Erik Ipsen AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

This book is a tribute to Rockefeller Group employees past and present, who had the vision and conviction to develop and then redevelop a tower that, in the words of Time Inc. cofounder Henry Luce, was “built for work,” not for a single period of time in the history of New York City, but for yesterday, today, and tomorrow.

President & Chief Executive Officer Daniel J. Moore

Executive Vice President, Core Holdings Bill Edwards

Senior Vice President, Asset Services John Pierce

Chief Communications Officer Dwayne Doherty

Senior Vice President, Rockefeller Group Business Centers, Inc.

Assistant Vice President, Marketing Amy Ankeles

Editorial Director Beth Sutinis

Art Director Dirk Kaufman

Photo Editor Katherine Bourbeau

Production and Prepress Peter X. Ksiezopolski

Copy Editor Stephanie Engel

Proofreader Hillary Leary

Indexer Wendy Allex

Special thanks to: Christine Roussel, Rockefeller Center Archivist; Bill Hooper, Archivist, Meredith Corp.; Katherine Bojsza and Christopher Jend, Pei Cobb Freed & Partners; Laaren Brown; and Nancy Ellwood, this project’s original editor

Copyright © 2020 Rockefeller Group, Inc.

Published by Rockefeller Group International, Inc. 1271 Avenue of the Americas, 24th Floor New York, NY 10020

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-578-80884-0

Printed and bound in the United States of America

MADE by X: Signature Printing, East Providence, RI | Superior Bindery, Braintree, MA Edition

First

Contents rtunity of a Lifetime 10 One Owner Takes All 24 The Rockefellers ..................................... 36 Rockefeller Center Rises ............................... 39 Nelson A. Rockefeller ................................. 58 Time & Life Era A Modernist Model 62 Wally Harrison 69 1959 Stats & Facts 86 The First Six Decades 88 Charles & Ray Eames 95 Tenant Map 102 Western Beachhead 107 Time Triumphant .................................... 114 Walking the Halls at the Time & Life Building ........... 119 Henry R. Luce ....................................... 120 Tower Reborn Decisions to Make 124 Designing History 131 A Greener, Brighter 1271 134 A Leadoff Home Run 136 Current Tenants 138 Transforming 1271 Pane by Pane 145 Beyond the Walls 150 Notes, Credits, Index, In Gratitude 155

OPPORTUNITY OF A LIFETIME

Introduction

This volume salutes the builders of 1271 Avenue of the Americas and all those who made it stand out in a changing city. They did so with creativity, wit, artistry, and sharp takes on events, spun out from this place over more than half a century.

We also cheer those who, beginning a little over five years ago, reimag ined, reclad, refurbished, and repopulated this tower with new tenants brim ming with bold plans and ambitions.

The clock has started on 1271’s second life, as a state-of-the-art 21st-century behemoth with a landmarked mid-century lobby. It is up to the new tenants—Major League Baseball, prominent law and financial firms, and many others—to fulfill the prophecy Time Inc. cofounder Henry R. Luce made as he laid the cornerstone of the Time & Life Building at 1271 Avenue of the Americas in the summer of 1959. He predicted his edifice would “hatch new adventures in the permanent revolution which is the American dream.”

Since then we have witnessed building booms, the first steps on the moon, and the dawn of the digital age. We have also experienced the city’s near bankruptcy, the attacks of 9/11, and a global coronavirus pandemic. Over those decades, New York City has more than once swung from global magnet for talent and capital to urban charity case seeking bailouts—only to soar again.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 12 INTRODUCTION

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS OPPORTUNITY OF A LIFETIME 15

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

What lies ahead, we cannot say. But the history of this tower, not to mention Rockefeller Center’s 90-plus years, offers inspiration for future generations. Work began on the complex only weeks after the crash of 1929 and steamed ahead as the nation spiraled into the Great Depression. Today, Rockefeller Center ranks among the city’s top addresses. Within it, a reborn 1271 stands out as a slightly younger monument to resilience. It towered above others as the home of the world’s largest media company, and is now chockablock with a dozen top-drawer tenants, all primed to fulfill Henry Luce’s dream and stamp their marks on the world.

“We knew we had a once-ina-lifetime opportunity; we’d have an empty building. Since 1271 was going to be empty, that gave us the chance to think about anything we wanted to think about: we could rip apart the building; we didn’t have to work around tenants and worry about their safety. My prejudice was to make it a modern tower . . . a 21st-century product.”

—Dan Rashin Co-CEO, Rockefeller Group, 2016–2018

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS OPPORTUNITY OF A LIFETIME 21

HISTORY

Part I

One owner takes all

Acres of forests of hickory, chestnut, and oak, teeming with wildlife, occasionally giving way to marshes, meadows, and pastureland: this was the city-owned “Common Lands” on the island of Manhattan, stretching for 4 miles north of Wall Street, the epicenter of the first capital of a new republic at the close of the 18th century.

Hard to believe, then, that in 1807, the city council felt confident enough to form a commission to map out New York’s future. Four years later, that effort culminated in a proposal for a rectilinear grid to overlay Manhattan’s vast midsection. This was the plan the city would grow by: the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811. The people, the enterprises, the buildings would come in good time, but now there existed—in pen and ink on paper, anyway—a dozen avenues and 155 streets to lend shape to their ambitions.

Commissioners’ Plan of 1811

Commissioners’ Plan of 1811

24 PART I • HISTORY

WHEN GEORGE WASHINGTON took the oath of office as president on the balcony of Federal Hall on Wall Street on April 30, 1789, the new nation’s capital extended north only as far as today’s Broome Street, less than a mile away.

THIS PORTION OF James S. Kemp’s drawing of the gridiron proposed by the 1807 Commission shows Elgin Garden overlaying what would come to be 47th to 51st Streets between 5th and 6th Avenues (below).

Hosack’s Elgin Botanic Garden

Hosack’s Elgin Botanic Garden

26 PART I • HISTORY

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS ONE OWNER TAKES ALL 27

By the late 1830s, those crisp black lines on the grid plan began to take hard shape. There soon emerged a network of paved streets, on which some of the city’s wealthiest citizens erected sumptuous confections of brick, brownstone, and marble. On August 15, 1858, the city’s first Catholic archbishop, John Hughes, went further. He elevated the middle of Manhattan to a celestial plane by laying the cornerstone for St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the gothic edifice that would take up an entire city block across Fifth Avenue from Dr. Hosack’s garden. By the time St. Patrick’s was consecrated in 1879, the area had seen huge changes, among them Fifth Avenue’s rise to the status of the city’s premier residential thoroughfare, the place where Vanderbilts and Astors chose to reside. On the side streets, more modest homes and, later, apartment buildings took shape.

ST. PATRICK’S CATHEDRAL under construction, circa 1875. Critics call the project “Hughes’s Folly” for being so far outside the city’s center far downtown (left).

LOTS ON FIFTH Avenue are claimed and built up around St. Patrick’s throughout the Gilded Age, often multiple times over (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

CENTRAL PARK ICE skaters take their exercise with the Dakota apartments in the distance, 1890. The Park lives up to its ideal as a place for New Yorkers of all means and backgrounds to enjoy “refreshing rest” (above).

THE WEST SIDE of bustling Fifth Avenue looking uptown from 51st Street (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 30 PART I • HISTORY

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS ONE OWNER TAKES ALL 31

Over time, Fifth Avenue took on an increasingly commercial tone as upscale stores elbowed out many of the early mansions. One avenue west, an even bigger change arrived with a roar in the 1870s: the Sixth Avenue elevated railway. The trains brought thousands of people from as far south as the Battery, at Manhattan’s southern tip, to as far north as West 58th Street. They also brought soot, grime, and the screech of steel on steel, and—beneath the rails—a thoroughfare as antithetical to sunny, affluent Fifth Avenue as could be imagined.

THE GILDED AGE in New York City is a transitional time: Sixth Avenue, circa 1903, is busy with pedestrian, horse and carriage, and elevated train traffic.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS ONE OWNER TAKES ALL 33

By the early 20th century, speakeasies and brothels proliferated like mushrooms after a rain; under the Sixth Avenue El, and east of it, Columbia’s rental income suffered. Still, this large parcel had an increasingly rare distinction—it all belonged to a single owner. In 1928, that status drew the attention of a group of New York’s great and good, intent on finding a site for a new home for the Metropolitan Opera. They envisioned a very different Upper Estate: the launchpad for a new kind of urban development, one with a grand opera house at its midblock core, ringed by a trio of commercial towers.

THIS VIEW OF 51st Street at the southeast corner of Sixth Avenue shows the main core of the Rockefeller Center site, predevelopment. St. Patrick’s twin spires are visible an avenue away on Fifth.

Rendering of Benjamin W. Morris’s never-built Metropolitan Opera House

Rendering of Benjamin W. Morris’s never-built Metropolitan Opera House

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 34 PART I • HISTORY

ONE OWNER TAKES ALL 35

THE ROCKEFELLERS

JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER and John D. Rockefeller, Jr., 1925 (left)

PATRIARCH JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER and his only son, Junior, sit for a family portrait with Junior’s wife, Abby, and their six children (above).

J

ohn D. Rockefeller is best known as the founder, owner, and decades-long driver of America’s largest petroleum empire, the Standard Oil Company, estab lished in 1870. Through it, he controlled the lion’s share of American oil refining, not to mention huge stakes in oil production and transportation. All this easily powered Rockefeller to the rank of America’s richest individual, as well as one of its most controversial—and most sued. Found guilty before the U.S. Supreme Court of antitrust violations in 1911, Standard Oil was broken into nearly three dozen still formidable competing units. They included those that became Exxon, Amoco, and Chevron.

Rockefeller was a devout Baptist, Sunday school teacher, teetotaler, and nonsmoker who retired to his Westchester estate overlooking the Hudson in Pocantico Hills at the age of 63. There he lived on for another 34 years, enjoying golf, cycling, and philanthropy— founding enduring institutions, from the University of Chicago to his eponymous foundation, and giving away more than $500 million.

His only son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., continued to fund good works on a grand scale, among them restoration of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia and donation of the East River site in Manhattan for the United Nations Headquarters (designed by a team led

by Rockefeller Center architect Wallace K. Harrison). Arguably, Junior is best remembered for his union with Abby Greene Aldrich, which yielded six children. Their second son Nelson became head of Rockefeller Center at 30 and went on to serve as governor of New York and, later, vice president under Gerald Ford; young est son David headed Chase Manhattan Bank. Abby herself became a towering figure in philanthropy as a cofounder of the Museum of Modern Art and numer ous other arts and women’s advocacy projects.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

36 PART I • HISTORY

CROWDS FILL WALL Street in lower Manhattan following the stock market crash of 1929 (right).

THE ROCKEFELLER BROWNSTONE at No. 4 West 54th Street seems imposing until Junior builds his outsize white mansion at No. 10. Both lots and several around them would eventually be given to a trust to build the Museum of Modern Art (below).

lived and worked—razed. Demolition began that summer. It ran for a few months until it hit a wall.

When the stock market crashed that October, plans for the new opera house were shelved. Instead, Junior, whose family mansion on West 54th Street stood almost in sight of the deepening pit he now leased, had to come up with plan B.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

Rockefeller Center rises

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., opted to press ahead with an all-commercial complex, roughly along the lines set forth in the old master plan but with a soaring office tower at its core in place of the concert hall. The complex would develop as a carefully planned, state-of-the-art private city within the city. It would even include its own new midblock promenade running from West 48th Street up to West 51st—an addition that created a dozen new, highly desirable corner locations for retailers.

To detail this vision, a committee of three design firms set up shop together on two floors of a building next door to Grand Central Terminal under the inauspicious name of “Associated Architects.” Nonetheless, the early omens were good. With bold plans beginning to take shape, venerable Architectural Forum magazine hailed the complex as “the outstanding proj ect” of 1932. Maybe so, but in hindsight, Wallace K. Harrison, the designer coordinating the group, described the experience as “pure hell for the archi tects.” Among other revelations, Harrison insisted the firms had agreed to work together only because “they were paid by Mr. Rockefeller.”

