18 minute read

La ciudadela de Shincal Una arquitectura políticamente correcta

The citadel of Shincal ~ Politically correct architecture

En la medida en que el Imperio se expandía y se alejaba de su centro político y ceremonial, buena parte de su reconocida monumentalidad tendía a disminuir, a adaptarse, y en ciertos casos, a mimetizarse con el entorno geográfico y cultural. Esto podría ser un reflejo de la flexibilidad de las estrategias de dominación de los incas, sobre todo en aquellos territorios más alejados de la metrópoli. Sin embargo y simultáneamente, la elite dominante del Cusco no transaba al momento de imponer ciertos patrones estéticos y arquitectónicos que reafirmaran el carácter no solo funcional, sino también poderosamente simbólico del dominio imperial.

Advertisement

As the Inca Empire expanded ever farther from its political and ceremonial center, its remarkable monumental character tended to decline, change and sometimes adopt features of the cultural and geographic surroundings. This could reflect the flexibility of the Incas’ domination strategies, especially in territories that were furthest removed from the capital. At the same time, however, the ruling elite of Cusco refused to compromise on the required use of certain aesthetic and architectural patterns that reaffirmed not only the functions of imperial domination but also powerfully symbolized it.

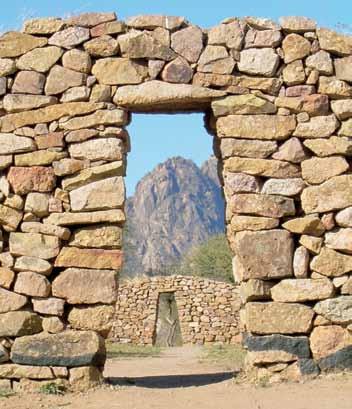

Ubicada en la provincia de Catamarca, en las cercanías del actual pueblo de Londres de Quinmivil, Shincal se encuentra en una meseta rodeada de cerros en el margen izquierdo del río Simbolar. No solo fue un importante centro administrativo y ceremonial del noroeste argentino, sino también una verdadera ciudadela inca. La zona propiamente urbana abarca más de 20 hectáreas cuyos edificios y viviendas albergaban a unos 800 habitantes. Seguramente su trazado fue diseñado por arquitectos e ingenieros provenientes del Cusco que reprodujeron, aunque en menor escala, la clásica estructura y organización urbana de la capital del Tawantinsuyu

Contaba con un ushnu o plataforma construida en piedra, donde se realizaban actividades administrativas y judiciales. Era también un centro ceremonial y podía, además, ser utilizado como oráculo. Sus clásicas kallankas, o grandes recintos rectangulares, respondían a necesidades diversas tales como centros de almacenamiento y de producción de textiles o como viviendas de funcionarios importantes. Estos edificios se distribuían alrededor

Located in the province of Catamarca, near the modern day town of Londres de Quinmivil in Northeastern Argentina, Shincal is sited on a rounded hilltop plateau on the left bank of the Simbolar River. More than a major administrative and ceremonial center for the region, it was also a true Inca citadel. The area is completely urbanized and covers around 20 hectares, with buildings and homes for some 800 inhabitants. Its layout was almost certainly designed by architects and engineers from Cusco, who created a smaller scale copy of the classic urban layout and structures found in the capital of Tawantinsuyu.

The center featured an ushnu, a raised stone platform used for administrative purposes such as court proceedings, but also for oracles and ceremonies. Its classical kallankas, great rectangular spaces, served a wide range of needs, being used for storage, textile production or as the residences of important officials. These buildings were distributed around a central plaza or aukaipata, which was

El trazado de Shincal fue diseñado por arquitectos e ingenieros incas que reprodujeron la clásica estructura y organización urbana de la capital del Tawantinsuyu

Shincal’s urban layout was designed by Inca architects and engineers who reproduced the classic urban structures and spatial organization of the capital of Tawantinsuyu de una plaza central o aukaipata, que era un lugar público ceremonial y de encuentro entre las autoridades incas y las autoridades y habitantes locales. En el entorno se encuentran dos plataformas construidas en dos cerros ubicados al oriente y al occidente de la plaza. Sus imponentes escalinatas de acceso parecen haber sido destinadas a rituales agrícolas y posiblemente también al culto solar durante las principales festividades estatales que se realizaban en los solsticios de invierno y de verano.

