Powerhouse creator NONA BAYAT is inspiring millions through her ftness journey

Smart traders don’t miss great opportunities

Find out more:

*Terms apply. Trading FX on margin is high risk and not suitable for everyone. Losses can exceed investments.

Powerhouse creator NONA BAYAT is inspiring millions through her ftness journey

Find out more:

*Terms apply. Trading FX on margin is high risk and not suitable for everyone. Losses can exceed investments.

Millions of people like to pursue some kind of healthy lifestyle, but if you dig into it you quickly learn that everyone’s motivations and goals are all over the map. Some people chase high performance—trying to get stronger or faster or more competitive at a favorite sport. Others are in search of a leaner or healthier or more confdent self. Many people like to exercise to clear their minds or improve their mood or their overall sense of well-being. And at least a few do it to justify an extra burger or pint of beer. But everyone has an interest in ftness because it makes their lives better in multiple ways. Several stories in this issue explore elite athletes and ftness leaders who are chasing excellence. Like Sam Hurley, a high jumper and pole vaulter at the University of Texas at Austin. His talents are extraordinary, but Hurley is clear that he will only reach his goals by maintaining a relentless work ethic. And while he tries to exercise and eat and sleep with constant intention, he also understands that having fun will help him succeed. He loves the feeling of fying when he jumps—it’s a kind of freedom, he says. That duality, exercising like it’s both work and play, would be good practice for even the most casual athlete. Also featured in this issue is a profle of creator Nona Bayat. Her ftness journey is uplifing in a totally diferent way, as she has built a massive social media following by inspiring millions of people, especially women, to forge a stronger version of themselves. She looks the part of a supremely ft human, with abs that appear molded from marble, but her present mission seeks to activate a ftness revolution more than pursue simple self-improvement. Lastly, there is an expanded version of our regular Train Like a Pro feature, this time highlighting pro wakeboarders

Meagan Ethell and Guenther Oka. Among other things, their approach illuminates the value of all the little things that impact ftness. They are conscientious about what they make for lunch and how they warm up for a workout and even how they carve out time for sporting hobbies that can inch them closer to their goals. They strive for mindfulness rather than single-mindedness.

These individuals, though blessed with remarkable talent, ofer instruction and inspiration to mere mortals who want to make their own ftness journey more rewarding. Get afer it!

These individuals offer instruction and inspiration to anyone who wants to make their own fitness journey more rewarding..

PHOTOGRAPHER

The Ojai, California–based photographer is a solid choice for sketchy assignments. He’s swum off the coast of Alaska capturing the training of the Coast Guard’s elite rescue unit and spent time with eagle masters in Mongolia during the dead of winter. For this issue, Bastien (shown on the right next to writer Mark Jenkins) leveraged his advanced climbing skills to photograph wind turbine technicians working hundreds of feet off the ground in central Idaho. He has worked for clients such as Patagonia, National Geographic, Outside, Apple and the Wall Street Journal. Page 114

PHOTOGRAPHER

“I always love it when I can shoot great athletes in motion,” says the New York–based sports and portrait photographer, who shot elite high jumper and pole vaulter Sam Hurley as well as ftness creator Nona Bayat for this issue. “I especially loved the pole vault location In Austin, where we could let Sam loose in a proper training facility.” Bugge, who is originally from Norway, has shot for the New York Times, Men’s Journal and commercial clients like Ferrari, FanDuel and Bloch. Pages 8 and 10

WRITER

“It was surreal to meet Nona in person after watching so many of her TikToks,” says the L.A.-based writer, who profled ftness creator Nona Bayat. “I’m always interested in how creators balance the personal and professional aspects of sharing their lives online. And I walked away from our conversation inspired to supercharge my own ftness routine.” Jarvey, a former staffer at Vanity Fair and the Hollywood Reporter, now writes a newsletter about the creator economy called Like & Subscribe Page 22

PHOTOGRAPHER

“I love working with Grace because she’s warm, welcoming and inclusive in any space she’s in,” says the photographer, who traveled to Wisconsin to shoot pro street snowboarder Grace Warner in her element. “She makes shooting photos in any scenario easygoing and relaxed and is down to work around any last-minute asks.” Rosemeyer, who is based in Burlington, Vermont, has shot for clients like the North Face, Vans, Burton, Thrasher and Transworld Snowboarding Page 74

PHOTOGRAPHER

The L.A.-based photographer had to cope with frigid temperatures, power outages and a fooded hotel before starting to shoot three NASCAR-related features in North Carolina. “But it was worth it—it wound up being one of my favorite shoots to date,” she says. “Getting a chance to witness some of the training and talent behind the scenes was defnitely worth a few cold showers.” Zumbrun’s clients include HarleyDavidson, Elle, Triumph and Husqvarna. Pages 42, 52 and 60

8

ELITE FITNESS

10

Sam Hurley

This dual-discipline athlete, social creator and NIL entrepreneur is the complete package 22

Nona Bayat

The ftness creator inspires millions to fnd empowerment through weight lifting

Train Like a Pro Pro wakeboarders Meagan Ethell and Guenther Oka share how they stay in top shape

40 NASCAR 42

Shane van Gisbergen

The veteran Kiwi driver breaks down his unexpected path to success

Picture Perfect Red Bull returns to NASCAR

Connor Zilisch

Accomplished beyond his years, the 18-year-old is racing toward stardom

Stop and Go

How one Trackhouse pit crew trains for success

Dale Earnhardt Jr.

The NASCAR legend and commentator joins Red Bull Soapbox Race

72 WINTER SPORTS 74

Grace Warner

For the pro street snowboarder, her passion for the culture runs deep 84

Red Bull Cascade

Bobby Brown’s freeskiing competition is raising the bar 92

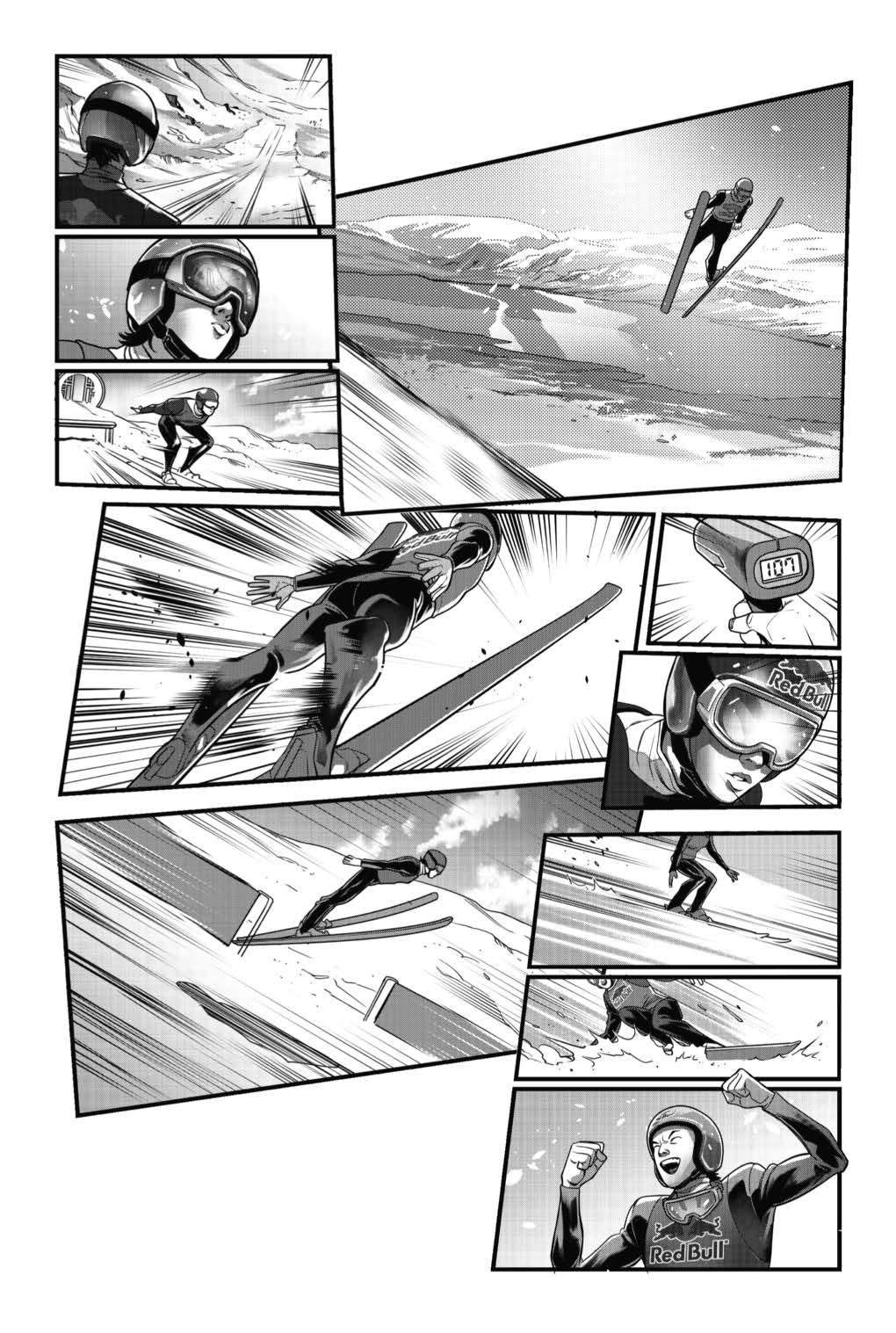

Ryōy ū Kobayashi

The Japanese ski jumper and cultural phenom who jumped farther than anyone, ever

100

WILD JOBS

102

Stunt Couple

Aurélia Agel and Justin Howell, a real-life couple, have fought to secure a place among Hollywood’s top stunt performers

114

Turbine Techs

Meet the men and women who have the technical skills and grit to fx wind turbines from dizzying heights

