JOURNAL

The Southwest: Conservation Close to Home

African

African

Kim Turner Lisa Bissi

Jennifer MacEwen

PREPRESS AND PRINTING Quad Graphics

Kim Turner Lisa Bissi

Jennifer MacEwen

PREPRESS AND PRINTING Quad Graphics

Follow @sandiegozoo & @sdzsafaripark. Share your #SanDiegoZoo & #SDZSafariPark memories on Twitter & Instagram.

The Zoological Society of San Diego was founded in Octo ber 1916 by Harry M. Wegeforth, M.D., as a private, nonprofit corporation, which does business as San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

The printed San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal (ISSN 2767-7680) (Vol. 3, No. 1) is published bimonthly, in January, March, May, July, September, and November. Publisher is San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, located at 2920 Zoo Drive, San Diego, CA 92101-1646. Periodicals postage paid at San Diego, California, USA, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, P.O. Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112-0271.

Copyright© 2023 San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. All rights reserved. All column and program titles are trademarks of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

If your mailing address has changed: Please contact the Membership Department; by mail at P.O. Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112, or by phone at 619-231-0251 or 1-877-3MEMBER.

For information about becoming a member of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, please visit our website at ZooMember.org for a complete list of membership levels, offers, and benefits.

Subscriptions to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journa l are $25 per year, $65 for 3 years. Foreign, including Canada and Mexico, $30 per year, $81 for 3 years. Contact Membership Department for subscription information.

As part of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s commitment to conservation, this magazine is printed on recycled paper that is at least 10% post-consumer waste, chlorine free, and is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is not responsible for any calculations on saving resources by choosing this paper.

From the beautiful coastline to the scenic mountains, and across the flourishing forests and vast desert landscape, we are constantly inspired by the wildlife that inhabits our Southwest conservation hub. As an organization based in San Diego, we benefit from living in one of the most biodiverse counties in the continental United States, and from the dynamic ecosystems throughout the Southwest. Here, we collaborate with many dedicated conservation partners, inspire millions to help protect nature, and work to meet the growing needs of wildlife.

Starting here in our own backyard, we connect people and communities to the transformative power of conservation, and share how each of us can make a difference for wildlife. From our 40 years of collaboration to bring the California condor back from the brink of extinction, to tracking mountain lions to understand how we can better coexist, to planting seedlings of iconic and critically endangered Torrey pines along our coastline, we are committed to being stewards of our region and champions for the wildlife we coexist with.

In this issue, you’ll learn more about the spirit of our conservation projects and the incredible wildlife thriving in our Southwest conservation hub. Through your support, we are making a meaningful impact in our community—for wildlife, people, and the planet we all share— working together as allies for wildlife.

Throughout our 107 years, we’ve gained unique expertise in caring for the world’s wildlife at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park. We are excited to start the next chapter of this legacy, as we usher in the largest endeavor in San Diego Zoo Safari Park history. The reimagined Denny Sanford Elephant Valley will transform the heart of the Safari Park and bring you closer to elephants than ever before. Not all of our guests get the opportunity to visit elephants’ native habitats in Africa and Asia, but at the Safari Park, you’ll gain a deeper appreciation for the lengths it takes for local communities to coexist with, and to help save, these gentle giants. Under the leadership of Safari Park Executive Director Lisa Peterson, we look forward to seeing what the new Elephant Valley will do for the future of elephant conservation, and for elephants worldwide.

Every conservationist needs inspiration to reach their full potential, and make the greatest difference for wildlife. As 2023 begins, we look forward to seeing you at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park—inspiring places to connect with wildlife and to find that special moment that changes your entire year.

Now, let’s take a journey through our own backyard in this issue of the Journal, as we explore our Southwest conservation hub.

Onward,

A. Baribault President and Chief Executive Officer

Comprised of a mosaic of landscapes including deserts, chaparral, scrublands, and more, the Southwest encompasses diverse ecosystems and equally distinctive wildlife.

SDZWA strives to protect this biodiverse hotspot— one of our eight conservation hubs.

As herbivores, desert tortoises get most of their needed moisture from their food. They can go for up to one year without access to fresh water.

The number of bird species—such as the California condor and burrowing owl—native to the Southwest.

It can take a boojum tree 50 to 100 years to mature and flower.

Javade Chaudhri, Chair

Steven S. Simpson, Vice Chair

Richard B. Gulley, Treasurer

Steven G. Tappan, Secretary

Rolf Benirschke

Kathleen Cain Carrithers

Clifford W. Hague

Robert B. Horsman

Gary E. Knell

Linda J. Lowenstine, DVM, Ph.D.

Judith A. Wheatley

‘Aulani Wilhelm

The population of Peninsular bighorn sheep in the US is currently divided among approximately eight ewe groups.

TRUSTEES EMERITI

Berit N. Durler

Thompson Fetter

George L. Gildred

Yvonne W. Larsen

John M. Thornton

A. Eugene Trepte

Betty Jo F. Williams

Paul A. Baribault

President and Chief Executive Officer

Shawn Dixon

Chief Operating Officer

David Franco

Chief Financial Officer

Erika Kohler

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo

Lisa Peterson

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo Safari Park

Nadine Lamberski, DVM, DACZM, DECZM (ZHM)

Chief Conservation and Wildlife Health Officer

Wendy Bulger

General Counsel

David Gillig

Chief Philanthropy Officer

Aida Rosa

The mountain yellow-legged frog’s clutch size varies from 15 to 350 eggs per egg mass.

Chief Human Resources Officer

David Miller

Chief Marketing Officer

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) protects and restores nature in eight conservation hubs on six continents. Below are recent discoveries and progress from around the world.

