...Anche i sogni im possibili

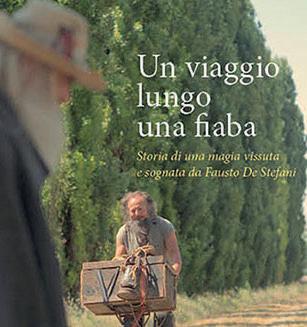

uin i esi o tto i a i Fausto De Stefani

S A S A Mattia Fabris

Mattia Fabris

Mattia Fabris

Mattia Fabris

Jacopo Maria Bicocchi

Jacopo Maria Bicocchi

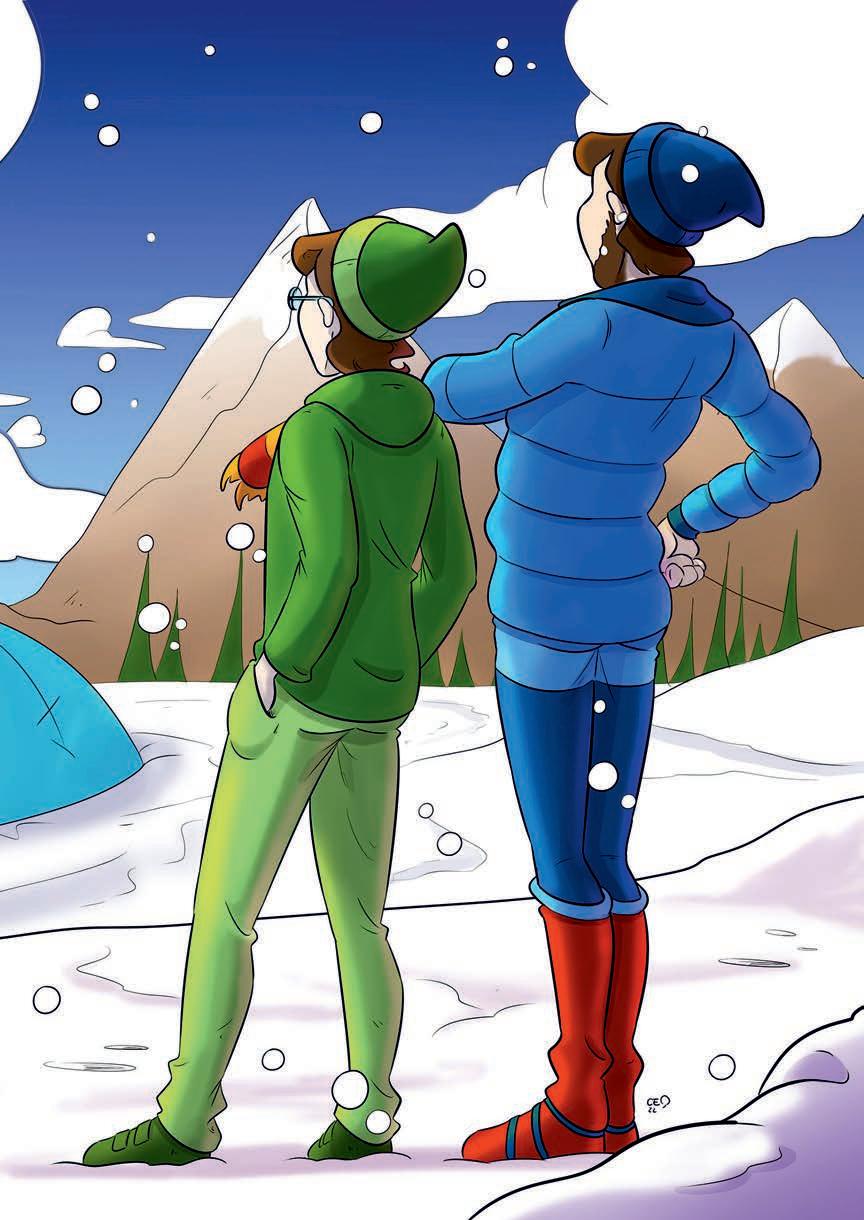

Siamo due amici. acciamo gli attori e amiamo la montagna. al desiderio di unire queste due passioni nato il nostro duo teatra le, la prima compagnia teatrale che coniuga teatro e montagna “Compagnia S legati”. nostri tre spettacoli, “ S legati”, “ n alt r o verest” e “...Anche i sogni impossibili l ttomila di austo e Stefani” sono sto rie di montagna. Sono storie grandi, epiche paradigmatiche, capaci di contenere anche le nostre, di parlare a tutti, montanari e non. Storie in cui possiamo riconoscere qualcosa di noi, dell uomo e della sua natura più profonda.

n dieci anni di attività abbiamo fatto più di repliche su tutto il territorio nazionale. nostri palcoscenici, oltre a quelli di tutti i tea tri italiani, sono le montagne rifugi alpini, comuni d alta quota, festival della montagna, dell avventura e dell outdoor, sedi CA e SA . acciamo spettacoli capaci di adattarsi a qualunque spazio e condizione, convinti che il teatro sia prima di tutto un mezzo per incontrare gli altri e, nel nostro caso, la natura, la sua bellezza e il suo silenzioso mistero.

l libro che state per leggere la traduzione su carta del nostro ulti mo lavoro “...Anche i sogni impossibili l ttomila di austo e Stefani”. o spettacolo nato dall incontro con una persona speciale e rara, una di quelle con una storia da raccontare, che va ben oltre i confini della montagna austo e Stefani.

Jacopo Maria Bicocchi Mattia Fabris

ontu a itin i a o ato io eati o e a asa e it i e i ontu a i an ita iano ea e ne a i ia ento e ne e a atu e e a onta na e e out oo e o so e i anni ien a a s i u ato un e o so i o uni a ione o i ina e in inea on i otto Sea in fo a ne a soste no a a o u ione ine ato a a e ette a ia e i ione i etta i a une o e e su o to i festi a u tu a i ost e a te asse ne usi a i Di a ti o a e si ni ato i soste no a o s i u o i a uni uo i i a o e a tisti o e a ienta e atti it i ontu a itin si o eta on a uni inte enti i so i a iet a i e o na iona e e inte na iona e

Decine di pubblicazioni tra libri e cataloghi, disponibili nei negozi o scaricabili gratuitamente dal sito.

Dozens of books and catalogues available in stores or as free download from the website.

Più di 70 film co-prodotti e/o sostenuti in vario modo, vincitori di numerosi riconoscimenti. More than 70 films co-produced or backed in various ways and recipients of numerous awards.

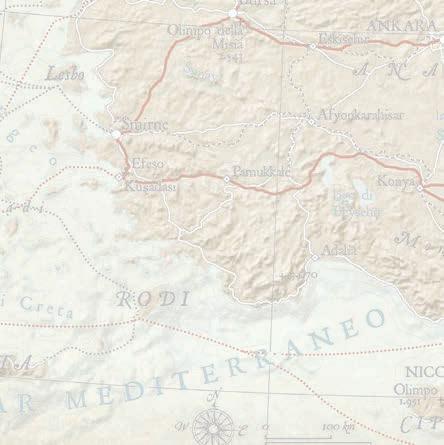

Un’accurata rappresentazione del territorio per descrivere cammini, itinerari, percorsi di gara

Accurate representation of the territory in descriptions of trails, routes and competition courses

Importanti progetti di solidarietà e cooperazione allo sviluppo in Nepal, Mongolia, Perù e Italia.

Major charity and development cooperation projects in Nepal, Mongolia, Peru and Italy.

Molteplici attività al sostegno dei giovani e di iniziative sociali e culturali: festival, concerti, mostre, teatro

Multiple youth support programmes and social and cultural initiatives: festivals, concerts, exhibitions, theatre

Il territorio e i luoghi d’eccellenza da conoscere e tutelare The region and its outstanding places to know and protect

Questa pubblicazione contiene i testi integrali dello spettacolo teatrale scritto e interpretato dalla Compagnia (S)legati.

This publication contains the complete text of the theatrical play written and interpreted by the company (S)legati

A Frida, Arturo, Marlene e Romeo. E agli adulti che diventeranno.

Il quindicesimo Ottomila di Fausto De Stefani

Testi di Disegni di

Jacopo Maria Bicocchi e Mattia Fabris

Michele Avigo, Agnese Blasetti e Micol Ceoletta

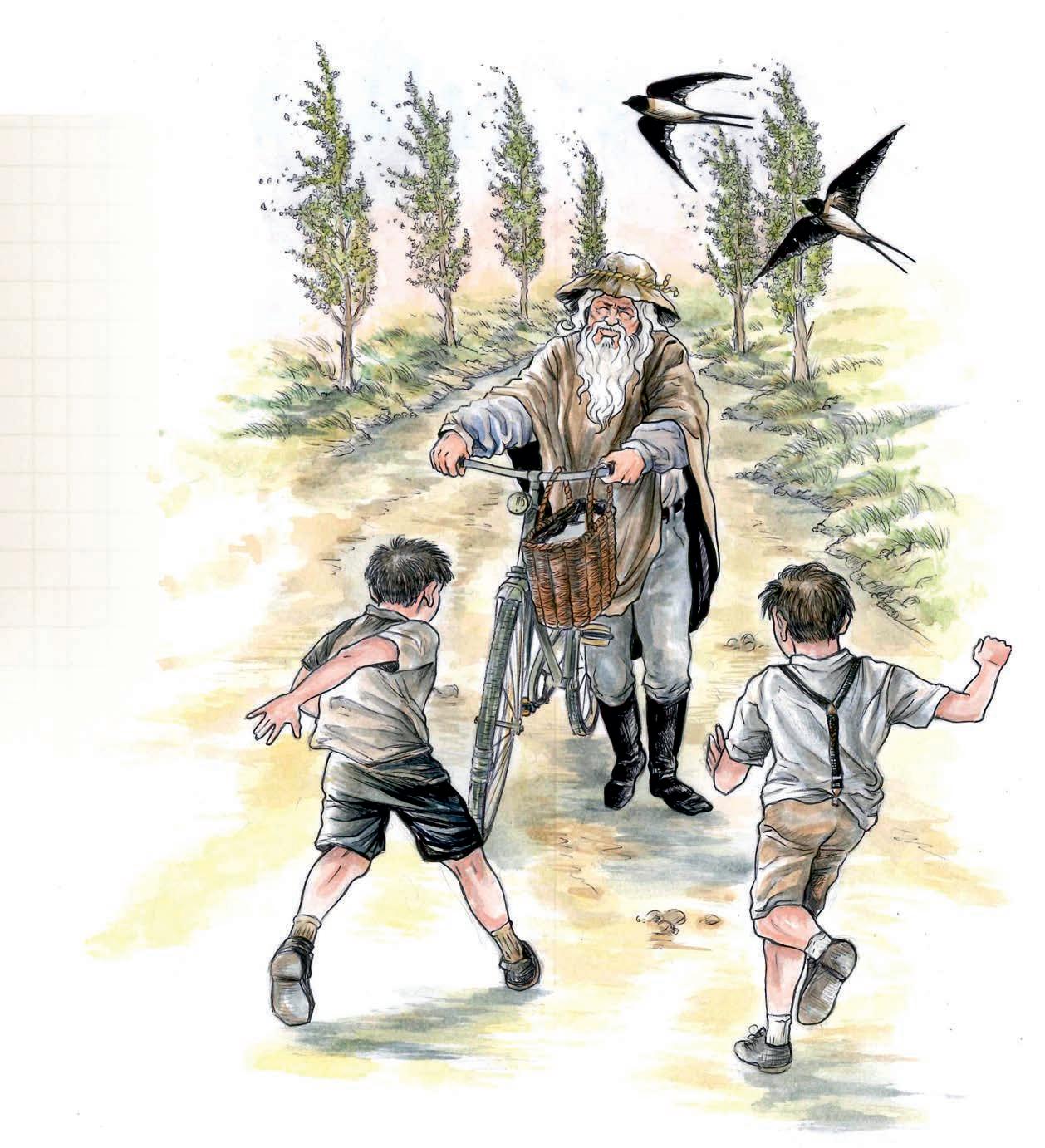

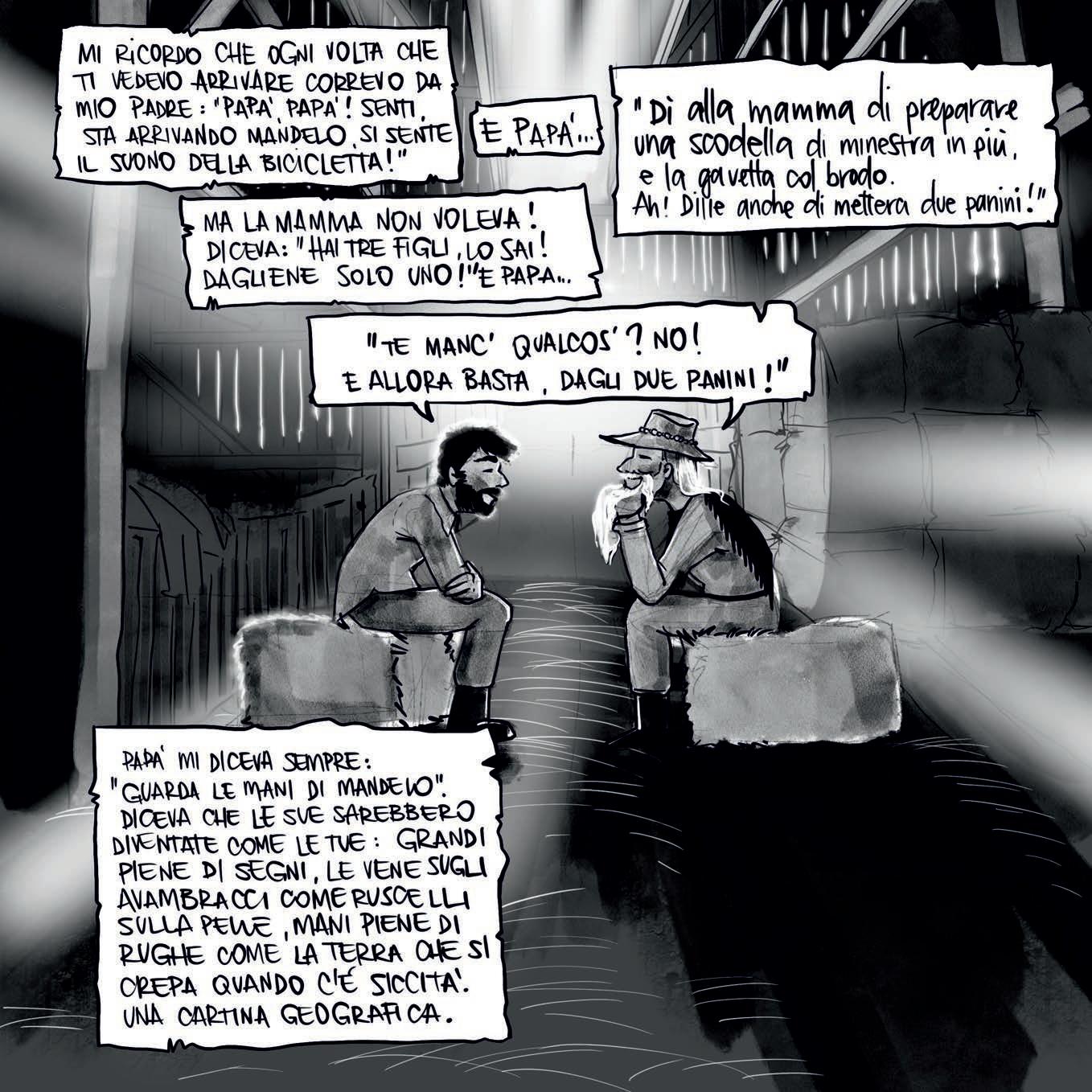

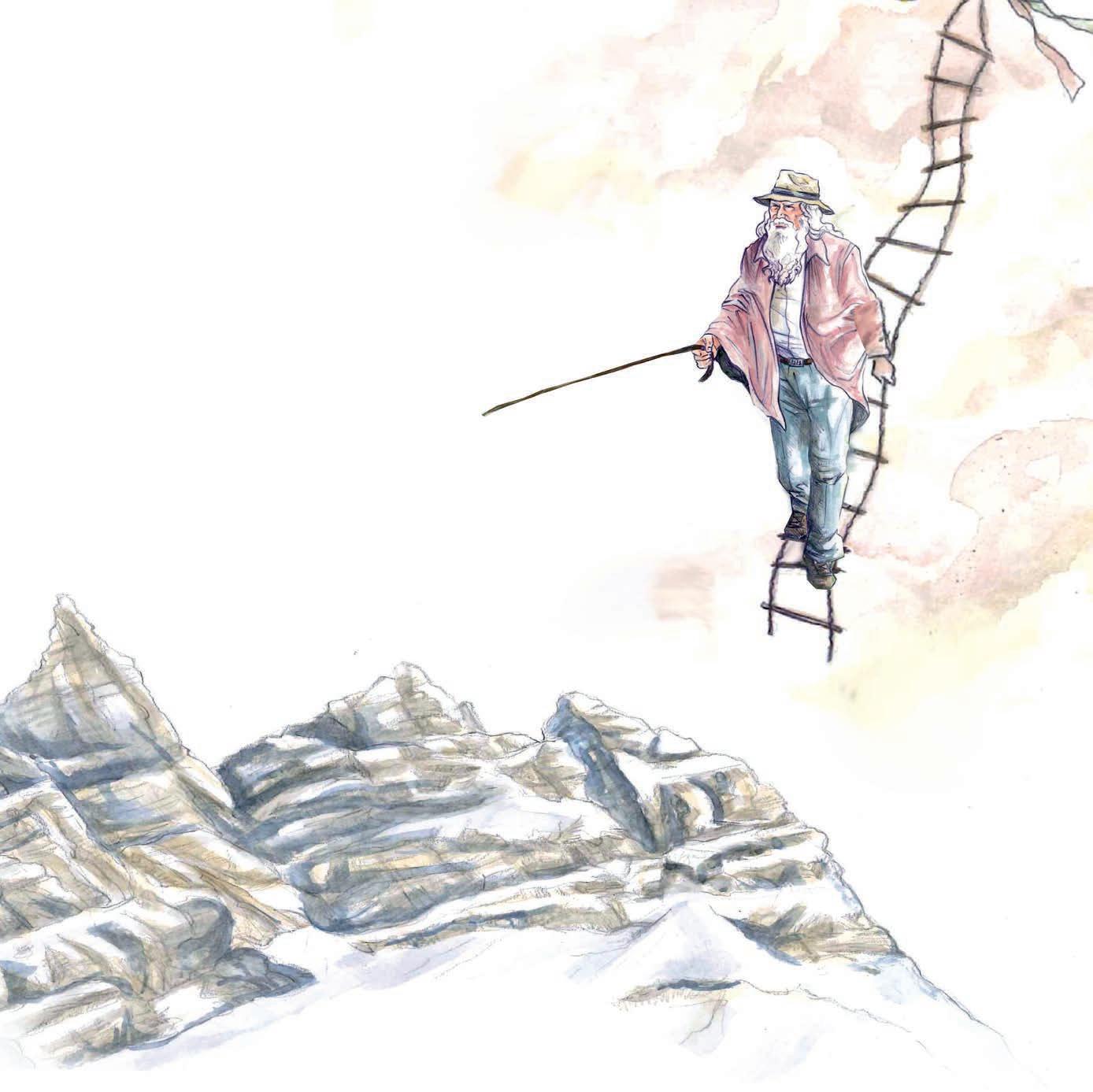

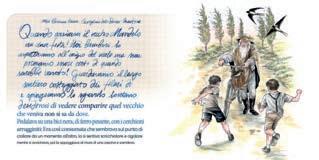

divedere comparire quel vecchio che veniva non si sa da dove.

