In November, more than a dozen Review editors attended the NSPA/JEA Fall Journalism Conference in St. Louis, and, for a third straight year, came home with the prestigious Best of Show award for the top single edition of any small-school newspaper.

“It was truly amazing to be honored for all of our hard work on that issue,” said sophomore design editor Amanda Brantley. “It was magical.”

Also at NSPA, sophomore design editor Serina Yan won rst place for her editorial cartoon. This year’s Editor-in-Chief Wilson Bailey and Executive Editor Ella Chen (’22) placed third for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion reporting (“16 years after Katrina, Hurricane Ida wreaks havoc, displaces alums from New Orleans to N.J."). Multimedia editor James Li and sophomore Annie Villa were awarded fth place in the Broadcast Feature Story category ("Mountain Biking Club hits the trail").

For the fourth straight year, the Review received the highest recognition for hybrid news (print and online): a Gold Crown, awarded by the Columbia Scholastic Press Association.

Individually, the CSPA Gold Circle winners included Ella Piper Cla y for rst place personal opinion (on-campus issues), Jennifer Liu for rst place cultural feature, Ellie Monday (’22) for second place sidebar writing, Diane Guo for second place cartoon portfolio, Diane Guo and Alice Xu for second place cartoon, Guo, Xu and Celine Huang (’22) for second place two-page design, and Huang for third place computer-generated art and illustration. The editorial board also placed second in editorial writing.

Annie Jones and Aleena Gilani won National Gold Medals from the National Scholastic Writing Awards in Journalism for “Protests spark fear, memories of 1979 Iranian Revolution" and “The struggle to conform: How Eurocentric beauty standards alter our self-perceptions," respectively.

The website was also named a Distinguished Site by Student Newspapers Online in March, marking four consecutive years of receiving the honor. Distinguished Sites meet criteria for six categories: continuous coverage, site excellence, story page excellence, excellence in writing, audience engagement and multimedia.

“At rst we struggled to get some of the badges because it was harder this year," said Multimedia Editor James Li. “But, ultimately, we came together as a team and got them."

The Review Online also received 10th place Best of Show for small school websites.

In the Private School Journalism Association Awards, publications earn points for each individual award their sta ers receive, and those points contribute to cumulative awards. The Review claimed the second place Blue and Gold award, meaning that it earned the second-highest number of points. Individual awards included rst place in Editorial Leadership, rst place News Writer of the Year (sophomore Elizabeth Hu), rst place Sports Writer (sophomore Katharine Yao), rst place Sophomore of the Year (Aleena Gilani), second place Versatile Journalist of the Year (Wilson Bailey), third place Sports Writer of the Year (Pierce Downey), second place Features Writer and third place Junior Writer of the Year (both Annie Jones), and third place Features Writer of the Year (Lily Feather).

Annie Jones will return as editor-in-chief along with Ella Piper Cla y. The Review Online will be led for a second year by Dawson Chang and rising junior Aleena Gilani, along with assistant online editors Emma Chang, Elizabeth Hu and Lucy Walker and online technical editor Arjun Maitra. Online section editors are Eshna Das, Aien Du and Alia Jiang. Video editor is Kenna Lee, photo editor is Katie Czelusta and social media editor is Virginia Carolyn Crawford. Deputy editors, who are responsible for assigning articles and training sta , are Lauren Baker, Mia Hong, Richard Liang and Lillian Poag. Lily Feather is the Managing Editor, who will be overseeing work ow. Print copy editors are Ellison Albright and Riya Nimmagadda.

Georgia Andrews will serve as the Executive Design Editor, heading a team of editors including Amanda Brantley, Serina Yan and Willow Zerr.

Print production editors are Dalia Sandberg and Lee Monistere, who will be tasked with handling the Review’s contest entries and editing articles.

Advisers for the Review are David Nathan, Shelley Stein (’88) and Sam Abramson.

After years of threatening a takeover of the Houston Independent School District, the Texas Education Agency began taking control of the largest school district in Texas on March 15. In a letter sent to HISD leadership, Morath announced that the current community-elected Board of Trustees would be replaced by a TEA-appointed Board of Managers on June 1. The current superintendent, Millard House II, will also be replaced by an agency appointee.

Students, teachers and parents across Houston met the news with outrage.

“This action is necessitated because of the conditions of the schools in Houston ISD. Houston has many schools that are outstanding, some of the best schools in the state, and in fact, large numbers of kids in Houston are truly ourishing,” said Texas Education Commissioner Mike Morath in an interview with Fox26. “But there’s also a number of students in Houston ISD who the district is simply not provided adequate supports for those students to be successful.”

“If the focus is on the kids, then you tell me how this bene ts the kids,” said Mayor Sylvester Turner during a news conference the day of the announcement. “TEA is selecting the board of managers. So who are they? The state deserves an F on how they have handled the process up to this point, just a at-out F.”

TEA rst attempted to assume control of HISD in 2019, in response to the “F” TEA accountability rating at Phillis Wheatley High School as well as nancial misconduct by trustees. HISD lawsuits temporarily prevented a takeover; Wheatley’s STAAR scores rose and their “F” became a “C”; and the tarnished trustees were eventually voted out. Since 2019, the amount of HISD schools scoring an A, B or C accountability rating rose from 82% to 94%.

Despite the improvements, the Texas Supreme Court ruled in TEA’s favor in January. In an interview with ABC13, Morath cited low scores at an unnamed HISD campus as the reason for the takeover.

“If these schools had better reports, and they got out of the failing zone, then it clearly showed that something was working and they were doing something right,” said Victoria Allen, a senior at Bellaire High School. “To have TEA come and take that over and possibly make changes to our schools and how they run is really inconsiderate and shows me how much the government doesn’t care about the actual welfare of schools. They just care about having power.”

Hundreds of students across the district have organized walkouts and protests in response to the takeover, and parents have voiced their concerns at chaotic TEA community meetings. Yet, the public outcry has resulted in little action from state leaders.

“It makes it feel like we’re protesting for nothing,” Allen said. “Our voices aren’t being heard, which is arguably the most aggravating part about this whole situation.”

Anna Oliva, a sophomore at Carnegie Vanguard High School, participated in a walkout when TEA announced the takeover in March. Student protesters walked around campus chanting “T-E-A go away” and carrying signs, but Oliva soon realized that she and her fellow students were “powerless.”

“We’ve been protesting, and there have been a lot of amazing students, especially at Carnegie, involved in spreading the message and organizing to try and stop the takeover,” Oliva said. “But there’s really nothing you can do at this point.”

Critics of the takeover question how the future Board of Managers will be able to lead the district, especially

since TEA does not require applicants to have a background in education. Junior Mackenzie Rice, whose father is an assistant principal at Westbury High School, says a board chosen by TEA would allow the state government to extend its control over HISD.

“It seems like a calculated political move on Texas Governor Greg Abbott’s part as he gears up for a [potential] presidential run,” Mackenzie said. “I would guess that they pick all prominent Houstonians to serve on this board. There will be a lot less autonomy, and these professionals who might not have any educational experience at all will deciding what learning looks like.”

Sehba Ali, CEO of KIPP Public Charter Schools, says the new Board of Managers may yet have the power to bene t the district — if they play their cards right.

“They can have a lot of power to make the right decisions for kids, but I think that it’s really going to depend on how they reach out to the community and get the community involved in their decisions,” Ali said. “They can make really smart decisions, but they will not be successful if they’re operating in a vacuum.”

Lamees El Beheary, a sophomore at Carnegie Vanguard High School, says the new Board’s goal of raising accountability scores in HISD campuses will mean an increased focus on standardized test scores.

“There is going to be way more standardized testing to make sure that people are getting ‘the education they need,’ when really, it’s going to be more STAAR prep,” El Beheary said. “All they care about is showing that we are learning when it is just shoving information at us.”

Mackenzie, who writes curriculum for K-12 schools, warns that a renewed focus on standardized testing would prevent teachers from customizing their curriculum.

“Teachers need to have the autonomy to create and adapt their classroom to best meet their students," she said. “Students are going to be at a fundamental disadvantage because cookie-cutter curriculum isn't bene cial."

Ali says state takeovers are a “mixed bag.” TEA successfully intervened in El Paso ISD and Beaumont ISD, but the takeover of North Shore ISD resulted in the permanent closure of the district. The enormity of HISD makes the outcome of the intervention even more unpredictable. It is the eighth-largest district in the country, serving over 189,000 students across 274 campuses.

“There isn’t one overwhelming example that we can point to and say, ‘that went really well,’” she said. “We’re going to expect a lot of upheaval, a lot of turnover of sta . That just creates a lot of disruption for the faculty and for the students.”

Ali expects that the takeover will lead to an increase in applicants to KIPP from HISD schools. Courtney Burger, Director of Admissions, says that St. John's could see a similar trend.

“Many HISD families are still trying to understand what the takeover will mean for their speci c school,” Burger said. “Many families may adopt a wait-and-see approach, but if things seem less than ideal in the fall, I suspect we will see an uptick in applications.”

While she admits Carnegie may not have the rockiest transition under the new HISD leadership, Oliva is still skeptical of the takeover.

“I don’t think they change Carnegie too much because I feel like the government wouldn’t really mess with a system that’s been working,” Oliva said. “But it’s our education and we hope to have some more autonomy over it.”

Sara Rose Caplan wants to come home. But she feels Texas isn’t safe for her anymore.

Feeling an urgency to speak on behalf of a community she believes is being ignored, Caplan (’11) wrote an open letter to SJS parents and alumni advocating for trans youth.

“It’s not learning about trans people that turns kids trans,” Caplan wrote on March 10th. “It’s not learning about themselves that makes trans kids sad.”

The 88th Texas Legislature has been in session since January and is set to end on May 29. In that time, the rights of trans children have been at the forefront of statewide politics, part of a growing national debate on trans rights.

