Publisher: Editor: Associate Editors: Editorial Director: Business Manager: Design and Layout:Ella Vorovitch Proofreading:Larissa Tchoumak

Rabbi Yoseph Y. Zaltzman Ella Vorovitch Rabbi Yisroel Karpilovsky Rabbi Dan Rodkin Mikhail Khazin

: Greater Boston Jewish Russian Center 29 Chestnut Hill Avenue Brighton, MA 02135

: 617-787-2200 617-787-4693 E-mail: exodus@shaloh.org Website: www.Shaloh.org

чистого оливкового масла, праздник победы маленького народа над большой армией. Но кроме при вычной и знакомой нам Хануки, с ее пончиками и латкес, с мерцанием свечей, в этом празднике скрыт глубокий внутренний смысл, который относится к еврейским жен щинам. Несмотря на то, что воевали мужчины и мужчины очищали Храм, искали масло и зажигали Менору, Хануку называют женским праздником. Потому что победа над греками в те далекие времена и сам праздник Ханука –во многом заслуга еврейских женщин. И не только Хану ка. Наши мудрецы говорят: «заслугами праведных жен щин вышел еврейский народ из Египта». Сохранив веру и надежду на будущее, они заботились о продолжении народа – рождении детей. А потом, когда евреи перешли море, Мирьям, сестра Моше и Аарона, побудила женщин с тимпанами в руках петь хвалу Вс-вышнему. Мидраш приписывает заслугам Мирьям и создание колодца, который сопровождал евреев во время их странствий по пустыне и высох после ее смерти. В Танахе рассказывается о пророчице и судье Дворе, мудрость и волевые решения которой помогли ее совре менникам вернуться к соблюдению заповедей Торы и одержать победу над многочисленными войсками кна анейского полководца Сисры. Наши мудрецы подчер кивают и мудрость Дворы по отношению к своему мужу –неученому человеку, которого она тактично и ненавяз чиво, так, что он не чувствовал ни малейшего давления и превосходства с ее стороны, подталкивала к учебе.

Примером отваги и героизма в Танахе является и Эстер, благодаря которой мы отмечаем праздник Пурим.

Какую роль сыграли женщины в истории Хануки? Греки запретили евреям делать обрезание, и многие «эллинизированные» евреи с радостью приняли это. Но еврейские женщины все равно делали обрезание своим сыновьям, чтобы скрепить Завет со Вс-вышним, хотя наказанием была смертная казнь. Мы помним про Хану, на глазах у которой убивали ее сыновей, отказавшихся поклоняться идолу. Когда пришла очередь младшего, седьмого сына, Хана сказала ему, чтобы передал наше му праотцу Аврааму: «Ты поставил один жертвенник, я – семерых в жертву отдала. У тебя это была только попытка, у меня – в действительности». Сыр и другие молочные блюда в Хануку мы едим в память о подвиге Йегудит, убившей греческого воена чальника. Главные качества женщины — душевная теплота и желание отдавать. Приобретая новые знания, она непре

менно делится ими даже на внутрисемейном уровне. Теилим говорит о женщине как об акерет абайт (основе дома). Именно женщина формирует атмосферу в доме и оказывает огромное влияние на мужа и детей, в том числе и в области учебы. Обсуждая с ребенком полу ченные знания, мать учится вместе с ним. Не случайно начиная с XVII века главной книгой для домашнего чтения сталa книга на идише «Цэна у-рэна», Яакова бен Ицхака Ашкенази, который поставил своей целью дать женщине, а также любому, кому сложно понять Писание и мидраш в оригинале, возможность читать их на понятном языке идише. Каждую субботу еврейская женщина читала вслух своим детям пересказ текста Торы с комментария ми, притчами и сказаниями, взятыми из Мидрашим. Ханука – это еще и хинух (воспитание). Комментируя заповедь, обязывающую нас учить детей наших, мудре цы употребляют слово леазир, одно из значений которо го можно обозначить как «сияние». Обучая детей, мы и сами поднимаемся на гораздо более высокий уровень. Следовательно, изучая Тору, женщина прилагает еще больше усилий к тому, чтобы ее окружение тоже повы шало уровень своих знаний. В каждом поколении были женщины, обладавшие совершенными познаниями внутреннего, скрытого смысла Торы. Например, в Талмуде говорится о Бру рии, дочери рабби Ханины бен Терадиона и жене рабби Меира. В книгах Средневековья встречаются упомина ния о женщинах, занимавшихся правкой текстов Торы после своих мужей. Шестой Любавичский ребе, раввин Йосеф Ицхак Шнеерсон, в своих воспоминаниях писал о том, что семья Алтер Ребе настаивала на необходимости распространения Торы среди женщин. Он и сам воспи тал своих дочерей в том же духе.

Сила женщины – в ее мудрости, в умении различать, видеть больше, чем говорят словами, чувствовать серд цем. Такими были наши праматери и героини Танаха. Их смелость, стойкость, доброта, милосердие, способность выдерживать испытания, готовность к самопожертво ванию, мудрость, мягкость, настойчивость и многие другие качества передались и нам. В каждой еврейской женщине есть внутренние силы, чтобы противостоять происходящему вокруг. И свечи Хануки напоминают нам об этом. Веселой Хануки!

С уважением, Элла Ворович

жается

телу. Однако ханукальные события связаны с освобождением от гнета духовного, как сказано: "Хотели заставить их забыть Твою Тору". И поэтому избавление от него отмечают более духовным образом – зажиганием огня масляных светильников. ХЛЕБ, ВОДА, ВИНО И МАСЛО Символика Скрытой Торы позволяет дать истолкование, которое раскры вает еще более глубокий смысл этой особенности праздника Хануки. Обобщающими компонентами трапезы являются хлеб, вода и вино. Все эти три вещи символизируют различные аспекты Торы, которая на языке Каббалы называется "пищей души". Хлеб и вода, жизненно необходимые для существо вания человека, соответствуют аспектам Открытой Торы, изучение которой необходимо еврею, чтобы знать, как жить и как себя вести. Вино, которое не является чем-то необходимым для существования человека, но прибавляет ему радость и жизненные силы, соответствует тайнам Торы. Их изучение наполняет действия человека глубоким осознанием и приносит воодушевле ние в его служение Творцу. Но есть еще один компонент – масло. Его отличие от предыдущих трех заключается

внимание на ту

чуда, которая уже произошла. Вече

зажигаем четыре ханукальные свечи, но на следующий день, в минху, в синагоге зажигают уже пять свечей. Мы ведем себя согласно мнению школы Гилеля. А по мнению школы Шамая, в первый день Хануки следует зажигать все восемь свечей, а затем каждый день уменьшать их количество на одну. По их мнению, вечером на четвертый день Хануки зажигают пять свечей, а в минху на следую

всеобщий характер.

этом

семь.

некоторые года еврейского календаря месяц

длится тридцать дней, и тогда новомесячье тевета продолжается два дня: тридцатого кислева и первого тевета. Седь мой день Хануки в этом случае выпадает на первое тевета, второй день новомесячья. Он является реализацией того, что в зародыше было заложено уже в первом дне Хануки, то есть в этот день у нас не просто имеется готов ность осветить самый холодный

бы масла не хватило на последний день, чудо не было бы поводом для радо сти – храмовый светильник целый день не нес бы миру свой свет. Нам важно не то, что горение было сверхъестественным, а то, что Вс-вышний помогает нам выполнять запо веди, даже когда вся логика жизни утверж дает, что это невозможно. Пусть это чудо останется с нами на весь год! ~ ~ ~ Ханукальный

декабря,

Хануки) • Если вы используете масло, приготовьте свечу (желательно из пчелиного воска), чтобы каждую ночь в качестве Шамаша зажигать ею ханукальные огни (всего 8 свечей для Шамаша). • Запланируйте покупку или приготовление ханукальных угощений (таких как пончиков и латкес). • Приготовьте волчки-дрейдлс и Хануке гелт (Ханукальные деньги) для детей.

Зажигать Менору каждую ночь 2. Предать чудо гласности смысл заповеди зажигания ханукальных свечей заключается в том, чтобы поведать о чуде. 3. Принято сидеть возле горящих ханукальных огней около получаса.

Что представляет собой Ханукальная Менора? Менора – это Ханукальный светильник, имеющий восемь ветвей для масляных или восковых свечей, и дополнительную ветвь, стоящую отдельно от остальных - для свечи Шамаш («Помощник»). Ханукальную Менору зажигают маслом или восковыми свечами. Поскольку чудо Хануки связано с оливковым маслом, предпочтительнее зажигать именно оливковым маслом. Стараются пользоваться хлопковыми фитилями, так как они горят ровным пламенем. Поскольку Ханукальная Менора - главный предмет выполнения заповеди, стараются, чтобы она была красивой (часто дают детям раскрашивать Меноры для Хануки). В дополнение к восьми ветвям Меноры должна быть девятая

солнца.

(примерно

тридцать

после захода солнца). В любом случае нужно позаботиться о достаточном

масла или о свечах нужного размера, чтобы они могли гореть как минимум 30 минут после наступления темноты. Стандартные ханукальные свечи как раз и горят около 30 минут. Если вы используете эти свечи, вам следует зажечь их после наступления темноты. В Шаббат время зажигания ханукальных огней несколько иное. Ханука в Шаббат. Когда Ханука совпадает с Шаббатом, действуют иные правила. В пятницу мы зажигаем ханукальные огни перед тем, как зажечь Субботние свечи. Для этого обязательно используем свечи большего размера, которые будут гореть как минимум 30 минут после наступления темноты. В субботу вечером ханукальные огни мы зажигаем после окончания Шаббата и прочтения Авдалы. КАК ЗАЖИГАТЬ СВЕЧИ?

