FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

A look at the Spanish Countryside from 1950’s to 2020’s

Clara Asperilla Arias

MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design Projective Cities (2020/2022) Architectural Association School of Architecture

2 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

She asked me where I lived, and I told her I didn’t really know. She smiled. You know, I once lived in Madrid. Do you know Madrid? Until very recently, I lived in Madrid. I have a son there; he went to work and got married there. One day he turned up at home in Soutomaior, I was peeling potatoes, and he said to me, come on, mum, get your stuff and come with me. And I said to him, but son, who will take care of the animals? Of the house? Who’s going to look after the house? And he said, look, mum, someone will look after the animals, we can leave them to the neighbours, no one will take the house. And that’s what we did. I went to Madrid.

-And did you like it, Madrid?

-What?

Manuel Rivas, “Un millón de vacas” (1989)

3 SPANISH COUNTRYSIDE 1950’S - 2020’S

4 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

5 SPANISH COUNTRYSIDE 1950’S - 2020’S ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ABSTRACT RESEARCH QUESTIONS, AIMS AND OBJECTIVES INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 01. PLANNED RURALITY - 1950’S 01.1. HISTORICAL CONTEXT: AUTARCHY 01.2. THE MODEL HOME: PRIVATE PROPERTY AND FAMILY 01.3. A HIERARCHICAL CENTRE: CHURCH, SCHOOL AND SOCIAL HOUSE 01.4. TERRITORIAL ISOLATION AND ITINERANT INFRASTRUCTURE CHAPTER 02: DISSOLVED RURALITY (1980’S) 02.1. HISTORICAL CONTEXT: TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY 02.2. FAMILIAR DISSOLUTION 02.3. POST-PRODUCTIVE RURALITY 02.4. MULTILOCAL COMMUNITIES CHAPTER 03: EXHAUSTED RURALITY (2020’s) 03.1. “HOLLOWED OUT SPAIN” 03.2. NO WAY BUT OUT: FEMALE RURAL EXODUS CHAPTER 04: PROPOSITIONS 04.1. PROBLEMATIZATION AND CRITICS 04.2. MAKING KIN 04.3. LEGISLATION 04.4. DESIGN SCENARIO: INSERTION IN VEGAVIANA CONCLUSION: FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY BIBLIOGRAPHY 06 08 10 12 16 18 22 48 72 88 90 92 98 110 116 118 130 134 138 142 152 172 206 212

6 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This dissertation would not have been possible if not for the support of the many people involved throughout this 18-month process. Firstly, I am extremely grateful to the Projective Cities staff who have supported me through the duration of my studies: I want to deeply thank Platon Issaias and Hamed Khosravi for their guidance, the many challenging conversations and the sharp questioning that have helped to bring the best out of this body of work. I am also grateful to Cristina Gamboa and Raül Avilla, not only for the extremely close support, but for opening my eyes to the programme in the first place. Thank you to Doreen Bernath for helping me to conceptualise my intuitions and transform them into specific research topics. Thank you also to Roozbeh Elia-Azar and Ioanna Piniara, your knowledge on London and Athens have provided us with the sharpest insight on two fascinating cities. I could not be more thankful to all of the Projective Cities cohort in 2020-2022 for the complete commitment and unquestionable support during these complicated years. It is strange and somehow paradoxical to write a thesis on the Architecture of Collective Living while living through a pandemic that confines the whole world to the interior of their home. However, the commitment and attentiveness that you provided through the programme has constructed a true network of care in unprecedented times.

I want to thank all of those who have been by my side while writing this dissertation. I particularly want to show my gratitude to my parents, Fernando and Carmen, for the unquestionable support and constant encouragement to embark on new projects. I could not have been able to take up the journey to London without you. Thank you also to my brother Martín for diving into my life in London, sneaking with me into the AA and accompanying me during the final weeks in the Brixton house. Thank you to my friends, Lucía, Gilen, Rocío, and all of those who supported me during the first year in Barcelona, and to my Projective Cities classmates, with whom I hope to continue debating with well into the future. Finally, thank you to Mike, whose love and infinite patience have been with me during the whole journey of this dissertation. The conversations I have with you are a constant motivation to take my ideas beyond, and this thesis would not have been the same without them.

This dissertation was supported by a bursary granted by the Architectural Association.

7

ABSTRACT

This dissertation examines the production of rurality through conditions of exodus between abandonment and colonisation1 in the “Hollowed Out Spain”2 across three key historical periods: 1950s, 1980s and currently the 2020s. The formation of the Spanish countryside as revealed in these periods shares the extended trend of rural depopulation in Europe, but presents a singular and intense case of demographic decline driven by specific sociopolitical, architectonic and territorial impositions.

Shrinking villages have not been able to retain productive ages, particularly the female population. Older generations have dwelled in extensive houses, and new generations keep exiting the countryside. State policies have been incapable of offering sufficient educational, cultural, health and care infrastructures for those who remain, prompting more of the younger generations to leave. These persistent conditions of exodus have produced particular subjects of rurality, manifested most profoundly across female generations having to settle or unsettle their roles within the dominant, patriarchal framework.

1 “Colonization” or “colonialism” is in this thesis utilized to refer to the internal phenomenon that occurred during the 20th century within the territory of the Peninsula, as a process of relocating the existing labour force within the country in order to transform inactive land into fertile land. It constituted an economic project for the extraction of natural resources within the unexploited domains of inland Spain. Similar projects took place in fascist European regimes -following an autarchic economic model- as a response to national economic crisis, as well as in other situations of scarcity such as the New Deal after the Great Depression in the USA.

“Colonialism” also refers to the power relations existing between rural and urban domains, where one acts as the producer of material goods for the other to consume. In this case, the power structures sit in central urban Madrid, and the capital acts as a drainage point extracting resources from its surrounding domains -inland Spain, today known as “Hollowed Out” Spain. In this sense, the source of material goods is the foreign domain, dominated by extractivist forces sitting in the capital city.

2 “Hollowed Out Spain” or “Empty Spain” is a term first coined by Sergio del Molino’s essay “La España vacía” (2016). Since its publication, the term has been broadly used to define Spain’s inner rural territory to make reference to the demographic decline that it is experiencing.

8 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

The recognition of a gender bias within this process of ongoing rural exodus provides the departing point in the construction of the connections between the landscape and the female body, the political control of territory and female subjects. The thesis will take a gender perspective throughout the whole dissertation, therefore the histories of colonisation and desertification of the Spanish countryside will be narrated through its female subjects, who conduct the different scales of the research from dwelling, household, settlement, to territory.

Departing from Chapter 1, focused on the 1950’s Francoist agrarian internal colonization – which redistributed the working population of Spain across its rural areas – as paradigmatic of this decade’s modes of living in rural Spain. The colonisation programme was asserted directly by the state and institutionally planned, which became instrumental to the political power and ideology: an imposed plan upon the countryside that was deliberately contrary to the traditional process of organic and self-determined settlement patterns. In Chapter 2, the investigation observes the evolution of these settlements in the following decades, particularly attending to the 1980’s Spanish subject who rapidly embraced a transition towards democracy and its inscription within a global economy, which in turn supposed the dissolution of rurality’s traditional pillars. As a result, the 1980’s witnessed the consolidation of a rural exodus led by the female subjects fleeing from an outdated environment. Lastly, a series of projective propositions are inserted in the present 2020’s -whose contemporary conditions are brought forward in Chapter 3- as a response to the experience of rural subjects who have reconciled states of colonization and exodus.

Moving from these periods, the critical lens is grounded in the late 20th-century feminist historical theories, such as Donna Haraway’s critical thinking. The application of these to understand past dictatorships in Europe is the key to grounding the polemics and propositions of the thesis. It is the lens through which critically analyse the space produced in the past decades, and actively take a stand in its redesign.

Finally, the research methodology will be based on case study drawn analysis and archival research in the case of Chapter 1; statistics and demographics will be central to arguing the contemporary phenomenon of rural desertification in Chapter 3. In Chapter 2, diagrammatic devices will be brought forward as paradigmatic of a change towards a post-agrarian Spain. Along with these traditional investigation tools, the use of pop culture case studies shapes a methodological framework where mediascape brings forward evidence of a radical cultural phenomenon that occurred in the 1980’s in Spain. Therefore, the dissertation constructs a dialogue between the regulatory language of geographers and planners and anthropological research methodologies.

9 SPANISH COUNTRYSIDE 1950’S - 2020’S

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- How are present and past conditions of exodus affecting the social and built environment of rural Spain?

- How have different notions of governance during the past seven decades affected the socio-spatial fabric of rural settlements and the definition of rurality itself?

- How have the disciplines of architecture and planning traditionally approached rurality, and what alternative approaches can be taken to examine and make propositions in rural Spain?

- At settlement scale: What are the social, spatial and legal protocols for the re-appropriation and reinvention of derelict, obsolete and empty spaces of Hollowed Out Spain?

- At block scale: What alternative models of socialisation and inhabitation emerge from the reinvention of the domestic block?

- At household scale: In a rural dwelling designed for the model 1950’s peasant family, what spatial alterations and additions can be proposed to adapt the housing typology to today’s multiple subjectivities and household structures?

10 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

- To alleviate rural exodus, by reading the Spanish countryside with a critical feminist lens.

- To challenge existing social, gender and labour norms by repurposing everyday space at the scale of the household, the block and the territory.

- To design protocols for self-care and self-provision in exhausted rural domains and communities.

- To carry out project tests for a non-determined, varied use of space, adaptable to multiple arrays of subjects and contemporary living conditions and necessities.

11 SPANISH COUNTRYSIDE 1950’S - 2020’S

INTRODUCTION

“Ours is no longer the century of expanding cities, but rather of deepening territories” (Marot, 2020)

“…in a tragic story with only one real actor, one real world-maker, the hero, this is the Man-making tale of the hunter on a quest to kill and bring back the terrible bounty (…) All others in the prick tale are props, ground, plot space, or prey. They don’t matter; their job is to be in the way…” (Haraway, 2019)

For centuries, rural and urban worlds have been clearly distinct spheres, yet interdependent. But since the Modern Age (1500-1900), with the expansion of urbanization and the rise of its superiority within the schema of progress, rurality in Europe has seen its own demise and gradual abandonment. Since the industrial revolution, the human carbon footprint has trodden deeper and deeper into the planet’s surface, transforming ecological cycles on a global scale (Marot, 2020). The growing human effects on Earth and the threat to ecological stability produced by an intensely extractive form of capitalism were the reason behind calling for the substitution of the Holocene for a new geological age. The Anthropocene, a term coined by ecologist Eugene Stoermer in the 1980’s (Haraway, 2019), refers to a geological period whereby humankind is understood to have been the active force in geological and climatic change due to intense extractive and production activities, both a consequence and a cause of which we can understand to be the expanding and interconnecting systems of urbanization.

While for the first time scientists are recognizing the human agency in changing the world’s ecological cycles, we can also understand that the globe and the broader concept of nature have often historically been defined as female or feminine. In the beginning of the 1970’s, Lovelock and Margulis coined the mythological name of Gaia -in opposition to the masculine Anthropos- to personify the planet Earth as a whole composite of beings, oceans, rocks and atmosphere.1 Parallelly, many discourses have established alleged analogies between urban-rural, culture-nature, which in many cases are reflections of gendered relationships among humans themselves. For example, essentialist ecofeminists in the 1970’s reinforced this dualism nature:women::culture:men, by arguing women are “closer to nature” as there is an inevitable affinity

1 Since the beginning, the term Gaia was contested by modern science because it made no distinction between the inanimate and the living matter, but personified the planet as a whole living organism.

12 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Rurality as marginalised otherness

between women’s reproductive biology and Nature.2 Also, in the geographical discourse, there has been a feminization of Nature, where landscape and the female body are compared and often depicted together in Western art.3

This dissertation does not accept these gendered analogies, but it acknowledges the underlying common principle that these discourses share: that of the identification of nature and rurality as a marginalized domain.

The correlation between a subordinate nature and the feminine reveals a power relationship between nature and culture, the rural and the urban -where the growing systems of urbanization act as drainage centres of material resources extracted from the rural surroundings- which in the ecofeminist discourse is compared to that between the male and female genders.

In other words, there is a power relationship that can be drawn from the urban-rural dichotomy. In particular, in the disciplines of architecture and urban design this unbalanced relationship is especially evident, as the rural is a largely neglected domain within an urban-biased discourse. Planners and architects have focused their efforts on issues of density, mobility, and organisation of all layers of urban centres, while rural communities have gone completely unnoticed – an example of this is Patrick Schumacher’s article ‘Don’t Waste Your Time in the Countryside’ (Cheng, 2018), where he warns against the ”disadvantage of design investment in rural situations [since] the number of people an architectural intervention affects is likely to be much lower” within rural domains and claims that “architecture is an inherently urban discipline”. This generalised attitude towards rurality denies the value of architecture at service of contexts that are not strictly productive under the capitalist market logic so that interventions in sparsely populated communities yield little benefit. The ecofeminist discourse, on the other hand, helps us to ground a position that demands to divert attention from the anthropocentricproductivist perspective to support a neglected territory and those who continue to inhabit it. By establishing the superiority of systems of urbanization the thesis counters and resists it by revealing the consequences, including the abandonment of the rural systems and all their capabilities and values.

Quotidian paths of everyday

The dissertation deepens its critique by detaching from traditional research methodologies that have been common in rural sociology and by taking an original stand in looking at the rural domain.

2 Essentialist ecofeminists’ use of terms as “Mother Earth” has been heavily criticized as very controversially consolidating the intrinsic reproductive role of women as procreators, caring of children, and responsible for ecological defense. On the contrary, anti-essentialist feminists argued that it is the effects of capitalist economies and urbanization upon landscape that have a bigger impact on women: their relationship with the environment derives from a closer daily interaction with natural resources as a result of tasks allocated within gender division of labour (Leach & Green, 1997).

3 As pointed out by Gillian Rose in “Feminism and Geography” (1993)

13 SPANISH COUNTRYSIDE 1950’S - 2020’S

When addressing issues related to the countryside, typical perspectives are those concerned with productivity of land and its external organization into agricultural modes of production. Land has been closely entangled with the notion of labour since the primary state of nature was considered unexploited, “a fund of raw material awaiting improvement” through means of agriculture production (di Palma, 2014). Cases such as internal colonization projects in fascist regimes during the beginning of the 20th century are paradigmatic of an approach based on the organization of land and people under the regime of productivity, and –male- agricultural labour. Disciplines of planning and economy have had, therefore, a “view from above” when addressing rurality. Even in the field of geography, the term landscape acquires the “ocular” meaning of “a portion of land that the eye can comprehend at a glance”. We have learned to read the environment from above, from the point of view of the observer who understands the rural domain as the backdrop against which to project our collective existence. (Rose & Dorrian, 2003) Nevertheless, this view of the territory from above, from the planners’ perspective, is confronted with a “view from below”, from the everyday lived space and the domestic. Approaching rurality from the domestic and the ecologies of care constitutes an original take and a major critique of the core argument of the thesis. It puts the focus of the dissertation on the quotidian paths of the everyday, rather than on the economic functioning and modes of production of the rural domain. Rooted within care ethics, this dissertation places people’s relationships at the heart of the debate in the Spanish countryside. As a result, rural women acquire a new protagonist role, “the mundane world of routine is the realm of women’s social life in a masculinist society” (Rose, 1993). With this in mind, the role of women in rural Spain during the last seven decades will be scrutinized; the underlying question reflects how domesticity has been constructed under the regime of rurality throughout the last 70 years in Spanish history.

In this sense, materialist feminism4 recognized that routine behaviours in undertaking everyday tasks within space are a reproduction of the social, economic, political and cultural structures of a community; it is within these mundane spaces and routines where power structures define and limit people’s behaviour. Therefore, a bottom-up study, from the interior to the wider domain, unveils the underlying condition of rural Spain.

Finally, the sense of “maintenance” is the third pillar of the dissertation: “maintenance” referred to a sense of responsibility (“response-ability”5), according to which we are aware of the ecological footprint left on the surface of the planet, and we recognize the time has come to imagine new ways of

4 As described by Dolores Hayden’s “The Grand Domestic Revolution” (1981).

5 Term redefined by Donna Haraway in “Staying with the Trouble” (2016).

14 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

A sense of maintenance

being in the world. Humans should urgently learn how to prosperously live in our damaged world, understanding its limits and acting within them. We must “learn how to live and die well on a damaged planet”. (Haraway, 2019) Unlike reactions that claim we have been walking towards a catastrophic way of living in the world which -in the human exceptionalism discourse- is impossible of change; the critical stand that is taken is that of assuming the planet’s damage is irreversible, but there is space for its partial cure.6

The thesis looks into depleted territories with a healing and caring attitude which -from the perspective of architecture- refers to the capacity to creatively re-think the built consequences that we have provoked on the landscape. “Care” -as defined by Joan Tronto- implies in the first place, to “reach out to something other than the self”, but also to:

“some kind of action [that] should be viewed as a species activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue and repair our “world” so that we can live in it as well as possible” (Cohen & Fenster, 2021)

The original notion of care is extrapolated from the realm of the domestic and applied at a planetary scale, understanding “care” as an attitude taken throughout scales. The capacity to creatively attend to depleted territories, conscious of the extinctions and the irreversible losses, but staying with the trouble that caused them; translated into an architectural strategy, the neglected environments of rural Spain will be preserved and altered from within. There will not be expansions or deletions, neither colonization of new territories or projects starting from scratch, but rather alterations on what is already there. Following the purpose of maintaining what exists and aiming to modify current landscapes, this thesis adopts a will for reinventing the exhausted, hollowed out and forgotten spaces of rural Spain.

6 Charles Mann suggested two attitudes can be taken in front of the current climate crisis, that of “wizards” or “prophets”. The first ones claim that our catastrophic lifestyle has led us to an irreversible crisis which is impossible of change. Therefore, science needs to alter the straight line of our path and take us in a different direction, tricking the reality to avoid the inevitable. The second ones, support the idea that humans should urgently learn how to prosperously live in the same direction, hand in hand with our damaged world, understanding its limits and wisely accompanying its processes. (Marot, 2020)

15 SPANISH COUNTRYSIDE 1950’S - 2020’S

16

PLANNED RURALITY

17

CHAPTER 01 · 1950’S

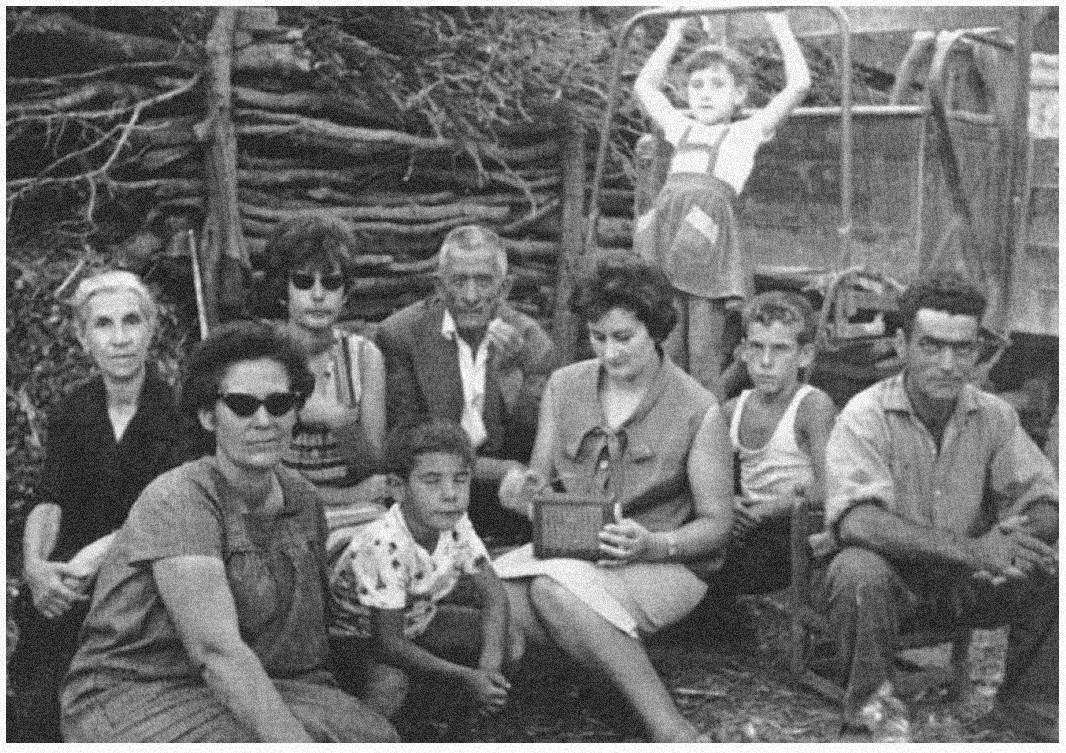

Watching the film “Tierra sin Pan”, shot by filmmaker Luis Buñuel in 1933 in Las Hurdes (Extremadura), may be a good way to get an insight into early 20th century rural Spain’s harsh reality (Fig.01). The images portray most of the Spanish rural peasants’ lives as miserable. Whenever they had the opportunity to work, wages were insignificant, barely enough to survive.

At that time, agriculture constituted the basis of the Spanish economy and occupied more than half of the working population (Pierre Malerve, 1983). Agriculture’s structure was that of large, unproductive latifundia and an excess labour force. This resulted in high unemployment figures where the average annual working time in Andalusia was a mere 130 days. (Thomas, 1976).

The social atmosphere was extremely unstable. In an attempt to improve the peasantry’s living conditions, the Spanish Republic approved the 1932 Agrarian Reform Law, creating high expectations of change among day labourers, but these were soon frustrated. The reform’s effects were very limited due to the Spanish politicians’ disinterest and lack of resources to finance the measures. The failure of Agrarian Reform was one of the main reasons for the Spanish Civil War in 1936.

