HEALTH, COMFORT AND WELLBEING IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT

The impact of biophilia in offices on workers’ health & wellbeing

BENV0027 VXGC7

1 . 0 I N T R O D U C T I O N

1 . 1 A I M S

1 . 2 L I T E R A T U R E R E V I E W M E T H O D S 1 . 3 S C O P E

2.0 PART ONE: CRITICAL REVIEW OF HEALTH, COMFORT AND WELLBEING FACTORS RELEVANT TO OFFICES

2.1 DEFINING HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN OFFICES

2.2 FACTORS AFFECTING HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN OFFICES

3.0 PART TWO: BIOPHILIA EXPOSURE, SIGNIFICANCE AND RECOMMENDATIONS

3.1 DEFINING BIOPHILIA & ITS SIGNIFICANCE IN OFFICES 3.2 BIOPHILIC DESIGN 3.3 RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE EXPOSURE OF BIOPHILIA & ITS IMPACTS ON HEALTH AND WELLBEING

4.0 PART THREE: CONCLUSIONS AND IDENTIFICATION OF KNOWLEDGE GAPS

5.0 PART FOUR: BLOG POST

6.0 REFERENCES

i C O N

T E N T S

Building for health and wellbeing bestows occupants the opportunity to benefit on multiple fronts. The dynamic of working spheres in the built environment is paramount for the productivity of individuals and the success of companies. Studies have proven that the quality of indoor environments affects occupants’ health, wellbeing, and productivity (Samet and Spengler, 2003). More relevantly, the quality of office indoor environments in which on average, full time workers spend a third of their day - 5 days a week in, occupies an essential role in promoting cognitive function, productivity, health, and wellbeing (Allen et al., 2015; Allen et al., 2016; MacNaughton et al., 2017). In a report recently conducted by the World Green Building Council (2014), statistics show that approximately 90% of business costs go into staff, 9% into property/rental costs, and the remaining 1% into energy costs. With people as the biggest asset and most valuable component in enterprises, it is with reason to address and question the places that are responsible in facilitating environments for human health, wellbeing, development, relationships, and social flow.

1 . 1 A I M S

The aim of this report is to assess the main factors affecting health, comfort, and wellbeing in offices before proceeding to address the impacts of biophilia in offices on worker’s health and wellbeing and providing recommendations of biophilic exposures.

1 . 2 L I T E R A T U R E R E V I E W M E T H O D S

In this regard, the report branches across a diverse field of literature that puts relevancy and context to the research at hand. The literature methodology adopts two approaches that help inform this study. Firstly, a snowball approach was undertaken through primarily reviewing Nigel Oseland’s recently published Beyond the Workplace Zoo, where the author addresses numerous environmental and psychological factors responsible in influencing health, comfort, and wellbeing of workers in offices. This also covers a high quality of reading material on biophilia, for which they are reviewed in the upcoming chapters.

D U C T I O N

1 . 0 I N T R O

01

Secondly, the same approach was adopted for Derek Clements-Croome’s review on creative and productive workplaces, where the author addresses numerous environmental factors on its influence and effectiveness in the workplace. By doing, the recent literature directs to state-of-the-art knowledge that assesses workplace environments through multiple criteria and in various scenarios.

Thirdly, a database base search was conducted through the Web of Science collection to further extend on research relevant for this report. The inclusion search criterion was based on the relevancy of environmental factors affecting health and wellbeing in office design, biophilia in office design, health, comfort, and wellbeing of workers in offices, and individual’s personality, psychology and physiology in built environment settings compared to that of nature. Through doing so, more significant insight was gained on the topic of offices in relation to the exposure of biophilia.

1 . 3 S C O P E

The current research is built on the premise that through understanding the main factors affecting health and wellbeing of occupants in work spheres, is to be a better understand the significance of biophilia and its impacts in working environments, and in effect outline potential exposure recommendations that better the development of organisations and people. Consequently, the report is structured in parts, and unfolds as follows:

• Part One: Critical review - Defining health, comfort, and wellbeing in relevance to office settings and reviewing building related and non-building related factors affecting health and wellbeing in offices.

