CONTENTS

Introduction

2022 Academic Task Force Members

A Message from Joell Angel-Chumbley

Chair, SEGD Academic Task Force

A Message from Cybelle Jones

CEO, SEGD

City as an Exhibition

Phenomenological Strategies for Narrative Architecture in Public Spaces

Veeksha Mehndiratta

Color Crush

Crafting multisensory digital-physical interactives in a science museum

Jungu Guo

Evolving Graphic Design

Yeohyun Ahn

Flow

The flow experience told through multi-generational voices of motorsport women

Naz Ertugrul

From the Mothers’ Movement to Cradlr

An Interaction Design for Refugee Children

Jing Zhou

#CONNECTED

Harnessing social media practices to foster meaningful connections in a hybrid world

Bhawika Mishra

Invitation To Interpret

Battleing Museum Threshold Fear

Chase Dougherty

Seldom Is Heard

Supporting the development of Historical Empathy through Adaptive Storytelling

Ciera Iveson

StoryCorps

The design of multi-sensory narrative experiences

Daphne Peters

Introduction

The Society for Experiential Graphic Design (SEGD) is a multidisciplinary network of designers, industry and technology specialists, educators, and students dedicated to experiential graphic design. We work in wayfinding, placemaking and identity, digital experience design, exhibitions, public installations, branded environments, and other aspects of EGD/XGD.

SEGD exists to “educate, connect and inspire” the global, multidisciplinary community of professionals, creating experiences that connect people to place. We are committed to knowledge sharing and continually raising the standards of practice in a design discipline that has the potential to enrich the lives of people wherever they work, play, shop, learn, travel, or gather.

SEGD’s education conferences, workshops, webinars, and courses span a wide swath of design practice areas including branded environments, exhibition and experience design, technology and interactive experiences, user experience, healthcare, practice and technical topics, wayfinding, accessibility, and the business of design.

SEGD actively collaborates with and provides outreach to design programs at internationally recognized colleges and universities. Our signature academic education event is the annual SEGD Academic Summit, immediately preceding the SEGD Conference each June. Design educators from around the world are invited to submit papers for presentation at the Summit and publication in SEGD’s blind peer-reviewed Communication + Place, which is published electronically on an annual basis. The Summit and e-publication are platforms for academic researchers to disseminate their creative work, models for innovation in curriculum, and best practices for research related to experiential graphic design.

2022 Academic Task Force Members

Chair: Joell Angel-Chumbley | University of Cincinnati DAAP, City of Cincinnati

Yeohyun Ahn | University of Wisconsin Madison

Aija Freimane | TU Dublin School of Creative Arts, Ireland

Angela Iarocci | Sheridan College

Michael Lee Poy | Ontario College of Design University

Christina Lyons | Fashion Institute of Technology

Tim McNeil | University of California Davis

Amy Rees | Drexel University, Exit Design

Debra Satterfield | California State University

Neeta Verma | University of Notre Dame

Willhemina Wahlin | Charles Sturt University

Michele Y. Washington | ashion Institute of Technology

For more information, please contact Cybelle Jones or Joell Angel-Chumbley.

Cover photo and journal design: Willhemina Wahlin

A Message from Joell AngelChumbley

Chair SEGD Academic Task Force

" "

The annual SEGD Academic

Summit . . . has become a forum for global design academics, researchers, and students to share their research, innovative curriculum, and projects.

The SEGD Academic Task Force (ATF) is a diverse team of US-based and international design faculty, researchers, and practitioners that collectively share research and resources to advance global academic design education and professional practice.

This year the ATF committed to multiple initiatives designed to promote knowledge and awareness of experiential graphic design with a strategic focus on the advancement of design education, research, and publication; diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion (DEAI) education and best practices; and student outreach.

The annual SEGD Academic Summit, a signature event produced by the ATF, has become a forum for global design academics, researchers, and students to share their research, innovative curriculum, and projects. This event is also great for industry members to reconnect with new ideas emerging from researchers today. The ATF sends out a Call for Papers and conducts a blind peer review of abstracts submitted from across the globe. The selected authors are then invited to present at the Summit and publish full papers in Communication + Place to highlight research and insights for professional development and education in the field of experiential graphic design.

If you are interested in learning more about the work of the SEGD Academic Task Force, please feel free to contact me at jangelchumbleymfa@gmail.com

A Message from Cybelle Jones

SEGD CEO"Our work . . . communicates important information and fuels a dialogue between users and the spaces they inhabit.

"The Society for Experiential Graphic Design (SEGD) exists to “educate, connect and inspire” the global, multidisciplinary community of professionals creating experiences that connect people to place.

We are an association of people who create content-rich, emotionally compelling, experiential spaces for a wide range of environments, from hospitals and transit hubs to museums and personalized digital destinations.

Our work creates a sense of place, helps people find their way, communicates important information and fuels a dialogue between users and the spaces they inhabit. We research, plan, design and build a diverse range of visual communications and information systems for the built and virtual environment.

Our community of educators, designers and makers strive to create environments that improve the human experience and share knowledge that raises the standards of design excellence in practice.

We hope that you will explore more about our educational and professional resources at www.segd.org

Cybelle Jones CEO, SEGDCity as an Exhibition

Phenomenological Strategies for Narrative Architecture in Public

Spaces

Veeksha Mehndiratta, Spatial Experience Designer, Architect, School of Planning and Architecture, Vijayawada, India

Abstract

Phenomenology in architecture involves orchestration of various physical and natural elements such as space, light and shadow, and material that ultimately craft an immersive experience. The integration of sensory perception as a function of a space informs this impression, that is abstract yet perceived by the user. Architecture is, often, ocular centric which foregrounds the hegemony of vision. Human perception is conditioned by various factors like lived experience, intellectual prowess, observational abilities etc. Therefore, every single perception is distinct.

Narrative architecture utilizes design elements to weave a storyline to communicate a message. This message can vary from a thematic environment like an exhibition to a space that communicates its function. Materiality, detail, composition, and form aid in expressing this message. It highlights the experiential dimension of a space. The design based on these lines can modify human behaviour in public spaces and contribute to the placemaking of a city.

Category: Architecture

Keywords: Experiential, Inclusive, Narrative, Phenomenology, Public Spaces, Sensory

Introduction

Exhibition spaces, including galleries and museums, have a controlled artificial environment. Brian O’Doherty describes, “The outside world must not come in, so windows are usually sealed off. Walls are painted white. The art is free to take on its own life” (O’Doherty, 1986). One can investigate what the highly controlled context of the modernist gallery does to the art object and what it does to the viewing subject by analyzing the ancient exhibitions. The Egyptian tomb chambers held paintings and sculptures that were regarded as magically contiguous with eternity but the tombs itself were designed to alleviate awareness of the outside world.

The high level of narrativity exists in these spaces in an extremely condensed fashion, which makes it challenging to recreate the thematic conversation in public spaces. Since themes are the overarching concept to a gallery, these environments successfully perform their function. Likewise, when an urban space performs its function or an activity, which may include buying- selling, walking, performing, sitting etc., it will be expressive of its character. Successful urban spaces are responsive to its users. Vibrant environments support myriad activities without losing its spatial quality. In fact, these events are what contribute to its character.

Approach

There is a plethora of inspiring and dedicated research carried on exhibition spaces, its visitor behaviour, and the application of narrativity in those spaces. Likewise, one can dive into studies done for urban areas, specifying the ways in which a responsive environment can be achieved. But the intersection of the two is yet to be unearthed. Understanding how the exhibitions narrate and engage can be utilized in creating urban spaces and consequently, exhibitions can be enriched with the temporal dimension that successful urban spaces boast. Undertaking two live case studies in the capital of India, Delhi, one from a museum typology—Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, Saket and another from an urban context Kashi Ram Shah Marg, West Delhi, the author explores the narrative and phenomenological aspects in both scenarios. The author then delves into a comparative analysis as a critique to the current state of public urban areas.