In 1939, once the war was over, Francisco Franco’s regime led an intense process of ruralization in line with its policy of turning the country into an autarchic regime . This fitted in with the fascist ideology in which the rural is idealised, but also tried to solve the food crisis that war and international isolation had provoked. Ruralism represented a retreat from a present crisis by turning to conservative solutions of a stable past (Ghirardo, 1989). The Spanish countryside, therefore, was the context where the regime could survive, so that Spain had to become a country of small farmers (Manuel Tuñón de Lara y José Antonio Biescas, 1980).

For this purpose, the National Institute of Colonization (INC, “Instituto Nacional de Colonización”) was created and an intense process of agrarian internal colonization was undertaken. Even though the regime’s propaganda publicised the process as an original initiative that would solve the problem of the Spanish countryside, in fact, the internal colonization plan was an initiative that had

18 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

01.1.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT: AUTARCHY

19 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.01 Agrarian peasant filmed from Luis Buñuel’s urban vision. “Las Hurdes. Tierra sin pan” (1933).

already taken place in Spain in previous years (Monclús Fraga & Oyón Bañales, 1983) as well as in other contexts, such as Mussolini’s Italian “bonifica” or Tennessee Valley Authority in the United States.

Real beneficiaries of colonisation were large landowners who, by using the mechanism of “reserved properties”, ensured that expropriations would not affect their most fertile lands. Also, their properties were highly economically revalued thanks to hydraulic infrastructures that were constructed. On the other hand, settlers were assigned small plots, with poor quality for agriculture (Liceras Ruiz, 1987-1988).

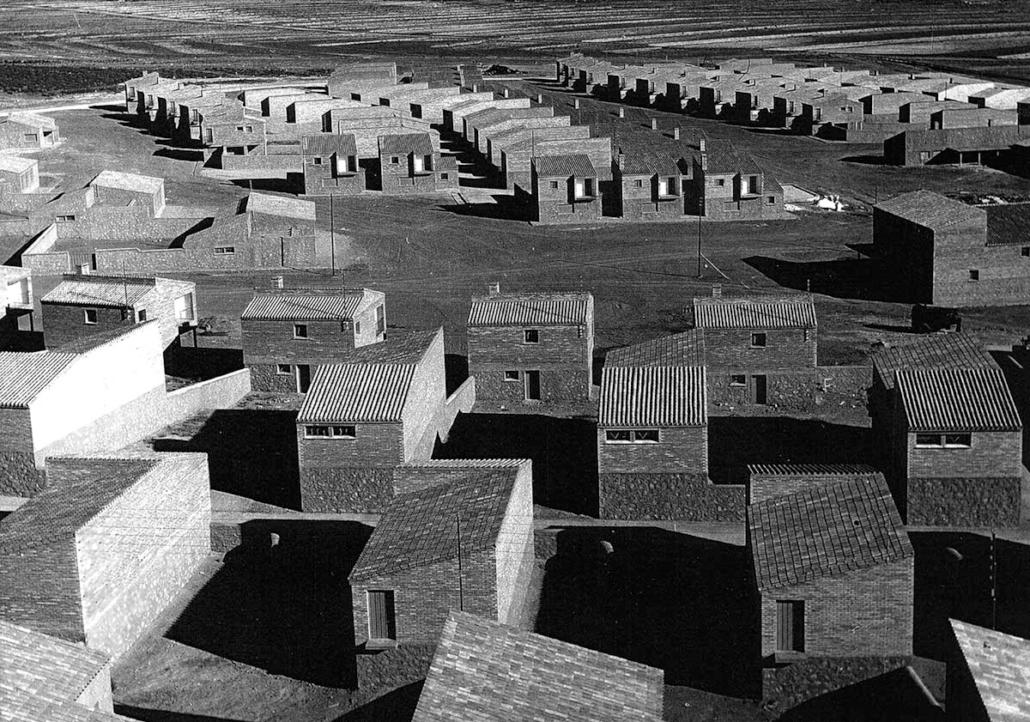

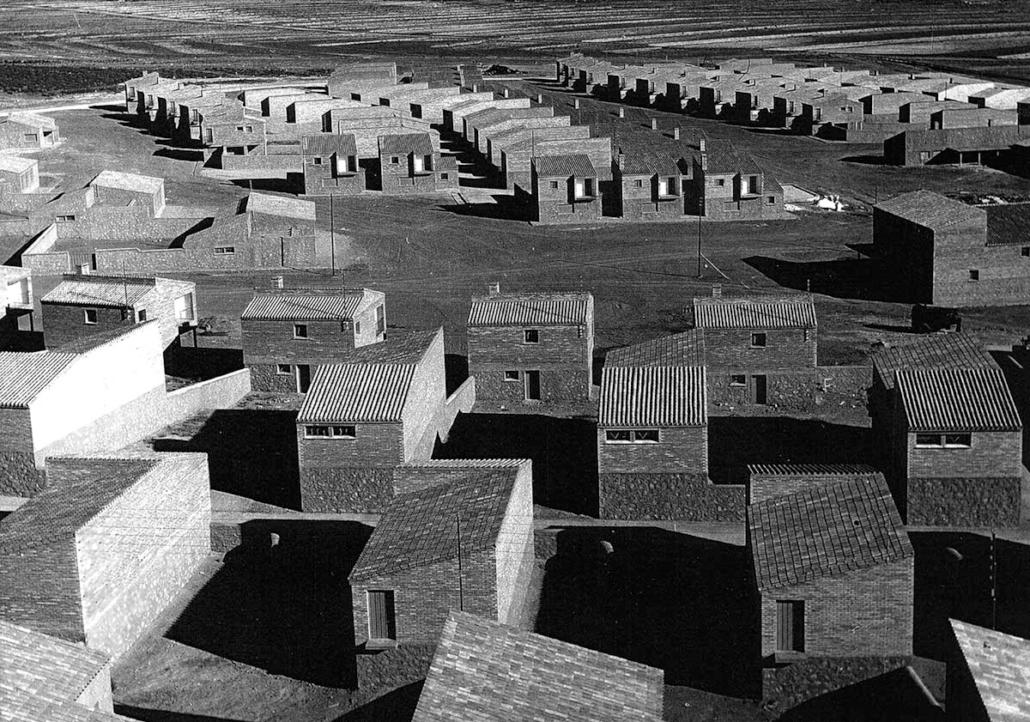

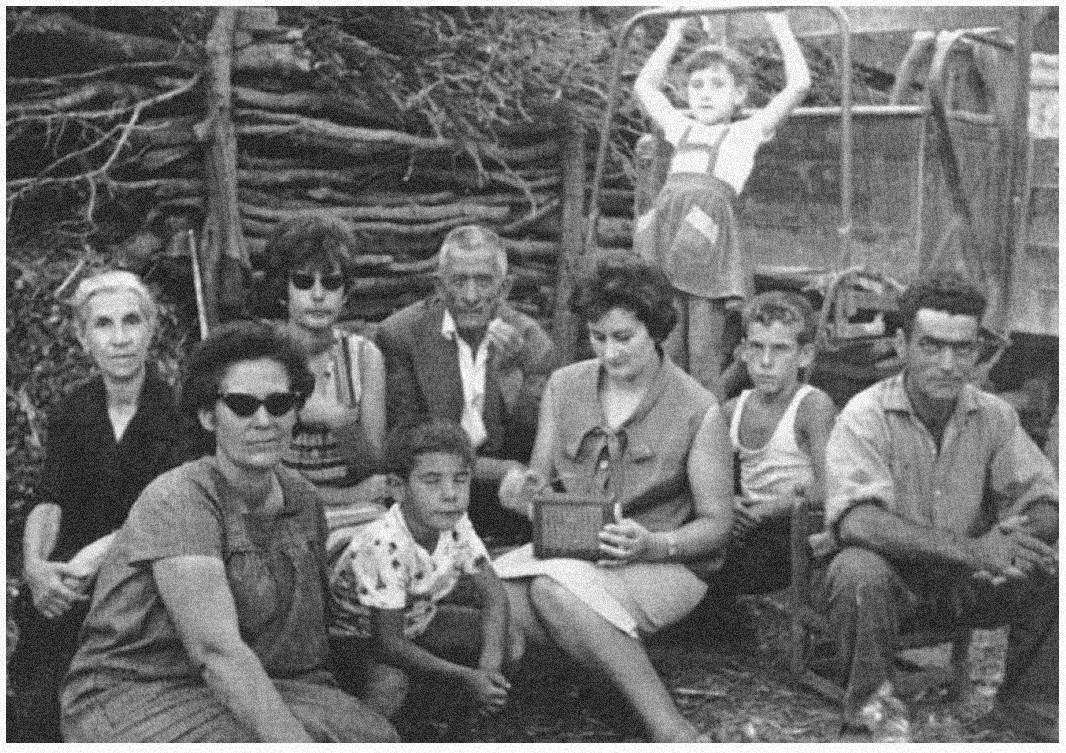

In the midst of a desolate, dry territory, while irrigation infrastructure was built, more than three hundred villages started to be constructed (Fig.02). Men considered “socially useful for the nation’s destiny” were chosen to populate them, people who demonstrated impeccable social, political and moral conduct. There, they were subjected to a structure of control designed to indoctrinate them in the Francoist moral, catholic values and ultimately, to create a “new fascist peasantry”.

20 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

River basin

Province division

Province capital

Colonization settlement

21 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

1969 1966 1964 1963 1962 1958 1957 1954 1953 1951 BELVÍS DE JARAMA VEGAVIANA EL REALENGO CAMPOHERMOSO LAS MARINAS CAÑADA DE AGRA LA VEREDA MIRAELRÍO PUEBLA DE VÍCAR JUMILLA SAN ISIDRO ALBATERA TORRES DE SALINAS 1955 VILLALBA DE CALATRAVA

Fig.02 Mapping of National Institute of Colonization’s settlements. Timeline of the settlements designed by architect Luis Fernández del Amo between 1951 and 1969.

01.2.

The model home

THE MODEL HOME: PRIVATE PROPERTY AND FAMILY

The instrumental tool that colonization made use of to organize the territory and mobilise population was private property, specifically in the form of single-family agrarian production and housing. Settlers were bound to the land through a contract that exchanged private property for labour; both agrarian and domestic. The second mechanism to fix population to the land was marriage and family: property was offered to a male peasant whenever he was married and able to have descendants, while his spouse would not have any right to property herself. Eligible candidates were those “socially useful men for the nation’s destiny”, meaning that they should have reading and writing skills, be aged between 25 and 50 years old, have a wife and children, not have any physical defects, or political background at odds with the regime.

In order to strongly bind settlers to their assigned property, unlike Italian bonifica – where a completely finished house was offered – Spanish peasants were given a minimally equipped house alongside the plot, which they then had to complete by carrying out secondary works, including electricity, plumbing, irrigation, etc. The completion of their home’s construction was a mechanism to create a sense of attachment to the assigned plot and to the village.

“We found the house half built, with no water or electricity, streets were full of mud. There were no doors, we had to put up blankets. A year and a half with no electricity, no water…”

Settler from Figarol.

Another strategy to ensure continuity was that of self-construction throughout time . The dwelling was designed as to be extendable as the family produced more descendants, so that more rooms could be added to the original house. This was a way to ensure that any surplus income was invested in the completion of the settlement.

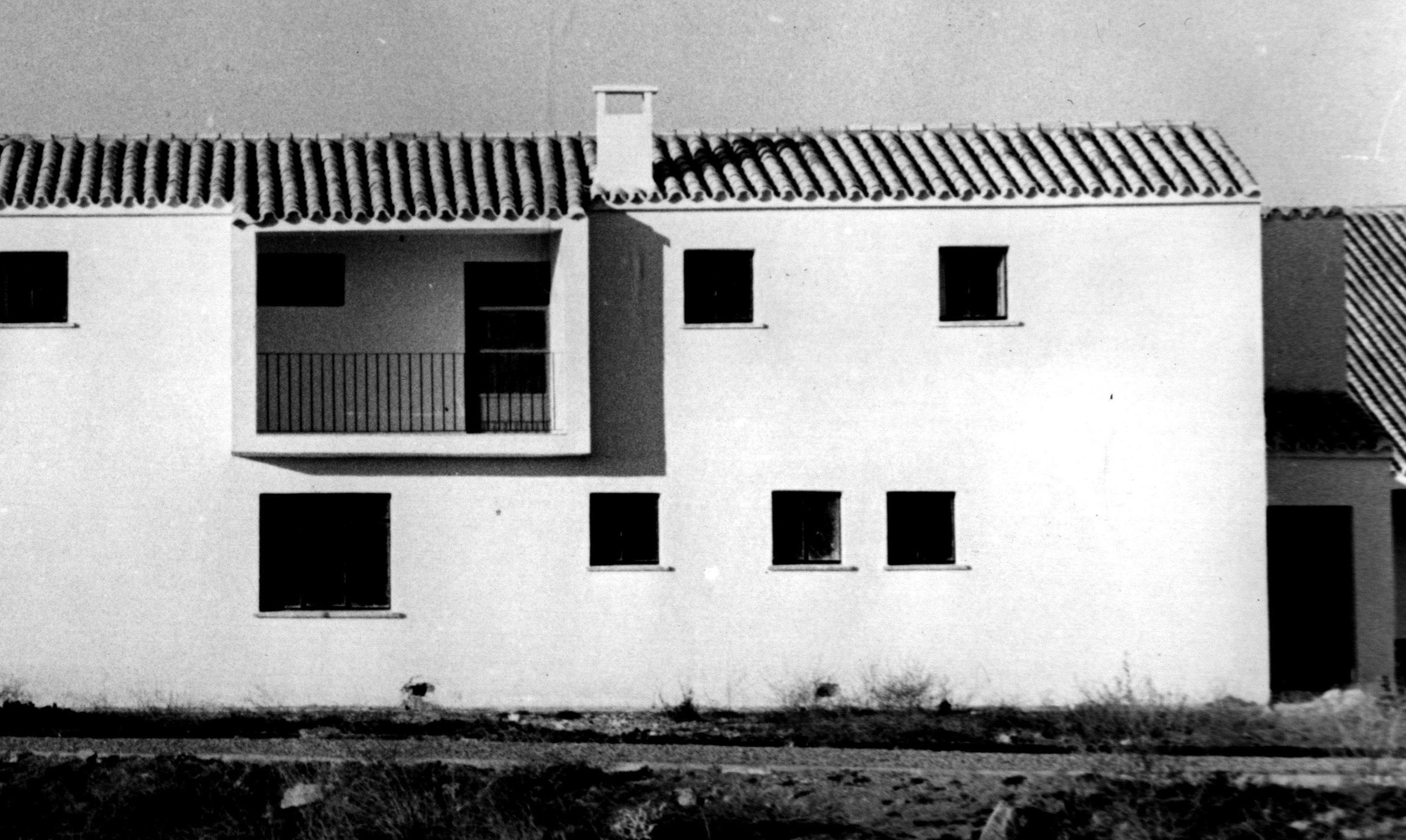

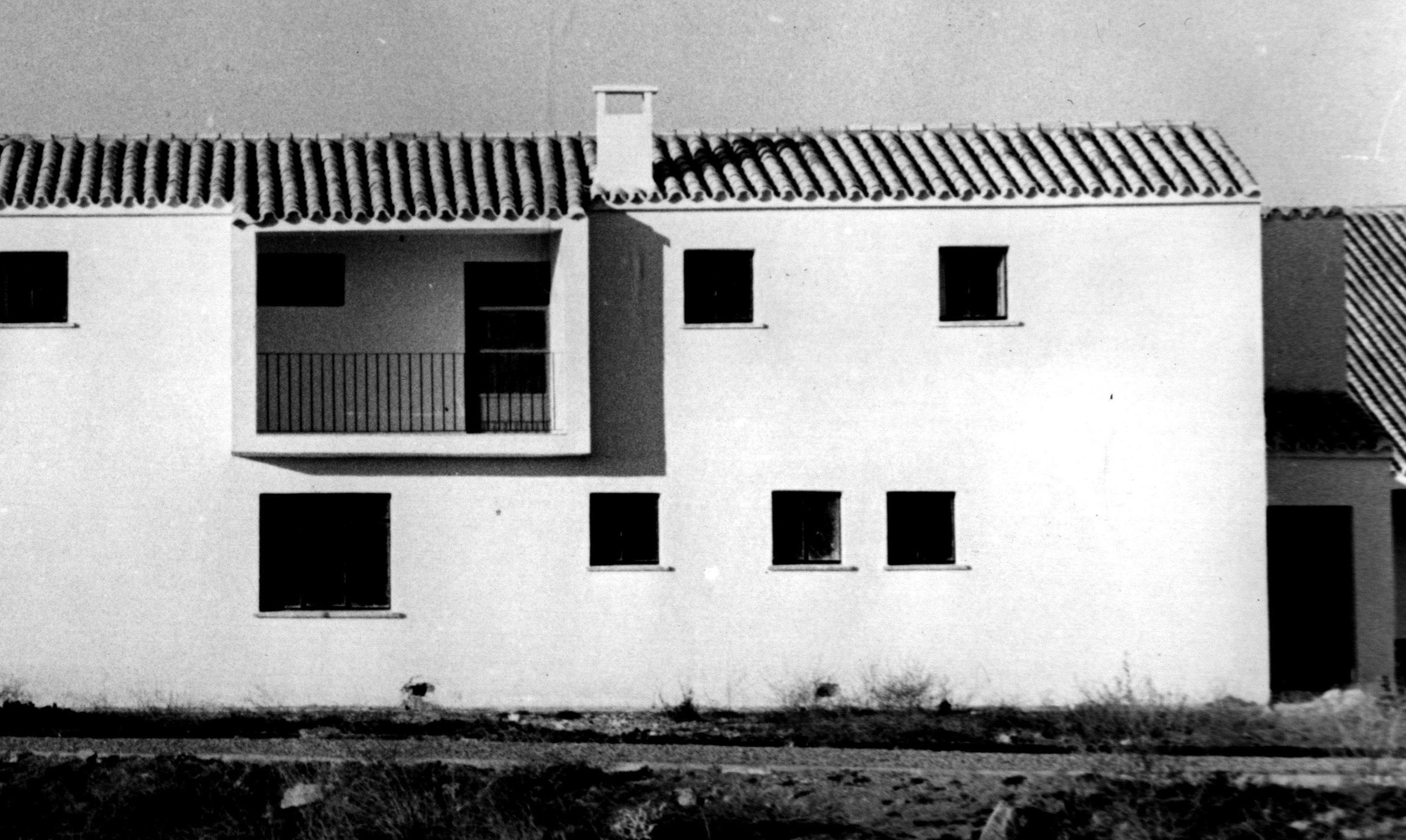

These backyard single-family houses were designed following a hygienic, functionalist logic which aimed to overcome previous traditional

22 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

rural typologies, considered immoral and unhealthy: “houses with no light or ventilation (…), without room to ensure the proper separation between parents and children of each sex (…) with distributions that “force promiscuity of people and animals” should be definitively outlawed” (Oyón Bañales, 1985). Therefore, in these domestic backyard types, there is a clear separation between animals’ and people’s dependencies and circulation. In every case there are two entrances, one to the main public space or boulevard, another one to secondary, “dirty” street (Fig.06-24)

Interior surfaces spanned from 75 to 140sqm, and compartmentalized, interior distribution of living room, kitchen, main bedroom and children’s bedrooms responded to a common, predetermined familial structure. The provision of three to five bedrooms evidenced the Regime’s aspiration for a fecund populace and made more attractive the idea of growing extensive families here than in cramped one-bedroom urban dwellings. Bedrooms were separated in terms of age and gender; these hierarchical divisions predetermined the model patriarchal, agrarian family. Centrally located on the ground floor was the kitchen-living room, between the main entrance and access to the backyard. This was a way to ensure the housewife controlled both the interior and the exterior of the house (Fig.04). Private space was linked to women, as a place for interiority and decency, while public space was related to men; this responded to the normative, idealized image of women as mother, spouse and housewife (Abellán, 2018).

