COVER SHEET FOR SUBMISSION 2023-2024

PROGRAM: Projective Cities, Taugh MPhil in Architecture and Urban Design

NAME: Arielle Lavine

SUBMISSION TITLE: Forest Children: How Educations of Indigenous and Settler Children Reinscribe the Colonial Order

COURSE TITLE: Dissertation

COURSE TUTOR: Platon Issaias, Hamed Khosravi

DECLARATION:

“I certify that this piece of work is entirely my own and that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of others is duly acknowledged.”

Signature of Student:

Date: April 22, 2024

1 Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Brian Massumi, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Athlone Contemporary European Thinkers (London New York: Continuum, 1988).

2 Decolonial Questioning is a methodology that aims to mobilize intergenerational white settler responsibility in the cultural sector. The inward turn is the first step in decolonial questioning. Leah Decter and Carla Taunton, “An Ethic of Decolonial Questioning: Exercising the Quadruple Turn in the Arts and Culture Sector,” in The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Art Histories in the United States and Canada (Routledge, 2022).

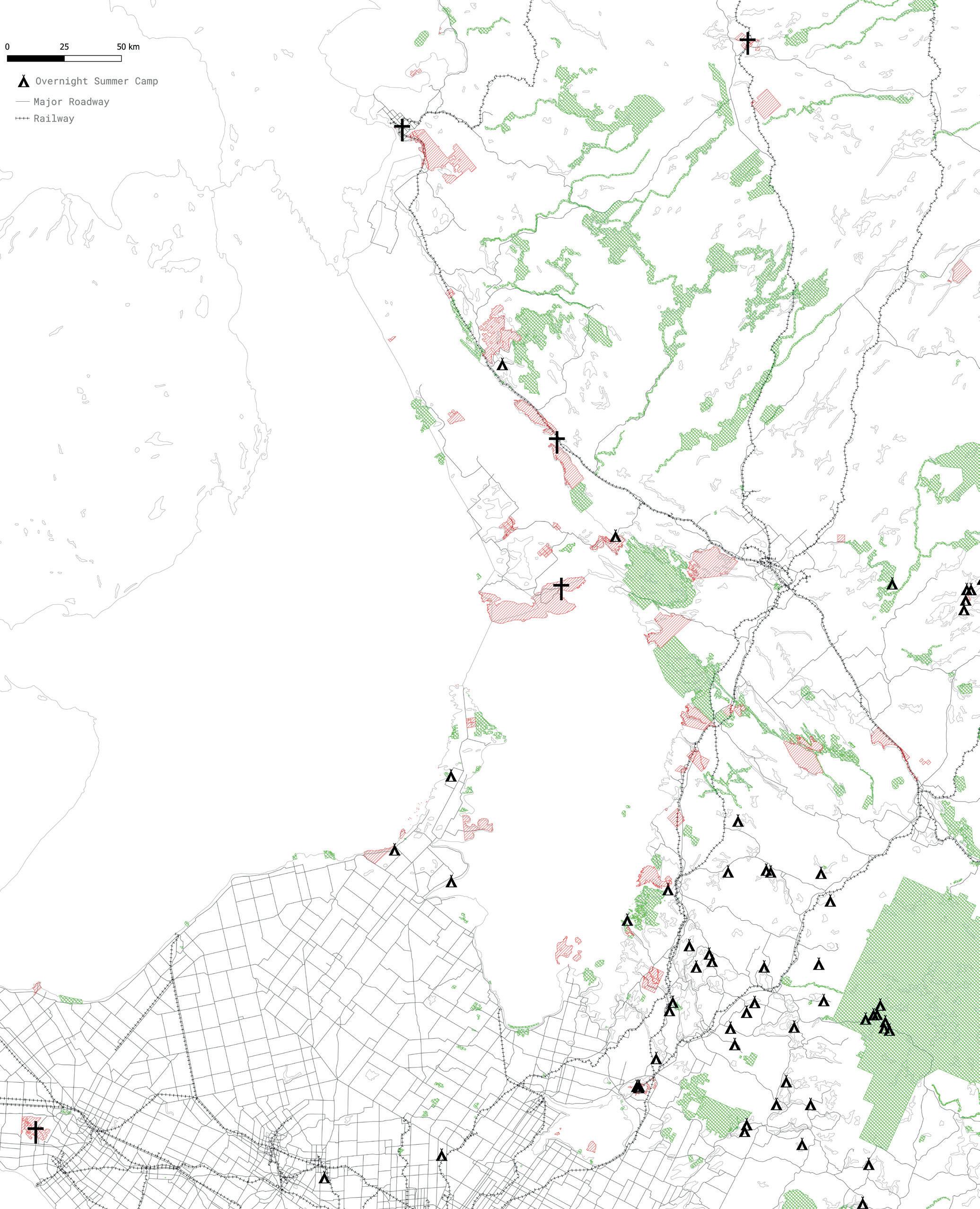

Land, its ownership and use are at the core of conflict between Indigenous nations and colonial powers In Canada over the twentieth century, youth camps, appropriated in different forms as ‘transformative’ educational projects were a key method, used by Settlers to solidify colonial rights. White Settler children attended Summer Camps set typically on forested lakeshores to “play Indian” as they learned to canoe, swim, build fires and to camp away from settled urban environments. Indigenous children were torn from the families and communities who had inhabited those lands for millennia and relocated to brick-and-mortar Residential Schools designed explicitly to civilise them, Christianize them, and sever their relationships with their language, culture, and land. Taken together, the two programs form an exemplary case of two simultaneous, dependent processes of Settler Colonialism: Indigenous dispossession and Settler possession. The analysis of how children—both Settler and Indigenous—were indoctrinated into colonial ideas about land ownership, Indigeneity and nationhood is at the heart of my thesis. I focus on a landscape that I also learned to be my home, the Precambrian shield in Ontario, Canada—the unceded lands of the Anishinaabek.

The thesis frames the histories of two residential educational institution—the Indian Residential School and the Woodcraft Summer Camp—in parallel, proposing a method for studying these separate projects as an assemblage in order to deepen our understanding of education within a settler colonial context.1 These two programs have been rarely discussed together in the context of the impact of settler colonialism. In relation to the ongoing theorisation of the camp, this thesis highlights distinct architectural typologies of the organised youth camp. Through a critical reading into how both Settler and Indigenous education missions were conceptualised, how they were promoted, and how distinct learning environments were spatialised, the thesis reframes the institutions as complimentary colonial strategies for territorial control and cultural colonisation.

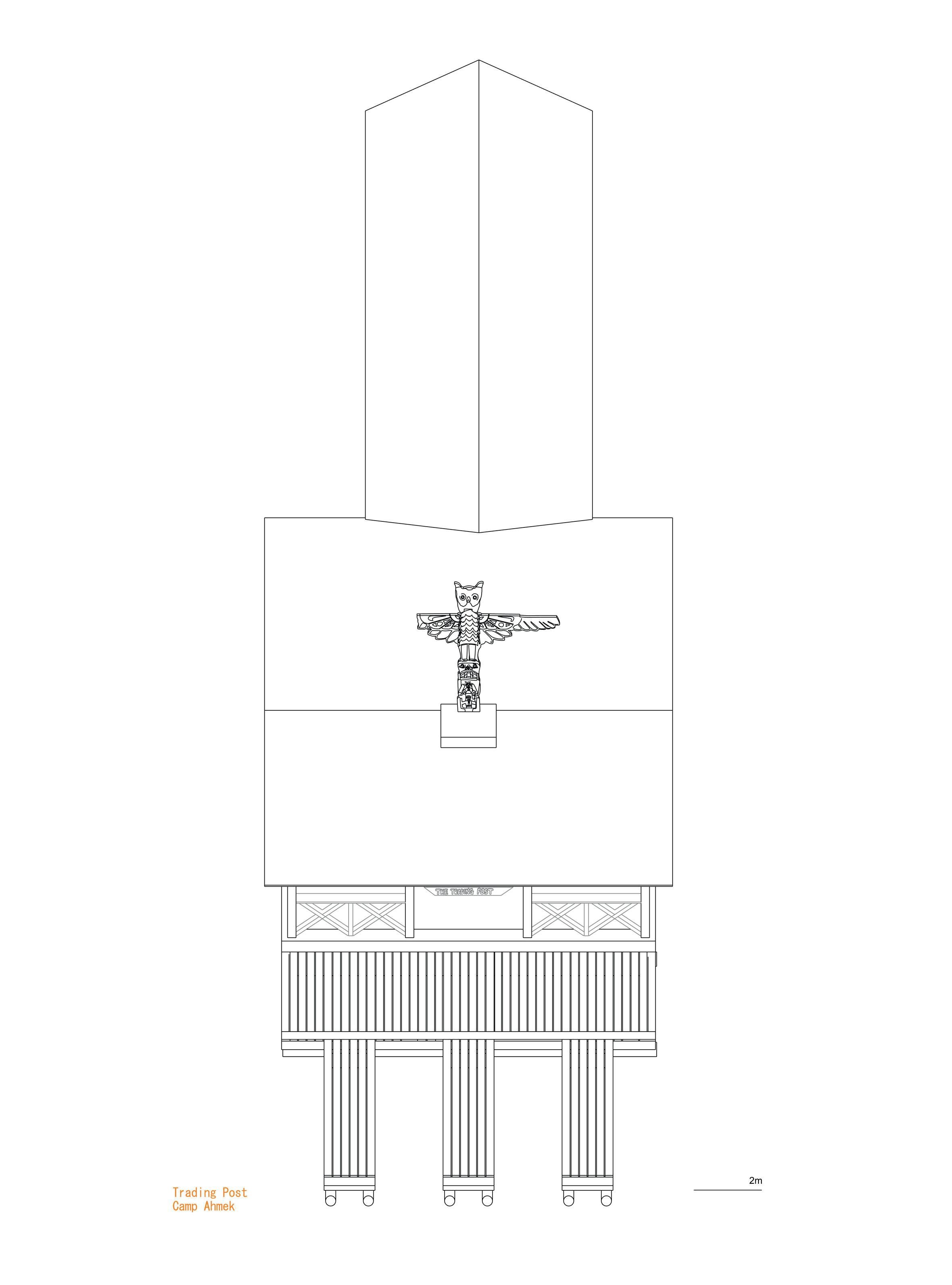

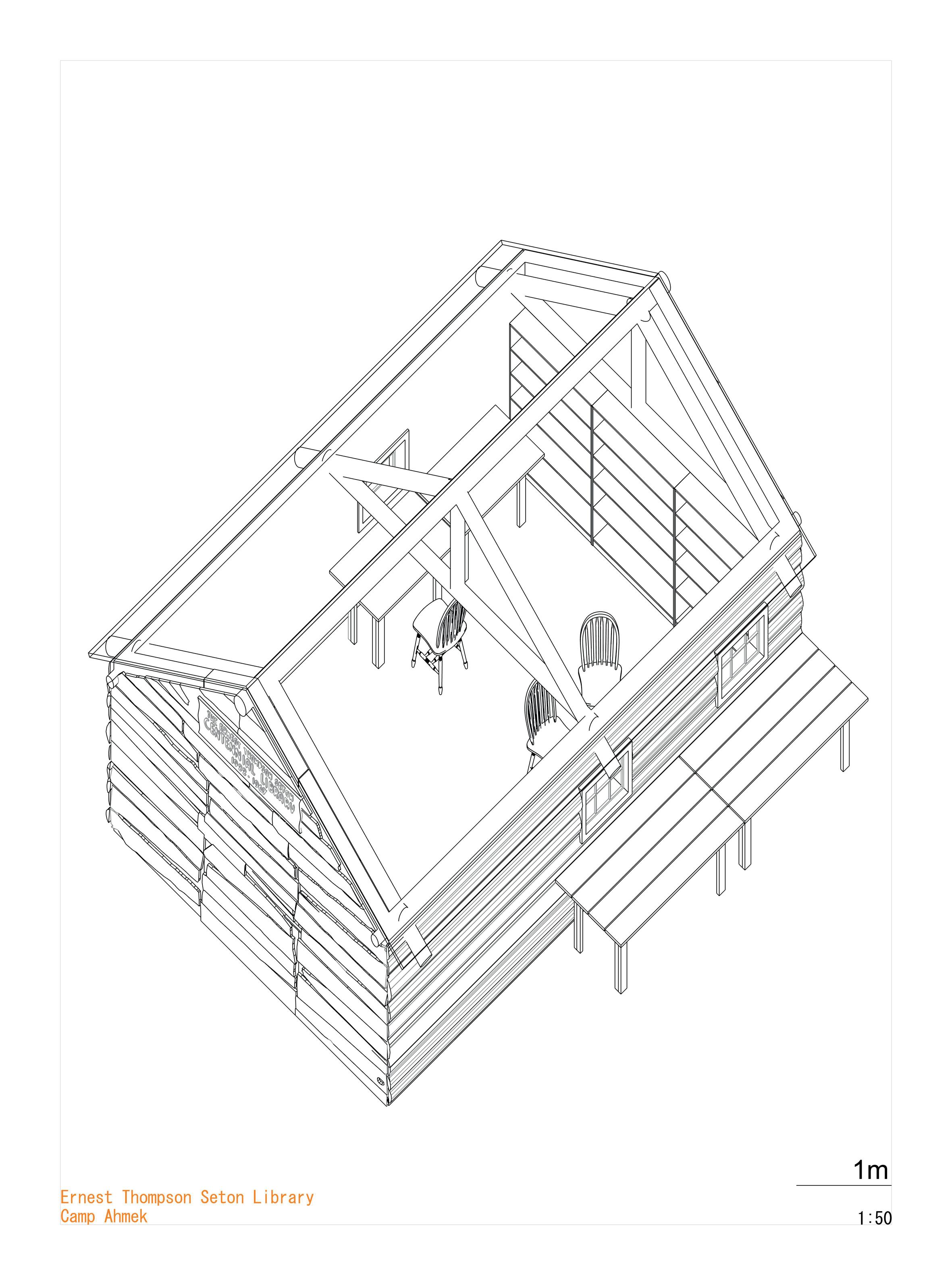

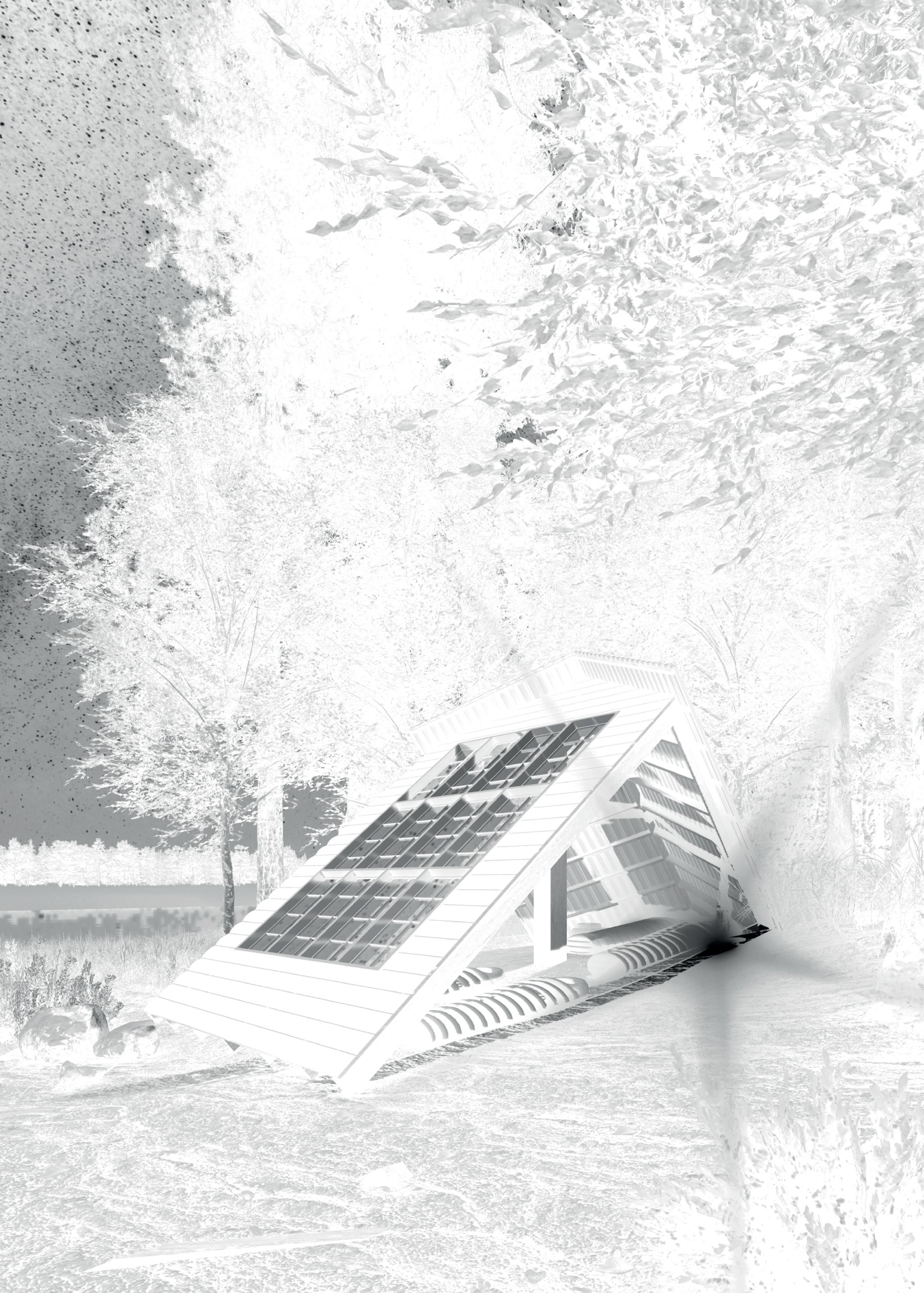

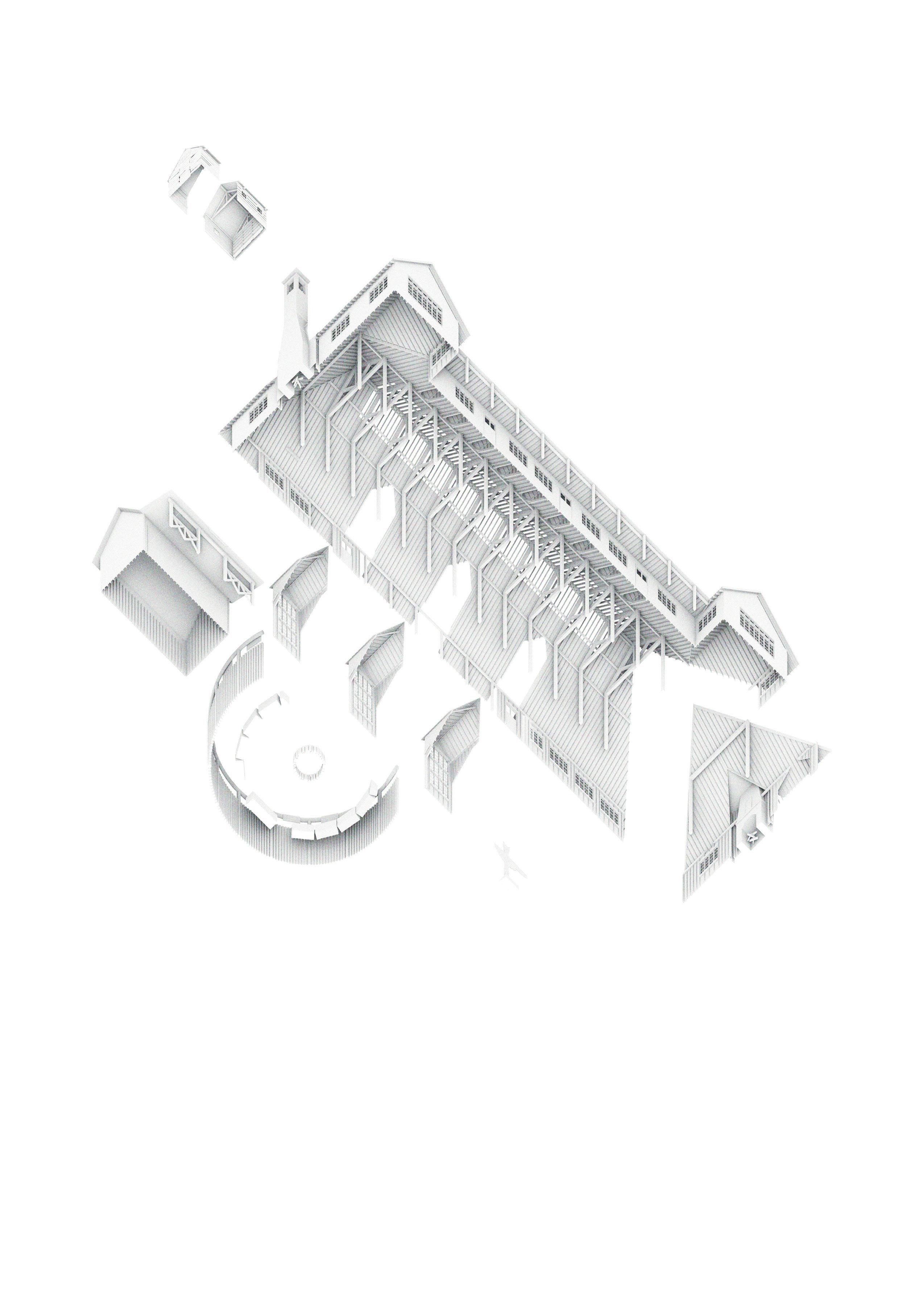

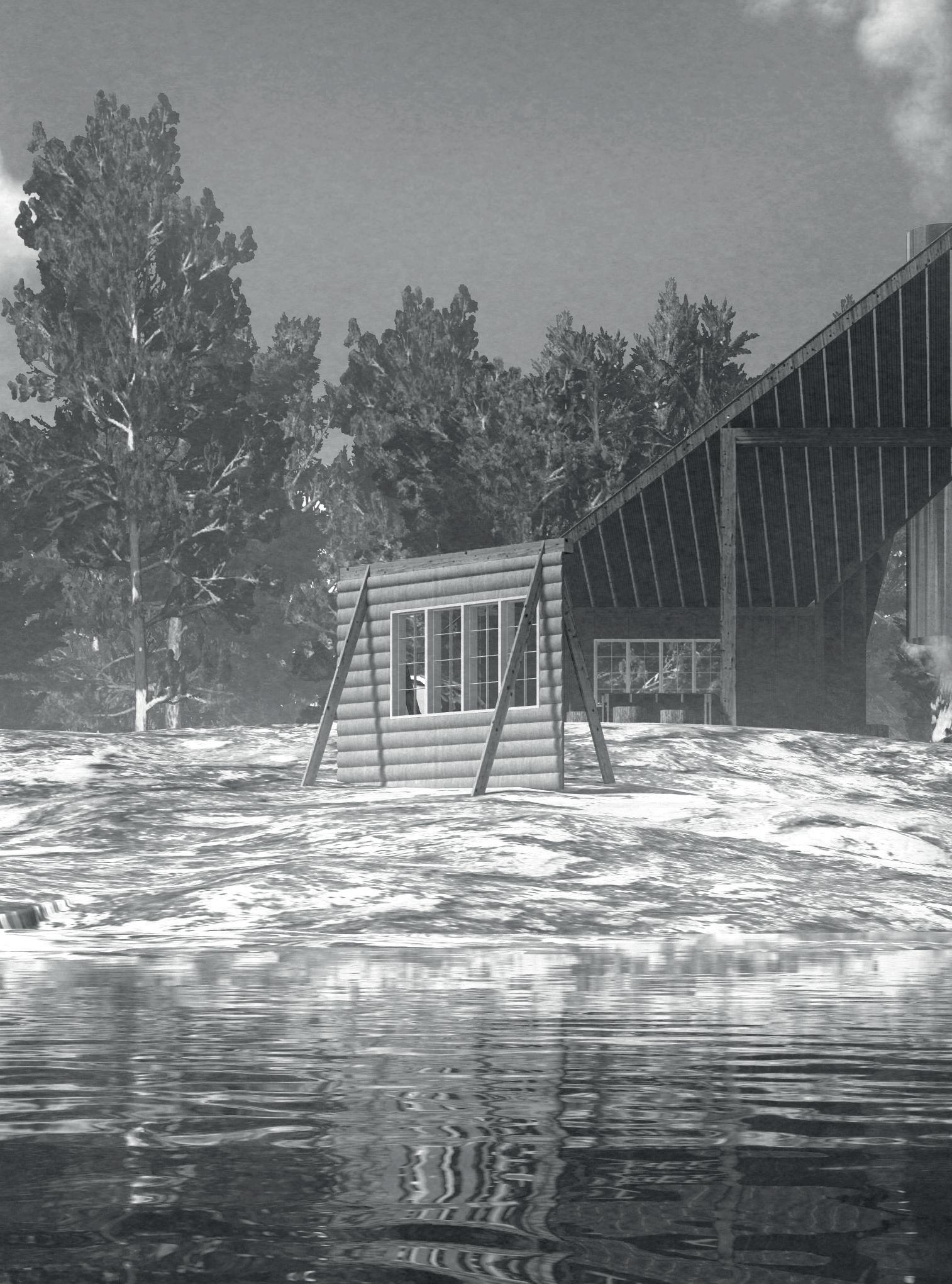

Though the camp has been co-opted for supporting the colonial agenda, as a spatial form, it has other roots. Necessitated by Indigenous calls for Land Back and to support a path of truth and reconciliation between Settlers and Indigenous peoples, the thesis uses typological design tests to propose a scenario to reframe the colonising operations of the Summer Camp. A design exercise focused on the land occupied by Camp Ahmek proposes a place for meaningful land acknowledgement and reviving education on Indigenous cultural practices. A future scenario for the disassembly, reuse and subversion of the material spaces that had contributed to the development of a colonial order operates to test the opportunities and limits of architecture for triggering change in the organisation and functioning of the camp. As an initial inward turn the thesis is concerned with the need for reconceptualising settler education in support of reasserting Indigenous sovereignty.2

3 Minton and Mckean, ‘We Must Not Forget What Happened to the World’s Indigenous Children | Aeon Essays’, 2023.

4 The “construction of Settler as an identity mirrors the construction of Indigenous in contemporary terms: “a broad collective of peoples with commonalities through particular connections to land and place”. Settler Canadian identities are reliant on the ongoing exercise of colonial power to provide attachment to and legitimacy on the land. Emma Battell Lowman and Adam J. Barker, Settler: Identity and Colonialism in 21st Century Canada (Winnipeg, Manitoba ; Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing, 2015), 2, 16.

5 Leah Decter and Carla Taunton, “An Ethic of Decolonial Questioning: Exercising the Quadruple Turn in the Arts and Culture Sector,” in The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Art Histories in the United States and Canada (Routledge, 2022).

Canada has recently been torn by the uncovering of what was known to be hidden: the remains in unmarked graves, of Indigenous children who had been subjects of the horrors of the Indian Residential School System in Kamloops, British Columbia. Grave sites at other former Residential School sites were subsequently and continue to be investigated. The revelations in the spring of 2021 were followed by massive media attention and an outpouring of grief by Indigenous communities. The glaring, undeniable horror of the revelation pitched the country into an intense period of self-reflection on the tragic consequences of forced assimilation. As Steve Minton reminds us, “when frameworks for dispossession become entrenched through educational, social, and political systems, settler states can compel their citizenry to ‘forget’ the horrors of colonisation, to deny that these things ever happened, and to aggressively demand that others join them in this deliberate cultivated collective ‘amnesia’.”3

I’m conscious that my relationships with my urban Toronto home and wilderness family-cottage are not like the relationships Indigenous peoples have with their homes in the same geographical locations. This thesis comes from my attempts to untangle the meaning of belonging in different imagined communities as they are defined by nations and educational settings. I do this as a third-generation Settler, with the set of landscapes I have learned to relate to as home—in what can be a possessive, all-encompassing way of “settler homemaking” as encouraged by Canadian social and political structures.4

In relation to the ongoing struggle and injustices against Indigenous nations, this thesis strongly positions itself in support of the reassertion of Indigenous sovereignty, and in the need for healing, truth, and reconciliation. In particular, the thesis should be read as an initial inward turn, offering reflections on Settler education on this history of our complicity to devastation.5

