Housing tHe ColleCtive

Architecture of Belonging in MuscAt

MohAMMed Al BAlushi

Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Taught Master of Philosophy in Architecture and Urban Design - Projective Cities

Architectural Association School of Architecture 2022 - 2024

Coversheet for submission 2023-2024

Programme:

Projective Cities, Taught MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design

Name(s): Mohammed Al Balushi

Submission title:

Housing the Collective: Architecture of Belonging in Muscat

Course title: Dissertation

Course tutor(s): Platon Issaias, Hamed Khosravi

Declaration:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my/our own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Signature of Student(s):

Date: 22nd of April 2024

To my sisters and to Ercan

Preface

My journey into the heart of Muscat’s urban landscape began out of a deep curiosity about the city’s architecture and the underlying principles of its urban planning. This thesis represents a confluence of academic inquiry and a profound personal exploration, delving into the ways in which legislative decisions, social dynamics, and architectural designs interweave to define the city’s identity. Through this exploration, I have sought to uncover the layers of influence that have shaped Muscat’s urban environment, turning a scholarly lens onto the city that has captivated my interest for over a decade.

The core of my investigation focused on the urban and architectural development of Muscat in parallel to the legislative frameworks governing urban development in Muscat, and consequences of these laws on the social housing neighbourhoods. Understanding these legal structures was crucial, as they serve as the backbone for the city’s architectural and social landscape. This analysis revealed how policy decisions ripple through the urban fabric, influencing everything from the skyline to street-level interactions. The commitment to digging beneath the surface of these policies underscored my research, aiming to reveal the broader implications of legislative actions on urban life.

Fieldwork played an instrumental role in this study, offering a tangible connection to the city’s heartbeat. Through interviews and neighbourhood observations, I gained insights into the everyday experiences of Muscat’s residents, particularly within social housing sectors. This handson approach allowed me to grasp the nuanced impacts of urban planning on diverse communities, spotlighting the challenges and opportunities faced by marginalized groups within the city’s evolving landscape.

A significant facet of my research was the examination of social housing policies and their effects on minority communities. This exploration aimed to unravel the complex interplay between urban planning decisions and the lived experiences of these populations. By delving into the narratives of displacement and community cohesion, my work sought to illuminate the ways in which urban environments can either foster or hinder social inclusivity.

The endeavour to bridge local observations with global urban studies theories presented a unique challenge, particularly in aligning the specificities of Muscat’s context with broader academic dialogues. This synthesis aimed to enrich the field of urban planning with nuanced perspectives drawn from a city that, while geographically distant from Western academic hubs, offers invaluable insights into the interdependencies of legislation, architecture, and community life.

This thesis, therefore, is more than an academic document; it is a narrative of my intellectual engagement with a city that, over 13 years, became a second home to me. It weaves together a personal connection with scholarly research, reflecting a commitment to understanding and enhancing the urban fabric of Muscat. Through this work, I aspire to contribute to a more nuanced and empathetic understanding of urban development, advocating for practices that respect the diversity and dignity of all city residents.

Abstract

Introduction

Research Statement

Chapter

Interlude

Chapter

Interlude I I II

Chapter II III

Paradigm: Welfare and Housing Reforms

Socialscape: Tracing Welfare Evolution

1.1.1 Introduction to Social Welfare in Oman

1.1.2 The Social Protection Fund

Habitat: Social Housing Policies

Outlook: Socio-Economic Horizons

1.3.1 Future of Social Housing: Bank of Maps Initiative

Absence

Transitions: Urban & Community Morphogenesis

Muscat: Continuity and Change

1.2.1 Muscat Pre Oil

1.2.2 Post Oil & Changes Urban Planning Policies

1.2.3 Land and Tribal Formation

1.2.4 Governance and Urban Planning Strategies

Neighbourhood: From Wadi Adai to Al Khoud

2.2.1 Wadi Adai

2.2.2 Al Khoud

Urban Program: Harvest Commons

Crossroads

Dynamics: Unfolding Typological Patterns

Kaleidoscope: Muscat’s Architectural Tapestry

3.1.1 Historical Layers and Cultural Dynamics

3.1.2 Muscat’s Architectural Evolution

3.1.3 Family Dynamics and Architecture in Muscat House: Dwelling Through Culture

3.2.1 Al Harthi Residence

3.2.2 Al Badi Residence

Typological Program: Adaptive Living

Conclusion

Bibliography Appendices

Abstract

https://www.sant.ox.ac.uk/research-centres/middle-east-centre/mec-archive

In Muscat, urban transformations driven by rapid economic growth and structural changes have precipitated notable shifts in housing patterns, particularly affecting the socio-spatial landscape for social housing communities. This research meticulously explores the intricate dynamics between architectural typologies and the lived experiences of these residents, shedding light on the critical role of spatial configurations within social housing in shaping communal interactions, fostering social cohesion, and influencing the everyday life of marginalized populations.1

The examination delves into the subtle yet profound spatial practices that emerge in the wake of displacement and social exclusion—practices that, while integral to the daily experiences of affected communities, remain largely unexplored in conventional urban development discussions. By unveiling these practices, the study challenges the traditional of urban development and architectural design in Muscat, advocating for a paradigm shift that centres the socio-spatial needs of marginalized groups within the urban planning discourse.

Central to this research is a critical evaluation of Muscat’s existing urban planning and architectural frameworks. The analysis contends that these frameworks often marginalize the unique socio-spatial needs of social housing residents, thereby necessitating a more inclusive and empathetic approach to urban design. Through a comparative analysis, enriched with global perspectives, the study underscores the potential for Muscat to adopt more socially responsive and inclusive urban planning methodologies.

The methodology of this study integrates multiple resources, encompassing academic literature, comparative case studies, and empirical fieldwork data. This multidisciplinary approach not only enhances the depth of the analysis but also situate the study within a broader context of urban planning, social housing, and community resilience literature. By intertwining these diverse insights, the research presents a nuanced understanding of how urban design and architectural decisions resonate with the socio-spatial experiences of social housing communities in Muscat.

Advocating for a re-imagined approach to social housing in Muscat, the study emphasizes the need for design and planning processes that prioritize social integration, communal well-being, and cultural sensitivity. It posits that adopting such an approach could significantly mitigate the negative impacts of urbanization on marginalized communities.

In its conclusion, the research extends beyond a mere critique of current practices, offering actionable recommendations by advocating for participatory design processes, culturally attuned planning, and communitycentric development strategies, the study aims to influence the future trajectory of urban development in Muscat, ensuring it is aligned with the principles of inclusivity, sustainability, and social justice.

1. The term “marginalized population” has evolved in its usage over time. Initially, in the early 1970s, it was used to describe populations residing outside the city walls in Old Muscat, primarily composed of minority ethnic groups such as the Baloch and Zanzibaris. Subsequently, the definition expanded to include individuals characterized by a monthly income of less than 400 OMR.

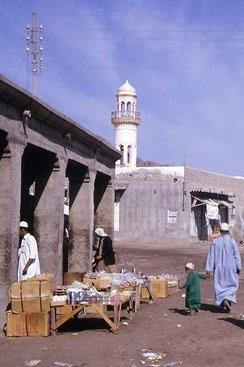

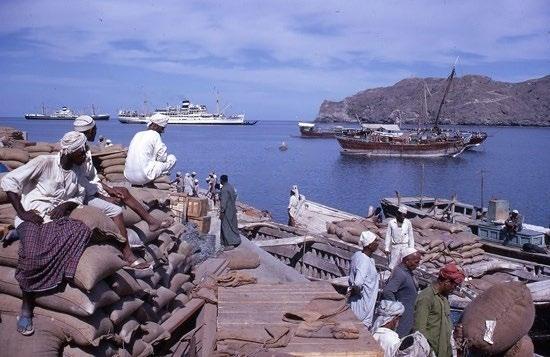

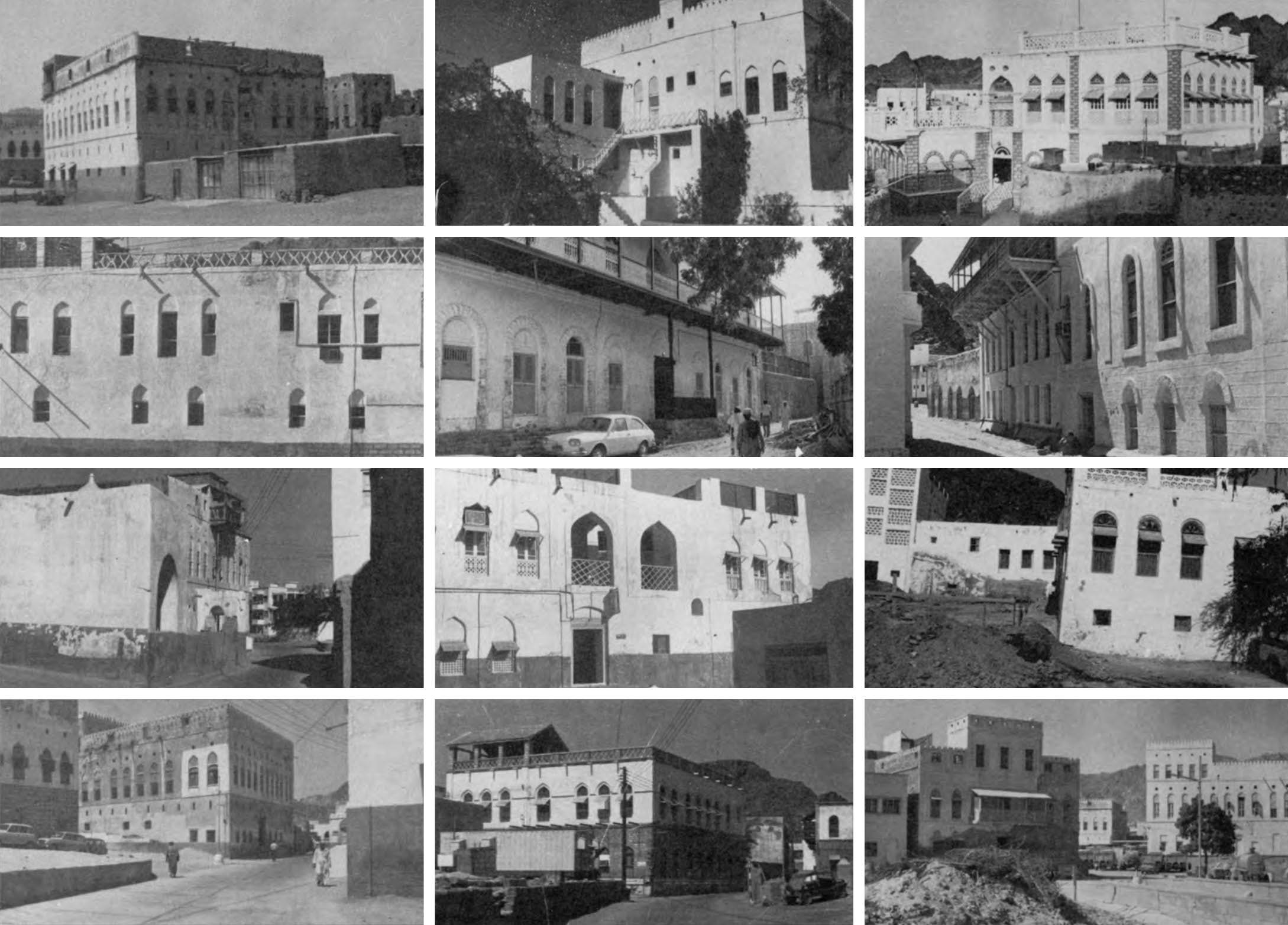

Figure 1: Fort Architecture in Muscat: Fort Mirani and Fort Jalali, 1977

Middle East Centre Archive, University of Oxford. Oxford, United Kingdom.

0

National Spatial Data Infrastructure. https://nsdig2gapps.ncsi.gov.om/nsdiportal

Introduction

The Sultanate of Oman, with its capital Muscat at the helm, presents an intriguing canvas for urban and architectural scholars. The city’s transformation, particularly over the last half-century, embodies a narrative of rapid modernization, cultural interplay, and socio-economic shifts, all of which have left indelible marks on its urban fabric and societal structures. This dissertation delves into the heart of Muscat’s urban metamorphosis, with a specific focus on its low-income communities, unravelling the threads of architectural and urban planning strategies that have shaped their living environments and, by extension, their societal interactions and well-being.

Muscat’s unique geographical setting, nestled between the Gulf of Oman and a harsh mountainous backdrop, has historically influenced its urban development. The strategic location fostered a rich trading history, which, coupled with the influences of various rulers and external powers over the centuries, has woven a complex socio-cultural and architectural tapestry. However, it is the post-1970 era, under Sultan Qaboos bin Said’s visionary leadership, that Muscat’s urban landscape witnessed transformation changes, catapulting the city into modernity while striving to retain its cultural ethos.2

The urban planning strategies adopted during this transformation period were aimed at modernizing Muscat, enhancing its infrastructure, and improving the quality of life for its residents. However, these strategies, while beneficial for the city’s overall development, engendered spatial and social segregation, particularly impacting its low-income populations. Neighbourhoods such as Wadi Adai and Al Khoud emerged as quintessential examples of this consequence, where the low-income residents found themselves on the peripheries of the urban and social fabric of Muscat.

This dissertation, through its granular examination of Wadi Adai and Al Khoud, seeks to uncover the nuanced interplays between urban planning policies and the lived experiences of low-income communities in Muscat. It posits that the spatial segregation and social exclusion observed in these neighbourhoods are not merely by-products of urbanization but are deeply intertwined with the planning strategies and socio-political undercurrents that have shaped Muscat’s urban trajectory.

The research methodology underpinning this study is meticulously crafted to capture the multi-dimensional aspects of urban planning and its socio-spatial implications. The literature review serves as the foundational pillar, providing a theoretical and contextual grounding for the study. It synthesizes insights from a wide array of sources, including scholarly articles, historical documents, and contemporary analyses, constructing a coherent narrative on urban planning evolution in Muscat and its impact on various demographics.

Complementing the literature review is an in-depth typological and policy analysis, which scrutinizes the architectural and planning paradigms adopted in Muscat. This analysis, informed by a rich tapestry of case studies and policy documents, offers a critical examination of the design patterns, regulatory frameworks, and urban planning ideologies that have influenced Muscat’s built environment and its socio-economic landscape.

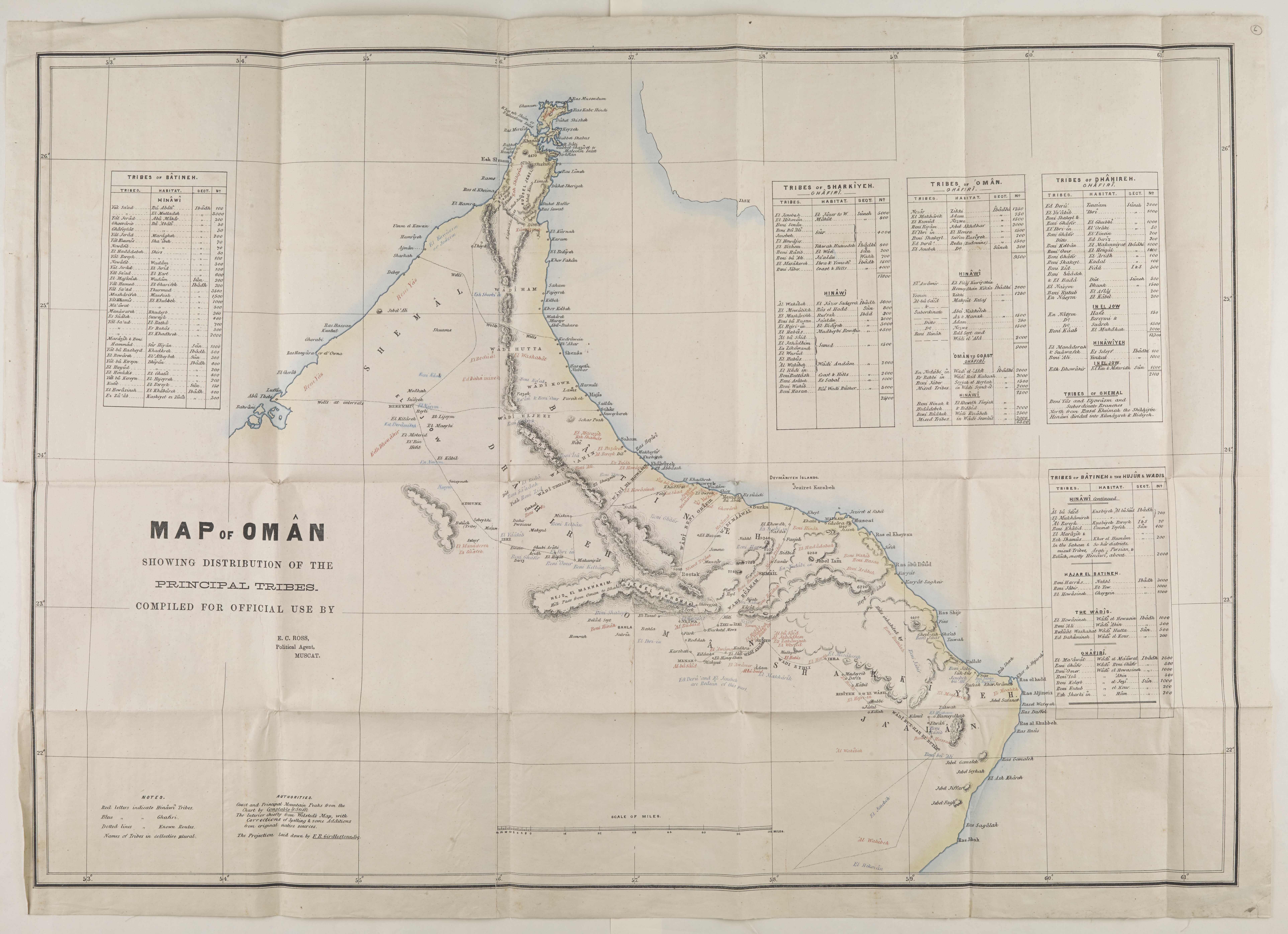

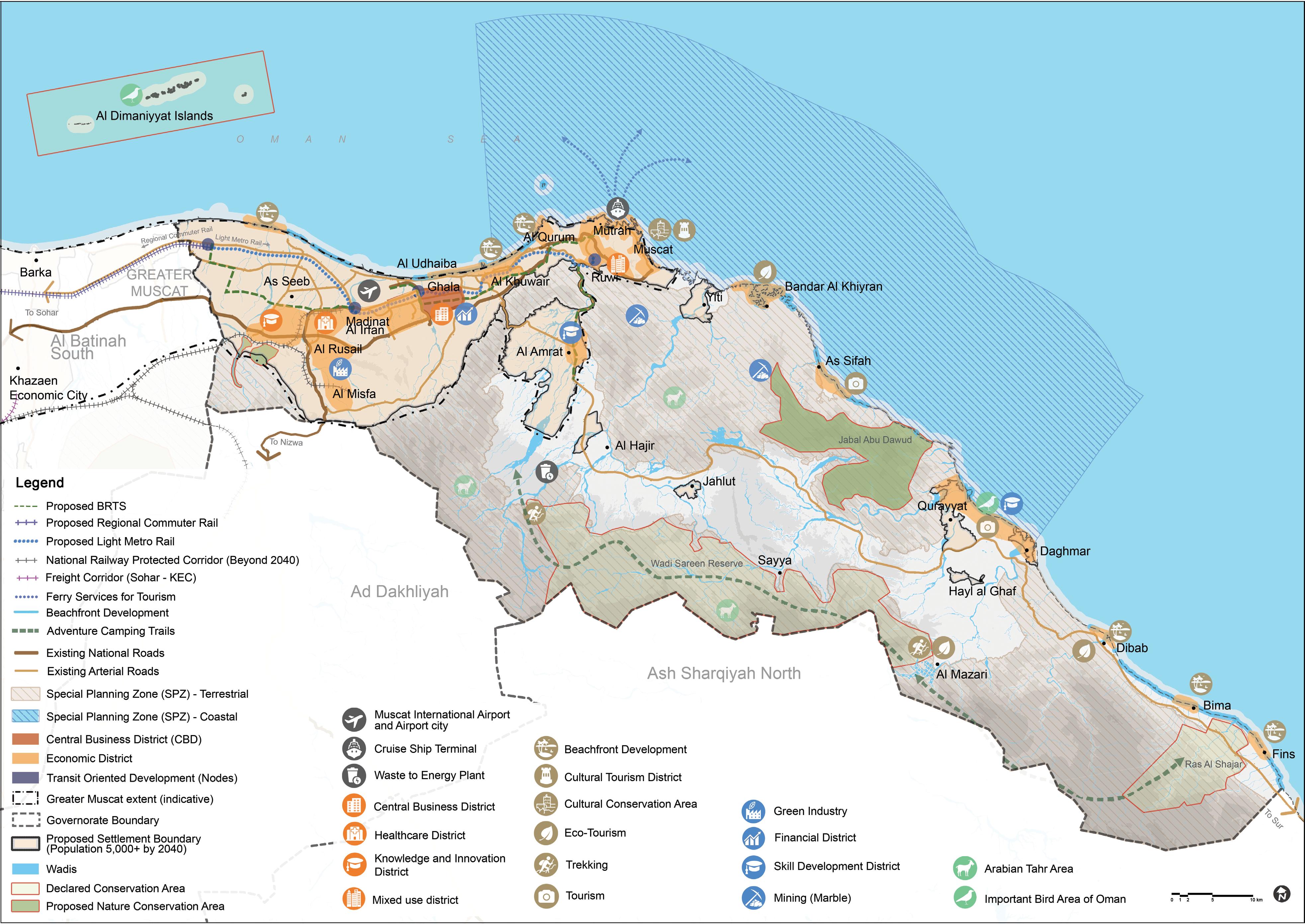

2: Geographic Mapping of Oman: Arabian Peninsula Location and Governorate Divisions

2. Jeremy Jones and Nicholas Ridout, A History of Modern Oman (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

The empirical fieldwork, constituting the third pillar of the methodology, introduces a vital human element to the study. Through site observations, interviews, and participatory workshops, the research captures the voices and narratives of the residents of Wadi Adai and Al Khoud, offering a ground-level perspective on the impacts of urban planning. This hands-on approach not only enriches the study with authentic insights but also fosters a deeper connection between the researcher and the community, ensuring that the findings are reflective of the lived realities.