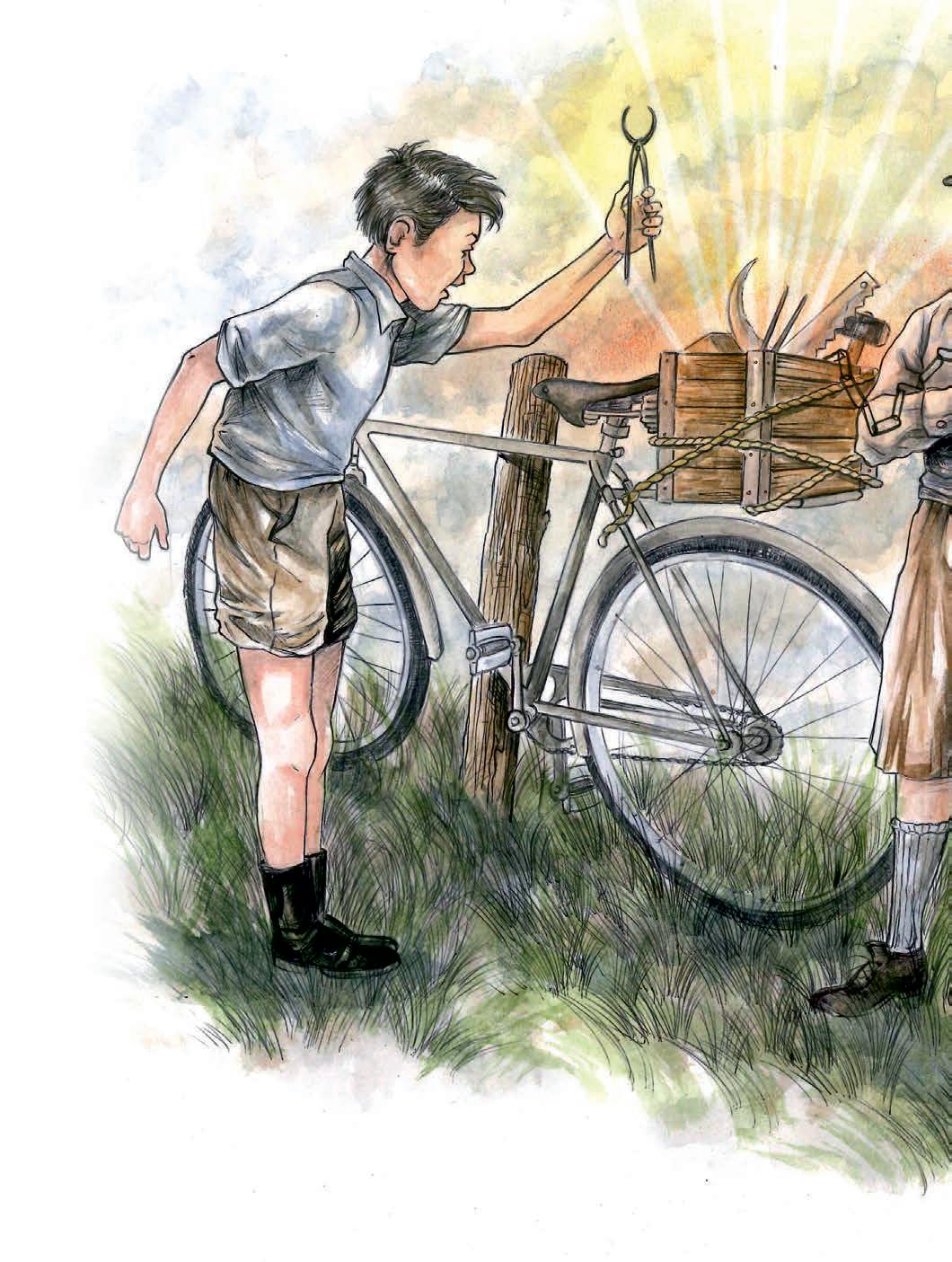

Portava una barba lunga fino al petto e bianca come il latte. La testa pareva scolpita, e la sua fronte era spaziosa e rugosa. Il naso pronunciato e la bocca nascosta da lunghi baffi. I capelli erano lunghi e mossi. Sembrava lo stregone uscito da un libro di avventure e la sua bici il suo destriero nero. Aspettavamo che il vecchio si allontanasse dalla bici e, una volta sicuri di non essere visti ci avvicinavamo per vedere cosa Mandelo portava con sé in quella cassetta di legno che teneva legata sul portapacchi.

- Ci sono un sacco di rottami!

- Cosa, cosa?

- C'è una pinza, una tenaglia arrugginita, c'è anche una roncola ma è senza manico! - E cosa se ne fa? - Boh,…Mandelo riutilizza sempre tutto non lo sai? C'è anche un falcetto. - E poi? - Poi c'è una cosa strana, sembra una specie di sega - Fà vedere…Una lucertola! - Dove?

- Ma no, la sega! Si chiama lucertola!

- Poi c'è un chiodo consumato, un cerchio di cartone e un sacco di filo di ferro…

- Basta adesso, andiamo via che se torna si arrabbia. - No aspetta…c'è anche un’ancora legata ad una corda… - Ma allora era un marinaio!

- Ma va! Era un montanaro. - Secondo me era un marinaio… - Io invece dico che era… -

Aspettavamo che Mandelo si avviasse verso la stalla dove qualcuno lo avrebbe ospitato per la notte. Poi, dopo cena, il vecchio accennava un richiamo e quello era il segnale: ”Comincia!”- gridavamo, e tutti assieme correvamo nella stalla, ci sedevamo in cerchio, in silenzio e aspettavamo. Lui accendeva una piccola lanterna, si sedeva con noi e poi restava

così, con gli occhi socchiusi a guardarci. I suoi modi ci intimidivano, ma poi cominciava a parlare e la sua voce accarezzava il silenzio e lo rendeva familiare. Non era una voce come tante, anzi, non somigliava a nessun'altra, era una voce abituata a dialogare con i fiori, con il cielo, con la terra. Era una voce che invitava l'immaginazione.

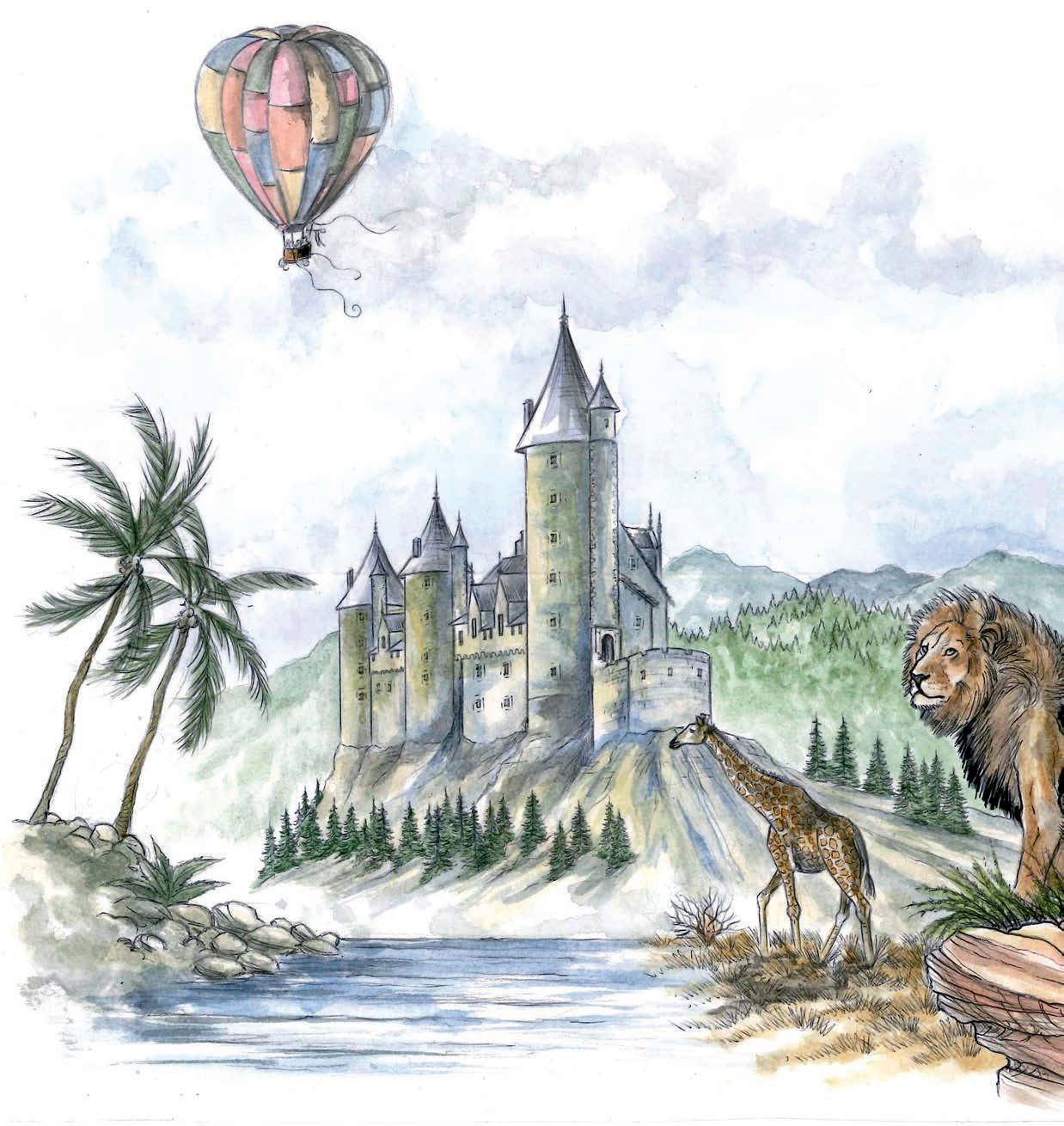

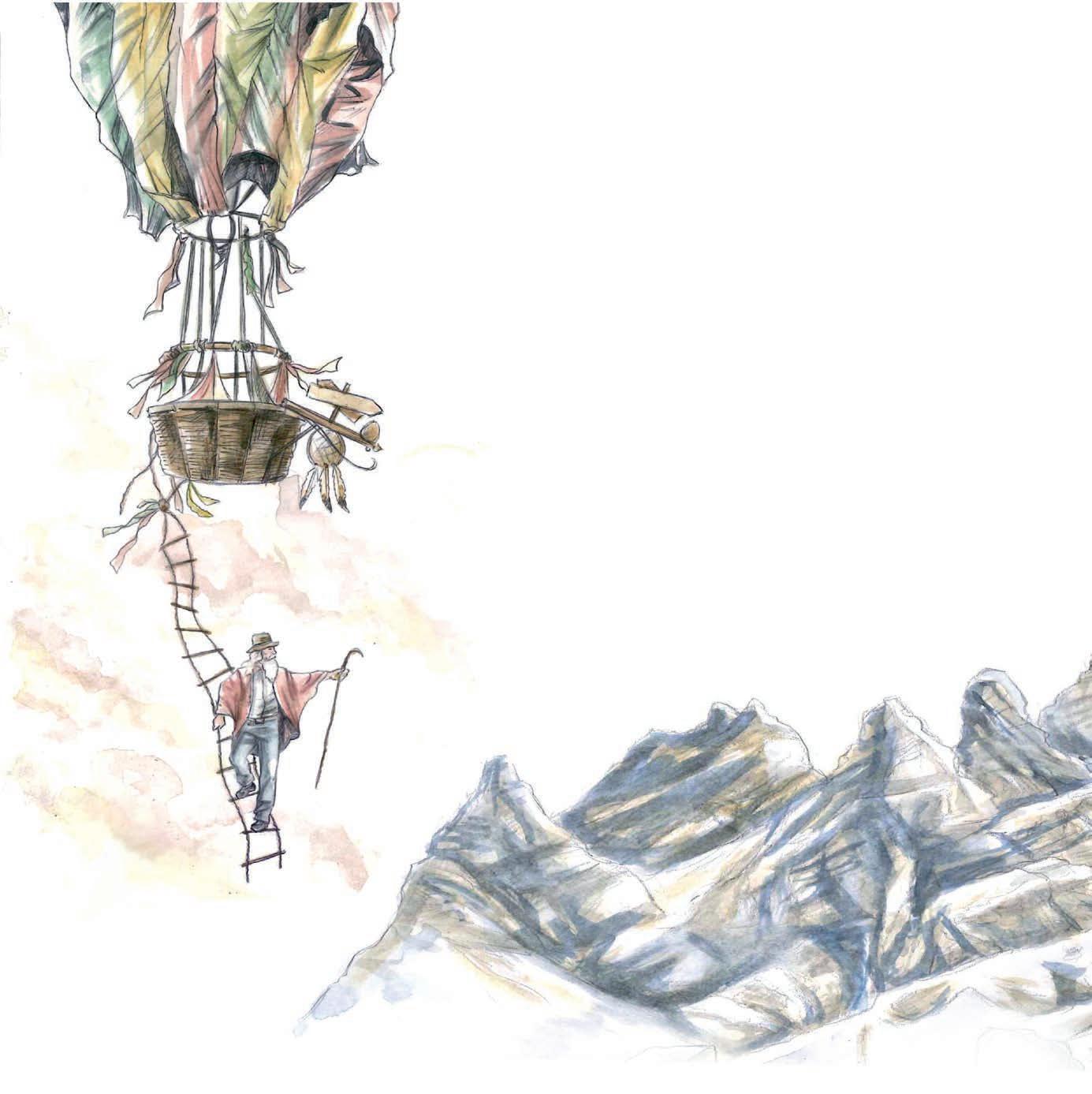

“Non potremmo farne a meno”, cominciava, “senza, non potremmo andare da nessuna parte!” “Senza cosa, senza cosa”, chiedevamo noi. “Mi serve una mongolfiera”, rispondeva sicuro. E si alzava di colpo, lasciandoci lì, trepidanti. Lo vedevamo armeggiare nella cassetta di legno che portava sul portapacchi, slacciare i legacci che ne tenevano chiuso il coperchio e poi riapparire con una stoffa bianca arrotolata sotto il braccio.

”Questo è solo un pezzo della mongolfiera” sentenziava, “apparteneva a un mio amico…basta qualche

rammendo e con questo posso volare sicuro, dove mi pare, trasportato dai venti.” “Ma perché vuoi partire in mongolfiera?”, domandavamo noi, ma Mandelo non rispondeva, era già salito sul cesto e noi già volavamo con lui. “Quello è un ruvido deserto” esclamava “e quella laggiù la vedete? Quella è l'acqua bambini! L'acqua, che tutto bagna e tutto disseta!” E noi vedevamo torrenti, ruscelli, laghi e oceani, poi l'ombra morbida della mongolfiera accarezzava il grembo delle valli e anneriva le rocce delle montagne*.

*Le montagne. Le prime che vidi furono quelle che il vecchio ci mostrò dalla sua mongolfiera.

Una sera d'inverno, quando il freddo costringeva i pochi abitanti delle cascine a riunirsi nelle stalle per scaldarsi attorno ai racconti degli adulti, sentimmo lo sferragliare della bicicletta di Mandelo affiorare dalla notte!

“Mandelo, Mandelo!” gridò subito qualcuno di noi.

“Dove sei stato, dove sei stato?” chiese uno dei bambini più grandi seduto su una balla di paglia.

“Oh beh….volete che ve lo racconto?” rispose lui sornione.

“Sì, sì, sì, racconta vecchio! Racconta!”

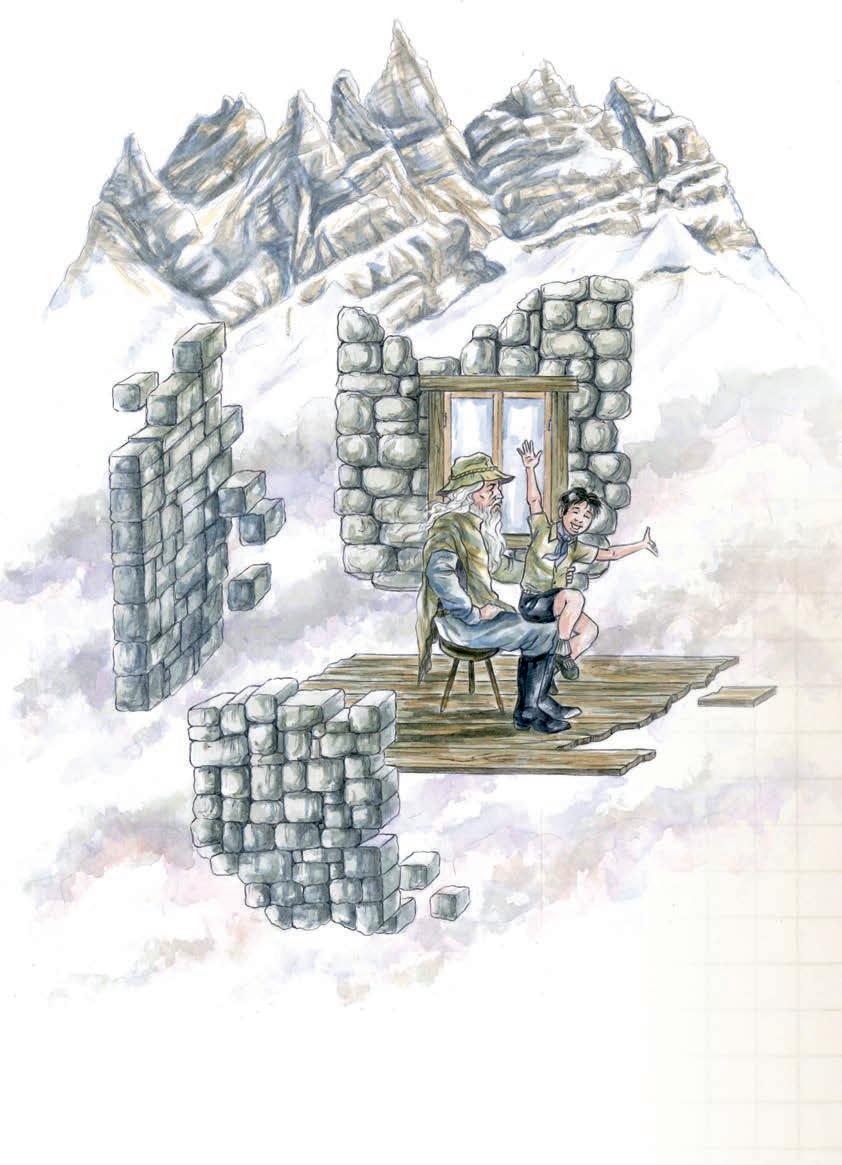

Mandelo allora si fece serio, si strinse nel vecchio pastrano e ci guardò tutti uno ad uno, come se cercasse la radice delle parole dentro ai nostri occhi, ai nostri cuori. Il mio sobbalzò, quando mi disse “tu, vieni, siediti sulle mie ginocchia”.

Mi guardai intorno: “io?”

“Sì, sì, tu, mi serve un aiutante stasera, siediti sulle mie ginocchia”. Intimorito e al contempo curioso, attraversai il cerchio e, raggiunto Mandelo, mi sedetti sulle sue vecchie gambe.

“Ecco la vedi”, disse facendomi spaventare, “la vedete?”

Le sue mani grosse e dinoccolate indicavano la porta semi aperta della stalla. Al di là di quella, contro l'ultima luce della sera, all'orizzonte, si scorgeva appena la montagna col cappello bianco, il monte Baldo.

“Quando sarete grandi potrete salirci da soli”, continuò, “quella è la montagna più alta del mondo, da lì si vede tutto e adesso…voglio portarvici con la mia mongolfiera; forza copritevi che farà freddo”. Non ce lo facemmo ripetere due volte, ci imbacuccammo alla bell'e meglio e ci preparammo all'avventura: “Guardate” disse ancora lui, “stasera le nubi sono fitte e scure ma noi ci passeremo in mezzo per sbucare lassù, dove ancora si vede il tramonto. Forza ragazzi salite con me!”

“Coraggio!”gridavalui,“cisiamoquasi, dobbiamosalireancorasevogliamo arrivareincima!Daigas,ragazzo,dai gas!”

Glialtribambiniriseroquandomividero arrossirementrefacevofintaditirareleve egiraremanopole.“Così,ragazzo,bravo, così!Cisiamoquasi!Lavedi?Quellaèla vetta,daliìsivedetutto!”

Esiìlavedevamo,lavedevodavvero. Sedutosullesueginocchia,ilpavimento terrosodellastalla,solo45cmsottodime, sparivaperlasciarespazioavoragini mozzafiatoestraordinaristrapiombiele muradellastallasiscioglievano,per diventareorizzontisterminatidove l'occhiosiperdevatralenuvolesottodi meeghiaccienevimillenarie. Ilvecchiostavaradicandoinmeilsognoe lafantasia.Forsequellasera,inquella stalla,siacceselascintilladiunavaga consapevolezza:perpotervivere pienamenteimieisogniavreidovuto spingermifinlassùeosare,assiemealmio vecchio,l'avventuradelviaggioinalto.

- Sei pronto? Dobbiamo ripartire.

- Mandelo? Ma che ci fai qui?

- Abbiamo fatto volare il nostro sogno, dobbiamo sentire che c'è sempre un altro sogno che vola più in alto, più lontano, solo così potremo inseguire anche quelli che sembrano impossibili.

- Anche quelli impossibili?

- Certo, altrimenti si perderebbero le sorprese a venire…vieni dài, sali sulla mia mongolfiera.

- Dove mi porti?

- Hai visto no, si vede da quassù, che la Terra è tonda, come si curva all'orizzonte, ma ti dirò una cosa: anche il tempo è tondo e si curva ad altri orizzonti.

- Il tempo?

- Sì, guarda.

Mandelo dall'alto della sua mongolfiera ci mostrava la Terra sotto di noi, la cascina rossa, i campi che terminavano al confine dei boschi, le regioni intere e da più in alto ancora la forma frastagliata dei continenti.

“Guardate laggiù” gridava nel vento, “viste dall'alto le cose si vedono meglio. Le proprietà, le staccionate, i giardini, i boschi…questo è mio, questo è tuo, i confini…quando ti alzi e vai in alto tutto è armonico!”

Mandelo era il nostro modo di apprendere la geografia e la natura degli uomini. La sua fantasia era inarrestabile, ci portò negli angoli più remoti del globo, dalle distese di ghiaccio del Polo Nord fino alle terre arse dei deserti africani.

“Avete visto? Guardate laggiù!

Tutti quei bambini dalla pelle nera che alzano le mani per salutarci. Sono come voi! Ma non sono felici, perché non hanno cibo nelle pancine, non hanno acqua per dissetarsi, dobbiamo scendere e portargli ciò che abbiamo.

E io seduto sulle sue ginocchia, spegnevo la fiamma che ci teneva in alto e atterravo con lui su quella terra lontana: l' Africa!

Kenya. Sole, baobab, savana, caldo, sole, safari, sole, leoni, leopardi, gazzelle, e in mezzo un enorme colosso di roccia: il monte Kenya. Africa, la culla dell'umanità!

E quando sei lassù, in cima al Continente Nero l'unico colore che vedi è il… bianco! Neve!

Qui! Sul più grande ghiacciaio africano! Chi l'avrebbe detto eh! Neve, neve, neve e roccia che sbuca dalle nuvole bianche proprio sotto di te.

E adesso? Che me ne faccio di tutto questo?

