WHERE VISION BECOMES STRUCTURE

RISA o ers a comprehensive suite of design software that work together to simplify even the most complex projects. As a result, engineers can work e ciently on a variety of structures in a mix of materials including steel, concrete, wood, masonry and aluminum. risa.com

COME VISIT US

NASCC: THE STEEL CONFERENCE Louisville, KY | April 2-4, 2025

BOOTH #211

Digital Issue

subscriptions@structuremag.org

EDITORIAL BOARD

Chair John A. Dal Pino, S.E. Claremont Engineers Inc., Oakland, CA chair@STRUCTUREmag.org

Kevin Adamson, PE Structural Focus, Gardena, CA

Marshall Carman, PE, SE Schaefer, Cincinnati, Ohio

Erin Conaway, PE AISC, Littleton, CO

Sarah Evans, PE Walter P Moore, Houston, TX

Linda M. Kaplan, PE Pennoni, Pittsburgh, PA

Nicholas Lang, PE Vice President Engineering & Advocacy, Masonry Concrete Masonry and Hardscapes Association (CMHA)

Jessica Mandrick, PE, SE, LEED AP Gilsanz Murray Steficek, LLP, New York, NY

Brian W. Miller Cast Connex Corporation, Davis, CA

Evans Mountzouris, PE Retired, Milford, CT

Kenneth Ogorzalek, PE, SE KPFF Consulting Engineers, San Francisco, CA (WI)

John “Buddy” Showalter, PE International Code Council, Washington, DC

Eytan Solomon, PE, LEED AP Silman, New York, NY

EDITORIAL STAFF

Executive Editor Alfred Spada aspada@ncsea.com

Managing Editor Shannon Wetzel swetzel@structuremag.org

Production production@structuremag.org

MARKETING & ADVERTISING SALES

Director for Sales, Marketing & Business Development

Monica Shripka Tel: 773-974-6561 monica.shripka@STRUCTUREmag.org

image by Remote Optix

STRONG. SECURE.

If seismic or high-wind challenges are important considerations for your next project, Vulcraft and Verco’s steel roof deck and PunchLok II® System is a valuable option to consider. Our team of experts can help you evaluate the variety of value-added sustainable solutions that Vulcraft and Verco offer to ensure that you have the right system in place.

Contact an expert today.

VULCRAFT VERCO

IMPROVED ECONOMY AND RESILIENCE WITH MAST FRAMES

By Jason Armes, SE; Gina Carlson, SE; and Leo Panian, SE

An innovative approach to seismic design of steel structures was taken for Samuel Merritt University’s new 10-story office, research, and academic building in downtown Oakland, California.

FEATURES

24

ENGINEERING ON DISPLAY

By Amy Barabas and Tom Barabas

With exposed CLT floors and steel framing, a large testing facility, and lattice brick work, the new building gives students numerous opportunities to see real-world engineering solutions

FOLLOWING THE EASTERN STAR

By Ryan Miller, SE, and Eric Fuller, SE

Converting a century-old meeting hall into a modern hotel requires meticulous attention to sequencing.

COLUMNS and DEPARTMENTS

Stephanie Slocum,

Michael O’Rourke, John Duntemann & John Cocca

Arun M. Puthanpurayil, Ph.D

John Dal Pino

Gwen P. Weisberg

Building Belonging in Structural Engineering

The

Thousand Little Things

By Stephanie Slocum, PE

Last week, I received a message from an earlycareer structural engineer—let’s call her Sarah. Despite graduating near the top of her class and landing a position at a prestigious firm, she was considering leaving the profession. “I just don’t feel like I belong here,” she wrote. “It’s not any one thing—it’s a thousand little things.”

Sarah’s story reflects an escalating workforce challenge. Employee engagement hit a 10-year low in 2024, costing an estimated $8.8 trillion in lost productivity globally. For structural engineers, NCSEA’s SE3 committee found that 55% of structural engineers have considered leaving the profession, with even higher percentages among women and non-white engineers. Only 30% consider our profession “attractive” compared to other STEM fields, and the top reasons cited for considering leaving were 1) stress and 2) work-life balance. Yet, those terms mean different things to different people, even those with identical qualifications. Successfully addressing these challenges requires understanding each individual’s unique context.

As structural engineers, we pride ourselves on systems thinking. We understand that structural performance depends on both individual components and how these components interact within the larger system. We analyze load paths, consider multiple failure modes, and account for how various elements influence each other. Yet, when it comes to supporting the people in our profession, we often forget these fundamental “systems-thinking” principles.

Ethical obligations within our profession are one place where systems thinking is commonly applied. For example, ASCE’s Code of Ethics, which I helped author, requires us to “treat all persons with respect, dignity, and fairness...” This professional obligation aligns with our core mission of protecting public health, safety, and welfare. Just as we wouldn’t design a structural component without understanding the complete system, we can’t effectively support our profession’s talent without understanding the personal, historical, and societal factors that influence workplace experiences.

The demographic trends speak to urgent action needed related to that talent pipeline. By 2030, the U.S. population over 65 will exceed those under 18. By 2045, the U.S. will be “minority white,” yet our engineers and architects together currently are 76.8% white and only 17.2% women. The impending student

“enrollment cliff” will further reduce our talent pool, with U.S. colleges expecting a 15% drop in students by 2039. These trends point to fewer structural professionals in the future; if we don’t create an environment where talented individuals want to stay, there may not be enough of us to meet demand—even if interest in STEM careers grows overall.

In structural analysis, we don’t assume every beam experiences the same loads or every foundation rests on identical soil conditions. Instead, good engineering requires us to investigate the specific site context, understand the unique challenges, and design solutions accordingly. Similarly, supporting individual success in our profession requires understanding each person’s unique context and creating environments where they can fully contribute their talents. Historical examples (severely limited due to max word count) demonstrate systemic barriers to success:

• Women’s financial autonomy was severely limited, with loans and credit cards requiring male cosigners until 1974.

• Discriminatory redlining prevented racial and ethnic minorities from accessing loans needed to buy homes or start businesses (illegal since 1968, with recent legal settlements as late as 2023).

• Escalating engineering education costs consume a much higher percentage of income and starting salaries compared to 20+ years ago.

These contexts do not define an individual’s potential to contribute to our profession, yet they (and many more often unseen challenges) directly impact how individuals relate to work. Instead, they represent systemic barriers that have historically constrained our profession’s ability to recruit and retain top talent.

The U.S.-based structural engineering profession’s nonprofits—ASCE’s SEI (of which I am currently President), ACEC’s CASE, and NCSEA—are uniquely positioned to address these challenges. With intentional, collaborative efforts and the ability to transcend regional political differences due to a broad national reach, we create pathways for learning, mentorship, and professional growth.

At SEI, our Professional and Technical Communities were designed to minimize silos. These communities serve as platforms for professional development. Focuses include developing codes and standards, creating sustainable design

resources, cultivating leadership, improving engineering education, and implementing mentorship programs. By bringing together people across the pro fession, we’re actively working to strengthen our profession’s talent pipeline.

Our path forward as a profession requires applying the same systems thinking we use in structural design to our professional ecosystem. This means:

• Creating intentional mentorship structures.

• Developing communication skills that bridge generational and cultural differences.

• Taking daily actions that recognize individual strengths and unique perspectives. Our profession’s future depends on creating systems that value the contributions of all types of structural professionals. We cannot allow political polarization to distract us from our fundamental ethical obligation to protect public health, safety, and welfare—an obligation that requires attracting and retaining talent from all backgrounds.

Take action today: join one of our professional associations like SEI, where you can mentor others and build connections across geographical and experiential boundaries. Seek out colleagues with different backgrounds and experiences. Understand that every human connection we build makes our profession stronger and better equipped to serve our communities. And remember—that small gesture of caring you make today could be the reason a talented engineer stays in our profession tomorrow. We all have this power. Will you use it? ■

Stephanie Slocum, PE, is the President of SEI and the Founder of Engineers Rising LLC, a firm that specializes in leadership and communications training and coaching.

structural DESIGN

Best Practices for Post-Tensioning Elongation Records

This article explores timeliness of review, the purpose of elongations and tolerances, evaluation of stressing records, and reasonable expectations for the involved parties.

