LEYENDAS

l the real true story of

l

l the real true story of

l

4

HOW TAOS PUEBLO FIREFIGHTERS RESCUED THE LEGENDARY CUB by Rick

Romancito

8

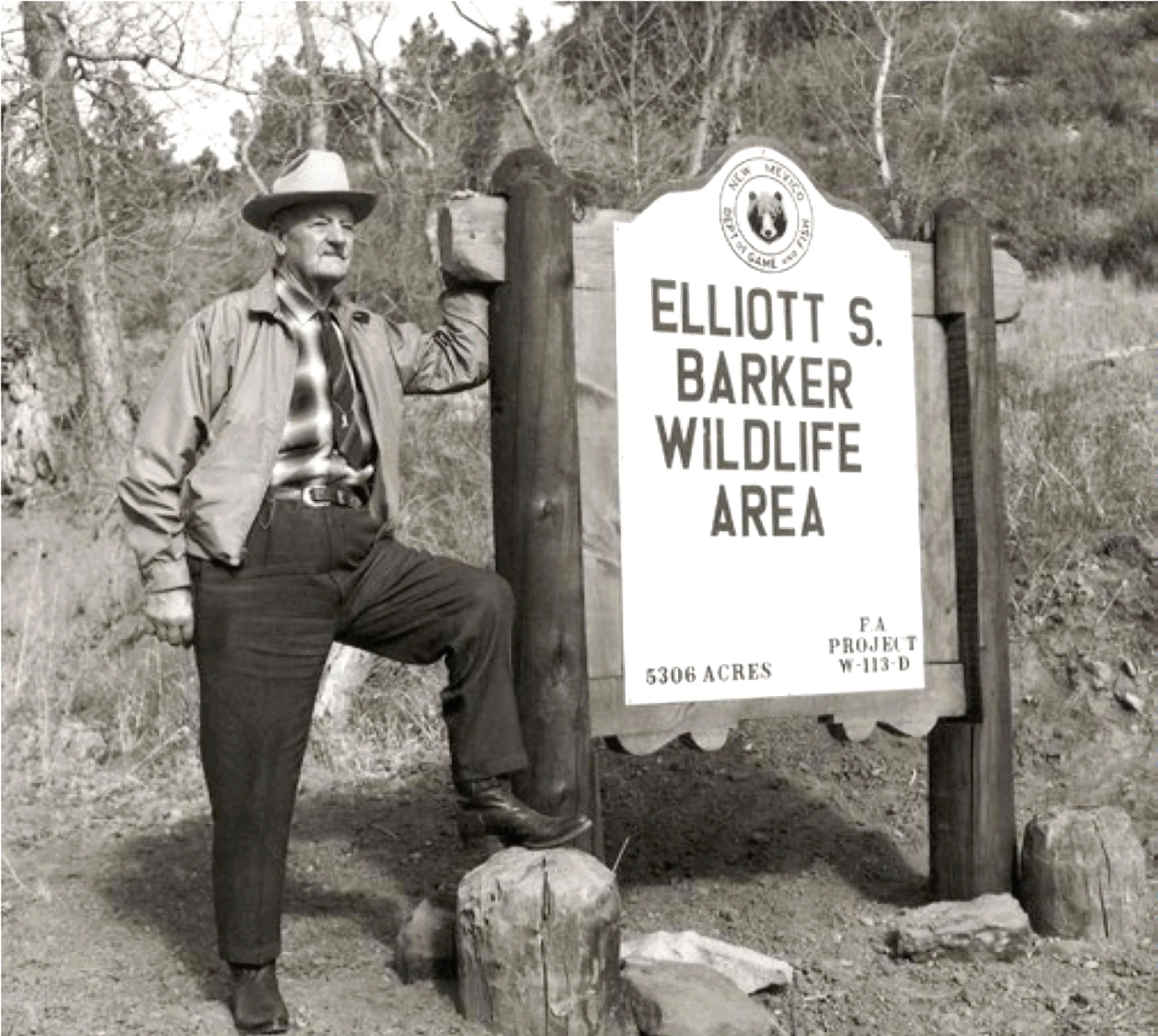

ELLIOTT BARKER LEFT HIS MARK ALL OVER NORTHERN NEW MEXICO by Ellen

Miller-Goins

HOW A TINY CUB BECAME A LIVING SYMBOL OF FIRE PREVENTION by Ellen Miller-Goins

12 DoughBelly Price

THE COWBOY SAGE OF TAOS

By Cindy Brown

TH IS AREA IS STEEPED IN HISTORY, LEGEND and myth and Leyendas — the first in our four-part Tradiciones publications — is our modest attempt to tell a few of these stories.

As always, the challenge is to narrow down which stories to tell. Sometimes the internet, that proverbial rabbit hole of information, leads the way. I was intrigued by Elliott Barker, the renown conservationist who figured so prominently in New Mexico’s 20th Century history.

In reading about Barker’s role in turning a little bear cub into Smokey Bear, I learned Taos Pueblo firefighters — the Snowballs — first found the little guy amid the charred remains of the Capitan Gap Fire. This led directly to a piece former Tempo editor Rick Romancito had written for the Taos News in 2022. You’ll find that story here along with my piece about Barker and his amazing contributions to New Mexico’s wildlife.

Also in our 26th Leyendas, Cindy Brown writes about the legendary Taoseño, DoughBelly Price, a cowboy, chuckwagon cook, bootlegger, writer and contemporary of Taos legend John Dunn, santero Patrociño Barela, socialite Mabel Dodge Luhan, and Tony Luhan of Taos Pueblo.

We hope you enjoy this year’s issue of Tradiciones: Leyendas. Drop me a line with your suggestions for next year!

Ellen Miller-Goins, Magazine Editor

BY RICK ROMANCITO

passes along history to younger generations by the telling of stories, but sometimes another version of the facts contradicts those ancestral accounts.