Dove la metto tutta questa bellezza, cosa mi porto a casa?

Mandelo, vecchio amico, dove sei? Come la spieghi tu questa cosa, l'alpinismo, l'impresa, che mentre la fai è già sparita tra le tue dita e di essa non resta nulla, se non…

A che serve se nulla resta?

Da quassù lo sguardo spazia fin dove il sole si incendia all'orizzonte e diventa un enorme palla rossa che si inabissa all'equatore.

È questo il mal d'Africa? Questa profonda nostalgia, questa sensazione di esser vivi anche se non sai che fartene di tutta questa vita? Alla fine non resta che tornare giù, ripercorrere la strada fatta a ritroso: neve, rocce, pendii, pietraie, prima ancora foresta, e savana, e sentieri e le strade sterrate fino a dove iniziano le baraccopoli che abbiamo attraversato in macchina mentre uscivamo dalla città.

Oh Mandelo, li ho visti davvero poi quei bambini dalla pancia gonfia che si scavano giacigli nelle discariche per godere del calore dei gas prodotti dalla fermentazione dei rifiuti.

Li ho visti, maledizione, organizzare partite di calcio con palloni fatti di stracci, mentre noi, con gli zaini caricati sul tetto della jeep, ci apprestavamo a compiere la nostra sedicente impresa.

Alla fine non resta che tornare giù sì, ma per tornare là, in mezzo a quella discarica, a quel fetente campo da calcio; scendere sì, perché forse è quella l'unica montagna che vale la pena scalare, quella montagna di rifiuti; forse la vera impresa è quella di quei ragazzini scalzi e sporchi che ogni giorno sopravvivono senza sapere se troveranno qualcosa da mettere sotto i denti. Scendere sì e: “Tenete bambini! Questi sono per voi”.

E rovesciare un sacco pieno di palloni di cuoio e una pompa per gonfiarli assieme, palloni veri, per giocare davvero, che rimbalzano davvero.

E sentire poi la voce della mia guida: “Attento”, mi dice, “non farli correre troppo che altrimenti gli vien fame e bruciano quel poco che hanno accumulato durante la giornata”.

Li ho visti Mandelo.

Nelle missioni, al villaggio di Nauro Moru, dove bianchi battevano le mani per farsi servire da neri in livrea con lo sguardo basso e sottomesso, no!

Ho visto le stesse missioni circondate da orti e giardini rigogliosi e bianchi andare, chiusi nelle loro Range Rover, a vendere i prodotti della terra, a gente senza nulla, no! Che me ne faccio di tutta questo ghiaccio che mi circonda. Che me ne faccio se laggiù, in quel misero villaggio, non c'è nulla?

“Oh che terra ricca e fertile sarebbe questa se ci fosse dell'acqua!” mi dice il capovillaggio. “Lo sai, l'Africa, se ce l'acqua, è un paradiso!”

“E quanto costa? Quanto costa costruire un pozzo, maledizione!”

“Un milione di lire” mi risponde scoraggiato, “è una cosa impossibile”. Restiamoinsilenzioperqualchesecondo,comedavantiadunmuroinvalicabilepoi,come d'istinto,senzaaccorgermene,buttolipochesempliciparole:“Lasaiunacosa?Anchei

sogniimpossibili.Melohadettoungiornounamico.”Etuttocambia.

Via,siva,sitornainItalia.Maconqueltarlo.

Siparla,sifannoincontri.Duecentomilalirequi.CinquantamilalirelàesitornainAfrica “Ecco,hoisoldi,facciamolo”.

“Cosa?”

“Ilpozzo,facciamolo.”

Eallorasicominciaa scavare:primaamano,poiarrivaancheunamacchina,roba inglese,robachevagiù,altrochesalire;quibisognascendere,scalareunamontagna rovesciata,chesiinabissasottolaterra.

Scenderebisogna,etrovarla!Sì,l'acqua,cheinquellaterraèpiùdell'oro!Sì,eccoacosa servetuttaquelghiacciolassù!Atrovarlodinuovoquasotto,liquido,oroliquido. Eccocosaresta:questopozzo,cheunannodopo,allafineabbiamocostruito.

Questopozzo,chenelgirodiunaltroannocambialesortidelpiccolovillaggiodi Korogocho.

Questopozzo,chel'annodopotornoancoraavisitare. Chenonsonomicaguaritodal mald'Africaanzi,tutt'altro,equestavoltapossotornarcifiero,sì, manondivanagloria,no, madiungestoconcreto,cheresta,chesipuòvedere,questopozzo,chesipuòtocc… “Aspetta,machecifalìquell'uomo?”

“Chi?”rispondeilcapovillaggio.

“Lì,quell'uomoafiancoalpozzo…”

“Dicecherappresentalaproprietà.”

“Laproprietà?”ribattoio, “machedice,l'abbiamofattonoiquelpozzo,l'abbiamodonato alvillaggio,non…”

“Dicecheèdi…”

“Equellemostrine?”lointerrompoio,“quellemedagliesulladivisa?Cosarappresentano?” “Nonlosappiamo”,continualui,“maèarmato,lovedi?Enonpermetteanessunodi prenderel'acquaseprimanonpaghi.”

Restoimmobile,insilenzio.

Poi,comeunondachevienedalontano, sentocheilsanguemontaalleorecchie,sento cheilKalashnikovchelosconosciutovestitodamilitareportaalcollofamontarrabbia, frustrazione,violenza.

“Mano,chefai,aspetta,èpericoloso.”

Hapaurailcapovillaggio,tuttinehanno,mailsanguegonfialeorecchie.Aspetto,sì,ma miappostoenonappenalomettegiù,ilKalashnikov,miavvicino,loprendoinmano.Lo sconosciutourla,miinsegue,maètroppotardi:prendoilfucileecomincioabatterlo, sbatterlolì,suunarocciafinoachesispaccainduepezzienonservepiùanulla.L'uomo continuaagridarenellasualinguachenoncomprendomaormainemmenosento.Urla,si avvicinaalzandolebracciaingestod'attacco,maètroppotardi:c'èunbastoneperterra, èduro,èunaspeciedimazza.Loprendod'istintoelosbattoforte,ilbastone,forte,manon sullaroccia,sullasuaschienalosbatto,finoachesirompe.Ilbastone.Eluinonurlapiù. Sialza,piano,eseneva. Mivolto.Ilcapovillaggiomiguarda. “Tornerà”,diceconl'espressionedichitiperdonaperunpeccatochenonsaidiaver commesso.“Torneranno.Questaèl'Africa”continua,“halaformadiunapistola,eilKenya èilcane.Scappa.“

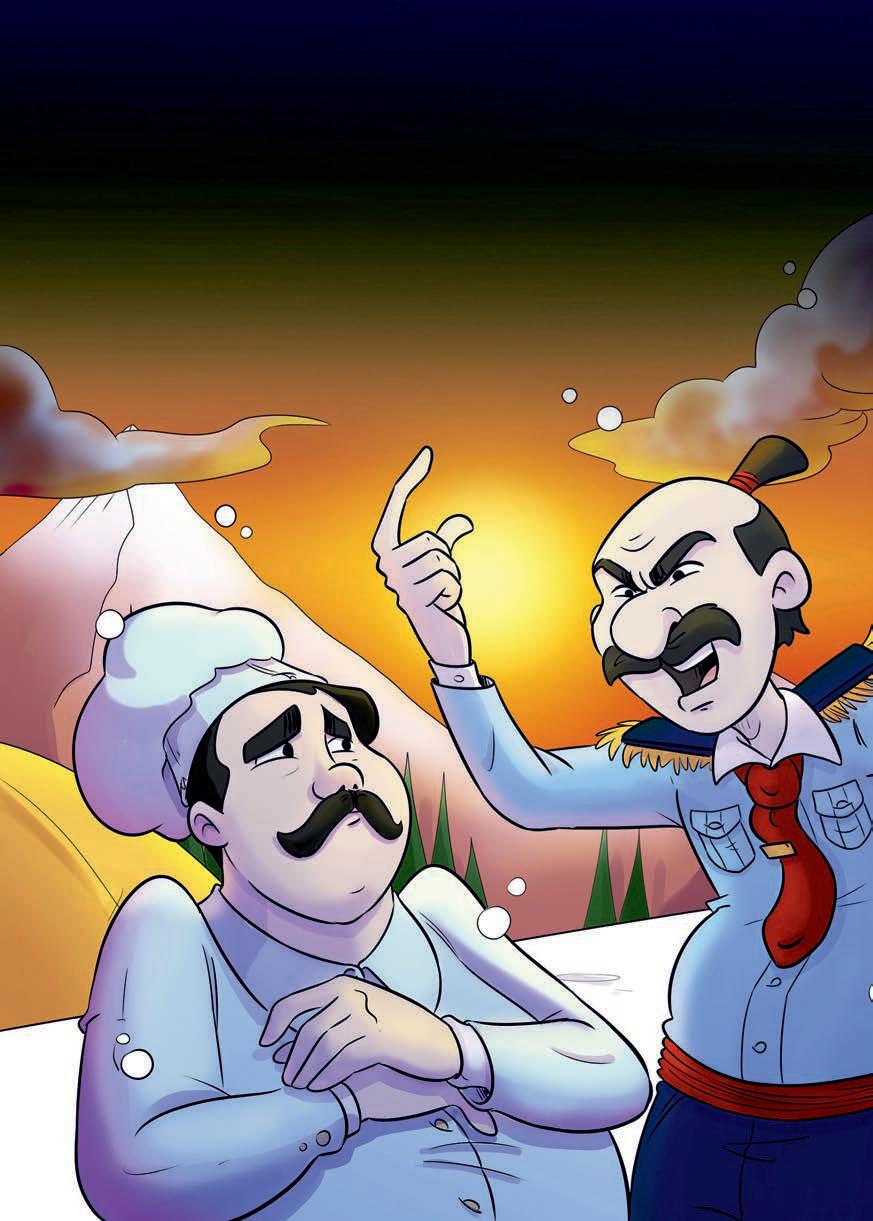

Testa Calda era un alpinista che aveva sempre la testa calda! Lui sperava che andando in montagna la sua testa si raffreddasse, ma anche in mezzo al ghiaccio la sua testa restava calda calda! Un volta, in una montagna lontana lontana, nella terra del Pakistan, Testa Calda era assieme al suo compagno di cordata Tobias Heymann, un grande musicista tedesco che faceva concerti al pianoforte n dall'altra parte del mondo. Con loro c'era anche un ufciale graduato, mandato da governo ad accompagnarli.

Testa Calda notò che, invece di usare le sue provviste, l'ufciale trafugava quelle della spedizione e si faceva servire da un portatore buono e umile che faceva anche il cuoco e lo umiliava ogni giorno trattandolo a male parole, come un servo.

Testa Calda si infuriava: “hai visto come tratta quel povero cuoco?“

“Sta buono”, gli diceva l'amico pianista, “quello è un ufciale, non si litiga con gli ufciali, è pericoloso.”

La notte seguente, prima di lasciare il campo base per tentare la vetta, Testa Calda sentì urlare fuori dalle tende, si affacciò e vide l'ufciale cattivo che picchiava forte il povero cuoco buono mentre era a terra.

Testa Calda non ci vide più, non si inlò nemmeno le scarpe, raggiunse l'ufciale cattivo e cominciò a riempirlo di botte.

Da quel giorno l'ufciale smise di trattare male il povero cuoco, certo, ma quanti pensieri aveva adesso Testa Calda! Cosa sarebbe accaduto al loro ritorno? Sarebbe nito davanti alla corte marziale?

Poi venne il giorno in cui Testa Calda e Tobias decisero di tentare la vetta.

C'era una forte tormenta, il vento sofava e urlava, e i due alpinisti se ne stavano in silenzio nella loro tendina a 7300 mt. Testa Calda sembra assente, come rapito da pensieri che gli impedivano di agire. Allora l'amico pianista, decise di fargli una sorpresa:

tirò fuori dallo zaino una piccola pianola. E si mise a suonare “Per Elisa”, di Beethoven lì, a 7300 mt di altezza in mezzo alla tormenta. Quella musica celestiale raffreddò la testa calda dell'alpinista che nalmente si sentì pronto. Il giorno dopo, per l'undicesima volta nella sua vita, Testa Calda raggiunse la vetta di un ottomila: il Gasherbrum 1. Ma ad attenderli in città, seduto dietro a una scrivania, c'era un generale temuto da tutti e tutte.

Il generale temuto da tutti e tutte ascoltò attento la relazione che l'amico pianista aveva scritto in difesa di Testa Calda. Ad un certo punto una porta si spalancò e comparve l'ufciale cattivo. Testa calda non lo salutò, ma si preparò alla punizione: in Pakistan quello che aveva fatto poteva costargli molto caro. Ci fu un lungo silenzio. Poi il generale si mise ad urlare forte! Si avvicinò all'ufciale cattivo e strappò dalla sua divisa le mostrine e i gradi” “Grazie per quello che avete fatto” disse poi rivolto a Testa Calda, “questi episodi sono frequenti, ma nessuno li racconta. Grazie, dunque, per il bene delle montagne e del turismo Pakistano”.

Testa Calda uscì dalla stanza. Sapeva che mentre la grande emozione provata in cima a quella montagna sarebbe svanita con il passare degli anni, quell'episodio

non lo avrebbe mai scordato, perché le uniche cose che rimangono indelebili nel tempo, anzi che si ravvivano più passano gli anni, sono le cose che fai per qualcuno che è stato meno fortunato di te.

Avevo uno zio di Milano, mi ricordo che era uno che non aveva paura di niente. Non aveva figli e io ero uno dei nipoti più giovani, ero molto amato, coccolato. Mi portava sempre con lui in val Brembana. Lui diceva che lì c'erano delle stelle alpine incredibili. Io gli ho detto che le stelle alpine non bisognava portarle a casa. Ma lui era un bracconiere di…tutto. Diceva: “bisogna sempre portare a casa qualcosa dalla montagna, salire per salire non ha senso”. Una volta camminavamo su di un prato alpino, salendo, ad un certo punto ci siamo trovati su delle roccette ma la roccia faceva schifo, si sbriciolava sotto gli scarponi. Lui mi ha detto: “Vieni via che è pericoloso.” “No”, ho risposto io, “voglio vedere cosa c'è più su”. Lui è rimasto indietro, lui che non aveva paura di nulla, non se la sentiva mica di salire dove stavo andando io. Sono salito nel punto più in alto e allora le ho viste: le stelle alpine, meravigliose. Allora ne ho strappato una e gliel'ho portata. È rimasto di stucco. Bisogna sempre portare a casa qualcosa dalla montagna, salire per salire non ha senso. Quante volte ho ripensato a quella frase. Aveva ragione, ma ora so che non si tratta di stelle alpine o di sassi. Si tratta di ciò che forse, lassù, hai trovato dentro di te. Ecco: credo che quella sia stata la prima volta che ho scalato una montagna. E l'ho fatto per vedere cosa c'era più in alto. Per la curiosità. Avrò avuto sì e no dieci anni. Ero molto piccolo, ma sa una cosa, di fronte alla montagna restiamo sempre piccoli piccoli. È proprio quando ti senti grande, invincibile che la montagna, senza che tu te lo aspetti, ti ridimensiona.

Atto unico per due attori.

Personaggi: Fausto De Stefani Papà

Una stanza d'ospedale, illuminata al neon. Fausto, con evidenti segni di deperimento è sdraiato su un lettino. Ha una flebo nel braccio. Si sente il bip di un monitor cardiaco. Entra il padre. Per tutta la scena il padre parla in dialetto mantovano.

Fausto: Ciao papà

Papà: Ciao Fausto

Fausto: Come stai?

Papà: Meglio di te. Ma io son più vecchio e i miei figli sono grandi.

Fausto: Ma quella è la montagna più alta del mondo papà.

Papà: Se lo dici tu (Pausa)

Papa: Come stai?

Fausto: Sto bene.

Papà: Cosa è successo?

Fausto: Mi sono sentito male. Per poco non ci lasciavo le penne. Là è tutto…

Papà: Là dove?

Fausto: Sull'Everest papà. Superati gli ottomila è tutto diverso. Stavamo salendo. Eravamo io e il De Marchi. Avevamo fatto anche

un buon lavoro sai? Primo campo, secondo campo, terzo campo. Avevamo una tendina. Eravamo a 8300 metri e io ho cominciato a sciogliere la neve…a quell'altezza bisogna bere, sai papà, è molto importante. E per farlo bisogna sciogliere la neve. Lì la neve non manca, ma bisogna scioglierla. E così ho riempito il pentolino di neve e ho acceso la bomboletta. Solo che quella non si scioglieva. Non capivo perché. Sono rimasto a guardarla. Poi ho sentito la voce di Giuliano che mi diceva: “Guarda che così la rovesci” e allora mi sono visto che avevo il pentolino in mano… e non riuscivo a coordinare i movimenti e quella poco acqua che avevo sciolto si era tutta rovesciata per terra. Mi sono preso il mal di montagna. Mi sono preso un edema polmonare. E io che ho sempre pensato che per me l'alta quota non fosse un problema. Per fortuna c'era il Giuliano. Che mi ha aiutato a venir giù da lì. Avevamo tutti e due congelamenti a mani e piedi ma lui mi è sempre rimasto a fianco. Dobbiamo ringraziare lui se siamo qui a parlare assieme. E alla fine nemmeno ci siamo saliti là sopra…bell'impresa eh, papà?

(Pausa)

Fausto: Papà, che mi dici?

Papà: Impresa…mah…potevi anche farne a meno no?

Lo Dzi è un pietra sacra del popolo tibetano. Significa luce, chiarezza, splendore. È una pietra dalle origini sconosciute ed è considerata un messaggio da parte delle divinità. Possederne uno significa diventare custode e alleato di forze misteriose e benevole che agiscono sul mondo per arricchirlo di bellezza. I tibetani credono che gli Dzi possano dissipare ogni sorta di negatività per chi li indossa. Di solito sono tramandate di generazione in generazione, di padre in figlio, garantendo protezione.

