PRO LEVEL POLYP EXTENSION

The Torch Coral

Taiyuan Reef

Parker's Reef Paradise

CRYPTIC SUPERSTARS

Krista Bedell has a degree in environmental science specializing in marine biology and is the owner of K&P Aquaculture, where she focuses on marine education. Tiny brittle stars are key members of any good cleanup crew. Read more on two common species here.

TAIYUAN REEF

Xuan Li is the founder of Blue Reef Studio in Taiyuan, China. Immaculate displays of mature colonies is a goal for many reefers, but it can be challenging to achieve. See what it took to create this masterful home setup.

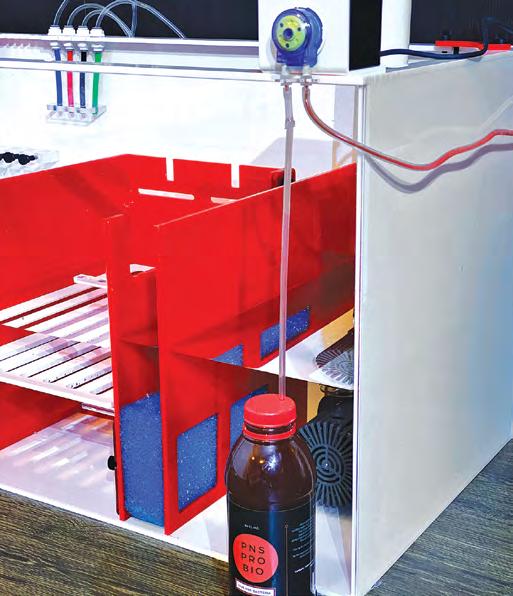

PNS BACTERIA: LIVE AQUARIUM FEED OF THE FUTURE?

Taras V. Pleskun is a professional aquaculturist employed at the Top Shelf Aquatics coral farm in Winter Park, FL. Our reefs depend on bacterial action for many functions, and this versatile group of bacteria has a lot to offer.

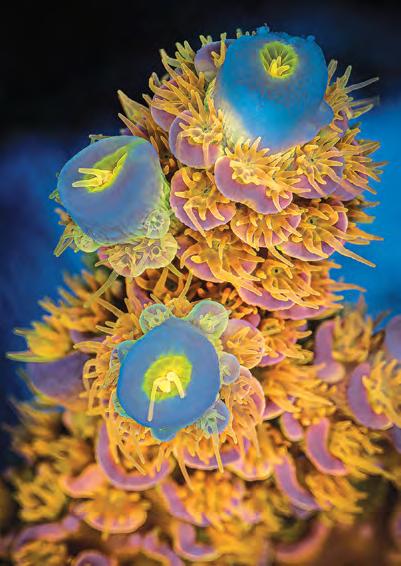

THE TORCH CORAL (Euphyllia glabrescens)

Vincent Chalias has been coral farming in Indonesia for 25 years. Torch corals have recently reached a new level of popularity (and pricing). Here you can learn more about their habitat, needs, reproduction, and physiology and see a few of today's hot morphs.

Kenny Lin is the founder of Pieces of the Ocean (POTO) and co-founder of ReefnBid.com. Assessing polyp extension is one of the best skills you can develop as a reefer. Here’s an article that’ll get you started.

PARKER’S REEF PARADISE

Sam Parker is an Australian IT professional with 12 years' reefing experience, which he shares on his YouTube channel, "Parker's Reef." An understanding of the hobby’s learning curve and a commitment to quality equipment allowed Sam to create this beautiful display.

PRODUCT REVIEW: REEF NUTRITION PAC - PODS

Jim Adelberg is the executive editor for RHM. Pac-Pods have several unique characteristics that will likely earn them a place in your fridge.

©

• Our online magazine now features videos within articles and product commercials from our advertisers. Experience the new issue on our website!

• Care to share your reefing, fragging, breeding, or husbandry success with the world? Contact us through our website with your article ideas.

• Reef-A-Palooza (Orlando)

- April 20–21, Orlando, FL – www.reefapaloozashow.net

• Reef-A-Palooza (New York)

- June 22–23, Secaucus, NJ – www.reefapaloozashow.net

• Reef-A-Palooza (Los Angeles)

- September 7–8, Anaheim, CA – www.reefapaloozashow.net

• Keystone Clash 2024

- October 4–6, Morgantown, PA – www.keystoneclash.com

Scan this QR code to register for your free digital subscription. You'll be the first to know when a new issue is released and get full access to archives on our website. You can also sign up for a hard-copy subscription for home delivery.

Fish stores! It's easy to stock Reef Hobbyist Magazine for your customers. We assist you in educating hobbyists on new products, husbandry techniques, and livestock. Contact one of our distributors below or email us through the " Contact Us" tab on our website to get stocked.

• All Seas Marine – www.allseaslax.com

• Aquarium Supply Distribution – www.aquariumsupplydistribution.com

• Bulk Reef Supply – www.bulkreefsupply.com

• CoralVue – www.coralvue.com

• DFW Aquarium Supply – www.dfwaquarium.com

• Pan Ocean Aquarium – www.panoceanaquarium.com

• ReefH2O – www.reefh2o.com

• Reef Nutrition – www.reefnutrition.com

• Segrest Farms – www.segrestfarms.com

www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com

Get full access to RHM archives

Watch videos and commercials in the multimedia magazine

Learn about new products from the top manufacturers

Sign up for a hard-copy subscription or FREE digital subscription

Follow us on Facebook @reefhobbyistmag

Follow us on Instagram @reefhobbyistmagazine

President Harry T. Tung

Executive Editor Jim Adelberg

Art Director Yoony Byun

Photography Advisor Sabine Penisson

Copy Editor Melinda Campbell

Proofreader S. Houghton

ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: advertising@rhmag.com or contact us on our website

www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com

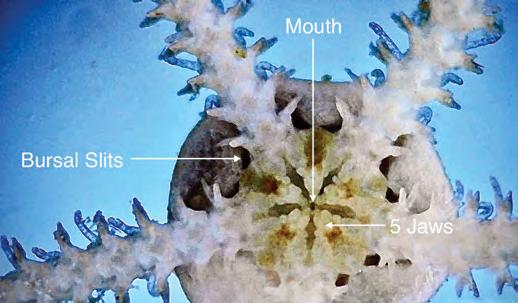

Tiny brittle stars come in many species and colors. These little hitchhikers, often referred to as micro brittle stars, rarely receive much recognition or attention. That's a shame because they are cleanup-crew superstars! There are currently around 2,200 species of brittle stars that have been identified, with 300 of these found in warm-water environments. And it's quite possible that there are many more species yet to be discovered. Given the high number of species, positive identification can be difficult, but the two most common species I'm asked to identify are Ophiocoma pumila and Amphipholis squamata

O. pumila is the larger of the two species, usually growing to a maximum size of 2 to 3 inches, and often has a maroon or red coloration with yellow and red bands running down its arms, separated by intricate patterns. Like many cryptic species, O. pumila is nocturnal and rarely emerges from the small crevices in the rockwork that it inhabits. I find these starfish busily cleaning up debris and detritus that settle underneath or within objects in the tank, such as corals, rockwork, frag racks, etc. This particular species is most commonly observed during times of spawning. When spawning occurs, O. pumila raises its central disk to the

highest point in the tank where the current is strongest, releasing sperm into the water column. These starfish can also be seen in large numbers, sticking their arms out of the rockwork, catching passing debris with their sticky and spiky arms. They then curl their arms in, pulling the food toward the center of the body where they have five jaws with teeth, called oral papillae.

