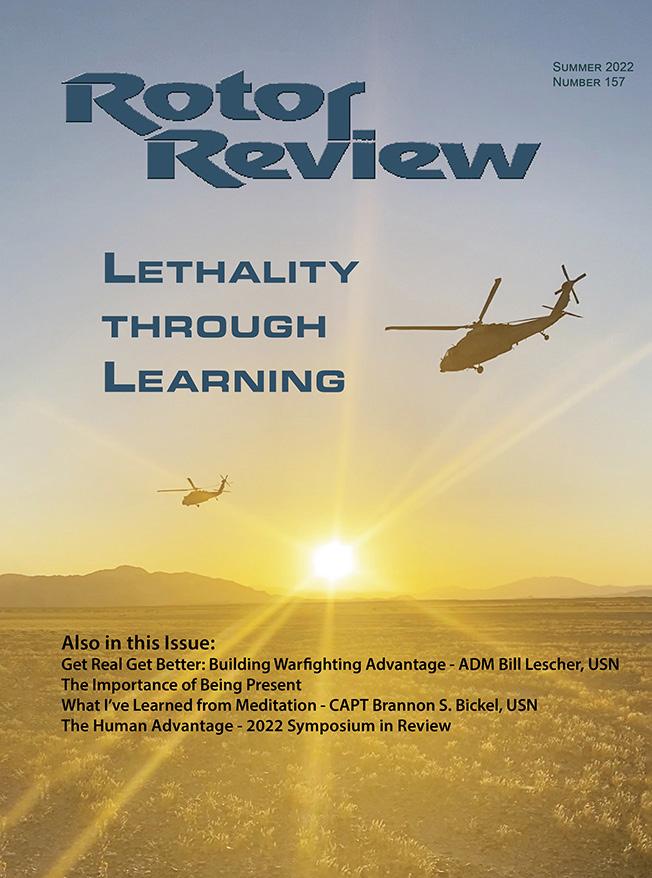

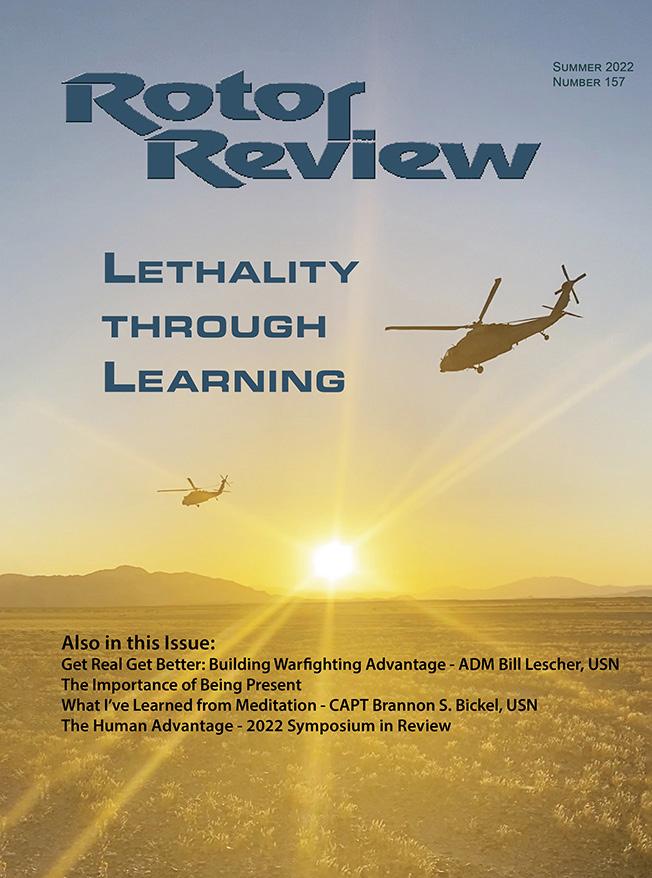

ity through L earning Also in this Issue: Get Real Get Better: Building Warfighting Advantage - ADM Bill Lescher, USN The Importance of Being Present What I’ve Learned from Meditation - CAPT Brannon S. Bickel, USN The Human Advantage - 2022 Symposium in Review Summer 2022 Number 157

L etha L

Summer 2022 ISSUE 157

About the cover: Two MH-60 Sierras from HSC-3 after conducting day TERF landings and training in El Centro.

USN.

Rotor Review (ISSN: 1085-9683) is published quarterly by the Naval Helicopter Association, Inc. (NHA), a California nonprofit 501(c)(6) corporation. NHA is located in Building 654, Rogers Road, NASNI, San Diego, CA 92135. Views expressed in Rotor Review are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies of NHA or United States Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard. Rotor Review is printed in the USA. Periodical rate postage is paid at San Diego, CA. Subscription to Rotor Review is included in the NHA or corporate membership fee. A current corporation annual report, prepared in accordance with Section 8321 of the California Corporation Code, is available on the NHA Website at www.navalhelicopterassn.org.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Naval Helicopter Association, P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578.

Rotor Review supports the goals of the association, provides a forum for discussion and exchange of information on topics of interest to the rotary force and keeps membership informed of NHA activities. As necessary, the President of NHA will provide guidance to the Rotor Review Editorial Board to ensure Rotor Review content continues to support this statement of policy as the Naval Helicopter Association adjusts to the expanding and evolving Rotary Wing and Tilt Rotor Communities .

FEATURES

Read Rotor Review on your Mobile Device

Did you know that you can take your copy of Rotor Review anywhere you want to go? Read it on your kindle, nook, tablet or on your phone. Rotor Review is right there when you want it.

Go to your App Store. Search for "Issuu." That’s the name of the platform that hosts Rotor Review (there is no charge for you to use this App).

To Download Issuu’s App

Create a login (this doesn’t have to be your NHA Login). They will send you a verification code – enter it per instructions. Next, enter “Rotor Review” in the search bar. Click on Rotor Review. Download to your device. Be informed, be entertained, be NHA.

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 2

Photo taken by LT Casey Keilty,

FOCUS: Lethality through Learning CNO Updates Professional Reading Program..........................................................................26 HC-7 Seadevils and HT-28 Hellions: Creating a Learning Culture.....................................27 LT Audrey “PAM!” Petersen, USN / HT-28 PAO Leadership, NATOPS…and Amazon...........................................................................................28 CDR Matt “Trash” Persiani, USN (Ret.) The Importance of Saying Something........................................................................................32 LT Andrew “Gonzo” Gregory, USN Ground Job Training – A Matter of Professionalism and Safety............................................34 LCDR Robin Dirickson, USN / HSC-8 Department Head The Good Ones Really Care!......................................................................................................36 CAPT Andy “Big Tuna” Berner, USN Clear Direction or Standardized Execution: ...........................................................................38 A Defense of Multi-Mission in Expeditionary HSC LCDR Rob “OG” Swain, USN CSG 5 Update................................................................................................................................45 LCDR Calvin "Spicy J" Kirtley, USN Inside the MQ-8: A Super JO's Perspective..............................................................................46 LT Bryan “Twilight” O’Loughlin, USN PEP, Part 4: Flight Operations in French Naval Aviation.......................................................48 LT Randy Perkins, USN NHA Symposium 2022 in Review.....................................................................................52 Get Started Telling Your Stories..................................................................................................82 Writing for the Right Reasons CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