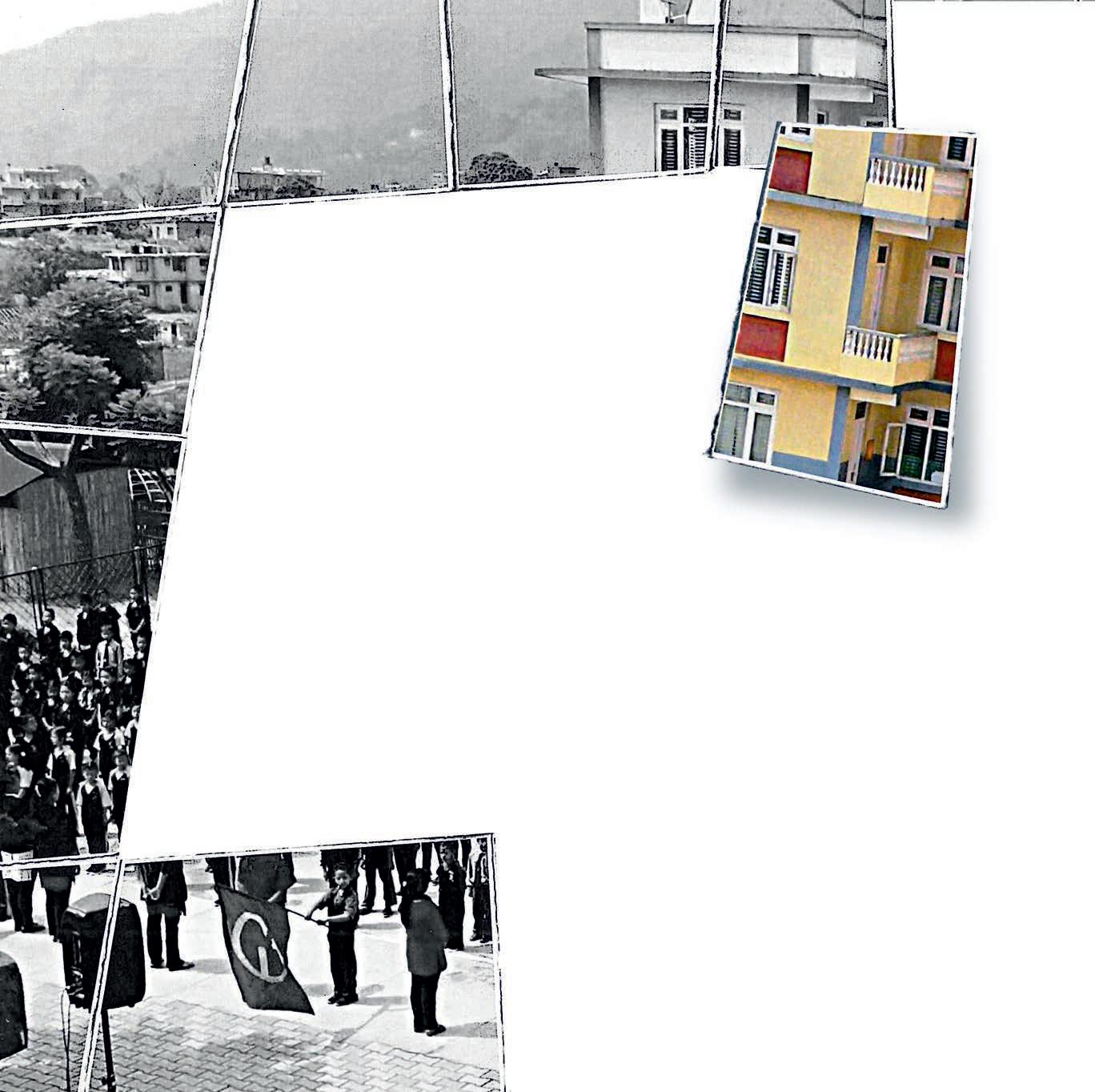

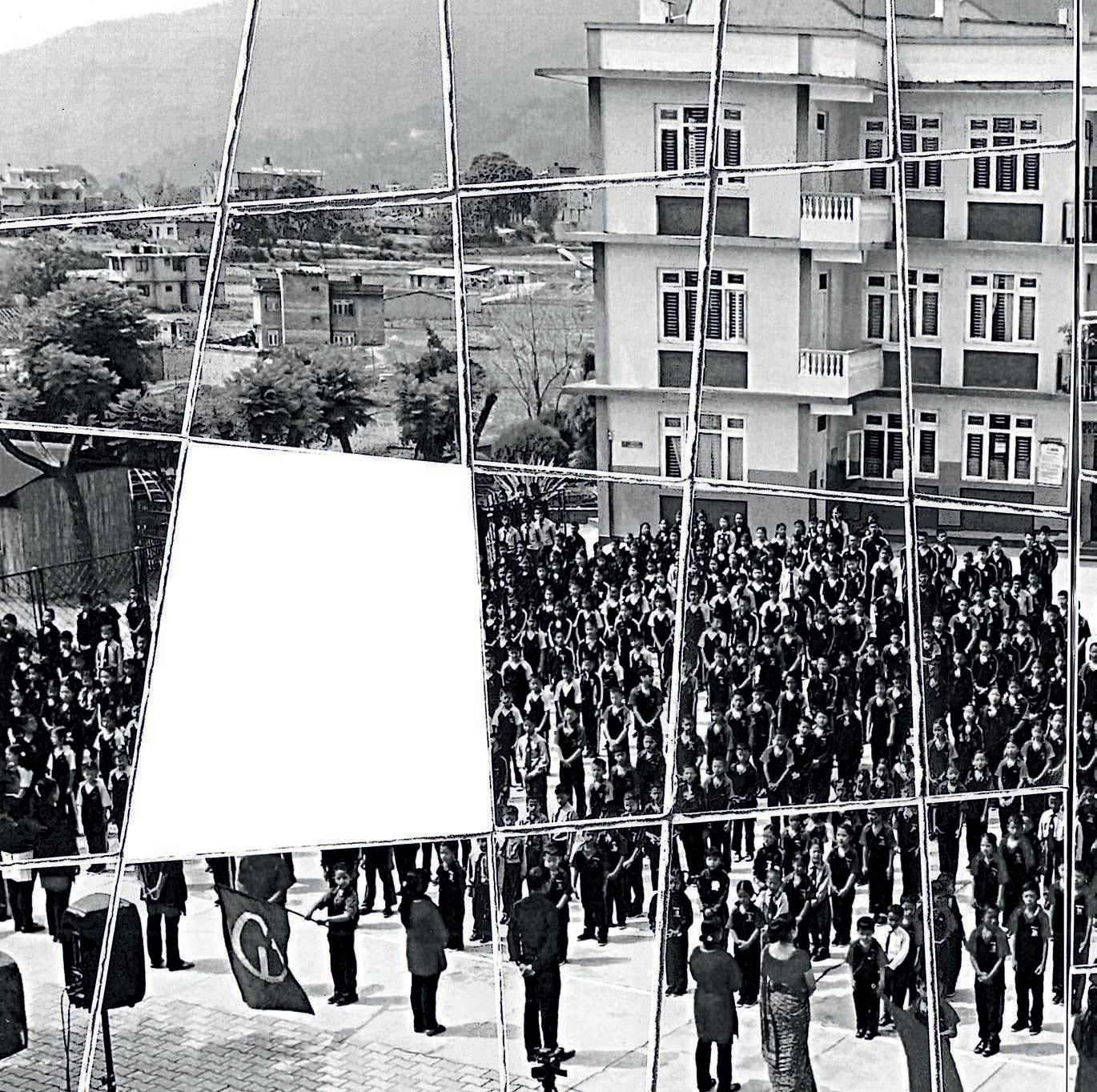

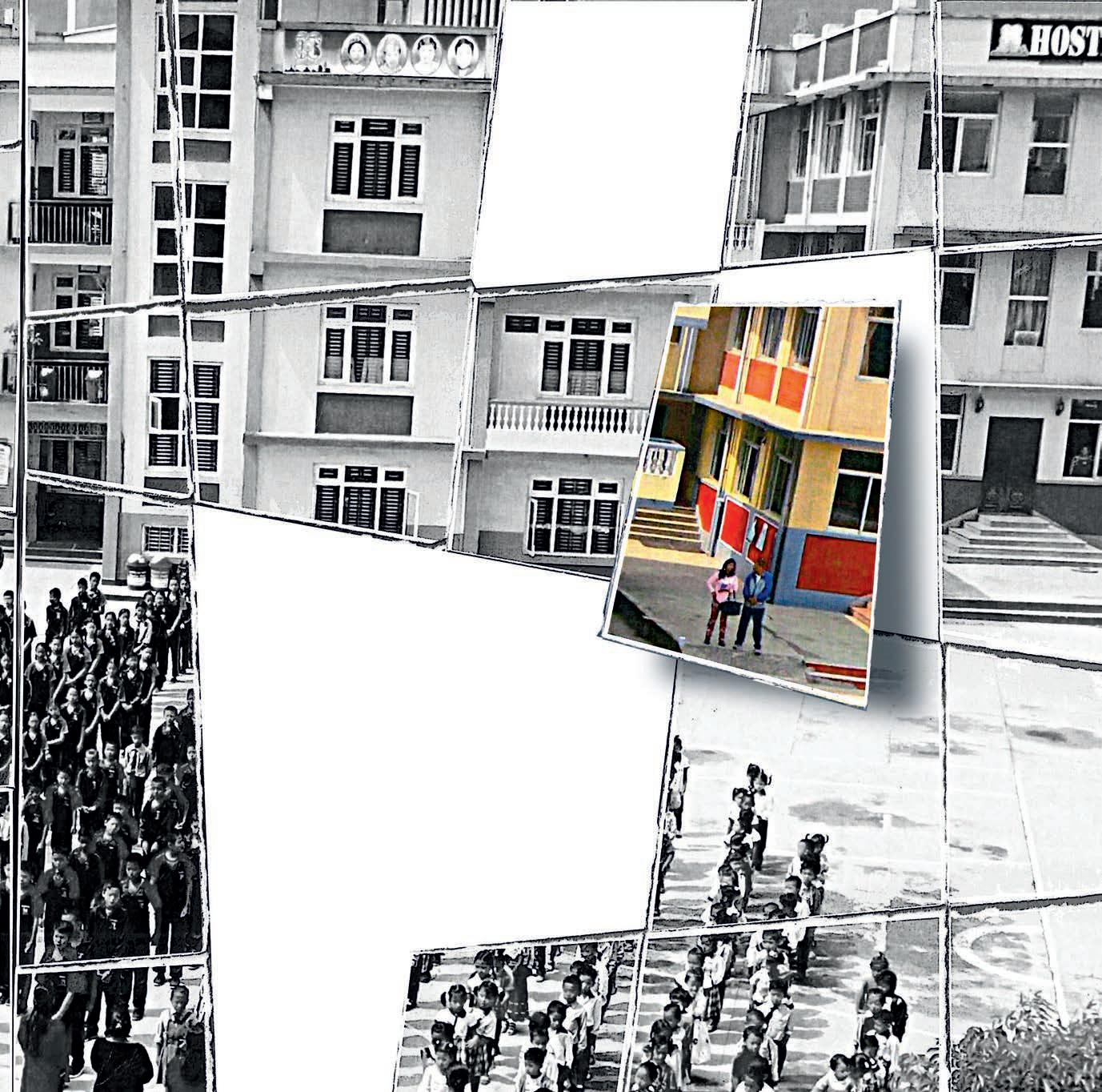

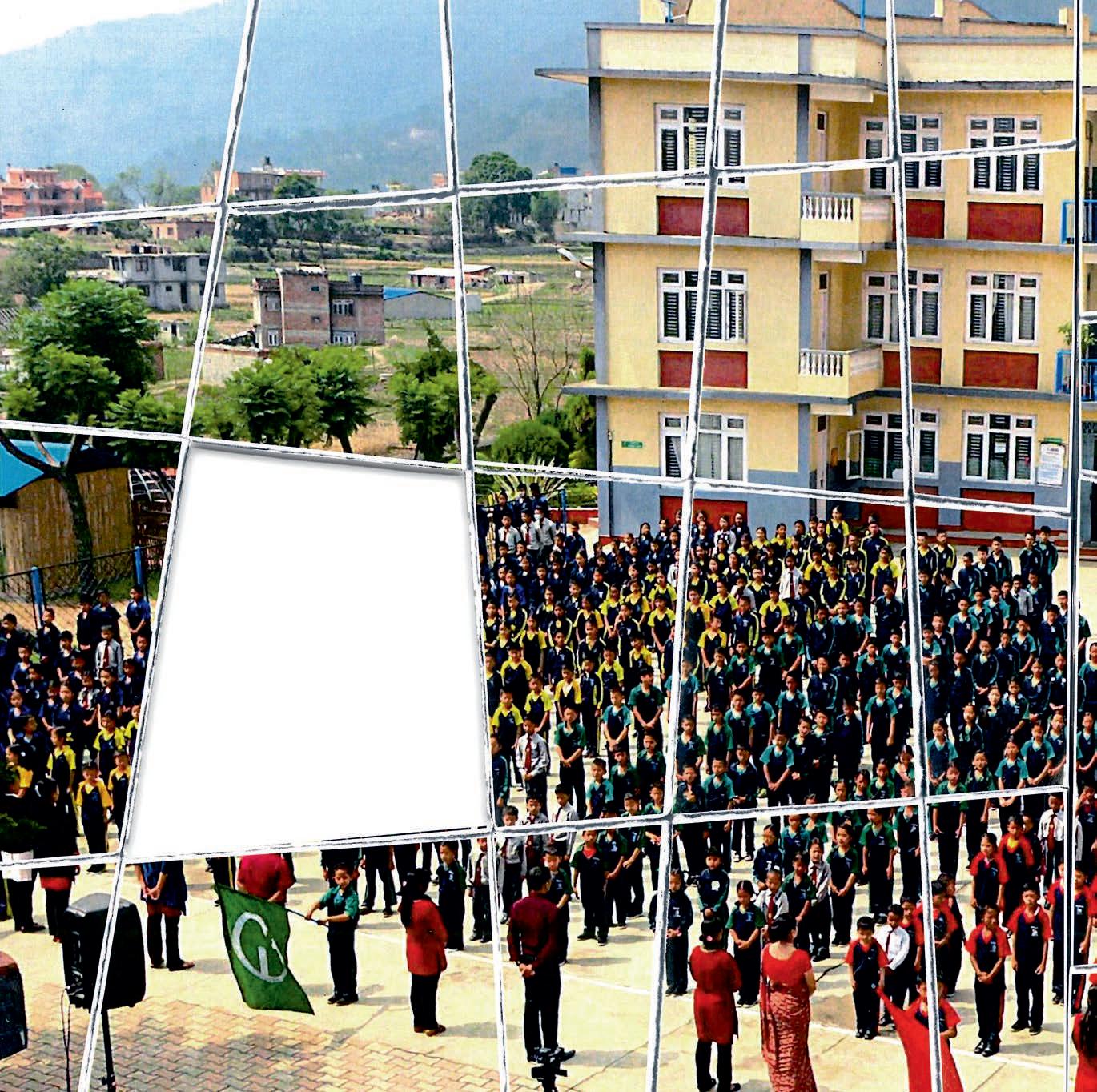

1998. Kathmandu.

C'è un negozietto di pietre preziose, nel centro della città. Il proprietario, o forse il commesso, è seduto per terra a gambe incrociate. Sta leggendo un libro aperto sulle sue ginocchia. È circondato da una specie di quiete che contrasta con il caos frenetico di quella città. L'uomo si chiama Lila e non alza lo sguardo nemmeno quando suona la campanella sopra la porta di ingresso ed entra un altro uomo. Lila non lo sa, ma l'altro uomo è uno dei pochi ad essere riuscito a scalare tutti i quattordici Ottomila del mondo. Quell'uomo è Fausto De Stefani. È appena rientrato da una spedizione. Non è andata bene, direbbe qualcuno, non è arrivato in vetta, ma per Fausto invece non ha alcuna importanza. É stata un’esperienza. Questo conta. Si guarda attorno, Fausto. È stupito. Di solito quando entra in un negozio viene subito assalito da qualcuno che cerca di vendergli ogni cosa ingaggiando una negoziazione che il più delle volte lo infastidisce. L'uomo seduto a terra invece continua a leggere in silenzio, fino a che per caso alza gli occhi. Anche lui è stupito perché l'uomo che ha davanti porta un Dzi al collo. Non ne ha quasi mai visti al collo di un occidentale e mai uno antico come quello.

Lila non lo sa ma lo dzi che Fausto porta al collo era del nonno del nonno del nonno di uno sherpa che ha scelto di interrompere la tradizione di famiglia e donarlo a Fausto in segno di gratitudine per avergli salvato la vita durante una spedizione, anni prima” “Buongiorno, benvenuto, posso aiutarla?” dice Lila con gentilezza Ancora non lo sanno, ma quel momento è l'inizio di qualcosa che durerà per oltre vent'anni. I due iniziano a parlare, scorre subito amicizia e simpatia.

Nei giorni successivi Lila accompagna Fausto a fare un giro nella sua città, Kirtipur, un borgo di 60.000 abitanti nella valle di Kathmandu, a 1300 m. di quota.

Finiscono davanti ad un edificio fatiscente.

“Volevo farti vedere questa scuola”, dice Lila, “l'abbiamo fondata io e altri amici. È una scuola per i bambini della primaria e dell'asilo. L'abbiamo chiamata Rarahil Memorial School”. “Rarahil? Cosa significa?”.

“E' un acronimo. Sono le iniziali di quattro giovani studenti che hanno perso la vita nel 1990 durante gli scontri per portare la democrazia nel Paese”. Fausto entra e ciò che vede lo lascia senza fiato. Le aule sono minuscole. Ci sono delle panche su cui stanno seduti pressati 20 bambini. I soffitti hanno gravi perdite. “Quando piove”, dice Lila “la scuola si allaga e diventa impraticabile. La ricreazione si fa in strada, in mezzo al traffico.”

Fausto sospira, non sa che dire. Ancora una volta è di fronte a una delle tante contraddizioni del paese che tanto gli ha dato negli ultimi vent'anni, ma si rende conto che questa volta si tratta di piaghe profonde, all'apparenza incolmabili.

“Le cose non vanno bene da noi.” Dice Lila. Fausto annuisce. Guarda le facce sorridenti dei bambini che a loro volta lo guardano curiosi.

Lila sa che Fausto è un occidentale. Sa che è un uomo credibile in occidente, sa che non ha davanti un turista qualsiasi ma qualcuno che conosce profondamente quella terra. Qualcuno che la ama. Gli esce quasi d'istinto: “Fausto, tu ci puoi aiutare?”

E lì, tutto si ferma.

Ci sono momenti nella vita, in cui tutto ciò che hai fatto, tutto ciò che sei stato, tutto ciò che hai visto, letto, ascoltato viene risucchiato in un unico punto, come l'acqua di un lavandino pieno a cui viene tolto il tappo.

“Fausto, tu ci puoi aiutare?”

Tutto, le esperienze, le ambizioni, le domande, i turbamenti si compattano in un unico punto, come una supernova che collassa prima di esplodere.

“Fausto, tu ci puoi aiutare?”

Come se i pezzi disordinati della tua vita si componessero in pochi secondi in un puzzle ordinato a comporre poche semplici parole:

“Sì, posso aiutare. Posso farlo.”

“Sì?” risponde Lila incredulo.

“Sì” dice Fausto e poi, dopo una pausa: “Non potremmo farne a meno. Senza, non potremmo andare da nessuna parte!“

“Senza cosa?”, chiede Lila confuso.

Ma Fausto non risponde. È nella vecchia stalla della Cascina Rossa adesso. “Senza cosa?” insiste Lila.

Sale i tanti gradini che portano in soffitta. Una soffitta per nulla polverosa, anzi, è ancora tutto ordinato e pulito là dentro, ogni cosa è al suo posto, ogni ricordo, ogni immagine, ogni parola. “Fausto, senza cosa?”

Fausto sa bene dunque dove andare. C'è una vecchia cassetta di legno, piena di robe vecchie che nessuno usa più. Slaccia i legacci che ne tengono chiuso il coperchio, la apre

e ne estrae un vecchio pezzo di stoffa rammendato.

Lila si preoccupa, non capisce: “Fausto, ci sei?”

Fausto arrotola con cura il pezzo di stoffa lo mostra a Lila: “Mi serve una mongolfiera Lila”

Lila è spiazzato: “No, Fausto, intendevo se puoi aiutare questi bambini…” Fausto li guarda.

I loro occhi osservano in silenzio quell'uomo misterioso, venuto non si sa da dove, con la lunga barba e le mani rugose e segnate come una cartina geografica. “Questo è solo un pezzo della mongolfiera bambini, basta qualche rammendo e con questo posso volare sicuro, dove mi pare, trasportato dai venti, guardate...

Lila vieni con me.” “Fausto cosa stai dicendo io…”

Ma è troppo tardi. Fausto ha già trascinato Lila nel cesto. E la mongolfiera già si sta sollevando sotto gli sguardi incantati dei bambini.

Lila vede allontanarsi i tetti di lamiera della piccola scuola sotto di sé, vede il povero edificio assediato dal cemento diventare sempre più piccolo, mentre il

rumore dei clacson diventa sempre più lontano. Da più in alto ancora, inizia a scorgere la periferia di Kirtipur, e il grande caos di Kathmandu, vede la forma disordinata e rumorosa della grande città e la cappa di smog che ne opprime i polmoni. “Dall'alto le cose si vedono meglio”, grida Fausto, “serve un terreno più in alto!”

“Un terreno? Un terreno per cosa!” risponde Lila nel vento.

“Per la scuola! Lila! Abbiamo bisogno di aria pulita, e di un posto spazioso, per costruirla. Ecco, laggiù, guarda, quello, quello è un posto perfetto, togli gas, Lila, togli gas”. E la mongolfiera di Fausto comincia a scendere trasportata dalla benevolenza dei venti fino a che atterra su un'altura deserta proprio sopra la piccola cittadina di Kirtipur. “Ecco” dice Fausto, “qui faremo la nostra scuola” “Qui?” Lila è esterrefatto. “Ma Fausto…qui il terreno costa troppo, è il luogo più caro della valle. Là invece i prezzi sono molto più abbordabili, possiamo…” “No”, lo interrompe Fausto “Laggiù al primo monsone la scuola verrà allagata, Dovrà sorgere qui.” “Ma, dove li troviamo i soldi?”

Fausto lo guarda fisso negli occhi. Poi con sicurezza risponde: “Non ne ho idea.” Una sola frase gli batte in testa, una frase custodita nel petto fin da quando era bambino: anche i sogni impossibili? Sì, anche quelli impossibili. E la mongolfiera di Fausto sussulta piano sotto i loro piedi mentre si solleva di appena 45 centimetri.

“Ma Fausto, dove andiamo adesso?” “Lo vedrai Lila. Lo vedrai. Sali piccola mongolfiera mia, abbiamo bisogno di te! La vedi Lila, sotto di noi? Quella è la vetta dell'Everest! Eccole le vette più alte del mondo; guardale, come sono piccole viste da quassù! Dài gas ragazzo mio! Dài gas! Soffiate venti! Guarda Lila, lo vedi quel vecchio rudere in mezzo a quell'enorme pianura piatta senza nemmeno una montagna? E' casa mia! Papà! Papà! Sono qui! Sono quassù, mi vedi!

“Fausto! Cosa ci fai lassù, scendi!”

“No papà, starò via per un pò. Voglio costruire una scuola in Nepal!”

“Una scuola?”

“Si papà. Tu che dici?”

“Fausto! Se devi fare una cosa falla beneeeee!!!”

Fausto sorvola l'Italia da cima a fondo. Per anni si è trovato a disagio a parlar di montagne e di imprese alle innumerevoli conferenze a cui viene invitato, ma ora finalmente sa di cosa deve parlare l'uomo che ha scalato tutti i quattordici Ottomila. Di una montagna sì, ma della più alta di tutte: una scuola da aprire in Nepal, sì, a Kirtipur sì, una scuola che dovrà essere grande e bella e piena di studenti! “Lila, dài gas!”

Ad ogni conferenza, incontro, conversazione in coda alla cassa del supermercato, Fausto parla, arruola, convince! “Dobbiamo volare ancora più in alto! Dài gas ragazzo mio, dài gas, soffiate ventiiiiiiiiiiiiii!

E' il 1998 e Fausto ha la determinazione di un uomo in grado di salire tutti gli ottomila e la capacità di sognare imparate sulle

ginocchia di Mandelo. Riceve incoraggiamenti, consensi, aiuti, sostegno. Ma nonostante tutto questo non è abbastanza. Fausto allora raddoppia le conferenze, dimezza le scalate, moltiplica gli incontri. Ma non è abbastanza. E allora Fausto… Non è abbastanza Fausto allora cerca di… “No, non è abbastanza! Fausto, così non ce la faremo mai! Serve di più! Molto, molto di più.” Lila e Fausto si guardano.

Poi Fausto cede: “Hai ragione Lila, servono altre

mongolfiere!”