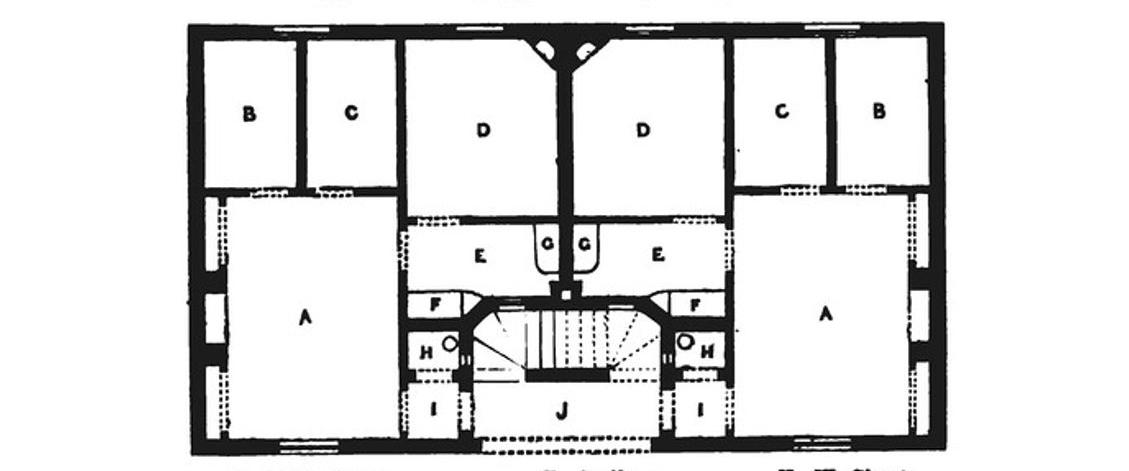

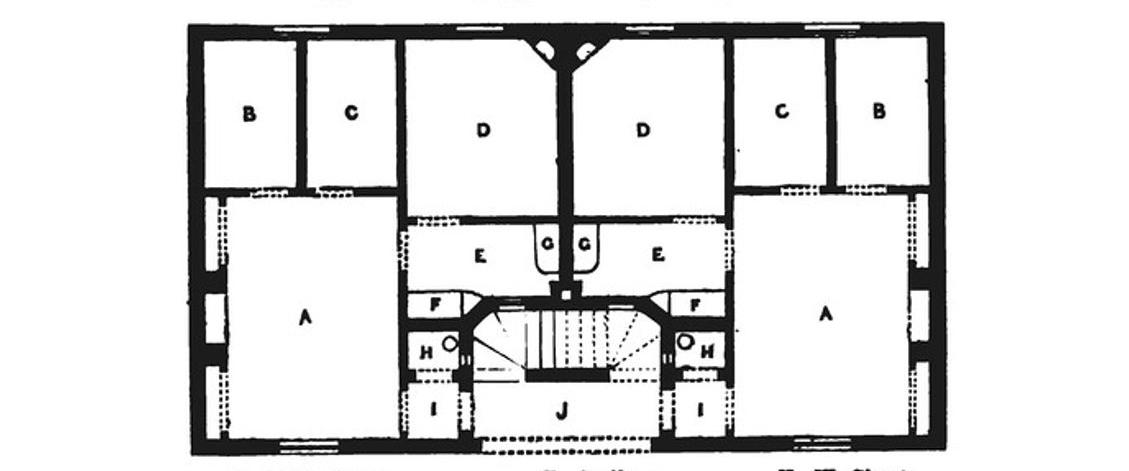

This moralistic design of the model rural dwelling is comparable to the reformist initiatives that intended to solve the housing problem for working classes in mid-18th century London by segregating the members of the household in different spaces. The plans of Henry Roberts’ “Model Houses for Four Families” (Fig.03) show two fundamental divisions: one between members

23 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.03 Henry Roberts’ Model House for Four Families (1803-76).

The model family

of the family, where the authority of parents was clearly stated; another between different families, so that each of them belonged to self-contained territories in order to limit inappropriate behaviours outside the household (Evans, 1997). Comparable to the disgust that working class living conditions provoked among social reformists in London, during 1930’s in Spain the precarious living conditions of peasant day-labourers were arising questions on the nature of Spanish peasantry’s morale. The model rural dwelling designed in Spanish rural colonies aimed to instil moral rectitude in rural population, according to the principles of the National-Catholic regime.

Familial relationships were not constructed after personal or affective choices, but rather as a medium to achieve a means of subsistence: family was the social contract through which male settlers accessed the possibility of landownership. The plot was granted whenever he met the requirements of having a wife and was capable of having descendants. This contract generated a state of “debt” that bound the settler’s family into the production system, meaning that after the assignation of the plot, the debt was only settled after an exchange for agrarian labour - usually fulfilled after decades cultivating the land. The internal colonisation project was a mechanism that rooted population in rural Spain via an indebted status.

The family became the minimum unit of production, where the patriarch is the head of the farmstate and descendants are labour force. Families with many children were promoted for the sake of the continuation of the agrarian production. By looking at the filmography produced by National Institute of Cinematography in the 1960’s, we can see how in films like “La gran familia” (“The big family”); “La familia y uno más” (“The family plus one”) (Fernando Palacios, 1962, 1965) or “La familia bien, gracias”(“The family is fine, thank you”) (Pedro Masó, 1979), this notion of the extensive family was instilled from the central government.1

In these settlements, the labour division between agricultural work and

1 During 1960’s, Spain lives a developmentalist process that affects film politics and pracwtices, giving birth to the so-called New Spanish Cinema (“Nuevo Cine Español”). Between 1962 and 1968, J.M. García Escudero leads the “Instituto Nacional de Cinematografía”, which incorporates the “Junta de Censura y Apreciación de Películas”, (Board of Classification and Censorship). His cultural policies supported a commercial and consumerist cinema, considering that State should not be supportive of cinema, but cinema should be supportive of State. (Barrachina) As García Escudero would say, “A film is a flag. We must have that flag unfurled” (Pavlovic, et al. 2008)

During 1960-70’s, 1272 films were produced for mass entertainment following a morally correct agenda in line with the regime ideology. In 1962, Fernando Palacios produces “The Big Family” (“La gran familia”), “película declarada de interés nacional” (mark of state-subsidized cinema) and pioneer of a subgenre in New Spanish Cinema: that of familiar enthronement and praise to procreation. In this line, in 1965, Palacios produces “La familia y uno más”, and in 1979, Pedro Masó directs “La familia bien, gracias”.

With a light tone, retransmitted in national TV channels during Christmas festivities, “The Big Family” is implanted in a generation’s collective imagery as the hyperbole of the desired, respectful familiar life.

24 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

25 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.04 Single-family backyard typology: compartmentalization and hierarchies. The incorporation of 3 to 5 bedrooms evidences the willingness to promote extensive families. The placement of the kitchen in a central position on the ground floor reinforces the role of the housewife as the administrator of the home.

BEDROOM SUPERVISION

KITCHEN INTERNAL CIRCULATION

EXTERNAL CIRCULATION

homelife is clearly distinct. The idealization of the private life disguised a form of unpaid labour concerned with fulfilment of domestic tasks and reproductive work: cleaning, cooking, giving birth, caring for children and the elderly, etc. Images of the documentary “Los colonos del Caudillo” (Palacios, 2013) witness the day-to-day life of a typical family living in a colonization settlement. Equipped with the standard machinery assigned to each family, the father goes out to the plot of land to work, helped by two sons. While the camera follows them towards the plot, the mother, grandmother and two daughters stay at home, their routine is not captured. It must be through testimonies and stories –often told by their husbands or sons – that it is possible to uncover the invisible archive of the routine of rural women in the 1950s.

In charge of unpaid work, women’s main role was intended to be limited to the interior of the dwelling, mainly to the living-kitchen and to the backyard, where agricultural dependencies housed small farm animals that contributed to the household’s economy and subsistence.

Even though the state declared its commitment to “free married women from the workshop and factory” when signing 1938 Labour Code, pointing at the home as one and only realm for married women, this “ideal” of exclusive dedication to the domestic was far from reality. In rural settlements, women joined their husbands in agricultural tasks in order to increase family income. Their work was indispensable for the household’s economic survival, and of course additional to traditional domestic role. Many talk about a “double work” of taking care of agricultural tasks on top of domestic ones. As the daughter of Veiga de Pumar settlers explains:

“My father’s daily life consisted in working the land with some machinery he had at his disposal, preparing land for fodder production: in spring, green grass silage; in summer, baling dry grass. He also helped in the maintenance of the stable. (…) my mother helped my grandmother with housework and raising four children. But she always took care of the animals, more than my father…”

S. Guntín, descendant of Veiga de Pumar settlers. (Interviewed by the autor on August 2021)

There were moments when reproductive tasks converged in the public space and allowed for women to share moments of socialization around collective infrastructure. In this sense, some historians refer to important moments of encounter that may have been fundamental in the construction of a collective memory. In the context of an agrarian reform based on irrigation plans, water infrastructure occupied a key place in these villages (Fig.05). E. Abujeta speaks of urban water furniture – fountains, troughs, canals – and everyday activities that emerged around them, especially before private water infrastructure reached each dwelling. Linked to reproductive tasks, these meeting points were fundamental for women’s everyday routine, invisible centres of communal labour and social connections. They became alternative meeting

26 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

points, where settlers held daily conversations about concerning issues, such as agricultural work, sale of crops or children’s education (Abujeta Martín, 2020). The photography of Joaquín del Palacio “Kindel”, friend of architect Luis Fernández del Amo and photographer of his works in 1950’s rural Spain, captured routinary scenes where women at that time exposed an outdoor domesticity around fountains and canals.

27 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.05 Woman making laundry in the public space, in a prefabricated concrete canal. Photograph by Joaquín del Palacio “Kindel” in El Realengo settlement, Alicante. Source: Fondo Fernández del Amo, Archivo Histórico COAM.

28 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Vegaviana (Cáceres). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1954.

Fig.06 Street view, residential front façade. Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

29 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Vegaviana (Cáceres). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1954.

Fig.07 Street view, residential back façade.

Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

30 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

0 5m

Vegaviana (Cáceres). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1954. Fig.08 Single-family backyard type.

31 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Vegaviana (Cáceres). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1954.

0 5m Service entrance Public entrance Productive circulation Public circulation Productive rooms Familiar rooms Backyard

Fig.09 Single-family backyard type. Access and dependencies.

32 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Cañada de Agra (Albacete). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1962.

Fig.10 Aerial view over residential block.

Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

33 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Cañada de Agra (Albacete). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1962.

Fig.11 Street view, residential front façade. Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

34 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

0 5m

Cañada de Agra (Albacete). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1962. Fig.12 Single-family backyard type.

35 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Productive circulation Familiar rooms 0 5m Service entrance Public circulation Public entrance Productive rooms Backyard

Cañada de Agra (Albacete). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1962. Fig.13 Access and dependencies.

36 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Villalba de Calatrava (Ciudad Real). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1955.

Fig.14 Street view, residential front façade. Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

37 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Villalba de Calatrava (Ciudad Real). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1955.

Fig.15 Street view, residential back façade. Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

38 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

0 5m

Villalba de Calatrava (Ciudad Real). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1955. Fig.16 Single-family backyard house.

39 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Productive circulation Public circulation Productive rooms 0 5m Familiar rooms Backyard Service entrance Public entrance

Villalba de Calatrava (Ciudad Real). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1955. Fig.17 Access and dependencies.

40 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

41 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Miraelrío (Jaén). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1964.

Fig.18 Street view, residential front façade. Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

42 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

0 5m

Miraelrío (Jaén). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1964. Fig.19 Single-family backyard house.

43 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Public circulation Productive rooms Familiar rooms Backyard 0 5m Service entrance Public entrance Productive circulation

Miraelrío (Jaén). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1964. Fig.20 Access and dependencies.

44 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Gimenells (Lleida). Alejandro de la Sota, 1946.

Fig.21 “El Generalísimo” street view.

Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

Source:

45 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Gimenells (Lleida). Alejandro de la Sota, 1946.

Fig.22 Domestic type, archive drawing.

Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

46 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

0 5m

Gimenells (Lleida). Alejandro de la Sota, 1946. Fig.23 Single-family backyard house.

47 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Service entrance Public entrance 0 5m Productive circulation Public circulation Productive rooms Familiar rooms Backyard

Gimenells (Lleida). Alejandro de la Sota, 1946. Fig.24 Access and dependencies.

01.3.

A symbolic centre

A HIERARCHICAL CENTRE: CHURCH, SCHOOL AND SOCIAL HOUSE

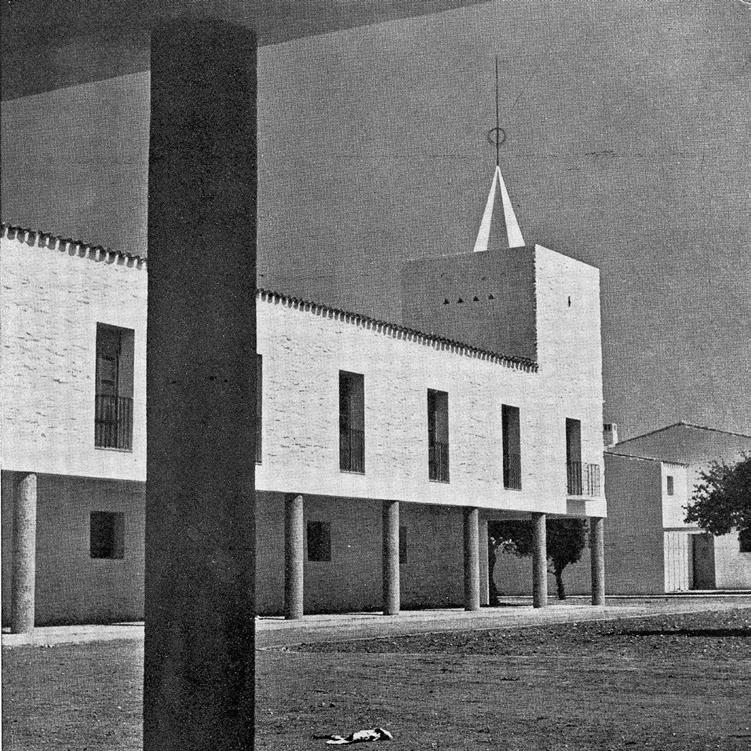

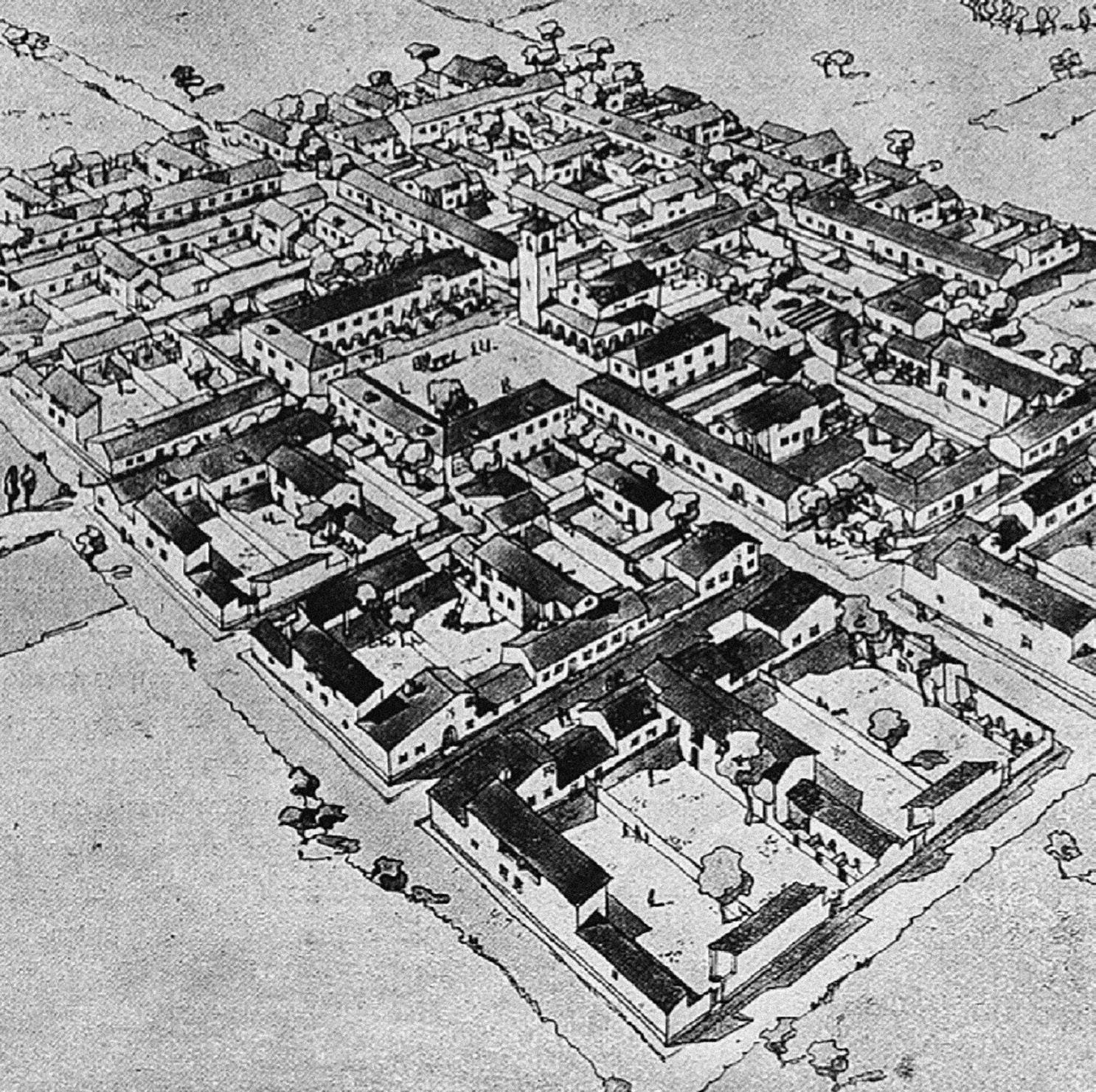

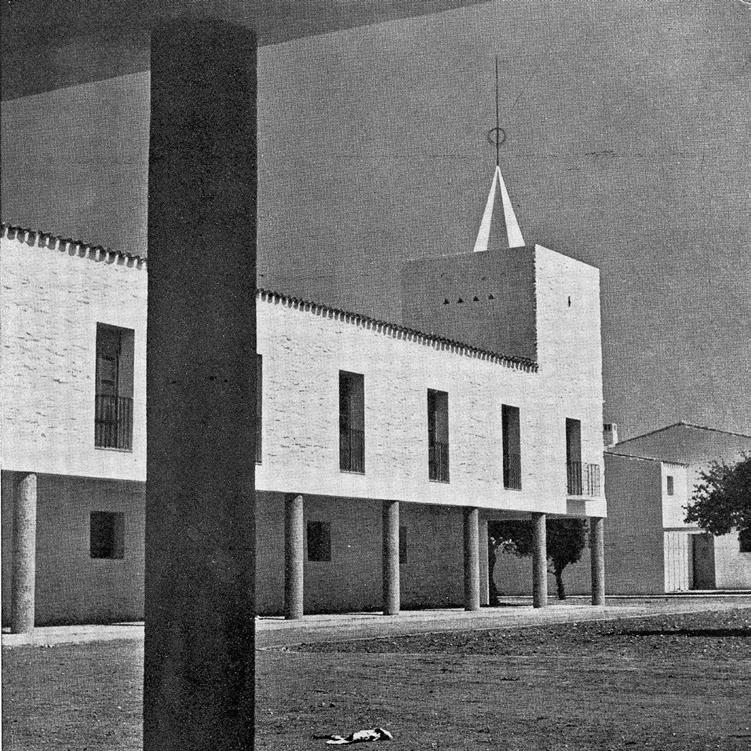

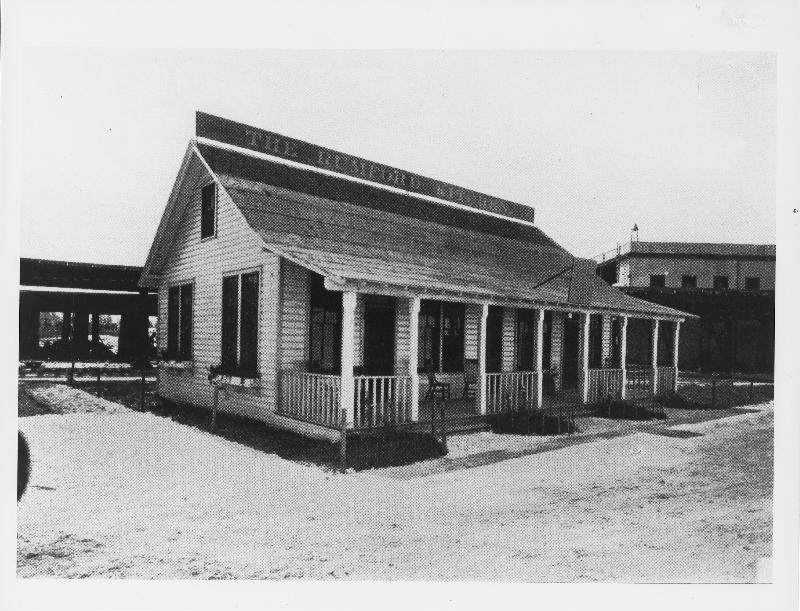

The highly geometrical urban schemes of colonization villages allocated single-family dwellings orbiting around a common, distinct centre. This was the place where institutional buildings were constructed, as well as settlers’ meeting point in their very scarce leisure time. From anywhere within the villages, visual axes pointed toward the omnipresent bell tower, vertically erected resembling the right arm in the Fascist’s salute (Ghirardo, 1989). Even though the design of the villages might differ from case to case, there is a common scheme of a central “plaza” giving onto main avenues and connecting administrative buildings and the religious centre; a set of secondary roads in a further grid, and a final peripheral delimitation marking the ideal size of the village.

Civic centres allocated all collective facilities. State, religious, health and intellectual institutions’ buildings, treated as free-standing monuments, reflected the state’s central power (Fig.25,26); the core of the settlement was both service and administration centre for the colonists and to secure the state’s control over them. Through this spatial arrangement, every activity aside from agrarian and domestic work took place under the surveillance of priests, doctors and teachers. (Monclús Fraga & Oyón Bañales, 1983).

The urban layout of these villages responded to a highly hierarchical society and as well as to a reformist attitude toward rurality (Fig.27-46). The fascist principle of “gerarchia” (hierarchy) was enthusiastically accepted by Rationalist architects, and it referred to a society in which authority and function strictly defined everyone’s place (Ghirardo, 1980). Space clearly defined everyone’s role within the ecosystem of the villages: artisans dwelled in specific typologies tailored to their role and different from settlers’ dwellings. Doctor’s home was allocated within the centre, while farmers’ ones were constructed towards the peripheries. These settlements constituted the materialization of a microphysics of power that transcended the planning of streets and buildings; it constructed an architecture oriented towards “the transformation of individuals: working on those whom it shelters, allowing the prey on their conduct, leading the effects of

48 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

49 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.25 State, religious, health and intellectual institutions’ buildings as free-standing monuments. Vegaviana (Cáceres), designed by architect L. Fernández del Amo.

power to them, offering them knowledge, modifying them” (López, 2010).1

The idea of modernizing the Spanish countryside involved every scale of the colonization plan: rural settlements became fields of experimentation for designers at that time. Young architects from Madrid, led by INC chief architect (1941-1975) José Tamés (Cordero Ampuero, 2014), took the colonization project as an opportunity to experiment with urban concepts that were taking place on the international stage. Architects were inspired by “Revista Nacional de Arquitectura” magazine, where the Radburn urban model, Letchworth garden city and Sitte’s composition theories were disseminated. Functionalist ideas such as separation and hierarchization of circulations were implemented as a way to modernize rural peasants’ lives (Oyón Bañales, 1985).

