2024

Communication + Place

Introduction

The Society for Experiential Graphic Design (SEGD) is a multidisciplinary community collectively shaping the future of experience design. We are designers of experiences connecting people to place.

We are a thought leader and an amplifier in the practice of experience design. Our work puts people at the center. We are motivated by our impact and our belief in the power of design to improve the human experience in the environments we create. We cultivate equity and inclusion because we value diversity in many forms, advocating for representation of all voices and equitable access to our profession. Learning is at the heart of our mission; we promote mentorship, knowledge-sharing, and continuing education. We build relationships, encourage strategic collaboration, and value a multidisciplinary, cooperative, and user centric-design process. We encourage sustainability, conservation, and preservation of resources to ensure a healthy future for our planet and its people. Our work is defined by professionalism, and we foster skill, judiciousness, and a code of ethics. Above all, we are propelled by the pursuit of excellence, challenging ourselves to make meaningful and inspiring work.

We live all of these values through the work of our committees, who support SEGD initiatives in education, inclusion, sustainability, and accessibility.

For over fifty years, SEGD has been the go-to resource for wayfinding, placemaking, and experience design. SEGD’s education conferences, events, and webinars span our practice areas including: branded environments, digital experiences, exhibition, placemaking, public installation, strategy / research / planning, and wayfinding. SEGD actively collaborates with and provides outreach to design programs at internationally recognized colleges and universities. Our signature academic education event is the annual SEGD Academic Summit, a two-day virtual event. Design educators and researchers from around the world are invited to submit papers for presentation at the SEGD Academic Summit and publication in SEGD’s blind peer-reviewed Communication + Place journal, which is published electronically on an annual basis. The Summit and e-publication are platforms for academic researchers to disseminate their creative work, models for innovation in curriculum, and best practices for research related to experiential design.

2024 Academic Task Force

Chair: Joell Angel-Chumbley | University of Cincinnati DAAP, City of Cincinnati

Yeohyun Ahn | University of Wisconsin Madison

Aija Freimane | TU Dublin School of Creative Arts, Ireland

Angela Iarocci | Sheridan College

George Lim | University of Colorado School of Environmental Design

Christina Lyons | Fashion Institute of Technology

Tim McNeil | University of California Davis

Muhammad Rahman | University of Cincinnati DAAP

Amy Rees | Drexel University, Exit Design

Loran Sanvido | University of Cincinnati DAAP

Debra Satterfield | California State University

Neeta Verma | Researcher, Designer, Educator

Willhemina Wahlin | Charles Stuart University

Michele Y. Washington | Design Researcher /Strategist

The annual SEGD Academic Summit … “engages our global audience through a series of dynamic panel and breakout sessions designed for a broader exchange of ideas and learning.”

On behalf of SEGD ‘Designers of Experiences - Connecting People to Place,’ and the Academic Task Force (ATF), we would like to thank the selected authors for sharing their transformative research to be published in the 2024 Communication + Place academic journal. Your contributions magnify our mission to provide learning opportunities and resources, promote the importance of the discipline of experience design, and continue to refine standards of practice for the field.

The SEGD Academic Task Force is a diverse team of US and international design faculty, researchers, and practitioners that collectively develop initiatives strategically focused on the advancement of diverse and inclusive design education, research, publication, and faculty/student professional development.

The annual SEGD Academic Summit, a signature event produced by the ATF, has become a forum for global design academics, researchers, and students to share their innovative research, curriculum, and projects. The ATF releases an annual Call for Papers and conducts an anonymous-peer review of submitted abstracts. The selected authors are then invited to present at the Summit and publish full papers in Communication + Place

The Summit programming also engages our global audience through a series of dynamic panel and breakout sessions designed for a broader exchange of ideas and learning. These multi-level conversations are critical to forging the pathway forward for diversity in design education and professional practice.

If you are interested in learning more about the work of the SEGD Academic Task Force, please contact Joell Angel-Chumbley, MFA, SEGD Academic Task Force Chair, at academic@segd.org.

Joell Angel-Chumbley SEGD Academic Task Force Chair

“We celebrate the meeting of new ideas and seasoned insight, making space for both emerging voices and the wisdom of experience.”

As the Society for Experiential Graphic Design (SEGD) continues to evolve, our focus remains on elevating emerging voices while honoring the expertise of experienced practitioners. SEGD fosters a space where fresh perspectives challenge our thinking and where knowledge is shared, expanded, and applied to shape the future of design.

Our community thrives through the dynamic exchange between students, professionals, and educators. Together, we create environments that positively impact people, places, and culture, contributing to a shared vision of transformative design.

In this year’s SEGD Communication + Place annual, we celebrate the convergence of new ideas and established insights. Emerging professionals bring energy and innovation that push us forward, while seasoned designers and educators provide the wisdom and guidance essential to growth. This collaborative spirit continues to fuel progress and deepen our understanding of how design shapes the human experience.

We hope you find inspiration in this publication and the diverse voices that represent the ever-evolving field of experiential design.

Cybelle Jones Chief Executive Officer, SEGD

A Death By a Thousand Designs

The Impact of Racial Inequity in Spatial Design

Jacquelyn Iyamah

Founder, Making the Body a Home

Abstract

This paper analyzes how the built environment powerfully perpetuates racial microaggressions, which are often referred to as “a death by a thousand cuts” by psychologists. Building off of Interior Race Theory, which argues that what we interact with in our interior environments can cause Black, brown and racialized people to have positive or negative racialized experiences — this paper articulates how everyday physical spaces can communicate underlying racist messages through visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, and gustatory related experiences.

Examples include naming all lecture halls after white males, or the creation of ‘ethnic’ aisles in grocery stores, or racially biased music selections in retail spaces. This paper will contribute to the field of experiential design by pushing practitioners to think intersectionally about race and space through the senses. It will call for placemakers to integrate racially equitable design principles into their work, in order to create spatial experiences that affirm the lived experiences of Black, brown, and racialized communities.

Introduction

When we work towards equity in interior design, building design, and experiential design, we often focus on accessibility, wellbeing, sustainability, and safety. However, there are countless ways in which interior space has also been designed to center whiteness and marginalize communities of color. Despite how detrimental this can be to racialized people, this topic is often overlooked in design and architectural theory and practice.

Racial microaggressions refer to the sly racist messages that Black, brown, and racialized communities continuously receive about our racial identities in a white supremacist society. These messages can be verbal or non-verbal, overt or covert, and intentional or unintentional. Chester M. Pierce coined the term ‘Microaggression’ in the 1970s to characterize the subtle ways in which he observed white students at Harvard marginalizing their Black peers.

When we think about racial microaggressions, we often focus on the interpersonal, how they show up between people. We think of the questions such as “Where are you really from?” and “You’re so articulate’, and actions such as a white woman clutching her purse when a Black man walks by, or a store owner following a Latine person around the grocery store. Rarely ever do we think about how racial microaggressions can show up between people and their built environment. About how sometimes, our physical environments are designed in ways that are invalidating, exclusionary or hostile towards Black, brown, and racialized communities. Derald Wing Sue et al refer to this as ‘Environmental Microaggressions’.

Many of us can enter a space and it will whisper, “You don’t matter,” “You’re less than,” or “You don’t belong here.” As Craig Wilkins expresses “At present, space is naturalized in ways that are — in varying degrees — problematic for anyone who is not white and male.” Living with these microaggressions makes you hyperaware. You learn to read the subtext in every design choice just to better understand whether you are welcome. These experiences are often invisible to those who aren’t racialized. But they are everywhere and can be experienced in a multitude of ways.

“Space is naturalized in ways that are — in varying degrees — problematic for anyone who is not white and male.”

Craig Wilkins

Approach

This paper is rooted in multi-dimensional forms of research, blending empirical exploration, theoretical exploration, and most importantly lived experience. This multi-faceted research methodology allows me to highlight the complex interplay between race and space.

