From Factory to Fireside: Dwelling with Small Manufacturing in London

Shi Yi

MPhil Projective Cities

Architectural Association School of Architecture 2022 - 2024

Shi Yi

MPhil Projective Cities

Architectural Association School of Architecture 2022 - 2024

Dwelling with Small Manufacturing in London

MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design

Projective Cities 2022/2024

This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of many people involved throughout this prolonged process. Firstly, I am grateful to the Projective Cities staff, who have supported me throughout my studies. I would like to deeply thank Platon Issaias and Hamed Khosravi for their knowledgeable guidance, commitment and constant support. I would also like to thank Doreen Bernath and Anna Font Vacas, whose knowledge and patience have helped shape this work and many others. I am also grateful to Roozbeh Elia-Azar, Cristina Gamboa and Daryan Knoblauch. It is an honour to have you as tutor.

I could not be more thankful to all my cohorts and colleagues in the Projective Cities in 2021-2024. I treasure meeting you all and sharing our valuable discussions, experiences in Athens, and shared moments. I would like to thank Chen Xiaochi for her warm help and support throughout the programme.

I want to thank all those who have been by my side during my studies and work in Beijing, Chengdu, and London. I am grateful to the friends and tutors who generously shared their resources and discussed my research and the architectural discourse in general. I want to express my gratitude to the Architectural Association for providing such enormous resources and opportunities.

Finally, I want to express my deepest love to my parents and girlfriend for their unconditional support, care and love.

The thesis takes the urban small-scale factories as its vehicle to interrogate the dynamic role of urban production space to uncover the malleable correlations between our working and living. Based on the context of London and taking the mixed-uses typology as the object of investigation, The thesis investigates the abject history of the rise and fall of urban manufacturing to construct a grand narrative of the city's material reality through a series of case studies, which reveal the spatial and socio-political implications of the small manufacturing in search of new living models that ask for reconciliation between factory and city.

The thesis is structured by three interlinking chapters: manufactured city, outdated work and the compensatory fantasy. Each chapter finds its conclusions by synthesizing the research into a product of design. These chapters set the stage for three explicit research paths that link small manufacturing with urban habitual through reading the urban configurations, labour politics and material culture. It offers a lens through which one can analysis the relationship between individuals, their work, and the rapidly evolving landscape of urban material production.

Moreover, the project not simply advocates reintroducing industry back to the city, nor intends to celebrate the progress of production methods in the digital era, but inquires inward on the fundamental contradictions embedded in the act of making, asking for reconciliation between factory and city.

Looking at the evolution of the relationship between a city and its production economy, one could read a long history of mutual shaping and interdependency, a history disrupted or interrupted by Industrial capitalism in the 19th century when the whole human society encountered a modern paradigm shift: the act of making once deeply intertwined with living at all front was intentionally enclosed, segregated and removed from its operator’s life. This transition, noted by Peter Behrens, the factory is not only a place of production but also a monument, as a Greek temple, needed to be isolated, secured and controlled.1

The co-existence of city and factory renders a tension in between the two figures, which forms people’s rituals, habits and norms. As described by Bianchetti, the city and factory touch each other in different ways. They are the internal horizon of each other, which raises the question about how we could live with industry in the city.2

1. Stanford Anderson, Peter Behrens and a New Architecture for the Twentieth Century (Mit Press, 2002).

2. Cristina Bianchetti, “Factory City: Towards a Critical Planning of Modes de Vie,” in Hybrid Factory, Hybrid City, ed. Nina Rappaport (New York, NY: Actar Publishers, 2022), 16.

“London is so often spoken of as if it were mainly a commercial emporium or distributing centre that it will be a surprise to many to learn that it is the seat of important manufactures and competes with provincial towns in several branches of industrial enterprise not commonly identified with the metropolis.”3

For a long time, London was rather considered as market destination than a manufacturing centre. However, in fact, from the 18th to the 19th century, London was the largest manufacturing city in the world. For its scarce operational space and extremely high land price, manufacturing businesses in London were relatively small and combined with other uses, most of the time with houses.

Argued by Saint, it is precisely this mix uses condition that provides London with the ability to resist the pressure toward segregation, which is more prominent in other comparable cities like Paris, Vienna and Berlin.4

In this sense, London was a unique case study city, where its production sectors accommodated themselves well in miscellaneous mix uses with the traditional house types, which provides us with an opportunity to discuss the way of living with manufacturing in a contemporary city.

Arendt has profoundly elaborated it in Arendt’s idea of homo faber5 and the concept

3. The Chamber of Commerce Journal 17, March 1898, 48.

4. Andrew Saint, ‘London’, AA Files, no. 2 (1982): 22–33, 29.

5. Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition, 1958.

of Aura by Benjamin6 that the act of making coincides with the essence of humanity, highlighting the importance of human creativity and craftsmanship.

Making in urban production means a protocol, a procedure of energy exploitation, and a complex operation process in which raw materials transform into products, creating material reality. In this flux of matters, the arrangement of storage, organisation of operation procedures and product distribution interwoven with other city functions, always formed in hybrid typologies; for instance, the small chocolate makers or other no-pollution businesses could be a decent neighbour in a residential courtyard.

Small manufacturing, unlike mass production, is not all about producing new things; instead, it could lead to a paradigm shift from a supply-and-consume mode economy to a maintenance and circular economy, which has been widely discussed across Europe.7

Modernity describes a propensity towards abstraction, in which everything is uprooted out of its totality to define generic frameworks rather than specific interventions, which renders the city as an inert object that cannot reflect and adapt to new needs and challenges.

6. Walter Benjamin, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, in A Museum Studies Approach to Heritage (Routledge, 2018), 226–43.

7. Iris Kaltenegger and Europan (Organization), EUROPAN15 Austria : Productive Cities. 2, Resources, Mobility, Equity / Editor: Iris Kaltenegger, EUROPAN Austria. (Zurich : Park Books, 2020).

Consequently, this project provides an alternative understanding of the city apart from economic abstractions and functional planning but through specific production activities, spaces, typologies, bodies and desires, manifested by the conflicts and struggles of daily routines facing material production. The city, especially in the global north, turns its face to knowledge production; as a result, the city either expels material production to the peripheral or conceals it in the service backstage. London’s manufacturing has declined significantly during the last 50 years. One prominent influence is the dramatic employment loss in the manufacturing sector. Between 1971 and 1996, London shed around 600,000 manufacturing jobs, and today, only 2.2% of jobs in London are manufacturing related.8

The abundance of needs of manufacturing products or services, such as painting, repairing and maintaining, encountering more and more depressed conditions of material production in the city constructs asymmetrical relationships and invisible exploitation, which renders the urgency and relevancy of this question to contemporary urban development.

These severe conditions force us to answer the question: why should we be embedded manufacturing inside the city? There are extensive discussions around the productive 8. Cities of Making, ‘The City of Making Report’ (Cities of making, 2018), https://citiesofmaking.com/cities-report.

cities and reintroducing industries back to the cities in Europe, focusing on the critique of zoning and rigid industrial planning, which fail to meet the need to mediate the relationship between cities and factories.9

However, in the uK, where land use is not strictly controlled by zoning code but a process of spatial negotiation with local planning authorities, and in London, where small manufacturing has been historically embedded inside the urban configurations, provides opportunities to learn from the past, finding lost qualities and opportunities in the separation of manufacturing and small industries from the city, at same time testing if we could achieve the same quality again by reintroducing manufacturing to the city.

While the land classification system in the uK gradually finds its limits in accommodating new uses such as dark kitchens, which are usually extensively combined with other uses, the city is finding opportunities to relocate creative and advanced manufacturing in former industrial sheds. In a scenario where urban and large-scale infrastructure grounds can seemingly be permeated by smaller and cleaner production mechanisms and units as well as logistic systems, the blurring of functional and structural limits may redefine and autonomously create new metropolitan configurations.10

9. See the exhibition: ‘The Good City Has Industry’, https:// www.architectureworkroom.eu/en/narratives/2756/agood-city-has-industry.

10. See We made that, ‘Made in London Report’ and ‘High

Facing the monotonic and less vitality urban economy and deteriorating employment situation—low employment rate, long working hours and unpaid jobs—the uK government proposed an Industrial Strategy in 2017, outlining a broader picture of a long-term development strategy aiming to ensure that all the area of uK benefit from a solid and prosperous economy through two approaches.11 Firstly, it identifies five foundations for boosting productivity across the business: ideas, people, infrastructure, business environment and place. Secondly, it calls for significant innovation within the industry. It identifies four Grand Challenges set to transform how people live and work in the city. These are AI and the Data Economy, the Future of Mobility, Clean Growth, and an ageing society. The strategy stresses the importance of manufacturing especially the high-value manufacturing sectors.12

Sreet Regenerations’ etc.

11. UK HM Treasury (2021), Policy Paper – Building Back Better: out plan for growth, https://www.gov.uk/government/ publications/build-back-better-our-plan-for-growth 12. ibid.