• Part Two: Biophilia exposure – Defining biophilia and its significance in offices, identifying measures of biophilic design, and providing recommendations on the exposure of biophilia with its impacts on health and wellbeing.

• Part Three: Conclusion – providing a summary of key points found through the research and highlighting knowledge gaps and limitations revealed within the scope of study.

• Part Four: Blog Post – Succinctly summarising parts one and two of the report and providing recommendations for designers on biophilia.

02

2.0 PART ONE: CRITICAL REVIEW OF HEALTH, COMFORT AND WELLBEING FACTORS RELEVANT TO OFFICES

2.1 DEFINING HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN OFFICES

In order to understand the terms ‘health’ and ‘wellbeing’ in office settings, it is important to first define those terms regarding components and functional relationships that include both society and the natural environment, as well as the built environment.

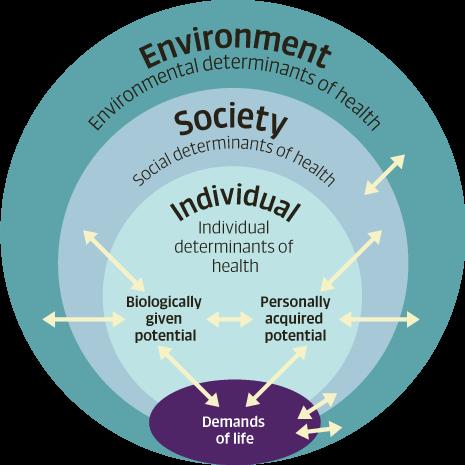

A concept that represents this for instance, is the Meikirch model of health. The model views aspects of health with consideration of people at the center. It posits that health ‘ is a state of wellbeing emergent from conducive interactions between individuals’ potentials, life’s demands, and social and environmental determinants’ and ‘occurs when individuals use their biologically given and personally acquired potentials to manage the demands of life in a way that promotes well-being’ (Bircher and Kuruvilla, 2014) where ‘demands can be physiological, psychosocial, or environmental, and vary across individuals and contexts, but in every case unsatisfactory responses lead to disease’ (Bircher and Hahn, 2016). Figure 2.1 expands on this by illustrating the Meikirch model of health as a non-linear system, meaning factors that determine health may be interlaced but do not act in proportion to the strength of one another. This subsequently, provides insight into the positioning of office workers’ health and wellbeing in the built environment.

