Beyond the Neighbourhood:

The Shi-Jie in Kaohsiung

Yu-Hsiang Hung

Projective Cities - MPhil. in Architecture and Urban Design_2013/15 Graduate School

Architectural Association School of Architecture

Research and Design Dissertation Jun. 2015

ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE GRADUATE SCHOOL PROGRAMMES

COVERSHEET FOR SUBMISSION 2013-14

PROGRAMME: MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design (Projective Cities)

TERM: Final Dissertation

STUDENT NAME(S): Hung, Yu-Hsiang

SUBMISSION TITLE: Beyond the Neighbourhood: The Shi-Jie in Kaohsiung

COURSE TITLE: Final Dissertation Submission

COURSE TUTOR: Sam Jacoby, Adrian Lahoud, Maria S. Giudici

SUBMISSION DATE: 25.06.2015

DECLARATION:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my/our own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Signature of Student(s):

Acknowledgements

would like to express my gratitude to my programme director Dr. Sam Jacoby for the guidance and commitment through the research project. Further, would like to thank Dr. Adrian Lahoud and Dr. Maria S. Giudici for the critical feedbacks.

am grateful to my dear colleagues Runze, Yana, Naina, Guillem, Simon, Yating, and Tanyi for the engagement with the project. Many ideas in the book were inspired from the conversations with them. am also grateful to my friend Cyan Jingru Cheng for the advices along the way.

A special thanks to Chao Wanlin for being the best companion ever. This work could not have been done without her.

Last but not least, this dissertation is dedicated to my parents. It is only possible through their love and faith on me.

ABSTRACT

Fig.1 Source: [accessed 18 July 2014] <http://kcginfo.kcg.gov.tw/Publish_Content.aspx?n=3D7C9BFC4F86BF4A&sms=FB76F1E6517A12DC&s=C2C72369BF672E78&chapt=6513&sort=3 >

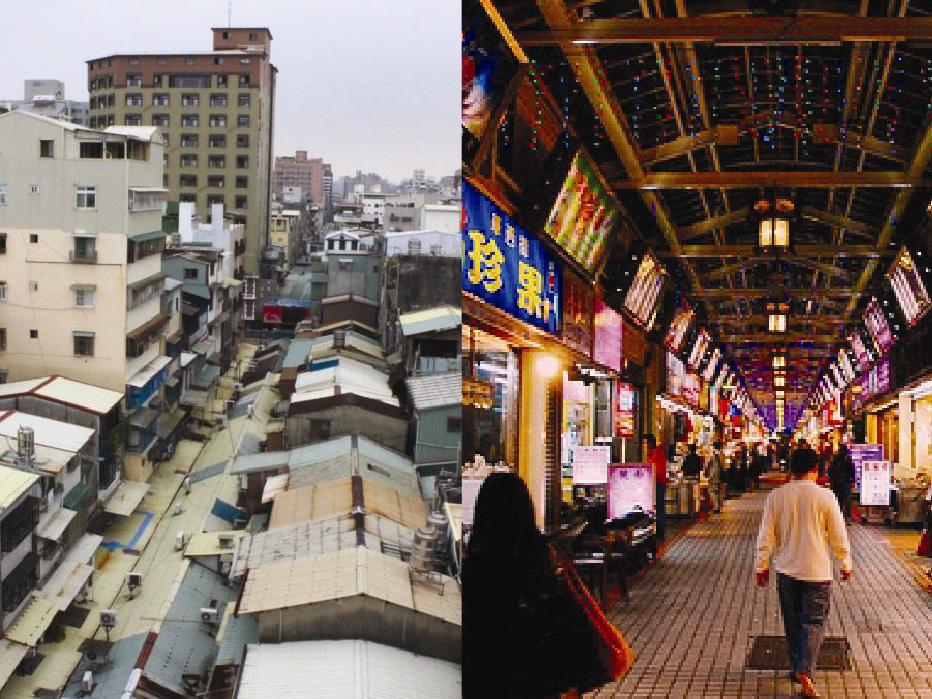

The ambitious vision of downtown Kaohsiung is constructing a hybrid of cultural centre and a science campus.(Fig. 1) The reality, however, is one of the post-industrial port area dominated by IKEA and other big boxes that are otherwise found in suburban industrial parks. This area was never envisioned as a city centre, and its historical Japanese colonization revealed a neighbourhood model based on educational nodes and Shi-Jie (market street). Hidden by recent urban developments, the historical urban model organized around a series of mixed-use Shi-Jie neighbourhoods. Unlike the street element in American Neighbourhood Unit, the Shi-Jie is a regularizing tool as well as the rooted urban component of the city.

Defining as a ‘science campus’, the downtown area is planned based on the concept of an industrial park with high vehicle accessibility, large zoning, mono-functionality where the street is conceived as a service infrastructure disregarding the existing urban fabric. Urban problem may arise. It also leads to the separation of the industrial park from the rest of the city and a division of work and living in the proposed industrial park. In addition, the new high-speed train is orienting the city’s growth to the northern suburbs, most of the newly-constructed higher education institutions are located away from the downtown area along this public transport line, expediting the transformation of downtown into a suburb effectively. All in all, a new model with interlinked infrastructural networks is required for the downtown area.

Therefore, this proposal investigates how these separated components of the city are incorporated and linked with different educational nodes and infrastructures. The sunken railway line in the northern part of the downtown area is a potential site. The problem of the site is the void left by the border between the north suburb and the downtown area; it poses the problem of how to integrate the neighbourhoods that separated from this infrastructural line. In order to address these problems, this proposal suggests using the ShiJie model as a mediating urban and architectural form in providing a counter proposal to accommodate the requirements of the original masterplan for the industrial park. My proposition enables the inverted street to inherit the Shi-Jie interspaces. By providing the communal spaces along the corridor, the new Shi-Jie has the ability of accumulating different social groups from the city and work beyond the neighbourhood.

1. Introduction

1_0. Kaohsiung Downtown Area as Suburbia

1_1. Research Questions

Disciplinary Question

Urban Question

Typological Question

1_2. Research Aims

New Shi-Jie as an Architecture for communication among social groups

Chapter 2. The Operative Urban Framework 23

2_0. Introduction: The educational node

2_1. Primary education as a node of a neighbourhood

2_2. Secondary education as the mediating node between urban and neighbourhoods

2_3. Tertiary education as the node of the metropolitan region

2_4. New Shi-Jie: The multi-scalar education node strategy for the sunken railway line

Chapter 3. The City Made of Urban Components 53

3_0. Introduction: the downtown challenged by various nodes through its history

3_1. The problem of the industrial science park in Kaohsiung downtown

3_2. The dispersed nodes development inherited from history

3_3. The leftover sunken railway line as a new urban unitary space

3_4. New Shi-Jie as an aggregation tool

Chapter 4. The Neighbourhood Idea Work beyond Its Scale

4_0. Introduction: the idea of the neighbourhood

4_1. The Perry Clarence’s Neighbourhood Unit for New York Suburb

4_2. The Japanese Shi-Jie Neighbourhood for Kaohsiung Downtown

4_3. The problem of the streets and education within the neighbourhood

4_4. New Shi-Jie as an inverted street

Chapter 5. Conclusion

5_1. Beyond the Shi-Jie neighbourhoods

5_2. The potential of further applications

Chapter 1. Introduction

1. Tsu-Lung Chou, Institutional evolution and challenge of urban planning in post-industrial Taiwan, in Bristow, M. Roger, Planning in Taiwan spatial planning in the twenty-first century, (Abingdon Routledge, 2010), p.74.

As Suburbia

The Kaohsiung downtown area by the former port was never a city centre. It was historically not even recognised as part of the port, but as a complementary town consisted of separated neighbourhoods in which its labour force could live in.

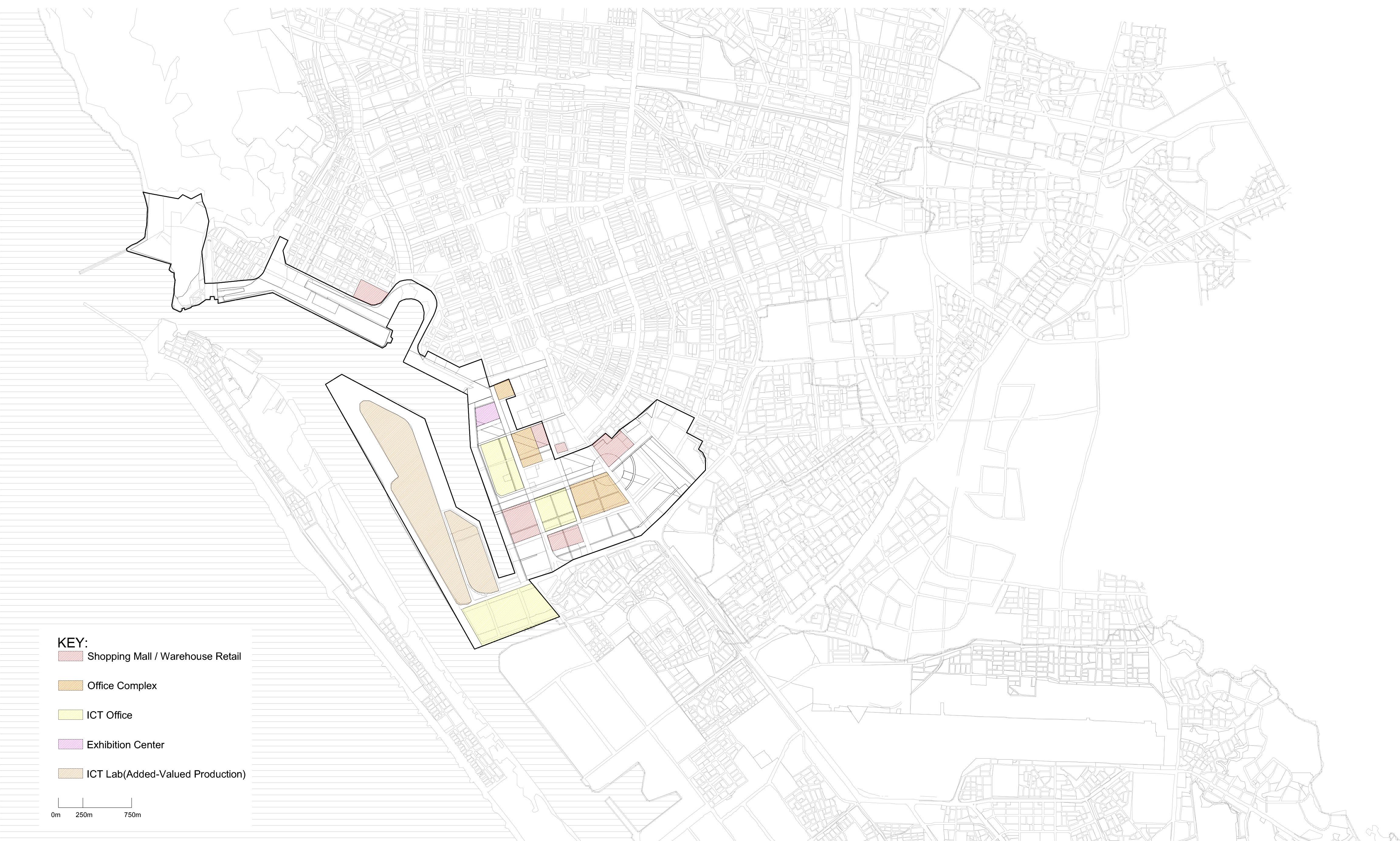

In 2000, the city government proposed the transformation of Kaohsiung Multifunctional Commerce and Trade Park to be a new city centre on the site of the former port. Converting a manufacturing industry to a knowledge-based industry, the park aimed at creating a synergistic environment for bio-technology labs and ICT industries. As Tsu-Lung Chou wrote: ‘This post-industrial shift is not confined just to industrial economic changes.1 Above all, this new development has overwhelmingly brought extensive changes to Taiwan’s political, spatial and social structures. ‘The project was to create a centre with cultural and economic functions and benefit from important infrastructural connections to southern Taiwan and revitalize the old port by connecting to the old downtown. Thus the construction of cultural, civic and tertiary industry-related facilities were proposed.(Fig. 2)

