The Characteristics and Complexities of the African Savanna

MARCH/APRIL 2023

on

SDZWA Adventures,

adventures.sdzwa.org

For details

all

visit:

Small Groups•Dedicated Hosts•Amazing Wildlife•Awe-inspiring Locations AUGUST 2024 Kenya Migration and Reteti Adventure Witness the migration from the Maasai Mara, with an exclusive visit to Reteti Elephant Sanctuary.

Photos by: Bella Falk/Alamy Stock Photo, SDZWA

Journey Through Our Conservation Work This issue of the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal focuses on the Savanna hub. To learn more about our collaborative conservation programs around the world, including our wildlife care at the San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park, visit sdzwa.org.

Contents

2 President/CEO’s Letter

3 By the Numbers

4 Findings

6 Meet Our Team

8 Hot Topics

26 Events

28 Wildlife Explorers Page

29 Last Look

Cover Story

10

Home on the Range

Translocating 21 eastern black rhinoceroses in Kenya is no small feat. It’s going to take a village (many of them, actually), and a lot of teamwork and collaboration.

16

E Pluribus Unum

“Out of Many, One.” There’s strength— and survival—in numbers, especially for naked mole-rats. Also known as the sand puppy, these burrowing rodents are a study in eusocial behavior.

22

Blowing in the Wind

Listen up—that sound you hear is the whistling thorn tree and its secret weapon, working together in perfect harmony to thrive.

24

Visualize It

Day or night, the African savanna is alive with activity. Take a closer look at some of the species—diurnal, nocturnal, and those in between—that call this enigmatic ecosystem home.

March/April 2023 Vol. 3 No. 2

Amazonia Jaguar

On the Cover: Black rhino Diceros bicornis. Photo by: Ken Bohn, SDZWA photographer.

16 22

10

Southwest Desert Tortoise & Burrowing Owl

African Forest Gorilla Asian Rainforest Tiger Oceans Polar Bear & Penguin Pacific Islands ‘Alalā Australian Forest Platypus & Koala

Photos

by: (Top) SDZWA, (Middle, Bottom) Tammy Spratt/SDZWA

Savanna Elephant & Rhino

SENIOR EDITOR Peggy Scott STAFF WRITERS

Donna Parham

Elyan Shor, Ph.D.

Ebone Monet

Alyssa Leicht

COPY EDITOR Eston Ellis

DESIGNER Christine Yetman

PHOTOGRAPHERS

Ken Bohn

Tammy Spratt

DESIGN AND PRODUCTION

Kim Turner

Lisa Bissi

Jennifer MacEwen

PREPRESS AND PRINTING Quad Graphics

Let's Stay Connected

Follow @sandiegozoo & @sdzsafaripark. Share your #SanDiegoZoo & #SDZSafariPark memories on Twitter & Instagram.

The Zoological Society of San Diego was founded in Octo ber 1916 by Harry M. Wegeforth, M.D., as a private, nonprofit corporation, which does business as San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

The printed San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journal (ISSN 2767-7680) (Vol. 3, No. 2) is published bimonthly, in January, March, May, July, September, and November. Publisher is San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, located at 2920 Zoo Drive, San Diego, CA 92101-1646. Periodicals postage paid at San Diego, California, USA, and at additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, P.O. Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112-0271.

Copyright© 2023 San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. All rights reserved. All column and program titles are trademarks of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. If your mailing address has changed: Please contact the Membership Department; by mail at P.O. Box 120271, San Diego, CA 92112, or by phone at 619-231-0251 or 1-877-3MEMBER.

For information about becoming a member of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, please visit our website at ZooMember.org for a complete list of membership levels, offers, and benefits.

Subscriptions to San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance Journa l are $25 per year, $65 for 3 years. Foreign, including Canada and Mexico, $30 per year, $81 for 3 years. Contact Membership Department for subscription information.

Transformational Conservation in the Savanna

Few places on Earth experience the complete transformation that occurs in the sprawling savannas of Africa. Defined by dramatic changes in weather, the savanna’s arid landscape, filled with dry brush that persists for half the year, becomes a lush grassland when the rainy season arrives and rejuvenates the biome. These distinct conditions shape how wildlife and people navigate the region and coexist with one another, as they adapt to the shifting balance in these ecosystems. As a part of the work in our Savanna conservation hub, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance proudly contributes to various initiatives across the region that support wildlife health and wildlife care, and promote human-wildlife coexistence.

Our approach to conservation in the African savanna and across the rangelands is rooted in collaboration and friendship. We partner with various organizations to promote communitybased solutions to regional challenges, and help preserve the ecosystems that wildlife and local communities both depend on. Together with Grevy’s Zebra Trust, we’ve formed a new partnership that will improve rangeland health in northern Kenya. Using methods passed down from traditional pastoralists, Grevy’s Zebra Trust is preserving grazing habitats that sustain the endangered Grevy’s zebra and many other species. As wildlife continues to adapt to the changing conditions across the rangelands, tracking their behavior becomes especially important for conservationists and the communities who coexist with them. Our partner, Save the Elephants, is an organization that helps track the movements of the world’s gentle giants and uses that information to foster harmony with local communities. Knowing the decisions elephants make every day helps conservationists protect them and find ways to help both wildlife and people to thrive.