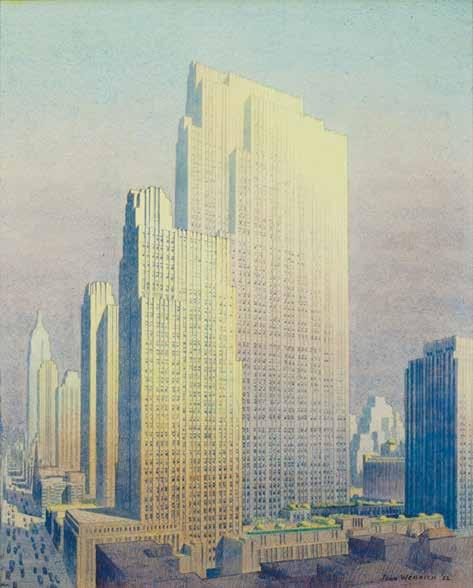

A COLOR RENDERING of Rockefeller Plaza by John Wenrich, 1932 (left)

AN ARCHITECTURAL PLAN of Rockefeller Center’s landscaped rooftops and gardens (right)

A COLOR RENDERING of Rockefeller Plaza by John Wenrich, 1932 (left)

AN ARCHITECTURAL PLAN of Rockefeller Center’s landscaped rooftops and gardens (right)

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS ROCKEFELLER CENTER RISES 39

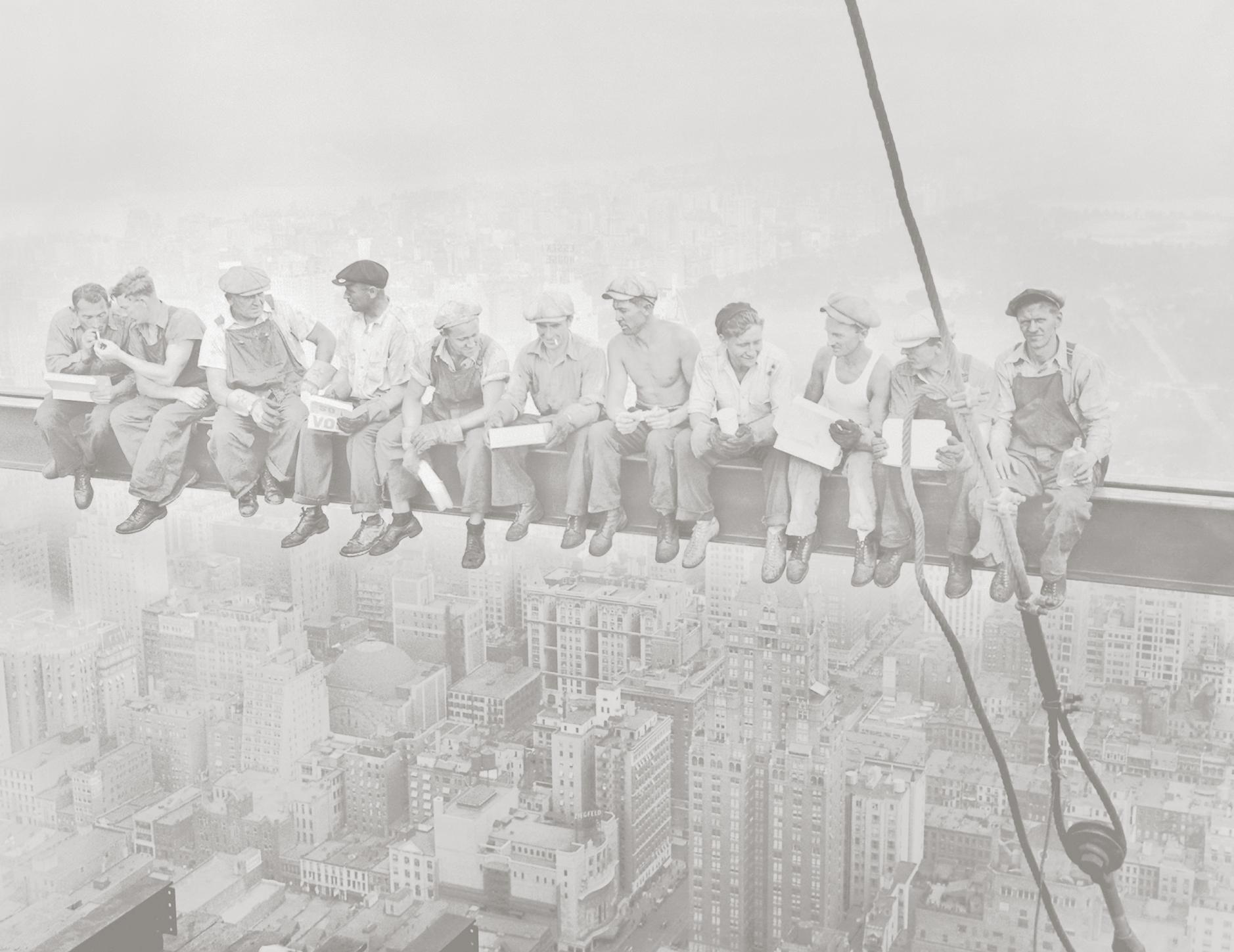

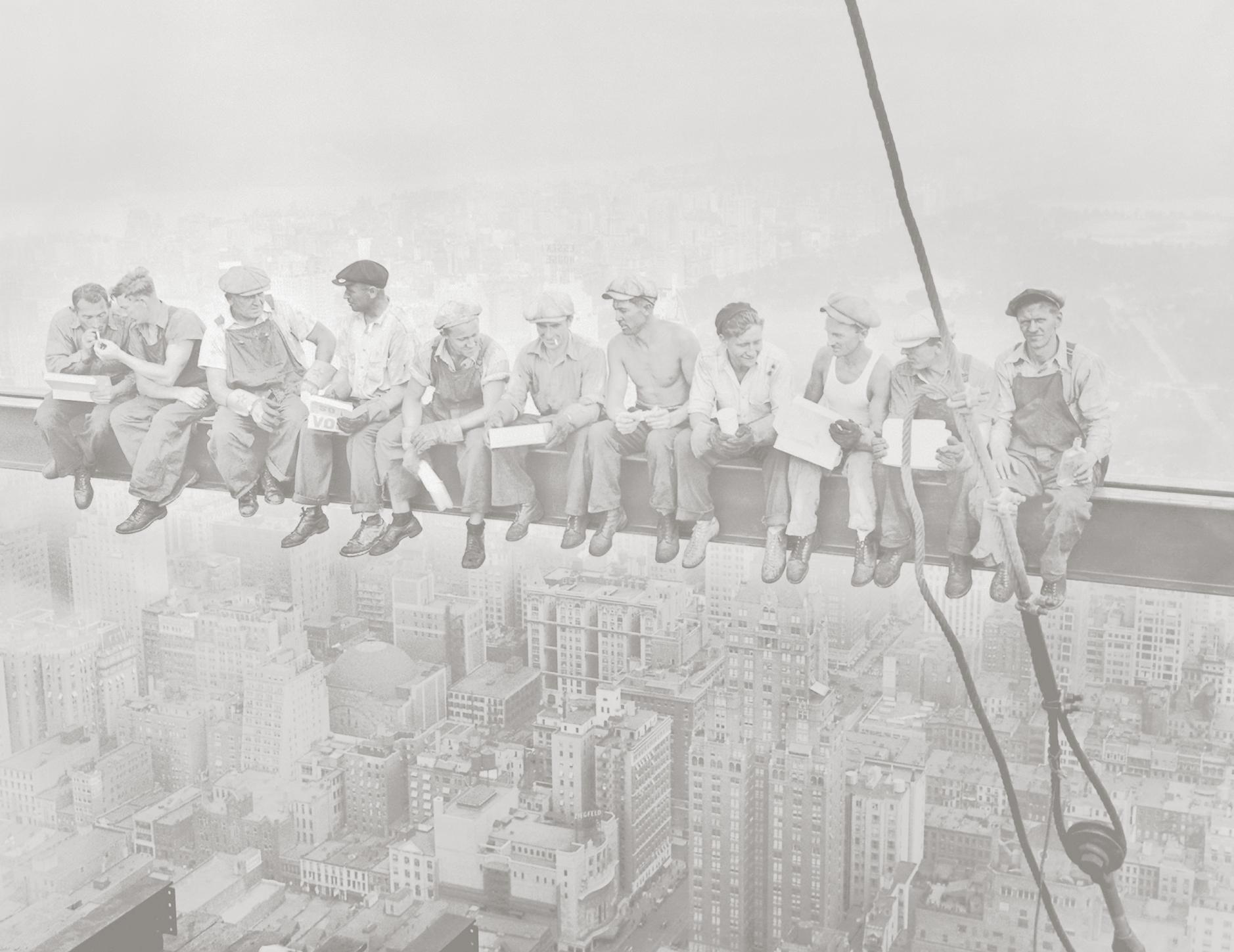

THE EXCAVATION OF the Rockefeller Center site continues on July 17, 1931. Development of the tract, purchased in 1928 by John D. Rockefeller, Jr., began May 17, 1930, and continued through 1939.

THE RCA BUILDING at 30 Rockefeller Plaza is under construction, August 1932 (left).

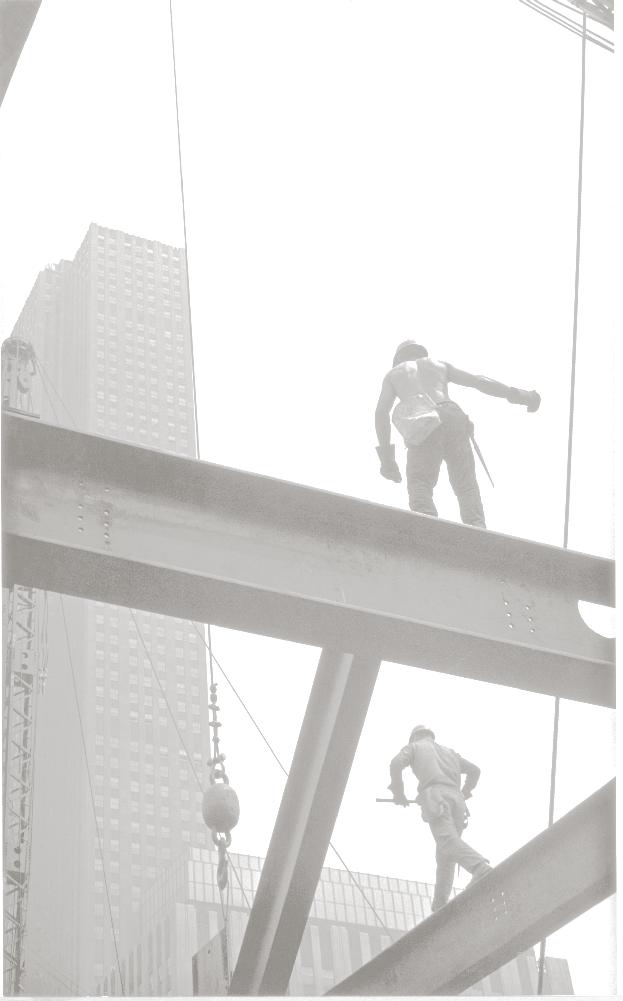

STEEL WORKERS TAKE a break from work on the RCA building 800 feet in the air on a crossbeam, September 1932 (above).

May 1931 and soon became the butt of jokes as “the Empty State Building.”

Despite the deepening economic gloom, Associated Architects beavered on. Construction on what would be the complex’s tallest spire, the RCA Building, began in March 1932. At 70 floors, it would reach 850 feet. Work on the site of Radio City Music Hall, where demolition had begun on May 5, 1931, also continued through 1932.

ROCKEFELLER CENTER RISES 43

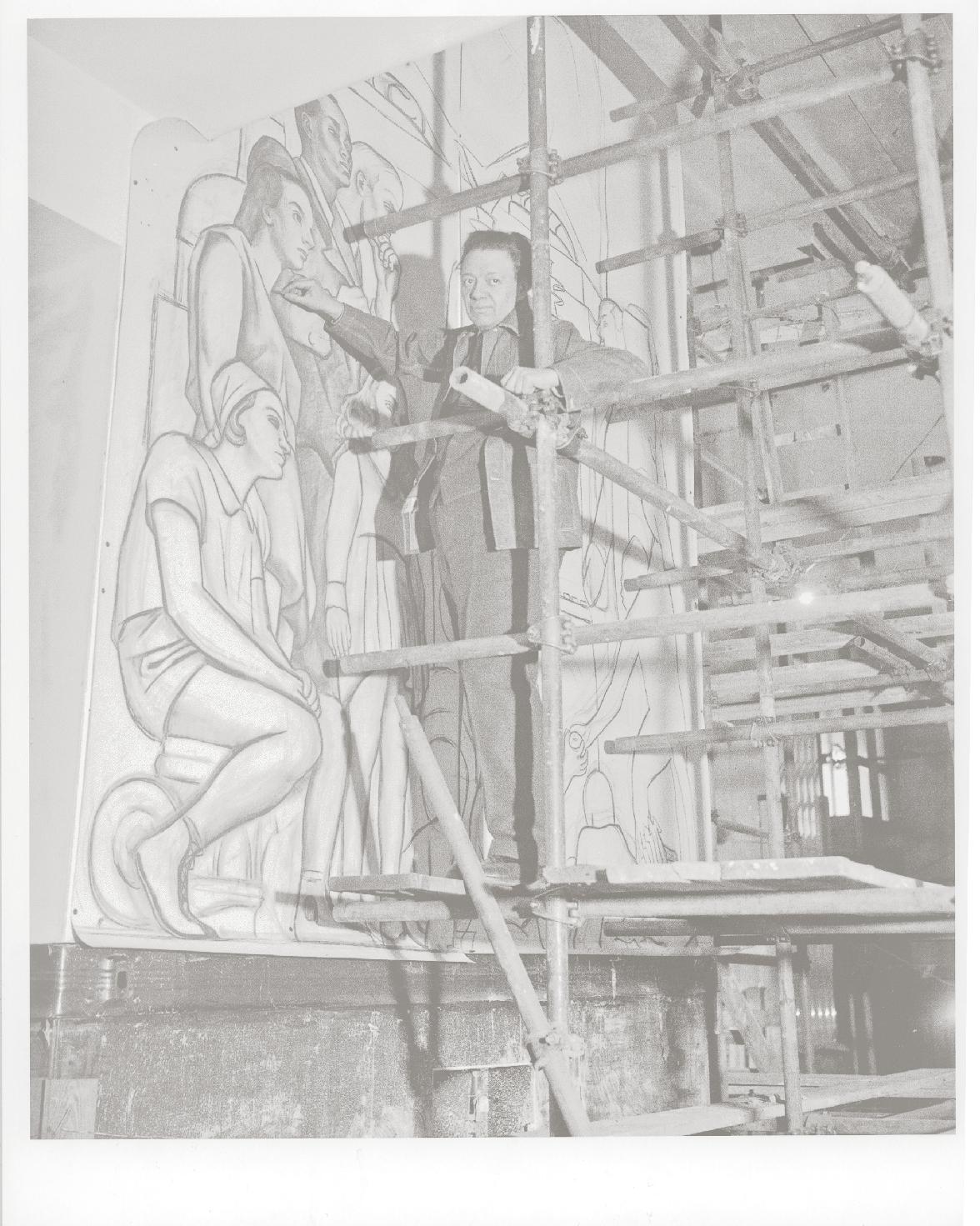

DIEGO RIVERA USES charcoal to sketch the RCA Building lobby fresco (left).

FRIDA KAHLO AND Diego Rivera in their NYC hotel room considering legal action following Rivera’s banning from the RCA Building, May 11, 1933 (below).

