Al organizar la conmemoración de los cien años de vida de nuestro estudio, decidimos vincular nuestro aniversario con un proyecto que abarcara a las numerosas generaciones que nos han acompañado durante este siglo y que tuviera un significado verdaderamente especial; que se pudiera compartir y disfrutar con la comunidad, y, a la vez, que se constituyera en un aporte a la identidad cultural del país. Por esta razón decidimos sumarnos al proyecto Santiago, cien años en imágenes, publicación que da cuenta de la evolución y transformación de Santiago entre 1916 y 2016, bajo la óptica de cuatro reconocidos fotógrafos: Odber Heffer, Enrique Mora, Antonio Quintana y Luis Weinstein, quienes, a través de sus imágenes, rescatan momentos significativos de la historia de la ciudad, retratan lugares y edificios emblemáticos, y ofrecen una singular mirada sobre la vida de los capitalinos en distintas épocas de ese período.

La ciudad se ha transformado a lo largo de las décadas y nuestro estudio también. Santiago era más pequeña y tranquila cuando Federico Villaseca abrió la primera oficina en la calle Agustinas esquina de Ahumada, en pleno centro comercial de Santiago, a tres cuadras de la Plaza de Armas. En ese momento su visión era desarrollar en Chile una nueva especialidad jurídica, incipiente en el país y que prometía un crecimiento exponencial: la propiedad intelectual. En estos cien años, ésta se ha extendido, universalizado y complejizado.

Nuestro estudio continúa avanzando sostenidamente, conservando la misma línea que nos ha distinguido desde un comienzo como equipo, y seguimos vinculados con nuestra ciudad, porque somos parte de ella y hemos crecido con ella. En los años setenta trasladamos nuestras oficinas a la floreciente comuna de Providencia y, luego, en el año 2000, a un moderno edificio, colonizador del barrio Nueva Las Condes. Es por eso que, con el propósito de celebrar y compartir nuestro centenario, decidimos involucrarnos en esta iniciativa, que grafica admirablemente cómo ha cambiado la ciudad que habitamos y cómo se proyecta hacia el futuro.

Agradecemos el apoyo de la Corporación Patrimonio Cultural de Chile y a todos los profesionales que, con su experiencia, dedicación y extraordinario compromiso, han permitido la publicación de esta obra.

Organizing the commemoration of the hundred years of life of our firm, we decided to link our anniversary with a project that embraces the many generations which have accompanied us during this century and have had a truly special meaning, one that could be shared and enjoyed by the community, and at the same time, act as a contribution towards the cultural identity of the country.

For this reason we decided to join the project Santiago, cien años en imágenes (Santiago, One Hundred Years in Photos), a publication that documents the evolution and transformation of Santiago between 1916 and 2016, through the lenses of four renowned photographers: Odber Heffer, Enrique Mora, Antonio Quintana and Luis Weinstein, who, through their images have captured significant moments of the city’s history, portraying places and landmark buildings, and offering a unique glimpse of the life of the capital’s residents during different times of that period. The city has changed over the decades as has our firm. Santiago was smaller and quieter when Federico Villaseca opened the first office in Agustinas street on the corner with Ahumada street, in the heart of the commercial downtown of Santiago, three blocks from the Plaza de Armas. At that point, his vision was to develop in Chile a new law speciality, just starting in the country and that promised an exponential growth: intellectual property. In these hundred years, it has expanded, universalized and become more complex.

Our firm continues to progress steadily, maintaining the same ethos that has set us apart from the beginning as a team, and we continue to be linked to our city, because we are part of it and have grown with it. In the decade of the seventies we moved our office to the flourishing borough of Providencia, and later, in 2000 to a modern building in the neighbourhood of Nueva Las Condes. This is why, in order to celebrate and share our centenary, we decided to get involved in this initiative, which admirably plots how the city we live in has changed and how it is projected into the future.

We thank the support of the Corporación Patrimonio Cultural de Chile (Cultural Heritage Corporation of Chile), and all the professionals, who with their experience, dedication and extraordinary commitment have enabled the publication of this work.

Estudio VillasEca Santiago, 2016

Estudio VillasEca Santiago, 2016

Este libro expone la relación de tres conceptos a partir de los cuales se propone explorar, revisar y mediatizar la ciudad de Santiago durante los últimos cien años: archivo, fotografía y ciudad.

Por archivo entendemos el ámbito en el que los testimonios, los documentos del pasado, han sido depositados para su conservación, donde mantienen –por tal motivo, y de forma apremiante– una punzante presencia sobre el presente. Esta disposición física es ineludible porque la fotografía, el segundo concepto, es un formato transparente y enigmático de información. La experiencia nos permite reflexionar en torno a la supuesta nitidez de la fotografía –esto que vemos ha sucedido– y a la vez conjeturar, insistentemente, al pasar por cada una de las imágenes que vemos, unas historias probables, verosímiles, que pinchan nuestra conciencia con preguntas como qué sigue, qué sucede y cómo termina esto Para darle continuidad a esa necesidad de relato posible, hemos elegido trabajar con la ciudad, el tercer concepto, y específicamente con Santiago. En este enfoque, entendemos por ciudad un escenario dinámico, pletórico de escenografías, donde se extienden, conforme al contexto, el pasado, el presente y el futuro, intercambiando sus duraciones y el sentido que tienen para cada uno de sus habitantes. La reunión de estos conceptos no es arbitraria. La necesidad de registro por parte del fotógrafo y la intuición escrutadora por parte del espectador de una fotografía tienen un encuentro elocuente en el archivo. Vemos una evidencia de esto en el uso extensivo que el internauta hace de las imágenes sobre la ciudad en las redes sociales, donde los documentos, transferidos de su materialidad original a una faz sutil y envolvente, lo digital, permiten construir

This book shows the relationship between three concepts through which we may explore, review and meditate on the city of Santiago during the last hundred years: archive, photograph and city.

By archive we understand the scope in which the testimonies, the documents from the past, have been stored for their conservation, where they are kept –for that reason, and in an urgent way– a stinging presence about the present. This physical disposition is unavoidable because the photograph, the second concept, is a transparent and enigmatic information format. The experience allows us to reflect on the supposed sharpness of the photograph –what we see has happened– and at the same time conjecture, insistently, passing through each one of the images we see probable stories, likely, that prick our conscience with questions such as what follows?, what happens? and to what end?

To give continuity to that need of possible narrative, we have decided to work with the city, the third concept, and specifically with Santiago. With this approach we understand by city a dynamic plethora of a scenic scenario, where it extends, according to the context, the past, the present and the future, exchanging its duration and the sense that they have for each one of its inhabitants.

The meeting of these concepts is not arbitrary. The need of the photographer to register and the searching intuition of the spectator of the photograph have an eloquent encounter in the archive. We see evidence of this in the extensive use that the internet users make of the images of the city in social networks, where the documents transferred from its original materiality to a subtle and enveloping face, the digital, allowing us to construct an experience

una experiencia en la que el archivo en la memoria del computador, la cámara o el sitio web convierte a todos los eventos, desde los más pequeños e insignificantes hasta los más intensos emocionalmente, en una mixtura personal y externa que escamotea las relaciones entre pasado, presente y futuro. Todo es ahora.

Trabajar en este contexto, por lo tanto, nos dirigió a los archivos, donde encontramos los soportes materiales de todas las imágenes aquí incluidas, para descubrir las distintas colecciones fotográficas, sus clasificaciones estandarizadas, las agrupaciones de fotógrafos y fotógrafas, en base a las cuales discutimos las diferentes representaciones de la ciudad, rememorando nuestras vivencias y, si nos era posible, las historias nacionales y las inadvertidas que con frecuencia pasan al olvido. Así, experimentado, el conjunto nos pareció infinito, pues todo era fundamental e indispensable. Teníamos opciones muy diversas, ideas contrapuestas. A través de las fotografías archivadas, Santiago se transformaba, por lo tanto, en el Aleph del cuento de Jorge Luis Borges: con una infinidad de imágenes, con cientos de posibilidades, saltábamos de lo pequeño a lo grande, con fotografías que pasaban a ser familiares, temiendo perder, con esto, la capacidad de sorprendernos y de sorprender. Decidimos, en consecuencia, seguir la ciudad mediante del trabajo de cuatro fotógrafos: Odber Heffer (1860-1945), Enrique Mora (1889-1958), Antonio Quintana (19041972) y Luis Weinstein (1957). Las colecciones de Heffer y Mora forman parte del Archivo del Centro Nacional del Patrimonio Fotográfico de la Universidad Diego Portales (Cenfoto-UDP); en el caso de Antonio Quintana, revisamos el Archivo Patrimonial de la Universidad de Santiago,

where the memory archive of the computer, the camera or web site makes all the events, from the smallest and most insignificant to the most intense emotionally, in a personal and external mixture that masks the relations between past, present and future. Everything is now.