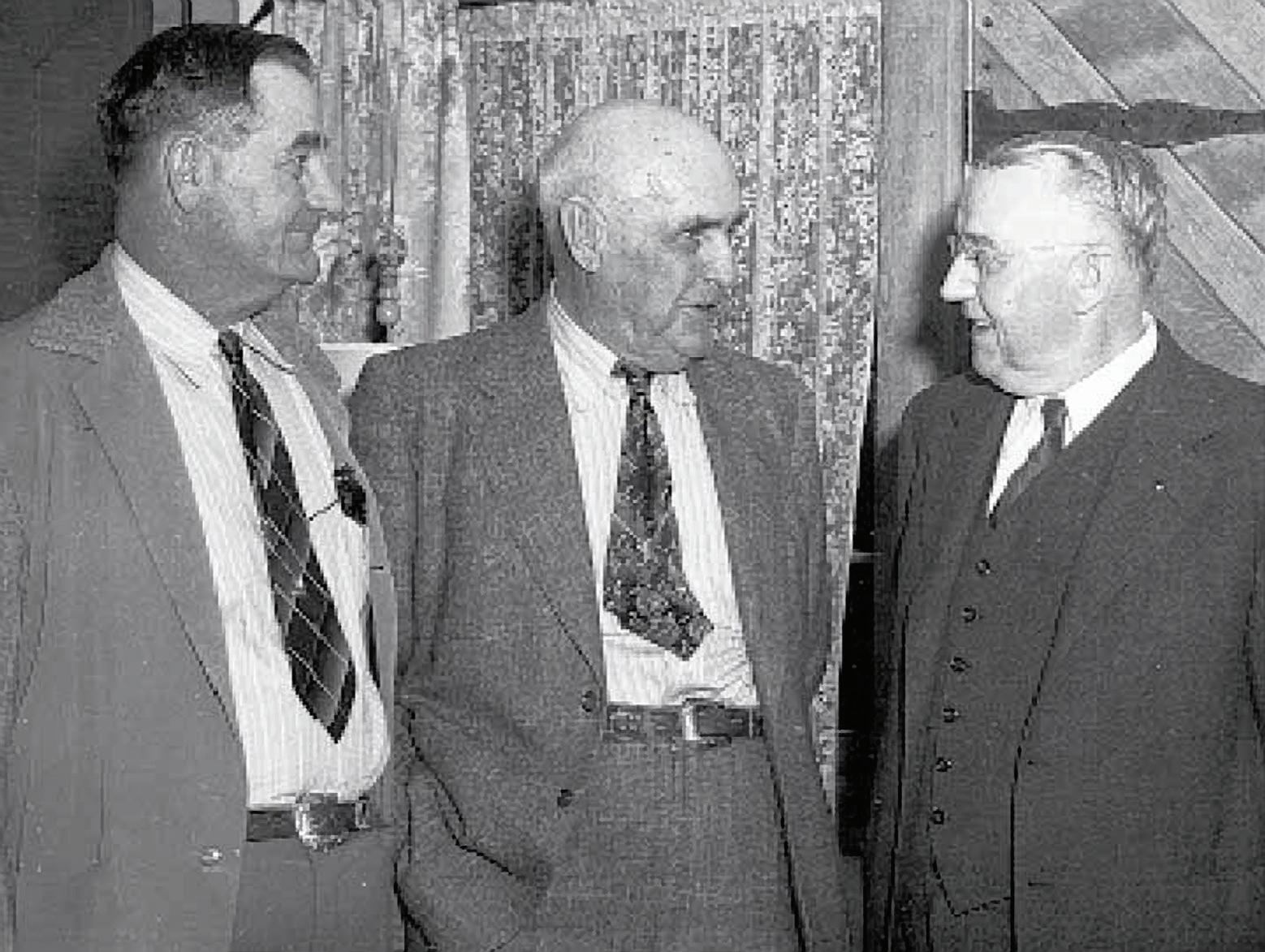

One of those contradictions was corrected July 9, 2008 at Taos Pueblo when the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) formally acknowledged the part played by firefighters from the Pueblo in the reallife rescue of the bear cub that took the name Smokey Bear, and honored two of the surviving original Snowballs — Adolph Samora and Paul Romero.

Smokey, whose campaign first began in 1944, unofficially became “Smokey the Bear” in a 1951 hit song. Songwriters Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins added “the” to fit the lyric. The icon of the cartoon bear that told generations of Americans to douse campfires, because “Only YOU can prevent forest fires,” took on flesh and blood during a fire in New Mexico’s Lincoln National Forest in 1950 when crews fighting a wildfire in Capitan Gap found a badly burned American black bear cub.

The story repeated in articles and books, including a 1960s comic book gave credit for the rescue to Army troops helping to fight the fire. The truth was that a volunteer crew from Taos Pueblo found the bear and turned it over to Forest Service supervisors.

In a November 2022 interview, Samora said he saw something coming through the ashes. “The ashes were deep, so he couldn’t recognize right away what it was and then he realized that what it was a little bear coming through those ashes,” said Gilbert Suazo Jr., who was translating for Samora from Tiwa.

The bear was later nursed to health and the cub’s tale was retold without ever mentioning the Taos Pueblo Snowballs fire crew that found him. Both Samora and Romero were teenagers when they boarded a bus with other men from Taos Pueblo for the day-long trip to fight the

The ashes were deep, so I couldn’t recognize right away what it was and then I realized that it was a little bear coming through those ashes.

Adolph

disastrous fire in the Capitan Mountains in 1950. Samora was 18 and Romero was 16.

It was at the start of that trip to the Capitan fire that the Taos Pueblo volunteer firefighters adopted the name “Snowballs.” According to a story related by Samora to BIA Regional Prevention Officer Val Christenson for publication in the BIA magazine “Smoke Signals,” one of the men looked at the white hard-hats worn by the firefighters and the white-capped Taos Mountain told the men they “looked like a bunch of snowballs.”

The name has stuck until the modern day to identify the forest firefighters from Taos Pueblo. Christenson, who attended the 2008 ceremony at Taos Pueblo, said he met some of the original Snowballs who found Smokey Bear and vowed to make their story known.

Rene Romero, who helped coordinate the ceremony with the BIA, said the event preserved the stories that have been passed down by the tribe’s elders.

“It’s about keeping the stories,” he said.

BY ELLEN MILLER-GOINS

only served with the Carson National Forest a few years. It could be argued his most important contribution during that time was his influence on Elliott Barker, a man who did more for conservation in the state of New Mexico than even Leopold himself.

Leopold famously proposed the world’s first wilderness area, the Gila Wilderness, established 100 years ago June 3, 1924. Forty years later, Barker’s testimony boosted passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964.

If you enjoy the Latir Peak, Wheeler Peak, Columbine-Hondo, or Pecos Wilderness Areas, or one of 13 other National Forest Wilderness Areas in New Mexico, know Barker played a part. If you hunt, fish or enjoy seeing herds of elk, mule deer, pronghorn antelope, turkey and other animals, know Barker played a huge part. A lifetime’s experience as a rancher, hunter, guide, fisherman, writer, and state game warden made him the perfect spokesperson for such disparate interests, but — and this is important — he came to believe someone needed to speak for wildlife, too. “Wildlife in the Southwest … has had a hell of a time surviving,” Barker wrote in Smokey Bear and the Great Wilderness

(1982). “The Merriam elk which is indigenous only to southern New Mexico… was exterminated in the 1880s without even a good museum specimen being left. …

The masked bobwhite quail was exterminated from New Mexico and Arizona. …

The Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep were exterminated by the turn of the century… . The desert or Mexican bighorns were exterminated from much of their range but managed to hang on in a few places in the States. … Pronghorn antelope were on the verge of extinction in 1917. … Rocky Mountain elk, once plentiful in New Mexico and Arizona, were all killed out by 1900.”

Barker noted black-footed ferret, kit fox, New Mexico black duck, Merriam turkey, grouse, and other New Mexico wildlife had seen serious — and in some cases, perilous — population declines as more and more humans settled statewide. “We must face the fact that wildlife — which once had exclusive use of its habitat — has had many of its rights taken away for man’s exclusive

use,” Barker wrote. “When will it stop?”

When he stepped into the role of the state’s first state game warden in 1931, Barker was riding a wave of sentiment that had begun back in the 19th century.

In the nine-part series “A century of wildlife management,” published by New Mexico Wildlife magazine in 2002–2003, John Crenshaw wrote, “In addition to wanton slaughter, burgeoning populations of people were simply eating their way through the game herds. … At the same time, sharply increased herds of sheep and cattle in post-Civil War New Mexico competed with big game for food and spread devastating diseases. … Even song birds — robins, bobolinks, finches, juncos, waxwings — were killed for the market and literally baked into pies.”

It was the alarming decline or, in the case of bison, near outright extinction that “nurtured a new conservation conscience,” Crenshaw wrote.