The opportunities we help create for wildlife through our Savanna conservation hub are directly tied to our work here at the San Diego Zoo and the San Diego Zoo Safari Park. We use the expertise we gain here in caring for the world’s wildlife, and share our key insights with partners across the globe.

Our conservation parks are also places where you can go on a journey with wildlife, and enjoy immersive experiences. As we look to the future, we can’t wait for the completion of the reimagined Denny Sanford Elephant Valley at the Safari Park, which will help transform the future of elephant conservation—in the savanna, in San Diego, and across the world.

As part of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s commitment to conservation, this magazine is printed on recycled paper that is at least 10% post-consumer waste, chlorine free, and is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is not responsible for any calculations on saving resources by choosing this paper.

Now, let’s take a literary safari through the African savanna, as we discover the fascinating stories around our conservation initiatives and our efforts to protect wildlife.

Paul A. Baribault President and Chief Executive Officer

2 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

Onward, JOURNAL

PHOTO BY: SDZWA

Iconic Savanna

Not a forest but not quite a desert, a savanna serves as a transition zone between a forest and a grassland. African savannas have wet seasons as well as intensely dry seasons. They’re home to iconic wildlife such as savanna elephants and white rhinos—two of SDZWA’s key species.

No Encephalartos woodii cycads remain in their native habitat. You can see one in Africa Rocks at the San Diego Zoo.

Years that a baobab tree can live in a savanna.

1,000

One individual lion can be identified by its whisker pattern, similar to a person’s fingerprints.

2023 Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Javade Chaudhri, Chair

Steven G. Tappan, Vice Chair

Gary E. Knell, Vice Chair

Steven S. Simpson, Treasurer

Richard B. Gulley, Secretary

TRUSTEES

Rolf Benirschke

Kathleen Cain Carrithers

E. Jane Finley

Clifford W. Hague

Linda J. Lowenstine, DVM, Ph.D.

Bryan B. Min

‘Aulani Wilhelm

TRUSTEES EMERITI

Berit N. Durler

Thompson Fetter

George L. Gildred

Robert B. Horsman

Yvonne W. Larsen

John M. Thornton

Executive Team

Paul A. Baribault

President and Chief Executive Officer

Shawn Dixon

Chief Operating Officer

David Franco

Chief Financial Officer

Erika Kohler

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo

Lisa Peterson

Executive Director, San Diego Zoo Safari Park

Nadine Lamberski, DVM, DACZM, DECZM (ZHM)

Chief Conservation and Wildlife Health Officer

Wendy Bulger

General Counsel

David Gillig

Chief Philanthropy Officer

Aida Rosa

Chief Human Resources Officer

David Miller

Chief Marketing Officer

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 3

BY

THE NUMBERS

0 1 PHOTOS BY: (TOP LEFT)

TAMMY SPRATT/SDZWA, KEN BOHN/SDZWA

½

Nearly half of Africa consists of savanna.

40+

Species of ungulates live in Africa’s savannas —the greatest diversity of hoofed mammals on Earth.

Wildlife

(SDZWA)

Stick Insect Eggs Arrive in San Diego

After a delay since 2020 due to wildfires in Australia and the COVID-19 pandemic, the San Diego Zoo received a cohort of Lord Howe Island stick insect Dryococelus australis eggs. The eggs represent SDZWA’s latest commitment in a 10-year partnership with Melbourne Zoo to recover this critically endangered insect. The San Diego Zoo is the only North American institution—and one of only two institutions outside of Australia—participating in the international breeding program. To safeguard this insect’s future, the ultimate goals of the collaboration include successful reintroduction onto islands within the Lord Howe island group, as well as maintaining thriving insurance populations.

' Io Spatial Ecology SDZWA collaborated with the State of Hawai'i and University of Hawai'i at Hilo to learn more about the 'io (Hawaiian hawk Buteo solitarius). The 'io is endangered; it is the only hawk native to Hawai'i and is found only on the Big Island. Last year, over 30 wild 'io were fitted with lightweight, noninva sive GPS transmitters that regularly upload data. The trackers shed much-needed light on 'io movement and ecology, and the data we collected will inform management actions to support 'io recovery. Further, because 'io are natural predators of the critically endangered 'alalā (Hawaiian crow Corvus hawaiiensis), these data will also inform future 'alalā reintroduction strategies.

Jaguar Surveys in Peru Continue

Our Amazonia hub team has two trail camera surveys set up in the Peruvian Amazon. The first survey, located in the Madre de Dios region of southwest Peru, is part of a longterm jaguar Panthera onca monitoring effort in logging concessions certified by the Forest Stewardship Council. This survey will give us detailed information on the population dynamics of jaguars, as well as the impact of certified forest management on the species. The second survey expands our work in the Ucayali region of central Peru, where we are surveying one of the last intact forest fragments close to the city of Pucallpa. This second survey will support an application to make this area a private conservation concession.

4 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

FINDINGS

San Diego Zoo

Alliance

protects and restores nature in eight conservation hubs on six continents. Below are recent discoveries and progress from around the world.

PHOTOS BY: (TOP) KEN BOHN/SDZWA, (MIDDLE) TAMMY SPRATT/SDZWA, (BOTTOM) SDZWA

Fur, feathers, slithery scales— Owala® loves wildlife. We stand proud in support of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. Learn more at OwalaLife.com

What is the coolest thing about your job?