1. Залейте масло или вставьте свечи в Менору. В первую ночь поставьте одну свечу в правом углу Меноры. На следующую ночь добавьте вторую свечу слева от первой, а затем добавляйте по одному огоньку каждую ночь Хануки, двигаясь справа налево. 2. Соберите всю семью вокруг Меноры. 3. Зажгите свечу Шамаш и возьмите ее в правую руку. (Левши держат ее в левой руке.)

4. Стоя произнесите соответствующие благословения.

5. Зажгите свечи. Каждую ночь сначала зажигайте новую (самую левую) свечу и продолжайте зажигать слева направо. (Свечи в Меноре мы расставляем справа налево, а зажигаем их - слева направо.)

Воскресенье, 18 декабря | 24 Кислева | Первая ночь Хануки

• Поместите одну свечу в правом углу Меноры. Прочтите все три благословения (см. справа)

• Зажгите свечу

19 - 22 декабря | 25-28 Кислева | С 2 по 5 ночь

• Поставьте необходимое количество свечей в правом углу Меноры. Прочтите первые два благословения (см. справа)

• Зажгите свечи, начиная с крайней левой. Пятница, 23 декабря | 29 Кислева | Шестая ночь | Ханука в Шаббат Особые инструкции перед Шаббатом Зажгите Менору раньше наступления Шаббата, перед тем, как зажечь Субботние свечи.

• Используйте достаточно масла или свечи большего размера, чтобы они горели как минимум в течение 30 минут после наступления темноты. • Поставьте шесть свечей. Прочтите первые два благословения (см. справа) • Зажгите свечи, начиная с крайней левой. Суббота, 24 декабря | 30 Кислева | Седьмая ночь | Ханука после Шаббата Зажигание ханукальных

Благословен Ты, Г-сподь, Б-г наш, Царь Вселенной, который освятил нас Своими заповедями и повелел зажечь свечи Хануки. Благословение № 2: БА-РУХ АТА, АДО-НАЙ ЭЛО-ЭЙНУ, МЕ-ЛЕХ А-ОЛАМ, ШЕ-А-СА НИ-СИМ ЛА-АВО-ТЕЙ-НУ БА-ЯМИМ А-ЭМ БИ-ЗМАН А-ЗЕ. Благословен Ты, Г-сподь, Б-г наш, Царь Вселенной, сотворивший чудеса для отцов наших в те времена, в эти же дни.

Благословение № 3: БА-РУХ АТА, АДО-НАЙ ЭЛО-ЭЙНУ, МЕ-ЛЕХ А-ОЛАМ, ШЕ-ЭХЕ-ЯНУ ВЕ-КИЕ-МАНУ ВЕ-ИГИ-АНУ ЛИЗМАН АЗЕ.

Благословен Ты, Г-сподь, Б-г наш,

(см. справа) • Зажгите свечи, начиная с крайней левой. Воскресенье, 25 декабря | 1 Тевета | Восьмая ночь Хануки • Поместите восемь свечей. Прочтите первые два благословения (см. справа)

• Зажгите свечи, начиная с крайней левой.

авайте закроем глаза и вообразим, что перед нами обычная еврейская женщина из далекого прошлого. Возможно, она помешивает что-то в подвешенной над огнем кастрюле, напевая своим дочуркам народную песенку на идиш. А может, она, раскатывая тесто для выпечки, уговаривает своих маль чишек идти в Хедер. Или торгуется с продавцами на рынке, и, добившись приемлемой цены, потрясает своими покупками, как оружием, подобно триумфатору, одержавшему победу. Скорее всего обычная еврейская женщина из прошлого действительно и помешивала что-то в кастрюле, и раскатывала тесто, и торговалась с продавцами, но при этом она еще и обладала внушительной силой в мире бизнеса.

Средневековые профессии

Во времена Талмуда прядение и ткачество являлись важными отрас лями промышленности, и женщины ткали и пряли, чтобы внести свою лепту в семейный доход; еще одним способом дополнительного дохода могла быть роль "плакальщицы" на похоронах. Однако поистине впечат ляет именно то, что средневековая еврейская женщина была коммерсан том. Христианство осуждало ростов щичество из-за библейского запрета: "Не давай в долг под проценты брату твоему" (Второзаконие 23:20); однако, поскольку евреи и христиане не счита лись "братьями", многие евреи брали на себя роль ростовщиков. Благодаря своим связям с еврейскими общинами по всему миру, они могли получать доступ к значительным средствам и зачастую станови лись незаменимыми для многих властителей и вельмож.

справля

успешнее, чем их мужья, что,

соответствовало их

природе.

женщин-предпринимате

также сыровары, и гусиные

и прачки, и самые бедные

- рыночные торговки. Боль

женщин, занимавшихся тор

вынуждены были работать,

было возможно, выступая

лоточников, владельцев ларь

вдовами:

занималась торговлей, прода вая товаров каждый месяц на сумму пять или шесть сот рейхсталеров. Кроме того, два раза в год я ездила на ярмарку в Брунсвик и каждый раз получала прибыль в несколько тысяч.»

состоятельность

и всегда занятая каким-то делом, она отличалась жизнелюбием и отвагой, и ее с любовью и опаской называли "казачкой". Многие писатели, повествующие о жизни в штетле, вспоминают, что никогда не видели, чтобы их матери спали. Женам ученых мужей приходилось брать на себя обязанности повседневной жизни, поскольку у их супругов было мало опыта и по уплате налогов, и по уходу за овощами или в уборке снега. Эта реальность побуждала многих женщин говорить буквально следующее: "Насчет того света, Олам Aба, то пусть мужчины только скажут, что без них нам туда не попасть. Если они не смогли справиться с этой жизнью сами здесь,то несомненно, нам придется делать работу за них и там". На самом деле, продуктивность в работе для женщин была настолько важна, что при поиске невесты, шидухa, многие родители искали девушку, владеющую польским языком, чтобы она могла вести дела с местными жителями. В некоторых письмах о сватовстве между рабби Шмуэлем из Кельма и его племянником будущая невеста описывается как "обученная чтению на иврите, польском, немецком ... и знакомая с русским алфавитом ".

обычно были заняты домашними делами и

по уходу за младшими детьми, в некоторых случаях молодые женщины работали, чтобы собрать на собственное приданое, как в случае Симхи, дочери раввина Зисселя Зива из Кельма. Она одновременно зарабатывала на приданое и помогала своим роди телям с финансами, управляя магазином. Девушки без приданого или финансовой стабильности работали в качестве домашней прислуги в богатых еврейских домах, чтобы в течение нескольких лет накопить достаточно средств для финансирования собственного шидуха. К девятнадцатому веку работа в магазине стала одним из самых распространен ных занятий для женщин, особенно для жен ученых Торы в Литве девятнадцатого века. Жена рабби Нафтали Амстердама держала пекарню, жена рабби Мейера Йоны Баренцкого была негоцианткой, а жена рабби Адерета из Понeвежа управляла мага зином сухих товаров. Во многих искренних письмах отражены переживания ученых раввинов, которые вынуждены были оставлять на своих жен многочисленные обязан ности, включая детей, бизнес и стареющих родителей, ибо часто уезжали в другие города на учебу. В начале двадцатого века в Америке в связи с ростом промышленности женщины перестали играть решающую роль в заработке семьи. По иронии судьбы, именно благодаря экономическим и социальным изменениям к лучшему, против женщин, которые действительно работали, фактически образовалась стигма. (Подобная ситу ация проложила путь и для второй волны феминизма в 1960-х годах, когда женщины боролись за собственную финансовую независимость). Так, хотя многие из наших матерей и бабушек, возможно, и были домохозяйками, вполне вероятно, что наши пра- и прапрабабушки были работящими бизнес-леди. На протяжении тысячелетий еврейская женщина использовала свои многочис ленные таланты, навыки и ресурсы для решения множества проблем - физических, духовных или финансовых. При необходимости она мужественно включалась в трудо вой процесс, добавляя новые обязанности к своему утомительно длинному списку, олицетворяя собой утверждение Раши о том, что женщина может одновременно "ухаживать за овощами, прясть лен, учить других женщин петь за плату и разво дить шелковичных червей". Обладая удивительной внутренней силой, упорством и верой, еврейская женщина исполняла различные роли, будучи домохозяйкой, матерью, женой, дочерью, кормилицей, помощницей и воспитательницей, сумев вырастить несколько поколений Б-гобоязненных и праведных еврейских сыновей и дочерей.

по празднику Ханука» восполняет недостаток информации. Обзор исторических событий, подробные разъяснения законов и обычаев, анализ религиозных и национальных аспектов праздника, перевод трудов Любавичского Ребе М.-М. Шнеерсона, комментированный

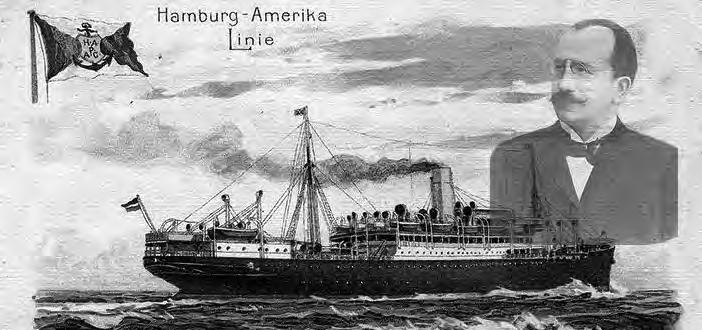

льберт Баллин был судовла дельцем из Гамбурга и, в принципе, одной из самых значитель ных личностей еврейской национальности в период Германской империи 1817—1918 годов. Он факти чески создал HAPAG — акци онерное общество, которое совершало рейсы через Атлантический океан, и стал генеральным директором крупнейшей судоходной линии в мире. Альберт родился в 1857 году в Гамбурге. Он был младшим в семье; в одних источниках указывается, что детей в семье было тринад цать, в других - что восемь. В любом случае, семья была многодетной, еврейской и набож ной. Отец семейства Самуил Джозеф Баллин был эмигрантом из Дании, а его мать Амалия (урожденная Малхен Майер) была из Альтона, Германия. Оба родителя происходили из выдающихся раввинских семей.