We must face the fact that wildlife — which once had exclusive use of its habitat — has had many of its rights taken away for man’s exclusive use. When will it stop?

Elliott S. Barker, American Conservationist

When we work together, we have the power to create positive change in our communities! That is exactly what our members do when they opt into Nusenda Credit Union’s Community Rewards program. They help us fund grants that support the arts, community services, education, environment and wildlife, and healthcare.

In 2023, the Nusenda Foundation granted more than $630,000 in Community Rewards to 108 organizations that are positively impacting the communities they serve! Our members and employees are committed to being positive contributors in the places we call home.

Learn more at nusenda.org

By the time New Mexico passed a protection law in 1880 “the bison were already gone,” Dave Arthun and Jerry Holechek wrote in “The North American Bison,” published by New Mexico State University.

While still a territory, New Mexico established a game department and appointed its first territorial game warden in 1903. Voluntary deputy game wardens and little to no legal muscle meant enforcement was spotty but it was a start.

Stewards of the land

Three-year-old Barker arrived in New Mexico with his family by covered wagon in 1889 and credits his life on a Sapello homestead with instilling a love for the outdoors — and planting the seeds for his conservationist views.

When a young man asked how someone with only a high school education who was raised on a ranch could be a conservationist, Barker replied, “Perhaps being ranch raised was a potent factor, and lack of a college education had nothing to do with it,” in his 1976 book “Ramblings in the Field of Conservation.”

Barker goes on to explain his family believed in good stewardship and would never tolerate waste. “If I left food on my plate it was put in the cupboard — we had no refrigerator — and I would have to eat it at the next meal before taking anything more on my plate,” Barker explained in “Ramblings.”

He notes his mother “Forbade us from taking any game that we did not need, or at a time that it was not in good flesh. That meant no venison from about February until September.”

While growing up on the ranch, Barker believed wholeheartedly in predator control. Like Leopold, he also recognized the vital role predators played in nature. “I do not now, nor have I ever favored extermination of any of God’s creatures, except perhaps house flies, body lice and bedbugs. Nor do I advocate pushing predators to the brink,” Barker wrote in “Smokey Bear and the Great Wilderness.”

He wrote, a little bitterly, of his disdain for unethical hunters “who shoot before making sure it’s legal game; those who kill whatever they see first; those who waste wild meat; those who carelessly handle firearms; those who disrespect the rights, privileges and property of others; those who are careless with campfires and fail to clean up their campsites; those who picket horses near streams, lakes and springs; those who damage lands and forage by off-road driving; those who violate game laws and who commit other illegal, damaging and thoughtless acts,” Barker wrote in “Smokey Bear and the Great Wilderness.”

Barker worked as a professional guide and hunter near the family’s ranch for two years before passing the U.S. Forest Service ranger examination. In “Smokey Bear and the Great Wilderness,” Barker recounted, “The exam consisted of compass surveying, marking timber to be cut, scaling logs, estimating distances by stepping off courses, saddling, unsaddling and packing horses with typical camp equipment: bedroll, provisions, cooking utensils and fire-fighting tools. I was familiar with those activities so it was easy.

“Six months later I was … offered a job as Assistant Ranger in the Jemez National Forest,” he continued. “Assigned to the Cuba district, I found it was a new addition to the forest to which the citizens, led by Epimenio Meira, were bitterly opposed. … The two rangers who were sent before me visited a saloon (bawdy house) near the village and were badly beat up, their horses unsaddled and turned loose. A passer-by loaded them into his wagon and took them home. They resigned and left the country in disgrace.”

Though fluent in Spanish and English, A.W. Sypher, Barker’s boss at the time, hoped to keep it a secret. “All went well for a time, but then two men got rough in their conversation, speaking of our ancestry in rather vile terms. I lost my temper and cursed them out in Spanish.”

Things quickly got out of hand and Barker wrote, “I was on the verge of drawing my pistol and firing a warning shot when Sypher burst in and Miera came out of his office. Miera bawled us out for ‘spying’ ... He asked how old I was; I said 22. He said, ‘When I was 22, I didn’t have much sense either.’ Then Sypher bawled me out for spilling our secret.”

By November 1909 that year, he went to work for the Pecos National Forest. Barker noted, “I helped lay out and supervise the

We increased the deer population from 65,000 to 200,000, antelope from 5,000 to 22,000, restored elk to many areas from which they had been exterminated in the 1800s, saved the prairie chicken from extirpation, provided and developed refuges for waterfowl and non-game birds; built lakes for fisheries and hatcheries to stock them.…

Elliott S. Barker, American Conservationist

building of new trails” and handled “predator control — mainly cougar and stockkilling bear.”

The most significant event during his tenure in Pecos, came “in March 1910 when I met Ethel M. Arnold, a mountain rancher’s lovely daughter. On May 17, 1911, she became my wife. She has followed me wherever duty called regardless of inconveniences and hardships.”

Meeting ‘America’s greatest authority on wildlife management’

A November 1912 transfer to the Carson National Forest near Tres Piedras might have caused consternation, Barker wrote,

and 39 bobcats,” he noted in “Smokey Bear and the Great Wilderness.” New Mexico’s game management, meanwhile, had gone through major changes. “The baldly partisan political appointment of Grace Melaven as state game warden in 1923 gave the Game Protective Association ammunition to shift hiring authority from the governor to the State Game Commission,” Crenshaw wrote. Commission appointee Federal Judge Colin Neblett interviewed Barker for the newly minted game warden position. “I told him I was interested in the game warden position only on condition that the Game Department would operate completely free of politics. The Judge smiled and said, “You beat me to it.’” Barker immediately divorced himself from state partisan politics by refusing to allow “a two percent assessment on all salaries of Game Department personnel to support State political parties.”