Narrative Environments

Paul Ricœur and Fredric Jameson argue that narrative is a crucial way to create a

sense of self and the world. According to Paul Cobley (Cobley, 2001), two contrasting schools of thought explain the beginnings of narrative. The first delves into the phylogenetic perspective, which posits that narrative is a product of cultural evolution. Secondly, ontogenetic view indicates that our brains are hard-wired to frequently build narratives and the ability to use language reinforces this perspective (MacLeod, 2012).

Narrative environments employ space to tell the story through a series of designed layers of elements that heighten the experience of users and fully immerse in the environment.

Elements of an Experiential Space

The chemistry and assembly of various elements mould the space which is ultimately perceived. One cannot exist without the other. Views unfold sequentially offering a concept of conceal and reveal incorporating exploration as a spatial journey. Buffers are places for a pause and contemplation (Pandya, 2014).

The categorization are as follows:

5. Colour

6. Temperature

7. Sound

8. Smell

3. Perceptual Elements

1. Materials

2. Texture

3. Mass and Void

4. Planes

5. Organisation & Sequence

6. Scale and Proportion

7. Movement

There exists no separation between physical and mental spaces. The word ‘environment’ is used and not ‘space’ since space describes a measurable distance to some extent, while environment incorporates the space, architecture, organisational layouts, levels, users, objects, and a correlation between all of these. We shape our world and the physical world in turn, shapes us (MacLeod, 2012).

Tripartite Network Model of Narrative Environments

The model theorizes that people cannot exist without place, nor can they exist without narrative and, consequently, they cannot exist without narrative in place (Austin, 2016).

The Tripartite Network Model or TNM for narrative environments is a nexus of three nodes: narrative, environment, and people. This triangulation connects narratology, architecture with its users which otherwise are studied as distinct disciplines (Figure 1).

"Experiential Architecture unfolds through time. The temporality juxtaposed with the movement helps the user immerse in a space.

"Figure 1: TNM Figure 2: Actantial Network

Narrativity in Urban Environments

Narratives prompt us that nothing exists in isolation. In fact, each activity in an environment triggers participation in events, traditions, and patterns of life. Every urban designer recognizes the significance of context. The relationship of a streetscape to a building is analogous to the link between narrative and identity. Without context, an individual building seems lost in space. Likewise, a person is deprived of identity without a spiritual, cultural, or intellectual context (Filep, 2014).

Design of an urban public realm is a spatio-temporal experience that reveals its dynamism by supporting various activities. A leisure square can incite riots and also invite street performances. Massey views this phenomenon as “a simultaneity of multiple trajectories.” Planner Gordon Cullen considers sequential flavour of the built space, fundamental to the experience of townscape. He posits that humans can sense being “outside”, crossing thresholds and being inside a spatial phenomenon. The celebrated architect, Le Corbusier, has also emphasised the sequential character of a promenade and how it influences the spatial experience. Urban Designer Mark Childs argues that “storytelling is part of urban design … stories of place can inform designers about the narrative fabric that is as much a critical part of the context of a site as the soil type” (Austin, 2016). In reference to the TNM, architecture, urban design and spatial design are part of the environmental node.

Weaving a Narrative

Dramatic Conflicts

Traditionally, dramatic conflicts are a literary device that stimulates tensions that causes another event or triggers people to act. In fact, drama is conflict. Without conflict there exists no drama. Research on the context of the environment aids in creating apt conflicts that blend seamlessly and are congruous in the urban narrative. This could entail seeking spatial clues that exist as patterns in the space. Other methods include gathering information through memory mapping, sensory mapping, and behavioural mapping.

Photography documentation can ease passive observation. The designers must be cognizant of the users’ movement and the environment, in order to accurately understand the intended users. Lack of research often results in failed placemaking proposals that are indifferent to the etched drama. Through this tool, users can be immersed in newfound aspects of a place, that were almost invisible to them prior.

Content

In the urban realm, apart from the users, the spatial environment are characters that communicate. Buildings, streets, and landscapes engage in a dialogue with the onlookers that meander through them. This movement is what heightens the

experience and builds an interaction. This is not possible with an audience with characters on stage, that lacks a spatio-temporal aspect. The overall narrative messaging and content must be consistent with all the shareholders.

Communicating a Narrative

This element can be used to devise a storytelling technique that connects the narrative node and the environment node in the TNM. People outside of the design industry don’t view space as a medium that communicates. Hence, it’s the in the scope of the designer to simplify those abstract symbolism that can be savoured by everyone. Depending on the context of the environment, the required dwell time for a user might differ. It can be influenced by providing social spaces, resting stops, leisure activities, etc. People enter spaces only when they are fully aware of what is offered. But the way that the information is conveyed needs to be carefully designed. This anticipation increases visitor satisfaction, once revealed and therefore, eager for more.

Non-Linear City Narratives

Non-linear storyshapes or sequences are spaces where visitors can go wherever they want and have the freedom to create their own path. Since cities don’t have a defined entry and exit point like an exhibition, they are non-linear. Lefebvre authored the word “rhythmanalysis” that describes urban spaces through the rhythms of social practices. The porous layers of cities are juxtaposed to create a meaning that the visitor unravels through various urban features. Successful placemaking not only harbours numerous meanings but also carries it forward through social practices. Therefore, the identity of the city is intertwined with the activities of the place.

Understanding Exhibitions

Role of Exhibitions Precedents in the Urban Realm

Narrative environments can cater to the commercial sector and the cultural sector. The priorities and purposes of these zones vary. Cultural narrative environments, such as cultural events and exhibitions, seek to educate and inform the masses. The urban public realm has a similar purpose that is aligned to inform its users. Hence, studying exhibition precedents will allow this dissertation to draw inferences that might be traced onto a more inclusive public domain.

History of Exhibitions

Most homes have informal compositions of valued belongings organized by preference that reveals the character and ideology of the resident. Similarly, in a commercial setting, retailers and merchants display their goods with careful consideration that might best appeal to their customer. Spiritual structures are designed in such a way that enhances artifacts by framing views that attract attention. The experiential quality is elevated by employing play of light and shadow, enclosure shifts etc. At the end of the eighteenth century, a number of such collections were combined and organized for public display. In many places Florence is an example—great works of art commissioned by patrons such as the Medici family merely had to be consolidated in palaces that were extended or adapted for the purpose of exhibiting them. (Hughes, 2013) The Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, housed in the revolutionary Crystal Palace, was a substantial milestone in the history of exhibitions. Designed by Joseph Paxton, it was an engineering marvel, modular components of steel and glass, that influenced architecture. Modern display techniques are essentially shaped by the art and design movements of the early twentieth century. These principles view walls and floors as “planes”, as if they were elements in an abstract sculpture. Modern Movement reinterpreted the rooms of buildings in new ways, using the language of “spatial relationships” and “volumes” to influence display environments. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York is responsible for the conception of the spare, minimal environment with white walls that Brian o’ Doherty critically analysed.

Elements of Exhibitions

1. Context: Analogous to any architectural project, the site is a key element in influencing the exhibition. An intimate connection to the site often gives life to a successful and immersive environment. Prudent positioning of built components, especially windows, in conjunction with wind directions and the sun path, would lead to an energy efficient building and lower the need for artificial temperature control.

2. The Visitor: “Engagement” is the process of addressing people directly, rewarding their attention, stimulating them, and providing them with new perspectives. By understanding the target audience, a designer can create an inclusive environment where they don’t feel like they don’t fit in. “Displays, such as those for children, have to be extremely well researched and targeted. What appeals to a five-yearold will not necessarily appeal to a tenyear-old, and a display that is intended to address both groups could prove to be a costly mistake if it is poorly researched.” (Hughes, 2013). Layering for diverse audiences is important to cater to the four types of visitors with differing levels of knowledge: -

1. The expert: This is the expert who hopes to extend their intellect. They may have covered most of the ground before, so they are interested in some of the least trodden paths. They might need a research facility, a screen, or a database of reference material, to explore some parts of the exhibition more deeply. They may wish to sit down, especially if they have an enquiry that could be time-consuming.