RIVERA’S MURAL IS covered to conceal the offending Lenin likeness until it can be destroyed (below left).

ARTIST LEE LAWRIE inspects Atlas (1934–1937) during installation in the forecourt of 630 Fifth Avenue. The heroic work was a collaboration with Rene Paul Chambellan (opposite).

Elsewhere, an array of public amenities and artworks, never before seen in New York City commercial buildings, gave the complex standout Prometheus at the foot of the RCA Building’s front door to the lush Channel Gardens that lured pedes trians off Fifth Avenue with a botanical show reminiscent of Dr. Hosack’s gardens a century earlier. Even Rockefeller Center’s flops seemed to bring it more fame, most notably the murals slated for the RCA Building’s lobby. There, celebrated Mexican painter Diego Rivera had been commissioned to craft an enormous centerpiece fresco. When Rivera, a fervent Marxist, worked his way to the spot in the mural where he revealed—larger than life—a triumphant image of Soviet hero Vladimir Lenin, the Rockefellers stepped in. They took away Rivera’s paints and chiseled his art off their walls. The ensuing howls of protest were loud, but short lived.

44 PART I • HISTORY

THE PROMETHEUS FOUNTAIN, created by Paul Manship in 1934.

THE PROMETHEUS FOUNTAIN, created by Paul Manship in 1934.

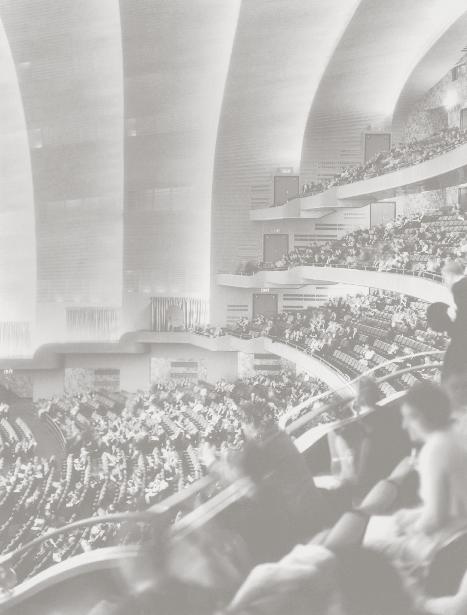

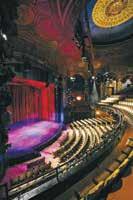

TWO DAYS AFTER Christmas 1932, Radio City Music Hall opens its doors to reveal 5,962 plush seats facing the world’s largest stage in a jaw-dropping Art Deco space. It is an arresting venue designed to make a statement for the whole Rockefeller Center complex. The theater also hints at an important future development, though it goes mostly unnoticed at the time: its doors open onto Sixth Avenue, where the designers anxiously anticipate the demolition of the old elevated railway—set to begin in 1938—and the dawn of a rosier commercial day.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS ROCKEFELLER CENTER RISES 49

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

gathered more litter than interest until management uncorked the concept of freezing a few inches of water for an ice-skating rink, open to all comers, smack-dab in the center of the city’s newest tourist attraction. Similarly, the center’s concourse level, one lightless floor below ground level, drew little attention at first, despite its dozens of shops and eateries. The ceremonial arrival of the center’s towering Christmas tree—a tradition that began offi cially in 1933—and legions of skaters each winter, however, soon kindled a yen for life down under. So, too, did the convenience of walking all the way from Fifth Avenue and West 48th Street as far as Sixth Avenue and West 51st Street, grabbing lunch and whatever else on the way, without ever having to venture outside into the elements. The 1940 arrival of the IND Sixth Avenue Line alongside the complex’s basements, aided by a new, Rockefeller-funded modernist subway mezzanine 20 years later, sealed the concourse’s status as a daily essential for tens of thousands of commuters and tourists.

ROCKEFELLER CENTER IS unique in New York in how it embraces being a public commons. The ice rink is an inviting attraction during the cold months (left); but the space is useful, too, in warm weather for events such as this 1948 dog show (above).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS ROCKEFELLER CENTER RISES 51

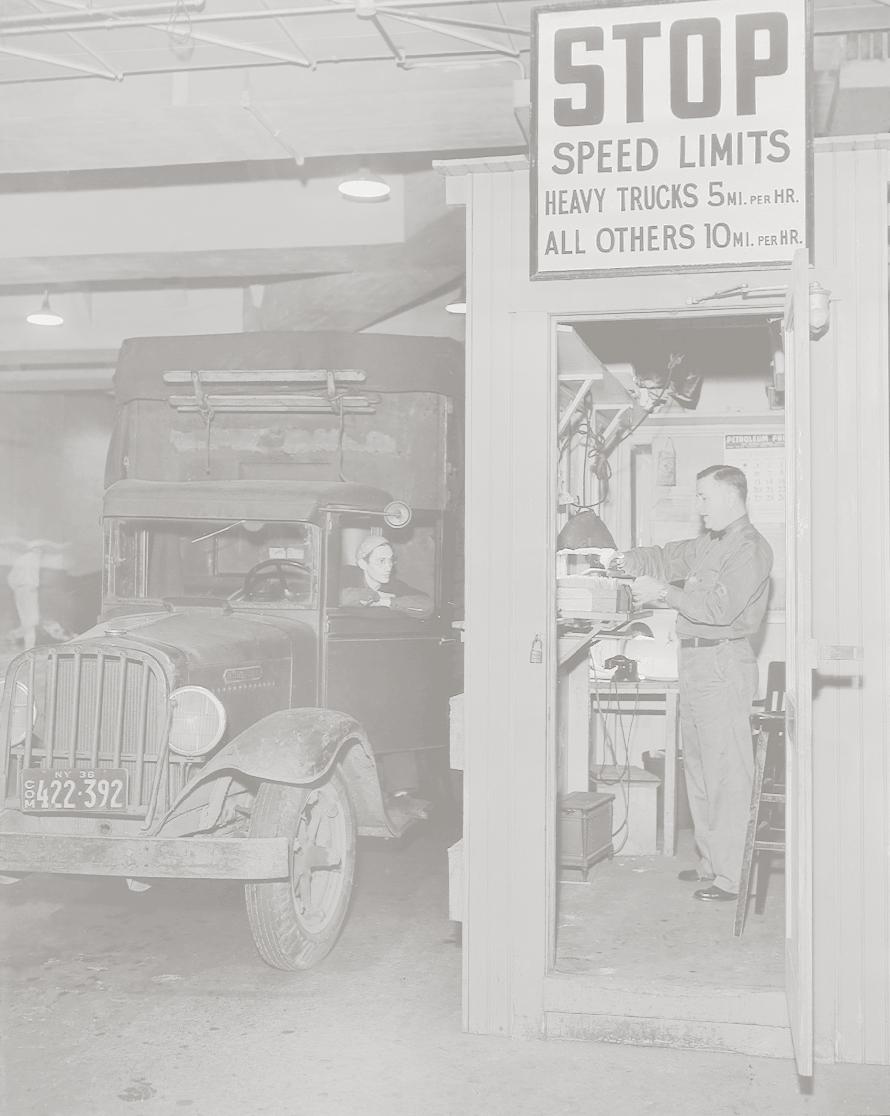

IN A CITY WITHOUT ALLEYS, novel underground loading docks solve a problem created by the grid plan of 1811. Many older cities had alleys for handling goods deliveries and trash removal. In New York, without those handy back doors, that activity shifts to the streets out front. Rock Center’s subterranean alternative brings a new order and efficiency to a key slice of midtown.

In a less sexy innovation, there was something else only the city’s largest private commercial development could offer. One more floor down from the concourse were loading docks that pulled hundreds of trucks off the streets each day via a web of industrial-scale elevators and ramps. This freed the streets up for cars, pedestrians, and a palpably more humane atmosphere. All told, the center had more bells and whistles than a Broadway musical. Still, it drew its detractors, including respected New Yorker architecture critic Lewis Mumford, who lambasted the place as “a series of bad guesses, blind stabs, and grandiose inanities.” Only over time would most observers concede that somehow it all worked, both aesthetically and functionally.

Rockefeller Center’s ramp system

Rockefeller Center’s ramp system

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 52 PART I • HISTORY

RENE PAUL CHAMBELLAN (in white shirtsleeves) and Lee Lawrie (dark suit) work on The Story of Mankind (1935), a massive-scale (22-foot by 15-foot) carved and colored limestone bas-relief that depicts human progress (right).

By 1936, with tenants already at work in its towers and some clamor ing for expansion space, efforts commenced on the project’s four-building Phase II. It boasted new homes for the Associated Press (at 50 Rockefeller Plaza, with a striking Isamu Noguchi sculpture— News —out front), Eastern Air Lines, and a bumptious 14-year-old magazine publisher, Time Inc., which had already outgrown its quarters at the newly constructed Chrysler Building. Foundation work at 9 Rockefeller Plaza, known as the Time & Life Building, began in the late spring of that year. By the following April, the 36-story tower, clad like all its Rock Center siblings in Indiana limestone, stood ready for business at the complex’s southern edge, on Rockefeller Plaza between West 48th and West 49th Streets. Its entrance on West 49th was renamed 1 Rockefeller Plaza. At the outset, Time Inc. took seven of its floors, plus a penthouse.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 54 PART I • HISTORY

ISAMU NOGUCHI CARVES and casts his sculpture News (1940) for the Associated Press Building. The artwork was, at the time, the largestever stainless-steel casting. It shows five newsgatherers looking for a scoop (left). The entrance to the original Time & Life Building at 9 Rockefeller Plaza (now 1 Rockefeller Plaza) is set off by another Lawrie collaboration, this time with colorist Léon V. Solon for their classic Art Deco work Progress (1937) (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS ROCKEFELLER CENTER RISES 55

Still, the occasion would have likely fallen far short of memorable had it not been for the center’s young new president, Nelson Rockefeller, Junior’s second-born son. He turned the day into a spectacle, with an audience of 500, honorary guests including Mayor Fiorello La Guardia, and a colorfully uniformed regimental band, plus live coverage on NBC Radio.

In its coverage of the ceremony, Forbes magazine trumpeted the complex’s new status as the city’s biggest visitor attraction, crediting that coup to one man: “The genius who has made Rockefeller Center uniquely attractive is Nelson A. Rockefeller. . . . Keep your eye on him.”

LEANING INTO THE microphone that morning at the final Rockefeller complex building dedication, Nelson confided that his father, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. “has always had a suppressed desire to drive a rivet.” November 1939 (left).

THE RCA BUILDING, brightly lit to show off its pale Indiana limestone in the city’s midtown jewel box (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 56 PART I • HISTORY

NELSON A. ROCKEFELLER

majored in economics and wrote his honors thesis on the explosive growth of Standard Oil under his grand father. In his senior year, Nelson put an interest in art to work by joining the junior board of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), a body that also included George Gershwin and a young architect, Philip Johnson. A year later, Nelson plunged deeper into that world by joining the board of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, at the invitation of J. P. Morgan, Jr., and also taking a seat on the committee assaying artwork for Rockefeller Center. In 1934, he launched a study of the center’s management for his father and began taking on ever more responsibility—efforts that culminated on

day to a working commercial office complex of 5 million square feet. Marketing that acreage had become the key thing, and Nelson Rockefeller its master practitioner.

Early on, he became a big booster for the complex’s magazine, Rockefeller Center Monthly, a glossy devoted to chronicling the center’s myriad happenings and achievements, including its growing stock of murals, sculptures, and paintings—from giant Atlas outside the International Building, across from St. Patrick’s, to the soaring airplanes featured in the murals of the Eastern Air Lines Building’s lobby. One of his early triumphs as pitchman came in 1936, with the founding of the Sidewalk Superintendent’s Club, an 80-foot-long

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 58 PART I • HISTORY

viewing platform from which club members could drink in all the details of the construction work at their leisure. By the end of the first week, 20,000 people had joined. Three months later, with chapters popping up across the nation, that figure had exploded to 750,000. Nelson himself traced the inspiration for his public relations coup to an insult suffered by his father, who one day had stopped dead on a truck ramp to check out the construction work, only to be shooed off by a burly guard who told him, “You can’t stand around loafing here.”

Nelson worked out of the family office, “Room 5600” in the RCA Building, a suite that took up the entire 56th floor. Early on, he established a close relation ship with Wallace Harrison, one that for years included sitting down most mornings for coffee together. Nelson needed to track the work that Harrison and Associated Architects were doing. But the two men had other things in common as well. They moved in similar social circles and shared a passion for modern art—and for installing as much of it as they could into prominent spots around Rockefeller Center. It was a passion

Nelson inherited from his mother, who served as vice president of the Museum of Modern Art until she eventually stepped down in favor of Nelson. In May of that year, that succession became official at the grand opening of MoMA’s permanent home three blocks north of Rockefeller Center, an event attended by Salvador Dalí, Lillian Gish, Edsel Ford, and 6,000 others. Participating by a radio link from Washington was President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who made an opening address. Nelson’s performance that evening as master of the moment won him a Time magazine cover story the following week.

For the next two decades—with occasional inter ruptions to serve in the State Department during World War II and to run for political office—Rockefeller Center remained the North Star of Nelson’s professional life. In 1958, that changed for good when he won the election for the first of his four terms as governor of New York. In 1974, President Gerald R. Ford tapped him to be vice president, a post he held through the end of the Ford administration in 1977. Nelson Rockefeller died two years later at the age of 70.

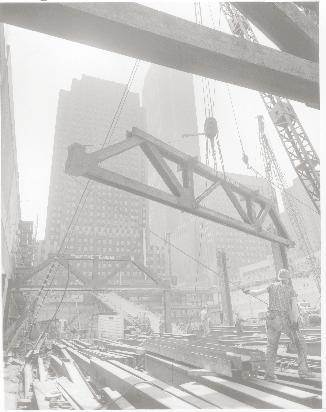

NELSON ROCKEFELLER SHAKES hands with ironworker John Corbett on the day the first steel is set in place: April 3, 1958 (opposite).

