PAULINE PERSPECTIVE

Arts Funding – Where Now?

Jennie Lee, Minister for the Arts 1964–1970

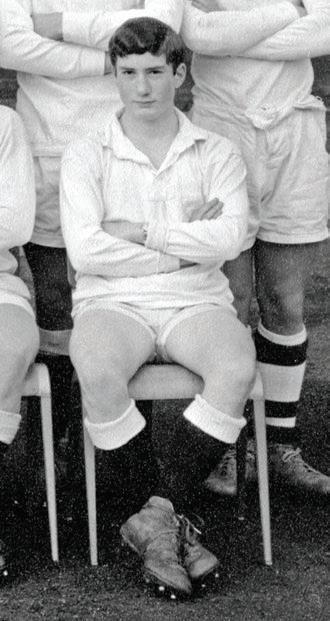

Ed Vaizey (1981-85) argues that the UK needs a reset

Jennie Lee, the first ever arts minister, appointed by Harold Wilson, said that all the arts wanted from government was “money, policy and silence”. It is a pretty fair and accurate summary of how successive British governments have approached the arts since Lee came to office in 1964.

I

was lucky enough to serve as David Cameron’s arts minister between 2010 and 2016. In fact, I held on for grim death until I had surpassed Lee’s record tenure. I also published the first White Paper on the arts since Lee herself. So it is fair to say that I operated somewhat in her shadow. Both Lee and I followed the same course, which on the whole has served the arts well in this country. First, money. It is fair to say that the arts tend to look to their Minister to extract as much cash as possible from the Treasury. I have always said to my (numerous) successors that they will simply be judged by the size of the cheque they hand over. Given that I took office when austerity cuts were being introduced, I suppose I could be regarded as a failure. Broadly speaking, the arts receive the bulk of their funding via the Arts Council. Originally set up after the war by John Maynard Keynes, it now supports hundreds of institutions with a budget of around £600 million. About half of this comes from the

36

ATRIUM

SPRING / SUMMER 2021

Lottery, for which John Major deserves huge credit. Lottery money (for heritage as well) transformed the climate for the arts, in particular allowing a huge range of capital projects throughout the country. Of course, being a Tory, Major’s contribution is barely acknowledged by the arts establishment. About a third of the income budget of the Arts Council goes on just five institutions – the Big Five – the Royal Opera House, The English National Opera, the Southbank Centre, the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre. Indeed, the first arts institution to be directly funded by government was the Royal Opera House, in the 1930s. All this means that there is little spare cash to go around to fund the hundreds of other arts venues that deserve support. In addition, the government funds directly the thirteen national museums, such as the British Museum, which adds a hefty chunk to its bill. Defining arts funding can be a tricky business. There is funding for English Heritage. Local councils contribute a great deal (though far

less than they used to thanks to the cuts in local government funding in the 2010s). The BBC is itself arguably a great contributor, with five orchestras, Radio 3 and extensive arts programming. The Department for Education funds a variety of arts projects, such as music education. Even the Ministry of Defence has a tiny line of spending supporting Regimental Museums. And there are other bodies such as the British Council that cover this beat as well. With a bit of creative accounting, you can argue that annual arts funding in this country easily tops a billion quid. Chuck in as much of the BBC budget as possible and you get to the many billions. This can be quite useful especially when people always bang on about how much the Germans spend, which was the constant refrain when I was in post. Nevertheless, there is not enough to go round – and always demands from interested parties for funding (music venues and brass bands spring to mind). But actually, this is a good thing. I am glad that we fund the arts