Working on this concept therefore, directed us to archives, where we find the material support of all the images included here, to discover the different photographic collections, their standardized classifications, the photographers groupings, on which basis we discuss the different representations of the city, remembering our experiences and, if it was possible, the national history and the unnoticed that frequently are forgotten. Thus, experimenting, the whole was infinite, because everything was essential and indispensable. We had a range of options, opposite ideas. Through the archived photographs, Santiago transformed, therefore in the Aleph of Jorge Luis Borges story: with an infinity of images, with hundreds of possibilities, we jump from the small to the big, with photographs that become familiar, afraid of losing with this the ability to surprise and amaze.

Therefore, we decided to follow the city through the work of four photographers: Odber Heffer (1860-1945), Enrique Mora (1889-1958), Antonio Quintana (1904-1972) and Luis Weinstein (1957). The Heffer and Mora collections are part of the Archive of the National Centre of Photographic Heritage of Universidad Diego Portales (Cenfoto-UDP); in the case of Antonio Quintana, we review the Heritage Archive of Universidad de Santiago, the Central Archive of Universidad de Chile and the Photographic and Audiovisual Archive of the National Library. With Luis Weinstein we

el Archivo Central de la Universidad de Chile y el Archivo Fotográfico y Audiovisual de la Biblioteca Nacional. En el de Luis Weinstein, trabajamos directamente con él, ya que comenzó a constituir su obra en la década del setenta y continúa documentado su entorno constantemente. En la revisión de los archivos advertíamos que cada uno de los fotógrafos había construido, sistemáticamente, una imagen de Santiago. Pero a la vez constatábamos, al detenernos en las fotografías de un fotógrafo, una ciudad fragmentada que –como si se tratara de un acuerdo tácito– el siguiente fotógrafo corregía con un nuevo plano, con otra mirada, que ampliaba el registro documental. Nos parecía, en definitiva, que las temporalidades de cada uno de los archivos sostenían la larga duración de la ciudad.

En este libro, además de ver la ciudad, percibimos los cambios en la práctica fotografía. Hoy, la disponibilidad de ésta nos hace creer que la calidad del fotógrafo es transparente, que yo puedo tomar esa fotografía también. Pero la diferencia no reside en la singularidad de cada una de las imágenes del pasado, sino en la existencia del archivo y la presencia del trabajo constante, de la problematización de la mirada, buscando persistentemente un nuevo plano, un nuevo conocimiento.

Hemos propuesto, entonces, a partir de un formato tradicional, el libro, y a partir de un objeto contemporáneo, la fotografía, un recorrido, una dimensión para experimentar Santiago. Una ciudad que nos parece inmanejable, dados todos sus cambios, y que a la vez posee rasgos de atemporalidad. Una ciudad que, en cualquier caso, podemos disfrutar a través de la mirada de sujetos que simplemente se propusieron caminarla, los fotógrafos.

worked directly, as he began his work in the seventies and keeps documenting his environment constantly. In reviewing the archives we noticed that each one of the photographers had systematically constructed an image of Santiago. But at the same time we verify, when we stopped in the photographs of a photographer, a fragmented city that –if it was a tacit agreement– the following photographer corrected with a new plane, with another view that increases the documentary record. It seems to us, that the time frames of each of the archives hold the length of the city.

In this book, in addition to watching the city, we saw the changes in the photographic practice. Nowadays, the availability of this makes us believe that the quality of the photographer is transparent, that I can take that picture too. But the difference is not in the uniqueness of each of the images of the past, but in the existence of the archive and the presence of the constant work, of the problematisation of the view, constantly searching for a new plane, a new knowledge.

Therefore we have proposed, based on a traditional format, the book, and from a contemporary object, the photograph, a journey, a dimension to experience Santiago. A city that seems to us unmanageable given all its changes, and at the same time have features of the timeless. A city that in any case, we can enjoy through the eyes of individuals that decided to explore it, the photographers.

Los cambios experimentados en Santiago en el transcurso de los últimos cien años se presentan, en las siguientes páginas, desde el lente de cuatro fotógrafos, quienes permiten identificar mutaciones y permanencias de la ciudad durante ese período. Los cuatro realizan un proceso selectivo de captura de imágenes y de significación de objetos, edificios, espacios públicos y prácticas. Por lo tanto, en la mirada que ofrecen para conocer la ciudad, el punto de vista y la perspectiva tienen una importancia tanto literal como metafórica, mientras que las imágenes consiguen testificar transformaciones difíciles de documentar de otra manera (Burke, Peter, Eyewitnessing. The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence, Londres, 2001, pp. 30-31).

Tan selectivo como el proceso de registro fotográfico es lo que se considera patrimonio de la ciudad. Así como se registra lo que en la mirada del fotógrafo es significativo, lo que posee valor o lo que está en riesgo de perderse se “patrimonializa”. Ése fue el origen de la primera regulación de monumentos nacionales en Chile, adoptada en 1925 –fuente de la ley de 1970, vigente hasta nuestros días–, la que obedeció, en parte, a las pérdidas de importantes piezas arquitectónicas en el cambio del siglo XIX al XX. Desde ese momento, la ciudad comenzó a ser protegida.

En estos cien años ha cambiado lo que se entiende como patrimonial o patrimonio. Las fotografías de este libro también reflejan ese cambio, que obedece no sólo a transformaciones de valores estéticos, sino además al modo de entender y vivir la ciudad. Los registros que aquí se presentan, obtenidos entre 1916 y 2016, exhiben justamente cómo ha variado la noción de patrimonio, desde la

The changes that Santiago has gone through in the past hundred years are presented in the following pages, through the lenses of four photographers who enable us to identify the mutations and continuities of the city during that period. The four perform a selective process of image capture and significance of objects, buildings, public spaces and practices. Therefore, in the view they offer to know the city, the point of view and the perspective have an importance both literal and metaphoric, while the images testify to transformations hard to document otherwise (Burke, Peter, Eyewitnessing. The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence, London, 2001, pp. 30-31.).

As selective as the photographic record process is what is considered as the heritage of the city. As is registered what in the view of the photographer is significant, what has value or what is at risk of being lost is “heritaging”. That was the origin of the first regulation of national monuments in Chile, adopted in 1925 –source of the law of 1970, still in force today–, which was due in part to the loss of important architectural examples in the transition from the XIX to the XX centuries. Since this moment the city began to be protected.

In this hundred years what it is understood as heritage has changed. The photographs in this book also reflect this change that is due not only to the transformations of aesthetic values, but also in the way of understanding and living in the city. The registry that is presented here, captured between 1916 and 1920, shows how the notion of heritage has varied, from the appraisal of the monumental, at the beginning of the period, up to the appreciation of daily life, well into the current century.

valoración de lo monumental, a inicios del período, hasta la valoración de lo cotidiano, ya entrado el actual siglo. Odber Heffer presenta el Santiago de la segunda y la tercera décadas del siglo XX, en particular entre 1916 y 1920. La selección se concentra, en su mayoría, en edificios y espacios públicos cuya construcción fue prácticamente contemporánea a su registro fotográfico. La inauguración de algunos de ellos coincidió con las celebraciones del primer centenario de la independencia de España, en 1910. Entre los edificios públicos significativos de esta muestra se encuentra el Palacio de los Tribunales, que, a cargo del arquitecto francés Emilio Doyère, comenzó a ser construido en 1905, aunque sólo sería inaugurado más de veinte después; y el antiguo Palacio de los Gobernadores, más tarde Palacio de los Presidentes y, a partir de 1882, utilizado como la sede institucional de Correos, que se remodelaría en 1908 con el lenguaje de los nuevos edificios públicos. En torno a la Plaza de Armas, Heffer también registró la fachada de la Catedral, que lucía su nueva altura y sus dos torres, levantadas tras las radicales transformaciones emprendidas por Ignacio Cremonesi a partir de 1897. En el repertorio también está el entonces recién inaugurado Parque Forestal, construido en la ribera sur del Mapocho –sector del antiguo basural– tras la canalización del río; esta obra, dirigida por Georges Dubois, se constituía así, para la ciudad, en un notable espacio público que, junto a su laguna, acompañaba al Museo de Bellas de Artes, flamante obra de Emilio Jecquier, inaugurada durante las celebraciones oficiales del Centenario. Todas estas iniciativas de inicios del siglo XX confirmaban la presencia de patrones europeos en la arquitectura y en el paisaje, cargados de nuevos lenguajes luego de la Exposición Universal de 1900.