2. The frequent traveller: This visitor is acquainted with the landmarks but would like to explore more. They are motivated by general curiosity rather than the need to pursue any specific information. To fulfil their needs, the designer can prepare an informed level of enquiry, through explanatory text, audiovisual displays etc.

3. The scout: The scout does not know the terrain but wants to pick up on the main landmarks. By ensuring legible signage and labelling that identifies a clearly defined path, the scout can be helped. This visitor needs a highly organized and accurate “top layer” of information.

4. The orienteer: They don’t know where to go in an exhibition. They may have been brought along by another visitor who has more understanding of what is being shown and has left them. They can be engaged with activities and options that might thrill them but also deliver a subtle message. (Hughes, 2013)

3. Internal Organization: Conventional exhibitions require the visitors to circulate through a sequence of interconnected spaces. These create natural divisions for showing the theme and content of an exhibition but, particularly in old buildings, the display surfaces are supporting walls and are permanent and unmovable. (Hughes, 2013).

4. Light: Other than illumination of objects, lighting is employed to create ambience and configure thematic spaces. The harmonious amalgamation of natural and artificial lighting influences the visitor behaviour and perception of exhibits. The various requirements include emergency lighting, lighting for maintenance staff, protection of objects, colour quality etc. Links to nearby exhibits must be created in a defined and specified manner. (Frey, 2011) Like theatre or films, exhibition lighting can generate hierarchies, channelizing the richest pools of light on the strongest exhibits. The exhibition experience should be easy on the eye, and the transitions from light to dark spaces should be carefully considered. Daylight is normally totally excluded if there are conservation considerations. The sun emits ultraviolet rays often degrades materials.

5. Materials: Each time period in history has its characteristic colours and materials associated with it. This influences the exhibition pieces and the surrounding space equally. White walls and the subtracting all additional elements from the environment claim to facilitate attention on the works. Yet ultimately the white walls tend to overshadow the mounted pieces. An ideal background is therefore a wall colour that is darker than the lightest point in the art piece. (Frey, 2011)

Since, museums hold valuable artifacts, fire performance of materials is of vital consequence. Materials that have high embodied energy are less favoured than ones that are renewable. Utilizing composite materials, such as plywood covered with laminates prevents reuse, is considered an inefficient use of resources.

Case Study: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA)

Kiran Nadar Museum of Art (KNMA), Saket in New Delhi, was established at the initiative of the avid art collector Kiran Nadar in January 2010. The private museum of art exhibits modern and contemporary works from India and the sub-continent. The 34,000 square feet museum space offers multiple screenings of films, stimulating curatorial programs, and curated walks. Celebrated exhibitions include “Unfoldings: The Route Map of Experience, a solo by Jayashree Chakravarty” and “Zarina: A Life in Nine Lines”. (KNMA, 2020)

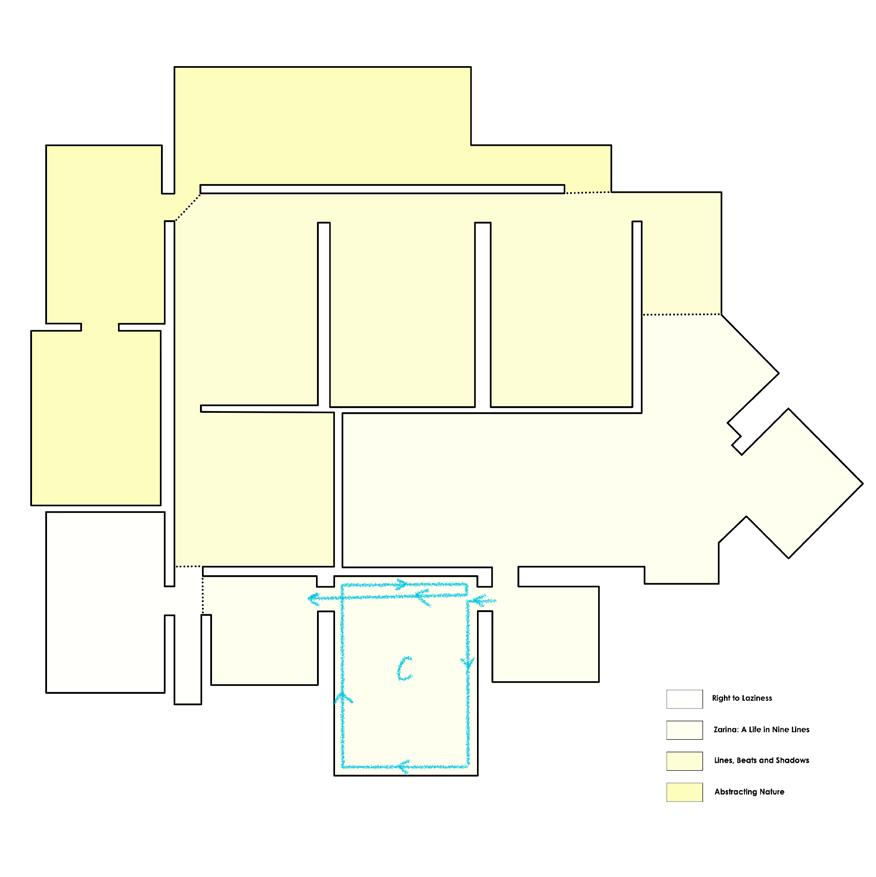

The plans show the approach from one theme to other with relation to the volumetric elements in the exhibition space.

The user circulation is also influenced by those along with the displays themselves.

Form

The entrance to the exhibition opens to a square space that partly frames the name of the show on the wall and the arches. This diagonal orientation to the first room in the sequence, utilizes the “hide and conceal” approach that pulls the visitor in.(Figure 4) Through the plan (Figure 5), we can observe the sequential organisation between different exhibitions that are curated. Zarina’s Nine lines use the spatial element of the arches as a contextual prop. It is synonymous with the threshold of the house she remembers. (Figure 6) All the flanked rooms act as a deeper dive into her life during partition and how she reminisces it. If you choose to fully navigate through the first display, you organically enter the “Right to Laziness” AV room. (Figure 7) The double way door that gives a peek of purple light, invites the visitor before turning right to the “Line, Beats and Shadows” curation. (Figure 8) The contrast between the emotion heavy exhibit pulls the visitor into an entirely different and immersive experience. After experiencing multi-media, one navigates through a corridor that leads you to the Lines, Beats and Shadows exhibit. The hide and conceal element are employed to intrigue the visitor into entering the room. The frame gives a teaser to the curation. (Figure 8) As one moves along, they encounter a direct opening to a space for the Abstracting Nature exhibit in front and on the left. To complete the narrative of Lines, Beats, and Shadows, the visitor must realise that the demarcation in the flooring materials used and turn right again. The contrast is subtle but enough to understand. (Figure 9)

Other photographic evidence to understand how spatial elements are used to provide navigational cues to the visitor.

• Use of different colour light to segregate

Case Study Analysis

Strengths:

1. The phenomenological factors like levels, frames, mass, and voids etc. are considered in the exhibition.

2. The visitors are not confused rather immersed in the storyline conveyed.

3. The lighting is appropriate to the displays

4. The narrative is conveyed metaphorically through the spatial dimension as well.

Weaknesses

1. The sequential movement is hindered due to lack of connections between the AV room. So, if an expert visitor wants to dive deeper, a loop cannot be covered.

2. The level differences between different flooring materials could be flush which would aid accessibility and an uninterrupted circulation.