For the empirical approach, the paper leans on the profound analysis of Chester M. Pierce’s pioneering concept of ‘Microaggressions’ (1974)’and extends Derald Wing Sue’s work on ‘Environmental Microaggressions,’ (2007) which highlights spatial experiences for racialized communities.

For the theoretical approach, the paper leans on my theoretical framework of Interior Race Theory, positing that the design elements that make up the interiors of our buildings— the decorative, atmospheric, spatial, material, structural, infrastructural, and furniture elements —can either obstruct or enhance positive racial experiences.

For the lived experience approach, the paper draws from my personal lived experiences with environmental racial microaggressions. This is pivotal, as there are nuanced ways in which Black, brown and racialized people experience space that are not fully captured or understood by the mainstream spatial design industry.

Environmental Racial Microaggressions

Sensory design is an approach to design that focuses on the human senses and how they interact with the built environment. Our environment is made up of things we can see, hear, smell, taste and touch. Whether we know it or not, when we design spaces, we are speaking to the senses. Though we often focus on visual cues when it comes to design, through my work, I have found that is possible to experience various environmental racial microaggressions through visual, auditory, tactile, olfactory, or gustatory design cues.

Visual Racial Microaggressions: These refer to racist messages in the built environment communicated through visual-related experiences.

Example

Healthcare clinics solely displaying medical diagrams and anatomical models of people with lighter skin in their waiting and patient rooms

Universities and schools naming most of their lecture halls, buildings, and cafeterias after white men

Public spaces memorializing colonial figures thourgh monuments

Implicit message

The health of people with darker skin is not a priority to medical practitioners or the medical field at large

The contributions and achievements of Black, brown and racialized people are not recognized or valued

Colonization should be celebrated because of the positive impact it has on white communities

Auditory Racial Microaggressions: These refer to racist messages in the built environment communicated through sound-related experiences.

Example

Cafes, restaurants, and stores solely playing music that palatable to white mainstream culture

Automated Eurocentric-sounding voices being used to make announcements to travelers in airports and trains

Home speech recognition systems are less able to understand Black voices

Implicit message

Music that isn’t widely known by white people is unacceptable or inappropriate in public space

Eurocentric voices are more neutral and appropriate in public space

Eurocentric accents are the norm, and everything else is “other”

Tactile Racial Microaggressions: These refer to racist messages in the built environment communicated through touch-related experiences.

Example Implicit message

Infrared soap dispensers or water faucets in public restrooms failing to detect dark skin

Retail stores in predominantly Black neighborhoods placing security screens on nearly every item

Hotels supplying guests with shampoos, conditioners, and lotions that don’t work for Black skin and hair

People with light skin are the main audience considered when designing products for public consumption

Black people are more prone to committing crimes such as stealing

Eurocentric beauty standards are the norm and thus Eurocentric beauty products are the norm

Olfactory Racial Microaggressions: These refer to racist messages in the built environment communicated through smell-related experiences.

Example Implicit message

Kitchen workplace signage that discourages employees from microwaving richly scented foods

White-owned wellness practices appropriating South Asian aromatherapy without proper acknowledgment

Waste facilities and dumps being placed near predominantly Black neighborhoods

Food that is not commonly consumed by white is “smelly” or “disruptive”

South Asian spiritual practices are “exotic” and commodifiable

Black, brown and racialized people are less deserving of experiencing pleasant scents

Gustatory Racial Microaggressions: These refer to racist messages in the built environment communicated through taste-related experiences.

Example Implicit message

Grocery stores placing foods eaten by Black, brown and racialized people in an “Ethnic” aisle separate from other foods

School menus that predominantly consist of dairy items such as cheese and milk even though most Black, Latine, and Asian people are lactose intolerant

Restaurants watering down a Black, brown or racialized group’s culture by using stereotypical decor or altering the way their food is traditionally cooked

Foods originating from Black, brown and racialized cultures are “other”

The dietary restrictions of racialized communities are not of importance

Appeasing white people’s tastes is more important than preserving the cultural memory of Black, brown or racialized people

The Impact

Some people may read these examples and think they are not that detrimental. But this is precisely why the term is called “microaggressions”. The prefix “micro” is intentionally used to draw attention to forms of racism that are frequently downplayed by white supremacist culture. Psychologists have referred to them as a “death by a thousand cuts” because of the deep harm they can cause to Black, brown, and racialized communities. The harm is incessant. A person running a couple of errands could experience several environmental racial microaggressions within the span of a few hours on any given day.

Imagine this — At 9 am you step into a doctor’s office, and the first thing that catches your eye is a series of medical diagrams. Every single illustration portrays white people. You feel discomfort, but try to brush it off. By 10 am you are on your way to the grocery store, you pass by a park with a monument commemorating a colonizer. You feel discomfort, but try to brush it off. By 10.30 am you’ve made it to the grocery store. You’re looking for a particular spice but can’t find it anywhere. When you ask a worker at the store, they let you know it’s in the “ethnic aisle” section at the back of the store. You feel discomfort, but try to brush it off. But eventually it all catches up to you. It always does.

In the research I’ve done on the impact of different forms of racism such as microaggressions — I have found that microaggressions diminish our health in a multitude of ways. Mentally, it’s the root of stress, anxiety, and depression. Emotionally, it breeds anger, shame, and confusion. Physically, it manifests as high blood pressure, heart disease, and weakened immunity. And spiritually, it corrodes the sense of self, leading to an internalized sense of inferiority tied to one’s racial identity.

Tackling the Problem

Through Theory

In 2022 I created Interior Race Theory which states that how we design our interior spaces impacts our racialized experiences, thoughts, feelings, and sometimes behaviors. While the theory initially centered on the home and objects, I have since expanded it to include the decorative, spatial, atmospheric, material, structural, infrastructural elements and furniture in our interior spaces. Interior Race Theory has helped create more awareness about the relationship between race and space in our interior environments.

It is often difficult for people to conceptualize the relationship between building design, interior design, construction, and race. More often than not, these forms of design are seen as race-neutral. Conversations about racism in the built environment typically focus on the external settings where we live and interact. As Todd Levon Brown states “The dialogue on the race in space has primarily been limited to the urban scales of city, neighborhood, community and street. Socio-spatial research that centers around race rarely addresses this phenomenon at the scale of architecture - the individual building or a particular development.”

“The dialogue on race in space has primarily been limited to the urban scales of the city.”

Todd Levon Brown Through Practice

I recently launched Making the Body a Home, as a design consultancy to help clients design spaces that resonate with the lived experiences of Black, brown and racialized communities. This will be actualized through leading educational workshops and talks, and consulting on spatial projects. But most importantly, I’ve developed the RED Standard™ — the first ever racial equity design standard for building design. Design firms can leverage this standard as they take on spatial projects.

Most built environment design frameworks in the form of policies, standards or guidelines, often focus on four criteria: accessibility, sustainability, wellbeing and safety. However, there has yet to be a design standard that specifically documents how to design racially equitable interior spaces in a tangible way. As a result, many architecture, design and construction firms don’t have a standardized grasp on how to design an interior space that is racially equitable. As Sarah Schindler states “... currently the ADA prohibits the construction of a separate entrance for disabled individuals, but the city of

New York is allowing developers to construct apartment buildings with “poor doors”—a separate entrance for low-income tenants in mixed-income buildings.”

“The city of New York is allowing developers to construct apartment buildings with ‘poor doors’...”

Sarah Schindler

Conclusion

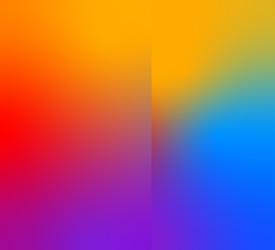

Due to the detrimental impact that environmental racial microaggressions can have, it is important that placemakers of all varieties become dedicated to designing spaces that are truly racially equitable. As the Society for Experiential Graphic Design states, experiential designers are “not just driven by how something looks, but how it serves audiences, how it communicates, and how it makes someone feel.” Our role is to begin to consider how racial microaggressions in the built environment make Black, brown and communities of color feel. However, this can only be achieved by having an equitable design process. Here is what a racially equitable design process can look like:

Curiosity

• Begin every project by considering how factors such as race and other identity markers may impact how a person may experience a space. Without intersectional thinking we may design spaces that work for some but not all.