Central to the dissertation is the critical analysis of the findings, where the theoretical, historical, and empirical strands converge to paint a comprehensive picture of the urban planning landscape in Muscat and its ramifications for low-income communities. This analysis not only highlights the gaps and challenges inherent in the existing urban planning paradigms but also propels the discourse forward, suggesting pathways toward more inclusive and empathetic urban development practices.

In synthesizing these diverse strands of research, the dissertation aims to contribute a nuanced perspective to the field of urban studies, offering a detailed exploration of the interconnections between urban planning, architectural design, and social equity. The case of Muscat, with its unique confluence of historical legacy and modern aspirations, provides a rich context for this exploration, offering lessons and insights that transcend its geographical boundaries.

The implications of this study are manifold, extending beyond academia to inform policy, practice, and community engagement. By elucidating the intricate dynamics between urban planning and social inclusivity, the dissertation advocates for a paradigm shift toward more equitable urban development strategies that foreground the needs and aspirations of all community members. Through a narrative that is both critical and constructive, the research underscores the potential for urban planning to be a catalyst for social change, fostering environments that are not only physically but also socially and culturally inclusive.

In conclusion, this dissertation, with its in-depth exploration of Muscat’s urban landscape, aims to spark a dialogue among urban planners, policymakers, architects, and community advocates, urging them to reconsider the socio-spatial dimensions of urban development. By interweaving the strands of history, theory, and empirical research, the study aspires to illuminate the path toward more sustainable, inclusive, and humane urban futures, where the architecture of the city resonates with the voices and dreams of all its inhabitants.

The escalating demand for social housing in Muscat underscores a critical need to examine the multifaceted architectural and urban planning challenges and opportunities, especially concerning the living experiences of low-income residents. Central to this exploration is understanding how the architectural and spatial designs within these environments impact social interactions, individual and collective movement, and the broader sense of community belonging. Moreover, the interplay between these spatial configurations and the wider urban context of Muscat raises significant questions about inclusivity, social integration, and community empowerment within the realm of social housing.

Architectural Influence on Social Dynamics:

Investigating the role that architectural layouts and urban design within social housing play in shaping the daily social interactions and communal life of residents. How do these physical environments either support or inhibit community engagement and social interaction among low-income groups?

Inclusivity and Community Integration:

Delving into how planning strategies can foster inclusive and cohesive communities. What role do spatial designs play in bridging or reinforcing social divides within the fabric of Muscat’s social housing neighbourhoods?

Adaptive and Future-Ready Housing Solutions:

Considering Muscat’s evolving socio-economic landscape, what adaptive strategies in social housing design can accommodate future needs? How can such strategies encapsulate cultural sensitivity, regulatory adaptability, and the desire for enhanced communal spaces and facilities?

Engagement and Empowerment through Design:

Exploring methodologies to re-envision the design process as a participatory and inclusive practice. How can architects and urban planners empower residents, fostering a deeper connection and sense of belonging towards their living environments through collaborative design processes?

Addressing these issues demands a comprehensive analysis of how architectural and urban design influences the quality of life, social cohesion, and sense of identity within low-income communities in Muscat. The implications of this research extend beyond theoretical insights, offering practical guidance for architects, urban planners, and policymakers committed to fostering more humane, inclusive, and dynamic urban habitats.

Research Questions

1. Impact of Architectural Design on Community Life:

How do the architectural design and spatial configurations within Muscat’s social housing impact the daily social practices and interactions of low-income residents?

In what ways do Muscat’s cultural nuances and traditional living patterns influence the spatial design of social housing, and how do these designs promote or inhibit communal life and a sense of belonging?

2. Spatial Design as a Catalyst for Social Integration:

How can spatial design within Muscat’s urban landscape act as a catalyst for enhancing social interactions and forging inclusive community networks within social housing areas?

What design strategies and spatial interventions can counteract historical segregation patterns and cultivate more integrated and socially vibrant neighbourhoods in Muscat’s social housing context?

3. Evolution and Innovation in Social Housing Design:

Given the dynamic socio-economic trajectory of Muscat, what innovative design approaches can future-proof social housing, ensuring adaptability and responsiveness to evolving resident needs.

How can architectural creativity within the constraints of social housing foster communal spaces and amenities that resonate with cultural traditions and contemporary communal living expectations?

4. Promoting Resident Engagement in Design:

What methodologies and frameworks can ensure that social housing design in Muscat is deeply inclusive, actively involving residents in shaping their living environments?

How can the design process be transformed to enhance resident participation, ensuring their narratives and experiences are integral to the creation of empowering and identity-affirming spaces?

Chapter I Paradigm

Welfare and Housing Reforms

Socialscape: Tracing Welfare Evolution

Habitat: Social Housing Policies

Outlook: Socio-Economic Horizons

The analysis of Oman’s social welfare reveals a nuanced understanding of the country’s socio-economic transformations and urbanization challenges. It delves into the evolution of the social welfare system in Oman, illustrating the transition from conventional support to structured, inclusive programs designed to enhance citizens’ quality of life. The evaluation underscores the necessity for policy shifts towards empowerment and highlights the multifaceted challenges hindering the effectiveness of social welfare programs.

Concurrently, the exploration of Oman’s social housing strategy uncovers the government’s role change from a direct provider to a facilitator, addressing the housing demands of an increasingly urban population. It critically examines the sustainability, effectiveness, and equity of social housing policies, advocating for innovative practices to bolster financial sustainability and housing accessibility.

Particular attention is given to the Bank of Maps initiative as a progressive model for communityinvolved housing design, emphasizing sustainability and adaptability. The interconnectedness of social welfare and housing is framed within Oman’s broader socio-economic landscape, proposing integrated policy approaches for comprehensive social protection and improved living conditions.

The social welfare landscape in Oman is intricately linked to its socioeconomic progression, embodying a framework designed to offer a safety net and support mechanisms to its populace.3 This framework is embedded within Oman’s national legislation and policy directives, underlining a steadfast commitment to upholding human dignity and advancing social justice.

Oman’s approach to social welfare is bifurcated into two main avenues: primary social welfare and comprehensive services.4 The former strives to guarantee a baseline quality of life, nurturing social solidarity and care through services, employment, and professional training organized by the Ministry of Social Development. Conversely, the comprehensive services track endeavours to provide a quality of life for diverse citizen segments, fostering national solidarity. This track is particularly attentive to the needs of the elderly, disabled, widows, and other vulnerable cohorts, aiming to secure their societal integration and promote inclusivity.

3 T. Al-Mamary, The Experience of Social Security in Oman (Oman: Ministry of Social Development, Sultanate of Oman, 2015).

4 Emad F. Saleh and Hammoud bin Khamis Al-Nawfali, “Social Welfare Policy Programs in Oman Sultanate: Reality and Challenges,” Asian Journal of Research in Education and Social Sciences (2022). https://doi.org/10.55057/ajress.2022.4.1.21.

5. Omer Ali Ibrahim and Sonal Devesh, “Socio-economic Dynamics of Social Insurance in Oman: A Model Approach,” International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 10, no. 2 (2020): 37-47. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijefi.9058.

The objectives underpinning Oman’s social welfare initiatives are multifaceted, targeting poverty alleviation, the promotion of social equity, and the uplifting of living standards. These initiatives are meticulously designed to cater to basic necessities, fortify social cohesion, and bolster national unity. They extend critical support to individuals and families grappling with emergencies, disabilities, or the challenges of advanced age, accentuating the prevention of social fragmentation and the reinforcement of familial and communal ties.

However, the implementation of Oman’s social welfare programs encounters numerous challenges across administrative, economic, legislative, and cultural spheres. Administrative hurdles often manifest as bureaucratic impediments, stalling effective policy execution. Economically, the heavy reliance on oil revenues introduces vulnerabilities, with market fluctuations potentially destabilizing welfare program funding. Legislative challenges call for an evolution of laws to resonate with contemporary needs, whereas cultural obstacles pertain to societal perceptions and norms that could detract from program efficacy, including entrenched gender roles and stigmatization associated with receiving aid.5

1.1.1 Introduction to Social Welfare in Oman

Figure 3: Socio-economic Insights: Fishermen at Seeb Beach, Muscat

A critical evaluation of Oman’s social welfare outcomes reveals a dichotomy: while the programs furnish vital support, they frequently stop short of empowering beneficiaries to achieve substantial life improvements and autonomy. The prevailing focus on immediate alleviation overshadows the imperative of long-term empowerment.6 Consequently, there is a compelling need for a paradigm shift towards programs that transcend basic assistance, equipping beneficiaries with the skills and opportunities necessary for self-sufficiency and active societal engagement.

To enhance Oman’s social welfare framework, several strategic recommendations are posited. Policy reformation should pivot towards capacity building and empowerment, ensuring a transition from ephemeral relief to enduring development. Economic diversification is critical to mitigating the dependency on oil revenues, thereby securing a more stable financial base for welfare initiatives. Additionally, engaging cultural and societal dynamics is vital to dismantle barriers to program effectiveness, advocating for gender equality, and dispelling stigmas associated with receiving aid, all of which are pivotal steps toward a more inclusive and effective social welfare system in Oman.

The “Family Income Support Benefit” program provides monthly financial assistance to families characterized by low income and limited earning potential. Eligibility for this benefit is determined by the family’s income level and the earning capabilities of its members. The benefit amount is calculated based on the number of family members and the family’s total income, with the goal of enhancing their living conditions.

Monthly payments are issued by computing the difference between the family’s actual income and a target level, which is determined by taking the square root of the number of family members. This calculation includes biological children and foster children as family members. Additionally, certain groups identified in the executive regulations of the Social Protection Law are also recognized as part of the family structure.

The following table illustrates the target level for the benefit, based on the number of family members in the household.

6 Noura Khalifa Alnasiri, “Evaluating Social Housing Adequacy in Oman” (Sultan Qaboos University, Sultanate of Oman, January 2016) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311649834

7. Haitham bin Tarik, Royal Decree 33/2021 Regarding the Systems for Pension and Social Protection, issued 24 Sha’ban 1442, corresponding to 7 April 2021, Official Gazette no. 1387 (11 April 2021). https://qanoon.om/p/2021/og1387/

Within the broader context of Oman’s social welfare system, the Social Protection Fund stands as a pivotal institution, tasked with overseeing and implementing the nation’s social protection initiatives. Established under Royal Decree No. (33/2021), this Fund operates as an autonomous entity endowed with administrative and financial independence.7 Its core mission revolves around the execution of the Social Protection Law and corresponding statutes, collaborating closely with relevant authorities to administer various programs focused on protection, empowerment, integration, care, and support for eligible groups.

8. Social Protection Fund, “Profile of the Social Protection System,” last modified 2022. https://www.spf.gov.om/.

The Fund’s objectives are designed to enhance the overall quality of life in Oman, ensuring social protection and care while fostering societal investment through the development and execution of targeted policies and programs across social and economic domains. It monitors the performance and impact of these initiatives, ensuring they align with Oman’s national objectives and contribute to the sustainability, integration, and equity of the social protection framework. 8

1.1.2 The Social Protection Fund

In terms of operational capabilities, the Fund is vested with the authority to propose and contribute to the development of general social protection policies, enhance the system’s reach and benefits, implement, and assess social protection programs, manage and invest funds both within and outside Oman, undertake relevant research, and coordinate improvements across various care, empowerment, and integration initiatives. It also engages in formal agreements and collaborations to fulfil its objectives.

The Fund administers several cash social protection benefits, including old age, childhood, disability, orphans and widows, and family income support benefits. Additionally, it oversees various social insurance branches, such as those covering occupational hazards, job security, maternity leave, and other non-routine leaves. Beyond these, the Fund manages a savings program, monitors the financial health of supplementary programs conducted by other entities, and coordinates with relevant authorities to enhance support, rehabilitation, empowerment, and integration programs, ensuring the protection and inclusion of the most vulnerable community members against exclusion, discrimination, or violence.

Integrating the functions and objectives of the Social Protection Fund into Oman’s social welfare narrative highlights a nuanced and structured approach towards cultivating a resilient and inclusive social safety net. This integration not only reinforces the nation’s commitment to social welfare but also underscores the strategic planning and coordination necessary to navigate the complexities of social protection, ensuring a coherent and effective system that aligns with Oman’s socio-economic ambitions and welfare ideals.

Figure 4: Institutional Document: Social Protection Fund Profile

Social Protection Fund, “Profile of the Social Protection System,” last modified 2022. https://www.spf.gov.om/.

1.2 Habitat: Social Housing Policies

Since its inception in 1973, Oman’s social housing policy has significantly evolved, transitioning from reliance on informal tribal support mechanisms to a structured policy framework, initially established under the Al Shabia Housing Law.9 This transition underscores the Omani government’s commitment to improving the living standards of its lowincome population by transforming from a mere provider of housing to an enabler that facilitates access to adequate housing through comprehensive policies and financial support.

The cornerstone of Oman’s social housing strategy is its three primary programs: the Residential Units Program, the Housing Assistance Program, and the Housing Loans Program. Each program is tailored to address the unique housing needs of different segments of the low-income population, fostering home-ownership and enhancing living conditions.

1. The Residential Units Program: Launched in the early 1970s, this program directly provides free housing units to Omani families with a monthly income threshold of 400 OMR or less.10 The government, under the directives of His Majesty the Sultan, constructs and distributes these units, particularly focusing on ensuring that they

are allocated to deserving families during the Sultan’s annual tours across various governorates. The Ministry of Housing is responsible for the selection of locations, design specifications, construction partners, and the determination of the size and layout of each unit based on family size and needs. This program primarily offers one-story houses in designated housing projects, each equipped with essential amenities to ensure a decent living standard for beneficiaries.

2. The Housing Assistance Program: Initiated in 1981, this program targets even lower-income brackets, providing financial grants to households earning 300 OMR or less per month. The grants are designed to aid in constructing new homes or renovating and expanding existing structures, with the amount capped at 25,000 OMR for three-bedroom units and 20,000 OMR for two-bedroom units. The assistance is non-repayable, emphasizing the government’s role in supporting its citizens’ housing needs without imposing future financial burdens on them.

3. The Housing Loans Program: Established in 1991, this program offers interest-free loans to individuals whose monthly income ranges between 301 OMR and 400 OMR, with the condition that

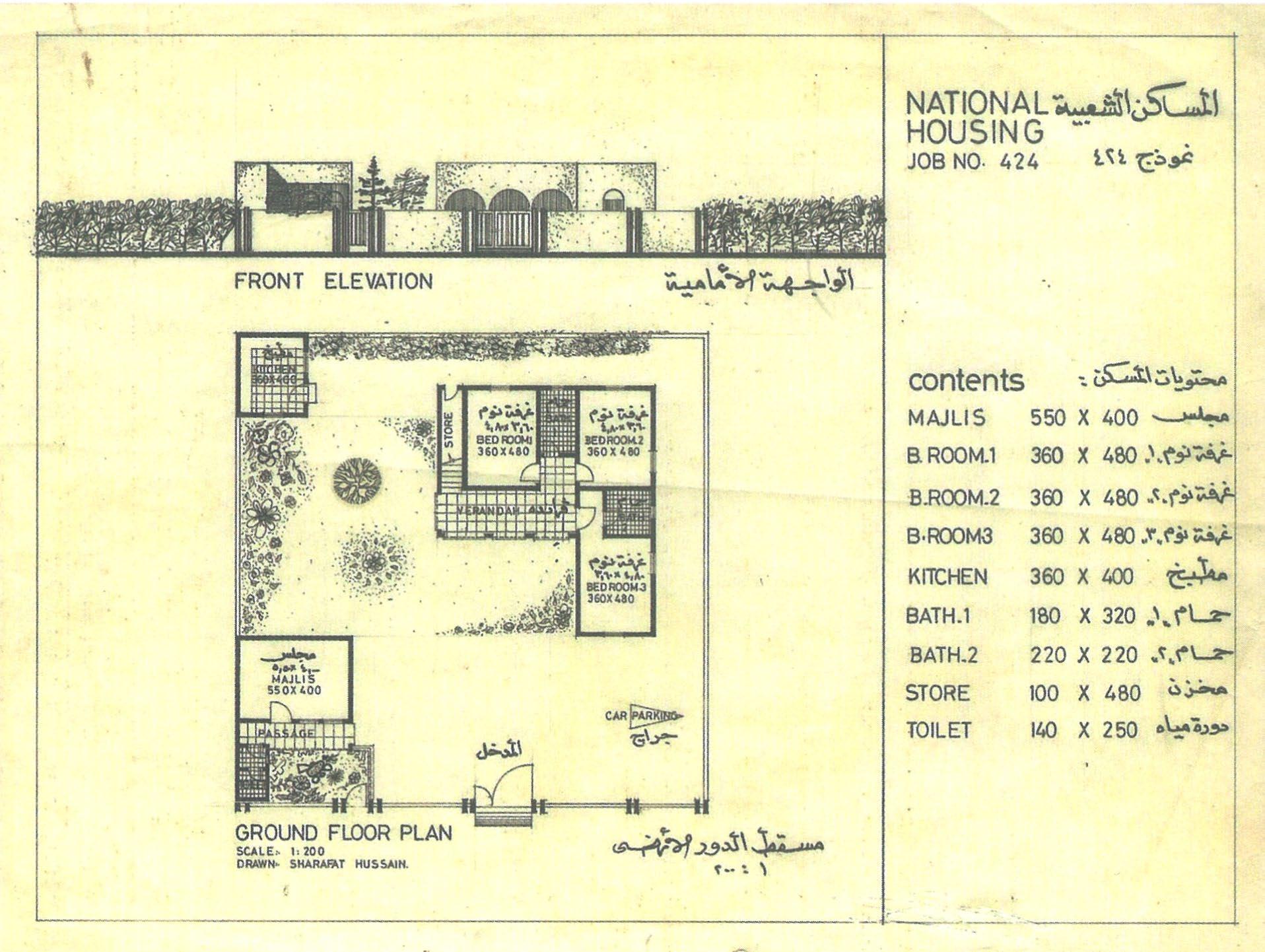

Figure 5: Architectural Dissemination: Social Housing Layouts by 2005

Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, Muscat, Oman.

the total household income does not exceed 600 OMR when the application is processed. The loans aim to support the construction or acquisition of new homes, offering up to 30,000 OMR repayable in manageable monthly instalments without exceeding 20% of the borrower’s income. This program reflects a strategic approach to empower citizens financially while ensuring they do not endure excessive debt.