By Bryan Allred, SE; Frank Malits, PE; and Neel Khosa

Reprinted with the permission of the Post-Tensioning Institute.

Post-tensioned (PT) structural systems provide effective framing solutions for a wide range of conditions, but cost effectiveness is heavily influenced by the timing of formwork cycling. For PT structures, review and approval of elongation records is a critical part of that process. This article focuses on cast in place concrete structures reinforced with unbonded post-tensioning strands which are typically used in one-way slabs, two-way slabs and beams/girder systems.

Timeliness of Review

The review process for stressing records can vary significantly across the country based on local jurisdictional requirements. In some areas, the Licensed Design Professional or Structural Engineer of Record (LDP/SEOR) does not need to be consulted if all measured elongations are within the ACI 318 allowed 7% tolerance. In these cases, the LDP/SEOR is only required to address out-of-tolerance conditions. In other areas, local jurisdictions require the LDP/SEOR to review and approve complete stressing records, even if all elongations are within tolerance, as a prerequisite step for the Contractor to cut tendon tails and continue with construction.

In the former case with out-of-tolerance conditions and in the latter case as a whole, the cycling of formwork is effectively halted until the LDP/SEOR responds. In the author’s experience, LDP/SEORs who exceed 2 days to review records do not prioritize their client and owner’s interests. In addition, reviewing elongation records for a concrete pour should take less than 60 minutes. If inattention persists, a delay claim may be forthcoming since the contractor is potentially losing significant time and money. Accordingly, the review and resolution of elongation records should be made a priority within design offices.

Timely review of stressing records also allows for faster completion of the tendon corrosion protection system. Starting with ACI 318-11, all structural building PT is required to be fully encapsulated in plastic sheathing and grease for corrosion protection. The tendon tails, however, are bare steel to accommodate stressing operations. The excess tendon tails cannot be cut until the stressing records are approved, at which time the encapsulation cap can be installed over the cut end to protect the tendon and the seated wedges. The longer the bare tendon is exposed to the elements, the potential for corrosion increases. Get the tendon ends protected as quickly as possible.

The Purpose of Elongation Records

Transferring the force from the PT strands to the concrete is critical to the performance of PT structures. Contractors must demonstrate they have complied with the contract documents, and the LDP/SEOR and building official must have confidence that the structural design has been successfully implemented. ACI 318-19 section 26.10.2(e) requires two separate actions to verify prestressing force and friction losses. First is a comparison of the measured strand elongation to a theoretical, calculated value. The second is verification of the jacking force for the rams, typically calibrated using a pressure gauge. These two actions are used individually as a check on the other.

The practical benefit of elongations is they can be observed and measured after installation of the PT force. If the inspector was not present during stressing, if the gauge pressure wasn’t recorded, or something unforeseen occurred, the elongations can still be measured as a simple way to estimate the approximate strand force. Another option would be to perform a lift-off test, which effectively is re-stressing the strands until the wedges release and recording that pressure/force. While lift-offs are performed for multiple reasons, it’s more efficient and safer for the field to measure the elongation at the tendon tail and back calculate the force. Lift-off tests can also damage the tendon. This is why elongation reports are so valuable for engineers, contractors, and inspectors. However, the elongation values need to be better understood and not used to generate unnecessary work.

Measuring elongations involves spray paint or construction keel, a straight edge, and a tape measure. Prior to stressing the strand, the inspector will place the straight edge against the slab edge and mark the exposed tendon (Fig. 1). After stressing, the same straight edge is placed against the slab edge and a tape measure shows the distance the mark has moved. This distance is the measured elongation of the strand, and the inspector will record a value for each tendon. The measuring process has its own built-in tolerance, as any measurement does.

The measured elongation is then compared to the theoretical, calculated value and the difference is documented in the report. The authors highly recommend the elongation record include the allowed +/-7% deviations from the theoretical value and the actual percentage difference between the measured and calculated values (Table 1). This helps the LDP/ SEOR quickly identify potential issues that may need contractor and

Fig. 1. Exposed strands of unseated wedges are marked with paint prior to stressing.

PT Supplier input to resolve. A typical report should provide a strand identification (color code), plan location, length of each strand and the gauge pressure of the jack.

The authors also strongly encourage the LDP/SEOR to review the equipment calibration prior to the start of construction. PT suppliers should calibrate their equipment between projects and within 6 months per PTI.

Understanding ACI 318 Elongation Tolerance

The tendon force and theoretical elongation are related based upon the strength and materials equation Δ = P*L / (A*E), where Δ is the strand elongation, P is technically the average force in the strand, but typically approximated by engineers as the anchorage force as prescribed in ACI 318-19 section 20.3.2.5, L is the length of the strand from anchor to anchor, and A and E are the strand cross-sectional area and modulus of elasticity, respectively. The theoretical elongation for each tendon is calculated by the PT supplier using the specific material properties and strand layout and is reported on the PT shop drawing submittal.

It is important for the LDP/SEOR to understand the force in the strand is not precisely proportional to the measured elongation. They are correlated, but an under-elongated strand does not immediately indicate a reduced force. There will always be differences between the theoretical and actual elongation. For example, PT suppliers, when calculating elongations, will typically use the straight-line distance between slab edges as the tendon length. In reality, a tendon is likely not to be straight due to penetrations, embedded elements or slab openings. Similar precision arguments can be made regarding friction loss, wedge seating, actual vertical tendon profile and the actual tolerance in the inspector measurements.

The ACI Code tolerance for elongations was implemented decades ago to account for numerous factors in stressing and measuring a PT strand. Concrete buildings are not constructed in a vacuum, and nothing is perfect. The 7% tolerance is not stating the code is “ok” with 93% of the force shown on the drawings. It acknowledges there will be slight differences between the theoretical and measured elongations, and provided they are small enough, that is expected and acceptable.

Out of Tolerance Elongation Records

When elongation measurements deviate from the allowable range, the design and construction team must collaboratively identify the cause. Generally, the PT supplier is to first reconfirm the elongation calculations by checking material properties and other calculation inputs. For example, on a recent project, a last-minute change to a construction joint location caused tendon lengths to differ from that used in the elongation calculations. The problem was quickly identified, and the elongation calculations were revised. If there are broken tendons or major elongation deviations, the PT supplier can conduct a more complex variable force calculation to provide additional information to the design team.

The role of the concrete contractor is to identify anomalies such as malfunctioning jacking equipment, observed anchorage slip, localized concrete defects, or other issues that could affect elongations. The role of the LDP/SEOR is to determine the impact of potentially deficient tendon forces on their structural design. All parties should collaborate on appropriate repair techniques should it come to that, to fix the problem and minimize further damage.

Short Tendon Effects

Another commonly misunderstood aspect of elongation reports is an out-of-tolerance result for short length tendons. Tiny differences between small elongation values can result in large percentage deviations. A 20-foot-long strand should elongate approximately 1-5/8 inches. However, an extra 3/16-inch wedge seating loss will produce a 12% out-of-tolerance deviation. This condition may incorrectly indicate a low force and possibly result in unnecessary remedial work. The Post-Tensioning Manual 7th Edition recommends ¼ inch be added to the theoretical elongation for strands shorter than 40 feet to account for these effects. In addition, the authors recommend relying more on verifying the applied jacking force and to view short tendon elongations with an informed eye.

Table 2. Strand “Force” from Measured Elongations

Friction Loss Calculations

The PT supplier prepares friction-loss calculations, which do not constitute a “design” of the PT system but are a verification of the theoretical tendon force for a given configuration. The tendon force is a function of many variables, but the material modulus of elasticity, angular coefficient, and wobble coefficient are specific to a given PT Supplier’s material.