In a recent video interview with the Review, Caplan described her letter as a way of “trying to strategically shout at the void.” She chose to specifically address the St. John’s community, an influential group of people that she is personally connected to.

“I am not an outsider coming in to scold you about a theoretical problem. Trans people aren’t an abstract political talking point,” Caplan wrote. “I am a part of your community. I am your classmate, your friend, your neighbor.”

I am a part of your community. I am your classmate, your friend, your neighbor.

Although Caplan was initially skeptical that her message would reach her intended audience, “a lot more people read it than I assumed would."

Dozens of students reposted the letter on their Instagram stories. It dominated conversation at family meals and in PRISM board meetings. Several students even forwarded the letter to PRISM sponsor Kristiane Stapleton.

“It was bold and brave and urgent,” Stapleton said. “It was necessary.”

Caplan’s own high school experience is a classic coming-of-age story: She was head prefect, swim team captain and Harvard graduate — “you could not have been more SJS Not-Without-Honor Prestigious Scholar

Athlete than I was,” Caplan wrote. She had it all, except the “context to understand myself.” And she was miserable.

By the time Caplan graduated from St. John’s, she suspected that she was “some kind of queer,” but she did not even know that trans people existed. The only LGBTQ+ representation Caplan saw came in the form of crude comedies and low-brow cultural tropes.

College expanded her horizons. Caplan discovered trans influencer Natalie Wynn, a popular social media creator, who helped her realize that a trans person “can be smart, funny and witty,” not just a murder victim on CSI. Seeing a successful, visible trans woman was a revelation. Soon after, Caplan realized that she herself was trans.

After college, Caplan moved to California and, over the next few years, gained confidence in her identity. This personal shift mirrored an increasingly tolerant and accepting attitude in broader society. The federal government implemented protections for same-sex relationships and medical transitioning. In 2015, the Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges legalized same-sex marriage in all 50 states. In 2019,

the Equality Act was passed, prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity in employment, education and public businesses.

More recently, in the summer of 2021, U.S. passport applicants no longer need to submit medical certification to change the gender written on their passports. An “X” gender marker was made available last April to designate a citizen as nonbinary or gender nonconforming.

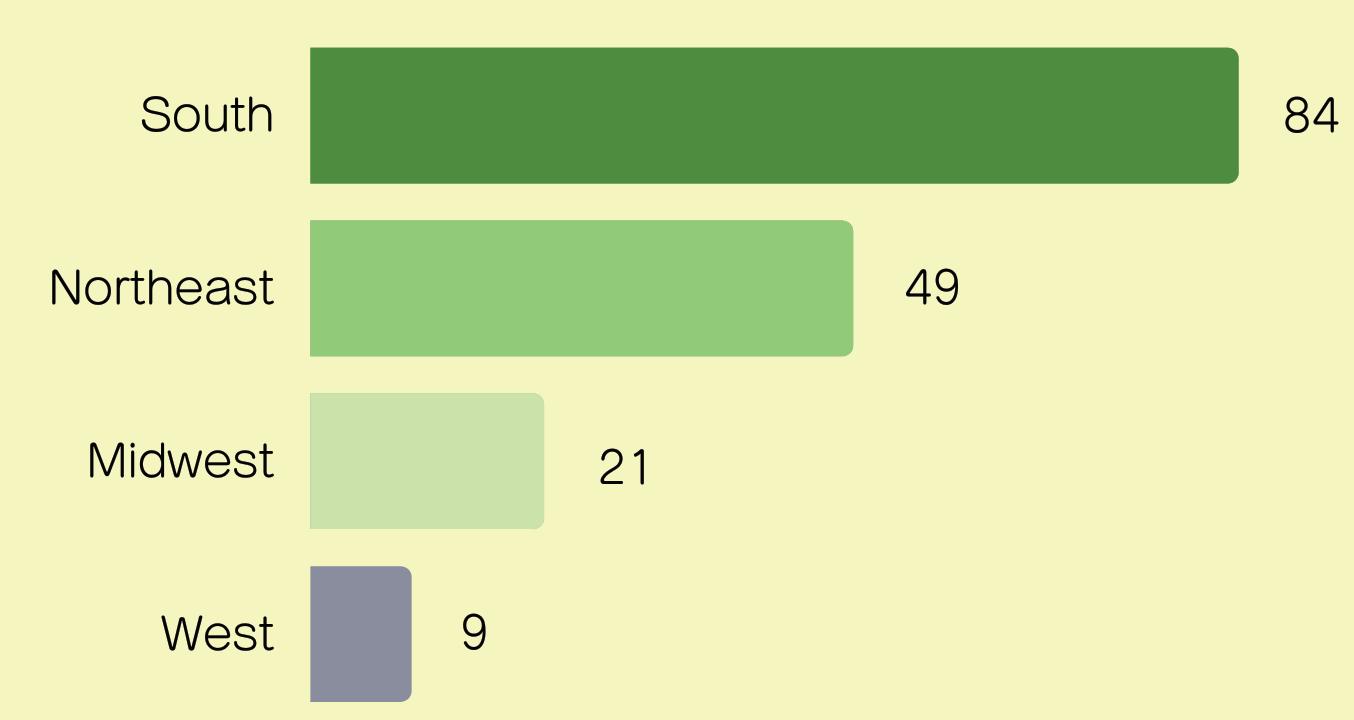

Ten years ago, transgender rights were not a pressing issue for politicians, but the current climate is far more precarious. Now, although trans rights are far more accepted socially, they are under more legislative scrutiny. 57 bills restricting gender-affirming care have been proposed in Austin in 2023 alone. Many of the these are supported by prominent Houston-area representatives.

According to Axios Houston, legislators have proposed more “anti-trans” bills in Texas than in any other state. These bills would restrict medical transitions for minors, make it more difficult for someone to change their gender on official documents, prevent athletes from competing on college sports teams that do not match their assigned genders and prohibit drag performances on public property. Houston-area representatives introduced more than two dozen of these bills.

“My hope is that the pendulum is going to come back down soon. We’ve hit some extremes,” said Director of Community Engagement and Young Conservatives Club sponsor D’Hania Hunt. “Then more people that are more educated and have more wherewithal with them can bring the pendulum back down and move things forward again.”

Caplan thinks members of today's trans community have the context to understand their identities — they are just not allowed to express them.

“It's just very different kinds of suffering,” Caplan said. “One is a suffering of not knowing and one is a suffering of knowing.”

You could not have been more SJS Not-Without-Honor Prestigious Scholar Athlete than I was.

In her letter, she explained that her family has always placed immense importance on their southern heritage. Caplan’s parents moved back to the United States from Saipan, an island in the northern Pacific, before she was born to ensure that she was a seventh-generation Texan. Though she lives in California, her Texas roots run deep.

“There's anti-trans and anti-queer bills being passed in states all over the country,” she said. “But I feel the ones in Texas the strongest, selfishly because I like being able to go back and visit friends and family — and I want to feel safe doing that.”

Among those who read Caplan’s letter were PRISM board members Jack Lovett and Shaheen Merchant, who are both trans.

On March 24, at the first PRISM assembly since 2019, Lovett, a senior, noted in her speech to the Upper School that St. John’s has come a long way in promoting inclusivity over the last decade: “It would be impossible for a trans student to stand on this stage, let alone be out on our campus.”

In California, Caplan feels safe expressing her trans identity, but Texas legislators are trying to prevent transgender youth from transitioning. In her letter, Caplan called these bills a "legal war" against queer teens.

When Merchant started her sophomore year, she was still presenting masculine even though she knew it was not right for her. Over the course of the year, she began testing the limits of the dress code — and when she wore a skirt to school, she was threatened with suspension. A year later, Merchant is now allowed to present more feminine.

When asked about Caplan’s letter, Merchant said, “I was glad she did because someone has to. It can be really hard to do something when you're in the thick of it, but she has a little more confidence and power.”

In public schools across the country, many teachers are legally obligated to out students or ignore their preferred names and pronouns.

Arkansas, Mississippi, Virginia and West Virginia have already banned transgender students from competing on school sports teams that do not match their assigned gender. The Virginia government also adopted a model policy through the Department of Education that asks college faculty and staff to refer to trans students by their given names and pronouns unless a parent files a written petition; it also requires colleges not to disclose trans students’ identities to their parents.

While clothes and pronouns may seem trivial, Merchant cautions that “people can underestimate how little things in your life can add up if it's happening every day.”

Lovett presents less feminine than she would like, citing recent violence against trans people in Texas. According to the Dallas Morning News, Texas leads the nation in transgender murders. She is terrified that, if she were to present more feminine, she would be vulnerable to attack.

Caplan, too, fears for the consequences of the new legislation in her home state.

“I’m afraid that the extreme rhetoric of the American Right will inspire someone to beat me up if they see me walking out of the Kolache Factory or Goode Company,” she wrote.

Stapleton has noticed a climate of fear and anxiety permeating circles of queer students and allies. Most, she said, “don't understand the need for this legislation.”

“What’s happening in Texas is part of a larger political attempt to demonize trans people,” Stapleton said. “While I’m alarmed and upset by this happening in Texas, I am even more alarmed and upset that it is not just one bill; it is part of a larger wave.”

It can be really hard to do something when you're in the thick of it, but she has a little more confidence and power.