Facing the housing crisis, the contemporary city shows great interest in industrial intensification and co-location mix-uses by combining residential with manufacturing, which is always by stacking houses on top of the production spaces. 13

These strategies, proposing a series of win-win solutions that not only intervene in the industrial decline but also aim at delivering housing, seem over-optimistic. Real estate speculation is still supported by political motivations, and the asymmetrical spatial relationship between production and consumption is still prominent. Moreover, the dichotomies of dirty and clean work, thinker and operator, are still common sense in mass media and constantly derogate manufacturing works. The potential of urban small manufacturing becomes more apparent with a new understanding of the nuance of this sector. Small manufacturing needs to be redefined to challenge the existing framework and common narrative of manufacturing reading as an independent role detached from the city.

13. We Made That, ‘Industrial Intensification and Co-Location Guidance’ (Greater London Authority, 2019), https:// www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/industrial_intensification.pdf.

The thesis is intended primarily for an audience of policymakers and planning decision-makers and will be of particular interest to those who work in the field of manufacturing and the creative industry.

However, we must clarify that the thesis is not about crafting as a nostalgic art expression. Although the scale of investigated companies is sometimes relatively small, the crucial point is that it has to be a production sector business in that the ultimate products are goods rather than services.

The thesis is to initiate and inform debate about the future of manufacturing in the metropolis like London, by reintroducing small manufacturing and exploring hybrid typologies that could graft working and living together.

The project sees the prevailing debate on productive urbanism as great opportunity to reintegrate the act making with our dwelling and creating new living modes, through which people could be more engaged with the things they made.

The thesis is aiming to redefine urban manufacture, work and space, and its relationship with urban environment, apart form a perspective of an abstract economy, but to propose a new living model with manufacturing.

- How could the industrial remains be integrated into contemporary urban production ecosystem?

- How could urban Light Industry combine with other uses, to formulate a new Mixed-used typology?

- How to instrumentalise this hybrid typology in the urban production network to challenge the supply-consume economy model?

- How to instrumentalise architectural knowledge in the collective decision-making process as social capital, which would facilitate the marginalised worker community with more professional and equitable abilities in negotiating with other parties of interests such as the government and real estate companies?

Manufactured city investigates the city's manufacturability, asking how the city been manufactured and how it manufactures itself. Through out this Chapter, the City manufactures itself and reinforces its manufacturability mainly through three pillars: morphology assemblage, typology evolution and conflict and legislation implementation. The Chapter, therefore, structured with this three pillars, investigating how architecture is been used to in create

or incorporate with the city's manufacturability. The architecture of hybridity portrays the small scale manufacturing as a hybrid mediator through which reciprocal relationships are created by linking material productions with the urban habitual, which essentially is to structure a form of life.

South Shoreditch, a compact area in the north of the City of London, was noted as the furniture manufacturing centre dating back to the nineteenth century. This proximity to the market has significantly shaped its historical ethos as the craftsmen’s home, which specialised in finished goods, not limited to furniture but clothing or coach making, which significantly led to the national fashion trends and tastes. Indeed, the importance of the South Shoreditch economy to the English furniture industry was twofold: as a production centre and as its commercial heart. This hybrid condition was embedded in urban configurations and building typologies.

The spectrum of London’s furniture trade in the 19th century could be broadly divided into two polar: the retail market in the West End and the wholesale market in the East End.14 The 19th-century wholesalers, who adopted an overall control by integrating each step of production into the selling of final products,

were the market makers, creating an ecology that connected everyone, rendering the whole area a district specialised for furniture making. As Charles Booth observed in the 1880s in describing the East End:

“Each district has its character- its peculiar flavour. One seems to be conscious of it in the streets. It may be in the faces of the people, or in what they carry – perhaps a reflection is thrown in this way from the prevailing trades –or it may lie in the sounds one hears, or in the character of the buildings.”15

The specialised block is an apparatus of assimilation, working as the city’s backdrop to resonate everybody’s life, within which people could locate themselves in the urban spatial and economic fabric. This assimilation is so strong that even women and children, whose roles used to be kept in the domestic space apart from the public, were involved and programmed as a chain of the production process by allocating them to specific roles and tasks. The book Family and Kinship in East London described a multi-layered interdependency between individuals and communal in the East End.16 These relationships, manifested in the proximity, subcontracting, family and community kinship, further articulate themselves

Source:

Source:

on the urban configuration and composition.

“When I first started in Brick Lane, every shop there was something to do with wood and the furniture industry. I used to collect our timber in hand cart and wheel it back to factory. I used to go up the road for all our nails and screws. You would go in there and say,‘Can I have two pound of nails?’ And they would weigh them out for you on the scales, that was ow it was done.”17

Moving goods and raw materials was challenging for the pre-machine-age workers. It needed great efforts and resources with extensive collaboration and negotiation. The city, therefore, reflects these needs in its morphologies by juxtaposing different types of space to accommodate various modes of occupation, enabling easy exchanges and collaborations in its proximity.

It was true for Peter Hall’s observation of East London manufacturing: “The real assembly line ran through the streets.”18 However, the production relations were far from linear. Instead, it was a network where production activities were highly integrated with each other and with urban configuration.

The 19th century small industries in the East End significantly relayed on the putting-out system or subcontracting system,

17. “The Last East End Chair Frame Makers”, https://spitalfieldslife.com/2017/06/04/the-last-east-end-chair-framemakers.

18. Peter Hall, Industrial London, 227-8.

which was developed to systematically decentralise production to large, unskilled and low-paid workers.19 Large amount of flows of goods, activities and people need to be effectively reorganised. These multiple networks and fluxes had their spatial counterparts in an urban structure, allowing relative permeability and synergies across scales. Accordingly, the city embraced the connectivity and linkage between exterior and interior spaces. Production spaces were not confined to factory buildings but spread across blocks according to the division of labour. Production activities extended to yards, streets, and larger areas, allowing material and labour movement to cross property lines and boundaries, which are now more rigidly defined. Ownership was not solely tied to buildings and land; instead, it was based on usage rights, making sharing facilities and spaces more readily accepted in the production process.

19. Giorgio

‘Boundless Competition: Subcontracting and the London Economy in the Late Nineteenth Century’, Enterprise & Society 13, no. 3 (2012): 504–37.

The South Shoreditch exemplifies an urban structure that is supportive of a dynamic ecology of crafts and manufacturing, living and working. The juxtaposition, superimposition and the intersection of production activities and circulations create a network of production, which could be read as the ecology of material production.

Conceptualised in these productive morphologies, the act of making was not only an industrial activity that happened within the realm of factories but was rendered as a layer of communication of needs and values mediating the relationship between individuals and communal. This communication layer not only constructs the mixture of uses but also builds concrete social, economic and political affiliations of the urban population, which creates a strong sense of identity.

“That, so far, no generally applicable law governing the formation and development of hybrids has been successfully formulated can hardly be wondered at by anyone who is acquainted with the extent of the task, and can appreciate the difficulties with which experiments of this have to contend.”20

Borrowed from biology, hybridity has been used to describe an ability to create a new identity by combining different elements. Accordingly, hybridity is a strong image that not only creates spaces but is also reflective of the urban condition.

As noted by Joseph Fenton in the hybrid building in Pamphlet Architecture 11, “The hybrid building is a barometer recording the evolution of our society. Each new juxtaposition reflects a willingness to confront the present and to extend exploration into the future.” 21

The productive hybridity implies a proactive historical process in combining complex elements, types of uses and spaces in the typological evolution of small manufacturing space in London. This evolution manifests the city’s

Fig 07. (Opposite) The Harris Lebus Cabinet Works, Tottenham Hale,1900s.

Source: Harris Lebus Archive.

20. Gregor Mendel, from his Experiments in Plant-Hybridisation, 1866.

21. Joseph Fenton et al., Pamphlet Architecture 11-20. (New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 2011).

manufacturability of adapting itself to the changing need of production methods and relations.22 The mixed-use type of architecture was extensively used in furniture trading and manufacturing in the East End, which encompassed several separate stages and categories: workspaces for manufacturing, showroom-warehouses assem-

22. Cristina Bianchetti, “Factory City: Towards a Critical Planning of Modes de Vie,” in Hybrid Factory, Hybrid City, ed. Nina Rappaport (New York, NY: Actar Publishers, 2022), 16.

blage for displaying and storing, timber yards and saw-mills for supplying.23

The extremely small-scale workspace is the garret master’s house, comprising all his living and working in a compact room or attic. The garret master usually stands for a single man living long, but sometimes several garret masters may share tenancies in one slum house. They worked within their home, producing only one or two items a week either to order or speculatively, wandering on the street market with the products on their borrows or carts to be hawked

23. Joanna Smith and Ray Rogers, Behind the Veneer: The South Shoreditch Furniture Trade and Its Buildings (Swindon, England: English Heritage, 2006), 21.

