JUAN GRIMM

ACERCA DE JUAN, un arquitecto que hace paisaje ABOUT JUAN , an Architect who Landscapes

Texto por Mathias Klotz Text by Mathias Klotz

LA LUPA DE GRIMM GRIMM'S MAGNIFYING LENS

Texto por Aniket Bhagwat Text by Aniket Bhagwat

INICIOS Y PRIMERAS APROXIMACIONES AL PAISAJISMO BACKGROUND AND FIRST APPROACH TO LANDSCAPE DESIGN

Texto por Mitzi Rojas Text by Mitzi Rojas

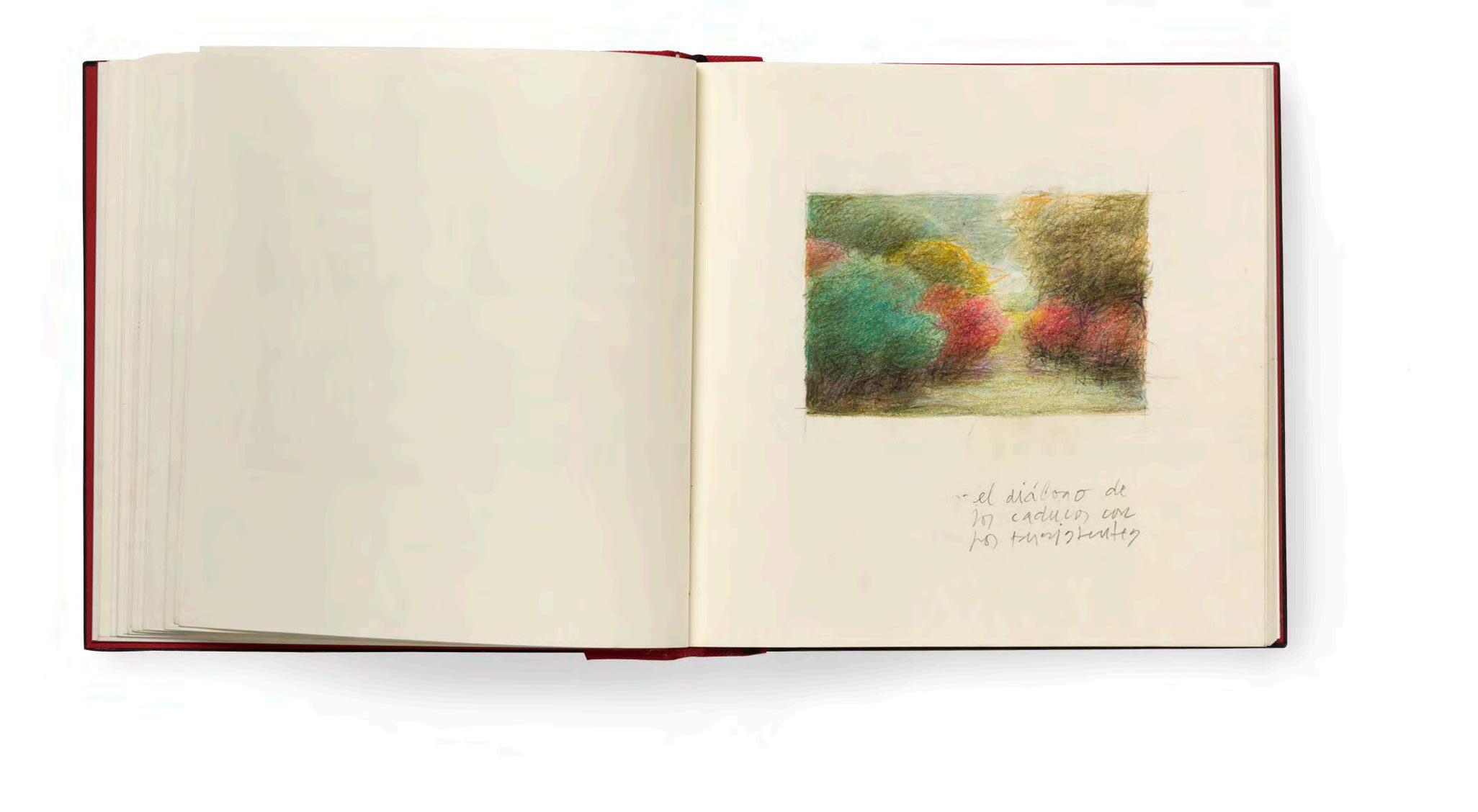

CUADERNOS DE VIAJE TRAVEL JOURNAL

Texto por Juan Grimm Text by Juan Grimm

PROYECTOS PROJECTS

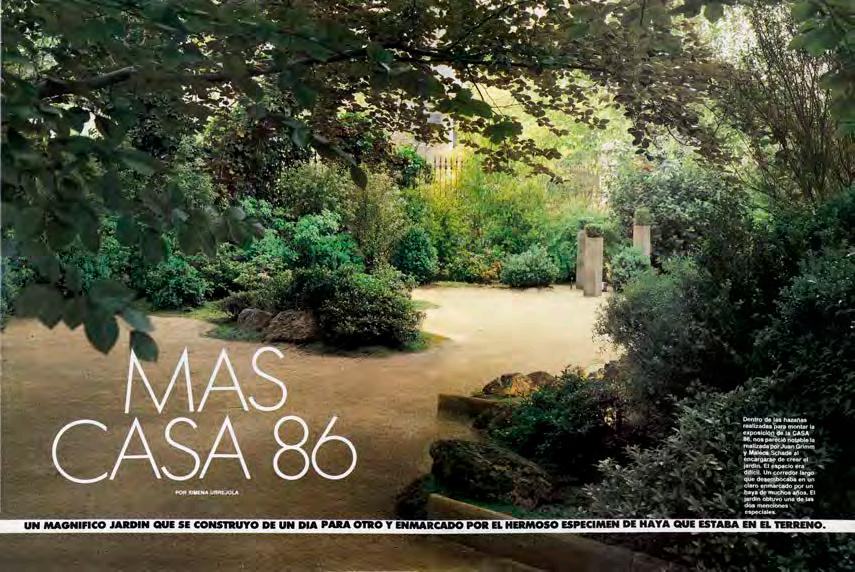

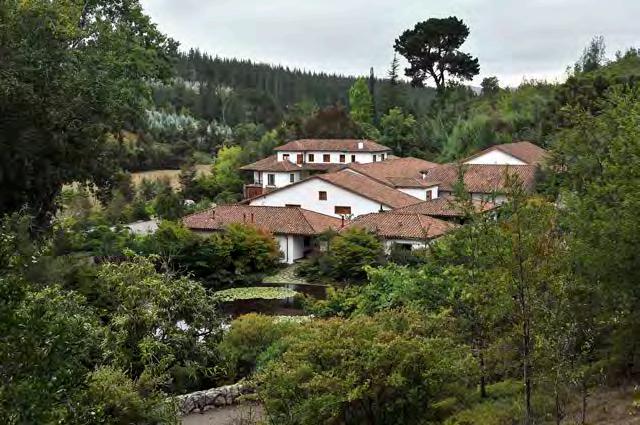

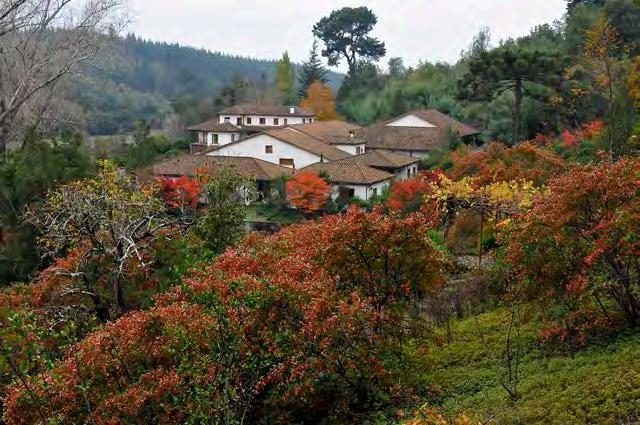

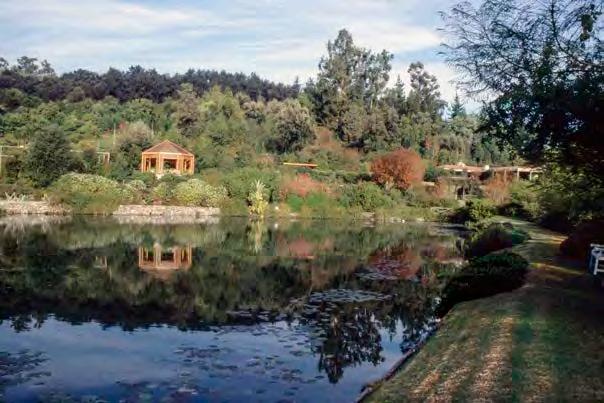

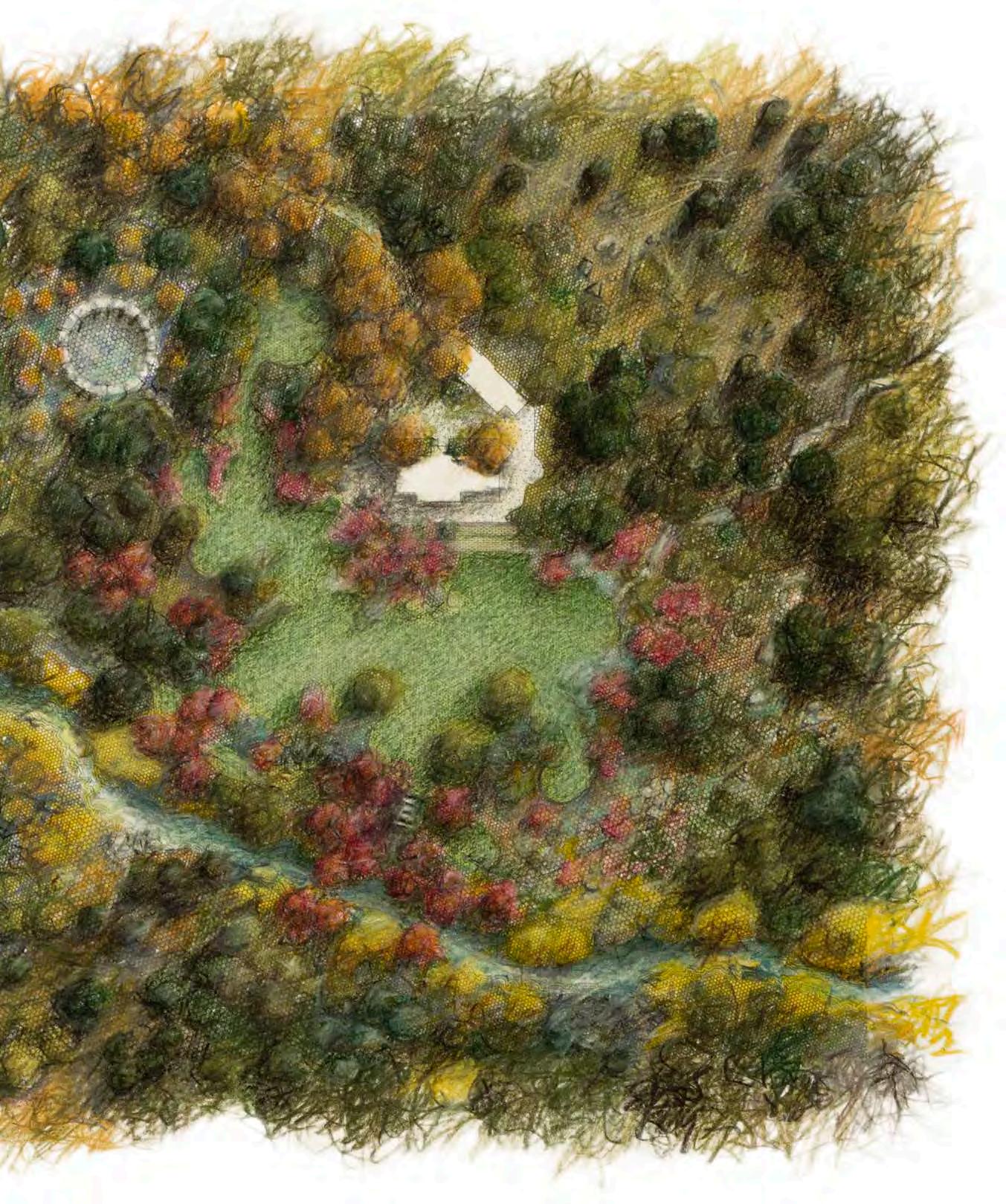

JARDÍN CHILOÉ CHILOÉ GARDEN

PARQUE EL ROBLE EL ROBLE PARK

JARDÍN AMADORI AMADORI GARDEN

JARDÍN URUBUMBA URUBAMBA GARDEN

JARDÍN BAHÍA AZUL BAHÍA AZUL GARDEN

PARQUE LAGUNAS SAN NICOLÁS LAGUNAS SAN NICOLÁS PARK

PARQUE BARROS BARROS PARK

JARDÍN BOHER BOHER GARDEN

PARQUE ALLENDE ALLENDE PARK

JARDÍN MORITA MORITA GARDEN

GLOSARIO | GLOSSARY

| ACKNOWLEDGEMENT BIOGRAFÍAS | BIOGRAPHIES

Juan Grimm, primero arquitecto, por siempre paisajista, desde pequeño se fascinó con los espacios infinitos del cielo y el mar; por mirar los paisajes desde varias perspectivas y descubrir cómo las formas de la naturaleza se entremezclan con las formas que crea el hombre en el relieve tejiendo una nueva trama. “El jardín debe seducir al espectador y transportarlo a un mundo donde el goce por la naturaleza estimule la libertad personal”, dice Juan Grimm, y desde esa premisa es que su búsqueda no tiene límites, así como sus jardines no tienen fin, y donde para él es fundamental incorporar los referentes naturales del entorno sea un río, una quebrada, una selva o el mismo desierto porque son esos elementos los que extienden esta atmósfera, los que insertan un jardín en un paisaje mayor.

Han pasado 18 años desde que se publicó la última monografía de Juan Grimm y llegó el momento de una nueva publicación: un libro que abra las puertas de sus jardines a un amplio público, que pueda dar a conocer su pensamiento, sus experiencias, su método de trabajo a futuras generaciones. El desafío era grande: teníamos que ser capaces de desarrollar un libro que estuviera a la altura de las obras de Grimm y que contribuyera a ampliar el conocimiento de su obra, con el convencimiento de que es un trabajo que amerita ser visto y estudiado.

Para lograr estos objetivos nos propusimos crear una libro amable y visual, que plasmara y transmitiera este gran

Juan Grimm was an architect first, but he has always been a landscape designer. Ever since he was a child he has been fascinated by the infinite spaces of the heavens and the seas, looking at landscapes from various perspectives and seeing how the different shapes of nature combine with those made by man to create a new vision. “A garden should seduce the spectator and take them to a world where the enjoyment of nature stimulates personal freedom,” he says, and this premise sends him on a quest without limits, reflected in his borderless gardens where he sees it as essential to incorporate aspects of the natural environment�be it a river, a gulley, a jungle or the desert itself� because these are the elements that perpetuate the atmosphere he is seeking to create, the ones that place the garden in a wider landscape.

It has been 18 years since the last monograph on Juan Grimm’s work so the time is ripe for a new publication: a book that brings his gardens to a wider public, a book that shares his thinking, experiences, and working methods with future generations. The challenge was great: we needed to produce a book worthy of Grimm’s works and that would also help to enhance understanding of his practice in the knowledge that it deserves to be seen and studied.

To achieve these objectives, we set out to create a visually inviting book that captures and transmits Grimm’s

conocimiento: su experiencia con la vegetación nativa chilena, sus investigaciones con los paisajes extranjeros como sus expediciones a Uruguay, Argentina o Perú , su obsesiva búsqueda de un paisaje para cada lugar. Para ampliar la difusión, generamos una alianza con Hatje Cantz, con quienes compartimos una visión común, y sumamos a socios claves –como LarrainVial que nos han permitido llevar a cabo este magnífico libro.