A. squamata, also known as the Dwarf Brittle Star or Brooding Snake Star, is much smaller in size than its more conspicuous cousin, reaching only about 0.75 inch in total. It is usually white, brown, beige, or cream colored. A. squamata is the only species in the genus Amphipholis to be found across the world, including here in the Pacific Northwest in the Puget Sound area. It's believed that their long larval stage, spent drifting among and feeding on plankton, allows them to be widely distributed by the ocean's currents. They also have photocytes in their arms, which are cells that produce bioluminescence. The faint glow produced by these cells can be useful in escaping predators, as the starfish can drop a glowing arm as a distraction, allowing for a quick escape. I usually find this species hiding in macroalgae, particularly in Codium spp.

Another cool fact about these starfish is that they can reproduce in two ways: reproductive vegetation (splitting themselves in half) or broadcast spawning. They are viviparous hermaphrodites, meaning they possess both male and female reproductive organs and give live birth. This flexibility is advantageous when reproducing, as it allows for them to either clone themselves or increase genetic diversity through sexual reproduction. Spawning generally occurs during changes in water quality or temperature or even in response

to something as simple as scraping the glass of the tank. Some individuals will broadcast sperm into the water while others hold the fertilized eggs within their respiratory cavities until the offspring reach juvenile stages. According to many studies, A. squamata reaches peak luminescence at spawning time, but it is still unknown why. Once the eggs hatch and begin to grow into juveniles, they are released through bursal slits on the end of the arms closest to the central disc. In O. pumila, the larvae, also known as gastrulae, spend up to three months as free-swimming zooplankton before settling and metamorphosing into juvenile starfish.

Both of these species also happen to be burrowers and can be extremely helpful in aerating the sandbed or cleaning out little spots in the rock where waste tends to build up. In the wild, this foraging activity by starfish may be so extensive that it can change the layout and appearance of the seafloor. Mainly detrivores, these stars are excellent scavengers that feed on decaying material in the tank. Neither of these species is harmful to healthy corals or fish.

These mini brittle stars have between one and seven arms. I mostly see five to six arms on the two species mentioned. The arm lengths vary due to their ability to split in half and regrow the other half of their bodies.

O. pumila captured the attention of many researchers due to the light sensors covering their bodies. They have no eyes but have the incredible ability to detect light and move quickly away to skulk back into the shadows. These sensors are called opsins. Some studies show brittle stars can be conditioned to learn differences in light intensities in association with feedings. This demonstrates their ability to recognize patterns in their environment to help them find food.

Over the past several years of studying these two species, we have just begun to unlock their true star potential. They are not only an essential part of a healthy and balanced ecosystem but also capable of helping us understand and utilize their specialized superpowers. They have been studied in respect to the regeneration of their body parts, bioluminescence, and microevolution, and they have even been used in the sciences of neurobiology and robotics. This is just scratching the surface of what these two species are truly capable of doing. But for our purposes, what's most important is that they are excellent cleanup-crew members that are easily capable of breeding in captivity and help us keep our tanks looking great. R

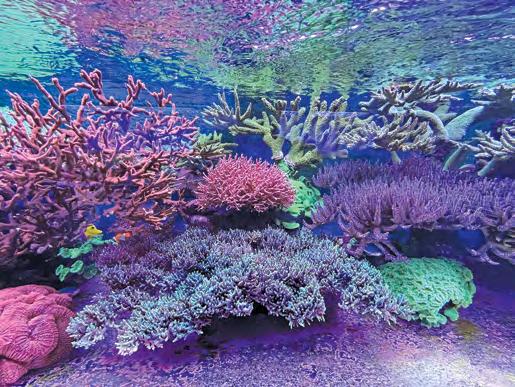

I'm from Taiyuan, China, and I remember seeing an indoor saltwater tank for the first time in 2001. It felt very dreamy and wonderful and created a deep, enduring memory. In 2007, I embarked on a long journey to learn about reefkeeping. Following several years of study and research, I finally built a 170-gallon reef tank designed for SPS (small-polyp stony) corals in 2011.

After going through the initial break-in stage and losing many corals, the system settled into a period of stability. My corals began growing faster, and I had more time every day to enjoy my tank. In 2014, I was honored by Reef Central as a tank of the month, which made me very proud and deepened my interest in the hobby. By 2015, the thriving corals had outgrown their display. I started to plan a bigger system to accommodate the large colonies.

In July 2015, my new setup was finally completed. It is actually two systems: a 260-gallon system with a 6.5-foot main display and a 330-gallon system with two shallow end-to-end displays. The 330-

gallon system is composed of twin 6-foot tanks that were previously used as frag tanks.

In February 2016, I experienced a catastrophic equipment failure. Due to a malfunction of my dosing pump, a solution containing 2,500 grams of calcium chloride was released into the tank. All the corals experienced RTN (rapid tissue necrosis), and nearly all of them ended up dying. I felt so lost at the time and had no motivation to continue. However, after taking a break for 3 months, I looked at the empty main display tank and began to imagine. The journey had started again.

The main display tank was restarted in May 2016, marking its new beginning. I began growing corals again from scratch. More reputable equipment brands were chosen, and a smaller-capacity calcium chloride reservoir was installed to prevent overdosing in case of another equipment failure. The GFO (granular ferric oxide) and activated carbon reactors were also removed.

For water circulation, I believe that if there are few fish, the flow rate of the return pump does not need to be excessive. I have been using a return pump with a flow rate of 2,100 gallons per hour for almost 9 years without any problems. However, I encountered some challenges with the wave pumps. Initially, I started with two EcoTech MP60s. As the corals grew larger, the high-speed water flow caused a lot of damage to the SPS, so I replaced them with three MP40s.

I currently change 48 gallons of water every 2 weeks. I have always used Tropic Marin Pro-Reef sea salt at a specific gravity of 1.026. Because the SPS grow relatively fast, I supplement 10 mL of Tropic Marin K+ and A- every day. In addition to trace elements, I also add alkalinity, calcium, magnesium, and potassium every day. Stability of these basic elements is required for a successful system.

The lights for this tank run for 10 hours a day: 2 hours of dimmer lighting and 8 hours of intense lighting. While many reefers like to go heavy on actinics to highlight the fluorescence of corals, I prefer a fuller spectrum that makes the corals and fish look more natural. To achieve this, I set my white-light output at 80 percent.

I trim the SPS colonies once a month to maintain the current aquascape. They share the tank with several large LPS (large-polyp stony) corals. I really enjoy the visual effect of mixing SPS and LPS corals in my displays.

