Credits

© 2021

Authors

Delmis del C. Alicea Segarra, EdD, Jorge Casillas Maldonado, MS

Co-Authors

Ivonne Bejarano Rodríguez, PhD, Diana M. Beltrán Rodríguez, MS, Brenda M. Soler Figueroa, MS

Science Edi ng

Yasmín Detrés Cardona, PhD, Ariel E. Lugo, PhD, Lesbia L. Montero Acevedo, BS

Science Advisor

Juan G. González Lagoa, PhD

Edi ng

Ruperto Chaparro Serrano, MA, Delmis del C. Alicea Segarra, EdD, Cris na D. Olán Mar nez, MA

English edi ng

Lynne M. Hinkey, PhD

Readers

Álida Or z Sotomayor, PhD, María M. Montalvo Ortega, EdD, Neysa Rosario García, MA

Brenda L. Estévez Moreno, BS

Contributors

Carlos J. Carrero Morales, MPA, Carmen Zayas San ago, MS

English Transla on and Edi ng

Wilmarie Cruz Franceschi, MA

Graphic Design and Layout

Delmis del C. Alicea Segarra, EdD, Oliver Bencosme Palmer, BA

Photography

Oliver Bencosme Palmer, BA, Ruperto Chaparro Serrano, MA, Guillermo Damiani Ríos, Efraín Figueroa Ramírez, BS, Juan G. González Lagoa, PhD , Mydalis M. Lugo Marrero, MA, Julia S. Mignucci Sánchez, PhD, Janne e Ramos García, BS

Footage for the “El manglar” video

Efraín Figueroa Ramírez, BS, Rául Omar Or z Arroyo, MAG

Theme guide

Alessandra Otero Ramos, MIS

Prin ng

Raúl Omar Or z Arroyo, MAG, Delmis del C. Alicea Segarra, EdD

Publica on number UPRSG-E-298

ISBN: 978-1-881719-79-3

The University of Puerto Rico Sea Grant Program understands the need to have an educa onal tool to aid instructors during the teaching-learning process regarding the marine and coastal resources of the Puerto Rican archipelago. With this goal in mind, we have taken it upon ourselves to produce this Educa onal Guide about mangroves which includes a theme background, a presenta on with notes for instructors, different ac vi es, and the daily lesson plans necessary for teaching. This guide, with resources designed for the 4th through 12th grades, offers various lesson plans about mangroves in a structured, easy-to understand and interdisciplinary manner. The daily lesson plans are aligned with the standards and specifica ons required by the Department of Educa on of Puerto Rico, easing their inser on into the classroom. The ac vi es presented promote ac ve learning, allowing the students to build their own learning, making the process pleasant, a rac ve and interes ng. We hope this manual will prove useful when teaching about our marine and coastal resources and likewise foster in our young people a deeper apprecia on for this ecosystem and mo vate them to promote its conserva on and protec on.

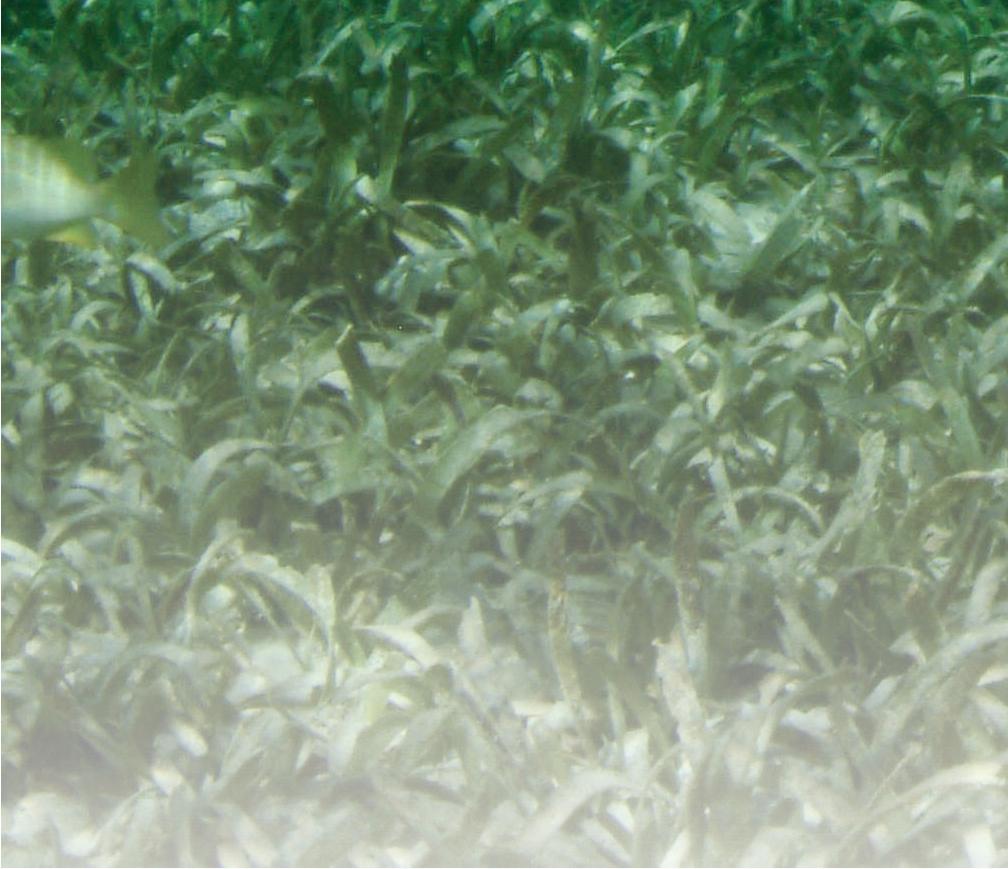

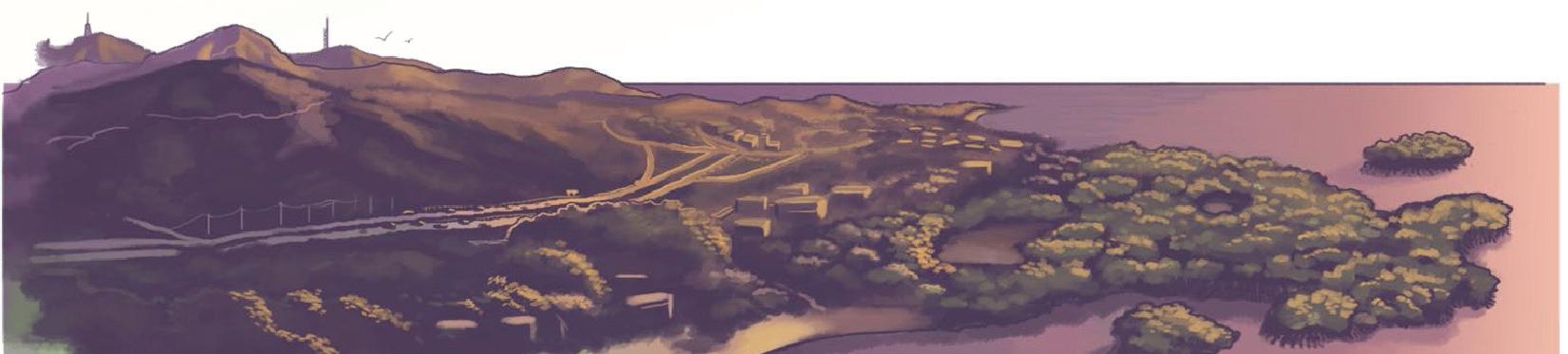

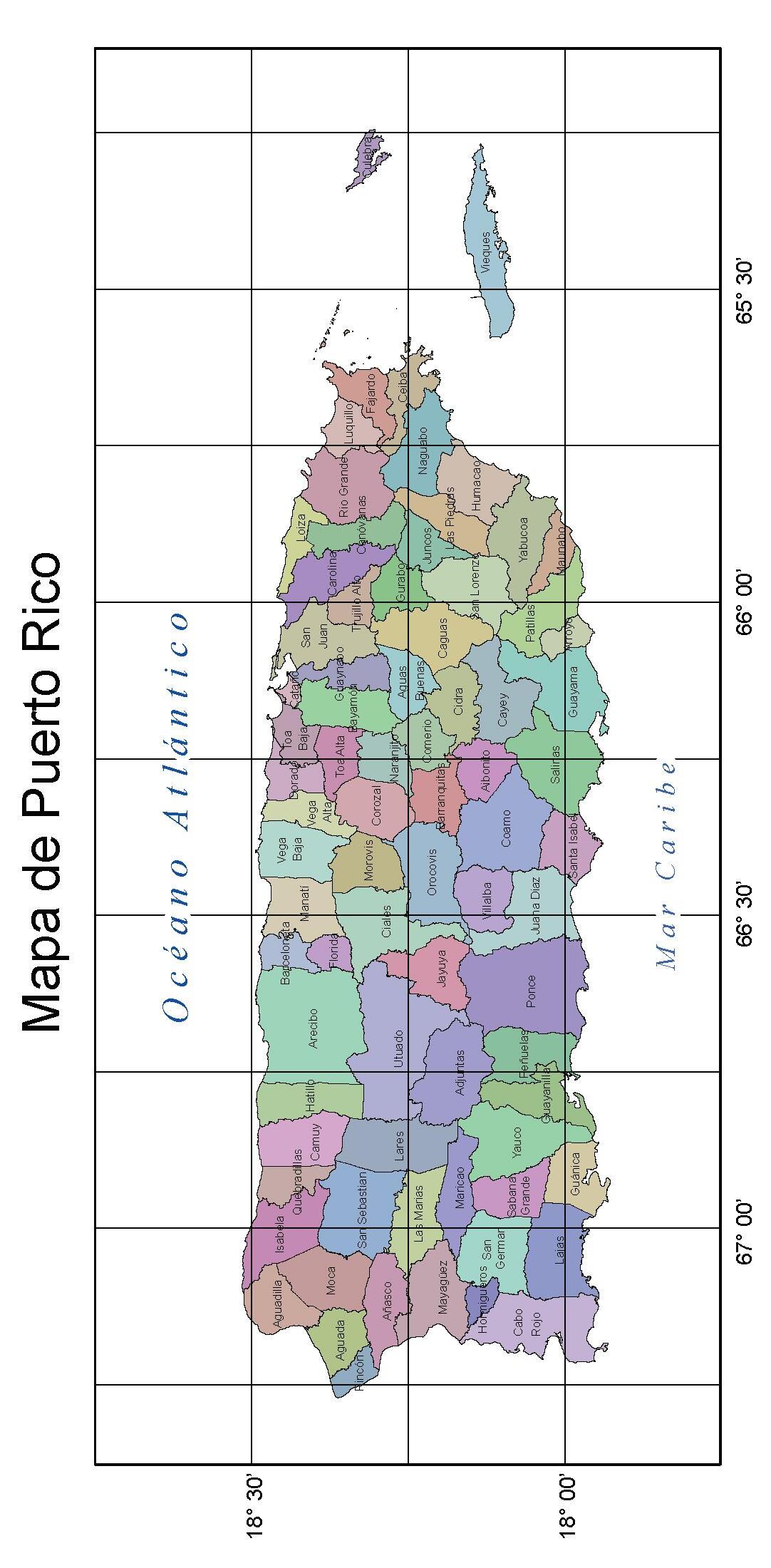

An ecosystem is a community of organisms which interact amongst themselves and with their environment, including non-living elements. Each one of these ecosystem’s components influences the others, and all are vitally important for the preserva on of their way of life. Puerto Rico has a territorial expanse of 3,587 square miles (including its more than one hundred islands and cays), and within this area, one may find eight main ecosystems: tropical rainforest, subtropical dry forest, sand beaches, rocky shores, coral reefs, seagrass meadows, mangroves, and lagoons.