Restoring wildlife to the land

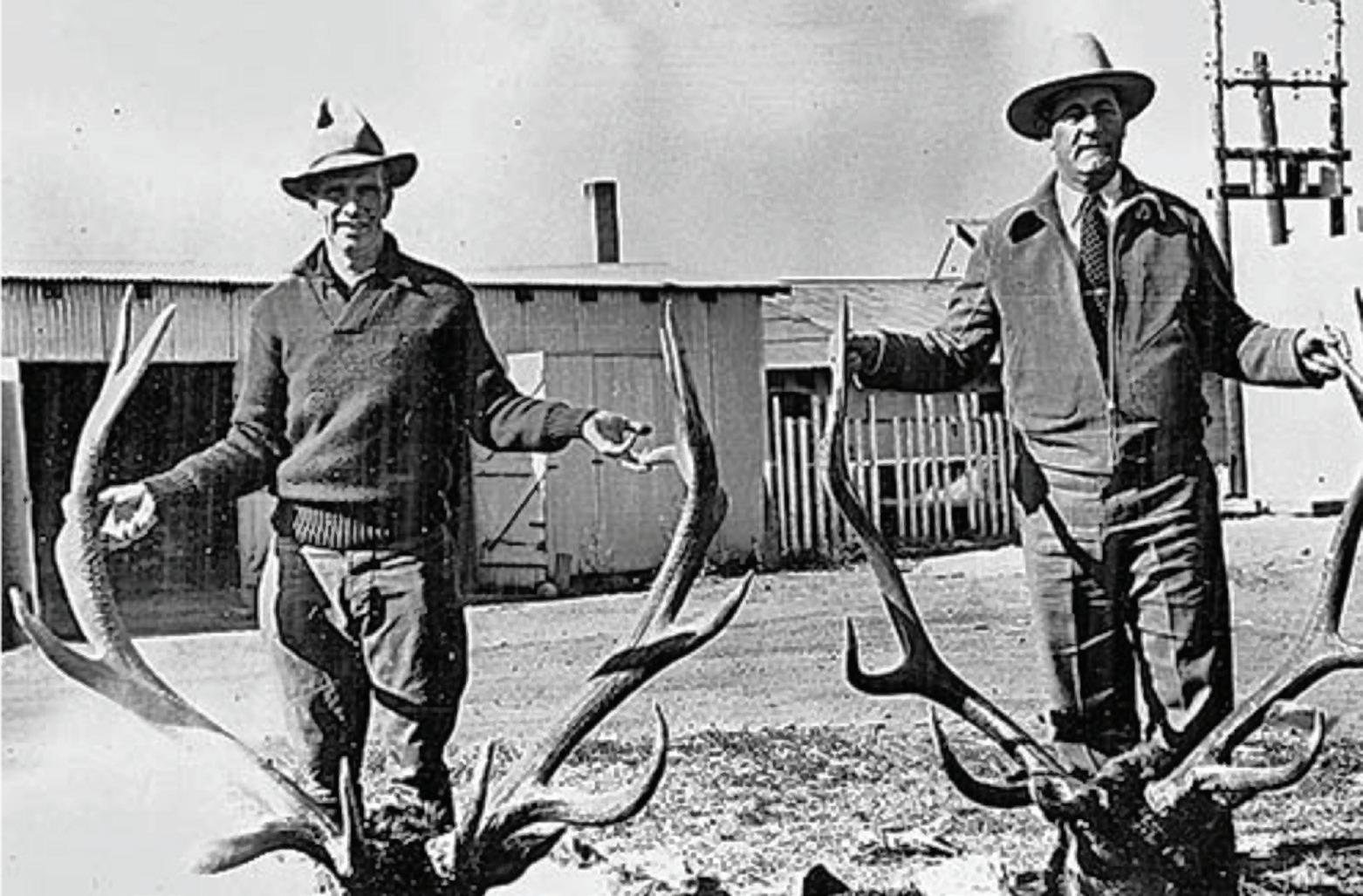

In the job he held until 1954, Barker reintroduced elk into the Pecos Wilderness and bighorn sheep into the Pecos and Sandia mountains. “We increased the deer population from 65,000 to 200,000, antelope from 5,000 to 22,000, restored elk to many areas from which they had been exterminated in the 1800s, saved the prairie chicken from extirpation, provided and developed refuges for waterfowl and non-game birds; built lakes for fisheries and hatcheries to stock them.”

The Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, passed in 1937, provides funding for states and territories to support wildlife restoration, conservation, and hunter education and safety programs. Using these funds, Barker said, “We initiated acquisition and development of key wildlife and fisheries areas, such as Cimarron Canyon, Pecos River Terrero tract, Charette, Fenton and Wall Lakes and others,” he noted in “Smokey Bear and the Great Wilderness.”

were it not for Aldo Leopold. “I have always considered it a great privilege to have worked under, and later associated with, that wonderful man who later became Dr. Aldo Leopold, America’s greatest authority on wildlife management.”

In 1913, a life-threatening illness nearly killed Leopold and in 1914 he was assigned to district headquarters in Albuquerque. That fall, Barker was promoted to deputy forest supervisor for $130 a month and moved to Taos. It wasn’t long before he moved up as supervisor. “My position as Supervisor involved more public relations work. … Here, as always, my knowledge of Spanish was a great asset. Even the Taos Pueblo Indians spoke more Spanish than English.”

During World War I Barker joined the National Guard. “I was appointed a first lieutenant in the home National Guard, a deputy U.S. Marshal and chairman of the Taos County Red Cross.”

When “the terrible flu epidemic hit Taos like a tornado … it fell to me to take the lead in doing all things possible to relieve suffering and save lives. We turned a church and a school building into makeshift hospitals. I had a priest and a dentist as my assistants and no one ever worked harder than they did.

“In 60 days we lost 10 percent of Taos County’s population,” he continued. “My two assistants escaped, but on Nov. 8 [1918], it hit me, suddenly and hard. I was in a semi-coma for nine days. I didn’t know the armistice had been signed until two weeks afterward.”

Barker said post-illness depression led to his decision to resign and go back into ranching, a profession he pursued until the Great Depression ended everything for him and so many other farmers and ranchers.

He tried, unsuccessfully, to go back to the Forest Service.

“Then I recalled that in 1926 when Harry Chandler, publisher of the Los Angeles Times Mirror, bought the fabulous Vermejo Park ranch, he’d tried to get me to work for him as wildlife and predator control manager at an attractive salary. I was doing well on the ranch at the time and passed it up. So I wrote to Mr. Chandler, asking if he could still use me and he answered, ‘Yes, we need you but any salary I could offer under present conditions would be an insult.’ I wrote saying, ‘Won’t you please insult me?’”

Barker went to work for “$150 a month plus a house to live in, a cow, chicks and horses” and noted, “During the year I was there I took 16 mountain lions, 46 coyotes

Using federal funds, Barker oversaw the purchase of the Colin Neblett Wildlife Area that encompasses Cimarron Canyon State Park, the upper Pecos River valley, and the Heart Bar Wildlife Management area. His department established fish hatcheries statewide, including The Red River Fish Hatchery, built beginning in 1941. “Red River is one of the largest hatcheries in the Southwest,” Barker wrote.

Barker helped found the National Wildlife Federation and served on its board of directors, received an honorary doctorate degree from New Mexico State University, and received numerous other conservation and literary awards. While he did not rescue Smokey Bear he was key to Smokey Bear’s evolution from cartoon to real-life symbol.

At Barker’s behest, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish donated Smokey to the Forest Service in Washington, D.C., specifying the cub should become a symbol of forest-fire prevention and wildlife conservation. Smokey lived for more than 26 years at the National Zoo and became the most recognized animal in the world.

Through his testimony Barker helped secure the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964 leading to wilderness designation for millions of acres throughout North America. “There are those who assert that a bit of lumbering here, some mining there, and all that goes with such operations will not impair the wilderness character of the area, nor prevent its enjoyment by wilderness riders, hikers, campers and other visitors. Those who make such claims have either never had a wilderness experience or their souls are too dead to appreciate it. A wilderness trip with such operations going on would be like trying to enjoy grand opera with the area surrounded by jackhammers,” he said in “Smokey Bear and the Great Wilderness.”

Barker died in Santa Fe, in 1988 at age 101. His wife Ethel died Feb. 9, 1996 at 102. They had three children, Barker wrote, “who have produced for us 10 grandchildren, 14 great-grandchildren and [at this writing in 1982] one great-great-grandson.”

A mountain west of Elk Mountain near the Pecos Wilderness and a wildlife management area near Cimarron are named after Barker, as are a Girl Scout Camp and trail complex in Angel Fire. Another naturalist and noted conservationist, John Muir, wrote, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” Barker understood this to his core. l

Can

Transportation

•

• Friendly visits

• Go for a walk with member

•

• Software help and tutoring

BY ELLEN MILLER-GOINS

PEOPLE WHO EITHER GREW UP IN NEW MEXICO OR WHO picked up the 1960 comic illustrating one version of a little bear rescued from the aftermath of a New Mexico fire believe they know the story behind America’s most famous bear. But — as Rick Romancito’s story in this issue shows — the truth is more … complicated.