• Conduct research with and not for Black, brown and racialized people to truly understand their nuanced needs, desires, and experiences in the interior built environment. Allow people to brainstorm what the racially inclusive space should feel like.

Creativity

• Design in ways that mitigate how the design elements can cause racial inequities and how people who manage or use the space may cause racial inequities. Our job as designers is not just to come up with solutions to physical spatial problems, but also to come up with solutions to social spatial problems.

• Leverage racial equity standards, such as the RED Standards™ so that you have clear criteria to follow as you design a space. In the same way that designers leverage sustainability, accessibility, or wellbeing standards, there is a need to leverage racial equity standards when creating a space.

Commitment

• Work with a racial equity expert to conduct racial equity impact assessments and audits of your space throughout the design process to ensure that you have mitigated many of the harms that may take place.

• Commit to long-term engagement with Black, brown and racialized communities beyond the initial design and construction phases of a project. This allows you to get a deeper understanding of what is working well and what needs improvement.

From builders, to architects, to interior designers, to experiential designers — I want to see more of us thinking about the lived experiences of Black, brown, and racialized people as we design residential, commercial, and cultural spaces. Communities of color deserve to experience homes, cafes, restaurants, schools, offices, stores, and museums that allow us to feel safe, welcome, and celebrated.

Resources

Brown, T.L. (2019). Racialized Architectural Space: A Critical Understanding of its Production, Perception and Evaluation. Architecture_MPS. Vol. 15(1). https://doi. org/10.14324/111.444.amps.2019v15i3.001

Gore, S. (2023, February 24). Interior race theory is a creative way to decolonize our homes. Architectural Digest. https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/ interior-race-theory-design-concept

Iyamah, J. O. (2024). Interior Race Theory: Using Interior Objects to Resist Harmful Racial Conditioning. Journal of Interior Design, 49(1), 12-16. https://doi. org/10.1177/10717641231217430

Making the body a home. Making the Body a Home. (2024). https://makingthebodyahome.co/

Pierce, C. (1970). Offensive mechanisms. In F. B. Barbour (Ed.), The Black seventies (pp. 265–282). Boston, MA: Porter Sargent. Library of Congress Catalog Number 74133967

Schindler, S. (2015). Architectural Exclusion: Discrimination and Segregation Through Physical Design of the Built Environment. The Yale Law Journal, 124(6), 1934–2024. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43617074

Sue D. W., Capodilupo C. M., Torino G. C., Bucceri J. M., Holder A. M., Nadal K. L., Esquilin M. (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. The American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.27

Wilkins, C. L. (2007). The aesthetics of equity: Notes on Race, space, architecture, and Music. University of Minnesota Press.

Artificial Minority Combating Unconscious Biases Embedded in Facial Recognition Technology

Emily Tse Exhibit Designer, Nationwide 360

Abstract

Our unconscious biases have been a problem in the past, present, and now in the upcoming future. These biases — racial bias, gender bias, and age bias — perpetuate discrimination in facial recognition technology. The paper is a compilation of the research conducted to implement an exhibition design that spread public awareness of algorithmic injustice in facial recognition technology.

Part I of the paper includes the research that explores biases in facial recognition technology. This section also discusses how participatory museum techniques are used to encourage dialogue and promote empathy. Additionally, primary research was conducted in which expert interviewees contributed to the understanding of technology as a system of power and ways to orchestrate workshop programming. Two iterations of prototype testing and a survey collected opinions on facial recognition technology. Both primary and secondary research were fundamental to the development of the exhibition project in part II.

Part II of the thesis paper contains the concept and design development of the exhibition project. The exhibition “Artificial Minority” will bring public awareness to AI ethics, which will encourage responsible research and application. It focuses on people and how their lives were impacted. First-person narratives are written in exhibit diaries. These diaries reveal the repercussions of biased AI, but it also explores the potential of facial recognition to improve people’s quality of life and the efforts underway that combat unethical AI. The participatory museum techniques researched in part I are incorporated into the exhibition. These techniques, such as role-play and workshop programming, will provide ways to spark dialogue and foster awareness of current provocative issues.

The exhibition project was presented to exhibition design industry professionals at the FIT Capstone Event on December 8, 2023. Many of them found the exhibition informative and thought-provoking. People found this topic timely with the current state of technology. One judge wrote “Overall a very current topic, and almost too much to still learn about this topic to put into one exhibition. But such an important topic, and important to create more awareness.” Another judge wrote “Balanced sequence of hard facts, emotional stories, hands-on workshops, and illuminations. Potentially overwhelming data, tamed yet effective.”

Introduction

“One in two American adults is in a law enforcement face recognition network.” — Georgetown Law1

Humans have biases, both unconscious and conscious. These biases unintentionally seep into technology — technology that is globally deployed. One example is facial recognition, which is used by the law enforcement to find missing children, uncover firearms trafficking, and identify suspects of shootings and child sex trafficking.2 Facial recognition is also a tool used to reduce medical errors — the third leading cause of death in the US. 3 It can detect early symptoms of stroke by analyzing facial features. “Every technology is a double-edged sword,”4 said Dr. Fei-Fei Li, a pioneer in the AI and healthcare space.

Advocacy organizations have made huge steps toward public awareness of the biases in algorithms. Researcher Dr. Joy Buolamwini started her non-profit Algorithmic Justice League (AJL) back in 2016 when she was a graduate student at MIT.5 She has been working with legislators to get regulations on facial recognition. In June 2023, Buolamwini met with President Biden in an AI ethics discussion.6 In addition, the American Civil Liberties Union7 (ACLU) and Big Brother Watch8 in the UK actively defend privacy rights against facial recognition systems.

The efforts from advocacy organizations protect people’s right to privacy against facial recognition software. Surveillance systems use this technology without

1. Georgetown Law. “The perpetual line-up.” https://www. perpetuallineup.org/ (2016).

2. Parker, Jake, “Facial Recognition Success Stories Showcase Positive Use Cases of the Technology.” https://www.securityindustry. org/2020/07/16/facial-recognition-success-stories-showcasepositive-use-cases-of-the-technology/ (2023).

3. John Hopkins. “Study Suggests Medical Errors Now Third Leading Cause of Death in the U.S.” https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/ media/releases/study_suggests_medical_errors_now_third_leading_ cause_of_death_in_the_us (2016).

4. Bryer, Tania and Revesz, Rachael. “Dr. Fei-Fei Li: The benevolent scientist.” https://www.cnbc.com/fei-fei-li-the-biggest-perils-andopportunities-in-ai/ (2019).

5. AJL. “Our mission.” https://www.ajl.org/about (Accessed 2023).

6. Democracy Now. “How AI Is Enabling Racism & Sexism: Algorithmic Justice League’s Joy Buolamwini on Meeting with Biden.” https://www.democracynow.org/2023/6/22/joy_buolamwini_on_ai_ risks (2023).

7. ACLU. “Face Recognition Technology.” https://www.aclu.org/ issues/privacy-technology/surveillance-technologies/face-recognitiontechnology (Accessed 2023).

8. Big Brother Watch. “About Big Brother Watch.” https:// bigbrotherwatch.org.uk/about/ (Accessed 2023).

obtaining consent from people. Buolamwini advocates that “If you have a face, [then] you have a place in the conversation.” Exhibitions are one method that can be used to encourage people to join conversations about AI ethics.