The LDP/SEOR must assume a final effective PT force to produce a rationale design based on a finite number of tendons in a concrete member. Most seasoned PT designers assume a force of about 27 kips per tendon. This effective force assumption must be documented on the structural contract documents and should be verified by the friction loss calculations. The supplier is demonstrating their product can provide the force assumed as the basis of design by the LDP/SEOR. The PT supplier is not “designing” the PT system. An analogy would be rebar mill certs for deformed reinforcing steel. In many cases, LDP/ SEOR insist the PT supplier is the “PT designer” because of the friction loss calculations, which they then use as an improper basis to demand additional submittals and evaluations that are not properly the purview of the PT supplier.

Force Certifying Letters

In some areas of the U.S., PT suppliers are required by LDP/ SEORs to determine and “certify” the final installed forces based upon the measured elongations—even for tendons within the allowable 7% deviation range. Table 2 is an example of this process. This does not have a useful purpose other than to spread liability and slow the elongation review process. It is questionably unethical to require the PT supplier to “certify” construction put in place by others. The implied liability is enormous and may violate some State professional licensing laws. The authors strongly encourage all who engage in this practice to cease immediately.

Structural contract documents also might mandate: “PostTensioning Supplier shall have an Engineer supervise the stressing operations and issue a letter certifying that the prestressing forces have been transferred to the structure. The letter should also address and resolve any discrepancies.”

This specification is wildly inappropriate in the author’s opinion. The LDP/SEOR should understand the proper role of the PT supplier prior to requiring these types of letters. The PT Supplier controls the manufacturing process. The PT material is typically required to be fabricated at a PTI-certified plant, which is an ANSI certified program. Additionally, the PT Supplier has shared control over stressing equipment. After the initial calibration, onsite equipment maintenance is beyond the control of the PT supplier. The PT Supplier does not have a consistent field presence to supervise or monitor the construction phase. In the past, the PT Supplier might conduct a pre-pour jobsite visit, but this practice has become mostly obsolete due to the commonplace adoption of recognized PTI certification programs for installers, stressors and inspectors. Furthermore, the PT Supplier is not involved with the formwork, PT installation, rebar installation, concrete placement, stressing operations or elongation measurement and reporting.

Requiring the PT supplier to certify forces is not required by any code that we are aware of, adds time to the elongation review process, and increases the PT supplier’s liability for out-of-scope construction (which increases their cost to cover that risk). If the PT supplier is contracted to

fulfill the requirements shown on the structural documents, then they have already committed to providing the listed force.

Conclusion

The collective industry goal should be to advance practices and procedures that contribute to the sound design and construction of cost-effective PT structures, in a manner that is reliable, fair, and reasonable for all. ■

Bryan Allred, SE, F.P.T.I., is the Vice-President of Seneca Structural Engineering, Inc. in Newport Beach, California. He currently is a member of the Technical Advisor Board, Building Design and Education Committee of PTI, ACI 423 and is the co-author of the book “Post-Tensioned Concrete, Principles and Practice, 4th Edition”.

Frank Malits, PE, F.A.C.I., F.P.T.I. is a principal structural engineer with Cagley & Associates in Rockville, Maryland. He currently serves as a member of ACI 31825, ACI 301-26, and the PTI Technical Activities Board.

Neel Khosa is President of AMSYSCO, which is a PT Supplier in Chicago, IL. He

M-10 and

structural DESIGN

Adhesive Bond Performance of CFRP-Patched Concrete

Research shows epoxy adhesives fall short as gamechangers for CFRP patch bonding in damage resistance.

By Dr. Martin Brandtner-Hafner

In civil engineering, modern materials and techniques are crucial for enhancing the durability and strength of concrete structures. Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) patches have emerged as an effective solution for rehabilitating beams, columns, slabs, and walls, offering high tensile strength, lightweight properties, and corrosion resistance. These patches improve load capacity and structural performance, addressing environmental and operational challenges. As the field advances toward sustainable solutions, refining CFRP patching techniques is key. This article discusses interfacial fracture analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of adhesively bonded CFRP patches in reinforcing and rehabilitating concrete structures.

A review of literature highlights extensive research on CFRP for strengthening and refurbishing concrete structures. Studies focus on improving load capacity, ductility, crack resistance, and durability to extend service life.

Key sources include Mays, Biolzi et al., and Frhaan et al., who demonstrate the effectiveness of externally bonded CFRP strips in boosting beam capacity. Research by Golham et al. and Wu et al. validates CFRP use for beams and slabs under varied conditions. Environmental impacts, such as tropical climates or heat, are examined by Hashim et al. and Al-Rousan. Methodologies range from experimental tests to finite element modeling for predicting structural behavior. The ACI Committee 440 provides a valuable design guide for Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) systems, while Nanni explores CFRP applications in civil engineering, highlighting

their versatility. Despite significant advancements, existing studies often focus on epoxy adhesives, limiting insights into CFRP-toconcrete interface failures with varied adhesives. Using a holistic fracture analysis addresses this gap by investigating shear-induced failures at adhesive-bonded CFRP interfaces, offering new insights into reinforcement techniques.

Materials and Methods

Basic Considerations

The evaluation of concrete structures falls into two categories: bulk assessment using continuum mechanics which focuses on technical stresses, and surface reinforcement assessment, where traditional methods may be insufficient. Various safety evaluation methods for bonded CFRP patches are documented, primarily using standardized continuum mechanics approaches such as compression, flexure, shear, and pull-off tests. Pull-off tests, standardized by the American Society for Testing and Materials’ ASTM D7234, Standard Test Method for Pull-Off Adhesion Strength of Coatings on Concrete Using Portable Pull-Off Adhesion Testers, 2021, and ASTM C1583, Standard Test Method for Tensile Strength of Concrete Surfaces and the Bond Strength or Tensile Strength of Concrete Repair and Overlay Materials by Direct Tension (Pull-Off Method), 2010, are particularly effective for assessing adhesion in multi-material composites.

Failure Analysis of Bonded CFRP Patches

Bonded CFRP patches aim to dampen, delay, or stop crack propagation. Figures 1 and 2 show the test specimen design: concrete blocks with U-shaped notches on each front, where CFRP strips were adhered. A cross-section view (Detail X) illustrates how CFRP patches counteract crack formation under mode-I bending-tensile stress, demonstrating their effectiveness in mitigating crack progression. Mode-I bending tensile stress refers to the stress

developed when a crack opens perpendicular to its plane under bending loads, such as in a beam or plate. Unlike pure tensile loading (like pull-off tests), bending focuses stress near the crack, better simulating how real structures fail under combined stresses. This method provides more realistic insights into material and joint behavior, especially under complex, service-like conditions.

In the study, three types of CFRP damage patches under mode-I loading were analyzed via interfacial fracture analysis. Figure 3 illustrates the damage types:

• Type A (left): The patch fails to stop crack propagation, as

mode-I loading and crack opening damage the fiber-matrix interface. This occurs due to brittle adhesives, like epoxy, which lack crack sensitivity and damping.

• Type B (middle): The crack initiates in the concrete and extends into the adhesive layer. Adhesive systems with high crackdamping properties can confine the crack within the adhesive, optimizing failure behavior. This makes Type B preferable for design.

• Type C (right): A combination of Types A and B, where the crack penetrates the adhesive and damages the patch. Although suboptimal, Type C performs better than Type A.

Evaluation Procedure

Test Candidates

The performance of various adhesive systems through fracture analysis was investigated to evaluate their interfacial reliability in CFRP-to-concrete bonding. The three adhesive types—epoxy, polyurethane, and silyl-modified polymers (SMP)—were tested for their effectiveness in bonding CFRP patches under shear loading. While epoxy adhesives dominate practical applications, research on alternative systems using fracture analysis remains limited. Details on the materials are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1 shows a compilation of the three types of adhesives used for bonding concrete structures of this study. Specifications are taken from product sheets of the manufacturers.