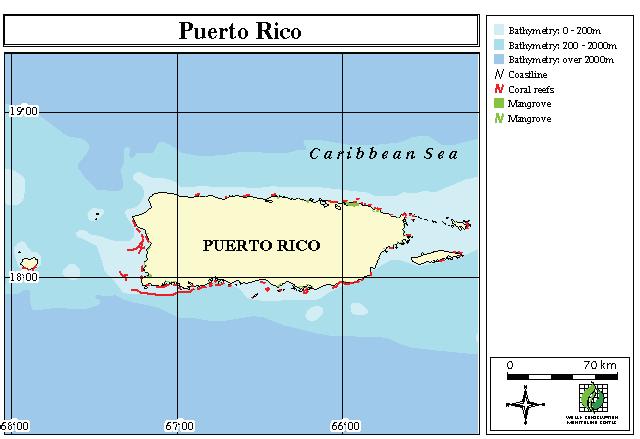

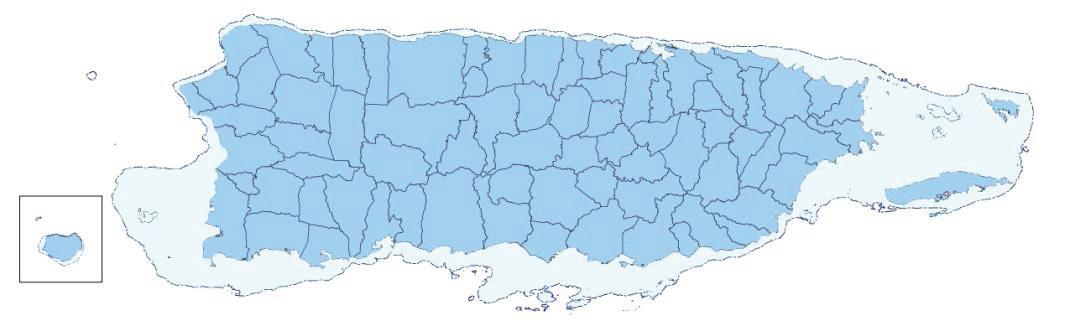

Out of the aforemen oned ecosystems, five are marine ecosystems, and we can find them across the islands 700 miles of shoreline. With the Atlan c Ocean to the north and the Caribbean Sea to the south, the difference in distribu on in these ecosystems is very notable. This can be observed in the variable presence of mangroves throughout Puerto Rico’s shores. The diversity showcased by the marine ecosystems culminates in an interes ng and enriching educa onal adventure.

For decades, Puerto Rico has a ributed li le ecologic and economic value to mangroves, forests composed of trees especially adapted to thrive in coastal areas, because of their appearance and and occasional odor of decaying organic ma er smell. This percep on could not be more mistaken – mangroves are cri cally important for the healthy development of both terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Without mangroves, the seagrass meadows and coral reef ecosystems would not exist as we know them. The biological diversity and the health of these two ecosystems directly depend on the

mangrove’s health. Addi onally, mangrove forests protects our coasts from erosion, strong winds and storm surges, and serve as habitat for many species during their juvenile life stage. Any person who has visited a mangrove forest, whether walking a trail, kayaking, or visi ng the bioluminescent bays, knows that this is a priceless experience. These are just a few reasons why our children need should familiar with this valuable ecosystem.

Once we begin to comprehend how important these resources are, we can strive to use them in a wise manner. As Puerto Ricans, we need to have a sense of stewardship towards out marine ecosystems. For this to happen, we need to know and understand the most common ecosystems in our archipelago, such as the mangroves. It is precisely this limited knowledge regarding the func on and importance of our ecosystems which leads to uncontrolled and poorly planned development in these areas. By integra ng concepts about our coastal ecosystems into school curricula, students will gain awareness and apprecia on for the benefits of caring for mangroves, conserving them and protect them for future genera ons. We will also rediscover our true geographical iden ty as Caribbean islanders.

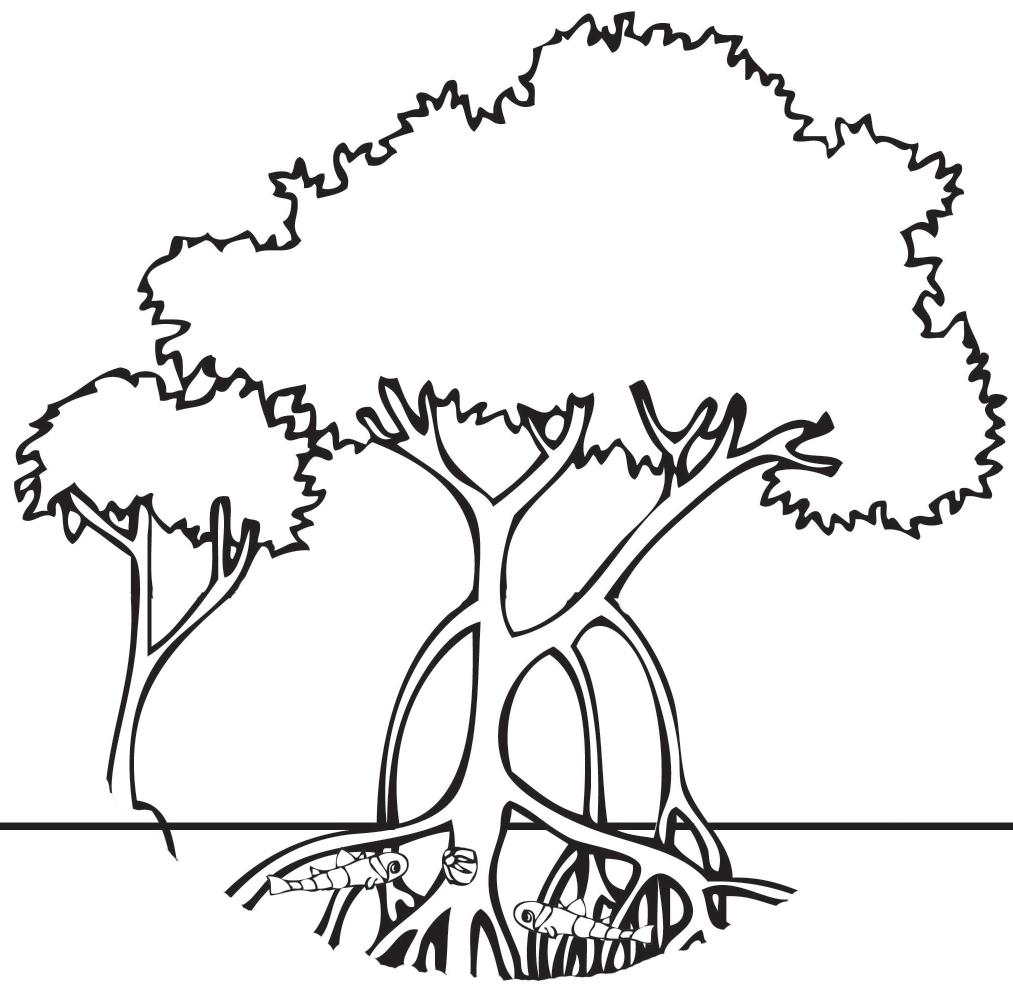

A mangrove forest is a habitat mainly comprised of a group of mangrove trees, growing on the coastline between the sea and the land. Mangroves are commonly found in wetlands or estuaries, where seawater meets and mixes with freshwater from rivers, intermi ent streams, rain runoff or subterranean sources.

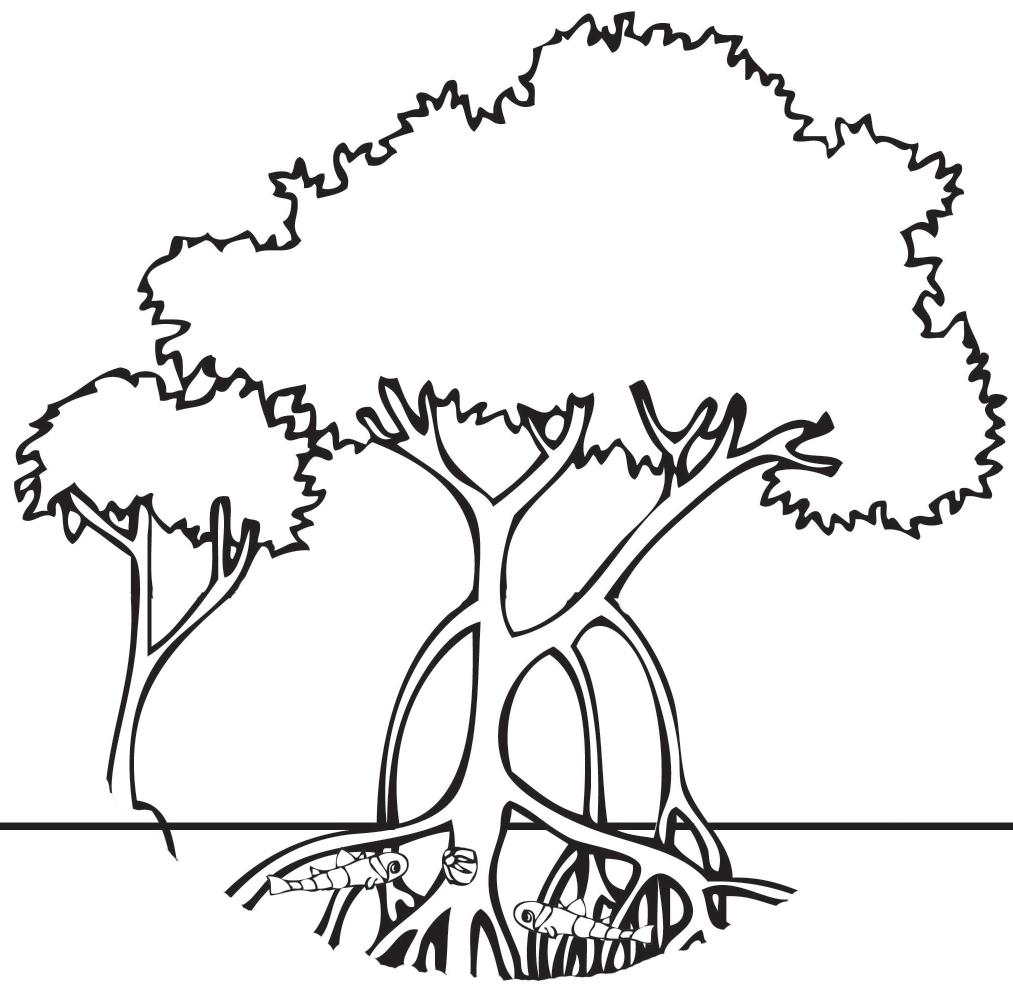

A mangrove tree is a tree or shrub that features special physiological and anatomical adapta ons which allow it to thrive in the extreme condi ons typical to the li oral zone between land and sea (Figure 2). The low-lying lands in this area are known for the frequent water intrusions, high salinity, and poor aera on.

Mean high water mark

Mean low water mark

Generally speaking, a mangrove forest develops in places that gather the following five condi ons

1. Mangrove trees need warm temperatures. These should be between 60-86 oF (15-30 oC). The temperature is a determining factor for mangrove distribu on throughout the world (Figure 1), limi ng their development to the tropical and subtropical regions between 30 degrees N and 30 degrees S.

2. Areas with low exposure to waves and surges, with small chance of erosion, are ideal in aiding seeds and young plants se lement.

3. Mangrove development is also greater in zones offering alluvial substrates, rich in organic material (such as silt).

Alluvial substrate - deposit of watertransported sediments

Estuary – habitat in which seawater becomes diluted as it mixes with freshwater draining from the mainland.

Li oral zone (inter dal zone) - coastal area under the direct influence of the rising or subsiding des.

Mangrove - tree or shrub with special adapta ons which allow it to thrive in high salinity and poorly oxygenated condi ons.

Mangrove forest – habitat chiefly comprised of mangrove trees.

Propagule - the mangrove’s viviparous seed, it is a plant in the early stages of development.

Wetland - areas influenced by aqua c systems and terrestrial systems which are frequently flooded.

4. Mangroves occupy land tracts in which strictly terrestrial plants could not survive, such as areas frequently flooded by seawater

5. Coastal regions with low slopes have a wider li oral zone and therefore provide a more expansive area for mangrove establishment.

Mangrove trees can grow up to a height of approximately 148-164 feet (45-50 m) when situated in op mal condi ons. This may be observed near the equator, where there is a good availability of nutrients, wide expanses of inter dal zones, and rela vely constant, high temperatures. In places with more strenuous condi ons (non-op mal temperatures, very arid soil or extremely high salinity), a mangrove tree only grows as a 3-6 feet (1-2 m) tall shrub.

1. Mangrove thickets are connected to the seagrass meadows and coral reefs. They help retain and stabilize the sediments coming from the mainland, and help control substrate erosion. These trees absorb nutrients and pollutants from the water and are therefore key to clear, clean waters. Mangrove thickets also help reduce freshwater influx into the sea, and are highly produc ve systems. Many fish and crustacean larvae grow and develop in the mangrove thicket habitats before migra ng to other marine ecosystems.

2. Mangroves, like any other plant, use solar energy for photosynthesis, producing oxygen in the process. Photosynthesis allows the mangrove tree to transform solar energy into organic material such as leaves, wood or flowers. Organisms capable of this are known as primary producers.