Yankee in King Arthur’s Test Pilot School

“3D” Putbrese, HX-21 www.navalhelicopterassn.org 3 EDITOR -IN - CHIEF LT Michael "Bubbles" Short, USN michaelshort91@gmail.com MANAGING EDITOR Allyson Darroch rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org COPY EDITORS CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.) helopapa71@gmail.com LT Luke "TUC" Vaughn, USN luke.vaughn1@navy.mil AIRCREW EDITOR AWR1 Aaron Messner, USN mess.aaron@gmail.com COMMUNITY EDITORS HM LT Molly "Deuce" Burns, USN (HM) mkburns16@gmail.com HSC LT Alden "Caspr" Marton alden.marton@navy.mil LT Tyler "Benji" Benner tbenner92@gmail.com LT Andrew Gregory Andrew.L.Gregory92@gmail.com LT Fred "Prius" Shaak fshaak@gmail.com HSM LT Elisha "Grudge" Clark., USN (HSM) elishasuziclark@gmail.com LT Johnattan "Snow" Gonzalez, USN (HSM) johnattang334@gmail.com USMC EDITOR Maj. Nolan "Lean Bean" Vihlen, USMC nolan.vihlen@gmail.com USCG EDITOR LT Marco Tinari, USCG marco.m.tinari@uscg.mil TECHNICAL ADVISOR LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) chipplug@hotmail.com HISTORIAN CDR Joe Skrzypek, USN (Ret.) skrzypek@yahoo.com Editorial Staff DEPARTMENTS Editors Emeriti Wayne Jensen - John Ball - John Driver Sean Laughlin - Andy Quiett - Mike Curtis Susan Fink - Bill Chase - Tracey Keefe Maureen Palmerino - Bryan Buljat - Gabe Soltero Todd Vorenkamp - Steve Bury - Clay Shane Kristin Ohleger - Scott Lippincott - Allison Fletcher Ash Preston - Emily Lapp - Mallory Decker Caleb Levee - Shane Brenner - Shelby Gillis Chairman’s Brief ......................................................................................................................6 Executive Director's View.........................................................................................................7 National President's Message................................................................................................8 National J.O. President Message ...........................................................................................9 Vice President of Membership Report................................................................................10 From the Editor-in-Chief......................................................................................................12 Scholarship Fund Update .....................................................................................................14 Historical Society.....................................................................................................................16 View from the Labs ..............................................................................................................19 CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.) On Leadership.........................................................................................................................20 Get Real Get Better: Building Warfighting Advantage ADM Bill Lescher, USN Commodore's Corner...........................................................................................................22 The Importance of Being Present What I’ve Learned from Meditation - CAPT Brannon S. Bickel, USN Report from the Rising Sun................................................................................................24 LCDR R. "OG" Swain, USN Industry and Technology.........................................................................................................66 Redefining the Golden Hour CAPT Christopher “chet” Misner, USN (Ret.) Squadron Updates ................................................................................................................68 “The” Rotorhead Rumble - CAPT Mark Vanderberg, USN (Ret.) HSM-79 Establishes New Spain Detachment, CNAL Presides - PO3 D.S. Randol, USN HSM-51 Change of Command - LT Mark S. Nankervis, USN “Assassin” visits NASWF - LT Laura “Bambi” Lutz, USN HSM-78 Attends the First All-Female Air Show - ENS Savannah Pankow, USN Helo History............................................................................................................................74 Main Rotor, Meet Tail Rotor - Craig Thorson The Rotary Wing Angels - Brian Miller Marco Monoplane - Maj. Jean F. Rydstrom, USA Off Duty ..................................................................................................................................80 Wings of Gold by Beverly Weintraub - Reviewed by LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) Radio Check ..........................................................................................................................85 Change of Command ...........................................................................................................88 Engaging Rotors ....................................................................................................................92 Signal Charlie .........................................................................................................................96 RDML William Terry, USN (Ret.) CAPT James Frederick Ponzo, USN (Ret.) CAPT Melvin A. Runzo, USN (Ret.) CAPT John Scott Kistler, USN (Ret.) LCDR Thomas L. Phillips, USN (Ret.) ©2022 Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., all rights reserved

Ben

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 4 Gold Supporter executive patronS Our Thanks to Our Corporate Members - Your Support Keeps Our Rotors Turning To get the latest information from our Corporate Members, just click on their logos. Small BuSineSS partnerS Platinum SuPPorterS

National Officers

President....................................CDR Emily Stellpflug, USN

Vice President

Eli Owre, USN

Executive Director...............CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

Business Development..............................Ms. Linda Vydra

Managing Editor, Rotor Review .......Ms. Allyson Darroch

Retired Affairs

Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.)

Legal Advisor...............CDR George Hurley, Jr., USN (Ret.)

VP Corp. Membership..........CAPT Tres Dehay, USN (Ret.)

VP Awards...........................................CDR Ian Adams, USN VP Membership

VP Symposium 2023

James Teal, USN

Eli Owre, USN

Secretary..........................................LT Jimmy Gavidia, USN

NHA Branding and

Shaun Florance USN

Senior HSM Advisor.............AWRCM Nathan Hickey, USN

Senior HSC Advisor ......AWSCM Darren Hauptman, USN

Senior VRM Advisor........AWFCM Jose Colon-Torres, USN

Directors at Large

Chairman...............................RADM Dan Fillion, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Gene Ager, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Chuck Deitchman, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Tony Dzielski, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Greg Hoffman, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Mario Mifsud, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Matt Schnappauf, USN (Ret.)

LT Alden Marton, USN

AWRCM Nathan Hickey, USN

Ed Johnson, USN

CDR Santico Valenzuela, USN

Region 5 - Pensacola Director

Jade Lepke, USN President

Region 6 - OCONUS Director

Annie Otten, USN

McKiernan, USN

Derek Brady, USN President

Jonathan Dorsey, USN

5

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

........................................CDR

..................CDR

...............................LCDR

.............................CDR

Special Projects........................................................VACANT

Gear...............LT

President .............................CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.) Executive VP/ VP Ops ...CAPT Todd Vandegrift, USN (Ret.) VP Plans................................................CAPT Jon Kline, USN VP Scholarships ..............................Ms. Nancy Ruttenberg VP Finance ...................................CDR Greg Knutson, USN Treasurer........................................................Ms. Jen Swasey Webmaster........................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.) Social Media .............................................................VACANT CFC/Special Projects ...............................................VACANT NHA Historical Society President............................CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.) Vice President……...…....CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.) Secretary................................LCDR Brian Miller, USN (Ret.) Treasurer..........................CDR Chris Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.) S.D. Air & Space Museum...CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.) USS Midway Museum....CDR Chris Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.) Webmaster........................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.)

Region 1 - San Diego Directors ............................ ..... CAPT Brannon

USN CAPT

CAPT

CAPT

President ............................ CDR

-

Director ....................................... CAPT

President ...........................................CDR

Co-President.................................CDR

-

Director ..................................CAPT

President........................................CDR

4 -

Director...........................................CAPT

............................

Naval Helicopter Association, Inc. P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578 (619) 435-7139 www.navalhelicopterassn.org NHA Scholarship Fund

Regional Officers

Bickel,

Ed Weiler, USN

Sam Bryant, USN

Nathan Rodenbarger, USN

Dave Vogelgesang, USN Region 2

Washington D.C.

Andy Berner, USN

Tony Perez, USN

Pat Jeck, USN (Ret.) Region 3

Jacksonville

Teague Laguens, USN

Dave Bizzarri, USN Region

Norfolk

President

..........................................CAPT

........................................CDR

'22 Fleet Fly-In Coordinator..LT Connor

.........................................CAPT

................................CDR

Junior Officers Council Nat’l Pres / Region 1 ….... LT Alden "CaSPR" Marton, USN Region 2 ......................................................................VACANT Region 3 ....................... LT Bryan “Schmitty” Schmidt, USN Region 4 ...................................LT Lei “REPTAR” Acuna, USN Region 5 ..................LT Connor "Humpty" McKiernan, USN Region 6......................................................LT Dan Beck, USN NHAHS Committee Members CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.) CAPT Mike

(Ret.) CAPT Arne

CAPT Jim

(Ret.) LCDR Brian

(Ret.) CDR Mike

(Ret.) CDR

CDR Chris

Drew Hamblen CDR D.J. Hayes, USN (Ret.) CAPT C.B. Smiley,

(Ret.) CAPT J.M. Purtell,

CDR H.V. Pepper,

(Ret.) CAPT A.E. Monahan, USN (Ret.) CAPT Mark R. Starr, USN (Ret.) CAPT A.F. Emig, USN (Ret.) Mr. H. Nachlin CDR H.F. McLinden, USN (Ret.) CDR W. Straight, USN (Ret.) CDR P.W. Nicholas, USN (Ret.)

Reber, USN

Nelson, USN (Ret.)

O’Brien, USN

Miller, USN

Brattland, USN

John Ball, USN (Ret.)

Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.)

USN

USN (Ret.)

USN

Navy Helicopter Association Founders

Italian Racing and Symposium 2022

By RADM D.H. “Dano” Fillion, USN (Ret.)