2. Tsu-Lung Chou, Institutional evolution and challenge of urban planning in post-industrial Taiwan, in Bristow, M. Roger, Planning in Taiwan spatial planning in the twenty-first century, (Abingdon Routledge, 2010), p.86.

However, ‘this post-industrial shift has imposed a subsequent spatial impact upon Taiwan. In southern Taiwan it has created huge idle government-developed industrial estates.2 Thus, despite of being conceived as a cultural centre and tertiary economy, it functions as an industrial park in terms of architectural and urban aspects. The reality of the masterplan is dominated by big-box retail shops such as IKEA and Costco. Buildings simliar to suburban business parks are typically fed by highways. Therefore the masterplan of the new downtown is suburban in character. In addition, while a key principle of tertiary education is communication. The interaction among different disciplines produces greater outcomes than individual disciplines. The proposed masterplan is still based on solo large zoning plots, with tertiary education buildings set in plots that are inaccessible by walking. Further, the set-backs of buildings isolate them from the urban fabric. As a result, streets are not spaces for exchange but merely a service infrastructure. Its spatial organisation separates different sectors within the plan and from the city. It reveals once again that the proposal is nothing more than a suburban centre.

Another evidence is the downtown area is historically a suburban, due to the Japanese occupation from 1895 to 1945. The area was originally created without much civic or trading facilities support to maintain a population of labourers.

