Atlas of Collective Living Design and Research

Atlas of Collective Living Design and Research

TERM I

PARTS, UNITS AND GROUPS : Analysis of architectural precedents

From Brewing Democracy to Brewing Flat Whites: The Evolution of the Coffee House Arielle Lavine

Mediated Centres: Broadcasting the Public Space Christos Smyrniotis

Common, Ordinary, Everyday Life: The City As Platform Kok Seng(Bryan) Chee

Unveiling the Cosmos: Astronomical Observatories Luis Young

Inhabited Infrastructure: Living Bridges

Mohammed Al Balushi

Kitchen: A Gendered Space Xiaochi Chen

Behind the Elevation: Study of Metropolitan Police Station Yi Shi

Live in Low Rise, Life in High Density Yuanbo Jia

Typical Plan

Zhijun Lei

TERM II

SCALES: FROM THE ROOM TO THE CITY

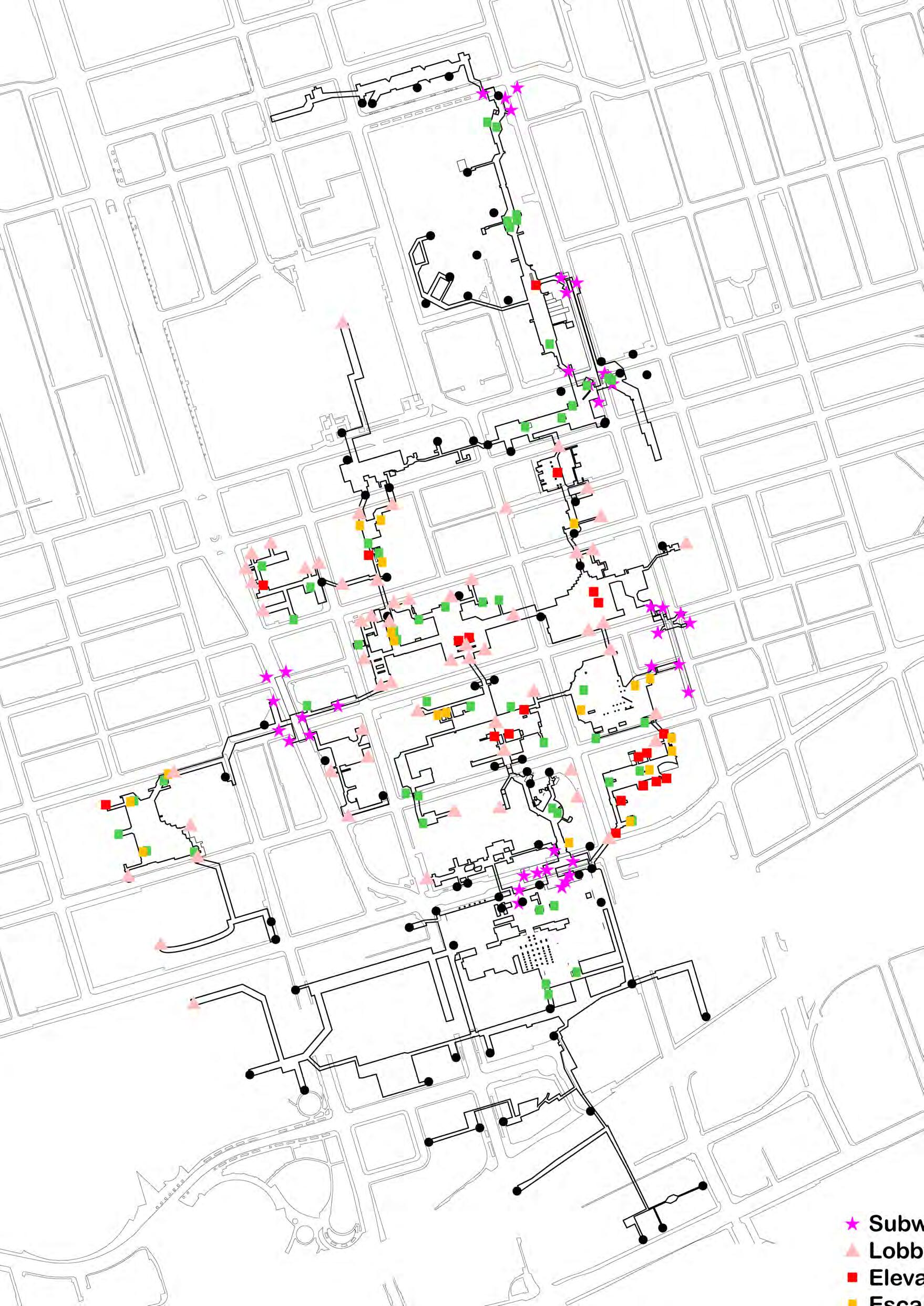

The Path: The Urbanism of the Commuter-Consumer Arielle Lavine

Constructing Britishness: The Landsbury Estate Christos Smyrniotis

Festival As a Project: From Social Culture to Nature Culture Kok Seng (Bryan) Chee

Unveiling Layers: Redensification in the Highbury Quadrant Estate Luis Young

From Muscat to London: A Multi-Scalar Journey Mohammed Al Balushi

Rethinking the Dialogue Between People and Community: Gender issues in Historical and Modern Urban Planning Xiaochi Chen

The Idea of North: The common Frameworks of the Collective Living in Beijing Yi Shi

Station Transforms, Transformed Station Yuanbo Jia

Marketplaces and Metropolises Zhijun Lei

TERM I STUDIO

PARTS, UNITS AND GROUPS: ANALYSIS OF ARCHITECTURAL PRECEDENTS

Taught MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design (Projective Cities)

In Term 1 of Projective Cities, students investigate different organizational, formal, programmatic, and material particularities that define the Architecture of Collective Living through series of historic and contemporary case studies, allowing the framing of a design approach and development of. A common theme is established as a starting point for each individual research agenda.

The different political, economic, social, and cultural dimensions are reflected in a number of parameters that emerge by a series of conflictual aims and ambitions. Different concepts of social, familial and gender relations, management and decision-making protocols, procurement models, public and private development strategies define the diagrammatic and formal relations of how we live together. All these points define a network of diagrammatic relations that emerge in a series of conflicts and their interrelated scales through which housing and the city are conceptualised: the scale of architecture, its specificity and typological analysis, the urban scale, its configuration, limits, and centralities but also the political and socio-economic realities that organise it, the national scale and the establishment of a citizenry, and finally the regional scale and its economic and geopolitical realities.