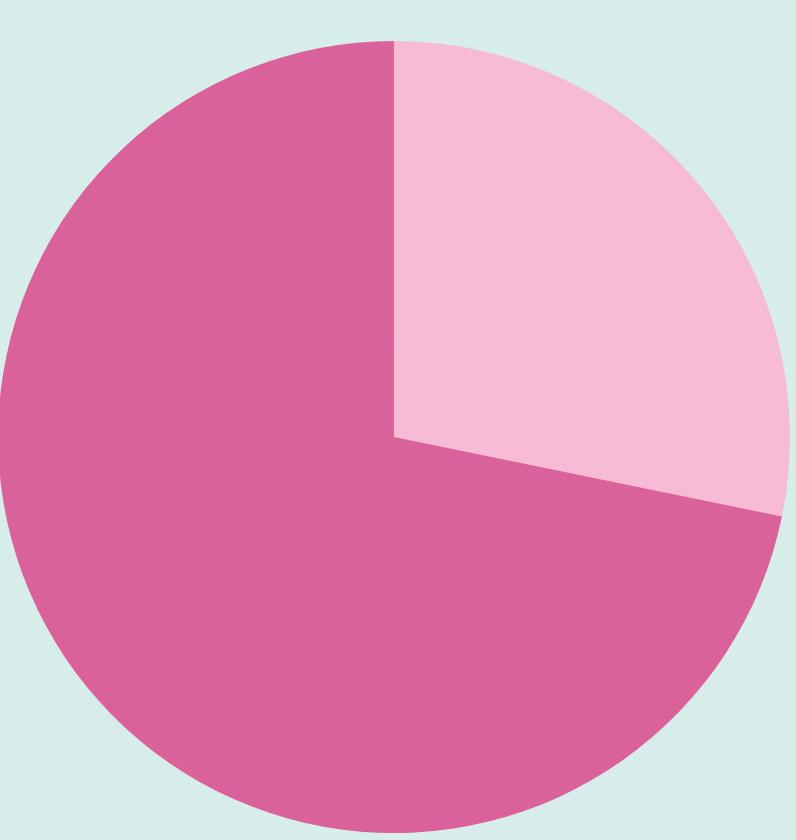

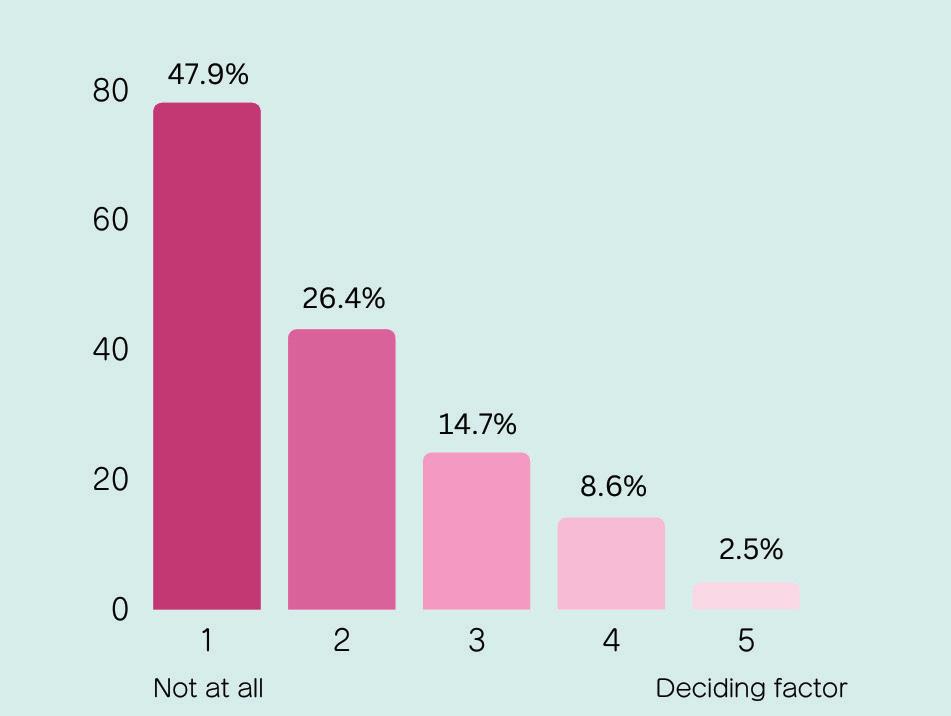

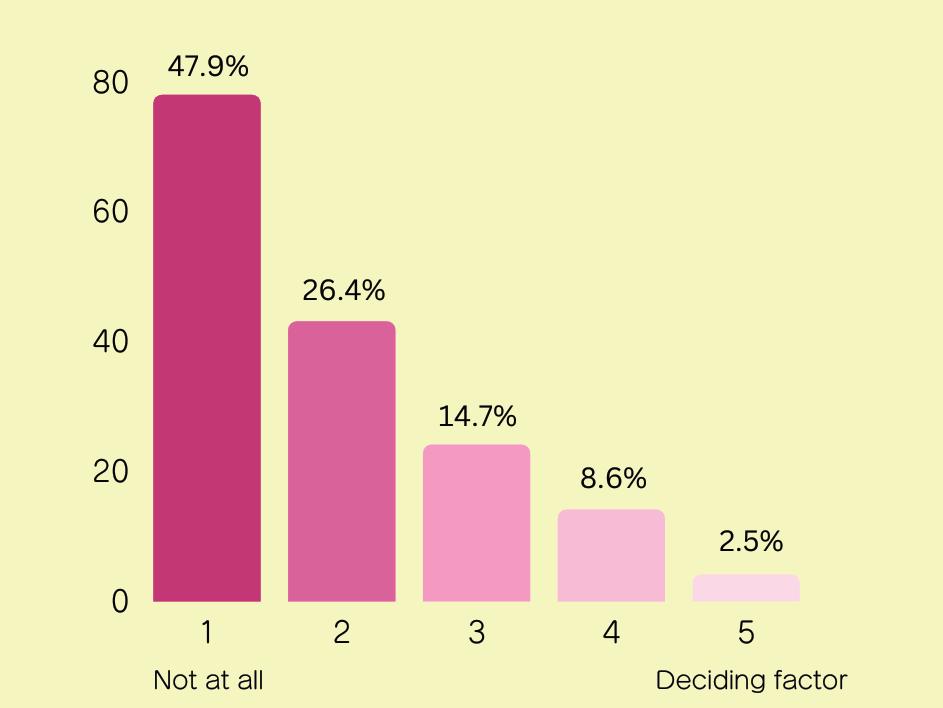

SHAHEEN MERCHANTYounger generations, which have been exposed to dialogue around LGBTQ+ identity for most of their lives, are taking action. According to the Pew Research Center, 63% of Gen Z and millennial voters said they know someone who is trans, while just 28% of people over 74 said the same. Nearly 80% of adults under 40 support the Equality Act, while less than 50% of Americans aged 75 and older agree. Additional research has found that 62% of Gen Z agreed that trans men are men and trans women are women. Stapleton says that protecting affirming spaces like PRISM is essential to student wellbeing.

“As the rest of the world tells you that it’s not okay to be yourself, it becomes even more vital that we preserve spaces for exploration, community and joy,” Stapleton said.

Caplan acknowledges the role that members of the St. John’s play in “waging this crusade.”

“That also means that the current political situation was almost certainly caused by many members of the SJS community, and that even more of you allowed it to happen by passively standing by,” Caplan wrote. “If that sounds harsh, it’s meant to.”

At the end of her letter, Caplan pleaded with the audience to remember trans kids who aren’t old enough to escape and to take into account the families who live in fear of being punished for loving and supporting their children. “Please, for a second,” she wrote. “Consider what y’all are letting happen!”

PHOTO | Sara Rose CaplanMarci Bahr has contributed a lot to St. John’s, including her own hair. For three years, she has repeatedly grown it out, partnered with a high school student, and chopped it off for Locks of Love.

After 31 years directing Community Service, coaching students, founding many beloved traditions and eating an immense amount of jalapeños, Bahr is retiring. Her role running the school’s volunteer efforts has included planning annual service trips to Costa Rica, running the Concessions operation and organizing the holiday drive.

Bahr began her St. John's career as a first-grade teacher before working as the Lower School Curriculum Coordinator for 11 years. She then taught English until 2004, when she took the position as Upper School Community Service Coordinator.

“My goal was to prepare children for the real world and to train them with the skills that they need to lead,” Bahr said.

Bahr began as a co-leader of the Community Service Department but quickly became its sole director. In the 19 years she has served as the Upper School Community Service Coordinator, she has raised the total number of service hours from 5,000 to 50,000.

“She has left a long-lasting legacy of serving and giving back to our community, and she's truly encouraged every single student at St. John's to give their time and talent,” said sophomore Community Service Officer Sammie Anaipakos.

Bahr started the grant that funds community service projects, recently

named in her honor. She also founded the long-running Costa Rica community service summer trip in 2006, on which students teach English and math in rural primary schools.

“These things have been really important to me and for the CommServe program, and I hope they will continue,” Bahr said.

According to senior Community Service Officer Lucia Varma, Bahr is determined, engaged and authoritative, and she makes sure everyone sticks to their “beginning-ofthe-year promises.”

“She taught me a lot of difficult lessons and how to work with people, even when it's not easy,” Varma said.

Community Service Officer and junior Mackenzie Rice admires Bahr for her ambition.

“She doesn't stray away from really largescale community service projects because she knows how big of an impact they have,” Rice said.

On top of all of her community service initiatives, she has also coached Girls’ JV Tennis for 17 years.

Kalyani Pandya, a freshman on the JV tennis team, said Bahr makes everyone feel confident in their own abilites and puts their needs before her own.

“On the tennis court, she'll play with us just to make us all feel included, and there’s a big sense of community,” Pandya said.

This year, Bahr has found unique ways to teach court positioning by tying doubles partners together using a ribbon. The JV team has successfully used this method in practice matches.

“After practicing with the ribbon, it was

Aweek after her shoulder surgery, Class 4 teacher Susan Simpson was struggling to carry out the simplest of tasks. One evening, as she considered the easiest way to prepare her next meal, a comforting smell wafted into her home. To her surprise, Tom McLaughlin was standing on her doorstep with a homemade lasagna.

After five years, McLaughlin is departing as Head of Lower School.

In 2018, McLaughlin moved from San Antonio to serve as the Interim Head of Lower School. He quickly adjusted to the new role, forming bonds with students and faculty.