Despite these structured efforts, Oman’s social housing sector faces challenges exacerbated by rapid urbanization since the 1970s. The escalating urban population, escalating from 3% in 1950 to 80% in the early 2000s, has intensified the demand-supply gap in housing. Projects like Wadi Adai have encountered delays in essential services such as water and road infrastructure, while the remote locations of some housing initiatives have led to community segregation and impeded socio-economic integration.11

The financial sustainability of social housing projects also poses a significant challenge, with the costs often surpassing the government’s ability to recuperate investments through subsidies and payments. This

11

financial strain hinders the capacity for new developments and calls for a diversification of housing solutions to include low-cost plots, core housing, and enhancements in rural settlements, catering more effectively to the diverse needs of low-income populations.

Furthermore, while Oman’s social housing policy has succeeded in providing shelter, there is a recognized need for improvements in design, features, services, infrastructure, accessibility, and cultural relevance to elevate the overall adequacy and effectiveness of housing solutions.

The narrative of social housing in Oman is deeply intertwined with the country’s broader socio-economic changes and challenges in urbanization and modernization. The government must address the escalating housing demand, ensure equitable distribution, and enhance the quality and variety of housing solutions. Future policy directions should incorporate comprehensive planning, sustainable practices, and community engagement to adapt to the evolving needs and expectations, ensuring the social housing sector’s resilience and responsiveness in Oman’s dynamic socio-economic landscape.

Figure 6: Architectural Documentation: Floor Plans and Sections of Early Social Houses in Muscat Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, Muscat, Oman.

Noura Khalifa Marzouq Al Nasiri, “Planning, Policy and Performance: An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Social Housing Policy of Oman” (PhD diss., The University of Queensland, 2015), School of Geography, Planning, and Environmental Management.

Figure 7: Three-Dimensional Analysis: Axonometric View of a Social Housing Unit Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, Muscat, Oman.

1.3 Outlook: Socio-Economic Horizons

The socio-economic landscape and urbanization dynamics in Oman reveal an intricate interplay of various factors influencing social insurance and housing sectors. From 2002 to 2016, the country witnessed relatively low social insurance coverage, with only 12.1% for actively insured individuals and 6.6% for the elderly. Economic indicators like per capita GDP, fixed capital formation, and inflation have been identified as significant influencers of social insurance coverage. Concurrently, Oman’s urban population surged from 3% in 1950 to 80% in the early 2000s, fuelled by economic development, high fertility rates, in-migration, and an increasing expatriate population.12

The rapid urbanization has posed challenges for social housing in Oman, struggling to meet the escalating urban housing demands. The government’s limited financial capacity has constrained its ability to support the housing needs of a broader population segment. The inefficiency in recovering the costs of social housing projects and the lack of cost-reduction initiatives through innovative construction approaches have further strained the resources.

Moreover, the placement and infrastructure development of social housing projects have been critical issues. Delays in providing essential

A. S. Al-Harthy, “Housing in Oman: An Investigation into Social Housing,” paper presented at the World Congress on Housing, Coimbra, Portugal, September 2002.

13. Omer Ali Ibrahim and Sonal Devesh, “Socio-economic Dynamics of Social Insurance in Oman: A Model Approach,” International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 10, no. 2 (2020): 37-47. https://doi.org/10.32479/ijefi.9058.

services like water supply and road infrastructure, as seen in the Jibrin housing project, have exacerbated the challenges for residents, affecting their living conditions and integration into urban life.13

The interconnection between social insurance and housing sectors becomes evident when considering the broader socio-economic factors impacting Oman’s urbanization and social welfare. While economic growth and demographic shifts influence social insurance coverage, they also drive urbanization and shape the housing sector’s demands and challenges.

Recognizing these interconnected challenges, the Omani government is transitioning towards a more enabling role in housing, promoting policies and initiatives that facilitate affordable housing solutions and support the low-income population. This holistic approach aims to address not only the coverage issues in social insurance but also the adequacy and accessibility of housing, thereby enhancing the overall socio-economic well-being in Oman. Through integrated strategies that consider both social insurance and housing needs, Oman is working towards sustainable development and improved social welfare for its populace.

Figure 9: Urban Development: Recent Social Housing Neighbourhood Projects

1.3.1

Figure 10: Standardized Housing Design: Pre-Approved Layout in the “Bank of Maps” Initiative

“Maps Bank,” Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, accessed December 24, 2023, https://webapps.housing.gov.om/mapsbank/.

Future of Social Housing: Bank of Maps Initiative

The Bank of Maps, a project launched by the Ministry in 2023, is at the forefront of this change, embodying a new approach to housing design and community involvement. By inviting architectural and consulting offices to participate in the Bank of Maps competition, the Ministry is fostering a collaborative environment where diverse ideas and creative solutions can emerge. This inclusive approach not only democratizes the design process but also ensures that the resulting housing models are reflective of the needs and aspirations of the community they are intended to serve.

The structure of the competition, divided into two phases, acclaimed to ensures a comprehensive assessment of each design. The initial phase focuses on the conceptual and aesthetic aspects of the housing models, while the second phase delves into the practical and technical details. This evaluation process prospects that the final designs are not only visually appealing but also feasible, sustainable, and cost-effective.

A key aspect of this initiative is its emphasis on sustainability and adaptability. The requirement for designs to be sustainable is a response to

14. “Maps Bank,” Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, accessed December 24, 2023, https://webapps.housing.gov.om/mapsbank/.

global environmental concerns, ensuring that the social housing sector in Oman contributes positively to the ecological balance. Moreover, the focus on flexibility and expandability addresses the dynamic nature of family life, allowing homes to evolve in tandem with the changing needs of their inhabitants.14

The competition is set to enrich the social housing landscape in Oman by introducing a range of high-quality, modern designs. These designs, tailored to the unique size and dynamics of the Omani family, will elevate the living standards of beneficiaries. Furthermore, the option for beneficiaries to choose from a variety of designs or even propose their own ensures that individual preferences and needs are respected and catered to.

The Bank of Maps initiative simplifies the process of obtaining and implementing housing designs. By providing a repository of pre-approved designs, the Ministry significantly reduces the time and effort involved in designing and constructing a home. This efficiency not only benefits the beneficiaries but also streamlines the administrative processes of the Ministry.

*Oxford English Dictionary https://www.oed.com

16

17.

Interlude I Did You Make It Out of That Town Where Nothing Ever Happened?

Absence noun /’æbsəns/

Absence

The fact of somebody being away from a place where they are usually expected to be; the occasion or period of time when somebody is away.*

Considering that absence is an active form of action, what effect do we exert on the city once we leave? How does the city respond to the small empty void we leave behind? Reflecting on Muscat now, I wonder whether my absence has made an impact on the city’s landscape. In his experimental piece 4’33” (pronounced “four thirty-three”), American musician John Cage radically explores the elements of duration in media, introducing silence as an entity parallel to sound. The presentation of silence as an entity, rather than a subsidiary, prompts us to reconsider the actions associated with neglect.15 What is the impact of an individual’s absence on a city as vibrant as Muscat?

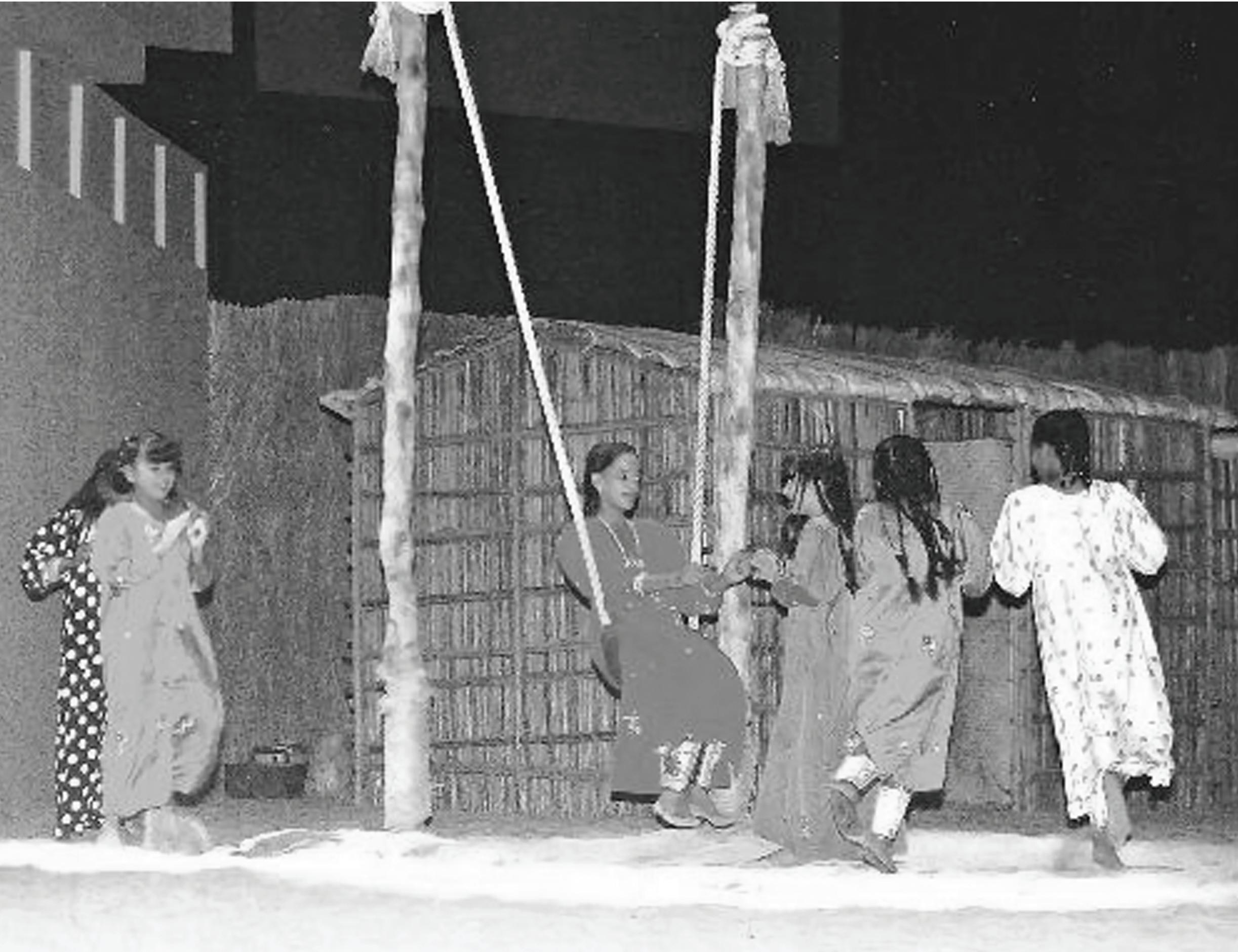

In his book “Poetics of Space,” French philosopher Gaston Bachelard writes, “I should say: the house shelters day-dreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.”16 I believe cities retain their dreams, or their “soul,” as metaphysicians might say. In Oman, when someone mentions “balad,”17 it refers to the village. Muscat is seen as a temporary abode, a place for work and leisure, distinct in its offerings. While many millennials leave their villages for Muscat, seeking refuge and alternating between absence and presence, they oscillate between chosen lives and harsh realities, with nostalgia’s guilt lurking beneath continuous estrangement. Does this estrangement stem from a hidden feeling that Muscat isn’t our place, or that it behaves differently from other cities by not imposing itself on our memories, thus not fully representing us? Is Muscat a place of transience, where life, tied to the village, encompasses our work, social life, and solitude?

John Berger, in his book “The Success and Failure of Picasso,” analyses the Spanish society of Picasso’s era, highlighting a regional ignorance fostered by the 16th-century government. This ignorance arose alongside an increase in government positions with high salaries, leading to a middle class disconnected from the understanding of production and capital. This disconnection resulted in a lack of initiative, creativity, and scientific curiosity. Such patronage allowed the state to exert authority, ensuring the

15. John Cage, Silence: Lectures and Writings (London: Boyars, 1987).

. Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space (New York: Penguin Books, 2014), 6.

“Balad” in Arabic translates to “country” and is used in this context to mean “home.”

middle class’s dependence and alignment with state institutions, perpetuating traditional approaches to religion and nationalism.18 This scenario fostered stagnation, evident in the absence of curiosity and initiative, mirroring the control mechanisms in Omani society. Researcher Ali Al-Rawahi notes that societies with greater freedoms and electoral representation are likely to experience historical shifts that can propel societal advancement. He suggests that social movements and political parties act as chronological markers, documenting changes and influencing societal dynamics, thus transforming mere work into purposeful activity and countering values like consumption, surrender, and choicelessness.19

Similarly, the political climate profoundly influences social life, stifling the emergence of political or social movements and fostering an institutionalized silence. This silence, mandated by state institutions, censors any attempts at differentiation, be it through writing, media, or any societal contributions. Saudi writer Ahmed Hakeel, in “Paths and Cities,” reflects on this enforced silence, noting it’s not the tranquillity that’s problematic but the enduring of it without introspection, which might lead to a passive engagement with time or an inward focus devoid of broader narratives. He contrasts this with city life, where the abundance of external stimuli fosters engagement and change. Reflecting on Hakeel’s insights, one might question how much Muscat aligns with this concept of a city.20 Can its tranquillity prompt a reconnection with the past, and is such retrospection beneficial if it doesn’t conflict with modern progress? Yet, there’s a risk that this enforced calm could alienate Muscat’s inhabitants, shaping them in profound ways and potentially hindering adaptability and change.

In an interview with Dr. Yasser Elsheshtawy, Professor of Architecture at Columbia University in New York about his book published by Routledge Publishers entitled “Temporary Cities: Resisting Transience in Arabia”, different communities in Gulf cities are seen as living in these cities temporarily, and that is only the social side of the matter, while the physical side is that Gulf cities were designed to be temporary and not long-lasting. Furthermore, expatriate workers, particularly those with limited incomes, do not have clear legal rights, despite their role in the existence of these cities. However, these workers are forced to feel the immediacy of staying in this place by these practices, not only that, but these temporary structures become in a sense the embodiment of cities that will disappear with any upcoming crisis.21 There are, however, some differences between Muscat and the Gulf cities, both of which should be treated with great caution and sensitivity. In the

18

rest of Gulf cities, modernity is based on rejecting history, and we may appear, at some point, to oppose this notion, until that model becomes accepted. It may be necessary to reconcile the past and present, and to look carefully at the present problems, as well as the importance of confronting them rather than waiting for violent or coercive events to cause change, “Historical obsession shapes the sense of life of the educated bourgeoisie.” In order for us to understand our relationship to this place, we must understand our relationship to its history.

Reiner Stach writes about the history of Prague, where Kafka grew up, and how it was inhabited by two groups of Germans and Czechs, Czechs who thought they were just visitors for a period of time. Thus, they lag behind the Germans in terms of modernity at the time, “what tourists see as a mysterious bouquet of symbols and slogans engraved on buildings and architectural styles, is not considered by the city’s residents as magic, but rather lines of continuous conflicts, even with the conditions of a rapidly evolving capital, it reminds him that he lives in an urban conflict area. What comes to his head from the past of this city are not ghosts or expressions of magic, but rather social struggles.”22 However, it seems that this type of conflict in our city has not been mentioned until now and we have not recognized it. Muscat seems to be an ideal place, with its simple face that has not yet been engulfed by huge buildings, with its vast and empty spaces, like the football fields scattered throughout the country, and with even simple equipment, be it on the beaches, or in the desert. But in Muscat, why do we choose those places and not others? I am reminded of a passage that I read from Marcel Proust’s famous novel “In Search of Lost Time” in which he says in the discussion of the arts of war: “A battlefield that has not been and will not be, over the centuries, a single battlefield. And if it was a battlefield, it was because it combined some conditions in the geographical location, geological nature, and even defects that would impede the opponent (such as a river, for example, cutting it into two parts) that made it a battlefield that suffices the purpose. It was, then, and it will always be. You do not set up a painting workshop by taking refuge in any room, and you do not make a battlefield by taking refuge in any place. There are places already lined up.”23

The intersection of lives in Muscat’s public spaces raises intriguing questions about collective experiences and ownership. The convergence in these areas often stems from tension, particularly noticeable in a society experiencing a period of rigidity, where emotional expression seems curtailed. Institutions, appearing stoic and detached, actually grapple with a pervasive indifference as they attempt to foster environments conducive to expression and interaction. Michel Foucault’s perspective on

John Berger, Success and Failure of Picasso (New York: Random House, 1980).

19 Ali Al Rawahi, Marx in Muscat: Researches on the Physical Structure, Distribution of Wealth, and the Historicity of Laws (Beirut, Lebanon: Jadawel S.A.R.L, 2017).

20 Ahmad Hakeel, Muruq Wa-Mudun (Hawalli, Kuwait: Sufya, 2019).

21 Yasser Elsheshtawy, Temporary Cities: Resisting Transience in Arabia (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2019).

22. Reiner Stach and Shelley Laura Frisch, Kafka: The Early Years (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017), 116.

23. Marcel Proust and Mark Treharne, In Search of Lost Time, vol. 3, 7 vols. (London: Penguin, 2003).

power — not as centralized but as a network of unseen forces — resonates profoundly in this context, suggesting that no public space remains untouched by institutional influence.24 In Muscat, the interplay of forces, shaped by circumstance yet imposingly strict, begs reflection on the shared significance of place, a meaning yet to be fully grasped.

We should heed the echoes of a bygone era where people congregated to witness events, directly engaging with unfolding narratives, a practice increasingly rare in today’s mediated world. This direct engagement, where news and public interest were propelled by word of mouth and direct observation, suggests a vital, communal approach to understanding and participating in the city’s life. By sharing stories, whether in barbershops, beauty salons, or common gathering places, we may inch closer to the essence of Muscat, continually rediscovering the city we inhabit.