Architecture of Collective Living therefore opens up a discussion of how the urban can be understood through specific architecture and its design, and how its effect as an urban armature is not only of spatial importance, but equally organised by larger political and social discourses.

The spatial organization of the Architecture of Collective Living is reflected on a series of informal and formal relations between subjects, spaces, structural and non-structural elements, objects, and protocols of use and occupation. Any form of collective living is characterised by this multiscalar network of power relations that is specific and particular to each social group and collective that lives together. A series of asymmetries and conflicts emerge that require a resolution framework or at least protocols of conduct. What architecture does is to set up some of these parameters, mainly the definition of units, the relations between parts and the way groups of spaces and people are organised.

Architectural typologies of collective living are shaped by these distinct social diagrams but could vary spatially and formally.

Typically, collective living organises part to whole relations that set levels of interaction between individuals: rooms, dwelling units, horizontal and vertical circulations, spaces of collective activities and programmes, complexes, and larger groupings. Distinct types such as courtyards, towers, linear blocks and composite and hybrid types organize the ways and the spaces these different interactions could occur.

Collective living and its politically, historically, socially, economically, and culturally specific characteristics have the capacity to challenge the fundamental diagram of modernity: domesticity. The domestic is a spatial and social diagram that sets very specific hierarchies and relations :gender, age, and programmatic. Today, the single-family dwelling is challenged by the realities of contemporary urban environments. New subjectivities have emerged: many live outside family structures, a younger generation shares housing and working spaces, an increasingly precarious and migrant working force requires short term, serviced accommodation, elderly population has become more present and active in cities across the world.