Source: Drawn by Author.

around the dealers and retailers. At the end of the 19th century, this type of manufacturing combined with living was considered a slum to be removed in the clearance movement. At that time, working in a shared domestic space was quite common. One existing build is on Fournier Street, where the furniture makers appropriated the house originally developed for Huguenot silk weavers in the 18th century. unlike the regular Georgian houses that place staircases in the middle of

the house to integrate multiple floor circulation, the staircases in the ‘weavers’ house’ were intentionally placed just behind the front door, indicating the houses were designed for shared tenancy since this arrangement of the staircase was to prevent occupants in the different floor from intruding on each other. Works were sometimes shared among the tenants in the building, and evidence could be seen in Charles Booth’s survey of London life and labour: Mrs Sturger, an upholsterer whose business was carried on ‘in a small way of business’ from her parlour at 22 Curtain Road in the 1889.24

With their open, flexible and adaptable internal configurations, these types of buildings were purposefully designed to accommodate the multiple, changing forms of inhabitation. In the second part of the 19th century, society started to rethink the way in which machinery and division of labour change society.25

Source: Drawn by Author.

24. Charles Booth, interview with Mrs Sturger/A/7, p. 303

25. David Pye, The nature and art of workmanship(The Herbert Press 1995), 27.

Source: Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

Fig 12. (Opposite) Houses and Shops, 99-101 Worship Street, Finsbury, London, 1863.

Source: RIBA Collections.

The Worship St. Workshops, designed by Philip Webb, a combination of houses, shops and rear workshops, was a representative building of a prevailing repercussion of the Arts and Crafts moments. Although the Arts and Crafts movement evolved in the city, at its heart was nostalgia for rural traditions and ‘the simple life’, which meant that living and working in the countryside was the ideal to which many of its artists aspired. Therefore, this building attempted to prompt a form of life to fulfil a pastoral living and working fantasy.

Fig 13. (Previous opposite) Isometric drawing shows the combination of house entrance with shop front, 99-101 Worship Street, Finsbury, London, 1863.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 14. (Previous) Houses and Shops, 99-101 Worship Street, Finsbury, London, 1863.

Source: RIBA Collections.

Fig 15. (Opposite) Axonometric, Lamp Manufactory Company in No.10~14 Leonard St, London, 1883.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, there was a significant shift towards constructing workshops as independent premises for specific types of production rather than as extensions of other buildings. There were large scale industrial developments in the city, like the Leonard Street built in the 1870s, a terrace of workshops, equipped with large shop windows on the ground floor; these workshops could serve dual purposes, functioning as both showroom-warehouses and, if machinery was installed, as factories. The Iron cranes and take-in door on the main façade indicate that these are self-contained workshops. The goods it processed were no longer intermediate products but final productions.

The lamp manufactory was one of the occupants on Leonard Street, accommodating 75 male workers in the upper floor workshops, specialised in particular production procedures, such as japanning, painting, and metal and tin working. The ground floor was used as a showroom where two female shopkeepers were employed to introduce and lead the customers to go upstairs and see how the newest products were made on-site. Displaying and manufacturing were integrated within this type of building, where production was not secured and isolated but highly exposed, exhibited and could be physically experienced.

16. Ground floor plan and basement plan of the terraced workshops, Leonard Street, Shoreditch, London, 1880s.

Source: Drawn by Author.

17. Floor plan, Lamp Manufactory Company in No.10~14 Leonard St, London, 1883

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 18. (Opposite) Warehouses in Leonard Street, Shoreditch, Hackney,

Source: Photograph by Peter Marschall, 1988.

There were few big cabinet establishments in the East End. One example would be William Walker and Son on Bunhill Row in 1883. It was known as the steam cabinet maker for employing the steam power in production. The building comprised two four-story workshops, ground-floor showrooms, warehouses under a giant steel roof with skylights for maximum light and bridges for circulation of goods and people. Raw materials and sawmills were kept in the timber yards in the back of the building. Although these big factories got the whole process in-house, there were still extensive corporations between these big premises and independent cabinet makers.

Fig 19. The steam cabinet works of William Walker and Sons, depicted on a trade card of the 1880s. The machinery was located on the ground floor beneath the workshops, while the yard was used as a packing space and wood store.

Source: Museum of Home, London.

Fig 20. (In the two following pages) Typological matrix, and functional analysis.

Source: Drawn by Author.

These hybrid architectures create a series of archetypes by combining different uses and elements into a mixed-used type. Co-existing of multi-scalar businesses creates inclusive diversity and adaptation in the area, which would significantly stimulate corporations and negotiations. The assemblage of archetypes formulates an eco-system of furniture making.

This typology evolution manifests a proliferation of using architecture to create separations in need of fulfilling the fast-changing need of industrial production, which is further developed by modern architecture, a propensity towards a more defined dichotomy between space for production and reproduction.

During the wars, most factories were moved out of London to avoid being attacked, as they were the prior targets during the Blitz. The war not only caused severe damage to the factory buildings but also generated a common sense that the city needed to reorganise its industry, taking action on the deteriorating sanitation and pollution issues in the city centre. The authorities viewed this as a great opportunity to propose a new urban plan to rebuild and regenerate London.26

The County of London Plan of 1943 prescribed distinct zones of activity, recommending the decentralisation of London’s industry. It was acknowledged that moving industry from the city is not as simple as moving the factory buildings. Moreover, it is to rebuild the social and economic relationships elsewhere;

26. E. J. L. Griffith, Moving Industry from London, The Town Planning Review, Apr. 1955, Vol.26, No.1, 52.

in short, it is to create a new life outside the city.

Particularly in the East End, constellating with small factories and workshops, due to their close ties with the local community, could not just be relocated. Instead, there was a need to maintain them in proximity to the residences of their workforce, consolidating them within affordable premises.27

Coinciding with this perception, at the end of their influential book Family and Kinship in East London, Michal Yang and Peter Willmott wrote:

“The sense of loyalty to each other amongst the inhabitants of a place like Bethnal Green is not due to buildings. It is due far more to ties

27. J. H. Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie, County of London Plan,(HM Stationery Office,1944), 97–8.

of kinship and friendship…In such a district community spirit does not have to be fostered, it is already there. If the authorities regard that spirit as a social asset worth preserving, they will not uproot more people, but build the new houses around the social groups to which they already belong.”28

The planning authorities widely acknowledged this investigation and observations. Therefore, they recommended the building of flatted or ‘unit’ factories to keep the industry local as well as intensify them, which were believed suitable for clothing, light engineering,

28. Michael Dunlop Young and Peter Willmott, Family and Kinship in East London, Pelican Books (Harmondsworth : Penguin Books, 1957). 165–6.

light chemicals and chemists preparations, and the furniture Industry.

The flatted factory on Long Street, Shoreditch, London, was one of the first generation unit factories built by LCC in 1958.29

The scheme comprises three four-story blocks

The of The unit The workshops The in The a The triangular The site The with access yards

29. The Units Factory in Long St., Shoreditch, 1958. SC_ PHL_02_0910_58_3430, London Metropolitan Archives.

Source: RIBA Collections.

Source: RIBA Collections.

and stores. There are 56 basic units of 1,200 sq. ft each, which may be divided or combined in various ways to give a range of workshop sizes from 300sq.ft to 2,400 sq. ft. Instead of using a corridor to access each workshop, the long slab building is divided into several distinct units to prevent disturbance from each other. Each unit approached with a central circulation core containing a staircase, goods and passenger lift, lavatories and ducts. The building achieved a maximum

open internal space by centralising all auxiliaries in a minimised semi-exterior space, using pre-casted concrete columns and beams with grey brick infill panels on a regular grid, which occupants could further subdivide according to their respective needs.

Differentiating from some big factories utilising their iconic façade as an advertisement for their products30 the flatted factories, since they were designed for small businesses emphasising flexibility and efficiency, are the architecture of utilitarianism rejecting any redundant representations.

However, the flatted factories scheme did not work as expected and failed in the 70s; with their good heart of accommodating local industry to help keep the workers and their families in place, these factories were either demolished or transformed into other uses.31

24. Aladdin Ltd, Greenford. Architect: Nicholas & Dixon Spain, 1933. Factories facing on to busy highways or railway lines were often floodlit, with the building itself serving as an advertisement for its products - oil lamps.

Source:Architects’ Journal, 31 August 1931, and photograph by Jon Bolter.

Fig 25. (Opposite) Typical Floor Plan, Flatted Factory, Shoreditch, London, 1958.

Source: Drawn by Author.

30. Jon Bolter, The works: Factories in London, 1918-1939, Part 1(AAFiles, 1998, No.36), 46.

31. In fact, most flatted factories were eventually demolished because the basic workshop unit, lacking corridors, was too large to be converted into residential spaces. Additionally, both then and now, there was greater interest in regenerating the remnants of old factories for office use.