03

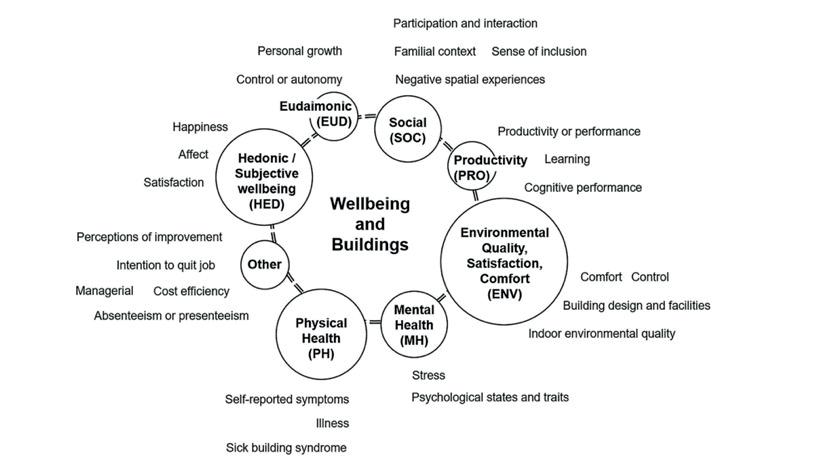

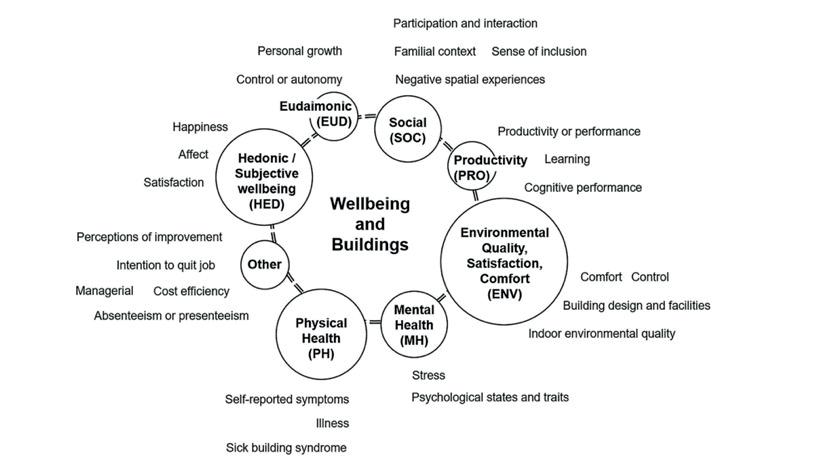

It is also worth recognising how health may be interlaced with wellbeing. The Constitution of the World Health Organization (1946) defines health as a state of ‘complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. Wellbeing in the latter, expands on mental capital that encompasses cognitive and emotional resources and more elaborately, mental wellbeing refers to ‘individuals’ ability to develop their potential, work productively and creatively, build strong and positive relationships with others, and contribute to their community’ (Beddington et al., 2008). To put this in context of the built environment along with identifiable parameters, Hanc, McAndrew and Ucci (2018) illustrate a conceptual framework that expands on themes and subthemes in wellbeing and buildings, as seen in figure 2.2. While the presented framework is based on the scope of the research, with the circle sizes proportional to the number of papers examined that mention the themes, it is a finding worth emphasizing as it highlights relations among different factors in wellbeing and buildings reviewed in various studies.

In other words, health and wellbeing, generally and in office settings, are a product of complex interactions among factors of environmental, physiological, psychological and personal notions along with organisational and universal resources. These factors pose the ability to affect people in various ways. Section 2.2 will proceed to review factors affecting health and wellbeing in offices.

04

2.2

FACTORS AFFECTING HEALTH AND WELLBEING IN OFFICES

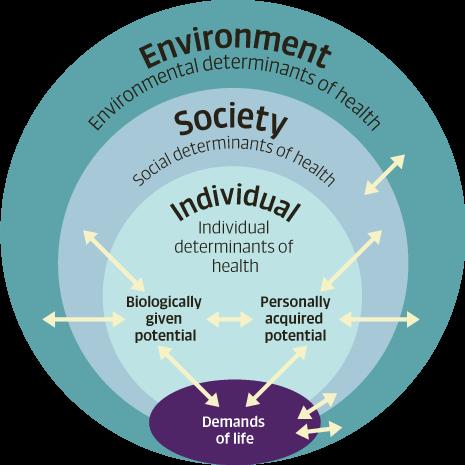

While it has been covered that health and wellbeing are influenced by numerous determinants, it is implicit to realise how work occupies a central role. It shapes an individual’s life opportunities, provides resources, and benefits, and impacts personal feelings and physical outcomes. Working conditions – whether environmental, physical, or psychosocial, may contribute to physical illness or mental distress (Sorensen et al., 2021). Figure 2.3 explores the determinants of workers’ health and wellbeing more broadly than that encompassing an office scale. The model illustrates pathways that are influenced by enterprise as well as personal characteristics. It is important to note that there remains limitation within this framework; determinants of health and wellbeing are dynamic, complex systems with multiple interactions and not all factors are captured in this representation.

05

While health and wellbeing are a product of numerous tangible and in-tangible contributions, building related environmental qualities in the workplace constitute hygienic factors that are a basic human need, and hold the capacity to directly affect people’s health welfare. Likewise, non-environmental building and non-building related factors also play an equally important role in how worker’s feel and are affected by their workplace. While these factors are several, a few primary ones are listed as follows:

Environmental factors:

- Indoor Air Quality & Ventilation

- Thermal Comfort

- Lighting & Daylight

- Acoustics & Noise

Non-environmental building related factors:

- Interior Design

- Biophilia & Views

Non-environmental, non-building related factors:

- Environmental Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Personality Theory

- Motivation Theory

- Inclusivity & Diversity

Table 2.1 serves an overview of the impacts these factors have on workers’ health and wellbeing in offices.