The reality of the real estate market, the available design tools and building methods and standards are not necessarily reflecting upon the above transformations. Often, the challenges of new forms of collective living are tackled as a financial problem, or an issue of density and lifestyle. However, historically collective living and forms of living together has had the capacity of opening up social and spatial imagination. Today, there is an array of incredibly interesting experimentation in collective living protocols and architectural configurations, such as new forms of cooperatives that have proposed new types of collective living units, such as the ‘cluster apartment’. Moreover, public administrations and private stakeholders are seeking new ideas that would allow for an imaginative transformation of how people live in cities, in urban and rural areas across the world.

Thus, one of the challenges arising from the Architecture of Collective Living is how architecture can respond to changing political, cultural, economic, and urban contexts and how to propose new effective design ideas and models. What is the agency of architecture? How do we develop a pedagogical model that

allows for a more effective relation between academic institutions and practice?

Based on the studied type, the identified formative diagrams, and typological transformations, a short design exercise is proposed by each student. Learning from the case studies, each has selected his/her own target site and will formulate relevant research questions, to address a project for a (new) form of collective living for specific subjects. The synthesis of historical analyses, their embedded social and familial relations, modes of production, and forms of association, in relation to specific sociopolitical context of the chosen site, have generated a frame of relations, and organizational diagrams that are developed into a series of projective drawings, models, writings, and moving images.

THE EVOLUTION OF THE COFFEE HOUSE

Our contemporary industrialized society runs on caffeine. Drinking coffee–in a disposable paper cup, thermos on the go, or during a peaceful moment at home–defines many people’s daily routines. The café today is a ubiquitous space, recognizable by its token beverage but also for its spatial signifiers (such as the café table, the coffee machine, and the bar counter). The word ‘café’ alone is a signifier, where in contemporary gentrifying developments a trendy café easily takes the place of other community amenities and social spaces. The symbolic space of the café is enhanced by its representation in media, which has been important to not only the marketing of coffee but also to the culture and work ethic created around it. The cafe, by necessity, distances itself from the fraught history of coffee.

Anthropologist Ray Oldenburg fights for the contemporary café as an essential public social space, or “third place” between the home and the workplace. The café as an interior program has served numerous architects’ explorations and theories on the public interior, democratic gathering space, and on what constitutes a universally comfortable space. Notably Adolf Loos’ Café Museum which puts the Metropolitan figure on centre stage, and Christopher Alexander’s Linz Café. Alexander chose a café as the perfect interior programme to express his theories on comfort and the timeless way of building.

The modern café is so saturated with displaced symbols— immutable mobiles—that the café exists in a transitory and mobile state, more important in the minds of its users than the physical place itself. Meanwhile the political and public forum function of the café have been pushed out by the commodification and

corporate exploitation of the café space. The threshold of the café experience, which is displaced through the takeaway cup, stages both the familiar and the strange as it moves.

This research responds to Oldenburg’s proposition about the contemporary café by exploring the typological evolution of the café space. Between each of the six chosen case studies, the fashions and architectural styles changed, though certain objects and arrangements form a common thread between them.

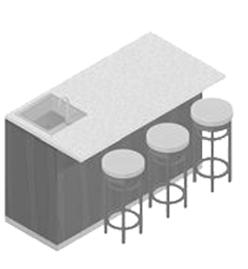

The signifiers of the café space – the marble café table of the Caffe Florian is examined through a design exercise – reproducing the marble table through contemporary materials and processes. It presents a challenge: the heavy marble leg against the moveable paper cup. If the marble table anchors the coffee experience in a specific place, so the consumption is about both the drink and the space, the disposable cup unbinds the coffee from its setting, while still holding a significance to a social and leisure ritual of the coffee drinking. A 1:20 model inside the 1:1 reproduction of the marble table explores the staging elements of the café. One room is a recreation of the Senate Room of the Caffe Florian, and its mirror is the contemporary café – flipping the seating arrangement with the inclusion of outlets, bar height seating and counters facing the exterior of the room. The café in this scenario is no longer a space turning its occupants into actors on stage, but background characters in a productive setting.

Study of the Senate Room, Caffè Florian Venice, 1720

This research project examines the infrastructure of telecommunication networks, specifically the transmission of messages over long distances. The study focuses on the telecommunication tower, a structure developed and utilised throughout the 20th century as an antenna carrier for transmitting messages. Through this case study, the project aims to reveal how the introduction of towers and their technology have impacted the concept of the public realm and its urban spatial manifestation.