Al llegar los incas a la región, sometieron en forma relativamente rápida a los cacicazgos locales diaguitas y calchaquíes, integrándolos a su sistema. Estos pueblos ya trabajaban las minas metalíferas de oro, plata, cobre y estaño de las sierras de Quinmivil y de Belén, cuya explotación, junto con la industria textil, fue reorganizada por los incas en beneficio del Estado. Como capital provincial, Shincal fue un centro de recaudación de tributo y de redistribución de bienes, y su influencia parece haber abarcado parte de Catamarca, de Tucumán y de Salta. Como cada pueblo y ciudad del Imperio, estuvo conectada al Qhapaq Ñan, lo que permitía su fluida comunicación con la capital cusqueña y con las regiones más distantes del Tawantinsuyu used as a public ceremonial space and as a meeting place for Inca authorities and local inhabitants. Nearby were the sites of two platforms, built on hills located to the east and west of the plaza. The imposing stairways leading up these platforms seem to have been designed for agricultural rituals, and perhaps also for Sun worship during the State’s main religious festivals, held at the summer and winter solstices.

Luego de la invasión española, Shincal volvió a ser ocupada. En 1558, Juan Pérez de Zurita fundó la ciudad de Londres de Quinmivil utilizando los muros incas originales y el acueducto urbano. Sin embargo, con el inicio de las prolongadas rebeliones calchaquíes, la ciudad debió ser abandonada y refundada aguas abajo.

When the Incas arrived in the region, they quickly subjugated the local Diaguita and Calchaquí rulers, integrating them into their own system as nobles. These groups were already engaged in gold, silver, copper, and tin mining in the highlands of Quinmivil and Belén, and both mining and textile production were reorganized by the Incas for the benefit of their state. As the provincial capital, Shincal was the center for taxation and the redistribution of goods, over an area that apparently included part of Catamarca, Tucumán, and Salta. Like every other town and city in the Empire it was connected to the Qhapaq Ñan, allowing rapid communication with the most distant regions of Tawantinsuyu and with the capital of Cusco.

Shincal was occupied once again after the Spanish invasion. In 1558 Juan Pérez de Zurita founded the city of Londres de Quinmivil, making use of the original Inca wall and the urban water supply system. However, after prolonged resistance from the Calchaquí, the old town was abandoned and a new city was founded downriver.

re-crossing the andes

The Maipo Valley and the southern frontier of Tawantinsuyu

Una vez sometidos los zuríes a su jurisdicción, Tupac Inca Yupanqui continuó hacia el sur por el borde oriental hasta alcanzar las nacientes del Río de la Plata. Sin embargo, decidió no adentrarse en esas regiones, sino que desde allí, desde “las espaldas de Chile” y desde donde “el Sol sale”, se dirigió con su ejército al poniente atravesando la ancha y majestuosa cordillera de los Andes:

Once the Zuri within his jurisdiction had been overcome, Tupac Inca Yupanqui continued to the south along the eastern side of the Andes until reaching the headwaters of the Río de la Plata. However, he decided not to penetrate this region further; rather, from here, from “the backside of Chile”, the place where “the Sun rises”, he directed his army to the west, across the wide, majestic Andes Mountains:

“…y tomando la mano derecha ansi como iba pasó los puertos y cordilleras de nieve y montañas altas sujetando y conquistando todo lo que ansi por delante hallaba e ansi llegó a la provincia de Chile y halló en ella gente muy belicosa y muy rica y próspera de oro e habido con ellos su reencuentro sujetólos y como ya los tuviese pacíficos preguntó que de dónde había habido tanta riqueza de oro…

(Juan de Betanzos, 1551)

“… and turning to the right, he went up through the mountain passes, the snowy ranges and the high peaks, taking control of and conquering everything he encountered on his way, and thus arrived in the province of Chile, and found there a warrior people, very rich and prosperous, with much gold, and after fighting and overcoming them asked where they had obtained such a wealth of gold …

(Juan de Betanzos, 1551)

Sin duda, los incas avanzaron más al sur del valle del Maipo, pero su control político y militar no logró ser realmente estable y su presencia solo consistió en puestos defensivos. En efecto, algo más al sur de Santiago, se iniciaba un espacio de frontera no solo geopolítica, sino también con fuertes componentes simbólicos y culturales, como puede apreciarse por los restos arqueológicos y por las tradiciones orales incas.