Part I Exhibition Thesis

Facial recognition technology is a biometric identification technology that detects facial features to verify an individual’s identity. It is used in high-stakes scenarios including healthcare, law enforcement, the justice system, and transportation. First, it detects if a face is present in an image or video. Then, it analyzes facial landmarks such as the shape of cheekbones or the distance between the eyes. Finally, it compares the facial landmarks to a unique faceprint of the individual. 9

“The machine is simply replicating the world as it exists, and they’re not making decisions that are ethical. They’re only making decisions that are mathematical.” —Meredith Broussard, data journalism and professor 10

Discrimination in facial recognition technology has been prevalent from hobby projects to globally-deployed applications. These systems are biased because they are built by humans. There is bias in the sample training data, which overrepresented and underrepresented different populations. Additionally, inconsistent labels of training data led to biased algorithms.11

Secondary Research of Unjust Facial Recognition Technology

Gender Shades is a 2017 algorithm audit conducted by Buolamwini. It verified that IBM and Microsoft algorithms misclassified darker females more often than lighterskinned people and males. Buolamwini created a dataset called “Pilot Parliaments Benchmark.” It consisted of 1270 images of parliament members from Rwanda, Finland, South Africa, Iceland, Senegal, and Sweden. Buolamwini found that IBM and Microsoft algorithms had accuracies of 99% when classifying images of lighter males. Whereas, when classifying darker females, IBM

9. AWS. “What is Facial Recognition?” https://aws.amazon.com/ what-is/facial-recognition/ (Accessed 2023).

10. Kantayya, Shalini, director. Coded Bias. Netflix, 2020. 1 hr., 25 min. https://www.netflix.com/title/81328723

11. IBM. “Shedding light on AI bias with real world examples.” https:// www.ibm.com/blog/shedding-light-on-ai-bias-with-real-worldexamples/ (2023).

has 65% accuracy and Microsoft has 80% accuracy.12 In 2016, Detroit’s facial recognition surveillance system “Project Green Light” was rolled out to communities — mostly in Black communities. White and Asian populations were not as heavily surveilled compared to Black populations.13

Primary Research of Expert Interview I

An interview was conducted with FIT English Assistant Professor Dr.Subhalakshmi Gooptu, an expert in Asian diasporic, critical race, and transnational gender studies. Gooptu’s analysis specifically focuses on how technologies of reproductive control shaped indentured women’s experiences. Connecting this to the present, her research sees the connections to current fights for reproductive justice and how assisted reproductive technology perpetuates racial inequality throughout the world. She researches “Who was the technology experimented on?”, “Who is it serving?”, “Who is being used for surrogacy?”, and “Who is it empowering?”

“All of technology is a question of power,” said Gooptu. Technology is a broad term and enforces “a system of power.” There is unequal access to technology. While it benefits one population, it also harms another population. This perspective resonated with Dr.Cathy O’Neil’s, author of Weapons of Math Destruction, concern “What worries me about AI is power. It’s really about who owns the code.”14

Primary Research with Surveys

Surveys were distributed to obtain perspectives and experiences with facial recognition. It explored the public’s perspectives on facial recognition and its usage in various applications including law enforcement, education, healthcare, transportation, corporations, and retail.

Thirty-six participants completed the surveys. The surveys were distributed on the campus at the Fashion Institute of Technology (87%) and in the Moynihan Train

12. Ibid.

13. Najibi, Alex. “Racial Discrimination in Face Recognition Technology.” https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2020/racialdiscrimination-in-face-recognition-technology/ (2020).

14. Kantayya, Shalini, director. Coded Bias. Netflix, 2020. 1 hr., 25 min. https://www.netflix.com/title/81328723

10-question survey with qualitative and quantitative questions.

Hall (13%) in New York. Subjects ranged from age 19 through age 64. Gender identity distribution was 68% female, 27% male, and 5% non-binary.

The following are some responses to the open-ended question: What do you think about facial recognition?

• “Facial recognition is a great resource as long as the data of the users is being stored securely. It’s also not appropriate for kids in my opinion.”

• “I think facial recognition in national and private circumstances is good, but giving law enforcement and corporations more power over the working man is fundamentally wrong.”

• “People need to be able to decide for themselves whether or not it’s okay and in what context. It needs to be an opt-in.”

• “Highly embrace new technology such as facial recognition. Proper usage and regulations need to be taken care of.”

• “I think it’s cool for Face ID to unlock my phone but I don’t want to be constantly monitored and scanned when out in public.”

55.5% of the participants rated 8,9, or 10, and 19.4% rated 1 to interacting with facial recognition daily.

22.2% do not support the usage of facial recognition in law enforcement.

• “I think it is a complement to what has been always done.”

• “I think it’s dangerous, easily misused, and often biased and racist.”

• “I am highly skeptical and think bad outcomes outweigh the good. I want to consent to my image being calculated. I prefer personal, self-serving facial recognition that I consent to.”

• “I don’t know enough to have an informed opinion. Doesn’t seem to be that useful to me.” The following are some responses to the question: What positive experience(s) did you ever have with facial recognition?

• “Opening my phone without using my hands.”

• “Ease in turning on my phone and its use as a replacement for typing passwords.”

• “To unlock my iPhone quickly and get through airport immigration faster.”

• “I used it when I passed the customs and it was super fast.”

• “Phone safety of tracking offenders/criminals (sometimes - unless they change their face).”

• “Not mine: finding missing/trafficked people — especially children seems to be the ‘most good’ use.”

• “Google Photos sorting is helpful when searching my personal images and unlocking my phone.”

The following are some responses to the question: What negative experience(s) did you ever have with facial recognition?

• “My phone sometimes doesn’t recognize me.”

• “I don’t like how easy it is to find me online. It makes it very difficult to keep personal and professional separate.”

• “Not a negative experience but I feel weird about my face being scanned by random devices. I don’t feel secure about it.”

• “Invasion of Privacy.”

• “When I was on exchange abroad, I felt as though the government had cameras everywhere and I felt like I was being watched and analyzed.”

• “Not being accurate/would detect my face in the dark with a mask or anything on your face (but this is in reference to phone security only).”

• “The fact that the federal government has the ability to detect a face then use satellite imaging to track down said person’s exact whereabouts and path is indicative of the fall of the “free west” and greater human error in general..”

The survey results suggested that people were concerned about the safety of the biometric data. Participants were concerned about the accuracy of the algorithms and the power the government gains by recording our facial data.

Secondary Research of Participatory Techniques

Complicated topics such as AI ethics can be broken down into simpler concepts that encourage everyday audiences to understand. Nina Simon, author of The Participatory Museum, wrote “When people have safe, welcoming places in their local communities to meet new people, engage with complex ideas, and be creative, they can make significant civic and cultural impact.”15

15. Simon, Nina. The participatory museum. Museum 2.0, (2010).

In The Participatory Museum, Simon included many case studies of participatory museums:

• A powerful example of provocative programming is a traveling exhibition called “Dialogue in the Dark.” Since 1988, it has had 6 million visitors. Tour guides who are visually impaired guide visitors in complete darkness through stressful scenarios like a crosswalk or supermarket. Follow-up studies found that visitors remembered this experience even after five years had passed since visiting. Visuallyimpaired tour guides gained self-confidence after helping visitors through the experiences.16

• A provocative exhibition at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg separates white and non-white visitors starting from the entrance. Visitors are given tickets with labeled racial identities. There are two visitor journeys that “intentionally alienates people, makes them frustrated, and can generate discussion out of that frustration.”17

• In 2000, Denmark created the Human Library event where visitors check out a 45-minute meeting with a human book to openly talk about their stereotypes and prejudice. The experience challenges stereotypes and it is “a chance to unjudge someone.” “The Human Library is a place where difficult questions are expected, appreciated, and answered. We publish people as open books.”18

These participatory museum methods kept visitors engaged and sparked conversations about difficult topics. It builds empathy among the audience and helps them understand from different perspectives. Role-play was adopted in the exhibition design in part II. Inspired by the Human Library, the applied thesis exhibition also told stories from first-person narratives.