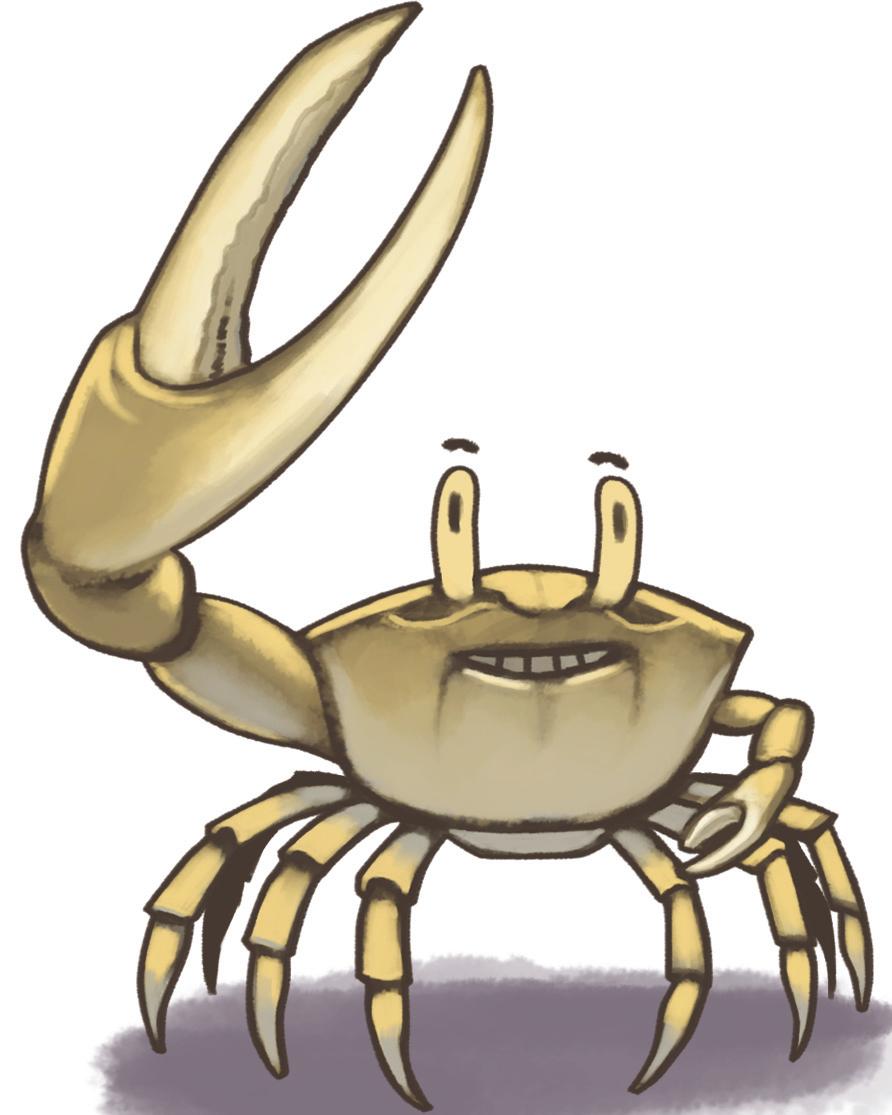

3. Many other species such as crabs, shrimps and bu erflies feed on the leaves, flowers and other organic material produced by the mangroves. These organisms are known as primary consumers. The organisms which feed on the primary consumers, such as seagulls and fish, are known as secondary consumers. In this manner, mangrove forests fulfill a vital role as the base of the food chain, and are highly produc ve ecosystems.

4. Mangrove thickets are important habitats providing food and shelter for many marine species, including mammals, amphibians, birds, rep les, plants, fish, and invertebrates.

5. They serve as nursery zones (offer shelter to species in their juvenile stages), refuge and feeding grounds for many commercially important species such as snapper, lobster and conch.

6. Mangrove thickets offer a nes ng and res ng area for several migratory bird species like the prairie warbler, endemic species like the yellow-shouldered blackbird, or resident species like the American yellow warbler.

7. Mangrove roots stabilize and retain sediments along the shore, protec ng the coast from erosion driven by wind and wave ac on. This is par cularly important during strong surf events like hurricanes, tsunamis or storms.

Primary consumers – Organisms which feed on primary producers.

Primary producers – Organisms which can transform solar energy into ma er through photosynthesis.

Secondary consumers - Organisms which feed on primary consumers.

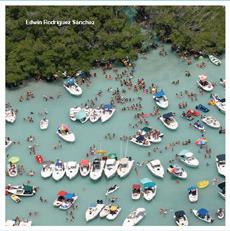

8. Mangrove forests offer recrea onal opportuni es and benefits to both residents and visitors alike.

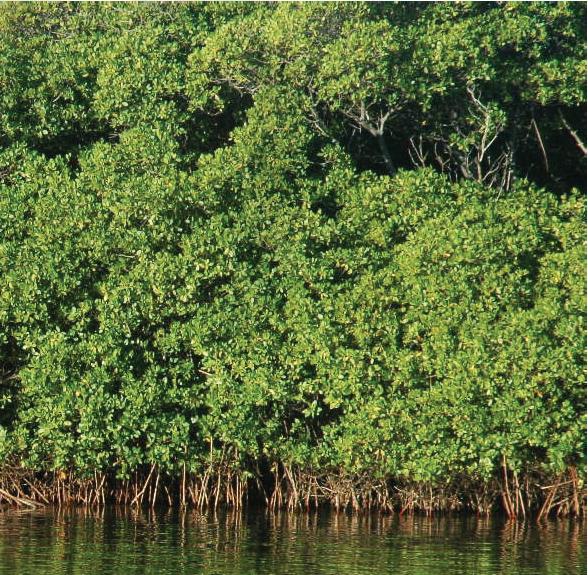

The largest mangrove forest in Puerto Rico can be found in the northeast coast (Figure 5), in the Piñones area in Loíza. The north coast mangrove forests are associated with the freshwater influx from rivers and lagoons (basin and riparian mangroves), and from runoff (bank mangroves). Because the Atlan c Ocean features such heavy surf condi ons, mangrove forests on the north coast develop only in loca ons protected from these condi ons. Throughout the southern coast, on the other hand, mangrove forests present a thick border on the coasts (border mangroves) and the cays (cay mangroves). The submerged land shelf in this zone is wider and fla er than the one on the north coast, and the surf and wave condi ons presented by the Caribbean Sea are much calmer than that of the Atlan c Ocean.

There are around 54 mangrove species worldwide. Of these, about ten can be found within the Caribbean region, and only four within Puerto Rico:

a. Red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle)

b. Black mangrove (Avicennia germinans)

c. White mangrove (Laguncularia racemosa)

d. Bu onwood (Conocarpus erectus)

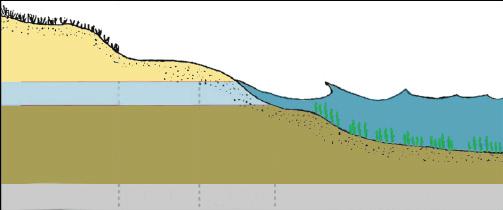

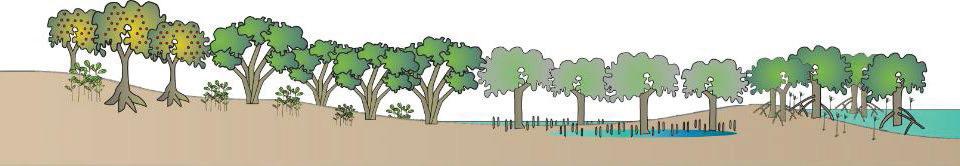

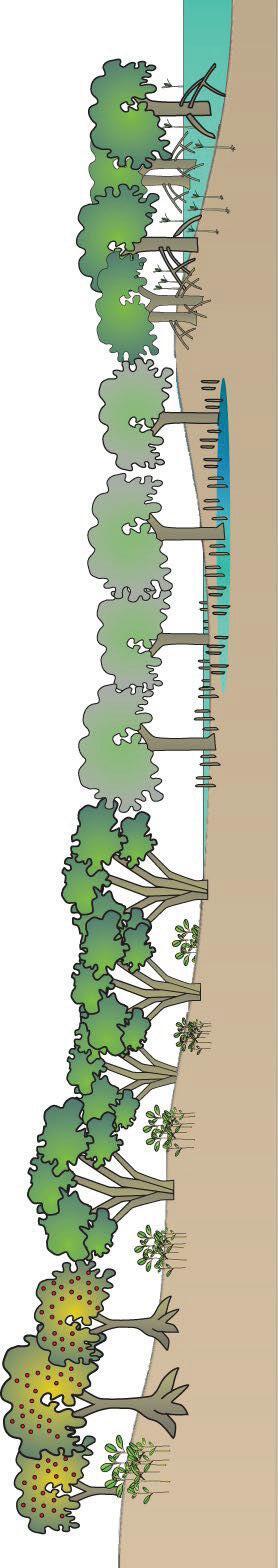

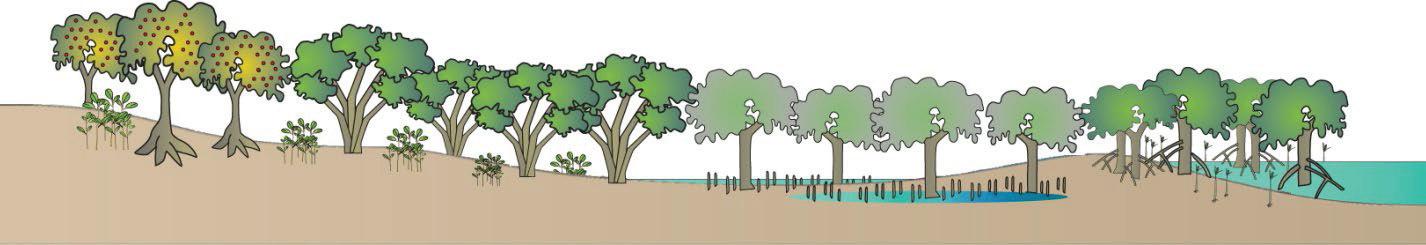

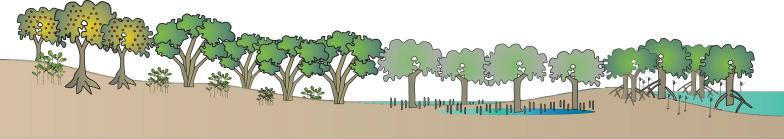

The four mangrove species found in Puerto Rico can be easily iden fied by their main dis nc ve characteris cs: leaf shape, flower and fruit shape, presence of aerial prop roots and presence of pneumatophores; as well as their localiza on inside the mangrove forest. The trees tend to be

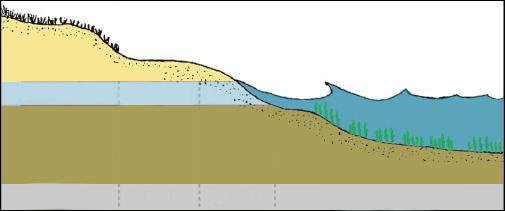

distributed in a sequence perpendicular to the coast, from the sea to the mainland. This distribu on is known as zona on (Figure 6). Zona on is characterized by the adapta ons each mangrove species has to the terrain’s extreme condi ons, such as:

• Tolerance to salinity. The species which are be er adapted to high salinity are on the soil furthest from the li oral zone. During the low de, this soil is exposed to the wind and the sun; some of the water evaporates and some filters down through the sediment, leaving behind salt crystals. In the zones closer to the sea, on the other hand, the salts are dissolved in water and are therefore less salty.

• Adapta ons to life in poorly-aerated soils. Mangrove forests are highly produc ve habitats with very high levels of organic decomposi on (for instance, leaves, wood and flower). Some of the bacteria in charge of decomposing this organic material draw their energy from oxygen. However, oxygen content in these soils is low, due in part to the soils being flooded and being composed mainly of fine sediments, which limit aera on. Therefore, a good amount of the organic decomposi on taking place in mangrove forests is performed by anaerobic bacteria which can survive and work in the absence of oxygen.

• Capacity to become established in unstable substrates (waterlogged and muddy soils). Soils in direct contact with the sea tend to be more saturated with water, are usually more unstable and unconsolidated, whereas those soils which are further from the sea tend to be firmer.

Aerial prop root - root growing outwards from the main tree trunk in a s lt shape.

Pneumatophore - type of root which grows upwards from the soil. They are a feature of both the black and white mangrove trees.

Zona on - mangrove species distribu on perpendicular to the coast.

Figure 6. Mangrove tree zona on on a gradient, from the sea towards the mainland. The bo om of the image shows a blue gradient star ng at the sea, which becomes red in representa on of the increasing salinity. Then, it turns blue again, symbolizing that the soil condi ons in that area are prac cally the same as further inland (low salinity, good oxygena on).

Figure 6. Mangrove tree zona on on a gradient, from the sea towards the mainland. The bo om of the image shows a blue gradient star ng at the sea, which becomes red in representa on of the increasing salinity. Then, it turns blue again, symbolizing that the soil condi ons in that area are prac cally the same as further inland (low salinity, good oxygena on).