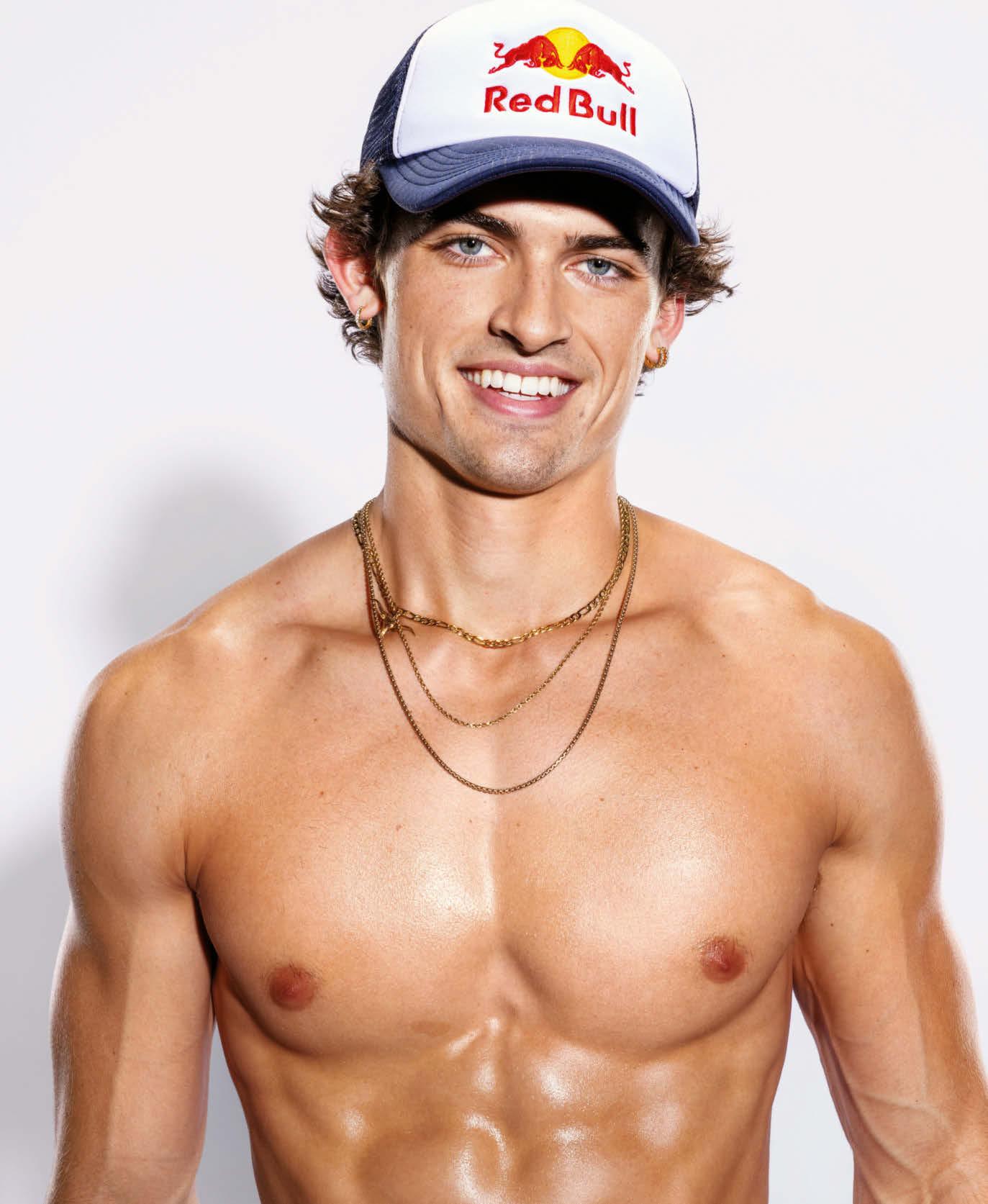

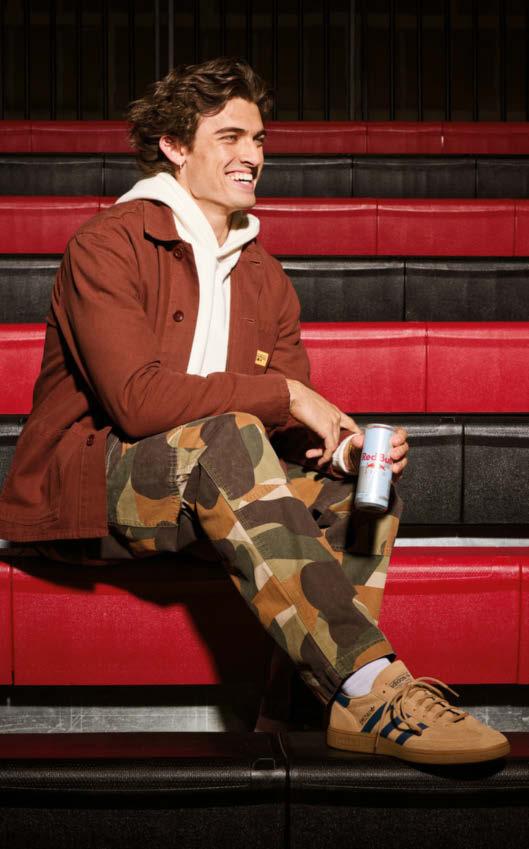

A rare dual-discipline athlete, a powerful social creator and a groundbreaking NIL entrepreneur, Sam Hurley is a force to be reckoned with.

“I would rather be stressed about having too much on my plate than worried about not having enough,” says Hurley, who was photographed in Austin, Texas, on January 5.

Sam Hurley is in love. It’s a blustery January afternoon as a nasty cold front begins to blow through Austin, Texas, but the collegiate track-and-field star is talking about how deeply he loves his crazy life. Hurley, 21, has this optimistic energy that is impossible to fake.

The young man with the tousled hair and the piercing blue eyes and the chiseled torso and the easy smile seems to have it all. He’s got world-class potential that he’s pouring into two track-andfield disciplines—the high jump and the pole vault—that basically nobody attempts to double up at the highest level. He’s a legitimate brand, with millions of followers on social media and corporate partners at his doorstep. He’s smart and modest and curiously thoughtful.

It’s easy to get seduced by all the cinematic highlights and overlook the hurdles he’s cleared along the way. Like the three times he ripped his quad last year, meaning he often couldn’t walk and barely was able to compete in his junior year at the University of Texas. Or the time nearly everyone in his high school turned on him—because of, of all things, TikTok. It’s easy to admire the rippled abs and the sculpted deltoids without really imagining the eternally grueling labor put in at the gym. Don’t kid yourself—it takes a lot of work to be Sam Hurley.

Nonetheless, Hurley seems to be enjoying himself and comfortable in his own skin no matter what he is doing—whether he’s jumping a foot over his own height or documenting the minutiae of his daily life or lifting to failure at the gym. Ask him what it’s like to jump seven feet or vault 18 feet: “It’s the feeling of being free,” he says. Ask him about his seemingly boundless natural talent and he’ll tell you about the sacrifices and the work it will take to realize it. Ask him about fishing and be prepared for a long and passionate answer.

“I know who Sam Hurley is,” he says to me early in a wideranging interview. That’s not something you hear 21-year-olds say every day.

But he means it.

“This is a full-time job,” says Hurley, who claims he thinks about winning an NCAA title hundreds of times a day.

“It’s not like I train and go to the track and then I’m off for the day.”

Hurley’s origin story unfolds in Fayetteville, a small, leafy city tucked into the northwest corner of Arkansas. While many contemporary sports fans may first think of Eugene, Oregon, when it comes to American track-and-field history, Fayetteville has solid credentials to back up the nickname “Track Capital of the World.” To wit, between 1984 and 2013, the Arkansas Razorbacks won a mind-boggling 41 national championships in cross-country, indoor track and track and field.

“Fayetteville is the reason I started track and field,” Hurley says. “Growing up, I was the biggest Razorbacks fan and went to every track meet. From such a young age, I was surrounded by Olympians every day. Even as a kid I was like, ‘This is what I want to do.’ And I still feel that way.”

Hurley got involved in the sport very early by American standards. When he was 8 or 9, one of his older brothers had a friend who pole vaulted and actually had a runway and pit in his backyard, and one day Sam, his brother and their dad went by to check it out. Someone asked the youngster if he wanted to

give it a go—“I said yeah, let’s do it,” Hurley recalls. “I had so much fun … I basically haven’t stopped since then. Even when I was a little kid I had a plan to compete collegiately and then go pro.”

Lots of kids harbor fantasies to become a pro athlete, but Hurley was blessed with the kind of speed and athleticism (and an obsessive streak for training) to make that dream a realistic goal. He showed promise in multiple disciplines but focused most on pole vaulting and high jumping.

When he was still in elementary school, Hurley began traveling regionally and then nationally to compete in higherlevel track meets. “I would hop in my dad’s truck and he would drive me everywhere—we went to meets in Jacksonville, Chicago, California, West Virginia, New York and Texas when I was in fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth grade. That’s pretty uncommon for a kid at that age.”

All that early competition and family support (and talent) paid dividends. Over the course of his high school career, Hurley

A very rare elite dual-discipline jumper, Hurley has cleared 7’3” in the high jump and 18’ 1 ¹/4” in the pole vault.

assembled a dominant record, demonstrating his elite potential in his two favorite disciplines and his remarkable athleticism beyond those specialties. In 2021, following his junior outdoor season, he was named the top track-and-field athlete in the state. His dominance in Arkansas is hard to overstate. His junior year, he not only won the state championship in the high jump, pole vault, long jump and decathlon; he missed winning the 110-meter hurdles race by one hundredth of a second, altogether scoring 40 points individually to lift his high school to a state championship. Overall, he led Fayetteville High School to a total of three indoor and outdoor state titles.