Invitamos a quienes han trabajado con Grimm: al arquitecto Mathias Klotz, con quien ha realizado varios proyectos, y a Mitzi Rojas, colaboradora por más de 20 años, y a quienes entregan una visión internacional de su trabajo en el mundo, como Aniket Bhaqwat.

El resultado es un libro como un cuaderno de viajes, donde aparecen los recuerdos de infancia de Juan Grimm, sus primeras inspiraciones, sus héroes, sus maestros. Donde también están presentes su conocimiento y sus técnicas que Grimm entrega de su puño y letra.

En sus 30 años de carrera, Juan Grimm ha construido más de mil hectáreas de paisaje: una variedad de proyectos que difícilmente podríamos incluir en un solo libro, pero hemos seleccionado muchas imágenes que ejemplifican aspectos puntuales de su pensamiento y dejamos para el final diez de sus proyectos emblemáticos, con sus planos, plantas e historias.

“Al recorrer y contemplar un buen jardín, nos quedan en la memoria, por sobre la forma o la estructura, las sensaciones que el entorno nos provoca”, escribe Grimm en el libro. Lo suyo es crear atmósferas, jugar con las luces y sombras del

expertise: his experience with native Chilean vegetation, his research into overseas landscapes�and his expeditions to Uruguay, Argentina and Peru�and his obsessive search for a landscape to fit each place. To achieve wider distribution, we joined forces with Hatje Cantz�with whom we share a common vision�and added key partners, like LarrainVial, who made it possible for us to produce this magnificent book.

We invited people who had worked with Grimm to contribute: the architect Mathias Klotz, with whom he created several projects, and Mitzi Rojas, his partner for more than 20 years, as well as the Indian landscape architect Aniket Bhagwat, who offers an international perspective on Grimm's impact.

The result is a book that reads like a travel journal and features Juan Grimm’s childhood memories, his early inspirations, his heroes and his masters. It also provides a full account of his expertise and techniques.

In his 30-year career, Juan Grimm has built over thousand hectares of landscapes: such a range of projects could hardly be expected to fit into a single book, but we have selected many images that demonstrate specific aspects of his thinking, leaving ten of his most iconic projects, as well as their plans, plants and stories, until the end.

“When you walk through and observe a good garden, the sensations one experiences in the environment stay with you, especially the form or structure,” writes Grimm. His talent is to create atmospheres, to play with the lights and shadows of a place and create intimate, mysterious nooks and crannies, to combine native and exotic plants... to invite people in and

lugar, armar rincones íntimos y misteriosos; incluir plantas nativas y exóticas, invitar, dejarse sorprender. Cada una de sus obras es un cuento nuevo que quiere ser leído. Juan Grimm que casualmente lleva el apellido de los famosos escritores alemanes de cuentos para niños en cada uno narra una historia diferente. Está el cuento de Chiloé, donde logró crear un paisaje exuberante. Está su cuento en Urubamba, donde se potenció el carácter fértil y montañoso de la zona, y está su cuento regalón, su propio jardín en Bahía Azul, su laboratorio para experimentar y aprender de plantas nuevas.

Y está este libro donde se muestran varios jardines escondidos, donde aparece el nombre de cada planta (su nombre científico en un glosario al final), donde se devela la relación del paisajista con sus clientes (a muchos de los cuales contagió con su pasión por la naturaleza); está su fascinación por los bosques de araucarias, por el paisaje de las Galápagos, por el desierto de Atacama, por la vegetación nativa de Los Molles. Está su historia como paisajista, su incansable preocupación por conservar y recuperar los paisajes de Chile; está su genuina contribución a la arquitectura y a la sociedad. Está su sueño hecho realidad.

then surprise them at every turn. Juan Grimm�who shares a surname with the famous storytellers�tells a different tale with each of his works. There is the story of Chiloé, where he created a vivacious, exuberant landscape; Urubamba, where he enhanced the area’s fertile and mountainous characteristics and that of his own garden in Bahía Azul, which he uses as a laboratory for experimentation and to learn about new plants. And there is this book, which reveals many of his hidden gardens, providing the name of each plant (and its scientific name in the glossary), exploring the landscaper’s relationship with his clients (many of whom caught his enthusiasm for nature), and his fascination with Araucarian forests, the landscape of the Galápagos, the Atacama desert and the native vegetation of Los Molles. Here is the story of Juan Grimm the landscaper, his endless commitment to preserving and restoring the landscapes of Chile and his genuina contribution to architecture and society. This is his dream come to life.

Qué duda cabe, que en términos de HABITAR, no hay experiencia más sublime que el encuentro y la convivencia con lo natural.

Pero cualquiera que haya experimentado el contacto con la naturaleza en su estado salvaje, además de admirarla y conmoverse, habrá caído en la cuenta de que a pesar de observarla y a veces incluso tocarla, esta relación solo es posible establecerla como visitante, y como tales requerimos de un dispositivo que lo facilite, sea este un barco, una nave espacial, un traje de buceo, un par de esquíes o la cuerda de un andinista.

Para los navegantes les resulta evidente que por más hermoso y sorprendente que sea el entorno por el que navegan, esta relación solo les es posible desde el barco y que en caso de abandonarlo, tarde o temprano esta misma naturaleza que admiran es su estado salvaje, literalmente los absorberá.

Es por esto que el hombre ha debido domesticar esta naturaleza para poder habitarla, y es en esta permanente tarea de domesticación que ha nacido el concepto de paisajismo, como una suerte de restaurador del paraíso perdido.

Y si bien esta primera domesticación fue de mediana escala, con una sociedad preferentemente rural que construyó a lo largo de los siglos un equilibrado paisaje agrícola, desde mediados del siglo pasado hizo crisis con el masivo desplazamiento de la sociedad rural a centros urbanos.

Esto hace que hoy sea especialmente urgente atender a la importancia y el rol del paisajismo como disciplina madre de un futuro viable, especialmente en nuestras ciudades y pueblos, que han arrasado con todo, y en las nuevas e inmensas urbanizaciones que se levantan aceleradamente a lo largo de

There is no doubt that in terms of truly LIVING, there is no experience more sublime than the encounter and coexistence with nature.

But anyone who has experienced contact with nature in its wild state, in addition to admiring it and being moved by it, will have come to realize that although one can observe and sometimes even touch it, one can establish this relationship only as a visitor and only with equipment to facilitate it, be it a ship, a rocket, a diving suit, a pair of skis, or a climber’s rope.

For sailors, it is evident that however beautiful and surprising the environment they are navigating, this relationship is only possible from their vessel, and that should they abandon it, sooner or later this same nature that they are admiring in its wild state will literally consume them.

That is why, unfortunately, man has had to domesticate nature in order to inhabit it, and it was in this constant task of domestication that the concept of landscaping was born, as a sort of restoration of a paradise lost.

Although domestication began on a moderate scale in predominantly rural societies that built balanced agrarian landscapes over the centuries, since the middle of the last century the situation has become critical with the massive displacement of rural society to urban centers.

This makes it particularly urgent today to address the importance and role of landscaping as the mother discipline of a viable future, especially in our cities and towns that have swept everything before them, and in the new and immense metropolitan areas that have sprung up along our coasts,

nuestras costas, valles y montañas, consumiendo miles y miles de hectáreas agrícolas o muchas veces en su estado natural.

No importa la sofisticación del espacio que hayamos construido, ni la riqueza de los materiales incorporados. Un lugar habitable, rodeado de un entorno que integre la naturaleza de manera adecuada, hace que tengamos paz, y seamos felices. Pero esta evidente relación virtuosa no es fácil de lograr y si es que se alcanza, requiere de especial atención para preservarla (de esto se ocupan los grandes paisajistas).

El paisajismo se puede trabajar en diversas escalas y grados de sofisticación. Este puede desarrollarse desde un pequeño patio interior, un jardín, un parque o llegar a ser una intervención a escala territorial.

Independiente de su escala, de la riqueza o sofisticación de sus especies, este entorno artificial que hemos construido y que nos rodea por todas partes, puede ser muy distinto en términos de calidad, por la mera existencia o inexistencia de elementos bien posicionados, una sombra bien aprovechada o una fragancia discretamente percibida, una especie hídricamente adecuada.

Recuerdo de niño haber admirado sencillos parrones en los patios de algunas casas, construidos con tubos de alcantarillado sin otra pretensión que la de dar sombra y algunos racimos. Esos patios eran infinitamente mejores que los patios de muchas casas, por el solo hecho de poder tenderse en una hamaca a dormir la siesta a la sombra de estas parras y mirar las hojas a contraluz.

Juan Grimm ha trabajado y domina todas las escalas.

Su trabajo maneja luces y sombras, crea intimidad, establece atmósferas, funde, mezcla y amalgama elementos naturales preexistentes y/o propios del lugar con otros nuevos, a veces exóticos, que sumados construyen un nuevo paisaje que se caracteriza por el equilibrio, por la fusión de planos y esencialmente por la difusión de los límites.

En los paisajes construidos por Juan, no se sabe con certeza donde termina la intervención y donde comienza lo ajeno, sea esto natural o artificial.

Juan se apodera de lo ajeno y lo incorpora, dando profundidad a lugares que no lo tienen. Una de las primeras

valleys and mountains, consuming thousands and thousands of hectares of agricultural land or, often, virgin land.

The sophistication of the space we have built, and the wealth of materials we have used in the process, do not matter. A habitable place, set in an environment that appropriately incorporates nature, allows us to live in peace and be happy. But this self-evidently virtuous relationship is not easy to achieve and if it is achieved, requires special care if it is to be preserved.

(This is the job of the great landscapers).

Landscaping can be carried out on different scales and with different degrees of sophistication, ranging from a small inner courtyard, a garden, or a park, to a major territorial intervention.

Regardless of its scale or the wealth or sophistication of the species it includes, this artificial environment that we have built and that surrounds us everywhere can differ greatly in terms of quality, depending on whether the elements are well or poorly positioned: the presence of shade where it is needed, discreetly perceptible fragrances, or species well-adjusted to the available water.

I remember as a child admiring the simple vines in the yards of some houses, built with sewer pipes and without pretence other than to give shade and some fruit. Those yards were infinitely better than the patios of many houses, for the simple fact that one could stretch out in a hammock and nap in the shade of the vines and look through the leaves towards the light.

Juan Grimm has worked on and dominates all the scales. His work handles light and shadow, creates intimacy, establishes atmospheres, melts, mixes and amalgamates the pre-existing natural elements of the place, and/or its own features, with new, sometimes exotic ones. Together, they construct a new landscape characterized by balance, a fusion of planes and a softening of limits.

In one of Juan’s landscapes one cannot be sure where the intervention ends and the extrinsic begins, be it natural or artificial.

Juan takes control of the extrinsic and incorporates it, giving depth to places that lack it. One of the first lessons

lecciones que aprendí de él fue cuando me dijo que si tenía un jardín muy pequeño, lo que había que hacer era llenarlo de árboles muy cerca unos de otros y así se vería inmenso.

Juan trabaja desde jardines minúsculos hasta grandes urbanizaciones en contextos naturales urbanos y agrícolas.

Con Juan nos conocimos hace 25 años y, aunque nunca habíamos hablado, compartíamos una manera de entender y transformar los entornos.

Acaso una mezcla de intervencionismo respetuoso aunque generalmente radical, con el empeño puesto en que pareciera haber estado o haber sido así desde siempre.

Era pasar inadvertido, aparentar no aparentar. Construir lo adecuado pero no por mimesis, sino como el complemento que podía encajar bien en ese lugar y hacer de él un lugar mejor.

Esta afinidad, que en mi caso era algo netamente intuitiva, en el suyo correspondía a una elaboración reflexiva, basada en su experiencia como arquitecto, en su admiración y conocimiento de Burle Marx, Oscar Prager, en el trabajo de otros arquitectos y en su tránsito desde la arquitectura hacia el paisaje.

De niño, siendo Boy Scout, al llegar a dirigir a su patrulla se dio cuenta de que el orden espacial de los elementos le obsesionaba, y que lo suyo era proyectar el espacio habitable, lo que quedó de manifiesto una vez tuvo que ausentarse del campamento mientras lo montaban y al regresar hizo desarmar y volver a armar todo, ya que no estaba construido de acuerdo a sus instrucciones…

Desde entonces hasta ahora, el trabajo de Juan ha sido profundamente rotundo y marcado por su manera de hacer las cosas.

Juan busca una y otra vez reproducir una secuencia de planos que se van fundiendo, tal como lo hacen nuestras cordilleras, especialmente cuando las miramos desde lo alto de sur a norte, cuando sucesivas escalas de grises las van diluyendo una tras otra.

Generalmente Juan parte con un entorno inmediato con planos y niveles más bien cartesianos y abstractos, para luego ir deconstruyendo la geometría e invadiéndola con una naturaleza que irrumpe y recupera el terreno cedido, así como

I learned from him was when he told me that if he had a very small garden, what he would do was fill it with trees very close to one another and it would look immense.

Juan’s work ranges from miniscule gardens to large urbanizations in natural, urban, and agricultural contexts.

Juan and I met twenty-five years ago, and although we had never spoken we shared a way of understanding and transforming environments. It was a mixture of respectful but generally radical interventionism, with a determination to make a space appear to have always been like we changed it to be. The idea was to go unnoticed, to appear not to appear. To build the right thing not by mimesis, but as the complement that could fit well in that place and make that place a better place.

This affinity, which in my case was purely intuitive, in him responded to reasoning, based on his experience as an architect, his admiration for and knowledge of Burle Marx, Oscar Prager, the work of other architects, and his transition from architecture to landscape.

As a boy, when as a boy scout, when he came to lead his patrol, he realized that the spatial arrangement of the elements obsessed him, and that his thing was to plan the camp as a living space. This compulsion became clear one day when he had to leave the camp while they were still building it, and when he returned made them dismantle and re-assemble everything since it was not built according to his instructions…

From then until now, Juan's work has been quite absolute and stamped by his way of doing things.

Juan tries again and again to reproduce a sequence of merging planes, just like our mountain ranges when we look at them from a summit from south to north and see their successively paler shades of gray reaching into the far distance.

Generally, Juan starts with an immediate environment using quite Cartesian and abstract planes and levels and then goes about deconstructing the geometry and invading it with a nature that bursts in and takes over the yielded land, just as the waves at the sea’s edge advance on the sand as the tide rises.

Faced by the natural environment, Juan operates in the vicinity, proposing a complement where man’s rationality

las olas en la orilla del mar avanzan por la arena en la medida que la marea sube.

Frente al entorno natural, Juan propone en la cercanía el complemento donde la racionalidad del hombre determina y enmarca unos límites cuya función no es otra que la de dar escala, mientras que en el fondo busca una y otra vez la fusión, sin importar si está trabajando entre medianeras con 9 metros de fondo o en la Patagonia con un horizonte infinito.

Nada en su propuesta no está deliberadamente medido, estudiado y previsto. Sus obras se caracterizan por la precisión. Cada trazo y cada especie, cada color y cada textura, tienen un momento y un papel que jugar.

Ama a Burle Marx y rebate las ideas de Gilles Clement, aunque su propuesta está mucho más cercana a este último, sobre todo en sus trabajos más íntimos, donde con emoción señala aquellos lugares donde la naturaleza ha brotado de manera espontánea y comienza poco a poco a colonizar y fundirse con su propuesta, de una manera no programada.

Juan trabaja la topografía la profundidad, con una clara noción de la perspectiva. Él va abriendo y cerrando planos, apropiándose de lo suyo y de lo ajeno en una búsqueda persistente de la profundidad y la continuidad. Su conocimiento de las especies nativas y exóticas dotan a sus obras de una riqueza que se sostiene entre otras cosas por utilizar una siempre muy limitada paleta de especies, tal como sucede en nuestro paisaje natural.

Juan es esencialmente un paisajista del paisaje chileno, y como tal ha sido y es el referente que ha tenido nuestra generación, los que bien o mal han desarrollado sus propuestas fuertemente influidos por su trabajo.

De niño, Juan tuvo una pesadilla recurrente en donde veía como se derrumbaba el muro del fondo del jardín su casa materna y aparecía por unos instantes un hermoso paisaje, profundo hasta el horizonte, el que luego volvía a desaparecer con la reconstitución del muro (una especie de jardín del Gigante Egoísta al revés).