JUNIOR ATTENDS SENIOR’S funeral, accompanied by his five sons, to right of John D.: David, Nelson, Winthrop, Laurance, and John D., III, May 26, 1937 (above).

GOVERNOR NELSON ROCKEFELLER and his grandchildren Peter and Meile, photographed in 1960 at the Rockefeller home in Pocantico Hills, New York (top right).

ELECTION NIGHT, NOVEMBER 4, 1958: Nelson wins the New York gubernatorial race (bottom right).

NELSON ROCKEFELLER SHAKES hands with ironworker John Corbett on the day the first steel is set in place: April 3, 1958 (opposite).

JUNIOR ATTENDS SENIOR’S funeral, accompanied by his five sons, to right of John D.: David, Nelson, Winthrop, Laurance, and John D., III, May 26, 1937 (above).

GOVERNOR NELSON ROCKEFELLER and his grandchildren Peter and Meile, photographed in 1960 at the Rockefeller home in Pocantico Hills, New York (top right).

ELECTION NIGHT, NOVEMBER 4, 1958: Nelson wins the New York gubernatorial race (bottom right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS ROCKEFELLER CENTER RISES 59

TIME & LIFE ERA

Part II

A modernist model

From the staging alone, passersby on the afternoon of May 16, 1957, could have guessed that the hubbub across the avenue from Radio City Music Hall had something to do with Rockefeller Center. After all, only the Rockefellers could have brought together on one barren, block-long site a German band featuring five Tyrolean tootlers, a bevy of television news cameras, an audience of several hundred, and two men in business suits and white gloves wielding jackhammers: Center board chair Nelson Rockefeller and Time Inc. editor in chief Henry R. Luce.

In his speech that day, Rockefeller hailed their groundbreaking for the new Time & Life Building as the “most important moment” for the Center since his father had decided to go ahead with his commercial city within the city in the darkest days of the Depression. This would be not just another tower, the complex’s 16th. It would be the first to rise up on the far side of Sixth Avenue. For decades, anything west of Sixth Avenue was on the wrong side of the tracks. The Sixth Avenue elevated train that had long blighted the area was closed in late 1938 and completely razed by April 1939. In 1945, to mark the transformation, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia rechristened Sixth Avenue the Avenue of the Americas.

The ambitions of Nelson Rockefeller and Mayor La Guardia in transform ing the city meshed neatly with Henry Luce’s vision for his rapidly growing media empire. Outgrowing the extant Time & Life Building at 1 Rockefeller Plaza was a concern, but the businessman Luce had his eye on another type of expansion, the sort that comes with wanting to make a mark on the physical city with a new home for his empire.

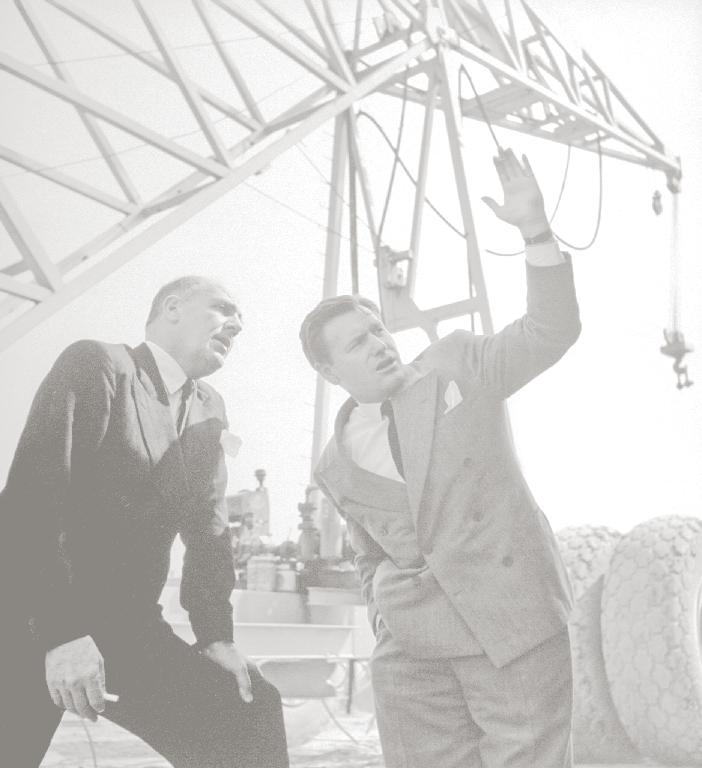

BREAKING GROUND ON the western frontier: Henry Luce and Nelson Rockefeller glove up and get to work in front of a Hugh Ferriss pencil rendering of the new Time & Life Building. The drawing previews how 1271 will sit against the backdrop of Rockefeller Center.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 62 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

DWARFED BY A massive model of the Time & Life Building, Laurance Rockefeller points out a plaza feature to Rockefeller Center president G. S. Eyssell (above).

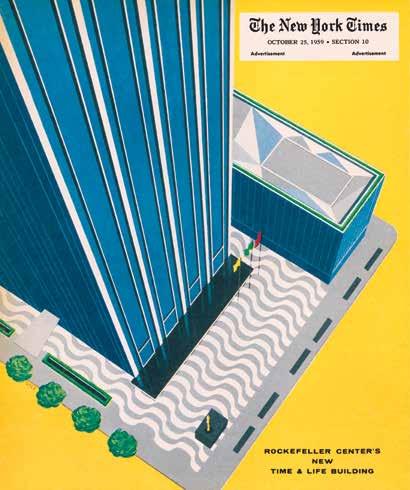

AN AERIAL-VIEW DRAWING of the new Time & Life Building in the context of Rockefeller Center, looking southwest. Illustrated by W. David Shaw, the New York Times advertisement supplement, October 25, 1959 (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 64 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 66 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

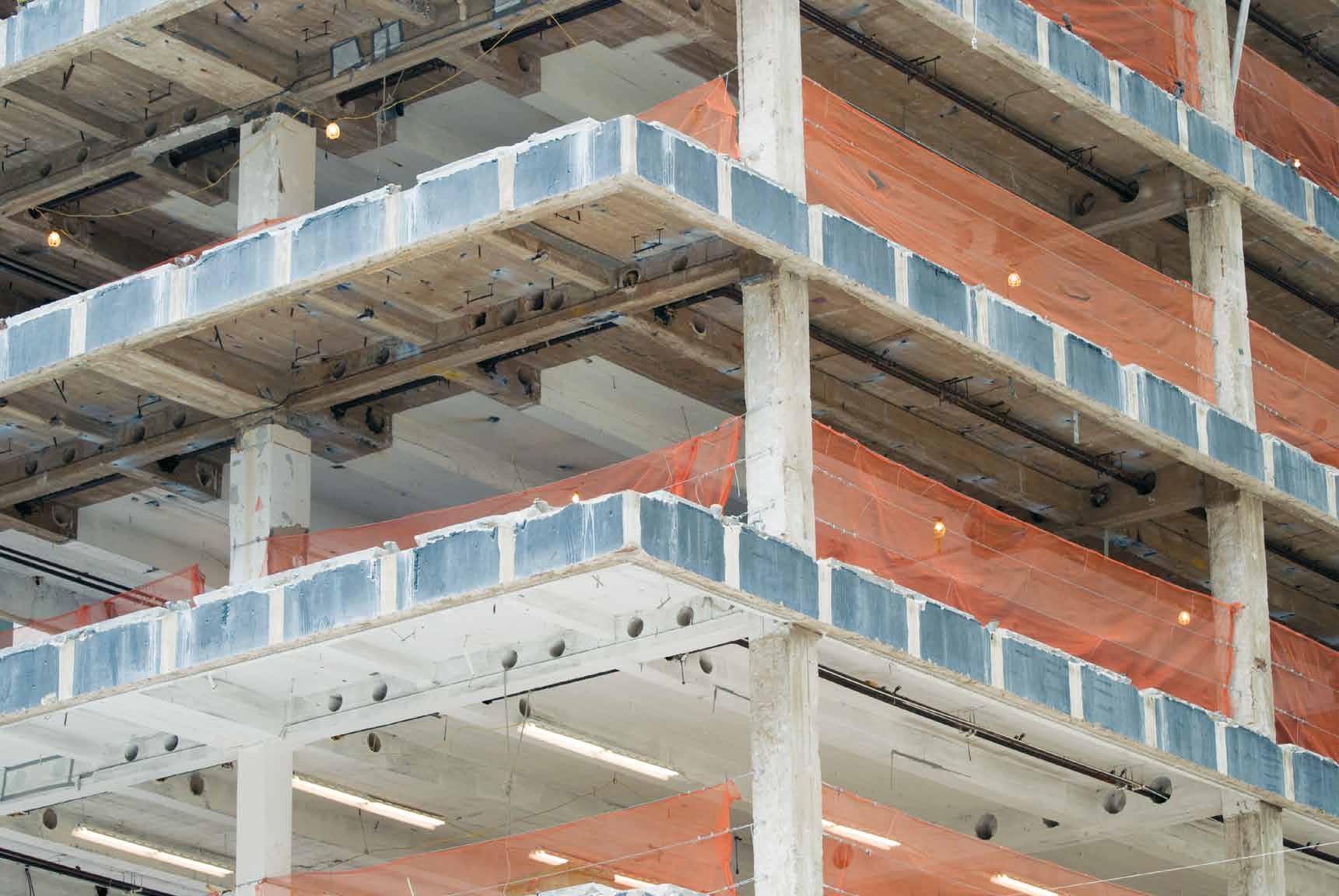

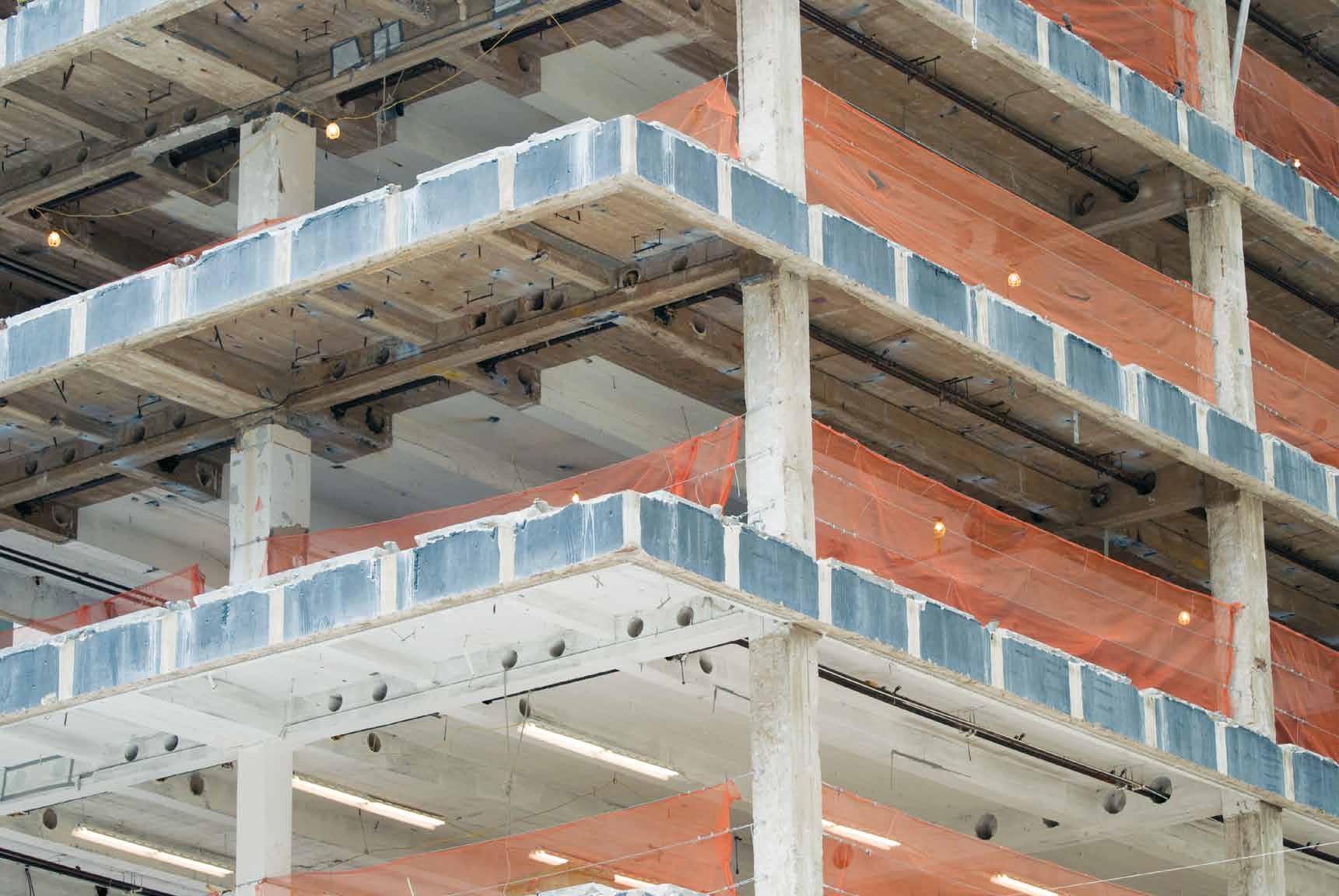

FOUNDATION WORK BEGINS on the massive pit, seen from above Sixth Avenue (far left). A steelworker signals “boom up” to the crane operator (top). Workers pour concrete over reinforcing bars (bottom).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS A MODERNIST MODEL 67

On the eve of the groundbreaking and more than two years from the building’s opening, tenants had already lined up for 65 percent of the space. Half of it, 20 floors’ worth, would house Time Inc. and 2,000 employees of its magazines, including Time , Fortune , Life , and Sports Illustrated.