Odber Heffer shows Santiago of the second and third decades of the XX century, specifically between 1916 and 1920. The selection focuses mainly on buildings and public spaces whose construction was almost contemporary to his photographic record. The inauguration of some of them coincide with the celebration of the first century of independence from Spain in 1910. Among the significant public buildings of this display are the Palacio de los Tribunales (Law Courts) designed by the French architect Emilio Doyère, which began construction in 1905 but was inaugurated more than twenty years later; and the former Palacio de los Gobernadores (Governors’ Palace), later the Palacio de los Presidentes (Presidents’ Palace), and from 1882 used as the Post Office Headquater, remodelled in 1908 with the language of the new public buildings. Around the Plaza de Armas, Heffer also registered the façade of the Cathedral that showed its new height and its two towers, built after the radical transformations undertaken by Ignacio Cremonesi from 1987. In the repertoire is also the newly inaugurated Forestal Park, built on the south bank of the Mapocho River –in the area of an old garbage dump– after the channeling of the river. This work, directed by George Dubois, constituted itself for the city in a remarkable public space with a lake accompanied by the Fine Arts Museum, a brand new work by Emilio Jecquier which was inaugurated during the official celebration of the Centenary. All these initiatives of the beginning of the twentieth century confirmed the presence of European patterns in the architecture and the landscape, loaded with new languages after the Universal Exhibition of 1900.

Las vistas panorámicas de Heffer muestran una ciudad aún baja, pese a que exhibe los primeros –y notables– edificios de altura. Es el caso del Palacio Ariztía, de Alberto Cruz Montt, construido en 1917, y el edificio de la Bolsa de Comercio, también a cargo de Jecquier e inaugurado ese mismo año. Aunque la selección de Heffer evoca principalmente al centro histórico, además es posible apreciar monumentos en nuevos sectores, como la Virgen inaugurada en 1908 en el cerro San Cristóbal.

Un Santiago de monumentos y de emblemáticos edificios públicos republicanos caracteriza la colección de imágenes de Heffer, pero también se observan en ella cualidades de la ciudad de inicios del siglo XX, con sus característicos pavimentos, instalaciones del telégrafo y antiguos faroles, que aparecían como signos de modernización, mientras la Alameda todavía lucía una apacibilidad que cambiaría prontamente.

El lente de Enrique Mora, en fotografías seleccionadas del período 1936-1959, da cuenta de una ciudad que ha variado significativamente sus proporciones. De partida, se ha expandido desde su centro histórico en distintas direcciones, sobre todo hacia al oriente. Las imágenes de Mora registran, en el segundo tercio del siglo XX, el florecimiento de áreas verdes en la ribera del Mapocho. Al Parque Forestal se sumaba el Parque Gran Bretaña –diseñado por el paisajista vienés Óscar Prager–, renombrado como Parque Balmaceda a mediados de la década del cuarenta. Las imágenes capturadas en torno a la conocida Plaza Italia también testifican la expansión hacia oriente, mientras se imponen los edificios Turri, levantados en 1929 con el apoyo de la Caja de Crédito Hipotecario y en cuya planta baja se

The panoramic views of Heffer show a still low-rise city though it exhibits the first –and remarkable– tall buildings as in the case of Ariztia Palace, by Alberto Cruz Montt, built in 1917, and the building of the Stock Exchange, also by Jecquier and inaugurated in the same year. Although the selection of Heffer mainly evokes the historical downtown, it also is possible to appreciate monuments in new areas such as the Virgin inaugurated in 1908 on San Cristobal Hill.

A Santiago of monuments and emblematic republican public buildings characterize the images collection of Heffer, but one also sees in them qualities of the city of the beginning of the twentieth century, telegraph installations and old street lamps that appeared as signs of modernization, meanwhile the Alameda still proffered a mildness that soon would change.

The images of Enrique Mora, in selected photographs of the period 1936-1959, reveal a city that has significantly changed its proportions, starting with the expansion from its historical centre in different directions, especially to the east. The images of Mora register in the second third of the twentieth century, the flourishing of green areas on the banks of the Mapocho River. To the Forestal Park the Gran Bretaña Park was added –designed by the Viennese landscaper Óscar Prager– renamed as Balmaceda Park in the mid-forties.

The images captured around the famous Italia Square also testify to the expansion to the east, while the Turri building erected in 1929 with the support of the Caja de Crédito Hipotecario (Mortgage Savings Bank), and in whose ground floor the Baquedano Theatre was inaugurated (today

inauguraría el Teatro Baquedano –hoy Teatro Universidad de Chile. Contigua a este notable conjunto caracterizado por un naciente lenguaje arquitectónico, la Estación Pirque o Providencia, parte de un patrimonio hoy desaparecido, fue asimismo registrada por Mora. La estación, testimonio del rico clasicismo de Jecquier, tuvo corta vida. Construida a partir de 1905, fue demolida al iniciarse la década del cuarenta, debido a la ejecución de nuevos planes urbanos, entre los que se encontraba el proyecto de Diagonal Oriente y el del Parque Bustamante. Así, en medio de un Santiago que crecía y se transformaba gradualmente en metrópoli, algunas piezas desaparecieron. El centro histórico también cambió significativamente. Las imágenes de la Alameda, avenida cada vez con mayor movimiento, a menudo contienen la de la Iglesia de San Francisco, uno de los más representativos recuerdos de la ciudad colonial. Inaugurada oficialmente en 1927, trece años después del inicio a su construcción, la Biblioteca Nacional, en su conexión con el cerro Santa Lucía y la Alameda, daba cuenta de una ciudad que comenzaba a dejar atrás su escala modesta y acotada. Mora destaca, ya en ese período, el auge del comercio y los automóviles en el sector. En tanto, sus vistas panorámicas revelan la convivencia entre el nuevo y el viejo Santiago, mientras tomaba más presencia la altura, cambio central en relación a los registros de Heffer, en cuyas imágenes, desde todos sus ángulos, se imponía la cordillera.

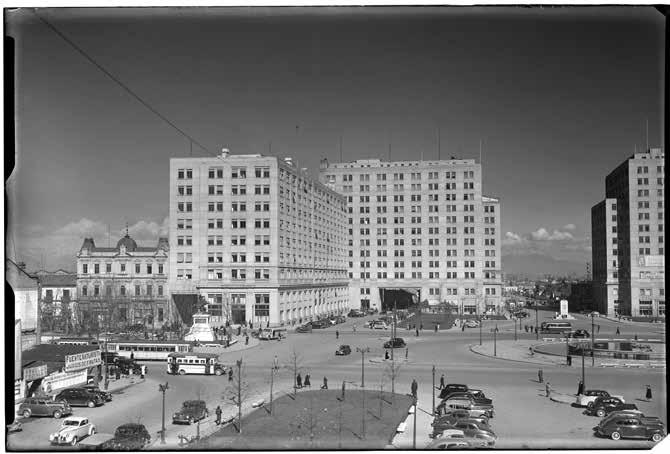

Pero el registro más sugerente de las transformaciones en el centro histórico en los años treinta es el grupo de imágenes que Mora tomó del Barrio Cívico. Este gran proyecto urbano, anhelado desde los albores del siglo XX,

Universidad de Chile Theatre). Next to this remarkable set characterized by an emergent architectural language, the Pirque Station or Providencia, part of a heritage now disappeared, was also registered by Mora. The station, testimony to the rich classicism of Jecquier, had a short life. Build in 1905 it was demolished at the beginning of the forties, due to the implementation of new urban plans, which included the project of Diagonal Oriente (road) and Bustamante Park. Thus, in the middle of a growing Santiago, gradually transforming into a metropolis, some buildings disappeared.

