STRATEGIC VISION for

Taiwan Security

America’s Shifting Stance on the Middle East

Osama Kubbar

Democracy in Tunisia

Ezzeddine Abdelmoula

Syria’s Deadly Decade-long Conflict

Marwan Kabalan

Online Voices Shape Qatar Crisis

Saleh Rashid Al Naemi

Crafting Security Policy in Philippines

Rommel C. Banlaoi

India and US Face the Dragon

Raviprasad Narayanan US Seeks Partners in Deterrence

Richard Wei-Yi Chen & Jaime Miguel Ocon

The Middle East

Special Issue w Summer, 2021 w ISSN 2227-3646

STRATEGIC VISION for Taiwan Security

Submissions: Essays submitted for publication are not to exceed 2,000 words in length, and should conform to the following basic format for each 1200-1600 word essay: 1. Synopsis, 100-200 words; 2. Background description, 100-200 words; 3. Analysis, 800-1,000 words; 4. Policy Recommendations, 200-300 words. Book reviews should not exceed 1,200 words in length. Notes should be formatted as endnotes and should be kept to a minimum. Authors are encouraged to submit essays and reviews as attachments to emails; Microsoft Word documents are preferred. For questions of style and usage, writers should consult the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors of unsolicited manuscripts are encouraged to consult with the executive editor at xiongmu@gmail.com before formal submission via email. The views expressed in the articles are the personal views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliate institutions or of Strategic Vision Manuscripts are subject to copyediting, both mechanical and substantive, as required and according to editorial guidelines. No major alterations may be made by an author once the type has been set. Arrangements for

should be made with the editor. Cover photograph of a CH-47 Chinook

Aviation Brigade’s area

helicopter flying over the 28th Expeditionary Combat

East is courtesy of

Smith.

reprints

of operations in the Middle

Eric

Special Issue w Summer, 2021 Contents Biden’s Middle East Policy .............................................................4 Tunisia’s Struggle for Democracy ................................................. 9 Continuing Conflict in Syria........................................................ 15 Social Media and the Qatar Diplomatic Crisis ............................ 22 The Philippines’ Quest for Security .............................................26 India and US Seek Closer Ties to Balance China ........................ 34 US Strengthens Partnerships to Bolster Deterrence .................. 40 Osama Kubbar Ezzeddine Abdelmoula Marwan Kabalan Saleh Rashid Al Naemi Rommel C. Banlaoi Raviprasad Narayanan Richard Wei-Yi Chen &

Ocon

Jaime Miguel

Editor

Fu-Kuo Liu

Executive Editor

Aaron Jensen

Editor-at-Large

Dean Karalekas

Editorial Board

Chung-young Chang, Fo-kuan U

Richard Hu, NCCU

Ming Lee, NCCU

Raviprasad Narayanan, JNU

Hon-Min Yau, NDU

Ruei-lin Yu, NDU

Li-Chung Yuan, NDU

Osama Kubbar, QAFSSC

Rashed Hamad Al-Nuaimi, QAFSSC

Chang-Ching Tu, NDU

STRATEGIC VISION For Taiwan Security (ISSN 2227-3646) Special Issue, Summer 2021, published under the auspices of the Center for Security Studies and National Defense University.

All editorial correspondence should be mailed to the editor at STRATEGIC VISION, Taiwan Center for Security Studies. No. 64, Wan Shou Road, Taipei City 11666, Taiwan, ROC.

Photographs used in this publication are used courtesy of the photographers, or through a creative commons license. All are attributed appropriately.

Any inquiries please contact the Associate Editor directly via email at: xiongmu@gmail.com.

Or by telephone at:

+886 (02) 8237-7228

Online issues and archives can be viewed at our website: https://en.csstw.org/

© Copyright 2021 by the Taiwan Center for Security Studies.

From The Editor

The editors and publishers of Strategic Vision would like to wish our readers well this summer season. World affairs remain as dynamic and complex as ever and we wish to keep our readers abreast of broader developments. To that end, we offer this special issue which takes a special focus on developments in the Middle East. For this special issue, we are honored to be working in collaboration with members of the Qatar Armed Forces Strategic Studies Centre.

We open this issue with Dr. Osama Kubbar, a senior consultant and strategic advisor at the Qatar Strategic Studies Center, who looks at the Biden administration’s challenges and policies in the Middle East. Next, Dr. Ezzeddine Abdelmoula looks at Tunisia’s challenges in developing democracy. Dr. Abdelmoula is the manager of research at the Al Jazeera Center for Studies.

Dr. Marwan Kabalan, who serves as the head of the Diplomatic Studies Programme at the Doha Institute for Post-Graduate Studies, examines the obstacles to peace in Syria. Saleh Rashid Al Naemi looks at how social media empowered Qatari citizens during the Gulf diplomatic crisis. Mr. Al Naemi is a senior engagement and communications specialist at Qatar University.

Dr. Rommel C. Banlaoi analyzes how the Philippines balances security policy between the United States and China. Dr. Banlaoi is a professor in the Department of International Studies at Miriam College in Quezon City, Philippines. Dr. Raviprasad Narayanan, an associate professor at the Center for East Asian Studies, School of International Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, looks at how India and the United States are strengthening relations amid the growing assertiveness from China.

Finally, Richard Chen and Jaime Ocon, who currently serve as research assistants at the Taiwan Center for Security Studies, examine the Biden administration’s new deterrence strategy in the Indo-Pacific.

We hope you enjoy this issue, and look forward to bringing you the finest analysis and reporting on the issues of importance to security in the Taiwan Strait and the Asia-Pacific region.

Dr. Fu-Kuo Liu Editor Strategic Vision

Articles in this periodical do not necessarily represent the views of either the TCSS, NDU, or the editors

Regional Complexities

While it is too early to fully assess, it looks as though US President Joe Biden is crafting a new Middle East policy that is based on containment, assertiveness, and multilateral engagement. While Biden will work hard to dismantle the legacy in the region of his predecessor, former US President Donald Trump, one thing that will not change much is the US approach to the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Biden has already signaled to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) that the United States will not continue to support the war on Yemen, and has removed the Houthi movement from its list of terrorist organiza-

tions. In turn, the KSA has made noticeable changes to its foreign policy, namely a reconciliation with Qatar, and declaring its intention to end the war in Yemen and pursue sincere rapprochement with Iran.

Biden has offered an olive branch to Iran and intends to start a new chapter with that country, to attempt to push its leaders to rehabilitate Tehran’s foreign policy. In Libya, Washington is getting more involved with an apparent major push for a peaceful end to that country’s decade-long civil war. However, the new US administration does not yet have a firm strategy. Since Turkey is an active player in Libya, the strained Turkish-US and Turkish-EU relationships

4 b

Dr. Osama Kubbar is a senior advisor and strategist in the fields of international relations, national security, advanced technology and cyber security. He can be reached for comment at okabbar@yahoo.com

Strategic Vision, Special Issue (Summer, 2021)

Biden administration faces a range of challenging issues in the Middle East Osama Kubbar

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken meets with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah, the West Bank.

photo: Ron Przysucha

are hindering the possibility of a speedy resolution.

Although it is still early days in the Biden administration’s first term, some changes in US policy towards the Middle East are already apparent. The recent Palestinian-Israeli conflict, which erupted on May 10, 2021, forced the administration to react. Initially, the future of the Palestine-Israeli conflict did not rank high on Biden’s diplomatic to-do list. However, after the recent Gaza conflict, which required intensive US diplomatic efforts, the Biden administration had to move quickly to reorder their priorities as they sought to stabilize the Israel-Hamas ceasefire, craft a reconstruction aid plan for the Palestinians, and prevent a recurrence of what became Biden’s first foreign policy crisis.

Biden received wide international criticism for what was seen as an unfair policy during the recent Palestinian-Israeli conflict: The United States blocked the UN Security Council (UNSC) from issuing a resolution condemning Israel; it also delayed the UNSC meeting—a move that was widely interpreted as giving Israel license to intensify its mission and eliminate as many targets as possible before the UNSC meeting. Moreover, Biden declared his support for Israel, and stated that Israel has the right to defend itself. In addition, the Biden administration has approved a US$735 million sale of precision-guided weapons to Israel.