Selected Site: Kashi Ram Shah Marg, West Delhi, India

The mixed-use 16 Meters, two-way street, supports MIG and HIG residential buildings, Commercial DDA Markets, Open Spaces. Parks, Hospitals, and schools.The author has seen the Marg transform through a period of 22 years. Unaltered zoning pattern with an increase in vehicular traffic, has impacted the narrative of the area. The spill-over activities on the pedestrian paths seemed vibrant but now they exploit this extent.

Site

Urban Characters

Various shareholders interact with the street from day through night. Once they are correctly identified, the narrative experienced by each character can be mapped. The characters are:

Residents, Passer-by’s

5. Public Transport

Auto Rickshaws, E-Rickshaws, Rickshaws

Urban Elements

Myriad elements interlaced in the street influence movement, behaviour, and the mood of the shareholders.

1. Parks vehicles

2. Stalls

3. Trees

4. Road shoulders

5. Animal droppings

6. Poles

7. Wires

8. Material Undulation

9. Construction Debris

Behavioural Activity Mapping

The legend for all the maps shown below can be referenced.

The pedestrian starts from Ambika Vihar till the Sai Baba Mandir road. In this route, they have a discontinuous journey due to parked cars, ramps, speed brakers, animal droppings, level differences due to change in paving materials and heavy traffic around DDA Markets.

There is a single bus line that plies on Kanshi Ram Shah Marg that enters through Sai Baba Road till the end of the street. Since the bus is huge, other characters on the street have to be cautious even if they are “following the traffic rules”. We can see the influence of this ideology through the movement map. It barely stops or curves for any urban element except for a cow.

The GH13 gate that opens towards our street is an Exit only gate. This doesn’t stop the residents from bringing cars to shop for their groceries. The round about turn traced just outside the DDA Market, creates heavy traffic jams along with endless fights.

The most interesting movement among all the characters is that of the smaller public transits. They are influenced by the pedestrian movement; therefore, they need to occasionally pull over on the footpath or the side of the road to pick customers up. This slows down the traffic and make them vulnerable as well. An organic meandering path can be traced which is dynamic and temporal.

Analysis of Character Paths

Using the analysis, one can observe 4 hotspots in the marg:

1. This is the largest extent that curbs traffic flow, pedestrian routes etc. The existence of the ‘T’ junction is probably what attracted so many users and commercial buyers into that particular GH14 DDA Market. Ironically, the ‘T’ junction is also what deteriorates the Marg further. The tree reducing the road shoulder, carts and hawkers setting up in the busy area alleviates order on the street.

2.and 3. Areas are smaller yet influenced by the landmarks that they are. One is the entrance for the GH13 colony and the other the GH13 DDA Market. The extent is smaller, but as a frequent visitor, one can surely comment that both markets are equally congested.

4. This zone is in close proximity to the Ambika Vihar Gate. But it becomes a hotspot due to cramming of so many urban elements that it becomes difficult to navigate through them (as any character).

Sketches highlighting the layered narrativity through myriad activites

ANALYSIS AND RESULTS:

Comparative analysis

1. Elements of Exhibition

As discussed above, there are 5 elements of an exhibition. A deeper dive into how those elements is being employed in an urban context shall now be addressed.

1. Context: The setting is an urban environment, subject to various users and influential factors as we have filtered above. The key consideration, then, for context in an urban narrative should be of the temporal nature of the street. A dynamic process rarely yields analogous results. The only flexibility that can be tapped into, is to design spaces that support vibrant activities.

2. Visitor: The 4 types of visitors can be identified in an urban context as well. For example.

o The expert, in terms of movement and activity, can be understood as the user who uses the street most efficiently. Maybe, a resident who goes to Kendriya Vidyalaya, plays in the DDA park, eats Aloo Tikki from the stall in the market, loiters around on a scooter in the evening and goes back home.

o The frequent traveller are the public transits that have their movement influenced by other users, pedestrians. They are acquainted with the landmarks, but they interact further with a general “curiosity”.

o The scout needs a top-level layer of information to get around the environment. Buses are scouts that interact with the main landmarks i.e., the bus stops.

o The orienteer describes a passer-by who uses this street to get to another street on the morning of Raksha Bandhan. They forgot to buy Mithai and have to stop by the seasonal stalls that opens up on the footpath. They then go about their way.

3. Internal Organisation: The sequential interlacing of functional spaces determines the quality of circulation. Natural demarcations using repetition of similar functions, like vegetable vendors or repair shops, encourage seamless transitions.

4. Light: The only shading devices for pedestrians are trees. They are big old local trees like Banyan and amla trees. This influences the user behaviour.

The walkway is mostly unshaded, which drastically reduces the number of people on the street, in summers. At night, pools of light from the streetlights creates hierarchies, which catches attention. Transitions from light to dark spaces haven’t been considered, which increases the intensity of glares of the vehicles’ headlights.

5. Materials: The construction materials used are appropriate for the functions of that space but the transition from one to the other is abrupt and often illmaintained. This causes an interruption in the movement flow. This is true for both pedestrians and vehicles.

Experiential Elements

The amalgamation of the physical, natural, and perceptual elements creates experiential qualities in the spatial environment. The natural and perceptual elements have been discussed. The physical elements can be recognized as follows:

Physical Elements: The physical elements include floors, Walls, Columns, Windows, Door, Roof, and Stairs. Now, in a context of a street, these archetypes don’t apply.

o One can consider the Marg to a be a long corridor with shorter walls, open to sky setting and a paved/tar flooring treatment.

o The stairs have a single flight with a single step that, instead of providing a storey difference, changes your character role in the street narrative. Hero to Anti- Villain.

o The experiential approach to a door and window is usually to give a different perspective or frame a view. This concept is missing on the street. Even the actual windows of the houses don’t open up into the street. No spill over activity is observed. This creates an isolated narrative which seems detached from the story that unfolds in the residential communities.

Evaluation of the street narrative

• Dramatic Conflicts

As discussed earlier, dramatic conflicts stimulate tensions that causes another event or triggers people to act. These conflicts don’t actually need to be perceived. In fact, as observed, urban elements such as construction debris, animal droppings, hanging wires from the poles triggers pedestrians to act. Are these deliberately placed? Obviously not. In fact, these conflicts aren’t desirable. It is an actual conflict in the urban setting.

What do the streets communicate? The movement of the shareholders are key to understanding the dialogue.

1) Pedestrians: They need safety when they share the street with other users. Since, they are the most vulnerable and meek. They have to move if a vehicle or a cow moves up behind them. This character profile is too biased. Streets are meant to prioritise pedestrians therefore they need to fulfil the narrative of being the “hero”.

2) Vehicles: The cars and buses have the upper hand in the street. Their movement is pivotal in the changing the narrative of the environment. They almost seem like the anti-villain of the narrative. They need to be kept in check.

3) Public Transit: Buses are public transit as well, but they are huge. The electric rickshaws and auto-rickshaws are still humanised to most part. Their movement is influenced by the pedestrian’s movement. They are like the best friend of the hero. Their organic movement impacts the street character, largely influenced by their size and speed.

Conclusion

o Tripartite Network Model: The TNM is employed in the process of designing environments that hope to connect people to the narrative in the given space. While, coming to the urban spaces, the analysis of this report portrays the importance of referencing the model, in creating a holistic understanding of a narrative environment.

o City as an exhibition is not a endeavour in weaving a narrative in urban sphere which is a relatively untouched research topic globally. In the Indian context where every culture has rich heritage, tradition and therefore narrative, it is only natural to bring this topic forward for the authorities and experts to utilise in the development proposals.

o The research question dealt with were:

1. How can a phenomenological research investigation onto architectural elements provide a narrative for the city?

2. To evaluate behavioural patterns revealed through these phenomenological prompts.

Scope and Limitations

The scope has been realized purely through a phenomenological bottom-up approach. Public spaces including exhibitions and streets were analysed and compared to make generalized conclusions. the structural aspect of the concerned architectural features hasn’t been detailed upon. Since the research topic outlines a qualitative analysis, the findings would be of based solely on the users’ experience. The cultural bias plays a key role in influencing the behavioural patterns.