Not surprisingly, a lot of the top collegiate track programs in the U.S. tried to recruit Hurley, who also had excellent grades and an impressive résumé of volunteer work. In the end, he was offered scholarships to five of the nation’s top programs— UCLA, USC, Texas, LSU and Oregon. He took some flack locally for not seriously considering the University of Arkansas. “Fayette’s

my home forever,” Hurley says. “But after spending my whole life there I needed to know what else is out there in the world.”

In the end, he picked the Texas Longhorns. “It’s an amazing support system here in Austin,” Hurley says. “The education, the facilities, the support within the staff—all of my top priorities were met here. And I love my coach.”

But while everything about the decision came easy for Hurley, the transition from high school to college sports wasn’t a breeze. “High school sports were a blast—I mean, I basically won every meet for four years,” he recalls. “And when I got to Texas and started competing, I got humbled. I learned that everyone there was as good as I’d been in high school.”

That realization was sobering, but it was also an inflection point for Hurley, a chance to reassess his dreams and how hard he was willing to work to make them come true.

Hurley remembers that challenging period well, just as he remembers the moment he formulated his response. “That’s when I was like, ‘I have it in me—let’s see where I can take this.’ ”

There is another Sam Hurley origin story that also begins in Fayetteville. Back when he was in fifth or sixth grade, Hurley began to make videos and post them on social. “I always wanted to do something in front of the camera,” Hurley says. “I’d make little skate edits, football edits, frisbee edits or just film stuff with my friends upstairs, and post them on YouTube. Whatever we were doing, I was filming and then editing it. I just loved that.”

This is of course something that tens of millions of kids like to do, but for Hurley it turned into something bigger. Back when he was a freshman in high school, a girl in one of his classes had a new app called TikTok and he decided to download it and post a video. “From the get-go, the videos just started blowing up,” he laughs. “I kept going at it and the numbers kept increasing. And TikTok started blowing up and getting huge, and luckily I was on there pretty early, posting super consistent stuff and kind of took off with it.”

Those early videos are cute and harmless—a kid with great hair doing backflips off of boats and trendy dances with some clever edits—but back in school he would learn a hard lesson: that not everyone enjoys other people’s success. “Since I was really good at track, the juniors and seniors were always cool with me,” he recalls. “But when I started TikTok, they switched up so quick. I was just doing something different, and doing something different isn’t always accepted in people’s heads.”

What followed was the kind of low-level bullying that many kids experience. Hurley remembers being spit on and guys trying to trip him in the hallway and suddenly sitting alone at lunch, and soon he realized that he only had a handful of friends he could count on. “That whole school year was pretty rough,” Hurley admits, quickly pivoting to the valuable lessons the experience taught him. “It was hard to be that young and go from feeling like everyone at the school was my friend to having only four or five friends. But I learned that a little bullying wouldn’t stop me from chasing my dreams, and I found out who’s actually my friend or not.”

The following year, after he had more success in sports and his TikTok audience went from big to huge, the bullying ended and everyone wanted to be his friend again. But the unpleasant experience would prove valuable as he navigated the rest of his adolescence and continued to find success as an athlete and a creator. Above all, he says, he learned the value of always being himself and knowing who would always be in his corner. “I know who Sam Hurley is, and I always need to be Sam Hurley, no matter what people say or when they say it.”

That decision, to be himself and keep posting, has paid off. Today, Hurley has more than 4.5 million combined followers on TikTok and Instagram. He views it as both a means of selfexpression and a business.

Much like how he got on TikTok in the earliest days of the platform, Hurley was able to perfectly time his involvement in new rules that allow college athletes to receive compensation for their personal brands. Known now as NIL—short for name, image and likeness—these new rules came into effect the summer before Hurley enrolled at the University of Texas and freed him to make marketing and publicity deals with brands. Now his partners include Dick’s Sporting Goods, Raising Cane’s, Hollister, TurboTax and Red Bull.

Hurley’s social feed makes his life look like an exciting and fun-loving fairy tale, but surely there is an immense amount of work and pressure involved in juggling a full-time academic load, an elite collegiate athletic career, a hands-on social media juggernaut and business relationships with various corporations. Nonetheless, Hurley has zero complaints. “This takes a lot of work,” he admits. “I want to do more business endeavors. I want to jump higher. I want better grades. All that takes work. I’d rather be stressed about having too much on my plate than worried about not having enough. And I’m learning to balance it all.”

But somehow, he’s making it work. “When I first saw all the other things he’s doing, I thought what am I getting into,” says Jim Garnham, the vertical jumping coach on the Texas track team, who has worked with Hurley for four years now. “But he takes care of business. There’s never been a distraction. Sam trains extremely hard—it’s always high intensity.”

“I am 100 percent intentional for every rep at the gym.”

In an era of specialization in elite sports, very few athletes try to compete in two disciplines with significantly different physical demands, like the high jump and pole vaulting. But that’s exactly what Sam Hurley is continuing to do.

If you watch Hurley high jump or pole vault, the controlled manner of his approaches belies just how fast he is. “The two events have really different demands and jumping techniques,” he says. “The pole vault requires a lot of core and shoulder and grip strength, while the high jump isn’t really about upper-body strength. But my speed and power output off the ground are the reasons I’ve had success in both.”

Hurley—who stands 6’2” and weighs about 175 pounds—is a bit shorter and more solid than most elite high jumpers. His size is, on paper, better suited for elite success in the pole vault. But to date, the high jump remains his strongest event. “It’d be cool to be 6’5” for the high jump, but at the end of the day, it’s just who can jump the highest,” says Hurley, whose performance backs

that up. After his humbling freshman campaign, Hurley doubled down on his training and methodically improved his jumping.

Last year, he cleared a personal best of 7’3”. To put that in perspective, that jump was only 3.5 inches short of the top three in the U.S., typically the position one needs to qualify for the World Championships or the Olympics. Hurley is confident he can close that gap. “Most of those guys have five or six more years of training and preparation than me,” he says. “I think that as long as I stay consistent and remember this is a full-time job, I’ll get there.” Garnham, his coach, thinks he’s ready to jump 7’5” this year. And while his pole vaulting isn’t quite at the same level, Hurley is quickly closing that gap. At an indoor meet in Albuquerque in late January, he cleared 18 feet 1 ¼ inches, a new personal best that makes him No. 2 all-time at the University of Texas. “He’s just so fast and explosive—he has massive potential in the pole vault,” says Garnham. “I think he’s capable of jumping 6 meters [about 19’8”]. If you do that, you’re elite and going to Diamond League meets.”

Hurley plans to turn pro and compete around the world after he graduates in May. “I’ll just keep doing what I’m doing—I just won’t have to go to class anymore.”

“I try to stay true to myself and make other people feel good.”

That’s the level that Hurley sees himself at, too—in both events. And he’s convinced that his path to that kind of success will require more than mere physical and technical development. “A lot of it will depend on my mentality,” he says. “This is a fulltime job—it’s not like I train and go to the track and then I’m off for the day. It’s my diet; it’s my sleep; it’s the company I keep. I go to sleep at 10 p.m. on Friday night so I can wake up and train at 6 a.m. It’s a 24/7 job.”

Last year was not easy for Hurley—he was sidelined for much of the track season after tearing his quad on three separate occasions. “The reason I’m kind of confident with my mentality and mindset is because of the trials and tribulations I’ve been through,” he says, buoyed by his injury-free status entering the 2025 season. “Showing resilience gives me confidence in myself.”

Like many top athletes, Hurley doesn’t pause when asked if he has explicit goals he’s expecting to achieve. It’s extremely hard to succeed in elite sports if you don’t have confidence in yourself and clear objectives. “I haven’t won a national championship, and I want to win a national championship as bad as I want to breathe,” Hurley says, talking about his goals for his final season at Texas. “I think about it hundreds of times a day. I understand what it will take, and I don’t mind the work it will take and I’m willing to make the sacrifices. Every bite of food I take, everything I do, ultimately, I’m thinking about that.”

But Hurley is determined that his career will continue even after his college eligibility is over. “I’m definitely planning to go pro and go to meets around the world,” he says, noting that he’s never been to Europe, Asia or South America and is stoked to visit them all. He knows there are a number of incremental steps he needs to master along the way, but Hurley wants to climb as high as he can go—to Diamond League meets, World Championships and of course the Olympics.

“I’m 100 percent intentional at every practice and for every rep at the gym and every film session—and I do that every day,” he says, explaining the work ethic that he hopes will lift him to glory. “If you aren’t willing to do that, you’re not going to be a top dog.”

As our interview winds down, I ask Hurley to expand upon his earlier declaration, “I know who Sam Hurley is.” But this time to more explicitly express what he knows about himself, the things beyond his 18-foot vaults and his 4.5 million followers and his chiseled midsection that define his character. The 21-year-old scratches his chin—it’s not a question he gets every day—but then an interesting conversation ensues.

First we talk about his hobbies and interests—the kinds of things that are harder to grasp flipping through TikTok or watching a big track meet. Like his love of fishing—mostly bass fishing at lakes in the Texas Hill Country but also saltwater fishing for redfish and speckled trout on the coast or fly-fishing on rivers when he has the time. Fishing is peace for Hurley.

Then we talk about music: his obsession with Bob Dylan (and Timothée Chalamet) after seeing A Complete Unknown; his affinity for EDM fueled by his brother, Hootie, a globe-trotting DJ; his love for R&B and indie. “I guess above all, I listen to a lot of country,” he says. “I’m still a country boy from Arkansas.”

Then we discuss the places in the world he’s most excited to see. His father lived in Singapore for a while, so he’d like to visit the island nation with his dad. He’s always wanted to visit Australia and Brazil and more than a few places in Europe. Once this final semester at Texas is done, that sort of travel will begin.