It is important to bear in mind, however, that Washington considers Hamas a terrorist organization, and is therefore constrained against negotiating with the group directly. The Hamas movement is the most popular among Palestinians, and is the most active in the conflict with Israel. Moreover, its

political arm rules the Gaza strip. Therefore, it is difficult to envision a peace process without including Hamas in the negotiations.

Iran remains a serious concern, and Biden has clearly stated his intention to re-enter the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) and pursue diplomacy with Tehran on a wider range of issues. This move is in line with rebuilding the shattered transatlantic cooperation, since the EU is in favor of keeping the JCPOA intact. However, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken has affirmed that Washington is “a long way” from rejoining the 2015 pact, which the United States quit under Trump.

Softened rhetoric

Biden has softened his rhetoric with Iran without changing America’s core demands, and Tehran has picked up on the positive signals from Washington and in turn signaled its own willingness to discuss options. Iran is suffering from the comprehensive US sanctions, and the COVID-19 pandemic has added more stress on the Iranian regime and people. While negotiations have resumed between the different parties, an agreement is far from being reached. For a start, Iranian and US positions on the nuclear deal are further apart than optimists would like to admit. Iran is deeply reluctant to re-engage in a deal that demands severe constraints on the country’s civilian nuclear program but stops well short of offering full sanctions relief. Despite the deadlock, the fact that they are talking is a good sign to all parties, and it will certainly ease the tensions and lead to an agreement. The conflict in Yemen and its serious humanitarian impact may offer a particular opportunity for progress. The coalition between the KSA and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is already pursuing a diplomatic solution to the conflict, and they made an offer of a cease-fire to the Houthis, providing a strong indication that they want to bring an end to the war.

Regional Complexities b 5

“Iranissufferingfromthecomprehensive US sanctions, and the COVID-19 pandemic has added more stress on theIranianregimeandpeople.”

Biden has made it clear that he will stop US support for the KSA-UAE coalition, and he has taken a good step by reversing the Trump-era policy by removing the Houthi movement from the list of terrorist organizations. Biden has created momentum in the region by appointing a special envoy for Yemen and making it a priority. The administration is also working with its European counterparts to align their Yemen policies and throw their combined weight behind a diplomatic process that can finally deliver muchneeded peace to the country and potentially unlock a wider regional security dialogue. The Houthi movement has openly dismissed the proposal of a truce, however. With the Saudi proposal to end the war, Washington must now press Iran and the Houthis to commit to peace.

With regard to Libya, there is little indication that US inertia on Libya will shift under Biden. Libya remains a low-priority ever since the murder of US ambassador Christopher Stevens in Benghazi in 2012. Given that Biden was reportedly against the 2011 in-

tervention, it seems even less likely that he will prioritize any effort to stabilize the country.

So far, US strategy in Libya is to back the UN-led peace process. However, the absence of a clear White House policy on Libya has allowed several countries to expand their influence in the country. The fact that United States has virtually no presence on the ground means that the level of leverage it can bring to bear is limited in comparison with other players.

Recently, the Biden administration has named a new envoy for Libya ahead of that country’s planned elections in December 2021, signaling the intent to elevate US efforts to end foreign military involvement there and conclude a long period of post-revolution turmoil.

US-China competition is very different in the region. China is aiming for economic expansion and collaboration, while the United States is more focused on security guarantees and cooperation. The United States has been the main security guarantor and arms supplier in the region for a very long time, and this

6

b STRATEGIC VISION

The war in Yemen has caused great suffering for the population, especially for children, such as nine-month old Mohammed.

photo: Peter Biro

is reflected in its military presence and arms sales.

China has emerged as the top importer of oil from the nations of the Persian Gulf. Given the Gulf Corporation Council nations’ dependency on oil exports, the Gulf is increasingly tied to China economically, especially in light of the pandemic and the global economic downturn. China is also engaged with Iran through long-term investments. China has become the only outside power that has strong political and trading ties with every major country in the region. This means that the Middle East is reemerging as an arena of great-power competition. China’s growing influence in the Middle East does not yet directly threaten any vital US interests, yet China’s deepening alignment with Iran and its regional non-governmental actors pose long-term risks to US forces, partnerships, and commercial access.

Through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China has succeeded in forging connections with the majority of the countries in the region. The list of countries that have endorsed the BRI and committed in one form or another to partnering with China includes Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the UAE. Also, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait have all hired China’s Huawei Corp. to build their 5G telecom infrastructure, in defiance of US pressure.

Even Israel is resisting US pressure to limit its commercial interactions with China. A Chinese stateowned enterprise has a 25-year operational lease on the Israeli port at Haifa. China is also investing hundreds of millions of dollars per year in the Israeli tech sector, despite the Trump administration’s monthslong charm offensive to persuade Israel to pull away.

The level of interest and influence of China in the Middle East region is not surprising, and it has been growing steadily for the last two decades. Beijing’s strategy is to achieve its objective without accruing entanglements in the various regional political struggles and crises.

While it is too early to assess the Biden adminis-

tration’s policy toward the Middle East, many experts have stated that he will try to project fairness and balance. Many former US moves in the Middle East have been strategic, and therefore, it is difficult to see Biden making any dramatic policy changes.

These strategic US policy decisions are primarily related to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the pullout of Afghanistan, and from the region at large, and the Iranian nuclear deal.

As for the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, the current stand of the Biden administration does not serve US interests. The United States backed the Israeli assault on the Gaza strip, and this has created wide regional and international resentment, which will certainly cause further damage to US credibility and to Biden’s intentions of rebuilding the shattered US image. As for Hamas, Washington cannot continue to ignore the elephant in the room. By definition, a peace process must be negotiated with a party you have differences with, not the party that you already have a political and security alignment with—in this case, the Palestinian Authority. As such, Biden has not demonstrated any balance or fairness in his handling of this sensitive issue.

In regard to the Iranian nuclear deal, it is certainly a positive move for the US to go back to the JCPOA agreement. It is a win-win-win situation for US, Iran, and the region. It is essential to stay close to Iran in order to push for a softening of the Iranian regime’s behavior. This is good for the Iranian people as well, as they deserve to have a hope for a decent life. USIran rapprochement will also reflect positively on the region at large, it will ease regional tensions and promote stability and prosperity. A successful agreement would also reduce the foreign policy divergence

Regional Complexities b 7

“Yemen is a chip that Iran will use inmultiplebargains,bothregionally andinternationally.”

between the United States and its European allies over Iran, potentially paving the way for European businesses to restart their Iranian activities.

Biden has stressed the need to end the war and the humanitarian crisis in Yemen. The situation in Yemen is very complicated, since Iran is a key player, and therefore, Yemen is a chip that Iran will use in multiple bargains, both regionally and internationally.

Crisis in Libya

Last, but not least, is the Libyan crisis. The United States has yet to develop a clear strategy for dealing with Libya, while Libya has become a theater for international disputes; Turkey-EU, Turkey-US, US-EU-Russia and other regional players as well, such as Egypt, the UAE, and KSA. It is only Turkey that is working with a genuine plan, which involves pushing to force a ceasefire, ending the civil war, and pushing forward the political process. Washington needs to seek a position on Libya that approaches Ankara’s, which would be an all-round win for the United States, Turkey, Europe and Libya. Restoring order in Libya is critical to America’s transatlantic

allies and to energy supplies. The following policy recommendations would help the US to better pursue its policy objectives in the region.

First, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict is important to regional stability. Isolating Hamas does not help the cause and the United States, as well as other players, have to include Hamas in any future arrangements if they are sincere about finding a fair solution that will bring peace. Second, a disciplined approach towards Iran is the right way forward. Staying close to Iran and re-integrating it into international society will go a long way toward bringing peace to many of the region’s conflicts. Iranians deserves to have a life of dignity and hope. Imposing sanctions on Iran does not help in this regard.