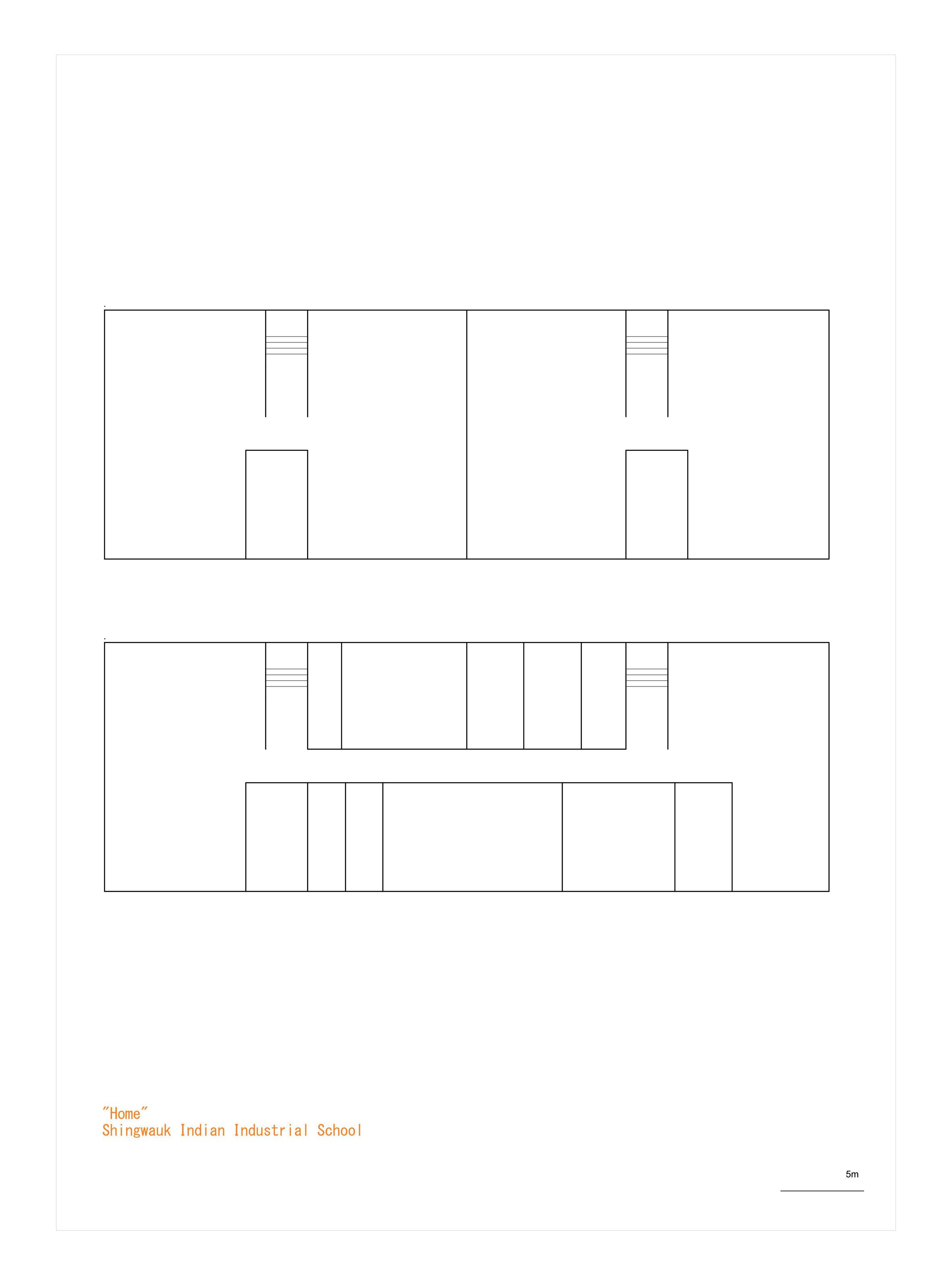

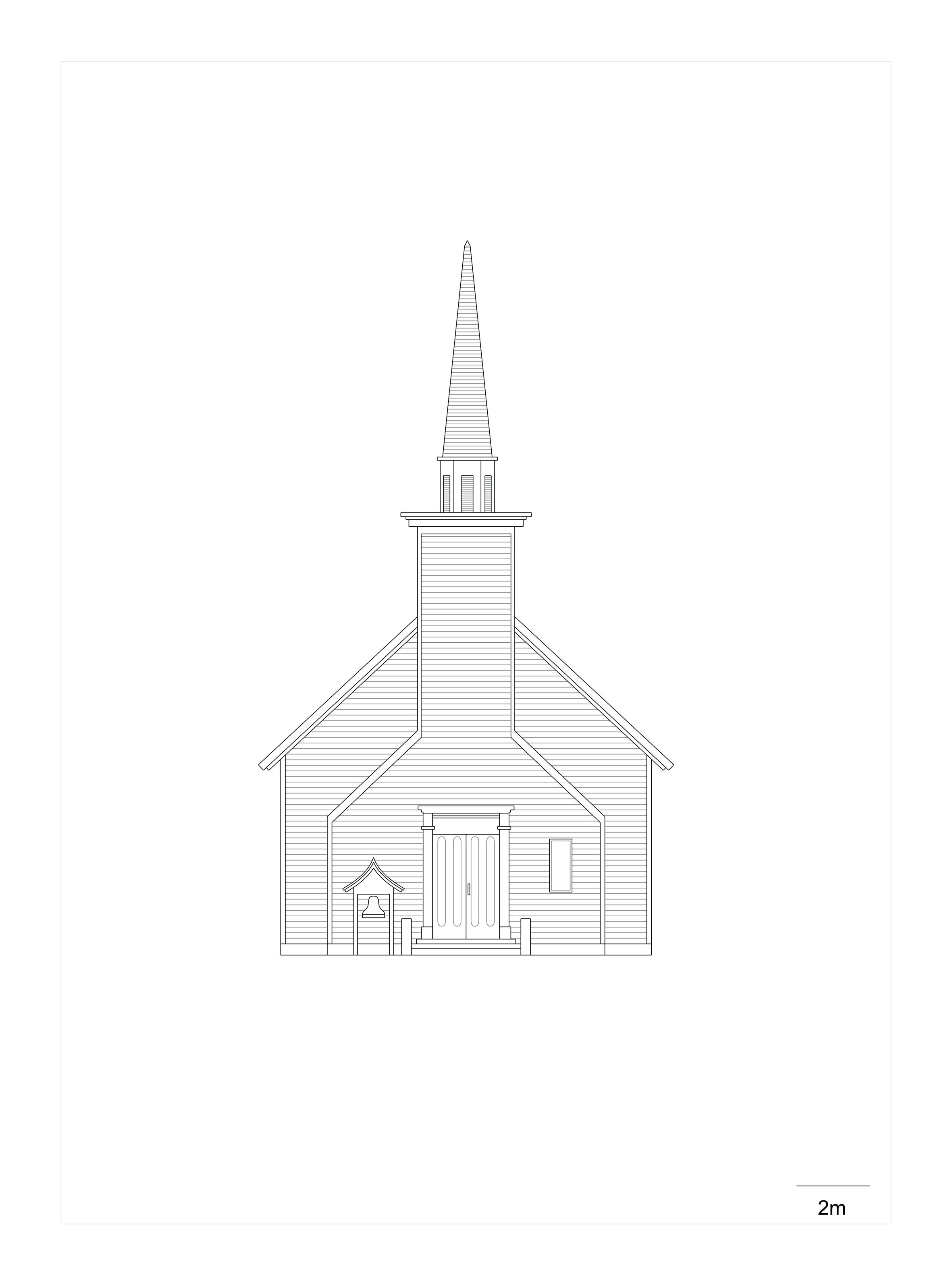

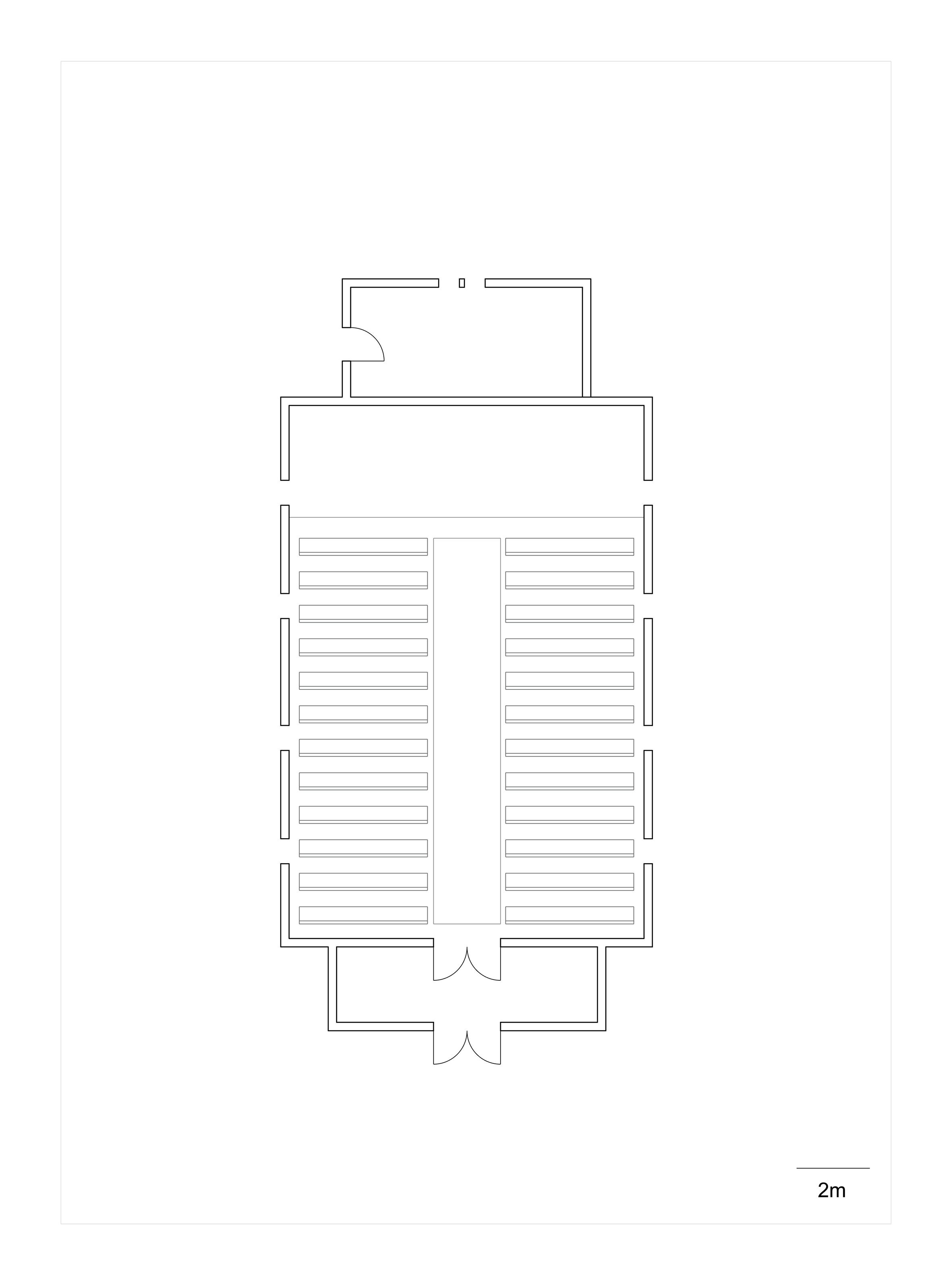

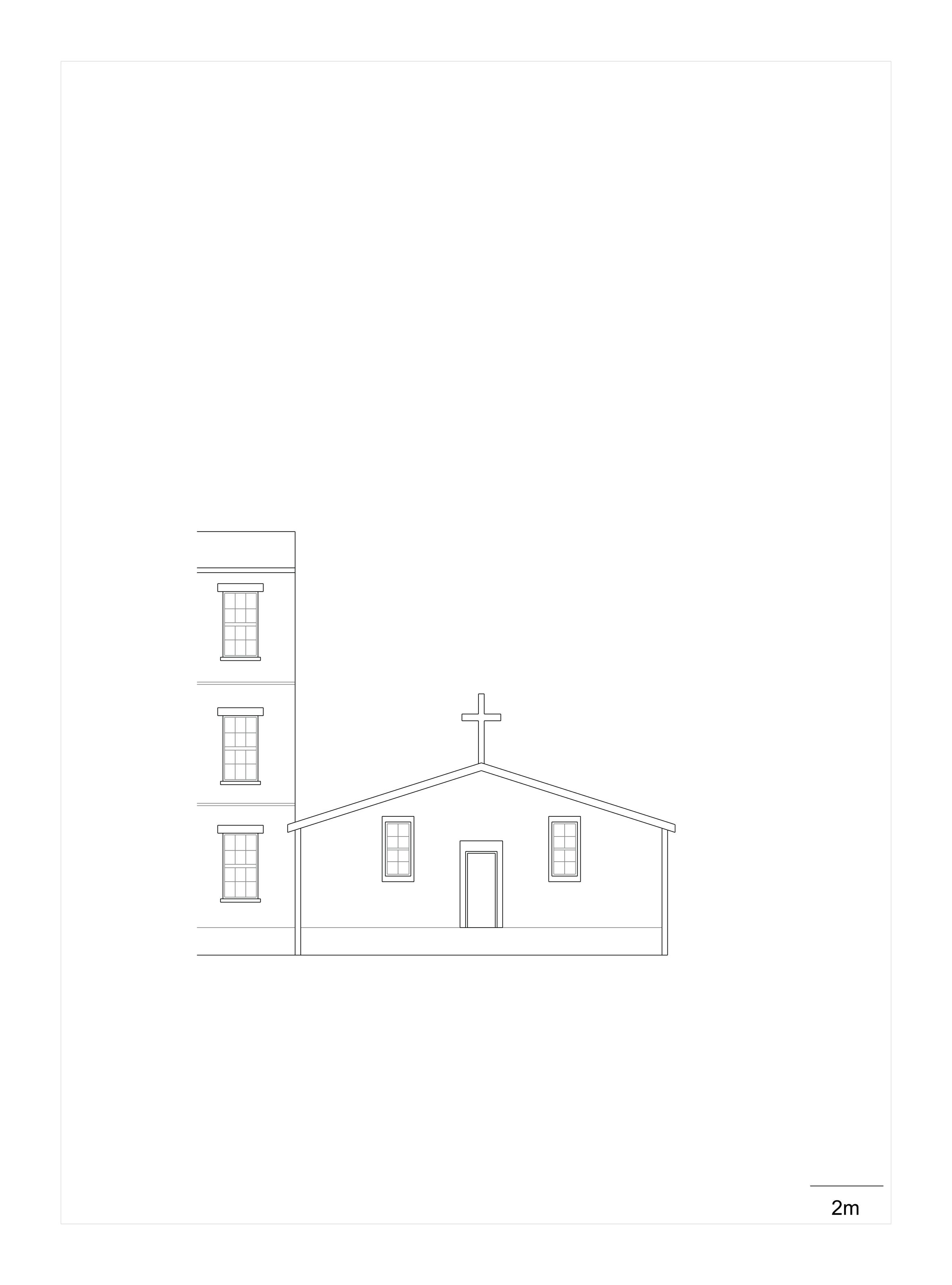

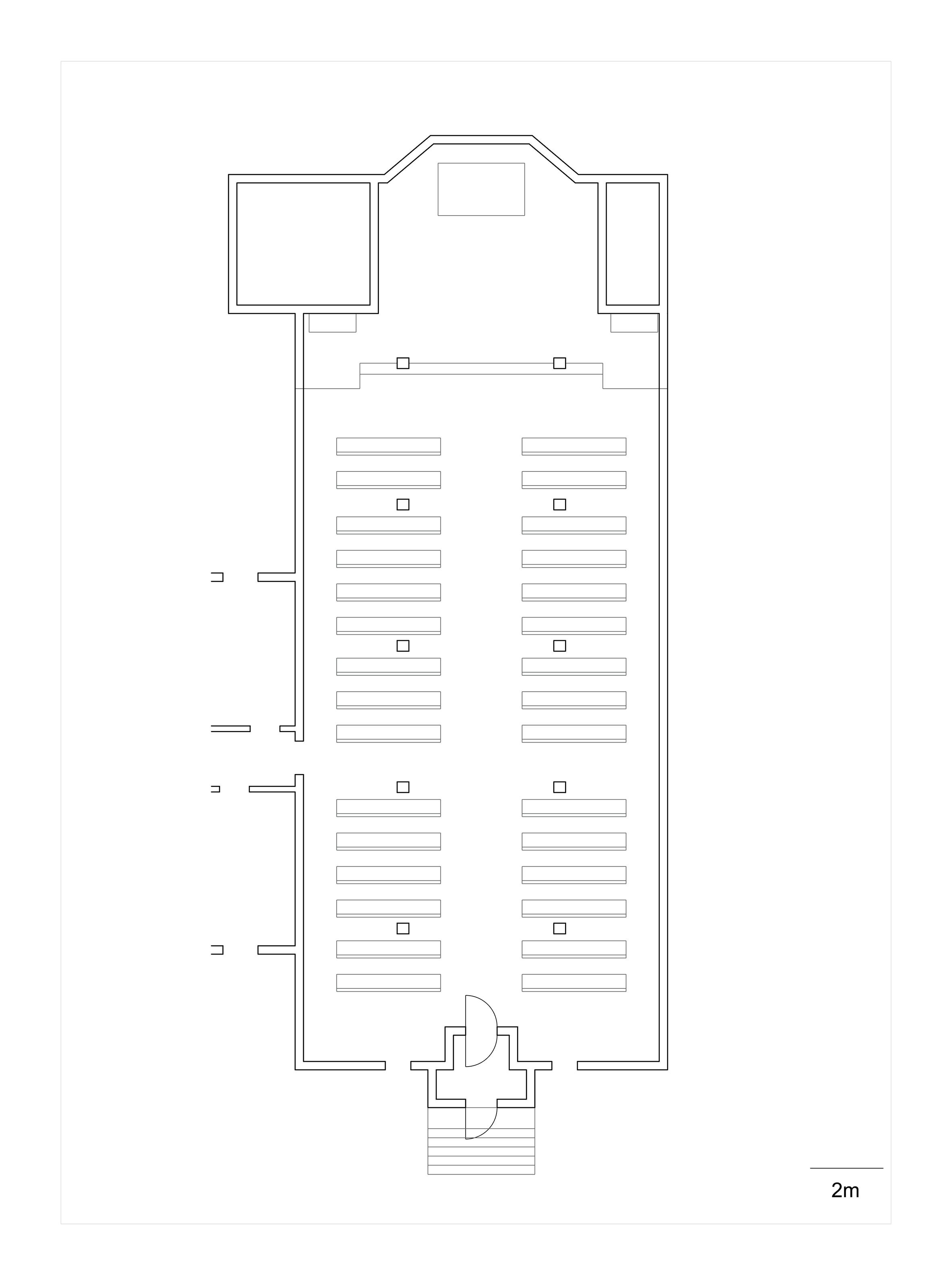

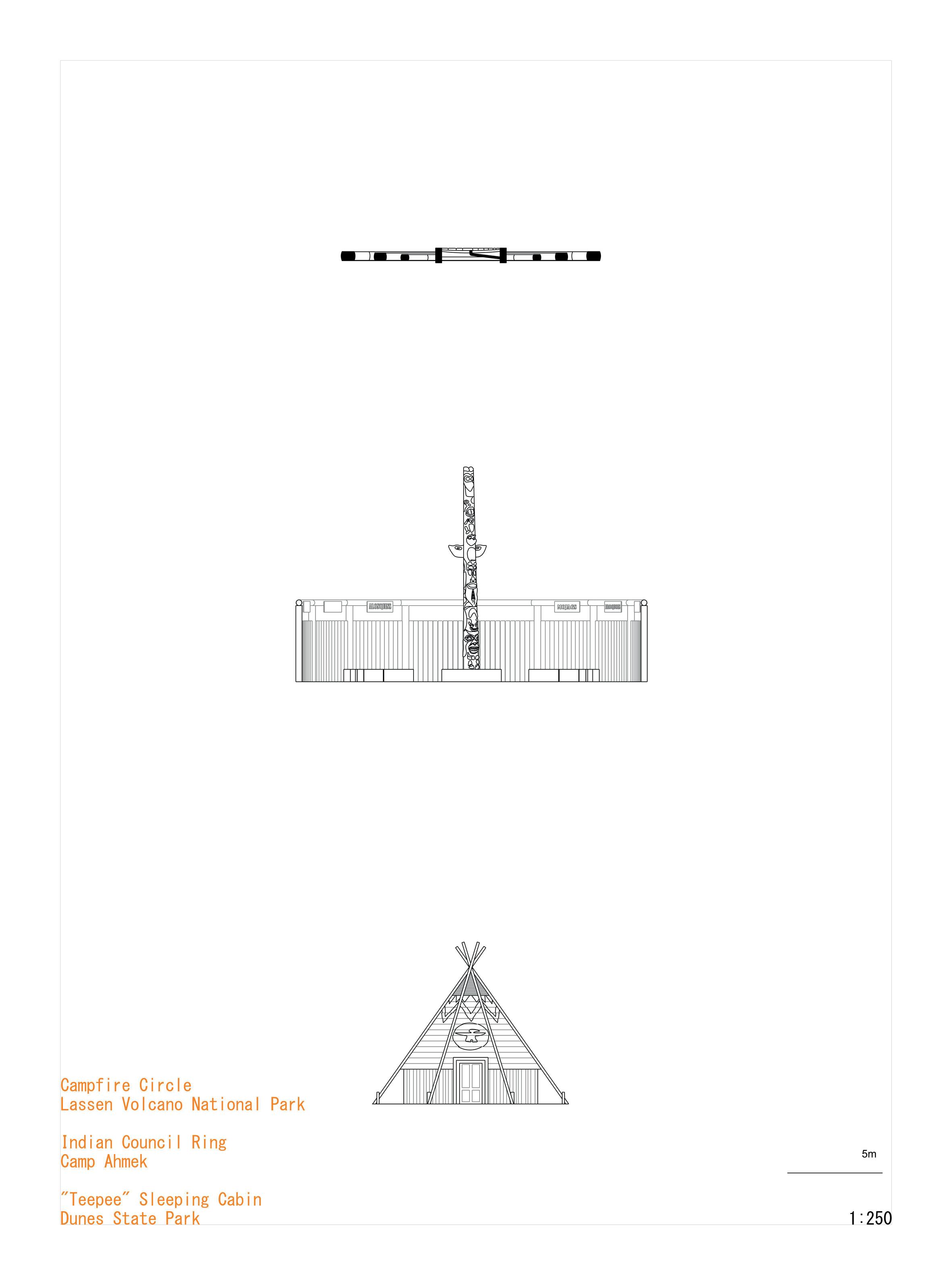

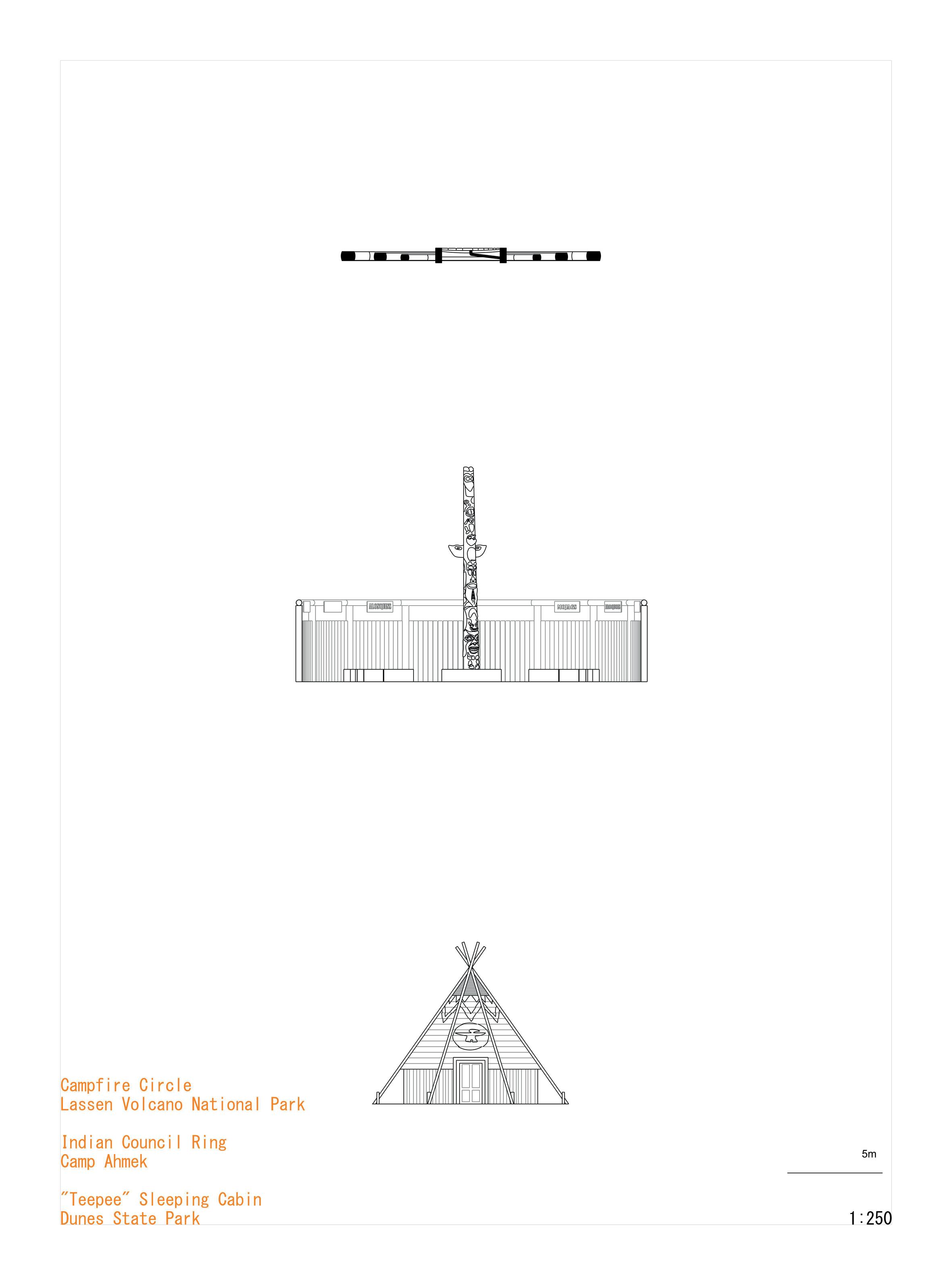

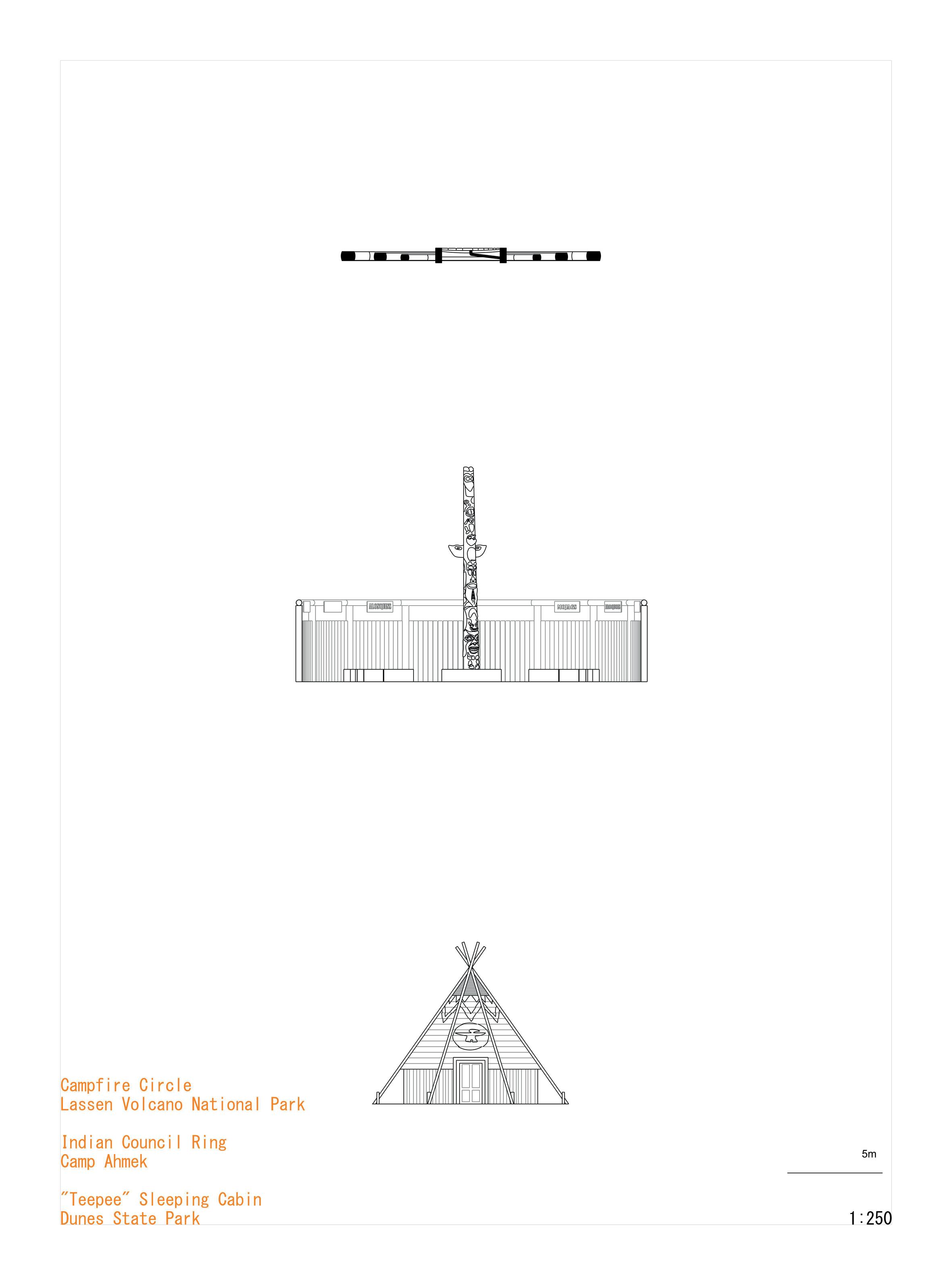

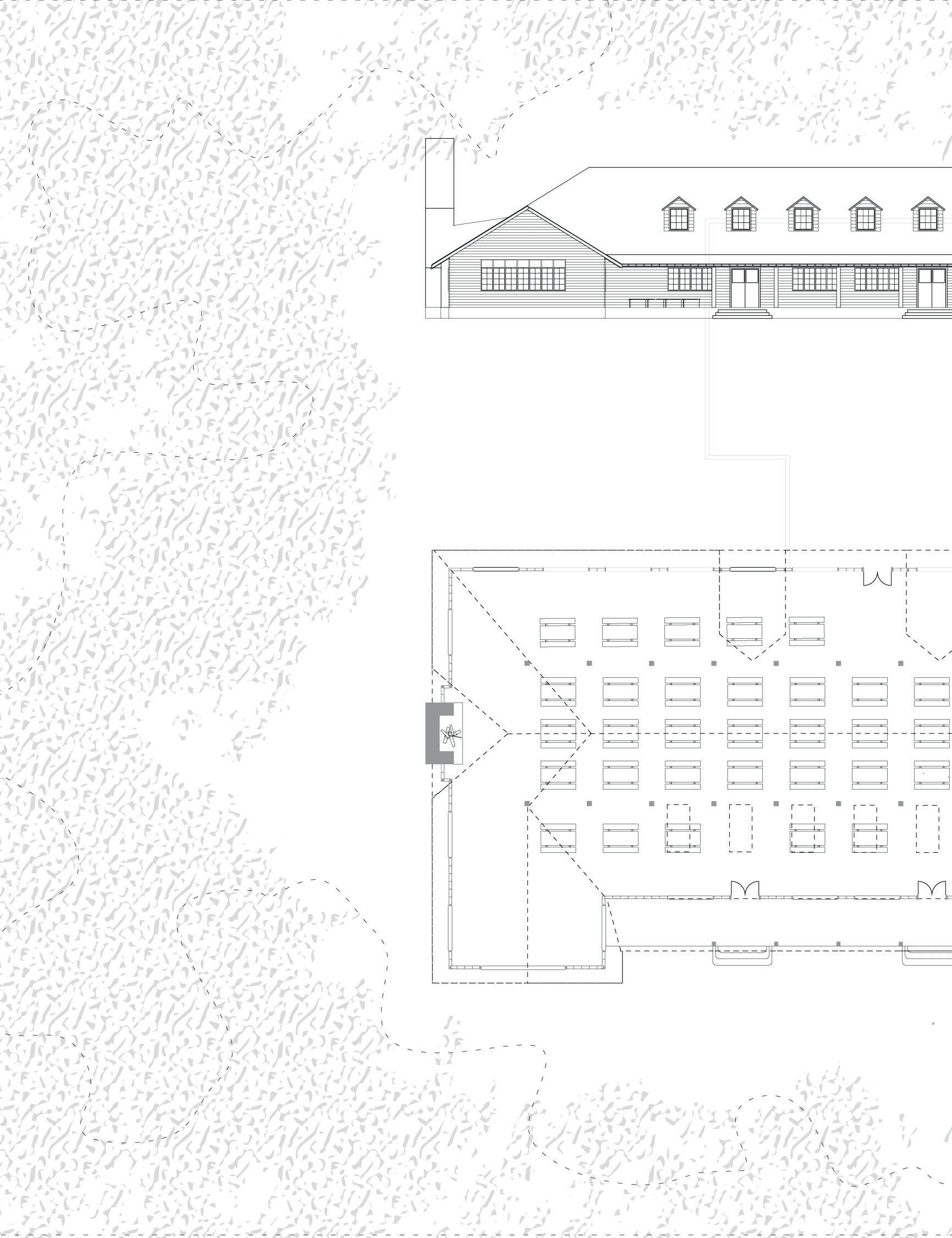

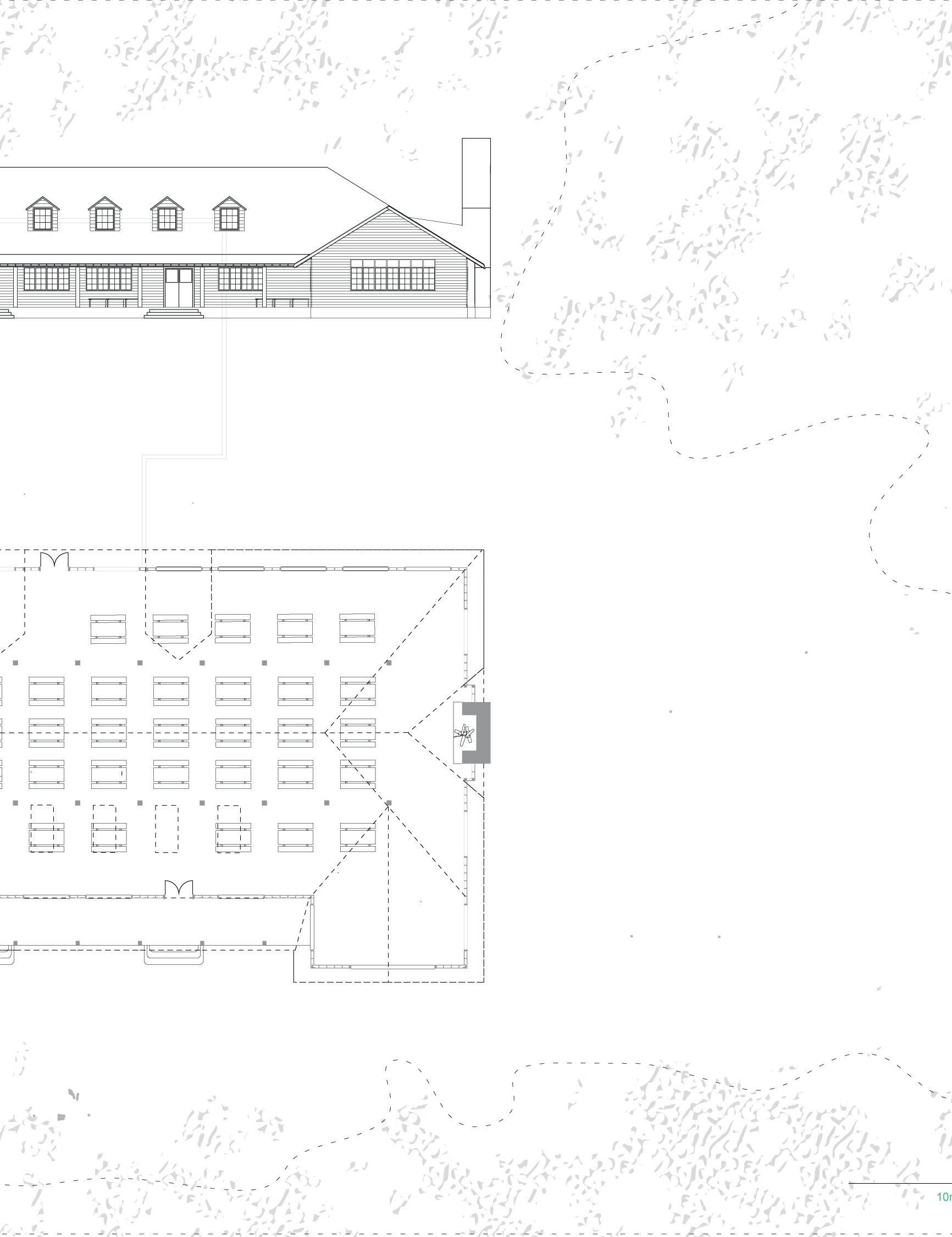

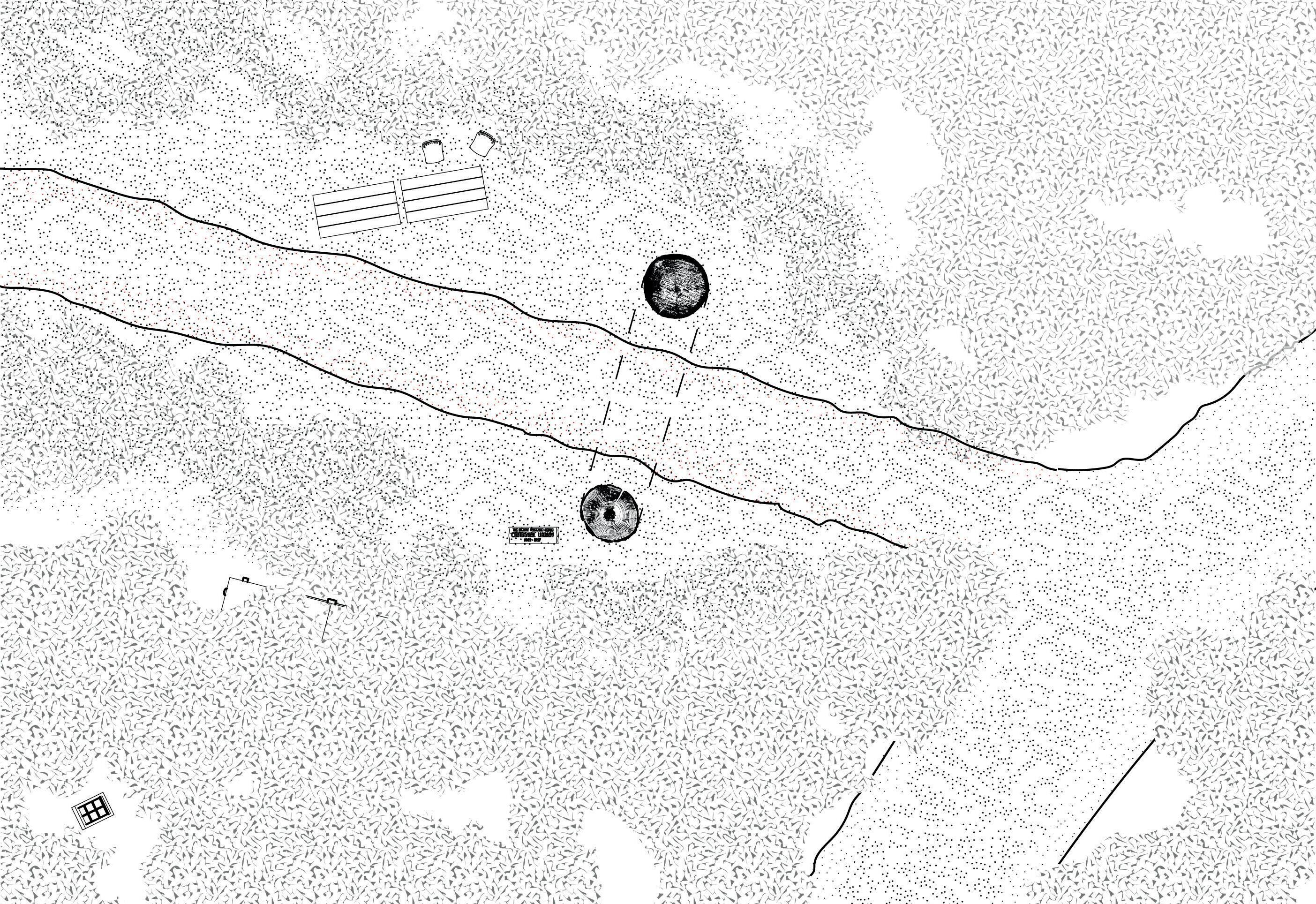

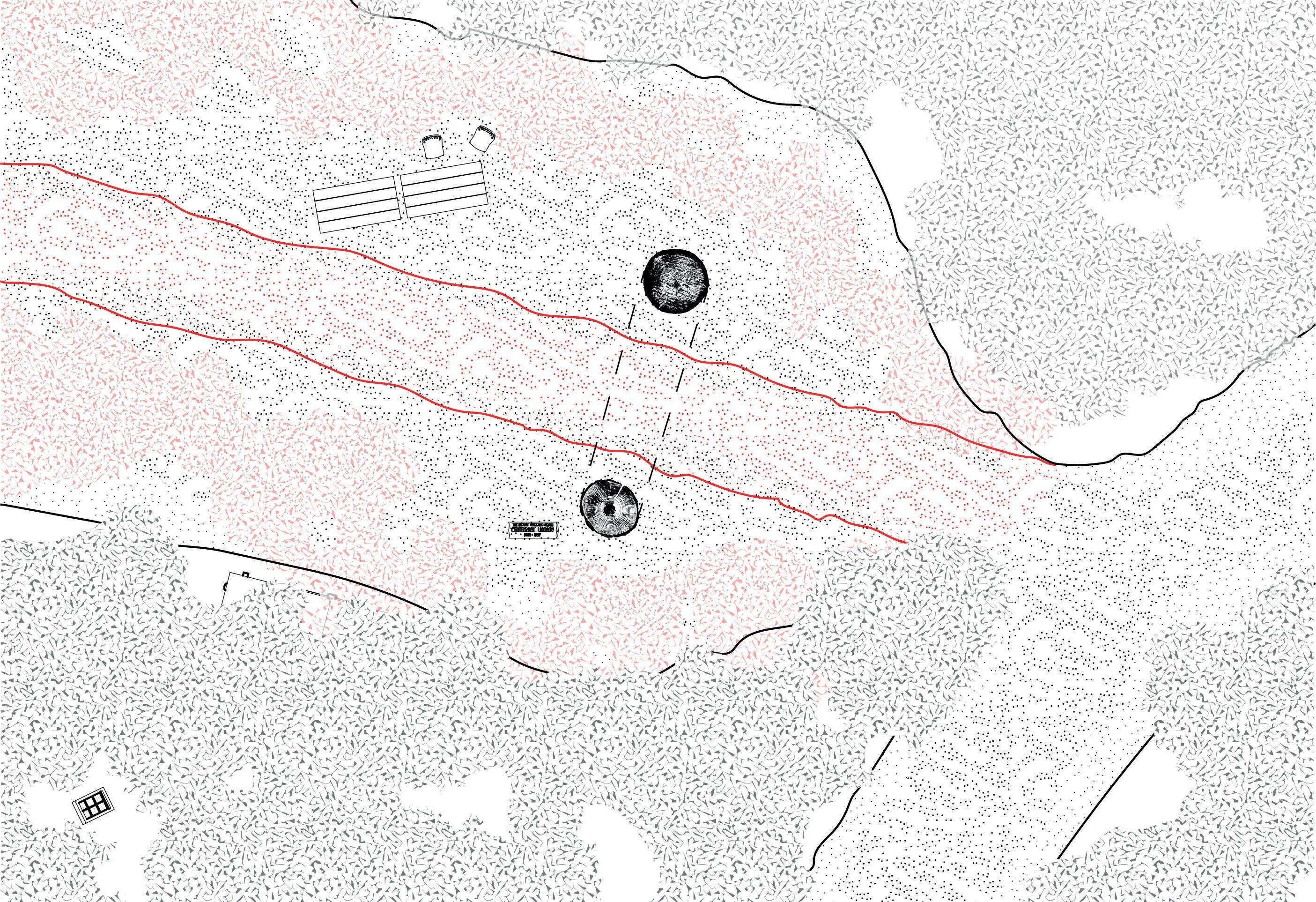

Previous page:

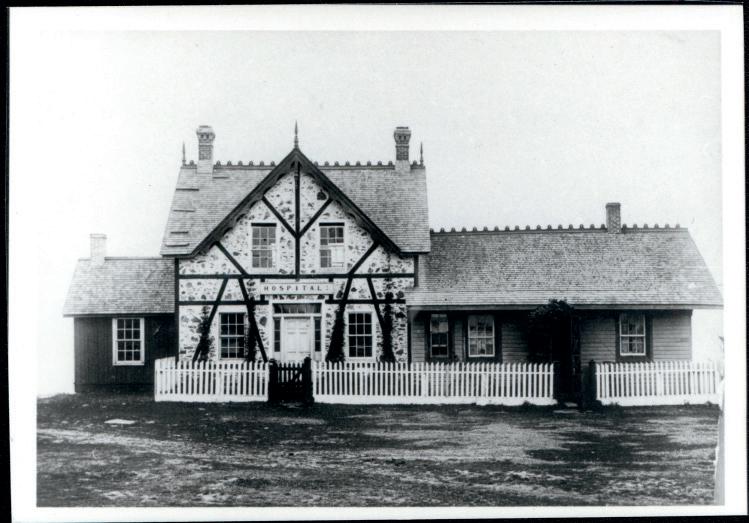

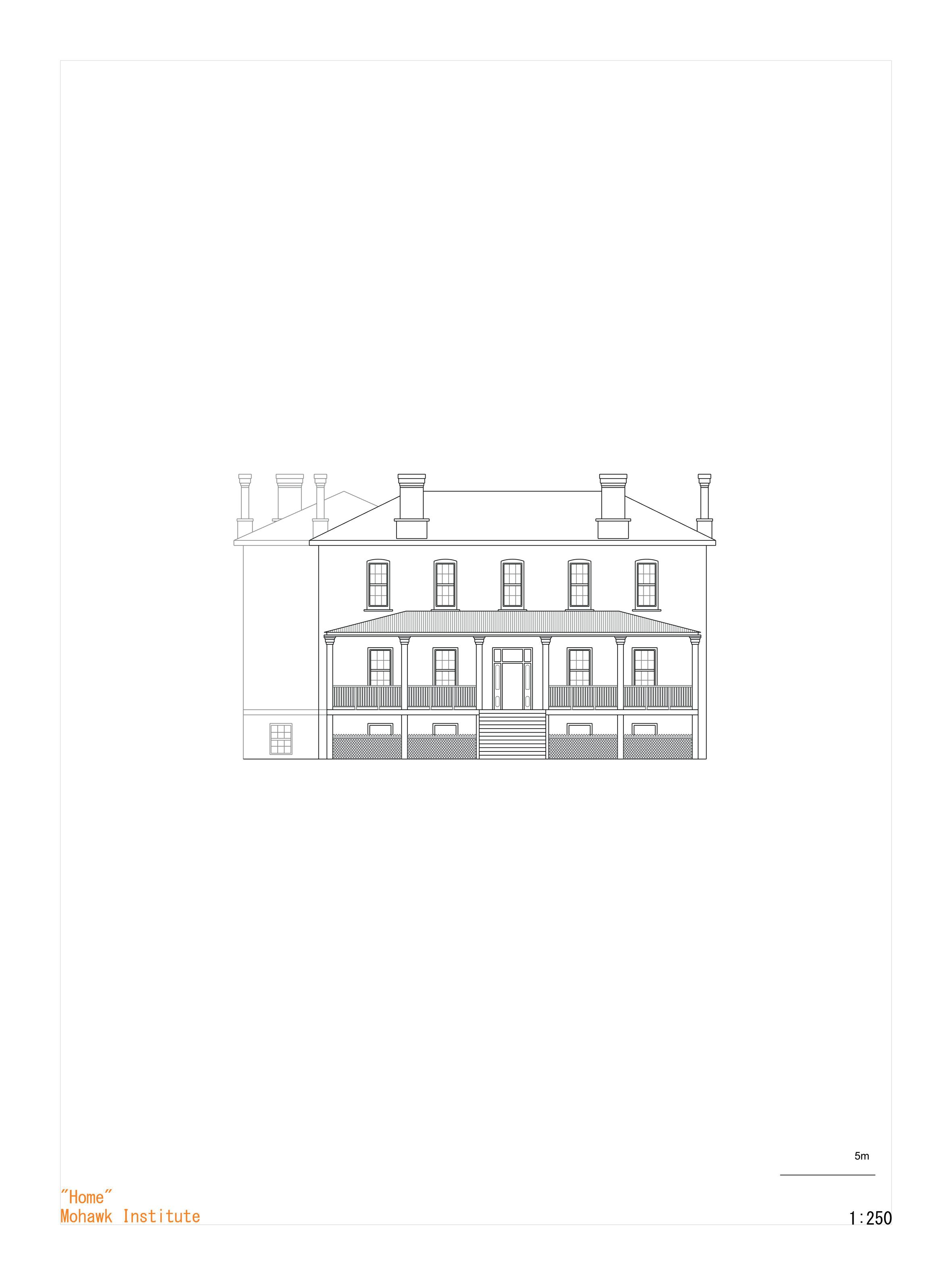

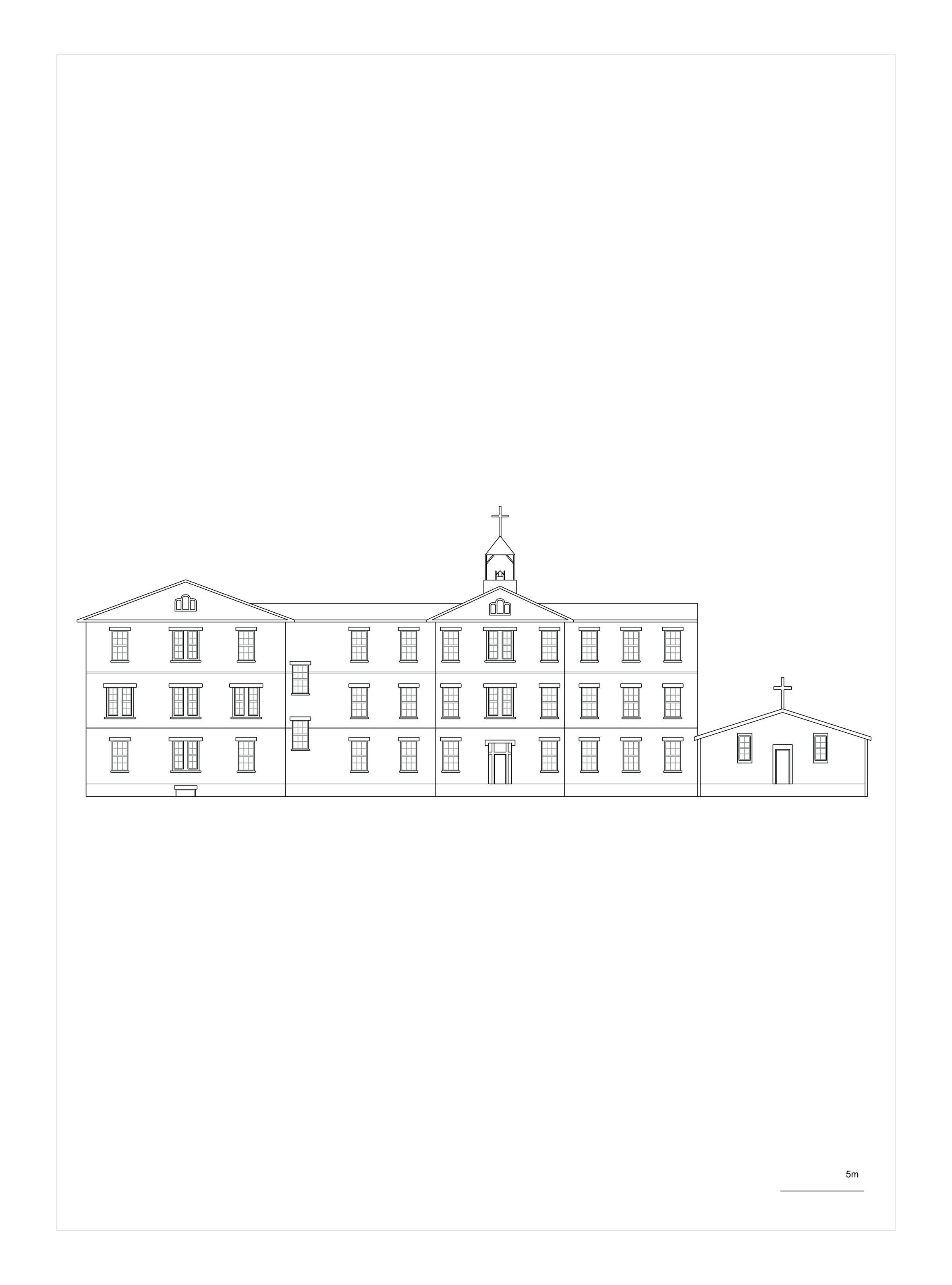

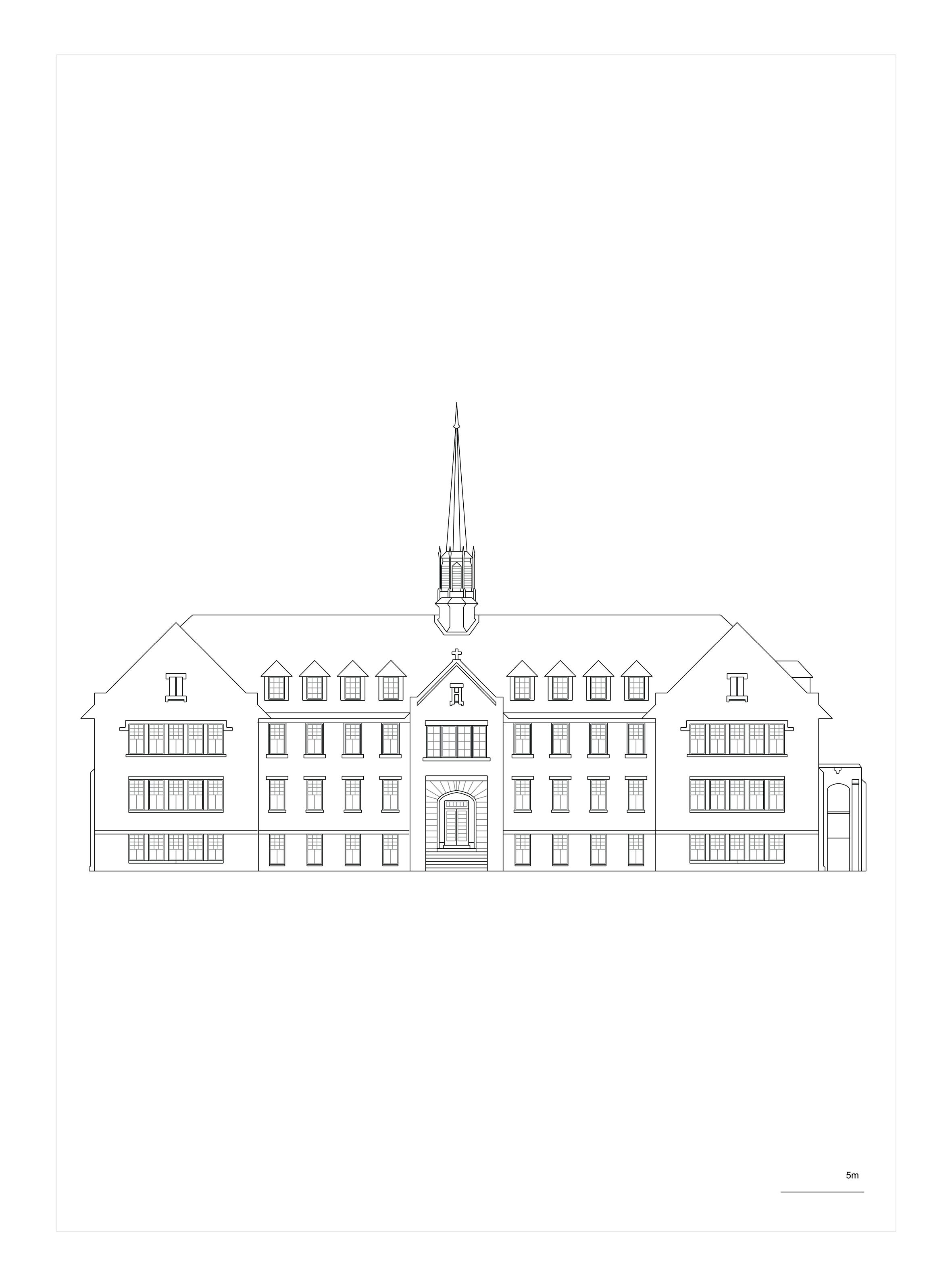

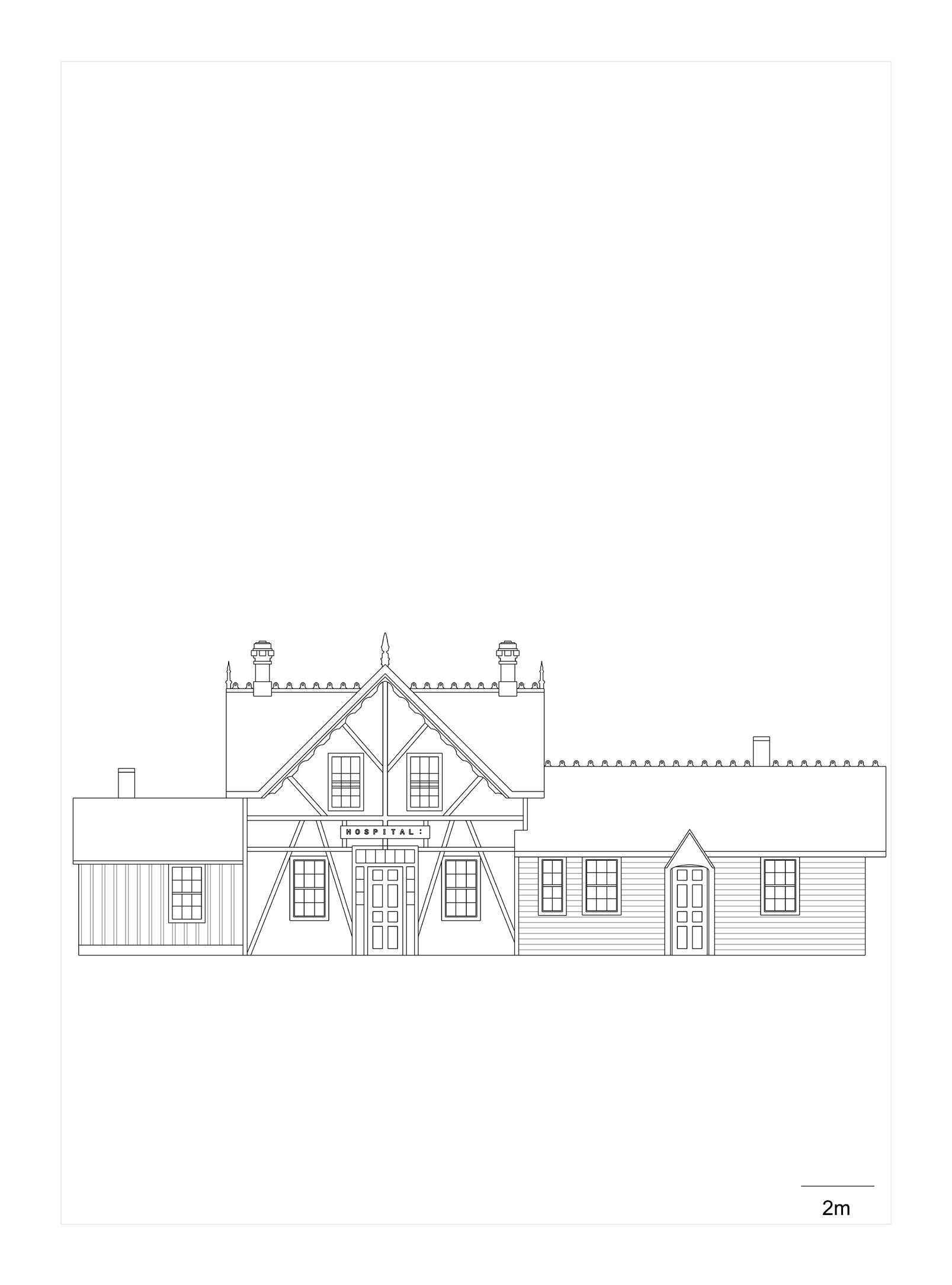

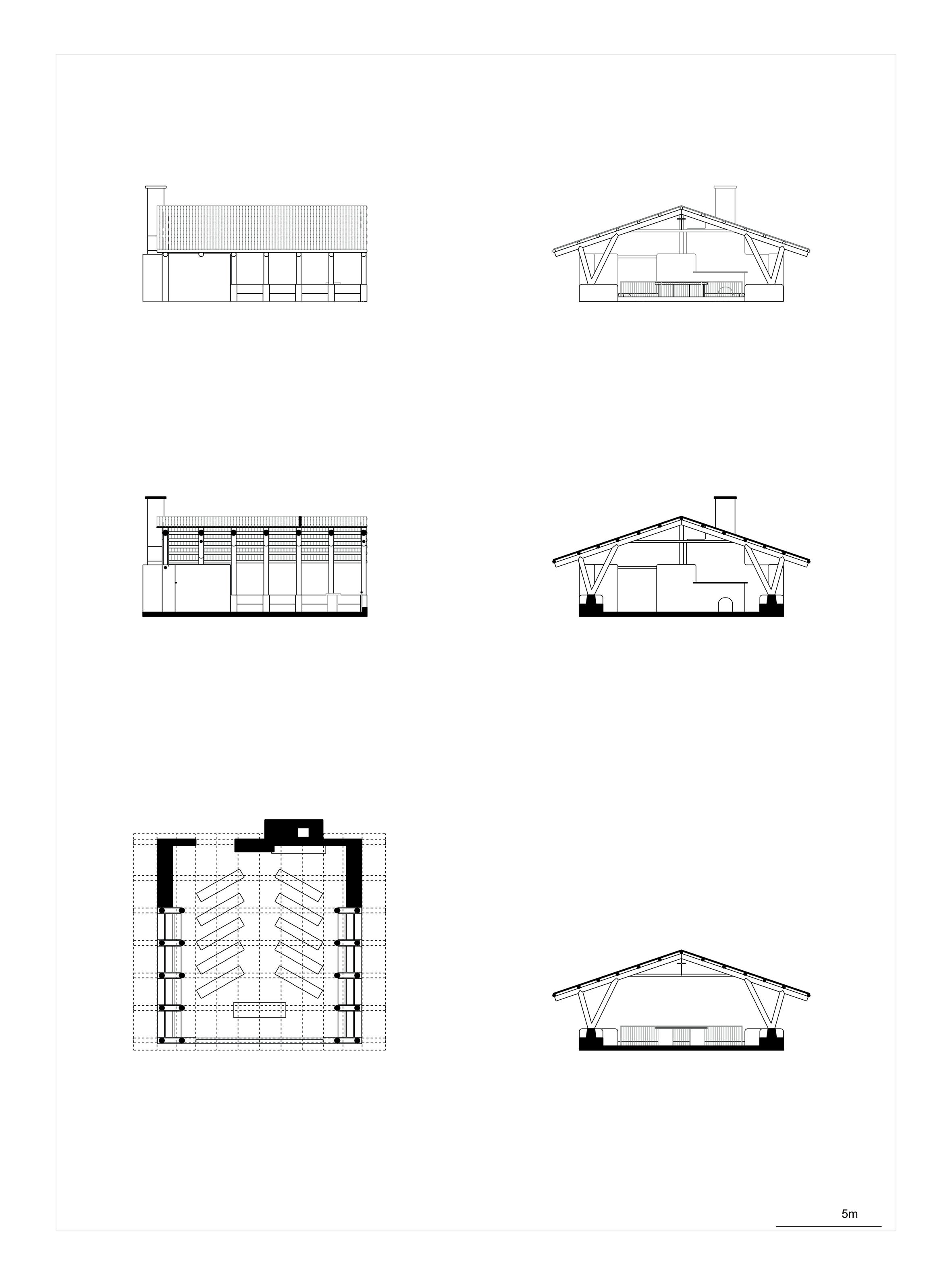

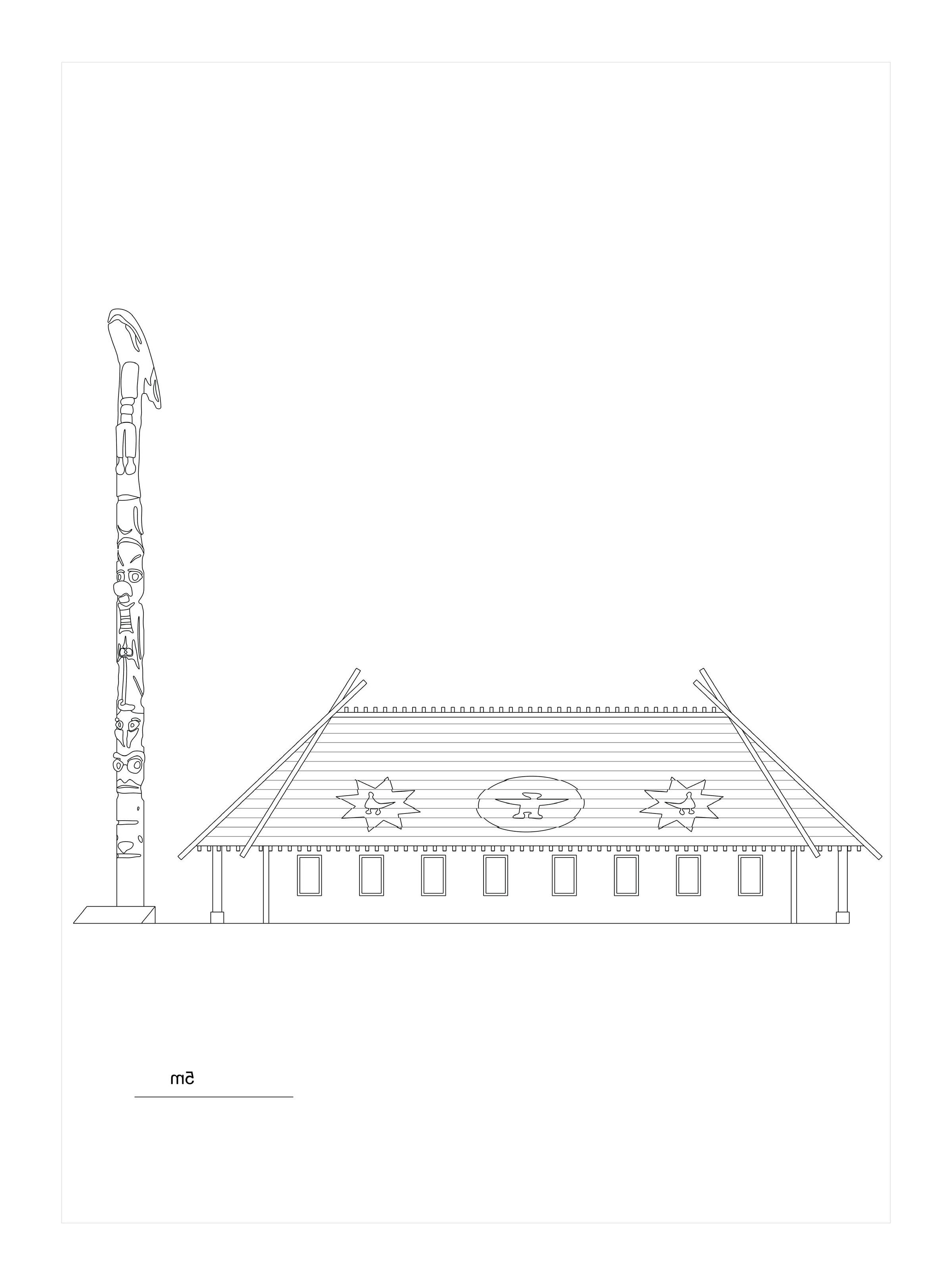

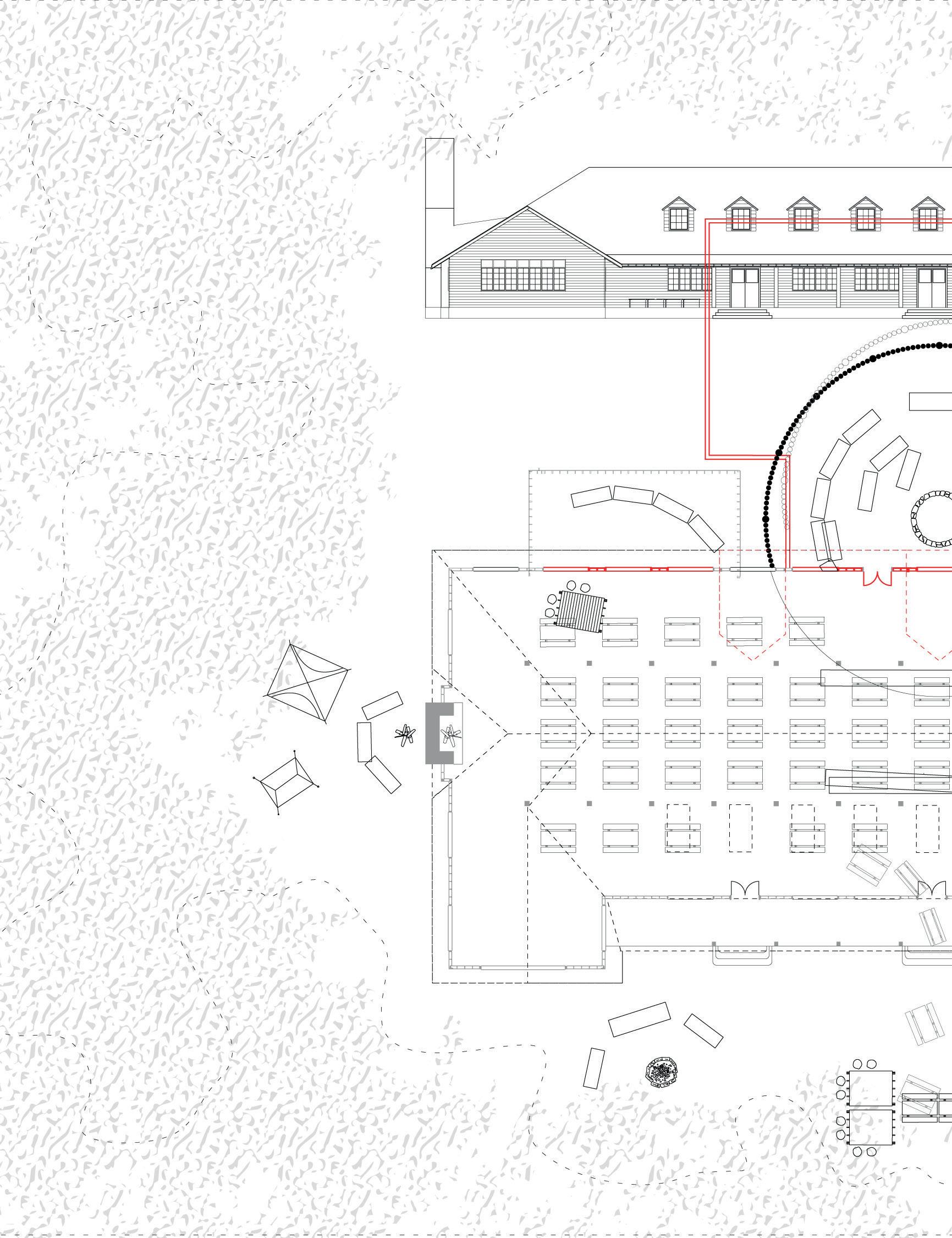

Fig. 1 Elevation of Shingwauk Indian Residential School main hall, constructed 1935.

Fig. 2 Elevation of Camp Ahmek dining hall, constructed 1937.

To emphasise my point about the contested issues at stake, I’m going to reiterate: the land that the case studies of the thesis are situated are the unceded territory of the Anishinaabek peoples, who still occupy this land. The work was written mainly from the AA School, in London, England—a place I am privileged to study at on a visa as a Canadian citizen. This distance from my home in Canada, working in the UK and immersed in a school setting is itself not unlike a form of camp environment. The community at the AA and especially my classmates in Projective Cities formed my camp family over the last 18 months.

I am grateful and honoured by the opportunity to learn from and contribute to the body of work and legacy of Projective Cities. Thank you to my professors: Hamed for believing in my project and for encouraging me to aim high, and for your guidance and supervision the entire way through. Platon, for continuously challenging me and helping me to reframe my beliefs. Anna and Doreen, for profoundly changing my relationship with writing. Thank you for helping me to see writing as a form of design and working with me on the structure and clarity of the work. The Projective Cities course has reframed my past education and work in architecture and has motivated me to look at sites I’ve known my whole life differently. It has been incredibly rewarding to have the space and intellectual support in the programme to develop my research and design interests in a deeper and structured way.

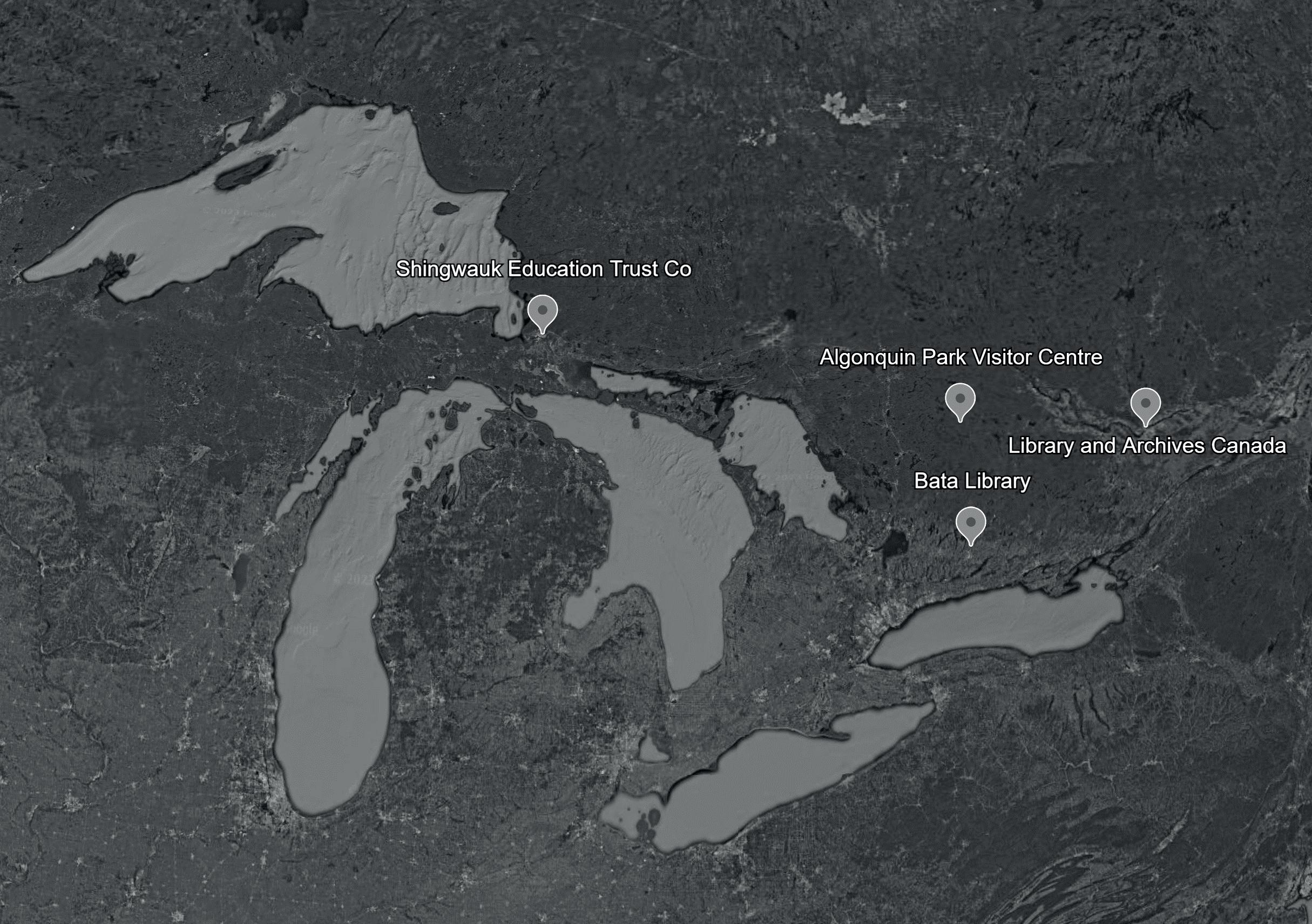

Thank you to the archivists at Shingwauk Residential School Centre, Trent University, and Algonquin Park Archives for your assistance both in-person and over email. Thank you, Chelsie, for sharing the experiences of your family and community at the former Shingwauk Residential School. Your Truth Walk was extremely informative to this thesis and an inspiration to me to see the strength it takes to engage in the work of truth and reconciliation in the face of ongoing injustices.

Thank you to my family for your generosity in supporting me in pursuing postgraduate studies in London. A big thank you to my mother Sarah, who became my informal research assistant and editor on multiple occasions over the past year, accompanying me to Sault Ste. Marie and Peterborough, Ontario, and London, England. Thanks for encouraging me to see the positive impact possible from engaging in this work, and for engaging in conversation with others that have more knowledge and personal connection to the places I discuss. Thank you to my aunt Lissa for being a mentor to me, for your time, care, and investment in my thesis and in my personal growth through postgraduate studies. Thank you Arslan for your constant support, for keeping me motivated through difficult moments, and for your design input that gave this work strength.

6 Canadian Geographic & Google Earth Voyager, & National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, 2017.

7 The Land Back Manifesto, https://landback.org/manifesto/

8 “Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig,” https://shingwauku.org/

Indian Affairs The Department of Indian Affairs was an arm of the federal government of Canada that historically managed IndigenousCanadian relations, and until the 1970s, implemented policies that explicitly aimed to segregate and assimilate Indigenous peoples. In 2011, it became Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, and is now known as Indigenous and Northern Affairs.

Indian Residential Schools (IRS) (1873 - 1996) Government-funded, church-run institutions, whose mandate was to strip Indigenous children of their culture and spiritual identity. By forcibly separating Indigenous children from their families, resi deprived students of their cultural heritage and community connections, leaving them isolated and vulnerable to abuse.6

Land Back Land Back is a decentralized campaign that seeks to re-establish Indigenous sovereignty and jurisdiction with political and economic control of their ancestral lands. It encompasses “the reclamation of everything stolen from the original people: land, language, ceremony, food, education, housing, healthcare, governance, medicines, and kinship.”7 The movement emerged in the late 2010s among Indigenous peoples in Australia, Canada and the United States.

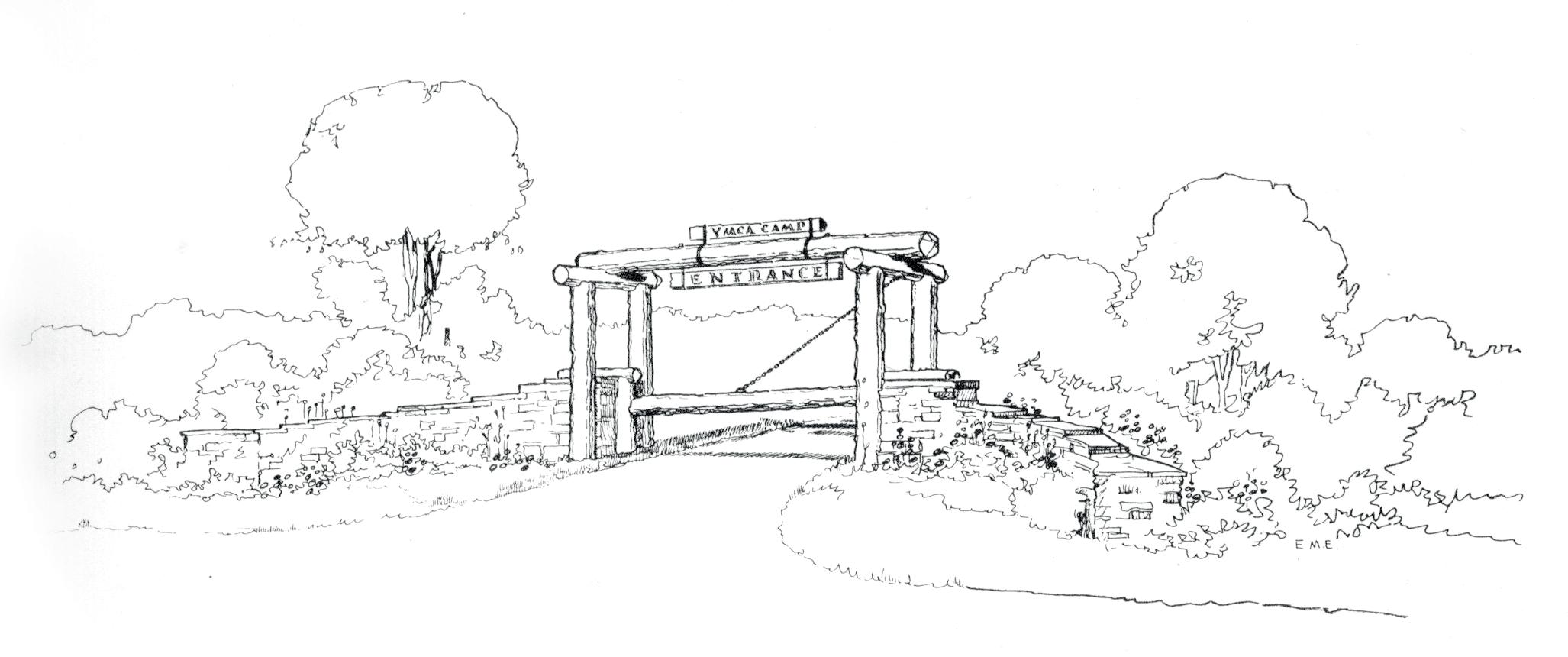

Ontario Camping Association (OCA) Founded 1933. Interests encompassing the development and maintenance of high camping standards in the field of camping for children and an appreciation of the wider aspects of the camping movement. Responsible for the development and implementation of standards for Ontario’s children’s camps, and in 1941, with the Provincial Department of Health, made the licensing of all camps mandatory.

Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig (SKG) A Centre of Excellence in Anishinaabe Education, opened on the site of the former Shingwauk Indian Industrial School. This university’s mission is to preserve the integrity of Anishinaabe knowledge and understanding in cooperation with society to educate the present and future generations in a positive, cooperative, and respectful environment.8

Shingwauk Residential School Centre (SRSC) Shingwauk Residential School Centre, operating out of the previous Shingwauk Indian Industrial School, redeveloped as part of Algoma University. The SRSC is one of the leading research centres and archives focused on Indian Residential Schools.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) Established in 2008 to document the history and lasting impacts of the Canadian Indian Residential School System. In the commission’s final report from 2015, they concluded that forcible assimilation practices, targeting 150-thousand Indigenous children over almost 100 years amounted to cultural genocide. The final report also included a list of 94 actionable policy recommendations meant to aid the healing process in two ways: acknowledging the full, horrifying history of the residential school system, and creating systems to prevent these abuses from ever happening again in the future.