24 Michel Foucault and Alan Sheridan, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin Books, 2020).

Chapter II Transitions

Urban & Community Morphogenesis

Muscat: Continuity and Change

Neighbourhood: From Wadi Adai to Al Khoud

Urban Program: Harvest Commons

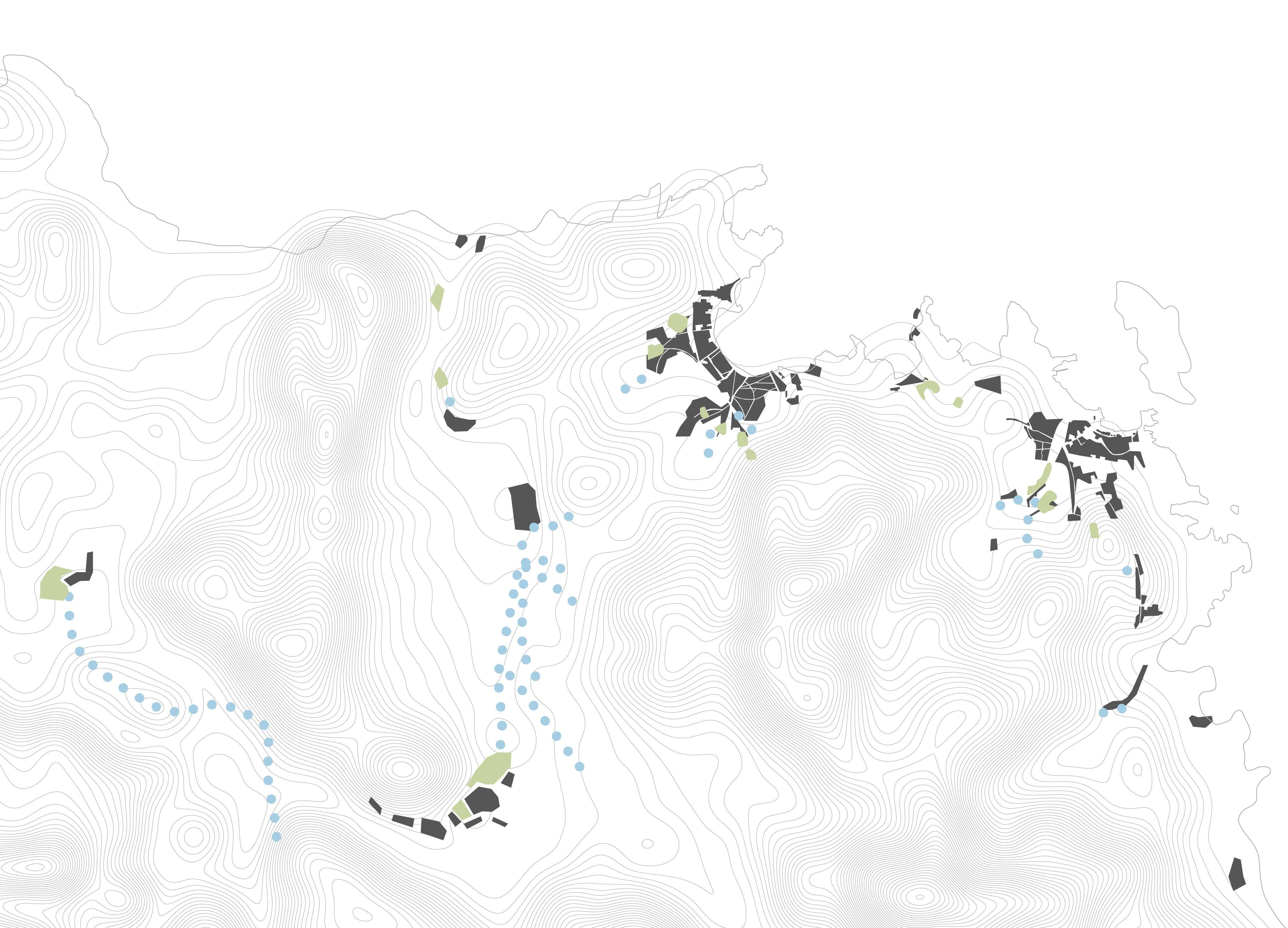

Muscat’s architecture and urban planning is deeply rooted in local traditions, reflecting the socioeconomic activities and environmental conditions of the region. Before the oil’s discovery, the compact urban structure promoted community interaction and utilized indigenous materials and methods, signifying a sustainable approach to the harsh desert environment.

Post-oil, Muscat experienced rapid urbanization and modernization, necessitating a shift in urban planning policies that focused on infrastructure development, zoning regulations, and comprehensive master planning to support the growing urban population and economic diversification.

The regulations impact was multi-scalar, the case studies of Wadi Adai and Al Khoud neighbourhoods illustrate the challenges of rapid and unplanned urban development. This analysis reveals how such growth has impacted social, political, and cultural dimensions, leading to systemic negligence and deteriorating living conditions.

The design delves into posing critical questions on how architecture can foster community interaction and integrate traditional elements into modern designs. The design outlines objectives and constraints in designing community-focused and culturally resonant spaces, emphasizing the importance of using local materials, incorporating green spaces, and enhancing community engagement through design.