The most common species of mangrove in Puerto Rico is the red mangrove. It is usually found in direct contact with the sea, thus becoming the first mangrove species encountered on the coastline, going from the sea towards the land (Figure 6).

Leaves: Red mangrove leaves are large (8-10 cm in length, 4-5 cm in width), thick and with a waxy texture, which prevents water loss and slows decomposi on. The leaves are simple, opposite (Figure 8) and are usually grouped at the ps of the branches.

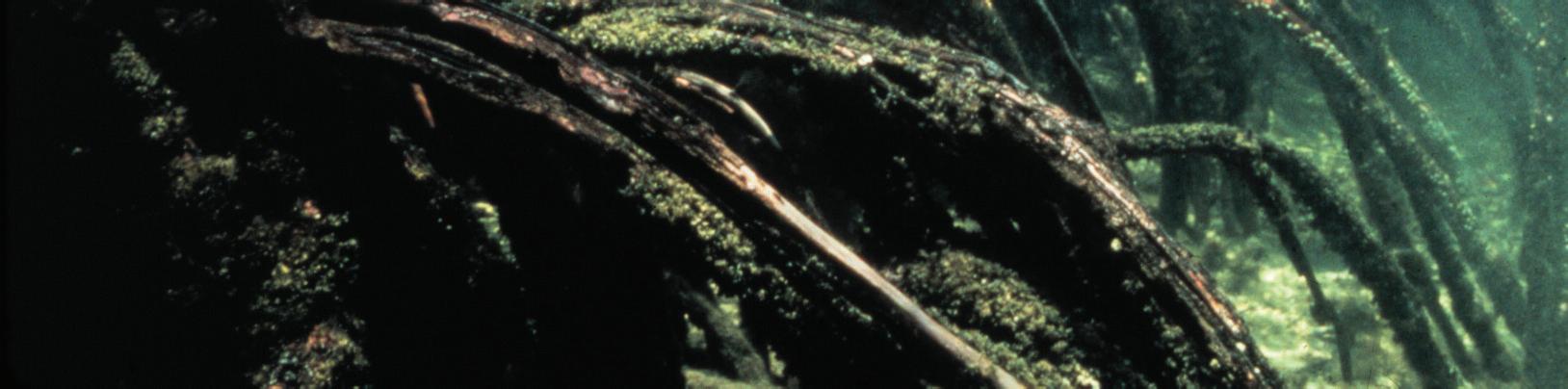

Roots: The red mangrove is the only mangrove presen ng aerial prop roots, which branch out of the trunk or from the lateral branches and droop towards the ground like s lts (Figures 7 and 9). These roots provide the tree with more stability, allowing it to become established in finelysedimented, poorly consolidated soils. Furthermore, the aerial roots fulfill vital func ons such as nutri on, aera on and salt filtra on. The roots filter the salt through osmosis so that the tree can absorb the water necessary to survive. If the mangrove absorbed salt, it would dehydrate.

Bark: The bark covering this mangrove’s roots (Figure 10) contains tannins, organic substances which protect it against bacterial decomposi on and give it a characteris c reddish coloring (tannins are also present in red wine). Also, the bark on the roots and trunk feature pore-like structures called len cels (Figure 11), which aid in the mangrove’s gas exchange (breathing). This is an adap ve response, since the trees grow in poorly-oxygenated or anoxic soils. Red mangrove bark is complete and uniform, differing from other mangrove species.

Figure 7. Red mangrove ecosystem, Puerto Rico.

Figure 8. Red mangrove leaves.

Figure 9. Red mangrove aerial prop roots.

Figure 10. Bark on the red mangrove roots.

Figure 7. Red mangrove ecosystem, Puerto Rico.

Figure 8. Red mangrove leaves.

Figure 9. Red mangrove aerial prop roots.

Figure 10. Bark on the red mangrove roots.

Flowers: Red mangrove flowers are small, approximately 2.5 cm in diameter, with four thick, lanceolate sepals (Figure 12). The flowers have four white petals which turn dark and fuzzy inside, along with eight stamen. Flowers are o en present year-round.

The red mangrove’s fruit germinates while s ll a ached to the tree (Figure 13a). It matures in about two to three months, and develops into an embryo, known as a propagule (Figure 13b). The propagule grows while a ached to the tree for 11 or 12 months, and by the me it detaches, it is already a small plant, with two leaves at the top ready to photosynthesize and establish itself as a new red mangrove tree (Figure 14).

The propagules growing among the established mangrove roots tend to develop as small shrubs of about 1.5 meters in height due to the limited amount of sunlight they receive. These young, small trees are called the dormant forest, and serve as a reserve popula on. When a full-grown mangrove tree dies, a space opens up and allows sunlight to reach the substrate. The small, dormant trees, usually living in the shadow of their larger counterparts, readily take advantage of these new and favorable sunlight and space condi ons and quickly grow to their full size. Thus, the dormant forest eventually replaces the main one through a cyclical process. This is a crucially important process to mangrove forest survival, especially a er suffering the effects of strong weather events like hurricanes or tsunamis. On the other hand, if the propagule falls into the water, it floats to the surface and is transported by currents, since its small trunk is corklike. Ini ally, it floats horizontally, but as it absorbs water, its bo om part becomes heavier and sinks, orien ng the propagule ver cally. Upon reaching a flat surface, the propagule has the chance of establishing itself as a new mangrove tree. This reproduc ve mechanism allows red mangroves to disperse and colonize areas distant from the usual coastal mangrove zones (such as cays).

lenticels

peduncle sepals

Figure 11. Len cels on the red mangrove tree roots.

Figure 12. Red mangrove flower, with some of their parts. (petals, sepals, peduncle, stamen)

Figure 13b. Red mangrove propagule.

Figure 13a. Red mangrove fruit.

stamen

lenticels

peduncle sepals

Figure 11. Len cels on the red mangrove tree roots.

Figure 12. Red mangrove flower, with some of their parts. (petals, sepals, peduncle, stamen)

Figure 13b. Red mangrove propagule.

Figure 13a. Red mangrove fruit.

stamen

Dormant forest - group of small mangrove trees inhabi ng the shadows from the main forest.

Len cels - projec ons from the tree’s trunk and root surfaces, having a pore to aid in gas exchange.

Osmosis - movement of water molecules through a semipermeable membrane, from an area of higher water concentra on to one with less water concentra on.

Sepals - each of the harder, greenish leaves which form the flower’s calyx.

Stamen - the flower’s male reproduc ve organ, containing pollen.

Tannins - organic substances present in the red mangrove’s vegetal ssue and which provide its characteris c reddish hue; tannins also offer protec on against bacterial decomposi on.

Figure 14. Propagule established in so substrate.

Figure 16. Dormant forest near ground level.

Figure 15. The tannins featured by the red mangrove may give the surrounding water a reddish appearance.

Figure 14. Propagule established in so substrate.

Figure 16. Dormant forest near ground level.

Figure 15. The tannins featured by the red mangrove may give the surrounding water a reddish appearance.

The black mangrove (Figure 17) tends to be located behind the red mangrove, in sal er and less aerated soils. This species tolerates more strenuous climate condi ons and is associated with poor soils or soils with high salinity.

Main characteris cs:

Leaves: The black mangrove’s leaves are smaller than the red mangrove’s, and are lanceolate, with a sharp point at the apex (Figure 18). The dorsal surface (the top side of the leaf) is green, while the ventral surface (the bo om side of the leaf) is yellowish green and opaque (Figure 19). Black mangrove leaves are opposite (begin at the same point on the branch, but in opposite direc ons) and serve as the tree’s salt excretory organs (Figure 18). The salt crystals are deposited on the dorsal surface through stoma. This process ensures that the tree maintains the necessary water it needs for its survival. Older leaves tend to accumulate higher concentra ons of salt before falling off and showing burn spots due to the “magnifying glass” effect created when sunlight is filtered through the salt crystals.

Roots: The black mangrove features a system of super cial roots around the trunk. This system has several long projec ons which protrude from the substrate upwards. These projec ons are known as pneumatophores (Figure 20). The pneumatophores are long and slender (reaching a height of up to 20 cm), and their func on is to allow the mangrove to perform aera on (breathing) in poorly oxygenated soils. Because of their appearance and func on, they are o en referred to as “snorkel roots.”

Bark: The black mangrove tree’s bark has a smooth bark while in the juvenile stage, before becoming fissured. It has a black or dark gray color, with a yellowish interior (Figure 23).

Flowers: Black mangrove flowers are small (0.2 - 0.5 cm in diameter, 0.5 cm in height), with white petals. They bloom in dense clusters (Figure 21).

Fruit: The black mangrove’s fruit is shaped like a small, fla ened, oval capsule (Figure 22). The embryo develops while s ll a ached to the parent tree, and fixes itself onto the substrate upon falling. If it falls into the water, the embryo can float for several weeks, sustaining itself on the cotyledons, un l it reaches an appropriate place on which to se le.

Apex - the outer end of a leaf or branch.

Cotyledons - the shape in which the first leaf of a seed-bearing plant embryo appears.

Dorsal surface - the top side of a plant’s leaf.

Stoma - small pore-like orifices located on a leaf’s surface; they are in charge of regula ng gas Exchange and minimizing water loss.

Ventral surface - bo om or inferior surface on a plant’s leaf.

Figure 23. Black mangrove bark. Figure 20. Black mangrove pneumatophores. Figure 21. Black mangrove flowers. Figure 22. Black mangrove fruit.