Fig. 2. Overview of prepared specimens. A) Pure notched concrete block; B) CFRP patch prepared with epoxy adhesive; C) CFRP patch prepared with polyurethane adhesive; D) CFRP patch prepared with silyl-modified polymer adhesive; and E) Specimen dimensions. Source & Credit: FRACTURE ANALYTICS.

Fig. 3. Schematic depiction of the three types of damage to bonded CFRP patches on concrete under mode-I loading. Source & Credit: FRACTURE ANALYTICS.

Table 1. Evaluated Adhesive Bonding Systems Used on Concrete Interfaces

Table 2. Compilation of Mode-I Loading Results of Bonded CFRP Patches Compared to Pure Concrete

Source: FRACTURE ANALYTICS. MPa = Megapascals. J/ mm² = Joules per millimeter squared. Std. Dev. = Standard Deviation

Test Setup

A setup was applied so that specimens were adhesively bonded to concrete plates and cured for seven days at room temperature (Figure 4). Testing was carried out in a laboratory on a universal testing machine. The fracture analytical events were accomplished in quasi-static loading for six samples per series. Several evaluation parameters were identified, with the results presented in Table 2. Further details about the method can be requested from FRACTURE ANALYTICS.

Results and Discussion

Basic Considerations

Two key fracture-analytical parameters—flexural notch strength

(σfn), and specific fracture energy (GF)—are used to derive an empirical structural safety factor (SF) according to Brandtner-Hafner. The results are summarized in Table 2.

The CFRP Patching Effect

A new method for evaluating the effectiveness of CFRP patching uses three adhesive systems under mode-I loading. Figure 5 illustrates the debonding process for a CFRP-patched concrete specimen. The dashed black line represents the quasi-brittle failure of an unreinforced specimen, where a primary crack forms after maximum load, propagating stably until complete separation. In contrast, the solid red line depicts the patched specimen using a SMP-based adhesive. At approximately half the maximum load (~60 Newtons (N)), Inflection Point 1 marks the onset of CFRP patch load-bearing, allowing the force to increase progressively. This increase continues until reaching 100 N, which corresponds

to 83% of the concrete-only strength of 120 N. At the peak stress point of the CFRP patches, a secondary crack initiates within their interface. The debonding process still remains stable and tough, as the flexible adhesive absorbs significant fracture energy, acting as a damping agent and providing a notable safety gain. Once the force drops to below half of the maximum load (Inflection Point 2), secondary cracks propagate until complete separation at rupture. The so-called "Safety Gain Zone," the area between Inflection Points 1 and 2, indicates the absorbed fracture energy, highlighting the desirable safety benefits of this reinforcement.

Finally, to foster a better understanding of how the bonding characteristics of the three adhesive systems influence the failure behavior of patched CFRP, Figure 6 illustrates the fracture patterns observed during the experiments.

• Section A: This shows fiber-matrix cracking in an epoxybonded patch. It corresponds to failure type A in Figure 3. Such failures arise from the brittle nature of epoxy adhesives, where cracks propagate along the fiber-matrix interface. This brittle behavior is a key limitation of epoxy-based systems.

• Section B: Here, interface delamination is evident in a

Fig. 4. Detailed illustration of test setup. Source & Credit: FRACTURE ANALYTICS.

polyurethane (PUR)-bonded patch. It corresponds to failure type B in Figure 3. The CFRP patch separates from the concrete substrate at the adhesive interface, often due to poor adhesion or mismatched mechanical properties between the CFRP and the PUR adhesive.

• Section C: This depicts a mixed failure mode in a patch bonded with silyl-modified polymer (SMP). It corresponds to failure type C in Figure 3. The failure combines fiber-matrix cracking and interface delamination, reflecting the material’s more complex behavior. SMP adhesives are tougher than epoxy, enabling better crack damping and stronger bond integrity, making them a more versatile option for such applications.

The investigation underscores the pivotal role of adhesive selection in the performance of CFRP patches for reinforcing concrete structures under mode-I loading. The analysis of epoxy, polyurethane, and silyl-modified polymers revealed significant differences in their ability to mitigate structural vulnerabilities. While epoxy allows primary cracks to propagate, polyurethane and SMP adhesives demonstrate superior crack damping and delay. Fracture analysis and Modified Compact Tension (MCT) measurements show that SMP adhesives absorb significantly more fracture energy than epoxy and polyurethane. Hybrid adhesives, combining epoxy’s strength with SMP’s fracture energy absorption, emerge as a promising solution for enhancing CFRP patch effectiveness. The findings

Fig. 5. Overview of the loading behavior of tested CFRP patch systems on the example of polyurethane adhesive. Source & Credit: FRACTURE ANALYTICS.

highlight the importance of balancing strength and fracture energy absorption in adhesive selection to optimize CFRP performance. Future applications should integrate these insights, particularly by exploring hybrid technologies to advance adhesive selection and application practices for concrete structures.

In conclusion, the study suggests reevaluating the industry’s reliance on epoxy adhesives. Emphasis should shift toward alternative systems and hybrid formulations, alongside long-term performance studies, to support the development of sustainable and resilient infrastructure. ■

Full references are included in the online version of the article at STRUCTUREmag.org

Dr. Martin Brandtner-Hafner, born in Austria, pursued his studies in industrial engineering and materials science at the Vienna University of Technology. Following his doctoral research on “The Empirical Safety Evaluation of Structural Adhesives,” he established FRACTURE ANALYTICS, a private R&D consultancy specializing in the empirical evaluation and certification of adhesives, composites, and multimaterial interfaces.

Fig. 6. Fracture patterns of various cracked CFRP patch variations. Section A: fiber-matrix cracking of EPOXY bonded patch, Section B: interface delamination of PUR bonded patch, Section C: Mixed failure of SMP bonded patch. Source: this study.

Engineering on Display

With exposed CLT floors and steel framing, a large testing facility, and lattice brick work, the building gives students numerous opportunities to see real-world engineering solutions.

By Amy Barabas and Tom Barabas

The Engineering Design and Innovation (EDI) building is the new gateway to innovation on the expanding west campus at Penn State University Park. With large, column-free spaces, exposed structure, lattice pattern brick, and expansive glass, the 105,000 square feet structure provides an opportunity to witness engineering at every turn. Sprinkled throughout the building are nearly 10,000 square feet of machine shops and manufacturing labs. Topped with five long-span raised roof monitors with clerestory windows for natural light, the fourth level open loft provides students and teachers with a flexible maker space. Isolated from the classroom portion, a three-story high bay housing two 20-ton gantry cranes and a substantial strong wall/reaction floor delivers a unique testing area for experimental research.

CLT Hybrid Structure—Design Challenge 1

Early design iterations for the classroom structure examined multiple solutions for the building framing system, and it appeared initially that a traditional concrete on metal deck with steel beam composite construction would be the least expensive option. However, as the push for sustainability gained momentum and the design and construction teams learned more about CLT and a possible hybrid solution, the decision to use CLT was made.

The project grid consists of a 32-foot spacing in the north-south direction and beam spans of 25-foot, 6 inch, 54 foot, 6 inch, and an additional 12 foot, 8 inch cantilever in the east-west direction. The dimensions were critical in the decision to switch from a traditional composite system to a hybrid system. With a composite floor, two beams would be required within each bay to keep the deck span to approximately 11 feet. However, with five-ply CLT, the deck span could increase to more than 16 feet, allowing one beam to be removed in each bay.