Therefore, there are similarities between villages such as Vegaviana or Esquivel (Tordesillas, 2010) (Cordero Ampuero, 2014) and suburban models such as Radburn: circulations from home to workplace (either driving a car in suburbia or riding a cart in rural Spain), and pedestrian ones are distinctly separated for a civilized, ordered life. Main boulevards (10-12m wide) differ from secondary streets and cart streets, for animals’ independent circulation. This parallel between these new, fascist rural communities and American suburbia has also been widely supported in Diane Ghirardo’s “Building New Communities”.

The monumentalization of the boulevards, which lead to the center of the village, was intended to take up the idea of the civic promenade, as a way to bring straight and dignified “urban” life to the deepest rural areas of central Spain.

Rural settlers meant to build a collective memory from scratch. They originally came from different places, strangers to each other, arriving at settlements still under construction. Unlike the Italian “borghi” and “podere”, granted as finalised architecture products, the collective effort for Spanish colonies’ self-completion triggered a feeling of belonging and mutual aid behaviours (Seco González, 2019). Their isolated location in the territory provoked certain intensity among neighbour relationships which, in opposition to relationships of friendship, were not selective, but based on dialectics and consensus, with no possibility of change (Camarero, 1996). In these highly closed contexts, the way to relate to each other was not through selective friendship, but rather through tracing familial genealogies; the church or the cemetery, places for familial celebration, acquired a central role in the social life of these villages.

50 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

1 Foucault, M., Vigilar y castigar, Madrid, Siglo XXI, 2005, p. 177

Separation of circulations

Socialization networks

51 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.26 In the centre of Vegaviana village, the school, the town hall and the church.

School Church Townhall

52 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Vegaviana (Cáceres). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1954.

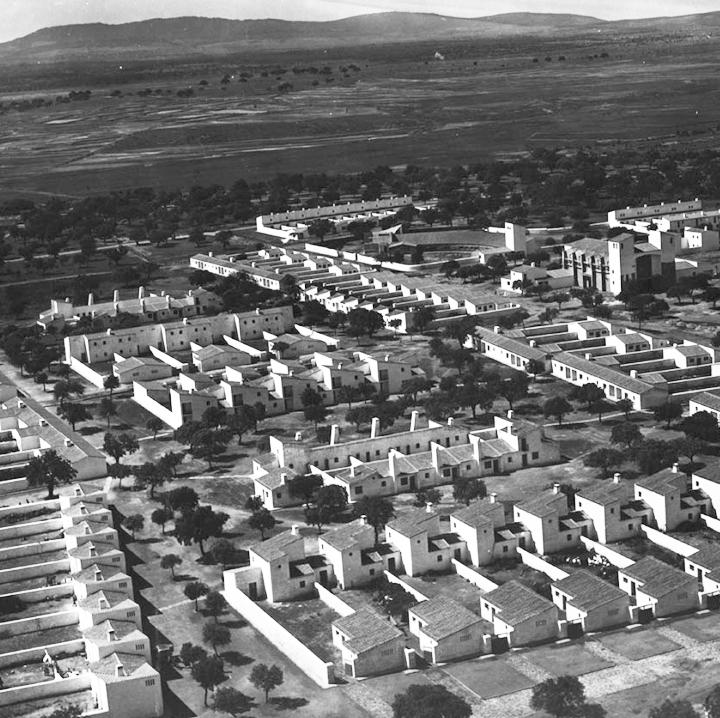

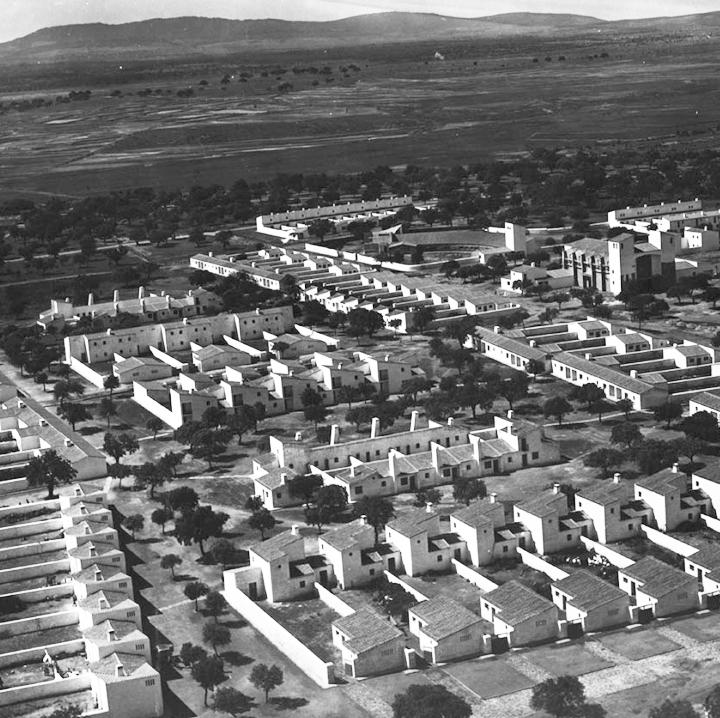

Fig.27 Aerial view.

Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

0 100m

53 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

0 100m

Fig.28 Vegaviana, 1954. Settlement plan.

54 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Domestic interior Agriculture production 100m 0 Church School Social house Main circulation Social house (women) Other Private plot 0 100m

Fig.29 Vegaviana, 1954. Domestic built spaces and agriculture and farm dependencies.

55 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY Domestic interior Agriculture production 100m 0

Church School Social house Main circulation Social house (women) Other Private plot 0 100m

Fig.30 Vegaviana, 1954. Institutional collective equipment: architectural landmarks.

56 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

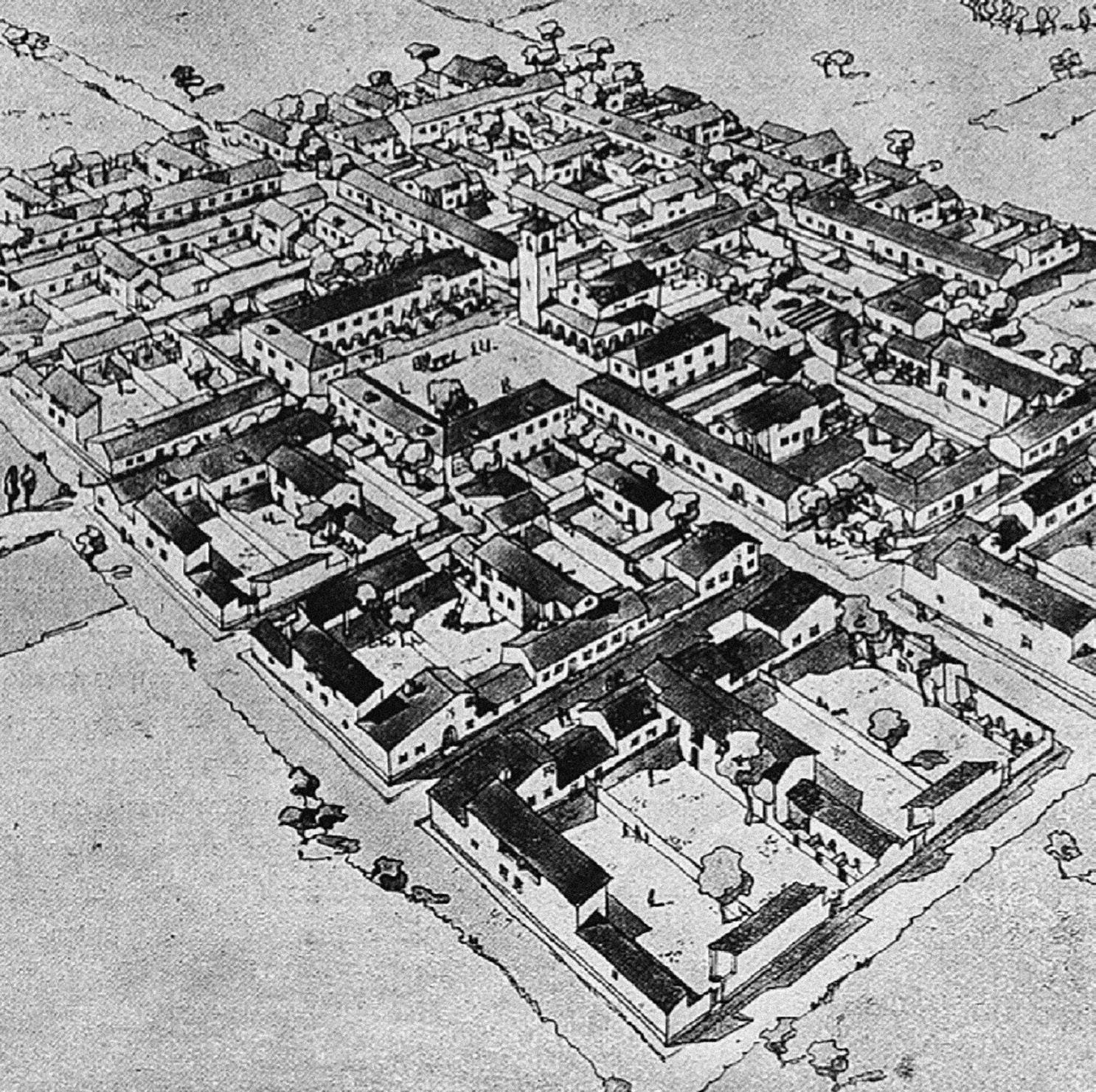

Cañada de Agra (Albacete). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1962.

Fig.31 Aerial view.

Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

57 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.32 Cañada de Agra, 1962. Settlement plan.

0

100m

58 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Fig.33 Cañada de Agra, 1962. Domestic built spaces and agriculture and farm dependencies.

100m 0

Domestic interior Agriculture production

59 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY Domestic interior Agriculture production 100m 0

Church School Social house Main circulation Social house (women) Other Private plot 0 100m

Fig.34 Cañada de Agra, 1962. Institutional collective equipment: architectural landmarks.

60 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Villalba de Calatrava (Ciudad Real). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1955.

Fig.35 Aerial view.

Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive) 0 100m

61 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

0 100m

Fig.36 Villalba de Calatrava, 1955. Settlement plan.

62 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Domestic interior Agriculture production 100m 0 Church School Social house Main circulation Social house (women) Other Private plot 0 100m

Fig.37 Villalba de Calatrava, 1955. Domestic built spaces and agriculture and farm dependencies.

63 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.38 Villalba de Calatrava, 1955. Institutional collective equipment: architectural landmarks.

Church School Social house Main circulation Social house (women) Other Private plot 0 100m

64 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Miraelrío (Jaén). Luis Fernández del Amo, 1964.

Fig.39 Aerial view.

Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

0 100m

65 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

0 100m

Fig.40 Miraelrío (Jaén), 1964. Settlement plan.

66 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Fig.41 Miraelrío (Jaén), 1964. Domestic built spaces and agriculture and farm dependencies.

100m 0

Domestic interior Agriculture production

67 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY Domestic interior Agriculture production 100m 0

Church School Social house Main circulation Social house (women) Other Private plot 0 100m

Fig.42 Miraelrío (Jaén), 1964. Institutional collective equipment: architectural landmarks.

68 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Gimenells (Lleida). Alejandro de la Sota, 1946.

Fig.43 Aerial view.

Source: Archivo Histórico COAM (Madrid Architects College, Historical Archive)

69 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

0 100m

Fig.44 Gimenells, 1946. Settlement plan.

70 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Domestic interior Agriculture production 100m 0 Church School Social house Main circulation Social house (women) Other Private plot 0 100m

Fig.45 Gimenells, 1946. Domestic built spaces and agriculture and farm dependencies.

71 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY Domestic interior Agriculture production 100m 0

Church School Social house Main circulation Social house (women) Other Private plot 0 100m

Fig.46 Gimenells, 1946. Institutional collective equipment: architectural landmarks.

01.4.

TERRITORIAL ISOLATION AND ITINERANT INFRASTRUCTURE

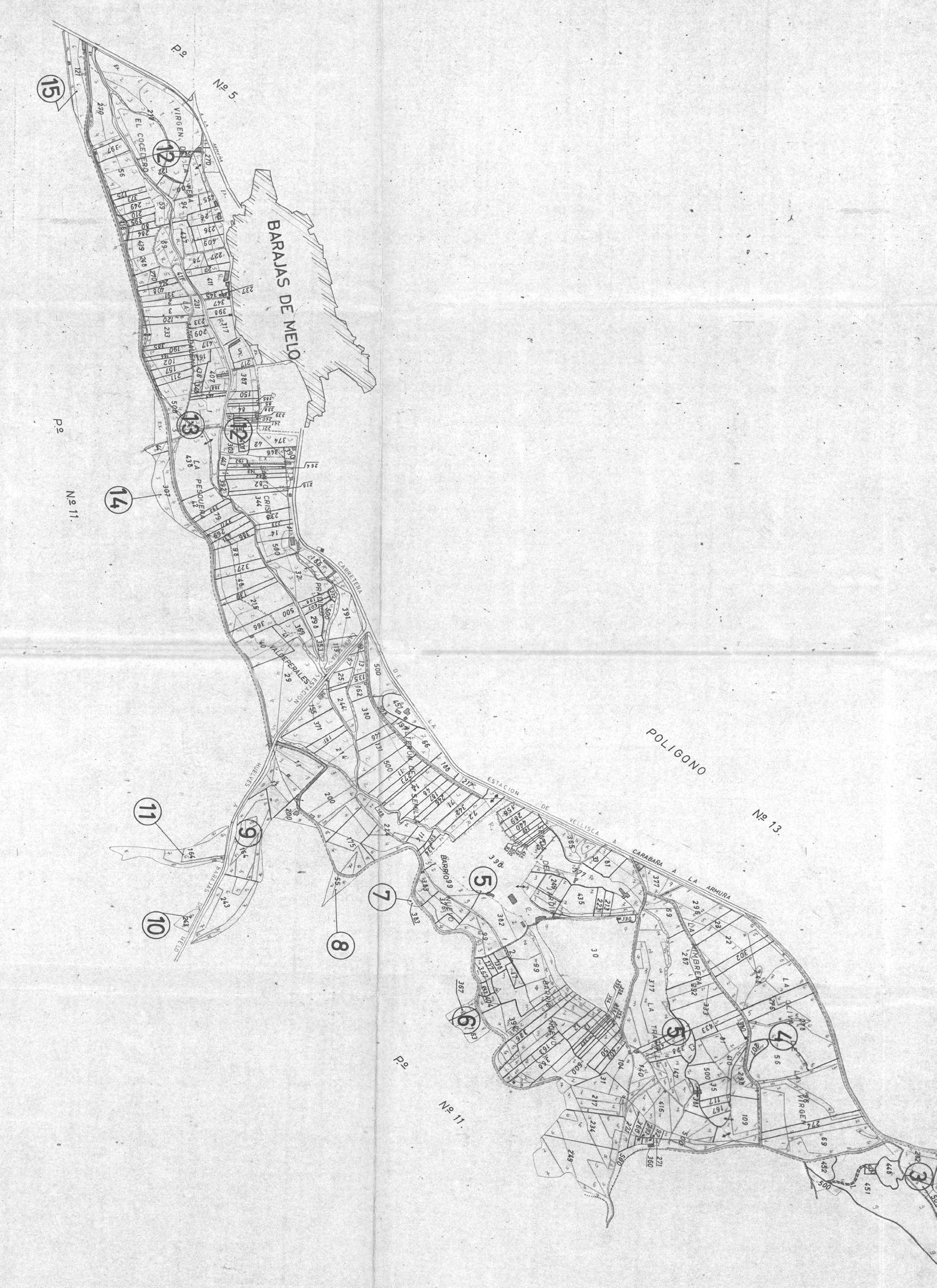

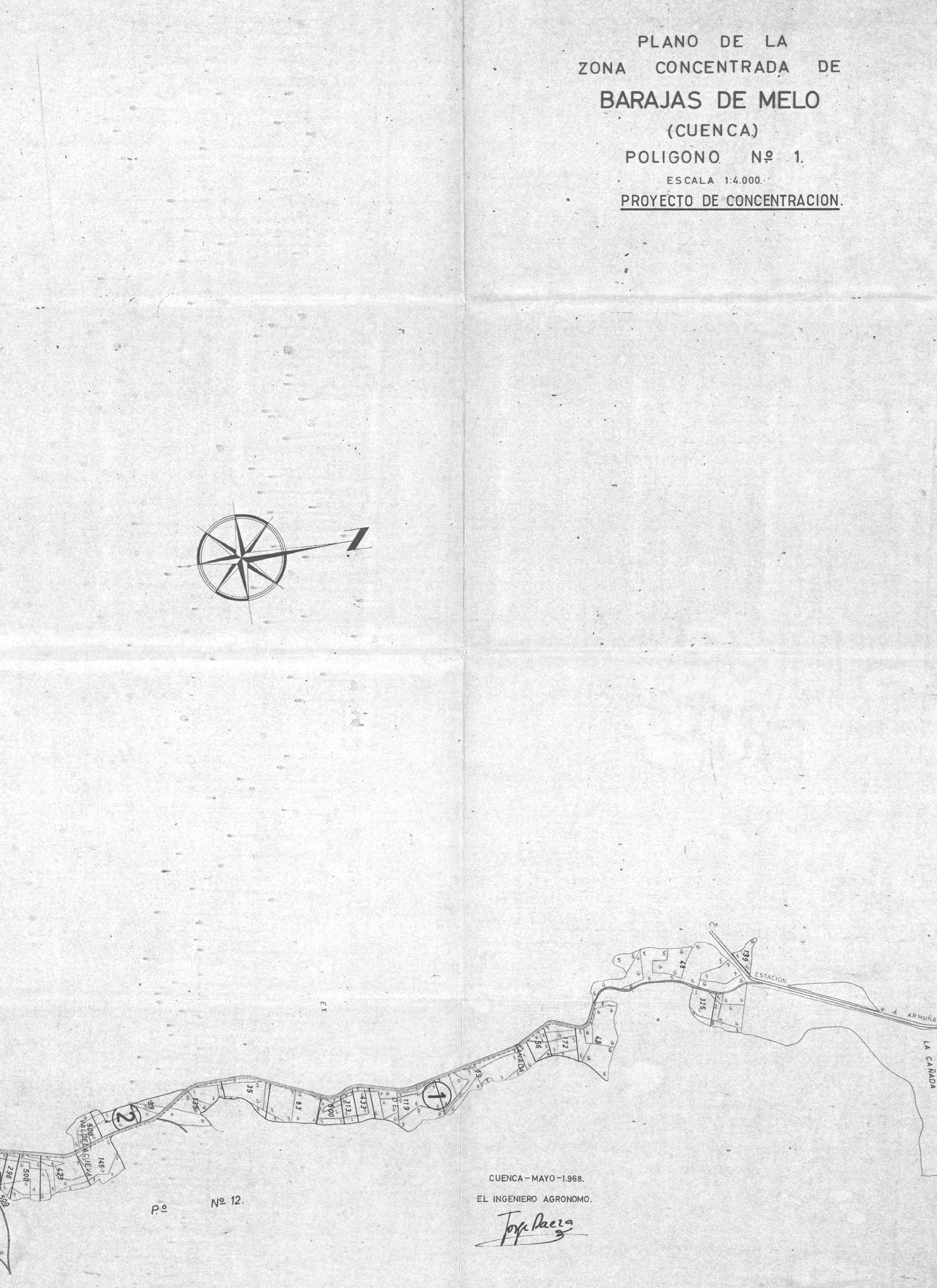

Colonization villages were built in arid territories – considered less valuable and unproductive – in the interior of the peninsula. Of almost three hundred settlements, more than half of them were located in Extremadura and Andalusia. Sixty thousand families were allocated, 28,000 dwellings were built, in the largest urban development operation in rural Spain’s history (Benito 2004).

Spanish colonies were deliberately built according to a territorially disseminated scheme, along river basins (Fig.48-50), following a logic of selfsufficiency and self-isolation. When looking at the 1932 diagram by Urbanology Seminar (Seminario de Urbanología) (Fig.47), it is evident there was no interest in creating interdependencies among neighbouring settlements. Authors have compared these with the Italian colonization scheme, where small “podere” depended on further administrative centres – “borghi” – and therefore allowed settlers from different villages to converge in their daily lives.

When deciding which settlement scheme was best for Spanish colonization, the debate considered Italian “bonifica”’s dispersed model – where dwellings were placed on the agrarian plot itself – or to construct a compact urban centre. Although some initial proposals followed the Italian case, most of them were grouped into small, isolated settlements. This favoured social control over a traditionally revolutionary and anarchist peasantry (Cordero Ampuero, 2014). Also, this type of organization arranged collective life and activities in advance, so that they were somehow similar to urban life (Tordesillas, 2010).

Since the beginning of the 20th century, the “issue” of rural communities’ isolation had been addressed from the perspective of urban elites, even though they were responding to different political and ideological agendas. At a time when technology did not allow any other form of communication, itinerant infrastructure was the medium through which cultural-educational differences between urban and rural were overcome. In these cases, information was unidirectionally provided, and its management became a source of power and control over the territory by promoting new patterns of behaviour among EDUCATIONAL

72 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Designing isolated settlements

Educating the rural

INSTITUTION FAMILY UNIT EDUCATORS INFORMATION ROUTE INDIVIDUAL

=500

=100

GUADALQUIVIR RIVER BASIN SETTLEMENTS A,B,C,D,E,F,G,H

GUADALMELLATO RIVER BASIN

(...)