I usually don't feed the corals separately since I rely on the nutrients produced by the fish and the system itself. This method seems to

be very helpful for nutrient balance. I prefer not to stock fish that are picky eaters, and I use various types of dry food from different brands to feed them.

Since the nutrients required for coral growth are in balance with the nutrients provided by the fish waste, I stopped adding various carbon sources 2 years ago. The filter bags and skimmer are all that are required to achieve complete balance. I don't like to run systems with extremely low nutrient levels because it doesn't seem beneficial to the health of corals.

The maintenance of this tank is now very simple. In addition to adding basic elements and feeding the fish, the remaining chores include regularly cleaning equipment, replacing filter bags, and cleaning the

tank. The tank walls are cleaned every 2 days, and the two 7-inch filter bags are replaced about once a week. The wave pumps are soaked and cleaned with citric acid every 2 months, and the return and skimmer pumps are soaked and cleaned every 6 months.

System Volume: 260 gallons

Display: 80" × 30" × 22"

Sump: 60" × 24" × 16"

Lighting: (3) Philips CoralCare V1

Skimmer: Royal Exclusiv Bubble King SM250

Return Pump: Royal Exclusiv Red Dragon 3, 80 watts

Water Circulation: (3) EcoTech Marine MP40

Dosing: Kamoer

SPECIFICATIONS (SHALLOW SYSTEM)

System Volume: 330 gallons

Tanks: (2) 71" × 30" × 16"

Sump: 71" × 24" × 16"

Lighting: (4) Orphek V4, (2) Orphek OR3

Skimmer: Royal Exclusiv Bubble King SM250

Return Pump: Royal Exclusiv Red Dragon 3, 80 watts

Water Circulation: (4) EcoTech Marine MP40

Dosing: Kamoer

The original purpose of the shallow system was to grow out frags. However, I wanted to explore creating additional natural reefscapes, so two special SPS tanks were born. These tanks carry over the style of the tall display with very simple structures.

The shallow tanks use Orphek V4 fixtures for lighting, with the light cycle set identically to the main system. All channels of the lights are

set to 90 percent power output, and this light spectrum is also quite natural looking. In terms of water quality, this system maintains the same basic chemistry as the main system except for a significant deficit of nitrogen and phosphorus. I attribute this to the twin tanks having low fish loads, which results in low system nutrients and unhealthy corals. Increasing the feeding amount and adding coral food did not solve the problem. In the end, I chose to use a titration pump to add nitrogen and phosphorus boosters to achieve better results.

Temperature: 77–81° F

Specific Gravity: 1.026

Nitrate: 1–3 ppm

Alkalinity: 7.0–7.5 dKH

Calcium: 400–430 ppm

Phosphate: 0.02–0.05 ppm

Magnesium: 1,300–1,350 ppm

So far, my biggest challenge has been dealing with an unknown parasite. In 2018, a black parasite infected the SPS corals in my shallow system. Whatever it was, it was tenacious, deadly, and unfazed by any medications I tried. Even manual treatment of the corals failed to yield any results, and their health continued to deteriorate. After losing nearly all the SPS corals in the shallow system, the parasite eventually disappeared. It took more than 2 years and was a heartbreaking time for me. This experience taught me the importance of a quarantine tank, which led me to set up a separate 70-gallon aquarium for the inspection and treatment of new corals.

One of my favorite things about reefkeeping is creating mature aquascapes using large coral colonies, just as we see in nature. Only when colonies grow large enough to accommodate hiding fish are the most beautiful aquascapes achieved. It requires the aquarist to be very invested, very careful, and very diligent. My recipe for success is to build systems that are as simple and efficient as possible. The more complex the setup, the more likely unpredictable problems will occur. In the future, I hope to build a larger display with even bigger coral colonies and create a reefscape that reflects the impact and beauty of Mother Nature's reefs. R

“These purple nonsulfur bacteria seem to be able to colonize a diverse range of environments and grow optimally under photoheterotrophic conditions. Thus, given their ability to utilize substrates known to be present in corals, such as acetate and glutamate, and to use near-infrared wavelengths not absorbed by Symbiodiniaceae species, the coral colony could offer an array of microenvironments where these bacterium’s niche preferences are met.” (Ricci 2022)

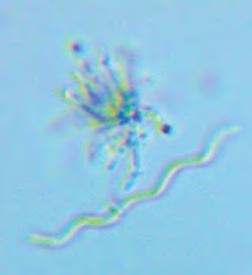

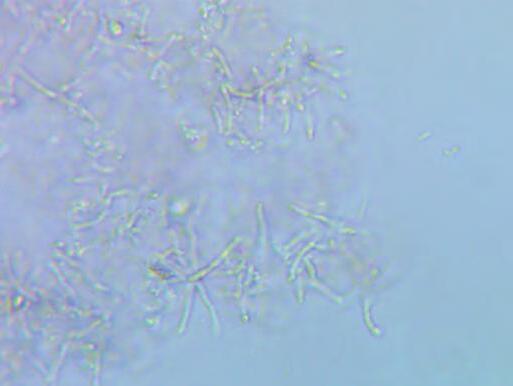

Microbes are the food of the future. This is becoming an inarguable fact within the realms of global agriculture, space exploration, nanotechnology, and even the reef aquarium industry. Indeed, all "higher" forms of life are directly dependent upon the products of a vast amount of microbial activity. Many microbes can obtain energy from non-biological resources such as light or inorganic chemical reactions. Like microscopic factories, certain bacteria can use this energy to produce the essential building blocks of life (proteins, lipids,

carbohydrates, pigments, etc.). And they do so faster, more efficiently, and at higher densities than any plant or animal.

A well-established coral reef aquarium is a living testament to the nutritional efficiency of microbes. Bacteria play a baseline role in reef nutrition. In fact, the largest portion of a coral’s natural planktonic diet consists not of phytoplankton or zooplankton but of bacterioplankton. This is why the reef aquarium industry is increasingly embracing the deliberate feeding of bacteria to corals, as is already done with the deliberate addition of microalgae to reef tanks. In this approach, regular dosing with live bacteria not only nourishes corals but establishes a rich microbiome that fulfills a wide array of ecological needs and helps stabilize the aquarium habitat.

In the water column, bacteria are subject to direct capture by corals, zooplankton, and other filter feeders. On the rocks and sand, they transform waste into protein-rich biofilms. Inside the guts of fish and

invertebrates, they pre-digest food and enhance immune functionality. Within the tissues of corals, they stabilize symbiotic Symbiodinium algae, sustaining the corals' health and color. With certain types of multipurpose bacteria, the lines between live food, probiotic, and bioremediator can get pretty blurry.

We are presently witnessing many exciting advancements in the selection, cultivation, and distribution of certain bacterial species that possess ideal characteristics for use as live microbial aquaculture feeds. The first major criterion is whether the microbe is digestible and nutritious. The second is whether it can survive and successfully colonize various microhabitats in the reef aquarium (and what beneficial functions it will perform if it survives). Finally, it must not cause disease or produce toxins.