“Già”, dice Lila. “Ma nel cielo oltre a noi non ci sono altre mongolfiere. I due restano in silenzio mentre guardano il cielo nuvoloso. Poi, d'un tratto, il volto di Lila si deforma in una smorfia di stupore: “Fausto, guarda! Guarda laggiù! Quella…Quella è una mongolfiera!

grossa e veloce di questa! Leggi la scritta sul pallone! “Fondazione senza frontiere?” dice Lila senza capire. “Si!” Risponde Fausto, “E' già atterrata in molti altri posti, ha già portato sogni, speranza e bellezza in Brasile, Papa Nuova Guinea, Ruanda, Uganda, Cile, Venezuela, Indonesia. Anselmo! Siamo qui!! Da questa parte dietro di te! Forza Lila, dobbiamo raggiungerlo! Anselmooooooo!!! Aspettaci! Siamo qui dietro di te!” La mongolfiera di Anselmo vola alta nel cielo. Nel cesto fa capolino un uomo elegante, dal viso aperto e luminoso. Quando si volta alza le braccia in segno

di saluto:

“Fausto! Ma che ci fai su quella piccola mongolfiera?”

“Anselmo!” risponde Fausto entusiasta, “abbiamo bisogno di te, del tuo aiuto! Voglio costruire una scuola in Nepal per i bambini che non possono studiare. Ma non voglio solo costruirla, dovrà anche essere la scuola più bella di tutto il Nepal.”

“La più bella di tutto il Nepal?” risponde Anselmo divertito. “Delmondo,Anselmo!Lapiùbelladelmondo!Vogliochegliocchideibambini sianoinondatidigioiaebellezza!Anselmo,tucipuoiaiutare? Anselmononcipensaunattimo,“SiFausto,posso.Possiamofarlo.Portamia vederequellochehaiimmaginato!”

Ementreleduemongolfieresfreccianobraccetto attraversoilNepal,FaustoeLilanonsmettanodi raccontare:“Dovràesseretuttosenzailminimo scopodilucroAnselmo,dovràessereaccessibilea tutti,lerettedeiragazzipiùabbientisosterranno quelledeimenofortunatiedovràesserciun refettorioeunamensaeunconvittoperiragazziche abitanotroppolontanoeinfine,Anselmo,dovrà esseretuttonepalese!Personale,strutture,operai, materiali,insegnanti,tutto!Dobbiamofareinmodo

chetuttosiaautonomo,noicontrolleremosolochelecosefunzioninobene!”

E'il1999.VengonofattiiprogettiinItalia,vagliati,rifattierifattiancora,fino ache,nel 2000,ilnuovoedificiodella“RarahillMemorialSchool”iniziaad esserecostruito.Tuttosembrafilareliscio,finoacheungiornoFausto,nelbel mezzodelcantiereoperosointerrompeilavori. “Vabuttatogiù.Questopilastrovabuttatogiù.Haundifetto.Vabuttatogiù erifattodacapo!”

Glioperailoguardanoinsilenzio.PoiLilaprendeparola:“Ma…Faustoormai, l'hannofatto…”

“Lila,nonsidiscute.Vabuttato giù.Seunacosalafacciamo,la facciamobene!”Ecosìperogni piccoloparticolare,ogni imperfezione,ogniminimainezia fuoriposto.Faustosupervisiona, monitora,controllapersonalmente ognidettaglio,ogniprogresso. Controlla,chenonsirisparmisui materiali.

Controlla,cheognispesasiavagliata approvataerendicontata. Controlla,chetuttovengafattoinregolae trasparenza,cimettelafaccia,ilcuoreeancheil corpoquando,laseraprimadell'inaugurazione, restaalavorareconglioperaifinoalle3.00del mattino,pertrasportaresullaschienasacchidi ghiaiadaspargeresulfangodelgrandecortile antistanteallastrutturadellamaterna, primaria,secondaria,convittoperiragazzi piùpoveri.

Èilmaggiodell'anno2003 eilnuovoedificiodella RarahilMemorialSchool vedefinalmentelaluce. Lastessachebrillanegli occhideicentinaiadi studenticheospita,degli insegnantiedelleautorità Nepalesi...

Anche i sogni impossibili vecchio mio, me lo hai insegnato tu…

...

mentre gli anni passano.

MentresottogliocchiattentidiFaustolascuolacresce.

Mentrenel2007vieneinauguratol'istitutoprofessionaleaindirizzoturisticoambientale. Mentretrail2009eil2012 vienecostruitalamensa,ilaboratoriprofessionali,unambulatorio pediatricoevieneampliatoilconvitto.

Mentreiprimidiplomatitrovanolavoroesispecializzanoperproteggereevalorizzareilloro paese,Faustovolaserenoedolce,traNepaleItalia,traItaliaeNepalfinoachetornalàdove tuttoèiniziato.Inquelladistesapiattaemonotonacheèl'altamantovanaesiposalì,proprio vicinoallaCascinaRossa,dove,sconosciutadatutti,c'èunacollinapiccolapiccola,consoloun boschettoeunpòd'erbaincolta,cheguardaversoilmontepiùaltoditutti,ilmonteBaldo. Glielahalasciataunamicopocoprimadiandarsene:“LaCollinadiLorenzo”.Cosìsichiamaoggi quelluogocheFaustochiamacasaecheneltempohacuratoeamatoaalpuntoda trasformarloinungrandeLunaParknaturalisticodelladellafantasia.

C'èlacasettadiJackLondon,cisonoletendetepeedeinativiamericani, c'èlageermongola,c'èunenormepratoincolto.Suglialberièpienodicasettepergliuccelli,ci sonopavonichegiranoliberitraglicespugli,gattichesistruscianosullegambedeivisitatori, sculturedilegnospuntanodaognianfratto, eovunquesututto,sventolanofilaridibandierinetibetanearicordarele montagneeilorospiriti. SuquellacollinaogniannoFaustoaccogliemigliaiadibambinichearrivanoperimpararea conoscerelanaturaeadascoltarestoriedipopolilontaniemondisconosciuti. Liesploranoqueimondieleascoltanoquellestorie,standosedutisulleginocchiadiunvecchio. QuelvecchiosichiamaFaustoDeStefani. Halabarbabiancaeicapellilunghi,lemanisegnatedallarocciaeraccontadiunvecchio,che,in sellaaunavecchiabicciclettaportavaaibimbilaleggerezzadeisognieilcoraggiodiinseguirli.

(DesenzanodelGarda1982)sièlaureatoinLetterepressol'UniversitàdiVerona. AVeronaha collaboratoconl'associazioneculturale Cyrano Comics perlosviluppodiunpercorsoartistico dedicatoalfumetto.Hadisegnatofumetti,copertineeillustrazioniper Delmiglio Editore, Liberedizioni, Gam Edizioni.Hacollaboratoconl'Associazione Cronaca di Topolinia perla realizzazionediunaseriediillustrazionisugliindianid'America.Inoccasionedel centocinquantesimoanniversariodell'Unitàd'Italiaharealizzatounaseriediillustrazioniatema risorgimentaleperilvolume Unità d'Italia: il grande sogno.Isuoilavoripiùrecentisonoivolumi afumetti: Sulle sponde del Mississippi susoggettoesceneggiaturadiMassimilianoValentinie Il bosco dei ricordi,incuisiesprimecomeautorecompleto,entrambiperedizioniSegnid'Autore. Insolubilia,susoggettoesceneggiaturadiBrunoCodenotti,èilsuoterzoeultimolavoro,in ordineditempo,per Segni d'Autore.PerMonturaEditinghaillustratoilvolume La collina di Lorenzo sutestidell'alpinistaFaustodeStefani.

Èillustratriceepittricefreelance.Isuoimoltepliciinteressiperarte,letteraturaesportoutdoorsi riflettononellostiledellesueillustrazioni,chespazianodaidelicatiacquerelli,aifumettieallastreetart, mantenendosempreuntoccopersonale.Harealizzatoleillustrazionidellungometraggio "Finale '68" (presentatoalTrentoFilmFestivalnel2018),hacuratoletavoledellaguidadiarrampicatadi AndreaGallo Finale'51 eedèl'autricedelleillustrazionidelManualepergiovaniStambecchi scrittodaIreneBorgnaperSalani.H acollaboratoconilCorrieredellaSeraperl'insertospeciale dedicatoallaletteraturaperragazzi. Grazieallatecnologiariescealavorarepraticamenteovunque.I mpossibiledatenereferma,non riesceaimmaginareunaltromododivivere. Senonstadisegnando,lasipuòtrovareappesaallaroccia,ingiropersentieri,oamollo nell'acquadelmare.

" "

MicolCeolettaLaureatainIngegneriaEdile-Architettura,decidedifaredellasuapassioneunlavoro,quindi conunesamedistatoprontoadadornaresolounaparete,lascialastradadicaseecalcolie insegueilsuosognodifarelafumettistaedisegnatrice.

Inizialmentecollaboraconpiccolecaseeditrici,tracuiCyranoComics,DelMiglioEditore, FestinaLenteEdizionieFigurineItalia.Disegnaperaziendepersonaggietavoledifumetto, tracuiTerzomillennium,BimBau,LotoeBimbostore.Dal2020collaboraconToysCenter comedisegnatriceedal2021conWinterVideocomestoryboarder. Sempreallaricercadinuovesfide,collaborainquestobellissimoprogettodiMonturacome illustratrice.

“Lapartepiùinteressanteemeravigliosadiquestolavoro,èchenonsifiniscemaidi imparare”econquestospiritosperadipotercontinuareinquestamagnificaprofessione,in cuisogniefantasiadiventanorealtà.

Gliartisti

Gliartisti

I nostri ringraziamenti vanno a Fausto De Stefani, su tutti, che ci ha permesso con generosità e fiducia di scartabellare nei suoi ricordi e pensieri.

Ai nostri preziosi compagni di "viaggio su carta": Agnese Blasetti, Michele Avigo, Micol Ceoletta, alla loro enorme disponibilità e creatività.

A Richard Ferrari, il cui sguardo di insieme si è rivelato fondamentale, incontrarlo è stato un privilegio.

A Roberto Giordani, che insieme a Montura ha creduto in questa impresa e l'ha sostenuta dall'inizio alla fine e a Claudio Marenzi, che unitosi in corsa alla nostra cordata, ha da subito condiviso totalmente il progetto.

A Roberto Bombarda, senza di lui questo progetto non sarebbe mai cominciato; a Nikola Lukovic e Valentina Sembenotti, che con lui hanno condiviso il viaggio di Montura Editing.

Grazie poi a Gisella ed Erika, che sempre supportano (e sopportano!) con amore il nostro lavoro.

E infine grazie a Cristina Pezzoli. Senza di lei noi, Jacopo e Mattia, non ci saremmo mai incontrati.

Testi:

Jacopo Maria Bicocchi e Mattia Fabris

Illustrazioni: Michele Avigo, Agnese Blasetti, Micol Ceoletta

Fotografie: Alessandro Tamanini, Fausto De Stefani, Giampaolo Calzà, Archivio Montura

Coordinamento editoriale: MONTURA Ufficio Comunicazione/Montura Edit (Roberto Bombarda - Nikola Lukovic)

Traduzioni: Traduzioni Madrelingua - Isola Vicentina (Vi) Grafica e impaginazione: Studio Bi Quattro - Trento Stampa: Saturnia Snc - Trento

Editore: Montura Editing - Montura Srl - Via Trento, 138 - 36010 Zané (Vi) ISBN: 9791280802088 www.montura.it Copyright © Montura Editing 2022

Tutti i diritti riservati. Nessuna parte di questa pubblicazione può essere riprodotta o trasmessa in qualsiasi forma o con qualsiasi mezzo senza l'autorizzazione scritta dell'editore.

Tipo di carta e caratteristiche: Interno stampato su carta Gardamatt Art delle Cartiere del Garda da g 170 certificata PEFC.

Inserti stampati su carta Magno Natural della Sappi Papier Holding da g 170 certificata PEFC.

Copertina stampata su carta Gardamatt Art delle Cartiere del Garda da g 350 certificata PEFC.

Finito di stampare a Trento nel mese di Dicembre 2022

Questo prodotto è realizzato con materia prima di foreste gestite in maniera sostenibile e da fonti controllate.

Oltre 70 film co-prodotti o sostenuti, con sponsorship o product-placement. Opere che hanno partecipato a festival, che in parte sono ora presenti su piattaforme o sul sito aziendale.

E decine di altri film, serie e programmi tv sostenuti con fornitura di prodotti.

Più di 90 libri editi come Montura Editing o sostenuti da Montura, con oltre 200 mila copie distribuite gratuitamente in 20 anni, sempre in cambio di una donazione “libera e responsabile” a favore di progetti di solidarietà.

More than 70 films co-produced or funded through sponsorships or product placement. Films that have been featured at festivals, some of which are now available on the company website and various platforms. And dozens more films, series and TV programmes supported by the supply of products.

More than 90 books published by Montura Editing or backed by Montura, with over 200,000 copies distributed free of charge over 20 years, always in exchange for “free and responsible” donations to charity projects.

montura.it

...ANCHE I SOGNI IMPOSSIBILI

M. Fabris e J. Bicocchi, 2022

ALLE ORIGINI DELLA GUARIGIONE: SCIAMANESIMO E NEUROTEOLOGIA D. Bellatalla e R. Baldissone, 2022

SCALARE IL TEMPO. 70 ANNI DI TRENTO FILMFESTIVAL AA.VV., 2022

DONNE DI TERRE ESTREME Caterina Borgato, 2021/2022

IN ASCOLTO NOMADE

L. Bosi - P. Ligabue, 2021

VIAGGIO NEL MONDO DEI BAMBINI Manuela Ruaben, 2021

IL GRANDE VIAGGIO D.Bellatalla - S.Rosati, 2020

SULLE ANDE CON LE SCARPE BUCATE Giancarlo Sardini, 2020/2022

FEELING ON TOP OF THE WORLD Enrico Tettamanti, 2020

CAMMINO NATURALE DEI PARCHI U.Antonelli e altri, 2019

LA COLLINA DI LORENZO Fausto De Stefani, 2019/2022

I MILLE VOLTI DELLO SCIAMANO David Bellatalla, 2019

MANI NUOVAEDIZIONE

Fausto De Stefani e Erri De Luca, 2019

LAYLA NEL REGNO DEL RE DELLE NEVI Reinhold Messner, 2019, Erikson Ed.

VALLE DELLA LUCE ALPINISMO NELLE VALLI DELLA SARCA E DEI LAGHI Alessandro Gogna e Marco Furlani, 2019

DI PIETRE E PIONIERI, DI MACCHIA E ALTIPIANI Michele Fanni, 2018

IT’S MY HOME FOR THREE MONTHS Alessandro de Bertolini, 2018

LA RESINA R.Carbonera-A.Rasi Caldogno, 2018

RESISTANCE

Roberto Mantovani, 2017

LA MONTAGNA PRESA IN GIRO G.Mazzotti-M.Corona, 2017

UN VIAGGIO LUNGO UNA FIABA Fausto De Stefani, 2018 (ristampa)

RAGNATELE Collettivo Boschilla, 2018

KAZAKHSTAN

A.Segre-S.Falso, 2016

MARTINO L’ARROTINO Martino Viviani, 2017

UN PAESE MILLE PAESAGGI L’Altro Versante, 2017

E.GHERSI

SULL’ALTIPIANO DELL’IO SOTTILE David Bellatalla, 2016

IN NOME DELL’ORSO

Matteo Zeni, 2016

IL DET GIUSEPPE ALIPPI Luisa Rota Sperti,2016

SKYRUNNER. IL CORRIDORE DEL CIELO Bruno Brunod, 2016, Mondadori Ed.

VOLUNTEERS

AA.VV., 2014

PRIMA DELLA NEVE A.Segre e S.Falso,2013

#001 MOON LANDING AA.VV., 2011

FOTOTREKKING I GRANDI AUTORI AA.VV., 2011

FANGO AA.VV., 2011

DOLOMITI NEW YORK AA.VV., 2010

LA SCIMMIA ED IL BOOMERANG Nicolò Berzi, 2009

UNO MONTURA DIVERSO G.Malfer-V.Stefanello, 2009

ALDILÀ DELLE NUVOLE Fausto De Stefani,2009

UNO MONTURA PEOPLE 08 G.Malfer-V.Stefanello, 2008

ALPINISTI SOTTO ACETO Manuel Lugli, 2008

UNO MONTURA CONFINI G.Malfer-V.Stefanello, 2007

I COLORI DEL GRIGIO G.Marzari-G.Malfer, 2005 ROCKMASTER G.Malfer-V.Stefanello, 2005

50 ANNI DI SOCCORSO

ALPINO A ROVERETO M.Zandonati, 2005

UNO MONTURA VIAGGIO G.Malfer-V.Stefanello, 2004

Altrettante pubblicazioni sono state realizzate con il sostegno o con la collaborazione di MONTURA Maggiori informazioni su www.montura.it e nei MONTURA STORE E numerosi altri progetti editoriali, tra i quali 4 raccolte delle pagine pubblicate su “Internazionale”. A similar number of titles published with the support or collaboration of MONTURA. Further information on www.montura.it and in MONTURA STORES.

Many other publications, including four collections of articles published in Internazionale magazine.

BANGLA VENICE

Emanuele Confortin, 2022

RISPET Cecilia Bozza Wolf, 2022

SARABANDA AL MARGINE DEL CIELO L. Bich - G. Rossi, 2022

UN VIAGGIO NELLE ALPI Roberta Bonazza, 2022

IL SERGENTE DELL’ALTOPIANO F. Massa - T. Brugin, 2021

TAKE AWAY

Renzo Carbonera, 2021

INEDITA Katia Bernardi, 2021

NEVER GIVE UP LAURA ROGORA Pietro Bagnara, 2021

IL CERCATORE D’INFINITO

F.Massa e A.Azzetti, 2020

LOS PICOS 6500 Marco Busacca, 2020

KINNAUR, HIMALAYA

Emanuele Confortin, 2020

VALLE DELLA LUCE Alberto e Lia Beltrami, 2020

CACHONNE SUPRA A SCIARA G.Musarra-M.Brunello, 2020

CHOLITAS P.Iraburu, J.Murciego, 2019

MANASLU: BERG DER SEELEN Gerald Salmina, 2019

ANI, LE MONACHE DI YAQUEN GAR Eloïse Barbieri, 2019

ROLLY Pietro Bagnara, 2019

ENTROTERRA.

MEMORIE E DESIDERI DELLE MONTAGNE MINORI Collettivo Boschilla, 2018

SILENCE Bernardo Giménez, 2018

SENZA POSSIBILITÀ DI ERRORE Mario Barberi, 2018

RESINA

Renzo Carbonera, 2017

LA PELLE DELL'ORSO Marco Segato, 2016

PICCOLA PATRIA Alessandro Rossetto, 2013

ALPI Armin Linke, 2011

IO SONO LI Andrea Segre, 2011

KENO CITY, YUKON Paola Rosà, Antonio Senter, 2019

FINALE 68 Gabriele Canu, 2018

ITACA NEL SOLE Fabio Marcari, Tiziano Gaia, 2018

IT’S MY HOME FOR THREE MONTHS A.De Bertolini, L.Pevarello, 2018

PAGINE DI PIETRA Federico Modica, 2018

DA ROVERETO AD AUSCHWITZ Giampaolo Calzà, 2018

RESET, UNA CLASSE ALLE SVALBARD Alberto Battocchi, 2017

OLTRE IL CONFINE A.Azzetti, F.Massa, 2017

DUSK CHORUS A.D’Emilia, N.Saravanja, 2017

POSTINI DI GUERRA A.Gonnella, D.Centrone, 2017

INSIDE

Marc Daviet, 2017

A VENTIQUATTRO MANI Luca Zambolin, 2017

BREZNO POD VELBOM Alberto Dal Maso, 2017

PRENDIMINGIRO Stefano Castioni, 2017

MINGONG

Davide Crudetti, 2016

BETWEEN HEAVEN AND ICE Federico Modica, 2016

SOLO DI CORDATA Davide Riva, 2016

ALBERI CHE CAMMINANO Mattia Colombo, 2015

IL MURRÀN Sandro Bozzolo, 2015

REVELSTOKE, UN BACIO NEL VENTO Nicola Moruzzi, 2015

CORRERE PER L’ESSENZIALE Alberto Ferretto, 2015

I SOGNI DEL LAGO SALATO Andrea Segre, 2015

L’ALPINISTA Giacomo Piumatti, 2015

VINO DENTRO

Ferdinando Vicentini Orgnani, 2013

AL DI LA DELLE NUVOLE Alessandro Tamanini, 2013

LA PRIMA NEVE Andrea Segre, 2013

VERTICALMENTE DEMODÈ Davide Carrari, 2012

CHANGE Petr Pavlicek, 2012

IL TURNO DI NOTTE LO FANNO LE STELLE Edoardo Ponti, 2012

LINEA 4000 Giuliano Torghele, 2012

IL RICHIAMO DEL KLONDIKE Paola Rosà, 2010

ARIA Davide Carrari, 2008

E numerose altre produzioni cinematografiche e tv. Numerous other film and TV productions.