73 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.47 Territorial occupation diagrammes: Agro Pontino’s colonization (ONC) vs. Spanish colonization project (INC). Based on the 1932 diagram by Urbanology Seminar.

Ha G E C A N M P Q O B D F H LITTORIA CENTRAL SETTL. SETTL.

SETTL.

SETTL.

SETTL.

SETTL.

SETTL.

SETTLEMENTS M,N,O,P,Q LITTORIA BURGO

=100 inhabitants =500

vi

v

iii

iv

ii

i O.N.C. ROMA

inhabitants

Ha G E C A N M P Q O B D F H LITTORIA CENTRAL SETTL. SETTL.

SETTL.

SETTL.

SETTL.

vi SETTL. v

iii

iv

ii SETTL. i O.N.C. ROMA

CAMPOHERMOSO

PUEBLOBLANCO

SAN ISIDRO DE

Colonization settlement

"Cortijos" and "ventas" (farmsteads)

Riverbasin Paths

New property divisions

74 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Fig.48 Territorial implementation of Campohermoso, San Isidrio de Níjar, Puebloblanco and Atochares, four colonization villages in Almería region. Parcelization of the river basin into private agricultural plots.

0 ATOCHARES

NÍJAR

1km

ATOCHARES

Settlement's influence area

Colonization settlement

Production sectors

75 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.49 Areas of influence of each colonization village, relegated to equally extensive territorial sectors.

SAN ISIDRO DE NÍJAR

PUEBLOBLANCO

CAMPOHERMOSO

76 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

77 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

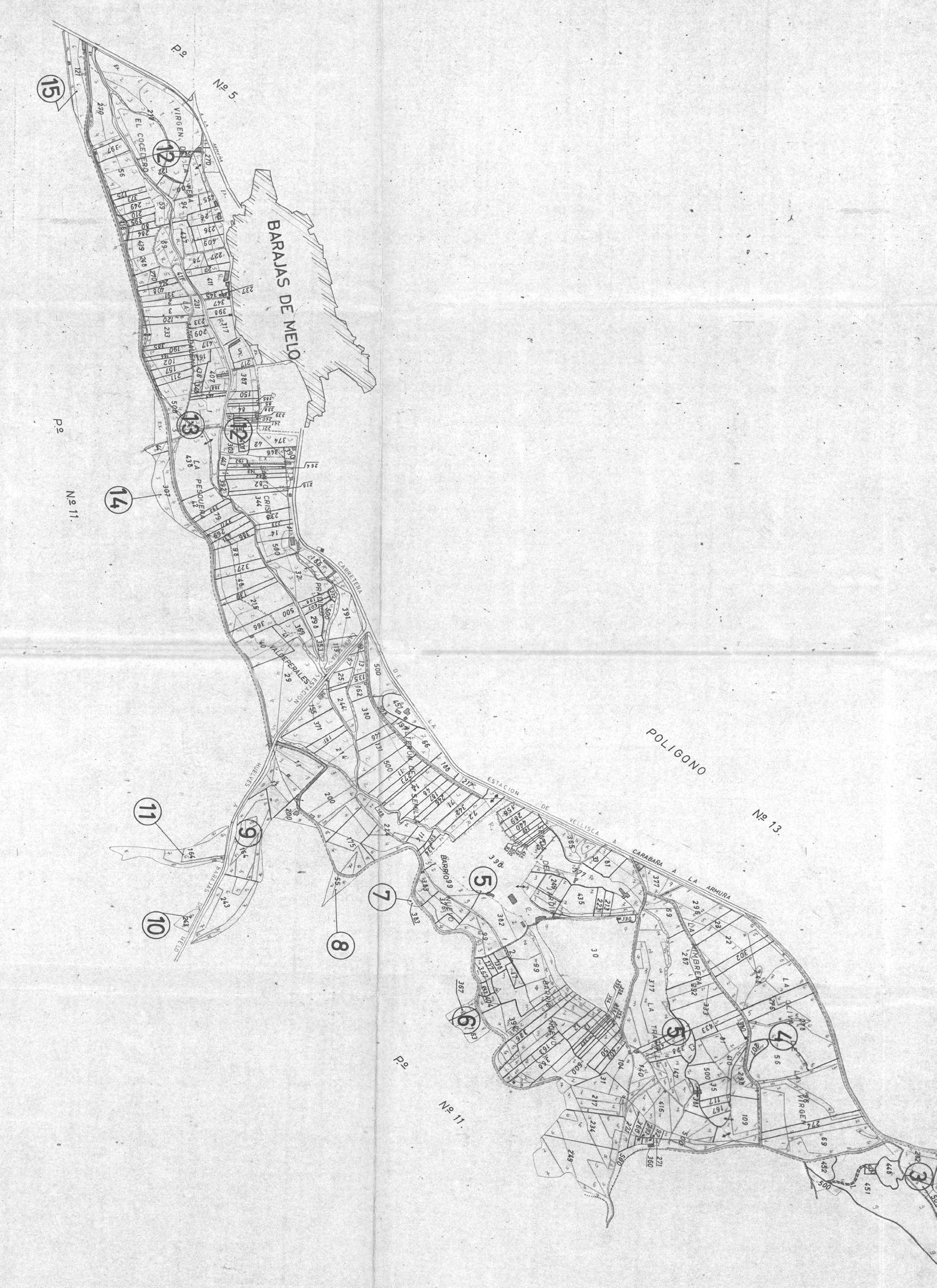

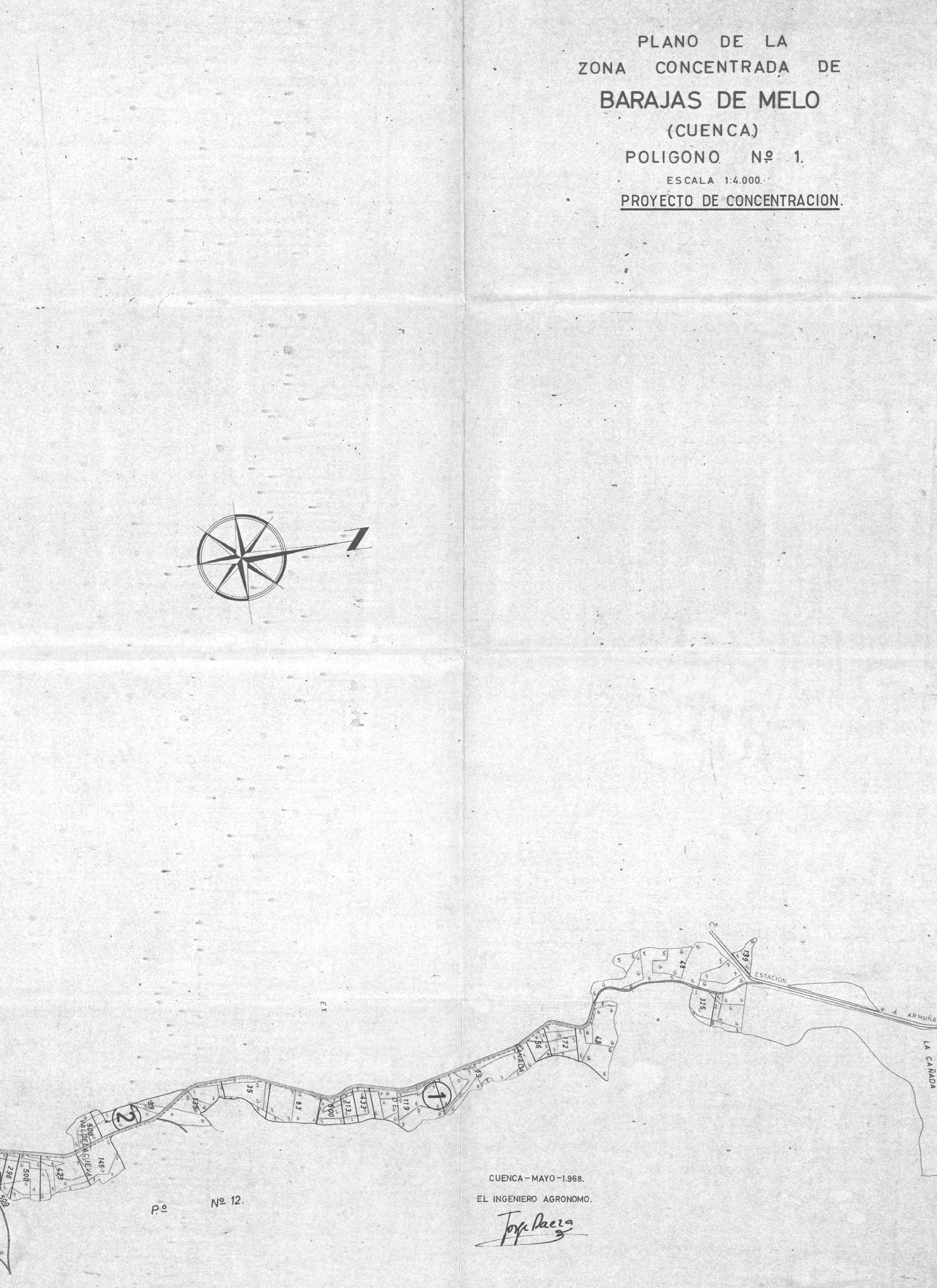

Fig.50 Land division along Barajas de Melos river basin (Cuenca), 1968. Source: “Ministerio de Agriculture, Pesca y Alimentación” Central Archive (MAPA)

rural dwellers (Otero Verzier, 2016).