And he’s effusive about his love of extreme sports. For Hurley, getting a Red Bull sponsorship was the culmination of a lifelong romance. He was big into skating growing up and had a Ryan Sheckler poster in his bedroom. (They haven’t met— yet.) He also is a big fan of pro surfing and cliff diving. (“I actually went through a cliff diving phase when I was 15,” he says. “My parents hated that—they told me I need to stop.”)

He describes the meaning of getting his Red Bull cap from twotime Olympic champion Armand “Mondo” Duplantis, quite likely the greatest pole vaulter of all time. “That was a super surreal moment,” he recalls. “I really admire Mondo—part of it is just respecting his greatness but I really admire his consistency and dedication.” Other idols include LeBron James (“I mean, he’s the GOAT”) and MMA fighter Jon Jones (“I’m not a huge fight fan, but I look up to champions who have this eat-or-be-eaten mentality”).

And then, after all this impressionistic conversation about his passions and inspirations, he segues to the heart of the matter— the things that define Sam Hurley on the deepest level. Now he circles back to the lessons he learned after seeing how fickle some so-called friends are and how hard some injuries can be to bounce back from and the way your family, inner circle and sense of self give you the power to be yourself.

“I really try to stay true to myself and to make other people feel good,” he says, describing the intangible things that fuel and center his success. “Growing up my mom always said, ‘You may not remember what people tell you, but you’ll always remember how they make you feel.’ I’m proud of the way I treat people and stay true to myself no matter what.”

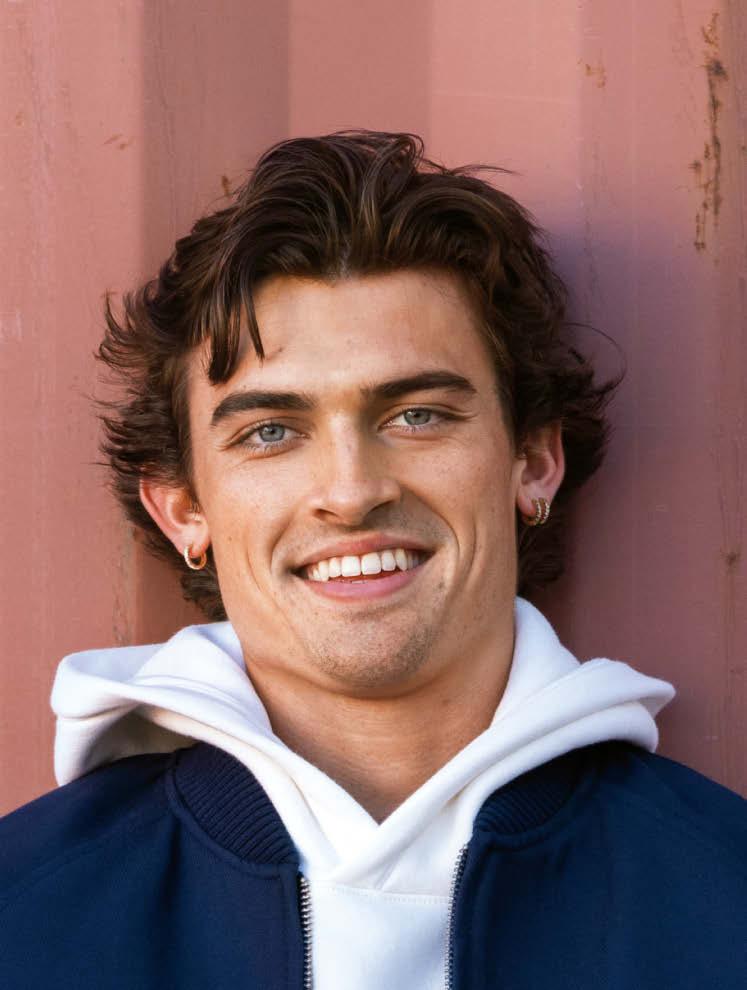

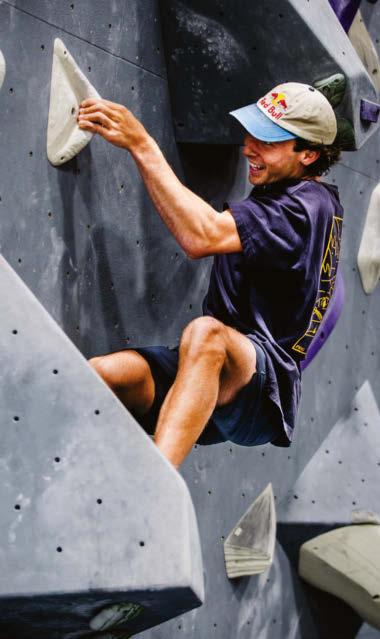

Fitness creator Nona Bayat inspires her millions of followers to fnd empowerment through weight lifting.

about Nona Bayat is her abs. Smooth and defned, like they’ve been etched into her torso; they’re not just undeniably impressive—they’re aspirational. I dare you to catch a glimpse of them on TikTok—where Bayat spends her days squatting, crunching and curling under the gaze of her 3.7 million followers—and not click on the next video in the hopes of learning how you can acquire a set of your own.

To see them in person is just as remarkable. And presently they’re on full display inside a sun-flled Hollywood studio as Bayat hovers in a high plank position over a pair of dumbbells. She waits for someone to adjust her long, sleek ponytail and then slowly lowers herself into a push-up as lights fash and a camera shutter snaps. Music bumps while crew members bustle about, but Bayat barely seems to register the hubbub, her mind focused on displaying the correct form. This isn’t just a photo shoot; it’s also a workout. And Bayat doesn’t even break a sweat.

There was a time when being observed this closely would have made Bayat so anxious that her palms would become clammy, her armpits damp. Now every time she records a video showing of her gleaming abs, her toned arms, she is quietly commanding respect. For the discipline she’s shown to build her powerful physique, yes, but also for her whole journey to become the 25-year-old in the center of the frame here on this blustery January afernoon, the one with the sweet face, determined gaze and conviction that she was meant to help others, particularly women, fnd their own power and strength through ftness.

“I view weight lifing as life changing,” Bayat tells me afer she’s slipped a pair of pink-accented black track pants over the skintight cerulean workout set she wore for the photo shoot. “It’s the one form of exercise that you truly can see a diference in your mental and your physical health in a short amount of time. And it’s so empowering as a woman to be muscular, to be strong, to take up space.”

on January 7.

Physically speaking on a literal level, Bayat doesn’t take up much space at all. Though her thighs are rock hard and her biceps bulging, they’re contained in a slight 5-foot-1 (or maybe 5-foot-2, she isn’t totally sure) frame. Today, Bayat speaks with pride about being “short and strong,” but she spent her childhood feeling uncomfortable in her own skin. Born in Iran, she moved to Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley when she was a baby, and the otherness she felt growing up as an immigrant, mixed with her debilitating shyness, formed a potent recipe for anxiety.

“I felt like I didn’t belong, and I wanted to hide myself in any way that I could,” Bayat says. It wasn’t until her younger brother, Amir, introduced her to weight training that she began to feel comfortable in her own body. “The gym gave me confdence,” she says.

During her fnal years in high school, Bayat became obsessive about perfecting her strength-training routine. She studied up on the science of lifing, aided by YouTube videos from bodybuilder Jef Nippard. “He’s science based and shows evidence when he talks about workouts,” she says. “Everything I do, it’s all research backed. I will research the heck out of everything before I talk about it.”

“I want to empower women to be the strongest version of themselves.”

When ftness creator Nona Bayat wants to get serious in the gym, she turns on classical music. “It helps me concentrate and it doesn’t distract me from the mind-to-muscle connection, which I focus on a lot when I work out,” says Bayat, who’s built a following of 3.7 million on TikTok with videos breaking down the gym routines and healthy recipes that keep her body absolutely shredded. Here she names four tracks that are currently in heavy rotation on her workout playlist.

JOEL SUNNY

“Luminary” (2023)

“Joel Sunny plays the violin like no other. Whenever I listen to ‘Luminary’ I feel like I’m a character in A Court of Thorns and Roses. If you read ACOTAR, it’s very empowering as a woman, and I think [this song] just makes me feel like I’m Feyre or Nesta. It pushes me extra hard in the gym because it makes me not Nona. I become someone else.”

GIBRAN ALCOCER

“Idea 9” (2023)

“Alcocer is the composer I listen to the most. The way that he plays is just so unique. When I listen to ‘Idea 9’ my brain feels mellow. It’s very calm. It’s slower than ‘Luminary,’ but that also helps me concentrate when I’m at the gym.”

SHINIGAMI

“I Feel Too Much” (2021)

“There’s a genre of music that is really popular in the ftness community called phonk, and this is a song that I really like in that genre. It’s a lot darker than my classical music, but it pushes me. It makes you feel like you’re in a video game or an action movie.”

DRAKE

“The Motto” (2011)

“ ‘The Motto’ gives me throwback vibes. It makes me feel like a boss. If I’m getting sluggish and I need a really big boost, I’ll put that on and I’ll be like, ‘Oh OK. You know what? Get to work.’ ”

Weight lifing can be intimidating for young women, but Bayat found a safe space to learn at an all-female gym near her house. “She was my main motivator for becoming ft and staying disciplined,” says childhood friend Emily Yun, who recalls how Bayat would drag her to the gym for daily twohour sessions afer school. “Her energy is contagious in all forms.”