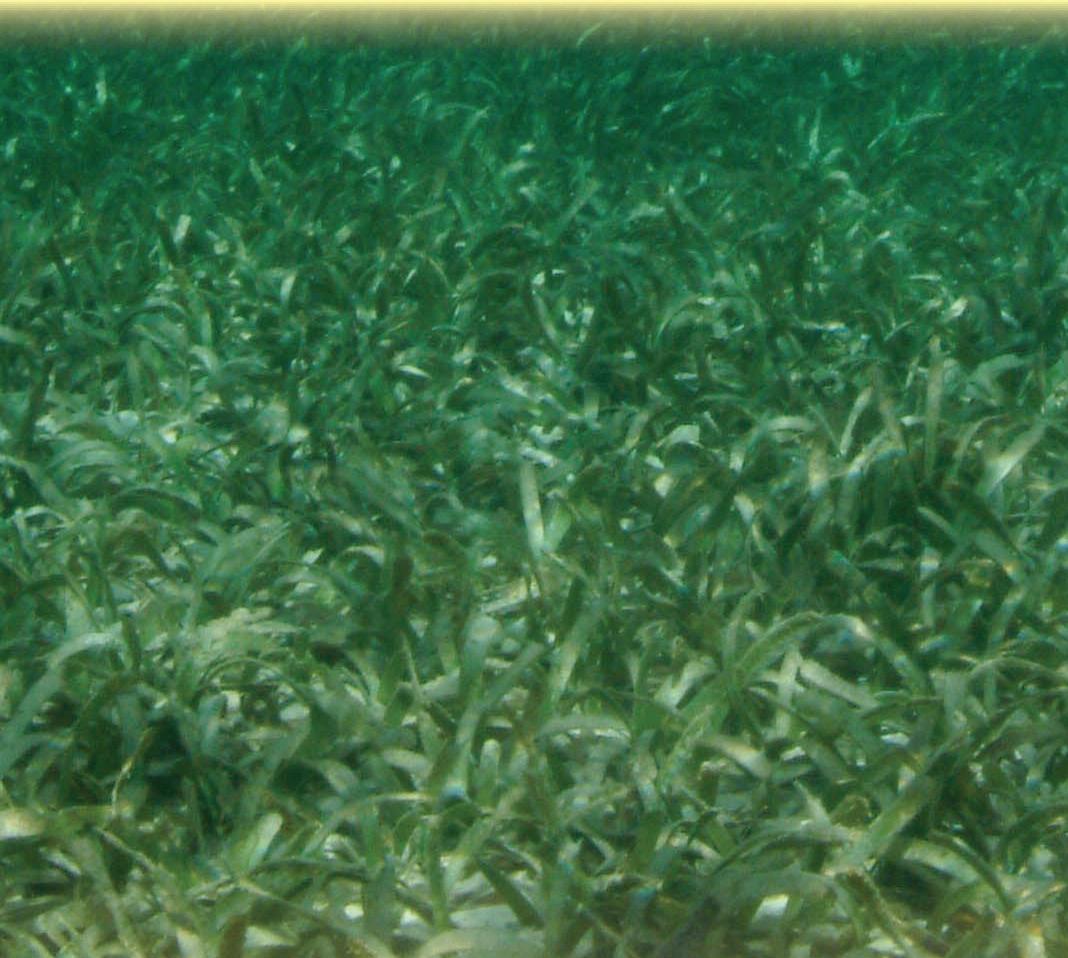

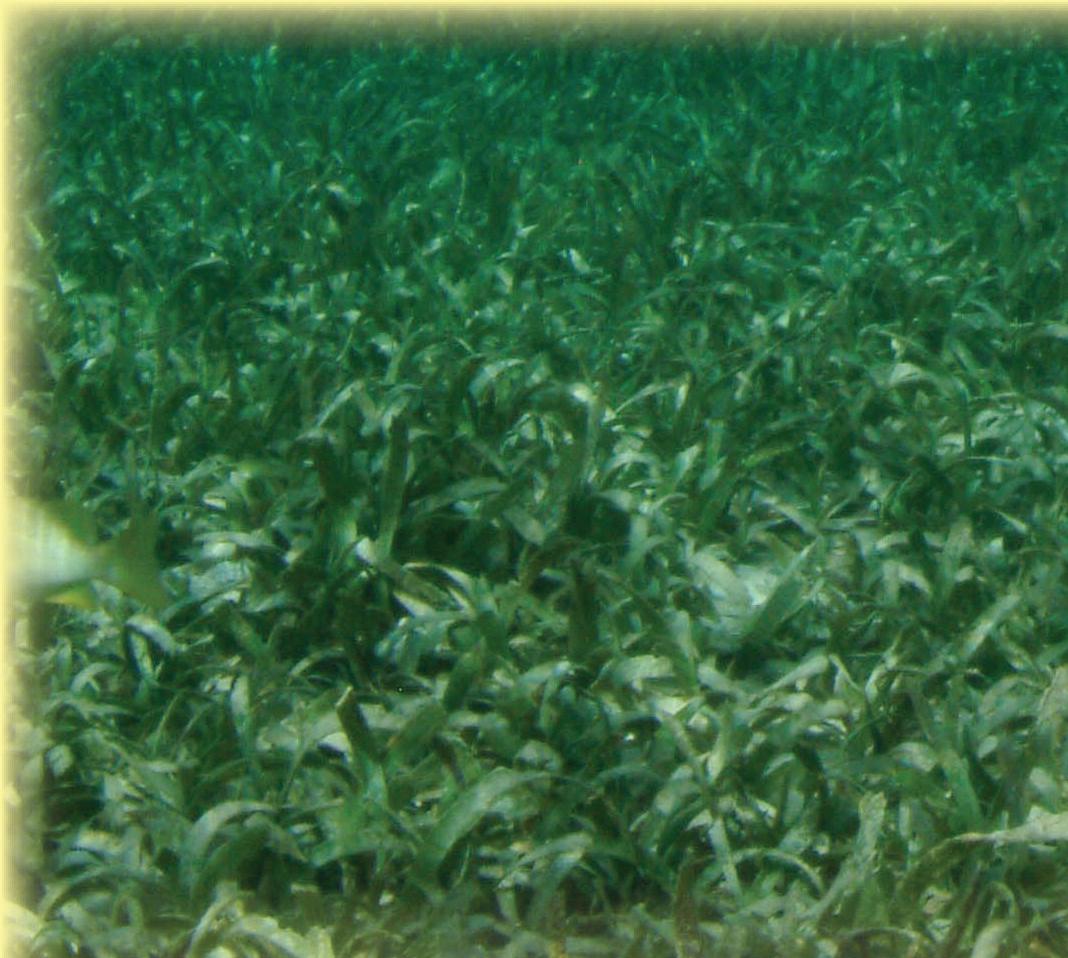

White mangroves (Figure 24) are typically located behind the black mangroves, towards the mainland and in salty, poorly-aerated soils. This mangrove, however, can also grow in low-salinity environments. It develops op mally in sandy substrates.

Main characteris cs:

Leaves: White mangrove leaves are thick, oblong (oval) shaped, with a rounded apex. They are opposite, simple, and have a leathery texture. The dorsal surface is grayish green, while the ventral surface is lighter colored (Figure 25a). These leaves feature two glands at the pe ole base, which are in charge of excre ng excess salt from the mangrove in order to maintain a healthy hydra

Roots: Like the black mangrove, white mangroves have a super trunk, with long projec ons growing upwards from the substrate, known as pneumatophores have special ssue at the pneumatophores are shorter and fla er than those on the black mangroves (Figure 26a).

Figure 24. White mangrove ecosystem, Puerto Rico.Bark: Unlike other mangrove species, white mangrove bark is fissured along the length of the trunk (Figure 26b).

Flowers: White mangrove flowers are small (0.2 to 0.3 cm) and plen ful, and their external parts fused to form a tube with five triangular lobes or teeth. At the end of the tube, it grows five ny, rounded petals, about 0.1 cm long. The flowers grow in clusters, forming inflorescences (groups of flowers on the branches) that can measure 3 to 7 cm in length (Figure 27).

Fruit: White mangrove fruits are small, with lengthwise ridges. When immature, they are green. They turn brown as they ripen (Figure 28). The seed usually begins to germinate while the fruit is s ll a ached to the tree. Generally, the embryo develops just before falling off the tree. If it falls into the water, the seeds float and are dispersed by the currents.

Bu onwood (Figure 29) can be found in the inter dal zone furthest from the sea, in low-salinity, elevated, sandy soils, where it mixes with terrestrial vegeta on. Because of this, some field experts do not consider it a true mangrove.

Bu onwood usually grows as a shrub, although in some cases, provided it receives op mal condi ons, it may grow as a fairly large tree, between 15-23 feet (5-7 m) tall. In Puerto Rico, it usually forms small forests along rocky shores. It may also be found bordering very low-salinity lagoons that are distant from the shore.

Main characteris cs:

Leaves: The bu onwood’s leaves are ellip cal and small (4-9 cm long and 2-3 cm wide). It is the only mangrove tree species with alterna ng leaves. The leaf pe ole is small and, like the white mangrove, has two small salt-excre ng organs on each side (Figure 30a). Like all the other mangrove species men oned, it needs to eliminate salt to maintain proper hydra on.

Flowers: Bu onwood flowers are ny (0.2 cm wide), green and fragrant, and grow in large numbers to form round inflorescences measuring 0.6 -12.5 cm in diameter (Figure 30b).

Fruit: Bu onwood gets its name from the shape of its fruit. The round inflorescences become a brown, round, aggregated fruit, similar to a ny pinecone or bu on. (Figure 30c). Each fruit contains a large number of seeds.

Main disturbances affec ng the mangroves in Puerto Rico

Natural

Sea level rise - In the best case scenario, it would reduce the inter dal zone which mangroves can colonize; in the worst case scenario, it could submerge and exterminate exis ng mangrove forests.

Hurricanes and tsunamis - They create strong winds, rainfall events and storm surges which could poten ally tear mangroves from the substrate.

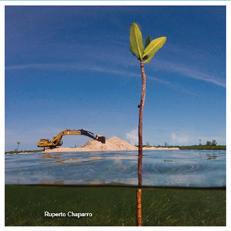

Coastal urban development - The increase in human popula on in coastal zones has increased wood clearing (including cu ng down mangrove forests), which increases soil erosion and sediment discharge reaching the sea.

Mangrove forest clearing - Usually, mangrove forests are cut so that urban development may occur. Their wood is also harvested and used as construc on material for building fish traps, because of the wood’s resilience to water.

Increased boat traffic on shallow waters - This removes sediments on the bo om (which are usually anoxic; that is to say, without oxygen), and resurfaces the contaminants and toxic substances in the water, to the detriment of water quality and mangrove health, as well as risking the wellbeing of mangrove forest inhabitants.

Increased presence of nutrients, fer lizers and other contaminants - Discharge from rivers or runoff nega vely affects water quality, hurts mangrove health, and risks the wellbeing of mangrove forest inhabitants.

Trash - The des bring in trash which gravely affects the many species inhabi ng the mangrove forest.

Changes in water flow - Altera ons and/or construc on on the coast cause changes in water flow. This changes the water’s characteris cs, such as its temperature or salinity, and can cause widespread ex nc on in the mangrove forest.

In order to preserve these valuable ecosystems, several key issues must be addressed, such as:

coastal development;

effec ve management of runoff, used waters and garbage;

waste reduc on through the use of the three R’s: Reducing the use of disposable materials, Reusing objects as much as possible, and Recycling.

The Department of Natural and Environmental Resources of Puerto Rico (DRNA, by its Spanish acronym) has developed a plan for mangrove protec on and conserva on in Puerto Rico. This plan responds to the public policy established by Law #23, the DRNA Organic Law from June 20, 1972.

There are also a series of federal laws protec ng Puerto Rico’s wetlands. The United States Environmental Protec on Agency (EPA) has a website where any ci zen may anonymously report viola ons to the laws:

h p://www.epa.gov/region02/water/wetlands/viola ons.html

Aerial prop root - root growing outwards from the main tree trunk in a s lt shape.

Alluvial substrate - deposit of water-transported sediments

Apex - the outer end of a leaf or branch.

Bank mangrove - a type of mangrove that develops in zones adjacent to rivers and lagoons, which have li le water flow and which receive li le influence from the des.

Border mangrove - a type of mangrove which grows along the coast, usually in bays and open lagoons, and exposed to low to moderate waves. This type of mangrove is not associated to freshwater influx.

Cay mangrove - mangroves that develop into islands close to the shore. These mangroves are exposed to low to moderate waves.

Cotyledons - the shape in which the first leaf of a seed-bearing plant embryo appears.

Dormant forest - group of small mangrove trees inhabi ng the shaded undergrowth areas of the main forest, among its roots. They grow quickly when sunlight and spa al condi ons become op mal, such as when older trees die off because of strong winds or hurricanes.

Dorsal surface - top or superior surface of a plant’s leaf.

Estuary - habitat in which seawater becomes diluted as it mixes with freshwater draining from the mainland.

Inflorescence - array or group of flowers at the end of a plant’s stalk or a tree’s branch.

Len cels - projec ons from the tree’s trunk and root surfaces, having a pore to aid in gas exchange.

Li oral zone (inter dal zone) - coastal area under the direct influence of the rising or subsiding des.

Mangrove - tree or shrub with special adapta ons which allow it to thrive in high salinity and poorly oxygenated condi ons.

Mangrove forest - habitat chiefly comprised of mangrove trees; they grow in the inter dal zone, in the space between the sea and the land.

Osmosis - movement of water molecules through a semipermeable membrane, from an area of higher water concentra on to one with less water concentra on.

Pe ole - the leaf’s peduncle, or the stem through which it is a ached to the plant stalk.

Pneumatophore - type of root which grows upwards from the soil. They are a feature of both the black and white mangrove trees.

Primary consumers - Organisms which feed on primary producers (the ones that perform photosynthesis).

Primary producers - Organisms which can transform solar energy into ma er through photosynthesis.

Propagule - the mangrove’s viviparous seed, it is a plant in the early stages of development.

Riparian mangrove - it is a type of mangrove which develops in zones under the influence of rivers and water runoff, and are influenced by the des.

Secondary consumers - Organisms which feed on primary consumers.

Sepals - each of the harder, greenish leaves which form the flower’s calyx.

Stamen - the flower’s male reproduc ve organ, containing pollen.

Stoma - small pore-like orifices located on a leaf’s surface; they are in charge of regula ng gas exchange and minimizing water loss.

Tannins - organic substances present in the red mangrove’s vegetal ssue and which provide its characteris c reddish hue; tannins also offer protec on against bacterial decomposi on.

Ventral surface - bo om or inferior surface on a plant’s leaf.

Wetland - area influenced by aqua c systems and terrestrial systems which are frequently flooded or saturated with superficial or subterraneous water for a period of me.

Zona on - mangrove species distribu on perpendicular to the coast.

References:

CONABIO-CONANP. (2009). Mangle blanco (Laguncularia racemosa). Fichas de especies mexicanas. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad y Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, México, D.F.

Ecología. Estuarios. Consulted on November 3, 2012. h p://memo.com.co/ecologia/estuario.html

Environmental Protec on Agency (EPA). Wetlands Viola on - Ini al Complaint Form. Consulted on November 3, 2012. h p://epa.gov/region02/water/wetlands/viola ons.html

Feller, I.C. y Sitnik, M. (1996). Mangrove Ecology: A manual for a Field Course. Smithsonian Ins tu on. Washington, DC.

González Lagoa, J.G. y González Toro, C. (2010). Encuentro con el mar. Puerto Rico: Programa Sea Grant.

Li le, E. y Wadsworth, F.H. (1995). Common Trees of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. U.S. Department of Agriculture - Forest Service.

Mcleod, E. & Salm, R. V. (2006). Managing mangroves for resilience to climate change. Gland, Switzerland: The World Conserva on Union (IUCN).

Muñoz-Hincapié, M. (2007). Manual del Botero y Charlas Ecológicas. Puerto Rico: Departamento de Ciencias Marinas. Universidad de Puerto Rico, Recinto universitarios de Mayagüez.