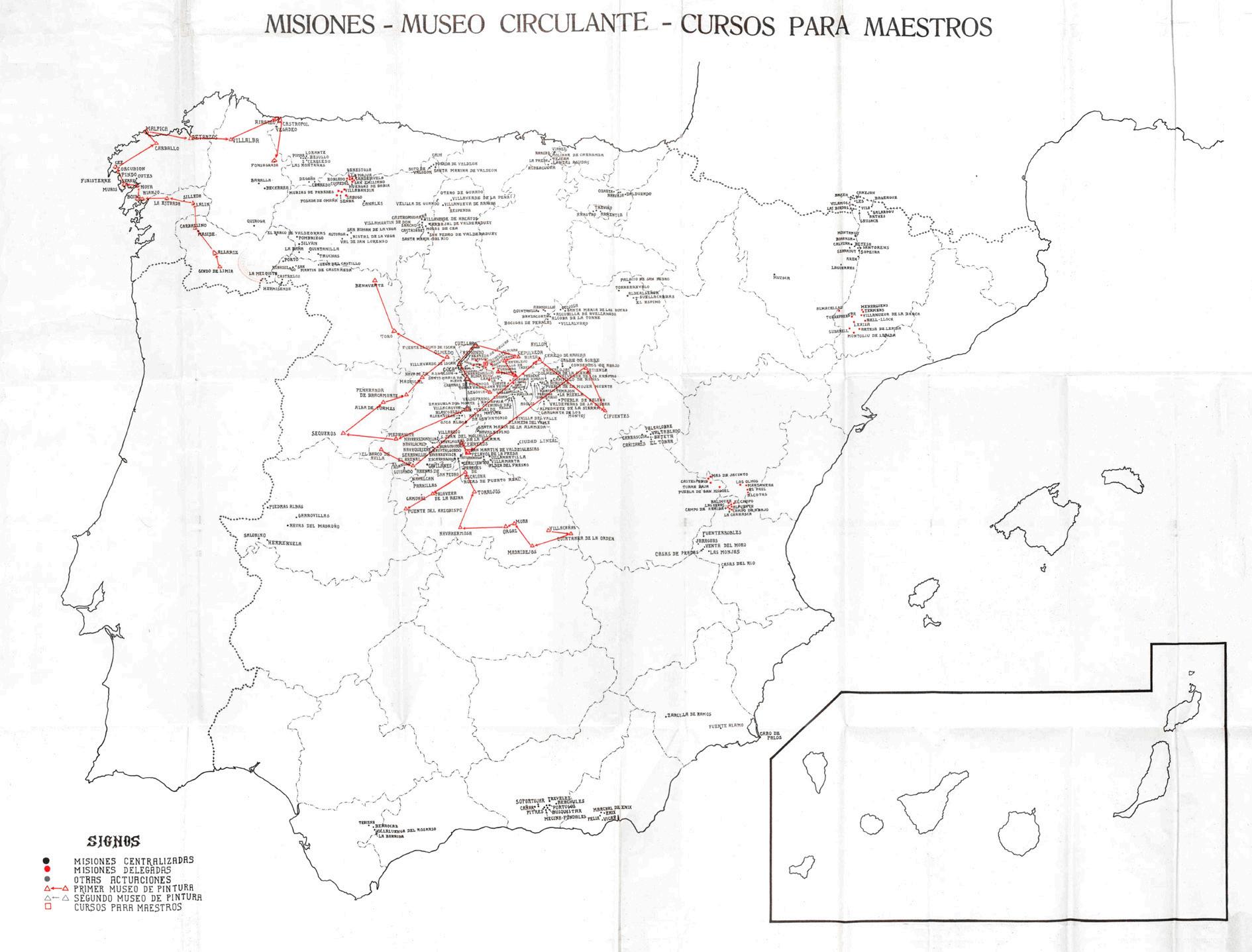

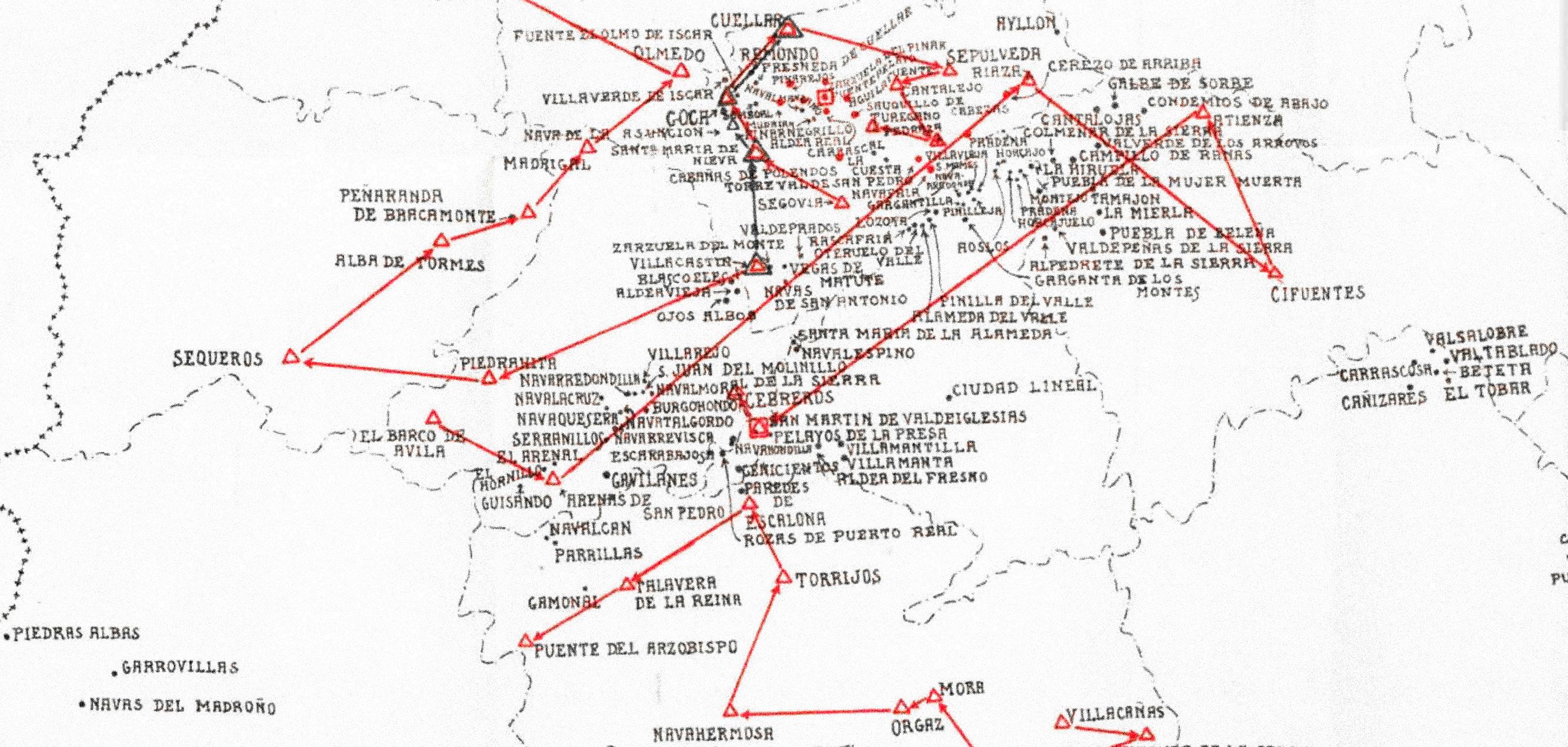

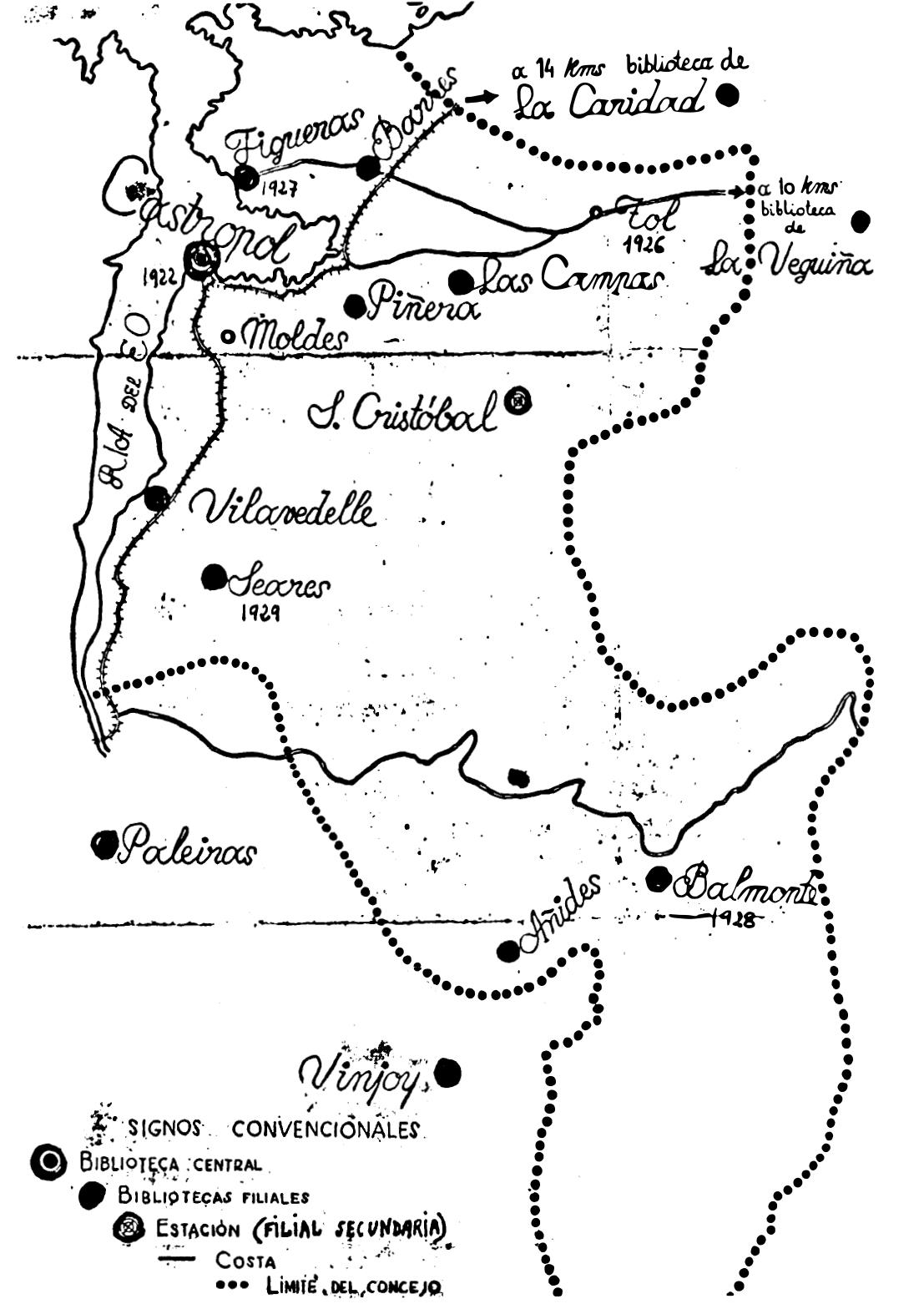

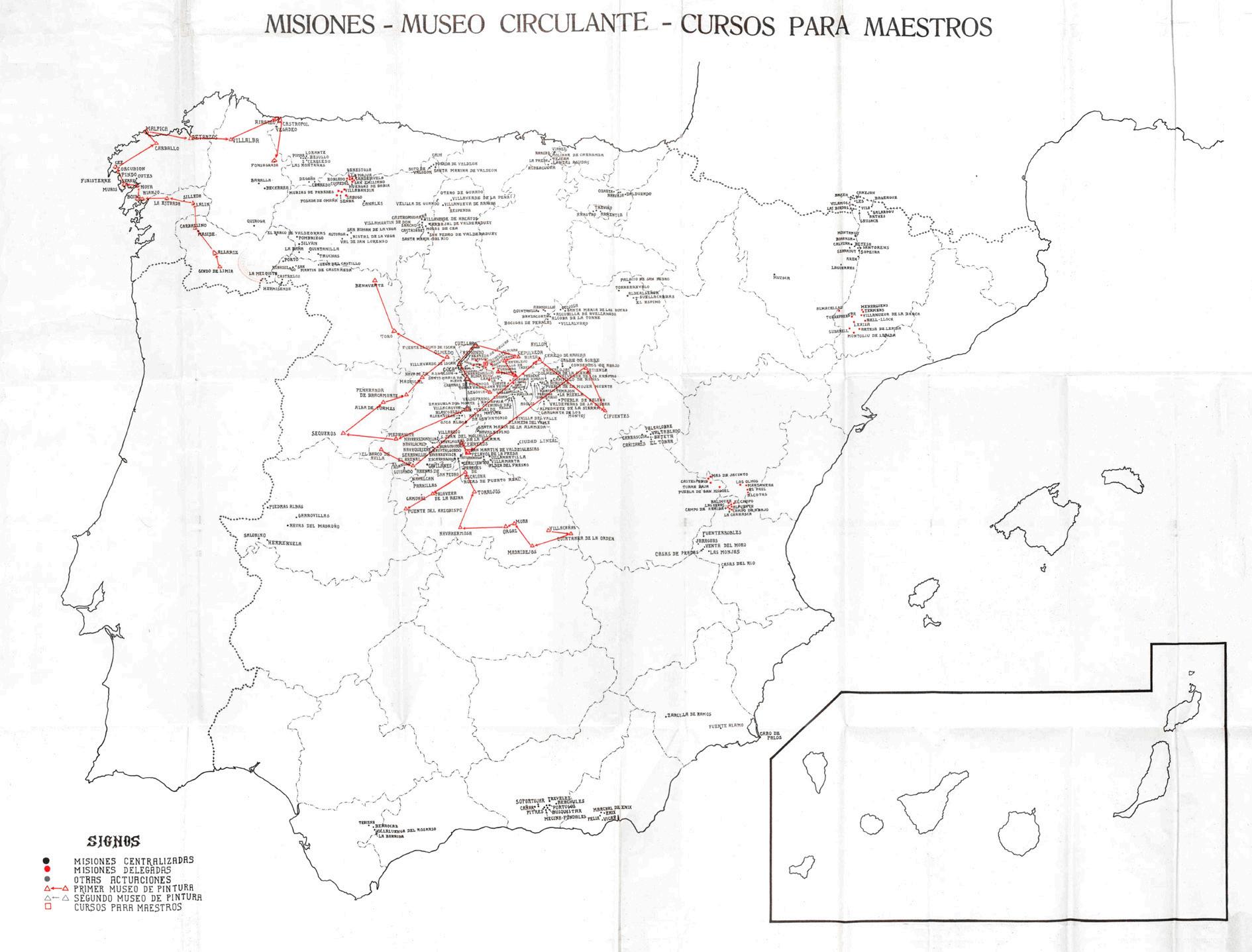

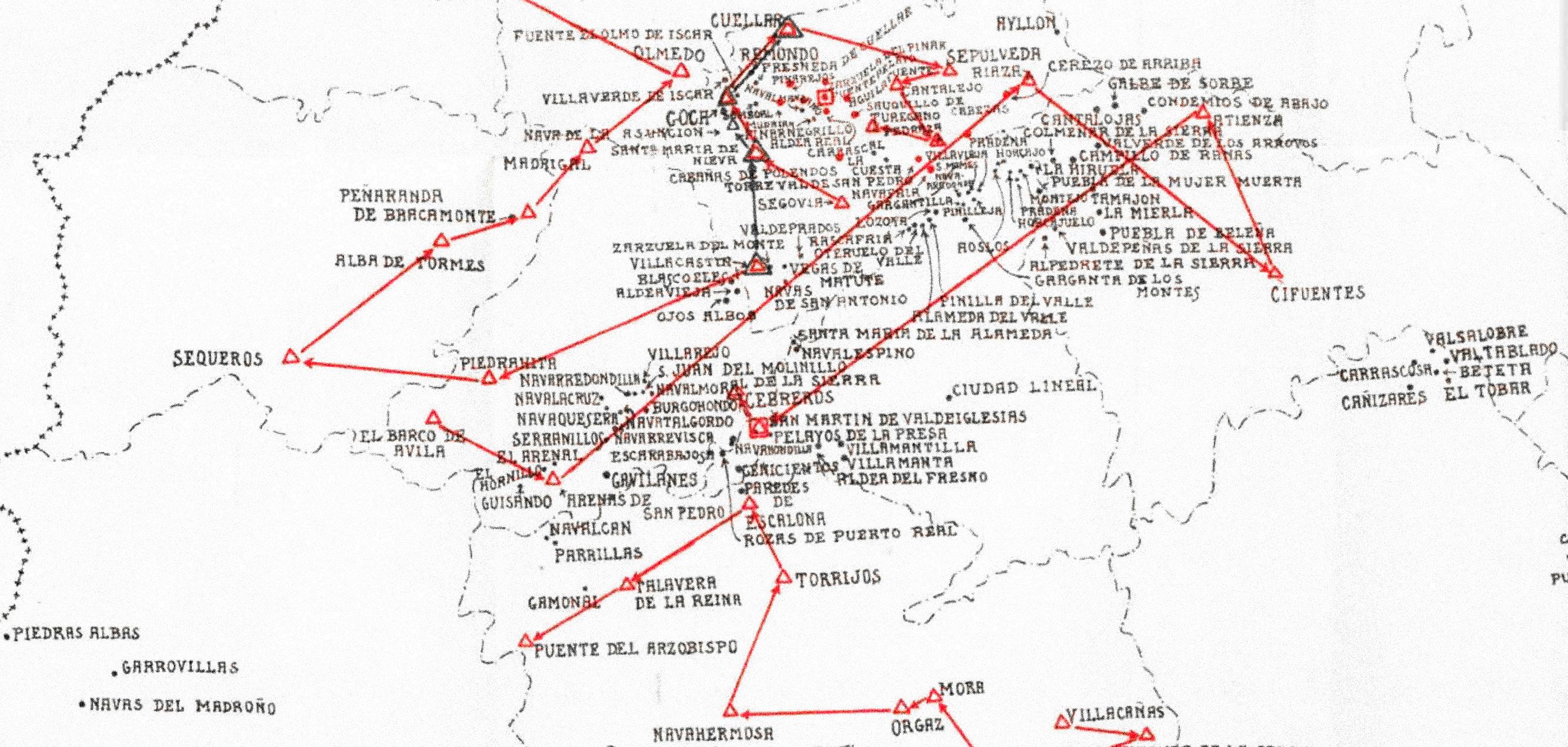

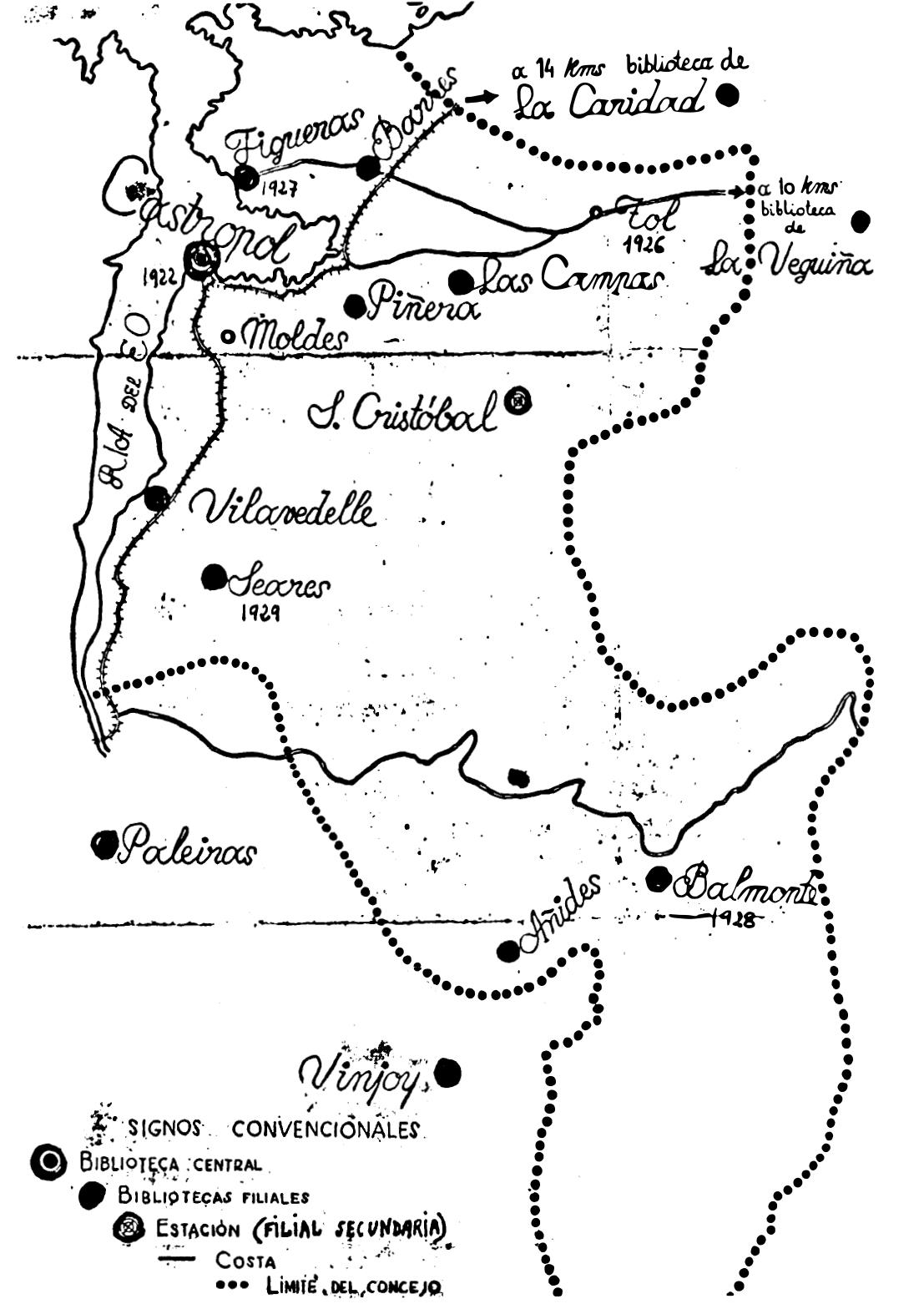

For example, between 1931 and 1939, “Misiones Pedagógicas” (Pedagogical Missions) was a cultural solidarity project promoted by “Institución Libre de Enseñanza” (Free Learning Institute), the National Pedagogical Museum and the Ministry of Public Instruction. It was an initiative carried out during the Second Republic by vanguardist artists and intellectuals who organized expeditions from Madrid (Fig.52,53) to bring academia – in the form of the People’s Circulant Museum, the People’s Chorus, the Theatre and a number of libraries – to the remotest rural areas around the capital (Fig.57,58).

Similarly, after 1939 in rural Spain, “Falange”’s “Sección Femenina” (Women’s Section) became a fundamental educational tool during the dictatorship (Fig.51). This women’s organization’s role consisted in indoctrinating rural women, particularly those living in colonization villages (Reus Martínez & Blancafort Sansó, 2016). Peasant women were considered crucial subjects in the indoctrination of family and social structure: they were the first ones in learning National Catholicism and its ensuing values and transmit these to the rest of the family.

To achieve this, “Instructoras Rurales” (Rural Instructors) designed a specific training to which every woman was exposed (Reus Martínez & Blancafort Sansó, 2016), and trained them in domestic tasks such as cooking, dressmaking, canning technique. This retrograde and deeply sexist education was instilled in a mostly illiterate female population. (Fig.56)

1955

19581955

1959

1961

1961

1961

1961

1961 -

1966

Mancha

Real

Bedmar

Jimena

Larva

Solera

Noalejo

Belmez

Mor.

Cárchel

Garcíez

The model that “Sección Femenina” promoted was that of a submissive, docile woman towards the regime and masculinity in general, obliged to remain silent, behave in good manners, without standing out when gesturing or moving. She must sacrifice and be satisfied with those sacrifices (Balinot, 2019). The indoctrination efforts had their results in the sense that until the 1970’s, this model was assumed by most of the Spanish female population, becoming compliant with certain established norms, from dressing codes to the way they sat and occupied their time, to the way they expressed themselves and

78 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

- 60YEARTOTAL VILLAGE MOTHERS 105 Source: (Paz, 2003) 183 265 210 65 45 80 100 35 48 30 65 50 30--------------18 87 50

-

GIRLS

Jódar MEN

-

WOMEN

PARTICIPANTS TO "SECCIÓN FEMENINA" ITINERANT SCHOOLS IN SIERRA DE MÁGINA

thought (Regas, 2012). Women were not allowed to study or work without their husbands’ permission; they would not leave their marriage at the risk of social stigma, economic instability and loss of their children. Women were not legally able to acquire property nor open bank accounts, and they were absent from public life; civilly, they were non-existent.

“The only mission assigned to women in the nation’s tasks is the household. Therefore, at the moment (…) we will extend the work initiated in our formation schools to construct a family life so pleasant for men, that within the home they will find everything that was previously lacking… ”1 Pilar Primo de Rivera, founder of Sección Femenina (Preston, 1998).

79 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

2 R1 1 4 R4 R3 3 4 R2 2 R2 FOR MAIN CLASSROOM ASSEMBLAGE R1) R2) R3) ELECTRONIC GROUP R4) KITCHEN

CULTURE

SCHOOL") 2) BROTHERHOOD

INDUSTRIES") 3) HEALTHCARE R1 4) HOUSING R4 R3 1 A 3

1 Pilar Primo de Rivera (1907-1991), was sister of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, creator of Falange. She founded and directed Sección Femenina. This quote is extracted from a speech given after the Civil War.

1)

("HOME

("RURAL

Fig.51 “Sección Femenina”’s truck pieces and assemblage. Itinerant infrastructure for educating the rural peasantry.

80 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Fig.52 Circulant Museum’s itinerary, departing from the central capital Madrid to inland Spain. Source: Patronato de Misiones Pedagógicas, 1934.

81 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.53 People’s Chorus and Theatre performances. Again departing from central capital Madridwhere Free Learning Institute was located – to inland rural Spain. Source: Patronato de Misiones Pedagógicas, 1934.

INDIVIDUAL ROUTE INFORMATION EDUCATORS FAMILY UNIT EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION INDIVIDUAL ROUTE INFORMATION EDUCATORS FAMILY UNIT EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTION

82 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Fig.54 Diagramme showing a unidirectional circulation of information within these itinerant educational infrastructures. Representative of both Pedagogical Missions and Sección Femenina’s approach to education and culture in rural Spain.

83 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.55 In the 1930’s, Catropol’s Circulating Library created a network of book exchanges within the region. Source: Coronado, 2003

84 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

85 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.56 NO-DO’s propagandistic images showing “Sección Femenina”’s work. Source: https://www.rtve.es/alacarta/videos/revista-imagenes/catedras-ambulantes/2867240/

Source: https://www.casamemorialasauceda.es/2021/04/24/las-misiones-pedagogicascultura-y-bibliotecas-para-el-pueblo/; accessed 01.04.2021

86 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Fig.57 People’s Theatre representation.

87 CHAPTER 01: PLANNED RURALITY

Fig.58 Copies of Velázquez from El Prado Museum are exhibited in Cebreros, Ávila. Source: https://www.casamemorialasauceda.es/2021/04/24/las-misiones-pedagogicas-cultura-ybibliotecas-para-el-pueblo/; accessed 01.04.2021

88

DISSOLVED RURALITY

89

CHAPTER 02 · 1980’S

HISTORICAL CONTEXT: TRANSITION TO DEMOCRACY 02.1

Spain’s political transition marked the change from Franco’s dictatorial regime to a democratic system similar to that of other Western democracies. During the second half of the 1970s and early 1980s, Spanish society underwent one of the most profound changes in its history. It is worth noting that, although there were specific political individuals who encouraged it, it was Spanish society as a whole, eager to get rid of a stagnant and repressive dictatorship, that was the real protagonist of change.

The end of the regime’s international isolation from the 1960’s was a consequence of the Cold War, which led Western countries, led by the US, to seek global support against communism. In 1953 the “Madrid Pacts” were signed, which allowed four US military bases to be installed in Spain in exchange for economic and military aid. Franco’s regime began to be accepted by the West without having to adopt any kind of democratizing measure. From then on, an intense process of economic development began. In 1959, the Stabilisation Plan was approved, and the regime attempted to give an image of moderation to the outside world.

Abundant, cheap labor attracted foreign investment. Large quantities of tourists started to enter for the first time in decades, and the “Spain is different” campaign turned Spain into a tourist paradise to be exploited. All of this under an international context of economic growth fueled by low energy prices. Spain’s GDP grew by 17.7 percent in just a few years; it shifted from an agrarian society to an urban one.

Prior to his death, Franco prepared everything for the dictatorship to endure. However, political and social tension led king Juan Carlos I to entrust Adolfo Suárez with the task of putting an end to Franco’s regime and establishing democracy. The process led to the approval of the Political Reform Law in 1976, in a referendum that received 94% support.

A year later, constituent elections were held, and to the astonishment of many, the result showed that Spain was “red”. The PCE (Communist Party) and PSOE (Socialist Party) won the majority of the votes. The Constitution was approved in December 1978. The political transition was completed with the

90 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

“Moncloa Pacts”, which made it possible to balance the Spanish economy and prepare it to enter the European Economic Community.

In 1981, three years after the new democratic Constitution’s signature, a few nostalgic militaries attempted a coup d’état. Spanish society’s response and defense of democracy were evidenced during 1982 elections: PSOE won the general elections by an overwhelming majority of 202 deputies out of 350 seats; the regime’s supporters were not represented.

In summary, in barely three years, Franco’s institutions were dismantled and replaced by democratic ones. The speed with which the events took place can be explained by the fact that Spanish society had evolved and demanded a political system in line with its life aspirations that had nothing to do with the canons imposed by the regime. In the words of Felipe González (former PSOE Prime Minister):

“If this society has shown anything, it is that even before Franco’s death it was already living with attitudes that did not correspond to the superstructural crust that Francoism represented. Without that attitude, the democratic change would not have been possible”.

(Ayensa, 2004)

91 CHAPTER 02: DISSOLVED RURALITY

· DIVORCE ACT · Abortion Law 2000 1980 1900 1920 1940 1880 1960 1990 1970 1950 1930 1910 1890 1870 · CATHOLIC CHURCH · July 7th, DIVORCE ACT · Equity between spouses · Rape crimes · Abortion (partial) · Voluntary sterilisation MODIFICATION 1870 1875 1932 1937 1939 DICTATORSHIP DEMOCRACY TRANSITION II REPUBLIC I REPUBLIC RESTORATION 1978 1981 1982 1983 1984 · May, Adultery · Oct., Contraceptives LEGALISATION · Equity among progeny · Nationality mother's kins · Civil Marriage Act · Civil Marriage Act CRIMINALISATION

Fig.59 Timeline of the familial legislation’s evolution during the last century in Spain. During the Transition to democracy years, the familial legislation that had prevailed for the previous decades was radically upgraded.

02.2.

These changes are represented across Spain’s contemporaneous mediascape, while these particular political concerns found expression in “La Movida”, counter-cultural movement born during the Transition. Pedro Almodovar’s early filmography is a reflection of a cultural phenomenon that shaped the 1980’s decade. The location of his plots in domestic spaces evidence how an entire generation was finally questioning the prevailing social standards:

The scene takes place at dinnertime, in a tiny kitchen with a strident flower-print wallpaper. A pink light illuminates a housewife, who, with a deeply annoyed expression, peels onions impatiently. Her husband enters the kitchen and confronts her, the dispute comes to blows. He slaps her in the face, and after some moments of struggling, she grabs the nearest object – a bony “jamón” leg- and strucks a mortal blow to his head. In this scene from “What Have I Done To Deserve This?!” (1984) (Fig.60), Pedro Almódovar portrays – in barely 20 seconds- the dissolution of the traditional Spanish family.

Almodóvar’s filmography constitutes one of the major references of “La Movida”; a movement which emerged as a sudden eruption of energy of a society repressed for so long. The director was able to portray not only those marginalized subjectivities – transgenders, homosexuals, women…-, but also evidenced the “burst of the ludic” and the pursuit of hedonism that Spanish society was living. In the 1980’s, when – as seen in the previous section - the political climate was immersed in transcendence, countercultural artists made use of frivolity as a medium of protest against the Francoist past. Almodóvar’s first feature film “Pepi, Luci, Bom and Other Girls Like Mom” became an emblem of the movement, acclaimed as one of the most irreverent pieces of cinema that the director has produced. In his early “pink” period – as Paul Julian Smith coined the first works in the director’s trajectory - Almodóvar focused on one of his main pivotal themes: women’s sexual dissidence, female characters and their newfound agency in post-Franco Spain (Pavlovic, Álvarez, Blanco-Cano, Osorio, & Sánchez, 2008).

In “What Have I Done To Deserve This?!”, the film criticizes the role of women as housewives: the placement of the camera inside the electric appliances

92 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

A filmic approach: La Movida movement

FAMILIAL DISSOLUTION

93 CHAPTER 02: DISSOLVED RURALITY

Fig.60 By recreating the murder of Gloria’s husband in “What have I done to deserve this?!” (1984), Pedro Almodóvar represents the dissolution of Spanish traditional family.

Fig.61 In “Pepi, Luci, Bom and other girls like Mom” (1980), he unveils one of his main topics: Spanish women and their newfound agency in post-Franco Spain

evidence Gloria’s invisibilization, only observed by those objects which she routinary utilizes.

Similarly, in “Pepi, Luci, Bom…” he centres the movie around the transformation of women’s roles. It is around the secondary character, Luci, where a feminist critique is unveiled: Luci, representative of the sacred figure of the housewife (remember the canon imposed by “Sección Femenina”) is subverted as she is incited by the rest of the characters to immerse in 1980’s hedonism (Fig.61). Pepi – symbol of a new generation of free-thinking womenlearns from Luci how to knit – a typical housewife skill-, while she teaches Luci about sadomasochism. Throughout the movie, her character evolves from a submissive housewife, married to an abusive man, to a woman with deviant sexual desires, symbolizing a general shift in Spanish women’s role after the death of Franco.