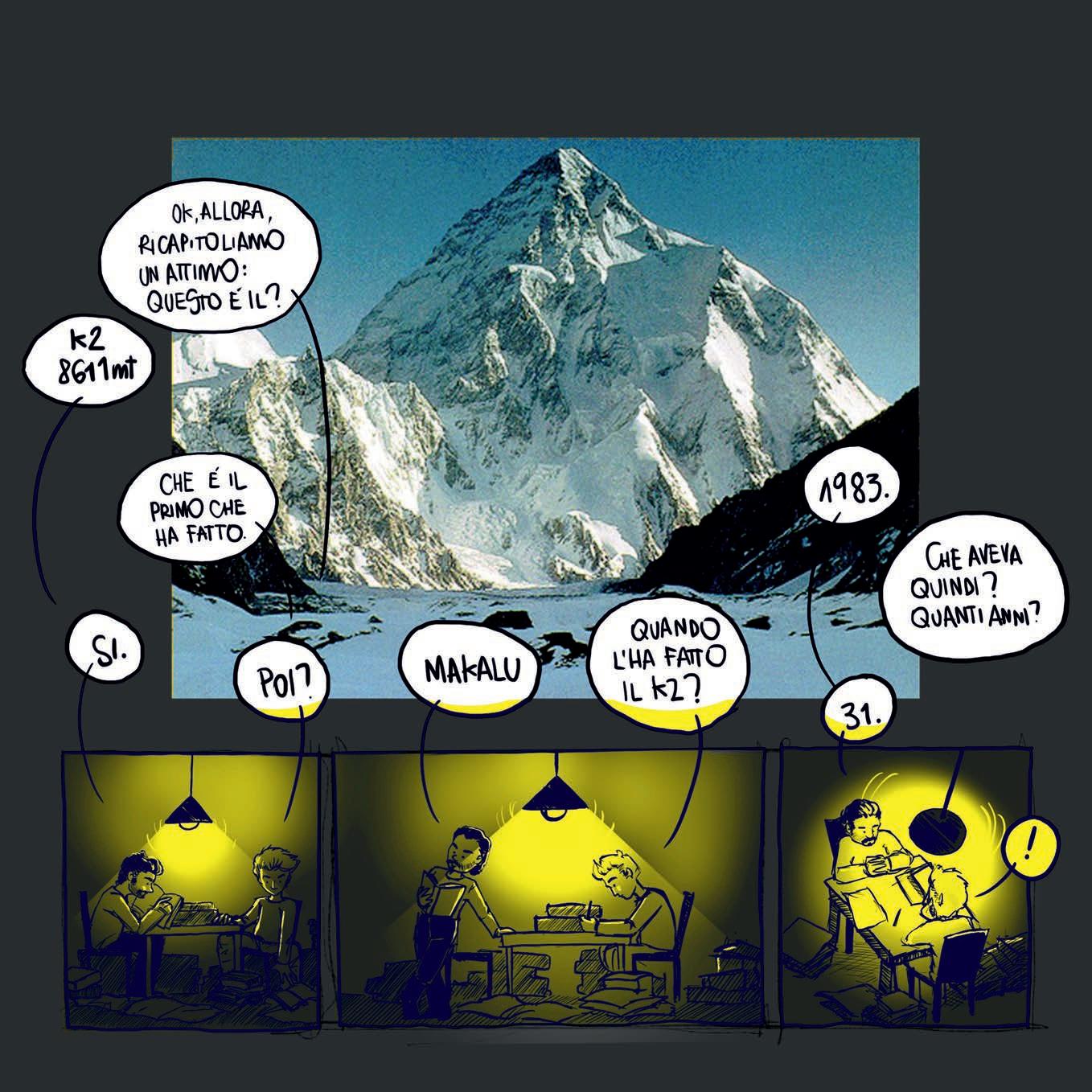

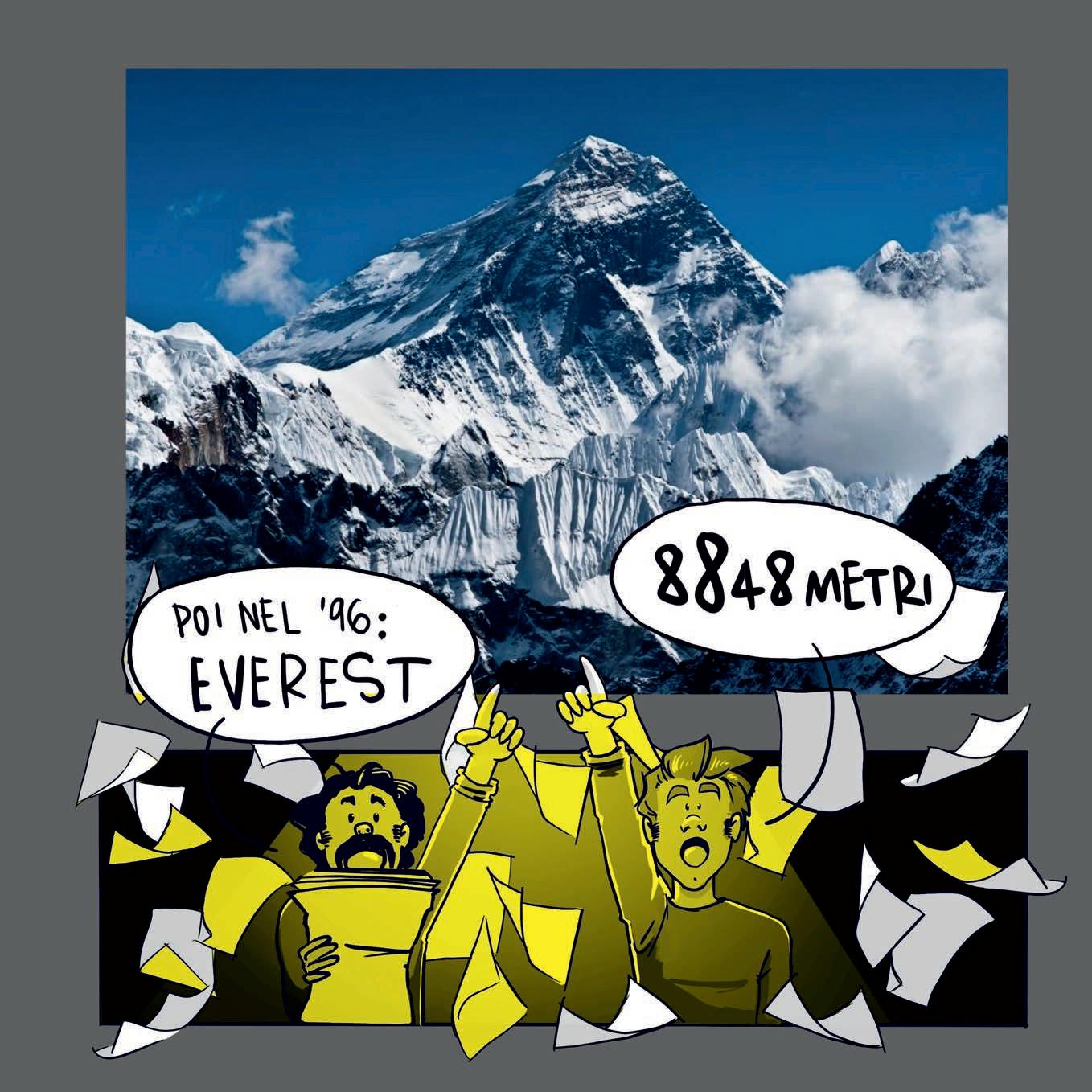

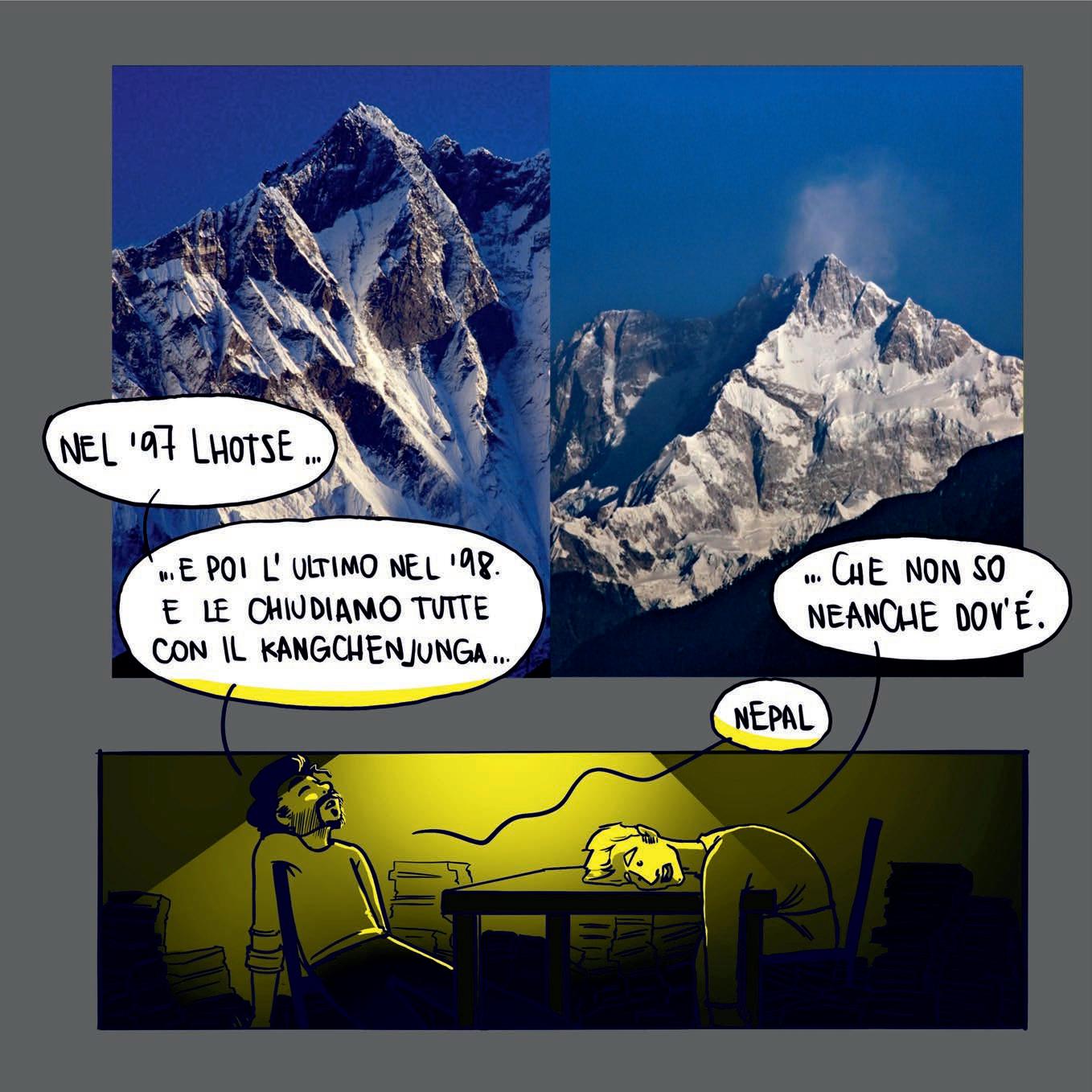

MATTIA: Right, let's just recap for a moment: this is the...? acopo: 211 metres.

MATTIA: That was the first one he scaled? acopo: Yes Mattia: And then? acopo: Makalu

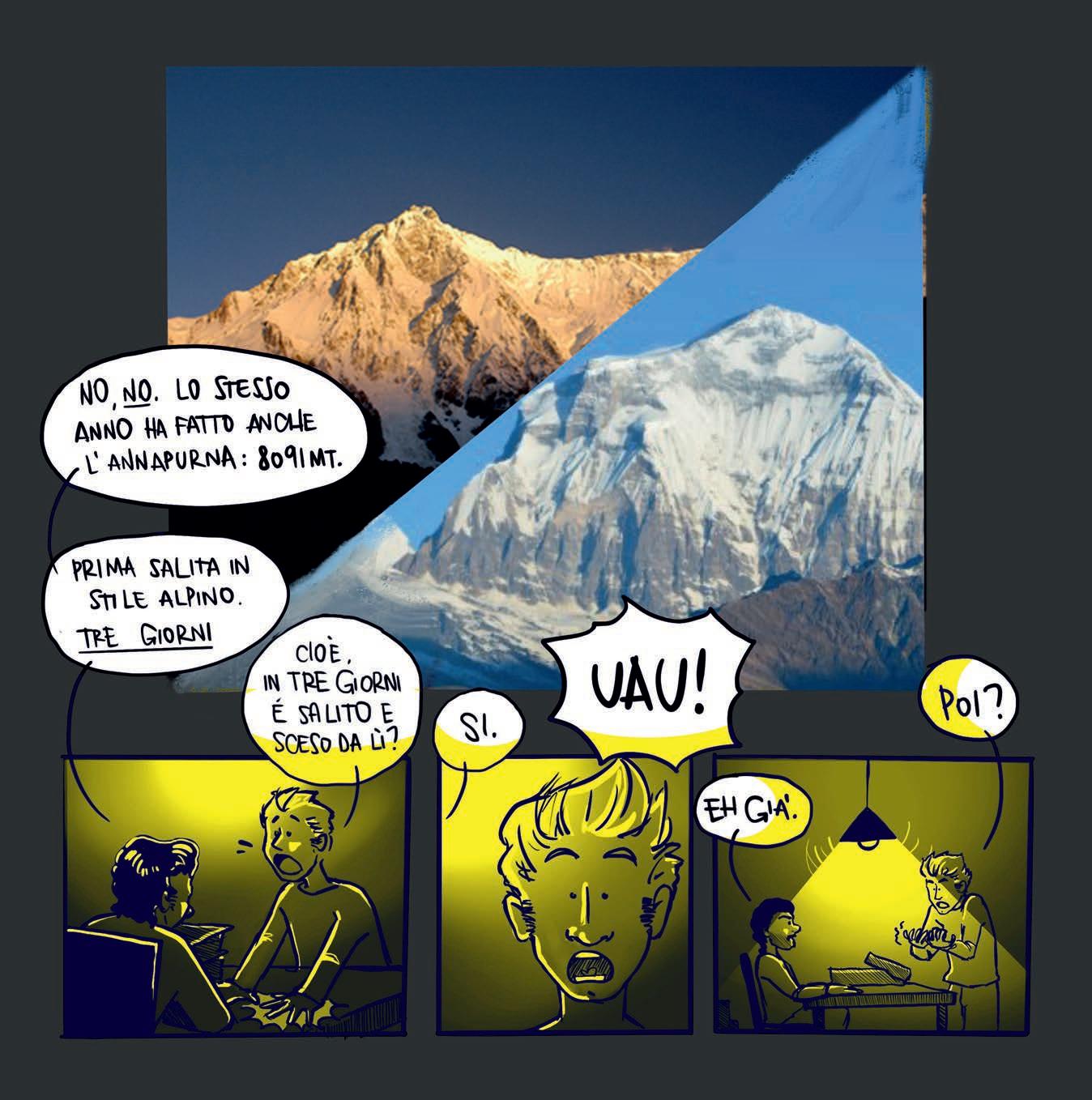

Mattia: When did he do the 2? acopo: 19 3 Mattia: When he was... how old again? acopo: 31 Mattia: And then? acopo: Makalu, which is 1 metres. Mattia: When was that? acopo: 19 . Then, the following year, he scaled Nanga Parbat's 12 metres Mattia: And the next year? acopo: No, no, the same year, he also completed the Annapurna: 091 metres and his first alpine-style climb. Three days!

Mattia: You mean he ascended and descended in three days? acopo: That's right.

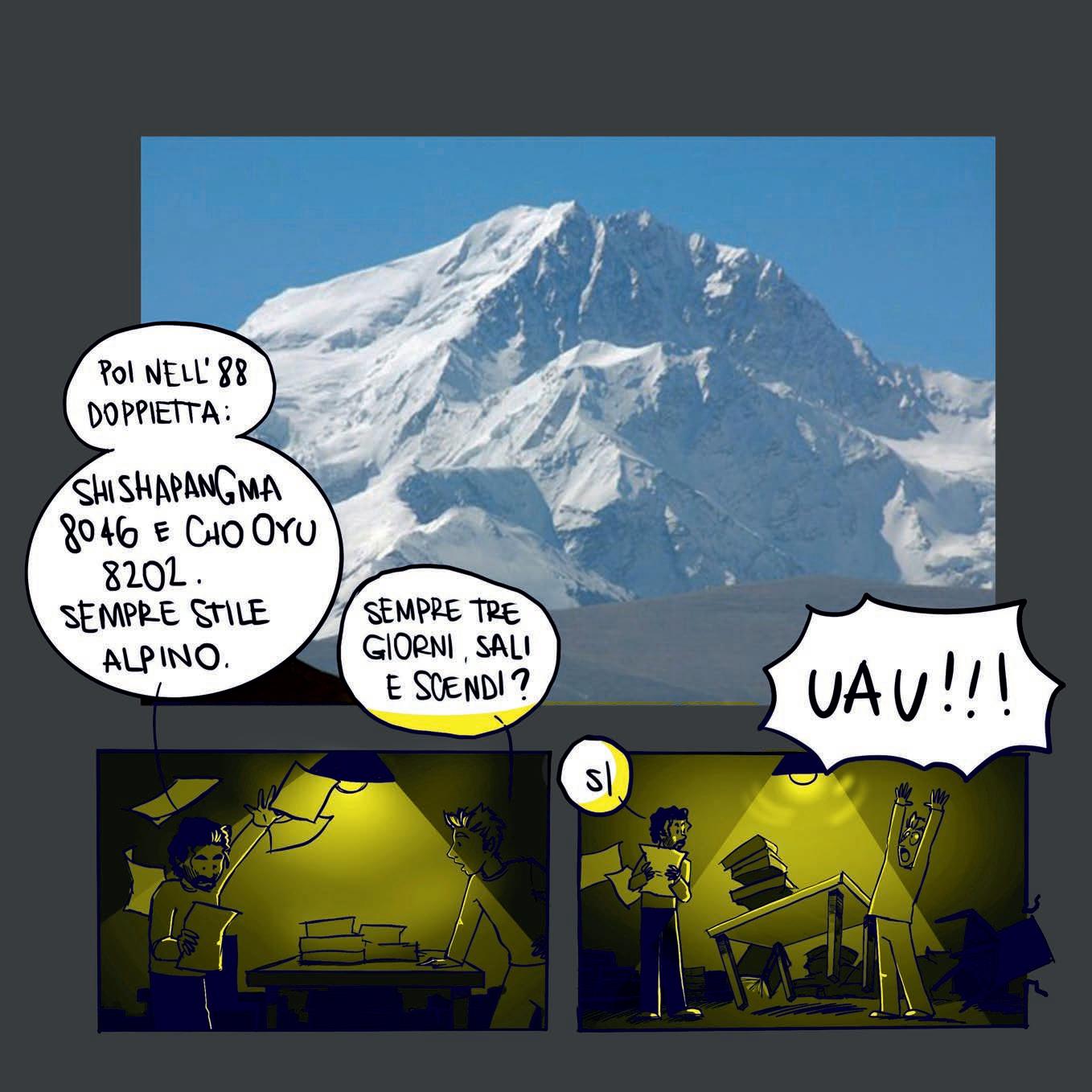

Mattia: Wow! acopo: I know, right. Mattia: What came next? acopo: Another eight-thousander? Mattia: Yes, yes, all 1 acopo: Well in fact, there are only 1 eight-thousanders! Mattia: You're right... please continue. acopo: ... Next was: ' , Gasherbrum II Mattia: How many metres is that? acopo: 03 Mattia: And that was ' acopo: Then in ' , he knocked two off his list: Shishapangma, 0 metres, and Cho yu: 202, again both alpine style. Mattia: And 3 days up and down too? acopo: That's right.

Mattia: Wow! acopo: Then... in ' 9...

Mattia: The Berlin Wall fell! acopo: And he instead climbed: the north-eastern ridge of haulagiri, sitting at 1 metres. Mattia: ... how many have we done now? acopo: We're at .