Cuando los incas llegaron a los valles centrales de Chile se encontraron con un desafío de proporciones hacia el sur. La tradición señala que Tupac Inca envió desde aquí a sus capitanes a reconocer la zona del río Maule. Una vez de regreso, éstos “dijéronle que era un río ancho y poblado en partes de alguna gente”, pero el Inca decidió que ya era hora de comenzar el retorno puesto que:

Of course, the Incas did advance further south than the Maipo Valley, but their political and military control was always tenuous beyond that point, and their presence consisted of defensive positions only. In effect, the lands just south of Santiago were a frontier land of not only geopolitical but cultural and symbolic importance, as archeological remains and Inca oral tradition itself attest to.

When the Incas came to the central valleys of Chile they encountered strong resistance to the south. As usual, Tupac Inca sent his captains to scout out the land beyond— the Maule River region to the south. Upon their return, they told him that the region had a wide river and was populated in parts by some groups of people”, but the Incas decided that its was time to go home, as:

“había mucho tiempo que habían salido de la ciudad del Cusco y que ya habían visto lo que hasta allí había, que le parecía que de allí se debían devolver.

(Juan de Betanzos, 1551)

“a lot of time had passed since they had left the city of Cusco and since they had already seen what there was there, it seemed best to return home.

(Juan de Betanzos, 1551)

El valle del río Maipo sería, finalmente, la frontera sur del Tawantinsuyu. Y como toda frontera de importancia, debía legitimarse y revestirse de sacralidad. Es así como encontramos, en pleno valle central de Chile, la frontera simbólica elegida por los incas. El cronista español Gerónimo de Vivar describe con cierta prolijidad los límites del territorio conquistado, donde la naturaleza y quienes la habitaban establecían, una vez más, los límites de la cartografía incaica. Hacia el sur de la llamada Angostura de Paine se iniciaba la provincia de los purun auca:

In the end, the Maipo Valley was to be the last southern border of Tawantinsuyu. And like all major borders, it had to be officially established and consecrated. Thus we find in the middle of Chile’s Central Valley the symbolic boundary chosen by the Inca ruler. The Spanish chronicler Gerónimo de Vivar describes at some length the threshold of the conquered territory, where nature and the local inhabitants established once more the limits of the Incas’ reach. The narrow pass called “Angostura de Paine” marked the beginning of the province of the purun auca:

“

…está esta provincia de los poromocaes que comienza de siete leguas de la çiudad de Santiago que es una angostura y ansi la llaman los españoles… y aquí llegaron los yngas quando vinieron a conquistar esta tierra. Y de aquí adelante no pasaron. Y en una sierra de una parte de [la] angostura hacia la cordillera toparon una boca y cueva, la qual está hoy dia y estará. Y della sale viento y aun bien rezzio. Y como los yngas lo vieron fueron muy contentos, porque decían que avian hallado ‘guayra huasi’ ques como si [se] dijese ‘la casa del viento’. Y alli poblaron un pueblo… ”

(Gerónimo de Vivar, 1558)

“… is the province of the poromocaes [purun auca] which begins seven leagues from the city of Santiago, which is an “angostura”, as the Spanish call it … and the Incas arrived here when they came to conquer these lands. And they got no further. And on a mountain within the pass they came to an opening and cave, which is still there today and always will be. And from it the wind blows very strongly. And the Incas saw this place and were very happy, because they said they had discovered ‘guayra huasi’ which means ‘the house of the wind’. And there they established a town … ”

(Gerónimo de Vivar, 1558)

El cordón montañoso de la Angostura, que mantiene su nombre hasta la actualidad, se ubica a unos 56 kilómetros al sur de la ciudad de Santiago y constituye la divisoria de aguas de las cuencas del río Maipo por el norte y del Cachapoal por el sur, uniendo la cordillera de los Andes y la de la Costa.

Es sumamente interesante la relación entre la tradición oral, mediatizada por la mirada española del siglo XVI, con lo que aporta la arqueología regional, que señala a esta zona como un espacio de límite, no solo estatal, sino también previo a la llegada del Inca. El cordón montañoso de Angostura era la zona límite de la denominada Cultura Aconcagua.