Telecommunication devices have influenced the creation of modern urban spaces by allowing for distant, instantaneous information exchanges and extended reach. They have enabled social networks to detach from physical space, liberating planning from the constraints of proximity requirements in the scope of more interconnected societies. Telecommunication systems have partially appropriated the field of the public sphere, which was previously manifested through formal public spaces where social networks would emerge. The introduction of telecommunication technology affected the notion of the public sphere, which became disembodied, while public space was reframed as a leisure space.

As such, radio wave technology has allowed networks to refer to a vast field on a potentially global scale. This detachment of public events and public space, along with the infinity of events and individuals that could occupy the public stage, has led to a necessary selection process for information chosen for broadcasting and formulated into narratives and messages. Central media institutions have acted as practical masters of this process, producing a curated, mono-directional, broadcasted public sphere. As a result, they have become a new type of urban social centre, a "mediated centre" 1, in which the conditioning of reality carried by central media became the field of production of symbolic power through the definition of realities, normalities, and mass subjectivities.

During the 1950s, radio wavelengths became available to the general public, under the scope of public service, through domesticated devices such as antennas and TV sets that connected with central infrastructural entities such as studios, broadcasting stations, and antennas. In the process, the effect of mediation was multiplied.

The telecommunication tower, an architectural type developed during the period, acted as the infrastructural and symbolic centre of the new network. These monumental structures were designed to represent their context's technological and cultural progress while also becoming symbols of their cities. Made to see and be seen, towers enclose programms that surpass their infrastructural role and become representational spaces of centrality. The line of sight becomes the generator of the structure, oscillating between infrastructure and spectacle. More than antennas, they are public spaces, tourist destinations, panoramas, and spaces of leisure and consumption that operate in parallel with apparatuses that, through their architecture, reproduce the myth of central media as distributing agents of the public sphere.

The ascend to the panorama is framed as the primary ritual of the passage from the ordinary to the spaces of reality construction. Barriers, security checks, and ticket admissions highlight the importance of private machinic areas, establishing the difference between those inside and outside the tower. The apparatus room, the most actant of the spaces in the scope of the network, is deliberately black-boxed, protecting the authority of the apparatus. The moment the visitor passes through the apparatus room encapsulates the naturalised conditions sustained by the ritual and exposes the state of a believed participation in the apparatus. The apparatus room is primarily an obscured void that coexists with culture's well-maintained desires.

1. Nick Couldry, “Media Rituals: Beyond Functionalism,” Media Anthropology, 2005

Right: Urban Sections

Common, Ordinary, Everyday Life

The City As Platform

Today, the word “platform” seems common, has been widely used, and has been populated in the digital world in recent decades. Looking at the origin of the word itself, “platform” is derived from the middle French “plateforme,”which means “platform” or “flat surface.” Within the dictionary, platforms carry one of the three common definitions. First, it is an elevated stage that involves a theatrical experience between the performer and audience where speeches and performances are made. The second is a raised floor that caters to any purpose. The third is an opportunity to communicate ideas and information to a group of people.

Platforms have a long history as an architectural element in architectural development. For example, the use of the ground and raising the floor as a platform has been commonly practised for everyday life activities and ritual ceremonies such as cooking, sleeping, and socio space—domestic platform, such as long house or “rumah panjang” in the Borneo island. A public platform, on the other hand, is well captured in the orchestra of the ancient Greek theater, where it involves a theatrical experience through the stage between the performance and audience participation. (Dogma. 2021)

Platform adoption has accelerated in the digital age, particularly with the recent pandemic, as evidenced by Uber, Deliveroo, Zoom, Facebook, and others.At a glance, platforms as a subjectivity provide opportunities for networking, cross-collaboration, information exchange, and making the impossible possible. The concept of platform has now been expanded from only dealing with its physical aspects, such as surface, materiality, border, edges, and levels, to include Habermas’ suggestion of the public sphere.

