tradiciones special edition honorar a nuestros hÉroes

DQ

OROTHY BRETT came to Taos in 1924 at the invitation of D.H. and Frieda Lawrence, and would spend her remaining years here drawing and painting subjects rooted in Northern New Mexico DAWN FIESTA (DETAIL)

TAOS IS DEFINITELY A

DIFFERENT KIND OF PLACE

— unique in its colorful history and characters — that live on in local legend.

Some of these legends are known only to the people of Northern New Mexico, and bind us together in a shared mythology.

Taos News loves to bring you these quixotic stories each year in Tradiciones: Leyendas (Legends). Look for more special sections to come in the following weeks — on roots and arts — and a salute to our Unsung Heroes.

In this year’s issue, Josephine Ashton unearths a forgotten radio interview to bring us an image of a Modernist Taos painter in her profile on Dorothy Eugenie Brett. Her story begins on page 4.

Padre Antonio José Martínez was a pivotal political, spiritual and cultural leader during New Mexico’s transition from Mexican governance to the U.S. in the mid-1800s. David Fernandez has his story on page 8.

And Cindy Brown brings us the legend of the Taos Revolt of 1847 and the gruesome fate of the first U.S. civil territorial governor, Charles Bent. Read it for yourself on page 12.

We hope you enjoy this year’s issue of Tradiciones: Leyendas. These are among the unique stories and legends that continue to haunt Taos.

Michael Tashji, Special Sections Editor

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 2 Dorothy

Brett, Untitled, 1958

TAOS NEWS STAFF ROBIN MARTIN, OWNER CHRIS BAKER, PUBLISHER JOHN MILLER, EDITOR MICHAEL TASHJI, SPECIAL SECTIONS EDITOR PAUL GUTCHES, CREATIVE DIRECTOR CHRIS WOOD, ADVERTISING DIRECTOR MARY CHÁVEZ, BUSINESS MANAGER SHAWN ROBERTS, CIRCULATION DIRECTOR HEATHER OWEN, DIGITAL EDITOR SHANE ATKINSON, SALES MANAGER TYLER NORTHROP, MEDIA SPECIALIST S’ZANNE REYNOLDS MEDIA SPECIALIST JASON RODRIGUEZ, PRODUCTION MANAGER ZOË URBAN, GRAPHIC DESIGNER TAOS NEWS 226 ALBRIGHT ST. TAOS, NM 87571 575-758-2241 TAOSNEWS.COM Dorothy

IMAGE OF A MODERNIST TAOS PAINTER BY JOSEPHINE ASHTON Padre Antonio José Martínez A TRULY GREAT MAN OF TAOS AND EL NORTÉ BY DAVID FERNANDEZ Taos Revolt AND THE DEMISE OF TERRITORIAL GOVERNOR CHARLES BENT BY CINDY BROWN LEYENDAS Contents

Eugenie Brett

I’ve worked as an educator, administrator business owner, your State Representative and your Senator for over 40 years. Through it all I’ve held one guiding principle: Serving my fellow Taoseños and neighbors. If I can help, please call me at 575-770-3178.

A LEGENDARY LEGACY OF INNOVATION: BRIDGING GENERATIONS WITH TECHNOLOGY

Kit Carson Electric Cooperative (KCEC) has served Taos, Colfax, and Rio Arriba Counties since 1944, providing electricity to its over 30,000 members. KCEC has been a community leader in economic development for decades. From propane, to internet to achieving the goal of 100% daytime solar, KCEC has been on the forefront of a new utility business model for the country.

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 3 Like a good neighbor, State Farm is there.® 575-737-5433 wanda@wandalucero.com is not what you did for yourself. It’s what you did for the next generation. Photo: Morgan Timms, Taos News Above Self Roberto “Bobby” J. Gonzales State Senator, District 6 Democrat Paid for by the Committee to Re-Elect Roberto “Bobby” J. Gonzales, Roberto “Bobby” J. Gonzales Treasurer

THIS INSTITUTION IS AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY PROVIDER AND EMPLOYER kitcarson.com

DOROTHY EUGENIE BRETT

Image of a Modernist Taos Painter

BY JOSEPHINE ASHTON

BY JOSEPHINE ASHTON

THE YEAR — 1969 There were three major national television networks. No Internet. No social media. But there was radio. I stumbled onto an audio interview. The interviewer, a nameless DJ with a New York accent. The interviewee was none other than the British painter who’d become — thanks to D.H. Lawrence and Mable Dodge, and her own spirit of adventure — known as a Taos “Modernist,” Hon. Dorothy Eugenie Brett

In answer to the interviewer’s question, “When did you first meet Lawrence?” Brett (in that sturdy voice we on this side of the pond recognize as a Britisher who is confidently sure of herself) explained as if it were yesterday, “In Hampstead. We had a little house in Hampstead. In 1914 — just when the war had started.”

“Who took you there?”

“A young painter who had met [Lawrence] and was determined I should meet him. But I was scared. I was always scared of those people. Anyway —I went there to tea. It was a tiny little house. Tiny! It was incredible that Frieda could get into it. She was huge. But we had tea there and that started the whole thing.”

The interviewer was more interested

in Brett’s relationship to D.H. Lawrence, who was already well-known, but had not yet come to Taos, than Brett’s own accomplishments. It was her studies at London’s Slade School of Art where she first met novelist Lawrence, and others in the Bloomsbury Group.

Born November 11, 1883 into a family of the British aristocracy, her later life in Taos — and eventually, in 1938, becoming an American citizen — must have seemed like stepping through a time warp into another world. Taos would be home until her death in August 1977.

“What was your opinion of [Lawrence] when you first met him?”

“We just clicked. Immediately. Immediately. We sat on a little bench in front of the fire, and we had a wonderful time. I think he had a great feeling of protection for me — I don’t know quite how to explain that.”

“So, you felt that from the very beginning?”

“Yes. He sort of took me under his wing.”

From “the very beginning,” Brett would visit with the Lawrences — who also lived in the London suburbs, not far from Brett’s “little Queen Anne house” — they would come to her place for tea.