NHA Symposium 2022 was like no other in the history of NHA. VCNO 1v1 with JOs and 04s, nobody else, and folks spoke their minds and the organization is better for that event! Keynote speaker, Navy Spouse of a Navy Seal, and two ladies discussing family planning options for married and single members of the rotary wing aviation team, topics that have never been addressed at Symposium. Navy spouses of retired senior leaders and folks who did their time and left the service, and all became extremely successful entrepreneurs; first ever for NHA. Suffice it to say that with the exception of three events, all the events at Symposium were first of a kind!! You, the membership, and our industry partners are why there were so many "First-Evers," because you gave us the pros and the cons of previous symposiums, and we listened and adjusted accordingly. We received much feedback during the event. When I asked folks what they liked/disliked, they gave me feedback; plenty of it and I truly appreciate it and I promise the organization is listening. Callsign “SLAM” gave me an earful at Top Golf, and it was very objective, professional and will benefit the organization! Thanks to all who made this event happen (CAPT Jim “Super-G” Gillcrist has listed virtually everyone who made Symposium a success) so I just want to recognize all the spouses who supported their favorite NHA member attending and call out CAPT "SteveO" Thomas and CDR Emily “ABE” Stellpflug; these two LEADERS shouldered darn near all the heavy lifting for the event. Young warriors from multiple AW shops, ready rooms and the hangar bay were the energy bombs throughout the event. The real veterans of all things NHA Symposium are the ladies and gentlemen at NHA Headquarters on North Island; their guidance is always instrumental in the organization’s success!

So, as we look at rotary wing aviation through an optic of “Lethality through Learning, I am confident we can reflect on topics from Symposium 22 that educated all of us and therefore I will argue, if need be, are making all of you frontline fighters better!!” Thank you for all the feedback and I truly mean it, we are your organization!

So, why the “Italian racing” wording in the article title….well some of you have heard this before ;

“Why are there no rear-view mirrors on Italian race cars?”

“Because what is behind you is of no importance!” ............ HSL/HSM

Pilot

After Action Reports for Symposium 2022 are complete and now we (your organization) are laser spot on Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In 2022 and NHA Symposium 2023!

We will make you proud and please keep the feedback coming!!! (I wonder if “SLAM” will call me?)

As always, I am, V/r and CNJI (Committed Not Just Involved), Dano

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 6 Chairman’s Brief

Symposium

Shoutout - Norfolk’s Human Advantage Made the Difference

By CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

The 2022 Symposium in Norfolk proved to be a huge success on many levels. The going in position was to do things differently and mix it up (listen and deliver on input received from the previous Symposium). The VP for Symposium, CAPT Steve-O Thomas, gave commander’s intent and the Fleet Angels / Norfolk HSC Volunteer Team led by LT Tyler “Kuzco” Bothel crushed the planning and execution. From theme to logo, from Keynote Speaker, Jamie Cochran, to VCNO Calls with DHs and JOs, and from an Aircrew Challenge at the Oceanview Pier to Top Golf, Symposium was new and different. Even the Second Sea Tour Panel was new, and value added. Other guest speakers such as Katy Hendrickson, CAPT Sunita Williams, Andy Harold, and Joy Doyle enriched our members. RDML “Pepper” McCoy connected with Navy and Industry leadership at the VIP Lunch. Bottom line: The Norfolk HSC Community was the “human advantage” for Symposium. A cast of all stars deserve a shoutout to include the HM-14/15 Bus Drivers, Kuzco, Gonzo (HSC-2), Kelly, TWON, AWSCM Nord, BOJ, MEEP, ABE, Reptar, Zoo, Rhino, Fatty, CaSPR, Frizzle, WYLD BILL, Big Bird, Bus, Bubbles, IKE, Quiet Riot, Gonzo (HSC-3), Squids, Prius, JoJo, Homeskool, Rumspringa, Musband, LiMP, Whiz, Juddy, Llama, Chastity, Dimitri, DQ, Average, McMuff, and Milkman. Additionally, a big thanks to Ronnie Boone, owner and operator of the Oceanview Fishing Pier, who hosted the Aircrew Challenge – his enthusiastic support was huge.

Getting JOs and Aircrew more involved in NHA from coast to coast as Regional Reps, in production of Rotor Review Magazine, in social media outreach, in planning and execution of regional events, and in the planning and execution of Symposium and Fleet Fly-In creates a stronger organization that offers a richer experience. For this reason, we are starting the planning for the 2023 Symposium at Harrah’s Resort Southern California. The VP for Symposium is CDR Eli “Whiz” Owre, and we are putting the JO & Aircrew Volunteer Team together, pulling talent from HSM-41, HSC-3, VRM-50, and Region 1 Squadrons.

Exceeding 3,000 active members this year was a strategic priority. Currently, NHA is at 3,051 members. Membership remains the lifeblood of the organization, and it is NHA’s “human advantage!”

• Please keep your membership profile up to date.

• If you should need any assistance at all, give us a call at (619) 435-7139 and we will be happy to help – you will get Linda, Mike, Allyson, or myself.

Warm regards with high hopes, Jim Gillcrist.

P.S. A final shoutout to LT Mike “Bubbles” Short as Magazine Editor-in-Chief is appropriate. He poured his heart and soul into the magazine, and it shows in the caliber of the content. Thanks Bubbles for “raising the bar” and making Rotor Review so much better!

P.P.S. Lastly, a “final salute” to Vice Chief of Naval Operations (VCNO), ADM Bill Lescher, for an incredible Naval career and for his years of strong support to NHA – never too busy to be involved – we hope you enjoy the “On Leadership Column” in this issue. For his entire body of work within the Rotary Wing Community, the NHA Board of Directors recognized ADM Lescher as recipient of the 2022 NHA Lifelong Service Award.

With admiration from the NHA Staff: “Fair winds and following seas!”

Every Member Counts / Stronger Together

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 7 Executive Director’s View

Oceanview Fishing Pier serves as an awesome VFR check point!

Old Dog, New Tricks?

By CDR Emily “ABE” Stellpflug, USN

As a former MH-60S pilot now transitioned to the CMV-22 Osprey, there are many moments that I struggle to learn and adapt to a new aircraft and mission. Years of experience in any craft can make a person resistant to change and growth. Can an old dog learn new tricks? The short answer is—we must. To be masters of our craft, we must remain curious and eager to evolve as our aircraft, threats, and tactics shift.

There is a Zen Buddhism concept called Shoshin meaning “beginner’s mindset.” This concept “refers to having an openness, eagerness, and lack of preconceptions when studying a subject, even when studying at an advanced level, just as a beginner in that subject would." Most of us learn best when being exposed to material for the first time. That is probably why we still remember ditties from flight school such as “down, right, idle, turn." The “beginner’s mindset” challenges a person to approach a problem or new skill with the same curiosity as if seeing it for the first time.

What is it about being an old dog that can make a person resistant to learning and change? I can think of many factors that may come into play—ego, fear of failure, stubbornness, laziness—just to name a few. Those are barriers that must be overcome as we hone our skills as aviators. Each time we step into a debrief, we should have an open mind and set our egos aside in order to learn and grow from that event. That is a critical piece of our aviation culture and key to success.

This Rotor Review explores "Lethality through Learning" and the importance of our Rotary Force being willing to learn and evolve. I would challenge each of us to read the articles with a beginner’s mindset in order to discover all that this issue has to offer!

Fly Safe!

V/R ABE NHA Lifetime Member #481

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 8 National President's Message

Training Perspective

LT Alden "CaSPR" Marton, USN

If you haven’t had a chance to see Top Gun 2: Maverick, I’d recommend stopping right now and watching it. The movie is a high-production example of this issue's theme in action: "Lethality through Learning." While I don’t condone throwing NATOPS into the trash can on your first day, the bedrock of the movie is how training adapts to the warfighting landscape. How do we train to the limit of human ability? What can we do to get the edge? What are we doing as the rotary wing community to push our human advantage?

I’ve had an opportunity to see some of the dramatic changes across the aviator pipeline, and I can’t express how different it is as compared to when I was going through a mere 8 years ago. VT Primary is testing Project Avenger where individual ability determines the number of training events. Once a pilot demonstrates mastery of a skill or event, they move onto the next unit, tailoring training syllabi pilot-to-pilot to expedite training pipelines. HT Advanced is revolutionizing the training simulators by connecting with live ATC members in their sims and by implementing augmented reality simulators for student walk-ins. They’ve even got an allglass cockpit replacement for the TH-57, the TH-73. Everywhere you look, the Naval Aviation Enterprise is finding unique ways to change our training pipeline for the better. While we still focus on the content of training and readiness, it’s refreshing to see such a focus on how we learn.

While the importance of tactical training opportunities cannot be stressed enough, my naivety made me believe that onthe-job training was the building block of strong naval leaders. That being “in the thick of it” was, pound for pound, the most important developmental leadership trait the Navy had to offer. At this recent Symposium, I found myself in company with the Commander of Naval Personnel Command, RADM Alvin Holsey. As I waxed philosophical on these thoughts of leadership, RADM Holsey stopped me short and provided perspective which resonated. He countered that higher education and continued academic learning is not only helpful, but it is critical for quality leadership. Rigorous academics through our War Colleges, NPS, and civilian institutions can open the apertures for problem solving. Exposure to different ideas transform into the sharpest weapons the military can offer – critical thought and adaptability. We have historically looked at higher education as a “good deal” instead of treating it with the importance it has on our personal development and combat prowess. Over the last decade, the U.S. Navy and DoD have had a mindset shift where education opportunities in the form of education grants, remote learning, tours with industry, etc. come together to create a new model Naval Officer – taking from all aspects of experience to innovate, adapt and overcome. Our upper echelons have recognized this return on investment and the Fleet is more lethal because of it.