Strength is something you build over months of careful commitment. Internet fame can spark much faster. Bayat’s frst brush with virality came in 2020, during her junior year at UCLA. On a whim, she asked her roommate to flm her “ab day” workout and posted an amateurish 12-second TikTok video splicing together her moves. Back then, TikTok was still an emerging social media app best known for videos of fresh-faced teens trying out silly dance trends, and Bayat didn’t expect anyone to watch her quick gym session. “I was like, ‘No one knows that I’m posting here. It’s kind of a safe space for me to share my passion,’ ” she recalls. But the next day, during a psychology class, one of Bayat’s classmates told her she’d gone viral. “I pulled up my account and the video was at 500,000 views,” says Bayat. She couldn’t believe how many people the clip had reached, but buoyed by the response, she started posting her workouts daily. Amid the crushing isolation of the global pandemic, TikTok became a lifeline. “I found my community through TikTok,” she says. “It flls that hole in me.” But at the time, she was far too focused on completing her psychology degree and going to medical school to consider turning her growing following into anything more than a giant virtual friend group. “I was so convinced that I was going to become a doctor,” she says. “When I was 9 years old, my grandfather passed away from cancer. I was pulled out of class and we went to Iran and were in and out of the hospital a lot. Seeing how that impacted my family made me curious about the human body. It sparked an interest in being in health care.”

But when her med-school acceptance letter arrived in the mail (she declines to say from where in case she decides to reapply in the future), she didn’t feel any excitement. She decided she’d rather devote all her energy to being a ftness creator. “I saw the impact that I was making on a global level,” says Bayat. “So many young girls were messaging me saying, ‘You changed my life.’ I kind of liked that. I was helping people in another way. Afer being in this industry, I realized that I really like preventative health. I want to treat you before you get sick.”

At frst Bayat’s parents didn’t understand. “In our culture, if you’re not a doctor or lawyer, you’re a failure in some sense,” she says, explaining that, as the frst person in her family to attend college, she felt a lot of guilt for not following through with the plan. “They took the risk of trusting me, and I think it paid of.”

To put it lightly. Today, Bayat has 5 million followers across her social media channels; partnerships with brands like Gymshark, Bloom Nutrition and Red Bull; and a ftness app on which she’ll guide you through workouts and meal planning (for $99.99 per year). This year she plans to launch a podcast. As her business has grown, her parents have come around. As proof of Bayat’s ability to infuence, she’s even got her dad doing regular home workouts and her mom training at the gym.

In an industry where bombast typically is rewarded with more and more views, Bayat’s persona is refreshingly reserved. She rarely speaks in her videos and ofen shoots her workouts with a baseball cap pulled down low over her eyes, the better for avoiding unwanted stares at the gym. When she’s not at the gym, she’s probably curled up on the couch with a copy of the latest hit romantasy novel or socializing with her tight-knit group of friends, which includes fellow ftness creators Arev, Elena Stavinoha and Lilly Sabri.

Bayat doesn’t always offer her followers a window into life outside the gym, but one of her goals for the year is to become a little more of an open book. “I’m trying to share more and talk more,” she says. When she does, she’s learning that it can lead to rewarding encounters. The day afer the photo shoot, for instance, she’ll post to TikTok that the wildfres blazing a path of destruction through Los Angeles have forced her to evacuate her home. And on Instagram she’ll share that she’s taking a short break from social media while she heals from a nerve issue brought on by the stress of the evacuation. “I’m never vulnerable online. I’ve had a lot of things happen to me throughout my social media career, but I still posted daily. This was my frst time being like, ‘Hey, I need to take a step back,’ tells me when we touch base a few days later, afer she’s been allowed to return home. The response from her followers has surprised her. “I think it brought us a lot closer.”

For all the ways social media has enriched Bayat’s life, it has complicated it too. Last year she went through a period of burnout, during which, she says, “I did not even want to step foot in the gym.” Working out had long been a passion. Now it had become her job, and she was spending around three hours at the gym each day capturing content and working out. Watching her videos from that time, it’s hard to tell what she was going through, but behind the scenes she established some boundaries that helped her fnd new balance. She now limits her gym time to an hour or less. Some days are for creating content; other days are purely for working out. And she has two separate gyms—one where she flms her videos and another where no cameras are allowed. She also limits her screen time to just 30 minutes a day.

Five years into her social media journey, Bayat no longer considers herself a shy person—a good thing, since she’s now likely to be recognized at the airport or out on a walk with her Cavapoo, Bambi. “At frst it was so diferent,” says Amir—who, when he’s not studying to become a dentist runs an infuencer marketing frm to help Bayat and other ftness creators connect with brands—regarding his sister’s online fame. “We didn’t know anyone who was internet famous. It was interesting to get used to, but she never took it as a negative. She’s always been very grateful for it.”

TikTok has become a comfortable home, Bayat says, in part because it helps her reach her target audience of young women. “It’s the only platform where a woman in ftness isn’t sexualized and we’re respected,” she says. “Fitness as a whole, especially weight lifing, is so male dominated, so it’s just really nice to see women in that space.”

We are speaking on a day when many of her peers are scrambling to prepare for a possible ban of TikTok in the United States, but Bayat doesn’t seem concerned. “The stronger your connection is with your community, they’ll follow you anywhere,” she says.

Bayat’s still fguring out where she’s going. She hasn’t closed the door on attending medical school one day, but she’s got a lot of other big goals, too. “This journey has shown me a lot about who I am and what I want in this world,” she says, her face breaking into a smile as she contemplates how far she’s already traveled. “I want to empower women to be the strongest version of themselves. I’m showing young girls around the world that you can fnd your strength. You can be anyone you want.” It’s a message to her followers, but also to herself.

LEGENDS NEVER TAKE THE EASY WAY.

TOUGHNESS. MADE TOUGHER.

The next evolution of all-terrain tires is here. The BFGoodrich® All-Terrain T/A® KO3 tire raises the bar in toughness and durability. Again. Designed to do it all, the KO3 tire has better wear performance than the KO2 tire, the excellent sidewall toughness you’ve come to expect, and is made to grip, even in the worst of conditions. Legends are written in dirt. It’s time to write yours.

Meagan Ethell and Guenther

Oka share insights on how they get into winning shape and stay healthy in a highimpact sport.

“When we go to the gym, we really focus on movements that give us more strength and mobility out in the water,” says Oka, who along with Ethell was photographed in Orlando on November 6.

A pro since 2012, Ethell has earned her place as a groundbreaker in the sport. She is an eight-time world champion and has won the sport’s most prestigious contest, the Masters, eight times.

Oka, who turned pro in 2015, has won an X Games gold medal, fve national titles and six world championships. He’s also passionate about video projects like his 2024 edit “Wake Glades.”

The love for wakeboarding, which was born when they were kids, is still going strong.

Meagan Ethell and Guenther Oka are sitting in the living room of their home in Orlando. Gleaming, powerful his-and-hers towboats are moored in the canal just steps from the house. The couple lives and breathes wakeboarding.

Ethell, who grew up outside Chicago, took up the sport when she was 8. “It didn’t feel so serious at first, and I think I just made steady progression,” Ethell, now 28, recalls. But she turned pro when she was only 15 and made an immediate impact in the sport. “Wakeboarding doesn’t have a set of rules like most sports,” she says, describing her love of riding. “You can take it and do whatever you want with it. The freedom is kind of unlimited.”

Oka, meanwhile, grew up in Cincinnati and had his first experiences being towed behind a boat before he was in grade school. He moved to Orlando to pursue a pro career when he was just 17 and hasn’t looked back. “I love the art of doing an action sport where I’ve got full creativity over how I express myself,” says Oka, now 26. “And it’s this time when I can go out and my brain totally shuts off and I’m there, locked in in the present moment.”

Since those formative years, you could say their careers have worked out. Together they have 14 world championship titles and scores of other big wins. And over the years, as the stakes got bigger and the injuries more consequential, they came to realize that passion, creativity and outsized talent would only take them so far—that they’d have to take their off-the-boat fitness, nutrition and mental training more seriously to get and stay on top.

Along the way, the two rising stars became a couple, and they got married this past fall. “What we have and share, being pro athletes who do the same sport but are also in a relationship, it is just such an uncommon thing,” Ethell says. “It just makes it so much easier to achieve what we want to because we know we have our partner’s support no matter what.”

Oka, beaming, agrees. “We’ve been on such an unbelievable journey throughout our careers—both separately and also together,” he says. “We’ve been able to travel the world and experience so much together. It’s just been the best ride ever.”

“I love the freedom of wakeboarding,” says Ethell. “It’s such a creative sport; I can put my own twist on it without a ton of rules.”

Oka and Ethell always try to start multidisciplinary training days on the water. “Even if I have a list of planned activites, I try to prioritize wakeboarding as the frst one that gets taken care of,” Oka says. “The battery level on the body’s at 100 percent—it’s fully charged—and I can kind of give everything I can to my craft. I can use whatever’s left over at the gym, or in the ocean, or things like that.”

Ethell says their on-the-water training shifts with the professional calendar.

“During competition season, my focus is what I need to do in order to succeed at contests—things like perfecting new tricks,” she says. “But in the offseason, it’s a little bit less structured. I try to just go back to the feeling of having fun.” She adds that learning tricks that will stand out in a pro contest is mentally and physically taxing. “The process usually involves a bunch of highs and lows,” she admits. “But I ultimately fnd that process fun.”

When they’re home in Orlando, the couple trains at a gym called New Dimensions that is popular with world-class wakeboarders. “We don’t spend time doing bench presses or squats because that doesn’t refect what we’re doing on the water—out there we’re twisting, turning, jumping and fipping,” Oka says. “So the movements we do at the gym cover the way our bodies and specifc muscles are moving to help us maintain strength and mobility out on the water.”

“Recovery is a huge part of what we do. Sometimes we spend more time recovering than we spend training in the water.” —Ethell

Both athletes have worked through serious injuries, so rebuilding function and preventing future issues is a focus at the gym. “Working in the gym has made me more mindful of my body,” Oka says. Ethell agrees. “Doing rehab on a torn ACL helped kick-start gym life for me and made me hyperaware about my body,” she adds, admitting that it’s more work than fun. “Getting stronger is gratifying, but it’s less exciting than wakeboarding.”