| continues on 6

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 4

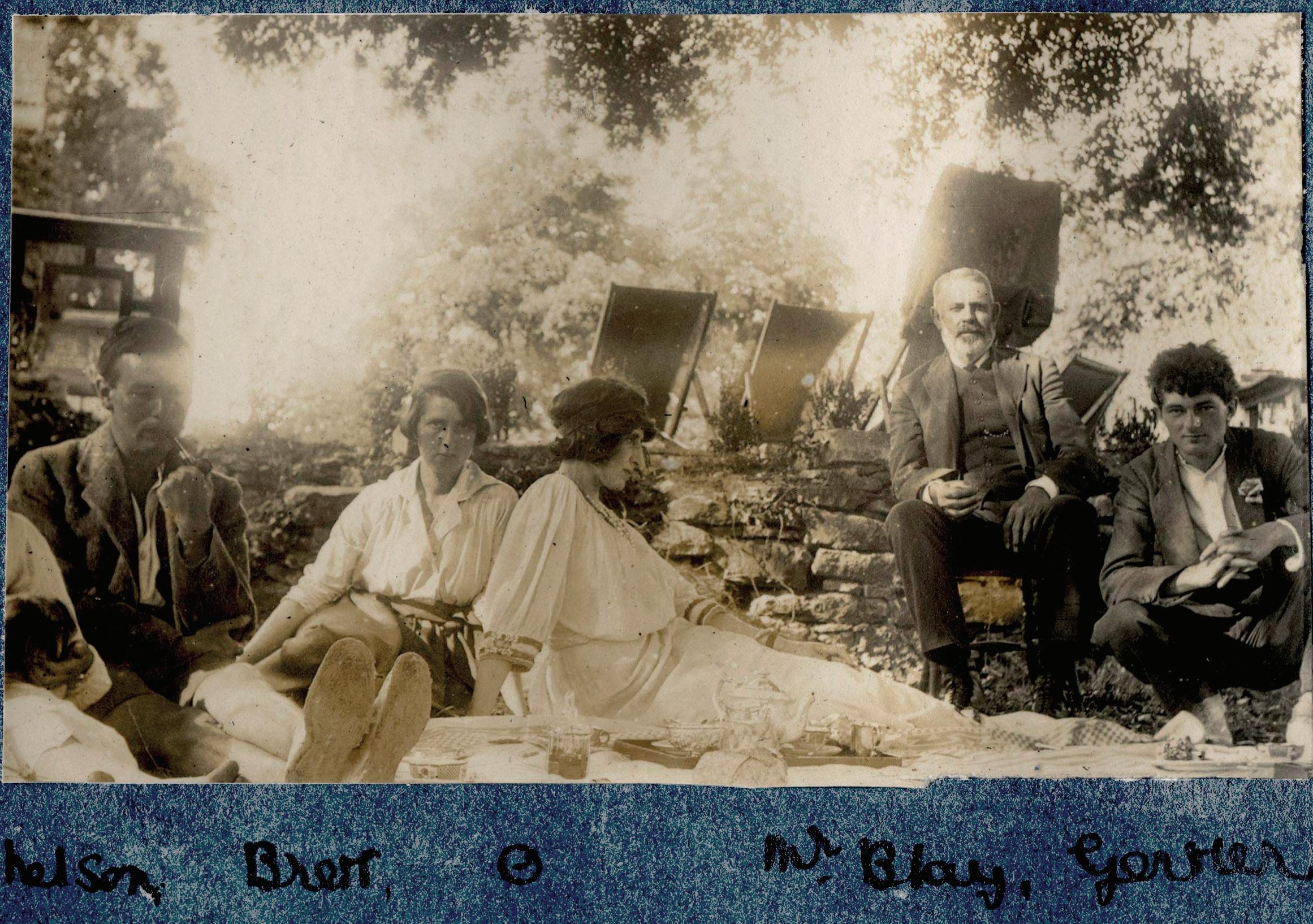

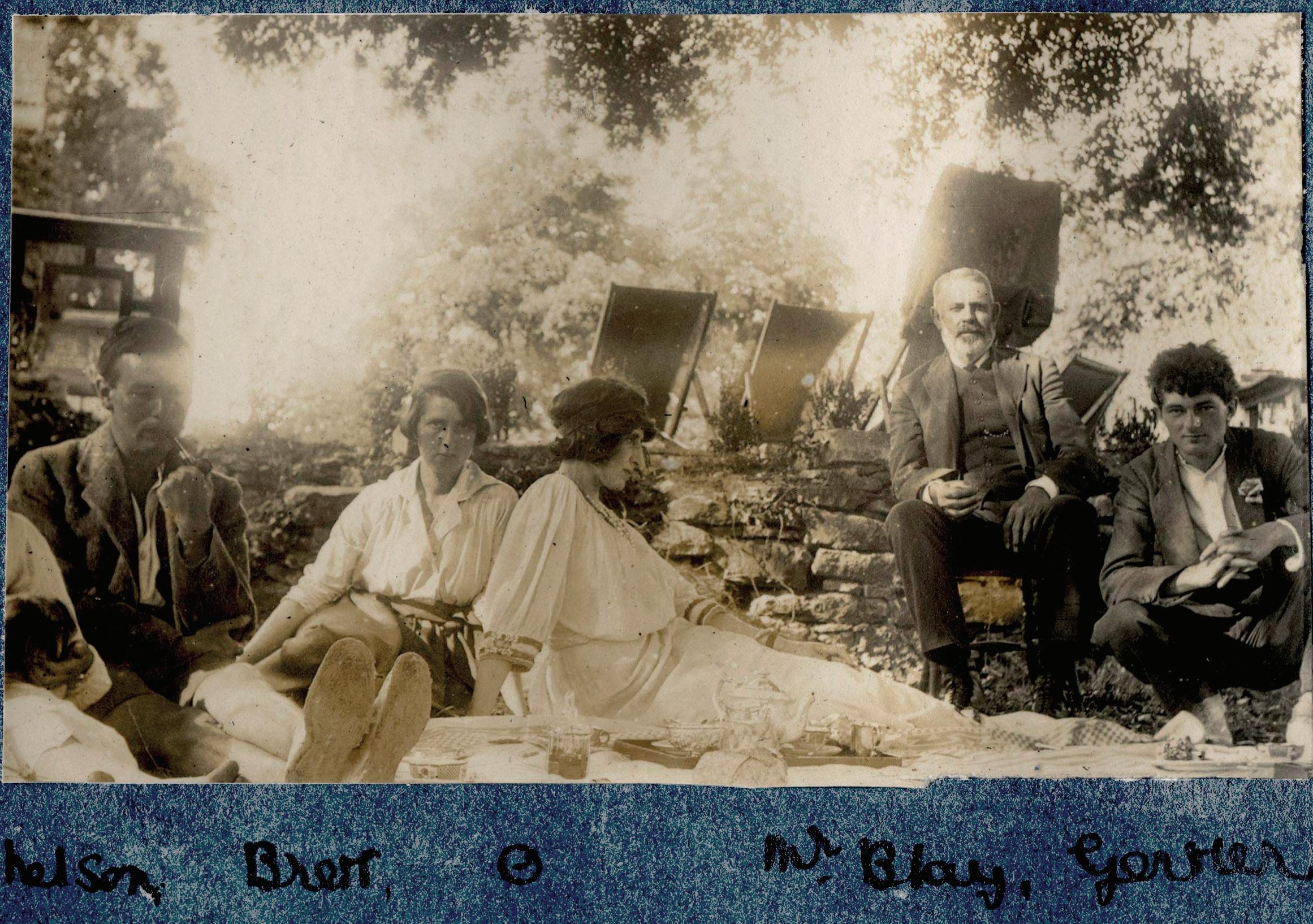

Brett, Dorothy. Photograph by Cady Wells. COURTESY MABEL DODGE LUHAN PAPERS, BEINECKE RARE BOOK AND MANUSCRIPT LIBRARY. Geoffrey Nelson; Hon. Dorothy Eugénie Brett; Lady Ottoline Morrell; Mr. Blay; Mar Gertler. COURTESY NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

Portrait of Dorothy Brett, 1931

Rio Grande ATP, Inc. is celebrating 45 years helping your family members and friends find recovery from substance use disorder. We offer intensive outpatient programs, medically assisted treatment and peer support. There are many Paths to Recovery in our strong and resilient communities.

Rio Grande has been and continues to be there for all those seeking a new way of life.