With these requirements in mind, commercial aquaculturists have long relied on several species of PNSB. These mainly anaerobic phototrophs belong to the Proteobacteria phylum and are loosely related to some traditional biofilter genera (e.g., Nitrobacter), best known for their roles in ammonia/nitrite oxidation. PNSB differ from these relatives in that they possess "Swiss army knife" metabolic capabilities, allowing them to occupy an unusually broad array of biochemical niches. However, their preferred form of metabolism is photoheterotrophy, where energy is acquired from light while carbon used for growth is acquired from external organic compounds. PNSB use bacteriochlorophylls and carotenoid pigments to harvest light. These pigments not only enhance coloration, but the latter additionally serve as powerful antioxidizing agents that stabilize energy exchange and prevent cellular damage.

Groundbreaking bacteria-ina-bottle manufacturers are now selectively cultivating a diverse and growing library of microbial assets for use as live feed. This includes well-studied species such as Rhodopseudomonas palustris, Rhodospirillum rubrum, and Rhodobacter sphaeroides. These and other PNSB species have been shown to possess great potential as foods and supplements for various coral, fish, and invertebrate species.

HOW DO PNSB FEED CORAL REEFS?

Wild reef ecosystems are fundamentally dependent on microbial forage. There is a plethora of corals, anemones, sponges, sea fans, molluscs, sea cucumbers, fan worms, porcelain crabs, etc. that have specifically evolved to feed on planktonic bacteria. Many of these species are virtually unknown in the aquarium industry because, in captivity, they are known to starve to death or otherwise mysteriously wither away. The availability of high-density microbial live feeds

is advantageous, and perhaps even critical, for keeping many of these filter-feeding organisms alive in the aquarium. These bacteria satisfy the needs of those animals that prefer the tiniest bites (e.g., picoplankton). Some PNSB, such as R. palustris, form rosettes of a few cells to thousands of cells, which make for a considerable payoff for those species that prefer bigger bites.

This is not to say that photosynthetic corals do not benefit from regular feedings of PNSB. There are many zooxanthellate species in the hobby that will likely benefit from routine exposure to this food source. PNSB become highly available to filter-feeders the second they enter the aquarium. These bacteria lack a protective cell wall, making them easily digestible. Each cell is a bundle of concentrated fuel complemented with antioxidizing pigments. Over time, these pigments accumulate in the tissues of corals and other filter feeders. Perhaps even more importantly, certain carotenoid pigments may neutralize harmful photooxidants produced by zooxanthellae in intensely illuminated environments (as in small-polyp stony coral tanks).

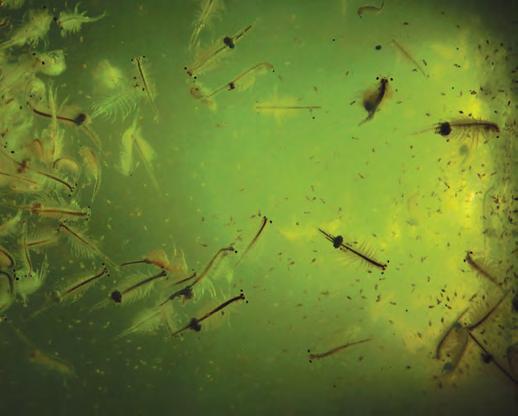

Larger filter feeders are not the only reef organisms that can utilize bacterial forage. Various live zooplanktonic feeds such as Artemia, Moina, ciliates (e.g., Euplotes), rotifers (e.g., Brachionus), and copepods (e.g., Apocyclops, Tigriopus, Tisbe, Parvocalanus, Oithona) have been shown to possess varying abilities to consume PNSB from the plankton as well as from biofilms on the rock, sand, glass, etc. The same bacterial consumption that benefits corals and clams benefits these zooplankton, providing them with nutritionally dense, probiotic-rich meals.

PNSB cells may also colonize the guts of these zooplankton, further improving their growth. Routinely dosing a reef aquarium with PNSB is a great way to increase the population and nutritional quality of zooplankton forage. When a coral or fish consumes a PNSB-fed rotifer or copepod, it is receiving the concentrated nutrition of millions of bacterial cells. It is also likely consuming living PNSB cells that can colonize and enhance the gastrointestinal systems of larger organisms up the food chain.

Researchers have conducted many studies on the multifold benefits of feeding PNSB to commercially farmed marine shrimp species such as the Pacific White-legged Shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei ), Tiger Prawn (Penaeus monodon), and Kuruma Prawn (Marsupenaeus japonicus). Shrimp fed a diet that includes live R. palustris and Rhodobacter capsulatus cells reliably exhibit greater and faster growth, increased survival, and decreased incidence of disease. It appears that PNSB cells colonize the gastrointestinal tract of these various species, enhancing their digestion and immunological hardiness.

Aggregated

PNSB are shown to be able to colonize the gastrointestinal systems of fish as well. Increased growth and survival have been observed in farm-raised Flathead Catfish (Pylodictis olivaris), Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus), and Silver Carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) when fed pellets inoculated with live R. palustris and R. rubrum cells. Koga et al. (2002) extracted live R. palustris cells from the gut of wild Ayu Sweetfish (Plecoglossus altivelis), demonstrating that PNSB occur as a natural component of the fish gut flora.

Together, these studies offer ample evidence that various PNSB species can provide probiotic benefits and contribute to overall gut flora diversity in a multitude of fish and invertebrate species.

Corals both directly feed on and recruit PNSB in the wild. When preyed upon as planktonic forage, microbes provide a highly digestible package of nutrition. Microbes can also be recruited whereby they are allowed to live within various coral and sponge species. R. palustris and other PNSB have been observed living inside coral tissues. In this

Healthful dietary compounds travel up the food chain—for example, from PNSB to copepods to small fish. | Taras

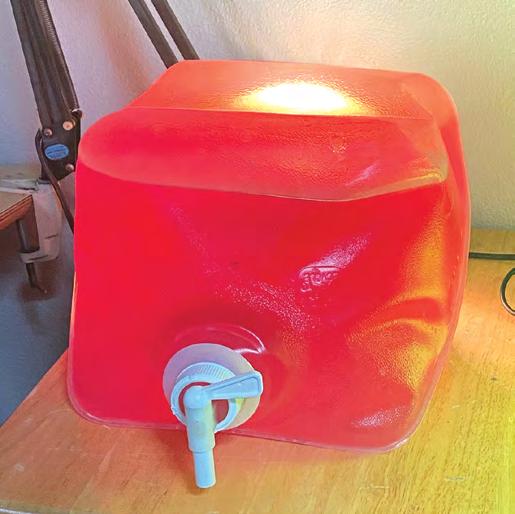

Reefkeepers can maintain a sizable supply of live PNSB with only a clear collapsible container and a standard 60-watt desk lamp. | Chris Spalding

relationship, the microbe provides a reliable source of needed nutrition to the coral or its symbiotic algae while scavenging their waste.

PNSB can perform diazotrophy, through which they convert nitrogen gas to ammonia (i.e., nitrogen fixation). They are also capable of

"phosphorus mining" whereby insoluble phosphates are made available for photosynthesis. Providing a localized, third-party source of nutrients, vitamins, and other resources to Symbiodinium is one means of enhancing the critical symbiosis between algae and coral.