Whether it’s ice baths, compression boots or red-light therapy, Oka and Ethell use a variety of recovery modalities. “As elite athletes, we’re always looking for a 1 percent edge,” Oka says.

Wakeboarding’s super duo are passionate home chefs. “Being a pro athlete has opened my eyes to nutrition,” Ethell says. “I’ve always loved to cook, and learning how to properly fuel my body has gotten me excited to learn new recipes. And having a partner who has an equal mindset about that just makes cooking healthy food that much easier.” Oka, a bit of a prep specialist, adds, “We’ve got the teamwork thing dialed!”

“We’re big on prepping in advance,” Oka says. “We want to make cooking a bit easier after wakeboarding or hard training at the gym.”

Both athletes like to explore other sports. Oka likes foiling, Ethell has been hitting the climbing gym for several years, and both like to surf. “We’re pretty much nonstop the entire summer, so we don’t really have time to do these other sports that we enjoy,” says Ethell, who thinks climbing is a good time—and good for upper-body strength. “It’s really nice in the offseason to give our minds a break from wakeboarding and focus on something fun, without pressure or expectations.”

“Having other hobbies is fun and lets us take a beginner mindset to bringing new things back to our sport.” —Oka

Veteran Kiwi driver Shane van Gisbergen breaks down his unexpected path to NASCAR success.

“I’ve found my place to be,” says

Shane van Gisbergen is what you’d call a fast learner, especially when it comes to racing. He was obsessed with cars growing up in New Zealand, forsaking other childhood hobbies, TV time or even hangouts with friends to turn laps around the family farm on a Suzuki quad bike. His dad taught him how to drive at age 9, just in time for him to start racing go-karts. In his early teens, van Gisbergen began his career climb racing kazoo-looking cars called Formula Vees and won the rookie of the year award in 2005. Three years later, at just 18, he reached the big time: V8 Supercars, Oceania’s top stock-car series. He’d go on to win 80 races and three championships, distinguishing himself as one of the best-ever drivers at that level.

Still, it wasn’t until 2023 that van Gisbergen, 35, landed on the radar of American stock-racing fans when he stunned the field at a NASCAR Cup race on the streets of Chicago, where he survived wet and wild conditions en route to grabbing the checkered. After spending last year cramming in all the NASCAR racing experience he could get—from the entry-level ARCA Series to the triple-A-level Xfinity Series, where he finished 12th in the standings—van Gisbergen (or SVG, as he’s come to be known in this hemisphere) will now compete in his first full-time Cup season with Trackhouse Racing, an upstart franchise part owned by the performer Pitbull. The road ahead won’t be easy; IndyCar’s Sam Hornish Jr. and F1’s Juan Pablo Montoya are two in a number of proven winners who have struggled to find similar success in NASCAR. But van Gisbergen, who comes to NASCAR better equipped than most would-be crossover stars thanks to his experience in Supercars, could well set a new standard—not that he’s making any bold predictions for himself or anything. “I’m learning so much and having so much fun doing it,” he says. “I’ve found my place to be.” On his way in to work—on this day, a virtual reconnaissance mission inside a racing simulator—the easygoing Kiwi reflected on the effort to launch his racing career from New Zealand, his epic victory in Chicago, and why it pays to set modest expectations.

THE RED BULLETIN: Did you ever see yourself winding up in NASCAR?

SHANE VAN GISBERGEN: Growing up in Australia and New Zealand, V8 Supercars are pretty much all I wanted to race. There were a few Kiwis who were very good in that series—and I got in when I was 18. I did that until the end of 2023. I had an amazing career and really enjoyed my time there. But, yeah, I had this opportunity to come up and race NASCAR and it went really well in our first race. It was perfect timing for me to make a career change, I guess.

Before we get to that ace triumph—the first time a driver had won his Cup debut in 60 years—let’s talk about the odds against Kiwi racers. IndyCar’s Scott Dixon, maybe New Zealand’s best-ever racing export, has said his racing dream never would’ve come true if his father hadn’t sold off shares of his career stock to area businessmen who were keen for him to succeed. What did it take to get you off the island? It was sort of the same thing; you can’t do it without having amazing people support you the whole way. One of the biggest ones for me is [an auto dealership franchise called] the Giltrap Group. If you look at pretty much any Kiwi driver, they have Giltrap on their helmet visor—and it’s a real privilege to wear that. I was in one of their junior formula cars, and they helped me come through the ranks all the way to NASCAR, where they’re still supporting everything I do. It’s an unreal thing what they’ve done for Kiwis in New Zealand.

But starting out, it seemed more achievable for me to become a pro racer by going to Australia than if I had gone to America or Europe. Because that was the thing, to copy the Scott Dixon model. A lot of people go straight to Europe. Marcus Armstrong, who’s in IndyCar right now, started out in Europe and was even in the Ferrari academy for a few years.

Was your family big into racing?

My father was into rallying a lot in the ’80s and kept going until me and my sister came along—and had us racing quads and bikes. He supported me all the way. In Australia he’d come to a lot of races, but it’s a bit harder now that I’m over here.

Racing was pretty much everything when I was younger. Every year this magazine called Speed Sport would promote a racing scholarship that was a big deal in New Zealand at the time; they’d give money to race in Formula Vee. The first year I tried out, one of my friends won it and went on to race quite successfully that year. I tried again the next year and took up karting while I waited, just to learn circuit racing a little better. Ultimately, I won the scholarship on my third try, in 2004, and started racing Formula Vee. Then in the years after, I raced Formula Ford and Toyota—the three sort of junior single-seat categories in New Zealand.

By the end of that Toyota season, I got to test V8 Supercars for Stone Brothers Racing, which was one of the top teams at the

time, and did pretty well. There was this team called Team Kiwi Racing that had their cars run by Stone Brothers. Halfway through the 2007 season they lost their driver, and I got thrown in at 18 years old—a massive jump in competition and probably one I wasn’t ready for. But I finished off the season without embarrassing myself. The next year, Stone Brothers promoted me to the main team. It was awesome to go from pretty much straight out of school to achieving my dream.

So no part of you was targeting F1 as the ultimate stop?

I was halfway decent at open wheel, but, you know, I’ve always been a pretty big guy. Most of those open-wheel guys look like they should be 14 years old. When I was in Toyota Series, I was overweight and struggling with speed because I was so heavy. So I ended up going more in the touring-cars direction, which is exactly where I wanted to be.

I can remember Roger Penske slinking away from a NASCAR event to catch a private plane to Oz in hopes of checking out the Supercars championship. Was there much of a NASCAR presence on that scene then? Similarly, are Australasia racing fans up on the NASCAR scene?

Not really. I followed NASCAR a bit when [Aussie Cup driver] Marcos Ambrose was racing. But when he stopped, I didn’t really

pay much attention again until [Trackhouse co-owner] Justin Marks launched Project 91 in 2022, with the goal of letting the world’s best driver have a go in NASCAR. When they kicked off the cultural exchange with 2007 F1 champion Kimi Räikkönen, I wasn’t sure I’d ever have a chance to do it. But I put out feelers through former NASCAR Cup driver Boris Said.

Boris knew Justin and sort of started the conversation. To my great surprise and joy, Justin reached out and told me, “There’s a new race happening in 2023 on a street track that I think you’d be perfect for. Gimme a few months to find some sponsors and partners.” That was an awesome conversation, just because I didn’t go into it thinking something would come of it. A few months later, Justin called and said, “Yeah, this is gonna happen,” and it ended up being on a weekend where I didn’t have a Supercars race. Pretty epic how it all worked out.

Was that your first time racing in America?

No, I had raced a few times in IMSA and the Daytona 24. Definitely the first time in Chicago.

NASCAR’s too, in the city proper. It was also their first crack at staging a road-course race. As I remember, it was a roller coaster weekend that culminated in a wet and wild race. What was the view from the cockpit?

It was a pretty awesome weekend for me! I don’t get too fussed about the weather and stuff. Being that I was a visitor, and it was a one-off experience, I just tried to make the most of it—focus, do my best, enjoy myself. I had a blast.

How do V8 Supercars compare with Cup cars? A lot of drivers who come into NASCAR from open wheel can spend years making the adjustment—if they ever do.

They’re reasonably similar in some ways. We do a lot of street circuits in Supercars, but ours are quite different. NASCARs are very, very heavy, though, and a lot less nimble—but still just a car in the end. You just kind of adapt. I did as much studying as I could. And away we went.

Let’s talk about that slip-and-slide race, finally: The rain really threw a spanner in the works. Anytime the frontrunners got settled, a puddle would come along and wipe them out, throwing the race into chaos. Yeah, the race was pretty standard at the start—wet. I was kind of up front and led for a bit and then hovering around second or third. But then we kind of got screwed by an extended weather delay, which screwed up our strategy and put all of the good cars at the back. But it was fun coming through the field. A few guys made mistakes. We had some awesome battles. Yeah, it all worked out.

Can you describe your feelings in victory lane? Did you come away thinking all Cup wins would be that easy?

Well, it definitely wasn’t easy. I had a great bunch of people around me. That makes a huge difference. I felt comfortable right away in the first practice. I knew what to expect. We had a really good plan. My crew chief, Darian Grubb, he’s an amazing guy with so much experience. We were really right on it from the start. It was an awesome thing to share that moment in victory lane with him and the other members of the Trackhouse team, because a lot of the people on the team hadn’t ever won a race before. That’s how unexpected it was.

So at what point does the vibe go from “Man, that sure was something!” to “Are you sure you can’t stick around?”

After that, I decided to come back and do another Cup race—the road-course race at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, home of the Indy 500. During that weekend, they asked me if I wanted to run the truck-series race as well, which was down the road at Indianapolis Raceway Park—a little oval circuit. It was very tough, but I had a blast and thought NASCAR could be a lot of fun. Then it just kept snowballing from there. I got the opportunity to race in the Xfinity Series, and a few Cup races for learning last year. I did a lot more racing than I thought I was gonna do.