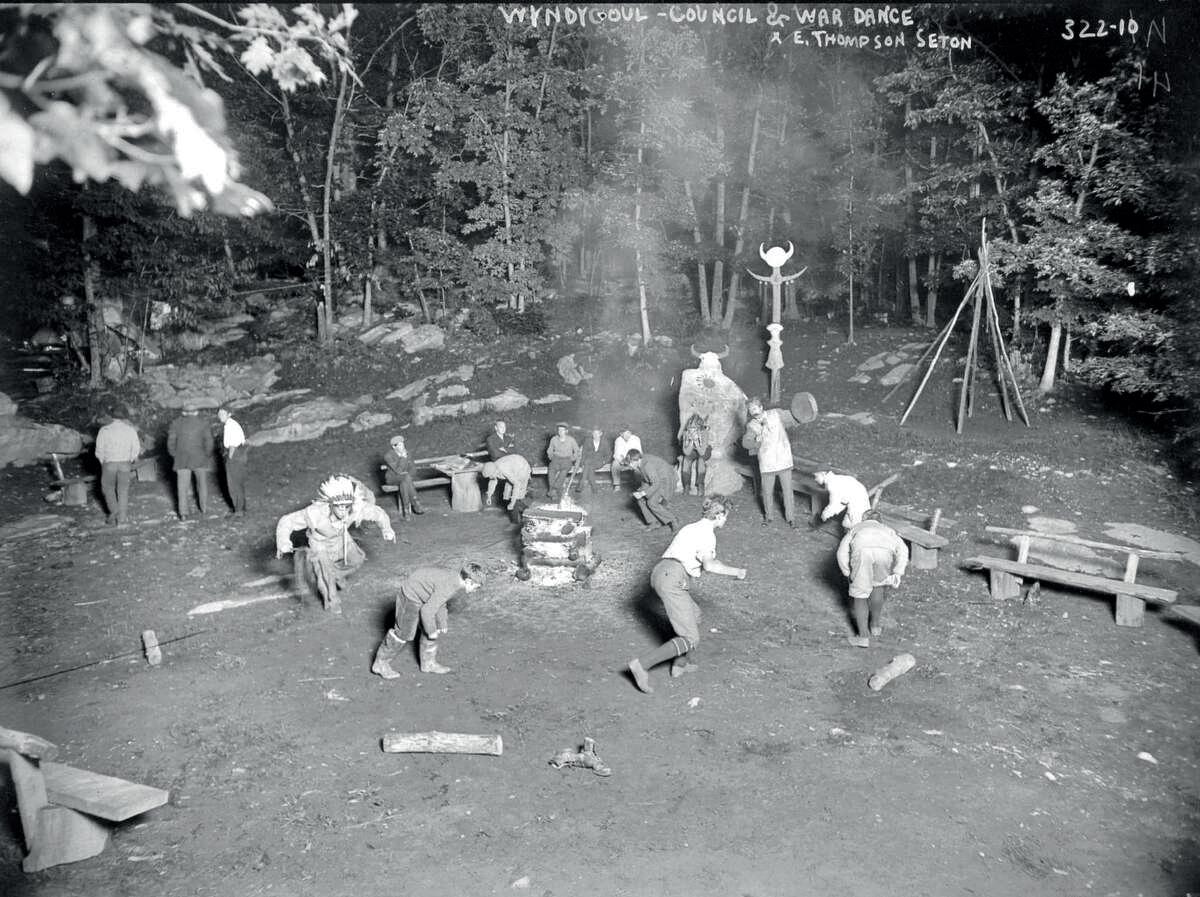

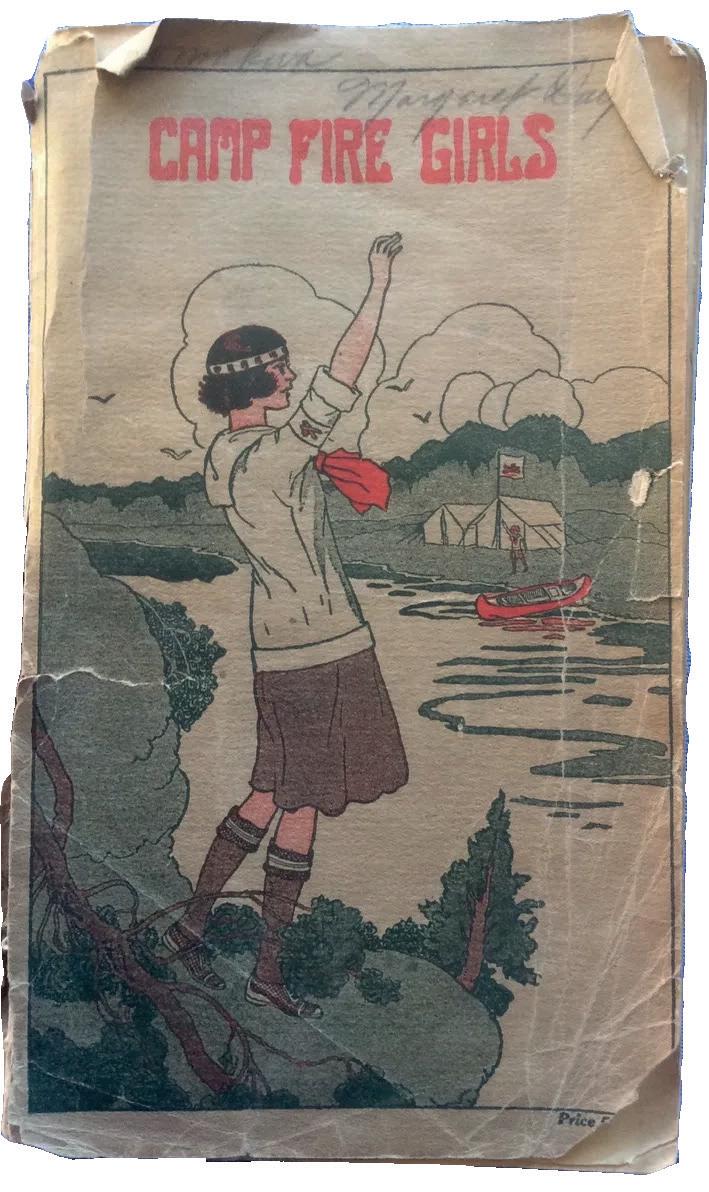

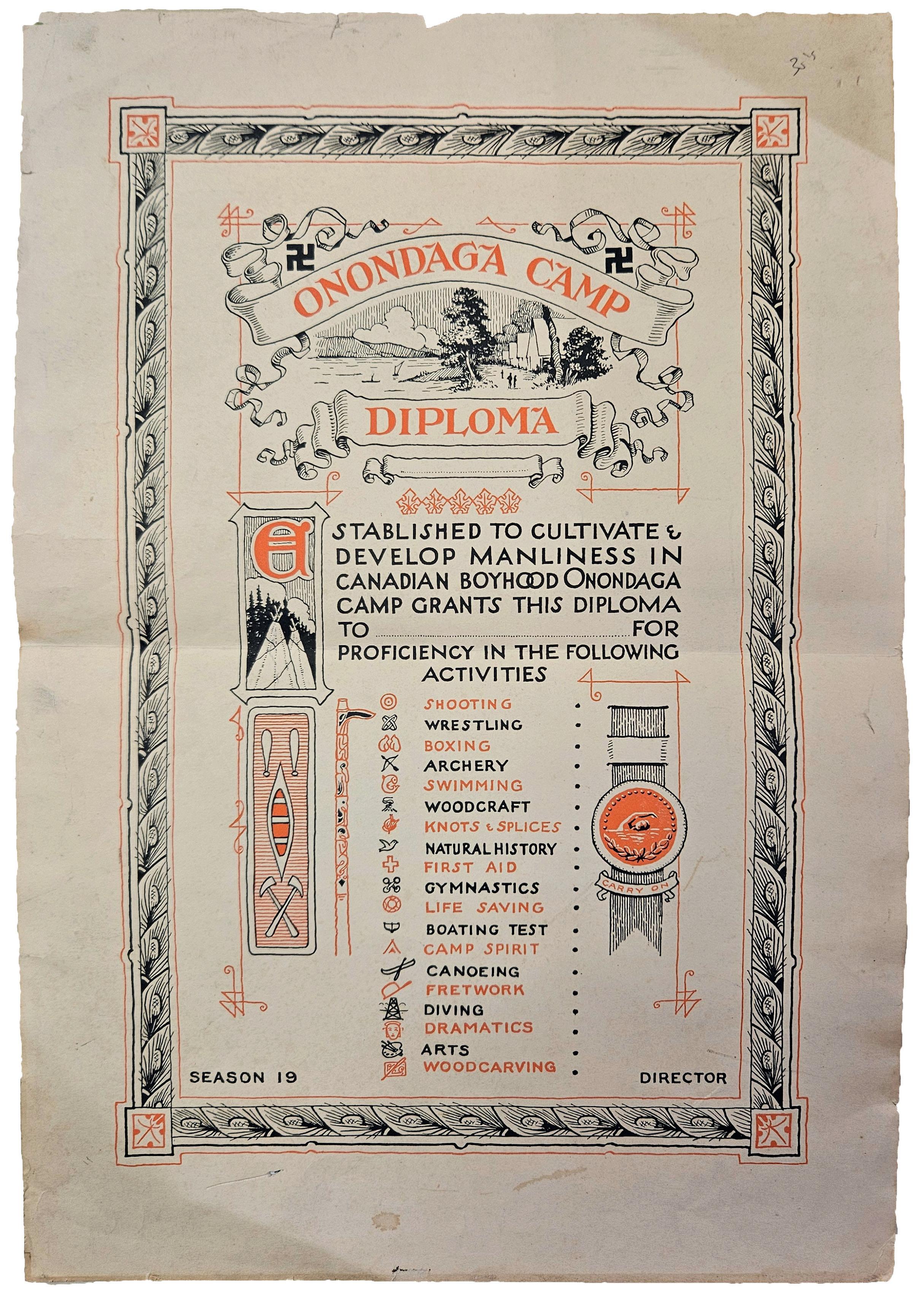

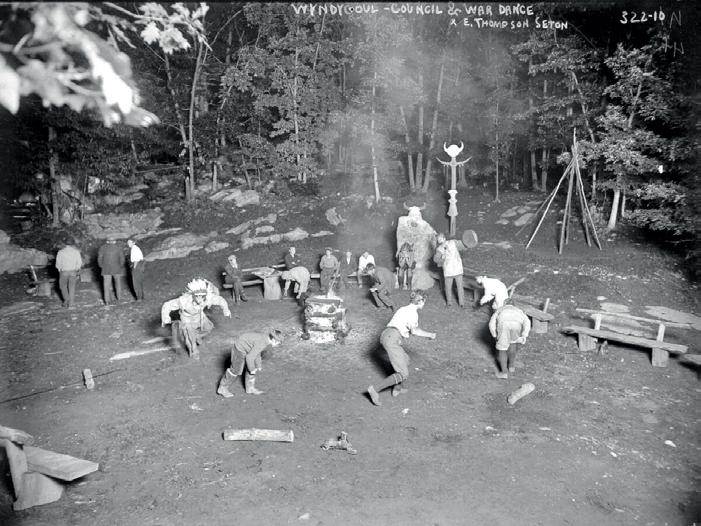

Woodcraft Indian Movement The Woodcraft Indian Movement was founded in 1902 by White Canadian Naturalist Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946). The program relied on the appropriation of Indigenous cultural practices and encouraged primarily white boys, followed a few years later by girls (The Camp Fire Girls, 1912) in collective, ritualized role-playing as the mythical Indian.

Key Figures

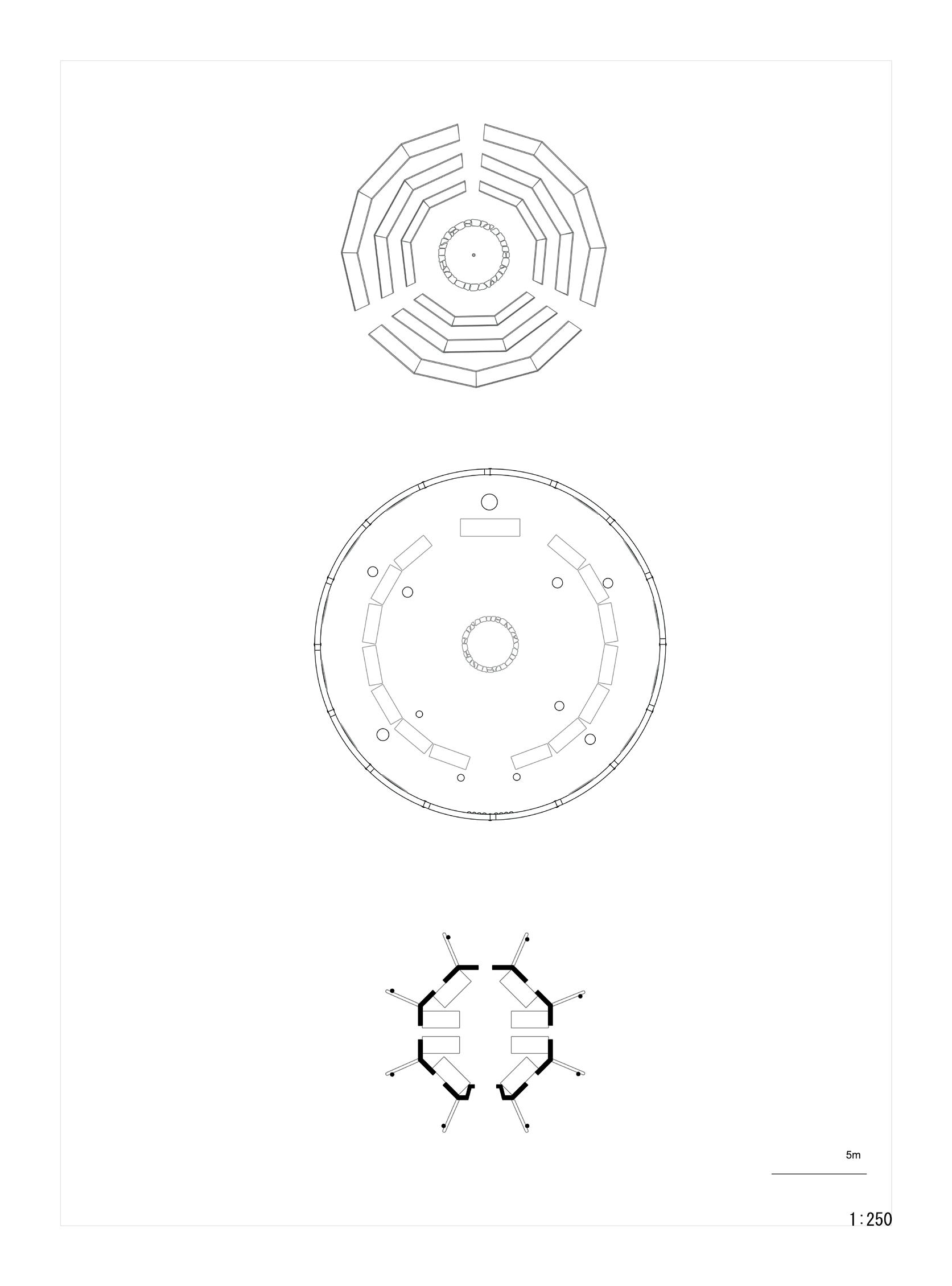

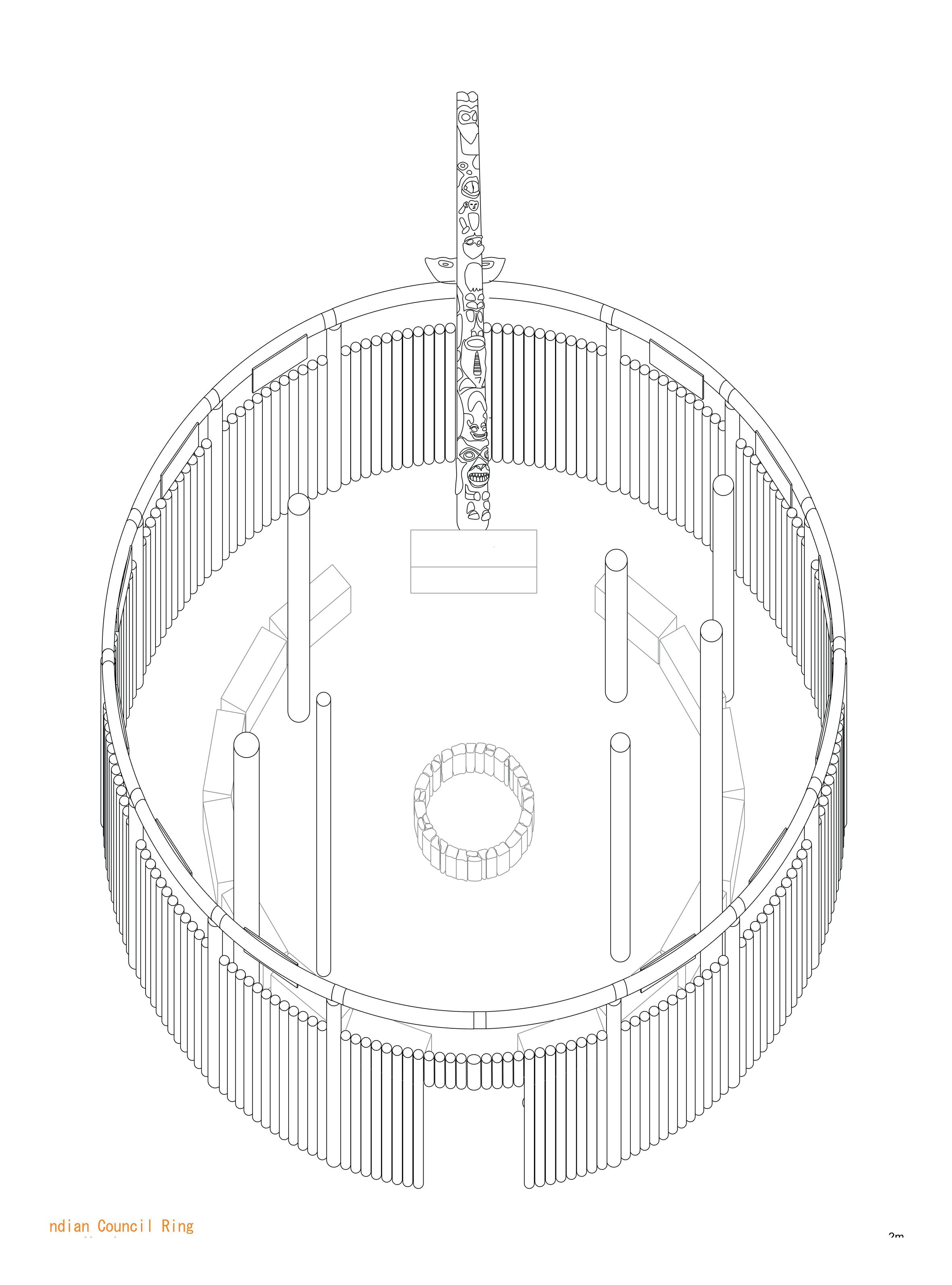

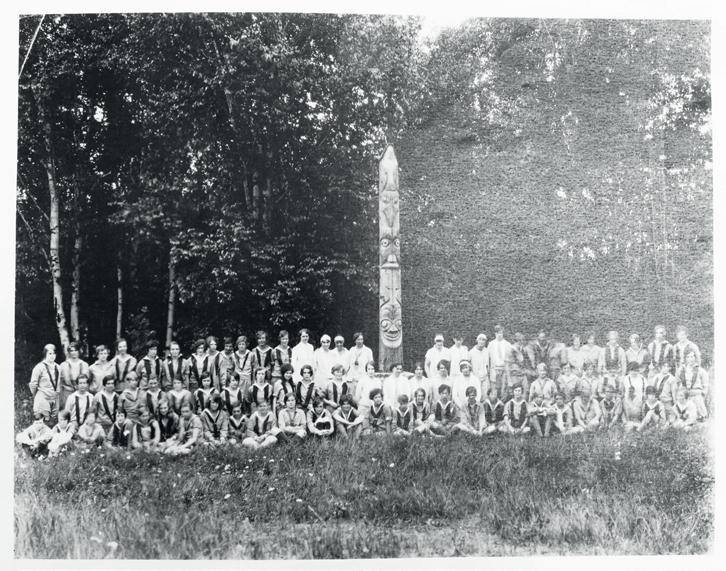

Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946) English, emigrated to British North America in 1866. Worked as an artist and naturalist. Founder of the Woodcraft Indian Movement. Published Two Little Savages; Being the Adventures of Two Boys Who Lived as Indians and What They Learned (1906) based on his childhood experience of “playing Indian.” Author of Wild Animals I Have Known (1898) and other animal stories. Seton’s movement also began the Indian Council Ring Tradition, including a structure that versions of can still be found at many Summer Camps.

Nickolas Flood Davin (1840-1901) Lawyer, journalist, and politician, born in Ireland (then part of the UK) and moved to North America. Considered one of the architects of the Canadian Indian Residential School System. Author of the 1879 Report on Industrial Schools for Indian and Half-Breeds, or The Davin Report, commissioned by the Canadian government in which he advised the federal government to institute residential schools for Indigenous children.

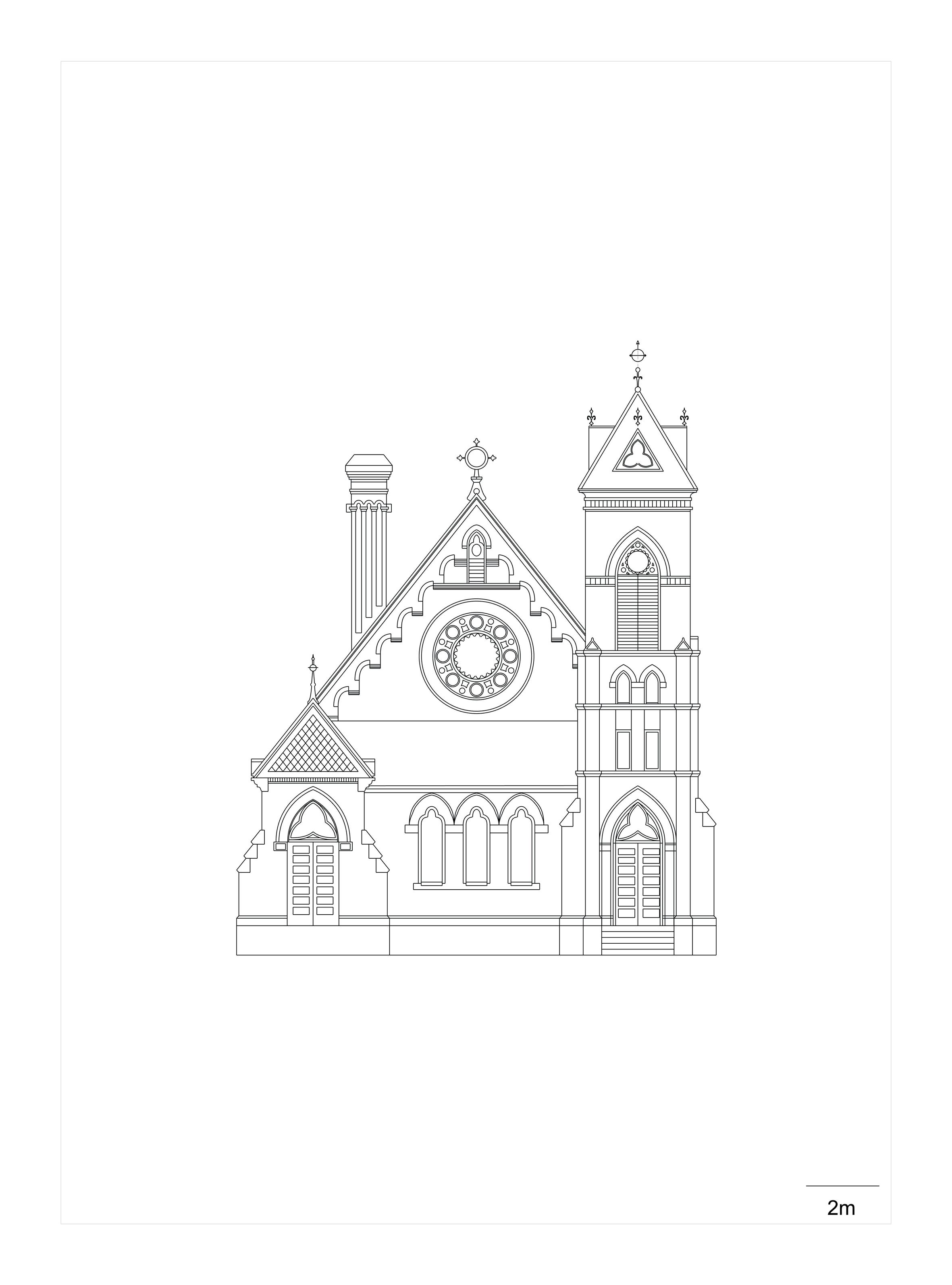

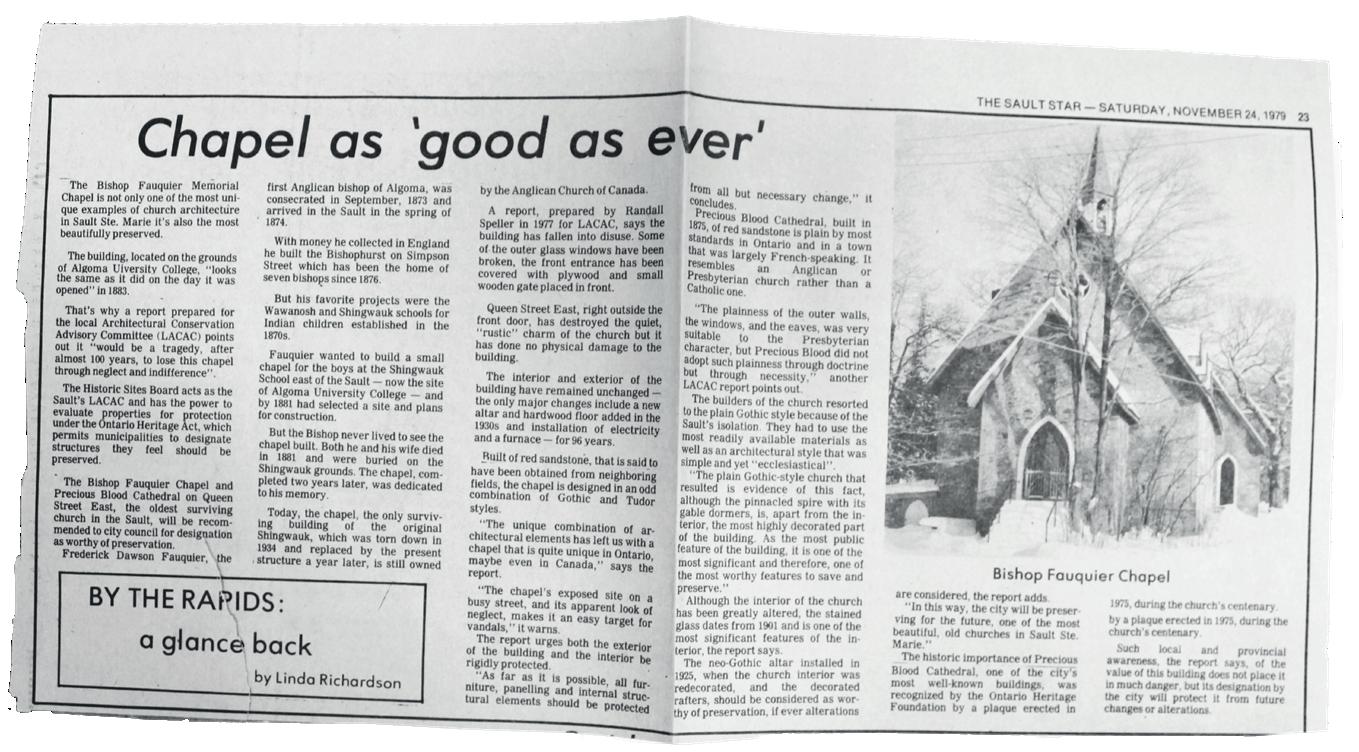

Reverend E. F. Wilson (1844-1915) English Missionary. Founder and first Principal of the Shingwauk Indian Industrial School. Wilson also acted as architect of multiple structures of the institution, including the initial design of the Bishop Fauquier Memorial Chapel.

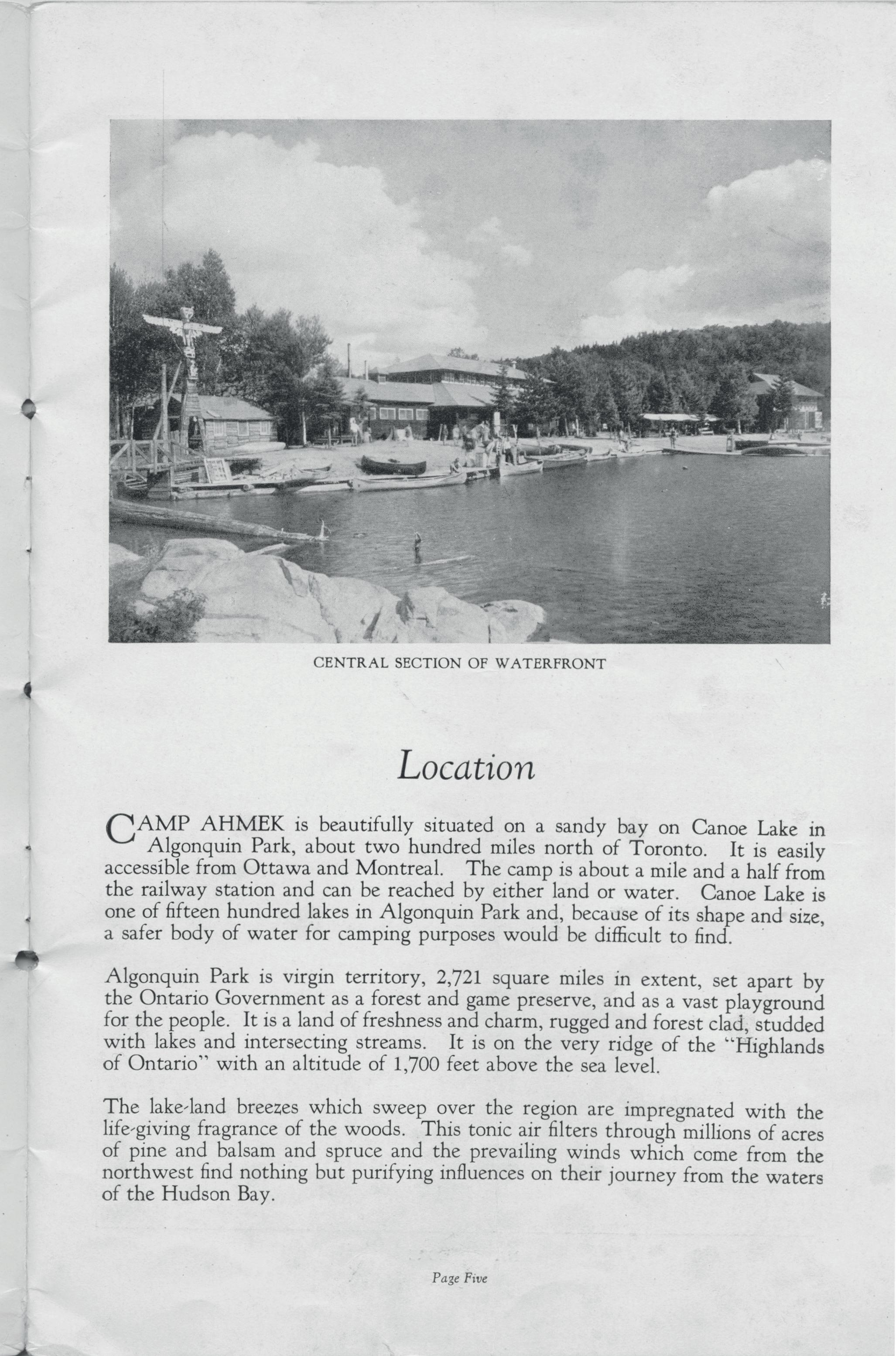

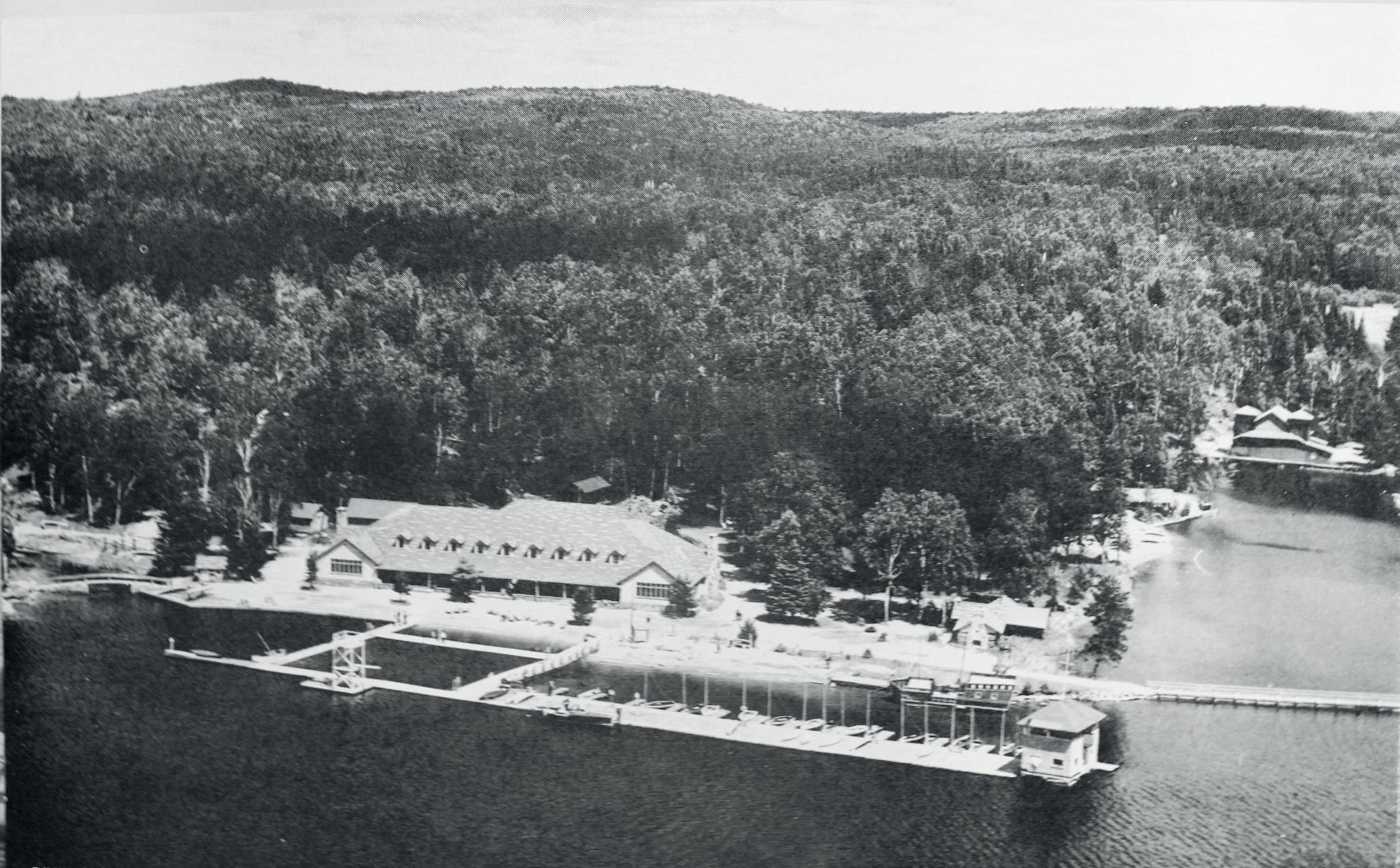

Taylor Statten (1882-1956) Boer War veteran, an educator associated with the national YMCA, and the founder of Camp Ahmek (1921) on Canoe Lake, Algonquin Park, Ontario. Statten was also one of the founding members of the Ontario Camping Association (1933).

0.1 Research Questions

0.2 Aims and Objectives

0.3 Methodology

0.4 Structure of the Thesis

9 Irit Katz, The Common Camp: Architecture of Power and Resistance in Israel-Palestine, 2022.

10 1831 was the year that the Mohawk Institute opened—the first Indian Residential School in Canada, which was at the time under British Colonial rule. It was not until 1867 with the passing of the British North America Act that First Nations education becomes a federal responsibility.

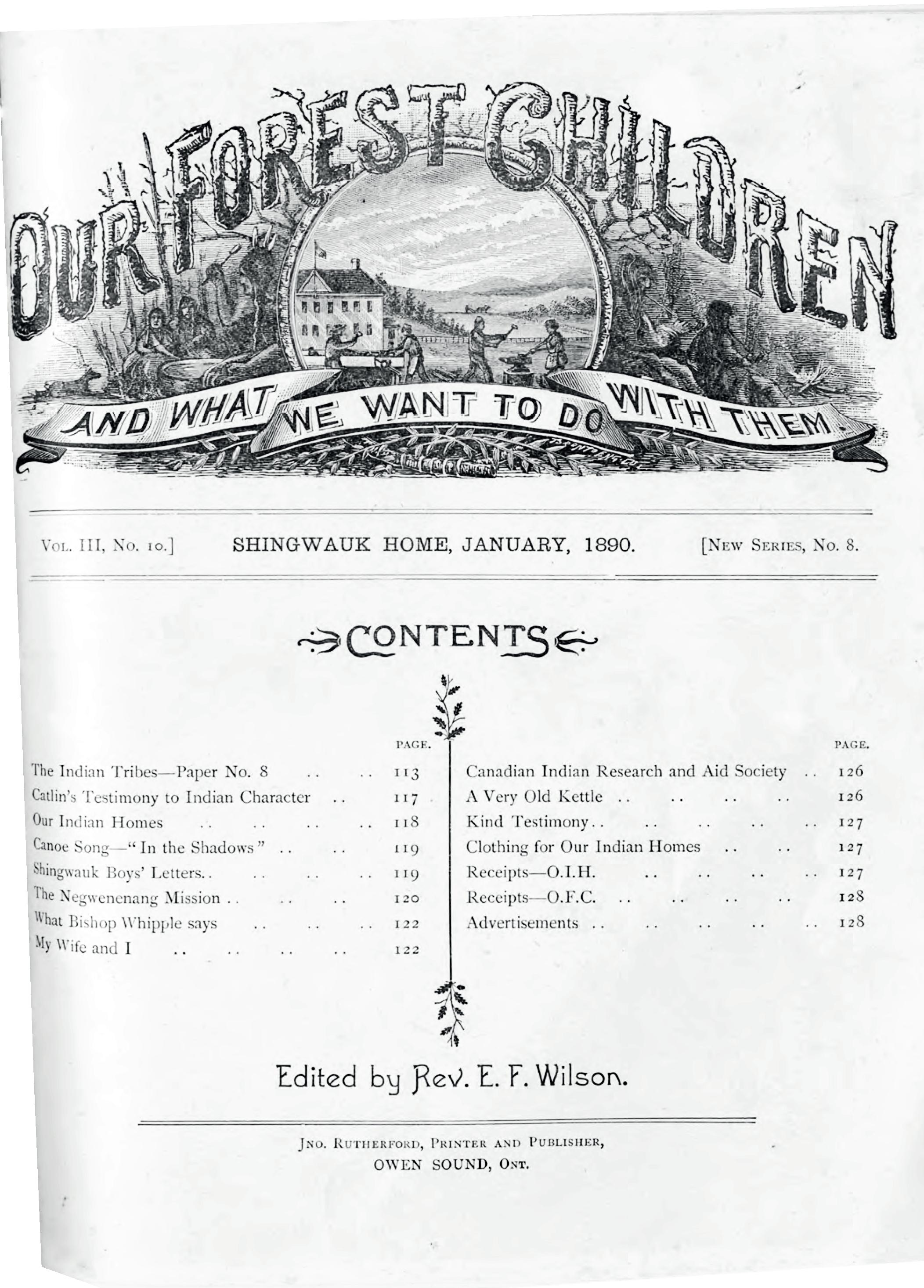

11 Our Forest Children periodical was established in 1887, and was superseded by Canadian Indian October 1890. It was printed with the labour of Indigenous boys who were students at Shingwauk. These publications served to advertise the mission of the Residential Schools to the British and Settler Canadian public and solicit donations.

12 The last federally-funded Indian Residential School, Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, closed in 1997.

13 In 1879, Canada’s first Prime Minister Sir John public and engaged Nicholas Flood Davin to investigate boarding schools for Indigenous children in the United States as a possible model for assimilation in Canada. Davin advised that a federally funded system of Industrial schools should be established throughout the country. The strategy came to be called “aggressive civilisation”. (Davin, Nicholas Flood, 1879, “Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half- breeds,” Winnipeg, MB, p. 2, [http:// archive.org/ details/cihm_03651/]).

14 Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada, “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada,” December 14, 2015, https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/ eng/1450124405592/1529106060525

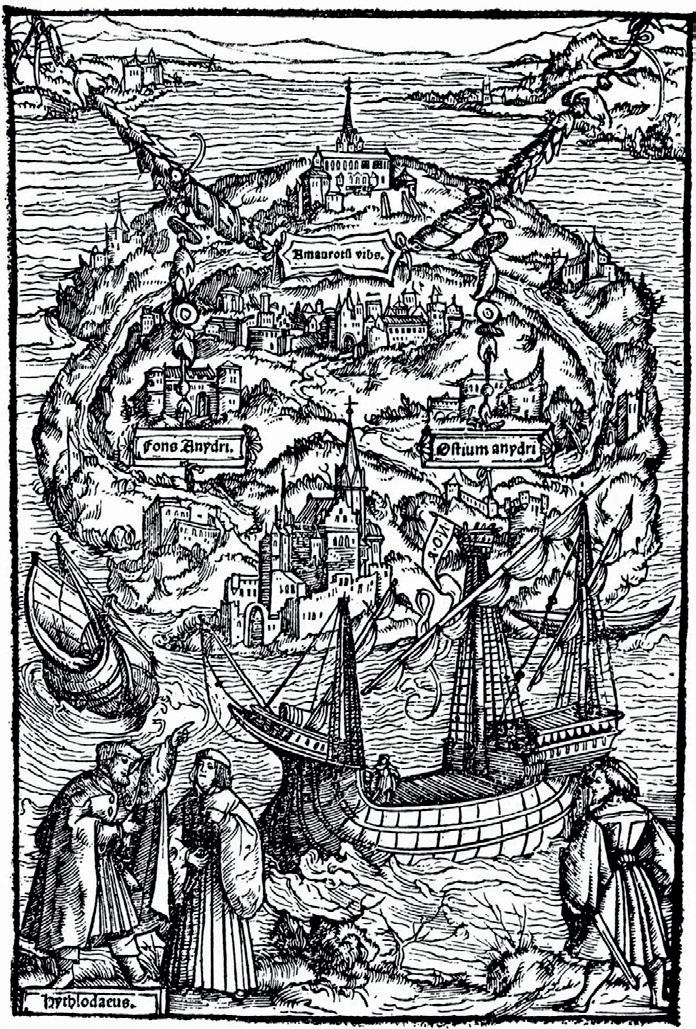

On Turtle Island (the Indigenous name for North America), people had been camping long before the arrival of Settlers. Only it was Settlers who labelled Indigenous semi-nomadic settlements as such, proceeding to imitate them in their own more permanent camps imposed onto these Indigenous lands. In European etymology, the camp at one point meant a training ground. But it has other roots. The focus of the thesis is on the camp as an instrument by which modern societies can be administered, negotiated, and reorganised.9

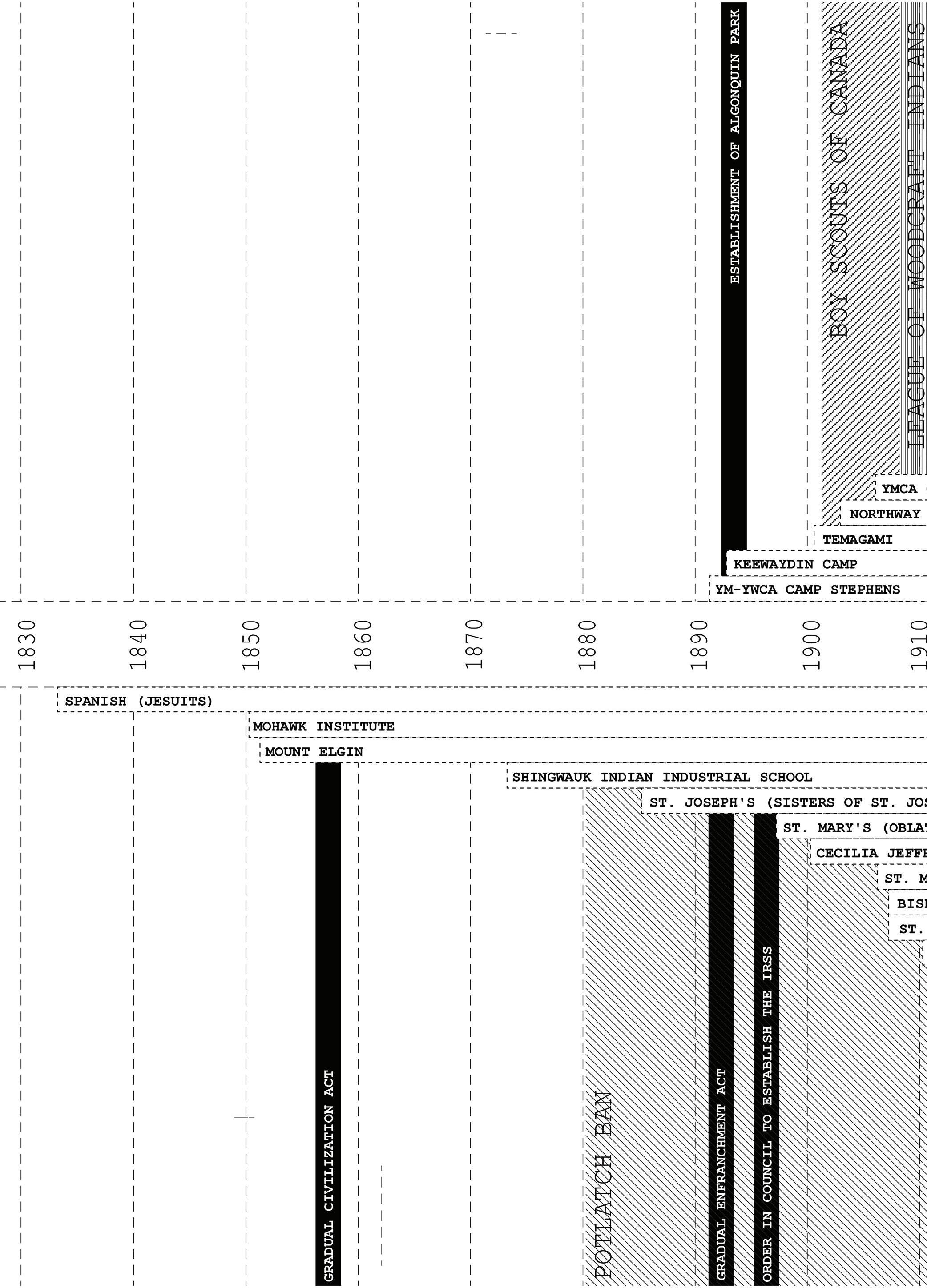

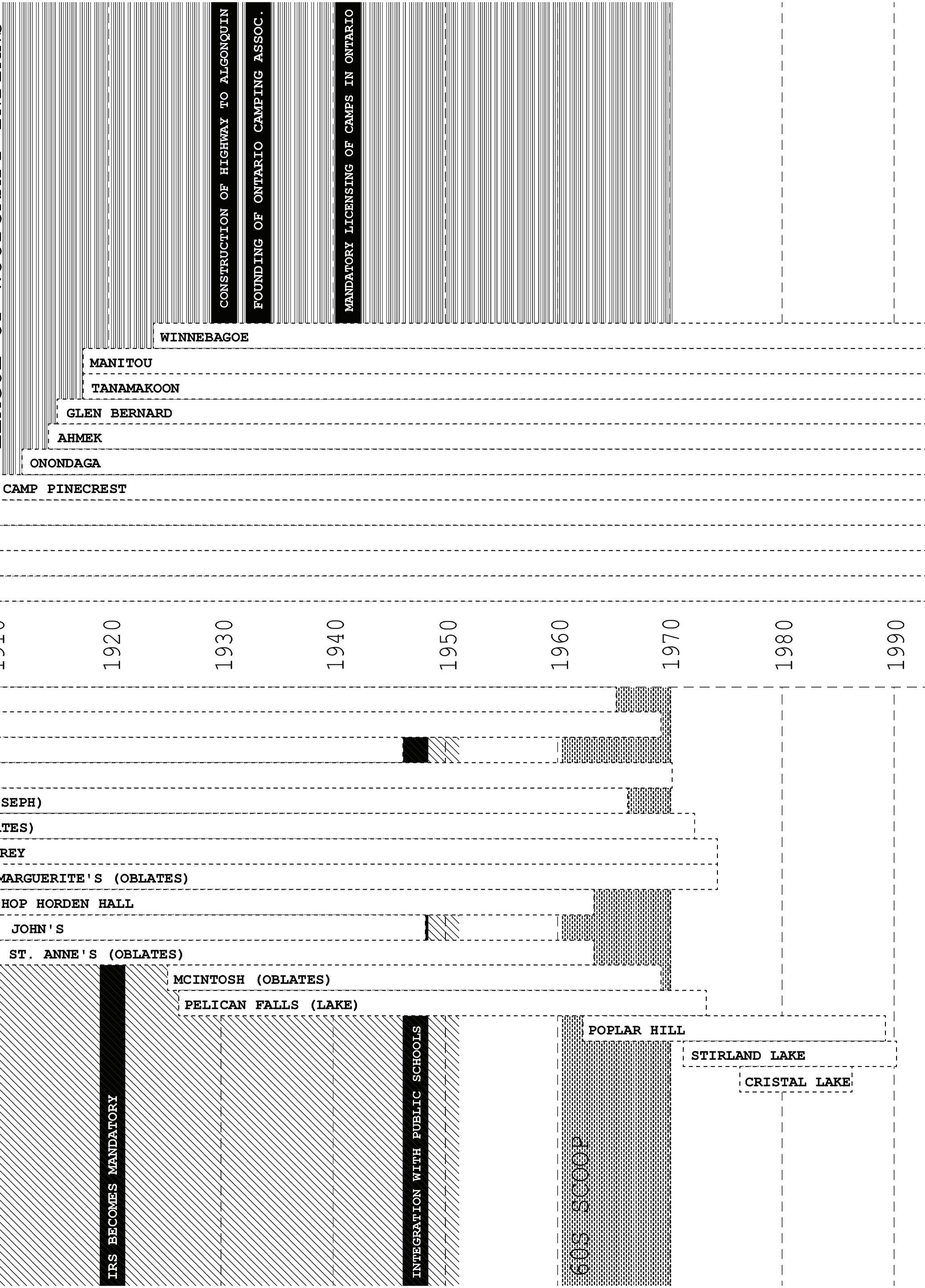

The thesis argues that two forms of the youth camp, organised as institutions of “education” under the settler state, can be reread as an exemplary case of complimentary colonial strategies for Indigenous dispossession and Settler possession. Both of these forms of the camp, I argue, acted in parallel to project a colonial hierarchy of inhabitants in Canada.

Arriving in Canada in 1831, the camp was appropriated by Catholic Missionaries in the name of progress, to indoctrinate Indigenous children into a Christian way of life.10 To begin this historical retelling, I refer to a periodical published in 1890 from the Shingwauk Indian Industrial School in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, from which the thesis borrows its title.

Reverend E. F. Wilson’s (1844-1915) Our Forest Children And What We Want To Do With Them stands as an explicit record of the institution’s mission.11 The Shingwauk School for Boys and the Wawanosh School for Girls were founded by Wilson in 1873 and stayed in operation until 1970. Wilson had come to Canada from London, England, belonging to the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

This system of boarding schools, the first type of camp of focus in the thesis—known formally as the Indian Residential School System (IRS)—spread across Turtle Island with the political and financial backing of the Canadian and American governments. Policy behind the system in Canada began with the Ryerson Experiment in 1845, followed by the Gradual Civilization Act (1857), the Gradual Enfranchisement Act (1869), the Indian Act (1876), and the Davin Report (1879)—that passed along the responsibility for Indigenous education from British Colonial rule, to the Dominion of Canada, and then down to the Indian Affairs Department, a branch of Canada’s federal government until 1997.12 All the while operated by multiple denominations of the Christian church. ‘Work Camps’ more accurately describe these schools, which are estimated to have targeted more than 150,000 Indigenous children between 1883 and 1996. The system was set up with the intention of civilising and Christianizing Indigenous children. Attempting to sever their bonds with their communities, families, cultural identities, and lands. In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada concluded that this program of “aggressive civilization”13 was responsible for a cultural genocide.14

4 Illustration depicting Indigenous children labouring the fields in front of Shingwauk Home, in contrast with the “primitive ways” surrounding the central image. By Rev. E. F. Wilson in Wilson, Our Forest Children and what we want to do with them, 1890.

15 Though it may be unlikely Seton ever referred to his pupils as ‘forest children’, the flexibility of the title could suggest a second meaning in the context of White campers led in playing Indian.

16 Playing Indian extends well before and past these dates, though these are the years identified by Sharon Wall as being most widespread at summer camps in Ontario. Sharon Wall, The Nurture of Nature: Childhood, Antimodernism, and Ontario Summer Camps, 192055, Nature/History/Society (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009).

17 Ibid.

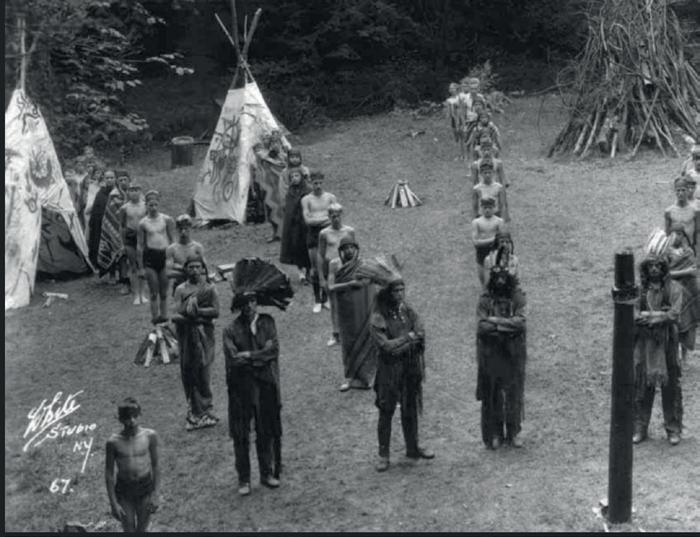

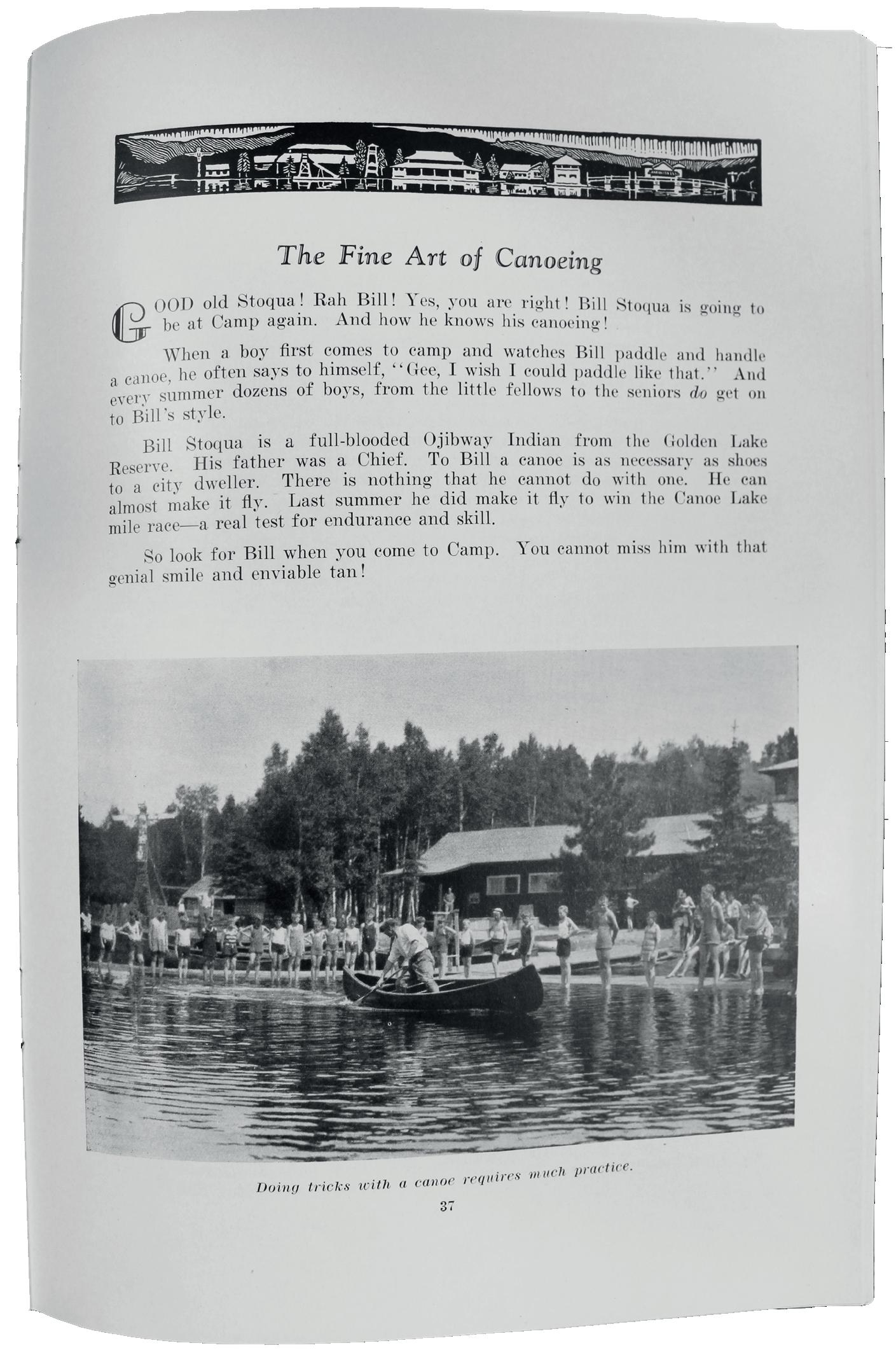

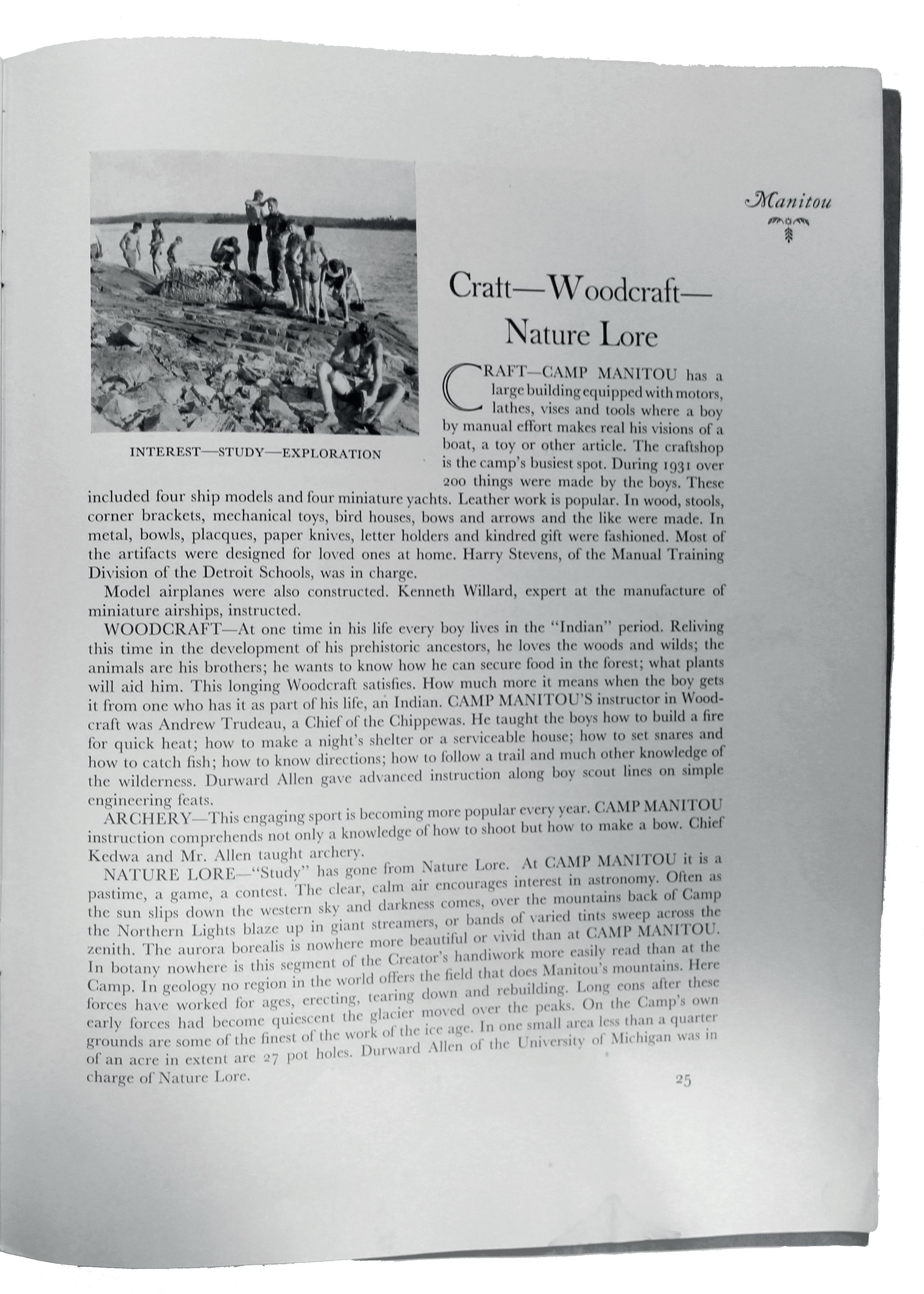

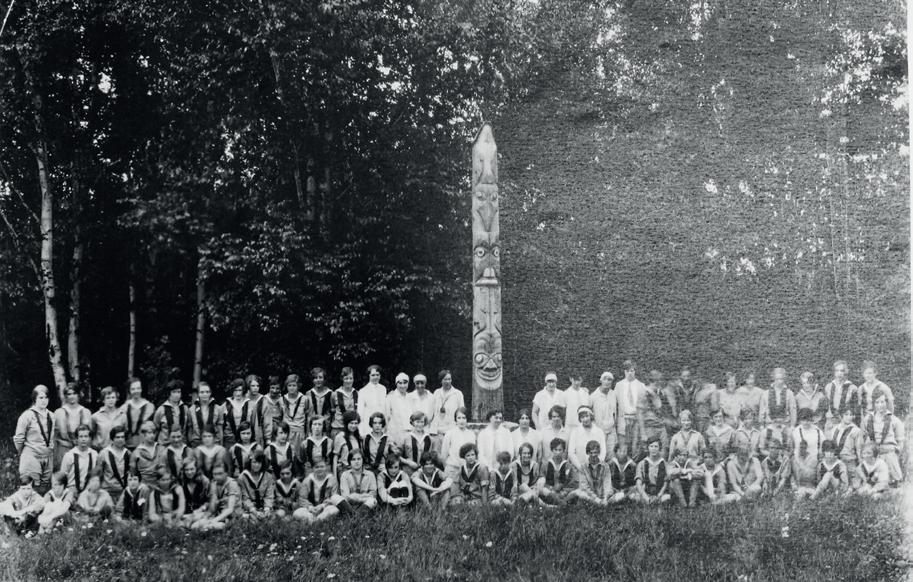

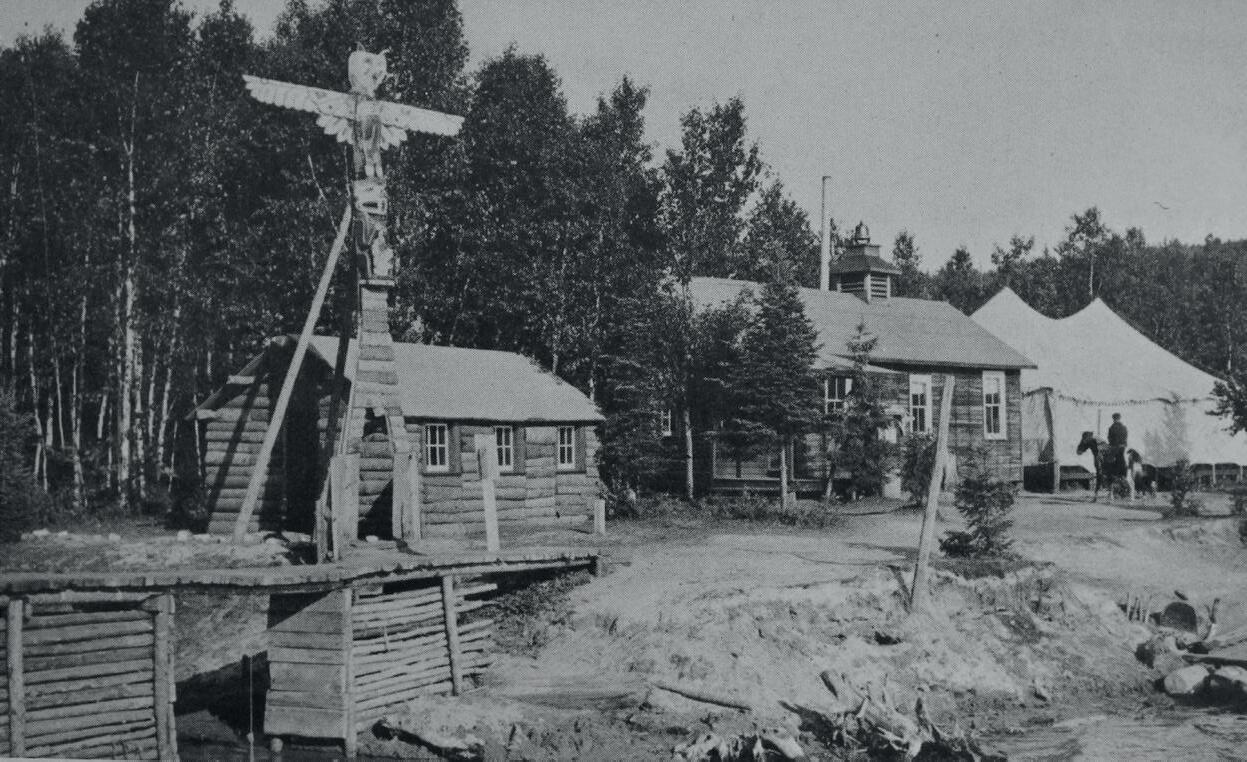

At almost the same critical moment in time (a decade after the publication of Our Forest Children), Ernest Thompson Seton (18601946), an English born Canadian author, artist, and naturalist, founded the Woodcraft Indian Movement (1902). Seton along with the leadership of the Boy Scouts of America (1910) were appropriating the camp as another form of youth training ground. Except they were focused on the education of Settler children. Seton’s ‘forest children’ were White boys whom he introduced to the ways of Native Americans through appropriated chants and rituals around his Indian Council Ring structure in upstate New York.15 These properties in the “wilderness” became the places where the new middle class could escape the perils of the modern city to reclaim this now emptied territory and idealized landscape. As a formalised type, the Woodcraft Summer Camp, and the phenomenon of playing Indian proliferated in Ontario between 1920-1955.16 Not only popular at private, for-profit camps located in the Muskoka, Algonquin, and Temagami regions, catering for well-to-do, upwardly mobile, middle- and upper-class clientele, but also fresh-air camps run by churches, charities, and other non-profit organisations, catering to the poorest sector of Ontario’s working class.17 These camps allowed Settlers to strengthen community while learning a specifically designed set of skills oriented towards forming a bond with the landscape—fundamental to the process of Canadian nation building.