“I immediately knew he would bring so much fun and happiness to the campus,” said Andrew Herman, current Assistant Head of Lower School, who will become the Interim Head in July.

McLaughlin had the interim title removed after just four months, giving him the opportunity to pursue his main goal of creating an environment in which students could feel passionate about learning.

“It is my deliberate practice to go out of my way to find and cultivate joy,” McLaughlin said.

Over the past half decade, McLaughlin aimed to maintain the principles of honor and compassion at school. During his first year, he designed bracelets with the Honor Code for every student. Every week during

Flag, a time when students gather around the flagpole to discuss upcoming events, he reminds students to act with kindness.

“He really makes a point to prioritize acting with responsibility, independence and joyfulness to connect with the greater St. John’s mission,” Class 2 teacher Sarah Allison said.

During the pandemic, the staff needed to figure out how to provide hands-on experiences to help students learn. McLaughlin guided teachers to design “take home kits" with classroom materials, books, Legos, stickers and activities for every student.

“He brought a lot to the table with how we could change up the curriculum, and it required a lot of out-of-the-box problem solving,” Herman said.

Not only has McLaughlin been a role model for students, but he has also strengthened the faculty bonds. In 2020, McLaughlin and Herman went to the home of every faculty member to let them know he was available if needed.

“One of McLaughlin's gifts is that he understands the importance of a balance between life and work," Simposon said.

McLaughlin prioritized service learning and utilized his faculty and the School’s resources to help others.

“He has been there for me on my professional journey and really helped me grow in my role, which I'm very thankful for,” Herman said.

easier to distinguish where my partner was on the court,” freshman Lydia Huang said. Bahr also manages the concessions stand, utilizing the profits for the CommServe department's grant fund.

To round out her robust list of activities, she has sponsored the Student Affairs Council for the last 17 years.

“She's left very large shoes to fill,” said Dan Havel, an art teacher and seven-time co-leader of the Costa Rica trip. “She is very much a workaholic. I don't know how she has time to sleep.”

Bahr’s influence extends beyond the Upper School.

“She does it all. In any role I've had here at St. John's, I've worked with her,” said Marie Matter, the previous Middle School

Community Service leader and current fourth grade teacher. Bahr often works with the Lower School on book drives and a project called Young Advocates, in which fourth graders research local nonprofits. While working in the Lower School, she also started the fifth grade Greek Olympics. Bahr plans to move to Colorado next year, where she will be volunteering at an intercultural family center that supports immigrants and refugees.

“I've got a big life outside of school," she said. “I know that I will be busy, busy, busy, but this place will always have a special place in my heart."

McLaughlin and his sizable collection of stuffed giraffes will be moving to the northeast to be closer to his family. Students and faculty are planning a special surprise before he leaves to commemorate his time at St. John’s, but they were sworn to secrecy and would not disclose any details.

“We are wishing him the best and we're excited for him, but we will definitely miss him in the Lower School,” Herman said. Changes are also happening in the Middle School, where Chia-Chee Chiu is departing as Head of Middle School to serve in a similar capacity at Shady Hill School in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

During the peak of COVID, Chiu came to St John’s to live closer to her family in Austin. When the School gradually transitioned back to in-person learning, she strengthened her relationship with the community by going to each advisory to introduce herself to the students.

During her time as Head of the Middle School, Chiu enjoyed the smaller moments

when students came together.

“During eighth grade graduation, I was on stage getting goosebumps because of the way everyone supported each other,” Chiu said.

After serving two stints as interim Division Head, Megan Henry, who currently serves as the Director of K-12 Academic Programs, will become the next Head of Middle School.

“I know there is a lot of work, but it is a huge honor, and I really want to make it a great next chapter,” Henry said.

As the school year comes to an end, Chiu hopes that the Middle School remains an environment that fosters growth, compassion and learning.

“I love middle school kids because, at the end, they stand a little taller and have a better sense of themselves,” Chiu said. “Leaving is bittersweet, and I am going to miss the people who make up the school and make it the special place it is.”

It is my deliberate practice to go out of my way to find and cultivate joy.

TOM MCLAUGHLINTom McLaughlin helps with Lower School carpool every morning. PHOTO | Katie Czelusta

She has left a long-lasting legacy of serving and giving back to our community.

SAMMIE ANAIPAKOS

After downing their 16th shot of espresso and devouring the last of their Doordash order, the team of four seniors and one junior rushed to complete their data before 9 p.m., the end of the 14-hour competition.

On March 6, the team, which included seniors Ananya Das, Caden Juang, Oliver Lin, Addison Spiegel and junior Ben Lu, worked relentlessly to research and compose a 20-page paper over this year’s M3 Challenge prompt that modeled electric bike growth.

The Mathworks Math Modeling Challenge is a competition that tasks upperclassmen with using mathematics to solve a real-world problem.

The paper included three parts: modeling the growth of the e-bike market, analyzing the causes of the sudden spike in e-bike purchasing, and the impacts of e-bike growth on both Europe and the US. The team concluded that the increase in e-bike riders was due to more online attention and a decrease in lithium battery prices. The team also determined that the growing popularity of e-biking would improve overall health of riders in both the US and Europe.

Hundreds of teams participated in the M3 Challenge from across the US and UK. After three rounds of judging from a panel of expert mathematicians, six teams were selected for an all-expenses-paid trip to New York City to present their research for a final round of judging.

The St. John’s team was notified on the night of prom that they had advanced to the final round.

science or social sciences,” Gao said. “For example, elections usually have a statistician who is making predictions, calling certain districts or states for candidates.”

Das said that the high-pressure competition equipped her with new team-building skills that will serve her well in her eventual career.

“It was really nice to be able to practice with a team, and having to do it in 14 hours was also a super great experience,” Das said. “Learning how to collaborate under the pressure of a time crunch was a valuable skill to learn.”

The robot was named, prophetically enough, Omen. And for opponents in the First Tech Challenge competition, Omen indeed spelled doom.

Unlike the popular battle bots TV shows, the FTC competition issues a different challenge each year, but none involve the destruction of enemy robots.

The FTC is a national robotics competition for students in grades seven to 12, who spend months designing and developing a robot.

This year, the prompt was Powerplay. Teams programmed robots to push, pick and place cones in specified areas or on poles of varying sizes to score points. The robots are controlled by a combination of preprogrammed automation and manual driving.

St. John’s began participating in FTC in 2017 with only a handful of students, and over the last few years, the program has split into three different teams for the Engineering Club, Engineering Capstone class and the Robotics class.

A product of the Engineering Capstone Project, the highest level of engineering course offered at the School, Omen squared off against opponents, maneuvering throughout the arena in a red and black blaze.

Despite lacking the opportunity to take any year-long or advanced economics courses, many St. John's alumni end up in jobs or majors related to economics.

Last year, Lin, Das, senior Harris Lee and Duncan McLaren ('22) took first place in the National Economics Challenge. The graduating seniors have passed the torch to underclassmen, giving them the resources they themselves did not receive.

The Economics Club, founded last year by Lin and Das, gives students the opportunity to pursue their interests in economics and encourages club members to enter competitive Quiz Bowl-style economic challenges.

“The competitions act like stepping stones because they give people something to look forward to and a goal to study towards,” Lin said. Instead of having a vague desire to learn economics, students feel a need to learn economics in order to do well in the competitions.

To have it not just be a solo passion project, but a shared one, was the most enjoyable thing.

Das especially enjoyed bonding with her team in the build-ups to competitions.

“Group study sessions, taking tests together, quizzing each other, going to restaurants after a study session — everything involves the team,” Das said.

Sophomore Mark Doan appreciated the collaborative preparation for the Harvard Economics Challenge.

A month later, they delivered their presentations to and fielded questions from a panel of judges in New York City.

Following a nerve-wracking wait, the team was awarded second place, which included a ceremonial giant check for the $15,000. The M3 competition awarded $100,000 total to the finalists. Members of the SJS team will each receive a $3,000 college scholarship.

According to math teacher Eric Gao, who accompanied the team to New York, each member brought their own specialized skill set to the project. Although primarily a math competition, the M3 Challenge is a team event first and foremost.

“We had people that were really good at programming and could write algorithms or implement the models in computer language,” Gao said. “We had people that were very good at writing and could make strong arguments, and we had people that understood the math of which model to choose.”

Specialization allowed the team to work more efficiently, but it also sometimes led to tension.

“We were all arguing over which model to employ,” Das said. “A lot of fighting resulted from some really bad communication, but we ended up resolving it by learning to communicate more effectively and just trusting the team.”

Gao also praised the M3 competition for teaching applied math, which he says has strong real-world applications.

“The field of mathematics that M3 is involved in, applied math, has a lot of overlap with other disciplines, such as

Competition begins at the local level, and for those that qualify, the regional, state and national level. Participants are judged for both game performance and sportsmanship.

The Capstone team advanced to the state competition, while the Engineering Club and SJS Robotics teams made it to regionals. The Robotics class team, Glowbotics, placed third at the local level.

Sponsors Matthew Bounds and Franco Posa, who both teach engineering, were excited about the level of participation and success of the groups.

“Last year we were pretty much at the bottom of the charts in the regional competition, and this year we went all the way to the state competition,” Bounds said. “It's very quick progress with a pretty small group.”

Senior Rhyder Swen, captain of the Robotics team, is optimistic about the future of robotics at St. John’s.

“I really hope more people get involved in the club so that you have people participating in robotics for more than just one or two years," Swen said.

Bounds and Posa are looking to expand the program beyond the Upper School. After a morning workshop with Class 4 students, Bounds and Posa were impressed with the enthusiasm and potential of the younger students. Including young students in future engineering programs would foster their skills before they even reach high school.

“It’ll become a pipeline, and they can get better, but it’ll also build a community together in advance,” Posa said.

“I hope that over time, we will build it across the whole school.”