All of this is cause for reflection. Take one step back and look at the last two paragraphs from the perspective of the first Rotary Wing Aviators. Simulators, Masters Degrees, Augmented Reality… we are a completely different group of pilots and aircrew than when we started in 1948. The geo-political landscape has changed drastically and while we still have tail pedals and rotor blades, the advancement of technology, training, and education create a flying cadre more resilient than it has ever been. Our rotary wing legends fought the toughest enemies of their day, but our enemy is changing. We’ve needed to change accordingly, exposing our aircraft and our people to some of the toughest challenges our creativity can invent. These developments in how we learn are how we become the toughest and most lethal pilots and aircrew in the world. Cue “Danger Zone” by Kenny Loggins https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=siwpn14IE7E.

NHA events are a hotbed for these reflective moments. The planning for the 2022 Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-in and the 2023 NHA Symposium in San Diego is underway and I can’t express how excited we are to see more of these conversations in-action!

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 9 NHA JO President Update

Fly Navy, Alden “CaSPR” Marton

VP for membership Report

Three Thousand is a Milestone

By LCDR Bill "WYLD Bill" Teal, USN

CNAF, NATOPS, NAMP, IETMS, SEAWOLF, Wing SOPs, and Squadron SOPs, we have an instruction for everything we do. This is what standardizes us, and ensures we accomplish missions and maintenance the way they are intended to be done: safely, efficiently, and correctly, and in a repeatable manner. But how many times have you checked something extra? Pulled on that hose to make sure it’s secure? Touched that castle nut or cotter key to make sure it was all the way in? Verified the movement on a control or control surface? That check isn’t in the publication. It is not part of the preflight, or postflight, or the Daily or Turnaround Inspection, yet you check it.

Why? Experience.

With as many publications as we have, as many mishap reports, hazard reports, or ASAPs, it is just not possible to capture all of the organizational knowledge that is out there. However, this knowledge is imperative to our success, our advantage, and our lethality.

Organizational knowledge can be difficult to retain and transfer to everyone who may need it. However, a strong community with a common mission and values can foster a culture of expanding organizational knowledge, thus making the organization more effective, successful, and lethal.

As part of NHA, you possess that organizational knowledge. The experience to check that hose on pre-flight; the experience to slightly lower the collective before a hard left bank and the experience to respond to the compressor stall because the anti-ice valve has stuck again are part of our common knowledge. We pass that same knowledge through this publication, through social functions like Symposium and Fleet Fly-in, and through routine ready room discussions. This is lethality through learning on display everyday. It is what makes our organization and organizational knowledge strong. It proves that we are stronger together and why every member counts.

Every time I reached a new milestone, I was told there is so much more to learn. I know we haven’t stopped learning and that our capabilities continue to grow as individuals and an organization. So, the next time you are hanging out, talking shop, and come across someone with a gem of insight, a different perspective, a creative solution or just sound advice, encourage them to join NHA and increase our organizational knowledge, our lethality.

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 10

Congratulations to Our Newest Lifetime Members We are NHA - in it for Life! 230 Jim Raimondo 331 Scott Pritchard 637 David Valsassina 636 Mike Wellman 635 Brad Cadwall 634 Rob Meyer 633 Larry Carello 848 Dan Thomas 526 Francis Atkinson 632 Scott Hatch 980 Chris Pinar 626 Scott Moak 631 Michael Simonetti 628 Larry McCullen 720 Jeffrey Storer 625 Zach Humphreys 623 Carl Hess 624 John Pelzer 629 David Farrell 630 Joshua Kautzman 622 Wade McConvey 621 Roger Rich 779 Brett Elko 617 Mike Kilman 618 Patrick Boensel 614 Tom Beard 616 Andrew Pagliarulo 994 James Thomas 613 Tim Matthews 615 Tim Saye 612 George Aguilar 608 Cullen Hankes 609 Daniel Smith 610 Mathew Kiser 606 Joshua Avila 607 Jared Powell 605 Reed Carr 604 Robert Bixby 601 Jim Schmitt 602 Elizabeth Janca 603 Chad Westfall 599 Bruce Pollock 598 Nathan Marshall 596 Gregory Dewindt 597 Ian Grover 595 Ronnie Fleming 594 Joe Stuyvesant 592 Adam Patterson 593 Hannah Vincent 591 Chad Glasscock 590 Curtis Shaub 589 Nick Schnettler 778 Justin Eckhoff 585 Nathaniel Wilson 586 Ben Allen 588 Jack Lahey 619 James Stranges 582 Justin Tate

Max Beep Awards at Symposium

The 2nd Place Max Beep prize was awarded to the HSC-12 "Golden Falcons." CAPT Weiler, Commodore HSCWP, accepted the symbolic check for $1000 on their behalf.

The 3rd Place Max Beep prize was awarded to the HSM-75 "Wolf Pack." CDR Mashuda accepted the symbolic check for $500 on behalf of the Wardroom.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 11

The 1st Place Max Beep prize of $1500 was awarded to the HSC-21"Blackjacks."

From the Editors-in-Chief

Esteemed Readership,

This will be my final column as Editor-in-Chief of this fine publication. At the release of this issue, I’ll be turning my duties over to LT Annie “Frizzle” Cutchen, a friend and fellow Fleet Angel of HSC-2. Rotor Review #157, themed “Lethality through Learning,” seems like an appropriate conclusion for my time with the magazine. My time as head of the Rotor Review Editorial Staff has been, if nothing else, a journey of learning.

Serving as the Editor-in-Chief of Rotor Review has been one of the great honors of my nine year naval career. This position has allowed me to interact with outstanding thinkers, writers, and leaders from across the Naval Rotary Wing Community. It has given me the opportunity to expand my comfort zone and professional knowledge while leading a passionate and professional editorial staff in the publication of two years’ worth of issues. We set out with a goal to curate and publish content that was relevant, thoughtful, and entertaining. We sought out submissions from contributors with ideas that could take our community forward. I believe we have been, and will continue to be successful in these aspirations.

To the NHA Staff and community leadership, thank you for trusting and empowering me to lead the full spectrum of this magazine’s editorial process.

To our contributors and columnists, thank you for your dedication to community-advancing thought leadership. Without the high quality pieces you consistently provide, there would be nothing for us to publish.

To Rotor Review’s Community Editors, thank you for your commitment to this magazine. Your tireless editorial efforts have allowed us to produce issue after issue of excellent material.

I am immensely proud of the work we’ve been able to accomplish together, but the work continues! It is critical that members of our community continue to write about their experiences, problems, and solutions, and submit them to professional publications like this one. We all learn and grow through the sharing of ideas. I am grateful for the opportunity to have served as Rotor Review’s Editor-in-Chief. As always, thanks for reading!

V/r, LT Mike “Bubbles” Short

For those of you I have not yet had the opportunity to meet, my name is LT Annie “Frizzle” Cutchen. I come from a long Navy lineage, spent my first tour with the HSC-6 Screamin’ Indians, and am now proud to call myself a Fleet Angel. I am very excited to take over the role of Editor-in-Chief, but recognize that I have some massive shoes to fill.

When Bubbles announced that he was searching for a relief, I jumped on the opportunity. I had seen how the position facilitated communication with the Naval Rotary Wing Community past and present. I also noted what an outstanding forum Rotor Review is for you all to promulgate information and push the agenda you care about.

There has yet to be a moment in the editorial process that I do not feel an immense sense of pride to be a part of this incredible community. During the turnover process, I was met with a few surprises—luckily all of which were positive and in tune with the theme of this issue. I did not realize that I would have the opportunity to again work alongside so many of my incredible mentors including CAPT Steve “SteveO” Thomas, CDR Emily “ABE” Stellpflug, and CDR Ian “Zoo” Adams to name a few. I have also had the privilege to gain some new mentorship from RADM Fillion, CAPT Gillcrist, and Allyson Darroch. This list would not be complete without the mention of LT Mike “Bubbles” Short.

Bubbles has been an incredible peer mentor in and outside of the context of Rotor Review. He embraces “Lethality through Learning” to his core. That man is an incredible instructor and a huge part of his success is that he constantly has a learning mentality. Mike, thank you for entrusting me to take the torch. You have put so much time and effort into making this magazine the incredible publication that it is today and I hope to continue to do justice to your vision.