Отец Альберта стал нищим в результате пожара в Гамбурге в 1842 году. Этот пожар продолжался по всему городу три дня, с пятого по восьмое мая, а дым был виден за 50 километров. В результате погибло полсотни человек, и сгорело 1700 строений, включая несколько важных общественных зданий. В 1851 году отец Альберта основал имми грационное агентство Morris & Co, которое сотрудничало с т.н. Union Line — судоходной линией в Северной Атлантике.

Альберт Баллин окончил школу в 17 лет. В 1874 году Баллин-старший умер, и Альберту пришлось заняться семейным бизнесом. В 1875 году, после совершеннолетия, он стано вится полноценным партнером Morris & Co.

В 1882 году на долю Morris & Co. прихо дилось 17% миграций в Соединенные Штаты Америки, что принесло Альберту Баллину экономическую стабильность и приличную прибыль. В это же время он купил так

Gesellschaft, или Hamburg-America Line),

в 1888 году и вовсе был

после чего он

Morris & Co.

HAPAG Альбертом

компания

судоходную линию в

августе 1914 года, вскоре после начала войны, он организовал кооператив, который занимался закупкой продуктов питания из других стран. Альберт Баллин был особенно обеспокоен тем, что государство управлялось некомпетентными политиками и одержимыми властью воен ными.

После поражения Германии суда HAPAG, как и весь другой флот, были разделены между победи телями. Бал лина хотели публично признать капиталистом и арестовать. В эти тяжелые дни Аль берт Баллин занимался вопросами движения мор ского транс порта, который должен был помочь населению пережить голод.

8 ноября

манией капитуляции. Похороны Альберта состоялись 13 ноября в Гамбурге, на клад бище Ольсдорф, а похоронную речь произнес немецкий банкир и политик, а так же давний друг Макс Варбург.

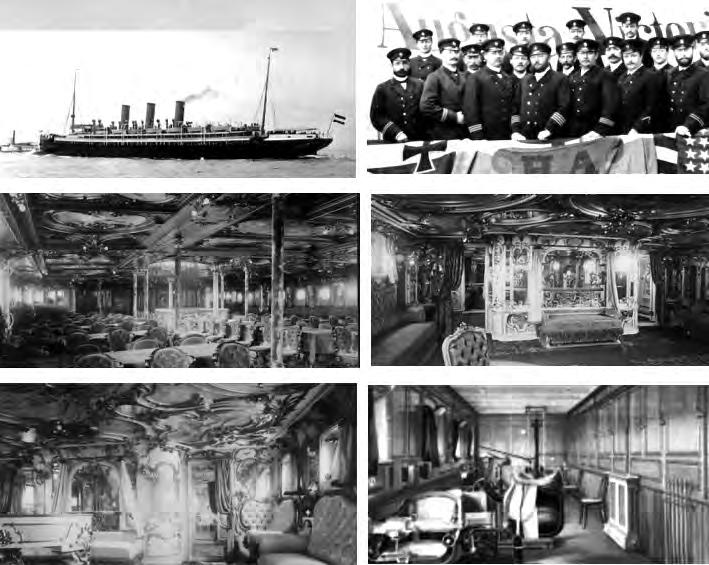

Альберт Баллин внес множество усовер шенствований в пассажирские перевозки.

Например, он предложил использовать про межуточную палубу в суднах, чтобы сделать перевозку мигрантов дешевле.

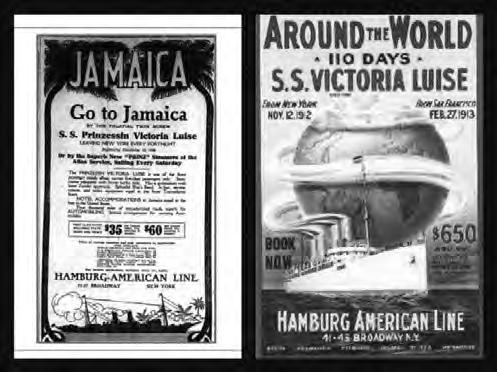

Поскольку зимой трансатлантические рейсы были менее популярны из-за плохой погоды и неспокойного моря, Баллин решил провести эксперимент и в 1891 году отправил пароход “Августа Виктория” на Средиземно морье как “образовательный и прогулочный круиз”.

Эксперимент прошел успешно — все места выкуплены, пассажиры довольны, прибыль не утеряна. Первый в мире прогулочный круиз ный лайнер покинул Куксхафен, Германия, 22 января 1891 года, а сам круиз длился 57 дней, 11 часов и три минуты.

Собственно, таким образом и роди лось понятие “круиз”, в каком мы знаем его сегодня. Эта форма морского путешествия стала популярной

быстро, и многие судоходные компании дополнили круизами свои программы. Для иммигрантов, которых перевозили на судах HAPAG, Альберт Баллин создал так назы ваемые “залы эмиграции”, площадью более 55 тысяч квадратных метров в районе Гам бурга Ведделе. Там располагалось 30 отдель ных зданий, которые состояли из спальных и жилых районов, столовых, ванных комнат, эстрадной сцены для концертов, церкви, синагоги и медицинского

питание было включено в стоимость билетов. Благодаря строгому медицинскому контролю во время выезда и въезда в страну, отторже ние эмигрантов властями было, в основном, предотвращено — карантин, в среднем, не превышал 3%.

Некоторые из “эмигрантских залов”, которые были снесены в 1963 году, вскоре были реконструированы, а в июле 2007 года они превратились в город-музей “BallinStadt”, который в народе называют имми грационным музеем Гамбурга.

Современники Альберта часто подчеркивали, что общество Гамбурга не до конца при няло Баллина. Осо бенно это касалось старых городских семей торговцев и адвокатов, которые воспринимали Альберта скорее как выскочку, но не как професси онала. По словам биографа Баллина Сюзанны Виборг, он был “полностью гамбуржцем,

Альберт Баллин был членом еврейской общины Гамбурга и часто жертвовал на благо творительность. Его особенно интересовали акции по борьбе с тропическими болезнями и туберкулезом. Как уже говорилось ранее, Баллин не скрывал своей религиозной при надлежности и был заинтересован в том, чтобы евреи могли избежать дискриминации.

За всю свою жизнь А льберт Баллин был удостоен множества наград, в том числе Медали Красного Креста, Ордена Красного Орла и прусского Ордена Короны. В его честь даже было названо судно от компании HAPAG, которое было введено в эксплуатацию в 1923 году, но в 1935 году его уже переименовали по требованию национал-социалистов.

Также офисное здание в Гамбурге, которое называется Meßberghof с 1938 года, изна чально, со времени своей постройки в 1924 году носило название Ballinhouse в честь Аль берта Баллина.

называют древом жизни, человек сравнивается с деревом полевым. Чтобы подтвердить этот тезис, приведу краси вую хасидскую майсу, которую писатель Яков Шехтер публикует в своем замечательном сбор нике хасидских рассказов «Голос в тишине».

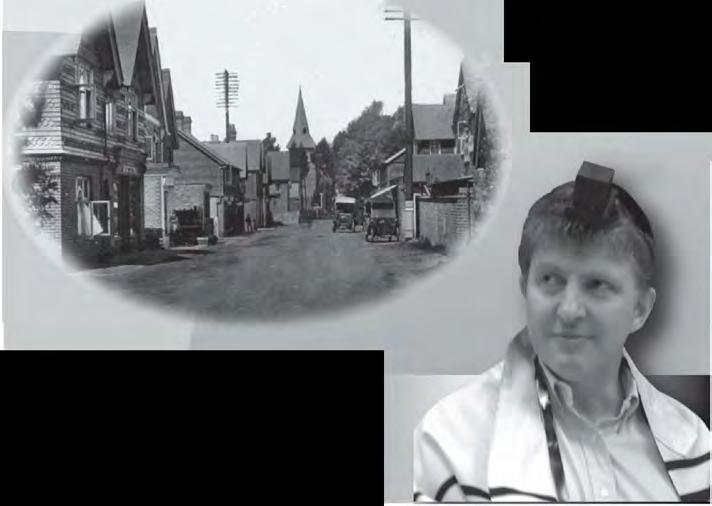

Посреди местечка Надворна (так евреи называли местечко Надворная в Галиции) стоял небольшой деревянный дом с тремя окошками на главном фасаде и крохотной светелкой над средним окном. В углу дворика, окруженного крепким забором из некрашеного штакетника, располагался колодец со скрипучим журав лем. В двух других углах возвышались крытые дранкой дровяные сараи. Четыре старые вишни, казалось, свысока взирали на кусты крыжовника и малины в чахлом палисаднике. В доме жил ребе Мордехай, и к этому нека зистому строению со всей Галиции приезжали евреи за помощью и благословением. О све телке, где ребе принимал посетителей, ходили многочисленные легенды. Хасиды называли ее «вышним чертогом», имея в виду, что человек, удостоившийся в нее попасть, словно подни мался над грубой явью материального мира, оказываясь между землей и небом. Судьей в Надворна служил Владислав Замой ский, потомок древнего шляхетского рода. Род давно обнищал, и от всего славного достояния судье перепала только наследственная спесь. В местечке судья был полновластным правителем, слова поперек ему никто не решался сказать. Ребе Мордехай жил так, словно никакого судьи в Надворна не существовало, и это до зубовного скрежета бесило пана Замойского. Он давно искал повод показать ребе, кто здесь хозяин, но поскольку налоги служка вносил исправно, а сам ребе Мордехай из дому почти не выходил, свести с ним

от служки «барашка в бумажке», и размеры этого «барашка» не позволяли ему действовать нахра писто и грубо, как приказал судья.