Desde entonces Juan es el paisajista que recrea nuestro horizonte sin horizonte una y otra vez y que quiere traer la cordillera al patio de nuestra casa, así como lo hizo Prager en el Parque Providencia.

determines and frames certain limits, the function of which is none other than to give scale, while in the background time and again he seeks fusion, irrespective of whether he is working between nine meter-wide party walls or in the Patagonia with an infinite horizon.

There is nothing in his proposal that he has not deliberately measured, studied and foreseen. Precision characterizes his work. Each stroke and each species, each color and each texture, have their moment and a role to play.

He loves Burle Marx and rebuts the ideas of Gilles Clement, although his proposal is much closer to the latter, above all in his most intimate works, in which he points with feeling to those places where nature has burgeoned spontaneously and begins gradually to colonize and merge with his proposal, in an unplanned way.

Juan works with topography and depth, with a clear notion of perspective. He opens and closes planes, takes control of what he has and what is extrinsic in a persistent search for depth and continuity. His knowledge of native and exotic species endows his works with a wealth that is sustained, among other things, by the constant use of a very limited palette of species, as in our natural landscape.

Juan is essentially an artist of the Chilean landscape, and as such he has been and remains the reference of our generation, who have developed their proposals, successfully or otherwise, strongly influenced by his work.

As a child, Juan had a recurring nightmare in which he saw the back wall of the garden of his mother’s house collapse, revealing for a moment a beautiful landscape stretching to the horizon, which he then saw disappear again when the wall was rebuilt (a kind of Selfish Giant’s garden in reverse).

Since then, Juan has been the landscape designer who recreates our horizon without horizon again and again, and who wants to bring the Andean mountain range into the patio of our homes, just as Prager did in Providencia park.

Los jardines son conversaciones con la naturaleza. Pero también conversaciones con uno mismo. Se trata de mirar a través de la niebla mental, buscando una visión más clara de lo que existe. Y a la inversa, se trata de una difusión, por la cual lo diferenciado se mezcla hasta volverse borroso.

Son actos deliberados de autoconsciencia.

Teatros de poder, de piedad, de placer, de religión o de imágenes del paraíso, a través del tiempo y el lugar, han visto muchas representaciones. Hábilmente sustentados por un escenario de disposiciones espaciales, tierra que respira y que crea el suelo, sobre el cual los diversos estados de ánimo del agua y las diversas plantas se desarrollan en el tiempo y las estaciones cambiantes.

En oposición al calor despiadado y la arena, jardines frescos entre paredes húmedas; como suplico a la naturaleza, una manera codificada de recrearla; en tierras generosas, abrazando u ordenando la naturaleza de manera que el jardín se convierta en un atalaya desde cuya altura contemplar el mundo.

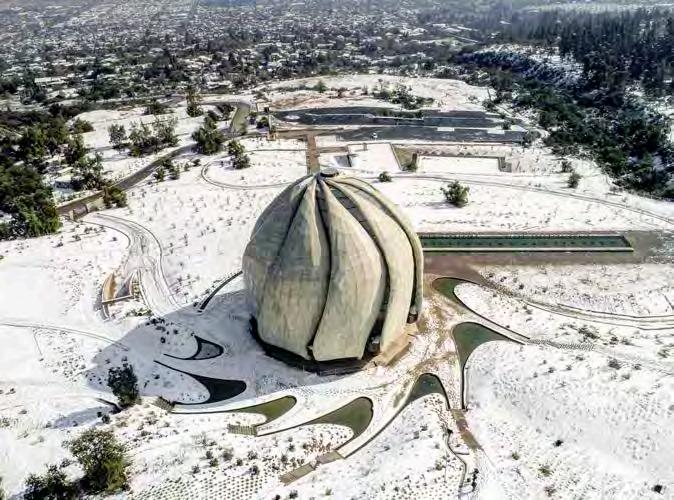

En una historia que ha atravesado el mundo y el tiempo, los jardines de Juan Grimm son un manuscrito que requiere muchos niveles de decodificación para revelar su significado.

El nivel inmediato y evidente revela unos jardines realizados con gran habilidad y una profunda empatía con y un gran conocimiento de las plantas.

Su tierra natal, una fina cinta trenzada, ofrece una naturaleza que es exagerada, irrealistamente conmovedora e increíblemente variada. Según su propio reconocimiento, esa es su inspiración y no necesita ningún otro estímulo.

Gardens are constructed conversations with nature and yet soliloquies with oneself. They are also about peering through a mental haze looking for a vision clearer than the reality. And conversely, they are about diffusion, wherein distinctiveness blurs to obscurity.

They are deliberate, self-conscious acts.

Theaters of power, piety, pleasure, religion or images of paradise, through time and place, they have seen many enactments. Ably supported by a stage of spatial arrangements, land that breathes and creates the base upon which many moods of water and plants perform in time and changing seasons.

In rejection of merciless heat and sand, cool and moist walled gardens; in supplication to nature, a codified way of recreating it; in lands of generous nature, embracing it, or ordering it so that the garden becomes a perch from which to survey the world.

In a history that has spanned the world and time, Juan Grimm's gardens are a palimpsest that requires many layers of decoding to reveal their meaning.

The immediate and apparent reveals gardens crafted with great skill and a deep empathy for and knowledge of plants. The braided thin ribbon that is his land, offers nature that is exaggerated, unrealistically poignant and incomprehensibly varied. By his own admission, it is his inspiration and he needs no other stimuli.

While this alone puts his work amongst those of distinction, it hardly explains it.

Aunque de por sí esto coloca su obra entre las más singulares, difícilmente la explica.