I get to see wildlife in their native habitat almost every day. Tourists pay handsomely for a chance to see the “Big Five”—the lion, leopard, black rhino, savanna elephant, and African buffalo—while seeing them is part of my job. I also get to interact with communities and other people committed to wildlife conservation, who inspire me to continue doing what I do. I am also fortunate to work with San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance scientists who lead wildlife conservation programs in Kenya.

What has surprised you about working with SDZWA?

One of my most surprising experiences was being asked to ride on the SDZWA Rose Parade float during the New Year’s parade. The experience confirmed that SDZWA values our wildlife conservation efforts.

Who or what inspires you?

The story of black rhino conservation in Kenya inspires me. In the 1970s, black rhino numbers were about 20,000 individuals, but due to poaching, the population declined to fewer than 300 in the 1980s. In the 1990s, the government, together with other stakeholders, established black rhino sanctuaries to help breed and increase the population of the species in the country. Today, Kenya’s black rhino population is approximately 800 to 900 individuals. We have also seen black rhinos’ numbers increasing in areas where they were decimated completely, including on community land (territory that belongs to a community, rather than an individual or company). This is a story of hope. It inspires me, and gives me hope that we can turn a challenge into an opportunity. It also gives me hope that the challenges we are currently facing can be circumvented and have a positive story.

What was a turning point or defining moment in a project or program you’ve worked on?

In 2006, I was a novice in wildlife conservation. Then I attended an environment seminar in Florida (USA) and Pretoria (South Africa). It was a game changer. I realized to what extent wildlife conservation was facing a myriad of threats and challenges. Henceforth, I decided to continue dedicating my skills to wildlife conservation. Looking down memory lane, I can say that today, I feel very happy that I have been involved in conservation of critically endangered wildlife such as the black rhino, hirola, and Grevy’s zebra.

What is your favorite animal? Why?

The black rhino. It has very poor eyesight, but a very strong sense of smell. The rhino makes use of that strong element to survive. The species reminds me to use my best talents, and to focus on what I have, not on what I don’t have. Doing that can help you achieve so much.

What do you see as the future of wildlife conservation?

Wildlife conservation faces myriad challenges, ranging from climate change, habitat loss due to the ballooning human population, diseases, and concerns associated with human-wildlife coexistence, just to mention a few. The good thing is, we already know what challenges are facing wildlife conservation, and we have realized that the solution lies in working with all stakeholders, including communities, to address these challenges. With good coexistence, there is a future for wildlife. We all need to know conservation is about people. The community conservation model is a great opportunity, and gives hope and a future to wildlife conservation.

MEET OUR TEAM

Stephen Chege, B.V.M., M.Sc.

Q

6 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023 PHOTO BY: KEN BOHN/SDZWA

As conservation program manager representing SDZWA’s programs in Kenya, Dr. Chege plays a crucial role in projects involving black rhinos, hirola, Grevy’s zebras, and other wildlife species.

Q Q Q Q Q

Sip, Snack, Save Species

Stay fueled up by enjoying a delicious treat at one of our specialty snack stands on your next visit. The San Diego Zoo and San Diego Zoo Safari Park thank our partners for their continued support!

Joining Forces:

SDZWA scientist Shifra Goldenberg, Ph.D., and social science researcher Tomas Pickering, Ph.D., explore how the Alliance collaborates with a network of institutions to support community-based conservation.

The semiarid savannas of Kenya’s northern rangelands support a rich diversity of wildlife, including drylandsadapted species like the endangered Grevy’s zebra Equus grevyi, the beisa oryx Oryx beisa, an ecological guild of African vulture species, and the second largest population of elephants in Kenya. This ecosystem, on which

so many people and wildlife depend, undergoes dramatic seasonal changes as dry periods give way to biannual pulses of fresh vegetation and abundant standing water. The people who live in this region are pastoralists, for whom herding livestock is the dominant livelihood as well as their cultural heritage.

For pastoralists and wildlife alike, the dynamic patchwork of the savanna and its

associated seasonal and spatial variability in resources necessitate the use of large areas for survival. Movement and connectivity are key. If adequate rain doesn’t fall in one area, localized rainfall elsewhere may provide needed pasture until greener periods arrive. During the wet season, ephemeral pools and flowing seasonal riverbeds free wildlife and livestock from the anchoring effect of permanent water, allowing them to traverse

8 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

HOT TOPICS

Conservation Requires an Alliance

areas, and to reach distant resources that are inaccessible during the dry season. Deep knowledge and use of this large and perennially changing landscape generates the resiliency necessary for people and wildlife to survive the harshest periods.

Because of the need for wildlife to move vast distances to track seasonal resources, the functional ecosystem of the savannas in Kenya’s northern rangelands is extensive. It encompasses a much broader range than government-protected areas alone. Most rangelands and wildlife exist in community-owned and -managed lands. In northern Kenya, community-based conservation is growing. Such efforts recognize the rights, and the historical and current contributions, of local and Indigenous communities to maintain wildlife biodiversity. Communities are championing a new model of improving livelihoods while conserving wildlife. And community-based efforts expand wildlife conservation to scales far larger than national parks and reserves could ever possibly cover.

In northern Kenya, a network of conservation organizations is working to address these challenges, each tackling unique wildlife threats and opportunities, with local support and goals driving priorities and successes.