The Angostura range, which retains its name today, is located about 56 kilometers south of the city of Santiago and is the dividing line between two water basins— the Maipo River basin in the north, and Cachapoal in the south, running between the Andes and Coastal mountain ranges.

It is interesting to decipher the relationship between oral tradition, mediated by the 16thCentury Spanish perspective, and the contributions of regional archeology, which indicates that the zone was a frontier space not only during Inca times but also before. For instance, the Angostura chain was also the southern boundary of the ancient Aconcagua Culture.

El pueblo y lugares sagrados mencionados por el cronista Vivar habrían correspondido al límite meridional de un efectivo dominio político incaico en la zona, establecido y sustentado en estrategias de alianza con las poblaciones locales. Se trata de las ruinas de Chada, ubicadas sobre un desfiladero desde el cual se obtiene una excelente vista de las rutas de acceso y circulación. Al oeste, por la falda de la cordillera, pasaba el camino incaico. Hacia el este, en el cerro Challay, se encuentra lo que parece haber sido la boca y cueva Huayra Huasi, que consiste en dos cavernas ubicadas en cada uno de sus extremos y que son visibles desde las ruinas del pueblo. El sitio de Chada presenta un trazado arquitectónico complejo y manifiesta la coexistencia de grupos diaguitas procedentes del norte como mitmakunas del Inca, con poblaciones locales de la Cultura Aconcagua. En este sentido, las tradiciones orales y la arqueología parecen dialogar, señalando esta combinación de espacios sagrados, políticos y sociales.

The people and sacred places mentioned by the chronicler Vivar corresponded to the southernmost limit of effective Inca political control of the zone, which was established and maintained through a strategy of alliances with local populations. Though now in ruins, Chada was one such place. It is located on a narrow pass with a sweeping view of access and transit routes. To the west, the Inca Trail passed by at the foot of the mountains. To the east, on Cerro Challay, is what appears to have been the opening and cave of Huayra Huasi, which consists of two caverns located on opposite sides of the mountain and visible from the ruins of the town. The site of Chada has a complex architectural plan and displays evidence that Diaguita groups from the north lived here as mitmakunas of the Incas alongside local residents of the Aconcagua Culture. Here, oral traditions and archeology seem to be in dialogue, pointing to a combination of sacred, political and social spaces.

Al sur de la Angostura de Paine, en el Cerro Grande de La Compañía, conocido también como Cerro del Inga, está el asentamiento más meridional del Tawantinsuyu. Es un sitio fortificado que controla visualmente una extensa área de la región.

To the south of the Angostura de Paine, on the mountain of Cerro Grande de La Compañía, also known as Cerro del Inga, the Inca built the southernmost settlement of Tawantinsuyu. This is a fortified site that affords a commanding view of the surrounding area.

La sacralización de este paisaje le otorga una especial valorización como espacio simbólico. La Angostura, que albergaba “la casa del viento recio”, denotaba una determinada manera de concebir, organizar y ritualizar el entorno natural. Es muy sugerente la semejanza que existía entre este lugar sagrado de los confines del Tawantinsuyu con uno de los sitios ceremoniales del sistema de ceques del valle del Cusco donde, según cuenta décadas más tarde el sacerdote jesuita Bernabé Cobo, había una waka en el camino del Collasuyu denominada Huayra, que era una quebrada en una angostura donde, según contaban, se metía el viento, y cuando soplaban “recios vientos”, los incas le hacían ofrendas y sacrificios.

Como en el corazón del Imperio, la organización ritual del espacio conquistado en las provincias parece estar replicando el modelo cusqueño. La Angostura del viento señalaba un hito o un límite en el proceso de expansión incaica. Era en la Angostura, según señalaba Vivar, donde se iniciaba la “provincia de los poromocaes”, “promaucaes” o purun auca, clasificación social o “étnica” que, como sabemos, los incas utilizaban para definir a aquellos pueblos y espacios geográficos aún no sometidos al “orden” político y cultural del Tawantinsuyu

The consecration of this landscape gives it a special symbolic value. The Angostura pass, which contains “the house of strong wind”, illustrates a particular way of envisioning, organizing and ritualizing the natural environment. It is very interesting to note the link between this sacred place, within the boundaries of Tawantinsuyu, and a certain ceremonial site in the Cusco Valley. As the Jesuit priest Bernabé Cobo reported decades after this period, there was a waka on the Collasuyu trail called Huayra, located in a ravine within a narrow pass where the wind blew through, so the story goes, and when the “howling winds” blew, the Incas made offerings and sacrifices there.