06

Factors Affecting Health & Wellbeing

Indoor Air Quality & Ventilation

Key Findings

Poor air quality can contibute to the transmission of infectious disease and cases of respiratory illness, allergies, asthma and increase the likelihood of sick building syndrome.

High levels of CO2 have a negative effects on memory performance, subjective workload and perceived fatigue.

Supporting References Limitation / Bias / Argument

Thermal Comfort

High levels of CO2 have a negative effect on decision making performance.

behaviour, where lower temperature can lead to aggression, while higher temperature can lead to both apathy and aggression affecting business decision making.

Motivation and performance improve when occupants are thermally comfortable. Warm discomfort has more negative effects on both attributes than cold discomfort.

Subjects’ heart rate, respiratory ventilation, end-tidal partial pressure of CO2

oxygen saturation decreases in a room temperature of 30°C vs. 22°C, implying negative affects on health and work effort.

Light of different colours affects blood pressure, pulse, respiration rates, brain activity, and biorhythms.

Light conditions that facilitate positive cognition.

Varying levels of daylight intensity, colour, and hue, yield a good working environstimulation.

(Fisk, 2000) (Maula et al., 2017) (Satish et al., 2012)

(Cao and Wei, 2005)

5 out of 10 of the studies reviewed by the source took place in atypical settings - bias estimates of potential respiratory illness.

Experiment focused on tasks with high concentration and eliminated noise. Results cannot be generalised in cases of teamwork.

Questions the extent to which outdoor air supply can be reduced.

Study suggests that temperature is only one of three weather variables affecting people’s mood, daylight and length of nightime also play a role.

(Cui et al., 2013) (Lan et al., 2011)

The change of human performance could better be explained by change of motivation than the change of air temperature.

Small sample size (N=12).

Lighting & Daylight

People in high illumination spaces of around 1000 lux are more inclined to sustain attention.

Lighting levels raised from 300 lux to 2000 lux allow for an increase in productivity.

Bright light exposure prompts better mood, vitality and alleviating distress.

(Tanner, 2008)

N/A

(Knez & Kers, 2000)

(van Bommel & van den Beld, 2004)

Can yet convey different responses.

in dynamic may not result in the same outcome.

(Zhang et al., 2020)

(Kerkhof & Licht, 2002)

(Partonen & Lönnqvist, 2000)

May cause discomfort.

May cause discomfort.

May cause non-visual effects such as melatonin suppression, heart rate and alertness variations.

07

Factors Affecting Health & Wellbeing

Acoustics & Noise

Key Findings

Sounds of nature aid physiological stress recovery.

Supporting References Limitation / Bias / Argument

Interior Design

25% of noise perception is attributed to sound level while 75% are from personal and psychological factors, with 65% of variance in work performance, concentration and speech interference, being personal.

spaces for: choice, collaboration, concentration, creativity, comfort, control,

care, co-location and co-creation. Elsewise, health and wellbeing is compensated for.

Exposure to natural settings relieves occupant’s stress.

Attention Restoration Theory proposes that nature is able to reduce mental fatigue and improve concentration, by restoring directed attention.

(Alvarsson, Wiens and Nilsson, 2010) (Oseland and Hodsman, 2018)

Study used short durations of environmental sounds, which limits the generalizability of the results.

Limitation on how acoustic resolve noise issues.

(Oseland, 2022) (Usher, 2018) Needs to designed adequately to avoid poor conceptions of an open interventions on saving space and costs.

Biophilia

& Views

Environmental Psychology

After having exposed subjects to 4-6 days of backpacking in the wilderness, performance on a creativity, problem-solving task increased by 50%.

Natural environments (forests in particular) promote lower concentrations of cortisol, lower pulse rate, lower blood pressure, greater parasympathetic nerve activity, and lower sympathetic nerve activity compared to city environments.