This attitude against retrograde ideas was the backbone for the approval of new familial legislation during the Transition, which was not only political but also religious, social and cultural. Franco’s regime had left in the Church’s hands the control of Spaniards’ private lives, which had to be conducted according to the most backward Catholic canons: divorce was abolished; equality between legitimate and illegitimate children was annulled; contraceptives, adultery and cohabitation were criminalised; unequal rights were established according to sex inside and outside marriage; education was handed over to the Catholic Church, mixed gender’s co-education was forbidden; Catholic marriage was re-established as the only possible marriage and large families were encouraged. Broadly speaking, this was the legal framework regulating the Spanish family.

Although during its last year Franco’s regime undertook some changes1 , the democratic institutions that emerged in the Transition repealed all these norms: in 1978 the sale and distribution of contraceptives were legalised; that same year, adultery was decriminalised - before, women were punished for an act of infidelity; men only in the case of introducing the mistress into the marital home. In 1981, the law on divorce and civil marriage was approved; in 1983, voluntary sterilisation and partially abortion were decriminalised; the crimes of rape and abduction were modified to be equal in terms of sex. For rape, forgiveness does not extinguish prosecution. The rights of marital and non-marital children are equalised. In the words of Iglesias de Ussel (Ussel, 1990) “there was a shift from the family as an institution to the family based on personal interaction” (Fig.59).

The feminist movement, often linked to anti-Franco militancy, reemerged and awakened a generation of women who felt they were decades

1 In May 1975, an amendment to the civil law was passed which gave married women the capacity to act. She could now, for example, buy a house or open a bank account without her husband’s consent.

94 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

A new familial legislation

Revival of the feminist movement

Dissolution of rurality

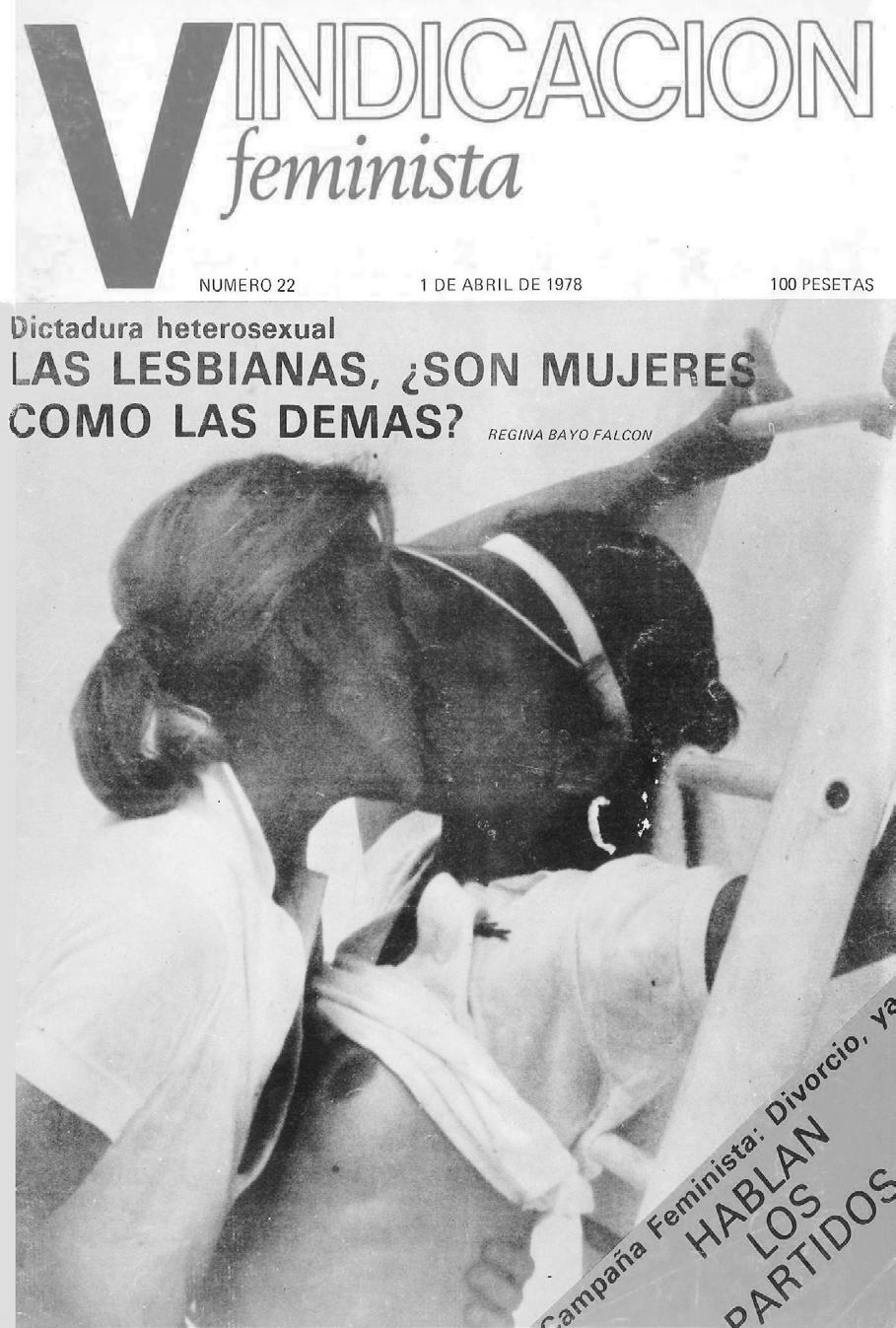

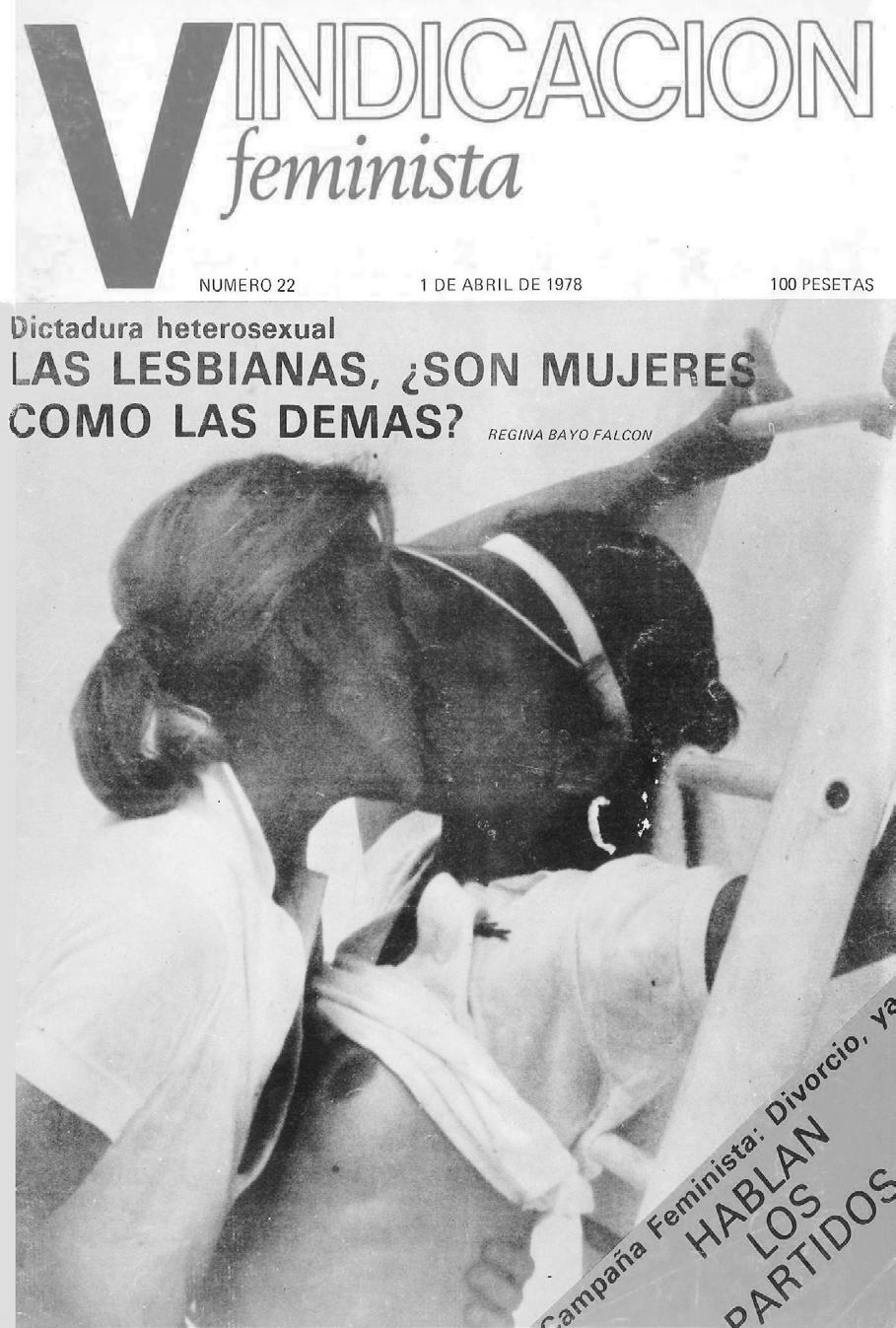

behind. The first magazine dedicated exclusively to the analysis and situation of women in Spain, “Vindicación feminista” (Fig.62,63), was published in 1976; “Jornades Catalanes de la Dona” (Catalan Women’s Conference) was held in the same year. In 1977, LaSal, a feminist bar-library and one of the Transition’s most important alternative and countercultural spaces, opened in Barcelona’s Raval neighbourhood, where women’s art was given a place.

Together with the critique and dissolution of the institutional family, from 1970-80’s there have been major socioeconomic changes that reshaped the notion of rurality. Rural sociology has traditionally differentiated between rural society and its antagonist, urban society. This distinction was grounded around the agrarian activity taking place within the countryside; a self-contained society defined by familial units entirely devoted to the primary sector economy, consumer of great amounts of space yet situated in isolated, dispersed locations within the territory.

Sorokin and Zimmerman, founders of Rural Sociology, have defined rural society as Agriculture = Habitat = Culture. Nevertheless, a series of changes towards the modernization of the country rapidly affected socio-spatial rural Spain, completely altering the traditional conception of rural society.

According to Luis Camarero and Sancho Hazak, two major changes shaped contemporary Spanish rurality: firstly, a process of de-agrarisation that took place once Spain was inscribed within the European economic context. Rurality is not a synonym for agricultural production anymore and therefore, is not defined by its economic activity. Isolationism emerges as the second variable: rural societies as closed and self-contained, isolated, on the margins of progress and modernity; a notion countered by information and communication technologies development. Finally, the third pillar traditional rurality is built on is the familial unit; a pillar which, as seen in the previous section, is equally questioned.

As a result, sociologists such as Camarero, Mormont or Clocke speak of the dissolution of the concept of rurality and the need to eliminate the ruralurban duality. Society is no longer determined by its environment, but by the system in which it is embedded. Nowadays, rurality is a social construction that sometimes is injected even in urban environments, and is defined by the system within which that community is inscribed rather than its location in space. And, on the contrary, the social reality of rural areas is as unexpectedly complex as those found in urban areas. (Camarero & Oliva, 2016)

95 CHAPTER 02: DISSOLVED RURALITY

Headlines claiming: “Domestic

96 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

Fig.62 “Vindicación Feminista”, a publication born in 1976, was one of the symbols of Spanish feminism’s re-emergence during the Transition.

labor, is it work?” and “Are lesbians women, like the others?”

97 CHAPTER 02: DISSOLVED RURALITY

Fig.63 Maria Telo, feminist jurist and activist, was interviewed in the magazine “Vindicación Feminista”, explaining her position against the forgiveness law against rape. Source: http://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/

“De-agrarianisation” refers to an agricultural population’s gradual loss of importance in society, as well as the gradual dissolution of agricultural activities’ centrality in shaping rural lifestyles. (Camarero & Oliva, 2016) This process changed the rural world’s social and economic structures, including Spain in the 20th century’s last decades (Fig.66).

After 1960’s economic liberation, the reconfiguration of the agrarian world started shifting from traditional agriculture to modern agriculture, according to the logic of the capitalist market. Franco’s regime moved from an agrarian discourse that exalted agriculture as a way of life, with bucolic references to the artisan farmer or settler, to that of an agricultural entrepreneur. In the words of the Minister of Agriculture at that time, Rafael Cavestany, the change would have to consist of “fewer peasants and better agriculture” (Pulgar, 2006)

However, the modernization of Spanish agriculture was not consolidated until 1986, with Spain’s entry into the European Economic Community, Spanish agriculture’s integration into the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and the international agri-food system. The entry coincided with the emergence of the so-called third agri-food regime, which left regulation and management of production in the hands of corporations, to the detriment of family farmers, who were asked to reduce their production and stay at home (Camarero & Oliva, 2016).

The globalisation process, a concern for environmental deterioration and the depletion of resources led the European Commission in 1991 to propose a new objective for the CAP. Rural development should not depend solely on the agricultural sector, it should foster new forms of economic activity that would contribute to maintaining rural population sustainability and consolidate rural regions’ economy (Fig.64). (Comisión de las Comunidades Europeas, 1991) Consequently, CAP adopted measures to encourage rural economy’s

98 FROM AUTARCHY TO SYNERGY

POST-PRODUCTIVE RURALITY

Tertiarization of the countryside

02.3.