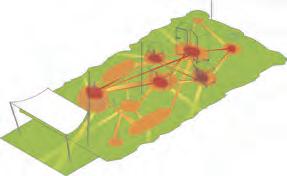

Through the research, it shows us that the small “urban platforms” are even more important in the city. To cultivate a democratic public sphere, it is necessary for us to able imagine such platforms are able to be disperse as many as possible in our everyday space and neighbourhood. The city as a platform is to encourage each of us come together as a collective to be creative in create, claim, collaborate and activate every corner of the urban as common space.

The design exercise attempts to investigate the idea of the platform as a typology by deconstructing and extracting the fundamental aspect of case studies. In conclusion, the research is an attempt to emphasize the notion of affordance and to redefine the platform as an alternative common for collective living in urban space.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Switzerland, 1999.

Unveiling the Cosmos: Astronomical Observatories

Luis Young

Unveiling the Cosmos: From Ancient to Modern Astronomical Observatories in the UK.

The Act of Obelisking explores the territoriality of the obelisk by, firstly, shifting the conceptual interrogation from the obelisk-object to the obelisking-process; and secondly, by means of a combined method of writing, re-writing and re-drawing specific references as evidence of obelisk-ing as figures of territory.

Formally, the obelisk can be defined as a standing stone, a monolith — a single quarried stone of Aswan granite. In objective historical terms, the obelisk is burdened with appropriation. They are objects of monumental colonization and immigrants in their own right, seeking refuge — seeking an existential grounding — in places that are not their own. It must be emphasized that in conceptualizing the obelisk as an affectual-thing, which serves as an intermediary in the process of recalibration, its history of appropriation is critically considered as not to undermine the integrity that collective memory holds in connecting temporal boundaries within a single (and assembly of) urban artefacts amongst the city.

While honouring the obelisk’s history, this project explores a further appropriation of the obelisk, albeit this time semantically, into a verb: To obelisk (v.) is the process of negotiating and recalibrating territory — transcending its confines as a 3-dimensional object — into an affectual-thing, what Heidegger describes as concrete space, allowing one to identify with the environment as meaningful in the figuration of territory.

1 The City Observatory, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK.

2 The Royal Observatory of Greenwich, London, England, UK.

3

4

5

6

Inhabited Infrastructure: Living Bridges

Amidst the vast tapestry of human ingenuity and remarkable architectural achievements, bridges have stood as iconic symbols of connectivity and progress. They have served as gateways, seamlessly linking diverse landscapes, cultures, and individuals. However, within this realm of boundless possibilities lies a captivating notion—the metamorphosis of these unassuming structures from mere conduits of passage into thriving spaces of human inhabitation. This project delves into the concept of inhabited bridges, contemplating the profound implications that arise from redefining their function.

Inhabited bridges challenge the conventional understanding of space and purpose, blurring the boundaries between transportation and habitation. They breathe life into the static, transcending the ordinary to embrace the extraordinary. By imbuing these structures with vitality, a new symbiotic relationship is forged between architecture and humanity, offering a more profound and intimate connection.

As the bridge’s purpose undergoes a transformative shift, its physical form may also evolve. Balconies and alcoves emerge, providing spaces for contemplation and observation. Gardens gracefully cascade down its edges, infusing vitality into the surrounding infrastructure. Skylights and windows beckon natural light to playfully dance upon the bridge’s surfaces, eroding the barriers between inside and outside. With each alteration, the bridge becomes a microcosm of human existence, mirroring our capacity to adapt and flourish in ever-changing circumstances.

This project invites the reader to perceive inhabited bridges as more than mere flights of fancy or architectural reveries. They embody a profound shift in perspective, inviting us to re-evaluate the spaces we occupy and the purpose we assign to them. By meticulously selecting case studies situated within diverse urban contexts, the aim is to explore this unique “typology” while simultaneously transcending the limits of our imagination. It impels us to envision a world where structures become living embodiments of our collective aspirations.

This is the moment when we liberate the bridge from all constraints, enabling us to observe the dynamics of interaction. It is the impact of the vast upon the minuscule, the fusion of the artificial with the natural—an extraordinary meeting place where the restrictions of conventionality become inconsequential, leaving us with nothing but the pure essence of dialogue.

Right: Figure Ground Plans of The Selected Case Studies.