The historical downtown also changed significantly. The images of the Alameda, avenue with increasing movement often contain the San Francisco Church, one of the most representative memories of the colonial city. The National Library inaugurated officially in 1927, thirteen years after the beginning of its construction with its connection with Santa Lucía Hill and the Alameda, show a city that had begun to leave behind its modest and limited scale. Mora highlighted in that period the rise of trade and the cars in the sector. Meanwhile its panoramic views reveal the coexistence between the new and old Santiago, while the heights assumed more presence, the main change in relation to the register of Heffer, in whose images the mountains were dominant from every angle. But the most evocative record of the transformations of the historical downtown in the thirties is the group of images that Mora took of the Civic Quarter. This great urban project, desired since the dawn of the twentieth century, had been the most significant renovation of the traditional historical centre. Discussed for decades and

había constituido la más significativa renovación del tradicional centro histórico. Discutido por décadas, y aprobado finalmente en 1937, el plan incorporó las ideas del austriaco Karl Brunner, contratado por el gobierno central como asesor urbanista, y fue realizado por la primera generación de urbanistas chilenos. Las fotografías de Mora exponen la envergadura de este proyecto, que contaba con mecanismos de expropiación y una normativa para regular su altura, y prometía hacer de Santiago una capital moderna. La selección de fotografías de Antonio Quintana, de entre 1950 y 1960, exhiben las nuevas proporciones de Santiago al promediar el siglo XX El fotógrafo captura ciertas imágenes menos espectaculares que las anteriores. Tal es el caso de los conventillos, los que, pese a ubicarse en sectores céntricos, denotan el cambio en el registro de una mirada monumental a una mirada más social de la ciudad. Las fotos de Quintana incorporan al habitante, cuya presencia se hace notable en el uso de edificios, espacios públicos y monumentos, muchos de los cuales habían sido concebidos por Heffer como flamantes piezas de inicios del siglo XX Ilustrativo de ese cambio, en relación a los fotógrafos mencionados, es el registro del Parque Forestal, presentado hasta entonces en su dimensión monumental, y que ahora aparece como un espacio habitado y disfrutado por los habitantes de la ciudad. En el centro de ésta, las proximidades del cerro Santa Lucía, la Iglesia de San Francisco y las estaciones de trenes se ven pobladas por transeúntes en un entorno cotidiano. De igual modo, el transporte público protagoniza varias escenas fotográficas, con usuarios esperando subir a un bus o recorriendo la ciudad en su interior. La importancia del comercio no sólo es relevada

finally approved in 1937, the plan incorporated the ideas of the Austrian Karl Brunner, hired by the central government as urban planner advisor and was carried out by the first generation of Chilean planners. Mora’s photographs expose the magnitude of the project, which included expropriation mechanisms and legislation to regulate building height, and promised to make Santiago a modern capital.

The photograph selection of Antonio Quintana, between 1950 and 1960, exhibit the new proportions of Santiago midway through the twentieth century. The photographer captured some less spectacular images than the previous ones. Such is the case of the slums, which, although located in central areas, denote the change in the registration from a monumental view to a more social view of the city. The photographs of Quintana incorporate the inhabitant whose presence is noticeable in the use of buildings, public spaces and monuments, many of which were conceived by Heffer as flamboyant pieces of the early twentieth century.

Ilustrative of this change in relation to the aforementioned photographers, is the record of the Forestal Park, presented until then in its monumental dimensions and now appears as an inhabitated space and enjoyed by the city inhabitants. In the centre of it the proximities of Santa Lucía Hill, San Francisco Church and the train stations are populated by passers-by in everyday surroundings. Similarly, public transport is the protagonist of several photographic scenes with users waiting to board a bus or walking around the city. The importance of trade is not only shown by the images, but they also capture their relation with the inhabitants, while the Central Market offers new meanings as it opened more properly to the public. Thus, the

por las imágenes, sino que éstas también capturan su relación con los habitantes mientras el Mercado Central ofrece nuevos significados al abrirse con mayor propiedad al público. Así, el Santiago que presenta Quintana es, definitivamente, una ciudad más ruidosa y con nuevos afanes de desarrollo.

La participación de los habitantes en una urbe más compleja, menos monumental y que sobrepasa sus antiguos límites físicos y prácticas sociales es confirmada además por la dimensión política que introduce Quintana a través de imágenes referidas a propaganda y campañas políticas, que se instalan sobre emblemáticos edificios públicos.

Las fotografías de Luis Weinstein permiten reconocer la ciudad entre el último tercio del siglo XX y la actualidad. En su selección de fotos, aquellos monumentos y espacios públicos, pulcros y distantes a inicios del siglo pasado, aparecen en uso y habitados por santiaguinos que son identificados e individualizados por género, grupo social y grupo etario. Incluso el propio fotógrafo parece identificarse al mostrar su cámara e introducir nuevos ángulos de captura.

La acción del ciudadano en Santiago, y sus implicancias, queda de manifiesto en la propuesta de Weinstein. El impacto de la publicidad en los edificios y espacios públicos es cada vez mayor, mientras las marchas y manifestaciones también adquieren cierto protagonismo. Similar es el caso de la basura, que acapara una imagen significativa del Santiago actual en zonas centrales. En esa relación entre el habitante y su entorno urbano, la ciudad aparece en construcción y en movimiento, de una manera más dinámica.

Una importante novedad que presenta la selección de este último período es el registro de prácticas y oficios,

Santiago presented by Quintana is definitely a noisier place and with new airs of developing city.

The participation of the inhabitants in a more complex, less monumental city that surpasses its former physical limits and social practices, is confirmed by the political dimension introduced by Quintana through the images related to propaganda and political campaigns that are installed on landmark public buildings.

The photographs of Luis Weinstein allow us to recognize the city between the last third of the twentieth century and today. In his photo selection, those monuments and public spaces, neat and distant from the beginning of the las century, appear being used and inhabited by Santiago’s citizens who are identified and individualized by gender, social and age group. Even the photographer seems to identify himself by showing his camera and introducing newly-captured angles.

The action of the citizen in Santiago and its implications, are reflected in the proposal of Weinstein. The impact of advertising on the buildings and public spaces is progressively bigger, while the marches and demonstrations also gain some prominence. Similar is the case of the garbage, which assumes a significant place of contemporary Santiago’s central areas. In this relation between the inhabitants and their urban environment, the city appears as under construction and in movement in a more dynamic way.

An important novelty shown in the selection of this latter period is the registration of practices and occupations, a fact that is not circumstantial because by the end of the twentieth century the heritage was no longer synonymous

hecho que no es circunstancial, pues a fines del siglo XX el patrimonio ya no era sinónimo de monumentos, sino que comenzaba a relacionarse con el habitante y su vida cotidiana. En rigor, la comunidad empezó a hacer cada vez más evidente su participación en temas ciudadanos, por ejemplo mediante organizaciones de la sociedad civil, siendo activa a la hora de significar y gestionar su patrimonio. Estos registros constatan, en consecuencia, los avances efectuados desde la protección de lo material hacia lo inmaterial. Por último, una nueva imagen de modernidad parece consignarse en las imágenes de Weinstein. Fotografías tomadas desde dentro del automóvil como una manera de conocer, recorrer y, en definitiva, vivir la ciudad confirman que ese tipo de vehículo, que tímidamente aparecía en las fotografías de Mora como objeto de modernidad, ahora es una pieza común del paisaje urbano y, en pleno siglo XXI, el habitante recorre y conoce la ciudad desde él. Otra pieza de Weinstein que remarca la expresión de un nuevo Santiago es la Torre Entel, hito de las telecomunicaciones de Santiago a partir de 1974. Su notable altura, la mayor de la ciudad por largo tiempo, simbolizaba la imagen del Santiago empresarial que se buscaría proyectar en la década del ochenta.

En definitiva, ya entrado el siglo XXI las vistas y las construcciones en altura priman en el repertorio de imágenes de la ciudad. Esto ofrece, por una parte, un nuevo paisaje urbano y, por otro, termina por hacer más difusa la presencia de la cordillera, mientras el habitante de la ciudad gana un espacio en el que estaba completamente ausente en 1916.

with monuments, but began to relate to the inhabitants and their daily lives. Strictly speaking, the community began to make it participation in public issues increasingly evident, for example through civil society organizations being active at the time to represent and manage its heritage. This registration state, in consequence, shows the progress made from the protection of the material towards the immaterial.

Finally, a new image of modernity seems to be consigned in the images of Weinstein. Photographs taken from inside the car as a way to know, explore and, ultimately, live in the city confirm that kind of vehicle that timidly appeared in the photographs of Mora as an object of modernity, now is a common component of the urban landscape, and in the twenty first century the inhabitant explores and knows the city through it. Another work by Weinstein that highlights the expression of a new Santiago is the Entel Tower, a milestone of the telecommunications of Santiago since 1974. Its remarkable height, the tallest in the city for a long time, symbolizes the image of the entrepreneurial Santiago that was projected in the eighties.