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 5 “ ’Once upon a time’ is one of the most magical phrases you’ll ever read.” – Unknown The Taos County Bookmobile began operating in the early 1940’s. Its shelves held books that pushed the imagination. It gave rural areas a sense of belonging to the county, state and the nation. taoscounty.org Community Rewards® in Action Making Positive Change, Together! Insured by NCUA Equal Opportunity Lender When we work together, we have the power to create positive change in our communities! That is exactly what our members do when they join Nusenda Credit Union’s Community Rewards program. They help us fund grants that support the arts, community services, education, environment and wildlife, and healthcare. In 2022, Nusenda Foundation provided $630,000 in Community Rewards grants to 97 organizations statewide who are positively impacting the communities they serve! Our members and employees are committed to being positive contributors in the places we call home. Learn more at Nusenda.org @NusendaCU Sky Mountain Wild Horse Sanctuary That’s what we call The Power of WE®. Rio Grande ATP, Inc. is celebrating 45 years helping your family members and friends find recovery from substance use disorder. We offer intensive outpatient programs, medically assisted treatment and peer support.

are many Paths to Recovery in our strong and resilient communities. Rio Grande has been and continues to be there for all those seeking a new way of life.

Possible Discover Your Path to Wellness Una Vida y Sana/ A Good and Healthful Life

There

Recovery is

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 6 Untitled “Christmas Eve at Taos Pueblo,” 1961

DURING THE WAR — WWI

— Lawrence went to Australia, and Brett, who’d done a portrait of Lawrence, continued painting celebrities.

“We didn’t see him until he came back — in 1924, it must have been.”

“1923,” the interviewer corrected.

“And then, he wanted four of us to come over. I was the only one who came over with him.”

“When he came back in 1923, he’d already been to Taos?” the interviewer asked.

“Oh yes! He’d been here. From Australia — he came here. And then, he went back to England — wanted to collect [other artists] and me. They all agreed to come but they backed out — except me.”

“Tell us what he wanted to do here, and why he wanted you all to come.”

“He wanted to form a little colony. You know — one of those idyllist colonies? Up at the ranch here. But of course, it failed. It would have failed anyway, you know. Those things always do. They never succeed.”

But Brett would succeed.

After coming to Taos in 1924, she was deeply befriended by D.H. and Frieda, and by Mabel Dodge — who was sometimes less than friendly. But at Mabel’s soirees, Brett would meet artists, writers and performers living in Taos or visiting from the East Coast or from across the big water, fascinated with the creative magic and landscape of Taos.

Brett would hesitantly begin painting Southwest scenes. She had seen “her first American Indian when she was five,” according to an Owings Gallery, Santa Fe, bio, “attending a performance in London of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.”

Still, Brett was hesitant about portraying those she came to consider her deepest friends — as ‘noble savages” — although with their permission, she did support herself selling these images to tourists. She, Mabel Dodge and Frieda Lawrence were known in Taos society as the “Three Fates.”

Brett’s early works, from 1919 through 1958, including nude figures, landscapes and aristocratic portraits that can be seen on the TATE Museum website. Other works and her later New Mexico-themed art are housed at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., the New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, the Roswell Museum, Roswell, N.M. and in the Millicent Rogers Museum and the Harwood Museum of Art, both in Taos.

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 7

Study for “Buffalo Dance, Taos Pueblo,” 1948

“Bridal Procession,” 1968

Untitled (Fantasy Scene)

“Horsemen,” 1966 “Birth of a Star,” 1959

“The Pawnee Horse Thief”