PNSB cells living symbiotically within a coral have the potential to enhance proper physiological balance not only by recycling essential resources but also by discouraging the runaway growth of other microbes that are harmful. For example, through their own synthesis of powerful antibiotics such as streptomycin, PNSB apparently prevent invasion by opportunistic Vibrio bacteria. Alloul et al. (2021) demonstrated that R. palustris, R. capsulatus, R. sphaeroides, and R. rubrum all suppressed Vibrio parahaemolyticus and V. campbellii in agar plate trials. R. palustris is widely used to help control vibriosis in farmed shrimp.

PNSB are widely used in fish and shrimp farms as an economical live aquaculture feed. Among the handful of PNSB used for this purpose, R. palustris has gained the most attention due to its impressive nutritional content:

1. High Protein Content: Proteins are essential for growth, development, and the overall health of aquatic organisms. R. palustris is known to have a high protein content, typically ranging from 40 to 60 percent (in some cases, over 70 percent) of dry weight, making it a valuable protein source in aquaculture feeds.

2. Amino Acid Profile: Amino acids are the building blocks of proteins and play crucial roles in various physiological processes.

R. palustris offers a favorable amino acid profile. It contains a wide range of amino acids, including essential amino acids that cannot be synthesized by aquatic animals and must be obtained from their diet; it is especially rich in lysine, methionine, and threonine, which are essential for growth and development.

3. Omega-3 Fatty Acids: R. palustris is capable of synthesizing omega-3 fatty acids, such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). These fatty acids are highly beneficial for fish and other aquatic organisms, as they contribute to healthy growth, reproduction, and improved immunity. Incorporating R. palustris into aquaculture feeds can enhance the omega-3 fatty acid content of the feed and subsequently benefit the cultured organisms.

4. Lipid Content: While R. palustris is not particularly high in lipids, it does contain a moderate amount. This can be beneficial as a feed component, especially for certain cultured species that require some level of lipids in their diet.

5. Vitamins and Minerals: R. palustris can provide a range of vitamins and minerals necessary for health and growth. These include B vitamins such as cobalamin, thiamine, and riboflavin, as well as bioavailable essential minerals like phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium.

6. Versatile Food Source: R. palustris can utilize various carbon sources, including organic compounds as well as carbon dioxide. This versatility allows it to grow in a variety of conditions and efficiently convert different substrates into biomass, making it a flexible nutritional source for aquaculture feeds. For example, as a photosynthetic bacterium, R. palustris can utilize light energy to fuel its own growth. This capacity allows it to thrive in illuminated

conditions, making it especially sustainable and cost effective as a feedstock.

While PNSB generally exhibit promising characteristics, further study is required to optimize their cultivation, processing, and incorporation into aquaculture feeds. Additionally, considerations such as the specific nutritional requirements of the target species, the digestibility of the bacteria, and potential interactions with other feed ingredients should be considered when formulating these products. As such, more research is required to fully understand their potential and develop appropriate feeding protocols for the typical home aquarist.

The future of live aquarium feeds has arrived. We are already seeing a renewed interest in the reef microbiome—the base of reef ecosystems. With this comes a new focus on photosynthetic bacteria that can nourish the reef aquarium in a holistic manner. Here, rather than a non-living food that pollutes the aquarium water, we have a natural live food that cleans the water. By fusing functions of live food, probiotic enhancer, and biofilter, PNSB address the need for a natural balance in the reef aquarium. Waste can be continuously recycled into valuable nutritional compounds, and this nutritional benefit is then propagated throughout the various fish, inverts, and corals of the aquarium through bacterial consumption. Dosing PNSB is a way of delivering substantive pulses of nutrition into the reef, much in the same way wild reefs enjoy a microbial pulse with every tide. R

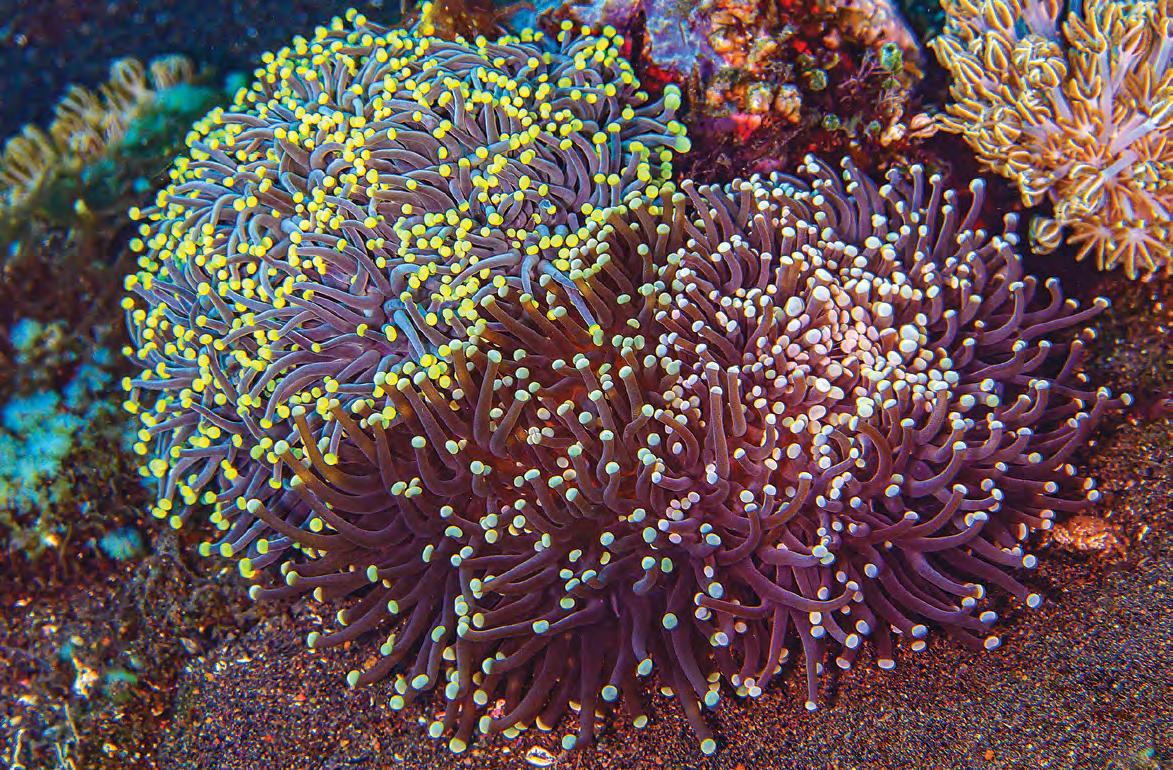

The Torch Coral, scientifically known as Euphyllia glabrescens, is a captivating species that has always been very popular among reef hobbyists. In recent years, however, it has become one of the most sought-after coral species in the hobby. There have been many new color morphs collected, farmed, and named. And recently, the quantity of online forum posts and videos about this coral has made it clear that Torch Coral enthusiasm is at an all-time high. Consequently, the most desirable morphs have attained new levels of collectibility and pricing. In this article, we will delve into the biology of E. glabrescens, explore its natural habitat, discuss the basic color combinations available, examine its care requirements, and touch on propagation techniques.