Floor framing design began with verifying allowable span lengths for the CLT panels with respect to strength and vibration. Various CLT manufacturer tables were reviewed to arrive at the final thickness of the CLT panel given the chosen beam spacing and the species of wood the architect preferred. The design team determined that 2 inches of normal weight concrete topping reinforced with 6x6-W1.4xW1.4 W.W.R. above the CLT panels would suffice for acoustic concerns. At the time of the design, limited references were available detailing design for vibration with a CLT hybrid system. The team chose to analyze the CLT by following Chapter 7 of the CLT Handbook and to analyze the

Photo by Warren Jagger

Photo by Warren Jagger

The CLT floor and steel beam framing were left exposed to highlight the building's structural characteristics.

non-composite steel beams by following the vibration requirements set forth in AISC Design Guide 11. Due to the long spans, many of the supporting steel beams increased in size and required the additional dead load that the 2 inch topping provided to remain under the recommended acceleration tolerance limit of 0.5%.

The lateral system for the classroom section consisted of steel braced frames and moment frames relying on the CLT panels to act as a diaphragm. Details between the CLT panels and the steel beams were carefully reviewed to ensure that the diaphragm forces were properly transferred into the lateral system. MTC ASSY Kombi screws were used between the underside of the top flange of the steel beams and the underside of the CLT for both CLT panel to steel beam typical connections as well as CLT chord splices. MTC ASSY Ecofast screws and ¾-inch thick sheathing strips were used along the top side of the CLT panels for panel splices. Both size and spacing were based on the shear per linear foot that need to be transferred.

The EDI building, designed under IBC 2015, is Type IIIB unprotected combustible construction with a 2- hour fire rated exterior bearing wall between the existing garage and the new building. As such, the steel beams and bottom of CLT could remain exposed.

Overall, because the steel beams were not composite, they increased in weight, while the total number of pieces used decreased. The combined weight of the CLT with the additional 2 inches of normal weight topping was very similar to that of the composite slab on deck, so column and footing sizes remained comparable to what they would have been with a traditional steel building. There was a learning curve for the entire design team and increased coordination between disciplines. However, the speed of installation of the CLT panels coupled with the reduced embodied carbon, confirmed that this was the correct design choice for the project.

Strong Wall/Reaction Floor—Design Challenge 2

Part of the high bay program required a strong wall and reaction floor that will be used to complete testing on new and innovative structural products and designs. The strong testing walls and floors each have a grid of pipe sleeves that run through the wall and floor allowing for Dywidag tie rods which are used to anchor the testing apparatus to the wall and floor.

Completed strong wall reinforcing prior to pouring concrete.

Isolation joint detail between high bay and classroom to mitigate vibration transmission.

Strong wall reinforcing layout.

The force is transmitted to the testing specimen by a hydraulic actuator that is set to deliver a specific force at a given frequency.

The strong wall is 30 feet tall and 2 feet thick between pilasters and buttresses. In plan, it is L-shaped with the long leg approximately 60 feet and the short leg 23 feet, 8 inches. The high bay’s west wall location was set by an adjacent existing parking garage. The space between the west wall and the back side of the strong wall, including testing wall pilasters, had to maintain clearance for a scissor lift to pass between the two. To provide the maximum amount of testing space in front of the strong wall, and maintain the clearance behind it, it was determined that the longer wall would be reinforced with shallower pilasters and allow for testing that required a lower loading capacity. The shorter wall reinforced with longer T- shaped buttresses provides areas for testing at a higher loading capacity.

The short wall was designed for 250 kips at the top and mid-height of the wall, while the long wall was designed for 150 kips at the top and mid-height of the wall, apart from the free end which had a reduced load of 110 kips. The reaction floor is 2 feet thick and has a clear span of 8 feet, 10 inches between 14-inch-thick walls below the testing floor. The wall and floor thickness were limited based on a request to keep the Dywidag rod length reasonable for the users of the facility. So, in addition to the vertical and horizontal reinforcement on each face, the walls and floor required #5 single leg stirrups at 6 inches on center in both directions. Post-tensioned tendons were also installed vertically within the wall to help limit cracking and improve overall performance.

For several reasons, the design team specified that the strong wall be poured monolithically with no joints. During the design team’s research, including discussions with other teams that had built strong walls, it was discovered that the difficulty of leveling the concrete and the preparation of the construction joint were common issues that this team chose to avoid. The alignment of formwork between separate pours

was also a concern that would be alleviated by a single pour. The wall was specified to limit surface irregularities to 1/16”, so eliminating any variables that could allow misalignment was critical.

The wall contains over 250 tons of reinforcing steel and 450 post tension cables, resulting in a level of congestion a standard concrete mix could not feasibly overcome. To meet this challenge, the concrete supplier designed a self-consolidating concrete mix that met all the specified requirements. Typically, full liquid hydrostatic head must be considered for self-consolidating concrete when designing the formwork. With a formwork height of 30 feet, the pressure on the forms at the base of the wall would be considerable. To ensure the proposed upgraded formwork would work, the concrete subcontractor performed mix specific studies to determine cure rates while keeping pressures below the allowable pressure of the upgraded formwork system. Additional mix considerations included a shrinkage reducing admixture and smaller aggregate due to the reinforcing congestion.

Isolation Joint—Design Challenge 3

While the high bay is a 3-story open space, the original design included a shared basement wall between the high bay and the classroom side, as well as shared framing between the high bay roof and the fourth level CLT floor. After discussions with the vibration consultant, consideration was given to mitigate vibrations created by both testing performed in the high bay and overhead crane use from impacting the classrooms and offices. This resulted in unique isolation details along the first floor and a full -height expansion joint above grade. The addition of the expansion joint lead to the need for a separate lateral system for the high bay, comprised of CMU shear walls, steel braced frames and moment frames.

by

Photo

Warren Jagger

to be 5 5/8 inches wide to satisfy the stress requirements.

RECORDS

Eliminate the hassle of resubmitting your

College transcripts

Exams results

Employment verifications

Professional references each time you apply for licensure in an additional state.

Build your NCEES Record today. ncees.org/records

Photo by Warren Jagger

The raised roof monitors with clerestory windows and open floor plan create a lively and energetic maker space.

Low Carbon Concrete—Design Challenge 5

Having significantly reduced the embodied carbon on the project by using CLT, the design team set their sights on lowering the carbon in the concrete. Since the addition of low carbon concrete was introduced late in the project, the requirements were considered an alternate to be vetted by the Construction Manager. Due to cure times of concrete with high supplemental cementitious materials (SCM), only certain elements of the building were included for the alternate mixes. These included elements that could take longer to reach strength without affecting the schedule, such as the footings, interior and exterior foundation walls, and the interior topping.

The concrete supplier used a combination of slag and E5 Liquid Fly Ash to replace the portland cement. The footing and interior wall mixes were able to receive the highest replacement of portland cement (48%), while the exterior walls and interior topping mixes were only marginally better due to w/c ratio and placement concerns. However, all the concrete mixes beat the National Ready Mixed Concrete Association regional benchmarks, which are typically less than 20% SCM, helping the project reach its sustainability goal.

From the CLT to the strong wall, many of the EDI’s challenges were novel to both the design and construction teams. Thanks to extensive coordination and collaboration, discussions with other engineers and builders and open communication, the project was completed successfully. With this project, along with the rest of the expanded west campus, it is an exciting time for Penn State Engineering. ■

Amy Barabas, PE and Tom Barabas, PE are both Principals at Hope Furrer Associates, State College Office. They are also both alumni of Penn State and truly proud to be a part of this project.

CRSI’s popular design Guides are indispensable resources for structural engineers, educators, students, building officials, and individuals studying for licensing exams.

Print and digital versions available! Visit the CRSI web store for specially priced packages!

Seismic Design Guide for Steel Reinforced Concrete Buildings

Design Guide on the ACI 318 Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete

Photo by Warren Jagger

The purpose of this Design Guide is to assist in the proper application of the earthquake provisions in the 2019 edition of Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-19) and Commentary (ACI 318R19) for cast-in-place concrete buildings with nonprestressed steel reinforcing bars. Visit www.crsi.org

Design Checklists

With over 140 worked-out examples, this unique Design Guide assists in the proper application of the provisions in the 2019 edition of Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-19) for cast-inplace concrete buildings with nonprestressed reinforcement.