Third, it is very important to restrain Saudi Arabia and the UAE. Both countries are major culprits in most of the region’s conflicts, Yemen and Libya in particular. As the world learned during the administration of former US President Barack Obama, a cautious US to the Middle East does not work. Improvements can only be attained through the enactment of a US policy that is more assertive, fair, and multilateral. n

8 b STRATEGIC VISION

US Air Force Lt. Col. Zachary returns from a mission at Prince Sultan Air Base in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

photo: Carl Clegg

Delicate Democracy

Tunisia’s fledgling democracy needs consolidation and strengthening Ezzeddine Abdelmoula

Ten years have elapsed since the democratic transition process was initiated in Tunisia after that country’s 2010-2011 revolution. Although many consider the Tunisian democratic experience a success story, especially compared to the rest of the Arab Spring countries, the challenges facing this young democracy are enormous, both internally and externally. Theoretically, it could be argued that, after a decade of transition, with regular free and competitive elections, this North African country has now entered what transitologists call “consolidation phase.” In practical terms, however, Tunisia’s democracy is still fragile and is not immune from a reversal wave. Internally, the political class

was deeply divided, and political parties still do not seem to have developed a solid common ground favorable for democracy so it becomes the only game in town. Externally, the environment in the Middle East region is generally hostile to democracy, and some countries in the region are actively pursuing and supporting an anti-democracy agenda.

In December 2010, a group of Tunisian citizens demonstrated in Sidi Bouzid after a street vender committed self-immolation to protest against an insult made by a local public authority staff member. Within just a few days, demonstrations spread all over Tunisia and turned into a popular uprising forcing President Ben Ali to flee the country in January 2011.

b 9

Dr. Ezzeddine Abdelmoula is manager of research at the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies. He can be reached at abdelmoulae@aljazeera.net

Strategic Vision, Special Issue (Summer, 2021)

Crowds in Tunis, Tunisia at the historic Africa Celebrates Democracy concert in November 2011.

photo: Mo Ibrahim Foundation

Among the protestors’ demands were freedom, dignity, social justice, and a change of the political system. The wide-ranging popular participation and the type of demands expressed by demonstrators turned what started as a local protest into a popular uprising, and eventually, into a full-fledged revolution.

The Arab Spring

The Tunisian revolution triggered a region-wide movement of popular uprisings known as the Arab Spring, which grew to encompass Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Syria, and Bahrain. While the uprisings in Egypt, Libya, and Yemen succeeded in toppling Presidents Mubarak, Gaddafi, and Saleh, the regimes in Bahrain and Syria remained unchanged. The transition processes in these countries followed different paths due to their different domestic and regional contexts. Among them, Tunisia is the only country that managed to establish a democratic system, making it the first Arab democracy, thought it faces

ongoing challenges.

When the Arab Spring was sparked in late 2010, democratic demand was high on the agenda of demonstrators throughout the Arab region. Although the popular uprisings succeeded in toppling the regimes in four of these countries, the transitional processes failed to establish democratic systems, except for the Tunisian case. Various factors contributed to this exception, including the consensus among political elites, the vibrancy of civil society, and the long tradition of constitutionalism in this country. This was unlike in Egypt, Libya, and Yemen where that role was played by the military. This was crucial in keeping the process in the hands of politicians and civilian actors. These factors paved the way for a dynamic transition and created the necessary conditions for the emergence of the first Arab democracy.

Over the last ten years, Tunisians have managed to bring together the building blocks for a working democratic system. They first drafted a new constitution in which power is decentralized and distributed

10 b STRATEGIC VISION

Tunisian Parliament Building in Tunis, Tunisia.

photo: Yamen

among the main state institutions, to consolidate democratic values and avoid a return of authoritarianism. Between 2011 and 2019 there have been six elections at the parliamentary, presidential, and municipal levels of government. All elections, according to reports from local and international observers (including those of the European Union) met international standards. They were free, transparent, and competitive as they were all organized by an independent committee. For the first time in decades, Tunisia started to be ruled by elected bodies and representatives chosen by the people through the ballot box. The number of political parties multiplied after the revolution, which offered them unprecedented opportunities to participate in the governance of the nation and engage wide-ranging constituencies of various political and ideological tendencies. The press enjoys a great deal of freedom and the Tunisian media have been ranked by international organizations as number one in the Arab region in terms of press freedom. Debates and talk shows on radio and television address all sorts of social, economic, and

political issues without censorship or pressure from the government.

What has been achieved in Tunisia in this decade was remarkable, especially if we compare it to the rest of the Arab Spring countries. Building democracy in a regional setting that is traditionally hostile to this form of governance is not only challenging, but also unique and requires particular attention. This uniqueness, which caused some to call it the Tunisian exception, may have reached a point where moving forward is no longer possible without taking certain steps to consolidate it. The following set of challenges shows how fragile the democratic process in Tunisia has become, and how difficult it is to proceed with the same practices and the same order of national priorities.

The political system is not complete and some of its basic components are yet to be established. On top of these components is the constitutional court, which should have been set, according to the new constitution, in 2015. The increasing polarization that characterizes the current political situation makes

Delicate Democracy b 11

Major General Gregory Porter, Tunisian Defense Minister Abdelkarim Zbidi, and Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for African Affairs Michelle Lenihan.

photo: Wyoming National Guard

it even more difficult for political actors to agree on forming this crucial institution. The need for a constitutional court resurfaced recently amidst rising tensions between President Kais Saied on the one hand, and Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi and the Parliament on the other, regarding the interpretation and enforcement of certain articles of the constitution.

is the third major challenge facing Tunisia’s fragile democracy.

The second major setback has been in electoral law, which was designed to secure maximum representation by giving more chances to smaller parties and independent candidates to win seats, versus bigger parties and political coalitions. This law was initially drafted in 2011 to prevent the return of a single party system of the sort that used to dominate the parliament, the government, and all political life before the revolution. After ten years of experience, it has become clear that current electoral law is no longer suitable for a stable democracy. The legislative elections of 2014 and 2019 both resulted in a fragmented parliament with no clear majority to any political party. No party is able to form a government or implement its policies without having to enter into a wide coalition, which is not always possible. Even when a number of parties manage to come together and form a government, the chances for such coalitions to hold together for a long time and survive disagreements and party politics are minimal. This was the case in Tunisia after the 2019 elections in particular, where three heads of government had to go to parliament to win confidence votes within a single year. When uncertainty becomes the rule and political instability dominates, governments usually cannot deliver, especially on the social and economic levels. This

The most serious weakness of Tunisian democracy is certainly the failure of politicians to translate political success into socioeconomic achievements. All the indicators in this regard look gloomy, and may cause a wave of reversal that would threaten the democratic process as a whole. Unemployment rates rose from 14 percent before the revolution to nearly 18 percent in 2021. All the successive governments that have been formed since 2011 failed to introduce effective measures to bring unemployment down. Corruption is spreading in different forms, and poverty topped 15 percent of the population. The purchasing power of Tunisians has deteriorated dramatically due to inflation and the continuous devaluation of the Tunisian Dinar. The danger in this developing situation is that the specter of poverty is no longer looming over only low-income people; it is increasingly threatening the middle class. This danger becomes more significant when it starts to generate popular anger and widening distrust of the entire post-revolution political class and the democratic process in general.

Rising popular anger

It is surprising that the political elites, who managed to navigate complicated processes and agreements throughout the past decade to build a democratic system, have failed to deliver on what really matters to ordinary citizens. If the political class continues to fail to improve the people’s socioeconomic conditions—now a matter of urgency—Tunisia’s fragile democracy will lose its already shrinking social base. Under such circumstances, instead of working collectively to consolidate the stability and sustainability of the post-revolution system, the main challenge will be to secure the survival of the system against rising popular anger and dissatisfaction. The number of social protests that took place over the last few

12 b STRATEGIC VISION

“ThemostseriousweaknessofTunisian democracy is certainly the failure of politicianstotranslatepoliticalsuccess into socioeconomic achievements.”

months in different parts of Tunisia shows that this scenario cannot be ruled out, and needs to be considered more seriously.