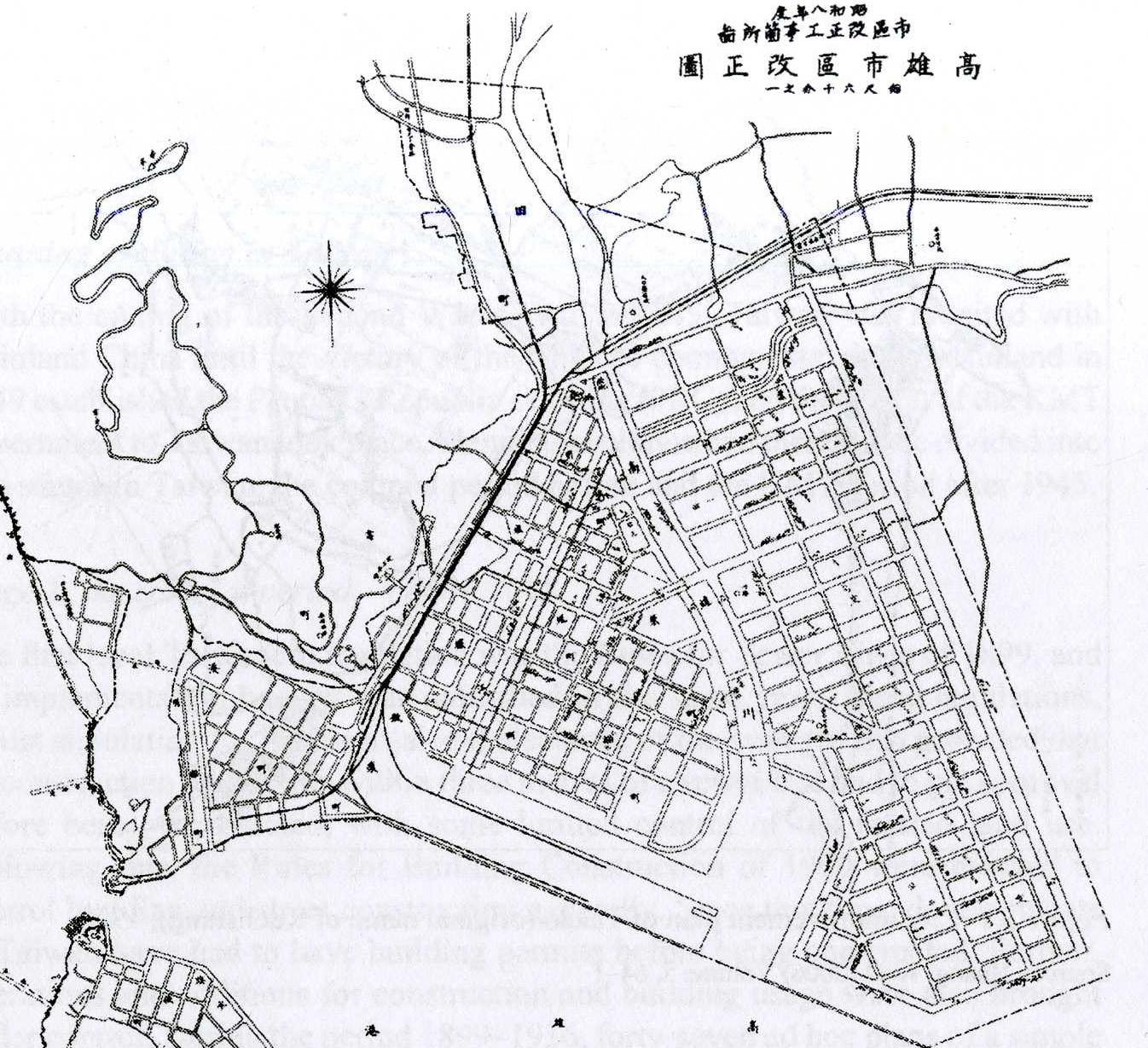

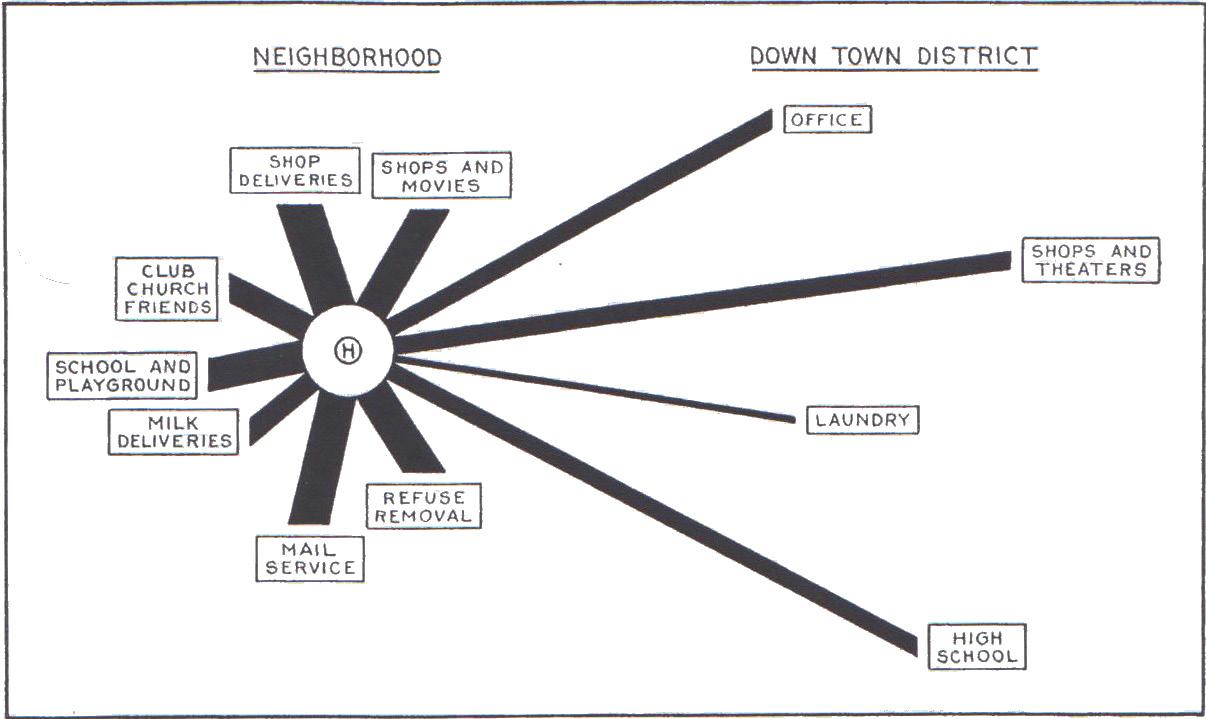

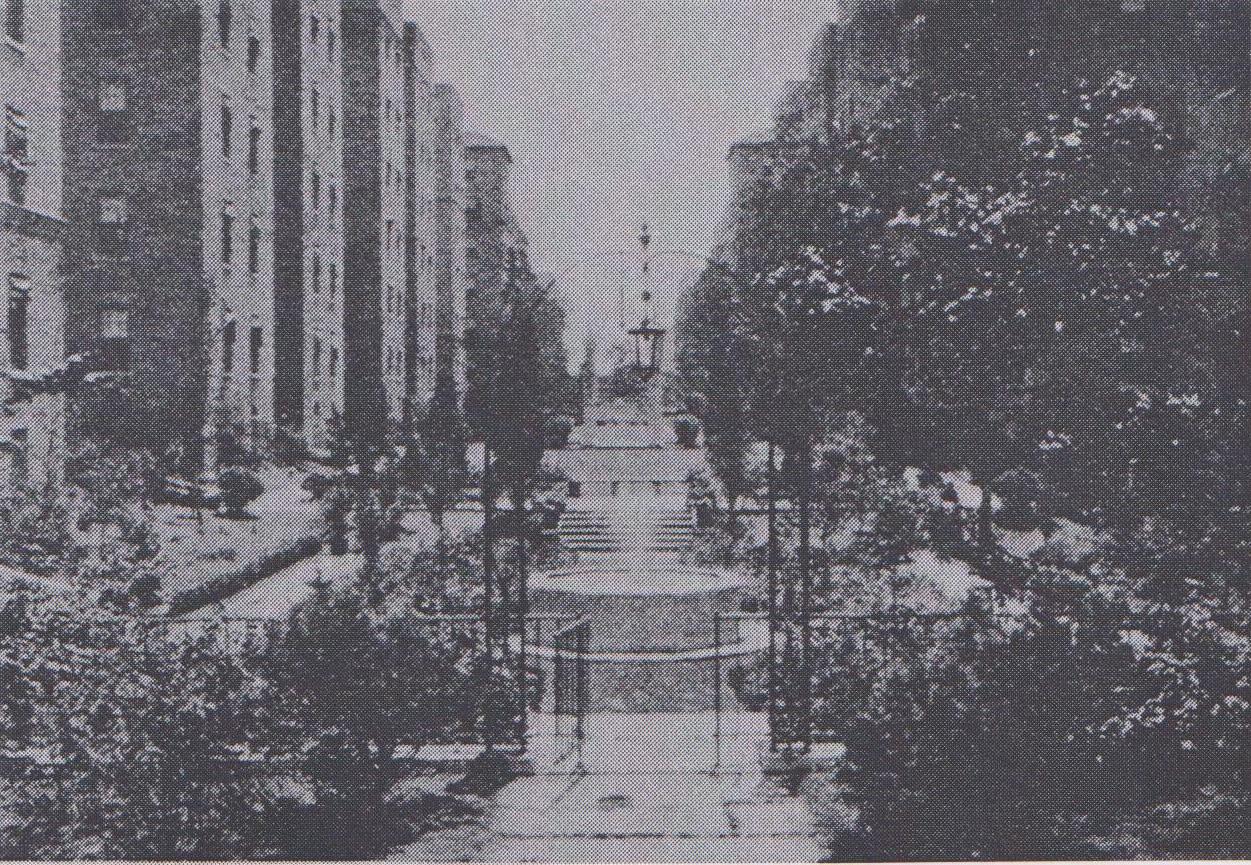

It consisted of large and distinct neighbourhoods. This cellular neighbourhood model had two elements: primary education and Shi-Jie. The model centres on primary education is formed by the Shi-Jie, a covered market street. This Shi-Jie street defines a neighbourhood within an urban block. Along an urban corridor, each building contains vertically distributed working and living functions and opens up on the ground to the street. The Shi-Jie Neighbourhood thus is a mixed-use urban component comprising of working, living and educational functions. Hence, argue that it could be a model worthwhile to re-evaluate in the current masterplan that lacks this kind of activity and intensity. However, this urban model is currently only applicable to neighbourhood scale but not the proposed tertiary industry on a larger metropolitan scale.

To overcome the conflict between zoning and cellular organization,(Fig. 3,4) the downtown area therefore needs another model to integrate tertiary education. The urban campus provides a potential model for this, as Kees Christiaanse claims that it creates an intermediate scale between the large urban complex and each campus building, by embedding in the fabric of the city It benefits from a proximity to the city, and its specific spatial organization can be a highly possible urban strategy for building labs, classrooms, and facilities close to the neighborhood and students’ academic lives strengthened through an informal intellectual exchange. The urban campus correspondingly does not only mingle communal facilities with other university faculties, but the amenities on adjacent streets are also evolved. This eventually raises the question of what kind of model can be created by the neighbourhood idea of the Shi-Jie in respect of education and urban corridors on different scales? I therefore scutinise the historical development of the downtown area and how the relationship between city and urban components can be defined by multi-scalar education, which I term as educational nodes

Fig.4

The Top Source: The Shi-Jie Neighbourhoods by HouYi Zheng (1932)

The bottom Source: [accessed 18 July 2014]

<http://www.ikea.com/ms/zh_TW/img/local_store_info/ kaohsiung/KHS.jpg>

3. Kerstin Hoeger and Kees Christiaanse, eds. Campus and the City-A Joint Venture? (ETH, Zurich: gta Verlag, 2007), p.18.

4. Pier Vittorio Aureli, eds. Rome the centre(s) elsewhere a Berlage Institute project (Milan Skira, 2010), p. 9.

5. Jen-Jia Lin and Cheng-Min Feng, Transportation planning in Taiwan, in Bristow, M. Roger, Planning in Taiwan spatial planning in the twenty-first century, (Abingdon Routledge, 2010), pp.199-200.

6. Clarence Perry, Neighbourhood and Community Planning, (New York, USA: Routledge, 1929), p.24.

7. Gin-Xian Wu, The Analysis of Kaohsiung Urban Development and Planning during the Japanese Colonisation (unpublished PHD dissertation, directed by Dr. Shi-Meng Huang, National Taiwan University, 1988), p. 167.

Different educational nodes already affect the former railway line, which is therefore a good site. The proposal is defined by three scales of education, primary, secondary, and tertiary education and examines how education and the city combine in urban corridors that create communal activities.

The primary education was the node of neighbourhood within a 500-metre walking distance linked by the primary roads. For public transport commuting, the secondary educational node was considered as part of the urban park system that attached to the urban parkway and linked to larger urban area. However, the Kaohsiung downtown area now is defined by highways. Being pushed to the edges of the downtown, tertiary functions are isolated and self-sufficient centres. The problem of suburbanisation and isolate knowledge production is therefore aggravated.

If the ‘everywhere centre’4 is the reality of Kaohsiung, the crux of the problem of tertiary education is how to interact with other nodes and parts of the city. The nature of the downtown is comprised of discrete urban components but not ‘a masterplan’ or single centre as evident from the historical development of Kaohsiung. In an article, Jen-Jia Lin states that over the past 50 years, the more secondary industry developed, the longer roads became. This increased the transport infrastructure, especially expressways. But the masterplan for the downtown redevelops the post industrial sitethat were isolated by the expressways and railways. Moreover, the recent development of infrastructural nodes such as Zouying High Speed Rail station orient urban growth northwards while the new harbour grows to the south of the downtown. The city is disintegrated. The purpose of this project is hence to propose an alternative development in which different parts of the city are designed through the idea of neighbourhoods at different scales.