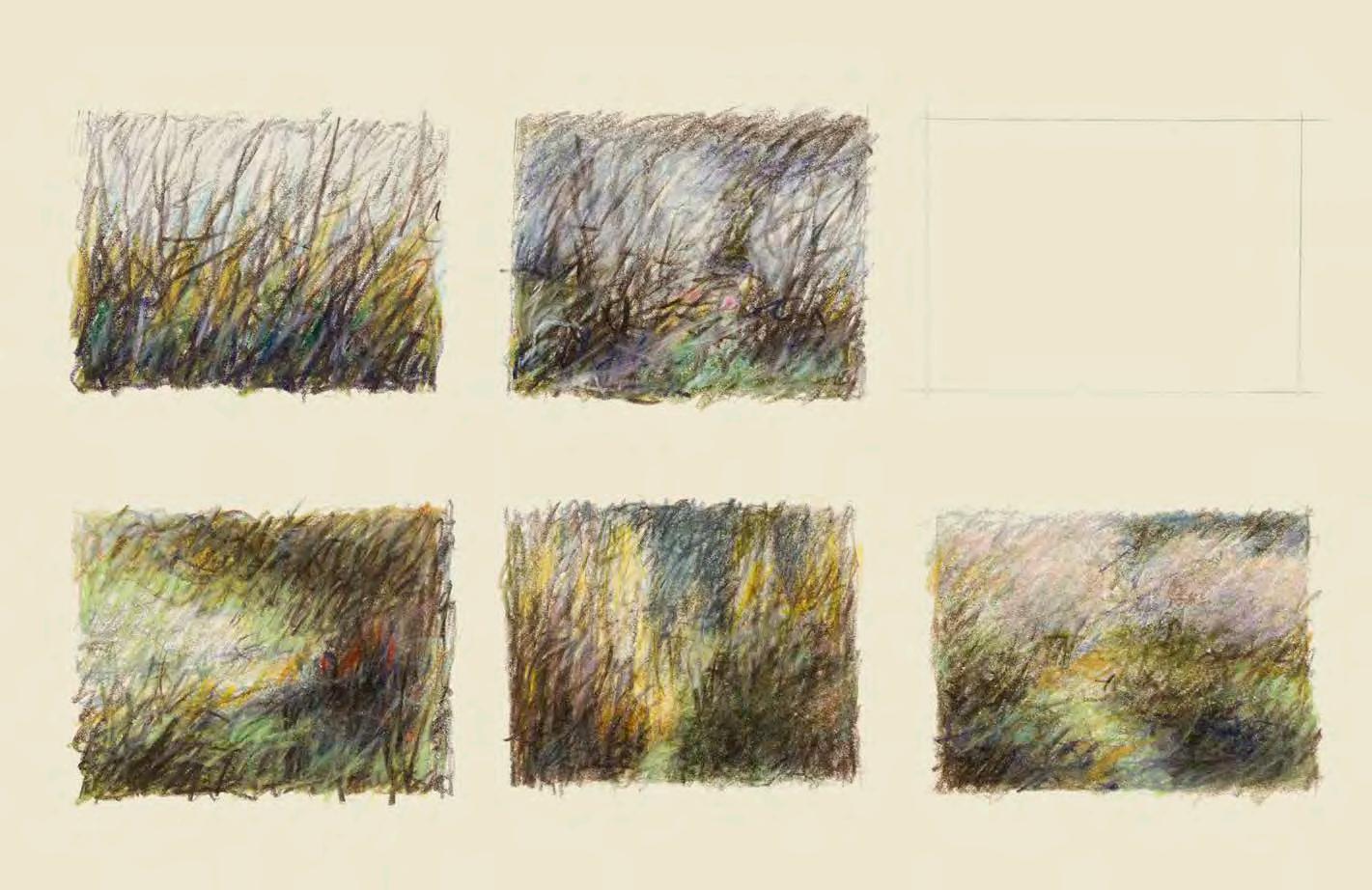

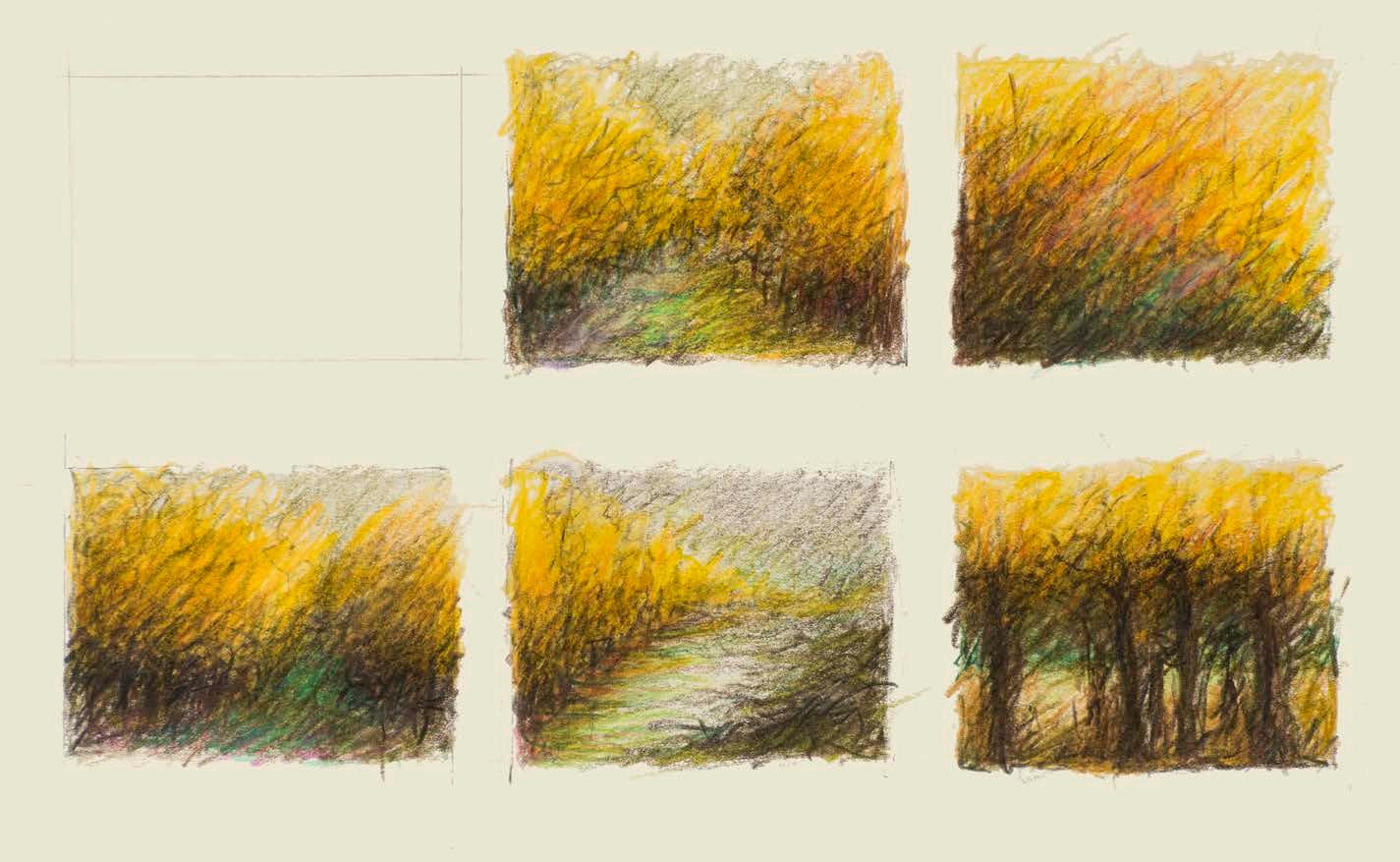

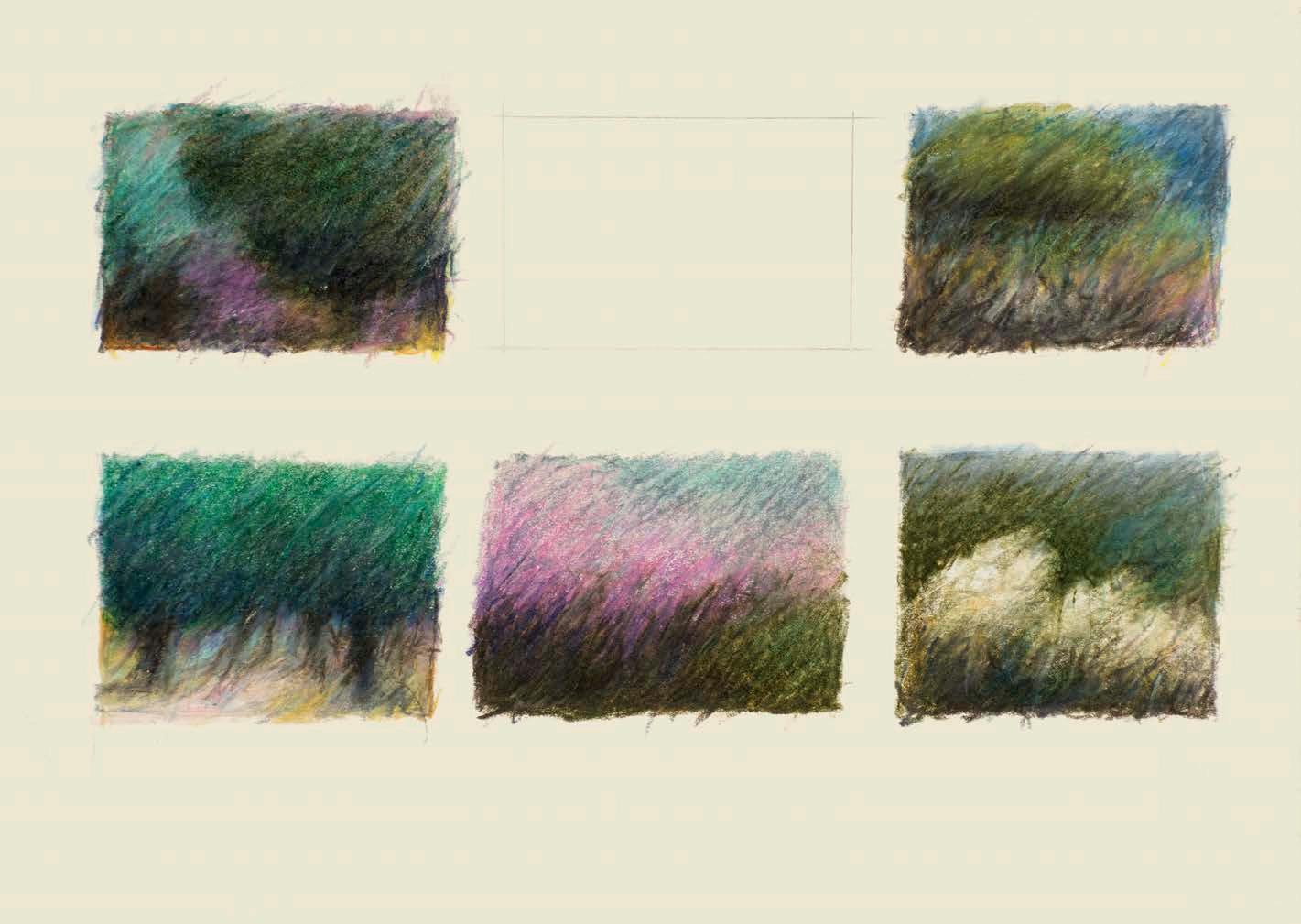

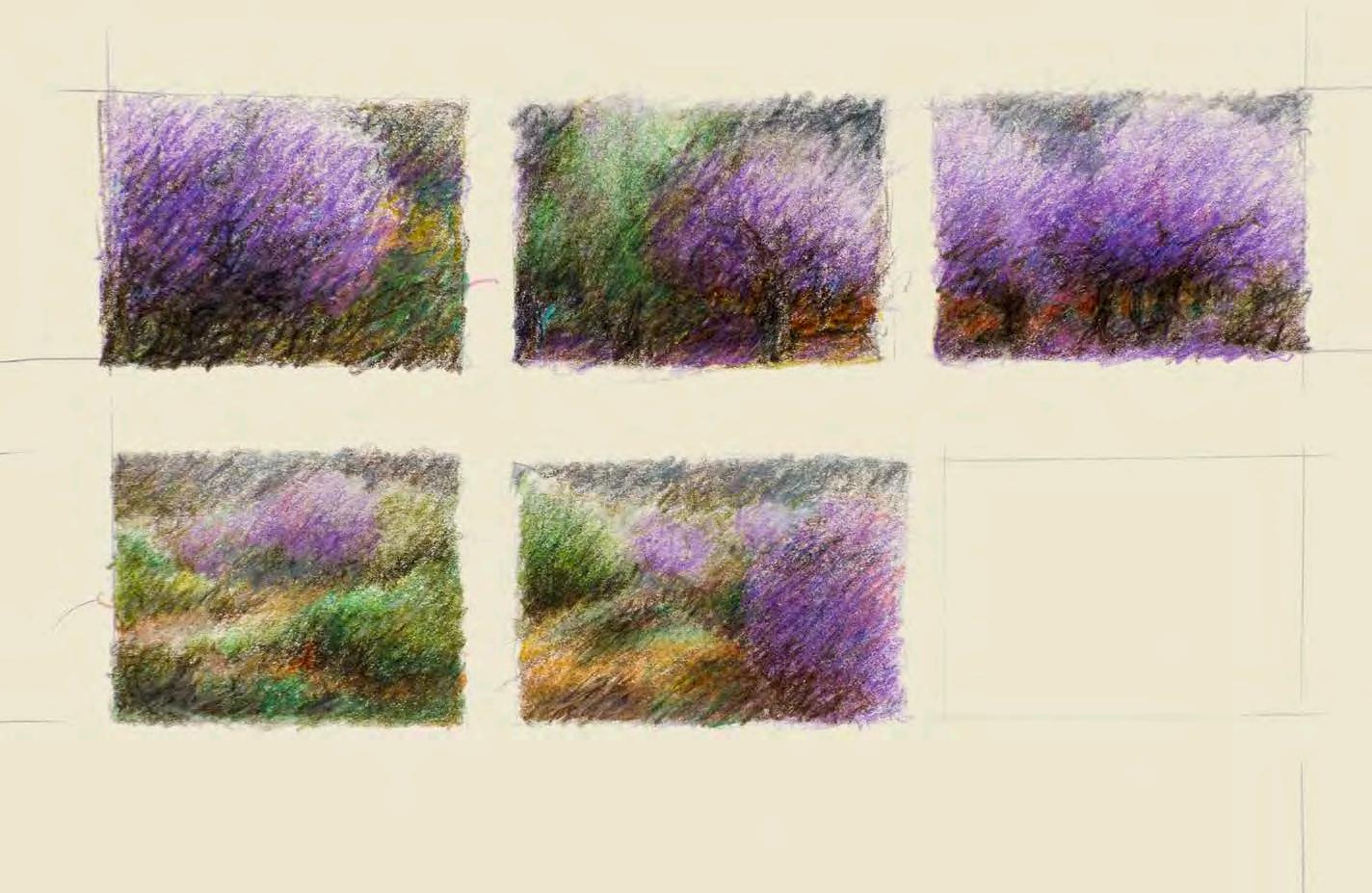

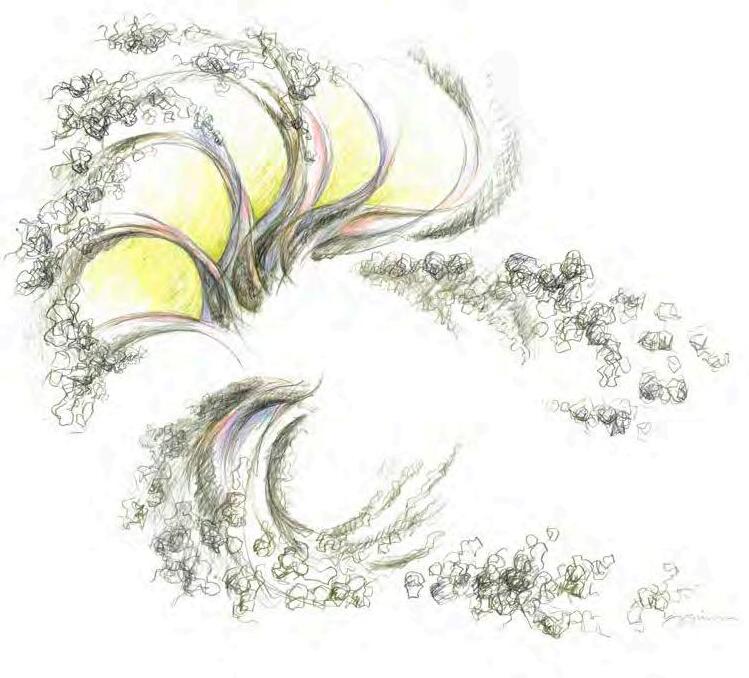

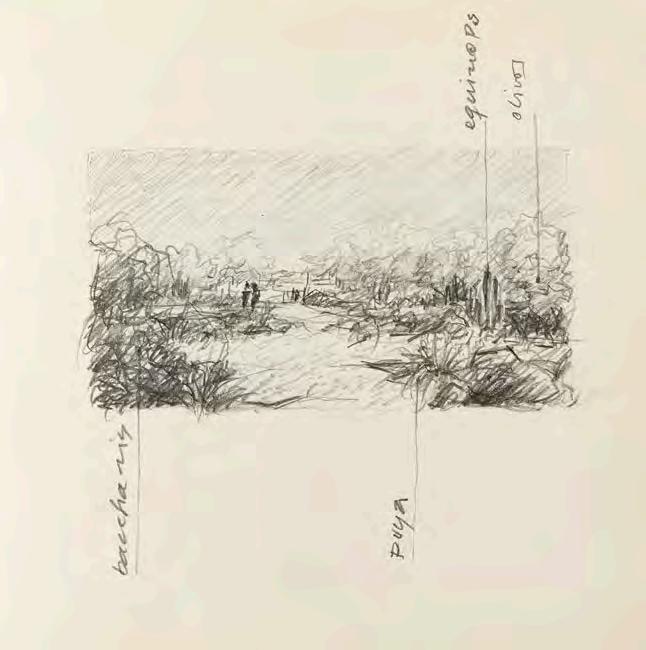

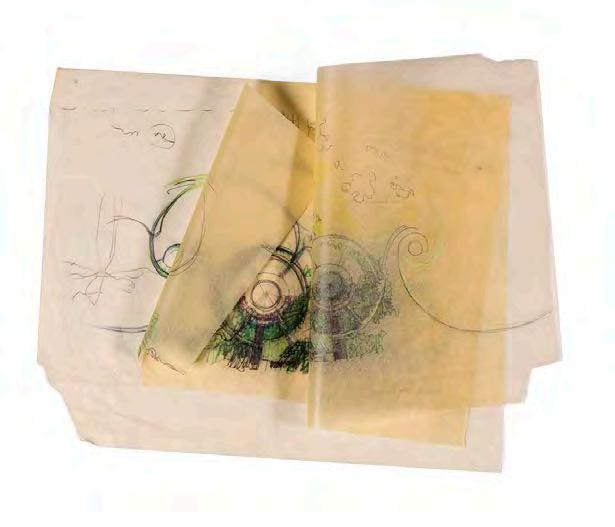

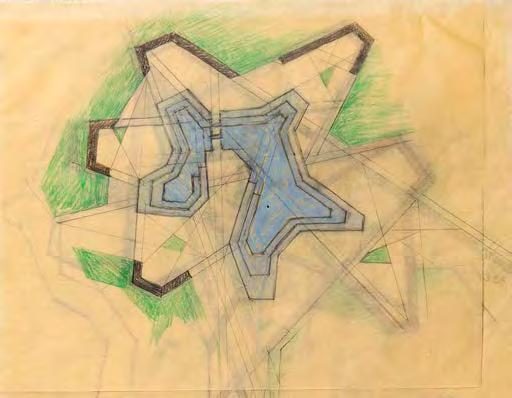

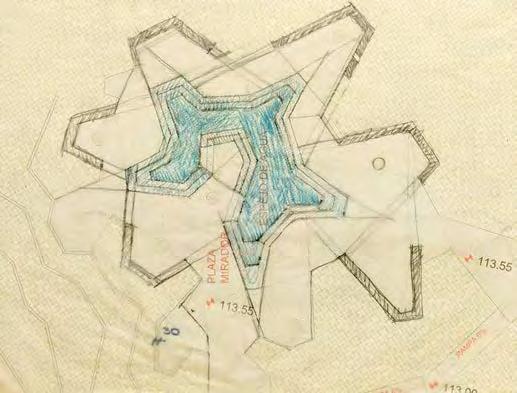

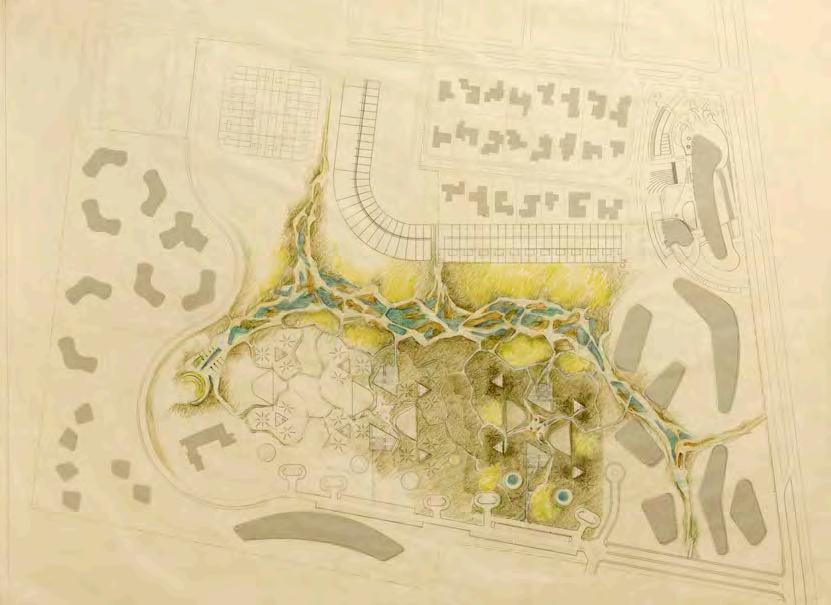

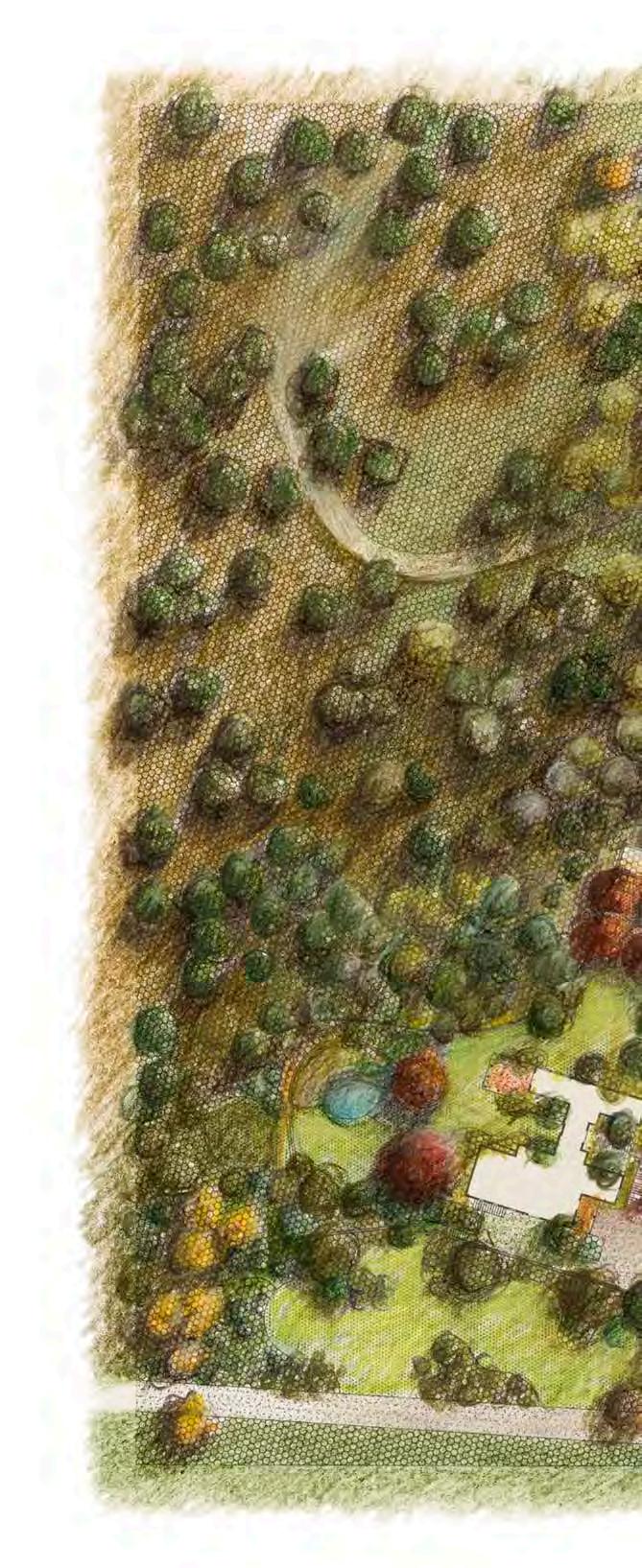

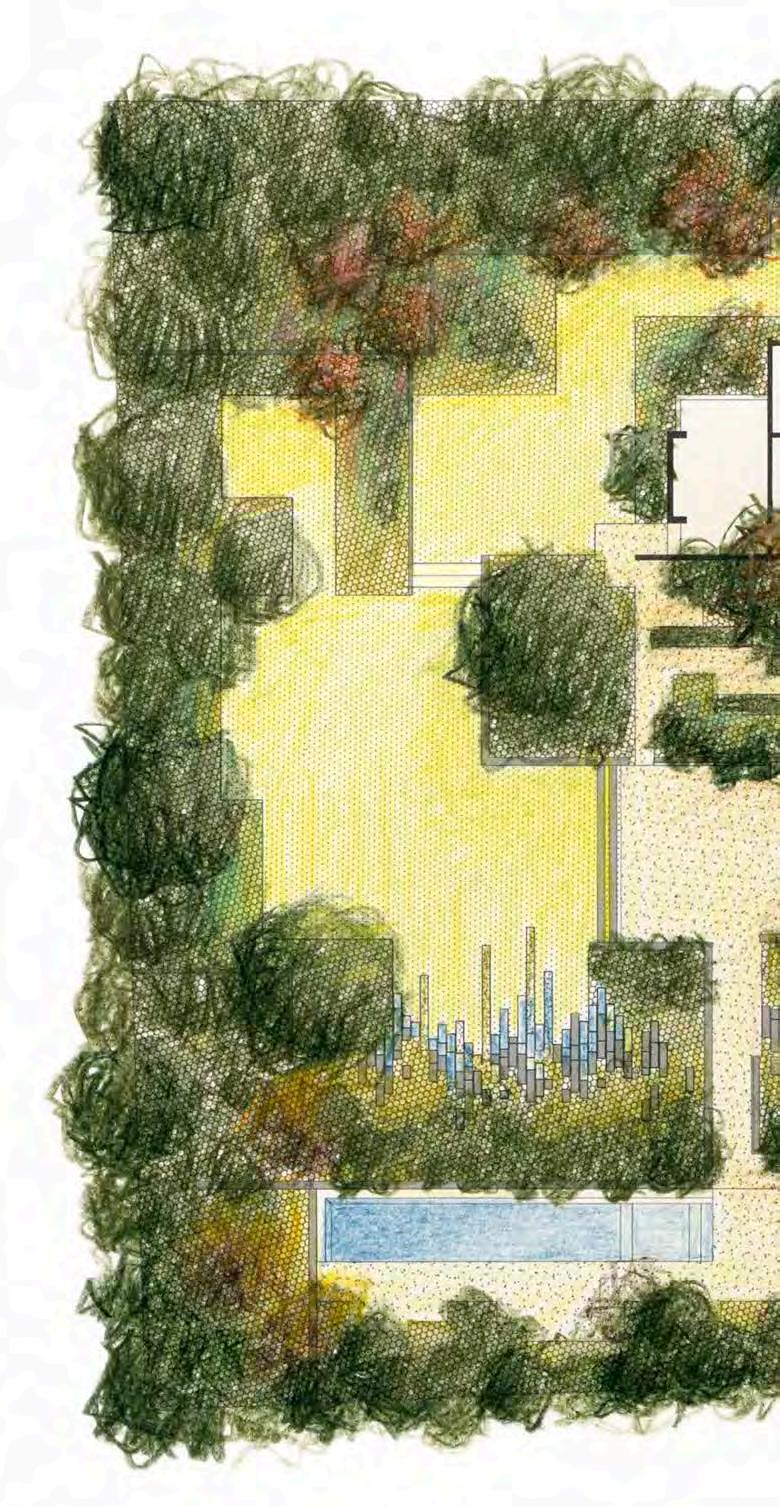

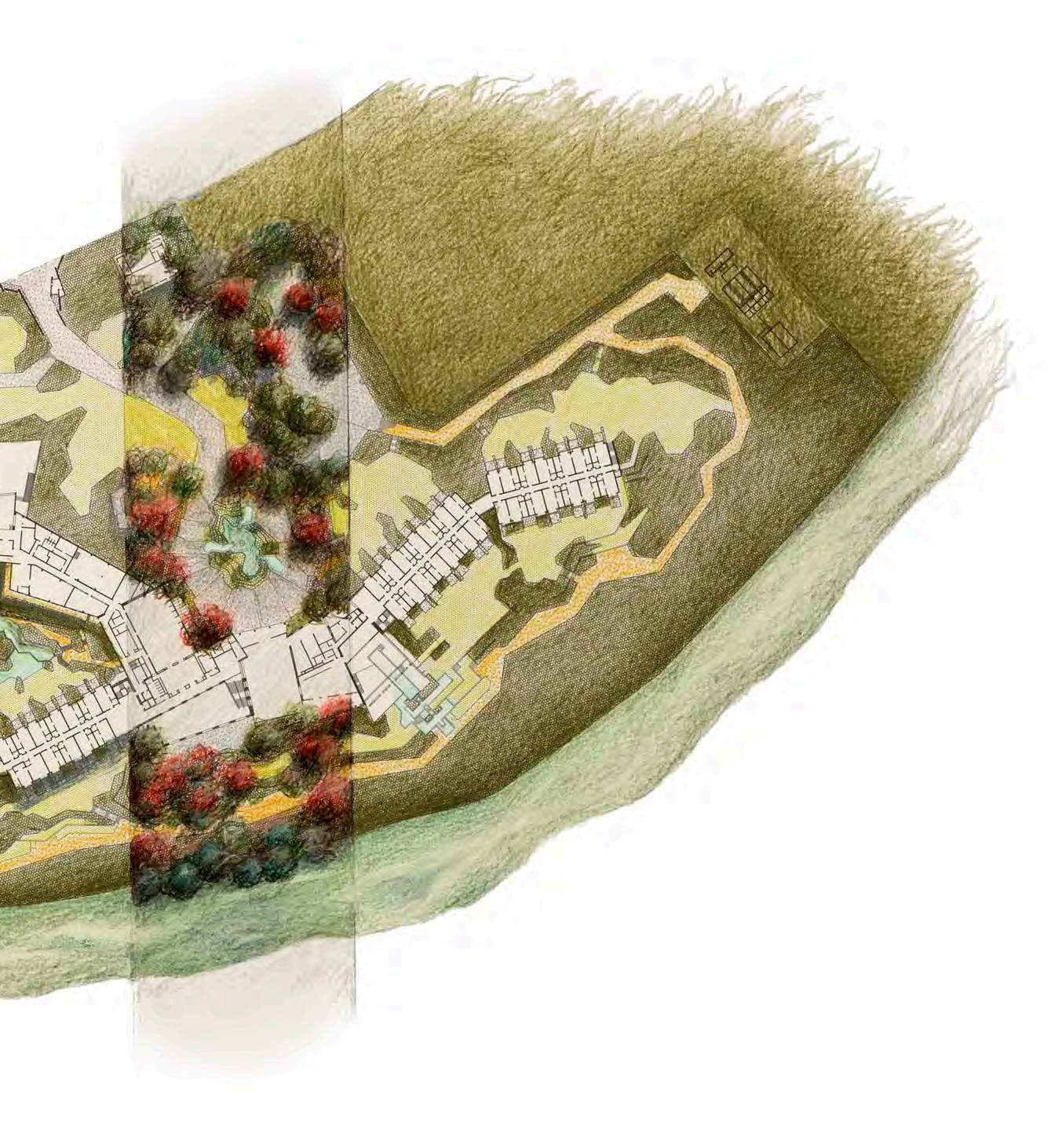

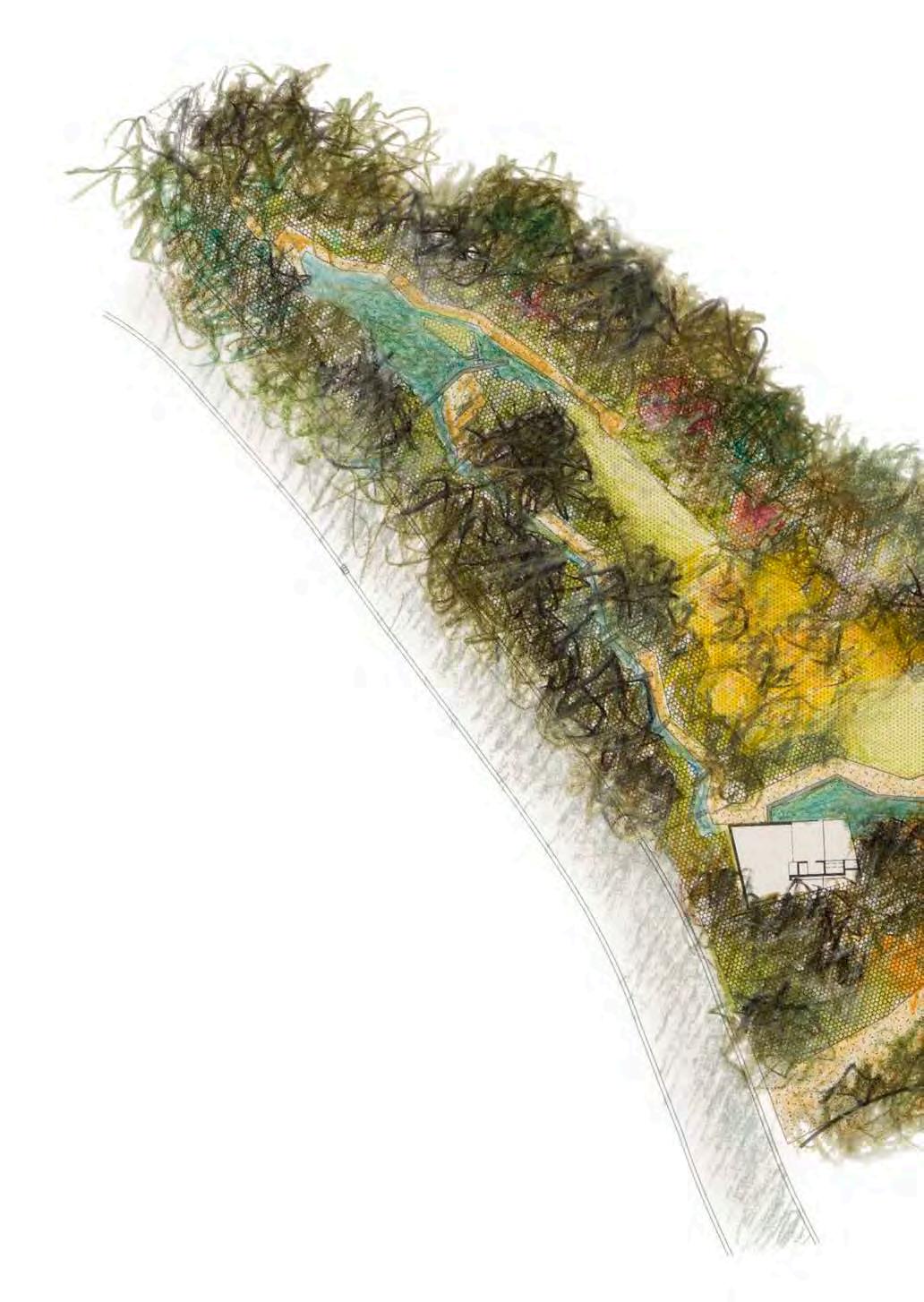

Un estudio de los planos que dibuja Grimm revela una mente de pintor, que redacta un manual incrustado de recordatorios y significados.

Lo que revelan esos planos no es otra cosa que una amplia e intuitiva formación del espacio. De hecho son mapas empíricos, hechos con marcadores indelebles que acaso solo él puede usar para ordenar sus pensamientos. Así mantiene en su sitio las relaciones mayores, a fin de poder esculpir la tierra con el ojo de un artista que trabaja en miniatura.

Nada en los planos revela la estructura de una corporeidad real.

Compáralo con los delicados tapices de Gertrude Jekyll, en donde el refinamiento del resultado se puede anticipar.

Además, estos jardines son imposibles de percibir en su totalidad.

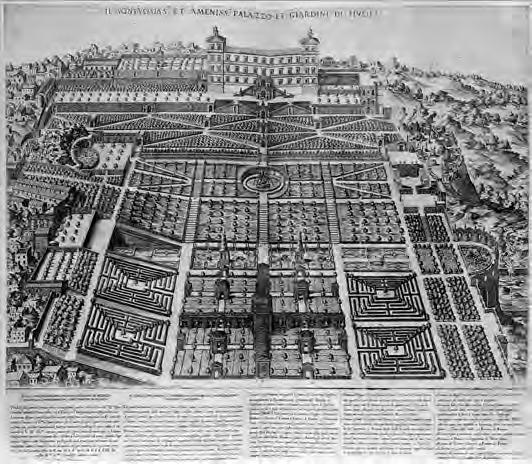

El grabado de Étienne Dupérac para la Villa d’Este, en Tivoli, le permite a la mente imaginar su estructura y su cuerpo; aunque no plasma las colinas sobre las cuales se ubica, aún así capta la esencia del relato.

La obra de Grimm desafía esa representación de la construcción mental.

Sus jardines son espacios cuidadosamente orquestados con final abierto, donde las fronteras están definidas por el cielo, el océano y las montañas. Y a diferencia de los jardines clásicos, donde era la composición lo que se hallaba invariablemente en foco, su obra no se completa sin la naturaleza extendida (a pesar de la innegable belleza natural de su tierra, que normalmente debería bastar para bajarle los humos a la mano del hombre), y es detallada, claramente delineada y llena de una deslumbrante belleza al mismo tiempo sensual, vana y nostálgica, inquebrantable en su propósito de no ser domesticada por su más amplio lienzo. Esto merece cierto debate.

En presencia de marcos de belleza natural, históricamente los jardines han ordenado a la naturaleza y han creado una disposición interna, de la cual el resultante contraste suscita diálogo.

A study of the plans he draws reveals a painter’s mind, drawing up a manual embedded with reminders and meanings.

These are not plans that reveal anything but a broad intuitive formation of the space and are in fact empirical charts with indelible markers that perhaps only he can use to order his thoughts. He thus keeps the bigger relations in place so that he can chisel away at land with the eye of a miniature artist.

Nothing in the plans reveals the construct of the actual physicality.