Dorothy Brett | continues from 4

LA

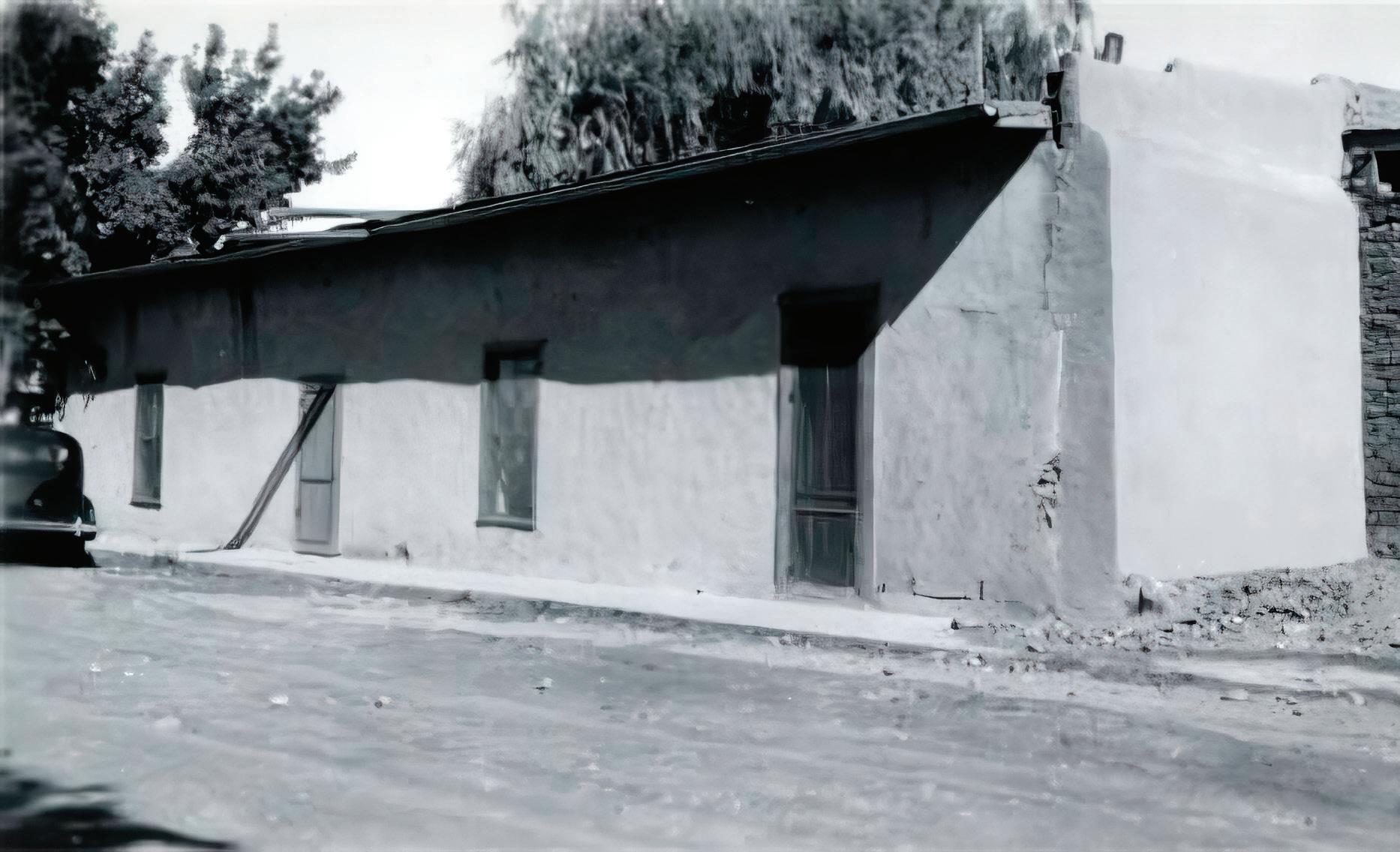

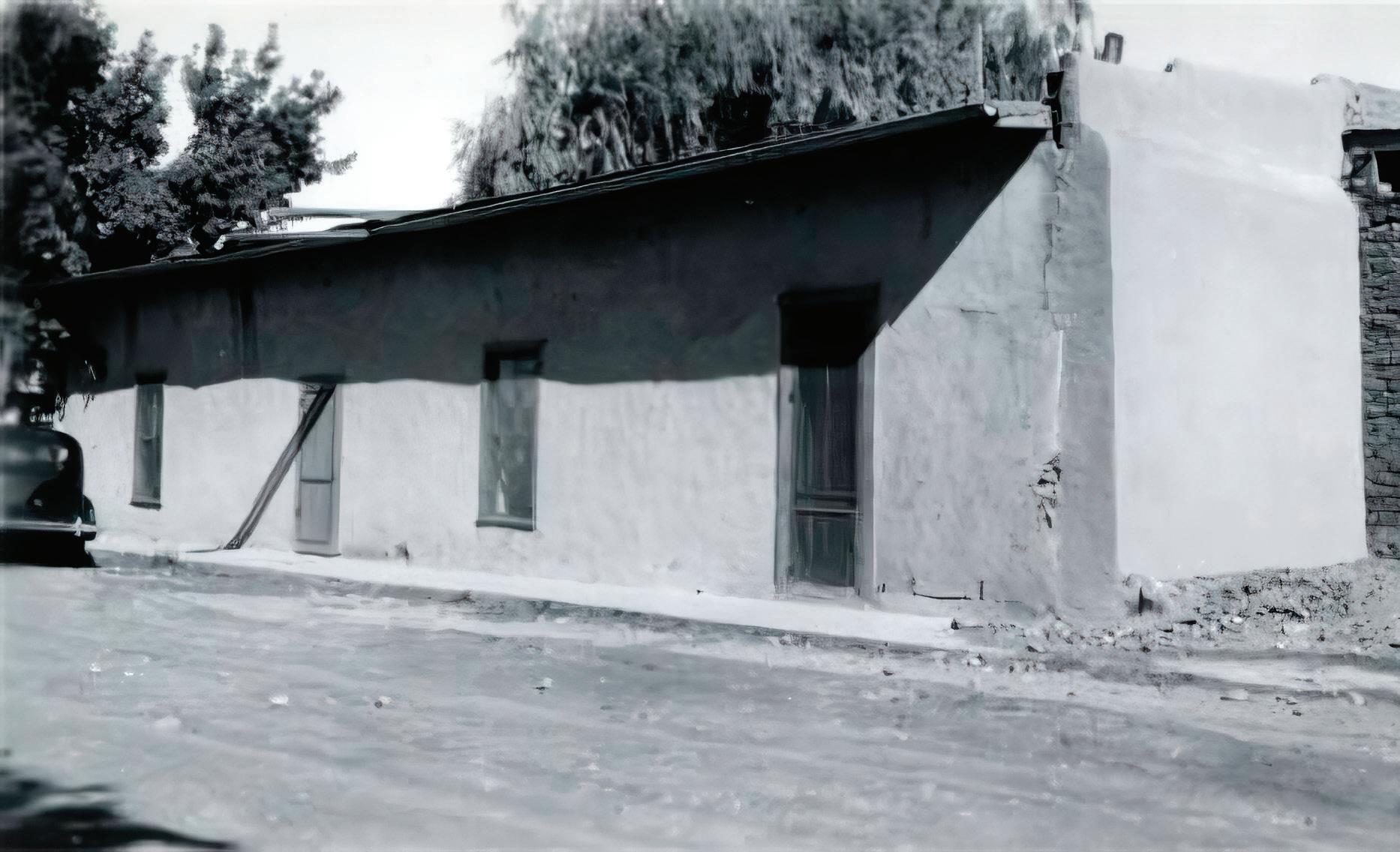

Martínez. The home is one of few Northern New Mexico, late-Spanish Colonial period “great houses” remaining in the American Southwest. The Martínez Hacienda now serves as a museum and cultural learning center, along with the E. L. Blumenschein Home and Museum, as part of the Taos Historic Museums.

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 8

Reverend Antonio Martinez, Taos, New Mexico, 1848?

COURTESY OF THE PALACE OF THE GOVERNORS PHOTO ARCHIVES (NMHM/DCA). NEGATIVE NUMBER: 011262

Photo by Highsmith, Carol M., 2021. COURTESY OF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

HACIENDA DE LOS MARTINEZ IN TAOS, NEW MEXICO , the once-residence of Padre Antonio José

Padre Antonio José Martínez

A TRULY GREAT MAN OF TAOS AND EL NORTÉ

BY DAVID FERNANDEZ

T HE PRIEST PADRE ANTONIO JOSÉ MARTÍNEZ —

born Jan. 16, 1793 and died July 27, 1867 — was the very famous pastor at our Lady of Guadalupe Parish for over thirty years and was a pivotal political, spiritual and cultural influence during the transition of power from Mexican governance to the U.S. in the mid-1800s.

He was a gifted and powerfully charismatic individual who, as the appointed priest and spiritual leader of the expansive and far-flung region of the Taos parish and various mission areas in El Norté, was the undisputed central religious authority of the region.

He was highly educated and literate, and deeply knowledgeable as well about the secular, political and economic systems of the governing Mexican administration and the Northern Capital of Santa Fe, and he was prophetic about the impending takeover of Nuevo Mejico by “los Americanos.”

Martínez was the leading and most influential Native-born personality of El Norté, and indeed, all of New Mexico in a traumatic time of earth-shaking changes in the state as well as in the Catholic Church. He was a personage of tremendous and enduring accomplishments; and yet he also underwent heart-breaking and ironic tragedy, especially in the last years of his life as the Priest of Taos.

His legacy as “the honor of his country,” or “la honra de su pais” persists to this day, along with some controversial aspects of his exceptional life as the central figure of his times in El Norté.

A very much larger-than-life bronze statue of him is now set in Taos Plaza to commemorate his civic and political works, while curiously at the same time he is barely mentioned in the realm he loved the most, which was the church from which he was excluded in those last years of his life.