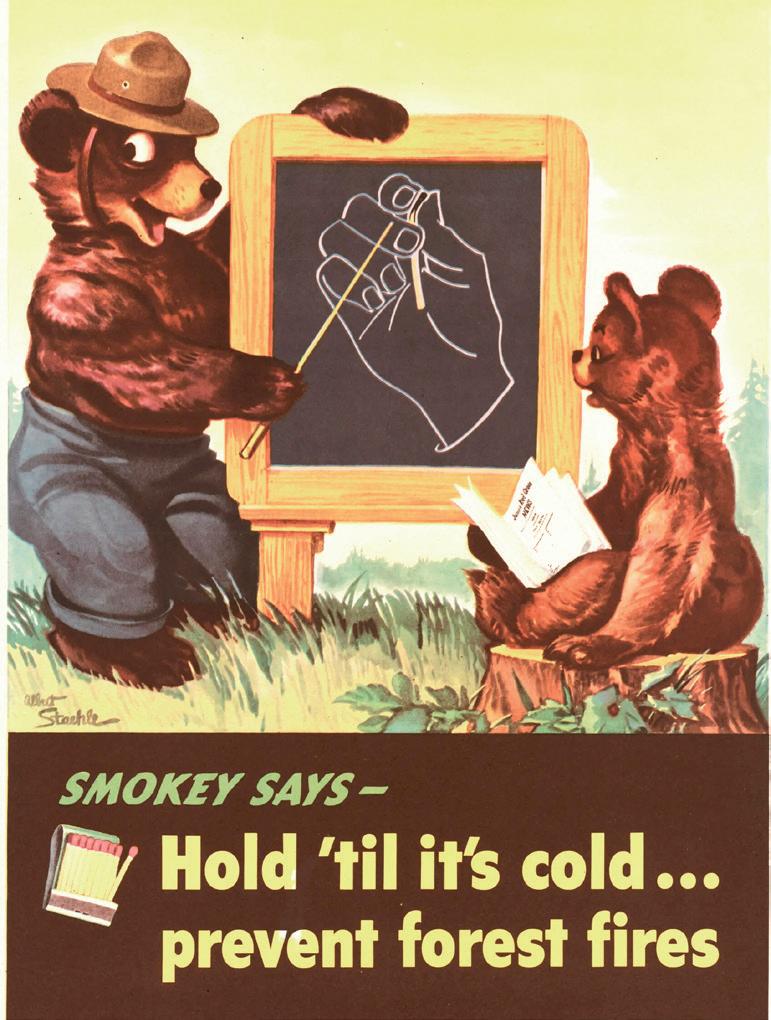

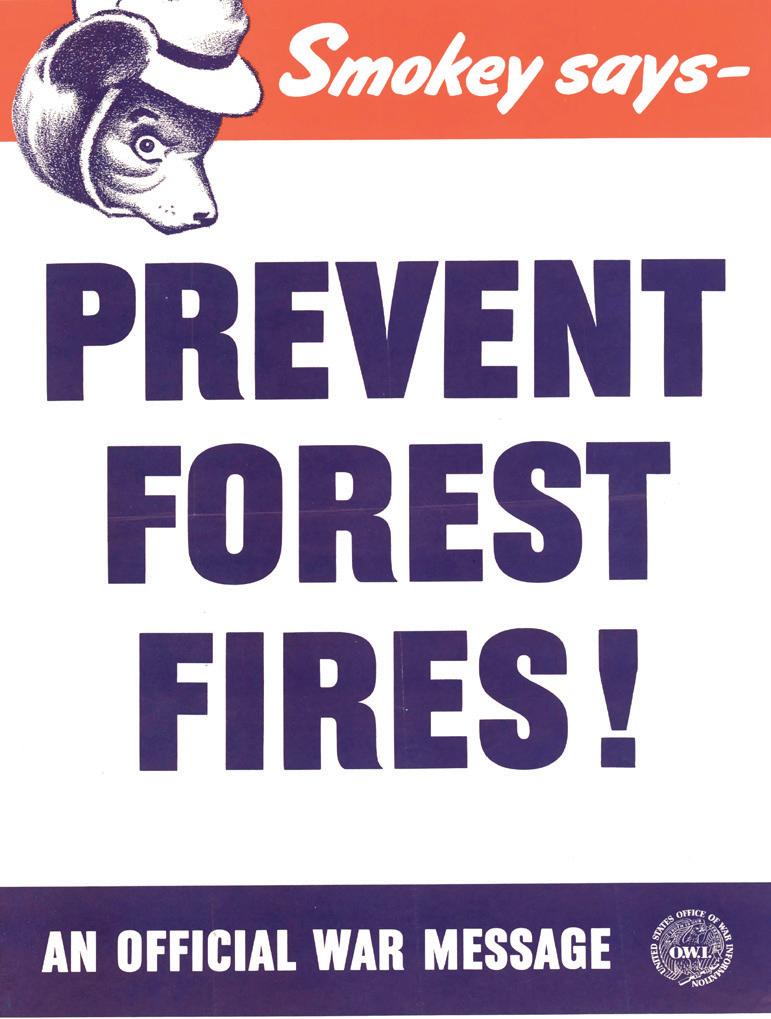

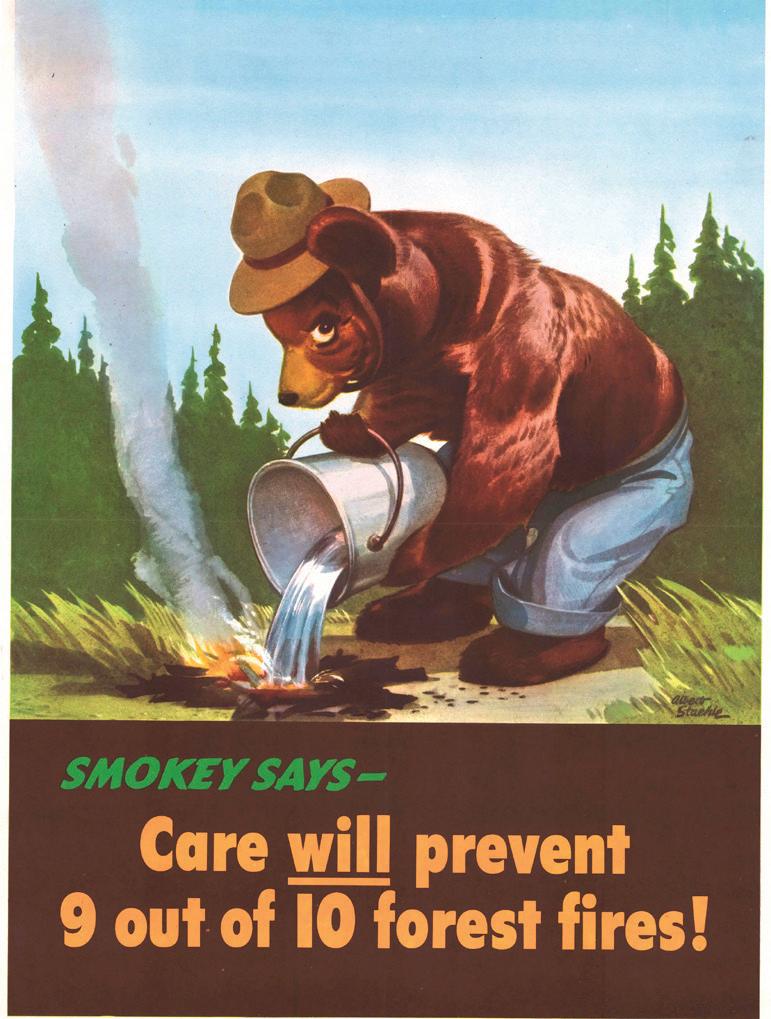

The first Smokey Bear was the imaginative creation of artist Albert Staehle — many years before the forest fire in New Mexico’s Capitan Mountains. According to a History Channel story by Erin Blakemore, Smokey Bear was a direct response to one of the few attacks by the Japanese on the continental U.S.