Ultimately, well into the twenty-first century, the views and high-rise buildings prevail in the repertory of images of the city. This provides on the one hand a new urban landscape, and on the other, ends up making the presence of the mountains more diffuse, meanwhile the inhabitant of the city earns a space which was completely absent in 1916.

Contemplar fotografías tiene siempre algo de nostálgico: nos hace percibir, a veces con una extraña mezcla de tristeza y alegría, algo que ya fue. Esas imágenes, tan reales como ilusorias, contribuyen a construir el andamiaje de nuestra memoria y de nuestro ser. El teórico francés Roland Barthes insinuó que la traducción del término “fotografía” al latín es imago lucis opera expressa. Leo esta definición en el sentido de que la fotografía es como una imagen dibujada por la luz de modo instantáneo, una radiografía delgada y precisa del continuo flujo del tiempo que fija un momento histórico. Toda fotografía es un acto histórico, en cuanto siempre se sitúa en el pasado: en el mismo instante de su toma ya es un hecho consumado. Es histórico también porque siempre contiene al menos el fragmento de una historia. La referencia a Barthes y a su libro La cámara lúcida no es casual, pues ocuparé aquí su distinción entre studium y punctum para hablar de algunas imágenes incluidas en este volumen que, en tal sentido, me parecen particularmente significativas. Por studium se entiende aquella actividad ejercida con aplicación y gusto por el conocimiento, de carácter cultural, genérico e informativo. No es algo que conmueve, no te hace vibrar. Por el contrario, el punctum produce un remezón telúrico, pincha algo en tu ser. Es esa azarosa interferencia, ese pequeño detalle involuntario, que se asienta en nuestra subjetividad liberando nuestra imaginación.

Las fotografías a las cuales aludiré son, justamente, las que más me pinchan, partiendo por la del Parque Forestal (pp. 62-63) de Odber Heffer (1916-1930), que considero la más incisiva de todas, quizás por el hecho de que vivo cerca del lugar representado pero no me “hallo” ahí.

Contemplating photographs is always something nostalgic: it makes us perceive, sometimes with a strange mix of sadness and joy, something that already happened. Those images, as real as illusionary, help to build the scaffolding of our memory and of our being. The French theorist Roland Barthes insinuated that the translation of the term “photography” to Latin is imago lucis opera expressa I read this definition in the sense that photography is like an image drawn by the light instantaneously, a thin and precise capture of the continuous flow of time that records a historical moment. Every photograph is a historical act, as it is always set in the past: at the very moment it is taken it is already a consummated fact. It is also historical because it always contains at least a fragment of a story. The reference to Barthes and his book Camera Lucida is not a coincidence, because I will use here his distinction between studium and punctum to talk about some images included in this volume, which in that sense seems to me particularly significant. By studium it is understood as activity carried out with application and desire for knowledge, with cultural character, generic and informative. It is not something that moves, it doesn’t make you vibrate. By contrast, punctum produces a seismic aftershock, touching something in your being. It is this random interference, that little involuntary detail that settles in our subjectivity, freeing our imagination.

The photographs I will refer to are precisely those that touch me, starting with the one of Forestal Park (pp. 62-63) by Odber Heffer (1916-1930), which I consider the most insightful of all, maybe because I live near the place represented but I don’t “see myself” there. I don’t

No reconozco en ella mi hábitat cotidiano. Sin embargo, es precisamente este extrañamiento, esta unheimlichkeit (término alemán para denotar aquella sensación que se produce cuando uno no es en casa), lo que gatilla mi imaginación.

¿Cómo llegó el lago al Parque Forestal? Porque de un lago se trata; hay botes en él. ¿Se debe a que la naturaleza imita al arte? Desde el primer instante en que vi esta fotografía, me sentí inmerso en un paisaje holandés. Me recordó esa gran tradición de pintura paisajística; de hecho, existe un cuadro de 1689 de Meindert Hobbema, La avenida de Milderhamis, que en sustancia representa lo mismo que esa imagen del Parque Forestal: un camino de tierra flanqueado por una arboleda, una construcción rural a la derecha y un lago a la izquierda, con la ciudad como telón de fondo.

Al concebir el Parque Forestal, ¿el paisajista tenía en mente la pintura de Hobbema? En Chile, al igual que en el resto de Sudamérica, se importaron imágenes mentales de Europa para implantarlas en el territorio nacional, aunque eso atentara contra lo autóctono y, por ende, contra la sustentabilidad de los paisajes. ¿Los paisajes chilenos no eran suficientemente hermosos o agradables? ¿O simplemente la memoria ancestral (y desde luego nostálgica) de los conquistadores impedía advertir su belleza latente? Con todo, y más allá de la justificación ética de su génesis, este paisaje acuático emana una fascinación todavía vigente. ¿Sería posible realizarlo en la actualidad? Imaginémonos un lago en el Parque Forestal hoy en día. La calidad de vida que generaría. A las ciudades contemporáneas les hace mucha falta este tipo de cápsulas espaciales, de núcleos atmosféricos condensados. Para sacudir a sus habitantes y sacarlos de su cotidianeidad.

recognize in it my daily habitat. However, it is precisely this estrangement, this unheimlichkeir (German term to denote the feeling that occurs when one is not at home) which triggers my imagination. How did the lake end up in Forestal Park? Because it is a lake, there are boats in it. It is because nature imitates art? From the first moment I saw this photograph, I felt immersed in a Dutch landscape. It remind me of that great tradition of landscape painting; in fact, there is a painting from 1689 by Meindert Hobbema, The Avenue at Milderhamis, that in substance represents the same as that the image of the Forestal Park: a dirt road flanked by trees, a rural construction on the right and a lake on the left, with the city as a backdrop. When conceiving Forestal Park, did the landscaper have the Hobbema painting in mind? In Chile, as in the rest of South America, mental images of Europe were imported to implement them in Chile, although that threatens the indigenous and therefore the sustainability of the landscapes. Chilean landscapes were not pretty or nice enough? Or simply the ancestral (and of course nostalgic) memory of the conquerors prevented them from appreciating the latent beauty? However, and beyond the ethical justification of its genesis, this aquatic landscape raises a fascination still prevalent. Would it be possible to do it today? Let’s imagine a lake in Forestal Park nowadays. The quality of life it would generate. Contemporary cities lack these types of spatial capsules, atmospherically condensed nuclei to shake their inhabitants and take them out of their daily lives.

The photographs of Enrique Mora (1936-1959) are part of the Heffer family of images, with urban scenes

Las fotografías de Enrique Mora (1936-1959) son parte de la familia de imágenes de Heffer, con escenas urbanas que combinan arquitectura y paisaje. Me pinchan sobre todo aquellas que rodean mi casa, que historian mi hábitat. Añaden capas de información a lo que experimento diariamente, densificando mi memoria. Me territorializan. A fin de cuentas, fortalecen mi identidad y mi arraigo. La Plaza Italia de Mora (p. 74) muestra el Parque Forestal desde otra perspectiva, y no permite corroborar si el lago aún existía, aunque lo dudo. Asombra ver la disposición delicada y armónica de las figuras urbanas. En una perfecta coreografía se balancean piezas arquitectónicas con paisajísticas, de igual tamaño y volumetría (los árboles tienen la misma altura que los edificios). Lo que perturba de esta escena, independientemente de que se parezca demasiado a una pintura paisajística, es su perfección. Todo está limpio. Así lo atestiguan las dos áreas verdes en primer plano, perfectamente aseadas, sin personas apropiándose de su superficie para efectuar actividades de ocio. Son como joyas que se admiran por su belleza, pero no se tocan, pues podrían estropearse.

La triangulación de mi hábitat concluye con la toma de la Iglesia de San Francisco en la actual Alameda (p. 87). Hay en ella varios elementos que estimulan mi fantasía. Sobre todo la Pérgola de las Flores, instalada ahí para formalizar la venta de flores a la salida de misa y tutelada por una imagen de la Virgen del Socorro, traída desde España por Pedro de Valdivia y a la que se le atribuye haber permitido la conquista definitiva de estos territorios. Se trata de la consagración del imaginario importado por sobre el imaginario autóctono. Por eso, en agradecimiento, Valdivia ordenó la construcción

that combine architecture and landscape. Those images that surround my house that document my habitat touch me especially. They add layers of information to what I experience daily, densifying my memory. They territorialize me and, in the end, strengthen my identity and roots.