Yet, his great works in both church and state are undeniable — even in the

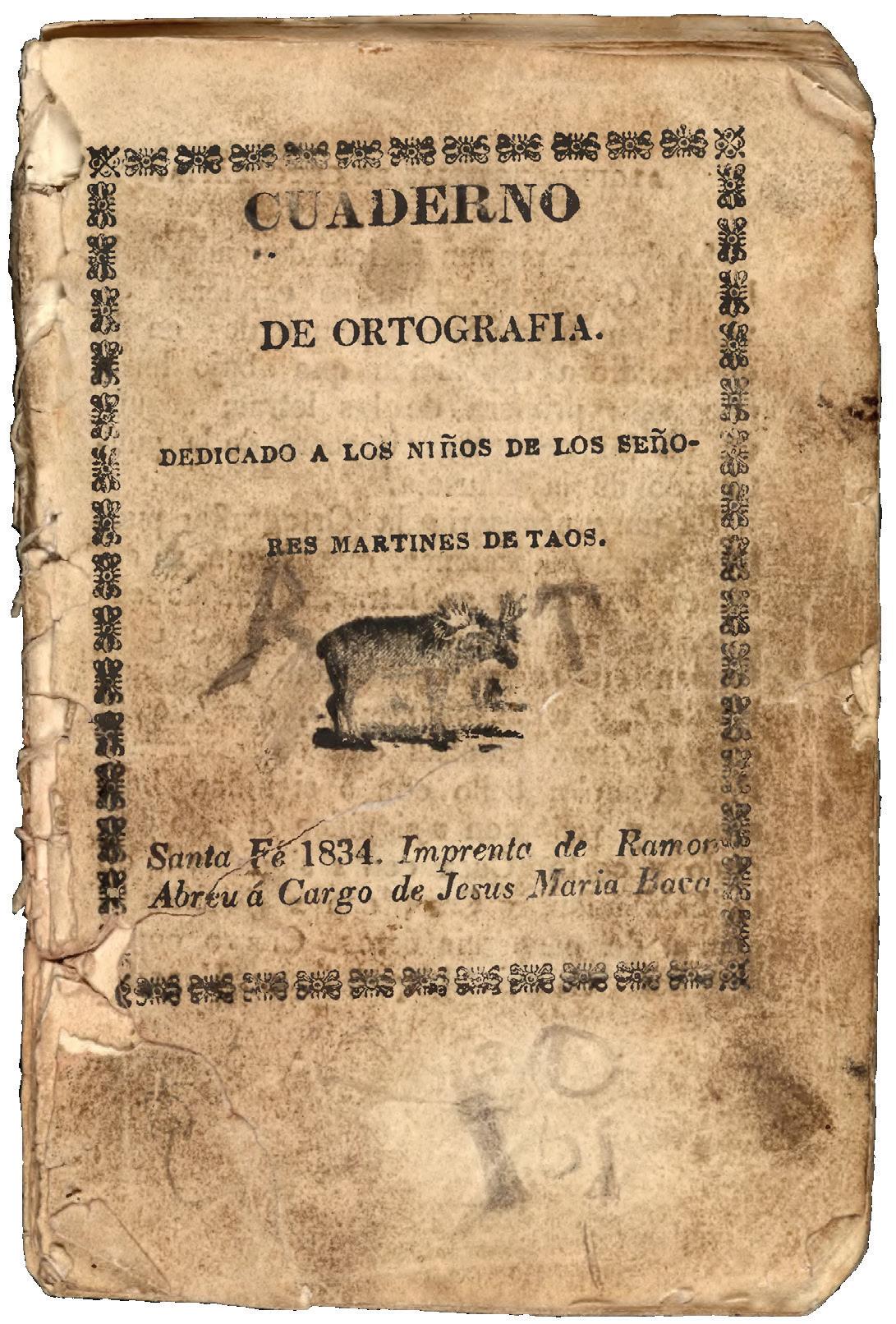

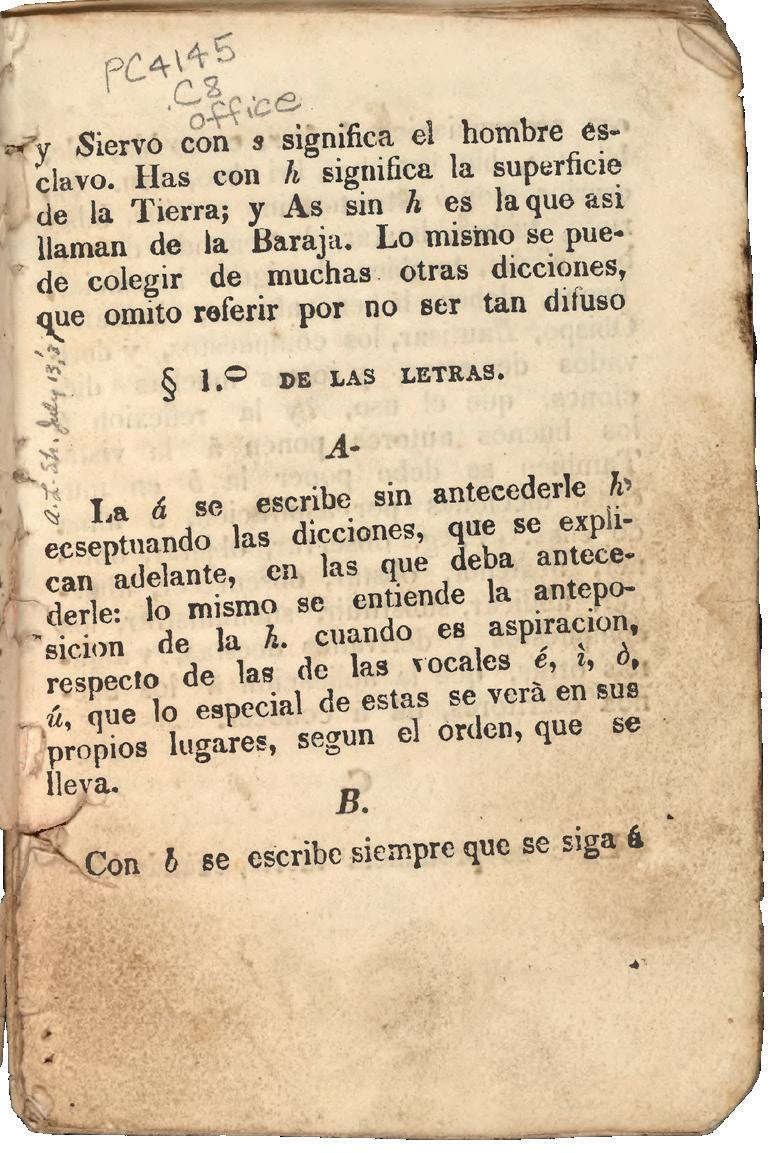

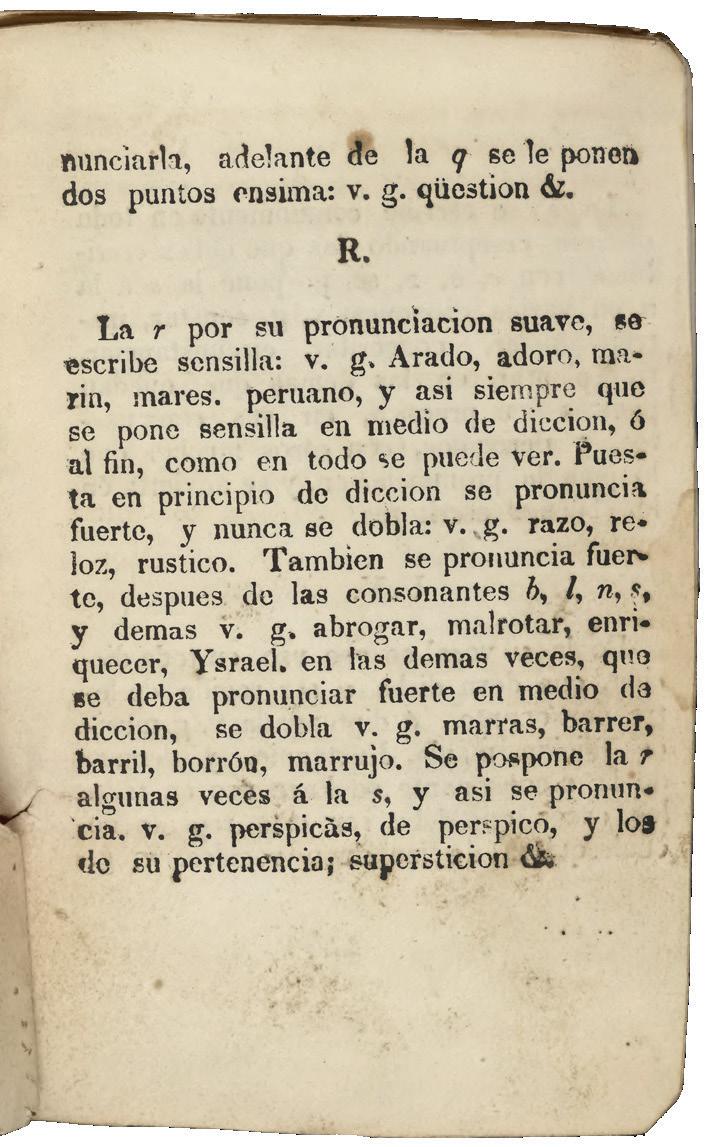

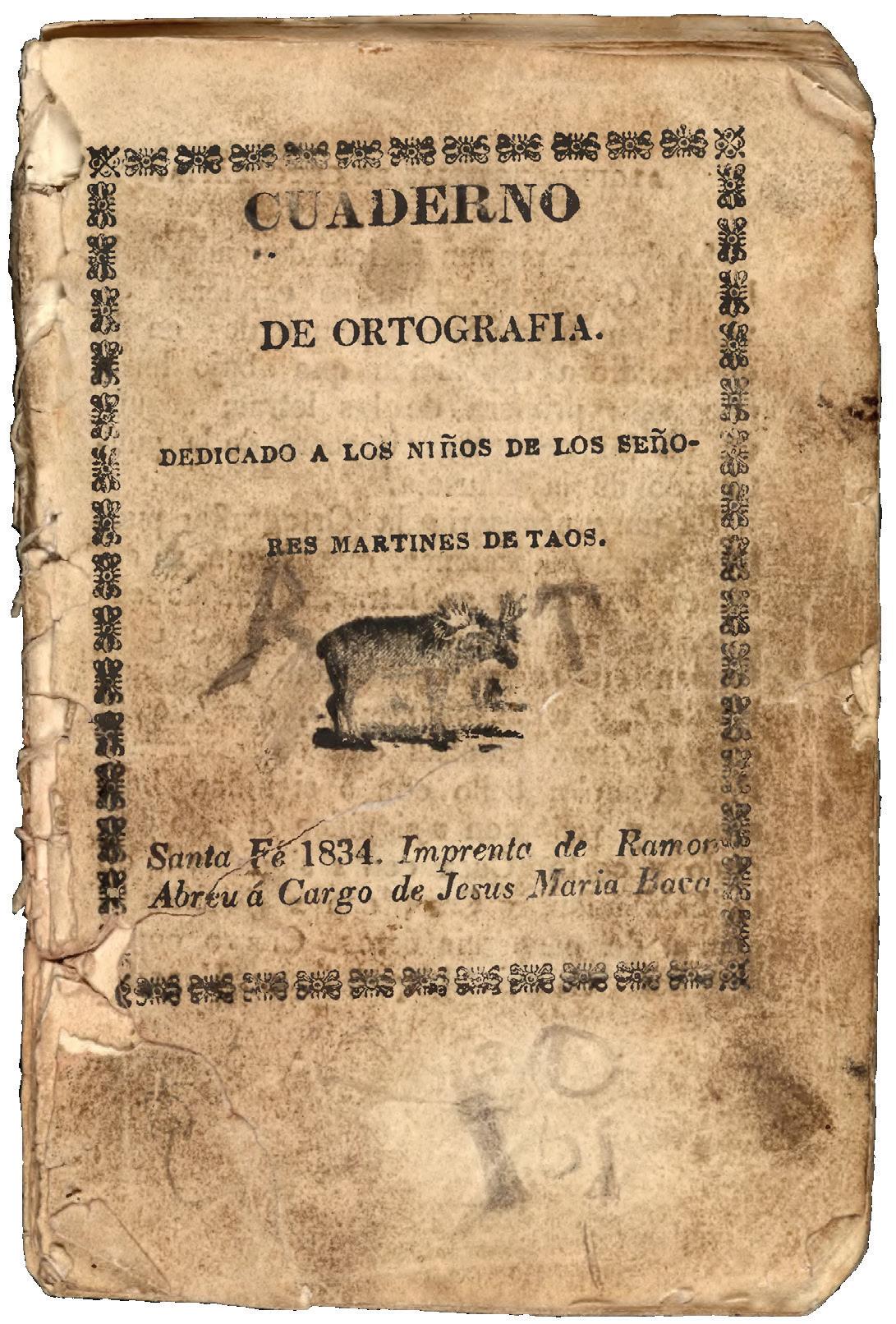

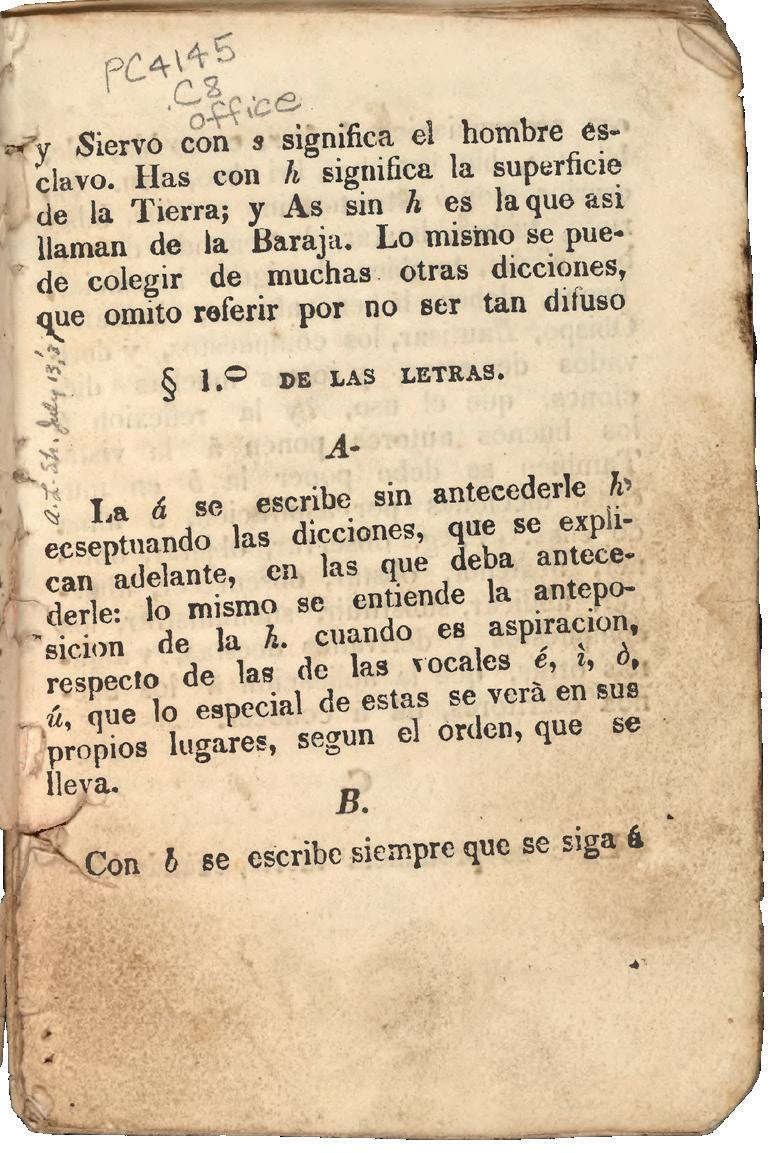

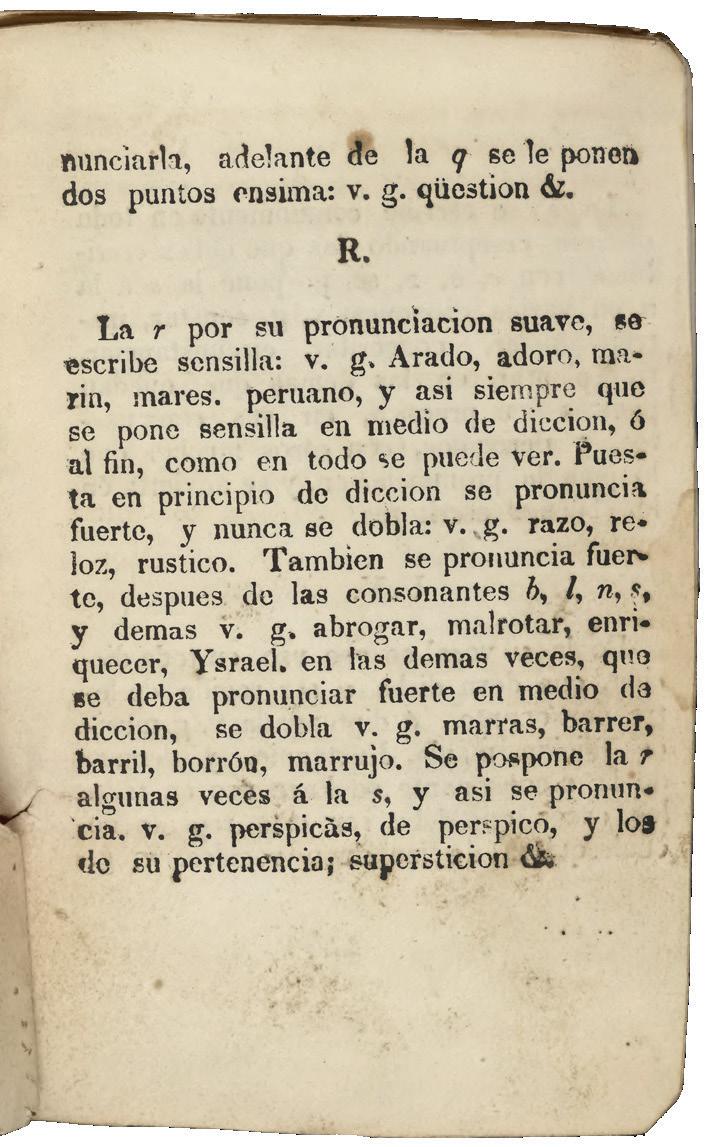

This Spanish-language schoolbook on the use and pronunciation of the letters of the alphabet and the rules of punctuation is the first book printed in New Mexico. In 1834, Mexican official Ramón Abréu brought a printing press from Mexico to Santa Fe, where Abréu and press operator Jesús María Baca produced the book under the direction of Father Antonio José Martínez (1793-1867).

Martínez, a priest who founded schools in the Taos area and was an active supporter of Mexican independence, purchased the press the following year and moved it to Taos. Baca also moved to Taos to work the press, which Martínez used to print books for the schools he established, as wellas to print religious and political tracts.

face of his personal priestly tragedy — and his influence in both continues. Here is an outline of his story:

Antonio José Martínez was born in Abiquiú, N.M., the eldest son of Don Severino Martínez and Dona Maria del Carmel Santisteban. In 1804, the family moved to Taos where their home, La Hacienda de los Martínez, is now a regional cultural center and living museum. Antonio José loved learning and studying. He married Maria de la Luz Martin of Abiquiú in 1812, but she died giving birth to their daughter, also named Maria de la Luz, who, in turn, died at age 12.

He decided for the priesthood and entered the Tridentine Seminary of Durango, Mejico, where his intellectual brilliance shone. He was ordained a priest on Feb. 10, 1822, at age 29, and celebrated his first Mass on Feb. 19 of that year.

Padre Martínez returned to Taos and preached his first sermon there on April 20, 1823; then appointed as the first secular priest at Abiquiú in 1825; and then on July 23, 1826 he became the pastor in Taos, and a great history began.

He proved to be a servant-leader of the people and worked zealously to improve their lives in every way and by his spiritual inspiration. He opened a co-educational school for the youth, and a Minor Seminary for boys who might be called to the priesthood and was instrumental in the formation of several native-born priests.