Our African Forest hub team donated two of our retired field vehicles to the Limbe Wildlife Centre (LWC) in Cameroon. Coming at a vital time for LWC, the vehicles will be essential in transporting fresh vegetation from farms on the flanks of Mount Cameroon (an active volcano, renowned throughout Africa for its rich, fertile soils) back to LWC. At LWC, conservation workers feed the vegetation to primates rescued from the commercial bushmeat trade. This project also enables women’s groups in the area to earn income by selling vegetation that would otherwise be waste.

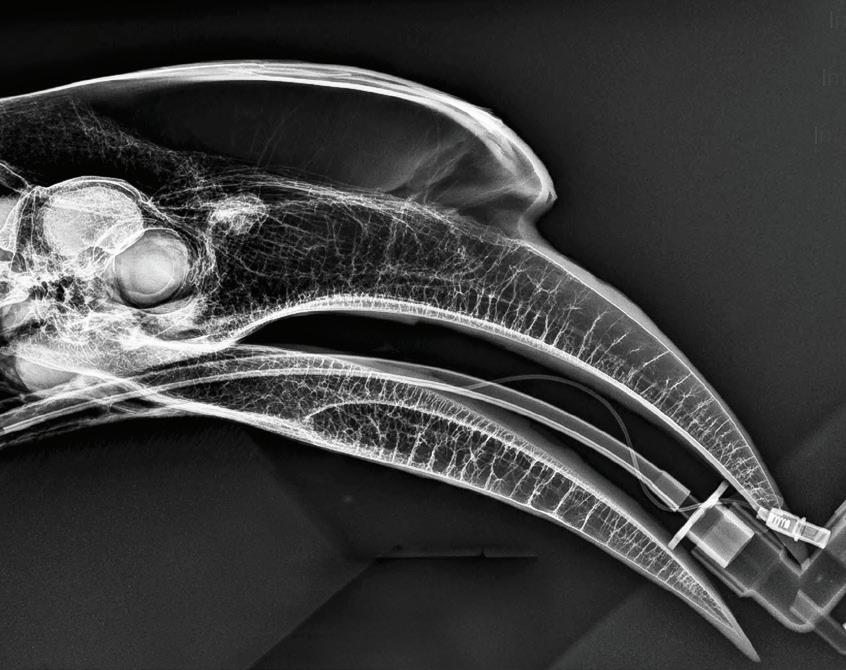

One of the last remaining North American parrot species, the endangered thickbilled parrot Rhynchopsitta pachyrhyncha exists today only in the high elevation pine forests of northern Mexico. Parrot populations are declining due to habitat loss and the impacts of climate change. To track where and when these birds move throughout the year—and therefore, to determine locations in need of protection—SDZWA partnered with Mexico’s Organización Vida Silvestre and outfitted parrots with radio transmitters mounted on noninvasive harnesses that are worn like backpacks. This innovative technology has revealed previously unknown migratory routes and a nesting site. These data will inform parrot conservation and sustainable forest management strategies.

Our Community Engagement and Horticulture teams created a survey to investigate motivations for harvesting wild orchids in Vietnam. The questionnaire asks orchid collectors about illegal trading practices such as selling wild-harvested orchids internationally, as well as the respondents’ level of “conservation-mindedness.” The goal of the project is to find opportunities to engage with communities who may be harvesting orchids unsustainably. Ideally, we hope to bring these communities into collaborative conservation efforts, such as propagation of endangered species that these individuals may already have in their collections.

SDZWA’s Native Plant Gene Bank team made the first-ever seed collection of prairie false oat Sphenopholis interrupta californica. This species of native grass was presumed extinct until recently, when two individuals were rediscovered in northern San Diego County by local botanists. Their discovery marked the first documentation of prairie false oat in over 100 years, and the first documentation of this grass in the United States. More of the individual plants have been identified, and with support from the San Diego Association of Governments, our team collected and banked seed from seven individuals, safeguarding this rare “lost” species and preserving regional native botanical heritage.

The excitement of participating in scientific studies that tip the balance in favor of species’ survival is extraordinarily cool. Relatedly, seeing young people who think science is cool and want to make a difference is right up there, too.

What book or film influenced you or made a strong impression?

A book that had a big influence on me was Albert Schweitzer’s Out of My Life and Thought. As for movies, I’m kind of a classicist: The Gay Divorcee or Viva Las Vegas

What has surprised you about working with SDZWA?

I guess it is that I have spent my whole career with the organization. The innovation in conservation science and wildlife health that SDZWA has fostered has been a game-changer. I’ve never wanted to be anywhere else.

What do you see as the future of wildlife conservation?

The One Plan approach of the International Union for Conservation of Nature-Species Survival Commission (IUCNSSC) is the road map that provides the best options for the future and recognizes the crucial need

for biobanking, especially for using cellular approaches to genetic rescue.

What was a turning point or defining moment in a project or program you’ve worked on?

Out of many, one was when I realized that the new technology of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) could allow non-invasive genetic analysis of wild gorilla populations, and a significant project fell into place. Postdoc Karen Garner, supported by Ruth Keesling and the Morris Animal Foundation, produced the first analysis of mountain gorillas and informed subsequent conservation planning.

What is your favorite animal? Why?

I am partial to donkeys. But my favorite things are the processes that produce the diversity of species, the legacy of which we must responsibly steward. So, it’s an appreciation of evolution that I find so compelling.

Who or what inspires you? Stars. We are part of a universe beyond our comprehension, and we are here on a planet where life has evolved and produced, to quote Darwin, “endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful [that] have been, and are being, evolved.” We can commit to seeing it thrive.

What is the coolest thing about your job?

Oliver Ryder, Ph.D.

As the Kleberg Endowed Director of Conservation Genetics, Oliver Ryder works with a team of scientists using genomics and cellular technologies to contribute to conservation efforts for numerous species. He also is active in developing and promoting cryobanking of living cells, like those in our Frozen Zoo®, through a global network, as resources for conservation applications and genetic rescue.