E. glabrescens belongs to the family Euphylliidae and is commonly referred to as the Torch Coral due to its long, tubular corallites that resemble a torch. Colonies are phaceloid, and corallites are 20 to 30 millimeters in diameter and spaced 15 to 30 millimeters apart. The skeletal walls are thin, with sharp edges. Septa are non-exsert; first- and second-order septa plunge steeply toward the center of the corallite. There are no columella.

Torch Coral polyps have large tubular tentacles with knob-like tips. Its tentacles look very similar to those of a Long Tentacle Plate Coral (Heliofungia actiniformis) or Magnificent Sea Anemone (Stichodactyla

magnifica). Torch Corals are found all over the Indian Ocean and West Pacific Ocean region. The scientific name "glabrescens" is derived from the Latin word "glaber," meaning smooth, which refers to the coral skeleton's smooth, non-granulated appearance.

Large colonies of Torch Corals are very rare, but large fields of smalland medium-sized colonies are quite common in certain places. This is likely due to the fact that it's a brooder coral that produces free-swimming larvae that can either drop or drift.

E. glabrescens is commonly found on reef flats and shallow reef slopes, often exposed to quite a bit of current and some swell. Though its depth range is broad, from 6 to 120 feet, it is most commonly found between 24 and 45 feet deep.

One reason this species thrives in moderately exposed areas is the abundance of food in the water column. This makes the back eddy areas behind very strong currents the preferred locations for these corals.

Colonies with the largest-diameter polyps are often located in protected and turbid waters, while colonies with skinny corallites are usually found in more agitated waters.

One of the most alluring aspects of Torch Corals is their stunning array of colors, ranging from subtle pastels to vibrant fluorescents. Here are the common colors observed in E. glabrescens:

• Brown/Beige: This is the pigment coloration of zooxanthellate symbiotic algae. In the absence of significant pigments, the underlying brown or beige color of the coral skeleton becomes more apparent.

• Dark Gray/Black: The Black Torch is also very popular, having dark tentacles with brightly colored tentacle tips.

• Green: This is a common coloration in Indonesia but pretty rare in Australia. Different shades of green exist, from very dark to very bright metallic, almost fluorescent yellowish green.

• Yellow/Gold: Some Torch Corals showcase yellow or gold hues, and these are the most sought after. Here again, many shades exist, from dark gold to bright fluorescent yellow.

• Green and Gold: Many different combinations exist, with each one having a specific commercial name. Mouth septal marks, tentacles, and tips can have different colorations.

• Tentacle Tips: The tips can exhibit many different colorations. Gray, yellow, orange, and green are the most common.

I have observed gold, green, and brown specimens in the same locality. The gold ones are the rarest. In my opinion, this coloration is probably a genetic trait and not related to habitat.

Zooxanthellae pigments can sometimes show a light red luminescence under modern aquarium lighting, but it can only be observed under very specific lighting conditions.

Successfully maintaining E. glabrescens in a reef aquarium requires careful attention to water parameters, lighting, and water flow. Here are the key factors to consider:

• Lighting: Torch Corals require moderate- to high-intensity lighting to support their symbiotic zooxanthellae.

• Water Flow: Adequate water flow is essential. These corals like well-agitated water when they are acclimated properly

and healthy. However, high-velocity water flow with very abrupt directional changes can stress the coral and hinder its feeding capabilities. Striking a balance is crucial for the well-being of Torch Corals.

• Water Parameters: Maintaining stable water parameters is critical for the health of E. glabrescens. Parameters such as temperature, pH, salinity, and nutrient levels should all be stable. E. glabrescens is very sensitive to alkalinity swings. These can trigger a bacterial infection known as brown jelly disease, which can quickly kill this coral.

• Feeding: While Torch Corals derive significant nutrients from photosynthesis, they also benefit from supplemental feeding. Small meaty foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids, such as brine shrimp, Mysis shrimp, and other zooplankton, or specialized coral foods of small particle size can be offered to enhance their nutritional variety and growth. It is also likely that phytoplankton is a very important component of their diet.

Propagating Torch Corals in a reef aquarium might involve either sexual or asexual reproductive methods. Understanding these methods can contribute to the sustainability of captive populations.

• Asexual Reproduction: Single Torch Coral polyps will split into two heads every few months when healthy. Many Torch Corals are now produced by farms through asexual reproduction. A single polyp is cut off from a donor colony and grown on its own until it can be harvested again. Indonesia produces a lot of maricultured Torches, but many of them may not be sustainably cultured.

• Sexual Reproduction: Torches are brooders, which means they take up sperm from nearby colonies and subsequently fertilize eggs internally. Larval release usually happens around 8 days following the full moon and can go on for several days. Less than 2 hours after sunset, larvae can be seen swimming along the tentacles, followed by a series of contractions. Fully formed larvae are then released through the mouth or by piercing through

the tentacle walls. The larvae already contain zooxanthellae and are ready to immediately settle and metamorphose within 48 hours. Some sink to the base of the mother colony, and some float and drift away to disperse with the current. Sexual reproduction of Torch Corals often happens in captivity, but commercial production with this method is still on the horizon, as early growth is very slow. It takes 1 to 2 years to get a larva to a single-polyp size that's commercially valuable.

Buying from a reputable source with healthy colonies and proper quarantine techniques are paramount. In recent years, the use of broad-spectrum human antibiotics to treat Torch Coral infections has become widespread. This is usually only required after poor handling and should be left to the professionals, as the treatment water needs to be disinfected with chlorine before being discarded. And using human medicines for animals and discarding them in the sewage system can lead to the creation of antibiotic resistance.

E. glabrescens stands as a captivating example of the intricate beauty found in coral reef ecosystems. Its biology, diverse coloration, and unique reproductive strategies make it a fascinating subject for both scientific study and aquarium hobbyists. By understanding its natural habitat, color variations, and proper care requirements, aquarists can successfully cultivate and appreciate the beautiful Torch Coral in reef aquariums. As we continue to explore and understand the wonders of marine life, the sustainable propagation and conservation of species like E. glabrescens becomes essential for the preservation of coral reef ecosystems around the world.

KENNY LIN

KENNY LIN

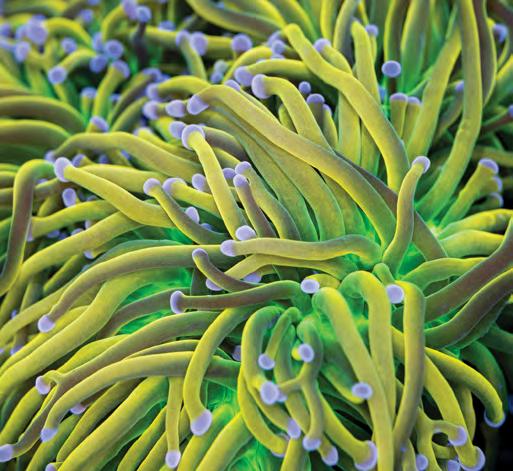

In the wild, many Acropora corals extend their feeding polyps exclusively at night. This is a strategy to avoid predation from hungry fish that are feeding during the day. But in the captive environment of our reef tanks, polyp predation is generally absent, and corals eventually learn to exploit this feeding opportunity. Once corals are fully acclimated, we should expect to see good polyp extension (PE) even during the day. A coral with its polyps extended is a coral that is willing and able to feed. A coral that does not extend its polyps is generally unhappy, with a few exceptions.