To the point where Trackhouse says, “How ’bout we sign you up to run full-time?”

Basically, yeah, that’s what they did.

So what changed? Is there a mentality shift that comes with going from racing NASCAR part-time to full-time?

Not really, no. It’s racing. That’s what we do. The biggest thing is, now that I’m racing every week I’ve got to prep with my guys. I’m in the sim every week. It’s that sort of thing. The schedule’s more intense. But for me, that’s what I want to be doing.

not to do donuts,”

Trackhouse’s four-driver roster takes Project 91’s foreign exchange to the next level. Besides yourself, there’s NASCAR’s Mexican champ, Daniel Suarez, and four-time Indy 500 winner Helio Castroneves of Brazil. What’s the shop talk like between you three?

It’s been awesome talking to them. Daniel and Ross Chastain, our Cup vet (don’t leave him out!). It’s amazing how open they are. Anything I ask about racing ovals in particular they happily share—and I won’t hesitate to pay back the favor when the road courses swing around. We’re making each other better. Overall, as a team, I think we keep getting better and better.

So what’s reasonable to expect from you this season? Is rookie of the year too much to ask, given your one-off track record? Honestly, I never set any goals or have aspirations of myself. I just try to do my best. I know that I’ve got a huge opportunity here, and I’m trying to make the most of it. You know, it’s a huge step outside my comfort zone, coming over here and racing something different. Other than really wanting to improve on ovals this year, I’m not putting any expectations on results or championship positioning. If we win some races, that’s great and I’m sure we’ll celebrate. But I just want to take the season as it comes and have fun doing it.

After a 14-year absence from NASCAR, Red Bull has returned to the Cup Series as a primary sponsor of the Trackhouse Racing Team. The livery here will adorn the No. 88 Chevrolet of Shane van Gisbergen in five Cup races this year, beginning with the Pennzoil 400 in Las Vegas in March and culminating at the Hollywood Casino 400 in Kansas City in September. The branding will also appear on the No. 87 Chevrolet of Connor Zilisch when he makes his NASCAR Cup debut at the EchoPark Automotive Grand Prix in Austin in March.

@teamtrackhouse

Mature and accomplished beyond his years, Connor Zilisch is racing toward stardom.

Zilisch, only 18, has already won professional races in a variety of vehicles and shows staggering promise to succeed at the highest level.

The typical 18-year-old walks a familiar path in life. Friends. Fun. Finding themselves. Figuring out the contours of responsibility. Thankfully, these teenagers generally don’t face an onslaught of questions about whether their future success hinges on them becoming an all-time great in their selected field.

Connor Zilisch is far from your typical 18-year-old. Most of the questions he gets are about what comes next, and how high can he climb in his sport. Presently, the sport is NASCAR—the National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing, the pinnacle of stock-car racing in the world—and Zilisch has already been hailed as its Next Big Thing. It’s a label bestowed on those blessed with the talent, temperament, determination, drive and, most of all, hype to deliver on that promise.

The arrival has happened so quickly. Just a few years ago, NASCAR wasn’t on Zilisch’s radar—and vice versa. On the surface, he was just your normal kid you’d struggle to pick out of a crowd. “Two years ago, I thought I’d quit racing and go to college at this point in my life,” the young driver says. “Then things took a turn.”

And now everything has changed. Zilisch has already shown that he’s not just capable of winning—he’s capable of winning in nearly every kind of car he climbs into. With that kind of versatility and talent, it’s hard for anyone—including himself—to say what exactly the future will bring. But rest assured it will be fast.

Unlike stick-and-ball sports, motorsports encompasses a huge landscape with numerous significant championships using diverse types of machinery. Drivers can pursue open-wheel disciplines, such as Formula 1 or IndyCar, stock-car series like NASCAR or sports car racing competitions such as those governed by the IMSA (International Motor Sports Association).

Each path requires a different degree of funding to race, and a need to adapt or adjust to wildly different types of cars in terms of horsepower, downforce and weight. Generally, in a modern sports era that rewards specialization, it’s acknowledged that whichever path you choose, you race near your home or in your home country first and stay as close to that discipline as possible.

“There wasn’t really an end goal,” Zilisch says about his early driving years. “F1 was a fever dream because of how expensive it is. I understood that from a young age. Unless something crazy happened, it wasn’t possible. But there was sports car racing, and growing up I watched that and wanted to compete in the biggest endurance races there are.”

Lots of kids have talent and big sporting dreams, but few of them get realized like this. A critical inflection point came when Zilisch was only 11, when he moved from Mooresville, North Carolina, where he was born and bred, to Europe to chase his racing dream. He had showcased his potential racing go-karts since he was 5, but this was a whole new level.

It sounds like the start of a movie script. Zilisch’s father, Jim, worked full-time in the financial sector and couldn’t afford to take time off work to travel for weeks at a time to see his son race. So Connor traveled to Europe with his good friend, American mechanic Gary Willis. They were based mainly in Desenzano del Garda, Italy, a small town in Lombardy on the shores of Lake Garda.

“I told my dad this is what I wanted to do,” Zilisch explains. “Gary and I would fly over and we’d have an apartment or Airbnb for three to four weeks. We’d hit Italy, Spain, France—basically all Western Europe. Looking back on it now, I didn’t realize how insane it was. Those were the coolest days of my life.”

Like any pair of friends, they also appreciated their time apart. “I have so many stories to tell about going over there. But one is that Gary would get sick of me throughout the day, so he’d say, ‘Oh, I need some alone time,’ ” Zilisch laughs. “I’d grab a bike and ride to dinner at this small town in Northern Italy, and I’m a 10-, 11-yearold kid who doesn’t speak the language and goes to eat dinner by

“I’m a normal kid. But I know when I have to be a professional.”

myself. It’s times like that I can look back on and say ‘Wow, I can’t believe I did that.’ That shaped me into the person I am today.”

Growing up on another continent and learning how to lose frequently taught Zilisch a lot from the ages of 11 to 15 about racing and life. “It took me a long time to be successful, and it was a struggle at first, I can’t lie,” he says. “A lot of the other American kids would come over for one or two races and they’d struggle, and then they’d quit. I kept trying and got better. That taught me a lot. I learned how to lose before I won. That’s so important in racing because you’re going to lose a lot more than you win.”

The pinnacle of Zilisch’s years spent abroad came when he captured the 2020 CIK-FIA Karting Academy Trophy. He was 14 at the time, and the first American to do so. In layperson’s terms, he was the world’s best karter in an internationally recognized competition, racing his peers in identical equipment. Globally, his performance raised eyebrows.

“I wanted to succeed over there, and I feel like I got set up better by the end of my time there,” he says. “It’s tough at times to accept the losing and understand that. But learning it at a young age was super beneficial.”

Another young teammate of Zilisch’s would play a huge role in his career advancement.

A chance meeting with 2014 NASCAR Cup champion turned Fox Sports broadcaster Kevin Harvick (ironically nicknamed “Happy” for his sardonic wit) and son Keelan changed everything. Keelan was a go-karter who also plied his trade in Europe and was on the same team. The elder Harvick spotted Zilisch, and soon a new path of racing in NASCAR emerged.

“It wasn’t until I met Keelan and Kevin to where I became interested in NASCAR, and if it wasn’t for that, I wouldn’t be where I am today,” Zilisch notes. “Kevin introduced me to the sport, took me under his wing and made it possible for me to start this journey. I’m forever grateful for Kevin and what he’s done for me. I didn’t go to Europe to race go-karts to prepare myself for NASCAR. Had I done that, I would have done ovals, quarter midgets, legends, stuff like that. It came by a surprise, but I’m glad I did.”

Paths opened in the NASCAR community, including a meeting with Zilisch’s now team owner, Justin Marks, who runs Trackhouse Racing. The Nashville-based team has sought to brand and operate differently from traditional race teams and signed Zilisch as a development driver in 2024.

What followed was a season of success for Zilisch that still seems hard to believe. The racer returned to America and won a fullseason scholarship from Mazda to compete in its MX-5 Cup championship in 2022. The cars are best described as 2.0-liter, four-cylinder “buzzing hornets” that make for some of the best pure door-to-door racing in the country. “MX-5 Cup is still my favorite series to have raced in,” he says. “It’s 45 minutes of organized chaos. Every part of that race is insanity, but so much fun.”

Over the next two seasons, he competed in an unusually wide range of racing vehicles, encompassing high-powered sports cars classified as Trans-Am 2 (TA2) and high-downforce aerodynamic prototypes called Le Mans Prototype 2 (LMP2), as well as stock cars and trucks in three different series: ARCA Menards Series, NASCAR Xfinity Series and NASCAR Camping World Truck Series. He rates the LMP2 and the TA2 cars as his favorites due to their visceral downforce and power, although he’s got a fond spot for each car he drives.

His 2024 season racing all five of those cars, plus MX-5, is the equivalent of an 18-year-old basketball rookie also playing pro baseball, football, hockey and soccer in the same season.

If that sounds crazy, imagine what it would be like if he won in multiple series, including in his debut in two of them, in two of the biggest races. But that’s exactly what he did.

He opened the year as part of a four-driver, class-winning LMP2 lineup at the 2024 Rolex 24 at Daytona. Drivers rotate through the car for several hours at a time like a relay event, and Zilisch was one of the two young drivers his Era Motorsport team entrusted to finish the mentally taxing, 24-hour endurance race.

If that wasn’t enough to launch a hype campaign, he also won the Mission 200, his NASCAR Xfinity Series debut, at Watkins Glen in the Finger Lakes region of New York, driving for Dale Earnhardt Jr.’s JR Motorsports Chevrolet team.