How do we continue to improve? We take lessons learned from those who came before us. We build upon the strong foundation constructed before our time. With that in mind, I am excited to announce the theme of our Fall 2022 Issue (Rotor Review #158) is “Past Informs the Present.” We are excited to hear what historical events (both recent and long past) have informed our modern-day operations and influenced you. This upcoming issue covers now through January of 2023. Some important events in that timeframe include Sikorsky Aircraft Company 100th Anniversary (2023), Gulf Coast Fleet Fly-In themed “Next Generation,” and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DE&I) Summit to name a few. Rotor Review staff looks forward to hearing from you on this comprehensive theme.

Please enjoy RR #157 and show your appreciation to Bubbles when you see him!

V/r, LT Annie “Frizzle” Cutchen

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 12

Letters to the Editors

It is always great to hear from our membership! We need your input to ensure that Rotor Review keeps you informed, con nected and entertained. We maintain many open channels to contact the magazine staff for feedback, suggestions, praise, complaints or publishing corrections. Please advise us if you do not wish to have your input published in the magazine. Your anonymity will be respected. Post comments on the NHA Facebook Page or send an email to the Editor-in-Chief. Her email is annie.l.cutchen.mil@us.navy.mil or to the Managing Editor at rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org. You can use snail mail too. Rotor Review’s mailing address is: Letters to the Editor, c/o Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., P.O. Box 180578, Coro nado, CA 92178-0578.

RADIO CHECK

The theme for Rotor Review #158 is “Past Informs the Present.” Those of us who currently have the privilege of spending our days with rotors turning overhead couldn’t operate as knowledgeably, safely, and efficiently as we do if not for the foundation set by those who came before us.

Naval Aviation as a whole has an incredible history which can be broken down further into squadron, aircraft, and even individual history. “There I was,” “lessons learned,” and “open kimono” conversations happen in wardrooms and messes across the world. From these, we learn from our Navy and Coast Guard Shipmates and fellow Marines about how to be better in and out of the aircraft.

What are some historical events that have set the stage for what rotary wing aviation is today? What mission sets have you performed that you have seen grow and develop into modern day operations? Is there any particular historical event, big or small, that has made an impact on you and the decisions you have made? What is your “there I was” that impacted you and your career? Do you have advice for the next generation of rotary wing aviator to make them better based on your experiences?

We want to hear from you! Please send your responses to the Rotor Review Editor-in-Chief at the email address listed below.

V/r, LT Annie “Frizzle” Cutchen Editor-in-Chief, Rotor Review annie.l.cutchen.mil@us.navy.mil

Articles and news items are welcomed from NHA’s general membership and corporate associates. Articles should be of general interest to the readership and geared toward current Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard affairs, technical advances in the rotary wing / tilt rotor industry or of historical interest. Humorous articles are encouraged.

Rotor Review and Website Submission Guidelines

1. Articles: MS Word documents for text. Do not embed your images within the document. Send as a separate attachment.

2. Photos and Vector Images: Should be as high a resolution as possible and sent as a separate file from the article. Please include a suggested caption that has the following information: date, names, ranks or titles, location and credit the photographer or source of your image.

3. Videos: Must be in a mp4, mov, wmv or avi format.

• With your submission, please include the title and caption of all media, photographer’s name, command and the length of the video.

• Verify the media does not display any classified information.

• Ensure all maneuvers comply with NATOPS procedures.

• All submissions shall be tasteful and in keeping with good order and discipline.

• All submissions should portray the Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard and individual units in a positive light.

1. All submissions can be sent via email to your community editor, the Editor-in-Chief (annie.l.cutchen.mil@us.navy.mil , or the Managing Editor (rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org). You can also use the USPS mail. Our mailing address is Naval Helicopter Association Attn: Rotor Review P.O. Box 180578 Coronado, CA 92178-0578

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 13

Tell Us What You Think!

Apply…Donate

By CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.) / President NHA LTM #4 RW#13762

From the annals of the NAS Norfolk LP Hangars, come the Legends of Wings of Green and Gold. This quarter, “How I lost my first flight jacket.”

As the NHA Scholarship guy, I meet a lot of aviators and aircrew and am surprised in the variety of flight clothing now available, worn on base, and off. Intrigued by these various offerings, I looked back in comparison on the various flight gear rules in place at NAS Norfolk (back in the day) - my experience beginning with the demise of Brown Shoes in the Bi-Centennial Year to their welcomed reappearance in 1988.

1976-77 Facts, leading to the loss of my first flight jacket…April 1976, I arrived at my Fleet squadron fresh out of TRACOM only to retire my brown shoes in June. We weren’t flying much anyway (CNO’s MC rate for RH-53Ds was 30%) and things in Norfolk, like the uniform of the day, took on a strange amount of significance, and seemed sort of formal, because…

• We shared the base (environs) with 2 four stars (the Unified CinC and the Fleet CinC) and a bevy of 3 stars (e.g., AirLant, SubLant, SurfLant), and probably a dozen 2 stars

• Khakis were summer only – mid-May to October – and Brown Shoes were banned (‘76 to ‘88) during these sad years… and in return we had “salt and peppers…” (Hoorah?)

• Flight suits could be worn in the hangar/on the flight line only…. but you had to be on the flight schedule

• Important point - flight jackets were flight clothing – hangar and flight line only, and no flight jackets in or out of the gate

• Winter blue (prescribed) required a tie and ribbons (not so bad, most JOs only had one row anyhow…) and a clean white combination cover or the (“hard hat") made the “two hat” gambit tough to engage

• Leaving the squadron area (to memorize the exchange, get a haircut, or grab a ‘Sub’ at the flight line geedunk) required the uniform of the day, normally as described above

• Note to self…avoid Gilbert Street, NOB’s main thoroughfare, and most of NOB. If unable, do not fail to salute any oncoming black sedan, festooned with stars and miniature flags flying from the forward fenders.

OK, stage set. Late one cold, mid-February morning, one of HM-12’s Ops JOs was tasked with a ‘cross-base’ errand which would require time aboard NOB, coinciding with the lunch hour. I was asked to come along, and knowing that the OAT was about 36oF in light rain and slush, yelled across the Line Shack, “OK, but first, let me grab my reefer!” This caused the normally loud and busy Line Shack to come to a complete and silent halt, as all hands stopped to see what, exactly, the young JG kept in his locker.

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 14 Naval Helicopter Association Scholarship Fund

Reefer

I opened my locker, swapped my flight jacket for my Reefer (officer’s pea coat) and locked the door, leaving the Line Division plane captains to wonder about the LTJG’s Reefer –was it still in the locker or did he take it with him?

Hours later, returning to the hangar, I found my locker open … and empty. I have always wondered if the thief just wanted the flight jacket, or…that he thought the locker contained a different kind of reefer… and not finding what he was looking for and not to be completely disappointed, took my flight jacket as a consolation.

Moral: When in doubt, salute…or something

And now for something completely different.

This year, 2022, we had 50 highly qualified candidates apply for sixteen $3,500 scholarships. We announced our selectees at the Annual Symposium in May and published the results in the Rotor Review. It was a good year and followed our Strategic Plan to increase scholarship amounts by $500 each year. This year, we will raise the scholarship value to $4000.

This summer, our goal is to raise an additional $12,000 (or three $4,000 scholarships) by 31 August to make up for recent unrealized investment losses and replace some corporate sponsorships that dropped off unexpectedly. Your donation can support our next scholarship winners while we rebuild our investment portfolio to ensure growth and long-term sustainment.

Please consider giving to or establishing a memorial or legacy fund (ex., NHASF General Memorial Fund, the HS-5 Night Dipper Legacy/Bill Roop Memorial, or the H-53/Big Iron Legacy) to preserve the legacy of our communities and heroes with either an annual “pass-through” or a scholarship in perpetuity.

Also, consider re-joining or extending your current membership in the NHA as a new Lifetime Member. Some will say, “Wait, I paid my dollar and got my card in the 80’s…” like I did. But those were different times. Today, it’s about sustained growth of the association.

I look forward to your support in the 2022-23 scholarship rounds and seeing you at the NHA National Symposium in May 2023 at Harrah’s SoCal Resort!

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 15

Dial BR-549

Summer in San Diego

By CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.) / President, NHAHS LTM#46 / RW#16213

Well…

it doesn’t seem possible but it is summer again in San Diego. This is the post NHA Symposium edition of the Rotor Review Magazine and a lot has happened since the gathering in Norfolk 11-13 May 2022. While I was unable to travel to Norfolk for the 2022 Symposium because of a recurring medical problem, I am happy to make the following report with regards to the NHA Symposium activities.