Cryopreservation and biobanking are trending terms that are often linked to saving species or preventing extinction. But what do they entail, and how are they different?

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Wildlife Biodiversity Bank safeguards irreplaceable materials in six distinct biobanked collections (see page 24). Each of these contains different plant and animal sample types that have specific storage and preservation requirements. All six are biobanks—storage places for biological samples—but only the Frozen Zoo® uses cryopreservation, which keeps the banked materials viable (living).

The Frozen Zoo subset of the Wildlife Biodiversity Bank holds living, cryopreserved fibroblast (skin and connective tissue) cells and reproductive materials (sperm, ova, embryos, and tissue)

from over 10,600 individuals and 1,200 mammal, bird, reptile, amphibian, and fish species. There are many representatives from San Diego County, including mountain yellow-legged frogs, burrowing owls, Pacific pocket mice, and Pacific pond turtles.

A unique quality of these cryopreserved materials is that although they are frozen, they are viable. Typically, very low temperatures are lethal to unprotected cells—for example, when plants succumb to a hard freeze, or when layers of skin are damaged by frostbite. But if we can maintain the viability of frozen cells, they provide an invaluable resource for wildlife conservation—in ways beyond what non-living material such as DNA or museum skins can accomplish. Many of the current genetic rescue tools require cryopreserved materials like those archived in the Frozen Zoo. These include assisted

reproductive technologies such as artificial insemination, in vitro fertilization, and intracytoplasmic sperm injection; and also other tools like cloning, karyotyping, and generating induced pluripotent stem cells from reprogrammed fibroblasts. Recently, skin cells in our collection were provided to collaborators to produce clones of two endangered species: a Przewalski’s horse and a black-footed ferret.

Vials from the Frozen Zoo can be thawed years, or even decades later, and the cells remain viable. So, how is that possible? Cryopreservation, a process of preserving cells and tissues at very low temperatures without causing cell death, is the key. The methods are different for the reproductive cells and somatic cells (body cells like fibroblasts), but both require a cryoprotectant to keep the cells viable while frozen. Cryoprotectants like dimethyl sulfoxide and glycerol prevent

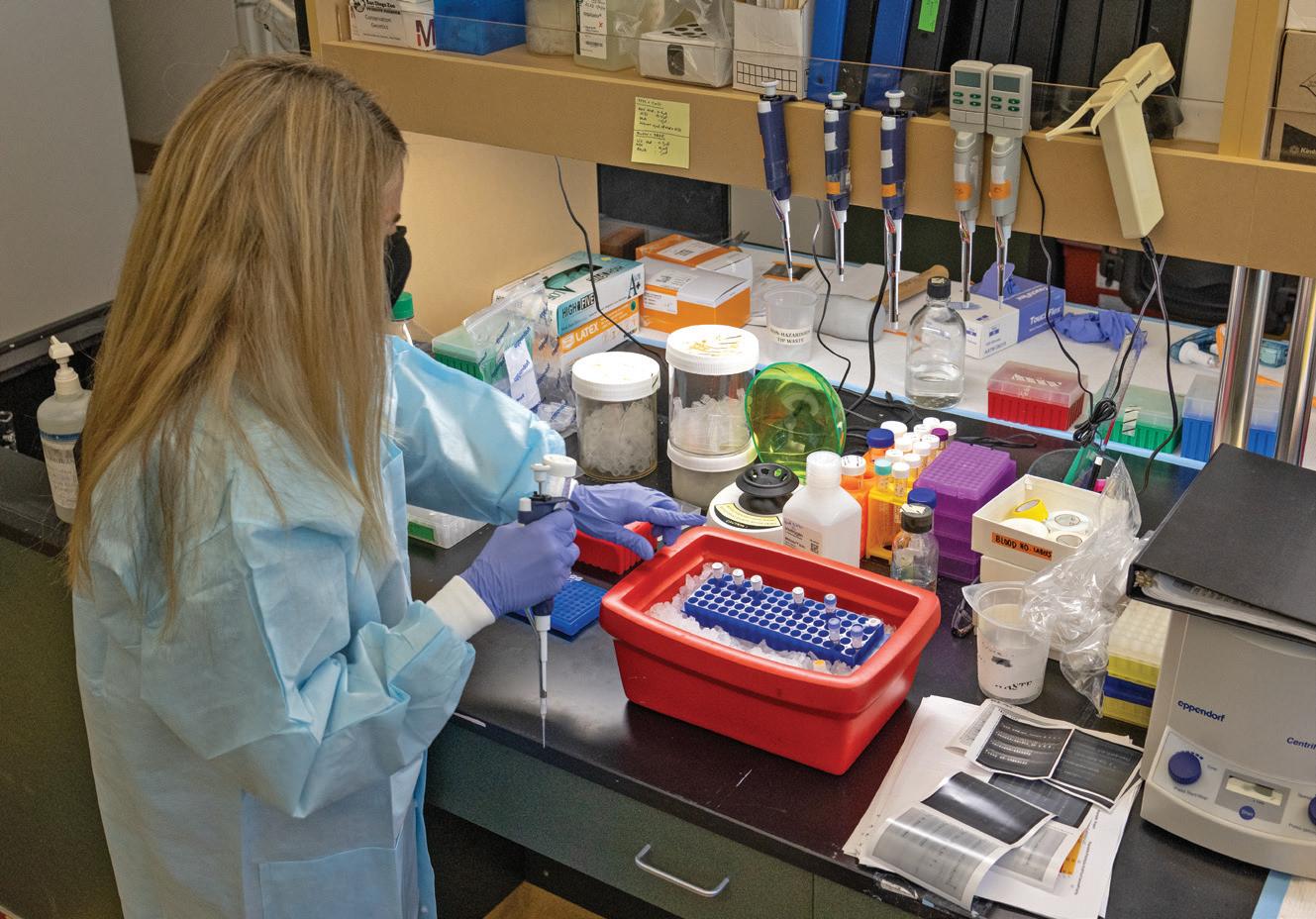

Marlys Houck, B.S., CG(ASCP)CM, curator of SDZWA’sFrozen

Zoo® ,

explains how banking on cryopreservation to help save species can reap significant returns.