Ramírez Mella, J. Los manglares: ¿Existe un plan de manejo para los manglares? Consulted on November 3, 2012. h p://cremc.ponce.inter.edu/manglares/manejo.htm

Universidad Pública de Navarra. Iden ficación de plántulas con claves dicotómicas. Consulted on November 3, 2012. h p://www.unavarra.es/servicio/herbario/htm/plantula_BAMH_01.htm

• A mangrove is a tree with special adaptations which allow it to survive in the littoral zoneʼs harsh conditions.

• The littoral zone is located where land and sea meet, and is characterized by being frequently flooded and featuring high salinity and poor aeration.

• A mangrove is a plant, tree or shrub, typical to the li oral or inter dal zone, which are very tolerant to high salinity and poor aera on in the soil.

• In the li oral zone, the soil is subjected to frequent water incursions (flooding), because of their exposure to dal changes in the sea (high and low des); the soil is poorly aerated and features high salinity.

• Mangrove wood is of excellent quality, and is very resistant to rot. In the past, mangroves were cut down to use their wood for cooking or to build fish traps, since they remain in good condi on even a er long periods underwater. In modern mes, mangroves are protected, and it is forbidden to cut them in Puerto Rico.

•A mangrove forest is a forest ecosystem which grows along the coastline and in mainly composed of mangrove trees.

•Mangrove forests are common in wetlands or estuaries where seawater meets and mixes with freshwater coming from rivers, rainwater runoff or subterranean sources.

• Defini on: A mangrove forest is a habitat composed of salt-resistant trees (mangrove trees of one or several species) which occupy the line between sea and land, and areas close to the river mouths which open to the sea. Mangrove forests are only found in tropical and subtropical la tudes.

• Wetlands and estuaries are zones in which seawater meets and mixes with freshwater coming from rivers, rainwater runoff or subterranean sources.

Mangroves can be found in tropical and subtropical regions, in warm temperatures oscillating around 60-77 F (15.5-25 C).

http://www.madrimasd.org/blogs/universo/2011/02/02/138188

• Temperature is a determining factor in world mangrove distribu on, limi ng mangrove forests to tropical and subtropical regions between the 30 degrees north and 30 degree south la tudes.

•Areas slightly exposed to waves and surf surges are ideal for good mangrove forest development.

•Alluvial substrates present in frequently-flooded land favors mangrove forest development.

•Coastal regions with mild slopes have a wide littoral zone, on which mangrove forests can grow.

• Areas exposed to mild waves and surf surges are less likely to be eroded, which makes them ideal for mangrove forests, since it fosters good propagule se lement.

• Soils featuring alluvial substrates are rich in organic material (like silts) which aids mangrove growth.

• Mangrove forests occupy soils on which strictly terrestrial plants could not survive, such as soils frequently flooded by saltwater.

There is a larger distribution of mangrove forests in the southern Puerto Rico region than the north coast.

• The largest mangrove forest in Puerto Rico can be found in the northeastern coast (Figure 5), at the Piñones area in Loíza. The north coast’s mangrove forests are associated with freshwater ingress through lagoons and rivers (bank mangroves), and from rainwater runoff (riparian mangroves). Due to the Atlan c Ocean’s strong surf and surge condi ons, the north coast’s mangrove forests only develop in places protected from these harsh condi ons. Along the south coast, on the other hand, mangrove forests extensively border the coast (border mangroves) and cays (cay mangroves). The underwater seabed is wider and fla er than the one on the north coast, and the surf and surge condi ons on the Caribbean Sea are much calmer than the Atlan c Ocean’s.

• Sugges ons: Here the teacher can point out the loca ons on Puerto Rico which foster mangrove forest development; keep in mind that the green areas represent presence of mangrove forests.

• The teacher must emphasize that mangroves are more common in the southwest, south, and northeast regions in Puerto Rico. Also, they can perform an exercise with the students that can incorporate geography, by iden fying the townships in which mangrove forests may be found.

• Worldwide, there are about 54 species of mangrove.

• In Puerto Rico, there are four species. These are:

– Red mangrove (Rhizophoramangle)

– Black mangrove (Avicenniagerminans)

– White mangrove (Lagunculariaracemosa)

– Buttonwood(Conocarpuserectus)

• Out of the 54 species of mangrove exis ng around the world, approximately 10 may be found in the Caribbean area, and only 4 in Puerto Rico.

Mangrove species are distributed in perpendicular order on the coast (zonation), which depends on factors such as:

• toleranceto salinity,

• adaptations to life in poorly-aerated soils, and

• ability to become established on unstable soils.

High salinity

• Different mangrove species are arranged in perpendicular fashion along the coast, from the sea towards the mainland. This distribu on is known as zona on, and it depends on each mangrove species’ adapta ons to the extreme soil condi ons.

• Please observe the zona on shown by the four mangrove species we have in Puerto Rico in the image above.

• We can see that the red mangrove is the first species encountered, always in direct contact with the water.

• Immediately a er the red mangrove, we come upon black mangroves, located further up the coast. It has special adapta ons that allow it to survive in higher salinity concentra ons.

• A er the black mangrove, we can o en find white mangroves. As shown in the diagram, white mangroves can be found further from the water because, much like the black mangrove, it has special adapta ons for life in high salinity condi ons. Black and white mangroves can o en become established in the same areas, so that the posi ons of these two species may be interchangeable.

• Lastly, we may find bu onwood. This mangrove usually grows in the coastal zones furthest from the sea, where exposure to the sea water is minimal. Soils in this area have the least salinity satura on as well as the most oxygena on, and bu onwood readily mixes in with terrestrial vegeta on.

Buttonwood White mangrove Black mangrove Red mangrove

Buttonwood White mangrove Black mangrove Red mangrove

The diverse mangrove species can be identified by some distinctive traits, such as::

– leafshape,

– flowerand fruitshape,

– presence/absenceof pneumatophores, and

– placementalongthehabitat.

Sugges on: The teacher might take this opportunity to review basic botany concepts.

• Red mangroves are in direct contact with the water.

• This species features aerial prop roots which branch off from the tree trunk and droop towards the ground below.

• The underwater roots create a complex network that comprises a crucially important habitat to many marine organisms, especially during their juvenile life stages.

• The most common mangrove in Puerto Rico is the red mangrove. This tree is the main cay builder seen along the coasts, such as those around La Parguera (Lajas), Cabo Rojo and Guayama, among other townships.

• Red mangroves are commonly found in direct contact with the water. It is the first species encountered along the coastline, going from the sea towards the mainland.

• The red mangrove is the only species presen ng aerial prop roots, which branch off the main tree trunk and droop towards the ground below in s lt-like fashion.

• These aerial prop roots fulfill life-sustaining func ons such as nutri on and aera on and, in their underwater parts, comprise an important habitat which serves as a haven for mainly juvenile organisms.

• The roots aid in soil stabilization.

• The bark is pale olive green. However, the interior is reddish.

• The roots are covered in lenticels, pore-like structures which aid in the mangroveʼs gas exchange.

• These roots provide be er stabiliza on to red mangroves, which allows this species to thrive in so sediment areas and resist high wind and surf condi ons. The roots also trap and stabilize sediments.

• The red mangroveʼs leaves are large, thick, and have a waxy texture.

• They are simple leaves, opposite, and often grouped along the branch tips.

• Red mangrove leaves are large (8-10 cm long and 4-5 cm wide), thick and waxy, which inhibits their decomposi on and water loss.

peduncle sepals

petals

•Flowersare small.

• Each peduncle can sprout between 2-4 flowers.

• Sugges on: The teacher might take this opportunity to review basic botany concepts.

Red mangrove flowers present 4 sepals, 4 white petals, and 8 stamen.

Red mangroves flower throughout the year.

• The

white petals turn dark and fuzzy as me progresses.

These are plants which are fully developed by the time they fall from the tree and become settled in the substrate.

Red mangroves are hermaphrodites; it can be selfpollinized, or become wind pollinized.

The seed sprouts within the fruit (vivipary).

Red mangroves spread through propagules.

Propagules are small, lanceolate trees.

The root develops in the widest section.

By the time it drops from the tree, it already features many lenticels, a stalk, and its first two leaves.

When it drops from the tree, the propagule anchors itself to the substrate and grows into a mangrove tree.

If it falls into the water, the propagule may float for up to a year until it finds an appropriate place to anchor itself and begin to grow.

• When a propagule falls into the water, it floats and is readily transported to other loca ons by sea currents. Although it begins to float horizontally, it quickly begins to absorb water and, due to its torpedo-like shape, it gains more water weight on its thicker, bo ommost part and starts floa ng upright and ver cal.

• This is a very successful reproduc on method which has allowed for the development of cays we commonly find around our coasts.

• Black mangroves develop behind the red mangroves, on soils with higher salinity and less oxygen.

• The tree trunk is gray or black.

• It features pneumatophores, root projections which protrude from the ground and aid in the mangroveʼs gas exchange (O2, CO2)

• Black mangroves have a superficial root system featuring long, fingerlike projec ons which grow out from the substrate and can reach heights above 20 cm above ground. These projec ons are called pneumatophores.

• Pneumatophores are long and slender, and their func on is to allow mangrove aera on in poorly oxygenated soils.

• Remember that plant roots need oxygen for op mal development. For instance, earthworms are a great help to plant development, as they create tunnels which aid the flow of oxygen in the soil.

• Black mangrove leaves grow in opposite array.

• They are lanceolate, with a pointy apex (leaf tip).

• Black mangroves exude salts on the dorsal surface of the leaf, forming crystals.

• Black mangrove leaves are smaller than those of the red mangrove, and are lanceolate shaped with a pointy apex (leaf p).

• The dorsal (top side) part of the leaf is green and the ventral (bo om side) is opaque and yellowish green.

• The leaves on a black mangrove are the main salt excre ng organs featured in the tree. Salt crystals can o en be found on the leaf’s dorsal side, deposited there by the stoma.

• Older leaves can accumulate high salt concentra ons before falling off, and o en present burn spots due to the “magnifying glass” effect created when sunlight is filtered through the salt crystals.

• Theflowersare small, and maybe whiteor yellow. Theybloomin dense clusters.

• Features4 whitepetals and 4 stamen.

• Thefruitisanoval capsule.

• Insidethefruit, the seedbeginsto germinatebefore dropping.

• Theseedsare released fromthefruitonce it fallsintothewater.

• The black mangrove’s fruit is shaped like a small, fla ened, oval capsule .

• The embryo develops while s ll a ached to the parent tree, and fixes itself onto the substrate upon falling.

• If it falls into the water, the embryo can float for several weeks un l it reaches an appropriate place on which to se le.

•Itistypically located behind the black mangroves, towards the mainland and in salty, poorly-aerated soils.

• Thewhite mangroveʼs bark is rugged and fissured along the length of the trunk. Itislightcolored.

• White mangroves are typically located behind black mangroves, heading towards teh mainland, in salty, poorly-aerated soils.

• It develops op mally in sandy substrates.

• White mangrovefeaturespneumatophores thataidin gas Exchange.

• Thesepneumatophoresare shorterthanthe onesonblackmangroves.

race

• Theleavesare opposite.

• The leaves are simple, thick, and oblong (oval) shaped.

• White mangrove leaves are thick, oblong (oval) shaped, with a rounded apex ( p).

• The dorsal surface is grayish green, while the ventral surface is lighter colored.

Thewhitemangrove features two glands at the petiole base, which are in charge of excreting excess salt

White mangrove flowers are small (0.2 to 0.3 cm), white and plentiful.

Thepetalsare tube-shaped.

• White mangrove flowers are small (0.2 to 0.3 cm) and plen ful, and their external parts fused to form a tube with five triangular lobes or teeth.

• At the end of the tube, it grows five ny, rounded petals, about 0.1 cm long.

• The flowers grow in clusters, forming inflorescences (groups of flowers on the branches) that can measure 3 to 7 cm in length.

• Thefruitfeatureslengthwiseridges, and iscolored greenwhenitisimmature. Itturnsbrownas it ripens.

• Thesingle seedwithinthefruitisviviparous.

• Generally, the embryo develops just before falling off the tree.

• If it falls into the water, the seeds float and are dispersed by the currents.

• The fruit is drupe. A drupal fruit is a fleshy or pulpy fruit. Other drupal fruits include peaches, plums and mangoes.

• Buttonwoodcan be foundin elevated, low-salinity, sandysoils.

• Ithas elliptical, alternateleaves(theonlymangrove speciesin Puerto Rico to featurethis).

• Leavesfeaturetwoglandsonthepetiolewhichexcrete excesssalts.

• Bu onwood can be found in the inter dal zone furthest from the sea, in low-salinity, elevated, sandy soils, where it mixes with terrestrial vegeta on. Because of this, some field experts do not consider it a true mangrove.