NHAHS accomplished the following:

Presented the Oldest Helix Award to 91 year “young” Captain Paul L. “Scratch” Hryskanich, USN (Ret.) – which was very well received with Scratch accepting the award to a standing ovation.

NHAHS presented for the first time the Silver Crew Chief Award to Master Chief Bill Moss, USN (Ret.) who is the oldest (read the wisest and most experienced) Naval Helicopter Crew Chief alive.

Another first…NHAHS presented the Golden Crew Chief Award to Master Chief Drew Smith, USN at a Region One Retired Luncheon after the Symposium as Master Chief Smith was unable to travel to Norfolk to accept the award. This award is presented to the oldest (read the wisest and most experienced) Naval Helicopter Crew Chief on Active Duty. Master Chief Smith will retire in November 2022 and is looking for his relief who will be the recipient of the next award at the 2023 Symposium.

CAPT Dave Zinger, USN (Ret.) was Awarded the Mark Starr Pioneer Award by CDR Joe Skrzypek, USN (Ret.) after the Symposium. Joe drove up the coast and presented Dave the award at his home with his wife in attendance.

I would like to acknowledge and thank all those who participated in the Top Golf Charity Event that supported both the NHA Historical Society and the NHA Scholarship Fund which was held on the last day of the Symposium on Friday Night in Virginia Beach. I heard it was a great time and raised some much-needed funds for both organizations.

I would also like to recognize Katherine Gillcrist who coordinated an Opportunity Basket Drawing at Symposium which everyone enjoyed and again raised money for both organizations. Katherine thank you for dedicating your time and efforts to coordinate this event. Well done!

Last bit of Symposium business…I would like to pile-on and congratulate CAPT Chuck Deitchman, USN (Ret.) for what has been an outstanding Navy career and all the support that he has provided NHA, the NHA Historical Society and the NHA Scholarship Fund over the years while working for Sikorsky. Chuck thank you on behalf of the entire Rotary Wing Community and Helicopter Family. We wish you and Nancy all the best in retirement!

Update on the SH-60F Project for the Front Gate at NASNI.

I would like to acknowledge the support and very generous donations made by Mr. Dan McKinnon, Benny Hunziker, Sikorsky, a Lockheed Martin Company and General Electric (GE). Your donations are greatly appreciated and we couldn’t do a project of this magnitude without your support. Those people and two companies have been major contributors to the project thus far. For a complete list of donors, see the list here at https://sh60fhoas.navalhelicopterassociation.org/donors/. See the adjoining page if you might be interested in making a donation. I would point out that the engraved brick donations are a nice way to make a lasting tribute to your name or the name of someone else who has served in support of the Helicopter Community by purchasing a brick that will be built into the base of the monument. The SH-60F project is coming along and the plan is to dedicate the project in 2023, commemorating the 55-year anniversary of Clyde Lassen’s Rescue that was performed on 19 June 1968.

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 16

Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society

Mark Starr awardee CAPT Dave Zinger and Mrs. Zinger

Display Aircraft Wash and Upkeep

I would like to recognize the leadership provided by Chief Matt Fleshman from the HSC Wing who planned and coordinated the last aircraft wash at Flag Circle on Thursday, May 19, 2022. This was the second wash performed by a group of volunteers and was a very successful evolution with everyone having a good time while earning 6 hours of volunteer service time toward their Military Outstanding Volunteer Service Award. A BIG “Thank You” goes out to Chief Fleshman, Mr. Walt Loftus and all those volunteers who helped wash the aircraft! Well done!

The next aircraft wash is planned for Friday, September 30, 2022 and will be coordinated and performed by the Chief Selects. I would also like to recognize and thank Mr. Steve Snietzel from Sunbelt Rentals for agreeing to donate a manlift so we can get up to those hard-to-reach areas. In a related project, USS Midway artisans along with volunteers from the Reserve Wing and HSC-85 performed a major paint touch-up effort on the H-3 Sea King at Flag Circle.

NHAHS is also working on helping to make a movie about HC-7 Sea Devils. We continue to raise funds for what will be a two hour documentary film on the squadron for television.

I would also like to thank the pilots and aircrew who supported the fly-over for the LCDR Tom Phillips Memorial Services on Saturday, June 25 which was held on board the USS Midway Museum. We appreciate your flying tribute to Tom.

That is it for now. Consider making a donation to the SH-60F Display Helicopter on a Stick. Until then, keep your turns up.

Display aircraft wash at Flag Circle Aircraft are looking good.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 17

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 18 Mail Checks to: Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society, Inc. (NHAHS) NASNI SH-60F Project PO Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578 To donate with Paypay visit https://www.nhahistoricalsociety.org/indexphp/donations/ and click on the Paypal icon or copy and paste this link in your browser https://www.paypal.com/donate?token=dUz7iSsDDUkFxuXCIsSpZE5lRrmAZ7M5diK1LRJ315ULqrsnyvU3nuz4WHPu0z4ZBCW7xiw34NubTIs Paypal Donation Link Computer Rendition of NASNI Stockdale Entrance with SH-60F on a Pedestal

Lethality through Learning

By CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

Our Rotor Review editors have teed up a great topic that flowed naturally from our 2022 NHA Symposium. While most think of “learning” as something that happens in a schoolhouse, for our community this happens every day: in ready rooms, during flight briefings, in the line shacks, and just about everywhere.

Without getting all misty-eyed about it, we should celebrate this. The way we do things is so different from the way things work in other parts of government and in industry. There, you could likely have a boss you report to who is just your manager and does not impart any “learning” to you, except to ensure that you follow all the rules and regulations of the organization.

How different it is from the way we bring along a recent FRS graduate. I’m using an aviator example, but this happens throughout a squadron. That FRS grad learns every day as a copilot until he or she acquires enough flight hours to be considered for Helicopter Aircraft Commander. The learning continues until that designation is conferred, but it doesn’t stop there. Not by a long shot.

Even experienced squadron aviators must continue to learn and take NATOPS Checks, Instrument Checks and other learning experiences across the board. Then, there is the whole learning experience of pre-deployment workups where in addition to honing your aviation skills, you learn about the ship you are deployed aboard.

Look, none of this is designed to have us beat our chests and proclaim: “We are the best and everyone else has it wrong.” Far from it, that’s not the purpose. Rather, it is to encourage us to treat those evolutions that seem like a pain as learning opportunities, not as something that has to be endured to get to some point or finish line.

Okay, so I suspect you get all that, and thus far I’ve talked about individual learning. What about learning as a squadron? That is just as important – maybe more important – as what pilots, aircrewmen or maintenance or other specialists learn in their individual roles and responsibilities. If you – especially your commanding officers, executive officers, department heads and master, senior and chief petty officers want to help this process, I recommend the book: "The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization" by Peter Senge.

I was exposed to this book years ago in graduate school and it has become a classic in the field. Here is just one editorial review:

Learning organizations are possible because, deep down, we are all learners. No one has to teach an infant to learn. In fact, no one has to teach infants anything. They are intrinsically inquisitive, masterful learners who learn to walk, speak, and pretty much run their households all on their own. Learning organizations are possible because not only is it our nature to learn but we love to learn. Most of us at one time or another have been part of a great team, a group of people who functioned together in an extraordinary way– who trusted one another, who complemented one another’s strengths and compensated for one another’s limitations, who had common goals that were larger than individual goals, and who produced extraordinary results. I have met many people who have experienced this sort of profound teamwork–in sports, or in the performing arts, or in business. Many say that they have spent much of their life looking for that experience again. What they experienced was a learning organization. The team that became great didn’t start off great–it learned how to produce extraordinary results.

Take the book for a test drive – you may find it helpful in upping your game in making your squadron a learning organization – and a more lethal one.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 19 View

from the Labs

On Leadership

"On Leadership” is a feature column in which Rotary Wing Flag Officers submit articles on leadership topics of their choosing.

Get Real Get Better: Building Warfighting Advantage

By ADM Bill Lescher, USN

For 42 years, I’ve had the immense privilege of serving as a Navy leader, a naval aviator, and a proud member of the rotary-wing community. The opportunity to work with many of you, from the flight line to the halls of the Pentagon, has been deeply rewarding, and I continue to be impressed with the caliber of our team and the work we do together in support of our country.