– Вера у нас такая, – объяснил служка. – А чтоб зараза не распространилась, ребе велел каждому заходящему в Cукку выпивать по ста кану водки. Не хотите проверить?

– Правильная у вас вера, – заметил пристав, приняв внутрь стакан и вежливо

AgarkovBoris 1 Tevet 25 December

Agroskin Ilya 28 Shevat 19 February

AgroskinRakhil 6 Tevet 30 December

AkselerodIsrail 11 Tevet 4 January

Antonovskaya Aleksandra21 Kislev 15 December

AranskayaOlga 5 Tevet 29 December

AronchikShimon23 Shevat 14 February

AronovRaisa15 Kislev 9 December

Aronova Raya 6 Shevat 28 January

BabitskiyAvraham 27 Tevet 20 January

BakalinskiyAleksandr26 Shevat 17 February

BaramVevl 21 Tevet 14 January

BarkanBlyuma1 Shevat 23 January

BarshaiYevsei30 Shevat 21 February

Bavly Donald Albert 29 Tevet 22 January

BeilinAdelle25 Kislev 19 December

Bekker Riva 19 Tevet 12 January

Berdichevskaya Ariadna3 Shevat 25 January

Berenshtein Zoya 16 Kislev 10 December

BerlinRachil6 Shevat 28 January

Berlin Yuri 2 Tevet 26 December

BiksonShaina 20 Tevet 13 January

BlayvasBoris 2 Tevet 26 December

BlockMarilyn8 Kislev 2 December

BotvinnikSofia26 Shevat 17 February

BregerChana13 Kislev 7 December

BrombergSemen 12 Tevet 5 January

BrookMaria 20 Tevet 13 January

Brook Monya 5 Tevet 29 December

BrudniyIon 17 Shevat 8 February

BrudnoGalina22 Shevat 13 February

Buzik Leva 2 Tevet 26 December

CherninYakov8 Kislev 2 December

ChernyakAlexander26 Shevat 17 February

ChernyavskiyZakhar 8 Tevet 1 January

ChesinFeiga1 Shevat 23 January

ChestuhinNikolay27 Kislev 21 December

ChigrinskayaRaisa13 Kislev 7 December

Dashevsky Lev 15 Tevet 8 January

DavidovichLida 29 Tevet 22 January

DavidsonRakhil22 Shevat 13 February

DayenEsther 23 Tevet 16 January

Deych Lev 13 Tevet 6 January

DiklerMalvina3 Shevat 25 January

DimontSima7 Kislev 1 December

DrizikDmitri26 Shevat 17 February

Dubenskiy Lev 22 Shevat 13 February

DubinskyTzvi Hirsh 14 Tevet 7 January

DymkovSolomon22 Kislev 16 December

DzhurinskayaMalka20 Kislev 14 December

EdelmanEsther24 Kislev 18 December

ElentukhNochum18 Shevat 9 February

EngelsonSonia21 Shevat 12 February

Erusalimskaya Milka Rudi 15 Tevet 8 January

EsterkinSimon26 Kislev 20 December

EydelmanLeonid 9 Tevet 2 January

FabricantElia25 Shevat 16 February

FayermanYona2 Shevat 24 January

Fayner Aron 24 Tevet 17 January

FeldmanMirel19 Shevat 10 February

FeldmanYakov10 Kislev 4 December

FleyshmanVilyam 26 Tevet 19 January

Fred Polina 16 Tevet 9 January

Freyman Akiva 4 Shevat 26 January

Frid Debora30 Kislev 24 December

FrimermanFrida7 Kislev 1 December

FrimermanIsroel 21 Tevet 14 January

FrushEnta22 Shevat 13 February

Fuksman Leya 2 Shevat 24 January

FuksmanPinchas3 Shevat 25 January

FurmanGalina11 Kislev 5 December

GadaevEsther 1 Tevet 25 December

GafanovichKhana9 Shevat 31 January

Geisberg Riva 29 Tevet 22 January

Gekht Lazar 22 Tevet 15 January

Gekht Vera 4 Tevet 28 December

GellerSolomon28 Shevat 19 February

GelmanYefim20 Kislev 14 December

GendlerChaya13 Kislev 7 December

GershmanDavid23 Kislev 17 December

Giller Vladimir14 Shevat 5 February

GilmanAlexander 3 Tevet 27 December

GincharAleksander19 Kislev 13 December

GlickmanVladimir 8 Tevet 1 January

GofmanGrigoriy9 Shevat 31 January

Goftarsh Mira 28 Tevet 21 January

GoldinMichael17 Kislev 11 December

GolmshtokSofia12 Shevat 3 February

GolodMarina28 Shevat 19 February

GolubchikSemion28 Shevat 19 February

Gommershtadt Boris23 Kislev 17 December

GorelikDmitriy 7 Tevet 31 December

GorelikRakhil24 Kislev 18 December

GorelikYakov14 Shevat 5 February

Gorenshteyn Fanya 6 Tevet 30 December

GorodnitskiyMark 26 Tevet 19 January

GozmanMichael 14 Tevet 7 January

GranovskyMichael 16 Tevet 9 January

Green Leon Eliyahu 7 Tevet 31 December

Grin Yakov 18 Tevet 11 January

Gritz Anna11 Kislev 5 December

GuralnikTamara 27 Tevet 20 January

GurevichMaria14 Kislev 8 December

Gurevich Raya 2 Tevet 26 December

Gurevitch Leah 7 Tevet 31 December

GurshmanSavely 23 Tevet 16 January

HitrikZachar16 Shevat 7 February

HolodenkoPesya 11 Tevet 4 January

IsurinSamuil15 Shevat 6 February

Itkin Tsalya8 Kislev 2 December

Kachka Chaim19 Shevat 10 February

Kalyuzhny Etya 27 Kislev 21 December

KanevskiyYakov21 Shevat 12 February

KarpovskyHirsh 11 Tevet 4 January

Katz Sofia17 Shevat 8 February

KavalertzikJoseph8 Kislev 2 December

KazakovaLilya26 Kislev 20 December

KhavkinaMargarita14 Shevat 5 February

Khayut Anna28 Kislev 22 December

Khayut Avrohom26 Shevat 17 February

Khazan Dovid5 Shevat 27 January

KholodenkoDavid12 Kislev 6 December

KholodenkoMoshe 16 Tevet 9 January

Kigel Arkadiy28 Shevat 19 February

Kigel Israel 13 Tevet 6 January

Kitaygorodskaya Alla13 Shevat 4 February

KlebanovDavid15 Shevat 6 February

Klimovskaya Kira 29 Tevet 22 January

Klimovsky Manya 8 Shevat 30 January

Klyukgaupt Manya 22 Shevat 13 February

Knobel Abba8 Shevat 30 January

Kofman Moishe29 Kislev 23 December

Kofman Sarah17 Shevat 8 February

KoifmanZalman26 Shevat 17 February

KonevskyShimon10 Kislev 4 December

KorsunskyAbram 23 Tevet 16 January

Kostrak Moisha7 Shevat 29 January

Kostrak Moishe7 Shevat 29 January

Kotlarova Genya 3 Shevat 25 January

KoyshmanAlexander20 Kislev 14 December

KozhushnyanMikhail22 Shevat 13 February

KrayzlerArkadiy 7 Tevet 31 December

Kremer Sophia6 Shevat 28 January

Krishtal Val 8 Tevet 1 January

Kritz Brocha28 Shevat 19 February

Kritz Mikhail15 Shevat 6 February

Kroll Ella11 Kislev 5 December

Kukes Gisya13 Shevat 4 February

KupermanSimon29 Kislev 23 December

Kusaev Ilya 12 Kislev 6 December

Kutikov Aron 30 Kislev 24 December

Kutikov Valeri8 Shevat 30 January

Ladyzhenskaya Miriam5 Shevat 27 January

LakovitskyOlga 11 Tevet 4 January

LangmanAnna17 Kislev 11 December

Lapido Tsezar23 Shevat 14 February

Lapsker Moisei 29 Tevet 22 January

Laskin Eugenia 16 Tevet 9 January

LevikovaLilya8 Shevat 30 January

Levit Sofia7 Kislev 1 December

Levitas Lev 28 Tevet 21 January

Levy Nina 6 Tevet 30 December

LeybovichIrina23 Shevat 14 February

Lifshits Minna8 Kislev 2 December

LikhtmanEkaterina 23 Tevet 16 January

LitovskyAlexander30 Shevat 21 February

LitvakArkadiy 4 Tevet 28 December

LitvinValentin14 Kislev 8 December

Lobanov Aron 13 Shevat 4 February

LobanovaRaisa24 Shevat 15 February

LubomirskiyKalman 29 Tevet 22 January

LubomirskiyMotel 7 Tevet 31 December

LuvishchukSamuel 26 Tevet 19 January

LyanskyaInna23 Kislev 17 December

LyubarskyValeriy13 Kislev 7 December

Margolin Tatyana 30 Adar 1 21 February

MatusovskiyRaisa 22 Tevet 15 January

MelnikovMikhail 15 Tevet 8 January

MeylichFelix25 Shevat 16 February

MeylichJoseph8 Kislev 2 December

MilyavskiyYankel22 Kislev 16 December

MitnikLeonid 13 Tevet 6 January

MitnikVictor13 Kislev 7 December

MogilevskySarah 9 Tevet 2 January

Mostovoy Pesach13 Shevat 4 February

MounitsMendel5 Shevat 27 January

NarinskyBoris28 Kislev 22 December

NeplokYefim6 Shevat 28 January

NisenzonEric 14 Kislev 8 December

Obrant Raya 9 Shevat 31 January

OchakovskyYoudko27 Kislev 21 December

OstrovskayaRivekka 1 Tevet 25 December

OzerskiyPeter 1 Tevet 25 December

Pais Channa25 Shevat 16 February

PalatnikRivka 29 Tevet 22 January

PartenskyRakhil15 Kislev 9 December

PerelMikhael28 Kislev 22 December

PevznerChaya Liba28 Kislev 22 December

PeyselRasel14 Shevat 5 February

Pilyampolskaya Faina27 Shevat 18 February

PipkoRita11 Kislev 5 December

Podberezina Roza 3 Tevet 27 December

PolnarevIsay13 Kislev 7 December

PolurShmil 12 Tevet 5 January

PovorozhnukMaria15 Shevat 6 February

RabinovichGitta 9 Tevet 2 January

RabkinBoris 29 Tevet 22 January

RachlisShifra 10 Tevet 3 January

RakhlisHersh 10 Tevet 3 January

RakhlisHuna 10 Tevet 3 January

RakhlisIzzi 10 Tevet 3 January

RakhlisNakhemni 10 Tevet 3 January

RakhlisNeta 10 Tevet 3 January

RakhlisRosa 10 Tevet 3 January

Rakov Freeman Joan 15 Tevet 8 January

RapoportBlyuma3 Shevat 25 January

RaskinaBronya19 Kislev 13 December

RayevskyMichael 4 Tevet 28 December