Contrast this with Gertrude Jekyll’s delicate tapestry, where the refinement of the outcome is somewhat anticipated.

These gardens are also impossible to perceive in their entirety. Étienne Dupérac’s engraving for Villa d'Este at Tivoli allows the mind to imagine its structure and body; while it does not capture the hills on which it sits, it still captures the essence of the narrative.

Grimm's work, in contrast, defies such a capture of mental construction.

His gardens are carefully orchestrated open-ended spaces where boundaries are defined by the sky, ocean and mountains. And unlike classical gardens where composition was the unwavering focus, his work is incomplete without the extended nature, (despite the undeniable natural beauty of his land which should normally be sufficient to humble the hand of man) and is detailed, sharply crafted and full of startling beauty that is sensuous, vain and wistful at the same time, unflinching in its resolve not to be tamed by its larger canvas.

This deserves some discussion.

In the presence of natural settings of beauty, gardens historically have ordered nature and created a setting from within, in which the contrast kindles dialogue. No garden perhaps does it as well as the Nishat Bagh in Kashmir.

Or, on the other hand, inspired by Lorrain and Poussin, the gardens of Kent, Brown and Repton, attempted to merge and disguise their hand and assume a subterfuge that does not reveal the human intervention.

Acaso ningún jardín lo hace tan bien como el de Nishat Bagh en Kashmir.

O bien, en el otro extremo, los jardines de Kent, Brown y Repton, inspirados por Lorrain y Pousin, intentaron mezclar y disfrazar su intervención, asumiendo un subterfugio que no develara la mano humana.

Los jardines de Grimm no hacen ni lo uno ni lo otro. Y tal vez sea por eso que Grimm se cuenta entre los pocos que han abierto un camino único. Pues no elige ni un lenguaje de contradicción, ni de contemporización, ni de servilismo, sino uno de tempestuoso desafío.

Acaso sus jardines intentan capturar el espíritu inesperado e impetuoso de una tierra dotada de volcanes, que en cualquier momento pueden hacer erupción resplandeciente.

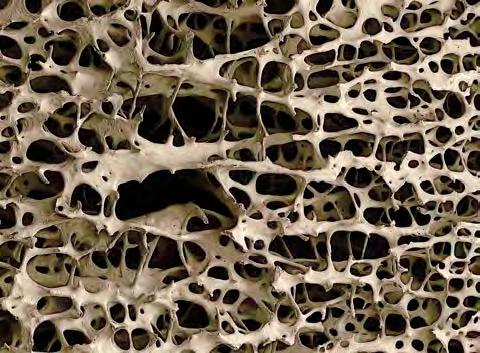

Un espectáculo de la naturaleza que requiere una mirada no advertida. La maliciosa singularidad está pixelada de belleza fractal.

Vale la pena mencionar la obra de Roberto Burle Marx que en una tierra infinitamente más amplia, pero con habitantes naturales similares y separada por una generación debe proyectar su sombra sobre el campo de Grimm.

Grimm's gardens do neither. And perhaps this is where he is among the few who have set a path that is unique. For he neither chooses a language of contradiction nor of appeasement, nor of servility, but one of tempestuous challenge.

His gardens seek to capture the unexpected impetuous spirit of a land dotted with volcanoes that can burst in a dazzling spectacle anytime.

A spectacle of nature that demands that the gaze is not averted, and the disingenuous singularity is pixilated with fractal beauty.