The ritual organization of conquered space in the provinces seems to have been modeled after the model established in the heart of the Empire.

La apropiación o la creación de nuevos sitios sagrados para que las provincias adoraran era una práctica muy común. Así lo indicaría el caso de Huayra Huasi, en los confines simbólicos de la expansión incaica al momento de la llegada de los españoles, como parece indicarlo más al norte la gran waka del volcán Aconcagua.

The ‘Angostura’ of the wind was a milestone or a limit to the process of Inca expansion. It was in the ‘Angostura’, according to Vivar, where the “province of the poromocaes’ began (as already mentioned, ‘poromocaes’ or purun auca were a social or “ethnic” designation that the Incas used for those peoples and geographic places that had not yet been subordinated to the “political and cultural order” of Tawantinsuyu).

The appropriation and creation of new sacred sites for worship in the provinces was common Inca practice, and the site of Huayra Huasi, established within the symbolic limits of the Inca expansion at the time of the Spanish arrival, is a case in point. The same practice also seems to apply to the great waka on Mount Aconcagua, located further north.

Monte Aconcagua

Capacocha y alianzas

Mount Aconcagua

The Capacocha ceremony and political alliances

Geográficamente, el amplio valle del Aconcagua corresponde a una zona de transición ecológica y climática entre una región irrigada por sucesivos ríos de mediano caudal con otra hacia el norte que comienza a ser predominantemente árida, conocida como Norte Chico. En el cordón cordillerano ubicado al oriente y coronando las cumbres nevadas de la región, el monte Aconcagua se levanta sobre la cabecera del valle con sus casi 7 mil metros de altitud, y se erige como la más alta cumbre de la cordillera de los Andes. En su contrafuerte sudoeste y a 5.300 metros sobre el nivel del mar se encontró en 1985 el enterratorio de un niño acompañado de un ajuar funerario característico del ceremonial y ofrendas incas denominado capacocha

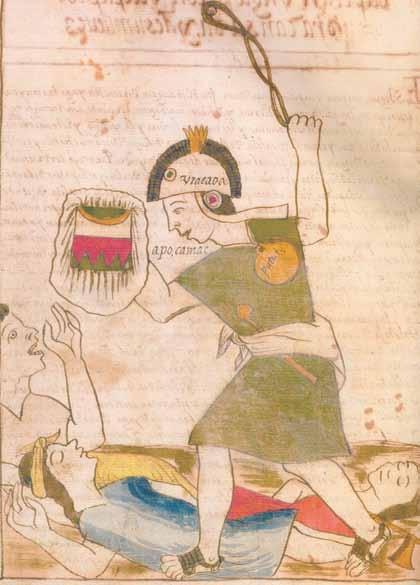

La capacocha o sacrificio a las wakas era una de las ceremonias más importantes del Tawantinsuyu Este ceremonial implicaba un largo proceso que comenzaba con el traslado, desde las distintas provincias, hacia el Cusco, de ofrendas destinadas al sacrificio en honor al Inca. Estas ofrendas consistían en bienes u objetos de alto valor cultural y económico y, solo eventualmente, en personas —niños y niñas o adolescentes— que eran transportados a la ciudad sagrada por grandes comitivas encabezadas por los caciques y elites locales.

Geographically, the broad Aconcagua Valley is a transition zone between two ecologies—one that is watered by several moderately large rivers and another, further north, that is the beginning of a predominantly arid region known as the Norte Chico. Towering above the snow-capped peaks of the mountain chain located east of the valley, Mount Aconcagua rises up from the valley floor to an altitude of close to 7000 meters above sea level. It is the highest peak in the Andes range. In 1985, on the southwest buttress at 5300 meters above sea level, a burial chamber was discovered with a boy inside, accompanied by grave goods that are typically found associated with the Inca Capacocha ceremony.