“To have it not just be a solo passion project, but a shared one, was the most enjoyable thing,” Doan said.

Das also emphasized the importance of economics and its far-reaching impact.

“At any business, corporation or industry, economics is ingrained into the system,” Das said. “You need a basic understanding of economics; simple notions like supply and demand or labor force are vital.”

When Lin registered for the National Economics Challenge, another prestigious competition for students interested in economics, friends told him that there was no way St. John’s could win. “The same five teams win every year,” they said. “It's a waste of time.”

Despite the naysayers, the trio of juniors won the challenge and the $4,000 prize.

This year, the Economics Club entered two four-person teams in the HEC, which took place in Boston on April 8. Students participated in trivia against other schools, testing their knowledge of fictional scenarios, vocabulary and history. Participants were also given the opportunity to listen to a lecture from Nicholas Gregory Mankiw, who served as Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers from 2003 to 2005.

As the Economics Club grows, sophomore Lucy Janssens hopes it will continue to push the limits.

“There's definitely more opportunities for growth,” Janssens said. “We haven't hit our peak just yet, so I'm excited to take it even further in future years.”

Lin & Brandon WuLearning how to collaborate under the pressure of a time crunch was a valuable skill to learn.

MOLLY BAUGHMAN (4 YEARS) RECEPTIONIST

COURTNEY BORDEN (5 YEARS) CLASS 2

ANA BRANDON (7 YEARS) SPANISH

LUCY DIBLASI (7 YEARS) KINDERGARTEN

BECKY FRANKLIN (7 YEARS) CLASS 1

TOM MCLAUGHLIN (5 YEARS) HEAD OF LOWER SCHOOL

SONAM SHAHANI (4 YEARS)

CLASS 5 LANGUAGE ARTS/ SOCIAL STUDIES

Things every Upper School student has experienced: taking their class photo, signing the Honor Code and watching Isabella Gidi perform. Gidi is ubiquitous, whether it be in dance, musical theater, playwriting or choir.

Her voice is distinct; according to choir director Scott Bonasso, it falls somewhere between a heavier mezzo and a high, light coloratura. Most audience members have probably never detected a nervous tremor in her voice, yet for someone who seems able to perform anywhere, at any time, Gidi has struggled intensely with stage fright.

As a sophomore, she started to feel nervous before an out-of-school singing showcase where she was supposed to deliver a solo performance of “Wishing You Were Somehow Here Again” from “Phantom of the Opera.”

Gidi ended up crying so much on the car ride and backstage that her throat clogged up, rendering her unable to perform her solo.

The incident reinforced her fear that people thought she was a bad singer, which led to negative feelings about her past performances. When she did receive praise, she did not believe it.

Bonasso recalls that Gidi would often tell him that she felt like she had not given her best performance due to nerves.

“It’s just one of those things you have to keep doing over and over and over,” he said about performing.

In order to conquer her stage fright, after the debacle Gidi pushed herself to take on any opportunity to perform.

“There’s something inside of me that, when I’m scared of it, I have to keep doing it,” Gidi said. “Any single opportunity I have to sing, I take it, because I owe it to myself to stop being scared.”

A year later, Gidi performed “Wishing You Were Somehow Here Again” at the Kantorei Concert in March.

Bonasso, who is well aware of how debilitating stage fright can be, advised Gidi to try singers’ breathing, a technique meant to minimize the physical effects of nerves on the body.

Because nervousness causes shortness of breath, it can be detrimental to live singing, according to Bonasso. He added that the best thing to happen to a young singer during a performance is for “something spectacularly awful to go wrong.”

If a young singer’s worst nightmare comes true, they realize they can deal with anything and move on.

Her performance in March was the turning point.

“Every time I’ve seen her sing now as a soloist, her voice is firing on all cylinders,” Bonasso said.

When considering which song to perform, Gidi sits down at the piano until she finds what feels right.

“I feel a deep connection with all the songs I’ve performed. They are often the ones I sing at home when I’m trying to release something,” Gidi said.

She once volunteered to perform when Chapel Guild needed a last-minute performer to fill in — just two hours before Chapel started. Yet she originally intended to turn down the opportunity because she was not “the kind of person who could perform on two hours notice.”

Instead, she asked herself, “Would the person I want to be — the person who doesn’t have stage fright — would she say yes?” Gidi decided that she would, and that was when she became the person that she had always wanted to be.

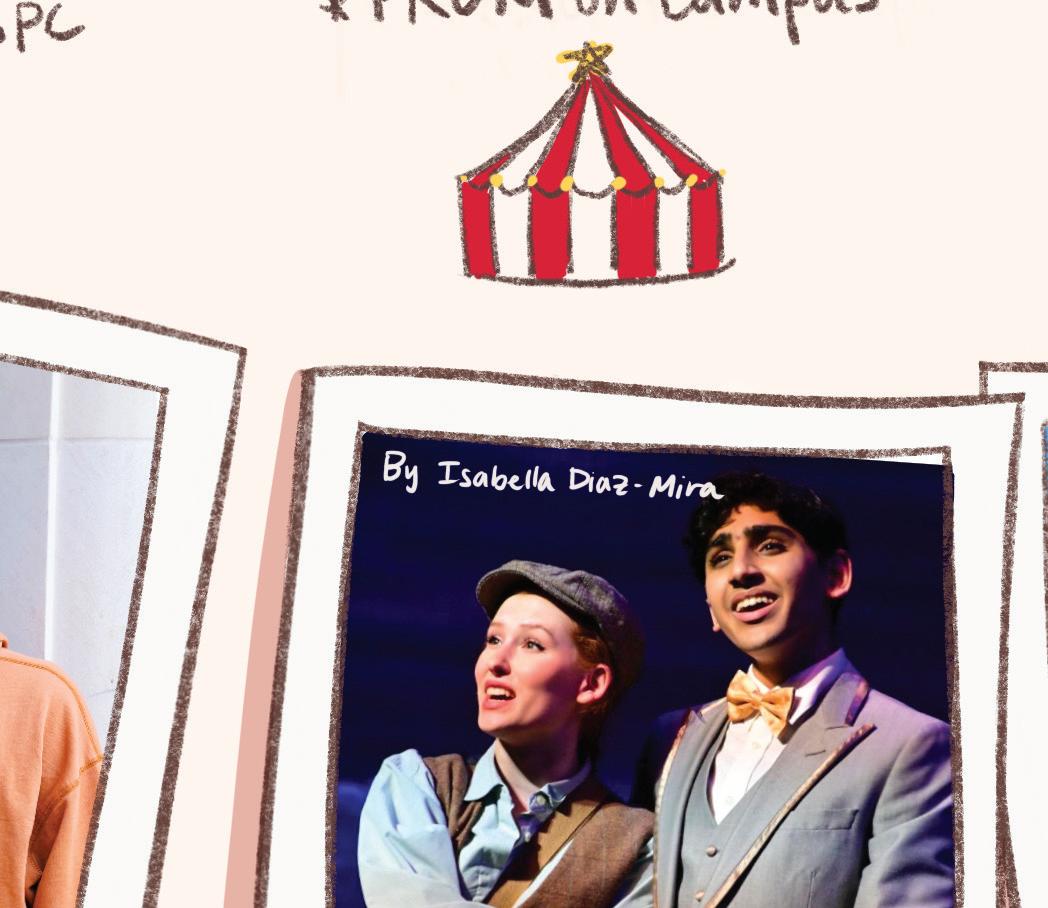

Now as a senior, all her hard work has paid off. In addition to performing in Chapel twice — and giving a senior Chapel talk — Gidi also performed in the music assembly, the Kantorei Concert, the “Classic With A Twist" dance performance and the musical, Nice Work If You Can Get It.

Gidi’s character, Eileen Evergreen, was a spoiled senator’s daughter who believed she was the world’s finest interpreter of modern dance.

Upper School Theater Director Jamie Stires Hardin gave her an idea of what the character’s movement would look like, but encouraged her to experiment and play with it.

“She was able to tackle something that, in anyone else’s shoes, maybe would’ve been more cautious or apprehensive,” Stires Hardin said.

Gidi, who never saw herself as a funny person, spent hours developing the character, including creating a signiture, albeit questionable, interpretation of modern dance. Stires Hardin noticed how open Gidi was to taking risks with the comedic aspect of the performance.

“She really owned that character,” Stires Hardin said. Off stage, Gidi continues to hone her craft.

“There are kids that will get to a point where they feel that they’ve arrived, and they rest on their laurels,” Bonasso said. “She doesn’t. She’s a relentless worker.”

Gidi was also elected choir president in a landslide vote. Bonasso said that she brings a “demonstratively contagious joy” to choir.

“With kids auditioning for roles and trying to angle for solos, you never know how much you’re dealing with someone at a surface level, but she is just such a genuinely sweet person,” Bonasso said. “It’s almost like she doesn’t realize how talented she is.”

Bonasso went as far as to describe Gidi as “the anti-diva.”

The responsibility that Gidi looked forward to the most as choir president was conducting Chorale during the Spring Choral Concert. Every spring, Bonasso picks a song that is suitable for a beginning conductor but is still a legitimate Chorale-level piece. This year’s choice was Eric Whitaker’s “The Seal Lullaby.”

“The student conductor walks out, they conduct the piece and then they accept the applause. It’s somewhat unique to our program,” Bonasso said.

Gidi, who will be attending Harvard College in the fall to study physics, skipped a meet-and-greet for accepted students in order to perform at the concert.

“I want to leave St. John’s having done what I always dreamt about doing,” Gidi said.

Bonasso was not at all surprised by Gidi’s decision to perform.

“It’s a capstone movement for a student like her who has worked her way up through the levels, and I knew she wouldn’t have missed it," he said. “I knew that for sure.”

At the concert, Gidi commanded the attention of the choir, seamlessly sweeping her arms in fluid, controlled motions, as the choir brought the “Seal Lullaby” to life.