Kitchen: A Gendered Space

Bech-Danielsen defined the kitchen as the most gendered spaces in the historical dwelling. The economic crisis after the First World War resulted in an absence of servants in the market. As a result, kitchen design became a dynamic subject in architecture, and women’s responsibilities in society and in the family experienced a tremendous evolution. Over the past one hundred years, the domestic kitchen effectively mirrors the transformation of women’s identities in the family.

My central hypothesis is that despite the diminishing of the women’s sense of imprisonment in the modern kitchen, the gendered differences in the kitchen remains. This research will firstly advance a more nuanced understanding of the power dynamics of Western domestic kitchens in the twentieth century. Subsequently, it will challenge the conventional meaning of how the modern kitchen influenced the transformation of female subjectivities. Furthermore, attention is directed to explore the status of reproductive labor in social construction.

Kitchen design has oscillated between having a central versus supportive role in the home. From being part of the main space of the dwelling, to being separated and hidden in a closed, defined room, to once again being open and flexible. The initial semi-open kitchen was used by servants and housewives, and the kitchen was an auxiliary space in the dwelling. Then, when the family unit became the basic unit of society, functional space had to be kept to a tolerable size. Now, the mainstream lifestyle of modern society requires compact layouts and semi-open spaces for maximum use.

Being a good wife and mother means a woman must perform the labor of reproduction; and cooking at home remains the mark of a woman’s identity today, regardless of the increased involvement of men in the kitchen. No matter how modern the design is, as long as patriarchy exists, the gender gap in the kitchen will not be eliminated.

“The blue Lamp” is a British film in the 1950s about a policeman named George Dixon and his life. At the beginning of the film, it opens with a bystander announcing:

“To this man, until today, the crime wave was nothing but a newspaper headline. What stands between the ordinary public and this outbreak of crime: what protection has the man in the street to this armed threat to his life and property? At the old Bailey, Mr. Justice Fennimore in passing sentence for a crime of robbery with violence gave this plain answer: “ This is perhaps another illustration of the disaster caused by insufficient numbers of police. I have no doubt that on of the best preventives of crime is the regular uniformed police officer on the beat.”¹

This construction of the crime problem and its solution reflect that the British police lived with the unrealistic belief that they were no more than ordinary citizens in uniform and that they could rely on the assistance and positive support of the public. Then, the truth is the majority of people had little contact with police in their daily life.

Apart from those fictional assumptions, the police stations are widely considered by the mass as “the home of policemen”. Admittedly, since the end of the 19th century, police were born from concepts to institutions; the police stations was regarded as the core facility sitting at the center of this department. Behind the Elevation: Study of

1 The Blue Lamp, Film (General Film Distributors, 1950), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1C_6_tPj33A.

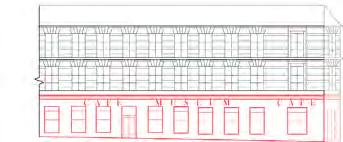

DESIGN PROPOSITION: FAÇADE PROJECT TO PLAN

The spatial nesting and sequencing; circulation operation; room hierarchy, and juxtaposition transfer the police station into a sophisticated device of policing, which articulate the control, surveillance and power structure embedded within the building.

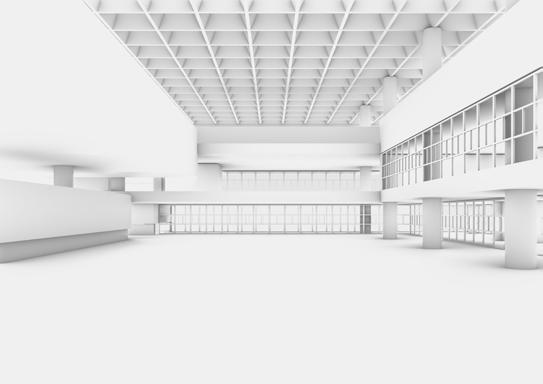

At present, high-rise buildings are the preferred solution to the housing problem in more cities, but this has led to a certain extent of isolation for the residents of high-rise buildings, with completely vertical repetitive floors and closed walls that clearly divide the interior from the exterior, leaving the occupants inside with no connection to the outside environment other than visual transparency. As a result, the residents are largely deprived of communal life and living becomes a mere survival.