Future Research Scope

This report investigates the current scenario of the narrative that exists. This methodology can be employed to suggest and inform new techniques for the urban realm that caters to need identified.

Resources

Austin, T. Narrative Environments and Experience Design, 2016

Cobley, P. Narrative: The New Critical Idiom. Routledge, 2001

Filep, C. V. (2014). Built Narratives, 2014

Frey, B. S. Designing Exhibitions. Birkhäuser, 2011

Hughes, P. Exhibition Design, 2013

Ian Bently, A. A. Responsive environments, 1985

KNMA. About Section. Retrieved from https://www.knma.in/knma

MacLeod, S. Museum Making: narratives, architectures, exhibitions, 2012

O’Doherty, B. Inside the White Cube, 1986

Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin, 2012

Pandya, Y. Elements of Spacemaking, 2014

Color Crush

Crafting multisensory digital-physical interactives in a science museum

Jungu Guo, MFA / Creative Technologist

Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago

Abstract

Color Crush is a digital-meets-physical interactive installation developed inhouse for a temporary gaming exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry Chicago (MSI), spanning from fall 2019 to March 2020. It reinterprets and reimagines an ensemble of classic games: Connect Four, Arcade Basketball, and Candy Crush, allowing multiple players to throw tangible colored balls “into” a virtual gaming world — a game that blurs the boundary between the physical and digital, resulting in a whimsical and communal play experience.

This paper walks through the behind-the-science stories of developing Color Crush, reflects upon its design process and challenges encountered, and shares valuable lessons learned from designing, prototyping, and iterating a digital-physical game from the perspective of an in-house creative technologist. The effective adoption of the iterative game design methodology combined with close internal crossdepartmental collaboration led to an innovative game that not only fulfilled project experiential goals but also provided welcoming and engaging experiences for guests.

Captivating and technically demanding exhibits are not and should not be out of reach for science museums. This paper attests to the possibility of seamlessly delivering a meaningful and impactful play experience from scratch in a science museum. By embracing creative technology as an expressive interpretive medium and espousing a guest-centered design philosophy, science museums can truly lend themselves to a future of transformative possibilities.

Category: Multisensory Designed Experiences

Keywords: Game Design, Digital-Physical Interactive, Guest-Centered Design, Co-Design Additional Images: https://www.junguguo.com/color-crush

Introduction

In August 2019, MSI hosted Bit Bash, a Chicago-based annual festival showcasing experimental, unique, and collaborative games from the independent game development community. Their intent was to bring video game culture into the museum space and provide guests with one-of-a-kind play experiences. In alignment with MSI’s vision to inspire the inventive genius in everyone, the weekend-long event was presented as an incredible mashup of science, art, and hands-on exploration that encouraged guests to explore how they interact with video games and to discover how game creators approach their medium.

The gaming event was such a success that MSI later decided to create its own temporary gaming exhibit to further embrace the potential of gaming in uniting people with joy and igniting curiosity. The MSI exhibit design team envisioned the interactive exhibition to be an immersive and inclusive playground where guests would play unique multisensory digital games featuring unconventional interfaces and embodied interactions (Dourish 2004), experience moments of delight as they interact with one another in new and unexpected ways, and also connect with each other through a shared sense of joy and discovery.

That meant we were not interested in traditional screen-based computer games, mobile games, or console games. Instead, we keenly reached out to the alternative controller gaming communities and indie game developers who create games that either challenge the norms or push the boundaries of what gaming is. We set the following experiential criteria for the games we were searching for: They should be fun and joyful; they should enable social interaction, especially between intergenerational groups; they should be accessible to all skill and interest levels as well as physical abilities; they should be experientially exclusive, meaning you cannot play them at home.

While we were curating games from the outside world, we were also entertaining the idea of creating our own game for the exhibit, so that part of the exhibit would display our own creative voice. Having a bespoke component of the exhibit allowed for full control, from concept to implementation, giving us the flexibility to keep it as a living and evolving exhibit element that could be customized along the way to fit our unique needs and contexts.

The Iterative Game Design Methodology

As the digital and interactive media specialist on the design team, the task of making a game of our own creation fell on my shoulders. I was given total carte blanche over my creative process. From the onset, I adopted a classic iterative design cycle comprised of ideation, prototype, playtest, and evaluation (Sharp and Macklin 2019). It’s important to keep in mind that, as game designers, we are essentially making a play machine that generates play, and the play only begins when the players do. Instead of designing the play experience itself, we are designing the rules and affordances that may or may not result in the desired experience we intended, and the best way to bridge that gap is to create prototypes and use player feedback to inform design decisions. This is why, even though the exhibit design process was a milestone-based waterfall model, it was crucial for me to employ an iterative and agile design process for my own local project management.

Ideation

In my initial research and brainstorming, one of my inspirational sources was classic analog and digital games that offer powerful hooks for evoking communal and nostalgic fun. Building off of these time-tested positive gaming experiences could be low-hanging fruit for hitting the experiential criteria. The other advantage of referring to these established games was that they are self-explanatory and intuitive, and capitalizing on their affordances would help to lower the entry barrier to play allowing people of all ages and all skill levels to engage.

My creative response was Color Crush, a game inspired by the shared accessibility, simplicity, and playability among Connect Four, Arcade Basketball, and Candy Crush (and maybe a bit of Tetris) - each was a classic title of the gaming context it represented (party game, arcade game, and mobile game). My idea was to reimagine and recontextualize these classic games by mixing up their affordances with a whimsical and digital twist, creating a familiar yet unfamiliar experience.

The primary game mechanics were simple: players would throw colored physical balls through some hoops into a virtual gaming world. With the help of a combination of physical and digital technology, the physical balls would look like they were falling into a digital grid. Players get base points by getting balls into the hoops. When several balls line up horizontally, vertically or diagonally they get canceled and the players score more points. The game has both compete and co-op modes. Players need to work together or against each other and rack up as many points as possible before the time runs out (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Concept sketch of Color Crush

Figure 1: Concept sketch of Color Crush

Prototypes

As soon as the team decided to move forward with Color Crush, I started turning the idea into something concrete by creating prototypes. Prototyping often flushes out issues and unintended or unexpected results—which is exactly what should happen. This is also the goal of the iterative approach. We want to leverage failure early in the process to make sure the game is hitting the design goals and providing the intended play experience.

It should also be noted that prototyping should be driven by questions, enabling us to keep the game’s development on track. I made multiple prototypes in an evolving manner to answer various questions in different phases (Figure 2). My early prototypes strove to answer core experiential questions: was the game feasible? Playable? Enjoyable? Was it emotionally and intellectually impactful? Could players understand the game’s concept and its connection to the exhibit theme? Only after these critical questions were answered did I move on to focus on usability and logistic issues.

Technical Prototype

Technical prototypes explore the technical solutions of a game. Usually, it’s not best practice to start with prototyping the technicality of a game. But since the core mechanics of Color Crush were dependent upon the color sensors correctly registering the colors of the coming balls, it’s therefore imperative to first find out the capabilities and constraints of the sensors. Is it possible to achieve the illusion of the physical ball turning into a digital one? How predictable is the sensor’s color reading? How many different types of color would work stably with the sensor? These were the key aspects that make or break the core experience of the game, so I felt the need to make sure they were sorted out first.

Core Game Prototype

After figuring out the fundamental technical problems, I started building the physical aspect of the game on a scale closer to my intention. I used low-cost offthe-shelves basketball toy sets that could be customized into flexible and scalable modular structures made of tubes and joints, which made them perfect for fast prototyping. With some tinkering and trial-and-error, I started to bring all the core parts together to see how the whole game felt and played. And more questions came to mind. How should the different components of the game interact? What is the optimal height of the hoops and their distance from the players? What is the ideal number of hoops/columns and rows of the game grid? Are the physical and digital aspects of the game well balanced? Both I and our internal staff playtested the prototype in order to answer some of those questions.