In addition to these domestic challenges, the regional environment is not supportive of democracy. The neighbor to the east Algeria—the “big sister” as Tunisians call it—is not as interested in any particular form of political system as it is in stability. To the southeast, Libya has been devastated by an intermittent civil war since 2014, and only recently have Libyans got together again and engaged in a political process under the umbrella of the United Nations. If Libya stabilizes and succeeds in building a solid political consensus that can pave the way for a democratic transition, then Tunisia’s democracy will gain a much-needed ally in the region. The most disturbing element in this regard is what has been known as the counterrevolution. Led and financed by some rich conservative countries in the Persian Gulf, the counterrevolution acted early after the Arab Spring and played a significant role in the 2013 coup in Egypt. The same countries tried to implement the same anti-democratic agenda in Libya by supporting a former general in the Libyan army, Khalifa

Haftar, to wage a war against the internationally recognized consensus-based national unity government in Tripoli. In Tunisia, the counterrevolution agenda has taken various forms, including financially supporting local anti-democratic actors, such as political parties, members of parliament, and media outlets. It is true that these strategies have so far failed to overturn the Tunisian democratic process, but this young democracy remains threatened both internally and externally. To keep the democratic process on track and consolidate it, and to prevent Tunisia from reverting to autocracy or plunging into chaos, Tunisian leaders should take the following steps.

Steps to consolidate democracy

First, they must proceed with the completion of the political system by establishing a constitutional court. This is not going to be an easy task given the mounting tensions between the president, the prime minster, and the parliament. But, since the deadlock is in essence political, not constitutional, there is a need to engage civil society to play a greater role in bringing all parties together to take part in a national dialogue.

Delicate Democracy b 13

The historic Kasbah Mosque in Tunis was completed in 1190.

photo: Casual Builder

Tunisia has accumulated significant experience when it comes to national dialogue. In 2013, a coalition of four civil society organizations led by the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT) succeeded in bringing together the main political actors to discuss a roadmap designed to resolve a mounting political crisis. The multiparty dialogue concluded with a mutual agreement to form a coalition government and proceed to the finalization of the new constitution. In 2015, this quartet was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts to overcome the political crisis and put the democratic transition process back on track. Backed by years of experience in contract negotiation, a rich political engagement, and significant international recognition, the UGTT is once again best positioned to provide an effective vehicle for national dialogue. The dialogue structure, agenda, and parties should be mutually defined by the UGTT, the president, the government, and the political parties represented in parliament.

Second, major amendments must be introduced into the electoral law so that future elections produce

a clear majority, whether in favor of one party or a coalition of parties. Unlike the current situation, a clear majority ensures that governments are formed easily, are stable, and are able to implement their visions and policies, and more importantly, accountable for their successes and failures alike.

Third, socioeconomic conditions must be improved so that the people are able to regain their trust in the political class and continue to support the democratic system, and to show that democracy can deliver. This can be achieved by employing effective mechanisms to fight the widespread corruption, treating all citizens fairly and equally in collecting state revenues, and combating tax fraud and evasion, as well as reducing bureaucracy to encourage private initiatives and to support small and medium-sized businesses.

Finally, Tunisia must diversify its economic partners to diminish the long-established domination of Europeans, and open up its economy to benefit from seemingly limitless opportunities in Asia and Africa. The first step in this regard would be to consolidate relations with neighboring Libya and Algeria. n

14 b STRATEGIC VISION

US forces train with military members from Morocco, Tunisia, and Senegal during Exercise African Lion 21.

photo: Nathan Smith

Decade of Despair

A retrospective of Syria’s decade-long conflict shows little signs of closure Marwan Kabalan

In March 2021, the Syrian crisis reached its tenth year, with no end in sight. All parties to the conflict appear to be stuck in a vicious cycle as they continue to make the wrong decisions since the early days of the crisis. At the beginning of the Arab Spring, the Syrian regime thought that it was immune to revolution. A mere six weeks before the crisis, President Bashar al-Assad explained in an interview with the Wall Street Journal why his country was unlikely to go through the turmoil that hit Tunisia and Egypt. “Unlike Egypt and Tunisia, the foreign policy of my government enjoys tremendous

support amongst Syrians,” he said. The opposition, on the other hand, thought that a Libya-like scenario could be repeated in Syria, and hopes for foreign intervention to help overthrow the regime persisted. Yet, when foreign intervention occurred, it came in favor of the regime. Eventually, the conflict drew in fighters from all corners of the world and dozens of countries got involved, turning it into a region-wide sectarian and geopolitical confrontation.

The early insurgency phase of the Syrian civil war was marked by the formation of the Free Syrian Army in July 2011 by a group of disaffected army officers.

b 15 Strategic Vision, Special Issue (Summer, 2021)

Dr. Marwan Kabalan is the head of the Diplomatic Studies Programme at the Doha Institute for Post-Graduate Studies. He can be reached at marwan.kabalan@dohainstitute.org

A Kurdish YPG fighter. Several Western sources have described the YPG as the most effective force in fighting ISIL in Syria.

photo: Kurdishstruggle

Angered by a government crackdown against largely peaceful protesters, these officers mounted a rebellion against the regime of Bashar al-Assad. An Arab League mission was sent in December 2011 to monitor the situation and bring about a peaceful solution to the crisis. The mission was abruptly ended shortly afterwards as fighting continued across the country.

In April 2012, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan was designated as the UN-Arab League joint Special Representative for Syria. He was entrusted with the task of finding a solution to the conflict. A six-point peace plan was agreed upon by the United Nations Security Council but never implemented. On June 30, 2012, the Geneva communiqué was issued after a meeting of the UN-backed Action Group for Syria. It included a roadmap to solve the conflict. Fighting continued and escalated nonetheless.

The use of chemical weapons in the Syrian conflict was first reported on March 19, 2013, in the town of Khan al-Assal, northeast of Aleppo. A much larger-scale chemical attack occurred in the suburbs of Damascus on August 21, 2013. The Ghouta chemi-

cal attack was deemed the deadliest use of chemical weapons since the Iran-Iraq war, with estimated casualties of more than 800. The Syrian regime agreed to surrender its arsenal of chemical weapons afterwards, in compliance with a US-Russian agreement, to avoid a military strike by US forces.

Signs of radicalization

The Syrian opposition started to show signs of radicalization in early 2012 with the formation of the al-Nusra Front, an Al-Qaeda affiliated group. The surge in sectarian politics in Syria and Iraq led to the rise of a more radical group: the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). ISIL presented itself as the champion of Sunni Muslims against the rise of Shia power and Iran’s expansionist policies. Considering itself as the only representative of orthodox Islam, ISIL waged Jihad against almost everybody else and fought for control of territories with al-Nusra, the Syrian opposition factions, and indeed the Syrian regime. To counteract ISIL and what it perceived as

16 b STRATEGIC VISION

Sunni rebellions in Syria and in Iraq, Iran established Shia militias. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states supported the Sunni groups, and a war by proxy ensued, with Syria serving as the main battleground.

Under US President Barack Obama, the United States tried to keep its intervention in the Syrian conflict to a minimum. In June 2014, however, ISIL launched a major attack from its bases in east and northeast Syria. This sent shockwaves across the region when it defeated the US-trained Iraqi army and captured Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city. On June 30, 2014, from al-Nuri Mosque in Mosul, the ISIL leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, declared the Islamic Caliphate. The fall of Mosul, the defeat of the Iraqi army, and the seizure of US-made equipment including 2,300 Humvee armored vehicles, was a major blow to the Obama administration. Faced by the resounding defeat of the Iraqi army, a reluctant Obama dispatched US troops back to Iraq to fight ISIL. A USled international coalition to destroy ISIL was formed in September 2014. To the chagrin of Turkey, the US

turned to Syrian Kurds to help eliminate ISIL. It established, trained, and armed the Syria Democratic Forces (SDF), the backbone of which is the Kurdish Peoples Protection Units (YPG).