A vial holding over 1 million viable blackfooted ferret fibroblasts (skin cells) cryopreserved in the Frozen Zoo. The other vials hold cells from additional endangered species.

the formation of ice crystals, which would destroy the cells by piercing their delicate membranes, causing the nucleus and cytoplasm to disperse.

To establish a fibroblast cell line that will be banked in the Frozen Zoo, we start with a tissue sample, usually collected soon after an animal dies. Biopsy vials containing media with nutrients and antibiotics keep the tissue hydrated, and prevent bacterial or fungal growth during transport at ambient temperature to the tissue culture lab. Here, in a controlled environment, we dice the tissue into small pieces and mix it with an enzyme that releases individual cells from the connective tissue. Soon, they begin to attach to the bottom of a flask, where they grow and divide, making a thick carpet of cells. It takes weeks of incubation and nurturing by specially trained cell culturists to expand the cells into more

flasks, until there are around 10 million cells. Then, they are collected and mixed with the cryoprotectant, and divided into multiple vials that will be frozen and added to the ever-growing collection. The process for freezing the reproductive materials is very different, and takes another team of specialists.

It’s imperative to cryopreserve samples of as many species as possible, because we can’t always predict which populations may drop to critically low levels next. Each vial we add to the Frozen Zoo today provides hope for wildlife conservation in the future.

The author lifts a rack of cells out of one of the Frozen Zoo cryotanks.

“But in the end, it’s only a passing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must pass. A new day will come. And when the sun shines it will shine out the clearer.”

– J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings

Can an animal be both endangered and common at the same time? At first, the two terms might seem contradictory. In the conservation community, “threatened,” “endangered,” and “rare” are adjectives we apply to the species most at risk of disappearing forever from Earth. On the other hand, we might call the plants and animals we see or interact with on a regular basis “common,” so abundant and well adapted that even in our modern, urbanized world, we still bump into them regularly. How can it be that a species is both common and at risk of disappearing? The surprising answer consists of equal parts animal biology and human psychology. And no species more perfectly embodies the contradictions—common and rare, everywhere but nowhere, widespread but at perilous risk—than Southern California’s mountain lion Puma concolor.

The Paradox of the Puma Mountain lions—also known as cougars, pumas, and panthers—are adaptable, and make their home across a huge range of habitats, from Canada to the tip of South America. More often than we are aware, they are peacefully coexisting and sharing their habitat with us. Just the fact that they are still here in the Golden State is a remarkable testament to their intelligence, resourcefulness, and ability to adapt to a changing world. Targeted as threats to people and domestic livestock, mountain lions (along with their fellow apex predators, wolves and grizzly bears) were hunted by Spanish, Mexican, and US settlers throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, with increasing focus and technological sophistication. Between 1906 and 1963, California issued a statewide bounty that resulted in over 12,000 mountain lions killed. By the early 20th century, gray wolves and the mighty grizzly bear were gone from California’s landscape, but mountain lions persisted.

Legal protection began in 1972, and in 1990, the passing of Proposition 117 gave mountain lions special protection under California law—a rarity among states with the species. Since these protections were put in place, mountain lion numbers have slowly increased across the state. However, despite legal protection, life in the shadow of human progress hasn’t been easy. Proposition 117 banned the sport hunting of mountain lions, but allowed for exceptions. For example, mountain lions can be killed if they pose a threat to public safety. Freeways form impenetrable barriers to mountain lions, accounting for many mortalities.

Mountain lions face additional challenges, too. The same freeways that connect our cities create islands of habitat for mountain lions and other species, preventing them from dispersing to find new territories. The inability of mountain lions to move between these isolated islands has multiple

consequences: they are cut off from the gene flow that maintains vital genetic diversity; diseases can spread more rapidly; and there is increased competition between individuals for limited resources. Moreover, almost all mountain lions in California tested by researchers are positive for rodenticides, some of which are illegal in the state. One study of Southern California mountain lions found that just over half of all individuals will survive to the next year.

More often than we are aware, mountain lions are peacefully coexisting and sharing their shrinking habitat with us. As development encroaches on wilderness areas, frequent contact with people is inevitable, maintaining the illusion that mountain lions are common or even “overpopulated,” when in fact, local populations are closer than ever to extinction.

Our partners at the University of California, Davis California Mountain Lion Project (CMLP) are addressing modern threats to California’s mountain lions, and we are collaborating with them on several key projects. To address loss of mountain lions through depredation permits, we are working together to study and test deterrents. We are using trail cameras and GPS collars to track mountain lion movement through locations where we experimentally set small noise- and light-making devices. Some of these devices play recordings that are neutral to domestic animals and people, but frightening to mountain lions. Our study will identify tools that landowners can use to teach mountain lions to keep a healthy distance—protecting the lives of livestock and pets.

In Orange County’s Santa Ana Mountains, mountain lions are surrounded on all sides by development and freeways. Here, CMLP is working to develop monitoring techniques that will allow researchers to detect declines in population size or health, generating accurate models of population size by combining data from remote trail cameras, GPS collars, and scat. They are collecting genetic information and

In Good Hands: Mountain lions are captured and anesthetized in order to collect biological samples and place GPS collars for monitoring. Animals are provided with supportive care such as oxygen, and monitored carefully by permitted veterinarians and biologists.