The task before them is not easy. Living with savanna wildlife in communal land management settings comes with diverse and interconnected challenges. Communities organize their decisions through systems of governance, maintain open landscapes with infrastructure development through land use planning, and manage livestock grazing and crop production. At the same time, they find ways to coexist with large, clever, and potentially destructive mammals like lions, leopards, and elephants; and they work to control commercial poaching of species like rhinos and elephants, and subsistence poaching for wild meat during droughts. All of these issues are difficult to solve and require community, science, and governance. They require an alliance.

In northern Kenya, a network of conservation organizations is working to address these challenges, each tackling unique wildlife threats and opportunities, with local support and goals driving priorities and successes. SDZWA’s Kenya Rangelands Program in the Savanna conservation hub partners with many of them to better understand and address the complex challenges that communities and wildlife face. For example, SDZWA supports the Lion Governors program of Ewaso Lions, which leverages the status of elders in Samburu society to strengthen training in human-lion coexistence. SDZWA also supports the Healing Rangelands program of Grevy’s Zebra Trust, which relies on pride in communal land ownership and dedication to livestock health to implement pasture restoration, erosion control, and responsible livestock management practices. Both of these programs leverage existing cultural institutions and long-term relationships to implement sustainable solutions. Healthier grasslands affect the abundance and distribution of prey populations on which carnivores depend, and positive attitudes toward sometimes dangerous and destructive wildlife foster participation and interest in other conservation initiatives.

Dollar for Dollar Gift Match Challenge!

Thanks to a generous donor, gifts of $100 or more toward SDZWA's community-based conservation work in the savanna region will be matched dollar for dollar, up to $100,000. Please consider making a gift toward our partnerships in Kenya and help us get closer to meeting the challenge.

sdzwa.org/KenyaMatch

These examples demonstrate the interconnectivity of multiple challenges and solutions. These organizations, along with other SDZWA partners, including Northern Rangelands Trust and Save the Elephants, enhance the capacity of local communities to manage wildlife. As community-based conservation gains momentum internationally, we are working to strengthen our alliances to champion its success in northern Kenya.

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 9

PHOTOS BY: SDZWA, (TOP RIGHT) KEN BOHN/SDZWA

HOME RANGE on the

Bringing Black Rhinos Back to Loisaba

BY TOMAS PICKERING, PH.D.

he planned translocation of 21 eastern black rhinoceroses Diceros bicornis michaeli to a new sanctuary in Kenya will be an exciting and crucial step for the continued recovery of this critically endangered species.

THowever, the majestic animals that will live in Loisaba Conservancy won’t be able to simply walk over. Teaming up with Kenya Wildlife Service, Loisaba Conservancy, The Nature Conservancy, and Space for Giants, San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance (SDZWA) is making considerable efforts to establish this sanctuary and return rhinos

to this landscape. But why is this action needed? And, what will it mean for other wildlife, and for neighboring communities?

A Matter of Space— and Survival

This range expansion is needed to create space for the black rhino population to grow. We are excited to be a part of the

effort to return rhinos to this landscape. But where did their once-sizable population go in the first place?

International demand for rhino horn led to formidable poaching in the 1970s and 1980s, crashing the black rhino population in Kenya—from more than 20,000 to fewer than 300 animals by 1987. The Kenyan government

10 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

prioritized their conservation, and their numbers are growing again. At last count (in 2021), there were 897 individuals in 15 areas—all specially safeguarded from the looming threat of poachers. This is a success story, in and of itself. Yet now, black rhino numbers are reaching the carrying capacity of many of these spaces. Population growth

rates have slowed, with juvenile survival and birth rates falling. It is clear that these megaherbivores need more room to establish territories for breeding, and to find plentiful leaves to browse from shrubs and trees. SDZWA has stepped up to help create more space for black rhinos to roam and grow, supporting the Loisaba community in

establishing an anti-poaching ranger unit and constructing a rhino sanctuary fence protecting 40 square miles of quality rhino habitat. Our work going forward is to collaborate with Loisaba’s new rhino-monitoring team to scientifically evaluate strategies to overcome risks inherent in this translocation, such as diseases, vegetation

shifts, lack of community tolerance, and potentially negative rhino interactions with each other or with fencing.

Leading the Charge for Change

Rita Orahle, rhino conservation officer at Loisaba, will lead the rhino monitoring team. Though new to working with rhinos,

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 11

PHOTO BY: SDZWA

she brings technical skills and conservation experience. Rita has expressed her excitement about helping with this species’ recovery, and says she already admires them for their mothers’ fearless protective behaviors over threatened calves. SDZWA is working closely with Rita to address risk from the rhino fencing.

In conservation, fences can be both helpful and unfavorable. They protect species threatened by poaching and help people coexist with wildlife, but they also prevent wildlife from moving to gain access to food, water, or mates. Mobility is especially important for migratory species and in environments like northern Kenya, where frequent droughts require wildlife to move long distances to find greener patches. To address this challenge, Loisaba Conservancy is constructing a low electric fence that allows many species to pass under or jump over it. The fence will feature corridor openings specifically designed to accommodate all wildlife except rhinos.