Italia Square by Mora (p. 74) shows Forestal Park from another perspective, and doesn’t corroborate whether the lake still existed, though I doubt it. It amazes me to see the delicate and harmonious arrangements of the urban figures. Architectural pieces balance with landscape in perfect choreography, of the same size and volume (the trees are the same height as the buildings). What disturbs one in this scene, beyond the fact that it looks a lot like a landscape painting, is its perfection. Everything is clean. As demonstrated by the two green areas in the foreground, perfectly neat, no people encroaching on its surface to pursue leisure activities. They are like jewels that are admired for their beauty, but they are not touched, as they could be damaged.

The triangulation of my habitat concludes with the shot of the San Francisco Church in the present day Alameda (p. 87). There are several elements in it that stimulate my fantasy. Especially the Pérgola de las Flores, installed there to formalize the flower selling at the end of a mass and guided by an image of the Virgin of Socorro, brought from Spain by Pedro de Valdivia, which is credited with having allowed the definitive conquest of these territories. It is consecration of the imported imaginary over the native imaginary. Therefore, in gratitude, Valdivia ordered the construction of a hermitage that through the centuries

de una ermita que a través de los siglos se ha ido constituyendo en la actual Iglesia de San Francisco, considerado el monumento arquitectónico más antiguo del país.

La fotografía, en su estructura compositiva, se parece a Las meninas de Diego Velázquez. En ese juego de miradas entrecruzadas, de convertir al espectador en un partícipe dinámico de la obra, el pasado colonial se contrapone a la nueva vida, en la vereda opuesta, en un espacio caracterizado por medios de transporte: un carruaje con caballo, un tranvía y lo que parece ser un auto Ford A, fabricado en Santiago.

En esa oposición visual, en ese duelo de períodos históricos, la Iglesia de San Francisco se ve acorralada, con las espaldas contra la pared. Ya cierta del inexorable avance del progreso, y de su inminente olvido, la Virgen del Socorro, a través del campanil, lanza una mirada cómplice, casi suplicante, hacia la Virgen asentada en la cumbre del cerro San Cristóbal. Es el último tributo a la imagen de la Inmaculada Concepción. Lo inmaculado hace tiempo que se desvaneció, acaso por la fuerza gravitacional del punctum de esta imagen, anidado a los pies del Santa Lucía y del San Cristóbal. Con la prepotencia típica de la modernidad, un edificio blanco en alturas, solitario, tosco y medio curvado sobre si mismo, trata de mediar entre ambos cerros. Sabe que es el representante de un imaginario por venir y que el tiempo está de su lado. Será por eso que ni siquiera siente compasión o vergüenza por la mirada desolada de la Virgen del Socorro.

Si esta primera serie de fotografías la he asociada principalmente con el imaginario de las pinturas históricas y de la incidencia del imaginario religioso importado por los

has evolved into what today is the San Francisco Church, considered the country’s oldest architectural monument. The photograph, in its compositional structure, is reminiscent of Las Meninas by Diego Velásquez. In this game of cross glances, making the viewer a dynamic participant in the work, the colonial past is opposed to the new life, in the opposite sidewalk, is a space characterized by transport: a horse and carriage, a tram and what it seems to be a Ford A, manufactured in Santiago.

In this visual opposition, in the duel of historical periods, the San Francisco Church is cornered with their backs against the wall. Sure of the inexorable march of progress, and of its imminent forgiveness, the Virgin of Socorro, through the campanile, casts a complacent gaze, almost pleadingly, to the Virgin seated on the summit of San Cristobal Hill. It is the final tribute to the image of the Immaculate Conception. The immaculate long ago vanished, perhaps due to the gravitational force of the punctum of this image, nested at the foot of Santa Lucía and San Cristóbal Hills. With the typical arrogance of modernity, a white building high, lonely, crude and slightly curved in on itself, tries to mediate between both hills. It knows that it is the representative of imagery yet to come and that time is on its side. Perhaps that’s why it doesn’t even feel compassion or shame for the desolate look of the Virgin of Socorro.

If this first set of photographs I have associated mainly with the imagery of historical paintings and the incidence of the religious imaginary imported by the conquistadors to settle in this new territory, the series that follows reflects my personal imagery on settling in

conquistadores para establecerse en este nuevo territorio, la serie que sigue refleja mi imaginario personal para asentarme en Chile, mi país de adopción. No sé explicar la razón, pero una de mis primeras impresiones de Chile ha sido la de una italianidad desfasada, como si Chile reflejase la Italia de hace un tiempo.

Chile, en rigor, no ha sido mi único país de adopción. Anteriormente lo fue también Alemania, donde pasé mi infancia de inmigrante, lo que desencadenó un profundo deseo de encontrar mis raíces; algo como una búsqueda de la italianidad perdida o desplazada. El anhelo lo pude cumplir, al menos parcialmente, cuando me fui a estudiar en Milán. Sin embargo, esa estabilidad, por así llamarla, me duró muy poco, porque una vez terminados mis estudios me vi catapultado al otro lado del Atlántico, y lo que tenía que ser una breve aventura, acotada a un periodo de dos o tres años, se ha extendido hasta hoy día.

El paisaje italiano latente lo descubro en las fotografías de Antonio Quintana (1950-1960). Así, el niño que hace zarpar su bote en el espejo de agua en el Parque Bustamante (p. 109) me recuerda a los niños que aparecen en el cine italiano, desde aquellos que con sus miradas marcaron el neorrealismo hasta los que masturbándose sueñan con Malena, pasando por el pequeño de Cinema Paradiso anhelando los tiempos perdidos. Son niños que se caracterizan por su inocencia, su toque de malicia, su despreocupación y una capacidad de asombro que en la actualidad ya no encuentra su lugar en el mundo.

También la elegancia de los paseos dominicales es un fenómeno típico de esos tiempos. Una elegancia y una felicidad (esta última debido quizás al hecho de que aún

Chile, my adopted country. I can’t explain why, but one of my first impressions of Chile has been of an outdated Italianism, as if Chile reflects Italy of a while ago. Chile, strictly speaking, hasn´t been my only adopted country. Previously it was Germany, where I spent my immigrant childhood which triggered a deep desire to find my roots; something like a search for a lost or displaced Italianism. I fulfilled the longing, at least partially when I went to study in Milan. However, that stability, so to speak, didn’t last long, because once I finished my studies I saw myself catapulted across the Atlantic, and what should have been a short adventure, limited to a period of two or three years, has extended until today.

The latent Italian landscape I discovered in the photographs of Antonio Quintana (1950-1960). Thus, the child that sails his boat in the mirrored water in Bustamante Park (p. 109) reminds me of the children that appear in the Italian movies, from those that with their looks marked the neorealism to those who masturbate dreaming of Malena, passing through to the little one in Cinema Paradiso longing for lost eras. Children characterized by their innocence, their touch of malice and an ability to astonish that currently no longer finds a place in the world.

Additionally, the elegance of Sunday strolls (paseos) is a typical phenomenon of those times. An elegance and happiness (the latter due maybe to the fact that there was still faith in progress and a better future) that can be seen for example in the clam sellers in the market (p. 129).

The haircut, wavy, Clark Gable style, of the character in foreground attests to an elegance that the less favoured social classes have been losing.

había fe en el progreso y un futuro mejor) que se aprecia por ejemplo en los vendedores de almejas en el mercado (p. 129). El corte de pelo, ondulado, a lo Clark Gable, del personaje en primer plano atestigua esa elegancia, que las clases sociales menos favorecidas han ido perdiendo.

A su vez, la Vespa capturada en el centro de Santiago (p. 139) me asienta de inmediato en la Italia de los años cincuenta, cuando fue inmortalizada por Gregory Peck y Haudrey Hepburn en la película Vacaciones en Roma Y desde que Federico Fellini sentó a Anita Ekberg en una Vespa, ésta se transformó en el símbolo de la dolce vita. Es curioso que cuando Italia proyectaba este nuevo imaginario urbano, que conquistaría al mundo, la Vespa tampoco se encontraba en su tiempo. No le era suficiente su realidad: añoraba el American style of life

Un tercer elemento que caracteriza el paisaje italiano de exportación son los Fiat 600, tal como aparecen en la fotografía (p. 146) de Luis Weinstein (1975-2016). Aun así, no es tanto este auto característico el que en esa escena atrae mi atención como el carretón, que se sigue viendo hasta hoy. La asociación que se me produce al respecto es con una fotografía que Leonard Freed tomó en Sicilia en 1975 y que está protagonizada por un pescador que lleva un atún en una carretilla, una escena muy similar a la capturada por Weinstein, lo que confirma el aserto de que la insondable profundidad del ser humano es y siempre será la misma en cualquier parte del mundo.