Psychological processes cause different people to perceive the same environment differently, enabling different responses at different times.

The concept of behavioural settings expands on people’s behaviour through pre-conceived social etiquette associated with a particular environmental setting.

of sync with human evolution, consequently not meeting inate human needs, and performance.

(Beil and Hanes, 2013) (Kaplan, 1995) (Atchley, Strayer and Atchley, 2012) (Park et al., 2009)

Small sample size (N=15).

Proposed that certain types of natural stimuli may elicit responses that are not restorative.

Use of electronic technology was prohibited - there is an inability to determine if the results were solely from exposure to nature.

Although the study conducted short-span exposures to stimuli (approx. 30 min total of viewing and walking), outcomes of other natural settings may differ to that of forests.

(Lewin, Heider and Heider, 1936) (Barker, 1968)

interpreted differently.

Responses to workplace settings may lack ecological validity.

Evolutionary Psychology

Preferences of work environments are

The savanna hypothesis implies settings of natural landscapes or settings provide people with comfort during stressful and

(Oseland, 2022) (Chatterjee, 2014)

The survival of the human species implies the capability to adapt and adjust to changing environments.

There is a research gap on landscape preferences. The savanna hypothesis alone cannot serve as an ideal principle.

08

Factors Affecting Health & Wellbeing Key Findings

Introverts prefer calmer and subtle workspaces while extroverts prefer stimulating environments.

Supporting References Limitation / Bias / Argument

Personality Theory

Introverts and extroverts need different magnitudes of stimulation. People perform better when they are stimulated, in turn this increases levels of arousal.

(Oseland, 2022) (Yerkes and Dodson, 1908)

Causes implications in task performance and collaboration when preferences are not met.

Too much stimulation can lead to stress, while under-stimulation leads to lethargy and fatigue.

Motivation Theory

For performance to reach maximum capacity and direct motivation, fundamental needs of self-actualisation, esteem, belonging, safety and physiological health need to be met.

Workers should not have to declare personal circumstance and be made to feel like a special case for the workplace to meet their needs.

(Maslow, 1943) considered active motivators. Raises questions about how motivation can

(Usher, 2018)

Inclusivity & Diversity

Neurodiverse people recognise certain designs as over- or under-stimulating, confusing and stressful.

(Oseland, 2022)

Assumption that a homogenous design will suit everyone will cause discomfort, underperformance and worsen wellbeing.sider a range of typologies.

To further encompass the influences these factors, have on workers, the presented table in table 2.2, serves as an illustration on three mental illnesses that can present symptoms of inconducive health and wellbeing impacts in the workplace.

Work-related symptoms of Depression

• Trouble concentrating

• Trouble remembering

• Trouble making decisions

• Impairment of performance at work

• Sleep problems

• Loss of interest in work

• Withdrawl from family, friends, co-workers

• Feeling pessimistic

• Feeling slowed down

• Fatigue

Work-related symptoms of Anxiety Disorders

• Feeling apprehensive and tense

•

•

Work-related symptoms of Burnout

• Becoming cynical, sarcastic and critical at work

• getting started once at work

• More irritable and less patient with co-workers, clients and customers

• Lack of energy to be consistently productive at work

• Tendancy to self-medicate with alcohol or drugs

09

3.0 PART TWO: BIOPHILIA EXPOSURE, SIGNIFICANCE AND RECOMMENDATIONS

3.1DEFINING BIOPHILIA & ITS SIGNIFICANCE IN OFFICES

To better expand on the exposure of biophilia within work spheres, one must first recognise what the term means and implies.

Most familiarised as the ‘innate human affinity to nature’ by Edward O. Wilson, biophilia encompasses numerous meanings. Wilson’s book titled biophilia (1984) introduces the term as ‘the innate tendency to focus on life and lifelike processes.’ Kellert, Heerwagen and Mador (2008) elaborate on this by defining biophilia as ‘the inherent human inclination to affiliate with natural systems and processes, especially life and life-like features of the nonhuman environment.’