It bears mentioning that, in a land infinitely larger than Grimm's country but with similar natural habitats and separated by a generation, Roberto Burle Marx's shadow must be large.

No doubt Grimm is influenced by his work, and yet in many ways, he chooses to take a path that is almost antithetical.

Whereas Marx’s work is that of a masterful painter, Grimm's is that of a master perfumer, one who can distill nature, and arrange it in ways where the scent, distinct in parts, blends along the boundaries and, in doing so, presents a memory that colludes with the original source.

Sin duda Grimm ha influido por su obra. Y sin embargo, en muchos sentidos, él elige tomar un camino que es casi una antítesis.

Mientras que la obra de Marx es la de un pintor experto, la de Grimm es la de un maestro perfumero que puede destilar naturaleza y disponerla de manera tal que el aroma, diferenciado por sectores, se mezcla a lo largo de los límites; y en consonancia con ello, presenta una memoria que conspira con la fuente original.

Y utiliza una geometría reconocible. En parcelas pequeñas, casi con timidez. Aparentemente, porque el entorno no le permitía condensar o porque la mano del hombre era inevitable, de manera que no había muchas maneras de distribuirlo. En niveles, en estanques de agua que pronto parecen querer encontrar su estado natural.

Unos 200 años atrás, Repton esbozó los principios del paisajismo.

“La perfección del paisajismo consiste en los cuatro requisitos siguientes. Primero, debe desplegar las bellezas naturales y esconder los defectos de cada locación. Segundo, debe dar la apariencia de extensión y libertad, disfrazando o escondiendo cuidadosamente los límites. Tercero, debe ocultar de manera estudiada cada interferencia del arte. Cuarto, todos los objetos de mera conveniencia o confort, si no pueden volverse ornamentales o convertirse en partes apropiadas del paisaje general, deben ser removidos u ocultados”.

La belleza precisa de los jardines de Grimm, donde realiza sin ningún esfuerzo las máximas de Repton, oculta su verdadera relevancia.

Lo que este diseñador persigue en pleno siglo XXI, es utilizar el jardín como un lugar para contar relatos sociales y culturales; o utilizarlos como un espejo con el cual se puede visualizar el estado de nuestro planeta, su naturaleza y su vida urbana. Grimm elige una estrategia seminal y perdurable. Simplemente extrae lo mejor de la naturaleza y sostiene una lupa delante. Así, hace imposible no recordar nuestras pérdidas y nuestra nostalgia. Al hacerlo, apela a nuestra afinidad, genéticamente asentada, por las ecologías naturales que alimentan al planeta.

He also uses recognizable geometry. In small parts�almost diffidently. Seemingly because the setting did not allow him to distill naturally or the hand of man was inevitable, so that there was little way to dispense it. In steps, in pools of water that quickly seem to want to find their natural state.

About two hundred years ago, Repton outlined the principles of landscape gardening.

“The perfection of landscape gardening consists in the four following requisites. First, it must display the natural beauties and hide the defects of every situation. Secondly, it should give the appearance of extent and freedom by carefully disguising or hiding the boundary. Thirdly it must studiously conceal every interference of art. Fourthly, all objects of mere convenience or comfort, if incapable of being made ornamental, or of becoming proper parts of the general scenery, must be removed or concealed.”

The precise beauty of Grimm's gardens where he achieves Repton's maxims effortlessly conceals their real import.

The designer’s pursuit in the 21st Century is to use the garden as a place to recount social or cultural narratives; or use them as a mirror with which to view the state of our planet, its nature and its urbanity.

Grimm chooses a seminal and an enduring device. He simply extracts the best of nature and holds a magnifying glass to it, and makes it impossible for us to not be reminded of our loss and our nostalgia; and in doing so he appeals to our genetically embedded affinity for the natural ecologies that nourish the planet.

Juan Grimm Moroni nació en la ciudad de Santiago en abril de 1952, en una familia tradicional donde primaba el sentido del orden y la responsabilidad.

Durante los veranos, los Grimm Moroni se instalaban en la costa, costumbre que despertó desde temprano el interés de Juan, el segundo de siete hermanos, por el mundo natural.

Los veraneos de mi niñez fueron importantes y marcadores. Bajábamos a la orilla del mar y yo, en vez de jugar a la pelota con mis hermanos, me escapaba a caminar por la playa Aguas Blancas, en Maitencillo. Ahí me gustaba mirar los pájaros, las rocas, el mar. Fue durante esas largas temporadas de verano que empecé a prestar atención, a fascinarme con los espacios infinitos del cielo y el mar.

Estas vivencias dieron pie a mi gusto por armar lugares protegidos y con vistas lejanas. Recuerdo que había un boldo enorme que me encantaba visitar: me metía debajo y experimentaba esa sensación de ver sin ser visto.

También íbamos ocasionalmente al campo y andábamos a caballo. De muy niño me familiaricé con los huertos. Las tardes de juego con mis hermanos son inolvidables: construíamos pequeñas ciudadelas con caminos de barro para autitos y camiones, donde yo exigía ser el único encargado de construir las plazas y los jardines.

Juan Grimm Moroni was born in Santiago, Chile, in April 1952 into a family where a sense of order and responsibility was central to the household.

The Grimm Moronis would spend summers on the coast, and it was thanks to that family tradition that, from a young age, Juan�the second of seven children�took an interest in nature.

My summers as a child were important, and they left a permanent mark on me. We would go down to the beach and, while my siblings kicked a ball around, I would go off by myself, walking down the Aguas Blancas beach in Maitencillo. I used to enjoy looking at the birds, the rocks, the sea. It was during those long summers that I first started to take notice of the vast sea and sky that have fascinated me ever since. Those experiences paved the way for my pleasure in putting together sheltered places with views into the distance. I remember that there was an enormous boldo tree that I used to love to go see: I would sit under it and revel in that sensation of seeing without being seen.

We would also go to the countryside on occasion, where we would ride horses. As a young boy, I learned a fair amount about vegetable gardens. The afternoons I spent playing with my brothers and sisters are unforgettable: we would build small

Recuerdo las visitas a las casas de mis tíos, los enormes árboles añosos, los extensos jardines y los espejos de agua bajo los cedros, espacios alucinantes para mí.

De la infancia también recuerda una pesadilla nocturna bastante especial:

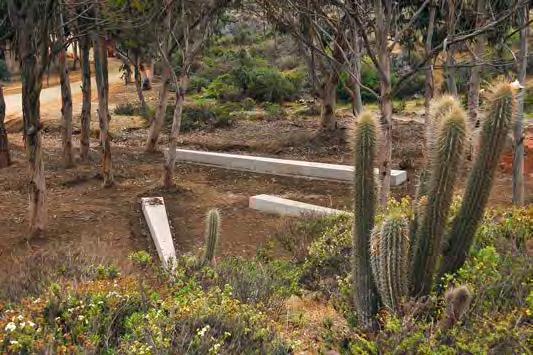

Me encontraba en la terraza de un dormitorio ubicado en la casa de mis padres, frente a un estrecho jardín que me separaba del muro medianero. De pronto, súbitamente, la pared se derrumbaba, lo que me permitía extender la vista hasta el mar y el horizonte. Sin embargo, momentos después, el muro se cerraba y solo quedaba un pequeño cerro de tierra con algunos cactus encima. Como telón de fondo se veía el muro de ladrillo fiscal emboquillado con mortero. Había desaparecido de golpe esa magnífica imagen del océano azul grisáceo y brillante, había desaparecido el infinito. Hoy me asombro de lo que sucedía en ese sueño, debido al fuerte vínculo que tiene con algunos conceptos que, años más tarde, serían fundamentales al momento de estructurar un jardín.

cities with mud roads for cars and trucks. I insisted on taking full charge of constructing the plazas and gardens.

I remember the visits to my aunts and uncles’ homes with their enormous age-old cedar trees, large gardens, and reflecting pools I was dazzled by those places.

From his childhood, he also remembers, however, a strange nightmare:

I was in a large balcony off a bedroom at my parent’s house, one that opened onto a narrow stretch of yard before the party wall with the house next door. Suddenly, that wall collapsed, allowing me look out into the horizon as far as the sea. Then the wall turned into a small mound of dirt with some cacti growing out. In the background there was an old brick wall. That magnificent image of shimmering gray-blue ocean had vanished suddenly, as had the sense of endlessness. Even today I am astonished by what happened in that dream, since it is closely tied to some of the ideas that, years later, would be crucial to how I structure a garden.

Una vez terminada la educación escolar, Grimm ingresó a Arquitectura en la Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (PUCV), donde permaneció dos años. A pesar del poco tiempo, la vivencia fue memorable, puesto que las enseñanzas del oficio estaban relacionadas con el arte, la poesía, la escultura, el diseño, e incluso con la música y la danza.

Los profesores de la PUCV tenían un modo particular de enfrentar la enseñanza: exigían que los proyectos que presentaban los estudiantes nacieran de la observación directa de la ciudad y del paisaje, a través de dibujos, croquis y escritos.

Todo surgía en la calle, nada era inventado. Este método nos obligaba a construir espacios de acuerdo a un proceso de investigación en terreno, procedimiento que por lo general se llevaba a cabo en caminatas por Valparaíso y Viña del Mar.

El primer objeto de intervención en el que trabajó Juan Grimm se inspiró en la geografía, en ese entorno particular y en la condición de miradores que muestran ambas ciudades. Sin tener conciencia de ello, Grimm había elaborado un proyecto de paisajismo.

Tras la experiencia en Valparaíso, Grimm se trasladó a Santiago a continuar la carrera en la Universidad Católica de Chile (UC).

Por aquellos años, Juan estableció amistades que tuvieron una fuerte influencia en su desarrollo profesional. Fue el caso del diseñador Marco Correa y el escenógrafo Sergio Zapata, con los cuales conoció nuevos mundos que abrieron su mirada a otras expresiones culturales y que lo hicieron percatarse de puntos de vista desconocidos.

Al mismo tiempo, Grimm se incorporó en calidad de dibujante a la oficina del reconocido arquitecto Horacio Acevedo. Allí se familiarizó con la obra de la Escuela de la Bauhaus y conoció el trabajo de Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe y Frank Lloyd Wright.

El ambiente que existía en la oficina, los amigos que la visitaban, la mirada estética de Acevedo, la prolijidad en la

After graduating from high school, Grimm began studying architecture at the Universidad Católica de Valparaíso (PUCV). Though he was enrolled for only two years, the experience proved memorable since the instruction there was tied to art, poetry, sculpture, design, and even music and dance.

The method used by the professors at the PUCV was unique. They required students to base their projects on direct observation of the city and of landscapes rendered in drawings, sketches, and notes.

It all came from what was happening in the street nothing was made up. That method meant that we had to build spaces on the basis of field work, of on-site research, mostly carried out during walks in Valparaíso and Viña del Mar.

Juan Grimm’s first intervention was tied to geography, specifically to lookouts in both those cities. Unwittingly, he had developed a landscaping project.

After his brief studies in Valparaíso, Grimm moved to Santiago to further his education at the Universidad Católica de Chile (UC).

During those years, Juan developed friendships that would prove important to his career. He met, for instance, fashion designer Marco Correa and set designer Sergio Zapata, with whom he discovered new worlds and cultural expressions, as well as previously unknown perspectives.

He began working as a draftsman for celebrated architect Horacio Acevedo. It was at his firm that Grimm came into contact with the Bauhaus School and the work of Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

The atmosphere at Acevedo’s office, those who frequented it, Acevedo’s own vision, the professionalism with which he worked, his avant-garde approach to design and architecture, the physical premises themselves with their minimalist and modern style, along with Acevedo’s fascination

manera de trabajar, el vanguardismo en cuanto a diseño y arquitectura, la oficina en sí misma, que era de estilo minimalista y moderno, más la fascinación de Acevedo por la cultura y el arte japoneses, transformaron todos los parámetros estéticos que Grimm manejaba hasta entonces.

Conocí a Horacio Acevedo a través de su hijo Jaime, mi compañero de curso en Arquitectura. Horacio fue un gran arquitecto becado en Estados Unidos, en Japón y otros países , un hombre refinado y sensible, gran admirador de Mies van der Rohe. Él me regaló un libro de la Bauhaus firmado por Gropius, libro que para mí se convirtió en una auténtica joya. Pero lo más valioso que recibí de Horacio fue que aprendí a observar de un modo diferente. Horacio fue también la primera persona que me habló de jardines en una conversación. Me dijo algo que quedó grabado para siempre en mi memoria: “En el jardín no puedes poner nada de colores fuertes o de texturas grandes en primer plano, porque eso impide mirar a lo lejos; lo que se sitúa en el primer plano tiene que ser muy tenue”. Así era su propio jardín. Sin lugar a dudas que Horacio fue mi primer gran maestro.

Durante los últimos años de universidad, Grimm conoció a Esmée Cromie, una paisajista inglesa que impartía clases de Ecología y Medio Ambiente. Juan fue primero alumno y luego ayudante de Cromie, instancia que le permitió profundizar sus observaciones y apreciaciones de la naturaleza, ya no desde un punto de vista meramente intuitivo, sino desde una perspectiva más científica.

Esmée era una profesional que mantenía una postura firme ante el paisajismo y la relación con la ecología, una visión vanguardista para la época, que comprendía el papel que debía cumplir la arquitectura del paisaje en el cuidado y la conservación del planeta.

with Japanese culture and art, all conspired to utterly transform Grimm’s aesthetic criteria.

I met Horacio Acevedo through his son, Jaime, a classmate of mine at architecture school. Horacio was a great architect who had been awarded fellowships to study in the United States, Japan, as well as other countries. He was a refined and sensitive individual and a great admirer of Mies van der Rohe. One precious gift he gave me was a book on the Bauhaus signed by Gropius�a real gem. But the most valuable gift I got from him was how to observe things differently. Horacio was the first person to ever speak to me about gardens in the course of a conversation. One thing he told me is etched in my memory: “In a garden, you must never put anything with strident colors or textures in the front, because that keeps you from looking in the distance; what goes in foreground must be very subtle.” That’s what his own garden was like. Horacio was unquestionably my first mentor.

In his final years at university, Grimm met Esmée Cromie, an English landscape designer and professor of ecology. Juan was first her student and then her teaching assistant. Thanks to those experiences, he was able to deepen his observation and appreciation of nature, no longer guided solely by intuition, but also by science.

Esmée was a professional with a rigorous stance on landscape design and its relationship to ecology. Her vision was avant-garde for the time in that it understood the role that landscape architecture should play in taking care of and conserving the planet.

It was at this stage that Juan discovered Oscar Prager, who would become an important point of reference for him.

En esta etapa Juan descubrió a Oscar Prager, que pasó a convertirse en un referente muy importante para él.

La profesora Marta Viveros nos dio a conocer la obra de Oscar Prager. Debíamos hacer un ejercicio de levantamiento y estudio de un trabajo de Prager en Santiago, y me correspondió el jardín que realizó en la embajada de Inglaterra. Debo admitir que dicho jardín no me emocionó del todo, pues habían realizado intervenciones posteriores a su construcción original. Al enterarme de que una de sus obras era el Parque Providencia que yo visitaba desde niño , comencé a observarlo y a estudiarlo con dedicación. En ese parque largo y angosto, flanqueado por un par de avenidas importantes, Prager creó en los bordes dos masas vegetales relevantes, que conformaban un gran espacio central a modo de pradera y que enmarcaban visualmente la cordillera. En esa área jugaban los niños, se hacían picnics y se encumbraban volantines.

Prager dispuso de senderos para el paseo y el descanso en los espacios laterales bajo la sombra de los árboles, que fueron plantados siguiendo la misma formación y densidad con que se desarrollan espontáneamente en las quebradas de la zona central de Chile. Algunas especies nativas que aún subsisten en el parque son peumos, quillayes, bellotos, maitenes y boldos. También los exóticos alcornoques. Sin embargo, los arbustos que cerraban la vista por los costados, más varias especies de árboles caducos, han desaparecido. Ello ha significado perder parte del legado que nos dejó este gran paisajista.

En 1978 se llevó a cabo la II Bienal de Arquitectura. Allí, en el Concurso de Arquitectura Joven, Grimm compitió contra quinientos proyectos provenientes de todo Chile. El hecho de haber ganado el certamen fue crucial para posicionarse en el mundo profesional.