Primary Research of Expert Interview II

A second interview was conducted with Isabella Bruno who is the Learning and Community Lead at the Smithsonian Office of Digital Transformation. Her expertise in workshop programming provided insight into the workshop design of the exhibition design in part II. When designing workshops, Bruno suggested distilling down questions into one clear question. It is better to ask one concise question rather than a few similar questions. Additionally, she suggested that workshops can be separated into groups that are assigned different tasks simultaneously and convene afterward.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Human Library. “About The Human Library.” https://humanlibrary. org/about/ (Accessed 2023).

Exhibit 1 is a world map of skin tone distribution. A participant places a sticker where their parents were from on a world map showing skin tone distribution.

Bruno’s insights were very helpful in the experience design of the real-world impact workshop in the applied thesis exhibition where visitors learn how to practice AI responsibly. It is important to set a shared agenda in the introduction to the workshop. Then, participants have a common goal and individual roles. Additionally, Bruno mentioned the importance of embracing silence and giving space for participants to think. It is fundamental to have some ideas and develop viewpoints before listening to others.

Primary Research of Prototype Testing I

I designed three exhibits to prompt conversations about biases in facial recognition. The participants had ten minutes to explore the interactions. They may go through the exhibits silently or converse about what they think and feel with other visitors.

Exhibit 1

The first one was a world map showing the distribution of light and dark-colored skin distribution.19 The prompt said, “Place a sticker where your parents come from.” Visitors placed heart stickers on the map. From this interaction, I hoped visitors would notice that skin tone bias is a worldwide problem.

19. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. https://kids.britannica.com/students/ assembly/view/52059 (2012).

Exhibit 2

The second interaction is three boxes labeled Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. Visitors open the boxes and see three-panel brochures showing the misclassifications of our heroes in history such as Sojourner Truth, Michelle Obama, and Oprah Winfrey. The algorithms misidentified women as male with confidence scores of approximately 70%.

Participant 1 suggested “It would be interesting to see not only the things that they get wrong, but also the things that they get right.” Having both correct and incorrect classifications show visitors which phenotypes (light-skin males) are usually correctly classified versus phenotypes (dark-skin females) that are commonly misclassified.

Exhibit 3

The third interaction displays eight boxes labeled male, female, child, adult, Caucasian, Hispanic, Black or African American, and Asian. There are three boxes filled with images of human faces.20 Visitors categorize the faces by gender, age, and race by placing the images in the eight boxes.

20. Gupta, Ashwin. “Human Faces.” Kaggle. https://www.kaggle.com/ datasets/ashwingupta3012/human-faces (2020).

Exhibit 2 shows Microsoft, Google, and Amazon algorithm misclassifications.

Participant 2 observed, “These were super effective where [categorizing] adult, child — people were totally comfortable. Male, female — a little less. Race — nobody wants to put anybody in a box.” This activity sparked a discussion where participants questioned “What does it mean to be inclusive? Is it sort of a proliferation of categories so we get more and more granular categories or is it the obliteration of categories altogether?”

Participant 3 suggested, “I wonder if this can be done with alternate sets of inputs that are meaningless to the real world. Take nuts for instance, it can have different colors, different sizes, all these sets of variables and you can use that as a way of showing what it can do and what it can’t do. After you see all the things that it gets wrong, then say how it gets people wrong. [This helps] understand why it’s being applied wrong.”

Participant 4 suggested a facilitated experience where the facilitator would “step in and say how do you know somebody is Asian or Female?” She said “If you can create an exhibit where people are asking what do I

At exhibit 2, visitors read examples of misclassifications of our heroes in history

Exhibit 3 is the categorization of gender, age, and race.

At exhibit 3, visitors sorted images into eight boxes labeled male, female, child, adult, Caucasian, Hispanic, Black or African American, and Asian.

Participants randomly selected attributes to create their fictional persona.

really want machine learning to do for me, what is the value of computer vision, what do I want it to do, how can I advocate for my government to set limits or for research to investigate the questions that I think are the most interesting, then that’s an amazing exhibit.”

Primary Research of Prototype Testing II

The next prototype testing analyzed how participants responded to stories from people who were impacted by facial recognition, both positively and negatively. Twelve participants adopted fictional personas and reflected on the true stories from their own perspectives and their personas’ perspectives.

Adopt-A-Persona

Participants first adopt fictional personas with randomized names, ages, gender identities, ethnicities, jobs, and Fitzpatrick skin type. Fitzpatrick skin type is a 6-point scale that describes how skin responds to ultraviolet light. Type I is white skin that burns and never

tans whereas type VI is black skin that never burns and tans easily.1 Participants randomly chose their demographics from a box of stickers.

Read and Reflect

After adopting personas, visitors read diaries of people who were impacted by facial recognition. Next, they write or draw how they felt and how their personas would feel about the story.

1. Ward WH, Lambreton F, Goel N, et al. Clinical Presentation and Staging of Melanoma. In: Ward WH, Farma JM, editors. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications; 2017 Dec 21. TABLE 1, Fitzpatrick Classification of Skin Types I through VI. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/books/NBK481857/table/chapter6.t1/ doi: 10.15586/codon. cutaneousmelanoma.2017.ch6

Visitor ID card.

Seventeen diaries of people impacted by facial recognition.

Participants were photographed during the prototype.

Content of the seventeen diaries of people impacted by facial recognition.

Participants reflected on the diaries from their own perspective and their persona’s perspectives. Some received responses of how participants felt were:

• “I feel dumbfounded at the lack of due process and mistakes that were made by the officers. Computers are tools used by people that do not and cannot omit responsibility. Honestly ridiculous! I feel sad Robert feels humiliated. It is not his fault.”

• “I feel a little confused because I am not very aware of police laws.”

• “Conflicted. I think this is a great use of facial recognition — to help abused children, but it’s a slippery slope.”

• “No sympathy, that’s the way it goes. I’m sure this moment won’t impact his life beyond one night.”

• “Glad corruption is coming to light, this feels like a horrible and icky thing to do.”

Some responses from the perspective of the fictional personas were:

• “As a journalist I see this too often to be surprised. It still hurts though to hear someone being falsely accused.”

• “My persona being a GenZ, possibly knows about facial technology through TikTok and she is happy the offender is in jail.”

• “My persona is a young person, however, I feel like he should have consciousness about specific topics. I feel a bit confused because he is also Hispanic, so I’m not sure.”

• “No sympathy, I’m sure he doesn’t truly know what prejudice really feels like.

The feedback I got from participants of this prototype was that it was difficult to reflect on the stories from the personas because of the numerous demographic categories. Participant 1 said “I felt a little odd. Writing with the persona that I was asked by you just because it’s like an experience that I can’t know, you know?” Participant 2 agreed “There were so many categories to kind of try to piece together a persona, so many disparate elements.”

The strongest motivator when reflecting on the diaries from the fictional persona was occupation instead of other demographics such as ethnicity, age, gender identity, or skin type. Participant 3 said “I was a journalist who lived in Alaska and I was responding to a violent police act. So I could kind of say, as a journalist, I think

Participants reflect on how they felt and how their personas would feel.

this person would be very curious about how this went wrong and where I’m wrong, as well as the over-policing of Native communities.”

The activity did not change opinions about facial recognition, but it broadened participants’ knowledge of the technology. Participant 1 said “I don’t think it changed my view, but the story about using facial recognition to find kids who are being posted and videos of them being sexually abused online. I was like, well, that’s the use, I hadn’t considered. I’m kind of anti-AI facial recognition, but I hadn’t considered that use for it before. And that, like, you know, that’s that might have planted a seed that might grow, we’ll see.”

Seven key concepts of the exhibition.

Part II Exhibition Project

The concept development was a proposal of the exhibition “Artificial Minority” that would take place at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. It would be an eleven-month exhibition sponsored by the National Institute of Standards and Technology. “Artificial Minority” encourages visitors to understand individuals whose lives were positively and negatively affected by high-stakes facial recognition technology.