They further propose that this tendency is biologically encoded in human beings as evolutionary processes proved it instrumental in enhancing physical, emotional, and intellectual health over the course of history. The authors explain how this has come to be by stating: “Most of our emotional, problem-solving, critical-thinking, and constructive abilities continue to reflect skills and aptitudes learned in close association with natural systems and processes that remain critical in human health, maturation, and productivity.” Crucially, Kellert and Wilson (1993) raise the notion that biophilia encompasses a human dependence on nature that extends beyond sustenance to also include the need for aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive, and even spiritual meaning, and satisfaction.

This sheds light on how the inclusion of biophilia in offices may be regarded as a necessity in terms of providing workers with their evolutionary and contemporary human needs. Not only it is limited to that, but biophilia engages involuntary attention that is effortless and does not require conscious focus, and thus allows for an individual to be restored and transformed by it without the realisation (Montgomery, 2013). It is even studied that the brain’s responses to biophilic landscapes involve neuronal ensembles that encode the feeling of pleasure and reward (Chatterjee, 2014). While it may be difficult to outline biophilic parameters and imposing variables on its impacts, it is evident that biophilia occupies an important role on the greater population and more precisely on worker’s health and wellbeing in offices.

10

BIOPHILIC DESIGN

There are various ways to include biophilic measures in office design and allow workers the health and wellbeing benefits attributed from its exposure. Firstly, it is important to identify the different types of biophilic measures that can be applied into built forms prior to recommending how they should be applied, to what extent and impacts this may have on worker’s health and wellbeing.

Kellert, Heerwagen and Mador (2008) propose two dimensions of biophilic design: Organic or Naturalistic and Place-based or Vernacular. The authors pose organic or naturalistic dimensions to be defined as ‘shapes and forms in the built environment that directly, indirectly, or symbolically reflect the inherent human affinity for nature.’ – where direct experience implies ‘unstructured contact with self-sustaining features of the natural environment’, indirect experience implies ‘contact with nature that requires ongoing human input to survive’ and symbolic experience implies ‘no actual contact with real nature, but rather the representation of the natural world’. On the other hand, they pose, place-based or vernacular dimensions to be defined as ‘buildings and landscapes that connect to the culture and ecology of a locality or geographic area.’- in relevance of biophilic exposure within the context of offices, this will be overseen in the presented recommendations.

Additionally, Browning, Ryan and Clancy (2014) organise biophilic design into three categories: Nature in the Space, Natural Analogues, and Nature of the Space – the authors direct that nature in the space implies ‘the direct, physical and ephemeral presence of nature in a space or place’, natural analogues imply ‘organic, non-living and indirect evocations of nature’ and nature of the space implies ‘spatial configurations in nature’. These allow for subthemes that direct how biophilic elements can be incorporated into the built environment.

Figure 3.1 illustrates biophilic attributes raised by Kellert, Heerwagen and Mador (2008) and design principles organised by Browning, Ryan and Clancy (2014) – further illustrating similar components within both propositions that direct the inclusion of biophilia in offices.

11

3.2

Direct Experience of Nature

• Light

• Air

• Water

• Plants

• Animals

• Weather

• Natural landscapes & ecosystems

• Fire

Indirect Experience of Nature Experience of Space and Place

• Images of nature

• Natural materials

• Natural colors

• Simulating natural light and air

• Naturalistic shapes and forms

• Evoking nature

• Information richness

• Age, change, and the patina of time

• Natural geometries

• Biomimicry

• Visual connection with nature

• Non-visual connection with nature

• Non-rhythmic sensory stimuli

•ability

• Presence of water

• Dynamic & diffused light

• Connection with natural systems

• Biomorphic forms & patterns

• Material connection with nature

• Complexity & order

Nature in the Space Natural Analogues

• Prospect & refuge

• Organized complexity

• Integration of parts to wholes

• Transitional spaces

•

• Cultural and ecological attachment to place

• Prospect

• Refuge

• Mystery

• Risk/Peril

Nature of the Space

3.3 RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE EXPOSURE OF BIOPHILIA & ITS IMPACTS ON HEALTH AND WELLBEING

Following this, a table on the recommended exposures, as raised by Kellert, Heerwagen and Mador (2008) and Browning, Ryan and Clancy (2014), is presented to encapsulate the types of biophilic design measures that can be applied in offices, and their subsequent impact on health and wellbeing (table 3.1). Although not all themes are covered, as this would be an extensive list, the following categories proved to be integral components of biophilia. Recommendations from the International WELL Building institute are also included as they provide a more guiding sense of quantitative measure that represents how biophilia can be more practically integrated in offices – implication from this however will, be discussed later on.