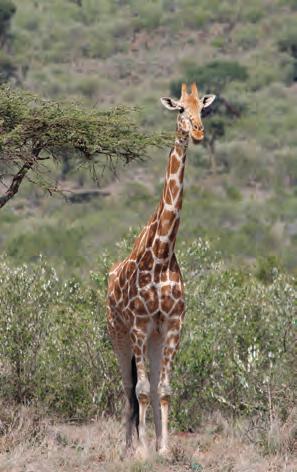

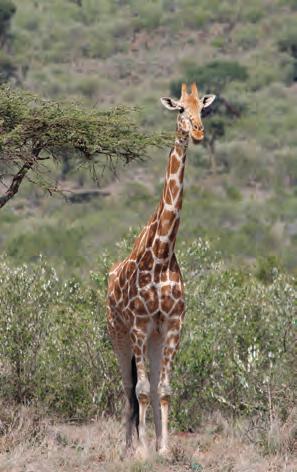

But how will other wildlife that share this landscape—including endangered wildlife like Grevy’s zebras Equus grevyi and reticulated giraffes Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata—interact with the fence and corridors? We anticipate that there may be collisions, and possibly even some fatalities. Rita’s work will help evaluate the effectiveness of the flagging that makes the fence more visible to wildlife. Wildlife here will learn where this new boundary exists, and where it is permeable.

Watching Closely

As the rhinos establish territories, find water sources, and create communal middens (dung heaps), where they communicate through scent, Rita and her team will document the rhinos’ behaviors, including interactions with one another and with

other wildlife (which may not be used to seeing rhinos in their habitat). With support from SDZWA, they will monitor the rhinos for diseases. Rita and SDZWA conservation scientists will also monitor the rhinos’ body condition, as well as vegetation changes—such as how plant species are shifting over time. We are excited to see this rhino population grow.

Connecting with the Past—and the Future

Black rhinos disappeared from Loisaba and the surrounding community areas 50 years ago. Some of the older people within the Laikipiak Maasai and Samburu pastoral communities remember seeing the

12 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

Range Rovers: Opposite page, top left: Rita Orahle leads rhino research and monitoring at Loisaba. Opposite page, bottom left: Rita Orahle and Laiyon Lenguya establish cameras for monitoring the new wildlife corridor. This page, clockwise from top: A black rhino pauses after taking a drink at Ol Pejeta Conservancy; Endangered Grevy’s zebras also benefit from the added security; Endangered reticulated giraffes are being reintroduced to rhinos lost from the landscape 50 years ago.

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 13

PHOTOS BY: SDZWA

Just Browsing: Black rhinos consume large amounts of leaves from shrubs and trees, opening habitat for many other grazing species.

14 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

last few individuals in the area. A few even remember the name of the last individual, Lotemere, who was named in honor of the elder responsible for guarding him. Among these Maa-speaking people, rhinos are called emuny, or in the national language of Swahili, kifaru. Many people in these communities supported the black rhinos’ return—including one clan, the Laiser, who see the rhinoceros as their representative, kindred animal.

Research guided by SDZWA’s social science team is evaluating community support, attitudes, and expectations around potential benefits and costs of the rhino translocation. Prior to the rhino translocation, 88 percent of community members agreed with the overall rhino conservation plan. Not only are most people excited at the prospect of seeing—or having their children see—black rhinos again, but they hope to gain benefits from added tourism, security, and jobs. However, people also worry that the new rhino sanctuary will limit where they can graze their livestock (the basis of their livelihood and culture), or that rhinos may attract poachers—criminals—to their community. We hope our conservation work, along with engagement from Rita and her rhino monitoring team and Loisaba’s community officers, will help address these and other community concerns. Community support is important for the longterm success of rhino conservation. For example, community members can help give early warnings when poachers are around or, one day, could even decide to extend rhino territory into conservation zones they manage.

Our collaborative science to understand fences, rhino behaviors, and people’s attitudes and tolerance may help identify best practices for establishing other rhino sanctuaries, or even—in the future—an interconnected network of protected areas for rhinos. Ideally, over time, rhino conservation will require less fencing and will have greater community support to ensure no poaching occurs. Internationally, we must find ways to end demand for rhino horn and safeguard the future of all rhino species. (SDZWA also works to address illegal wildlife trade in Southeast Asia.) We aspire to build a future where black rhinos can move freely across the Kenyan landscape. For now, our work continues to strengthen and spread rhinos’ ranges—one protected area at a time.

Tomas Pickering, Ph.D., is an SDZWA social science researcher.

PHOTO BY: SDZWA SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 15

E Pluribus Unum

“Out of Many, One”

BY DONNA PARHAM

For naked mole-rats, it’s one for all, and all for one. You won’t see naked molerats in the deserts and dry savannas of eastern Africa, but they’re there, scurrying—backward and forward— through elaborate burrow systems that can be 18 feet deep. Their location under the earth makes them challenging to study in their native habitat, and most of what we know about their surprising behavior comes from studies in managed care.