In several important ways, the new 48-story, $70 million, 1.5-millionsquare-foot Rockefeller Center tower broke the mold. The Time & Life Build ing was the first in which the chief tenant held a large stake. As the property’s 45 percent owner, Time Inc. not only shared in its financial risks and rewards, it also had a strong voice in decisions about the tower’s look, layouts, and more. Henry Luce and his son and advisor Henry III (Hank) used that voice liberally as members of the design committee.

NELSON ROCKEFELLER (center in dark tie) and Time Inc. president Roy E. Larsen toss coins for luck into the foundation pit at the Time & Life Building worksite.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 68 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

Tborrowed heavily from its successful Rockefeller Center siblings, beginning with its architects.

To design the property, the joint venture RockTime Inc. turned to the firm of Harrison, Abramovitz & Harris. Its lead partner, Wallace K. Harrison, had played a central role in designing the original complex and several of its towers, including the original 36-story Time & Life Building on Rockefeller Plaza.

Beginning in the early 1930s, Harrison had developed a close working relationship with Nelson Rockefeller that came to underpin many of the archi tect’s biggest projects. Harrison biographer Victoria Newhouse called the two-man act “one of the most remarkable relationships between a powerful client and an outstanding architect.”

Early on in his career, Worcester-born Wally Harrison worked as a draftsman for McKim, Mead & White, the firm behind the imposing Beaux-Arts-style Pennsylvania Station on New York’s Seventh Avenue. Harrison contin ued his formal education at the École des Beaux-Arts

in Paris and via a traveling fellowship through Europe and the Middle East during his McKim, Mead days. A few years later, Harrison headed a team of hundreds of architects churning out school designs for the New York City Board of Education in a huge Brooklyn loft. That effort, which also required considerable organi zational and management skills, served him well in a later series of prominent projects for which he had to harness together the talents of some of the world’s top architects. Among the products of those team efforts were the United Nations Headquarters along the East River (on land donated by the Rockefellers), Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts on Manhattan’s west side, and the 1939 and 1964 world’s fairs in Flushing, Queens. His work at Rockefeller Center was the longest running of Harrison’s team efforts, stretching well over 30 years, deep into the 1960s with his work on the XYZ Buildings. To lead those later projects, Harrison turned to Michael M. Harris, a younger partner in his firm and his deputy, who had led the planning for the UN and who did most of the work on the Time & Life Building.

APRIL 1931, ARCHITECTS

Raymond Hood, Wallace Harrison, and L. Andrew Reinhard with a model of Rockefeller Center (top left).

WALLY HARRISON AND Nelson Rockefeller watch construction of concrete houses financed by Rockefeller, 1949 (above).

TIME INC. VICE president Weston C. Pullen, Jr., president of Rockefeller Center G. S. Eyssell, and Wallace Harrison look at plans (bottom left).

WALLY HARRISON

A MODERNIST MODEL 69

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

A TURBOPROP AIRCRAFT engine creates storm conditions for a dynamic weather test on a mockup of the Time & Life Building façade. Garden City, New York, 1958 (above).

A TWO-STORY MOCKUP was erected in Astoria, Queens to test out designs, December 1957 (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 70 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 72 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

THE SIDEWALK SUPERINTENDENT’S Club, a popular Rockefeller Center attraction revived for the construction of the Time & Life Building, is a fun public relations stunt. The enclosed shed made space for dozens of looky-loos to view the action. The Club gives out membership cards and has informal rules. It serves a practical purpose, too: keeping gawkers from getting in the way (left).

FOR THE GRAND reopening of the Sidewalk Superintendent’s Club on July 2, 1957, Marilyn Monroe swans into town via helicopter from her Hamptons summer home two hours late. She misses host Laurance Rockefeller— who couldn’t wait any longer—by mere moments. Using a comically large match, Marilyn lights a super-size firecracker that touches off a very real blast of dynamite in the pit of the Time & Life Building site nearby (above).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS A MODERNIST MODEL 73

LOOKING NORTHEAST ON September 26, 1958 at the 50th Street side of the rising building, the extension wraparound is visible in the left foreground. The Time & Life Building was two months from topping out (left).

ROCKEFELLER CENTER CELEBRATES the holiday season with two Christmas trees in 1958. To mark the topping out of steelwork on the Time & Life Building, construction crews hoist a 35-foot lighted tree to the newly minted 48th floor (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 74 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

While the façade features soaring columns sheathed in the same Indiana limestone as on the spire’s older siblings across the avenue, behind that stonework are steel beams that hold the building up, along with air-con ditioning duct work. Exiling those traditional tower innards to the exterior, the publisher’s design committee argued, would give the interior cleaner lines and fewer obstructions, making it easier to lay out.

This became especially important in light of Time Inc.’s decision to use a new system of moveable glass-topped partitions to wall off some floors into modular offices of as little as 75 square feet, each made up of basic building-block modules measuring 4 feet by 4 feet 8 inches. This flexible partitioning allowed for a more efficient use of the acreage; the company calculated it saved the equivalent of an entire 28,000-square-foot office floor with this innovation. Meanwhile, the tower’s curtain wall, which had more glass and less stone than the earlier Rock Center buildings, used clear rather than tinted glass, yielding brighter interiors. This was less a detail and more a crucial decision for a building that housed print publications and art directors who relied on the natural light to review graphic designs and photos.

AN UNFINISHED INTERIOR floor is a presage of the modern open-plan office environment. With no columns to interrupt the main work space, the floors could be configured uniquely for Time Inc. and to each tenant’s specifications (above).

WORKING IN TWO-PERSON teams, construction workers install the curtain wall. The limestone columns are set 28 feet apart; aluminum mullions between them create a soaring pin-striped effect, and the rest is glass (left).

MOVEABLE PARTITIONS CREATE offices around the perimeter, leaving the interior areas available for cubicles and traffic. Henry Luce had his eye on cost efficiency with this plan; it would allow Time Inc. to expand and contract, making space available for subleasing (right).

76 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

A VIEW OF the northern elevation under construction. The building’s extension—also known as the bustle, podium, or wraparound—gives the 51st Street view a different look from its 50th Street counterpart (opposite).

X MARKS THE spot on the newly installed curtain wall. Accidental collisions with newly fixed vision glass are avoided by marking with paint (top left).

A LARGE TEAM of glaziers is necessary to install a 9 feet 5 inches by 14 feet 5 inches pane of glass into the ground floor windows of the Time & Life Building (top right).

LAURANCE ROCKEFELLER ( Board Chairman, Rockefeller Center, Inc.) and Henry R. Luce (cofounder and editor in chief, Time Inc.) at the laying of the cornerstone (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS A MODERNIST MODEL 79

As the first Center building conceived and constructed in the 1950s, Time & Life brought exuberantly fresh elements to the Rockefeller Center design repertoire. These included the outdoor plaza’s pavement, which boldly drew on the Avenue of the Americas vibe with serpentine bands of white and gray terrazzo inspired by Brazil’s Copacabana Beach promenade.

In finely polished form, these bands snake indoors across a lobby dominated by four elevator banks, each wrapped in burnished stainless steel panels that rise 16 feet from the floor to the dark red glass ceiling. Summing up the lobby as worthy of official landmark status—which it duly received in 2002—the Landmarks Preservation Commission cited it as “one of the most striking interiors in New York City.”

THE SUNDAY NEW YORK TIMES special advertisement section for October 25, 1959, was a modernist showpiece of shape and color (above).

A VIEW OF the north lobby shows how the rightangled shapes on the ceiling, service core, and Fritz Glarner’s mural play against the swirling terrazzo floor to create dynamic movement. As the 2002 Landmarks Preservation Commission report notes, “To further accentuate this, the direction of the brushed finish in each panel alternates between horizontal and vertical” (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 80 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS A MODERNIST MODEL 81

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 82 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

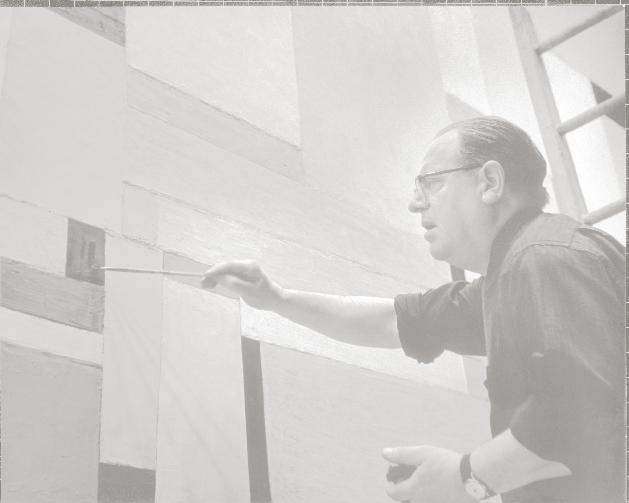

TWO MASSIVE PIECES of abstract art solidify the lobby’s triumph as a modernist gem. The east side of the lobby boasts a 40 feet by 15 feet rectilinear mural by Swiss artist Fritz Glarner, Relational Painting #88 (left, top and bottom). At the west end of the lobby, Portals —a 42 feet by 14 feet work of nickel, bronze, and glass by German artist Josef Albers—is affixed to the marble wall (right, top and bottom).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

As uniquely new as its lobby is, the Time & Life Building apes its predecessors with features such as a sub-basement 40 feet down, accessible to trucks via ramp and elevator for easy off-street deliveries and removals. One level up, it has its own extension of the complex’s pioneering retail and pedestrian concourse. In this case, the concourse permits direct under ground access from the lobby to the subway line beneath the avenue. There, Rockefeller Center Inc. made a bold move, agreeing in 1958 to pay the MTA $2 million to lease the northern end of the station’s mezzanine and give the raw space a modernist makeover, adding shops and throwing in cleaning and maintenance of the space for 20 years. For tenants, the new link became a popular perk. Meanwhile, the New York Times credited the rent paid to the transit authority with “saving” the city from a hike on the 15-cent subway fare.

Paying off in less tangible ways was the design’s fealty to other Rockefeller Center traditions, including sizeable expanses of public space and the prom inent use of modern art. The original complex had 3½ acres of landscaped gardens on its roofs and elsewhere, including the Channel Gardens and the trees ringing its sunken plaza. Time & Life had substantial setbacks from the property line that left a quarter of the plot wide open. This allowed for a 70-foot-deep plaza with shallow pools and mushroom fountains fronting Sixth Avenue and a 30-foot-deep promenade along West 50th Street.

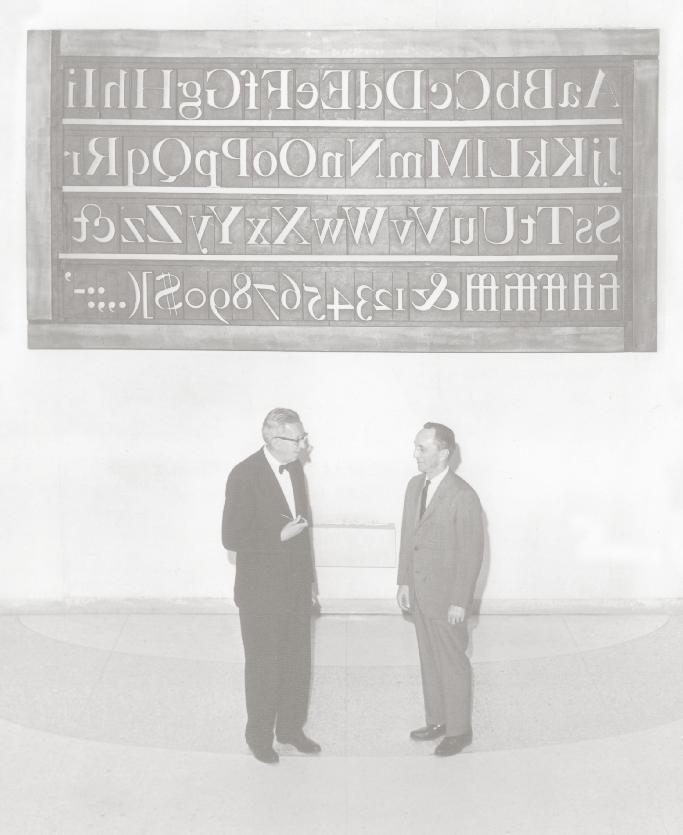

CONCEIVED BY FRANCIS BRENNAN, a Fortune magazine art director, this installation is a 1-ton sculptural homage in bronze to a favorite Fortune typeface, Caslon 471. Brennan explained that “the sculpture is symbolic of the basic working tool of Time Inc.—the letters of the alphabet. And there is nothing more beautiful than a tool” (above).

AERIAL VIEW OF the plaza and promenade where they converge at Avenue of the Americas and 50th Street, 1960 (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 84 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

$78,000,000

Final construction cost

1.5 million

Square feet of rentable space

2 Years between start of foundation work and arrival of first tenant

215,000

Weight in tons of rock and soil removed during foundation work 31,000 Weight in tons of structural steel 320,000

Bolts in steel frame 34,000 Rivets in steel frame

More than 100 Number of workers who erected frame 33 Weeks to complete steel frame (on November 24, 1958)

Weight in pounds of limestone cornerstone laid by Rockefeller Center chairman Laurance Rockefeller and Time Inc. editor in chief Henry Luce on June 23, 1959

Weight in pounds of documents and memorabilia inside copper box behind cornerstone 369,000 Square feet of glass on façade 7,000 Windows Weight in tons of architectural aluminum 32 Passenger elevators Escalators

Skyscrapers on Sixth Avenue between 42nd and 57th Streets upon comple tion of T&L Building (RCA Building was the other) Capacity of diners in 48th-floor Hemisphere Club

28

Distance in feet between façade’s white limestone columns 82,000 Plot size in square feet 28,000 Original tower floor area in square feet Minimum size in square feet of Time Inc. writer’s cubicle

21

Number of floors originally rented by Time Inc. (6 were sublet)

4 feet by 4 feet 8 inches

Dimensions of basic interior workspace module

800

30

600

6

2

300

75

86 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA 1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

General contractors

George A. Fuller Company and John Lowry, Inc.