Marta Viveros, one of my professors, introduced my classmates and me to Oscar Prager’s work. One of our assignments was to make an in-depth study of a Prager project in Santiago, and I ended up with the garden he designed for the British Embassy. I have to admit that I was not all that taken with the garden there had been later interventions in the original design. When I learned that he had also designed the Parque Providencia, which I had frequented since I was a child, I started to examine it much more closely. At the edges of that long and narrow park flanked by two major avenues Prager had placed two large vegetable masses to shape a central meadow-like space that framed the view of the mountains. That was a space where children played, where people had picnics and flew kites. Prager put in trails and a rest area on the lateral spaces under the shade of trees planted in a formation and at a density that mirrored how they grew naturally in the ravines in central Chile. Among the native trees still found in the park are Chilean peumo, soap-bark tree, belloto, maitenes, boldos, as well as the exotic cork oaks. The bushes that narrowed the view from the sides and a number of species of seasonal trees have disappeared which means we have lost part of the legacy left by this great landscape designer.

In 1978, the II Bienal de Arquitectura was held and Grimm, along with five hundred others from around Chile, submitted a project to the Young Architects Competition. He won the contest, which did much to bolster his incipient career.

Once he had earned his degree, Grimm gradually veered toward landscape design; his approach was largely intuitive and he taught himself along the way. Early on, he taught a studio class in the Landscape Design Department at the Instituto Incacea and later at the Universidad de Chile.

Una vez titulado de arquitecto, Grimm se fue acercando al paisajismo guiado por la intuición y por cierto impulso autodidacta. Al principio, ejerció como profesor de taller en la carrera de Paisajismo en el Instituto Incacea y luego en la Universidad de Chile. La experiencia fue determinante para Juan, una forma de aprendizaje antes de realizar la mayoría de sus trabajos de diseño de los jardines. “Lo que hacía en ese entonces con los alumnos era buscar, a través de ejercicios plásticos y de observación, órdenes en la naturaleza y en los paisajes, para luego aplicarlos en un diseño personal o de grupo”.

Los ejercicios perseguían agudizar la percepción del espacio, para así llegar a comprender los volúmenes que lo integran, evitando ver el paisaje como si se tratase de una foto: “Un buen análisis de entorno exige mirar el espacio desde muchas perspectivas”. Para Grimm era vital inculcar la importancia de la libertad y la búsqueda de un lenguaje propio en la práctica del paisajismo. “No me interesaba que los alumnos memorizaran fórmulas ni siguieran al pie de la letra los patrones de estilos y modas imperantes, sino más bien que las propuestas se fundaran en ideas originales”.

En aquella época, Juan entabló una amistad profesional con Hans Muhr, que también era profesor en Incacea, amistad que se mantiene hasta hoy. “Cuando conocí a Juan haciendo clases de paisajismo , los dos éramos autodidactas. Hasta ese momento nuestra formación de arquitectos no incluía más que ciertos esbozos de lo que hoy podríamos considerar la disciplina del paisaje. En consecuencia, ambos nos sentíamos privilegiados por haber cultivado una importante capacidad de asombro ante la observación de la naturaleza”, recuerda Muhr.

Muhr y Grimm vislumbraron huellas a seguir en el camino señalado por Prager y en las propuestas avanzadas de Cromie. Se dieron cuenta de que la concepción basal del paisajista ha de consistir en entender el orden natural y primigenio, en asimilar sus lógicas, dinámicas y geometrías. “Aprender sin maestro y al mismo tiempo enseñar lo que íbamos descubriendo día a día agrega Muhr es un proceso que requiere de rigor y de una dedicación especial. Ese primer encuentro

That experience proved decisive for Juan as it provided him with instruction before he embarked on most of his work in garden design. “What I did with the students back then was to use visual exercises and exercises in observation to find an order in nature and in landscapes that we would later apply to individual or group design projects.”

The exercises were geared to honing perception of space in order to grasp the volumes that make it up, thus avoiding seeing the landscape as just a photograph. “A good analysis of the environment means looking at the space from many different perspectives.” In his teaching, Grimm was extremely concerned with conveying the importance of freedom and the search for a language of one’s own in landscape design. “I didn’t care whether or not the students memorized formulas or followed to a tee guidelines on style or trends; what matter was that their proposals be based on original ideas.”

During those years, Juan and his colleague Hans Muhr, fellow professor at Incacea, became friends (indeed, they still are). “I met Juan teaching landscape architecture. We were both self-taught; until then, our training in landscape architecture was just an iota of what would today be considered a true education in landscape design. We considered ourselves privileged to have cultivated a sense of wonder before nature,” Muhr recalls.

Muhr and Grimm sensed a path to be followed in the work and proposals of Prager and of Cromie. They grasped that the basic conception of landscape design consists of understanding the underlying natural order, of heeding its logics, dynamics, and geometries. “Learning with no teacher while also teaching what we ourselves were discovering on a daily basis required special rigor and dedication,” Muhr goes on. “That first encounter put us in an optimal position to construct an approach all of our own to the discipline.”

While Muhr and Grimm currently work independently, they have joined forces on submissions to major prizes and competitions, such as those for the construction of Parque Araucano and of Parque Bicentenario, both in Santiago. Although they did not win either competition,

nos ubicó en una posición inmejorable para ir construyendo un acercamiento propio a la disciplina”.

Si bien en la actualidad cada uno sigue un camino profesional propio, Muhr y Grimm formaron una dupla para presentarse en concursos importantes, como la construcción del Parque Araucano y el Parque Bicentenario, ambos ubicados en Santiago de Chile. A pesar de que ninguna de las propuestas ganó, la calidad de la primera les aseguró un cupo para participar en un congreso internacional en Buenos Aires, presidido por Burle Marx, en donde obtuvieron el primer lugar.

Años después, como profesional a cargo de nuevos proyectos en la Universidad Católica, Muhr le encargó a Grimm el Parque San Joaquín, desafío que analizaron y discutieron en conjunto. En suma, Muhr ha sido un consejero neutral y generoso, preponderante para Grimm en diferentes

they were asked to participate in an international congress in Buenos Aires on the merit of their submission for Parque Araucano. At the contest in Buenos Aires, which was presided over by Burle Marx, they were awarded first prize.

Years later, as the head of new projects at the Universidad Católica, Muhr invited Grimm to design Parque San Joaquín�a challenge they analyzed and grappled with together. Muhr, thus, has been a generous and objective counselor to Grimm at different junctures over the course of his career. At present, they are both working on the design of a 148-acre park at the foot of the Andean Cerro del Medio in the Lo Barnechea section of Santiago.

Soon after graduating, Grimm joined the Marta Viveros and Esmée Cromie firm. He started as an assistant and stayed on for three years. It was there that he first came

momentos de su carrera. Hoy por hoy, ambos desarrollan el diseño de un parque público de 60 hectáreas ubicado en la precordillera de Santiago (Cerro del Medio, en Lo Barnechea). Recién titulado, Grimm se incorporó a la oficina de Marta Viveros y Esmée Cromie: ingresó en calidad de ayudante y permaneció durante tres años. Allí tuvo por primera vez contacto directo con proyectos profesionales de diseño de jardines. Aprendió técnicas de expresión gráfica y el modo de desarrollar una propuesta formal de paisajismo.

into direct contact with professional-quality garden-design projects. He learned graphic techniques and how to develop a formal landscaping proposal.

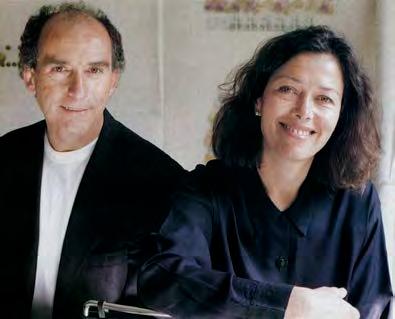

Juan Grimm instaló un estudio propio en 1982. Al poco tiempo, conoció a María Angélica Schade, o Maleca, una joven paisajista titulada de Incacea con quien trabajó durante 25 años.

Ella vivía con su familia en una antigua casona con mucha historia ubicada en Rinconada de Chena, rodeada de un parque repleto de árboles enormes y añosos. Al conocer el lugar quedé muy sorprendido con el cuidado y respeto que ella dedicaba para que la vegetación creciera sin restricciones, libre, silvestre. Había generosidad y cariño, tanto en el frondoso jardín que cuidaba, lleno de exuberantes hortensias y de diferentes aromas, como en los enormes arreglos de flores silvestres dispuestos dentro de la casa. Maleca construía atmósferas y llevaba con mucha pertinencia el manejo del voluptuoso mundo natural que la rodeaba. En los parques que ella me mostraba, y también en los jardines de su casa, aprendí sobre la plenitud que alcanza la naturaleza cuando permitimos que se desarrolle sin intervenciones. Esto me hizo mirar

Juan Grimm opened his own firm in 1982. Soon thereafter, he met María Angélica Schade, or Maleca, a young landscape architect with a degree from Incacea; they would work together for twenty-five years.

She lived with her family in an old mansion located in the Rinconada de Chena section of Santiago. The historical house was surrounded by a yard full of huge old trees. When I first visited the place, I was struck by her dedication to and respect for the vegetation; she did everything so that it could grow freely, wildly, boundlessly. Her generosity and care were evident in both the lush garden full of exuberant hydrangea and steeped in many different scents and in the large arrangements of wild flowers scattered around the house. Maleca was able to create an atmosphere; she skillfully navigated the voluptuous natural world around her. In the different yards she showed me and in the gardens of her own home, I first understood the bounty of nature when we let it take off on its own. That enabled me to appreciate simplicity in garden design, that is, the importance of not over-designing.

Visiting Maleca’s house in Cachagua was a source of great inspiration. That “pretty hut,” as she called it, was nestled between cliffs—a truly unique setting. She loved showing me the wild orchids blossoming amidst the sea figs that stretched over the hills.

17.

ARQ,

el jardín desde el valor de la sencillez en el diseño, o, dicho de otro modo, la importancia de evitar el sobrediseño.

Conocer la casa de Maleca en Cachagua fue una gran inspiración. Esa “linda choza”, como la llama ella, se ubica en un paisaje de acantilados, un entorno único. Allí le encantaba mostrarme las orquídeas silvestres en plena floración entre las docas, que se extendía libremente sobre las lomas.

Maleca y Juan aprendieron botánica y taxonomía juntos; juntos adquirieron las nociones necesarias para asociar las plantas en un jardín; y juntos se percataron de cómo estas asociaciones llegan a formar un conjunto único en cuanto a forma, color y textura.

Tras dos décadas de trayectoria, la oficina de Juan Grimm se consolidó entre las más prestigiosas del país. Entonces ocurrieron algunos cambios importantes: comenzó a recibir encargos de mayor escala, como parques de gran envergadura y solicitudes públicas. La demanda por obras civiles aumentó y fue necesario contratar nuevos dibujantes y arquitectos. Por su parte, Maleca decidió seguir un camino independiente por razones personales.

La gran diferencia tras su partida fue que dejé de contar con la persona idónea para discutir acerca de la vegetación de los proyectos. Cuando llegaba el momento de definir los espacios, la calidad y la elección de plantas, las asociaciones entre ellas y, en fin, la atmósfera que deseaba darle al jardín, todo eso lo conversaba con Maleca. Yo diría que la adolescencia profesional la vivimos juntos. La adultez llegó por cuenta propia. Cuando recién comenzaba en el oficio, un viejo y experimentado viverista me dijo: “Tú serás paisajista cuando veas crecer un alcornoque”. Bueno, hoy, después de 30 años, ya vi crecer el alcornoque.

Maleca and Juan learned botany and cultivated plant taxonomy together; together, they acquired the principles at play in combining plants in a garden and gained appreciation of how those combinations form a whole with unique shape, color, and texture.

Over the course of two decades, the Juan Grimm firm became one of the most prestigious in the country. Grimm began to receive larger commissions, like major gardens and yards, as well as public projects. As the volume of the public commissions grew, he had to hire new draftsmen and architects. For personal reasons, Maleca decided to pursue a different path.

After she left, I no longer had the ideal interlocutor, the perfect person with whom to discuss the vegetation aspect of projects. Maleca was the one with whom I worked out the structure of spaces, the quality and choice of plants and how to combine them, in sum, the garden’s overriding atmosphere. I would say that we grew up together professionally. When we became adults, we went our separate ways. When I was just getting my start in landscape design, a man of great experience who ran an important plant nursery told me “you’ll be a landscaper when you’ve seen a cork oak grow.” Well today, some thirty years later, I can say I have seen one grow.

Desde sus inicios en el oficio, Juan Grimm comprendió la importancia de documentar los jardines que construía: él mismo sacaba las fotografías con especial dedicación. Fotografiar era parte del trabajo, al igual que hacer el plano, visitar al cliente o plantar. “En mi opinión, la fotografía de un jardín debe mostrar todo aquello que se quiso lograr con el diseño, como, por ejemplo, la relación con el paisaje original, los nuevos órdenes establecidos y las diferentes perspectivas”.

Grimm fotografiaba el jardín al cumplir un año de plantado, buscando los mejores encuadres posibles de la vegetación joven. Con el correr de los años, la carga de trabajó aumentó y le resultó difícil encontrar el tiempo necesario que aquella fase requería. Contrató entonces a diferentes fotógrafos, pero ninguno lograba rescatar lo que él deseaba ver reflejado. Eso hasta que conoció a Renzo Delpino, quien, pese a no ser fotógrafo profesional, logró satisfacer las expectativas del paisajista. De ahí en adelante, Delpino se convirtió en el fotógrafo oficial de Grimm, que a su vez le enseñó los fundamentos del paisajismo. Las imágenes de Renzo llegaron a interpretar a la perfección el modo en que Grimm aprecia un jardín.

Al principio, él me acompañaba y observaba con inusual detención mientras yo tomaba las fotos. Yo lo veía interesado en la cámara y en el manejo de los lentes. Y frecuentemente me hacía preguntas relacionadas con el procedimiento. Para decirlo en pocas palabras: el caso de Renzo es el del discípulo que superó al maestro. Renzo no hace jardines, sino que los retrata, pero su habilidad es tal que sus fotos captan a la perfección la mirada del paisajista. Además, la rigurosidad que demuestra en el oficio es notable.

From early in his career, Juan Grimm understood the importance of documenting the gardens he designed. He himself took the photographs with great dedication. Photographing the garden was part of the project, just like designing it, conversing with the client, and planting. “In my view, photographs of a garden should show everything the design hoped to achieve: the relationship to the surrounding landscape, the new orders established, as well as different views.”

Grimm would photograph each garden one year after its planting, looking for the best possible angles from which to shoot the young vegetation. As the years passed and he had more and more work, he had trouble finding the time to take the photographs himself. He hired a number of different photographers, but none of them was able to capture what he was after until he met Renzo Delpino. Though not a professional photographer, he was able to meet Grimm’s expectations. Delpino became Grimm’s official photographer, and Grimm taught him the basics of landscaping. Eventually, Renzo’s images became the perfect interpretation of how Grimm envisions a garden.

At first, he would come along with me and watch carefully as I took the photos. I noticed that he was interested in the camera and in the different lenses. He would often ask me questions about what I was doing. In short, Renzo is an example of the disciple who becomes greater than the mentor. While Renzo does not make gardens but portray them, his photographs thanks to his impressive skill perfectly capture the landscape designer’s vision. Furthermore, his rigor is striking.

Los artículos en revistas especializadas (arquitectura y paisajismo), sumados a la publicación de diferentes trabajos de Grimm en libros extranjeros, han contribuido a divulgar su obra y a que esta trascienda más allá de Chile.