Like a hive of honeybees, a single naked mole-rat “queen” is the only reproductive female in the colony. She mates with 1 to 3 reproductive males, and bears a litter of up to 20 offspring, 5 or 6 times a year. All the other molerats in the colony are workers who keep their subterranean world humming along. That makes the naked mole-rat Heterocephalus glaber one of a handful of eusocial mammals. (The other is the Damaraland mole-rat Cryptomys

Huddle Up: (Left)

PAGE): KEN BOHN/SDZWA SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 17

PHOTOS BY: (THIS PAGE): TAMMY SPRATT/SDZWA, (PREVIOUS

Naked mole-rats don’t internally regulate their body temperature as well as most mammals do. In fact, thermoregulation is mostly behavioral. An overheated mole-rat can move to lower, cooler parts of the tunnel system. One way to keep warm is by huddling.

damarensis of southern Africa.) The prefix “eu” in the term “eusocial” means, “good, true, genuine,” and it is a clue that the behavior of these rodents goes beyond merely social. A naked mole-rat colony is more like an ant, honeybee, or termite colony than a group of small mammals.

Who’s Who in a Mole-rat Colony

Amid the dozens (or sometimes hundreds) of naked mole-rats in a colony, the queen is the only reproductive female. Finding a mole-rat queen in the naked mole-rat habitat at the Zoo’s Wildlife Explorers Basecamp is like a real-life game of Where’s Waldo? (Challenging, but you will eventually spot her.) She’s the largest naked mole-rat in the colony, and also the only one with visible, nub-like teats. You might find her patrolling the tunnels or possibly resting smack in the middle of a pile of squirming naked mole-rats. A few (usually just one to three) of the next-largest in the colony are reproductive males—the only ones that breed with the queen.

As for nonbreeding members of the colony, researchers have noted size-linked differences in behavior among them. Along with juveniles, the smallest adults do most of the work. “They gnaw through the earth to dig burrows, they look for roots and tubers underground, and they are constantly moving dirt,” says Nicki Boyd, curator of applied behavior at the San Diego Zoo. She has been caring for naked mole-rats since 1992, when they first came to the Zoo. “When the queen is in the nest, nursing pups, they may take chunks of food to her.” They also care for her offspring. They clean and carry neonates to the nest, where they groom them, nudge them, and keep them warm.

The largest nonreproductive adults don’t work as much, but along with the reproductive males, they play an important role in defending the colony from snakes or from incursions of neighboring mole-rats. “Because of their thick necks, I call them the ‘pit bulls’ of the colony,” says Nicki. And while most mole-rat workers are protected within the tunnel system, the largest mole-rats take on the risky role of kicking soil out onto the surface, a behavior called “volcanoing” because of the mound of earth that piles up outside of an opening.

Long Live the Queen

High levels of hormones in the queen’s urine help her maintain reproductive dominance. “When the other females are exposed to that hormone, they don’t even ovulate,” says Nicki. It’s typical for all of them—including the queen—to defecate and urinate in specific shared areas, called latrines, which are often dead-end tunnels. That means every naked mole-rat in the colony comes in contact with the queen’s urine.

The queen asserts dominance behaviorally, too. “The queen doesn’t just lie there—she patrols the area and keeps order in the colony,” says Nicki. A queen shoves the others around, and she walks right on top of them when they pass in the tunnels. These behaviors play an important role in reproductive repression, and help the queen maintain dominance.

The death of a queen typically initiates what Nicki calls

DID YOU KNOW?

Naked molerats have about 100 fine hairs distributed on their body.

18 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

PHOTO BY: TAMMY SPRATT/SDZWA

What’s Cool about Naked Mole-rats?

1

They’re a lot alike. It’s no surprise that a colony shares a lot of the same DNA. What’s more surprising is that the DNA among different colonies is also quite similar.

2

They can survive in an extremely low-oxygen environment. In fact, they can go as long as 18 minutes without any oxygen at all.

3

They can close their mouth behind their teeth when they are gnawing through earth.

4

They rarely get cancer.

5

For a tiny rodent, they live a long time—up to 30 years. A mouse the same size might live two or three years.

6

They eat their food twice (or more). They get more nutrients out of their food by eating their poop. They share poop, too, which also contains symbiotic bacteria that benefit digestion.

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 19

a “mole-rat war,” as several females fight— often to the death—for the position. “They shove, push, and bite each other—kind of like rams butting heads,” she says. With incisors sharp and strong enough to gnaw through concrete, puncture wounds are common, prompting studies that have found naked mole-rats don’t feel pain the same way we do. “We monitor the wounds, but we have to let them work it out themselves as they would in their native habitat,” says Nicki.

Over 30 years of caring for and learning about naked mole-rats, Nicki has also seen instances when the next-largest female

has stepped into the role of queen with little violence. She’s even seen two queens in a colony. “That was really strange, but maybe the queen’s hormones weren’t strong enough to keep a second female from ovulating,” she postulates.

Once there is a new queen, what happens next is “really unheard of for a mammal,” says Nicki. No matter how old the new queen is, her spine lengthens, and she grows. “Even if she’s 10 or 15 years old—her vertebrae grow, so that she can accommodate large litters.” Then, the new queen starts breeding with reproductive males. Agonistic interactions become rare,

and social order is restored. Soon, workers will have a new litter of pups to care for.

At the Zoo, you can find these fascinating rodents in the McKinney Family Spineless Marvels Invertebrate building at Wildlife Explorers Basecamp. Although naked mole-rats are mammals (which, of course, do have internal skeletons, including vertebrae), “we thought it made a lot of sense to make the connection with the leafcutter ants and honeypot ants around the corner, and the bees upstairs,” says Nicki. “They are a fossorial mammal that acts as an insect colony does. It’s a fascinating story of biodiversity.”