Whatever Gidi’s future holds, she knows that music will be a part of it.

“I’ve thought about this a lot — when I go to college and don’t have Chapel to sing whenever I like, am I going to lose the opportunity to perform?” she said. She plans to audition for every choir Harvard has. “I love music. I love contributing to that beauty.”

NANCY VERLY (2 YEARS) KINDERGARTEN

MIDDLE SCHOOL CHIA-CHEE CHIU (3 YEARS) HEAD OF MIDDLE SCHOOL

CLARK ELLIS (5 YEARS) SCIENCE

DASHELLE FABIAN (4 YEARS) WORLD LANGUAGES

CAROLINE GOLSON (3 YEARS) ENGLISH

ANNA THOMAS (3 YEARS) HISTORY

SARAH WATSON (2 YEARS) MATHEMATICS

KELLY WHITE (8 YEARS) SCIENCE

UPPER SCHOOL

MARCI BAHR (31 YEARS) COMMUNITY SERVICE

AUDREY ETTINGER (3 YEARS) SCIENCE

LUIS GAMBOA (1 YEAR) WORLD LANGUAGES

LETTY REZA (3 YEARS) MATHEMATICS

ATHLETICS

VINCE ARDUINI (12 YEARS) DIRECTOR OF ATHLETICS

ERIN WIERZBA (4 YEARS)

GIRLS’ HEAD SOCCER COACH/PE

FINE ARTS

BRITTANY GARMON (10 YEARS)

THEATRE SHOP MANAGER

Isabella Gidi played a frivolous intepreter of modern dance in the spring musical. PHOTO | Isabella Diaz-MiraIt is rare to find a director of clinical services who can take a patient's vitals and perform a solo from Hayden’s “Missa Brevis" mass, but that’s exactly what Colleen Kimball can do.

Over the past 25 years, Kimball has performed in renowned concert venues, worked in a trauma unit and directed clinical services at Presbyterian School. She joined the St. John’s community this year.

As a child, Kimball was known for her interest in service and music. She wanted to move to India so she could work with Mother Teresa, but she also loved singing along to Barbra Streisand and Judy Garland records. Little did she know that she would excel in both fields.

While she was a student at St. Agnes Academy, she was selected for an audition-only vocal group and began performing in musicals. As a senior, she starred as Mabel in Gilbert and Sullivan’s “The Pirates of Penzance,” which helped develop her classical and operatic technique.

That same year, her choir director encouraged Kimball to pursue music studies but pushed back against the idea of her double majoring in music and anything else.

“You’re gonna have to do this 100 percent,” he said. “Don’t bother with splitting your brain and thinking you need a backup — you have to focus only on music and go all the way because you can always change later, so you have to go for it now.”

Kimball graduated from the University of North Texas because of its acclaimed vocal program and then earned her masters at Boston University Opera Institute. With the contacts she cultivated in Boston, she moved to New York, found an agent and quickly started booking gigs.

Despite getting paid to perform, the work was not steady enough to make ends meet, so Kimball also worked at the Young Adults Institute, an agency that helps disabled people find jobs. The Young Adults Institute allowed her to serve others, while singing provided an opportunity for her to entertain an audience — which, she later realized, was another form of service.

“When I switched [to nursing], I strongly wanted to do something that was connected with serving people,” Kimball said. “At the time, I couldn't see how music was doing that. Years later, I realized I actually was serving people.”

While in New York, she completed a oneyear performance certificate at Juilliard Opera Center.

The most difficult part of her vocal training was competing against other sopranos for roles. Kimball preferred a collaborative environment to the cutthroat competition. Ensemble casts allowed her to create friendships in the otherwise ruthless world of opera. She cited Mimi from “La Bohème” and the Queen in “Night of the Magic Flute” as two of her favorite roles.

Touring productions typically allot one week for rehearsals followed by two weeks of performances in each new city. Kimball lived this nomadic lifestyle while caring for her young daughter. Even though childcare was included in the touring contract, she tried to alternate touring and performing in New York.

Kimball’s office at Young Adults Institute was six blocks away from the World Trade Center. She witnessed the attacks on Sept. 11, 2001 and helped 300 people find their way home before spending five hours walking back to her apartment.

A cloud of toxic smoke lingered in the air for weeks, and high security blockades remained in place for a year. The culture of fear in post-9/11 New York City, combined with stress and fatigue from constant travel, led her to reflect on how her job affected her family.

In 2003, after a year of reflection, she decided to effectively end her singing career by canceling all her upcoming performances — some of which had been booked two years in advance — and moving her family back to Houston.

“The stress of it was really starting to take a toll on me — traveling and living that life out of a suitcase and not knowing where your next check was going to come from and fighting to keep the career alive,” she said. “I hit that place where I just knew that I didn't want to continue anymore.”

After her move, she volunteered at MD Anderson while figuring out her next step. The nurses she worked with encouraged her to attend nursing school because her personality fit the job.

After finishing nursing school, she worked in the Ben Taub Level 1 trauma center before switching gears to become the head nurse at Presbyterian School. She was happy to work in education because it was a more comfortable, familiar environment. Kimball’s father was a professor at St. Thomas University and taught for 54 years, so Kimball knew what it was like being around students all the time.

Five years after the end of her singing

career, she finally came to terms with her decision. Although she did not regret quitting, she still spent time processing the grief. Unlike other professions, she says, an artist’s passion keeps them emotionally connected to their profession.

“Artists are not created; they're born. If you deny the passion, it's going to come out sideways somehow,” Kimball said. “You have to have the courage to just not quit until you're really ready.”

After seven years of working as a registered nurse at Presbyterian, Kimball decided to become a nurse practitioner.

In December, choir director Scott Bonasso asked Kimball to perform in the Choral Orchestral Festival, her first public performance since 2003. At first, she rejected the idea, but later agreed after hearing students perform in Chapel.

“We ask the students to be brave. Well, we old people can, too,” she said. “I took myself back to that mindset of giving someone else a gift. I just tried to stay in that frame of mind and realize it was a blessing that he asked.”

Bonasso enjoyed the collaboration with Kimball because of her professional attitude and commitment to performance. While many soloists meet Bonasso for the first time during dress rehearsal, Kimball rehearsed with an accompanist and communicated with Bonasso to prepare for her performance.

Although her day-to-day life no longer involves performing complex arias, Kimball still carries aspects of her first profession. She notes that her work as an artist helped her develop her presentation skills, confidence, and ability to create relationships.

Megan Henry, the Director of K-12 services, says that Kimball's artistic expression is reflected in her empathy while taking care of patients.

“An artist learns to be tremendously in

touch with the human spirit. You have to develop great empathy to know what the music is trying to portray,” said Henry, who has worked in the Fine Arts Department and performed in the Houston Symphony Chorus. “She has developed this incredible empathy for the human condition and the human spirit. She carries that into the work she does as a nurse and as our director of clinical services.”

Looking back, Kimball’s motivation to keep working boils down to passion. Her interest in learning motivated her to earn five degrees and succeed in two fields. She also attributes her motivation to the emphasis and dedication her parents placed on education.

“I love that you've got teenagers who are on the precipice of their whole world — there's so many possibilities,” she said. “It's like watching a flower blooming, and every year the flower gets brighter and more beautiful until we let you guys fly.”

Just a few weeks ago, Kimball participated in a faculty version of “The Masked Singer." Even though she wore a ridiculously large eyeball mask for her performance of “Part of Your World” from “The Little Mermaid,” her distinctive voice shone through.

Kimball has no regrets. She is content with her career and maintains that she made the right decision to get into music — and when to stop. She encourages students to wholeheartedly commit to their passions.

“Do it 100 percent and without apologies. You can’t just be in it halfway,” she said. “Later in your life, you can always do something else. If the day comes when you know in your heart that you've done as much as you're comfortable doing, then you can stop. But if you even have the inkling that that's what you want, you gotta go for it.”

My childhood memories of driving around Houston consist of power lines, frontage roads and standstill traffic watching heat rise off the concrete. As a passenger, Houston was a sprawling, marshy eyesore. I never thought of my hometown as a destination.

Movies and television shows glamorized Los Angeles and New York. I was stuck in the middle.

And then I got my drivers license. What once seemed like a disorganized conglomeration of strip malls and urban sprawl suddenly became a city teeming with offbeat neighborhoods and top-tier restaurants. I discovered the potholed streets of Montrose where the average

block consists of a new high rise, a 1940s bungalow and a neighborhood gay bar on the same block. I took advantage of Houston’s exceptional food culture: Roostar for bánh mì, Pondicheri for lamb keema and Star Pizza for Ben’s deep dish. It was like living in an entirely different place.

Don’t get me wrong — Houston still has its faults. Loop 610 remains a hellscape save for select midnights and early Sunday mornings, the Galleria’s unapologetic commercialism draws you in and tests your tenacity to make it out alive. Winter means wearing shorts and a puffer jacket to withstand 37 degrees in the morning and a balmy 82 at noon.

But Houston’s afflictions are canceled

out by H-E-B tortillas, the Rodeo carnival and Astros games at Minute Maid Park.

I spoke recently with my grandmother, a proud graduate of Lamar High School ('58), about my newfound love for my hometown. As a kid, I watched her use her expert knowledge of Houston’s streets to elude traffic jams. Today, I follow those same shortcuts. Despite our age gap, we share an affinity for Houston’s gritty charm.

The city has always offered the opportunity for both independent discovery and shared family experiences across generations, but it took a drivers license and maturity for me to properly realize it.

My horizons have certainly broadened

since receiving my license, but I know that there is still so much to explore whenever I come home from college.

In my mind, Houston was never on par with other great American cities, but I have since come to appreciate the city of bayous, Beyoncé and barbecue for the Gulf Coast gem that it is.

I leave for New York City soon, but I know when I return to visit in November, a wall of humidity will greet me outside of George Bush Intercontinental’s Terminal C.