Today, the city’s industry faces a much more severe condition than in the 50s. Facing the decline of vacancy rate of industry job, loss of industrial lands, housing crisis and gentrification, the London Planning Authority introducing policies that simultaneously aim to halt the further loss of industrial capacity and to mediate the housing and industry in the city.32

The limitation of land provision stimulates the competition of land between housing and industry. However, the competition became increasingly unfair; housing became the preferred use and won almost every match since it could not only raise the land exchange value in a short time frame but also because it provides accommodation for the working force in the higher value economic sectors, which is seen as the highest value by neoliberalism economy. Real estate is a process towards de-mixing for purity. Moreover, real estate speculation is often supported by political motivations33 , with financial sectors and the mass media, by which the dichotomy between space for life and for work is reinforced.

Fig 26. (Previous opposite) Flatted factories(Known as Regent Studio), Ada Street, Hackney, London,1944.

Source: The Courtauld Institute of Art. CC-BY-NC.

32. The London Plan 2021, (London: Greater London Authority, 2020).

33. Rast, Joel, “Manufacturing Industrial Decline: The Politics of Economic Change in Chicago, 1955–1998”, Journal of Urban Affairs 23-2(2001) 175–90.

27. London Indstrial Land Distribution

Source: Industrial Intensification Report, WeMadeThat, 2017.

Accordingly, there is clearly a need for the local authority to find a new typology that combines light industry with housing into a reciprocal relationship, upon which unconventional socio-political agenda could be implemented and prescribed distinction could be challenged. However, the London planning authority attempted to promote an ambitious win-win solution: deliver more houses and, at the same time, accommodate existing industrial businesses and projected future demands. However, the solution that stacks houses on top of an industrial space somehow seems over-optimistic and over-simplified.34 Moreover, with little political and social intervention, the aim soon reduced to housing oriented, by which the city could deliver more houses within mixeduse developments on industrial land.35

28. (Opposite top) Stacked large industrial; (Opposite bottom) Stacked medium industrial with residential. Source: Industrial Intensification and Co-Location Guidance, WeMadeThat, 2019.

34. “Industrial Intensification Primer”, (London: Greater London Authority, 2015), 25.

35. Jessica Ferm, ‘Governing Urban Development on Industrial Land in Global Cities: Lessons from London’, in Critical Dialogues of Urban Governance, Development and Activism, ed. Susannah Bunce et al., London and Toronto (UCL Press, 2020), 115–29, 122.

The design intervention proposes a Municipal Enclave as an urban laboratory, a test ground that enables radical interventions and strategies taking place to challenge the prescribed framework of industry management in London. The Enclave project proposes a 500m by 500m square territory in South Shoreditch, Hackney, imposing a series of multi-scalar and mixed-used spaces of urban manufacturing into the urban fabric to regenerate the city's manufacturability. This Enclave Project should be read as a city within the city, which is excluded from the territory and connects exterior infrastructurally in a way that the Enclave could detour from the existing dominant power of Real Estate and the Housing Crisis.

Fig 29. Evolving context in the enclave territory illustrates the dynamic urban fabric and configuration.

The spatial elements related to an urban industry, such as monuments, car parking, industrial remains, production yards and streets, are selected, mapped, and organised into a laminated city mapping. A superimposed nine-square grid system, which frames a piece of city as an urban laboratory, indicates an equal distribution of production units and facilities in the Enclave.

The superimposed grid and the mapping of manufacturing elements materialise a visible structure of the urban material production, a framework of combining manufacturing with other uses, within which a series of multi-scalar architecture could be introduced to the Enclave and further categorised as block, yard and room.

Shoreditch Makers

Building

1. The enclave has 33 industrial remains and the total gross floorplan area: 1,076,391 sq ft. Proposed addition space is 53,819 sq ft.

2. After 25 years under the scheme, the rentable manufacturing space in enclave would raise to 1,130,210 sq ft.

3. Shoreditch & Old Street 2024 Grade B office rent: £55~£60 per square feet; Industrial Rent: £34~£40per square feet.

4. Slope of the cost of rent is estimated base on the east end Grade B office rental price from 2001 to 2017.

5. Funding and Tax reduction is not considered.

6. All source of data come from Savills

The Enclave Project Team proposed an alternative institutional framework of land development in the Enclave, aiming at detouring from the dominant of housing real estate and rental office market, which crystalise and stratify the city into a banal desert, bringing in more parties of interests and establishing reciprocal relationships. As the operational subject, the Project Team is a non-profit corporation whose responsibilities are establishing a platform for local makers, funding, stimulating an ecology for small manufacturing businesses, and bargaining with landlords. The diagram evaluates the Enclave Project Team's profitability, using previous rental market data to project a Break-even point of cost and revenue 40 years after implementing the scheme. For the project team: the major costs include the long-term tenancy rents and refurbishment expenses; the main revenue includes the deducted rents, funding from local authorities and the management fee, which is 10% of the yearly income of the small manufacturing businesses. underpinned by this institutional framework, small manufacturing businesses could be easier to initiate. The policy paves the road for small manufacturing to combine with other uses in the city centre.

The Threshold factory introduces a linear production layout aimed at enhancing connections between different urban blocks. This design utilises the existing yards along the property line, expanding the shared wall between buildings to facilitate the movement of goods and production processes. Additionally, it repurposes unused offices and industrial remnants as workspaces. As a result, the design breaks through boundaries and redefines the threshold by effectively utilising leftover urban space.

The Matrix is featured as a metropolitan hybrid, a compound of various types of uses accommodating in an extremely dense block. Its nesting spaces derive from its dynamic spatial configurations in history. However, rental and co-working offices destroy this dynamic relationship and interdependency. The increasingly high rents have filtered any uses apart from office or high-end apartments. In this case, small diversified businesses such as cloth makers, designer studios, and art spaces have been driven to the centre of the block, which is inaccessible to the public, leaving the

peripheral space vacant for the offices.

Reconceptualised as a replica of the Enclave Project, the Matrix adopts a similar approach to organising, distributing and structuring the small manufacturing space. Therefore, the Matrix tests the idea of a city's adaptivity and manufacturability by providing space interchangeability.

Adopting the Enclave's development policy, the Matrix rejects the uprootedness but intends to be a long-run project with incremental interventions. Existing occupants are encouraged to reach out connections with the newcomers, the small manufacturing business. To facilitate this need, the design proposal would gradually reconfigure the ground floor plan by removing the party wall while the connections reach out.

By employing the existing circulation core, manufacturing could combine with other uses vertically. With the material production counterpoint to all the occupants, the Matrix becomes a metropolitan hybrid block that envisages a mode of living involving material production.

Bolter, Jon. ‘The Works: Factories in London, 19181939. Part 1’. AA Files, no. 36 (1998): 41–54.

———. ‘The Works: Factories in London, 1918-1939: Part 2’. AA Files, no. 37 (1998): 17–32.

Borsi, Katharina, Didem Ekici, Jonathan Hale, and Nick Haynes, eds. Housing and the City. London: Routledge, 2022. https://doi. org/10.4324/9781003245216.

Brown, Richard. ‘Creative Factories: Hackney Wick and Fish Island’, n.d.

Carmichael, Katie. ‘The Hat Industry of Luton and Its Buildings’, n.d.

Cities of Making. ‘The City of Making Report’. Cities of making, 2018. https://citiesofmaking.com/cities-report/.

Croxford, Ben, Teresa Domenech, Birgit Hausleitner, Adrian Vickery Hill, Han Meyer, Alexandre Orban, Victor Muñoz Sanz, Fabio Vanin, and Josie

Warden. FOuNDRIES OF THE FuTuRE: A Guide for 21st Century Cities of Making. Tu Delft Bouwkunde, 2020. https://doi.org/10.47982/BookRxiv.9.

Davis, Howard. Working Cities: Architecture, Place and Production. London: Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429448515.

Fenton, Joseph, Ken (Kenneth Lancet) Kaplan, Lebbeus Woods, Mike Cadwell, Michael Silver, and Mary-Ann Ray. Pamphlet Architecture 11-20. New York : Princeton Architectural Press, 2011.

Ferm, Jessica. ‘Governing urban Development on Industrial Land in Global Cities: Lessons from London’. In Critical Dialogues of urban Governance, Development and Activism, edited by Susannah Bunce, Nicola Livingstone, Loren March, Susan Moore, and Alan Walks, 115–29. London and Toronto. uCL Press, 2020. https://www.jstor.org/

stable/j.ctv13xps83.16.

Greater London Authority. ‘The_london_plan_2021. Pdf’. Greater London Authority, 2021. https:// www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/the_london_plan_2021.pdf.

Griffith, E. J. L. ‘Moving Industry from London’. The Town Planning Review 26, no. 1 (1955): 51–63.

Hall, Peter. The Industries of London Since 1861. Hutchinson university Library, 1962.

Julius, Leslie. ‘The Furniture Industry’. Journal of the Royal Society of Arts 115, no. 5130 (1967): 430–47.

Karjalainen, Joni, Sirkka Heinonen, and Amos Taylor. ‘Mysterious Faces of Hybridisation: An Anticipatory Approach for Crisis Literacy’. European Journal of Futures Research 10, no. 1 (10 September 2022): 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40309022-00207-5.