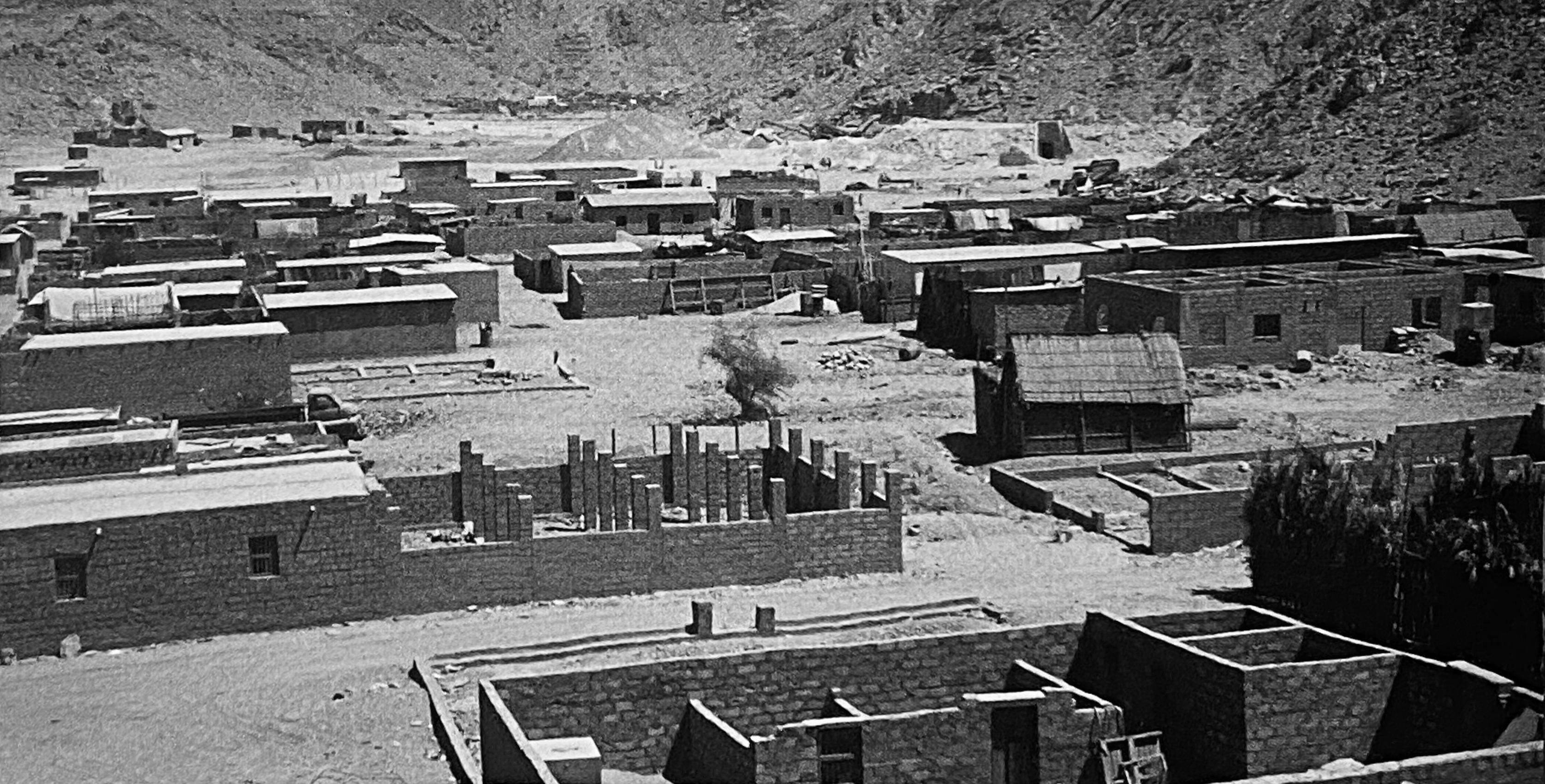

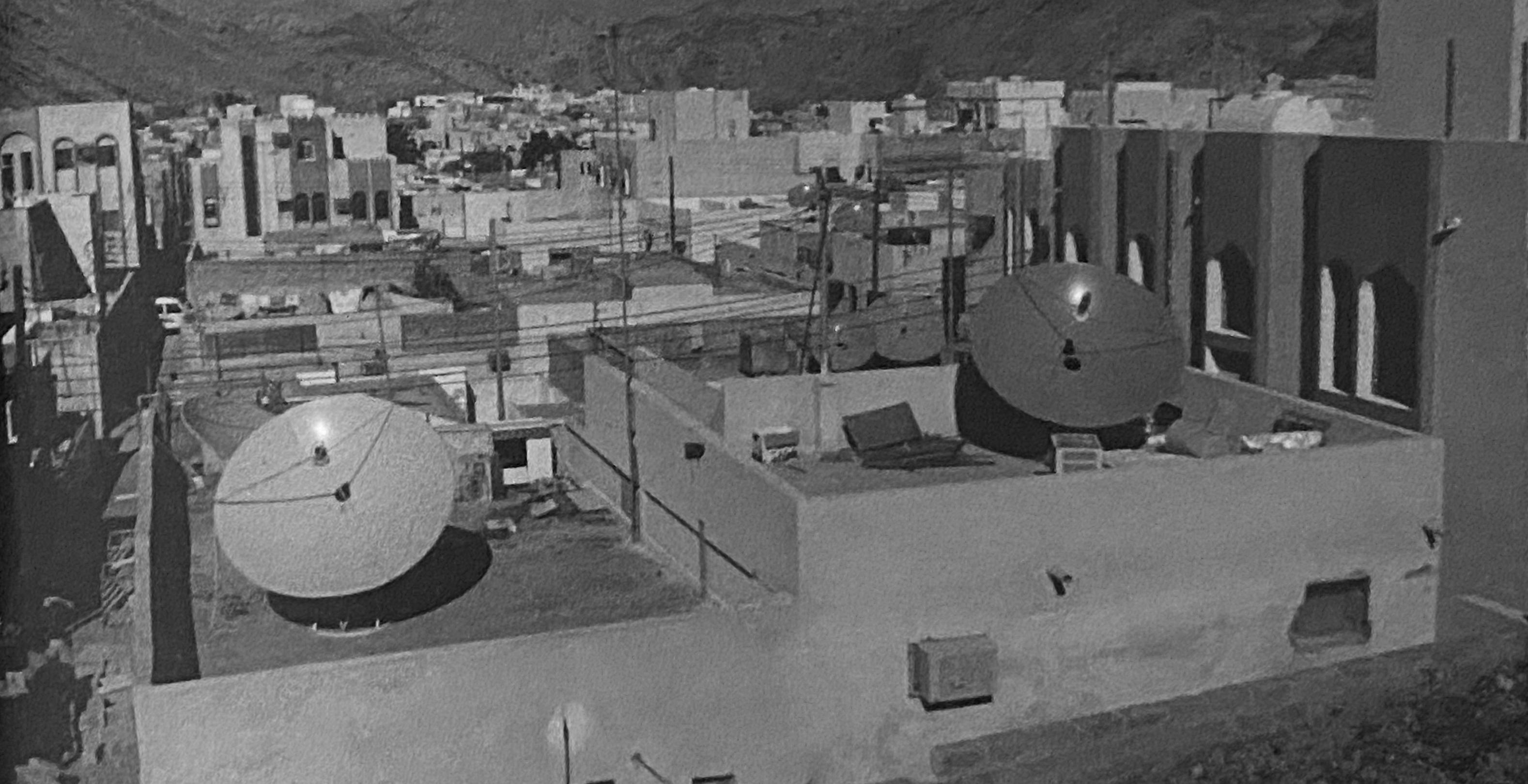

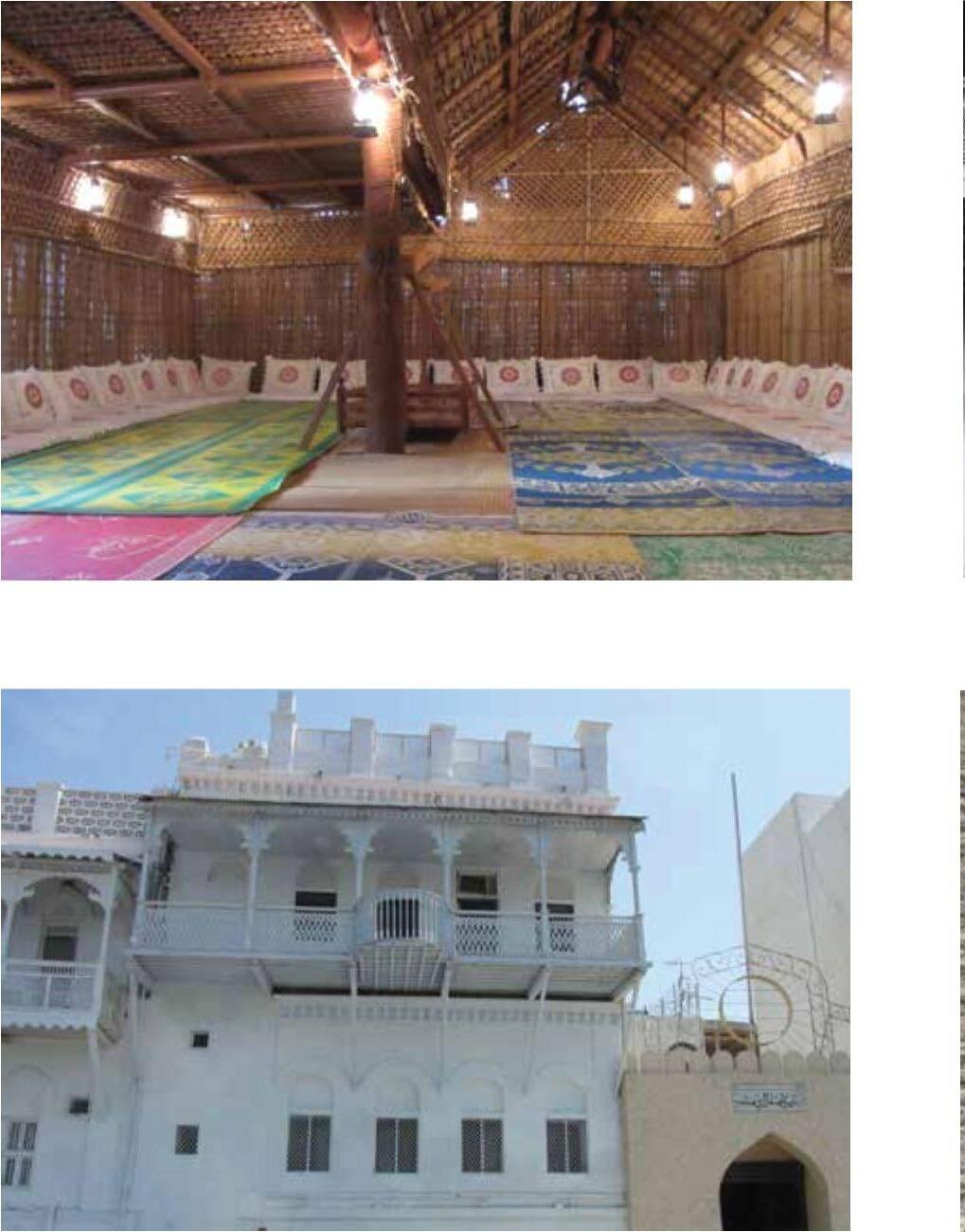

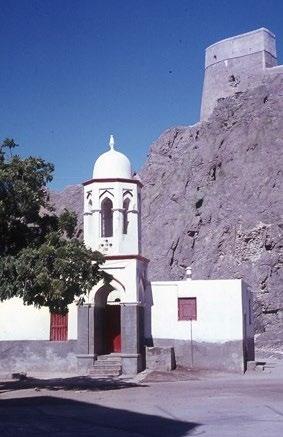

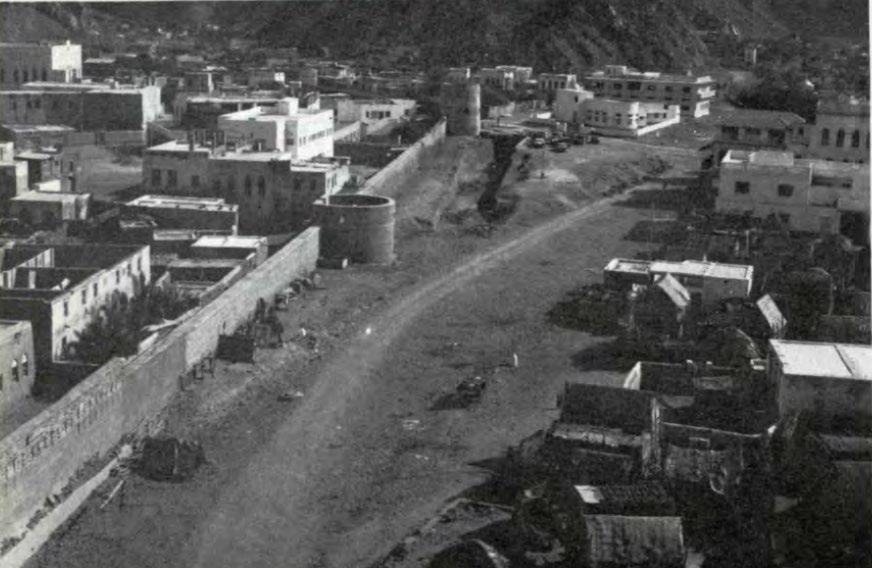

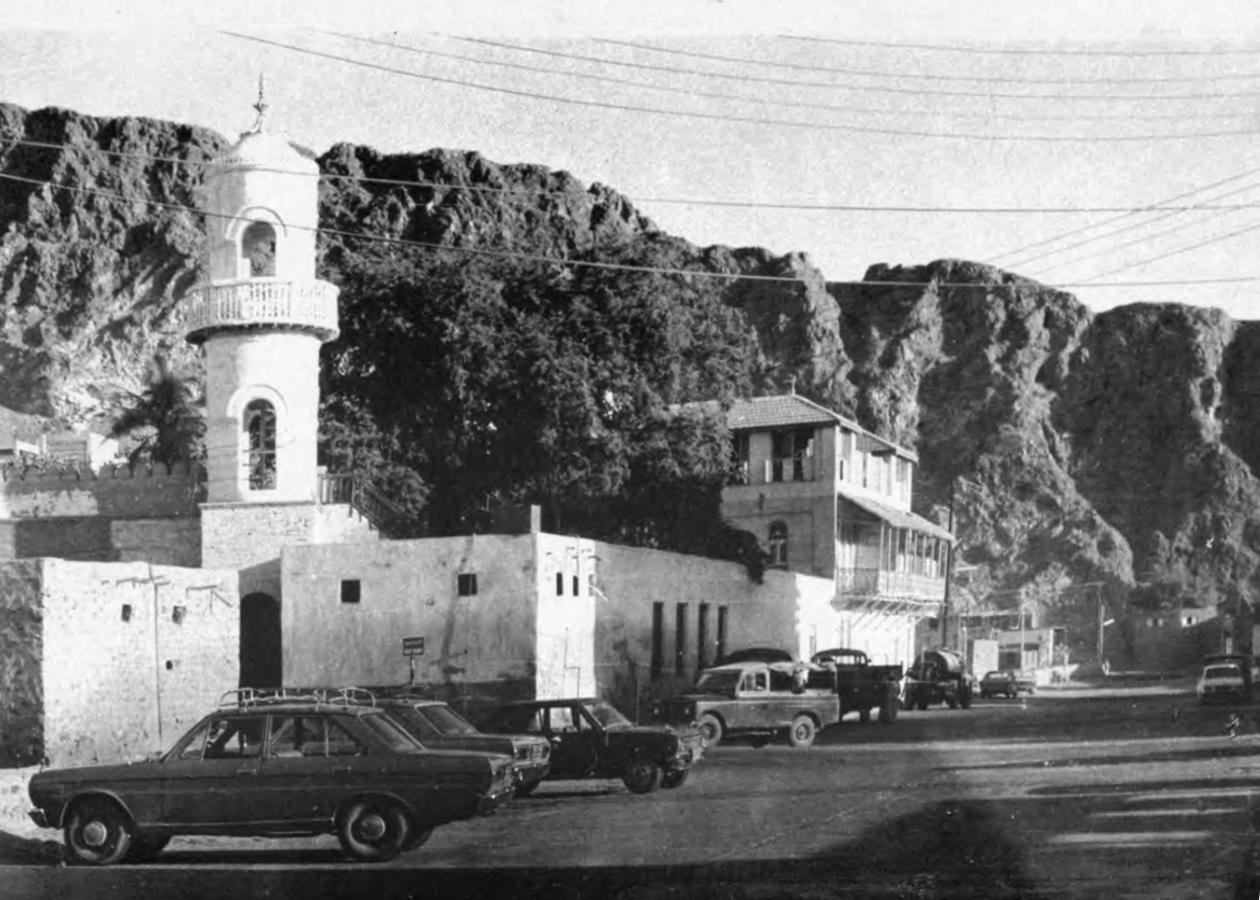

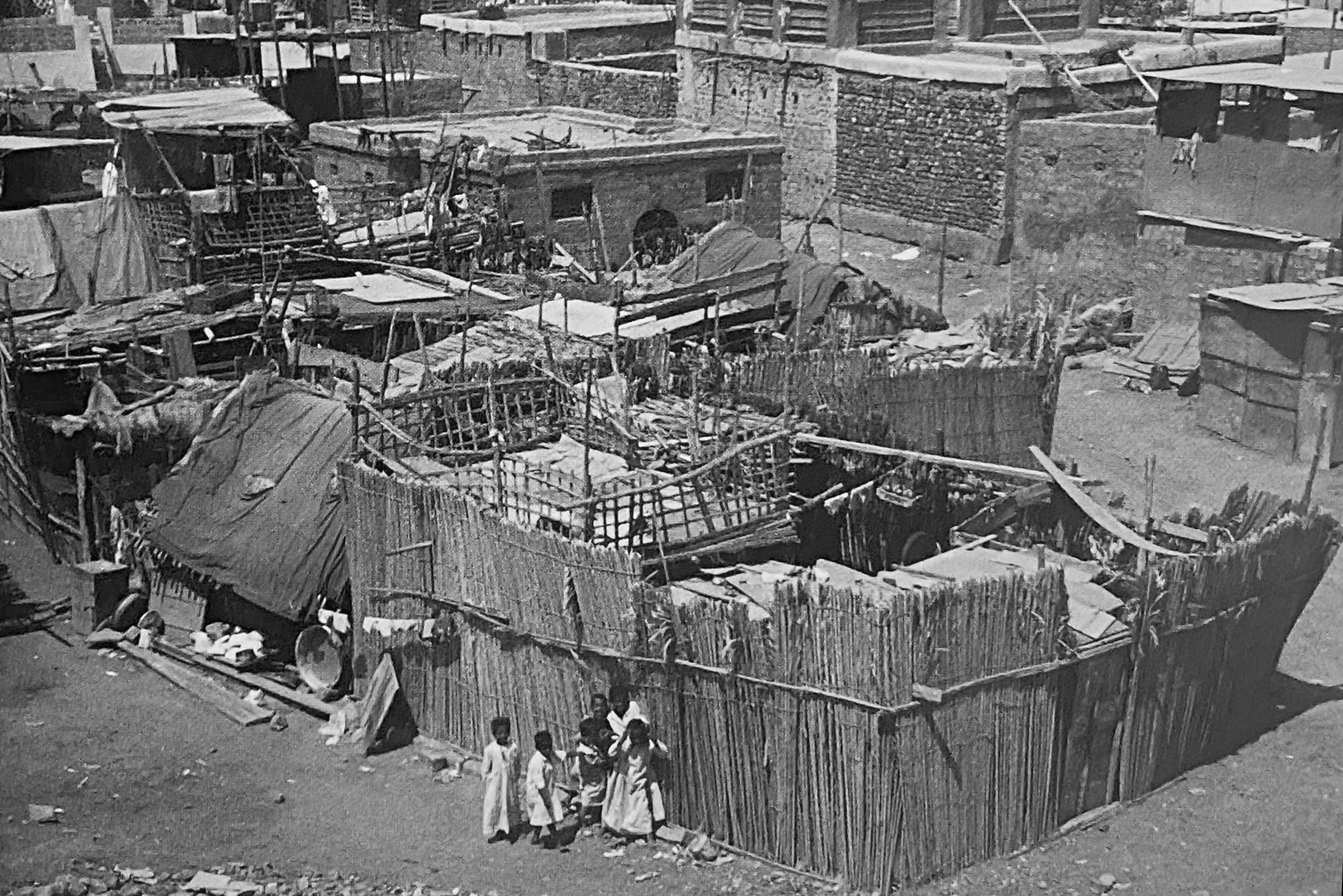

Before the discovery of petroleum, Muscat was deeply rooted in traditional architectural norms, with a strong reliance on local industries like fisheries, commerce, and agriculture, shaping the urban landscape significantly. The region’s rich historical and cultural heritage influenced the development of settlements around essential natural resources and strategic points for trade and defence. The urban structure was compact, promoting community interaction and social cohesion.25

The architecture and urban design of pre-petroleum Muscat were modest and integrated traditional souks, mosques, and residential areas as core urban elements. The architectural style reflected the region’s climate and cultural practices, utilizing local materials and methods to adapt to the desert environment, like using the wind-tower to as a cooling system. This organic urban planning evolved over time to meet the community’s needs, signifying a closely-knit society focused on sustainability and resilience in the challenging desert context.26

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.05.044.

“Middle East Centre Archive, St Antony’s College.” Oxford College Archives. https://oac.web.ox.ac.uk/middle-east-centre-archivest-antonys-college.

27. Mahbubur Rahman, “Three Decades of Omani Architecture: Modernisation, Transformation and Direction,” Journal of Research in Architecture & Planning 2003, no. 01 (December 2003): 52-68. https://doi.org/10.53700/jrap0212003_5.

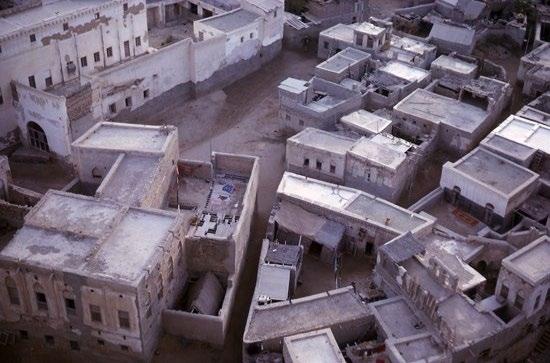

During the 16th century, the Portuguese invasion impacted Muscat’s urban form, introducing significant architectural and urban changes that are still identifiable today. The Portuguese era marked the construction and adaptation of many key features in Muscat, with Albuquerque describing the city as a vibrant trade hub. The subsequent decline in the 19th century saw Muscat lagging in socio-economic development due to its over-reliance on traditional sectors and the fragmentation caused by tribal divisions.27

28. Bernhard Heim, Marc Joosten, Aurel von Richthofen, and Florian Rupp, “On the Process and Economics of Land Settlement in Oman” Springer International Publishing (April 16, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41412-018-0066-7.

Before the oil era, Muscat’s social structure was characterized by traditional tribal systems that influenced all aspects of life, from settlement patterns to governance. Tribal leaders played crucial roles in the community, with tribal affiliations shaping the socio-economic and political landscape. The society was marked by strong communal ties, with a collective approach to resource management and decision-making.28

The discovery of oil brought significant transformations, catalysing urbanization and modernization, and altering Muscat’s urban and social frameworks. However, the legacy of its pre-oil era—marked by traditional urban forms, tribal structures, and a focus on communal living—continues to influence the societal fabric and urban landscapes of Muscat.

2.1 Muscat: Continuity and Change

1.2.1 Muscat Pre Oil

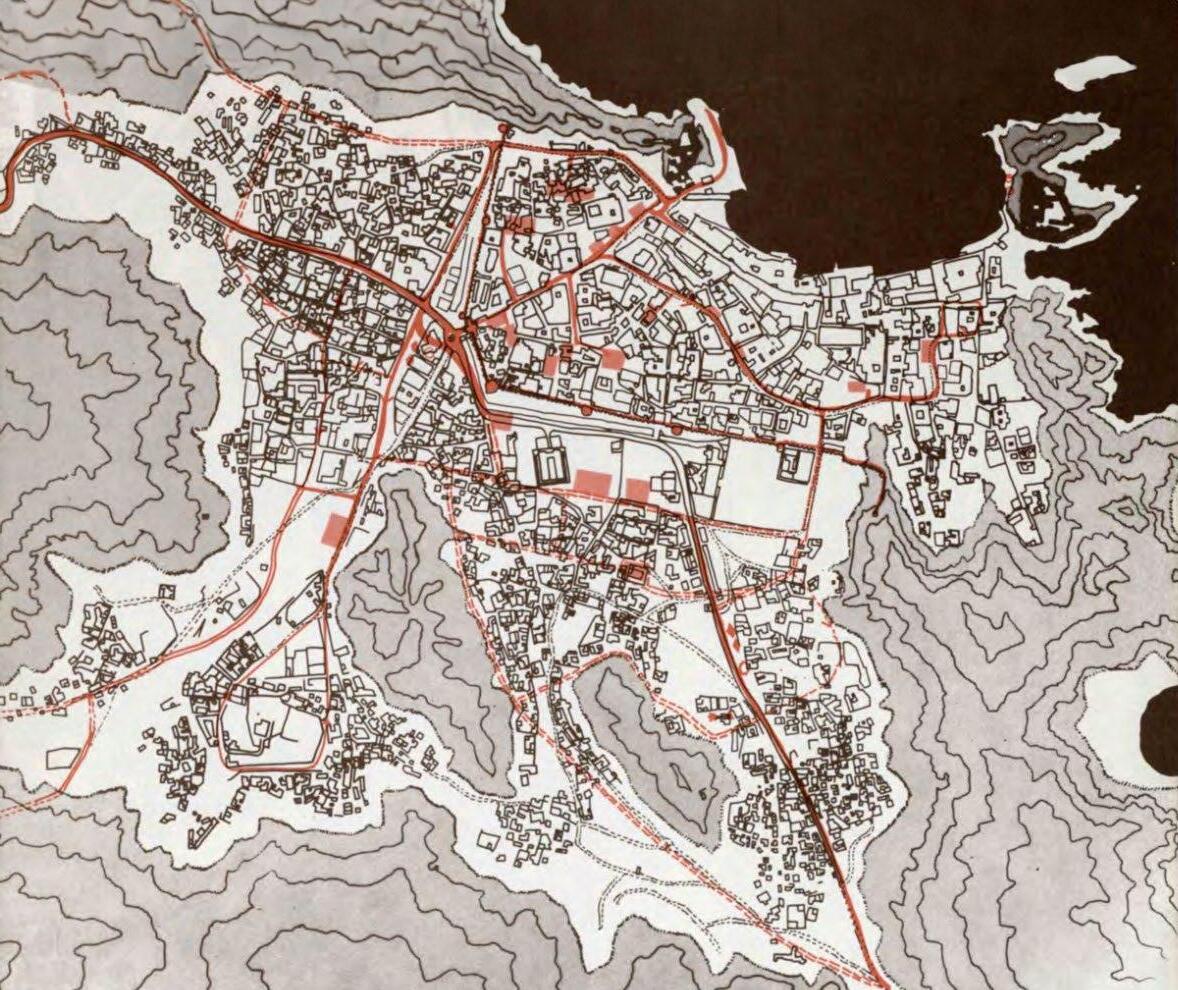

Figure 12: Historical Cartography: Muscat City Map, 1972

Noor Alkamali, Najwa Alhadhrami, and Chaham Alalouch, “Muscat City Expansion and Accessibility to the Historical Core: Space Syntax Analysis,” Energy Procedia 115 (2017).

25. Jeremy Jones and Nicholas Ridout, A History of Modern Oman (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

26. Salma Samar Damluji, The Architecture of Oman (Reading: Garnet Publishing, 1998).

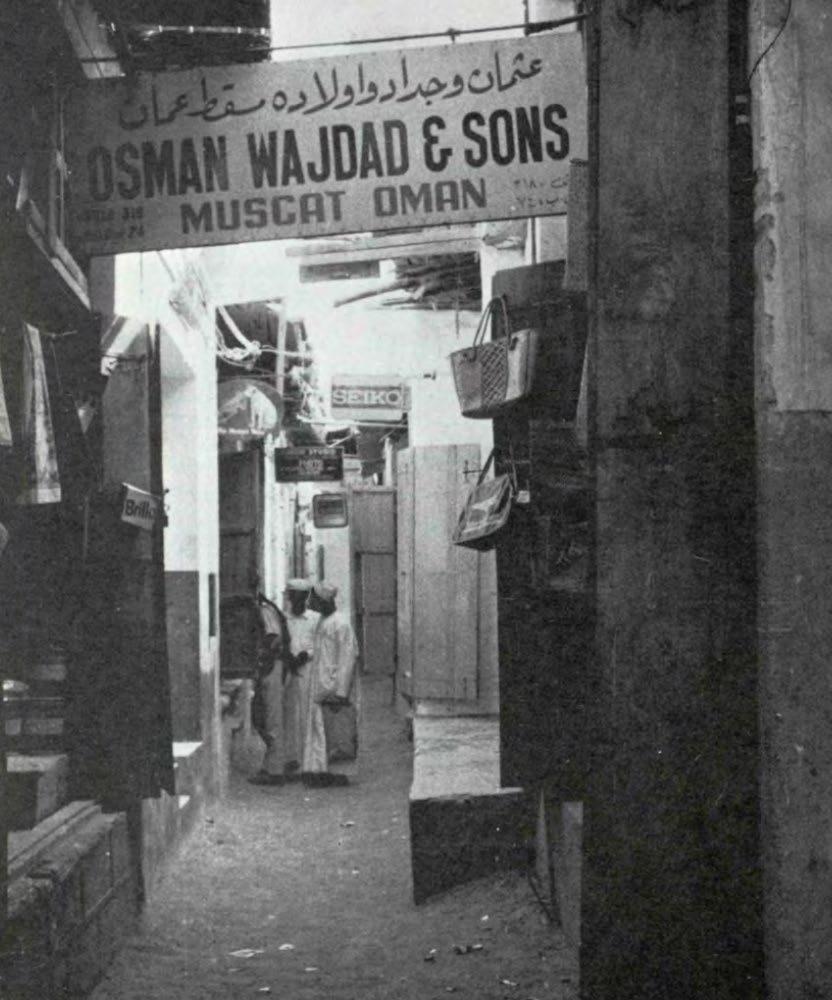

Figure 13: Historical Perspective: Life in Muscat Before Oil Discovery Through Archival Photos

Post Oil & Changes Urban Planning Policies

Following the discovery of oil, Muscat underwent a significant transformation, marked by rapid urbanization and modernization, which was propelled by the burgeoning economic prosperity. This new era necessitated a paradigm shift in urban planning policies to support the expanding urban landscape and its associated needs.29 A major focus was placed on the development of modern infrastructure, with substantial investments directed toward enhancing roads, utilities, and public services to support the growing urban populace. The expansion and improvement of transportation networks, alongside increased access to basic amenities, were central to this developmental thrust, aiming to elevate urban mobility and the overall quality of urban life.

In tandem with infrastructure development, Muscat witnessed a strategic shift toward formalized land use planning. The implementation of zoning regulations marked a move to regulate urban expansion and promote efficient utilization of land resources.30 Such regulations were instrumental in delineating distinct zones for residential, commercial, and industrial uses, prospecting to foster a more organized and coherent urban development.

29.Terence Clark, “OMAN: A Century of Oil Exploration and Development,” Asian Affairs 39, no. 3 (November 2008), ISSN: 0306-8374 (Print), 1477-1500 (Online) https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raaf20 30 Steffen Wippel, Regionalizing Oman: Political, Economic and Social Dynamics (Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2013).

Figure 14: Institutional Evolution: Development of Architectural and Urban Planning Bodies, 1970-2020

Khalfan Al Shueili, “Towards a Sustainable Urban Future in Oman: Problem & Process Analysis (Muscat as a Case Study)” (PhD diss., Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow School of Art, 2015).

31. Aurel von Richthofen, “Spatial Diversity and Sustainable Urbanisation in Oman” (Dr. Ing. diss., ETH Zurich, March 2019). https://doi.org/10.24355/dbbs.084-201901220928-0.

The era also saw the advent of comprehensive master planning, which aimed to organize urban growth in a systematic manner. These master plans were pivotal in outlining strategies for land use, transportation, housing, and environmental conservation, ensuring that urban development was both structured and aligned with broader development goals.

The drive toward economic diversification significantly influenced urban planning strategies. By promoting sectors beyond oil and gas, such as tourism, manufacturing, and services, urban planning policies began to reflect a broader economic vision, supporting infrastructure and development initiatives that catered to a diversified economic base.31

Collectively, these changes in urban planning policies post-oil discovery in Oman underscored a comprehensive shift toward modernization, sustainability, participatory planning, and economic diversification. These shifts were crucial in navigating the challenges posed by rapid urban growth and leverage the opportunities of economic transformation, thereby shaping the contemporary urban landscape of Muscat.

Since 1958: Muscat Development Department

Figure 15: Demographic Mapping: Distribution of Main Arab Tribes Around Muscat

“India Office Records and Private Papers.” Qatar Library https://www.qdl.qa/get-highlighted-words/81055/ vdc_100157213849.0x000095.

JebelSeyho

32 Sonja Nebel and I. Urban Oman: Trends and Perspectives of Urbanisation in Muscat Capital Area (Zürich: LIT Verlag GmbH & Co. KG Wien, 2016).