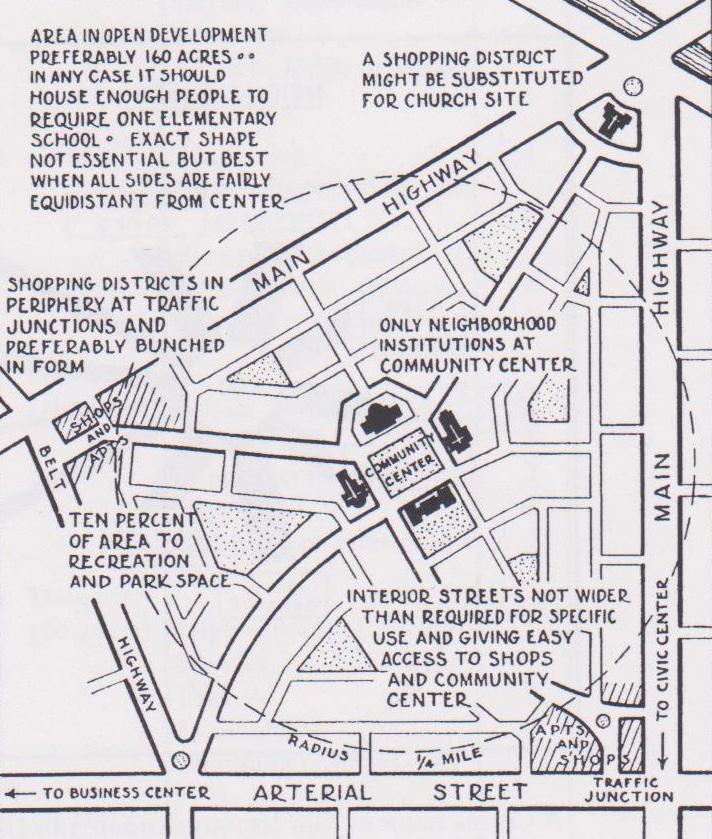

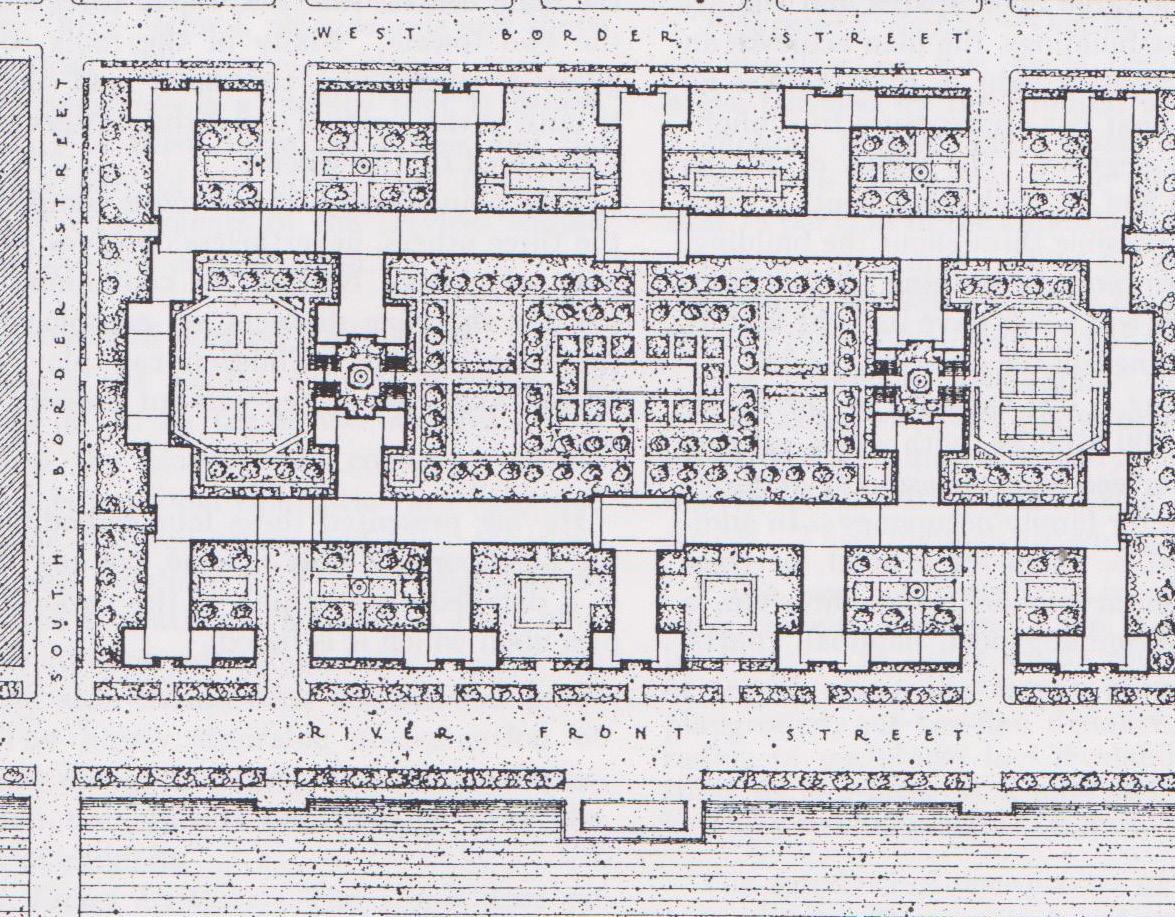

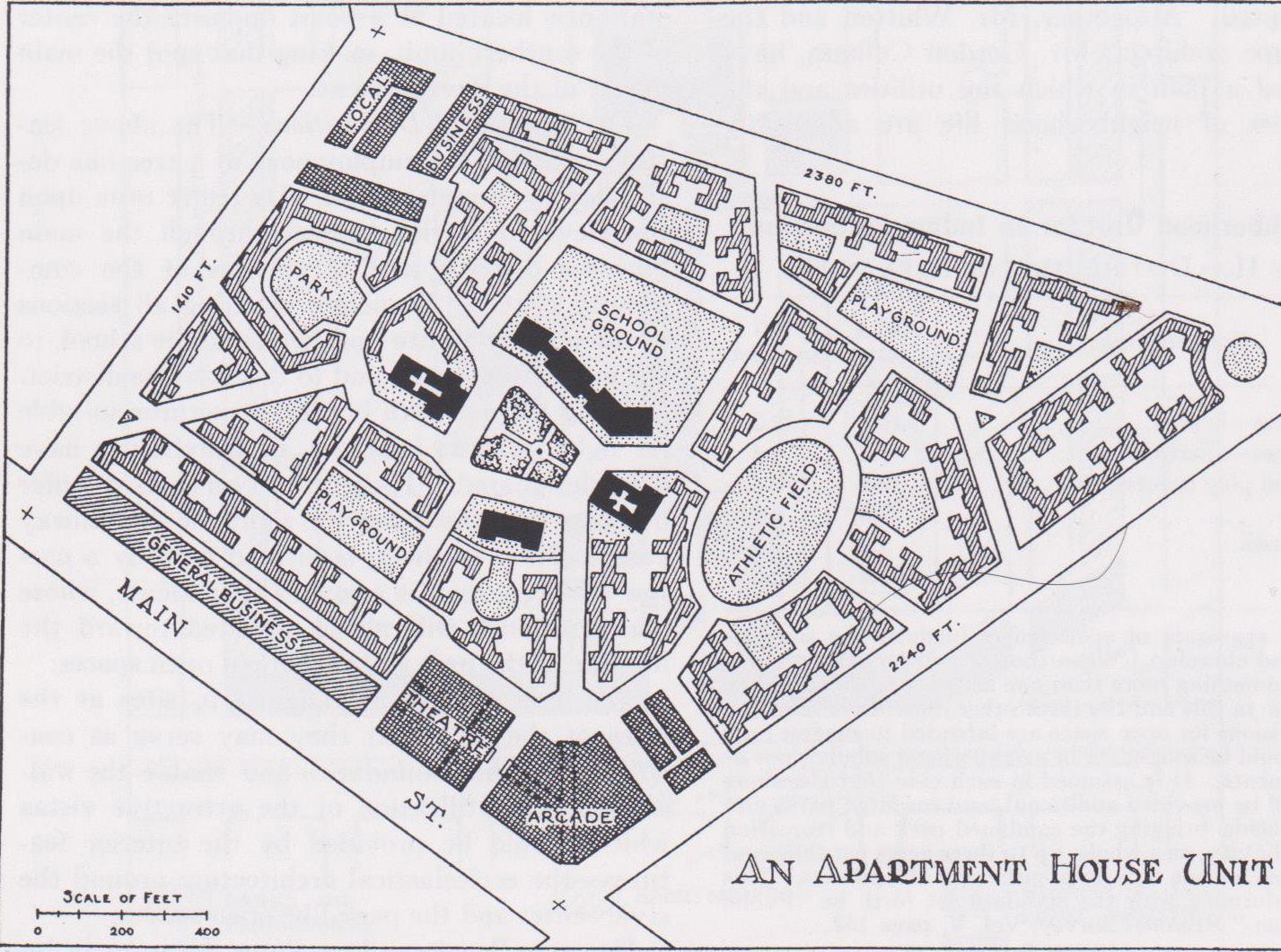

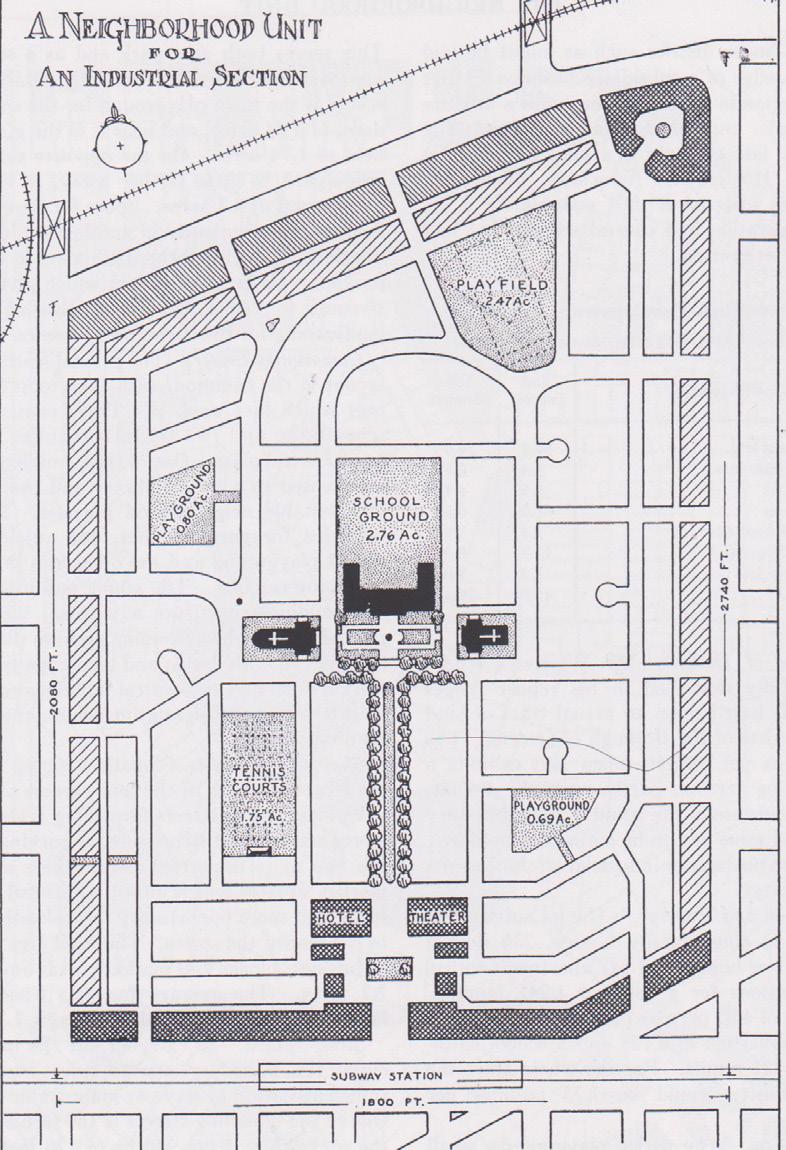

The downtown area was historically a marshland with small settlements in the Ching Dynasty. During the time of invasion the south east Asia, the Shi-Jie Regularisation created the neighbourhood model of the Japanese. The idea of neighbourhood, as a study by Clarence Perry reveals, is that of a cellular unit for a group of single families.6 It centres on primary education as the Shi-Jie Neighbourhood does, as confirmed by a study conducted by Gin-Xian Wu.7 Both are defined by a 500 metre walking radius and primary education, but in the Taiwanese case also by the Shi-Jie (the market street). It is of great importance to distinguish the Clarence Perry’s Neighbourhood Unit from the Shi-Jie Neighbourhood.

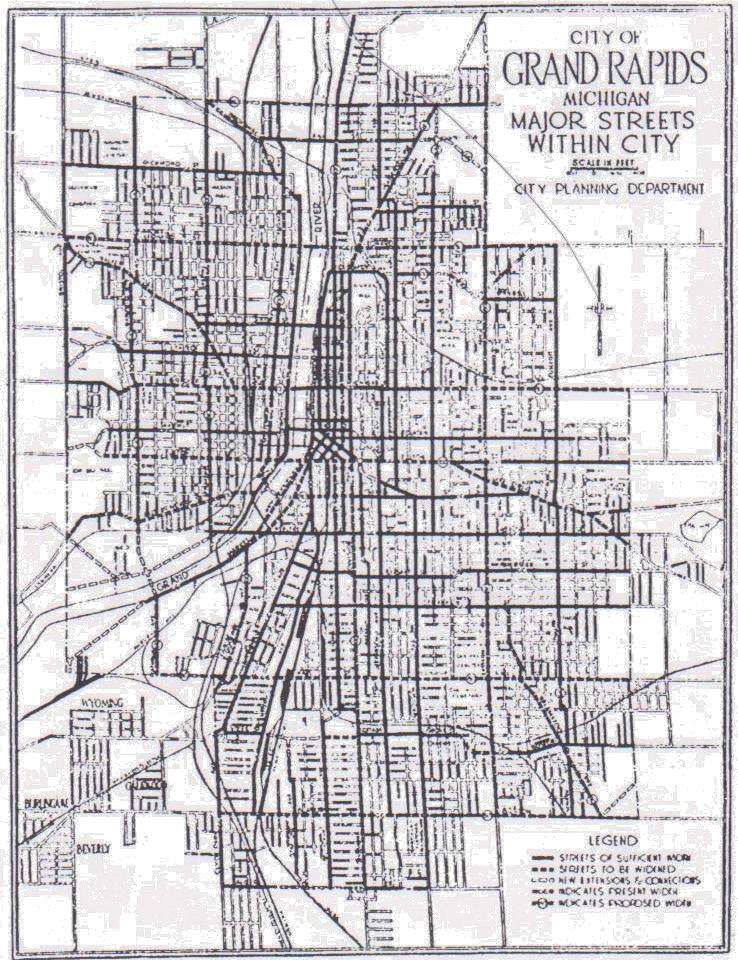

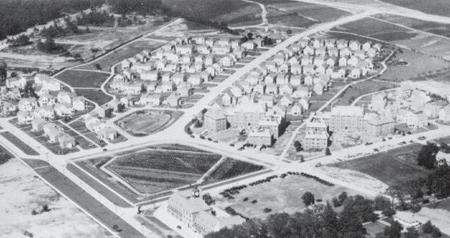

1_1. Research Questions

In 1929, the Clarence Perry’s Neighbourhood Unit was invented as a planning tool in America after World War II, while the city was divided into cellular by the highways influenced by Howard’s Garden City model, It proposed a cellular structure containing primary education and residential area in a centre-to-periphery arrangement surrounded by highways. It was a suburban model separating living from work in the city centre. The model creates a self-contained neighbourhood and, as Perry stated, is for a social group in a particular time and space. Radburn city in New Jersey adopted a similar idea of a large autonomous neighbourhood.