What I wish to emphasise here is the contrast, and the irony in these educational programs—both at a moment near the foundation of two movements—a period of aggressive assimilation policies aimed at Indigenous people, and at the same time, a conceptualisation of a method for indigenizing a Settler population—who were meant to replace the original inhabitants of the land.

The thesis rereads these simultaneous processes by which the original inhabitants were removed and then replaced by settlers in the process of building Canada. The newly conceptualised category of adolescents became the test subjects for experiments in the design of national culture.

How is the territory constructed and instrumentalized through the camp? How do the two types of camp together define and organise a shared territory of colonial expansion, prioritising the dominant culture?

How much was Settler society aware of the nature and mission of the IRS, and how did Settler society and the Summer Camp more specifically define itself in relation to the IRS and Indigenous peoples and nations?

How can the two types of camp be studied on the same plane of existence? How did the camps interact with each other?

How can distinct building and camp typologies be defined in terms of form and function? How can the types be distilled as a set of actions acting on the de-territorialised subjects they define (that is their forest children)? 18

How can land reclamation and respect of Indigenous sovereignty structure our thinking as spatial practitioners to transform these sites?

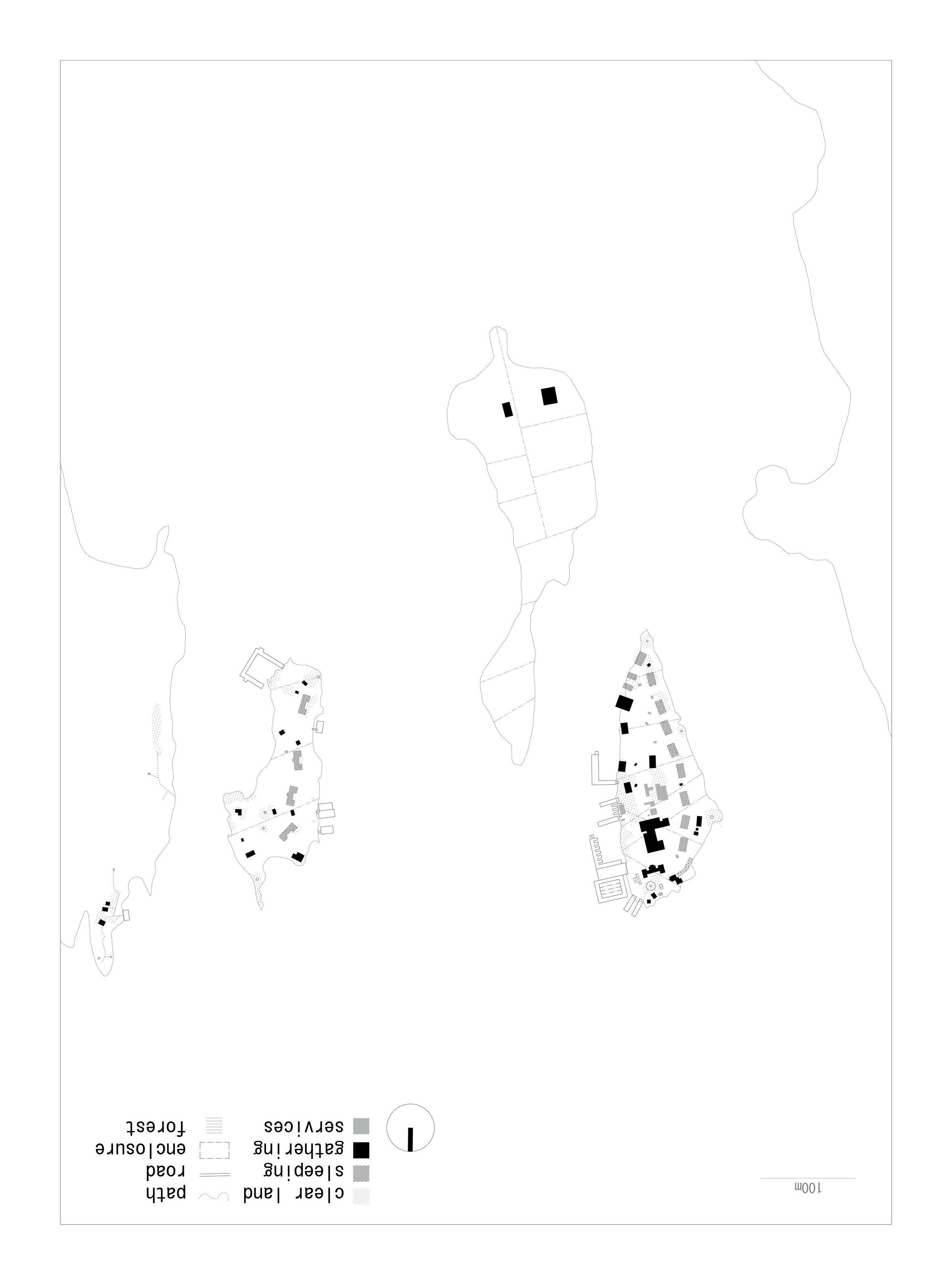

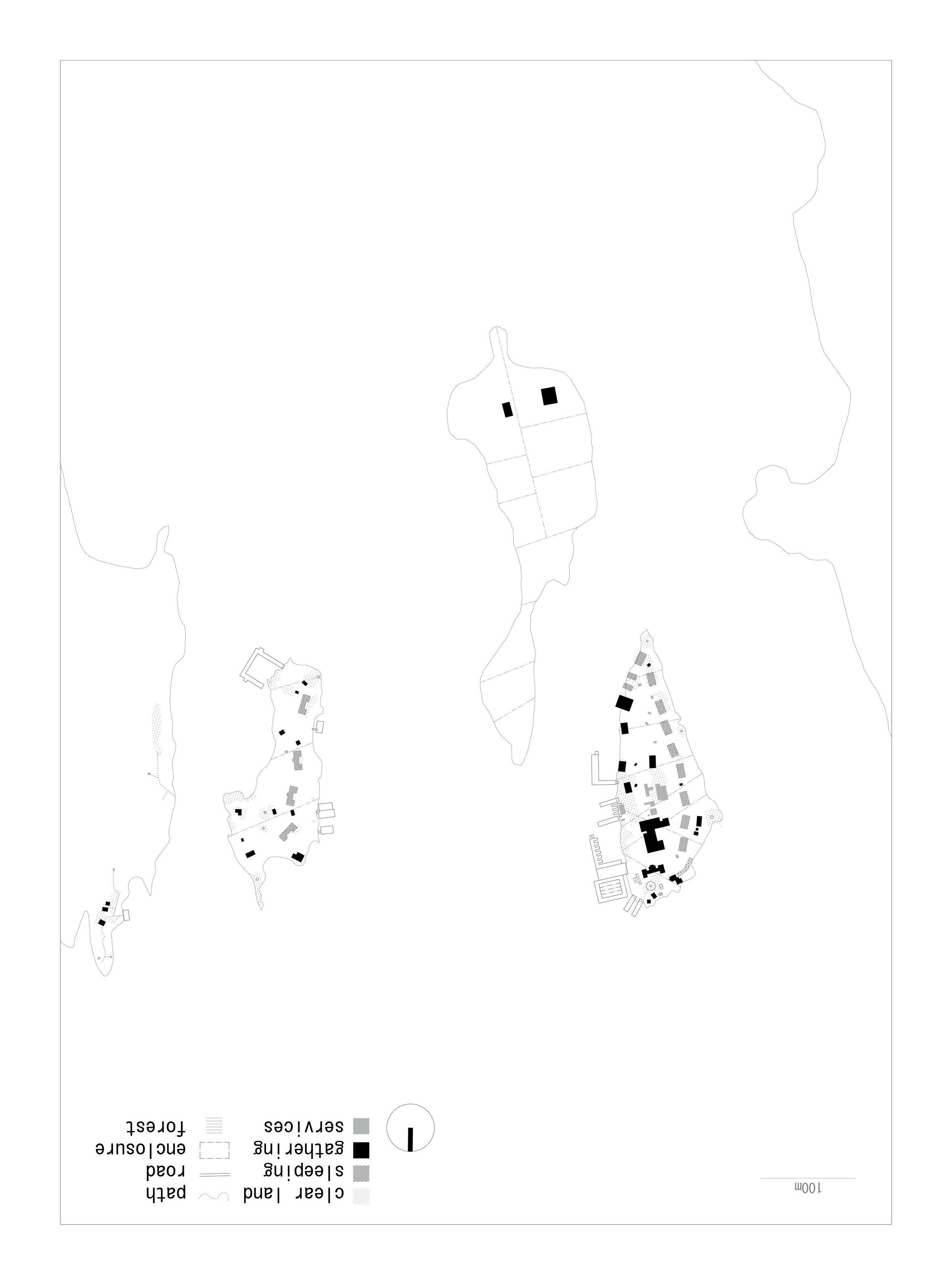

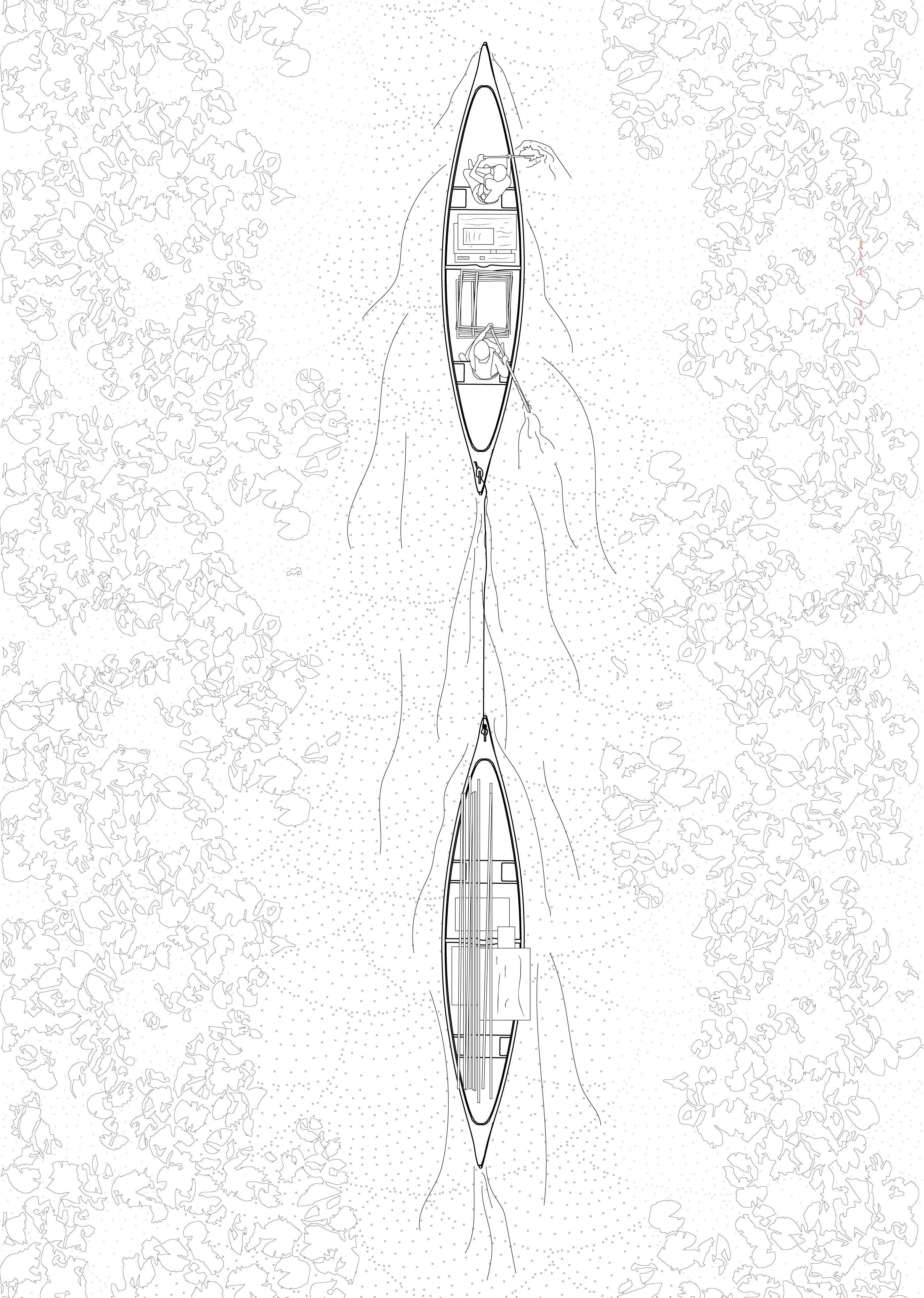

Through the analysis of two distinct typologies of the youth camp: the Indian Residential School for Indigenous children and the Woodcraft Summer Camp for Settler children—the thesis aims to understand the instrumentality of the camp as it has been utilised to forward the settler colonial agenda in Canada. The research attempts to redefine and connect the diagrams that each camp represent as related projects of indoctrination and as spatial conditions of the camp. By tracing politically charged flows of cultural capital (or the barbaric transmission of culture19) that make up much of the curriculums at each institution, I trace a pattern of cultural appropriation (simply, theft) that is established by Settlers justified by destructive ideologies. Through paralleling the operations of Indigenous dispossession and Settler possession as the architectures of these institutions are set up to perform, the thesis reflects on the agency of spatial design in affecting how belonging within a nation, as well as landscape is negotiated and controlled. The thesis argues across what are mostly separate bodies of research and material traces to argue on the tensions between their co-existence. I argue that the colonial tendencies of these programs can be defined in terms of their relationality as an assemblage, as they evolved over the twentieth century. The camps are read as a layer of the constructed territory of Canada.

By first nuancing our understanding of the camp diagram and its relation to the spatial delineation of wilderness, on the propositional level the thesis proposes a scenario for reclaiming the diagram as sites of truth and methods for reconciliation. Finally, the thesis strategises on the spatial possibilities opened up by Indigenous calls for Land Back, informing design tests related to on the land education and design that prioritises reestablishing Indigenous sovereignty.

20 Their founders—Taylor Statten (Ahmek) and Mary Edgar (Bernard)—were later founding members of the Ontario Camping Association (OCA). Their writings and pedagogies were very influential in Ontario’s camping movement and wider field of education.

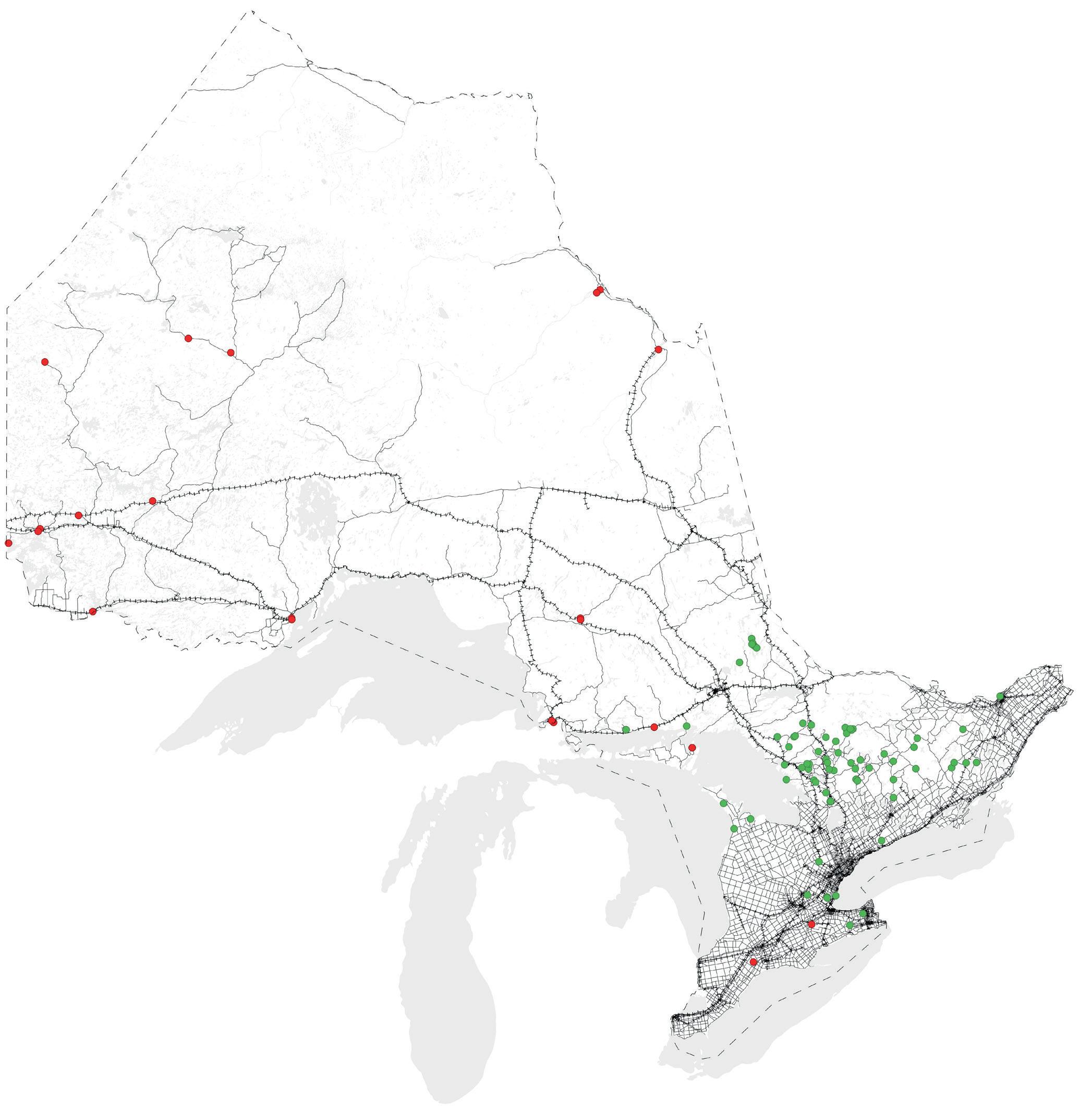

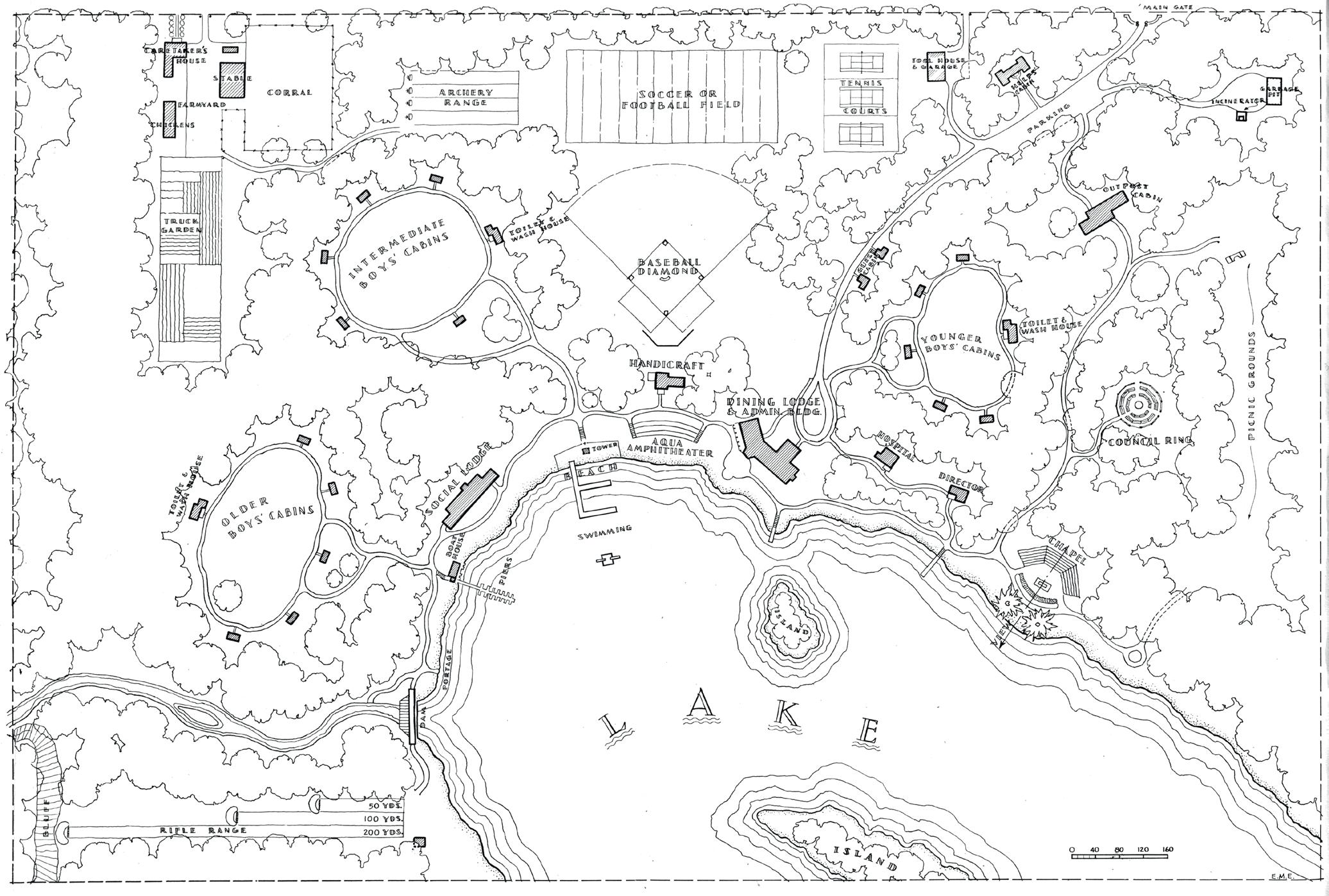

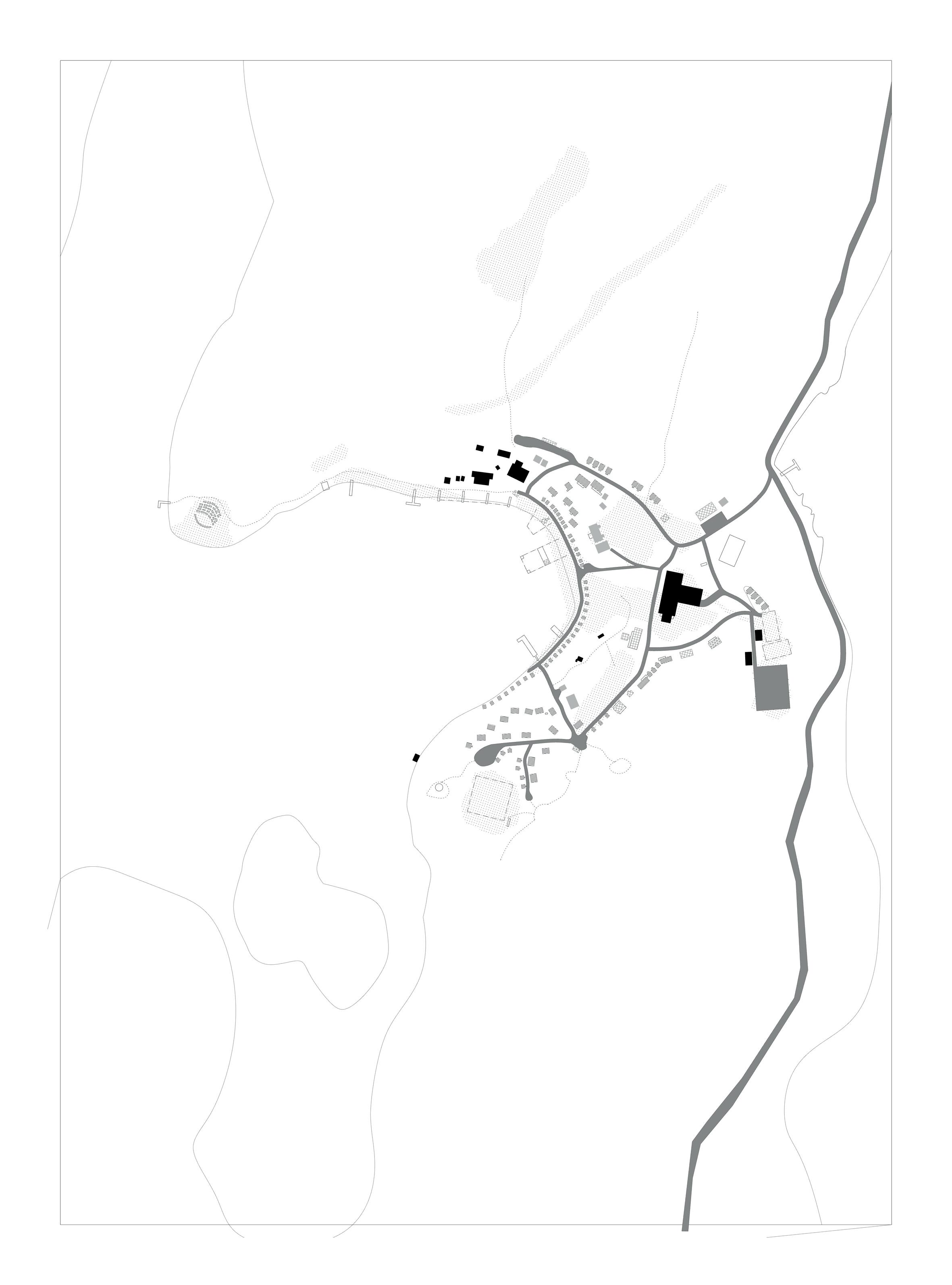

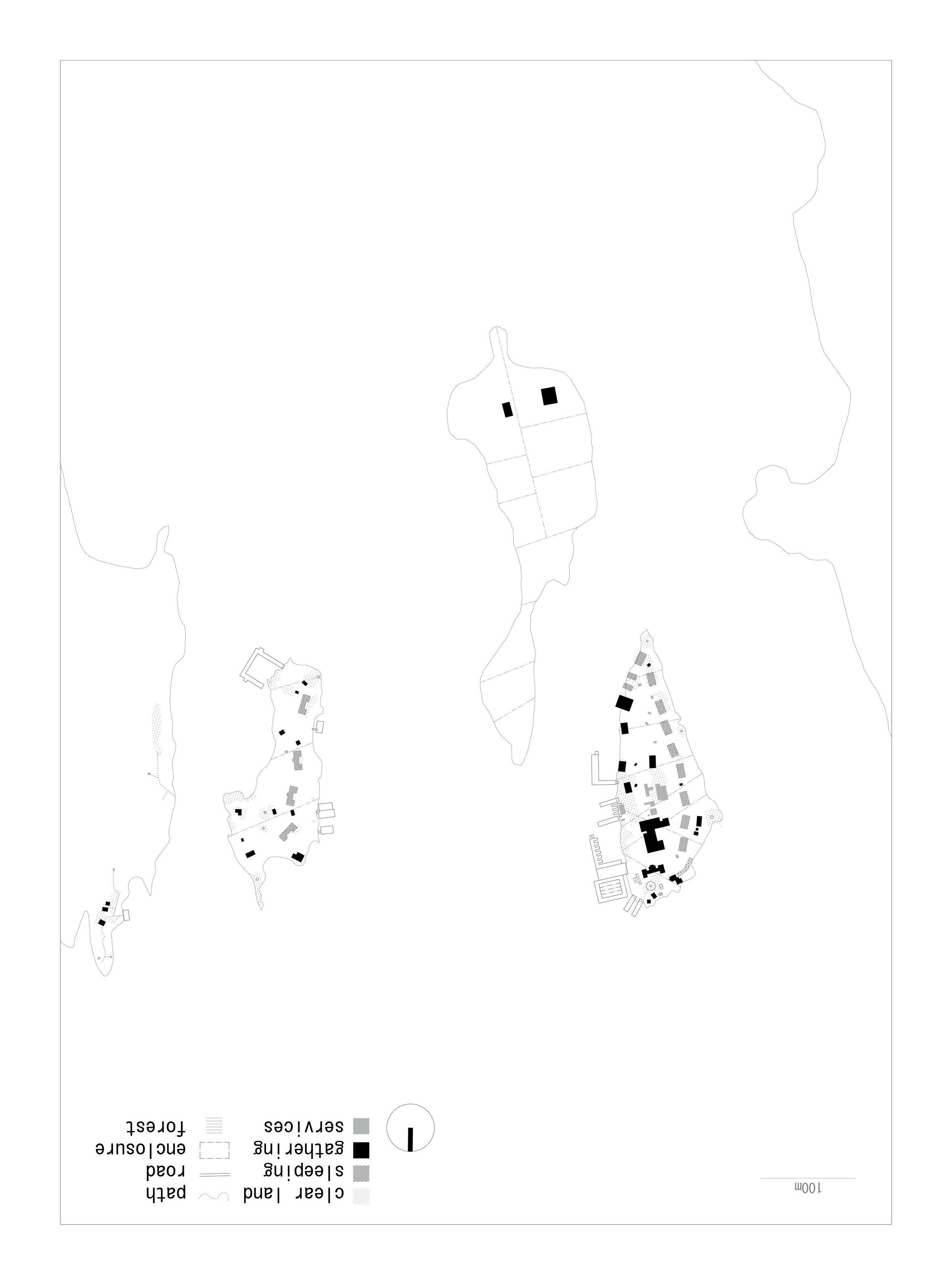

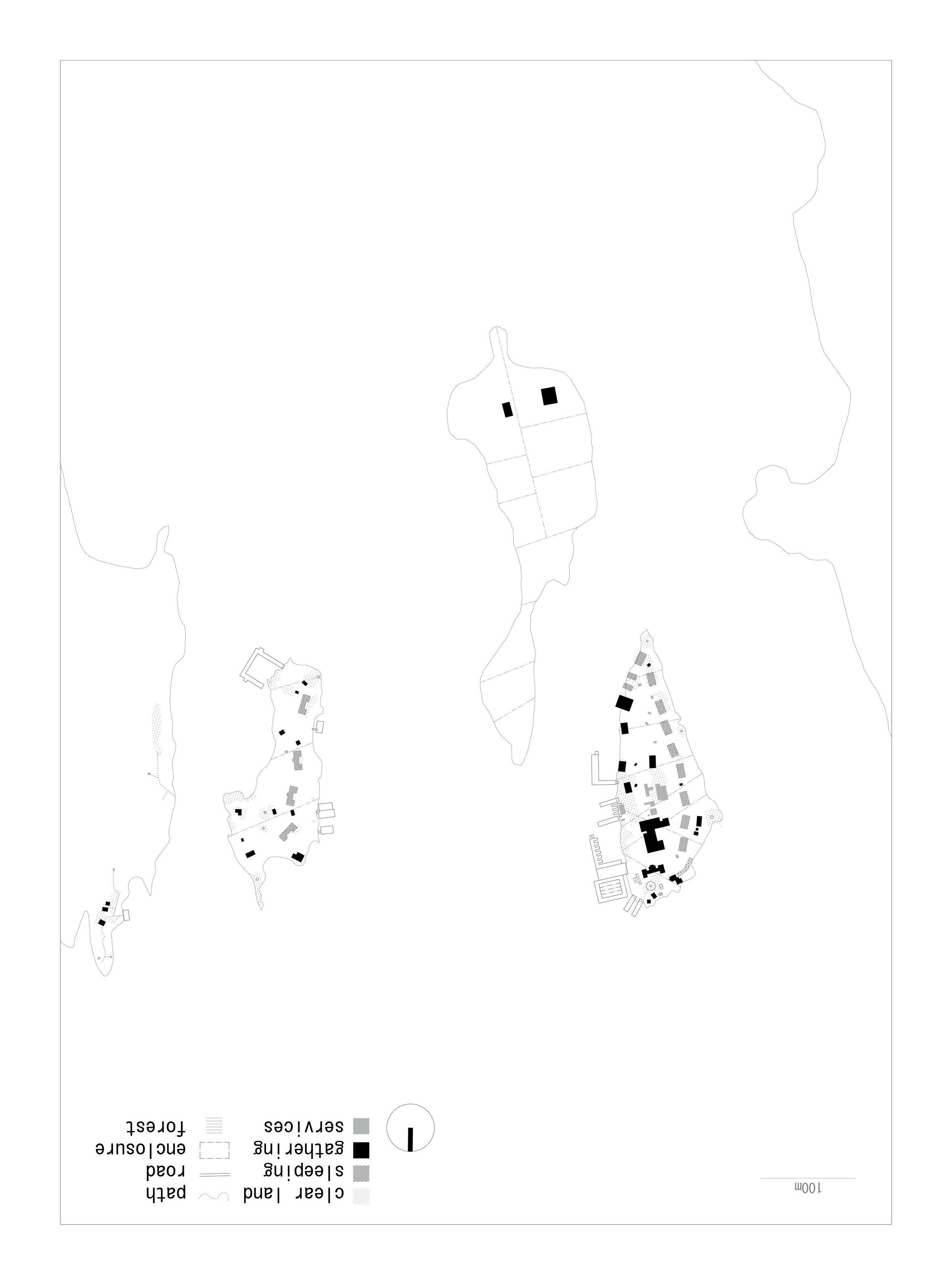

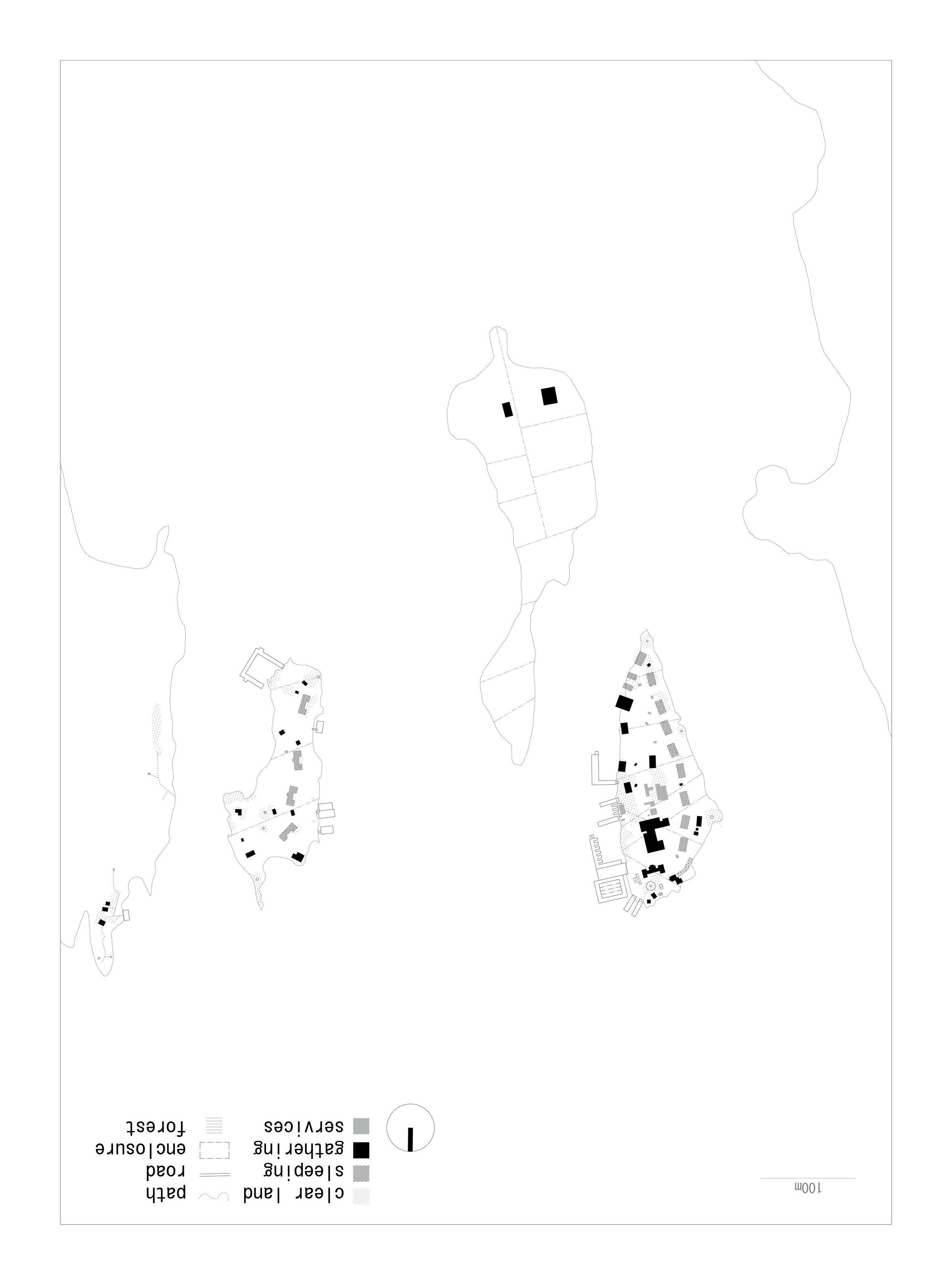

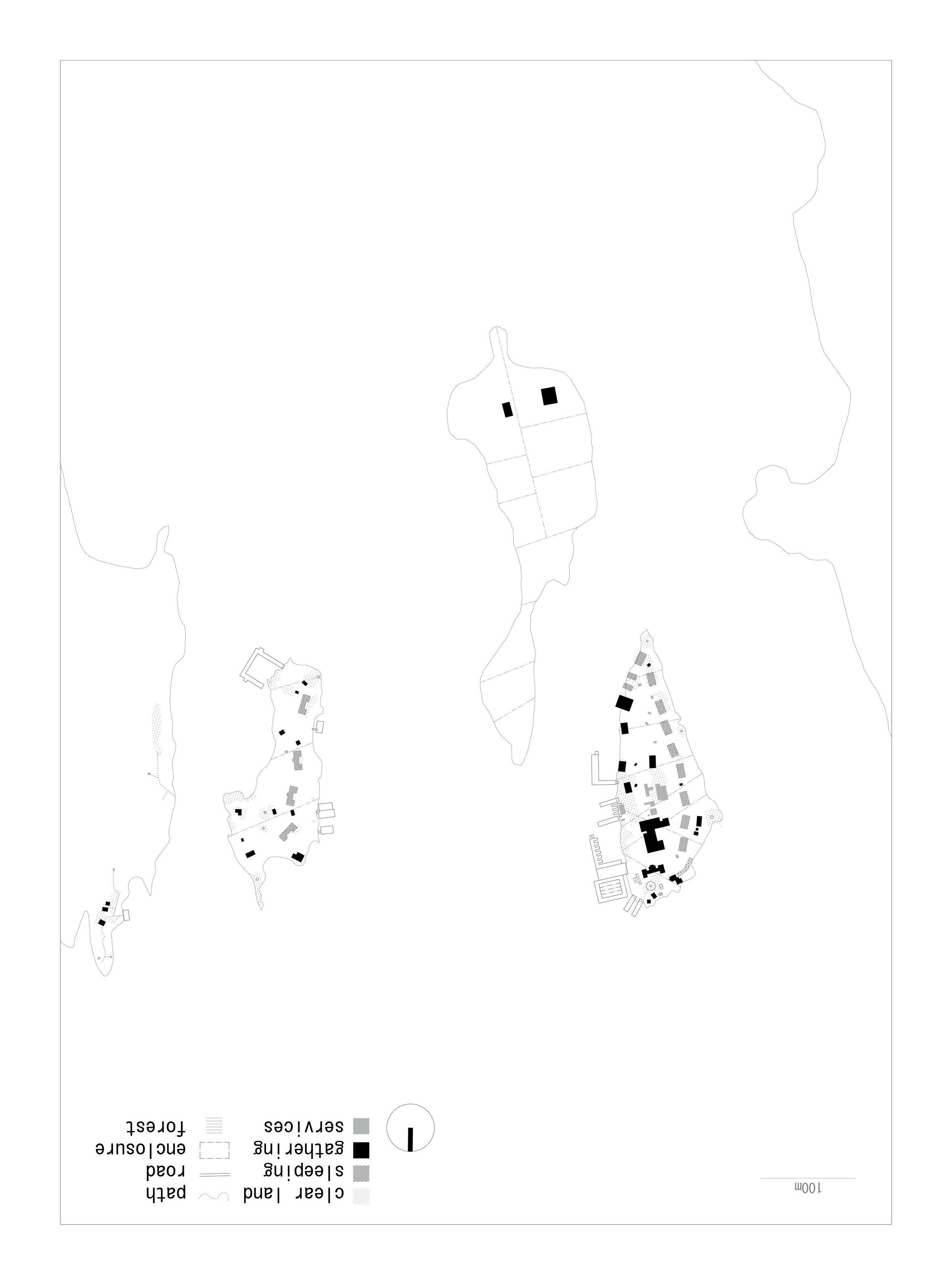

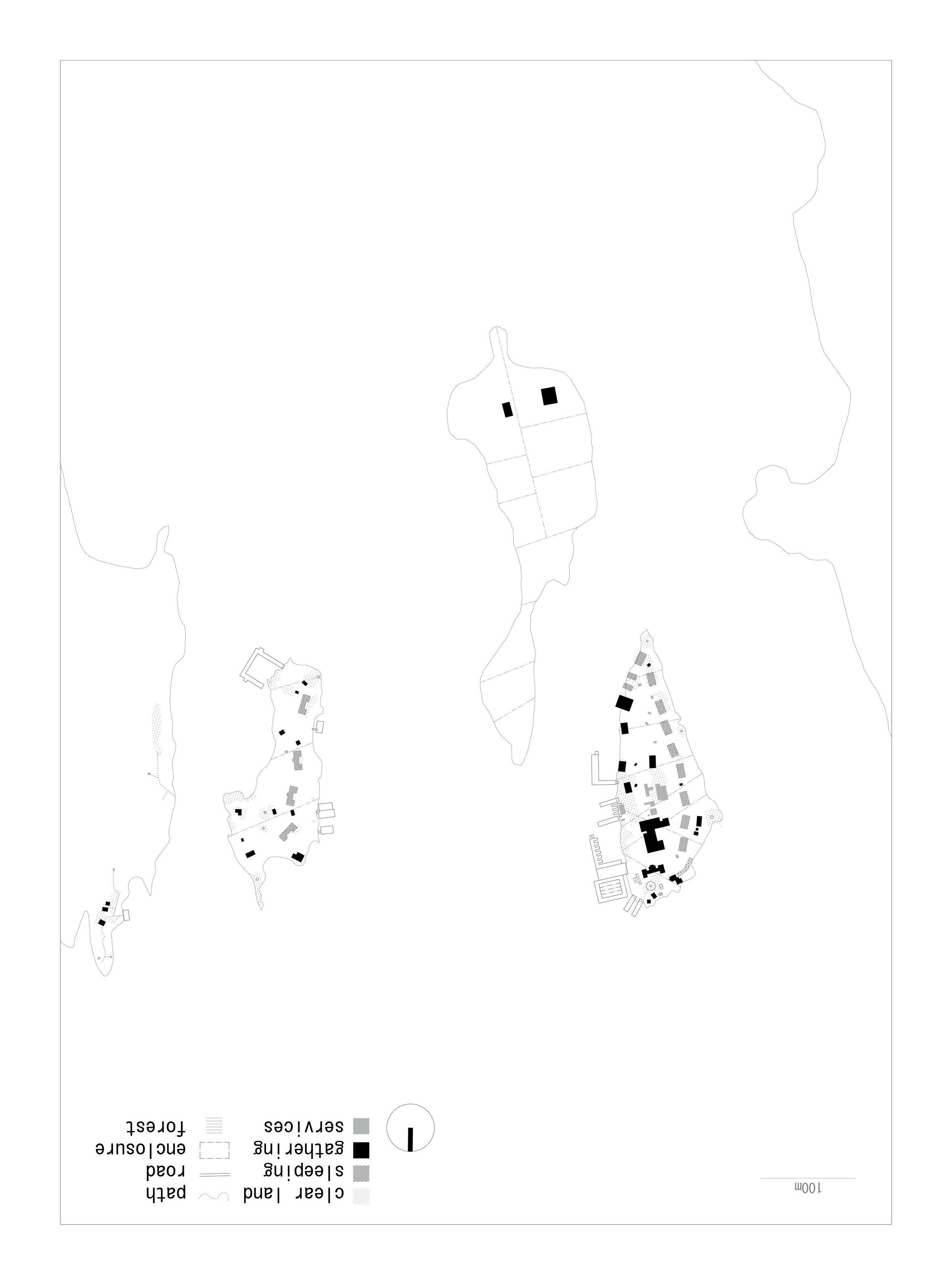

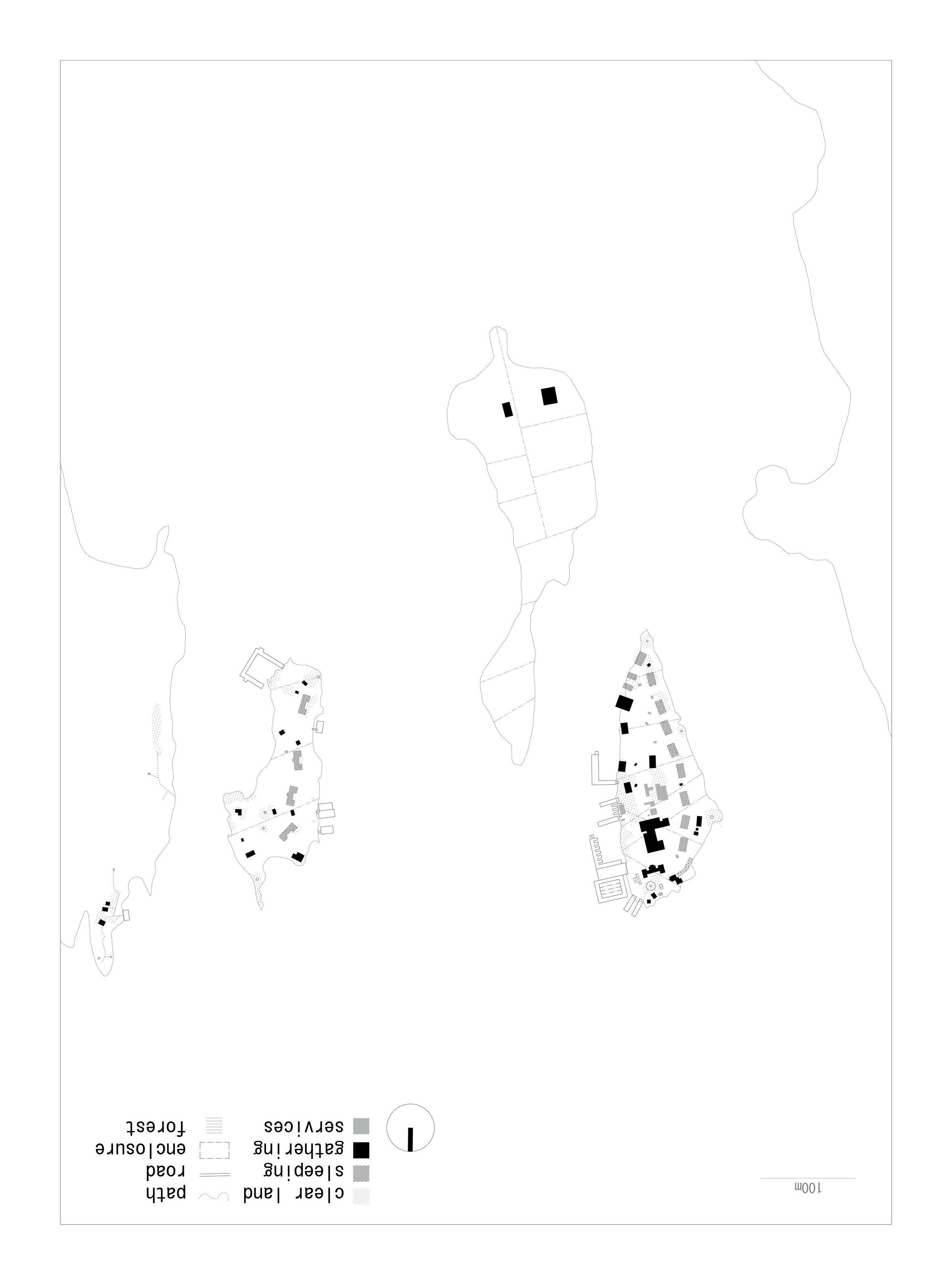

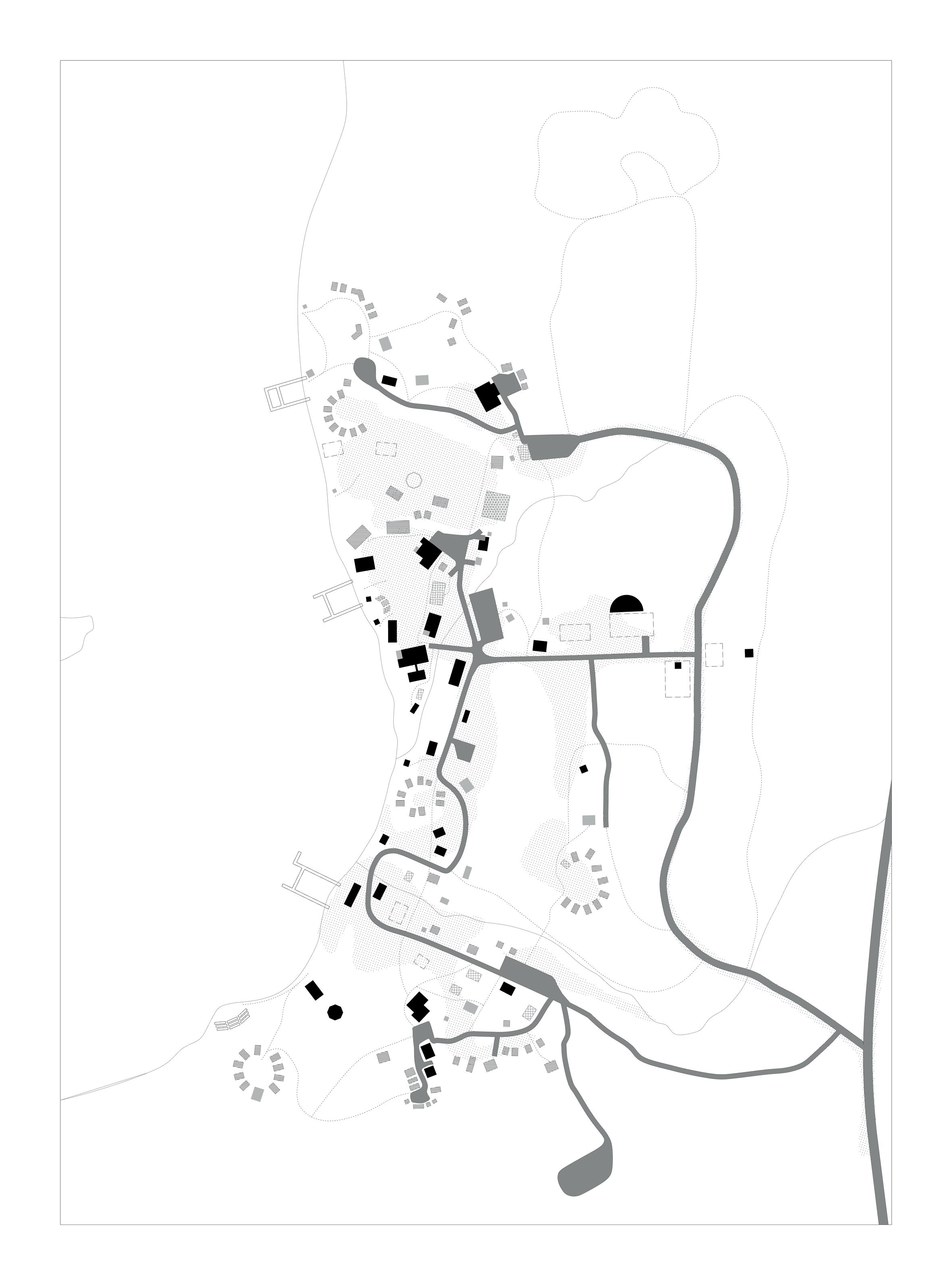

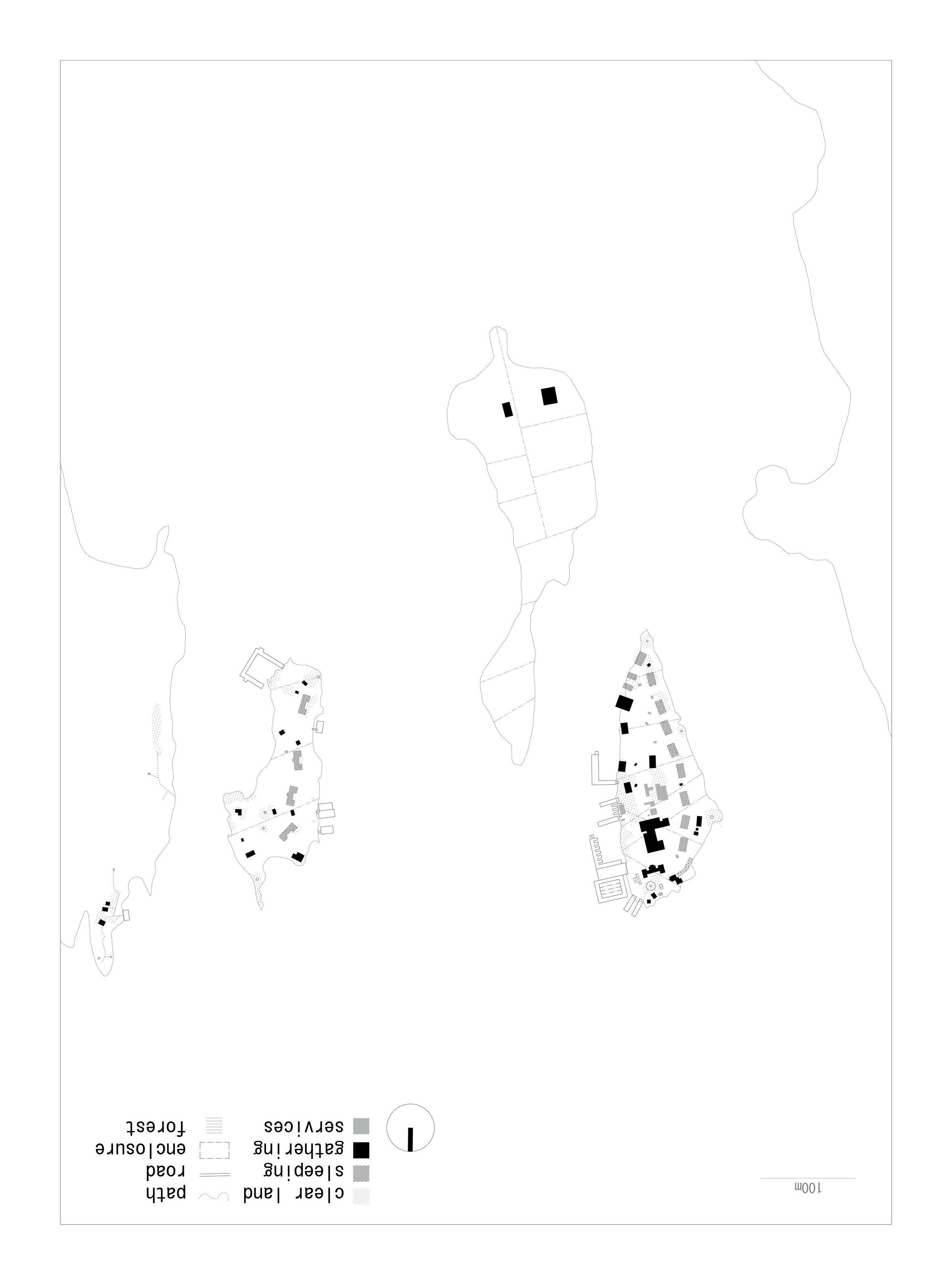

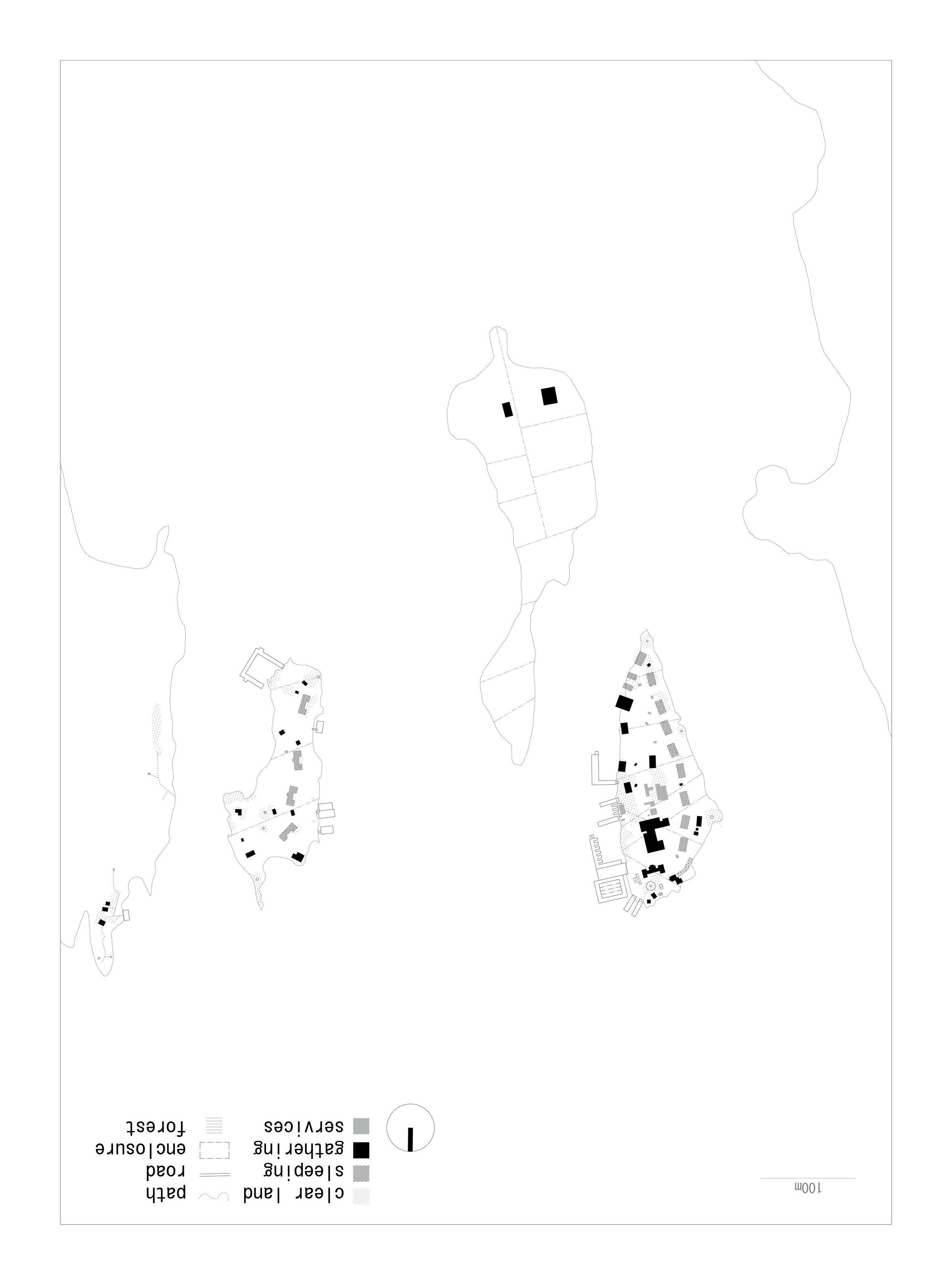

The main body of the thesis follows material traces of six case studies: three summer camps active in Seton’s Woodcraft Indian Movement and three Indian Residential Schools.