Reichman Asya 14 Shevat 5 February

RekhtmanValeriy 23 Tevet 16 January

RismanMichael 12 Tevet 5 January

RodkinSonia 28 Tevet 21 January

Rodman Yunya 27 Shevat 18 February

RosenzweigMendel17 Kislev 11 December

RozenfeldSemen3 Shevat 25 January

Rozenman Dora 10 Shevat 1 February

Rozenvayn Nekhama14 Kislev 8 December

Rozhnatovsky Zoya 18 Kislev 12 December

Rubinshtein Anton 5 Tevet 29 December

RubnichHenya17 Shevat 8 February

Rudyak Ezra 19 Shevat 10 February

Ryftin Dora 27 Kislev 21 December

SavelskiVladimir 7 Tevet 31 December

SchmidtMark26 Shevat 17 February

SeletskayaMyron 6 Tevet 30 December

SeletskayaRochel30 Kislev 24 December

SemenovaSofia19 Shevat 10 February

ShafirovichIda18 Kislev 12 December

Shane Tevya 20 Kislev 14 December

ShapiraDina 5 Tevet 29 December

ShapiroMottel 18 Tevet 11 January

ShapiroZlata25 Kislev 19 December

SharshunskiyYankel17 Kislev 11 December

SheinmanPolina30 Shevat 21 February

ShermanAnna14 Shevat 5 February

ShevelenkoLubov 7 Tevet 31 December

ShevelenkoShulim 4 Tevet 28 December

SheynYakov30 Adar 1 21 February

ShichmanterDavid 3 Tevet 27 December

ShifonYakov13 Kislev 7 December

ShifrinChaya27 Shevat 18 February

Shigel Sara 4 Tevet 28 December

ShkolnikBronislava 7 Tevet 31 December

Shleifer Maya 23 Kislev 17 December

ShleiferSamuel 27 Tevet 20 January

ShnayderAleksandr 27 Tevet 20 January

Shnayder Aron 12 Shevat 3 February

ShneiderVictor 11 Tevet 4 January

ShneidermanDavid9 Shevat 31 January

ShrayberArkadiy10 Kislev 4 December

ShugalDina 14 Tevet 7 January

ShugolJoseph20 Shevat 11 February

ShulkinMichael27 Shevat 18 February

ShumyacherChaya18 Kislev 12 December

ShumyacherMusya18 Kislev 12 December

ShumyacherZachar18 Kislev 12 December

ShvedSima23 Kislev 17 December

SilkisZilya 12 Tevet 5 January

SklyarEfim12 Kislev 6 December

SkorochodLuba 16 Tevet 9 January

Smagarimskaya Nechama28 Shevat 19 February

Smushkina Etka 14 Kislev 8 December

SokiryanskiyMark 14 Tevet 7 January

SokolLudmila 6 Tevet 30 December

SolodarLeonid 14 Tevet 7 January

SorkinIosif22 Kislev 16 December

SorkinOlga29 Shevat 20 February

Soybelis Mitya 18 Kislev 12 December

StarkovnikMalka27 Shevat 18 February

StolyarSimon18 Kislev 12 December

SuppornikDaniil 25 Tevet 18 January

SuppornikRohel 26 Tevet 19 January

SyrkinArnold11 Shevat 2 February

TaksirRaisa7 Shevat 29 January

TanenbaumNaum17 Shevat 8 February

TanfilyevDavid 9 Tevet 2 January

TeishevMaxim1 Shevat 23 January

Tendler Asya 12 Shevat 3 February

TendlerMikhail17 Shevat 8 February

TraininaAnna3 Shevat 25 January

TrotskayaRosalia13 Shevat 4 February

TseytlinRachil 25 Tevet 18 January

TsirkinSamuel15 Kislev 9 December

TurovskyAnatoly11 Kislev 5 December

TverskayaMusya24 Kislev 18 December

TverskayaMusya23 Kislev 17 December

UrmanBoris 22 Tevet 15 January

UrovitskayaGalya25 Kislev 19 December

VaninovLiya3 Shevat 25 January

VarshavskySofia 11 Tevet 4 January

Vaysband Roza 14 Shevat 5 February

Velinzon Aron 1 Shevat 23 January

VernikovElya19 Shevat 10 February

VernikovGalina16 Shevat 7 February

VinitskiyInna23 Shevat 14 February

VishneverMargarita 28 Tevet 21 January

VolfsonSholom29 Kislev 23 December

VoschinNikolay9 Shevat 31 January

Vyrovlyanskay Rochel Leah 25 Shevat 16 February

VyrovlyanskyKhatzkel 5 Tevet 29 December

VysokyNaakh 3 Tevet 27 December

VysokyShlomo 11 Tevet 4 January

WeisbergLeonid14 Kislev 8 December

Yaglom Akiva 4 Tevet 28 December

YangarberVictor10 Shevat 1 February

ZaborovskyNikolay30 Shevat 21 February

ZaetzElena28 Kislev 22 December

ZakutaJanna15 Shevat 6 February

ZaltsmanZakhar12 Shevat 3 February

Zandel Raya 30 Kislev 24 December

ZaytzevBoris 8 Tevet 1 January

ZelfondBronya2 Shevat 24 January

ZhermuskaLiliya23 Shevat 14 February

ZhuravlevaNatalia23 Kislev 17 December

ZilberSamuel16 Kislev 10 December

Zolotorevskaya Berta21 Kislev 15 December

The Shaloh (Rabbi Yeshayahu Horowitz) observes that Chanukah has a bearing and effect on the entire world. In his words:

Chanukah, when the rededication of the Holy Temple took place, has to do with the renewal of the world, for the world was created for the sake of the Torah and the fulfillment of the Mitzvahs. The Greeks attempted to abolish the Torah and Mitzvoth among the Jewish people. When the Hasmonoim prevailed over them, the Torah and Mitzvoth prevailed and thus the world was renewed.... And just as Creation began with “Let there be light,” so the Mitzvah of Chanukah begins with the lighting of candles.

The connection of Chanukah with the lighting of candles may further be elaborated on the basis of the special quality of the Mitzvah of the Chanukah Light, as has been discussed elsewhere at length. Briefly:

All Mitzvoth produce effects in the world (as indicated in the Shaloh, above), but the effect is not always discernible to the physical eye or not discernible immediately upon the performance of the Mitzvah.

For example, the Mitzvah of charity, which is the “core” of all the Mitzvoth, carries the reward of life and sustenance to the giver of charity and to his family, and brings vitality to the world. But this does not come about in the direct manner of cause and effect as in the case of planting and reaping, and the like, and is certainly not plainly evident to the physical eye, or understood by “secular” thinking.

Similarly in regard to the general performance of each and every Mitzvah, whereby the Light of the En Sof (The Infinite) is suffused in the world, as indicated in the verse, “for a Mitzvah is a candle and the Torah is light” It is not the kind of light that is visible to the physical eye.

There is a preeminence in the Mitzvoth connected with lighting candles—such as in the Holy Temple of old, and the Shabbat and Yom Tov candles in the home, etc.—in that the effect of the action, the appearance of light, is immediately visible; indeed it has to be visible to all who are in the house, which is actually illuminated by this light.

Among these latter Mitzvoth, the Mitzvah of kindling the Chanukah Light is unique in that it is required to be displayed to the outside, in accordance with the rule that it should be placed “at the entrance of the home, outside,” (if possible, or in the window). Thus every passer-by, including non-Jews, immediately notices the effect of the light, which illuminates the outside and the environment. Moreover, it becomes common knowledge in advance that Chanukah is coming and Jews everywhere will observe the precept of lighting candles that will illuminate the darkness of the night (since lighting time of the Chanukah lamp is after sunset), lighting up the outside.

From what has been said above about the physical effects of the Chanukah candles, it becomes apparent what their spiritual effects are: The Chanukah Light has the special quality of illuminating the darkness of the spiritual “outside,” the exile in its plain sense, as well as the inner “exile,” namely, the darkness of sin and of the evil inclination (they alone being the cause of the exile, in the ordinary sense, as it is written, “Because of our sins we have been exiled from our land”); and this act of illumination

takes immediate effect, without requiring any prior explanation (i.e. even without preparation on the part of the “outside”).

* * *

Inasmuch as the concept of Chanukah is a most comprehensive one, and, as quoted above, it has to do with the “renewal (restoration and perfection) of the world,” it is clear that the Mitzvoth connected with Chanukah contain special comprehensive instructions, that is, practical teachings for the daily life and conduct, and also the order in which the Chanukah Mitzvoth are observed indicates a general and essential guiding principle. Some of them are as follows:

The essential thing is the deed. First and foremost must come the practical act, the first Mitzvah of Chanukah being the lighting of the candles, the time of which is immediately after sunset on the day before Chanukah.