Having the same elements similar to the American neighbourhood unit, the Shi-Jie Neighbourhood was however utilised in a different way. The difference is the street element. In the Neighbourhood Unit, it was used as a service infrastructure, for land division and mechanical supplies. The Shi-Jie on the other hand is a regularising tool and sanitary infrastructure9 and is covered by a roof creating a market street.

In the vicinity of this street, the neighbourhood developed, with the provision of a central common space inside an urban block. Shi-Jie is therefore a type of arcade, according to its definition as an interiorised street connecting both ends of an internal block.10 It also connects external and internal spaces in a block, as well as private and public spaces. Hence, the centre of the block is not privately owned and enclosed, but an open space on the ground level.11 Along the Shi-Jie, there are interspaces between corridor and frontage. The first layered interspaces are defined by the market strolls and trolleys from each frontage. The second layer is defined by a colonnaded space set into each unit at ground level. The third layer is the open ground floor plan used for trading. The Shi-Jie thus is a ground-based type that converts the street into a shared space with different stakeholders.

Although this model works mainly at the neighbourhood scale, the importance of the street as an infrastructure has the potential of working beyond this scale. As the model developed, it was transformed into part of the circulation infrastructure in the downtown area, and brought different social groups together. It became a productive type. Thus, the Shi-Jie Neighbourhood can work at different scales and accommodate different social groups including the new tertiary education in Kaohsiung. The Shi-Jie Neighbourhood is a means to organise the sunken railway line as an inverted street serving the tertiary education as a connecting spine that links the institutions but also the surrounding urban fabric.

8. Clarence Perry, Neighbourhood and Community Planning, (New York, USA: Routledge, 1929), p.23.

9. Lih-Horng Chen and Hung-Chih Shih, Land use planning in Taiwan: a history, in Bristow, M. Roger, Planning in Taiwan spatial planning in the twenty-first century, (Abingdon Routledge, 2010), p.30.

10. Johann Friedrich Geist, Arcades, The History of a Building Type, (Cambridge, MA MIT Press, 1983), p. 4.

11. Philippe Panerai and Jean Castex, eds, Urban Forms-The Death and Life of the Urban Block. (Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 2004), pp. 162-164

Disciplinary Question

Thus, developing this model is not just on a neighbourhood scale but also an urban scale, the research question is:

- How can a neighbourhood idea be reconceptualised for a downtown area?

- How can education centres act as urban nodes in relation to their infrastructures on different scales and become instruments of urban planning in Kaohsiung?

This is a question that fits into a general problem that revolves around how education centres can be re-conceptualised as nodes that are practical and habitable in operational ways.

Urban Question

Problems arise from the Kaohsiung downtown area because the cellular model cannot work on metropolitan scale; the high speed rail station is moving the centre of the city northwards, and the new science campus is located on post-industrial land, creating suburban conditions in the city centre. This altogether challenges the idea of the downtown as a centre and raises the following urban question:

-What kind of downtown area can be created by a neighbourhood idea based on various education layouts and commercial activities on different scales?

-How can the historical urban diagram of education and Shi-Jie be re-evaluated?

Typological Question

Linked to the urban question is an architectural one:

- What are the potentials of the Shi-Jie type and its hierarchies of interspaces?

- How can the Shi-Jie type demonstrate as a model of living and working to provide new educational infrastructures and link the typology to an urban scale?

1_2. Research Aims:

New Shi-Jie as Architecture for communication among social groups

The downtown not only becomes ‘a city centre’ but ‘an effective suburb’ identified by multi-scalar education nodes. The industrial science park has to be restructured as tertiary education settling at the downtown area. Thus, the project investigates how these separated urban components of the city incorporate and link up with education nodes of different scales and streets and how the tertiary education is relocated along the sunken railway line.

However, the site faces the problems of the void left by the border between the railway and the old downtown area; posing a question of how to integrate the larger neighbourhoods that are separated by this infrastructural line. It is therefore a counter proposal that contains the requirements of the original masterplan as a new science campus along the sunken railway line. On an urban strategic level, the framework incorporates the intensity of different parts of the city into the site. Besides, the railways line itself bridges different social groups commuting by metro stations and high-speed rail terminus. It is thus an instrument for aggregating different educations and institutes.

In order to re-discover the relationships between education and streets, this proposal interweaves the three scales of education and infrastructure. It is reckoned as a new Shi-Jie project at a neighbourhood, urban and metropolitan scale. The east-west axis is the main spine accumulating education. The strips along the perpendicular north-south axis are increasing the lateral permeability of the main spine with the surrounding neighbourhood and territory-wide education. The project thus has the ability of affecting the historic downtown to its south and drives the northern Kaohsiung development together with the Zouying high-speed rail development, connecting the site with the larger territory.

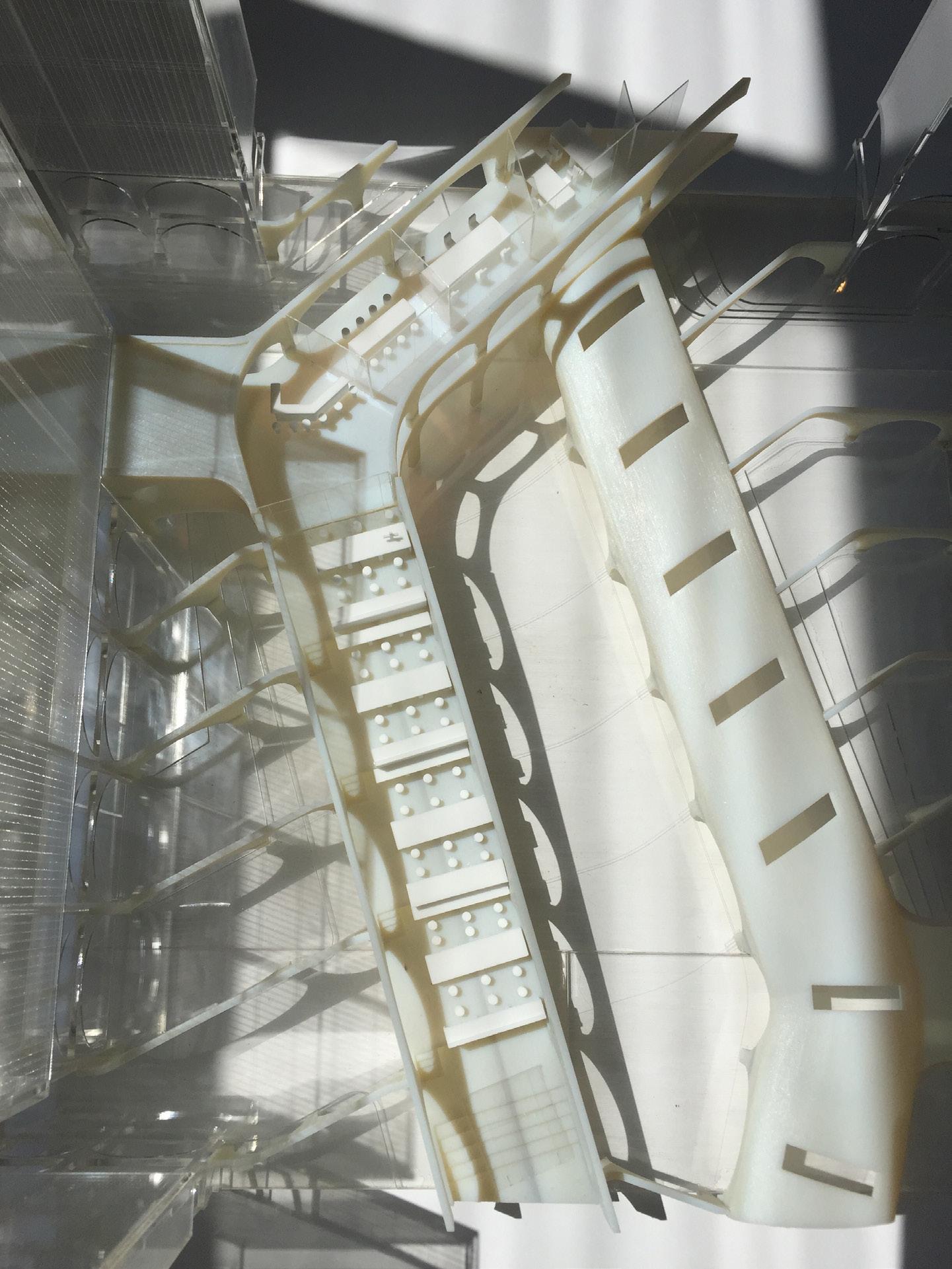

At the architectural level, the proposal explores the Shi-Jie as an Inverted Street idea with its interspaces. Unlike the industrial science park, my proposition no longer relies on the zoning of plots and accumulates communal facilities such as retails, cloisters, shared lab spaces, classrooms and auditorium spaces along the former railway line. To organise these institutes into an urban campus onto the sunken railway, the organisational diagram of new Shi-Jie section not only has similar hierarchical circulation with the urban campus in plan but also keeps the permeability on the ground level with layered interspaces. Moreover the transformation of the Shi-Jie neighbourhood by overlapping its elements is the means to increase the intensity of the proposal.

The creation of various morphologies by adopting the campus lab idea as a series of campus yards mediates the internal space of the city with its surrounding fabric along the sunken railway. Thus, it converts this leftover infrastructural line into a new unitary space of the city.

Whilst the interspaces created by the colonnades were originally recognised as a street front, the proposal develops the element as a definer of the street itself. It releases the element from the street front by interweaving different demands from each institution and building and expanding the colonnade into a series of arches. It incorporates parts of the buildings such as the colonnades, atriums, and lobbies to deepen areas of communication. It thus attracts social groups and common activities to the inverted street under one single roof. However, in order to address more than one scale, the proposal also explores more variations of the relationships between Shi-Jie and education in the urban plan by transforming a ‘single linear street’ into ‘many streets’.