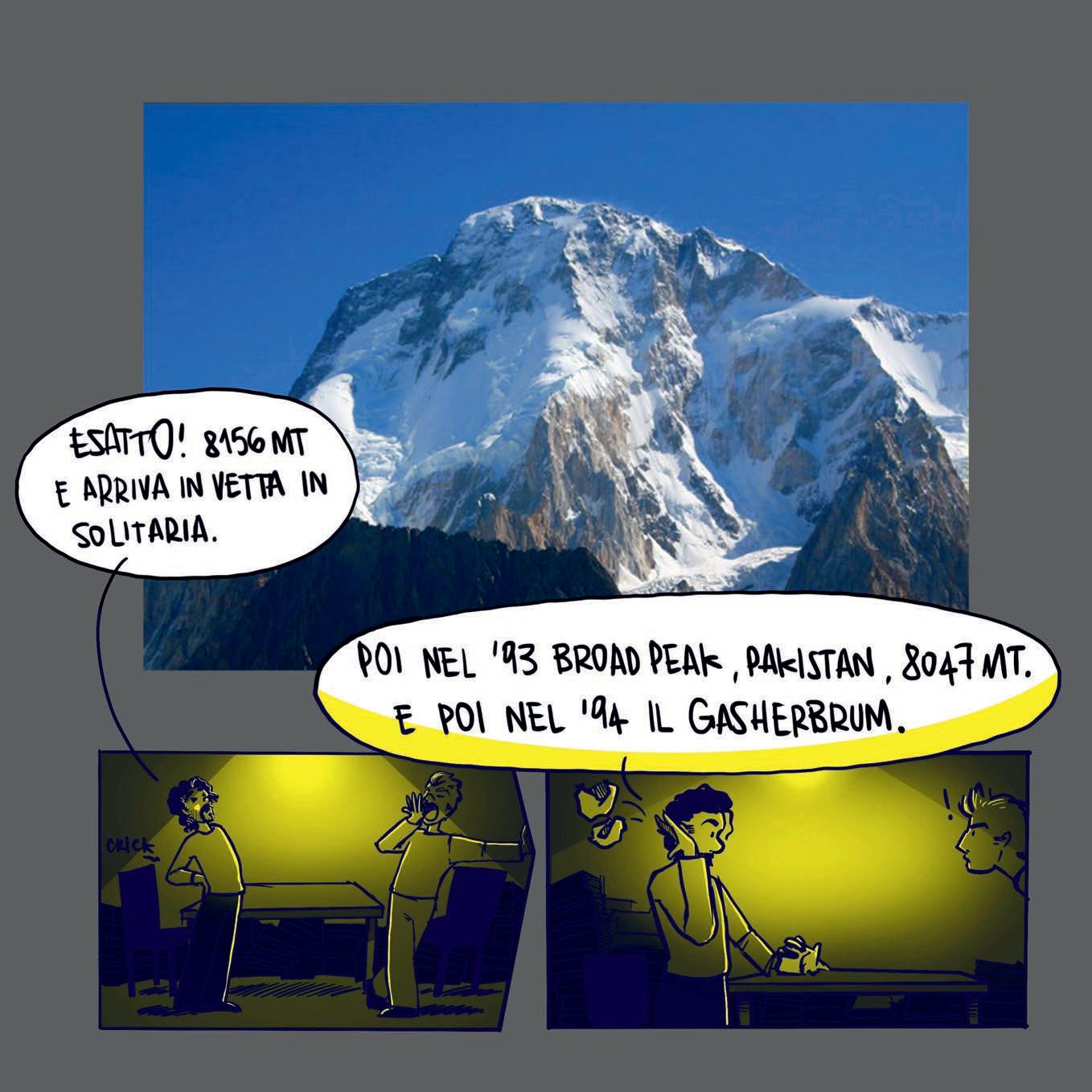

Mattia: Right, which was next? acopo: 1990. Manaslu, the north-eastern face route with a time trial. Mattia: You mean, he timed himself? acopo: Exactly! He reached the 1 -metre summit alone, followed by Broad Peak, Pakistan, 0 metres in '93. And in '9 , there was the

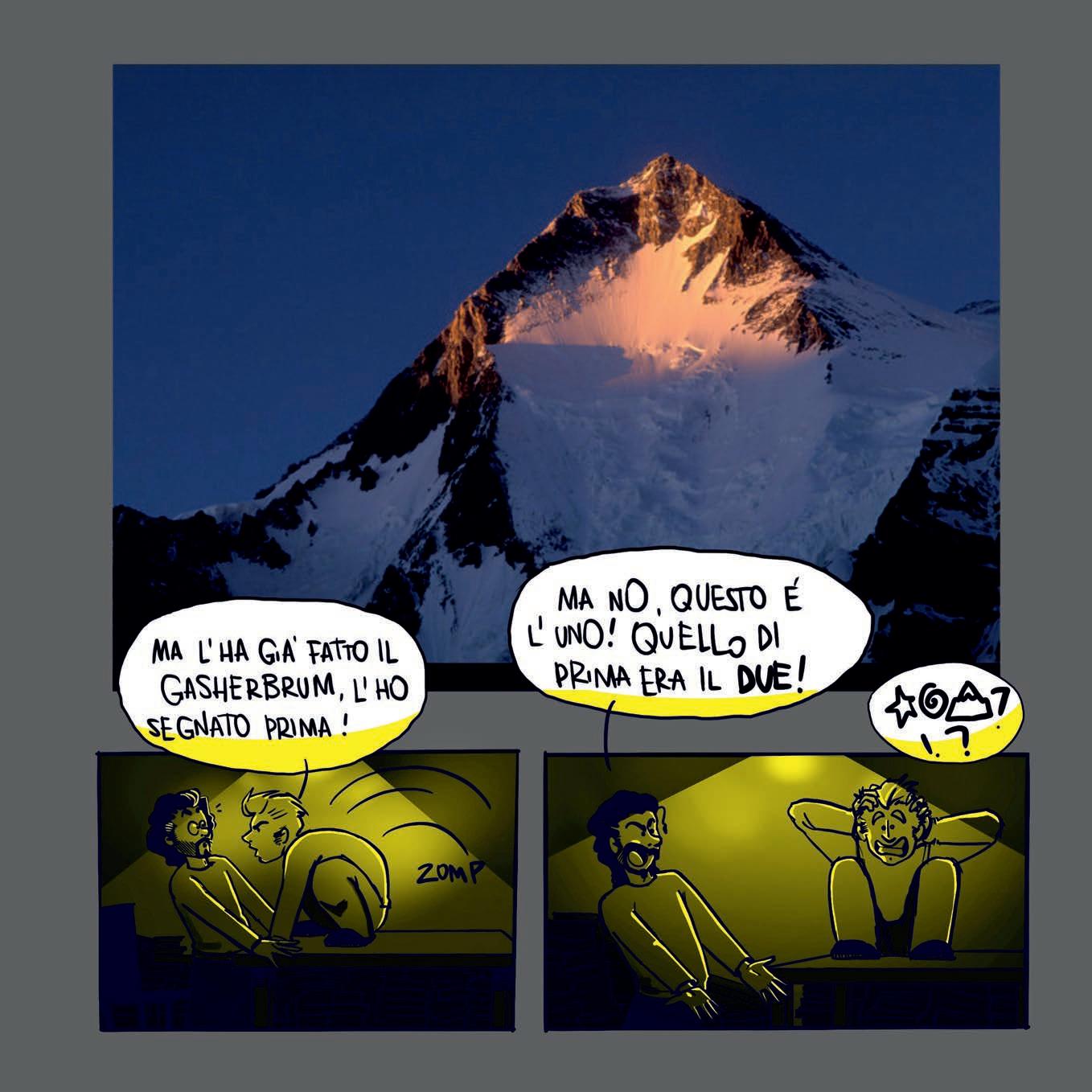

Mattia: But he'd already done the Gasherbrum, no? I've already got that one written down. acopo: Ah no, this time was Gasherbrum one! The first one was number 2. Mattia: ... acopo: Then, in '9 : Everest. Mattia: metres! acopo: Followed by Lhots e in '9 and the last but not least was in '9 ... hangchendzonga... Mattia: I don't even know where that is! acopo: Nepal. Mattia: So, he scaled the first in? acopo: ' 3 Mattia: And the last in '9 . acopo: It took 1 years. Mattia: How long did it take Messner? acopo: Sixteen. Mattia: Well done, Fausto! ... What about Moro? acopo: He didn't do them all. Mattia: What do you mean? acopo: He completed ... and then called it a day... Mattia: How many people have climbed all fifteen ei ght-thousanders? acopo: Fourteen Mattia: Yes, of course, fourteen. How many have achieved this feat? acopo: ... some say 3... in short: 3 or people... Mattia: Since the records began? acopo: Yep Mattia: So, are you telling me that , 00,000,000 people live on this planet and only 3 of them have climbed all the eight-thousanders? acopo: In history, not just those still with us. Mattia: What percentage is that? acopo: Hmm... let me work it out... Mattia: 0.00000 0 . So, only 0.000000 of humans have trod where Fausto has? acopo: Yes, and he is the second Italian to have done so and the sixth in the world. Mattia: W W! So, he is one of the fittest mountaineers in the world. acopo: That he is. Mattia: So, I should start right here the mountains when writing this book? acopo: No, wait! Let's start with what we said earlier, with the highest of them all. Mattia: Ah yes, now I remember. acopo: Write: “Fausto e Stefani reached his highes t ever heights... at just cm

19 0 Cascina Rossa. Castiglione delle Stiviere. Mantua, Italy. Whenever old Mandelo visited, a party would always ensue! We children used to wait at the beginning of the avenue for him, but we could never be sure when he was coming!

We would look down the wide path flanked by rows of poplars and look away again, eager to see that old man appear from who knows where.

He would ride a black heavy iron bike with rusty rims. It was so old and rickety that it always seemed to be o n the brink of collapse it could be heard creaking and groaning as it approached and would be propped against the farmhouse wall, before Mandelo would deign to get off. The man himself had a chest-length beard that was as white as snow. His head, on the other hand, looked sculpted, and his broad forehead was lined with wrinkles. He was also made distinctive by his pronounced nose and mouth nestled beneath a long moustache. The old man's hair was long and wavy.

He could easily be mist aken for a wizard out of a Sci-Fi novel, and his bike, the trusty black steed.

We would wait for the old man to dismount his bike and once we were sure that he could no longer see us, we would approach to see what he had brought with him this time,in that wooden crate that he kept tied to the pannier rack.

- ust a load of junk!

- What, it can't be?

- There's a pair of pliers, rusty pincers and a pruning knife... but it has no handle!

- What does he plan to do with that?

- Who knows... Mandelo always reuses everything, didn't you know? There's even a sickle.

- What else?

- There's this strange thing, it looks like some kind of saw

- Let's see... A lizard!

- What! Where?

- No, the saw silly! It's called a lizard!

- There's also a worn nail, a cardboard circle and lots of wire...

- That's enough now, if he catches us, he'll be angry.

- No, wait... there's also an anchor tied to a rope...

- Perhaps he was once a sailor!

- No way! He was a mountaineer.

- Nah, I reckon he was a sailor...

- Well, I thi nk he was a...

- uick, he's coming! Let's make ourselves sparse...

We would wait for Mandelo to enter the stable, where someone would put him up for the night. Then, after dinner, the old man would make the call and that was the signal we were all waiting for: “It's starting,” we would shout and all run at the same time into the stable, where we would then sit in silence in a circle and wait patiently. He would light a small lantern, sit with us and remain still, peering at us with his half- closed eyes. His manner would intimidate us, but as soon as he began to speak, his voice would cut through the silence and put us all at ease.

Mandelo's voice was unlike any other, it would stir the flowers, sky and the earth, and stimulate the imagination.

“We couldn't do without it” he began, “without it, we wouldn't be able to go anywhere!” “Without what, Mandelo, without what?” we asked. “I need a hot-air balloon,” he replied with all the confidence in the world. And with that, he would get up suddenly, leaving us all there, anxiously expectant.We could see him fumbling around in that wooden crate he carried on the pannier rack, unfastening the ties that held the lid closed and then reappearing with white fabric rolled up under his arm. “This is just a piece of the balloon,” he declared, “it belonged to a friend of mine... just a few touch-ups here and there, and then I will be able to fly safely, wherever I desire, and let the wind carry me to my destination.”

“But why do you want to leave in a balloon?” we would ask him, but Mandelo didn't answer, he had already climbed into the basket, and we were flying right there beside him.

“There's a harsh desert below,” he exclaimed, “and you see that over there? Well, that's water, children! Water which wets everything and quenches all thirst!”

And we could see streams, brooks, lakes, oceans and the like. Then the balloon's billowing shadow caressed the bosom of the valleys and darkened the mountain ro cks.

E ... he mo ntains. he rst ones ever sa ere the ones the old man sho ed s rom his hot air balloon.

ne winter evening, when the bitter cold forced the farms' few residents to gather in the stables and warm up as the adults told stories, we heard the distinctive rattle of Mandelo's bicycle emerge from the night!

“Mandelo, Mandelo” one of us immediately shouted. “Where have you been, please tell us where you've been?” asked one of the older children who was sitting on a bale of straw. “Hmm, let me see now, what would you like me to tell you?” the old man replied coyly. “Yes, please te ll us. We want to hear all about it! o tell!”

Mandelo's expression suddenly turned grave, he wrapped himself in his old overcoat and looked at each of us, one by one, as if he were looking for the root of the words in our eyes and hearts. Mine jumped a mile when his gaze lingered on me and he said, “you boy, come sit on my lap.”

I looked around in astonishment: “me?”

“Yes, yes, you boy, I need a helper tonight, come and sit on my lap.”

I crossed the circle with terror yet wonder coursing through my veins. When I reached Mandelo, I sat down on his old legs. “ o you see that?” he asked, startling me in the process, “can you see that, boy?”

His big yet lanky hands were pointing to the stable's half-open door. Beyond that, against the last light of the evening, a snow-capped mountain, MountBaldo, was barely visible on the horizon.

“When you grow up, you'll be able to go up there on your own,” he continued, “that's the highest mountain in the world. From up there, you will be able to s ee everything and right now... I want to take you there with my balloon. Hurry, and wrap up warm, it will be cold.”

We didn't need to be told twice, we bundled up as best we could and prepared ourselves for the adventure: “Look,” he said again, “tonight the clouds are thick and dark, but we will pass through them to emerge where the sunset can still be seen. Come on boys, ascend with me!”

And the hot-air balloon... it took flight.

“Be brave!” he shouted “we're almost there. We have to climb a little higher if we want to reach the top! Give it some more gas, boy, give it some more gas!”

The other children laughed at me when they saw me blush as I pretended to pull levers and turn knobs, “That's right, you've got it, boy!

We're almost there! o you see it? That's the summit, you can see everything from there!”

And yes, we saw it... I truly did see it. Whilst sat on Mandelo's knees, the earthy ground just cm below me disappeared to make way for breathtaking chasms and extraordinary overhangs. Th e walls of the stables flattened to become endless horizons in which your gaze could but stretch to the clouds and the thousand-year-old ice and snow below.

Thanks to the old man, the dream and fantasy was taking root in me. Perhaps that very evening, in the same stable, an idea was vaguely planted in my mind: in order to live my dreams to the fullest, I would have to push myself to the highest heights and dare, together with my old man, of a high-altitude adventure.

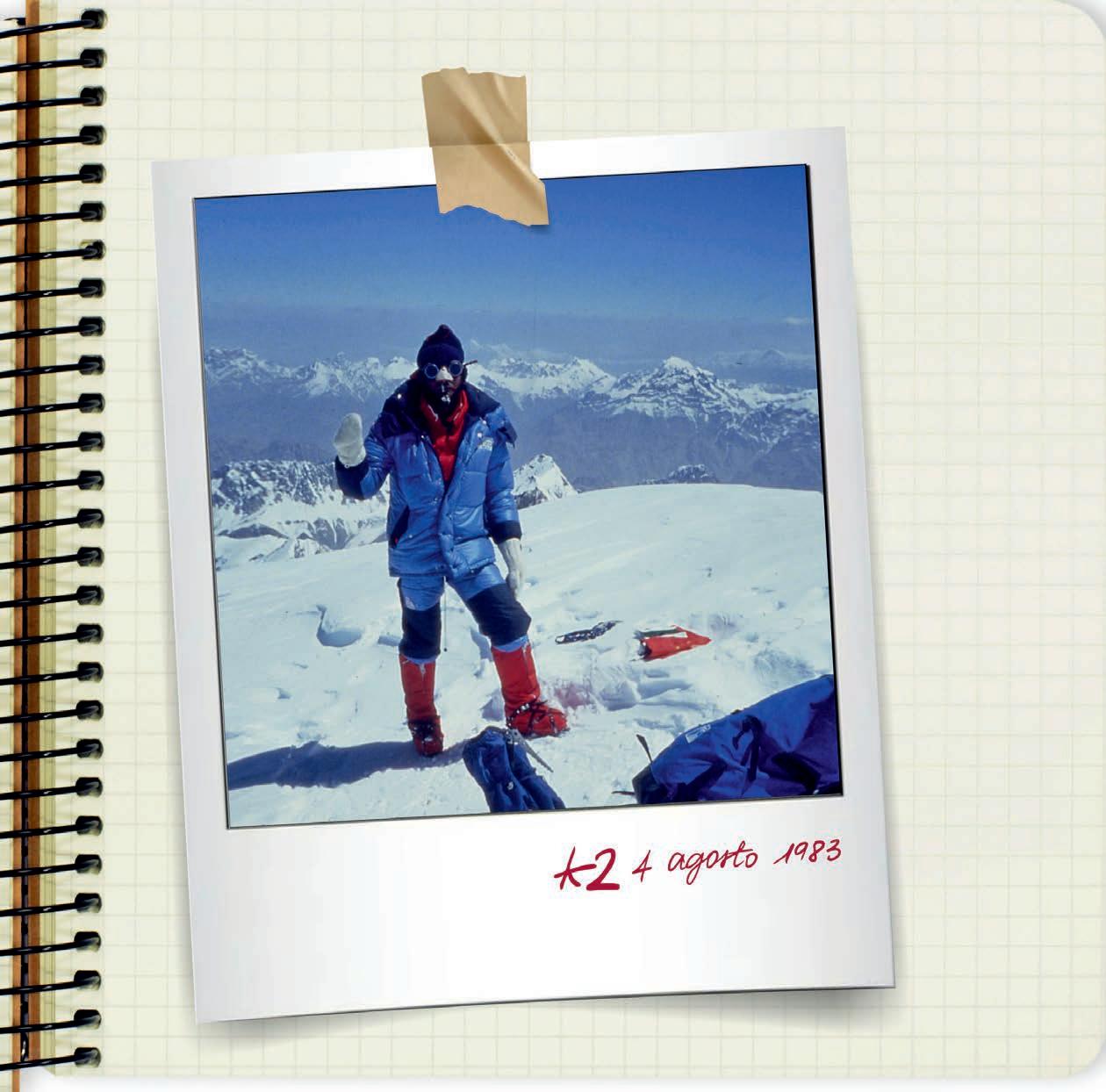

Ahhhhhh! Yes, I could see the summit now! I could see the earth's curved horizon. I saw the unlun range stretch 2000 km in front of me from Pamir in Tajikistan to the inghai province, even up to where the Taklamakan esert begins, and Tibet's Trans- arakoram Tract, the valley through which we had travelled to reach the camp. No shit, I was actually at the top of my first eight-thousander. The 2!

NORTH RIDGE, CHINESE SIDE OF THE 2. ust four days after Czech mountaineer osef Rakoncaj and Italian Agos tino daPolenza, reached the 2 summit. The Francesco Santon-led expedition, made up of 23 mountaineers and roughly 1 volunteers from the SAT an alpine club operating in the Italian province of Trento departed on the 2 th of April from the Sarpolago Valley, with a caravan of 119 camels in tow. From that point onwards, the expedition continued on foot, without the help of the Sherpa, along with tons of material that had to be carried. n the 3rd of August 19 3, the day in questio n, it was the Italians' turn Fausto e Stefani and Sergio Martini to attempt the feat with no supplemental oxygen and in pure Alpine style.

0 0 19

We leave at .00 am from the eagle's nest at 900 metres. From here, the ridge rises along a series of very steep rocky pinnacles we make good pace but the higher we climb, the more we find unstable rock and dangerous ice.

We waste a lot of time. ne step with crampons, ice axe, another step with crampons. Then pause. Every 10 metres or so we have to rest there is very little oxygen and our blood is thickening. It honestly takes it all out of you.

ne step with crampons, ice axe, another step with crampons. Then pause. We pass the huge hanging glacier to the left of the crest of rocks. But the wind is starting to ramp up: if we reached the top with the wind like this, surely we would be overwhelmed? What now, we ask ourselves?

Change of plans, we'll wait here. We're at 00 metres! ust 1 0 metres from the summit. But the choice has been taken away from us... it is late, much later than expected, so we will reach the summit tomorrow and then we will descend. We don't have sleep ing bags, but we won't mention that either. The original plan was to climb with a light load and descend the same day, not spend the night on the wall. Bivouacking at more than 000 metres, right in the middle of the socalled death zone, is not something that you ever account for. “Let's dig a hole,” we think, but we find only rock in sight. There's little to dig. In the end, we make do as best we can in a sort of niche, step or cleft, if you like.

It is .00 pm. It's already been 12 hours since we l eft. Now is not the time to make grand speeches. Too many words would only complicate things. It's better to act. We do all the things that need to be done.

But that's not the only reason why. Words have power. Uttering the wrong ones coulddistract, confuse or even lower our mood. Sat in this 00-metre-high bivouac, with the temperature around - 0 C, you don't want to talk. You risk disturbing your partner or even yourself.

You just pray for the time to pass. But it never does. So, you just keep quiet and wait. And you count: the hours, minutes and seconds. Until the first dim morning light graces us with its presence.

When I try to get up, I find that I cannot move because a layer of

frozen snow has formed on my stomach. In order to free myself, I have to punch myself. But this is nothing compared to the big rookie mistake I made last night: I was leaning against the wall of ice with my head. I had my cap and hood on of course, but the cold seemed to go straight through me. T herefore, I decided to put my hand between my head and the wall, to make a gap. But that was a stupid idea. Because the circulation has stopped. It becomes immediately apparent as soon as I pick up the ice axe, as I am in pain and find it di cult to move my hand. There is no doubt about it, I have lost two fingers. But now is not the time to dwell on it, we have to get back on track: one step with crampons, ice axe, another step with crampons, pause.

After hours of climbing, we are approaching the su mmit's last few metres. They seem endless. Yet just before I step foot on the highest point, something instantaneously bursts inside me. Something that has been simmering below the surface for days, months, years, perhaps even forever.

An explosion of happiness like something I have never felt before goes off in my chest. I feel like I am about to reach so much more than the top of this summit. I am about to reach a part of me. Something of mine that, during my 30 years on this planet, I ha d not yet had the chance to meet, but which had always been waiting for me up here, at , 11 metres above sea level. We are at the top of 2, the mountain with the least repetitions in the world.

From here, in the midst of a breathtaking view, I recognize Gasherbrum, Broad Peak, Muztag Tower and the Hidden Peak. I can still not control the tears streaming from my ecstatic eyes. The effort, the ability to be able to say, “I did it” and the beauty of the world seen from such an inaccessible place .

I did it, I actually did it.

Today is Wednesday, the th of August 19 3. For the first time in my life, my head is in the clouds, yet my feet are firmly planted on the ground. A dream has become reality. As real as you and me.