20 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

Hard at Work: Every naked mole-rat has a job to do. Zoo guests can watch them as they go about their work (top and left). The mole-rat queen’s job is to produce offspring (bottom right).

PHOTOS BY: KEN BOHN/SDZWA

Spread your wings.

featuring

MARCH 18 THROUGH MAY 14

Spring brings the perfect chance to get outdoors, spend time with family, and experience the sights, sounds, and tastes of the season! From special entertainment and culinary creations to amazing wildlife encounters like Butterfly Jungle Safari (additional ticket required), come make spring memories to last a lifetime!

BLOWING IN THE WIND

Whistling Thorn Trees and the Sound of Symbiosis on the Savanna

BY PEGGY SCOTT

BY PEGGY SCOTT

DID YOU HEAR THAT?

If you’re on the African savanna and near a particular type of tree, you’re listening to the duet of two species—one botanical and one arthropodan—working together in perfect harmony to survive.

22 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

The Giving—and Receiving—Tree

Native to the savannas of Africa and commonly found in the Serengeti, the whistling thorn tree Vachellia drepanolobium is a tall (up to 18 feet), swollen-thorn acacia. Its hardy, termite-proof wood can be used to make tool handles and fencing, or for kindling; and the gum is sometimes collected for use as glue. Adorned with small white flowers, the whistling thorn sports leaves comprised of tiny leaflets, as well as seed pods and, most notably, three-inch-long spikes on its branches. Sprinkled throughout the leaflets are modified thorns, called stipular spines, which are joined at the base by large, hollow bulbs—about one inch in diameter—called domatia.

As with other African acacias, these thorns serve as protection from the hungry mouths of herbivores like giraffes and elephants. But should an animal find those tasty morsels irresistible, the whistling thorn has a secret weapon in those round, empty spheres—thousands of them, in fact: ants!

Scurrying Security System

Within the swollen thorn bulbs of the whistling thorn tree, four ant species— Crematogaster nigriceps, C. mimosae, C. sjostedti, and Tetraponera penzigi—have made themselves right at home. They bore holes into the bulbs and settle in, enjoying shelter and the nectar the trees provide. When the wind blows, the spiky appendages become natural whistles, resulting in the sound that gives the tree its common name. But the ants aren’t just providing a soundtrack to the tree’s life; they defend the whistling thorn against tree-grazing mammals. When a branch is disturbed, ants swarm out of the holes—into the mouths and up the noses of the unlucky nibblers. This home security system is crucial, because, unlike other acacia trees, the whistling thorn tree doesn’t have toxic chemicals that would keep snackers at bay. In exchange, the ants have access to the tree’s nectar, and a safe place to live. It’s a win-win situation, notes Adam Graves, director of horticulture at the San Diego Zoo. “The way these organisms have evolved to help each other survive shows firsthand the amazing symbiotic relationships that can evolve in nature,” Adam explains. “These iconic trees in the landscape have an amazing story, and we’re lucky to be able to share them with our visitors!”

Come see—and perhaps hear—for yourself. At the Zoo, a whistling thorn tree lives in Africa Rocks, and at the Safari Park, one has put down roots at the Fishing Village Bridge at Mombasa Lagoon.

PHOTOS BY: TAMMY SPRATT/SDWA

WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 23

SAN DIEGO ZOO

VISUALIZE IT

BY DAY AND BY NIGHT

The savanna teems with a rich variety of wildlife, both during the day and at night. During the day, diurnal wildlife are awake and active. At night, nocturnal species emerge. Life hums with activity around the clock—take a peek!

By Alyssa Leicht | Illustrations by Amy Blandford

24

Activity patterns may depend on variable conditions. For instance, little or no moonlight makes hunting easier at night.

DIURNAL

Pygmy Falcon

Common Waxbill

Giraffe

Impala

Elephant

Zebra Carcass

Lappet-faced Vulture

Dwarf Mongoose

Dung Beetle

DID YOU KNOW?

Some wildlife aren’t strictly diurnal or nocturnal. Lions, for example, hunt, feed, and mate at any time of day and night.

NOCTURNAL

Veldkamp’s Bat

Leopard

Thomas’s Bushbaby

African Grass Owl

African Savanna Hare

Bat-eared Fox

Termites

Aardvark

25

March and April Hours*

San Diego Zoo

Most days 9 a.m.–5 p.m.

Extended Hours for Spring Break

San Diego Zoo

Safari Park

9 a.m.–6 p.m. sdzwa.org

March &

SAN DIEGO ZOO

619-231-1515

*Exceptions apply. Programs and dates are subject to change—please check our website for the latest information and requirements for visiting.