In this sense, the new Shi-Jie is considered not only as an aggregation tool which stimulates interactions between different institutes but also a new organisational diagram for the city. To achieve this, the project starts with the Shi-Jie Neighbourhood and then develops this into a new arcade type. The design proposal is meant to synthesize not only the idea of educational nodes but also the utility of the diagrams that emerge from the enlarged Shi-Jie Neighbourhood. It organises the ground level by using different layered of interspaces accommodating communal facilities on the central space. And it stretches the building interior onto the street with shared spaces. Thus the inverted street is not formed by surrounding architectures but is the architecture forming the space. Therefore, this proposal is not limited to the design outcome but also provides an example of the general typological potentials and urban ideas defined by the Japanese Shi-Jie Neighbourhood, enhancing the ability of bridging different social groups together.

Chapter 2. The Operative Urban Framework

- How can a neighbourhood idea be reconceptualised for a downtown area?

- How can education centres act as urban nodes in relation to their infrastructures on different scales and become instruments of urban planning in Kaohsiung?

2_0. Introduction: The educational node

The suburbanisation has disintegrated the downtown into pieces as an effective suburbia identified by three levelled educations. To reorganise these fragments into a comprehensive urban territory, it is fundamental to reassess what these educations’ roles are in terms of urban aspect and how they interrelate with each other as a framework. It should be applicable to the city development and the future knowledge-based society in Kaohsiung downtown area. Thus the idea of Educational Node is to reconceptualise the relationships between the educations and their urban corridors in relation to their scales.

The idea originates from the study of the urban campus. It is because the idea is to create an intermediate scale between urban surroundings and its architecture.12 (Fig. 5) The study of UCL Bloomsbury campus is one of the examples based on this idea. Moreover, in order to enhance the collaboration between deferent institutes, the idea of the urban campus not only mixes communal facilities with other university faculties, but also involves the amenities on adjacent streets.(Fig. 6) This relationship promotes the provision of the labs, classrooms and facilities in the vicinity of the neighbourhood and enhances students’ academic lives through an informal intellectual exchange for a knowledge-based society.

Although the UCL campus is adjacent to the vibrant area with urban amenity in the vicinity and public transportation accessibility, it fails to serve as an urban campus for many reasons of lacking interspaces in relation to the urban corridors in different scales. In order to formulate the perimeter block, the quadrangles interiorise the urban activities in the centre of the block and the campus buildings form the urban walls, with only a few access points to interact with the surroundings. It turns the urban circulation inside the campus buildings only known by university members.(Fig. 7) Besides, there is a lack of interspaces between the campus buildings along the main corridor in Malet Place. As a result, it does not only isolate the campus from the city but also divides a campus into mere functional buildings.

In short, the idea of urban campus is not about the proximity to the urban surroundings but is also influenced by how its interspaces interact with the urban fabric. Another precedent can clarify this idea which can be found in the precedent of the Trinity College Dublin School of Pharmacy and Genetics.

This project is the final phase of the campus masterplan as the new front door embracing the neighbourhood in the vicinity. Apart from the UCL model interiorising the urban corridor into the campus building, this institute is exteriorising its architectural corridors into urban circulation space. Two arcade spaces between the educational facilities not only create paths from the surrounding neighbourhood to the campus but also define the scale of the community street.(Fig. 8) In view of replacing the atrium between the old structure and the new extension, a path is provided that links to other departments in the campus. Besides, it acts as a gathering place for students to informally meet up with other students and lecturers. The inner street is converted into a city path in the urban block.(Fig. 9)

Located alongside the street are open plan laboratories consisting of biology and chemistry labs opposite to the old part. Performing scientific experiments are arranged to be part of the daily life. The second atrium within the plural addition also serves as a large seminar space and even hosts special events such as breakfast meetings. By doing so, it forms the edge of the lab campus and becomes part of the city fabric.13 At the end, this project not only just concludes the last phase of the campus masterplan, but a group of vigorous artifacts plays an ambiguous role between the architecture and the city. Education and the city are knitted together by these two arcades in relation to the communal activities defined by both sides on the ground.

Thus, the educational area is not merely a solitary building situated at the urban fabric, but also the intersection between knowledge and the neighbourhood via these corridors. The educational area is actually the node firmly embedded within the city to drive urban development around it and bridging different social groups with these communal spaces.

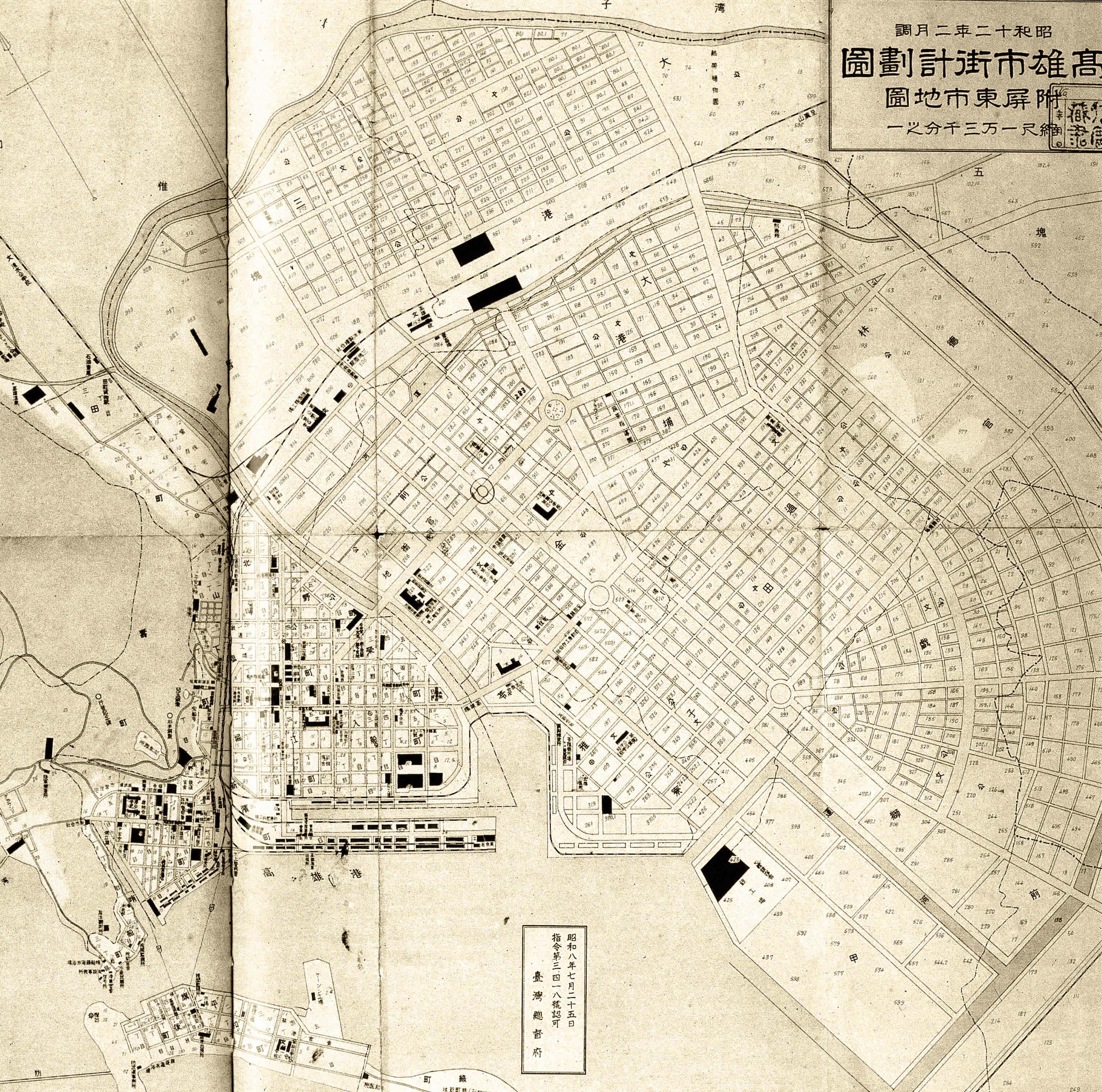

Before I further argue the relationship between education and the city in Kaohsiung, it is of paramount importance to set out an operative framework in the project driven by educational nodes in respective of their multiple scales. This notion originated from the City Improvement Plan of downtown Kaohsiung created by the Japanese. The purpose of the plan was only to provide a purely functional area supporting the port with education and sanitary infrastructures. The idea is demonstrated by the primary education nodes in the existing Kaohsiung downtown area on a neighbourhood scale.

Fig.9 The Atrium of Trinity College Dublin School of Pharmacy & Genetics, by Scott Tallon Walker Architects (1997)

2_1. Primary education as the node of a neighbourhood

The neighbourhood idea in the masterplan originally intended to exert the regime of Japanese governance from the primary education node.14 These primary education nodes in the plan were organized around a mixed use community within a five hundred metre walking radius by using the Shi-Jie (market street) as a regularising tool. The notion of Shi-Jie arose in response to the problem of the mortality rate of Japanese soldiers during this period. The issue of the masterplan therefore was largely based on the idea of hygiene, and a sewage system built in 1908. Da-Gou-Ding was one of the sewage systems first covered by the market street, leading to the idea of Shi-Jie.(Fig. 11)

It is the model of the regularising tool in the masterplan driven by the covered corridor lined on both sides with shops in the internal block, centralizing the neighbourhood’s activities around the primary education node.15 Thus, the node system of the primary education area is based on the cellular idea, within walking distance for pupils. Besides, the alleys running from the Shi-Jie are linked through the community roads to the primary ones, creating community corridors for each neighbourhood.

However, the notion of primary education nodes only works on neighbourhood scale. Hence, a further question is proposed regarding the location of other educational nodes in relation to urban scale and further beyond the Kaohsiung downtown area.

Fig.15 Source: [accessed 18 July 2014] <http://www.nsysu.edu.tw/ezfiles/0/1000/pictures/852/ part_59200_7981122_57808.jpg>

19. Kuei-Lin Hsu eds. The History of Kaohsiung, Section 6: Education, (Kaohsiung City Government, 1985), pp. 62-63.

20. Yu-Hsiang Hung, The Laboratory in the Campus (unpublished essay, Architectural Association, 2013), p. 1.

2_3.