Kropotkin, Petr Alekseevich. Fields, Factories, and Workshops; or, Industry Combined with Agriculture and Brain Work with Manual Work. New York: Putnam, 1907. https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl. title.18827.

Lavington, Maccreanor, Gort Scott, and Graham Harrington. ‘Vacant Ground Floors in New Mixed-use Development’, 2016.

Mark, Brearley. ‘Atelier Brussel Productive Metropolis’, 2016. https://www.architectureworkroom. eu/en/projects/528/atelier-brussel-productive-metropolis.

Muir, Frances, and Levent Kerimol. ‘Industrial Intensification Primer’. Greater London Authority, 2017.

Rappaport, Nina, ed. Hybrid Factory, Hybrid City. New York, NY: Actar Publishers, 2022.

———. Vertical urban Factory / by Nina Rappaport., 2015.

Rappaport, Robert N. Lane, Nina, ed. The Design of urban Manufacturing. New York: Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429489280.

Riello, Giorgio. ‘Boundless Competition: Subcontracting and the London Economy in the Late Nineteenth Century’. Enterprise & Society 13, no. 3 (2012): 504–37.

Saint, Andrew. ‘London’. AA Files, no. 2 (1982): 22–33.

Sendra, Pablo, Richard Sennett, and Leo Hollis. Designing Disorder : Experiments and Disruptions in the City / Pablo Sendra and Richard Sennett., 2020.

Smith, Joanna, and Ray Rogers. Behind the Veneer: The South Shoreditch Furniture Trade and Its Buildings. Swindon, England: English Heritage, 2006.

Vanin, Fabio. ‘Making in the Brussel Altas’. Cities of making, 2022. https://citiesofmaking.com/inthe-making/.

Young, Michael Dunlop, and Peter Willmott. Family and Kinship in East London / Michael Young and Peter Willmott. Pelican Books. Harmondsworth : Penguin Books, 1957.

Zertuche, L. N., H. Davis, S. Griffiths, B. Dino, and L. Vaughan. ‘The Spatial Ordering of Knowledge Economies: The Growth of Furniture Industry in Nineteenth-Century London’. Proceedings - 11th International Space Syntax Symposium, SSS 2017, 1 January 2017, 95.1-95.22. http://www.11ssslisbon.pt/proceedings/cities-and-urban-studies/.

Fig 01. (Previous) The Domeview yard.

Source: Assemble Studio, 2019.

Fig 02. (Previous) The map of industrious Shoreditch in 1912. Source: Adam Dant, 2010.

Fig 03. (Opposite) The map of South Shoreditch in a 500m square.

Source: Drawn by author according to Goad Insurance Map in 1889.

Fig 04. (Opposite) The map of South Shoreditch in a 500m square: Building use analysis.

Fig 05. (Opposite) The map of South Shoreditch in a 500m square: Factories and Warehouses.

Fig 06. urban Ground Floor Plan, based on The map of South Shoreditch in a 500m square.

Fig 07. (Opposite) The Harris Lebus Cabinet Works, Tottenham Hale,1900s.

Source: Harris Lebus Archive.

Fig 08. The Weaver’s Attic. Source: Unknown.

Fig 09. Garret Master’s house, in the Alley of Cheshire Street, Bethnal Green, London, 1890s.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 10. (Previous) Floor Plans, Section, Elevation of the No.14 Fourneir Street, Spitalfields, London, 1726.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 11. Close-up of the weatherboarded mansard boxes with pantile roofs, Huguenot weavers houses, Fournier Street, Spitalfields, London, 1722.

Source: Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections.

Fig 12. (Opposite) Houses and Shops, 99-101 Worship Street, Finsbury, London, 1863.

Source: RIBA Collections.

Fig 13. (Previous opposite) Isometric drawing shows the combination of house entrance with shop front, 99-101 Worship Street, Finsbury, London, 1863.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 14. (Previous) Houses and Shops, 99-101 Worship Street, Finsbury, London, 1863.

Source: RIBA Collections.

Fig 15. (Opposite) Axonometric, Lamp Manufactory Company in No.10~14 Leonard St, London, 1883.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 16. Ground floor plan and basement plan of the terraced workshops, Leonard Street, Shoreditch, London, 1880s.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 17. Floor plan, Lamp Manufactory Company in No.10~14 Leonard St, London, 1883

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 18. (Opposite) Warehouses in Leonard Street, Shoreditch, Hackney,

Source: Photograph by Peter Marschall, 1988.

Fig 19. The steam cabinet works of William Walker and Sons, depicted on a trade card of the 1880s. The machinery was located on the ground floor beneath the workshops, while the yard was used as a packing space and wood store.

Source: Museum of Home, London.

Fig 20. (In the two following pages) Typological matrix, and functional analysis.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 21. Stepney Reconstruction Area Plan, 1943.

Source: Metropolitan Archive, London.

Fig 22. (Opposite) Main elevation, Flatted Factory, Shoreditch, London, 1958.

Source: RIBA Collections.

Fig 23. Rear elevation, Flatted Factory, Shoreditch, London, 1958.

Source: RIBA Collections.

Fig 24. Aladdin Ltd, Greenford. Architect: Nicholas & Dixon Spain, 1933. Factories facing on to busy highways or railway lines were often floodlit, with the building itself serving as an advertisement for its products - oil lamps.

Source:Architects’ Journal, 31 August 1931, and photograph by Jon Bolter.

Fig 25. (Opposite) Typical Floor

Plan, Flatted Factory, Shoreditch, London, 1958.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Fig 26. (Previous opposite) Flatted factories(Known as Regent Studio), Ada Street, Hackney, London,1944.

Source: The Courtauld Institute of Art. CC-BY-NC.

Fig 27. London Indstrial Land Distribution

Source: Industrial Intensification Report, WeMadeThat, 2017.

Fig 28. (Opposite top) Stacked large industrial; (Opposite bottom) Stacked medium industrial with residential.

Source: Industrial Intensification and Co-Location Guidance, WeMadeThat, 2019.

Fig 29. Evolving context in the enclave territory illustrates the dynamic urban fabric and configuration.

Fig 30. View on the Rivington Street.

Source: Photograph by Author.

In his book, The Craftsman, Richard Sennett articulates three interlinking troubles that constantly marginalise and demoralise the craftsman and degrade the idea of craftsmanship. The first trouble is the attempts of institutions to motivate the crafts workers to make them more productive. The second lies in the way skills are developed, and the third is the paradox of absolute standard and practical standard, in which the craftsman is pulled in contrary directions.1

These three troubles rendered the organisation of craftsmanship in modern society into an ambivalent condition: on the one hand, the society has systematically and ideologically belittled the worker associated with material production; on the other, it constantly romanticises and eulogises the crafts and craftsmanship.

1. Richard Sennett, _The Craftsman / Richard Sennett._ (London : Allen Lane, 2008). 52.

The question of why urban manufacturing is constantly in precarious condition and abject form can not be attributed to environmental and economic considerations, like dirtiness and pollution, which could be easily solved with new production approaches, such as Industrial 4.0 and digital fabrication. However, it is more rooted in the production relations and politics of labour.

The question asked by Sennett at the beginning of his book, how people could engage practically but not necessarily instrumentally, becomes even more critical for today's city, a place that rejects corporal experience.

“At different moments in Western history practical activity has been demeaned, divorced from supposedly higher pursuits.Technical skill has been removed from imagination, tangible reality doubted by religion, pride in one’s work treated as a luxury.”2

2. Richard Sennett, The Craftsman (London : Allen Lane, 2008). 21.

The workshop was recognised as craftsman’s home physically and spiritually. Christianity embraced the work of craftsmen since it could counteract the human propensity toward self-destruction and bring peace and productivity. Early Christian morality viewed free time as a temptation and leisure as an invitation to laziness, seducing and distracting man from his work.3

This fear was attributed particularly to woman, for which their feet need to be bound domestically, and their hands need to be occupied with needles. This relationship

3. Ibid. 55.

was materialised in the patriarchal workshop, where work and life mixed face-to-face in a highly hierarchical relationship. The workshop, therefore, is a place that integrates a bunch of people using different forms of authority to formulate a strong relationship alternative to the mode of family.

Karl Marx, Charles Fourier, and Claude Saint Simon envisaged the workshop as a place where the dichotomy between labour and life dissolves, allowing for the synthesis of work, personal development, and community belonging.