When, in February 1942, a Japanese submarine shelled an oil field outside Santa Barbara, California, in addition to “a national invasion panic,” Blakemore writes. “The specter of devastating fires loomed large. … State forestry services and the Forest Service joined the newly created War Advertising Council to create the Cooperative Forest Fire Prevention Program in 1942. Public service advertising, and posters urging the public to aid the war effort by preventing forest fires were soon splashed across the country.” In 1944, Disney lent Bambi to the effort for one year, then Staehle, who was already known for his illustrations of cute animals, “created the first poster of a cartoonish bear pouring water on a campfire,” Blakemore wrote. “The Forest Service named the character after a former firefighting legend, New York assistant fire chief Smokey Joe Martin.” Then in 1950, Taos Pueblo Snowballs reported finding a bear cub — initially named “Hot Foot Teddy” — amid a charred landscape. In “The Capitan Gap Fire, the Taos Snowballs and Smokey Bear,” Val Christianson of the National Interagency Fire Center wrote, “There are numerous accounts of various

soldiers picking up the animal and eventually bringing it back to camp, but that initial encounter with the Snowballs on the fire line is what endears Smokey to Native American firefighters.”

In “Smokey Bear the Living Symbol” by the Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department, two humancaused fires fueled by high winds made the blaze “impossible to control.” As the famous comic recounts, soldiers from Fort Bliss, Texas, helped battle the Capitan Gap Fire, but so did the Mescalero Redhats and, as Romancito wrote, the Taos Pueblo Snowballs.

According to several accounts, the tiny cub was first spotted shuffling through the ashes, then pried from a charred tree and brought back to camp by the soldiers. New Mexico game warden Ray

[In 1944, Albert] Staehle created the first poster of a cartoonish bear pouring water on a campfire. The Forest Service named the character after a former firefighting legend, New York assistant fire chief Smokey Joe Martin.

Erin Blakemore, History Channel

Bell, who had been flying over the fire for the fire boss, knew the bear needed medical attention so he flew the bear to Santa Fe where Dr. Ed Smith could treat the cub’s burns. Bell and Smith were concerned when the bear would not eat. Elliott Barker wrote in “Smokey Bear and the Great

OPPOSITE

Wilderness,” “When told of the cub’s refusal to eat properly, [Bell’s daughter] Judy insisted they take him home, saying, ‘I know mother can made him eat whether he wants to or not.’

“Judy’s mother, Ruth, mixed pablum, honey and milk into a paste and forced it into Smokey’s mouth. Soon he began to suck on the paste and to swallow some. That was the turning point. … He recovered beautifully.”

The Bells soon discovered housing a wild animal was a challenge and described the cub as a “mite domineering” so, according to Baker, “Ray and I talked to Forest Supervisor K. D. Flock about having our cub made into SMOKEY BEAR, a symbol of fire prevention and wildlife conservation. Flock was enthusiastic and wrote to the Regional

Forester in Albuquerque about it. Amazingly, Flock got a negative reply. Since he wouldn’t go over the Regional Forester’s head, we took the liberty and did so ourselves.

“As soon as Chief Forester Lyle Watts and his public relations officer, Clint Davis, learned of Smokey’s story, they called me and begged us to donate him to the Forest Service and have him domiciled at the National Zoo where he would be made the living symbol of forest fire prevention. I agreed to this plan but insisted that wildlife conservation be included in the long-range goal.”

When commercial airlines insisted Smokey fly in the cargo hold, Barker wrote, “Ray called his friend and fellow pilot, Frank Hines, at Hobbs, New Mexico, and he volunteered to fly Smokey in a

Piper Cub plane to Washington D.C. … As the plane was readied for flight, a nowfamous artist, Will Shuster, painted a replica of the Forest Service’s Smokey Bear symbol on the side of the plane.

“I personally wanted to accompany Smokey to Washington, but urgent business prevented me from going, so I sent my assistant, Homer Pickens. They were greeted by large crowds in Oklahoma City and Chicago. The little bear was already a national figure.”

The orphan cub, now officially known as Smokey Bear, was housed at the National Zoological Park and for 26 years served as the living symbol for fire prevention.

Barker wrote, “Smokey … was given a secretary to answer his letters from young people which reached an average of a thousand a day. He was given his own zip code number and he earned over a million dollars from the use of his name in appropriate advertising. The Forest Service now estimates that his influence in forest fire prevention has saved millions of human and animal lives far beyond the many millions of dollars’ worth of timber.”

Smokey died in November 1976, and was buried at Capitan, near Lincoln National Forest. The Capitan Ranger District was renamed after the bear in 1960, and later combined with another district to become the present-day Smokey Bear Ranger District.

“Yesterday a friend asked if I were coming to Capitan to pay my last respects to Smokey,” Barker wrote. “I said, ‘No, but I will attend the ceremonies in observance of the last rites of SMOKEY BEAR and pay tribute to his unprecedented accomplishments.’”

Despite his disappointment the Forest Service never used Smokey for conservation messaging, Barker wrote, “I am proud to have assisted the little cub when I did.”