Mechanical engineers

Syska & Hennessy, Inc.

Structural engineers

Edwards & Hjorth

Steel fabricator

Bethlehem Steel Corporation

Interior designers

Alexander Girard, Gio Ponti, Charles and Ray Eames, William Tabler, and George Nelson & Company

Marilyn Monroe presides over official opening

tower’s topping out

Height in feet of tree atop 48th floor

Colored lights on tree

Weight in tons of tree and supports

Colored lights on strings stretching from roof to 6th floor

65

Length of pavilion in feet

PR pitch

“Scientifically designed for the kibitzing comfort of the ancient and loyal order of amateur excavation engineers”

16

Height in feet of 1-ton Santa bolted to building

PR pitch

“New York’s loftiest holiday landmark”

A MODERNIST MODEL 87 1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

The first six decades

On the morning of October 23, 1959, the moving vans began streaming into the loading docks in the sub-basement of the new Time & Life Building at 1271 Avenue of the Americas. By the time the last of their loads had landed eight days later, 4,200 cartons plus furniture and rugs had been unpacked. Only then did floors 5 and 6 stand ready for the tower’s first tenants: 850 employees of American Cyanamid. Late the following month, the American Petroleum Institute took its turn, moving into offices on the 7th floor.

Not until the new year did the staff of a Time Inc. arm, Sports Illustrated , follow suit. At 6 p.m. on January 6, these employees became the first Time Inc.-ers to begin the migration to new, air-conditioned quarters, 22 years after a far smaller company had set up shop on seven floors at 9 Rockefeller Plaza. On Sixth Avenue, SI took over floors 19 and 20, near the bottom of an unbro ken series of Time Inc. offices stretching from 18—which housed Fortune —to 34, where top brass labored beneath 13-foot ceilings (the tallest in the tower by 4½ feet, save for the top two floors, which are 16 feet).

FEBRUARY 8, 1960 is move-in day for Donahue & Coe secretary Marie Brownell; she types her way across the Avenue of the Americas on the way to the ad agency’s new offices at the Time & Life Building (below).

THE ELEGANT TIME & LIFE Reception Center is a main attraction for visitors to the building and, when the center’s drapes were open, for passersby on Avenue of the Americas. The center runs the length of the avenue adjacent to the fountain. The reception desk to the left of the stairs sits under a mezzanine which features a library with bound editions of Time-Life publications (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 88 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

BY PUTTING THE main entrances on 50th Street rather than on the avenue, the Time & Life Building’s plaza became a renowned gathering place. Busy, lively, and barrier-free, it invited strolling, meeting, and lounging.

CHIC TOUCHES IN the elevator landings included wall-mounted floating planters alternating with round sand-filled ashtrays (left).

THE 33RD-FLOOR CONFERENCE room had retractable pocket doors for reconfiguring the space (above).

THE FIRST SIX DECADES 93

Lower down, in addition to the magazines, each with its own editorial and business staff, were such largely Life -driven curiosities as New York’s largest photo lab, as well as the world’s largest library of images, several million of them tucked into dozens of filing cabinets on the 28th floor.

While Time Inc.’s tastes in interior design emphasized efficiency over aesthetics, the company did spring for some special touches, including reception areas that reflected each publication’s unique personality. On floors 27 through 29, which featured the Life editorial offices, that standout detailing came courtesy of designer Charles Eames, who was also respon sible for the publisher’s main reception area in the lobby, with its towering windows looking out across the plaza and its fountains.

work for short-term seating or as side tables.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 94 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

CHARLES & RAY EAMES

team of Charles and Ray Eames.

A year earlier, he had let the Eameses mine Time Inc.’s vast photo library for images for a film they were making. Now, Luce asked the couple to design Time Inc.’s reception areas and executive chairs. The former are long gone, but the hyper-plush latter live on cour tesy of furniture maker Herman Miller, Inc. Among their fans was Luce’s son Hank, who carted off to London three Time-Life Lobby Chairs in 1966. (Hank Luce was Time ’s new bureau chief there.)

Not a bad gig for the daughter of a vaudeville theater owner from California and the son of a rail road security officer from St. Louis, but it’s no surprise they landed it. By the time they met at Michigan’s Cran brook Academy of Art in 1940, both had shown prom ise: Ray as an abstract painter, Charles as an industrial designer.

Along with friend Eero Saarinen, designer of the St. Louis Arch and dozens of other mid-century archi tectural marvels, Charles later garnered first place honors for the Eames’s plywood “organic chair” at a MoMA-sponsored show. The Eameses would also use plywood to craft innovative, lightweight leg splints for injured U. S. Navy sailors in World War II.

CHARLES AND RAY Eames (top left); the famous Eames Executive Chair (top right and above), known better as the Time-Life Lobby Chair, was an iteration of the Eames Lounge Chair, commissioned by Herman Miller and released in 1956. Charles Eames tweaked the design to create the Lobby Chair: a taller, more upright, and narrower version, suitable for an office setting rather than a men’s club or living room. It was both comfortable and functional, with luxe Scottish black leather down-filled upholstery and an aluminum frame on a swivel base.

THE FIRST SIX DECADES 95 1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 96 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

A TIME INC. art department bathed in light (left). A private office and secretary’s desk separated by a modular wall partition (above). The Life photo lab (right).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS THE FIRST SIX DECADES 97

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 98 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

TIME INC. ENJOYED the use of the 250-seat auditorium atop the tower’s seven-story extension, which wraps around its western and northern flanks. That space, which included meeting areas and a bar, was orchestrated in high mid-century modern style by the Italian designer Gio Ponti.

THE REMODELED AUDITORIUM has a long outdoor deck with 270-degree views (left). Ponti designed the original space with flexibility in mind (right); the rooms could be set for banquets, smaller receptions, or theater seating, and were suitable for feting the great and the good, including John F. Kennedy shown here at the elbow of host Henry Luce (above).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS THE FIRST SIX DECADES 99

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 100 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

In the early years, an eclectic mix of tenants came and went in the building. Initially, the highest office floor, 46, housed Whitney Communi cations, headed by John Hay Whitney, whose résumé included stints as U.S. ambassador to Great Britain, president of the Museum of Modern Art, and publisher of the New York Herald Tribune .

The Rockefeller Foundation, one of the nation’s biggest philanthropies, occupied floors 41 and 42 at a time when the focus of its work was shifting toward agriculture. That meant, among other projects, funding for a new international rice institute in Asia, whose seeds were later credited with aiding the green revolution that helped stave off famines worldwide.

Several ad agencies, including McCann Erickson Inc. on 38, spread their creative wings in 1271. Oil-industry firms—a leading tenant category across all of Rockefeller Center from its very earliest days—were also well represented. In addition to the American Petroleum Institute, Shell Oil had floors 2 and 3, and Reed Roller Bit, maker of oil-well drilling bits, found a home on 37.

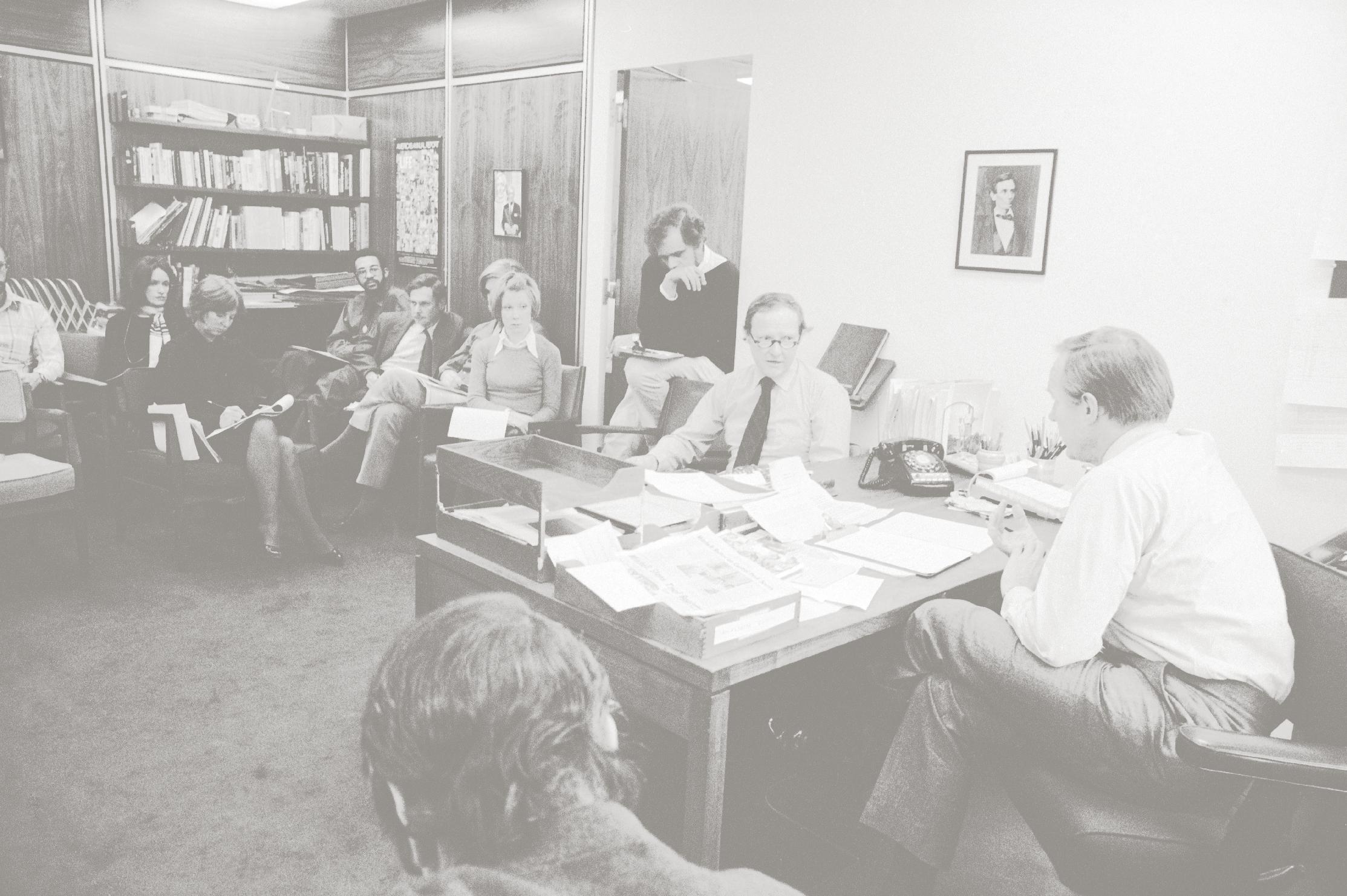

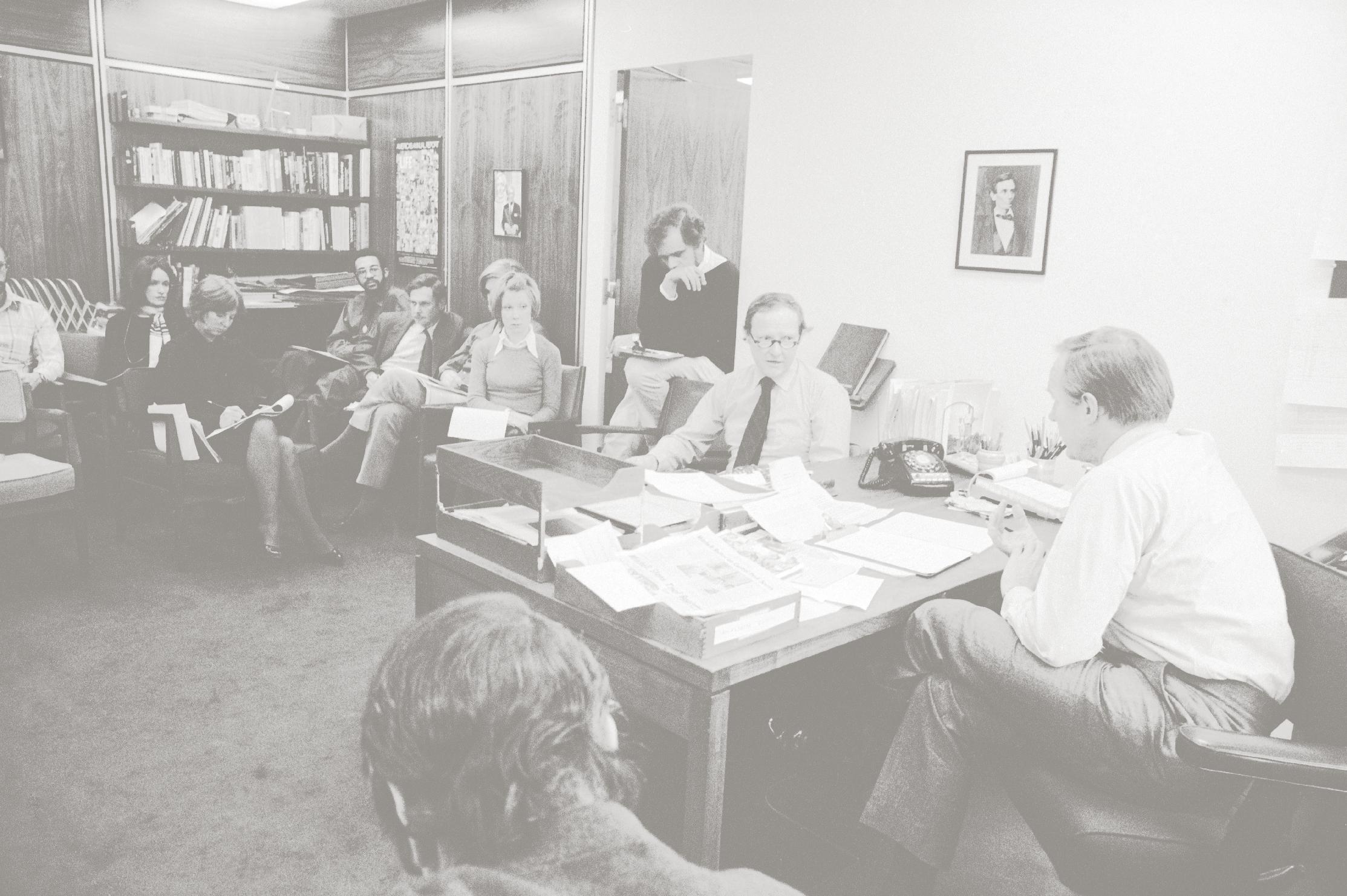

THE FIRST PEOPLE staff meeting in the office of founding managing editor Dick Stolley (behind desk), March 1, 1974 (left).