The Capacocha, the sacrifice to the wakas, was one of the most important ceremonies in all of Tawantinsuyu. The ceremony was a lengthy affair and began with a collection of offerings being sent from different provinces to Cusco for the ritual sacrifice in honor of the Inca. The offerings consisted of goods or objects with cultural or economic value, though later the Incas began to sacrifice boys, girls and adolescents, who were accompanied to the sacred city by large retinues led by local chiefs and elites.

En el Cusco se realizaban suntuosos festejos y banquetes y se celebraba un ceremonial a las divinidades y a las grandes wakas metropolitanas, a las que se sacrificaba una parte de las ofrendas, y las restantes se enviaban nuevamente a las respectivas provincias. Se iniciaba entonces el recorrido de regreso, a veces por miles de kilómetros, hacia los diferentes destinos. Cada conjunto de ofrendas iba destinada a una waka en particular cuyo ceremonial y cuidado estaba a cargo de “sacerdotes” o especialistas del culto.

La capacocha de mayor envergadura se realizaban solo en ciertas ocasiones, por ejemplo, al iniciarse el gobierno de cada Inca o cuando su salud o su poder estaba en riesgo; al iniciarse una nueva campaña de conquista o para apaciguar a las wakas al producirse una catástrofe de cualquier índole. Existían capacochas de diferente jerarquía y objetivos y, entre ellas, el sacrificio humano se restringía a situaciones muy especiales que así lo ameritaran.

In Cusco, elaborate celebrations and feasts were held, along with a special rite to honor the deities and the major wakas in the city, where some of the offerings were left. The rest were sent back to the respective provinces in processions that sometimes covered thousands of kilometers. Each group of offerings was sent to a particular waka under the care of special “priests” or religious specialists, who also performed the ceremony at the destination.

Large-scale Capacocha were held only on very special occasions such as when a new Inca was invested, or when the current Inca’s health or power was threatened. They were also performed at the beginning of a new campaign of conquest or to appease the wakas after a natural disaster. There were different kinds of Capacocha ceremonies, each with its own level and purpose. Among these, human sacrifice was reserved for very special occasions.

En el centro ceremonial de Pachacamac en la costa central del Perú, los incas construyeron un Templo al Sol. Por sus anchos caminos de acceso se realizaban multitudinarias procesiones y se ofrendaban bienes de alto valor; en ocasiones, seres humanos.

In the ceremonial center of Pachacamac on the central Peruvian coast, the Incas built a Temple to the Sun. Its wide entryways were used for large processions, and the offerings made included valuable goods and sometimes even humans.

La capacocha legitimaba la dominación cusqueña y la integración religiosa, económica y política del Tawantinsuyu. En especial las que incluían sacrificios humanos, cumplían un rol importante en la intermediación entre el mundo de lo divino y el de los poderes políticos. Los niños o adolescentes ofrendados a las wakas se convertían en oráculos que “hablaban”, como intermediarios entre las divinidades y el Inca. Cada oráculo era regularmente consultado sobre los siguientes períodos productivos y ciclos agrícolas. Pero también informaba respecto a las condiciones políticas que pudieran producirse en las provincias. En ese sentido, la capacocha era un ritual que inauguraba y renovaba la relación política entre el Inca y las autoridades regionales. De hecho, cuando había sacrificios humanos, los muchachos o muchachas ofrendados solían pertenecer a los linajes de los gobernantes locales. A cambio de ello, el Inca otorgaba un mayor reconocimiento a su autoridad.

The Capacocha ceremonies legitimized Inca domination and fostered the religious, economic and political integration of Tawantinsuyu. Those that involved human sacrifice played an especially important role in forging a link between the divine world and living political authorities. The children and adolescents offered to the wakas became oracles who acted as intermediaries between the gods and the Inca leaders. Oracles were consulted regularly at the beginning of the growing season or production cycle. But they also gave advice about political conditions in the provinces. In that context, the Capacocha ritual established and renewed the political relationship between the Incas and local authorities. In fact, in ceremonies involving human sacrifice, the girls or boys offered frequently belonged to a local ruler’s own kinship line. In exchange for this sacrifice, the Incas offered greater recognition of the local leader’s authority.

Pequeñas figuras humanas y de camélidos elaboradas en plata y mullu que se ofrendaban en el ceremonial de la Capacocha (Museo Arqueológico de La Serena).

Small figurines of humans and camelids made of silver and mullu shell were offered during the Capacocha ceremony (Museo Arqueológico de La Serena).