• Bu onwood usually grows as a shrub.

• The bu onwood’s leaves are ellip cal and small (4-9 cm long and 2-3 cm wide).

• The leaf pe ole is small and, like the white mangrove, has two small salt-excre ng organs on each side.

• The flowers are tiny, green and fragrant.

• Clusterand grow intoglobe-shaped, rounded inflorescences.

• Eachglobecontains severalseeds.

• Bu onwood flowers are ny (0.2 cm wide) and grow in large numbers to form round inflorescences.field experts do not consider it a true mangrove.

• Buttonwood gets its name from the shape of its fruit, similar to a tiny pinecone or button.

• Buttonwoodisnot considereda true mangrove, butrather, a peripheralspecies.

• Mangroves s are e carbon n sinks s and g oxygen n producers rs r .

• Mangrove e forests s provide e home and g shelter r for r many p y species s and d their youngg.

• Mangroves s protect t the e coasts s from g strong p g winds s and d waveses.

• As all other forests, mangrove forests have global importance since they absorb carbon dioxide (CO2) during their photosynthesis process. They also release oxygen as a waste product.

• By consuming atmospheric carbon dioxide, mangroves help reduce the Earth’s greenhouse effect and therefore, reduce climate change (global warming).

• Photosynthesis lets the mangrove convert solar energy into organic material such as leaves, flowers and wood. The organisms capable of doing this are known as primary producers.

• They serve as nursery zones (offer shelter to species in their juvenile stages), refuge and feeding grounds for many commercially important species such as snappers, land crabs, lobsters and conch.

• Mangrove forests are characterized by their enormous biological diversity. In a mangrove forest, one can find a large number of bird, fish, crustacean and mollusk species.

• Mangroverootsand leavesdecomposeand becomeinorganic nutrientsand substancesthatotherorganismsuse.

• Mangrovesretainand stabilizesedimentsand pollutants comingfromtheshore, helpingcleanthewatersflowinginto thesea.

• Mangrove forests are highly produc ve habitats and they export some of that energy in the form of biomass or nutrients for other ecosystems. For instance, fish and crustacean larvae grow and develop in mangroves, and later migrate to other marine ecosystems.

• Mangrove trees absorb nutrients and pollutants from the water, and are therefore fundamentally important to keeping the waters clean and clear.

• Seagrasses and corals thrive in clear waters that allow sunlight to reach the bo om so that the grasses and microalgae associated to coral polyps can perform photosynthesis.

• Mangroveforestsare nestingareasformanybirdspecies, and are importantrestingzonesformigratorybirdspecies.

• Mangrovesprovideeconomicbenefitsto human communities (e.g. eco-tourism, fishery).

• Mangrovesare partof thegreatmangrove‒seagrassmeadow ‒coral reefecosystem.

• Mangroves are zones in which many birds nest and rest, including the African ca le egret, or some endemic species such as the yellow-shouldered blackbird.

• Mangrove health depends on seagrass meadow and coral reef health. These three ecosystems are interconnected and depend on each other.

American yellow warbler. Photo by MaisidraVega.

Mangrove forest canal, Ensenada Grande, Culebra Photo by: Gonzalo Dean.

American yellow warbler. Photo by MaisidraVega.

Mangrove forest canal, Ensenada Grande, Culebra Photo by: Gonzalo Dean.

• One of the current problems mangrove forests face is that, due to their place between the sea and the mainland, trash from both sea and land affect them, harming all the species which inhabit it.

• Many mangrove trees have been cut to make way for construc on or to access the beach (docks, ar ficial beaches like Playita Rosada, in La Parguera). In the photo supplied above, we can see how several homes occupy an important part of the coastline, previously formed only of mangrove trees.

Normal waterflowchangescause mangroveforestfiresdueto excessivesalinityin thesoil.

• This is an example of how mangrove forests have been affected in the Cabo Rojo, PR, area, more specifically near the entrance to Playuela (Playa Sucia).

• A er a hurricane, water flow to the area became modified and restricted; the water became sal er and warmer, and caused the death of the mangrove trees (mostly black mangroves) that lived there.

Dr. Juan G. González

Dr. Juan G. González

Between1980 and 2005, anestimated20% -30% of mangroveswerelostworldwide.

In Puerto Rico, the1970ʼs presenteda considerable lossin mangroveforests.

Thanksto legal protectionsincethe1980ʼs, mangrove coveragehas beenslowlyrecoveringthroughouttheisland.

• In the past, large tracts of mangrove forests have been lost worldwide.

• Thankfully, the undertaken mangrove forest management measures have shown posi ve results. In the last decades, important increases in mangrove forest coverage in the Caribbean have taken place, including in our local area.

Time: 1 period

Teaching strategy: ECA

What are mangroves and mangrove forests?

What are mangroves and mangrove forests?

Types of mangrove forest Types of mangrove forest

Objec ves:

Phases: explora on, conceptualiza on and applica on

Teaching method: demonstra ve, inquiry-based, ac on or ac vity

Teaching technique: coopera ve work, discussion, homework

Assessment technique: open ques ons, graphic organizer, puzzle

Integra on with other subject ma ers: Biology, Ecology

Materials:

• Mangroves: Teacher’s Manual

• Mangrove-shaped graphic organizer slide

• Mangrove characteris cs chart

• Puzzle with pictures of the four mangrove types

• Magnifying glass

Depth of knowledge level:

Level I: Memory thinking

Level II: Process thinking

A er studying the topic What are mangroves and mangrove forests? and the types of mangrove, the student will be able to:

• correctly define a mangrove tree. (conceptual)

• explain what is a mangrove forest. (conceptual)

• explain each mangrove’s characteris cs. (conceptual)

• compare and contrast mangroves with other common trees. (procedural)

• iden fy the four (4) types of mangrove found in Puerto Rico (white mangrove, black mangrove, red mangrove and bu onwood). (procedural)

• share their knowledge with their peers. (a tudinal)

1. Gree ngs

2. Administra ve business – roll call, etc. (performed internally)

3. Reflec on: “If there are no mangrove forests, then the sea will have no meaning. It is like having a tree with no roots, for the mangroves are the roots of the sea.” Andamanese fisherman. Taken from: The Mangrove Decade and Beyond (1990-2001) h p://www.mssrf. org/csr/csr-pub/03-Mangrove%20decade%20and%20beyond.pdf.

4. The teacher will begin class by projec ng a graphic organizer shaped like a red mangrove tree on the board. In the ‘Leaf’ sec on, the teacher will write the ‘Mangrove’ concept, and ask students to men on their thoughts on the concept. The resul ng words or phrases will be placed in the mangrove root area.

5. Later, the teacher will ask the students to use the men oned words and phrases and build a defini on of ‘Mangrove tree’. The teacher may aid the students when making their defini on by asking: Is the mangrove a tree? What’s the difference between a mangrove tree and other trees commonly found in Puerto Rico? What are the similari es? Students may also make a list of the differences and similari es between a mangrove tree and a regular tree such as a mango, avocado or breadfruit tree, or an oak, mahogany, holywood (guayacán), Spanish elm, or any other tree commonly found in their area.

6. Having defined what a mangrove tree is, students will then have to explain what a mangrove forest is.

Mangrove tree: a tree or shrub that can grow in places in which the soil is permanently or temporarily flooded; it may also grow in the water. It is a very tolerant plant that can adapt to both salt water and fresh water sources such as rivers or lagoons. A mangrove tree may grow in hypersaline waters, or soils less saturated with salt (Programa Semillas para el Ambiente, 2006-07).

Mangrove forest (general defini on students may provide): a forest formed by tropical trees typical to coastlines, that feature special adapta ons for growing in saline and flooded environments.

Mangrove forest (formal defini on): a forest ecosystem comprised of tropical trees typical to coastlines that feature special morphological adapta ons that allow it to grow in saline and flooded environments with poor soil oxygena on, and poor seed germina on condi ons. These forests are subject to periodical dal ac on and are dominated by one or more arboreal mangrove species.

Mangrove forests fulfill an important func on in protec ng the coasts against wind- and wave-driven erosion, feature high produc vity, and shelter a large variety of aqua c,

amphibian and terrestrial organisms. Also, they serve a cri cal role in coastal and con nental shelf fisheries, since they provide habitat for the juvenile stages of hundreds of fish, mollusk and crustacean species. Moreover, they serve as temporary habitat for many northern and southern migra ng bird species (Diccionario Enciclopédico Dominicano de Medio Ambiente, 2012). Finally, mangrove forests keep coastal waters clean by trapping sediment. Because of this, mangroves accrete, or collect soil and are considered “land builders.”

1. A er having clearly defined mangrove trees and mangrove forests, the teacher will split the class into four (4) groups and give them a chart describing the four (4) types of mangrove and their most prominent features. Then, each group will receive a jigsaw puzzle with a photograph of a mangrove species. The photo includes the tree itself, and close-ups of the roots, leaves, seeds and flowers.

2. The students must build the puzzle and glue their pieces onto an 11”x17” poster board. Once the pieces have been glued, students will observe the photo carefully, using a magnifying glass to compare the photo with the characteris cs presented in the chart. In this manner, they will iden fy the species of mangrove they received. This ac vity can be performed as a race, in which the first group to finish may receive a small prize, such as a s cker, a complete photo of a mangrove, etc. (The prize is up to the teacher.)

Alternate op on: If the classroom is computer-enabled, the teacher may search for free jigsaw puzzle making so ware using the mangrove tree photographs. One sample of this free so ware is BrainBreaker 5, but there are many other op ons. It is worth men oning that neither the Sea Grant Program nor the University of Puerto Rico endorse any par cular program or brand.

3. Following the previous step, each sub-group of students will present to the rest of the group the completed photograph and will report on which mangrove tree species it is. They will explain the characteris cs they observed and what led them to their conclusion. The teacher will use this opportunity to discuss and explain the topic with the students.

Note: The teacher must be fully knowledgeable about these characteris cs, so that the discussion is effec ve and informa ve. Please read the mangrove species characteris cs sec on thoroughly.

1. To conclude the class, retake the red mangrove graphic organizer from the beginning of class and ask a volunteer to explain, in his/her own words, what mangrove trees and forests are.

2. Then, the students can summarize what they have studied in class about mangrove types, men oning the main characteris cs that set them apart from other mangrove species. This will indicate the level of learning and objec ves achieved.

Main characteris cs:

Red mangrove: aerial prop roots and propagules

Bu onwood: seed is bu on-shaped, ny green flowers in clusters

Black mangrove: salt on leaf surface (it excretes salt through its leaves), prominent, long pneumatophores

White mangrove: salt-excre ng glands at the leaf pedicel, shorter pneumatophores than on black mangroves

3. Any remaining ques ons about the subject will be addressed.

Note: If the puzzles were glued to cardboard, selected students may put them up on the classroom wall while the lecture on mangrove species is taking place.

If the teacher wishes to reuse the pieces, the constructed puzzle may be laminated before cu ng it. This way, once the students have finished building the puzzle and using the image as an aid while covering the subject, the puzzle may be put away and reused at a later date.

Homework:

1. Students will be asked to find images of the different mangrove types found in Puerto Rico. The images must be of a suitable size to be glued to a map. Students may use different sources, such as the internet.

Praxis reflec on:

The reflec on will be performed by the teacher a er class is concluded.

Reasonable accommoda on:

Reasonable accommoda on will be offered to all students who need it. Students with physical or cogni ve difficul es will be offered reasonable me in which to do their tasks, tutoring during office hours and all the necessary opportuni es, according to their par cular cases.

Ocean literacy: Essen al principles and fundamental concepts

Principle 5: “The ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems.”

e. The ocean is three-dimensional, offering vast living space and diverse habitats from the surface through the water column to the seafloor. Most of the living space on Earth is in the ocean.

Content standards and grade expecta ons

Biological sciences

Standard: Theme Organiza on Levels and Structure

Expecta ons and indicators:

From molecules to organisms: Processes and structures

1.B.CB1.EM.2 Makes observa ons with the inten on of describing the structures needed by plants and animals so they can grow and thrive.

3.B.CB1.EM.1 Observes and describes pa erns in plant characteris cs to determine their classifica on. Deduce that plants (grasses, shrubs and trees) have a set of structures that aid their classifica on.

3.B.CB1.EM.2 Iden fies plants according to their structure and the many kinds of stalks: grasses have not developed hardened woody structures and are so ; woody plants have developed hardened structures; roots (fibrous, ramified, or primary); and leaves (simple or compound, and according to the vein pa ern: parallel, penninerve, or palminerve; according to their margin: en re, undulate, dentate, serrated or lobate; and according to their stemming: alternate, opposite or basal).

4.B.CB1.EM.2 Men ons and poses arguments about the func onal advantages of the structural adapta ons.