The effect of every human act must also contribute a measure of light to illuminate the “outside”—as indicated by the Chanukah Light which is placed “at the entrance of the home, outside.”

The motivation and purpose of every human act should be only to fulfill the Will of the Holy One, blessed be He. Thereby one partakes, so to speak, of the holiness of the Holy One, as the first blessing before the lighting reads: “...Who has sanctified us by His commandments and commanded us to kindle the Chanukah Light”

After performing the Mitzvah act with the blessings preceding it and the recital after it, follows the Evening Prayer (for the lighting of the Chanukah Lamp comes before the eveniing prayer), which includes a special prayer of praise to G d during the days of Chanukah—V’Al Hanissim.

Although a Jew has to do what he can in the natural way, he must at the same time realize that the essential thing is to have absolute trust in G d, for success is from G d, as we say in Hallel, “This came from G d; it is wondrous in our eyes.” EM

Now here’s an interesting difference between Chanukah and Purim: Both holidays have a small scroll—called a megillah—that tells their story. Purim has the Megillah of Esther. Chanukah has the Megillah of Antiochus.

On Purim, we are required to read that megillah publicly at night, and again in the day. But on Chanukah, there’s no such requirement. Yes, there have been communities that read the Megillah of Antiochus in the synagogue on Chanukah. Indeed, some Yemenite communities still keep this custom. But it’s done without a blessing, since all agree that it was never instituted by any rabbinical authority.

Another distinction between these two megillahs: The Talmud tells that Esther requested from the Men of the Great Assembly, which included prophets together with sages, that they “write my story for all generations.” And indeed, the Megillah of Esther was inducted into the exclusive set of twenty-four books of Tanach.

The Megillah of Antiochus, on the other hand, is not considered a sacred work. Rav Saadia Gaon, the foremost authority for Jews in the 10th century, held it in high esteem. He wrote that the Hasmoneans, Judah, Shimon, Johanan, Jonathan, and Eliezer, sons of Mattathias, wrote this megillah about their own experiences, and similar to the book of Daniel, they wrote it in the language of the Chaldeans (Aramaic). He translated it into Arabic along with his translations of other books of Tanach. Nevertheless, it was never inducted into Tanach, as was the Megillah of Esther. The distinction gets yet sharper when we consider the names of these two megillahs. The Megillah of Esther is named after the heroine of the story. The Megillah of Antiochus is named after the villain!

None of this is coincidental. Something is going on over here that represents a deep distinction between the dynamics of Purim and Chanukah.

The stories of both Purim and Chanukah are about taking a real dark situation and turning it around for the good. But there are two ways of effecting this transformation.

In the story of Purim, the royal decree to eliminate the Jewish population was transformed into royal support for a Jewish victory over

those that desired their elimination. The house of Haman became the house of Mordechai.

In the story of Chanukah, the dictatorship of a foreign, insane megalomaniac who forbade Jewish practice and demanded he be worshipped led to the liberation of the Temple in Jerusalem and a miracle of light.

Yet, while Purim pulls inward, Chanukah radiates light outward.

On Purim, the Megillah of Esther is read in the synagogue. The Purim feast and exchange of foodstuffs, as well as the gifts to the poor, is done principally within the Jewish home.

So it makes sense that the story of Haman and King Achashverosh is also pulled inward, to become a sacred book of Torah named after a righteous Jewish heroine, and read each year by decree of the sages. The telling of the machinations and greed of these villains becomes a mitzvah, just as the house of Haman became the house of Mordechai. Pulled into the Torah and declared a mitzvah, they are transformed.

The miracle of Chanukah, on the other hand, is about shining light outward, and to the outside. The original requirements for the Chanukah menorah stipulate that it be lit only once it is dark. And where? “At the door of your house, on the outside.” Why? As the

Talmud states, “to publicize the miracle.”

Who are we publicizing it to? That becomes obvious from another requirement: Until when can you light it? Until the marketplace is quiet. Until all the stragglers have gone home, including, the Talmud says, the Tarmodai.

Who are the Tarmodai? Merchants from the Syrian city of Tarmod (a.k.a. Tadmur, a.k.a. Palmyra) who were known for staying late in the market at night, collecting leftover wood. They were also known for having rebelled against King Solomon, and for having acted as mercenaries in the destruction of both Temples.

And it’s with these people that we measure the ultimate darkness that Chanukah can reach!

Which means: The celebration of Chanukah is meant to reach all those people out there as they are out there. Where Purim deals with the dark characters of this world by transforming them into players in a holy book of Torah, the light of Chanukah reaches into the thick darkness of night, as darkness remains darkness, outside of the holiness of Torah, and shines even there. Nothing is excluded, and nothing is changed.

That’s why we absorb the message of Purim by being pulled into the words of a megillah, while the message of Chanukah is broadcast out there by shining the light of a menorah.

Even the megillah for Chanukah remains an outsider. It’s named after the enemy, written entirely in Aramaic, and remains in a realm the sages of Israel called “outside writings”— meaning, outside the realm of the sacred works of Tanach. And so, of course, reading it is not a mitzvah—just a permitted act.

What is the point behind all this “outsideness?”

Because this light is the light of divine wisdom, for which there is no “outside.” As the Baal Shem Tov taught, “G dliness is everything. Everything is G dliness.” We just need light to see it there.

And there is no better light for that than Chanukah light. EM

Rabbi Tzvi Freeman, a senior editor at Chabad.org, is the author of Bringing Heaven Down to Earth and more recently Wisdom to Heal the Earth. To subscribe to regular updates of Rabbi Freeman's writing or purchase his books, visit Chabad.org. Follow him on Facebook @RabbiTzviFreeman.

He was 137 years old. He had been through two traumatic events involving the people most precious to him in the world. The first involved the son for whom he had waited for a lifetime, Isaac. He and Sarah had given up hope, yet G d told them both that they would have a son together, and it would be he who would continue the covenant. The years passed. Sarah did not conceive. She had grown old, yet G d still insisted they would have a child. Eventually it came. There was rejoicing. Sarah said: “G d has brought me laughter, and everyone who hears about this will laugh with me.” (Gen. 21:6) Then came the terrifying moment when G d said to Abraham: “Take your son, your only one, the one you love… and offer him as a sacrifice.” (Gen. 22:2) Abraham did not dissent, protest or delay. Father and son travelled together, and only at the last moment did the command come from heaven saying, “Stop!” How does a father, let alone a son, survive a trauma like that?

Then came grief. Sarah, Abraham’s beloved wife, died. She had been his constant companion, sharing the journey with him as they left behind all they knew; their land, their birthplace, and their families. Twice she saved Abraham’s life by pretending to be his sister.

What does a man of 137 do – the Torah calls him “old and advanced in years” (Gen. 24:1) – after such a trauma and such a bereavement? We would not be surprised to find that he spent the rest of his days in sadness and memory. He had done what G d had asked of him. Yet he could hardly say that G d’s promises had been fulfilled. Seven times he had been promised the land of Canaan, yet when Sarah died he owned not one square inch of it, not even a place in which to bury his wife. G d had promised him many children, a great nation, many nations, as many as the grains of sand in the seashore and the stars in the sky. Yet he had only one son of the covenant, Isaac, whom he had almost lost, and who was still unmarried at the age of thirty-seven. Abraham had every reason to sit and grieve.

Yet he did not. In one of the most extraordinary sequences of words in the

Torah, his grief is described in a mere five Hebrew words: in English, “Abraham came to mourn for Sarah and to weep for her.” (Gen. 23:2) Then immediately we read, “And Abraham rose from his grief.” From then on, he engaged in a flurry of activity with two aims in mind: first to buy a plot of land in which to bury Sarah, second to find a wife for his son. Note that these correspond precisely to the two Divine blessings: of land and descendants. Abraham did not wait for G d to act. He understood one of the most profound truths of Judaism: that G d is waiting for us to act.

How did Abraham overcome the trauma and the grief? How do you survive almost losing your child and actually losing your life-partner, and still have the energy to keep going? What gave Abraham his resilience, his ability to survive, his spirit intact?

I learned the answer from the people who became my mentors in moral courage, namely the Holocaust survivors I had the privilege to know. How, I wondered, did they keep going, knowing what they knew, seeing what they saw? We know that the British and

American soldiers who liberated the camps never forgot what they witnessed. According to Niall Fergusson’s new biography of Henry Kissinger, who entered the camps as an American soldier, the sight that met his eyes transformed his life. If this was true of those who merely saw Bergen-Belsen and the other camps, how almost infinitely more so, those who lived there and saw so many die there. Yet the survivors I knew had the most tenacious hold on life. I wanted to understand how they kept going.

Eventually I discovered. Most of them did not talk about the past, even to their marriage partners, even to their children. Instead they set about creating a new life in a new land. They learned its language and customs. They found work. They built careers. They married and had children. Having lost their own families, the survivors became an extended family to one another. They looked forward, not back. First they built a future. Only then –sometimes forty or fifty years later – did they speak about the past. That was when they told their story, first to their families, then to the world. First you have to build a

future. Only then can you mourn the past.

Two people in the Torah looked back, one explicitly, the other by implication. Noah, the most righteous man of his generation, ended his life by making wine and becoming drunk. The Torah does not say why, but we can guess. He had lost an entire world. While he and his family were safe on board the ark, everyone else – all his contemporaries – had drowned. It is not hard to imagine this righteous man overwhelmed by grief as he replayed in his mind all that had happened, wondering whether he might have done something to save more lives or avert the catastrophe.

Lot’s wife, against the instruction of the angels, actually did look back as the cities of the plain disappeared under fire and brimstone and the anger of G d. Immediately she was turned into a pillar of salt, the Torah’s graphic description of a woman so overwhelmed by shock and grief as to be unable to move on.

It is the background of these two stories that helps us understand Abraham after the death of Sarah. He set the precedent: first build the future, and only then can you

mourn the past. If you reverse the order, you will be held captive by the past. You will be unable to move on. You will become like Lot’s wife.