When I first arrived in London, I was struck by the fact that I was in the suburbs with an unobstructed view of the city centre’s tall buildings, something that is not possible in most developed cities, but in London there are such low-rise, high-density, postwar residential buildings that were built as council houses for the working class to rent at affordable rents. Because of the change in ownership of these houses at the end of the last century as a result of legislation relating to the privatisation of housing, they are still available on the rental and sale market and are in good condition today. By comparison with high-rise residential buildings, I believe that it is the high spatial quality provided by the private open spaces of open terraces and open courtyards that are prevalent in this type of housing that make these homes, which are over 50 years old, still attractive in the rental market.

This research analyzes some representative architectural precedents, studies the distribution of indoor space and private open space and public space in the building and the connection between these spaces, trying to summarize why more public event has a chance to happen.

Regarding the design, I think the most interesting thing about this type of building is its sections, and the sections undoubtedly

present the most connections between the floor slabs and the individual slabs themselves, so I extracted the two architectural elements, the floor slabs and the stairs, as the main part of my design, and wanted to downplay any other architectural elements, especially the walls, in order to achieve a floating effect.

THOUGHTS ON HIGH-RISE OFFICE BUILDINGS

When I first considered collective living, I thought that although I didn’t know what the ideal state of collective living would be, it certainly wouldn’t be boring and repetitive. As I connected the concepts of boredom and repetition, I found what I considered to be the “most boring” and “highest repetition” thing—the Typical Plan. I found the opposite of an ideal life and tried to use it as a starting point for finding an ideal life. I sought to discover the Atypical Plan within the Typical Plan. However, as I conducted my research, I realized that repetition doesn’t necessarily equate to boredom, especially when it holds unlimited potential.

1. High-rise Building

Before talking about Typical Plan, let’s start with high-rise buildings, because they are inseparable. High-rise building is a very special kind of building. It used to be a symbol of the city’s prosperity and development. In 1890 high-rise building was the future of American. It had also been criticized. With the downturn in the economy and the start of the City Beautiful Movement, the development of tower has declined. No matter how people’s attitude changes, with the completion of the first high-rise building, skyscraper has become an indispensable part of the city. Unlike low-rise buildings and multistorey buildings highrise building is a behemoth, so it was destined for the limelight, attracting numerous compliments and criticisms. It was the development of economic, technological and social forces in the great twentieth century that created it. High-rise building closely links architectural design and technology. Firstly, as said before, its emergence is inseparable from the development of technology. For example, it’s impossible to build a 10-storey building without

elevator. Not only that, the development of high-rise building also tightly dependent on technology: Structure limits the height of the building and affects the layout of plan; artificial lighting changes the depth of office; heating, ventilation and curtain wall offer a possibility for buildings to reach unprecendented heights.

It is the close combination of architectural design and technology and its business model (users lease offices from skyscraper owners) that lead to the formation of a unique plan type – Typical Plan. The former limits what a skyscraper can be; the latter makes a claim that try to keep the most potential for the plan, because this is the kind of space that business needs.

2.Typical Plan

The Typical Plan is the optimal solution for balancing the interests of many aspects under the existing technological conditions. The essence of it is to provide a no quality space. Koolhaas comments Typical Plan: “… it is equivalent of atonal music, seriality, concrete poetry, art brut; it isarchitecture as mantra.” Typical Plan was the result of the development of the tower, which is now being stripped from the tower.

Typical Plan can be used to guide the design of high-rise building. It in turn helps architects to reconcile technology and architectural space, and its own composition is as empty as possible. Typical Plan is therefore not only the most characteristic part of high-rise building, it is also the core of this kind of building.

Joanna Merwood-Salisbury, Chicago 1890 : The Skyscraper and the Modern City / Joanna Merwood-Salisbury., Chicago Architecture and Urbanism, 2009.

Ibid., 116-26.

Iñaki Abalos and Juan Herreros, Tower and Office : From Modernist Theory to Contemporary Practice, Rev. ed. of Spanish original, 2003, 4.

Rem Koolhaas et al., S, M, L, XL : Small, Medium, Large, Extra-Large, 1995, 337. Ibid., 338.