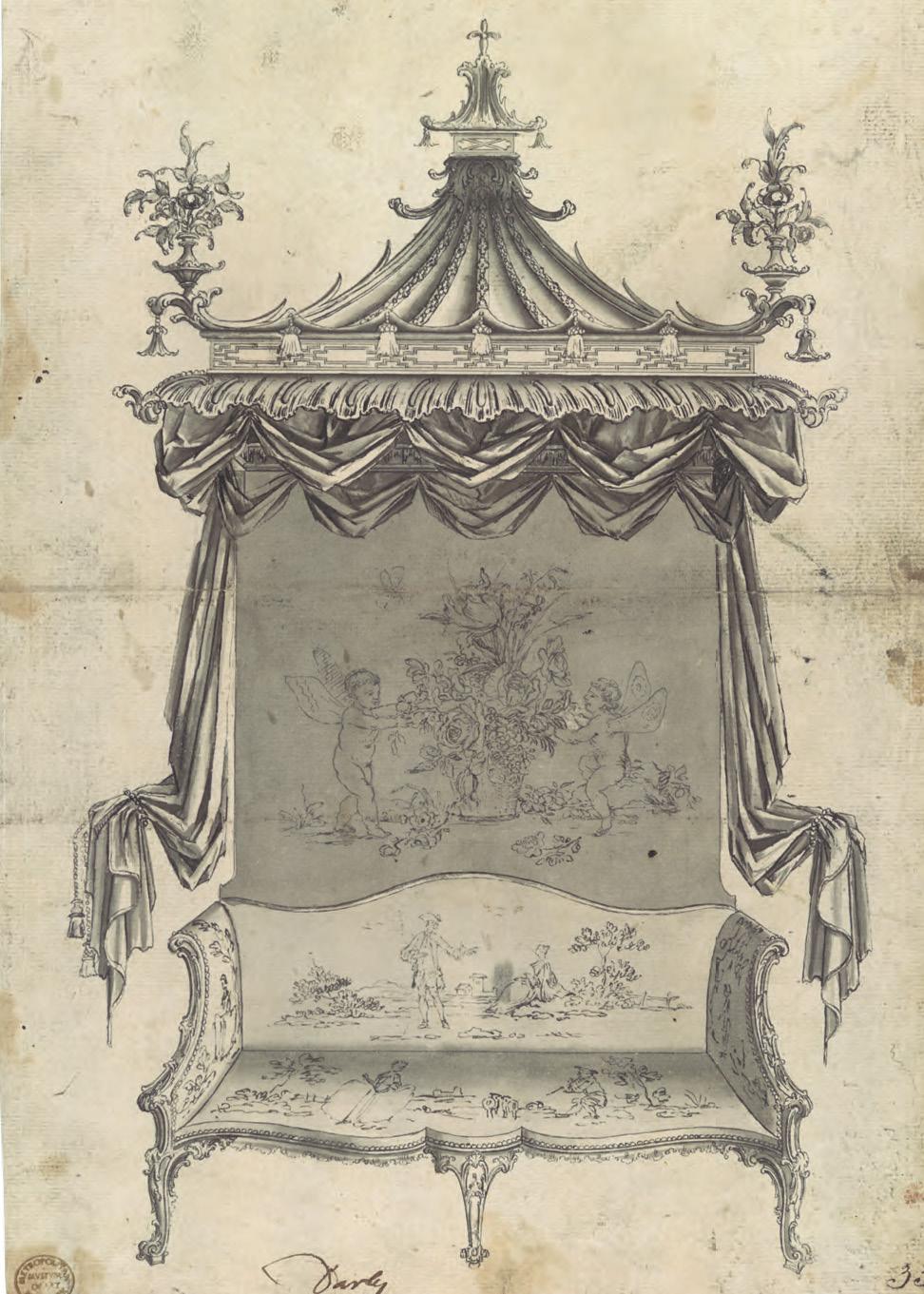

In his book, The Gentleman and Cabinet-Maker’s Director, the famous Georgian cabinet maker Thomas Chippendale added all the information necessary for a craftsman to make the piece: the dimensions and the moulding profiles, indicating the drawings were used for illustrating Chippendale’s standard and in house crafts training. Moreover, this collective training and learning scenario is further evidenced in Chippendale’s ‘confession’ that part of the drawings in his book was developed by the craftsman in his shop.4

His workshop in Saint Martin Lane articulates the spatial repercussions. The premises accommodated forty to fifty craftsmen, divided into several specified studios, such as a

4. Morrison H. Heckscher, Chippendale’s Director: A Manifesto of Furniture Design (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2018). 33.

Source: The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director,

Fig 03. (opposite) A Chair, designed by Thomas Chippendale, For his book.

Source: The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director, 1759.

1.

2. Yard

3. Showrooms

4. Store Room; Chair Room

5. Oven

6. Drying Room For Deals

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

feather studio, glass studio, and upholstered studio. A covered passage between two houses, one of which was Chippendale’s dwelling, led to the long interlocking yards, around which the promises incorporated its residences, showrooms and workshops for the different crafts, formulating a hybrid working and living model. Although this may be seen as an early example of the division of labour described by the pin factory by Adam Smith, 19th-century cabinet manufacturing still involved a high level of crafts skills.5

Therefore, the interlocked courtyards must be interpreted as a communal space where craftsmen deal face-toface with knowledge sharing and craft training.

5.

Source: Drawn by Author.

The organisation of craftsmanship in pre-industrial era were based on two exclusive efforts: the urban guild and apprenticeship system. The guild were corporations that attempted to solidify and regulate craftsmen to gain collective reputations. The apprenticeship system enables knowledge to transmit through out generations aiming to keep secrets and make it sustainable. The urban guild could be viewed as an urban workshop, whose ruler used his authority to regulate his subordinates, say apprentices, journeymen, and housewives.

“The apprentice shall and will diligently, faithfully, soberly and honestly, according to the best of his knowledge, skill and ability, serve the masters.... during the said term. and obey, observe, and fulfil all instructions, orders, and lawful commands of the masters and those put in authority under them.”6

“The masters will accept the apprentice as an apprentice during the said term, and by the best means that they can, will instruct him, or cause him to be instructed in the branches of the business of a manufacturing engineer”7

As illustrated in the apprentice indenture, both the masters and apprentices were assigned specific responsibilities intended to build a reciprocal relationship and expecta-

6. Indenture of 1904, quoted in HMSO 1928b, pt. VI, App. E, pp. 192-6.

7. Indenture ibid. (a).

Fig 05. (Previous) Craftsman in the workshop making frames for furniture. J. L. Green & Vardy Ltd, 79 Essex Road, London, 1930s.

Source: RIBA Collections

Fig 06. Apprenticeship Indentures, England, 1719.

Source: British Library.

Source: Wellcome Collection.

tion. As Cronin argues, what was absent at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century was precisely the expectation and reciprocal relationship between the apprentice-learner and the master.8

However, in the second half of the 19th century, the pervasive trends of using cheap, unskilled workers and child apprentices stimulated a broader social and political gaze on the legitimacy of the apprentice system, which manifested the decline of this system.9

8. Bernard P. Cronin, Technology, Industrial Conflict and the Development of Technical Education in 19th-Century England (London: Routledge, 2019), 103.

9. see the descriptions in The People in the Abyss by Jack London and Condition of the Working Class in England by Friedrich Engels

“We have gone in too much for cheapness at the cost of quality, and that had tended very much to degrade our handicraft skill...the apprenticeship has broken down here...(and) cannot much longer be maintained.”10

10. Hansard Samuelson, reports of the Royal Commissioners on Technical Institution, (London, 1881), 527.

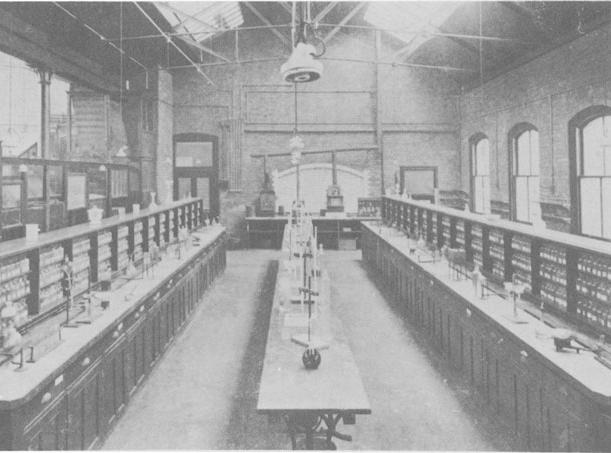

08. Finsbury Technical College, 1883-1926. The building remains and is used as Shoreditch County Court. Source: Imperial College Archives.

The advent of mass production envisaged a paradigm shift in crafts education: in the apprentice system, education was integrated into the workplace and seen as a primary responsibility of employers, which had transcribed to one in which such learning opportunities were available only outside of the workspace in the form of after-working classes offered through a patchwork of state-supported institutions. The notion of a free contract and labour market with a wage system was widely accepted in society, which rendered the old practices of apprenticeship as an outdated system either undesirable or impracticable, which bound workers with asymmetrical relationships by legal and moral obligation. This apprenticeship was considered the culprit for the miserable condition of the working class. Consequently, it was urgent to develop a new education system that could not only train

Source: From City & Guilds of London Institute Prospectus form,1912-13.

workers to fulfil the needs of novel production methods but also mediate the deteriorated relationship between employers and workers.

Initiated from the Technical Institution Act in 1889, the emergence of technical education was not a natural evolution of the British education system since it stemmed from the anxiety between national competitions11 and grew in a firm idea of separation, which detached education from workspace.