The Residential Schools were chosen as case studies for this thesis based on the accessibility of archival materials and relevant scholarship, as well as their location in Southern Ontario. The Mohawk Institute (Anglican, 1831-1970) was Canada’s first IRS, in Brantford, Ontario. Second is the Shingwauk Indian Industrial School (Anglican, 1873-1970) in Sault Ste. Marie. The third case study is the Spanish Indian Residential School (Roman Catholic, 1913-1965), near the town of Spanish Ontario.

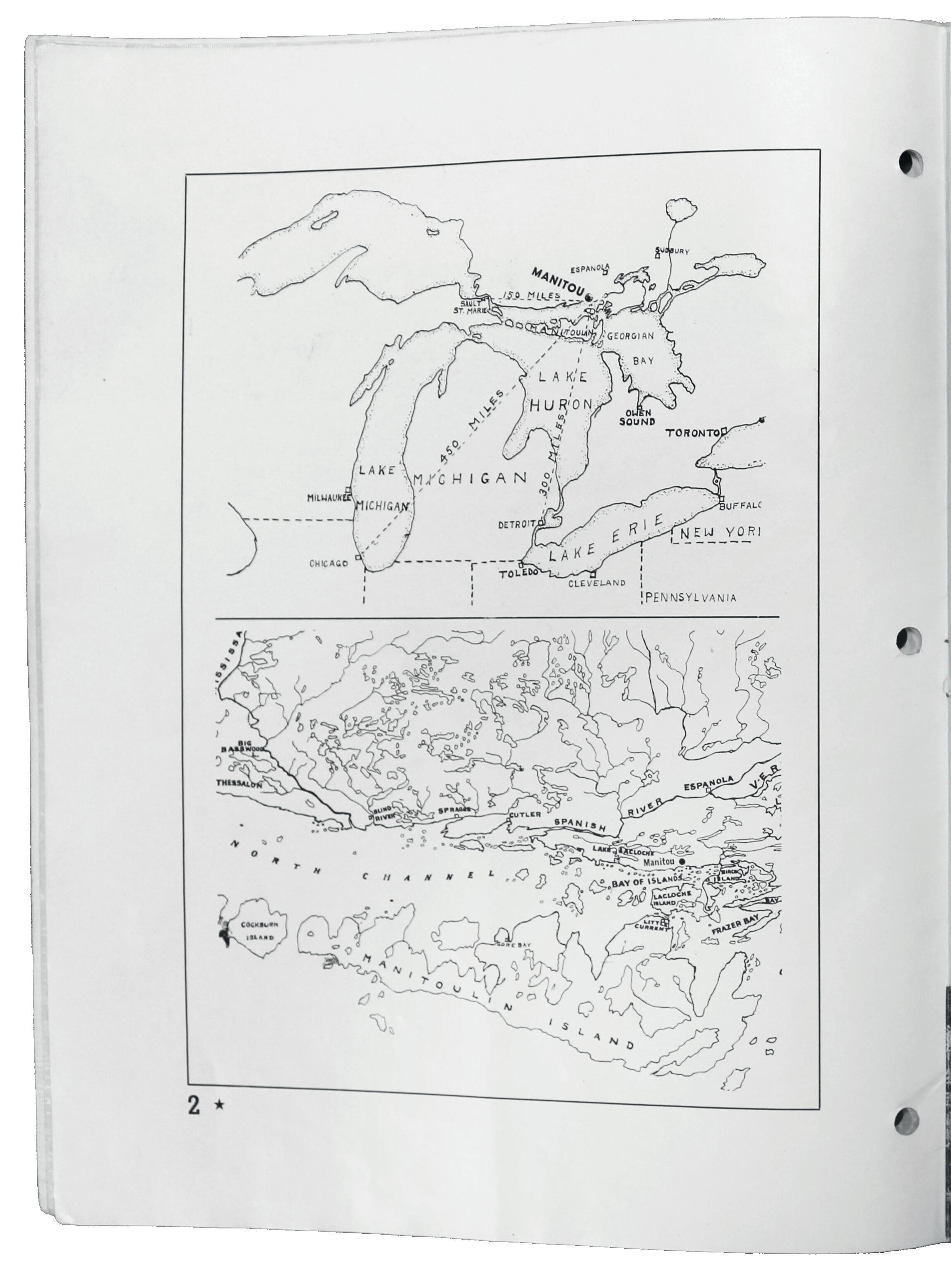

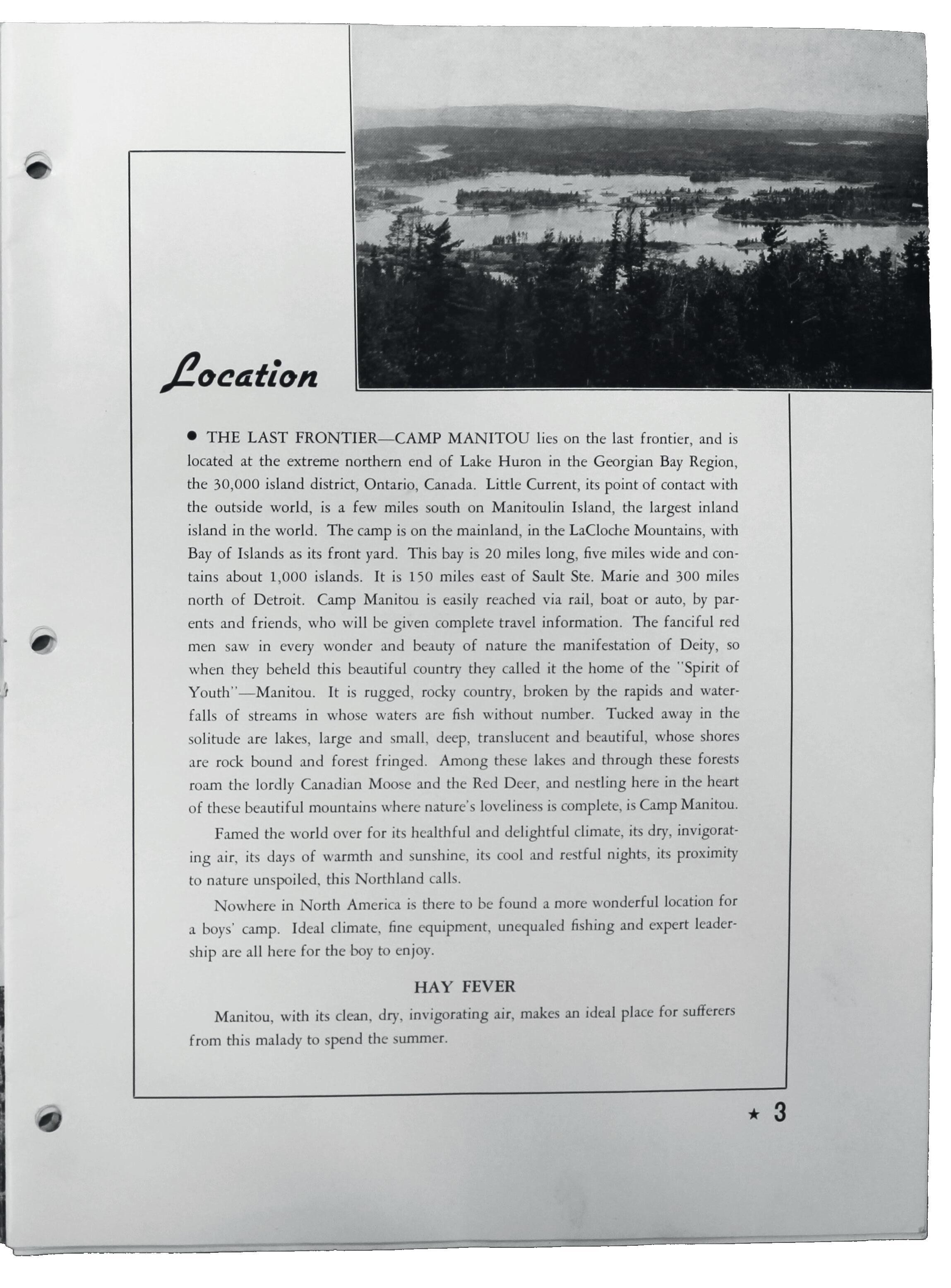

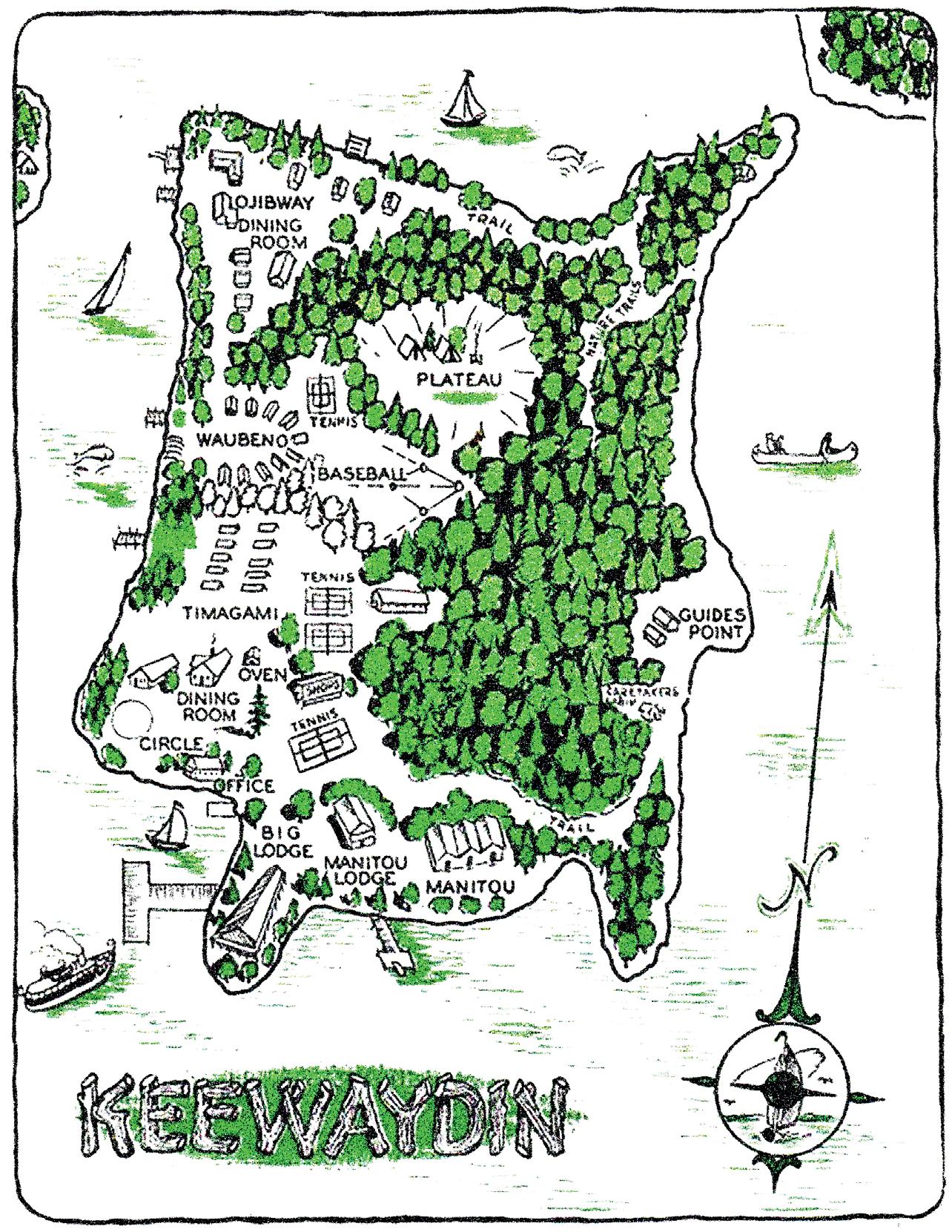

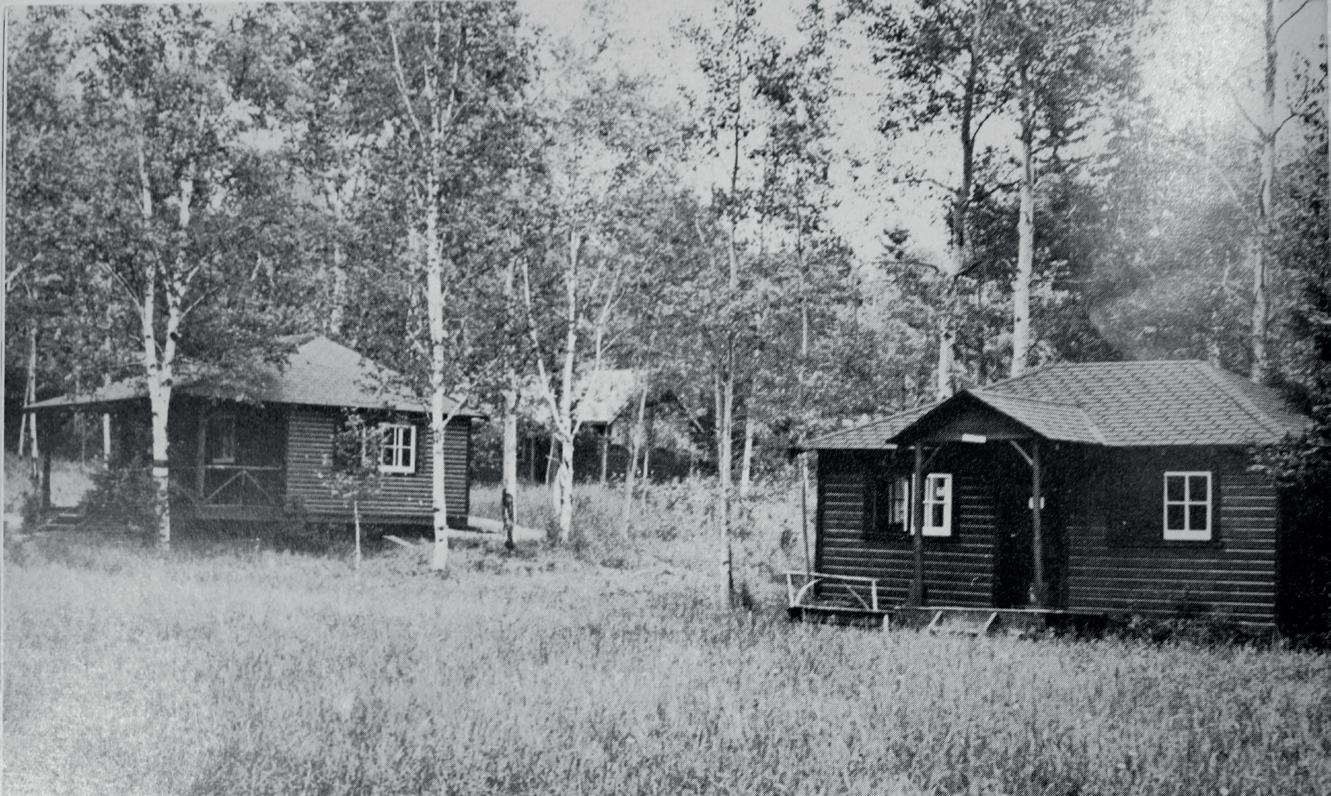

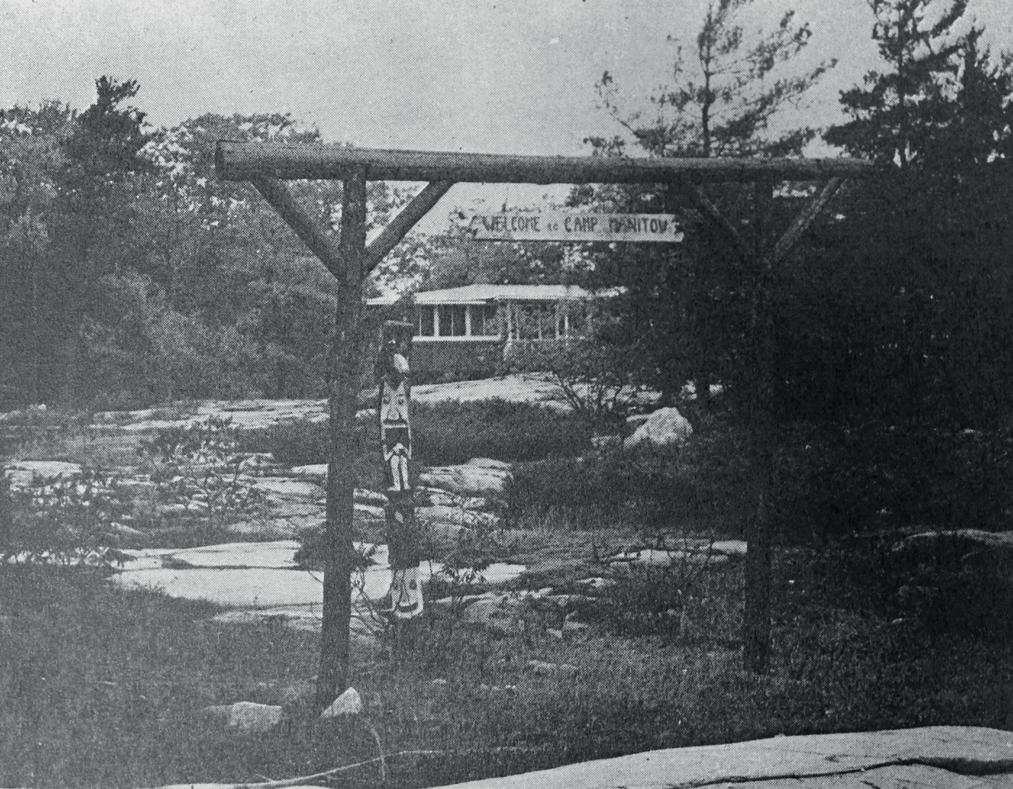

Three Summer Camps were chosen as case studies based on the availability of archival material and relevant scholarship. Camp Ahmek for Boys (1921 - present), in Algonquin Park, and Camp Glen Bernard for Girls (1922 - present), near Sundridge ON, are among the most well-known and researched summer camps in Ontario.20 The third summer camp case study is Camp Manitou (1925 - present), near Whitefish Falls, Ontario, chosen based on the availability of materials, and the camp’s proximity to Spanish Indian Residential School. In their early years, Ahmek and Glen Bernard were non-denominational religious camps, and slowly transitioned to fully secular programming. Camp Manitou is a Christian camp. The programming at all three also included an “Indian Program”.

All three summer camps are still in operation. Each were contacted by email to inform them of my research interests and to ask for architectural records of their property and buildings. Due to the difficulty of travelling to the summer camps, and because each are still operating as private businesses, site visits were not possible. Camp Ahmek declined my request to visit their property and directed me towards the Algonquin Park Archives for any publicly available information. Glen Bernard Camp did not respond to my request. Camp Manitou directed my questions on the history of different buildings to

their archives now held by the Diocese of Algoma, transferred to the Shingwauk Residential School Centre (SRSC) Archives at Algoma University.

Two of the chosen case studies of Residential Schools offered tours of their sites. I took a virtual tour of the Mohawk Institute in December 2023, organised by the Woodland Cultural Centre, and spent one week at the former site of the Shingwauk IRS (now Algoma University) in September 2023. This time was spent looking through the archives at SRSC and to go on a Truth Walk organised by the SRSC and led by a family member of survivors of the school.

To support the analysis of the case studies, archival materials were curated through the following criteria for collection:

Image of the Camp: How is camp space described, drawn, and organised? How are the individual components (spaces for sleeping, eating, and distinct learning spaces) of the camps’ purpose framed within the pedagogy of the institution? How are the camps’ missions promoted?

Typological Instrumentality of the Camp: What was the perceived “problem” with the children defined by their race and how were the “educations” framed as a corrective?

Camp as a Strategy: How is the site for the camp chosen, and what ideas about the territory was this choice based on?

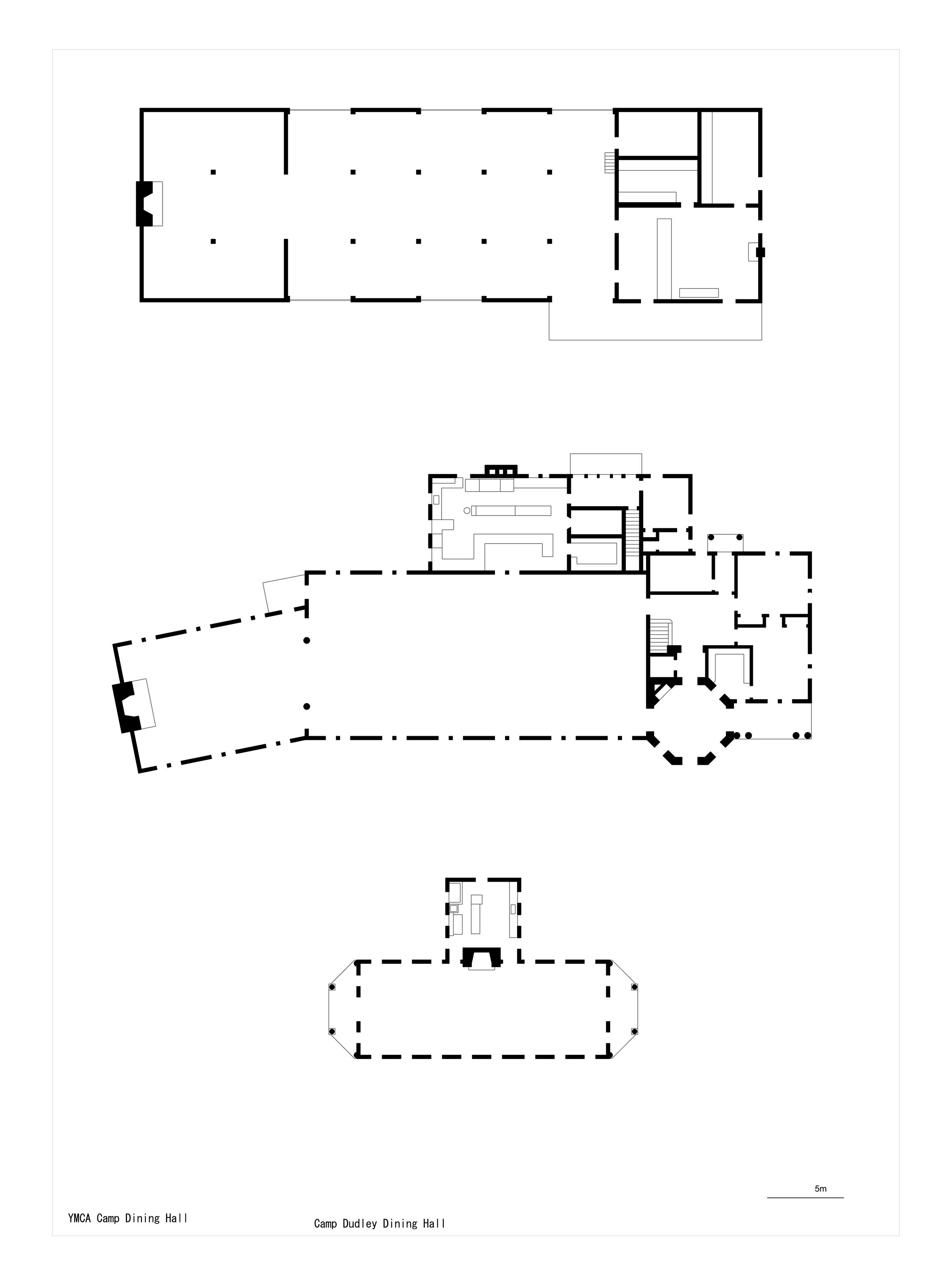

Through an exercise of redrawing and cataloguing the architectures of each case study under different operations, an association unfolds between the IRS and the Woodcraft Summer Camp which have not been previously studied together. Curated into a self-made archive including promotional materials, education manuals, and policy documents, paralleling these materials reveals ideological tensions as well as similarities in the materials produced by each institution.

21 The collection includes plans of residential schools, on-reserve Day Schools, houses, churches, council houses, jails, hospitals, and farm buildings.

Magdalena Milosz, “Instruments as Evidence: An Archive of the Architecture of Assimilation,” Journal of the Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada 41, no. 2 (January 2016): 3–10.

22 The centre was founded in 1979 under the original vision of Ojibway Chief Shingwaukonse (1773-1854) who imagined a cross-cultural educational project committed to Indigenous rights, self-determination, and modern community development.

“The Shingwauk Project | Shingwauk Residential School Center,” 2023.

23 The Algonquin Park Archive is dedicated to the education, interpretation, and conservation of Algonquin park and its heritage. The museum collection started in 1946 with a tent set up at Cache Lake that housed a small group of natural history specimens.

Four physical archives were the key sources for this work:

The collections of Library and Archives Canada (LAC) in Canada’s capital city contains a substantial collection of plans generated by the Department of Indian Affairs.”21 Magdelena Milosz (2016) analysed this archival collection of plans as the major piece of evidence of the ways in which the government used architecture as a significant tool to enact its racist policies by constructing entire built worlds.

Second, the Shingwauk Residential School Centre (SRSC) at Algoma University in Sault Ste. Marie, operating out of the transformed Shingwauk Hall.22 Their archives contain documents and photographs chronicling the experiences at residential schools, records of the Anglican Diocese of Algoma which ran the schools at Shingwauk, journals of E. F. Wilson, transcripts of interviews with former students, annual reports of the Department of Indian Affairs among many other collections.

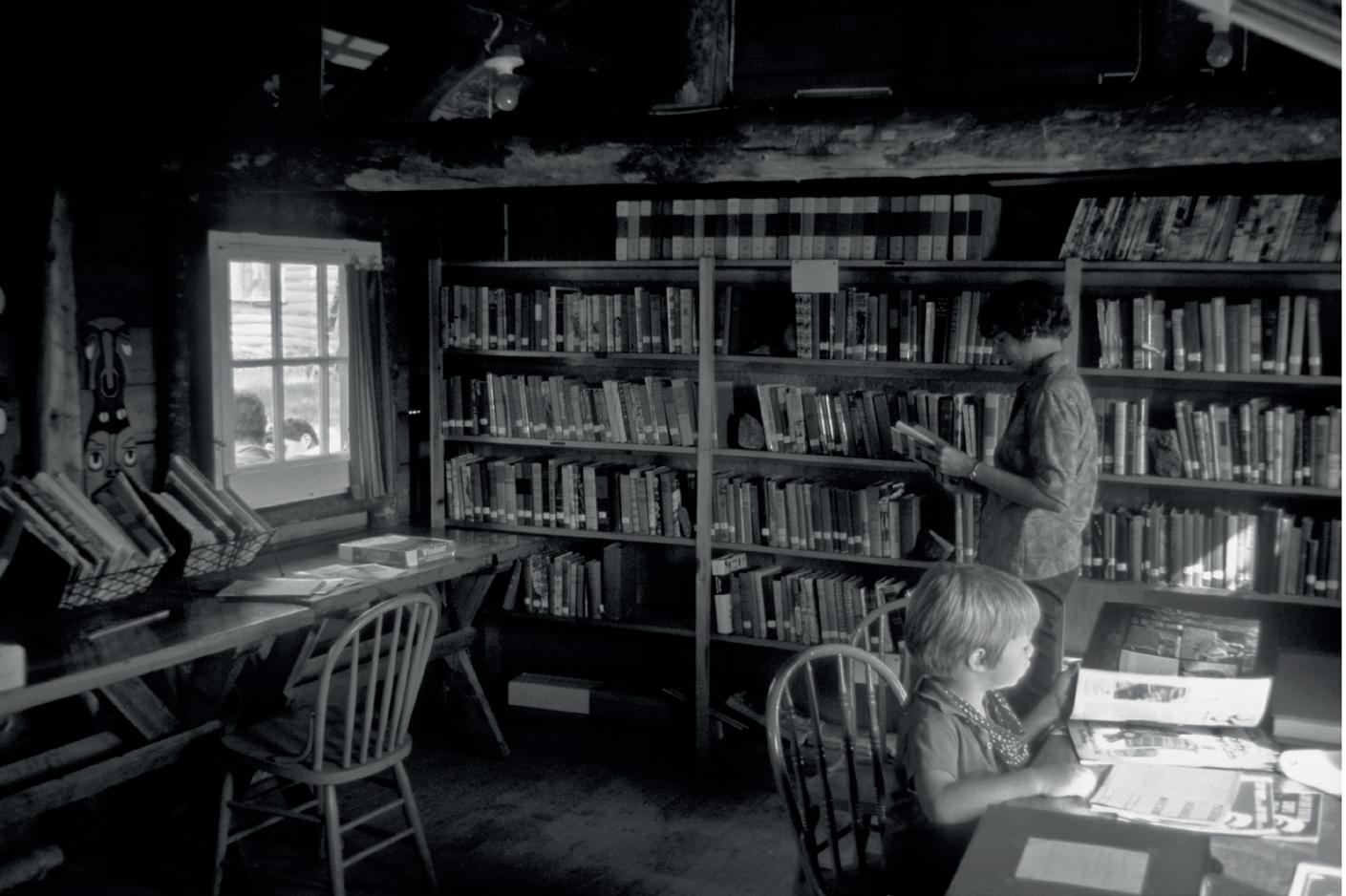

Third, the Trent University Archives (T.U.A.) in Peterborough, Ontario holds the Ontario Camping Association (OCA) fonds, a Camping Book Collection, as well as multiple fonds/collections of many prominent individuals in the private camping sector. Materials include organisational records of the OCA, promotional materials (brochures, photographs, newsletters from member camps). The camping book collection is a valuable resource highlighting trends in educational mission, strategy, and pedagogy of the camping movement.

Finally, the Algonquin Park Archives (APPAC) is the repository for “artifacts of significance to the natural and cultural history of Algonquin Park” and is owned by the Ontario government, with substantial operating assistance from a registered Canadian charity.23 The Archives holds some historical information on commercial recreational leases of summer camps in the wilderness park.

Together these four archives, owned by different Canadian institutions (Algoma University, Trent University, and the Provincial and Federal Governments) contain a great deal of information documenting instrumental movements in the history of Canada. This includes the Residential School System, policies aimed at segregating and

assimilating Indigenous peoples, the camping movement, history of playing Indian, education at the core of Canadian national identity, and Wilderness Preservation movements. Still, these archives tell very little of the entire story. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) was founded to document the stories and experiences of survivors and family members with Indian Residential Schools across the country. These accounts reveal the true, terrible nature of the IRS system. These include many accounts of emotional, physical, and sexual abuse on the children by individuals who were meant to be educators, and representatives of the church. These experiences, which those of us unaffected can never fully fathom, are not present in the institutionally held archives focused on in this thesis. Most of the documents presented in the following chapters are materials produced by the institutions themselves, in the interest of their own promotion. This exercise therefore is focused on what Settlers did and are doing. By combining the materials from these four archives, the aim is to re-narrate these histories in a way that holds Settlers accountable for our intergenerational actions in Indigenous cultural genocide.

24 Sam Jacoby, Drawing Architecture and the Urban, 1st ed. (Chichester, West Susses, UK: John Wiley & Sons, 2016).

Over four chapters, the thesis analyses the Indian Residential School and the Woodcraft Summer Camp.

Chapter 1 sets up the theoretical framework of the thesis: the relationship between education, territorial policies, cultural colonisation, and the “camp as a type” as the essential device that was used to achieve these goals.

Chapter 2 and 3 form the main body of the thesis. They each form a multi-scalar argument about the objectives and operations of the case studies, as read through their image, typological instrumentality, and strategy. Chapter 2 focuses on the Indian Residential School, Chapter 3 on the Woodcraft Summer Camp. Analytical re-drawings support the discussion in each through a typological analysis.24 Archival materials support the discussions on the image of the camps.

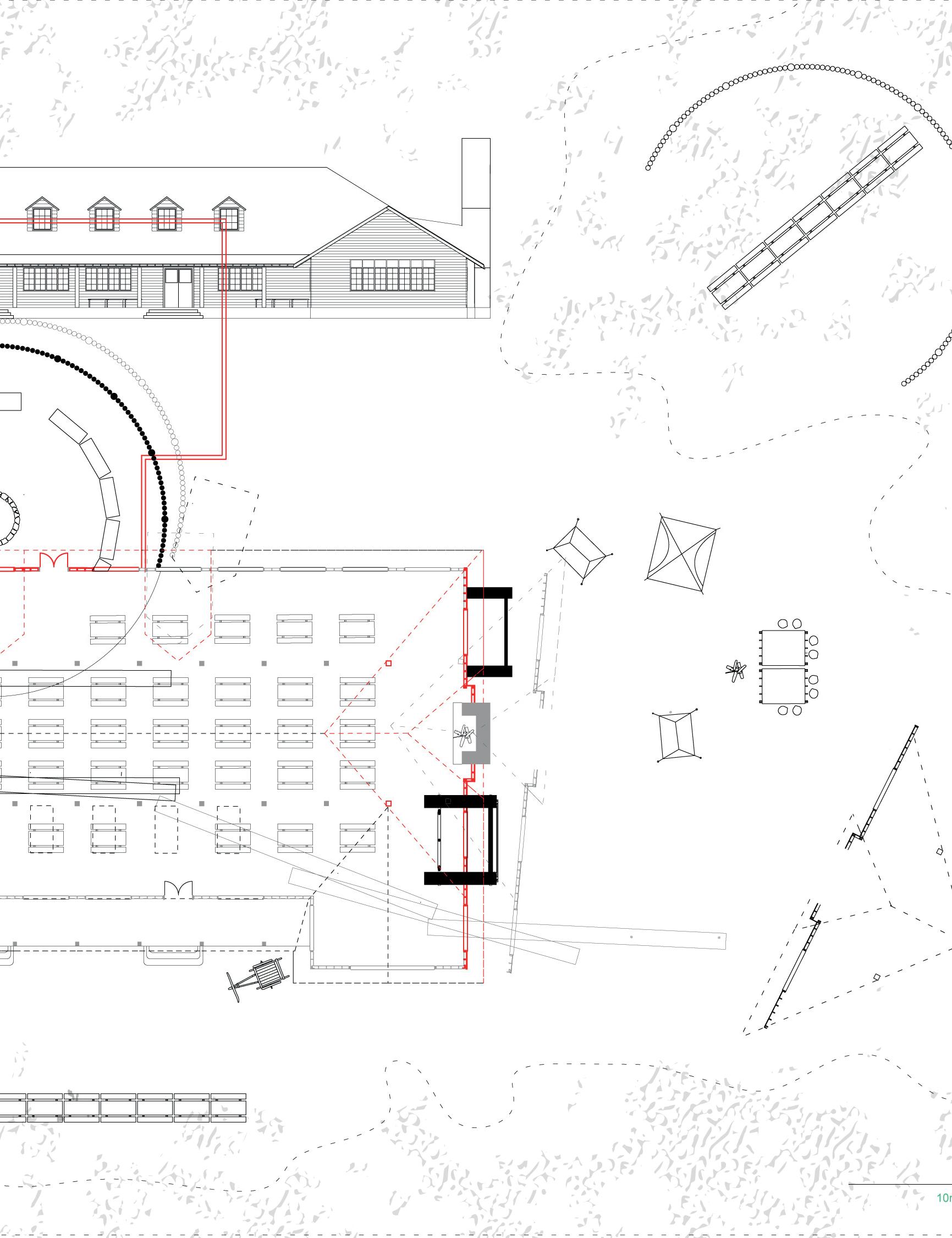

Finally, Chapter 4 reflects on the history through the present moment, making an argument for the typological transformation of the Summer Camp, demonstrated through a design exercise at Camp Ahmek. As a Settler, I think the summer camp is the appropriate place for my design response to the learning through this process.

For the TRC, truth purposely comes before reconciliation. The first three chapters of my thesis are intended to further efforts to uncover more truths, multiply the hi(stories) told about these institutions. The fourth chapter shifts focus to reconciliation, returning to the present to think about the future.

1.1 A Hike to Spanish Indian Residential School, 1927 and Theoretical Associations

25 Amanda Shore, “Towards a Pedagogy of Solidarity: Uprooting Traditions of Racial Plagiarism and Cultural Appropriation at Camp Ahmek” (Montreal, Quebec, Concordia University, 2020.

26 “Constellation,” Oxford Reference, accessed April 4, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/ oi/authority.20110803095633862

27 Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, and Brian Massumi, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Athlone Contemporary European Thinkers (London New York: Continuum, 1988).

28 Thomas Nail, “What is an Assemblage?”, Project MUSE, 2017.

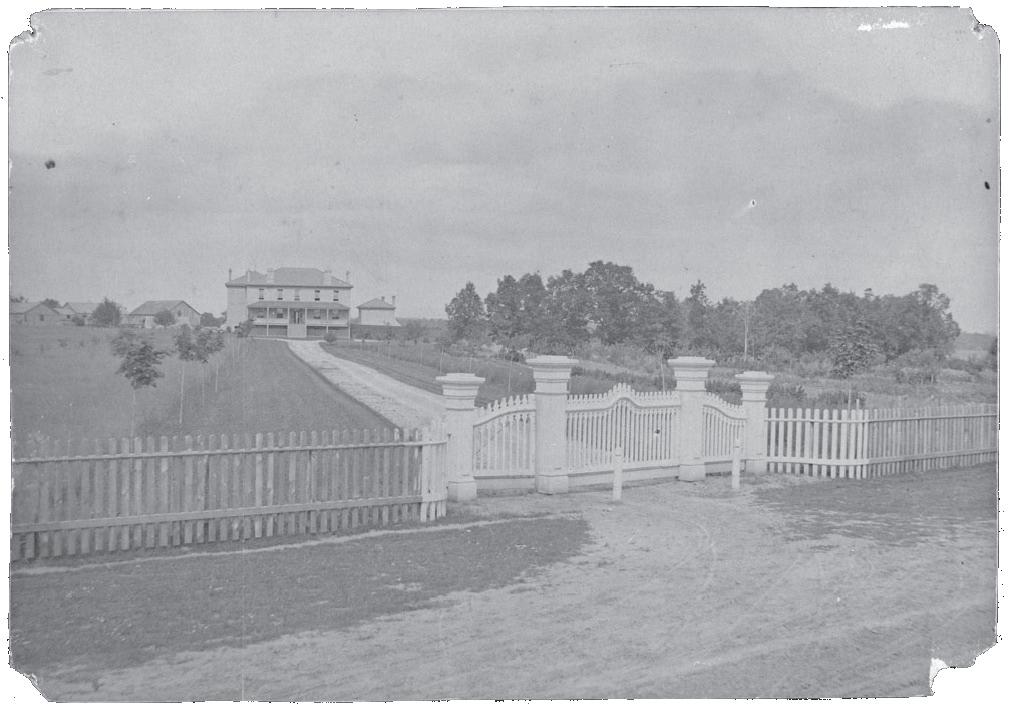

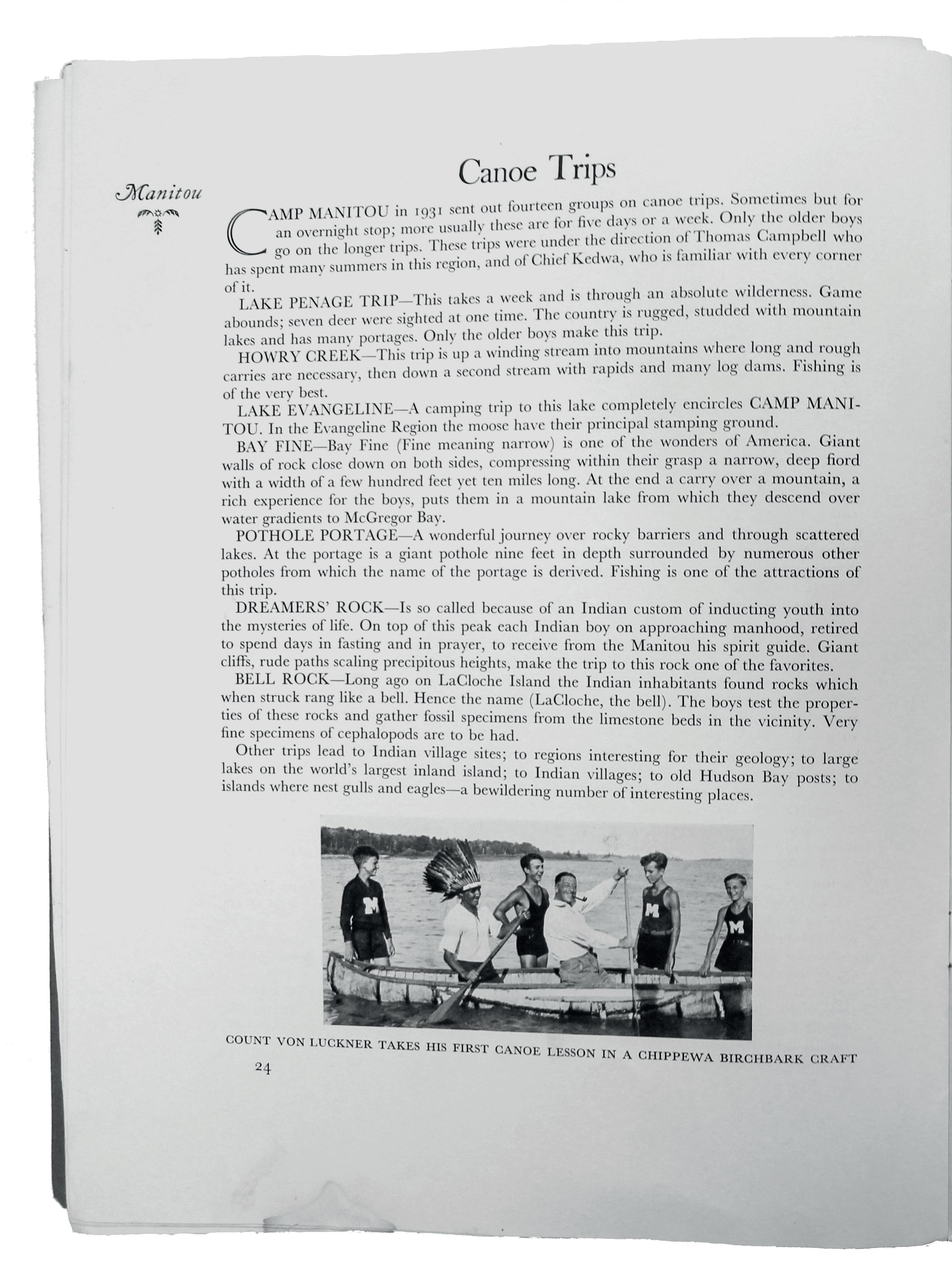

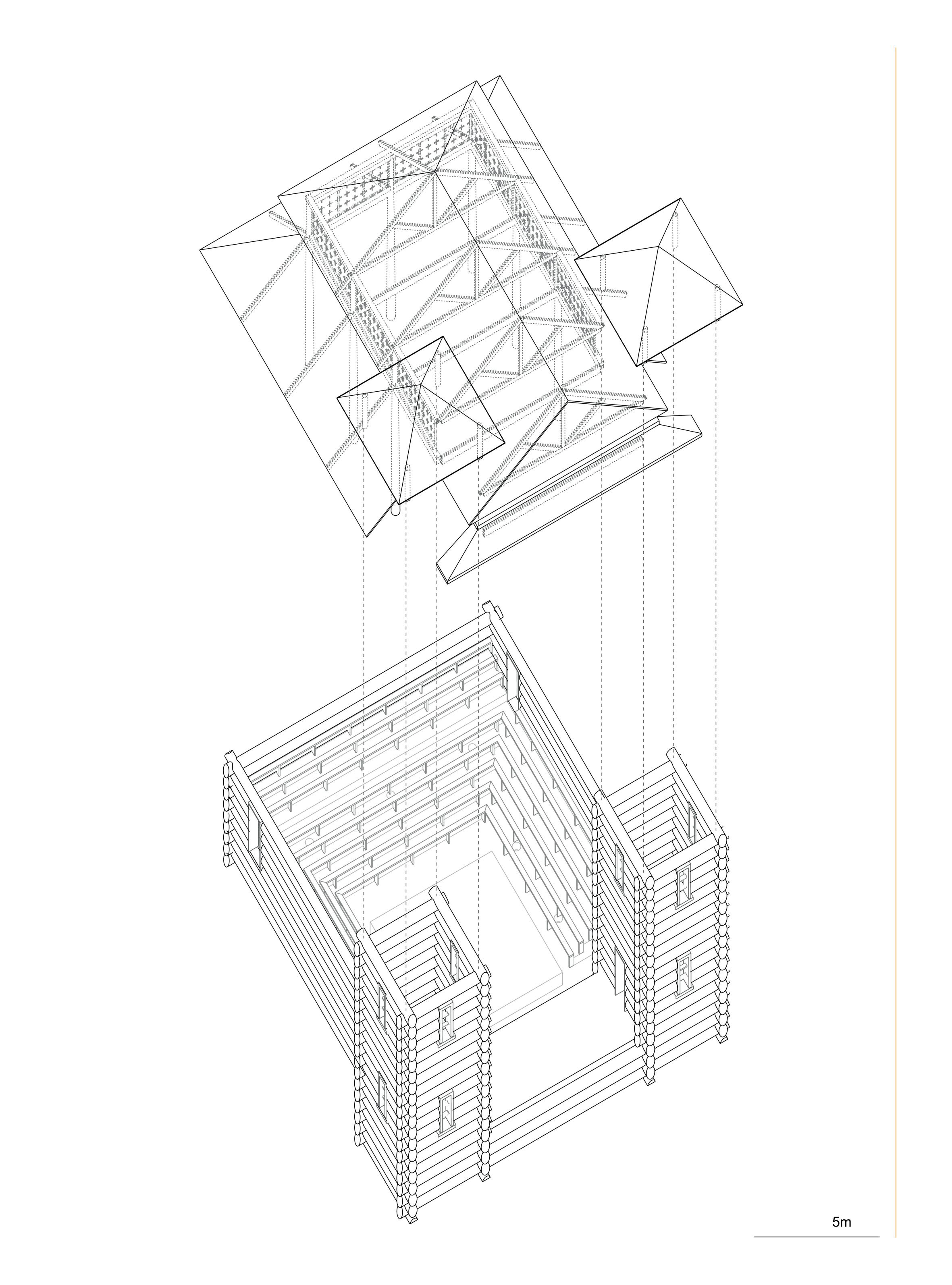

In 1927, a group of young White boys with a counsellor travelled from Camp Manitou on a hike for around three days to see the Residential School near Spanish, Ontario. (Fig. 14)

The details of the hike, and the boys’ reactions are described in Camp Manitou’s 1927 brochure, only two years after the camp opened. This event is used to introduce some of the theoretical work that was considered to support the arguments in the thesis. It is relevant to note here that no significant scholarship has proven a direct relationship between White Settler Summer Camps and Indian Residential Schools. In her thesis in 2020, Amanda Shore suggested that the correlating narratives of the two education systems indicates that Summer Camps benefitted from legislated Indigenous erasure.25 My thesis cannot claim to prove a direct relationship between the two education systems, though it makes headway in collecting, contrasting, codifying, and finally re-exhibiting the existing material culture, representations, and physical architectural evidence of the two systems. The theories referenced in this chapter provide additional lenses to frame a discussion about a conditional relationship between the two.

The event of the hike can be described as a constellation. Constellations allow us to perceive relations between objects or ideas. It is at once subjective and objective, giving individual ideas their autonomy without isolating them.26 This hike looks different depending on the readers perspective. Today, with an awareness of the true nature of the Residential Schools, this description seems shocking. But this event evidences a connection between what are commonly discussed as separate territories—or separate wildernesses. The wilderness in which the Summer Camp reigns, and the wilderness where Residential Schools are located—meaning far from home, unfamiliar territory. Their histories intersect. Not only operating in the same physical territory, but at this moment in time, between these programs there was a pedagogical and ideological alignment.

Presenting these constellations allows for a discussion on the camps on a shared plane of co-existing parts. This could also be imagined as a constructed geological layer defined by the state’s territory of influence.27 The concept of assemblage is useful to connect this network of different education systems. Assemblage theory offers a different way of thinking about the relations between parts and wholes. The assemblage constructs or lays out a set of relations between self-subsisting fragments—what Deleuze calls “singularities”.28 Deleuze and Guattari (2003) insist that “every assemblage is basically territorial ...

29 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 503-504.

30 Contact zones are most often trading posts or border cities where the movement of people collide. Ian Buchanan, “Contact Zone,” in A Dictionary of Critical Theory (Oxford University Press, 2010), https://www.oxfordreference. com/display/10.1093/ acref/9780199532919.001.0001/ acref-9780199532919-e-145

31 The concept occupied an important place in the colonialism of 19th century North America, factoring into Canada’s efforts to push west and north, settling the Prairie Provinces and the Arctic. The solution to the threat of American expansionism proved to be Canadian expansionism. Amanda Robinson, “Manifest Destiny,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, December 19, 2019, https://www. thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/ article/manifest-destiny

[and] the territory makes the assemblage.”29 This thesis brings together two youth camps – the network of Residential Schools and the network of Summer Camps, as an assemblage of heterogeneous elements which share certain features: conditions (the settler colonial state), elements (spaces for eating, sleeping, learning social behaviours and rituals, and other skills as defined by the camp), and agents (policies dictating the operation of these camps). This concept is also translated into a method for structuring the thesis. Bringing the two camps under the same method of analysis—and then arranging them into a parallel dialogue in two consecutive chapters.

Mary Louise Pratt’s term “contact zone” offers another reading of the boys hike to the Residential School. From Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (1992) originally describing social places (understood geographically) and spaces (understood ethnographically) where disparate cultures meet and try to come to terms with each other. It is relevant to post-colonial studies as a general term for places where White western travellers have encountered their cultural, ethnic, or racial other and been transformed by the experience.30 The scenario described in this brochure of a contact zone is entirely artificially staged and mediated. Demonstrating an instance about the image of these camps, where in traversing from their own Summer Camp to the school for Indigenous children—their “other”, stopping along the way to view beautiful landscapes, a particular understanding of the nation—and their place within it—is formed. The same ideologies that justified the systemic violence in the Indian Residential School System saw White people as the rightful heirs to these cultures that they understood to be dying out. For example, the idea of Manifest Destiny represented the idea that it was America’s right—its destiny—to expand across all of North America.31

32 Giorgio Agamben and Daniel Heller-Roazen, Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2020). Discussed by Irit Katz in, ‘“The Common Camp”: Temporary Settlements as a Spatio-Political Instrument in Israel-Palestine’, The Journal of Architecture 22, no. 1 (2 January 2017): 54–103, https:// doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2016.1 276095

33 “Bare Life,” Oxford Reference, accessed February 27, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1093/ oi/authority.20110803095446660

34 Geoffrey Paul Carr, “’House of No Spirit’ : An Architectural History of the Indian Residential School in British Columbia” (Text, 2011), https://open.library.ubc.ca/ collections/24/items/1.0071770, 153.