Allí reside uno de los grandes aportes de la fotografía, expresado así por Freed: “En última instancia, la fotografía es lo que eres. Es la búsqueda de la verdad en relación a uno mismo. Y la búsqueda de la verdad se convierte en un hábito”.

In turn, the Vespa moped captured in downtown Santiago (p. 139) immediately reminds me of Italy in the the fifties, when it was immortalized by Gregory Peck and Audrey Hepburn in the film Roman Holiday. And since Federico Fellini sat Anita Ekberg on a Vespa, this became the symbol of the dolce vita It is curious that when Italy was showing off this new urban imaginary, that would conquer the world, the Vespa wasn’t of its time either. Its reality wasn’t enough: it longed for the American way of life

A third element that characterizes the Italian export landscape is the Fiat 600, as shown in the photograph (p. 146) by Luis Weinstein (1975-2016). Still, it is not this characteristic car that attracts my attention in that scene as much as the cart, which can still be seen today. The association that comes to mind is a photograph by Leonardo Freed in Sicily in 1975 whose protagonist is a fisherman carrying a tuna in a wheelbarrow, a very similar scene captured by Weinstein, which confirms the assertion that the unfathomable depths of the human being are and always will be the same anywhere in the world.

There lies one of the greatest contributions of photography, expressed by Freed like this: “Ultimately, the photograph is what you are. It is the search of the truth in relation to oneself. And the search for truth becomes a habit”.

That habit is recognizable precisely in Weinstein, who delves into this exploration of truth or the idiosyncrasies of this country in continuous search of itself, a search reflected in the physiognomy and gestures of it characters. The anonymous characters, immersed in daily life (p. 144), wandering and moving around the downtown streets of Santiago especially captivate me.

Ese hábito es reconocible justamente en Weinstein, quien ahonda en esta exploración de la verdad o de la idiosincrasia de este país en continua búsqueda de sí mismo, búsqueda que se refleja en la fisonomía y los gestos de sus personajes. Me cautivan sobre todo los sujetos anónimos, inmersos en su cotidianeidad (p. 144), deambulando y desplazándose por las calles céntricas de Santiago.

Ya no hay una escenografía de por medio y tampoco una coreografía de actores. Ha desaparecido la búsqueda de un imaginario ajeno, y sólo se pueden constatar unos hábitos que ya calaron en la realidad local. Son como los paisajes urbanos que a menudo es posible registrar desde el interior de un taxi, en ese corto trayecto espacio-temporal que nos suspende brevemente de nuestras preocupaciones y afanes para permitirnos una mirada desapegada y sin compromiso con el entorno. El taxi actúa como un dispositivo paisajístico móvil (pp. 154-155), desde cuyas ventanas captamos fragmentos del vaivén urbano y de la idiosincrasia de los habitantes de la ciudad.

Pero justo cuando el lente fotográfico parecía encontrar su foco, cuando parecía encontrar la verdad en relación a sí mismo, se produce el fuera de servicio tan típico en estas latitudes. Un cortocircuito que anula todos los esfuerzos conseguidos hasta ese momento. La imagen más sintomática de este desenfoque es la de la anciana bajando las escaleras de metro, con su vestido floreado que se desdibuja para emparejarse con el fondo de mosaicos (p. 163), y donde los protagonistas son las sombras fugaces y no los cuerpos reales.

There’s no longer a scenography on the way nor a choreography of actors. The search for alien imagery has disappeared, and habits that have permeated the local reality can only be observed. It is like the urban landscape that often is possible to register from inside a taxi, in that short space-time journey that briefly relieves us of our worries and duties to allow a detached and commitmentless view of our environment. The taxi acts like a mobile landscape device (pp. 154-155), from whose windows we capture fragments of urban swing and the idiosyncrasies of the inhabitants of the city.

But just when the photographic lens seemed to find its focus, when it seems to find the truth in relation with itself, the off duty so typical of these latitudes occurs. A short circuit that annuls all efforts achieved until then. The most symptomatic image of this blur is the one of the old lady walking down the stairs of the subway, with her flowered dress that fades to match a mosaic background (p. 163), and where the protagonists are fleeting shadows and not real bodies.

Odber Heffer (1860-1945) nació en Canadá y se avecindó en Chile a fines del siglo XIX. Aquí comenzó a trabajar en el estudio Leblanc de Valparaíso, el que luego compró y trasladó a Santiago. Adquirió renombre a principios del siglo XX al explotar el carácter comercial de la fotografía, retratando a la élite de la época y dando cuenta del afrancesamiento y las modas de la capital.

Odber Heffer (1860-1945) was born in Canada and established in Chile by the end of the ninetieth century. Here he started working in the Leblanc Studio in Valparaiso, which later he bought and transferred to Santiago. He gained popularity by the beginning of the twentieth century by exploiting the commercial features of photography, portraying the elite of the time and the fashions of the capital.

Monumento Genio de la libertad donado por la comunidad italiana para el centenario de la independencia. Genio de la libertad Monument, donated by the Italian community for the celebration of the centenary of Chilean Independence.

Vendedores de flores en el acceso a la Iglesia de San Francisco. Los primeros mesones se instalaron en 1910 para ordenar el trabajo de las floristas. Flower sellers in the entrance of the San Francisco Church. The first stalls were installed in 1910 to tidy the work of the flower sellers.

Acceso principal al cerro Santa Lucía, construido en 1902 por el arquitecto Víctor Villeneuve. Main Access of Santa Lucía Hill, built in 1902 by the architect Víctor Villeneuve.

Palacio Undurraga, ubicado en la esquina de la calle Estado y la Alameda, construido entre 1911 1915 por el arquitecto catalán Felipe Forteza. El edificio fue demolido en 1976. Undurraga Palace, located on the corner of Estado and Alameda Streets, built between 1911 and 1915 by the Catalan architect Felipe Forteza. The building was demolished in 1976.

Casa Central de la Universidad de Chile. El edificio fue construido entre 1863 y 1872, bajo la dirección de Fermín Vivaceta. Main Administrative Building of Universidad de Chile, built between 1863 and 1872, under the direction of Fermín Vivaceta.

Palacio Díaz-Gana, construido por Teodoro Burchard en 1875. Luego fue adquirido por la familia Concha y pasó llamarse Palacio Concha-Cazotte. Fue demolido en 1935.

Díaz-Gana Palace, built by Teodoro Burchard in 1875. Later it was bought by the Concha family and was renamed ConchaCazotte Palace. It was demolished in 1935.

Estación Central de Ferrocarriles, inaugurada en 1857 y remodelada en 1897, cuando se incorporó la actual estructura metálica. Central Train Station, inaugurated in 1857 and remodelled in 1897, when the current metallic structure was incorporated.

La Plaza Argentina, frente a la Estación Central, fue inaugurada en 1903. Argentina Square, in front of Central Train Station, inaugurated in 1903.

Jardines

Galería San Carlos, que estaba ubicada en el costado oriente de la Plaza de Armas, detrás del Portal Mac-Clure.

La galería fue demolida en 1925, luego de un incendio.

San Carlos Gallery, that was located in the east side of Plaza de Armas, behind Portal Mac-Clure. The Gallery was demolished in 1925, after a fire.

Bolsa de Comercio de Santiago, construida entre 1913 y 1917, en la esquina de Bandera Moneda. El edificio fue diseñado por Emilio Jecquier.

Stock Exchange of Santiago, built between 1913 and 1917, on the corner of Bandera and Moneda streets. The building was designed by Emilio Jecquier.

Edificio Ariztía, construido en 1921 por Alberto Cruz Montt y Ricardo Larraín Bravo. Es considerado el primer rascacielos de Santiago, ubicado en el barrio de la Bolsa.

Ariztía building, built in 1921by Alberto Cruz Montt and Ricardo Larraín Bravo.

Considered the first skyscraper of Santiago, located in the Bolsa neighbourhood.

Ministerio de Guerra y Marina, emplazado frente a La Moneda, donde hoy se encuentra la Plaza de la Constitución. Fue demolido en la década de 1930 con motivo de la remodelación del Barrio Cívico. Ministry of War and Marine, in front of La Moneda Palace, where today is the Constitution Square. It was demolished in the 1930s due to the remodelling of the civic neighbourhood.

Fuente Alemana, obra de Gustavo Eberlein. Donada por comunidad alemana para el centenario de la independencia, la escultura está emplazada en Parque Forestal. Fuente Alemana (German Fountain), designed by Gustavo Eberlein. Donated by the German community for the celebration of the centenary of Chilean Independence, the sculpture Forestal Park.