There are many factors that impact polyp extension in Acropora corals. Some of the most important to consider are stable water parameters and adequate flow, lighting, and filtration. Polyp extension can be reduced by fish predation, pests, and other irritants.

If you ever shine a light into your tank at night, you will see coral behaviors that you don't see during the day. For example, the axial polyps (polyps on new tips) are fully extended at night, with some appearing almost translucent and colorless due to a lower concentration of symbiont algae (e.g., Symbiodinium). This is usually a good indication of a happy coral.

Radial polyps (the older polyps), on the other hand, tend to extend just as much (or little) during day or night. Radial polyps are generally smaller and have darker pigmentation, corresponding to higher symbiont densities.

If you see no PE during both the day and night of a 24-hour period, it is worth investigating to see if something may be bothering the coral, whether it's mechanical (fish nipping or a stinging neighbor), biological (pest or parasite), or chemical (unstable water parameters).

In addition to heterotrophic feeding, corals require an array of micro- and macronutrients, such as nitrogen, phosphorus, magnesium, manganese, iron, copper, and zinc, to sustain their metabolism. Some of these nutrients are measured in high concentration in the waste of many of the reef fish we keep. In one scientific study, biologists measured the fecal micronutrient content of 570 individual fish across 40 species and found high nutrient composition in their fecal waste. The study specifically pointed out that tangs, particularly in the genus Acanthurus, and certain species of Chromis excrete waste with relatively high concentrations of micronutrients (e.g., magnesium, manganese, iron, and zinc) that are known to contribute to the metabolic functions of corals. I believe that allowing fish to break down food into usable micronutrients that our corals need to thrive is a great natural alternative to dosing individual nutrients. I've found that systems with a heavy bioload of fish, supported by adequate filtration, often produce the best PE from corals.

Understanding the factors that can negatively affect PE gives us the ability to diagnose and eliminate these problems to improve our corals' health and appearance. Some of these factors include

pests and parasites, fish nipping, poor water chemistry, insufficient/ improper water flow, and lighting of the wrong strength or spectrum.

Pests and parasites are the most common reasons for poor PE in Acropora corals. It's important to thoroughly inspect and quarantine all corals before adding them to a display. Always dip corals with a solution designed to target the common coral pests, and make sure to remove any frag plug or hard substrate base that may come with new corals, as these are common hiding places for pests.

The two most common parasites affecting PE in acros are Red Bugs (Tegastes acroporanus) and Acro-eating Flatworms ( Amakusaplana acroporae). Both of these slowly stress corals and can eventually cause lethal damage. Other nuisance critters to keep a close eye out for include white bugs, black bugs, acro-eating spiders, and vermetid snails.

Fish that are obligate corallivores eat Acropora polyps as a part of their natural diet. If you keep these types of fish, it almost guarantees the absence of PE during the day.

The most well-known fish in the hobby that nip at Acropora polyps include dwarf angelfishes and butterflyfishes. Some species of filefishes and blennies are also known to be coral nippers.

Be aware that some fish considered reef-safe can all of a sudden start nipping at corals. We have seen Copperband Butterflyfish nipping acans and Hippo and Powder Blue Tangs nipping smallpolyp stony (SPS) corals.

Maintaining good water chemistry is vital for Acropora corals. Natural levels of salinity, pH, nitrate, magnesium, phosphate, and calcium are all important for PE.

Acropora corals also require a constant level of alkalinity. Any fluctuations of alkalinity over even a short period are extremely problematic and can manifest in a reduction of PE.

Some SPS corals just don't have long polyps. Many of the smoothskinned, deep-water types won't have much noticeable PE. Others are characterized by long polyps and impressive PE, such as A. millepora and A. tenuis. Regardless, the nighttime behavior of extending axial polyps still holds true.

Acropora corals are stationary and rely on good water flow to thrive. Inadequate flow can lead to a range of challenges, including insufficient food, nutrients, gas exchange, and waste removal. A lack of water flow also allows algae and/or detritus to build up on a coral's surface, causing polyps to retract. In the wild, corals are subjected to strong currents that obviate these concerns. In our tanks, we should try to provide vigorous water movement while

avoiding constant direct flow, as this can damage the corals' polyps and tissue.

SPS corals with low light requirements do not fare well under intense lighting, and corals that require intense lighting will not cope well with dim lighting. Acropora corals receiving too much light will retract their polyps to protect from oxidative stress, which can cause changes in chlorophyll and algae density, resulting in bleaching.

If the lighting conditions are within a new coral's requirements and poor PE persists, the coral may still be adapting to the new lighting, so be patient.

While corals can synthesize amino acids through the bacteria and zooxanthellae that they host, they also uptake amino acids directly from sea water. Many products available to hobbyists that contain amino acids are based on this knowledge.

According to Goreau et al. (1971), additions of amino acids in low concentrations, such as glycine, alanine, phenylalanine, and leucine, have been shown to elicit feeding responses in corals, such as the opening and swelling of coral tissues. There are a number of different amino acids, and not all offer the same effect.

Other organisms can also benefit from the addition of these amino acids, including the unwanted ones like Aiptasia anemones and cyanobacteria. Without knowing the exact types of amino acids being offered in today's products, it's important to remember that having a healthy bioload of fish that are well fed may offer the same if not a greater benefit.

Polyp extension in SPS corals like Acropora is one of the best indicators of health and stability in a reef aquarium. Learning what full, healthy polyp extension looks like and how to address poor polyp extension has been critical to my success with these corals. I hope that some of the advice and tips in this article will help you provide your corals with an optimal environment. They will thank you with fully extended polyps in due time. R

RESOURCES CITED

1. Hemond, E. M., Kaluziak, S. T., & Vollmer, S. V. (2014). The genetics of colony form and function in Caribbean Acropora corals. BMC Genomics, 15, 1133.

2. Goreau, T. F., Goreau, N. I., & Yonge, C. M. (1971). Reef corals: Autotrophs or heterotrophs? Biological Bulletin, 141(2), 247-260.

3. Ferrier-Pagès, C., Sauzeat, L., & Balter, V. (2018). Coral bleaching is linked to the capacity of the animal host to supply essential metals to the symbionts. Global Change Biology, 24(7), 3145-3157.

www.reefhobbyistmagazine.com

I'm a 40-year-old reefer from the southern part of Australia. I've had some pretty eclectic hobbies and passions in my time, from being a professional drag-bike racer for over a decade to competitive pinball playing and, of course, reefkeeping.