Martínez acquired “the first printing press west of the Mississippi,” and

published a newspaper, El Crepusculo de la Libertad (The Dawn of Liberty), and printed a variety of parochial sacramentary forms, as well as ministry manuals for use by priests.

He used his political talents effectively as an advocate for the people, including the Native Pueblos of El Norté, who he believed were being mistreated by those in power.

In fairness, it should also be mentioned that some do consider his relationship with Native Puebloans to be controversial, as the Priest of Taos.

Martínez served in the Mexican Departmental Assembly for New Mexico, and then after American assumption of administration in 184748, he headed the United States Territorial Assembly. He was the influential and central personage who sought the best outcomes from these mighty and traumatic geopolitical changes and events, but his most unsettling challenge then arrived, through the Church of which he was a priest.

In 1851, Rev. Jean Baptiste Lamy of France was named by the Catholic Pope as the Apostolic Vicar of New Mexico, whose ecclesiastical jurisdiction from Santa Fe replaced that from far-away Durango, Mejico; and conflict arose between Martínez and Lamy, who was soon anointed as Bishop.

Padre Martínez had advocated for his Spanish and native New Mexican people who might not have grasped the immense changes at hand and, as their leader, he came into direct conflict with the agents of change, including Bishop Lamy. This opposition caused Lamy to censure, suspend and excommunicate Padre Martínez from the Church. The bishop’s rationale was that the Priest of Taos was in violation of and had written

against the order and discipline of the Church.

Bishop Lamy chose the view that the priest had ignored his censure and was continuing to say Mass and administer the Sacraments of the Church, and had published against Lamy’s policies, and so he said he “was forced to excommunicate the Padre.”