Complete Game Prototype

Once I arrived at a complete game prototype that embodied the full play experience and was able to be played through from start to finish, our team started to invite actual museum visitors for formal playtesting. Would the game successfully deliver the expected sense of whim and fun? How might types of audiences behave and react differently to the game? Would they prefer to compete or collaborate? Real player reactions and feedback brought the game to life and might raise questions that were not anticipated during internal testing.

Lessons Learned from Prototypes

Use A Modular Structure

Flexibility and fast prototyping are of the essence in early design phases. As mentioned, I used a modular toy set with building blocks of tubes and joints to create various customized structures. It allowed me to test around with different physical configurations and tweak and adjust as I saw fit. A modular structure is also easy to assemble and disassemble, which proved very helpful especially when dedicated prototyping spaces are scarce on our museum floor and the prototype needs to be transported and installed from place to place.

Cultivate A Digital Fabrication Skillset

With a basic knowledge of digital fabrication and the easy accessibility of prototyping resources like Fab Lab which can be found in most museums, I was able to utilize 3D printing and laser-cutting to create customized parts for my physical structures. For example, the off-the-shelf modular components came with certain joint types that are limiting, but I was able to model and 3D print the customized joints I wanted, saving valuable time and project budgets.

Keep Different Prototypes For Different Uses

The modular structure I used was made of plastic and assembled together through loose joints. Despite its flexibility and travel-friendliness, it was flimsy and did not offer the best usability. For instance, lightweight foam balls were used to reduce the hitting force on the structure. As we finalized our game design, we started to build a more sturdy structure out of wood and fixed it onto walls, so that we could test other more aggressive ball materials, and guests did prefer vinyl balls which are heavier than foam balls. The downsides are obvious: it was hard to make changes and it didn’t transport easily. I kept both versions to accommodate varying prototyping conditions, which proved a wise decision when later I had to bring the game to a different city for presentation.

Prioritize Flexibility

It’s highly recommended to prioritize technological flexibility over systematic robustness so that we can make quick changes and tweak variables on the fly in order to respond to emergent behaviors and unexpected dynamics. Very often we get pleasant surprises from these spontaneous changes that later end up shaping game experiences in a compelling way.

Wizard of Oz

Even though we shouldn’t get fixated on making every technical detail work early in the process, imperfect technology sometimes comes across as annoying, disruptive, and distracting. That’s where the Wizard of Oz comes to the rescue. The idea is to fake the unpolished - but essential - technological aspect of the game and make players feel like it’s working seamlessly, never knowing that it’s the game’s creator pulling the veil in front of them. This allowed you to focus on the most important experiential aspects of the game instead of getting bogged down in technical imperfections.

Playtests

As soon as I had a guest-ready prototype, I reached out to our Guest Experience Department to help me facilitate playtest sessions and see how my game played out. Here is a three-step best practice I would like to share:

Step 1: Come up with a plan

Before playtesting, our team laid out a formative evaluation plan for determining the issues we would like to explore. The plan included questions about basic details like: when and where will we do the playtest, how long will the playtest session be, how do we want to set up the game, who will be on the playtest team, and what types of audience do we want to test the game with?

The plan also included playtest protocol: how do we introduce the game, how do we structure the interview and conversation around the game, how are we going to capture the feedback, who will observe and take notes, etc.? And most importantly, the team should identify what everyone wants to learn from the playtest.

Step 2: Playtest with guests

During playtesting, one of the toughest things is to sit back and pay attention to the playtest itself — and try not to intervene too much. It’s important to observe what players do and to listen to what they say while playtesting. After players finish

playing, make sure to leave time to discuss the game with them, but keep in mind not to ask leading questions like, “Do you think the game is fun?” Instead, ask openended questions like, “How did you feel while playing the game? How did you figure out your strategy in the game?” The goal here is to gain insights into the factors that resulted in the playtester’s reactions to the game; playtesters shouldn’t be guided by the organizers’ assumptions. Capturing verbal and non-verbal clues will help us gain insight into our game and inform the next design decisions we take.

Step 3: Collect and evaluate

After playtesting, we compared and collated our notes, synthesized insights and learnings, and developed an action plan regarding our next steps. This tells us that documentation is pivotal during playtesting: we should take notes and record videos so that we can review them later. We want to be able to cross-reference them to accurately explain what happened, and even try to uncover subtle details that went unnoticed during playtesting. To analyze feedback, the aspects we could consider are gameplay, usability and interface, technical problems and bugs, player comments, observations, ideas and next steps. In the case of our playtesting for Color Crush, here are some of the gameplay insights that came out of the playtest:

Facilitated Mode for Exhibit Programming

As I finalized the game through iterations, our Guest Experience team started exploring potential exhibit program options. Together we discussed the goals and possibilities for a facilitated program about game design using a modified version of Color Crush, where facilitators could change some aspects of the game to guide a structured conversation around game design with guests.

The program’s goal is to allow guests to not just play a game but also think like a game designer by allowing them to change the game elements of Color Crush. To achieve this, it is desirable to have adjustable parameters within the software that the facilitator can control to change the game in real time. To that end, I developed a mobile software that allows facilitators to remotely change different parameters of the game to create a facilitated experience.

We quickly set up another round of guest-facing prototypes to test out the feasibility of a facilitated exhibit program. In this program, guests will explore how challenges in games increase motivation. They will start by playing a collaborative connect three game by tossing colored balls into a basket above a screen. Guests will then discuss how they can make the game more interesting or increase their motivation to play by adding new challenges to the game. After playing the new level, guests will then find connections between designing appropriately

challenging games and how challenges in their daily lives increase their motivation.

The outcome was very positive. Having a handheld remote control device really helped our facilitators open up informative conversations with our guests around game design. And that’s where the benefit of creating a game of our own reality shows up. To quote our Director of Exhibit and Collection Division, “This could be an ever-evolving prototype throughout the exhibit. I really like the idea of a facilitated interaction that gets people thinking like a game designer. If we co-designed a game with our guests that could be a lot of fun.” (Figure 3)

Presenting at 2022 alt.ctrl.GDC

It’s a great pity that right when we were wrapping up the exhibit design phase and about to enter fabrication and development, COVID-19 struck and the exhibit was brought to an abrupt halt. In March 2022, Color Crush was shortlisted to be one of the 15 games to be presented at alt.ctrl.GDC, the most renowned alternative controller game exhibition. Since alt.ctrl.GDC was in a very similar vein as MSI’s unrealized gaming exhibit, Color Crush in a sense managed to fulfill its purpose by being resurrected in a venue different than originally intended. (Figure 4)

In its three-day debut, Color Crush received an influx of conference attendees generating new waves of player feedback. Applying the same iterative method and mindset, I kept tweaking and polishing the game on-site by assimilating fresh and valuable insights into further iterations in order to cater to the GDC environment and context. At some point, everything finally came together, and an effective, intentional and structured game flow was established as the following:

• Set-up: Introduce the core game rules and personalize some of the gameplay parameters (e.g., timer, game mode, etc.) according to players’ configuration for an optimal experience.

• Warm-up: The countdown will start as soon as the first ball is tossed into the hoop. This serves as a warm-up exercise allowing players to get familiarized with the physical aspect of the game.

• Build-up: As players get more comfortable with the game, a ball of a new color was introduced as a bomb power-up that they could use strategically to clear up some of the clustered areas on the grid.

• Level-up: In the middle of the game, elements of randomness start to kick in. A moving block would occur and push around any balls it touches. Players hence need to take into account the timing of their throwing and adjust their strategies accordingly.

"This could be an everevolving prototype throughout the exhibit. If we co-designed a game with our guests that could be a lot of fun.