We remain the most powerful Navy in the world. In 2021, the Navy-Marine Corps team flew over 1 million hours and steamed 22,000 days. We operated all over the world, from the Arctic to the South Pacific, protecting the nation’s interests and promoting American prosperity. No other Navy comes close to this level of global impact. The contributions that rotary-wing aviators make on a daily basis to this naval power, from hunting submarines, to providing maritime ISR, to supporting heavy-lift logistics, have been exceptional in making our Navy stronger and more lethal.

The core of our strength has always been our people and a Navy culture that values learning. Throughout the major conflicts in our history, our Sailors have learned and adapted to meet every challenge. As CNO stated back in January, “History shows the navy which adapts, learns and improves the fastest gains an enduring warfighting advantage.”

The evolution of the rotary-wing community offers a great example of the impact of those who embrace a learning mindset. From the early days of limited Search and Rescue birds, to the multi-mission, multi-domain war machines we have today, our best Sailors learned and incorporated new technology and tactics to deliver a strong warfighting advantage.

But we should be clear-eyed to the reality that our maritime superiority is in jeopardy. As we transition from two decades of primarily supporting land forces ashore in the Violent Extremist Organization (VEO) fight, we now face near-peer adversaries intent on overtaking our military dominance and challenging the international rules-based order. China is our pacing challenge, driving a shift to a sea control fight and threatening our advantage with sizeable investments in military capability, industrial capacity, technological development, and civil-military fusion. Russia’s specialization in Undersea Warfare and their destabilizing actions in Europe clearly endanger our NATO allies.

Once again, we find ourselves at the forefront of Strategic Competition, facing real and dangerous threats to our homeland and way-of-life. We must work together powerfully to accelerate our maritime advantage in this critical decade.

Across every organization in the Navy, we must ask ourselves: Are we doing enough to prepare for combat?

In our very best teams, the answer is ‘yes.’ We see highperforming leaders who embrace the learning culture needed to deliver the advantage we need. These leaders are obsessed with finding poor performance in their units. They fix problems when they’re small by systematically identifying and addressing the underlying root causes, and build inclusive teams that learn.

But over years of studying Navy performance in depth, I have seen unacceptably large variability in how we lead. In contrast to our strongest leaders and units, I see areas in our Navy where our ability to learn and improve has dulled, driven by behaviors that oppose learning. We see leaders who struggle to perform and fail to promote the learning mindset that drives our best-performing commands. Our least effective leaders have grown up in the Navy to believe that, to get ahead, they must grind through the friction of status quo processes, keep problems within the lifelines, work barriers to improvement without asking their boss for help, and solve the problems most constraining their improvement by pouring resources and activity on it rather than seeking to understand and correct root causes.

Too often across our Navy, this kind of leadership has resulted in problem-solving by addition of more instructions, more process, and more complexity. Over time, this approach, combined with an unwillingness to accept any level of failure, has overwhelmed our people with activity and bureaucracy.

While we were able to muscle through the damage from this kind of behavior in the counter-VEO fight, it is insufficient

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 20

Tactical Operations Training at HSM-41

for Strategic Competition with China and Russia today. The inconsistent practice of Navy-best leadership and problemsolving behaviors is the greatest constraint we have to accelerating warfighting advantage.

As we deeply studied our tragic mishaps, areas of sustained weak performance, and the winning behaviors of our strongest commands, we’ve seen recurring similarities in the best leadership practices leading to our best outcomes and the root causes leading to our worst outcomes.

This learning is core to our intent to build on strong core values and Navy-proven best practices to bring consistency across the Navy to how we lead and learn.

This is what the Get Real Get Better leadership standard provides.

Get Real Get Better has focused our learning to the essential, most impactful, leadership behaviors that are both significantly different from common Navy behavior and consistently practiced by our very best Navy leaders. These behaviors come with measurable standards to hold ourselves accountable.

Building on our core values, Get Real means having the courage to transparently self-assess—to build teams that embrace frank, hard, looks at our performance and understand our actual strengths and shortcomings. Get Better is the commitment to improve—to be self-correcting: taking pride in high standards and fixing problems together when they’re small, before they grow large and complex, focusing on what matters most in a disciplined way.

These principles are how our best commands throughout the Navy learn and build winning teams today.

Throughout the next few months, you’ll be hearing more about the Get Real Get Better leadership standard as we work to bring consistency to how Sailors lead. In the long-term, this initiative includes reforms to our talent management and personnel systems (such as changes to FITREPs, Evals, and promotion board precepts) so that we reward and promote Sailors who embrace this proven way of leading. Additionally, we’ll teach and reinforce these leadership and problem solving best-practices throughout a Sailor’s career, from accession pipelines to milestone schools, so that they are better prepared to lead and solve problems in the future.

As we work to bring more consistency to learning and leadership in the Navy, here are three Get Real Get Better leadership behaviors you can start doing today.

Act transparently, up and down the chain of command. Fixing problems at speed requires strong self-assessment and bold “Get Real” conversations with each other.

Transparency allows us to align on standards and goals, and understand whether we are meeting them. We see the power of transparency in how we mission plan and debrief flights, with no-holds-barred feedback—regardless of rank—and a focus on what didn’t go well rather than just the good. This strong behavior of “embracing the red” performance in order to learn must come alive in every part of Navy work, from readiness generation, to weapons development, to personnel issues. Unless we Get Real through hard conversations with each other, we cannot Get Better.

Focus on what matters most. Our Get Better commitment to continuously self-correct requires each of us to prioritize risks and understand root cause. Taking the few extra steps to define the problem, “ask why five times,” or identify friction points will lead to better results because we are solving the real problem and learning along the way. Instead of rushing in with temporary solutions or added requirements and complexity, we must use proven methods to focus effort to the most impactful actions, and put solutions in place that last. When working to solve problems, our strongest leaders are the ones who take pride in removing barriers for their people. This can be done inside a department, at the squadron-level or across the wing. Measure yourselves on the opportunities to do so.

Build learning teams. Every leader must foster a culture of trust and respect in their commands, where Sailors can feel empowered to learn, innovate and contribute. Our teams cannot effectively learn absent the trust established by strong care and respect for our people. Our teams cannot embrace the red absent the trust that engenders frank and honest conversations. Caring for and respecting our people manifests in how we train and mentor them as individuals, equipping them with the tools and skills they need to excel in any environment they might encounter. We’ve seen as well that learning teams require leaders who clearly specify ownership of problems and opportunities so the team understands exactly how to collaborate to support making their team better.

There’s much more to Get Real Get Better, but if we lead more strongly in just these three ways, we’ve learned that we can powerfully improve our ability to adapt, learn and improve, the keys to winning in combat.

It starts with each of us. With key roles across our Navy, you are the generation that will meet the challenges ahead and, should conflict come in this critical decade, lead in combat. How you lead and learn today drives the Navy culture that we’ll have when the fight starts. For us to win, this must be a learning culture, building on how our best teams lead and solve problems today. I am confident that Get Real Get Better is the right approach, and that you are the right ones to make it come alive.

https://www.dvidshub.net/video/820228/vcno-speaks-nhasymposium

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 21

The Importance of Being Present – What I’ve Learned from Meditation

By CAPT Brannon S. Bickel, USN

Besides the universal leadership traits of courage and humility, Naval leaders must be able to listen and be present in the current moment. Being present builds the connections that we make with others. In addition to character and competency, connection is a critical component in the Navy Leader Development Framework. Our connections bring us closer together as a combat element, as a detachment, squadron, and as a Rotary Wing Community. Connections at work not only build trust in each other but also confidence that we will prevail when we find ourselves in a crisis. NHA is our connection between HSM, HSC, HM, VRM, USCG, and USMC. It is also our connection to the past – the leaders and heroes who have come before us – the proverbial “giants on whose shoulders we stand.” My relationships with our retirees from the community motivate me to be better. I certainly enjoy their sea stories but I am most proud to tell our story to them. Stories of the demanding work that you all put in everyday to fly and train with our Air Wings, onboard our carriers, destroyers, cruisers, military sealift vessels, and littoral combat ships. Stories about how we battled through COVID-19 to deploy carrier strike groups and an amphibious readiness group on time during a global pandemic. The mental toughness required to fly, fight, and fix aircraft on deployment without the previous reward of an overseas port visit. Sustainment deployments, unplanned surges in support of our National Defense Strategy, deterring peer actions that would threaten allies or the sovereignty of nations, and the freedom to navigate on the open oceans of the Indo-Pacific, North Atlantic, Mediterranean and Black Seas. This is all challenging work that has had a tax on our mental state. Being present in our daily lives helps reduce that mental stress and enables us to stay connected to those around us.