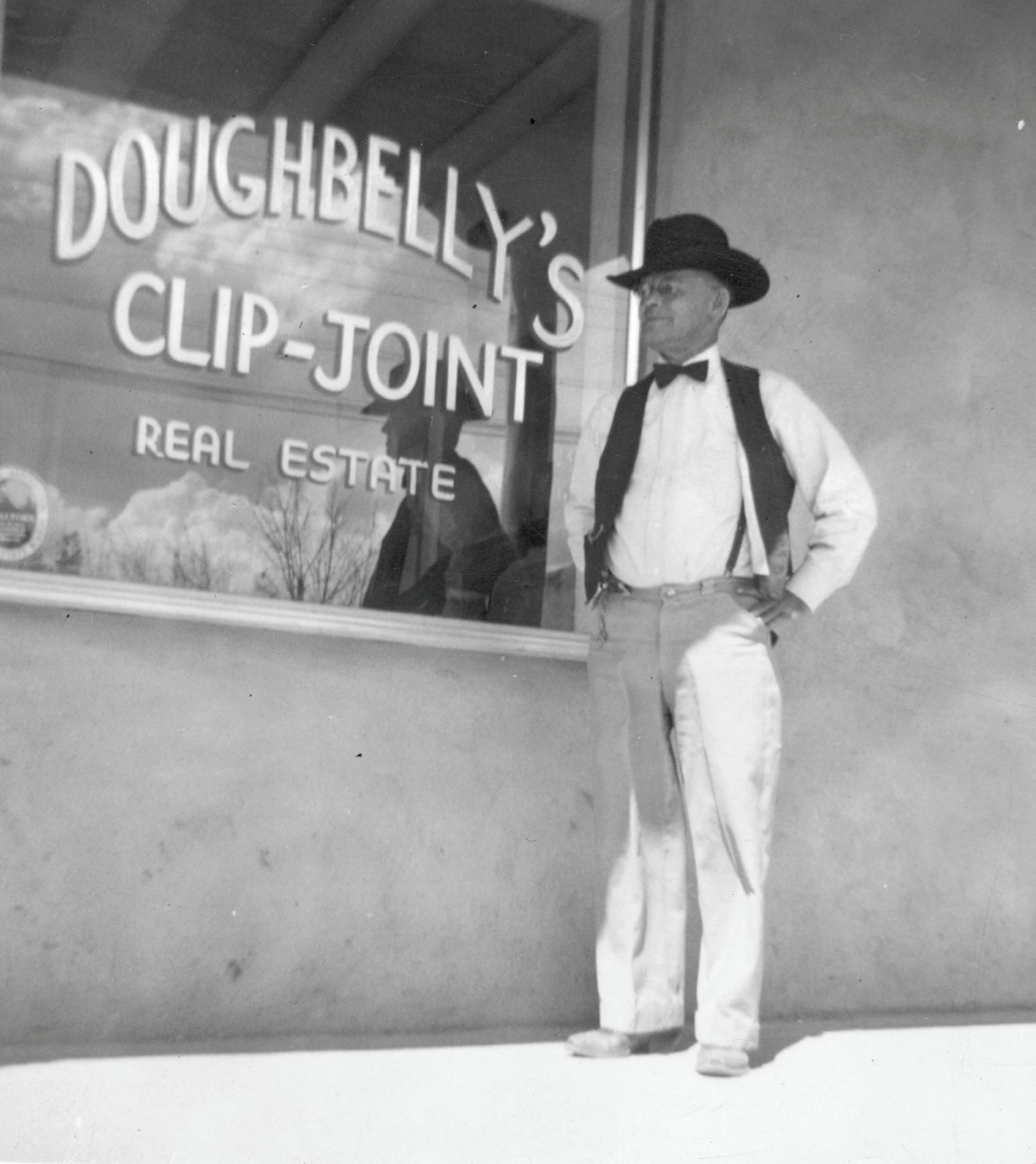

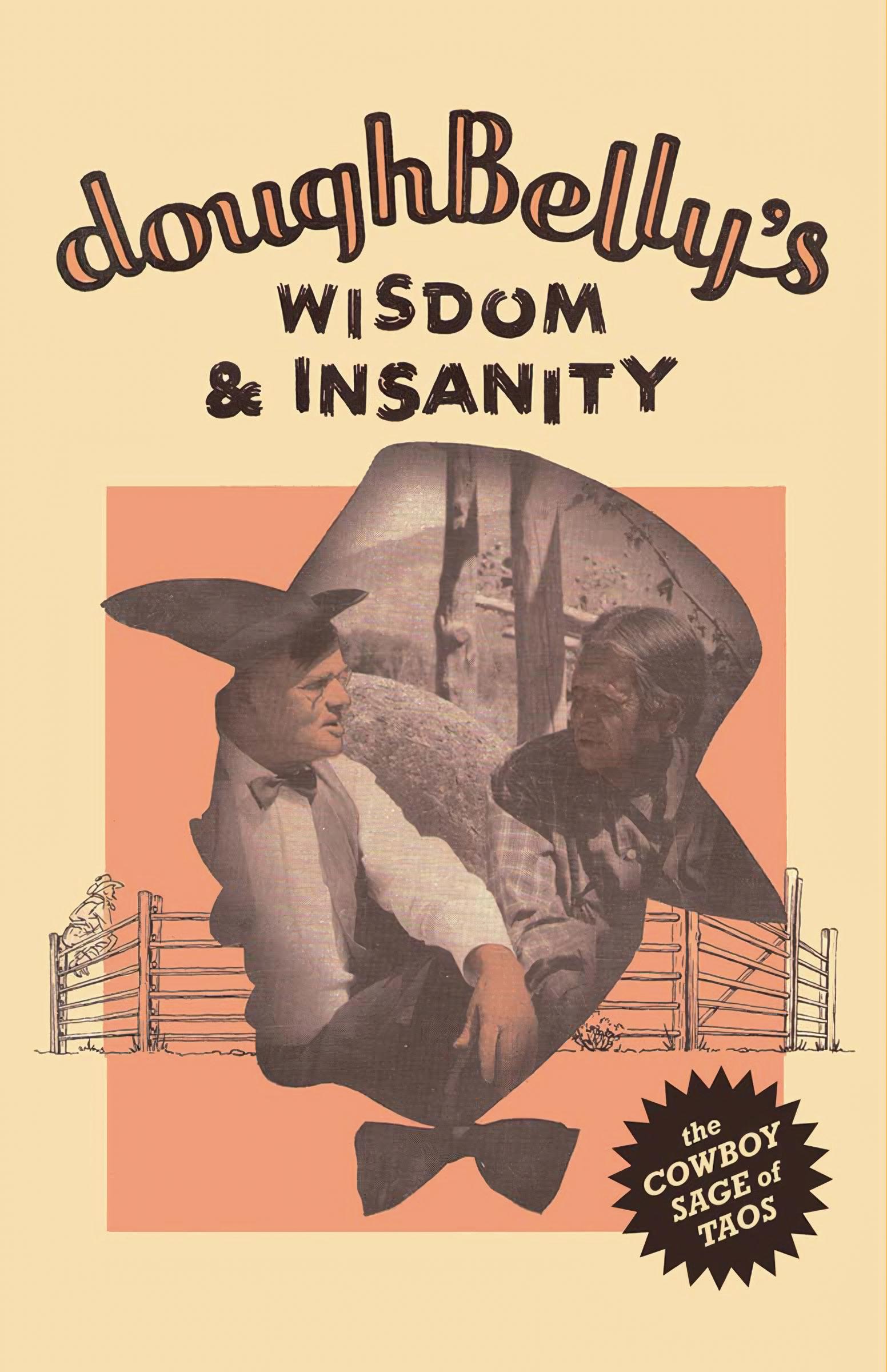

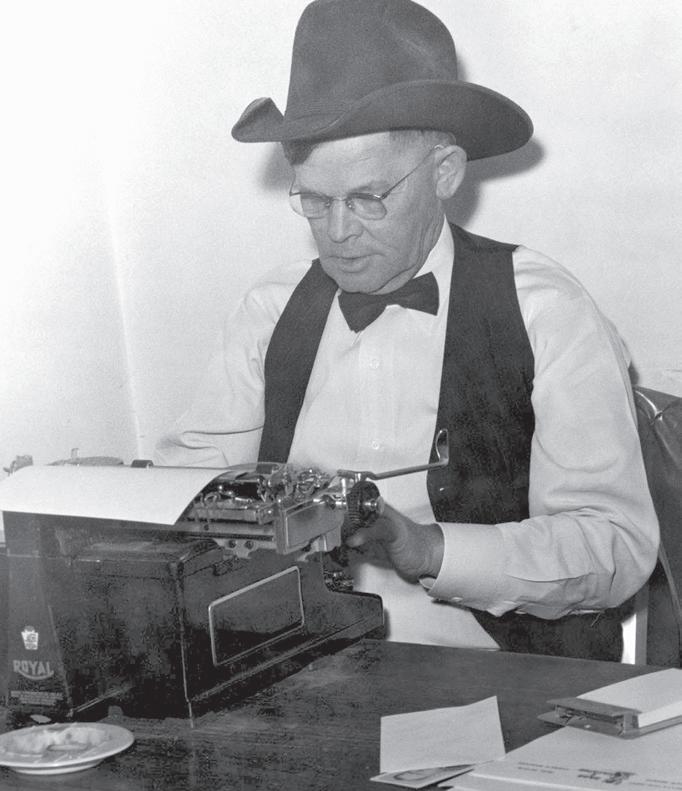

BY CINDY BROWN

DOUGHBELLY PRICE WAS A TAOS CHARACTER WHO LIVED FROM 1897 TO 1963. He was a cowboy, chuckwagon cook, bootlegger, writer, and contemporary of Taos legend John Dunn, santero Patrociño Barela, socialite Mabel Dodge Luhan, and Tony Lujan of Taos Pueblo. Although there are no monuments to DoughBelly in Taos, the story of his life captures a colorful era of 100 years ago in the country and in Taos.

After years of bronco riding and appearances in Wild West shows, DoughBelly settled in Taos where he was known as a real estate agent who used his particular brand of humor and honesty to sell property. He was also a sharp-eyed observer and wrote a column on topics including politics, taxes, Joseph Stalin, visiting royalty, gambling, and the discrimination against Native people for El Crepusculo, the predecessor to the Taos News, as well as for the Taos News itself.

DoughBelly’s writings were gathered into several books including the 1954 publication “Doughbelly’s Wisdom & Insanity,” the book’s cover calling him the “Cowboy Sage of Taos.” The book was reprinted last year just in time for the 70th anniversary of its original publication, with a new introduction by Jim O’Donnell, history professor and univer-

DoughBelly, a reformed cowhand, bootlegger, rodeo star and crap-table dealer is perhaps the lowest-pressure real estate salesman in the business.

LIFE Magazine, October 1949

sity librarian at Arizona State University. O’Donnell met DoughBelly in Taos in the spring of 1959 when O’Donnell was nine years old and ever since he has been fascinated by DoughBelly’s wit, wisdom, and sense of humor.

“I like to remember Taos of 65-70 years ago,” O’Donnell recounted. “My family was visiting Taos and went to an art opening. For a little kid growing up on a military base in Southern New Mexico, the art opening was like landing on another planet. It was a snapshot of when more artists were discovering Taos. Then I met DoughBelly. He left quite an impression. I hadn’t met a lot of real cowboys myself. DoughBelly was wearing boots, jeans, patterned shirt and maybe a hat. I remember a little old man sitting in an office welcoming but full of himself.”

Steven Carroll Price

DoughBelly was born Steven Carroll Price on January 8, 1897 in Arkansas as the sixth of eight children. According to an article in El Crepusculo, dated July 26, 1951, written on the occasion of the publication of another of DoughBelly’s books called the (S)Crap Book, “In his youth Dough won the Southwestern championship for bronc riding in 1925, and placed second in bulldogging. Later the same year he took first place as bareback rider in the Ascott Park rodeo at Los Angeles. He was associated with the W.H. Kennedy Carnival in 1914, appearing in the big rodeo at Dewey, Oklahoma. In 1923 he joined the Wild West show of the old Hagenbeck & Wallace Circus and traveled to all sections of the U.S., including Madison Square Garden in New York City,”

After a bronc bucked him off and landed on his leg, DoughBelly joined cattle drives as a chuckwagon cook. He said his name was born when the cowboys he was feeding noticed he often had more dough on his round little belly than in the bowl that he used to make biscuits. (DoughBelly’s name has been spelled many different ways. The man himself spelled it doughBelly.)

DoughBelly comes to Taos

DoughBelly came to Taos in 1926 and by 1944, he had opened a real estate office that he named DoughBelly’s ClipJoint Real Estate. According to MerriamWebster dictionary, a clip joint is slang for place of public entertainment, such as a nightclub that makes a practice of defrauding patrons, by overcharging or any business that makes a practice of overcharging,