Companions to the CRSI Design Guides on ACI 318-19, these Design Checklists are easy-to-use lists of essential items that must be completed when designing and detailing steel reinforced concrete structural members in accordance with the 2019 edition of the ACI 318 Building Code.

ADVERTISEMENT–For Advertiser Information, visit STRUCTUREmag.org

The lattice brick above the glass pop-out maintains the facade aesthetic while allowing light into the interior lounge space.

Following the Eastern Star

Converting a century-old meeting hall into a modern hotel requires meticulous attention to sequencing.

By Ryan Miller, SE, and Eric Fuller, SE

Abuilding that sits vacant for decades is a target. Graffiti, broken windows, rodent infestation, roof leaks, and sun deterioration all attack it until it becomes a blight in the cityscape. If that building is an unreinforced brick masonry structure in seismic country, the odds of that building making a comeback are slim. Such was the case for the Eastern Star Hall in Sacramento, California. Thankfully the Eastern Star Hall's listing on the National Historic Register improved its chances of survival.

Top: A staircase leading to the mezzanine room, bar and restaurant above is a focal point of the finished entry lobby of the Eastern Star Hall.

Right: A temporary bracing platform was utilized at the lobby area gable walls.

Opposite page: Structural steel is installed around the temporary bracing.

The Order of the Eastern Star is an international organization that involves women in the Masonic Order. It was established in 1850 by Master Mason Dr. Rob Morris whose mission was to share Masonic principles with women. The first chapter in Sacramento, CA, was formed in 1879. The Order began to grow quickly such that by the 1920s there were five chapters in Sacramento. Scheduling events among the five chapters within the existing facilities at the Masonic Lodges proved challenging, so the Order of the Eastern Star held fundraising events to construct a new building. Local firm Coffman, Sahlberg, and Stafford Architects designed the Eastern Star Hall in the Classical Revival style, and it was built by the Masons themselves in 1928.

By the end of the 20th century, as membership in the Order was declining, the building went unused. They tried renting out the building to non-Masonic organizations, however the age of the building and resulting code violations, such as the lack of an elevator, eventually prevented its further use. By 1992, the Eastern Star Hall was the only surviving building out of four in the United States that were built specifically for the Order of the Eastern Star. The building was vacant for roughly two decades. Hume Development purchased the property in 2018 with a preservation-forward focus. Their vision to preserve the main facade, the entry lobby with its staircase, the portion of auditorium floor above the lobby, and the east and west brick walls for the full length of the building would bring a contemporary and much-needed revitalization of the property. Although foundation settlement had caused

cracking in the brick walls and the auditorium floor to be out of level, the finishes were in fairly good condition. The interior lodge rooms and most of the auditorium would be demolished and replaced with an eight-story, 128-room hotel while still retaining the original character and charm that the public once knew. Therein lies the intriguing structural challenge of demolition and reconstruction amid constraints of existing elements on a tight downtown site.

Purpose Built

With a footprint of 70 feet by 145 feet and an exterior wall height of 62 feet, the original building looks more like a five-story building even though it is only three stories. From the main entry lobby, a grand staircase wraps around each side of the atrium as it guides visitors up to either the main lodge rooms or to the third-floor auditorium 30 feet above the lobby. The two main lodge rooms are 60-foot square and boast ceiling heights of 20 feet. The auditorium features stadium seating at the south and a stage at the north, with 10-foot-deep steel angle roof trusses above that clear-span the building, providing a large open ballroom for special events. The building also has a full basement complete with a kitchen and stage used for banquet events.

The lobby with adjacent lounge rooms extends 36-feet from the main entry facade. Additional lounge room mezzanines are halfway up the staircase. The existing

structure comprised wood solid sawn floor joists supported by steel wide-flange girders and columns on shallow foundations. The exterior unreinforced masonry (URM) shear walls are largely non-load bearing due to the embedded steel columns within the walls.

While the construction materials of the original building are common among structures of this era, the unique geometry and layout of the interior spaces sets the stage for the complex conversion that revitalized the building.

Internal Bracing Systems

Achieving Hume Development’s vision proved to be a formidable task. The most challenging aspect of the project was the sequencing of demolition and reconstruction. An approach to stabilize the three facades and the lobby with its staircase was developed using a bracing system installed on the interior of the building; external bracing was not feasible due to the close proximity of adjacent buildings. The internal bracing was designed using loading criteria from American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) 37 Design Loads on Structures During Construction. It was carefully woven into the existing structure

so that it did not inhibit the removal of the existing structure while also staying out of the way of future permanent construction.

The predominant bracing for the east and west exterior walls involved a series of vertical steel trusses cantilevered from the foundation and spaced at about 16 feet on-center. The trusses integrated the existing W10 steel columns that were buried in the URM walls and one level of interior columns as the chords of the trusses. Additional columns were spliced onto the interior columns and interlaced with steel HSS diagonal braces. The bracing trusses were supported on existing exterior wall footings and new micropiles at the interior columns. Each individual piece of the bracing truss was located with an eye toward the future new construction so that it did not prevent installation of the final structural system.

The bracing at the existing lobby area required a different solution because a portion of the existing auditorium floor and the lounges below were to remain. The URM walls extended another 30 feet above the auditorium floor to the highest gable end peak. These were braced by adding two temporary levels of wood diaphragms above the existing auditorium floor. The diaphragms spanned to URM return walls or to temporary steel braced frames. Diagonal wood kicker braces stabilized the gable end walls down to the temporary floor.

Mat slab reinforcing within the exterior unreinforced masonry was 28 inches thick and installed at the existing basement level.

Additionally, the upper temporary floor had a waterproofing layer installed to help keep rainwater off the existing lobby finishes below. Installation and removal of all temporary elements were coordinated in tandem with the new structural elements. Where a temporary element passed through the new structural floor, it was treated as an opening in the floor and subsequently patched back after removal of the bracing. The only location where a new gravity beam conflicted with the bracing system was where the floor deck was vertically shored with temporary stud walls to complete the floor diaphragm and thereby brace the existing walls. Only then was the bracing system deconstructed and the final beam inserted to support the floor.

Integrating New Elements With Existing Construction

The new 86,000 square foot structure for the eight-story hotel consisted of concrete-over-metal-deck floors with steel beams and columns supported on a mat slab foundation. The steel beams were aligned with guestroom demising walls and corridor walls to implement 10-foot floor-to-floor heights. This system was inserted into the shell of the perimeter URM walls and enveloped the existing lobby at floors five through eight.

A mat slab foundation 28-inches-thick was installed at the existing basement level. The mat slab was analyzed using CSI SAFE which provided demands at the interface with the existing URM wall footing along the perimeter. This interface was evaluated and detailed with epoxy dowels to consider the mat and the wall footing as integral members. The new lateral system consisted of buckling-restrained braced frames tucked into corners and tightly placed along edges of the building. Where the braced frame columns landed on the existing wall footing, that portion of the footing was cut out and replaced with a new reinforced grade beam element within the mat slab. This was especially important at the corner columns to ensure that the frame column was properly supported by the mat.

The new lateral system serves as the primary lateral support for the existing structure. The 2016 California Building Code (CBC) governed design of all new systems, however the 2016 California Existing Building Code - Appendix A1 (CEBC) was used to evaluate the out-of-plane capability of the existing URM walls. These walls spanned the short 10-foot floor-to-floor distance where the concrete diaphragms delivered out-of-plane loads to steel buckling-restrained braced frames. The three-wythe URM walls easily met the heightto-thickness ratios of the CEBC. For loading parallel to the URM walls, the connection to the floor was detailed to allow movement of the floor relative to the wall such that the wall was decoupled from in-plane lateral forces of the new structure and only resisted its own inertial seismic loads. This was achieved by wrapping foam on the epoxy rebar dowel tension ties so that they had room to flex in-plane for the expected building drifts.