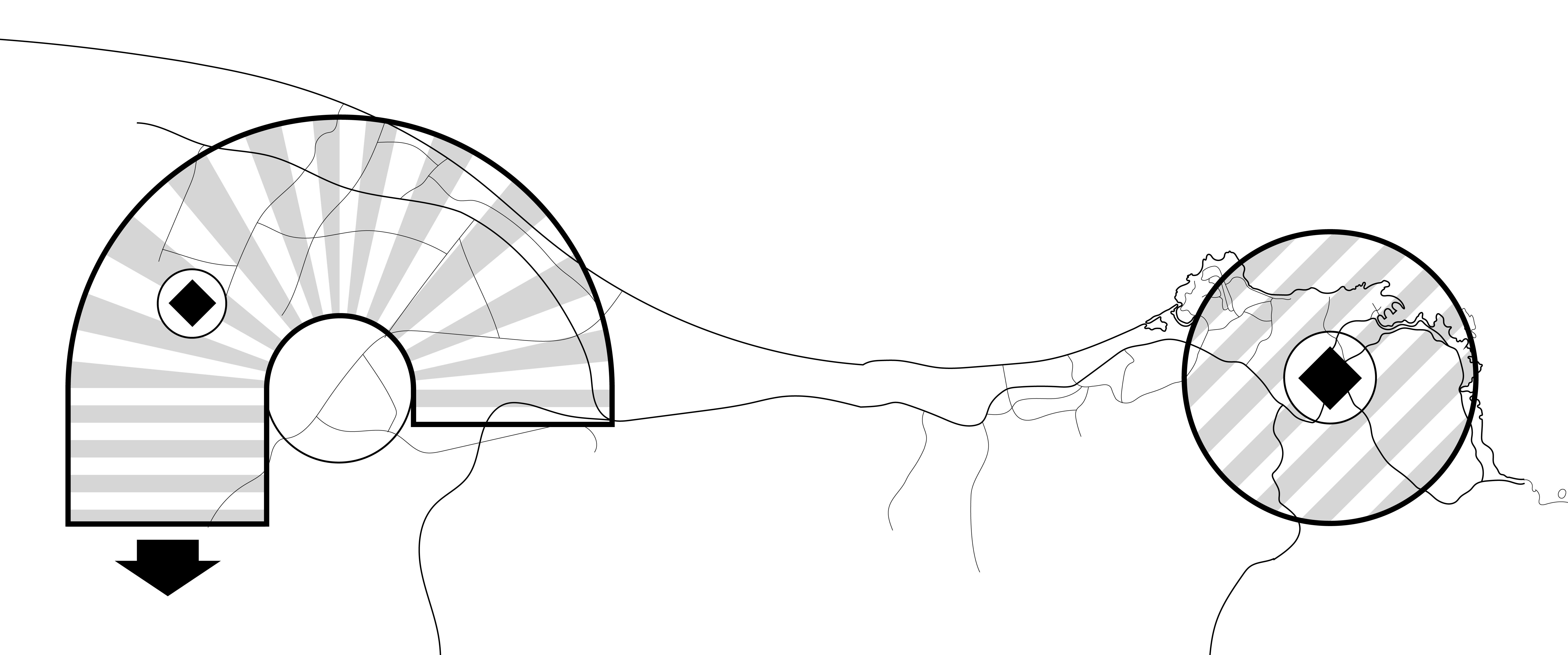

Figure 16: Procedural Analysis: Plot Acquisition and Government Services Diagram

Hamad Al Gharibi, “Urban Growth from Patchwork to Sustainability” (PhD diss., Technische Universität Berlin, January 2015). https://doi.org/10.14279/depositonce-4314.

some areas, even those over twenty years old, lack basic amenities like water distribution or waste treatment facilities.

Historically, plot allocation faced inconsistencies, with periods of backlog and surges in distribution, influenced by procedural and technical adjustments. The introduction of housing benefits and loans for low-income families and rural housing developments indicates a broader government effort to address housing needs across different societal segments.

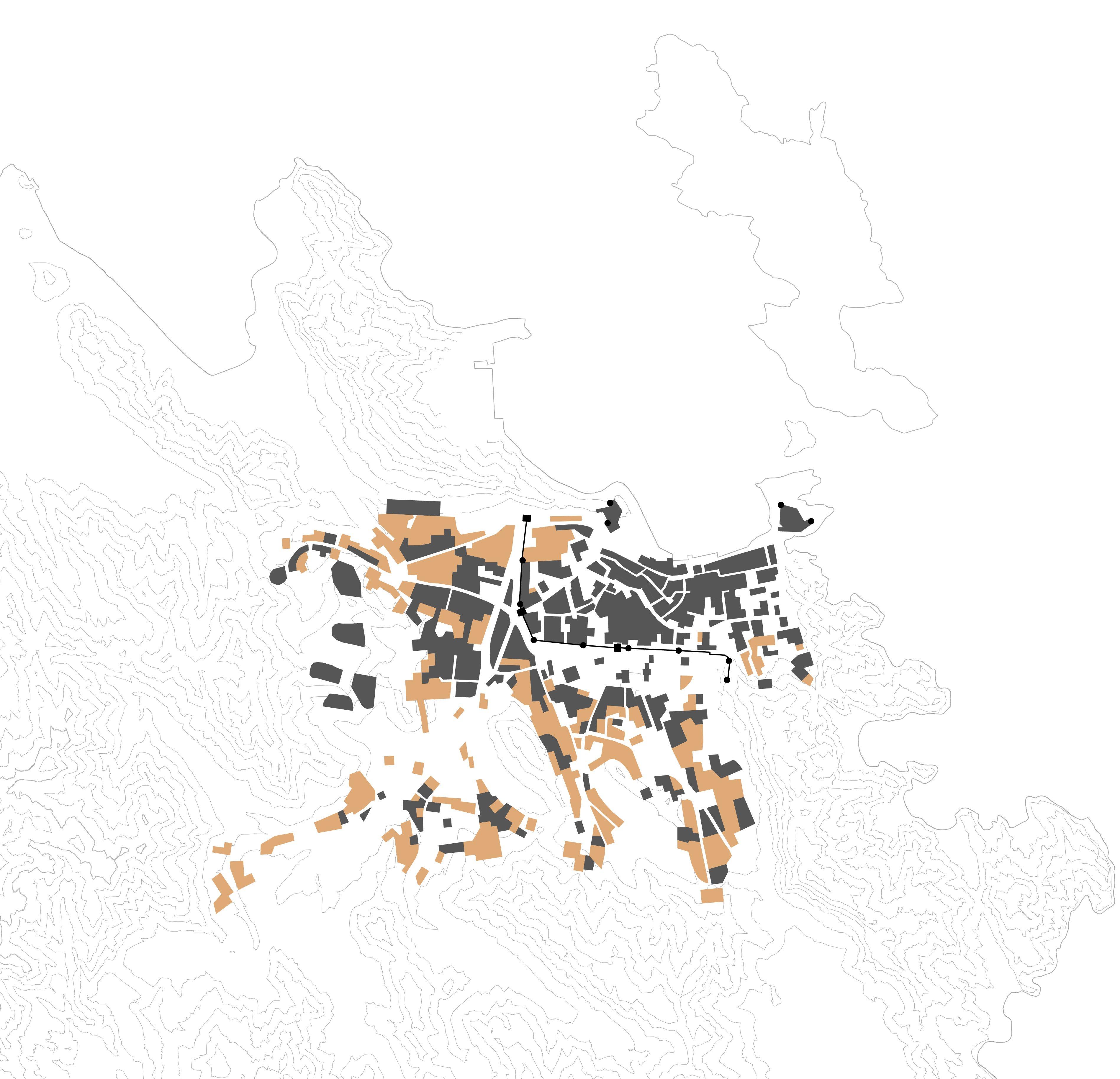

The land lottery system contributes to unsustainable urban sprawl, necessitating high resource consumption and promoting car-based mobility. The absence of land management and taxation exacerbates issues like land speculation. The government’s strategy, while intending to provide equitable land access, often results in plot allocation in areas distant from economic centres, challenging the system’s efficacy and transparency.33

Tribal affiliations significantly influence social and urban organization, with historical settlement patterns reflecting tribal territories. The persistence of tribal identities and bonds continues to shape economic, political, and social dynamics, influencing modern urban settlement

Weidleplan and Muamir. Regional Plan for

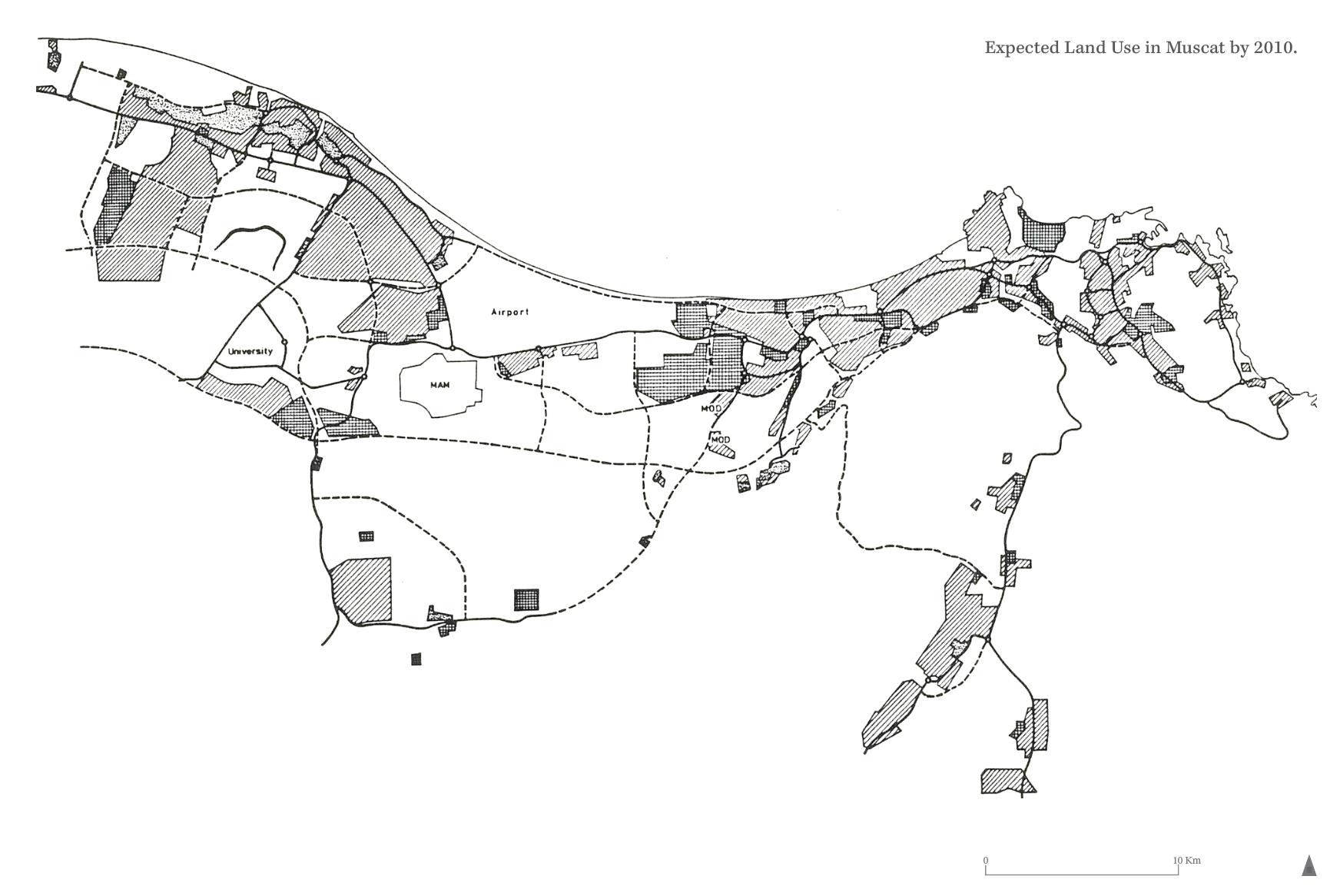

Municipality Boundary

Urban Area Boundary Boundary of M.O.D. and Airport Town Center (Urban Area) District Center (Urban District) Special Center

33 Wolfgang Scholz, “Appropriate Housing Typologies, Effective Land Management and the Question of Density in Muscat, Oman,” Sustainability 13, no. 22 (2021): 12751 https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212751.

34 Bernhard Heim, Marc Joosten, Aurel v. Richthofen, and Florian Rupp, “Land-allocation and clan-formation in modern residential developments in Oman,” City Territory Architecture 5, no. 8 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-018-00846.

35 Mamdouh Shouman, “Deserts In The City: White Land And Regime Survival In The Gulf” (PhD diss., Georgia State University, 2017). https://doi.org/10.57709/11180049.

patterns and possibly undermining centralized land allocation efforts. The government’s initiative, while fostering a mixed modern society, must contend with the deep-rooted tribal structure that influences the citizens’ preferences and decisions in land allocation and urban development.34

Comparative studies, such as those by Shouman (2017), highlight the broader Gulf region’s challenges with land speculation and urban planning, emphasizing the need for a nuanced understanding of Muscat’s unique context.35 The land lottery system’s implications on housing affordability and market dynamics underscore the interconnectedness of urban planning, social structures, and economic policies in shaping the urban future.

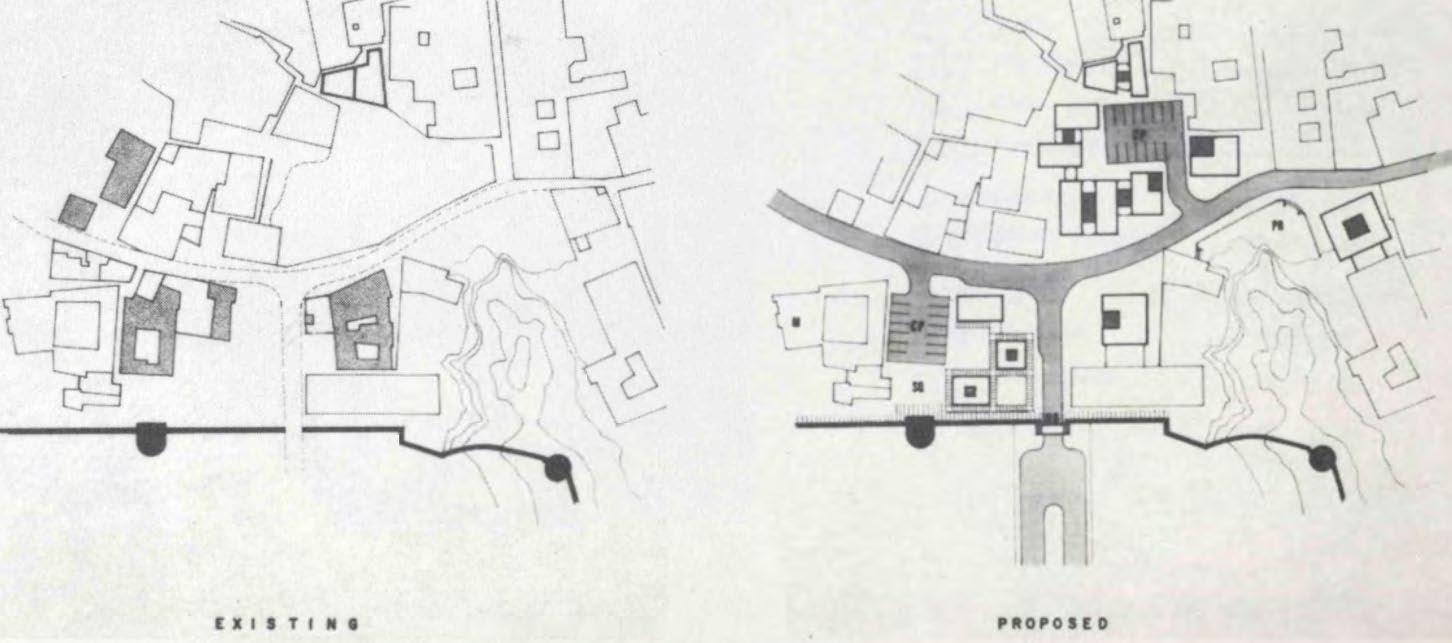

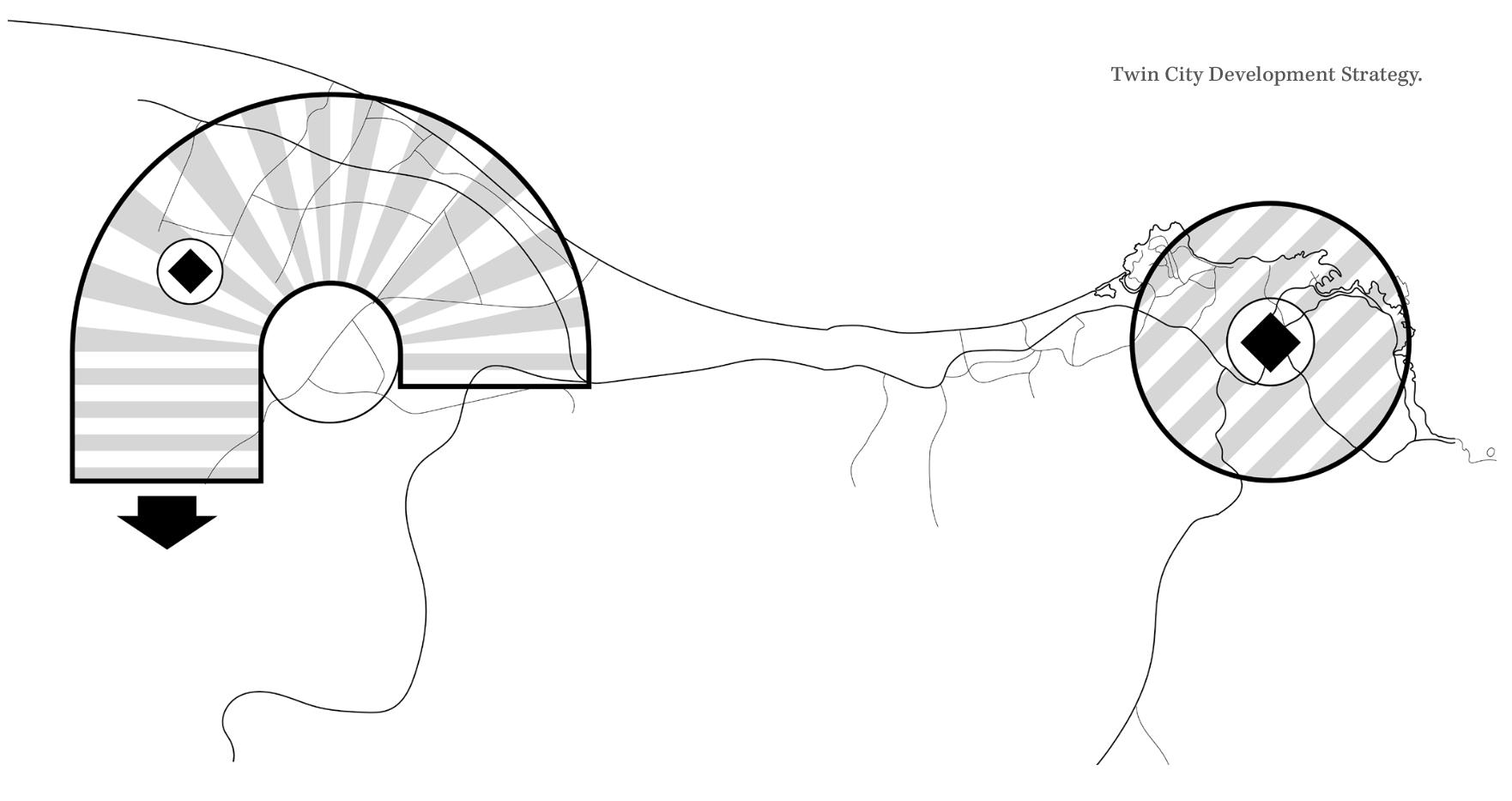

Figure 17: Urban Planning: Twin-City Development Plan with Focus on New Urban Centres

Muscat Region, Structure Plan and Housing Study for Muscat Area, 1991.