I've been in the aquarium hobby for about 12 years now. I started with a 9 liter (~2.5 gallons) freshwater tank and instantly fell in love with it. And, as I usually do, I investigated taking the enjoyment to the next level: reefkeeping. At that point, I wanted a big custom build but decided it would be wise to dip my toe in the water first with an all-in-one system to minimize my learning curve in the hobby. I soon found a secondhand Red Sea Max 130 that fit the bill. Within a couple of months, I felt I knew enough to jump into the deep end with a large 6-foot, custom-built system.

After finding a local fish store that I worked well with and trusted, we got to work on building and fitting out the new tank. It was a

really beautiful system that received a lot of recognition in the reefing world. But after 7 years, I shut it down in its prime to focus my time, money, and effort on my next dream-reef build.

Looking back, the choice to go with an all-in-one tank as a first system was wise. It really simplified the learning curve for someone completely new to the hobby as I was. I learned that our equipment needs, methodologies, and approaches change (probably more often than they should) and that a flexible system is always going to serve us well. I also learned that buying quality equipment saves money in the long run. The difference in purchase price is forgotten quickly in light of the benefits of lasting quality. Another key lesson was to never trust woodwork around marine aquariums. Accidents happen, and sometimes water gets where it shouldn't. My fear around the structural integrity of the stand holding this 2,200-pound

glass box of water inside my house was the ultimate tipping point for wanting to upgrade and go with an extruded aluminum stand. Lastly, I learned the value of entrusting experts to do what they do best.

This current system is a culmination of everything I've learned in the hobby over the past 12 years and every penny I've managed to put aside over the same time. I wanted to build a no-compromise reef (within my own financial means, anyway) with every detail thought out and planned as best as I could. Based on the progress of this tank over its first 3 years, I feel I've achieved that goal. I think too many of us get caught up in a whirlwind when setting up a new tank and make some irreversible decisions that we regret down the road. If you want your tank to continue to operate smoothly for years, don't be afraid to spend a number of months in the planning phase; it will pay dividends!

With all that in mind, I went for a custom Waterbox tank on a custom-designed aluminum slot stand. I cladded it with some gorgeous custom-made kitchen cabinetry and a motorized canopy.

The light frame is made up of a sit/stand desk that has been flipped upside down and bolted to the stand. This gives me the ability to raise and lower the lights at the press of a button and provides easy access through the top of the tank for mounting corals or doing maintenance.

The lighting consists of three Philips CoralCare Gen2 fixtures, four Orphek OR3 strips, and a number of Kessil A360X and A500X fixtures spread around to highlight particular corals.

Flow is managed by four EcoTech VorTech MP60s, a couple of big Tunzes, and a couple of AquaIllumination Nero 7s recently added to target dead flow zones.

Under the stand, there is a custom-made Hmahli acrylic sump that houses several Abyzz A200 return pumps, a Cove skimmer, plenty of ceramic media, a Kessil-powered refugium, a slew of automated testers (Mastertronic, KH Guardian, Reef Factory Smart Tester), and some other assorted equipment.

I use a big Seatorch calcium reactor to maintain my elements. Apart from that, I am a fan of the Reef Moonshiners program for trace elements, as it really makes sense to me and the results are incredible.

Outside the house by the adjacent wall is a custom-made storage box that houses my chiller, a Pentair UV system, an RODI (reverse osmosis/deionization) system, and a CO2 scrubber.

I've had a number of fish for over 10 years now, and they are absolutely members of the family. None more so than my hybrid Tigerpyge Angelfish, a half Eibli and half Lemonpeel aptly named Prius.

There are some other really personable fish in the tank, including a Gem Tang, Mustard Tang, Purple Tang, Sand Perch, Flame Hawks, and some schooling fish (chromis and anthias).

Nitrate: 5 ppm

Alkalinity: 8.5 dKH

Calcium: 440 ppm

Phosphate: 0.06 ppm

Magnesium: 1,450 ppm

I feed a mix of frozen Ocean Nutrition foods once a day, occasionally adding some Hikari and New Life Spectrum pellets (usually to show off to guests) and some nori a couple of times a week.

The future plans for the tank are really just to enjoy it. I've documented the entire thought process, build, additions, challenges, and results on my YouTube channel, "Parker's Reef."

Reefing is a constantly evolving intersection of science, technology, fun, and learning. The fact that we all get to share in it together makes it the best. I have really enjoyed the friendships I've made in this hobby and getting to share the journey with so many likeminded reefers out there. R

Over the last 20 years, I've reviewed products from advertisers and non-advertisers alike. Generally, I see a product that I think will be of interest to our readers, and I reach out to the manufacturer for their product to review. A while ago, Reef Nutrition (who is kind enough to sponsor the food required for my fish-breeding endeavors) sent along some of its newest pod offering for me to try, and I believe that for some of you, this product will be a game-changer.

First, I need to confess that I'm a lazy reefer. I spend a fair bit of time looking for the easiest ways to maintain optimal conditions in my various systems. And this brings us to the first reason I really appreciate Pac-Pods. Sized in the range of 500–800 microns, these copepods are as close to a universal coral food size as anything I've used. They are small enough to be effectively captured and consumed by my SPS (small-polyp stony) corals and big enough to feed my Favia and Blastomussa corals. And on the fish side, my various small gobies can easily see and eat the individual pods, and so can my Chalk Bass and Royal Grammas, which are in the 3- to 4-inch range. My large clownfish, however, at around 5 inches, cannot see individual Pac-Pods. Luckily, Pac-Pods are packaged in an alginate solution that keeps the pods together for a while if introduced into a low-flow area of the tank. So even my 5-inch clownfish can efficiently feed on these pods. The convenience of a single food that doesn't require defrosting and rinsing and can feed everything from the smallest coral polyps to medium-sized fish is most welcome.

But convenience is of no importance if the nutritional value of the food is poor. And this brings us to the second reason I'm a fan of this product. Pac-Pods are wild-collected copepods from the North Pacific that are frozen shortly after harvest. This preserves much of the vitamins, minerals, enzymes, amino acids, and trace elements found in the wild copepod. Despite the best efforts of processed food manufacturers to add critical nutritive elements back into their products, nothing beats the array of natural nutrients from a wild product. According to the Reef Nutrition website, Pac-Pods are "Naturally rich in carotenoids, protein, omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids, and waxy esters for growth."

Another concern is how much the physical processing damages the whole organism, and I'm pleased to say that under high-power magnification, very few (I estimate under 5 percent) of the pods in my sample are not whole. This is critical because copepods are a very nutritionally dense food, and putting a lot of broken up pods into any system both pollutes the system's water and reduces the nutritional value of what the fish and corals consume.

This food is also gamma irradiated to protect consumers' tanks (and the environment) from pathogens and pests.

In summary, I think the combination of convenience, coupled with this product's nutritional value, size, and alginate base, make it one of the best single food sources for our mixed reefs. I still feed my fish pellets, and I still feed my corals live pods and rotifers because I believe a mix of foods is always best, but when I want a fast, nutritional feed for both fish and corals, I find myself reaching for Pac-Pods more and more often.