By June 2015, Moscow had grown extremely concerned about the ability of the Syrian regime to survive as the Turkey-backed opposition forces came very close to the heartland of the Assad regime. The July 2015 US-Turkish agreement to establish an ISIL-free zone in the northwest of Syria must have also troubled Moscow. Having clinched a nuclear deal with Iran, Moscow feared, Obama might grant Turkey a free hand in the Syrian conflict without having to worry about Iran’s response. The Iran nuclear deal in itself may have also contributed to Moscow’s

Decade of Despair b 17

Free Syrian Army rebels fighting against Assad militias on the outskirts of the northwestern city of Maarat al-Numan in Idlib, Syria.

“For many years, Russia, Iran, and Turkeyhavebeenbitterrivalsinthe Syriancivilwar,supportingdifferent sides in the conflict.”

photo: Freedom House

decision to intervene in Syria. Moscow feared a possible US-Iran understanding on Syria that would not necessarily respect its own interests. The Russians also sought to secure a foothold on the shores of the Mediterranean by taking the Syrian port of Tartus. Having all that in mind, Russia decided to take the initiative, go on the offensive, and lead a direct military intervention in the Syrian conflict.

Taking sides

For many years, Russia, Iran, and Turkey have been bitter rivals in the Syrian civil war, supporting different sides in the conflict. Russia and Iran backed the Syrian regime, providing military, financial, and political support. Turkey supported the Syrian opposition and provided a safe haven for its political and military leadership. The relationship between Turkey and Russia in particular reached its lowest ebb in November 2015 when Turkey shot down a Russia fighter jet near its border with Syria. Relations improved afterwards, however, when both Iran and Russia condemned the July 2016 failed military coup in Turkey, expressing sympathy with Turkish

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. This rapprochement with Russia enabled Turkey to launch its first large-scale military operation inside Syria, Operation Euphrates Shield, in August 2016, wherein Turkish troops and Turkey-backed Syrian opposition factions recovered more than 2,000 square kilometers from ISIL and the Kurdish YPG fighters on the western bank of the Euphrates. The battle of Aleppo in December 2016 allowed Russia and Turkey to identify common interests in Syria. This led to the launching of the Astana process, which Iran joined later.

In January 2018, and with the help of Turkey, Russia hosted the Syrian Congress of National Dialogue in Sochi. The Congress brought together representatives from the Syrian regime and elements of the Turkey-based opposition. Its main objective was to set the stage for the launching of the constitutional committee. Former UN special envoy to Syria, Staffan de Mistura, also attended the meeting wherein an agreement was charted between him and the Russians to form a constitutional committee to rewrite the Syrian constitution as the basis for ending the conflict. After almost two years of negotiations and consultations, the committee was established in

US Army soldiers on patrol in Raqqa, Syria.

photo: Delil Souleiman

18 b STRATEGIC VISION

September 2019. It held its first meeting in Geneva on October 30, 2019. Since then, the committee has held several more meetings, but so far, little progress has been made.

American withdrawal

In February 2019, then-US President Donald Trump declared that ISIL had been 100% defeated in Syria and that he was ready to leave the Syrian territories east of the Euphrates River. To avoid creating a power vacuum and to silence critics who charged that the US was repeating its mistakes in Iraq (wherein a premature departure in 2011 allowed al-Qaeda to thrive and eventually become ISIL), Trump accepted an offer made during a phone call on October 6, 2019, with Turkish president Erdogan to take over the ISIL battle in Syria. The agreement with Turkey triggered a wave of anger in the United States. The president was attacked by both sides of the aisle for “selling out” his Kurdish allies (especially the YPG), who had fought

in the war against ISIL.

Turkey’s paramount concern in Syria has always been the Kurdish question: It is Ankara’s ultimate objective to eliminate the threat posed by the YPG, which Turkey considers to be the Syrian branch of the PKK, and hence a terror group. Therefore, when Trump decided to withdraw, Turkey seized on the opportunity and launched its third military operation inside Syria to eliminate the YPG.

To contain the storm, Trump sent his vice president to Ankara to negotiate an end to the Turkish operation. On October 17, 2019, the United States and Turkey reached an agreement wherein Turkey, agreed “to pause its offensive for 120 hours to allow the United States to facilitate the withdrawal of the YPG forces from the Turkish-controlled safe zone.” It was striking that the ISIL leader, Al-Baghdadi, was located and killed in northwest Syria near the Turkish border just ten days after the inking of the US-Turkey pact. It also came a week after the October 22 Erdogan-Putin summit in Sochi, wherein

Decade of Despair b 19

Russian soldiers clear mines near the war-torn Syrian city of Aleppo.

photo: Russian Ministry of Defense

the two leaders agreed to push back Kurdish fighters from a safe zone along the Turkey-Syria border. Turkey and Russia may have played a key role in locating Baghdadi and in sharing intelligence with the United States in order to help president Trump justify his decision to withdraw from Syria. For completely different reasons, both countries have a vested interest in a US pull-out from Syria. Under pressure, however, Trump agreed to keep a few hundred US soldiers east of the Euphrates to control Syria’s oil and gas fields and prevent Iran from establishing a land corridor between Iraq and Lebanon through Syrian territory.

Solidifying power

Having regained almost 70 percent of Syrian territories, the Assad regime is likely to remain in power for the foreseeable future. Assad will seek to reclaim and solidify power in all major urban centers of the country. However, Damascus is likely to face increasing economic difficulties, as the United States contin-

ues to maximize pressure through the Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act. The US sanctions stipulated in the Act are aimed at preventing the regime from declaring victory and forcing it to accept a negotiated solution to the crisis. Nevertheless, many fear that ordinary Syrians will suffer the most from the US sanctions, with Iraq’s notorious food-for-oil program

still very much alive in people’s memory.

Emboldened by US support, the SDF will further consolidate their position in the eastern part of the country and slowly begin to establish their own autonomous institutions. This could lead to a backlash from the area’s Arab majority, since Iran, Russia, and Turkey are all trying to woo the Arab tribes in the region to help expel US forces and suppress independence aspirations by the Kurds. Turkey will retain

“After the partial withdrawal of the US forces from the east of Syria in October2019,attacksbyISILsleeper cells increased.”

20 b STRATEGIC VISION

A shop in the weapons market in Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan.

photo: Eugene Khor

control of the 30km-deep safe-zone it claims as a buffer against the SDF. Russia will continue to patrol the safe zone, and in so doing aid in further entrenching the Syrian regime’s presence in the northeast of the country.

Prolonged US presence

With the complete loss of its territories, the threat of ISIL has been greatly reduced, though it is not completely eliminated. After the partial withdrawal of the US forces from the east of Syria in October 2019, attacks by ISIL sleeper cells increased. The Pentagon, which opposed former president Trump’s decision to withdraw from Syria, will likely use this under US President Joe Biden as a pretext to justify a prolonged military presence in the eastern provinces of the country.

The Syrian regime will attempt to create an economically viable zone in the parts of the country it controls, predominantly in the west. The govern-

ment will face a huge challenge, however, in trying to control the deteriorating economic situation. There is little clarity on how the government plans to deal with rampant inflation, US sanctions, and fuel shortages, especially given the poor economic conditions of its two main allies: Russia and Iran. With the lack of outside aid, the regime might end up ruling over a failed state.

Given the intransigence of the regime’s delegation during the meetings of the constitutional committee, and the voting rules within the committee, a political solution remains only a distant possibility. However, even if the remote eventuality of an agreement materializes, it is hard to see how fair and transparent elections can be held as long as the regime keeps control of the army and the security forces. Breaking this deadlock will require co-operation between the five big powers in the Syrian conflict: the United States, Russia, Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. The necessary conditions for any such cooperation are as yet non-existent. n

Decade of Despair b 21

When official security forces failed to defend the Yazidi population of Sinjar against ISIL purges in 2014, the Sinjar Resistance Unit (YBS) was set up.

photo: Kurdishstruggle

Emerging Voices

Social media provides Qatari citizens greater voice in international disputes

Saleh Rashid Al Naemi

The gulf crisis involving Saudi Arabia and Qatar erupted in June 2017 when Saudi Arabia and a coalition of countries accused Qatar of engaging in terrorism. The evolution of technology has provided a new platform for conflict engagement and resolutions in virtual space. The emergence of social media platforms such as Twitter has helped Qataris to challenge others in the Gulf region to show their digital nationalism by depicting the positive things that are happening in Qatar, such as economic growth and diversification of the local economy. Most Qataris and citizens of blockading nations used social media to promote their respec-

tive narratives and counter-narratives relating to the Gulf crisis. Social media gives people the opportunity to express themselves and challenge prevailing social problems in society.