"

• Wrap-up: In the last 30 seconds, the game enters a fever mode, and whatever colors of balls players throw into the screen will become a wild card, meaning color doesn’t matter anymore and players just need to step up their physical game in the last stretch.

• Follow-up: Players take a moment to recover from the physical and emotional excitement. As lots of players from that event are also game creators, they also show great interest in learning about the development process of the game and having an informative conversation about game design.

Structuring the game flow in this manner created a progressive and coherent experience that effectively engaged players on physical, affective, and cognitive levels. Visitors left with a moderately exercised body (physical), a memorable experience with their companions or strangers (affective), and a new perspective and understanding of games as embodied interfaces and powerful social objects (cognitive) (Simon 2010) (Figure 5).

Conclusion

Science museums don’t always have the resources or see the need to incorporate the knowledge and capabilities of creating guest-centered digital interactives. MSI’s Color Crush demonstrated the exciting potential of including creative technologies as an internal design resource, which presents unparalleled advantages over outsourcing projects to external agencies:

• Firstly, it responds effectively to institutional needs. Being part of the core design team allowed me to work closely and synergistically with our exhibit developers, Guest Experience staff, and other critical stakeholders. With conversations constantly happening back and forth, it was much more likely to create exhibit experiences that were rooted in our exhibit vision and operational needs.

• Secondly, it can be agile and human-centered. Fast iteration and sufficient playtesting are crucial for creating not just games, but any touchpoints of interactive nature. Having easy access to museum guests on a regular basis through prototyping is therefore hugely instrumental in delivering meaningful and authentic experiences.

• Thirdly, it activates the maker community. Most science museums are equipped with abundant and accessible prototyping facilities like Fab Lab, maker spaces, and fabrication shops. Leveraging these resources allows expertise and lessons to flow organically between the front-of-house and back-

Figure 4: GDC visitors paly against each other

Figure 4: GDC visitors paly against each other

• of-house, strengthening the maker/tinkerer ecosystem they are already building.

• Lastly, there are also embedded marketing opportunities. Making digital-physical games/interactives is itself a hands-on creative problemsolving process that perfectly exemplifies the spirit and mission of science museums. By practicing what they preach, they invariably tell the most inspiring and authentic stories of innovation and creativity.

Multisensory digital interactive play is one of the most powerful experiential engagements in science museums. MSI’s Color Crush intends to display that museums are capable of developing technically advanced and gripping experiences by adopting a nimble, collaborative, and guest-centric design ethos. Through championing digital literacy and endorsing the potential of design thinking, science museums can enliven and relaunch themselves as innovative and inspiring meaning-making spaces in an increasingly competitive experience economy (Pine and Gilmore 2019).

Resources

“Alt.ctrl.GDC.” Game Developers Conference, 13 May 2022, https://gdconf.com/alt-ctrl-gdc. Bit Bash. “Chicago’s Alternative Games Festival · Bit Bash Chicago.” Bit Bash, 30 Aug. 2021, https://bitbashchicago.com/

Dourish, Paul. Where the Action Is: The Foundations of Embodied Interaction. MIT Press, 2004.

Pine, B. Joseph, and James H. Gilmore. The Experience Economy: Competing for Customer Time, Attention, and Money. Harvard Business Review Press, 2019.

Sharp, John, and Colleen Macklin. Iterate: Ten Lessons in Design and Failure. The MIT Press, 2019.

Simon, Norma. The Participatory Museum. Museum 2.0, 2010.

Evolving Graphic Design

Yeohyun Ahn, MFA/Assistant Professor, Graphic Design Program, Art Department, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Abstract

Graphic Design has been a predominantly white and European-centric academic area deeply rooted in Bauhaus, a German art school from 1919 to 1933, combining crafts and the fine arts to approach constructive and universal design for mass production. It has dominated modern graphic design for over 100 years. Visual design education is rapidly shifting from Western and printcentric to diversifying with emerging technology and globalization. This research investigates the future of graphic design education, research, and practices, crossing boundaries among creative coding, 3D printing, Guerrilla projection, speculative design, sound, data visualization, augmented reality with activism, and cultural identity impacted by globalization. The research creates an original exhibition design that frames a newly curated exhibition. The curated collection showcases evolving graphic design, including technically diverse and culturally inclusive voices and approaches. The virtual gallery for the show, www.evgd. org, is designed and developed to embrace national and global audiences.

Category: perspectives

Keywords: creative coding, 3D printing, Guerrilla projection, speculative design, sound, data visualization, augmented reality with activism, and cultural identity impacted by globalization

Additional Images: http://www.evgd.org

Specific aims/research questions

It aims to create an original and impactful exhibition and research opportunities for academically underrepresented and marginal graphic design educators in the United States. Visual design education in the US is historically European-centric, and technically print design dominated mass production. Print design is a core of graphic design education, research, and practices. It is deeply rooted in Bauhaus. It was a German art school from 1919 to 1933, integrating crafts and the fine arts to approach rigorous, constructive, and universal design. Bauhaus design philosophy and design style have academically dominated modern graphic design education in the United States for over 100 years. Now visual design education in the US is hugely demanded to decolonize, extend, and diversify from Western and print-centric to cross-disciplinary and inclusive graphic design education and practices. The research aligns with new emerging technology and globalization of visual design education. It incubates the inclusive and technically diverse visual communication in the US’s academically conservative graphic design education.

Significance

Long-established Graphic Design education in the US is academically homogenous. It has been driven by print design, and it is culturally Western-centered. Conventional graphic design educators of the US strive to sustain their dated professional roles as print designers. Their invisible academic efforts are hugely collective and invisibly aggressive. They are academically exclusive to adopting new emerging technology but more welcomed to industry-standard commercial software like Adobe CC (Creative Clouds). Present-day graphic designers must pay a monthly subscription to use Adobe CC. Pioneers of visual design education in the US started integrating Creative Coding in the early 2000s at MIT Media Lab. Creative Coding is an art and design movement to create software by artists and designers for free distribution, initiated by Johan Maeda, Ben Fry, and Case Reas at MIT Media Lab. It enhances technical independence, not relying on profit-driven computer graphic software companies. Also, it enables the integration of diverse new mediums such as live sound and data input. Computational visualization has already been embedded into graphic design education by using computational design thinking. The code-driven design research has been nationally and internationally disseminated since the 2000s. Still, these are invisibly and systematically excluded and underrecognized from the US’s conservative professional graphic design communities.

Graphic Design education has traditionally seen European-oriented and whitecentered design as the standard to measure achievement. Visual design educators who explore cultural identity have been doubted, ignored, and treated as unprofessional. It is brushed off by Western-centered design perspectives in the US’s homogenous professional graphic design communities. Most of the US’s academically marginalized visual design educators are pioneers of alternative,

extended, and inclusive design, crossing boundaries among new emerging technology and cultural identity. It routinely challenges them to deal with inequitable academic opportunities and recognition. They suffer from a lack of supporting systems, connections, and resources to explore innovative graphic design education and research. They have limited opportunities to present their works in exhibitions and publications from exclusive professional graphic design communities. They destine to compete with other academic areas such as digital art and fine arts to seek alternative venues for research opportunities, which are very competitive. The invited design educators for the exhibition are highly recognized by prestigious, peer-reviewed, national, and international conferences and exhibitions in digital arts and fine arts as artists, but they have been underrated by their mother professional graphic design communities of the US. There is no data, survey, statistics, or research related to academic marginality and exclusion in the traditional graphic design education in the US. The study aims to provide essential exhibition and research opportunities for the academically marginalized but highly regarded visual design educators of the US.

