of paddletail and one-spot snapper, Tumahokua (South)Pass.

At first approach from the sea, Ran-

giroa looked the same as it had on our first visit 14 years before. But once we had dropped anchor, we realized that it now supports both a much larger local population and more tourists. There were correspondingly more dive and snorkel boats, but happily it didn’t seem to have affected the marine life. While we didn’t see any manta rays this time, we instead were approached by an inquisitive great hammerhead. Being investigated by this iconic and critically endangered shark while floating 50 feet down, a quarter of a mile out to sea, in the disorienting world of the bottomless blue ocean, was an unforgettable experience.

ON OUR FIRST visit, we had circumnavigated Rangiroa’s lagoon, reveling in the flat water and brisk winds, one of us

always on bow lookout for coral bommies (most of the lagoons in the Tuamotu remain uncharted once you get away from the pass and village). We had taken about a week over it—the lagoon is nearly 1,500 square kilometers—and we’d stopped at several lovely motu, the two of us all alone with the coconut trees and the reef fish. That little cruise had been perhaps the biggest highlight of our entire trip around the world. We knew we wouldn’t be able to replicate it—most of life’s best memories cannot be—and so instead we focused on diving the pass and the outer reefs. We did a couple of sunset dives, during one of which we saw big schools of tangs and surgeonfish spawning in little dances in the water column. But before we left the atoll—and French Polynesia—we did make two more sails over the rippled la-

goon. Once again, we had the beautiful palm-fringed motu to ourselves, and we passed a few lazy days strolling the coral beaches and snorkeling from Celeste.

WE SAILED BACK up to the pass on the day of our departure for our 2,400-mile passage to Hawaii, sliding through at just the start of the ebb. As we went, we were visited by Rangiroa’s favourite residents, its pod of bottlenose dolphins, perhaps the same dolphins we had seen leaping clear of the standing waves all those years before. Rangiroa was every bit as wonderful as we’d remembered, and we were every bit as sad to be leaving.

And so, once again, as we watched Rangiroa recede in the waves astern, we vowed to ourselves that one day we’ll return.

By Hans Tammemagi

By Hans Tammemagi

Avoyage aboard a narrowboat is, I discovered, completely different from other boats

I’ve been on. First and foremost, is the leisurely pace. For 10 days, Skylark inched along the old canals of Scotland, often passed by walkers on the towpath. I had ample time to ponder the meaning of life and question the frenetic rush that normally envelopes us.

A NARROWBOAT IS a throwback to ancient times. Years ago, bulk goods were transported by water on canals crisscrossing the countryside, cleverly using water, effectively for free, to flow in and out of locks which would lift boats up and down the varying height of the landscape. But in the early 1900s the railway came along, sounding the death knell for working narrowboats, which now survive strictly for recreation. At 63 feet long and a little under seven feet wide Skylark looked like

a long 20-ton cigar, and handled about the same.

Life aboard was easy for my wife Ally and me, as Cherie and David, good friends with ample experience in narrowboats as well as on their own sailing craft, took charge. We puttered from the Falkirk Wheel to Edinburgh and back along the Union Canal, which was built in 1822. Then we proceeded a little way toward Glasgow along the Clyde and Forth Canal (built in 1790).

OUR ADVENTURE STARTED at the renowned Falkirk Wheel, which raises and lowers boats a dizzying 35 metres (115 feet) replacing 11 locks. The wheel is a dramatic modern contrast to old fashioned canal locks, which have been operating for more than two centuries with the giant timber doors being opened and closed manually.

The Falkirk Wheel lifts boats up and down by rotating like a giant Ferris wheel. Unique in the world, it is a marvel of technology. Giant gears surrounded us as we sat in our boat in a caisson filled with water so it exactly balanced the weight on the opposite side of the spindle. As a result, very little energy is required to

rotate the wheel.

At the top, the views of the countryside were phenomenal! Then, Skylark cruised through the new Rough Castle Tunnel with its psychedelic lighting and two new locks, then the Falkirk Tunnel with dripping water, stalactites and rockhewn sections.

To Ally’s delight, all modern conveniences were present aboard including showers, flush toilets, a modern kitchen with fridge and stove and central heating. Under David’s tutelage we learned to steer and to deal with tasks such as cleaning weeds from the propeller and filling the water tank. We also became quite familiar with each other

as we squeezed by in the narrow confines.