Today, social media gives people the opportunity to take part in important public discourses. The use of virtual ethnographic research via contextual interviews of online Qatari volunteers with recent tweets supporting Qatar against accusations of terrorism has helped to determine the rise of digital nationalism in Qatar. The tweets were a critical form of data, and this study utilized trending hashtags during a two-week period beginning on June 5, 2017, which corresponds

22 b

Saleh Rashid Al Naemi is a senior engagement and communications specialist at Qatar University. He can be reached for comment at salehalnaemi@gmail.com

Strategic Vision, Special Issue (Summer, 2021)

The Amiri Diwan is the sovereign body and the administrative office of the Amir. It is the official workplace and office of the Amir of the State of Qatar.

photo: Alex Sergeev

with the start of the blockade on Qatar. The selection of appropriate tweets and their translation from Arabic to English was used to produce reliable findings. Information from other online sources such as Facebook was also used, as well as online interviews with a number of Qatari citizens who participated in online forums during the virtual conflict. Defense of Qatar is one of the main factors which caused Qataris to take part in a Twitter war with citizens in other countries, such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia.

The diplomatic crisis between Saudi Arabia and Qatar led to the emergence of a new form of nonkinetic war. The crisis led to the development of a virtual war waged on social media between Qataris and netizens in the UAE, Egypt, and Bahrain— countries that had cut diplomatic ties with Qatar. The coalition banned Qatari planes and ships from using their airspace and maritime territory. The coalition accused Qatar of supporting terrorism in violation of a 2014 Agreement by Gulf Corporation Council members. The 2014 agreement required

member states to avoid funding terrorist groups. Qatar conceded that it had provided aid to Islamist groups, but not to militant groups such as al-Qaeda. The situation led to full-blown crisis between the Saudi-led coalition and Qatar. Controversial allega-

tions were posted on websites claiming that Qatar’s Emir was in support of Iran, which is the main rival of Saudi Arabia. Even though the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Qatar denied this allegation, the situation soured relations between Qatar and other major countries in the Gulf region. Reports emerged claiming that the UAE was responsible for hacking the Qatar News Agency website. Media outlets associated with Saudi Arabia claimed that Qatar sought to create a crisis in the Gulf region by financing terrorist groups.

Emerging Voices b 23

Located on the coast of the Persian Gulf, Doha is the capital of Qatar and its most populated city. It is also the economic center of the country.

photo: Flashpacker Travelguide

“Qatariscapitalizedontheirsocialmediapresencetoexpresstheirfeelings andnationalprideindefenseoftheir leaderandtheirsovereigncountry.”

The diplomatic crisis was also important because it had potential strategic ramifications. Qatar has good international relationships with influential countries such as the United States, France, and the United Kingdom. Perhaps most importantly, the US military relies heavily on Al Udeid Air Base to project power into the Gulf region. Qatar also hosted the FIFA Club World Cup 2019, which greatly raised Qatar’s profile in the international community.

Improving unity

The main elements necessary for understanding the rise of digital nationalism are the use of digital nationalism to fight misinformation, influence social media to promote digital nationalism, and the impact of digital nationalism on improving the unity of the

ment decisions and policies. Allegations of terrorism were repeated in local and international media organizations. Without a strong counter-narrative, the news would have destroyed the reputation and influence of Qatar’s leaders internationally. The soft power and diplomatic influence of Qatar would have declined significantly.

Posting and sharing fake news is easy and it has a significant influence on public perceptions in Qatar. Traditional media would not have allowed outraged Qataris to defend their leader from allegations. Digital media provides another approach for adversaries to spread falsehoods against other countries. The countries responsible for propagating allegations against Qatar are long-standing enemies, and this has helped to evoke the nationalism of Qatari citizens.

people against external political aggression. Online and traditional media serves an important role in protecting the image of the country against misinformation and external attacks. Media has evolved over time and has given people the means to communicate with their leaders more directly. The government can adopt media to influence perceptions and decision-making in society. Similarly, people will use social media to influence the formation of govern-

Interactive counterarguments on social media help to promote digital nationalism, because of the interactive nature of social media platforms. Social media channels have the capacity to reach many viewers at the same time. The digital sites help the citizens to obtain information and reliable facts to defend their positions effectively. Attacks against Qatari leadership were also seen as an attack on personal identity by some Qatari citizens. This gave rise to a hashtag

24 b STRATEGIC VISION

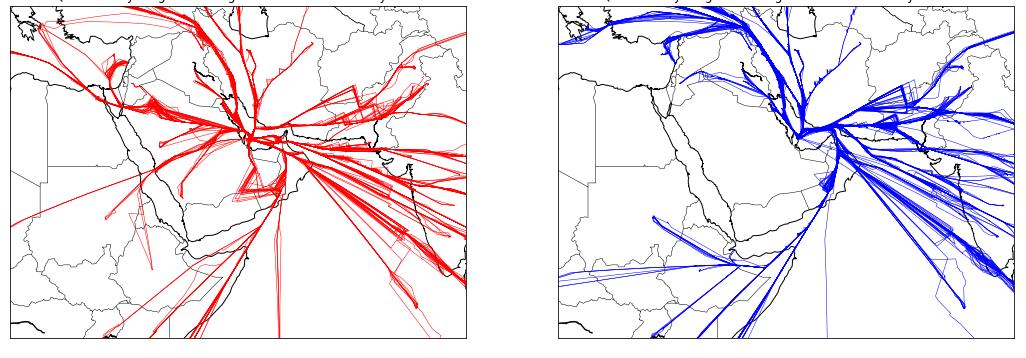

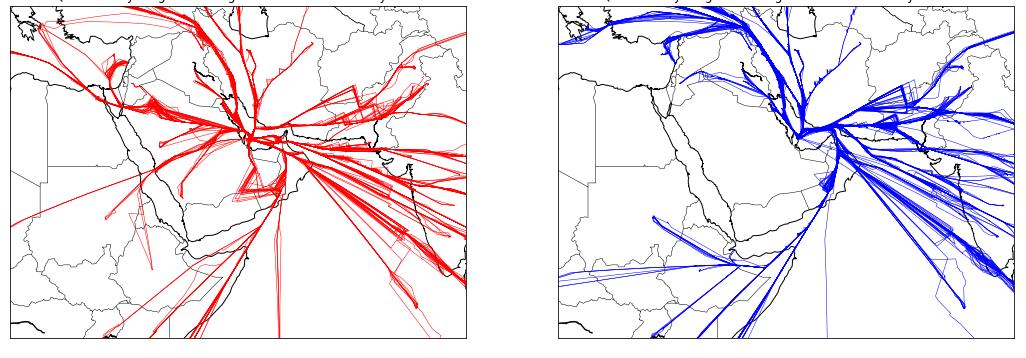

The impact of the diplomatic crisis for the flightpaths of Qatar Airways is shown in before (red) and after (blue) comparisons.

image: Dmc49

photo: Sonse #Tamim_The_Glorious

war, with titles such as #QatarNotAlone, and support for the Emir of Qatar with #Tamim_The_Glorious.

Social media provides a good platform for Qatari nationals to express their opinions and explore issues relating to their national identity, as well as to help them fight for the interests of the Qatar nation.

Jocelyn Sage Mitchell and Ilhem Allagui researched digital transformations and social empowerment in the Middle East and North Africa region. They note that “digital nationalism has emerged from the opportunity for the individual citizens to defend their countries from pioneers of cyberconflicts.” In this vein, Qataris capitalized on their social media presence to express their feelings and national pride in defense of their leader and their sovereign country.