Approach (design, methods, and analysis)

The exhibition showcases evolving and inclusive graphic design, crossing boundaries among visual design education, new emerging technology, and globalization. The show will include interactive posters, non-traditional typography, generative motion graphic and brand identity, tangible typography by using 3D printing, sound and data visualization, virtual reality, extended book art and printmaking, mural project, Guerrilla projection, documentary film, and augmented reality for activism, etc. The curated exhibition will invite 18 outstanding graphic design educators of the US who are highly regarded but academically undervalued and depreciated from conservative, homogenous, and print-centric professional graphic design communities. All the exhibitors are highly selective. Their groundbreaking visual design research with new technology and globalization is recognized nationally and internationally. The author initially selected the exhibitors with 15 years of professional connections and networks in graphic design in the US to initiate this unprecedented collective effort as an exhibition without a budget. The associate curators, Prof. Moon Jung Jang at the University of Georgia and Prof. Heather Quinn at Washington University in St.Louis, invited an extended range of graphic design educators from prestigious art schools to teaching institutions and tenured professors adjunct faculty in graphic design. All of the invited exhibitors were eager to collaborate with this multi-institutional and unprecedented collaboration in the visual design education of the US.

This research creates the generative exhibition design from logo, poster, wayfinding, banner, exhibition catalog, website, and virtual gallery for the exhibition in collaboration with Prof. Takeyeom Lee, Assistant Professor at Iowa State University.

"The exhibition showcases evolving and inclusive graphic design, crossing boundaries among visual design education, new emerging technology, and globalization.

"

Photo by Yeohyun Ahn

Photo by Yeohyun Ahn

Generative poster design using computer vision to i nteract with the audience by using a web camera.

Photo by Yeohyun Ahn

Photo by Yeohyun Ahn

Generative poster design using computer vision to i nteract with the audience by using a web camera.

The exhibition design is modern, original, experimental, and forward-looking to deliver the exhibition theme. The design methodology, Design Thinking, is employed to design a user-friendly and inclusive interface design for the exhibition website and virtual reality gallery for the web. The virtual gallery is built for all invited works in digital formats from in-person exhibitions. The exhibition is held from May 24, 2022, to June 24, 2022, at the Art Loft Gallery and Backspace Gallery, located in the Art Loft Building, Gallery 7 at the Humanities in the Art Department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The website www.evgd.org is developed for global exposure and to tap into an extensive network for academically marginalized graphic design educators, diverse ranges of designers and artists, and underserved audiences. The exhibition visitors will gain new in-person and immersive virtual experiences for new evolving graphic design. It will incubate new visual design perspectives, being extended, open-minded, alternative, diverse, and inclusive graphic design education, practices, and research of the United States.

Conclusion

The initial project team was presented at DEL (Digitally Engaged Learning) in Between Webinar on May 14, 2022, with the panel discussion, “Trans-disciplinary graphic design, art research, and practices in higher education.” The panel, “Crossing boundaries: Alternative, extended and trans-disciplinary graphic design education and research” was hosted by AIGA DEC (Design Educators’ Community) Kick-Off on June 25, 2021. It was presented at Chicago’s 110th CAA (College Art Associations Conference) 2022: Design Incubation Colloquium. The exhibition and the symposium, Evolving Graphic Design, in partnership with the SEGD (Society of Experiential Graphic Design). It is funded by Wisconsin Alumni Foundation and the Bringtingham Fund. The Division of Diversity, Equity, and Educational Achievement, Art and Computer Science Department, and Global Engagement Office in the School of Education at the UW-Madison sponsored the exhibition. As a hybrid, the symposium will be at the UW-Madison on June 23-24, 2022. All the exhibitors’ presentations (or artist talks) at the symposium will be professionally recorded and documented. SEGD published the exhibition catalog on their website. With a YouTube channel, all the professionally edited videos will be uploaded and open to the public through www.evgd.org. University of Georgia, Illinois State University, Texas State University, and Iowa State University will consider hosting the travel exhibition or symposium contingent on their institutional funding approval.

Resources

Ball, Maddie. How to Start Creative Coding. London: University Arts London. October 2019. https://www.arts.ac.uk/study-at-ual/short-courses/stories/how-to-start-creative-coding

Chris Calori, David Vanden-Eynden, Signage and Wayfinding Design, Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley, 2015

David Gibson, The wayfinding handbook, NYC NY: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009

Erik Bär, and Stan Boshouwer, Worlds of Wonder, Amsterdam, Netherlands: BIS Publisher, 2019

Exhibition Design, Philip Hughes, London. Lauren King Publihsing, 2015

Winton, Alexandra Griffith. The Bauhaus, 1919–1933, October 2016. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/bauh/hd_bauh.htm

Flow

The flow experience told through multi-generational voices of motorsport women

Naz Ertugrul, MFA Exhibition and Experience DesignerThesis Statement

Today’s audiences are often chronicle-obsessed and co-dependent on smartphones to record moments for social appearance and photo likes, which results in a lack of presence in the moment and disengagement with the intentions of the setting.

Repurposing the use of smartphones in interpretive experiences to break the barrier between the camera lens and the individual can enable audiences to chronicle experiences for the purpose of fostering a deeper awareness of and connection to themselves, and their surroundings.

The use of customized smartphone applications as tools that can enhance the activation of the designed environment will facilitate audiences to identify and chronicle their meaningful moments, codeswitch throughout their experience, and create their own journey.

Abstract

The thesis statement has put forth the alteration in the definition of utilizing mobile phone technology. This allows it to become a tool for a deeper manifestation of immersion with the content, the environment and most importantly within and among other individuals. Current designed immersive settings most often lack the quality of delivering the complex narrative to audiences through smartphone technologies: they often remain on the surface by obtaining the profile of photo backdrops and referring to the needs of chronicling of audiences on social media platforms. However, the thesis research investigates ways of applications for transforming the current descriptions of interpretive spaces by enabling technological devices to work in versatile methods to create a deeper sense of awareness within and among audiences.

Category: Experiential Design, Exhibition Design

Keywords: Flow State, Female Motorsport Racing, Reshaping Smartphone Technology

The exhibition project tackles this argument point by allowing technology to become a gateway for achieving enhanced states of immersion. Thus, this puts a framework around the initial segment exhibition subject, flow state, which sets a foundation on understanding the methods and activities that initiate the temporary unique state of absolute focus and immersion. In continuation, the second segment of the exhibition pinpoints the subject of female motorsport racing: a subject that requires high levels of concentration and immersion to the present moment to complete. The project recognizes flow as a connecting medium from designed experiences to smartphone technology applications to motorsport racing. The exhibition identifies each of the 7 concepts with the intensities of experiencing flow and translates into 7 unique multi-sensorial activities for audiences to experience. From a steering wheel to a magnifying mirror glass, the mobile device and its customized applications become an essential guide in activating the designed setting and enhancing the levels of audience immersion.

Introduction

High levels of immersion are interconnected with presence in the moment and awareness of the surrounding setting. Creating seamless, personalized integrations of smartphone technologies and flexible user interfaces initiate enhanced immersion and intimate interactions. This leads to significant experiences that target the individual as well as the collective group in designed settings.

Flow is defined as a state of total immersion while participating in an activity that creates an optimal setting for the experiencer. In light of this, the exhibition covers the subject of Csikszentmihalyi’s flow experience, and sets a stage to convey the enhanced future of female Formula One (F1) racing. Flow, the exhibition, investigates the activities that are a part of motorsport racing that trigger flow state, as well as activities that impact the mind, the body, and the soul for a wholesome immersive experience.

The exhibition targets an audience ranging from young rising female athletes to young uninitiated women from different backgrounds and interests, encouraging them to become more involved in the subject of racing and potentially pursue it as a career or a hobby. The exhibition project consists of multiple partnerships between FIA (the head organization of F1 and Series), Apple (a smartphone technology company) and Adobe (a design software company).

The exhibition project is set to travel between cities which hold significance to F1 Racing and motorsport history. These cities include Miami, Silverstone, Singapore and Abu Dhabi.

Thesis Argument