Something of this deep truth drove the work of one of the most remarkable survivors of the Holocaust, the psychotherapist Viktor Frankl. Frankl lived through Auschwitz, dedicating himself to giving other prisoners the will to live. He tells the story in several books, most famously in Man’s Search for Meaning. He did this by finding for each of them a task that was calling to them, something they had not yet done but that only they could do. In effect, he gave them a future. This allowed them to survive the present and turn their minds away from the past.

Frankl lived his teachings. After the liberation of Auschwitz he built a school of psychotherapy called Logotherapy, based on the human search for meaning. It was almost an inversion of the work of Freud. Freudian psychoanalysis had encouraged people to think about their very early past. Frankl taught people to build a future, or more

precisely, to hear the future calling to them. Like Abraham, Frankl lived a long and good life, gaining worldwide recognition and dying at the age of ninety-two.

Abraham heard the future calling to him. Sarah had died. Isaac was unmarried. Abraham had neither land nor grandchildren. He did not cry out, in anger or anguish, to G d. Instead, he heard the still, small voice saying: The next step depends on you. You must create a future that I will fill with My spirit. That is how Abraham survived the shock and grief. G d forbid that we experience any of this, but if we do, this is how to survive.

G d enters our lives as a call from the future. It is as if we hear him beckoning to us from the far horizon of time, urging us to take a journey and undertake a task that, in ways we cannot fully understand, we were created for. That is the meaning of the word vocation, literally “a calling”, a mission, a task to which we are summoned.

We are not here by accident. We are here because G d wanted us to be, and because there is a task we were meant to fulfil. Discovering what that is, is not easy, and often takes many years and false starts. But for each of us there is something G d is calling on us to do, a future not yet made that awaits our making. It is future-orientation that defines Judaism as a faith, as I explain in the last chapter of my book Future Tense.

So much of the anger, hatred and resentments of this world are brought about by people obsessed by the past and who, like Lot’s wife, are unable to move on. There is no good ending to this kind of story, only more tears and more tragedy. The way of Abraham is different. First build the future. Only then can you mourn the past. EM

Rabbi Dr. Sir Jonathan Sacks, of blessed memory, was the former Chief Rabbi of the UK and the Commonwealth and a member of the House of Lords. He was a leading academic and respected world expert on Judaism. He was the author of several books and thousands of articles, appeared regularly on television and radio, and spoke at engagements around the world.

One of the great principles of the future redemption and the coming of Moshiach, is that no one can accurately predict exactly what will happen or how it will happen. Even though we have many prophecies, many found in the Book of Daniel, that delve into the events leading up to that time to come, their predictions are cloaked in allegories and mystical visions. They are concealed to such a degree that we would be hard pressed to understand what exactly they are referring to until the events actually unfold. Perhaps this is meant to keep us on our toes, or leave room for multiple possible scenarios for how the redemption will come about. But it doesn’t stop people from trying to gain insight and crack the code.

About eight hundred years ago, Maimonides wrote a famous letter of encouragement to the Yemenite Jews who were being persecuted. He wrote about the "little horn" mentioned in chapter seven of the Book of Daniel. Maimonides suggested that the little horn might be referring to a certain wicked Assyrian-Greek king from the Chanukah story.

Around three hundred years later, when Jews were being expelled from Spain, Rabbi Don Isaac Abarbanel wrote a commentary explaining how events occurring then may have been predicted by Daniel. He wrote that though the details of his interpretation may be incorrect, nevertheless, G d does not lie, and He will certainly redeem His people. When that happens, even someone who is not so learned will be able to witness the events as they transpire and see how Daniel clearly predicted them.

Indeed, Daniel predicted what would happen in the time of Redemption, and the Jewish people in exile yearned so much for Redemption. It is therefore no surprise that, throughout the centuries, many sages tried to see if perhaps Daniel was describing the world events of their time. Daniel lived during the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem. G d, in His mercy, revealed to him visions of the future Redemption, so that the Jewish nation would know that even though they are exiled and dispersed throughout the world, a time will come when, their mission

DANIEL WAS DESCRIBING THE WORLD EVENTS OF THEIR TIME.

having been accomplished, they will return.

The little horn that Maimonides writes about is part of a vision that Daniel saw one night: Four winds stir up a great sea, and four beasts emerge from the sea. Each beast is described in great detail. The fourth beast has ten horns, and a little horn emerges from it. G d renders judgment. And then Daniel sees someone who is brought up in clouds before G d, and is given rulership over all the nations of the world forever. Rashi writes that this person refers to Moshiach.

During World War Two, battles were fought on lands surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Germany, Russia, Great Britain and the US were the main powers in this war. Details of the vision, which aptly describe these nations and current events, can perhaps be discussed in another article. But for now suffice it to say, that this vision seems to clearly describe current times. Knowing this can inspire renewed optimism that the Redemption is very close.

The Rebbe taught that regarding the Redemption, a central component is that we need to have trust. On many occasions the Rebbe explained how trusting in G d can bring His blessings more quickly. As the Rebbe was wont to say, "Tracht gut vet zain gut" — think good and it will become good. One time when I was a student in Yeshiva we began a custom of singing the song “He redeemed my soul in peace” during the month of Kislev, the month of redemption. The song was composed in commemoration

of the Alter Rebbe, the first Chabad Rebbe, from czarist imprisonment and his complete exoneration of charges of treason. In the end, the czarist regime became friendly supporters, and the Alter Rebbe returned the favor by assisting in the war against Napoleon.

In general, the month of Kislev is often referred to as the month of redemption because of the Chanukah miracle (when G d "saved the few from the many") and because of the Alter Rebbe's miraculous release. When we look at current events, we see clearly how G d is protecting His people. When was the last time we saw so many people stand up to defend Jews, as we've seen with recent incidents of celebrities spewing antisemitic rhetoric? After several years of inconclusive elections and sociopolitical instability, it looks like Israel will finally have a stable government, and one that is proudly committed to Jewish identity and Jewish values. Iran's regime is beset by demonstrations which threaten to topple the government, and which is preventing Western powers from signing a nuclear deal with Iran, a deal that would have essentially gifted one hundred billion dollars a proven state sponsor of terror and a regime bent on the destruction of Israel. The list goes on and on. Redemption seems so close. Maybe it's even closer than we think. We just need to open our eyes to see it unfolding before us. EM

Yoseph Janowski lives in Toronto, Canada.

The phrase “We want Moshiach now” expresses simply the desire for Moshiach to quickly arrive. But there are many different ways of expressing this besides the word “want.” By Divine Providence, children have chosen the word “want” to express their desire for Moshiach, and there is a profound lesson to be derived therein. To understand the differences in nuance, and the precise connotations of the word “want,” let us examine the same word (or a derivative of it) in a completely different context. The word is “wanting,” meaning lacking or missing, as in “some details are wanting.” Indeed, the dictionary definition of “want,” besides to desire or to wish, is “to feel a desire for, as for something absent, needed .. to feel the need of.” Thus a main difference in nuance between want and any other word expressing desire, is a connotation of deficiency.

This then is the cause of the apathy and complacency so prevalent regarding Moshiach. It stems from a basic misconception of their relationship to Moshiach and his coming. He and the redemption are viewed, at best, with the same desire that one would have for any pleasurable thing. Nice to have, adding the final touch to life, certainly worth waiting for — but something we can get along without. To such a person we present the clarion cry of “We want Moshiach now.” Moshiach is not a mere additional luxury, a future state of bliss to be smugly awaited in complacent serenity. Moshiach is an urgent want, a necessity, as basic as food and drink — without which we are wanting. Can we sit passively by and not do our utmost to fulfill this most basic of wants?

DANIEL PREDICTED WHAT WOULD HAPPEN IN THE TIME OF REDEMPTION, AND THE JEWISH PEOPLE IN EXILE YEARNED SO MUCH FOR REDEMPTION. IT IS THEREFORE NO SURPRISE THAT, THROUGHOUT THE CENTURIES, MANY SAGES TRIED TO SEE IF PERHAPS

by Rabbi Dan Rodkin

by Rabbi Dan Rodkin

QI notice that lighting candles is a big part of Judaism. We light candles every Friday for Shabbat, we light candles on every festival, there is a tradition of lighting candles at a wedding, and Chanukah is all about candles. What is the connection between candles and spirituality? Are the candles just there to add ambiance, or is there a deeper reason as well?

Light is a central cornerstone of existence. “Let there be light” was among the first utterances of Creation, because that is in a sense the mission statement for life. In human terms, light is almost always used as a metaphor for goodness – the light at the end of the tunnel, lighting up someone’s life. A candle, specifically, represents the physicalspiritual dichotomy of existence; the wick represents the physical, the body, while the flame represents the spiritual, the soul.

There is something about a candle that makes it more spiritual than physical. A physical substance, when spread, becomes thin. Spirituality, when spread, expands and grows.

When you use something physical, it is diminished. The more money you spend, the less you have; the more gasoline you use, the more empty your tank becomes; the more food you eat, the more you need to restock your pantry. But spiritual things increase with use. If I use my wisdom to teach, the student learns, and I come out wiser for it; if I share my love with another, I become more loving, not less. When you give a spiritual gift, the recipient gains, and you lose nothing.

This is the spiritual property that candles share. When you use one candle to light another, the original candle remains bright. Its light is not diminished by being shared; on the contrary, the two candles together enhance each other’s brightness and increase light.

We sometimes worry that we may stretch ourselves too thin. In matters of spirit, this is never the case. The more goodness we spread, the more goodness we have. By making a new friend, you become a better friend to your old friends. By having another child, you open a new corridor of love in

your heart that your other children benefit from, too. By teaching more students, you become wiser.