Client Description

The client is the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), a US Department of Commerce agency established in 1901. NIST’s mission statement is “to promote U.S. innovation and industrial competitiveness by advancing measurement science, standards, and technology in ways that enhance economic security and improve our quality of life.”1 In 2000, NIST created the Face Recognition Vendor Testing Program (FRVT), which conducts evaluations on facial recognition technology. This research provides recommendations to the government on how this technology should be used.

1. NIST. “About NIST.” https://www.nist.gov/aboutnist#:~:text=Mission,improve%20our%20quality%20of%20life. (2022).

Exhibition Site Description

The site is at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. “Artificial Minority” takes place at the 6,000-square-foot gallery on the third floor.2 Cooper Hewitt was chosen because of their mission to educate, inspire, and empower people through design.”3

Additionally, in 2019, Cooper Hewitt hosted public events for The Museums + AI Network, which was driven by 50 professionals and 200 public members. Hosting the exhibition in the Cooper Hewitt facilitates outreach to the local design community.4 Murphy and Villaespesa wrote “Museums, as social purpose institutions, must reflect upon their professional standards, alongside the law when it comes to developing and implementing AI technologies.”5

2. Cooper Hewitt. “Architectural Fact Sheet.” https://www. cooperhewitt.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Architectural-FactSheet-Formatted_PACC-Edits_PGM061614_2.pdf (2014).

3. Cooper Hewitt. “About Cooper Hewitt.” https://www. cooperhewitt.org/about/#:~:text=our%20mission,and%20 empowers%20people%20through%20design (2023).

4. Cooper Hewitt. “Curator, Computer, Creator: A Discussion on Museums and AI in the 21st Century.” https://www.cooperhewitt. org/2019/10/15/curator-computer-creator-a-discussion-onmuseums-and-ai-in-the-21st-century/ (2019).

5. Murphy, Oonagh, and Elena Villaespesa. AI: a museum planning toolkit. Goldsmiths, University of London, (2020).

Audience Description

The primary audiences are high school students, college students, and adults. The motivator type is the “Explorer” — people who are curious about learning about various topics. In 2022, a survey conducted by the PEW Research Center on 11,000 Americans suggested that people may not be aware of how much AI infiltrates our lives. 44% of the sample think they do not interact with AI daily. Only 30% of the sample had high awareness of the AI incorporated in chatbots, music recommendations, emails, fitness trackers, ad placement, and security cameras.1

Introductory Area

Entering the exhibition, visitors learn about the field of facial recognition. In the introductory area, they see an infographic describing how facial recognition technology works.2

1. Kennedy, Brian, Alec Tyson, and Emily Saks. “Public awareness of artificial intelligence in everyday activities.” https://www.pewresearch. org/science/2023/02/15/public-awareness-of-artificial-intelligencein-everyday-activities/ (2023).

2. Zhang, Xin, Thomas Gonnot, and Jafar Saniie. “Real-time face detection and recognition in complex background.” Journal of Signal and Information Processing 8, no. 2 (2017): 99-112.

An infographic in the introductory area.

The aluminum spotlight sculpture represents the goal of the exhibition, which is to spread public awareness of biases in algorithms.

A model showing the Adopt-A-Persona kiosks and rows of stacked books to symbolize the exhibition’s theme on people’s stories.

Visitors read diaries and write how they feel and how their persona would feel in response to the stories.

Visitors plug in megaphone cables and listen to people talking about incidents when they were impacted by facial recognition such as when Robert Williams was wrongfully arrested by the police because of algorithmic misidentification.1

1. ACLU. “Wrongfully Arrested Because of Flawed Face Recognition Technology.” https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=Tfgi9A9PfLU&t=99s&ab_ channel=ACLU (2020).

Diaries Stations of Robert Williams and Andrew Conlyn.

Visitors sit under the directional speakers and listen to longer interviews of people’s experiences with the technology. For example, NY Times journalist Kashmir Hill talks about her eventful investigation on Clearview Al, a company who created a database of social media photos which they then sold to law enforcement.1

1. Hill, Kashmir. “The Secretive Company That Might End Privacy as We Know It.” https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/18/technology/clearviewprivacy-facial-recognition.html (2020).

Adopt-A-Persona Area

Entering the Adopt-A-Persona stations, visitors take a personality quiz and get a fictional persona and RFID card. Throughout the exhibition, there are four diary stations where people read true stories of people impacted by facial recognition and they reflect on these stories from their perspectives and personas’ perspectives. Their responses are recorded and they see responses from other visitors.

Everyday Activities Area

Afterward, visitors see a projection map of environments where facial recognition is heavily used such as airports, concert venues, supermarkets, and police stations. With motion-gesture sensors, they identify where the cameras are. As they walk along the narrow hallway with laser beams and security cameras, they see what the computers detect and recognize. They realize how facial recognition technology is inconspicuously incorporated into our lives.

Facial Recognition as a “Double-Edged Sword” Area

Next, visitors see a tri-fold wall with hanging plaques describing how facial recognition is used in the justice system, healthcare, surveillance, etc. One side is labeled “pros” and the other is labeled “cons.”

Public Trust Area

Visitors enter into a darkened room filled with acrylic sheets with vinyl-printed graphics. They activate light by stepping on trigger pads allowing them to read about advocacy efforts from AJL, ACLU, and Big Brother Watch.

“How much do I have to change myself to fit in?” Area

Visitors take part in a recreation of Buolamwini’s Aspire Mirror by wearing a personalized paper mask and choosing a face filter of someone they aspire to.1

Bias-Busting Area

At the bias-busting area, visitors learn to navigate through human biases such as similarity bias and conformity bias by playing the “Monopoly of Biases.”

1. Buolamwini, Joy. “Aspire Mirror.” https://www.aspiremirror.com/ (Accessed 2023).

Visitors decide which areas are pros or cons of facial recognition usage.

They learn about NIST’s facial recognition audits and how they mitigate algorithmic bias by setting measurement standards for the technology.

Visitors point to security cameras on a projected video of streets.

Visitors see projected videos of the computers detecting and identifying people.

A model showing acrylic panels and scaled figures.

Visitors see mirror tiles and paper masks that they can personalize with markers.

They wear their paper masks and go to the interactive tabletop.

A projector projects an interactive game on the floor and a motion sensor captures the visitors’ gestures.

First a visitor jumps to roll the virtual dice. Then moving to the designated spot, a prompt pops. Inspired by the family feud game, the prompt explains a type of bias and directs the player to list the most common bias abuse in a situation. For instance, if we land on similarity bias, we have to name the top 4 common attributes an employer might hire someone if they share the same characteristic; two attributes would be: same college and same hobby.

They answer critical questions about training data and application deployment.1

1. The Museums + AI Network. “AI: A Museum Planning Toolkit.” https://themuseumsai.network/toolkit/ (2019).

On a scale of one through five, visitors vote on “how much they supported facial recognition.”

Workshop Area

Visitors see a workshop where they are tasked with creating an AI start-up following an AI ethics workflow from the Museum + AI Network.

Exit Area

Exiting the workshop, visitors recycle their ID cards in the voting bins. They are reminded to share their experiences with facial recognition with the graphic of Buolamwini’s quote, “If you have a face, you have a place in the conversation.”1

Discussion

The goal of the exhibition “Artificial Minority” was to spread public awareness of biases embedded in facial recognition. It focuses on people and how their lives were impacted. It reveals the repercussions of biased AI, but it also explores the potential of facial recognition to improve people’s quality of life and the efforts underway that combat unethical AI. Visitors are encouraged to reflect on the stories and share their own experiences with facial recognition.

1. AJL. “Become an agent of change.” https://www.ajl.org/ take-action#:~:text=If%20you%20have%20a%20face,resist%20 harmful%20uses%20of%20tec. (Accessed 2023).