Two shotcrete shear walls were placed against the primary URM entry facade with cutouts where the existing windows occurred. The purpose of these shotcrete walls was two-fold: to support gravity loads from the new fifth-floor framing as it extended over the top of the existing lobby, as well as to provide in-plane shear resistance for the main facade. Since the new steel lateral system was decoupled from the perimeter URM walls, special care was taken at this level. The interface of the fifth floor to the existing URM wall included a seismic joint with slide bearings to allow the perimeter walls to only resist their own in-plane inertial loads, while out-of-plane loads

Project Team

SER: Buehler

Owner: Hume Development

Architect: HRGA

Contractors (primary and specialty): Market 1 Builders

Structural Software Used: CSI SAFE, ETABS, and RAM Structural System

were supported by the new concrete diaphragm. The new concrete walls rested on a pair of micropiles at each end and included pile caps detailed to underpin the existing facade wall to mitigate settlement that had opened up a 2-inch crack between the lobby area and the northern portion of the building.

Anchoring into the URM walls was achieved using drill and epoxy bolts or rebar. Concrete elements such as shear walls utilized epoxy rebar dowels while steel elements utilized threaded bolts. Capacities for the anchors were taken from the ICC code report for the epoxy system since most of the URM walls in the building were three-wythes in thickness as the code report requires. However, some anchors were required in the two-wythe former parapet of the east and west walls. For these instances, a project-specific anchor testing program was performed by pull-testing anchors installed in a portion of the parapet that was ultimately slated for demolition to justify usage of epoxy anchors in the 8-inch URM.

Keeping the eight stories below the CBC high-rise floor limit of 75 feet required that the new third floor be set 16 inches lower than the existing third floor level. Due to space constraints in the guestroom layout, it was determined that the recess to accommodate a wheelchair lift and stairs connecting the existing level to the new level needed to occur within the existing framing. This recess required about 10 inches of an existing 16-inch steel beam be cut out. The beam was strengthened by adding a new wide-flange beam welded to the underside that extended beyond the cutout portion to connect the existing beam to its supporting girder.

A New Beginning

The hotel welcomed its first guests in January 2023. Visitors can enjoy the renovated lobby and learn about the Order of the Eastern Star and Sacramento history in the reading room adjacent to the lobby. The guestrooms include a kitchenette and workstation which are attractive to those who need a longer-term stay option, perhaps when visiting patients at nearby Sutter Medical Center. The third-floor bar is open to the public to enjoy the character of this unique building. The Eastern Star Hall is once again thriving in the community thanks to the vision of the development and design teams. ■

Ryan Miller, SE, LEED AP, is an Associate Principal at Buehler (rmiller@ buehlerengineering.com). Eric Fuller, SE, is a Principal at Buehler (efuller@ buehlerengineering.com). Miller and Fuller have over 60 years of combined experience spelunking through existing buildings seeking hidden structural treasures.

Improved Economy & Resilience With Mast Frames

By Jason Armes, SE; Gina Carlson, SE; and Leo Panian, SE

The challenges of selecting the appropriate seismic system involve the trade-offs and compromises between architectural design, space planning, construction cost, and seismic performance. For Samuel Merritt University’s (SMU) new high-rise research, and academic building in downtown Oakland, California, an iterative design approach resulted in a novel and cost-effective structural system that provides an unobstructed floor plan and superior seismic performance. Working closely with the developer, contractor, and architect team, Tipping, as the structural engineering team, investigated different design strategies, including moment frames, dual systems, conventional Buckling Restrained Braced (BRB) frames, and Buckling Restrained Mast-Frames (BRBM) to develop the most effective approach. This allowed the team to make detailed comparisons of

Rendering of Samuel Merrit University's new campus headquarters in Oakland, California (Courtesy of Perkins & Will).

Project Team

Structural Engineer: TippingArchitect: Perkins&Will

Owner: Samuel Merritt University

Developer: Strada Investment Group

Contractor: Hathaway-Dinwiddie Construction Company

Steel Fabricator: The Herrick Corporation

BRB Supplier: CoreBrace

architectural impact, material use, and seismic performance to arrive at the preferred solution.

The system ultimately selected is a variation of the conventional BRB frame, which incorporates a vertical mast or strongback element. This configuration, referred to as a Buckling Restrained Braced Mast (BRBM) frame, effectively separates the elastic and energy dissipating components of the system resulting in a more resilient and reliable structure. The mast element consists of a vertical truss that is designed to stay elastic and work in conjunction with BRB devices, which yield and dissipate seismic energy.

The BRBM system has been used in previous projects, but the SMU example is the largest and tallest application of the innovative system. The compact footprint of the BRBM frames allowed them to be largely concealed within permanent demising walls. Their inherent redundancy allowed for fewer frames in the building and significantly reduced the number of BRB devices, both minimizing the impact to interior spaces and resulting in overall cost savings.

Case Study

The new high-rise building will serve as the flagship campus for Samuel Merritt University. The nursing and health science education

Structural System Summary

• Plan Dimensions: 218 feet by 115 feet

• Height: 146 feet to roof, with 23-foot deep basement

• Bay Spacing: 23 to 42 feet

• Floor Assembly: 6¼-inch lightweight concrete slab over metal decking on wide-flange beams and columns

• Seismic Load Resisting System: Buckling restrained braced frames with mast elements

• Foundation: Mat slab supported on unimproved soil

facility, which is slated to open in 2026, will feature classrooms, laboratories, clinics, offices, and community gathering spaces. Though the building is located on a dense urban site, setbacks from neighboring buildings allow for a large majority of the facade to consist of a glazed curtainwall providing views and access to natural light. An offset vertical circulation core allowed for large unobstructed classrooms and flexibility for lab planning.

Initial Design Concepts With Moment Frames & Dual Systems

During the conceptual design phase, Tipping initially investigated a moment frame system to ensure that the variety of uses could be flexibly accommodated. Frame member sizes were governed by seismic deflection criteria and were proportioned to limit the maximum interstory drift to 2.0%. The resulting system required numerous frame lines with deep beams, heavy columns and intersecting columns with custom shapes. It also came with a significant cost premium due to the relatively high quantity of steel required, estimated at 9 pounds per square foot of floor area. Due to its inherent flexibility and increased propensity for damage, the momentframe system provided the least resilient approach.

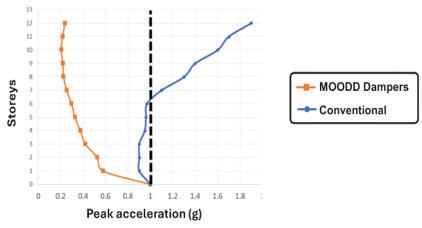

Estimated maximum drifts for the design basis earthquake (DBE), comparing response spectrum analysis (RSA) and non-linear response history analysis (NLRHA), with limits for Risk Categories (RC) II and III.

The structural design team also evaluated a dual system, which combined BRB frames in each direction to supplement the moment frames. The intent was to leverage the stiffness of the limited number of brace frames to limit drift and reduce the overall quantity of steel. Due to incompatibilities in stiffness between the moment frames and braced frames, effective load-sharing between them was difficult to achieve. This dual system would still rely on heavy moment frames to resist a minimum of 25% of the total seismic load, as required by the ASCE 7 code. With the addition of 40 BRBs, the dual system resulted in a slight reduction of overall steel quantity, with estimated total of 8.7 pounds per square foot of floor area, and a modest improvement in performance, with an estimated inter-story drift of 1.85%. While the dual system was an improvement over the moment-frames alone, it provided only limited gains in performance or economy.

Key advantages of the BRBM system include its ability to maintain an open floor plan and maximize facade transparency while significantly improving seismic performance.

Buckling Restrained Brace (BRB) System

In further exploring potential design solutions, the design team investigated concentrically braced frames relying entirely on BRBs. Due to the limited number of frame bays that were available to locate diagonal braces, the system needed to be designed for a 30% increase in lateral loads to account for the lack of redundancy

Illustration shows inelastic mechanism of BRBM frame, with yielding BRBs on the left half working in tandem with an elastic mast on the right. The mast truss incorporates W14x665 columns and W14x233 diagonals and is capacity-designed to protect against overload.