I will throw my luggage in the trunk, turn on Mix 96.5 and hop on 59 back home — eager to keep exploring the city I’ve come to love.

Freshman Avery DiNardo had been fostering Griff, a German shepherd about four years old, for a few hours when she discovered him in the bushes of a neighborhood park with a possum in his mouth. Griff emerged from the bushes and showed off the possum to DiNardo’s father, who, three minutes later, was finally able to pry the creature free. After escaping from the dog, the possum scurried away unharmed.

DiNardo described the experience as “slightly disturbing,” but she and her family laugh about it now. After two months, they helped get Griff adopted by an ex-military officer who worked with military German shepherds. The officer still sends them photos of Griff.

WHO'S A GOOD DOG?

Zhang messaged her and, in a few days, had a tiny black-and-white piglet in his home. Her coloring matched Mumu’s perfectly, and they often lay together on Mumu’s dog bed.

“When you take them home and you nurture them,” Zhang said, “their personalities are brought out in the best way.”

He also fostered a “giant pink pig” from Cypress, who had been a beloved pet but had outgrown her owner’s home. His love for his fostered pigs inspired him to create the Pig Club, an outlet for students to learn and converse about pigs.

Zhang relocated the pink pig to a ranch and the little black-and-white one to a new home. She is happy, Zhang said, to live in a comfortable, air-conditioned home rather than a muddy pen in Cleveland. Currently, Zhang has five turtles, ten beta fish and two dogs living in his house.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, animal shelters experienced a 70% increase in fostering, which cleared space in already overcrowded shelters.

DiNardo became interested in fostering during the pandemic, when she raised a litter of five kittens until they were ready to be adopted.

Since then, she has fostered kittens and multiple breeds of dogs with her sister.

“You get to feel like you’re making a difference while also having fun at the same time,” DiNardo said.

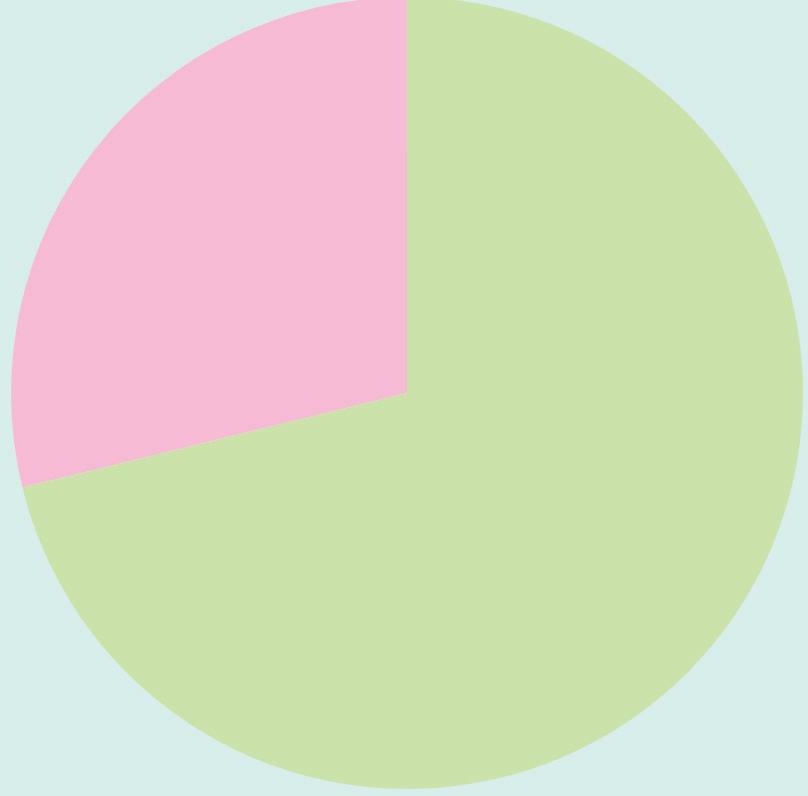

But that quarantine-inspired fostering craze seems to have ended: in mid-2021, some shelters reported that animals were sent back. In 2022, 7.6 million animals entered shelters around the country. Due to the overwhelming number of animals, 2.7 million were euthanized.

Fostering involves providing a temporary or permanent home to animals in shelters, like dogs, cats, birds and hamsters. Initially, the process of fostering usually includes interviews and meetings, but the more animals someone fosters, the less paperwork is involved.

“It’s really convenient because we can take animals in, foster them, and give them back to the shelter,” DiNardo said. “By helping the shelters, you are making a difference.” The city of Houston’s animal shelter and adoption facility, BARC, reported that the euthanasia rate increased from 4.9 to 14.9% in 2022. One of the most effective ways to reverse this trend is to foster animals, which opens space in shelters and prevents euthanization.

Two years ago, junior Evan Zhang found an “overweight and adorable” dog on BARC’s website. He went straight from school to PetSmart, where he purchased a cartful of dog supplies, then drove to the shelter.

He and his family loved the dog, christening her Mumu because her black and white spots reminded them of a cow, and made her their “forever pet.” Since then, his family has fostered 30 kittens, 25 dogs and 50 more miscellaneous animals, from ducklings to pigs.

A few days after taking his freshman year final exams, Zhang stumbled upon a woman’s Instagram post featuring her pigs. One piglet lived in a rarely cleaned concrete pen in the woman’s backyard in Cleveland, Texas. The woman was pregnant and had a toddler and could not properly care for all of her pigs.

A few years ago, Assistant Dean of Students Lori Fryman started dog-walking. Her sister, who was a regular volunteer at the Houston Humane Society, inspired her to get involved by occasionally walking shelter dogs. Yet she soon realized that the shelter needed much more than dog walkers. Knowing that a litter of puppies would be too much of an undertaking, she started fostering kittens.

With a few months of fostering experience under her belt, Fryman received a call from the Houston Humane Society that four kittens had been dropped off and needed immediate fostering. Fryman agreed to take them but was surprised when she received a litter of days-old mewlers needing round-the-clock care and attention.

The only possible solution, she figured, was to bring the kittens to school.

“It was a full-time thing,” she said.

For the next couple of weeks, Fryman smuggled the kittens to her office in a fruit box every morning. She thought she had gotten away with it — until one of her colleagues with a cat allergy started complaining.

Once they get to the stage where they find their legs and learn to play, it's just a lot of fun.

LORI FRYMAN“Between classes, I would get out syringes and cotton balls and feed them,” Fryman said. “I was determined to keep them alive. Once they get to the stage where they find their legs and learn to play, it’s just a lot of fun.”

Now, she fosters a new litter every year.

Ten years ago, biology teacher Paula Angus began fostering through the Homeless and Orphan Pet Endeavors, as well as caring for stray cats in her own neighborhood. During winter, Angus took in a cat and her four kittens until the weather became warmer.

Fostering was a win-win: she got to spend time with adorable animals and train them so that they were more likely to be adopted.

“You're helping both the animals and shelters out,” Angus said.

Through animal training courses and weekend events hosted by Homeless and Orphan Pet Endeavors, she has

learned how to safely feed, nurture and care for outdoor animals. Though Angus no longer fosters cats, she still volunteers to “neuter, spay and feed outdoor cats.”

The purpose of fostering, Angus said, is to acclimate an animal to living indoors and interacting with people.

“It doesn’t take too much time, and it just makes the animals so much more adoptable,” she said.

Review adviser David Nathan is a self-professed cat person, but over the past 20 years, he has learned to love dogs, too. After owning a pair of Saint Bernards and then golden labradors, he finally adopted two cats. When his wife learned about a Saint Bernard wandering the streets in February, the couple agreed to foster him. They took him in, cleaned him up and named him Toblerone — Toby for short.

For two months, Toby responded well to training and medical treatment. The Nathans strongly considered permanent adoption.

You get to feel like you're making a difference while also having fun at the same time.

AVERY DINARDOOn the night of April 18, as Nathan walked into his bedroom after an evening softball game, Toby was lying on the floor, seemingly asleep. Possibly thinking that Nathan was an intruder, Toby jumped up and bit his leg.

After she took Toby into another room, Nathan’s wife Mandy rushed her husband to the emergency room, where he received 17 stitches. After a few days, the bite became infected, which led to a hospital stay where he received antibiotics. After a month, he is finally walking normally. “It could have been much worse,” he said. “Sometimes dogs have histories that you just can’t know.”

Because he could not be safely adopted, Toby had to be put down.

According to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, more than 920,000 shelter animals are euthanized anually. The most common dogs found in shelters are pit bulls, German shepherds and chihuahuas, breeds that are stigmatized due to centuries-old superstitions that make it harder to find foster homes for them.

Some nearby shelters that offer foster pets are Furry Texans, HOPE, BARC, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals and Houston Humane Society. Even if you are unable to foster, you can still help out by donating food, toys or money. Shelters including Houston PetSet, Pet Connect and Save a Purrfect Cat Rescue are all looking for volunteers who are older than 16.

“You help a lot of people find the right animals,” said junior Evelyn Arouty, a volunteer at Houston’s SPCA. “I enjoy watching it because you see them bonding with the animal in the end.”

When you take them home and you nurture them, their personalities are brought out in the best way.

EVAN ZHANG

More than 2.6 million animals enter shelters each year. Here's how the Mavs are helping.

By Aien Du & Aila Jiang

By Aien Du & Aila Jiang

In elementary school, Julia Wyko ’s classmates would secretly order lip balms from her by depositing sticky notes in a designated locker. The young entrepreneur would collect the orders at the end of the day and distribute her product the next day in the carpool lane. Today her “underground operation” has evolved into Zeal Cares, a lip balm business that donates products to patients with pediatric cancer for every tube sold.

Over the past seven years, Wyko has partnered with more than 30 hospitals across 18 states. Next year, she will attend the Kelley School of Business at Indiana University, and she plans to continue expanding Zeal Cares.