Linking people

Social media is also an effective channel through which to improve solidarity among citizens, as social media platforms link people from diverse backgrounds. Allegations against Qatar from netizens in neighboring countries challenged the sovereignty and reputation of the nation. This in turn provided

an opportunity for the Qatari government to join forces with Qatari nationals to counter those narratives. Many Qatari citizens responded, displaying a high level of support for Qatari leadership. In a developing country where leaders are not elected by the people, digital nationalism became a unifying force.

The Gulf crisis created on online dispute, which led to the rise of digital nationalism in Qatar. The blockade of Qatar increased the level of solidarity among its citizens and increased the consolidation of the national identity. The influence of digital nationalism contributed to the failure of the blockade against Qatar. Digital platforms have led to the development of sites for people to express themselves in solidarity and nationalism. Social media become an important tool to mobilize people to resist the blockade. Twitter hashtags provided an effective way for Qatar nationals to show their national unity and promote national slogans. The tweets were a useful reflection of how users conceived bravery, strength, pride, and dignity towards the sovereignty of Qatar. In the future, digital nationalism will likely play an increasingly prominent role in disputes between states. n

Emerging Voices b 25

The Combined Air Operations Center at Al Udeid Air Base oversees air operations for more than 20 countries.

photo: Airman Magazine

Hedging Bets

Philippines seeks security by walking difficult line between US and China

Rommel C. Banlaoi

China and the United States have always been formidable factors in the formulation and implementation of Philippine foreign and security policy. As a close Asian neighbor, China has friendly relations with the Philippines dating back to the 9th century, even before the arrival of Western colonial powers. These long centuries of friendship resulted in China’s deeply rooted economic, cultural, and political influence on Philippine domestic politics and foreign relations.

The United States, on the other hand, has left an enormous indelible mark on Philippine cultural, economic, social, and political life as an erstwhile colonial master from 1898 to 1946. Filipinos even

describe Americans as distant relatives as a result of strong colonial experiences. During the period of colonial rule, Americans, in return, described Filipinos as their “little brown brothers” because of the way Filipinos embraced the American way of life.

Thus, the present US-China rivalry has been affecting the advancement of Philippine national interests. While the People’s Republic of China (PRC) remains the Philippines’ neighbor, Philippine foreign relations have been strongly entangled with the United States, being a distant relative forged by a formal alliance.

The Philippines and the United States have been formal security allies since the signing of the Mutual Defense Treaty in 1951. In fact, the United States rec-

26 b

Dr. Rommel C. Banlaoi is Professorial Lecturer at the Department of International Studies, Miriam College. He is also the President of the Philippine Association for Chinese Studies.

Strategic Vision, Special Issue (Summer, 2021)

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte speaks at the World Economic Forum in Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

photo: World Economic Forum

ognizes the Philippines as its oldest security ally in Asia. Prior to that, the Philippines was a US colony for almost half a century. As a former colonial master and a current formal ally, there is no doubt that the United States has an enormous influence in shaping Philippine foreign relations.

During the Cold War, Philippine foreign policy was in fact identical with American foreign policy, because of their existing security alliance. Though the post-Cold War period led to the re-examination of this alliance in the context of the Philippines’ attempt to assert a more independent foreign policy with the termination of the Military Bases Agreement in 1991, the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on the United States resulted in the reinvigoration of this alliance. Despite Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s rhetoric of separating from the United States in order to promote friendlier ties with the PRC, the United States continues to provide an important anchor for Philippine security and foreign policy. The 2017 Battle of Marawi demonstrated that the alliance was useful for the Philippines to help it

confront common threats with technical assistance, intelligence sharing, and military support from the United States. Recent developments in the South China Sea (SCS) also raise the strategic importance of the United States to counter the PRC’s growing presence and influence in the area.

Conflicting ideologies

While there is no doubt that relations between the Philippines and China can be considered as centuries old, their current formal ties only normalized in 1975. From 1946 to 1974, the Philippines declared the PRC a threat because of ideological conflicts in the Cold War. Their diplomatic relations soured in 1995 when China occupied Mischief Reef, which falls within the Philippines’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). But in 2005 the two countries declared the dawning of a golden age of bilateral ties with increased cooperation, despite the SCS dispute. They suffered, however, the lowest moment of their bilateral relations in 2013 when the Philippines filed an international

Hedging Bets b 27

Philippine Department of National Defense Undersecretary Cesar Yano presides over the opening of the 36th Balikatan Exercise.

photo: US Department of State

arbitration case against the PRC on the South China Sea as a result of the 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff. Also, the PRC built artificial islands within the Philippines’ EEZ in 2013. However, the two countries enjoyed new heights in their bilateral ties in 2016, when Duterte implemented a paradigm shift to bring the Philippines into China’s orbit. In 2018, the leaders of the two countries declared a state of comprehensive strategic cooperation in the 21st century as a result of PRC President Xi Jinping’s visit to Manila.

US President Joe Biden’s assumption of office in January 2021, and the growing international activism of Xi, are arguably putting the Philippines on a tightrope. Biden wants to reassert US global leadership while Xi seeks to promote his vision of new global governance.

In his Interim National Security Strategic Guidance (INSSG) released in March 2021, Biden recognized the growing US rivalry not only with the PRC, but also with Russia and other authoritarian states. Biden also lamented that China’s increased assertiveness with its growing power is creating new threats to US global interests. Thus, Biden is urging friends and allies to prevail in strategic competition with the PRC.

According to the INSSG, “By restoring US credibility and reasserting forward-looking global leadership, we will ensure that America, not China, sets the international agenda, working alongside others to shape new global norms and agreements that advance our interests and reflect our values.”

A shared future for mankind

Xi, on the other hand, continues to advocate for an alternative global system based on his idea of community and a shared future for mankind. In his recent remarks at the study session of the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) that was celebrating its centennial anniversary this year, Xi urged party leaders to make friends in order to present an image of a “credible, loveable and respectable China.” To this end, he tasked his officials to be “open and confident, but also modest and humble” when communicating with the world.

Indeed, US-China rivalry is heating up under the respective leadership of Biden and Xi. Amidst this competition, the Philippines is applying a strategy which small states have long used with great powers,

28 b STRATEGIC VISION

Armored vehicles of the Philippine Army take part in the Kalayaan Parade in Luneta, Philippines.

photo: Rhk111

by promoting friendly relations with the PRC while maintaining the security alliance with the United States. In doing so, the Philippines, particularly under Duterte, has moved to an active, small-state diplomacy and is risking its security alliance with the United States through its appeasement policy towards the PRC.

While the Duterte administration is promoting friendly relations with Beijing, it still continues “to work closely with the United States on a number of significant security and economic issues.” Though critical of the US military presence in the Philippines, the Duterte administration is not hampering the United States from conducting freedom of navigation operations in the SCS. His government even facilitated entry of US troops into the West Philippine Sea (WPS) during the Trump administration, as well as during the Biden administration. Though the Philippine government refused to join US-led military exercises in the SCS in order to avoid conflict with the PRC, Manila did provide access to US warships entering the WPS.

Amidst the growing US-China geopolitical rivalry in the Indo-Pacific region, the Philippine government upholds the centrality of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in promoting regional security. Its National Security Policy underscores that, “ASEAN centrality is important as it will

allow the region to manage the impacts of geopolitical rivalries among major powers.” Thus, the Philippine government supports the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, another major document informing the Philippines’ Indo-Pacific security policy and strategy.

The ASEAN Outlook recognizes that the AsiaPacific and the Indian Ocean “are amongst the most dynamic in the world as well as centers of economic growth for decades.” As a result, it observes, “These regions continue to experience geopolitical and geo-

Hedging Bets b 29

“ThePRCneedsthePhilippines toreduceWashington’slongestablished influence in the Indo-Pacific.”

Rodrigo Duterte and Xi Jinping shake hands and pose for photographers at the Boao State Guesthouse on April 10, 2018.

photo: Government of the Philippines

strategic shifts. These shifts present opportunities as well as challenges.” Since Southeast Asia is at the center of the Asia Pacific and the Indian Ocean, the Philippine government regards ASEAN as an important conduit in the promotion of security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region.