Design elements such as plywood backwalls with various wood veneers and gel stains represent the diversity of human skin tones. Wood is paired with acrylic to represent transparent AI and the efforts undertaken to turn the cryptic black box into a glass box. Triangular graphic elements representing voices add a sense of urgency to the tone of the exhibition. Extended experiences such as a digital exhibition and gamified marketing collateral continue the conversation outside of the exhibition.

Conclusion

The exhibition project applied the knowledge learned from the research in part one of the paper. Background information on how facial recognition technology works was incorporated in the infographics and timeline of technological advancement in the introduction area. Participatory museum techniques such as role-play with fictional occupations encourage visitors to empathize and view facial recognition from various perspectives such as police officers, lawyers, or journalists. They are also encouraged to share their own positive and negative experiences with facial recognition. The AI

ethics design toolkit by the Museum and AI Network was incorporated into the real-world impact workshop to allow visitors to practice a responsible AI workflow where they ask critical questions during data training and implementation.

The primary interview with Dr. Subhalakshmi Gooptu introduced the notion that “technology is a question of power.” There is unequal access to it and it can benefit one group while harming another group. The interview with Isabella Bruno shared the methods to facilitate workshops and create a comfortable environment for visitors to reflect and contribute. Prototype testing showed how people react to facial recognition classification and diaries of people impacted by the technology. Surveys gathered information about people’s opinions on facial recognition usage in different industries. Both primary and secondary research were fundamental to the development of the exhibition project.

Next Steps

The exhibition project was presented to exhibition design industry professionals at the FIT Capstone Event on December 8, 2023. Many of them found the “Artificial Minority” informative and thought-provoking. People found this topic timely with the current state of technology. One judge wrote “Overall a very current topic, and almost too much to still learn about this topic to put into one exhibition. But such an important topic, and important to create more awareness.” Another judge wrote “Balanced sequence of hard facts, emotional stories, hands-on workshops, and illuminations. Potentially overwhelming data, tamed yet effective.”

People were curious about what happens after the exhibition and how visitors can make an impact. The exhibition “Artificial Minority” would be a way to start and continue conversations about AI ethics. Public awareness of algorithmic bias can encourage responsible practices among researchers and legislators.

A scaled model of the entire exhibition.

Resources

ACLU. “Face Recognition Technology.” https://www.aclu. org/issues/privacy-technology/surveillance-technologies/ face-recognition-technology (Accessed 2023).

ACLU. “Wrongfully Arrested Because Face Recognition Can’t Tell Black People Apart.” https://www.aclu.org/ news/privacy-technology/wrongfully-arrested-becauseface-recognition-cant-tell-black-people-apart (2020).

AJL. “Become an agent of change.” https://www. ajl.org/take-action#:~:text=If%20you%20have%20 a%20face,resist%20harmful%20uses%20of%20tech. (Accessed 2023).

AJL. “Our mission.” https://www.ajl.org/about (Accessed 2023).

AWS. “What is Facial Recognition?” https://aws.amazon. com/what-is/facial-recognition/ (Accessed 2023).

Big Brother Watch. “About Big Brother Watch.” https:// bigbrotherwatch.org.uk/about/ (Accessed 2023).

Bryer, Tania and Revesz, Rachael. “Dr. Fei-Fei Li: The benevolent scientist.” https://www.cnbc.com/fei-fei-li-the-biggest-perils-andopportunities-in-ai/ (2019).

Buolamwini, Joy. “Aspire Mirror.” https://www. aspiremirror.com/ (Accessed 2023).

Cooper Hewitt. “About Cooper Hewitt.” https:// www.cooperhewitt.org/about/#:~:text=our%20 mission,and%20empowers%20people%20through%20 design (2023).

Cooper Hewitt. “Architectural Fact Sheet.” https:// www.cooperhewitt.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/ Architectural-Fact-Sheet-Formatted_PACC-Edits_ PGM061614_2.pdf (2014).

Cooper Hewitt. “Curator, Computer, Creator: A Discussion on Museums and AI in the 21st Century.” https://www. cooperhewitt.org/2019/10/15/curator-computer-creatora-discussion-on-museums-and-ai-in-the-21st-century/ (2019).

A collection of brainstorming models and prototypes.

Discussion with Capstone Judges.

Democracy Now. “How AI Is Enabling Racism & Sexism: Algorithmic Justice League’s Joy Buolamwini on Meeting with Biden.” https://www.democracynow.org/2023/6/22/ joy_buolamwini_on_ai_risks (2023).

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. https://kids.britannica.com/ students/assembly/view/52059 (2012).

Georgetown Law. “The perpetual line-up.” https://www. perpetuallineup.org/ (2016).

Gupta, Ashwin. “Human Faces.” Kaggle. https://www. kaggle.com/datasets/ashwingupta3012/human-faces (2020).

Hill, Kashmir. “The Secretive Company That Might End Privacy as We Know It.” https://www.nytimes. com/2020/01/18/technology/clearview-privacy-facialrecognition.html (2020).

Human Library. “About The Human Library.” https:// humanlibrary.org/about/ (Accessed 2023).

IBM. “Shedding light on AI bias with real world examples.” https://www.ibm.com/blog/shedding-lighton-ai-bias-with-real-world-examples/ (2023).

John Hopkins. “Study Suggests Medical Errors Now Third Leading Cause of Death in the U.S.” https://www. hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/study_ suggests_medical_errors_now_third_leading_cause_of_ death_in_the_us (2016).

Kantayya, Shalini, director. Coded Bias. Netflix, 2020. 1 hr., 25 min. https://www.netflix.com/title/81328723

Kennedy, Brian, Alec Tyson, and Emily Saks. “Public awareness of artificial intelligence in everyday activities.” (2023).

Murphy, Oonagh, and Elena Villaespesa. AI: a museum planning toolkit. Goldsmiths, University of London, (2020).

Najibi, Alex. “Racial Discrimination in Face Recognition Technology.” https://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2020/ racial-discrimination-in-face-recognition-technology/ (2020).

NIST. “About NIST.” https://www.nist.gov/aboutnist#:~:text=Mission,improve%20our%20quality%20 of%20life. (2022).

Parker, Jake, “Facial Recognition Success Stories Showcase Positive Use Cases of the Technology.” https://www.securityindustry.org/2020/07/16/facialrecognition-success-stories-showcase-positive-usecases-of-the-technology/ (2023).

Simon, Nina. The Participatory Museum. Museum 2.0, (2010).

The Museums + AI Network. “AI: A Museum Planning Toolkit.” https://themuseumsai.network/toolkit/ (2019).

Ward WH, Lambreton F, Goel N, et al. Clinical Presentation and Staging of Melanoma. In: Ward WH, Farma JM, editors. Cutaneous Melanoma: Etiology and Therapy [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Codon Publications; 2017 Dec 21. TABLE 1, Fitzpatrick Classification of Skin Types I through VI. Available from: https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481857/table/chapter6.t1/ doi: 10.15586/codon.cutaneousmelanoma.2017.ch6

Zhang, Xin, Thomas Gonnot, and Jafar Saniie. “Real-time face detection and recognition in complex background.” Journal of Signal and Information Processing 8, no. 2 (2017): 99-112.

Building an Anti-Racist Practice Through Critical Making Experiences

In

the Time-Based Media Classroom

Andrea

Cardinal

Assistant Professor of Design, Bowling Green State University

Abstract

The learning of complex subject matter, such as racism, is most effective when it is an intentional process of constructing meaning from information and experience (Watson & Reigeluth, 2008). As designers, we aim to take complex content and make it compelling for the user, connect it to their own life experiences, and hopefully affect their future actions and beliefs. As educators, we aim to impart our knowledge and concrete skills to our students so that they can become confident, ethical shapers of our media and culture.