12

Kellert, Heerwagen and Mador (2008) Direct Experience of Nature

Biophilic Exposure Recommendation

Light Be directed deep into interior spaces by means of glass walls and clerestories, with ad-

Utilising the contrast of lighter and darker areas to experience light in motion.

Plants Include abundant, ecologically connected, and local rather than exotic and invasive species of plants.

Weather temperature, barometric pressure, and humidity.

Impacts on Health & Wellbeing

Contributes to comfort and satisfaction.

Reduces stress, contributes to physical health, improves comfort, and enhances performance and productivity.

Satisfying and stimulating.

Indirect Experience of Nature Images of Nature

Include photographs, paintings, sculpture, murals, video, and computer simulations.

Emotionally and intellectually satisfying.

Natural Materials Incorporate wood, stone, wool, cotton, and leather. Stimulating effects.

Natural Colours

Organised Complexity

Integration of Parts to Wholes

Introduce complex spaces through variability and diversity, and organised spaces through connection and coherence. and opportunities.

Integration of a central focal point that occurs either functionally or thematically.

Use of “earth” tones characteristic of soil, rock, and plants. Facilitates movement and Experience of Space and Place

Tends to people’s preference of settings.

Mobility Clear pathways and points of entry. Fosters feeling of security. Absence may cause confusion and anxiety.

Browning, Ryan and Clancy (2014) Nature in the Space

Visual Connection with Nature

Non-visual Connection with Nature

Non-rhythmic Sensory Stimuli

Include a visual connection that can be experienced for a minimum of 5-20 min. per day.

Improves mental engagement/ focus, and positively impacts attitude and overall happiness.

Favor nature sounds over urban sounds. Reduces systolic blood pressure and stress hormones.

Thoughtful selection of plant species for window boxes that will attract bees and butter-

Positively impacts heart rate, systolic blood pressure and sympathetic nervous system activity.

Material Connection with Nature

Complexity & Order

Natural Analogues Biomorphic Forms & Patterns

Incorporate biomorphic forms or pattern on 2D or 3D structures.

Choose real materials over synthetic variations.

Prioritize artwork and material selection, and schemes that reveal fractal geometries and hierarchies.

Observes view preference.

Decreases diastolic blood pressure.

Positively impacts perceptual and physiological stress responses.

13

Browning, Ryan and Clancy (2014) Nature of the Space

Biophilic Exposure

Prospect

Recommendation

Provide focal lengths between 6-30 metres depending on the depth of the space, and include high ceilings.

Health & Wellbeing Impacts

Reduces stress, boredom and fatigue.

Refuge Include spaces with low ceilings. Improves concentration and perception of safety.

Mystery Design for play with shadows and depths. Incorporate curving wall edges.

Outdoor Biophilia

A minimum of 25% of the project site area features accessible landscaped grounds or rooftop gardens.

Induces pleasure responses.

Standards (Biophilia I & IIqualitative | WELL Standard, n.d.)

X

Within the 25% at minimum, 70% are of plantings that include tree canopies.