Tertiary education as the node of the metropolitan region

The tertiary education layouts in Kaohsiung reveal problem between the campuses and the metropolitan region. The first tertiary education outlet in Kaohsiung, National Sun Yat-sen University, was built in the downtown area in 1980.19 Although its location was close to the city centre, the notion of this campus design was based on the greenfield idea, sitting along the coastal line that is accessible by vehicles only It provides a discrete environment that involved academic activities to foster knowledge sharing in quiet surroundings.20

It created a fragmented part being isolated from downtown. The problem has aggravated over the last twenty years. As one of the major cities of Taiwan, Kaohsiung however has spent the least amount of expenditure on higher education. In the past two decades, the government has increased investment in higher education in Kaohsiung. Nevertheless, these campuses were situated away from the downtown area and clustered around the region of Zuoying high speed rail station - the northern part of Kaohsiung metropolitan territory.

Fig.14 The Tertiary Education nodes in Metropolitan Kaohsiung, by Yu-Hsiang Hung (2015)

This is because the transport line links up the major cities in Taiwan, especially the capital city, Taipei. It thus changes the city’s growth orientation along this corridor into the northern suburban area of Kaohsiung metropolitan area, which is mainly served by the highway system. Apart from being considered as the suburban centre, the node of higher education also splits from the existing city’s fabric, which challenges downtown as a centre.

In short, the problem of the three types of educational nodes is portrayed through the gradient of proximity, i.e. from the closest to the urban fabric corridor until where the corridor breaks away from the city. It is because the city plan never creates the idea of “a centre”, therefore the question of whether the development of Kaohsiung could be positioned as a suburb is anticipated, according to the definition of these three scales of educational nodes.

Since the tertiary educational nodes have now been detached from the city fabric, it thus forces me to envisage another question as follows: Can we seek a new form of tertiary education as a network in Kaohsiung embedded within the condensed urban area, like the precedent of Trinity College Dublin School of Pharmacy and Genetics, driving part of a city development for a coming knowledge-based society in Kaohsiung?

2_4. New Shi-Jie: The multi-scalar educational node strategy for the

sunken railway line

The research in this dissertation aims at elaborating and conceptualizing the educational nodes with a theoretical and methodological framework. It also aims at systematizing the design process, in the specific case of Kaohsiung downtown area.

The method then investigates the historical development of the downtown area. The notion of the Shi-Jie Neighbourhood in relation to primary educations is the way to start. Through the different relationships between the city and the urban components being identified by multi-scale educations in relation to their urban corridors, it also investigates a design approach which builds on the idea of the Educational Node. It arises in the downtown area and its territory.(Fig.17) Based on multi-scalar research of the metropolitan, it comes up with an urban operative framework as the starting point of this project and aims to accommodate the tertiary education embedded within Kaohsiung downtown area.(Fig. 18)

Kaohsiung downtown area is thus not conventional city centre and it should be re-considered though a new approach of rationalising the situation. Although it now can be identified by those three educations, there are still missing links between the tertiary education and the city. Furthermore, those problems drive the city as, effectively, a suburb. It probes the question of how they interrelate with the metropolitan region as an operative urban framework.

Fig.19 Source: [accessed 18 July 2015] <http://www.skymight.com/cust/kcn/uploads/tadnews/111111+11(4).jpg>

The current industrial park area has to be repositioned as tertiary education as part of the downtown area. Through the different relationships between the city and the urban components being identified by multi-scale educations in relation to their urban corridors, a design approach which builds on the idea of the Educational Node is investigated too. It arises in the downtown area and its territory. The leftover railway line is affected by different education nodes as the suitable site to re-establish the new tertiary education layout. The existing site condition is highlighted by the educations in relation to their scales and infrastructures. They shape the nature of various scales of this project. It examines how the educations and the city are knitted by urban corridors in respect of the ground communal activities.(Fig. 19)

However, the site faces the problems of the void left by the border between the railway and the old downtown area; posing a question of how to integrate the larger neighbourhoods that are separated by this infrastructural line.(Fig. 22) It is therefore a counter proposal that contains the requirements of the original masterplan as a new science campus along the sunken railway line.(Fig. 20, 21)

On an urban strategic level, the framework attracts the intensity of different parts of the city into the site. Besides, the railways line itself bridges different social groups coming from the metro stations and the high-speed rail terminus. It is primarily an instrument for accumulating different educations and institutes. In order to re-discover the relationships between education and streets, this proposal interweaves the three scales of education and infrastructure. It is conceived as a new Shi-Jie project at neighbourhood, urban and metropolitan scale.

The first layer is to highlight the linkages via different neighbourhoods to the edge of the sunken railway line.(Fig. 23) The second layer is to illustrator the urban parkway to the edge of the sunken railway line. (Fig. 24) The third layer is to reveal the current developments driven by the expressways and high speed rail at the edge of the downtown.(Fig. 25) Then, the framework found of the masterplan with the three layers empowers the sunken railway line as the new Shi-Jie to furthered develop part of the downtown area.(Fig. 26)

The east-west axis is the main spine of the hub accumulating the urban function programmes with secondary educations and museums. Strips along the north-south axis are increasing the lateral permeability of the main spine with the neighbourhoods in the south and territorial related programmes with university campus in the north.(Fig. 27) The spine and the strips tie into and consolidate the separated neighbourhoods and become new starting point of the downtown area. The New Shi-Jie thus has the ability of affecting the historical part and driving the northern part of the city as Zouying high speed rail region development, sewing up the site into the larger territory.(Fig. 28)

In short, the tertiary education in Kaohsiung downtown area reveals problem in the metropolitan region. It is defined by the highways and nestled up to the edge of the downtown with isolated institutes in the open field. In this connection, the tertiary educations become the self-sufficient nodes disconnected from the city’s fabric. It thus exacerbates the problem of suburbanisation and isolates the knowledge production from the downtown area. If the ‘everywhere centre’21 is the reality of Kaohsiung, the problem of the new tertiary education layout has to consider how it can interact with other scales of nodes and different parts of city related to the sunken railway line. In this sense it leads to the problem of the City Made of Urban Components.

Chapter 3. The City Made of Urban Components

- What kind of downtown area can be created by a neighbourhood idea based on various education layouts and commercial activities on different scales?

- How can the historical urban diagram of education and Shi-Jie be re-evaluated?

3_0. Introduction: the downtown challenged by various urban components through its history

This region is defined by three stages of governance through their city areas within the southern territory of Taiwan.(Fig. 29) Dating back to the Japanese occupation (1895-1945) period, it was a demarcation between the middle era of the Ching Dynasty (the early 19th century) and the KMT regime (after 1945).45 It was the period where the salt fields were gradually transformed to the downtown area today. These three phases contributed to the development of the downtown and metropolitan area with multi-scalar urban components nowadays.(Fig. 30)

Fig.10 Source: [accessed 18 July 2014] <http://www.nsysu.edu.tw/ezfiles/0/1000/pictures/852/ part_59200_7981122_57808.jpg>

23. Jen-Jia Lin and Cheng-Min Feng, Transportation planning in Taiwan, in Bristow, M. Roger, Planning in Taiwan spatial planning in the twenty-first century, (Abingdon Routledge, 2010), pp.199-200.

Owing to the secondary industrial development in the past, one of these components nowadays can be identified by the site for the industrial science park. Its development was driven by the abandoned railway and highway systems.(Fig. 31) In an article, Jen-Jia Lin stated that over the past 50 years, the more secondary industry has developed, the greater the length of roads created.23 As a result, the development of suburbanisation has expedited through the construction of transport infrastructures, in particular the expressway system. Moreover, the post industrial site is in fact purposely reconstructed for tertiary institutions in the downtown area and translated it into a massive fragmentation in the city.

Besides, the downtown area was predominantly marshes fields scattered with small settlements in Ching Dynasty. It then later dominated with the Shi-Jie neighbourhood components created by the Japanese during the Shi Jie Regularisation. Moreover, the recent development of infrastructural nodes such as the Zouying High Speed Rail station, encouraged the northward growth of the city and the emergence of the mega-harbour in the southern periphery of the downtown. Coupling with the problem of Educational Node, the proposition of the ‘a conventional city centre’ with ‘an everywhere urban components’ is challenged.

The nature of the downtown is how discrete urban components shape it rather than being conceived as ‘a masterplan’. The notion of not being the centre of the metropolitan Kaohsiung is challenged. The downtown is in fact comprised of a series of separate components with designated functions in respect of their part of the city. Therefore, argue these components inherited from the historical development should co-orperate within the operative framework in preparation for the tertiary knowledge production of the metropolitan region.

Fig.31 The Operative Infrastructure Framework of Kaohsiung by Yu-Hsiang Hung (2014)

3_1. The industrial science campus component in Kaohsiung downtown

Fig.10 Source: [accessed 18 July 2014] <http://www.nsysu.edu.tw/ezfiles/0/1000/pictures/852/ part_59200_7981122_57808.jpg>

24. Tsu-Lung Chou, Institutional evolution and the challenge of urban planning in post-industrial Taiwan, in Bristow, M. Roger, Planning in Taiwan spatial planning in the twenty-first century, (Abingdon Routledge, 2010), pp.85-86.

World Trade Organization membership and connected trends from emerging China has been to force drastically Taiwan’s development trajectory into a new post-industrial format. Thus, this shift has imposed a subsequent spatial impact upon urban Taiwan. In central and southern Taiwan it has created huge idle government-developed industrial campuses (2000 hectares in total; 590 hectares in Kaohsiung). More specifically, high-tech industries grew steadily whilst the traditional manufacturing factories closed or moved out overseas, mainly to China. Along with the steady growth of service industries and high-tech industries, knowledge based industries have become the core sector of the Taiwan economy.

Since the 1990s, Kaohsiung has embarked a series of economic growth initiatives due to the competition from emerging China, which has drastically pushed Taiwan’s development trajectory into knowledge-based development.24 An prominent example was evident in 2000. The city government created a huge idle government-developed industrial science campus as ‘A’ centrality for the tertiary knowledge production in the downtown area.(Fig. 32) Although this area was used to be the supporting section for industrial and port facilities, the post-industrial part can now be considered as an opportunity to infill a science campus with knowledge economies in the urban surroundings, as a result of the service industries moving to China and the port shifting to the southern part of the city.(Fig. 33)

As an industrial science campus, it aims to attract ICT industrial offices, biotech research labs, last-mile manufacturing and related commercial businesses as a new node for knowledge-based industries in the Koahsiung Multifunctional Commerce and Trade Park in the downtown area. This has entailed extensive problems to the Kaohsiung downtown area. The vision of this science campus is originally based on the model of the Hsinchu Science-based Industrial Park.