This image of a California mountain lion is from a trail camera in the Safari Park Biodiversity Reserve, a 900-acre protected area in San Diego’s North County.

measuring physical characteristics indicative of inbreeding, such as kinked tails and abnormal sperm, which were also seen in the critically endangered Florida panther (a different localized population of the same species). In collaboration with SDZWA, CMLP is also studying how mountain lion habitat use, especially in urban areas, impacts their exposure to toxins and disease, especially those that are shared with people and domestic animals.

CMLP and collaborators have identified six populations of mountain lions in Southern and Central California that are at risk of population decline, even in some cases to the point of local extinction, due to high levels of mortality, small population sizes, loss of habitat, and loss of genetic diversity. These threats are of enough concern

that these six populations are currently being considered for listing under the California Endangered Species Act, which would afford them additional protections. Two of these populations—the Santa Ana Mountains and the Eastern Peninsular Range—are right in the backyard of the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. SDZWA is proud to be working with CMLP to advance the science needed to conserve these icons of the Southwest.

Charlie de la Rosa, Ph.D., is natural lands program manager for SDZWA; Jessica N. Sanchez, DVM, M.S., Ph.D., Dipl. ACVPM, Dipl. Epidemiology, is a postdoctoral fellow in disease investigations.

If the idea of a trip to Mexico conjures up images of sunsplashed beaches, you might be surprised to find yourself breathing the crisp, cool, pine-scented air in the rugged mountains of Sierra San Pedro Mártir National Park.

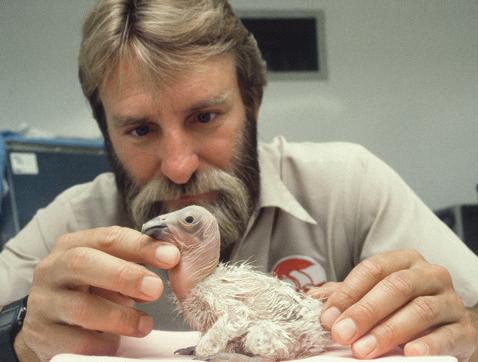

Just 150 miles from San Diego (as the crow—or condor—flies), the 180acre Sierra San Pedro Mártir (SSPM) National Park lies midway between the Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Cortez, in Baja California, Mexico. It’s home to native wildlife like bighorn sheep, mountain lions, woodpeckers, golden eagles, and a small but thriving flock of California condors. The condor flock in Baja California began with birds that hatched in managed care and were introduced to SSPM by US and Mexico wildlife managers and biologists. “We introduced condors there every year

BY DONNA PARHAM

BY DONNA PARHAM

for 10 years or so,” says Ignacio (Nacho) Vilchis, Ph.D., associate director of recovery ecology for San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA). As the birds reached adulthood, they found mates; and eventually, some parents started fledging their own chicks.

Alas, in 2015, the smooth operation abruptly halted due to several unforeseen factors, including turnover within governmental agencies in Mexico and changes in export/import regulations of both countries. As a result, from 2015 to 2022, no birds moved across the border. “We were at a standstill,” says Nacho. “Many of the changes in Mexico’s agencies resulted in a loss of institutional knowledge.” When Mexico’s division of endangered species became the responsibility of the National Commission of Natural Protected

Areas (Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, or CONANP), Nacho says, “We had to start from scratch.” After a huge collaborative effort with CONANP, everything is now aligned. In April last year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), CONANP, and SDZWA moved two condors across the border.

Introducing condors to the native habitat is a cautious process. For six months or more, juvenile condors fly, roost, and interact within the protection of an enormous aviary, constructed around tall pine trees. As young birds get accustomed to their new surroundings, biologists provide food. They also put food outside the aviary, which attracts the local condor flock, as well as other scavengers. “Condors are super hierarchical,” Nacho says.

For the first time in seven years, California condors from the US conservation breeding program are once again Baja-bound.

,

,

“The new birds learn the pecking order of the flock before being released. And, when scavenging predators show up for the free food, the condors also learn what to be afraid of—while they are still safely within the aviary.”

Persistence in re-establishing the California condor introduction site in Baja California is about more than just expanding the range of these endangered birds. “Baja California is one

of the best available habitats for condors,” Nacho says. “There’s much less hunting, so there is far less lead in the environment.” That makes the condors in Baja California less susceptible to lead poisoning—the number one cause of mortality in free-flying condors in the US. (Condors ingest lead fragments when they eat the remains of wildlife shot with lead ammunition.)

Other contaminants are far less common in Baja California, too. Nacho was part of a team of conservation scientists who investigated the

Nacho Vilchis

associate director of recovery ecology

1983

Eggs rescued from condor nests are incubated and hatched at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. Over the next two years, SDZWA incubates, hatches, and raises a total of 12 condors.

1987

California condors are Extinct in the Wild. There are 27 at the Safari Park and the Los Angeles Zoo: 10 rescued from the native habitat, and 17 that were reared in managed care.

1988

“Molloko” hatches—representing the first successful mating, egg-laying, and hatching of a California condor in managed care, at the Safari Park.

1992

The first California condors raised in managed care (from rescued eggs) are reintroduced in California’s Los Padres National Forest.

The first wild-hatched chicks of reintroduced birds fledge, in Arizona and California.

California’s Ridley-Tree Condor Preservation Act takes effect, requiring the use of nonlead ammunition when hunting wildlife in California.

presence of contaminants in stranded marine mammals—an abundant source of food for condors in both California and Baja California. (See box below.) By comparing sources of possible food from both areas, they found that stranded marine mammals from California had larger presence of contaminants like mercury, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), and the breakdown products of DDT, versus stranded marine mammals from the Gulf of California. Their findings back research showing that condors can ingest contaminants when they feed on the carcasses of marine mammals that have accumulated these persistent toxins. Information like this can be important when planning condor reintroductions.