35 Irit Katz, “‘The Common Camp’: Temporary Settlements as a Spatio-Political Instrument in Israel-Palestine,” The Journal of Architecture 22, no. 1 (January 2, 2017): 54–103, https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365 .2016.1276095

36 Charlie Hailey, Camps: A Guide to 21st-Century Space (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2009), 3-4.

37 Irit Katz discusses many varieties, including tent camps were erected by ‘pioneer’ Zionist settlers in remote frontier areas in what was then Palestine. Coincidentally, it was during the British rule of Palestine (19171948) that detention camps were constructed by British authorities to prevent illegal Jewish immigrants/refugees from entering the country. Irit Katz, The Common Camp: Architecture of Power and Resistance in IsraelPalestine (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2022).

The term camp is employed with a multiplicity of meaning and associations in this thesis. To clarify, I refer to both the Indian Residential School (IRS) and the Woodcraft Summer Camp as two typologies of the camp. The focus is on how the common form of the camp was explicitly and implicitly co-opted by the settler colonial agenda. Giorgio Agamben’s theory of sovereign power and the state/space of exception presented in Homo Sacer – Sovereign Power and Bare Life (1995) brought the idea of the camp to the frontline of academic research, as it places the camp at the centre of modern biopolitics together with the figure of the homo sacer (a person stripped of any human and political existence, banned from society).32 As it relates to the youth camp, the concept of bare life reduces the prospects of the life of a particular child to their biology and takes no interest in or account of the actual circumstances of their life.33 Geoffrey Carr (2011) extends Agamben’s thought into the study of colonial history and place to argue that the IRS should be considered within this field of spaces of exception.34

In the more recent theorisations on the camp, Irit Katz (2022) describes the camp as a spatial instrument emerging in the 19th century and since proliferating globally, “being created by and for different populations under the modern state order. Camps are used as a versatile instrument for the rearrangement of people in space, whether employed by national and colonial powers, both by authoritarian regimes and democracies, as instruments of control, or constructed ad hoc by displaced populations as makeshift spaces of refuge.”35 Katz’ designation of the common camp then describes two main distinctions: organised as instruments of control (top-down) or constructed as makeshift spaces of refuge (bottom-up). Charlie Hailey (2009) extends the categorisation of spatial forms of the camp to three categories: camps of autonomy (of choice), control (strategic camping areas regulated by systems of power), or necessity (of relief and assistance).36 While Katz book more clearly defines camps that could fall under Hailey’s categories of control or necessity, his third category of autonomy could be covered by Katz descriptions of camps of resistance or refuge.

The camp’s association with the colonial frontier was present all over the world in the early 20th century.37 In its forms studied in this thesis, the camp is related to the construction of the idea and spatial delineation of wilderness and is discussed as a core example of social engineering and landscape alteration instrumental to the colonial agenda of cultural colonisation and territorial expansion in Canada. I focus on two types of youth educational camps as architectural instruments used to manipulate both land and population in order to pursue political interests. Like the objective of Katz’ study, my research on

16-17 Description of Camp Ahmek’s property. From the 1927-28 season brochure. Algonquin Park Archives, I-3-1d.

38 The camp sensibility is described by Susan Sontag in “Notes on Camp”.

39 Charlie Hailey, Preface, Queer as Camp

40 Sontag, “Notes on Camp”, Note 43.

41 For more on the dark side of “Camp”, see Astrid M. Fellner, ‘Camping Indigeneity: The Queer Politics of Kent Monkman’, in The Dark Side of Camp Aesthetics (Routledge, 2017).

educational projects reveals a crucial aspect of the way the territory is still constructed and negotiated by the state, Settlers, and Indigenous peoples inhabiting it.

The thesis also utilises “Camp”, as an adjective, describing a sensibility associated with the exaggerated, and artificial.”38 Kenneth B. Kidd and Derritt Mason’s anthology Queer as Camp (2019) is dedicated to the “Camp” and Summer Camp relation. Of relevance to this thesis is the anthology’s framing of “camp” as a method utilised by the Summer Camp in its narration of the imaginary Indian. For example, the Summer Camp’s totem pole is not an authentic totem pole, but a “totem pole”— its owned by a White settler as a piece of art. It is not nature in which the Summer Camp is located but “nature”—it’s part of a highly organised and regulated category of wilderness, protected land, maintained for temporary leisure camping. Hailey (2019) also concedes that ““Camp” is method,” even though its method can be instrumentalized towards very different means.39 According to Susan Sontag, the method of “Camp” “introduces a new standard: artifice as an ideal, theatricality.”40 This irony speaks to the dark side of “Camp” in its use towards building nationalism.41

Pierre Bourdieu explores how the social order is reproduced, and inequality persists across generations through education and cultural reproduction. State mandated education, in particular, is engaged to promote a particular ideological agenda. Considering my own public-school education in Canada, “history” only starts with the colonial encounter. In a settler colonial context, the primary interest in education by the dominant power is for the cultural reproduction of the dominant order. In the present when formal education is the primary means by

which an individual can achieve economic and social success and the ability to participate in intellectual life, this motive of education is more implicit.

Education was distinctly defined as character building by school promotors who were involved in both the Indian Residential School System as well as in promoting public education for immigrant Settlers.42 For French and English Settlers for whom the integrity of the family structures were respected, education came as a second priority to reproductive, economic, and labour prosperity (which were also the key aspects of settling the land). Among non-white immigrant families, cultural values were less respected, and school promoters viewed the cultural reproduction of these groups as a threat to the social order and unity of White society. When compulsory school laws were first implemented for Canadians in 1871, though parents believed that public schooling would improve their children’s academic prospects, school promoters were more interested in character formation, shaping values, inculcation of political and social attitudes, and proper behaviour. This was the context in which education for Indigenous children—first through on-reserve Indian Day Schools followed by the Indian Residential School System was conceptualised. Meanwhile the summer camp and their “Indian programs” were interested in seeking a balm for the non-Native experience of modernity. Sharon Wall (2009) suggests that “it reflected a modern desire to create a sense of belonging, community, and spiritual experience by modelling anti-modern images of Aboriginal life.”43

Seeing the relation between education, cultural colonisation, territorial control and expansion, and the ‘camp as a type’ as the means to achieve these goals, I now shift to the architectural scale and describe how these camps are designed to operate.

42 Children of immigrant families were also targeted for assimilation. Chad Gaffield, “History of Education in Canada,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, ed. Dominique Millette, July 15, 2013, https://www. thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/ article/history-of-education

43 Sharon Wall, The Nurture of Nature: Childhood, Antimodernism, and Ontario Summer Camps, 1920-55, Nature/ History/Society (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2009).

2.1 1:1 Propaganda of the Indian Residential School

2.2 1:20 Markers of Civilisation

2.3 1:100 Spaces for Alienation

2.4 1:500 Sites for Isolating

2.5 1:500,000 The IRS and Place Thought

44 Bryanne Young, “‘Killing the Indian in the Child’: Death, Cruelty, and SubjectFormation in the Canadian Indian Residential School System,” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 48, no. 4 (2015): 63–76.

45 Joshua Whitehead, “Finding We’Wha”: Indigenous Idylls in Queer Young Adult Literature,” in Queer as Camp: Essays on Summer, Style, and Sexuality, ed. Kenneth B. Kidd and Derritt Mason, First edition (New York: Fordham University Press, 2019), 227.

46 Thomas King describes the social and historical configurations of the Indian: “North American popular culture is littered with savage, noble, and dying Indians, while in real life we have Dead Indians, Live Indians, and Legal Indians.” Thomas King, The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America (Minneapolis, Minn: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2013), 53.

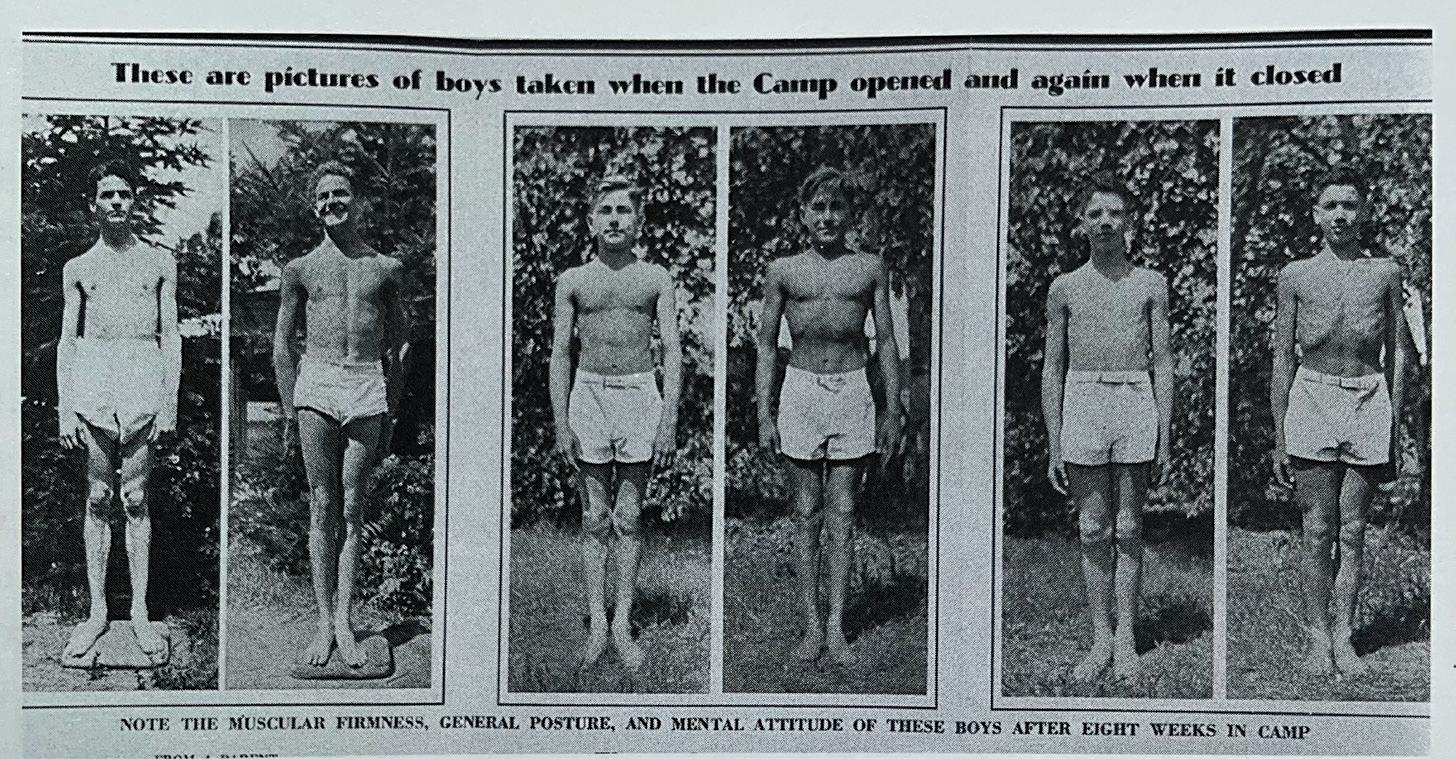

At both the Indian Residential School and the Woodcraft Summer Camp, it is not just the buildings and the landscapes which were conceived and territorialized. The subjectivities of children were designed as well—to fit the imperative of unifying a Canadian nation. Together, and separately, the subjects (Indigenous and Settler) had to become forest children. At the scale of the body (1:1), the design of the forest child is the ultimate operation of both institutions.

In the founding phrase of the Canadian Indian Residential Schools, to kill the Indian in the child, the body politic of the IRS was made explicit. Bryanne Young (2015) argues that the objective described by this mandate, conditioned by the principles of liberal political thought and infected by settler-colonialism, “created the conditions under which child residents of the school lived and died.”44

Joshua Whitehead (2019) writing about the Summer Camp, points out “there is something paradoxical at play in the desire to capitalize on Indigeneity as a transformative space for white adolescents to enter and emerge from as civilized adults”.45 The point they are both making, is that entering into the nation-state as a full-fledged and civilised adult requires the death of the Indian, both the real (at the Residential Schools) and the inherited fake Indian (through role play at the Summer Camp).46 These camps are biopolitical projects concerned with not only deciding the future subjectivities of children as part of the nation, but whether Indigenous children lived or died.

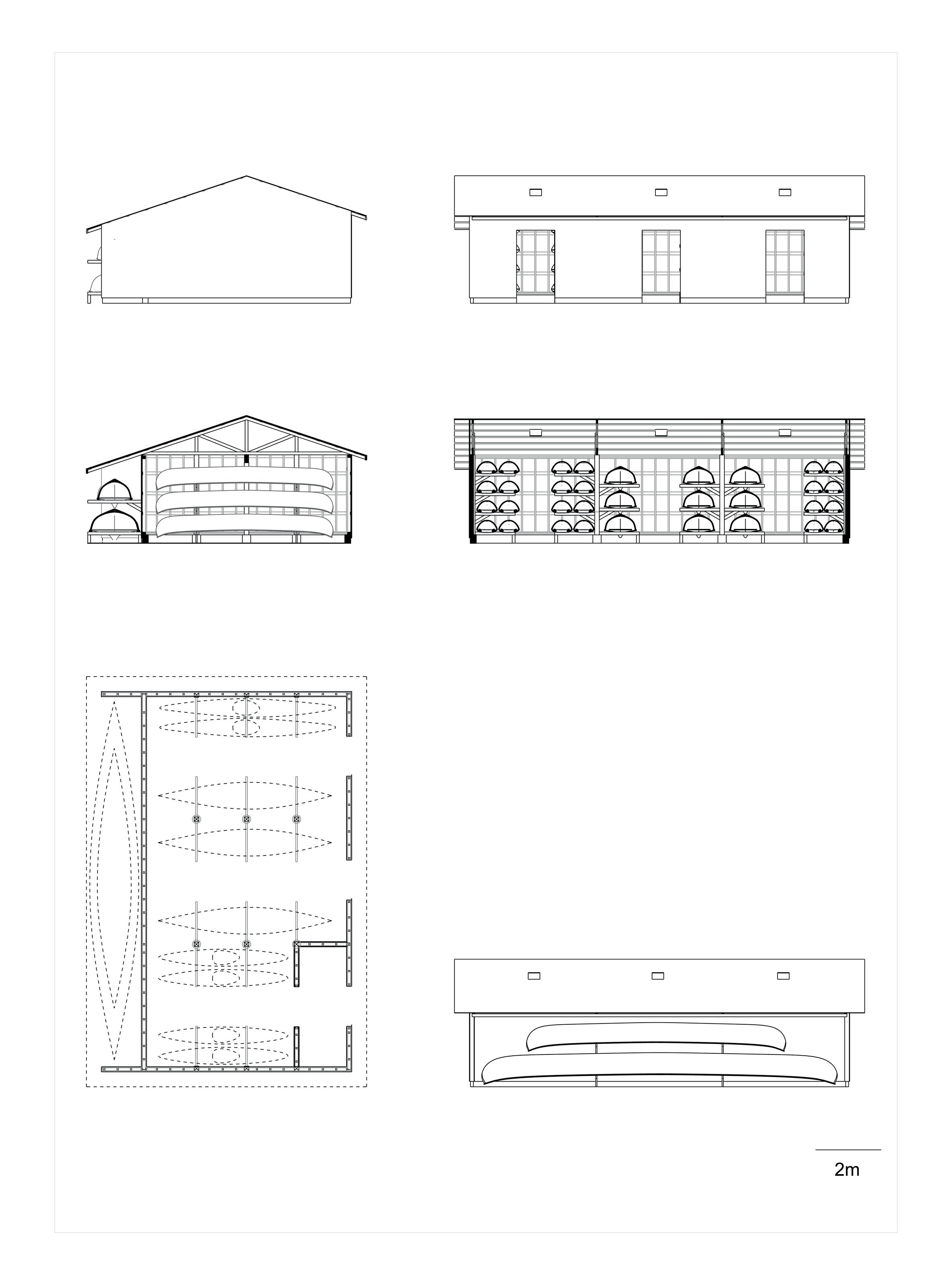

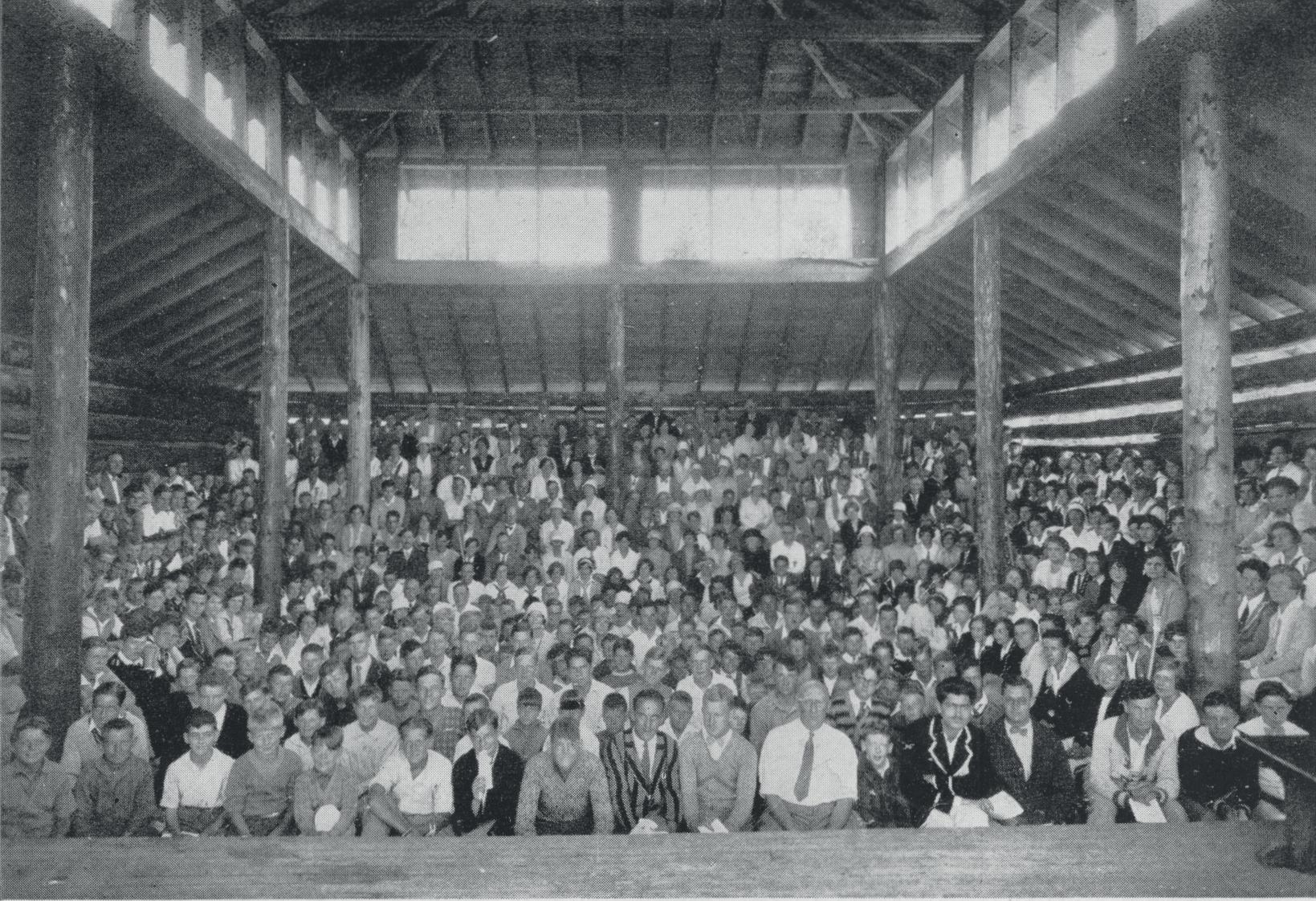

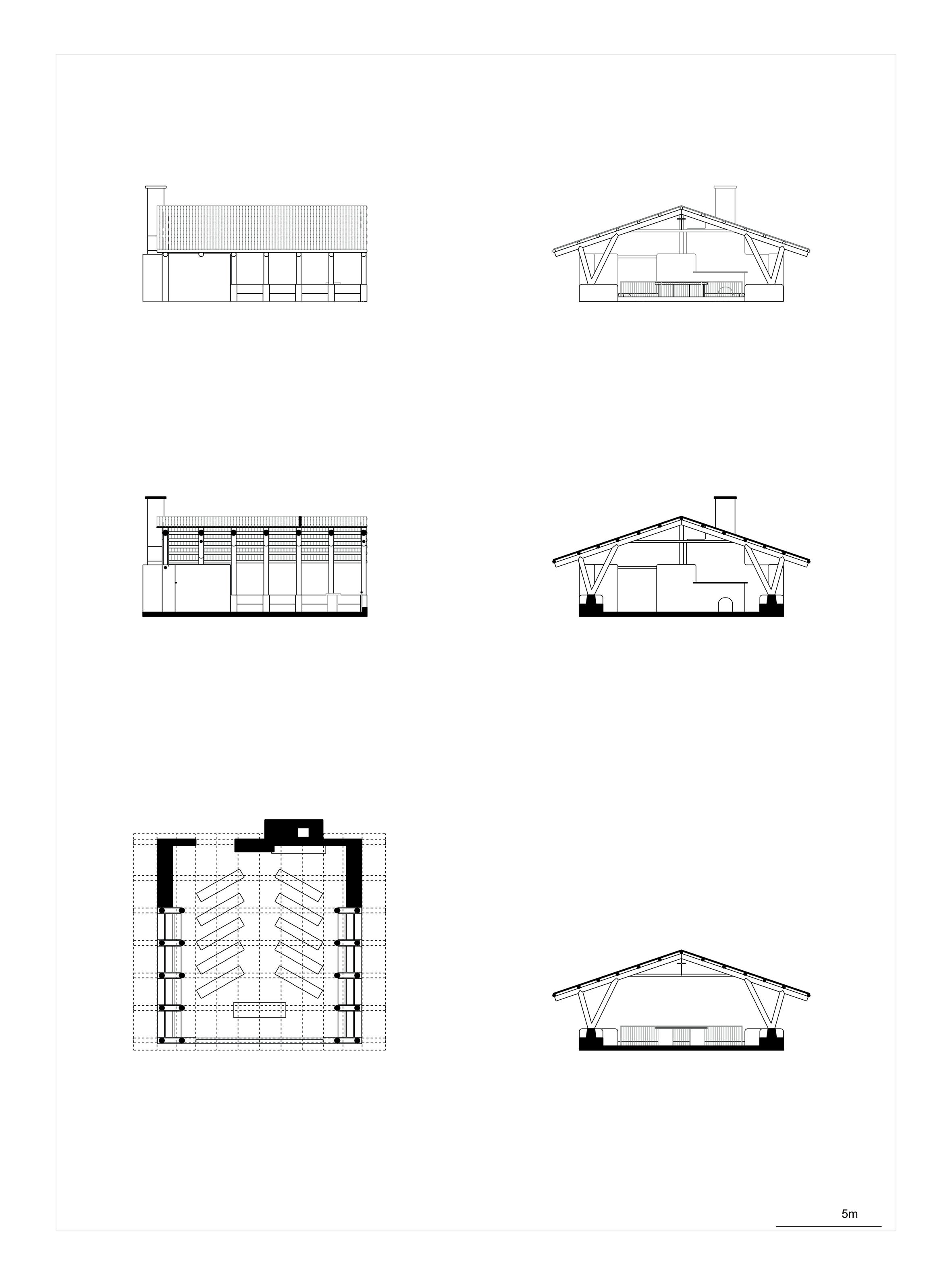

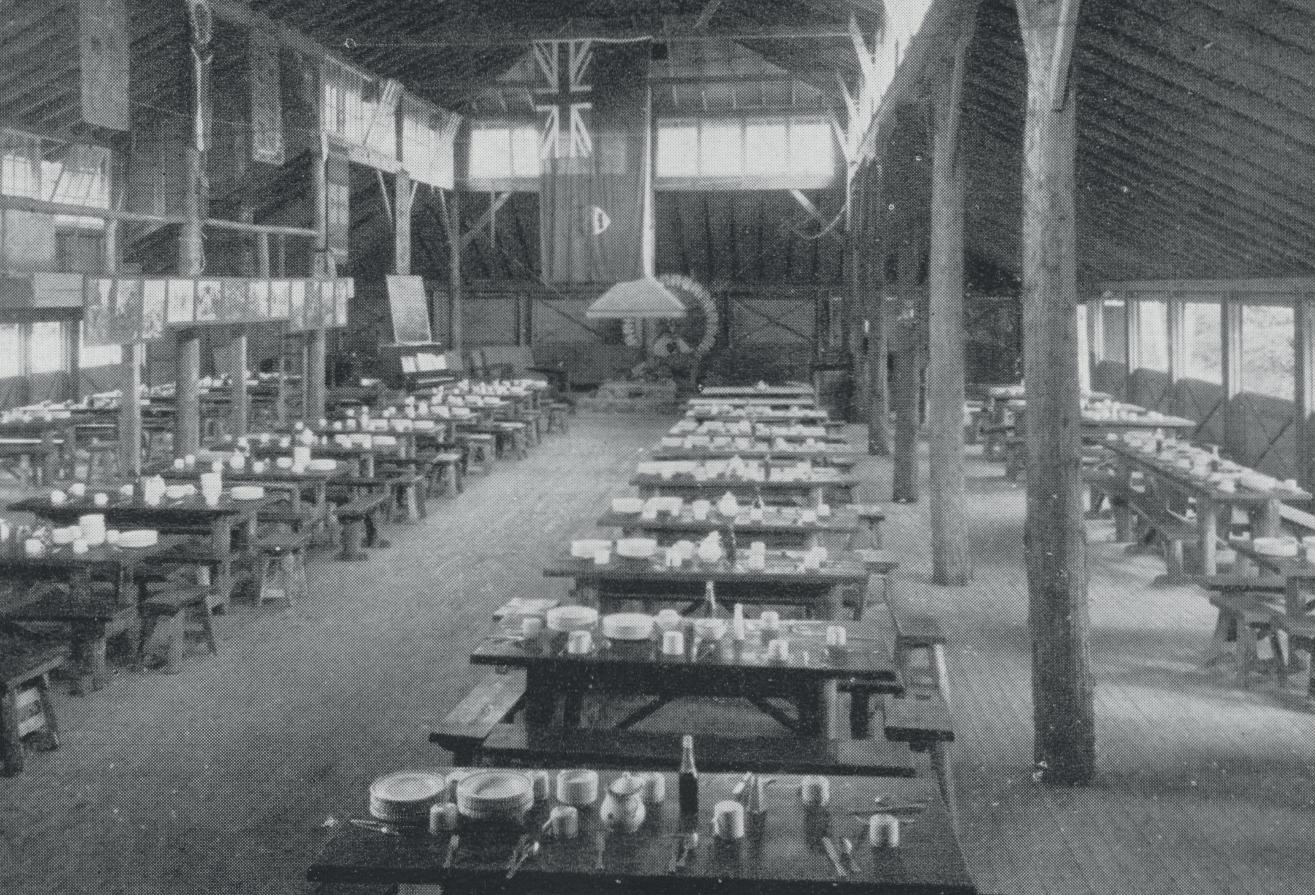

The architectures of each institution play an important role. In their simplest function, as residential camps they encompass spaces for eating, sleeping, and learning. None of these spaces were this simple. The adjacent analysis of architectural forms and representations of the institutions that follows reveals not only simultaneous processes of indoctrination of children, but the carrying out of biopolitical projects based on catastrophic ideologies. Without forming a complete history, the selected materials curate and constellate a collection of frictions and associations in the images, architectures, and strategies of these two educational programmes.

Warning:

The following chapter may contain distressing details. At least 150,000 First Nations, Inuit and Métis children were forced to attend the government-funded residential schools from the 19th century to 1996, when the last one closed. They lived in substandard conditions and endured sexual, physical, and emotional abuse. A 24-hour national Indian Residential School Crisis Line is available at 1-866-925-4419 to support former students and others affected by a residential school experience.

47 Public testimonial praising Shingwauk Indian Residential School’s mission, printed in E. F. Wilson’s Our Forest Children and what we want to do with them, 1890. The periodical (one of many forms of propaganda) was thought to “bring the reader into direct contact with the red race” and earnestly solicit contributions to the cause.

48 Brady, Miranda J., and Emily Hiltz. ‘The Archaeology of an Image: The Persistent Persuasion of Thomas Moore Keesick’s Residential School Photographs’. TOPIA: Canadian Journal of Cultural Studies 37 (April 2017).

I believe the principles which you apply for the purpose of elevating the Indians as a race, morally and socially, are certainly about the only ones that promise success, as all endeavours to influence grownup people, to tear them from their old-accustomed associations, are almost sure to fail.47

(Public Testimonial, Our Forest Children Periodical, 1890).

A return home from Indian Residential Schools was a false notion. The objective of the Canadian institutions, as it was clearly outlined in its founding mandate to kill the Indian in the child, was aggressive assimilation, in which a child’s identity was taken from them. When children did return home after sometimes years away, they would be left unable to communicate with their parents because they would speak different languages, they had trouble bonding haven forgotten or never learned collective traditions like fishing and hunting. Many were abused, and many died as we are reminded through testimonies of the TRC and the ongoing investigations to locate unmarked graves on the sites of former Residential School sites across the country.

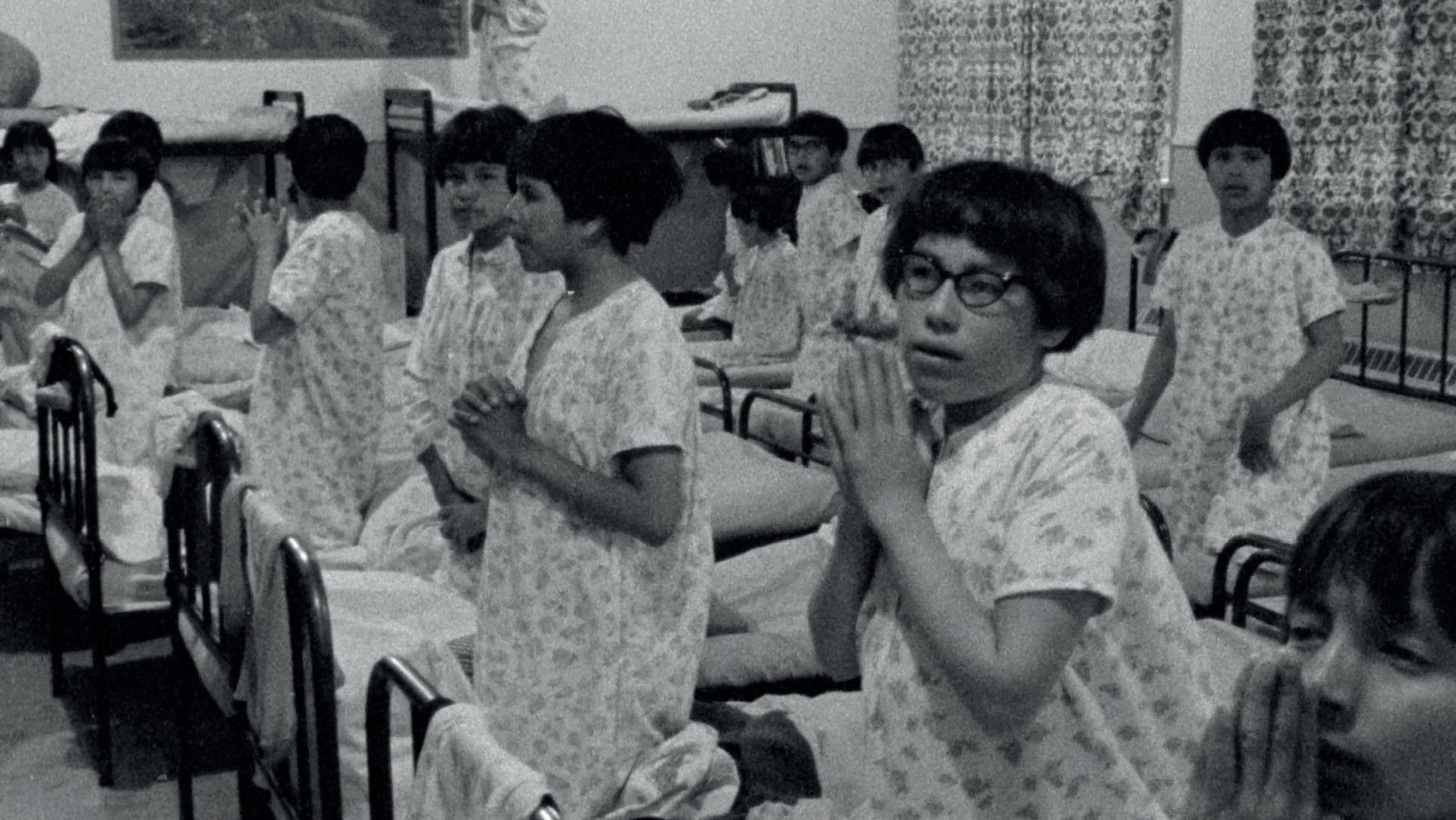

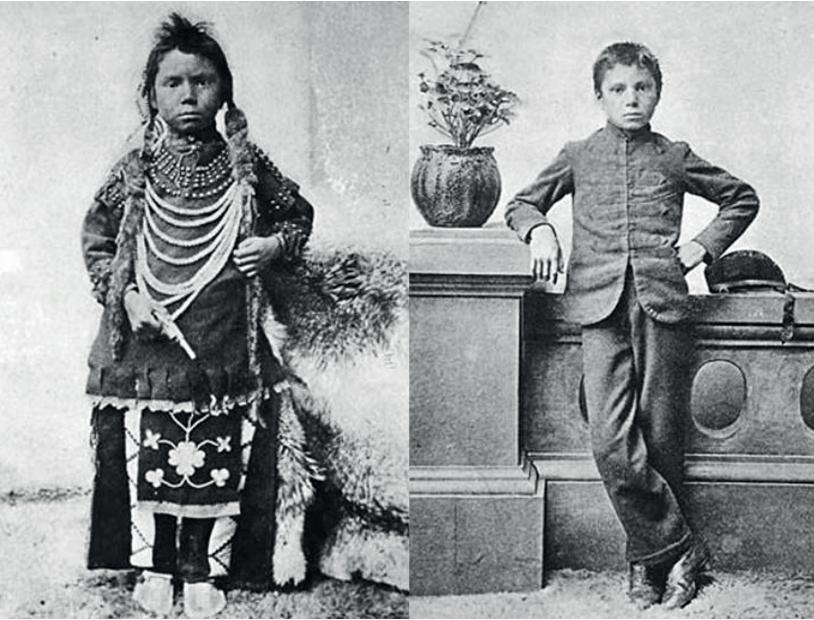

The first translation of the mandate of the IRS, to kill the Indian in the child, was as propaganda. All kinds of staged photographs—children in ‘civilised’ clothing replacing ‘traditional’ dress, attending church services or learning useful trades reported to the Canadian public the honorary work of the schools.

The before-after photos of Thomas Moore Keesick (Fig. 23) have become some of the most iconic and prolific images signifying Canada’s dark legacy of Indian Residential Schools. Taken in 1890s and appearing in an 1896 Department of Indian Affairs Annual Report, the photos were meant to demonstrate Keesick’s successful assimilation through the Regina Indian Industrial School. In one reading, these images may not be just brute expressions of a powerful colonising influence but desperate attempts by insecure institutions seeking legitimacy.48 But photos of children used to promote the system were not always as easily distinguishable as propaganda.

A similar publication to Wilson’s 1890 Our Forest Children is a 1939 church publication for parishioners, a pamphlet celebrating its work in “Indian and Eskimo Residential Schools”. This pamphlet solicited public funding in the way of help if they would adopt an Indian boy or

49 Sharon Wall, “‘To Train a Wild Bird’: E.F. Wilson, Hegemony, and Native Industrial Education at the Shingwauk and Wawanosh Residential Schools, 1873-1893,” Left History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Historical Inquiry and Debate 9, no. 1 (December 1, 2003), https://doi.org/10.25071/19139632.5619

50 Transcript from Archives of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, “How Residential Schools Were Sold to the Canadian Public”. CBC. 25 June 2018. https:// www.cbc.ca/archives/cbc-tvvisits-a-residential-schoolin-1955-1.4667021

51 Concept from: Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Second edition (London: Zed, 2012). Discussed in: Chris T. Cornelius : My House Has Feathers (February 8, 2023)

girl in one of the Indian Boarding Schools. $30 per child was required, and contributors would be sent the name, age, school, and a photo of the child.49 This example speaks to the institution’s mis-reliance and fetishization of the Indigenous body to generate pity (or empathy) from the public.

In 1955, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) broadcasted an educational video about the purpose of the IRS:

Orphans, convalescents and those who live too deep in the bush for day school: these are the students of the Residential School in remote Moose Factory, Ontario. For ten months a year, these native children start each day with a religious service before heading to classes. A CBC Television crew visits the school to salute Education Week— and here, the education is all about how to integrate into mainstream Canadian society. Principal Eric Barrington dispenses first aid among his many other duties. He heads one of Canada’s 69 Indian Residential Schools scattered in key locations as far north as the Arctic Circle. They have a total of 11,000 pupils, orphans and convalescents. Those who live too far in the wilderness to get a daily school. They learn not only games and traditions such as the celebration of St. Valentine’s Day but the mastery of words which will open to them the whole range of the ordinary Canadian curriculum.50

Not only were Canadians encouraged to see the system of Residential Schools in a positive way, but these materials were spatialising the field of state-run education in the landscape. Linda Smith (2012) describes the spatial vocabulary of colonialism that can be applied to this example. In three terms: the line (map/survey/territory), the centre (orientation to system of power), and the outside (territory/ people in oppositional relation to the centre).51 Remote education as the IRS is described in the video’s voice over, was put in strong contrast to education in urban centres which was associated with progress and intellectual life.

These examples respond to the image of the IRS—how the mission of the institution was translated into something Canadians could understand, and even support—through the projection of the mission—to kill the Indian in the child—onto the bodies of children. At the larger scale, the mission is translated into an architecture.

Fig. 26-30 Stills from C. B. C. Archives, 1955. “Residential school in remote Moose Factory, ON”. Note that the first shot locates the school on a map of Canada.

Fig. 31 (page 56-57) Children dressed in Sunday clothes outside of Bishop Fauquier Memorial Chapel, n.d., 1949-1977. SRSC, 2013-077/008/012.

52 Davin, Report on Industrial Schools, 11.

53 “Missionary Work among the Ojebway Indians, by Edward Wilson (1886)”. Chapter XL. Our Indian Homes.

54 Agreement between His Majesty the King and Rt. Rev. D. J. Schollard, D. D. Bishop of the Diocese of Sault Ste. Marie regarding the Wikwemikong Industrial School. Department of Indian Affairs, 1911. SRSC Archives. “

In the following two statements, Nicholas Flood Davin and E. F. Wilson lay out “problems” they see with Indigenous children, singling them out as a threat to the nation, and at the same time suggesting actions the schools must perform.

In Nicholas Flood Davin’s 1879 report on “Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds” (The Davin Report), Davin boldly declares: “The Indian, I repeat, is not a child, and he is the last person that should be dealt with in a childish way. He requires firm, bold, kindly handling and boundless patience.”52

In Wilson’s Missionary Work among the Ojibway Indians (1886), he speculates on the likelihood of success of the mission of the Indian Homes (Residential Schools). He references camping out:

“Will their love for a wild life ever be eradicated? Perhaps not. Why should it? Our boys, all of them, thoroughly enjoy a “camp out,” such as we have sometimes in the summer, but scarcely one of them would wish to go back and spend his whole life in this manner. … We don’t wish to un-Indianize them altogether, we would not overcurb their free spirit; … Let them hand down their noble and good qualities to their children. But in the matter of procuring a livelihood let us, for their own good, induce them to lay aside the bow and fish-spear, and, in lieu thereof, put their hand to the plough, or make them wield the tool of the mechanic.”53

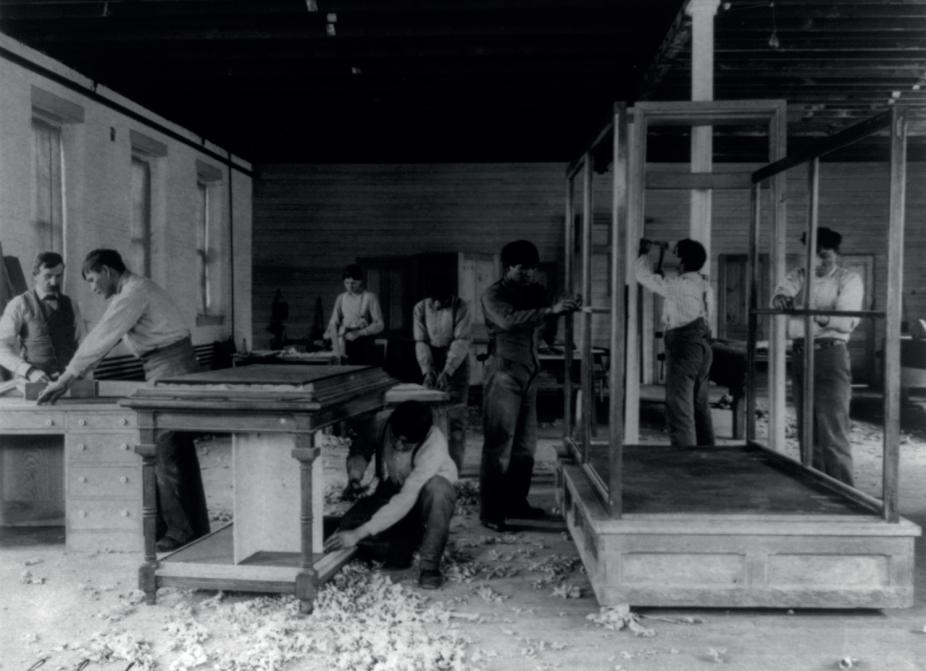

Boys were meant to be instructed in gardening, farming, care of stock, and industries related to local requirements. Girls were meant to have instruction on cooking, laundry work, needlework, general housewifery, and dairy work. In a 1911 agreement between the Crown and the management of Wawanosh, (the partner school to the boys’ Shingwauk) in consideration of compensation from the Crown, the agreement stressed that the branches of the education were intended to show the children the duties privileges of British citizenship, the fundamentals of the Canadian government, and “training them in such knowledge and appreciation of Canada as will inspire them with respect and affection for the country and its laws.”54

As these views were given a physical form, the purpose was to assert Settler presence and domination through the design of built environments and the reframing of the territory.

55 Indian Day Schools, like the Residential Schools were intended to assimilate Indigenous children by eradicating their cultural practices, languages, and traditions.

56 René R. Gadacz, “Longhouse,” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, September 30, 2007, https://www. thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/ article/longhouse

57 David Fortin and Brian Porter interview, “Property Division at Six Nations of the Grand River: A Conversation with Brian Porter”, Fortin & Blackwell, Delineating Nation State Capitalism, 142-155.