SPORTS ILLUSTRATED MANAGING editor Gilbert Rogin (left) and assistant managing editor Ken Rudeen review layouts, April 23, 1981 (above).

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS THE FIRST SIX DECADES 101

TENANT MAP

Occupants of the Time & Life Building: The Early Years

sublet (presumably by Time Inc.) 43, 45, 47

The Rockefeller Foundation 41

Westinghouse Electric Corp. 39

Blackwood Hodge + M. G. Kletz + Reed Roller Bit 37

sublet (presumably by Time Inc.) 35

corporate publicity; Time/Life International; FYI ; 33 telephone room; archives

Life market research; Life advertising sales 31

Life editorial 29

sublet (presumably by Time Inc.) 27

Time editorial; wire room 25

Time publishing; P.D.I.; New York subscriptions 23

sublet (presumably by Time, Inc.) 21

Sports Illustrated publishing; House & Home ; 19 tear sheets; Architectural Forum editorial & sales sublet (presumably by Time, Inc.) 17

Donahue & Coe, Inc. 15

N. W. Ayer & Son 11

sublet (presumably by Time Inc.); office of the building 9

American Petroleum Institute 7

American Cyanamid Company 5

Shell Oil Company 3

(retail) Manufacturers Trust; 1 La Fonda Del Sol Restaurant; Russell Stover; American Airlines; Custom Shop Shirtmakers; Union News; Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 102 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

The Hemisphere Club

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS THE FIRST SIX DECADES 103 48–49 Hemisphere Club, Tower Suite 46 Whitney Communications 44 General Aniline & Film Corp. 42 The Rockefeller Foundation 40 Pan American International Oil Company 38 McCann-Erickson Inc. 36 mechanical floor 34 Time Inc. corporate executive; Time Inc. corporate production 32 sublet (presumably by Time Inc.) 30 Life publishing; Life editorial; Life circulation; general promotion 28 Life picture collection; photo lab; Life circulation; art department 26 comptroller/editorial reference 24 cable desk & overseas bureaus; teletype; Time editorial; legal; duplicating; U.S. and Canada News Service 22 central services; personnel; Time letters; medical; staff relations 20 Sports Illustrated editorial; ad promotion; central lists 18 Fortune publishing and editorial; Architectural Forum editorial & sales 16 Donahue & Coe, Inc. 14 Gannett advertising sales; Newhaven Corp. 12 Curtiss-Wright Corporation 10 mechanical equipment floor 8 New York advertising sales; auditorium 6 American Cyanamid Company 4 American Cyanamid Company 2 Shell Oil Company John Hay Whitney, media mogul, Whitney Communications Corporation The Rockefeller Foundation’s initiatives—such as the International Rice Research Institute— aim to identify need and alleviate suffering worldwide. Members of the press and the American Petroleum Institute— the trade organization for the oil and natural gas industry— discuss literature for an automobile tour promotion, 1965.

Shell Oil gas pump

From the outset, bragging rights as 1271’s second-most visible tenant (next to the publisher/co-owner itself) went to La Fonda del Sol, Rockefeller Center’s biggest restaurant, which boasted 400 seats spread over seven dining rooms arrayed along the lobby’s western side. It was owned by Restaurant Associates, itself a 1271 tenant, which also ran the Tower Suite up on 48. For several years, the Tower Suite reigned as the city’s highest restaurant, open only for dinner. Its quarters doubled as the home of the members-only Hemisphere Club from noon to 4 p.m. Both establishments featured chairs designed by Charles Eames. Oddly enough, with no elevator service above the 46th floor, the top-of-tower acreage was originally written off as suitable solely for storage space, until a small lift rising two stories was providen tially installed just before the tower opened. Ground-level tenants included Custom Shop Shirtmakers, the bank Manufacturers Trust, famed candy purveyor Russell Stover, and Merrill Lynch. There was a similarly eclectic mix one floor down in the concourse that included one of the nation’s largest barbershop chains. Over the succeeding decades, as Time Inc. expanded via a mix of new publications and a fast-growing cable TV arm, it took over the bulk of the building. As fate would have it, one of the last non-Time tenants, up on the 46th floor, was the final remnant of investment bank Lehman Brothers, which famously went bankrupt in 2008.

THE HEMISPHERE CLUB initiation fee set executives back $1,000. Annual dues were $360 (left).

RESTAURANT ASSOCIATES PRESIDENT Jerome Brody (seated center) enjoys the food at his company’s restaurant, La Fonda Del Sol, July 1960 (below).

FOOD PREP AT La Fonda del Sol. The restaurant’s graphic look is courtesy of famed architect and designer Alexander Girard (right).

104 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS THE FIRST SIX DECADES 105

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 106 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

AN AERIAL PHOTOGRAPH of midtown taken in February 1969 shows the excavated pits south of the Time & Life Building ready for XYZ Buildings development (left).

A RENDERING OF the Time & Life and XYZ Buildings site plan shows the precinct as a cohesive unit (top).

A WIDE-ANGLE PHOTO essay declares, “Rockefeller Center . . . has burst its boundaries and established a handsome 48-story bridgehead on the west side of Manhattan’s Avenue of the Americas.” Life, April 4, 1960 (above).

Western beachhead

When Rockefeller Center and Time Inc. trumpeted plans to build their tower at 1271 Sixth Avenue in 1956, they touched off a construction explosion that was to reverberate up and down the avenue for decades. At the time, Architectural Forum magazine credited the proposed tower with establish ing a “decisive beachhead across the avenue [that] clears the way . . . [and] opens a wide frontier for an expanding city.” In his book New York 1960, architect Robert A. M. Stern noted it had “profound repercussions on the westward expansion of midtown and the future of Sixth Avenue.” Today, Sixth Avenue alone boasts more acres of modern office space than do most entire American cities.

Two years after Time & Life’s opening, the Equitable Life Assurance Society cut the ribbon on its new headquarters across West 51st Street to the north. Not to be outdone in its own backyard, Rockefeller Center upped the ante in 1963, uncorking plans to erect not one but a trio of pinstriped—two white, one pink—block-long towers, dubbed the XYZ Buildings, running south along Sixth Avenue from West 50th down to 47th Street. All were designed by Michael M. Harris of Harrison, Abramovitz & Harris. Site demo lition work for the first and largest of these—the 54-story, 2.1-million-squarefoot Exxon Building—began in 1968. Following on its heels to the south came McGraw-Hill, opening in 1972, and Celanese a year later. To the north, both Sperry Rand and Burlington Industries built headquarters, and Hilton Hotels and Rockefeller Group erected a blue-glass behemoth with 2,200 rooms kitty-corner from “Black Rock,” CBS’s imposing new headquarters, which spanned the block along Sixth Avenue from West 52nd to West 53rd Street.

Two decades after his company had touched off the land rush, Time Inc. chairman Andrew Heiskell reflected on those intervening years, noting:

“This is a tough city that tests your character but offers unparalleled opportu nities for individuals and corporations alike.” By then, Time had passed the test with flying colors, with new magazines, a cable TV outfit called Home Box Office, and other business arms all joining the Time Inc. fold, pushing the headquarters head count to nearly 2,500.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS WESTERN BEACHHEAD 107

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 108 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

WITH THE WAY paved by pioneering Rock-Time Inc., the westward expansion of midtown continues with CBS’s headquarters at 51 West 52nd Street, known as “Black Rock” for its dark granite façade (left).

HERE COMES THE neighborhood! The western expansion continues with the Equitable Life Assurance Building (left of Black Rock), which was completed shortly after the Time & Life Building in 1960; in the background at right is the New York Hilton; and in the foreground at right, ABC TV’s headquarters is underway at 1330 Avenue of the Americas, October 20, 1964 (right).

Powerful as all that new development proved to be in boosting employ ment, tax revenues, and the city’s global zeitgeist, it still proved no match for the ebbs and flows of the U.S. economy or the vicissitudes of urban life. By the 1970s, New York City had hit its roughest patch in decades, as crime soared, public infrastructure—from bridges to subways to highways—crum bled, schools failed, and companies and citizens fled for leafier environs. Truth be told, Time Inc., McGraw-Hill, and many others had eyed the city’s exits as far back as the 1950s. Ultimately, they stayed put, but many others— including IBM, General Foods, and Reader’s Digest—decamped. The city officially plumbed bottom in 1978, when New York turned to Washington for emergency funding to stave off bankruptcy, only to be turned down flat by President Gerald Ford. The five-word headline in the next day’s Daily News

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS WESTERN BEACHHEAD 111

New York took charge of its fate, cleaning up its fiscal act by leveraging assets and calling a halt to damaging short-term borrowing. The national economy emerged from the era of 1970s stagflation and the city came up along with it. The new prosperity was a thin veneer over racial tensions and, increasingly, a haves versus have-nots class struggle. In the late 1980s, another crisis hit town: crack cocaine and an attendant spike in crime. Tellingly, Time printed a brokenhearted twist on Milton Glaser’s famous “I Love NY” logo on its cover in September 1990, with the tagline “The Rotting of the Big Apple.” Back then, few places reeked of that decay quite like the neighborhood one block west of 1271 Avenue of the Americas. Times Square had become infamous for its proliferation of peep shows and porn shops. There, long-sputtering efforts at a cleanup finally began to yield results, most famously with Disney’s 1993 decision to make over the big New Amsterdam Theatre on West 42nd Street into, of all things, a family entertainment center.

By decade’s end, blue-chip businesses including publisher Condé Nast, accounting giant Ernst & Young, law firm Skadden, Arps, and global news service Reuters had all announced plans to settle into new Times Square towers. And topping things off, Broadway attendance for the 1998–1999 season hit a record 11.6 million. Out on Sixth Avenue, the availability of office space slid to 3.8 percent of the total stock, the lowest in midtown.

THE WALT DISNEY Company’s investment in Times Square real estate in the 1990s was the commercial development boost city leaders were looking for, although many New Yorkers were ambivalent about the Disneyfication of their town.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 112 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS WESTERN BEACHHEAD 113

Time triumphant

When Henry Luce moved his company into 1271 Sixth Avenue early in 1960, magazines were still the big thing, accounting for 86 percent of corporate revenues. A decade later, that share had shriveled to half, as faster-growing businesses outpaced stalwarts including Time, Fortune, Life, and even the relatively new Sports Illustrated

Crowds massed out in front of 1271 in 1962, hoping to glimpse John Glenn and the six other Project Mercury astronauts on the scene to celebrate a long string of Life cover stories.

In the dead of winter in 1964, Sports Illustrated released its first “Swimsuit Issue.” Newsstand sales rocketed. So did subscription cancellations.

died at home in Phoenix, Arizona on February 28, 1967, 38 years— nearly to the day—after the demise of Briton Hadden, his erstwhile classmate, kindred spirit, and cofounder. To mark the moment, Time ended its unbreach able ban on running cover stories about the deceased in the March 10, 1967, issue.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 114 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

1960 1961

In 1968, the growth story shifted to the company’s big thrust into book publishing, as it snapped up venerable Little, Brown and Company and expanded TimeLife Books.

In 1972, Money became the first addition to the magazine roster since SI ’s 1954 debut, but that year also brought a major setback.

In the final issue of the year, Life quietly announced that it was suspending publi cation—a victim of another picture-centric medium, television.

At the World Chess Championship in Reykjav í k in 1972, American grandmaster Bobby Fischer faced Russian foe Boris Spassky. Both insisted on sitting in posh executive chairs designed in 1959 by Charles Eames for the Time & Life lobby. Two were flown in (and Fischer won, comfortably).

In the November 12, 1973, issue of the magazine, Time itself made news by breaking its 50-year run of no editorials with an impas sioned call for the resignation of President Richard Nixon. A special “The Healing Begins” issue nine months later, after Nixon’s resigna tion, racked up newsstand sales of 527,000 copies, the most ever.

In 1969, the Time-Life Exhibition Center just inside the tower’s north entrance opened the Man to the Moon show, which spilled out onto the plaza where crowds gawked at a 37-foot-tall model of the Saturn V rocket next to a 23-foot-long Lunar Module.

Meanwhile in 1972, in a little-noticed move, the company bought a small stake in a fledgling pay-TV operator that it rechristened Home Box Office. Three years later, HBO broke new ground, becoming the first network to broadcast via satellite. This gave Time Inc. a pioneer’s edge that it honed by creating dramatic content that drew hordes of new subscribers. HBO’s first-ever movie broadcast was the Henry Fonda–Paul Newman picture Sometimes a Great Notion

A year later, Life alum Dick Stolley started People, the company’s 14th magazine. It boasted a circulation of 1 million, but reviews were mixed, with William Safire of the New York Times lambasting it as “vacuous” and “demeaning.”

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS TIME TRIUMPHANT 115

1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974

In 1978, “Letters to the Editor” staffers counted cancellations at 187—a new Swimsuit Issue record—due to the revealing beach looks of models Maria João and Cheryl Tiegs, who famously sported a fishnet suit.