Nacho is looking to a bright future for Baja California’s condor population. “We are hoping to move two more condors to the Baja California introduction site this spring, and another four or five per year for the next three years,” says Nacho. The latest Baja California reintroduction is a testament to the persistence of SDZWA conservation scientists, along with our partners in the California Condor Recovery Project and the government of Mexico.

“Assessing Marine Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals in the Critically Endangered California Condor: Implications for Reintroduction to Coastal Environments,” is published in Environmental Science and Technology, May 17, 2022. Our science team, including Ignacio Vilchis, Ph.D., Christopher Tubbs, Ph.D., and Rachel Felton, were part of the research team that led this study; along with San Diego State University scientists, in collaboration with Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada and the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

California condors in breeding centers and other managed-care facilities California condors flying in their native habitatConservation biologists determine which condor chicks will eventually be reintroduced, and where. “They determine the genetics of every chick that hatches in managed care and calculate the mean kinship [how related a bird is to all the other condors] for each of them,” explains Nacho. "They also take into account sex ratio and logistics such as transportation.” Historically, juvenile birds selected for introduction at the Baja California site have come from the propagation program at the Safari Park.

California condors are reintroduced when they are about two years old. By that time, they have spent a year or so among other condor fledglings in a remote socialization habitat—isolated from human activity—where they learn how to interact with each other. To encourage them to avoid human activity, food enters through a chute in the wall, and pools are drained and rinsed from the outside.

At the time of reintroduction, California condors are black-headed juveniles. They reach maturity—and develop their beautiful bald head—at about six years, and that’s when they begin pairing up.

Torrey pines’ roots help stabilize the soil they grow in.

In 1982, the first of only 22 remaining California condors arrived at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park, launching what was to become a critical conservation program for the iconic Southwest species over the next 4 decades. This also marked the launch of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s (SDZWA) enduring commitment to innovative, science-based conservation. Our conservation portfolio has since grown to include hundreds of species from ecosystems around the world, but our roots in San Diego run deep, and our dedication to protect local wildlife and landscapes— for and with our Southern California community—is stronger than ever.

With our idyllic climate and picturesque scenery, San Diego draws residents and visitors from all over the world. Our natural spaces are among our unique assets: San Diego County is one of the most biodiverse counties in the contiguous United States, hosting a range of wildlife found nowhere else on Earth. San Diego and surrounding Southern California

counties are concentrated with a diversity of ecoregions (regional ecosystems) including coasts, deserts, grasslands, forests, mountains, and freshwater systems. It is this variety of ecoregions that makes the Southwest an ideal home for both wildlife and people.

But with continuous human population growth and the mounting effects of climate change, we have increasingly tipped the scales away from sharing—and into threatening— our local wild spaces. And sharing our natural spaces goes beyond equitably divvying-up landscapes. Because these spaces influence the fundamental stability of our home, we must safeguard our ecoregions as a balanced whole. The health of wildlife, environments, and people are profoundly interconnected, and when we coexist and protect nature, we are protecting our own well-being.

There are countless reasons—tangible and philosophical, personal and communal—to protect nature. But among the most important reasons is that nature provides ecosystem services: direct or indirect benefits to people that are generated by wildlife and/or the interactions of wildlife with the physical environment. Fresh air, clean water, food

sources, and climate regulation are examples of ecosystem services.

Southern California is no exception to relying on ecosystem services. The table on page 20 describes some of the services that we can attribute to our local wildlife. Although these examples are only a few of the many species and ecosystem services we enjoy, they underscore the fact that our ecoregions and endemic wildlife sustain our ability to live and thrive here.

Even though different ecosystems in the Southwest have distinct and unique characteristics, they are functionally and physically connected, and their interactions produce the overall character of our home landscape. The anatomy of our landscape is like a patchwork quilt, with fabric patches joined to form panels, and panels then joined to create the quilt that warms us. In the same way, wildlife, environments, and people join to form ecoregions, and ecoregions join to create the home that sustains us. The thread that binds our home is woven from factors that maintain our well-being, such as a stable climate, intact habitats, and native biodiversity.

Cutting out pieces of fabric or thread may cause a quilt to unravel. Likewise, eliminating wildlife or natural spaces may cause our ecoregions to collapse, and damaging our connecting thread compromises the integrity and livability of our home.

Safeguarding our health requires holistic approaches that embrace our surroundings. To address this need, SDZWA and our partners are actively working to protect our local wildlife and natural spaces. In our Southwest hub, we manage conservation projects that address more than 40 endemic species (including those identified in the table on page 20) across our local ecoregions.

Collaborating with our community is of the utmost importance in achieving sustainable conservation outcomes. Expanding the burrowing owl population in Ramona with San Diego Habitat Conservancy, planting seedlings in Torrey Pines with the California Department of Parks and Recreation (State Parks), and releasing mountain yellow-legged frogs in the San Jacinto Mountains with the University of California, Los Angeles are just a few examples of the field work that we

do side-by-side with dozens of nonprofit, academic, and government agency partners.

The people in our community are also key allies. Through SDZWA’s Conservation Science field trips and teacher workshops, students, teachers, and community groups from Southern California (as well as nationally and internationally) learn about and partake in conservation efforts. Participants engage firsthand with our conservation scientists and take away lessons about how we can be stewards for a thriving world. One of SDZWA’s newest programs, the Native Biodiversity Corps, is a summer program for San Diego high schoolers to learn about local wildlife, and to design and plant native gardens on their school campuses. We also welcome community volunteers,

diverse in skills and expertise, to implement their passion for conservation alongside our teams in the field and on grounds at the San Diego Zoo and the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

SDZWA is a proud leader in preserving the health and natural heritage of our San Diego home and Southern California neighborhoods. It is through collaboration that we engage and inspire conservation allies. It is a network of allies—a network that includes all of us, working together as a community—that will allow us to increase our impact and reach the holistic conservation solutions that will benefit wildlife, ecosystems, and people: in our own home and for the world, today and for the future.