The Finsbury Technical College was recognised as the first technical college of Eng11. Considerable influence caused by the Paris Exhibition of 1869

Source: Historic England Archive.

land in 1883. It was designed to be a ‘model trade school for the instruction of artisans and other persons preparing for intermediate posts in industrial works.’12

The college offered opportunities for daytime and evening study, and subjects included building, design, drawing, engineering, mathematics and science. The daytime class was a general provision: ‘training on broad, practical and scientific principles’, which connected to the careers of Civil, Mechanical, Electrical and Chemical industries. The night time classes were designed for apprentices, workers, and supervisors, who conducted practical courses like cabinet making, colour, and decoration. In 1886, the day class attracted about 155 students around 14 to 19 years old; in contrast, 900 students attended the night class courses. Most of them were full-time workers aged around 14 to 40. The separation of time reflected the propensity of educational ideas which similarly separated mental and practical activities.13

12. W. H. Brock, ‘Building England’s First Technical College: The Laboratories of Finsbury Technical College, 1878–1926’, in The Development of the Laboratory: Essays on the Place of Experiments in Industrial Civilization, ed. Frank A. J. L. James (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1989), 155.

13. Bernard P. Cronin, Technology, Industrial Conflict and the Development of Technical Education in 19th-Century England (London: Routledge, 2019), 206.

Basement | Machine and Workshops 0 2 6 12m

floor | Workshops

floor | Lecture Room

0 2 6 12m

floor | Laboratory

and Construction of Applied Science and Art Buildings, and Their Suitable Fittings and Sanitation, with a Chapter on Technical Education, London.

The four-storey plain-brick building consisted of classrooms, workshops and laboratories, which were arranged around a modest atrium as the only communal space shared by all the students and staff.

The architect could not envisage such amounts of students the college could ever attract; nevertheless, the absence of a library, refreshment room, terrace, or common room neither for students or staff reflects the intentions behind the idea of technical education that rather than creating life and experiences within the college, the architect and the City & Guilds of London Institute were more interested in how it could effectively train more skilled workers.

Compared with the conventional apprentice model, which conducts a face-to-face learning in doing process under the supervision of the master, the new technical education system, with its factory-like architecture, practical curriculums, and utilitarian philosophy, failed to function as a compensation and substitution for the old system.

The workshops of nineteenth century London were unusually small since the manufacturing premises in East End were constrained by limited space and high land prices, the unable to invest in capital-intensive equipment.1 Consequently, efficiency and profitability could only be achieved through intensified labour, which initiated the subcontracting system and gave birth to the role of a middleman.

“The real assembly line runs through the streets” is a famous analogy made by Peter Hall, explaining the way commodities took shape within the structured landscape of interconnected material and commercial fluxes, which precisely described the work of middleman, who associated trades by distributing tasks and materials, gathering by-products and assembling into finished products in their commercial warehouses.2

1. George Dodd, Days at the Factories (C. Knight & Company, 1843), 5.

2. Peter Hall, The Industries of London Since 1861 (Hutchinson University Library, 1962), 227~8.

Source: London School of Economics Archive.

Fig 14. In 1901-2, Horace Warner took photos of East End street, whose route coincide with Charles Booth’s survey about the condition of East London. Source: Photograph by Horace Warner, 1901.

17. Production organisation in Shoreditch, London, 1889.

Source: Drawn by Author.

Source: Drawn by Author.

The commercial warehouse, a combination of showroom and warehouse, was employed by a subcontractor as an interface between the spheres of production and consumption. The products were brought from subcontracting craftsmen, workshops or factories, assembled and finished onsite or nearby, and then stocked and displayed before passing to the high street retailers.3 Furniture was

displayed on an uninterrupted ground floor, categorised by type and stacked closely to each other, sometimes suspended from the ceiling. Additionally, some fully furnished rooms were decorated with different styles as showcases for the latest fashions and tastes. The upper floors were used to store goods ‘in the white’ — unpolished and upholstered. The finishing process is usually delivered by workshops on the top floor or nearby.

The warehouse’s basement was used to assemble and pack the finished products into crates. Therefore, it needed to remain half a floor above the ground to allow light, ventilation and easy access to goods. The take-in doors, light wells, hoists, and wall cranes manifested the everyday confrontation between production and consumption. The internal arrangement was a condensation of the subcon-

tracting system that rendered the warehouse a liminal space, a spatial incarnation of the middleman. In essence, the subcontracting system that connects one to others’ needs and working time is a power structure that informs decision-making of which type of work should be celebrated and which needs to be concealed. Consequently, the small manufacturing works could be concealed from the public, and the workers’ bodies would dissolve into the city’s fabric.

The power of the middleman and wholesalers declined at the beginning of the 20th century since the system had become too complex to be effectively managed. Therefore, department stores and retailers tended to buy products directly from producers, indicating that the same concealment and control could be achieved solely through its architecture.

High Street: A Spatial Instrument

The high street, ubiquitous in the British city, is commonly considered diverse and inherently mixed. However, the concept was initially invented as a spatial model designated to host from those of “first and last sort of building” to “the greatest bigness for Citizens, or other Persons of extraordinary Quality”.4

The model was invented under the mercantilism regime, in which the market was underestimated, and domestic commerce was suppressed. Reflected on legislation, high street was once designated by the common court as the only legal place for commerce, condemning any by-lane trade to be of the black market.5 Consequently, it was constructed as an upgrade of muddy anarchic markets, providing a clean, ordered and easily controlled urban structure to retain urban morality.

While the nation gradually shifted toward Laissez-faire capitalism in the mid-19th century, the notion of the free market significantly challenged the previous idea of viewing luxury as vice and accepting that individual interests could contribute to the public good.

The high street, a sensitive model, therefore, was driven into a paradoxical condition: on the one hand, it has to embrace the free market, asking for free movements of goods and people; on the other hand, it sought more order than ever it was. As a result, strict rules and regulations were implemented.

Evidenced by regulations on the appear-

4. 19 CAR. II. c.18, The Rebuilding of London Act 1666

5. ibid.

Fig 24. West Hill looking east towards the town centre of Wandsworth and its High Street. Keall’s dispensing chemist’s shop on the left was one of a small chain in the area.

Source: Wandsworth Historical Society.

ance of shopfronts, use of light, street sanitary and the differentiation of back and front space of the street, the urban production and distribution finally reduced reliance on the liminal warehouse and shifted to the more efficient high street model, which was orchestrated as a spatial instrument for order.6

6. John A. Dawson, ‘Futures for the High Street’, The Geographical Journal 154, no. 1 (1988): 1–12, (https://doi. org/10.2307/633470), 3.

“an agency for peace, security, and segregation which, by its very nature, limits the horizon of experience— Reducing noise transmission, differentiating movement patterns, suppressing smells, stemming vandalism, cutting down the accumulation of dirt, impeding the spread of disease, closeting indecency and abolishing the unnecessary”.7

The long history of how the city constantly depresses small manufacturing spaces manifests this segregation sometimes by violence but in most situations by the invisible framework, protocol and social engineering. For instance, there is still no suitable land classification and suitable regulation for the dark kitchen, a game-changing role raised during the pandemic, which completely challenged the city’s food production and consumption.

Differentiating from traditional restaurants, dark kitchens avoid providing any dining space; instead, the customers can only order online, and the food will be delivered by deliverymen in a delicate food box. Illustrated in a standard dark kitchen designed by Foodstars(one of the successful

7. Robin Evans, “Figures, Doors and Passages,” in Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (London: Architectural Association, 1997), 89–90.

Fig 25. Previous Dark Kitchen model designed by Foodstar in 2018.

Source: https://foodstarsuk.com/

Fig 26. (Following Page) A plain dark kitchen interior.

Source as above.

dark kitchen suppliers), the space consists of a series of rentable kitchen units that facilitate basic kitchenware. The machine-like space encapsulates noise, small and smoke in its interior and only leaves a small window for passing the food as its interface to the outside. Therefore, it was inextricably concealed in the city’s backstage, in which the production space becomes an endless interior within which frictionless parallel worlds are constructed.

The asymmetrical relationship between the city and its production sector is outlined in these buildings. The contemporary city lacks visibility of manufactural work and workspace, which renders today’s online platforms such as food ordering, uber, and E-commercial platforms as the contemporary middleman with the algorithm as its new prosthesis.

Fig 27. New Version of Dark Kitchen model designed by Foodstar in 2023. Source: https://foodstarsuk.com/

Contemporary production has entirely shifted from Fordism using linear assembly lines and hierarchies of subcontractors, imposing a series of standardised objects for mass consumption, to Post-Fordism production, processing materials in different times and spaces, organising autonomous workers into extended supply networks by emphasising performance and efficiency (Supply-Chain management).

From the perspective of workers, the evolution of the production method is a propensity toward abstraction, which produces forms with flexible, interchangeable and indeterminate content. Abstraction means uprooting something essential from its totality to define generic frameworks rather than specific solutions.