Even at a young age, she was well are of what these patients needed.

Before she cornered the preteen lip balm market, she learned about a friend who had begun undergoing chemotherapy treatment for cancer. Wyko discovered that many patients experienced dry skin and lips, an often overlooked side e ect.

After making hand exfoliant as a Mother’s Day project at her Montessori school, she was inspired to branch out and make lip balms.

Wyko began her search for the perfect formula at Sephora and down the skincare aisles of grocery stores. She attempted numerous reformulations and conducted exhaustive research into lip balm ingredients before nally landing on a recipe that worked. Today, she still makes small batches of her products in her kitchen, melting and mixing shea butter, argan oil and jojoba oil over the stovetop. Wyko then had to make a brand for herself. When searching for a company name, she landed on the word zeal, meaning “great energy or enthusiasm in pursuit of a cause.”

After establishing her business to launch the philanthropic component of her mission, she contacted hospitals to ensure that her lip balms reached patients in need. When she contacted MD Anderson, she was prepared for rejection: “What's the worst they can say?”

After some dead ends, a “logistical miracle” eventually connected her with a pediatric program manager who approved her proposal.

At MD Anderson, Wyko hosted avor

counters where patients could choose from 16 standard avors, including key lime, raspberry pomegranate and chocolate mint, as well as a few limited-edition ones. Because cancer patients often experience higher sensitivity to scents and avors, Wyko has created products with a range of potency.

“She has clearly done her research,” said St. John’s parent Rebecca Hunt, who was recently diagnosed with breast cancer.

“Even at a young age, she was well aware of what these patients needed.”

In 2018, while Wyko was hosting her rst avor counter, Kendra Scott was also hosting an event at MD Anderson.

A similar concept to Wyko ’s, Kendra Cares brings custom jewelry-making to the pediatric wards of hospitals. Tom Nolan, the CEO of Kendra Scott, loved the mission behind Zeal Cares and o ered to give Wyko some pointers on how to grow her business. Nolan later reached out and invited Wyko to the Kendra Scott headquarters in Austin.

“I love the brand she has built, and I love what she stands for,” Nolan said. “I wanted to help.”

By the time she entered the Upper School, Wyko had been featured by multiple publications and was selling products in local outdoor markets and stores.

Not only did Wyko impact those beyond school, but she also helped within the community. After nding out about Hunt’s cancer diagnosis, Wyko dropped o lip balms of every avor at her house, along with owers and a card.

“It’s odd when you nd someone so young that you can look up to even when you’re older,” Hunt said, “and she’s de nitely someone that I look up to.”

Wyko has also collaborated with parents to design cards and create little inserts to include with Zeal Care’s lip balms as teacher’s gifts or charitable donations.

still looking for ways to ensure her dorm room does not become a product laboratory and shipping warehouse. Wyko says that her goal this summer is to spend a lot of time guring out a place where she can manufacture the lip balms.

While creating a business from the ground up has not been easy, Wyko has discovered that people are often willing to help. Founding Zeal Cares has given her opportunities to learn skills such as product research, development and marketing.

“Her work really opened my eyes,” Hunt said. “I have always wanted to give back, and to see someone so young with such big passion was inspiring me to take a chance and try something new.”

Wyko is determined to continue expanding her business, possibly making other skincare goods or adding SPF to her lip balms. While she will continue managing her company in college, she is

“I've de nitely grown a lot,” Wyko said. “I'm more con dent with who I am as a person, which has helped me run my company.”

Beyond hospitals, Zeal Cares products are currently available at Kuhl Linscomb, Magpie’s Gifts and online at zealcares.com.

Additional reporting by Ellison Albright

REBECCA HUNT

REBECCA HUNT

I love the brand she has built and love what she stands for.

TOM NOLAN

When Bella Hendricks applied to St. John’s while an eighth grader at Pin Oak Middle School, friends teased her for being interested in an institution associated with elitism.

“I feel like everyone was under the impression that all private schools are snobby and pretentious,” she said.

Like Hendricks, many students apply to two or more of the independent schools in Houston, including Episcopal, Kinkaid and St. John’s.

Although Knights, Falcons and Mavericks often live in the same neighborhoods, play on the same club teams together and socialize on weekends and at annual events like Cotillion, students have not come to a consensus on which is the preppiest of the prep schools.

“Honestly, we think St. John’s is just as preppy, if not more so, than us,” said Thomas Carr, a junior at Kinkaid. “Y’all are in the heart of River Oaks — it’s those people who have the reputation for being more elitist.”

Emmy Heath, a sophomore at Kinkaid, said that the Mavericks’ reputation as academic high-achievers fuels their notoriety.

“It’s extremely competitive there,” she said, “and there’s too much pressure for them to be smart. They’re too academically focused, but they brag about it all the time like it’s cool or something.”

We're always teasing each other for fun, because Episcopal and St. John's just have that kind of bond.

According to Carr, the Mavericks’ elitist image is further reinforced by the aesthetic of the traditional student attire.

“The students at St. John’s have to wear real uniforms, which is embarrassing,” he said.

One of the highlights of Kinkaid Week is Dress Like Kinkaid Day, in which seniors

In April 2022 , Memorial High School administrators hired taser-wielding, horse-riding police officers to prevent students from jaywalking. "That would never be a problem at your school," one Memorial student said. ILLUSTRATION | Lucy Walker

deck themselves out in sparkling tiaras, purple tennis sweaters and other Falcon-esque regalia. Meanwhile, Kinkaid seniors “Mock the Mavs” by donning thick taped-up glasses and pigtail braids and posing with their TI-84 calculators.

“It’s a super cool tradition,” Carr said. “It’s fun walking around campus and just seeing a bunch of nerds everywhere.”

Sta ers on the Knight Times, the Episcopal school newspaper, say the Mavericks t the ultimate nerd trope.

“The biggest stereotype for St. John’s is that its students are very academically focused, very hardworking,” said senior Mark-Anthony Mey, student council vice president and Knight Times sta er. “I know a lot of St. John’s students personally, and I just know y'all are always super, super busy with schoolwork.”

In their October issue, the Knight Times published a cartoon featuring a trick-ortreater decked out in nerd garb: taped glasses, suspenders, a bow tie — the works.

When asked what their costume was, the trick-or-treater said, “a Maverick, duh.”

“Obviously, there’s that competitive aspect of our relationship because of sports, but I know it’s never meant in a rude way,” Mey said. “We’re always teasing each other for fun, because Episcopal and St. John’s just have that kind of bond.”

It's cool to be smart, to like school, to be passionate about what you're learning, and to challenge yourself.

Carr adds that, despite their athletic rivalry, the relationship between the schools inspires camaraderie between the student bodies rather than hostility.

“At the end of the day, it’s all just friendly competition,” Carr said. “St. John’s is Kinkaid’s rival school, and we make fun of you all the time, but we love y’all, too.”

As neighbors to the Falcons, however, students at Memorial High School have polarizing takes on each member of the independent school trio.

“Memorial de nitely loves Kinkaid more, and I don’t really know much about Episcopal except for the fact that they’re probably rich like the rest of your trio,” said Meghan Kao, a junior at Memorial. “But St. John’s? You’re just over there studying in the corner.”

For Kao, even the campus security manifests the cultural chasm between Memorial and St. John’s. In April 2022, Memorial hired police on horseback to crack down on student jaywalking.

Everyone knows the only real Houston priavte schools are the holy trinity: St. John's, Kinkaid, and Episcopal.

“I guess it’s been e ective, because who wants to get chased down by a horse with tasers?” Kao said. “That would never be a problem at your school, being in River Oaks and all.”

St. John’s students, apparently, jaywalk o -campus, according to students at the

high school across the street.

“Sometimes, when I’m leaving school, I see St. John’s students just walking wherever,” said Tara Suttitum, a junior at Lamar High School. “That’s really all I know about you guys: you’re smart, and you guys don’t really care about crosswalks or tra c lights; you just walk wherever you want to walk.”

Three years ago, Hendricks ignored the teasing and enrolled at St. John’s. Now a junior, she “thrives” in a community where academic achievement is celebrated, not stigmatized.

Director of Admission Courtney Burger has seen this same situation play out time and time again as applicants to St. John's face peer pressure regarding the academic stereotypes surrounding the School.

“There are high schools where it’s cool to be something else,” she said. “But here, it’s cool to be smart, to like school, to be passionate about what you’re learning, and to challenge yourself both inside and outside the classroom.”

There's too much pressure for them to be smart. They're too academically focused, but they brag about it like it's cool or something.

Burger admits that the School is not for everyone. According to Burger, for students who want to live the high-school experience they see on TV, St. John's just might not be the right t.

“That’s why there are so many other great choices in Houston,” she said. “But for kids that are looking to come here, that is their choice. In applying here, they choose academics — they choose us.”

Most Upper School students don’t give a passing glance to the yers that litter the hallways. They are mere decorations, always circulating with new, bright colors to advertise an upcoming theatrical performance, club meeting or forum. For four years, these yers only served as reminders of events that I had already gotten emails about. They faded into the background.

Then I started noticing a few with SJS logos on them. Out of pure boredom, resting my chin on my hand in the Academic Commons, I noticed large armchairs blocked o with signs that reserved them for people whose names were just generic enough that I wouldn’t question them. I followed these signs until I found a poster advertising an upcoming event called AlumNight.

My rst question was why an alumni event was being advertised to students who had yet to graduate and were therefore not invited. Then it got stranger.

The closer I read, the more outrageous the yers became, with mentions of senior pranks, treehouses on the quad and so many other speci c inaccuracies in this alternate timeline that I couldn’t be sure it was satire.

Some of the yers advertised people who would be attending AlumNight, complete with AI-generated yearbook photos that fell right into the uncanny valley of unsettlingly unhuman. Other yers waxed nostalgic about absurd “historical” events including cult meetings, a sinister “incident of ’97” and graveyards beneath the school.