Favoring native plants in their diet, tortoises digest and disperse the seeds as they move around, thus sustaining desert plant diversity. Native plants best support other native wildlife, and because they are drought tolerant, these plants do not put a strain on our limited water supply.

Mountain yellowlegged frog Rana muscosa

Pacific pocket mouse Perognathus longimembris pacificus

Owls keep populations of pests (such as rodents) in check, thus preventing them from overgrazing—and therefore damaging—crops and wild grasses. Controlling the number of small animals also maintains the balance of the food web.

Frog tadpoles eat algae, and in doing so, they keep the water clean and prevent clogged waterways. Adult frogs eat invertebrates, thereby controlling the number and spread of disease vectors like mosquitoes.

Torrey pine needles retain fog, creating cloud-like moisture that condenses and “rains” onto the soil below, which supplies the habitat with water. Further, the pines’ roots help stabilize the soil they grow in—a particularly important function on coastal bluffs.

As they dig their burrows, these mice till the soil, encouraging effective movement and storage of water and nutrients. Healthy soils support plant growth and help temper the effects of climate change-induced drought and wildfires.

Hands-on Conservation: (Above, left) SDZWA scientists and our partners release mountain yellow-legged frogs in the streams of the San Jacinto Mountains, helping boost numbers of these critically endangered amphibians. Right: a local high schooler helps create a native plant garden on her school’s campus as part of SDZWA’s Native Biodiversity Corps.

Desert tortoise Gopherus agassizii

Desert Grassland

Coastal sage scrub Coastal sage scrub

Streams, ponds, and vernal pools

Athene cunicularia

Torrey pine Pinus torreyana

Hands-on Conservation: (Above, left) SDZWA scientists and our partners release mountain yellow-legged frogs in the streams of the San Jacinto Mountains, helping boost numbers of these critically endangered amphibians. Right: a local high schooler helps create a native plant garden on her school’s campus as part of SDZWA’s Native Biodiversity Corps.

Desert tortoise Gopherus agassizii

Desert Grassland

Coastal sage scrub Coastal sage scrub

Streams, ponds, and vernal pools

Athene cunicularia

Torrey pine Pinus torreyana

Imagine wandering through the heart of the African savanna, immersed in the sights and sounds of the grasslands. Vistas on either side of the path transport you to a place filled with wonder as you experience up close the sheer majesty of connecting with a herd of African elephants. It’s where wildlife dreams meet reality. It’s the Denny Sanford Elephant Valley at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.

Stepping into the world of Elephant Valley, you will feel a powerful bond with wildlife as you walk in tandem with the largest land mammals on the planet. Their mammoth size, silent strength, and graceful movements will leave you awestruck. Elephant Valley will be unlike anything you’ve ever experienced before—and unlike anywhere else on Earth.

Construction began recently on the multisensory experience, which takes place near ponds and trickling streams that flow into expansive watering holes. To date, we have raised $38 million from nearly 3,000 donors toward our $60 million fund-raising goal. In Elephant Valley, you’ll be able to join the herd and observe as they gather to swim, splash, and cool off together on hot summer days. These streams will also flow

Across from the watering holes, grassy meadows will become the perfect place for family picnics, giving you unparalleled opportunities to connect at eye level with wildlife care specialists and elephants, as the herd dips into the watering holes directly in front of you.

During your expedition, shaded rest areas line the pathway, so you can relax and “live” among the elephants. And with the family of elephants just a few feet away, these serene moments will give you the incredible opportunity to make eye contact with one another, creating a powerful connection that lasts a lifetime.

As global leaders with more than 100 years of elephant care expertise, we share a century of knowledge and experience with partners around the globe. Elephant Valley will become a reimagined haven for our

family of elephants and the epicenter of our conservation efforts to protect, save, and care for elephants worldwide. Since 2016, SDZWA has partnered with the Reteti Elephant Sanctuary, where orphaned elephant calves are nurtured and their futures brightened. It’s an inspiring, special place where communities have come together for the benefit of elephants and people alike. The creation of Elephant Valley is exciting—and that enthusiasm is spreading. “I can’t wait for our guests to experience a completely reimagined Elephant Valley here at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park,” says Lisa Peterson, Safari Park senior vice president and executive director. “I’m passionate about this one-of-a-kind transformation, because it offers a whole new way to connect with our elephant family, and it shines a light on the ways we’re all connected, too. Elephant Valley is where your family and our elephant family become one.”

—Lisa Peterson

San Diego Zoo Safari Park Senior Vice President and Executive Director

I can’t wait for our guests to experience a completely reimagined Elephant Valley here at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park.”

“

The Wildlife Biodiversity Bank is the umbrella term for all the biological materials—organized into six subcollections (described below)—preserved by SDZWA. We have living and non-living materials, stored either frozen or non-frozen, and together they represent an invaluable collection of scientific information that is applied toward advancing wildlife health, care, education, and conservation. SDZWA is at the forefront of collaborative global biobanking efforts: teams across SDZWA contribute and utilize materials, and we receive and share samples and data with hundreds of scientists worldwide.

Biobanks like ours have become an essential means to save species in the face of increasing biodiversity loss. Further, as novel technologies emerge, biobanks lay the foundation for trailblazing conservation solutions by bridging today’s samples to tomorrow’s scientific potential.

By Elyan Shor, Ph.D. | Illustrations below by Amy BlandfordBodily fluids, blood components (plasma and serum)

The samples in our Clinical Repository can be analyzed for the presence of elements such as viruses, antibodies, hormones, or minerals; understanding the samples’ composition is critical in making decisions about wildlife health, management, and care. Our plasma collection ensures that we can administer plasma transfusions to a range of species when needed in emergency veterinary cases. Studying samples in this subcollection also allows scientists to develop novel diagnostic tools and protocols, benefitting wildlife around the world.