Fig.32 The Zoning Districts of Science Campus in the Kaohsiung Downtown Area, by Yu-Hsiang Hung (2014)

Fig.10 Source: [accessed 18 July 2014] <http://www.nsysu.edu.tw/ezfiles/0/1000/pictures/852/ part_59200_7981122_57808.jpg>

It was the first successful model for research institutions’ aggregation in Taiwan built by the national government which started in 1980. Established as the research hub for promoting the industry via the new economic engine, this park includes industrial, residential, and research zones, as well as public utilities. There are also two national universities, the National Chiaotung University and the National Tsinghua University, and a major government research institute. It was conceived as the national Government demonstration project to foster the so-called ‘synergy effect’ among government research institutes, universities, and private high-technology firms. Easily accessible communal spaces between different institutes and departments are essential.25 (Fig. 34)

25. Manuel Castells, Peter Hall, Technopoles of the World- the making of twenty first century industrial complexes,(London Routledge, 1994), p.100.

26. Manuel Castells, Peter Hall, Technopoles of the World- the making of twenty first century industrial complexes,(London Routledge, 1994), p.108.

However, the layout park in fact is based on the suburban idea for former agricultural lands. It is barely related to the downtown area of Hsinchu that was entirely bypassed in this development. Owing to its highly accessible transportation system connected by highway and railway, it is possible for engineers and executives to commute from the Taipei area, a preferred residential area equipped with quality education institutions and urban amenities.26 Under this circumstance, the infrastructure element is insignificant but a transportation device for conveying people from one place to another plays a pivotal role. Separation of work and live therefore aggravates the problem of suburbanisation.

27. Manuel Castells, Peter Hall, Technopoles of the World- the making of twenty first century industrial complexes,(London Routledge, 1994), p.109.

Moreover, the companies in the park pay a limited amount of tax to the local government. It is because most of the headquarters and sales department of companies remain in the capital, Taipei, a substantial amount of corporate income contributed to Taipei. Since the local government is unlikely to benefit from this growth, the isolation of high-technology complex from the rest of the region has not sparked off any of their interest. As a matter of fact, the government-initiated project became an entrepreneurial industrial centre that successfully solicited the support ofsome of the most advanced technological centres.27 Hsinchu thus provides material evidence of the impact of the city and its downtown area. The development logic of the industrial science campus follows the footsteps of Kaohsiung downtown area by virtue of its success in economy and lands owned by the national state from post-industry site.

Although Kaohsiung industrial science campus is situated in an impeccable location in the inner city, 28 the problem eventually emerges because the layout campus is still based on the concept of an industrial park with a high degree of car accessibility, extreme zoning, mono-functionality and interiorisation of spaces.(Fig. 35) Besides, despite of the area being adjacent to the metro transport system, the area of the masterplan is characterised by the problem of local walking inaccessibility and isolation. Te emptiness of demolishing the facilities left over from peripheral check points has separated it from surrounding neighbourhoods.(Fig. 36) Therefore, the infrastructure element, the street, is not a space of communication but the leftover for land subdivision and service utility provisions.

On an architectural scale, the masterplan covers the industrial zones between the downtown area and the harbour, with a large proliferation of mono-functional and interiorized buildings, such as generic ICT office towers and slabs, big box shopping centres and research laboratories in separate districts, disregarding the existing fabric of the city.(Fig. 37, 38)

Ultimately, this park is dominated by big boxes of commercial activities and has become nothing more than a commercial centre. It further accelerates the development of the downtown area into a suburb. In this connection, the question of how the historical growth of the downtown area has influenced the contemporary urban expansion within this suburban development should be addressed in the following section.

Fig.39 Source: Source: [accessed 18 July 2014] < http://tupian.baike.com/a0_00_74_01300000206900 131130749657115_jpg.html >

3_2. The dispersed nodes development inherent from the history

The historical expansion also attributed to the current dispersed development. Due to the customised house and coastal security line, the first phase is regarded as a border of downtown area today It was dominated by salt marshes within two major settlement areas: Zuoying in the north and Fengshan in

Fig.23 The Urban Components of Kaohsiung by Yu-Hsiang Hung (2015)

29. Jen-Jia Lin and Cheng-Min Feng, Transportation Planning in Taiwan, in Bristow, M. Roger, Planning in Taiwan spatial planning in the twenty-first century, (Abingdon Routledge, 2010), pp. 199-200.

However, during the third phase, the downtown area was considered as the economic hub within residential areas and secondary industries supported by expressway systems29 that connect to other major cities and the capital Taipei through Zuoying suburb. Recently, the southern high speed rail terminus has been located in the Zuoying area, creating an infrastructural component within the city periphery. In this regard, the Zuoying area has not only become another transport infrastructure component but also a node of gathering university campuses that previously discussed in the section on Tertiary education as the node of the metropolitan region. It aggravates the problem of attracting the city’s development from the downtown area to the northern suburbs. These urban components therefore emerged as mini cities within specific functions to serve a particular part of the city. The components also concurrently have a tendency to de-link from the immediate spaces around them.30 (Fig. 41)

30. Graham, Stephen and Simon Marvin, Splintering urbanism networked infrastructures, technological motilities and the urban condition,( London Routledge, 2001), pp. 358-359.

These horizontal segregations with urban components, reflecting the nature of Kaohsiung, are difficult to be interpreted and understood. Besides, it resists the conventional distinctions and categories that a ‘A’ city centre required to be. Under such circumstances, the communal spaces are incomprehensible and exacerbate the problem of the urban segregation. The city is therefore disintegrated into pieces of components.31

31. Graham, Stephen and Simon Marvin, Splintering urbanism networked infrastructures, technological motilities and the urban condition,( London Routledge, 2001), p. 119.

Fig.42 The Educational Nodes along the Sunken Railway by Yu-Hsiang Hung (2015)

3_3. The leftover sunken railway line as a new unitary space

To overcome this condition, it requires intense concentration of highly capable, interlinked infrastructure networks.32 Together with the problems of Educations as Nodes, they create a dialectical relationship between the idea of a centre and an ‘everywhere node’33 embedded within the operative framework. If suburban development is the situation of Kaohsiung, shall scrutinise what new unitary space as the Shi-Jie Neighbourhoods is hidden in the historical downtown urbanisation during Japanese colonisation.

Unlike the industrial science park in downtown that separates itself from the surroundings, the sunken railway line in the northern part of the downtown area is a site with great potential for implementing the design proposal. This intensive urban environment offers an opportunity to gather the knowledge-based labour force through various public transport systems.(Fig. 42) On a metropolitan scale, the railway promotes the city growth northwards into the Zuoying suburb as its location at the intersection between the northern edge of the downtown area and the Zuoying centre. On an urban scale, the site is a linear, 2-km long band forming the boundary within three metro stations. One is the central station of the city, which also links to the high speed and mainline railway station, bridging this area to a lager territory. Another is the Science and Technology Museum station clustered with Kaohsiung Medical University that centralise various urban activities. The other one is the Ho-Bin Primary school station, linking to the neighbourhood scale. It therefore ties the design proposal to multi-scalar educational nodes that interlinked through different forms of transport infrastructures.

The sunken central railway brings the opportunity for new development of the city. It therefore faces two main issues: leaving a void at the border between the railway and the city centre, and how to integrate the larger neighbourhood which used to be separated from this infrastructural line. In order to address these problems, this proposal suggests adopting the Shi-Jie type as a mediating urban and architectural form. The design aims to provide a counter proposal to accommodate the requirements of the original masterplan for the science park on this infrastructure.

35.

3_4. New Shi-Jie as an aggregation tool

Regarding the new idea of infrastructure, Graham reckons that it is a relatively new subject which allows architecture to be more and less isolated in its own territory.34 Besides, Hauck points out that infrastructure such as sewerage systems or railway stations has significantly transformed the urban fabric and guaranteed the contemporary city a steady chain of supply and mobility.35

The new Shi-Jie thus re-evaluates how the tertiary education originally proposed on the industrial park can be consolidated into intensive urban conditions as a form of urban campus along the infrastructural line. It is to reorganise different educational nodes on a different scale as an alternative of the current suburban conditions in Kaohsiung. My proposition addresses two questions: how does this downtown area relocate its new tertiary education onto the former central railway as an aggregation tool of developing the city part by part, and how can the historical model within the downtown area, in terms of the Shi-Jie Neighbourhood, be relevant in regulating this infrastructural line.(Fig. 43)

On the morphological level, the strategy is to modify the way of infrastructural utilities in the industrial science park. The streets are recognised as the leftover voids in-between institutes and districts because the service purely functions as ‘customised’ infrastructures for this park. By adopting the idea from Shi-Jie, the market street element as the communal space for different social groups should be able to translate the strategy into the plan.(Fig. 44) It accommodates the shared facilities on the ground floor such as neighbourhood shop lots, school cloisters, teaching labs, classrooms and auditorium spaces above the former railway line, in view of preparing an energetic promenade axis for the urban campus. Besides, in order to reverse the horizontal segregation development of the city, the proposal intends to relatively densify the Shi-Jie model with its market street and education elements vertically.

Albeit the space along this axis becomes a vertical urban campus on a new public transportation infrastructure, it is a new type of arcade space, refunding the inaccessible infrastructure line in the central block back to the public.(Fig. 45) Then, it enables the space to be capable of sewing up different deferent parts of the city. To achieve that, the proposal maintains the permeability on the ground level with layered interspaces. The axis’s edge is subsequently binded with colonnades and atrium spaces coupling with every building from the campus axis is enhanced.

Besides, in response to the boundary emerged between this campus and the city, this corridor centralises variations of morphologies, ranging from campus lab precedents to a series of campus yards that are mediated with its surrounding fabric along the sunken railway.(Fig. 46) The new Shi-Jie thus goes beyond the conventional campus and elevates the territory and its interlinked infrastructural connections as a new scale of a campus typology.(Fig. 47, 48) It becomes an instrument of aggregation for accelerating communications between institutes. The new Shi-Jie therefore questions the separation of the city and a centre for the city at the same time, by addressing this tool accumulating the city development part by part along this space. In response to the City Made of Urban Components, the purpose of this project hence is not to develop an aggressive centrality of the city, but an alternative as the new Shi-Jie type by creating different parts of the city incrementally and extracting the ideas from the neighbourhoods subject to their scales.(Fig. 49)

In this connection, the new Shi-Jie is not only regarded as an aggregation tool for architecture but also as an organisational diagram for a city. This proposal also examines the separation of different departments in accordance with the science park arrangement by creating demand-sensitive tool-kits of campus lab morphologies during the ongoing development process. It aims at integrating the educational nodes, infrastructures, and the territory into this system as a new urban model which was originated from the Shi-Jie Neighbourhood. It therefore furthers the discussion to the Idea of the Neighbourhoods.

Chapter

4.

The Neighbourhood Idea Works beyond Its Scale

- What are the potentials of the Shi-Jie type and its hierarchies of interspaces?

- How can the Shi-Jie type demonstrate as a model of living and working to provide new educational infrastructures and link the typology to an urban scale?