In 1987, Sports Illustrated special contributor George Plimpton followed up his decades-earlier stints pitching with the Yankees and quarterbacking with the Lions with “The Curious Case of Sidd Finch,” a joke for SI ’s April Fools’ Day issue that laid bare the inside story of Siddhartha Finch, Buddhist monk turned Mets 168 mph fastballer.

longtime quarters on 1271’s 15th and 16th floors, HBO decamped to a building of its own, down Sixth Avenue on the corner of West 42nd Street. There it went on to bring the world such shows as Sex in the City, The Sopranos, and Game of Thrones

In 1986, more than 50 years after agreeing to form Rock–Time Inc. to jointly build and own 1271 Avenue of the Americas, Time Inc. sold its stake back to Rockefeller Group.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 116 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986

In 1996, the company got even bigger, swallowing Turner Broadcasting System, Inc., founder in 1980 of Cable News Network. For four years beginning in 2002, CNN’s American Morning news show aired from 1271.

Three Greenpeace demonstrators scaled the building early one morning in 1994, unfurling a 50-foot banner protesting Time ’s use of chlorine-bleached paper.

America’s bestselling news magazine got its own star treatment in the winter of 1991, when an 18-person camera-wielding platoon from cable network C-SPAN spent five days roaming Time ’s lair, chronicling the birth of one issue.

In what many called Time Inc.’s biggest move since its founding, the company made a deal in 1989 that ranked as a literal name-changer. It merged with the entertainment company Warner Communications, a longtime Rockefeller Center neighbor, whose hold ings included Warner Bros. Pictures. The combined entity, Time Warner, overnight became the world’s largest media company, with $10 billion in revenues.

rumor that the Tower Suite restaurant on the 48th and 49th floors was the first to have servers greet diners with “Hi, my name is Jennifer, and I’ll be your waiter tonight.”

In the early 1990s, the company continued to add new titles to its magazine roster, including Martha Stewart Living, Entertainment Weekly, and Vibe.

In the early 1990s, the company continued to add new titles to its magazine roster, including Martha Stewart Living, Entertainment Weekly, and Vibe.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS TIME TRIUMPHANT 117

1992 1993 1994 1995 1996

Mad Men moved to the Time & Life Building. Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce spread its wings on 34, Time Inc.’s old executive floor, but 1271’s lobby, plaza, and views got their own star turns. The New York Times praised Mad Men ’s new home as the “perfect location for an upstart firm nurturing an image of being cutting edge.” The New York Observer predicted the new “tenant” would make the building “hip.”

In 2010, the ad agency at the center of the hit television show

Time Inc. was spun off from Time Warner in 2014.

The publisher was acquired by Des Moines, Iowa–based Meredith Corporation in January 2018 for $2.8 billion.

In 2017, Time Inc. moved downtown to 225 Liberty Street.

daydreaming Life photo editor laboring at 1271 in the magazine’s waning days.

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 118 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

WALKING THE HALLS AT THE TIME & LIFE BUILDING

Some only dropped in. Others stayed decades: boldfaced names and copy-desk grammarians, models and moguls, poets and astronauts, porters and sculp tors, golfers and architects. They were the people who filled the pages, drew in the readers, and made the money that powered the world’s largest maga zine publisher during its half-century-plus run at 1271 Avenue of the Americas.

Calvin Trillin wrote for Time for several years in the early 1960s. He overlapped with another famous jour nalist, John Gregory Dunne, who spent five years with Time —long enough to warn his wife, Joan Didion, who started as a columnist for Life in 1970, to gird herself for the publication’s “perniciously mindless editing.” She heeded his advice and quit soon thereafter.

In the early 1960s, John McPhee wrote for Time ’s “Show Business” section.

In 1969, U.S. poet laureate and novelist James Dickey judged that year’s Time Inc. employee poetry contest from his home in Columbia, South Carolina.

Over the years, Time wrote reviews of the various iterations of the company’s employee cafeteria. She frequently complimented the prices; the food, less often.

Frank Deford, who once credited Sports Illus trated with making sportswriting “respectable,” joined that magazine as a staff writer in 1962. He followed a long line of distinguished contributors including A. J. Liebling, who penned a piece on the famous Manhattan boxing gym Stillman’s; Wallace Stegner, who waxed eloquent on Yosemite National Park; William Faulkner, who wrote about the 1955 Kentucky Derby; and John Steinbeck, who delved into his interest in various sports.

“Authors, Authors,” a regular one-page feature appearing in Time Inc.’s weekly in-house newspaper, FYI, chronicled recent books penned by Time Inc.-ers. In the summer of 1989, for example, it listed 14 such volumes. Among them were a biography of legend ary journalist Ida Tarbell and a book of photos by one

(CLOCKWISE, FROM TOP LEFT) Frank Deford—who played for the Globetrotters’ rivals, the New York Nationals, in 1973—in the Time Inc. office; John Steinbeck, who famously penned a “non-essay on sports” for Sports Illustrated in 1965; jockey Eddie Arcaro and his interviewer, William Faulkner, at the Derby, 1955; Sophia Loren cuddling “Eisie”; Time reporter Calvin Trillin interviewing Freedom Rider John Lewis as he boards a bus for Montgomery, 1961; Alfred Eisenstaedt in the photo archives, Time & Life Building, 1986.

of Life ’s original photographers, Alfred Eisenstaedt, who had 90 Life covers to his credit, not to mention his famous shot V-J Day in Times Square of a sailor ecstati cally embracing a young woman. In 1961, he spent two weeks shadowing Sophia Loren for a Life profile. She called him “Eisie” and said he looked like an obstetrician.

TIME TRIUMPHANT 119

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

HENRY R. LUCE

Laying the cornerstone for his company’s nearly completed headquarters in June 1959, Time Inc. editor in chief Henry R. Luce spoke less of the tower itself than what he saw it spawning. “It certainly will be heard from, across the nation and around the globe. And so, the Time & Life Building . . . will hatch new adventures in the permanent revolution which is the American dream, and the promise of freedom.”

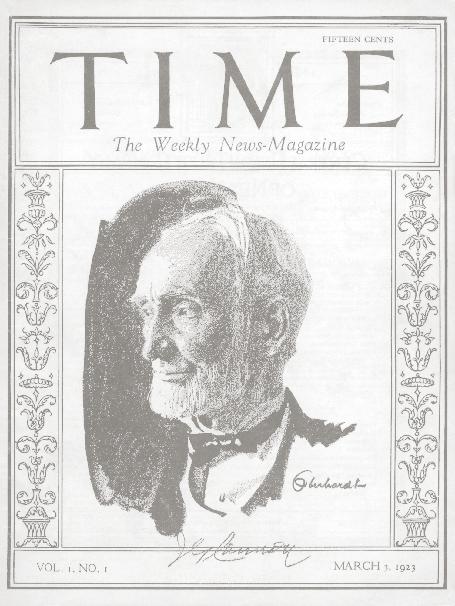

As the China-born child of a Presbyterian mission ary from Scranton, Pennsylvania, and cofounder at 23 of a magazine publisher that grew to be the world’s largest, Luce knew a lot about revolutions as well as the American dream. At 15, he arrived in New York en route to boarding school in Connecticut, where he quickly established himself as a star pupil, an editor of the school paper, and a close friend of Brooklyn-born Briton Hadden, with whom his fate would be inter twined for nearly 15 years. Both men moved on to Yale, where Luce served as managing editor of the college paper to Hadden’s chairman. In 1918, they agreed to someday launch their own magazine. In 1923, they quit their day jobs at the Baltimore News and debuted a 27-page issue of Time, with Hadden as editor in chief and Luce as business manager. In an unusual move, they agreed to switch roles annually. By the end of the following year, buoyed by the magazine’s combination of brevity, tight focus, and energetic writing, circulation

hit 70,000 copies, the company stood toe-deep in black ink, and Luce was still business manager.

On February 27, 1929, Time ’s sixth anniversary, Hadden died at the age of 31 after a lengthy decline, amid a growing rift with his longtime collaborator. Thus began Luce’s decades as the company’s undis puted leader. In one of his first moves as a solo act, Luce fulfilled a long-held dream in 1930 by launching a business magazine and vowing to deliver stories that would help his readers find success. Now, as a budding media mogul able to charge a princely $1 per copy for each Fortune issue, Luce upped the ante. He signed on Margaret Bourke-White as the company’s first full-time photographer, commissioned covers by famous artists including Diego Rivera, and lured top-drawer writers such as Archibald MacLeish and James Agee. In the early '30s, Luce went multimedia, producing a weekly radio show on CBS in which actors read the parts, and later targeting moviegoers with his March of Time news reels, shown in thousands of theaters.

In 1935, Luce married his second wife, playwright and journalist Clare Boothe. Two years later, Time Inc. launched Life, a photocentric magazine like one Boothe had once advocated for as a managing editor of Vanity Fair. Instead of the usual Luce-ian well-defined readership, Life embraced everybody—a mass audi ence hungry for the magazine’s trove of more than 200

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

120 PART II • TIME & LIFE ERA

HENRY R. LUCE and Briton Hadden in a detail from a photo of the Yale News board, 1920 (opposite top left).

TIME, VOL. 1, No. 1, March 3, 1923 (opposite top right)

HENRY AND CLARE Luce, Fairfield, Connecticut, 1936 (opposite left)

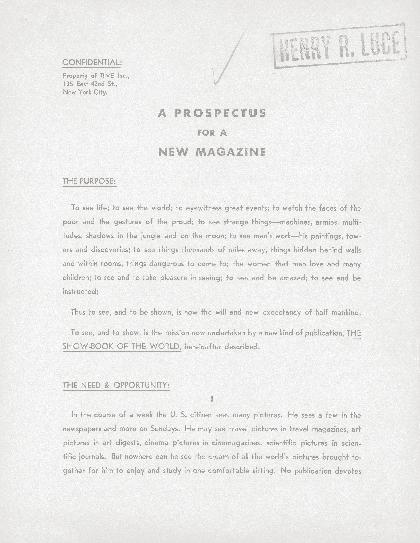

THE CONFIDENTIAL PROSPECTUS for Life describes the mission of the new publication as “to see and be amazed; to see and be instructed” (top left).

images each week. In Life ’s prospectus, Luce had prom ised “the biggest and best package of pictures for a dime.” Within a year, circulation topped 1.5 million. At its peak, it would exceed 8 million.

A man of strong opinions, a staunch Republican, and a true believer in America’s destiny to dominate, Luce lambasted President Franklin D. Roosevelt for everything from the New Deal’s manhandling of private enterprise to FDR’s reluctance to take up arms against the Nazis. After the war, as a staunch anti-Communist, especially in a Chinese context, Luce savaged Harry Truman for sacking General Douglas MacArthur in 1951, at the height of the Korean War. Luce went on to vigorously support the presidential candidacy of Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, who later named Clare Boothe Luce America’s ambassador to Italy.

In 1960, Senator John F. Kennedy came to the Time & Life Building for an audience with Luce and his staff. Crowds gathered to greet him. Unmoved, Luce endorsed Republican Richard Nixon, but still managed to earn a seat in the president’s box at Kennedy’s inauguration. On February 28, 1967, three years after announcing his retirement—and one day after the 38th anniversary of Briton Hadden’s death—Henry R. Luce died of a heart attack.

MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE’S MONUMENTAL photo of the Fort Peck Dam is the arresting cover shot on the first issue of Life (top right).

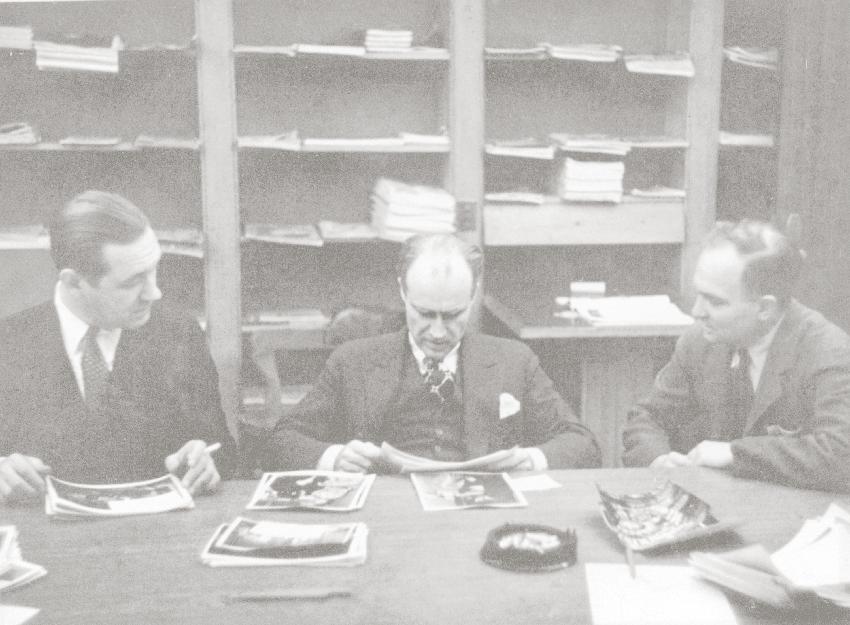

HENRY R. LUCE in a photo review with executives John S. Billings (left) and Daniel Longwell (right) at a Life meeting, 1936 (above).

HENRY R. LUCE, 1960 (right)

1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS

TIME TRIUMPHANT 121

TOWER REBORN

Part III

Decisions to make

In recent years, many people have played signif icant roles in the reimagining of 1271 Avenue of the Americas, the 48-story, 2.1-million-squarefoot tower that first unlocked its revolving doors in 1959 to a parade of the great, the good, and tens of thousands of others. Now, four years after the last tenants departed and the physical trans formation commenced, the erstwhile Time & Life Building has reopened to new generations of tenants. This is the story of that modern miracle, told by the key people who made it possible.

THE BIGGEST ADDITION on the tower’s Sixth Avenue face is the stainless steel canopy that flares up from 1271’s wraparound extension back toward the tower, visually linking the two; at the rear of the breezeway is a notable subtraction: that part of the extension had been clad with limestone and is now curtain wall.