The winning text messages flowed like water on Lake Lloyd on the Daytona Beach infield and Seneca Lake near Watkins Glen. “It was insane, honestly,” Zilisch admits. “I never realized how many people care about me, follow me and keep track of me,” he says, estimating roughly 500 notifications received after each race.

The driver says that he responded to every single message. “If they’re going to take the time to congratulate you, they care enough, so I need to be sure to respond to them,” he says. “It was surreal to see how many people reached out after those races.”

Zilisch says he has learned to make preparation a priority, without overpreparing to compete in races. “When I was younger, I had trouble when I had nerves and I’d choke or fumble a race,” he explains. “It’s tough not to get yourself hyped up. That’s a detriment to the end goal. Now I keep the mindset of it’s just another race.”

Seeking the life of a typical 18-year-old isn’t realistic at this point. Zilisch is racing multiple series, representing major companies, brands and sponsors and showcasing a significant chunk of his life on social media. So how the heck does he balance all those demands while still trying to be a somewhat normal kid?

“It’s a good question, actually,” he ponders, offering some insight into his social media intentions. “A lot of parents [of young athletes] find someone to run their kid’s social media. Social wasn’t as big when I grew up, but personality was. But now, if you have someone else running your social media, that’s the only thing people see of you—and that’s not you. It may get to the point where it’s necessary, but until then, I want to make my social about me and personalize it.”

The 2025 season gives Zilisch a chance to add to his legend. He’s set for the full 2025 NASCAR Xfinity Series season, a 33-race commitment, with JR Motorsports as Trackhouse Racing’s development driver and Chevrolet-affiliated driver. He also opened the year trying (without success) to defend his Rolex 24 win, this time in a Trackhouse by TF Sport–entered Corvette he raced with three other drivers. He will make his NASCAR Cup Series debut early in 2025 at 18. It’s the equivalent of a basketball player leaping straight to an NBA game from high school.

The goal is to keep winning, contend for a championship and pursue a full-time move up to Cup in the near future.

How does he handle the noise? “It’s important not to listen to it,” he says. “When you win, you get hyped up and told how good you are. Then the next week when you run 15th, they’ll tell you, ‘You suck.’ I can’t let what people say affect my preparation for the race or how I race. I won’t let people tell me I’m the greatest thing ever when I’m not there yet.”

After the last 12 months, his maturity and reflection on what he’s achieved shines through. “It’s funny that everyone always tells me, ‘Oh, you’re so mature for your age,’ ” he laughs. “With my friends, I’m the jokester. I’m a normal kid. But I have a switch in me that I know when I need to be a professional. I’ve met the right people at the right time and really won the right races, I guess! Getting linked up with Trackhouse, Justin Marks and others has done so much for me not only as a driver but as a person. They’re making sure that in every aspect of my life I feel comfortable and am in the right place to succeed.”

Zilisch pauses to summarize the success he’s had so far. “It’s been a crazy last 12 months, way beyond what I could have ever imagined,” he says. “I’m trying to soak it all in and enjoy it all. I’m still a kid, and I’m trying to enjoy my childhood while I can because you only get that once. It’s tough to remember that at times, when you’re a professional athlete and trying to make a career out of it. I have to enjoy it and have fun. It’s hard not to have fun when you have success, though!”

Specialization and sports science are transforming how NASCAR teams recruit and train pit crews. Here’s an intimate look at how one Trackhouse crew, full of elite athletes from other sports, seeks perfection.

On a bitterly cold January afternoon, a gray race car flies into a mock pit road beside Trackhouse Racing headquarters in Concord, North Carolina, and the carefully orchestrated choreography of the NASCAR pit crew begins. Three guys jump out in front of the car, to be ready on its right side when it stops, and narrowly avoid getting clipped. Tire carrier Jeremy Kimbrough lugs two 40-pound tires; Aslan Pugh, the jackman, hauls a 20-pound jack; and front tire changer Ryan Mulder holds an air gun to unscrew the tire’s lone lug nut. Just as the car stops, rear tire changer JP Kealey, also toting an air gun, scampers behind the car. Gasman Evan Marchal, the final man on this crew, remains on the left side of the car, his 12-gallon gas can already filling the tank as the driver brakes.

About .8 seconds after the car is stopped, the jackman, with one powerful push, has the right side of the car raised off the ground. Both air guns whizz loudly as the two tire changers remove the front and back tires’ lug nuts. With one second gone, both have been removed and rolled to the wall. Within three seconds, new tires are on, the car is lowered, and the crew sprints around to the opposite side. By five seconds, the jack has the left side of the car off the ground. At seven seconds, the two remaining tires have been replaced. A second later, the car, with four fresh tires and a full tank, is ready to go.

It’s an explosive, chaotic endeavor, requiring an athleticism that might be overlooked by the casual fan. In fact, it’s an athleticism that was overlooked even by teams for much of

and an

and timing

NASCAR’s history. Back in the day, pit crews often were staffed by the mechanics and engineers who worked on the cars. In recent years, though, NASCAR teams have realized the advantages of recruiting and training a pit crew that’s made up of athletes rather than gearheads. “Teams found out really fast that guys who can train all day and worry just about pit stops can do it a lot faster than guys who have to build and set the cars up,” says Shane Wilson, a pit coach at Trackhouse (and jackman on driver Ross Chastain’s No. 1 car).

Recent rule changes at NASCAR have accelerated this specialization. In 2021, NASCAR cars switched from using five lug nuts to hold each tire in place to a single, center-locking lug nut. Pit stops have consequently gotten shorter—and the

margin for error has gotten tighter. One or two tenths of a second slower in the pit might mean 20 extra car lengths on the track. So now pit crews are seeking athletes with explosive speed and an ability to handle high-pressure situations.

Trackhouse Racing is one of the outfits taking this change seriously. They employ and train several pit-crew teams, recruiting many of them from elite college and professional sports backgrounds (including a front tire changer, Josh Bush, who won a Super Bowl with the Denver Broncos). The Red Bulletin recently observed a day of training with the five men who pit Shane van Gisbergen’s No. 88 car. Here, in their own words, they discuss the mental and physical preparation for the job.

and other Trackhouse

Played football at Appalachian State and for the (then) Washington Redskins

33 years old, 5’10”, 235 pounds

My pops used to watch NASCAR, but I never really got into it. After I was done with football, a teammate told me about NASCAR and I got involved with the Drive for Diversity program [a developmental NASCAR program that trains athletes from diverse backgrounds]. They had a combine, where they tested our agility and strength, and taught us how to operate the equipment. The first time I put on a tire, I hit it perfectly.

The most physical part is running with the tires and trying not to get hit. I’ve gotten clipped eight or nine times. On the field, I was a linebacker, and that lateral quickness has helped me. I work on both ends of the car: the right rear and the left front. Ultimately, when that car leaves, I’m the last line of defense.

In racing, unlike in football, you don’t have another team trying to hinder you. This is more of a battle with yourself. A race might have eight stops. Can we execute eight times in a row? We’ve got to keep it simple. We’ve done this millions of times. It’s pretty monotonous, but I’ve learned over the years that’s when you’ve got to perform your best. Consistency is boring sometimes, and that’s the challenge and beauty of it.

Played football at UNLV 36 years old, 6’7”, 290 pounds I played football at UNLV, and [now Trackhouse pit crew coach] Shaun Peet gave a presentation. When my final season was over, I went to Michael Waltrip Racing for two weeks and started learning. When I started 15 years ago, I was a jackman. But I could never hang a tire, so I transitioned to gasman.

To get a perfect pit stop, everything has to be perfect. If you’re chasing a tenth of a second and one person is off, that’s huge. Being an offensive lineman has helped me. Pass protection is similar to gassing, in terms of footwork. As the car is coming in, I’m power-stepping down. When I reach back to exchange gas cans, that’s like a lineman’s kick step, where I’m opening up my hips. It’s all about change of direction, agility and athleticism. Situational awareness is huge. Sometimes it’s more important to get the car out of pit road fast than to get it completely full of gas.

For me, the hardest adjustment is the travel. In football, you go to six or seven away games. Now I’m traveling to 37 away games. My first couple years I was on the road for 150 days. As you get older, that takes a toll. So I try to take care of myself during the week. From a mental standpoint, the most important thing is staying even-keeled. I need to be able to forget a bad stop, forget a good stop and approach the next one like nothing happened.

Played lacrosse at Roger Morris and in the National Lacrosse League

36 years old, 6’0”, 200 pounds

I grew up playing lacrosse all summer and hockey all winter. I was a lot more gifted offensively in lacrosse. In hockey, I spent a lot of time in the penalty box. Shaun Peet was from Canada like me, and we connected while I was playing pro lacrosse. He gave me an opportunity to come down here and try out for the pit crew, and I decided to retire from lacrosse and do this.

One of my strengths is my speed in getting to the car. Hand-eye coordination is also really important for a tire changer, as is an ability to be calm in the chaos. In my first races, I’d kind of black out going over the wall. After the stop, I’d forget what had happened. Now it’s like time slows down.

I’ve gotten much better at moving on from mistakes. You have to separate one stop from the other. I like to tell myself, “Everything is progress.” Even a bad stop is progress, because you’re one step closer to the next stop. In my lacrosse career, I overanalyzed a lot. I still try to watch film and be as physically and mentally prepared as possible—but on race day, I try to go in with a blank slate. I have a ritual: I like to take two deep inhales with my nose and one exhale out of my nose. It’s kind of cheesy but I tell myself I’m the best at this, and then once that car hits pit road, I let it all go.

35 years old, 5’10”, 195 pounds

I grew up around dirt-track racing. My mom drove and my dad built the cars. I started dating somebody in high school whose cousin lived in North Carolina and was pitting for Tony Stewart. Talking to him made me realize this could be a realistic career path. When I graduated, I moved to North Carolina. That was 17 years ago. I was at Stewart-Haas for 11 years, but it closed last year. Trackhouse brought me in for a tryout and made me an offer.