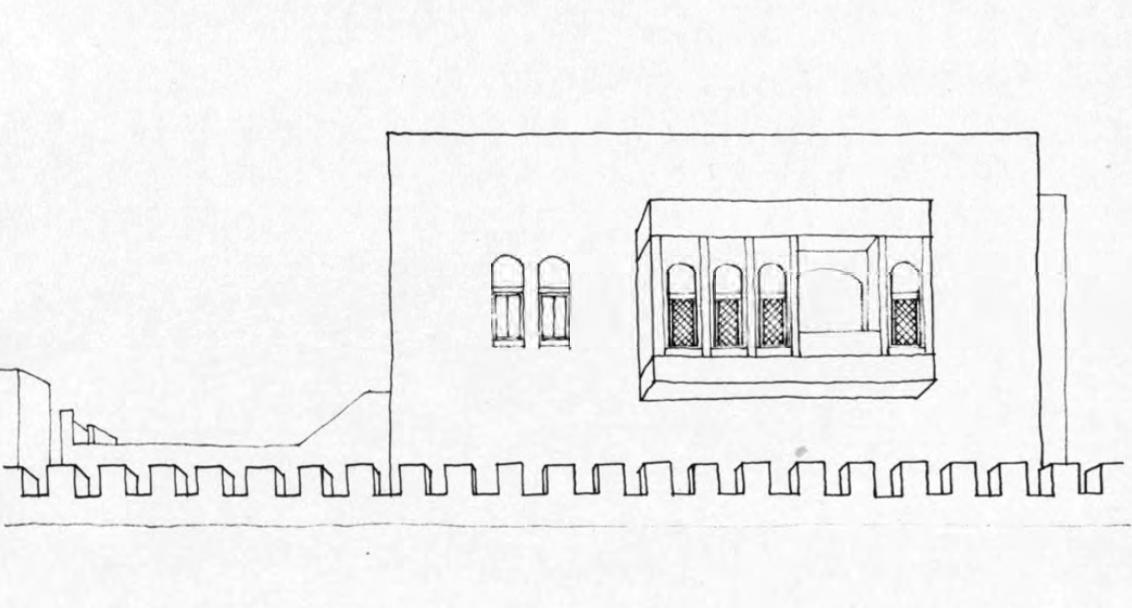

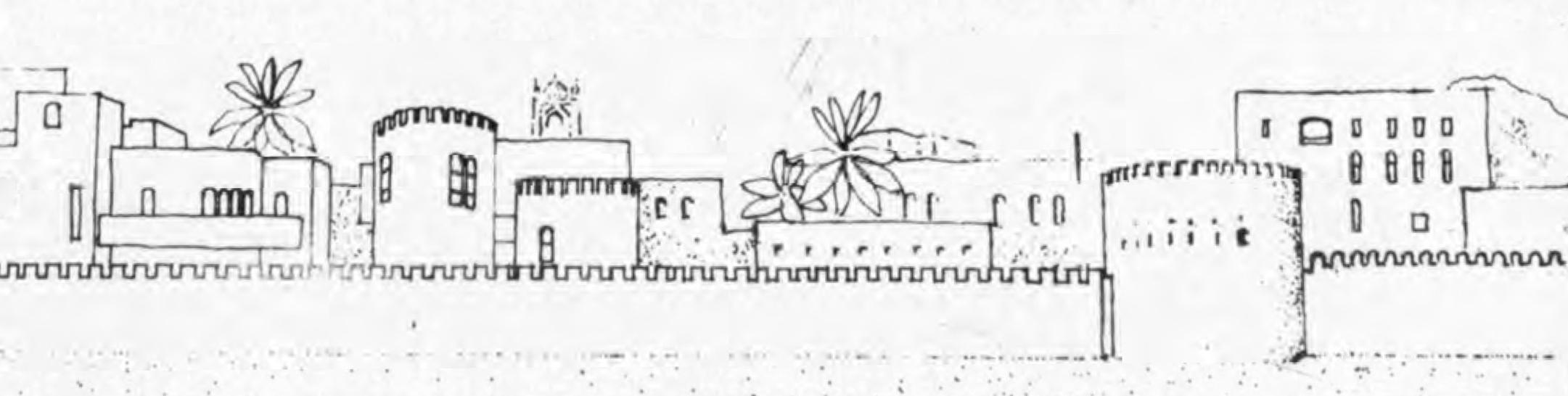

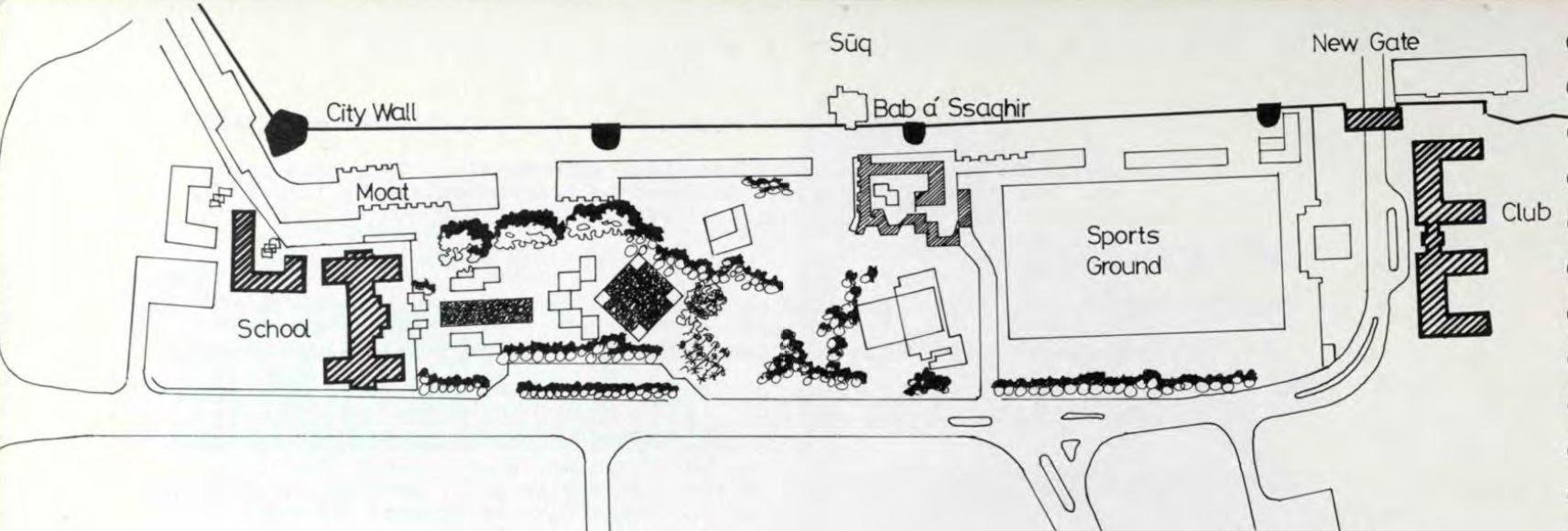

Figure 18: Architectural Heritage: Significant Buildings in Old Muscat According to Makiya Plan

Makiya Associates, “Muscat City Planning - Proposed Preservation Study” (working paper, 1972).

1.2.4 Governance and Urban Planning Strategies

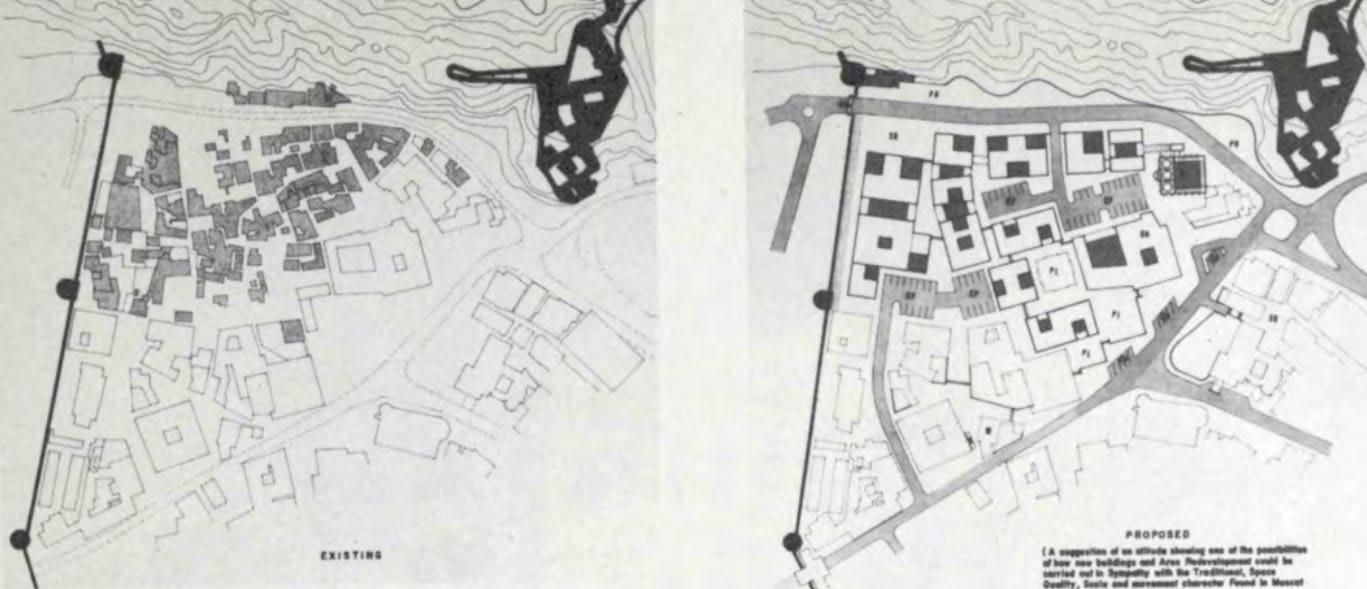

From 1970, Muscat witnessed remarkable transformations in urban planning, marking milestones in the city’s development journey. These changes reflect an evolving urbanization narrative, where strategic spatial planning played a crucial role in transitioning from traditional settlement patterns to a future-oriented urban planning paradigm.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Muscat and Muttrah began to modernize, with the Greater Muttrah Development Plan by John R. Harris and Partners initiating a structured urban planning approach. This period saw Muscat evolve from a cluster of traditional settlements to a city with a vision for the future, emphasizing modern facilities and services. The Harris plan, flexible in nature, considered various developmental paths for Muscat, aiming to balance its historical essence with its emerging roles in governance, culture, and tourism. 36

By 1972, the involvement of the Swedish firm VIAK further refined urban planning in Muscat, focusing on detailed zoning and regional

37. Khalfan Al Shueili, “Towards a Sustainable Urban Future in Oman: Problem & Process Analysis (Muscat as a Case Study)” (PhD diss., Mackintosh School of Architecture, Glasgow School of Art, 2015).

38. Belgacem Mokhtar, “Modern Transformations in the Urban Social Structure in Muscat City,” Journal of Arts and Social Sciences [JASS] 5, no. 1 (2014): 5. https://doi.org/10.24200/jass.vol5iss1pp5-20.

development, stretching from Sidab to Seeb. The same year, Makiya Associates Consultants drafted a comprehensive master plan, which integrated conservation efforts with urban development, emphasizing Muscat’s architectural heritage preservation.37

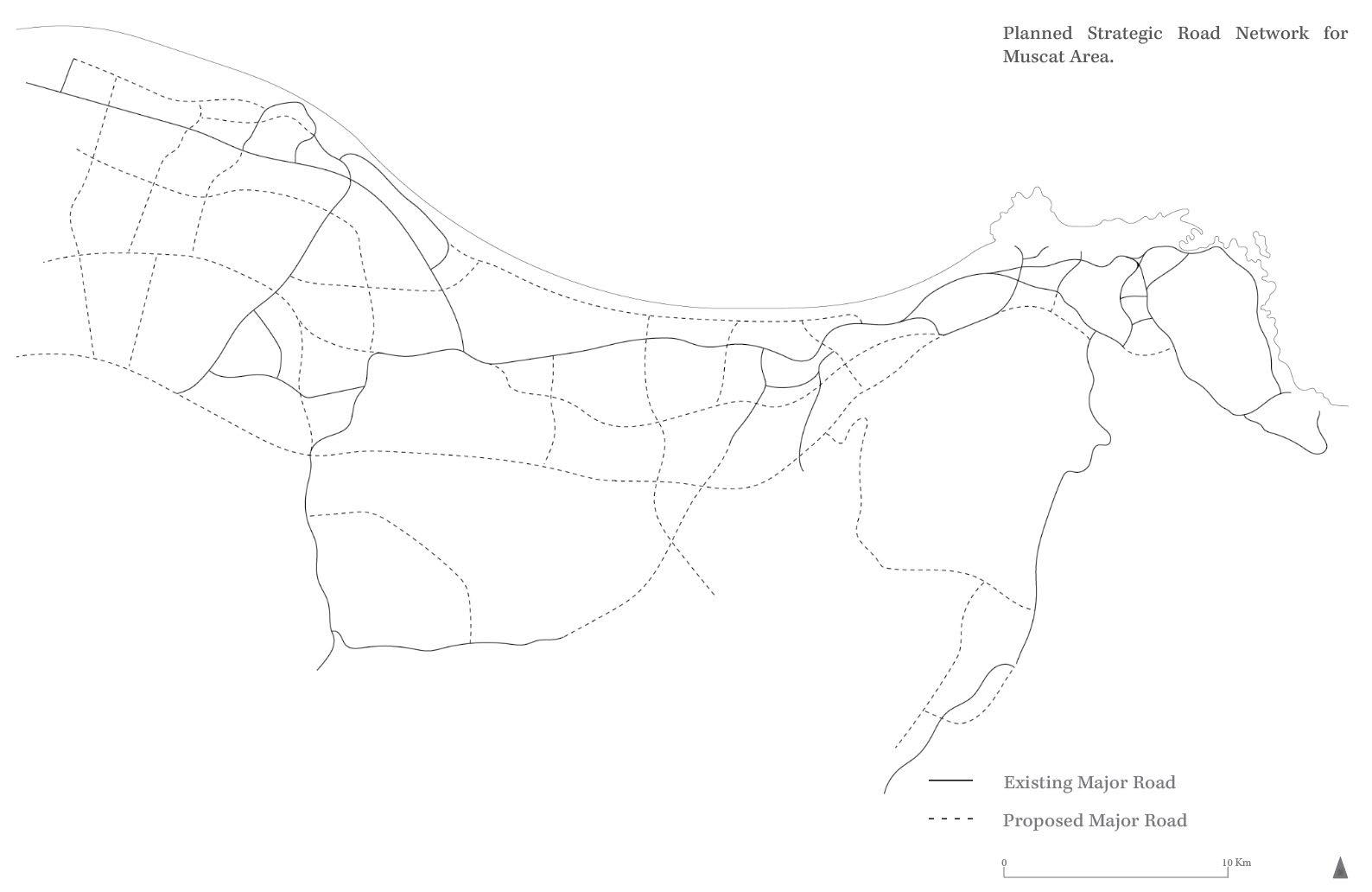

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, urban planning efforts like the Capital Area Structure Plan and the Muscat Regional Plan, developed by Llewellyn-Davies Weeks, Weidleplan, and Muamir, focused on integrated land use policies and human resource mobilization.38 These plans advocated for a poly-central development model, moving away from concentrated urban growth to a more distributed framework, laying the groundwork for Muscat’s modern urban landscape.

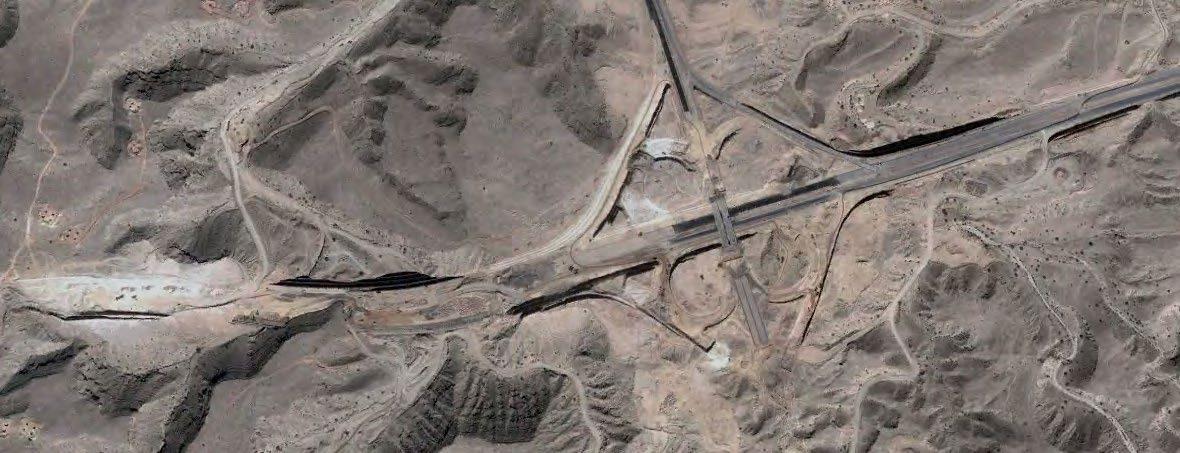

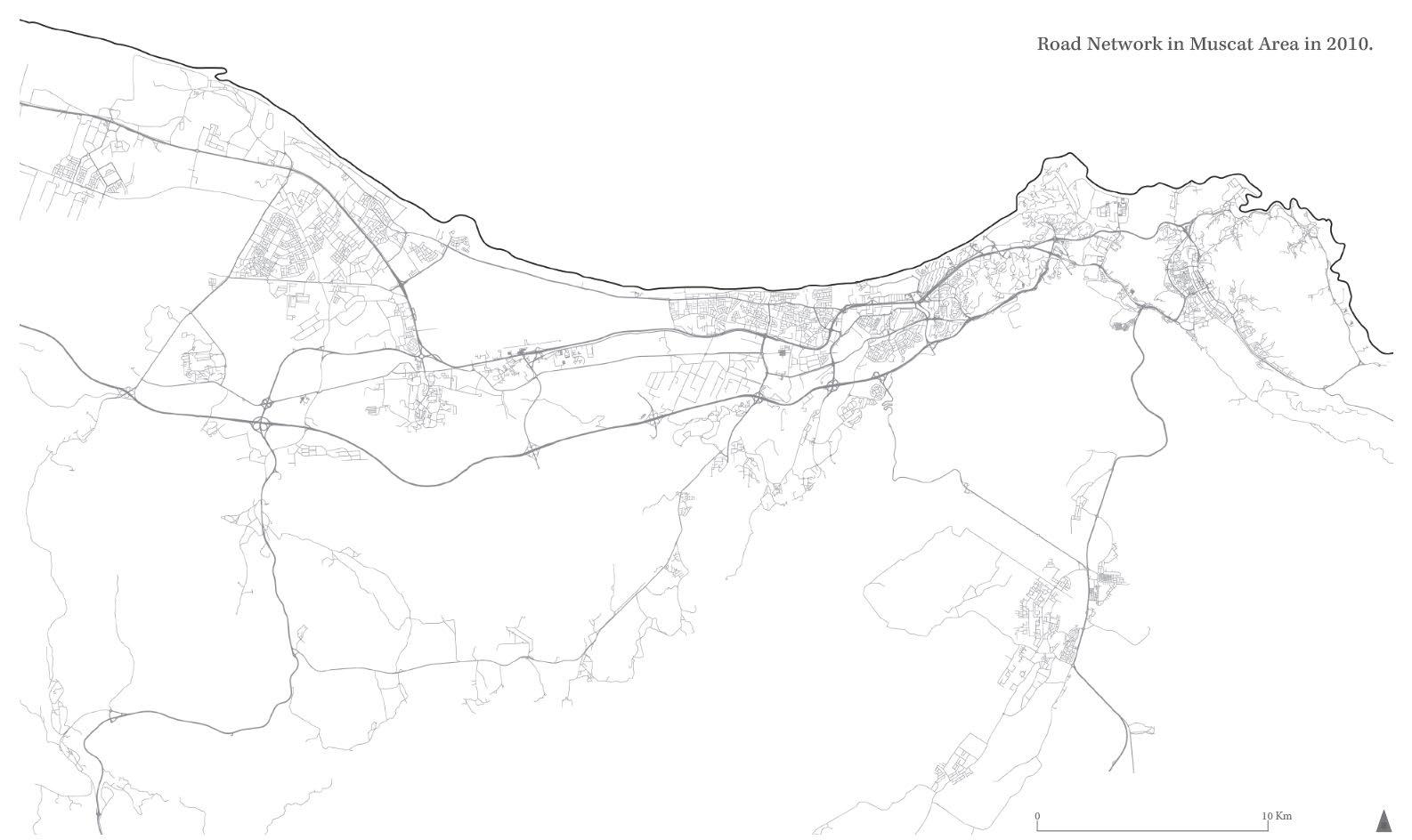

Parallel to these strategic planning initiatives, Muscat experienced diverse urban growth patterns, including the emergence of secondary urban centres, ribbon development, and scattered development. The construction of new infrastructure like the dual-carriageway from Muttrah’s Corniche to Ruwi and the Sultan Qaboos Highway facilitated urban linkage and expansion but also brought challenges like traffic congestion and the commercialization of land uses.