Padre Martínez rejected the validity of the “excommunication” and continued as a priest until his death. This conflict caused deep divisions in the Parish community, which in some ways are evident to this day. Yet, Padre Martínez still commands the respect of both sides of the religious issue, however, and his legacy remains otherwise strong and secure as a bedrock foundation-stone of the “new” era of Taos and El Norté after Spanish, then Mexican, and now American governance.

And the foundational spiritual bedrock of the Taos and El Norté region remains as solid and nurturing as it was even before the arrival of Padre Martínez and the subsequent succession of priests and clergy, although he is rightfully acknowledged here as the most prominent and influential and even prophetic personality of his era and the region of El Norté today.

El Norté has weathered much, even through cataclysmic, and dramatic, and traumatic circumstances. And yet, it can be truthfully said that our native and millennial and centuries-old spiritual and cultural leadership which has guided the people here remains and continues to hold sway. Padre Martínez was one of the luminous guides of our singular story in El Norté.

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 9

OF

The book is reproduced here in its entirety beginning with the above outside cover, and continuing with all interior pages on the next page. COURTESY LIBRARY

CONGRESS | continues on 10 CUADERNO DE ORTOGRAFIA

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 10 Padre Antontio José Martínez | continued from 9 The contents of the first book printed in New Mexico, “Quaderno de Ortografia”

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 11 115 LA POSTA RD | 575-737-9300 | WWW.TAOSCF.ORG REVITALIZING THE HOME OF A TAOS COUNTY LEGEND ALDO LEOPOLD CABIN A COLLABORATIVE PROJECT BETWEEN UNITED STATES FOREST SERVICE TAOS COMMUNITY FOUNDATION

TAOS REVOLT

And the demise of Territorial Governor Charles Bent

BY CINDY BROWN

LIKE CERTAIN PARTS OF TAOS HISTORY , the story of the Taos Revolt of 1847 and the fate of the first U.S. civil territorial governor is layered in complexity, contradiction, mystery and violence. What is clear is that in January of 1847, a group of Taos Pueblo and Hispano men attacked the home of Governor Charles Bent, a merchant who was appointed territorial governor the year before. They shot him with arrows and guns until he was dead.