All of us took turns at the tiller as we glided past villages with old stone houses, and fields of bright yellow canola next to verdant green barley. We often stopped to visit nearby pubs, shop or join other walkers and bikers on the towpath.

STRANGELY, SEVERAL OF the fisher people we encountered had powerful magnets attached to their lines instead of lures. One couple proudly showed us old coins and other metal paraphernalia they had “caught.”

I became an ornithologist of sorts, as feathered creatures including mallards and their flotillas of fluffy

youngsters, swans, magpies, herons, crows, moorhens and gulls, constantly surrounded us, all treating Skylark like a mother. One tiny cygnet rode on her swan mother’s back, partially hidden under a large white wing.

One of my favourite urban stops was the historic town of Linlithgow (population 13,000). We explored the ruins of Linlithgow Palace, where Mary, Queen of Scots was born in 1542 and St. Michael’s Church with its unique Crown of Thorns spire.

The United Kingdom encourages the recreational use of its canals and we were delighted that clean facilities, including toilets, showers and occasionally laundries, could be accessed with a key provided to

us at the beginning of the voyage. A map of the canal guided us to moorage sites, water accesses, aqueducts, grocery stores and pubs. The elegant arcs of old stone bridges were much awaited as we compared their numbers to the map to determine our exact location.

AFTER THREE DAYS, Skylark arrived at the Edinburgh Quay, the eastern end of the Union Canal, located conveniently only minutes from the city centre. There was no charge for docking the boat and on arrival and departure the Leamington Lift Bridge was opened for free, although we had to pre-book the time.

The four of us spent two days exploring Edinburgh. Compared to

western Canada, the history and architecture is ancient and impressive. We visited the ramparts of the 900-year-old castle, which is balanced on a volcanic plug. We joined throngs of tourists and descended the Royal Mile to the Scottish Parliament and the Palace of Holyrood, the residence of King Charles when in Scotland. Closes, or narrow, winding alleys, leading off the Royal Mile, beckoned us. In the shadowy Advocates Close we discovered the Devil’s Advocate pub where, savouring a local ale, I tried to develop a frothy moustache. In the Dunbar Close, eight distinct areas were laid out in the fashion of a 17th century garden. What a delight to have this restful, charming escape in the middle of

a bustling city!

In the morning, the Leamington Bridge lifted and we sailed out of Edinburgh Quay. After a few days of gentle puttering, we were back at the Falkirk Wheel. We descended, had Skylark checked by ABC Boat Hire and then set off toward Glasgow along the Forth and Clyde Canal.

Although built in 1790, more than three decades before the Union Canal, the Forth and Clyde is wider and straighter. Numerous locks are located at the western end, but we only passed through the first four in the east, as we sailed just part way toward Glasgow. The locks were tended by two keepers, who guided us in and out, raised and lowered the paddles that released water and closed the heavy, wooden lock doors by pushing heartily. Then they bicycled

to the next lock to repeat the process. We moored just past the Glasgow Road Bridge and found the nearby Stable Hotel, where we happily consumed pints of amber ale. In the morning, we motored leisurely back

to the Falkirk Wheel and ended a wonderful journey.

EVEN BEFORE LEAVING, I was already yearning for the slow pace of a narrowboat.

of the importance of boat balance and heel angle, but that judgement comes from other indicators. I would suggest the most important heel angle references are forestay angle to the horizon upwind, and mast angle to the horizon downwind. Wait, what? These sound like the same thing. Well, yes and no. Upwind, the helmsperson will typically be sitting to windward, eyes focused forward, with a clear view of the water ahead, the jib luff and telltales and the forestay angle relative to the horizon. The good crew is also aware of the angle of heel using these same references. One additional input is helm balance, directly connected to heel angle. A little too much weather helm will signal that some sort of action is required. Perhaps a slight feather up, maybe traveller down or a mainsheet ease or possibly a repositioning of crew weight. All these things are factors in maintaining the optimum angle of heel, along with all the usual sail trim controls. The goal is to balance point with power so that the underwater foils work most efficiently. Heel angle is an important piece of the speed puzzle!

Every sailboat will have an optimum angle of heel for a given wind strength and sea state, both upwind and downwind. It seems like a simple enough concept, but arriving at the right answer can be more complicated and not always clear. Let’s explore heel angle and how it relates to achieving the best performance from a variety of boats in different conditions.