Although conventional wisdom would say naming his real estate office in such a way might discourage business, apparently the opposite was true. In a profile that ran in Life Magazine in October 1949, the magazine reported DoughBelly’s office did $300,000 in annual business, which was more than the other three competitors combined. Taos at that time had a population of 965 people.

The magazine described him in this way, “DoughBelly, a reformed cowhand, bootlegger, rodeo star and crap-table dealer is perhaps the lowest-pressure real estate salesman in the business.”

When asked the reason for his success by Life magazine, DoughBelly is reported to have said, “People hear the truth so little that when they do they think it’s comical.”

According to local press, DoughBelly also found time to act as an emcee for Taos Plaza entertainment, run rodeos in Red River and Eagle Nest, lend a hand at Taos horse races on Sundays, and talk with visitors to town. He was a close friend of John Dunn’s and wrote his obituary for El Crepusculo. He was married to Ada Louise Wilson Price and they had two children. The end of the line for DoughBelly DoughBelly died June 8, 1963 and is buried in the Sierra Vista Cemetery in Taos. According to his obituary that ran June 10, 1963 in The Santa Fe New Mexican, “Taos lost one of its best known citizens Saturday when DoughBelly Price passed away.”

The obituary quoted an introduction by Richard Hubler to the 1960 DoughBelly book, “Short Stirrups” saying, “In Taos, N.M. lived DoughBelly Price, a man who for 50 years has made his living by being a character. He has been a cowpuncher, bootlegger, petty thief, champion rodeo rider, short order cook, gambler, shortchange artist, con man, carnival grifter, unorthodox real estate agent and champion of human rights. A pugnacious little man in high heels, he has never gotten over the fact that nature sawed his a little short. As a cowboy and champion bronc rider, the fact that the stirrups had always to be taken up on all the bad horses he has ever ridden; has been an everlasting tragedy to DoughBelly.”

DoughBelly’s body was conveyed for burial by a horse-drawn wagon followed by a riderless horse with boots hanging from the saddle horn, as requested by DoughBelly in tribute to his days as a cowboy. Hundreds of friends lined the street to watch the procession according to the Taos News from June 13, 1963.

When O’Donnell returned to Taos in the mid-1990s looking for signs of DoughBelly, he was surprised to find very few. DoughBelly’s books were hard to come by. O’Donnell finally discovered the Dean of Fine Arts at the University of New Mexico had made reel-to-reel recordings in the 1950s, including one of DoughBelly singing. He got recordings on cassette tape and set out to build his

own homage to DoughBelly.

“He was probably the first chuckwagon cook to get his own website,” said O’Donnell referring to the 1995 website he created to honor DoughBelly. An early innovator in the field, O’Donnell produced a website that linked to those recordings of DoughBelly singing — a marvel at the time.

DoughBelly was one of the last of his kind — a real cowboy and a real Taos character.

“A new day begins not only for the American Indian, but for all Americans in this country.”

— Cacique Romero, 1970 Upon the Return of Blue Lake

TAOS PUEBLO

In December of 1970, former President Nixon and congress authorized the return of Blue Lake and 48,000 acres of sacred land to Taos Pueblo. The decades long effort of Taos Pueblo representatives helped restore pueblo lands and the continuation of millenniums-old traditions. Perhaps equally as important, it set a precedent for self-determination for Native Americans.