En las calles Ismael Valdés Vergara Monjitas se construyeron elegantes residencias desde las que podían disfrutarse las vistas del Parque Forestal su laguna. Ismael Valdés Vergara and Monjitas streets elegant residences were built from which views of Forestal Park and its lake Constitution Square could be enjoyed.

En 1905, el Parque Forestal tenía más de un kilómetro de largo y casi doscientos metros de ancho, en él se habían plantado ocho mil árboles, incluidos los tradicionales plátanos orientales. In 1905, Forestal Park was more than kilometre long and almost two hundred meters wide, and it had eight thousand trees, including the traditional plane trees.

Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, construido por Emilio Jecquier e inaugurado en 1910, para la celebración del centenario de la independencia. National Museum of Fine Arts, built by Emilio Jecquier and inaugurated in 1910, for the celebration of the centenary of Chilean Independence.

Academia de Bellas Artes, en el costado poniente del Palacio de Bellas Artes, en el que actualmente funciona el Museo de Arte Contemporáneo. Academy of Fine Arts on the west side of the Palace of Fine Arts, where the Museum of Contemporary Arts is currently located.

Enrique Mora (1889-1958) nació en España y llegó a Chile en 1911. Inició su carrera en Puerto Montt como corresponsal de El Diario Ilustrado y las revistas Zig-Zag y Sucesos A comienzos de los años treinta se trasladó a Santiago y abrió el estudio Foto Mora. Al poco tiempo empezó a desarrollar la postal fotográfica, retratando tanto la capital como el resto del país.

Enrique Mora (1889-1958) was born in Spain and arrived in Chile in 1911. He began his career in Puerto Montt as a correspondent for El Diario Ilustrado and Zig-Zag and Sucesos magazines. By the beginning of thirties he moved to Santiago and opened the Foto Mora Studio. Soon he began to develop postcard photography, portraying both the city and the rest of the country.

La Plaza Italia recién remodelada en 1927, cuando se instaló en el centro la estatua del general Manuel Baquedano y pasó llamarse Plaza Baquedano. Italia Square, just remodelled in 1927, when the statue of General Manuel Baquedano was installed in the centre and began to be named Baquedano Square.

La Plaza Baquedano en los años treinta, con la Estación Pirque, diseñada por Emilio Jecquier, construida entre 1905 y 1911 y demolida en 1943. Baquedano Square in the thirties, with the Pirque Station, designed by Emilio Jecquier and builted between 1905 and 1911, demolished in 1943.

Vista panorámica hacia el norte de la Alameda. Destacan el edificio Ariztía, el Palacio Undurraga y la Casa Haviland, donde hoy está el edificio Santiago Centro. Panoramic view to the north of the Alameda. Highlights include the Ariztía building, Undurraga Palace, and Haviland House, where today the Santiago Centro building stands.

Ahumada esquina Huérfanos, donde se encontraba la Confitería Lucerna, muy popular en los años treinta y cuarenta. Desapareció tras un incendio en 1949.

Ahumada Street corner with Huérfanos Street, where Lucerna Confectionery used to be, very popular in the thirties and forties. Disappeared in 1949 after fire.

Estado con Plaza de Armas. Atrás, a la derecha, el edificio Oberpaur; construido en 1929 por Sergio Larraín Jorge Arteaga, está considerado el primer edificio moderno levantado en Chile.

Estado Street with Plaza de Armas. Behind, in the right, the Oberpaur building, built in 1929 by Sergio Larraín and Jorge Arteaga, considered the first modern building constructed in Chile.

el poniente desde la Iglesia de

Vista desde La Moneda hacia el suroriente, en la que destacan la Iglesia de los Sacramentinos y la cordillera, cuando recién se comenzaba construir el Barrio Cívico.

La Moneda Palace to the south west, highlights include the Sacramentinos Church and the mountains, when the construction of the Civic District began.

Los edificios que conforman el Barrio Cívico fueron construidos entre 1937 y 1950, bajo la normativa establecida por decreto que fijó las condiciones de diseño. The buildings that shape the Civic District were built between 1937 and 1950, under the regulations established by decree that defined the design conditions.

El urbanista Karl Brunner propuso dejar un espacio vacío al norte y al sur del Palacio de la Moneda para realzar el concepto de institucionalidad del Estado. The urbanist Karl Brunner proposed to leave an empty space by the south and north sides of La Moneda Palace, to highlight the concept of an institutional state.

Estación Mapocho, construida en 1910 por Emilio Jecquier. En 1987 dejó de funcionar como estación ferroviaria luego se convirtió en centro cultural. Mapocho Train Station, built 1910 by Emilio Jecquier. Stopped working railway station 1987, and become cultural centre.

Estación Central, punto de partida de los tranvías que circulaban por Alameda. Central Train Station, starting point for the trams that ran along the Alameda.

Plaza Argentina, frente Estación Central. Argentina Square, in front of Central Train Station.

Estación Central, punto de partida de los tranvías que circulaban por Alameda. Central Train Station, starting point for the trams that ran along the Alameda.

Plaza Argentina, frente Estación Central. Argentina Square, in front of Central Train Station.

Pistas de carrera del Club Hípico de Santiago. La primera carrera en este club se corrió el 20 de septiembre de 1870. Race track of the Equestrian Club of Santiago. The first race in this club was on the 20th of September of 1870.

Club Hípico de Santiago, proyectado por el arquitecto Josué Smith Solar e inaugurado en 1923. Equestrian Club of Santiago, designed by the architect Josué Smith Solar and inaugurated in 1923.

Antonio Quintana (1904-1972). Pionero de la fotografía documentalsocial en Chile. Su trabajo se caracteriza por el alto compromiso político, la innovación técnica y la formalización de la enseñanza de la disciplina. Imprimió una profunda huella, siendo precursor de una visualidad que marcaría el desarrollo de la fotografía en el siglo XX en el país.

Antonio Quintana (1904-1972).Pioneer of social documentary photography in Chile. His work is characterized by the high political commitment, technical innovation and the formalization of the teaching of the discipline. He left a strong footprint, being a precursor to a visual style that would mark the development of photography in the twentieth century in the country.

Transporte público en los años cincuenta. Public transport in the fifties.

Edificaciones detrás del Barrio Cívico, comenzando la década de 1950. Buildings behind Civic Quarter, at the beginning of the fifties.

Los cités fueron construidos entre 1870 y 1960, como solución habitacional para obreros, en reemplazo de los conventillos. The cités where built between 1879 and 1960, as a housing solution for workers, as replacement of conventilllos

Cité en el barrio Santiago Poniente. Atrás se ve la Iglesia de San Lázaro, ubicada en la calle Ejército.

Cité in the east neighbourhood of Santiago. Behind it could be seen San Lázaro Church, located in Ejército Street.

Luis Weinstein (1957) nació en Santiago y es uno de los más destacados fotógrafos de la escena chilena actual. Su abundante obra documental –que viene desarrollando desde la década de 1970– registra sobre todo hombres y mujeres en escenas cotidianas, enmarcadas en el paisaje de la ciudad. Ha publicado numerosos libros con sus imágenes.

Luis Weinstein (1957) was born in Santiago and is one of the most prominent photographers of the current Chilean scene. His abundant documentary work – which has been developing since the seventiesregisters mainly men and woman in daily scenes, framed within the city landscape. He has published numerous books with his images.

Carretones y carretelas se ven cada vez menos en la ciudad, pero sus colores y adornos son parte del patrimonio gráfico nacional. Carriages and wagons are seen less and less in the city, but their livery and decorations are part of the national graphical heritage.

Vista en altura desde el edificio Ariztía, en el barrio de la Bolsa; al fondo, la Torre Entel.

Inaugurada en 1999, la Torre Oriente es uno de los primeros edificios en altura construidos en el sector de Nueva Las Condes. Inaugurated in 1999, a Oriente Tower is one of the first high-rise buildings constructed in the Nueva Las Condes area.

La Gran Torre Santiago tiene trescientos metros de altura y es el edificio más alto de América Latina. The Gran Torre Santiago is three hundred meters high and is the tallest building in Latin America.

Torre de la Industria, construida en 1994 por el arquitecto Juan Echenique Industria Tower, built in 1994 by the architect Juan Echenique.

La Torre Oriente fue diseñada por la oficina de arquitectos Alemparte Morelli. Oriente Tower was designed by the architect’s office Alemparte Morelli.