EFIRST OFF, JUST for clarity, zero degrees of heel is when the mast is fully upright. Five degrees of heel is when the mast is leaning to leeward that amount. Minus five degrees is when the mast is angled to windward. Make sense? Many boats will have a heel indicator, commonly referred to as an inclinometer or clinometer. These are more often located near the front of the cockpit, usually within normal line of sight of the helmsperson, although not always. It’s been my experience that most racing crews don’t pay all that much attention to this instrument. Guilty as charged. Now, I’d like to qualify that a bit by stating that most racing crews are indeed very aware

DOWNWIND, THE GOAL is the same, but the game is different. While upwind sailing is more about minimum course adjustments and maintaining a constant angle of heel, downwind sailing is often quite the opposite. It’s fascinating to watch a fleet of boats round a weather mark and observe how they spread out, with a variety of initial course choices. I’d describe upwind sailing as static and subtle, aside from choosing one tack or the other. Downwind sailing is generally more active and dynamic, unless we’re talking small dinghies, where physicality comes into play both upwind and down. Sailing downwind also encourages more changes to heel angle, especially when there’s wave action and pressure changes on the course. Crew movement contributes to those heel angle changes and can assist in steering the boat, rather than relying solely

on the rudder. Immersing one side of the hull is an effective method of helping to head up or to bear away. Most boats tend to rock a little when sailing downwind, with the masthead swinging through as much as 10 or 20 degrees without having a negative effect on performance—in fact, quite the contrary. One final indicator of heel angle that I find useful upwind and down, is to look aft to where the deck and transom intersect and line them up with the horizon. This perspective lets you view the smoothness of the wake and whether the rudder drag is excessive or not.

NOW, GETTING BACK to every sailboat having an optimum angle of heel for any given condition. A Martin 242, for instance, is a light boat with a fine forward U-shaped bow section, flat-

tening amidships, with a nice clean run aft. The keel is high aspect, short chord length. The rudder is well aft and quite large in area. The rig is three quarters fractional, with swept back spreaders, a large main and a small jib. Sailed with a crew of three or four, this keelboat responds to small trim adjustment upwind, minimum helm movement and precise heel angle both upwind and down. In very light air 10 to 15 degrees is optimum. An easily driven, quick to accelerate hull, things change in a hurry as the Martin powers up. Start moving the weight to weather, while maintaining perhaps eight to 12 degrees of heel as the breeze increases and once fully powered up, a little flatter is OK. The Martin will fool you into thinking you can trim tighter and point higher. This will typically not pay off. It’s bet-

ter to put the bow back down a bit and get some feel back. It’s a balancing act and it all revolves around the angle of point and the angle of heel. Once into full hike conditions the angle will likely increase to 12 to 13 degrees without suffering, as the underwater shape remains relatively symmetrical even when heeled a little. Compared to a much beamier boat like a J-24, with its smaller rudder and a shorter keel, the J sails best when flat, keeping the keel working and the immersed hull shape symmetrical. Back to the Martin and downwind sailing heel angle. The main is big, the spinnaker is what I would call midsized. The rig is far forward on the deck, and again in light air the Martin likes a bit of heel, 10 degrees perhaps, weight forward and to leeward, pole forward and low, speed first, then gradually

soak down and flatten whenever possible, especially when pressure builds. When the boat slows, come up again before the flow disappears to keep the chute lifting and the boat moving. Once the breeze hits 10 knots, the pole can be squared, and the boat flattened to no heel at all. In 12 to 15 knots of breeze it’s about running deep, with the pole fully squared and even -5 degrees of heel. This balances the rudder totally, and even prompts the boat to soak down even more. Very few boats can sail low and fast like a 242! With the wind approaching 20, I’d put the bow back up five degrees, pole forward a couple of feet and the boat totally flat, with weight aft. This prevents a windward roll and keeps the sail plan over the centre of buoyancy of the hull, making control the priority.

FINALLY, LET’S LOOK at a very different boat, the six metre. I’ve had the pleasure of racing a couple of these in a few regattas, but I enjoyed the experience and hopefully learned a few things along the way. Modern six metres are narrow and heavy, with lots of wetted surface, a large keel, trim tab, wings and a high aspect rudder. The classic six has only a rudder on the trailing edge of the keel. It’s a different animal. Both have large fractional rigs (fully adjustable fore and aft) along with running backstays, big mains, genoas and massive, round spinnakers. The name of the game in light air upwind is to develop as much power as possible. With the entire crew sitting to leeward inside the boat, helmsman to leeward, it’s wishful thinking that any heel can be encouraged, but every little bit helps. The heel