The Philippine government supports ASEAN centrality “as the underlying principle for promoting cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region, with ASEANled mechanisms, such as the East Asia Summit, as platforms for dialogue and implementation of the Indo–Pacific cooperation, while preserving their formats.” The Philippines regards the ASEAN Outlook as an important “guide for ASEAN’s engagement in the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean regions.”

Apparently, the Philippine government is playing both sides, between the two major powers, because of the realization that the PRC needs the Philippines

to reduce Washington’s long-established influence in the Indo-Pacific, while the United States needs the Philippines to counter Beijing’s rising influence in the region. In the United States, there is an admission that the Philippines is a very strategic country. According to Michael Green and Gregory Poling at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, “The alliance with the Philippines is an important anchor for US presence in Southeast Asia. The region is central to emerging US-China competition and crucial to our national interests. The alliance made important strides under the Obama administration but has come under strain since 2016 with the election of Rodrigo Duterte as president. Without putting the military and political relationship with Manila back on stable footing, it is difficult to see how we can accomplish our goals of upholding freedom of the seas and deterring Chinese aggression in the South China Sea and beyond.”

Weakening US alliances

For the PRC, on the other hand, the Philippines is also important for achieving its goal of weakening the existing network of US alliances in Asia, which is

30 b STRATEGIC VISION

A US Marine Corps F-35B conducts aerial refueling with a KC-135 Stratotanker from Kadena Air Base, Japan, over the Pacific Ocean.

photo: Daryn Murphy

“Beijingwillonlybeemboldenedto pursue this course with Duterte in office, as he has demonstrated not only anti-American, but also proChinaproclivities.”

viewed in Beijing as strategic containment. According to Derrick Grossman of the RAND Corporation, “China, in spite of Duterte’s VFA [Visiting Forces Agreement] reversal, is likely to continue seeing opportunity to disrupt and potentially even divide the US-Philippines alliance. Beijing will only be emboldened to pursue this course with Duterte in office, as he has demonstrated not only anti-American, but also pro-China proclivities. Thus, the United States along with its other allies and partners should not expect the PRC to back down anytime between now and the end of Duterte’s tenure in 2022, which is likely to make this period particularly turbulent.”

There are risks in playing both sides in the major-power game, however. Leaders in the CCP may doubt the sincerity of the Philippines’ friendship with China, considering that Manila continues to maintain its security alliance with the United States. On the other hand, the United States may question the loyalty

of the Philippines in the alliance for being friendly with the PRC. In this situation, it is imperative for the Philippines to effectively apply the hedging strategy being practiced by other small states in dealing with major powers involved in strategic competition. Hedging encourages small states to take both sides, rather than choose one side. Small states hedge to compensate for their weakness, and to overcome their lack of hard power to advance their national interests. Hedging has become the primary response of most states in the Indo-Pacific to address strategic uncertainties unleashed by increasing competition between the PRC and the United States on key regional security issues. Rather than to choose and be torn between a close neighbor and a distant relative, hedging will allow the Philippines to get the best of both worlds in the ongoing US-China major-power rivalry now occurring in the Indo-Pacific, and on the world stage. n

Hedging Bets b 31

US Secretary of State John Kerry chats with President Duterte while on a state visit to the Philippines in July, 2016.

photo: US State Department

A Common Enemy

Beijing’s Increasing assertiveness driving New Delhi closer to Washington Raviprasad Narayanan

We are all witnesses to, and participants in, the unsettling emergence of a new world order, beginning with the Asia-Pacific. After a decades-long acceptance of Pax Americana, Washington is facing challenges in the economic and strategic realms from an emergent Pax Sinica: a world order with Chinese characteristics. US President Joe Biden, a Democrat, is not very different from his predecessor, Donald Trump, a Republican, when it comes to foreign strategic policy. This surprising consistency on how to handle China indicates a policy continuity in Washington. Early indications point to strategic instabilities becoming a new tem-

plate in the Asia-Pacific region. This article examines the position adopted by India as it witnesses the beginnings of a new Cold War with Asian characteristics, between United States and China: a redux with strategic posturing by both sides, impinging on New Delhi’s policy choices.

The early decades of India’s external engagements since its independence in 1947 were marked by the adoption and articulation of a foreign policy of nonalignment in a post-war world where bloc rivalry had polarized international relations. If there was a bilateral engagement between established democracies in Asia that had fallen short of expectations, it was un-

32 b Strategic Vision, Special Issue

Dr. Raviprasad Narayanan is associate professor at the Centre for East Asian Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He can be reached at raviprasad.narayanan@gmail.com

(Summer, 2021)

Chinese soldiers stationed near the Indian border at Sikkim. PLA and Indian troops have clashed in the disputed area, with injuries on both sides.

photo: BMN Network

doubtedly that between Washington and New Delhi. The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was an early expression by countries that had gained their freedom from colonialism. What gave ideological impetus to the NAM was the structure of the United Nations comprising a couple of colonial powers, which left many countries in Africa and Asia a legacy of economic privation and political stagnation.

India’s growing role

Several decades after the end of the Cold War, a sobering assessment is taking place between three members of the United Nations Security Council—the United States, France, and the United Kingdom—on a growing role for India in security matters. China and Russia are watching India’s shift towards the United States on security matters. A renewed push on both sides—Washington and New Delhi—is being undertaken to correct a decades-long drift and to arrive at a mutually satisfactory relationship where economic connectivity and strategic congruence merge into a real bilateral bond with institutional heft, unencum-

bered by the problems of the past. In other words, the form and substance of the bilateral relationship between the two countries was divergent with very little, if any, common ground for a long time. India’s nonalignment was, to the United States, akin to being a member of the former Soviet bloc. If current trends are to be seen as a bilateral and multilateral systemic shift epitomized by the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, then we are witnessing an epochal moment in geopolitics with India and the United States beginning a strategic symmetry. Why? Of course, the emergence of China is driving the two countries closer together.

The United States has shown continuity in identifying China as a threat. The Republican Party under Trump and the Democratic Party led by incumbent President Biden are united on precious few issues, but on this they are in agreement: China, as the potential largest economy in the world with an investment and security architecture already in place, poses a very real, existential risk to Washington’s position as the upholder of democratic values. To the United States, the post-World War II era exemplified economic suc-

A Common Enemy b 33

Capt. Eric Anduze, right, speaks with Indian Navy Vice Chief of Naval Staff Vice Adm. G. Ashok Kumar.

photo: Sean Lynch

VISION

cess at home while rebuilding war-ravaged economies decimated by the fight against fascism. Then came the threat posed by another ideology: Communism. The implosion of the Soviet Union in 1991 ended the Cold War for certain, but it unleashed new vectors in strategic affairs, with Westphalian norms being challenged by quasi-states and non-state actors. Many were flummoxed by the emergence of China as an economic power player. As China expands in economic terms, its behavior is increasingly a unilateral affair of enforcing ideas and ideology—the latter being far more worrying.

Alternative to BRI

Biden’s Build Back Better World (B3W) global infrastructure spending initiative has been welcomed, up to a point. A continuation of the effort, begun by Trump, to offer an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, B3W is domestic policy in the United States, which is grappling with the intricacies of

China’s economic growth reaching levels where technology will be the determinant. This would negate the boots-on-the-ground approach that has made the United States the paramount strategic power. The US Innovation and Competition Act, which builds upon the Endless Frontier Act of 2020, seeks to invest US$200 billion on semiconductors, wireless broadband, artificial intelligence and drones, with more federal oversight into technologies being developed.

From India’s perspective, B3W is an illustration of how the United States is trying to advance its interests, even as the odds are against an entity with immense resources and determination. The aspect that is most welcomed by India are the prospects of

34 b STRATEGIC

Indian engineers represent their country at an international robotics competition.

“India’s nuclear tests at Pokhran invitedglobaleconomicsanctionsand thefreezingofloansandgrants,the only exception being humanitarian aid.”

photo: WorldSkills