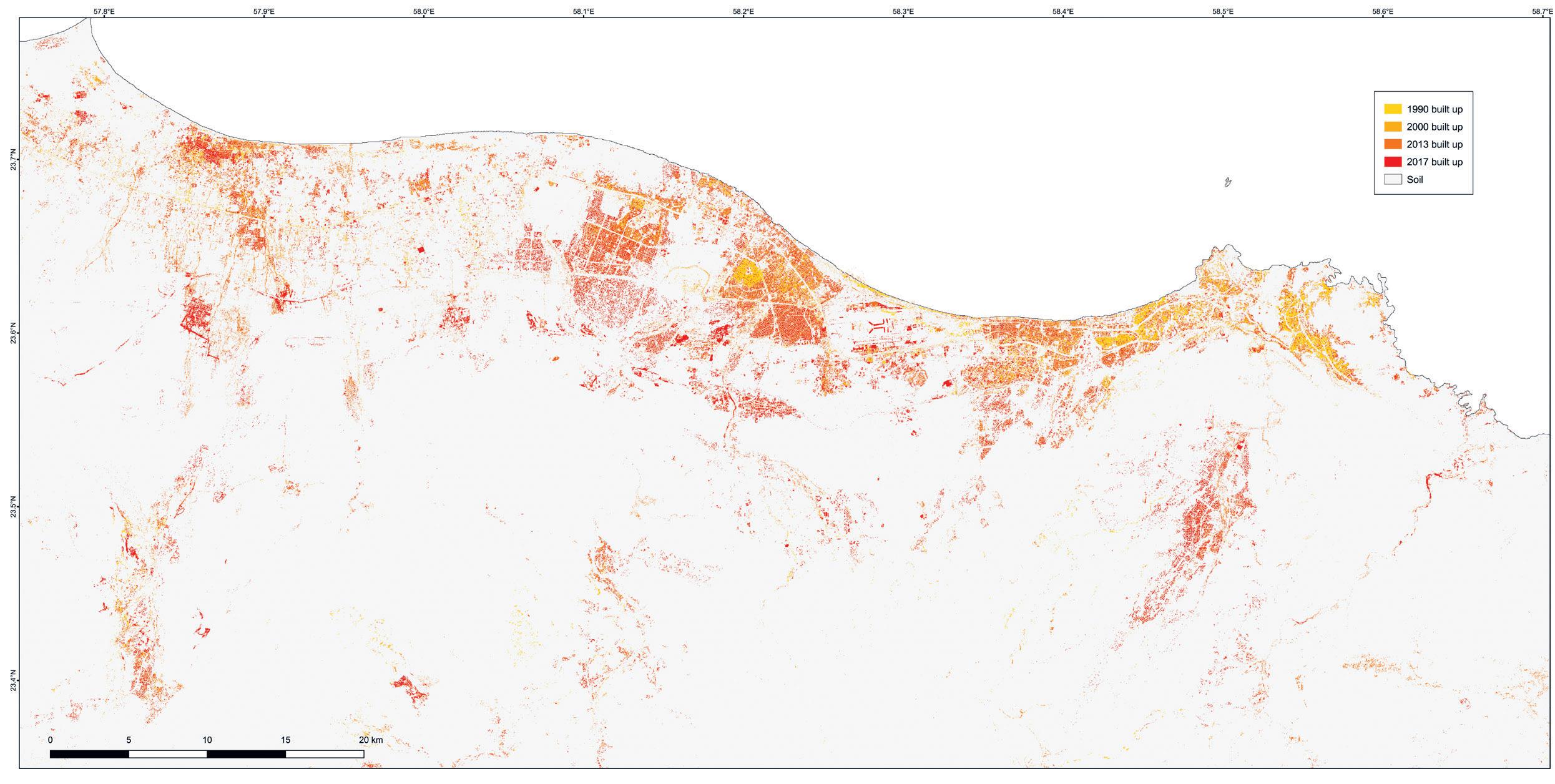

Figure 19: Urban Studies: Expansion of Urban Density in Muscat

Fred Scholz, Muscat Then and Now: Geographical Sketch of a Unique Arab Town (Berlin: 2014).

R. Harris, Muscat and Greater Mutrah Development Report (London: John R. Harris Architects, 1970).

Figure 20: Satellite Imagery of Urban and Road Network Development

Sonja Nebel and I. Urban Oman: Trends and Perspectives of Urbanisation in Muscat Capital Area (Zürich: LIT Verlag GmbH & Co. KG Wien, 2016).

Number

Suq (for men)

Environmental and geographical constraints further complicated urban planning, especially in low-income areas, necessitating significant investments in infrastructure. By the 2000s, the introduction of the Oman National Spatial Strategy (ONSS) and later, the Greater Muscat strategy, aimed to guide sustainable development while preserving Oman’s cultural and environmental assets.39

The evolution of urban centres like Bosher, Seeb, and the growth corridors like Ruwi-Qurum-Khuwair-Athaiba, illustrate Muscat’s transition into a city of multiple urban nodes. This transformation was supported by infrastructure developments like the Muscat Express-way, aimed at improving mobility and addressing traffic bottlenecks.40

Overall, Muscat’s urban planning history and its urban expansion patterns highlight a gradual shift from ad-hoc development to strategic, holistic urban planning. These efforts aimed at sustainable growth, balancing modernization with cultural and environmental preservation, and addressing the challenges of rapid urbanization.

39 Naima Benkari, “Urban Development in Oman: An Overview,” WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment (2017). https://doi.org/10.2495/sdp170131. 40 Aurel von Richthofen, “No Urban Desert! Emergence and Transformation of Extended Urban Landscapes in Oman,” in Ruralism - The Future of Villages and Small Towns in an Urbanizing World (2016), 256-267.

Figure 22: Comparative Urban Study: Settlement Structures in Muscat Before and After 1970

Wolfgang Scholz, “Appropriate Housing Typologies, Effective Land Management and the Question of Density in Muscat, Oman,” Sustainability 13, no. 22 (2021): 12751

Figure 23: Long-Term Urban Strategy: Muscat Governorate Regional Spatial Strategy, 2040

Ministry of Housing and Urban Planning, National Spatial Strategy, Regional Spatial Strategy, Muscat Governorate. Extended Executive Summary 2020.

Background and Context: The evolution of Wadi Adai from an industrial base to a residential hub exemplifies the consequences of rapid urbanization devoid of a strategic and holistic plan. The area’s transformation, primarily driven by the construction activities related to Mina Qaboos port, showcases how unplanned growth can disrupt socio-economic stability and pose enduring challenges for residents. The decision to relocate displaced families to Wadi Adai inadvertently resulted in a unique amalgamation of industrial, residential, and governmental zones, revealing inherent tensions and discrepancies in urban planning methodologies.

Displacement and Resettlement: The narrative of Wadi Adai’s urban transformation is marked by the abrupt displacement of residents during the expansion of Ruwi hospital, highlighting the inhumane aspects of uncontrolled urban sprawl. The hasty and poorly organized resettlement process, coupled with insufficient housing funds, reflects a systemic disregard for marginalized community welfare, illustrating the dire consequences of neglecting the rights and dignity of displaced populations amidst rapid urbanization.

Physical Development & Urban Planning: The urban trajectory of Wadi Adai, significantly shaped by the Ministry of Land, reveals the complex and sometimes contradictory nature of urban planning. The ministry’s approach, lacking in community engagement, resulted in a uniform yet architecturally diverse landscape, a paradoxical outcome of the uniform plot size requirements and dense development mandates. However, the absence of clear guidelines for building style, height, and car mobility considerations indicates a policy focus on immediate housing needs over comprehensive, sustainable urban development.

Living Conditions: The living standards in Wadi Adai highlight the adverse consequences of inadequate urban planning, with residents grappling with substandard infrastructure, health risks, and compromised safety. The neighbourhood’s layout, characterized by poor road conditions and insufficient basic services, has led to detrimental health and social outcomes, emphasizing the need for a more responsible and human-centric approach to urban development.

2.2 Neighbourhood: From Wadi Adai to Al Khoud

2.2.1 Wadi Adai

Figure 24: Time-Lapse Architectural Study: Wadi Adai First House in 1976 and 2002

Fred Scholz, Muscat Then and Now: Geographical Sketch of a Unique Arab Town (Berlin: 2014).

Figure 25: Urban Design: Wadi Adai Neighbourhood Plan

Commercial Residential Wadi

Perceptions & Stigmatization: Wadi Adai’s image as a locality for disadvantaged groups has had profound implications on its residents, affecting their social interactions and perpetuating a cycle of stigma and exclusion. The enduring societal biases against the neighbourhood’s inhabitants, particularly immigrants and labourers, have had tangible impacts on their lives and opportunities, calling for a more inclusive and empathetic urban planning perspective that addresses these deep-rooted prejudices.

Response to Challenges: Despite various initiatives by Omani authorities to address housing challenges in Wadi Adai, the measures have fallen short of addressing the core issues comprehensively. The absence of essential services and the logistical challenges posed by the neighbourhood’s isolation underscore the need for an integrated approach to urban planning that transcends mere physical development, aiming to enhance overall living conditions, infrastructure, and social integration within the community.

Wadi Adai’s central communal area, with a mosque, a school, and several underutilized commercial establishments, does not provide the welldesigned public spaces needed for community activities. The area to the north is relegated to car parking, while the expansive but arid western wadi is neglected. The settlement’s alleyways, too narrow for communal gatherings, have been re-purposed for car parking in the absence of adequate facilities.

Despite these limitations, the communal spaces in Wadi Adai play a crucial role in the social fabric of the community. They foster a complex network of social interactions among the residents, even though potential sites for social infrastructure are overlooked due to uncertainties about their ownership.

Figure 26: Urban Space Limitations: Inappropriateness of Narrow Alleys for Communal Activities

Analysis of Wadi Adai

Figure 27: Community Space Analysis: Design and Utilization of Central Communal Areas

The lack of communal spaces significantly diminishes pedestrian activity, with most residents opting for vehicular transport. This observation underscores the pressing need for enhanced infrastructure to transform existing and potential areas into vibrant centres for community life, thus improving social cohesion and interaction within Wadi Adai. Such changes could mitigate the current dual-use of communal areas for social engagement and sanitation, addressing the nuanced challenges of community life in the area.

Reflecting on Wadi Adai’s history, its socio-economic struggles are rooted in the displacement of its original settlers, predominantly free labourers, to this once remote locale. This historical backdrop is manifest in the neighbourhood’s deteriorating housing and overall maintenance.

Nonetheless, Wadi Adai exhibits a remarkable resilience. The survival of businesses in the central area, despite their dilapidated condition, signifies ongoing commercial activity that serves the local populace. The continuity of these shops, though in an uncertain state, reflects the community’s adaptability to its socio-economic environment.

The concept of urban stigma is relevant to Wadi Adai, given its lower economic status and the living conditions there, influencing its reputation. Yet, the community facilities and collective experiences of its residents illustrate a neighbourhood’s capacity to adapt and evolve in response to its challenges.

In summary, Wadi Adai’s experience is marked by socio-economic stigma and infrastructural deficiencies. However, the community’s enduring spirit of resilience is evident. The neighbourhood’s adaptation, through the development of communal facilities and shared experiences, demonstrates a profound ability to adjust and thrive, even amidst adversity.

Figure 28: Land Use Strategy: Car Parking Utilization of Northern Open Areas

Figure 29: Unused Urban Spaces: The Case of the Western Wadi

Figure 30: Spatial Representation: Axonometric View of Wadi Adai Neighbourhood

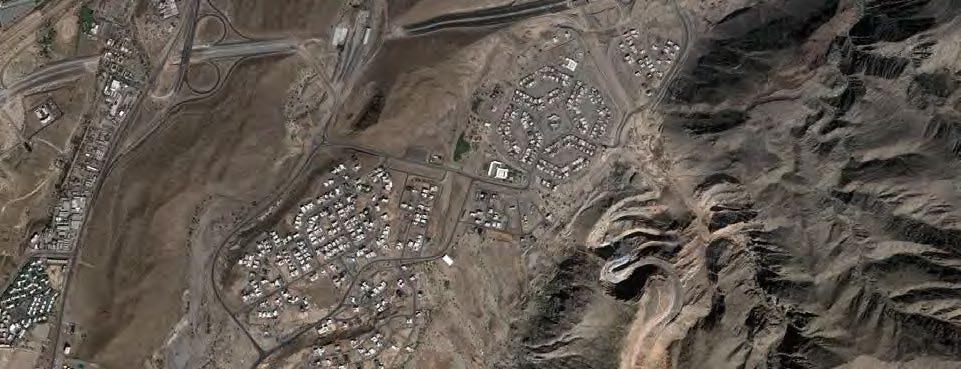

Figure 31: Aerial Perspective: Drone Photography of Wadi Adai Neighbourhood

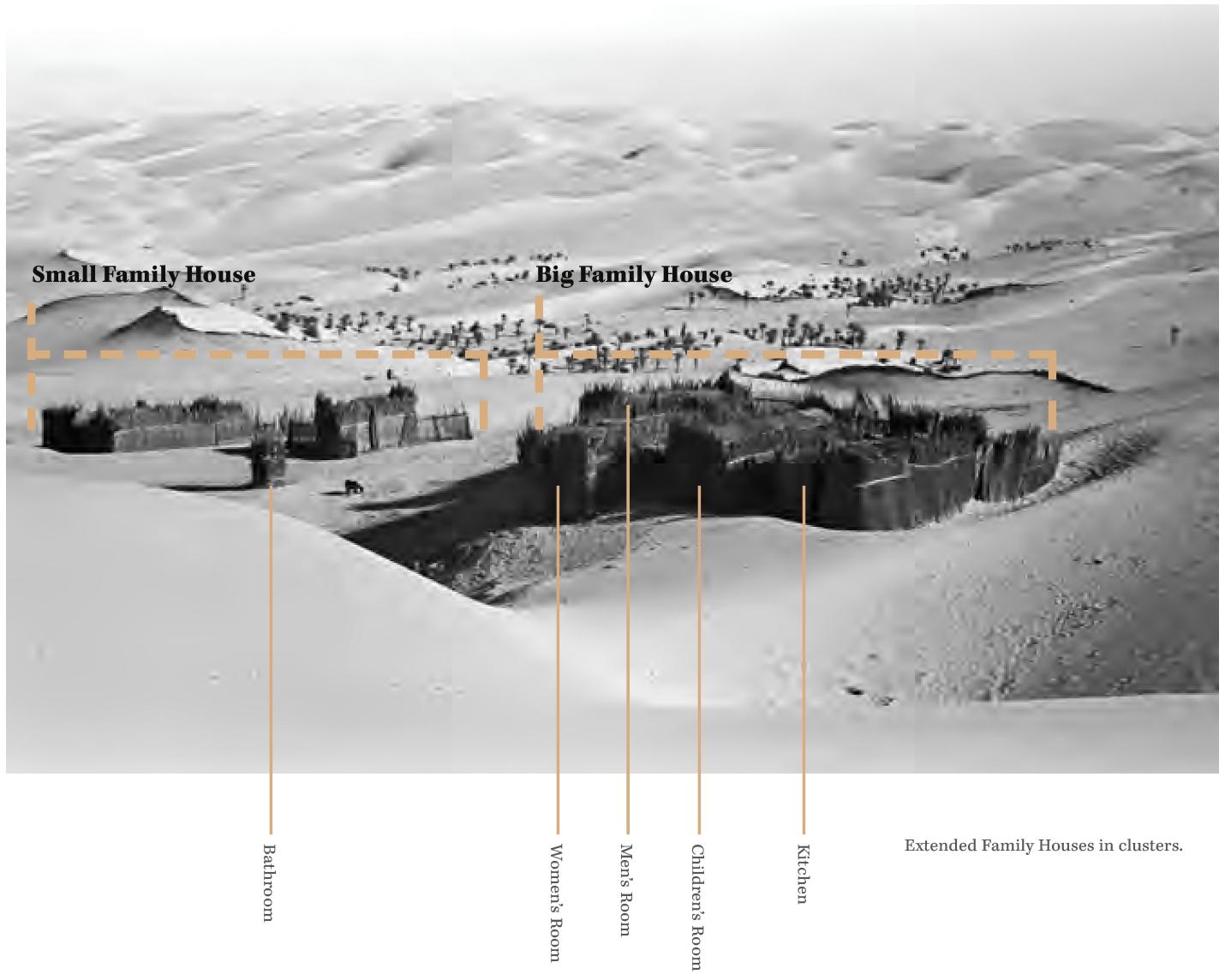

Background and Context: The metamorphosis of Al Khoud, once an isolated landscape, into a burgeoning community epitomizes Oman’s urban evolution across social, political, and economic dimensions. Located 50 kilometres from Muscat’s core, Al Khoud initially suffered from an absence of fundamental infrastructure and amenities. This transformation was ignited by the resettlement of displaced families in 1984, incorporating various ethnic groups like Baloch, Arabs, and Africans. The unexplained segmentation of these ethnicities into colour-coded wings, such as the Yellow Wing for Baloch, unveils the intricate underlying tensions characterizing the area.

Displacement and Resettlement: The forced relocation of families from Muscat’s fringes to Al Khoud symbolizes the push and pull of urban growth. This 50-kilometre shift to a secluded locale was marked by systematic segregation into ethnic-based “wings,” indicating governmental directives that overlooked cultural identities. Resistance from certain tribes resulted in governmental conflicts, demolitions, imprisonments, and palpable inequalities. Particularly affected were fishermen and farmers, who were compelled to depend on governmental assistance, altering their social

standing .Interviews with residents suggest that the displacement’s ethnic segmentation might have stemmed from latent intergroup tensions. While some individuals capitalized on new opportunities, others lost traditional livelihoods, which forced them into reliance on state aid. The forced removal triggered opposition, particularly among Arab tribes, culminating in governmental conflicts.

Physical Development & Urban Planning: Family sizes and assigned “wings” shaped Al Khoud’s architectural planning and construction, though the reasoning behind such determinations remains ambiguous. Absence of specific building regulations or reasons for dense development underscore this lack of clarity.

While the construction of a university acted as a catalyst for urbanization, the absence of strategic oversight led to disparities and inequitable growth across zones. An initial deficiency in infrastructure exposes a disconnect between urban planning and residents’ necessities. Underutilized vast plots between houses indicate untapped potential to rejuvenate the area.

2.2.2 Al Khoud

Figure 32: Urban Vacancy: Aerial View of Empty Plots in Al Khoud

Figure 33: Social Housing Analysis: Distribution by “Wing” Colour in Al Khoud

Living Conditions: Initially, Al Khoud was marked by primitive living conditions, including a dearth of roads and essential services. The gradual development of amenities contributed to a prolonged low quality of life, mirroring societal apathy toward the displaced populace. Housing constraints dictated by wings and familial sizes further infringed on individual choices.

Perceptions & Stigmatization: Al Khoud was rife with stigmatization, especially in areas like the Yellow Wing, inhabited by the Baloch population. Unemployment and drug abuse became sources of prejudice, with urban stigma echoing this community’s experiences. The perception of housing for disadvantaged citizens led to social marginalization, exposing deeper societal stratifications and imbalances.

Response to Challenges: The government’s response to Al Khoud’s challenges was twofold. While they offered some support, such as affordable housing schemes and financial aid from the Oman Housing Bank, there remained a deficit in essential services and significant hurdles in accessing employment and shopping areas. A punitive approach, evident in forced relocations and imprisonments, contrasts with sporadic responsiveness.