What are things that we can do to be more present in daily life? Personally, I can turn away from distractions when I’m talking to my spouse or children. If the TV is on or music is playing in the background, turn it off and be present in the conversation. I’m guilty of using my phone at the dinner table. You can hear the dialogue, “Sorry babe, it’s a work issue I have to handle.” If we want to truly be present for our family, it would be better to leave the phone somewhere else or turn on the do not disturb function. We can dedicate quiet time for reflection every day. What I’ve learned from meditation is that a simple practice devoted to a focus of attention whereby

one does not respond to every itch, sound, or annoyance can have a powerful effect on one’s ability to focus on what’s profoundly important when not meditating. I’m not trying to reach a different state of mind or harness a new skill that will make me more mindful. I already have the skills to be mindful. I just need to be present and aware to recognize that I live life moment by moment. Meditating is being aware for a fixed period of time. The answer that we’re looking for is found during many moments of awareness throughout the day – being present and leaving our worries and anxiety aside.

Meditation helps me build the critical skills of concentration, clarity, authenticity, gratitude, and equanimity. These are qualities that I’m trying to improve. I think those are skills that would make us all better leaders.

So back to the question, how does meditation make me better – more resilient, tough under pressure, and lethal? Through the practice of meditation, I can slow down my response and allow myself to focus on what is profoundly important in the moment. It calms the inner voice that brings so much chaos into my daily life. I can filter out noise and act on the most important thing. The practice better enables clarity in crisis and drives a conditioned response like that first step of every emergency procedure – step 1: Take a breath. The more we can prepare for the day when we are called to action, the better. Building mental toughness is just as important as building physical toughness.

In a broader context, building combat lethality is a herculean effort, but a simple practice of daily discipline can have a profound effect on our individual toughness. That toughness builds as we train, operate, and practice our tactics, techniques, and procedures. Through repetition, like a weightlifter, our mental muscles are honed into precision, and we gain confidence in our ability to operate the next time. Those building blocks eventually turn into credible combat power and demonstrate to our adversaries that we are willing to impose a cost to protect the solidarity of nations, to strengthen alliances, and to protect freedom of navigation. As Americans, it’s more than our moral obligation. We have a direct and visceral interest in maintaining the rules-based order of the world and protecting our way of life. 330 million American citizens are counting on us!

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 22 Commodore's Corner

Navy Core Values: The Guiding light for our Sailors and the World

LCDR Rob “OG” Swain, USN

Aisatsu ( ) Naval Helicopter Association! I’m writing to you in the midst of CVW-5 preparations for our annual summer patrol aboard USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76). While I personally relish the challenges and rewards of life in the forward deployed naval force (FDNF), I will not deny that for the thousands of families stationed in Japan, annual deployments call for a level of sacrifice unique to the FDNF optempo. The proximity of our global competitors, the immediacy and unpredictability of their actions, and the operational availability of U.S. forces oblige our units to “get ready and stay ready.” Whether at sea or training ashore, when fatigue, complacency, or cynicism begin to cast a shadow over service, allow our Navy’s core values to provide a “guiding light” toward resilience–more to follow on that later.

The demands of continuously operating forward deployed challenges our units to directly engage with the Navy core values of honor, courage, and commitment on a daily basis. Honor – the privilege to live in a foreign country requires each individual Sailor to demonstrate integrity and respect to themselves, their shipmates, and the population of the host nation. Courage – the regional security imperative to deploy inside contested and disputed territory can prove volatile. It takes courage to own the decision making and risks which carry strategic implications. Commitment – effective leaders recognize that the all-volunteer nature of our Navy is what makes us most lethal. Every service member who raises their hand and takes the oath understands that they commit to selflessly serve ideals greater than their own desires. While all three core values shape the ethos and cultural foundation of our Navy, no virtue is attainable without the courage to take the hard road and defend what is right and just. In this segment of Report from the Rising Sun (RFTRS), we’re going to talk about courage.

One of the greatest examples of American ingenuity, Thomas Edison, contributes beautifully to the historical discourse on courage. In 1931, during his final public address, Edison shared:

"My message to you is: be courageous! I have lived a long time. I have seen history repeat itself again and again. I have seen many depressions in business. Always America has come out stronger and more prosperous. Be as brave as your fathers before you. Have faith! Go forward!"

When I first read this quote in John Maxwell’s book, Success is a Choice, I wondered if Edison bore any affiliation with Japan during his life and work. I am not an Edisonian historian, so I googled “Edison…Japan.” The search generated an exciting tale intertwined with examples of commitment and courage which I am eager to share.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Edison had joined the ranks of international inventors seeking to commercialize the incandescent lamp (light bulb). Incandescent lamps function by using electricity to heat a thin strip of material, called a filament, until the material grows hot enough to glow and produce light. This cohort of inventors and engineers faced a litany of issues keeping the lamps aglow – some light bulbs will only stay illuminated for short periods of time, others can function longer but at costs preclusive to large scale commercialization.

Undeterred by failure, Edison demonstrated commitment to the objective. Later in life, he said that between 1878-1880 he and his assistants “tested no fewer than 6,000 vegetable growths, and ransacked the world for the most suitable filament material.” After trial and thousands of errors, Edison concluded that carbonized cotton demonstrated the properties he was looking for in a light bulb filament. His carbonized cotton light bulb remained lit for a record 14 hours.

Through all of his endeavors toward discovery, Edison understood the force-multiplying impacts of a strong team aligned through clear guidance and a commonly understood vision. Edison leaned heavily on his network of assistants to load-share, synergize ideas, and sustain constant vigilance despite failures. One of his assistants returned to the New Jersey laboratory with a souvenir bamboo hand fan from Japan. Edison carbonized a fiber from the fan and the bamboo filament burned for 1,000 hours. Without delay, Edison sent his team all over the world to find the best bamboo.

Rotor Review #157 Summer '22 24 Report from the Rising

Sun

One of these assistants, William Thomas Moore, journeyed to Japan and was received by the Japanese Prime Minister in Tokyo. The Prime Minister directed Moore to Yamata, a small town on the outskirts of the ancient city, Kyoto. There, on Mount Otokayama, bamboo grows in forests surrounding a twelfth century shrine. The priests from Iwashimuzu Hachimangu shrine assisted Moore in harvesting bamboo samples to bring back to New Jersey. Edison proceeded to standardize the bamboo filament and bamboo remained in commercialized light bulbs for the next 24 years.

In 1934, three years after Edison’s death, the Japanese commissioned a memorial on Mount Otokayama dedicated to the man who brought light to Japan. Yamata City established annual festivals on Edison’s birthday (Edison Setai-San) and the day of his death (Edison Hizen-Sai). Seven years later, shortly after Japan launched their attack on Pearl Harbor and war erupted between our two nations, the Japanese government instructed Iwashimuzu Hachimangu shrine to tear down the monument honoring a national of the enemy

state. The Shinto priests defiantly responded, “Science has no borders.” Due to the courage and commitment of those Japanese priests to their principles, the monument remained standing throughout World War II, and Mount Otokayama still hosts visitors to the Edison memorial today.

Navy core values shape the fundamental beliefs of our sea service, but honor, courage, and commitment are virtues threaded through the common tapestry of human history. They provide a bridge which transcends culture, language, nationality, and geography. By reflecting on and choosing to live by Navy core values in and out of the aircraft, you set a global standard of excellence. This is an example which affirms to our partners and allies that they should continue to look to the United States as the paragon of freedom, democracy, and virtue, thus emboldening them to join in deterrence of coercion and aggression around the world. Be courageous! Have faith! Go forward! Fly Navy! And standby for future Reports from the Rising Sun.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 25

CNO Updates Professional Reading Program

Chief of Naval Operations (CNO), Admiral Mike Gilday, released an update to the CNO Professional Reading Program on May 6.

The CNO-Professional Reading Program consists of 12 books and is a mix of writing genres including fiction, non-fiction, military, strategy, management, and technology, among others. “A learning mindset is essential to accelerating our warfighting advantage,” said Gilday. “A Navy that learns, adapts, and improves the fastest will be the most successful. Knowledge sharing is essential to creating a learning culture.”

The goal of the program is to contribute to a culture dedicated to warfighting and learning, while simultaneously supporting the personal and professional development of Sailors beyond that of their primary designator or rating.

This is a graphic made for Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Mike Gilday's Professional Reading List 2022. U.S. Navy photo by Chief Mass Communication Specialist Amanda Gray.

“We are driving a Fleet-wide campaign of selfimprovement,” said Gilday. “We must foster an organization that supports and empowers Sailors to have an independent quest for knowledge through reading and information sharing. What you know and how fast you learn is relevant in this era of strategic competition.”