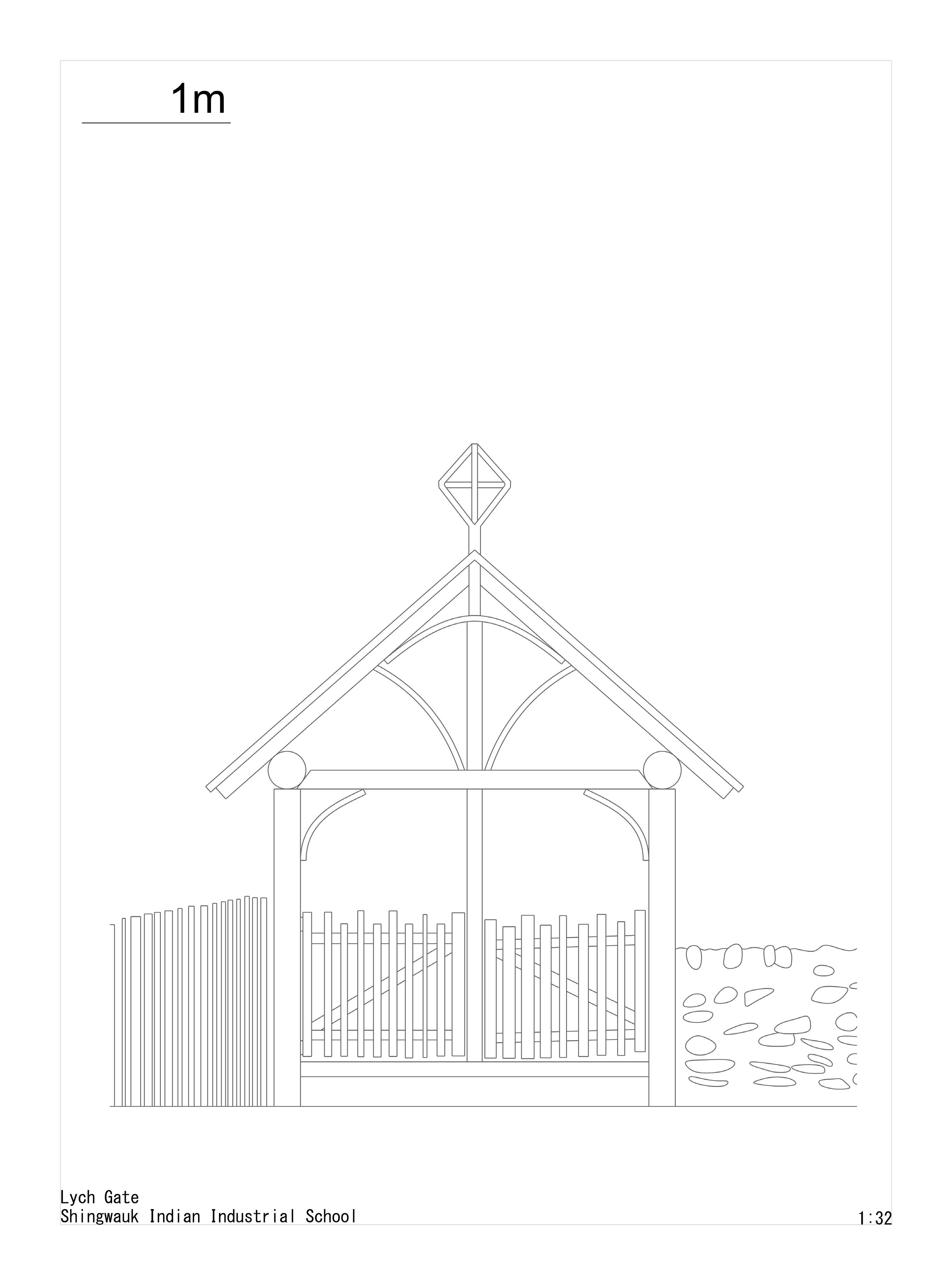

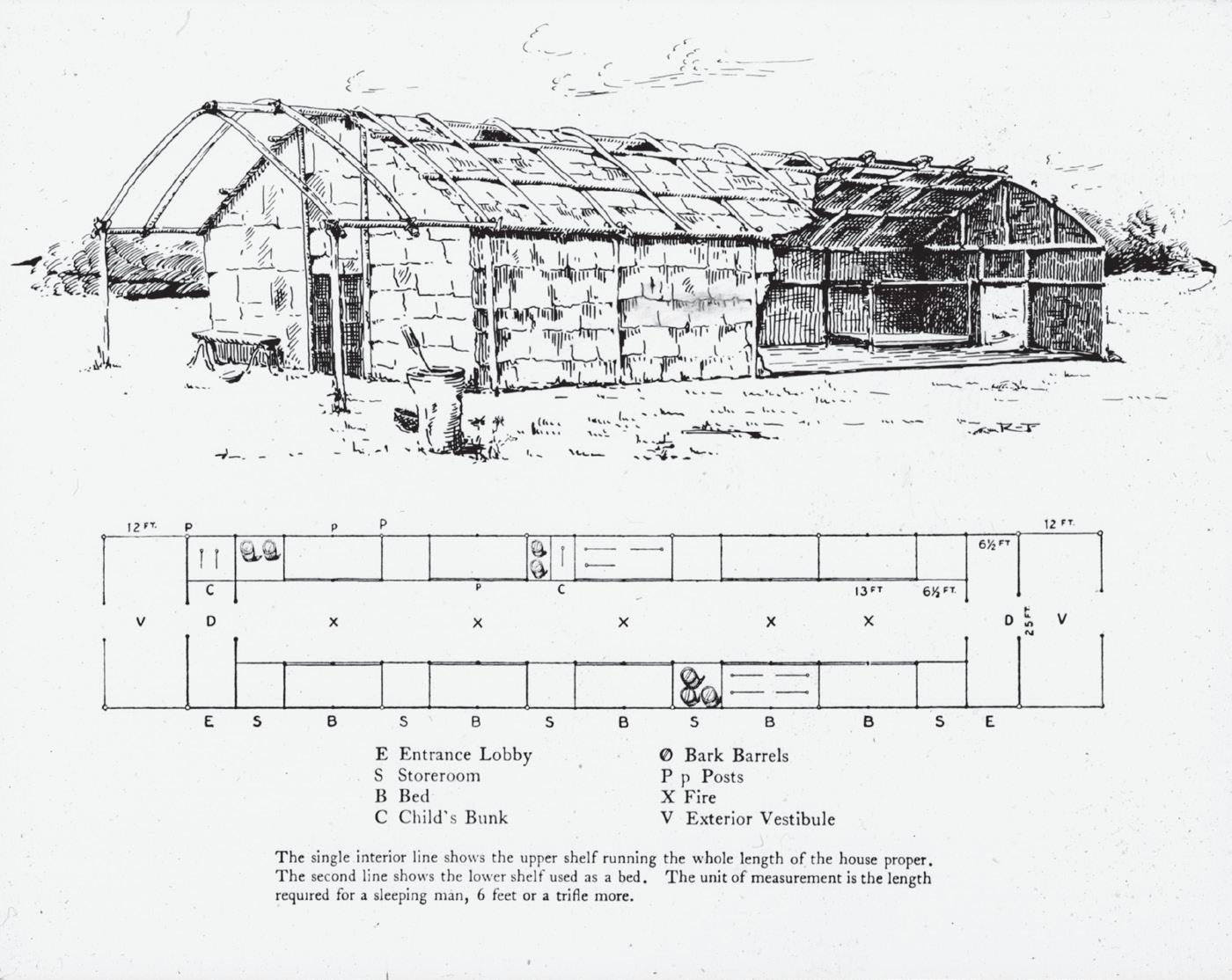

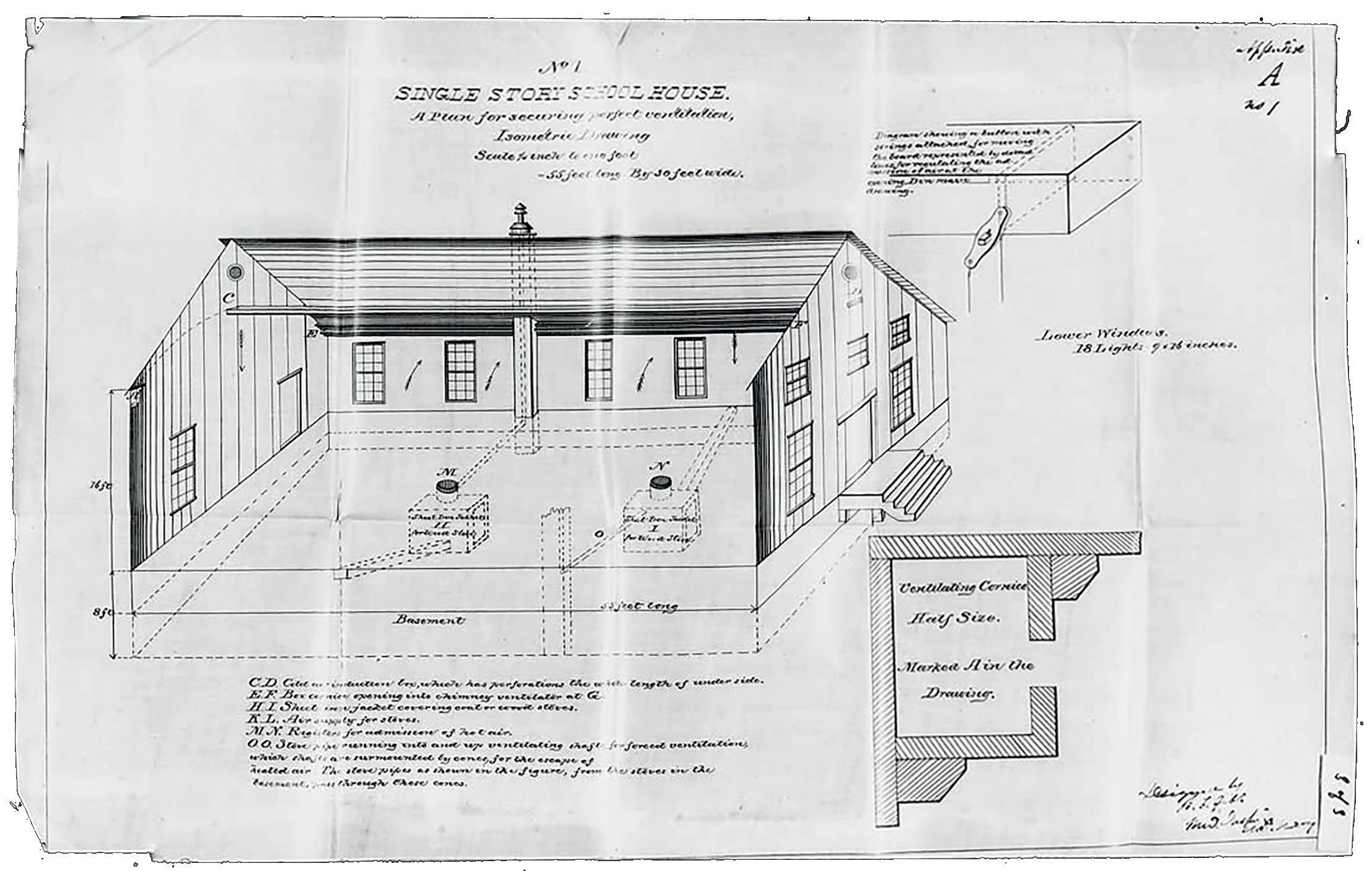

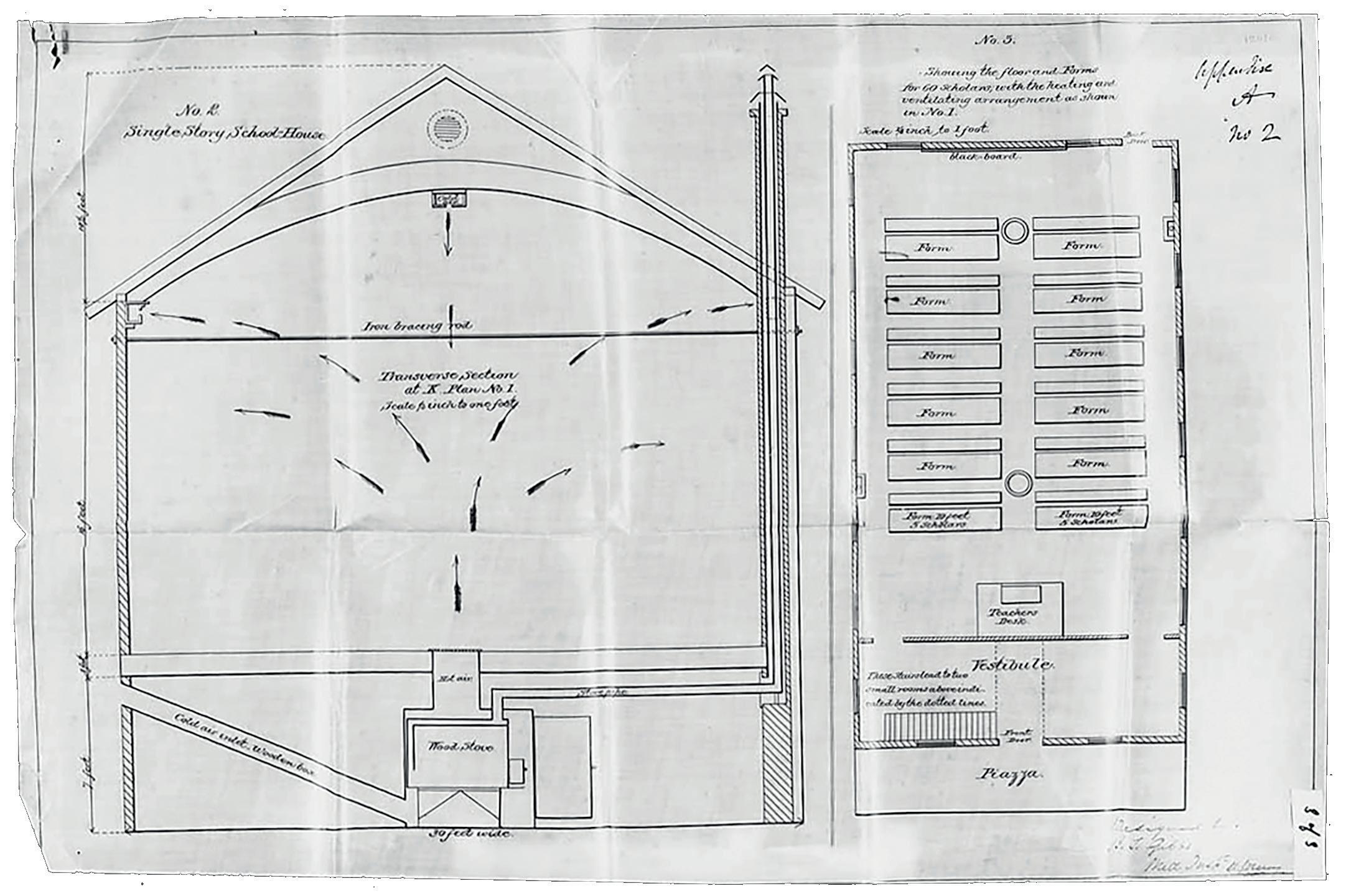

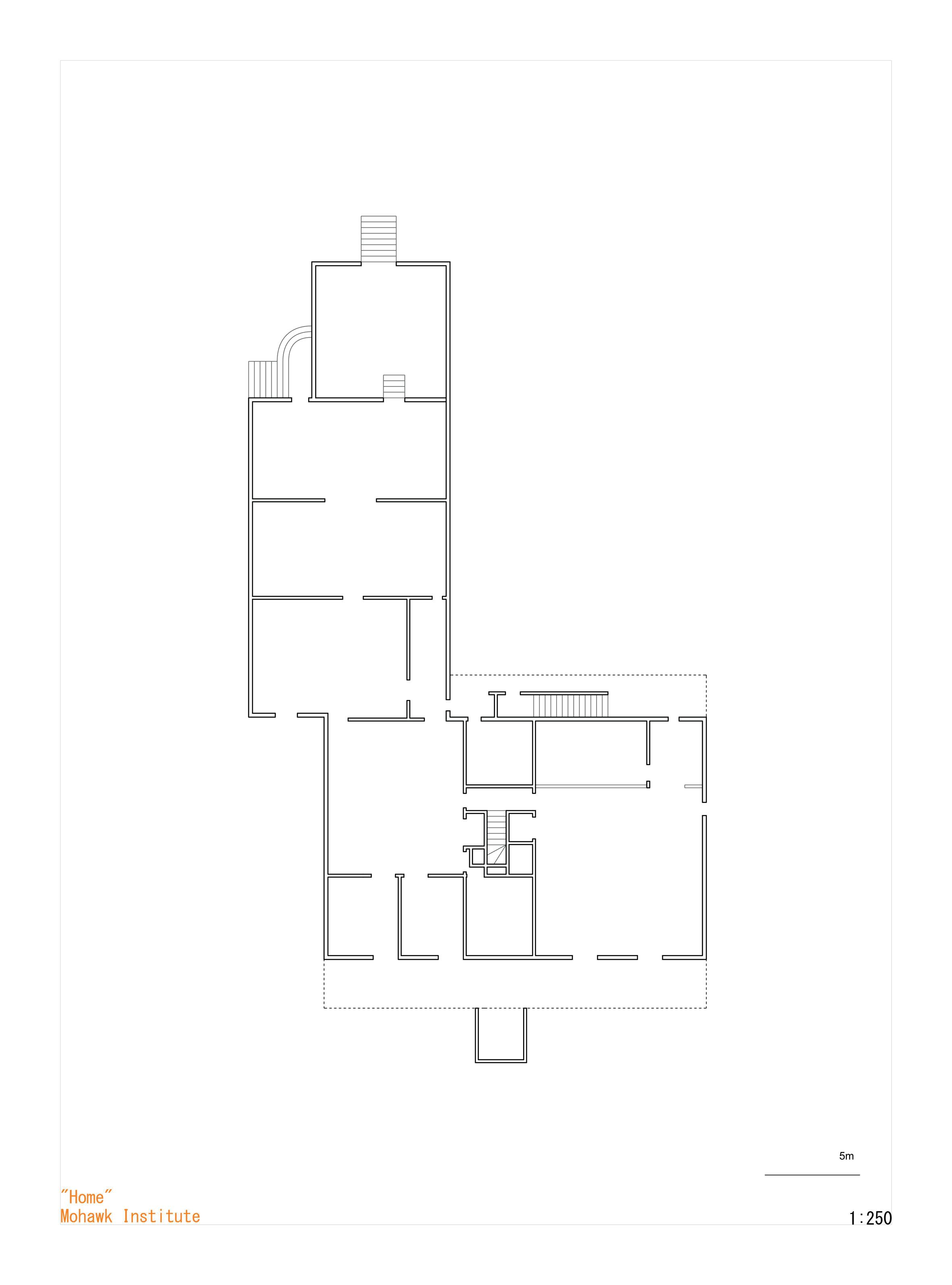

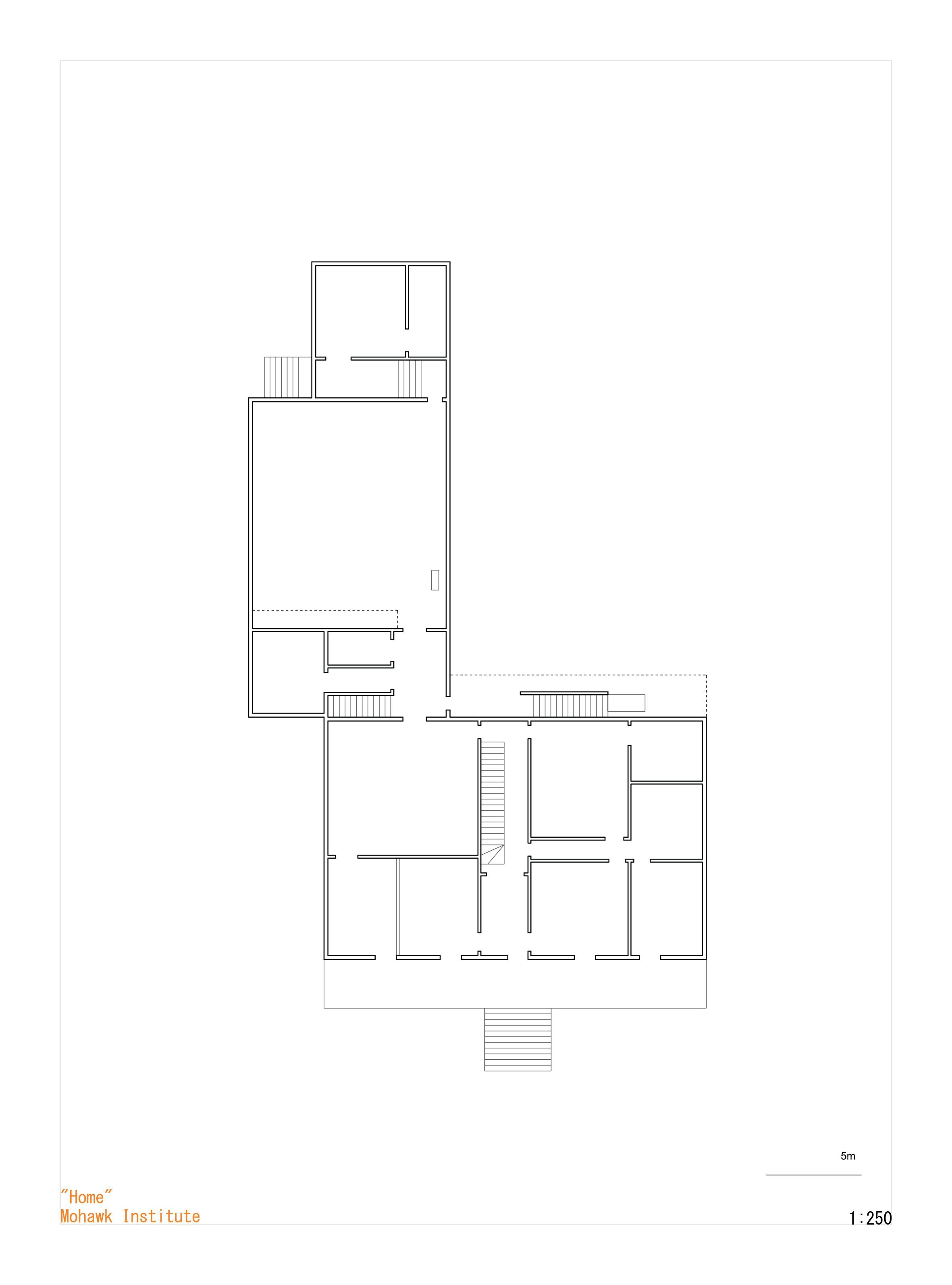

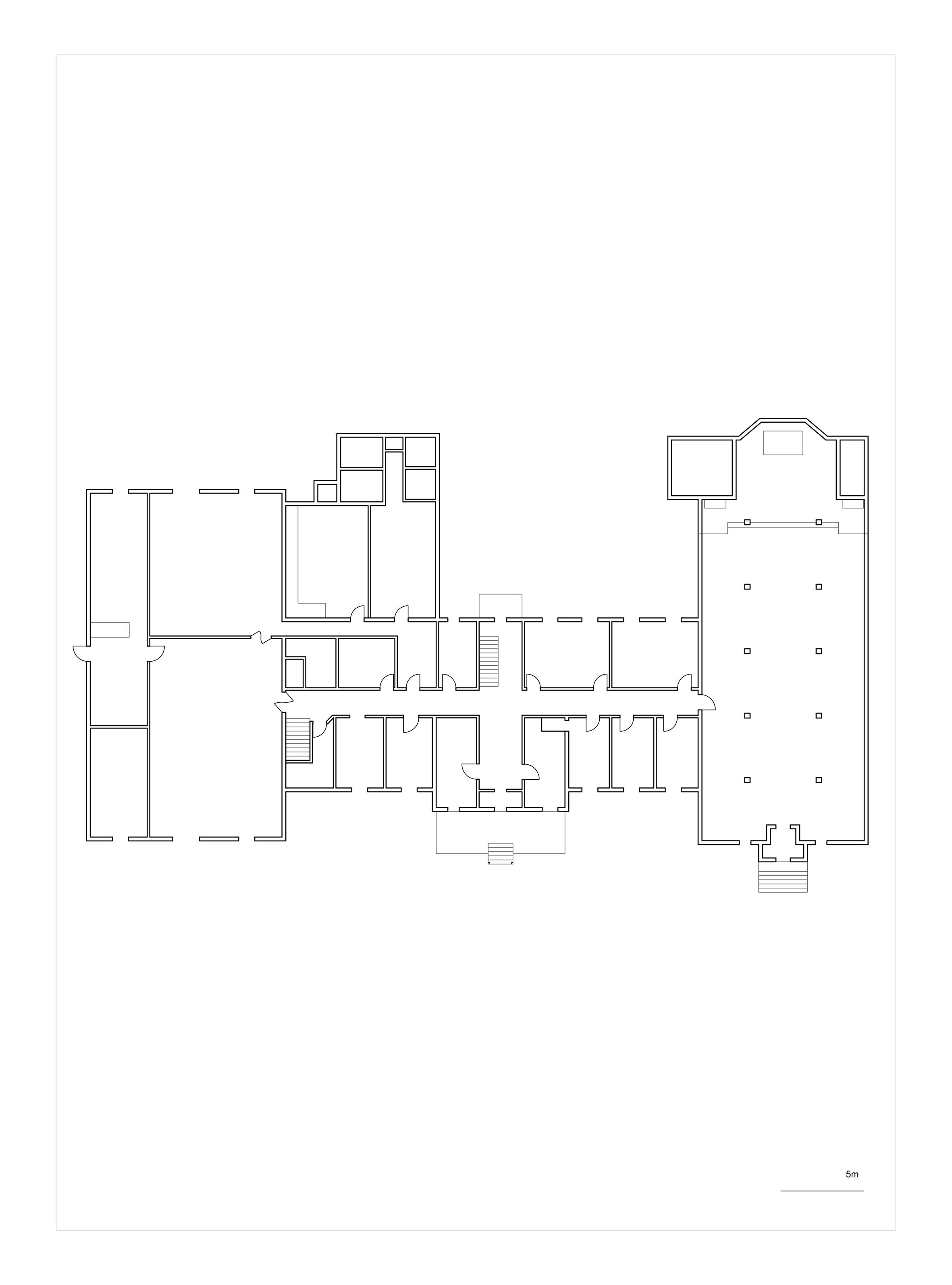

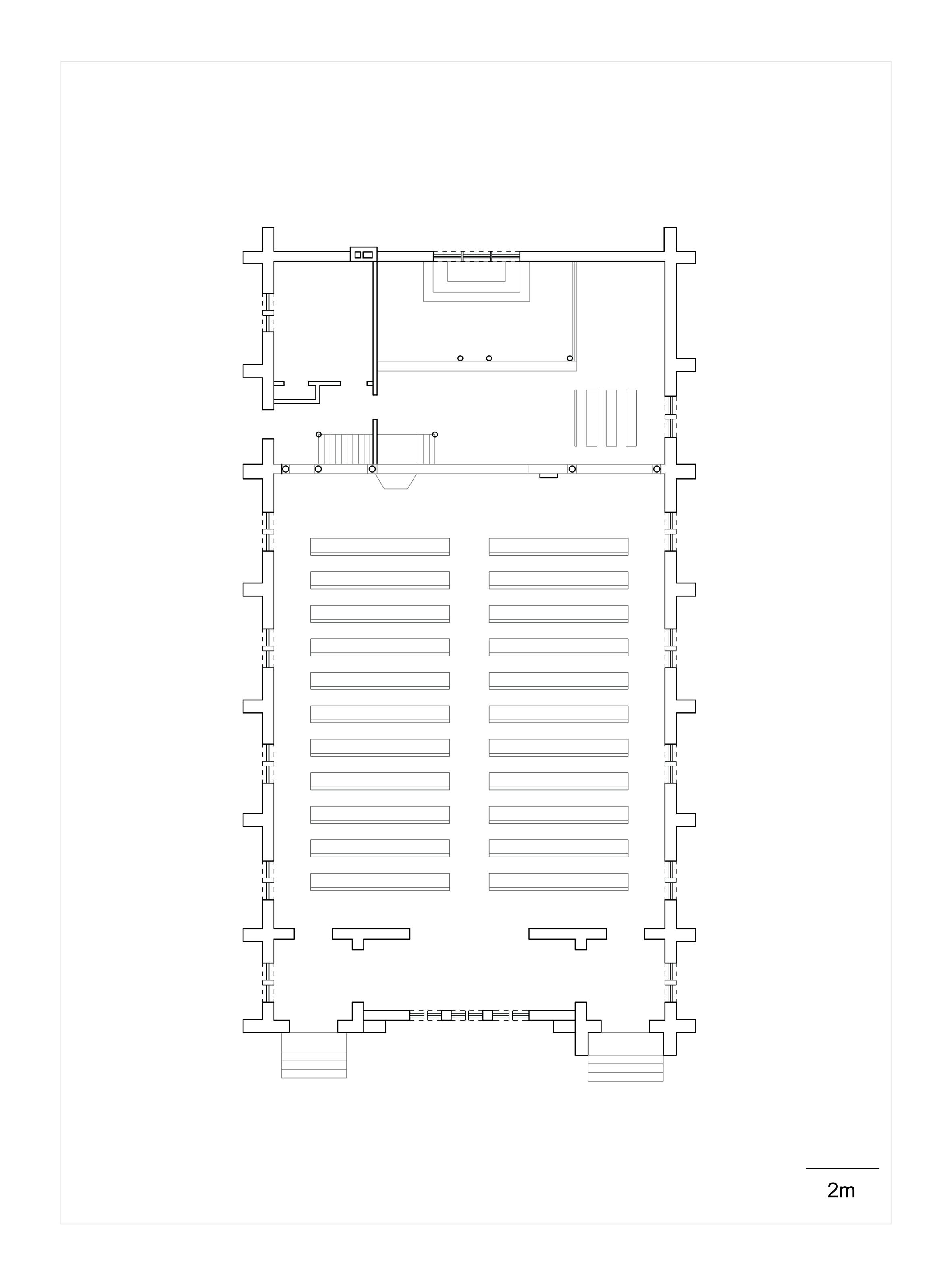

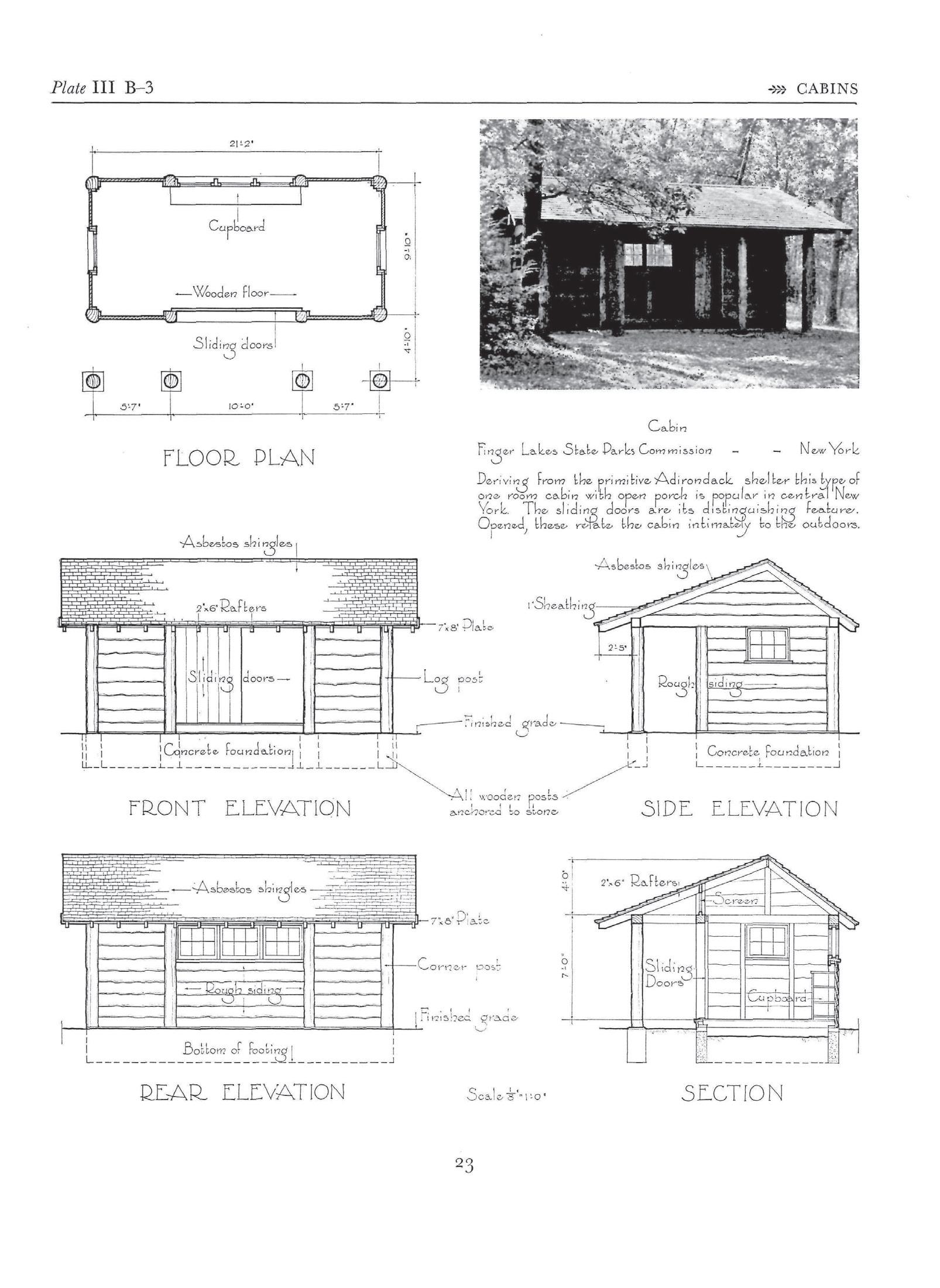

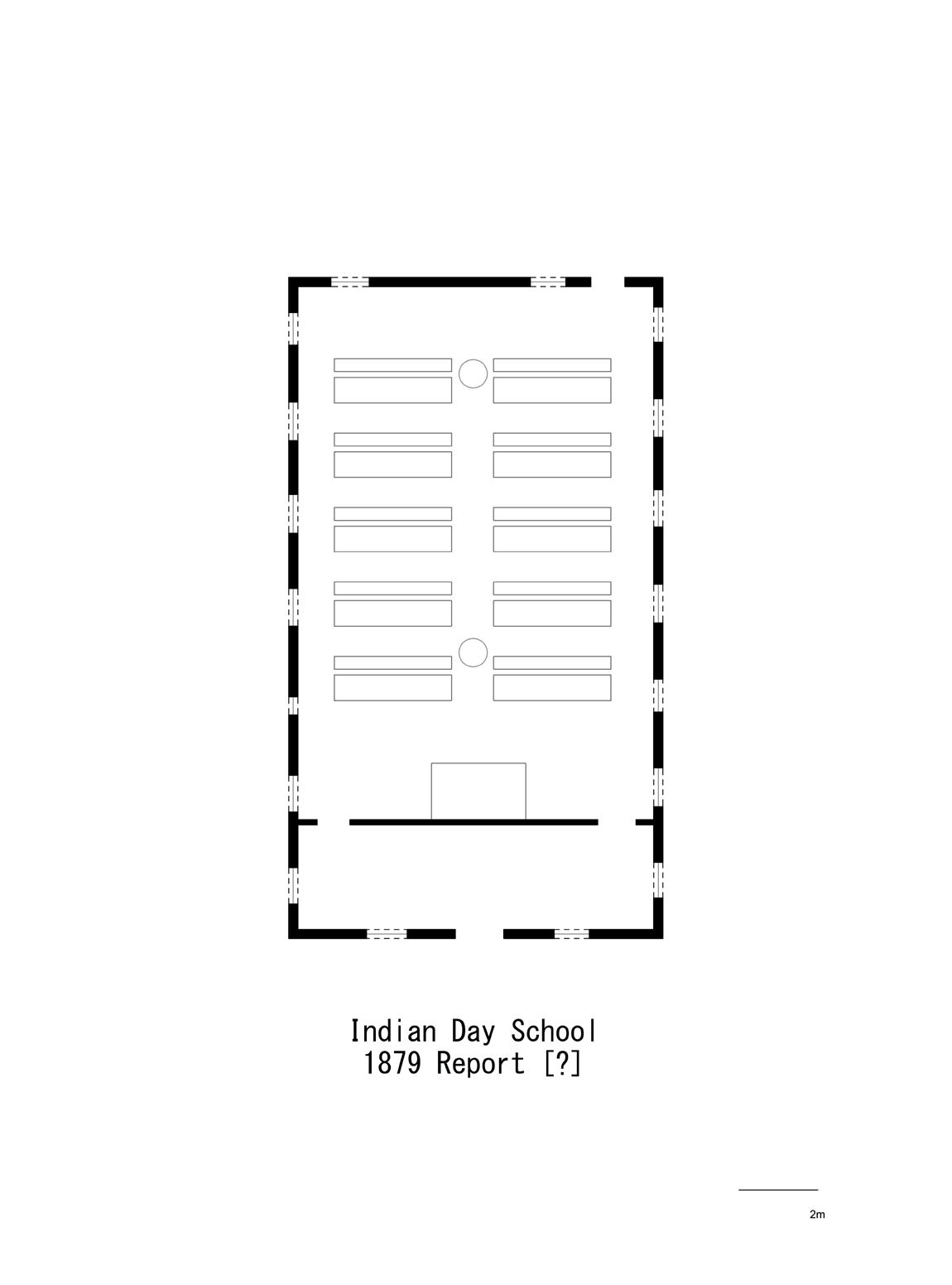

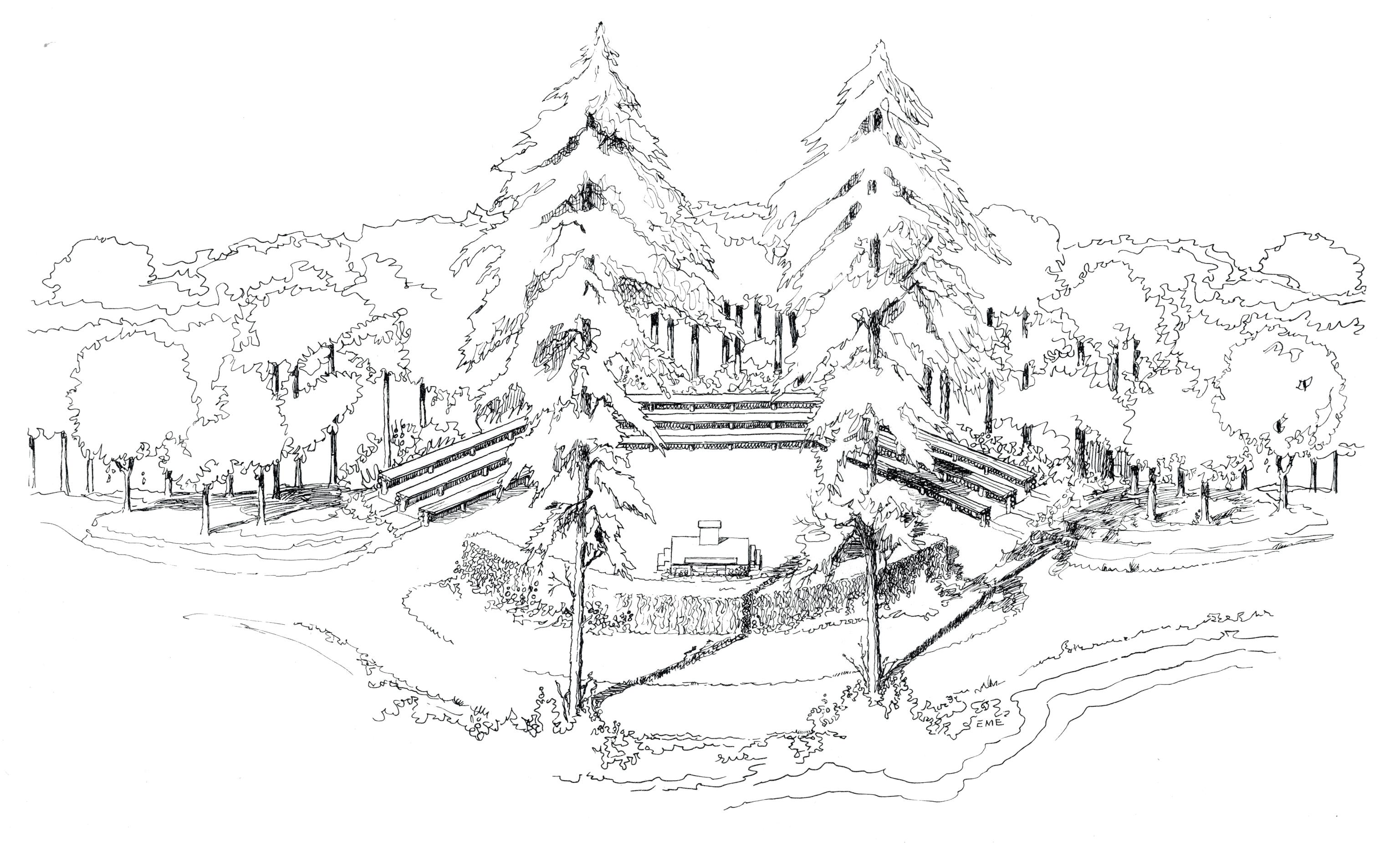

The Davin Report includes a few architectural diagrams that can be interpreted as an explanation of how the strategy should be implemented on multiple scales. The first of them a diagram of a single-story schoolhouse (Fig. 34-35). It was used for on-reserve Indian Day Schools, which preceded the off-reserve Residential Schools.55 The enclosure shown in the diagram incorporates a heating and ventilation system designed to work invisibly, out of view under the floor and within the walls of the classroom. Any views or connection to the exterior are minimal. This architecture is designed to alienate the children, to purposely run counter to what Indigenous children would be familiar with. In their own settlements, the heat source would be central, and gatherings organised around it. For example, communication in longhouse structures (Fig. 33)—the house type of northern Iroquoian-speaking peoples—follows a non-hierarchical social structure.56 Rather than sitting in classrooms for reading, writing, and arithmetic, education for Indigenous children could be based on storytelling.57

58 Geoffrey Carr’s PhD goes into depth on the troubling typologies of the Indian Residential School, and also surveys several conflicting opinions on the topic of commemorating the institutional remnants of this history. Geoffrey Paul Carr, “’House of No Spirit’ : An Architectural History of the Indian Residential School in British Columbia” (Text, 2011), https://open.library.ubc.ca/ collections/24/items/1.0071770

59 This was also a tactic to prevent future fires. The first Shingwauk Home was burnt down (possibly deliberately by students) shortly after it opened.

60 Carr avoids the term “school” as this label suggests not only kinship with a broad spectrum of institutions, but also implies a place of salubrity and self-improvement. Carr, “’House of No Spirit’ : An Architectural History of the Indian Residential School in British Columbia.”, ii.

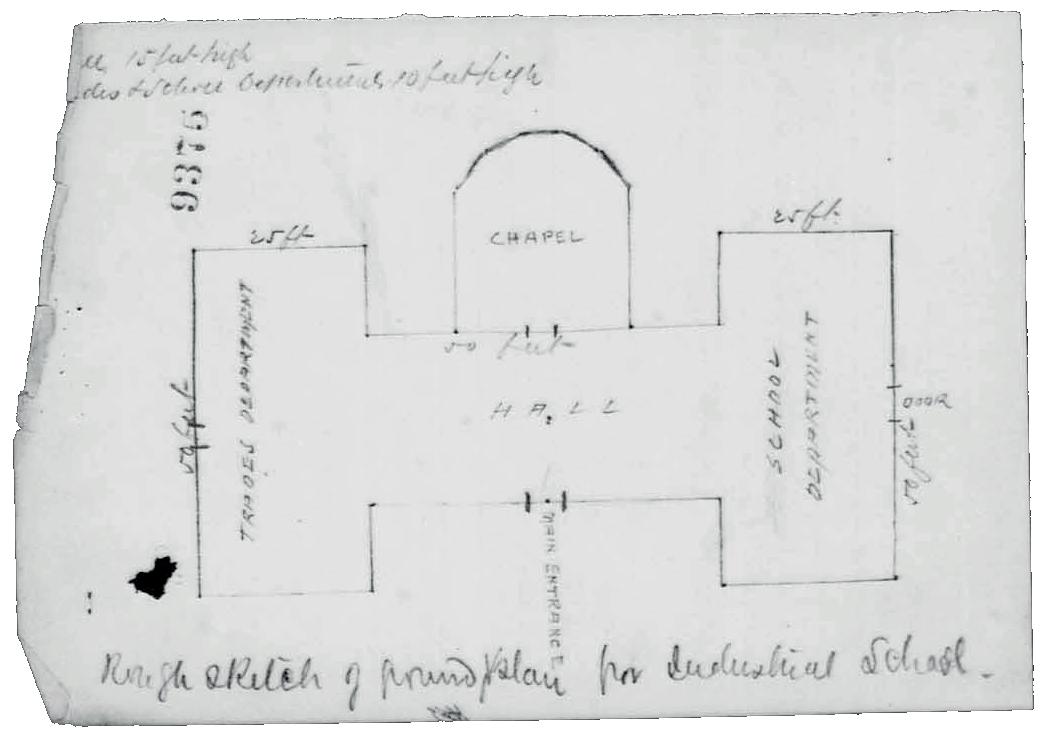

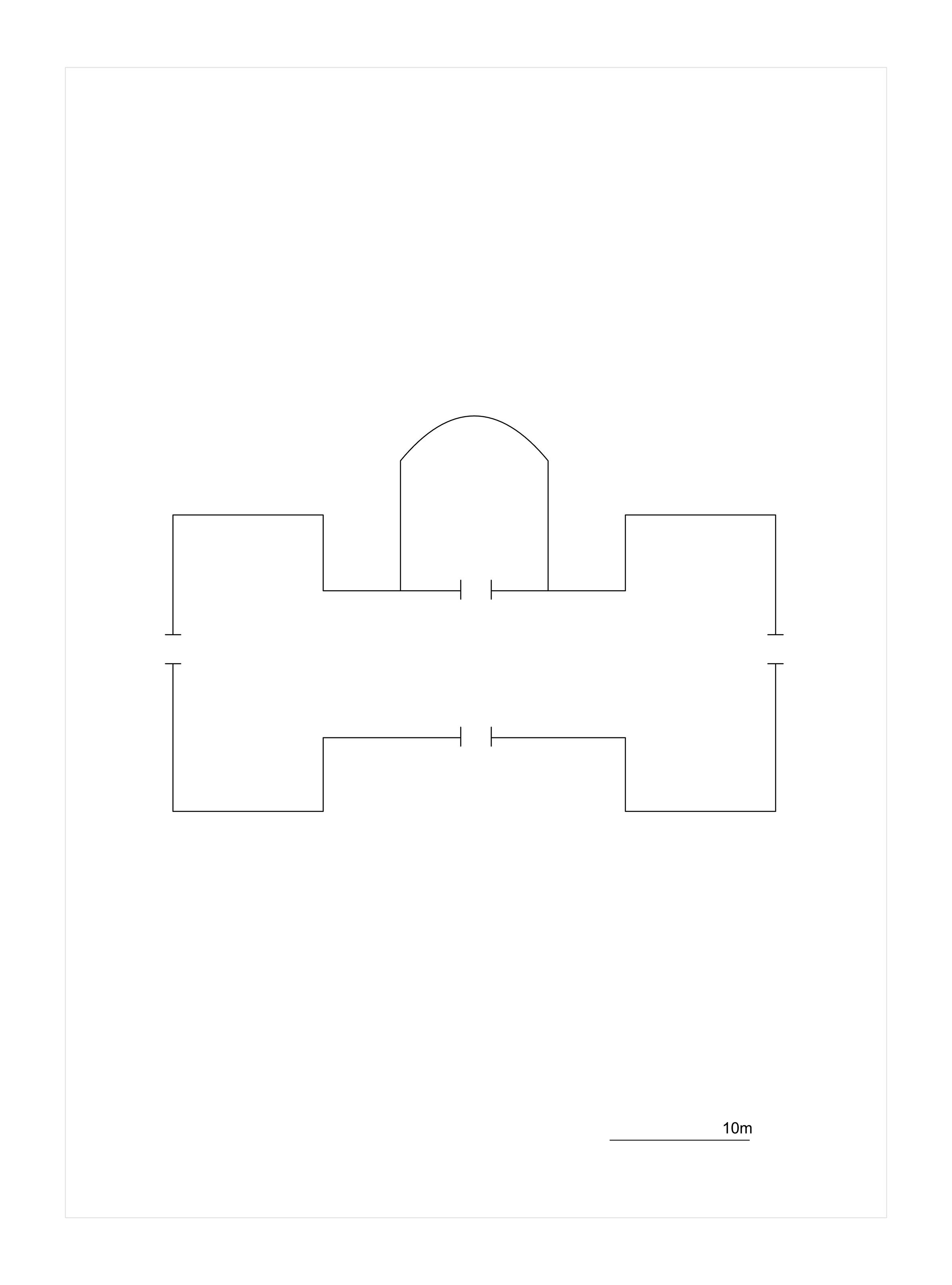

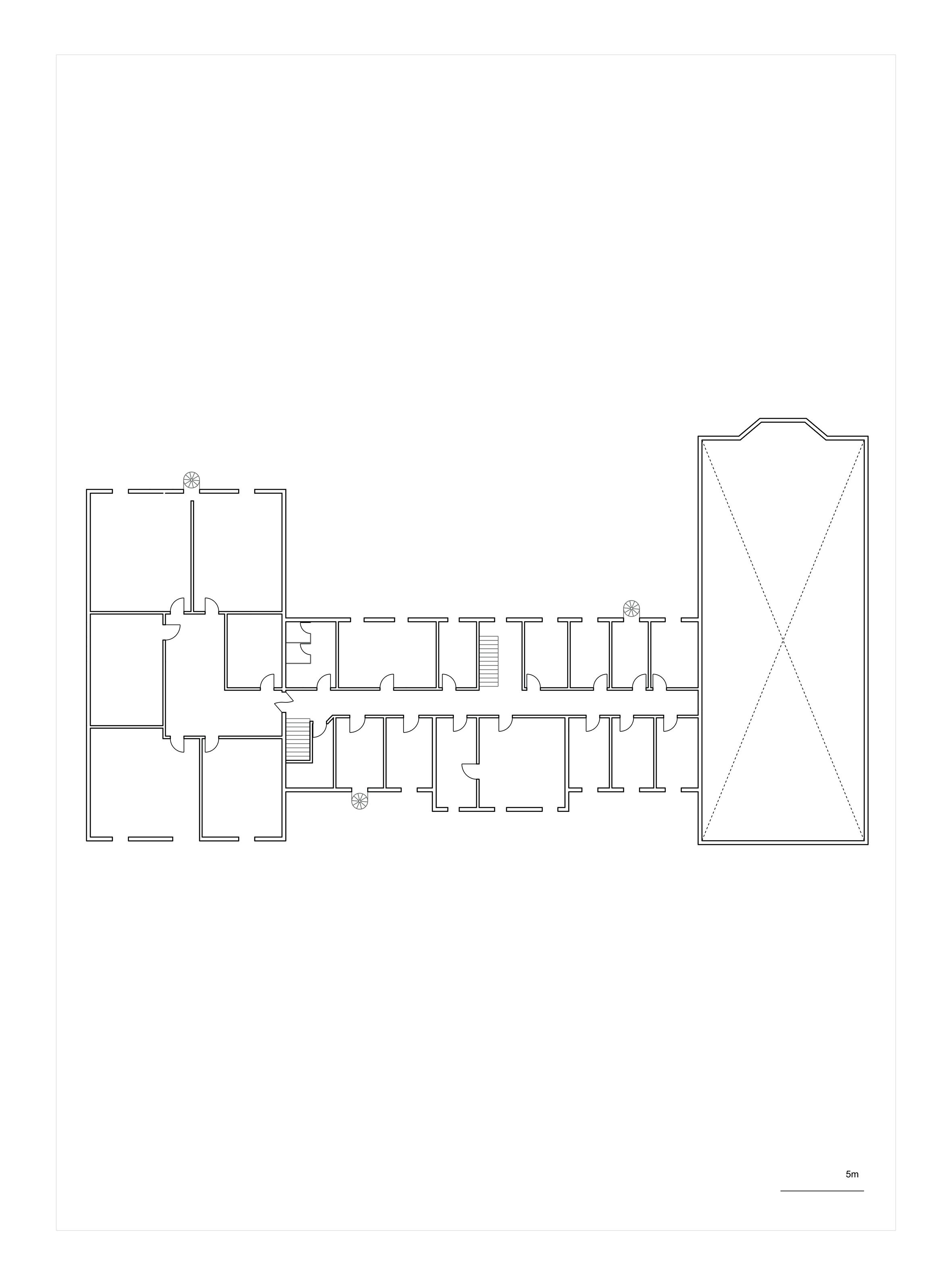

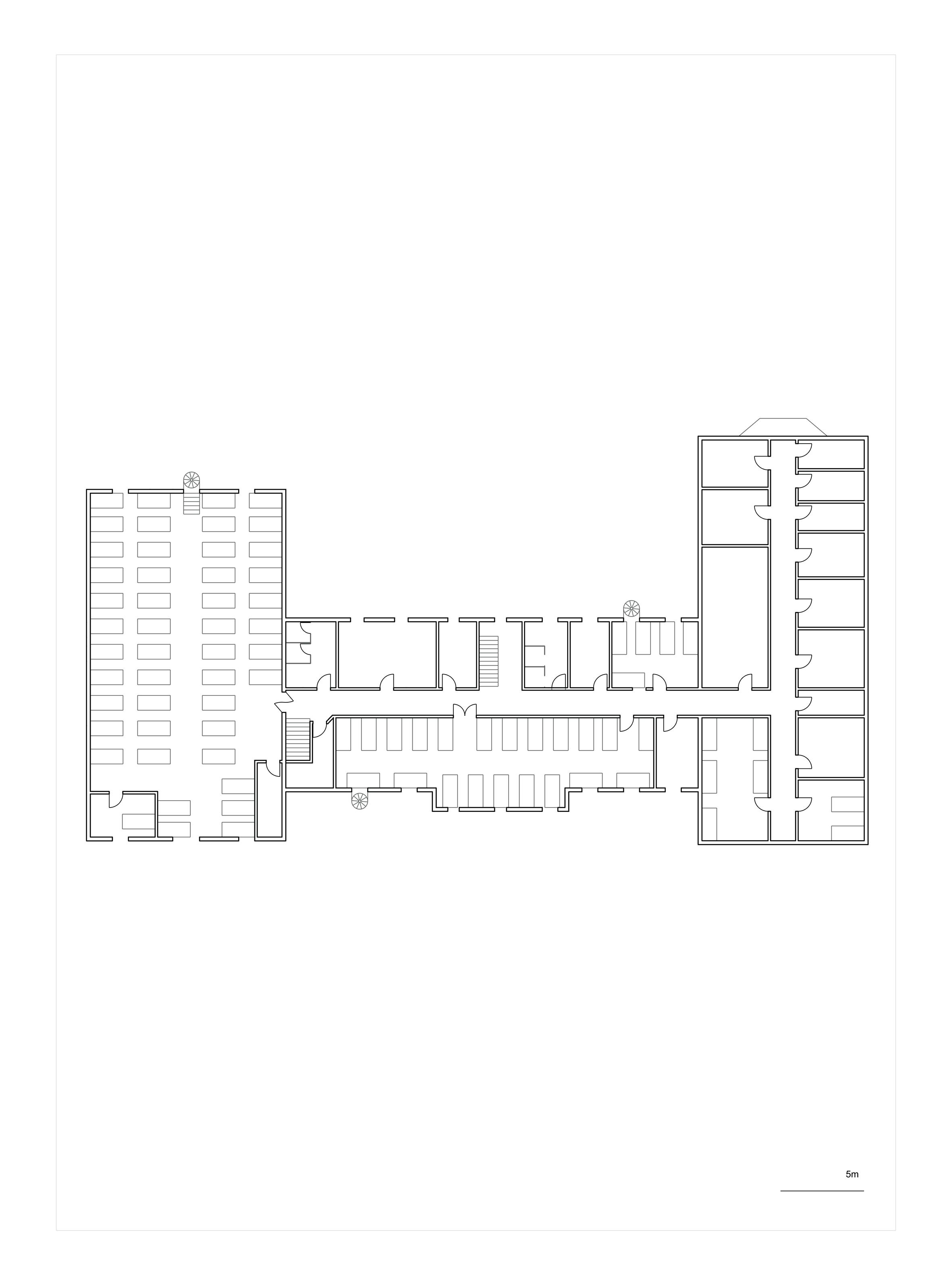

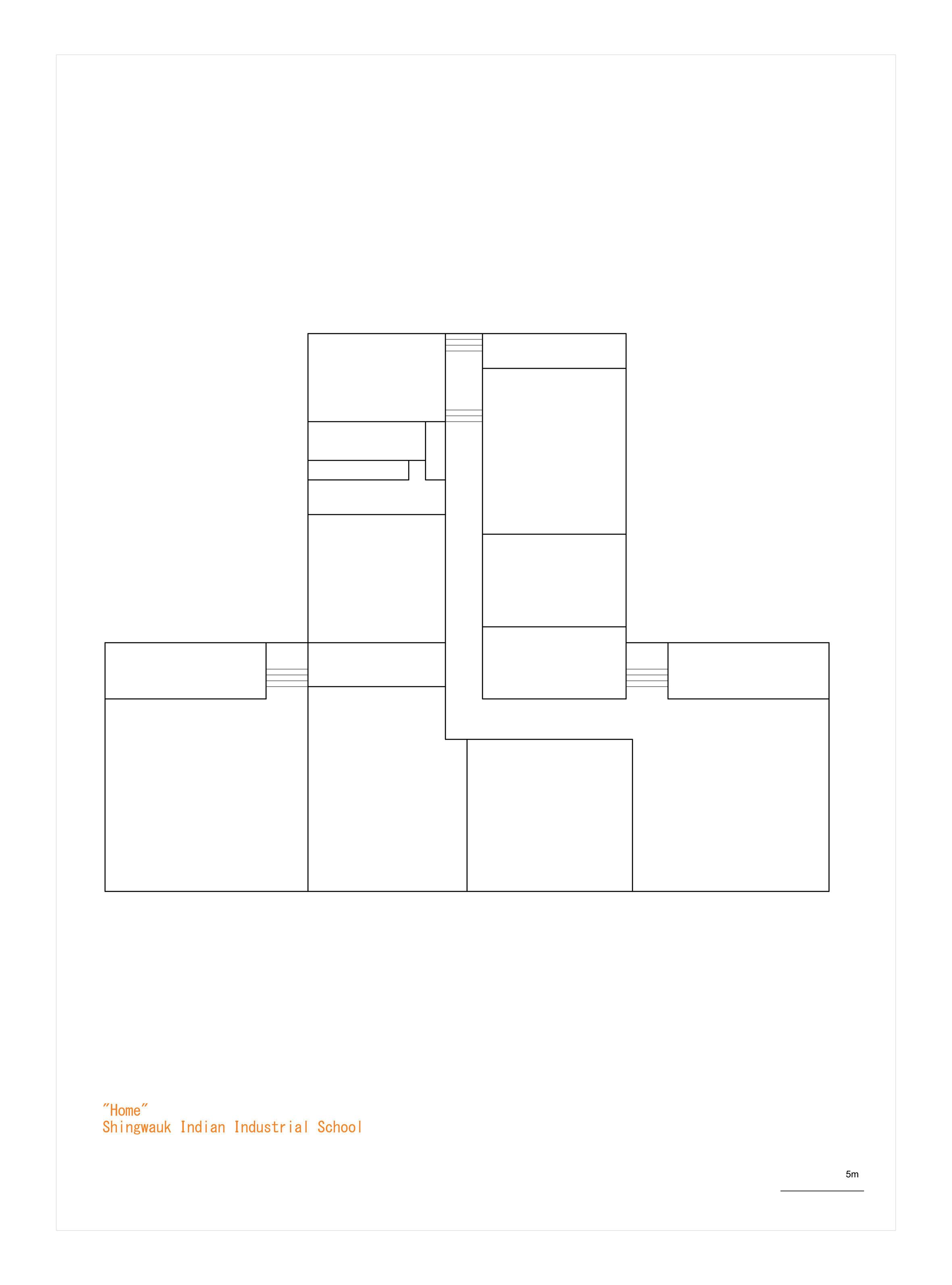

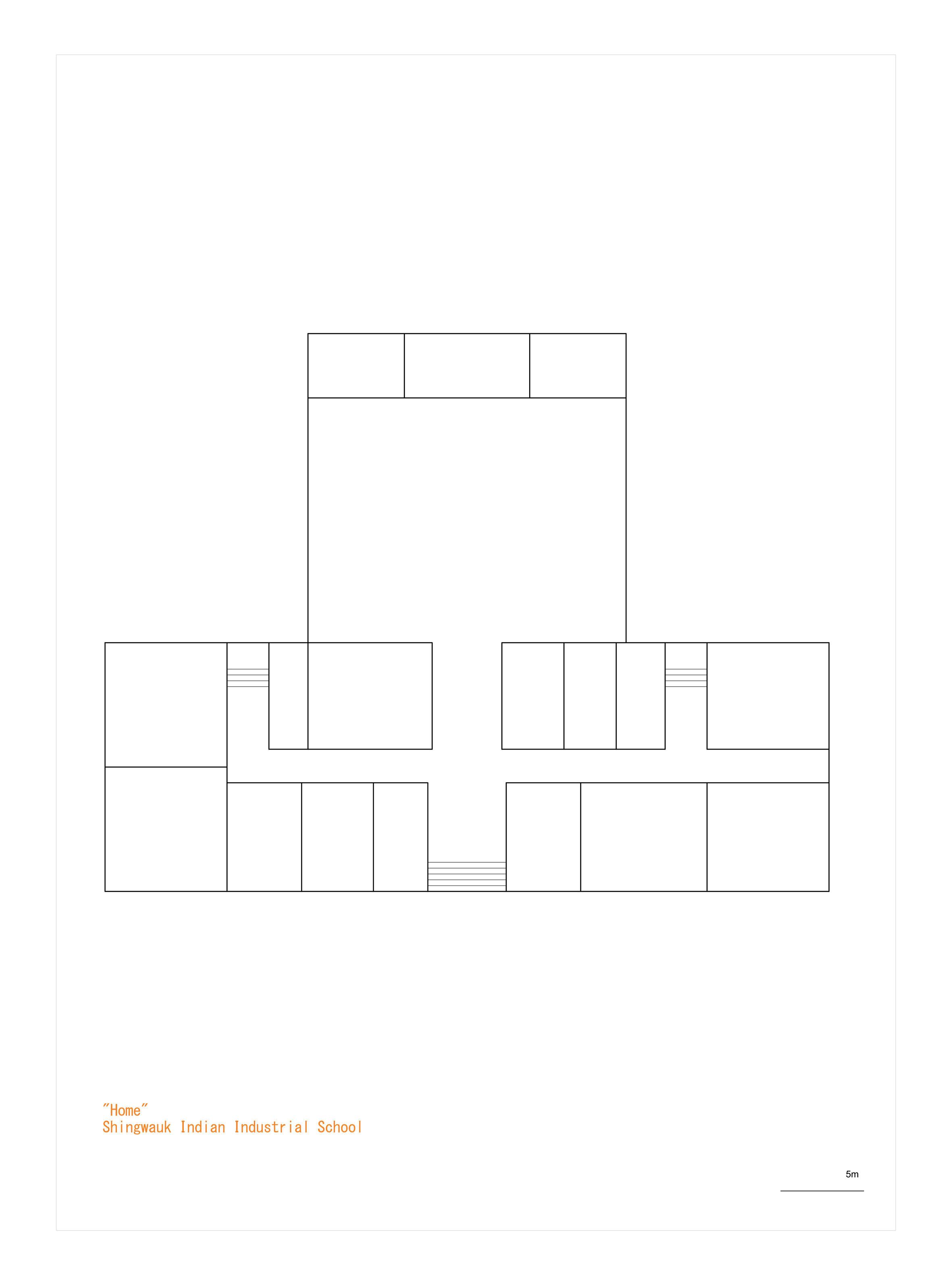

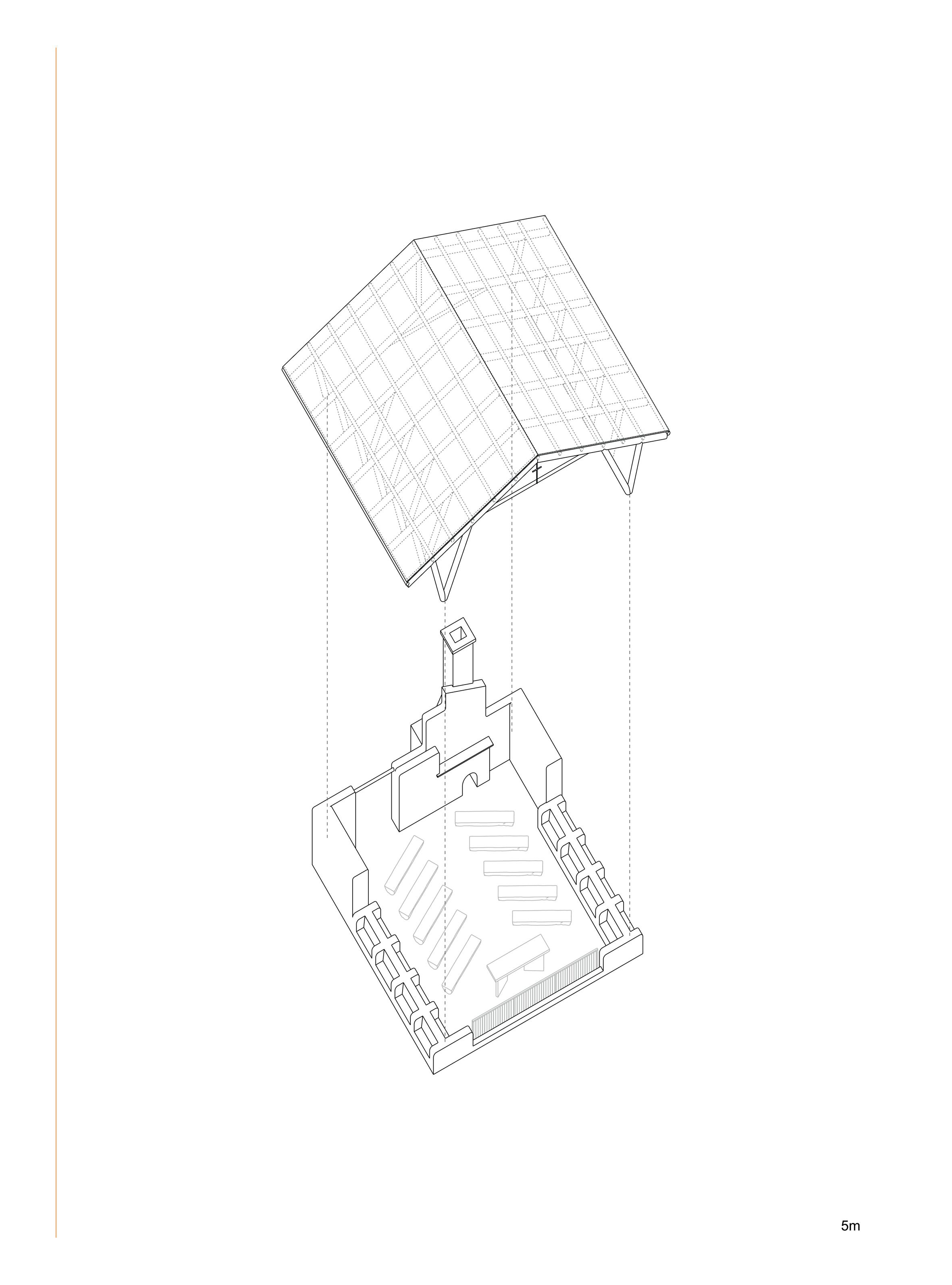

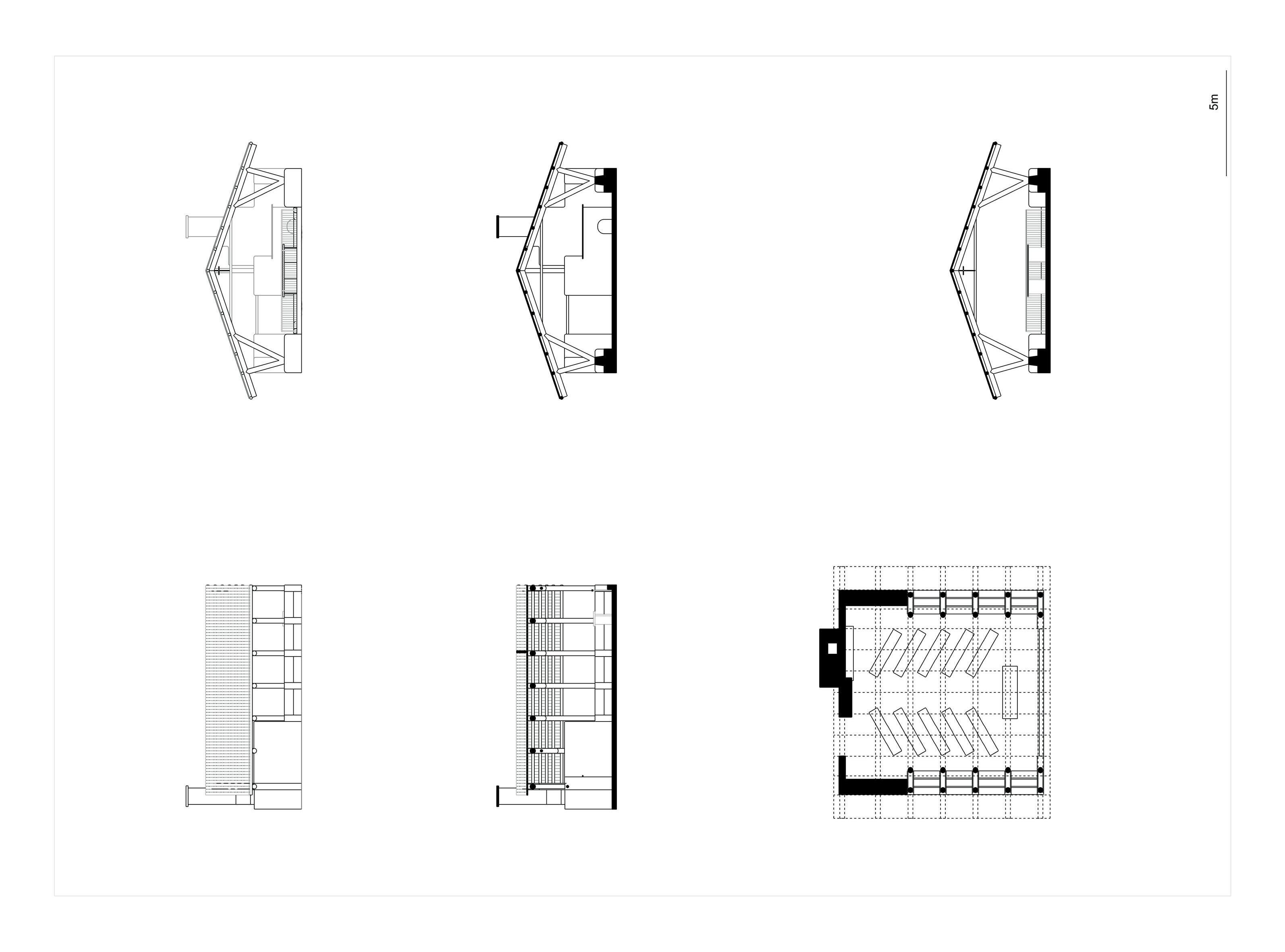

Also in Davin’s report is a parti diagram which distills the overall logic of the main hall. Without yet indicating any materiality or scale, it was in these initial sketches, likely inspired on Davin’s visit to American Indian Schools, that the Canadian IRS was given form. The diagram fits the programming of what would make up residential schooling into a crucifix plan. The three pillars of the education as defined in the diagram was a trades department in the left wing, school department in the right, and religious instruction at the top. A hallway connects each. These large structures would also contain dining rooms, classrooms, workshops, a chapel, and dormitories. Other functions were spread around the site in smaller purpose-built buildings. Any time outside these structures were heavily monitored and would usually be for farm work or other chores on the property. This massive structure represents the apex of civilised settler culture imposed on Indigenous life.58 Initially constructed in wood frame, the buildings were rebuilt of stone as to signal their permanence and indestructability.59 Geoffery Carr (2011) asserts that rather than schools, these structures represent coercive devices targeting colonised Indigenous subjects who were taught to no longer feel at home in their own societies.60

61 Carr defines two generations of schools for Indigenous children. The purpose of the first generation (day schools and industrial schools) was full assimilation into Euro-Canadian society and focused on training in occupations including homemaking for girls and trades and farming for boys. The second generation Indian Residential Schools built between 1910-1930s served a segregationist program. Carr, “House of No Spirit,”, 42.; Milosz, ‘Instruments as Evidence’.