Contemporary production calculates measures, predicts and even creates the needs

Source: Encyclopédie of

Source:

and desires of consumption. In other words, production is no longer based on needs but desires.8 These structural and temporal changes require new architectures to reorganise and re-program the autonomous producers to meet the performance and efficiency standards.

8. The way of advertising has accordingly shifted to a method that must now emerge from a community of users seeded by influencers(KOLs) to whom products are sent for social broadcasting. Consumers are no longer passive actors but more reflective of the production process.

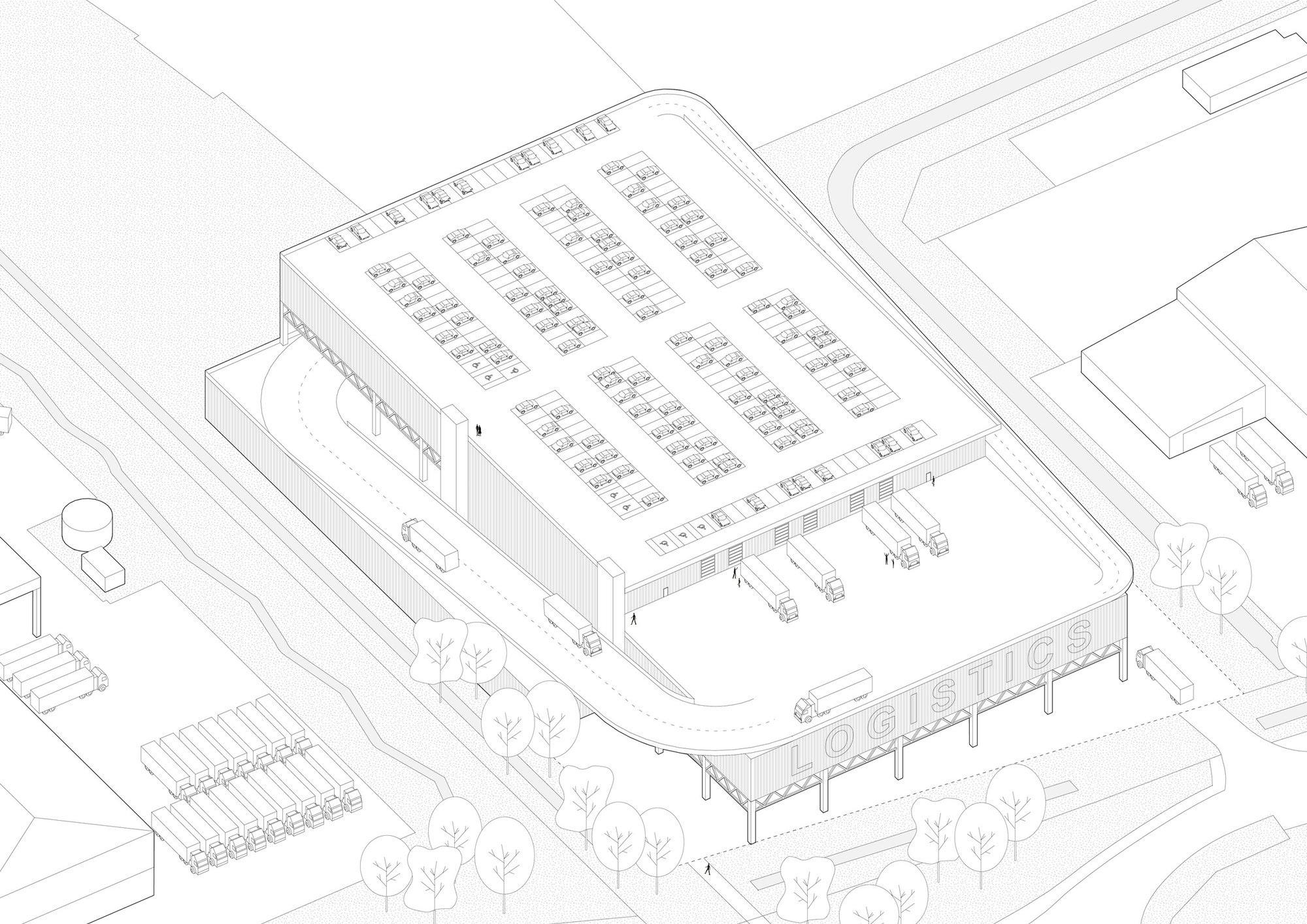

Logistics is the founding principle of the neoliberal economy. The contemporary city, therefore, becomes a place of fluxes that renders any forms of friction as obstacles. While obstacles have been removed in a frictionless world, circulation manifests itself as rationalisation of space.

“The space of logistics is therefore defined in relation to the power that operates it. In order to reach a specific place more quickly and easily, geographical features are manipulated and new infrastructures constructed. However, this greater connectivity is achieved at the cost of erasing all obstacles…Such a process is never peaceful.”9

The previous boundaries between the logistics space and the city built by large distribution centres, ports, and data centres have devolved. The logistics seek ways to integrate with the city’s fabric and incorporate with other city functions. For instance, London’s planning authorities are finding ways to accommodate creative industry and advanced

9. Hamed Khosravi, Taneha Kuzniecow Bacchin, and Filippo LaFleur, Aesthetics and Politics of Logistics (Humboldt Books, 2019), 23.

small-scale manufacturing in previous industrial shed.10 Since the city has already blurred the functional and structural boundaries, small manufacturing units and its logistics systems could gradually permeate back into the dense urban fabric from which they were once expelled. The small manufacturing space needs to readapt these frictionless movements of goods, capital, and information, which enable the forms of control and measurement that ensure the fluxing demands are satisfied in a timely and efficient manner.

In both the flux and abstraction, workers and their bodies have been reduced as infrastructure.11 In fact, it is not a novel process that the worker’s body has always been through reduction and degradation. From the 18th century, cabinet makers used furniture catalogues as design standards to achieve pro-

11. Luis Andueza et al., ‘The Body as Infrastructure’, Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 4, no. 3 (1 September 2021): 799–817

Source: Winterthur Library Digital Collections.

duction in advance to the efforts of implementing machine tools for accuracy to fulfil the interchangeability, and finally, these historical efforts on materials have all put on labour and work rendered them as pure resource and capital. In his explanation about the capitalist labour process, Marx reads humans as the time’s carcase. He writes,

“It is no longer the worker who employs the means of production, but the means of production who employ the worker.”12

Re-conceptualising the body as infrastructures by Gandy in his Cyborg urbanism, urban infrastructural space functions less as the prosthesis of the human body; the body, therefore, becomes the extension of those infrastructures, subsumed under the requirements of smooth circulation and accumulation of capital.13 This understanding builds connections between workers, their bodies, and urban infrastructure by viewing the body as part of the urban infrastructure, through which one can actively take action and intervene in the process.

12. Marx, 1990:425

13. Matthew Gandy, ‘Cyborg Urbanization: Complexity and Monstrosity in the Contemporary City’, _International Journal of Urban and Regional Research_ 29, no. 1 (2005): 26–49

There are few commodities from direct production; indeed, contemporary manufacturing, particularly in the urban territory, for its relatively limited operational space, relies on the reorganising and reassembling of demanding by-products. Moreover, struggling with the limited storage space, the small manufacturing premises exerted effort to cut inventories and celebrate just-in-time production. undoubtedly, these challenges all ask for a more adaptive and efficient way of using the city’s logistics infrastructures; likely, the old massive urban distribution centres are nothing but rigid in this case. In fact, small urban manufacturing never stops developing ways of moving materials and products across dense city fabric, inspiring the City Logistics concept.

Fig 33. An electrical tricycle as a prevailing way of moving cargo in the city is one of the strong images of our era, emblematic of the intersection between urban mobility innovation and sustainability efforts.

Source: Exhibition: Staging the era. Curated by the Artist: Cao Fei.

“City logistics is the process for optimising the logistics and transport activities by private companies in urban areas while considering the traffic environment, the traffic congestion, and energy consumption within the framework of a market economy.”14

Small-scale interventions incorporate logistics with the city’s fabric, using alternative vehicles like cargo bicycles or tricycles, electric trucks and vans with less pollution and better passing ability in traffic congestion.

14. Eiichi Taniguchi, Russell Thompson, Tadashi Yamada, and Ron Van Duin, City Logistics: Network Modelling and Intelligent Transport Systems (London: Pergamon, 2001).

Fig 34. (Previous) Moving a prop sofa in the city through the supply chain of creative industry, manifests a close connection between culture production and city’s manufacturing business.

Source: The film(still 6’00’’): London Made: Exploring the links between London’s culture and industry by We Made that.

urban mobility centres are another smallscale intervention of city logistics that derives from the idea of utilising the leftover space in the city centre to manage goods movements and provide social and recreational spaces for logistics workers. For instance, London has incorporated big logistics companies such as DPD and uber to transfer parking buildings in the city centre into mobility centres, which are inefficiently used during their off-peak hours.15

These mobility centres are expected to reduce the overall milage and emissions and to relieve the traffic congestion in central London. Moreover, they are introduced as a new role not to extend and smoothen the logistics circulations but to build new social connections within the logistic system.