As seen from the point of view of the American government and the family of Governor Bent, the group was an unruly mob of locals that attacked the family home without justification with the intent to kill the governor.

From the point of view of many at the Taos Pueblo and among the local Hispano families, the Americans were unwelcome invaders and the rule of the U.S. territorial government threatened local land grants and other ways of life that had existed for hundreds of years.

By 1847, the Taos Pueblo had already been here for many centuries — since time immemorial, according to its people. The Spanish had lived in New Mexico since the first explorers arrived more than 300 years previously, except for the years between 1680 and 1692 when they were evicted from the area as a result of the Pueblo Revolt. The territory of New Mexico had been part of Spain until 1821 and was still a part of Mexico in 1847.

T HE FACTS, AS REPORTED BY TERESINA BENT SCHEURICH

Early the morning of Jan. 19, 1847, a group of Taos Pueblo and Hispano men came to the Bent home in downtown Taos and broke down the doors and attacked from the roof, according to an account written by Teresina Bent (later Scheurich) who was a young girl of five at the time.

When asked what the group wanted, one replied, “We want your head, gringo. We do not want for any of you gringos to

govern us — as we have come to kill you.” Although the governor tried to reason with the group, they began to shoot him with arrows and guns. The governor’s wife Ignacia Jaramillo Bent, her sister Josefa Jaramillo Carson (wife of Kit Carson), a Mrs. Rumalda Boggs and an Indian servant whose name is not known, dug a hole in a wall.

They all went through the hole into the next house, including the children and Governor Bent, who had arrows lodged in his head. Mrs. Bent and the Indian servant remained in the house outside the passage. When the rebels discovered the hole in the wall, the servant stood in front of Mrs. Bent to protect her and was killed. Mrs. Bent was struck with the butt of a gun but survived.

The crowd discovered where Bent had gone and shot at him, scalped him while he was still alive, and took his clothes. After he was dead, some of the rebels wanted to kill the whole family, but cooler heads prevailed, and the rest of the family was spared.

The others killed that day and into the next included the town sheriff, Simeon Turley — the owner of the mill and distillery — and several others. Seventeen people were killed in Taos as part of the revolt, and others died in the following days throughout the region.

A question that lingers in the mind after reading Teresina Bent’s account is whether the crowd killed Governor Bent because he was a representative of the unwelcome U.S. territorial government

or because they had a personal grudge against him.

Historian and University of New Mexico Professor Sylvia Rodriguez offered the following insights on this question: “No doubt the especially brutal murder of Charles Bent was rooted in personal as well as political grievances. He had worked for many years to spy for and support American takeover and the overthrow of Mexican rule, engaged in extensive land speculation and acquisition. Bent’s Fort was a major outpost of American economic and industrial incursion. He held Mexicans in contempt, may have never actually married Ignacia Jaramillo (sister to Josefa, Carson’s wife), never became a Mexican citizen, or converted to Catholicism (Carson converted but was still somehow a Mason). Both he and Carson hated Padre Martínez (it was mutual) and he was a staunch Mason like all pillars of the new American order. He overestimated his popularity or security

among Taoseños when he ignored rumors of local resistance and returned to Taos on the eve of the revolt, when he refused to meet with petitioners from Taos Pueblo asking for the release of prisoners in the Taos jail.”

WHAT HAPPENED NEXT

Depending on which account you read, what happened next was either an appropriate punishment for the crime of killing Bent and the others — or a heinous act of violence without justification. Almost 400 American soldiers and volunteers under the command of U.S. Col. Sterling Price marched north from Santa Fe. They arrived in Taos on Feb. 3 after skirmishing with the rebels at the village of Santa Cruz de la Canada and near Embudo.

Some of the rebels had taken refuge in the San Geronimo Church on the Taos Pueblo that had been rebuilt after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Price found the pueblo to be a “place of great strength, admirably calculated for defence,” reports Hampton Sides in his biography of Kit Carson, “Blood and Thunder.”

For two hours, Price ordered the artillery to bombard the church. When that didn’t destroy it, the soldiers began to hack away at the adobe bricks, and eventually set the roof on fire. Price then rolled his six-pounder — a howitzer that fired a six-pound shell packed with grapeshot — from fifty yards away, at the church. When a hole opened up in the church wall, the cannon was moved closer and it fired hot shrapnel into the church, killing most of those inside, according to Sides.

Over two hundred people, mostly women and children, were killed; the church was in ruins — never to be rebuilt. Other rebels were captured and, after a

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 12

Governor Charles Bent

Present day San Geronimo Church on the plaza at Taos Pueblo. Its construction was completed in 1850. St. Jerome is the patron saint of Taos Pueblo designated by the Catholic church. COURTESY RICK ROMANCITO

trial presided over by the father of one of the men who had been killed in the revolt, many of the rebels were found guilty of murder or treason, and were hung in Taos Plaza and elsewhere.

LOOKING BACK

Earlier this year, the 176th anniversary of the Taos Revolt, Taos Pueblo Gov. Gary J. Lujan told Rick Romancito for a Taos News article titled “The Taos Revolt and the history we must never forget,” “The church — sitting there destroyed — is a continual reminder of our interaction with the United States as a result of that uprising in 1847. What followed was the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which, I think, settled the imposition of new rule and brought everyone to the table — but what it did not do was [settle] any kind of reparations from the United States in terms of the men, women and children who were killed in the church. So, the church is a continual reminder of that.”

GOVERNOR BENT MUSEUM

The home of Governor Bent has been preserved as a private museum. Tucked in a corner among the galleries and shops of downtown Taos, the home holds artifacts from Governor Bent’s life and times as well as collections of arrowheads, snake skins and other mysterious artifacts.

The hole that was dug in the wall is still visible, along with some of the tools used to dig the hole. Articles about the governor adorn the walls along with some of the family’s clothing. A chair that belonged to the governor is also part of the collection.

The family of Thomas Noeding has owned the building since the 1950s; in 1959, it was turned into a museum. Noeding has been working at the museum for the last 40 years. He has read widely about the Taos Revolt and says, “The rebels were just defending their country. But I don’t know why the rebels had to kill all these people. That got everybody stirred up.”

The Church Fire

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 13

The former home of Territorial Governor Charles Bent.

The ruins of San Geronimo church at Taos Pueblo, destroyed by American soldiers in 1847 in retaliation for the Taos insurrection.

Found exclusively in next week’s edition

The incontrovertible truth, according to Larry Martinez

Taos Mountain Casino is proud to honor those who both exemplify the best of the past and who help us weave it into the future. These people are our own links in what continues to be an unbroken circle of tradition at Taos Pueblo.

tradiciones: leyendas taos news / sept. 14, 2023 14

2023 Taos Pueblo officials from left, Fiscale Damon Lujan, Lieutenant Fiscale Joseph L. Concha, Head Fiscale Harold T. Lefthand, Tribal Secretary Daniel R. Lucero, Governor Gary J. Lujan, Lieutenant Governor Anthony B. Suazo, Second Sheriff Gordon M. Martinez, Second Fiscale Anthony L. Mirabal, and Fiscale Kevin Whitefeather Cordova. Not pictured is First Sheriff Sholden Lujan.

Legendary: A people who have fought for their culture and land through decades of challenges.

Rick Romancito/ For the Taos News

BY JOSEPHINE ASHTON

BY JOSEPHINE ASHTON