So there is indeed a deeper significance to the candles. Let’s look at the wedding custom you mentioned, because it sheds some light on the matter (pun intended). The prevalent custom is for the bride and groom to each be escorted with two candles, one on each side, which are usually held by their parents or whoever is escorting them to the chuppah (wedding canopy). The numerical value of the Hebrew word for “candle” (ner) is 250. According to the Talmud, a man has 248 limbs and a woman has 252.Together, they have 500. Thus, the two candles (250+250=500) symbolize the union of husband and wife. In a similar vein, the numerical value of G d’s directive to Adam and Eve, “Be fruitful and multiply” (peru u’revu), is 500, the same numerical value as two candles. So yes, the candles are beautiful. But what they symbolize is even more exquisite: the unification of two souls, and the blessings of joy, happiness and family, and the transcendence of spirit over matter and the spiritual illuminating the physical. This is one of the more spiritual reasons why we light candles on Shabbat and festivals.

Once a year, we celebrate this truth for eight days and nights, celebrating the power of light. There are 36 candles in total lit over the course of the Chanukah holiday, corresponding to the 36 tractates of the Talmud, since the oral Torah was the primary focus of the Greek war against Jewish heritage. They knew there was no way to erase the written Torah, since it was ingrained in the form of thousands of Torah scrolls. So they focused their attack on the oral Torah. We kindle the Chanukah menorah, recalling that miraculous victory of quality over quantity, spirit over materialism, right over might. And pray for the day when such victories are no longer "miracles", but the way things are in this world. EM

Rabbi Dan Rodkin is the Executive Director of the Greater Boston Jewish Russian Center. You can Ask the Rabbi at rabbi@shaloh.org.

It is commonly accepted that the age of modern psychology began at the end of the 19th century. The way we understand ourselves today is very much defined by the thinking of William James, then Sigmund Freud, who some call the Father of Psychology, followed by Carl Jung, BF Skinner and other great psychologists of the 20th century.

I would like to submit that the Father of Psychology is actually a man who lived a century earlier, and has yet to be recognized as the true pioneer of modern psychology.

That man was Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812), and he offered the most sophisticated and comprehensive view to date on the nature of the human psyche and its struggles.

Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s (also known as the Alter Rebbe) immense contribution can be appreciated by contrasting it with the prevalent view on the psyche.

The big issue facing psychology is of course the human struggle between our conflicting drives. On the lowest end of the spectrum is our selfish need to survive and experience pleasure. On the next rung, our practical need to co-exist, to love and be loved and live productive lives. Then we have our ethical values and our conscience. And finally, our higher, spiritual and transcendental dimensions.

Human anxiety is a result of our conflicting voices. How we treat and mistreat others is determined by which force controls our behavior. Vulnerable and impressionable children, of course, are the first to suffer the consequences and are hurt the deepest by our clashing drives colliding with each other. And we all begin our lives as children. Then, these children grow up and have to pick up the pieces, try to heal from their wounds and rebuild their lives.

The rest is history – your history and mine, the history of every person alive today struggling with the disparate forces that shape our personalities and define our life choices. A vicious cycle indeed.

Plaguing thinkers from the beginning of time is the million-dollar question: Who is the real you? Or more precisely: Which of our drives is the most powerful one? Which

is most dominant?

The prevalent theory – which can be coined the Darwinian-Freudian model –argues that the most powerful and most basic human drive is selfish survival.

Humans are fundamentally no different than other creatures, and indeed have evolved from the same ancestors. According to Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection, variation within species occurs randomly and the survival or extinction of each organism is determined by that organism’s ability to adapt to its environment. Another name Darwin (1809-1882) gave Natural Selection was “the preservation of favoured races in the struggle for life.”

Darwin did not speak in psychological terms. Indeed, he avoided applying his theory to the social and religious arena. It was apparently British philosopher Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) who first used the term “survival of the fittest” as a central tenet of what became known as “Social Darwinism.” He applied (or some say misapplied) Darwin’s idea of natural selection to justify European domination and colonization of much of the rest of the world. Social Darwinism was also widely used to defend the unequal distribution of wealth and power in Europe

and North America at the time. Poor and politically powerless people were thought to have been failures in the natural competition for survival. Subsequently, helping them was seen as a waste of time and counter to nature. Rich and powerful people did not need to feel ashamed of their advantages because their success was proof that they were the most fit in this competition.

In the psychological realm, Freud (18561939) posited that the most basic of all human instincts is the “Id,” the primal, unconscious source for satisfying all mans’ basic needs and feelings. It has only one rule: The “pleasure principle:” “I want it and I want it all now.” The id wants whatever feels good at the time, with no consideration for the reality of the situation or the good of others.

Then there is the “Ego,” the rational part of the mind that relates to the real world and operates via the “reality principle,” recognizing that you can’t always get what you want. The Ego realizes the need for compromise and negotiates between the Id and the Superego, which might be called the moral part of the mind. The Superego is an embodiment of parental and societal values. It stores and enforces rules. The Ego’s job is to get the Id’s pleasures but to be reasonable and bear the long-term consequences in mind. The Ego denies both instant gratification and pious delaying of gratification.

Freud described the human personality as being: “…basically a battlefield. He is a darkcellar in which a well-bred spinster lady (the superego) and a sex-crazed monkey (the id) are forever engaged in mortal combat, the struggle being refereed by a rather nervous bank clerk (the ego).”

Thus an individual’s feelings, thoughts, and behaviors are the result of the interaction of the id, the superego, and the ego. This creates conflict, which leads to anxiety, which in turn generates all types of defense mechanisms.

Though Freud may not have directly correlated his theories to Darwin’s, it’s irresistible to avoid the parallels, and how each complements the other. If humans are merely “billion year old bacteria” and

essentially no different than any other animal fighting for survival, then it would make absolute sense that our most dominant drive is fixation on our own needs and pleasure, even at the expense of others. “Survival of the fittest.”

Obviously, there are many variations of this theory. There are also many opinions that fundamentally disagree with Freud. Still, despite the differences, the prevailing view tends to lean toward the DarwinianFreudian model.

One of the sad consequences of this viewpoint is the lack of expectation we can have of each other. If our most natural self is the need to survive and the narcissistic pursuit of pleasure, then what can we really expect of people?! Can we really be disappointed if someone ends up hurting others in his/her own driving need for pleasure? Can we even blame the person? After all, we are sophisticated “bacteria” just trying to survive in a hostile environment… Yes, we can expect of humans to create superimposed rules, like “red lights” and “green lights” so that we can coexist and not destroy each other. But that is superimposed, not our natural state.

It’s interesting to note, that the original German for Freud’s Ego is “ich,” yet another manifestation of the “self.” So even as the Ego negotiates between the Id and the Superego, it still is fundamentally self motivated. [Superego, Uber-ich, can be translated as a dimension that is above –that transcends – the ego. But it can also mean a superman, ultra ego].

If you take it to the anarchist extreme, one can even question our entire justice system. Are we really expecting people to be better, or are we just trying to keep the “store” intact so that we don’t self-destruct. In other words, if the “cat were let out of the bag,” anarchy would prevail. So we need subjective, arbitrary rules to maintain order.

No wonder fear is the most commonly used tool in education, and punishment is the most popular deterrent to crime. Since people are essentially animals, with an ominous Id lurking within, never knowing when it will strike, we can’t depend or trust that people will just do the “right thing” and

“rise to the occasion.”

That sure sounds harsh, doesn’t it?! And indeed, I amplified certain points in order to crystallize the issues, but I have not distorted any of them, and the description above more or less describes contemporary psychological theory.

No doubt that many of us are surely repulsed by this dark perspective on human nature. You may wonder: What about the soul? What about the beautiful acts of nobility and heroism we witness time and again? What about all those people who paid heavy, selfless prices for their beliefs and for protecting others?

How does all human virtue and dignity fit into the Darwinian-Freudian model?

And what about the inner voice that resonates so deeply in most people that good must prevail? And the disturbing feelings we feel when innocent people are hurt? Is all that yet another evolutionary aberration — a quirk — that is inconsistent with the cardinal law of “survival of the fittest”?! Or is it the other way around: Perhaps the good in humans is the most dominant force, and the current “low-end” model may be flawed.

These are excellent questions. Indeed, these and other vital questions are catalysts that compel us to recognize that there is a serious gaping hole in the DarwinianFreudian model.

After all, no one has ever seen the human psyche. By definition the unconscious defies conscious human observation. Let alone the soul. So, basically all theories about the psyche are as subjective and arbitrary as the people positing these theories and their own life experiences.

No one is blaming Freud or other psychologists. But all they really could offer us is based on their personal psychological experiences. Perhaps some of them were surrounded predominantly by Id-like experiences, which informed their observations and conclusions? Had they truly experienced the selflessness of the soul, they may have incorporated other theories into their models.

All that is speculation. Let’s get back to history.

Preceding all these thinkers, was Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s psychological model, which is defined by three revolutionary principles:

1. Human self-control is inherent, not acquired.

2. The essence of a human is good and Divine; the Yid, not the Id.

3. Even mans’ intrinsic self and selfishness (“itness”) is rooted in the Essence of the Divine Self.

Here’s a brief overview of Rabbi Schneur Zalman’s model.

A person carries two voices, two souls: The animal soul and the Divine one. In the words of Ecclesiastes, “The human spirit ascends on high; the spirit of the beast descends down into the earth.” They are in constant struggle, with the animal soul seeking instant gratification and pleasure (like the Id), and the Divine soul seeking transcendence and unity. The animal spirit wants to be “more animal,” hence more selfego. The Divine spirit wants to be “more Divine,” more selfless.

The domain of the animal manifests in the impulsive emotions, while the domain of the Divine spirit rests in the reflective mind, which can control and temper impulsive reactions. A young child for instance, is controlled entirely by emotion, and yells out “I want it and I want it all now.” Similarly the animal within us selfishly barks “give, give.” As our minds develop we gain the ability to reflect, repress, temper or channel our impulses.

The question of course is, as mentioned earlier, which is our most dominant force?