As design educators, we are responsible for cultivating humans who are cognizant of how they replicate biases within the interlocking systems of structural inequality, including white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, capitalism, ableism, and settler colonialism (Design Justice Network, 2016). We must eliminate the harms perpetuated by wellmeaning design professors, professionals, and students when working on altruistic community-based projects. And while many of us encourage our students to be empathetic creators, it is not enough to merely imply anti-racism through “community engagement” or “design thinking” projects or by “decolonizing” syllabi. It needs to be explicit.

This paper will focus on current pedagogical and creative research using the process of the development of motion graphics and the production of interactive storytelling websites to move end-users and, maybe more importantly, our students toward a reflective level of cognition (Norman, 2004) regarding their own biases. The global aim is to move all audiences to this level of action by simultaneously engaging more of their sensory faculties—visual, auditory, and subtle digital interactions with this media.

Using a combination of a Critical Making Approach when teaching timeline-based software and the Design Justice Network Framework, Cardinal recently analyzed her design pedagogy to determine how to best engage students in addressing the effects of racism within our communities.

This paper and presentation will introduce examples of current motion graphics projects by design students on developing an anti-racist practice. In our course, students learn about historical and contemporary inequalities of anti-Black racism within our region through current data and locally produced media that tell our neighbor’s stories. This comprehensive approach allows students to uncover and acknowledge their cultural biases while developing their time-based media, user interface, and interaction skills. Attendees and readers can assess if their pedagogical approach would be served by teaching this form of visual communication to drive cultural change in their locales.

Introduction

Design is 75% white, and it is roughly 53% female (DATA USA: Graphic Designers, 2022). My student body has typically reflected these statistics, skewing even more heavily toward young white women. They generally come from areas around Ohio and Michigan, typically from upper and middle-class white families. While some identify as LGBTQIA or have various disabilities, few hold multiple marginalized identities, and most have been afforded many privileges in their access to education and artistic experiences. In 2019, inspired by my new position at Bowling Green State University and my study of the framework developed by the Design Justice Network (DJN, 2016 – see inset of principles), I reassessed my approach to design pedagogy with more intentionality and focus. The DJN principles were informed significantly by the work of scholar Patricia Hill Collins in her text, Black Feminist Thought, where she coined the term matrix of domination (Collins, 2009). The matrix of domination describes the interlocking systems of structural inequality, which include white supremacy, heteropatriarchy, capitalism, ableism, and settler colonialism. “Design justice urges us to explore the ways that design relates to domination and resistance” at personal, community, and institutional levels (Costanza-Chock, 2020). I was also profoundly inspired by the memoir HEAVY by writer and educator Kiese Laymon, in which he details his experience teaching at a predominately white private institution. Considering the matrix, my students’ and my own biases, I asked myself the following questions: what kind of student am I developing? Are the white women I teach in my “socially engaged” courses, with my “decolonized syllabi,” ever genuinely addressing their own implicit biases? How was I unintentionally fortifying or diverting their power? And how could I better design the experience in my classroom to address racism, specifically anti-Black racism, in our communities?

Using these guideposts, I re-wrote my Time-Based Graphic Design courses to no longer focus on animation, video editing, or UI prototyping for self-promotional purposes but to be a 16-week course on building an anti-racist practice through a critical-making process. The course framework references various curricula that I have engaged with as a learner, particularly the YWCA’s Dialogue To Change, the Creative Action Lab’s How Traditional Design Thinking Protects White Supremacy, and Campus Compact’s Anti-Racist Community - Engaged Learning: Principles, Practices, and Pedagogy, Co-Creating an Anti-Racist Community of Practice Where You Are

Design Justice Network Principles

Principle 1

We use design to sustain, heal, and empower our communities, as well as to seek liberation from exploitative and oppressive systems.

Principle 2

We center the voices of those who are directly impacted by the outcomes of the design process.

Principle 3

We prioritize design’s impact on the community over the intentions of the designer.

Principle 4

We view change as emergent from an accountable, accessible, and collaborative process, rather than as a point at the end of a process.*

Principle 5

We see the role of the designer as a facilitator rather than an expert.

Principle 6

We believe that everyone is an expert based on their own lived experience, and that we all have unique and brilliant contributions to bring to a design process.

Principle 7

We share design knowledge and tools with our communities.

Principle 8

We work towards sustainable, community-led and -controlled outcomes.

Principle 9

We work towards non-exploitative solutions that reconnect us to the earth and to each other.

Principle 10

Before seeking new design solutions, we look for what is already working at the community level. We honor and uplift traditional, Indigenous, and local knowledge and practices.

“You cannot change any society unless you take responsibility for it, unless you see yourself as belonging to it and responsible for changing it.”

Grace Lee Boggs

In addition, the course synthesizes dozens of regional and national media and resources culled from continuing education trainings at Bowling Green State University’s Center for Faculty Excellence and the University of Michigan Ginsberg Center for Community Service and Learning (See Appendix A: Selected Resources List). These materials articulate the types and effects of anti-Black racism and offer solutions for recognizing and addressing disparities. At the start of the course, we spend a brief time on broader historical stories and figures with which most of us are considerably more familiar. Instead, the focus is on local and contemporary media so my students understand that racism is not from another time or another place but is here and is now. They are typically astounded by the statistics and shaken by the stories.

This paper will describe the pedagogical approach to the course as a whole, focusing on the development of motion graphics using Adobe After Effects while also learning how to develop an anti-racist practice for themselves. For the latter half of the course, they put these concrete and abstract skills to use, along with previous knowledge gained in our UX/UI course, to build a comprehensive interactive storytelling website prototype in Figma. Because the affordances of motion and interactive time-based work can engage more of the user’s (and the designer’s) senses more comprehensively, we can move them to a reflective level of emotion more effectively (Davis, 2012). The reflective level of cognition is where future actions and beliefs are affected (Norman, 2004), and experiences intentionally designed with this in mind can become essential agents of transformation within our culture.

Methodology

In 1997, the American Psychological Association researched Learner-Centered approaches to education. It developed a set of Principles in the following categories: Cognitive and Metacognitive Factors, Motivational and Affective Factors, Developmental and Social Factors, and Individual Differences Factors (inset, abbreviated for this publication). Watson and Reigeluth summarize multiple other studies regarding learnercentered approaches that emphasize the “importance of customization and personalization” with regard to instruction and stress that learners be “treated as co-creators of the learning process.” They advise that education should involve the broader community more explicitly and that learning tasks are “authentic tasks, often in real community environments” (Watson & Reigeluth, 2008). While their research focused on K-12 educational settings, our higher-ed classrooms are well-positioned to institute their recommendations more comprehensively. Design education is particularly well suited for this approach because design work requires us to thoroughly research our topic and client, determine a structure and point of view for an intended audience, and create engaging assets that communicate our findings. We already employ several of the outlined methodologies, albeit with less explicit or intentional construction. With the content of this course, I have considered these approaches more carefully, given the stakes of the task.

“The learning of complex subject matter is most effective when it is an intentional process of constructing meaning from information and experience” (Watson & Reigeluth, 2008). Week by week, I present the statistics and stories of anti-Black racism alongside the steps one must take to address the biases inherent in all of us

through our dominant white supremacist culture. We analyze how that came to be—and understand that as designers, we are amongst the most culpable. We shape culture through the media we produce. And if we are not intentionally deconstructing those biases, we are unintentionally replicating them. Collins addresses the design of our culture expressly, indicting those of us creating the visuals that saturate our psyches— “Taken together, these prevailing images...represent elite white male interests...moreover by meshing smoothly with intersecting oppressions of race, class, gender, and sexuality, they help justify the social practices that characterize the matrix of domination in the United States” (Collins, 2009).

Again, if we do not help our students intentionally deconstruct their inherent biases, they will unintentionally replicate them in the media they produce. As educators, we are called to confront these realities within our spheres of influence to ensure that our students are cognizant of the biases and how they show up in their design work.

Figure 1. Ibrahim, Andrew M. “A Surgeon’s Journey Through Research & Design.” A Surgeon’s Journey Through Research & Design, 2019, https://www.surgeryredesign.com/.