Expecta ons and indicators:

The inheritance and varia ons in characteris cs

1.B.CB3.EM.1 Makes observa ons, describes and groups plants, animals and humans according to characteris cs that make them similar or different.

Standard: Interac ons and Energy

Expecta ons and indicators:

From molecules to organisms: Processes and structures

K.B.CB1.IE.3 Dis nguishes and describes different types of habitat in which living creatures live and adapt.

Expecta ons and indicators:

Biological evolu on: unity and diversity

2.B.CB4.IE.1 Recognizes ecosystems as places in which living and non-living things interact. Iden fy different aqua c (freshwater, such as rivers and creeks) and terrestrial (forests, deserts) ecosystems.

ons about biodiversity in terrestrial and aqua emphasizing in comparing ecosystem diversity.

2 2.B.CB4.IE.3 3 Makkes d direct obbserva ons b about b bi d odiiver i sity i in terrestriial l and d aqua c systems, in comparing

Standard: Conserva on and Change

Expecta ons and Indicators:

From Molecules to Organisms: Processes and Structures

4.B.CB1.CC.1 Defines, iden fies and uses evidence to prepare arguments about the adap ve mechanisms plants and animals feature that allow them to survive and react to changes in the environment.

Physical Sciences

Standards: Subject Structure and organiza on levels

Expecta ons and indicators:

The subject and its interac ons

4.F.CF1.EM.1 Measures, compares and contrasts the subject’s physical proper es.

6.F.CF1.EM.1 Groups and classifies the subject by its chemical and physical proper es.

References:

Diccionario Enciclopédico Dominicano del Medio Ambiente. Zonación. Consulted on October 7, 2012, through h p://www.dominicanaonline.org/diccionariomedioambiente/ es/definicionVer. asp?id=615

University of Puerto Rico’s Sea Grant Program. (2010). El manglar. Consulted on October 18, 2012, through h p://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ac5amhWk2-Y&list=UU83zZurmP8H44OtoKVfpmqA&i ndex=19&feature=plcp

Programa Semilla para el Ambiente. (2006-07). Manglares. Consulted on October 18, 2012, through h p://www.proambientepr.org/semillas/temas_educa vos/manglares/

Taken and adapted from: http://www.edupics.com/coloring-page-mangroves-i9469.html

Characteristics

University of Puerto Rico

Mayagüez Campus

Sea Grant Program

Mangroves

Types of mangrove

Types of mangrove

Mangrove Red White Black Buttonwood

Roots Prop roots, tangled, aerial No prop roots, feature pneumatophores

Leaves Large, thick, waxy and oval-shaped

Oval-shaped, and with two glands at the petiole base

Flower

Small, with four White petals

Oval-shaped and brown

Fruit

Germinates on the tree itself, and is known as a propagule

Small and bountiful; feature five tiny petals, white and rounded

It is small, and features lengthwise ridges; when it is unripe, it is green, but it turns brown as it ripens

Feature pneumatophores (long, projecting roots) N/A

Lanceolate (sharply pointed on one end) and with salt crystals on the surface

Small, with white petals, and growing in dense clusters

Small, ellipticalshaped, and alternate; Features 2 glands

Tiny, green and forming globeshaped inflorescences (groups of flowers)

Capsule-shaped, small, oval and flattened; it is yellow

Round fruit, shaped like a decorative button

Time: 1 period

Teaching strategy: ECA

Mangrove zona on, geographic distribu on and zona on, distribu on necessary condi ons for mangrove development necessary condi ons for mangrove

Objec ves:

Phases: explora on, conceptualiza on and applica on

Teaching method: demonstra ve, inquisi ve, ac on or ac vity

Teaching technique: lecture, review, puppet demonstra on

Assessment technique: open ques ons, labyrinth

Integra on with other subject ma ers: Biology, Ecology, Geography

Materials:

• Mangroves: Teacher’s Manual

• Mangroves PowerPoint presenta on

• Story: Pepe Uca’s Treasure

• Puppets/masks

• Maze

• Mangrove zona on illustra on

• World map illustra ng mangrove forest growth

• Map of Puerto Rico

• Small printouts of red mangrove picture

Depth knowledge level:

Level I: Memory thinking

Level II: Process thinking

Level III: Strategic thinking

* Content standards and grade expecta ons from the Puerto Rico Department of Educa on Science Program can be found at the end of each lesson plan.

* Fact sheets, assessment tools and other educa onal material to be used during each class are included at the end of each lesson plan and in the Guide’s CD.

A er studying the themes and topics related to mangrove zona on, geographic distribu on and the necessary condi ons for mangrove forest development, students will be able to:

• explain worldwide geographic mangrove forest distribu on. (conceptual)

• jus fy the reasons mangrove forests grow develop where they are found. (conceptual)

• explain the zona on concept adequately. (conceptual)

• locate some of the areas in Puerto Rico that feature mangrove forests. (procedural)

• iden fy the condi ons necessary for mangrove forests to grow and thrive. (procedural)

• correctly iden fy mangrove forest zona on in Puerto Rico. (procedural)

• share informa on with their peers. (a tudinal)

1. Gree ngs

2. Administra ve business – roll call, etc. (performed internally)

3. Reflec on: “There is always an open book for all eyes: nature.”

Jean Jacques Rousseau4. The teacher will begin by reviewing the concepts studied in the previous class. Using the jigsaw puzzles previously solved, the teacher will ask ques ons so that students review the concepts. If desired, the teacher can use the “The Mangroves” PowerPoint presenta on to offer an in-depth explana on of what a mangrove and a mangrove forest are, and the four types of mangrove found in Puerto Rico (this should be a review and therefore, not involve much more than 5 minutes).

1. A er reviewing the concepts and recalling the main characteris cs shown by the four types of mangrove, the teacher will instruct students to listen to a story. The students should take note of the Puerto Rico loca ons that feature mangrove forests and which the main character visits. They should also remember the places in which mangrove forests are less developed.

Note: The teacher should drama ze the story with the puppets/masks provided in this guide (specifically, within the El Tesoro de Pepe Uca storybook). The book includes a model so that the teacher can construct the puppets. Teachers may also use the provided models and make masks, so that students can act out the story, if so desired. If the teacher cannot make the puppets or masks, then s/he can employ ac ve storytelling techniques and drama ze the characters’ voices and expressions.

2. A er reading the story, the teacher will hand out a schema c map of Puerto Rico. Students must glue the mangrove depic ons (drawings or photographs), assigned the previous day, around

the map, focusing on the areas that support mangrove forests. If the students failed to bring the pictures, the teacher can hand out the ones included within this plan. These can be printed on adhesive labels or on paper that the student can tape to the map.

To help students remember the story and aid them when performing the ac vity, the teacher can ask the following ques ons:

Where did Pepe come from? Where was his home? In what area of Puerto Rico did his journey begin? Where did he meet Lulo?

Where was it that the dog tried to eat them?

Where were they when the iguana tried to give them direc ons? When the big wave washed them out to sea, what part of Puerto Rico was that? Were there any big mangrove forests in that area?

3. A er the students finish their maps, the teacher can use the presenta on slide showing the areas in Puerto Rico that hold mangrove forests, emphasizing the areas mangrove forests can be found and were not featured in the story.

4. Later, the students will be asked: Why does Puerto Rico have mangrove forests in some places but not in others? The teacher may remind them of the story, when Pepe and Lulo say goodbye to the wise Mulato. What did Mulato tell the main characters about the area they were in?

The students must reply that mangroves don’t thrive in the northwestern coast of Puerto Rico because the waves are too strong and don’t allow proper mangrove growth.

5. The teacher should also remind students about other factors, such as temperature, which affect mangrove forest development. These trees only grow in tropical or subtropical regions. Here, the teacher may present the slide featuring the world map which shows the places mangrove forests grow. If there isn’t a computer or projector available, the teacher may photocopy the map included in this plan and give it to the students.

1. In closing, the teacher will show students the picture illustra ng the general zona on mangrove forests follow and will ask them to use the knowledge acquired during this and the previous class, and iden fy the mangrove types seen in the picture and observe the order in which they grow. This is how the teacher can verify the students’ learning, and help students be er grasp mangrove zona on. The teacher can specify that mangroves tend to grow in a par cular order which may change according to the loca on’s physiography (physical geography).

Zona on - The distribu on of plants or animals into specific zones according to such parameters as al tude or depth, each characterized by its dominant species. (Oxford Dic onaries, 2016).

Generally, the red mangrove is first (near and in the water). Then comes the black mangrove, followed by the white mangrove, and lastly, bu onwood (González y González, 2010). Black and white mangroves can mix within the same area. The posi on of these two trees can be switched.

Homework:

1. Students will be given a maze to help Boba find Pepe and Lulo’s home. A er they find their way through the labyrinth, students should write a story describing the journey home through Puerto Rico’s western coast.

Praxis reflec on:

The reflec on will be performed by the teacher a er class is concluded.

Reasonable accommoda on:

Reasonable accommoda on will be offered to all students who need it. Students with physical or cogni ve difficul es will be offered reasonable me in which to do their tasks, tutoring during office hours and all the necessary opportuni es, according to their par cular cases.

Ocean literacy: Essen al principles and fundamental concepts

Principle 5: “The ocean supports a great diversity of life and ecosystems.”

f. Ocean habitats are defined by environmental factors. Due to interac ons of abio c factors such as salinity, temperature, oxygen, pH, light, nutrients, pressure, substrate and circula on, ocean life is not evenly distributed temporally or spa ally, i.e., it is “patchy”. Some regions of the ocean support more diverse and abundant life than anywhere on Earth, while much of the ocean is considered a desert.

h. Tides, waves and preda on cause ver cal zona on pa erns along the shore, influencing the distribu on and diversity of organisms.

Content standards and grade expecta ons

Biological sciences

Standard: Theme organiza on levels and structure

Expecta ons and indicators:

From molecules to organisms: Processes and structures

5.B.CB1.IE.1 Acknowledges some of the factors affec ng plant growth, such as the presence or absence of the Sun or a light source, space, the presence or absence of water, minerals, terrain, and types of soil.

Standard: Interac ons and energy

Expecta ons and indicators:

Biological evolu on: unity and diversity

3.B.CB4.IE.2 Builds an evidence-based argument to explain how, given a par cular environmental se ng, some kinds of organisms thrive, some survive with difficulty, and others perish.

Standard: Theme organiza on levels and structure

Expecta ons and indicators:

Earth systems

4.T.CT2.EM.4 Interprets and analyzes map data to describe pa erns in the Earth’s characteris cs.

References:

Biology Online. Zona on. Consulted on September 24, 2016, through h p://www.biology-online.org/ dic onary/Zona on

Oxford Dic onaries. Zona on. Consulted on September 24, 2016, through h ps://en.oxforddic onaries. com/defini on/zona on

It was a bright, sunny day. There was a slight breeze, and the waves moved back and forth gently. Life in the mangrove forest was enviously peaceful. Everybody went about their usual daily rou nes: the pelicans and the frigate birds scouted for sardines and herrings; the yellow warblers, bu erflies and bees darted among the flowers; ny fish searched for food and hid among the red mangrove’s roots to hide from bigger fish like tarpons and barracudas. The younglings played and Pepe Uca, a young fiddler crab, walked around the wetland, thinking about his life up un l that moment. He’d lived his en re life there with his family, among the mangroves, with the birds and the fish. He had plenty of food, a beau ful home, and friends who offered support and affec on.

It was a perfect life. And yet, ever since he was li le, he had always wondered about life beyond the mangrove forest. He always asked himself about other places, of what life would be like elsewhere. He felt an inexplicable anxiety and he felt as if something was missing. He needed to feel excitement, have adventures, and live through different experiences that would allow him to discover the world. That day, while observing the sea, he made his decision. —“I’m leaving!” —he firmly said to himself: —“I’ll explore other places and find my des ny.”

He spent the rest of the day planning his journey, imagining all the things he would see. At dusk, when everyone else was off res ng, Pepe gathered enough food for several days and marched off. He le his mangrove forest, le the familiar salt flats of La Parguera, and began his travels across the southern coast of Puerto Rico. He felt nostalgia as he le everything behind, but he was excited because he would discover new places. The days went by and Pepe marveled at all the things he saw: tall palm trees, huge mountains, the blue sky, an everchanging sea, and plants and animals he’d never seen before. In the distance, he could see something that resembled a mangrove forest. However, he would have to cross something to reach it - a flat area with a hard, rough and hot surface. Several huge, noisy objects went along this surface, moving at great speeds. They scared him, but they could not dampen his adventurous spirit. So he decided to cross as quickly as he could. He was so scared when those great objects went past him! Nervous and shaking all over, he managed to get to the other side. He

stopped for a moment to catch his breath and gather his strength. But while he was res ng, he heard footsteps, and a shy voice that said: —“How could you cross that dangerous street, all full of cars? Did you look both ways before you did that?”