WELL

Indoor Biophilia Application of wall and potted plants, covers X Water Feature

At least one water feature for every 9,290 m² in developments larger than that area being at least 1.8 m in height or 4 m² in area with ultraviolet sanitation or other technology. X

14

4.0 PART THREE: CONCLUSIONS AND IDENTIFICATION OF KNOWLEDGE GAPS

It has been covered that biophilia educes positive impacts on stress reduction, cognitive performance, emotion, and mood, and promisingly several other health and wellbeing contributions that were not reviewed in this study due to limitations within the adopted methodological approach. Even though international standards recognise building recommendations of biophilia in elements such as daylight, natural ventilation, and sound, it is necessary to point out that recommendations of biophilic exposure are better translated through qualitative measures rather than quantitative as they are also a representation of physical and psychological and not merely environmental contributions. As covered prior, biophilia is to provide the essence of ‘innate affinity to nature’ – and this cannot be quantified, doing so would only oppose its definitive nature.

There remain limitations on how to quantify ideal levels of its inclusion with a lack of information on its qualitative requirements, individual preference and impact, innate human needs, and the dimensions of its targeted context as variation. This yet means that, its contribution to the built environment can be fruitful and creative, and underpinning this through prescriptive measures in building standards would be very difficult and false to the essence of human evolution and the course of natural processes.

There is yet a knowledge-based limitation on how biophilia is affected by social, economic, and environmental determinants of health and wellbeing, and what effect they may have on conceptual and practical biophilic approaches. Even with an extensive account of variables, there remains a need for understanding more accurately the definitive impacts on health and wellbeing from qualitative biophilic exposures.

In cases where quantitative and qualitative exposures of biophilia are accounted for, conducive health and wellbeing become more definitive – and this is a challenge that continues to face scientists and researchers today. Verily, the variance in biophilia may occur at different scales during different times, but accounting for its diverse and broad measures allows it to be more accurately understood terms of its contributions to health and wellbeing, and hence its application in offices and other forms of the built environment.

15

Prior to becoming a designer, do you remember the kind of problems or issues facing society you wanted to solve with your creative ideas? They seemed straightforward to tackle and resolve then…yes? But that was a time before you got in architecture school and became aware of the complex systems and countless factors that make up what it means to have made a good design.

Much like the case there, health and wellbeing encompass more than the mere judgement of a vegan diet and a stress-free mind. They are products of components and functional relationships that include society, the natural environment and built environment at large. In other words, health is a state of wellbeing emergent from likely interactions between a person’s potential, meeting their life’s demands, and social and environmental factors (Bircher and Kuruvilla, 2014). Whereas wellbeing refers to a person’s ability to develop their potential, work productively and creatively, and build strong and positive relationships with others (Beddington et al., 2008). Now this prompts the question, how is this

16 5.0 PART FOUR: BLOG POST

chosocial, may contribute to physical illness or mental distress if they are

where the average full time worker spends a third of their day - 5 days a week in, occupies an essential role in promoting cognitive function, productivity, health, and wellbeing (Allen et al., 2015; Allen et al., 2016; MacNaughton et al., 2017). Studies have proven that daylight affects blood pressure, pulse, respiration rates, brain activity, and biorhythms (Tanner, 2008), thermal comfort yields higher levels of motivation and improves performance (Cui et al., 2013) and natural sounds can aid physiological be emphasize and contemplation on the word natural here.

The reason why people want to go bag packing around Europe is the in. Our human inclination to gravitate towards nature has much moretems and processes than the simple liking of it (Kellert, Heerwagen and evolutionary and contemporary needs as human beings and betters our types of biophilic measures can be applied into built forms, and in parperformance, and even emotion and mood (Browning, Ryan and Clancy, 2014; Kellert, Heerwagen and Mador, 2008). As raised from the research by Kellert, Heerwagen and Mador (2008) these could range from, including abundant, ecologically connected, and local species of plants to allow a direct experience of nature, or using “earth” tones with characteristics of soil, rock, and plants to manipulate an indirect experience of nature or even introducing complex spaces through variability and diversity, and organised spaces through connection and coherence to enhance the experience of space and place.

Instead of having workers squeeze onto stress balls all day, let themment - let biophilia challenge and guide the way you design for people, all for the bettering of people.

17

18 6.0 REFERENCES

19

20

21

VXGC7 BENV0027 HEALTH, COMFORT AND WELLBEING IN THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT HEALTH COMFORT AND WELLBEING ESSAY 10 JANUARY 2022