(Z) = San Diego Zoo

(P) = Safari Park

MARCH 25–APRIL 9

Spring Break

Extended Hours at the Zoo

Extend your adventure! Enjoy even more time to discover amazing wildlife and explore everything there is to see and do at the Zoo with expanded springtime hours, 9 a.m. to 7 p.m. Albert’s Restaurant has special spring break hours, too—visit zoo.sandiegozoo.org/alberts for more information. (Z)

MARCH 17, APRIL 21

Plant Days

On these special days, you can take a rare look inside the Zoo’s Orchid House from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., learn about the Zoo’s botanical collection from horticulture staff on the Botanical Bus Tour at 11 a.m., and check out the Carnivorous Plant Greenhouse from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. (Z)

OFFERED DAILY Wildlife Wonders

At the Zoo’s Wegeforth Bowl amphitheater, wildlife care specialists will introduce you to wildlife ambassadors representing San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s conservation work around the world in Wildlife Wonders, presented daily at 2 p.m. Learn about amazing wildlife—from the Amazon to right here in our own backyard in San Diego—and find out what everyone can do to help conserve wildlife and the world we all share. Presentation runs 15 to 20 minutes. (Z)

MARCH AND APRIL, SELECTED DAYS Early Morning Explorers

Join Dr. Zoolittle for jokes, games, and a little magic before the Zoo opens for the day! Enjoy exclusive earlymorning access to Wildlife Explorers Basecamp, where you can explore wildlife habitats, water feature learning, and play with the whole family, Recommended for families with children ages 3 through 12, this limited-time experience includes special activities only available for Early Morning Explorers. Book online or call 619-718-3000. (Z)

26 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

EVENTS

SAFARI PARK

MARCH 18–MAY 14

Spring Safari featuring Butterfly Jungle

Spring brings the perfect chance to get outdoors, spend time with family, and experience the sights, sounds, and tastes of the season. From special entertainment and culinary creations to amazing wildlife encounters like Butterfly Jungle Safari (additional ticket required), come make spring memories to last a lifetime! For full details, visit sdzsafaripark.org. (P)

MARCH AND APRIL, SELECTED DATES

All Ages Roar & Snore with Butterfly Jungle Sleep over at the Safari Park, experience up-close wildlife encounters, and get an exclusive look at Butterfly Jungle. For details and reservations, call 619-718-3000. (P)

APRIL 8

Nativescapes Garden Tour

A free guided walking tour through the 4-acre Nativescapes Garden, representing 500 native Southern California species, begins at 10 a.m. (P)

APRIL 22–23

Wild Weekend: Southwest

On this special Earth Day weekend, join us at the Safari Park to discover the intricate and diverse wildlife flourishing right here in our own backyard—the incredible Southwest. For more information, please visit sdzwa.org/wildweekend. (P)

MARCH AND APRIL, SELECTED DATES

Supreme Roar & Snore Safari

The Supreme Roar & Snore Safari— available on All Ages and Adults Only sleepovers—offers a whole new level of adventure at the Safari Park! You’ll soar into camp on the Flightline Safari zip line (subject to availability), take a Night Vision Safari to view wildlife through night vision binoculars, and later settle in for the evening in your own private tent. The next morning, enjoy reserved VIP viewing of wildlife ambassador encounters, then take a Wildlife Safari through savanna habitats for an up-close view of wildlife. Call 619-718-3000. (P)

OFFERED DAILY Cart Safaris

Sit back in the comfort of your own Safari cart, as you enjoy a 60-minute guided tour of the Safari Park’s spacious African or Asian savanna habitats, led by one of our knowledgeable guides. Book online or call 619-718-3000. (P)

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE / SDZWA.ORG / 27

April

Visit the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Explorers website

to find out about these and other animals, plus videos, crafts, stories, games, and more!

sdzwildlifeexplorers.org

Paper Roll Pachyderm

Because of the big role they play in changing their habitat—pushing over and uprooting trees, creating new habitats for other species—elephants are often called the “engineers” of their ecosystem. Here’s your chance to build one of nature’s best builders. With just a few items from around the house, create your own mighty mammal!

What you’ll need to get started:

Paper Roll

Scissors Markers or Paint & Brush Tape or Glue

Have fun creating your own paper roll elephant using the example below, or scan the QR code for detailed instructions and a printable template on the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Explorers website.

Eyes x2

Optional: Add googly eyes for a fun effect!

DID YOU KNOW?

African elephants have ears shaped like the continent of Africa!

Ears x2

Trunk

28 / SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE ALLIANCE JOURNAL / MARCH/APRIL 2023

Background Illustration by: Alfadanz/iStock/Getty Images

LAST LOOK

The Przewalski’s horse was deemed extinct in the wild in the 1980s. Fortunately, the foresight of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance conservation scientists made sure this species’ story would go on. Kurt, pictured above, is the first-ever clone of a Przewalski’s horse—the genetic copy of a stallion that lived more than 40 years ago and whose DNA was absent from the living population. Kurt was named in honor of one of those conservation pioneers, Dr. Kurt Benirschke, who founded our conservation science efforts and our Frozen Zoo® in the 1970s.

Photographed by Ken Bohn, SDZWA photographer.

ALLIANCE

/ 29

SAN DIEGO ZOO WILDLIFE

/ SDZWA.ORG

JOURNAL

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance

P.O. Box 120551, San Diego, CA 92112

San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance presents

Rendezvous In The Zoo

Saturday, June 17, 2023 6:30 to 11:30 p.m. at the San Diego Zoo

Bon voyage meets bon appétit at the annual R•I•T•Z gala!

Make your reservations today at ritz.sandiegozoo.org

or contact Karl and Leslie Bunker: 619-426-3817 • RITZ@sdzwa.org

Proceeds benefit the reimagined Denny Sanford Elephant Valley at the San Diego Zoo Safari Park

BY PEGGY SCOTT

BY PEGGY SCOTT