productive rurality

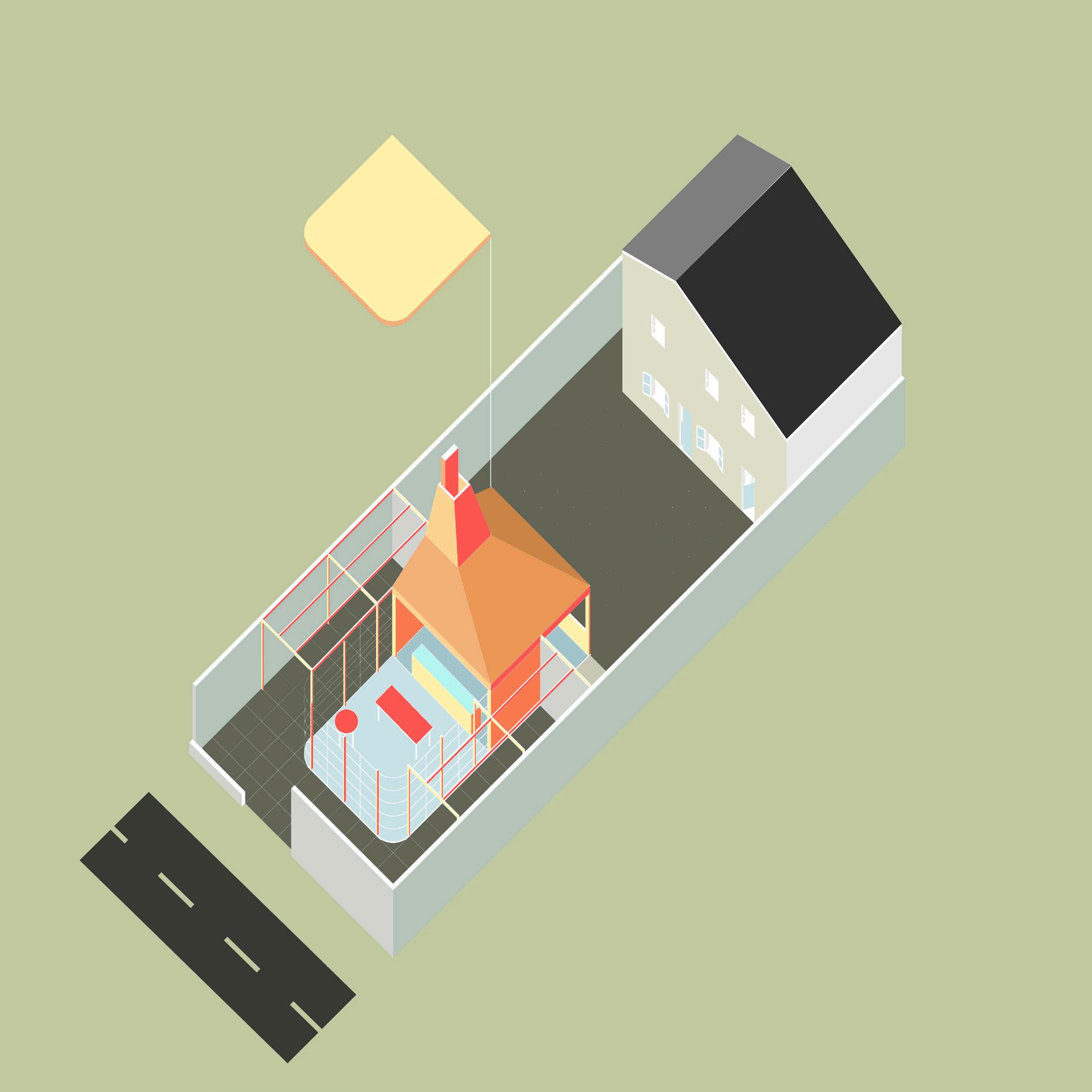

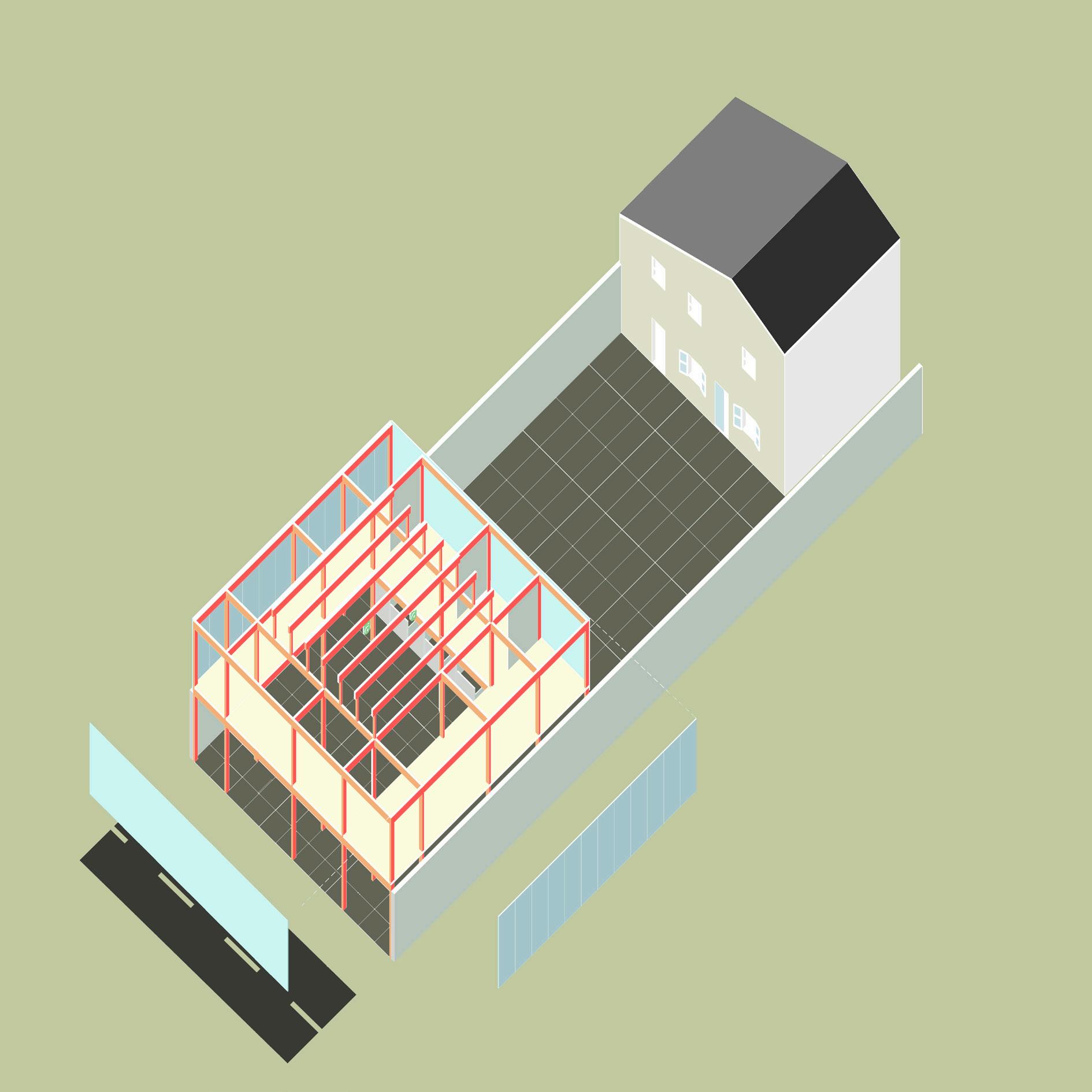

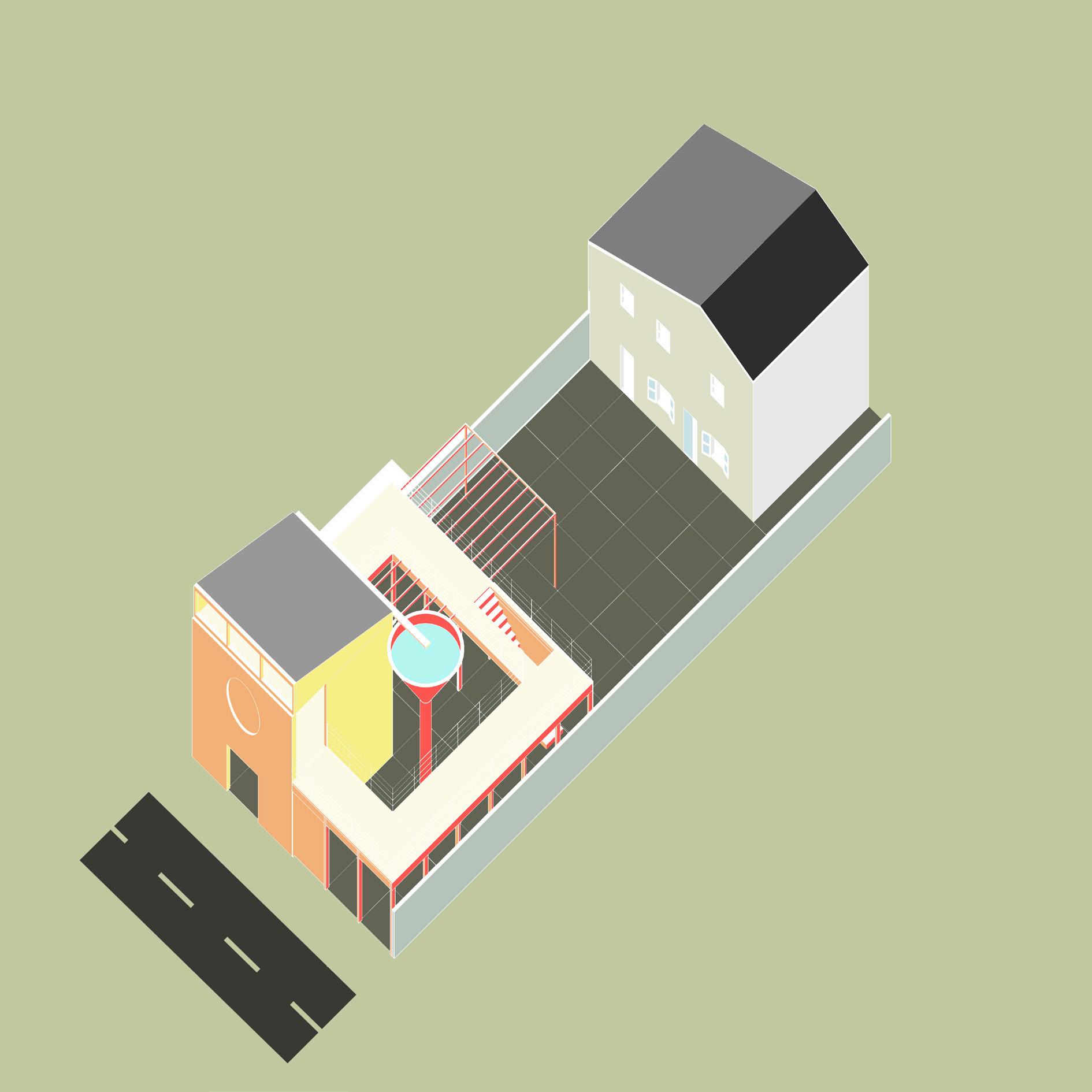

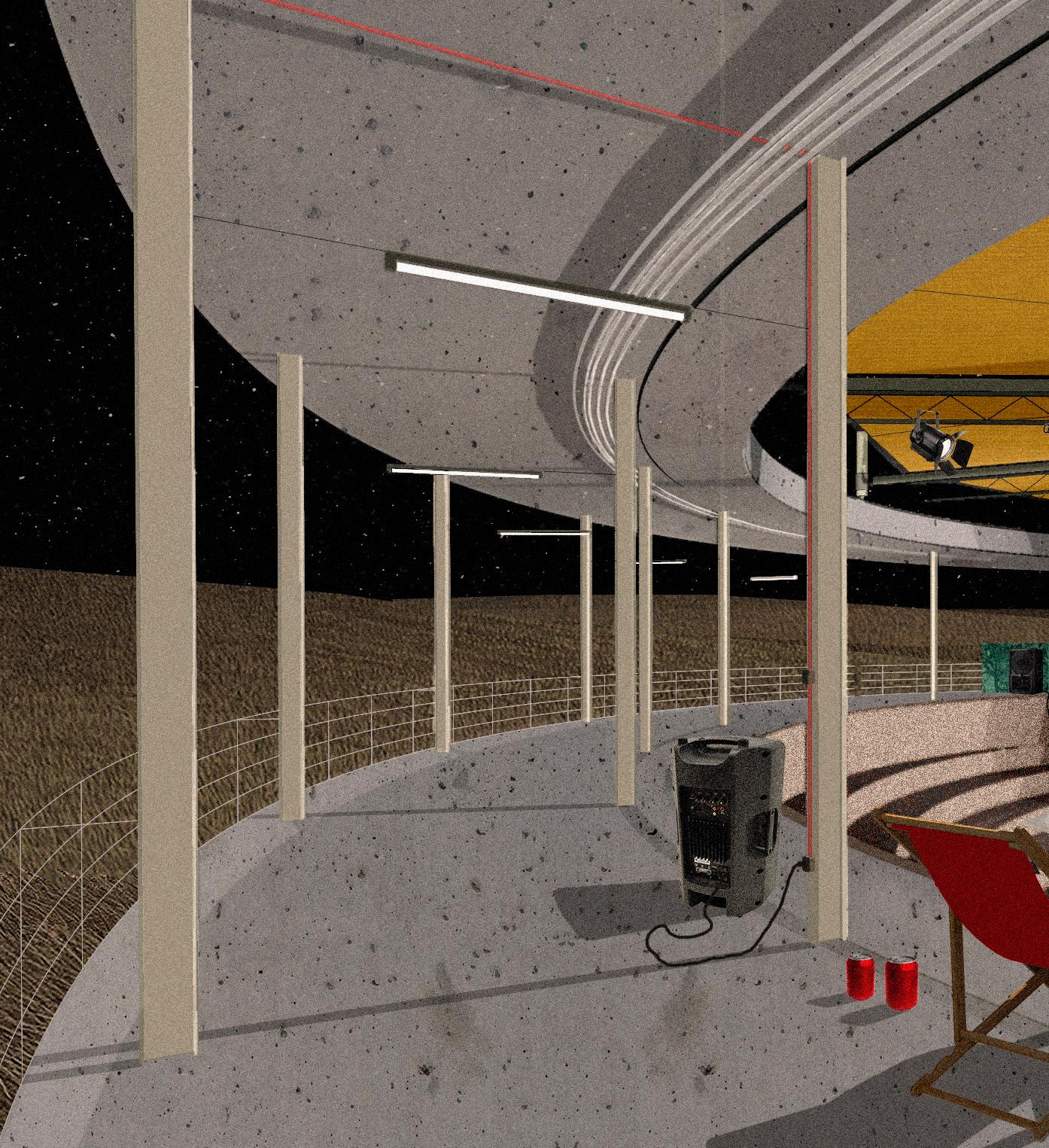

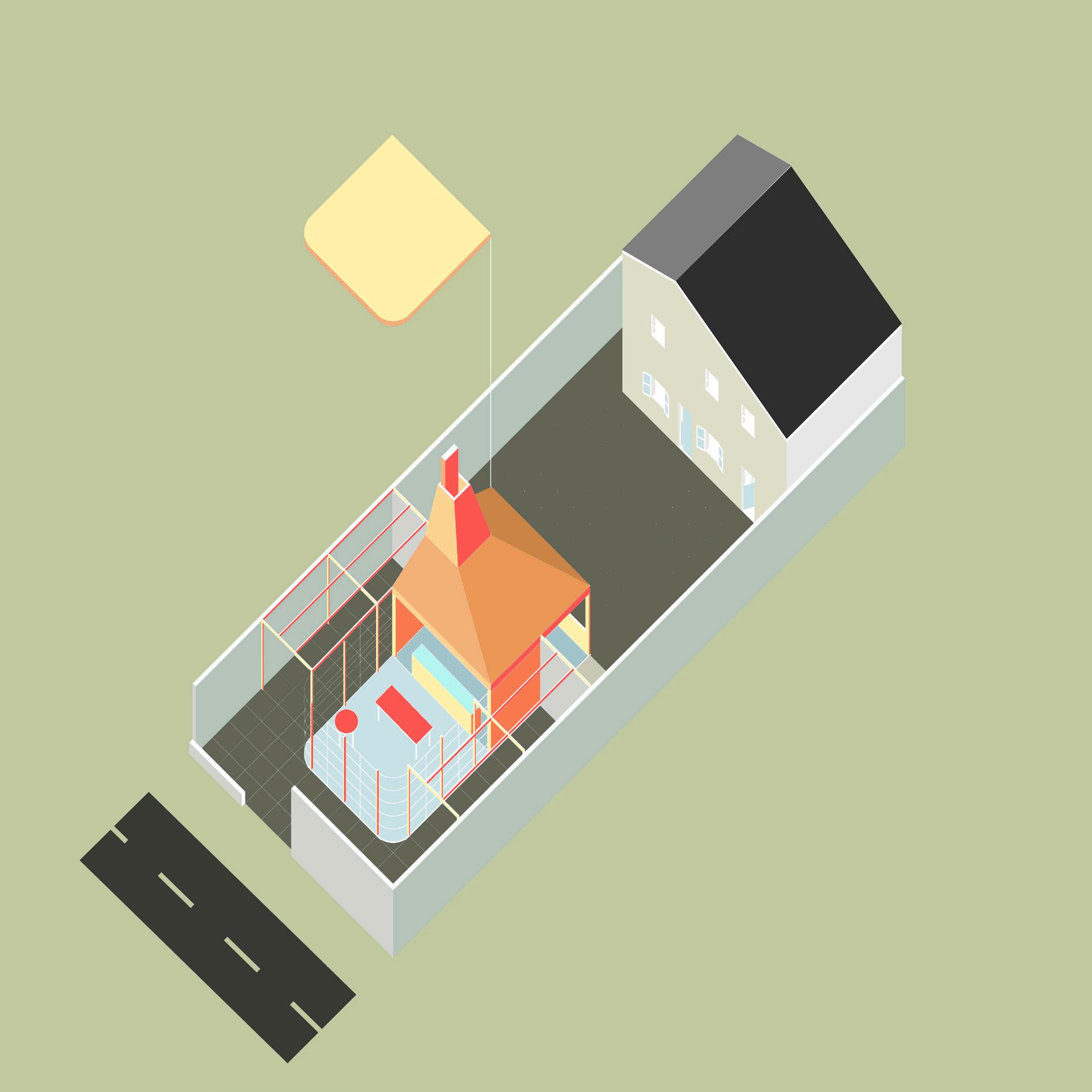

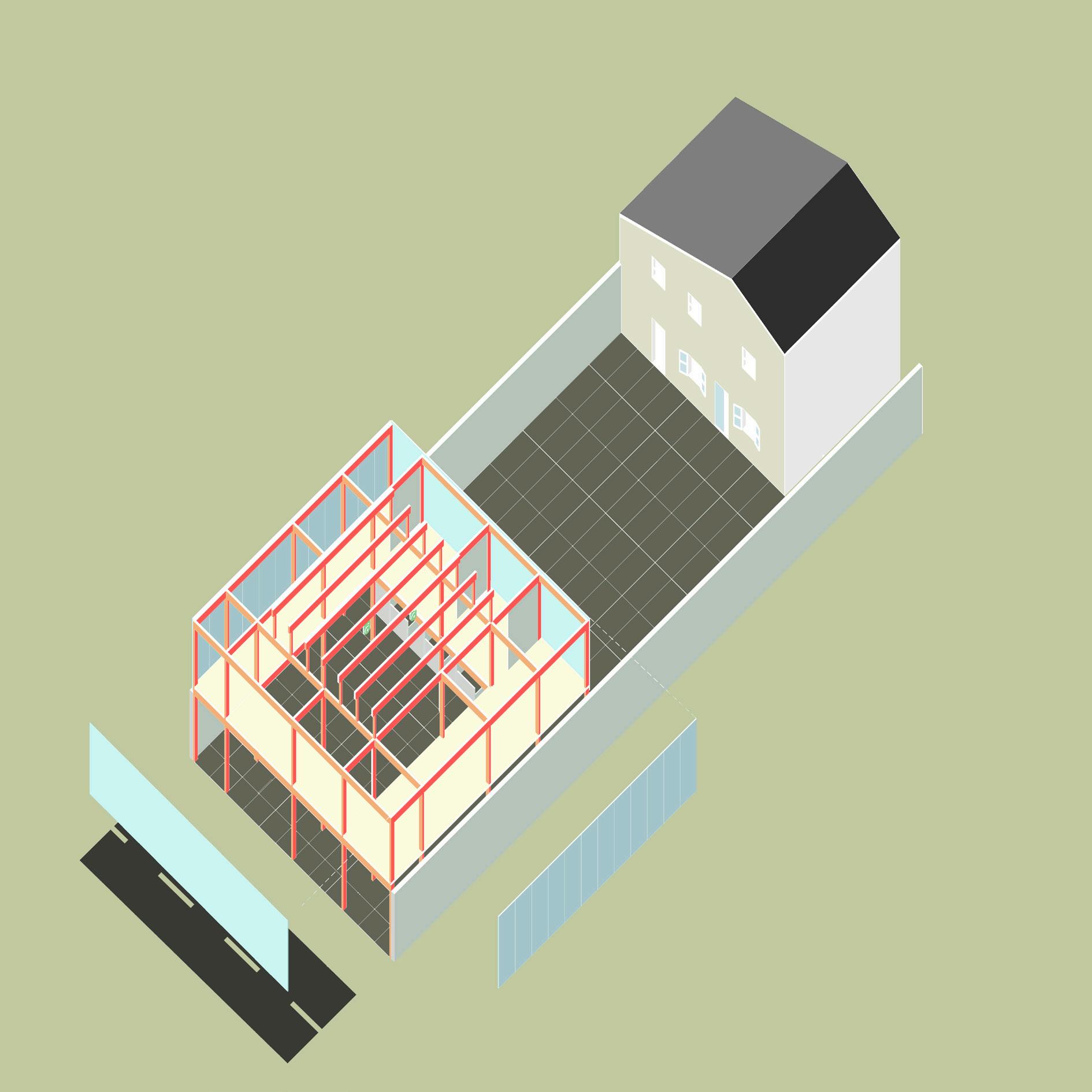

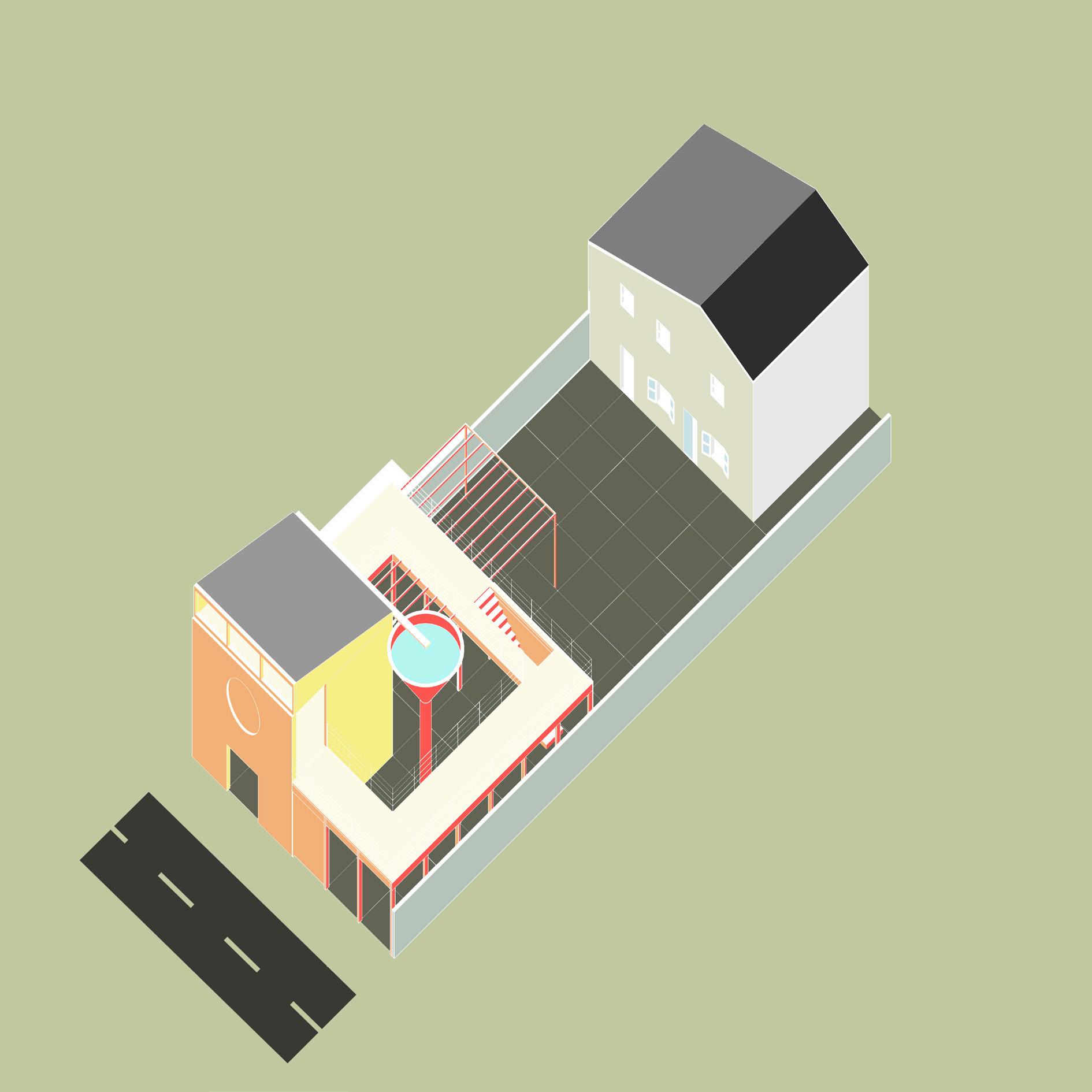

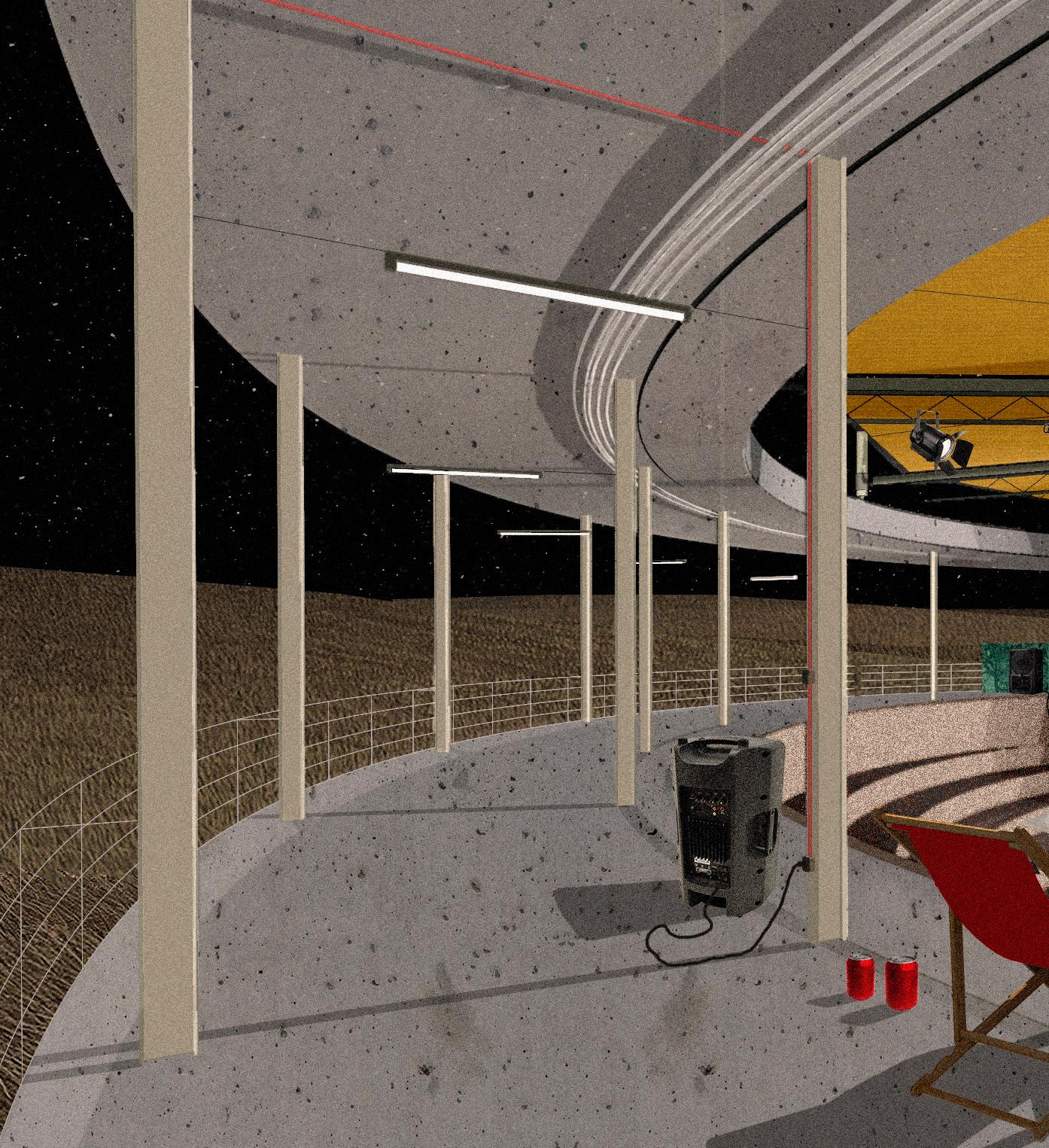

diversification through programmes such as LEADER. 1