Cells, gametes (sperm and eggs), embryos

This collection of living materials is the most extensive and most utilized resource of its kind in the world. Study of these materials empowers us to expand our understanding of evolution and our view of the diversity of life on Earth. With applications including assisted reproductive technology and stem cell technology, the Frozen Zoo has the potential to restore genetic diversity in populations of threatened species. These materials also contribute to the landmark global initiative to sequence the genomes of all eukaryote species on Earth.

Seeds, plant cuttings, and herbarium vouchers (pressed and dried specimens)

The goal of our Native Plant Gene Bank is to conserve material that can be propagated from all 134 of San Diego County’s rare and threatened plants. Seeds are the main material we collect and curate, but we also maintain collections in our nurseries, labs, and cryogenic tanks. Our collections provide insurance against catastrophic loss of a plant population or species. Conservation scientists are working to ensure the stored materials can be revived and grown into plants for restoration purposes.

Tissues, microbes, DNA, and RNA

The samples banked in the Pathology Archive are acquired post-mortem. These samples provide an important window into the health of wildlife populations. The collection’s tissues, pathogens, slides, and photos are a resource to inform care and conservation decisions. Though no animal lives forever, samples taken post-mortem can extend the scientific afterlife of animals for decades or even hundreds of years, throughout which they may continue to contribute to the global scientific community’s understanding of wildlife health.

Tissues, DNA, blood, and cells

Our banked DNA (extracted from banked cells, blood, and tissues) can be used to sequence and analyze wildlife genomes, which clarifies individual and species-level genetic makeup. This information is crucial in illuminating wildlife physiology, behavior, and evolution. We use genetic tools to monitor and manage species in their native habitats and under human care, as well as to study genetic bases of diseases and the evolutionary potential of species to survive and adapt in our rapidly changing world.

Skeletal replicas, items naturally shed or lost (e.g., feathers and leaves)

The artifacts in this subcollection are teaching tools. These items are used by our educators in contexts such as tours, school programs, and engagement with guests on site. Artifacts are a multisensory resource that allow us to engage with people of all ages and learning styles, and they provide a key touchpoint for our guests to establish personal

with wildlife.

San Diego Zoo* 9 a.m.–5 p.m.

San Diego Zoo Safari Park* 9 a.m.–5 p.m. sdzwa.org

619-231-1515

*Programs and dates are subject to change—please check our website for the latest information and requirements for visiting.

(Z) = San Diego Zoo

(P) = Safari Park

FEBRUARY 4–5

Celebrate good fortune this Lunar New Year at the Zoo and Safari Park! The dates for the 2023 event have changed since our calendar issue’s publication—so plan on visiting February 4 and 5 for Wild Weekend: Asian Rainforest to experience the incredible wildlife from this dynamic ecosystem, special Lunar New Year activities, and so much more! For more info, visit sdwa.org/lunarnewyear (Z)

On these special days, guests can take a rare look inside the Zoo’s Orchid House from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., learn about the Zoo’s botanical collection from Horticulture staff on the Botanical Bus Tour at 11 a.m., and check out the Carnivorous Plant Greenhouse from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. (Z)

OFFERED DAILY Wildlife Wonders

At the Zoo’s Wegeforth Bowl amphitheater, wildlife care specialists will introduce you to wildlife ambassadors representing San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s conservation work around the world in Wildlife Wonders, presented daily at 2 p.m. Learn about amazing wildlife—from the Amazon to right here in our own backyard in San Diego—and find out what everyone can do to help conserve wildlife and the world we all share. Presentation runs 15 to 20 minutes. (Z)

OFFERED SELECT DAYS Inside Look Tour: Paws & Claws

During this 90-minute tour, your guide will escort you around the Zoo in a deluxe cart, stopping to enjoy special experiences featuring our lions, tigers, and bears and a talk with a wildlife care specialist. Book online or call 619-718-3000. (Z)

Celebrate good fortune this Lunar New Year at the Zoo and Safari Park! The dates for the 2023 event have changed since our calendar issue’s publication—so plan on visiting February 4 and 5 for Wild Weekend: Asian Rainforest to experience the incredible wildlife from this dynamic ecosystem, special Lunar New Year activities, and so much more! For more info, visit sdwa.org/lunarnewyear (P)

FEBRUARY 1–28

Seniors Free Seniors age 65 and older get free admission to the San Diego Zoo Safari Park throughout the entire month of February. For full details, visit sdzsafaripark.org. (P)

Adults Only Roar & Snore Safari: Wild About You Learn about mate selection, mating behaviors, and love in the animal world at this adults-only sleepover at the Safari Park. For reservations, call 619-718-3000. (P)

Sit back in the comfort of a Safari cart, as you enjoy a 60-minute guided tour of the Safari Park’s spacious African or Asian savanna habitats, led by one of our knowledgeable guides. Book online or call 619-718-3000. (P)

The San Diego Zoo Safari Park’s Lion Camp welcomed three new residents: eight-year-old female African lions Malika, Zuri, and Amira. The feline trio made themselves right at home in their “mane” cave before venturing out into their habitat. And Lion Camp is certainly a family affair— not only are the three lionesses sisters, they’re also the great-grandcubs of the Safari Park’s beloved male lion Izu and lioness Mina, who lived here for 18 years.

Photographed by Ken Bohn, SDZWA photographer.

By becoming a monthly donor and joining our community of Wildlife Heroes, you make a brighter future possible. Wildlife Heroes are the heartbeat of everything we do at San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, and every recurring gift adds up to make a big difference. Every single penny makes an impact for wildlife in need.

Your support fuels critical conservation around the globe, inspiring hope for wildlife worldwide. Become a Wildlife Hero today

San

San