For a body shop mechanic from the Po Valley, this is no small feat. Holy shit!

- Are you ready? It's time to leave.

- Mandelo? What on earth are you doing here?

- We gave our dream wings. We humans must feel that there is always another dream that can fly even higher or further and only in this way, will we be able to chase those that seem impossible.

- Even the impossible ones?

- Yes, otherwise you would miss all the surprises to come... let's go, hop on my balloon!

- Where are we going?

- You have already seen, no? You can see that from up here, the earth is round and cu rves around the horizon, but I'll tell you one more thing: even time is round and curves to other horizons.

- Time?

- Yes, look. Take a look around, my boy!

From the top of his hot-air balloon, Mandelo would show us the land below... our home the red farmhouse the fields that stopped dead at the edge of the woods, the entire regions and from even further up, the jagged-shaped continents. “Look over there,” he would shout into the wind, “you can see things better from above. The prope rties, fences, gardens and woods... this is mine, this is yours, here are the borders... when you get up and go up, everything falls into place!”

Mandelo was our way of learning about geography and the nature of men. His imagination knew no bounds it took us to the most remote corners of the globe, from the ice expanses of the north pole to the scorched lands of the African deserts.

“ o you see? Look over there! See all those black-skinned children waving their hands to greet us? Th ey are just like you! But they are not as happy because they have no food to fill their bellies or water to quench their thirst. We must go down there and bring them what we are lucky enough to have. Turn off the gas, my boy, turn off the gas...” And from his lap, I extinguished the flame that kept us aloft and landed with him on that faraway land: Africa!

Mattia: Hang on! acopo: But how did he get to Africa?

Mattia: Let's recap: the first Italian to climb Mount enya's Nelion Peak, at 1 metres. That was in...? acopo: 19 9.

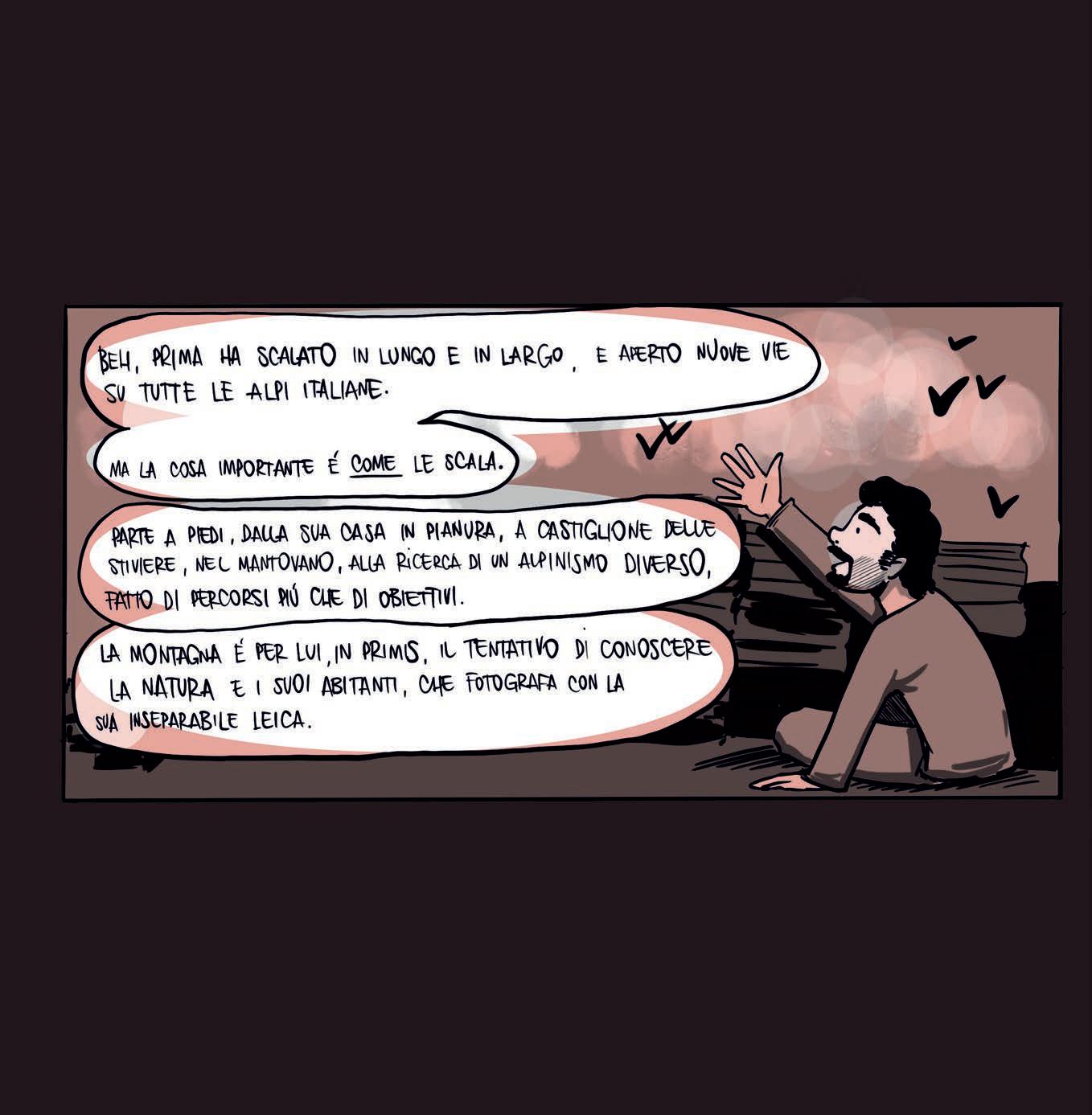

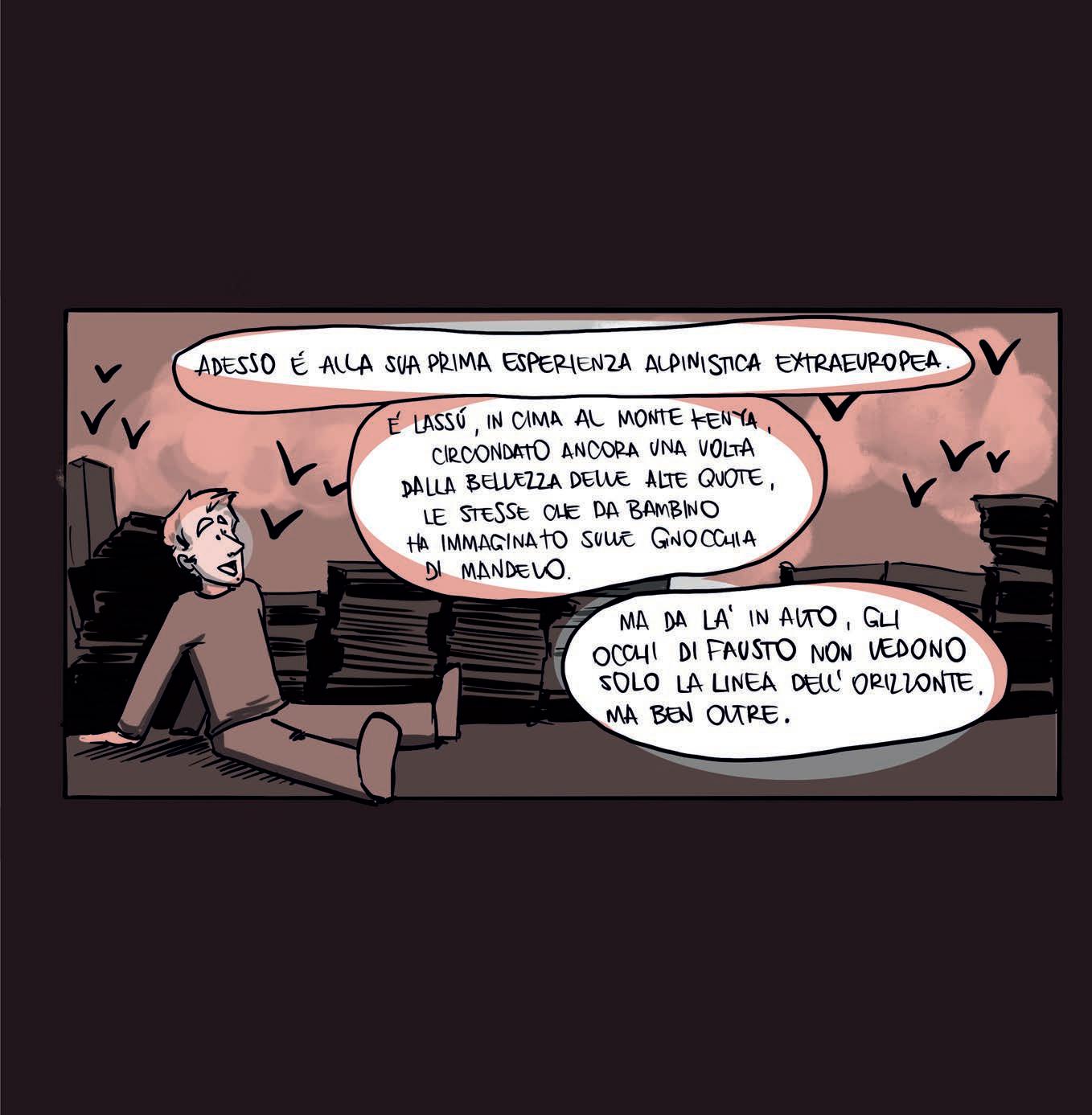

Mattia: He was only 2 years old then. And before that? acopo: Well, first he climbed far and wide and opened new routes on all the Italian Alps. But the most important thing is how he climbed them: he set off on foot from his lowland home in Castiglione delle Stiviere, Mantua, in search of a different kind of mountaineering, made up of routes rather than objectives. For him, the mountains were his first attempt to get to grips with nature and it s inhabitants, which he snapped with his Leica camera this went wherever he went! Mattia: And now he is on his first non-European mountaineering experience. He is up there, on the top of Mount enya, surrounded once again by the beauty of the high altitudes, the same ones that he had imagined all those years ago as a child perched on old Mandelo's lap. But from up there, Fausto eyes not only the horizon, but much further.

THE O

MOUNTAIN enya. Sun, baobabs, savannah, hea t, sun, safari, sun, lions, leopards, gazelles and in the middle of an enormous colossus of rock: Mount enya.

Africa, the birthplace of humanity! And when you are up here, the only colour you can see for miles is... white! Snow! Here! n Africa's largest glacier! Now, who would have thought, eh? Snow, more snow and rock peeking out of the white clouds just below you. And now? What am I going to do with all of this?

Where do I put all this beauty, what can I take home with me?Mandelo, old f riend, where are you? How do I explain this thing that I'm doing... mountaineering, because by the time I make it all the way to the top, it is already out of my grasp, and nothing tangible remains.

What's the use if nothing remains?

From up here, the gaze sweeps as far as the sun can light up the

horizon, before becoming a huge red ball that sinks into the equator. Is this the sickness of Africa of which we speak? This deep nostalgia, the feeling of being alive even if you don't know what to do with all this life? In the end, all that remains is to go back down, retrace the same path: snow, rocks, slopes, stony ground, followed by forest, savannah, trails and dirt roads that lead to where those same slums we passed in the car, begin.

h Mandelo! I really saw them, those children with swollen bellies digging beds in the landfills to enjoy the warmth of the gases produced as the waste ferments.

I saw them, God damn it, play football with balls made of rags, while we, with our backpacks secured to the roof of the eep, were preparing to carry out our self-styled calling.

In the end, all that remains is to go back down there, to the middle of that dump, with the putrid football field. Go back down, yes, because perhaps that is the only mountain worth climbing, becau se that mountain of waste is the real challenge after all for those dirt-ridden, barefoot kids who survive every day without knowing whether they will find a scrap to eat. Yes, I'll go down there and say: “ eep them, kids! These are for you”.

And overturn a sack full of leather balls and a pump to inflate them together real balls that actually bounce so that they can really play. And then I hear my guide's voice in my ear: “Careful now,” he tells me, “don't let them run around too much, ot herwise they'll get hungry and burn what little they have accumulated during the day.”

I saw them, Mandelo.

In the village of Nauro Moru, white men snap their fingers to be served by black men in livery with low, and submissive eyes. What! I saw the village surrounded by lush white gardens and vegetable patches, where people, sat comfortably in their Range Rovers, would go and sell the products of the earth to peoplewho had nothing. That can't be right?

What can I do with all this ice that surrounds me? What should I do if down there, in that impoverished village, there is nothing?

“ h, what a rich and fertile land this would be if there were water,” the village chief tells me. “You know, in Africa, where there is water, there is paradise!

“And how much does it cost? How much does it cost to build a well,

damn it!” “ ne million lire,” he replies discouraged, “it's a lost cause.” We remain silent for a short while, as if faced with an impassable wall, and then, as if by i nstinct yet without realising it, I say a few simple words: “ o you know what? Even impossible dreams an be a hieved. A friend told me that, a long time ago.” And right then, everything changed.

I went away, returned to Italy. But carried that nugget of knowledge with me.

I talked with and met people. Two hundred thousand lire here. Fifty thousand lire there, and then I returned to Africa. “Here, I have the money. Let's do this thing!” “What thing?”

“The well, let's do it!”

And then th e digging began: first by hand, until a machine arrived. A British contraption that would go down, rather than what I was used to doing, going up. Here, you would have to go down, climb an overturned mountain which sinks under the earth.

You have to dig down to find it! Yes, water... it's worth more than gold here! And that's why all the ice is way up there! So, it can be found once more below, this liquid, liquid gold.

Now, here's something that is left: that well which we eventually buil t a year later. That well which, in the space of another year, changes the fate of the small village of orogocho. That well, which I also returned to visit the following year. I'm not cured of the so-called African sickness, far from it, but this time I can come back and be proud but not in a vain way of this concrete gesture which remains, can be seen and most importantly, can be touch...

“Wait a minute, what's that man doing over there?” “Which man” asks the village chief?

“The one over t here, next to the well...”“He says he owns it.”

“He owns it?” I rebuke. “I hope you tell him that we made that well, we donated it to the village, not...”

“He says it's from...”

“And those badges?” I interrupt him, “those medals on his uniform? What do they represent?”

“We don't know,” he continues, “but he's armed, don't you see? And he doesn't allow anyone to take any water unless they pay first.”

I just stand there, as silent and as motionless as a statue. Then, just like a wave crashing into the shore, I feel the blood rush to my ears and that alashnikov that the unknown soldier is wearing around his neck causes anger, frustration and even aggression to bubble up to the surface.

“No, wait, what are you doing, he's dangerous.”

The village chief is afraid, everyone is, but the rush of blood drowns out the sound.

I do wait, lie in wait and as soon as the man puts the alashnikov dow n, I grab hold of it. The stranger is shouting and chasing after me, but it is too late: I start banging and beating the rifle against a rock until it splits into two pieces and can no longer be used. The man continues to shout in a language that I do not understand, but at some point, I don't even hear him any longer. He approaches me menacingly, raising his arms as if he is about to attack, but he's not quick enough: there's a hard club-like stick on the ground. I instinctively pick it up and s trike it with all my force on the soldier's back, until it breaks. The stick of course. And suddenly, the man stops shouting. He slowly gets up and walks away. I turn around. The village chief is looking at me. “He'll be back,” he says with the expression of someone who forgives you for a sin you don't yet know you've committed. “They'll be back. his is Africa,” he continues “it's shaped like a gun, and enya is the dog. I'd get out of here now if I were you.”

Ma ndelo: Let's go! More gas, my boy, more gas. You went a step too far this time!Fausto: Mandelo! I don't know what got into me, I was finally able to do something and then I had to run away. I ruined everything I was arrogant.

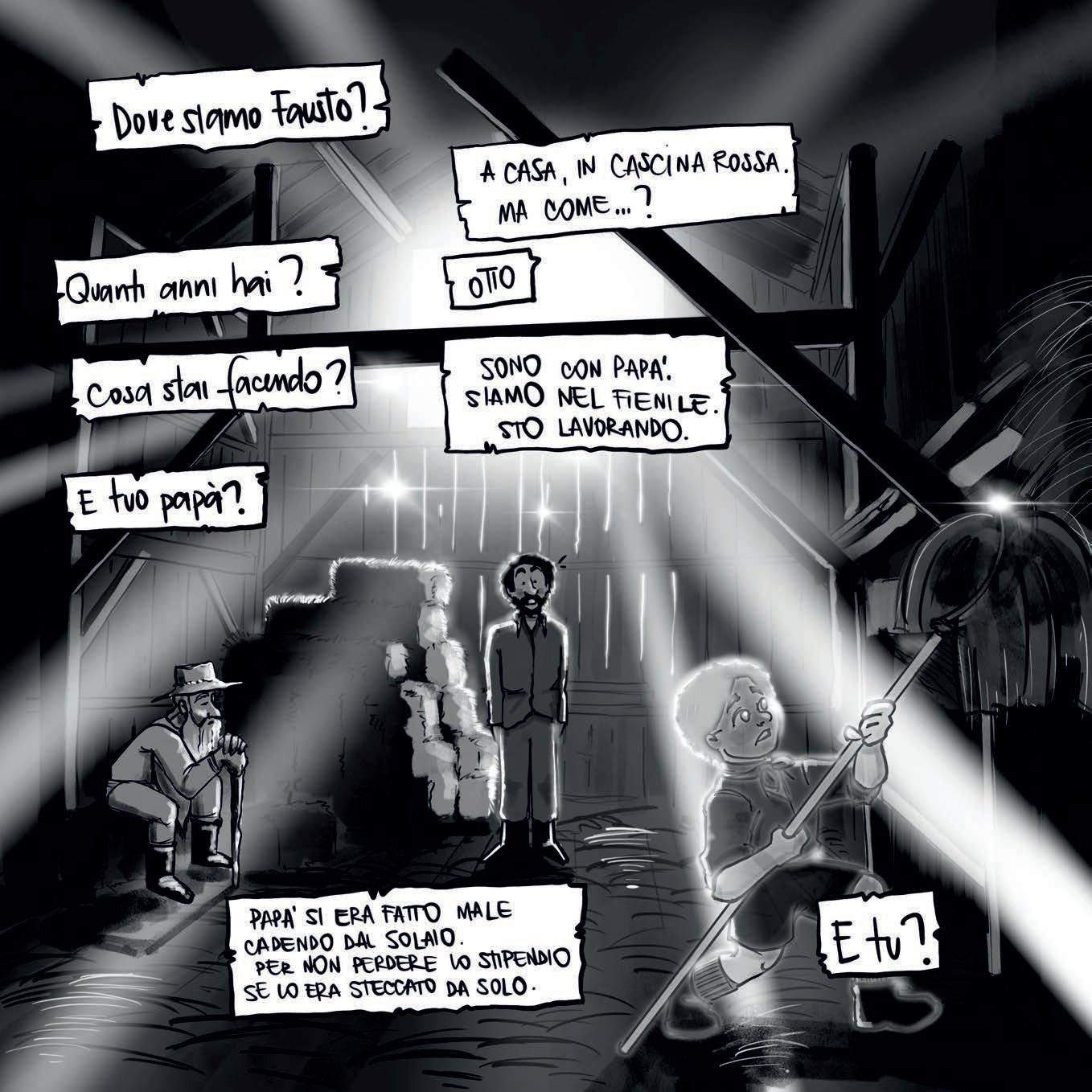

Mandelo: No, nothing is ever lost. We have a saying that the beginning is often the end, and the end is a beginning. Where are we? Fausto: At home, Cascina Rossa. But how...? Mandelo: How old are you, boy?

Fausto: Eight.

Mandelo: What are you doing?

Fausto: I'm with my pa pa. We are in the stable. I'm helping him out. Mandelo: And your papa

Fausto: Papa hurt his foot when he fell from the loft. In order to not lose his salary, he made a makeshift splint.

Mandelo: And you?

Fausto: I would wake up at two in the morning to do the milking. I wanted to do what I could to help.

For example: Every time that I saw the woodpile getting low, I would go out and look for dry pieces of wood. Papa would work all day long: in the stable, chicken coop and vegetable patch. In the eve ning, he would be so tired! He didn't even have enough strength left in him to tell me a story.

Mandelo: Stories are important for children! Fausto: You were there, you told us stories.

T GETHER: Cheers!

Mandelo: Children, those of you who are reading, have I ever told you the tale of Hot Head?

Hot Head was a mountaineer who always suffered from a hot head! He hoped his head would cool down on the mountains, but even when he reached the snow-covered areas, his head would still be boiling hot! ne day, on a faraway mountain, in the land of Pakistan, Hot Head was with his climbing partner Tobias Heymann, a great German musician who played piano concerts all over the other side of the world.

A non-commissioned o cer had also been sent by the government to ac company them on their journey. Hot Head noticed that, instead of using his own provisions, the o cer stole the expedition ones and was served by a good and humble porter who was also a cook he humiliated this man every day by treating him badly, just like a servant. Hot Head was outraged: “Have you seen how he treats that poor cook?”

“Calm down,” his pianist friend told him, “that is an o cer, you don't argue with o cers, they are dangerous.”

The following night, before leaving the ba se camp to attempt the climb to the summit, Hot Head heard shouts outside the tents he poked his head out and saw the bad o cer giving the poor cook a beating while he was on the ground.

Hot Head couldn't take any more, he didn't even stop to put on his shoes before approaching the bad o cer and beating him up.

From that day on, the o cer stopped treating the poor cook badly, but Hot Head was now fraught with worry! What would happen when they returned?

Would he be court-martialled?

Then came the day when Hot Head and Tobias decided to attempt the summit.