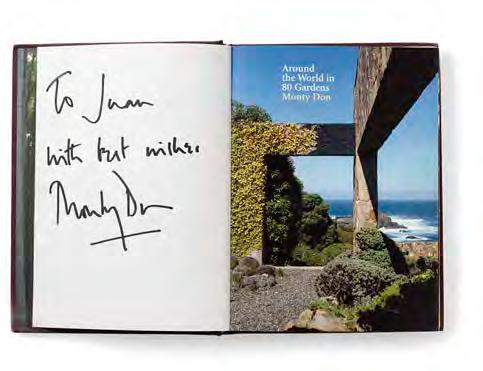

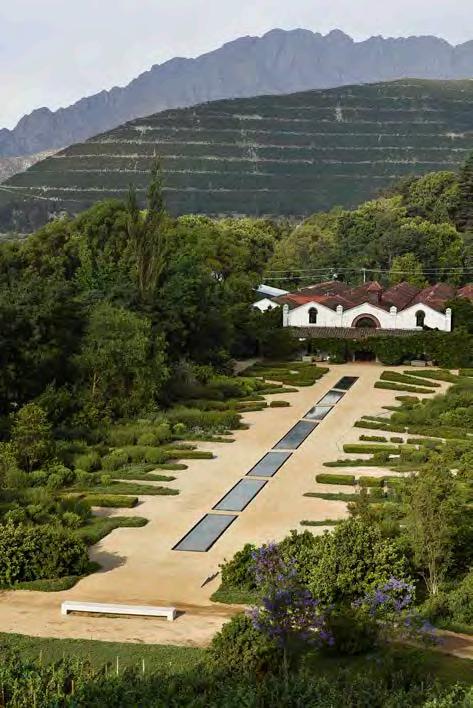

Un buen ejemplo de lo anterior es Around the World in 80 Gardens, 1 libro que la BBC también lanzó en formato de reportaje televisivo y que incluye los jardines más representativos de varios países, con el objeto de dar a conocer la multiplicidad de expresiones culturales que coexisten en el mundo. De Sudamérica se consideraron obras pertenecientes a Burle Marx (Brasil), Carlos Thays (Argentina) y Juan Grimm (el jardín de Bahía Azul, en Los Vilos). El reconocido botánico y escritor Monty Don formó parte del comité editorial que seleccionó el trabajo de Grimm: “Su obra busca integrar la mano del hombre con el paisaje natural y las plantas. Esto provoca una transformación significativa y, en mi opinión, es uno de los mejores trabajos de paisajismo en el planeta”.2

Para mí esta publicación fue una confirmación del valor que cobra insertar adecuadamente el proyecto en el paisaje, y la toma de conciencia de lo importante que es hacer un jardín con vegetación nativa.

Gracias a Around the World in 80 Gardens, el trabajo de Grimm se hizo conocido en Europa, Australia y Estados Unidos, lo que, a la vez, estimuló el interés por su obra y le significó comenzar a recibir invitaciones para dictar conferencias en diferentes países.

Thanks to articles published in architecture and landscaping magazines, as well as the inclusion of different projects by Grimm in books published abroad, his work is well known both in Chile and beyond.

Around the World in 80 Gardens1, for instance, is a book that the BBC published to accompany a television show featuring the most representative gardens of a number of countries. The aim was to show the range of cultural expressions in landscape design the world over. The South American landscape architects included were Burle Marx (Brazil), Carlos Thays (Argentina), and Juan Grimm (specifically his garden for Bahía Azul in Los Vilos). Distinguished botanist and writer Monty Don formed part of the editorial board that selected Grimm’s work. Regarding Grimm, Don stated that his work “seeks to integrate the hand of man with the natural landscape and plants. This makes for a meaningful transformation, and in my opinion, some of the best landscape work on the planet”.2

For me, that publication was confirmation of the value of successfully inserting the project into the landscape, and the awareness of how important it is to make a garden using native plants and flowers.

Thanks to Around the World in 80 Gardens, Grimm’s work has become known in Europe, Australia, and the United States. Interest in his designs has grown, and he has begun to receive invitations to give lectures in different countries.

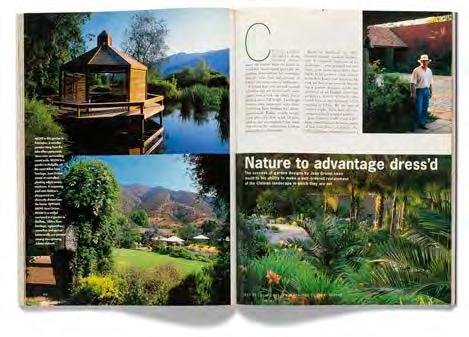

22. “NATURE TO ADVANTAGE DRESS’D” , House & Garden, marzo, 1998, Londres, Reino Unido. p. 108-111, Publicación de Parque Barros, Fundo El Alto, Chiñigue, Chile, 1993, Parque Vial, Fundo La Ramirana, Rancagua, Chile, 1987 y Parque Allende, Parcela Esmeralda, Quillota, Chile, 1985

23. “AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 GARDENS” , Monty Don (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008), p.122-125. Jardín Bahía azul

22-23. Fotografías, Jorge Brantmayer

22. “NATURE TO ADVANTAGE DRESS’D”, House & Garden, March 1998, 108-111. London, UK. Publication of Parque Barros (Fundo El Alto. Chiñigue, Chile, 1993); Vial Park (Fundo La Ramirana, Rancagua, Chile, 1987); and Allende Park (Esmeralda Plot, Quillota, Chile, 1985)

23. "BAHÍA AZUL GARDEN" , Monty Don, Around the World in 80 Gardens (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008), 122-124

22-23. Photographs, Jorge Brantmayer

A lo largo de mis 30 años de carrera profesional, he mantenido una incesante y profunda reflexión en torno a la naturaleza y al paisaje como expresiones de vida.

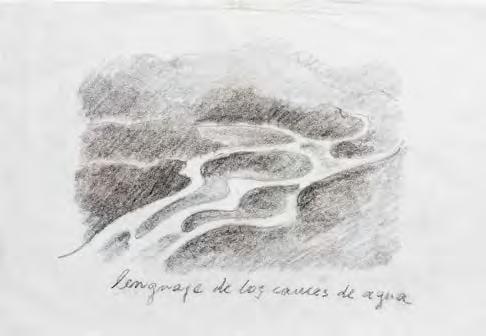

En cada lugar, el planeta nos ofrece una lectura que viene determinada por un orden, fruto de las características de la geografía que, a su vez, ha sido estructurada en secuencias y moldeada por el clima y los eventos naturales. Comprender el valor de la belleza del paisaje en el sentido de una dinámica propia, que es el resultado de la evolución de millones de años e incorporarlo al diseño, buscando siempre recuperar la secuencia y la armonía del entorno natural, interrumpida por la intervención del hombre, es un aporte muy valioso que el paisajista puede hacer.

“Creo que las condiciones que definen las características únicas de un paisaje están asociadas a su topografía, a la vegetación que la viste, al agua y a la lectura del movimiento que se revela a través de los matices de sus formas, colores y texturas… Por lo que debemos ser capaces de incorporar a nuestra obra la secuencia del paisaje que nos ocupa y ordenarla inspirados en ese pequeño pedazo de mundo”.1

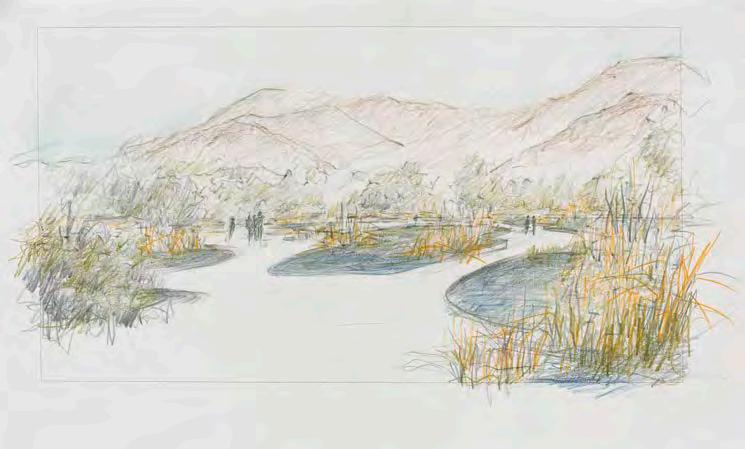

Al recorrer y contemplar un buen jardín, nos quedan en la memoria, por sobre la forma o la estructura, las sensaciones que el entorno nos provoca. El jardín debe seducir al espectador y transportarlo a un mundo en donde el goce por la naturaleza estimule la libertad personal. En esta manifestación

Over my thirty-year career, I have consistently focused on nature and the landscape as expressions of life itself. Everywhere on Earth, the planet provides us with a ‘reading,’ so to speak, determined by an order, by specific geographical characteristics that, in turn, have been structured in sequences and shaped by the weather and by disruptions in nature. Perhaps the most valuable contribution a landscape designer can make consists of appreciating the beauty of the landscape, its own dynamic born of millions of years of evolution, and incorporating it into the design while respecting the sequence and harmony of the natural environment altered by human intervention.

“I believe that what makes a landscape unique is its topography, the vegetation that covers it, the presence of water, and the interpretation of movement revealed by nuances in form, color, and texture... Our designs must uphold the landscape’s specific sequence, and bring order to it, drawing inspiration from that small corner of the world.”1

After exploring or viewing a well-designed garden, what stays with us more than the form or structure are the emotions it engenders. The garden must seduce viewers and take them into a world where delight in nature sparks personal freedom. All of our senses participate in that artistic expression, reacting to scents, degrees of humidity, colors, and textures, but mostly to the perception of life�the great

de arte actúan todos nuestros sentidos, que reaccionan frente al perfume, a la humedad, a los colores y texturas, especialmente ante la percepción de la vida, que es el gran sentido que tiene hacer jardines. Es por esta razón que me resulta difícil hablar de ellos, o mostrarlos a través de planos y fotografías, o explicar cómo se han ido desarrollando a lo largo del tiempo. Más que una muestra de parques y jardines, quisiera referirme a un proceso que tiene que ver con la búsqueda de las herramientas para hacer el jardín, donde he tratado de encontrar lo sustancial, para que así, junto con la experiencia vivida y los conocimientos adquiridos, se pueda concretar una obra paisajística que denote una identidad propia.

Hoy mi obra ha evolucionado con una constante y persistente búsqueda en concretar estos pensamientos referidos a la naturaleza y a la forma de intervenir en ella haciendo jardín.

meaning that underlies the task of landscaping. That’s why it is so hard for me to speak of gardens, to show them in designs or photographs, or to explain how they have developed over time. Rather than simply show parks and gardens, I would like to discuss my process: how I try to discover the essence of a space. The appropriate tools, along with experience and acquired knowledge, make it possible to produce a truly unique and distinctive landscape design.

Today my work has evolved in a constant and tireless attempt to express my thoughts on nature as applied to the task of making gardens.

Los paisajes naturales que he recorrido han pasado a constituir referentes para mis jardines. El que mejor conocí durante la niñez, el paisaje marino, es el que más me atrae hasta hoy. Pero también hay otros, en los que he encontrado lecturas memorables de los órdenes de la naturaleza que luego incorporo en mis jardines.

The natural settings I have visited are points of reference in the gardens I design. Even today, the marine landscape I knew so well as a child is the one that most appeals to me. But there are others that also left their mark and have inspired interpretations of nature and its order, going on to form part of the gardens I design.

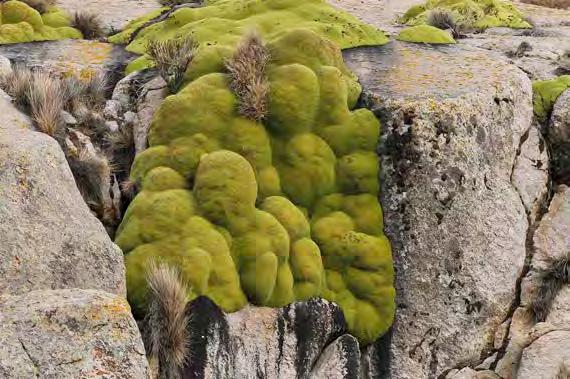

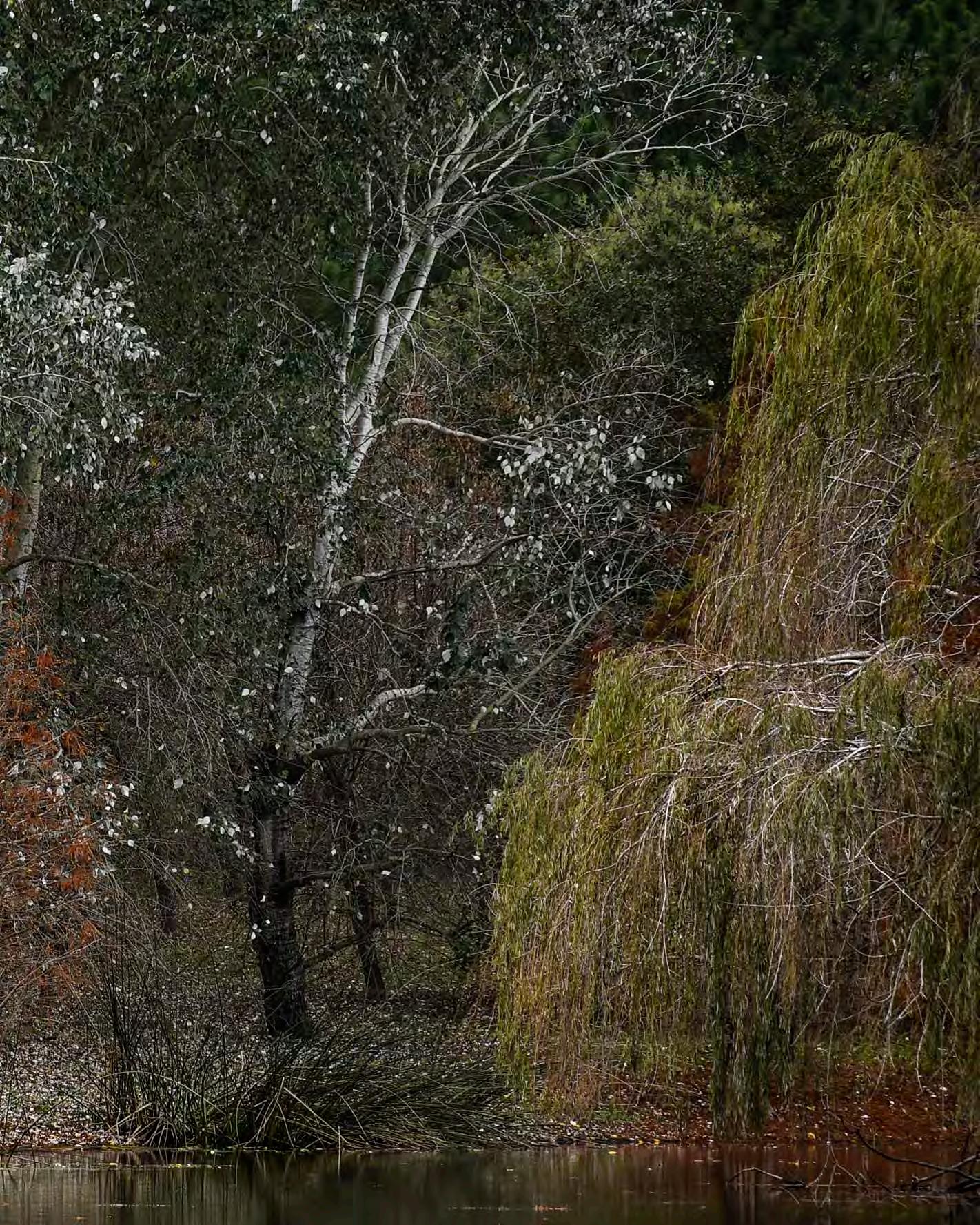

Este paisaje es uno de los más impresionantes que he conocido. En los bosques de araucarias de Chile y Argentina distingo un diálogo entre dos tipos de órdenes. El primero corresponde a bosques de araucarias gigantes de grandes troncos rígidos. El segundo orden está dado por el sotobosque que crece bajo ellas, sobre todo en otoño, cuando los berberis, ñirres y pastos grises crean una bruma de vapor que se mueve por debajo de estas verdaderas columnas arbóreas. Ambos órdenes establecen un diálogo por contraste muy llamativo.

Durante el invierno, cuando cae la nieve, desaparece gran parte del sotobosque y solo se mantienen los candelabros, como enormes esculturas. Se genera así una lectura absolutamente clara del paisaje, que lo hace único en el mundo y que representa de manera evidente los órdenes de la naturaleza.