Construction of BRBM frame showing uniform member sizes and connections.

of the system. This led to heavy, built-up column sections and very large BRB members, particularly at the lower stories, where the lateral loads were the highest.

Despite the redundancy penalty, the BRB frame system offered a significant improvement in terms of cost, performance, and impact to the architectural design. This approach resulted in a significantly reduced quantity of steel for the lateral load resting system, estimated at 3.2 pounds per square foot of floor area. The system incorporated a total of 100 BRB devices and resulted in a significantly reduced maximum inter-story drift of 1.70%.

While this represented a reasonable and cost-effective solution that met the basic design goals, there was an opportunity to further improve the seismic resilience of the building. Our analysis showed that despite the fact that seismic drift was well below the code limit, the BRB devices were only partially mobilized to resist seismic shaking. The team observed that most of the lateral deformation and damage tends to concentrate at individual stories and components rather than being more evenly distributed, significantly limiting overall seismic resilience.

BRB Mast System

To mitigate these shortcomings and develop a more optimal scheme, the design team investigated a system that incorporates a vertical mast or strongback within the braced frame to augment the BRBs. This variation of the conventional BRB frame effectively separates the elastic and energy dissipating components of the system to better control structural response and improve seismic performance. This approach relies on a full-height truss, made of conventional wide-flange sections, that works in conjunction with the yielding BRB devices to improve the redundancy and performance of the system. The rigidity and strength of the mast significantly reduces the maximum expected seismic drift and ensures a more uniform drift distribution throughout the height of the building. This effectively eliminates story mechanisms and localization of damage resulting in a more resilient and reliable structure.

By interconnecting all of the BRB devices throughout the height of each frame, they are fully utilized and capable of sharing loads between stories. This effectively improves the redundancy of the system and eliminates the 30% penalty, leading to increased efficiency.

These advantages can be gained with minimal or no cost premium over a conventional BRB-only frame system. Ultimately, this approach resulted in an estimated steel quantity of 480 tons or 3.7 pounds per square foot of floor area for the lateral load resisting system. This represents a slight increase from the conventional BRB-only system, owing largely to the incorporation of the vertical truss that serves as the mast. However, this system used only 50 BRB devices, making up the cost of the additional steel quantity.

The maximum drift for the BRBM system under the design basis earthquake (DBE) was estimated to be 1.20% using a Response Spectrum Analysis (RSA) and 1.30% using a Non-linear Response History Analysis (NLRHA). The ratio of maximum-to-average drift over the height of the building was 1.09, indicating a relatively uniform drift profile with no concentration of story deformations. This

level of performance is a significant improvement over conventional practice that can provide measurable gains in seismic resilience.

The BRB mast frame system was designed using the prescriptive procedures outlined in Chapter 12 of ASCE 7-16 and the AISC Seismic Provisions for BRB frames described in Chapter 5.5, using an R-value of 8. The design method was adapted for the treatment of the mast truss and extensively validated using non-linear static and dynamic analyses.

Each frame-bay incorporates a mast truss on one side and a single BRB device on the other. The mast side is typically proportioned to be slightly narrower than the BRB-side, making the devices more efficient in resisting horizontal loads and longer allowing increased deformation capacity. Under elastic load levels, the mast truss resists roughly 40% of the total base shear. Because the truss is designed to remain elastic under all loading conditions, it can make all of the BRB devices in the frame to share the total load. This allows the BRBs to be more uniformly sized throughout the height rather than becoming increasingly larger towards the base, simplifying detailing and avoiding extreme proportions.

To ensure that the system performs as intended, the mast members were proportioned using capacity-design principles, an approach that is analogous

Illustration of BRBM base connection that uses a shear lug to transfer horizontal forces and four 10-foot long, 2.5-inch diameter, high-strength rods to resist overturning tension forces, while allowing rotational flexibility.

Mast frame construction with facade and fire proofing partially installed.

to the design of columns in the frames. Once the BRB sizes were determined using a preliminary response spectrum analysis and optimized for a more uniform distribution of forces, the forces in the mast truss were amplified to reflect the maximum anticipated loads that could be delivered by the yielding BRBs. Initially this consisted of applying an overstrength factor of 2.5 to estimate the required demands on mast members. This approach was reasonably effective for estimating the maximum loads on the mast truss. To validate this critical assumption, we deployed non-linear analyses to capture the inelastic response of the system and refine the design of the mast members and BRBs.

To allow the mast frames to rock and pivot more freely about its base and prevent overstressing the gravity support columns, the design team developed an improvised pin connection that could resist large shear and overturning axial forces while allowing rotation. The detail relied on direct steel-to-steel contact at the base connections to deliver axial compression and shear. To transfer tension forces, Tipping called for long high-strength rods to anchor the base of the mast.

The design was submitted for plan review and approved through a conventional permitting process, which did not require a special Alternate Materials and Methods Request or formal peer review.

Conclusions and Take-aways

The implementation of BRBM frames represents a significant advancement in the seismic design of steel structures, particularly for high-rise applications like Samuel Merritt University’s flagship campus. Through an iterative design process that evaluated various structural systems,

including moment frames, dual systems, and conventional BRB frames, the BRBM system emerged as the optimal solution, balancing costeffectiveness, architectural flexibility, and seismic resilience.

Key advantages of the BRBM system include its ability to maintain an open floor plan and maximize facade transparency while significantly improving seismic performance. By integrating a vertical mast truss with BRB devices, the system minimizes story drift, eliminates damage concentrations, and enhances system reliability, resulting in improved structural response during earthquakes. This innovative approach also reduces the overall number of BRB devices and avoids excessive column and beam sizes, addressing common architectural and economic challenges associated with traditional systems.

The design process underscores the importance of tailoring structural solutions to project-specific needs and site constraints. The use of advanced analytical techniques, such as non-linear static and dynamic analyses, further validated the BRBM system’s capacity to meet stringent safety, serviceability, and resilience requirements. This achievement not only sets a precedent for future seismic designs but also highlights the potential of collaborative engineering to drive innovation. ■

Leo Panian is a Principal with Tipping and served as the Structural Engineer of Record for the project. Gina Carlson is an Associate Principal with Tipping and served as the Project Director. Jason Armes is an Associate with Tipping and served as the Project Manager and Technical Lead.

codes and STANDARDS

Roof Snow Drifts Due to Ground Snow

In some circumstances, such as low eave height and strong winds, snow that originally fell on the ground can contribute to a roof top snow drift.

By Michael O’Rourke, John Duntemann & John Cocca

For the last 40 years, design provisions in the United States for roof snow drift loads have accounted for snow which originally fell on one portion of the roof and was transported by wind into a snow drift atop another portion of the roof. Specifically, for a leeward drift roof at a step, the upwind fetch lu references the upper-level roof snow source area. Similarly for a windward drift at a roof step, lu addresses the lowerlevel roof where the snow originally fell and eventually ended up in the drift. Finally, for a gable roof with a east-west ridgeline, the across the ridge drift (aka the unbalanced load) atop the northern portion of the roof, l u is that for the southern portion of the roof. Note in all these cases, snow which originally fell on the ground is not considered as an expected snow source for a roof top snow drift.

However, in certain circumstances, snow which originally fell on the ground can contribute to roof snow drift formation. In one real-world case, the building was a hog containment structure in the Midwest with a roof eave relatively close to the ground surface. The gable roof drift was larger than what one would expect for the roof’s upwind fetch lu

A second case involved a school building in the Buffalo area which experienced the Blizzard of 1977. According to Wikipedia, the total snow fall was over 8 feet in some places, while peak daily wind speeds were in the 45 to 70 mph range. As sketched in Figure 1, Roofs A and C were one story portions of the school while Roof B (thought to be a gymnasium space) had a higher elevation. A windward drift “snow