62 These are just a few of the stories shared during the Woodland Cultural Centre’s Virtual Tour of the Mohawk Institute.

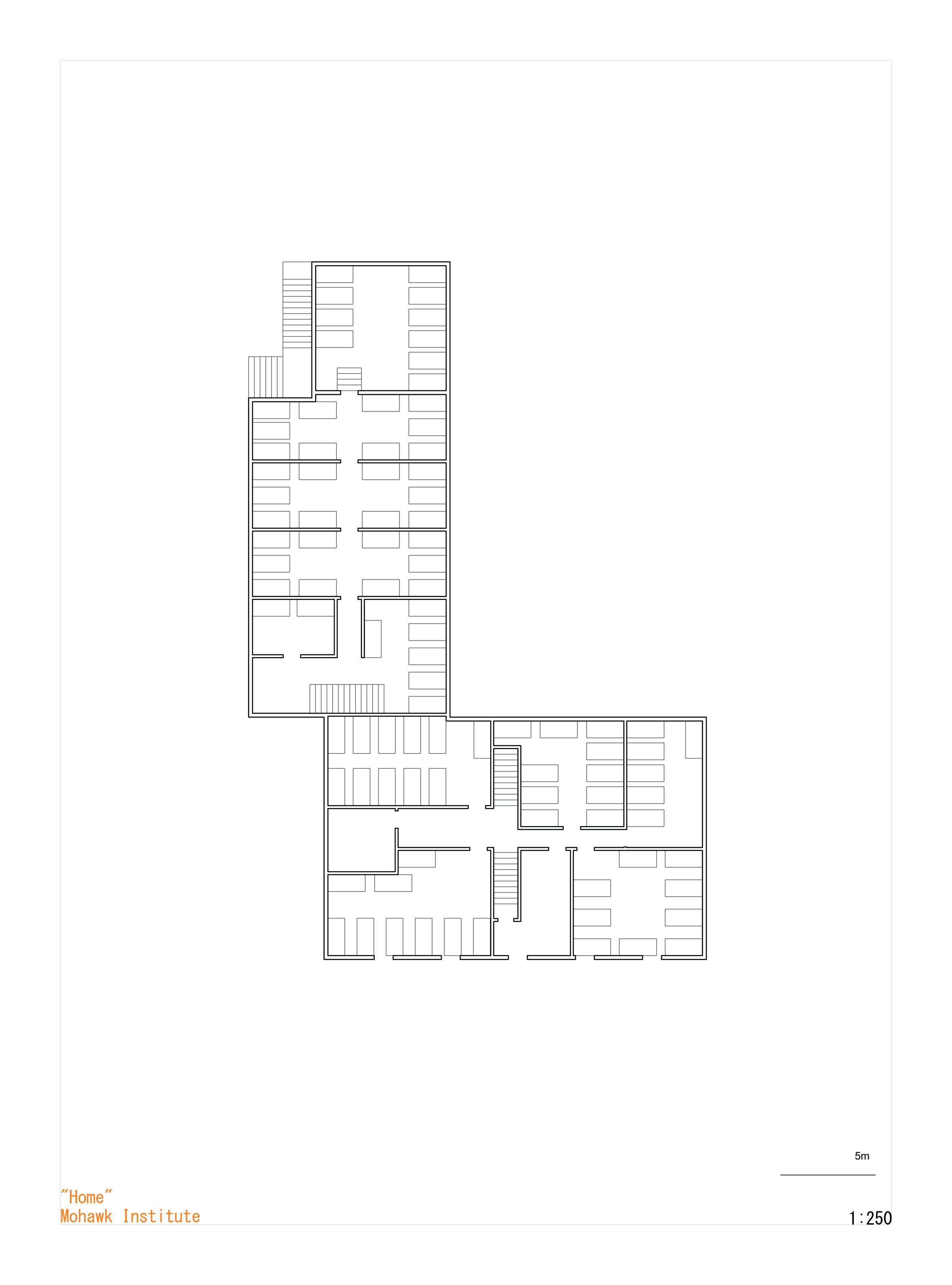

The Mohawk Institute’s second main hall (Fig. 46), standing from roughly 1879-1903 belonged to the first generation of schools for Indigenous children, designed to hasten full assimilation.61 These are followed by the Spanish IRS (built 1913, Fig. 50) and Shingwauk’s second main hall (built 1935, Fig. 54) which belong to the second generation of Indian schools.

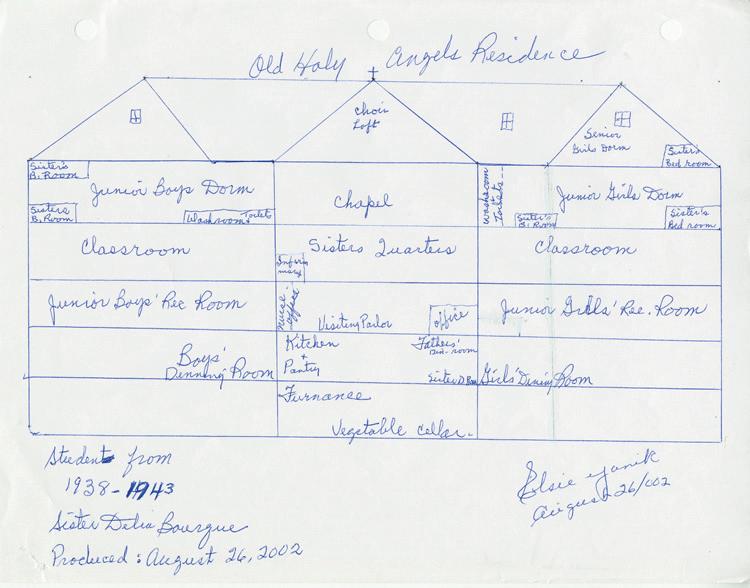

Survivor testimonies relate specific parts of these structures to memories of harm. At the Mohawk Institute, the basement was a location of sexual abuse, noise disguised by the boiler room. The space under the staircase was used for solitary confinement. In other areas of the building, children found solidarity in each other’s company. In their playroom in the basement, children could secretly speak their own languages.62

The spaces shown in the following drawings are defined not to allow participation in White Settler society as equals, but rather to form a working class. Indigenous children are introduced to the machinery of Western civilisation to ultimately define them as savage. The children become Indians—as the identity is constructed in opposition to White civilised society.

Fig. 38 Old Holy Angels Residence Floor Plan drawn by Elsie Yanik, 2002. Student from 1938-1943. Algoma University Archives 2015-054/001/005/001.

Fig. 39 (right) Organisational Chart of the IRS.

British Consulate

Federal Gov.

Dept of Indian A airs

Provincial Gov.

maintenance sta physicians (exams, health, sanitation, hygiene, first aid)

kitchen sta cleaning sta

Oblates

Mennonites

Presbyterian Church

Anglican Church

United Church

Sisters of Saint Joseph Roman Catholic Church

Daughters of the Heart of Mary

ADMINISTRATION STAFF

SUPERINTENDENT OPERATIONS STANDARDS & POLICY FUNDING civilising removal of Indigenous people from lands

assimilation

“kill the Indian in the child” break familial bonds

EDUCATORS PROGRAMME LEADERS

CAMP OBJECTIVES CHILDREN

building a working class interrupt cultural transmission adjustment to Canadian Society christianising

religion home economics carpentry sewing farming organization / agency private church tax Society for the promotion of Christian Knowledge arithmetic english geography

Boys work. From top:

40

41

Fig. 42 Farming or building work on the grounds of Spanish IRS, 1925.

Girls work. From top:

5m Spanish Indian Industrial School

interior conditions.

63 Nickolas Flood Davin, Report on Industrial Schools for Indians and Half-Breeds, 1879, 12.

64 Fortin and Blackwell, “C\a\n\a\d\a Delineating Nation State Capitalism.”

65 Davin, 11.

66 Davin, 12.

67 Davin, 14-15.

68 Jennifer N. Harvey, “Landscapes of Conversion: The Evolution of the Residential School Sites at Wiikwemkoong and Spanish, Ontario” (Master of Arts in Humanities, Sudbury, Ontario, Canada, Laurentian University, 2019).

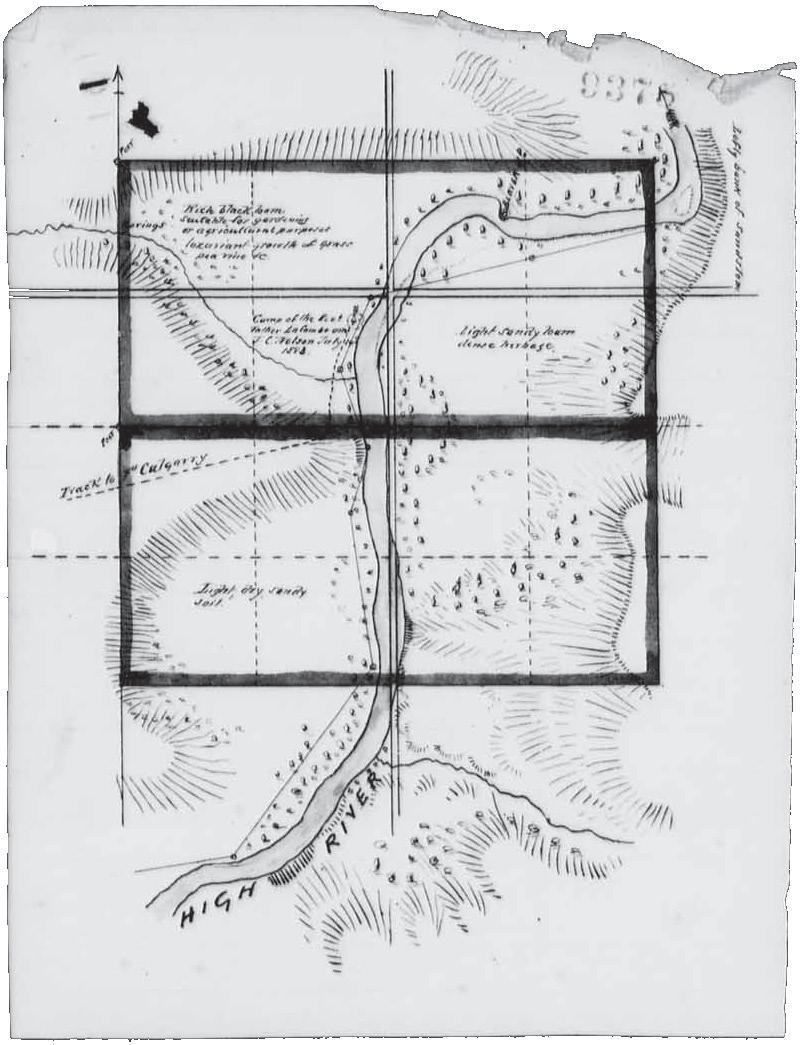

The properties of the Residential Schools often extended over a hundred acres. In the Davin Report, which included a rough sketch of the resources offered by a site (Fig. 58), Davin laid out his recommendations for site selection. Schooling was seen as imperative to the project of settling and keeping the children constantly “within the circle of civilized conditions”63. The IRS was a purposeful incision into the structure of the family, meant to disturb and reorganise Indigenous societies. Meanwhile through unfair and unjust treaties, Indigenous peoples were removed from large territories of “resource rich land” and onto small Reserves (as many have truthfully described as leftover land64).

Davin recommended that “the moment there exists a settlement which has any permanent character, then education in some form or another should be brought within reach of the children.”65 In his view, schools laid by missionaries scattered over the whole continent wherever Indigenous people exist were “monuments of religious zeal and heroic self-sacrifice”.66 For the establishment of new Industrial Schools, he recommended that schools be established on various sites near trading posts, natural resources, permanent settlements, and specific to different populations of Indigenous groups. The schools were to be of different denominations and levels of religiousness in order to demonstrate the fullness and variety of the European worldview.

67

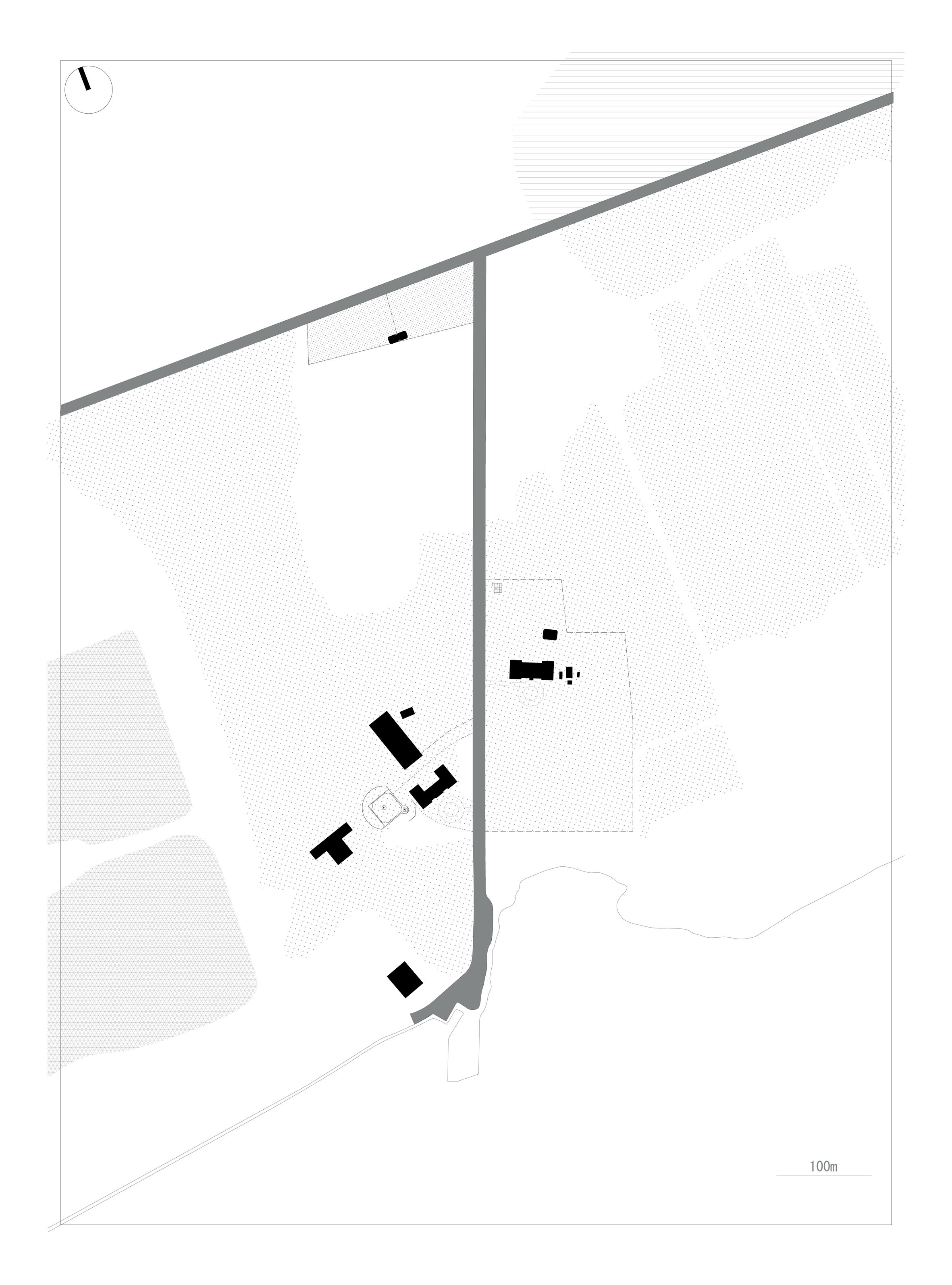

The sites were clear cut, often fenced off, with the forests relegated to the boundaries of the property. Water was another natural barrier, further separating the schools from home communities. Jennifer Harvey (2019) describes that these greenspaces were on the fringes of the sites where children were not allowed to be. There was no access to land that was familiar to them. It was removed from the immediate surroundings by the demands for agriculture and surveillance.68

The architecture and its surrounding landscape function as an interface through which Indigenous children were re-taught to understand and relate to the land. The site organisation of the IRS followed the traditional urban thought of Christianity. In this tradition, urban movement was focused on two centres: the cathedral and the home. Most of the vocational skills taught at the schools were catered towards looking after the domestic home or homestead. Other weekly rituals centred on religious instruction at the chapel, usually on-site.

Fig. 57 Drawn Map of good location for a Residential School. Indian Affairs. (RG 10, Volume 3674, File 11,422) Public Archives Canada.

69 Written from Wilson to the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs regarding the education, civilization, and Christian training of the rising generation of "poor down trodden and yet intelligent people". Wilson had been inspecting some of the largest Institutions in the US, learning about their education plan and amount of state funding. Letter to the Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, Ottawa, from E. F. Wilson. SRSC Archives. Synod of the Diocese of Algoma Fonds, 2013-117/002/003, 27/01/1887.

70 Shingwauk’s Industrial era lasted 59 years (1875-1934). E. F. Wilson, Missionary Work among the Ojibway Indians, 1886, chapter XL

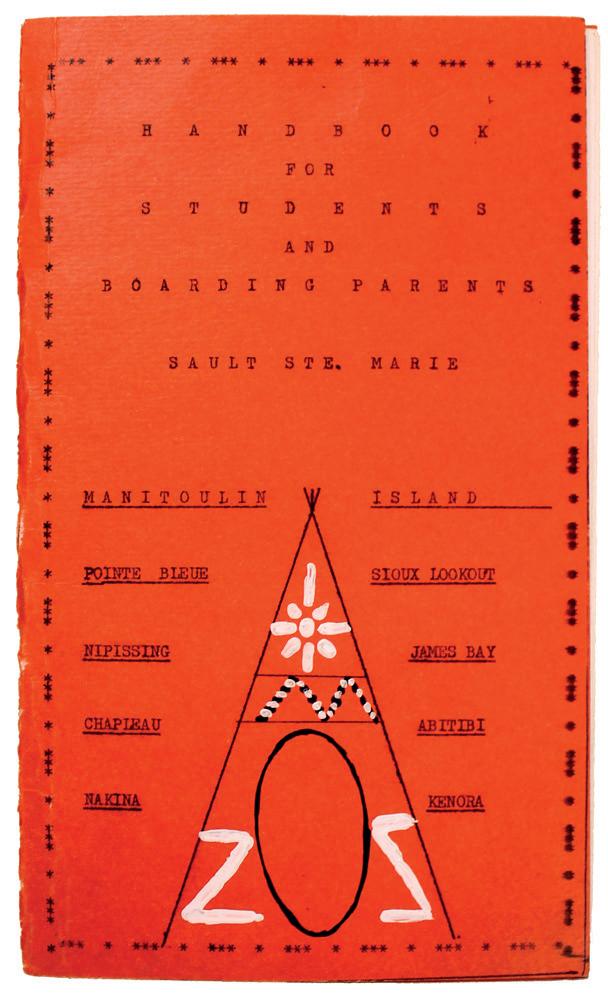

71 “Handbook for Boarding Parents”, Shingwauk Indian Residential School, n.d., likely 1954-64. SRSC.

72 Indigenous children were put in catalogues, newspapers, all part of effort to fracture families and communities and force assimilation, continue the genocide on indigenous people. From federally mandated Residential Schools to provincially controlled child welfare system. Many children went to families in the US or to Montreal, many worked on farms (as child labourers).

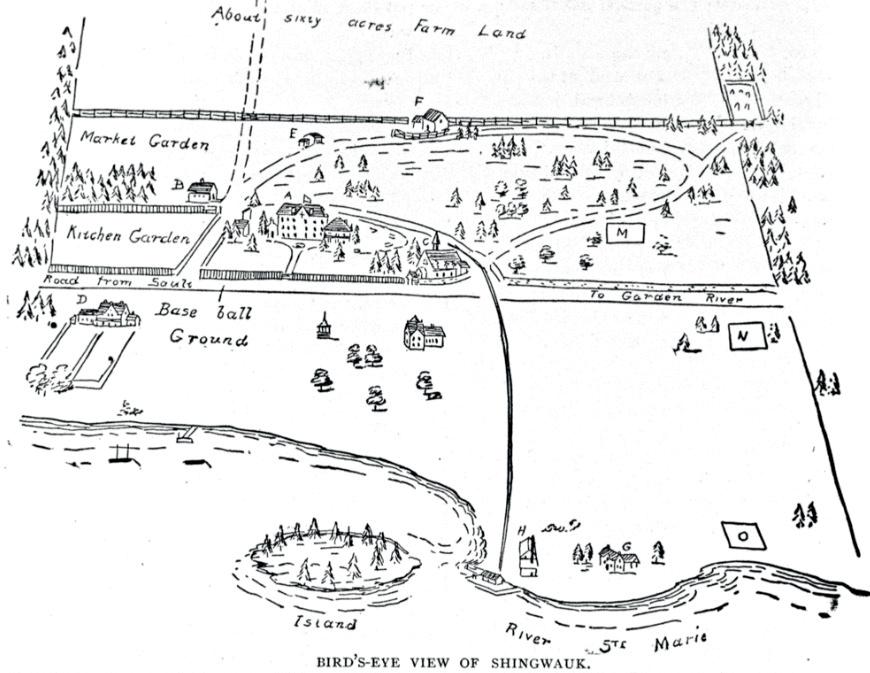

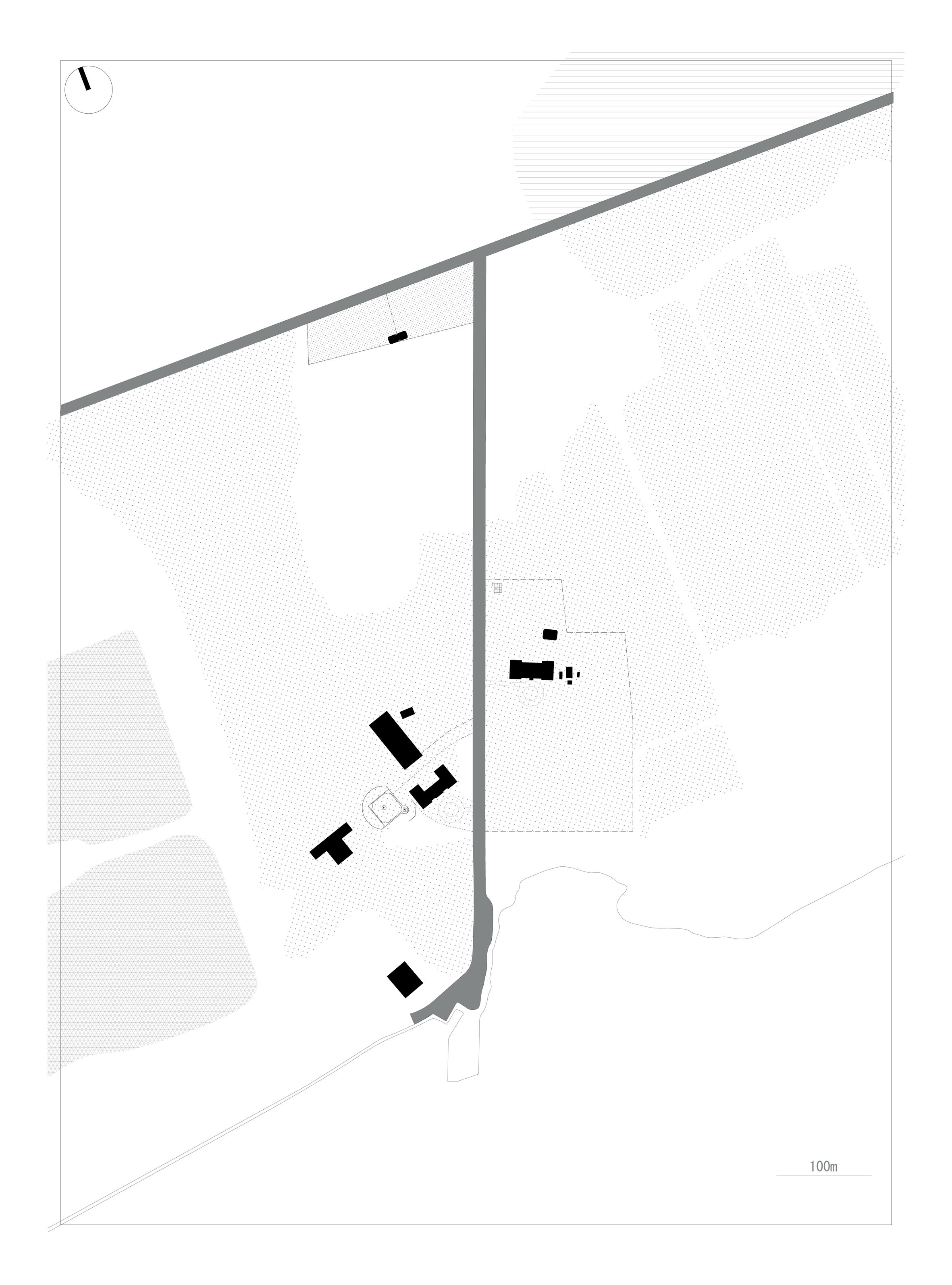

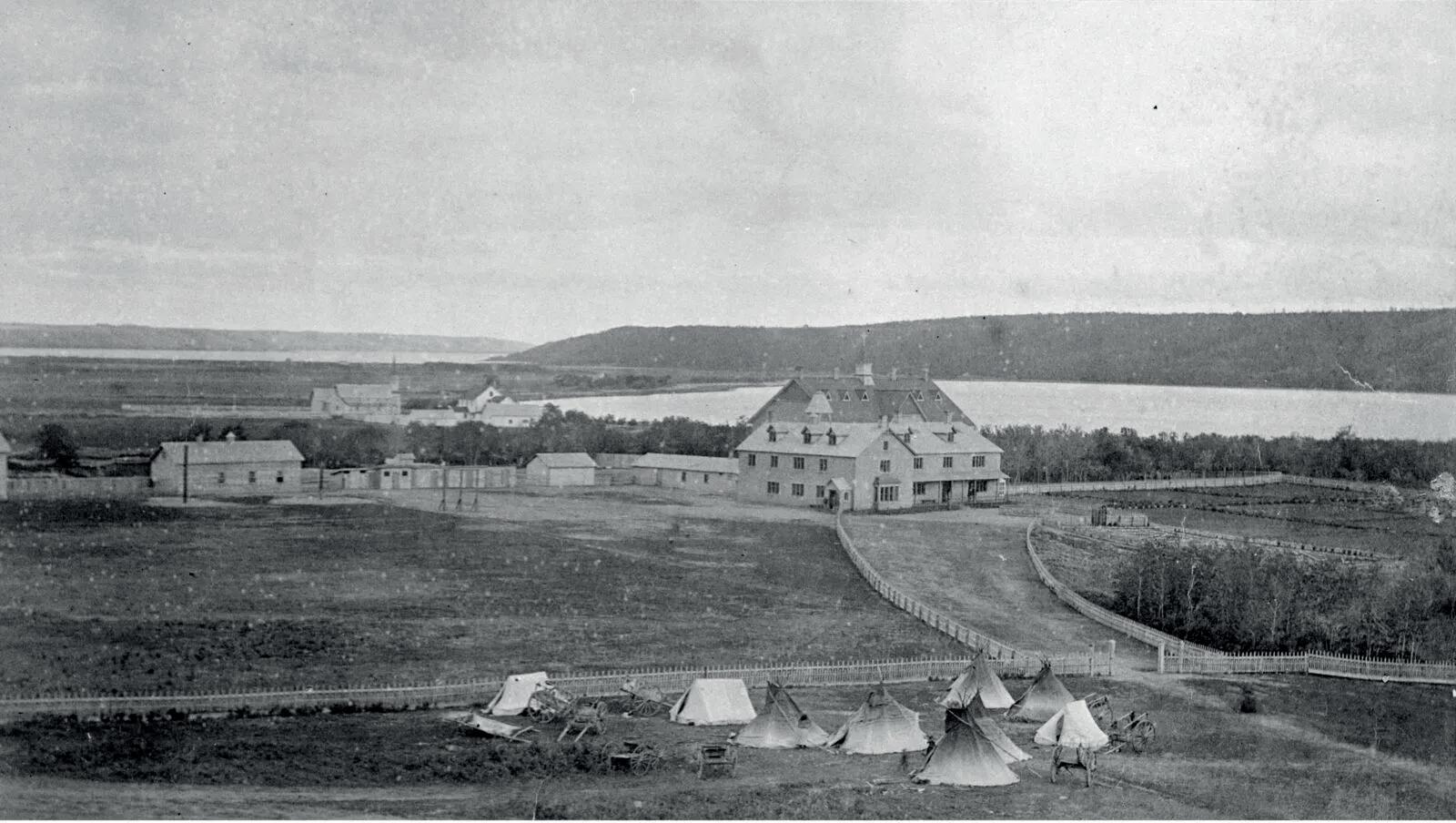

Wilson’s choice of location for Shingwauk followed Davin’s model. Sault Ste. Marie was at a crossing point of steamboat lines, soon to be near the site of railway lines, and visible to the public on a prominent spot on the river.69 90.5 acres of land was acquired for ‘Indian Education’.

During the industrial school era, the grounds witnessed many enterprises, industries, and programs. A working farm with livestock, dairy, a storehouse, barn, and stable, a hospital, the principal’s family residence, and a chapel with cemetery occupied the grounds. There were various other outbuildings where vocational skills such as carpentry, printing, tailoring, shoemaking, and weaving were taught. Towards the 1930s, the various trades and infrastructure that made up ‘industrial education’ were dismantled in favour of a new program of rudimentary formal education.70 In the 1940s and 1950s, Canada began to integrate the Indian Residential School system with the Public School system. These changes are reflected in materials produced by the Shingwauk School at the time. This “Handbook for Boarding Parents” (Fig. 64) was addressed to Canadian families who took in Indigenous pupils in Sault Ste. Marie so the children could attend the public schools.71 This preceded another damaging era for Indigenous Children through what is known as the 60s scoop.72

Fig. 64 Handbook for Students and Boarding Parents, Sault Ste. Marie. n.d. [likely 1954-1966] SRSC, Synod of the Diocese of Algoma Fonds, 2013117/002/005.

History: Inventory of Spanish Residential School Explored,” The Eastern Door (blog), June 27, 2016.

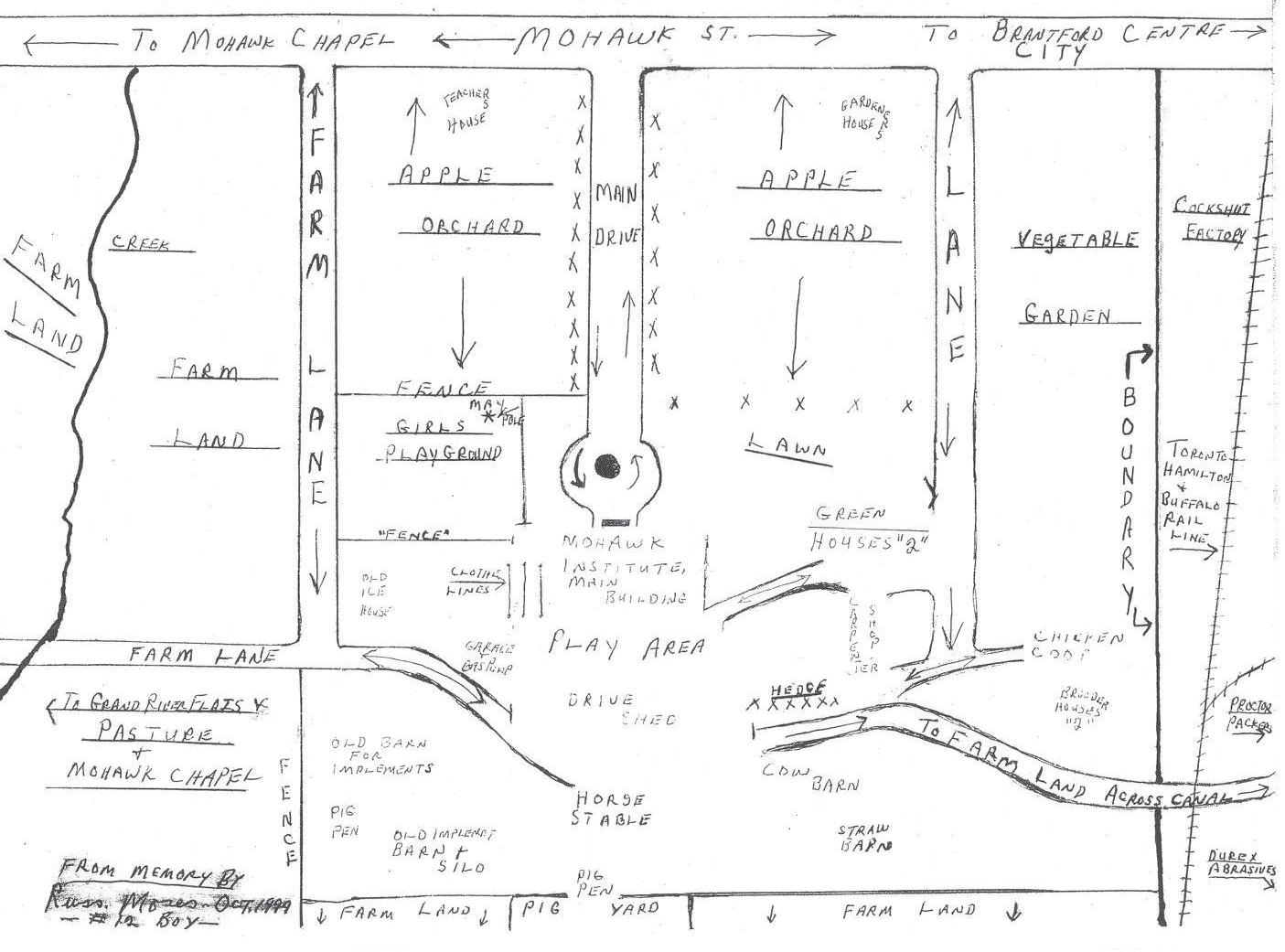

The Mohawk Institute was situated on 10 acres of land, surrounded by the Six Nations Indian Reserve No. 40. This land was returned to the reserve upon the closure of the IRS. The school also used made use of a 200-acre Manual Labour Farm, and the 220-acre Parsonage.

A sketch of the site plan of the Mohawk Institute (Fig. 68), scribed from memory by a survivor, shows to the extent of which the land was organised as a productive landscape. The drawing also marks the clear boundaries that were imposed onto the children’s freedom. Fences, roads, rail lines, and farmland that surround the main building on all sides.

The construction of the Indian Residential School at Spanish River again followed the same recommendations. This time, on the north shore of Lake Huron, half a mile south of the village of Spanish on the Canadian Pacific Railway branch line from Sudbury to Sault Ste. Marie on a 300-acre lot.

The main structures at Spanish were built of stone, with a full basement, containing dormitories, classrooms, dining rooms, a kitchen, laundry room, furnace room, and reception area. Barns, stables, a mill, and several annexed buildings used as storerooms were also used by the school (Fig. 71). The school produced eggs, chickens, beef, veal, potatoes, turnips, and carrots.73 73

2.5 1:500,000

74 Vanessa Watts, ‘Indigenous Place-Thought and Agency Amongst Humans and Non Humans (First Woman and Sky Woman Go On a European World Tour!)’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 2, no. 1 (4 May 2013), https://jps.library. utoronto.ca/index.php/des/ article/view/19145.

The sites of the Residential Schools were often described in terms of their availability of resources, and the positive changes of cultivation done to the land. This colonial view was also meant to set an example for how the children should relate to the land—as a site for extraction. Vanessa Watts discusses a problem with non-Indigenous ways of thinking about land and place, where we separate ontology and epistemology (the way of thinking about the land and the experience of being on the land). In Indigenous traditions, ontology and epistemology are inseparable. “Settler common sense”, weaves the way Settlers “think place” into every aspect of Canadian society.74

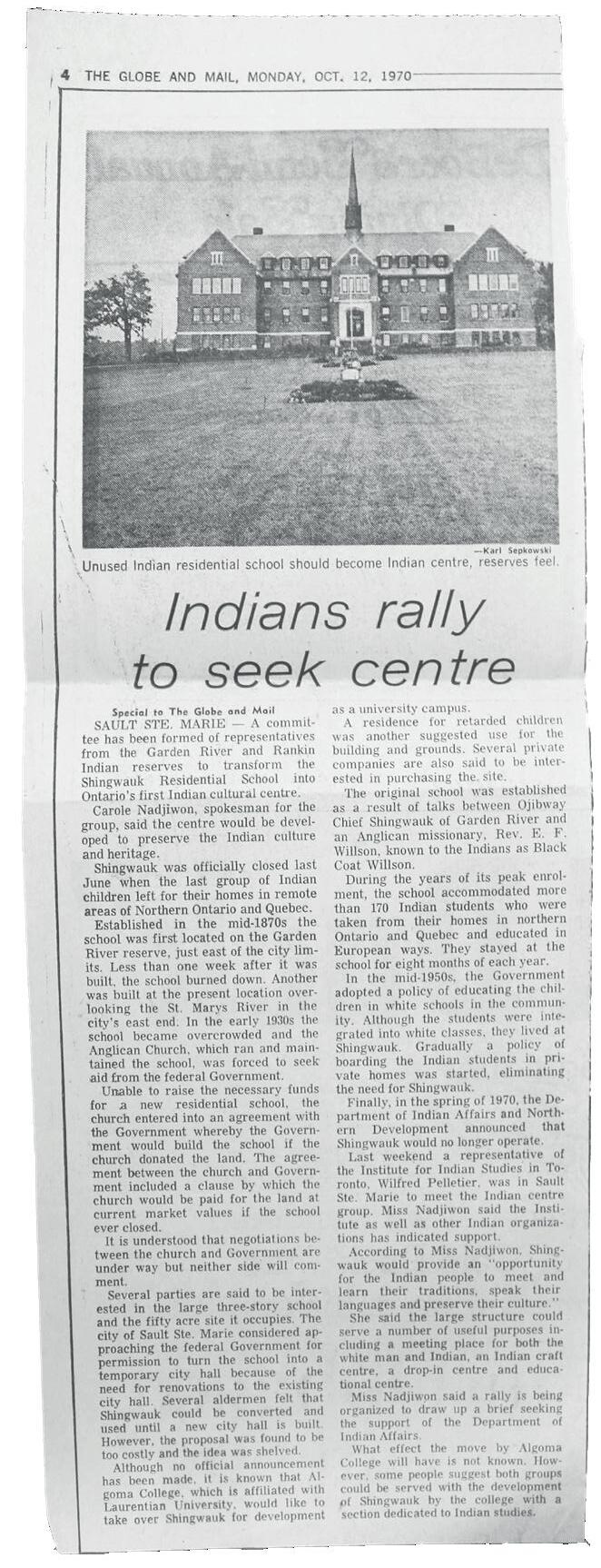

Fig. 74 Newspaper clipping from The Globe and Mail (1970) On one hand, Indigenous communities rallying for their rights to this site, and the need for Indigenous education led by Indigenous educators.

Fig. 75 On the other hand, the claiming of these buildings as important heritage by a local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee. (The Sault Star (1979)).

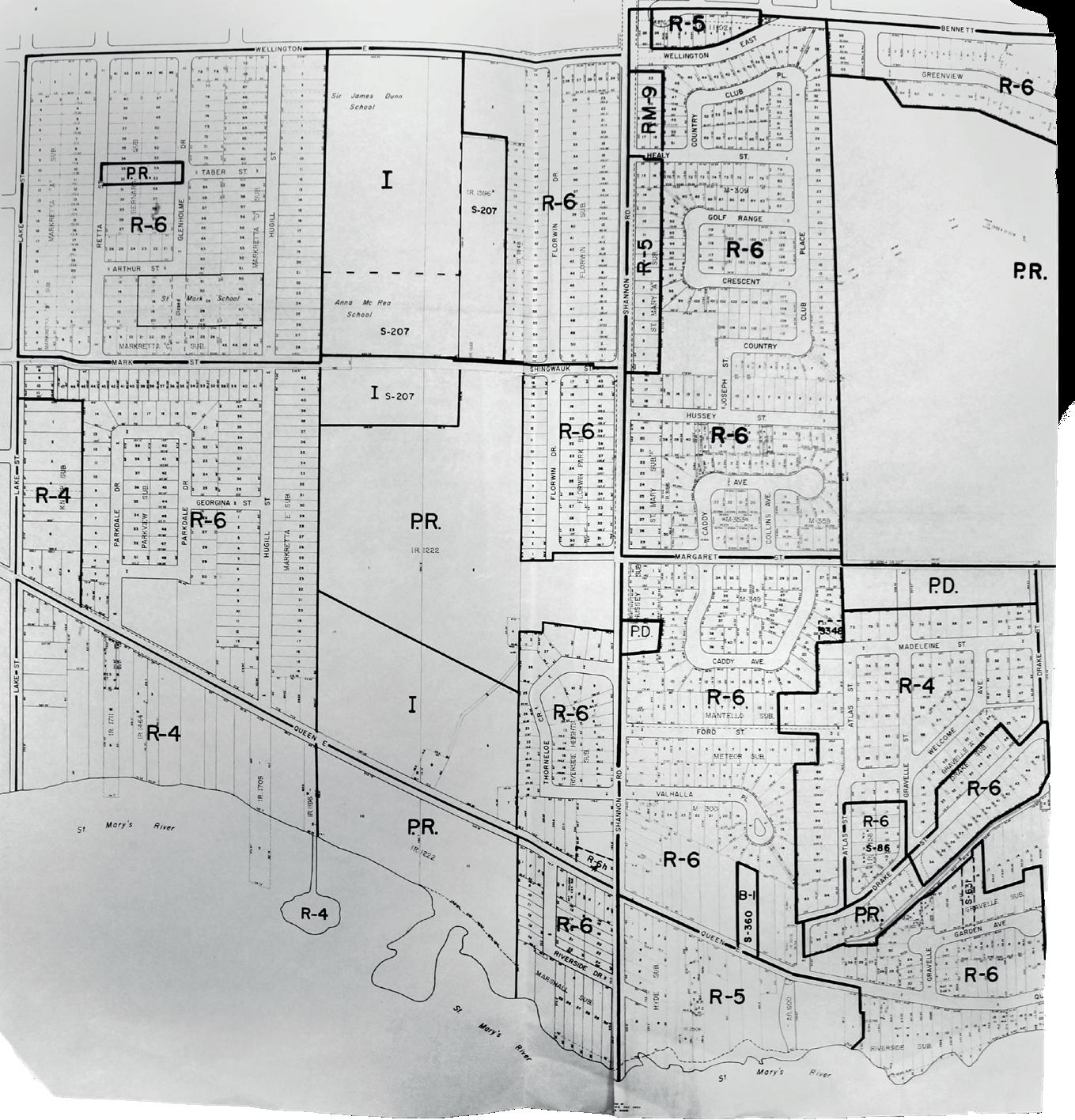

Fig. 76 In reality, shortly after Shingwauk closed, the surrounding land was subdivided and consumed by the city as suburbs. SRSC.

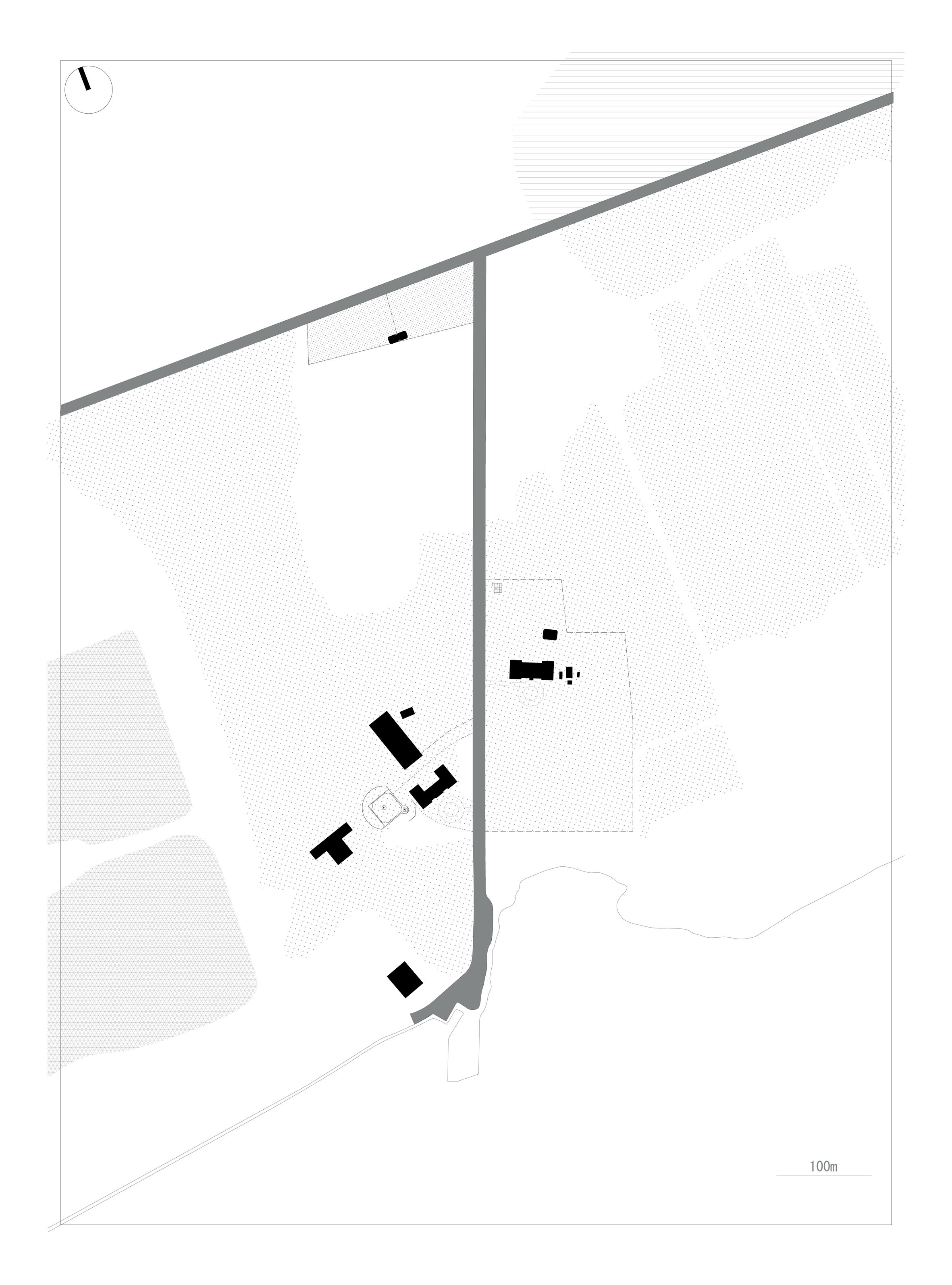

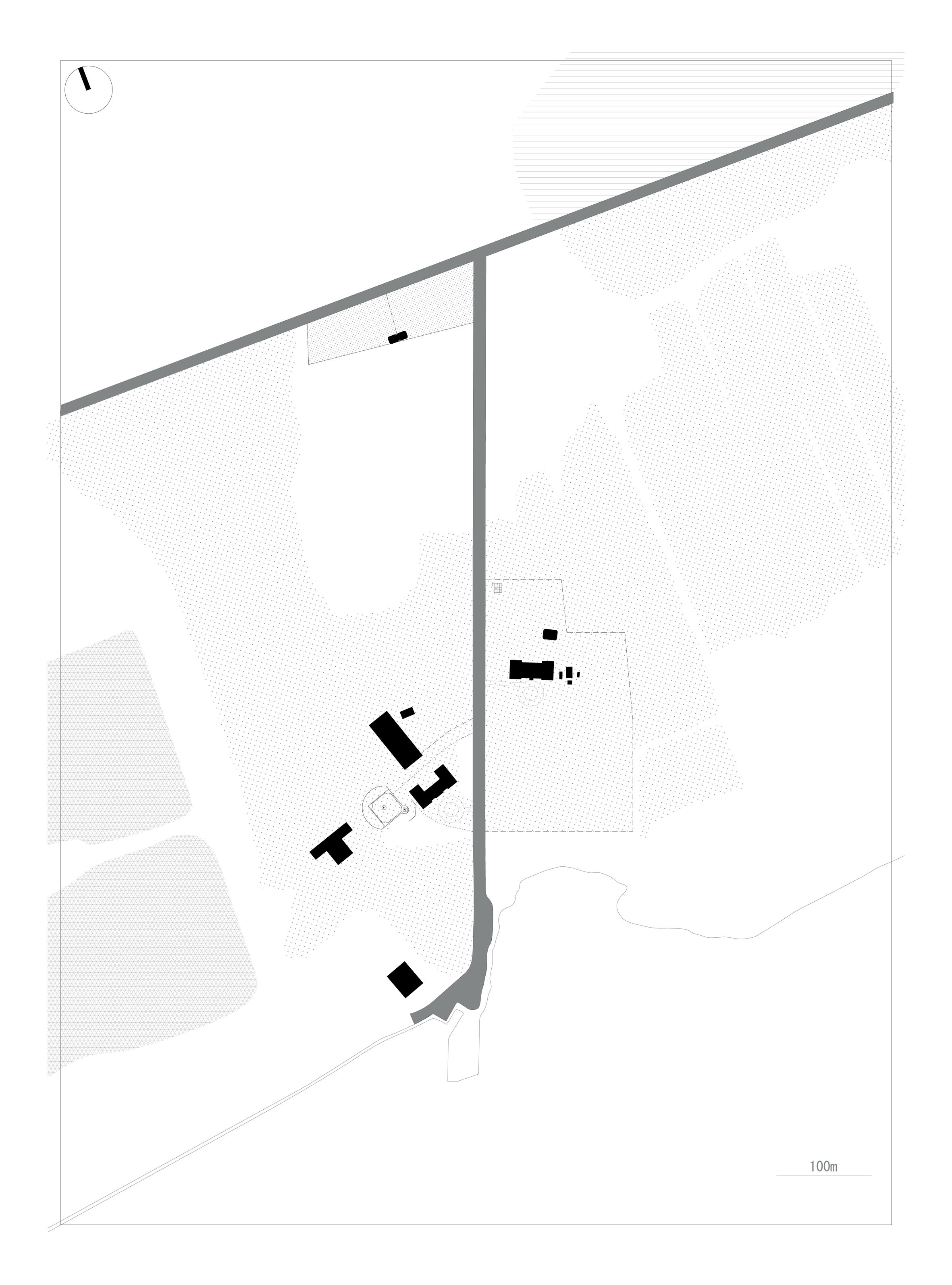

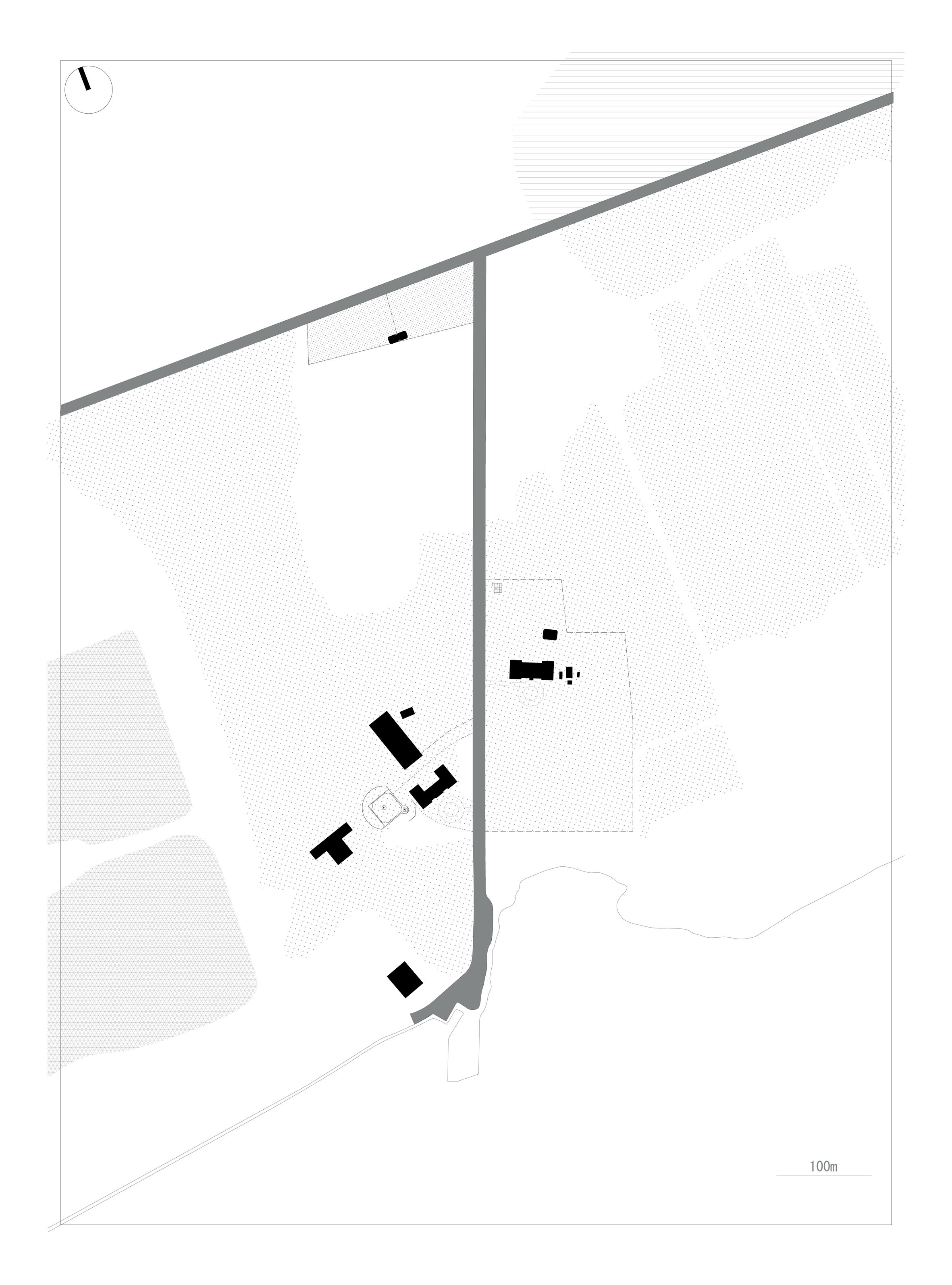

3.1 1:500,000 Wilderness Nimbyism

3.2 1:500 Staging Utopia

3.3 1:100 Spaces for Collectivising

3.4 1:20 Markers of Wilderness

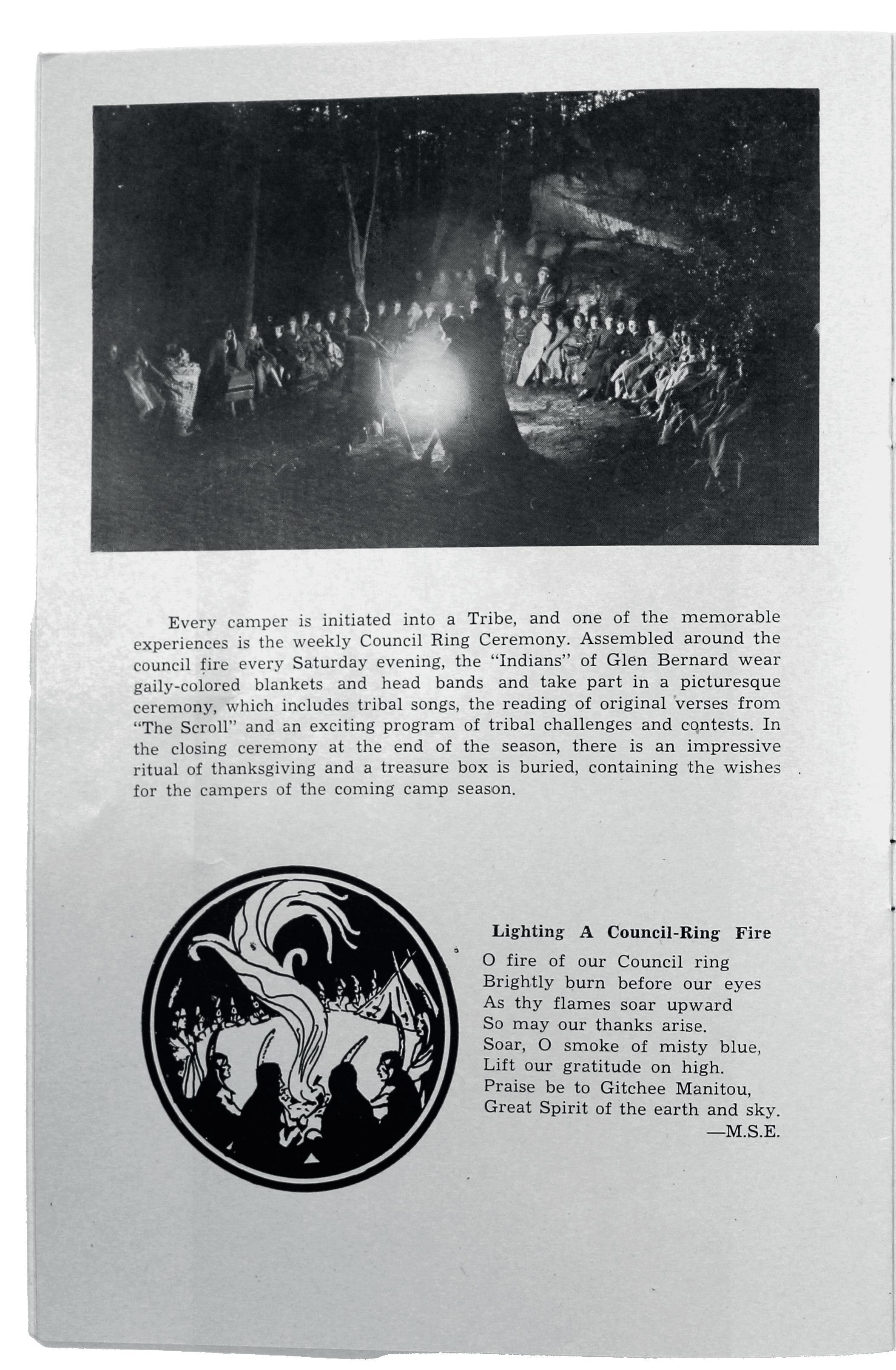

3.5 1:1 Becoming Leader